Rhythms in the Cosmos and in the Human Being

GA 350

25 July 1923, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

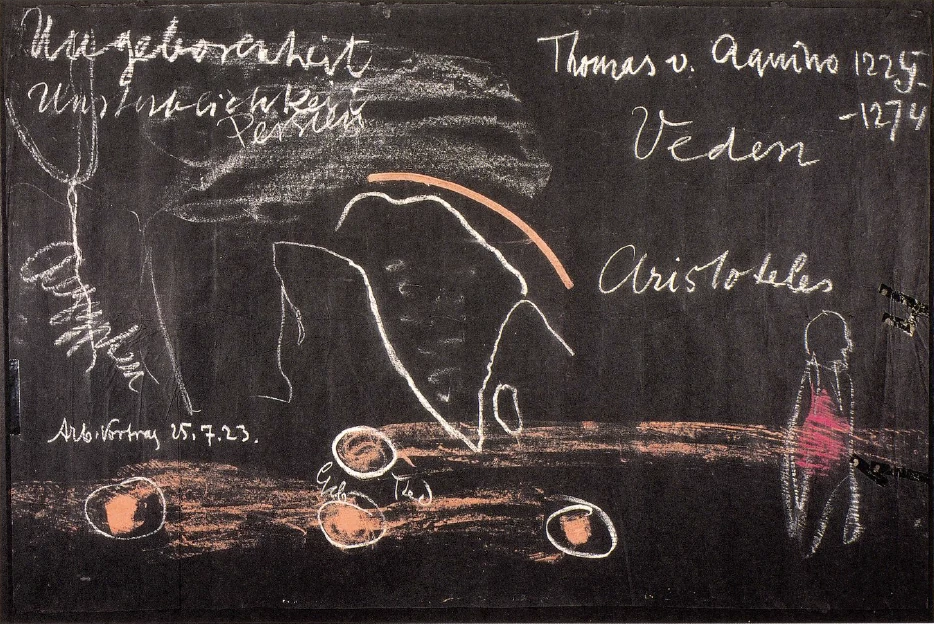

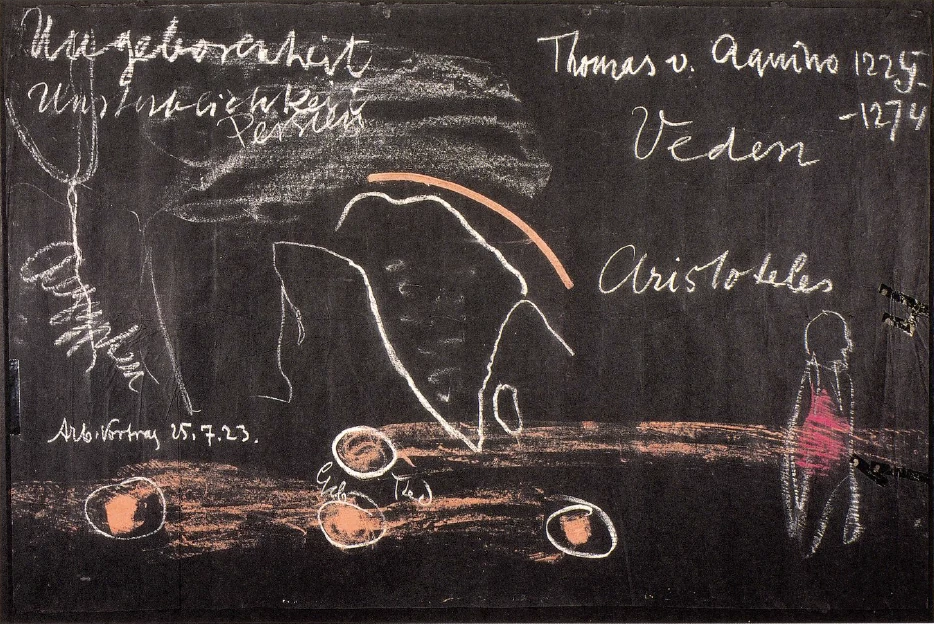

The Emergence of Conscience in The Course of Human Development; Unbornness and Immortality — The Teaching of Aristotle and the Catholic Church

Well, gentlemen, if you still have something on your minds today or want to ask something, I ask that you do so.

Question: One of the wonderful things about being human is having a conscience. When you have done something, you think about it. And even if you no longer think about things that have happened, you still know that you have a conscience. It would be interesting to ask whether conscience can be killed in such a way that you can forget it. The way humanity is today, one would actually have to assume that conscience has been killed in a large part of humanity.

Dr. Steiner: You see, gentlemen, that is actually a big question, but it is related to what we have just said in the previous lectures. I have tried to explain to you in turn how the human being, who consists of matter, also contains an etheric body – that is, a body of a completely different nature that cannot be perceived or seen with the ordinary senses – then an astral body and an ego organization, we could also say: an ego body. The human being has these four parts.

Now we have to imagine what a person actually becomes when they die. As I have often told you, when a person sleeps, the physical body and the etheric body remain in bed. The astral body and the I go out and are then no longer in the physical body and etheric body. But when a person dies, then, of what the person has, the physical body is discarded. It is then a truly physical body; the other three parts, the etheric body, the astral body and the ego, then go out. I told you that the etheric body remains connected to the ego and the astral body for a few more days. Then it also separates, as I have described to you, and then the person lives in what is his ego and his astral body. As he now lives on and on, he lives in the spiritual world that we are actually exploring through spiritual science in this life on earth. So that we can say: Now we know something of a spiritual world here on earth; then we will be inside.

But after some time we come back down to earth. We pass through a spiritual world, just as we pass from birth to death in earthly life, and then come back down again. We take on the physical body given to us by our parents and so on. That is where we come down from the spiritual world. So before we came here to earth, we were spiritual beings, let us say. We have descended from the spiritual world. You see, gentlemen, that is an extraordinarily important fact for man to know that he comes down from the spiritual world with his ego and with his astral body. Otherwise it cannot be explained at all how it is that man, when he grows up, somehow speaks of the spirit. If he had never been inside the spiritual world, he would not speak of the spirit at all.

You know that once upon a time people on earth did not talk as much as certain people do today about life after death, but people talked a lot about life before they came down to earth. In ancient times, people talked much more about what happened to a person before he took on flesh and blood than about what happened afterwards. In ancient times it was much more important for people to remember that they were souls before they became human beings on earth. Now, I have spoken even less about the development of humanity on earth, but today we will talk a little about this development of human beings on earth.

If we go back in time about eight to ten thousand years, we would find a rather desolate life here in Europe. There is still a rather desolate life in Europe. In contrast, about eight thousand years before our present time, there was an extraordinarily developed life in Asia. In Asia, we have (it is drawn) here a country, it is called India. There is the island of Ceylon, up above would be the mighty river, the Ganges, up there is a mountain range, the Himalayas. In this India, which is in Asia, and also a little above it, lived people who, as I said, had a very highly developed spiritual life eight thousand years ago. Today I call them Indians. At that time the word Indian did not yet exist. But today we call it India, and that is why I use this expression. If you went back and asked these people, 'What do you call yourselves?' they would say, 'We are the sons of the gods!' because they described the land where they were before they were on earth. There they themselves were still gods, because men in those days, when they were spiritual, called themselves gods. They would also have said in answer to the question, what do you become when you fall asleep: When we are awake we are men, when we fall asleep we are gods. Being gods only meant being different from when we are awake, being more spiritual.

These people had a particularly high culture, and for them it was not so important to talk about life after death, but about life before one was born, about this life among the gods, as they said.

You see, there are no external records of these people. But of course these people lived on – you know, there are still Indians today – and in much later times they wrote great poetic works that are called the Vedas. Veda is the singular, Vedas the plural. Veda actually means “word”. They said to themselves: the word is a spiritual gift, and what people wrote in their Vedas was what they still knew from the other world. In those older times they knew much more, but what can still be studied externally through books today is what is in the Vedas. That was written much later. But in what is written in the Vedas, which was written down much later, you can see that these people still knew firmly: Before man descended to earth, he was in a spiritual world.

Now, if we go back about six thousand years to our time, we already have a less highly developed culture here. Culture is declining in India. What scholars today still describe as ancient Indian culture has already declined from its original height. But a culture is developing in the north (it is being drawn) – that is Arabia, of course – but in the north, up there, a culture is developing in the place that later became Persia. That is why I called it the ancient Persian culture. A completely different culture is developing there. It is quite remarkable. You see, if you go back to these ancient Indians, who lived two thousand years before these people, then you find everywhere among these ancient Indians that they actually value the earthly world very little. They always think that they came into the earthly world from the spiritual world. They knew this very well. They did not value the earthly world at all; they valued the spiritual world. They said they felt like outcasts, and what was on earth was not particularly important to them. And here, six thousand years before our time, in the land now called Persia, there came for the first time a certain appreciation of the earth. Earthly life was respected. This earthly life was respected to such an extent that people said to themselves: Yes, light is very, very precious, but the earth is also very precious with its darkness. And so the view gradually developed that the earth is just as precious and that it fights with heaven. And this battle between heaven and earth was developed over two or three thousand years as a concept that had particular significance for these people.

