World Economy

GA 340

30 July 1922, Dornach

Lecture VII

We have now seen how the economic system as a whole takes its course; we have seen how purchase or sale, loan and gift act as impelling factors, motive factors, within this system. Let us realise at once that there can be no economic system without this interplay of loan, gift and purchase. The influences, which create the economic values (of which we have already spoken from one aspect) and lead to the forming of price, will therefore proceed from these three factors: purchase, loan and gift. The important thing is to understand how the three factors work in the forming of price. Only by perceiving this, shall we succeed in any degree in formulating the price problem.

It is very necessary that we should have a distinct view of the real nature of separate economic problems. In this respect our present Economic Science is full of unclear ideas—ideas which, as I have often explained, become confused mainly because they try to grasp at rest what is in constant movement.

Granting then that gift, purchase and loan are inherent in economic movement, let us consider what in our present-day economy are—if I may so call them—the principal factors of rest. Let us turn for a moment to what is perhaps one of the commonest topics nowadays and a principal source of the errors that find their way into Political Economy. People talk of “Wages,” and they talk of them in such a way as to make them look like the price of Labour. If the so-called wage-earner has to be paid more, they say: “The price of Labour has gone up.” If he has to be paid less, they say: “Labour is cheaper.” Thus they actually speak as though a kind of sale and purchase took place between the wage-earner who sells his Labour and the man who buys it from him. But this sale and purchase is fictitious. It does not in reality take place. That is the trouble in our present economic conditions. On all hands we have hidden or masked relationships—relationships which develop in a way not in accordance with what in a deeper sense they really are. I have spoken of this before.

Value in the economic system, as we have already seen, can only arise in the exchange of products—in the exchange of commodities or—more generally—of economic products. It cannot arise in any other way. But what follows? If value can only arise in this way, and if moreover the price of the value is to be arrived at along the lines laid down yesterday (that is, by seeing that the producer of a given product receives, as its counter-value, what he will require to satisfy his needs during the production of another like product)—if this is to be possible, the various products must, as it were, reciprocally determine one another's value. And, after all, it is not difficult to see that this is what actually happens in the economic process. Only it is masked by the fact that money steps in between the objects exchanged. But the money is not the important thing. We should not take the slightest interest in money if it did not foster the exchange of products, making the process not only more convenient but less expensive. We should have no need of money if it were not for the fact that when a man brings a product to the market—under the influence of the division of Labour—he cannot be bothered to fetch what he needs from wherever it may happen to be; instead, he takes money for it, so that he may supply his needs later on at his own convenience. In fine we may say: It is the mutual tension, arising between the various products in the economic process, which must be concerned in the forming of prices.

Let us consider from this point of view the so-called wage-nexus, that is, the Labour-nexus. We cannot really exchange Labour for anything; since, as between Labour and anything else, there is no possibility of reciprocal determination of value. We may fancy that we are paying for Labour, we may even actualise this fancy by letting in the wage-nexus. But we do not really do anything of the sort. In reality, even in the Labour or wage-nexus, it is values which are exchanged. The worker produces something directly; he delivers a product, and it is this product which the enterpriser [Unternehmer] really buys from him. In actual fact, down to the last farthing, the enterpriser pays for the products which the workers deliver to him. It is time we began to see these things in their right light. The enterpriser buys products from the worker; and after he has bought them it is his business to impart to them a higher value, by making use of the conditions present in the social organism and by his own enterprising or “undertaking ” spirit. It is really this which gives him his profit. He gains on the transaction because, having bought the commodities from his workers, he is able by his “knowledge of the market” (we must not shirk unpleasant expressions) to enhance their value.

Thus, in the Labour-nexus we are dealing with a true purchase. And, ladies and gentlemen, we cannot speak of a surplus value arising through the Labour-nexus as such. All we can say is that in such and such circumstances the price which the enterpriser pays is not according to the true price, of which we spoke yesterday; and this is a thing we shall often find in the economic process—that, although the products reciprocally determine one another's values, although they have their real values, these values are not actually paid for in the course of commercial dealing. It is easy enough to see that all values are not really paid for. Take the case of a manufacturer on a small scale, who suddenly inherits a large legacy. Tired of the whole factory business, he decides to sell his stock-in-trade, and does so at an absurdly low price. That does not mean that the commodities decrease in value; it only means that the true price is not paid. Thus in actual economic intercourse prices are constantly being falsified. We must not forget this. In the course of commercial dealing prices may often be falsified. But there is, nevertheless, a true price. The commodities sold by the man in the above example are worth just as much as the same commodities produced by someone else.

Now that we have tried to make it clear that the wage-nexus does really involve a purchase, let us consider what is involved by rent—by the price of land. You see, the conditions under which the price of land originates are not those of a mature economy. To take an extreme instance, we may consider how a piece of land may have come under the control of particular persons by conquest, that is, by the exercise of force. Even here, no doubt, the element of exchange will enter in to some extent; the invader will have granted certain portions of the conquered territory to those who helped him to victory. Here, then, at the starting-point of an economic process we have something that is not properly economic. The process is not really economic; it is a process to which we can only apply the word “power” or “right.” By means of power, rights are gained—rights, in this case, over land. Thus we have the economic domain bordering on the one hand on these relationships of right and power.

But what is it that takes place under the influence of such relationships of right and power? This is what happens continually: The man who has the free right of disposal over land looks after himself better than those others whom he attaches to himself as labourers—who deliver the products to him by their Labour. I am speaking now not of the Labour, but of the products of the Labour; it is the products of Labour with which we are concerned. The others have to deliver more to him than he delivers to them. This, indeed, is only the prolongation of his relationship to them of conquest or right. Now, what is this excess of what they give him over what he gives them? What is it, in other words, that falsifies the price relationship in this case? It is none other than compulsory gift! Here, then, the relation of giving comes in, with the sole difference that the man who is to make the gift does so not of his own free will, but by compulsion; it is in fact a compulsory gift. That is what happens in relation to the land. Through the compulsory gift, the price which farm-products really ought to have in terms of other products is actually raised.

Thus the price of all things capable of subjection to such relationships of “right” has an inherent tendency to rise above its true level. So, for instance, if foresters or huntsmen are living with farmers, the foresters and huntsmen will come off better than the farmers. Farmers, among forest people, have to pay higher prices to the foresters for what they give them—higher prices, that is to say, than the true exchange prices as between their respective products, for the simple reason that in forestry, more than anywhere else, it is as a pure matter of right that the owner has the thing at his disposal and determines prices. Farming requires some real Labour; but in forestry, hunting and the like, we come very near to the pure “Labour-less” valuation—a valuation proceeding solely from relationships of right and power. Again, if handicraftsmen are living among farmers, the prices once again will tend to rise above their true level on the farmer's side; while on the other hand they will sink beneath the true level as against handicraft. Life is dearer for handicraftsmen among farmers; life is comparatively cheaper for farmers among handicraftsmen (assuming there are enough of them to make any appreciable difference). Handicraftsmen among farmers will find life comparatively dearer. Thus, the sequence governing this tendency for prices to rise above or to sink below their true level is as follows: First, forestry, then farming, then handicraft and, lastly, the entirely free spiritual work. These are the lines along which we should approach the problem of price-formation in the economic process.

There is a tendency, an inherent tendency, in the economic process to create rent. The economic process tends, as it were, of its own accord, to submit itself to this necessity of paying more dearly for farm products than for other things. This tendency obtains where there is division of Labour—and all our remarks have reference to a social organism in which there is division of Labour. This tendency is called forth through the fact that what I had to repeat twice over a few days ago, to the bewilderment of a large number of the audience (namely that the man who provides for himself lives more expensively and for that reason must take more for his products, must estimate them at a higher value than one who gets his products in free commercial dealing from others), that this simply does not come in in the case of farming.

In relation to the various branches of industry, ladies and gentlemen, this has a very real meaning, albeit you may have to think a very long time to find your way to that meaning. But in respect to agriculture and forestry it has no meaning. We must never forget that, when we are dealing with realities, the various concepts only hold good for certain regions; they change for other regions. This is equally true in other walks of life. What is a means of healing for the head, is pernicious—is a means to disease—for the stomach; and vice versa. And so it is in the economic organism. For example, if it were at all possible for the farmer not to provide for himself, the rules we apply for the general circulation of commodities would be right in his case, too. But the fact is, he can do no other than provide for himself; for within the economic process the entire agriculture of a social organism forms of its own nature a single entity, however many individual landowners there may be. Accordingly, the farmer must in every case keep back, from the totality of his products, what he has to provide for himself. Even if he gets it from another farmer, in reality he is still keeping it back. The farmer is essentially a man who provides for himself. Hence he is obliged to value his goods more expensively. The consequence is that prices must rise on his side.

