Physiology and Therapeutics

GA 314

8 October 1920, Dornach

Lecture II

Today I wish to make a link with what I said yesterday at the conclusion of the lecture. I pointed then to a personality who was driven by his philosophical instincts, as it were, from knowledge of the soul-spiritual into an intimation of the connection of this soul-spiritual with the physical-bodily existence of the human being. This was Schelling. I said that out of these instincts Schelling not only occupied himself with theoretical medicine but also with all kinds of therapeutic treatments. I do not know whether this resulted in greater or lesser satisfaction for the patient than is the case with many well-trained physicians, for this question of how much improvement in a person's condition can be attributed to therapeutic measures is, in most cases, a very problematic one if it is not looked at inwardly.

This instinct arose in Schelling out of the entire disposition of his soul, and from this he acquired a principle. It would certainly be good if this became a kind of inner principle for every physician, became an inner principle so that the physician would coordinate his entire practical conception of the nature of the healthy and sick human being out of this principle. I quoted Schelling's own words, which show a kind of daring. He simply said, “To know nature means to create nature.” Generally what is first noticed when a genius comes forth with such an expression is its quite obvious absurdity, for no one seriously believes himself capable, as an earthly human being in the physical body, of creating anything out of nature simply by knowing nature. Obviously in technology there is continuous creation, but there it is not a matter of really creating something in the way that Schelling meant; rather, by putting things together, by a composition of the forces of nature, nature in turn is given the opportunity to create in a particular way and through a particular arrangement, and so on. With this sentence, therefore, we have fundamentally to do with an absurdity that a man of genius laid at the foundation of all his thinking.

Yesterday I indicated another sentence that could be contrasted with, “To know nature means to create nature,” and this sentence would be, “To know the spirit means to destroy the spirit.” This last sentence was probably not expressed by Schelling in such a fundamental way. In modern times, however, a person who once again approaches a spiritual science, developing his own spiritual investigation, sees that both these sentences basically point back to an ancient knowledge from inspiration. Schelling, who certainly was by no means an initiate but simply a man of genius, could arrive at the first sentence out of his instinct. When a person pursues the kind of spiritual investigation that was not being done in Schelling's time, this sentence immediately recalls a resounding from ancient wisdom. Then one is carried over to the other sentence, which resounds in a similar way from ancient wisdom. Neither sentence can be comprehended with the customary modern intellectual knowledge that we apply in our sciences. Considered either in relation to each other or by themselves, these phrases are absurd. They both point, however, to something of the greatest importance in the human organization, something as important for the healthy condition as for the diseased condition.

When we consider outer nature in relation to the finished processes of nature, we can say nothing more than that “To know nature means at most to recreate nature in thoughts.” Therefore what we call our thoughts bring us no further than recreating nature since they lack the inner formative force; this is what we develop in our thinking, in the soul life permeated by thoughts, by mental images. It has been pointed out previously, however, that this soul life permeated by mental images is basically nothing but what emancipates itself from the physical-etheric organism at the time of the change of teeth, what the human being therefore has within the physical-etheric organism until the change of teeth.

What is active in the human physical-etheric during the childhood years, what truly engages in a creative activity, thus remains in a weakened form, toned down in the soul life as a world of pictures or a world of thoughts or mental images, in short, as a world force in thoughts and mental images, a force in its creative substantiality. It simply sits in our organism; what we know from age seven on simply sits within our organism in an organizing way. It creates there, but not at all, in the same as we are able to see it creating in outer nature; we see it creating within our own organism. Thus if a child were already a sage and were able to express himself not about outer nature but rather about what goes on within him, if the child were able to look within to his inner nature and penetrate nature there, he would say, “To know this nature means to create this nature.” The child would simply saturate himself with the creating forces, would become one with these creating forces. And in his medical instinct, in his physiological instinct, Schelling merely stated something that for the entire later life is absurd; he drew forth something from the age of childhood and extended it by saying, as it were: all this knowing in old age is nothing but a faint web of images; if one were able to know as a child, one would have to say that to know actually means to create, means to develop creative activity. We are able to see this creative activity, however, only in our own inner being.

What is it, therefore, that actually confronts us as creative activity in our own inner being, which is expressed in a genius such as Schelling as I have indicated? It is true, isn't it, that the nature of genius is generally based on the fact that the person retains a certain childlike quality in later life. Those people who age no matter what happens and who take up aging in a normal way, as it were, take it up appropriately never become geniuses. It is people who carry into later life something of a positive, creative-childlike element who bear the quality of genius. It is this childlike element, this positive creative element, this knowing-creative element that—if I want to express myself in a simple way—does not have time to know things outwardly because it turns the forces of knowledge inward and begins: to create. This is the heritage that we bring with us in entering physical existence through birth. We bring with us the forces of organization, and we can perceive them, as it were, through spiritual science. And a person like Schelling sensed them instinctively.

Anyone who acquires such perception knows that these soul-spiritual forces that permeate the organism in an organizing way in the first period of childhood do not completely cease being active with the change of teeth. They have undergone only one stage. They become suppressed, as it were, to a lesser degree of activity so that later we definitely still retain in us the organizing forces. We have conquered in ourselves, however, the memory-forming element that entered consciousness with the change of teeth, detaching itself thereby from the organization. We have taken memory from its latent state into its liberated state; we have received as a soul-perceptive force our growth force, our force of movement, our force of balance, which were active in a correspondingly heightened degree in the first period of childhood. You can see from this, however, that in normal human development, this organizing force, this growth force, must be transformed to a degree into something soul-spiritual, let us say, into the force of memory, into the thought-forming force.

Let us assume, now, that too much of this organizing force active in the first period of childhood were held back due to some process; picture a development in which insufficient forces of organization were transformed into the memory-forming force. These forces then remain stuck below in the organism; they are not carried properly into sleep each time a person falls asleep but rather continue to course through the organism between falling asleep and awakening.

If an individual engaged in medical, physiological-phenomenological research in the direction I can only suggest in this short course of lectures, he would be led to the insight that it is possible for forces in the human organism[,] that should actually enter the soul-spiritual at the proper turning-point in life instead[,] to remain below in the physical organization. Then what I spoke to you about yesterday occurs. If the normal degree of organization-forces is transformed with the change of teeth, then in later life we have the proper degree of forces in the organism to organize this organism in accord with its normal shape and normal structure. If we have not done this, however, if we have transformed too little, then the organizing forces that remain below appear somewhere and we encounter new formations, carcinomatous formations, about which I spoke yesterday. In this way—just as Troxler suggested in the first half of the nineteenth century—we can study the process of becoming ill or of illness that occurs in the moments of transition in later life.

We can then compare this with childhood illnesses, for obviously childhood illnesses cannot have the same origin, because they appear in an early stage of life when absolutely nothing has yet been transformed. If one has learned the origin of illnesses in later life, however, one has also acquired a capacity to observe what underlies the origin of illnesses in childhood. One finds the same thing, in a certain way, only from another side. One finds that there is too much of the soul-spiritual force of organization in the human organism when childhood illnesses arise. To an individual who has acquired the capacity to perceive along these lines, such things appear especially significant when considering the phenomena of scarlet fever or measles in childhood. With these he can see in the child's organism how the soul-spiritual, which otherwise functions in a normal way, begins to stir; he sees how it is more active than it should be. The whole course of these illnesses becomes comprehensible the moment one really sees this restless stirring of the soul-spiritual in the organism as the basis of illness.

Now, I beg you to consider my next sentence very precisely, for I never go a step further than is justified by the deliberations preceding it, even if much may be suggested only sketchily; everywhere I merely indicate how far one can go, so I am not drawing a conclusion here. I am simply saying that now one is not far from recognizing something that is extraordinarily important to recognize for a true knowledge. First we must arrive at the point of recognizing that in an illness of the human organism during later life, one that goes in the direction of new formations, there is too much of the organizing force that results in an island of organization, so to speak. When we have reached this point we are not far from saying that, if the later period of life points in this way back to earliest childhood, this indicates ultimately that what reveals itself in childhood points back to the time before birth or, let us say, before conception; it points back to the soul-spiritual existence of the human being before he was clothed with a physical body. A person suffering from childhood illnesses is simply someone who brought along too much of the soul-spiritual from his prehuman, pre-earthly life; this excess then lives itself out in the childhood illnesses.

