Curative Eurythmy

GA 315

14 April 1921, Dornach

Lecture III

In order to proceed in an appropriate manner, we will prepare the grounds today for certain matters to be deepened physiologically and psychologically tomorrow, considering the forms which consonants take in eurythmic movement. In what has been developed as the form involved in consonantal movement consideration has been truly given to everything which must be taken into account when man attempts to penetrate into the outer world through speech. The person who sets himself the task of observing speech will see that man's confrontation with the outer world must consist on the one hand of living into the world vigorously; of making himself selfless and living out into the world. In the vowels he comes to himself; in the vowels he goes within and unfolds his activity there. In the consonants he becomes in a way one with the outer world although to varying degrees. These varying degrees of unification with the world are manifest in certain practices within language as well. In the development of the consonantal element in eurythmy, particularly in reference to the sensible-super-sensible observation of which I so often speak in introducing eurythmy performances,—it is necessary to take into consideration whether the human being objectifies himself. To discover whether man extroverts himself completely in order to grasp the spiritual element in the things outside him in a spoken sound, or if, despite this objectification of himself, he remains more within and does not go completely out of himself but instead reproduces the external within himself. That is a major distinction, by reason of which I must ask Mrs. Baumann to be so good and show us first of all the movement for “H”. Now please disregard this H-movement altogether and Mrs. Baumann will demonstrate the F-movement. And now keep an eye on what you can observe here in these two different movements. You can observe what is present by virtue of the human instinct in the attempt to enunciate the sound in question. Consider the pronunciation of H: actually you say H-a, you follow up with a vowel. It is impossible to sound a consonant without it being tinged by a vowel, you follow it up with an “A”. The pure consonant is vocalized, combined with a vowel. If you consider the “F” you will find that man's linguistic instinct places an “E” in front of it: e-F. Here the opposite occurs: an E is set before it.

Through the foregoing you will perceive that when man utters an “H” he makes a greater effort to uncover through speech the spiritual in the external object; when he utters an “F” his effort is directed more towards reexperiencing the spiritual within himself. Therefore the manner in which the consonant arises is entirely different, according to whether the vowel tinges the consonant from the front or from the back, if I may use this manner of expression in respect to the nature of consonantal articulation. This you will find conveyed in the form you have observed.

Perhaps Miss Wolfram will do the “H” once again. H: here you have an energetic unfolding in the outer world, one doesn't wish to remain in oneself, one wants to go out and live in the external. F: you see the decided effort to avoid entering into the outer world too sharply, to remain in the inner.

Now when one takes this into consideration, one can carry on from here to form a mental picture of various matters which, although they must become part of eurythmy, were, to begin with, unnecessary as far as we have been concerned with eurythmy as art, but which will become necessary the more this art is extended to other languages. The moment one says not “ef” but “fi”, in that moment it is a different matter; in that moment one attempts to embrace the external with the sound as well. This is indicative of an important historical fact: In ancient Greece people attempted to grasp the external even in those things in respect to which modern man has become inward. You see how one can follow into the outermost fringes of man's experience what I have expressed for example, in The Riddles of Philosophy:1Published by the Anthroposophic Press, Inc., New York, 1973. this going out and taking hold in the external world of what man today already experiences entirely inwardly in his ego. The reason why spiritual science is not accepted on the grounds of such things is solely that the people of our civilization are in general too lazy. They have to take too many things into account in order to come to the truth, and they want to make it easier for themselves. But that just won't do. They want to make everything easier for themselves; and that won't do.

That, for the present, in respect to one element which flowed into the formation of the consonants. If we want to understand the formation of consonants in the field of eurythmy, then we should consider a second element which I believe people pay less attention to nowadays in teaching, even in physiology, speech physiology, than the third element which we will come to in a moment. In order to form an impression, I will ask you to compare once again. Here it is important that one form a contemplative picture. Naturally, one cannot penetrate to the very end of that which one has in such a picture, to the concept.

Perhaps Mrs. Baumann will be so good and make the H again, and once the tone has faded away, Mrs. Baumann will make a D for us. One must pay attention in this case to the following: When you contemplate the H, you will find the movement for it deviates greatly to begin with from what takes place in speaking it; since—in respect to the characteristic of which I am thinking at the moment—the eurythmic element must be polar to the actual process in speech. You know that the speech process as I presented it the day before yesterday is a reflecting back from the larynx. The eurythmic process must express this outwardly. It expresses it in movement. In certain instances one must go over to the exactly opposite pole. This is particularly characteristic of H and D; in the case of other consonants this element must be toned down. Now, what sort of a sound is H? H is esentially a breath sound. The H is actually brought into being through blowing. In the case of H you have a decided shoving thrust2stossige wirkung in eurythmy where you have to blow. When you utter “D” you have this thrusting effect in the pronunciation. We must polarize this by transforming it into the characteristic movement that was present in D. Thus the thrusting quality of speech is lamed when one conveys the sound through movement.

So you see that precisely this characteristic must be taken into particular account, when one has either a breath sound or a plosive sound. Now sounds are not only either breath or plosive sounds. But by what reason are they one or the other? You see, when one has a decided breath sound, one expresses by means of the blowing the fact that one really wants to go out of oneself; in the thrusting, that this going out of oneself is difficult, that one would like to remain within. For this reason the eurythmic transposition of the sound must take place in the manner you have seen.

Now one also has sounds that carefully connect the inward with the outward; sounds that are actually physiologically so constituted that with them one states that one is bringing to a standstill, arresting, that in which one would like to be active in such a manner that the inward would immediately become outward, where one would enter into the movement immediately with the whole human being. This is decidedly evident in only one sound in our language: the R, which is, however, for this reason the most inclusive sound; one would like to run after the speech organism with every limb, as I would like to express it, when one says R. Actually with R one strives to bring this pursuit to rest. The lips want to follow when they pronounce the labial R, and bring this running-after to a halt, the tongue wants to follow when it speaks the lingual R, and finally the palate wants to follow when the palatal R sounds. These three R's are distinctly different from one another, but are nevertheless one; in eurythmy they are expressed thus (Mrs. Baumann: R). The bringing-in-swing of what one usually brings to a standstill is expressed. Thus it is precisely the running after the movement of the sound that comes to expression in the R. And when one wants to bring the other element to expression, one can express the labial R by carrying the movement further downwards; the lingual R can be made more in the horizontal and the palatal R rather more upwards. By this means one can modify the R-sound in the eurythmic movement. But you see that the form is determined by leaving the vibrations of the R in the background and bringing the “running-after” to expression.

A similar sound where one has, not a vibrating, but a sort of wave in the movement is the L (Miss Wolfram: L). You sec that there is something of the same movement in it as in the R; but the running-after is mild and comes to rest. It is a wave rather than a vibration that comes to expression.

That is what is connected innerly, physiologically, with the shading through the vowel element of the consonantal sound, and with the shading through feeling, which already leads to a greater extent into the physical. One arrives at the outermost division of the sounds by considering the organs; if we compare once again the respective movements we will arrive at the most extreme, the most external principles of division through our contemplative picture. (Mrs. Baumann: B) That is a B, and now we will continue directly perhaps with a T. (Mrs. Baumann: I). Now you can see from the position—which as the third element must be taken into account and which makes itself quite apparent to the sensible-super-sensible contemplation—that in the case of B we have to do with a labial sound and in the case of T with a dental sound. (Miss Wolfram: K) K: here one starts with the position and the essential lies in the movement. Isere we have to do with a palatal sound which in its pronounciation, in the tone in which it is spoken is the quietest, but which is transformed in movement into its polar opposite when performed outwardly in eurythmy. The consonants overlap in respect to their characteristics; one division extends into another. The following may serve as an aid.

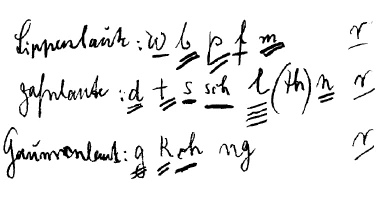

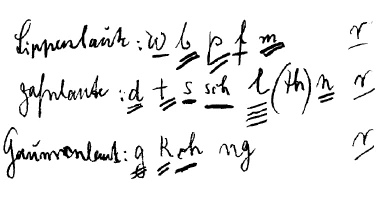

Take the labial sounds—I'll write out only the most distinctive of them: V, B, P, F, M. You can determine to what extent the vowel colouring is involved by pronouncing the sounds; I don't need to indicate that. Let us take the dental sounds D, T, S, Sh, L, the English Th, and N. And now the palatal sounds: G, K, Ch, and the French Ng, more or less. We will have to write the R in everywhere, since it has its nuances everywhere:

Labial sounds: V, B, P, F, M R

Dental sounds: D, T, S, Sh, L, (Th), N R

Palatal sounds: G, K, Ch, Ng R

Considering the process of division from the other point of view now, I will underline with white where we have to do with a definite breath sound: V, F, S, Sh and Ch as well, more or less. These would be the decided breath sounds. I will underline in red where we have to do with what are clearly plosive sounds: B, P, M, D, T, N, and then perhaps G and K. The vibratory sound is R. We have to do with a distinct undulent sound—which, because of the soft transformation in the movement, must be in a sense of an inward character—fundamentally only in the case of L.

