Waldorf Education and Anthroposophy II

GA 304a

30 August 1924, London

XII. Educational Issues II

First I must thank Mrs. MacMillan and Mrs. Mackenzie for their kind words of greeting and for the beautiful way they have introduced our theme. Furthermore, I must apologize for speaking to you in German followed by an English translation. I know that this will make your understanding more difficult, but it is something I cannot avoid.

What I have to tell you is not about general ideas on educational reform or formalized programs of education; basically, it is about the practice of teaching, which stands the test of time only when actually applied in classroom situations. This teaching has been practiced in the Waldorf school for several years now. It has shown tangible and noticeable results, and it has been recognized in England also; on the strength of this, it became possible, through the initiative of Mrs. Mackenzie, for me to give educational lectures in Oxford. This form of teaching is the result not only of what must be called a spiritual view of the world, but also of spiritual research. Spiritual research leads first to a knowledge of human nature, and, through that, to a knowledge of the “human being becoming,” from early childhood until death. This form of spiritual research is possible only when one acknowledges that the human being can look into the spiritual world when the necessary and relevant forces of cognition are developed. It is difficult to present in a short survey of this vast theme what normally needs to be acquired through a specific training of the human soul, with the goal of acquiring the faculty of perceiving and comprehending not just the material aspects of the human being and the sensory world, but also the spiritual element, so that this spiritual element may work in the human will.

However, I will certainly try to indicate what I mean. One can strengthen and intensify inner powers of the soul, just as it is possible to research the sense-perceptible world by external experiments using instrumental aids such as the microscope, telescope, or other optical devices, through which the sense world yields more of its secrets and reveals more to our vision than in ordinary circumstances. By forging inner “soul instruments” in this way, it is possible to perceive the spiritual world in its own right through the soul’s own powers. One can then discover also the fuller nature of the human being, that what is generally understood of the human being in ordinary consciousness and through the so-called sciences is only a small part of the whole of human nature, and that beyond the physical aspect, a second human being exists.

As I begin to describe this, remember that names do not matter, but we must have them. I make use of old names because they are known here and there from literature. Nevertheless, I must ask you not to be put off by these names. They do not stem from superstition, but from exact research. Nevertheless, there is no reason why one should not use other names instead. In any case, the second human member, which I shall call the etheric body, is visible when one’s soul forces have been sufficiently strengthened as a means for a deeper cognition (just as the physical senses, by means of microscope or telescope, can penetrate more deeply into the sense world). This etheric body is the first of the spiritual bodies linked with the human physical body.

When studying the physical human being only from the viewpoint of conventional science, one cannot really understand how the physical body of the human being can exist throughout a lifetime. This is because, in reality, most physical substances in the body disappear within a period of seven to eight years. No one sitting here is the same, physically speaking, as the person of some seven or eight years ago! The substances that made up the body then have in the meantime been cast off, and new ones have taken their place. In the etheric body we have the first real supersensible entity, which rules and permeates us with forces of growth and nourishment throughout earthly life.

The ether body is the first supersensible body to consider. The human being has an ether body, just as plants do, but minerals do not. The only thing we have in common with the minerals is a physical form. However, furnished with those specially developed inner senses and perceptions developed by powers of the soul, we come to recognize also a third sheath or member of the human being, which we call the astral body. (Again I must ask you not to be disturbed by the name.) The human being has an astral body, as do animals. We experience sensation through the astral body. An organism such as the plant, which can grow and nourish itself, does not need sensation, but human beings and animals can sense. The astral body cannot be designated by an abstract word, because it is a reality.

And then we find something that makes the human being into a bearer of three bodies, an entity that controls the physical, etheric, and astral bodies. It is the I, the real inner spiritual core of the human being. So the four members are first the physical body, second the etheric body, third the astral body, and finally the human I-organization. Let those who are not aware of these four members of the human being—those who believe that external observation, such as in anatomy and physiology, encompasses the entire human being—try to find a world view! It is possible to formulate ideas in many ways, whether or not they are accepted by the world. Accordingly one may be a spiritualist, an idealist, a materialist, or a realist. It is not difficult to establish views of the world, because one only needs to formulate them verbally; one only needs to maintain a belief in one or another viewpoint. But unless one’s world views stem from actual realities and from real observations and experiences, they are of no use for dealing with the external aspect of the human being, nor for education.

Let’s suppose you are a bridge builder and base your mechanical construction on a faulty principle: the bridge will collapse as the first train crosses it. When working with mechanics, realistic or unrealistic assumptions will prove right or wrong immediately. The same is true in practical life when dealing with human beings. It is very possible to digest world views from treatises or books, but one cannot educate on this basis; it is only possible to do so on the strength of a real knowledge of the human being. This kind of knowledge is what I want to speak about, because it is the only real preparation for the teaching profession. All external knowledge that, no matter how ingeniously contrived, tells a teacher what to do and how to do it, is far less important than the teacher’s ability to look into human nature itself and, from a love for education and the art of education, allow the child’s own nature to tell the teacher how and what to teach.

Even with this knowledge, however—a knowledge strengthened by supersensible perception of the human being—we will find it impossible during the first seven years of the child’s life, from birth to the second dentition, to differentiate between the four human members or sheaths of which I have just spoken. One cannot say that the young child consists of physical body, etheric body, astral body and I, in the same way as in the case of an adult. Why not?

A newborn baby is truly the greatest wonder to be found in all earthly life. Anyone who is open-minded is certain to experience this. A child enters the world with a still unformed physiognomy, an almost “neutral” physiognomy, and with jerky and uncoordinated movements. We may feel, possibly with a sense of superiority, that a baby is not yet suited to live in this world, that it is not yet fit for earthly experience. The child lacks the primitive skill of grasping objects properly; it cannot yet focus its eyes properly, cannot express the dictates of the will through limb movement. One of the most sublime experiences is to see gradually evolve, out of the central core of human nature, out of inner forces, that which gives the physiognomy its godlike features, what coordinates the limb movements to suit outer conditions, and so on. And yet, if one observes the child from a supersensible perspective, one cannot say that the child has a physical, etheric, and astral body plus an I, just as one cannot say that water in its natural state is composed of hydrogen and oxygen. Water does consist of hydrogen and oxygen, but these two elements are most intimately fused together. Similarly, in the child’s organism until the change of teeth, the four human members are so intimately merged together that for the time being it is impossible to differentiate between them.

Only with the change of teeth, around the seventh year, when children enter primary education, does the etheric body come into its own as the basis of growth, nutrition, and so on; it is also the basis for imagination, for the forces of mind and soul, and for the forces of love. If one observes a child of seven with supersensible vision, it is as if a supersensible etheric cloud were emerging, containing forces that were as yet little in control because, prior to the change of teeth, they were still deeply embedded in the physical organism and accustomed to working homogeneously within the physical body. With the coming of the second teeth they become freer to work more independently, sending down into the physical body only a portion of their forces. The surplus then works in the processes of growth, nutrition, and so on, but also has free reign in supporting the child’s life of imagination. These etheric forces do not yet work in the intellectual sphere, in thinking or ideas, but they want to appear on a higher level than the physical in a love for things and in a love for human beings. The soul has become free in the child’s etheric body. Having gone through the change of teeth the child, basically, has become a different being.

Now another life period begins, from the change of teeth until puberty. When the child reaches sexual maturity, the astral body, which so far could be differentiated only very little, emerges. One notices that the child gains a different relationship to the outer world. The more the astral body is born, the greater the change in the child. Previously it was as if the astral body were embedded in the physical and etheric organization. Thus to summarize: First, physical birth occurs when the embryo leaves the maternal body. Second, the etheric body is born when the child’s own etheric body wrests itself free. Due to the emergence of the etheric body we can begin to teach the child. Third, the astral body emerges with the coming of puberty, which enables the adolescent to develop a loving interest in the outside world and to experience the differences between human beings, because sexual maturity is linked not only with an awakening of sexual love, but also with a knowledge gained through the adolescent’s immersion in all aspects of life. Fourth, I-consciousness is born only in the twenty-first or twenty-second year. Only then does the human being become an independent I-being.

Thus, when speaking about the human being from a spiritual perspective, one can speak of four successive births. Only when one knows the condition of the human being under the influence of these successively developing members, can one adequately guide the education and training of children. For what does it mean if, prior to the change of teeth, the physical body, the etheric body, the astral body, and the I cannot yet be differentiated? It means that they are merged, like hydrogen and oxygen in water. This, in turn, means that the child really is as yet entirely a sense organ. Everything is related to the child in the same way a sense impression is related to the sense organ; whatever the child absorbs, is absorbed as in a sense organ.

Look at the wonderful creation of the human eye. The whole world is reflected within the eye in images. We can say that the world is both outside and inside the eye. In the young child we have the same situation; the world is out there, and the world is also within the child. The child is entirely a sense organ. We adults taste sugar in the mouth, tongue, and palate. The child is entirely permeated by the taste. One only needs eyes to observe that the child is an organ of taste through and through. When looking at the world, the child’s whole being partakes of this activity, is surrendered to the visible surroundings. Consequently a characteristic trait follows in children; they are naturally pious. Children surrender to parents and educators in the same way that the eye surrenders to the world. If the eye could see itself, it could not see anything else. Children live entirely in the environment. They also absorb impressions physically.

