World Economy

GA 340

25 July 1922, Dornach

Lecture II

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is precisely in this sphere of Political Economy that the first conceptions and ideas which we have to develop cannot but be a little complicated—and for a perfectly genuine reason. For you must imagine the economic process, considered even as a world-economy, as a thing of perpetual movement. As the blood flows through the human being, so do goods, as merchandise or commodities, flow by every conceivable channel through the whole economic body. And we must conceive, as the most important thing within this economic process, all that takes place in buying and selling. That, at least, is true of the economic life of today. Whatever else there may be—and we shall of course have to consider the most varied impulses contained in the economic life—whatever else there may be, the subject of Economics comes home to a man directly [when/if] he has anything to buy or sell. In the last resort the instinctive thinking of every naive man on economic matters culminates in the process taking place between buyer and seller. Fundamentally, this is what it all comes to.

Consider now: What is it that counts when buying and selling are considered in the economic process? The thing that a man cares about will always be the price of a commodity, the price of the piece of goods concerned. In the last resort all the most important economic considerations really merge in this question of Price. All the impulses and forces that are at work in economics culminate at length in Price. We shall, therefore, first have to consider the problem of Price, but it is by no means a simple problem. You need only consider the most simple case: At a given place, A, we have a certain commodity: at place A it has a certain price. But suppose it is not bought there but is first transported to another place, B. Our endeavour will then be to add to the price whatever transport charges had to be paid from A to B. Thus the Price changes in the process of circulation. There we have the simplest—if I may put it so, the flattest—instance: but of course there are far more complex cases.

Assume, for instance, that at a given date a house in a large town costs so much. Fifteen years later the same house may perhaps cost six times as much: nor need we imagine that the main cause of the rise in price lies in the devaluation of money. On the contrary, let us assume that this is not the case. The rise in price may simply lie in this: that in the meantime many other houses have been built around it: the other buildings, now situated in its neighbourhood, greatly increase the value of the house. Nay, there may be ten or fifteen other circumstances accounting for the rise in price. Truth to tell, we are never in a position to apply some general statement to the single case—to say, for instance: The price of houses, or railways, or cereals, can he uniquely determined, at a given place, from certain specified conditions. To begin with, we can say little more than this: that we must observe how the price fluctuates with place and time. Then, perhaps, we can trace some of the conditions whereby at a given place a given price actually emerges. But there can be no such thing as a general definition stating how the price of a thing is composed: that is an impossibility. Again and again one is astonished to find Price discussed in the ordinary works on Economics, as though it were possible to define it. We simply cannot define it, for a price is always concrete and specific. Altogether, in economic matters, it is impossible to get anywhere near the realities by definitions.

I once witnessed the following case: In a certain district land is comparatively cheap. There is a Society with a more or less famous man in its midst. The Society buys up all the cheap plots of land, and prevails upon the famous man to build himself a house there. Then the plots of land are offered for sale. They can be offered at a considerably higher price than they were bought for, for the simple reason that the famous man has been persuaded to build himself a house there.

Such instances will show you how indeterminate are the conditions on which the price of a thing depends in the economic process. Of course, you may say, such developments must be counteracted. Land reformers and people with similar aims try to resist these things. Through various artificial measures they desire to establish a kind of just price for all things. Of course one can do so: but, economically considered, the price is not changed thereby. In the above instance, for example, when the plots of land are sold at a higher price, we can take the money away again, in the form of a high property-tax. Then the State will pocket the difference: but the reality remains as before. In reality the increase in price has taken place just the same. You can take preventive measures, they will but obscure the issue. The price will still be what it would have been without them. You only bring about a redistribution: and it is no true economic thinking to say that the land has not increased in price during the last ten years, simply because you have obscured the matter by artificial measures. Economic Science must stand firmly on its feet, on a basis of reality. In Economics we can only speak of the conditions obtaining at a given time and at the actual place to which we are referring. Needless to say, anyone who desires the progress of mankind will still come to the conclusion that such and such things are to be changed. But, to begin with, things must be observed in their immediate reality at the particular moment. From all this you will see how impossible it is to approach such a concept as this—the most important in Economics (I mean the concept of Price)—by seeking to grasp it with sharply defined notions. In the science of Economics we can make no progress by this means: quite other ways must be adopted. We must observe the economic process itself.

Yet the problem of Price is of cardinal importance: all our efforts must be directed to this. We must observe the economic process, and try, as it were, to catch the point where (at any given place and time) the actual price of a given thing results from all the underlying economic causes.

Now if you take the ordinary economic doctrines, you will generally find three factors mentioned—three factors, through the interplay of which the whole economic process is supposed to take its course. They are: Nature, human Labour and Capital. It is true that we can say to begin with: Tracing the economic process we find these three: that which comes from Nature, that which is achieved by human Labour and that which is derived from, or directed by means of, Capital. But if we take Nature, Labour and Capital simply side by side in this way, we shall not grasp the economic process in a living way. On the contrary, we shall be led to many one-sided points of view—a fact to which the history of economic theory bears eloquent witness. Some say that all Value is inherent in Nature and that no especial value is added to the substance of natural objects by human Labour. Others believe that all true economic Value is really impressed on a piece of goods, on a commodity, by the Labour which, as they some-times say, is crystallised in the commodity. Or again, the moment you place Capital and Labour merely side by side, you will find persons saying on the one hand: In reality it is Capital which alone makes Labour possible and the wages of Labour are paid out of the accumulated Capital. On the other side it is said: No, the only thing that produces real Value is Labour, and all that Capital obtains for itself is the surplus value abstracted from the yield of Labour.

Ladies and gentlemen, the fact is this: Consider the things from the one point of view, and the one is right: consider them from the other point of view, and the other is right. Over against the reality, such ways of thinking remind one of many a method in book-keeping—put the item here and this will be the result: put it there, and that will. One can speak with strong apparent reasons of surplus value, saying that this is abstracted from the wages of Labour and appropriated by the capitalist to himself. But one can say with equally good reasons, that, in the whole connection of economic life, everything is due in the first place to the capitalist, who can only pay his workers from what he has available for the wages of Labour. For both these points of view there are very good and very bad reasons. In fact, none of these ways of thinking comes near the reality of economics. Excellent as a basis for agitations, they are of no importance in a serious economic science. Quite other foundations must be found if we would hope for progress in economic life.

Up to a certain point, of course, all these systems have their justification. Adam Smith, for instance, sees the real, original value-forming factor in the work or labour that is expended on things. Here again excellent reasons can be brought forward in support of this view. Such a man as Adam Smith certainly did not think in a stupid or nonsensical way. Nevertheless, here again there is the underlying idea of taking hold of something static and giving it a definition, whereas in the real economic process things are in perpetual movement. It is comparatively simple to form concepts of the phenomena of Nature—even the most complicated—as compared with the ideas which we require for a science of Economics. Infinitely more complicated, variable and unstable are the phenomena in Economics than in Nature—more fluctuating, less capable of being grasped with any defined or hard and fast concepts. In effect, an altogether different method must be adopted. You will only find this method difficult in the first lessons: but as a result of it—you will presently see—we shall discover the only real and possible foundation for a science of Economics.

To begin with, we may say that to this economic process, which we must now consider, three things contribute: Nature, human Labour and (thinking, to begin with, of the purely external economic aspect) Capital. To begin with, ladies and gentlemen!

But lest us consider at once the middle one of these three, namely, human Labour. Let us try to form a conception of it by going down, as I indicated yesterday, into the sphere of animal life. Let us observe, instead of the economy of peoples, the economy of sparrows, the economy of swallows.

Here, you see at once, Nature is the basis of economy. True, even the sparrow has to do a kind of work: at the very least, he must hop about to find his food. Sometimes he has to hop about a very great deal in the course of a day to find what he requires. The swallow building her nest also has to do a kind of work, and she again has much to do to build it. Nevertheless, in the true economic sense, we cannot call this “work,” we cannot call it “Labour.” We shall make no progress in economic ideas if we call this labour. For if we observe more closely, we shall have to admit: The sparrow and the swallow are organised precisely in such a way as to do the very things—fulfil the very functions—which they fulfil in finding their food, etc. They simply could not be healthy if they had no opportunity to move about in this way. It is part and parcel of their organisation: it belongs to them, no less than their legs and wings. In seeking to build up economic concepts, we can therefore leave out of account what we might here call a mere “apparent Labour,” a “semblance of Labour.” In such cases Nature is taken just as she is, and the single creature, merely to satisfy its own needs or those of its nearest kin, carries out the corresponding “semblance of Labour.” If, however, we wish to determine what is “Value” or “a Value” in the true economic sense, we must disregard this apparent Labour. And this must be our first object—to approach a true concept of “economic value.”

