The Kingdom of Childhood

GA 311

15 August 1924, Torquay

Lecture IV

I have shown you how between the change of teeth and the ninth or tenth year you should teach with descriptive, imaginative pictures, for what the children then receive from you will live on in their minds and souls as a natural development, right through their whole lives.

This is of course only possible if the feelings and ideas one awakens are not dead but living. To do this you must first of all yourselves acquire a feeling for the inward life of the soul. A teacher or educator must be patient with his own self-education, with the awakening of something in the soul which may indeed sprout and grow. You may then be able to make the most wonderful discoveries, but if this is to be so you must not lose courage in your first endeavours.

For you see, whenever a man undertakes an activity of a spiritual nature, he must always be able to bear being clumsy and awkward. A man who cannot endure being clumsy and doing things stupidly and imperfectly at first, will never really be able to do them perfectly in the end out of his own inner self. And especially in education we must first of all kindle in our own souls what we then have to work out for ourselves; but first it must be enkindled in the soul. If once or twice we have succeeded in thinking out a pictorial presentation of a lesson which we see impresses the children, then we shall make a remarkable discovery about ourselves. We shall see that it becomes more and more easy for us to invent such pictures, that by degrees we become inventive people in a way we had never dreamt of. But for this you must have the courage to be very far from perfect to begin with.

Perhaps you will say you ought never to be a teacher if you have to appear before the children in this awkward manner. But here indeed the Anthroposophical outlook must help you along. You must say to yourself: Something is leading me karmically to the children so that I can be with them as a teacher though I am still awkward and clumsy. And those before whom it behoves me not to appear clumsy and awkward—these children I shall only meet in later years, again through the workings of Karma.1Dr. Steiner retained the ancient oriental word “Karma” in speaking of the working of human destiny in repeated lives on earth. See Rudolf Steiner:Theosophy,chap. II. The teacher or educator must thus take up his life courageously, for in fact the whole question of education is not a question of the teachers at all but of the children.

Let me therefore give you an example of something which can sink into the child's soul so that it grows with his growth, something which one can come back to in later years and make use of to arouse certain feelings within him. Nothing is more useful and fruitful in teaching than to give the children something in picture form between the seventh and eighth years, and later, perhaps in the fourteenth and fifteenth years, to come back to it again in some way or other. Just for this reason we try to let the children in the Waldorf School remain as long as possible with one teacher. When they come to school at seven years of age the children are given over to a teacher who then takes his class up the school as far as he can, for it is good that things which at one time were given to the child in germ can again and again furnish the content of the methods employed in his education.

Now suppose for instance that we tell an imaginative story to a child of seven or eight. He does not need to understand all at once the pictures which the story contains; why that is I will describe later. All that matters is that the child takes delight in the story because it is presented with a certain grace and charm. Suppose I were to tell the following story: Once upon a time in a wood where the sun peeped through the branches there lived a violet, a very modest violet under a tree with big leaves. And the violet was able to look through an opening at the top of the tree. As she looked through this broad opening in the tree top the violet saw the blue sky. The little violet saw the blue sky for the first time on this morning, because she had only just blossomed. Now the violet was frightened when she saw the blue sky—indeed she was overcome with fear, but she did not yet know why she felt such great fear. Then a dog ran by, not a good dog, a rather bad snappy dog. And the violet said to the dog: “Tell me, what is that up there, that is blue like me?” For the sky also was blue just as the violet was. And the dog in his wickedness said: “Oh, that is a great giant violet like you and this great violet has grown so big that it can crush you.” Then the violet was more frightened than ever, because she believed that the violet up in the sky had got so big so that it could crush her. And the violet folded her little petals together and did not want to look up to the great big violet any more, but hid herself under a big leaf which a puff of wind had just blown down from the tree. There she stayed all day long, hiding in her fear from the great big sky-violet.

When morning came the violet had not slept all night, for she had spent the night wondering what to think of the great blue sky-violet who was said to be coming to crush her. And every moment she was expecting the first blow to come. But it did not come. In the morning the little violet crept out, as she was not in the least tired, for all night long she had only been thinking, and she was fresh and not tired (violets are tired when they sleep, they are not tired when they don't sleep!) and the first thing that the little violet saw was the rising sun and the rosy dawn. And when the violet saw the rosy dawn she had no fear. It made her glad at heart and happy to see the dawn. As the dawn faded the pale blue sky gradually appeared again and became bluer and bluer all the time, and the little violet thought again of what the dog had said, that that was a great big violet which would come and crush her.

At that moment a lamb came by and the little violet again felt she must ask what that thing above her could be. “What is that up there?” asked the violet, and the lamb said, “That is a great big violet, blue like yourself.” Then the violet began to be afraid again and thought she would only hear from the lamb what the wicked dog had told her. But the lamb was good and gentle, and because he had such good gentle eyes, the violet asked again: “Dear lamb, do tell me, will the great big violet up there come and crush me?” “Oh no,” answered the lamb, “it will not crush you, that is a great big violet, and his love is much greater than your own love, even as he is much more blue than you are in your little blue form.” And the violet understood at once that there was a great big violet who would not crush her, but who was so blue in order that he might have more love, and that the big violet would protect the little violet from everything in the world which might hurt her. Then the little violet felt so happy, because what she saw as blue in the great sky-violet appeared to her as Divine Love, which was streaming towards her from all sides. And the little violet looked up all the time as if she wished to pray to the God of the violets.

Now if you tell the children a story of this kind they will most certainly listen, for they always listen to such things; but you must tell it in the right mood, so that when the children have heard the story they somehow feel the need to live with it and turn it over inwardly in their souls. This is very important, and it all depends on whether the teacher is able to keep discipline in the class through his own feeling.

That is why when we speak of such things as I have just mentioned, we must also consider this question of keeping discipline. We once had a teacher in the Waldorf School, for instance, who could tell the most wonderful stories, but he did not make such an impression upon the children that they looked up to him with unquestioned love. What was the result? When the first thrilling story had been told the children immediately wanted a second. The teacher yielded to this wish and prepared a second. Then they immediately wanted a third, and the teacher gave in again and prepared a third story for them. And at last it came about that after a time this teacher simply could not prepare enough stories. But we must not be continually pumping into the children like a steam pump; there must be a variation, as we shall hear in a moment, for now we must go further and let the children ask questions; we should be able to see from the face and gestures of a child that he wants to ask a question. We let him ask it, and then talk it over with him in connection with the story that has just been related.

Thus a little child will probably ask: “But why did the dog give such a horrid answer?” and then in a simple childlike way you will be able to show him that a dog is a creature whose task is to watch, who has to bring fear to people, who is accustomed to make people afraid of him, and you will be able to explain why the dog gave that answer.

You can also explain to the children why the lamb gave the answer that he did. After telling the above story you can go on talking to the children like this for some time. Then you will find that one question leads to another and eventually the children will bring up every imaginable kind of question. Your task in all this is really to bring into the class the unquestioned authority about which we have still much to say. Otherwise it will happen that whilst you are speaking to one child the others begin to play pranks and to be up to all sorts of mischief. And if you are then forced to turn round and give a reprimand, you are lost! Especially with the little children one must have the gift of letting a great many things pass unnoticed.

Once for example I greatly admired the way one of our teachers handled a situation. A few years ago he had in his class a regular rascal (who has now improved very much). And lo and behold, while the teacher was doing something with one of the children in the front row, the boy leapt out of his seat and gave him a punch from behind. Now if the teacher had made a great fuss the boy would have gone on being naughty, but he simply took no notice at all. On certain occasions it is best to take no notice, but to go on working with the child in a positive way. As a general rule it is very bad indeed to take notice of something that is negative.

If you cannot keep order in your class, if you have not this unquestioned authority (how this is to be acquired I shall speak of later), then the result will be just as it was in the other case, when the teacher in question would tell one story after another and the children were always in a state of tension. But the trouble was that it was a state of tension which could not be relaxed, for whenever the teacher wanted to pass on to something else and to relax the tension (which must be done if the children are not eventually to become bundles of nerves), then one child left his seat and began to play, the next also got up and began to sing, a third did some Eurythmy, a fourth hit his neighbour and another rushed out of the room, and so there was such confusion that it was impossible to bring them together again to hear the next thrilling story.

Your ability to deal with all that happens in the classroom, the good as well as the bad, will depend on your own mood of soul. You can experience the strangest things in this connection, and it is mainly a question of whether the teacher has sufficient confidence in himself or not.

The teacher must come into his class in a mood of mind and soul that can really find its way into the children's hearts. This can only be attained by knowing your children. You will find that you can acquire the capacity to do this in a comparatively short time, even if you have fifty or more children in the class; you can get to know them all and come to have a picture of them in your mind. You will know the temperament of each one, his special gifts, his outward appearance and so on.

