The Evolution of the Earth and Man

and the Influence of the Stars

GA 354

9 September 1924, Dornach

Lecture X

Rudolf Steiner: Good morning, gentlemen! Are there any questions?

Written question: Mars is near the earth. What effect does that have upon the earth? What is known about Mars?

Dr. Steiner: There has been a great deal of talk recently about the nearness of Mars to the earth, and the newspapers have made utterly futile statements without even a rudimentary understanding of what this means. We must not attach prime importance to these external circumstances in the planetary constellations due to the relative positions of earth and sun, because the influences arising from them do not really amount to very much. It is interesting that there has been all this talk about the proximity of Mars, because every planet, including the moon, is constantly coming nearer to the earth, and the planets are undergoing a process that will finally end in all of them uniting again with the earth, forming a single body.

Of course, if it is imagined, as most people imagine today, that the planets are solid bodies just like the earth, the expectation could well be that if they were to unite with the earth, this would mean the end of all life on our globe! But no such thing will happen, because the degrees of density of the various planets are not the same as that of the earth. If Mars, for instance, were actually to come down and unite with the earth, it would not be able to lay waste the land but only to inundate it. For as far as investigation is possible—it can never be done with physical instruments but only through spiritual science, spiritual vision—Mars consists primarily of a more or less fluid mass, not as fluid as our water but, shall we say, more like the consistency of jelly, or something of that kind. There are also dense components, but they are not as densely solid as those of our earth. Their consistency would be more comparable to that of the antlers or horns of our animals, which form out of the general mass and dissolve back into it again. So we must realize that the constitution of Mars is entirely different from that of our earth.

Now a great deal is said about “canals” existing on Mars. But why “canals”? There is nothing to be seen except lines, and these are called canals.18See Rudolf Steiner, Occult History, Lecture V: “... so-called canals on Mars. There it is a matter of certain streams of force which correspond to an earlier stage of the earth ...” In one sense that is correct, but in another, incorrect. As Mars is not solid to the degree that the earth is solid, one cannot, of course, speak of canals as we know them on the earth. But it can be said that on Mars there is something rather similar to our trade winds. You know that the warm air from the Torrid Zone of the earth, from Africa, streams toward the cold North Pole, and the air from the cold North Pole streams back toward the central region of the earth. So that if looked at from outside, such lines would indeed be seen, but they are the lines of the trade winds, of the air currents in the trade winds. There is something rather similar on Mars. Only everything on Mars is much more full of life than on the earth. The earth is a dead planet in a far stronger sense than Mars, on which everything is still more or less living.

I want to mention something that can help you to understand the character of Mars' relation to the earth. We know that the sun, to us the most important of all the heavenly bodies, is the sustainer of a very great deal on the earth. Think of the sun as we know it from day to day. At night you see the plants drawing in their blossoms because the sun is not shining on them. By day they open again to be irradiated by the sun. Very many things depend upon the spread of sunlight over one part of the earth and the spread of darkness over another part when the sun is not there. But if you think of a whole year, you could not conceive of the plants growing in the spring if the sun's power did not return. Again, when the sun loses power in the autumn, the plants fade away, all life dies and snow falls.

Quite obviously, life on the earth is connected with the sun. Indeed, we humans would be unable to breathe the air around us if the sun were not there, if the rays of the sun did not make the air suitable for us to breathe. The sun is undeniably the most important heavenly body for us. Just think what a different story it would be if the sun were not-as it appears-to go around the earth every twenty-four hours but instead took twice that time! All life would be slower. So all life on earth depends upon the revolution of the sun around the earth. In reality, of course, the sun does not revolve around the earth, but that is how it appears.

The influence of the moon is of less significance for man, but nevertheless it is there. When you remember that the tides ebb and flow according to the moon, that they have the same rhythm as the moon's revolution, you will realize with what kind of power the moon works upon the earth. And then it will also be clear that the time of the moon's rotation around the earth has a definite significance. If you were to investigate how the plants develop when the sun has shone upon them, you would also find evidence of the influence of the moon. Thus the sun and the moon have a tremendous influence upon the earth. We can recognize the lunar influence from the time of the rotation, that is, from the time it takes for the moon to become full moon, new moon, and so on. We can recognize the influence of the sun from its rising and setting, or from the fact that it acquires its power in the spring and loses it in the autumn.

And now let me tell you something. You all know of the existence of the grubs of cockchafers. These little worm-like creatures are particularly harmful when they eat up our potatoes. There are years when the potatoes are unharmed by these troublesome little maggots, and then there are years when simply nothing can be done because the grubs are everywhere at work. Well now, suppose there has been a year when the grubs have eaten nearly all the potatoes—if you wait now for four years, the cockchafers will be there in great numbers, because it takes them four years to develop from the grubs. There is a period of approximately four years between the appearance of the grubs—which, like all insects, first have a maggot form before becoming a chrysalis—and the fully developed insect. The grub needs four years to develop into the cockchafer. Naturally, there are always cockchafers, but if there are only a few grubs some year, four years after that there will only be a few cockchafers. The number of cockchafers depends upon the number of grubs that were present four years earlier.

We can see quite clearly that this period of time is connected with the rotation of Mars. The course of propagation of certain insects shows us the kind of influence that Mars exercises upon the life of the earth. But the influence is rather hidden. The influence of the sun is quite obvious, that of the moon not obvious to the same extent, and the influence of Mars is hidden. Everything for which intervals of years are needed on the earth—as in the case of grubs and cockchafers—is dependent upon Mars. So there you see a significant effect of Mars.

Of course someone may say that he doesn't believe this. Well, gentlemen, we ourselves can't possibly make all the experiments, but anyone who doesn't believe what I've said should do the following: he should take the grubs he has collected in a year when they are very numerous and force their development artificially in some container. Within the same year he will find that the majority of them do not develop into cockchafers. Such experiments are never made because these things are not believed.

However, we come now to the essential point. The sun has the most powerful influence of all. But it exerts its greatest influence upon everything on the earth that is dead, that must be called to new life every year—while the moon influences only what is living. Mars exerts its influence only upon what exists in a more delicate form of life, in the sentient realm. The other planets have their influence upon what is of the nature of soul and spirit. The sun, then, is the heavenly body that works the most strongly; it works into the very minerals of the earth. In the minerals the moon can do nothing—nor Mars. If the moon were not there, no animal creature could live and move about on the earth; there could only be plants on the earth, no animals. Again, there are many animal creatures that could not have intervals of years between the larva-stage and the insect if Mars were not there. You see how closely all things are connected.

For instance, we might ask ourselves: When do we human beings become fully grown? When do we stop in the process of our development? Obviously very early, at the age of about twenty or twenty-one. And yet even then something continues to be added. Most people do not actually grow any more, but something is added inwardly. Until about our thirtieth year we do really “increase”; but then, for the first time, we begin to “decrease”. If we compare this with happenings in the universe, we get the time of the rotation of Saturn.

So the planets exercise their influence upon the more delicate conditions of growth and of life. Hence we can say: When, like all the planets, Mars comes near the earth, we must not attach primary importance to this outer nearness.

What is of far greater importance is how things in the universe are connected with the finer, more delicate states and conditions of life.

You must remember that the constitution of Mars is quite different from that of the earth. As I said, Mars is not densely solid in the sense in which today the earth is solid, But I described to you quite recently how the earth too was once in a condition when mineral, solid matter took shape for the first time, how there were then gigantic animals which, however, had as yet no solid bones. Mars today is in a condition similar to that of the earth in that earlier epoch and therefore also has upon it those living beings, those animal beings which the earth had upon it at that time. And “human beings” on Mars are as they were on the earth at that time—still without bones. I described this to you when I was speaking of an earlier period of the earth. These things can be known. They cannot become known by the means employed in modern science for acquiring knowledge; nevertheless it is possible to know these things. If, then, you want to have an idea of what Mars is like today, picture to yourselves what the earth was like in a much earlier age: then you will have a picture of Mars.

You know that on the earth today, the trade winds blow from the south to the north, from the north to the south. These streamings were once much denser than the air; they were currents of fluid, watery air: so it is on Mars today. The air currents on Mars are much more full of life, much more watery.

Jupiter consists almost entirely of air, but again somewhat denser than the air of the earth. Jupiter today represents a condition toward which the earth is now striving, which it will attain only in the future.

And so in the planetary system we find certain states or conditions through which the earth also passes. When we understand the planets in this sense, we understand them rightly.

Has anyone something else to ask about this subject? Perhaps Herr Burle himself?

Herr Burle: I am quite satisfied, thank you!

Question: In one of your last lectures you said that the scents of flowers are related to the planets. Does this also apply to the colors of flowers and colors of stones?

Dr. Steiner: I will repeat very briefly what I said. It was also in answer to a question that had been asked. I said that flowers, and also other substances of the earth, have scent—something in them that exercises a corresponding influence upon man's organ of smell. I said that this is connected with the planets, that the plants and, similarly, certain substances, are “big noses,” noses that perceive the effects coming from the planets. The planets have an influence upon life in its finer, more delicate forms-here, once again, we must think of the finer forms of life. And it can be said that the plants really do come into being out of the scent of the universe, but this scent is so rarefied, so delicate, that we human beings with our coarse noses do not smell it.

But I reminded you that there can be a sense of smell quite different from that possessed by man. You need think only of police dogs. A thief has stolen something and the police dog is taken to the spot where the theft has been committed; it is conveyed to him in some way that a thief has been there and he picks up the scent; then he leads the police on the trail and the thief is often found. Police dogs are used in this way. All kinds of interesting things would come to light if one were to study how scents that are quite imperceptible to a human being are perceptible to a dog.

People have not always realized that dogs have such keen noses. If they had, dogs would have been used earlier to assist the police. It is only rather recently that this has been discovered. Likewise, people today still have no conception of what indescribably delicate noses are possessed by the plants. As a matter of fact, the entire plant is a nose; it takes in the scent of the universe, and if its structure is such that it gives back this cosmic aroma in the way that an echo gives back a sound, it becomes a fragrant plant. So we can say: The scents of flowers, of plants in general, and also other scents on the earth, do indeed relate to the planetary system.

