Curative Eurythmy

GA 315

13 April 1921, Dornach

Lecture II

Today I intend to discuss matters related to the vowel element in eurythmy. We need only to recall—as it is known to us through spiritual science—that vowels express more that which lives inwardly in man as feelings, emotions and so on. Consonants describe more that which is outwardly objective. When we remain within the realm of speech, these two statements are valid: vowels, more expression, revelation of the inwardness of feeling; we reveal ourselves to an extent in the vowel, that is to say, we reveal what we feel towards an object. Through the movements which the tongue, the lips and the palate perform, the consonants conform themselves more plastically to the outward forms of objects—as they are spiritually experienced, naturally—and attempt to reconstruct them. And so basically all consonants are more reproductions of the outward form-nature of things. However, one can actually only speak of vowels and consonants in this manner when one has an earlier stage of human evolution in mind in which in fact the evolution of speech was given and in which—since the individual sounds were always to a degree connected with movements of the body—the movement of the whole body and of the limbs as well was self-evident. This connection has been loosened, however, in the course of man's development. Speech was removed more to the interior and the possibilities of movement, of expression through movement, ceased. Today in normal life we speak largely without accompanying our speech with the corresponding movements. In eurythmy we bring back what attended the vowels and consonants as movements and thus bring the body into movement again. Now we must realize that when we pronounce vowels we omit the movement and make the vowel inward, that previously joined in the outward movement to an extent. We take something away from it on its path to the interior. We take the movement away. Thus we restore to the vowel in outer movement what we have taken away from it on its inward-going path. In the case of the vowel, matters are such that the outward movement is of exceptional importance in the search for the transferal of the effect of the vowel, eurythmically expressed, onto the whole man. That is what we must take into account here.

In speaking of vowels today, we will speak purely of the meaning of that which is eurythmically vocalized in movement. Here it is very important that one develops a feeling for what flows into the movement. That one develops a perceptive consciousness which tells one whether that which is happening in the respective human limb is a stretching, a rounding, or such. One must decidedly acquire a specific consciousness for this. In what pertains to vowels it is extremely important that one feels the movement made or the position taken up. That is what is important. Starting from here, we will transpose each of the vowels from the eurythmic into the therapeutic.

Practically demonstrated (Mrs. Baumann): a distinct “I” made by stretching both arms. This stretching should be carried out in such a way that one then returns (to the rest position; the ed.) and performs the same movement somewhat lower, returns again, and does it with both (arms) horizontal. Now we go back and, if you had the right forward at first, now, as you go lower, you must take the right to the back, and now to the front, now a bit back again, and then somewhat deeper. Now I don't want to trouble you further with that, but if one wanted to carry it out, one could make it more complicated by taking more positions; one would then start with the “I”, return, do it a little further on, go hack, a bit further on, and so forth, so that one has as many “I”-positions as possible, carried out from above to below, always returning (to the rest position; the ed.). When these movements are performed, they are an expression for the human being as a person. The entire individual person is thereby expressed.

Now we could notice for example that some child, for that matter a grown up person, cannot express himself properly as a person. He is somehow inhibited in the expression of himself as a complete individuality. He might be a dreamer in a certain sense or something similar. Or, if we think of a physical abnormality—in the case of a child, for example, that he doesn't learn to walk properly, he walks clumsily—or if in the case of an adult we notice that it would be desirable for hygienic or therapeutic reasons that the person learn to walk better, this particular exercise would be very good for this. When grown-ups step out too little in their stride, when they don't reach out properly with their steps, it always means that the circulation suffers under it. The circulation of the blood suffers under an insufficiently outreaching gait. So when people walk in this way (lightly tripping; the ed.), that has a consequence that the circulation becomes in some fashion slower than it should be in that person. Then one must attempt to have this person learn to step out again, and by having him do this exercise, one will be certain to attain one's goal. Then the person will have greater and more penetrating results in learning to walk properly. Thus one can say that in essence this modified “I”-exercise furthers those people who—I will express it somewhat radically—cannot walk properly. It can be summed up approximately so: for people who cannot walk properly.

You can extend the exercise further, and, with the addition of a sort of resumée of what Mrs. Baumann has done, it will be that much more effective Now try to do the whole exercise without bringing the arms back (to the rest position; the ed.) so that you reach the last position only by turning: turning in a plane, quick, quicker and quicker. The “I”-exercise as it was first demonstrated and described can be intensified in this way and will benefit those people who cannot walk properly. It will then be extraordinarily easy to bring them to walk properly. One can admonish them to walk properly and their efforts to walk in a different manner will bring suitable results as well.

Now Mrs. Baumann will demonstrate an “U”-exercise for us. The arms quite high up, and back to the starting position, now a bit lower, back again, a little lower, now horizontal, back again, now below, back again, and again below; that is the principle of it. And now do it straightaway so that you start above maintaining the “U” as you move downwards; and now do it increasingly quickly so that at last you reach quite a speed.

Please keep this in mind as the manner in which to execute the “U”-exercise. If I were to summarize again in the same fashion as earlier, I would call this the movement for children or adults who cannot stand. In the case of “I” we had those who cannot walk, with “U”, we have those who cannot stand.

Now not being able to stand is to have weak feet and to become very easily tired when standing. It would also mean, for example, that one could not stand long enough on tiptoe properly, or that one could not stand on one's heels long enough without immediately becoming clumsy. Standing on tiptoe or on the heels are no eurythmic exercises, but they should be practised by people who have weak legs, who tire easily while standing or who can't stand properly at all. To be unable to stand properly is to be easily tired in walking as well. That is a technical difference: to walk awkwardly and to tire in walking are two different things. When the person is tired by walking, one has to do with the “U”-exercise. When the person walks clumsily or when as a result of his whole constitution it would be desirable for him to learn to step out with his feet, that can be technically expressed as being unable to walk. However, to be tired by walking would be technically expressed as not being able to stand. And for such people the “U”-exercise is especially appropriate. This is interrelated with matters with which we must deal once we have come a bit further.

Now please do the “O”-movement: quite high up and back (to the rest position; the ed.) and now somewhat lower, back again, lower still, and so on. Now do it so that you make the “O”-movement above; feel distinctly the rounding of the arms within the movement as you glide down. When you glide down with the “O”-movement it must remain an “O”. Now increasingly faster.

You would see this exercise complete in its most brilliant application if you had here in front of you a really corpulent person. If a child or grown-up becomes unnaturally fat, then this is the exercise to be applied. By making the “O” so often and by extending it to this barrel-shaped body at the end—then it is really a barrel that one describes outside oneself—that which forms the opposite pole to those dynamic tendencies at work in making a person obese is in fact carried out. One can apply it very well hygienically and therapeutically, and you will be convinced that a tendency to become thinner actually appears when you have such people carry out this movement, especially when they practise other things as well which we have as yet to discuss. But at the same time it is of special significance in this exercise that you have the person practise only so long as he can without sweating heavily and becoming too warm. If one wishes to attain the desired effect, one must try to conduct the exercise so that the person can always rest in between.

Now Mrs. Baumann will make an “E”-movement, quite high above. It is a proper “E”-movement only when this hand lies on the other so that they touch. Now return (to the rest position; the ed.), then somewhat lower, the right hand over the left arm, and then, so that it is really effective, we will do it so that it lies increasingly further back and now again from above to below; then the “E” must be done so that it penetrates thoroughly. And now, in bringing it down, you must move (the crossing) further back, so far that you split the shoulder seam at the back. Now this is the exercise that will be especially advantageous for weaklings, that is to say, for thin people rather than fat people, for those people in whom the weakness comes distinctly from within, but is organically conditioned. It must be organically caused.

Another exercise which can be considered parallel to this should be applied with some caution as it affects the soul more closely. It is the following: make an “E” to the rear as well as you can and as far up as you can. That really hurts. It is a movement that is in itself a bit painful and that is indeed the purpose. It should be practised with those children or adults in whom there are psychological grounds for becoming thin, such as being worn down and so on. Since one must in principle be careful in approaching from the outside with healing by such spiritual means, this too must of course be applied with caution. That means that one must inspire a child who has failed or who shows signs of depression so that he takes heart when one will have him do these exercises. If one concerns oneself with the child otherwise by comforting him and caring for his soul, then one can have him do these exercises as well.

You can see that in the case of all these things it is to a degree a matter of extending what comes to expression in artistic eurythmy in a certain manner. This is especially true in respect to the vowels.

Now it is very important that we make the following clear to ourselves. You know that the vowel element can be developed in this fashion, and that it is in essence the expression of the inward. One must only grasp through feeling and contemplation that which takes place. One must bear in mind that the person concerned, the person who carries out these things in order to be healed, must feel them; in “E” he feels that one arm covers the other. In the case of “O” however, something more comes into consideration. In “O” one should feel not only the closing of the circle, but the bending as well. One should feel that one is building a circle. One should feel the circle that runs through it. And in order to make the “O” particularly effective one should make the person doing it aware as well that he should feel as though he himself or someone else were to draw a line along his breastbone, thus by means of feeling, closing the whole to the rear in spirit; as if one were to experience something like having a line drawn on the breastbone by oneself or someone else.