Let’s take the case of a father with a disposition to anger and to sudden outbursts of fury, who lives closely with a child. He does all kinds of things, and his anger is expressed in his gestures. The child perceives these gestures very differently than one might imagine. The young child perceives in these gestures also the father’s moral quality. What the child sees inwardly is bathed in a moral light. In this way the child is inwardly saturated by the outbursts of an angry father, by the gentle love of a mother, or by the influence of anyone else nearby. This affects the child, even into the physical body.

Our being, as adults, enters a child’s being just as the candlelight enters the eye. Whatever we are around a child spreads its influence so that the child’s blood circulates differently in the sense organs and in the nerves; since these operate differently in the muscles and vascular liquids which nourish them, the entire being of the child is transformed according to the external sense impressions received. One can notice the effect that the moral and religious environment of childhood has had on an old person, including the physical constitution. A child’s future condition of health and illness depends on our ability to realize deeply enough that everything in the child’s environment is mirrored in the child. The physical element, as well as the moral element, is reflected and affects a person’s health or illness later.

During the first seven years, until the change of teeth, children are purely imitative beings. We should not preconceive what they should do. We must simply act for them what we want them to do. The only healthy way to teach children of this age is to do in front of them what we wish them to copy. Whatever we do in their presence will be absorbed by their physical organs. And children will not learn anything unless we do it in front of them.

In this respect one can have some interesting experiences. Once a father came to me because he was very upset. He told me that his five-year-old child had stolen. He said to me, “This child will grow into a dreadful person, because he has stolen already at this tender age.” I replied, “Let us first discover whether the boy has really stolen.” And what did we find? The boy had taken money out of the chest of drawers from which his mother habitually took money whenever she needed it for the household. The mother was the very person whom the boy imitated most. To the child it was a matter of course to do what his mother did, and so he too took money from the drawer. There was no question of his thieving, for he only did what was natural for a child below the age of the second dentition: he imitated. He only imitated what his mother had done.

When this example is understood, one knows that, in the case of young children, imitation is the thing that rules their physical and soul development. As educators we must realize that during these first seven years we adults are instrumental in developing the child’s body, soul, and spirit. Education and upbringing during these first seven years must be formative. If one can see through this situation properly, one can recognize in people’s physiognomy, in their gait, and in their other habits, whether as children they were surrounded by anger or by kindness and gentleness, which, working into the blood formation and circulation, and into the individual character of the muscular system, have left lasting marks on the person. Body, soul, and spirit are formed during these years, and as teachers we must know that this is so. Out of this knowledge and impulse, and out of the teacher’s ensuing enthusiasm, the appropriate methods and impulses of feeling and will originate in one’s teaching. An attitude of dedication and self-sacrifice has to be the foundation of educational methods. The most beautiful pedagogical ideas are without value unless they have grown out of knowledge of the child and unless the teachers can grow along with their students, to the extent that the children may safely imitate them, thus recreating the teachers’ qualities in their own being.

For the reasons mentioned, I would like to call the education of the child until the change of teeth “formative education,” because everything is directed toward forming the child’s body, soul, and spirit for all of earthly life. One only has to look carefully at this process of formation. I have quoted the example of an angry father. In the gesture of a passionate temperament, the child perceives inherent moral or immoral qualities. These affect the child so that they enter the physical constitution. It may happen that a fifty-year-old person begins to develop cataracts in the eyes and needs an operation. These things are accepted and seen only from the present medical perspective. It looks as if there is a cataract, and this is the way to treat it, and there the matter ends; the preceding course of life is not considered. If one were ready to do that, it would be found that a cataract can often be traced back to the inner shocks experienced by the young child of an angry father. In such cases, what is at work in the moral and religious sphere of the environment spreads its influence into the bodily realm, right down to the vascular system, eventually leading to health or illness. This often surfaces only later in life, and the doctor then makes a diagnosis based on current circumstances. In reality, we are led back to the fact that, for example, gout or rheumatism at the age of fifty or sixty can be linked to an attitude of carelessness, untidiness, or disharmony that ruled the environment of such a patient during childhood. These circumstances were absorbed by the child and entered the organic sphere.

If one observes what a child has absorbed during the stage of imitation up to the change of teeth, one can recognize that the human being at this time is molded for the whole of life. Unless we learn to direct rightly the formative powers in the young human being, all our early childhood education is without value. We must allow for germination of the forces that control health and illness for all of earthly life.

With the change of teeth, the etheric body emerges, controlling the forces of digestion, nutrition, and growth, and it begins to manifest in the realm of the soul through the faculty of fantasy, memory, and so on. We must be clear about what we are educating during the years between the second dentition and puberty. What are we educating in the child during this period? We are working with the same forces that effect proper digestion and enable the child to grow. They are transformed forces of growth, working freely now within the soul realm. What do nature and the spiritual world give to the human being through the etheric body’s forces of growth? Life—actual life itself! Since we cannot bestow life directly as nature does during the first seven years, and since it is our task to work on the liberated etheric body in the soul realm, what should we, as teachers, give the child? We should give life! But we cannot do this if, at such an early stage, we introduce finished concepts to the child. The child is not mature enough yet for intellectual work, but is mature enough for imagery, for imagination, and for memory training. With the recognition of what needs to be done at this age, one knows that everything taught must have the breath of life. Everything needs to be enlivened. Between the change of teeth and puberty, the appropriate principle is to bestow life through all teaching. Everything the teacher does, must enliven the student. However, at just this age, it is really too easy to bring death with one’s teaching.

As correctly demanded by civilization, our children must be taught reading and writing. But now consider how alien and strange the letters of the alphabet are to a child. In themselves letters are so abstract and obscure that, when the Europeans, those so-called superior people, came to America (examples of this exist from the 1840s), the Native Americans said: “These Europeans use such strange signs on paper. They look at them and then they put what is written on paper into words. These signs are little devils!” Thus said the Native Americans: “The Palefaces [as they called the Europeans] use these little demons.” For the young child, just as for the Indians, the letters are little demons, for the child has no immediate relationship to them.

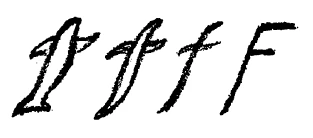

If we introduce reading abstractly right away, we kill a great deal in the child. This makes no sense to anyone who can see through these matters. Consequently, educational principles based on a real knowledge of the human being will refer to the ancient Egyptian way of writing. They still put down what they had actually seen, making a picture of it. These hieroglyphics gave rise to our present letters. The ancient Egyptians did not write letters, they painted pictures. Cuneiform writing has a similar origin. In Sanskrit writing one can still see how the letters came from pictures. You must remember that this is the path humanity has gone on its way to modern abstract letters, to which we no longer have an immediate relationship. What then can we do? The solution is to not plague children at all with writing and reading from the time they begin school. Instead, we have them draw and paint. When we guide children in color and form by painting, the whole body participates. We let children paint the forms and shapes of what they see. Then the pictures are guided into the appropriate sounds.

Let’s take, for example, the English word fish. By combining the activity of painting and drawing with a brush, the child manages to make a picture of a fish. Now we can ask the child to pronounce the word fish, but very slowly. After this, one could say, “Now sound only the beginning of the word: ‘F.’” In this way the letter F emerges from the picture that was painted of the fish. One can proceed in a similar way with all consonant sounds. With the vowels, one can lead from the picture to the letters by taking examples from a person’s inner life of feeling. In this way, beginning at the age of seven or eight, children learn a combined form of painting and drawing. Teachers can hardly relax during this activity, because painting lessons with young children inevitably create a big mess, which always has to be cleaned up at the end of the lesson. Yet this inconvenience must be carried by the teacher with understanding and equanimity. The first step is for the children to learn to create resemblances of outer shapes, using color and form. This leads to writing. In learning to write, the child brings the whole body into movement, not just one part. Only the head is involved when we read, which is the third step, after writing. This happens around the ninth year, when the child learns to read through the activity of writing, which was developed from painting.

In doing this, the child’s nature gives us the cue, and the child’s nature always directs us in how to proceed. This means that teachers are forced to become different human beings. They can’t learn their lessons and then apply them abstractly; they must instead stand before the class as whole human beings, and for everything they do, they must find images; they must cultivate their imagination. The teachers can then communicate their intentions to the students in imperceptible ways. The teachers themselves have to be alert and alive. They will reach the child to the extent that they can offer imaginative pictures instead of abstract concepts.

It is even possible to bring moral and religious concepts through the medium of pictures. Let us assume that teachers wish to speak to children about the immortality of the human soul. They could speak about the butterfly hidden in a chrysalis. A small hole appears in the chrysalis, and the butterfly emerges. Teachers could talk to children as follows: The butterfly, emerging from the chrysalis, shows you what happens when a person dies. While alive, the person is like the chrysalis. The soul, like the butterfly, flies out of the body only at death. The butterfly is visible when it leaves the chrysalis. Although we cannot see the soul with our eyes when a person dies, it nevertheless flies into the spiritual world like a butterfly from the chrysalis.

