Third Scientific Lecture-Course:

Astronomy

GA 323

11 January 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture XI

We have now gained the most essential premises for a study of some aspects at least of celestial and also of earthly-physical phenomena. In human nature, once again, we have the very significant contrast (to ascertain which, as you will readily understand, we must leave the animal out of account to begin with)—the contrast between the organisation of the head and that of the metabolic system including the limbs. As we have seen, if we wish to relate Man to the Cosmos, we must assign the metabolic system to what is earthly,—what comes to man in a radial direction. Whereas we must assign the forming of the head to all that derives from the great Sphere,—that sends its lines of influence, as it were from the celestial Sphere towards the centre of the Earth, even as the radius reaches outward with its lines of influence to its surroundings. We saw this in the construction of the typical long bones or tubular bones by contrast to the skull-bones, the latter being sphere-like, or like a sector of a sphere.

Envisaging this difference, we must relate it, to begin with, to what appears to us in the relation of the Earth to the Celestial Sphere. You are of course aware, how the scientific consciousness of our time departs from what the naive human being, untouched by any learning, would judge of the appearance of the celestial sphere, the movements of the stars upon it, and so on. We speak of the ‘Apparent aspect’ of the celestial vault. In contrast to it, as you know, we have a picture—a World-picture—gained in a fairly complicated way by interpreting the apparent movements, and so on. Upon this picture—the form of picture which has evolved through the great changes in cosmology since the Copernican era—we are wont to base all our considerations of celestial phenomena.

Today I take it to be generally realised that this World-picture does not represent absolute reality. We can no longer maintain: What is presented to us by this picture, say, as the planetary movements or as the Sun's relation to the Planets, is the true form of the underlying reality, while what the eye beholds is mere appearance. I hardly think any competent person would adopt this standpoint nowadays. Yet he will still have a feeling that he at least gets nearer to a true conception when he proceeds from the apparent picture of the celestial movements—fraught, he will say with illusionary factors (yet after all, we must admit, objectively observed)—to the interpretation of it by mathematical Astronomy.

The question now is, do we really gain a comprehensive view of the phenomena in question if we only base our picture of the World on this, the customary kind of interpretation. As we have seen, when we do so we are in fact only basing it on what the head-man ascertains, so to speak. We base it on the aspect which emerges for man's powers of observation, aided perhaps by optical instruments. But as we saw, for a more comprehensive interpretation of the World-picture we must have recourse to all that is knowable by man, of man. We emphasised how to this end the form of man must be seen in the light of a true science of metamorphosis. Then too we must bring in the evolution of man and of mankind. In a word, concerning the celestial phenomena, or some of them at least, we cannot look for enlightenment till in our efforts to interpret them we go as far as this, calling to our aid whatever can be known of man.

Let us then presuppose what we arrived at in former lectures—the kind of qualitative mathematics, learned from the human form and growth and evolution. With this in the background let us take our start from what meets the eye—from what is said to be the mere appearance of the Heavens—asking ourselves how we may find the way to reality? Let us then ask, dear friends: What does the eye behold, what do we learn empirically, by simple observation? Then we can try to fill in the picture with what is given by the whole structure of man, both in morphology and evolution. First we will ask the question as regards those stars which are commonly described as fixed stars. I shall no doubt be repeating what is well-known to most of you, yet we must call it to mind for only by so doing, only from the facts as seen, taking them all together, shall we be able to advance to the ideas.

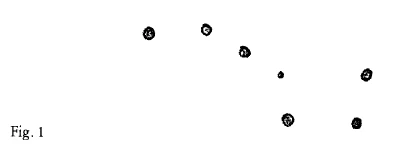

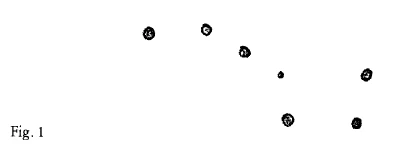

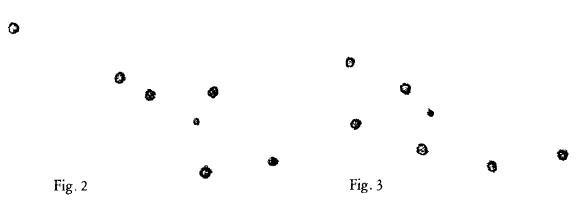

What then do we see as to the movement of the fixed stars, so-called? We must consider longer periods of time, since in short periods the Heaven of fixed stars presents practically the same picture year by year. Only when taking longer epochs do we find that it no longer presents the same uniform picture, but that the whole configuration changes. We can envisage it by taking one example; what we shall find in one region of the Heavens would be found in other regions too. Take then this constellation, which you know so well, the “Great Bear” or “Plough” in the Northern sky. Today it looks like this (Fig. 2). Acquaint yourselves with the minute displacements of the so-called fixed stars which have been ascertained, and which agree with what is shown by very ancient star-maps, although the latter are not always reliable. Sum up the minute displacements and calculate what the constellation will have looked like very long ago, and you get this appearance (Fig. 1). You see, the fixed stars, so-called, have undergone considerable displacements. About 50,000 years ago, if we may reckon it from the minute changes observed, the constellation will have looked like this. If we continue to sum up the ascertainable displacements for the future,—assuming, as we surely may do, that they will continue at least approximately in the same direction—we may conclude that 50,000 years from now the constellation will have this appearance (Fig. 3).

Just as this constellation changes in the course of years—for we have only chosen it as an example—so do the others. Thus when we make our drawings, of the Zodiac for instance in its present form, we must be clear that the form of it changes in the course of time—if we may thus include time in our calculations and in interpreting them.

We must therefore regard the celestial sphere as undergoing changes within itself, ever changing its configuration,—changing the aspect of the starry Heavens which we behold in the fixed stars,—though the perpetual change is scarcely perceptible in shorter periods. Naturally, our observations here cannot go very far, nor can we do very much by way of interpretation, though as some of you will know, modern experiments enable us to ascertain even those movements of the stars which are along the line of sight,—towards us or away from us. Yet it remains very difficult to interpret the ever-changing aspect of the starry heavens. In the further course we shall be asking, what human value and significance is to seek in the interpretation.

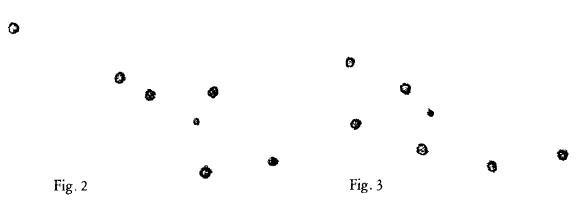

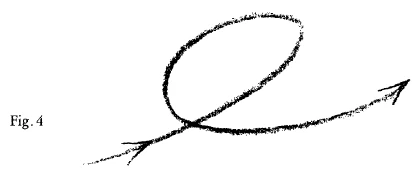

Having considered the movements of the fixed stars, let us now ask after the movements of the planetary stars. The movement of the planetary stars as we behold it is indeed complicated. The movement we observe is such that if we follow the path of a planet, in so far as it is visible, we see it moving in a curve of peculiar shape—different for the different planets and different too for the same planet at different times. From this we have to take our start. Take for example the planet Mercury. Precisely when it is nearest to us, its path is of peculiar form. In a certain direction it seems to move across the Heavens. Study it daily when visible, we see it moving thus; but them it turns and makes a loop, and then goes on as I am showing (Fig. 4).1In Figures 4 to 7 only one of the many varieties of loop which actually occur is shown in each case. It makes one such loop in a so-called synodical period of revolution. This then we may describe as the movement of Mercury—to begin with at least, so far as observation is concerned. The rest of the path is simple, only at certain places do the loops occur.

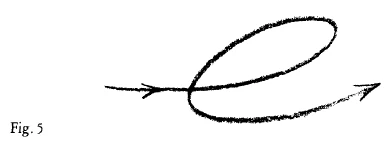

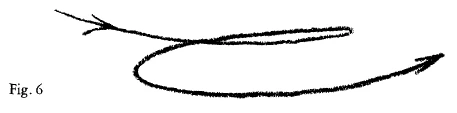

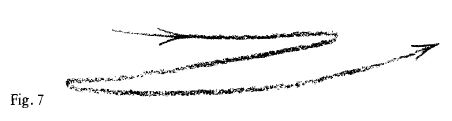

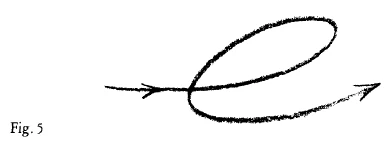

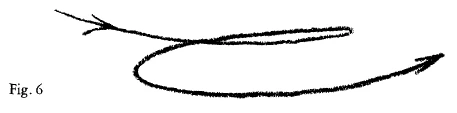

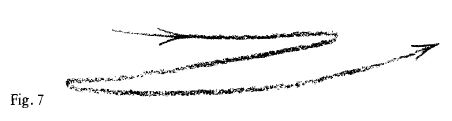

Passing to Venus we have a similar phenomenon, though somewhat different in shape and form. Venus moves onward thus, then turns and then moves on, thus (Fig. 5). Here as a rule there is only one loop in the course of a year, and, once again, when the planet—as we conclude from other astronomical data—is nearest to us. Now to Mars: Mars has a similar path, only flatter. We may draw it somewhat like this (Fig. 6). In this case, you see, the loop is more compressed, but the appearance is still that of a loop,—distinctly so. Often however the path (both of this and other planets) is so formed that the loop is completely dissolved, flattened away until it is no more. The path is loop-like, though not an actual loop. (Fig. 7) We will pass by the planetoids, interesting though they are, and look at Jupiter and Saturn. We find them too describing loops or loop-like paths. They again do it when nearest the Earth—and only once a year. As a general rule they make a single loop each year.