Now we want to make an “A”: we return (to the rest position; the ed.), now we make an “A” somewhat lower, return again, make an “A” horizontally, back, make an “A” somewhat lowered, back, an “A” very deep, back, then to the rear; that you need to do only once, but return first (to the rest positon; the ed.). And now make the “A” above and without changing the angle bring it down, and, again without the feeling that you change the angle, to the back.

This exercise can he really effective only if one has it clone frequently. And when one has it repeated frequently, it is the exercise to be used with people who are greedy, in whom the animal nature comes particularly strongly to the fore. So if you have in school a child who is in every way a proper little animal, and in whom the condition has an organic cause, when you have him do this exercise, you will see that it has for him a very particular significance.

In the case of these exercises you can observe once again that if they are to be introduced into the school it will be necessary to organize the children into groups especially for them. You will soon become convinced that the children do these exercises much less gladly than the other eurythmic exercises. While they are eager to do the others, one will most likely have to persuade them to do these, as they will react at first as children often react to taking medicine: with resistance. They won't be particularly happy about it, but that is of no especial harm in the exercises having to do with “O”, “U”, “E”, and “A”; in the case of “I” it is somewhat harmful when the child doesn't enjoy it. One must try to reach the stage where the children delight in the “I”-exercise as we have clone it. In the case of the others, “U”, “O”, “E”, and “A”, it is not especially damaging if they carry out the exercise on authority, and knowing that it is their duty to do it. With “I” it is important that the children have pleasure in doing it as it affects the whole individual, as I have said

already.

You will profit further by coming to terms with the following: the “I” reveals man as a person, the “U” reveals man as man, the “O” reveals man as soul, the “E” fixes the ego in the etheric body, it permeates the etheric body, strongly with the ego. And the “A” counteracts the animal nature in man.

Now we will follow the various workings further. If you have a person with irregular breathing, who is in some fashion burdened clown by his breathing and such like, you will be able to bring this person to normal breathing by applying the vowels. You will be able to achieve in particular the distinct articulation of the consonants by means of these exercises, as that is greatly facilitated through the practice of the vowels. When you notice that certain children cannot manage to form certain consonants with the lips or the tongue—for the palatal sounds (Gaumenlaute) it is less applicable, although for the labial and lingual sounds exceptionally good—it will be of great help to the children with difficulties in this respect, when one tries to have them do such exercises as early as possible.

You will also notice that when people tend to chronic headaches, to migrane-like conditions, these can be appreciably alleviated through the practice of the vowels. So in the cases of chronic headaches and chronic migrane symptoms, as well as when people are foggy-headed, these things will be particularly applicable. Similarly, if you employ the exercises which we have done today for children who cannot pay attention, who are sleepy, you will awaken them in a certain sense to a state of awareness. That is a hygienic-didactic angle of a certain significance. It will be observed that sleepy-headed adults can definitely be awakened in this way as well. And then one will notice that when a person's digestion is too weak or too slow, that by means of these exercises this slow digestion and all that is known to be connected with it, can be changed for the better.

In certain forms of hygienic eurythmy it would be good to have the movements—which are carried out with the arms only in artistic eurythmy—done with the legs as well where possible, only somewhat less forcefully, as I am about to describe. Now you will ask how one can make an “I”, for example, with the legs? It's very easy. One must only stretch out the leg and feel the stretching in it. The “U” would be simply to stand with full awareness on both legs, so that one has a distinct stretching feeling in both. “O” with legs must be learned, however. One should really accustom the people with whom one finds it necessary to do the “O”-exercise ih the manner that I have described, to do the “O” with the legs as well. That consists in pointing the toes somewhat, but only very slightly, to the outside and then trying to stand in this manner and hold one's position. One must thereby stand on tiptoe, however, and bend outward, remain so standing a moment and then return to the normal position; then build it up again and so on.

It is necessary to take into account the relationship existing between the possibilities of organically determined inner movement in the middle man and the lower man. This is such that movement done for the lower man should be carried out at only one-third the strength. Thus when you have someone carry out the “O” movement as we have seen it, you must have the feeling that what is done later for the legs and feet requires only one-third of the time and thus only a third of the energy expended. It will be especially effective, however, when you place this in the middle, so that you have, let us say, A and then A again, with B, the foot movement, in the middle (see the table); it will be particularly effective to have them together.

one-third one-third one-third

A B A

Arm Foot Arm

It will also be especially effective to do the same in connection with the “E”-exercise for the feet, by really crossing the feet.

But one must stand on tiptoe and lay one leg over the other so that they touch. Again, one-third, and placed, if possible, in the middle. That is something which it would be particularly good to have done by children, and by adults as well, who are weaklings. They will naturally be hardly capable of doing it, but that is exactly why they must learn to do it. In precisely these matters one sees that that which it is most important for various people to learn is that which they are most incapable of doing. They must learn it because it is necessary to the recovery of their health.

“A” (with the legs; the ed.) is also necessary; I have already demonstrated it to you yesterday. It consists in assuming this spread position while standing insofar as it is possible on tiptoe. That should also be introduced into the A-movement and it will be particularly effective there.

Now one can also intensify all the exercises that we have just described by carrying them out in walking. And you will achieve a great deal for a weak child, for example, when you teach him to do the “E”-motion as we have just done it in walking; he should walk in such a manner that he always touches each leg alternately. In taking a step forward he crosses over first with one leg, then with the other, so that he always crosses one leg over the other, so that he places one leg at the hack and touches it with the other in front. Naturally he won't move ahead very well, but it is good to have this movement carried out while walking. You will say that complicated movements appear as a result; but it is good when complicated movements appear.

Now I want to bring it to your attention that what we have said about the vowel element should be sharply distinguished to begin with from what we will practice tomorrow in respect to the consonants. The consonantal element is such that it generally expresses the external, as we have already said. In speech as well the consonant is so formed that a reconstruction, an imitation of the outer form comes into being through the formative motions of lips and tongue. Now the consonants have, as we will see tomorrow, very special sorts of movements and it lies within these forms of movement to make the consonant inward again in a certain manner by giving it eurythmic form. It is internalized. That which it loses in the outward-going path of speech is restored to it. And, whether one is contemplating them in eurythmy as art or performing them for personal reasons, in the case of consonants it is particularly important to have, not a feeling in the way one does with a vowel, a feeling of stretching, of bending, or of widening and so on, but to imagine oneself simultaneously in the form that one carries out while making the consonants, as though one were to observe oneself.

Here you can see most clearly that one must admonish the artistic eurythmists not to mix the two things; the artistic eurythmists would not do well to observe themselves constantly as they would rob themselves of their ability to work unselfconsciously. On the contrary, when you have a child or a grown-up carry out something having to do with consonants, it is important that they photograph themselves inwardly in their thought as it were; then in this inward photographing of oneself lies that which is effective; the person must really see himself inwardly in the position that he is carrying out and it must be performed in such a manner that the person has an inner picture of what he does.

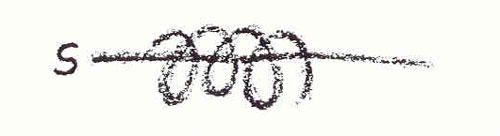

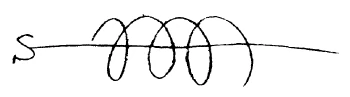

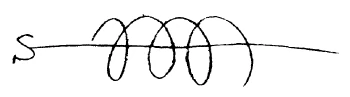

If you would be so good (Miss Wolfram) as to show us an “M” as a consonant, first with the right hand, now with the left, but taking it backwards, now taking the right hand back, and “M” with the left hand and now with both hands, that can be multiplied in various ways, of course. Now an “M”—we will start with this example; to begin with, what is it as speech? In speech “M” is an extraordinarily important sound. You will experience its importance in speech, and in speech physiology as well, if you contrast it with the “S”. Perhaps Mrs. Baumann will make a graceful “S” for us now, right, left, and now with both hands.

Now to begin with it appears that you have the feeling, or should have the feeling when the “S” is done that you encounter something within you—it is the etheric body namely (at this point Dr. Steiner made the corresponding movement; the ed.); so that you have a snake-like line. This serpentine may approach a straight line in the case of a particularly sharply pronounced “S” and can even be represented as a straight Iine. By contrast, when you look at the “M” that was just performed, you should have the feeling—even when the organic form is carried out inwardly—that it is really not the same thing. And so the “M” is that which counters the “S”-direction when laid against it and that is in essence the great polarity between an “S” and an “M”; they are two polar sounds. “S” is the truly Ahrimanic sound, if I may speak anthroposophically, and the “M” is that which mitigates the properties of the Ahrimanic, makes it mild; if I may express it so, it takes its Ahrimanic strength from it. So when we have a combination of sounds directly including “S” and “M”, for example “Samen” (seed) or “Summe” (sum), we have in this combination of sounds first the strong Ahrimanic being in “S”, whose sting is then taken from it by the “M”.