Consider the animal economy once more. There we may say: Nature alone is the value-forming factor. If we now ascend to man, that is, to political economy, it is true we still have—from the side of Nature—the same starting-point of “Nature Value.” But the moment human beings no longer provide merely for themselves or for their nearest kindred, but for one another, “human Labour,” properly so called, comes into account. Indeed, the moment a man no longer uses the Nature-products for himself, but stands in some relation to other human beings—if only to the extent of bartering his goods with theirs—what he then does becomes, in relation to Nature, “human Labour.” Here we arrive at the one aspect of Value in Political Economy. It arises thus: Human Labour is expended on the products of Nature, and we have before us in economic circulation Nature-products transformed by human Labour. It is only here that a true economic value first arises. So long as the Nature-product is untouched, at the place where it is found in Nature, it has no other value than it has, for instance, for the animals. But the moment you take the very first steps to put the Nature-product into the process of economic circulation, the Nature-product so transformed begins to have economic value. We may therefore characterise this economic value as follows: “An economic value, seen from this one aspect, is a Nature-product transformed by human Labour.” Whether the human Labour consists in digging or chopping, or merely moving a product of Nature from one place to another, is irrelevant. If we are seeking the determination of Value in general, then we must simply say: “One value-forming factor is human Labour, transforming a Nature-product so as to pass it into the economic process of circulation.”

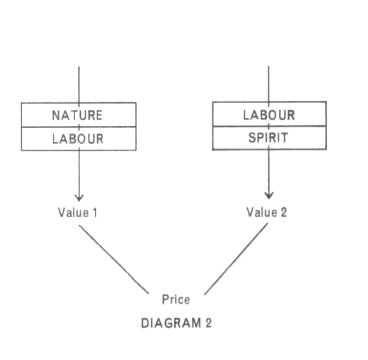

If you consider this, you will see at once how very fluctuating is the value of a piece of goods circulating in the economic life. For Labour is something always present, perpetually being expended on the goods. You cannot really say what Value is—you can only say: Value appears in a given place and at a given time, inasmuch as human Labour is transforming some product of Nature. That is where Value emerges. To begin with, we cannot and will not try to define Value: We simply point out the place where it appears. I will put this down diagrammatically. (see Diagram 2) Here on the left side of the drawing we have Nature as it were in the background. Human Labour approaches Nature: what then becomes visible—appearing, as it were, through the interplay of Nature and human Labour—that is the one aspect of economic value? It is by no means a faulty image if we say, for instance: Look at a black surface or at anything black through a luminous medium and you will see it blue. According as the luminous medium is thick or thin, you will see various shades of blue: according as you shift it, its density will vary: it is for ever fluctuating. So it is

with Value in the economic life, it is really none other than the appearance of Nature through human Labour. And that, too, is always fluctuating.

To begin with, we are gaining a few abstract indications and little more: but these will give us our bearings during the next few days and help us to reach more concrete things. After all, you are accustomed to this: for in all sciences one takes what is most simple to begin with.

You see, labour as such has no purpose at all in Economics. A man may chop wood, or he may get up on to a wheel like this. (There are such wheels for the benefit of fat people who go on climbing from step to step; the wheel goes round under them, and so they hope to get thinner.) The man who treads this wheel may be doing just as much work as the one who chops wood. To consider Labour as Marx did, when he said that we should look for its equivalent in the amount that is consumed in the human organism by the Labour, is a colossal piece of nonsense. For the same amount is consumed whether a man chops wood or dances about on this wheel. How much is done in the human being is not the point in Economics. We have already seen how the subject of Economics borders on uneconomic matters. Purely economically speaking, it is quite unjustifiable to point to the fact that Labour uses up the human being's forces. I mean it is unjustifiable in this connection, where, to begin with, we wish to establish a concept of Labour in the sense of Economics. Indirectly it is of great significance, for on the other side the needs of men have to be cared for. But Marx's way of thinking at this point is a colossal piece of nonsense.

What do we need in order to take hold of “Labour” in the economic process? It is necessary, to begin with—quite apart from the human being—to observe how the Labour enters into the economic process. This labour (of the man on the wheel) does not enter it at all: it simply adheres to the man himself. The chopping of wood, on the other hand, does enter the economic process. The one thing that matters is: How does the Labour enter the economic process? The answer is this: Nature is everywhere transformed by human Labour and only in so far as Nature is transformed by human Labour do we create real economic values on this one side. If, for instance, we find it necessary for our bodily health, having worked upon Nature in some way, to dance a little or to do Eurhythmy in the intervals, all this may of course be judged from another standpoint: but what we do in the intervals cannot be described as work or Labour in the economic sense, nor can it be regarded as in any way a factor creating economic values. Seen from another side, it may well be creating values, but we must first get our concepts pure and clear concerning economic values as such.

Now there is a second, altogether different, possibility for economic values to arise. It is this: We turn our attention to labour as such: we take labour as the given thing. To begin with, as you have seen just now, labour, economically speaking, is some-thing neutral and irrelevant. But it becomes an economic value-creating factor the moment we let it be directed by the intelligence of man. I must now speak in a somewhat different sense from before. Even in the most far-fetched cases, you can imagine some-thing that would otherwise not be Labour at all being transformed into real Labour by human intelligence. If it occurs to a man, in order to get thinner, to set up that apparatus which we spoke of in his bedroom and practise on it, there will be no economic value in it. But, if somebody winds a rope round the wheel and uses it to drive some machine, the moment this is done, that which would not otherwise be Labour at all, in the economic sense, is turned to good account by the Spirit. Incidentally the fellow who treads the wheel will get thinner just the same, but the essential point is this: Through the Spirit—by intelligence, reflection, perhaps even speculation—Labour is given a certain direction: the various units of Labour are brought into certain mutual relations, and so on.

Thus, we may say: Here we have the second aspect of the value-forming factors in Economics. Here Labour stands in the background, and before it is the Spirit which directs the Labour. Labour shines through the Spirit, and this creates once more an economic value. As you will soon see, these two aspects are present everywhere. Having shown in this diagram (left) how an economic value emerges when we have Nature appearing through Labour—if we now wish to represent diagrammatically what we have just explained, we shall have to put Labour in the background and in the front of it the spiritual, which gives it a certain modification (right).

These are the two essential poles of the economic process. There are indeed no other ways in which economic values are created. Either Nature is modified by Labour, or Labour is modified by Spirit (human intelligence). The outer expression of the Spirit, in this connection, is in the manifold formations of Capital. Economically, the Spirit must be looked for in the configurations of Capital: these at any rate are its outward expression. We shall realise the facts more clearly when we come to consider Capital as such, and then Capital as a monetary medium.

So you see there can be no question of arriving at a definition of economic value. Once more you need only consider on how many circumstances—on the cleverness or stupidity of how many different people—the modification of Labour by the Spirit in any given instance will depend. There is every kind of fluctuating condition. Nevertheless, this fact will always be in evidence: The value-creating factors in the economic process will always be found at these two opposite poles.

Suppose now we find ourselves at any given point within the economic process. The economic process takes its course in the activities of buying and selling. Buying and selling are essentially an exchange of values: there is, in fact, no other exchange than that of values. Properly speaking, it is wrong to speak of an exchange of goods. The “goods ” that play a part in the economic process—whether they appear as modified products of Nature or modified Labour—are always values. It is always the values that are exchanged. Whenever a process of buying and selling takes place, values are exchanged. Now what is it that emerges in the economic process when value and value, as it were, impinge on one another in the process of exchange? It is Price. Wherever Price emerges, it is always through the impact of value on value in the economic process. For this reason you cannot think truly about Price if you have in mind the exchange of mere goods. If you buy an apple for a penny, you may say that you are exchanging one piece of goods for another—the apple for the penny. But you will make no progress in economic thinking along these lines. For the apple has been picked somewhere and then transported, and it may well be that various other things have been done around it. All this is Labour which has modified it. What you are dealing with is not an apple but a Nature-product transformed by human Labour, representing an economic value. In Economics we must always take our start from values. Similarly, the penny represents not a piece of goods but a value, for after all (or so at any rate we must suppose) the penny is but the sign for the fact that there is present, in the man who has to buy the apple, another value which he exchanges for it.

Today I am anxious for you to get a clear insight into this fact: In Economics we must not speak of “goods ” but of “values” as the elementary thing. It is wrong to try to consider Price in any other way than by envisaging the interplay of values. Value set against value gives you Price. And if, as we saw, value itself is a fluctuating thing, incapable of definition, may we not say that when you exchange value for value, Price which arises in the process of exchange is a fluctuating thing raised to the second power?