There are, however, two ways teachers can proceed. If they feel inwardly superior to the children, they will not succeed in using this simile. They may think they are very smart and that the children’s ignorance forces them to invent something that gets the idea of immortality across, while they themselves do not believe this butterfly and chrysalis “humbug,” and consider it only a useful ploy. As a result they fail to make any lasting impression on the children; for here, in the depths of the soul, forces work between teacher and child. If I, as the teacher, believe that spiritual forces in nature, operating at the level of the newly-emerged butterfly, provide an image of immortality, if I am fully alive in this image of the butterfly emerging from the chrysalis, then my comparison will work strongly on the child’s soul. This simile will work like a seed, and grow properly in the child, working beneficently on the soul. This is an example of how we can keep our concepts mobile, because it would be the greatest mistake to approach a child directly with frozen intellectual concepts.

If one buys new shoes for a three-year-old, one would hardly expect the child to still be wearing them at nine. The child would then need different, larger shoes. And yet, when it comes to teaching young children, people often act exactly like this, expecting the student to retain unchanged, possibly until the age of forty or fifty, what was learned at a young age. They tend to give definitions, meant to remain unchanged like the metaphorical shoes given to a child of three, as if the child would not outgrow their usefulness later in life! The point is that, when educating we must allow the soul to grow according to the demands of nature and the growing physical body. Teachers can give a child living concepts that grow with the human being only when they acquire the necessary liveliness to permeate all their teaching with imagination.

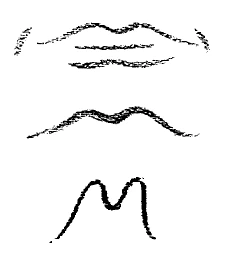

We need education that enlivens the human being during the years between the change of teeth and puberty. The etheric body can then become free. For example, take the word mouth. If I pronounce only the first letter, “M,” I can transform this line as picture of a mouth to this:

Similarly, I can find other ways to use living pictures to bridge the gap to written letters of the alphabet. Then, if the intellect (which is meant to be developed only at puberty) is not called on too soon, the ideas born out of the teacher’s imagination will grow with the child. Definitions are poison to the child. This always brings to mind a definition that once was made in a Greek philosophers’ school. The question, “What is a human being?” received the answer, “A human being is a creature with two legs and no feathers.” The following day, a student of the school brought a goose whose feathers had been plucked out, maintaining that this was a human being—a creature with two legs and without feathers. (Incidentally, this type of definition can sometimes be found in contemporary scientific literature. I know that in saying this I am speaking heresy, but roughly speaking, this is the kind of intellectual concept we often offer children.)

We need rich, imaginative concepts, that can grow with the child, concepts that allow growth forces to remain active even when a person reaches old age. If children are taught only abstract concepts, they will display signs of aging early in life. We lose fresh spontaneity and stop making human progress. It is a terrifying experience when we realize we have not grown up with fantasy, with images, with pictures that grow and live and are suited to the etheric body, but instead we grew up merely with those suited to abstraction, to intellectualism—that is, to death.

When we recognize that the etheric body really exists, that it is a living reality—when we know it not just in theory but from observing a developing child—then we will experience the second golden principle of education, engraved in our hearts. The golden principle during the first seven years is: Mold the child’s being in a manner worthy of human imitation, and thus cultivate the child’s health. During the second seven years, from the change of teeth to puberty, the guiding motive or principle of education should be: Enliven the students, because their etheric bodies have been entrusted to your care.

With the coming of puberty, what I have called the astral body is freed in a new kind of birth. This is the very force that, during the age of primary education until the beginning of puberty, was at the base of the child’s inmost human forces, in the life of feeling. This force then lived undifferentiated within the latent astral body, still undivided from the physical and etheric bodies. This spiritual aggregate is entrusted to the quality of the teachers’ imaginative handling, and to their sensitive feeling and tact. As the child’s astral body is gradually liberated from the physical organization, becoming free to work in the soul realm, the child is also freed from what previously had to be present as a natural faith in the teacher’s authority. What I described earlier as the only appropriate form of education between the change of teeth and puberty has to come under the auspices of a teacher’s natural authority.

Oh! It is such great fortune for all of life when, at just this age, children can look up to their teachers as people who wield natural authority, so that what is truth for the teacher, is also very naturally truth to the students. Children cannot, out of their own powers, discriminate between something true and something false. They respect as truth what the teacher calls the truth. Because the teacher opens the child’s eyes to goodness, the child respects goodness. The child finds truth, goodness, and beauty in the world through venerating the personality of the teacher.

Surely no one expects that I, who, many years ago, wrote Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path: A Philosophy of Freedom, would stand for the principle of authoritarianism in social life. I am saying here that the child, between the second dentition and puberty, has to experience the feeling of a natural authority from the adults in charge, and that, during these years, everything the student receives must be truly alive. The educator must be the unquestioned authority at this age, because the human being is ready for freedom only after having learned to respect and venerate the natural authority of a teacher. Only after reaching sexual maturity, when the astral body has become the means for individual judgments, can the student form judgments instead of accepting those of the teacher.

Now what must be considered the third principle of education comes into its own. The first one I called “the formative element,” the second one “the enlivening element.” The third element of education, which enters with puberty, can be properly called “an awakening education.” Everything taught after puberty must affect adolescents so that their emerging independent judgment appears as a continual awakening. If one attempts to drill subjects into a student who has reached puberty, one tyrannizes the adolescent, making the student into a slave. If, on the other hand, one’s teaching is arranged so that, from puberty on, adolescents receive their subject matter as if they were being awakened from a sleep, they learn to depend on their own judgments, because with regard to making their own judgments, they were indeed asleep. The students should now feel they are calling on their own individuality, and all education, all teaching, will be perceived as a stimulus and awakener. This can be realized when teachers have proceeded as I have indicated for the first two life periods. This last stage in education will then have a quality of awakening. And if in their style, posture, and presentation, teachers demonstrate that they are themselves permeated with the quality of awakening, their teaching will be such that what must come from those learning will truly come from them. The process should reach a kind of dramatic intensification when adolescents inwardly join with active participation in the lessons, an activity that proceeds very particularly from the astral body.

Appealing properly in this way to the astral body, we address the immortal being of the student. The physical body is renewed and exchanged every seven years. The etheric body gives its strength as a dynamic force and lasts from birth, or conception, until death. What later emerges as the astral body represents, as already mentioned, the eternal kernel of the human being, which descends to Earth, enveloping itself with the sheaths of the physical and etheric bodies before passing again through the portal of death. We address this astral body properly only when, during the two previous life periods, we have related correctly to the child’s etheric and physical bodies, which the human being receives only as an Earth dweller. If we have educated the child as described so far, the eternal core of the human individuality, which is to awaken at puberty, develops in an inwardly miraculous way, not through our guidance, but through the guidance of the spiritual world itself.

Then we may confidently say to ourselves that we have taken the right path in educating children, because we did not force the subject matter on them; neither did we dictate our own attitude to them, because we were content to remove the hurdles and obstacles from the way so that their eternal core could enter life openly and freely. And now, during the last stage, our education must take the form of awakening the students. We make our stand in the school saying, “We are the cultivators of the divine-spiritual world order; we are its collaborators and want to nurture the eternal in the human being.” We must be able to say this to ourselves or feel ashamed. Perhaps, sitting there among our students are one or two geniuses who will one day know much more than we teachers ever will. And what we as teachers can do to justify working with students, who one day may far surpass us in soul and spirit, and possibly also in physical strength, is to say to ourselves: Only when we nurture spirit and soul in the child—nurture is the word, not overpower—only when we aid the development of the seed planted in the child by the divine-spiritual world, only when we become “spiritual midwives,” then we will have acted correctly as teachers. We can accomplish this by working as described, and our insight into human nature will guide us in the task.

Having listened to my talk about the educational methods of the Waldorf school, you may wonder whether they imply that all teachers there have the gift of supersensible insight, and whether they can observe the births of the etheric and astral bodies. Can they really observe the unfolding of human forces in their students with the same clarity investigators use in experimental psychology or science to observe outer phenomena with the aid of a microscope? The answer is that certainly not every teacher in the Waldorf school has developed sufficient clairvoyant powers to see these things with inward eyes, but it isn’t necessary. If we know what spiritual research can tell us about the human being’s physical, etheric, and astral bodies and about the human I-organization, we need only to use our healthy soul powers and common sense, not just to understand what the spiritual investigator is talking about, but also to comprehend all its weight and significance.

We often come across very strange attitudes, especially these days. I once gave a lecture that was publicly criticized afterward. In this lecture I said that the findings of a clairvoyant person’s investigations can be understood by anyone of sane mind who is free of bias. I meant this literally, and not in any superstitious sense. I meant that a clairvoyant person can see the supersensible in the human being just as others can see the sense-perceptible in outer nature. The reply was, “This is what Rudolf Steiner asserted, but evidently it cannot be true, because if someone maintains that a supersensible spiritual world exists and that one can recognize it, one cannot be of sane mind; and if one is of sane mind, one does not make such an assertion....” Here you can see the state of affairs in our materialist age, but it has to be overcome.