Perhaps you will make a “H” for us (Miss Wolfram). When you really look at the “H”, when you feel yourself really within this “H”, then, you will say to yourself: there is something in this “H” which reveals itself as unequivocally Luciferic. It is the Luciferic in the “H”, then, which comes to expression here. And now try to observe yourself—here the feeling is less important than the contemplation of it—try to observe yourself, when Mrs. Baumann does it for us now, how it is when one does the “H” and allows it to go over immediately into an “M”. Make the “H” first and let it carry over by and by into an “M”. Now take a look at it. In this movement you have the whole perception of the mitigation of the Luciferic, of its sting being taken from it, brought to expression. The movement is truly as if one would arrest Lucifer. And, one can also hear it if you simply think about it—today's civilized man can actually no longer reflect properly on these things. If someone wants to agree to something Luciferic, but immediately diminishes the actual Luciferic element, the eagerness of his assent, then he says, “Hm, hm”. There you have the “H” and the “M” placed really very close to one another and you have the whole charm of the diminished Luciferic directly within it.

From this you can see that as soon as one turns to the consonantal element, one must immediately turn to the observation of the form as well. That is the essential thing and tomorrow we will speak about it further.

Zweiter Vortrag

Ich habe vor, heute einiges über das vokalische Prinzip in der Eurythmie vor Ihnen zu besprechen. Wir brauchen uns nur zu vergegenwärtigen, wie aus der Geisteswissenschaft uns bekannt ist, daß Vokale eigentlich mehr aussprechen dasjenige, was im Inneren des Menschen lebt an Gefühlen, an Emotionen und so weiter. Konsonanten, die drücken mehr dasjenige aus, was das äußerlich Gegenständliche ist. Bleiben wir also innerhalb der Sprache, so gelten diese beiden Sätze: Vokale mehr Ausdruck, mehr Offenbarung für das Innere der Gefühle; wir offenbaren gewissermaßen uns im Vokal, also dasjenige, was wir über einen Gegenstand empfinden, was wir über einen Gegenstand fühlen. Konsonanten passen sich mit den Bewegungen, die Zunge, Lippen, Gaumen und so weiter ausführen, mehr plastisch an die äußere Form der Gegenstände an, die aber natürlich dann geistig empfunden werden, versuchen sie nachzubilden. Es sind so im Grunde alle Konsonanten eine Nachbildung mehr des äußerlichen Formseins der Dinge. Nun aber kann man so im Grunde genommen nur sprechen über Vokale und Konsonanten, wenn man im Auge hat einen früheren Zustand der Menschheitsentwickelung, einen Zustand, in dem eigentlich die Sprachentwickelung gegeben war, und in dem das Bewegen des ganzen [Leibes], also der Glieder des Leibes eine Selbstverständlichkeit war, in dem gewissermaßen die einzelnen Laute immer mit Bewegungen des Leibes verbunden waren. Diese Verbindung ist ja im Laufe der Menschheitsentwickelung gelockert worden. Die Sprache wurde mehr überhaupt nach dem Inneren genommen und die Bewegungsmöglichkeiten, die Bewegungsausdrücke hörten auf, und im gewöhnlichen Leben sprechen wir heute, ohne viel die Sprache mit den entsprechenden Bewegungen zu begleiten. In der Eurythmie holen wir nun wiederum dasjenige, was an Bewegungen die Vokale und Konsonanten begleitet hat, heran und bringen so den Körper wiederum in Bewegung. Nur müssen wir jetzt uns darauf besinnen, daß wir gewissermaßen bei dem Vokalsprechen die Bewegung weglassen und den ganzen Vokal, der gewissermaßen vorher in der äußeren Bewegung mitgelebt hat, daß wir diesen Vokal verinnerlichen. Wir nehmen ihm etwas weg auf seinem Wege nach innen. Wir nehmen ihm die Bewegung weg. Daher ist es beim Vokal so, daß wir dasjenige, was wir ihm auf dem Wege nach innen weggenommen haben, daß wir ihm das in der äußeren Bewegung wiederum geben. So daß beim Vokal alles so liegt, daß bei ihm außerordentlich viel auf die äußere Bewegung ankommt, wenn wir nun den Übergang suchen wollen von der Wirkung dieses Vokals, eurythmisch ausgedrückt, auf den ganzen Menschen. Das ist dasjenige, was wir dabei berücksichtigen müssen.

Also indem wir heute vom Vokalischen sprechen, sprechen wir so rein von der Bedeutung desjenigen, was bewegungsmäßig, eurythmisch vokalisiert wird. Und es handelt sich da sehr darum, daß man sich eine Empfindung von dem erwirbt, was in die Bewegung gewissermaßen hineinfließt. Also daß man sich ein Anschauungsbewußstsein erwirbt, ob dasjenige, was mit dem entsprechenden Gliede des Menschen geschieht, ob das ein Strekken ist, ob es ein Runden ist und dergleichen. Man muß durchaus sich davon ein deutliches Bewußtsein erwerben. Das ist beim Vokalischen außerordentlich wichtig, daß man gewissermaßen die Bewegung oder die Haltung, die gemacht wird, fühlt. Das ist das Wichtige. Und von da ausgehend wollen wir jetzt einmal einzelne Vokale aus dem Eurythmischen ins Therapeutische herüberholen.

Praktisch vorgeführt (Frau Baumann): Ein deutliches I durch Strecken mit beiden Armen. Dieses Strecken, das müßte man nun so bewirken, daß man jetzt wiederum zurückgeht [in die Ausgangsstellung] 1Frühere Herausgeber-Hinweise «Ruhestellung» jetzt ersetzt durch «Ausgangsstellung», wie Rudolf Steiner selbst sagt bei den Anweisungen zur U-Übung. und jetzt dieselbe Bewegung etwas tiefer ausführt, wieder zurückgeht und beides horizontal macht. Jetzt gehen wir wieder zurück, und wenn Sie zuerst rechts vorne waren, so nehmen Sie jetzt, indem Sie nach unten gehen, rechts rückwärts, und nun nach vorn, jetzt etwas zurück und wiederum etwas tiefer. Nun will ich Sie nicht weiter plagen, aber wenn man nun das ausführen sollte, so könnte man es noch mehr komplizieren dadurch, daß man noch mehr Stellungen nimmt, daß man also geradezu von dem I ausgeht, zurückgeht, ein wenig weitermacht, wiederum zurückgeht, ein wenig weitermacht und so weiter, so daß man möglichst viele solche I-Stellungen hat, die man von oben bis nach unten macht mit immer wiederum Zurückgehen der Sache [in die Ausgangsstellung]. Wenn man diese Bewegungen ausführen läßt, dann ist das ein Ausdruck für die menschliche Person. Es drückt sich die ganze individuelle Person dadurch aus.

Nun können wir zum Beispiel die Bemerkung machen: Irgendein Kind oder meinetwillen auch ein erwachsener Mensch kann sich nicht ordentlich äußern als Person. Er ist irgendwie verhindert, als volle Individualität sich zu äußern. Er wäre also in gewissem Sinne vielleicht ein Träumer und dergleichen. Oder aber, wenn wir an ein physisches Übel denken bei einem Kinde, würden wir haben, sagen wir das physische Übel es lernt nicht ordentlich gehen, es geht ungeschickt, oder wir bemerken auch noch bei einem Erwachsenen, daß es wünschenswert ist, daß er aus gewissen hygienischen oder therapeutischen Gründen besser gehen lernt, dann wird diese Übung zunächst für diesen Zweck außerordentlich in Betracht kommen. Bei Erwachsenen bedeutet ja das, wenn sie einen, sagen wir zu wenig ausschreitenden Schritt haben, daß sie nicht ordentlich ausgreifen mit ihrem Schritt, das bedeutet eigentlich immer, daß darunter ihre Blutzirkulation leidet. Die Blutzirkulation leidet unter einem nicht genügend ausgreifenden Schritt. Also wenn die Leute so gehen (trippelnd), so hat das immer zur Folge, daß die Blutzirkulation in irgendeiner Weise langsamer wird, als sie für die betreffende Individualität werden soll. Dann muß man versuchen, daß diese Person weiter ausschreiten lernt, aber man wird ein sicheres Ziel erreichen, wenn man sie diese Übung machen läßt. Dann wird sie eben die größeren und durchgreifenderen Erfolge haben in bezug auf das ordentliche Gehenlernen. So daß man sagen kann, diese modifizierte I-Übung, die ist im wesentlichen fördernd für die Personen, die - nun, ich drücke es erwas radikal aus - nicht ordentlich gehen können. So kann man es ungefähr fassen für Personen, die nicht ordentlich gehen können.