We have then to consider certain movements on the part of the fixed stars, and the movements of planets. The movements of fixed stars occupy gigantic periods, judged by our standards of time. The movements of the planets comprise a year or fractions of a year and reveal from time to time strange deviations from their ordinary path, loop-lines of movement, in effect. The question now is, what are we to make of these two kinds of movement? How to interpret the loop-movement for example? It is a very big question. Only the following reflection can lead towards any kind of interpretation of the loop-movements.

In all our human observation the fact is that we are quite differently related to our own conditions and to those things which are not our own;—which take place apart from us, outside us, so to speak. You need only recall how it is with objects: The enormous difference between your relation to any object of the so-called outer world and to an object inside yourself, which you, so to speak, are sharing-in with your own inner experience. If you have any object before you, you see it, you observe it. What you yourself are living in—your liver, your heart, even your sense-organs to begin with you can observe. There is the same contrast, though not quite so strongly marked, with regard to the conditions in which we are living in the outer world. If we ourselves are in movement and if it is possible for us to remain unconscious of how we bring about the movement, then we may well be unaware of our own movement and therefore leave it out of account in judging outer movements. That is to say, though we ourselves are in movement, we leave this out; we deem ourselves at rest and envisage only the external movement.

It is on this reflection, in the main, that the interpretation of movements amid the celestial phenomena has been based. You are aware, it has been argued: Man, at a certain point on Earth, shares of course in the spatial movement of his earthly habitation (eg the circling movement of his latitude) but knows it not and hence regards, what he sees happening in the Universe outside him, as a real movement in the opposite direction. The argument has been abundantly made use of! The question now is: How might this principle be modified if we take into account that in man's organized (if I may so express it) radially, whilst in our head-man we are oriented spherically. If it were then a fundamental feature of our own state of movement that we relate ourselves differently to the Radius and to the encompassing Sphere, this fact would somehow make itself felt in what appears to us in the outer Universe.

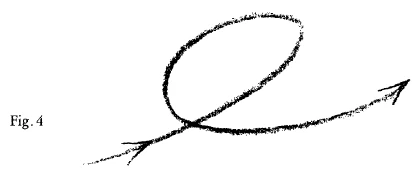

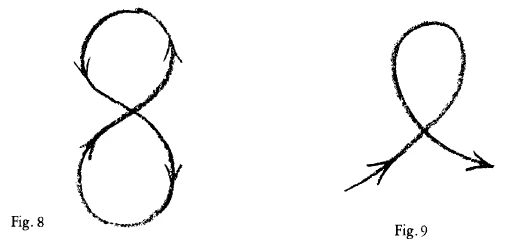

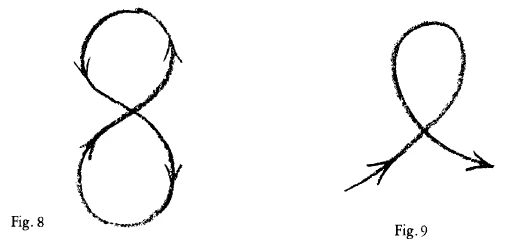

Imagine what I have said to be in some way true. Suppose for instance that you yourself were moving thus (Fig. 8),—you were describing a Lemniscate. Let us assume however that the Lemniscate you were describing was not exactly like this, but that by variation of the constants the form of Lemniscate were brought about in which the lower branch did not close (Fig. 9). Assume then that a Lemniscate arises which by a certain variation of the constants is open on one side. The curve is mathematically feasible, and if you find the right way, you can certainly draw it into the human form and figure.

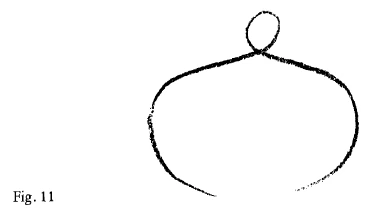

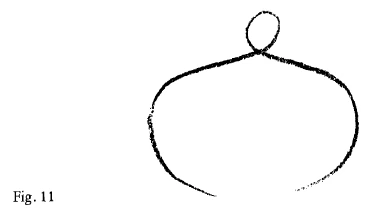

Say now that this were the surface of the Earth (Fig. 10). We should have to draw, somehow in relation to the Earth, what passes through our limb-nature and then in some way turns, goes through our head-nature and then back again into the Earth. Say you could truly draw into the nature and organisation of man such an open Lemniscate; we should be justified in saying: There is an open Lemniscate of this kind in man's nature. The question is, is it of real significance to speak of such an open Lemniscate in human nature? It is indeed. You need only make a deeper morphological study; you will find the Lemniscate, either in this or in some modified form, in diverse ways inscribed in human nature. These things have not been gone into with due method. I advise you, try it. (As I said, we are only giving indications for further work; diligent research is needed.) Try it; investigate the curve that arises if you trace the middle line of a left-hand rib, then go past the junction into the vertebra, then turn and go back along the right rib (Fig. 11). Bear in mind what it must signify that as you go along this line—rib-vertebra-rib—various inner relationships of growth must play their part, not only quantitatively but qualitatively; then you will find in the Lemniscate with its loop-formation a morphological key to the whole system. Going upward from thence to the head-organisation, the farther you go upward, the more will you find it necessary to modify the form of Lemniscate. At a certain point you must imagine it transformed; the transformation is already indicated in the forming of the sternum, where the two come together. When you get up into the head there is a far-reaching metamorphosis of the lemniscatory principle. Study the whole human figure—the contrast above all of the nerves-and-senses organisation and the metabolic,—you get a Lemniscate tending to open out as you go downward and to close as you go upward. You also get Lemniscates—though highly modified, with the one loop extremely small—if you follow up the pathway of the centripetal nerves, through the nerve-centre and outward again to the termination of the centrifugal nerve. Follow it all in the right way: Again and again you will find this Lemniscate inscribed in man's nature,—man's above all. Then take the animal organisation with its manifestly horizontal spine. You will find it differing from the human, in that the Lemniscates, whether the downward loop be open or closed to some extent, are far less modified, less varied than they are in man. Moreover in the animal their planes are more parallel, whereas in man they are variedly inclined and askew to one another.

It is an immense and very promising field of work,—this ever-deepening elaboration of morphological study. And as you apprehend these tasks, you will appreciate the outlook of such men—of whom there have always been a few—as Moritz Benedikt for instance, whom I have mentioned before. Benedikt had many fruitful thoughts and good ideas. As you may read in his memoirs, he regretted how little possibility there is of speaking to doctors of medicine from a mathematical standpoint or with the help of mathematical notions. In principle he is quite right, only we have to go still farther. Ordinary mathematics, reckoning in the main on rigid forms of curve in a rigid Euclidean space, would help us little if we tried applying it to organic forms. Only by seeking, as it were, to carry life itself into the realms of mathematics and geometry as such, by thinking of the independent and the dependent variable in an equation as being subject to an organic and inherent variation, as illustrated yesterday for the Cassini curves (Variability of the first and of the second order), only thus shall we make progress. But if you do this immense possibilities will be opened up. It is indeed already indicated in the principles applied when constructing cardioid or cycloid curves; you must only not fall back again into rigidity of treatment.

Apply this principle—the inner mobility, as it were, of movement in itself—to Nature. Try to express in equations, this that ‘moves the moving’. You will then find it possible, mathematically to penetrate what is organic. You will come to say, for it can well be formulated thus: The axioms of rigid space—space immobile in itself—lead to an understanding of inorganic Nature. Conceive a space that is inherently mobile—or algebraic equations whose very functionality is in itself a function—and you will find the transition to a mathematical understanding of organic Nature. This incidentally is the method which should accompany the efforts now being made to investigate the transition-forms from inorganic Nature to organic, as regards shape and form at least. Valueless apart from this, they have a future if this method be applied.

Take now the presence of the loop-making tendency in the human body and compare it with what confronts us, admittedly in a more irrational form, in the forms of movement of the planets. You will then realise: The 'apparent movements’ of the planets, as we are wont to call them, in a most striking way inscribe, in forms of Movement in the Heavens, what in the human body is a Form as such—a characteristic, fundamental figure. Therefore, to say the least, we must in some way correlate this basic form in the human body and these phenomena in the Heavens. And we shall now be able to say: Behold the loop. It always appears when the planet is relatively near the Earth,—therefore when we, being on the Earth, are in a special relation to the planet. Consider the position of the Earth in its yearly course and our position on the Earth. (We must refer it back to our own formative period, the embryo-period of our life, needless to say.) Consider in effect how we are alternating between a position relative to the planet wherein we turn our head towards the planetary loop and a position where we take leave of the loop and at length turn our head away from it. We in our process of formation are thus related to the planet: We are exposed at one time to the planet's loop and at another to the remainder of its path. We can therefore relate, what lies nearer to our head, to the loop, and what belongs more to the remainder of our body, to the planetary path outside the loop.