It has been asked whether this also applies to the colors of plants and flowers. As I said, the plant takes shape out of the aroma of the universe and throughout the year it is exposed to the sun. While the form of the plant is shaped by the planets out of the cosmic fragrance, its color is due to the sun and also to some extent to the moon. The scent and the color of plants do not, therefore, come from the same source; the scent comes from the planets, the color from the sun and moon. Things don't always have to come from the same source; just as one has a father and a mother, so the plant has its scent from the planets and its colors from the sun and moon.

You can see from the following that the colors of plants are connected with the sun and moon. If you take plants that have beautiful green leaves and put them in the cellar, they become white, they lose every trace of color because the sun has not been shining on them. They retain their structure, their form, because the cosmic fragrance penetrates everywhere, but they don't keep their color because no sunlight is reaching them. The colors of the plants, therefore, undeniably come from the sun and, as I have said, also from the moon, only this is more difficult to determine. Experiments would have to be made and could be made, by exposing plants in various ways to moonlight; then one would certainly discover it.

Does anyone else want to say something?

Herr Burle: I would like to expand the question by asking about the colors of stones.

Dr. Steiner: With stones and minerals it is like this. If you picture to yourself that the sun has a definite influence upon the plants every day, and also during the course of a year, then you find that the yearly effects of the sun are different from its daily effects. The daily effects of the sun do not bring about much change in the color of the plants; but its yearly influence does affect their color.

However, the sun has not only daily and yearly effects; it has other, quite different effects as well. I spoke to you about this some time ago, but I will mention it again.

Imagine the earth here. The sun rises at a certain point in the heavens, let us say in the spring, on the twenty-first of March. If in the present epoch we look at the point in the heavens where the sun rises on the twenty-first of March, we find behind the sun the constellation of the Fishes (Pisces). The sun has been rising in this particular constellation for hundreds of years, but always at a different point. The point at which the sun rises on the twenty-first of March is different every year. A year ago the sun rose at a point a little farther back, and still farther back the year before that. Going back through a few centuries we find that the point at which the sun rose in spring was still in the same constellation, but if we go back as far as the year 1200 AD. we find that the sun rose in the constellation of the Ram (Aries). Again for a long time it rose in spring in the constellation of the Ram. Still earlier, however, let us say in the epoch of ancient Egypt, the sun rose in the constellation of the Bull (Taurus); and earlier than that in the constellation of the Twins (Gemini), and so on. So we can say that the point at which the sun rises in spring is changing all the time.

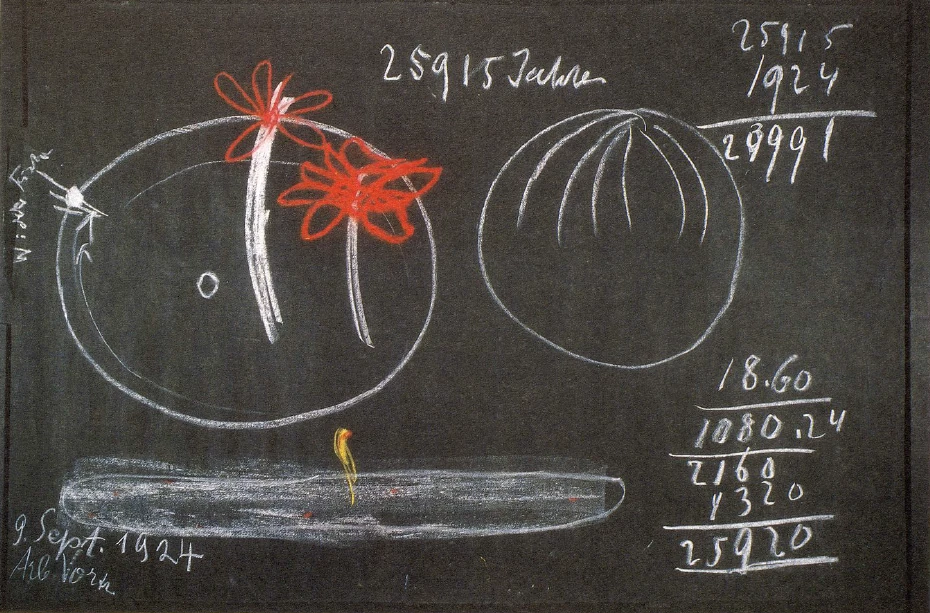

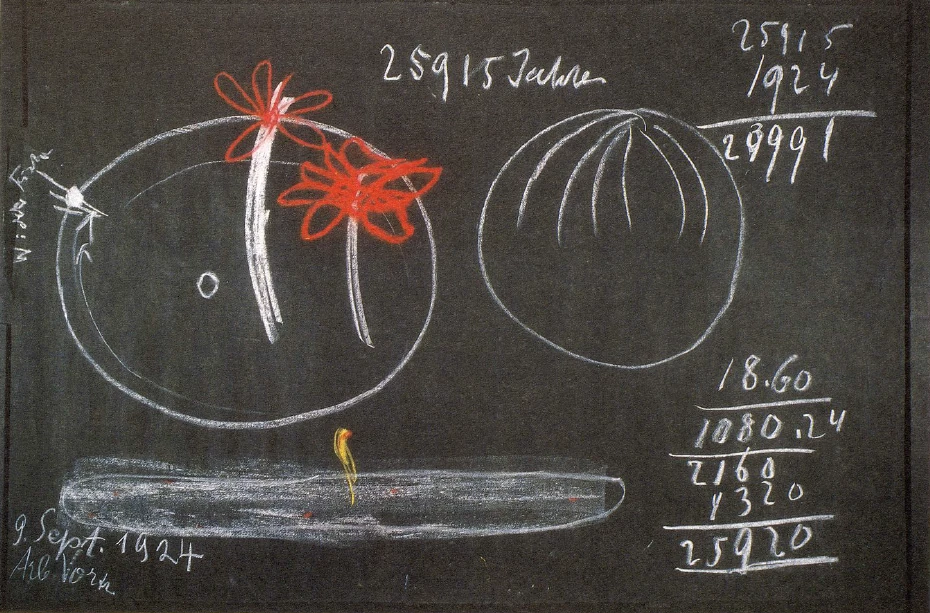

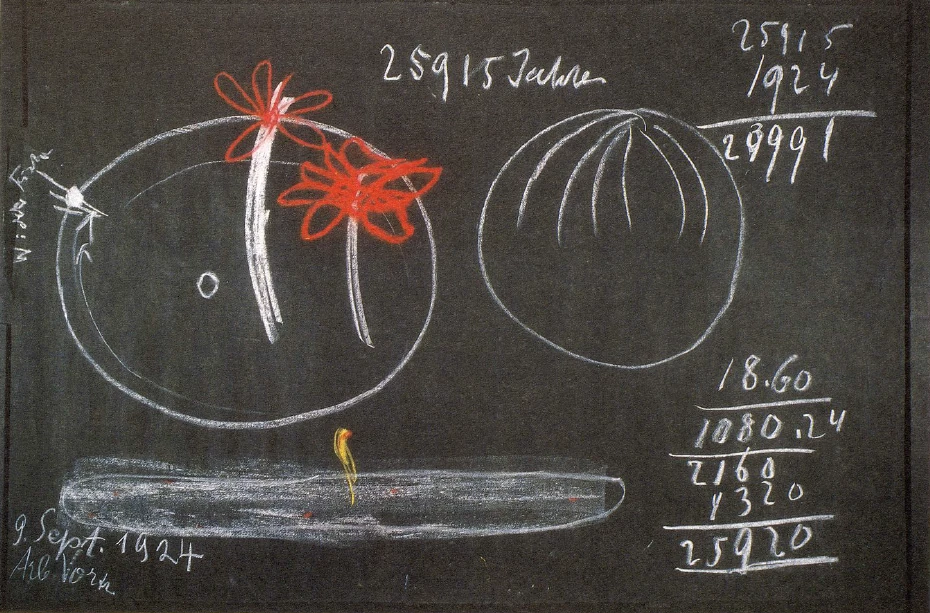

This indicates, as you can see, that the sun itself moves its position in the universe; I say it moves its position—but only apparently so, for in reality it is the earth that moves its position. That, however, does not concern us at the moment. In a period of 25,915 years, the point at which the sun rises in spring moves the whole way around the zodiac. In the present year—1924—the sun rises at a certain point in the heavens. 25,915 years ago, that is to say, 23,991 years before the birth of Christ (25,915 minus 1924) the sun rose at the same point! Since then it has made one complete circuit. The sun has a daily circuit, a yearly circuit, and a circuit that takes it 25,915 years to complete. Thus we have a sun-day, a sun-year and a great cosmic year consisting of 25,915 years.

That is very interesting, is it not? And the number 25,915 is itself very interesting! If you think of the breath and remember that a man draws approximately 18 breaths a minute, you can reckon how many breaths he draws in a day. Eighteen breaths a minute, 60 x 18 in an hour = 1,080 breaths. How many breaths, then, does he draw in a day, that is to say, in 24 hours? Twenty-four times 1,080 = 25,920, which is approximately the same as this number 25,915! In a day, man breathes as many times as the sun needs years to make its circuit of the universe. These correspondences are very remarkable.

Now why am I telling you all this? You see, to give color to a plant, the sun needs a year; to give color to a stone, the sun needs 25,915 years. The stone is a much harder fellow. To bestow color on a plant the sun makes a circuit lasting one year. But there is also a circuit which the sun needs 25,915 years to complete. And not until this great circuit has been completed is the sun able to give color to the stones. But at any rate it is always the sun that gives the color. You will realize from this how widely removed the mineral kingdom is from the plant kingdom. If the sun did not move around yearly in the way it does, if it only made daily circuits as well as the great circuit of 25,915 years, then there would be no plants, and instead of cabbage you would be obliged to eat silica—and the human stomach would have to adjust itself accordingly!