In our teachers' meetings, which are the heart of the whole school life, the single individualities of the children are carefully discussed, and what the teachers themselves learn from their meetings, week by week, is derived first and foremost from this consideration of the children's individualities. This is the way in which the teachers may perfect themselves. The child presents a whole series of riddles, and out of the solving of these riddles there will grow the feelings which one must carry with one into the class. That is how it comes about that when, as is sometimes the case, a teacher is not himself inwardly permeated by what lives in the children, then they immediately get up to mischief and begin to fight when the lesson has hardly begun. (I know things are better here but I am talking of conditions in Central Europe.) This can easily happen, but it is then impossible to go on with a teacher like this and you have to get another in his place. With the new teacher the whole class is a model of perfection from the first day!

These things may easily come within your experience; it simply depends on whether the teacher's character is such that he is minded to let the whole group of his children with all their peculiarities pass before him in meditation every morning. You will say that this would take a whole hour; this is not so, for if it were to take an hour one could not do it, but if it takes ten minutes or a quarter of an hour it can be done. But the teacher must gradually develop an inward perception of the child's mind and soul, for it is this which will enable him to see at once what is going on in the class.

To get the right atmosphere for this pictorial story-telling you must above all have a good understanding of the temperaments of the children. This is why the treatment of children according to temperament has such an important place in teaching. And you will find that the best way is to begin by seating the children of the same temperament together. In the first place the teacher has a more comprehensive view if he knows that over there he has the cholerics, there the melancholics, and here the sanguines. This will give him a point of vantage from which he may get to know the whole class.

The very fact that you do this, that you study the child and seat him according to his temperament, means that you have done something to yourself that will help you to keep the necessary unquestioned authority in the class. These things usually come from sources one least expects. Every teacher and educator must work upon himself inwardly.

If you put the phlegmatics together they will mutually correct each other, for they will be so bored by one another that they will develop a certain antipathy to their own phlegma, and it will get better and better all the time. The cholerics hit and smack each other and finally they get tired of the blows they get from the other cholerics; and so the children of each temperament rub each other's corners off extraordinarily well when they sit together. But the teacher himself when he speaks to the children, for instance when he is talking over with them the story which has just been given, must develop within himself as a matter of course the instinctive gift of treating the child according to his temperament. Let us say that I have a phlegmatic child; if I wish to talk over with such a child a story like the one I have told, I must treat him with an even greater phlegma than he has himself. With a sanguine child who is always flitting from one impression to another and cannot hold on to any of them, I must try to pass from one impression to the next even more quickly than the child himself does.

With a choleric child you must try to teach him things in a quick emphatic way so that you yourself become choleric, and you will see how in face of the teacher's choler his own choleric propensities become repugnant to him. Like must be treated with like, so long as you do not make yourself ridiculous. Thus you will gradually be able to create an atmosphere in which a story like this is not merely related but can be spoken about afterwards.

But you must speak about it before you let the children retell the story. The very worst method is to tell a story and then to say: “Now Edith Miller, you come out and retell it.” There is no sense in this; it only has meaning if you talk about it first for a time, either cleverly or foolishly; (you need not always be clever in your classes; you can sometimes be quite foolish, and at first you will mostly be foolish). In this way the child makes the thing his own, and then if you like you can get him to tell the story again, but this is of less importance for it is not indeed so essential that the child should hold such a story in his memory; in fact, for the age of which I am speaking, namely between the change of teeth and the ninth or tenth year, this hardly comes in question at all. Let the child by all means remember what he can, but what he has forgotten is of no consequence. The training of memory can be accomplished in subjects other than story-telling, as I shall have to show.

But now let us consider the following question: Why did I choose a story with this particular content? It was because the thought-pictures which are given in this story can grow with the child. You have all kinds of things in the story which you can come back to later. The violet is afraid because she sees the great big violet above her in the sky. You need not yet explain this to the little child, but later when you are dealing with more complicated teaching matter, and the question of fear comes up, you can recall this story. Things small and great are contained in this story, for indeed things small and great are repeatedly coming up again and again in life and working upon each other. Later on then you can come back to this. The chief feature of the early part of the story is the snappish advice given by the dog, and later on the kind loving words of advice uttered by the lamb. And when the child has come to treasure these things in his heart and has grown older, how easily then you can lead on from the story you told him before to thoughts about good and evil, and about such contrasting feelings which are rooted in the human soul. And even with a much older pupil you can go back to this simple child's story; you can make it clear to him that we are often afraid of things simply because we misunderstand them and because they have been presented to us wrongly. This cleavage in the feeling life, which may be spoken of later in connection with this or that lesson, can be demonstrated in the most wonderful way if you come back to this story in the later school years.

In the Religion lessons too, which will only come later on, how well this story can be used to show how the child develops religious feelings through what is great, for the great is the protector of the small, and one must develop true religious feeling by finding in oneself those elements of greatness which have a protective impulse. The little violet is a little blue being. The sky is a great blue being, and therefore the sky is the great blue God of the violet.

This can be made use of at various different stages in the Religion lessons. What a beautiful analogy one can draw later on by showing how the human heart itself is of God. One can then say to the child: “Look, this great sky-violet, the god of the violets, is all blue and stretches out in all directions. Now think of a little bit cut out of it—that is the little violet. So God is as great as the world-ocean. Your soul is a drop in this ocean of God. But as the water of the sea, when it forms a drop, is the same water as the great sea, so your soul is the same as the great God is, only it is one little drop of it.”

If you find the right pictures you can work with the child in this way all through his early years, for you can come back to these pictures again when the child is more mature. But the teacher himself must find pleasure in this picture-making. And you will see that when, by your own powers of invention, you have worked out a dozen of these stories, then you simply cannot escape them; they come rushing in upon you wherever you may be. For the human soul is like an inexhaustible spring that can pour out its treasures unceasingly as soon as the first impulse has been called forth. But people are so indolent that they will not make the initial effort to bring forth what is there in their souls.

We will now consider another branch of this pictorial method of education. What we must bear in mind is that with the very little child the intellect, that in the adult has its own independent life, must not yet really be cultivated, but all thinking should be developed in a pictorial and imaginative way.

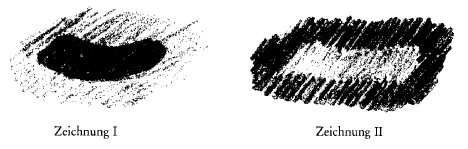

Now even with children of about eight years of age you can quite well do exercises of the following kind. It does not matter if they are clumsy at first. For instance you draw this figure for the child (see drawing a.) and you must try in all kinds of ways to get him to feel in himself that this is not complete, that something is lacking. How you do this will of course depend on the individuality of the child. You will for instance say to hi: “Look, this goes down to here (left half) but this only comes down to here (right half, incomplete). But this doesn't look nice, coming right down to here and the

other side only so far.” Thus you will gradually get the child to complete this figure; he will really get the feeling that the figure is not finished, and must be completed; he will finally add this line to the figure. I will draw it in red; the child could of course do it equally well in white, but I am simply indicating in another colour what has to be added. At first he will be extremely clumsy, but gradually through balancing out the forms he will develop in himself observation which is permeated with thought, and thinking which is permeated with imaginative observation. His thinking will all be imagery.

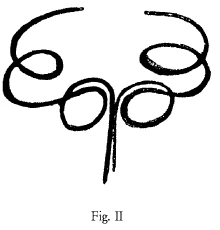

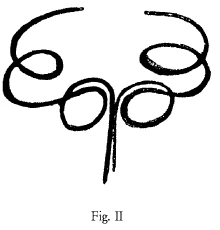

And when I have succeeded in getting a few children in the class to complete things in this simple way, I can then go further with them. I shall draw some such figure as the following (see drawing b. left), and after making the child feel that this complicated figure is unfinished I shall induce him to put in what will make it complete (right hand part of drawing). In this way I shall arouse in him a feeling for form which will help him to experience symmetry and harmony.

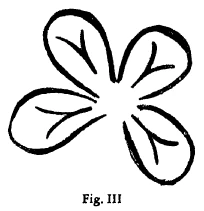

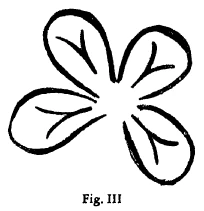

This can be continued still further. I can for instance awaken in the child a feeling for the inner laws governing this

figure (see drawing c.). He will see that in one place the lines come together, and in another they separate. This closing together and separating again is something that I can easily bring to a child's experience.

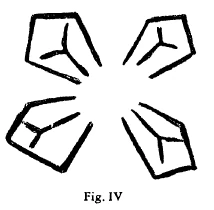

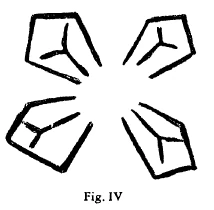

Then I pass over to the next figure (see drawing d.). I make the curved lines straight, with angles, and the child then has to make the inner line correspond. It will be a difficult task with children of eight, but, especially at this age, it is a wonderful achievement if one can get them to do this with all sorts of figures, even if one has shown it to them beforehand. You should get the children to work out the inner lines for themselves; they must bear the same character as the ones in the previous figure but consist only of straight lines and angles.