Then, if we go back about three or four thousand years, we come to a land where Arabia extends into Africa, where the Nile flows: Egypt. The Egyptians and also those who were actually sitting over there in Asia, more towards the west, and more towards Europe, they received the Earth even more willingly. And so, if we go back three or four thousand years, we find that these Egyptians, who were the third type of people, so to speak – Indians, Persians, Egyptians – these people built these huge pyramids. But what they did above all was this: they harnessed the Nile. They canalized the Nile, which every year floods the land with its fertile soil, so that these floods could benefit them in all directions. To do this, they developed what is known as geometry. They needed it. Geometry and the art of surveying were now being developed. People grew to like the Earth more and more. And you see, to the same extent that people grew to like the Earth, they became less aware that they had come from a spiritual world. I would say that they forgot more and more about it because they grew to like the Earth more and more, and to the same extent it became more important to them to say to themselves: 'We live after death'.

Of course, we have seen that life after death is assured to man, but people in the past, before the Egyptians came, did not think about immortality at all. Why? Because it was a matter of course for them. When they knew that they came from a spiritual world and had only accepted the physical body, then they had no doubt at all that they would arrive in a spiritual world after death. But in Egypt, where people thought less about their stay in the spiritual realm before their life on earth, the Egyptians were very afraid of dying. This huge fear of dying is actually not much older than three or four thousand years. The Indians and the Persians had no fear of death. So one can actually prove that the Egyptians had this terrible fear of dying. Because, you see, if they had not had this terrible fear of dying, then today these Englishmen and the others could not go to Egypt and then exhibit the mummies in their museums! Because in those days people were embalmed with all kinds of ointments and other substances. They placed and preserved them in the coffin as they looked during their lifetime. People were embalmed and made into mummies because it was thought that if the body is kept together, the soul will remain present for as long as the body has on earth. The body was preserved so that the soul would not suffer any harm. You see, that is the fear of dying. So with all their might, the Egyptians wanted to achieve immortality through earthly matter. But these Egyptians still knew an extraordinary amount, which was later completely lost.

And the next people that particularly stand out to us are in the north of Egypt, in Greece, in present-day Greece. But ancient Greece was very different. You see, the Greeks had almost completely forgotten about life before birth. Only a few people in particularly high schools, which were called mysteries, still knew about it. But on the whole, in Greek civilization, the spiritual life before birth had already been completely forgotten, and the Greeks loved earthly life most of all. And that is why a philosopher emerged in Greece, his name was Aristotle, in the 4th century BC. You see, now we are getting close to the Christian era. Aristotle was the first to put forward a view that had not existed before. He put forward the view that not only is the body of a person born when a child is born, but also the soul of a person is born. So in Greece, the view first emerged that the soul of a person is born with the body, but that it is then immortal, so it goes through death and lives on in the spiritual world. Only Aristotle then put forward a peculiar view. Aristotle had actually forgotten everything that was wisdom in ancient times, and he then put forward the view: the soul is born at the same time as the body. But when a person dies, the soul remains in such a way that it has only had this one earthly life behind it. It must then look back forever only on what the one earthly life is.

Imagine what a terrible view that is! So if someone on earth has done something bad, they will never be able to make amends for it, but will always have to look back and see the image of what they have done wrong. This is Aristotle's view.

Then Christianity came. In the very first centuries, Christianity was understood a little. But when the Roman Empire adopted Christianity and Christianity took root in Rome, it was no longer understood there. It was not understood.

Now there were always councils within Christianity. The high dignitaries of the church came together and determined what the great flock of believers should believe. The view was formed that there are shepherds and sheep, and the shepherds then determined at the councils what the sheep should believe. At the eighth of these councils, it was now determined by the shepherds for the sheep that it was heretical to believe that man had lived in the spiritual world before his birth. So the old views of Aristotle became Christian church dogma! And as a result, humanity was virtually forced to know nothing, not even to think about the fact that man came down from the spiritual world with a soul. They were forbidden.

When materialists say today: The soul is born with the body and is nothing but physical – then that is nothing more than what people have learned from the church. That is precisely why people today believe that they go beyond the church when they are materialists. No, people would never have become materialists if the church had not abolished the knowledge of the spirit. For at this eighth general, ecumenical council in Constantinople, the spirit was abolished by the church, and that remained so throughout the Middle Ages. Only now, through spiritual science, do we have to realize again that the human being was also there as a soul before he was on earth. That is the important thing, that is the most important thing.

Anyone who follows the development of humanity on Earth clearly sees that originally the knowledge existed that people, before descending to Earth, are in a spiritual existence. This was only gradually forgotten and later even abolished by a council decision.

Now we must only realize what this means. Imagine, people who lived up to the Egyptians, so in ancient millennia, they knew: Before you walked around on this earth, you were in the spiritual world. Yes, they did not just bring down from the spiritual world some kind of general, vague knowledge, but they brought down from the spiritual world the awareness that they had lived with other beings. And from that they also brought down their moral impulses. What I should do on earth, I see from the way these earthly things are, these old people said; what else should I do, I just need to remember what was before birth. They brought down their moral impulses from the spiritual world. You see, if you asked people in those ancient times: What is good? What is evil? — then they said: Good is that which the beings among whom I was before I was on earth want; evil is that which they do not want. But each individual said that to himself. Now, gentlemen, that has been forgotten.

In Greece, there was now something very strange. In Greece, they have forgotten so far that there is a life before birth, that Aristotle said: The soul is born with the physical body. - So people had no idea that they had already lived before birth. But they sensed something in themselves from this life. Whether you know something or not, that has no influence on reality. I can always say: there is no table behind me, I don't see any table [hitting the table on my way back], but the table is still there, even if I don't see it. Life before birth remained, and people felt it within themselves. And that is what they started to call conscience in Greece. In Greece, the word conscience first appeared around the 5th century BC. Before that, the word conscience did not exist. So the word conscience comes from the fact that people forgot about prenatal life, pre-earthly life, and what they still felt of it within themselves, they gave a word to it. And since that time it has remained so. People feel prenatal life in themselves, but they say: Well, that's just the way it is; it arises down there somewhere and then it shoots up - but they don't pay any further attention to it.

You see, that was good for the church. Because what could happen now from the church? Yes, gentlemen, in the past, when everyone knew that they had lived as a soul before they descended to earth, people said: What we know of our previous life, of our life before birth, is moral. - Now the Greeks only felt conscience. And then later came the church, which now administered conscience. Isn't that right, it took over and said: You don't know what you should do. The sheep don't know, the shepherds do! And it made rules and administered conscience.

You see, it was necessary that the spirit was abolished at a council, because then what was left of the human spirit as conscience could be administered. And then the church said: No, nothing existed in man before he was on earth. The soul is born with the body. Anyone who does not believe this is of the devil. But we, as the church, we know what it is like in the spiritual world and what man has to do on earth. — That is how the church took possession of conscience.

This can still be proven in detail. Because, you see, that still played a role well into the 19th century, sometimes in a quite dreadful way. For example, in the 1830s and 1840s in Prague there was a man named Smetana. This person was the son of a Catholic church servant, who was of course a devout Catholic. He had the feeling that one has to believe what the church prescribes; one knows from the spiritual world what the church prescribes. Now he had a son. The people at that time were somewhat ambitious and sent their children to grammar school. But in the grammar schools that were in Prague in the last century, you didn't actually learn very much. Basically, you learned very little. So young Smetana was educated at grammar school. And that was just the way it was: the one who was supposed to learn anything at all then became a priest. So young Smetana also became a priest. In those days in Prague, and also in the rest of Austria, priests were employed as teachers in the higher schools as well. And so it happened that when he himself had to teach, he read somewhat different books than those prescribed for him by the church as a priest. Yes, through this he gradually came to doubt, namely about a dogma. He said to himself: What is it actually so terrible that a person should be born, spend his life on earth, then go through death and now, if he was a bad guy, should only look at it forever - the church even painted that with the necessary pictures - what he did as a bad guy on earth and should never have the opportunity to improve!

Now, you see, this man, Smetana, lived in a religious house. But when he became a teacher, it became a little too cramped for him in the religious house; so he moved into a secular apartment and read more and more – there were no anthroposophical books available at the time – the books of Hegel, Schelling and so on, which at least gave something, a beginning of something reasonable. In this way he became more and more doubtful about the so-called eternity of punishment in hell, because according to Aristotle, a bad person goes through death and must live eternally in his wickedness. But the doctrine of the eternity of the punishment of hell arose from this, and was then established by the church in the form of a council. This doctrine is, of course, not a Christian one, but is that of Aristotle. It is not true at all that the doctrine of the punishment of hell is a Christian doctrine; it is from Aristotle. But that was not clear to people.

But this Smetana realized it. So he started teaching something that was not quite in line with the teachings of the Church. It was in 1848 that he taught something that was not quite right. At first he received a terrible warning, a huge letter written in Latin, in which he was told that he should now return repentant to the fold of the church, because he had caused enormous offence to the shepherds by teaching the sheep something that was not prescribed by the shepherds. He replied to this first letter, written in Latin, saying that he thought it hypocritical to say anything other than what one is convinced of. Then a second letter in Latin arrived, which admonished him even more seriously. And when he no longer answered this, because it would have been useless, it was announced one day in all the churches in Prague that a very important celebration was to take place because one of the lost sheep, who had even become a shepherd, had to be excluded from the church.