In the future there will be no choice but to allow oneself to be driven beyond the fruitless, materialistic approaches in which physiological and therapeutic matters remain stuck today, to be driven on to a soul-spiritual approach. It will soon be seen that what arises in spiritual science does not occur because the spiritual investigator is too little grounded in physical research, because he is, as it were, a dilettante in physical research (though I must add parenthetically that many who call themselves spiritual investigators are, in fact, dilettantes, but this is not how it should be). It is not necessary for the spiritual investigator to be grounded too little in physical research in order to become a spiritual investigator; rather he must be even more immersed in physical research than the ordinary natural scientist. If he sees through phenomena more intensively, he will be driven by the phenomena themselves into the soul-spiritual, especially when it comes to illness.

The sentence, “To know the spirit means to destroy the spirit,” is actually an absurdity similar to the first sentence, yet this sentence also points to something that must be recognized, that must be penetrated. Just as the sentence, “To know nature means to create nature,” points us to the first age of childhood, and actually to life before birth—if we extend it in the right way—so the sentence, “To know the spirit means to destroy the spirit,” leads us to the end of a person's life, to what kills the human being. You need only hold to this sentence in a paradoxical way—“To know the spirit means to destroy the spirit”—and you will find how one must not follow it but how it nevertheless exists in life as something continually being approached asymptotically.

For an individual who doesn't simply grasp knowledge aggressively but develops self-perception in the right way, to know the spirit means to see continual processes of breakdown, continual processes of destruction in the human organism. When we look into the creative age of childhood in the same way, we can see continuous upbuilding processes, but upbuilding processes that have the peculiarity of actually dimming consciousness. Therefore we are dreaming, we are half-asleep in childhood; our consciousness is not fully awake. Our own earthly spirituality, namely the conscious spirituality of pressing back the growth activity, is what actually organizes us inwardly. The moment this force enters consciousness, it ceases to permeate us with organizing forces to the same degree as before.

In looking into the age of childhood one witnesses the work of upbuilding forces, though forces that weaken consciousness; in the same way one witnesses the breakdown processes when surrendering oneself to perceiving the developed thinking processes, but these breakdown processes are particularly suited to making our consciousness clear and luminous.

Modern physiological science pays little attention to this, although this is perfectly obvious in physiology's revelations, as obvious as can be. If you direct your attention to the real revelations of modern physiology, you will see that everything known about the physiology of the brain makes it quite clear that with soul-spiritual processes occurring consciously we do not have to do with any kind of growth forces or forces that take up nourishment; rather we have to do with processes of elimination in the nervous system, with breakdown processes, with a continuous slow dying.

It is death that is active in us when we surrender ourselves to what is spiritually active in our consciousness. And just as we look through the unconscious creating forces to the beginnings of life, so we look through the conscious conceptual forces that reveal themselves as destructive forces; they reveal themselves as what begins to take hold of us more and more as we grow into earthly life, to break us down, and finally to lead us to confront earthly death; we see through these forces to the other end of life, to death. Birth and death—or, let us say, conception, birth, and death—can only be understood by taking the spiritual into consideration.

And what wants to be expressed in the sentence, “To know the spirit means to destroy the spirit,” is this: if a person wishes only to gaze into the spirit, to take it up more or less naively, to take it up in the same way that outer nature is taken up, then that individual would have to dam up what is active in this thinking, conceptual, sensing and feeling activity; the breakdown would have to be prevented. This means that in such a moment a person would have to diminish, to weaken, the power over the spirit, the inner consciousness, to the point of unconsciousness, to a working of the spiritual in unconsciousness. He would have to come to the point of forming something spiritual out of himself, of pressing something spiritual out of himself, as it were. To do this, however, he could not remain conscious, because the organization cannot be carried into this breakdown process, into this spiritual process.

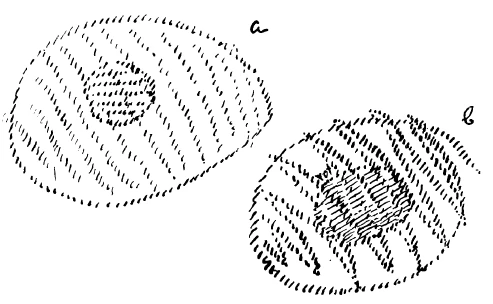

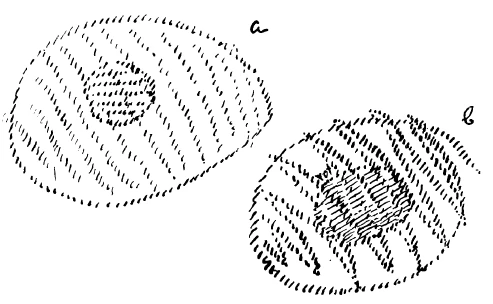

Thus we can say that on the one hand we have the processes of organization that consist of the fact that we have the form-skeleton of the human organism, as it were (see drawing a), into which the organizing force (drawing b, red) enters as something spiritual. (Of course this is now considered abstractly.) On the other hand, as I have described in the second case, we have the form-skeleton of the human organism, but we do not wish to allow it to be permeated by the organizing force, by the force that weakens our consciousness to a certain extent: instead we wish to drive out the organizing force, which we now want to know as spirit (see drawing c). We cannot go along with our ego, however, because this is bound to the organism.

We have the other side as well, the side in which man clearly begins to develop the spiritual, that is, to develop will activity in the spiritual. This permeation with will activity remains unconscious, sleeping, as it were, dreaming; based in this permeation with will activity is a soul-spiritual element that we actually bring forth from our organization without consciousness. Here we have the other side, the manic side, the frenzied side, in which the human being goes mad; we have the varying forms of the so-called mental illnesses. Whereas with physical illnesses we have a soul-spiritual element that does not belong in the physical organism (drawing b), with the so-called mental illnesses we have something in the psychological realm that drives out of the physical-etheric something that should remain within it (drawing c). Something is driven out of the organism.

Today we will see what we arrived at yesterday illuminated from the other side. This viewpoint can lead us still further. We will see tomorrow the fruitful therapeutic consequences that can be arrived at particularly from this viewpoint, consequences that can then be confirmed absolutely in life, proving themselves in the most outward practice of medicine, in practical therapeutic measures.

If we are looking for the cause of physical illness, we must ultimately seek it in the spirit going astray in the organism. This should certainly not be pursued abstractly. Anyone who does not understand the relationship between the soul-spiritual and the physical organism should really stay quiet about these matters. Only with knowledge of the soul-spiritual element can one come to know the specific aspects of this: where in one organ or another there is too strong a force of organization, a hypertrophied force of organization, as it were; these details can be arrived at only if one knows the soul-spiritual concretely. The soul-spiritual element is made concrete in the same way as the physical-bodily element in the liver, stomach, and so on, and one must know this soul-spiritual element (of which psychology has no intimation) with its constituents, its members, just as well as we know the physical-sensible. And if the relationships between the two are known, then one can often indicate—even out of the soul-spiritual findings encountered with the human being—where there is some kind of excessive organization in a particular organ. In every case that is not the result of an external injury, such an origin can be indicated.

On the other hand, if we are considering the so-called mental illnesses, we remain purely in abstractions if we believe that anything can be gained from a half-baked phenomenology, if we believe that simply by describing soul-spiritual abnormalities one can arrive at anything (though to describe them is, of course, most useful). With such descriptions one can naturally create a sensation among laymen, because it is always interesting to learn how a person who has gone mad deviates from life's normal standard. Anything unusual is interesting, and in our time it is still rare to deviate in this way from normal life. But to remain stuck in simple description should not be the important thing. It is particularly important not to press on from that point to the dilettantish judgment that in such cases the soul and spirit are ill and that the soul and spirit can be cured somehow by soul-spiritual measures, as is commonly dreamed up by those who remain stuck in abstractions.

Indeed not. Particularly with the so-called mental illnesses it is absolutely clear that in every case one can indicate where the diminished organization of some organ resides. An individual who truly wishes to know the nature of melancholia or hypochondria driven to the point of mental illness must not wade around in the soul element; he should rather attempt to determine, from the condition of the abdominal organs of the person in question, how the diminished organization is influencing the person's abdominal organization. He should attempt to determine how a force of organization that works less strongly than normal allows something to precipitate out, so to speak—just as in chemistry one precipitates something out of a solution so that a sediment occurs—how a diminished force of organization in the physical-bodily element, which would otherwise be permeated by the force of organization, precipitates something out and how this precipitate is then present in the organism as something physical-bodily, how it is deposited in what takes place in the liver, gall, stomach, heart, and lungs. These processes are not so accessible to investigation as one would like nowadays, when people prefer to stick to the crude aspects—for histology also remains at the crude level. Psychology is necessary to such an investigation, but in every case it is necessary to lead the study of so-called mental illnesses back to the bodily condition.