It follows that there is an inherent tendency to create rents in the economic process. The only question will now be: How to make these rents harmless in the economic life? But in the first, place we must know that this tendency to create rent exists. If you abolish rents, in one form or another they will be created again, for the simple reason which I have just explained.

You see, for the same reason which underlies the tendency in the economic process to create rent, there arises, on the other hand, the tendency of the industrialists to devalue Capital, to make Capital cheaper and cheaper. We shall best understand this tendency if we get it clear to begin with that Capital cannot really be bought, True, there are dealings in Capital; people “buy” Capital. But every such purchase of Capital is once again merely a masked relationship; in reality we do not buy Capital, we only borrow it. Yet, in the end, even if the relationship is apparently other, you will always be able to unmask it and expose the loan character of industrial Capital. I say expressly, of industrial Capital, for if you extend the principle to rents it is no longer the case. But it is certainly the case with industrial Capital, for the simple reason that there is a constant tendency to undervalue, as compared with other things, that which depends on the human Will—that is to say, handicraft or manufacture and entirely free activity (at this point in the diagram). Industrial Capital is altogether implicated in the free activity of the Spirit; hence it is constantly being devalued; and we may say, on this side (Diagram 4), there is inherent in the economic process a tendency, while we create rents, to lower industrial Capital, to make it lower and lower in value. Just as things become more and more expensive on the one side, on the side of ground-rent, so do they become cheaper and cheaper on the other side, on the side of Capital. Capital has a permanent tendency to go down in its economic value, or rather in its economic price. Rents have a permanent tendency to rise in price.

There is also another reason from which you will see that industrial Capital must inevitably go down. We said just now that in farming one cannot help providing for oneself. It is just by this self-provision that the rise in the value of farm-products is brought about. At the same time you will see that in the case of industrial Capital, where the loan principle predominates, one cannot provide for oneself; one cannot provide for oneself with Capital. What one does provide for oneself must be included in the balance sheet nowadays in precisely the same way as what one borrows—if the balance sheet is to be correct. Since, therefore, at this point (Diagram 4) one cannot provide for oneself, it follows that the opposite tendency obtains—the tendency towards lower prices.

Everything depends on our seeing clearly through these relationships in the economic process. For then we shall see that it is by no means easy to establish true prices. The true price is constantly being upset by the fact that, on the one hand, there are things appearing on the market which tend to be too high in price, while, on the other hand, there are things appearing which tend to be too low in price. And since the price is settled by exchange, being in the middle, between the two, it is continually exposed to these influences. You can observe this very clearly in the economic process. In the same measure in which the products of forestry and agriculture grow more expensive, those produced by free human activity grow cheaper. Thus there arise those relationships of tension which give rise to social unrest and discontents. This, therefore, is the most important question in relation to the formation of price: How can we deal with the natural tension which exists in the creation of prices, as between the values accruing to goods arising out of the free will of man, and the values accruing to those goods in the production of which Nature participates? How can we get at this tension? How can we equate the one, the downward, tendency with the other, upward tendency?

Through division of Labour, more and more highly differentiated products arise. You need only remember how simple are the products arising, let us say, among a hunting or forest community. Here the price difficulty scarcely comes into question; but as soon as agriculture is added to forestry, the difficulty begins. In effect, the difficulty lies in the differentiation; the further the division of Labour extends, and new needs arise in the process, the more does the differentiation of products increase, and the difficulties connected with price-formation accumulate. The more varied are the products, the more difficult does it become to bring about their reciprocal valuation—and the valuation can only be reciprocal. This may be seen from the following comparison: There is a reciprocal valuation even in the case of products only slightly differentiated one from another—say, for instance, wheat and rye and other agricultural products. But follow the thing out over a long period of time and you will find the relationship of reciprocal valuation as between wheat, rye and other cereals remains fairly stable. If wheat goes up, the other cereals go up; if wheat goes down, the other cereals go down with it. This is due to the fact that there is comparatively little differentiation between these products; as soon as the differentiation becomes greater, this constancy no longer obtains. For it may well happen, through various events in the social organism, that some product which someone has been accustomed to exchange for another suddenly shoots up in price, while the other may go down at the same time. Think what revolutions are thus brought about in economic relationships. Altogether the things that happen in the economic world depend far more on the relative risings and fallings in price than on any other circumstance. It is by the relative rise and fall in prices that the difficulties of life itself are introduced into the economic sphere. As to whether the products as a whole rise or fall—if they all rose or fell uniformly, it would concern us very little. What interests people is that the different products rise or fall to a different extent. This fact is emerging in a very tragic way just now, under the present economic conditions. Products rise and fall in varying measure. Money-values especially are rising and falling, but in the money-values we simply have stored up what were once upon a time real values. By this rising and falling, an entire mingling and confusion is now being brought about in society.

From this we can see that there is another way, too, in which we must look at the factors operative in the economic organism. We took our start from the several factors which are enumerated by orthodox Economics, but we saw that the mere enumeration of Nature, Capital and Labour leads us no farther. Precisely when you add what we have said today to what has been said before, you will see that the pricing or valuing of Nature-products does not come about through purely economic relationships, but also through relationships of right or title; while, on the other hand, the valuing of industrial Capital is influenced by the free human Will with all that it unfolds when it is active in public life. Consider all that is necessary in order to collect a sum of Capital for a given purpose. Here the free human will comes in. Where lending is concerned, free human will has a very great part to play—indirectly perhaps, for the man who wants to keep savings is naturally going to invest those savings; but whether he ever saves at all, or not, is an expression of his Will. Here, then, the free human Will plays a real part. Now, if we take this into account, we shall find yet another classification of the economic factors beside the one which we have been considering hitherto.

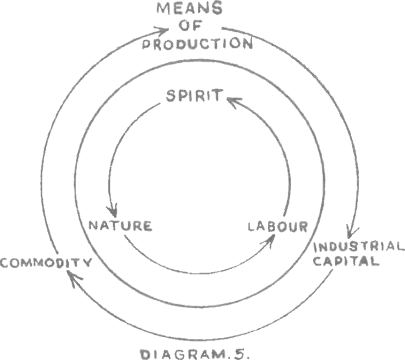

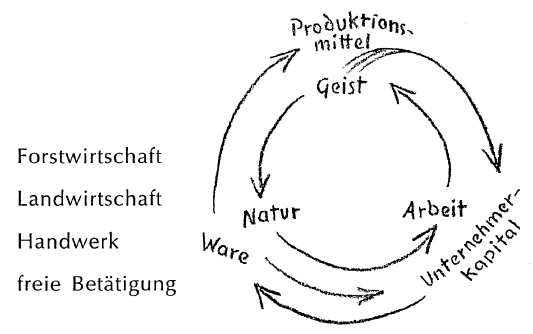

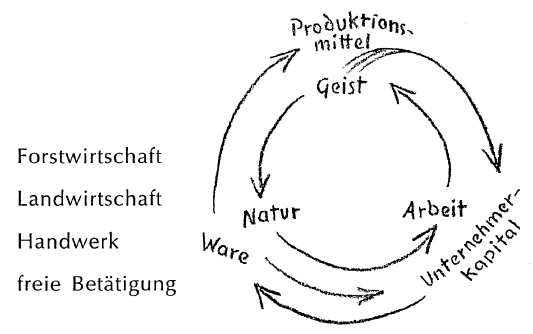

Up to now I have given you a diagrammatic classification. I showed: There is Nature, but value only arises through Nature elaborated, that is to say, it only arises when Nature moves in the direction of human Labour; and again, value will only arise through human Labour when it moves on towards Capital, i.e., towards the Spirit. In this way the tendency arises to return again to Nature. This, as we saw, can be prevented by leading over the excess Capital, not into the land, where it would become fixed, but into free spiritual undertakings where it vanishes, save for the remnant which must continue as a kind of seed, by which the economic process may be fertilised and maintained.

Now, in addition to this movement which begins from left to right (see (Diagram 5) there is another movement. The former movement, as we have seen, gives rise to elaborated Nature, organised or articulated Labour, and emancipated Capital—Capital, that is to say, which figures only within undertakings dependent on mind or Spirit—active Capital. The other movement does not lead to the creation of values in this way, the preceding element always being taken on by the next, but goes in the opposite direction; the first movement runs counter-clockwise, the second clockwise. Here, in the first movement, something arises through the former member always working on into the next; in the other movement something arises through the fact that that which flows in one direction receives, as it were, what is flowing in the other direction and embraces it. You will see what I mean directly. Remember that Capital is, properly speaking, Spirit realised in the economic process; so that I can write at this point “Spirit”—which gives us Nature, Labour and Spirit. Now when the Spirit absorbs and receives the elaborated Nature (Nature transformed by Labour)—when it does not merely lead it on into the economic process in the continued counter-clockwise movement, but absorbs it—Means of Production arise. What we call means of production is something different—it is in quite an opposite process of movement—from a Nature-product which has been elaborated for consumption. It is a Nature-product taken in charge by the Spirit—a Nature-product which the Spirit needs. From the pen which I possess as my means of production to the most complicated machinery in a factory, means of production

are, as it were, Nature grasped by the Spirit. Nature can be elaborated and sent on in this direction, in which case it becomes Capital; or it can be sent in the other direction, in which case it becomes means of production.