Among those who had to distribute the notices everywhere that this important celebration was to take place was the church servant, old Smetana, the father. He had remained a devout Catholic. You can now imagine what it means that the whole of Prague has been summoned to condemn Smetana's son, to condemn him to be forever excluded from the church and so on, and that his father had to carry the leaflets himself! Yes, the church was never as full in Prague as it was on that day. All the churches in Prague were full to bursting. And from all the pulpits it was proclaimed that the apostate Smetana was being excommunicated.

The consequence of this was – of course, the germ of consumption lay in the Smetana family – that first the sister died of grief, then the old father died of grief, and after that Smetana himself died of grief, of suffering, after a short time. But that was not the point, was it, but the point was that Smetana no longer proclaimed the story of the eternity of hellish punishment, as he understood it.

This is all connected with the development of the idea of conscience in humanity. For that which man retains of his pre-earthly life lives in him and speaks in him as conscience. And from the standpoint of conscience one can say: Conscience cannot come from the material substance of the earth. For just imagine, let us say, someone has a terrible craving. There have been cases of this. Then it is the substances in his body, the substances of the earth, that push and nudge him to have this craving. Then conscience tells him: But you must fight these cravings. Yes, gentlemen, that would be just as if conscience also came from the body as if someone were to walk backwards and forwards at the same time. It is nonsense to say that conscience comes from the body. Conscience is connected with what we bring down from the spiritual world from our pre-earthly life when we descend to earth. But as I have explained it to you, the awareness that conscience comes from the spiritual world has been lost for earthly people, and for people like Smetana, whom I told you about earlier, it only dawned on him again in the 19th century through this terrible thing of hellfire. Conscience belongs to the person themselves. A person carries their conscience within them. What use would all the conscience in the world be to you if you were to pass through death and then realize for all eternity what a bad fellow you were? You couldn't help yourself. Having a conscience wouldn't mean a thing!

So that one can say: If that is the human being (he is drawn), then conscience lives in the human being. Conscience is that which he has brought with him into earthly life from the spiritual world. Conscience says within him: You should not have done that, and you should not have done that. The earthly person says: I will do that, I desire that. Conscience speaks differently because it comes from the eternal human being. And then, when the human being has discarded the physical body, only then does he realize: You yourself are what has always spoken in your conscience. You just didn't notice that during the time of earthly life. Now you have gone through death. Now you have become your own conscience. Your conscience is now your body. Before, you had no conscience. Now you have your conscience, with which you continue to live after death.

But to the conscience one must also ascribe a will. You see, all the things I have told you have come true. The Greeks had forgotten the pre-earthly life. The church had raised to dogma that one may not believe that there is a pre-earthly life. The conscience has been completely misunderstood. All this had been fulfilled. And now, of course, there have also been great scholars. But these great scholars in the Middle Ages were, of course, under the impression that there can be no such thing as a pre-earthly life. The church forbids believing it.

In this conflict stood, for example, a man like Thomas Aquinas, who lived from 1225 to 1274. As a Catholic priest, he had to comply with what the Catholic Church prescribed. But he was a great thinker. And with regard to what I have told you today, he had to say: When a person dies, he only has the contemplation of his earthly life, always and forever, never otherwise. He contemplates that. So what does Thomas Aquinas do? Thomas Aquinas attributes only reason to man for all eternity, but no will. Man must contemplate this after death, but he can no longer change it. Thomas Aquinas was one of the greatest Aristotelians of the Middle Ages precisely because he said: If a person has done something bad on earth, he must look at it forever; if a person has done something good, he looks at the good forever. - So only the knowledge, not the will, was attributed to the soul.

That is not true. It is true that after death you see what you were in terms of good and evil, but that you retain the will, the full strength of your soul, to change that. So, of course, when you look at your life, you see how it was, then you live in the spiritual world and see what should have been different. Then the urge comes by itself to go back down to make the necessary improvements. Of course, mistakes will be made again, but then the following lives will always follow, and the person will achieve the goal of complete human development.

What Thomas Aquinas was still obliged to do in the Middle Ages, to believe only in knowledge and not in the will, still afflicted people in the 19th century as much as it did Smetana. It is to be attributed to this that other people came along in the 19th century who were furious about knowledge. This all originated in the dogma of the punishment of hell; only people did not see through it. Schopenhauer, for example, was filled with rage at the realization and now attributed everything to the will. Yes, but if you now ascribe everything to the will again, then this will is too stupid and foolish. Therefore, Schopenhauer attributed the whole creation of the world and everything to the foolish will. And those people who have thought about it have experienced terrible inner conflicts, just as Smetana experienced in Prague. There have been many such cases; this is just an excellent example of which the difficulties have been written down. There have been many such people.

And so we must be clear about this: Man has his conscience as an inheritance from his pre-earthly life. It is the spirit that speaks in conscience. That which we already were before we were man on earth has entered the flesh and speaks in conscience. And when we have laid aside the body, then the soul will continue to speak in conscience after death, but not unconsciously, but having a will and having to make amends, having to be active.

You see, that is the difference between anthroposophy and everything that is contained in Christian dogmatics today, for example. In Christian dogmatics, this inner power of the human soul, which can create, is not known. Rather, the human being dies and can only look at what he has created in one earthly life, because in that one earthly life the soul is born with the body. So if you want to present it schematically, you have to say: If this is a human being's one life on earth (upper drawing, circle), it also begins with the soul, and when the person now dies – there is birth, there is death – then his soul life expands into all eternity. I don't want to go to the second board with my drawing anymore, because that is too expensive, I would even have to have a third one! Only knowledge, only the intellect, is destined to do nothing but contemplate the evil of earthly life for all eternity, because the intellect is born with the physicality of earthly life. The first materialist was actually the one who established this dogma, was actually Aristotle.

Now, anthroposophy finds that there is not only one earthly life, but also successive earthly lives. A person always has something left over from the previous life, which he does not know exactly, but which is within him: that is conscience. Now he lays down the body, in his conscience he lives on. There (lower drawing, red left) is now basically only conscience until the next birth. Now (middle circle) there is conscience again in the form of a voice that speaks; now (red right) it lives in the outside world, is there again. And the human being is actually the one who always creates his new lives on earth. Of course, this is something that particularly annoys the doctrine that does not want to grant anything to the human being at all, that wants to look at everything as if the human being were a creature. He is not a mere creature, but there are creative powers in him. And that is precisely the difference between anthroposophy and the other views: anthroposophy's research brings out that these creative powers are in man, man is also creative. He is not only created, but he is creative. And one of the most creative things in him is precisely his conscience, because that is what remains for us as a sacred inheritance from our pre-earthly life and what we carry out again when we pass through death.

This is precisely what modern science still has from the Church, and it is precisely on this point that one should really see very clearly. Because the thing went like this: From over there in Rome, only that which was logical on one side and materialistic on the other came. Then the modern peoples adopted that. But in the German language, sometimes a remnant of the old has remained in a completely different way, only you don't recognize it again. That is very strange. In this you can see how man is connected with the great events.

If you look at these countries up in Asia today – Siberia – they are actually areas that are very sparsely populated, but they were once heavily populated. The rivers were much, much mightier then. Siberia is a land that has gradually dried up and risen, and people then moved west, across to Europe. This is due to the elevation of Siberia. And in this way, many ideas that were present in Asia came to Europe by a different route, and these ideas live on in European languages. Therefore, one must say: The further west one goes, the less this notion of conscience is present. But the very word conscience shows that the people who formed the word conscience had a feeling that there is something in man. And what does the word conscience actually mean? We have just said what it means: It is the inheritance from what is pre-earthly life, what remains in humanity. But what does the word conscience mean? When you look at life on earth and say to yourself: the events that will happen in two or three years are uncertain, but that a person has a spirit within them that was there before their earthly existence and that remains after their earthly existence, that is certain. And the word conscience is also connected with certainty, and it is the most certain thing there can be. So that in the word conscience is already indicated that which is eternal in man. It is very significant that conscience contains something different than, for example, 'conscience' or something similar in Western languages. Conscience is that which is 'known together' on earth: con-science – that which is accumulated from earthly knowledge. But that which lives in man as conscience and is designated by the word conscience is the most certain thing there can be, something that is not vague but completely certain. And it is absolutely certain that man on earth not only believes in life after death – an opinion held by Aristotle and the church faithful – but also develops a will to shape it better and better, to shape the earth better and better again and again out of the spirit, that therefore the will also lives after death, as does knowledge. With Thomas Aquinas, only knowledge had life. Now we must realize that the will has life. You see, gentlemen, it is indeed so: one does not need to belittle someone who centuries ago in his time was a great 249

great scholar, such as Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century, because he taught in his time what was taught in his time. But it is quite another thing if Thomas Aquinas taught what could only be taught in the 13th century than if, as is currently happening in Paris, a Thomas Society is founded to teach the same teach the same as was taught in those days, just as Leo XIII. commanded for all priests and scholars of the Catholic Church in the 19th century to say only what Thomas Aquinas taught in the 13th century. Today, Thomas would not say that either! And these two things confront each other in the world, something like the Thomas Society in Paris, which wants to lead people back again, and anthroposophy, which teaches the present, that which a present human being is. And above all, when you look at something like conscience, it is important that it leads you to the eternal in man. But the eternal cannot be properly understood if one does not also look at the pre-earthly life, if one only looks at that which actually arose only since the Egyptian period as the post-earthly life, as the so-called immortality.

