The Roots of Education

GA 309

15 April 1924, Bern

Lecture Three

In the preceding lectures I have repeatedly spoken of how important it is that teachers turn their attention in particular toward the drastic changes, or metamorphoses, that occur during a child’s life—for example, the change of teeth and puberty. We have not fully developed our observation of such changes, because we are used to noticing only the more obvious outer expressions of human nature according to so-called natural laws. What concerns the teacher, however, arises in reality from the innermost center of a child’s being, and what a teacher can do for the child affects a child’s very inner nature. Consequently, we must pay particular attention to the fact that, for example, at this significant change of teeth, the soul itself goes through a transformation.

Memory Prior to the Change of Teeth

Let us examine a single aspect of this soul-life—the memory, or capacity for remembering. A child’s memory is very different before and after the change of teeth. The transitions and developments in human life occur slowly and gradually, so to speak of the change of teeth as a single fixed event in time is only approximate. Nevertheless, this point in time manifests in the middle of the child’s development, and we must consider very intensively what takes place at that time.

When we observe a very young child, we find that the capacity to remember has the quality of a soul habit. When a child recalls something during that first period of life until the change of teeth, such remembering is a kind of habit or skill. We might say that when, as a child, I acquire a certain accomplishment—let us say, writing—it arises largely from a certain suppleness of my physical constitution, a suppleness that I have gradually acquired. When you watch a small child taking hold something, you have found a good illustration of the concept of habit. A child gradually discovers how to move the limbs this way or that way, and this becomes habit and skill. Out of a child’s imitative actions, the soul develops skillfulness, which permeates the child’s finer and more delicate organizations. A child will imitate something one day, then do the same thing again the next day and the next; this activity is performed outwardly, but also—and importantly—within the innermost parts of the physical body. This forms the basis for memory in the early years.

After the change of teeth, the memory is very different, because by then, as I have said, spirit and soul are freed from the body, and picture content can arise that relates to what was experienced in the soul—a formation of images unrelated to bodily nature. Every time we meet the same thing or process, whether due to something outer or inner, the same picture is recalled. The small child does not yet produce these inward pictures. No image emerges for that child when remembering something. When an older child has a thought or idea about some past experience, it arises again as a remembered thought, a thought “made inward.” Prior to the age of seven, children live in their habits, which are not inwardly visualized in this way. This is significant for all of human life after the change of teeth.

When we observe human development through the kind of inner vision I have mentioned—with the soul’s eyes and ears—we will see that human beings do not consist of only a physical body that can be seen with the eyes and touched with the hands. There are also supersensible members of this being. I have already pointed out the first so-called supersensible human being living within the physical body—the etheric human being. There is also a third member of human nature. Do not be put off by names; after all, we do need to have some terminology. This third member is the astral body, which develops the capacity of feeling.

Plants have an etheric body; animals have an astral body in common with humans, and they have feeling and sensation. The human being, who exists uniquely as the crown of earthly creation, has yet a fourth member—the I-being. These four members are entirely different from one another, but since they interact with one another they are not generally distinguished by ordinary observation; the ordinary observer never goes far enough to recognize the manifestations of human nature in the etheric body, the astral body, or I-being. We cannot really aspire to teach and educate, however, without knowing these things. One hesitates to say this, because it may be regarded as fantastic and absurd within the broader arena of modern society. It is nevertheless the truth, and an unbiased knowledge of the human being will not disagree.

The way that the human being works through the etheric body, astral body, and I-being is unique and is significant for educators. As you know, we are used to learning about the physical body by observing it—living or dead—and by using the intellect connected with the brain to elucidate what we have thus perceived with the senses. This type of observation alone, however, will never reveal anything of the higher members of human nature. They are inaccessible to methods of observation based only on sense-perception and intellectual activity. If we think only in terms of natural laws, we will never understand the etheric body, for example. Therefore, new methods should be introduced into colleges and universities. Observation through the senses and working in the intellect of the brain enable us to observe only the physical body. A very different training is needed to enable a person to perceive, for example, how the etheric body manifests in the human being. This is really necessary, not just for teachers of every subject, but even more so for doctors.

The Etheric Body and the Art of Sculpting

First, we should learn to sculpt and work with clay, as a sculptor works, modeling forms from within outward, creating forms out of their own inner principles, and guided by the unfolding of our own human nature. The form of a muscle or bone can never be comprehended by the methods of contemporary anatomy and physiology. Only a genuine sense of form reveals the true forms of the human body. But when we say such things we will immediately be considered somewhat crazy. But Copernicus was considered a bit mad in his time; even as late as 1828 some leaders of the Church considered Copernican theories insane and denied the faithful any belief in them!

Now let’s look at the physical body; it is heavy with mass and subject to the laws of gravity. The etheric body is not subject to gravity—on the contrary, it is always trying to get away. Its tendency is to disperse and scatter into far cosmic spaces. This is in fact what happens right after death. Our first experience after death is the dispersal of the etheric body. The dead physical body follows the laws of Earth when lowered into the grave; or when cremated, it burns according to physical laws just like any other physical body. This is not true of the etheric body, which works away from Earth, just as the physical body strives toward Earth. The etheric body, however, does not necessarily extend equally in all directions, nor does it strive away from Earth in a uniform way. Now we arrive at something that might seem very strange to you; but it can in fact be perceived by the kind of observation I have mentioned.

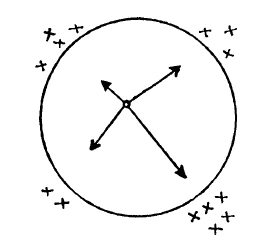

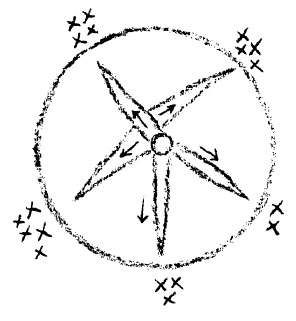

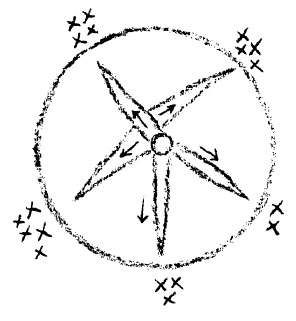

When you look up into the heavens, you see that the stars are clustered into definite groups, and that these groups are all different from one another. Those groups of stars attract the etheric human body, drawing it out into the far spaces. Let’s imagine someone here in the center.

The different groups of stars are drawing out the etheric body in varying degrees; there is a much stronger attraction from one group of stars than from another, thus the etheric body is not drawn out equally on all sides but to varying degrees in the different directions of space. Consequently, the etheric body is not spherical, but, through this dispersion of the etheric, certain definite forms may arise in the human being through the cosmic forces that work down from the stars. These forms remain in us as long as we live on Earth and have an etheric body within us.

If, for example, we take the upper part of the thigh, we see that both the form of the muscle and the form of the bone are shaped by influences from the stars. We need to discover how these very different forms can arise from different directions of cosmic space. We must try to model these varying forms in clay, and we will find that, in one particular form, cosmic forces act to produce length; in another the form is rounded off more quickly. Examples of the latter are the round bones, and the former are the more tubular bones.

Like sculptors, therefore, we must develop a feeling for the world—the kind of feeling that, in ancient humankind, was present as a kind of instinctive consciousness. It was clearly expressed in the Eastern cultures of prehistory, thousands of years before our era; but we still find it in Greek culture. Just consider how contemporary, materialistic artists are often baffled by the forms of the Greek sculptors. They are baffled, because they believe the Greeks worked from models, which they examined from all sides. But the Greeks still had a feeling that the human being is born from the cosmos, and that the cosmos itself forms the human being. When the Greeks created their Venus de Milo (which causes contemporary sculptors to despair), they took what flowed from the cosmos; and although this could reveal itself only imperfectly in any earthly work, they tried to express it in the human form they were creating as much as possible. The point is that, if you really attempt to mold the human form according to nature, you cannot possibly do it by slavishly following a model, which is the contemporary studio method. One must be able to turn to the great “cosmic sculptor,” who forms the human being from a feeling for space, which a person can also acquire.

This then is the first thing we must develop. People think they can gauge the human form by drawing a line going through vertically, another through the outstretched arms and another front to back; there you have the three dimensions. But in doing this, they are slaves to the three dimensions of space, and this is pure abstraction. If you draw even a single line through a person in the right way, you can see that it is subject to manifold forces of attraction—this way or that, in every direction of space. This “space” of geometry, about which Kant produced such unhappy definitions and spun out such abstract theories—this space itself is in fact an organism, producing varied forces in all directions.

Human beings are likely to develop only the grosser physical senses, and do not inwardly unfold this fine delicate feeling for space experienced in all directions. If we could only allow this feeling for space to take over, the true image of the human being would arise. Out of an active inner feeling, you will see the plastic form of the human being emerge. If we develop a feeling for handling soft clay, we have the proper conditions for understanding the etheric body, just as the activity of human intellect connected with the brain provides the appropriate conditions for understanding the physical body.

We must first create a new method of acquiring knowledge—a kind of plastic perception together with an inner plastic activity. Without this, knowledge stops short at the physical body, since we can know the etheric body only through images, not through ideas. We can really understand these etheric images only when we are able to reshape them ourselves in some way, in imitation of the cosmic shaping.

The Astral Body in Relation to Music

Now we can move on to the next member of the human being. Where do things stand today in regard to this? On the one hand, in modern life the advocates of natural science have become the authorities on the human being; on the other hand we find isolated, eccentric anthroposophists, who insist that there are also etheric and astral bodies, and when they describe the etheric and astral bodies, people try to understand those descriptions with the kind of thinking applied to understanding the physical body, which doesn’t work. True, the astral body expresses itself in the physical body, and its physical expression can be comprehended according to the laws of natural science.