From all these things you may see how futile it is to try to take hold of values and prices with the idea of finding a firm and fixed ground in Economics: and it is still more futile, if your object is to influence the economic process in practice. Something altogether different is needful—something that lies behind all these things. You may see this from a very simple consideration.

Consider this for a moment: Nature appears to us through human Labour. Suppose we obtain iron at a given place under extraordinarily difficult conditions. The value that is thus produced through human Labour is a modified object of Nature. If at a different place iron is to be produced under far easier conditions, it may happen that an altogether different value will result. You see, therefore, that we cannot grasp the reality in the value itself: we must go behind the value. We must go back to that which creates the value: here alone can we gradually find our way to the more constant conditions on which we can exercise a direct influence. The moment you have brought the value into economic circulation, you must let it fluctuate with the economic organism as a whole. Consider the finer constitution of a blood corpuscle: it is different in the head and in the heart and in the liver. You cannot say: We will now seek the true definition of blood. The most you can do is to consider what are the more favourable foodstuffs in the one case and in the other. Likewise there is no point in talking round and round about Value and Price. The important thing is to go back to the primary factors, back to that which, if rightly formed, will actually bring forth the proper price. The proper price will then emerge of its own accord.

In the study of Economics it is quite impossible to stop short at definitions of Value and Price. We must always go back to the real origins whence the economic process is nourished, on the one hand, and by which, on the other hand, it is regulated—Nature on the one hand, Spirit on the other.

In all economic theories of modern time, this has been the difficulty: they have always tried to hold fast at the outset that which is really fluctuating. As a result, one who can see through these things finds himself confronted not with wrong definitions—scarcely any of them are wrong: they are generally quite right! (Though, it is true, one must make an exceedingly bad shot to say: The amount of Labour corresponds to that which has been expended and has to be restored in the human body: it corresponds, therefore, to the expenditure of substance. Such a statement is really a howler, and he who makes it has failed to see the simplest things). No, the point is that even men of considerable insight, in developing their theory of Economics, have stumbled again and again over this obstacle: They have tried to observe at rest things that are always in a state of flux. For the things of Nature one can and must often do so: there, however, it suffices to observe the state of rest in a quite different way: and if we have to observe a state of movement, all we have come to do in the modern science of Nature is to regard it as though it were composed of a multitude of tiny states of rest and jump from one to the other. For when we integrate, we regard even movement as if it were composed of states of rest.

On the model of such a science we cannot study the economic process. This, therefore, must be said: The first thing needful in grappling with the science of Economics is to consider how, on the one hand, Value appears inasmuch as Nature is transformed by human Labour—Nature is seen through human Labour—while, on the other hand, Value appears inasmuch as Labour is seen through the Spirit. These two origins of Value are the real polar opposites: they differ as, in the spectrum, the one—the luminous or yellow pole—differs from the other—the blue or violet. You may well hold fast this picture: As in the spectrum the warm colours appear on the one side, so on the one side there appears the Nature-value which will show itself more in the formation of rents. On this side we perceive Nature transformed by Labour. On the other side there appear to us instead those values which are translated into Capital: here we see Labour transformed by the Spirit. Then, indeed, Price can arise, inasmuch as values of the one pole impinge on values of the other. Or again, the several values within the one pole come into mutual interaction. The point is that every time, wherever it is a question of price-formation, there will be a mutual interaction of value and value. We must therefore disregard everything to do with the substances and materials themselves; we must look away from all this and begin by seeing how values are formed, on the one side and on the other. Then we shall be able to press forward to the problem of Price.

Zweiter Vortrag

Es werden die ersten Begriffe, Anschauungen, die wir zu entwickeln haben gerade auf volkswirtschaftlichem Gebiete, etwas kompliziert sein müssen, und das aus einem ganz sachlichen Grunde. Sie müssen sich vorstellen, daß die Volkswirtschaft, auch wenn wir sie als Weltwirtschaft auffassen, in einer fortwährenden Bewegung ist, daß, ich möchte sagen, wie das Blut durch den Menschen, so die Güter als Waren auf allen möglichen Wegen durch den ganzen volkswirtschaftlichen Körper hindurchfließen. Dabei haben wir dann als die wichtigsten Dinge innerhalb dieses volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses aufzufassen dasjenige, was sich abspielt zwischen Kauf und Verkauf. Wenigstens muß das für die heutige Volkswirtschaft gelten. Was auch immer sonst vorliegen mag - und wir werden ja die verschiedensten Impulse, die im volkswirtschaftlichen Körper enthalten sind, zu besprechen haben -, was aber auch immer vorliegen mag: die Volkswirtschaft als solche kommt an den Menschen heran, wenn er irgend etwas zu verkaufen oder zu kaufen hat. Was sich zwischen Käufer und Verkäufer abspielt, ist das, wonach schließlich alles instinktive Denken über die Volkswirtschaft jedes naiven Menschen abzielt, gipfelt, und worauf im Grunde genommen alles ankommt.

Nun, nehmen Sie nur einmal dasjenige, was da sich geltend macht, wenn innerhalb der volkswirtschaftlichen Zirkulation Kauf und Verkauf in Betracht kommen. Das, worauf es dem Menschen ankommt, das ist der Preis irgendeiner Ware, irgendeines Gutes. Die Preisfrage ist überhaupt zuletzt diejenige Frage, auf die die wichtigsten volkswirtschaftlichen Auseinandersetzungen hinauslaufen müssen; denn im Preis gipfelt alles, was in der Volkswirtschaft eigentlich an Impulsen, an Kräften tätig ist. Wir werden also gewissermaßen zuerst das Preisproblem ins Auge zu fassen haben; aber das Preisproblem ist kein außerordentlich einfaches. Sie brauchen ja nur an den einfachsten Fall zu denken: Wir haben an einem Orte, A, irgendeine Ware, die hat an diesem Orte A einen bestimmten Preis; sie wird dort nicht gekauft, sie wird weitergefahren. Es muß angestrebt werden, daß dann zu dem Preis hinzukommt dasjenige, was notwendig war, an Frachtgut zu bezahlen bis zum zweiten Orte, B. Der Preis ändert sich während der Zirkulation. Das ist der einfachste, ich möchte sagen der platteste Fall. Aber es gibt ja natürlich viel kompliziertere Fälle.

Nehmen Sie an, sagen wir, ein Haus in einer größeren Stadt kostet zu irgendeiner Zeit so und so viel. Nach fünfzehn Jahren kostet dasselbe Haus vielleicht sechs- oder achtmal so viel. Und dabei brauchen wir gar nicht, indem wir von dieser Preiserhöhung sprechen, daran zu denken, daß etwa die Hauptsache in der Geldentwertung liege. Das wollen wir gar nicht annehmen. Die Preiserhöhung kann einfach darin liegen, daß mittlerweile viele andere Häuser ringsherum gebaut worden sind, in der Nähe andere Gebäude liegen, die den Wert des Hauses besonders erhöhen. Es kann durchaus in zehn, fünfzehn anderen Umständen liegen, daß dieses Haus im Preis erhöht worden ist. Wir sind niemals eigentlich in der Lage, im einzelnen Falle etwas Generelles zu sagen, etwa zu sagen: Bei Häusern oder bei Eisenwaren oder bei Getreide liegt vor die Möglichkeit, für irgendeinen Ort eindeutig aus irgendwelchen Bedingungen heraus den Preis zu bestimmen. — Wir können zunächst eigentlich nicht einmal viel mehr sagen als: Wir müssen beobachten, wie der Preis schwankt mit dem Ort, mit der Zeit. - Und wir können einzelne von den Bedingungen vielleicht verfolgen, durch die an einem konkreten Orte der. Preis sich gerade herausstellt in der Weise, wie er ist. Aber eine allgemeine Definition, wie der Preis sich irgendwie zusammensetzt, die kann es nicht geben, die ist eigentlich unmöglich. Daher muß es immer wieder und wiederum überraschen, daß wir in gebräuchlichen nationalökonomischen Werken so über den Preis gesprochen finden, als ob man den Preis definieren könne. Man kann ihn nicht definieren; denn der Preis ist überall ein konkreter, und mit jeder Definition hat man gerade bei volkswirtschaftlichen Dingen eigentlich etwas gegeben, das nicht einmal annähernd irgendwie an die Sache herankommt.

Ich habe zum Beispiel einmal den Fall erlebt: In einer Gegend sind die Grundstücke recht billig. Eine Gesellschaft hat in ihrer Mitte einen ziemlich berühmten Mann. Diese Gesellschaft kauft sich nun sämtlich die billigen Grundstücke und veranlaßt dann den berühmten Mann, in dieser Gegend sich ein Haus zu bauen. Dann werden die Grundstücke ausgeboten. Sie sind um wesentlich teureres Geld auszubieten, als sie gekauft worden sind, bloß dadurch, daß man den berühmten Mann veranlaßt hat, sich dort ein Haus hinzubauen.