And now, what arises at this point with the help of means of production can move on and be taken in charge in turn by human Labour. Just as Nature is here received by the Spirit, so can the means of production (in the widest sense of the term) be received in turn by Labour. What have we then, when Labour receives the means of production—when means of production and Labour are united? It is Industrial Capital, for in effect industrial Capital consists in this very union. Thus if you follow the process out, you get a movement whereby means of production and industrial Capital coalesce.

And if this movement be now continued, so that Nature (albeit another portion of Nature) from time to time receives what has been produced with the help of means of production a and industrial Capital, then and then only does there arise in the economic process what we may call Commodity in the proper sense. For the commodity is at once taken over by the process of Nature. Either it is eaten, in which case it is taken up very decidedly by Nature; or it is used or otherwise destroyed. In short, a thing becomes a commodity by the very fact that it returns to Nature.

So that you may say: We have now traced out the movement, which is inherent in the whole economic process and which contains the three factors: Means of Production, Industrial Capital and Commodity. Here, at this third point in the diagram, the distinction becomes unusually difficult; for when the thing we are seeking is shifting to and fro in the process of exchange proper—that is, in purchase and sale—it is extraordinarily difficult to distinguish whether it is moving in this direction or in that—whether it is a commodity or something that cannot be called a “commodity” in the true sense of the word. How does a piece of goods become a “commodity”? In describing this counter-clockwise movement, to make the nomenclature quite exact, I ought really to write “goods” instead of “commodities” and in the opposite movement I ought to write “commodity”; for a “commodity” may be defined as a piece of goods in the hands of the tradesman, the merchant who offers it for sale and does not use it himself.

Today my main purpose was that we should acquire such concepts as point to the true relationships in the economic process. These true relationships are again and again being diverted, by falsified processes, into a mode of operation which introduces constant disturbances into the economic process. Continually to smooth out and compensate for the disturbances is one of the essential tasks of Economics. People keep on saying that we ought to get rid of the evils of economic life; and they are inclined to have at the back of their minds the notion: “Then everything will be all right and the earthly paradise will begin.” But that is just as though you were to say: “I should like, once and for all, to eat so much that I need never eat any more.” I cannot do that; for I am a living organism wherein ascending and descending processes must constantly be taking place. Such ascending and descending processes must equally be present in the economic life; there must be the tendency on the one hand to falsify prices by the forming of rent, and on the other hand the tendency to lower prices on the side of industrial Capital. These tendencies are present all the time, and we must understand them in order to obtain, as far as possible, those prices which represent a minimum of falsification.

To this end it is necessary, by direct human experience, to take hold of the economic process as it were in the nascent state—to be within it all the time. The individual can never do this; nor can a society above a certain size. (A society, for example, such as the State). It can only be done by Associations growing out of the economic life itself, and able therefore to work out of the immediate reality of the economic life. The greater the technical accuracy with which we study the economic process, the more are we led to recognise that the required institutions must grow out of the economic life itself. Then, they will be able to observe the kind of tendencies that are at work and how these can be counteracted.

Siebenter Vortrag

Wir haben uns nun klargemacht, wie die Gesamtvolkswirtschaft so verläuft, daß als treibende Faktoren, als bewegende Faktoren drinnen sind: Kauf, beziehungsweise Verkauf, Leihung und Schenkung. Wir müssen uns schon klar sein darüber, daß ohne dieses Ineinanderspielen von Leihen, Schenken, Kaufen eine Volkswirtschaft nicht bestehen kann. Was also im Volkswirtschaftlichen die Werte, von denen wir ja _ von der einen Seite her schon gesprochen haben, erzeugt, was also zu der Preisbildung führt, das wird hervorgehen aus diesen drei Faktoren, aus Kauf, Schenkung, Leihung. Es handelt sich nur darum, wie diese drei Faktoren drinnen in der Preisbildung spielen. Denn, erst wenn wir einsehen, wie diese Faktoren in der Preisbildung spielen, werden wir zu einer Art Formulierung des Preisproblems kommen können.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß man wirklich ordentlich hinsieht, worin denn die einzelnen volkswirtschaftlichen Probleme bestehen. In dieser Beziehung ist ja unsere Volkswirtschaft voll von ganz unklaren Vorstellungen, Vorstellungen, die hauptsächlich unklar dadurch werden, daß man, wie ich schon öfter auseinandergesetzt habe, das, was in Bewegung ist, in Ruhe erfassen will.

Betrachten wir einmal unter der Voraussetzung, daß in der volkswirtschaftlichen Bewegung Schenkung, Kauf und Leihung drinnen sind, ich möchte sagen, die wichtigsten Ruhefaktoren unserer Volkswirtschaft. Sehen wir uns einmal dasjenige an, wovon gerade in der Gegenwart am allermeisten gesprochen wird, und durch das eigentlich am meisten Irrtümer in die Volkswirtschaftswissenschaft. kommen. Man spricht vom Lohn und benennt wohl den Lohn auch so, daß der Lohn aussieht wie der Preis für die Arbeit. Man sagt, wenn man einem sogenannten Lohnarbeiter mehr bezahlen muß, die Arbeit sei teurer geworden; wenn man einem sogenannten Lohnarbeiter weniger bezahlen muß, sagt man, die Arbeit sei billiger geworden; spricht also tatsächlich, wie wenn eine Art Kauf stattfinden würde zwischen dem Lohnarbeiter, der seine Arbeit verkauft, und demjenigen, der ihm diese Arbeit abkauft. Aber dieses ist nur ein fingierter Kauf. Das ist gar kein Kauf, der in der Tat stattfindet. Und das ist ja das schwierige an unseren volkswirtschaftlichen Verhältnissen, daß wir eigentlich überall kaschierte, maskierte Verhältnisse haben, die sich anders abspielen, als sie eigentlich sind im tieferen Sinn. Ich habe das ja auch schon früher erwähnt.

Wert in der Volkswirtschaft kann ja nur entstehen — das haben wir schon ersehen können - im Austausch der Erzeugnisse, im Austausch der Waren oder überhaupt volkswirtschaftlicher Erzeugnisse. Auf eine andere Weise kann Wert nicht entstehen. Aber Sie können leicht einsehen: Wenn nur auf diese Weise Wert entstehen kann, und wenn der Preis des Wertes so zustande kommen will, wie ich das gestern auseinandergesetzt habe, daß berücksichtigt werden soll, wie für jemand, der ein Erzeugnis hervorgebracht hat, ein solcher Gegenwert für das Erzeugnis erhältlich sein soll, daß er die Bedürfnisse befriedigen kann, die er hat, um ein gleiches Erzeugnis wieder herzustellen - wenn das möglich sein soll, so müssen ja die Erzeugnisse sich gegenseitig bewerten. Und schließlich ist es ja nicht schwer, einzusehen, daß im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß sich die Erzeugnisse gegenseitig bewerten. Es wird nur kaschiert dadurch, daß das Geld zwischen dasjenige tritt, was ausgetauscht wird. Aber das ist nicht das Bedeutsame an der Sache. An dem Geld hätten wir nicht das geringste Interesse, wenn es nicht das Austauschen der Erzeugnisse förderte, bequemer machte und auch verbilligte. Wir hätten Geld nicht nötig, wenn es nicht so wäre, daß derjenige, der ein Erzeugnis auf den Markt liefert - unter dem Einfluß der Arbeitsteilung -, zunächst sich nicht abmühen will, um dasjenige, was er braucht, da zu holen, wo es vorhanden ist, sondern eben Geld dafür nimmt, um dann sich wiederum in der entsprechenden Weise zu versorgen. Wir können also sagen: In Wirklichkeit ist es die gegenseitige Spannung, welche zwischen den Erzeugnissen eintritt im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, die mit der Preiserzeugung zu tun haben muß.