Of course such illnesses may seem less interesting as a result, but this is nevertheless the case. It naturally seems more interesting if a hypochondriac can say that his soul life is active in such-and-such a way in the soul-spiritual cosmos than to say that there is a diminished force of organization in his liver. It is more interesting to look for the causes of hysteria, let us say, in the soul-spiritual; it is more interesting than if one simply points to the metabolic processes of the sexual organs when speaking of hysterical phenomena or if one speaks of irregularities in the metabolism that spread throughout the organism. Little will be learned about these things, however, if the investigation is not pursued in this way.

Spiritual science is not always simply seeking the spirit. This can be left quietly to the spiritualists and other interesting people—interesting because they are rare, though unfortunately they are not rare enough! Spiritual science does not incessantly speak about spirit, spirit, spirit; rather it attempts really to lay hold of the spirit, and it tries to pursue its effects and succeeds by means of this in reaching the correct place for a comprehension of the material. It is certainly not so arrogant as to try to explain mental illnesses abstractly by mental means; instead it leads, particularly in the case of mental illness, to a material grasp of mental illness.

One may thus say that it points in a clarifying way to some interesting phenomena. One need not look back very far—perhaps still with Griesinger and others, or in the pre-Griesinger era in psychiatry—to discover that not so long ago psychiatrists also at least incorporated the bodily condition in their diagnoses. But what has become more and more common today? It has become commonplace for psychiatrists to flood us with descriptions of illness in their literature that merely describe the soul-spiritual abnormalities, so that here materialism has actually led us into an abstract soul-spiritual domain. This is its tragedy. Here materialism itself has led away from materialism. This is what is so remarkable about materialism, that in certain regards it leads to a misunderstanding, to a lack of comprehension of the material world itself. One who pursues the spirit as a real fact, however, also pursues it where it works its way into the material and where it then withdraws so that the material is deposited, as in the so-called mental illnesses.

I had to present these things as a foundation in order to offer guidelines in relation to the therapeutic aspect tomorrow. What we discover when the physiological therapeutic domain is fructified with spiritual science also has a social aspect. Life is remarkable in that everywhere we are driven into the social element if we are not seeking the scientific in an abstract withdrawal, in an academic existence estranged from life, but rather in the life-filled comprehension of human existence, of human community, if we are seeking with a truly living science. As an example, we have an extraordinarily interesting social phenomenon in recent evolution: through the split of humanity upward into a bourgeois aristocracy and downward into the proletariat, we can see how the one-sided aristocratic nature is taken hold of by a false seeking after the spirit, by materialism in the spiritual realm, while the proletarian nature is taken hold of by a certain spiritualism in the material realm.

What does that mean—spiritualism in the material realm? It means remaining stuck when seeking the origins of existence. The proletariat has thus developed scientific materialism as a view of life at the same time as the aristocratic element has developed the teachings of the spirit materialistically. While the proletariat has become materialistic, the aristocracy has become spiritualistic. If you find spiritualists among the proletariat, they did not grow out of their own proletarian soil; rather it is a mimicry, it is simply imitative, merely something that penetrated the proletariat by an infection—I will speak about infection tomorrow—with the aristocratic-bourgeois element.

And if you see among the aristocracy the development of materialism, coming to behold spirits materially as one looks at flames, so that materialism is carried into the most spiritual, wanting to see the spiritual materially, then we see this growing out of the original, decadent one-sidedness that emerged from the universally human, from the totality inclining to the aristocratic, to the bourgeois element, infected by the aristocratic element.

If what applies to the spirit is compelled to remain in matter, because it has not been drawn out by an appropriate education or the like, if in its spiritual seeking the proletariat is compelled to remain in matter, then materialism develops as a view of life. Materialism was developed by the proletariat as a view of life in the materialistic understanding of history, for example. Materialism was developed by more aristocratic people as spiritualism, for spiritualism is materialism, masked materialism, which does not even remain honest enough to acknowledge it; instead it lies and maintains that those who profess things materialistically are actually spiritual. After this divergence, we will continue tomorrow with our studies.

Zweiter Vortrag

Ich will anknüpfen an dasjenige, was ich gestern am Schlusse dieser Betrachtungen gesagt habe. Es handelte sich darum, daß hingewiesen wurde auf eine Persönlichkeit, die gewissermaßen durch ihre philosophischen Instinkte getrieben worden ist von der Erkenntnis des Geistig-Seelischen in ein Ahnen des Zusammenhanges dieses GeistigSeelischen mit dem physisch-leiblichen Dasein des Menschen. Es handelt sich um die Persönlichkeit Schellings, und ich habe gesagt, daß aus diesen Instinkten heraus Schelling sich ja auch nicht nur in theoretischer Medizin, sondern mit allerlei Heilbehandlungen praktisch betätigt hat. Ich weiß nicht, ob dies mit größerer oder geringerer Befriedigung geschehen ist, als es bei manchen gut präparierten Ärzten geschieht. Denn diese Frage, wieviel durch einen Heilprozeß zur Besserung eines Menschen beigetragen wird, ist ja in den meisten Fällen, wenn man es nicht gerade innerlich anschaut, ohnedies eine sehr problematische. Schelling hat aber aus dieser ganzen Seelenverfassung heraus, aus der ihm dieser Instinkt geworden ist, ein Prinzip gewonnen, von dem man allerdings sagen kann, daß es gut wäre, wenn es eine Art inneres Prinzip für jeden Arzt würde, so würde, daß der Arzt gewissermaßen seine ganze praktische Anschauung vom Wesen des gesunden und kranken Menschen aus diesem Prinzipe heraus einstellen würde. Und ich habe eben die Schellingschen Worte selber angeführt. Sie sind eine Art von Kühnheit. Er sagte einfach: Die Natur erkennen heißt die Natur schaffen. — Nun, nicht wahr, dasjenige, was einem zuerst auffallen muß, wenn jemand, der ein genialischer Mensch ist, einen solchen Ausspruch tut, das ist ja die ganz offenbare Absurdität dieses Ausspruches. Denn niemand wird sich im Ernste zutrauen, daß er als irdischer Mensch im physischen Leibe imstande ist, irgend etwas von der Natur durch das Naturerkennen auch zu schaffen. Selbstverständlich wird in der Technik fortwährend geschaffen, aber da handelt es sich ja nicht darum, etwas wirklich in dem Sinne zu schaffen, wie es Schelling meint, sondern nur durch eine Zusammenstellung, Komponierung der Naturkräfte der Natur Gelegenheit zu geben, ihrerseits zu schaffen in einer bestimmten Weise und durch eine bestimmte Anordnung und so weiter. Also wir haben es im Grunde genommen zu tun mit einer Absurdität, die ein genialischer Mensch seinem ganzen Denken doch eigentlich zugrunde legt. Und ich habe Ihnen gestern einen anderen Satz angeführt, welcher dem: Die Natur erkennen heißt die Natur schaffen — entgegengestellt werden kann und der da heißen würde dann: Den Geist erkennen heißt den Geist zerstören. — Diesen letzteren Satz hat wohl Schelling nicht in einer so grundsätzlichen Weise ausgesprochen. Aber derjenige, der nun in der neueren Zeit wiederum an Geisteswissenschaft herantritt und eigenes Geistesforschen entwickelt, der sieht, daß im Grunde genommen beide Sätze zurückweisen auf uralte Erkenntnisinspirationen. Gewiß, Schelling, der nach keiner Richtung hin ein Eingeweihter war, sondern einfach ein genialischer Mensch, Schelling hat aus seinen Instinkten heraus den einen Satz geprägt. Dieser eine Satz erinnert einen sogleich, wenn man nun solche Studien macht, die eben in der Zeit Schellings nicht gemacht worden sind, daß er anklingt an uralte Weistümer. Dann wird man herübergetragen zu dem anderen Satze, der in einer ähnlichen Weise aus uralten Weistümern heranklingt. Beide Sätze sind mit der gewöhnlichen heutigen Verstandeserkenntnis, die wir in unseren Wissenschaften anwenden, nicht irgendwie zu begreifen. Beide sind eigentlich so nebeneinander betrachtet und für sich betrachtet eine Absurdität. Sie weisen aber auf Allerwichtigstes in der Menschheitsorganisation, sowohl für den gesunden wie für den kranken Zustand, hin.