These three organizational principles—the vowel colouring, the blowing, thrusting, vibrating and undulating, and all that which has to do with the external division (into dental labial and palatal sounds; the ed.)—all this comes to expression in the forms given for eurythmy. It must be clear to you, of course, to what degree these principles of division affect each other, however. When we have to do with L, for example, we have to do with a distinct dental sound which must have all the characteristics of a dental sound, and then we have to do with a gliding sound, with an undulant sound, which must have the characteristics of a wave. Apart from that, it has a strong connection to the inward. We have to do with a colouring from within outwards, at least in our language. We don't say “le”, but “el”; here we have the transition from older forms in which people reached yearningly into the exterior world and where as a result a word was used in order to express such an event, in order to bring this going over into the external to proper expression. Thus in each of the letters we have to do with a likeness of that which is taking place inwardly.

Before we consider the consonants individually, let us contemplate the following. Yesterday we were able to show that A—which we also studied in its metamorphosis—has to do with all those forces in man that make him greedy, which organize him according to animal nature: the A in fact lies nearest to the animal nature in man, and in a certain sense one can say that when the A is pronounced it sounds out of the animality of man. And certainly as spiritual investigation confirms A is the sound which was the very earliest to appear in the course of both the phylogenetic evolution as well as the ontogenetic evolution of man. In ontogenetic evolution it is somewhat hidden of course; there is a false evolution as well, as you know. The A was the first sound to appear in the evolution of mankind, however, resounding to begin with entirely out of the animal nature. And when we tend towards A with the consonants, we are still calling on what are animal forces in man. As you could see yesterday, the whole sound is actually formed accordingly. If we use the sound therapeutically in the manner in which it presented itself to our souls yesterday we can combat that which makes children, and grown-ups too, into smaller and larger animals. With such exercises we can have very respectable results in the de-animalization of man.

And now let us go on to the sound U, for example. We said yesterday that this is the sound we use therapeutically when a person cannot stand. You saw hat yesterday. It is the sound which in a certain respect expresses its physiologic-pathologic connection already in the manner in which it is formed in speech. The U is spoken with the mouth and the openings between the teeth constricted to the greatest degree and with the lips somewhat extended, in such a way, however, that the mouth opening is narrowed and the lips can vibrate. You can see that in speaking one seeks an essentially outward movement with the U. In the pronounciation of U the attempt to characterize something moving predominates. Thus with the eurythmic U the physiologic opposite occurs: the ability to hold one's stand is called forth. This is present in the U in artistic eurythmy as well, at least as a suggestion.

If you now take a look at the other vowels you will find a progressive internalization. In the case of the O you have the lips pushed together towards the front and the opening of the mouth reduced in size—there is at least an attempt to reduce the size. This is transformed into the polar opposite in the encompassing gesture of the 0-movement in eurythmy. Precisely in such things the natural connections are to be perceived. In the manner in which O is employed in speech certain forces are present. And in languages in which O predominates one will find that the people have the greatest propensity to become obese. That may really be taken as a guideline for the study of the physiologic processes connected with speech. If one were to develop a language consisting principally of modifications of O, where people had to carry out the characteristic mouth and lip formation of the O continuously, they would all become pot-bellied. If with the O, on the one hand, one has this propensity to become big-bellied, as I would like to call it, it is easy to understand why when reversed the O represents on the other hand that which combats this obesity when it is carried out eurythmically and in the metamorphosis demonstrated yesterday.

The state of affairs is different with E, for example. A language that is rich in E will engender skinny people, weaklings. And that is related to what I said yesterday about the treatment of thin people, and thus of weaklings, in relation to the significance of E. You will remember that I said that in the case of weaklings particularly the E-movement with its given modification is to be applied.

Now in respect to all these matters it is necessary to take one thing into account, however: if one considers the forms outwardly one does not come to the truth of the matter; one must grasp them inwardly in the process of their becoming. One must concentrate less on what comes to outward expression and more on the tendency involved. The tendency to become fat can be combated by means of the O and the tendency to remain thin by the E. Attention must be drawn to these matters because when eurythmy is used for therapeutic purposes, it is necessary to take the forces that are present in the upper man and tend to a widening, and the forces present in the lower man tending to the linear, more into consideration. Thus I must say that when man utters the O he actually broadens the living element.

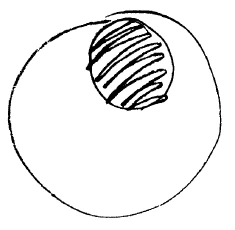

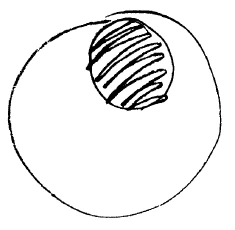

You see, when I draw it roughly, the head of man is in a way a sphere and spiritual-scientifically it is a proper reproduction of the earth sphere. It is a copy of all those forces that are centralized in the sphere of the earth and it is developed by that which lies in the forces of the moon. This latter builds it up in such a manner that it becomes a sort of earth-sphere. Of course, this is all actually connected with cosmology, cosmogeny. As the earth-phase proceeded out of the moon-phase, so out of the forces that are so powerfully at work in building up the human head—which of itself, of course, intends to become a sphere and is modified only by the breast and the other part of the body being attached to it and altering the spherical form—so out of the moon-building forces the head is formed. If it were left to itself the head would become a proper sphere. That is not the case because the other two parts of the human organism are connected with the head and influence its shape.

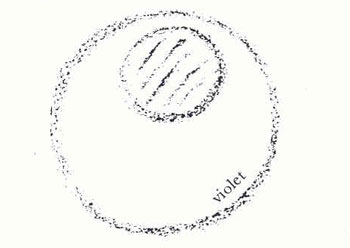

When one pronounces the O one tries to bring that which finds its expression in the spherical form of the head to expression in the entire etheric head. One makes the effort to form a second head for oneself (see the violet in the drawing) and one can really say that in uttering the O man puffs himself up like his head—he puffs himself up, he blows himself out and awakens thereby the forces that give him at the other pole the tendency to become fat. These things can really be taken pictorially as well. His inflating of his own head gives him the tendency to become fat. When one wants to counteract this tendency to become, etherically speaking, a fat-head—not really a fat-head, but etherically a fat head—to become a big head, then one must attempt to round it off from the other side, to take it back into oneself. And that is the protest of the fathead. Therefore an O is fanned at the opposite pole. All the individual sounds have a nuance of feeling, namely, which is deeply established in the organism, because it lies in the unconscious; hence the import of the inner being of the sound. For the person who looks at the matter in a super-sensible manner the frog who would like to blow himself up into an ox, you see, is the one from whom a cannon-like O tone would continuously proceed if he were able to fulfill his intention. That is the peculiarity of it—one must explain by means of such things if one wishes to understand these matters inwardly.

With the E it is distinctly the reverse. In E one wants to take hold of oneself inwardly, wants to contract together inwardly. For that reason there is the touching of oneself in the eurythmy, this becoming aware of oneself: you become aware of yourself, simply, when you place the right arm upon the left, just as when you feel an object outside yourself, when you take a hold of it, you become aware of yourself. It would be even more clearly expressed if you simply grasped the right arm with the left hand—in art only an indication of all these things can be given—when you grasp the right arm with the left hand you are feeling yourself. This contacting oneself has come to expression especially in the eurythmic E. And this touching oneself is carried out throughout the whole human organism. You can study this touching of oneself simply by studying the relationship of the nerve Process in the human back, those that ordinary physiology mistakenly call the motory nerves and those that are called sensory.

Here where the motor nerve, which is basically a sensory nerve too, comes together with the sensory nerve, a similar sort of clasping occurs. The fact is that the nerve-strands on the human back continually form an E. In this forming of the E lies the way in which man's inward perception of himself which is factually differentiated, in the brain, comes into being. Yesterday we attempted to reproduce this E-building which actually takes place in a plane; you will find that what we attempted to reproduce shows through the outward movement and the position of the movement how this inward E-making in man sums itself up into the vertical. As the head puffs itself out and wants to become a horn-blowing cherub, this E-process, this pulling-oneselftogether-in-points, sums itself up in the vertical, in the upright line. It is a continuous and successive fastening together of E's which stand one above another; that expresses clearly what one observes taking place in weaklings. They have the tendency to continuously stretch their etheric bodies. They want to extend the etheric body rather than to pull it together into a point, which would be the real antithesis to the activity of the head. That is not the case however: they try to stretch the etheric body thereby making a repetition of the point. And this extension which makes its appearance in people who are becoming weak—not the extension in the physical, but in the etheric body—will be counteracted by shaping that E of which we spoke yesterday.