Betrachten wir von diesem Gesichtspunkt aus einmal das sogenannte Lohnverhältnis, das Arbeitsverhältnis. Wir können nämlich gar nicht Arbeit gegen irgend etwas austauschen, weil es zwischen Arbeit und irgend etwas eigentlich keine gegenseitige Bewertungsmöglichkeit gibt. Wir können uns einbilden — und die Einbildung realisieren, indem wir eben das Lohnverhältnis eintreten lassen -, daß wir die Arbeit bezahlen; in Wirklichkeit tun wir es nicht. Was in Wirklichkeit geschieht, ist etwas ganz anderes. Was in Wirklichkeit geschieht, ist dieses: daß auch im Arbeits- oder Lohnverhältnis Werte ausgetauscht werden. Der Arbeiter erzeugt unmittelbar etwas, der Arbeiter liefert ein Erzeugnis; und dieses Erzeugnis kauft ihm in Wirklichkeit der Unternehmer ab. Der Unternehmer bezahlt tatsächlich bis zum letzten Heller die Erzeugnisse, die ihm die Arbeiter liefern -— wir müssen schon die Dinge in der richtigen Weise anschauen -, er kauft die Erzeugnisse dem Arbeiter ab. Und dann hat er die Aufgabe, daß er diesen Erzeugnissen durch die allgemeinen Verhältnisse im sozialen Organismus, nachdem er sie abgekauft hat, einen höheren Wert durch seinen Unternehmungsgeist verleiht. Das gibt ihm dann in Wahrheit den Gewinn. Das ist dasjenige, was er davon hat, dasjenige, was ihm möglich macht, daß er, nachdem er die Waren von seinen Arbeitern gekauft hat, sie durch - nennen wir das übelberüchtigte Wort - die Konjunktur an Wert erhöht.

Wir haben es also im Arbeitsverhältnisse mit einem richtigen Kauf zu tun. Und wir dürfen nicht sagen, daß da unmittelbar im Arbeitsverhältnis ein Mehrwert entstünde. Sondern wir dürfen nur sagen, daß der Preis, den der Unternehmer bezahlt, durch die Verhältnisse eben nicht derjenige ist, von dem ich gestern gesprochen habe. Aber das werden wir auch noch weiterhin im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß finden, daß zwar die Erzeugnisse sich gegenseitig ihre Werte bestimmen, ihre wirklichen Werte haben, daß diese Werte aber im Verkehr nicht bezahlt werden. Sie werden im Verkehr nicht bezahlt. Daß nicht alle Werte im Verkehr bezahlt werden, das können Sie ja unglaublich leicht einsehen. Denken Sie doch nur einmal: Wenn irgend jemand, sagen wir, Fabrikant ist, kleiner Fabrikant ist und plötzlich eine reiche Erbschaft macht, und ihm die ganze Geschichte mit der Fabrik zu dumm wird, so kann er beschließen, dasjenige, was er noch hat an Waren, unglaublich billig zu verkaufen. Die Waren werden deshalb nicht weniger wert, nur wird nicht der wirkliche Preis bezahlt. Es wird der Preis im volkswirtschaftlichen Verkehr gefälscht. Darauf müssen wir sehen, daß eben überall der Preis im volkswirtschaftlichen Verkehr gefälscht werden kann. Deshalb ist er aber doch da. Die Waren, die dieser Fabrikant verkauft, sind ja nicht weniger wert als die gleichen Waren, die ein anderer erzeugt.

Nun, nachdem wir versucht haben, uns klarzumachen, daß wir es im Lohnverhältnis eigentlich mit einem Kauf zu tun haben, wollen wir uns nun einmal fragen, mit was wir es zu tun haben bei der Bodenrente, bei dem Preis für Grund und Boden. Der Preis von Grund und Boden entspringt ja ursprünglich nicht dem Verhältnisse, das in der fertigen Volkswirtschaft da ist. Um, ich möchte sagen, ein sehr radikales Verhältnis anzuführen, braucht man ja nur hinzuweisen darauf, daß Grund und Boden zum Beispiel durch Eroberung, also durch Entfaltung von Macht, in die Verfügung von irgendwelchen Menschen übergegangen ist. Irgend etwas von einem Tausch wird auch da zugrunde liegen. Es wird zum Beispiel derjenige, der Helfer hat bei der Eroberung, einzelne Teile des Bodens an diese Helfer abtreten. Wir haben also da im Ausgangspunkt der Volkswirtschaft nichts eigentlich Wirtschaftliches. Der ganze Prozeß ist nicht eigentlich wirtschaftlich. Der ganze Prozeß, der sich da abspielt, ist so, daß wir nur anwenden können das Wort Macht oder Recht. Durch Macht werden Rechte erworben, Rechte auf Grund und Boden. So daß wir tatsächlich das Volkswirtschaftliche auf der einen Seite anstoßen haben an Rechts- und Machtverhältnisse.

Was geschieht aber unter dem Einfluß von solchen Rechts- und Machtverhältnissen? Nun, unter dem Einfluß von solchen Rechts- und Machtverhältnissen geschieht fortwährend das, daß der Betreffende, der das freie Verfügungsrecht über den Grund und Boden hat, sich selber besser abfindet, als er die anderen abfindet, welche er zur Arbeit heranzieht, welche ihm die Erzeugnisse durch Arbeit liefern. Ich rede jetzt also nicht von der Arbeit, sondern von dem Erzeugnis der Arbeit. Denn diese Erzeugnisse der Arbeit sind es, die in Betracht kommen. Es muß ihm mehr abgeliefert werden — das ist ja nur die Fortsetzung seines Eroberungs-, seines Rechtsverhältnisses —, es muß ihm mehr abgeliefert werden, als er den anderen gibt. Was ist denn dasjenige, was da mehr abgeliefert wird, als er den anderen gibt, was also das Preisverhältnis fälscht, was ist denn das? Ja, das ist ja nichts anderes als eine Zwangsschenkung. Sie haben also hier durchaus das Schenkungsverhältnis eintretend, nur eben, daß der Betreffende, der die Schenkung zu tun hat, sie nicht freiwillig tut, sondern dazu gezwungen wird. Es tritt eine Zwangsschenkung ein. Das ist dasjenige, was hier gegenüber dem Grund und Boden der Fall ist. Durch die Zwangsschenkung wird aber der Preis, den eigentlich die Produkte als Tauschpreis haben sollten, die auf dem Grund und Boden erzeugt werden, im wesentlichen erhöht.

Daher ist der Preis all desjenigen, was der Unterwerfung unter solche Rechtsverhältnisse fähig ist, mit der Tendenz behaftet, über seine Wahrheit hinaus zu steigen. Wenn Forstmenschen, Jäger, mit Landwirten zusammenleben, kommen die Forstmenschen besser weg als die Landwirte. Landwirte unter Forstmenschen müssen nämlich den Forstmenschen für das, was ihnen geliefert ist, höhere Preise bezahlen als die reinen Austauschpreise wären zwischen den Produkten der Forstwirtschaft und denen der Landwirtschaft, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil die Forstwirtschaft am meisten nur durch das Rechtsverhältnis in die Verfügung desjenigen, der die Preise bedingt, hineingebracht werden kann. Bei der Landwirtschaft muß schon eine wirkliche Arbeit aufgebracht werden; bei der Forstwirtschaft stehen wir noch sehr nahe der arbeitslosen Bewertung, die eben ganz allein aus Rechts- und Machtverhältnissen hervorgeht. Und wenn unter Landwirten Handwerker leben, so haben die Preise wiederum die Tendenz, gegen die Landwirtschaft höher, als die Wahrheit ist, zu steigen, und gegen das Handwerk hin niedriger sich zu senken, als die Wahrheit ist. Handwerker unter Landwirten leben teurer; Landwirte unter Handwerkern, wenn also die Minorität in Betracht kommt, verhältnismäßig billiger. Handwerker unter Landwirten leben verhältnismäßig teurer. So daß also die Stufenfolge dieser Tendenz, daß die Preise über die Wahrheit hinaussteigen oder unter die Wahrheit hinuntersinken, daß die Reihenfolge diese ist: am meisten ist das bei der Forstwirtschaft der Fall, dann kommt die Landwirtschaft, dann kommt das Handwerk und dann die vollständig freie Betätigung. So müssen wir die Preisbildung innerhalb des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses aufsuchen.