You see, gentlemen, it was only three or four millennia ago that people began to talk about being immortal, that they do not die with the soul as the body dies. But before that, people said that they were not born as a soul either, as the body is born. They had a word meaning that we would have to call 'unborn' today. That was one side. And immortality is the other side. Not even the languages today have a different word than immortality! The word unbornness must arise again. Then one will say: Conscience is that in man which is not born and does not die. Only then will one be able to truly appreciate conscience. For conscience has meaning for man only when one can truly appreciate it.

Well, then, on Saturday at nine o'clock, gentlemen.

Die Entstehung des Gewissens im Verlaufe der Menschheitsentwickelun; Ungeborenheit und Unsterblichkeit — Lehre des Aristoteles und der Katholischen Kirche

Nun, meine Herren, wenn Sie heute noch etwas auf dem Herzen haben ‚oder fragen wollen, so bitte ich, das zu tun.

Frage: Etwas Wunderbares, das der Mensch an sich hat, ist das Gewissen. Wenn man etwas getan hat, denkt man daran. Und auch wenn man die Sachen, die vergangen sind, nicht mehr denkt, so weiß man aber doch, man hat ein Gewissen. Es wäre interessant, zu fragen, ob das Gewissen auch so getötet werden kann, daß man es vergessen kann. $o wie die Menschheit heute ist, müßte man eigentlich annehmen, daß das Gewissen bei einem großen Teil der Menschheit getötet ist.

Dr. Steiner: Sehen Sie, meine Herren, das ist eigentlich eine große Frage, aber sie hängt schon zusammen mit dem, was wir gerade in den vorangehenden Vorträgen gesagt haben. Ich habe Ihnen ja der Reihe nach versucht zu erklären, wie in dem Menschen, der aus Stoff besteht, außerdem noch enthalten sind ein Ätherleib — also ein ganz anders gearteter Leib, den man mit den gewöhnlichen Sinnen nicht wahrnehmen und nicht sehen kann -, dann astralischer Leib und Ich-Organisation, wir könnten auch sagen: ein Ich-Leib. Diese vier Teile hat der Mensch.

Nun müssen wir uns vorstellen, wie der Mensch eigentlich wird, wenn er stirbt. Ich habe Ihnen ja schon öfter gesagt: Wenn der Mensch schläft, dann bleibt im Bette liegen der physische Leib und der Ätherleib. Der astralische Leib und das Ich, die gehen heraus, die sind dann nicht mehr im physischen Leib und Ätherleib. - Wenn der Mensch aber stirbt, dann wird von dem, was der Mensch hat, der physische Leib abgelegt. Der ist dann ein wirklich physischer Körper; die drei anderen Teile, der Ätherleib, der astralische Leib und das Ich, die gehen dann heraus. Ich sagte Ihnen ja, der Ätherleib bleibt noch ein paar Tage mit dem Ich und dem astralischen Leib verbunden. Dann trennt er sich auch, so wie ich es Ihnen beschrieben habe, und dann lebt der Mensch in demjenigen, was sein Ich und sein astralischer Leib ist. Wie er nun weiter und weiter lebt, da lebt er in derjenigen geistigen Welt, die wir in diesem Leben auf Erden eigentlich durch die Geisteswissenschaft ergründen. So daß wir sagen können: Jetzt wissen wir hier auf Erden etwas von einer geistigen Welt; dann werden wir drinnen sein.

Nun kommen wir aber nach einiger Zeit wiederum herunter auf die Erde. Wir gehen ebenso, wie wir von der Geburt zum Tode gehen im Erdenleben, dann durch eine geistige Welt durch und kommen wiederum herunter. Wir nehmen den physischen Leib an, der uns von unseren Eltern und so weiter gegeben ist. Da kommen wir aus der geistigen Welt herunter. Wir waren also, bevor wir hier auf die Erde gekommen sind, sagen wir geistige Wesen. Wir sind von der geistigen Welt heruntergestiegen. Sehen Sie, meine Herren, das ist eine außerordentlich wichtige Tatsache, daß der Mensch weiß, er kommt aus der geistigen Welt mit seinem Ich und mit seinem astralischen Leib herunter. Es ist sonst gar nicht erklärbar, wodurch der Mensch überhaupt, wenn er aufwächst, irgendwie vom Geiste redet. Wenn er niemals im Geistigen drinnen gewesen wäre, so würde er gar nicht vom Geiste reden.

Sie wissen ja, es haben einmal auf Erden die Menschen gar nicht so viel wie heute gewisse Menschen vom Leben nach dem Tod gesprochen, aber viel haben die Leute gesprochen vom Leben, bevor sie auf die Erde heruntergekommen sind. In alten Zeiten hat man überhaupt viel mehr gesprochen von dem, was mit dem Menschen war, bevor er Fleisch und Blut angenommen hat, als von nachher. In alten Zeiten war es den Menschen viel wichtiger, daran zu denken, daß sie Seelen waren, bevor sie Erdenmenschen geworden sind. Nun, von der Entwickelung der Menschheit auf Erden habe ich Ihnen noch weniger gesprochen, aber wir wollen auf diese Frage hin heute ein bißchen von dieser Entwickelung der Menschen auf Erden sprechen.

Wenn wir etwa, ich will sagen, acht- bis zehntausend Jahre zurückgehen in der Zeit, dann würden wir hier in Europa ein recht wüstes Leben finden. In Europa ist da noch ein recht wüstes Leben. Dagegen war dazumal, achttausend Jahre etwa vor unserer jetzigen Zeit, ein außerordentlich entwickeltes Leben in Asien drüben. In Asien haben wir ja (es wird gezeichnet) hier ein Land, Indien heißt es. Da ist die Insel Ceylon, oben wäre der mächtige Fluß, der Ganges, da oben ist ein Gebirge, Himalaya. In diesem Indien, das also in Asien drüben ist, und auch etwas darüber, da wohnten Menschen, die eben, wie gesagt, vor achttausend Jahren ein ganz hochentwickeltes Geistesleben hatten. Ich nenne sie heute Inder. Dazumal hat es dieses Wort Inder noch nicht gegeben. Aber man nennt das heute Indien, und deshalb gebrauche ich diesen Ausdruck. Nicht wahr, wenn man zurückgehen würde und würde diese Menschen fragen: Wie nennt ihr euch denn selber? — so würden die Menschen sagen: Wir sind die Göttersöhne! -, weil sie bezeichnet haben das Land, wo sie waren, bevor sie auf der Erde waren. Da waren sie selber noch Götter, denn die Menschen haben sich dazumal, wenn sie geistig waren, Götter genannt. Sie würden auch auf die Frage, was werdet ihr denn, wenn ihr einschlaft, gesagt haben: Wenn wir wach sind, sind wir Menschen, wenn wir einschlafen, sind wir Götter. — Götter sein hat nur bedeutet, anders sein als beim Wachen, mehr geistig sein.

Diese Menschen haben also eine ganz besonders hohe Kultur gehabt, und denen war es nicht so wichtig, zu reden vom Leben nach dem Tode, sondern vom Leben, bevor man geboren worden ist, von diesem Leben unter den Göttern, wie sie gesagt haben.

Sehen Sie, irgendwelche äußeren Urkunden sind von diesen Menschen nicht vorhanden. Aber diese Menschen haben natürlich weitergelebt - Sie wissen, es gibt ja auch heute noch Inder -, und in viel späterer Zeit haben sie dann große dichterische Werke geschrieben, die man die Veden nennt. Veda ist die Einzahl, Veden die Mehrzahl. Veda heißt eigentlich das «Wort». Man hat sich gesagt: Das Wort, das ist eine Geistesgabe, und das, was die Leute in ihren Veden geschrieben haben, das war dasjenige, was sie eben noch wußten aus der anderen Welt. In d ser älteren Zeit haben sie viel mehr gewußt, aber dasjenige, was heute noch durch Bücher äußerlich studiert werden kann, das ist eben das, was in den Veden steht. Das ist viel später geschrieben worden. Aber bei dem, was in den Veden steht, was viel später aufgeschrieben worden ist, sieht man, daß diese Menschen noch fest gewußt haben: Bevor der Mensch herunterstieg auf die Erde, ist er in einer geistigen Welt gewesen.