However, the astral body itself, in its true inner being and function, cannot be understood by those laws. It can be understood only by understanding music—not just externally, but inwardly. Such understanding existed in the ancient East and still existed in a modified form in Greek culture. In modern times it has disappeared altogether. Just as the etheric body acts through cosmic shaping, the astral body acts through cosmic music, or cosmic melodies. The only earthly thing about the astral body is the beat, or musical measure. Rhythm and melody come directly from the cosmos, and the astral body consists of rhythm and melody.

It does no good to approach the astral body with what we understand as the laws of natural science. We must approach it with what we have acquired as an inner understanding of music. For example, you will find that when the interval of a third is played, it can be felt and experienced within our inner nature. You may have a major and minor third, and this division of the scale can arouse considerable variations in the feeling life of a person; this interval is still something inward in us. When we come to the fifth interval, we experience it at the surface, on our boundary; in hearing the fifth, it is as though we were only just inside ourselves. We feel the sixth and seventh intervals to be finding their way outside us. With the fifth we are passing beyond ourselves; and as we enter the sixth and the seventh, we experience them as external, whereas the third is completely internal. This is the work of the astral body—the musician in every human being—which echoes the music of the cosmos. All this is at work in the human being and finds expression in the physical human form. If we can really get close to such a thought in trying to comprehend the world, it can be an astonishing experience for us.

You see, we are speaking now of something that can be studied very objectively—something that flows from the astral body into the human form. In this case, it is not something that arises from cosmic shaping, but from the musical impulse streaming into the human being through the astral body. Again, we must begin with an understanding of music, just as a sculptural understanding is necessary in understanding the etheric body’s activities. If you take the part of the human being that goes from the shoulder blades to the arms, that is the work of the tonic, the keynote, living in the human being. In the upper arm, we find the interval of the second. (You can experience all this in eurythmy.) And in the lower arm the third—major and minor. When you come to the third, you find two bones in the lower arm, and so on, right down into the fingers.

This may sound like mere words and phrases, but through genuine observation of the human being, based on spiritual science, we can see these things with the same precision that a mathematician uses in approaching mathematical problems. We cannot arrive at this through any kind of mystical nonsense: it must be investigated with precision. In order that students of medicine and education really comprehend these things, their college training must be based on an inner understanding of music. Such understanding, permeated with clear, conscious thinking, leads back to the musical understanding of the ancient East, even before Greek culture began. Eastern architecture can be understood only when we understand it as religious perception descended into form.

Just as music is expressed only though the phenomenon of time, architecture is expressed in space. The human astral and etheric bodies must be understood in the same contrasting way. We can never explain the life of feeling and passion with natural laws and so-called psychological methods. We can understand it only when we consider the human being as a whole in terms of music. A time will come when psychologists will not describe a diseased condition of the soul life as they do today, but will speak of it in terms of music, as one would speak, for example, of a piano that is out of tune.

Please do not think that anthroposophy is unaware of how difficult it is to present such a view in our time. I understand very well that many people will consider what I have presented as pure fantasy, if not somewhat crazy. But, unfortunately, a socalled “reasonable” way of thinking can never portray the human being in actuality. We must develop a new and expanded rationality for these matters. In this connection, it is extraordinary how people view anthroposophy today. They cannot imagine that anything exists that transcends their powers of comprehension, but that those same powers can in fact eventually reach.

Recently, I read a very interesting book by Maeterlinck translated into German. There was a chapter about me, and it ended in an extraordinary and very amusing way. He says: “If you read Steiner’s books you will find that the early chapters are logically correct, intelligently thought-out and presented in a perfectly scientific form. But as you read on, you get the impression that the author has gone mad.” Maeterlinck, of course, has a perfect right to his opinions. Why should he not have the impression that the writer was a clever man when he wrote the first part of the book, but went mad when he wrote the later part? But simply consider the actual situation. Maeterlinck believes that in the first chapters of these books the author was clever, but in the last chapters he had gone mad. So we get the extraordinary fact that this man writes several books, one after the other. Consequently, in each of these books the first few chapters make him seem very smart, but in later chapters he seems mad, then clever again, then mad, and so on. You see how ridiculous it is when one has such a false picture. When writers—otherwise deservedly famous—write in such a way, people fail to notice what nonsense it is. This shows how hard it is, even for such an enlightened person as Maeterlinck, to reach reality. On the firm basis of anthroposophy we have to speak of a reality that is considered unreal today.

I-being and the Genius of Language

Now we come to the I-being. Just as the astral body can be investigated through music, the true nature of the I-being can be studied through the word. It may be assumed that everyone, even doctors and teachers, accepts today’s form of language as a finished product. If this is their standpoint, they can never understand the inner structure of language. This can be understood only when you consider language, not as the product of our modern mechanism, but as the result of the genius of language, working vitally and spiritually. You can do this when you attempt to understand the way a word is formed.

There is untold wisdom in words, way beyond human understanding. All human characteristics are expressed in the way various cultures form their words, and the peculiarities of any nation may be recognized in their language. For example, consider the German word Kopf (“head”). This was originally connected with the rounded form of the head, which you also find in the word Kohl (“cabbage”), and in the expression Kohlkopf (“head of cabbage”). This particular word arises from a feeling for the form of the head. You see, here the I has a very different concept of the head from what we find in testa, for example, the word for “head” in the Romance languages, which comes from testifying, or “to bear witness.” Consequently, in these two instances, the feelings from which the words are formed come from very different sources.

If you understand language in this inward way, then you will see how the I-organization works. There are some districts where lightning is not called Blitz but Himmlitzer. This is because the people there do not think of the single flashes of lightning so much as the snakelike form. People who say Blitz picture the single flash and those who say Himmlitzer picture the zig-zag form. This then is how humans really live in language as far as their I is concerned, although in the current civilization, they have lost connection with their language, which has consequently become something abstract. I do not mean to say that if you have this understanding of language you will already have attained inward clairvoyant consciousness, whereby you will be able to behold beings like the human I. But you will be on the way to such a perception if you accompany your speaking with inner understanding.

Thus, education in medical and teacher training colleges should be advanced as indicated, so that the students’ training may arouse in them an inner feeling for space, an inner relationship to music, and an inner understanding of language. Now you may argue that the lecture halls are already becoming empty and, ultimately, teacher training colleges will be just as empty if we establish what we’ve been speaking of. Where would all this lead to? Medical training keeps getting longer and longer. If we continue with our current methods, people will be sixty by the time they are qualified!

The situation we are speaking of is not due in any way to inner necessity but is related to the fact that inner conditions are not being fulfilled. If we fail to go from abstractions to plastic and musical concepts and to an understanding of the cosmic word—if we stop short at abstract ideas—our horizon will be endless; we will continue on and on and never come to a boundary, to a point where we can survey the whole. The understanding that will come from understanding sculpting and music will make human beings more rational—and, believe me, their training will actually be accelerated rather than delayed. Consequently, this inner course of development will be the correct method of training educators, and not only teachers, but those others who have so much to contribute to educational work—the doctors.

The Therapeutic Nature of Teaching

Given what I spoke of in the introductory lectures concerning the relationship between educational methods and the physical health of children, it should be clear to you that real education cannot be developed without considering medicine. Teachers should be able to assess various conditions of health or disease among their children. Otherwise, a situation will arise that is already being felt—that is, a need for doctors in the schools. The doctor is brought in from outside, which is the worst possible method we could adopt. How do such doctors stand in relation to the children? They do not know the children, nor do they know, for example, what mistakes the teachers have made with them, and so on. The only way is to cultivate an art of education that contains so much therapy that the teacher can continually see whether the methods are having a good or bad influence on the children’s health. Reform is not accomplished by bringing doctors into the schools from outside, no matter how necessary this may seem to be. In any case, the kind of training doctors get these days does not prepare them for what they must do when they are sent into the schools.

In aiming at an art of education we must provide a training based on knowledge of the human being. I hesitate to say these things because they are so difficult to comprehend. But it is an error to believe that the ideas of natural science can give us full understanding of the human being, and an awareness of that error is vital to the progress of the art of education. Only when we view children from this perspective do we see, for example, the radical and far-reaching changes that occur with the coming of the second teeth, when the memory becomes a pictorial memory, no longer related to the physical body but to the etheric body. In actuality, what is it that causes the second teeth? It is the fact that, until this time, the etheric is almost completely connected with the physical body; and when the first teeth are forced out, something separates from the physical body. If this were not the case, we would get new teeth every seven years. (Since people’s teeth decay so quickly nowadays, this might seem to be a good thing, and dentists would have to find another job!) When the etheric body is separated, what formerly worked in the physical body now works in the soul realm.

If you can perceive these things and can examine the children’s mouths without their knowledge, you will see for yourself that this is true. It is always better when children do not know they are being observed. Experimental psychology so often fails because children are aware of what is being done.

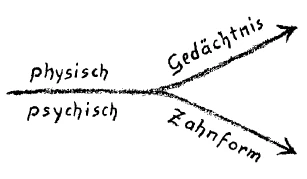

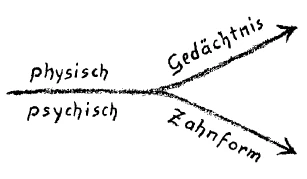

You can examine a child’s second teeth and find that they have been formed by the etheric body into a modeled image of the memory; and the shape of the teeth created by the etheric will indicate how the memory of the child will develop. Except for slight alterations in position here or there, you cannot physically change the second teeth once they are through—unless you are able to go so far as, for example, the dentist Professor Romer. He has written a book on dentistry—a new art of medicine based on anthroposophic principles—where he speaks of certain changes that can be effected even after the second teeth are established. But this need not concern us further.