So I believe you will see now how there is an inward connection between the eurythmic element involved and the human formative tendencies, how what is present in him as formative tendencies has been drawn out of the human being. The fact is that these formative tendencies which express themselves first in growth, in the forming of man, in his configuration, become specialized and localized once again in the development of the speech organism, this special organism. There these formative tendencies—which are otherwise spread out over the entire person—are to an ex-tent accumulated. In developing eurythmy we turn and go back again. We proceed from the localized tendency to the whole man, thus placing in opposition to the specialization of the human organization in the speech organism another specialization, the specialization in the will-organism. The whole human being is indeed an expression of his volitional nature insofar as he is metabolic and limb organism throughout. One can move this or that part of the head too, and therefore the head is also in a certain sense limb-organism. That can be demonstrated by those people who are capable in this respect of a hit more than others. People who can wiggle their ears and so on, they can show very clearly how the principle of movement of the limbs, how the limb-nature extends into the organization of the head. The whole human being is in this respect an expression of the volitional. When we go on to eurythmy we express that once again. Before we proceed to working out the sounds particularly, to the special manner of forming them and further to the combinations of sounds tomorrow, I would like to speak in closing of something historical.

The movement of the will and the movement of the intellect, you see, constitute two sorts of evolution of power which proceed in man at different velocities. Man's intellect develops quickly in our age, volition slowly, so that as part of the whole evolution of mankind we have already surpassed our will with our intellect. In our civilization it is generally manifest that the evolution of the intellect has overtaken the evolution of the will. The people of today are intensely intellectual, which precisely does not imply that they can do much with their intellect; they are strongly intellectual, but they hardly know what to do with their intellect; for that reason they know so little intellectually. But what they do know intellectually they treat in such a manner as though within it they could function with a certain certainty. Will develops slowly. And to practise eurythmy is, apart from everything else, an attempt to bring the will back into the whole evolution of mankind again. If eurythmy is to appear as a therapy the following must be pointed out: It must be said that the over-development of the intellect expresses itself particularly in the organic side effects of the evolution of speech as well. Our speech development today in our modern civilization is actually already something which is becoming inhuman through its superhuman qualities insofar as we learn languages today in such a manner that we have so little living feeling left for what lies in the words. The words are actually only signs. What sort of feeling do people still have for that which lies in words? I would like to know how many people go through the world and become aware in the course of learning the German language for example, that the rounded form which I have just drawn is expressed in the word “Kopf” (Head), which has a connection with “Kohl” (cabbage), and for which reason one also says “Kohlkopf” (cabbagehead), which is actually only a repetition; the rounding is metamorphosed according to the situation. That is what is expressed here. In the Romance languages, “testa, testieren”, is expressed more what comes from within, the working of the soul through the head. People have no more feeling for the distinctions within language; language has become abstract. When you walk, you walk with you feet. Why do we say “Füsse” (feet)? You see, that is a metamorphosis of the word “Furche” (furrow) which came about because it was seen that one traces something like a furrow when one walks. The pictorial element in language has been completely lost; if one wishes to bring this pictorial element back into language, then one must turn to eurythmy.

Every word that is experienced unpictorially is actually an inward cause of illness; I am speaking in coarse words now—but then we have only coarse words—of something which expresses itself in the finer human organism. Civilized mankind suffers chronically today from the effects which learning to speak abstractly, which the failure to experience words pictorially, has upon it. The results are so far-reaching that the accompanying organic side effects express themselves as a very strong tendency towards irregularities in the rhythmic system and a refusal to function of the metabolic system in those people who have made their language abstract. However, we can actually do something about what is being spoilt in man today through language, which he acquires of course in early childhood, and which, if it is acquired in an unpictorial way, really produces conditions leading later on to all kinds of illnesses. We can actually do something about overcoming this with the help of therapeutic eurythmy. Thus curative eurythmy may be introduced in a thoroughly organic manner into the course of therapy as a whole.

It is truly so: the person who understands that developing oneself spiritually has always something to do with becoming ill—we must take becoming ill in the course of spiritual development into the bargain—must also taken into consideration that one can fight, not alone through outward physical studies, but also by outward means, this process of becoming ill which is due to our civilization. We put soul and spirit into the movements of eurythmy and combat thereby what, on the other side, soul and spirit do themselves, though often in earliest childhood, in such a manner that the effect of their activity when it develops in later life must be felt to be the cause of illness.

Dritter Vortrag

Wir werden nun, um entsprechend vorwärtszukommen, heute in Anknüpfung an Formen des Konsonantierens zunächst einiges, ich möchte sagen vorbereiten, das wir dann morgen physiologisch und psychologisch vertiefen wollen. Nun, dasjenige was ausgebildet ist als Form des Konsonantierens, bei dem ist wirklich durchaus Rücksicht genommen auf alles, was in Betracht kommt, wenn der Mensch versucht, sprachlich in die Außenwelt einzudringen. Wer die Sprache beobachten will, der wird ja sehen, wie das Sich- Auseinandersetzen des Menschen mit der Außenwelt darinnen bestehen muß, daß der Mensch in einem Falle gewissermaßen sehr stark sich hinauslebt in die Außenwelt, daß er sich sehr stark entselbstet und in die Außenwelt hinauslebt. Beim Vokalisieren verselbstet er sich, beim Vokalisieren geht er nach dem Inneren und entfaltet da seine Tätigkeit. Beim Konsonantieren wird er gewissermaßen eins mit der Außenwelt, aber in verschiedenen Graden. Und dieses in verschiedenen Graden Einswerden mit der Außenwelt, das drückt sich auch in gewissen Betätigungen innerhalb der Sprache durchaus aus. Und es muß natürlich bei der Ausbildung des eurythmischen Konsonantierens, gerade bei diesem sinnlich-übersinnlichen Schauen, von dem ich oftmals spreche in den Einleitungen zu eurythmischen Kunstvorstellungen, bei diesem sinnlich-übersinnlichen Schauen muß scharf berücksichtigt werden, ob der Mensch nun vollständig sich hinausobjektiviert, um gewissermaßen das Geistige, das draußen in den Dingen ist, in dem Laut zu erfassen, oder ob er mehr, trotz des Sich-Objektivierens, noch im Inneren bleibt und nicht eigentlich ganz hinausgeht, sondern im Inneren noch das Äußere nachbildet. Da ist ein großer Unterschied, und ich bitte aus diesem Grunde, vielleicht ist Frau Baumann so gut und macht uns zunächst, sagen wir, vor eine H-Bewegung. Und jetzt, bitte, wenden Sie den Blick ganz ab von dieser H-Bewegung und Frau Baumann wird nun eine F-Bewegung vormachen. Und jetzt behalten Sie gut im Auge dasjenige, was Sie bei diesen verschiedenen Bewegungen, bei diesen zwei voneinander verschiedenen Bewegungen da beobachten können. Sie können da beobachten dasjenige, was Sie aus dem menschlichen Instinkt heraus in dem Aussprechen, in dem Auszusprechenversuchen des betreffenden Lautes darinnen haben. Nehmen Sie das Aussprechen des H. Eigentlich sprechen Sie ja dieses H in Wirklichkeit Ha; eigentlich sprechen Sie ja einen Vokal nach. Sie können ja auch einen Konsonanten nicht erklingen lassen, ohne daß er durch einen Vokal tingiert wird. Sie sprechen ein A nach. Der reine Konsonant wird vervokalisiert. Und wenn Sie nun das F betrachten, dann werden Sie sehen, daß aus dem menschlichen Sprachinstinkte heraus ein E vorgesetzt wird: eF. Es wird das Entgegengesetzte gemacht, es wird ein E vorgesetzt.

Daraus ersehen Sie, daß, indem der Mensch ein H spricht, er sich mehr bemüht, das Geistige durch die Sprache in dem äußeren Objekt draußen aufzusuchen; indem er ein F spricht, bemüht er sich mehr, das Geistige im Inneren nachzufühlen. Daher ist die Entstehung des Konsonantischen eine ganz verschiedene, je nachdem man versucht, die vokalische Tingierung von vorne oder von hinten zu machen, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf in bezug auf das Konsonantieren. Und das werden Sie sehen ausgedrückt in der Form, die Sie gesehen haben.

Vielleicht macht Fräulein Wolfram das H noch einmal. Also H, da haben Sie das starke Aufgehen in die Außenwelt, man will nicht in sich bleiben, man will heraus, um im Äußeren zu leben. Das F: Sie sehen das starke Bestreben, nicht allzuscharf in die Außenwelt zu gehen, sondern im Inneren zu verbleiben.

Nun aber, wenn man das berücksichtigt, dann wird man natürlich von da ausgehend über manches, was auch schon ins Eurythmische einfließen muß, eine Vorstellung bekommen, die zunächst noch nicht nötig war, soweit wir die eurythmische Kunst betreiben, die aber nötig werden wird, je mehr die eurythmische Kunst ausgedehnt wird auf die verschiedenen Sprachen. In dem Augenblick nämlich, wo man nicht eF sagt, sondern Fi, in dem Augenblicke ist das anders, in dem Augenblicke versucht man auch, mit diesem Konsonanten das Äußere zu umfassen, und es weist das auf eine wichtige historische Tatsache hin. In Griechenland, im alten Griechenland versuchten ja die Menschen das Äußere zu erfassen selbst in solchen Dingen, wo der moderne Mensch schon innerlich geworden ist. Sie sehen, wie man bis in die äußersten Ranken des menschlichen Erlebens verfolgen kann dasjenige, was ich zum Beispiel in den «Rätseln der Philosophie» ausgedrückt habe, dieses Herausgehen des Menschen und das Erfassen in der Außenwelt desjenigen, was der heutige Mensch im Ich schon ganz innerlich erlebt. Der Grund, warum aus solchen Dingen heraus die Geisteswissenschaft nicht angenommen wird, ist lediglich der, daß die Menschen im allgemeinen in unserer Zivilisation zu faul sind. Sie müssen zu viele Dinge berücksichtigen, um auf die Wahrheit zu kommen, sie wollen sich das einfacher machen. Aber das geht eben nicht. Sie möchten sich das alles einfach machen; das geht eben nicht.