Nun, wenn wir dann etwa sechstausend Jahre vor unsere Zeit zurückgehen, dann haben wir hier schon eine weniger hoch entwickelte Kultur. Da geht die Kultur zurück in Indien. Dasjenige, was von den Gelehrten heute noch beschrieben wird als alte indische Kultur, das ist schon von der ursprünglichen Höhe zurückgegangen. Aber es entwikkelt sich da im Norden davon (es wird gezeichnet) — das ist ja dann Arabien -, aber da im Norden davon, da oben, da entwickelt sich eine Kultur an der Stelle, wo später Persien ist. Ich habe sie deshalb die urpersische Kultur genannt. Da entwickelt sich eine ganz andere Kultur. Es ist ganz merkwürdig. Sehen Sie, wenn man zu diesen alten Indern zurückgeht, die also zweitausend Jahre vor denen hier gelebt haben, dann trifft man bei diesen alten Indern überall darauf auf, daß sie eigentlich die Erdenwelt sehr wenig schätzen. Sie denken immer, sie sind in die Erdenwelt von der geistigen Welt aus gekommen. Das wußten sie sehr genau. Die Erdenwelt schätzten sie gar nicht; sie schätzten die geistige Welt. Sie sagten, sie kommen sich wie ausgestoßen vor, und dasjenige, was auf der Erde war, war ihnen gar nicht besonders wichtig. Und da hier, also sechstausend Jahre vor unserer Zeit, in dem Lande, das man heute Persien nennt, da kam zum ersten Mal auf eine gewisse Schätzung der Erde. Man achtete das Erdenleben. Dieses Erdenleben, das achtete man so, daß man sich sagte: Ja, das Licht ist sehr, sehr wertvoll, aber die Erde ist auch sehr wertvoll mit ihrer Dunkelheit. - Und so bildete sich da allmählich die Ansicht aus, daß die Erde ebenso wertvoll ist, daß sie kämpft mit dem Himmel. Und diesen Kampf des Himmels mit der Erde, den bildete man für zweitausend, dreitausend Jahre aus als eine Ansicht, die für diese Leute besondere Wichtigkeit hatte.

Dann, wenn wir etwa drei- oder viertausend Jahre zurückgehen, dann kommen wir in ein Land, da von Arabien hinüber nach Afrika, wo der Nil fließt: Ägypten. Die Ägypter und auch diejenigen, die dann da drüben in Asien mehr eigentlich gegen den Westen saßen, schon mehr gegen Europa zu, die bekamen die Erde noch lieber. Und deshalb, wenn wir da drei-, viertausend Jahre zurückgehen, dann finden wir: Diese Ägypter, die also sozusagen die dritte Art von Menschen waren — Inder, Perser, Ägypter —, diese Menschen, die bauten diese riesigen Pyramiden. Aber was sie vor allen Dingen taten, das war: sie behandelten den Nil. Den Nil, der eben jedes Jahr das Land überschwemmt mit seiner fruchtbaren Erde, den kanalisierten sie, so daß ihnen diese Überschwemmungen nach allen Richtungen Nutzen bringen konnten. Dazu bildeten sie die sogenannte Geometrie aus. Die brauchten sie. Die Geometrie und Feldmeßkunst, das wurde da nun ausgebildet. Die Leute bekamen die Erde immer lieber und lieber. Und sehen Sie: In demselben Maße, in dem die Leute auf der Erde die Erde lieber bekamen, desto weniger wurde ihnen klar, daß sie aus einer geistigen Welt herübergekommen sind. Ich möchte sagen, das haben sie immer mehr und mehr vergessen, weil sie die Erde immer lieber bekommen haben, und in demselben Maße wurde ihnen wichtiger, sich zu sagen: Man lebt nach dem Tode.

Gewiß, wir haben ja gesehen, das Leben nach dem Tode ist dem Menschen gesichert, aber die Menschen haben früher, bevor die Ägypter gekommen sind, überhaupt nicht so stark an die Unsterblichkeit gedacht. Warum? Weil es ihnen selbstverständlich war. Wenn sie gewußt haben, sie kommen herunter aus einer geistigen Welt, haben den physischen Leib nur angenommen, dann haben sie gar nicht daran gezweifelt, daß sie nach dem Tode in einer geistigen Welt ankommen werden. Aber in Ägypten dahier, wo die Menschen schon weniger gedacht haben an den Aufenthalt im Geistigen vor dem Erdenleben, da haben die Ägypter diese riesige Angst bekommen vor dem Sterben. Diese riesige Angst vor dem Sterben, die ist eigentlich noch nicht viel älter als drei-, viertausend Jahre. Die Inder und die Perser haben keine Todesangst gehabt. Man kann also eigentlich nachweisen, daß die Ägypter diese furchtbare Angst vor dem Sterben gehabt haben. Denn, sehen Sie, wenn sie nicht diese heillose Angst vor dem Sterben gehabt hätten, dann könnten nicht heute diese Engländer und die anderen nach Ägypten gehen und die Mumien in ihren Museen dann ausstellen! Denn dazumal wurden die Leute so einbalsamiert durch allerlei Salben und Mittel. Wie der Mensch im Leben ausschaute, so haben sie ihn in den Sarg gelegt und aufbewahrt. Da wurden die Leute einbalsamiert und zu Mumien gemacht, weil man gedacht hat: Wenn man den Leib zusammenhält, dann bleibt auch das Seelische solange vorhanden, als es noch den Leib hat auf Erden. - Man hat den Leib aufgehoben, damit das Seelische nicht irgenwie Schaden leidet. Sehen Sie doch, das ist die Angst vor dem Sterben. Da hat man also mit aller Gewalt aus der Erdenmaterie heraus die Unsterblichkeit bewirken wollen bei den Ägyptern. Diese Ägypter haben aber trotzdem noch außerordentlich viel gewußt, was später ganz verlorengegangen ist.

Und das nächste Volk, das uns besonders auffällt, das ist dann etwas im Norden von Ägypten, in Griechenland, im heutigen Griechenland. Aber das alte Griechenland war ganz anders. Sehen Sie, die Griechen, die haben nun schon fast ganz vergessen gehabt das Leben vor der Geburt. Nur einzelne Leute in besonders hohen Schulen, die man Mysterien nannte, die wußten noch davon. Aber im ganzen war in der griechischen Zivilisation das geistige Leben vor der Geburt schon ganz vergessen, und die Griechen haben das Erdenleben am allermeisten geliebt. Und deshalb ist in Griechenland auch ein Philosoph aufgetaucht, Aristoteles heißt er, im 4. Jahrhundert vor der christlichen Zeitrechnung. Sie sehen, jetzt kommen wir schon an die christliche Zeitrechnung heran. Aristoteles, der hat zuerst eine Ansicht aufgestellt, die früher gar nicht vorhanden war. Er hat nämlich die Ansicht aufgestellt: Nicht nur der Leib des Menschen wird geboren, wenn ein Kind geboren wird, sondern auch die Seele des Menschen wird geboren. — Also in Griechenland taucht zuerst die Ansicht auf, daß die Seele des Menschen mit dem Leib geboren wird, dann aber unsterblich ist, also durch den Tod geht und in der geistigen Welt weiterlebt. Nur hat Aristoteles dann eine eigentümliche Ansicht aufgestellt. Aristoteles hat eigentlich schon alles vergessen gehabt, was Weisheit in alten Zeiten war, und er hat dann die Ansicht aufgestellt: Die Seele wird zugleich mit dem Leib geboren. Wenn aber der Mensch stirbt, so bleibt die Seele so, daß sie nur das eine Erdenleben hinter sich hat. Da muß sie ewig nur auf das zurückschauen, was das eine Erdenleben ist.

Denken Sie sich, was das für eine schreckliche Ansicht ist! Wenn also irgendeiner auf der Erde Schlechtes getan hat, so ist er in alle Ewigkeit nicht fähig, das irgendwie auszubessern, sondern muß immer zurückschauen, muß immer sehen das Bild, was er da Schlechtes gemacht hat. Das ist die Ansicht von Aristoteles.

Dann ist das Christentum gekommen. In den allerersten Jahrhunderten hat man das Christentum ein wenig verstanden. Als aber dann das Römische Reich das Christentum aufgenommen hat und in Rom sich das Christentum festgesetzt hat, hat man dort das Christentum nicht mehr verstanden. Man hat es nicht verstanden.

Nun gab es gerade innerhalb des Christentums immer Konzilien. Da sind die hohen Würdenträger der Kirche zusammengekommen und haben festgestellt, was die große Herde der Gläubigen zu glauben hat. Nicht wahr, da bildete sich die Ansicht: Es gibt Hirten und Schafe, und die Hirten haben dann auf den Konzilien festgesetzt, was die Schafe zu glauben haben. - Am achten dieser Konzile wurde nun festgelegt durch die Hirten für die Schafe, daß es ketzerisch sei, zu glauben, daß der Mensch vor seiner Geburt in der geistigen Welt gelebt habe. Also die alten Ansichten des Aristoteles, die wurden dann christliches Kirchendogma! Und dadurch wurde die Menschheit geradezu gezwungen, nichts zu wissen, gar nicht daran zu denken, daß der Mensch mit einer Seele aus der geistigen Welt heruntergekommen ist. Es wurde ihnen verboten.

Wenn heute die Materialisten sagen: Die Seele wird mit dem Körper geboren und ist nichts anderes als Körperliches —, dann ist das nichts anderes als das, was die Leute gelernt haben von der Kirche. Das ist es eben, daß die Menschen heute glauben, sie kommen über die Kirche hinaus, wenn sie Materialisten sind. Nein, die Menschen wären nie Materialisten geworden, wenn die Kirche nicht abgeschafft hätte die Erkenntnis vom Geist. Denn auf diesem achten allgemeinen, ökumenischen Konzil in Konstantinopel ist eben der Geist durch die Kirche abgeschafft worden, und das ist dann geblieben das ganze Mittelalter hindurch. Erst jetzt muß man durch Geisteswissenschaft wiederum darauf kommen, daß der Mensch als Seele eben auch da war, bevor er auf der Erde war. Das ist das Wichtige, das ist das ungeheuer Wichtige.