When the etheric body is loosened and exists on its own after the change of teeth, the building of memory leaves the physical realm and remains almost entirely in the element of soul; indeed, this fact can put teachers on the right track. Before this change, the soul and spirit formed a unity with the physical and etheric. After this, the physical—previously acting in conjunction with the soul—is expressed as the second teeth, and what collaborated with the physical in this process separates and manifests as an increased power to form ideas and as the formation and reliability of memory.

Once you have acquired such insight into human nature, you will discover much that will help in your teaching. You must permeate yourselves with this spiritual knowledge of the human being and enliven it in yourselves; your observations of children will then inspire you with ideas and methods for teaching, and this inner inspiration and enthusiasm will penetrate your practical work. The rules established in introductory texts on education produce only abstract activity in the soul. But what arises from anthroposophic knowledge penetrates the will and the efforts of teachers; it becomes the impulse for everything done in the classroom.

A living knowledge of the human being brings life and order to the soul of a teacher. But if teachers study only teaching methods that arise from natural science, they may get some clever ideas of what to do with the children, but they will be unable to carry them out. A teacher’s skill and practical handling of children must arise from the living spirit within, and this is where purely scientific ideas have no place. If teachers can acquire a true knowledge of the human being, they will become aware of how, when the etheric body is freed at the change of teeth, the child has an inner urge to receive everything in the form of images. The child’s own inner being wants to become “image.” During the first stage of life, impressions lack this picture-forming tendency; they are transformed instead into habits and skills in the child; memory itself is habit and skill.

Children want to imitate, through the movement of the limbs, everything they see happening around them; they have no desire to form any inner images. But after the change of teeth, you will notice how children come to know things very differently. Now they want to experience pictures arising in the soul; consequently, teachers must bring everything into a pictorial element in their lessons. Creating images is the most important thing for teachers to understand.

Teaching Writing and Reading

When we begin to view the facts, however, we are immediately faced with certain contradictions. Children must learn to read and write, and when they come to school we assume they will first learn to read, and after that they will learn to write in connection with their reading. Let’s consider, however, the reality of letters—what it means when we take a pen to paper and try to express through writing what is in the mind. What is the relationship between the printed letters of today and the original picture-language of ancient times? How were we taught these things? We show children a capital A and a lowercase a, but what in the world do these letters have to do with the sound “ah”? There is no relationship at all between the form of the letter A and the sound “ah.”

When the art of writing arose, things were different. In certain areas, pictorial signs were used, and a kind of pictorial painting was employed. Later, this was standardized; but originally those drawings copied the process and feeling of the sounds; thus, what appeared on paper was, to some extent, a reproduction of what lived in the soul. Modern characters, however, are alien to a small child’s nature, and it is little wonder that when certain early peoples first saw printed letters, it had a peculiar effect on them. When the people of Europe came among the Native Americans and showed them how they expressed their thoughts on paper, the Native Americans were alarmed and considered it the work of the devil; they were afraid of the little demons lurking behind those written letters. They immediately concluded that the Europeans engaged in black magic, since people have a habit of attributing to black magic whatever they cannot understand.

But what is the truth of the matter? We know that when we utter the sound “ah,” we express wonder and admiration. Now, it is very natural to try to reproduce this sound with the whole body and express it in a gesture of the arms. If you copy this gesture (stretching the arms obliquely above the head) you get the capital A. When you teach writing, you can, for example, begin with a feeling of wonder, and proceed with the children to some kind of painting and drawing, and in this way you can bring their inner and outer experiences into that painting and drawing.

Consider another example. I tell a girl to think of a fish and ask her to paint it (awkward though this may be). It must be done in a particular way, not simply as she might prefer, but with the head of the fish in front, like this, and the rest of the fish here. The child paints the fish, and thus, through a kind of painting and drawing, she produces a written character. You then tell her to pronounce the word fish—“fish.” Now take away the ish, and from fish you have arrived at her first written letter, f.

In this way a child will come to understand how pictorial writing arose, and how it developed into contemporary writing. The forms were copied, but the pictures were abandoned. This is how drawing the various sounds arose. You do not need to make a special study of how such things evolved. This is not really necessary for teachers, since they can develop them out of their own intuition and power to think. Have a boy, for example, paint the upper lip of a mouth, and then pronounce the word mouth. Leave out the outh, and you get the m. In this way you can relate all the written characters to some reality, and the child will constantly develop a living, inner activity.

Thus, you should teach the children writing first, and let today’s abstract letters arise from tangible reality; when a child learns to write in this way, the whole being is engaged in the process. Whereas, if you begin with reading, then only the head organization participates in an abstract way. In writing, the hand must participate as well, and in this way the whole human being is aroused to activity. When you begin with writing—writing developed through the formation of images and drawing forms—your teaching will approach the child’s whole being. Then you can move on to teaching reading; and what was developed out of the child’s whole being through drawing can be understood by the head. This method of teaching writing and reading will naturally take longer, but it will have a far healthier effect on the whole earthly life from birth to death. These things can be done when the practical work of the school flows out of a real spiritual knowledge of the human being. Such knowledge can, through its own inner force, become the teaching method in our schools. The desires of those who earnestly seek a new art of education live in this; but its essence can be truly found only when we are unafraid to look for a full knowledge of the human being in body, soul, and spirit.

Dritter Vortrag

Daß es sich darum handelt für einen Erzieher und Unterrichtenden, die Aufmerksamkeit vor allen Dingen zu lenken auf solche Lebensumschwünge, Lebensmetamorphosen, wie sie mit dem Zahnwechsel und der Geschlechtsreife eintreten, darauf habe ich schon in den verflossenen Vorträgen wiederholt hingewiesen. Die Aufmerksamkeit bei diesen Dingen wird gewöhnlich dadurch nicht voll entfaltet, weil man eben heute gewöhnt ist, die groben äußeren Offenbarungen der menschlichen Natur nach sogenannten Naturgesetzen allein ins Auge zu fassen, während dasjenige, was für den Erzieher in Betracht kommt, von dem innersten Mittelpunkt, vom innersten Zentrum des Menschen heraus wirkt, und auch wiederum dasjenige, was der Erzieher tut, in das innerste Zentrum des Menschen hineinwirkt. Und so ist es notwendig, daß man bei diesem Lebensumschwung, der mit dem Zahnwechsel eintritt, ganz besonders darauf aufmerksam wird, wie da das Seelische selbst ein ganz anderes wird.

Man braucht nur eine Einzelheit aus diesem Gebiet des Seelischen einmal recht ins Auge zu fassen: die Gedächtnis-, die Erinnerungsfähigkeit. Dieses Gedächtnis, diese Erinnerungsfähigkeit ist im Grunde genommen bei dem Kinde bis zum Zahnwechsel etwas ganz anderes als später. Nur sind beim Menschen die Übergänge natürlich langsam und allmählich, und ein solcher einzelner fixierter Zeitpunkt, der ist sozusagen nur der annähernde. Aber das, was vorgeht, das muß doch, weil sich dieser Zeitpunkt sozusagen in die Mitte der Entwickelung hineinstellt, ganz intensiv berücksichtigt werden. Wenn man nämlich das am ganz kleinen Kinde beobachtet, findet man, daß sein Gedächtnis, seine Erinnerungsfähigkeit eigentlich das ist, was man nennen könnte ein gewohnheitsmäßiges Verhalten der Seele. Wenn das Kind sich an etwas erinnert innerhalb der ersten Lebensepoche bis zum Zahnwechsel, so ist dieses Erinnern eine Art Gewohnheit oder Geschicklichkeit; so daß man sagen kann: Wie ich gelernt habe, irgendeine Verrichtung zu erreichen, zum Beispiel zu schreiben, so tue ich sehr vieles aus einer gewissen Geschmeidigkeit meiner physischen Organisation heraus, die ich mir allmählich angeeignet habe. - Oder beobachten Sie einen Menschen, wie er irgend etwas angreift in seinem kindlichen Alter, so werden Sie sehen, daß daran der Begriff der Gewohnheit gewonnen werden kann. Man kann die Art und Weise sehen, in die sich der Mensch hineingefunden hat, seine Glieder in der einen oder anderen Art zu bewegen. Das wird Gewohnheit, das wird Geschicklichkeit. Und so wird bis in die feinere Organisation des Kindes hinein Geschicklichkeit das Verhalten der Seele gegenüber dem, was das Kind getan hat aus der Nachahmung heraus. Es hat heute irgend etwas nachahmend getan, macht es morgen, übermorgen wieder, macht es nicht nur in bezug auf die äußeren körperhaften Verrichtungen, sondern macht es bis in das innerste Wesen des Körpers hinein. Da wird Gedächtnis daraus. Es ist nicht wie das, was später, nach dem Zahnwechsel, Gedächtnis ist. Nach dem Zahnwechsel gliedert sich das Geistig-Seelische ab von dem Körper, emanzipiert sich, wie ich früher schon gesagt habe. Dadurch kommt erst das zustande, daß ein unkörperlicher Bildinhalt, eine Bildgestaltung des seelisch Erlebten im Menschen entsteht. Und immer wieder, wenn der Mensch entweder äußerlich herantritt an dasselbe Ding oder denselben Vorgang, oder wenn eine innerliche Veranlassung ist, das Bild als solches hervorzurufen, so wird dieses Bild als solches hervorgerufen. Das Kind hat für sein Gedächtnis kein Bild, es rückt noch nicht ein Bild heraus. Nach dem Zahnwechsel tritt ein erlebter Begriff, eine erlebte Vorstellung als erinnerter Begriff, als erinnerte Vorstellung wieder auf; vor dem Zahnwechsel lebt man in Gewohnheiten, die nicht innerlich verbildlicht werden. Das hängt zusammen mit dem ganzen Leben des Menschen über dieses Lebensalter des Zahnwechsels hinaus.