Das sind Dinge, die Ihnen zeigen, von welchen unbestimmten Bedingungen der Preis einer Sache im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß abhängt. Sie können nun natürlich sagen: Ja, aber solchen Dingen muß man steuern. — Bodenreformer und ähnliche Leute stemmen sich gegen solche Dinge, wollen in einer gewissen Weise eine Art gerechten Preises für die Dinge feststellen durch allerlei Maßregeln. Das kann man; aber volkswirtschaftlich gedacht, wird dadurch der Preis nicht geändert. Man kann zum Beispiel, sagen wir, wenn so etwas geschieht und dann die Grundstücke teurer verkauft werden, man kann den Leuten das Geld wiederum in Form einer hohen Grundsteuer abnehmen. Dann steckt der Staat dasjenige, was abfällt, ein. Die Wirklichkeit hat man aber damit doch nicht ergriffen. In Wirklichkeit ist die Sache dennoch teurer geworden. Sie können also Gegenmaßregeln ergreifen, die kaschieren aber nur die Sache. Der Preis ist doch derjenige, der er geworden wäre ohne diese Maßregeln. Man macht nur eine Umlagerung; und volkswirtschaftlich gedacht ist das nicht, wenn man dann sagt, die Grundstücke sind nach zehn Jahren nicht teurer geworden, wenn man durch Maßregeln die Sache kaschiert hat. Es handelt sich darum, daß Volkswirtschaft mit beiden Beinen eben in der Wirklichkeit stehen muß, und man in der Volkswirtschaft immer nur sprechen kann von den Verhältnissen, die gerade in einem Zeitalter und gerade dort sind, wo man spricht. Daß die Dinge anders sein können, das wird sich natürlich dann für den ergeben, der den Fortschritt der Menschheit will; aber zunächst müssen die Dinge in ihrer augenblicklichen Wirklichkeit betrachtet werden. Daraus ersehen Sie, wie unmöglich es eigentlich ist, heranzugehen an so etwas, wie an den allerwichtigsten Begriff in der Volkswirtschaft: den Preis, und diesen Preis mit einem scharf konturierten Begriff erfassen zu wollen. So kann man nicht in der Volkswirtschaftslehre zu etwas kommen. Es müssen eben durchaus andere Wege. eingeschlagen werden. Der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß selbst muß betrachtet werden.

Trotzdem ist das Preisproblem das allerwichtigste, und wir müssen auf dieses Preisproblem hinsteuern, müssen also den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß ins Auge fassen und versuchen, gewissermaßen zu erhaschen den Punkt, wo irgendwo oder irgendwann der Preis sich aus den volkswirtschaftlichen Untergründen heraus für irgendeine Sache ergibt.

Wenn Sie nun die gebräuchlichen Volkswirtschaftslehren verfolgen, so finden Sie gewöhnlich dort drei Faktoren verzeichnet, durch deren Ineinanderwirken die gesamte Volkswirtschaft sich abspielen soll. Sie finden verzeichnet: die Natur, die menschliche Arbeit und das Kapital. Gewiß, man kann zunächst sagen: Wenn man den Volkswirtschaftsprozeß verfolgt, so findet man im Verlaufe desselben dasjenige, was von der Natur stammt, dasjenige, was durch menschliche Arbeit erreicht, und dasjenige, was unternommen wird oder geordnet wird durch das Kapital. Aber wenn man so, ich möchte sagen, einfach nebeneinander betrachtet Natur, Arbeit und Kapital, so wird man nicht lebendig den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß erfassen. Man wird gerade durch eine solche Betrachtung zu den mannigfaltigsten Einseitigkeiten geführt werden. Und das zeigt ja die Geschichte der Volkswirtschaftslehre. Während die einen meinen, aller Wert liege in der Natur und eigentlich käme kein besonderer Wert zu dem Stoffe der Naturobjekte hinzu durch die menschliche Arbeit, sind andere der Ansicht, daß eigentlich aller volkswirtschaftliche Wert aufgedrückt wird irgendeinem Gut, einer Ware, durch die, wie man wohl auch sagt, hineinkristallisierte Arbeit. Wiederum, in dem Augenblick, wo Sie Kapital und Arbeit nebeneinanderstellen, werden Sie auf der einen Seite finden, daß die Leute sagen, eigentlich ist es das Kapital, welches die Arbeit einzig und allein möglich macht, und der Arbeitslohn werde gezahlt aus der Kapitalmasse. Auf der anderen Seite wird gesagt: Nein, alles dasjenige, was Werte produziert, das ist die Arbeit, und das, was das Kapital erringt, ist nur der aus dem Arbeitsergebnis abgezogene Mehrwert.

Die Sache ist so: Betrachtet man von dem einen Gesichtspunkt die Dinge, so hat der eine recht; betrachtet man sie von dem anderen Gesichtspunkt, so hat der andere recht. Es kommt einem eine solche Betrachtung der Realität gegenüber eigentlich wirklich vor wie manche Buchhaltung: Setzt man denPosten da hin, kommt das heraus; setzt man ihn dort hin, kommt das heraus und so weiter. Man kann ganz gut mit sehr starken Scheingründen von Mehrwert sprechen, der eigentlich dem Arbeitslohn abgezogen ist und den sich der Kapitalist aneignet. Man kann mit ebenso guten Gründen davon sprechen, daß eigentlich im volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhange dem Kapitalisten alles gebührt und er nur aus dem, was er zum Arbeitslohn verwenden kann, eben seine Arbeiter bezahlt. Für beides gibt es sehr gute und auch sehr schlechte Gründe. Alle diese Betrachtungen können nämlich eigentlich durchaus nicht an die volkswirtschaftliche Wirklichkeit herankommen. Diese Betrachtungen sind gut als Grundlagen für Agitationen, aber sie sind durchaus nicht etwas irgendwie in der ernsten Volkswirtschaftslehre in Betracht Kommendes. Andere Grundlagen müssen zuerst da sein, wenn man überhaupt mit einem gewissen Recht von einer Fortentwickelung des volkswirtschaftlichen Organismus sprechen will. Nun, natürlich, bis zu einem gewissen Grade sind alle solche Aufstellungen schon berechtigt; und wenn Adam Smith zum Beispiel in der Arbeit, die verwendet ist auf die Dinge, den eigentlich wertbildenden Urfaktor sieht, so kann man eben auch dafür außerordentlich gute Gründe vorbringen. Solch ein Mann wie Adam Smith hat schon nicht unsinnig gedacht; aber dasjenige, was auch da zugrunde liegt, ist, daß man immer meint, man könne irgend etwas, was stillsteht, erfassen und dann eine Definition geben, während im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß alles fortwährend in Bewegung ist. Es ist verhältnismäßig einfach, über Naturerscheinungen Begriffe aufzustellen, selbst über die kompliziertesten, gegenüber denjenigen Anschauungen, die man braucht für eine Volkswirtschaftslehre. Unendlich viel komplizierter, labiler, variabler sind die Erscheinungen in der Volkswirtschaft als die in der Natur, viel fluktuierender, viel weniger zu erfassen mit irgendwelchen bestimmten Begriffen.

Man muß eben eine ganz andere Methode einschlagen. Diese Methode wird Ihnen nur schwierig sein in den allerersten Stunden; Sie werden aber schen, daß sich daraus ergeben wird, was man einer wirklichen Volkswirtschaftslehre zugrunde legen kann. Man kann sagen: In diesen volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, den man ins Auge zu fassen hat, laufen ein Natur, menschliche Arbeit und - also zunächst, wenn man auf das rein Äußere der Volkswirtschaft hinsieht — Kapital. Zunächst!