Nun, das zunächst in bezug auf das eine, was hineingeflossen ist in die Konsonantierung. Dann ist etwas zu berücksichtigen, wenn man die Konsonantierung ins eurythmische Gebiet hineingehend fassen will, dann ist etwas zu berücksichtigen, was heute, glaube ich, im Unterricht schon weniger berücksichtigt wird, auch in der Physiologie, bei der Lautphysiologie weniger berücksichtigt wird als das dritte, wozu wir dann gleich kommen. Um das zu veranschaulichen, bitte ich Sie, wiederum zu vergleichen. Hier handelt es sich darum, daß man sich die Anschauung erwirbt. Man kann natürlich nicht bis ins Ende desjenigen, was man mit der Anschauung macht, in den Begriff hinein.

Vielleicht ist Frau Baumann so gut, uns ein H nochmals zu machen, und jetzt, nachdem Sie das abtönen lassen, macht uns Frau Baumann ein D. Sie werden da folgendes zu beachten haben: Indem Sie das H anschauen, hat es eine Bewegung, welche sehr abweicht von dem, was zunächst im Sprechen vor sich geht, denn in bezug auf die Eigenschaft, die ich jetzt meine, muß das Eurythmische polarisch sich verhalten zu dem, was der eigentliche Sprechvorgang ist. Der Sprechvorgang, Sie wissen, ich habe es vorgestern dargestellt, ist ein Zurückreflektieren vom Kehlkopf aus. Der eurythmische Vorgang muß das äußerlich ausdrücken. Er drückt es aus in der Bewegung. Da muß man für gewisse Fälle durchaus ins ganz Polarische übergehen. Nun, was ist das H für ein Laut? Das H ist im wesentlichen ein Blaselaut. Es ist eigentlich ein Blasen, wodurch man das H zustande bringt. Will man das eurythmisch ausdrücken - und das H ist in dieser Beziehung besonders charakteristisch, bei den andern Konsonanten muß es wieder abgetönt werden, aber bei H und D zum Beispiel ist es besonders charakteristisch -, da haben Sie da, wo man blasen muß [im Aussprechen], eine ausgesprochen stoßige Wirkung in der Eurythmie. Wenn Sie D aussprechen, haben Sie im Aussprechen eine stoßige Wirkung. Die müssen Sie [in der Eurythmie] polarisieren dadurch, daß Sie sie überführen in diese eigentümliche Bewegung, die beim D da war. Also es wird gerade das Stoßige des Sprechens in den Bewegungen des Lautes abgelähmt.

So also sehen Sie, daß, je nachdem man Blaselaute oder Stoßlaute hat, gerade diese Eigenschaft besonders berücksichtigt werden muß. Nun sind die Laute ja nicht bloß Blaselaute und Stoßlaute. Wodurch aber sind die Laute Blaselaute und Stoßlaute? Sehen Sie, wenn man einen ausgesprochenen Blaselaut hat, dann drückt man in dem Blasen aus die Tatsache, daß man so recht stark hinaus möchte aus sich; in dem Stoßen, daß es einem schwer wird, das Hinausgehen aus sich, daß man darinnenbleiben möchte. Aus diesem Grunde muß ja auch die eurythmische Umsetzung des Lautes in der Weise erfolgen, wie Sie gesehen haben.

Nun aber hat man auch Laute, welche das Innere mit dem Äußeren sorgfältig verbinden, Laute, die eigentlich physiologisch so sind, daß man sagt, man bringt dasjenige, worinnen man sich eigentlich so betätigen möchte, daß das Innere gleich ein Äußeres wird, daß man gleich mit seinem ganzen Menschen in die Bewegung hineingeht, das bringt man zum Stillstand, das hält man auf. Und das ist in ausgesprochener Weise dann der Fall, eigentlich nur deutlich in unserer Sprache bei einem einzigen Laut, dem R, aber es ist deshalb auch das R der umfassendste Laut, weil man nämlich wiederum mit jedem Gliede, möchte ich sagen, dem Sprachorganismus nachlaufen möchte, wenn man das R ausspricht. Man hat eigentlich beim R das Bestreben, daß man das Nachlaufen zur Ruhe bringt. Die Lippen möchten nach, wenn sie das Lippen-R sprechen und bringen das Nachlaufen zur Ruhe, die Zunge möchte nach, wenn sie ein Zungen-R spricht, und endlich der Gaumen möchte nach, wenn das Gaumen-R ertönt. Diese drei R sind ja deutlich voneinander verschieden, aber sie sind doch wiederum eins, und in der Eurythmie drücken sie sich aus (Frau Baumann: R). Also es ist ausgedrückt das In-Schwung-Bringen desjenigen, was man sonst in Stillstand bringt. Gerade dieses Nachlaufen der Lautbewegung, das ist in diesem R zum Ausdruck gekommen. Und man wird, wenn man will das andere ausdrücken, das Lippen-R besonders dadurch ausdrücken, daß man die Bewegung weiter nach unten führt, das Zungen-R, indem man sie mehr in der Horizontalen macht, und das Gaumen-R, indem man sie mehr nach oben macht. Dadurch kann man modifizieren den R-Laut in der eurythmischen Bewegung. Aber Sie sehen, seine Form kommt zustande, indem man das Zitternde des R in den Hintergrund treten läßt und mehr das Nachlaufen in ihm zum Ausdrucke bringt.

Ein ähnlicher Laut, aber so, daß man nicht ein Zittern hat in der Bewegung, sondern eine Art Welle, ist das L (Fräulein Wolfram: L). Also, Sie sehen jetzt, es ist etwas von derselben Bewegung drinnen wie im R, aber es ist ein sanfteres zur Ruhe Kommendes, ein sanfteres Erfassen des Nachlaufens, es ist eben eine Welle im Gegensatz zum Zittern, was da zum Ausdrucke kommt.

Das wäre dasjenige, was sich bezöge innerlich, physiologisch, möchte ich sagen, auf das vokalisierende Tingieren des konsonantischen Lautes und auf das schon mehr ins Physische übergehende nun Tingieren mit dem Gefühle. Nun, die alleräußerste Einteilung gewissermaßen der Laute bekommt man dadurch zustande, daß man sich an die Organe hält, und da können wir etwa, indem wir wiederum vergleichen die entsprechenden Bewegungen, können wir für die Anschauung dasjenige entwickeln, was da an alleräußersten Einteilungsprinzipien, äußerlichsten Einteilungsprinzipien herauskommt. Nämlich nehmen wir einmal ein B (Frau Baumann: B). Das ist ein B, und jetzt schließen wir gleich an etwa ein T. Nun, Sie sehen aus dem, aus der ganzen Lage, die da als das dritte berücksichugt werden muß, die sich auch ganz anschaulich in der sinnlich-übersinnlichen Anschauung ergibt, Sie sehen aus der ganzen Lage, daß wir es in dem B mit einem Lippenlaut, in dem T mit einem Zahnlaut zu tun haben. (Fräulein Wolfram, machen Sie uns ein K) K: Da ist überhaupt von der Lage herausgegangen, und die Hauptsache liegt in der Bewegung. Da haben wir es mit einem Gaumenlaut zu tun, der in der Aussprache, in der Tonaussprache der ruhigste ist, der aber in die Bewegung übergehen muß, in seine polarische Gegenseite in der äußerlichen Eurythmisierung. Nun, es übergreifen sich die Konsonanten in bezug auf diese ihre Eigenschaften; die eine Einteilung greift eben in die andere hinein, und wir können etwa folgendes uns als eine Art Hilfe merken:

Nehmen Sie die Lippenlaute, ich will nur die allerausgesprochensten aufschreiben, etwa W, B, P, F, M. Inwiefern die vokalische Tingierung mitspricht, können Sie ja dadurch ergründen, daß Sie einfach die Sache aussprechen. Also das brauche ich nicht anzugeben. Nehmen wir jetzt die Zahnlaute: D, T, S, Sch, L, wozu wir auch das englische Th und N [nehmen können]. Und nehmen wir jetzt die Gaumenlaute: G, K, Ch, dann dieses französische, etwa Ng.

Und nun das R müßten wir eigentlich überall hinschreiben, denn es hat überall seine Nuance [es wird an die Tafel geschrieben].4An der Tafel wurden die Laute zwar in kleinen Buchstaben angeschrieben, wegen der besseren Lesbarkeit wurden im laufenden Text aber Großbuchstaben eingesetzt.