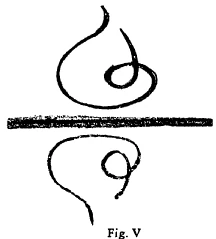

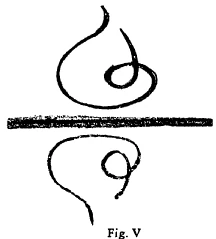

This is the way to inculcate in the child a real feeling for form, harmony, symmetry, correspondence of lines and so on. And from this you can pass over to a conception of how an object is reflected; if this, let us say, is the surface of the water (see drawing e.), and here is some object, you must arouse in the child's mind a picture of how it will be in the reflection. In this manner you can lead the children to perceive other examples of harmony to be found in the world.

You can also help the child himself to become skilful and mobile in this pictorial imaginative thinking by saying to him: “Touch your right eye with your left hand! Touch your right eye with your right hand! Touch your left eye with your right hand! Touch your left shoulder with your right hand

from behind! Touch your right shoulder with your left hand! Touch your left ear with your right hand! Touch your left ear with your left hand! Touch the big toe of your right foot with your right hand!” and so on. You can thus make the child do all kinds of curious exercises, for example, “Describe a circle with your right hand round the left! Describe a circle with your left hand round the right! Describe two circles cutting each other with both hands! Describe two circles with one hand in one direction and with the other hand in the other direction. Do it faster and faster. Now move the middle finger of your right hand very quickly. Now the thumb, now the little finger.”

So the child can learn to do all kinds of exercises in a quick alert manner. What is the result? If he does these exercises when he is about eight years old, they will teach him how to think—to think for his whole life. Learning to think directly through the head is not the kind of thinking that will last him his life. He will become “thought-tired” later on. But if, on the other hand, he has to do actions with his own body which need great alertness in carrying out, and which need to be thought over first, then later on he will be wise and prudent in the affairs of his life, and there will be a noticeable connection between the wisdom of such a man in his thirty-fifth or thirty-sixth year and the exercises he did as a child of six or seven. Thus it is that the different epochs of life are connected with each other.

It is out of such a knowledge of man that one must try to work out what one has to bring into one's teaching.

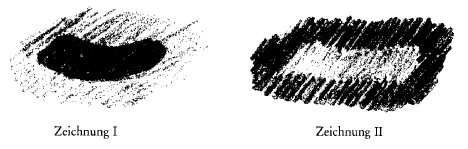

Similarly one can achieve certain harmonies in colour. Suppose we do an exercise with the child by first of all painting something in red •;see drawing a.). Now we show him, by

arousing his feeling for it, that next to this red surface a green surface would be very harmonious. This of course must be carried out with paints, then it is easier to see. Now you can try to explain to the child that you are going to reverse the process. “I am going to put the green in here inside (see drawing b.); what will you put round it?” Then he will put red round it. By doing such things you will gradually lead to a feeling for the harmony of colours. The child comes to see that first I have a red surface here in the middle and green round it (see former drawing), but if the red becomes green, then the green must become red. It is of enormous importance just at this age, towards the eighth year, to let this correspondence of colour and form work upon the children.

Thus our lessons must all be given a certain inner form, and if such a method of teaching is to thrive, the one thing necessary is—to express it negatively—to dispense with the usual timetable. In the Waldorf School we have so-called “period teaching” and not a fixed timetable. We take one subject for from four to six weeks; the same subject is continued during that time. We do not have from 8–9 Arithmetic; 9–10 Reading, 10–11 Writing, but we take one subject which we pursue continuously in the Main Lesson morning by morning for four weeks, and when the children have gone sufficiently far with that subject we pass on to another. So that we never alternate by having Arithmetic from 8–9 and Reading 9–10, but we have Arithmetic alone for several weeks, then another subject similarly, according to what it may happen to be. There are, however, certain subjects which I shall deal with later that require a regular weekly timetable. But, as a rule, in the so-called “Main Lessons” we keep very strictly to the method of teaching in periods. During each period we take only one subject but these lessons can include other topics related to it.

We thereby save the children from what can work such harm in their soul life, namely that in one lesson they have to absorb what is then blotted out in the lesson immediately following. The only way to save them from this is to introduce period teaching.

Many will no doubt object that in this kind of teaching the children will forget what they have learnt. This only applies to certain special subjects, e.g. Arithmetic, and can be corrected by frequent little recapitulations. This question of forgetting is of very little account in most of the subjects, at any rate in comparison to the enormous gain to the child if the concentration on one subject for a certain period of time is adhered to.

Vierter Vortrag

Ich habe ausgeführt, wie man versuchen soll, in schildernder, in Bilder darstellender Form in den Jahren zwischen dem Zahnwechsel und dem 9. und 10. Lebensjahre alles dasjenige an das Kind heranzubringen, was die Seele des Kindes dann aufnehmen soll, so aufnehmen soll, daß das Aufgenommene dann in naturgemäßer Weise weiterwirkt, weiterwirken kann durch das ganze Leben. Es ist das natürlich nur dann möglich, wenn man nicht tote Vorstellungen und Empfindungen in dem Kinde wachruft, sondern solche Vorstellungen und Empfindungen, die leben.

Um das zu können, muß man sich selber erst das Gefühl für das Leben des Seeleninhaltes aneignen. Man wird Geduld haben müssen als Lehrender und Erziehender mit der eigenen Selbsterziehung, mit dem Erwecken dessen in der Seele, was wirklich keimen und wachsen kann in der Seele. Man wird in dieser Beziehung an sich selbst die schönsten Entdeckungen machen können. Man darf nur nicht, um solche Entdeckungen machen zu können, den Mut gleich beim ersten Anhub verlieren.

Der Mensch sollte, wenn er irgendeine Tätigkeit beginnt, die eine geistvolle Tätigkeit sein soll, es eigentlich unter allen Umständen ertragen können, ungeschickt zu sein. Wer nicht ertragen kann, ungeschickt zu sein, die Dinge zuerst dumm und unvollkommen zu machen, der wird sie aus dem Innern heraus eigentlich niemals vollkommen machen können. Und insbesondere im lehrenden und erziehenden Beruf müssen wir erst dasjenige in unserer eigenen Seele entzünden, was wir eigentlich ausüben sollen; richtig entzünden. Wenn es uns gelingt, ein- oder zweimal bildhafte Darstellungen zu ersinnen, bei denen wir sehen, daß sie bei den Kindern einschlagen, dann werden wir nämlich eine merkwürdige Entdeckung an uns selber machen: Wir werden sehen, daß uns dann das Erfinden von solchen Bildern immer leichter und leichter wird, daß wir nach und nach so erfinderische Menschen werden, wie wir uns das von uns gar nicht vorgestellt hätten.

Aber dazu gehört eben, mutvoll zunächst vielleicht sehr weit neben dem Richtigen danebenzutapsen. Man kann ja sagen, dann sollte ich gar nicht Erzieher werden, wenn ich zunächst ganz ungeschickt an die Kinder herantrete! Ja, da muß Sie eben die anthroposophische Weltanschauung weiterbringen. Da müssen Sie sich sagen: Irgend etwas führt mich karmisch zu den Kindern, so daß ich auch als ungeschickter Erzieher einmal bei ihnen sein kann. Und diejenigen, bei denen ich nicht ungeschickt sein darf, die werden mir eben durch das Karma in späteren Jahren erst gebracht.

Dieses mutvolle sich Hineinwagen in das Leben braucht der Lehrer und Erzieher - wie überhaupt die Erziehungsfrage gar nicht eine Lehrer-, sondern eine Kinderfrage ist.

Und so möchte ich Ihnen gewissermaßen ein Beispiel geben für etwas, was so sich in die Seele des Kindes senken kann, daß es mit dem Kinde wächst und daß man auch später noch in der Lage ist, darauf zurückzukommen und spätere Empfindungen und Gefühle aus den ursprünglich gegebenen hervorzuholen.

Nichts ist nützlicher und fruchtbarer im Unterricht, als wenn Sie dem Kinde zwischen dem 7. und 8. Lebensjahre etwas in Bildern geben und später, vielleicht im 13., 14. Lebensjahre, wieder in irgendeiner Form darauf zurückkommen können. Gerade aus dem Grunde wird bei uns in der Waldorfschule versucht, die Kinder möglichst lange bei einer Lehrkraft zu lassen. Die Kinder werden, wenn sie in die Schule kommen, mit dem 7. Lebensjahre einer Lehrkraft übergeben. Die steigt dann mit den Klassen auf, soweit es eben geht. Das ist deshalb gut, damit die Dinge, die einmal keimhaft in dem Kinde veranlagt werden, immer wieder und wiederum den Inhalt der Erziehungsmittel abgeben können.