Nun aber, wenn wir gleich auf das Mittlere schauen, auf die menschliche Arbeit, versuchen wir uns eine Anschauung zu bilden dadurch, daß wir einmal heruntergehen - ich habe schon gestern solche Andeutungen gemacht - ins Feld des Tierischen und uns statt der Volkswirtschaft die Spatzenwirtschaft, die Schwalbenwirtschaft ansehen. Ja, da ist die Natur die Grundlage für die Wirtschaft. Der Spatz muß auch eine Art von Arbeit verrichten. Er muß mindestens herumhüpfen und dorthin hüpfen, wo er sein Körnlein findet, und er hat manchmal gar sehr viel zu hüpfen im Tag, bis er sein Körnlein findet. Die Schwalbe, die ihr Nest baut, muß auch eine Art Arbeit verrichten. Sie hat auch damit sehr viel zu tun. Dennoch, im volkswirtschaftlichen Sinn können wir das nicht Arbeit nennen. Wir kommen nicht weiter mit volkswirtschaftlichen Anschauungen, wenn wir das Arbeit nennen; denn, sehen wir genauer zu, so müssen wir sagen: Der Spatz, die Schwalbe sind eigentlich genau so organisiert, daß sie die Dinge, die sie gewissermaßen, um ihr Futter zu finden, ausführen müssen, daß sie gerade diese ausführen. Sie würden gar nicht gesund sein können, wenn sie sich nicht in dieser Weise bewegen könnten. Es ist eine Fortsetzung ihrer Organisation, die zu ihnen gehört, wie sie Beine haben oder Flügel haben. So daß wir in diesem Fall eigentlich durchaus von dem, was man hier eine Scheinarbeit nennen könnte, absehen können, wenn wir volkswirtschaftliche Begriffe aufbauen wollen. Wo die . Natur unmittelbar genommen wird und das einzelne Wesen, bloß um sich oder die Allernächsten zu befriedigen, die entsprechenden Scheinarbeiten ausführt, da müssen wir diese Scheinarbeiten eigentlich dann abziehen, wenn wir bestimmen wollen dasjenige, was im volkswirtschaftlichen Sinne Wert ist, ein Wert ist. Und darum handelt es sich zunächst, daß wir uns nähern einer Anschauung über den volkswirtschaftlichen Wert.

Wenn wir also in der Tierwirtschaft Umschau halten, so können wir nur sagen: Diese ist so, daß wertbildend für sie lediglich die Natur selber ist. Wertbildend ist für die Tierwirtschaft lediglich die Natur selber. Nun aber, in dem Augenblick, wo wir zum Menschen, das heißt zur Volkswirtschaft heraufkommen, haben wir allerdings von der Naturseite her den Ausgangspunkt des Naturwertes; aber in dem Augenblick, wo Menschen nicht bloß für sich oder ihre Allernächsten sorgen, sondern füreinander sorgen, kommt nun allerdings sofort dasjenige in Betracht, was menschliche Arbeit ist. Auch dasjenige, was der Mensch nun tun muß in dem Augenblick, wo er nicht bloß die Naturprodukte für sich verwendet, sondern wo er mit andern Menschen in irgendwelcher Beziehung steht und austauscht mit ihnen Güter, wird dasjenige, was er tut, der Natur gegenüber zur Arbeit. Und wir haben hier die eine Seite des Wertes in der Volkswirtschaft. Diese eine Seite entsteht dadurch, daß auf Naturprodukte menschliche Arbeit verwendet wird, und wir in der volkswirtschaftlichen Zirkulation Naturprodukte umgeändert durch menschliche Arbeit vor uns haben. Da entsteht eigentlich erst ein wirklicher volkswirtschaftlicher Wert. Solange das Naturprodukt an seiner Fundstelle ist, unberührt, solange hat es keinen anderen Wert als denjenigen, den es auch zum Beispiel für das Tier hat. In dem Augenblick, wo Sie den ersten Schritt machen, das Naturprodukt hineinzufügen in den volkswirtschaftlichen Zirkulationsprozeß, beginnt durch das umgeänderte Naturprodukt der volkswirtschaftliche Wert. In diesem Falle können wir diesen volkswirtschaftlichen Wert dadurch charakterisieren, daß wir den Satz aussprechen: Volkswirtschaftlicher Wert von dieser einen Seite ist Naturprodukt, umgewandelt durch menschliche Arbeit. - Ob diese menschliche Arbeit darinnen besteht, daß wir graben, daß wir hacken oder daß wir das Naturprodukt von einem Ort zum anderen bringen, das tut nichts zur Sache. Wenn wir zunächst die Wertbestimmung im allgemeinen haben wollen, so müssen wir sagen: Wertbildend ist die menschliche Arbeit, die ein Naturprodukt so verändert, daß es in den volkswirtschaftlichen Zirkulationsprozeß übergehen kann.

Wenn Sie das ins Auge fassen, dann werden Sie gleich haben das ganz Fluktuierende des Wertes eines in der Volkswirtschaft zirkulierenden Gutes. Denn die Arbeit ist ja etwas fortwährend Vorhandenes, die verwendet wird auf das volkswirtschaftlicheGut. So daß Sie eigentlich gar nicht sagen können, was Wert ist, sondern nur sagen können: Der Wert erscheint an einer bestimmten Stelle in einer bestimmten Zeit, indem menschliche Arbeit ein Naturprodukt umwandelt. - Da erscheint der Wert. Wir können und wollen den Wert zunächst gar nicht definieren, sondern wollen nur hindeuten auf die Stelle, wo der Wert erscheint. Das möchte ich Ihnen schematisch darstellen, möchte es Ihnen so schematisch darstellen, daß ich Ihnen sage: Wir haben gewissermaßen im Hintergrunde die Natur (siehe Zeichnung 2, links); und wir haben an die Natur herankommend die menschliche Arbeit; und dasjenige, was gleichsam durch das Ineinanderwirken von Natur und menschlicher Arbeit erscheint, was da sichtbar wird, das ist von der einen Seite her der Wert. Es ist durchaus kein falsches Bild, wenn Sie sich zum Beispiel sagen: Sie schauen sich eine schwarze Fläche, irgend etwas Schwarzes an durch irgend etwas Helles - Sie sehen es blau. Aber je nachdem das Helle dick oder dünn ist, ist es verschieden blau. Je nachdem Sie es verschieben, ist es verschieden dicht. Es ist fluktuierend..So ist der Wert in der Volkswirtschaft, der eigentlich nichts anderes ist als die Erscheinung der Natur durch die menschliche Arbeit hindurch, überall fluktuierend.

Wir gewinnen mit diesen Dingen zunächst nicht viel anderes als einige abstrakte Hinweise; aber diese werden uns in den nächsten Tagen orientierend sein, um die konkreten Dinge aufzusuchen. Nun, Sie sind es ja gewohnt, man fängt doch in allen Wissenschaften an mit demjenigen, was zunächst das allereinfachste ist. Sehen Sie, Arbeit an sich hat eben gar keine Bestimmung im volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhang. Denn, ob ein Mensch Holz hackt oder sich auf ein Rad stellt, es gibt solche, weil er dick ist und immer von der einen Stufe zu . der anderen steigt — sie geht hinunter — und er sich dadurch dünner macht: er kann dasselbe Quantum Arbeit leisten wie der, der Holz hackt. Arbeit so betrachtet, wie sie zum Beispiel Marx betrachtet, daß er sagt, man solle als Äquivalent suchen dasjenige, was aufgebraucht wird durch die Arbeit am menschlichen Organismus, das ist ein kolossaler Unsinn; denn aufgebraucht wird dasselbe, wenn der Mensch da auf dem Rad hinauftanzt, wie wenn er Holz hackt. Es kommt nicht darauf an im volkswirtschaftlichen Sinn, was am Menschen geschieht. Wir haben ja gesehen, daß die Volkswirtschaft an Unvolkswirtschaftliches angrenzt. Rein volkswirtschaftlich betrachtet, hat es keine Berechtigung, irgendwie darauf hinzuweisen, daß die Arbeit — wenigstens zunächst, um den Begriff der Arbeit volkswirtschaftlich hinzustellen — den Menschen abnützt. Es hat in einem mittelbaren Sinn Bedeutung, weil man wiederum für die Bedürfnisse des Menschen sorgen muß. Wie Marx die Betrachtungen angestellt hat, hat man es zu tun mit einem kolossalen Unsinn.

Nun, was ist da notwendig, um die Arbeit im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß zu erfassen? Da ist notwendig, daß man ganz vom Menschen zunächst absieht und hinsieht, wie sich in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß die Arbeit hineinstellt. Die Arbeit an einem solchen Rad stellt sich gar nicht herein, die bleibt ganz am Menschen haften; das Holzhacken stellt sich hinein in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß. Ganz allein darauf kommt es an wie sich die Arbeit in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß hineinstellt. Und hier handelt es sich eigentlich für alles, was in Betracht kommt, darum, daß die Natur überall verändert wird durch die menschliche Arbeit. Und nur insofern, als die Natur verändert wird durch die menschliche Arbeit, erzeugen wir volkswirtschaftliche Werte nach dieser einen Seite. Wenn wir zum Beispiel, sagen wir, es zu unserer leiblichen Gesundheit richtig finden, an der Natur zu arbeiten und dazwischen drinnen immer einmal ein bißchen herumzutanzen oder Eurythmie zu treiben, so kann das von einem anderen Standpunkte aus beurteilt werden; aber dasjenige, was wir dazwischen tun, darf nicht als volkswirtschaftliche Arbeit bezeichnet werden und nicht für irgendwie volkswirtschaftlich wertbildend angesehen werden. Von anderer Seite aus kann es wertbildend sein; aber wir müssen uns erst die reinlichen Begriffe bilden von den volkswirtschaftlichen Werten als solchen.