Wir können, wenn wir die äußere Natur betrachten, den fertigen Naturprozessen gegenüber nichts anderes sagen als: Die Natur erkennen heißt höchstens in Gedanken die Natur nachschaffen. Also dasjenige, was wir unsere Gedanken nennen und was es nicht weiterbringt als zu einem Nachschaffen der Natur, dem die innere Bildekraft fehlt, das entwickeln wir eigentlich in unserem Denken, in dem von Gedanken, von Vorstellungen durchtränkten Seelenleben. Aber es ist ja schon hingewiesen worden darauf, wie dieses von Vorstellungen durchtränkte Seelenleben im Grunde genommen nichts anderes ist als dasjenige, was sich um die Zahnwechselperiode herum aus dem physisch-ätherischen Organismus heraus emanzipiert, was man also bis zum Zahnwechsel hin im physisch-ätherischen Organismus des Menschen drinnen hat. So daß man dasjenige, was da im physisch-ätherischen Menschen kraftet in den Kinderjahren, was da wirklich eine schaffende Tätigkeit ausübt, eine schöpferische Tätigkeit, dann abgeschwächt hat, abgetönt im Seelenleben als eine Bilderwelt oder Gedankenwelt oder Vorstellungswelt, kurz, ich möchte sagen, als eine von ihrer schöpferischen Substantialität herunter verdünnte Weltenkraft, in den Gedanken, in den Vorstellungen drinnen. Es sitzt also einfach in unserem Organismus dasjenige, was wir vom siebenten Jahre ab erkennen, das sitzt einfach organisierend in unserem Organismus drinnen. Da schafft es. Da schafft es zwar nicht so, daß wir es sehen können schaffend in der äußeren Natur, aber da sehen wir es schaffend drinnen in unserem eigenen Organismus. So daß, wenn das Kind schon ein Weiser sein könnte und sich aussprechen könnte nun nicht über die äußere Natur, sondern über dasjenige, was in seinem Innern vorgeht, wenn das Kind in sein Inneres blicken und dort die Natur durchschauen könnte, dann würde es sagen, wie Schelling gesagt hat: Diese Natur erkennen heißt diese Natur schaffen -, denn da würde das Kind sich einfach durchimprägnieren mit den schaffenden Kräften, würde eins werden mit diesen schaffenden Kräften. Und Schelling hat in seinem medizinischen Instinkt, in seinem physiologischen Instinkt, nichts anderes getan als dasjenige, was für das ganze spätere Leben eine Absurdität ist, heraufgeholt aus dem Kindheitszeitalter und hat es herausgestoßen, indem er gewissermaßen gesagt hat: All dieses Erkennen im Alter ist doch nichts anderes als ein ohnmächtiges Bildergespinst; könnte man als Kind erkennen, dann würde man sagen müssen: Erkennen heißt eigentlich schaffen, heißt schöpferische Tätigkeit entwickeln. Aber wir können diese schöpferische Tätigkeit nur schauen in dem eigenen Inneren.

Was ist es denn eigentlich also, was uns da als schöpferische Tätigkeit in dem eigenen Inneren entgegentritt, was ein genialischer Mensch wie Schelling so ausspricht, wie ich es angedeutet habe? Nicht wahr, das Genialische beruht ja überhaupt darauf, daß der Mensch sich ein gewisses Kindliches im späteren Alter bewahrt. Diejenigen Menschen sind niemals genial, die unbedingt altern, die das Altern schon aufnehmen in einer gewissen normalen Art, wenn eben das entsprechende Alter herankommt, sondern diejenigen Menschen sind die eigentlich Genialischen, die hineintragen in das spätere Alter etwas positiv Schöpferisch-Kindliches. Es ist dieses Kindliche, dieses positiv Schöpferische, dieses erkennend Schöpferische, das gewissermaßen — wenn ich mich töricht ausdrücken will — nicht Zeit hat, nach außen hin zu erkennen, weil es die Erkenntniskräfte nach innen wendet und schafft. Das ist die Erbschaft, die wir mitbringen, indem wir durch die Geburt ins physische Dasein treten. Wir bringen Organisationskräfte mit, und wir können sie durch Geisteswissenschaft gewissermaßen schauen. Und ein solcher Mensch wie Schelling hat sie instinktiv geahnt.

Nun, ein jeder Mensch aber, der sich solches Schauen aneignet, weiß, daß die Dinge nicht so sind, daß etwa diese geistig-seelischen Kräfte, die da im ersten Kindheitsalter organisierend den Organismus durchtränken, etwa mit dem Zahnwechsel vollständig aufhören. Sie machen nur eine Etappe durch. Sie werden gewissermaßen auf eine geringere Wirkungsmenge herabgedrängt, so daß wir später durchaus noch organisierende Kräfte in uns haben. Aber wir haben uns erobert das Gedächtnisbildende, das mit dem Zahnwechsel in das Bewußtsein eintritt und sich dadurch loslöst von der Organisation. Wir haben das Gedächtnis aus seinem latenten Zustande in sein Freiwerden hereinbekommen, haben als seelische Anschauungskraft unsere Wachstums-, unsere Bewegungskraft, unsere Gleichgewichtskraft, die dann in entsprechend erhöhtem Maße im ersten Kindheitsalter wirken. Aber Sie sehen daraus, daß in der normalen Menschheitsentwickelung in einer gewissen Weise bis zu einem Maß herab diese organisierende Kraft, diese Wachstumskraft gewissermaßen umgewandelt werden muß in geistig-seelische, sagen wir, in Erinnerungskraft, in gedankenbildende Kraft. Nehmen wir aber an, durch irgendeinen Vorgang werde zuviel von dieser organisierenden Kraft, die im ersten Kindheitsalter wirkt, zurückgehalten, es sei einfach die Entwickelung so gestaltet, daß nicht genug Kräfte der Organisation in gedächtnisbildende Kraft umgewandelt werden, dann bleiben sie unten im Organismus stecken, dann werden sie gewissermaßen nicht mit jedem Einschlafen in den Schlaf ordentlich hineingetragen, sondern wirken vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen im Organismus weiter, durchrumorend den Organismus.

Man wird dazu geführt, wenn man die medizinische physiologisch-phänomenologische Forschung in der Richtung, die ich Ihnen hier in diesen kurzen Vortragszeiten nur andeuten kann, macht, einzusehen, daß es im menschlichen Organismus möglich ist, daß Kräfte, die eigentlich ins Geistig-Seelische hineingehen sollten im richtigen Lebensabschnitte, unten bleiben in der physischen Organisation. Dann ist dasjenige gegeben, wovon ich Ihnen gestern gesprochen habe, wenn das Normalmaß der Organisationskräfte sich umwandelt mit dem Zahnwechsel, dann haben wir ein solches Maß von Kräften im Organismus im späteren Lebensalter, das diesen Organismus nach seiner Normalgestalt und Normalstruktur durchorganisieren kann. Wenn wir aber das nicht haben, wenn wir zuwenig umwandeln, dann bleiben organisierende Kräfte da unten, treten irgendwo auf, und wir erhalten jene Neubildungen, jene karzinomatösen Neubildungen, von denen ich gestern gesprochen habe, und wir können auf diese Weise verfolgen den Prozeß des Erkrankens oder des Kränkens, wie der Mediziner Troxler sich in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts ausgedrückt hat, des Kränkens in dem späteren Lebensabschnitte. Und wir können dann vergleichen, wie es mit den Kinderkrankheiten nun steht, denn selbstverständlich können Kinderkrankheiten nicht denselben Ursprung haben, weil sie im kindlichen Lebensalter auftreten, wo durchaus noch nichts umgewandelt ist. Aber wenn man gelernt hat dasjenige, was an Krankheitsursachen im späteren Lebensalter auftritt, hat man sich ja auch eine Fähigkeit angeeignet, zu beobachten, wie es mit den Krankheitsursachen im Kindheitsalter liegt. Da findet man allerdings in einer gewissen Weise dasselbe, nur von einer anderen Seite her. Man findet, daß auch dann zuviel von geistig-seelischer Organisationskraft im menschlichen Organismus ist, wenn Kinderkrankheiten auftreten. Für denjenigen, der sich in dieser Richtung Anschauungsvermögen angeeignet hat, treten diese Dinge besonders kraftvoll hervor, wenn er das Phänomen des Scharlachs, der Masern während der kindlichen Zeit ins Auge faßt, wo er sehen kann, wie im kindlichen Organismus dasjenige, was sonst normalerweise funktionieren würde, das Geistig-Seelische, zu rumoren anfängt, wie es in einem höheren Maße wirkt, als es eigentlich wirken sollte. Der ganze Verlauf dieser Krankheiten wird verständlich in dem Augenblicke, wo man dieses Rumoren des Geistig-Seelischen im Organismus nun wirklich schauen kann als die Grundlage der Erkrankung. Und dann ist man nicht mehr weit — ich bitte, meinen Satz ganz genau ins Auge zu fassen, denn ich gehe nie einen Schritt weiter, als gerechtfertigt ist durch die vorhergehenden Erwägungen, wenn auch manches nur skizzenhaft gesagt werden kann, aber ich deute überall an, wie weit man gehen kann —, ich sage nicht, daß hier nun ein Schluß gezogen wird, sondern sage nur, man ist nicht mehr weit, etwas anzuerkennen, was außerordentlich wichtig ist anzuerkennen für ein wirkliches Wissen. Wenn wir dabei angelangt sind, zu erkennen, wie im menschlichen Organismus bei einer Erkrankung im späteren Lebensalter, die nach der Richtung der Neubildung geht, zuviel organisierende Kraft da ist, die also einen Überschuß gewissermaßen in einer Organisationsinsel ergibt, dann ist man eben auch nicht mehr weit davon, sich zu sagen: Weist so das spätere Lebensalter auf die früheste Kindheit zurück, so weist schließlich dasjenige, was sich in der Kindheit zeigt, auf die Zeit vor der Geburt oder sagen wir vor der Empfängnis zurück; es weist zurück auf das geistig-seelische Dasein des Menschen, das er durchlaufen hat, bevor er mit einem physischen Leibe umkleidet wurde. Ein solcher Mensch hat einfach zuviel mitgebracht an GeistigSeelischem aus seinem vormenschlichen Leben, vorirdischen Leben, und dieser Überschuß lebt sich in den Kinderkrankheiten aus. Es wird in der Zukunft gar nicht anders gehen, als sich hineintreiben zu lassen aus den unfruchtbaren materialistischen Betrachtungen, in denen wir heute namentlich im Physiologisch-Therapeutischen stekken, in eine geistig-seelische Betrachtung. Und man wird schon sehen, daß dasjenige, was in der Geisteswissenschaft auftritt, nicht etwa aus dem Grunde auftritt, weil der Geistesforscher zuwenig drinnensteht in der physischen Forschung, und weil er gewissermaßen ein Dilettant ist in der physischen Forschung, wobei ich in Parenthese durchaus sage, daß viele, die sich Geistesforscher nennen, allerdings solche Dilettanten sind, aber es ist dasjenige nicht das, was sein soll. Der Geistesforscher braucht nicht zuwenig drinnen zu stecken in der physischen Forschung, um Geistesforscher zu werden, sondern er wird Geistesforscher, wenn er gerade mehr drinnensteckt als der gewöhnliche Naturforscher. Wenn er die Erscheinungen intensiver durchschaut, dann treiben ihn die Erscheinungen schon selbst ins Geistig-Seelische hinein, insbesondere, wenn wir vom Kranksein zu sprechen haben.