Nun können Sie sie aber noch weiter ausführen, diese Übung, und sie wird ebenso nützlich sein, wenn Sie gewissermaßen das Resümee dessen, was jetzt Frau Baumann gemacht hat, noch hinzufügen. Jetzt versuchen Sie, diese ganze I-Übung, ohne Zurückbringen der Arme [in die Ausgangsstellung], so zu machen, daß Sie die letzte Stellung durch das bloße Drehen herauskriegen: Drehen in der Ebene, schnell, schneller, noch schneller. - Das würde also dasjenige sein, wodurch man diese I-Übung, die man zuerst so gemacht hat, wie wir es beschrieben haben, wodurch man diese dann steigert, und das würde zu dem Resultat führen, daß Personen dadurch gefördert würden, die nicht ordentlich gehen können. Es wird dann außerordentlich leicht sein, sie zum ordentlichen Gehen zu bringen. Man kann sie dabei noch ermahnen, daß sie ordentlich gehen sollen, und es wird außerdem dieses Anders-gehen-Lernen einen entsprechenden Erfolg haben.

Nun wird Frau Baumann so gut sein, uns eine U-Übung vorzumachen. Recht hoch hinauf, zurück die Arme, in die Ausgangsstellung zurück, jetzt ein wenig tiefer, wieder zurück, ein wenig tiefer, jetzt horizontal, jetzt wieder zurück, jetzt nach unten, jetzt wieder zurück, weiter nach unten; das ist das Prinzip. Und jetzt machen Sie es gleich so, daß Sie es nach oben machen und gehen Sie jetzt also, indem Sie herunterbewegen, - lassen Sie das U sein - und gehen Sie auf und ab und machen Sie es jetzt immer schneller, so daß Sie zuletzt eine ziemliche Schnelligkeit haben.

Das würde ich bitten, jetzt als die Ausführung 2Im Stenogramm steht hier für «Ausführung»: «Ausbewegung», was aber eher ein Hörfehler sein könnte. der U-Bewegung ins Auge zu fassen. Und es ist dieses - wenn ich mich jetzt in derselben Weise zusammenfassen sollte, wie ich es früher gesagt habe — die Bewegung für Kinder oder erwachsene Menschen, die nicht stehen können. Beim I hatten wir: die nicht gehen können, beim U: die nicht stehen können.

Nun, nicht stehen können heißt: überhaupt schwach mit den Füßen bestellt sein und sehr leicht ermüden beim Stehen. Es heißt auch zum Beispiel, nicht ordentlich genügend lange Zeit auf den Fußspitzen stehen können oder nicht genügend lange Zeit, ohne daß man gleich ungeschickt ist, auf den Fersen stehen können. Diese Übungen müssen ja bei Menschen gemacht werden — auf den Fußspitzen stehen können und auf den Fersen stehen können, das sind keine eurythmischen Übungen -, aber sie müssen von Menschen gemacht werden, welche schwach auf den Beinen sind, welche beim Stehen leicht müde werden oder welche überhaupt nicht ordentlich stehen können. Nicht ordentlich stehen können heißt auch: beim Gehen müde werden. — Also ich bitte, das ist technisch zu unterscheiden: Es ist etwas anderes, ungeschickt gehen oder beim Gehen müde werden. Wenn man also beim Gehen müde wird, so handelt es sich um die U-Übung. Ungeschickt sein beim Gehen oder eben durch seine ganze Konstitution es hervorrufen, daß es wünschenswert ist, daß man mehr ausschreiten lernt, das heißt, nicht gehen können, technisch gesprochen. Aber müde werden beim Gehen, das heißt, technisch gesprochen, nicht stehen können. Und für solche Leute ist diese U-Übung ganz besonders dasjenige, um was es sich handelt. Es ist dieses mit Dingen zusammenhängend, die wir dann, wenn wir weitergekommen sind, noch auseinandersetzen wollen.

Wenn Sie vielleicht so gut sind und jetzteineO-Bewegung machen, recht [weit] nach oben, und zurück [in die Ausgangsstellung] und jetzt etwas weiter nach unten, jetzt wieder zurück, wieder weiter nach unten und so fort. Aber jetzt machen Sie sie gleich so, daß Sie die O-Bewegung nach oben machen und jetzt aber richtig, also fühlen die Rundung der Arme in der Bewegung, indem Sie hinuntergleiten. Wenn Sie mit der O-Bewegung hinuntergleiten, so muß das O bleiben. Jetzt immer schneller und schneller.

Nun, diese Bewegung, die würden Sie vollständig sehen, meine Freunde, in der glanzvollsten Anwendung, wenn Sie jetzt hier vor sich hätten eine richtig dickliche Person. Wenn also ein Kind unnatürlich dicklich wird oder auch eine erwachsene Person unnatürlich dicklich wird, dann wird diese Übung diejenige sein, die man dann anwenden muß. Es ist alles dasjenige, was im eurythmischen O, wenn es also dauernd gemacht wird, dadurch, daß man es so oft macht, und daß man es zuletzt gewissermaßen zu diesem faßförmigen Körper hier erweitert - denn es ist ja ein Faß, das man umschreibt, das man außer sich umschreibt -, dadurch wird tatsächlich dasjenige ausgeführt, was der Gegenpol ist zu denjenigen dynamischen Tendenzen, welche im Dicklichwerden der Menschen wirken. Es ist dasjenige, was also sehr gut hygienisch und therapeutisch angewendet werden kann, und Sie werden sich wohl überzeugen, daß, wenn Sie diese Bewegung bei solchen Menschen ausführen lassen, daß dann in der Tat eine Tendenz auftaucht, dünner zu werden, insbesondere wenn Sie noch andere Dinge ausführen lassen, die wir noch besprechen wollen. Aber es ist gleichzeitig dieses, daß die Bewegung - gerade bei dieser Bewegung ist das von besonderer Bedeutung - daß Sie die Bewegung so lange ausführen lassen, daß die Person nicht zu stark schwitzt, nicht zu warm wird. Also man muß schon versuchen, diese Bewegung so ausführen zu lassen, daß man immer wiederum ausruhen läßt inzwischen, wenn man das erreichen will, was erreicht werden soll.

Nun wird Frau Baumann vielleicht so gut sein, uns eine E-Bewegung zu machen, recht hoch oben. Es ist erst eine E-Bewegung, wenn dieses drüber liegt, so daß es sich berührt. Nun gehen Sie zurück [in die Ausgangsstellung], etwas tiefer, Ihre rechte Hand über Ihren linken Arm, dann aber, damit das recht wirksam wird, machen wir es noch so, daß wir es mehr zurückliegend ausführen und jetzt wiederum von oben nach unten; denn das E muß gründlich gemacht werden. Und dann machen wir die eine Bewegung, indem wir das nach unten führen, die andere Bewegung, indem wir das nach unten führen, also weiter zurück, so lange, bis Sie sich da hinten die Ärmelnaht zerreißen. Nun, diese Bewegung ist diejenige, die fördernd sein wird insbesondere bei Schwächlingen, also bei Dünnlingen statt bei Dicklingen, bei solchen, bei denen das Schwachsein so recht von innen kommt, aber organisch bedingt ist. Es muß organisch bedingt sein.

Nun die andere Übung, die mit dieser parallel betrachtet werden kann, muß man dann mit einiger Vorsicht anwenden, denn sie geht mehr auf das Seelische, und sie ist die folgende: Wenn Sie ein E nach rückwärts machen, so gut Sie es können, und jetzt so weit herein,3In früheren Auflagen «herauf», im Stenogramm aber deutlich «herein» als Sie können. Das tut ernstlich weh. Das ist eine Bewegung, die als solche ein bißchen weh tut, und das ist auch der Zweck. Und es ist dieses auszuführen bei denjenigen Kindern oder erwachsenen Personen, bei denen seelische Gründe für das Dünnwerden vorliegen, abgehärmt sein und dergleichen. Da es überhaupt so ist, daß man vorsichtig sein muß mit einem von außen an den Menschen Herangehen mit Heilungen, von außen herangehen mit solchen geistigen Mitteln, so muß natürlich dieses auch mit Vorsicht angewendet werden. Das heißt also, man muß versuchen, auch die moralischen Einflüsse auf ein verzagtes Kind oder auf ein deprimiertes, auf ein Depressionserscheinungen zeigendes Kind anzuwenden und so weiter, wenn man es diese Übungen machen läßt. Wenn man sich aber mit dem Kinde sonst beschäftigt, daß man es tröstet, indem man es auch seelisch behandelt, so kann man es auch diese Übungen machen lassen.

Sie sehen daraus, daß es gewissermaßen bei allen diesen Dingen darauf ankommt, daß man dasjenige, was in der Eurythmie als Kunst zum Aus druck kommt, in einer gewissen Weise erweitert. Das gilt insbesondere für das Vokalische.