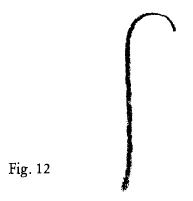

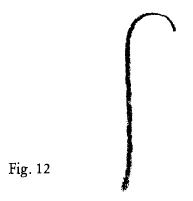

Take in addition what I said before, I said, with regard to the morphological relation of the tubular or long bone to the skull-bone: Try how you would have to draw it. Here, throughout the long bone, is the radius; then as you pass to the skull-bone you will have to turn, like this (Fig. 12). Project this turn, in relation also to the Earth's movement, outward into the Heavens. It is the loop and the rest of the planet's path! If we develop a feeling for morphology in the higher sense, we can do no other than assign the human form and figure to the planetary system.

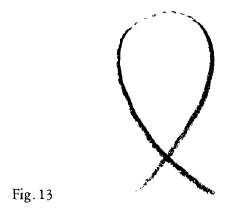

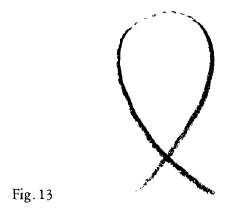

And now the movement of the fixed stars themselves:—The movements of the fixed stars will naturally be less concerned with the several movements of individual human beings. Think on the other hand of the whole evolution of mankind on Earth. Bear in mind all we have said in these days of the relation of the great Sphere to the human head-formation. You cannot but divine that there will be some relation between the metamorphoses of aspect of the starry Heavens, and of the evolution of mankind in soul and spirit. There is the vault of the great Sphere above us. It reveals only that part of the movements which would correspond to the loop among the planets (nay more, as it would seem, only to part of the loop; Fig. 13, dotted line). In the movements of fixed stars, the rest of the path is omitted. Our attention is drawn to this great differentiation: The planets must somehow correspond to the whole man; the fixed stars only to what forms the head of man. Now we begin to get some guidance, how to interpret the loop.

We human beings are in some way with the Earth. We are at some point on Earth and we move with it. We cannot but refer, what appears to us in projection on the vault of heaven, to the movements we ourselves are making with the Earth. For, as we move with the Earth (we ,must project this backward, once more, backward in time to the embryo-period of our life),—as we move with the Earth, what we have in us comes into being, formed as indeed it is by the very forces of movement. In the movements we see up yonder in their seeming forms and pictures, we have to recognise the cosmic movements we ourselves are making in the year's course. We realise it as we approach the true aspect of the loop-curve. (Downward of course we always see the loop still open. In the immediate aspect, it does not close at all. Looking at this alone, we should never get a complete path. We only get the complete path when contemplating the entire revolution.)

I am relating all this rather quickly. You must reflect on it in detail and try to see the different things together. The more minutely and scrupulously you do so, the more will you find that the planetary movements are, to begin with, images—images of—movements you yourself accomplish, with the Earth, in the year's course. (We shall see in time, how a synthesis arises from the different planetary movements.)

If then we see the human being as a whole and his projection to the Cosmos, we are led to recognise that the true form of movement of the Earth in the year's course will be the loop-curve or Lemniscate. We shall have to study it more closely during the next few days, but at this stage we are already led to conceive the path of the Earth itself as a loop-curve—quite apart now from its relation to the Sun or any other factor. What is projected then, for our perception, the planetary paths with the loops they make,—we must regard as the projection by the planets of the loop-path of the Earth on to the vault of Heaven, if we may formulate thus simply a very complicated set of facts. As to why, when the planet draws near the loop, we have to leave the rest of the path open during a relatively short space of time,—the reason lies in the fact that under certain conditions the projection of a closed curve may appear open. For example, if you were to make a Lemniscate, say of a flexible rod, and project the shadow of it on to a plane, you could easily make it so that the projection of the lower part appeared divergent and unclosed, whilst the upper part alone was closed; so the entire projection would become not unlike a planetary path. Quite simply in the shadow-figure, you could construct the likeness of a planet's path.

Elfter Vortrag

Es werden jetzt durch die vorhergehenden Betrachtungen die wesentlichsten Vorbedingungen geschaffen sein, um nun einiges von Himmelserscheinungen und auch von physikalischen Erscheinungen zu betrachten, natürlich nur von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus. Wir haben ja den großen, bedeutsamen Gegensatz in der Menschennatur charakterisiert zwischen der Organisation des Hauptes und der Organisation des Stoffwechselsystems, zu dem dann auch die Gliedmaßen zu rechnen sind. Dabei muß man, wie Sie ja leicht begreifen werden, von der tierischen Organisation absehen. Wir haben gesehen, daß, wenn wir den Menschen hinordnen wollen auf den Kosmos, wir zuzuordnen haben dasjenige, was Stoffwechselsystem ist, dem Erdhaften, demjenigen also, was sich zum Menschen verhält in einer Radialrichtung. Wir haben ferner gesehen, daß wir der Hauptesbildung zuzubeziehen haben alles dasjenige, was der Sphäre entspricht, was also gewissermaßen seine Wirkungslinien von der Sphäre nach dem Mittelpunkt der Erde hin so lenkt, wie der Radius in seinem Verlauf Wirkungslinien, die von ihm ausgehen, nach seiner Umgebung lenkt (Fig. 4 und 3). Wir haben uns das veranschaulicht an der Konstruktion der ausgesprochenen Röhrenknochen und an der Konstruktion des sphärenartigen oder Sphärensegment-artigen Schädelknochens.

Wenn wir nun diesen Unterschied ins Auge fassen, dann müssen wir ihn ja zunächst beziehen auf dasjenige, was uns im Zusammenhang zwischen Erde und Himmelssphäre erscheint. Sie wissen ja alle, wie das wissenschaftliche Bewußtsein heute sich unterscheidet von dem, was der naive Mensch, der etwa gar nicht berührt ist von irgendwelchen Schulerkenntnissen, hält von dem Aussehen der Sphäre, von den Bewegungen der Sterne über die Sphäre hin und so weitet. Und Sie wissen, daß das letztere ja bezeichnet wird als der «scheinbare Aspekt» unseres Himmelsgewölbes. Sie wissen, daß dem gegenübertritt dann ein Bild, ein Weltenbild, welches in einer sehr komplizierten Weise dutch Interpretation der scheinbaren Bewegungen und so weiter zustandekommt und das man gewöhnt ist in der Form, in der es sich aus dem großen Umschwung in den Anschauungen seit der kopernikanischen Zeit herausgebildet hat, der Betrachtung der Himmelserscheinungen zugrunde zu legen.

Es ist sich ja wohl heute jeder darüber klar, daß dieses Weltenbild nicht der absoluten Wirklichkeit entsprechen kann, daß man also nicht etwa sagen kann, dasjenige, was uns da entgegentritt zum Beispiel als Planetenbewegungen oder als Verhältnis der Sonne zu den Planeten, sei die wahre Gestalt des dabei Zugrundeliegenden, und dasjenige, was das Auge sieht, sei eben nur das Scheinbare. Auf diesem Standpunkte dürfte wohl heute kaum irgendein Urteilsfähiger stehen. Aber ein solcher wird doch das Gefühl haben, daß man sich von einem Scheinbilde, das durch allerlei Illusionsursachen in der Betrachtung hervorgerufen wird, mehr dem wahren Bilde nähert, indem man vorschreitet von diesem doch tatsächlich und sachlich zu beobachtenden Bilde zu dem, was die rechnende, beobachtende Astronomie daraus interpretierend macht.

Nun handelt es sich darum, ob es wirklich für eine umfassende Betrachtung der Naturerscheinungen auf diesem Gebiete tunlich ist, nur diejenige Art von Interpretation zugrunde zu legen zur Ausgestaltung eines Weltbildes, die gewöhnlich zugrunde gelegt wird. Sie haben ja schon gesehen, es wird dabei eigentlich nur dasjenige zugrunde gelegt, was sich gewissermaßen dem Kopfmenschen ergibt; was gewissermaßen der Aspekt ist, den sich das Beobachtungsvermögen des Menschen, auch das bewaffnete Beobachtungsvermögen des Menschen macht. Aber wir haben auf die Notwendigkeit hingewiesen, zu einer umfassenderen Interpretation dieses Weltbildes zu Hilfe zu nehmen alles dasjenige, was überhaupt vom Menschen gewußt werden kann; gewußt werden kann einerseits durch die Betrachtung seiner Gestalt. Wir haben zu diesem Zwecke hervorgehoben, wie man nach einer wahren Metamorphosenlehre diese Gestalt des Menschen zu betrachten hat. Andererseits haben wir auch hervorgehoben, daß zu Rate gezogen werden muß die Entwickelung des Menschen und die Entwickelung der Menschheit, und daß man eigentlich erst dann über gewisse Erscheinungen am Himmel eine Aufklärung erwarten kann, wenn man eben so weit geht in der Zuhilfenahme desjenigen, was man vom Menschen wissen kann, zur Interpretation der Himmelserscheinungen. Indem wir das voraussetzen, was wir in Anlehnung an die menschliche Gestalt und menschliche Entwickelung gewissermaßen wie eine qualitative Mathematik uns angeeignet haben, wollen wir nunmehr ausgehen von dem, was sich zunächst der äußeren Betrachtung als sogenanntes Scheinbild darbietet, und wollen dann versuchen, von diesem Scheinbilde aus die Frage zu stellen, wie der Weg nun sein könne zur entsprechenden Wirklichkeit.