Nun besteht aber im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß eine Tendenz, eine Eigentendenz, Bodenrente zu erzeugen, gewissermaßen von selbst dazu zu neigen, sich diesem Zwang zu unterwerfen, die Landwirtschaft teurer zu bezahlen als das andere. Diese Tendenz besteht, wenn Arbeitsteilung vorhanden ist; und alle unsere Auseinandersetzungen beziehen sich ja auf den sozialen Organismus, in dem Arbeitsteilung vorhanden ist. Diese Tendenz wird einfach dadurch hervorgerufen, daß bei der Landwirtschaft nicht das eintreten kann, was ich vor einigen Tagen - ich möchte sagen, zur gedanklichen Schwierigkeit von einer größeren Anzahl der verehrten Zuhörer zweimal sagen mußte: Der Selbstversorger lebt tatsächlich teurer, also muß er für seine Produkte mehr nehmen, eigentlich muß er sie sich höher berechnen als derjenige, der seine Produkte im freien Verkehr erwirbt von anderen. In bezug auf die Gewerbe hat das einen gewissen Sinn, wenn Sie sich auch durch eine lange Überlegung erst vielleicht vollständig hineinfinden in diesen Sinn. In bezug auf Landwirtschaft und Forstwirtschaft hat es aber keinen Sinn. Das ist eben gerade das, was man wissen muß gegenüber den Wirklichkeiten, daß die Begriffe immer nur gelten für ein bestimmtes Gebiet und sich für ein anderes Gebiet umändern. Das ist auch sonst in der Wirklichkeit der Fall. Was ein Heilmittel für den Kopf ist, ist ein Verderbnismittel, ein krankmachendes Mittel für den Magen, und umgekehrt. Und so ist es durchaus auch im volkswirtschaftlichen Organismus. Wenn es nämlich überhaupt der Fall sein könnte, daß der Landwirt nicht ein Selbstversorger wäre, dann würden für ihn auch die Regeln gelten, die man sonst vorbringen muß für die Zirkulation der Waren. Aber er kann gar nicht anders, als Selbstversorger sein; denn im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß fügt sich von selbst die gesamte Landwirtschaft eines sozialen Organismus zu einer Einheit zusammen, wenn auch einzelne Besitzer da sind. Und unter allen Umständen muß einfach derjenige, der Landwirt ist, das, womit er sich selbst versorgt, aus dem Umfang seiner Produkte zurückhalten. Wenn er es vom andern nimmt, so hält er es auch zurück. In Wirklichkeit ist er ein Selbstversorger, muß also seine Güter teurer bewerten. Und die Folge davon ist, daß sich die Preise nach dieser Seite erhöhen müssen.

Das heißt, im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß besteht einfach die Tendenz, Bodenrente zu erzeugen. Es handelt sich nur darum, wie man diese Bodenrente unschädlich macht im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß. Aber das ist notwendig, daß man weiß, daß die Tendenz besteht, Bodentente zu erzeugen. Sie können die Bodenrente abschaffen, sie wird in irgendeiner Form immer wieder erzeugt, aus dem einfachen Grunde, den ich eben jetzt auseinandergesetzt habe.

Aus demselben Grunde, aus dem im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß eine Tendenz besteht, Bodenrente zu erzeugen, aus demselben Grunde besteht nach der anderen Seite die Tendenz der Unternehmer, Kapital zu entwerten, immer billiger und billiger zu machen. Diese Tendenz wird man am besten verstehen, wenn man sich darüber klar wird, daß man ja Kapital nicht kaufen kann. Gewiß, es wird Kapital gehandelt. Man kauft Kapital. Aber jeder Kapitalkauf ist wiederum nur ein kaschiertes Verhältnis. In Wirklichkeit kaufen wir nicht Kapital, sondern in Wirklichkeit wird Kapital nur geliehen; auch dann, wenn scheinbar ein anderes Verhältnis stattfindet, werden Sie immer herausfinden können den Leihcharakter des Unternehmerkapitals. Ausdrücklich sage ich des Unternehmerkapitals; denn wenn Sie den Begriff ausdehnen auf die Bodenrente, so ist das nicht der Fall; aber durchaus bei dem Unternehmerkapital; und zwar aus dem einfachen Grunde ist das der Fall, weil dauernd die Tendenz besteht, dasjenige, was von dem menschlichen Willen abhängt - Sie sehen hier (siehe Zeichnung 4) das Handwerkliche und die freie Betätigung -, das gegenüber dem anderen zu entwerten. Unternehmerkapital ist ganz eingesponnen in die freie Betätigung. Es wird fortwährend entwertet, so daß wir sagen können: Wir haben nach dieser Seite (siehe Zeichnung 4) die Tendenz im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß — während wir die Bodenrente erzeugen -, das Unternehmerkapital herunterzubringen, es immer niedriger und niedriger zu machen, immer niedriger und niedriger zu bewerten. Wie es also nach der einen Seite hin, nach der Bodenrentenseite, immer teurer wird, wird es nach der Kapitalseite immer billiger. Das Kapital hat die Tendenz, fortwährend in seinem volkswirtschaftlichen Werte, oder eigentlich Preise, zu sinken, die Bodenrente hat die Tendenz, fortwährend in ihrem Preise zu steigen.

Auch noch einen andern Grund gibt es, aus dem heraus Sie einsehen können, daß das Unternehmerkapital sinken muß. Wenn Sie sich klarmachen, daß man in der Landwirtschaft nur Selbstversorger sein kann und gerade durch die Selbstversorgung hervorgebracht wird dieses (siehe Zeichnung 4) Hinaufsteigen in der Bewertung der landwirtschaftlichen Erzeugnisse, so können Sie sehen: Beim Unternehmerkapital, wo das Leihprinzip herrscht, da kann man nicht Selbstversorger sein. Man kann sich nicht selbst versorgen mit Kapital. Womit man sich selbst versorgen kann, das muß man heute in Bilanzen ganz genau so berechnen wie dasjenige, was man aufnimmt, wenn man eine richtige Bilanz aufstellen will. Da man sich also da (siehe Zeichnung 4) nicht selbst versorgen kann, so ist natürlich auch die entgegengesetzte Tendenz vorhanden, die Tendenz des Herabsteigens der Preise.

Gerade auf das Durchschauen dieser Verhältnisse im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß kommt es an; denn Sie werden daraus erkennen, daß die Herstellung von richtigen Preisen nicht etwas so ganz Einfaches ist. Die Herstellung von richtigen Preisen wird ja fortwährend beeinträchtigt dadurch, daß auf der einen Seite Dinge auf dem Markt erscheinen, die eigentlich im Preise zu hoch sein wollen, möchte ich sagen, und auf der anderen Seite Dinge erscheinen, die im Preise zu niedrig sein wollen. Da aber der Preis durch den Austausch bewirkt wird, ist auch dasjenige, was in der Mitte drinnen ist, fortwährend Störungen ausgesetzt. Sie können das auch im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß durchaus beobachten: in demselben Maße, in dem die landwirtschaftlichen und forstwirtschaftlichen Produkte teurer werden, werden die aus freier menschlicher Betätigung hergestellten billiger. Dadurch entstehen eben gerade jene Spannungsverhältnisse, welche die sozialen Unruhen bewirken, welche das sozial Unbefriedigende erzeugen. Und daher ist die allerwichtigste Frage in bezug auf Preisbildung: Wie gelangen wir dahin, die Spannung auszugleichen, die besteht in der Preiserzeugung zwischen der Bewertung der aus freiem menschlichem Willen entstehenden Güter gegenüber denjenigen Gütern, zu denen die Natur mitwirkt? Wie kommen wir dieser Spannung bei? Wie gleichen wir die eine Tendenz nach abwärts mit der anderen Tendenz nach aufwärts aus?

Innerhalb der Arbeitsteilung entstehen ja immer differenziertere und differenziertere Erzeugnisse. Sie brauchen sich nur zu erinnern, wie einfach die Erzeugnisse sind, die, sagen wir, innerhalb eines Jägervolks entstehen, das ganz von der Forstwirtschaft lebt. Da kommt eigentlich noch nicht viel in Betracht von der Schwierigkeit der Preisbildung. Wenn sich zur Forstwirtschaft die Landwirtschaft hinzugesellt, da beginnt es aber schon mit der Schwierigkeit. In der Differenzierung liegt nämlich die Schwierigkeit. Und je weiter und weiter sich die Arbeitsteilung ausbreitet und damit neue Bedürfnisse erzeugt werden, in demselben Maße nimmt die Differenzierung der Produkte zu und in demselben Maße häufen sich die Schwierigkeiten der Preisbildung; denn je verschiedener die Produkte, die Erzeugnisse voneinander sind, desto schwerer wird es, die gegenseitige Bewertung - und sie kann nur eine gegenseitige sein — zu bewirken. Sie können das daraus entnehmen, daß es ja eine gegenseitige Bewertung gibt bei nicht stark differenzierten Produkten, sagen wir bei Weizen, Roggen und anderen landwirtschaftlichen Produkten. Gehen Sie durch sehr lange Zeit hindurch: Sie werden finden, daß das Verhältnis in der gegenseitigen Wertgebung zwischen Weizen, Roggen und anderen Getreidesorten ziemlich stabil bleibt. Geht der Weizen hinauf, gehen die anderen Getreidesorten auch hinauf; geht der Weizen herunter, so gehen die anderen auch herunter. Das rührt davon her, daß durchaus eine geringe Differenzierung nur besteht zwischen diesen Erzeugnissen. Wird die Differenzierung größer, dann ist das durchaus nicht mehr der Fall, dann kann durch Ereignisse innerhalb des sozialen Organismus irgendein Produkt, das jemand gewohnt gewesen ist auszutauschen gegen ein anderes Produkt, hoch hinaufschnellen im Preis, das andere vielleicht hinuntergehen. Denken Sie sich, was dadurch für eine Umlagerung in den volkswirtschaftlichen Verhältnissen bewirkt wird. Dasjenige überhaupt, was in der Volkswirtschaft bewirkt wird, das beruht nämlich viel mehr auf den gegenseitigen Preissteigerungen und dem Preisfallen als auf irgend etwas anderem. Auf dem gegenseitigen Steigen und Fallen der Preise beruht ja dasjenige, was in die Volkswirtschaft hinein die Schwierigkeit des Lebens trägt. Ob schließlich die Produkte im Ganzen steigen oder fallen - wenn sie alle gleichmäßig stiegen oder fielen, das könnte eigentlich die Leute im Grunde recht wenig interessieren. Dasjenige, was sie interessiert, das ist, daß in verschiedenem Maße die Produkte steigen oder fallen. Das ist ja etwas, was, man möchte sagen, auf eine tragische Weise jetzt durch die gegenwärtigen wirtschaftlichen Verhältnisse eben herauskommt; dadurch, daß die Produkte in verschiedenster Weise steigen und fallen -— namentlich steigen und fallen die Geldwerte selbst, in denen aber aufbewahrt ist einfach früherer wirklicher Wert -, dadurch wird ja gegenwärtig eine völlige Mischung der menschlichen Gesellschaft zustande gebracht.