Wenn man mit denjenigen Mitteln des inneren Anschauens, des Seelenauges, des Seelengehörs, von denen gestern gesprochen wurde, den Menschen in seinem Werden beobachtet, dann sieht man, wie der Mensch nicht nur besteht aus diesem physischen Leib, den äußere Augen sehen, den Hände greifen können, wie er besteht aus übersinnlichen Gliedern. Ich habe schon gestern aufmerksam gemacht auf den ersten übersinnlichen Menschen sozusagen im physisch-sinnlichen Menschen drin: das ist der ätherische Mensch. Wir haben aber weiter ein drittes Glied der menschlichen Natur - man braucht sich nicht an Ausdrücken zu stoßen, eine Terminologie muß überall vorhanden sein -, wir haben den astralischen Leib des Menschen, der die Empfindungsfähigkeit entwickelt. Die Pflanze hat noch einen ätherischen Leib; das Tier hat einen astralischen Leib mit dem Menschen gemein, es hat Empfindungsfähigkeit. Der Mensch hat als Krone der Erdenschöpfung, als Geschöpf, das einzig dasteht, als viertes Glied die Ich-Organisation. Diese vier Glieder der menschlichen Natur sind nun total voneinander unterschieden. Aber sie werden nicht unterschieden in der gewöhnlichen Beobachtung, weil sie ineinander wirken, und weil eigentlich die gewöhnliche Beobachtung nur bis an irgendeine Offenbarung der menschlichen Natur aus der ätherischen Leibesorganisation, der astralischen oder der Ich-Organisation kommt. Ohne daß man diese Dinge wirklich kennt, ist eigentlich ein Unterrichten und Erziehen doch nicht möglich. Man entschließt sich sogar schwer, heute einen solchen Satz auszusprechen, weil er für die weitesten Kreise der heutigen zivilisierten Menschen grotesk wirkt, paradox wirkt. Aber es ist eben die Wahrheit; es läßt sich, wenn wirkliche unbefangene Menschenerkenntnis erworben wird, nichts gegen eine solche Sache einwenden.

Nun ist gerade das besonders eigentümlich, wie die menschliche Natur wirkt durch die ätherische, astralische und die Ich-Organisation. Das ist für das Erziehen und Unterrichten ins Auge zu fassen. Wie Sie wissen, lernen wir den physischen Leib kennen, wenn wir solche Beobachtungen entfalten, wie wir sie gewohnt sind am lebenden Menschen oder noch am Leichnam, und wenn wir benützen den an die Gehirnorganisation gebundenen Verstand, mit dem wir uns zurechtlegen dasjenige, was wir durch die Sinne wahrnehmen. Aber so lernt man nicht die höheren Glieder der menschlichen Natur kennen. Die entziehen sich der bloßen Sinnesbeobachtung wie auch dem Verstande. Mit einem Denken, das in den gewöhnlichen Naturgesetzen lebt, kann man zum Beispiel dem ätherischen Leibe nicht beikommen. Daher müßten in die Seminarbildung und in die Universitätsbildung nicht nur diejenigen Methoden aufgenommen werden, die den Menschen befähigen, lediglich den physischen Leib zu beobachten und mit einem Verstande zu beobachten, der an das Gehirn gebunden ist; sondern es müßte, damit eine gewisse Fähigkeit einträte, wirklich hinzuschauen auf die Art und Weise, wie sich zum Beispiel der Ätherleib im Menschen zeigt, eine ganz andere Art von Seminar- und Universitätsbildung da sein. Die wäre notwendig sowohl für den Lehrer auf allen Gebieten, wie namentlich auch für den Mediziner. Und die würde zunächst darin bestehen, daß man lernt, wirklich von innen heraus, aus der Entfaltung der menschlichen Natur heraus bildhauerisch zu modellieren, so daß man in die Lage käme, Formen aus ihrer inneren Gesetzmäßigkeit heraus zu schaffen. Sehen Sie, die Form eines Muskels, die Form eines Knochens wird nicht begriffen, wenn man sie so begreifen will, wie man es in der heutigen Anatomie und Physiologie tut. Formen werden erst begriffen, wenn man sie aus dem Formensinn heraus begreift. Ja, da tritt aber sogleich etwas ein, was für den Menschen der Gegenwart so ist, daß man es für halben Wahnsinn ansieht. Aber für den Kopernikanismus war es auch einmal so, daß er für halben Wahnsinn angesehen wurde, und eine gewisse Kirchengemeinschaft hat bis zum Jahre 1828 die kopernikanische Lehre als etwas Unsinniges angesehen, was verboten werden muß den Gläubigen. — Es handelt sich um das Folgende.

Betrachten wir den physischen Leib: er ist zum Beispiel schwer, er wiegt etwas, er ist der Schwerkraft unterworfen. Der ätherische Leib ist nicht der Schwerkraft unterworfen; im Gegenteil, er will fortwährend fort, er will sich in die Weiten des Weltalls zerstreuen. Das tut er auch unmittelbar nach dem Tode. Die erste Erfahrung nach dem Tode ist, die Zerstreuung des Ätherleibes zu erfahren. Man erfährt also, daß der Leichnam ganz den Gesetzen der Erde folgt, wenn er dem Grabe übergeben wird; oder wenn er verbrannt wird, verbrennt er so, wie jeder andere Körper verbrennt nach physischen Gesetzen. Beim ätherischen Leib ist das nicht der Fall. Der ätherische Körper strebt ebenso von der Erde weg, wie der physische Körper nach der Erde hinstrebt. Und dieses Wegstreben, das ist nicht ein beliebiges Wegstreben nach allen Seiten hin oder ein gleichförmiges Wegstreben. Aber da kommt das, was grotesk wirkt, was aber wahr ist, was eine wahre Wahrnehmung ist für die Beobachtung, von der ich gesprochen habe.

Wenn Sie den Umkreis der Erde nehmen: wir finden da draußen eine Sternansammlung, da wieder eine andere Sternansammlung, da eine, die wieder anders ist, und so sind überall bestimmte Sternansammlungen. Diese Sternansammlungen, die sind es, die den Ätherleib des Menschen anziehen, die ihn hinausziehen in die Weiten. Nehmen wir an, er wäre da — schematisch gezeichnet -, dann wird der Ätherleib von dieser Sternansammlung, die stark wirkt, angezogen; er will stark hinaus. Von dieser Sternansammlung wird er weniger stark angezogen, von anderen Sternansammlungen wird er wieder anders angezogen, so daß der Ätherleib nicht nach allen Seiten gleich gezogen wird, sondern nach den verschiedenen Seiten wird er verschieden gezogen. Es entsteht nicht eine sich ausbreitende Kugel, sondern indem der Ätherleib sich ausbreiten will, entsteht dasjenige, was durch die von den Sternen ausgehenden kosmischen Kräfte an einer bestimmten Form des Menschen gewirkt werden kann, solange wir leben auf Erden und den Ätherleib in uns tragen. Wir sehen, wie in einem Oberschenkel dasjenige, was den Muskel formt, aus den Sternen heraus, ebenso das, was den Knochen formt, aus den Sternen heraus kommt. Man muß nur kennenlernen, wie aus den verschiedensten Richtungen des Weltenraumes her Formen entstehen können. Man muß das Plastilin nehmen können und eine Form bilden können, bei der, sagen wir, die kosmische Kraft in die Länge wirkt, aber bei einer bestimmten Kraft so, daß sich eine Form früher abrundet als bei anderen Kräften. Man bekommt bei den Formen, die früher sich abrunden, den runden Knochen, bei den anderen einen Röhrenknochen.

Und so muß man eigentlich als Bildhauer ein Gefühl entwickeln für die Welt. Dieses Gefühl war schon ursprünglich in einem instinktiven Bewußtsein der Menschheit vorhanden. Und wir können es, während es im Orientalismus der vorhistorischen Jahrtausende ganz deutlich ausgesprochen war, auch noch im Griechentum verfolgen. Denken Sie nur, wie die heutigen naturalistischen Künstler oftmals verzweifelt sind gegenüber den Formen der griechischen Menschen in der Bildhauerei. Warum sind sie verzweifelt? Weil sie glauben, die Griechen haben nach Modellen gearbeitet. Sie haben den Eindruck, man habe dort bei den Griechen den Menschen nach allen Seiten beobachten können. Aber die Griechen hatten noch das Gefühl, wie der Mensch aus dem Kosmos heraus kommt, wie der Kosmos selber den Menschen formt. Die Griechen haben, wenn sie eine Venus von Milo gemacht haben, die die heutigen Bildhauer zur Verzweiflung bringt, das, was aus dem Kosmos heraus kommt, was nur etwas gestört wird durch die irdische Bildung, das hatten sie zum Teil wenigstens in die menschliche Organisation hineinverlegt. So handelt es sich darum, daß man einsehen muß: Will man den Menschen der Natur nachschaffen, so kann man gar nicht sich sklavisch halten an die Modelle, wie man Modelle heute in Ateliers hineinstellt und den Menschen sklavisch danach formt. Man muß sich wenden können an den großen kosmischen Plastiker, der die Form aus dem heraus erschafft, was dem Menschen werden kann als Raumgefühl. Das muß erst entwickelt werden: Raumgefühl!