Not every Waldorf teacher has the gift of clairvoyance, but every one of them has accepted wholeheartedly and with full understanding the results of spiritual-scientific investigation concerning the human being. And each Waldorf teacher applies this knowledge with heart and soul, because the child is the greatest teacher, and while one cares for the child, witnessing the wonderful development daily, weekly, and yearly, nothing can awaken the teacher more to the needs of education. In educating the child, in the daily lessons, and in the daily social life at school, the teachers find the confirmation for what spiritual science can tell them about practical teaching. Every day they grow into their tasks with increasing inner clarity. In this way, education and teaching in the Waldorf school are life itself. The school is an organism, and the teaching faculty is its soul, which, in the classrooms, in regular common study, and in the daily cooperative life within the school organism, radiates care for the individual lives of the students in all the classes.

This is how we see the possibility of carrying into our civilization what human nature itself demands in these three stages of education—the formative education before the change of teeth, the life-giving education between the change of teeth and puberty, and the awakening education after puberty, leading students into full life, which itself increasingly awakens the human individuality.

Formative education—before the change of teeth.

Life-giving education—between the change of teeth and puberty.

Awakening education—after puberty.

When we look at the child properly, the following thoughts may stimulate us: In our teaching and educating we should really become priests, because what we meet in children reveals to us, in the form of outer reality and in the strongest, grandest, and most intense ways, the divine-spiritual world order that is at the foundation of outer physical, material existence. In children we see, revealed in matter in a most sublime way, what the creative spiritual powers are carrying behind the outer material world. We have been placed next to children in order that spirit properly germinates, grows, and bears fruit. This attitude of reverence must underlie every method. The most rational and carefully planned methods make sense only when seen in this light. Indeed, when our methods are illuminated by the light of these results, the children will come alive as soon as the teacher enters the classroom. Teaching will then become the most important leaven and the most important impulse in our present stage of evolution. Those who can clearly see the present time with its tendency toward decadence and decline know how badly our civilization needs revitalization.

School life and education can be the most revitalizing force. Society should therefore take hold of them in their spiritual foundations; society should begin with the human being as its fundamental core. If we start with the child, we can provide society and humanity with what the signs of the times demand from us in our present stage of civilization, for the benefit of the immediate future.

Über Erziehungsfragen

Meine sehr verehrten Damen und Herren! Zuerst habe ich Mrs. Macmillan und Mrs. Mackenzie herzlich zu danken für die freundlichen, liebenswürdigen Worte, mit denen sie diesen Vortrag eingeleitet haben, für die schöne Art des Einleitens dessen, was ich hier auszuführen habe.

Dann habe ich Sie alle um Entschuldigung dafür zu bitten, daß ich in deutscher und nicht in englischer Sprache hier spreche. Es wird das ja natürlich die Verständigung etwas erschweren, allein es ist mir eben nicht anders möglich.

Dasjenige, was ich vorzubringen haben werde, ist nicht ein allgemeiner Reformgedanke, sind auch nicht einzelne Ideen über Erziehungs- und Unterrichtsziele, sondern es ist im wesentlichen die Schulpraxis, eine solche Schulpraxis, die eigentlich nur sich bewähren kann in der unmittelbaren Anwendung in der Schule mit den Kindern selbst. Aber diese Schulpraxis, die nun schon seit mehreren Jahren in der Waldorfschule ausgeübt wird und immerhin greifbare, merkbare Erfolge erzielt hat, die auch hier in England manche Anerkennung gefunden hat, durch die es möglich geworden ist zum Beispiel vor einiger Zeit unter der Protektorschaft von Mrs. Mackenzie in Oxford darüber Vorträge zu halten, diese Unterrichtsmethode ist durchaus herausgefunden aus demjenigen, was heute nicht bloß spirituelle Weltanschauung genannt werden muß, sondern spirituelle Forschungsmethode; eine spirituelle Forschungsmethode, welche zunächst zu einer Erkenntnis des Menschenwesens führt, dadurch zur Erkenntnis des werdenden Menschenwesens von der Kindheit bis zum Tode hin. Auf Grundlage einer spirituellen Forschung, die als Forschung allerdings nur möglich ist, wenn man zugibt, daß der Mensch imstande ist, in das Geistige, in das Spirituelle hineinzuschauen, nachdem er sich dafür seine Erkenntniskräfte ausgebildet hat. Es ist nicht möglich, in einer kurzen Betrachtung über Pädagogik dasjenige auseinanderzusetzen, was durch besondere Ausbildung der menschlichen Seele dazu führt, am Menschen und an der Natur nicht nur das Materielle mit den Sinnen zu schauen und mit dem Verstande zu begreifen, sondern auch das Geistige zu schauen, und es hereinzubekommen in die Seele, um es aufzunehmen in den Willen und um damit zu wirken. Aber man kann das. Geradeso wie man in der Lage ist, die Natur zu erforschen, wenn man sich für das äußere Experiment die Mittel verschafft, wenn man sich die Instrumente verschafft, Mikroskop, Teleskop, Spektroskop, durch die man sich das Sinnliche zubereitet, daß es mehr verrät, mehr ausdrückt, mehr offenbart, als es für die gewöhnlichen Sinne tut, ebenso kann man innerlich die Seelenkräfte erhöhen, intensiver machen. Dadurch kann man es dahin bringen, daß der ganze Mensch wahrnimmt durch dasjenige, was erst die Seele aus sich gemacht hat. Dann beginnt die Möglichkeit, das Geistige als solches wahrzunehmen. Dann aber entdeckt man auch am Menschen selber die volle Wesenheit dieses Menschen. Man entdeckt, daß dasjenige, was heute von dem allgemeinen Bewußtsein, von der sogenannten Wissenschaft am Menschen erkannt wird, daß das alles nur ein Teil ist, ein Glied an dem Menschen, und man entdeckt über dieses Physische hinausgehend zunächst dasjenige, was ich immer nenne - man braucht Namen, es kommt aber auf den Namen gar nicht an; man verwendet alte Namen, weil sie da und dort in der Literatur vorkommen, aber ich bitte, nicht an den Namen sich zu stoßen; sie entstammen keinem Aberglauben, sie entstammen durchaus exakter Forschung, ich könnte ebensogut einen anderen Namen geben -, das zweite also, was man an dem Menschen dann schaut, wenn man schon die Seele als vertieftes Erkenntniswerkzeug hat, so wie die äußeren Sinne hineinschauen, bewaffnet durch Mikroskop und Teleskop, es ist der ätherische Mensch, ein erster spiritueller Mensch, der sich als zweiter Mensch dem ersten eingliedert.

Wenn man den physischen Menschen studiert, so kann man ja, wenn man sich nur auf den Standpunkt der gewöhnlichen Wissenschaft stellt, eigentlich nicht begreifen, wie dieser Mensch sein ganzes Leben hindurch bestehen kann; denn in Wirklichkeit entfernen sich von unserem Leibe die meisten seiner Stoffe in einem Zeitraum von sieben bis acht Jahren. Sie sind alle nicht dieselben heute in Ihrem physischen Leibe, die sie waren vor sieben oder acht Jahren! Die Stoffe, die Sie dazumal in sich trugen, sind abgeworfen, andere haben sich angesetzt. Aber in dem ätherischen Leibe, in dem Ätherleibe haben wir das erste Reale, das einen beherrscht, durchdringt mit Wachstumskräften, Ernährungskräften.

In dem AÄtherleib haben wir den ersten übersinnlichen Leib. Diesen ersten übersinnlichen Leib hat der Mensch gemeinschaftlich mit den Pflanzen, nicht aber mit den Mineralien. Mit den Mineralien haben wir bloß den physischen Leib gemeinsam. Aber wir kommen durch dieses in der Seele herangezogene Schauen, durch die inneren Sinne bewaffnet, dazu, das dritte Glied zu erkennen - stoßen Sie sich wieder nicht an dem Namen -, den astralischen Leib. Den hat der Mensch mit dem Tier gemeinsam. Durch ihn kann er empfinden. Niemals braucht ein Wesen, das nur wachsen und sich ernähren kann wie die Pflanze, auch Empfindung zu haben. Der Mensch und die Tiere können empfinden. Das ist nicht etwas, was man mit einem abstrakten Worte bezeichnen kann, sondern das ist eine reale Wesenheit, der astralische Leib.

Dann findet man etwas, was einen zum Träger macht seiner drei Leiber, was den physischen, den ätherischen, den astralischen Leib beherrscht: das ist die Ich-Organisation, das eigentliche innere Selbst des Menschen. Also: Erstens physischer Leib, zweitens ätherischer Leib, drittens astralischer Leib, viertens Ich-Organisation des Menschen.