Und auf der anderen Seite, der Satz: Den Geist erkennen heißt den Geist zerstören — ja, das ist ja eigentlich eine ebensolche Absurdität. Aber auch dieser Satz weist auf etwas hin, was erkannt, was durchschaut werden muß. Nämlich gerade so, wie uns der Satz: Die Natur erkennen heißt die Natur schaffen — auf das erste Kindheitszeitalter hinweist, eigentlich noch auf das Vorgeburtliche, wenn wir ihn in der richtigen Weise schauend ausdehnen, ebenso weist uns der Satz: Den Geist erkennen heißt den Geist zerstören — auf des Menschen Lebensende hin, auf dasjenige, was das Ertötende im Menschen ist. Sie brauchen ja nur, ich möchte sagen, in paradoxer Weise sich an diesen Satz zu halten: Den Geist erkennen heißt den Geist zerstören —, dann werden Sie schon finden, wie man ihm nicht folgen darf, wie er aber trotzdem im Leben als etwas, dem man sich asymptotisch fortwährend annähert, da ist. Den Geist erkennen, das heißt für den, der nicht einfach, ich möchte sagen, daraufloserkennt, sondern der in richtiger Weise Selbstschau entwickelt: Sehen, Schauen, fortwährende Abbauprozesse, fortwährende Zerstörungsprozesse im menschlichen Organismus. So wie wir, wenn wir in das kindlich schaffende Zeitalter hineinsehen, fortwährende Aufbauprozesse sehen, Aufbauprozesse, die aber ein Eigentümliches haben, die uns eigentlich das Bewußtsein trüben. Deshalb träumen wir, schlafen wir halb im Kindheitszeitalter, deshalb ist das Bewußtsein nicht voll erwacht. Diese unsere eigene iirdische Geistigkeit, nämlich die bewußte Geistigkeit zurückdrängende Wachstumstätigkeit, ist dasjenige, was uns eigentlich durchorganisiert, und in dem Momente, wo diese Kraft ins Bewußtsein hereindringt, hört sie auf, uns in demselben Maße durchzuorganisieren, wie sie uns vorher durchorganisiert hat. Ebenso, wie man da zuschaut, indem man ins Kindheitsalter hineinblickt, den aufbauenden Kräften, aber bewußtseinslähmenden Kräften, so schaut man zu, indem man den entwickelten Denkprozessen schauend sich hingibt, Abbauprozessen, die aber dazu geeignet sind, als Abbauprozesse gerade unser Bewußtsein hell und klar zu machen.

Das ist dasjenige, was die moderne physiologische Wissenschaft allzuwenig berücksichtigt, obwohl sie es eigentlich in ihren Erscheinungen so offenkundig daliegen hat, wie man nur irgend etwas daliegen haben kann. Nehmen Sie sich die wirklichen Erscheinungen der modernen Physiologie einmal heran, und Sie werden sehen, nichts kann klarer belegt werden aus all dem, was man kennt über Gehirnphysiologie und dergleichen, also daß man es bei den eigentlich seelisch-geistigen Prozessen, die bewußt verlaufen, nicht zu tun hat mit irgendwelchen Wachstumskräften, mit irgendwelchen Kräften der Nahrungsaufnahme, sondern daß man es zu tun hat mit Ausscheidungsprozessen, durch das Nervensystem mit Abbauprozessen, daß man es zu tun hat mit einem fortwährenden langsamen Ersterben. Es ist der Tod, der in uns wirkt, indem wir uns hingeben an dasjenige, was geistig eigentlich in unserem Bewußtsein wirkt. Und ebenso, wie wir durch die unbewußt schaffenden Kräfte auf den Lebensanfang blicken, so blicken wir durch die bewußt vorstellenden Kräfte, dadurch, daß sie als zerstörende Kräfte sich uns enthüllen, als dasjenige sich enthüllen, was immer mehr und mehr anfängt, indem wir ins irdische Leben hereinwachsen, uns zu ergreifen, uns abzubauen und uns zuletzt dem irdischen Tode entgegenzuführen; wir sehen eben durch diese Kräfte zu dem anderen Ende des Lebens, nach dem Tode hin. Und nicht anders wird man Geburt und Tod, oder sagen wir Empfängnis, Geburt und Tod verstehen können, als dadurch, daß man das Geistige mit hereinnimmt. Und in dem Satze: Den Geist erkennen heißt den Geist zerstören — liegt eigentlich das, daß man damit sagen will: würde man nun auf den Geist hinschauen wollen, würde man ihn nicht mehr oder weniger naiv aufnehmen, würde man ihn eben so aufnehmen, wie man die äußere Natur aufnimmt, dann würde man dasjenige, was in dieser bewußten Denkund Vorstellungs- und Empfindungs-, Gefühlstätigkeit wirkt, zurückstauen müssen, man würde das Abbauen verhindern müssen. Das heißt, man müßte in dem Momente die Gewalt über das Geistige, das innerlich Bewußte, zur Unbewußtheit, zu einem Wirken des Geistigen in Unbewußtheit herunterstimmen, herunterlähmen. Man würde dazu kommen, ein Geistiges aus sich herauszubilden, ein Geistiges gewissermaßen aus sich herauszustoßen. Aber man könnte nicht mit dem Bewußtsein mit, weil man die Organisation nicht hineintragen kann in diesen Abbauprozeß, in diesen Geistprozeß. Und so können wir sagen: Während die Organisationsprozesse darinnen bestehen, daß wir gewissermaßen — natürlich ist das eine abstrakte Betrachtung jetzt — das Formgerüst des menschlichen Organismus haben (siehe Zeichnung a), in das sich hineinbegibt die organisierende Kraft (siehe Zeichnung b, rot) als Geistig-Seelisches, haben wir es im anderen Falle so — in dem zweiten Fall, den ich beschrieben habe —, daß wir hier das Formgerüste des menschlichen Organismus haben, aber es nicht durchdrungen sein lassen wollen von der organisierenden, von der bis zu einem gewissen Grade unser Bewußtsein lähmenden Kraft, sondern daß wir die organisierende Kraft, die wir als Geist nun erkennen wollen, heraustreiben wollen (siehe Zeichnung c). Wir können 'aber nicht mit unserem Ich mit, weil dieses an den Organismus gebunden ist. Wir haben die andere Seite, die Seite, wo der Mensch zwar anfängt, Geistiges zu entwickeln, im Geistigen namentlich Willenstätigkeit zu entwickeln. In der Durchdringung mit Willenstätigkeit, die unbewußt bleibt, gewissermaßen schlafend, träumend ist, beruht das, daß wir eigentlich ohne Bewußtsein ein Geistig-Seelisches herausbringen aus unserer Organisation. Wir haben die andere, die manische Seite, die tobende Seite, wo der Mensch toll wird, und die verschiedenen Formen der sogenannten geistigen Erkrankungen, die aber in nichts anderem bestehen als darinnen, daß wir hier bei den physischen Erkrankungen ein Geistig-Seelisches haben, das nicht hineingehört in den physischen Organismus (siehe Zeichnung b), während wir bei den sogenannten geistigen Erkrankungen im Psychisch-Seelischen aus dem Physisch-Atherischen etwas heraustreiben, was eigentlich drinnen sein sollte und was wir aus dem Organismus heraustreiben (siehe Zeichnung c). Wir sehen heute von der anderen Seite noch beleuchtet dasjenige, worauf wir gestern gekommen sind. Und die Sache ist so, daß uns gerade dieser Gesichtspunkt mehr leitet, wir werden morgen sehen, zu welchen fruchtbaren therapeutischen Konsequenzen man gerade durch diese Gesichtspunkte kommt, die sich dann durchaus im Leben bestätigen, die sich erweisen als die alleräußerste Lebenspraxis in der Medizin, als die therapeutische Praxis.