Da glaubt man eigentlich gewöhnlich, man kann eine Linie durch den Menschen durchziehen, eine Linie durch die ausgebreiteten Arme so und eine Linie so ziehen (es wird gezeichnet). Das sind die drei Raumesdimensionen. Man zeichnet ganz sklavisch den Menschen in die drei Raumesdimensionen. Das ist alles Abstraktion. Wenn ich durch den Menschen eine richtige Linie ziehe, habe ich ganz andere Zugkräfte so, ganz andere so und so, überall in den Raum hinein. Dieser geometrische Raum, der der Kantische Raum geworden ist, über den Kant so unglückliche Definitionen und Theorien gegeben hat, ein rein ausgedachtes Hirngespinst, ist in Wirklichkeit ein Organismus, der nach allen Seiten andere Kräfte hat. Weil der Mensch nur die groben Sinne entwickelt, deshalb entwickelt er nicht dieses feine Raumgefühl. Das kann man nach allen Seiten haben. Läßt man es walten, dann kommt wirklich der Mensch zustande. Aus dem innerlichen Erfühlen heraus kommt der Mensch zustande bildhauerisch. Und hat man ein Gefühl für dieses tastende Behandeln der weichen plastischen Masse, dann liegt in diesem Behandeln der weichen plastischen Masse die Bedingung für das Verstehen des Ätherleibes, so wie in dem Verstande, der an das Gehirn gebunden ist, und den Sinnesorganen die Bedingungen für das Verstehen des physischen Leibes liegen.

Es handelt sich darum, daß man erst die Erkenntnismethode schaffen muß: nämlich plastische Anschauung, die immer etwas verbunden ist mit plastischer innerer Tätigkeit. Sonst hört die Menschenerkenntnis beim physischen Leibe auf, denn der Ätherleib ist nicht in Begriffen, sondern in Bildern zu erfassen, die man doch nur begreift, wenn man sie in gewisser Weise nachformen kann, wie sie aus dem Kosmos heraus sind.

Dann kommen wir zu dem, was das nächste Glied der menschlichen Wesenheit ist. Wie gehen die Dinge heute? Da sind auf der einen Seite die herrschenden naturwissenschaftlichen Anschauungen und ihre Träger, die der heutigen Menschheit autoritativ das Richtige beibringen. Da stehen vereinsamt in der Welt ihrer Seelen verdrehte Anthroposophen, die auch davon sprechen, daß ein Ätherleib, ein Astralleib vorhanden ist. Sie erzählen die Dinge, die über den Ätherleib und den Astralleib zu erzählen sind. Da wollen die Leute, die gewöhnt sind an naturwissenschaftliches Denken, den Astralleib mit demselben Denken und denselben Methoden ergreifen wie den physischen Leib. Das geht nicht. Der Astralleib äußert sich im physischen Leibe; seine Außerung im physischen Leibe kann nach Naturgesetzen begriffen werden. Aber ihn selber nach seiner inneren Wesenheit und Wirksamkeit kann man nicht nach Naturgesetzen begreifen. Man kann den Astralleib begreifen, wenn man nicht nur äußeres, sondern inneres Musikverständnis hat, wie es auch vorhanden war im Orient, abgedämpft in der griechischen Zeit, in neuerer Zeit gar nicht mehr vorhanden ist. Geradeso wie der ätherische Leib aus der kosmischen Plastik heraus wirkt, so wirkt der astralische Leib aus der kosmischen Musik, aus kosmischen Melodien heraus. Im astralischen Leib ist irdisch nur der Takt; Rhythmus und Melodie wirken ganz aus dem Kosmos heraus. Und der astralische Leib besteht in Rhythmus und Melodie. Man kann nur nicht mit dem an den astralischen Leibherankommen, was man aus Naturgesetzen gewonnen hat, sondern man muß mit dem an den astralischen Leib herankommen, was man sich aneignet, wenn man ein inneres Musikverständnis hat. Dann wird man zum Beispiel finden, wenn eine Terz angeschlagen wird: Da ist etwas vorhanden, was vom Menschen erlebt, empfunden wird wie in seinem Inneren. Daher kann es da noch geben eine große und eine kleine Terz. So kann im menschlichen Gefühlsleben durch diese Gliederung der Skala ein beträchtlicher Unterschied hervorgerufen werden. Das ist noch etwas Inneres. Wenn wir zur Quint kommen, wird diese erlebt an der Oberfläche; das ist gerade eine Grenze des Menschen; da fühlt sich der Mensch, wie wenn er gerade noch darinnensteckte. Kommt er zur Sext oder zur Septime, dann fühlt er, wie wenn die Sext oder Septime außer ihm verlaufen will. Er geht in der Quint aus sich heraus, und er kommt, indem er in die Sext und Septime hineinkommt, dahin, daß er das, was da vorgeht in Sext oder Septime, als etwas Äußeres empfindet, während er die Terz als etwas eminent Inneres empfindet. Das ist der wirkende Astralleib, der ein Musiker in jedem Menschen ist, der die Weltenmusik nachahmt. Und alles, was im Menschen ist, ist im Menschen wiederum tätig und bildet sich aus in der menschlichen Form. Das ist etwas, was dann, wenn man einmal überhaupt herankommt an eine solche Betrachtung, geradezu erschütternd wirken kann im Begreifen der Welt.

Sehen Sie, das, was aus dem astralischen Leib in die Form übergeht, was aber nicht schon in der kosmischen Plastik begründet wird, sondern dadurch entsteht, daß der Musikimpuls vom Astralleib aus den Menschen durchzieht, das kann man auch direkt studieren, nur muß man mit Musikverständnis dem Menschen entgegenkommen wie vorher mit plastischem Verständnis, wenn man die Wirkungen des Ätherleibes studieren will. Wenn Sie den Teil des menschlichen Organismus nehmen, der von den Schulterblättern an beginnt und bis zu den Armen hin geht, so ist das eine Wirkung der im Menschen lebendigen Prim, des Grundtones; und kommen Sie zur Sekund, so ist diese im Oberarm gelegen. Die Dinge kommen durch Eurythmie zum Vorschein. Gehen wir zum Unterarm, so haben wir die Terz, haben wir in der Musik die große und die kleine Terz. Indem wir vorrücken bis zum Terzintervall, bekommen wir zwei Knochen im Unterarm; das geht so weiter selbst bis hinein in die Finger. Das sieht phrasenhaft aus; es ist aber durch eine wirkliche geisteswissenschaftliche Beobachtung des Menschen so fest zu durchschauen, wie für den Mathematiker das mathematische Problem zu durchschauen ist. Es ist nicht etwas, was durch schlechte Mystik herbeigeführt wird, sondern es ist exakt zu durchschauen. So daß, um diese Dinge zu begreifen, die Seminar- und Medizinbildung eigentlich von einem inneren Musikverständnis ausgehen müßte, von jenem inneren Musikverständnis, das in voller Besonnenheit wieder zu dem kommen muß, was selbst vor dem Griechentum das orientalische Musikverständnis war. Orientalische Baukunst begreifen wir nur, wenn wir begreifen, wie die religiöse Wahrnehmung in die Form hineingeschossen ist. Wie die musikalische Kunst nur in zeitlichen Erfahrungen sich ausdrückt, so die Baukunst in räumlichen. Den Menschen muß man seinem Ätherleib und seinem Astralleib nach ebenso begreifen. Und das Empfindungsleben, das Leben in Leidenschaft kann nicht begriffen werden, wenn man nach den Naturgesetzen, wie man sagt «psychologisch» begreifen will, sondern nur, wenn man mit denselben Seelenformen an den Menschen herangeht, die man im Musikalischen gewahrt. Es wird eine Zeit kommen, wo man nicht so sprechen wird, wie die heutigen Psychologen oder Seelenlehrer über irgendeine krankhafte Empfindung sprechen, sondern, wenn eine krankhafte Empfindung vorliegt, wird man so sprechen wie gegenüber einem verstimmten Klavier: in musikalischer Ausdrucksweise.

Glauben Sie nicht, daß die Anthroposophie nicht selber einsehen kann, wo die Schwierigkeit ihres Erfassens in der Gegenwart liegt; ich kann durchaus begreifen, daß es viele Menschen gibt, die so etwas, wie ich es da dargestellt habe, zunächst für phantastisch, ja für halb wahnsinnig halten. Aber mit dem, was heute vernünftig ist, ist eben leider der Mensch nicht zu begreifen, sondern man muß schon hinausgehen zu einem weiteren Vernünftigsein.