Wenn Sie nun den andern Gesichtspunkt der Einteilung nehmen, werde ich Ihnen weiße Striche darunter machen überall, wo wir es zu tun haben mit einem ausgesprochenen Blaselaut: W, F, S, Sch und etwa noch Ch. Das wären ausgesprochene Blaselaute. Ich werde Ihnen rote Striche darunter machen, wo wir es mit ausgesprochenen Stoßlauten zu tun haben: B,P,M,D,T, N, und das R ist ja ein Zitterlaut, dann wären noch etwa G und K. Der Zitterlaut ist dann das R; und mit einem ausgesprochenen Wellenlaut, der also in einem gewissen Sinne wegen des weichen Übergehens in die Bewegung innerlich sein muß, mit einem ausgesprochenen Wellenlaut haben wir es im Grunde genommen nur in demL zu tun (gelb).

Diese drei Einteilungsprinzipien, die vokalisierende Tingierung, das Blasen, Stoßen, Zittern, Wellen und alles dasjenige, was dann wiederum zusammenhängt mit dieser äußeren Einteilung [in Zahn-, Lippen- und Gaumenlaute], das kommt in den Formen, die da sind für das Eurythmisieren, kommt in diesen Formen zum Ausdrucke. Nur müssen Sie natürlich sich klar sein darüber, wie stark diese Einteilungsprinzipien wiederum einander alterieren. Wenn wir es also zum Beispiel mit dem L zu tun haben, haben wir es mit einem ausgesprochenen Zahnlaut zu tun, der also alle Eigenschaften des Zahnlautes haben muß, und dann haben wir es mit einem Gleitlaut zu tun, mit einem Wellenlaut, der die Eigenschaften des Wellens haben muß. Er ist aber außerdem sehr stark in das Innere gebunden. Wir haben es also mit einem, wenigstens in unserer Sprache, mit einem Tingieren von innen heraus zu tun. Wir sagen nicht: Le, sondern wir sagen: eL, und haben auch da den Übergang von älteren Formen, wo man überhaupt, ich möchte sagen, sehnsüchtig entwickelte ein äußeres Eingreifen und es daher sehr stark zustande kam, wo man also geradezu ein Wort 2ein Wort: lambda, der elfte Buchstabe des griechischen Alphabets. brauchte, um so etwas auszudrücken, um dieses Hinübergehen in das Äußere so recht zum Ausdrucke zu bringen. Wir haben es also bei den einzelnen Buchstaben durchaus zu tun mit einem Abbilden desjenigen, was innerlich vorgeht.

Nun sehen Sie, bevor wir jetzt die einzelnen Konsonanten durchnehmen, wollen wir uns noch das Folgende vor die Seele führen: Wir haben gestern bei dem A anführen können - und wir haben ja auch schon seine Metamorphose studiert -, wir haben anführen können, daß es zusammenhängt mit all denjenigen Kräften im Menschen, die ihn gierig machen, die ihn nach dem Animalischen hin organisieren. Das A liegt ja tatsächlich dem Animalischen im Menschen am nächsten, und man kann schon in einer gewissen Weise sagen, das A tönt aus dem Tierischen des Menschen, wenn es ausgesprochen wird, heraus. Und ganz gewiß ist das A, was ja auch durch die geistige Forschung bestätigt wird, ein Laut, welcher am allerfrühesten beim Menschen auftrat, sowohl in der phylogenetischen wie in der ontogenetischen Entwickelung. In der letzteren - Sie wissen ja, es gibt auch ein falsches Entwickeln -, in der ontogenetischen Entwickelung ist es natürlich etwas kaschiert; aber dasjenige, was zuerst aufgetreten ist in der menschheitlichen Entwickelung, das ist der noch ganz aus dem Tierischen herausklingende A-Laut. Und wenn wir bei Konsonanten nach dem A hintendieren, so appellieren wir auch noch an dasjenige, was in dem Menschen die tierischen Kräfte sind. Darauf ist ja der ganze Laut, wie Sie gestern haben sehen können, nun eigentlich geformt. Verwenden wir ihn nun therapeutisch, den Laut, so wie er gestern vor unsere Seele getreten ist, so bekämpfen wir also dasjenige, was namentlich Kinder, aber auch Erwachsene zu kleineren oder größeren Tierchen macht. Und wir können durch solche Übungen in der Enttierung des Menschen schon, ich möchte sagen, ganz Anständiges leisten.

Und nun gehen wir über zum Beispiel jetztzum U-Laut. Dahaben wir ja gestern gesagt, eristderjenige Laut, den wirtherapeutisch verwenden, wenn der Mensch nicht stehen kann. Sie haben das gestern gesehen; es ist derjenige Laut, welcher in einer gewissen Beziehung dadurch schon in seiner Formung ausdrückt diese seine physiologisch-pathologische Beziehung, welcher schon in seiner Formung als Sprachlaut ausdrückt,1Laut Stenogramm wörtlich: ... welcher schon in seiner Formung ausdrückt das, auch erst als Sprachlaut in seiner Formung ausdrückt das, daß ... daß das U ja gesprochen wird beim höchsten Grad des Zusammenschlusses des Mundes, der Zahnspalten, etwas vorgestreckten Lippen, so aber, daß die Mundspalte verengert wird und diese Lippen vibrieren dann. Sie sehen daraus, daß es eine beim Sprechen wesentlich äußere Bewegung ist, die man sucht im U. Es ist am stärksten versucht, das Bewegliche im Aussprechen des U heraus zu charakterisieren. Daher tritt beim eurythmischen U physiologisch das Gegenteil ein, das Hervorrufen der Standfestigkeit, was ja dann auch beim U 3Laut Stenogramm: beim Kunst-U in der Eurythmie. in der Kunst-Eurythmie wenigstens angedeutet vorhanden ist.

Wenn Sie dann die andern Vokale ins Auge fassen, so werden Sie sehen, daß wir eine fortschreitende Verinnerlichung des Vokales haben. Wenn Sie also das OÖ ins Auge fassen, ein Zusammenschieben, möchte ich sagen, der Lippen nach vorne, ein Verkleinern der Mundöffnung, und wenigstens die Bemühung der Verkleinerung der Mundöffnung; dieses wird ins Gegenteil hinüber polarisiert durch das Umfassende, was in der O-Bewegung beim Eurythmisieren liegt. Gerade bei solchen Dingen sieht man den natürlichen Zusammenhang der Sache. In dem sprachlichen Handhaben des O liegen schon durchaus gewisse Kräfte. Und in Sprachen, in denen das O besonders stark vorhanden ist, in solchen Sprachen wird die meiste Anlage bei den Menschen vorhanden sein zum Dicklichwerden. Sie können das durchaus als eine Richtlinie betrachten für das Studium der sprachphysiologischen Vorgänge.4Unklar im Stenogramm. Von Helene Finckh übertragen als «Forderungen», dann gestrichen mit Fragezeichen. Andere Lesart wäre «Vortragsstudien». Wenn man eine Sprache ausbilden würde, die im wesentlichen nur aus Modifikationen des O bestehen würde, wo also die Menschen die eigentümliche Lippen- und Mundformierung, die sie beim O vornehmen, immerfort ausführen müßten, so würden das alles Dickbäuche werden. Wenn man nun auf der einen Seite hat dieses, ich möchte sagen Tendieren zum Dickbäuchigen beim O, so wird man leicht verstehen können, warum das O umgekehrt wiederum die Bekämpfung des Dickbäuchigen darstellt, wenn es eurythmisch ausgeführt wird und in der entsprechenden Weise metamorphosiert wird, wie wir das gestern getan haben.

Anders ist die Sache zum Beispiel beim E. Eine Sprache, welche besonders E-reich ist, die wird eben Dünnlinge erzeugen, schwächliche Menschen erzeugen. Und damit hängt wiederum zusammen dasjenige, was ich gestern über die Behandlung von Dünnlingen, also von schwächlichen Menschen gesagt habe in bezug auf die Behandlung des E. Sie werden sich erinnern, daß ich also gerade gesagt habe: bei Schwächlingen ist die E-Bewegung mit ihrer Modifikation ganz besonders anzuwenden.

Nur bei allen diesen Dingen ist etwas zu berücksichtigen, nämlich das: Wenn man die Formen äußerlich betrachtet, dann kommt man nicht auf das Richtige, man muß sie in ihrem Werden innerlich erfassen. Man muß also weniger ins Auge fassen dasjenige, was sich äußerlich ausdrückt, sondern die Tendenz dazu. Die Tendenz zum Dickwerden, die ist es, die durch das O bekämpft wird, und die Tendenz, dünn zu bleiben, ist es, die durch das E bekämpft wird. Und darauf muß man schon deshalb aufmerksam machen, weil, wenn man die Eurythmie zu Heilzwecken anwendet, dann muß man mehr sehen auf die Kräfte, die vorhanden sind im oberen Menschen und die nach einer Weitung gehen, und die Kräfte, die im unteren Menschen vorhanden sind, die mehr nach dem Linienhaften hintendieren. So muß ich sagen, indem der Mensch das O ausspricht, weitet 5Stenogramm nicht eindeutig: «weitet» kann auch als «bildet» gelesen werden, ebenso «das Lebendige» als «das Folgende». er eigentlich das Lebendige.