Nun gibt es aber noch eine ganz andere Möglichkeit, daß ein volkswirtschaftlicher Wert entsteht. Das ist diese, daß wir auf die Arbeit als solche hinsehen und nun die Arbeit zunächst als etwas Gegebenes nehmen. Dann ist ja, wie Sie eben jetzt gesehen haben, diese Arbeit zunächst etwas volkswirtschaftlich ganz Neutrales, Irrelevantes. Sie wird aber in jedem Fall volkswirtschaftlich werterzeugend, wenn wir diese Arbeit durch den Geist, die Intelligenz des Menschen dirigieren ich muß da etwas anders sprechen als vorhin. Sie könnten selbst in den extremsten Fällen denken, daß etwas, was sonst gar nicht Arbeit ist, durch den Geist des Menschen in Arbeit umgewandelt wird. Wenn es einem einfällt, wenn einer jenes Rad benützt, es in sein Zimmer stellt und magerer werden will, so ist da kein volkswittschaftlicher Wert vorhanden. Wenn aber einer ein Seil herumzieht um das Rad und dieses Seil irgendwie eingreift, um eine Maschine zu treiben, so haben Sie durch den Geist dasjenige, was gar keine Arbeit ist, verwertet. Der Nebeneffekt ist der, daß der schon magerer wird; aber das, was hier eigentlich das Maßgebende ist, ist, daß die Arbeit durch den Geist, durch die Intelligenz, durch die Überlegung, vielleicht auch durch die Spekulation in eine gewisse Richtung gebracht wird, daß die Arbeiten in gewisse Wechselwirkungen gebracht werden und so weiter. So daß wir sagen können: Hier haben wir die zweite Seite des Wertbildenden in der Volkswirtschaft. Da, wo die Arbeit im Hintergrunde steht und der Geist vorne die Arbeit dirigiert, da scheint uns die Arbeit durch den Geist durch und erzeugt wiederum volkswirtschaftlichen Wert.

Wir werden schon sehen, daß diese beiden Seiten durchaus überall vorhanden sind. Wenn ich das Schema hier so gezeichnet habe (siehe Zeichnung 2, links), daß gerade der volkswirtschaftliche Wert erscheint, wenn wir durch die Arbeit hindurch die Natur erscheinend haben, so müßte ich das, was ich jetzt auseinandergesetzt habe, so zeichnen, daß wir da hinten die Arbeit haben und da vorne zunächst dasjenige, was geistig ist, was der Arbeit eine gewisse Modifikation gibt (siehe Zeichnung 2, rechts).

Das sind im wesentlichen die zwei Pole des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses. Sie finden keine anderen Arten, wie volkswirtschaftliche Werte erzeugt werden: entweder wird die Natur durch die Arbeit modifiziert oder es wird die Arbeit durch den Geist modifiziert, wobei der Geist im Äußeren vielfach in den Kapitalformationen sich darlebt, so daß in bezug auf die Volkswirtschaft der Geist in der Konfiguration der Kapitalien gesucht werden muß. Wenigstens sein äußerer Ausdruck ist da. Doch das wird sich uns ergeben, wenn wir das Kapital als solches und dann das Kapital als Geldmittel betrachten.

So sehen Sie ja, daß wir nicht sprechen können davon, daß eine Definition des volkswirtschaftlichen Wertes sich ergeben kann. Denn wiederum bedenken Sie nur, wovon das alles abhängt, von wieviel dummen und gescheiten Leuten es abhängt, daß irgendwo vom Geiste die Arbeit modifiziert wird. Da sind lauter fluktuierende Bedingungen vorhanden. Aber dafür gilt das, was anschauungsgemäß ist, immer: daß auf diesen zwei polarischen Gegensätzen die wertbildenden Momente im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß zu suchen sind.

Nun, wenn das der Fall ist, dann liegt das vor: Wenn wir irgendwo drinnenstehen im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, und der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß, ich möchte sagen, irgendwo beim Kauf und Verkauf sich abspielt, so haben wir im Kauf und Verkauf im wesentlichen Wertaustausch, Austausch von Werten. Sie finden keinen anderen Austausch als den von Werten. Eigentlich ist es falsch, wenn man von Güteraustausch spricht. Im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß ist das Gut, ob es nun modifiziertes Naturprodukt ist oder modifizierte Arbeit, ein Wert. Was getauscht wird, sind Werte. Darauf kommt es an. So daß ° Sie sich also sagen müssen: Wenn irgendwo sich Kauf und Verkauf abspielen, so werden Werte ausgetauscht. - Und dasjenige, was nun herauskommt im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, wenn Wert und Wert gewissermaßen aufeinanderprallen, um sich auszutauschen, das ist der Preis. Sie finden den Preis erscheinen niemals anders, als daß Wert an Wert stößt im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß. Daher kann man auch über den Preis gar nicht nachdenken, wenn man etwa an den Austausch von bloßen Gütern denkt. Wenn Sie einen Apfel um, ja, ich weiß nicht, sagen wir fünf Pfennige kaufen, dann können Sie ja sagen, Sie tauschen ein Gut aus gegen ein anderes Gut, den Apfel gegen fünf Pfennige. Auf diese Weise kommen Sie aber nie zu einer volkswirtschaftlichen Betrachtung. Denn der Apfel ist irgendwo gepflückt, ist dann befördert worden, es ist vielleicht um ihn herum noch manches andere geschehen. Das ist die Arbeit, die ihn modifiziert hat. Sie haben es nicht zu tun mit dem Apfel, sondern mit dem von Menschenarbeit veränderten Naturprodukt, das einen Wert darstellt. Und man muß immer ausgehen vom Wert in der Volkswirtschaft. Ebenso haben Sie es bei den fünf Pfennigen mit einem Wert und nicht mit einem Gut zu tun; denn diese fünf Pfennige sind doch wohl nur das Zeichen dafür, daß vorhanden ist in dem Menschen, der sich den Apfel kaufen muß, ein anderer Wert, den er eintauscht dafür.

Also, worauf es mir ankommt, ist das: daß wir heute zu der Einsicht kommen, daß es falsch ist, in der Volkswirtschaft von Gütern zu sprechen, daß wir sprechen müssen, als von dem Elementaren, von Werten, und daß es falsch ist, den Preis anders erfassen zu wollen, auf eine andere Art, als daß man das Spiel der Werte ins Auge faßt. Wert gegen Wert gibt den Preis. Wenn schon der Wert etwas Fluktuierendes ist, das man nicht definieren kann, dann ist ja, wenn Sie Wert gegen Wert austauschen, gewissermaßen dasjenige, was im Austausch entsteht als Preis, das ist etwas Fluktuierendes im Quadrat.

Aus all diesen Dingen kann Ihnen aber folgen, daß es also ganz vergeblich ist, irgendwie erfassen zu wollen Werte und Preise, um in der Volkswirtschaft auf festem Boden zu stehen und etwa gar in einen volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß eingreifen zu wollen. Dasjenige, was da in Betracht kommt, muß etwas ganz anderes sein. Das muß dahinterliegen und es liegt ja auch dahinter. Das zeigt eine sehr einfache Betrachtung.

Denken Sie sich nur einmal: Die Natur erscheint uns durch menschliche Arbeit. Wenn wir, sagen wir, Eisen an einem Ort gewinnen unter außerordentlich schwierigen Verhältnissen, so ist das, was als Wert herauskommt, durch menschliche Arbeit modifiziertes Naturobjekt. Wenn an einer anderen Stelle Eisen unter leichteren Verhältnissen produziert werden soll, so ist die Sache diese, daß eventuell ein ganz anderer Wert sich ergibt. Sie sehen also, daß man nicht am Wert die Sache erfassen soll, sondern hinter dem Wert sie erfassen muß. Man muß zu dem zurückgehen, was den Wert bildet, und muß da allmählich vielleicht auf die konstanteren Verhältnisse kommen, auf die man dann einen unmittelbaren Einfluß haben kann. Denn in dem Augenblick, wo Sie den Wert in die volkswirtschaftliche Zirkulation gebracht haben, da müssen Sie ihn im Sinne des volkswirtschaftlichen Organismus fluktuieren lassen. Geradesowenig wie Sie, wenn Sie auf die feinere Zusammensetzung des Blutkörperchens sehen, das anders ist im Kopf und anders im Herz und anders in der Leber, wie Sie da in der Hand haben zu sagen: Es ist darum zu tun, für das Blut eine Definition zu finden — darum kann es einem nicht zu tun sein, es kann einem nur darum zu tun sein, welches die günstigeren Nahrungsmittel sind in diesem oder jenem Falle; ebenso kann es sich niemals darum handeln, über den Wert und Preis herumzureden, sondern nur darum, daß man zu den ersten Faktoren geht, zu demjenigen, was dann, wenn es richtig formiert wird, eben den entsprechenden Preis herausbringt, der dann schon von selber so wird.