In dieser Beziehung sind die Menschen heute ganz merkwürdig, wie sie entgegenkommen der Anthroposophie. Sie können sich gar nicht vorstellen, daß etwas über ihr Fassungsvermögen vorläufig hinausgeht, und daß ihr Fassungsvermögen in Realität daran nicht herankommen kann. Jüngst habe ich da ein sehr interessantes Buch gesehen. Maeterlinck hat ein Buch geschrieben, es ist auch deutsch erschienen, und da ist auch ein Kapitel über mich, und das schließt in merkwürdiger Weise und auch furchtbar humoristisch. Er sagt: Wenn man die Steinerschen Bücher liest, so sind die ersten Kapitel logisch korrekt, durchaus verständig abgewogen und wissenschaftlich gestaltet. Dann aber kommt man, wenn man über die ersten Kapitel hinausliest, in etwas hinein, wo man sich denken muß, daß der Verfasser wahnsinnig geworden ist. — Das ist das gute Recht Maeterlincks. Warum soll er nicht den Eindruck haben können: Der ist ein Gescheiter, während er die ersten Kapitel geschrieben hat, er ist verrückt geworden, während er die folgenden Kapitel geschrieben hat. — Aber nun nehmen Sie die Realität dazu. Nun, Maeterlinck findet, daß in den Büchern die ersten Kapitel gescheit sind, in den folgenden Kapiteln wird der Verfasser wahnsinnig. Nun muß die merkwürdige Tatsache da sein: Er schreibt hintereinander Bücher, und bei den ersten Kapiteln macht er sich gescheit, bei den folgenden macht er sich wahnsinnig, dann wieder gescheit, dann wieder wahnsinnig und so weiter. Denken Sie, wie grotesk, wenn man so absieht von der Realität. Die Leute merken es gar nicht, wenn es solche mit Recht berühmte Schriftsteller schreiben, was für Wahnsinn darin steckt. Gerade an so erleuchteten Geistern wie Maeterlinck kann man studieren, wie schwer es ist, heute an die Wirklichkeit heranzukommen. Man muß auf dem Boden der Anthroposophie reden von einer Wirklichkeit, die heute als unwirklich angesehen wird.

Nun kommen wir auf die Ich-Organisation. Es handelt sich darum: Diese Ich-Organisation kann zunächst in ihrer Wesenhaftigkeit studiert werden - so wie der Astralleib in der Musik - in der Sprache. Also wird man sagen, alle, auch die Mediziner und Lehrer - bei den Lehrern wird dies schon zugegeben -—, müssen bei der heutigen Sprachformung stehenbleiben. Können sie dann auch die innere Konfiguration der Sprache verstehen? Nein, das kann nur derjenige, der die Sprache nicht als das ansieht, was unser Mechanismus daraus gebildet hat, sondern als etwas, in dem der Sprachgenius als etwas Lebendiges geistig wirkt. Der kann es, der sich übt, die Art und Weise zu verstehen, wie ein Wort konfiguriert wird. In den Worten liegt außerordentlich und ungeheuer viel von Weisheit. Der Mensch kommt dieser Weisheit gar nicht nach. Die ganze Eigentümlichkeit der Menschen kommt heraus in der Art und Weise, wie sie ein Wort bilden. Man kann die Eigenart der Völker aus der Sprache erkennen. Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel das Wort «Kopf». Das ist ursprünglich zusammenhängend mit dem Runden, das man auch am Kohl, den man auch Kohlkopf nennt, findet. Es wird aus der Gestalt heraus das Wort für den Kopf empfunden. Das ist eine ganz andere Verfassung des Ich, als zum Beispiel bei dem romanischen Worte «Testa», das von dem Zeugnisablegen, Testieren herkommt. Also aus ganz anderer Quelle heraus ist der Anlaß genommen worden, empfindungsgemäß das Wort zu bilden.

Wenn man in dieser inneren Weise die Sprache versteht, dann schaut man hinein, wie die Ich-Organisation wirkt. Es gibt Gegenden, in denen der Blitz nicht «Blitz» genannt wird, sondern «Himlizzer». Das sind Menschen, die Himlizzer sagen, die nicht das einfache schnelle Hinschießen des Blitzes, sonder das schlangenhaft Gegliederte sehen. Wer «Blitz» sagt, sieht das Hinschießen; wer «Himlizzer» sagt, sieht den Blitz in dieser Zickzackweise geformt. So lebt der Mensch seinem Ich nach eigentlich in der Sprache. Nur ist er als heutiger zivilisierter Mensch aus der Sprache herausgekommen; die Sprache ist abstrakt geworden. Ich sage nicht, daß derjenige, der so die Sprache versteht, schon inneres hellseherisches Bewußtsein hat, durch das er in Wesenheiten hineinschaut, die gleich sind der menschlichen Ich-Organisation; aber man kommt auf den Weg, in diese Wesenheiten hineinzuschauen, wenn man mit dem inneren Verstehen das Sprechen begleitet.

So soll sowohl an der medizinischen Schule wie an den Lehrerseminarien in der Richtung Bildung gepflegt werden, wie man sie haben muß, wenn man innerlich bestrebt ist, plastisch zu wirken, wenn Plastik aus dem Raumgefühl, inneres musikalisches Verständnis und inneres Sprachverständnis getrieben werden kann. Nun werden Sie sagen: Die Hörsäle sind ohnehin so leer, man machte am Ende die Seminarien schon auch noch so leer, wenn alles das hineinkäme. Wohin käme man da? — Man will das medizinische Studium fortwährend verlängern. Wenn das mit der Methode, wie es heute geschieht, fortgesetzt wird, wird es noch dazu führen, daß man im 60. Jahr fertig wird mit dem Medizinstudium! Das rührt nicht her von inneren Bedingungen, sondern davon, daß diese inneren Bedingungen nicht erfüllt sind. Geht man nicht über von abstrakten Begriffen zum plastischen Begreifen, zum musikalischen Begreifen, zum Weltenworte-Verstehen, dann wird, wenn man stehenbleibt beim abstrakten Begreifen, der Horizont ein unendlicher; man kann immer weiter gehen, weil man an keine Grenze kommt, von der aus man die Sache übersehen kann. Durch das innere Verständnis, das auftritt, wenn Plastik- und Musikbegreifen hinzukommt, wird der Mensch, weil er innerlich rationeller wird, in seinem Bildungsgang wahrhaftig nicht verzögert, sondern innerlich beschleunigt werden. So werden wir aus dem inneren Gang eine methodische Bildung der Pädagogen haben, wo die Lehrer und diejenigen gebildet werden, die in der heutigen Pädagogik ganz besonders mitzureden haben: die Ärzte.

Nachdem wir in den einleitenden Vorträgen gesehen haben, wie zusammenhängt mit dem ganzen Gesundheitszustand des Menschen die Art, wie erzogen und unterrichtet wird, ist es ohne weiteres klar, daß eine wirkliche Pädagogik gar nicht ohne eine Berücksichtigung einer wirklichen Medizin sich entwickeln kann. Es ist ganz unmöglich; der Mensch muß eben nach seinen gesunden und kranken Verhältnissen beurteilt werden können von demjenigen, der ihn erzieht und unterrichtet; sonst kommt dasjenige heraus, was man auch schon fühlt: Man fühlt schon, daß der Arzt notwendig ist in der Schule. Man fühlt es stark und schickt den Arzt von außen hinein. Aber das ist die schlechteste Methode, die man wählen kann. — Wie steht der Arzt zu den Kindern? Er kennt sie nicht; er kennt auch nicht die Fehler, die zum Beispiel vom Lehrer gemacht werden und so weiter. Die einzige Möglichkeit ist diese, daß man eine solche pädagogische Kunst betreibt, wo so viel Medizinisches drin ist, daß der Lehrer konstant die gesundenden oder kränkenden Wirkungen seiner Maßnahmen am Kinde einsehen kann. Aber wenn man von außen den Arzt in die Schule hineinschickt, dadurch ist noch keine Reform durchgeführt, auch wenn man sagt, der Arzt ist notwendig. Wenn die Bildung der Ärzte so ist wie heute, wissen die Ärzte nicht, was sie zu tun haben, wenn sie in die Schule hineingeschickt werden. In dieser Beziehung muß man einfach die Bildung kennenlernen, wenn man auf eine pädagogische Kunst hinstrebt, die auf der Grundlage der Menschheitserkenntnis steht. - Man scheut sich, indem man die Dinge ausspricht, aus dem Grunde, weil man weiß, wie schwer sie erfaßt und begriffen werden können. Aber gerade dieses zu glauben, daß man mit einigen aus der naturwissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung gewonnenen Begriffen den Menschen verstehen kann, ist ein Irrtum, und dieses einzusehen, ist eine der Lebensbedingungen in der Entwickelung der pädagogischen Kunst.

Erst wenn man solche Anschauungen hat, wird man einsehen können, wie radikal in die Menschennatur das eingreift, was zum Beispiel zur Zeit des Zahnwechsels geschieht, wenn eigentlich das Gedächtnis bildhaft wird, nicht mehr am physischen Leibe hängt, sondern nunmehr am ätherischen Leibe hängt. Denn welche Tatsache bringt eigentlich die zweiten Zähne hervor? Die Tatsache, daß bis zum Zahnwechsel der ätherische Leib dicht, ganz dicht mit dem physischen Leibe verbunden ist. Dann sondert er sich etwas ab; würde er sich nicht absondern, so würden wir alle 7 Jahre Zähne bekommen. Es wäre ja für den heutigen Menschen, der seine Zähne so rasch aufbraucht, ja schon notwendig; ich denke, die Zahnärzte würden schon eine andere Beschäftigung bekommen. Wenn der Ätherleib sich abgesondert hat, wirkt das, was früher im physischen Leib gewirkt hat, auf seelische Art. Für denjenigen, der solche Dinge betrachten kann, ist das der Fall, wenn er einem Kinde in den Mund schauen kann, ohne daß es das bemerkt. Es ist immer am besten, wenn es vom Kinde nicht bemerkt wird. Deshalb hat die Experimentalpsychologie so wenig Erfolg, weil sie vom Kinde so bemerkt wird. Man sieht die zweiten Zähne des Kindes: sie sind aus dem Ätherleib heraus gebildet und werden dann zum plastischen Bild des Gedächtnisses. An der Zahnkonfiguration kann man beobachten, was für ein Gedächtnis der Ätherleib veranlagt hat. Die Zähne kann man nicht anders machen; man kann da oder dort etwas abfeilen, aber man kann sie nicht anders machen. Etwas könnte man sie auch ändern, wenn die Medizin so gestaltet würde, wie sie Professor Römer gerade auf Grundlage anthroposophischer Einblicke, die er sich zu eigen gemacht hat, in seiner Schrift über Zahnheilkunde ausgesprochen hat — etwas könnte schon getan werden, wenn auch die zweiten Zähne gebildet sind. Aber sehen wir davon ab. Dasjenige, was im Seelischen hauptsächlich bleibt, die Gedächtnisbildung, das kann, abgesondert von dem, was physische Organisation ist, wenn der Ätherleib für sich ist, gerade den Erzieher und Unterrichtenden auf die richtige Fährte bringen. Nicht wahr, bis zum Zahnwechsel ist eine Einheit des Seelisch-Geistigen und des Physisch-Ätherischen da. Dasjenige, was physisch war und zusammengewirkt hat mit dem Psychischen, das kommt in der Zahnform zum Ausdruck. Was früher mitgebildet hat bei der Bildung der Zahnform, das sondert sich ab in idealer Steigerung der Kraft, wird Gedächtnisbildung, Gedächtnistreue und so weiter.