Sehen Sie, der Kopf des Menschen, der ist ja, wenn ich es grob zeichne, in einer gewissen Weise eine Kugel, und er ist auch geisteswissenschaftlich die richtige Nachbildung der Erdkugel. Er ist ein Abbild aller derjenigen Kräfte, die in der Erdkugel zentralisiert sind, und eigentlich aufgebaut wird er in seinem Werden durch dasjenige, was in den Mondenkräften liegt. Aber das baut ihn eben so auf, daß er eine Art Erdkugel wird. Das hängt ja mit der Kosmologie, mit der Kosmogonie eigentlich zusammen. Wie aus der Mondenphase die Erdphase hervorgegangen ist, so geht aus den mondbildenden Kräften, die so sehr stark an dem Aufbauen des menschlichen Kopfes betätigt sind, dann der Kopf des Menschen hervor, der ja eben von sich aus einfach eine Kugel zu werden trachtet, in seiner kugeligen Form nur modifiziert ist dadurch, daß Brust und der andere Leib daran hängen, die die Kugelform modifizieren. Wenn er sich selbst überlassen wäre, der Kopf, würde er eine richtige Kugel werden. Aber daß das nicht ist, das rührt davon her, daß die andern beiden Glieder der menschlichen Natur mit dem Kopf zu tun haben und seine Gestalt beeinflussen.

Wenn man nun O ausspricht, da versucht man dasjenige, was sich in der Kugelform des Kopfes zum Ausdrucke bringt, im ganzen Ätherkopfe zum Ausdruck zu bringen. Und da hat man das Bestreben, sich einen zweiten Kopf zu formen. Derjenige, der O ausspricht, der hat das Bestreben, richtig sich einen zweiten Kopf zu formen [äußere Kreislinie] (lila), und man kann schon sagen, im O-Aussprechen, da bläht sich der Mensch seinem Kopfe nach auf, er bläht sich auf, er bläst sich aus, und er erweckt gerade dadurch die Kräfte, die ihn an dem andern Pol zum Dicklichwerden veranlassen. Die Dinge sind schon auch bildlich anzuschauen. Er wird zum Dicklichwerden veranlaßt, indem er sich seinen Kopf selber aufbläst. Wenn man nun dieser Tendenz, wenn ich so sagen möchte: ätherisch zum Dickkopf zu werden - also das ist jetzt nicht ein dicker Kopf, sondern ätherisch ein Dickkopf zu werden, das heißt, ein großer Kopf zu werden -, wenn man dem entgegenarbeiten will, so muß man versuchen, ihn zu runden, auf der andern Seite wieder hereinnehmen. Und das ist der Protest des Dickkopfes. Es ist daher ein O polar ausgebildet. Die einzelnen Laute haben nämlich alle eine Empfindungsnuance, die wiederum im Organismus tief begründet ist, denn sie liegt ja im Unbewufßten, und daher das Bedeutsame des innerlichen Wesens der Laute. Sehen Sie, der Frosch, der sich gerne zum Ochsen aufblasen möchte, der ist wirklich für denjenigen, der die Sache sich so recht übersinnlich beschaut, der ist derjenige, von dem fortwährend müßte ausgehen, wenn er sich verwirklichen könnte, ein kanonenhaftes O-Tönen. Das ist das Eigentümliche, daß man eben muß auf solche Dinge, ich möchte sagen zum Verdeutlichen eingehen, wenn man diese Dinge innerlich verstehen will.

Beim E, da ist es deutlich umgekehrt. Sehen Sie, beim E, da ist eigentlich das vorhanden, daß der Mensch sich innerlich fassen will, sich innerlich zusammenziehen will. Daher ja auch in der Eurythmie das Berühren seiner selbst, dieses Gewahrwerden seiner selbst: Sie nehmen sich einfach wahr, wenn Sie den rechten Arm über den linken legen. Geradeso, wie wenn Sie einen Gegenstand draußen empfinden, wenn Sie ihn angreifen, so nehmen Sie sich selbst wahr. Noch deutlicher wäre das also ausgedrückt, wenn Sie einfach mit der linken Hand den rechten Arm umfassen würden - in der Kunst müssen die Dinge alle angedeutet sein -, aber wenn Sie hier das einfach fassen würden, so betasten Ste sich selber. Das Sichselber-Betasten, das ist in dem eurythmischen E besonders zum Ausdruck gekommen. Und dieses Sich-Betasten, dieses Sich-selber-Betasten, das ist ja durch den ganzen menschlichen Organismus durchgeführt. Und Sie können es studieren, dieses Sich-selber-Betasten, wenn Sie einfach das Verhältnis studieren, indem am Rücken des Menschen sich äußern diejenigen Nervenverläufe, die in der gewöhnlichen Physiologie irrtümlich die motorischen, und diejenigen, die die sensitiven genannt werden. Da, wo dieses Motorische, das aber im Grunde genommen auch ein Sensitives ist, da, wo dieses Motorische mit dem Sensitiven zusammenkommt, entsteht eine solche Art des Umfassens. Es ist so, daß tatsächlich die Nervenstränge fortwährend am menschlichen Rücken ein E bilden, und daß in diesem E-Bilden wirklich auch das Zustandekommen des Sich-innerlich-Fühlens des Menschen liegt, was dann nur im Gehirn differenziert zur Tatsache wird. Dieses E-Bilden, das also eigentlich in der Ebene verläuft, wir haben es gestern versucht nachzubilden. Und Sie werden sehen, daß das, was wir gestern versucht haben nachzubilden, direkt in der äußeren Bewegung und in der Bewegungslage andeutet, wie das innerliche E-Machen des Menschen sich eigentlich summiert zu der Vertikalen. Wie sich der Kopf aufplustert, wie der Kopf ein Blaseengel werden will, so summiert sich dieses E-Werden, dieses Sich-im-Punkte-Zusammenfassen, das summiert sich in der Vertikalen, in der Höhenlinie.

Es ist aber [ein] fortwährendes, aufeinanderfolgendes Sich-Zusammenfassen übereinanderstehender E’s; und das drückt ja wirklich aus, was nun deutlich hervorgeht, wenn man beobachtet Schwächlinge. Sie haben die Tendenz, ihren Ätherleib fortwährend zu strecken. Sie wollen ihn strekken, sie ziehen ihn nicht in einem Punkt zusammen, was der eigentliche Gegensatz wäre zu der Tätigkeit des Hauptes. Das ist nicht der Fall, sondern sie versuchen ihn zu strecken, eben dadurch ausführend die Wiederholung des Punktes. Und dieses Strecken, das sich zum Ausdrucke bringt eben gerade bei schwächlich werdenden Menschen, also nicht das Strecken im physischen, sondern das Strecken im Ätherleib, dieses Strecken ist es, dem entgegengearbeitet wird mit der Ausformung desjenigen E, von dem wir gestern gesprochen haben.

So, denke ich, können Sie schon sehen, wie zwischen dem, was eurythmisch vorliegt, und den menschlichen Bildungstendenzen ein innerer Zusammenhang ist, wie wirklich aus dem Menschen herausgeholt ist dasjenige, was in ihm als Bildungstendenzen vorhanden ist. Und es ist ja so, daß diese Bildungstendenzen, die sich zunächst äußern im Wachstum, in der Formung des Menschen, in der Ausgestaltung also, daß diese Tendenzen sich spezialisieren und lokalisieren wiederum in der Ausbildung des Sprachorganismus, dieses speziellen Organismus. Da sind sie gewissermaßen zusammengehäuft, die Bildungstendenzen, die sonst über den ganzen Menschen verbreitet sind. In der Ausbildung der Eurythmie gehen wir jetzt wiederum zurück. Wir gehen von den lokalisierten Tendenzen zu dem ganzen Menschen über und setzen so entgegen dem Spezialisierten der menschlichen Organisation im Sprachorganismus eine andere Spezialisierung, die Spezialisierung im Willensorganismus. Denn der ganze Mensch, insofern der ganze Mensch Stoffwechselorganismus ist und auch Gliedmaßenorganismus ist -, man bewegt ja auch am Kopfe so manches, also der Kopf ist auch in einem gewissen Sinne Gliedmaßenorganismus, und es kann ja sogar das anschaulich werden bei den Menschen, die dann etwas mehr können in dieser Beziehung; nicht wahr, Menschen, die die Ohren bewegen können und so weiter, die zeigen ja ganz deutlich, daß das Bewegungsprinzip, das Gliedmaßen-Bewegungsprinzip in die Hauptesorganisation hineingehen kann — der ganze Mensch ist in dieser Beziehung Ausdruck des Willensmäßigen. Das Willensmäßige, das drücken wir wiederum aus, wenn wir zur Eurythmie übergehen. Nun möchte ich zum Schlusse etwas erwähnen, bevor wir morgen dann weitergehen in der speziellen Ausarbeitung und Ausgestaltung der Laute, im weiteren zu den Kombinationen der Laute, ich möchte noch etwas Geschichtliches erwähnen.

