The Kingdom of Childhood

GA 311

14 August 1924, Torquay

Lecture III

Today we will characterise certain general principles of the art of education for the period between the change of teeth and puberty, passing on in the next lecture to more detailed treatment of single subjects and particular conditions which may arise.

When the child reaches his ninth or tenth year he begins to differentiate himself from his environment. For the first time there is a difference between subject and object; subject is what belongs to oneself, object is what belongs to the other person or other thing; and now we can begin to speak of external things as such, whereas before this time we must treat them as though these external objects formed one whole together with the child's own body. I showed yesterday how we speak of animals and plants, for instance, as though they were human beings who speak and act. The child thereby has the feeling that the outside world is simply a continuation of his own being.

But now when the child has passed his ninth or tenth year we must introduce him to certain elementary facts of the outside world, the facts of the plant and animal kingdoms. Other subjects I shall speak of later. But it is particularly in this realm that we must be guided by what the child's own nature needs and asks of us.

The first thing we have to do is to dispense with all the textbooks. For textbooks as they are written at the present time contain nothing about the plant and animal kingdoms which one can use in teaching. They are good for instructing grown up people about plants and animals, but we shall ruin the individuality of the child if we use them at school. And indeed there are no textbooks or handbooks today which show one how these things should be taught. Now the important point is really this.

If you put single plants in front of the child and demonstrate different things from them, you are doing something which has no reality. A plant by itself is not a reality. If you pull out a hair and examine it as though it were a thing by itself, that would not be a reality either. In ordinary life we say of everything of which we can sec the outlines with our eyes that it is real. But if you look at a stone and form some opinion about it, that is one thing; if you look at a hair or a rose, it is another. In ten years' time the stone will be exactly as it is now, but in two days the rose will have changed. The rose is only a reality together with the whole rosebush. The hair is nothing in itself, but is only a reality when considered with the whole head, as part of the whole human being. Now if you go out into the fields and pull up plants, it is as though you had torn out the hair of the earth. For the plants belong to the earth just in the same way as the hair belongs to the organism of the human being. And it is nonsense to examine a hair by itself as though it could suddenly grow anywhere of its own accord.

It is just as foolish to take a botanical tin and bring home plants to be examined by themselves. This has no relation to reality, and such a method cannot lead one to a right knowledge of nature or of the human being.

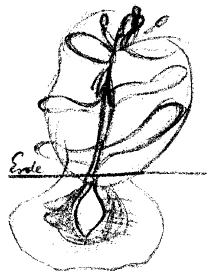

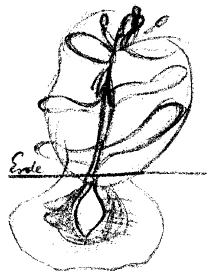

Here we have a plant (see drawing) but this alone is not the plant, for there also belongs to it the soil beneath it spread out on all sides, maybe a very long way. There are some plants which send out little roots a very long way. And when you realise that the small clod of earth containing the plant belongs to a much greater area of soil around it, then you will see how necessary it is to manure the earth in order to promote

healthy plant growth. Something else is living besides the actual plant; this part here (below the line in drawing) lives with it and belongs to the plant; the earth lives with the plant.

There are some plants which blossom in the spring, about May or June, and bear fruit in autumn. Then they wither and die and remain in the earth which belongs to them. But there are other plants which take the earth forces out of their environment. If this is the earth, then the root takes into itself the forces which are around it, and because it has done so these forces shoot upwards and a tree is formed.

For what is actually a tree? A tree is a colony of many plants. And it does not matter whether you are considering a hill which has less life in itself but which has many plants growing on it, or a tree trunk where the living earth itself has as it were withdrawn into the tree. Under no circumstances can you understand any plant properly if you examine it by itself.

If you go (preferably on foot) into a district in which there are definite geological formations, let us say red sand, and look at the plants there, you will find that most of them have reddish-yellow flowers. The flowers belong to the soil. Soil and plant make up a unity, just as your head and your hair also make a unity.

Therefore you must not teach Geography and Geology by themselves, and then Botany separately. That would be absurd. Geography must be taught together with a description of the country and observation of the plants, for the earth is an organism and the plants are like the hair of this organism. The child must be able to see that the earth and the plants belong together, and that each portion of soil bears those plants which belong to it.

Thus the only right way is to speak of the plants in connection with the earth, and to give the child a clear feeling that the earth is a living being that has hair growing on it. The plants are the hair of the earth. People speak of the earth as having the force of gravity. This is spoken of as belonging to the earth. But the plants with their force of growth belong to the earth just as much. The earth and the plants are no more separate entities than a man and his hair would be. They belong together just as the hair on the head belongs to the man.

If you show a child plants out of a botanical tin and tell him their names, you will be teaching something which is quite unreal. This will have consequences for his whole life, for this kind of plant knowledge will never give him an understanding, for example, of how the soil must be treated, and of how it must be manured, made living by the manure that is put into it. The child can only gain an understanding of how to cultivate the land if he knows how the soil is really part of the plant. The men of our time have less and less conception of reality, the so-called “practical” people least of all, for they are really all theoretical as I showed you in our first lecture, and it is just because men have no longer any idea of reality that they look at everything in a disintegrated, isolated way.

Thus it has come about that in many districts during the last fifty or sixty years all agricultural products have become decadent. Not long ago there was a Conference on Agriculture in Central Europe, on which occasion the agriculturists themselves admitted that crops are now becoming so poor that there is no hope of their being suitable for human consumption in fifty years' time.

Why is this so? It is because people do not understand how to make the soil living by means of manure. It is impossible that they should understand it if they have been given conceptions of plants as being something in themselves apart from the earth. The plant is no more an object in itself than a hair is. For if this were so, you might expect it to grow just as well in a piece of wax or tallow as in the skin of the head. But it is only in the head that it will grow.

In order to understand how the earth is really a part of plant life you must find out what kind of soil each plant belongs to; the art of manuring can only be arrived at by considering earth and plant world as a unity, and by looking upon the earth as an organism and the plant as something that grows with this organism.

Thus a child feels, from the very start, that he is standing on a living earth. This is of great significance for his whole life. For think what kind of conception people have today of the origin of geological strata. They think of it as one layer deposited upon another. But what you see as geological strata is only hardened plants, hardened living matter. It is not only coal that was formerly a plant (having its roots more in water than in the firm ground and belonging completely to the earth) but also granite, gneiss and so on were originally of plant and animal nature.

This too one can only understand by considering earth and plants as one whole. And in these things it is not only a question of giving children knowledge but of giving them also the right feelings about it. You only come to see that this is so when you consider such things from the point of view of Spiritual Science.

You may have the best will in the world. You may say to yourself that the child must learn about everything, including plants, by examining them. At an early age then I will encourage him to bring home a nice lot of plants in a beautiful tin box. I will examine them all with him for here is something real. I firmly believe that this is a reality, for it is an object lesson, but all the time you are looking at something which is not a reality at all. This kind of object-lesson teaching of the present day is utter nonsense.

This way of learning about plants is just as unreal as though it were a matter of indifference whether a hair grew in wax or in the human skin. It cannot grow in wax. Ideas of this kind are completely contradictory to what the child received in the spiritual worlds before he descended to the earth. For there the earth looked quite different. This intimate relationship between the mineral earth kingdom and the plant world was then something that the child's soul could receive as a living picture. Why is this so? It is because, in order that the human being may incarnate at all, he has to absorb something which is not yet mineral but which is only on the way to becoming mineral, namely the etheric element. He has to grow into the element of the plants, and this plant world appears to him as related to the earth.

This series of feelings which the child experiences when he descends from the pre-earthly world into the earthly world—this whole world of richness is made confused and chaotic for him if it is introduced to him by the kind of Botany teaching which is usually pursued, whereas the child rejoices inwardly if he hears about the plant world in connection with the earth.

In a similar manner we must consider how to introduce our children to the animal world. Even a superficial glance will show us that the animal does not belong to the earth. It runs over the earth and can be in this place or that, so the relationship of the animal to the earth is quite different from that of the plant. Something else strikes us about the animal.

When we come to examine the different animals which live on the earth, let us say according to their soul qualities first of all, we find cruel beasts of prey, gentle lambs or animals of courage. Some of the birds are brave fighters and we find courageous animals amongst the mammals too. We find majestic beasts. like the lion. In fact, there is the greatest variety of soul qualities, and we characterise each single species of animal by saying that it has this or that quality. We call the tiger cruel, for cruelty is his most important and significant quality. We call the sheep patient. Patience is his most outstanding characteristic. We call the donkey lazy, because although in reality he may not be so fearfully lazy yet his whole bearing and behaviour somehow reminds us of laziness. The donkey is especially lazy about changing his position in life. If he happens to be in a mood to go slowly, nothing will induce him to go quickly. And so every animal has its own particular characteristics.

But we cannot think of human beings in this way. We cannot think of one man as being only gentle and patient, another only cruel and a third only brave. We should find it a very one-sided arrangement if people were distributed over the earth in this way. You do sometimes find such qualities developed in a one-sided way, but not to the same extent as in animals. Rather what we find with a human being, especially when we are to educate him, is that there are certain things and facts of life which he must meet with patience or again with courage, and other things and situations even maybe with a certain cruelty, although this last should be administered in homeopathic doses. Or in face of certain situations a human being may show cruelty simply out of his own natural development, and so on.