Wenn man so hineinsieht in die menschliche Natur, kann man vieles schauen und aufnehmen in das Erziehen und Unterrichten. Man wird vor allen Dingen, wenn man ganz lebendig durchdrungen ist von einer solchen Menschenerkenntnis, wenn man den Menschen anschaut, dasjenige bekommen als Didaktik und Pädagogik, was einen wirklich innerlich enthusiasmiert, was einen als Lehrer innerlich begeistert, was übergeht in die Handhabung. Das, was sich richtet nach Regeln, die in den pädagogischen Anleitungsbüchern stehen, ist eine abstrakte innere Tätigkeit der Seele; dasjenige, was man bekommt aus wirklicher anthroposophischer Menschenerkenntnis, das geht über in das Wirken, in das Wollen; das wird Impuls des Tatsächlichen, das der Lehrer vollbringt in der Klasse. Man wird seelisch organisiert als Lehrer durch eine lebendige Menschenerkenntnis, während man durch dasjenige, was aus bloßer naturwissenschaftlicher Weltanschauung hervorgeht, eben zwar sehr gescheit wissen kann, was man mit dem Kinde tun soll, aber es nicht kann, weil es nicht in die Geschicklichkeit und lebendige Handhabung des lebendigen Geistes seitens des physischen Lehrers hineingeht. Und kann man das in sich durch eine wirkliche Menschenerkenntnis beleben, dann merkt man, wie dieser Ätherleib wirklich frei wird nach dem Zahnwechsel, wie aus dem Inneren des Kindes heraus das Bedürfnis da ist, alles in Bildern zu empfangen, denn innerlich will es Bild werden. In der ersten Lebensepoche bis zum Zahnwechsel wollen die Eindrücke nicht Bild werden, sondern Gewohnheit, Geschicklichkeit; das Gedächtnis selber war Gewohnheit, Geschicklichkeit. Das Kind will mit seinen Bewegungen nachmachen, was es gesehen hat; es will nicht ein Bild entstehen lassen. Dann kann man beobachten, wie das Erkennen anders wird; dann will das Kind in sich etwas empfinden, was wirkliche seelische Bilder sind; daher muß man jetzt im Unterricht alles in die Bildhaftigkeit hineinbringen. Der Lehrer muß selber dieses Bildlichmachen von allem verstehen.

Da stoßen wir aber sogleich, wenn wir anfangen, die Tatsachen zu betrachten, auf Widersprüche. Dem Kinde soll das Lesen und Schreiben beigebracht werden; wenn es an die Schule herankommt, denkt man selbstverständlich, daß man mit dem Lesen beginnen muß und das Schreiben damit in Verbindung haben muß. Aber sehen Sie, was sind heute unsere Schriftzeichen, die wir mit der Hand auf das Papier machen, wenn wir schreiben, um den Sinn von etwas, was in unserer Seele lebt, auszudrücken? Und was sind unsere Lettern erst, die in Büchern stehen, zu einem ursprünglichen Bildempfinden? Wie wurden diese Dinge uns beigebracht? Was hat denn in aller Welt dieses Zeichen «A», das dem Kinde beigebracht werden soll, oder gar dieses Zeichen «a», was hat das in aller Welt zu tun mit dem Laut A? Zunächst gar nichts. Es ist kein Zusammenhang zwischen diesem Zeichen und dem Laute A. Das war in jenen Zeiten, in denen das Schriftwesen entstanden ist, etwas ganz anderes. Da waren in gewissen Gegenden die Zeichen bildhaft. Da wurde eine Art — wenn sie auch später konventionell geworden ist — bildhafter Malerei gemacht, Zeichnungen, die die Empfindung, den Vorgang in gewisser Weise nachahmten, so daß man wirklich auf dem Papier etwas hatte, was wiedergab dasjenige, was in der Seele lebte. Daher ist es ja gekommen, daß, als dann primitivere Menschen diese sonderbaren Zeichen - für die Kinder sind sie ja natürlich sonderbar -, die wir heute als Schriftzeichen haben, zu Gesicht bekamen, sie ganz eigentümlich auf sie gewirkt haben. Als die europäischen Zivilisierten bei den Indianern in Amerika ankamen, waren die Indianer ganz besonders betroffen über diese Zeichen, die da die Menschen auf das Papier machten, wodurch sie sich etwas vergegenständlichten. Die Indianer konnten das nicht begreifen; sie sahen das als Teufelswerk an, als kleine Dämonen. Wie Dämonen fürchteten sie diese kleinen Zeichen; sie hielten die Europäer für schwarze Magier. Immer, wenn man jemand nicht versteht, hält man ihn für einen schwarzen Magier.

Nun nehmen Sie die Sache so: Ich weiß, eine Verwunderung wird ausgedrückt, indem man ausbricht in den Laut A. Es ist nun etwas ganz Naturgemäßes, wenn der Mensch mit seiner vollen Körperlichkeit nachzumachen sucht dieses A und es so auszudrücken sucht mit dieser Geste der beiden Arme. Nun machen Sie das einmal nach. (Die beiden Arme schräg nach oben gehoben.) Da wird schon ein A daraus! Und wenn Sie ausgehen beim Kinde von der Verwunderung und anfangen den Unterricht zu geben in malendem Zeichnen, dann können Sie inneres Erlebnis und äußeres Erlebnis in malendes Zeichnen und zeichnendes Malen hineinbringen.

Denken Sie das Folgende: Ich erinnere das Kind an einen Fisch und veranlasse es, wenn das auch unbequem ist, den Fisch zu malen. Man muß da mehr Sorgfalt anwenden, als man sonst in bequemer Weise gern getan hätte. Man veranlaßt es, den Fisch so zu malen, daß es da den Kopf vor sich hat und da den übrigen Teil. Das Kind malt den Fisch; jetzt hat es ein Zeichen durch malendes Zeichnen, durch zeichnendes Malen herausgebracht. Nun lassen Sie es aussprechen das Wort «Fisch». Sie sprechen F-isch. Jetzt lassen Sie weg das isch. Sie haben von «Fisch» übergeleitet zu seinem ersten Laute «F». Jetzt versteht das Kind, wie zustande kommt so eine Bilderschrift, wie sie zustandegekommen ist und übergegangen ist in späterer Zeit in die Schrift.

Das ist nachgeahmt worden, das andere ist weggelassen worden. Dadurch entsteht das Zeichen des Lautes. Man braucht nicht Studien zu machen, um diese Dinge herauszufischen aus der Art und Weise, wie die Dinge sich entwickelt haben. Das ist nicht unbedingt notwendig für den Lehrer. Er kann es bloß, wenn er durch Intuition, ja mit Phantasie die Dinge entwickelt.

Er sieht zum Beispiel den Mund; versucht, daß die Kinder die Oberlippe malen, daß es zum Malen der Oberlippe kommt. Jetzt bringt man es dahin, das Wort «Mund» auszusprechen. Wenn man jetzt das «und» wegläßt, hat man das «M». So kann man aus der Wirklichkeit heraus die ganzen Schriftzeichen erhalten. Und das Kind bleibt in fortwährender Lebendigkeit. Da lehrt man das Kind zuerst schreiben, indem sich die abstrakten Zeichen der heutigen Zivilisation aus dem Konkreten heraus entwickeln. Wenn man das Kind so an das Schreiben heranbringt, ist es als ganzer Mensch dabei beschäftigt. Läßt man es gleich lesen, so wird die Kopforganisation auch nur abstrakt beschäftigt; man beschäftigt nur einen Teil des Menschen. Geht man zuerst an das Schreiben, so nimmt man die Hand mit; der ganze Mensch muß in Regsamkeit kommen. Das macht, daß der Unterricht, wenn er aus dem Schreiben hervorgeht — nämlich einem Schreiben, das aus zeichnendem Bilden, aus bildendem Zeichnen entwickelt wird -, an den ganzen Menschen herankommt. Dann geht man über zum Lesenlernen, so daß dann auch wirklich mit dem Kopfe verstanden werden kann, was aus dem ganzen Menschen heraus im zeichnenden Malen, im malenden Zeichnen entwickelt worden ist. Da wird man etwas länger brauchen zum Schreiben- und Lesenlernen; allein es ist dabei auch die viel gesundere Entwickelung für das ganze Erdenleben von der Geburt bis zum Tode berücksichtigt.