Nun ist es sehr wichtig, daß wir uns das Folgende klarmachen. Sie wissen also, das Vokalische kann in einer solchen Weise ausgebildet werden, und es ist im wesentlichen der Ausdruck für das Innere. Allein man muß eine gefühlsmäßige, anschauungsmäßige Auffassung desjenigen haben, was da geschieht. Also bei demjenigen, den man diese Sachen dann zu Heilzwecken ausführen läßt, bei dem muß man durchaus darauf bedacht sein, daß er die Dinge fühlt, also beim E richtig das Bedecken des einen Gliedes durch das andere fühlt. Beim O kommt aber noch etwas in Betracht. Beim O soll nicht nur gefühlt werden dieses Kreisschließen, sondern es soll auch die Biegung gefühlt werden. Man soll also fühlen, daß man einen Kreis bildet. Also man soll den Kreis, der da durchgeht, fühlen. Und wenn besonders wirksam gemacht werden soll das ©, dann mache man denjenigen, der es macht, aufmerksam darauf, daß er fühlen soll außerdem so, wie wenn er selbst oder ein anderer ihm einen Strich längs des Brustbeines machen würde, so daß gewissermaßen das Ganze nach rückwärts geistig durch das Gefühl abgeschlossen ist; also, wie wenn man so etwas fühlte, wie wenn man selbst oder wenn ein anderer einem einen Strich machte am Brustbein.

Nun wollen wir ein A machen: Jetzt gehen wir wieder zurück [in die Ausgangsstellung], jetzt machen wir ein A tiefer, gehen wieder zurück, machen ein A horizontal, zurück, machen ein A gesenkt, zurück, machen ein A ganz tief, zurück, dann nach rückwärts; das brauchen Sie nur einmal zu machen, aber zurückgehen [in die Ausgangsstellung] zuerst. Und jetzt machen Sie das A oben und fahren, ohne den Winkel zu verändern, nach unten, jetzt ohne daß Sie das Gefühl haben, den Winkel zu verändern, gehen Sie nach rückwärts.

Diese Übung, die kann auch wirksam werden dadurch eigentlich nur, daß man sie recht oft ausführen läßt. Also recht oft ausführen lassen. Und wenn man sie recht oft ausführen läßt, dann ist sie die Übung, die man anwenden soll bei Personen, die gierig sind, bei denen die Tiernatur besonders stark auftritt. Also wenn Sie so richtig in der Schule zum Beispiel haben ein Kind, das so richtig ein kleines Tierlein ist nach jeder Beziehung — und das organisch bedingt ist -, und Sie lassen es diese Übung ausführen, so werden Sie sehen, daß sie für dieses Kind eine ganz besondere Bedeutung hat.

Diese Übungen, Sie sehen wiederum an ihnen, daß ja, wenn sie schulmäßig eingeführt werden sollen, es notwendig ist, daß man die Kinder besonders dazu einteilt, und man wird sich auch überzeugen, daß die Kinder diese Übungen weit weniger gerne machen als die eurythmischen Übungen sonst. Zu den eurythmischen Übungen drängen sie sich, bei diesen Übungen wird man ihnen jedenfalls höchst wahrscheinlich sehr zureden müssen; denn sie werden sich zunächst so verhalten dazu, wie sich Kinder oftmals gegen das Einnehmen von Arzneien verhalten. Sie werden keine rechte Freude daran haben, aber das schadet eigentlich bei diesen Übungen allen nicht besonders, die sich auf das U, O, E und A bezichen; bei dem I schadet es etwas, wenn die Kinder keine Freude daran haben. Da muß man versuchen, das zu erreichen, daß diese I-Übung, wie wir sie gemacht haben, den Kindern Spaß macht. Bei den andern ist es so, daß, wenn sie es auf Autorität ausführen und wissen, sie sollen es pflichtgemäß tun, da schadet es nicht besonders, bei dem U, O, E, A. Bei dem I ist es aber wichtig, daß die Kinder Spaß haben dabei, weil das auf die ganze individuelle Person geht, wie ich schon gesagt habe.

Sie werden noch etwas davon haben, wenn Sie etwa das sich zurechtlegen: Das I offenbart den Menschen als Person, das U offenbart den Menschen als Mensch, das O offenbart den Menschen als Seele, das E fixiert das Ich im Ätherleib, es prägt sehr stark das Ich in den Ätherleib hinein, und das A wirkt der tierischen Natur im Menschen entgegen.

Nun handelt es sich darum, diese verschiedenen Wirkungen noch weiter zu verfolgen. Wenn Sie einen Menschen haben, der unregelmäßige Atmung hat, irgendwie durch seine Atmung belästigt wird und dergleichen, dann werden Sie gerade durch die Anwendung dieses Vokalisierens es erreichen, daß dieser Mensch eine gewisse Normalisierung des Atmens erreicht. Insbesondere aber werden Sie durch diese Übungen erreichen, daß zum Aussprechen, zum deutlichen Aussprechen des Konsonantischen, dieses Vokalisieren von großem Vorteil ist. Also wenn Kinder möglichst früh, wenn man sieht, es gelingt ihnen nicht, gewisse Konsonanten mit den Lippen oder mit der Zunge zu formen -für Gaumenlaute ist es weniger anwendbar, aber für Lippen- und Zungenlaute außerordentlich gut-, wenn man es versucht, Kinder, die Schwierigkeiten in dieser Bildung haben, solche Vokalübungen machen zu lassen, so ist das wiederum außerordentlich förderlich für sie.

Man wird aber auch merken, daß, wenn Personen neigen zu chronischen Kopfschmerzen, migräneartigen Zuständen, daß man dadurch wesentliche Erleichterungen haben wird gerade durch dieses Vokalisieren. Also auch bei chronischem Kopfschmerz und bei chronischen Migräneerscheinungen, auch bei Eingenommenheit des Kopfes, werden sich diese Dinge ganz besonders gut anwenden lassen. Ebenso die Übungen, die wir heute gemacht haben, die ja bei gewissen Kindern - zum Beispiel, die gar nicht aufmerksam sein können, die verschlafen sind -—, wenn man sie bei diesen Kindern anwendet, so werden Sie diese Kinder in einem gewissen Sinne zum Gewecktwerden bringen. Also das ist eine hygienisch-didaktische Seite, die von einer gewissen Wichtigkeit ist. Aber auch bei erwachsenen Menschen wird sich das durchaus noch zeigen können, daß man, wenn sie Schlafmützen sind, daß man sie erwecken kann dadurch. Dann wird man merken, daß, wenn die Verdauung des Menschen schwach ist, träge ist, daß man gerade durch diese Übungen günstig eine zu träge Verdauung und dann natürlich auch alles das, was man als zusammenhängend betrachten muß mit einer zu trägen Verdauung, daß man das ganz besonders fördern kann nach der guten Seite hin.

Es würde aber nun auch bei einer gewissen hygienischen Eurythmie gut sein, wenn man womöglich versuchen würde, die Bewegungen, die eigentlich für die Kunsteurythmie bloß mit den Armen ausgeführt werden, wenn man diese, allerdings schwächer - ich werde gleich darüber noch sprechen -, ausführen ließe in einer gewissen Weise mit den Beinen. Nun werden Sie sagen, wie kann man zum Beispiel I mit den Beinen machen? Das geht sehr leicht. Man braucht ja nur das Bein vorzustrecken und das Strecken drinnen haben. Das U würde einfach dieses sein, daß man sich mit vollem Bewußtsein auf beide Beine stellt, so daß man ein deutliches Streckegefühl in beiden Beinen hat. Das O aber sollte man lernen mit den Beinen. Das besteht darinnen- und man soll schon auch Leuten, bei denen man notwendig findet, in der Weise, wie ich es beschrieben habe, die O-Bewegung auszuführen, die sollte man schon auch gewöhnen, die O-Bewegung mit den Beinen zu machen - , in entsprechender Weise etwas nach Außen stellen, aber wenig, die Zehen, und dann versuchen, in dieser Weise sich zu stellen. Aber auf den Zehenspitzen dabei stehen und nach auswärts biegen, ein wenig stehenbleiben, zurückgehen in die Normalstellung, wiederum das bilden und so weiter.