Question: Do the herbs that grow on mountains have greater healing properties than those that grow in valleys? If so, what is the explanation?

Dr. Steiner: It is an actual fact that mountain-plants are more valuable as remedies than those that grow in valleys, particularly than those we plant in our ordinary gardens or in a field. It is a good thing that this is the case, for if the plants growing in the valleys were just like those on the mountains, every foodstuff would at the same time be a medicine, and that would not do at all! The plants that have the greatest therapeutic value are indeed those that grow on the mountains. Why is this? All you need to do is to compare the kind of soil in which mountain-plants grow with that in which valley-plants grow.

It is a very different thing if plants grow wild, in uncultivated soil, or are artificially cultivated in a garden. Think of strawberries! Wild strawberries from the woods are tiny but very aromatic; garden strawberries have less scent, are less sharp in taste, but they can grow to an enormous size—why, there are cultivated strawberries as large as eggs! How is this to be accounted for? It is because the soil in the low-lying ground of valleys is not so full of stones that have crumbled away from the rock of the mountains. It is on mountains that really hard stone is to be found—the real mineral. Down in the valleys you find soil that has already been saturated and carried down by the rivers and is therefore completely pulverized. On the mountains there is also, of course, pulverized soil, but it is invariably permeated with tiny granules, especially, shall we say, of quartz, feldspar, and so on. Everywhere there are substances which can be used for healing. Very, very much can be achieved if, for example, we grind down quartz (silica) and make a remedy of it. We are then using these minerals directly as remedies.

The soil in low-lying valleys no longer contains these little stones. But on the mountains the stones are all the time crumbling from the rocks, and the plants draw into their sap the tiny particles of these stones, and that makes them into remedial plants.

Now the following is interesting. The so-called homeopaths—they're not right about everything, but they're right about a good many things—these homeopaths take substances and by grinding them finer and finer, obtain medical remedies. If the substance were used in its crude state it would not be a remedy. But you see, the plants themselves are the most precious homeopaths of all, for they absorb tiny, minute particles from all these stones, which otherwise would have to be refined and pulverized when a medicine is being prepared. So because nature does this far better than we could, we can take the plants themselves and use them directly for healing purposes. And it is a fact that the plants and herbs growing on mountains have far greater healing properties than those in the valleys.

You know, too, how the whole appearance of a plant changes. I spoke about the strawberry: the wild strawberry absorbs a large quantity of a certain mineral. Where does the wild strawberry thrive best? Where there are minerals that contain a little iron. This iron penetrates the soil and from that the strawberry gets its fragrant smell. Certain people whose blood is very sensitive get a rash when they eat strawberries. This is due to the fact that their blood in its ordinary state has sufficient iron and it is getting too much when they eat strawberries. If, then, some people with normal blood get a rash from eating strawberries, one can certainly advise someone whose blood is poor, to eat them! In this way their remedial value is gradually discovered. As a rule, the soil in gardens where the giant strawberries are growing contains no iron; there the strawberries propagate themselves without any impetus from iron. But people are rather short-sighted in this connection and don't follow things up for a sufficiently long time. It is a fact that by growing strawberries in soil that doesn't contain much iron, one can get huge berries, for the reason that the plants do not become fully solid. For think of it—if the strawberry has to get hold of every tiny bit of iron there may be in the soil, then it must have plenty of leeway! But that is a characteristic of the strawberry.

Suppose you look at soil. It contains very minute traces of iron. The strawberry growing in the soil draws these traces of iron to itself from a long way off, for its root has a strong force and attracts the iron from some distance away. Now take a wild strawberry from the woods. It contains a very strong force. Put this strawberry into a garden: there is no iron in the soil, but the strawberry has acquired this tremendous force already, it has it within itself. It draws to itself everything it possibly can, in the garden cultivation too, from a long way away, and nourishes itself exceedingly well. In a garden it does not get iron, but it draws everything else to itself because it is well able to do so. And so it becomes very large.

However, as I have said, people are very short-sighted; they do not observe things thoroughly. So they do not notice that although with garden cultivation they can produce huge strawberries for a number of years, this will only last for a certain time. The fertility then dies away, and they must bring in new strawberry plants from the woods. Fertility cannot be promoted entirely by artificial means; there must be knowledge of things that are directly connected with Nature herself

The rose is the best illustration of this. If you go out into the countryside you will see the wild rose, the dog rose, as it is called, Rosa canina. You know it, I'm sure. This wild rose has five rather pale petals. Why is it that it has this form, produces only five petals, remains so small and at once produces this tiny fruit? These reddish rose hips—you know them—develop from the wild rose. Well, this is due to the fact that the soil where the rose grows wild contains a certain kind of oil—just as the soil of the earth in general contains different oils in its minerals. We get oils out of the earth or out of the plants which have themselves absorbed them from the earth. Now the rose, when it is growing wild out there in the country, must work far and wide with its roots in order to collect from the minerals the tiny amount of oil it needs in order to become a rose. Why is it that the rose must stretch out so far, must extend the drawing power contained in its root to such a distance? The reason is that there is very little humus in the country soil where the rose grows wild. Humus is more oily than the soil of the countryside. Now the rose has a tremendous power for drawing oil to itself.

When the rose is near soil which contains humus, this is fortunate for it; it draws a great deal of oil to itself and develops not only five petals but a whole mass of petals, becoming the luxuriantly-petalled garden rose. But it no longer develops real rosehips because that would need what is contained in the stony soil out in the country. So we can make the wild rose into the ornamental garden rose when we transplant it into soil that is richer in humus, where it can easily get the oils from which to produce its many petals. This is the opposite of what happens with the strawberry: it is difficult for the strawberry to find in the garden what it finds out in the woods. The rose finds a great deal in the garden that is scarce along the roads and so it develops luxuriant petals; but then in fruit formation it remains behind.

So when we know what a particular soil contains, we know what will grow on it. Naturally, this is tremendously important for plant cultivation, especially for the plants needed in agriculture. For there, through manure and the substances added as fertilizers, the soil must be restored so that it will produce what is required. Knowledge of the soil is of enormous importance to the farmer. These things have been more or less forgotten. Simple country farmers used to apply the proper manure by instinct. But nowadays in large-scale agriculture not much attention is paid to the matter. The consequence is that in the course of the last decades nearly all our foodstuffs have greatly deteriorated in quality from what they were when those of us who are now elderly were children.

Earlier this year there was an interesting agricultural conference at which farmers expressed their deep concern for what will become of the plants, of the foodstuffs, if this tendency continues. And indeed, gentlemen, it will continue! In the coming century foodstuffs will become quite unusable if a certain knowledge of the soil is not regained.

We have made a beginning with agriculture in the domain of anthroposophical spiritual science. Recently I gave a course of lectures on agriculture near Breslau,19At Koberwitz, June 7–16, 1924. See Rudolf Steiner, Agriculture. and an association has been formed that will take up this work. And we too have done something here to help the situation. We are only at the very beginning but the problem is being tackled. Thus anthroposophy will gradually penetrate into practical life.

There are still some sessions to make up, so let us meet again next Friday.20This lecture was postponed to Saturday, Sept. 13

Zehnter Vortrag

Guten Morgen, meine Herren! Vielleicht ist eine Möglichkeit, daß Sie noch weitere Fragen haben?

Schriftliche Frage von Herrn Burle: Mars steht in Erdnähe. Welchen Einfluß hat das auf die Erde? Was weiß man überhaupt vom Mars?

Dr. Steiner: Nun, sehen Sie, in der letzten Zeit war ja immer wieder und wieder die Rede, daß der Mars in Erdnähe stehe, und die Zeitungen haben in der allerunnützesten Weise, in dertörichtesten Weise eigentlich von dieser Erdnähe des Mars gesprochen. Denn wir müssen durchaus auf diese äußeren Verhältnisse in der Planetenkonstellation, die mit entsprechenden Stellungen von der Erde und so weiter zusammenhängen, nicht den allergrößten Wert legen, weil diese Einflüsse, die von daher kommen, eigentlich keine besonders großen sind. Es ist überhaupt merkwürdig, daß in der letzten Zeit so viel von der Annäherung des Mars an die Erde die Rede war, weil ja jeder Planet, zum Beispiel auch der Mond, sich fortwährend der Erde nähert, und die Planeten sind schon in einem Zustande, der damit endigen wird, daß sie sich alle wiederum mit der Erde vereinigen werden, ein Körper mit ihr werden.

Allerdings, wenn man sich das so vorstellt, wie sich zumeist heute die Menschen die Planeten vorstellen, daß sie ebensolche feste Körper wie die Erde seien, dann könnte man schon erwarten, wenn sie mit der Erde zusammenkommen werden, daß sie alle lebenden Wesen auf der Erde überall anschlagen! Aber das wird nicht der Fall sein, denn die Planeten haben nicht dieselbe Festigkeit wie die Erde selber. Wenn der Mars zum Beispiel wirklich herunterkommen würde und sich mit der Erde vereinigen würde, dann würde er selber nicht das feste Land verheeren können, sondern er würde nur die Erde überschwemmen können. Denn der Mars besteht, soweit man dieses untersuchen kann — man kann ja diese Dinge eigentlich niemals mit bloß physischen Instrumenten untersuchen, sondern man muß da schon die Geisteswissenschaft, das geistige Schauen zu Hilfe nehmen -, wenn man sich also einläßt darauf, den Mars wirklich kennenzulernen, so besteht er vor allem aus einer mehr oder weniger flüssigen Masse, nicht so flüssig wie unser Wasser, aber, sagen wir, wie Gelee und solche Dinge. Also in dieser Weise ist er flüssig. Er hat allerdings auch feste Bestandteile, aber diese sind auch nicht so wie die auf unserer Erde, sondern sie sind so, wie etwa die Geweihe oder Hörner bei Tieren sind. Sie bilden sich heraus aus unserer Erdenmasse, und bilden sich auch wiederum zurück. So daß wir natürlich beim Mars eine ganz andere Beschaffenheit annehmen müssen, als diejenige unserer Erde ist.