Denken wir uns nun, wir bringen einem sieben- oder achtjährigen Kinde eine Bilder enthaltende Erzählung. Das Kind braucht die Bilder nicht sogleich zu verstehen. Warum das ist, werde ich Ihnen nachher sagen. Es handelt sich nur darum, daß das Kind angemutet wird dadurch, daß der Erzieher die Sache, ich möchte sagen, in graziöser Form vorbringt. Nehmen wir an, ich erzähle dem Kinde folgendes:

«Da war einmal in einem Walde, wo die Sonne durch Bäume drang, ein Veilchen, ein bescheidenes Veilchen unter einem Baume, der große Blätter hatte. Und das Veilchen konnte durch eine Öffnung, die durch die Baumkrone entstanden ist, hindurchschauen. Und das Veilchen sah, indem es hindurchschaute durch die weite Öffnung in dem Walde, den blauen Himmel. Das kleine Veilchen sah zum ersten Male den blauen Himmel, denn es war an dem Morgen dieses Tages eben erst aufgeblüht. Nun erschrak das Veilchen, als es den blauen Himmel sah und geriet in große Angst. Aber es wußte noch nicht, warum es in so große Angst geraten war.

Da lief ein Hund vorbei, ein Hund, der nicht gut aussah, der etwas bissig und böse aussah. Und das Veilchen fragte den Hund: Sag mir einmal, was ist denn das da oben, das Blaue, das so ist wie ich? - denn es war der Himmel auch blau, wie das Veilchen blau war.

Und der Hund in seiner Bosheit sagte: Oh, das ist ein riesengroßes Veilchen, wie du, und dieses riesengroße Veilchen ist so groß geworden, daß es dich mächtig schlagen kann.

Und das Veilchen bekam eine noch viel größere Angst, denn es glaubte, dieses Veilchen da oben wäre so groß gewachsen, weil es da sein sollte zum Schlagen von ihm selber. Und das Veilchen zog seine Blütenblätter ganz zusammen und wollte nicht mehr hinaufschauen zu dem großen Veilchen und verbarg sich unter einem großen Blatt des Baumes, das gerade durch einen Windstoß heruntergefegt wurde. Und so blieb es den ganzen Tag, indem es sich in seiner Angst versteckt hatte vor dem großen Himmelsveilchen.

Und als der nächste Morgen kam, da hatte das Veilchen die ganze Nacht noch nicht geschlafen, denn es hatte immer nur nachgedacht, wie es sich verhielte mit dem großen blauen Himmelsveilchen, von dem es geschlagen werden sollte. Und immer erwartete es, daf3 jetzt und jetzt der erste Schlag kommen sollte, und er war nicht gekommen.

Und am Morgen, da kroch das Veilchen hervor, weil es jetzt gar nicht müde war, denn es hatte die Nacht hindurch immer nachgedacht und war frisch und nicht müde - Veilchen werden müde, wenn sie schlafen und werden nicht müde, wenn sie nicht schlafen - und das erste, was das Veilchen sah, war die aufgehende Sonne und das Morgenrot. Und als das Veilchen das Morgenrot sah, da wurde es gar nicht ängstlich. Und es war innerlich erfreut und froh über das Morgenrot.

Nach und nach kam wiederum, als das Morgenrot sich verlor, der weißlich-blaue Himmel hervor. Er wurde immer blauer und blauer. Und das Veilchen mußte wieder denken, was der Hund gesagt hatte, daß das ein großes Veilchen wäre, was es selber schlagen würde.

Und siehe da, da kam ein Lamm vorbei. Und jetzt wollte das Veilchen wiederum fragen, was das da oben wäre. Was ist denn das da oben? sagte das Veilchen. Da sagte das Lamm: Das ist ein großes Veilchen, blau wie du selber. - Jetzt wurde das Veilchen schon wiederum ängstlich und meinte, es würde von dem Lamm nur wieder dieselbe Auskunft bekommen wie von dem bösen Hund. Aber das Lamm war gut und fromm. Und weil es so gute und fromme Augen machte, da fragte das Veilchen noch einmal: Ach, mein liebes Lamm, wird mich denn das große Veilchen da oben schlagen?

O nein, antwortete das Lamm, das wird dich nicht schlagen, das ist ein großes Veilchen, und seine Liebe ist so vielmal größer als deine eigene Liebe, als es mehr blau ist, als du mit deiner kleinen Gestalt blau bist.

Und da verstand das Veilchen gleich, daß das ein großes Veilchen ist, das gar nicht schlagen wird, sondern das so viel Blau hat, um so viel mehr Liebe zu haben, und daß das große Veilchen das kleine Veilchen schützen wird vor allem, was feindlich ist in der Welt. Und da fühlte sich das kleine Veilchen so wohl, weil alles, was es sah als Blau in dem großen Himmelsveilchen, ihm vorkam wie die göttliche Liebe, die ihm von allen Seiten zuströmte. Und es schaute das kleine Veilchen immer auf, wie wenn es beten wollte zu dem Gott der Veilchen.»

Wenn man so etwa den Kindern erzählt, dann werden sie zweifellos zuhören. Sie hören immer zu bei solchen Dingen. Nur, man muß aus einer solchen Stimmung heraus erzählen, daß die Kinder, wenn sie nun die Erzählung gehört haben, ein wenig das Bedürfnis haben, diese Erzählung auch innerlich seelisch zu verarbeiten. Das ist sehr wichtig. Und das hängt alles davon ab, wie man in der Lage ist, durch sein eigenes Fühlen die Kinder in Disziplin zu halten. Deshalb muf) man sogleich, wenn man so etwas bespricht, wie das, was ich eben besprochen habe, das Disziplinhalten daneben hinstellen.

Wir bekamen einmal eine Lehrkraft in die Waldorfschule, die konnte ausgezeichnet erzählen, ganz ausgezeichnet erzählen, aber sie machte auf die Kinder nicht den Eindruck, daß die Kinder in ganz selbstverständlicher Liebe zu ihr hinsahen. Was war die Folge? Wenn die eine anregende Erzählung gegeben worden war, dann wollten die Kinder sogleich eine zweite haben. Und die Lehrkraft gab nach, hatte eine zweite vorbereitet. Jetzt wollten die Kinder gleich eine dritte haben; die Lehrkraft gab nach, hatte eine dritte vorbereitet. Und so kam es zuletzt, daß diese Lehrkraft nach und nach nicht mehr genügend vorbereiten konnte. - Es ist ja auch notwendig, daß man nicht unausgesetzt wie mit einer Dampfpumpe fortwährend in die Kinder hineinpumpt - wir werden gleich hören, wie man abwechseln soll -, sondern es handelt sich darum, daß man jetzt weiter geht, daß man das Kind zunächst fragen läßt, daß man einem Kinde ansieht an seinem Gesichte, an seinen Mienen, es will einen etwas fragen. Man läßt es fragen und unterhält sich dann über die Frage mit dem Kinde in Anlehnung an die eben gegebene Erzählung.

So wird einen ein kleines Kind wahrscheinlich fragen: Warum hat denn der Hund eine so böse Antwort gegeben? - Da wird man dem Kinde dann schon in der ganz kindlichen Weise beibringen können: Der Hund ist ein Wesen, das zum Wachedienst bestimmt ist, der den Leuten graulich machen soll, der gewöhnt ist, die Leute vor sich fürchten zu machen. Und man wird dem Kinde erklären können, warum der Hund diese Antwort gegeben hat. Man wird ihm auch erklären können, warum das Lamm jene Antwort gegeben hat, die ich angegeben habe. Man wird in dieser Beziehung, nachdem man die Erzählung gegeben hat, lange mit den Kindern fortsprechen können, und man wird finden: Eine Frage bringt bei den Kindern gerade die andere. Alle werden zuletzt auf alles Mögliche und Unmögliche übergehen. Da handelt es sich darum, daß man in der Tat jene selbstverständliche Autorität, von der wir noch viel sprechen werden, in die Klasse hineinbringt. Sonst geschieht es, daß, während man sich mit einem Kinde unterhält, fangen gleich die anderen an Allotria, allerlei Unfug zu treiben. Und wenn man dann genötigt ist, sich umzudrehen und Verweise zu geben, so hat man schon verloren. Man muß gerade bei kleineren Kindern die Gabe haben, viel unbemerkt zu lassen.

So zum Beispiel konnte ich einmal einen unserer Lehrer sehr bewundern. Da war ein richtiger Range in der Klasse - jetzt ist er schon ganz ordentlich geworden nach ein paar Jahren -, und siehe da, während der Lehrer sich etwas in der ersten Bank mit einem Kinde beschäftigt hat, springt er flugs aus der Bank heraus und gibt dem Lehrer eins hinten drauf. Ja, wenn der Lehrer nun eine große Geschichte gemacht hätte, wäre der Junge immer ungezogen geblieben. Aber der Lehrer tat, als hätte er es nicht bemerkt. Gewisse Dinge muß man eben gar nicht bemerken und da durch das Positive wirken, durch die Art und Weise wiederum, wie man sich mit diesem Kinde im Positiven beschäftigt. In der Regel ist das Bemerken von Negativem etwas sehr Schlimmes.