Now what is really the truth about these soul qualities of man and the animals? With man we find that he can really possess all qualities, or at least the sum of all the qualities that the animals have between them (each possessing a different one). Man has a little of each one. He is not as majestic as the lion, but he has something of majesty within him. He is not as cruel as the tiger but he has a certain cruelty. He is not as patient as the sheep, but he has some patience. He is not as lazy as the donkey—at least everybody is not—but he has some of this laziness in him. Every human being has these things within him. When we think of this matter in the right way we can say that man has within him the lion-nature, sheep-nature, tiger-nature and donkey-nature. He bears all these within him, but harmonised. All the qualities tone each other down, as it were, and man is the harmonious flowing together, or, to put it more academically, the synthesis of all the different soul qualities that the animal possesses. Man reaches his goal if in his whole being he has the proper dose of lion-ness, sheep-ness, tiger-ness, the proper dose of donkey-ness and so on, if all this is present in his nature in the right proportions and has the right relationship to everything else.

There is a beautiful old Greek proverb which says: If courage be united with cleverness it will bring thee blessing, but if it goes alone ruin will follow. If man were only courageous with the courage of certain birds which are continually fighting, he would not bring much blessing into his life. But if his courage is so developed in his life that it unites with cleverness—the cleverness which in the animal is only one-sided—then it takes its right place in man's being.

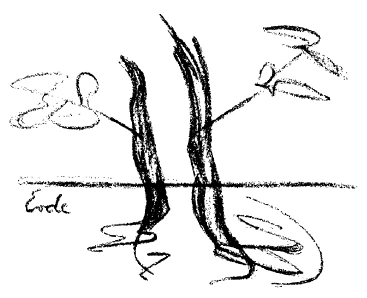

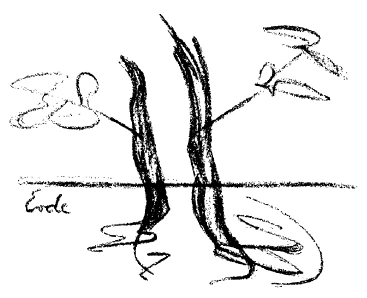

With man, then, it is a question of a synthesis, a harmonising of everything that is spread out in the animal kingdom. We can express it like this: here is one kind of animal (I am representing it diagrammatically), here a second, a third, a fourth and so on, all the possible kinds of animals on the earth. How are they related to man?

The relationship is such that man has, let us say, some

thing of this first kind of animal (see drawing), but modified, not in its entirety. Then comes another kind, but again not the whole of it. This leads us to the next, and to yet another, so that man contains all the animals within him. The animal kingdom is a man spread out, and man is the animal kingdom drawn together; all the animals are united synthetically in man, and if you analyse a human being you get the whole animal kingdom.

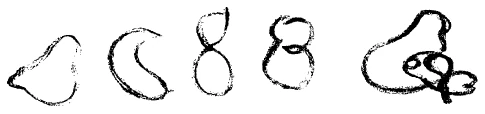

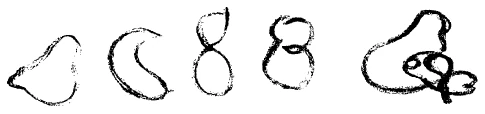

This is also the case with the external human form. Imagine a human face and cut away part of it here (see drawing) and

pull another part forwards here, so that this latter part is not harmonised with the whole face, while the forehead recedes; then you get a dog's head. If you form the head in a somewhat different way, you get a lion's head, and so on.

And so with all his other organs you can find that man, even in his external figure, has what is distributed amongst the animals in a modified harmonised form.

Think for instance of a waddling duck; you have a relic of this waddling part between your fingers, only shrunken. Thus everything which is to be found in the animal kingdom even in external form is present also in the human kingdom. Indeed this is the way man can find his relationship to the animal kingdom, by coming to know that the animals, taken all together, make up man. Man exists on earth, eighteen hundred millions of him, of greater or less value, but he exists again as a giant human being. The whole animal kingdom is a giant human being, not brought together in a synthesis but analysed out into single examples.

It is as though your were made of elastic which could be pulled out in varying degrees in different directions; if you were thus stretched out in one direction more than in others, one kind of animal would be formed. Or again if the upper part of your face were to be pushed up and stretched out (if it were sufficiently elastic) then another animal would arise. Thus man bears the whole animal kingdom within him.

This is how the history of the animal kingdom used to be taught in olden times. This was a right and healthy knowledge, which has now been lost, though only comparatively recently. In the eighteenth century for instance people still knew quite well that if the olfactory nerve of the nose were sufficiently large and extended backwards then you would have a dog. But if the olfactory nerve is shrivelled up and only a small portion remains, the rest of it being metamorphosed, then there arises the nerve that we need for our intellectual life.

For observe how a dog smells; the olfactory nerve is extended backwards from the nose. A dog smells the special peculiarity of each thing. He does not make a mental picture of it, but everything comes to him through smell. He has not will and imagination but he has will and a sense of smell for everything. A wonderful sense of smell! A dog does not find the world less interesting than a man does. A man can make mental images of it all, a dog can smell it all. We experience various smells, do we not, both pleasant and unpleasant, but a dog has many kinds of smell; just think how a dog specialises in his sense of smell. Nowadays we have police dogs. They are led to the place where someone has pilfered something. The dog immediately takes up the scent of the man, follows it and finds him. All this is due to the fact that there is really an immense variety, a whole world of scents for a dog. The bearer of these scents is the olfactory nerve that passes backwards into the head, into the skull.

If we were to draw the olfactory nerve of a dog, which passes through his nose, we should have to draw it going backwards. In man only a little piece at the bottom of it has remained. The rest of it is present in a morphosed form and lies here below the forehead. It is a metamorphosed, transformed olfactory nerve, and with this organ we form our mental images. For this reason we cannot smell like a dog, but we can make mental pictures. We bear within us the dog with his sense of smell, only this latter has been transformed into something else. And so it is with all animals.

We must get this clear in our minds. Now a German philosopher called Schopenhauer wrote a book called The World as Will and Idea. But this book is only intended for human beings. If a dog of genius had written it he would have called it The World as Will and Smell and I am convinced that this book would have been much more interesting than Schopenhauer's.

You must look at the various forms of the animals and describe them, not as though each animal existed in an isolated way, but so that you always arouse in the children the thought: This is a picture of man. If you think of a man altered in one direction or another, simplified or combined, then you have an animal. If you take a lower animal, for example, a tortoise, and put it on the top of a kangaroo, then you have something like a hardened head on the top, for that is the tortoise form, and the kangaroo below stands for the limbs of the human being.

And so everywhere in the wide world you can find some connection between man and the different animals.

You are laughing now about these things. That does not matter at all. It js quite good to laugh about them in the lessons also, for there is nothing better you can bring into the classroom than humour, and it is good for the children to laugh too, for if they always see the teacher come in with a terribly long face they will be tempted to make long faces themselves and to imagine that that is what one has to do when one sits at a desk in a classroom. But if humour is brought in and you can make the children laugh this is the very best method of teaching. Teachers who are always solemn will never achieve anything with the children.

So here you have the principle of the animal kingdom as I wished to put it before you. We can speak of the details later if we have time. But from. this you will see that you can teach about the animal kingdom by considering it as a human being spread out into all the animal forms.

This will give the child a very beautiful and delicate feeling. For as I have pointed out to you the child comes to know of the plant world as belonging to the earth, and the animals as belonging to himself. The child grows with all the kingdoms of the earth. He no longer merely stands on the dead ground of the earth, but he stands on the living ground, for he feels the earth as something living. He gradually comes to think of himself standing on the earth as though he were standing on some great living creature, like a whale. This is the right feeling. This alone can lead him to a really human feeling about the whole world.

So with regard to the animal the child comes to feel that all animals are related to man, but that man has something that reaches out beyond them all, for he unites all the animals in himself. And all this idle talk of the scientists about man descending from an animal will be laughed at by people who have been educated in this way. For they will know that man unites within himself the whole animal kingdom, he is a synthesis of all the single members of it.

As I have said, between the ninth and tenth year the human being comes to the point of discriminating between himself as subject and the outer world as object. He makes a distinction between himself and the world around him. Up to this time one could only tell fairy stories and legends in which the stones and plants speak and act like human beings, for the child did not yet differentiate between himself and his environment. But now when he does thus differentiate we must bring him into touch with his environment on a higher level. We must speak of the earth on which we stand in such a way that he cannot but feel how earth and plant belong together as a matter of course. Then, as I have shown you, the child will also get practical ideas for agriculture. He will know that the farmer manures the ground because he needs a certain life in it for one particular species of plant. The child will not then take a plant out of a botanical tin and examine it by itself, nor will he examine animals in an isolated way, but he will think of the whole animal kingdom as the great analysis of a human being spread out over the whole earth. Thus he, a human being, comes to know himself as he stands on the earth, and how the animals stand in relationship to him.

It is of very great importance that from the tenth year until towards the twelfth year we should awaken these thoughts of plant-earth and animal-man. Thereby the child takes his place in the world in a very definite way, with his whole life of soul, body and spirit.

All this must be brought to him through the feelings in an artistic way, for it is through learning to feel how plants belong to the earth and to the soil that the child really becomes clever and intelligent. His thinking will then be in accordance with nature. Through our efforts to show the child how he is related to the animal world, he will see how the force of will which is in all animals lives again in man, but differentiated, in individualised forms suited to man's nature. All animal qualities, all feeling of form which is stamped into the animal nature lives in the human being. Human will receives its impulses in this way and man himself thereby takes his place rightly in the world according to his own nature.