Es ist notwendig, daß man dabei berücksichtigt das Verhältnis, das besteht zwischen der Bewegungsmöglichkeit, der inneren organisch bedingten Bewegungsmöglichkeit für den mittleren Menschen und den unteren Menschen. Die ist so, daß sich dasjenige, was man ausführt für den unteren Menschen, also solch eine Bewegung, daß sich 3Im Stenogramm «daß man dieses ...», hier wurde entsprechend dem Satzanfang geändert in «daß sich dieses». dieses nur in Drittelstärke ausführen läßt. Also so daß Sie, wenn Sie jemanden die O-Bewegung, wie wir sie gesehen haben, ausführen lassen, so müssen Sie dann das Gefühl haben, daß, was Sie etwa hinterher machen lassen für die Füße und Beine, daß das nur ein Drittel der Zeit nimmt, also ein Drittels-Kraftaufwand ist, möchte ich sagen. Besonders wirksam wird es aber sein, wenn Sie es in die Mitte hinein verlegen, so daß Sie ein Drittel, ein Drittel, ein Drittel haben, so daß Sie also haben, sagen wir A und dann noch einmal A, und in der Mitte B, die Fußbewegung hinein (siehe Schema) und Sie zusammen haben ein Drittel, ein Drittel, ein Drittel, das wird von besonderer Wirksamkeit sein.

Von besonderer Wirksamkeit ist aber auch, dasselbe auszuführen im Zusammenhang mit der gezeigten E-Bewegung für die Füße, wo Sie die Füße richtig übereinanderlegen. Aber man muß auf den Zehenspitzen stehen und die Beine übereinanderlegen, so daß sich die Beine berühren. Wiederum ein Drittel und womöglich in die Mitte verlegen. Das ist etwas, was ganz besonders gut ausgeführt werden sollte bei Kindern und auch bei erwachsenen Personen, die Schwächlinge sind. Sie werden es natürlich um so weniger machen können, aber das ist gerade das, worauf es ankommt, daß sie es eben lernen zu machen. Und gerade bei diesen Dingen sieht man, daß für die verschiedenen Menschen dasjenige am wichtigsten ist zu lernen, was sie am allerwenigsten können. Das müssen sie dann lernen, weil es eben gerade zu ihrer Gesundung notwendig ist.

Das A ist ebenfalls notwendig, das habe ich Ihnen schon gestern gezeigt. Das besteht eben darinnen, daß man, sich womöglich auf die Zehen stellend, diese gespreizte Stellung einnimmt. Das soll ebenfalls in die ABewegung eingeführt werden und wird da ganz besonders günstig wirken.

Nun kann man aber alle Bewegungen, die wir jetzt beschrieben haben, auch noch dadurch steigern, daß man sie im Gehen ausführen läßt. Und Sie werden zum Beispiel ganz besonders viel erreichen für ein Kind, das schwach ist, wenn Sie es anleiten, die E-Bewegung im Gehen auszuführen, wie wir sie jetzt gemacht haben, aber so, wie wir sie jetzt gemacht haben, im Gehen auszuführen, aber außerdem es so gehen lassen, daß es sich abwechselnd immer berührt. Indem es vorschreitet, nimmt es das [eine Bein] herüber, dann das [andere], so daß es immer ein Bein über das andere stellt, so daß es immer das Zurückliegende 4«Zurückliegende» unklar im Stenogramm, könnte auch als «Zurückgehende» gelesen werden. mit dem andern nach vorwärts berührt. Es wird natürlich nicht gut vorwärtskommen; aber es ist doch dasjenige, was gut ist, ausführen zu lassen, also dieselben Bewegungen im Gehen auszuführen. Sie werden sagen, es kommen komplizierte Bewegungen dabei zum Vorschein; aber es ist gut, wenn solche komplizierten Bewegungen zum Vorschein kommen.

Nun möchte ich Sie noch darauf aufmerksam machen, daß dasjenige, was wir jetzt über das Vokalische gesagt haben, zunächst recht scharf gesondert werden soll von demjenigen, was wir morgen über das Konsonantische üben werden. Das Konsonantische, das ist im allgemeinen so, daß es das Äußere ausdrückt, wie wir schon gesagt haben. Der Konsonant wird ja auch in der Sprache so geformt, daß sich Lippen, Zunge namentlich, in einer solchen Weise formen, daß da eine Nachbildung, eine Imitation der äußeren Form vorliegt. Nun, das Konsonantische hat ja, wie wir morgen auch sehen werden, dann ganz besondere Arten von Bewegungen, und in diesen Bewegungsformen liegt es schon, daß der Konsonant in einer gewissen Weise wiederum verinnerlicht wird, indem er in eurythmischen Formen gegeben wird. Er wird verinnerlicht. Es wird dasjenige, was er in der Sprache auf dem Wege nach außen verloren hat, das wird ihm wiedergegeben, und beim Konsonanten, sowohl beim Anschauen, indem man Eurythmie als Kunst nimmt, wie namentlich wenn sie ausgeführt wird zum Zwecke der Person, wenn man sie ausführen läßt beim Konsonanten, ist es ganz besonders wichtig, daß man nun nicht etwa in derselben Weise wie beim Vokal ein Gefühl, also das Streckgefühl, das Biegegefühl, das Weitegefühl hat, sondern daß man beim Konsonanten gleichzeitig sich selbst in der Form vorstellt, die man ausführt, wenn man den Konsonanten macht, also wenn man sich gewissermaßen selber zuschaut.

Hier sehen Sie am allerdeutlichsten, daß man die Kunsteurythmisten ermahnen muß, nicht beide Dinge durcheinanderzuwerfen; denn die Kunsteurythmisten, die werden nicht gut tun, sich immer zuzuschauen, da werden sie sich die Unbefangenheit nehmen und so weiter. Dagegen, wenn Sie ein Kind oder eine erwachsene Person Konsonantisches ausführen lassen, so ist es wichtig, daß sie sich gewissermaßen mit dem Gedanken innerlich selbst abphotographiert; denn darinnen liegt das Wirksame, daß sie sich innerlich selbst abphotographiert, daß sie sich also gerade in der Stellung darinnen richtig innerlich sieht, die sie ausführt, und wenn das wirklich so ausgeführt wird, daß die Person eine innerliche Anschauung hat von dem, was sie ausführt.

Also, wenn Sie noch so gut sind, vielleicht uns vorzuführen, sagen wir ein M konsonantisch zuerst mit der rechten Hand, jetzt mit der linken Hand, aber das zurücknehmend, jetzt die rechte Hand ganz zurücknehmend, mit der linken Hand ein M machen, jetzt mit beiden Händen - das kann natürlich wiederum vermannigfaltigt werden in vielfacher Weise. (Fräulein Wolfram): Nun ein M - gehen wir von diesem Beispiel aus, ein M, was ist es denn zunächst sprachlich? Sprachlich ist das M ein außerordentlich wichtiger Laut. Sie werden ihn sprachlich empfinden in seiner Wichtigkeit, auch sprachphysiologisch in seiner Wichtigkeit empfinden, wenn Sie ihn im Gegensatz betrachten zu dem S. Vielleicht macht uns Frau Baumann jetzt ein graziöses S, rechts, links, jetzt mit beiden Händen.

Nun ist ja scheinbar zunächst das so, daß, wenn das $ ausgeführt wird, Sie das Gefühl haben werden oder haben müssen, daß Sie sich selbst mit etwas in Ihnen - es ist nämlich der Ätherleib - daß Sie sich mit etwas in Ihnen so bewegen (R. Steiner macht die Bewegung), eine Schlangenlinie haben. Diese Schlangenlinie, die darf bei einem besonders scharf ausgesprochenen S sich der Geraden sehr nähern und kann sogar als Gerade vorgestellt werden.

Dagegen, wenn Sie sich anschauen das M, welches eben ausgeführt worden ist, so müssen Sie das Gefühl haben, das ist eigentlich - wenn auch die organische Form, in der das ausgeführt wird, [ähnlich ist] - nicht genau dasselbe Element, nicht linienhaft dasselbe. Und so ist dann das M dasjenige, was sich, angelegt an die S-Richtung, sich entgegenlebt der S-Richtung, und das ist im Grunde genommen, sehen Sie, der große Gegensatz zwischen einem $ und einem M. Ein $ und ein M, das sind die zwei polarischen Laute.

Das S, das ist- wenn ich mich jetzt anthroposophisch ausdrücken darf — das S ist der eigentlich ahrimanische Laut, und das M ist dasjenige, was das Ahrimanische in seiner Eigenschaft mildert, abmildert, was ihm, wenn ich es so sagen darf, seine ahrimanische Stärke nimmt, das M. So daß, wenn wir unmittelbar einen Lautzusammenhang haben, in dem $ und M sich finden, wie zum Beispiel wenn wir den Lautzusammenhang «Samen» haben oder gar «Summe», dann haben wir in diesem Lautzusammenhang zuerst das stark ahrimanische Wesen im S, aber dann ihm die Spitze genommen im M.