Das ist so, wenn die Handhabung des Unterrichtes fließt aus wirklicher Menschenerkenntnis. Die wird durch ihre eigene Kraft zur Methode in der Schule. Das ist es, was gerade heute in den Wünschen drinnen lebt, die sich nach einer anderen Erziehungskunst sehnen, was aber in seiner Wesenhaftigkeit nur gefunden werden kann, wenn man sich nicht scheut, auf eine volle Menschenerkenntnis nach Leib, Seele und Geist wirklich einzugehen.

Fragenbeantwortung

Frage: Sind krankmachende Wirkungen von Erziehungsfehlern im Erwachsenenalter zu überwinden?

Gewiß kann der Erwachsene Krankheitskeime, die ihm in der Kindheit anerzogen worden sind, überwinden; aber es handelt sich doch eigentlich darum, daß diese Arbeit dem Erwachsenen erspart werden kann, wenn man eben richtig erzieht. Natürlich ist es etwas anderes, wenn man, sagen wir, in der Kindheit so erzogen wird, daß auf dem Umweg durch das Seelische zum Beispiel Gichtkeime in den Menschen gelegt werden. Wenn man nicht gichtig wird, kann man etwas anderes tun, als sich der Gicht widmen in den Vierzigerjahren. Das ist gewiß angenehmer! Man betrachte nur diejenigen Menschen, die an solchen Dingen leiden, was alles sie damit zu tun haben! Natürlich muß dann alles dasjenige getan werden, was diese Dinge beseitigen kann — aber die eigentliche pädagogische Frage berührt das ja nicht. Es scheint mir, daß es von vornherein unbedingt einleuchten muß, daß, wenn man seelisch und geistig die Zusammenhänge erkennt, man so erziehen muß, daß der Körper durch die Erziehung zu solchen Anlagen nicht kommt. Dasjenige, was so keimhaft veranlagt ist, muß, wenn es ausbricht in einem späteren Lebensalter, dann natürlich physisch-therapeutisch geheilt werden, und man sollte nicht allzuviel halten von seelisch-geistigen Kuren, die im hohen Alter angewandt werden. Es gehört viel dazu; insbesondere solche Keime, die so gründlich im Organismus sitzen, wie die durch die Erziehung aufgenommenen, sind außerordentlich schwer auszumerzen, obwohl sie wie alles Krankhafte bekämpft werden sollen.

Frage: Hat das Kind keine Kräfte des Ausgleiches in sich gegen die Schäden der Erziehung?

Die hat es schon in sich. Gerade in einer sachgemäßen Schule werden solche Kräfte des Ausgleiches wirklich entwickelt. Die Keime können aufgehen, müssen es aber nicht. Diese Kräfte müssen aber in Wirklichkeit aus den Anlagen des Kindes hervorgerufen werden. Frage: Wie sind Linkshänder in das Schreiben einzuführen?

Bei einem Linkshänder ist es schon notwendig, daß man versucht, möglichst viel dazu zu tun, ihn in einen Rechtshänder umzuwandeln. Nur wenn man sieht in der Praxis, daß es gar nicht gelingt, muß man natürlich mit der Linkshändigkeit fortarbeiten. Aber das einzig wünschenswerte ist, solche Linkshänder in Rechtshänder umzuwandeln; und das wird im wesentlichen ganz besonders mit Bezug auf das Schreiben, das zeichnende Schreiben meistens gelingen. Es ist im allgemeinen natürlich notwendig, daß man ein solches Kind, das man versucht, vom Linkshändigen zum Rechtshändigen überzuführen, sehr stark beobachtet; beobachtet namentlich, wie sehr leicht in einem gewissen Stadium, wenn man eine Zeitlang Anstrengungen gemacht hat, um die Linkshändigkeit in Rechtshändigkeit überzuführen, da gewisse Ideenflüchtigkeiten eintreten; daß das Kind auch unter Umständen wegen zu schnellen Denkens sich fortwährend im Denken ins Stolpern bringt, und dergleichen. Das muß man sorgfältig beachten und dann gerade die Kinder aufmerksam machen auf solche Dinge, weil es viel wesentlicher ist für die Entwickelung des ganzen Menschen, wie dieser Zusammenhang ist zwischen Arm- und Handentwickelung und Sprachzentrumentwickelung, als man gewöhnlich denkt; und vieles andere hat darauf einen Einfluß, ob ein Kind links- oder rechtshändig ist.

Frage: Ist es empfehlenswert, Kinder von 10 bis 12 Lebensjahren in der Spiegelschrift sich üben zu lassen?

Warum es eigentlich irgend empfehlenswert sein soll, einem Kinde von 10 bis 12 Jahren in Spiegelschrift Schreiben und Lesen beizubringen, ist mir nicht verständlich. Ich kann nicht annehmen, daß das aus irgendeiner Ecke des Lebens heraus irgend wünschenswert sein sollte. Die Sache ist so, daß wenn man zum geistigen Schauen aufsteigt, so bekommt man in der Regel für alles dasjenige, was noch wie eine Nachwirkung aus dem physischen Leben da ist, ein Spiegelbild. Es ist durchaus so, daß wenn man hinaufträgt in die geistige Welt ein Geschriebenes, so hat man oben ein Spiegelbild. Nehmen wir ein Beispiel: Jemand versuchte — ich will über diese Dinge ganz frank und frei sprechen - sich an eine Menschenwesenheit, die durch den Tod gegangen ist, an eine post mortem lebende Persönlichkeit zu wenden, und zu dem, was man da erlebt mit dieser Persönlichkeit, hätte man nötig irgendein Geschriebenes aus dem physischen Leben zum Vergleichen. Dann erscheint diese Schrift, die man sonst kennt, so wie sie geschrieben ist, so, wie wenn man sie in Spiegelschrift durchlesen würde. Es übersetzt sich das physisch in normaler Weise Geschriebene, wenn man ins Geistige hinüberschaut, in das Spiegelbild seiner selbst. Würde man einem Kinde künstlich Spiegelschrift beibringen, so würde man sehr viel tun, um das Kind erdenfremd zu machen, vor allen Dingen, um es fremd des Gebrauches seines Kopfes zu machen. Das sollte man nicht tun; es könnte das unter Umständen enden mit bedeutsamen seelischen und geistigen Störungen. Gerade die anthroposophische Erziehungskunst ist darauf bedacht, die Menschen nicht hinaufzuführen in Wolkenkuckucksheime, sondern sie auf das physische Leben vorzubereiten. Herausreißen könnte das Kind aus dem physischen Leben eine solche Maßnahme, es Spiegelschrift schreiben und lesen zu lehren.

Frage: Warum ist die Schreibrichtung in den europäischen Sprachen von links nach rechts, im Hebräischen von rechts nach links, im Chinesischen von oben nach unten?

Was die Anordnung der Schrift betrifft, Schreiben von links nach rechts und so weiter, so führt das in sehr starke Tiefen der Kulturgeschichte hinein. Es kann höchstens eine kleine Andeutung gegeben werden. Es handelt sich darum, daß in früheren Zeiten der menschlichen Entwickelung ein instinktives Schauen bei den Menschen vorhanden war, daß die Menschen die physischen Erscheinungen tatsächlich nicht so intensiv gesehen haben, wie sie das heute tun, dafür aber das in den physischen Erscheinungen lebende Geistige. Man stellt sich gewöhnlich nicht klar genug vor, wie anders der Mensch in alten Zeiten in die Welt geschaut hat als heute. Die Menschen denken so leicht, ein alter Grieche habe etwa zum Himmel hinaufgeschaut und habe die Bläue, weil das südliche Blau noch intensiver ist als das nördliche, in derselben Schönheit gesehen, wie es der heutige Grieche sieht. Das ist nicht der Fall. Das griechische Auge hat noch nicht so einen lebendigen Eindruck von dem Blau haben können. Das läßt sich nachweisen durch das Wort, das den Griechen fehlt. Die Griechen haben alles in mehr nach dem Rot und Gelb hinneigenden Nuancen gesehen, haben den Himmel mehr grünlich als bläulich gesehen. Das ganze Seelenleben der Menschen, insofern es auch von den Sinnen abhängig ist, hat sich im Laufe der Zeiten geändert. - Weil das Hebräische mit Recht genannt werden kann eine derjenigen Sprachen, die den lebendigen Zusammenhang haben mit der menschlichen Urschrift, so haben sie gerade dieses noch erhalten, den Zug von rechts nach links, der sich bei uns nur noch erhalten hat in dem Rechnen, das wir zwar auch als eine alte Erbschaft in unserer Zivilisationsära haben - eine viel ältere Erbschaft als unsere Handschrift -, von dem wir es aber nur nicht bemerken. Wenn Sie addieren oder subtrahieren, also rechnen — was aus morgenländischer Anschauung stammt -, so schreiben Sie zwar zunächst die Zahlen von links nach rechts, aber die Natur der Zahlen selbst erfordert von Ihnen, daß sie von rechts nach links die Rechnung machen. Daraus können Sie noch gut ablesen, wie unser Zahlensystem viel älteren Ursprungs ist als unser Schriftsystem. Das ist dasjenige, was darüber etwa zu sagen ist. Wenn Sie dann die Schrift nehmen im Chinesischen: Nun, da brauchen Sie nur den ganzen Habitus der chinesischen Kultur ins Auge zu fassen, die darauf angelegt ist, statt desjenigen, was wir ganz lebendig haben im Kosmos oder aus dem Kosmos — das Umkreisen um die Erde, die Richtung von links nach rechts oder von rechts nach links -, das hat der Chinese in seinem Gefühl nicht so. Er hat in der Richtung von unten nach oben oder von oben nach unten die zunächst älteste Richtung, in die sich das menschliche Fühlen hineinversetzen kann.

Frage: Zur Frage des Religionsunterrichts.