Why is it that people go about in the world today as though they had lost their roots? Anyone can see that people do not walk properly nowadays; they do not step properly but drag their legs after them. They learn differently in their sport, but there again there is something unnatural about it. But above all they have no idea how to think nor what to do with their lives. They know well enough what to do if you put them to the sewing machine or the telephone, or if an excursion or a world tour is being arranged. But they do not know what to do out of themselves because their education has not led them to find their right place in the world. You cannot put this right by coining phrases about educating people rightly; you can only do it if in the concrete details you can find the right way of speaking of the plants in their true relationship to the soil and of the animals in their rightful place by the side of man. Then the human being will stand on the earth as he should and will have the right attitude towards the world. This must be achieved in all your lessons. It is important—nay, it is essential.

Now it will always be a question of finding out what the development of the child demands at each age of life. For this we need real observation and knowledge of man. Think once again of the two things of which I have spoken, and you will see that the child up to its ninth or tenth year is really demanding that the whole world of external nature shall be made alive, because he does not yet see himself as separate from this external nature; therefore we shall tell the child fairy tales, myths and legends. We shall invent something ourselves for the things that are in our immediate environment, in order that in the form of stories, descriptions and pictorial representations of all kinds we may give the child in an artistic form what he himself finds in his own soul, in the hidden depths which he brings with him into the world. And then after the ninth or tenth year, let us say between the tenth and twelfth year, we introduce the child to the animal and plant world as we have described.

We must be perfectly clear that the conception of causality, of cause and effect, that is so popular today has no place at all in what the child needs to understand even at this age, at the tenth or eleventh year. We are accustomed nowadays to consider everything in its relation to cause and effect. The education based on Natural Science has brought this about. But to talk to children under eleven or twelve about cause and effect, as is the practice in the everyday life of today, is like talking about colours to someone who is colour blind. You will be speaking entirely beyond the child if you speak of cause and effect in the style that is customary today. First and foremost he needs living pictures where there is no question of cause and effect. Even after the tenth year these conceptions should only be brought to the child in the form of pictures.

It is only towards the twelfth year that the child is ready to hear causes and effects spoken of. So that those branches of knowledge which have principally to do with cause and effect in the sense of the words used today—the lifeless sciences such as Physics, etc.—should not really be introduced into the curriculum until between the eleventh and twelfth year. Before this time one should not speak to the children about minerals, Physics or Chemistry. None of these things is suitable for him before this age.

Now with regard to History, up to the twelfth year the child should be given pictures of single personalities and well-drawn graphic accounts of events that make History come alive for him, not a historical review where what follows is always shown to be the effect of what has gone before, the pragmatic method of regarding History, of which humanity has become so proud. This pragmatic method of seeking causes and effects in History is no more comprehensible to the child than colours to the colour-blind. And moreover one gets a completely wrong conception of life as it runs its course if one is taught everything according to the idea of cause and effect. I should like to make this clear to you in a picture.

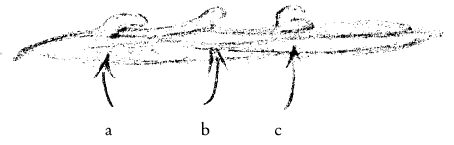

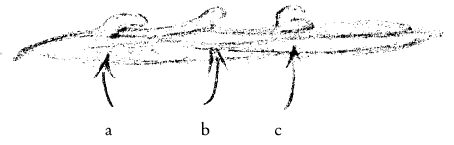

Imagine a river flowing along like this (see drawing). It has

waves. But it would not always be a true picture if you make the wave (C) come out of the wave (B), and this again out of the wave (A), that is, if you say that C is the effect of B and B of A; there are in fact all kinds of forces at work below, which throw these waves up. So it is in History. What happens in 1910 is not always the effect of what happened in 1909, and so on. But quite early on the child ought to have a feeling for the things that work in evolution out of the depths of the course of time, a feeling of what throws the waves up, as it were. But he can only get that feeling if you postpone the teaching of cause and effect until later on, towards the twelfth year, and up to this time give him only pictures.

Here again this makes demands on the teacher's fantasy. But he must be equal to these demands, and he will be so if he has acquired a knowledge of man for himself. This is the one thing needful.

You must teach and educate out of the very nature of man himself, arid for this reason education for moral life must run parallel to the actual teaching which I have been describing to you. So now in conclusion I should like to add a few remarks on this subject, for here too we must read from the nature of the child how he should be treated. If you give a child of seven a conception of cause and effect you are working against the development of his human nature, and punishments also are often opposed to the real development of the child's nature.

In the Waldorf School we have had some very gratifying experiences of this. What is the usual method of punishment in schools? If a child has done something badly he has to “stay in” and do some Arithmetic for instance. Now in the Waldorf School we once had rather a strange experience: three or four children were told that they had done their work badly and must therefore stay in and do some sums. Whereupon the others said: “But we want to stay and do sums too!” For they had been brought up to think of Arithmetic as something nice to do, not as something which is used as a punishment. You should not arouse in the children the idea that staying in to do sums is something bad, but that it is a good thing to do. That is why the whole class wanted to stay and do sums. So that you must not choose punishments that cannot be regarded as such if the child is to be educated in a healthy way in his soul life.

To take another example: Dr. Stein, a teacher at the Waldorf School, often thought of very good educational methods on the spur of the moment. He once noticed that his pupils were passing notes under the desk. They were not attending to the lesson, but were writing notes and passing them under their desks to their neighbours who then wrote notes in reply. Now Dr. Stein did not scold them for writing notes and say: “I shall have to punish you,” or something of that sort, but quite suddenly he began to speak about the Postal System and give them a lecture on it. At first the children were quite mystified as to why they were suddenly being given a lesson on the Postal System, but then they realised why it was being done. This subtle method of changing the subject made the children feel ashamed. They began to feel ashamed of themselves and stopped writing notes simply on account of the thoughts about the postal system which the teacher had woven into the lesson.

Thus to take charge of a class it is necessary to have an inventive talent. Instead of simply following stereotyped traditional methods you must actually be able to enter into the whole being of the child, and you must know that in certain cases improvement, which is really what we are aiming at in punishment, is much more likely to ensue if the children are brought to a sense of shame in this way without drawing special attention to it or to any one child; this is far more effective than employing some crude kind of punishment. If the teacher follows such methods as these he will stand before the children active in spirit, and much will be balanced out in the class which would otherwise be in disorder.

The first essential for a teacher is self-knowledge. If for instance a child makes blots on his book or on his desk because he has got impatient or angry with something his neighbour has done, then the teacher must never shout at the child for making blots and say: “You mustn't get angry! Getting angry is a thing that a good man never does! A man should never get angry but should bear everything calmly. If I see you getting angry once more, why then—then I shall throw the inkpot at your head!”

If you educate like this (which is very often done) you will accomplish very little. The teacher must always keep himself in hand, and above all must never fall into the faults which he is blaming his children for. But here you must know how the unconscious part of the child's nature works. A man's conscious intelligence, feeling and will are all only one part of his soul life; in the depths of human nature, even in the child, there holds sway the astral body with its wonderful prudence and wisdom.1For an elucidation of the “astral body” and other higher members of man's being, see Rudolf Steiner:The Education of the Child in the Light of Anthroposophy.

Now it always fills me with horror to see a teacher standing in his class with a book in his hand teaching out of the book, or a notebook in which he has noted down the questions he wants to ask the children and to which he keeps referring. The child does not appear to notice this with his upper consciousness, it is true; but if you are aware of these things then you will see that the children have subconscious wisdom and say to themselves: He does not himself know what I am supposed to be learning. Why should I learn what he does not know? This is always the judgment that is passed by the subconscious nature of children who are taught by their teacher out of a book.

Such are the imponderable and subtle things that are so extremely important in teaching. For as soon as the subconscious of the child, his astral nature, notices that the teacher himself does not know something he has to teach, but has to look it up in a book first, then the child considers it unnecessary that he should learn it either. And the astral body works with much more certainty than the upper consciousness of the child.

These are the thoughts I wished to include in today's lecture. In the next few days we will deal with special subjects and stages in the child's education.

Dritter Vortrag

Heute wollen wir noch einiges über das Allgemeinere der Erziehungskunst während der Lebensepoche zwischen dem Zahnwechsel und der Geschlechtsreife charakterisieren, um dann in der nächsten Stunde auf Spezielleres in der Behandlung einzelner Gegenstände und einzelner Lebenszustände eingehen zu können.

Wenn das Kind zwischen dem 9. und 10. Lebensjahr angekommen ist, dann kann es sich zunächst von seiner Umgebung unterscheiden. Der Unterschied zwischen Subjekt und Objekt - Subjekt = das Eigene, Objekt = das Andere - tritt eigentlich erst in diesem Zeitpunkt wirklich auf, und wir können dann beginnen, von Außendingen zu sprechen, während wir vorher diese Außendinge so behandeln müssen, als ob sie eigentlich eins wären mit dem Körper des Kindes. Wir sollen die Außendinge wie sprechende, handelnde Menschen behandeln, sagte ich gestern. Dadurch hat das Kind das Gefühl, daß die Außenwelt einfach eine Fortsetzung seines eigenen Wesens ist.