Wenn man nicht Disziplin halten kann, wenn man nicht die selbstverständliche Autorität hat - wodurch man sie erwirbt, werde ich ja noch besprechen -, dann kommt eben das heraus, was bei jener Lehrerin herausgekommen ist. Die betreffende Lehrkraft konnte eine Erzählung an die andere fügen, die Kinder waren immer in Spannung, nur durfte die Spannung nicht nachlassen. Wenn diese Lehrkraft nun übergehen wollte zu entspannen, was ja auch da sein muß - denn sonst werden die Kinder zuletzt vollständige Nervenbündel -, da ging das eine Kind aus der Bankreihe heraus, fing an zu spielen, das andere ging, um einige Turnübungen zu machen, das dritte machte Eurythmie, das vierte prügelte sich mit einem andern; ein anderes lief hinaus zur Türe, und so war bald ein Getriebe, daß man die Kinder nicht wieder zusammenbringen konnte, um die weitere spannende Erzählung zu hören.

Es handelt sich eben überall darum, aus welchem Milieu heraus auch das Gute in der Klasse behandelt wird. In diesen Dingen kann man wirklich die sonderbarsten Erfahrungen machen. Da handelt es sich dabei durchaus um so etwas, wie, ob die Lehrkraft selber Selbstvertrauen genug hat zu sich oder nicht.

Die Lehrkraft muß mit einem solchen Gemüte, in einer solchen Seelenstimmung in die Klasse hereinkommen, daß sie geeignet ist, sich wirklich in die Seele der Kinder ganz zu vertiefen. Wodurch erreicht man dieses? Dadurch, daß man seine Kinder kennt. Sie werden sehen, daß sich darinnen in verhältnismäßig kurzer Zeit eine Praxis erringen läßt, selbst wenn man fünfzig oder noch mehr Kinder in der Klasse hat. Man lernt seine Kinder kennen; man lernt seine Kinder vorstellen; man weiß, welches Temperament das einzelne Kind hat, welche Begabung es hat, welche Physiognomie es hat und so weiter.

Bei unseren Lehrerkonferenzen, die die Seele des ganzen Unterrichtes sind, werden gerade diese einzelnen Kinderindividualitäten sorgfältig besprochen, so daß das Hinschauen auf die Kinderindividualitäten das Wesentliche desjenigen bildet, was im Laufe der Lehrerkonferenzen die Lehrer selber lernen. Dadurch vervollkommnen sich die Lehrer. Das Kind gibt eigentlich eine große Anzahl von Rätseln auf, und im Lösen dieser Rätsel entwickeln sich die Empfindungen, die man in die Klasse hineintragen muß.

Daher kommt es, daß wenn eine Lehrkraft in der Klasse ist - man kann es manchmal erfahren -, die nicht innerlich selber erfüllt ist von dem, was in den Kindern lebt, so balgen sich die Kinder in der Klasse, wenn sie kaum fünf Minuten angefangen hat, geben gar nicht acht, treiben nur Späße. Man kann erleben, daß es dann nicht weiter geht mit einer solchen Lehrkraft; man muß sie durch eine andere ersetzen. Musterhaft ist die ganze Klasse vom ersten Tage an bei der anderen Lehrkraft!

Diese Dinge können Sie erleben. Es hängt lediglich davon ab, wie die Seelenverfassung der Lehrkraft ist; ob die Seelenverfassung wirklich so ist, daf% die Lehrkraft geneigt ist, morgens meditierend sich die ganze Schar der Kinder mit ihren Eigentümlichkeiten durch die Seele ziehen zu lassen.

Sie werden sagen: Dazu braucht man ja eine Stunde. Das braucht man nicht. Wenn man eine Stunde braucht, so kann man es eben nicht. Wenn man dazu zehn Minuten oder eine Viertelstunde braucht, dann kann man es. Gewiß, anfangs wird es schwierig gehen, aber nach und nach muß dieser innerliche psychologische Blick erworben werden, der es möglich macht, daß die Lehrkraft schnell die Dinge überschaut.

Sehen Sie, man muß, um die Stimmungen zu erzeugen, die notwendig sind, um dieses bildhaft Erzählerische in die Kinder hineinzubringen, vor allen Dingen einen guten Blick haben für die Temperamente der Kinder. Deshalb gehört es schon zur Methodik des ganzen Erziehungs- und Unterrichtsbetriebes, zunächst die Temperamente der Kinder entsprechend zu behandeln. Und es stellt sich heraus, daß die beste Behandlung für die Temperamente diese ist, zunächst einmal die Kinder gleichen Temperamentes zusammenzusetzen. Erstens ist es für den Lehrer übersichtlich, wenn er weiß, da drüben hat er die Choleriker, dort drüben hat er die Melancholiker, da die Sanguiniker. Er hat dadurch einen Anhaltspunkt zum Erkennen der ganzen Klasse.

Einfach schon dadurch, daß man das Kind nach seinem Temperament studiert und es nach seinem Temperament setzt, hat man wiederum an sich selber etwas getan, um in der Klasse die nötige selbstverständliche Autorität zu halten. Die Dinge kommen gewöhnlich aus anderen Untergründen, als man meint. Und innere Arbeit muß der Lehrende und Erziehende schon an sich verrichten.

Wenn Sie die Phlegmatiker zusammensetzen, so üben sie gegenseitige Selbstkorrektur. Sie werden sich nämlich so langweilig, daß sie mit der Zeit gegen das Phlegma Antipathie bekommen; dann wird es immer besser und besser. Die Choleriker prügeln sich und puffen sich und werden zuletzt der Prügel und Püffe der andern Choleriker überdrüssig. Und so schleifen sich die einzelnen Temperamente, gerade wenn sie zusammensitzen, außerordentlich gut aneinander ab.

Aber auch der Lehrende selber soll, indem er mit den Kindern etwa solche Dinge wie die eben gegebene Erzählung durchspricht, die selbstverständliche instinktive Gabe in sich entwickeln, das Kind nach seinem Temperament zu behandeln.

Habe ich ein phlegmatisches Kind, so behandle ich, wenn ich irgendwie im Anklange an eine solche Erzählung mit dem Kinde spreche, das Kind selber mit einem noch größeren Phlegma, als es selber hat. Ein sanguinisches Kind, das immer von einem Eindruck zum anderen läuft, bei keinem festhalten kann, bei dem versuche ich, die Eindrücke noch schneller wechseln zu lassen, als es selber sie behandelt. Einem cholerischen Kinde versuche man, möglichst in stößiger Weise, so daß man selber ins Cholerische hineinkommt, die Dinge beizubringen, und Sie werden sehen, wie es nach und nach sich abstößt in seiner Cholerik an der dargestellten Cholerik des Erziehers. Gleiches muß mit Gleichem behandelt werden. Nur darf man dabei nicht lächerlich werden. Und so bringt man es allmählich dahin, wirklich die Stimmung zu erzeugen, in der solch eine Erzählung nicht bloß gegeben, sondern auch besprochen werden kann.

Aber man bespreche eine Erzählung zuerst, ehe man sie wiederholen läßt. Die schlimmste Methode ist diese, eine solche Erzählung zu geben und dann zu sagen: Du, Edith Müller, mußt mir das jetzt wieder erzählen. - Das hat gar keinen Sinn. Ein Sinn kommt nur in die Sache, wenn über dieselbe gescheit oder töricht - man braucht in der Klasse nicht immer gescheit zu reden, es kann auch töricht geredet werden, man wird das zumeist zuerst tun - eine Zeitlang gesprochen wird. Dadurch wird dem Kinde die Sache zu eigen. Und dann kann man sich es eventuell wieder erzählen lassen. Das ist aber das weniger Wichtige. Denn zunächst ist nicht das das Wichtige, daß das Kind sich eine solche Sache gedächtnismäßig aneignet. Darauf kommt es sogar in diesem Lebensalter zwischen dem Zahnwechsel und dem 9. oder 10. Jahr, von dem ich jetzt spreche, sehr wenig an; es ist sogar besser, wenn man so rechnet, daß das Kind sich dasjenige gedächtnismäßig aneignen kann, was ihm bleibt, und das, was es vergißt, mag es eben vergessen. Auf die Ausbildung des Gedächtnisses kann man bei anderen Unterrichtsstoffen sehen als bei diesen Erzählungen, wie ich auch noch ausführen werde.