Da wollen wir zunächst uns die Frage vorlegen: Was bietet sich uns nach der Empirie, nach der Beobachtung, also gewissermaßen nach dem Augenschein - wir können ja nur versuchen, dasjenige, was der Augenschein darbietet, dann gewissermaßen auszufüllen mit dem, was die ganze menschliche Organisation nach Morphologie und Entwickelung darbietet -, was bietet uns zunächst der Augenschein, wenn wir diejenigen Sterne betrachten, die man gewöhnlich Fixsterne nennt? Ich wiederhole wohl jetzt für die meisten gut Bekanntes, aber wir müssen uns dieses gut Bekannte vergegenwärtigen, weil wir nur dadurch, daß wir die entsprechenden Beobachtungsresultate zusammenhalten, dann zu Begriffen fortschreiten können.

Was bietet uns die Bewegung der sogenannten Fixsterne? Da müssen wir natürlich längere Zeiträume zu Hilfe nehmen, denn in kurzen Zeiträumen ist es Ja so, daß der Fixsternhimmel im wesentlichen Jahr für Jahr dasselbe Bild darbietet. Erst dann, wenn längere Zeiträume ins Auge gefaßt werden, stellt sich heraus, daß allerdings über diese längeren Zeiträume hin der Fixsternhimmel keineswegs dieses gleichmäßige Bild darbietet, daß er in seiner ganzen Konfiguration sich verändert. Nun, wir wollen uns nur von einem Punkte ausgehend etwa diese Veränderung vor Augen stellen, denn dasjenige, was ein Gebiet darbietet, bieten ja in dieser Beziehung auch die anderen Gebiete dar. Nehmen Sie einmal diese Sternzusammenhäufung, die Sie gut kennen, den «Großen Bären» oder den «Wagen» am nördlichen Himmel. Diese Sternzusammenhäufung, sie sieht heute so aus (Fig.1). Wenn Sie sich bekanntmachen mit den Beobachtungen, welche die kleinen Verschiebungen der sogenannten Fixsterne liefern, die aber durchaus auch übereinstimmen mit demjenigen, was Sternkarten, die den älteren Zeiten angehören, darbieten, obwohl sie nicht immer ganz verläßlich sind, und wenn Sie durch Summierung dieser kleinen Verschiebungen diese Sternzusammenhäufung für einen sehr weit zurückliegenden Zeitraum errechnen, so sieht sie so aus (Fig. 2). Sie sehen, die einzelnen sogenannten Fixsterne haben sich wesentlich verschoben; das ganze Sternbild hat, wenn man es ausrechnet nach den kleinen Verschiebungen für einen Zeitraum, der etwa 50,000 Jahre hinter unsere Zeit zurückrückt, so ausgesehen.

Wenn wir die Verschiebungen, die wir konstatieren können, weiter summieren für die Folgezeit, wenn wir also voraussetzen, was ja durchaus eine zuverlässige Annahme ist, daß die Verschiebungen in demselben Sinn, oder wenigstens annähernd demselben Sinn, sich weiter vollziehen, dann wird in weiteren 50000 Jahren das Sternbild etwa so aussehen (Fig. 3). Und geradeso wie dieses Sternbild, das wir nur als ein Beispiel vor uns hinstellen wollen, sich so im Lauf der Jahre verändert, so verändern sich auch die anderen Sternbilder. Wenn wir uns in seiner heutigen Gestalt den Tierkreis aufzeichnen, so müssen wir durchaus uns klar sein, daß dieses ganze figurale Gebilde des Tierkreises, insofern wir rechnend interpretieren und die Zeit überhaupt in unsere Rechnung einbeziehen, eigentlich im Laufe der Zeit ein anderes Aussehen annimmt. Wir sehen also, wir haben die Sphäre so zu betrachten, daß sie sich gewissermaßen innerlich verändert, daß sie fortwährend, wenn auch dieses «fortwährend» natürlich in kleinen Zeitabschnitten nicht beobachtet werden kann, eine andere Konfiguration in bezug auf den Aspekt des Sternhimmels, der sich uns in den Fixsternen darbietet, zeigt. Die Beobachtungen können hier selbstverständlich zunächst nicht sehr weitgehend sein in bezug auf dasjenige, was wit für ihre Interpretation tun können, obwohl, wie einige von Ihnen wissen werden, gerade neuere physikalische Versuchsanordnungen gemacht worden sind, die es ermöglichen, auch die Bewegungen des Sternes, die in der Visierlinie liegen, also Bewegungen von uns weg und zu uns hin, zu konstatieren. Es bleibt aber doch eine große Schwierigkeit selbstverständlich immer übrig, dasjenige, was da eigentlich als der fortwährende Aspekt des Sternenhimmels sich darbietet, zu interpretieren. Es wird sich allerdings im weiteren Verlauf unserer Betrachtungen zeigen, inwiefern diese Interpretation irgendeinen menschlich bedeutungsvollen Wert haben könnte.

Nun, nachdem wir auf diese Weise gesehen haben, welches die Bewegungen der Fixsterne sind, wollen wir einmal nach der Bewegung der planetarischen Sterne fragen. Diese Bewegung der planetarischen Sterne, so wie sie sich uns darbietet, die zeigt allerdings einige Komplikationen. Die beobachtbare Bewegung ist so, daß man den Planeten, wenn man seine Bahn, soweit sie sichtbar ist, verfolgt, in einer Kurve sich bewegen sieht, die aber eine merkwürdige Gestalt annimmt, für die einzelnen Planeten verschieden und auch bei ein und demselben Planeten nacheinander verschieden, und die zunächst dasjenige ist, an das wir uns zu halten haben. Nehmen wir zum Beispiel den Planeten Merkur. Er zeigt uns gerade dann, wenn er am meisten in unserer Nähe ist, eine merkwürdige Gestaltung seiner Bahn. Gewissermaßen kommt er am Himmel in einer bestimmten Richtung daher. Wir sehen ihn in dieser Weise sich bewegen (Fig. 4), wenn wir ihn, da wo er sichtbar ist, täglich studieren. Dann aber wendet er sich um, bildet eine Schleife, und geht dann wiederum so fort. Diese Schleife bildet er einmal während eines Jahres. Das Phänomen ist zu beobachten beim Merkur gewöhnlich im Beginn des Jahres, und es ist dasjenige, was wir zunächst für die Beobachtung eben die Merkurbewegung nennen können. Die übrige Bahn ist einfach, nur an der einen Stelle zeigt er diese Schleife. Wenn wir zur Venus gehen, so zeigt uns diese eine ähnliche Erscheinung, nur etwas anders gestaltet. Sie bewegt sich so (Fig. 5), wendet sich dann um und geht so weiter. Wiederum finden wir nur eine einzige Schleife im Laufe des Jahres, und zwar auch wiederum dann, wenn uns der Planet, wie man eben nach anderen astronomischen Begriffen annehmen muß, am nächsten steht. - Wenn wir zum Mars gehen, so hat er auch eine ähnliche Bahn, nur ist sie mehr abgeflacht. Wir können die Bahn des Mars etwa so zeichnen (Fig. 6). Sie sehen, die Schleife ist hier mehr zusammengedrückt, aber man hat es auch mit einer Schleife, mit einer Schleifenerscheinung zu tun. Wir finden aber auch seine Bahn, oder die der anderen Planeten, oft so gestaltet, daß die Schleife sich förmlich aufgelöst hat; sie ist so abgeflacht, daß sie sich aufgelöst hat. Es ist also, könnte man sagen, nur eine schleifen-ZArdiche Bahn (Fig. 7). - Wenn wir dann absehen von den ja auch immerhin interessanten kleinen Planeten und betrachten den Jupiter oder den Saturn, so finden wir, daß auch diese beiden Planeten dann diese Schleife oder schleifenähnliche Bahn (wie Mars) ziehen, wenn sie der Erde besonders nahe sind, und nur einmal während des Jahreslaufes. Also, sie bilden im allgemeinen im Jahre eine einzige Schleife.

Nun haben wir da also zunächst von Fixsternen gewisse Bewegungen uns vorzuhalten und dann die Bewegungen von Planeten; von Fixsternen solche Bewegungen, die ganz offenbar Riesenzeiträume umfassen, wenn wit unsere Zeitvorstellungen zugrunde legen; von Planeten solche Bewegungen, welche das Jahr oder Teile eines Jahres umfassen, und welche uns durch eine kurze Zeit eben ganz merkwürdige Abweichungen von ihrer sonstigen Bahn in Schleifenlinien zeigen. Die Frage entsteht nun: Was sollen wir aus diesen zwei Arten von Bewegungen machen? Wie können wir zu einer Interpretation zum Beispiel dieser Schleifenbewegung kommen? Das ist ja in der Tat die große Frage. Und es kann nur die folgende Erwägung dazu führen, irgendeine Interpretation dieser Schleifenbewegung zu finden.