Das aber führt uns dazu, zu erkennen, daß wir die im volkswirtschaftlichen Organismus wirksamen Faktoren noch in einer anderen Weise anschauen müssen. Wir sind von dem ausgegangen, was die gewöhnliche Volkswirtschaft aufzählt, wenn von den Faktoren gesprochen wird, die in einem volkswirtschaftlichen Organismus darinnen sind, haben aber gesehen, daß mit der Aufzählung von Natur, Kapital und Arbeit eigentlich nichts erreicht werden kann. Denn, gerade wenn Sie zu dem schon früher Gesagten auch noch das heutige hinzufügen, so werden Sie sehen, daß ja die Preisbewertung der Naturprodukte eben nicht unter rein volkswirtschaftlichen Verhältnissen zustande kommt, sondern durch Rechtsverhältnisse; daß in die Bewertung des Unternehmerkapitals hineinspielt der freie menschliche Wille mit all demjenigen, was er entfaltet, wenn er sich im öffentlichen Leben betätigt. Denken Sie sich doch nur einmal, was man braucht, um ein Unternehmerkapital wirklich zu sammeln für irgend etwas. Da spielt der freie menschliche Wille hinein. In das Leihen spielt der freie menschliche Wille hinein. Vielleicht nicht direkt. Natürlich, derjenige, der Erspartes haben will, will es schon leihen; aber ob jemand überhaupt spart oder nicht, das ist schon ein Ausdruck des Willens. Es ist so, daß der freie menschliche Wille da ganz wesentlich hineinspielt. Wenn wir aber das berücksichtigen, so werden wir noch eine andere Gliederung der volkswirtschaftlichen Faktoren finden, als diejenige ist, die wir bisher betrachtet haben.

Ich habe Ihnen bisher eine schematische Gliederung gegeben, worin ich Ihnen gezeigt habe: Natur ist da, aber Wert wird erst durch die bearbeitete Natur, wenn sich Natur gegen Arbeit bewegt. Und Wert wird erst durch Arbeit, wenn sich diese gegen Kapital oder den Geist bewegt. Und dadurch entsteht die Tendenz, wiederum zu der Natur zurückzukehren, was ja dadurch verhindert werden kann, daß übergeführt wird dasjenige, was überschüssiges Kapital ist, nicht in den Grund und Boden, wo es fixiert wird, sondern in freie geistige Unternehmungen, wo es eben bis zu dem Rest verschwindet, der gewissermaßen als Samen weiterbestehen soll, damit der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß aufrechterhalten werden kann.

Und außer dieser Bewegung, die also hier (siehe Zeichnung 5) von links nach rechts geht und wodurch entsteht bearbeitete Natur, organisierte oder gegliederte Arbeit und emanzipiertes, bloß innerhalb der geistigen Unternehmungen figurierendes, sich betätigendes Kapital, außer dieser Bewegung gibt es noch eine andere Bewegung. Das ist nämlich diejenige Bewegung, welche nun nicht in die Verwertung hineinführt, so hineinführt, daß das Vorhergehende von dem Nächsten übernommen wird, sondern die im entgegengesetzten Sinn geht. Die eine Bewegung geht entgegengesetzt dem Uhrzeiger, die andere geht dem Uhrzeiger entsprechend. Bei der einen Bewegung entsteht etwas dadurch, daß gewissermaßen das vorhergehende Glied in das nächste eingreift; bei der anderen Bewegung dadurch, daß das, was hier (siehe Zeichnung 5) herüberfließt, auffängt, was hinüberfließt und es gleichsam umspannt. Sie werden gleich daraufkommen, was ich damit meine. Wenn Sie berücksichtigen, daß Kapital eigentlich verwirklichter Geist ist im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, so kann ich statt Kapital ja auch Geist schreiben, so daß wir haben: Natur, Arbeit und Geist.

Dann, wenn der Geist aufnimmt, was bearbeitete Natur ist, wenn er es nicht einfach in der fortschreitenden Bewegung, entgegengesetzt dem Zeiger einer Uhr, in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß hineinführt, sondern wenn er es aufnimmt, so entsteht das Produktionsmittel. Das Produktionsmittel ist nämlich etwas anderes: es ist eigentlich in einer ganz entgegengesetzten Bewegung als dasjenige, was für den Konsum bearbeitetes Naturprodukt ist. Es ist ein Naturprodukt, das in Empfang genommen wird von dem Geist, ein Naturprodukt, das der Geist haben muß. Von der Schreibfeder an, die ich als mein Produktionsmittel habe, bis zu den kompliziertesten Maschinen in der Fabrik, sind die Produktionsmittel gewissermaßen vom Geist erfaßte Natur. Die Natur kann bearbeitet werden und nach dieser Richtung geschickt werden: dann wird sie Kapital; oder nach der andern Seite geschickt werden: dann wird sie zum Produktionsmittel.

Ebenso aber kann dasjenige, was mit Hilfe des Produktionsmittels sich hier bildet, sich weiterbewegen und wiederum in Empfang genommen werden von der Arbeit. Geradeso wie hier von dem Geist die Natur empfangen wird, so kann von der Arbeit empfangen werden dasjenige, was also zum Beispiel Produktionsmittel eben ist im weitesten Sinne. Wenn von der Arbeit dasjenige empfangen wird, was Produktionsmittel ist, wenn also eine Verbindung entsteht zwischen dem Produktionsmittel und der Arbeit, dann liegt in dieser Verbindung das Unternehmerkapital. Das ist das Unternehmerkapital. So daß sich also, wenn Sie diesen Prozeß (siehe Zeichnung 5) verfolgen, eine Bewegung ergibt, die ineinanderschiebt Produktionsmittel und Unternehmerkapital.

Und wenn diese Bewegung sich jetzt fortsetzt, so daß fortwährend übernommen wird von der Natur - allerdings jetzt von einem anderen Teil der Natur als beim Konsumtionsprozeß -, so daß fortwährend übernommen wird von der Natur dasjenige, was mit Hilfe von Produktionsmittel und Unternehmerkapital hervorgebracht wird, dann entsteht erst im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß dasjenige, was eigentlich die Ware ist. Die Ware wird nämlich schon vom Naturprozeß übernommen. Entweder sie wird gegessen, dann wird sie sehr stark von der Natur übernommen, oder sie geht zugrunde, wird verbraucht kurz, es wird etwas Ware dadurch, daß es zur Natur wiederum zurückkehrt.

So daß Sie sagen können: Wir haben jetzt diejenige Bewegung verfolgt, welche drinnen steckt im ganzen volkswirtschaftlichen Vorgang und die die Faktoren enthält: Produktionsmittel, Unternehmerkapital, Ware. Hier (siehe Zeichnung 5), an dieser Stelle, wird die Unterscheidung außerordentlich schwierig sein; denn dasjenige, was beim eigentlichen Tausch, also beim Kauf und Verkauf, hin- und hergeht, an dem läßt es sich außerordentlich schwer unterscheiden, ob es in der Bewegung so hin ist oder so her, ob es eine Ware ist, oder ob es etwas ist, was nicht im wahren Sinn des Wortes Ware genannt werden kann. Denn, wodurch wird denn ein Gut eine Ware? Ich müßte eigentlich bei der Bewegung in dieser Richtung - entgegengesetzt dem Zeiger der Uhr -, wenn ich ganz genau benennen wollte, müßte ich herschreiben Gut und bei der rückläufigen Bewegung müßte ich schreiben Ware; denn Ware ist das Gut nur in der Hand des Händlers, des Kaufmannes, der es anbietet und nicht selbst benützt.