Wer nicht rechnet mit diesen vier Gliedern des Menschen, wer sich auf den Standpunkt stellt, daß die äußere Anschauung in der Anatomie und Physiologie den ganzen Menschen umfassen könne, der mag eine Weltanschauung begründen! Ideen behaupten kann man in der mannigfaltigsten Weise; sie mögen gelten oder nicht in der Welt; da mag der eine Spiritualist, Idealist, Materialist sein, Realist der andere. Weltanschauungen kann man begründen, denn man braucht sie nur auszusprechen, man braucht nur zu sagen, man glaube dies oder jenes; aber mit Weltanschauungen, die nicht den Wirklichkeiten, nicht den wirklichen Anschauungen, den wirklichen Erfahrungen entstammen, kann man weder beim äußerlich physischen Menschen etwas anfangen, noch in der Erziehung. Wenn Sie in bezug auf die Mechanik eine falsche Anschauung haben und Brückenbauer, Ingenieur werden, so wird Ihnen der erste Eisenbahnzug, der darüberfährt, diese Brücke einwerfen. Da zeigt sich, ob die Sache der Wirklichkeit entspricht. Ebenso zeigt sich das, wenn man in der Lebenspraxis mit dem Menschen zu tun hat. In Verhandlungen oder auch sonst, in Büchern, lassen sich Weltanschauungen, die man ausgedacht hat, gut verdauen. Erziehen kann man nicht mit ihnen; erziehen kann man nur mit wirklicher Menschenerkenntnis. Von dieser Menschenerkenntnis möchte ich sprechen, denn sie ist eigentlich die Vorbereitung für den Pädagogen. Alles übrige, was man noch so geistreich ausdenkt, daß man tun soll in der einen, in der anderen Weise, ist viel weniger wichtig, als daß der Pädagoge in jedem Augenblick hineinzuschauen vermag in die menschliche Wesenheit, und aus dem, was ihm die Kindesnatur selber sagt, seine Methode im Augenblicke aus der Liebe zur Erziehung, aus der Kunst zu erziehen, finden kann.

Nun stellt sich aber für denjenigen, der mit dieser, durch das Übersinnliche bewaffneten Menschenerkenntnis an das Kind herantritt, dar, daß man für die ersten sieben Lebensjahre, von der Geburt bis zum Zahnwechsel, im Kinde nicht deutlich unterscheiden kann dasjenige, was ich Ihnen deutlich nebeneinander angeführt habe. Man kann dem Kinde gegenüber nicht in derselben Weise sagen: es besteht aus physischem Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib und Ich, wie man das beim erwachsenen Menschen sagen kann. Warum?

Das Kind, indem es geboren wird, ist ja wirklich das größte Wunder, das es überhaupt innerhalb des Erdenlebens geben kann. Man muß es als solches größtes Wunder anerkennen, wenn man unbefangenes Verständnis dafür hat. Da tritt das Kind in die Welt mit noch unbestimmten Gesichtszügen, mit der fast noch nichtssagenden Physiognomie, mit den ungeschickten, unorientierten Bewegungen, und wir sagen uns wohl, indem wir das mit einiger Geringschätzung tun: der Mensch ist ja noch nicht von dieser Welt; er paßt noch nicht hinein in diese Welt. Er greift noch, wenn er irgend etwas ergreifen will, ungeschickt. Er kann sich mit seinen Augen noch nicht orientieren, kann noch nicht in seinen Gliedern dasjenige ausdrücken, was in seinem Willen liegt. Aber das ist ja das Wunderbarste, was der Mensch erleben kann, wenn aus dem Zentrum der menschlichen Natur nach und nach herauskommt aus den inneren Kräften dasjenige, was der Physiognomie ihre göttergleichen Züge gibt, was die Bewegungen sich der Welt gemäß orientieren läßt und so weiter. Wenn man mit übersinnlichem Auge an das Kind herantritt, so kann man dem Kinde gegenüber nicht sagen, das Kind besteht aus physischem Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib und Ich, so wie man dem Wasser gegenüber nicht sagen kann, so wie es ist, es bestehe aus Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff. Es besteht aus Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff, aber die beiden sind innig miteinander verbunden. So sind im kindlichen Organismus bis zum Zahnwechsel diese vier Glieder der menschlichen Wesenheit so innig miteinander verbunden, daß man sie zunächst nicht unterscheiden kann.

Erst mit dem Zahnwechsel, dem siebenten Jahre ungefähr, wenn die Kinder in die Primarschule hereinkommen, tritt deutlich aus der menschlichen Organisation der Ätherleib auf, den der Mensch als die Grundlage des Wachstums, der Ernährung und so weiter hat, und zugleich als die Grundlage für die Phantasie, für die Gemütskräfte, für die Liebekräfte. Es ist so beim Kinde, daß wenn man es im siebenten Jahr, mit dem Zahnwechsel, beobachtet, so ist es für den übersinnlichen Blick, als ob herausträte, ich möchte sagen, eine übersinnlich ätherische Wolke, welche dieselben Kräfte enthält, die bis zum Zahnwechsel noch tief eingetaucht waren in den physischen Leib und ungeschickt im Kinde wirkten, weil sie nicht gewöhnt sind, im physischen Leib zu wirken. Jetzt, mit dem Zahnwechsel, werden sie gewöhnt, für sich zu wirken und nur einen Teil herunterzusenden in den physischen Leib. Jetzt wirken sie auf der einen Seite in Wachstum, Ernährung und so weiter; aber auch frei wirken sie in der kindlichen Phantasie, noch nicht im Intellekt, noch nicht im Nachdenken, in Ideen, wollen aber in der Liebe zu den Dingen, zu den Menschen auf einer höheren Stufe hervortreten. Die Seele im Ätherleib ist frei geworden im Kinde. Das Kind ist im . Grunde genommen ein anderes Wesen geworden, indem es den Zahnwechsel durchgemacht hat.

Und dann ist eine andere Epoche, vom Zahnwechsel bis zur Geschlechtsreife. Indem das Kind geschlechtsreif wird, tritt jetzt, was man bisher wenig unterscheiden konnte, der Astralleib heraus. Man merkt nun, wie das Kind ein anderes Verhältnis zur Außenwelt gewinnt. Das ist deshalb, weil, je mehr sein Astralleib erst geboren wird, es ein anderes wird. Vorher steckte er im Grunde genommen drinnen in der physischen und ätherischen Organisation.

So daß wir sprechen können: Erstens von der physischen Geburt, wo das Kind den physischen Leib der Mutter verläßt. Zweitens von der Äthergeburt: da ringt sich los, richtig im Kinde geboren werdend, der ätherische Leib. Der macht, daß das Kind belehrt werden kann. Drittens, bei der Geschlechtsreife kommt heraus der astralische Leib. Der macht, daß es die Liebe nach außen tragen kann, daß es empfindet die Unterschiede von Menschen; denn es ist die Geschlechtsreife nicht bloß damit verknüpft, daß sie in die Geschlechtserkenntnis hineinführt, sondern in die Erkenntnis des Untertauchens in alle Dinge. Viertens, und die IchErkenntnis wird eigentlich erst mit dem einundzwanzigsten, zweiundzwanzigsten Jahre geboren. Der Mensch wird nicht früher ein vollständig selbständiges Ich.

So kann man sprechen, wenn man spirituell vom Menschen spricht, von aufeinanderfolgenden Geburten. Und nur derjenige, der nun weiß, wie der Mensch ist unter dem Einflusse dieser aufeinanderfolgenden Verhältnisse seiner verschiedenen menschlichen Glieder, der kann Erziehung und Unterricht lenken. Denn, was bedeutet es denn, daß beim Kinde bis zum Zahnwechsel noch nicht unterschieden werden können physischer, ätherischer, astralischer Leib und Ich? Daß sie ineinanderstecken wie Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff, ununterschieden? Das bedeutet, daß das Kind eigentlich noch ganz Sinnesorgan ist. Für das Kind gibt es noch nichts, als daß es Sinnesorgan ist, und es nimmt alles, was es aufnimmt, so auf wie ein Sinnesorgan.

Betrachten Sie das wunderbar gestaltete menschliche Auge: die ganze Welt ist dadrinnen, das Bild der ganzen Welt. Wir können sagen: draußen ist die Welt, drinnen ist die Welt. Beim Kinde ist es ebenso: draußen ist die Welt, drinnen ist die Welt; das Kind ist ganz Sinnesorgan. Wir Erwachsenen haben den Geschmack von Zucker durch Mund, Zunge, Gaumen. Das Kind durchdringt sich ganz mit Geschmack. Man habe nur Sinn dafür, ein Kind zu beobachten, wie es durch und durch Sinn ist, Geschmacksorgan. Und insofern es schaut, nimmt es ja Teil mit seinem ganzen Wesen am Schauen, es geht ganz in seiner Umgebung auf. Daher ist etwas Eigentümliches im Kinde vorhanden: es hat eine naturhafte Religiosität. Die Eltern, die Erzieher sind um das Kind herum, das Kind gibt sich hin, wie das Auge sich selbst hingibt. Wenn das Auge sich selber sehen würde, würde es das andere nicht sehen. Das Kind lebt ganz in der Umgebung; aber es nimmt sie auch ganz körperlich auf. Nehmen wir einen Fall: den Jähzornigen Vater neben dem Kinde. Der tut allerlei, die Wut drückt sich aus in seinen Gebärden. Ja, das Kind nimmt seine Gebärden ganz anders wahr, als der Mensch denkt. Das Kind sieht zugleich in den Gebärden die moralische Qualität des Vaters. Das was das Kind innerlich sieht, die Welt, wird moralisch durchleuchtet. So wird das Kind ganz innerlich durchsetzt von einem jähzornigen Vater, einer liebevollen Mutter, von irgend etwas bei irgend jemand anderem. Das breitet sich aus in dem Kinde bis in den physischen Körper hinein.