Nun handelt es sich darum, das Kind, wenn es das 9. oder 10. Jahr überschritten hat, in einige elementare Tatsachen, Wesenheiten der Außenwelt einzuführen, in die Tatsachen des Pflanzenreiches und des Tierreiches. Von anderen Gegenständen werden wir noch sprechen. Aber gerade bei diesen Dingen müssen wir sehen, daß wir das Kind so einführen, wie es die Menschennatur verlangt.

Das erste, was wir dabei tun müssen, ist eigentlich das, daß wir alle Lehrbücher wegwerfen. Denn so wie heute Lehrbücher beschaffen sind, enthalten sie nichts über das Pflanzen- und Tierreich, was man den Kindern eigentlich beibringen kann. Diese Lehrbücher von heute sind gut, um erwachsenen Menschen Kenntnisse von Pflanzen und Tieren beizubringen; aber wir verderben die Individualität des Kindes, wenn wir diese Lehrbücher in der Schule benützen. Und man kann schon sagen: Lehrbücher, Handbücher, welche Anleitung dazu geben, wie man in der Schule vorzugehen hat, sind eben heute nicht vorhanden. Es handelt sich nämlich um folgendes:

Wenn man dem Kinde einzelne Pflanzen vorlegt und an einzelnen Pflanzen dies oder jenes behandeln läßt, so hat man ja zunächst etwas getan, was keiner Wirklichkeit entspricht. Eine Pflanze für sich hat keine Wirklichkeit. Wenn Sie sich ein Haar ausreißen und dieses Haar betrachten, als ob es eine Sache für sich wäre, so hat das keine Wirklichkeit. Im trivialen Leben sagt man zu allem, was man mit Augen irgendwie begrenzt vor sich sieht, es habe eine Wirklichkeit. Aber es ist doch etwas anderes, ob man einen Stein, den man beurteilt, vor sich sieht oder ob man ein Haar oder eine Rose vor sich sieht. Der Stein wird nach zehn Jahren noch gerade dasselbe sein, was er heute ist, die Rose nach zwei Tagen nicht mehr; sie ist nur eine Realität am ganzen Rosenstock daran. Das Haar hat gar keine Realität für sich, es ist nur eine Realität mit dem ganzen Kopf, am ganzen Menschen. Und wenn man nun hinausgeht auf die Felder und Pflanzen ausreißt, dann ist es so, wie wenn man der Erde die Haare ausgerissen hätte. Denn die Pflanzen gehören zur Erde ganz genau so, wie die Haare zum Organismus des Menschen gehören. Ein Haar für sich zu betrachten, wie wenn es irgendwo für sich entstehen würde, ist ja ein Unsinn.

Ebenso ist es ein Unsinn, eine grüne Botanisiertrommel zu nehmen, Pflanzen nach Hause zu tragen und jede Pflanze für sich zu betrachten. Das entspricht nicht der Realität, und auf diese Weise ist es nicht möglich, daß man richtige Natur- und Menschenerkenntnis erwirbt.

Wenn Sie hier eine Pflanze haben (siehe Zeichnung D), so ist das allein nicht die Pflanze, sondern zu der Pflanze gehört noch dasjenige, was da als Boden darunter ist, unbegrenzt weit, vielleicht sehr weit. Es gibt Zeichnung I Pflanzen, die lassen noch Würzelchen in sehr großer Weite ausstrahlen. Daß dieses Stück Erde, in dem die Pflanze drinnen ist, in weitem Umkreise dazu gehört, das kann Sie die Tatsache lehren, daß man Dünger in die Erde hineingeben muß, wenn man von gewissen Pflanzen will, daß sie richtig wachsen. Fs lebt nicht bloß das Stück Pflanze, es lebt auch dasjenige, was hier ist (siehe Zeichnung D), es lebt mit, gehört zur Pflanze dazu; die Erde lebt mit.

Es gibt Pflanzen, die blühen im Frühling, sprossen auf gegen Mai, Juni und tragen ihre Früchte im Herbst. Dann verwelken sie, sterben ab. Sie stecken drinnen in der Erde, aber die gehört zu ihnen dazu. - Es gibt aber auch Pflanzen, die nehmen die Kräfte der Erde aus der Umgebung. Das wäre die Erde (siehe Zeichnung II); jetzt nimmt die Wurzel die Kräfte, die in der Umgebung sind, in sich auf. Weil sie jetzt die Kräfte in sich aufgenommen hat, kommen die Kräfte der Erde da herauf, es wird ein Baum daraus.

Was ist denn ein Baum? Ein Baum ist eine Kolonie von vielen Pflanzen. Ob Sie da einen Hügel haben, der nur weniger lebt und auf dem viele Pflanzen darauf sind, oder ob Sie den Stamm eines Baumes haben, wo in einem viel lebendigeren Zustand die Erde sich hineingezogen hat, das ist einerlei. Sie können gar nicht sachlich eine Pflanze für sich betrachten.

Fahren Sie über eine Gegend, oder noch besser, gehen Sie in einer Gegend, in der bestimmte geologische Formationen sind, zum Beispiel rot liegender Sand, und schauen sich die Pflanzen an: Es sind zumeist Pflanzen darauf mit gelb-rötlichen Blüten. Es gehören die Blüten zum Boden dazu. Boden und Pflanze ist eine Einheit, wie Ihre Kopfhaut und Ihre Haare.

Daher dürfen Sie mit dem Kind nicht einerseits Geographie und Geologie, andrerseits Botanik betrachten. Das ist ein Unsinn. Sondern Geographie, Beschreibung des Landes und Betrachtung der Pflanzen muß immer eines sein; denn die Erde ist ein Organismus, und die Pflanzen sind so wie Haare an diesem Organismus. Und das Kind muß die Vorstellung bekommen können, daß die Erde und die Pflanzen zusammengehören, daß jedes Stück Erde diejenigen Pflanzen trägt, die zu diesem Stück Erde gehören.

Es ist also richtig, daß Sie die Pflanzenkunde nur im Zusammenhange mit der Erde betrachten und dem Kinde eine deutliche Empfindung davon hervorrufen, daß die Erde ein lebendiges Wesen ist, das Haare hat. Die Haare sind die Pflanzen. - Sehen Sie, man sagt von der Erde, daß sie eine Schwerkraft habe, Gravitation. Die rechnet man zu der Erde dazu. Aber die Pflanzen gehören mit ihrer Wachstumskraft ebenso zu der Erde hinzu. Es gibt gar nicht eine Erde für sich und Pflanzen für sich, gerade so wenig, wie es in der Realität Haare für sich und Menschen für sich gibt. Das gehört zusammen.

Und wenn Sie das dem Kinde beibringen, was Sie aus der Botanisiertrommel herausnehmen und es benennen lassen, so bringen Sie ihm eine Unwirklichkeit bei. Das hat Folgen für das Leben; denn das Kind wird niemals von der Pflanzenkunde aus, die Sie ihm so beibringen, ein Verständnis dafür gewinnen, wie man zum Beispiel den Acker behandeln muß, wie man ihn lebendig machen muß mit dem Dünger. Ein Verständnis dafür, wie man den Acker behandeln soll, bekommt das Kind nur, wenn es weiß, wie der Acker mit der Pflanze zusammenhängt. Weil die Menschen in unserer Zeit mehr und mehr keinen Sinn für Realität mehr haben - ich habe Ihnen in der ersten Stunde gesagt, die Praktiker haben ihn am wenigsten, sie sind alle Theoretiker heute -, weil die Menschen von der Realität keine Spur mehr haben, deshalb betrachten sie alles für sich, alles gesondert.

Und so ist es gekommen, daß in vielen, vielen Gegenden seit fünfzig, sechzig Jahren alle Feldprodukte dekadent geworden sind. Es hat neulich in Mitteleuropa einen landwirtschaftlichen Kongreß gegeben. Da haben die Landwirtschafter selbst gestanden: Die Früchte werden so schlecht, daß man gar nicht hoffen kann, daß in fünfzig Jahren die Früchte noch genießbar sind für die Menschen.

Warum? Weil die Leute nicht verstehen, den Boden mit dem Dünger lebendig zu machen. Aber die Menschen können das nicht verstehen, wenn man ihnen solche Begriffe beibringt wie: die Pflanzen seien etwas für sich. Gerade so wenig, wie ein Haar etwas für sich ist, ist die Pflanze etwas für sich. Wenn das Haar etwas für sich wäre, gut, dann wäre es Ja einerlei, dann könnte man es, damit es wächst, in ein Stück Wachs oder Talg hineinstecken! Aber es wächst eben in der Kopfhaut.

Will man erkennen, wie die Erde mit der Pflanze zusammengehört, dann muß man wissen, in welche Art von Erde eine Pflanze hineingehört. Und wie man diese Erde noch düngen muß, das kann man nur dadurch wirklich erkennen, daß man Erde und Pflanzenwelt als eine Einheit betrachtet, daß man wirklich die Erde wie einen Organismus anschaut und die Pflanze als etwas, was innerhalb dieses Organismus wächst.

Dadurch aber bekommt das Kind von vornherein das Gefühl, auf einem lebendigen Boden zu stehen. Dies hat für das Leben eine große Bedeutung. Denn bedenken Sie nur, wie man sich heute vorstellt, daß die geologischen Schichten entstehen. Man stellt sich vor: Das hat sich so übereinandergelagert. Aber alles das, was Sie als geologische Schichten sehen, sind ja nur verhärtete Pflanzen, verhärtetes Lebendiges. Nicht nur die Steinkohlen waren früher Pflanzen, die mehr im Wasser als in der festen Erde wurzelten und dazugehörten zur Erde, sondern auch Granit, Gneis und so weiter sind von pflanzlicher und tierischer Natur her.