Sehen Sie, Willensbewegung des Menschen und Intellektbewegung des Menschen, das sind zwei Kräfteentwickelungen des Menschen, die mit verschiedener Geschwindigkeit vor sich gehen. Der Intellekt des Menschen entwickelt sich in unserem Zeitraum schnell, der Wille langsam. So daß wir jetzt schon als Angehörige der ganzen Menschheitsentwickelung mit unserem Intellekt den Willen überholt haben. Das ist die allgemeine Zivilisauionserscheinung, daß wir mit unserer Intellektentwickelung die Willensentwickelung überholt haben. Die Menschen sind heute sehr stark intellektuell, was eben nicht beweist, daß sie mit ihrem Intellekt auch viel anzufangen wissen. Sie sind eben sehr stark intellektuell, aber sie wissen nicht viel damit anzufangen; daher wissen sie intellektuell so wenig. Aber dasjenige, was sie intellektuell wissen, das fassen sie so auf, als ob sie in ihm mit einer gewissen Sicherheit wirken. Der Wille entwickelt sich langsam. Und Eurythmisieren ist zunächst auch, abgesehen von allem übrigen, ein Versuch, den Willen wiederum hereinzubringen in die ganze Menschheitsentwickelung. Und tritt dann die Eurythmie therapeutisch auf, so müssen wir doch auf das Folgende eben hinweisen. Wir müssen sagen: Die Überentwickelung des Intellekts, sie drückt sich auch aus besonders in den organischen Begleiterscheinungen der Sprachentwickelung. Unsere Sprachentwickelung, die ist eigentlich heute schon in unserer modernen Zivilisation etwas, was durch seine Übermenschlichkeit unmenschlich wird, indem wir heute Sprachen lernen so, daß wir so wenig noch ein Gefühl haben davon, ein lebendiges Gefühl haben davon, was in den Worten drinnen liegt. Es sind ja die Worte eigentlich nur Zeichen. Was haben die Menschen noch für ein Gefühl, was in dem Worte drinnen liegt? Ich möchte wissen, wie viele Menschen gehen durch die Welt und werden aufmerksam darauf, daß zum Beispiel speziell beim Erlernen der deutschen Sprache die Form der Rundung, des Rundens, was ich ja gerade aufgezeichnet habe, ist in dem Worte «Kopf», was mit Kohl zusammenhängt, daher man auch Kohlkopf sagt, was eigentlich nur eine Retuschierung ist; man metamorphosiert im Zusammenhange dieses Runden. Das ist da ausgedrückt. In romanischen Sprachen - testa, testieren -, da drückt sich das aus mehr von innen heraus, das seelische Wirken durch den Kopf. Dieser Unterschied dessen, was in der Sprache drinnenliegt, die Leute haben kein Gefühl mehr davon, die Sprache ist abstrakt geworden. Wenn Sie gehen, gehen Sie mit den Füßen. Warum sagen wir «Füße»? Ja, sehen Sie, das ist eine Metamorphose des Wortes «Furche», und ist entstanden dadurch, daß man angeschaut hat, daß man also eine Furche andeutet, indem man geht. Es ist durchaus verloren worden das Bildhafte, das in der Sprache liegt; und wenn man will dieses Bildhafte wieder hineinbringen in die Sprache, dann muß man eben zur Eurythmie greifen.

Nun ist jedes Wort eigentlich - ich spreche jetzt eine Tatsache, die sich im feineren menschlichen Organismus zum Ausdrucke bringt, die spreche ich mit groben Worten aus, aber wir haben ja nur grobe Worte -, jedes Wort, das ohne Bildlichkeit erlebt wird, ist eigentlich eine innerliche Krankheitsursache. Und man kann sagen: Die Zivilisationsmenschheit von heute leidet chronisch an demjenigen, was das abstrakte Sprechenlernen, das nicht mehr bildliche Empfinden der Worte in ihr bewirkt. — Das geht sehr weit, das geht vor allen Dingen so weit, daß diese organische Begleiterscheinung sich ausdrückt in einer sehr starken Neigung zum Unrhythmischwerden des rhythmischen Systems und zu einem Verweigern der Kräfte des Stoffwechsels von seiten des Menschen, der seine Sprache abstrakt gemacht hat. Und es ist so, daß man tatsächlich beikommen kann dem, was ruiniert wird an dem Menschen heute durch die Sprache, durch die Sprache, die ja im zarten Kindesalter erworben wird, die, wenn sie unbildlich erworben wird, wirklich Zustände hervorruft, die später sich auswachsen, auswachsen in allen möglichen Krankheitsformen, die eben aber auch wieder bekämpft werden können durch dasjenige, was therapeutische Eurythmie ist. So daß man also ganz organisch die Heileurythmie einfügen kann in die Heilbehandlung überhaupt.

Es ist durchaus so, daß, wer versteht, daß Geistig-sich-Entwickeln eigentlich immer etwas ist von Krankwerden — wir müssen schon einmal das mitnehmen, das Krankwerden in der geistigen Entwickelung -, der muß auch darauf bedacht sein, daß nun nicht bloß mit äußeren physischen Studien gekämpft wird gegen dieses Krankwerden durch die Zivilisation, sondern auch mit äußeren Mitteln. Wir legen in die Bewegungen des Eurythmisierens eben Seele und Geist hinein und können dadurch bekämpfen dasjenige, was auf der andern Seite Seele und Geist von sich aus tun, aber eben im zarten Kindesalter oftmals so tun, daß die Wirkung ihres Tuns, wenn es sich auswächst im späteren Alter, eben als Krankheitsursache empfunden wird. Das ist das, was ich heute sagen wollte.

Third Lecture

In order to move forward, we will now begin by looking at forms of consonant formation, which we will then explore in more depth tomorrow from a physiological and psychological perspective. Now, what has been developed as a form of consonance really takes into account everything that comes into consideration when a person tries to penetrate the outside world linguistically. Anyone who wants to observe language will see how human interaction with the outside world must consist of the human being, in a sense, living very strongly in the outside world, that he very strongly loses himself and lives in the outside world. When vocalizing, he becomes himself, when vocalizing, he goes inward and unfolds his activity there. When they produce consonants, they become, in a sense, one with the outside world, but to varying degrees. And this becoming one with the outside world to varying degrees is also expressed in certain activities within language. And of course, in the training of eurythmic consonantization, especially in this sensory-supersensory seeing that I often speak of in the introductions to eurythmic art performances, in this sensory -supersensible seeing, it must be carefully considered whether the person completely objectifies themselves in order to grasp, as it were, the spiritual that is outside in things in the sound, or whether, despite objectifying themselves, they remain more inside and do not actually go out completely, but still reproduce the outside inside. There is a big difference, and for this reason I would ask Mrs. Baumann to be so kind as to first demonstrate, let's say, an H movement. And now, please, turn your gaze completely away from this H movement and Mrs. Baumann will now demonstrate an F movement. And now keep a close eye on what you can observe in these different movements, in these two different movements. You can observe what you have in you from human instinct in the pronunciation, in the attempt to pronounce the sound in question. Take the pronunciation of the H. Actually, you pronounce this H as Ha; you actually pronounce a vowel. You cannot pronounce a consonant without it being tinged with a vowel. You pronounce an A. The pure consonant is vocalized. And if you now consider the F, you will see that, out of human linguistic instinct, an E is placed in front of it: eF. The opposite is done, an E is placed in front of it.

From this you can see that when a person pronounces an H, they make more of an effort to seek out the spiritual in the external object through language; when they pronounce an F, they make more of an effort to feel the spiritual within. Therefore, the formation of consonants is quite different, depending on whether one tries to make the vowel tinge from the front or from the back, if I may express myself in this way with regard to consonants. And you will see this expressed in the form you have seen.

Perhaps Miss Wolfram will do the H again. So H, there you have the strong opening up to the outside world, you don't want to stay inside yourself, you want to go out and live in the outside world. The F: you see the strong desire not to go too sharply into the outside world, but to remain inside.

Now, if you take that into account, then of course, starting from there, you will get an idea of some things that also have to flow into eurythmy, which was not necessary at first, as far as we practice the art of eurythmy, but which will become necessary the more the art of eurythmy is extended to the different languages. For at the moment when one does not say eF but Fi, at that moment it is different, at that moment one also tries to encompass the external with this consonant, and this points to an important historical fact. In Greece, in ancient Greece, people tried to grasp the external even in such things where modern man has already become internal. You see how one can trace to the outermost reaches of human experience what I have expressed, for example, in “The Riddles of Philosophy,” this going out of the human being and grasping in the outer world what today's human being already experiences quite inwardly in the ego. The reason why spiritual science is not accepted on the basis of such things is simply that people in our civilization are generally too lazy. They have to take too many things into account in order to arrive at the truth; they want to make it easier for themselves. But that is not possible. They want to make it easy for themselves; but that is not possible.

Now, that is first of all in relation to the one thing that has flowed into consonantization. Then there is something to consider if one wants to grasp consonantation in the field of eurythmy, something that I believe is given less consideration today in teaching, even in physiology, in the physiology of sound, less consideration than the third thing, which we will come to in a moment. To illustrate this, I ask you to compare again. The point here is to acquire the insight. Of course, it is not possible to fully grasp the concept of what one does with this insight.