Wie wir in der Umgebung eines Kindes sind, das geht in das Kind hinein, geradeso wie das Kerzenlicht in das Auge hineingeht. Aber es breitet sich das, wie wir in der Umgebung eines Kindes sind, soweit aus, daß sein Blut in den Sinnen anders zirkuliert, in seinen Nerven, indem diese arbeiten, in seinen Muskeln, in den Gefäßsäften, mit denen die Sinne versorgt werden, daß das ganze Wesen des Kindes sich nach dem bildet, wie die äußeren Eindrücke sind. Und noch wenn der Mensch ein Greis ist, dann merkt er die Wirkung desjenigen, was die moralisch-religiöse Umgebung in der Verfassung des Kindes, in dem physischen Körper des Kindes bewirkt haben. Des ganzen menschlichen Erdenlebens Gesundheit und Krankheit hängt davon ab, ob wir imstande sind, richtig tief genug einzusehen, daß im Kinde sich alles spiegelt, was in der Umgebung vorgeht. Nicht nur das Physische, sondern auch das Moralische spiegelt sich. Das Moralische, das sich spiegelt, wird wirksam in bezug auf Gesundheit und Krankheit.

Das Kind ist in den ersten sieben Lebensjahren, bis zum Zahnwechsel, ein rein nachahmendes Wesen, ein imitierendes Wesen. Wir können es nur dadurch erziehen, daß wir alles dasjenige, wovon wir meinen, daß es in dem Kinde entwickelt werden muß, in seiner Umgebung tun. Wir sollen nicht ausdenken: Was soll das Kind tun? - sondern wir sollen uns vor allen Dingen klar sein darüber, daß wir selbst es ihm vormachen müssen. Denn nichts anderes ist gesund für das Kind, als was wir ihm vormachen. Und nichts nimmt das Kind wahrhaftig in seine Organe auf, als was wir ihm vormachen.

Darinnen kann man seine Erfahrungen machen! Es kam einmal ein Vater zu mir, der unglücklich war darüber, daß sein vier-, fünfjähriges Kind gestohlen haben sollte. Er sagte: Das wird doch ein schrecklicher Mensch, denn er hat gestohlen. - Ich erwiderte: Wollen wir erst untersuchen, ob er wirklich gestohlen hat. Und was stellte sich heraus? Der Junge hatte Geld genommen aus der Kommode, an die die Mutter auch immer geht, wenn sie Geld braucht. Die Mutter ist dasjenige Wesen, das er am meisten nachahmt. Es ist ihm selbstverständlich, daß er das auch tut, was die Mutter tut. Er tut dasselbe, nimmt auch Geld aus der Kommode. Es ist gar keine Rede davon, daß er stiehlt, sondern er machte das, was naturgemäß ist dem Kinde bis zum Zahnwechsel: das Nachahmen. Er ahmte nur nach, was die Mutter auch getan hatte.

Gerade aber wenn man diese Dinge durchschaut, wird man wissen: es handelt sich darum, daß Imitation beim Kinde dasjenige ist, was es beherrscht bis hinein in seine leiblich-seelische Entwickelung, und daß wir nötig haben darauf zu sehen als Erzieher, daß wir in diesen ersten sieben Lebensjahren die Gestalter sind von Leib, Seele und Geist. Die Erziehung für die ersten sieben Lebensjahre muß eine gestaltende sein. Und derjenige, der das wirklich durchschauen kann, der kann selbst später, wenn er dem Menschen begegnet und seine Physiognomie, seinen ganzen Habitus sieht, sieht, wie er auftreten, gehen oder nicht gehen kann, er kann ablesen davon, ob Jähzorn oder ob Sanftmut, Besonnenheit in der Umgebung des Kindes war und bis in das Blut, in die Blutzirkulation, bis in die Muskeleigenheit hinein gestaltend auf das Kind gewirkt hat. Leib, Seele und Geist werden gestaltet in diesen Jahren, und wir müssen wissen als Lehrer, daß sie in diesen Jahren gestaltet werden. Aus diesem Wissen, aus diesem Impuls, und aus dem daraus entspringenden Enthusiasmus geht dasjenige hervor, was dem Lehrer die Methode gibt, die Gefühls-, die Willensimpulse; die hingebende, opferwillige Gesinnung ist vor allen Dingen dasjenige, was zugrunde liegen muß den pädagogischen Methoden. Die schönste pädagogische Methode hat keinen Wert, wenn nicht Kindeserkenntnis vorliegt, wenn nicht vorliegt dasjenige, wodurch der Lehrer mit dem Kinde so in eins zusammenwachsen kann, daß das Kind ihn nachahmen kann, daß das Kind das gestalten darf in seinen eigenen Qualitäten.

Ich möchte aus dem Grunde, den ich erörtert habe, die Erziehung des Kindes bis zum Zahnwechsel hin die gestaltende Erziehung nennen, denn da läuft alles hinaus auf die Gestaltung des Leibes, der Seele, des Geistes des Kindes für das ganze Erdenleben. Man muß nur hineinschauen in diese Gestaltung. Ich habe das Beispiel vom jähzornigen Vater angeführt. Das Kind sieht in den Gebärden des Jähzorns noch die moralischen Qualitäten. Das wirkt auf das Kind so, daß die Dinge in die physische Konstitution übergehen. Wir erleben vielleicht, daß bei einem fünfzigjährigen Menschen die Starkrankheit beginnt, der graue Star, der dann operiert werden muß. Man nimmt solche Dinge hin im Leben, ja, eben in dem Sinne, wie man heute die Dinge ärztlich ansieht. Es gibt auch Starkrankheit, sagt man. Aber man schaut nicht auf das ganze Leben hin nach wirklich tieferer Menschenerkenntnis. Würde man das tun, so würde man oftmals erkennen, daß die Starkrankheit beim Menschen oft zurückführt zu jenen inneren Schocks, zu denen das Kind geführt worden ist durch den jähzornigen Vater. Es ist bei diesen Dingen so, daß bis in die Gefäße hinein dasjenige geht, was in der moralischen, religiösen Umgebung wirkt und Gesundheits- oder Krankheitsanlage wird. Das tritt oftmals im späteren Leben zutage. Der Arzt diagnostiziert nach dem heute im Leben eigentümlichen Standpunkt. In Wahrheit werden wir darauf zurückgeführt, daß zum Beispiel die Gicht, der Rheumatismus im fünfzigsten, sechzigsten Jahr davon herrührt, daß in der Umgebung des Kindes Nachlässigkeit, Ungeordnetheit, Disharmonie geherrscht haben, was das Kind aufgenommen hat. Es ist ganz in das Organische hineingegangen.

So schaut man hinein in die Gestaltung, die der Mensch für das ganze Leben erhält, wenn man darauf hinschaut, was er als imitierendes Wesen bis zum Zahnwechsel aufnimmt. Wir müssen das Gestalten des Menschen beherrschen lernen, sonst haben alle Kleinkinderschulen gar keinen Wert, wenn wir nicht dasjenige in dem Kinde keimen lassen können, was gestaltend wirkt und das gesunde und kranke Leben beherrscht für das ganze Erdendasein.

Nun, mit dem Zahnwechsel kommt der Ätherleib heraus, dasjenige, was enthält die Kräfte der Verdauung, der Ernährung, des Wachstums, aber was auch seelisch sich äußert, und jetzt beim Kinde sich zu äußern beginnt in dem Heraufkommen der Phantasie, des Gedächtnisses und so weiter. Hier müssen wir uns klar sein, was wir eigentlich erziehen zwischen dem Zahnwechsel und der Geschlechtsreife.