Wenn wir fragen nach der Ursache einer physischen Krankheit, müssen wir sie eigentlich letzten Endes in einer Verirrung des Geistigen im Organismus suchen. Gewiß, man darf da nicht abstrakt vorgehen. Derjenige, der nichts versteht vom Zusammenhange des Seelisch-Geistigen mit dem physischen Organismus, der sollte eigentlich in diese Dinge nicht dreinreden. Denn man kann das Spezielle, wo irgendwo in einem Organ eine zu große Organisationskraft, eine, ich möchte sagen, hypertrophische Organisationskraft sitzt, nur erkennen, wenn man das Konkret-Geistig-Seelische, das in sich ebenso konkretisiert ist, wie das Physisch-Leibliche zur Leber, zum Magen und so weiter konkretisiert ist, wenn man dieses GeistigSeelische, wovon die Psychologie keine Ahnung hat, mit seinen Bestandteilen, mit seinen Gliedern ebenso kennt wie das PhysischSinnliche. Und wenn man die Beziehungen kennt zwischen beiden, dann kann man hinweisen aus dem oftmals sogar geistig-seelischen Befunde, der bei dem Menschen auftritt, wo irgendwo eine Art Überorganisation in irgendeinem Organe steckt. Man wird bei alledem, was nicht äußere Insulte sind, hinweisen können auf irgend solch einen Ursprung.

Umgekehrt, wenn man es nun mit Geisteskrankheiten zu tun hat, mit sogenannten Geisteskrankheiten, dann wird man ein Abstraktling bleiben, wenn man glaubt, aus einer halben Phänomenologie irgend etwas gewinnen zu können, wenn man glaubt, dadurch, daß man einfach die geistig-seelischen Abnormitäten beschreibt — was zu beschreiben ja sehr nützlich ist —, irgend etwas gewinnen zu können. Mit diesen Beschreibungen kann man natürlich Sensationen bei Laien sehr gut hervorrufen, denn es ist immer interessant, wie irgend jemand, der närrisch ist, abweicht von dem normalen Maß des Lebens. Denn interessant ist das Seltene, und es ist in unserer Zeit doch so, daß wenigstens noch als Seltenheit auftritt dasjenige, was in dieser Weise vom normalen Leben abweicht. Aber dabei stehenzubleiben, darum kann es sich nie handeln. Insbesondere kann es sich nicht darum handeln, etwa hinzutreiben zu dem laienhaft dilettantischen Urteil, daß der Geist und die Seele erkrankt seien, und daß man den Geist und die Seele nun irgendwie durch geistigseelische Maßnahmen, wie es sich die Abstraktlinge träumen, kurieren kann. Nein, gerade bei den sogenannten Geisteskrankheiten hängt es in eminentester Weise davon ab, daß man überall hinweisen kann darauf, wo die Unterorganisation irgendeines Organes sitzt. Derjenige, der eine bis zur Geisteskrankheit getriebene Melancholie oder Hypochondrie wirklich erkennen will, soll nicht im Seelischen herumwaten, sondern der soll versuchen, aus der Unterleibsbeschaffenheit des betreffenden Menschen zu erkennen, wie da die Unterorganisation in der Unterleibsorganisation des Menschen wirkt, wie eine unter dem normalen Maß wirkende Organisationskraft gewissermaßen etwas herausfallen läßt, wie man in der Chemie sagt; man fällt etwas heraus aus irgendeiner Lösung und dergleichen, so daß ein Bodensatz entsteht, wie dadurch eine zu geringe Organisationskraft Physisch-Leibliches, das sonst von der Organisationskraft durchdrungen wäre, herausfällt, wie es im Organismus als Physisch-Leibliches dann vorhanden ist, wie es abgelagert wird, was in Leber, in Galle, im Magen, im Herzen, in der Lunge vorgeht. Vorgänge, die allerdings nicht so bequem zu untersuchen sind, wie man gern möchte in unserer heutigen, an das Grobe — denn das Histologische ist auch ein Grobes — sich wendenden Zeit. Psychologien sind nötig zu einer solchen Untersuchung, aber überall ist es nötig, daß die sogenannten Geisteskrankheiten zurückgeführt werden auf körperliche Zustände.

Allerdings, sie werden dadurch weniger interessant. Aber es ist doch so. Es ist natürlich interessanter, wenn ein Hypochonder sagen kann, auf diese oder jene Weise ist sein Seelisches engagiert am geistig-seelischen Kosmos, als wenn man ihm nachweisen kann, daß in seiner Leber eine unterorganisierende Kraft ist. Oder es ist interessanter, im Geistig-Seelischen, sagen wir, die Ursache zu suchen für die Hysterie, interessanter, als wenn man einfach auf die Stoffwechselvorgänge der sexuellen Organe hinzuweisen hat, wenn man von den hysterischen Erscheinungen spricht oder auch von dem, was sich sonst im Organismus an Stoffwechselunregelmäßigkeiten ausdehnt. Aber erkennen wird man die Dinge nicht, wenn man sie nicht in dieser Weise verfolgt.

Geisteswissenschaft geht durchaus nicht darauf aus, immer nur den Geist zu suchen. Das mag sie ruhig den Spiritisten und anderen interessanten, weil auch seltenen Leuten — sie sind nur leider viel zu wenig selten! — überlassen; aber sie redet nicht fortwährend von Geist, Geist, Geist, sondern sie versucht, den Geist wirklich zu ergreifen, und sie versucht, seine Wirksamkeiten zu verfolgen und gelangt dadurch gerade an der rechten Stelle in ein Begreifen des Materiellen hinein. Sie hat gar nicht den Stolz, die Geisteskrankheiten auf geistige abstrakte Weise zu erklären, sondern sie führt gerade für die Geisteskrankheiten in eine materielle Auffassung der Geisteskrankheiten hinein.

So daß man sagen kann: Sie weist auf das interessante Phänomen erklärend hin, das sich — man braucht nur eine kurze Zeit zurückzublicken — vielleicht noch bei Griesinger oder anderen, oder in der Vor-Griesingerschen Zeit in der Psychiatrie findet, so daß sich zeigt, daß vor verhältnismäßig kurzer Zeit die Psychiater auch noch wenigstens den körperlichen Tatbestand einbezogen haben in ihre Diagnose. Was ist heute immer häufiger und häufiger geworden? Daß einen die Psychiater überhäufen in ihrer Literatur mit Krankheitsbildern, die lediglich eine Beschreibung der Abnormitäten des Geistig-Seelischen sind. So daß hier der Materialismus in ein abstrakt Geistig-Seelisches gerade hineingeführt hat. Das ist seine Tragik. Da hat er gerade aus dem Materiellen herausgeführt. Das ist das Merkwürdige für den Materialismus, daß er an gewissen Stellen gerade zum Unverständnis, zum Nichtbegreifen des Materiellen führt, während derjenige, der den Geist verfolgt als eine wirkliche Tatsache, ihn auch da verfolgt, wo er hineinwirkt in das Materielle, und wo er sich dann dem Materiellen entzieht, so daß das Materielle sich ablagert, wie in den sogenannten Geisteskrankheiten.