Perhaps Ms. Baumann would be so kind as to show us an H again, and now, after you have let that fade away, Ms. Baumann will show us a D. You will have to note the following: When you look at the H, it has a movement that differs greatly from what initially happens in speech, because in relation to the quality I am referring to now, eurythmy must behave in a polar manner to what the actual speech process is. The speech process, as you know, which I described the day before yesterday, is a reflection back from the larynx. The eurythmic process must express this externally. It expresses it in movement. In certain cases, one must go over into the completely polar. Now, what kind of sound is the H? The H is essentially a blowing sound. It is actually a blowing that produces the H. If you want to express this eurythmically – and the H is particularly characteristic in this respect; with the other consonants it has to be toned down again, but with H and D, for example, it is particularly characteristic – then where you have to blow [when pronouncing], you have a distinctly jolting effect in eurythmy. When you pronounce D, you have a jolting effect in your pronunciation. You have to polarize them [in eurythmy] by transferring them into this peculiar movement that was present in the D. So it is precisely the jolting quality of speech that is dampened in the movements of the sound.

So you see that, depending on whether you have blowing sounds or jolting sounds, this characteristic in particular must be taken into account. Now, sounds are not just blowing sounds and jolting sounds. But what makes sounds blowing sounds and jolting sounds? You see, when you have a pronounced blowing sound, you express in the blowing the fact that you really want to let something out of yourself; in the thrusting, that it is difficult for you to let something out of yourself, that you want to keep it inside. For this reason, the eurythmic translation of the sound must also take place in the way you have seen.

But now there are also sounds that carefully connect the inner with the outer, sounds that are actually physiological in such a way that one says one brings that in which one actually wants to be active, so that the inner immediately becomes an outer, so that one immediately enters into the movement with one's whole being, one brings that to a standstill, one holds it back. And this is particularly the case, actually only clearly in our language with a single sound, the R, but that is also why the R is the most comprehensive sound, because when you pronounce the R, you want to follow with every limb, so to speak, of the speech organism. With the R, you actually strive to bring the following to a standstill. The lips want to follow when they pronounce the lip R and bring the following to a standstill, the tongue wants to follow when it pronounces a tongue R, and finally the palate wants to follow when the palate R sounds. These three Rs are clearly different from each other, but they are also one, and they are expressed in eurythmy (Mrs. Baumann: R). So what is expressed is the setting in motion of that which is otherwise brought to a standstill. It is precisely this trailing of the sound movement that is expressed in this R. And if you want to express the other sounds, you can express the lip R in particular by continuing the movement downwards, the tongue R by making it more horizontal, and the palate R by making it more upwards. In this way, you can modify the R sound in the eurythmic movement. But you see, its form comes about by letting the trembling of the R recede into the background and bringing out more of the trailing in it.

A similar sound, but one in which there is no trembling in the movement, but rather a kind of wave, is the L (Miss Wolfram: L). So, you see now, there is something of the same movement in it as in the R, but it is a gentler coming to rest, a gentler grasping of the trailing, it is just a wave in contrast to the trembling that comes to expression.

That would be what relates internally, physiologically, I would say, to the vocalization of the consonant sound and to the tinging with feeling, which is now more physical. Now, the most extreme classification of sounds, so to speak, is achieved by sticking to the organs, and there we can, by comparing the corresponding movements again, develop for our understanding what emerges as the most extreme principles of classification, the most external principles of classification. Namely, let us take a B (Ms. Baumann: B). That is a B, and now we immediately follow it with a T. Now, you can see from the whole situation, which must be taken into account as the third factor and which also emerges quite clearly in sensory-supersensory perception, you can see from the whole situation that in the B we are dealing with a lip sound, and in the T with a tooth sound. (Miss Wolfram, give us a K) K: That has completely departed from the situation, and the main thing lies in the movement. Here we are dealing with a palatal sound, which is the quietest in pronunciation, in the pronunciation of the sound, but which must transition into movement, into its polar opposite in the external eurythmization. Now, the consonants overlap in terms of these characteristics; one classification overlaps with the other, and we can note the following as a kind of aid:

Take the lip sounds, I will only write down the most pronounced ones, such as W, B, P, F, M. You can find out to what extent the vowel tinge plays a part by simply pronouncing the sound. So I don't need to specify that. Now let's take the dental sounds: D, T, S, Sch, L, to which we can also add the English Th and N. And now let's take the palatal sounds: G, K, Ch, then this French one, Ng, for example.

And now we would actually have to write R everywhere, because it has its nuance everywhere [it is written on the board].4The sounds were written in small letters on the board, but capital letters were used in the running text for better readability.

If you now take the other point of view of classification, I will make white lines underneath wherever we are dealing with a pronounced fricative sound: W, F, S, Sch, and perhaps Ch. These would be pronounced fricative sounds. I will make red lines underneath where we are dealing with pronounced plosive sounds: B, P, M, D, T, N, and R is a trilled sound, then there would also be G and K. The trilled sound is R; and with a pronounced wavy sound, which in a certain sense must be internal because of the soft transition into the movement, we basically only have to deal with L (yellow) with a pronounced wavy sound.

These three principles of classification, the vocalizing tinge, the blowing, pushing, trembling, waving, and everything that is connected with this external classification [into dental, labial, and palatal sounds], come to expression in the forms that exist for eurythmy. Of course, you must be clear about how strongly these principles of classification alter each other. So when we are dealing with the L, for example, we are dealing with a pronounced dental sound, which must therefore have all the characteristics of a dental sound, and then we are dealing with a gliding sound, a waving sound, which must have the characteristics of a wave. But it is also very strongly bound to the interior. So, at least in our language, we are dealing with a tinge from within. We don't say “Le,” but rather “eL,” and here too we have the transition from older forms, where, I would say, an external intervention was developed with great longing and therefore came about very strongly, where one needed a word 2a word: lambda, the eleventh letter of the Greek alphabet. was needed to express something like this, to really express this transition to the outside. So with the individual letters, we are definitely dealing with a reflection of what is going on internally.

Now, before we go through the individual consonants, let us keep the following in mind: Yesterday, with the letter A—and we have already studied its metamorphosis—we were able to show that it is connected with all those forces in human beings that make them greedy, that organize them according to their animal nature. The A is indeed closest to the animalistic in human beings, and in a certain sense one can say that the A sounds out of the animalistic in human beings when it is pronounced. And certainly the A, as confirmed by spiritual research, is a sound that appeared very early in human beings, both in phylogenetic and ontogenetic development. In the latter — as you know, there is also a false development — in ontogenetic development it is naturally somewhat concealed; but what first appeared in human development is the A sound, which still resonates entirely from the animal realm. And when we add consonants after the A, we also appeal to what are the animal forces in humans. As you saw yesterday, the entire sound is actually formed on this basis. If we now use this sound therapeutically, as it appeared before our souls yesterday, we are combating what makes children in particular, but also adults, into smaller or larger animals. And through such exercises in the de-animalization of the human being, we can already achieve, I would say, quite respectable results.

And now let us move on to the U sound, for example. Yesterday we said that this is the sound we use therapeutically when a person cannot stand. You saw this yesterday; it is the sound which, in a certain sense, already expresses its physiological-pathological relationship in its formation, which already expresses this in its formation as a speech sound,1Literal stenogram: ... which already expresses in its formation, also expresses in its formation as a speech sound, that ... that the U is spoken with the mouth closed as tightly as possible, the teeth slightly apart, the lips slightly protruding, but in such a way that the mouth is narrowed and the lips vibrate. You can see from this that it is essentially an external movement that one seeks in the U when speaking. The strongest attempt is made to characterize the movement in the pronunciation of the U. Therefore, in eurythmic U, the opposite occurs physiologically, the evocation of stability, which is also at least hinted at in U 3According to shorthand: in the artistic U in eurythmy. in artistic eurythmy.

If you then consider the other vowels, you will see that we have a progressive internalization of the vowel. So if you consider the OÖ, a pushing together, I would say, of the lips forward, a reduction of the mouth opening, and at least the effort to reduce the mouth opening; this is polarized in the opposite direction by the encompassing movement that lies in the O movement in eurythmy. It is precisely in such things that one sees the natural connection between them. There are already certain forces at work in the linguistic handling of the O. And in languages in which the O is particularly strong, in such languages people will have the greatest predisposition to become overweight. You can certainly regard this as a guideline for the study of speech physiology. Another reading would be “lecture studies.” If a language were developed that consisted essentially only of modifications of the O, where people would have to constantly perform the peculiar lip and mouth formation they make when pronouncing the O, they would all become fat-bellied. If, on the one hand, we have this, I would say, tendency toward potbellies with O, then it is easy to understand why O, conversely, represents the fight against potbellies when it is performed eurythmically and metamorphosed in the appropriate way, as we did yesterday.

The situation is different with the letter E, for example. A language that is particularly rich in E will produce thin people, weak people. And this is related to what I said yesterday about the treatment of thin people, that is, weak people, in relation to the treatment of the E. You will remember that I said: in the case of weak people, the E movement with its modification should be applied in a very special way.

However, there is something to consider in all these matters, namely this: if one looks at the forms externally, one will not arrive at the right conclusion; one must grasp them internally in their becoming. One must therefore focus less on what is expressed externally and more on the tendency toward it. The tendency to become fat is what is combated by the O, and the tendency to remain thin is what is combated by the E. And this must be pointed out because, when eurythmy is used for healing purposes, one must pay more attention to the forces that are present in the upper human being and that tend toward expansion, and the forces present in the lower human being, which tend more toward linearity. So I must say that when a person pronounces the O, they expand 5Stenogram not clear: “expands” can also be read as “forms,” and “the living” as “the following.” he actually expands the living.