Nun wollen wir einmal ein klein wenig die Frage behandeln: Warum habe ich denn gerade eine solche Erzählung mit einem solchen Inhalte gewählt? Das ist aus dem Grunde geschehen, weil die Vorstellungen, die in dieser Erzählung spielen, mit dem Kinde wachsen können. Sie haben alles mögliche in der Erzählung, worauf Sie später zurückkommen können: Das Veilchen wird ängstlich, weil es das große Veilchen am Himmel sieht. Das braucht man mit dem kleinen Kinde noch nicht zu erörtern. Später, wenn man nötig hat, kompliziertere Lehrstoffe durchzunehmen, kann bei Gelegenheit, wenn irgendwo die Angst auftritt, auf dieses zurückgekommen werden. In dieser Erzählung tritt Kleines und Großes auf. Kleines und Großes kommt wiederholt, immer wieder und wieder im Leben vor und wirkt aufeinander; man kann später darauf zurückkommen. Vorkommt in dieser Erzählung aber vor allen Dingen zunächst der bissige Rat des Hundes, nachher der wohlwollende, liebevolle Rat des Lammes. Was kann da später, wenn das hervorgeholt wird, nachdem das Kind so etwas in der Seele liebgewonnen hat und reif ist dazu, an Betrachtungen angeknüpft werden über das Gute und das Böse, über die entgegengesetzten Empfindungen, die in der Seele wurzeln! Noch bei einem sehr reifen Kinde kann man auf diese einfache kindliche Erzählung wieder zurückkommen, kann ihm klarmachen, daß man ja oftmals nur Angst hat vor einer Sache, weil man sie mißversteht, weil sie schlecht dargestellt wird. Dieses Zwiespältige im Empfindungsleben, das man vielleicht später bei diesem oder jenem Lehrstoffe zu besprechen hat, kann in der wunderbarsten Weise gefunden werden, wenn man im späteren Leben auf diese Erzählung zurückkommt.

Und im Religionsunterricht, der ja erst später auftreten muß, wie schön ist diese Erzählung gerade zu benützen, indem man zeigt, wie das Kind die religiösen Gefühle entwickelt an dem Großen, das der Beschützer des Kleinen ist, und wie man das echte religiöse Gefühl entwickeln muß dadurch, daß man in sich dasjenige findet, was an dem Großen beschützend auftritt. Das kleine Veilchen ist ein kleines blaues Wesen. Der Himmel ist ein großes blaues Wesen. Daher ist der Himmel der blaue Gott des Veilchens.

Es wird das auf mehrfacher Stufe im Religionsunterricht zu benützen sein. Wie schön kann man später anknüpfen, vergleichen, wie das menschliche Innere selbst ein Göttliches ist! Man kann später zu dem Kinde sagen: Sieh einmal, dieses große Himmelsveilchen, der Veilchen-Gott, der ist ganz blau, in alle Weiten. Jetzt denkst du dir ein kleines Stück herausgeschnitten, das ist das kleine Veilchen. So ist Gott überhaupt groß wie der Welten-Ozean. Deine Seele ist ein Tropfen von Gott. Aber so, wie das Wasser des Meeres, wenn es einen Tropfen bildet, dasselbe Wasser ist wie das große Meer, so ist deine Seele dasselbe, was der große Gott ist, nur eben ein kleiner Tropfen.

Und so wird man es, wenn man die richtigen Bilder findet, für das ganze kindliche Alter einrichten können, daß man später auf diese Bilder wiederum zurückkommen kann, wenn das Kind reifer ist. Aber es handelt sich darum, daß der Lehrer selber Gefallen und Sympathie für diese Bildhaftigkeit findet. Und Sie werden sehen, wenn Sie ein Dutzend solcher Erzählungen durch Ihre Erfindungsgabe ausgebildet haben, dann können Sie sich gar nicht mehr retten; sie kommen überall, wo Sie gehen und stehen. Denn die menschliche Seele ist ein unversieglicher Quell, die es hervorbringen kann, wenn ihr nur einmal das Hervorzubringende auf der ersten Stufe entlockt ist.

Der Mensch ist nur so träge, daß er die ersten Anstrengungen nicht machen will, um dasjenige, was in der Seele drinnen sitzt, aus sich hervorzubringen.

Wir wollen uns nun einen anderen Zweig des bildhaften Lehrens und Erziehens einmal vor die Seele führen. Dabei wird es sich darum handeln, daß gerade bei dem ganz kleinen Kinde der Intellekt, der Verstand, der abgesondert in der Seele wirkt, noch nicht eigentlich ausgebildet werden soll, sondern alles Denken soll am Anschaulichen, am Bildlichen entwickelt werden.

Nun wird man schon mit etwa achtjährigen Kindern ganz gut Übungen der folgenden Art machen können, wenn sie auch zunächst ungeschickt sind: Man stelle zum Beispiel vor das Kind diese Figur hin (Fig. I, das Dunklere). Und nun versuche man auf alle Weise, das Kind dahin zu bringen, daß es aus sich selbst heraus das Gefühl bekommt: Das ist nicht fertig, da fehlt etwas. Man wird natürlich nach der Individualität des Kindes vorgehen müssen, um das Gefühl dieses Fehlens hervorzubringen. Man wird zum Bei spiel zu dem Kinde sagen müssen: Sieh einmal diese linke Hälfte, die geht doch bis da herunter, und die rechte nur bis dahin. Das ist doch nicht schön, wenn das eine ganz bis da herunter geht, das andere nicht, nur bis daher. Und so wird man das Kind allmählich dazu bringen, daß es diese Figur ergänzt, daß es wirklich empfindet: Die Figur ist nicht fertig, Fig. I die muß ergänzt werden. Und es wird das Kind dazu gebracht werden können, dieses zu der Figur hinzuzusetzen. Ich zeichne das rot, was das Kind natürlich auch weiß zeichnen kann; was von dem Kinde ergänzt werden soll, ist von mir durch eine andere Farbe angedeutet (Fig. I, heller). Das Kind wird sich zunächst höchst ungeschickt benehmen, aber es wird nach und nach im Ausgleichen von etwas ein denkendes Anschauen und ein anschauendes Denken entwickeln. Das Denken wird ganz im Bild bleiben.

Und habe ich einmal ein paar Kinder in der Klasse dazu gebracht, in dieser einfachen Weise die Dinge zu ergänzen, dann werde ich weiter vordringen können. Dann werde ich vielleicht noch diese Figur dem Kinde vorzeichnen (Fig. ID). Nun werde ich diese komplizierte Figur als unfertig von dem Kinde empfinden lassen und das Kind veranlassen, nun dasjenige, was geschehen kann zur Fertigstellung, zu machen (Fig. II, heller). Auf diese Weise werde ich in dem Kinde Formgefühl hervorrufen, Formgefühl, durch welches das Kind veranlaßt wird, Symmetrie, Harmonie zu empfinden.

Das kann nun wiederum weiter ausgebildet werden. Ich kann zum Beispiel dem Kinde ein Gefühl davon hervorrufen, welches die innere an- Fig. I geschaute Gesetzmäßigkeit dieser Figur ist (Fig. III). Ich bringe dem Kind diese Figur vor. Das Kind bekommt schon ein Gefühl davon, daß diese Linie hier zusammengeht, die andere Linie hier auseinandergeht. Dieses Sichschließen und Auseinandergehen, das ist dasjenige, was ich dem Kinde gut beibringen kann.

Jetzt gehe ich dazu über und mache folgende Figur dem Kinde vor (Fig. IV): Ich mache die krummen Linien zu geraden mit Ecken, und ich veranlasse das Kind, nun selber diese innere Linie in der entsprechenden Weise zu machen. Man wird manche Mühe haben mit achtjährigen Kindern; aber gerade bei Achtjährigen ist dann der Erfolg ein außerordentlich großer, wenn man sie veranlassen kann, auch wenn man es vorher gezeigt hat, bei weiteren Figuren das selber zu machen. Man muß das Kind dazu bringen, nun seinerseits die inneren Figuren nachzumachen, mit demselben Charakter, nur in der Eckigkeit vorzugehen.

Auf diese Weise erzieht man das Kind zum wirklichen Formgefühl, zum Empfinden in der Harmonie, in der Symmetrie, in dem Sichentsprechen und so weiter. Und dann kann man von solchen Dingen dazu übergehen, bei dem Kinde eine Vorstellung davon hervorzurufen, wie sich etwas spiegelt. Wenn hier (Fig. V) eine Wasseroberfläche ist, hier irgendein Gegenstand, ruft man in dem Kinde die Vorstellung hervor und zeigt ihm, wie sich das spiegelt. - Auf diese Weise kann man das Kind nach und nach in die Harmonien hineinführen, die sonst auch in der Welt herrschen.

Man kann dann auch dazu übergehen, das Kind an sich selber geschickt werden zu lassen im anschaulichen bildhaften Denken: Zeige mir mit deiner linken Hand das rechte Auge! Zeige mir mit deiner rechten Hand das rechte Auge! Zeige mir mit deiner rechten Hand das linke Auge! Zeige mir von rückwärts aus mit der rechten Hand die linke Schulter! Mit der linken Hand die rechte Schulter! Zeige mir mit der rechten Hand dein linkes Ohr! Zeige mir mit der linken Hand das linke Ohr! Zeige mir mit der rechten Hand deine rechte große Zehenspitze und so weiter. Man kann also das Kind an sich selber die kuriosesten Übungen machen lassen. Zum Beispiel auch: Beschreibe einen Kreis mit deiner rechten Hand um die linke! Beschreibe einen Kreis mit deiner linken Hand um die rechte! Beschreibe zwei Kreise, die die Hände ineinander bilden! Beschreibe zwei Kreise, mit der einen Hand nach der einen Seite, mit der anderen Hand nach der anderen Seite! Man lasse es immer schneller und schneller machen. Bewege schnell den mittleren Finger deiner rechten Hand! Bewege schnell den Daumen der rechten Hand! Bewege schnell den kleinen Finger!