Diese Dinge mußte ich zugrunde legen, wenn ich Ihnen nun auch einiges über Richtlinien mit Bezug auf das Therapeutische morgen andeuten möchte. Dasjenige aber, was wir so durch ein Befruchten des Physiologisch-Therapeutischen mit dem Geisteswissenschaftlichen finden, hat schon auch seine soziale Seite. Und es ist das Eigentümliche des Lebens, daß wir jetzt überall, wenn wir nicht in einem abstrakten Zurückziehen in ein lebensfeindliches Gelehrtendasein das Wissenschaftliche suchen, sondern in der lebensvollen Auffassung des menschlichen Daseins, des menschlichen Zusammenseins, dann gerade durch eine wirkliche lebendige Wissenschaft in das Soziale hineingetrieben werden. Denn wir haben zum Beispiel ein außerordentlich interessantes soziales Phänomen in der neuzeitlichsten Entwickelung vor uns. Wir sehen, wie durch (die Spaltung der Menschen auf der einen Seite hinauf in ein bourgeois-aristokratisches Wesen, auf der anderen Seite hinunter in das proletarische Wesen, das einseitig aristokratische Wesen ergriffen wird von einem falschen Geistessuchen, von dem Materialismus auf geistigem Gebiete, und wie das proletarische Wesen ergriffen wird von einem gewissen Spiritualismus auf materiellem Gebiete. Was heißt Spiritualismus auf materiellem Gebiete? Es heißt, stehenzubleiben, wenn man nach den Ursachen des Daseins sucht. Das Proletariat hat daher den wissenschaftlichen Materialismus als eine Lebensanschauung ausgebildet, in derselben Zeit, als das aristokratische Element die Geistlehre materialistisch ausgebildet hat. Während die Proletarier Materialisten geworden sind, sind die Aristokraten Spiritisten geworden. Denn wenn Sie unter den Proletariern Spiritisten finden, so ist das nicht aus dem eigenen proletarischen Kraut, sondern es ist «Mimicry», es ist nachgeahmt, es ist bloß etwas, was durch Ansteckung — ich werde morgen von Ansteckung sprechen — hinübergedrungen ist aus dem aristokratisch-bourgeoisen Element. Und wenn Sie unter Aristokraten den Materialismus auf der anderen Seite ausgebildet sehen also dadurch, daß sich die Geister materiell anschauen lassen, wie man Flammen anschaut, daß man also den Materialismus hineinträgt in das Allergeistigste und das Geistige materiell sehen will, dann wächst das aus jener ursprünglichen dekadenten Einseitigkeit, die sich aus dem Gesamtmenschlichen, aus der Totalität heraus hinwendet eben auf der einen Seite nach dem aristokratischen und nach dem bourgeoisen Element, das von dem aristokratischen Element angekränkelt ist. Wenn dasjenige, was sich, wenn es den Geist anwendet, gezwungen fühlt, in der Materie stehenzubleiben, weil es nicht durch entsprechende Schulbildung und dergleichen herausgezogen wird, wenn das Proletariat gezwungen wird, beim Geistsuchen in der Materie stehenzubleiben, dann entwickelt sich der Materialismus als Lebensanschauung. Der Materialismus wurde entwickelt von dem Proletariat als Lebensanschauung zum Beispiel in der materialistischen Geschichtsauffassung. Der Materialismus wurde entwickelt von den mehr aristokratischen Menschen als Spiritismus, denn der Spiritismus ist Materialismus, maskierter Materialismus, der dazu noch nicht einmal dabei bleibt, ehrlich sich zu bekennen, sondern der lügt und der behauptet, daß seine materiellen Bekenner spirituelle Geister seien. Nach dieser Reminiszenz wollen wir dann morgen in unseren Betrachtungen fortfahren.

Second Lecture

I would like to follow up on what I said yesterday at the end of these reflections. I referred to a personality who, driven by his philosophical instincts, moved from the recognition of the spiritual-soul realm to an intuition of the connection between this spiritual-soul realm and the physical-bodily existence of human beings. This personality is Schelling, and I said that, based on these instincts, Schelling was active not only in theoretical medicine but also in all kinds of practical healing treatments. I do not know whether this was done with greater or lesser satisfaction than is the case with some well-trained doctors. For the question of how much a healing process contributes to a person's recovery is, in most cases, a very problematic one anyway, unless one looks at it from within. However, Schelling derived a principle from this whole state of mind, from which this instinct became his own, and one can certainly say that it would be good if it became a kind of inner principle for every doctor, so that the doctor would, in a sense, base his entire practical view of the nature of healthy and sick people on this principle. And I have just quoted Schelling's own words. They are a kind of boldness. He simply said: To know nature is to create nature. Well, isn't it true that the first thing that strikes you when someone who is a genius makes such a statement is the obvious absurdity of that statement? For no one would seriously believe that, as an earthly human being in a physical body, he is capable of creating anything from nature by recognizing nature. Of course, technology is constantly creating, but this is not really creating in the sense that Schelling means, but only giving nature the opportunity to create in a certain way and through a certain arrangement, etc., by combining and composing the forces of nature. So, basically, we are dealing with an absurdity that a genius actually bases his entire thinking on. And yesterday I quoted you another sentence that can be contrasted with “To know nature is to create nature” and that would be: “To know the spirit is to destroy the spirit.” Schelling probably did not express the latter sentence in such a fundamental way. But anyone who approaches spiritual science in modern times and develops their own spiritual research will see that, fundamentally, both sentences refer back to ancient inspirations of knowledge. Certainly, Schelling, who was not an initiate in any direction, but simply a genius, coined the first sentence out of his instincts. When one undertakes studies that were not done in Schelling's time, this statement immediately reminds one that it echoes ancient wisdom. Then one is carried over to the other statement, which echoes ancient wisdom in a similar way. Both sentences cannot be understood in any way with the ordinary intellectual knowledge we apply in our sciences today. Both are actually absurd when viewed side by side and considered on their own. However, they point to the most important thing in the organization of humanity, both for the healthy and the sick.

When we observe external nature, we can say nothing else about the completed natural processes than this: to recognize nature means at most to recreate nature in our thoughts. So what we call our thoughts, which do not go beyond recreating nature and lack the inner power of imagery, we actually develop in our thinking, in our soul life, which is saturated with thoughts and ideas. But it has already been pointed out that this soul life, saturated with ideas, is basically nothing other than what emancipates itself from the physical-etheric organism around the time of tooth replacement, that is, what is present in the physical-etheric organism of the human being until tooth replacement. So that what is powerful in the physical-etheric human being in childhood, what really exercises a creative activity, a creative activity, is then weakened, toned down in the soul life as a world of images or a world of thoughts or a world of ideas, in short, I would like to say, as a world force diluted from its creative substantiality, in thoughts, in ideas. So what we recognize from the age of seven onwards is simply sitting there, organizing our organism. It is creating there. It is not creating in such a way that we can see it creating in the outer world, but we can see it creating inside our own organism. So that if the child could already be a wise person and could express itself not about external nature, but about what is going on inside, if the child could look inside itself and see nature there, then it would say, as Schelling said: To recognize this nature is to create this nature — for then the child would simply become imbued with the creative forces, would become one with these creative forces. And Schelling, in his medical instinct, in his physiological instinct, did nothing other than bring up from childhood what is an absurdity for the whole of later life, and he expelled it by saying, in a sense: All this recognition in old age is nothing more than a powerless web of images; if one could recognize as a child, then one would have to say: to recognize actually means to create, to develop creative activity. But we can only see this creative activity within ourselves.

So what is it, then, that we encounter as creative activity within ourselves, which a genius like Schelling expresses as I have indicated? Isn't it true that genius is based on the fact that people retain a certain childlike quality in later life? People who age unconditionally, who accept aging in a certain normal way when they reach a certain age, are never genius. Rather, genius is found in those people who carry something positively creative and childlike into later life. It is this childlike quality, this positive creativity, this recognising creativity, which, if I may express myself foolishly, has no time to recognise the outside world because it turns its powers of recognition inward and creates. This is the inheritance we bring with us when we enter physical existence through birth. We bring with us powers of organization, and we can see them, in a sense, through spiritual science. And a person like Schelling instinctively sensed this.