Es kam mir also heute hauptsächlich darauf an, daß wir uns Begriffe aneigneten, welche auf die wahren Verhältnisse im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß hindeuten, die durch die verfälschten Prozesse fortwährend in eine solche Wirkungsweise hineinkommen, daß der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß in der Tat fortwährend Störungen erleidet. Diese Störungen fortwährend auszugleichen, das ist eigentlich ein Wesentliches in der Aufgabe der Volkswirtschaft. Die Leute reden heute viel davon, daß man sollte die Schäden der Volkswirtschaft beseitigen, und haben so ein bißchen den Hintergedanken: Dann wird alles gut sein, dann ist so ungefähr das Paradies auf Erden. - Aber das ist so, wie wenn man sagte: Nun möchte ich doch einmal so viel essen, daß ich dann gar nicht mehr zu essen brauche. - Ich kann das nicht, weil ich ein Organismus bin, weil da fortwährend auf- und absteigende Prozesse sich entwickeln müssen. Diese auf- und absteigenden Prozesse müssen in der Volkswirtschaft da sein; es muß die Tendenz da sein, auf der einen Seite die Preise zu verfälschen durch die Bildung der Rente, auf der andern Seite muß die Tendenz da sein, die Preise zu erniedrigen gegen das Unternehmerkapital hin. Diese Tendenzen sind fortwährend da und müssen erfaßt werden, um möglichst die Preise so zu bekommen, daß die Fälschungen immer ein Minimum sind.

Dazu ist notwendig, den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß durch unmittelbare menschliche Erfahrung gewissermaßen im Status nascendi zu erfassen, immer drinnen zu stehen. Das kann niemals der einzelne, das kann auch niemals eine über eine gewisse Größe hinausgehende Gesellschaft, zum Beispiel der Staat; das können nur Assoziationen, die aus dem wirtschaftlichen Leben selbst herauswachsen und deshalb aus dem unmittelbaren lebendigen wirtschaftlichen Leben auch wirken können. Gerade wenn wir stark technisch betrachten den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, werden wir dazu geführt, anzuerkennen, daß aus dem Wirtschaftsprozeß selbst heraus sich die Institutionen bilden müssen, welche die Menschen so zusammenfassen, daß sie assoziativ drinnenstehen im unmittelbaren lebendigen Prozeß und nun beobachten können, wie die Tendenzen vorhanden sind und wie man den Tendenzen entgegenwirken kann.

Seventh Lecture

We have now clarified how the economy as a whole functions, identifying the driving factors, the motivating factors within it: buying, selling, lending, and giving. We must be clear that without this interplay of lending, gifting, and purchasing, a national economy cannot exist. So what generates value in the national economy, which we have already discussed from one perspective, and what leads to price formation, emerges from these three factors: purchasing, gifting, and lending. It is only a question of how these three factors play into price formation. For only when we understand how these factors play into price formation will we be able to arrive at a kind of formulation of the price problem.

Now it is a matter of really taking a close look at what the individual economic problems consist of. In this respect, our economy is full of very unclear ideas, ideas that are mainly unclear because, as I have often discussed, we want to understand what is in motion in a calm manner.

Let us consider, on the assumption that economic activity includes gifts, purchases, and loans, what I would call the most important factors of stability in our economy. Let us look at what is currently the most talked about topic, and which actually causes the most errors in economic science. People talk about wages and refer to them in such a way that wages appear to be the price of labor. They say that if you have to pay a so-called wage laborer more, labor has become more expensive; if you have to pay a so-called wage laborer less, they say that labor has become cheaper; in other words, they actually speak as if a kind of purchase were taking place between the wage laborer, who sells his labor, and the person who buys this labor from him. But this is only a fictitious purchase. It is not a purchase that actually takes place. And that is the difficult thing about our economic conditions, that we actually have concealed, masked conditions everywhere, which play out differently than they actually are in a deeper sense. I have already mentioned this before.

Value in the economy can only arise—as we have already seen—through the exchange of products, the exchange of goods or economic products in general. Value cannot arise in any other way. But you can easily see that if value can only arise in this way, and if the price of value is to be determined in the way I explained yesterday, taking into account how someone who has produced a product should be able to obtain such a countervalue for the product that he can satisfy the needs he has in order to produce the same product again — if that is to be possible, then the products must evaluate each other. And finally, it is not difficult to see that in the economic process, products evaluate each other. This is only concealed by the fact that money intervenes between what is exchanged. But that is not the important thing. We would not have the slightest interest in money if it did not promote the exchange of products, make it more convenient, and also reduce its cost. We would not need money if it were not for the fact that those who supply a product to the market—under the influence of the division of labor—do not want to go to the trouble of obtaining what they need from where it is available, but instead take money for it and then procure what they need in the appropriate manner. We can therefore say that, in reality, it is the mutual tension that arises between products in the economic process that must be related to price formation.

Let us consider the so-called wage relationship, the employment relationship, from this point of view. We cannot exchange labor for anything else because there is actually no mutual valuation possible between labor and anything else. We can imagine—and realize this imagination by entering into the wage relationship—that we are paying for the labor; in reality, we are not. What actually happens is something completely different. What actually happens is this: that values are also exchanged in the employment or wage relationship. The worker directly produces something, the worker delivers a product; and this product is actually purchased by the entrepreneur. The entrepreneur actually pays every last penny for the products that the workers deliver to him—we must look at things in the right way—he buys the products from the worker. And then he has the task of giving these products a higher value through his entrepreneurial spirit, through the general conditions in the social organism, after he has bought them. That is what actually gives him the profit. That is what he gets out of it, what enables him, after he has bought the goods from his workers, to increase their value through — let's call it the notorious word — the economic situation.

So in labor relations we are dealing with a real purchase. And we cannot say that added value is created directly in the labor relationship. Instead, we can only say that the price paid by the entrepreneur is not the one I spoke of yesterday due to the circumstances. But we will continue to find this in the economic process, that although the products determine each other's values, have their real values, these values are not paid for in trade. They are not paid for in trade. It is incredibly easy to see that not all values are paid for in trade. Just think about it: if someone, let's say, is a manufacturer, a small manufacturer, and suddenly comes into a rich inheritance, and the whole business with the factory becomes too stupid for him, he may decide to sell what he still has in goods at an incredibly low price. This does not make the goods any less valuable, it just means that the real price is not being paid. The price in economic transactions is being falsified. We must realize that prices in economic transactions can be falsified everywhere. But that does not mean that they do not exist. The goods that this manufacturer sells are no less valuable than the same goods produced by someone else.

Now that we have tried to make it clear to ourselves that we are actually dealing with a purchase in the wage relationship, let us ask ourselves what we are dealing with in the case of ground rent, the price of land. The price of land does not originally arise from the conditions that exist in the finished economy. To cite a very radical example, one need only point out that land has come into the possession of certain people through conquest, i.e., through the exercise of power. Some kind of exchange will also have taken place here. For example, those who had helpers in the conquest will cede individual pieces of land to these helpers. So, at the starting point of the national economy, we don't actually have anything economic. The whole process is not actually economic. The whole process that takes place there is such that we can only apply the word power or right. Rights are acquired through power, rights to land. So that, on the one hand, we actually have the national economy based on legal and power relationships.

But what happens under the influence of such legal and power relationships? Well, under the influence of such legal and power relationships, what happens is that the person who has the free right of disposal over the land compensates himself better than he compensates the others whom he employs to work and who supply him with the products of their labor. I am not talking now about labor, but about the product of labor. For it is these products of labor that are at issue. More must be delivered to him—this is only the continuation of his conquest, his legal relationship—more must be delivered to him than he gives to others. What is it that is delivered to him in excess of what he gives to others, what is it that distorts the price ratio? Yes, it is nothing other than a compulsory gift. So here you have a gift relationship, except that the person who has to make the gift does not do so voluntarily, but is forced to do so. A compulsory donation occurs. That is what is happening here with regard to the land. However, the compulsory donation essentially increases the price that the products produced on the land should actually have as an exchange price.

Therefore, the price of everything that is subject to such legal relationships tends to rise above its true value. When foresters and hunters live together with farmers, the foresters fare better than the farmers. Farmers among foresters have to pay foresters higher prices for what they supply them than the pure exchange prices between forestry and agricultural products would be, for the simple reason that forestry can only be brought into the disposal of those who determine prices through legal relationships. In agriculture, real work has to be done; in forestry, we are still very close to an unemployed valuation, which arises solely from legal and power relations. And when craftsmen live among farmers, prices tend to rise higher than they should be for agriculture and fall lower than they should be for crafts. Craftsmen living among farmers live more expensively; farmers living among craftsmen, if the minority is taken into account, live relatively more cheaply. Craftsmen living among farmers live relatively more expensively. So the sequence of this tendency, whereby prices rise above the true value or fall below it, is as follows: this is most evident in forestry, then comes agriculture, then crafts, and then completely free activity. This is how we must seek out price formation within the economic process.