Auch dafür bekommt man nur Verständnis, wenn man Erde und Pflanzen als Ganzes zusammen betrachtet. Es handelt sich ja bei diesen Dingen nicht bloß darum, daß das Kind Kenntnisse erhält, sondern darum, daß es die richtigen Empfindungen erhält. Das sieht man aber erst wiederum ein, wenn man eine solche Sache geisteswissenschaftlich betrachtet.

Denken Sie nur einmal, Sie sind von dem besten Willen beseelt, Sie sagen sich: Das Kind muß alles anschaulich lernen, also muß es auch die Pflanze anschaulich lernen. Ich halte es früh an, schön in einer schönen Botanisiertrommel Pflanzen hereinzubringen. Ich zeige ihm alles, denn es ist die Realität. Ich glaube nämlich, es ist die Realität, es ist ja Anschauungsunterricht. - Nur - man schaut eben dasjenige an, was keine Wirklichkeit ist. Mit diesem Anschauungsunterricht treibt man den ärgsten Unfug in der Gegenwart!

Da lernt das Kind die Pflanze so kennen, als ob es gleichgültig wäre, ob ein Haar in Wachs oder in einer Menschenhaut wächst. In Wachs wächst es ja nicht. Wenn ein Kind solche Begriffe aufnimmt, dann widersprechen sie ganz dem, was das Kind aufgenommen hat, bevor es aus der geistigen Welt heruntergestiegen ist auf die Erde. Denn da hat die Erde ganz anders ausgeschaut. Da trat dem Kinde, das heifßt der Seele des Kindes lebendig diese Zusammengehörigkeit des mineralischen Erdreiches und des Pflanzlichen, das herauswächst, entgegen. Warum? Weil das Kind etwas, was noch nicht mineralisch ist, sondern erst auf dem Wege ist, mineralisch zu werden, das Ätherische aufnehmen muß, damit es sich überhaupt verkörpern kann. Es muß sich in das Pflanzliche hineinwachsen. Und das Pflanzliche erscheint mit der Erde verwandt.

Diese ganze Empfindungsreihe, die das Kind erlebt, wenn es heruntersteigt aus der vorirdischen Welt in die irdische, diese ganze reiche Welt wird ihm konfus gemacht, chaotisch gemacht, wenn man es so anleitet, Pflanzenkunde zu lernen, wie man es gewöhnlich tut; während das Kind innerlich aufjauchzt, wenn es die Pflanzenwelt im Zusammenhang mit der Erde kennenlernt.

In einer ähnlichen Weise muß betrachtet werden, wie man das Kind in die tierische Welt einführt. Beim Tiere wird es ja schon der trivialen Betrachtung auffallen: Es gehört nicht zur Erde. Es läuft über die Erde dahin. Es kann an diesem Orte, an jenem Orte sein. Man hat es also mit ganz anderen Verhältnissen der Erde zu tun, als bei der Pflanze. Aber beim Tiere kann einem etwas anderes auffallen.

Wenn wir die verschiedenen Tiere, die auf der Erde leben, zunächst ihren seelischen Eigenschaften nach betrachten, finden wir grausame Raubtiere, wir finden sanfte Lämmer und auch tapfere Tiere. Zum Beispiel unter den Vögeln sind manche ganz tapfere Streiter; auch unter den Säugetieren haben wir tapfere Tiere. Dann finden wir majestätische Tiere, wie die Löwen. Wir finden die mannigfaltigsten seelischen Eigenschaften. Und wir sagen uns bei jeder einzelnen Tierart, diese Tierart sei dadurch charakterisiert, daß sie diese oder jene Eigenschaft hat. Wir nennen den Tiger grausam, und die Grausamkeit ist seine beträchtlichste, bedeutendste Eigenschaft. Wir nennen das Schaf geduldig. Geduld ist seine beträchtlichste Eigenschaft. Wir nennen den Esel träge, weil er, wenn er auch nicht in Wirklichkeit so furchtbar träge ist, ein gewisses Gebaren hat, das stark an die Trägheit erinnert. Namentlich ist der Esel träge im Verändern seiner Lebenslage. Wenn er es gerade in seiner Laune hat, langsam zu gehen, kann man ihn nicht dazu bringen, daß er schnell geht. Und so hat jedes Tier seine besonderen Eigenschaften.

Beim Menschen aber können wir nicht so denken. Wir können nicht denken, daß der eine Mensch zahm, geduldig, der andere grausam, der dritte tapfer ist. Wir würden es einseitig finden, wenn die Menschen so über die Erde verteilt wären. Sie haben schon auch in gewissem Sinne solche Eigenschaften in Einseitigkeit ausgebildet, aber doch nicht in solchem Maße wie die Tiere. Wir finden viel mehr gerade beim Menschen - und namentlich, wenn wir den Menschen erziehen wollen -, daß wir ihm zum Beispiel gewissen Dingen und Tatsachen des Lebens gegenüber Geduld beibringen sollen, anderen Dingen und Lebenstatsachen gegenüber Tapferkeit, anderen Dingen und Lebenslagen gegenüber vielleicht irgendwie sogar etwas Grausamkeit, obwohl das in homöopathischer Dosis an die Menschen heranzubringen ist. Gewissen Dingen gegenüber wird der Mensch einfach durch seine natürliche Entwickelung auch Grausamkeiten zeigen und so weiter.

Aber wie ist es denn da eigentlich, wenn wir diese seelischen Eigenschaften beim Menschen und bei den tierischen Wesen betrachten? Beim Menschen finden wir, daß er eigentlich alle Eigenschaften haben kann, wenigstens die alle Tiere zusammen haben. Diese haben sie einzeln für sich; der Mensch hat immer ein bißchen von allem. Er ist nicht so majestätisch wie der Löwe, aber er hat etwas von Majestät. Er ist nicht so grausam wie der Tiger, aber er hat etwas von Grausamkeit. Er ist nicht so geduldig wie das Schaf, aber er hat etwas von Geduld. Er ist nicht so träge wie der Esel - wenigstens nicht alle Menschen -, aber er hat etwas von dieser Trägheit an sich. Das haben alle Menschen. Man kann sagen, wenn man die Sache ganz richtig betrachtet: Der Mensch hat in sich Löwen-Natur, SchafNatur, Tiger-Natur, Esel-Natur. Alles hat er in sich. Nur ist alles in sich harmonisiert. Alles schleift sich an dem anderen ab. Der Mensch ist der harmonische Zusammenfluß oder, wenn man es gelehrter ausdrücken will, die Synthese von all den verschiedenen seelischen Eigenschaften, die das Tier hat. Und gerade dann ist das Rechte beim Menschen erzielt, wenn er in seine Gesamtwesenheit die gehörige Dosis Löwenheit, Schafheit, die gehörige Dosis Tigerheit, die gehörige Dosis Eselheit und so weiter richtig einführt, wenn das alles in rechtem Maße in den Menschen eingetaucht ist und mit allem anderen in dem richtigen Verhältnis steht.

Schon ein altes griechisches Sprichwort sagt sehr schön: «Tapferkeit, wenn sie sich eint mit Klugheit, bringt dir Segen. Wandelt die Tapferkeit jedoch allein, folget Verderben ihr nach.» Wenn der Mensch nur tapfer wäre, wie manche Vögel, die fortwährend streiten, nur tapfer sind, so würde er nicht viel Segensreiches im Leben für sich anrichten. Aber wenn die Tapferkeit so ausgebildet ist beim Menschen, daß sie sich mit der Klugheit vereinigt, so wie wiederum gewisse Tiere nur klug sind, dann ist es beim Menschen das Rechte.

Beim Menschen handelt es sich also darum, daß eine synthetische Einheit, eine Harmonisierung all desjenigen, was im Tierreiche ausgebreitet ist, vorhanden ist. So daß wir das Verhältnis so umschreiben können: da ist das eine Tier - ich zeichne schematisch -, da das zweite, eine dritte Tierart, eine vierte und so weiter, alle Tiere, die auf der Erde möglich sind.

Wie verhalten sich die zum Menschen?

So, daß? der Mensch zunächst so etwas hat (es wird gezeichnet) wie die eine Tierart, aber gemildert, er hat es nicht ganz. Und da schließt gleich das andere daran an (siehe Zeichnung), aber wiederum nicht ganz. Da geht das über in ein Stück von dem Nächsten, und dann schließt sich dieses daran an (siehe letzte Zeichnung der Reihe), so daß der Mensch alle Tiere in sich schließt. Das Tierreich ist ein ausgebreiteter Mensch, und der Mensch ist ein zusammengezogenes Tierreich; alle Tiere sind synthetisch vereint durch den Menschen. Der ganze Mensch analysiert, ist das ganze Tierreich.

So ist es auch mit der Gestalt. Denken Sie sich einmal, wenn Sie das menschliche Antlitz haben (es wird gezeichnet), und dieses hier wegschneiden (siehe Zeichnung) und etwas nach vorne setzen, wenn das also weiter nach vorne geht, wenn es nicht harmonisiert ist mit dem ganzen Antlitz, wenn die Stirne tiefer geht, wird ein Hundekopf daraus. Wenn Sie in einer etwas anderen Weise den Kopf formen, wird ein Löwenkopf daraus und so weiter.

Auch in bezug auf seine übrigen Organe kann man überall finden, daß der Mensch auch in der äußeren Gestalt gemildert, harmonisiert hat das, was auf die übrigen Tiere ausgebreitet ist.