Es ist ganz unmöglich, mit der volkswirtschaftlichen Betrachtung stehenzubleiben im Gebiet von Wert- oder Preisdefinitionen, sondern man muß überall zurückgehen zu demjenigen, was die Ausgangspunkte sind, also gewissermaßen zu demjenigen, woraus der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß seine Nahrung auf der einen Seite zieht und wodurch er auf der anderen Seite reguliert wird: also zu der Natur auf der einen Seite, zu dem Geist auf der anderen.

Das ist die Schwierigkeit gewesen bei allen volkswirtschaftlichen Theorien der neueren Zeit, daß man zunächst immer das fassen wollte, was fluktuierend ist. Dadurch ergaben sich für denjenigen, der die Sache durchschaut, im Grunde genommen fast gar keine falschen Definitionen, sondern lauter richtige. Man muß schon wirklich sehr danebenhauen, wenn man sagt: Die Arbeit entspricht dem, was wiederum ersetzt werden muß im menschlichen Organismus, sie ist aufgebrauchter Stoff. - Da muß man schon sehr danebenhauen und die gewöhnlichsten Dinge nicht sehen. Aber es handelt sich darum, daß auch wirklich recht kluge Leute durchaus gestrauchelt sind beim Ausbilden ihrer volkswirtschaftlichen Theorie daran, daß sie die Dinge, die im Fluß sind, in Ruhe haben beobachten wollen. Das kann man den Naturdingen gegenüber tun, muß es oftmals tun; aber da genügt es, in ganz anderer Weise das Ruhende zu beobachten. Wenn wir die Bewegung betrachten, so sind wir nur dazu gekommen in der Naturbetrachtung, sie aus kleinen Ruhen zusammengesetzt zu betrachten, die dann fortspringen. Indem wir integrieren, betrachten wir auch die Bewegung als etwas, was sich aus Ruhen zusammensetzt.

Nach dem Muster solcher Erkenntnis kann man nicht den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß betrachten. So daß man sagen muß: Dasjenige, worauf es ankommt, ist, zunächst anzufassen die Volkswirtschaftslehre bei der Art und Weise, wie auf der einen Seite erscheint der Wert, indem die Natur durch die Arbeit verwandelt wird, die Natur durch die Arbeit gesehen wird, auf der anderen Seite, wie der Wert erscheint, indem die Arbeit durch den Geist gesehen wird. Und diese beiden Entstehungen der Werte sind durchaus polarisch verschieden, so wie im Spektrum der eine Pol, der helle Pol, der gelbe Pol, von dem blauen, violetten Pol verschieden ist. So daß Sie schon das Bild festhalten können: so wie auf der einen Seite die warmen Farben erscheinen im Spektrum, so erscheint auf der einen Seite der Naturwert, der sich mehr in der Rentenbildung zeigen wird, wenn wir Natur durch Arbeit verwandelt wahrnehmen; auf der anderen Seite erscheint uns mehr der Wert, der sich in Kapital umsetzt, wenn wir die Arbeit durch den Geist verändert erblicken. Dann kann allerdings der Preis entstehen, indem Werte des einen Poles mit Werten des anderen Poles zusammenstoßen, oder indem Werte innerhalb eines Poles miteinander in Wechselwirkung treten. Aber jedesmal, wenn Preisbildung überhaupt in Betracht kommt, dann ist es so, daß Wert mit Wert in Wechselwirkung tritt. Das heißt, wir müssen ganz absehen von alle dem, was sonst da ist, von dem Stoffe selber, von alledem müssen wir absehen und müssen zunächst sehen, wie Werte gebildet werden auf der einen Seite und wie Werte gebildet werden auf der anderen Seite. Dann werden wir zu dem Problem des Preises vordringen können.

Second Lecture

The first concepts and ideas that we have to develop, particularly in the field of economics, will be somewhat complicated, and this is for a very practical reason. You must imagine that the economy, even if we consider it as a global economy, is in constant motion, that, I would say, just as blood flows through the human body, goods flow as commodities through the entire economic body in all possible ways. In this context, we must consider the most important things within this economic process to be those that take place between buying and selling. At least, that must apply to today's economy. Whatever else may be present—and we will have to discuss the various impulses contained within the economic body—whatever else may be present, the economy as such approaches people when they have something to sell or buy. What happens between buyer and seller is what ultimately all instinctive thinking about the economy of every naive person aims at, culminates in, and what basically matters.

Now, just take what comes into play when buying and selling are considered within economic circulation. What matters to people is the price of a particular commodity or good. The question of price is ultimately the question to which the most important economic debates must come down, because everything that actually drives the economy in terms of impulses and forces culminates in price. So, in a sense, we will first have to consider the problem of price; but the price problem is not an easy one. Just think of the simplest case: we have a commodity in a place, A, which has a certain price in this place, A; it is not bought there, it is transported further. The aim must be to add to the price what was necessary to pay for freight to the second place. B. The price changes during circulation. That is the simplest, I would say the most obvious case. But there are, of course, much more complicated cases.

Suppose, for example, that a house in a large city costs a certain amount at a certain point in time. After fifteen years, the same house may cost six or eight times as much. And when we talk about this price increase, we don't need to think that the main reason is currency devaluation. We don't want to assume that at all. The price increase may simply be due to the fact that many other houses have been built in the meantime, and there are other buildings nearby that particularly increase the value of the house. There may well be ten or fifteen other circumstances that have caused the price of this house to increase. We are never really in a position to say anything general about individual cases, such as to say: in the case of houses or hardware or grain, it is possible to determine the price for a particular location based on certain conditions. — For now, we can't really say much more than: we have to observe how the price fluctuates with location and time. And we can perhaps track some of the conditions that cause the price to turn out the way it does in a specific place. But there can be no general definition of how the price is somehow composed; that is actually impossible. Therefore, it must always come as a surprise that in common works of political economy we find price discussed as if it could be defined. It cannot be defined, because the price is concrete everywhere, and with every definition, especially in economic matters, one has actually given something that does not even come close to the matter at hand.

For example, I once experienced the following case: In one area, land is quite cheap. A company has a fairly famous man in its midst. This company now buys up all the cheap land and then persuades the famous man to build a house in this area. Then the land is put up for sale. It can be sold for considerably more money than it was bought for, simply because the famous man was persuaded to build a house there.

These are things that show you the uncertain conditions on which the price of something depends in the economic process. Of course, you can say: Yes, but such things must be controlled. — Land reformers and similar people oppose such things and want to establish a kind of fair price for things in a certain way through all kinds of measures. That is possible, but from an economic point of view, it does not change the price. For example, if something like this happens and the land is then sold at a higher price, you can take the money back from the people in the form of a high property tax. Then the state pockets the difference. But that does not address the reality of the situation. In reality, things have nevertheless become more expensive. So you can take countermeasures, but they only conceal the issue. The price is still what it would have been without these measures. You are only shifting the burden, and from an economic point of view, it is not true to say that land has not become more expensive after ten years if you have concealed the issue through measures. The point is that economics must have both feet firmly planted in reality, and in economics one can only ever speak of the circumstances that exist at a particular time and in a particular place. Of course, those who want humanity to progress will see that things can be different, but first of all, things must be viewed in their current reality. From this you can see how impossible it actually is to approach something like the most important concept in economics: price, and to try to grasp this price with a sharply defined concept. You cannot arrive at anything in economics this way. Completely different paths must be taken. The economic process itself must be considered.

Nevertheless, the price problem is the most important one, and we must address this price problem, i.e., we must consider the economic process and try to grasp, as it were, the point where, somewhere or at some point, the price for a particular item emerges from the economic foundations.

If you follow the usual economic theories, you will usually find three factors listed there, through whose interaction the entire economy is supposed to function. You will find listed: nature, human labor, and capital. Certainly, one can say at first glance that if one follows the economic process, one finds in its course that which comes from nature, that which is achieved through human labor, and that which is undertaken or organized by capital. But if one simply considers nature, labor, and capital side by side, so to speak, one will not be able to grasp the economic process in a living way. Such a view will lead to the most diverse forms of one-sidedness. And this is demonstrated by the history of economics. While some believe that all value lies in nature and that human labor does not actually add any particular value to natural objects, others are of the opinion that all economic value is actually imposed on some good, some commodity, by what is often referred to as crystallized labor. Again, when you compare capital and labor, you will find that, on the one hand, people say that it is actually capital that makes labor possible in the first place, and that wages are paid from the capital stock. On the other hand, it is said: No, everything that produces value is labor, and what capital gains is only the surplus value deducted from the results of labor.