Now, every person who acquires such vision knows that things are not so, that these spiritual-soul forces, which permeate the organism in an organizing way in early childhood, do not completely cease with the change of teeth. They are only going through a stage. They are, so to speak, pushed down to a lower level of activity, so that we still have organizing forces within us later on. But we have conquered the memory-forming faculty, which enters consciousness with the change of teeth and thereby detaches itself from the organism. We have brought memory out of its latent state into its liberation, and as a spiritual power of perception we have our growth, our movement, our balance, which then work to a correspondingly increased degree in early childhood. But you can see from this that in normal human development, to a certain extent, this organizing power, this power of growth, must be transformed into a spiritual-soul power, let us say, into a power of memory, into a power of thought formation. But let us assume that through some process too much of this organizing power, which is active in early childhood, is held back, if development is simply structured in such a way that not enough organizing forces are transformed into memory-forming power, then they remain stuck in the lower part of the organism, and in a sense are not properly carried into sleep with each falling asleep, but continue to work in the organism from falling asleep until waking up, rumbling through the organism.

If one conducts medical, physiological-phenomenological research in the direction that I can only hint at here in these short lectures, one is led to realize that it is possible in the human organism for forces that should actually enter the spiritual-soul realm at the right stages of life to remain below in the physical organism. Then what I spoke to you about yesterday occurs: when the normal measure of the organizing forces transforms with the change of teeth, we have such a measure of forces in the organism in later life that can organize this organism according to its normal form and normal structure. But if we do not have this, if we transform too little, then organizing forces remain down there, appear somewhere, and we get those new growths, those carcinomatous new growths that I spoke about yesterday, and in this way we can follow the process of becoming ill or sick, as the physician Troxler put it in the first half of the 19th century, of becoming sick in later life. And we can then compare how things stand with childhood diseases, because of course childhood diseases cannot have the same origin, since they occur in childhood, when nothing has yet been transformed. But once we have learned about the causes of illness in later life, we have also acquired the ability to observe the causes of illness in childhood. In a certain sense, we find the same thing, only from a different angle. We find that there is also too much mental and emotional organizational power in the human organism when childhood diseases occur. For those who have acquired insight in this direction, these things become particularly apparent when they consider the phenomenon of scarlet fever and measles during childhood, where they can see how, in the child's organism, what would normally function, the spiritual-soul, begins to rumble, how it works to a greater extent than it should actually work. The entire course of these diseases becomes understandable the moment one can truly see this rumbling of the spiritual-soul aspect in the organism as the basis of the illness. And then one is not far off — I ask you to consider my statement very carefully, for I never go a step further than is justified by the preceding considerations, even if some things can only be said in outline, but I indicate everywhere how far one can go — I am not saying that a conclusion is now being drawn here, but only that one is not far from recognizing something that is extremely important to recognize for true knowledge. When we have reached the point of recognizing that in the human organism, in the case of a disease in later life that tends toward new formation, there is too much organizing power, which thus results in a surplus, so to speak, in an island of organization, then we are not far from saying to ourselves: If later life points back to early childhood, then what manifests in childhood ultimately points back to the time before birth, or let us say before conception; it points back to the spiritual-soul existence that the human being went through before being clothed in a physical body. Such a person has simply brought too much spiritual and soul life with them from their pre-human life, their pre-earthly life, and this excess is lived out in childhood illnesses. In the future, there will be no other option than to let ourselves be drawn away from the barren materialistic considerations in which we are currently stuck, particularly in physiology and therapy, and into a spiritual and soul-based consideration. And we will see that what appears in spiritual science does not appear because the spiritual researcher is not sufficiently involved in physical research and because he is, in a sense, a dilettante in physical research, whereby I would like to add in parentheses that many who call themselves spiritual researchers are indeed such dilettantes, but that is not what should be the case. The spiritual researcher does not need to be insufficiently involved in physical research in order to become a spiritual researcher; rather, he becomes a spiritual researcher when he is more involved than the ordinary natural scientist. When he sees through phenomena more intensively, then the phenomena themselves drive him into the spiritual-soul realm, especially when we are talking about illness.

And on the other hand, the sentence: To recognize the spirit is to destroy the spirit — yes, that is actually just as absurd. But this sentence also points to something that must be recognized, that must be understood. Namely, just as the sentence: To know nature is to create nature — points to early childhood, actually even to the prenatal period, if we extend it in the right way, so too the sentence: To know the spirit is to destroy the spirit — points to the end of human life, to that which is deadly in human beings. You only need, I would say, to adhere to this sentence in a paradoxical way: To know the spirit is to destroy the spirit — then you will already find how one must not follow it, but how it is nevertheless present in life as something that one asymptotically approaches continuously. Recognizing the spirit means, for those who do not simply, I would say, recognize it, but who develop self-observation in the right way: seeing, looking, continuous processes of decay, continuous processes of destruction in the human organism. Just as when we look into the childish creative age, we see continuous processes of building up, processes of building up that have something peculiar about them, something that actually clouds our consciousness. That is why we dream, why we sleep half in childhood, why our consciousness is not fully awakened. This growth activity of our own earthly spirituality, namely the conscious spirituality that represses growth, is what actually organizes us, and the moment this force enters our consciousness, it ceases to organize us to the same extent as it did before. Just as one observes the constructive forces, but also the consciousness-paralyzing forces, when looking into childhood, so one observes, when devoting oneself to the developed thought processes, the processes of decay, which, however, are suitable for making our consciousness bright and clear.

This is what modern physiological science takes too little account of, even though it is actually as obvious in its manifestations as anything can be. Take a look at the real phenomena of modern physiology, and you will see that nothing could be more clearly proven from all that is known about brain physiology and the like namely that in the actual mental and spiritual processes that take place consciously, we are not dealing with any kind of growth forces, with any kind of forces of food intake, but rather with excretory processes, with processes of breakdown through the nervous system, with a continuous, slow dying away. It is death that works within us as we surrender to that which actually works spiritually in our consciousness. And just as we look at the beginning of life through the unconsciously creative forces, so we look through the consciously imaginative forces, through their revealing themselves to us as destructive forces, as that which, as we grow into earthly life, begins more and more to seize us, to break us down, and finally to lead us toward earthly death; we see through these forces to the other end of life, toward death. And one cannot understand birth and death, or let us say conception, birth, and death, except by taking in the spiritual. And in the sentence: To recognize the spirit is to destroy the spirit — what is actually meant is that if one were to look at the spirit, if one were to perceive it more or less naively, if one were to perceive it in the same way as one perceives external nature, then one would have to hold back that which is at work in this conscious activity of thinking, imagining, feeling, and sensing; one would have to prevent its deterioration. That is, at that moment one would have to tone down, paralyze, the power over the spiritual, the inner consciousness, to unconsciousness, to a working of the spiritual in unconsciousness. One would come to develop a spiritual aspect out of oneself, to push a spiritual aspect out of oneself, so to speak. But one could not take consciousness with one, because one cannot carry the organization into this process of reduction, into this spiritual process. And so we can say: while the organizational processes consist in the fact that we have, in a sense — of course this is an abstract consideration now — the form framework of the human organism (see drawing a), into which the organizing force (see drawing b, red) enters as spiritual-soul, in the other case we have — in the second case I have described — that we have the formative framework of the human organism here, but we do not want it to be permeated by the organizing force, which to a certain extent paralyzes our consciousness, but rather we want to drive out the organizing force, which we now want to recognize as spirit (see drawing c). But we cannot do this with our ego, because it is bound to the organism. We have the other side, the side where the human being begins to develop the spiritual, namely to develop will activity in the spiritual. The fact that we actually bring forth something spiritual and soul-like from our organism without consciousness is based on the penetration with will activity, which remains unconscious, dormant, dreaming, so to speak. We have the other, manic side, the raging side, where the human being becomes mad, and the various forms of so-called mental illnesses, which, however, consist of nothing other than the fact that in physical illnesses we have something spiritual-soul that does not belong in the physical organism (see drawing b), while in so-called mental illnesses we drive out of the physical-etheric something that should actually be inside and that we drive out of the organism (see drawing c). Today we see, illuminated from the other side, what we came to yesterday. And the fact is that this very point of view guides us more; tomorrow we will see what fruitful therapeutic consequences can be achieved precisely through these points of view, which are then confirmed in life and prove to be the ultimate practical application in medicine, in therapeutic practice.

When we ask about the cause of a physical illness, we must ultimately seek it in a deviation of the spiritual in the organism. Certainly, one must not proceed abstractly here. Those who do not understand the connection between the soul-spiritual and the physical organism should not really comment on these matters. For one can only recognize the specific situation, where somewhere in an organ there is too much organizational power, a I would say hypertrophic organizational power, only if one knows the concrete spiritual-soul aspect, which is just as concrete as the physical-bodily aspect is concrete in the liver, stomach, and so on, if one knows this spiritual-soul aspect, of which psychology has no idea, with its components and members just as well as the physical-sensory aspect. And if one knows the relationships between the two, then one can point out from the often even spiritual-soul findings that occur in humans where there is a kind of over-organization in some organ. In all cases that are not external insults, one will be able to point to such an origin.