Denken Sie sich, wenn Sie eine watschelnde Ente haben, etwas von dem, was da watschelt, haben Sie nämlich auch zwischen den Fingern, nur ist es da zurückgezogen. Und so ist alles, was im Tierreiche zu finden ist, auch an Gestalt, im Menschenreiche vorhanden. Auf diese Weise findet der Mensch sein Verhältnis zum Tierreich. Er lernt erkennen, wie die Tiere alle zusammen ein Mensch sind. Der Mensch ist vorhanden in den 1800 Millionen Exemplaren von mehr ‘oder weniger großem Wert auf Erden. Aber er ist noch einmal als ein Riesenmensch vorhanden. Das ganze Tierreich ist ein Riesenmensch, nur nicht synthetisiert, sondern analysiert in lauter Einzelheiten.

Es ist so: Wenn alles an Ihnen elastisch wäre, aber so elastisch, daß es nach verschiedenen Richtungen hin verschieden elastisch sein könnte, und Sie nach einer gewissen Richtung hin elastisch sich ausdehnen würden, so würde ein gewisses Tier daraus entstehen. Wenn man Ihnen die Augengegend aufreißen würde, würde wiederum, wenn es entsprechend elastisch sich aufdunsen würde, ein anderes Tier entstehen. So trägt der Mensch das ganze Tierreich in sich.

So hat man einmal in früheren Zeiten die Geschichte des Tierreiches auch gelehrt. Das war eine gute, gesunde Erkenntnis. Sie ist verlorengegangen, aber eigentlich erst verhältnismäßig spät. Zum Beispiel hat man im 18. Jahrhundert noch ganz gut gewußt, wenn dasjenige, was der Mensch in der Nase hat, den Riechnerv, wenn der genügend groß ist, nach hinten sich fortsetzt, so wird ein Hund daraus. Wenn aber der Riechnerv verkümmert und wir nur ein Stückchen vom Riechnerv haben, und das andere Stückchen sich ummetamorphosiert, so entsteht unser Nerv für das intellektuelle Leben.

Wenn Sie den Hund anschauen, wenn er so riecht, so hat er von der Nase nach hinten die Fortsetzung seines Riechnervs. Er riecht die Eigentümlichkeit der Dinge; er stellt sie nicht vor, er riecht alles. Er hat nicht einen Willen und eine Vorstellung, sondern er hat einen Willen und einen Geruch für alle Dinge. Einen wunderbaren Geruch! Die Welt ist für den Hund nicht uninteressanter als für den Menschen. Der Mensch kann sich alles vorstellen. Der Hund kann alles riechen. Wir haben ein paar, nicht wahr, sympathische und antipathische Gerüche; aber der Hund hat vielerlei Gerüche. Denken Sie nur einmal, wie der Hund im Geruchssinn spezialisiert. Polizeihunde gibt es in der neueren Zeit. Man führt sie an den Ort, wo einer war, der etwas stibitzt hat. Der Hund faßt sogleich die Spur des Menschen auf, geht ihr nach und findet ihn. Das alles beruht darauf, daß es wirklich eine ungeheure Differenzierung, eine reiche Welt der Gerüche gibt für den Hund. Davon ist der Träger der nach rückwärts in den Kopf, in den Schädel hineingehende Riechnerv.

Wenn wir den Riechnerv durch die Nase des Hundes zeichnen, müssen wir ihn nach rückwärts zeichnen (es wird gezeichnet). Beim Menschen ist nur ein Stückchen geblieben da unten, das andere ist umgebildet und steht hier unter unserer Stirn. Es ist ein metamorphosierter, ein transformierter Riechnerv. Mit dem bilden wir unsere Vorstellungen. Deshalb können wir nicht so riechen, wie der Hund, aber wir können vorstellen. Wir tragen den riechenden Hund in uns, nur umgebildet. Und so alle Tiere.

Davon muß man eine Vorstellung hervorrufen. Es gibt einen deutschen Philosophen, Schopenhauer, der hat ein Buch geschrieben: «Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung». Das Buch ist ja nur für Menschen. Hätte ein genialer Hund es geschrieben, so hätte er geschrieben: «Die Welt als Wille und Gerüche», und ich bin überzeugt davon, das Buch wäre viel interessanter als das Buch, das Schopenhauer geschrieben hat.

Man sehe sich die verschiedenen Formen der Tiere an, beschreibe sie nicht so, als ob jedes Tier für sich dastehen würde, sondern versuche, vor den Kindern immer die Vorstellung hervorzurufen: Sieh einmal, so schaut der Mensch aus. Wenn du dir den Menschen nach dieser Richtung verändert denkst, vereinfachst, vereinigt denkst, kriegst du das Tier. Wenn du zu irgendeinem Tiere, sagen wir zum Beispiel einem niederen Tiere, der Schildkröte, etwas hinzufügst, unten ein Känguruh, die Schildkröte über das Känguruh setzest, so hast du oben etwas wie einen verhärteten Kopf; das ist die Schildkrötenform in gewisser Beziehung. Und unten das Känguruh, das sind die Gliedmaßen des Menschen in einer gewissen Weise.

So kann man überall in der weiten Welt finden, wie man eine Beziehung herausfinden kann zwischen dem Menschen und den verschiedenen Tieren.

Sie lachen jetzt über diese Dinge. Das schadet nichts. Es ist ganz gut, wenn in der Klasse auch gelacht wird, denn nichts ist besser in die Klasse hineinzubringen als Humor. Wenn die Kinder auch lachen können, wenn sie nicht nur immer den Lehrer mit einem furchtbar langen Gesicht sehen und selber versucht sind, solche langen Gesichter zu machen und zu glauben, wenn man auf der Schulbank sitzt, muß man eben ein langes Gesicht machen - wenn das nicht der Fall ist, sondern wenn Humor hineingebracht wird, wenn man die Kinder dazu bringt, zu lachen, dann ist das das beste Unterrichtsmittel. Ernste Lehrer, ganz ernste Lehrer, die erreichen nichts mit den Kindern.

Also, da haben Sie das Tierreich im Prinzip, wie ich es Ihnen zunächst darstellte. Von Einzelheiten können wir dann sprechen, wenn Zeit dazu ist. Aber Sie ersehen daraus, daß der Mensch lehrend das Tierreich so behandeln kann, daß das Tierreich ein ausgebreiteter Mensch ist.

Das gibt für das Kind wiederum eine sehr, sehr feine, schöne Empfindung ab. Denn nicht wahr, das Kind lernt, wie ich Ihnen angedeutet habe, die Pflanzenwelt als zur Erde gehörig kennen, und die Tiere als zu sich gehörig. Es wächst das Kind mit dem ganzen Erdenbereich zusammen. Es steht nicht mehr bloß auf dem toten Erdboden, sondern es steht auf dem lebendigen Erdboden und empfindet die Erde als Lebendiges. Es bekommt allmählich die Vorstellung, es stehe auf dem Erdboden so, wie wenn es auf einem großen Organismus stünde, wie zum Beispiel auf einem Walfisch. Das ist auch die richtige Empfindung. Das allein führt in die ganze menschliche Weltempfindung hinein.

Und von den Tieren bekommt das Kind die Empfindung, als ob alle Tiere etwas Verwandtes hätten mit dem Menschen, aber auch die Vorstellung, daß der Mensch etwas über alle Tiere Hinausragendes hat, weil er alle Tiere in sich vereint. All das naturwissenschaftliche Geschwätz, daß der Mensch von einem Tiere abstamme, wird belacht werden von solchen Menschen, die so erzogen worden sind. Denn man wird erkennen, daß der Mensch das ganze Tierreich, die einzelnen Glieder synthetisch in sich vereinigt.

Ich sagte Ihnen, zwischen dem 9. und 10. Jahre kommt der Mensch so weit, daß er unterscheidet zwischen sich als Subjekt und der Außenwelt als Objekt. Er unterscheidet sich von der Umwelt. Früher konnte man nur Märchen, Legenden erzählen, wo die Steine und Pflanzen sprechen, handeln wie Menschen. Da unterschied sich das Kind noch nicht von der Umgebung. Jetzt, wo es sich unterscheidet, müssen wir es wiederum auf einer höheren Stufe mit der Umgebung zusammenbringen. Jetzt müssen wir ihm den Boden, auf dem es steht, so zeigen, daß der Boden in selbstverständlicher Weise mit seinen Pflanzen zusammengehört. Dann bekommt es einen praktischen Sinn, wie ich Ihnen gezeigt habe, auch für die Landwirtschaft. Es wird wissen, man düngt, weil man die Erde in einer gewissen Weise lebendig braucht unter einer Pflanzenart. Es betrachtet nicht die einzelne Pflanze, die es aus der Botanisiertrommel herausnimmt, als ein Ding für sich, betrachtet aber auch nicht ein Tier als ein Ding für sich, sondern das ganze Tierreich als einen über die Erde sich ausbreitenden, großen analysierten Menschen. Es weiß dann der Mensch, wie er auf der Erde steht, und es weiß der Mensch, wie sich die Tiere zu ihm verhalten.

Das ist von einer ungeheuren Bedeutung, daß wir in dem Kinde vom 10. Jahre an bis gegen das 12, Jahr hin diese Vorstellungen, Pflanze - Erde, Tier - Mensch, erwecken. Dadurch stellt sich das Kind mit seinem ganzen Seelen-, Körper- und Geistesleben in einer ganz bestimmten Weise in die Welt hinein.