So läßt man am Kinde selber mit rascher Geistesgegenwart allerlei Übungen machen. Was ist der Erfolg solcher Übungen? Wenn ein Kind solche Übungen um das 8. Lebensjahr herum macht, so lernt es durch solche Übungen denken, und zwar denken für das Leben. Wenn man direkt denken lernt durch den Kopf, so ist das nicht denken für das Leben, dann wird man später denkmüde. Dagegen wenn man in dieser Weise am eigenen Körper in schneller Geistesgegenwart auszuführende Bewegungen macht, bei denen nachgedacht werden muß, dann wird man später lebensklug; man wird einen Zusammenhang bemerken können zwischen der Lebensklugheit eines Menschen im 35., 36. Jahre und dem, was man an solchen Übungen hat machen lassen im 7. und 8. Jahre. So hängen eben die verschiedenen Epochen des Lebens zusammen.

Und aus dieser Menschenkenntnis heraus muß) man versuchen, wirklich das einzurichten, was man an das Kind heranzubringen hat.

So kann man auch gewisse Harmonisierungen in den Farben erreichen. Nehmen wir an, ich mache zunächst mit dem Kinde die Übung, daß ich solch eine Malerei bringe (siehe Zeichnung I). Jetzt bringen wir ihm bei, indem wir sein Gefühl erregen, daß neben dieser roten Farbfläche (innen) eine grüne Farbfläche sich harmonisch gut fühlen läßt. Das muß natürlich mit Farben ausgeführt werden, dann sieht man es besser. Jetzt versucht man dem Kinde klarzumachen: Ich werde die Sache einmal umdrehen. Schau, ich mache hier (innen) das Grün (Zeichnung II); was wirst du mir da rundherum machen? - Dann wird das Kind rundherum rot malen. Man bekommt dadurch, daß man diese Dinge macht, das Kind dazu, allmählich die Harmonik der Farben zu empfinden. Das Kind lernt wissen: Wenn ich hier in der Mitte eine rote Fläche habe, ringsherum Grün (Zeichnung I), so muß ich, wenn nun das Rot grün wird, das Grüne rot machen. Dieses Sichentsprechen von Farbe und Form auf das Kind wirken lassen, das ist von einer ungeheuren Bedeutung gerade in diesem Lebensalter gegen das 8. Jahr hin.

Was man braucht, um mit einem solchen innerlich zu gestaltenden Unterricht vorwärtszukommen, das ist - ja, ich muß es durch ein Negatives ausdrücken -, das ist: kein Stundenplan! In der Waldorfschule haben wir sogenannten Epochenunterricht, keinen Stundenplan. Die Beschäftigung mit einem Gegenstande wird vier bis sechs Wochen fortgesetzt. Wir haben nicht von 8 bis 9 Uhr Rechnen, von 9 bis 10 Uhr Lesen, von 10 bis 11 Uhr Schreiben, sondern wir nehmen eine Materie, mit der wir uns fortlaufend im Hauptunterricht beschäftigen, Morgen für Morgen vier Wochen lang. Erst dann wechseln wir, wenn die Kinder entsprechend weit gekommen sind. Wir wechseln niemals so ab, daß wir von 8 bis 9 Uhr Rechnen und von 9 bis 10 Uhr Lesen haben, sondern wir treiben Rechnen sechs Wochen lang für sich, wir treiben ein anderes Fach auch vier oder sechs Wochen lang für sich, je nachdem, was es ist. Wir haben nur in einzelnen Fällen, von denen ich noch sprechen werde, Stundenpläne. In der Hauptsache, bei dem sogenannten Hauptunterricht, haben wir strenge den Epochenunterricht eingeführt. Diese Epochen hindurch nehmen wir nur Gleichartiges, wie eines aus dem anderen hervorgeht.

Dadurch entheben wir das Kind des ungeheuer innerlich seelisch Störenden, daß es in einer Stunde Dinge auf seine Seele wirken lassen muß, die in der nächsten Stunde wieder ausgelöscht werden. Diese Dinge können nicht vermieden werden, wenn nicht dieser sogenannte Epochenunterricht eingeführt wird.

Gewiß, es wird gegen diesen Epochenunterricht vielfach eingewendet, daß die Kinder die Dinge wieder vergessen. Allein das ist ja eine Sache, die nur für einzelne Unterrichtsfächer, zum Beispiel für das Rechnen in Betracht kommt, und da kann man durch kleine Wiederholungen die Sache ausbessern. Für die meisten Unterrichtsfächer kann überhaupt dieses Vergessen keine große Rolle spielen, jedenfalls nicht im Verhältnis zu dem, was gewonnen wird, an Ungeheurem gewonnen wird dadurch, daß das Kind konzentriert eine gewisse Epoche hin bei einer Materie festgehalten wird.

Fourth Lecture

I have explained how, in the years between the change of teeth and the ages of 9 and 10, we should try to present to the child in a descriptive, pictorial form everything that the child's soul should then absorb, so that what is absorbed can then continue to have an effect in a natural way throughout life. Of course, this is only possible if one does not evoke dead ideas and feelings in the child, but rather ideas and feelings that are alive.

To be able to do this, one must first acquire a feeling for the life of the soul's content. As a teacher and educator, one must have patience with one's own self-education, with awakening in the soul that which can truly germinate and grow in the soul. In this regard, one will be able to make the most beautiful discoveries in oneself. In order to make such discoveries, one must not lose heart at the first attempt.

When embarking on any activity that is to be a spiritual activity, one should actually be able to endure being clumsy under all circumstances. Those who cannot bear to be clumsy, to do things stupidly and imperfectly at first, will never be able to do them perfectly from within. And especially in the teaching and educating professions, we must first ignite in our own souls what we are actually supposed to do; ignite it properly. If we succeed in devising one or two vivid images that we see have an impact on the children, then we will make a remarkable discovery about ourselves: we will see that inventing such images becomes easier and easier for us, that we gradually become more inventive than we ever imagined ourselves to be.

But this requires the courage to perhaps initially stray very far from the right path. One might say, then I should not become a teacher at all if I initially approach the children in a completely clumsy manner! Yes, that is where the anthroposophical worldview must help you. You must say to yourself: something karmically leads me to the children, so that even as an unskilled educator I can be with them. And those with whom I must not be unskilled will be brought to me by karma in later years.

Teachers and educators need this courageous venturing into life — just as the question of education is not a question of teachers at all, but a question of children.

And so I would like to give you, in a sense, an example of something that can sink into the soul of the child in such a way that it grows with the child and that one is still able to return to it later and bring out later sensations and feelings from those originally given.

Nothing is more useful and fruitful in teaching than when you give the child something in pictures between the ages of 7 and 8 and can come back to it later, perhaps at the age of 13 or 14, in some form. It is precisely for this reason that we at the Waldorf School try to keep the children with one teacher for as long as possible. When children start school at the age of 7, they are assigned to a teacher. The teacher then moves up with the class as far as possible. This is beneficial because the things that are planted in the child's mind can be revisited again and again and provide the content for educational materials.

Let us now imagine that we bring a seven- or eight-year-old child a story containing pictures. The child does not need to understand the pictures immediately. I will tell you why later. It is simply a matter of the child being impressed by the fact that the teacher presents the matter, I would say, in a graceful manner. Let us assume that I tell the child the following:

"Once upon a time, in a forest where the sun shone through the trees, there was a violet, a modest violet under a tree that had large leaves. And the violet could see through an opening that had formed in the tree canopy. And the violet saw, as it looked through the wide opening in the forest, the blue sky. The little violet saw the blue sky for the first time, for it had just blossomed that morning. Now the violet was frightened when it saw the blue sky and became very afraid. But it did not yet know why it had become so afraid.

Then a dog ran past, a dog that did not look good, that looked a little snappy and mean. And the violet asked the dog: Tell me, what is that up there, the blue thing that is like me? - for the sky was also blue, just as the violet was blue.

And the dog, in his malice, said: Oh, that's a giant violet, like you, and this giant violet has grown so big that it can beat you up badly.

And the violet became even more afraid, because it believed that this violet up there had grown so big because it was there to beat it up. And the violet closed its petals completely and did not want to look up at the big violet anymore and hid under a large leaf of the tree that had just been swept down by a gust of wind. And so it remained all day, hiding in fear from the big sky violet.

And when the next morning came, the violet had not slept all night, for it had been thinking all the time about how it would fare with the big blue sky violet, which was supposed to beat it. And it kept expecting the first blow to come any moment now, but it did not come.

And in the morning, the violet crawled out, because it was not tired at all, for it had been thinking all night long and was fresh and not tired—violets get tired when they sleep and do not get tired when they do not sleep—and the first thing the violet saw was the rising sun and the dawn. And when the violet saw the dawn, it was not afraid at all. And it was inwardly delighted and happy about the dawn.