Sehen Sie, man spricht fortwährend von Marskanälen, von Kanälen, die auf dem Mars sein sollen. Aber warum spricht man von Kanälen? Man sieht ja nichts anderes auf dem Mars als solche Linien (es wird gezeichnet); die spricht man als Kanäle an. Das ist richtig — und auch nicht richtig. Denn weil der Mars nicht in dem Sinne fest ist wie die Erde, kann man da natürlich nicht von solchen Kanälen sprechen, wie sie auf der Erde sind; aber man kann davon sprechen, daß so etwas Ähnliches auf dem Mars ist, wie unsere Passatwinde sind. Sie wissen ja, daß von der heißen Gegend der Erde, von Afrika, von der mittleren Erde, fortwährend die warme Luft nach dem kalten Nordpol geht, und vom kalten Nordpol die Luft wiederum zurückströmt nach dem mittleren Gebiet der Erde. So daß man, wenn man von außen die Sache ansehen würde, man auch solche Linien sehen würde; aber das sind Linien der Passatwinde, der Luftströmungen der Passatwinde. So ähnlich ist es auch beim Mars. Nur, beim Mars lebt alles viel mehr als auf der Erde. Die Erde ist in viel stärkerem Sinne ein erstorbener Planet als der Mars, auf dem mehr oder weniger noch die Dinge leben. Und da will ich Sie auf einiges aufmerksam machen, was Sie dazu bringen kann, einzusehen, wie es eigentlich mit dem Verhältnis von Mars zur Erde ist.

Wenn wir ausgehen von dem, was unser allerwichtigster Himmelskörper ist, von der Sonne, so wissen wir ja: die Sonne, die unterhält auf der Erde sehr vieles. Nehmen Sie nur einmal die gewöhnliche Tagessonne an. Sie können in der Nacht die Pflanzen ansehen: die ziehen ihre Blüten ein, weil sie nicht von der Sonne beschienen werden. Bei Tag öffnen sie sich wiederum, weil sie von der Sonne beschienen werden. Und so gibt es sehr, sehr vieles, was durchaus zusammenhängt mit der Verbreitung von Sonnenlicht über einen bestimmten Teil der Erde oder mit der Verbreitung von Finsternis über einen bestimmten Teil, also vom Nichtvorhandensein der Sonne. Aber während eines Jahres ist das ja deutlich. Sie können sich nicht denken, daß auf unserer Erde irgendwie im Frühling überhaupt Pflanzen wachsen würden, wenn nicht die Sonne in einer gewissen Weise ihre Macht bekäme. Und weil die Sonne im Herbst wiederum an Macht verliert, welken die Pflanzen ab, alles Leben erstirbt, der Schnee fällt auf die Erde. Also das Leben auf der Erde hängt mit der Sonne zusammen. Überhaupt, wir könnten gar nicht in der Luft, die da ist, atmen, wenn sie nicht da wäre, wenn nicht die Sonnenstrahlen uns die Luft geeignet machen würden. Also die Sonne ist schon unser wichtigster Himmelskörper. Aber denken Sie einmal, wie anders die Geschichte wäre, wenn die Sonne nicht in vierundzwanzig Stunden sozusagen scheinbar um die Erde herumginge, sondern in der doppelten Zeit! Dann würde alles Leben langsamer sein. Es hängt also von der Umdrehung der Sonne um die Erde - eigentlich ist es umgekehrt, aber es scheint doch so -— alles Leben auf der Erde ab.

Und wiederum, weniger bedeutend schon ist dem Menschen der Einfluß des Mondes, aber der ist ja trotzdem da. Und wenn Sie bedenken, daß sich nach dem Monde richten Ebbe und Flut, daß die dieselben Zeiten haben wie der Mondumlauf, so werden Sie sehen, mit welcher Kraft der Mond auf die Erde wirkt. Und dann können Sie ja auch sehen, wie die Umlaufszeit des Mondes um die Erde eine gewisse Bedeutung hat, wenn man untersuchen würde, wie auf der Erde die Pflanzen, wenn sie schon von der Sonne beschienen sind, sich entwikkeln. So würde man schon den Einfluß des Mondes finden. Also der Mond und die Sonne haben den allergrößten Einfluß auf die Erde. Und wir können diesen Einfluß erkennen aus der Umlaufszeit, aus der Zeit, in der der Mond wiederum voll wird, Neumond wird und so weiter. Wir können es bei der Sonne erkennen, je nachdem sie auf- und untergeht, oder im Frühling ihre Kraft bekommt, im Herbst ihre Kraft verliert.

Nun will ich Ihnen etwas sagen. Sie alle kennen die Erscheinung, daß es in der Erde die sogenannten Engerlinge gibt. Das sind kleine wurmartige Tiere, die uns namentlich schädlich sind, weil sie uns die Kartoffeln zerfressen. Aber sehen Sie, diese Engerlinge, die drohen unseren Kartoffeln nicht immer, sondern es gibt Jahre, wo unsere Kartoffeln ungeschoren bleiben von diesem Ungeziefer, und es gibt Jahre, in denen man sich gar nicht retten kann, wo furchtbar immer die Engerlinge da sind. Was sind denn eigentlich diese Engerlinge?

Sehen Sie, man kann das ja nachrechnen. Wenn ein Jahr dagewesen ist, wo diese Engerlinge uns die Kartoffeln zerfressen haben, und man wartet jetzt, bis das vierte Jahr darauf kommt - im ersten Jahr entstand nichts, im zweiten Jahr entstand nichts, im dritten Jahr entstand nichts; sehen Sie, meine Herren, in diesem vierten Jahr ist wiederum die Maikäferplage da. Da gibt es dann entsprechend viele Maikäfer, weil erst nach vier Jahren die Maikäfer herauskommen aus den Engerlingen, die vor vier Jahren da waren. So daß ungefähr die vierjährige Periode liegt zwischen dem Erscheinen der Engerlinge, die einfach, wie jedes Insekt, zuerst die Madenform, dann die Puppenform haben und so weiter, nach und nach entwickeln sie dann die Form des vollkommenen Insektes, so daß also die Engerlinge vier Jahre brauchen zu ihrer Entwickelung bis zum Maikäfer. Natürlich sind immer Maikäfer da; wenn im nächsten Jahr wenig Engerlinge da sind, sind im vierten Jahr auch wenig Maikäfer da. Es hängt eben so zusammen, daß die Masse der Maikäfer zusammenhängt mit den Engerlingen, die vor vier Jahren da waren.

Nun, wenn man diese Zeit nimmt, so sieht man ganz genau, daß das zusammenhängt mit der Umlaufzeit des Mars. Da sehen Sie also innerhalb der Fortpflanzung von gewissen Insekten, wie der Mars einen Einfluß auf das Leben der Erde hat. Das ist nur etwas versteckt. Bei der Sonne ist der Einfluß offenbar, beim Mond schon nicht mehr ganz offenbar, beim Mars versteckt. Alles dasjenige, was Zwischenzeiten braucht, zwischen den Jahren der Erde — also so wie die Engerlinge und Maikäfer, das hängt ab vom Mars. So daß man also da schon eine solche Wirkung sieht, die in der Tat bedeutsam ist.

Es könnte ja jemand sagen: Ich glaube dir das nicht. - Nun, meine Herren, wir können nicht alle Versuche allein machen, aber wer es nicht glaubt, der soll nur einmal das Folgende machen. Der soll irgendwo solche Engerlinge nehmen, die er in einem Jahr, wo es viele Engerlinge gibt, gewonnen hat, soll sie künstlich züchten irgendwo in einem Behälter, und in einem Jahr wird er sehen: die meisten Engerlinge kriechen nicht aus, werden keine Maikäfer. Natürlich macht man solche Dinge nicht, weil man an die Dinge nicht glaubt.

Nun kommt man auf dasjenige, um was es sich eigentlich handelt. Wenn man dabei auf die Sonne schaut, so hat sie den allerstärksten Einfluß. Aber die Sonne hat ihren hauptsächlichsten Einfluß auf alles dasjenige in der Erde, was tot ist und jedes Jahr ins Leben gerufen werden muß, während der Mond nur auf das Leben seinen Einfluß hat, nicht mehr auf das Tote. Der Mars hat zum Beispiel seinen Einfluß nur auf dasjenige, was im feineren Leben, in der Empfindung ist, und die anderen Planeten haben auf das Seelische und das Geistige und so weiter ihren Einfluß. So daß eigentlich die Sonne derjenige Himmelskörper ist, der am stärksten bis in die Mineralien hinein auf die Erde wirkt, denn in den Mineralien kann der Mond nichts machen, der Mars noch weniger. Kein Wesen würde auf der Erde kriechen und leben können als Tier, wenn nicht der Mond da wäre. Es könnten auf der Erde nur Pflanzen da sein, keine solchen Wesen. Viele solche Tiere könnten nicht eine Zwischenzeit an Jahren haben von der Larve bis zum Insekt, wenn nicht der Mars da wäre.

Und sehen Sie, eigentlich hängen alle Dinge so zusammen. Wir können uns zum Beispiel fragen: Wann sind wir denn ganz voll ausgewachsen, wenn wir uns als Menschen entwickeln? Wann hören wir denn auf, eine irgendwie zunehmende Entwickelung zu haben? Ja, sichtbarlich schon sehr früh, vielleicht schon mit zwanzig, einundzwanzig Jahren; doch setzt sich noch immer etwas an. Manche Menschen wachsen sogar nicht mehr, aber innerlich setzt sich immer noch etwas an. Bis gegen das dreißigste Jahr hin nehmen wir eigentlich zu, dann fangen wir erst an abzunehmen. Wenn wir wiederum mit dem Weltenall vergleichen, kriegen wir da die Umlaufszeit des Saturn heraus.