Wer die Menschheitsentwickelung auf der Erde verfolgt, der sieht ganz klar ein: Ursprünglich war das Wissen davon da, daß die Menschen, bevor sie zur Erde heruntersteigen, in einem geistigen Dasein sind. — Das ist nur nach und nach vergessen und später sogar durch Konzilbeschluß abgeschafft worden.

Nun muß man sich nur klar werden, was das bedeutet. Denken Sie sich einmal, die Menschen, die gelebt haben bis zu den Ägyptern hin, also in alten Jahrtausenden, die haben gewußt: Bevor du auf dieser Erde hier herumgewandelt bist, bist du in der geistigen Welt gewesen. - Ja, die haben nicht nur heruntergebracht aus der geistigen Welt so ein allgemeines verschwommenes Wissen, sondern die haben heruntergebracht aus der geistigen Welt das Bewußtsein, da haben sie mit anderen Wesen gelebt. Und davon haben sie heruntergebracht auch ihre sittlichen Antriebe. Was ich auf der Erde tun soll, das sehe ich aus dem, wie diese Erdendinge sind, haben diese alten Leute gesagt; was ich sonst tun soll, da brauche ich mich ja nur zu erinnern an das, was vor der Geburt war. Sie haben ihre sittlichen Impulse von der geistigen Welt heruntergebracht. Sehen Sie, wenn man die Menschen in diesen alten Zeiten gefragt hat: Was ist gut? Was ist böse? — dann sagten die: Gut ist dasjenige, was die Wesen, unter denen ich war, bevor ich auf der Erde war, wollen; böse ist das, was die nicht wollen. - Das hat aber jeder einzelne sich gesagt. Jetzt, meine Herren, hat man das vergessen.

In Griechenland, da gab es nun etwas sehr Merkwürdiges. In Griechenland hat man soweit vergessen, daß es ein Leben vor der Geburt gibt, daß der Aristoteles gesagt hat: Die Seele wird mit dem physischen Körper geboren. - Die Leute haben also gar keine Ahnung mehr davon gehabt, daß sie vor der Geburt schon gelebt haben. Aber sie haben etwas gespürt in sich von diesem Leben. Nicht wahr, ob man etwas weiß oder nicht weiß, das hat ja für die Wirklichkeit keinen Einfluß. Ich kann immerzu sagen: Hier hinter mir ist kein Tisch, ich sehe keinen Tisch [stößt im Zurückgehen an den Tisch an] -, aber der Tisch ist doch da, wenn ich ihn auch nicht sehe. Das Leben vor der Geburt blieb eben doch da, und die Menschen spürten es in sich. Und das fing man an in Griechenland das Gewissen zu nennen. In Griechenland kommt etwa im 5. Jahrhundert vor der christlichen Zeitrechnung zuallererst das Wort Gewissen auf. Vorher gab es das Wort Gewissen nicht. Also das Wort Gewissen kommt davon her, daß die Leute vergessen haben das vorgeburtliche Leben, das vorirdische Leben, und dem, was sie davon noch gespürt haben in sich, dem haben sie ein Wort gegeben. Und seit jener Zeit ist das so geblieben. Die Menschen spüren in sich das vorgeburtliche Leben, aber sie sagen: Nun ja, das ist halt so; das entsteht da unten irgendwo und dann schießt es herauf - aber sie kümmern sich nicht weiter darum.

Sehen Sie, das war gut für die Kirche. Denn was konnte denn jetzt geschehen von der Kirche? Ja, meine Herren, früher, wo jeder gewußt hat, daß er gelebt hat als Seele, bevor er auf die Erde heruntergestiegen ist, da haben die Leute gesagt: Sittlich ist das, was wir wissen von unserem früheren Leben, von dem vorirdischen Leben. - Jetzt spürten die Griechen nur das Gewissen. Und dann kam später die Kirche, die verwaltete nun das Gewissen. Nicht wahr, die fing die Sache auf und sagte: Ihr wißt ja nicht, was ihr tun sollt. Das wissen nicht die Schafe, das wissen die Hirten! - Und sie machte Vorschriften und verwaltete das Gewissen.

Sehen Sie, man brauchte das schon, daß man auf einem Konzil den Geist abschaffte, denn dann konnte man das, was dem Menschen vom Geiste geblieben war als Gewissen, eben verwalten. Und dann hat die Kirche gesagt: Nein, nichts ist vom Menschen dagewesen, bevor er auf der Erde da war. Die Seele ist mit dem Körper geboren. Wer das nicht glaubt, ist des Teufels. Aber wir, als Kirche, wir wissen, wie es in der geistigen Welt ausschaut und was der Mensch auf Erden zu tun hat. — Dadurch hat sich die Kirche des Gewissens bemächtigt.

Das kann man noch im einzelnen nachweisen. Denn sehen Sie, das hat ja noch bis ins 19. Jahrhundert hineingespielt, hat hineingespielt manchmal in einer ganz furchtbaren Weise. Da gab es zum Beispiel in den dreißiger, vierziger Jahren des vorigen Jahrhunderts, des 19. Jahrhunderts, in Prag einen Menschen, der hieß Smetana. Dieser Mensch war der Sohn eines katholischen Kirchendieners, der selbstverständlich ein frommer Katholik war. Der war der Empfindung, daß man dasjenige zu glauben hat, was die Kirche vorschreibt; von der geistigen Welt weiß man dasjenige, was die Kirche vorschreibt. Nun hatte er einen Sohn. Die Menschen waren dazumal etwas ehrgeizig und haben ihre Kinder auf das Gymnasium geschickt. Aber in den Gymnasien, die in Prag waren im vorigen Jahrhundert, da lernte man nicht eigentlich sehr viel. Man lernte im Grunde genommen recht wenig. So wurde denn der junge Smetana im Gymnasium aufgezogen. Und das war eben einmal so: Derjenige, der überhaupt etwas lernen sollte, der wurde dann Priester. So wurde auch der junge Smetana Priester. Dazumal war es ja in Prag und auch im übrigen Österreich so, daß man auch die hohen Schulen mit Priestern als Lehrer besetzte. Und so kam er nun dazu, daß er, als er selber zu lehren hatte, etwas andere Bücher las als diejenigen, die ihm als Priester von der Kirche vorgeschrieben waren. Ja, dadurch kam er allmählich in Zweifel hinein, namentlich über ein Dogma. Er sagte sich: Was ist das doch eigentlich Fürchterliches, daß der Mensch geboren werden soll, sein Erdenleben zubringt, nachher durch den Tod geht und nun, wenn er ein schlechter Kerl war, ewig nur anschauen soll — die Kirche malte das ja noch mit den nötigen Bildern aus — dasjenige, was er als schlechter Kerl auf der Erde vollbracht hat und niemals die Möglichkeit haben sollte, sich zu verbessern!

Nun, sehen Sie, dieser Mann, Smetana, hat in einem Ordenshaus gewohnt. Aber als er Lehrer geworden ist, wurde es ihm etwas zu eng im Ordenshaus; da hat er eine weltliche Wohnung bezogen, hat immer mehr und mehr — es waren ja dazumal noch keine anthroposophischen Bücher vorhanden — die Bücher von Hegel, Schelling und so weiter gelesen, die wenigstens etwas, einen Anfang von etwas Vernünftigem gaben. Da ist er immer mehr und mehr in Zweifel hineingekommen über die sogenannte Ewigkeit der Höllenstrafe, denn ein schlechter Kerl geht nach Aristoteles durch den Tod und muß ewig in seiner Schlechtigkeit leben. Daraus ist aber die Lehre von der Ewigkeit der Höllenstrafe entstanden, die dann durch die Kirche konzilmäßig festgesetzt wurde. Diese Lehre ist natürlich keine christliche, sondern diese Lehre ist diejenige des Aristoteles. Es ist gar nicht wahr, daß das eine christliche Lehre ist, diese Lehre von der Höllenstrafe; die ist von Aristoteles. Aber das war ja den Leuten nicht klar.

Diesem Smetana aber wurde es klar. Da hat er nun angefangen erwas zu lehren, was nicht ganz stimmte mit der Lehre der Kirche. 1848 war es gerade, da hat er etwas gelehrt, was nicht ganz stimmte. Da bekam er zunächst eine furchtbare Verwarnung, einen riesigen lateinisch geschriebenen Brief, in dem ihm bedeutet wurde, er solle nun reuig zurückkehren in den Schoß der Kirche, denn es hätte ungeheures Ärgernis erregt bei den Hirten, daß er die Schafe etwas lehrte, was nicht von den Hirten vorgeschrieben ist. Auf diesen ersten lateinisch geschriebenen Brief hat er noch geantwortet, daß er es für eine Heuchelei halte, etwas anderes zu sagen als dasjenige, wovon man überzeugt ist. Da kam ein zweiter lateinischer Brief, der ihn noch ernsthaftiger verwarnte. Und als er diesen nicht mehr beantwortete, denn es hätte keinen Zweck gehabt, da wurde eines Tages in allen Kirchen in Prag angekündigt, daß eine sehr wichtige Feier stattfinden solle, weil eines der verlorenen Schafe, das sogar ein Hirte geworden war, aus der Kirche ausgeschlossen werden müsse.