Ja, was erziehen wir denn? Wir erziehen dieselben Kräfte, welche die richtige Verdauung bewirken, dieselben Kräfte, die den Menschen wachsen lassen, die den Menschen von Kind auf zum großen Menschen heranwachsen lassen, die innerliches und äußerliches Wachstum ermöglichen. Und dasjenige, was wir in der Seele erziehen, ist nur das seelische Gegenbild der Wachstumskräfte. Was gibt denn die Natur, was gibt die geistige Welt dem Menschen durch die Wachstumskräfte des Ätherleibes? Das Leben, richtig das Leben! Was müßten wir dem Kinde geben, wenn wir jetzt nicht wie die Natur auf die Wachstumskräfte wirken können unmittelbar, naturhaft, wie das geschieht in den ersten sieben Lebensjahren, sondern wenn wir auf den freigewordenen Ätherleib in seelischer Weise wirken sollten? Was müssen wir denn da dem Kinde geben? Wir müssen Leben geben. Leben gibt man dem Kinde nicht, wenn man an das Kind Begriffe jetzt schon heranbringt. Das Kind ist noch nicht reif für den Verstand, für den Intellekt, es ist reif für das Bild, für die Phantasie, und auch für das Gedächtnis. Und wenn man es erkennen und die Erziehung in den ersten sieben Jahren eine gestaltende nennen kann, wenn da gestaltet werden muß, so muß jetzt geformt, belebt werden. Und alles muß belebt werden! Zwischen dem Zahnwechsel und der Geschlechtsreife ist das belebende Prinzip des Unterrichts das Richtige. Alles was ich als Lehrer tue, muß beleben. Aber man ertötet vieles leicht, gerade in diesem Lebensalter.

Sehen Sie, da müssen die Kinder ja, weil es in unserer Zivilisation selbstverständlich so berechtigt ist, herangebracht werden an das, was ja zum Lesen, zum Schreiben führt. Aber nun bedenken Sie: diese Buchstaben, die wir schreiben, die wir lesen, wie fremd sie eigentlich dem Menschen sind! Sie sind so fremd, daß, als die Europäer, diese «besseren Menschen» nach Amerika kamen - noch in den vierziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts sind Beispiele davon vorhanden -, da sagten die Indianer: Die Europäer haben da solche merkwürdigen Dinge auf dem Papier stehen, und das schauen sie an, und dann sprechen sie aus dasjenige, was da auf dem Papier steht, das sind kleine Teufel! - sagten die Indianer, und die Europäer, «die Blaßgesichter» nennen sie sie ja, die bedienen sich dieser kleinen Teufel! - Für das Kind sind die Buchstaben genauso wie für die Indianer kleine Dämonen; denn das Kind hat keine Beziehung zu den Buchstaben. Und wir ertöten ungeheuer viel, wenn wir das Kind gleich zum Lesen führen.

Es hat gar keinen Sinn für denjenigen, der die Dinge überschaut. Darum sagt eine auf das Wirkliche der Menschenerkenntnis gehende Erziehungsmethode: Schaue dir einmal an, wie die Menschen im alten Ägypten geschrieben haben, wo sie noch notiert haben, was sie gesehen haben, das haben sie ins Bild gebracht; daraus sind die ersten unserer heutigen Buchstaben entstanden. — Er schrieb nicht Buchstaben auf, er malte Bilderschrift. Die Keilschrift hat eine ganz ähnliche Grundlage. Der Sanskritschrift sieht man es heute noch an, wie sie aus dem Bild hervorgegangen ist. Denken Sie sich: das ist der Weg, den die Menschheit gemacht hat, um zu den heutigen abstrakten Buchstaben zu kommen! Nun führen wir das Kind an die heutigen abstrakten Buchstaben heran, zu denen es gar kein Verhältnis hat! Was hat man zu tun? Das hat man zu tun, daß man das Kind zunächst gar nicht mit Schreiben und Lesen plagt, sondern malendes Zeichnen, zeichnendes Malen an das Kind heranbringt. Es betätigt dabei den ganzen Leib, wenn man es anfangen läßt zu malen, es an die Farben und Formen heranbringt. Man lasse es in den einzelnen Formen nachahmen dasjenige, was es schaut, was es sieht; dann führt man hinüber dasjenige, was im Bilde ist, in dem Laut.

Ein Beispiel. Sie haben ja auch das englische Wort «fish»: Fisch. Nehmen wir an, wir lassen das Kind dazu kommen, daß es den Fisch im malenden Zeichnen, im zeichnenden Malen, aus der Farbe heraus schafft (es wird gezeichnet): Fisch. Jetzt lasse ich das Kind das Wort «Fisch» ruhig aussprechen; «fange bloß an», sage ich dem Kinde: F. Es entsteht aus dem Bilde, das ich hingemalt habe für den Fisch, das F.

So kann ich es machen für alles, was konsonantisch ist. Für die Selbstlaute finde ich, wenn ich das innere Seelenleben zu Hilfe nehme, wie ich das Bild überführen kann in den Buchstaben.

Auf diese Weise lernen die Kinder vom siebenten, achten Lebensjahre ab malendes Zeichnen, zeichnendes Malen. Man muß allerdings mehr achtgeben; es ist nicht so bequem, man muß nachher aufräumen; die Kinder machen alles schmutzig mit den Farben, es muß gereinigt werden; aber diese Dinge werden eben hingenommen werden müssen. Und man lernt zuerst aus der Farbe und Form heraus Ähnlichkeiten schaffen mit den Dingen draußen. Dann geht man über auf das Schreiben. Zunächst lernt das Kind schreiben, weil es damit den ganzen Körper in Bewegung bringt, nicht einen Teil bloß. Und dann geht man über zu dem Lesen. Das Kind gelangt im neunten Jahre etwa dazu, aus dem Schreiben heraus, das es aus dem Malen gebildet hat, das Lesen zu lernen. Auf diese Weise schaut man der Natur des Kindes ab, wie man es zu führen hat, läßt es sich von dem Kinde selber diktieren. Dadurch aber ist man als Lehrer genötigt, selbst ein anderer Mensch zu sein, nicht bloß seine Lektionen zu lernen und dann in abstrakter Weise anzuwenden, sondern mit seinem ganzen Menschen vor der Klasse zu stehen und zu allem, was man zu treiben hat, das Bild zu finden, selber Phantasie zu haben. Dann geht in imponderabler Weise das von dem Lehrer auf das Kind über. Aber man muß selbst lebendig sein. Wenn man in dieser Weise nicht bloß Begriffe hat, sondern Bilder hat, dann kommt man an das Kind heran. Man kann selbst die moralisch-religiöse Erziehung ins Bild bringen. Ich will dem Kinde sprechen über die Unsterblichkeit der Seele. Ich spreche ihm von dem Schmetterling, der in der Schmetterlingspuppe zuerst drinnen ist. Die Puppe bekommt ein Loch: der Schmetterling fliegt heraus. Ich mache dem Kinde klar: so ist es mit der menschlichen Seele. Solange der Mensch auf Erden ist, ist der Mensch die Puppe, und der Schmetterling fliegt sozusagen heraus, wenn der Mensch stirbt, als die Seele. Den Schmetterling sieht man, wenn er aus der Puppe ausschlüpft; die Seele sieht man nicht, wenn sie ausfliegt beim Tode.

Aber es gibt einen Unterschied. Nur ein Lehrer kann etwas erreichen damit, der nicht sich sagt: Ich bin so gescheit, so furchtbar gescheit, und das Kind ist dumm, ich muß etwas aussinnen, um die Sache zu veranschaulichen; ich selber glaube ja nicht an den ganzen Humbug von Schmetterling und Raupe, aber dem Kinde muß ich das so sagen. - Das wirkt gar nicht auf das Kind! Denn da sind unterseelische Kräfte zwischen dem Lehrer und dem Kind, die da wirken auf das Kind. Glaube ich selber daran, daß die geistigen Mächte in der Natur auf der Stufe des aus der Puppe ausfliegenden Schmetterlings ein Bild liefern für die Unsterblichkeit der Seele, stehe ich selber so darinnen, weiß ich, daß in der Natur überall Geist lebt, und daß der Schmetterling da ist, um den Menschen zu zeigen, daß da überall Geist ist, dann, wenn ich selber dran glaube, wirkt es auf das Kind. Dann ist es in der richtigen Weise keimend, auf das Kind wirkend.

Und auf diese Weise muß ich meine Begriffe beweglich halten. Da macht man ja die größten Fehler, wenn man gleich mit dem steifen Intellektuellen an das Kind herankommt.

Wenn man einem dreijährigen Kind Schuhe kauft, wird man nicht verlangen, daß es dieselben Schuhe mit neun Jahren tragen soll; es muß mit neun Jahren andere Schuhe tragen, die Schuhe müssen anders gemacht sein. Aber mit unseren Dingen, die wir dem Kinde lehren, machen wir es so. Wir lehren dem Kinde etwas; das mag so bleiben, und womöglich, wenn das Kind vierzig-, fünfzigjährig geworden ist, soll es immer noch so sein; wir geben Definitionen, die immer so bleiben sollen, und das ist geradeso wie die Schuhe, die es mit drei Jahren getragen hat und die später immer noch passen sollen! Wir sollen dem Kinde aus der Phantasie herausgeholte Bilder geben, die wachsen mit dem Kinde. Und darauf kommt es an, daß wir eine Erziehung geben, die die Seele so wachsen läßt, wie die Natur das fordert, wie der Leib wächst. Nur wenn wir selber als Lehrer solche Lebendigkeit haben, die Phantasie überall hineinzubringen, dann bringen wir dem Kinde lebendige Begriffe bei.