Sehen Sie, bei unserer menschlichen Beobachtung liegt ja das in durchgreifender Weise vor, daß wir in einer ganz anderen Art uns verhalten zu demjenigen, was unser eigener Zustand ist, und demjenigen, was nicht unser eigener Zustand ist, was also gewissermaßen, abgesehen von uns, außer uns sich abspielt. Sie brauchen sich ja nur daran zu erinnern, welch gewaltiger Unterschied ist zwischen der Art, wie Sie sich verhalten zu irgendeinem Objekt der sogenannten Außenwelt und zu einem Objekt in Ihrem eigenen Innern, das Sie gewissermaßen miterleben. Wenn Sie irgendeinen Gegenstand vor sich haben, so sehen Sie ihn, beobachten Sie ihn. Dasjenige, in dem Sie leben, Ihre Leber, Ihr Herz, die Sinnesorgane selber zunächst, das können Sie nicht beobachten. Dieser Gegensatz ist aber auch vorhanden, wenn auch nicht in demselben scharfen Maße, in bezug auf Zustände, in denen wir uns in der Außenwelt befinden. Wenn wir selber in Bewegung sind, können wir, wenn es möglich ist, unbewußt zu bleiben über dasjenige, was wir zu dieser Bewegung unternehmen müssen, von dieser Bewegung selbst nichts wissen und können dann unsere Eigenbewegung unberücksichtigt lassen gegenüber äußeren Bewegungen; wir können uns gewissermaßen, trotzdem wir bewegt sind, als in Ruhe befindlich ansehen und nur die äußere Bewegung ins Auge fassen. Das ist ja dasjenige, was im wesentlichen der Interpretation der Bewegung der Himmelserscheinungen zugrunde gelegt worden ist. Sie wissen, es ist gesagt worden, daß der Mensch ja selbstverständlich, indem er auf einem Punkt der Erde steht, die Bewegung des betreffenden Punktes auf dem Parallelkreis im Raum durchaus mitmacht, aber nichts davon weiß, sondern im Gegenteil dasjenige, was außer ihm geschieht, als eine entgegengesetzte Bewegung sieht. Und von diesem Prinzip hat man ja in ausgiebigster Weise Gebrauch gemacht. Nun fragt es sich, wie dieses Prinzip eventuell sich modifizieren könnte, wenn wir darauf Rücksicht nehmen, daß wir ja in der menschlichen Organisation eine wirkliche Polarität haben: daß wir organisiert sind als Stoffwechselmensch, wenn ich mich des Ausdrucks bedienen darf, im radialen Sinn, und daß wir orientiert sind als Hauptesmensch im Sphärensinn. Wenn nun unserer Eigenbewegung das zugrunde liegen würde, daß wir uns in verschiedener Weise verhalten würden in bezug auf den Radius und in bezug auf die Sphäre, dann würde das sich irgendwie bemerklich machen müssen in demjenigen, was uns in der Außenwelt erscheint.

Nun stellen Sie sich einmal vor, daß dieses, was ich jetzt gesagt habe, irgendeine reale Bedeutung hätte, daß Sie zum Beispiel sich selber bewegen würden in der folgenden Weise (Fig. 8), so daß Sie selber eine Lemniskate beschreiben. Aber nehmen wir zu gleicher Zeit an, daß Sie die Lemniskate nicht so beschreiben, sondern daß in einer gewissen Weise durch Variabilität der Konstanten die Lemniskate in der Weise entsteht, daß der untere Ast sich nicht schließt, so daß die Lemniskate diese Form hat (Fig. 9). Nehmen Sie an, daß also gewissermaßen eine Lemniskate entsteht, die durch die Variabilität, die Variation der Konstanten nach der einen Seite hin offen ist, dann werden Sie in dieser Kurve, die durchaus mathematisch denkbar ist, etwas haben, was, wenn Sie es in der richtigen Weise in die menschliche Gestalt einzeichnen, Sie in diese menschliche Gestalt durchaus hereinbringen. Nehmen Sie einmal an, das hier wäre die Erdoberfläche (Fig. 10). Wir würden in irgendeiner Weise im Verhältnis zur Erde dasjenige zu zeichnen haben, was durch die Gliedmaßennatur geht, was in irgendeiner Weise sich wendet, durch die Kopforganisation geht und wiederum zurückgeht in die Erde. Dann könnten Sie in die menschliche Natur, in die menschliche Organisation eine solche offene Lemniskate einzeichnen, und wir würden sagen können: Es gibt in der menschlichen Organisation eine solche offene Lemniskate. Nun entsteht aber die Frage, ob es eine reale Bedeutung hat, von einer solchen offenen Lemniskate in der menschlichen Natur zu sprechen.

Es hat eine Bedeutung, denn man braucht nur die menschliche Natur wirklich morphologisch zu studieren, und man wird finden, daß diese Lemniskate so oder etwas modifiziert in vielfacher Weise in die menschliche Natur eingeschrieben ist. Man verfolgt nur die Dinge nicht in wirklich systematischer Weise. Aber ich rate Ihnen, versuchen Sie einmal — wie gesagt, hier sollen ja zunächst nur Anregungen gegeben werden, und es sollte durchaus sehr emsig wissenschaftlich nach dieser Richtung gearbeitet werden -, versuchen Sie einmal, Untersuchungen darüber anzustellen, welche Kurve entsteht, wenn Sie die mittlere Linie der linken Rippe zeichnen, über den Anschluß der Rippe hinausgehen in den Rückenwirbel, da sich drehen und wiederum zurückgehen (Fig. 11). Bringen Sie in Anschlag, daß der Wirbel eine wesentlich andere innere Struktur aufweist als die Rippen, und bringen Sie in Anschlag, daß das bedeutet, daß bei diesem Beschreiben der Linie Rippe-Wirbel-Rippe, natürlich nicht nur quantitativ, sondern qualitativ, innere Wachstumsverhältnisse in Betracht kommen, dann werden Sie die Morphologie dieses ganzen Systems verstehen dutch die Lemniskate, durch die Schleifenbildung. Sie werden, je mehr Sie hinaufgehen zur Kopforganisation, notwendig haben, starke Modifikationen dieser Lemniskate vorzunehmen. Es wird ein gewisser Punkt eintreten, wo Sie genötigt sind, dasjenige, was ja schon vorbereitet ist in der Bildung des Brustbeines, das Zusammengehen der beiden Bögen hier (Fig. 11), sich eigentlich als verwandelt zu denken, aber Sie bekommen eine Metamorphose, eine Modifikation dieser Lemniskatenbildung, wenn Sie zum Haupte hinaufgehen. Und Sie bekommen, wenn Sie gewissermaßen studieren die gesamte menschliche Figur in dem Gegensatz von Sinnes-Nervenortganisation und Stoffwechsel-Organisation, eine nach unten auseinandergehende und nach oben sich schließende Lemniskate. Sie bekommen auch Lemniskaten, nur sind die Lemniskaten eben sehr modifiziert, die eine Hälfte durch die eine Schleife ist außerordentlich klein, wenn Sie den Weg verfolgen, der genommen wird von Zentripetalnerven durch das Zentrum zum Ende der Zentrifugalnerven. Sie bekommen überall eingeschrieben, wenn Sie die Dinge sachgemäß verfolgen, gerade in die menschliche Natur in einer gewissen Weise diese Lemniskate.

Und wenn Sie dann beim Tiere die tierische Organisation im ausgesprochen horizontalen Rückgrat nehmen, so werden Sie finden, daß diese tierische Organisation sich von der menschlichen Organisation dadurch unterscheidet, daß diese Lemniskaten, diese nach unten offenen Lemniskaten oder auch etwas geschlossenen Lemniskaten, beim Tier wesentlich weniger Modifikationen aufweisen als beim Menschen, namentlich aber auch, daß die Ebenen dieser Lemniskaten beim Tier immer parallel sind, während sie beim Menschen schiefe Winkel miteinander einschließen.