However, there is a tendency in the economic process, an inherent tendency, to generate ground rent, to tend, as it were, to submit to this compulsion to pay more for agriculture than for other sectors. This tendency exists when there is a division of labor; and all our discussions relate to the social organism in which there is a division of labor. This tendency is simply caused by the fact that in agriculture, what I had to say twice a few days ago—I would like to say, to the intellectual difficulty of a large number of the esteemed audience—cannot occur: the self-sufficient farmer actually lives more expensively, so he has to charge more for his products; in fact, he has to charge more than those who purchase their products from others in free trade. In relation to trade, this makes a certain sense, even if it takes a long time to fully understand this meaning. However, it makes no sense in relation to agriculture and forestry. This is precisely what one must know about reality, that concepts only apply to a specific area and change for another area. This is also the case in other areas of reality. What is a remedy for the head is a poison, a disease-causing agent for the stomach, and vice versa. And so it is also in the economic organism. If it could ever be the case that the farmer were not self-sufficient, then the rules that otherwise have to be applied to the circulation of goods would also apply to him. But he cannot help but be self-sufficient, for in the economic process the entire agriculture of a social organism automatically forms a unity, even if there are individual owners. And in all circumstances, the farmer must simply withhold from the totality of his products that which he uses to supply himself. If he takes it from others, he also withholds it. In reality, he is self-sufficient and must therefore value his goods more highly. The result is that prices must rise on this side.

This means that in the economic process there is simply a tendency to generate ground rent. It is only a question of how to render this ground rent harmless in the economic process. But it is necessary to know that there is a tendency to generate ground rent. You can abolish ground rent, but it will always be generated in some form, for the simple reason I have just explained.

For the same reason that there is a tendency to generate ground rent in the economic process, there is also a tendency on the other side for entrepreneurs to devalue capital, to make it cheaper and cheaper. This tendency is best understood when one realizes that capital cannot be bought. Certainly, capital is traded. Capital is bought. But every purchase of capital is, in turn, only a concealed relationship. In reality, we do not buy capital; in reality, capital is only borrowed. Even when a different relationship appears to exist, you will always be able to identify the borrowed nature of entrepreneurial capital. I expressly say entrepreneurial capital, because if you extend the concept to ground rent, this is not the case; but it is certainly the case with entrepreneurial capital, for the simple reason that there is a constant tendency to devalue that which depends on human will—here you see (see Figure 4) craftsmanship and free activity—in comparison to the other. Entrepreneurial capital is completely intertwined with free activity. It is constantly being devalued, so that we can say: on this side (see Figure 4), we have a tendency in the economic process — while we generate ground rent — to bring down entrepreneurial capital, to make it lower and lower, to value it lower and lower. So, just as it becomes more and more expensive on the one side, the ground rent side, it becomes cheaper and cheaper on the capital side. Capital has a tendency to continuously decline in its economic value, or rather its price, while ground rent has a tendency to continuously rise in price.

There is another reason why you can see that entrepreneurial capital must decline. If you realize that in agriculture you can only be self-sufficient, and that it is precisely self-sufficiency that brings about this (see Figure 4) rise in the valuation of agricultural products, you can see: With entrepreneurial capital, where the principle of borrowing prevails, it is not possible to be self-sufficient. It is not possible to be self-sufficient with capital. What you can be self-sufficient with must be calculated in balance sheets today in exactly the same way as what you take in if you want to draw up a correct balance sheet. Since you cannot be self-sufficient there (see Figure 4), there is naturally also an opposite tendency, the tendency for prices to fall.

It is precisely this insight into the economic process that is important, because you will recognize from it that establishing correct prices is not such a simple matter. The establishment of correct prices is constantly hampered by the fact that, on the one hand, things appear on the market that are actually too expensive, I would say, and on the other hand, things appear that are too cheap. But since the price is determined by exchange, even what is in the middle is constantly subject to disturbances. You can also observe this in the economic process: as agricultural and forestry products become more expensive, those produced by free human activity become cheaper. This creates precisely the tensions that cause social unrest and generate social dissatisfaction. And therefore, the most important question with regard to price formation is: How can we balance the tension that exists in price formation between the valuation of goods produced by free human will and those goods to which nature contributes? How do we deal with this tension? How do we balance the downward tendency with the upward tendency?

Within the division of labor, increasingly differentiated products are always being created. You only need to remember how simple the products are that are created, say, within a hunting community that lives entirely from forestry. In this case, the difficulty of pricing is not really a factor. But when agriculture is added to forestry, the difficulty begins. The difficulty lies in differentiation. And the further and further the division of labor spreads, creating new needs, the more the differentiation of products increases and the more the difficulties of pricing accumulate; for the more different the products are from each other, the more difficult it becomes to effect mutual evaluation—and it can only be mutual. You can see this from the fact that there is a mutual evaluation of products that are not highly differentiated, such as wheat, rye, and other agricultural products. Look at a very long period of time: you will find that the ratio in the mutual valuation between wheat, rye, and other cereals remains fairly stable. If wheat goes up, the other cereals also go up; if wheat goes down, the others go down too. This is because there is very little differentiation between these products. If the differentiation becomes greater, then this is no longer the case; events within the social organism can cause the price of a product that someone has been accustomed to exchanging for another product to skyrocket, while the price of the other product may go down. Imagine what kind of shift this causes in economic conditions. What happens in the economy is based much more on mutual price increases and price falls than on anything else. The mutual rise and fall of prices is what causes the difficulties of life in the economy. Whether products rise or fall in price overall—if they all rose or fell evenly, people would not really care very much. What interests them is that products rise or fall in price to varying degrees. This is something that, one might say, is now tragically evident in the current economic situation; the fact that products rise and fall in different ways—namely, the monetary values themselves rise and fall, but these values simply preserve earlier real values—is currently causing a complete upheaval in human society.

But this leads us to recognize that we must look at the factors at work in the economic organism in another way. We started from what ordinary economics lists when it speaks of the factors that are present in an economic organism, but we have seen that nothing can actually be achieved by listing nature, capital, and labor. For if you add what has been said earlier to what has been said today, you will see that the price evaluation of natural products does not come about under purely economic conditions, but through legal relationships; that the free human will, with all that it develops when it is active in public life, plays a role in the evaluation of entrepreneurial capital. Just think about what it takes to actually raise entrepreneurial capital for anything. Free human will plays a role in this. Free human will plays a role in lending. Perhaps not directly. Of course, those who want to have savings want to lend them; but whether someone saves at all or not is already an expression of will. It is the case that free human will plays a very significant role here. But if we take this into account, we will find a different structure of economic factors than the one we have considered so far.

So far, I have given you a schematic structure in which I have shown you that nature is there, but value is only created through the processing of nature, when nature moves against labor. And value is only created through labor when it moves against capital or the spirit. This creates a tendency to return to nature, which can be prevented by transferring surplus capital not into land, where it becomes fixed, but into free intellectual enterprises, where it disappears until only a remnant remains, which is to continue to exist as a seed, so to speak, so that the economic process can be maintained.

And apart from this movement, which here (see Figure 5) goes from left to right and produces cultivated nature, organized or structured labor, and emancipated capital that operates and is active only within intellectual endeavors, there is another movement. This is the movement that does not lead to exploitation, in which the preceding is taken over by the next, but rather moves in the opposite direction. One movement goes counterclockwise, the other clockwise. In one movement, something is created by the preceding link engaging with the next, as it were; in the other movement, something is created by what flows over here (see drawing 5) catching what flows over and, as it were, spanning it. You will soon understand what I mean by this. If you consider that capital is actually realized spirit in the economic process, then I can also write spirit instead of capital, so that we have: nature, labor, and spirit.

Then, when spirit takes in what is processed nature, when it does not simply introduce it into the economic process in a progressive movement, opposite to the hands of a clock, but when it takes it in, the means of production arises. The means of production is something else: it is actually in a completely opposite movement to that which is a natural product processed for consumption. It is a natural product that is received by the spirit, a natural product that the spirit must have. From the pen I have as my means of production to the most complicated machines in the factory, the means of production are, in a sense, nature grasped by the mind. Nature can be processed and sent in one direction: then it becomes capital; or sent in the other direction: then it becomes a means of production.

But in the same way, what is formed here with the help of the means of production can move on and be received again by labor. Just as nature is received here by the mind, so labor can receive what is, for example, a means of production in the broadest sense. When labor receives what is a means of production, when a connection is established between the means of production and labor, then this connection is entrepreneurial capital. That is entrepreneurial capital. So when you follow this process (see Figure 5), you see a movement that pushes the means of production and entrepreneurial capital together.

And if this movement now continues, so that what is produced with the help of means of production and entrepreneurial capital is continuously taken over from nature – albeit now from a different part of nature than in the consumption process – then what actually constitutes the commodity only arises in the economic process. The commodity is already taken over by the natural process. Either it is eaten, in which case it is very strongly taken over by nature, or it perishes, is consumed; in short, it becomes a commodity by returning to nature.