The fact is that if you look at things from one point of view, one side is right; if you look at them from the other point of view, the other side is right. Such a view of reality actually seems very similar to some forms of accounting: if you put the item there, you get this result; if you put it there, you get that result, and so on. One can quite reasonably speak of very strong apparent reasons for added value, which is actually deducted from wages and appropriated by the capitalist. One can speak with equally good reasons that, in an economic context, the capitalist is actually entitled to everything and only pays his workers from what he can use as wages. There are very good and also very bad reasons for both. All these considerations are actually completely irrelevant to economic reality. These considerations are good as a basis for agitation, but they are by no means something that can be taken into account in serious economics. Other foundations must first be in place if one wants to speak with any degree of justification about the further development of the economic organism. Well, of course, to a certain extent, all such assertions are justified; and when Adam Smith, for example, sees labor, which is used to produce things, as the primary factor that actually creates value, one can also put forward extremely good reasons for this. A man like Adam Smith did not think nonsensically; but what underlies this is the assumption that one can always grasp something that is static and then give it a definition, whereas in the economic process everything is constantly in motion. It is relatively easy to formulate concepts about natural phenomena, even the most complicated ones, compared to the concepts needed for economics. The phenomena in economics are infinitely more complicated, unstable, and variable than those in nature, much more fluctuating, much less comprehensible with any specific concepts.

One must simply adopt a completely different method. This method will only be difficult for you in the very first lessons; but you will see that it will result in what can be taken as the basis for a real economics. One can say: in this economic process that we have to consider, nature, human labor, and—at least when looking at the purely external aspects of the economy—capital are involved. At least!

Now, however, if we look at the middle, at human labor, we can try to form an idea by going down – as I already hinted at yesterday – into the animal kingdom and looking at the sparrow economy or the swallow economy instead of the national economy. Yes, nature is the basis for the economy. The sparrow also has to perform a kind of work. It has to hop around and hop to where it finds its grain, and sometimes it has to hop a lot during the day until it finds its grain. The swallow, which builds its nest, also has to perform a kind of work. It also has a lot to do with it. Nevertheless, in an economic sense, we cannot call this work. We will not get anywhere with economic views if we call this work; for if we look more closely, we must say: the sparrow and the swallow are actually organized in such a way that they do precisely those things they need to do in order to find their food. They would not be able to be healthy if they could not move in this way. It is a continuation of their organization, which belongs to them, just as they have legs or wings. So in this case, we can actually disregard what could be called apparent work if we want to develop economic concepts. Where nature is taken directly and the individual being performs the corresponding apparent work merely to satisfy itself or those closest to it, we must actually deduct this apparent work if we want to determine what is value in the economic sense. And that is what we are concerned with first of all, that we approach a view of economic value.

So when we look at animal husbandry, we can only say that it is such that only nature itself creates value for it. Only nature itself creates value for animal husbandry. Now, however, when we move up to humans, that is, to the economy, we do indeed have the starting point of natural value from the natural side; but the moment humans no longer care only for themselves or their immediate neighbors, but care for one another, what human labor is immediately comes into consideration. What humans must do at the moment when they not only use natural products for themselves, but also have some kind of relationship with other humans and exchange goods with them, becomes work in relation to nature. And here we have one side of value in the national economy. This one side arises from the fact that human labor is applied to natural products, and we have before us, in economic circulation, natural products transformed by human labor. This is where real economic value actually arises. As long as the natural product remains untouched in its place of origin, it has no value other than that which it has, for example, for animals. The moment you take the first step of adding the natural product to the economic circulation process, the economic value begins with the transformed natural product. In this case, we can characterize this economic value by saying: The economic value of this one side is natural product transformed by human labor. Whether this human labor consists of digging, hoeing, or transporting the natural product from one place to another is irrelevant. If we want to have a general definition of value, we must say: Value is created by human labor that transforms a natural product in such a way that it can enter the economic circulation process.

If you consider this, you will immediately see the fluctuating nature of the value of a good circulating in the economy. For labor is something that is constantly present and is applied to the economic good. So you cannot actually say what value is, but can only say: Value appears at a certain point in time when human labor transforms a natural product. That is where value appears. We cannot and do not want to define value at first, but only want to point to the place where value appears. I would like to illustrate this schematically, to illustrate it schematically in such a way that I say to you: we have nature in the background, so to speak (see drawing 2, left); and we have human labor approaching nature; and what appears, as it were, through the interaction of nature and human labor, what becomes visible there, is, on the one hand, value. It is by no means a false image if, for example, you say to yourself: you look at a black surface, something black, through something light—you see it as blue. But depending on whether the light is thick or thin, it is a different shade of blue. Depending on where you move it, it is of varying density. It fluctuates... So value in economics, which is really nothing more than the manifestation of nature through human labor, fluctuates everywhere.

At first, these things don't give us much more than a few abstract clues, but these will guide us in the coming days as we search for concrete things. Well, you are used to it; in all sciences, you start with what is simplest at first. You see, work in itself has no purpose in an economic context. Because whether a person chops wood or stands on a wheel, there are those who do so because they are overweight and always climb from one step to the next—it goes down—and in doing so they make themselves thinner: they can do the same amount of work as someone who chops wood. Work viewed in the way Marx views it, for example, when he says that one should seek as an equivalent that which is consumed by work on the human organism, is colossal nonsense; for the same is consumed when a person dances on the wheel as when he chops wood. In economic terms, it does not matter what happens to the person. We have seen that economics borders on non-economics. From a purely economic point of view, there is no justification for pointing out that work—at least initially, in order to define the concept of work in economic terms—wears people out. It has indirect significance because, in turn, human needs must be met. As Marx pointed out, this is utter nonsense.

So what is necessary in order to understand labor in the economic process? It is necessary to disregard human beings entirely at first and look at how labor fits into the economic process. The work on such a wheel does not fit in at all; it remains entirely attached to human beings; wood chopping fits into the economic process. The only thing that matters is how work fits into the economic process. And here, for everything that comes into consideration, it is actually a matter of nature being changed everywhere by human labor. And only to the extent that nature is changed by human labor do we produce economic values in this one respect. If, for example, we consider it good for our physical health to work in nature and in between to dance around a little or do eurythmy, this can be judged from another point of view; but what we do in between cannot be described as economic work and cannot be regarded as creating economic value in any way. From another point of view, it may create value, but we must first form clear concepts of economic values as such.

Now, however, there is another possibility for economic value to arise. This is that we look at work as such and take work initially as something given. Then, as you have just seen, this work is initially something completely neutral and irrelevant in economic terms. However, it becomes economically valuable in every case when we direct this work through the mind and intelligence of human beings—I must express this somewhat differently than before. Even in the most extreme cases, you could think that something that is not otherwise work is transformed into work by the human mind. If it occurs to someone to use that wheel, to put it in their room and want to lose weight, then there is no economic value. But if someone pulls a rope around the wheel and this rope somehow engages to drive a machine, then you have used your mind to utilize something that is not work at all. The side effect is that the person is already losing weight; but what is actually decisive here is that the work is directed in a certain direction by the mind, by intelligence, by reflection, perhaps also by speculation, that the work is brought into certain interactions, and so on. So we can say: here we have the second side of value creation in the economy. Where labor is in the background and the mind directs the work in the foreground, the work shines through the mind and in turn generates economic value.

We will see that these two sides are present everywhere. If I have drawn the diagram here (see drawing 2, left) that economic value appears precisely when we have nature appearing through work, I would have to draw what I have now explained in such a way that we have work at the back and at the front, first of all, that which is spiritual, which gives work a certain modification (see drawing 2, right).

These are essentially the two poles of the economic process. You will find no other ways in which economic values are created: either nature is modified by labor, or labor is modified by the spirit, whereby the spirit is often manifested externally in the formation of capital, so that in relation to the economy, the spirit must be sought in the configuration of capital. At least its external expression is there. But that will become clear to us when we consider capital as such and then capital as a means of money.

So you see that we cannot say that a definition of economic value can be arrived at. For, again, just consider what all this depends on, how many stupid and clever people it depends on, that somewhere the spirit modifies work. There are all kinds of fluctuating conditions. But what is obvious always applies: that the value-forming moments in the economic process are to be sought in these two polar opposites.