Hier liegt ein ungeheures Arbeitsfeld, ein Arbeitsfeld, welches uns darauf hinweist, das morphologische Element immer weiter und weiter auszubauen. Erst wenn man auf solche Dinge kommt, versteht man diejenigen Menschen, die es ja immer gegeben hat, wie Moriz Benedikt, den ich ja öfter schon erwähnt habe, der auf vielen Gebieten schöne Intentionen gehabt hat, ganz schöne Gedanken gehabt hat. Er bedauerte ungeheuer - Sie können das in seinen Lebenserinnerungen nachlesen -, daß so wenig die Möglichkeit vorhanden ist, zu Medizinern von einem mathematischen Gesichtspunkte aus, mit mathematischen Anschauungen, zu sprechen. Im Prinzip ist das durchaus berechtigt, nur muß man natürlich die Sache eigentlich erweitert denken, so daß man zu sagen hat, daß einem die gewöhnliche Mathematik, welche im wesentlichen die starren Linienformen zugrunde legt, und darauf aus ist, mit dem starren euklidischen Raum zu rechnen, einem wenig helfen würde, wenn man sie anwenden wollte auf die organischen Bildungen. Allein dann, wenn man sich dadurch hilft, daß man gewissermaßen in die mathematischen Gebilde, die geometrischen Gebilde selbst Leben hineinbringt dadurch, daß man dasjenige, was in einer Gleichung auftritt als unabhängige Veränderliche und abhängige Veränderliche, wiederum in einer gesetzmäßigen Weise innerlich veränderlich denkt, so wie in dem Prinzip, das wir gestern hervorheben konnten bei der Cassinischen Kurve selber: Variabilität der ersten Ordnung und Variabilität der zweiten Ordnung; wenn man sich in dieser Weise hilft, werden ungeheure Möglichkeiten eröffnet. Das ist im Grund genommen schon angedeutet in den Prinzipien, die man anwendet, wenn man etwa eine Zykloide oder eine Cardioide und so weiter beschreibt, wenn man nur auch da nicht mit einer gewissen Starrheit vorgeht.

Wenn man gewissermaßen dieses Prinzip der innerlichen Beweglichkeit des Beweglichen selbst anwendet auf die Natur und versucht, dieses Bewegende des Beweglichen in Gleichungen hineinzubringen, so ist es möglich, mathematisch hineinzukommen in das Organische selber. So daß man wird sagen können - es ist durchaus eine Möglichkeit, dies so auszusprechen -: Die Voraussetzungen des starren, in sich unbeweglichen Raumes führen einen zum Begreifen der unorganischen Natur; wenn man übergeht zu dem in sich beweglichen Raum oder auch zu Gleichungen, deren Funktionalität in sich selber eine Funktion darstellt, dann kann man auch den Übergang finden zu der mathematischen Auffassung des Organischen. Und das ist ja eigentlich der Weg, welcher, der Gestalt nach wenigstens, begleiten muß die ja sonst wertlosen, aber dadurch, daß man sie so begleitet, außerordentlich zukunftsicheren Untersuchungen, die heute angestellt werden über die Übergangsformen des Unorganischen in das Organische.

Und nun bitte ich Sie, nehmen Sie diese Tatsache, die Tatsache des Vorhandenseins der Schleifentendenz im menschlichen Organismus, und vergleichen Sie das mit demjenigen, was da allerdings zunächst in einer mehr irrationalen Form einem entgegentritt in den Bewegungsformen der Planeten, dann werden Sie sich sagen können: In dem, was man gewöhnlich die scheinbaren Bewegungen der Planeten nennt, ist in einer ganz merkwürdigen Art an den Himmel gezeichnet in Bewegungsformen dasjenige, was eine Gestaltform, eine Grund-Gestaltform im menschlichen Organismus ist. Und wir haben zum mindesten zunächst zuzuordnen die Grund-Gestaltform im menschlichen Organismus diesen Erscheinungen am Himmel. Wir werden jetzt uns sagen können: Wenn wir die Schleife betrachten, so ist es ja so, daß diese Schleife sich immer dann zeigt, wenn der Planet in Erdnähe ist. Jedenfalls zeigt diese Schleife sich, wenn wir selbst in bezug auf unsere Stellung auf der Erde in einem besonderen Verhältnis sind zu dem Planeten. Wenn wir einfach die Stellung der Erde im Jahreslauf der Erde und unsere eigene Stellung auf der Erde in Erwägung ziehen, dann finden wir - natürlich muß dann das zurückbezogen werden auf unser Bildungsleben, das Embryonalleben, das ist ja selbstverständlich -, wie wir abwechseln zwischen einer Lage, in der wir uns so zum Planeten befinden, daß wir unser Haupt seiner Schleife zuwenden, und einer Lage, in der wir wiederum aus der Schleife herausgehen und das Haupt zuletzt von der Schleife abwenden. Wir stehen also zum Planeten so, daß wir unsere Bildung aussetzen einmal seiner Schleife, einmal seiner übrigen Bahn. Dann können wir zuordnen eben dasjenige, was mehr nach unserem Haupte zu gelegen ist, der Schleife, dasjenige, was mehr unserem übrigen Organismus zugehört, dem, was als Bahn außerhalb der Schleife liegt.

Und nehmen Sie jetzt zu diesem dazu das, was ich sagte. Ich sagte Ihnen in bezug auf das morphologische Verhältnis des Röhrenknochens zum Schädelknochen: Versuchen Sie, wie Sie dieses morphologische Verhältnis zeichnen müssen. Sie müssen es so zeichnen, daß Sie hier den Radius haben durch den Röhrenknochen, und Sie müssen dann, indem Sie zum Schädelknochen übergehen, diese Wendung machen (Fig. 12). Projizieren Sie diese Wendung im Zusammenhang mit der Erdenbewegung auf den Himmel hinaus, so bekommen Sie ja eben eine Schleife und die übrige Bahn des Planeten. Wir können also nicht anders, wenn wir einen Sinn haben für eine morphologische Betrachtungsweise im höheren Sinne, wir können nicht anders, als die menschliche Gestalt dem Planetensystem zuzuteilen.

Und gehen wir jetzt an die Bewegung der Fixsterne heran. Diese Bewegungen der Fixsterne, die werden natürlich für die einzelnen menschlichen Bewegungen wenig in Betracht kommen, aber wenn Sie die Entwickelung der Menschheit auf der Erde betrachten und alles dasjenige ins Auge fassen, was wir in diesen Tagen hier gesagt haben von der Beziehung der Sphäre zu der menschlichen Hauptesbildung, dann werden Sie nicht anders können, als die Metamorphose des Himmelsaspektes in irgendeinen Zusammenhang zu bringen mit der Metamorphose der Menschheitsentwickelung in geistig-seelischer Beziehung. Da wölbt sich die Sphäre über uns, breitet nur denjenigen Teil der Bewegungen aus, der hier bei den Planeten der Schleife entspricht, zunächst sogar nur einem Teil der Schleife entspricht (Fig. 13, gestrichelt). Es ist also aus den Bewegungen der Fixsterne das weggelassen, was die übrige Bahn ist. Wir sehen da diesen gewaltigen Unterschied: Die Planeten müssen irgendwie zusammenhängen mit unserem ganzen Menschen, die Fixsterne nur mit unserer Hauptesbildung. Und jetzt eröffnet sich uns in einer gewissen Weise ein Ausblick, wie wir die Schleife zu deuten haben:

Wir sind ja als Menschen gewissermaßen zusammen mit der Erde. Wir befinden uns an irgendeinem Punkte der Erde. Wir bewegen uns mit der Erde. Dasjenige, was sich uns nun als Projektion am Himmelsgewölbe zeigt, das müssen wir zurückführen auf diejenigen Bewegungen, die wir mit der Erde selber ausführen. Denn indem wir mit der Erde selber Bewegungen ausführen, wiederum zurückprojiziert auf unser Embryonalleben, unsere Embryonalzeit, entsteht dasjenige, was in uns ist, was ja durch die Bewegungskräfte sich bildet. Und indem wir ja immer hier nach unten die Schleife eigentlich offen sehen - sie schließt sich dann ja auch nicht für den unmittelbaren Aspekt, wir würden sogar, wenn wir dieses betrachten, nicht einmal eine geschlossene Bahn bekommen, die bekommen wir erst, wenn wir den ganzen Umlauf beobachten - so haben wir die Notwendigkeit, in den Bewegungen, die wir da eben in ihren Scheinbildern sehen, wenn wir uns der Schleife nähern, dasjenige zu sehen, was wir selber als kosmische Bewegungen ausführen im Jahreslauf. Ich sage Ihnen das, ich möchte sagen, so schnell. Sie müssen sich das in allen Einzelheiten überlegen, was ich ausgesprochen habe, und müssen versuchen, die Dinge zusammenzuhalten. Je minuziöser und je genauer Sie sie zusammenhalten, desto mehr werden Sie finden, daß sich Ihnen das ergibt, daß Sie in den planetarischen Bewegungen zunächst Abbilder haben - wir werden sehen, wie sich dann die einzelnen planetarischen Bewegungen zusammenfügen -, Abbilder derjenigen Bewegungen, die Sie mit der Erde zusammen im Jahreslauf ausführen. Wir dürfen also, wenn wir in dieser Weise den totalen Menschen zusammenfassen, seine Projektion zum Kosmos ins Auge fassen, und dürfen als die Form der Bewegung der Erde im Jahreslauf dann die Schleifenlinie oder Lemniskate ansehen. Wir müssen das natürlich in den nächsten Tagen genauer studieren, aber wir sind zunächst dahin geführt, die Bahn der Erde selber, ganz abgesehen von irgendwelchen Beziehungen jetzt zur Sonne oder zu etwas anderem, aufzufassen als eine Schleifenlinie, und dasjenige, was sich uns in den Planetenbahnen mit ihren Schleifen projiziert, haben wir aufzufassen eben als die Projektion der Erdenschleifenbahn durch die Planeten hinaus in das Himmelsgewölbe, wenn man einen komplizierten Tatbestand so einfach ausdrücken darf. Und den Grund, warum wir da, wo sich der Planet der Schleife nähert, die übrige Bahn dann offen lassen müssen in einem verhältnismäßig kürzeren Zeitraum, den müssen wir darin sehen, daß wir ja unter gewissen Bedingungen eine geschlossene Kurve in der Projektion als eine offene erhalten können. Wenn Sie zum Beispiel aus einem biegsamen Stabe eine Lemniskate bilden würden, so können Sie durchaus eine solche Anordnung machen, daß Ihnen ein irgendwie geworfener Schatten so erscheint auf einer Ebene, daß Sie den unteren Teil nicht geschlossen, sondern auseinandergehend bekommen und den oberen Teil geschlossen, so daß also das Ganze ähnlich wird der Planetenbahn. Sie können einfach in der Schattenfigur die Ähnlichkeit mit der Planetenbahn konstruieren.