Vielleicht machen Sie uns noch ein H (Fräulein Wolfram). Wenn Sie das H nun richtig anschauen, wenn Sie sich so recht drinnen fühlen in diesem H, dann werden Sie sich sagen: In diesem H liegt etwas, was unmittelbar luziferisch sich ausnimmt. Es ist also das Luziferische in dem H, das da zum Ausdrucke kommt. Und nun versuchen Sie selbst jetzt anzuschauen — hier kommt es weniger auf das Fühlen als auf das Anschauen an -, versuchen Sie selbst jetzt anzuschauen, wenn Frau Baumann uns das jetzt machen würde, wenn man das H macht und es gleich übergehen läßt jetzt in ein M. Machen Sie das H zuerst und lassen Sie es langsam übergehen in ein M. Nun sehen Sie das einmal an. Da haben Sie die ganze Anschauung des Luziferischen abgemildert, ihm die Spitze genommen, in dieser Bewegung zum Ausdrucke gebracht. Diese Bewegung ist wirklich so, wie wenn man den Luzifer aufhalten würde. Es ist richtig so, wie wenn man den Luzifer aufhalten würde. Und es ist das ja für Sie auch hörbar, wenn Sie sich einfach darauf besinnen - der heutige Zivilisationsmensch kann sich eigentlich gar nicht mehr recht auf diese Dinge besinnen -, aber wenn Sie sich darauf besinnen: Wenn jemand zu etwas Luziferischem zustimmen will, aber das richtige Luziferische, das Eifrige des Zustimmens gleich herabmindert, so macht er «Hm, hm»; da haben Sie das H und das M eigentlich recht sehr aneinandergelegt, und da haben Sie die ganze Liebenswürdigkeit des herabstimmenden Luziferischen unmittelbar drinnen.

Daraus sehen Sie, daß, sobald man ins Konsonantische übergeht, man übergehen muß zugleich in das Anschauen der Form. Das ist das Wichtige, und davon wollen wir also morgen weiterreden.

Second Lecture

Today, I intend to discuss with you some aspects of the vocal principle in eurythmy. We need only remember what we know from spiritual science, namely that vowels actually express more of what lives within the human being in terms of feelings, emotions, and so on. Consonants express more of what is external and concrete. So, if we remain within the realm of language, these two statements apply: vowels express more, reveal more of our inner feelings; in a sense, we reveal ourselves in vowels, that is, what we feel about an object, what we sense about an object. Consonants, with the movements performed by the tongue, lips, palate, and so on, adapt more plastically to the external form of objects, which are then naturally perceived mentally and attempted to be reproduced. Basically, all consonants are more of a reproduction of the external form of things. But basically, one can only speak of vowels and consonants if one has in mind an earlier stage of human development, a stage in which language development was actually taking place and in which the movement of the whole body, that is, the limbs of the body, was a matter of course, in which, so to speak, the individual sounds were always connected with movements of the body. This connection has become weaker in the course of human development. Language became more internalized, and the possibilities for movement, the expressions of movement, ceased, and in everyday life today we speak without accompanying language with the corresponding movements. In eurythmy, we now bring back the movements that accompanied the vowels and consonants and thus bring the body back into motion. However, we must now remember that when speaking vowels, we omit the movement and internalize the entire vowel, which previously lived in the external movement. We take something away from it on its way inward. We take away its movement. Therefore, with the vowel, we give back to it in the outer movement what we have taken away from it on its way inward. So that with vowels, everything is such that an extraordinary amount depends on the external movement if we now want to seek the transition from the effect of this vowel, expressed eurythmically, to the whole human being. That is what we must take into account here.

So when we speak of the vowel today, we speak purely of the meaning of what is vocalized in terms of movement, eurythmically. And it is very important to acquire a feeling for what flows into the movement, so to speak. In other words, we need to acquire a visual awareness of what happens to the corresponding limb of the human being, whether it is stretching, rounding, or something similar. We must acquire a clear awareness of this. In the case of the vocal, it is extremely important to feel, as it were, the movement or posture that is being made. That is the important thing. And starting from there, we now want to transfer individual vowels from eurythmy to therapy.

Practical demonstration (Ms. Baumann): A clear I by stretching with both arms. This stretching should now be done in such a way that you go back [to the starting position] 1Previous editor's notes “resting position” now replaced by “starting position,” as Rudolf Steiner himself says in the instructions for the U exercise. and now performing the same movement a little lower, going back again and doing both horizontally. Now we go back again, and if you were at the front right at first, now go down, back to the right, and now forward, now a little back and again a little lower. Now I don't want to bother you any further, but if you were to do this, you could complicate it even more by taking even more positions, that is, by starting from the I, going back, continuing a little further, going back again, continuing a little further, and so on, so that you have as many I-positions as possible, which you do from top to bottom, always going back [to the starting position]. If you perform these movements, they are an expression of the human person. They express the whole individual person.

Now we can make the observation, for example, that a child, or for that matter an adult, cannot express themselves properly as a person. They are somehow prevented from expressing themselves as a full individual. In a sense, they might be a dreamer or something similar. Or, if we think of a physical ailment in a child, we would say that the physical ailment prevents them from learning to walk properly, they walk clumsily, or we also notice in an adult that it is desirable for them to learn to walk better for certain hygienic or therapeutic reasons, then this exercise will initially be extremely useful for this purpose. In adults, if they have, say, an insufficient stride, meaning that they do not reach out properly with their steps, this always means that their blood circulation suffers as a result. Blood circulation suffers from an insufficient stride. So when people walk like this (tripping), it always results in the blood circulation slowing down in some way, more than it should for the individual in question. Then you have to try to teach this person to take longer strides, but you will achieve a sure goal if you have them do this exercise. Then they will have greater and more thorough success in learning to walk properly. So you could say that this modified I-exercise is essentially beneficial for people who – well, I'll put it somewhat radically – cannot walk properly. That's roughly how you can describe it for people who cannot walk properly.

Now you can take this exercise even further, and it will be just as useful if you add, so to speak, the summary of what Ms. Baumann has just done. Now try to do this whole I-exercise without bringing your arms back [to the starting position], so that you get the last position by simply turning: turning in the plane, fast, faster, even faster. This would be the way to enhance the I exercise that we first did as described, and it would lead to the result that people who cannot walk properly would be encouraged to do so. It will then be extremely easy to get them to walk properly. You can still admonish them to walk properly, and this learning to walk differently will also have the desired effect.

Now Mrs. Baumann will be so kind as to demonstrate a U exercise for us. Quite high up, arms back, back to the starting position, now a little lower, back again, a little lower, now horizontal, now back again, now down, now back again, further down; that is the principle. And now do it right away, moving upwards, and now walk downwards, moving downwards – let that be the U – and walk up and down, doing it faster and faster, so that you end up walking quite quickly.

I would ask you to consider this as the execution 2In the shorthand notes, “Ausbewegung” is used here for “Ausführung” (execution), but this could be a hearing error. of the U movement. And it is this – if I were to summarize it in the same way as I said earlier – the movement for children or adults who cannot stand. With the I, we had: those who cannot walk; with the U: those who cannot stand.

Now, not being able to stand means having weak feet and tiring very easily when standing. It also means, for example, not being able to stand on tiptoes for a sufficiently long time or not being able to stand on your heels for a sufficiently long time without immediately becoming clumsy. These exercises must be done by people — being able to stand on tiptoes and on heels are not eurythmic exercises — but they must be done by people who are weak on their legs, who tire easily when standing, or who cannot stand properly at all. Not being able to stand properly also means becoming tired when walking. — So I ask you to make a technical distinction: it is one thing to walk clumsily and another to get tired when walking. If you get tired when walking, then the U exercise is what you need. Being clumsy when walking or, due to your overall constitution, finding it desirable to learn to stride more, means, technically speaking, not being able to walk. But getting tired when walking means, technically speaking, not being able to stand. And for such people, this U-exercise is particularly what it is all about. This is related to things that we will discuss further when we have progressed.

If you would be so kind as to now make an O movement, right [far] up, and back [to the starting position], and now a little further down, now back again, further down again, and so on. But now do it so that you make the O movement upwards, and now do it properly, feeling the curve of your arms in the movement as you glide down. When you glide down with the O movement, the O must remain. Now faster and faster.

Now, you would see this movement in its most brilliant application, my friends, if you had a really overweight person standing here in front of you. So if a child becomes unnaturally overweight, or even an adult becomes unnaturally overweight, then this exercise is the one that must be used. It is everything that is achieved in the eurythmic O, when it is done continuously, by doing it so often, and by ultimately expanding it, as it were, to this barrel-shaped body here—for it is indeed a barrel that one describes, that one describes outside of oneself—by doing this, one actually performs the opposite of those dynamic tendencies that cause people to become overweight. This is something that can be used very effectively for hygienic and therapeutic purposes, and you will probably find that when you have such people perform this movement, they do indeed tend to become thinner, especially if you have them perform other things that we will discuss later. But at the same time, it is important – especially with this movement – that you have the movement performed for so long that the person does not sweat too much or get too warm. So you have to try to have this movement performed in such a way that you always allow the person to rest in between if you want to achieve what you want to achieve.