Belebende Erziehung zwischen Zahnwechsel und Geschlechtsreife ist das, um was es sich handelt. Denn da wird der Ätherleib frei. Da müssen wir auch so recht lebendig alles gestalten. Zum Beispiel, nehmen Sie das Wort «Mund», das ja auch im Englischen «mouth» ist: ich spreche nur den Anfangsbuchstaben: M aus — ich komme auf das:

Mund, mouth. Und so werden Sie überall aus dem Lebendigen heraus die Möglichkeit finden, zu schaffen dasjenige, was dann im Schreiben auftreten soll. Dann wachsen die in der Phantasie gebildeten Begriffe heran, wenn der Intellekt, der erst kommen soll mit der Geschlechtsreife, nicht zwei Jahre früher angesprochen wird; Definitionen sind für das Kind Gift. Da möchte man sich immer erinnern an dasjenige, was einmal in einer griechischen Philosophenschule definiert worden ist: Was ist ein Mensch?-Ein Mensch ist ein Wesen, das zwei Beine und keine Federn hat. - Eine Definition, wie viele unserer wissenschaftlichen Definitionen sind. - Ich weiß, daß ich eine Ketzerei ausspreche! Am nächsten Tag brachte einer derSchülereine Gans mit, der er die Federn ausgerissen hatte, mit der Behauptung: das sei ein Mensch, ein Wesen, das zwei Beine und keine Federn hat! - So ungefähr sind die armen, die intellektualistischen Begriffe, die wir dem Kinde so peinlich gern beibringen wollen. Reiche Begriffe brauchen wir, die wachsen, so wie das Kind selber, und im späteren Alter dem Menschen Wachstumskräfte lassen. Bringen wir dem Kinde nur abstrakte Begriffe in diesem Lebensalter bei: wir tragen früh die Spuren des Alterns an uns. Wir verlieren die Lebhaftigkeit, wir altern früh, wir können nicht mehr recht vorwärts. Es ist etwas, was wir, ich möchte sagen, furchtbar empfinden, wenn wir so erzogen sind, daß wir nicht mit der Phantasie, mit dem Bild aufgewachsen sind, das wächst und lebt und dem Ätherleib angepaßt ist, sondern mit dem, das eigentlich im Grunde ein Ertöten darstellt: dieses Abstrakte, Intellektuelle.

So kann man, wenn man weiß, daß dieser Ätherleib da ist, daß dieser Ätherleib lebendig ist, wenn er nicht bloß abstrakte Theorie bleibt, sondern wenn man das Kind in seiner lebendigen Entwickelung anschaut, so kann man darauf kommen, dieses zweite, ich möchte sagen, goldene Prinzip der Erziehung in sich einzuschreiben. Für die ersten sieben Lebensjahre das goldene Prinzip: Gestalte den Menschen menschenwürdig, gesund; und in den zweiten sieben Jahren, von dem Zahnwechsel bis zur Geschlechtsreife, heißt das goldene Erziehungsprinzip: Belebe den Menschen, denn dir ist sein Ätherleib übergeben!

Mit der Geschlechtsreife wird nun wie durch eine neue Geburt dasjenige herausgelöst, was ich astralischen Leib genannt habe. Alles dasjenige, was als die innersten menschlichen Kräfte zugrunde liegt der eigenen Empfindung bis zur Geschlechtsreife, also gerade im primarschulmäßigen Alter, hat das Kind noch unvermischt, ungeteilt mit seinem physischen Leib und Ätherleib eben in diesem astralischen Leib beisammen; daher ist es naturgemäß hingegeben an die Empfindungen, an die Gefühlsweise, an die Phantasieweise des Lehrenden, des Erziehenden. Indem der astralische Leib frei wird von der physischen Organisation und also seelisch frei wirkt, erscheint das Kind erst herausgelöst auch aus dem, was bei ihm selbstverständlicher Autoritätsglaube sein muß. Denn all das, was ich beschrieben habe als die richtige Erziehung zwischen dem Zahnwechsel und der Geschlechtsreife, das muß unter dem Zeichen der selbstverständlichen Autortät stehen zwischen dem Kinde und dem Lehrenden, dem Erziehenden. Oh, es ist ein großes Glück für das Leben, wenn man gerade in diesem Kindesalter in selbstverständlicher Autorität zu dem Lehrenden, Erziehenden aufschauen kann, so aufschauen kann, daß einem das wahr ist, was wahr ist für den Lehrenden, den Erziehenden! Man unterscheidet noch nicht als Kind: Irgend etwas ist wahr, irgend etwas ist falsch; man verehrt die Wahrheit, weil etwas, was der Lehrer sagt, als wahr aufgefaßt wird; man verehrt die Güte, weil der Lehrer sie darstellt in dem, was er als die selbstverständliche Güte heranbringt; man verehrt die Schönheit, weil der Lehrer sie heranbringt. Die Wahrheit, die Güte, die Schönheit der Welt tritt in dem Erziehenden dem Kinde gegenüber.

Man wird mir, der ich vor vielen Jahren eine «Philosophie der Freiheit» schrieb, nicht zumuten, daß ich für das Autoritätsprinzip etwa im sozialen Leben eintrete. Dasjenige, was ich hier meine, ist, daß das Kind in selbstverständlicher Autorität stehen muß zwischen dem Zahnwechsel und der Geschlechtsreife, und in dieser Zeit alles, wie ich es dargestellt habe, lebendig empfangen muß. Also der Erzieher ist die eigentliche Autorität in diesem Alter, und der Mensch wird erst fähig zur Freiheit, wenn er die selbstverständliche Autorität des Erziehers verehren und achten gelernt hat.

Und ebenso wird er auch fähig, sich seines eigenen Urteils zu bedienen, nicht mehr des Urteils des Lehrers, des Erziehers, wenn er geschlechtsreif geworden ist und sein astralischer Leib der Träger des eigenen Urteils geworden ist.

Da tritt nun das auf, was das dritte Element in der Erziehung sein muß. Das erste nannte ich das gestaltende, das zweite das belebende. In diesem dritten Element der Erziehung, das eintritt mit der Geschlechtsreife, finden wir nur dasjenige berechtigt, was ich nennen kann: die erweckende Erziehung. Alles, was über die Geschlechtsreife hinausgeht, muß so wirken auf den jungen Menschen, auf den jungen Mann, das junge Mädchen, daß die Entstehung des eigenen Urteils, diese innere Selbständigkeit, wie ein fortwährendes Aufwachen erscheint. Wenn man über die Geschlechtsreife hinaus jemandem etwas von außen beibringen will, tyrannisiert man ihn, man versklavt ihn. Wenn man die ganze Erziehung so leitet, daß man von diesem Lebensalter ab, von der Geschlechtsreife ab, alles aufnimmt so, wie wenn jemand aus dem Schlaf erweckt wird - der Mensch hat bis dahin geschlafen in bezug auf die Beurteilung von dem oder jenem, es kommt ihm jetzt vor, als ob er sein eigenes Wesen aus sich herausruft — dieses Gefühl, daß es sein eigenes Wesen ist, das aus ihm herauskommt, daß der Lehrer ihm nur der Anreger, der Erwecker ist, das kann man entwickeln, wenn man so vorgeht, wie ich es ausgeführt habe für die zwei ersten Lebensalter; dann wächst man hinein in den Gebrauch seines eigenen Urteils, dann wird die spätere Erziehung, der Unterricht ein erweckender. Und wenn man als Lehrer, als Erziehender, seiner Gesinnung nach tief durchdrungen ist von diesem Erweckenden, dann weiß man auch im Stil, in der Haltung, im Vortrag alles so zu gestalten, daß dasjenige, was nun eigenes Urteil sein soll desjenigen, der belehrt, der erzogen wird, daß das wirklich aus dem Betreffenden herauskommt, daß es in einer gewissen dramatischen Steigerung geht bis dahin, wo er selber nun einsetzt mit dem inneren Betätigen, das gerade im astralischen Leib lebt.

Damit sprechen wir ja, indem wir in der richtigen Weise zum astralischen Leib sprechen, zu dem Unsterblichen des Menschen. Der physische Leib wird alle sieben Jahre ausgewechselt. Der ätherische Leib in seiner Kraft als dynamische Organisation geht von der Geburt bis zum Tode, beziehungsweise von der Konzeption bis zum Tode. Dasjenige, was unser astralischer Leib ist, der, wie gesagt, später herauskommt, ist der ewige Wesenskern des Menschen, der heruntersteigt, sich nur mit dem physischen und auch dem ätherischen Leib umkleidet und wieder durch die Pforte des Todes geht. Zu dem können wir in der richtigen Weise sprechen, wenn wir uns zuerst vor dem Zahnwechsel und der Geschlechtsreife in richtiger Weise hingestellt haben neben das, was der Mensch erst im Erdendasein empfängt: seinen Ätherleib, seinen physischen Leib. Erziehen wir da richtig in der Weise, wie es geschildert worden ist, dann entwickelt sich innerlich in wunderbarer Weise - nicht durch unsere Führung, sondern durch Führung der geistigen Welt selber dasjenige, was dann mit der Geschlechtsreife als der ewige Wesenskern des Menschen erwachen darf.