Eleventh Lecture

The preceding considerations will now have created the essential preconditions for considering some of the phenomena of the heavens and also of physics, naturally only from a certain point of view. We have characterized the great, significant contrast in human nature between the organization of the head and the organization of the metabolic system, which also includes the limbs. In doing so, as you will easily understand, we must disregard the animal organization. We have seen that if we want to relate the human being to the cosmos, we must assign the metabolic system to the earthly sphere, that is, to what relates to the human being in a radial direction. We have also seen that we must relate everything that corresponds to the sphere to the formation of the head, that is, everything that directs its lines of action from the sphere to the center of the earth, just as the radius in its course directs lines of action emanating from it to its surroundings (Figs. 4 and 3). We have illustrated this with the construction of the pronounced tubular bones and the construction of the spherical or sphere-segment-like skull bone.

If we now consider this difference, we must first relate it to what appears to us in the connection between the earth and the celestial sphere. You all know how scientific consciousness today differs from what the naive person, who is not at all influenced by any school knowledge, thinks about the appearance of the sphere, the movements of the stars across the sphere, and so on. And you know that the latter is referred to as the “apparent aspect” of our celestial vault. You know that this is contrasted with an image, a world picture, which is created in a very complicated way through interpretation of the apparent movements and so on, and which we are accustomed to taking as the basis for our observation of celestial phenomena in the form in which it has developed since the great change in views since the Copernican era.

Today, everyone is well aware that this world view cannot correspond to absolute reality, that one cannot say, for example, that what we see as planetary movements or as the relationship of the sun to the planets is the true form of what is involved, and that what the eye sees is only the apparent. Hardly anyone with the capacity for judgment would take this position today. But such a person would still feel that one approaches the true image more closely from an apparent image, which is caused by all kinds of illusions in observation, by progressing from this image, which can actually be observed objectively, to what calculating, observing astronomy interprets from it.

The question now is whether it is really feasible, for a comprehensive view of natural phenomena in this field, to base the development of a world view solely on the type of interpretation that is usually taken as a basis. As you have already seen, the basis for this is actually only what, in a sense, is apparent to the intellectual person; which is, so to speak, the aspect that the human faculty of observation, even the armed faculty of observation, makes. But we have pointed out the necessity of resorting to everything that can be known by human beings in order to arrive at a more comprehensive interpretation of this world picture; on the one hand, this can be known through the observation of its form. To this end, we have emphasized how, according to a true doctrine of metamorphosis, this form of the human being must be viewed. On the other hand, we have also emphasized that the development of the human being and the development of humanity must be taken into account, and that one can only expect to find an explanation for certain phenomena in the sky if one goes so far as to use what can be known about the human being to interpret the phenomena in the sky. Presupposing what we have acquired, based on the human form and human development, as a kind of qualitative mathematics, we will now start from what initially presents itself to external observation as a so-called illusory image, and then try to ask, based on this illusory image, what the path to the corresponding reality might be.

Let us first ask ourselves the question: What does empiricism, observation, or in a sense, what we see with our eyes, offer us? We can only try to fill in what we see with what the entire human organization offers in terms of morphology and development. What does what we see offer us when we look at the stars that are usually called fixed stars? I am now repeating what is well known to most people, but we must keep this well-known fact in mind, because it is only by holding together the corresponding observational results that we can then proceed to concepts.

What does the movement of the so-called fixed stars offer us? Of course, we have to consider longer periods of time, because in short periods of time, the fixed star sky essentially presents the same picture year after year. Only when longer periods of time are considered does it become apparent that, over these longer periods, the fixed star sky does not present this uniform picture at all, but that its entire configuration changes. Now, let us form a mental image of this change only from one point of view, because what one area presents in this respect is also presented by the other areas. Take, for example, the cluster of stars that you know well, the “Great Bear” or the “Wagon” in the northern sky. This cluster of stars looks like this today (Fig. 1). If you familiarize yourself with the observations provided by the small shifts of the so-called fixed stars, which, however, are entirely consistent with what star charts from earlier times show, even though they are not always entirely reliable, and if you calculate this star cluster for a very distant period of time by adding up these small shifts, it looks like this (Fig. 2). You can see that the individual so-called fixed stars have shifted significantly; the entire constellation, when calculated according to the small shifts for a period of time that goes back about 50,000 years, looked like this.

If we continue to add up the shifts that we can observe for the subsequent period, assuming, as is a reliable assumption, that the shifts will continue in the same direction, or at least approximately the same direction, then in another 50,000 years the constellation will look something like this (Fig. 3). And just as this constellation, which we are using only as an example, changes over the years, so too do the other constellations. When we draw the zodiac in its present form, we must be aware that this entire figurative structure of the zodiac, insofar as we interpret it mathematically and include time in our calculations, actually takes on a different appearance over time. So we see that we have to view the sphere in such a way that it changes internally, so to speak, that it continually shows a different configuration in relation to the aspect of the starry sky that presents itself to us in the fixed stars, even though this “continuously” cannot, of course, be observed in small periods of time. Of course, the observations cannot be very extensive at first in terms of what we can do to interpret them, although, as some of you will know, more recent physical experiments have been carried out that make it possible to observe the movements of the stars that lie in the line of sight, i.e., movements away from us and toward us. However, there remains, of course, a great difficulty in interpreting what actually presents itself as the constant aspect of the starry sky. In the further course of our considerations, it will become clear to what extent this interpretation could have any human significance.

Now that we have seen what the movements of the fixed stars are, let us ask about the movement of the planetary stars. This movement of the planetary stars, as it appears to us, does, however, present some complications. The observable movement is such that, when one follows the planet's orbit as far as it is visible, one sees it moving in a curve, but one that takes on a strange shape, different for each planet and also different for one and the same planet from one moment to the next, and which is initially the one we have to stick to. Take the planet Mercury, for example. When it is closest to us, it shows us a strange shape of its orbit. In a sense, it comes across the sky in a certain direction. We see it moving in this way (Fig. 4) when we study it daily where it is visible. But then it turns around, forms a loop, and continues on its way. It forms this loop once a year. This phenomenon can usually be observed in Mercury at the beginning of the year, and it is what we can initially call the Mercury movement for the purposes of observation. The rest of its orbit is simple; it only forms this loop at one point. If we go to Venus, it shows us a similar phenomenon, only slightly different in shape. It moves like this (Fig. 5), then turns around and continues on its way. Again, we find only a single loop in the course of the year, and again when the planet is closest to us, as we must assume according to other astronomical concepts. When we go to Mars, it also has a similar orbit, only it is more flattened. We can draw the orbit of Mars something like this (Fig. 6). You can see that the loop is more compressed here, but it is still a loop, a loop phenomenon. However, we also find that its orbit, or that of the other planets, is often shaped in such a way that the loop has literally dissolved; it is so flattened that it has dissolved. So, one could say that it is only a loop-like orbit (Fig. 7). If we then disregard the small planets, which are also interesting, and consider Jupiter or Saturn, we find that these two planets also follow this loop or loop-like orbit (like Mars) when they are particularly close to Earth, and only once during the course of the year. So, in general, they form a single loop per year.

So now we have certain movements of fixed stars to consider, and then the movements of planets; fixed stars have movements that obviously span enormous periods of time, if we take our concept of time as a basis; planets have movements that span a year or parts of a year, and which, over a short period of time, show us very strange deviations from their usual orbit in looping lines. The question now arises: what are we to make of these two types of movement? How can we arrive at an interpretation of this looping motion, for example? That is indeed the big question. And only the following consideration can lead us to find any interpretation of this looping motion.

You see, in our human observation, it is thoroughly evident that we behave in a completely different way toward what is our own state and what is not our own state, that is, what takes place outside of us, apart from us, so to speak. You only need to remember what an enormous difference there is between the way you behave toward any object in the so-called outside world and toward an object within yourself, which you experience, so to speak, from within. When you have an object in front of you, you see it, you observe it. But you cannot observe the things you live in, your liver, your heart, your sensory organs themselves. This contrast also exists, albeit not to the same degree, in relation to states in which we find ourselves in the outside world. When we ourselves are in motion, we can, if possible, remain unconscious of what we have to do in order to move, know nothing of the movement itself, and then disregard our own movement in relation to external movements; in a sense, even though we are moving, we can regard ourselves as being at rest and focus only on the external movement. This is essentially what has been taken as the basis for the interpretation of the movement of celestial phenomena. You know, it has been said that when a person stands at a point on the earth, he naturally participates in the movement of that point on the parallel circle in space, but is unaware of this; on the contrary, he sees what is happening outside of him as an opposite movement. And this principle has been used extensively. Now the question arises as to how this principle could possibly be modified if we take into account that we have a real polarity in the human organization: that we are organized as metabolic beings, if I may use the expression, in the radial sense, and that we are oriented as head beings in the spherical sense. If our own movement were based on the fact that we behave in different ways in relation to the radius and in relation to the sphere, then this would have to be noticeable in some way in what appears to us in the outside world.