Dadurch, daß wir dem Kinde eine Empfindung - und das alles muß eben empfindungsgemäß künstlerisch an das Kind herangebracht werden -, daß wir ihm eine Empfindung beibringen für die Zusammengehörigkeit von Pflanzen und Erdboden, wird das Kind klug, wird wirklich klug und gescheit; es denkt naturgemäß. Dadurch, daß wir ihm probieren beizubringen - sei es nur im Unterricht, Sie werden sehen, daß es dabei herauskommt -, wie es zu dem Tiere steht, lebt der Wille aller Tiere im Menschen auf, und zwar in Differenzierung, in entsprechender Individualisierung; alle Eigenschaften, alles Formgefühl, das sich in dem Tiere ausprägt, lebt in dem Menschen. Der Wille des Menschen wird dadurch impulsiert, und der Mensch wird dadurch in einer naturgemäßen Weise seiner Wesenheit nach in die Welt hineingestellt.

Warum gehen denn heute die Menschen in der Welt so, ich möchte sagen, entwurzelt von allem herum? Den Menschen, wenn sie heute in der Welt herumgehen, sieht man es schon an, sie gehen nicht ordentlich, sie treten nicht ordentlich auf, sie schleppen die Beine nach. Das andere haben sie im Sport gelernt, aber das ist dann wiederum etwas Unnatürliches. Aber vor allen Dingen, sie denken trostlos! Sie wissen nicht was Rechtes anzufangen im Leben. Sie wissen etwas anzufangen, wenn man sie an die Nähmaschine oder an das Telefon stellt oder wenn eine Eisenbahnfahrt oder eine Reise um die Welt arrangiert wird. Aber mit sich selbst wissen sie nichts anzufangen, weil sie nicht in entsprechender Weise durch die Erziehung in die Welt hineingestellt worden sind. Aber das kann man nicht dadurch, daß man die Phrase drechselt, man solle den Menschen richtig erziehen, sondern das kann man nur dadurch, daß man wirklich im Einzelnen, Konkreten so etwas für den Menschen findet, wie, daß man die Pflanze richtig in den Erdboden hineinsenkt und das Tier in der richtigen Weise neben den Menschen stellt. Dann steht der Mensch in der richtigen Weise auf dem Erdboden darauf, und dann stellt er sich in der richtigen Weise zur Welt. Das muß man durch den ganzen Unterricht erreichen. Das ist wichtig, das ist wesentlich.

Es wird immer darauf ankommen, daß wir für ein jedes Lebensalter dasjenige finden, was nach der Entwickelung des Menschen von diesem Lebensalter selber gefordert wird. Dazu brauchen wir eben wirkliche Menschenbeobachtung, wirkliche Menschenerkenntnis. Betrachten wir noch einmal die zwei Dinge, die ich eben auseinandergesetzt habe: Das Kind bis zum 9. oder 10. Jahre fordert die Belebung der ganzen äußeren Natur, weil es sich noch nicht unterscheidet von dieser äußeren Natur. Wir werden dem Kinde eben dann Märchen erzählen, Legenden, Mythen erzählen. Wir werden selber etwas erfinden für das Allernächstliegende, um dem Kinde in Form der Erzählungen, Schilderungen, der bildhaften Darstellungen künstlerisch dasjenige beizubringen, was seine Seele aus den verborgenen Tiefen, in denen sie in die Welt eintritt, herausholt. Wenn wir wiederum das Kind nach dem 9., 10. Jahre haben, zwischen dem 10. und 12. Lebensjahre, stellen wir es so in die Tier- und Pflanzenwelt hinein, wie wir es eben geschildert haben.

Nun muß man sich aber klar werden darüber, daß der heute so beliebte Kausalitätsbegriff, Ursachenbegriff, beim Kinde auch in diesem Lebensalter, im 10., 11. Jahre, noch gar nicht als ein Bedürfnis des Begreifens vorhanden ist. Wir gewöhnen uns ja heute, alles nach Ursache und Wirkung zu betrachten. Die naturwissenschaftliche Erziehung der Menschen hat es dahin gebracht, daß man überall nach Ursache und Wirkung alles betrachtet. Sehen Sie, dem Kinde bis zum 11. oder 12. Jahre so von Ursache und Wirkung zu reden, wie man es im alltäglichen Leben tut, wie man es heute gewohnt ist, ist gerade so, wie man dem Farbenblinden von Farben spricht. Man redet an der Seele des Kindes vorbei, wenn man in dem Stile redet, in dem heute von Ursache und Wirkung geredet wird. Vorerst braucht das Kind lebendige Bilder, bei denen man niemals nach Ursache und Wirkung frägt. Nach dem 10. Jahre soll man wiederum nicht Ursache und Wirkung, sondern Bilder nach Ursache und Wirkung hinstellen.

Erst gegen das 12. Jahr hin wird das Kind reif, von Ursachen und Wirkungen zu hören. So daß man diejenigen Erkenntniszweige, die es mit Ursache und Wirkung hauptsächlich zu tun haben, in dem Sinne, wie man heute von Ursache und Wirkung redet, die leblose Naturphysik und so weiter eigentlich erst in den Lehrplan zwischen dem 11. und 12. Lebensjahre einführen soll. Vorher sollte man über Mineralien, über Physikalisches, über Chemisches nicht zu dem Kinde reden. Es fügt sich nicht in das Lebensalter des Kindes ein.

Und weiter, wenn man Geschichtliches betrachtet, so soll das Kind auch bis gegen das 12. Jahr hin in der Geschichte Bilder bekommen, Bilder von einzelnen Persönlichkeiten, Bilder von Ereignissen, überschaubar schön gemalte Bilder, wo die Dinge lebendig vor der Seele stehen, nicht eine Geschichtsbetrachtung, in der man immer das Folgende als die Wirkung vom Vorhergehenden betrachtet, worauf die Menschheit so stolz geworden ist. Diese pragmatische Geschichtsbetrachtung, die nach Ursachen und Wirkungen sucht in der Geschichte, ist etwas, was das Kind ebensowenig auffaßt wie der Farbenblinde die Farbe. Und außerdem bekommt der Mensch eine ganz falsche Vorstellung vom Leben, vom fortlaufenden Leben, wenn man ihm alles immer nur nach Ursachen und Wirkungen beibringt. Ich möchte Ihnen das durch ein Bild klarmachen.

Denken Sie sich, da fließt ein Strom dahin (es wird gezeichnet). Er zeigt Wellen. Sie werden nicht immer richtig gehen, wenn Sie die Welle c aus der Welle b und diese aus der Welle a hervorgehen lassen, wenn Sie sagen, c ist die Wirkung von b, und b von a; es walten da unten in den Tiefen noch allerlei Kräfte, welche diese Wellen aufblasen. Und so ist es in der Geschichte. Da ist nicht immer das, was 1910 geschieht, die Wirkung von dem, was 1909 geschehen ist, und so weiter, sondern für diese Wirkungen aus den Tiefen der Strömung in der Entwickelung, was die Wellen aufwirft, dafür muß beim Menschen sehr frühzeitig eine Empfindung eintreten. Sie tritt aber nur ein, wenn man spät erst die Ursachen und Wirkungen einführt, gegen das 12. Jahr hin, und vorher Bilder hinstellt.

Es stellt dies wiederum Anforderungen an die Phantasie des Lehrers. Diesen muß er aber genügen. Er wird schon genügen, wenn er für sich Menschenkenntnis erwirbt. Und darum handelt es sich.

So wie man wirklich aus der Natur des Menschen heraus erzieht und unterrichtet, muß nun dem Unterricht, wie ich ihn eben dargestellt habe, die Erziehung in bezug auf moralische Qualitäten parallel gehen. Ich möchte da zum Schluß noch einzelnes hinzufügen. Auch da handelt es sich darum, daß man aus der Natur des Kindes abliest, wie man es zu behandeln hat. Wenn man dem Kinde schon mit sieben Jahren den Ursachen- und Wirkungsbegriff beibringt, handelt man gegen die Entwickelung der menschlichen Natur. Wenn man aber das Kind durch gewisse Dinge strafen will, so handelt man oftmals mit gewissen Strafen auch gegen die Entwickelung der menschlichen Wesenheit.

In der Waldorfschule konnten wir dabei ganz schöne Erfahrungen machen. Wie wird in gewöhnlichen Schulen oftmals gestraft? Kinder haben in der Stunde etwas nicht ordentlich gemacht, man läßt sie nachsitzen, und sie müssen zum Beispiel Rechnungen machen. Da hat sich in der Waldorfschule etwas Sonderbares herausgestellt mit drei oder vier Kindern, denen man gesagt hatte: Ihr wart unordentlich, ihr müßt nachsitzen und Rechnungen machen! - Da sagten die anderen: Da wollen wir aber auch dableiben und Rechnungen machen! - Denn sie sind so erzogen, daf3 das Rechnungenmachen etwas Gutes ist, nicht etwas, womit man bestraft wird. Man soll beim Kinde gar nicht die Meinung hervorrufen, daß Rechnungenmachen im Nachsitzen etwas Schlimmes ist. Deshalb wollte die ganze Klasse auch dableiben und nachsitzen und Rechnungen machen. Man soll also nicht Dinge wählen, die gar nicht eine Strafe darstellen können, wenn das Kind im geraden Seelenleben erzogen werden soll.