Zu denjenigen, die dazumal überall die Zettel verteilen mußten, daß diese wichtige Feier stattfinden solle, gehörte auch der Kirchendiener, der alte Smetana, der Vater. Der war nun ein frommer Katholik geblieben. Sie können sich nun denken, was das bedeutet, daß ganz Prag zusammengerufen worden ist, um den Sohn Smetanas zu verdammen, daß er ewig ausgeschlossen werden soll aus der Kirche und so weiter, ihn zu verdammen, und der Vater mußte selber die Zettel herumtragen! Ja, es war niemals in Prag die Kirche so voll als an diesem Tag. Alle Kirchen in Prag waren ganz voll. Und da wurde von allen Kanzeln verkündet, daß der abtrünnige Smetana von der Kirche ausgestoßen wird.

Die Folge davon war — natürlich lag der Keim zur Lungensucht in der Familie der Smetana -, daß zuerst die Schwester aus Gram starb, nachher starb der alte Vater aus Gram, und nachher starb Smetana selber nach kurzer Zeit aus Gram, aus Leid. Aber darauf kam es ja nicht an, nicht wahr, sondern es kam darauf an, daß Smetana nicht mehr die Geschichte von der Ewigkeit der Höllenstrafe verkündete, wie er sie auffaßte.

Das hängt alles zusammen mit der Entwickelung der Gewissensidee der Menschheit. Denn dasjenige, was der Mensch eben behält von dem Leben vor dem Irdischen, das lebt in ihm und spricht in ihm als Gewissen. Und vom Gewissen aus kann man sich sagen: Das Gewissen, das kann nicht aus dem Stoff der Erde kommen. - Denn denken Sie sich einmal, irgendeiner, sagen wir, hat ein furchtbares Gelüste. Das hat es ja schon gegeben. Dann sind es die Stoffe in seinem Leib, die Stoffe der Erde, die ihn drängeln und zwicken, daß er zu diesem Gelüste kommt. Dann sagt ihm das Gewissen:Du mußt aber diese Gelüste bekämpfen. — Ja, meine Herren, das wäre doch geradeso, wenn das Gewissen auch aus dem Körper noch käme, als wenn irgend jemand zu gleicher Zeit vorwärts und rückwärts gehen sollte. Es ist ja unsinnig, zu sagen, das Gewissen komme aus dem Leib. Das Gewissen ist eben mit dem, was wir herunterbringen vom vorirdischen Leben aus der geistigen Welt, wenn wir da zur Erde heruntersteigen, verbunden. Aber so wie ich es Ihnen dargestellt habe, ist eben das Bewußtsein, daß das Gewissen aus der geistigen Welt stammt, für die Erdenmenschen verlorengegangen, und bei solchen Menschen, wie dem Smetana, von dem ich Ihnen vorhin erzählt habe, ist es eben im 19. Jahrhundert durch diese furchtbare Sache von der Höllenstrafe wiederum aufgedämmert. Das Gewissen gehört dem Menschen selber an. Der Mensch trägt das Gewissen in sich. Was hülfe einem denn all das Gewissen, das man in sich trägt, wenn man durch den Tod durchgehen würde und dann ewig sehen würde, was man für ein schlechter Kerl gewesen ist? Man könnte sich ja da nicht helfen. Daß man Gewissen hat, hätte ja dann keine Bedeutung!

So daß man sagen kann: Wenn das der Mensch ist (es wird gezeichnet), so lebt in dem Menschen das Gewissen. Das Gewissen ist dasjenige, was er aus der geistigen Welt ins Erdenleben mit hereingebracht hat. Das Gewissen sagt in ihm: Das hättest du nicht tun sollen, und das hättest du nicht tun sollen. - Der irdische Mensch sagt: Das will ich tun, das wünsche ich. - Das Gewissen spricht anders, weil das Gewissen aus dem ewigen Menschen kommt. Und dann, wenn der Mensch den physischen Leib abgelegt hat, dann merkt er erst: Du bist ja selber das, was in deinem Gewissen immer gesprochen hat. Das hast du nur nicht bemerkt während der Zeit des Erdenlebens. Jetzt bist du durch den Tod gegangen. Jetzt bist du dein eigenes Gewissen geworden. Das Gewissen ist jetzt dein Leib. Früher hast du kein Gewissen gehabt. Jetzt hast du dein Gewissen, mit dem lebst du nach dem Tode weiter.

Aber dem Gewissen muß man auch einen Willen zuschreiben. Sehen Sie, alle die Sachen, die ich Ihnen gesagt habe, haben sich zugetragen. Die Griechen hatten vergessen das vorirdische Leben. Die Kirche hatte zum Dogma erhoben, daß man nicht glauben darf, daß es ein vorirdisches Leben gibt. Das Gewissen ist vollständig mißverstanden worden. Das alles hatte sich erfüllt. Und nun hat es natürlich fortdauernd auch große Gelehrte gegeben. Aber diese großen Gelehrten im Mittelalter, die standen ja unter dem Eindrucke: Ein vorirdisches Leben kann es nicht geben. Die Kirche verbietet, daran zu glauben.

In diesem Zwiespalt stand zum Beispiel ein solcher Mensch wie Thomas von Aquino, der von 1225 bis 1274 gelebt hat. Der mußte sich als katholischer Priester dem anbequemen, was die katholische Kirche vorschreibt. Aber er war ein großer Denker. Und in bezug auf das, was ich Ihnen heute gesagt habe, mußte er also sagen: Wenn der Mensch stirbt, so hat er nur die Anschauung seines Erdenlebens, immer bis in alle Ewigkeit, niemals anders. Er schaut das an. - Was tut also Thomas von Aquino? Thomas von Aquino schreibt dem Menschen nur den Verstand zu für alle Ewigkeit, aber keinen Willen. Der Mensch muß das anschauen nach dem Tode, aber er kann nichts mehr daran ändern. Dadurch war Thomas von Aquino gerade einer der größten Aristoteliker des Mittelalters, daß er sagte: Wenn einer etwas Schlechtes getan hat auf Erden, muß er es ewig anschauen; wenn einer etwas Gutes getan hat, schaut er ewig das Gute an. - Also nur die Erkenntnis, nicht der Wille wurde der Seele zugeschrieben.

Das entspricht eben nicht der Wahrheit. Der Wahrheit entspricht es, daß man zwar anschaut nach dem Tode, was man war im Guten und im Bösen, aber daß man den Willen, die ganze Seelenkraft beibehält, um das zu ändern. So kommt es, daß man natürlich, wenn man sein Leben anschaut, sieht, wie es gewesen ist, dann in der geistigen Welt lebt und sieht, was hätte anders sein sollen. Dann kommt das von selber, daß man wieder herunter will, um das entsprechend auszubessern. Natürlich kommen dann wieder Fehler, aber dann kommen immer die folgenden Leben, und der Mensch erreicht ein Ziel der vollständigen Menschenentwickelung.

Wozu Thomas von Aquino noch genötigt war im Mittelalter, nur an die Erkenntnis zu glauben, nicht an den Willen, daran haben nun die Menschen im 19. Jahrhundert noch so gekrankt wie dieser Smetana. Dem ist nun zuzuschreiben, daß dann im 19. Jahrhundert andere Leute gekommen sind, die eine förmliche Wut gekriegt haben auf die Erkenntnis. Das stammte noch alles von dem Dogma der Höllenstrafe her; nur haben die Leute das nicht durchschaut. Schopenhauer zum Beispiel hat eine förmliche Wut gekriegt auf die Erkenntnis und hat nun dem Willen alles zugeschrieben. Ja, aber wenn man nun dem Willen wieder alles zuschreibt, dann ist dieser Wille zu dumm und töricht. Daher hat Schopenhauer dem dummen Willen die ganze Weltenschöpfung und alles zugeschrieben. Und diejenigen Menschen, die nachgedacht haben, kamen eben zu solchen furchtbaren inneren Konflikten, wie der Smetana in Prag gekommen ist. Solche gab es sehr viele; das ist nur ein ausgezeichnetes Beispiel, dessen Schwierigkeiten niedergeschrieben worden sind. Solche Menschen gab es viele.

Und so müssen wir uns klar sein darüber: Der Mensch hat sein Gewissen als eine Erbschaft von seinem vorirdischen Leben. Da spricht der Geist in dem Gewissen. Das, was wir vor dem Erdenmenschen schon waren, das ist ins Fleisch eingetaucht und spricht im Gewissen. Und wenn wir den Leib abgelegt haben werden, dann wird die Seele im Gewissen nach dem Tode weiter sprechen, aber nicht ohnmächtig, sondern einen Willen haben und das ausbessern müssen, forttätig sein müssen.