Also auf die feineren Verhältnisse des Wachstums und Lebens haben wiederum die Planeten ihren Einfluß. So daß wir sagen können: Wenn sich, wie alle Planeten, der Mars der Erde nähert, so müssen wir auf diese äußere Annäherung nicht den allergrößten Wert legen, sondern es ist viel wichtiger, wie mit den feineren Verhältnissen des Lebens die Dinge im Weltall zusammenhängen.

Nun müssen Sie ja bedenken, daß der Mars ganz anders beschaffen ist als die Erde. Ich sagte Ihnen: In dem Sinne, wie die Erde heute Festes hat, hat der Mars nichts Festes. Aber, meine Herren, ich habe Ihnen ja beschrieben vor einiger Zeit, daß die Erde auch einmal in einem solchen Zustand war, daß sich das Mineralische, das Feste erst herausgebildet hat, daß da riesige Tiere gelebt haben, die aber noch keine festen Knochen hatten. Wenn wir heute den Mars nehmen, so ist der Mars in einem ähnlichen Zustand, wie die Erde früher war, hat also auch diejenigen Lebewesen, diejenigen Tiere, die die Erde dazumal hatte, und die Menschen sind auf dem Mars so, wie sie auf der Erde dazumal waren: noch ohne Knochen, wie ich es Ihnen beschrieben habe an einem früheren Erdenzustande. -— Das kann man wissen. Nur kann man es nicht wissen auf diejenige Weise, wie es die heutige Naturwissenschaft gewöhnt ist; aber man kann diese Dinge wissen. So daß man sagen kann: Willst du dir vorstellen, wie der Mars heute ist, so stelle dir vor, wie die Erde in einem früheren Zeitalter war; dann hast du das Aussehen des Mars.

Sehen Sie, heute haben wir Passatstrrömungen von Süden nach Norden, von Norden nach Süden. Einstmals waren diese Luftströmungen viel dicker; es waren flüssige, wäßrige Luftströmungen. So ist heute der Mars. Das sind solche noch lebendigere, noch viel wäßrigere, nicht luftförmige Strömungen auf dem Mars.

Der Jupiter zum Beispiel ist ja fast ganz luftförmig, nur wiederum etwas dichter als die Luft der Erde. Der Jupiter stellt, wenn wir ihn heute anschauen, einen Zustand dar, welchem die Erde erst zustrebt, wie die Erde erst in der Zukunft sein wird.

Und so sehen wir überall im Planetensystem gewisse Zustände, die die Erde auch durchmacht. Wenn wir die Planeten so verstehen, dann verstehen wir sie richtig.

Hat vielleicht jemand jetzt in bezug auf diese Frage noch etwas zu fragen, oder möchte noch etwas wissen? Vielleicht Herr Burle selber?

Herr Burle: Ich bin ziemlich befriedigt darüber.

Weitere Frage des Herrn Burle: Herr Doktor führte in einem der letzten Vorträge an, daß die Blumen in ihren Düften mit den Planeten zusammenhängen. Ist es mit den Farben der Blumen und mit dem farbigen Gestein auch so?

Dr. Steiner: Nun, ich will nur ganz kurz wiederholen, was ich gesagt habe. Es war auch auf eine Frage. Ich sagte: Die Blumen, und auch andere Stoffe der Erde duften, haben also dasjenige, was auf das Geruchsorgan des Menschen einen entsprechenden Einfluß ausübt. Ich habe Ihnen damals gezeigt, daß das zusammenhängt mit den Planeten, daß gewissermaßen die Pflanzen, und so ähnlich auch gewisse andere Stoffe, große Nasen sind, oder überhaupt Nasen sind, daß sie also wahrnehmen dasjenige, was als Wirkungen aus den Planeten kommt. Sehen Sie, auf das feinere Leben — da kommen wir wieder darauf, daß wir auf das feinere Leben übergehen müssen - haben die Planeten einen Einfluß; und wir können schon sagen: Die Pflanzen entstehen eigentlich aus dem Weltenduft heraus, der nur so dünn und fein ist, daß wir ihn mit unseren groben Nasen nicht riechen. Aber ich habe Sie dazumal aufmerksam gemacht darauf, wie man noch ganz anders riechen kann - ich meine nicht von sich aus, sondern etwas beriechen kann anders als der Mensch. Da brauchen Sie sich ja nur an die Polizeihunde zu erinnern. Die Polizeihunde, die macht man in entsprechender Weise darauf aufmerksam, daß da irgendwie ein Mensch war, der etwas gestohlen hat; dann nimmt der Polizeihund den Duft auf, und er führt einen auf die Spur, und man kommt schon manchmal, wenn er die Spur verfolgt, wohin der Dieb gegangen ist, an den Dieb heran. In dieser Weise werden ja die Polizeihunde verwendet. Zu allerlei ganz interessanten Dingen kommt man, wenn man verfolgt, wie diejenigen Düfte, die dem Menschen gar nicht wahrnehmbar sind, vom Hunde wahrgenommen werden.

Ja, aber, meine Herren, die Menschen haben nicht immer geahnt, daß die Hunde solche feine Nasen haben, sonst hätten sie schon längst die Hunde in Polizeidienste genommen. Man ist erst verhältnismäßig spät darauf gekommen. Und so ahnen die Menschen heute noch nicht, was die Pflanzen für ungeheuer feine Nasen haben. Die ganze Pflanze ist eine Nase, nimmt den Duft auf, und wenn sie gerade so gestaltet ist, daß sie, wie ein Echo den Ton zurückgibt, so den Duft wiederum zurückgibt, den sie aufnimmt, so wird sie eben eine riechende Pflanze. So daß wir sagen können: Vom Planetensystem hängen die Düfte der Blumen, der Pflanzen überhaupt, und auch andere Düfte auf der Erde schon ab.

Nun ist die Frage gestellt worden, wie das bei den Farben ist. Bei den Farben ist es so: Wenn die Pflanze sich gestaltet aus dem Weltenduft heraus, so ist sie ja wiederum gerade, wie ich es beschrieben habe, das Jahr hindurch der Sonne ausgesetzt. Und während die Gestalt der Pflanze aus dem Weltenduft heraus von den Planeten gebildet wird, wird die Farbe der Pflanze von der Sonne, auch etwas unter dem Einfluß des Mondes, gebildet. Also nicht von derselben Quelle her kommt der Duft und die Farbe. Der Duft kommt von den Planeten, die Farbe kommt von Sonne und Mond. Nicht wahr, es muß ja nicht alles von demselben kommen; geradeso wie der Mensch einen Vater und eine Mutter hat, so hat die Pflanze ihre Düfte von den Planeten, ihre Farben von Sonne und Mond.

Daß die Farben zusammenhängen mit Sonne und Mond, das können Sie aus folgendem entnehmen. Nehmen Sie Pflanzen, die ganz schöne grüne Blätter haben, setzen Sie sie in den Keller: sie werden nicht nur blaß, sondern sie schauen ganz weiß aus, werden ganz farblos, weil sie die Sonne nicht mehr beschien. Ihre Gestalt, ihre Form behalten sie, weil der Weltenduft überall hineingeht, aber die Farbe behalten sie nicht, weil die Sonne nicht hereinscheint. So also sehen Sie, daß die Farben durchaus kommen von der Sonne, und, wie gesagt — das ist etwas schwerer durchschaubar -, auch vom Monde. Da müßten erst wiederum Versuche gemacht werden, könnten auch Versuche gemacht werden; indem man die Pflanze dem Mondenlicht so und so aussetzt, würde man schon darauf kommen.

Vielleicht hat dazu jemand noch etwas zu sagen?

Herr Burle: Ich möchte die Frage erweitern: Wie ist es mit der Farbe der Gesteine?

Dr. Steiner: Bei den Gesteinen ist es nun so: Nicht wahr, wenn Sie sich vorstellen, daß jeden Tag die Sonne einen bestimmten Einfluß hat auf die Pflanzen, und auch während des Jahres einen Einfluß hat auf die Pflanzen, dann bekommen Sie eine Ansicht darüber, daß die jährlichen Sonnenwirkungen anders sind als die täglichen Sonnenwirkungen. Die täglichen Sonnenwirkungen können nicht viel ändern an den Farben der Pflanzen, aber die jährlichen Sonnenwirkungen, die machen den Eindruck auf die Farben der Pflanzen.

Aber es gibt ja nicht bloß tägliche oder jährliche Wirkungen der Sonne, sondern es gibt noch ganz andere Wirkungen der Sonne. Von denen habe ich vor längerer Zeit auch schon zu Ihnen gesprochen, will es Ihnen aber jetzt noch einmal zeigen.

Denken Sie sich einfach — scheinbar — die Erde hier (es wird gezeichnet). Die Sonne geht an einem bestimmten Punkte auf am Himmel, und nehmen wir an, wir prüfen den Aufgang der Sonne am 21. März, im Frühling, dann bekommen wir einen bestimmten Punkt am Himmel, wo die Sonne aufgeht. Sehen Sie, wenn wir heute hinschauen, wo die Sonne am 21. März aufgeht, da finden wir hinter dem Aufgang der Sonne das Sternbild der Fische. Das ist ein bestimmtes Sternbild. In diesem Sternbild der Fische geht die Sonne schon seit mehreren hundert Jahren auf, aber nicht immer an derselben Stelle, sondern dieser Punkt im Frühling, wo die Sonne am 21. März aufgeht, der rückt im Sternbild der Fische immer weiter und weiter. Sehen Sie, vor einem Jahr ist die Sonne ein Stückchen weiter zurück aufgegangen, noch weiter zurück wiederum vor einem Jahr. Also nicht immer geht die Sonne am selben Punkt auf. Da ist das Sternbild der Fische; so geht es durch die Jahrhunderte, ja noch länger: wir finden den Frühlingspunkt immer im Sternbild der Fische. Aber so war es nicht immer. Wenn wir zurückgehen würden ins Jahr 1200 jetzt haben wir 1924 —, wenn wir da zurückgehen würden, so würden wir finden: die Sonne ist gar nicht aufgegangen im Sternbild der Fische, sondern im Sternbild des Widders. Und wiederum lange Zeit hat man den Frühlingspunkt im Sternbild des Widders gefunden. Vorher noch, sagen wir zum Beispiel in der alten ägyptischen Zeit, da ist die Sonne nicht aufgegangen im Sternbild des Widders, sondern im Sternbild des Stieres, und noch früher im Sternbild der Zwillinge und so weiter. So daß wir sagen können: Die Sonne rückt immer vor mit ihrem Frühlingspunkt.