Oder ein anderes Beispiel: Dr. Stein, ein Lehrer in der Waldorfschule, hat sich manches sehr Gute, manchmal im Momente ausgesonnen in bezug auf die Erziehung. Er bemerkte einmal, daß seine Schüler sich unter der Bank Briefchen zureichten. Sie schrieben sich Briefe, gaben also nicht acht, und steckten die Briefe unter der Bank dem Nachbarn zu, und der wieder die Antwort zurück. Nun hat Dr. Stein nicht angefangen zu schimpfen über das Briefeschreiben und gesagt: Ich will euch bestrafen! - oder so etwas, sondern er hat ganz plötzlich angefangen, einen Vortrag über das Postwesen zu halten. Die Kinder waren frappiert, daß plötzlich über das Postwesen gesprochen wurde; aber sie sind dann doch darauf gekommen, weshalb über das Postwesen gesprochen wurde. Und diese feine Art, Übergänge zu finden, die beschämt dann. Die Kinder waren beschämt, und das Briefeschreiben hat aufgehört, einfach wegen der Gedanken, die er eingeflochten hat über das Postwesen.

Und so muß man Erfindungsgabe haben, wenn man eine Klasse leiten will. Man muß nicht stereotyp durchaus auf dasjenige gehen, was so hergebracht ist, sondern man muß sich tatsächlich in das ganze Wesen des Kindes hineinversetzen können und wissen, daß eine Besserung - und mit der Strafe will man ja schließlich eine Besserung unter Umständen viel eher eintritt, wenn auf diese Weise eine Beschämung hervorgerufen wird, aber ohne daß man sich an den Einzelnen wendet, daß das ganz unvermerkt vor sich geht, als wenn man im groben Sinne straft. Gerade auf diese Weise, wenn man mit einem gewissen Geist in der Klasse drinnen steht, richtet sich so manches ein, was sonst gar nicht ins Gleichgewicht zu bringen ist.

Vor allen Dingen fordert ja das Erziehen und Unterrichten von dem Lehrer Selbsterkenntnis. Er darf zum Beispiel nicht so erziehen wollen, daß er ein Kind, das Tintenkleckse gemacht hat auf das Blatt oder auf die Schulbank, weil es ungeduldig oder zornig geworden ist über etwas, was der Nachbar gemacht hat, nun anschreit wegen der Tintenspritzer: Du darfst nicht zornig werden! Zornig werden ist keine Eigenschaft, die ein guter Mensch haben darf! Ein Mensch muß nicht zornig werden, sondern in Ruhe alles ertragen! Wenn du mir noch einmal zornig wirst, dann, dann schmeiße ich dir das Tintenfaß an den Kopf!

Ja, wenn in dieser Weise erzogen wird, wie es sehr häufig geschieht, dann wird sehr wenig erreicht werden. Der Lehrer muß sich immer in der Hand haben; er darf vor allen Dingen nie in die Fehler verfallen, die er an seinen Schülern rügt. Da muß man aber wissen, wie das Unbewußte der Kinder wirkt. Das, was der Mensch an bewußtem Verstand, Gemüt, Wille hat, ist nur ein Teil des seelischen Lebens; im Untergrund waltet schon beim Kinde eben der astralische Leib mit seiner ungeheuren Klugheit und Vernünftigkeit.

Nun ist es mir immer ein Greuel gewesen, wenn ein Lehrer in einer Klasse drinnensteht, das Buch in der Hand hat und aus dem Buch heraus unterrichtet oder wenn er ein Heft hat, worin er sich aufnotiert hat, was er fragen will, und immer hineinschauen muß. Gewiß, das Kind denkt nicht gleich daran mit seinem Oberbewußtsein; aber die Kinder sind gescheit in ihrem Unterbewußtsein und man sieht, wenn man solches zu sehen vermag, daß sie sich sagen: Der weiß ja das gar nicht, was ich lernen soll. Warum soll ich das lernen, was der nicht weiß? Das ist immer das Urteil im Unterbewußten bei Kindern, die aus einem Buch oder Heft vom Lehrer unterrichtet werden.

Man muß auf solches Imponderable, auf solche Feinheiten im Unterricht außerordentlich viel geben. Denn sobald das Unterbewußtsein des Kindes, das Astralische, bemerkt, der Lehrer weiß etwas selber nicht, er muß erst ins Heft hineinschauen, dann findet es unnötig, daß es selber dies lerne. Und der Astralleib wirkt viel sicherer als das Oberbewußtsein des Kindes.

Ich wollte diese Bemerkungen einmal in diesen Vortrag einflechten. Wir werden spezielle Fächer und Erziehungsetappen beim Kinde dann in den nächsten Tagen einfügen.

Third Lecture

Today we want to characterize some of the more general aspects of the art of education during the period of life between the change of teeth and sexual maturity, so that in the next lesson we can go into more detail on the treatment of individual subjects and individual life situations.

When a child reaches the age of 9 or 10, it can begin to distinguish itself from its surroundings. The difference between subject and object — subject = the self, object = the other — only really emerges at this point, and we can then begin to talk about external things, whereas before we had to treat these external things as if they were actually one with the child's body. Yesterday I said that we should treat external things as if they were talking, acting people. This gives the child the feeling that the outside world is simply a continuation of its own being.

Now, when the child has passed the age of 9 or 10, it is a matter of introducing them to some elementary facts, entities of the outside world, the facts of the plant kingdom and the animal kingdom. We will talk about other subjects later. But with these things in particular, we must ensure that we introduce the child to them in the way that human nature requires.

The first thing we must do is actually throw away all the textbooks. Because textbooks today contain nothing about the plant and animal kingdoms that can actually be taught to children. Today's textbooks are good for teaching adults about plants and animals, but we spoil the individuality of the child when we use these textbooks in school. And it is fair to say that textbooks and manuals that provide guidance on how to proceed in school are simply not available today. The issue is this:

If you present individual plants to a child and have them examine this or that aspect of each plant, you have initially done something that does not correspond to reality. A plant in itself has no reality. If you pull out a hair and look at it as if it were a thing in itself, it has no reality. In trivial life, we say that everything we see with our eyes has a reality. But it is quite different whether we see a stone in front of us that we are judging, or whether we see a hair or a rose in front of us. After ten years, the stone will still be exactly the same as it is today, but after two days, the rose will no longer be the same; it is only a reality on the whole rose bush. The hair has no reality of its own; it is only a reality with the whole head, with the whole person. And when you go out into the fields and pull up plants, it is as if you had pulled the hair out of the earth. For plants belong to the earth just as hair belongs to the human organism. To look at a hair on its own, as if it had grown somewhere by itself, is nonsense.

It is equally nonsensical to take a green botanical drum, carry plants home, and look at each plant on its own. This does not correspond to reality, and in this way it is not possible to acquire a true understanding of nature and human beings.

If you have a plant here (see drawing D), that alone is not the plant, but the plant also includes what is underneath it as soil, extending indefinitely, perhaps very far. There are plants that allow their roots to spread out over a very large area. The fact that this piece of earth in which the plant is located belongs to it in a wide radius can be learned from the fact that fertilizer must be added to the soil if certain plants are to grow properly. It is not only the piece of plant that lives, but also what is here (see drawing D), it lives with it, belongs to the plant; the earth lives with it.

There are plants that bloom in spring, sprout around May or June, and bear fruit in autumn. Then they wither and die. They are stuck in the earth, but the earth belongs to them. However, there are also plants that draw energy from the earth around them. That would be the earth (see drawing II); now the root absorbs the energy that is in the environment. Because it has now absorbed the energy, the energy of the earth comes up from there and turns into a tree.

What is a tree? A tree is a colony of many plants. Whether you have a hill that is less alive and has many plants on it, or whether you have the trunk of a tree, where the earth has drawn itself into it in a much more alive state, it makes no difference. You cannot objectively consider a plant on its own.

Drive through an area, or better still, walk through an area where there are certain geological formations, for example red sand, and look at the plants: most of them have yellow-reddish flowers. The flowers belong to the soil. Soil and plants are a unit, like your scalp and your hair.

Therefore, you must not look at geography and geology on the one hand and botany on the other with the child. That is nonsense. Instead, geography, description of the land, and observation of plants must always be one and the same, because the earth is an organism, and plants are like hair on this organism. And the child must be able to grasp the idea that the earth and the plants belong together, that every piece of earth bears the plants that belong to that piece of earth.

It is therefore correct to consider botany only in connection with the earth and to give the child a clear sense that the earth is a living being that has hair. The hair is the plants. You see, we say that the earth has a gravitational pull, gravity. We attribute that to the earth. But plants, with their power of growth, also belong to the earth. There is no such thing as the earth on its own and plants on their own, just as in reality there is no such thing as hair on its own and people on their own. They belong together.

And when you teach this to children, taking things out of the botanical drum and letting them name them, you are teaching them something unreal. This has consequences for life, because the child will never gain an understanding from the botany you teach them of how, for example, to treat the field, how to make it come alive with fertilizer. The child will only gain an understanding of how to treat the field if it knows how the field is connected to the plant. Because people in our time have less and less sense of reality—I told you in the first lesson that practitioners have the least sense of reality; they are all theorists today—because people no longer have any trace of reality, they view everything separately, everything in isolation.

And so it has come to pass that in many, many regions, all field crops have become decadent over the last fifty or sixty years. Recently, there was an agricultural congress in Central Europe. There, the farmers themselves admitted that the fruits are becoming so poor that one cannot hope that in fifty years' time they will still be edible for humans.