Sehen Sie, das ist der Unterschied zwischen der Anthroposophie und zwischen alledem, was zum Beispiel heute in der christlichen Dogmatik enthalten ist. In der christlichen Dogmatik kennt man diese innere Kraft der menschlichen Seele, die da schaffen kann, nicht, sondern da stirbt der Mensch und kann nur ewig das anschauen, was er in dem einen Erdenleben gemacht hat, weil in dem einen Erdenleben die Seele mit dem Körper geboren wird. So daß man also, wenn man schematisch darstellen will, sagen muß: Wenn das ein Erdenleben des Menschen ist (obere Zeichnung, Kreis), so beginnt das auch mit der Seele, und wenn der Mensch nun stirbt - da ist Geburt, da Tod -, dann dehnt sich sein Seelenleben in alle Ewigkeit aus. Ich will nicht mehr, weil das ja zu teuer ist, mit meiner Zeichnung noch auf die zweite Tafel gehen, ich müßte sogar noch eine dritte haben! In alle Ewigkeit dehnt sich das aus: nur die Erkenntnis, nur der Verstand, der soll immer nur anschauen in alle Ewigkeit die Schlechtigkeit des Erdenlebens, weil ja der Verstand mitgeboren ist mit dem Physischen des Erdenlebens. Der erste Materialist war eigentlich der, der dieses Dogma festgesetzt hat, war eigentlich Aristoteles schon.

Nun, Anthroposophie findet, daß es nicht nur das eine Erdenleben gebe, sondern auch die aufeinanderfolgenden Erdenleben. Der Mensch hat immer vom vorhergehenden Erdenleben etwas übrigbehalten, das er ja nicht genau kennt, das aber in ihm sitzt: das ist das Gewissen. Jetzt legt er den Leib ab, in seinem Gewissen lebt er weiter. Da (untere Zeichnung, rot links) ist nun im Grunde bis zur nächsten Geburt lauter Gewissen. Jetzt (mittlerer Kreis) ist wieder Gewissen drinnen als eine Stimme, die spricht; jetzt (rot rechts) lebt es in der Außenwelt, ist wiederum da. - Und der Mensch ist eigentlich selber derjenige, der immer seine neuen Leben auf der Erde schafft. Allerdings, darüber ärgert sich natürlich diejenige Lehre ganz besonders, die dem Menschen gar nichts zuerkennen will, die alles nur so anschauen will, als wenn der Mensch ein Geschöpf wäre. Er ist nicht ein bloßes Geschöpf, sondern es sind Schöpferkräfte in ihm. Und das ist eben der Unterschied der Anthroposophie von den anderen Anschauungen, daß die Anthroposophie durch ihr Forschen herausbringt: Ja, diese Schöpferkräfte sind im Menschen, der Mensch ist auch schöpferisch. Er ist nicht bloß geschaffen, sondern er ist schöpferisch. Und zu zum Allerschöpferischsten in ihm gehört eben das Gewissen, denn das ist dasjenige, was uns wie eine heilige Erbschaft aus dem vorirdischen Leben geblieben ist und was wir wieder hinaustragen, wenn wir durch den Tod gehen.

Das ist geradezu eben das, was die moderne Wissenschaft noch immer von der Kirche hat, und gerade in diesem Punkte sollte man wirklich ganz genau sehen. Denn die Sache ist ja so gegangen: Da herüber nach Rom, da kam immer nur dasjenige, was logisch auf der einen Seite und materialistisch auf der anderen Seite war. Das haben dann die modernen Völker angenommen. Aber in der deutschen Sprache ist manchmal auf einem ganz anderen Weg noch ein Rest geblieben vom Alten, nur erkennt man es nicht wiederum. Das ist sehr merkwürdig. Darin erkennt man, wie der Mensch zusammenhängt mit den großen Ereignissen.

Wenn man heute diese Länder, die da oben in Asien liegen, anschaut - Sibirien —, so sind das eigentlich Gegenden, die sehr wenig bevölkert sind, aber sie waren einmal stark bevölkert. Da waren nur die Flüsse dort viel, viel mächtiger. Sibirien ist ein Land, das nach und nach ausgetrocknet ist, sich gehoben hat, und die Menschen sind dann nach Westen gezogen, nach Europa herüber. Das ist durch die Hebung von Sibirien entstanden. Und auf diese Weise sind viele Vorstellungen, die da in Asien waren, auf einem anderen Weg nach Europa hereingekommen, und diese Vorstellungen, die leben in den europäischen Sprachen weiter fort. Daher muß man sagen: Je weiter man nach Westen kommt, desto weniger ist diese Vorstellung vom Gewissen vorhanden. — Aber gerade das Wort Gewissen, das zeigt eben, daß man unter den Leuten, die das Wort Gewissen bildeten, ein Gefühl hatte: Da steckt etwas im Menschen. - Und was bedeutet eigentlich das Wort Gewissen? Was die Sache bedeutet, haben wir gerade gesagt: Es ist die Erbschaft von dem, was vorirdisches Leben ist, was im Menschentum drinnen bleibt. Aber das Wort Gewissen, was bedeutet es? Nicht wahr, wenn man das Erdenleben betrachtet und sich sagt: Die Ereignisse, die in zwei, drei Jahren sein werden, die sind unsicher, ungewiß, aber daß der Mensch in sich einen Geist hat, der vor seinem Erdendasein da war und der nach seinem Erdendasein bleibt, das ist gewiß. — Und mit dem Gewißsein hängt eben das Wort Gewissen auch zusammen, und es ist das Allergewisseste, was es geben kann. So daß also in dem Worte Gewissen schon hingedeutet ist auf dasjenige, was ewig ist im Menschen. Es ist sehr bedeutsam, daß Gewissen etwas anderes als Inhalt enthält, als zum Beispiel Conscience oder etwas ähnliches in den westlichen Gegenden. Conscience ist dasjenige, was «zusammengewußt» wird auf der Erde con-, conscience —, was sich zusammenballt aus dem Erdenwissen. Dasjenige, was aber als Gewissen im Menschen lebt und mit dem Wort Gewissen bezeichnet wird, das ist das Gewisseste, was es geben kann, was nicht unbestimmt, was ganz sicher ist. Und ganz sicher ist, daß der Mensch auf Erden nicht nur an ein Leben nach dem Tode glaubt - eine Ansicht, wie sie der Aristoteles und die Kirchengläubigen hatten -, sondern auch einen Willen entwickelt, es immer besser und besser zu gestalten, die Erde immer wieder und wiederum aus dem Geist besser und besser zu gestalten, daß also der Wille ebenso lebt nach dem Tode, wie die Erkenntnis lebt. Bei Thomas von Aquino hat nur die Erkenntnis bloß gelebt. Jetzt müssen wir uns klar sein, daß der Wille lebt. Sehen Sie, meine Herren, es ist schon so: Man braucht in der Tat durchaus nicht jemanden, der vor Jahrhunderten zu seiner Zeit ein gro 249

ßer Gelehrter war, wie Thomas von Aquino im 13. Jahrhundert, herunterzusetzen, weil er in der damaligen Zeit dieses gelehrt hat. Aber es ist etwas anderes, wenn der Thomas von Aquino dasjenige, was man im 13. Jahrhundert einzig und allein lehren konnte, damals gelehrt hat, als wenn man heute, wie es gerade jetzt wiederum geschieht in Paris, eine Thomas-Gesellschaft gründet, um dasselbe zu lehren, wie man es damals gelehrt hat, geradeso wie eben Leo XIII. für alle Priester und Gelehrten der katholischen Kirche geboten hat im 19. Jahrhundert, nur dasjenige zu sagen, was der Thomas von Aquino im 13. Jahrhundert gelehrt hat. Heute würde ja der Thomas das auch nicht mehr sagen! Und diese zwei Dinge stehen sich in der Welt gegenüber, so etwas wie in Paris eine Thomas-Gesellschaft, die die Menschen wiederum zurückführen will, und die Anthroposophie, die das Gegenwärtige lehrt, dasjenige, was ein gegenwärtiger Mensch ist. Und vor allen Dingen ist es wichtig, wenn man so etwas wie das Gewissen betrachtet, daß einen das stößt auf das Ewige im Menschen. Aber das Ewige kann man nicht richtig verstehen, wenn man nicht auch hinsieht auf das vorirdische Leben, wenn man bloß auf dasjenige hinsieht, was eigentlich erst seit der Ägypterzeit als das nachirdische Leben, als die sogenannte Unsterblichkeit entstanden ist.

Sehen Sie, meine Herren, erst vor drei, vier Jahrtausenden haben die Menschen angefangen zu reden davon, daß sie unsterblich sind, daß sie also nicht mit der Seele sterben, wie der Leib stirbt. Vorher aber haben die Leute gesagt, sie seien auch nicht geboren als Seele, wie der Leib geboren wird. Sie hatten eine Wortbedeutung gehabt, die wir heute Ungeborenheit nennen müßten. Das war die eine Seite. Und die Unsterblichkeit ist die andere Seite. Nicht einmal die Sprachen haben heute mehr ein anderes Wort als Unsterblichkeit! Das Wort Ungeborenheit, das muß wiederum aufkommen. Dann wird man sagen: Das Gewissen ist dasjenige im Menschen, was nicht geboren ist und nicht stirbt. Dann wird man erst das Gewissen richtig schätzen können. Denn das Gewissen hat nur eine Bedeutung für den Menschen, wenn man es richtig schätzen kann.

Nun, am Sonnabend dann, meine Herren, um neun Uhr weiter.