Ja, meine Herren, das weist ja darauf hin, daß sich die Sonne selber verschiebt im Weltenall! Die Sonne verschiebt sich - man müßte auch sagen: scheinbar, denn es ist die Erde, die sich verschiebt, aber darauf kommt es jetzt nicht an. Und wenn wir den Zeitraum nehmen von 25915 Jahren, so geht der Frühlingspunkt der Sonne ganz rund herum. So daß wir in diesem Jahr 1924 den Frühlingspunkt an einem bestimmten Punkt des Himmels sehen — wir haben heute 1924; vor 25915 Jahren schrieb man 23991 Jahre vor Christi Geburt: da ging die Sonne im selben Punkte auf! Einen ganzen Umkreis hat sie gemacht in der Zeit. Sie sehen, das ist sehr merkwürdig: Die Sonne geht scheinbar herum in einem Tag, die Sonne geht herum in einem Jahr, und die Sonne geht herum in 25915 Jahren. Wir haben einen Sonnentag, ein Sonnenjahr, und wir haben ein Weltenjahr, das große Weltenjahr, das 25 915 Jahre dauert.

Das ist überhaupt sehr interessant. Sehen Sie sich einmal diese Zahl 25915 an - eine höchst interessante Zahl! Denn wenn Sie den menschlichen Atemzug nehmen und bedenken, daß der Mensch etwa 18 Atemzüge in der Minute hat — rechnen wir uns einmal aus, wie viele er im Tag hat: wenn er in der Minute 18 Atemzüge hat, so hat er in einer Stunde 60 mal 18 = 1080 Atemzüge. Wie viele hat er in 24 Stunden, also im ganzen Tag? Vierundzwanzigmal mehr, also 25 920 Atemzüge — was ungefähr dasselbe ist, wie diese Zahl 25915! Der Mensch atmet in einem Tage so oft, als die Sonne Jahre braucht, um im Weltenall einmal herumzulaufen. Es ist sehr merkwürdig, daß in der Welt alles übereinstimmt!

Warum sage ich Ihnen das alles, meine Herren? Ja, sehen Sie, um einer Pflanze Farbe zu geben, braucht die Sonne ein Jahr; um einem Stein Farbe zu geben, braucht die Sonne 25915 Jahre! Das ist eben ein viel härterer Kerl, der Stein. Um einer Pflanze eine Farbe zu verleihen, geht die Sonne einmal im Jahr herum. Sie geht in ihrem Aufgangspunkt herum, steht im Frühlingspunkt tief, geht hinauf, wieder hinunter: das ist ein richtiger Umlauf innerhalb eines Jahres. Aber in 25915 Jahren ist wieder ein Umlauf da. Durch diese letzte Bewegung kriegt es die Sonne erst fertig, dem Stein die Farbe zu geben. Aber es ist immer die Sonne, die die Farbe gibt. Daraus sehen Sie auch zugleich, wie weit das Mineralreich vom Pflanzenreich absteht. Wenn die Sonne nicht jedes Jahr in der Weise herumginge, wie es eben der Fall ist, sondern wenn die Sonne nur Tagesumläufe hätte und nur den großen Umlauf von 25915 Jahren, so gäbe es keine Pflanzen, und Sie müßten statt Kohl Kieselsteine essen! Es müßte nur erst der menschliche Magen dazu eingerichtet sein.

Frage: Haben die Berg- und Alpenkräuter größeren Heilwert als die Talkräuter? Wenn das bei den ersteren der Fall ist, woher kommt dann der größere Heilwert?

Dr. Steiner: Sehen Sie, es ist schon der Fall, daß die Berg- und Alpenkräuter den größeren Heilwert haben als die Talkräuter, namentlich als die Kräuter, die wir in unseren gewöhnlichen Gärten oder auf dem Feld angepflanzt haben. Es ist ja auch gut, daß es so ist, denn würden im Tal unten ebenso die Pflanzen wachsen wie auf den Bergen, so würde ja jedes Nahrungsmittel zugleich ein Heilmittel sein. Das geht ja doch nicht an. Nun aber ist es schon der Fall, daß der hauptsächlichste Heilwert der Pflanzen darauf beruht, daß die Pflanzen, die Heilkräuter sind, auf den Bergen wachsen. Warum? Ja, da müssen Sie einmal vergleichen den Boden, aus dem die Bergpflanzen wachsen, mit dem Boden, aus dem die Talkräuter wachsen.

Sehen Sie, die Sache ist ja schon von großem Unterschied in bezug auf Wald und künstliche Gartenzucht. Nehmen Sie nur die Erdbeere: Wenn Sie Walderdbeeren haben, sind sie klein, aber sie sind sehr aromatisch; wenn Sie Gartenerdbeeren haben, sind sie nicht so geruchvoll, so prickelnd, aber sie können riesig werden; es gibt ja gar eigroße Gartenerdbeeren. Nun, worauf beruht denn das? Das beruht darauf, daß, wenn wir im Tal unten den Boden nehmen, der Boden nicht mehr so durchsetzt ist von dem, was so vom Gestein abbröckelt. Am Berg oben finden Sie ja das eigentliche harte Gestein, das eigentliche Mineral. Unten im Tal finden Sie eigentlich dasjenige, was schon vielfach durchschweramt ist, was schon vielfach von den Flüssen abgetragen ist, was also ganz zerklüftet und zerstäubt ist. Am Berg oben ist natürlich auch dieses Zerklüftete und Zerstäubte als Boden, aber immer auch von ganz kleinen Bröselchen, Körnchen durchsetzt, namentlich, sagen wir, von Quarz, Feldspat und so weiter. Da ist überall gerade dasjenige darunter, was wir ja auch wiederum zur Heilung benutzen. Wirklich Großes, Bedeutendes erreichen wir, wenn wir zum Beispiel das, was der Quarz, der Kiesel enthält, zerreiben und Heilmittel daraus machen. Da wenden wir direkt diese Mineralien als Heilmittel an.

Wenn der Erdboden unten im Tal ist, ist nichts mehr drinnen von diesem Gestein; wenn er oben auf dem Berge ist, da bröckeln diese Gesteine doch immer ab, verwittern, bröckeln ab. Da nimmt die Pflanze in ihre Säfte die ganz kleinen Teile von diesen Steinen auf, und das macht sie zu Heilpflanzen.

Sehen Sie, es ist ja interessant: Die Kunst der sogenannten Homöopathen, die nicht in allem Recht haben, aber in vielem Recht haben, beruht ja darauf, daß man Stoffe nimmt, sie ganz fein zerkleinert und immer feiner und feiner zerreibt, so daß man dadurch das Heilmittel bekommt. Wenn man die groben Stoffe nimmt, so kriegt man ja gar nicht das Heilmittel. Aber die Pflanzen, meine Herren, sind ja die kostbarsten Homöopathen, denn die nehmen ganz kleine, winzige Teilchen auf von all diesen Gesteinen, die man sonst zerreibt, wenn man die Heilmittel macht! Wir können also direkt, weil das ja von der Natur viel besser gemacht wird, die Pflanzen nehmen und mit den Pflanzen heilen. Aber es ist deshalb durchaus richtig, daß auf den Bergen, auf den Alpen die Pflanzen, die Kräuter viel mehr Heilwert haben als unten im Tal. Sie sehen ja auch, daß sogar das ganze Aussehen bei Pflanzen sich ändert. Ich habe es Ihnen eben bei der Erdbeere gesagt: Wenn die Erdbeere viel aufnimmt von einem gewissen Gestein, so wird sie eine Walderdbeere. Die Walderdbeere, wo gedeiht sie denn besonders? Die Walderdbeere gedeiht ganz besonders da, wo Gesteine sind, die ein bißchen Eisen enthalten. Dieses Eisen geht in den Erdboden herein; das geht in die Erdbeere hinein und von dem hat die Erdbeere ihren aromatischen Geruch. Daher bekommen gewisse Leute, die in ihrem Blute sehr empfindlich sind, einen Ausschlag, wenn sie Erdbeeren essen. Der Ausschlag rührt davon her, daß das Blut im gewöhnlichen Zustand schon genug Eisen hat; es bekommt zu viel Eisen, wenn sie Erdbeeren essen: sie bekommen einen Ausschlag. Daher kann man auch wiederum sagen: Während beim gewöhnlichen Blut manche Leute Ausschlag bekommen, ist beim eisenarmen Blut das Erdbeerenessen sehr gut. Auf diese Weise kommt man natürlich allmählich auf den Heilwert hinaus. Nun, in den Gartenanlagen, wo die Riesenerdbeeren gedeihen, da ist in der Regel der Boden so, daß kein Eisen drinnen enthalten ist; da pflanzen sich die Erdbeeren in der Regel nur durch sich selber fort, nehmen nicht diesen Antrieb vom Eisen auf. Die Menschen sind nur in dieser Beziehung etwas kurzsichtig; sie verfolgen die Dinge nicht lang genug. Man kann ja wirklich dadurch, daß man in eisenarmem Boden Erdbeeren züchtet, Riesenerdbeeren haben, gerade weil die Pflanzen sich nicht zusammenziehen, nicht fest werden. Denken Sie, wenn die Erdbeere darauf angewiesen ist, das bißchen Eisen, das da ist, anzuziehen, dann muß sie ja, wie man sagt, einen Riesenradius entwickeln! Das ist aber eine Eigenschaft der Erdbeere.