Gradually, as the dawn faded, the whitish-blue sky reappeared. It became bluer and bluer. And the violet had to think again about what the dog had said, that it was a big violet that it would beat itself.

And lo and behold, a lamb came by. And now the violet wanted to ask again what was up there. What is that up there? said the violet. Then the lamb said, “That is a big violet, blue like yourself.” Now the violet became frightened again and thought that it would get the same answer from the lamb as it had from the evil dog. But the lamb was good and pious. And because it had such good and pious eyes, the violet asked again, Oh, my dear lamb, will the big violet up there hurt me?

Oh no, replied the lamb, it won't hurt you. It's a big violet, and its love is so much greater than your own love, just as it is bluer than you are with your little form.

And then the violet understood that this was a big violet that would not hit it at all, but that it had so much blue that it had so much more love, and that the big violet would protect the little violet from everything hostile in the world. And then the little violet felt so comfortable, because everything it saw as blue in the big sky violet seemed to it like divine love flowing to it from all sides. And the little violet always looked up, as if it wanted to pray to the God of violets.

If you tell children stories like this, they will undoubtedly listen. They always listen to such things. However, you have to tell the story in such a way that, once the children have heard it, they feel a little need to process it internally, emotionally. That is very important. And that all depends on how you are able to keep the children disciplined through your own feelings. That is why, when discussing something like what I have just discussed, you must immediately emphasize the importance of maintaining discipline.

We once had a teacher at the Waldorf school who was an excellent storyteller, an excellent storyteller indeed, but she did not make an impression on the children that made them look at her with natural love. What was the result? When one stimulating story had been told, the children immediately wanted a second one. And the teacher gave in and had prepared a second one. Now the children wanted a third one right away; the teacher gave in and had prepared a third one. And so it came to pass that this teacher gradually became unable to prepare enough. It is also necessary not to constantly pump information into the children like a steam pump – we will hear in a moment how to alternate – but rather to go further, to let the child ask questions first, to see from a child's face and expressions that they want to ask something. Let them ask, and then discuss the question with the child based on the story just told.

A small child will probably ask: Why did the dog give such a nasty answer? Then you can teach the child in a very childlike way: The dog is a creature that is meant to guard, to frighten people, and is used to making people afraid of it. And you can explain to the child why the dog gave that answer. You can also explain why the lamb gave the answer I mentioned. After telling the story, you can continue talking with the children at length about this, and you will find that one question leads to another. Eventually, they will all move on to everything possible and impossible. The point is to bring that natural authority, which we will talk about a lot, into the classroom. Otherwise, while you are talking to one child, the others will immediately start messing around and causing all kinds of mischief. And when you are then forced to turn around and reprimand them, you have already lost. Especially with younger children, you have to have the ability to let a lot go unnoticed.

For example, I once greatly admired one of our teachers. There was a real troublemaker in the class—he has become quite well-behaved now after a few years—and lo and behold, while the teacher was busy with a child in the front row, he quickly jumped out of his seat and hit the teacher on the back. Yes, if the teacher had made a big deal out of it, the boy would have remained naughty. But the teacher pretended not to notice. Certain things should simply be ignored, and instead a positive influence should be exerted through the way in which one deals with this child in a positive manner. As a rule, noticing the negative is a very bad thing.

If you can't maintain discipline, if you don't have the natural authority – how you acquire it, I will discuss later – then you end up with the same result as that teacher. The teacher in question was able to string one story after another, and the children were always excited, but the excitement was not allowed to subside. When this teacher wanted to move on to relaxation, which is also necessary – otherwise the children end up completely frazzled – one child got up from the row of desks and started playing, another went to do some gymnastics, a third did eurythmy, a fourth got into a fight with another; another ran out the door, and soon there was such a commotion that it was impossible to get the children back together to hear the rest of the exciting story.

It is a matter of the environment in which the good in the class is dealt with. In these matters, one can really have the strangest experiences. It is definitely a question of whether the teacher has enough self-confidence or not.

The teacher must enter the classroom with such a disposition, such a state of mind, that they are able to truly immerse themselves in the souls of the children. How can this be achieved? By getting to know your children. You will see that this can be achieved in a relatively short time, even if you have fifty or more children in your class. You get to know your children; you learn to imagine your children; you know what temperament each child has, what talents they have, what their physiognomy is, and so on.

At our teachers' conferences, which are the soul of the entire teaching process, these individual child personalities are discussed in detail, so that observing the children's individual personalities forms the essence of what the teachers themselves learn during the course of the teachers' conferences. This is how teachers perfect themselves. Children actually present a large number of puzzles, and in solving these puzzles, the feelings that must be brought into the classroom develop.

That is why, when a teacher is in the classroom—as can sometimes be observed—who is not inwardly filled with what lives in the children, the children fight in the classroom within five minutes of the lesson beginning, pay no attention, and just fool around. It can be seen that things cannot continue with such a teacher; they must be replaced by another. The whole class is exemplary from the very first day with the other teacher!

You can experience these things. It depends solely on the state of mind of the teacher; whether the state of mind is really such that the teacher is inclined to meditate in the morning and let the whole group of children with their peculiarities pass through their soul.

You will say: That takes an hour. It doesn't. If it takes an hour, then you can't do it. If it takes ten minutes or a quarter of an hour, then you can do it. Certainly, it will be difficult at first, but little by little this inner psychological insight must be acquired, which makes it possible for the teacher to quickly grasp things.

You see, in order to create the moods that are necessary to bring this pictorial narrative into the children, you must above all have a good eye for the children's temperaments. That is why it is part of the methodology of the entire educational and teaching process to first treat the children's temperaments appropriately. And it turns out that the best way to deal with these temperaments is to first group children with similar temperaments together. First of all, it is easier for the teacher to keep track of the class if they know that the choleric children are over there, the melancholic children are over there, and the sanguine children are over there. This gives them a point of reference for understanding the whole class.

Simply by studying the child according to their temperament and placing them according to their temperament, you have in turn done something for yourself to maintain the necessary natural authority in the class. Things usually come from different sources than one might think. And teachers and educators must do the inner work themselves.

If you put the phlegmatic children together, they will correct each other. They will become so bored that, over time, they will develop an antipathy toward phlegmatic behavior; then things will get better and better. The choleric types fight and push each other around and eventually become tired of the fighting and pushing of the other choleric types. And so, when they sit together, the individual temperaments rub off on each other extremely well.

But the teacher himself should also develop the natural instinctive gift of treating the child according to his temperament by discussing things such as the story just given with the children.

If I have a phlegmatic child, when I talk to the child in response to such a story, I treat the child with even greater phlegmaticness than the child itself has. With a sanguine child, who always runs from one impression to another and cannot hold on to any of them, I try to let the impressions change even faster than the child itself processes them. With a choleric child, try to teach things in as abrupt a manner as possible, so that you yourself become choleric, and you will see how, little by little, the child's choleric nature is repelled by the choleric nature of the educator. Like must be treated with like. But you must not become ridiculous in the process. And so you gradually manage to create the right mood in which such a story can not only be told, but also discussed.

But discuss a story first before letting it be repeated. The worst method is to tell such a story and then say: “Edith Müller, you must now retell it to me.” That makes no sense at all. It only makes sense if the story is discussed for a while, whether intelligently or foolishly – you don't always have to talk intelligently in class, you can also talk foolishly, which is usually what you will do at first. This allows the child to make the subject their own. And then you can possibly have them repeat it to you. But that is less important. Because initially, it is not important that the child memorizes such a thing. At this age, between the change of teeth and the age of 9 or 10, which I am now talking about, it is of very little importance; it is even better to assume that the child can memorize what remains with them, and what they forget, they may simply forget. The training of memory can be seen in other teaching materials than these stories, as I will explain further.

Now let us briefly address the question: Why did I choose a story with this particular content? I did so because the ideas presented in this story can grow with the child. The story contains all kinds of elements that you can return to later: The violet becomes frightened when it sees the big violet in the sky. There is no need to discuss this with small children yet. Later, when it becomes necessary to go through more complicated teaching material, you can come back to this when fear arises somewhere. In this story, small and large appear. Small and large occur repeatedly, again and again in life, and influence each other; you can come back to this later. But what occurs in this story above all else is first the dog's snappy advice, then the lamb's benevolent, loving advice. What can be added later, when this is brought up, after the child has grown fond of it in their soul and is ready for it, to reflections on good and evil, on the opposing feelings that are rooted in the soul! Even with a very mature child, one can return to this simple, childlike story and make it clear to them that we are often only afraid of something because we misunderstand it, because it is misrepresented. This ambivalence in the life of feeling, which may have to be discussed later in this or that subject matter, can be found in the most wonderful way when one returns to this story later in life.

And in religious education, which must come later, how beautiful it is to use this story to show how the child develops religious feelings for the great one who is the protector of the small, and how genuine religious feeling must be developed by finding within oneself that which acts protectively in the great. The little violet is a small blue creature. The sky is a big blue being. Therefore, the sky is the blue god of the violet.