Now form a mental image of the situation in which what I have just said would have some real meaning, that you, for example, would move yourself in the following way (Fig. 8), so that you yourself would describe a lemniscate. But let us assume at the same time that you do not describe the lemniscate in this way, but that, due to the variability of the constants, the lemniscate is created in such a way that the lower branch does not close, so that the lemniscate has this shape (Fig. 9). Suppose that a lemniscate is created, so to speak, which is open on one side due to the variability, the variation of the constants. Then, in this curve, which is entirely mathematically conceivable, you will have something which, if you draw it in the right way into the human form, you can bring into this human form. Suppose that this here is the surface of the earth (Fig. 10). We would have to draw, in some way in relation to the earth, that which passes through the nature of the limbs, which in some way turns, passes through the head organization, and returns to the earth. Then you could draw such an open lemniscate into human nature, into the human organization, and we could say: there is such an open lemniscate in the human organization. But now the question arises as to whether it has any real meaning to speak of such an open lemniscate in human nature.

It does have meaning, because one only needs to study human nature morphologically to find that this lemniscate, in this or a slightly modified form, is inscribed in human nature in many ways. It's just that things are not pursued in a truly systematic way. But I advise you to try — as I said, this is only meant to be a suggestion for now, and very diligent scientific work should be done in this direction — try to investigate what curve is created when you draw the middle line of the left rib, go beyond the connection of the rib into the vertebra, turn there and go back again (Fig. 11). Bear in mind that the vertebra has a significantly different internal structure than the ribs, and bear in mind that this means that when describing the rib-vertebra-rib line, not only quantitatively but also qualitatively, internal growth relationships must be taken into account. Then you will understand the morphology of this entire system through the lemniscate, through the formation of loops. The higher you go up to the head organization, the more you will need to make significant modifications to this lemniscate. There will come a certain point where you will be compelled to think of what is already prepared in the formation of the sternum, the coming together of the two arches here (Fig. 11), as actually transformed, but you will obtain a metamorphosis, a modification of this lemniscate formation, as you move up towards the head. And if you study the entire human figure in terms of the contrast between sensory nerve organization and metabolic organization, you will see a lemniscate that diverges downward and converges upward. You will also see lemniscates, only the lemniscates are very modified, one half of the loop being extremely small, if you follow the path taken by the centripetal nerves through the center to the end of the centrifugal nerves. If you follow things properly, you will find these lemniscates inscribed everywhere, especially in human nature in a certain way.

And if you then take the animal organization in the distinctly horizontal spine of animals, you will find that this animal organization differs from the human organization in that these lemniscates, these downward-open lemniscates or even somewhat closed lemniscates, show significantly fewer modifications in animals than in humans, but also, in particular, that the planes of these lemniscates are always parallel in animals, while in humans they form oblique angles with each other.

Here lies an enormous field of work, a field of work that points us in the direction of expanding the morphological element further and further. Only when one comes to such things does one understand those people who have always existed, such as Moriz Benedikt, whom I have mentioned often, who had beautiful intentions in many areas and had very beautiful thoughts. He deeply regretted—you can read about this in his memoirs—that there was so little opportunity to talk to medical professionals from a mathematical point of view, with mathematical insights. In principle, this is entirely justified, but of course one has to think about the matter in broader terms, so that one has to say that ordinary mathematics, which is essentially based on rigid linear forms and aims to calculate with rigid Euclidean space, would be of little help if one wanted to apply it to organic formations. Only if one helps oneself by, as it were, bringing life into the mathematical structures, the geometric structures themselves, by thinking of what appears in an equation as independent variables and dependent variables as internally variable in a lawful manner, as in the principle that we were able to highlight yesterday in the Cassini curve itself: variability of the first order and variability of the second order; if we help ourselves in this way, enormous possibilities open up. This is basically already indicated in the principles that are applied when describing a cycloid or a cardioid and so on, provided that we do not proceed with a certain rigidity.

If one applies this principle of the inner mobility of the mobile itself to nature and attempts to incorporate this mobility of the mobile into equations, it is possible to enter mathematically into the organic itself. So that one can say – it is entirely possible to express this in this way –: the prerequisites of rigid, immobile space lead one to understand inorganic nature; if one moves on to space that is mobile in itself, or to equations whose functionality is itself a function, then one can also find the transition to the mathematical conception of the organic. And that is actually the path which, at least in form, must accompany the otherwise worthless, but thereby extraordinarily future-proof investigations that are being conducted today on the transitional forms from the inorganic to the organic.

And now I ask you to take this fact, the fact of the existence of the loop tendency in the human organism, and compare it with what initially appears in a more irrational form in the movements of the planets, and then you will be able to say to yourself: In what are commonly called the apparent movements of the planets, what is a form, a basic form in the human organism, is drawn in the sky in a very remarkable way in forms of movement. And we must at least initially assign the basic form in the human organism to these phenomena in the sky. We can now say to ourselves: when we look at the loop, we see that this loop always appears when the planet is close to Earth. In any case, this loop appears when we ourselves, in relation to our position on Earth, are in a special relationship to the planet. If we simply consider the position of the Earth in the course of the Earth's year and our own position on the Earth, then we find — of course, this must then be related back to our formative life, our embryonic life, that goes without saying — how we alternate between a position in which we are so situated in relation to the planet that we turn our head toward its loop, and a position in which we again leave the loop and finally turn our head away from it. We are thus positioned in relation to the planet in such a way that we expose our education once to its loop and once to its remaining orbit. Then we can assign that which is more related to our head to the loop, and that which is more related to the rest of our organism to that which lies outside the loop as an orbit.

And now add to this what I said. I told you about the morphological relationship between the long bone and the skull bone: try to draw this morphological relationship. You must draw it so that you have the radius here through the long bone, and then, as you move over to the skull bone, you must make this turn (Fig. 12). If you project this turn in connection with the Earth's movement onto the sky, you get a loop and the rest of the planet's orbit. So if we have a sense of morphological observation in the higher sense, we cannot help but assign the human form to the planetary system.

And now let us approach the movement of the fixed stars. These movements of the fixed stars will, of course, be of little consideration for individual human movements, but if you consider the development of humanity on Earth and take into account everything we have said here in recent days about the relationship of the sphere to the formation of the human head, then you cannot help but connect the metamorphosis of the celestial aspect in some way with the metamorphosis of human development in a spiritual and soul-related sense. The sphere arches above us, spreading out only that part of the movements which corresponds here to the planets of the loop, initially even only to a part of the loop (Fig. 13, dashed line). So what is omitted from the movements of the fixed stars is the rest of the orbit. We see this enormous difference: the planets must somehow be connected with our whole human being, the fixed stars only with our head formation. And now, in a certain way, a view opens up to us of how we are to interpret the loop:

As human beings, we are, in a sense, together with the Earth. We are located at some point on the Earth. We move with the Earth. What now appears to us as a projection on the vault of heaven must be traced back to the movements that we perform with the Earth itself. For by performing movements with the Earth itself, projected back onto our embryonic life, our embryonic period, we create what is within us, which is formed by the forces of movement. And since we always see the loop open down here – it does not close for the immediate aspect, we would not even get a closed path when we look at this; we only get that when we observe the entire cycle – so we have the necessity, in the movements that we see there in their illusory images, when we approach the loop, to see what we ourselves perform as cosmic movements in the course of the year. I am telling you this, I would like to say, so quickly. You must consider in detail what I have said and try to hold the things together. The more meticulously and accurately you hold them together, the more you will find that it becomes clear to you that you first have images in the planetary movements — we will see how the individual planetary movements then fit together — images of the movements that you perform together with the Earth in the course of the year. So when we summarize the total human being in this way, we can consider his projection into the cosmos, and we can then regard the loop line or lemniscate as the form of the Earth's movement in the course of the year. Of course, we will have to study this in more detail over the next few days, but we are initially led to understand the Earth's orbit itself, quite apart from any relationship to the Sun or anything else, as a loop line, and what is projected to us in the planetary orbits with their loops, we must understand as the projection of the Earth's loop orbit through the planets out into the vault of heaven, if one may express such a complicated fact in such simple terms. And the reason why we must leave the rest of the orbit open in a relatively shorter period of time where the planet approaches the loop must be seen in the fact that, under certain conditions, we can obtain an open curve in the projection from a closed one. For example, if you were to form a lemniscate from a flexible rod, you could arrange it in such a way that a shadow cast in some way would appear on a plane so that the lower part is not closed but diverging and the upper part is closed, so that the whole thing resembles the planetary orbit. You can simply construct the similarity to the planetary orbit in the shadow figure.