Sehen Sie, da wäre der Erdboden (es wird gezeichnet), dann sind da ganz winzige Spuren von Eisen in der Erde. Da wächst die Erdbeere, die zieht von weither diese Eisenspuren heran; die Wurzel der Erdbeerpflanze, die hat eine große Kraft, zieht von weither die Spuren des Eisens heran. Nehmen Sie jetzt die Erdbeere vom Wald. Setzen Sie diese Erdbeere in den Garten, so ist da ja kein Eisen, aber diese Riesenkraft, die hat sich die Erdbeere angewöhnt, die hat sie einmal. Daher zieht sie alles, was sie nur anziehen kann, von weither auch in der Gartenkultur heran, nährt sich also außerordentlich gut. Eisen kriegt sie nicht, aber sie zieht alles andere an, weil sie gut dazu veranlagt ist. Daher wird sie riesengroß.

Aber ich sagte: Die Menschen sind kurzsichtig; sie beobachten die Dinge nicht so, wie man sie eigentlich beobachten sollte, und deshalb sehen die Menschen nicht, daß sie in der Gartenkultur zwar viele Jahre hindurch Riesenerdbeeren pflanzen können, daß das aber nur eine Zeitlang geht. Dann erstirbt die Fruchtbarkeit, dann muß man neuerdings wieder nachhelfen mit denjenigen Pflanzen, denjenigen Erdbeeren, die man sich vom Walde holt. Es läßt sich eben einfach in bezug auf Fruchtbarkeit und so weiter nicht alles künstlich machen, sondern man muß diejenigen Dinge kennen, die durchaus mit der Erde und mit der Natur zusammenhängen.

Sie können das am besten sehen bei der Rose. Wenn Sie hinausgehen und Sie sehen draußen in der freien Natur die Rose, so ist das die Wilde Rose, die sogenannte Hundsrose, Rosa canina — Sie kennen ja diese Wilde Rose -, die hat fünf Blätter, ziemlich blasse Blumenblätter (es wird gezeichnet). Worauf beruht das, daß diese Hundsrose eine solche Form hat, daß sie fünf Blätter aufbringt und dann gleich die Früchte entwickelt? Diese rötliche Frucht — Sie kennen sie -, die Hagebutte, sie entwickelt sich aus der Hundsrose. Nun, das beruht darauf, daß der Boden, wo die Hundsrose wild wächst, in sich ein gewisses Ol hat, wie überhaupt der Erdboden verschiedene Ölsorten in seinem Gestein und so weiter hat. Wir gewinnen ja auch die Ole aus der Erde oder aus den Pflanzen, die es schon von der Erde aufgenommen haben. Nun, meine Herren, die Rose muß, wenn sie draußen wild wächst, riesig weit herum mit ihrer Wurzel wirken, damit sie das bißchen Öl zusammenkriegt aus den Mineralien, um eben Rose werden zu können. Woher rührt denn das, daß die Rose so weit ausgreifen muß, so weithin die Kraft ihrer Wurzeln, die Anziehungskraft ihrer Wurzeln erstrecken muß? Sehen Sie, das rührt davon her, daß der Boden draußen, wo die Rose wild wächst, sehr wenig Humus hat. Aber der Humus ist öliger als der wilde Boden draußen.

Nun hat die Rose eine Riesenkraft, das Öl überall heranzuziehen. Wenn es nahe ist wie beim Humusboden, dann hat sie es gut, die Rose, dann zieht sie viel Öl an, und sie entwickelt sich so, daß sie jetzt nicht nur fünf Blätter entwickelt, sondern eine ganze Masse, eine gefüllte Rose wird unseres Gartens. Nur entwickelt sie wiederum nicht eine eigentliche Frucht, weil dazu das andere gehört, was draußen ist im Boden, im Gestein. Wir können also die Rose, die Hundsrose, zur Zierpflanze machen, wenn wir sie in einen humusreicheren Boden, wo sie sich leicht ihre Ole verschaffen kann, aus denen sie ihre Blüte macht, versetzen können. Dann, meine Herren, ist es das Umgekehrte: Die Erdbeere, die findet dasjenige, was sie draußen in der Wildnis hat, in der Gartenkultur schlecht. Die Rose findet das, was sie draußen in der Wildnis wenig hat, gerade in der Gartenkultur sehr stark. Daher wird sie üppig in der Blüte, aber sie bleibt immer zurück in der Fruchtbildung.

Sehen Sie, wenn man weiß, wie ein Erdboden beschaffen ist, kann man ihm ansehen, was auf diesem Erdboden wächst. Das ist natürlich wiederum von ungeheurer Wichtigkeit für die Zucht von Pflanzen, namentlich zum Beispiel für die Zucht landwirtschaftlicher Pflanzen, denn da muß man eben durch die Düngungen und durch die Zusätze, die man zum Dünger macht und so weiter, eben den Boden so herstellen, daß dasjenige wächst, was wachsen soll. Und die Kenntnis des Bodens, das ist das ungeheuer Wichtige zum Beispiel für den Landwirt. Das hat man ja vollständig vergessen, daß das so wichtig ist. Aus dem Instinkt heraus treiben die einfachen Landwirte die richtige Mistdüngung. Aber wo die Landwirtschaft heute im Großen getrieben wird, da wird darauf nicht mehr so viel Rücksicht genommen. Die Folge davon ist, daß fast alle unsere Nahrungsmittel im Laufe der letzten Jahre, Jahrzehnte, viel schlechter geworden sind, wie sie waren, als wir, die wir jetzt ältere Leute geworden sind, kleine Buben waren.

Es hat vor kurzer Zeit, in diesem Jahre, eine interessante landwirtschaftliche Versammlung gegeben, wo die Landwirte ganz besorgt waren: Was soll aus den Pflanzen, aus den Nahrungsmitteln werden, wenn das so weitergeht? — Ja, meine Herren, es wird auch so weitergehen! Die Nahrungsmittel werden nach einem Jahrhundert ganz unbrauchbar sein, wenn nicht wiederum eine gewisse Kenntnis des Bodens Platz greift.

Damit haben wir ja schon durch die anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft in der Landwirtschaft angefangen. Ich habe einen landwirtschaftlichen Kurs in der Nähe von Breslau gehalten. Danach hat sich eine Vereinigung gebildet, die die Sache in die Hand nimmt. Auch wir haben hier etwas gemacht, haben uns schon in manchem am Realisieren beteiligt. Wir haben erst angefangen damit, aber die Dinge werden in Angriff genommen. So wird schon Anthroposophie allmählich auch ins praktische Leben eingreifen.

Wir müssen noch etwas nachholen; wir haben dann die nächste Stunde am nächsten Freitag, meine Herren.

Tenth Lecture

Good morning, gentlemen! Perhaps you have any further questions?

Written question from Mr. Burle: Mars is close to Earth. What influence does this have on Earth? What do we actually know about Mars?

Dr. Steiner: Well, you see, recently there has been repeated talk of Mars being close to Earth, and the newspapers have reported on this in the most useless and foolish way. For we must not attach the greatest importance to these external conditions in the planetary constellation, which are connected with corresponding positions of the Earth and so on, because these influences, which come from there, are not actually particularly great. It is strange that there has been so much talk recently about Mars approaching Earth, because every planet, including the moon, is constantly approaching Earth, and the planets are already in a state that will end with them all reuniting with Earth, becoming one body with it.

However, if one imagines this in the way most people today imagine the planets, that they are solid bodies like the Earth, then one might expect that when they come together with the Earth, they will strike all living beings on Earth everywhere! But that will not be the case, because the planets do not have the same solidity as the Earth itself. If Mars, for example, were to really come down and unite with the Earth, it would not be able to devastate the solid land itself, but would only be able to flood the Earth. For Mars consists, as far as this can be investigated — one can never really investigate these things with purely physical instruments, but must resort to spiritual science, spiritual vision — if one really sets out to get to know Mars, it consists primarily of a more or less liquid mass, not as liquid as our water, but, let's say, like jelly and such things. So in this way it is liquid. It does have solid components, but these are not like those on our Earth; rather, they are like the antlers or horns of animals. They form out of our Earth's mass and then recede again. So, of course, we have to assume that Mars has a completely different composition than our Earth.

You see, people are always talking about Martian canals, canals that are supposed to be on Mars. But why do they talk about canals? One sees nothing else on Mars but such lines (it is drawn); these are referred to as canals. That is correct — and also not correct. Because Mars is not solid in the same sense as Earth, one cannot, of course, speak of such canals as they are on Earth; but one can say that there is something similar on Mars to our trade winds. You know that warm air constantly flows from the hot regions of the Earth, from Africa, from the middle of the Earth, to the cold North Pole, and from the cold North Pole the air flows back to the middle of the Earth. So if you were to look at it from the outside, you would also see such lines; but these are lines of trade winds, the air currents of the trade winds. It is similar with Mars. Only, on Mars, everything lives much more than on Earth. The Earth is in a much stronger sense a dead planet than Mars, on which things still live more or less. And here I would like to draw your attention to something that may help you understand the relationship between Mars and Earth.

If we start with what is our most important celestial body, the sun, we know that the sun sustains many things on Earth. Just take the ordinary daytime sun. You can look at the plants at night: they close their flowers because they are not illuminated by the sun. During the day, they open again because they are illuminated by the sun. And so there are many, many things that are closely related to the spread of sunlight over a certain part of the Earth or to the spread of darkness over a certain part, i.e., the absence of the sun. But this is obvious during the course of a year. You cannot imagine that plants would grow on our Earth in spring if the sun did not exert its power in a certain way. And because the sun loses its power again in autumn, the plants wither, all life dies, and snow falls on the earth. So life on earth is connected to the sun. In fact, we couldn't even breathe the air that is there if it weren't for the sun, if the sun's rays didn't make the air suitable for us. So the sun is indeed our most important celestial body. But just think how different history would be if the sun did not appear to revolve around the earth in twenty-four hours, but in twice that time! Then all life would be slower. So all life on earth depends on the sun's revolution around the earth—actually, it's the other way around, but it seems that way.