Now, Ms. Baumann, would you be so kind as to show us an E movement, quite high up. It is only an E movement when this is above it, so that it touches. Now go back [to the starting position], a little lower, your right hand over your left arm, but then, to make it really effective, we do it in such a way that we perform it more reclined and now again from top to bottom; because the E must be done thoroughly. And then we do one movement by leading it downwards, the other movement by leading it downwards, i.e. further back, until you tear the sleeve seam at the back. Now, this movement is the one that will be beneficial, especially for weaklings, i.e. for thin people rather than fat people, for those whose weakness comes from within but is organically conditioned. It must be organically caused.

Now, the other exercise, which can be considered parallel to this one, must be used with some caution, because it is more psychological, and it is as follows: If you make an E backwards, as best you can, and now as far in as you can. That really hurts. It is a movement that hurts a little, and that is also the purpose. And it should be performed on children or adults who are thin for psychological reasons, who are emaciated and the like. Since one must always be careful when approaching people from the outside with healing, when approaching them from the outside with such spiritual means, this must of course also be applied with caution. This means that one must also try to apply moral influences on a despondent child or a depressed child, or a child showing signs of depression, and so on, when letting them do these exercises. But if one otherwise engages with the child, comforting them by also treating them spiritually, then one can also let them do these exercises.

You can see from this that, in a sense, what is important in all these things is to expand in a certain way what is expressed in eurythmy as an art. This applies in particular to the vocal aspect.

Now it is very important that we understand the following. You know that the vocal aspect can be trained in this way, and it is essentially the expression of the inner self. But one must have an emotional, intuitive understanding of what is happening. So, with those who are asked to perform these exercises for healing purposes, one must be very careful to ensure that they feel the things, that is, with the E, they really feel the covering of one limb by the other. With the O, however, there is something else to consider. With the O, one should not only feel this closing of the circle, but also feel the bending. One should therefore feel that one is forming a circle. One should feel the circle that passes through. And if the © is to be made particularly effective, then make the person performing it aware that they should also feel as if they themselves or someone else were making a line along their sternum, so that, in a sense, the whole thing is mentally completed backwards through the feeling; that is, as if one felt something like this, as if one themselves or someone else were making a line on one's sternum.

Now let's make an A: Now we go back [to the starting position], now we make an A lower, go back again, make an A horizontally, back, make an A lowered, back, make an A very low, back, then backwards; you only need to do this once, but go back [to the starting position] first. And now make the A at the top and move downwards without changing the angle, now without feeling that you are changing the angle, move backwards.

This exercise can only be effective if it is performed quite often. So have it performed quite often. And if you have it performed quite often, then it is the exercise that should be used for people who are greedy, for whom the animal nature is particularly strong. So if, for example, you have a child at school who is really a little animal in every respect — and this is due to organic reasons — and you let them perform this exercise, you will see that it has a very special meaning for this child.

These exercises, you will see again, if they are to be introduced in school, it is necessary to assign the children to them specifically, and you will also find that the children are far less enthusiastic about doing these exercises than the usual eurythmy exercises. They rush to the eurythmic exercises, but with these exercises you will most likely have to persuade them, because at first they will behave as children often behave when they are asked to take medicine. They will not really enjoy them, but that does not particularly harm anyone in the case of the exercises relating to U, O, E, and A. In the case of I, it is somewhat harmful if the children do not enjoy them. We must try to ensure that the children enjoy the I exercise as we have done it. With the others, if they do it on authority and know they have to do it as a duty, it doesn't do any particular harm with the U, O, E, A. With the I, however, it is important that the children enjoy it, because it affects the whole individual person, as I have already said.

You will benefit from this if you understand the following: I reveals the human being as a person, U reveals the human being as a human being, O reveals the human being as a soul, E fixes the ego in the etheric body, it imprints the ego very strongly into the etheric body, and A counteracts the animal nature in the human being.

Now it is a matter of pursuing these different effects further. If you have a person who has irregular breathing, who is somehow bothered by their breathing and the like, then by applying this vocalization you will achieve a certain normalization of their breathing. In particular, however, you will achieve through these exercises that this vocalization is of great benefit for pronouncing, for clearly pronouncing consonants. So if children, as early as possible, when you see that they are unable to form certain consonants with their lips or tongue—it is less applicable for palatal sounds, but extremely good for lip and tongue sounds—if you try to get children who have difficulties in this area to do such vocal exercises, this is in turn extremely beneficial for them.

However, you will also notice that if people are prone to chronic headaches or migraine-like conditions, this vocalization will bring them significant relief. So even in cases of chronic headaches and chronic migraine symptoms, as well as in cases of mental dullness, these things will be particularly effective. Similarly, the exercises we did today, which are suitable for certain children—for example, those who cannot concentrate, who are sleepy—if you use them with these children, you will, in a sense, wake them up. So this is a hygienic-didactic aspect that is of a certain importance. But even with adults, it may well turn out that if they are sleepyheads, they can be awakened by this. Then one will notice that if a person's digestion is weak and sluggish, these exercises can have a beneficial effect on sluggish digestion and, of course, on everything that must be considered related to sluggish digestion, promoting it in a particularly positive way.

However, it would also be good in a certain hygienic eurythmy if one tried, if possible, to perform the movements that are actually performed with the arms in artistic eurythmy, albeit in a weaker form – I will talk about this in a moment – in a certain way with the legs. Now you will say, how can one do I with the legs, for example? It is very easy. All you need to do is stretch your leg forward and maintain the stretch. The U would simply be to stand on both legs with full awareness, so that you have a clear feeling of stretching in both legs. But you should learn the O with your legs. This consists of—and you should also encourage people who you think need to do so to perform the O movement in the way I have described—getting them used to doing the O movement with their legs—placing them slightly outward, but not too much, the toes, and then trying to stand in this way. But stand on your tiptoes and bend outward, stay like that for a moment, return to the normal position, do it again, and so on.

It is necessary to take into account the relationship that exists between the range of motion, the inner organically determined range of motion for the middle human being and the lower human being. This is such that what one performs for the lower human being, i.e., such a movement, can only be performed at one-third strength. can only be performed at one-third strength. So when you have someone perform the O movement as we have seen, you must then have the feeling that what you have them do afterwards for the feet and legs takes only one-third of the time, that is, one-third of the effort, I would say. However, it will be particularly effective if you move it into the middle, so that you have one third, one third, one third, so that you have, let's say A and then A again, and in the middle B, the foot movement (see diagram), and together you have one third, one third, one third, which will be particularly effective.

It is also particularly effective to do the same in connection with the E movement shown for the feet, where you place your feet correctly on top of each other. But you have to stand on your tiptoes and place your legs on top of each other so that your legs touch. Again, one third and possibly move to the middle. This is something that should be done particularly well with children and also with adults who are weak. Of course, they will be less able to do it, but that is precisely what is important, that they learn to do it. And it is precisely in these things that we see that the most important thing for different people to learn is what they are least able to do. They must learn this because it is necessary for their recovery.

The A is also necessary, as I showed you yesterday. This consists of standing on your toes, if possible, and adopting this spread position. This should also be introduced into the A movement and will have a particularly beneficial effect there.

However, all the movements we have just described can also be enhanced by performing them while walking. And you will achieve a great deal, for example, for a child who is weak, if you instruct them to perform the E movement while walking, as we have just done, but in addition to performing it while walking, you also let them walk in such a way that they always touch alternately. As it progresses, it takes one leg over, then the other, so that it always places one leg over the other, so that it always touches the one behind 4“Behind” is unclear in the shorthand, could also be read as “behind”. with the other touching forward. Of course, it will not move forward well; but it is still good to have it perform the same movements as when walking. You will say that this results in complicated movements, but it is good when such complicated movements occur.

Now I would like to draw your attention to the fact that what we have just said about vowels should be clearly distinguished from what we will practice tomorrow about consonants. Consonants, as we have already said, generally express the external. In speech, consonants are formed in such a way that the lips and tongue are shaped to reproduce or imitate the external form. Now, as we will see tomorrow, consonants have very special types of movements, and it is in these forms of movement that the consonant is in a certain way internalized again by being given in eurythmic forms. It is internalized. What it has lost in language on its way outwards is given back to it, and with consonants, both when looking at them, taking eurythmy as an art, and especially when they are performed for the purpose of the person, when they are performed with consonants, it is particularly important that one does not have the same feeling as with vowels, i.e., the feeling of stretching, the feeling of bending, the feeling of widening, but that with the consonant one simultaneously imagines oneself in the form that one is performing when one makes the consonant, that is, when one watches oneself, so to speak.

Here you can see most clearly that one must admonish the eurythmists not to confuse the two things; because art eurhythmists will not do well if they always watch themselves, as they will lose their impartiality and so on. On the other hand, when you have a child or an adult perform consonants, it is important that they photograph themselves internally with their thoughts, so to speak; for therein lies the effectiveness, that they photograph themselves internally, that they see themselves correctly internally in the position they are performing, and if this is really done in such a way that the person has an inner view of what they are performing.