And again, the influence of the moon is less significant to humans, but it is still there. And when you consider that the tides are governed by the moon, that they have the same cycles as the moon's orbit, you will see the power with which the moon affects the Earth. And then you can also see how the moon's orbit around the Earth has a certain significance if you examine how plants on Earth develop when they are already exposed to the sun. In this way, you would already find the influence of the moon. So the moon and the sun have the greatest influence on the earth. And we can recognize this influence from the orbital period, from the time when the moon becomes full again, becomes a new moon, and so on. We can recognize it in the sun, depending on when it rises and sets, or when it gains its power in spring and loses its power in autumn.

Now I want to tell you something. You are all familiar with the phenomenon of so-called grubs in the earth. These are small worm-like animals that are particularly harmful to us because they eat our potatoes. But you see, these grubs do not always threaten our potatoes; there are years when our potatoes remain unscathed by these pests, and there are years when there is no escape, when the grubs are always there. What exactly are these grubs?

You see, you can calculate it. If there has been a year when these grubs have eaten our potatoes, and you now wait until the fourth year comes around—nothing happened in the first year, nothing happened in the second year, nothing happened in the third year; you see, gentlemen, in this fourth year, the cockchafer plague is back again. There are then a corresponding number of cockchafers, because it takes four years for the cockchafers to emerge from the grubs that were there four years ago. So there is a period of about four years between the appearance of the grubs, which, like every insect, first have the maggot form, then the pupa form, and so on, gradually developing into the form of the complete insect, so that the grubs need four years to develop into cockchafers. Of course, there are always May beetles; if there are few grubs next year, there will also be few May beetles in the fourth year. It is precisely because the mass of May beetles is related to the grubs that were there four years ago.

Now, if you take this time, you can see very clearly that it is related to the orbital period of Mars. So you can see how Mars influences life on Earth within the reproduction of certain insects. It's just a little hidden. The influence of the Sun is obvious, that of the Moon is not quite so obvious, and that of Mars is hidden. Everything that needs intermediate periods between the years of the Earth — such as grubs and cockchafers — depends on Mars. So you can already see an effect there that is indeed significant.

Someone might say: I don't believe you. Well, gentlemen, we cannot do all the experiments ourselves, but those who do not believe it should just do the following. They should take grubs that they have collected in a year when there are many grubs, breed them artificially somewhere in a container, and in a year they will see that most of the grubs do not crawl out and do not become cockchafers. Of course, people don't do such things because they don't believe in them.

Now we come to what this is actually about. If you look at the sun, it has the strongest influence. But the sun has its main influence on everything in the earth that is dead and must be brought to life every year, while the moon only has an influence on life, not on what is dead. Mars, for example, has its influence only on what is in the finer life, in the senses, and the other planets have their influence on the soul and the spirit, and so on. So that actually the sun is the celestial body that has the strongest effect on the earth, even down to the minerals, for the moon can do nothing in the minerals, and Mars even less. No creature could crawl and live on Earth as an animal if it weren't for the Moon. There could only be plants on Earth, no such creatures. Many such animals could not have an intermediate period of years from larva to insect if it weren't for Mars.

And you see, actually, all things are connected in this way. We can ask ourselves, for example: When are we fully grown when we develop as human beings? When do we stop having any kind of increasing development? Yes, visibly very early, perhaps as early as twenty or twenty-one years of age; but something is still accumulating. Some people do not even grow anymore, but internally something is still happening. Until around the age of thirty, we actually increase in size, then we begin to decrease. If we compare this again with the universe, we get the orbital period of Saturn.

So the planets have an influence on the finer aspects of growth and life. We can therefore say that when Mars approaches the Earth, as all planets do, we should not attach the greatest importance to this external approach, but rather to how things in the universe are connected with the finer aspects of life.

Now you must remember that Mars is very different from Earth. I told you: in the sense that Earth today has solid matter, Mars has nothing solid. But, gentlemen, I described to you some time ago that the Earth was once in such a state that the mineral, the solid, had only just formed, that huge animals lived there, but they did not yet have solid bones. If we take Mars today, Mars is in a similar state to what the Earth was in earlier, so it also has those living beings, the animals that the Earth had at that time, and the humans on Mars are like they were on Earth at that time: still without bones, as I described to you in an earlier state of the Earth. — That can be known. Only it cannot be known in the way that today's natural science is accustomed to; but these things can be known. So that one can say: If you want to imagine what Mars is like today, imagine what Earth was like in an earlier age; then you will have the appearance of Mars.

You see, today we have trade winds from south to north, from north to south. Once upon a time, these air currents were much thicker; they were liquid, watery air currents. That is how Mars is today. These are even more lively, even more watery, non-air-like currents on Mars.

Jupiter, for example, is almost entirely air-like, only slightly denser than the air on Earth. When we look at Jupiter today, it represents a state that Earth is striving toward, what Earth will be like in the future.

And so we see certain states throughout the planetary system that Earth is also going through. If we understand the planets in this way, then we understand them correctly.

Does anyone have any further questions or would like to know anything else about this topic? Perhaps Mr. Burle himself?

Mr. Burle: I am quite satisfied with that.

Further question from Mr. Burle: In one of his recent lectures, the doctor stated that the scents of flowers are connected to the planets. Is this also true of the colors of flowers and colored rocks?

Dr. Steiner: Well, I will just briefly repeat what I said. It was also in response to a question. I said: Flowers, and other substances on earth that have a scent, have something that exerts a corresponding influence on the human olfactory organ. I showed you at the time that this is connected with the planets, that plants, and certain other substances, are, in a sense, big noses, or noses at all, that they perceive what comes as effects from the planets. You see, the planets have an influence on the finer life — here we come back to the fact that we must move on to the finer life — and we can already say that plants actually arise from the scent of the world, which is so thin and fine that we cannot smell it with our coarse noses. But I drew your attention at the time to how one can smell in a completely different way — I don't mean on one's own, but how one can smell something differently from humans. You only need to think of police dogs. Police dogs are made aware in a certain way that there was a person who stole something; then the police dog picks up the scent and leads you to the trail, and sometimes, when he follows the trail to where the thief has gone, you can catch up with the thief. This is how police dogs are used. You can discover all sorts of interesting things when you follow the scents that are imperceptible to humans but can be detected by dogs.

Yes, but gentlemen, humans have not always suspected that dogs have such sensitive noses, otherwise they would have used dogs in police work long ago. It was only discovered relatively late. And so, even today, humans do not suspect what incredibly sensitive noses plants have. The whole plant is a nose, picking up the scent, and if it is designed in such a way that it echoes the sound, it echoes the scent it picks up, and thus becomes a scented plant. So we can say that the scents of flowers, of plants in general, and also other scents on Earth already depend on the planetary system.

Now the question has been asked how this applies to colors. With colors, it is like this: when the plant is formed from the world fragrance, it is, as I have described, exposed to the sun throughout the year. And while the shape of the plant is formed by the planets from the world fragrance, the color of the plant is formed by the sun, also somewhat under the influence of the moon. So the fragrance and the color do not come from the same source. The scent comes from the planets, the color comes from the sun and moon. It is not necessary for everything to come from the same source; just as humans have a father and a mother, plants have their scents from the planets and their colors from the sun and moon.

You can see from the following that colors are connected to the sun and moon. Take plants that have very beautiful green leaves and put them in the cellar: they will not only turn pale, but they will look completely white, become completely colorless, because they are no longer exposed to the sun. They retain their shape and form because the scent of the world enters everywhere, but they do not retain their color because the sun does not shine in. So you see that colors definitely come from the sun and, as I said—this is a little harder to understand—also from the moon. Experiments would have to be done to find out; by exposing the plant to moonlight in such and such a way, one would be able to figure it out.

Perhaps someone else has something to say about this?

Mr. Burle: I would like to expand on the question: What about the color of rocks?

Dr. Steiner: With rocks, it is like this: if you imagine that every day the sun has a certain influence on plants, and also has an influence on plants throughout the year, then you will come to the conclusion that the annual effects of the sun are different from the daily effects of the sun. The daily effects of the sun cannot change the colors of plants very much, but the annual effects of the sun do have an impact on the colors of plants.

But there are not only daily or annual effects of the sun; there are also completely different effects of the sun. I spoke to you about these some time ago, but I would like to show you again now.

Just imagine — apparently — the Earth here (it is drawn). The sun rises at a certain point in the sky, and let's assume we examine the sunrise on March 21, in spring, then we get a certain point in the sky where the sun rises. You see, when we look today at where the sun rises on March 21, we find the constellation Pisces behind the sunrise. That is a specific constellation. The sun has been rising in this constellation of Pisces for several hundred years, but not always at the same place. Instead, this point in spring, where the sun rises on March 21, moves further and further away in the constellation of Pisces. You see, a year ago, the sun rose a little further back, and even further back again a year before that. So the sun does not always rise at the same point. There is the constellation of Pisces; this has been the case for centuries, even longer: we always find the vernal equinox in the constellation of Pisces. But it wasn't always like that. If we were to go back to the year 1200—we are now in 1924—if we were to go back then, we would find that the sun did not rise in the constellation of Pisces at all, but in the constellation of Aries. And for a long time, the vernal equinox was found in the constellation of Aries. Before that, for example in ancient Egyptian times, the sun did not rise in the constellation of Aries, but in the constellation of Taurus, and even earlier in the constellation of Gemini, and so on. So we can say: the sun is always moving forward with its vernal equinox.