The Evolution of the Earth and Man

and the Influence of the Stars

GA 354

9 August 1924, Dornach

Lecture IX

Rudolf Steiner: Good morning, gentlemen! Perhaps someone has a question? We will not be able to meet again for a little while.

Herr Erbsmehl: I have a rather complicated question. I don't quite know how to put it. One knows that plants have different scents. This is also true of the various human races. You have already spoken to us, Dr. Steiner, about the evolution of humanity. A factor in this evolution must have been that each kind of being acquired what would benefit it. Different smells can be associated with the various races. so there must be some spiritual connection. Just as the plants have their scent from the earth, so the different races of human beings must have acquired their smell. How does this relate to human evolution?

Dr. Steiner: I will try to put the question in a way that will lead to what you have in mind. You have been thinking, have you not, of different kingdoms of nature: plants, animals, human beings. Also, we must not forget, minerals have different odors. Now smell is only one sense-perception and there are many other kinds. So perhaps we could say, the question is how the different smells belonging to the different beings of nature are related to the origin of these beings.

Well, let us first consider what causes smell. What is smell? You must realize first of all that people have varying reactions to a smell coming from an object or from other products of nature. For instance, in a place where people are drinking wine, someone who is a wine-drinker himself hardly notices the smell, while someone who never touches wine finds it extremely unpleasant either to be in a room where others are drinking wine or in a place where wine is stored. It is the same with other things. For instance, there are people, usually women, who can't stay in a room where there is a dog even for a short time without getting a headache. Different beings, therefore, are sensitive to smells in different ways. This makes it difficult at the very outset to get at the truth.

But what has been said applies not only to smell; it applies equally to other sense-perceptions. Imagine for a moment that standing where you are, you put your hand into water of, say 79 degrees or 80 degrees Fahrenheit. The water will not seem particularly cold. But if you have previously had your hand for some time in water of 86 degrees and then you plunge it into water of 80 degrees, the water will seem colder than it did before. This can be carried further. Think of a red surface. If the background is white, the red will seem very vivid to you. But if you paint the background blue, the red surface will lose some of its vividness. Everything, therefore, depends very largely upon how the human being himself is related to the things. This has led to the opinion that man does not perceive objects in themselves but only the effect they have upon him. We have spoken of this before. But we must get to the truth behind such things.

There is no question that a violet is easily distinguishable from the asafetida by its smell. The violet has a scent that is always pleasant; the asafetida has a smell that is offensive, that we want to avoid. It is also correct that different races have different smells. Someone with, shall I say, a sensitive nose will certainly be able to distinguish a Japanese from a European by their smell.

Now we must be clear as to what it is that causes smell. The fact of the matter is that any object with a smell or scent emits something that comes toward our own body in a gaseous or airy form. When nothing of this kind comes toward us, we cannot smell the object. And these gaseous substances must come into contact with our organ of smell, our nose. We can't smell a liquid as liquid, we can only taste it. We can smell a liquid only when it emits air, that is to say, gaseous substance. We don't smell our foodstuffs because they are fluid but because they emit air which then passes into us through our nose.

There are people who can't smell at all. The whole world is devoid of smell as far as they are concerned. Only recently I met a man whose incapacity to smell is a severe handicap to him because his work requires that he should be able to distinguish things by their scent. His defect is a grave disadvantage. The cause is, of course, imperfectly developed olfactory nerves.

And now let us ask: how is it that bodies or objects emit gas which may have a particular smell? Objects or bodies can be classified. There are solid bodies—they were called earthy bodies in earlier times; there are fluid bodies-they were called watery bodies in earlier times. People used to call water what we no longer classify as water. In earlier times everything fluid was called water, even quicksilver. Then there are gaseous or aeriform bodies. If we think of these three kinds of bodies—solid, fluid, and gaseous—one fact is particularly striking. Water is certainly fluid, but when it freezes to ice, it becomes a solid body. A metal—lead, for instance—is solid, but when you heat the lead sufficiently it becomes fluid, like water. So these different substances—solid, fluid, gaseous substances—can be led over into the other conditions. Even air can be solidified today, or in any case liquefied, and there is every expectation of being able to carry this further. Any object or body can be either solid, fluid or gaseous.

Any object that has a smell contains gas imprisoned, as it were, within it. We don't smell a solid body as such or a fluid body as such: we always smell a gas. But now, a violet is certainly not a gaseous body and yet we can smell it. Of what is a violet composed? It is obviously solid, yet it has scent. We must picture to ourselves that it contains solid constituents and between them something that vaporizes as gas. The violet contains gas that can vaporize. In order that this may be possible, the violet must be attracted to certain forces. When you pick a violet, you really only pick the solid part of it and you look at this solid part. But actually the violet does not only consist of the solid part that you pick. What the violet is, is enshrined in this solid part. One can say that the real violet, that which gives forth the fragrance, is actually a gas. It is there within the petals and the other parts of the flower—just as you stand in your shoes or boots. You are not your boots. And what has fragrance in the violet is not its solid part but its gaseous part.

When people look out into the universe they think that space is empty and that the stars are in this empty space. In times gone by, peasants believed that there was emptiness all around them as they moved about. Today everyone knows that there is air around us, not emptiness. So, too, we can know that in the universe there is no emptiness anywhere; either matter is there or spirit is there. It can be proved quite exactly that there is no emptiness anywhere in the universe. This is interesting to think about. I will prove it to you by an example.

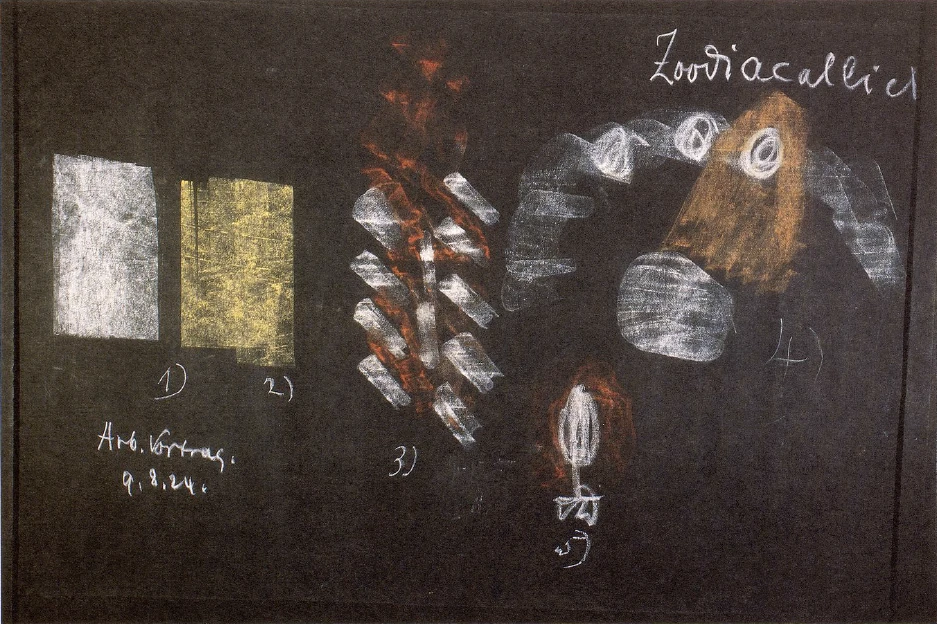

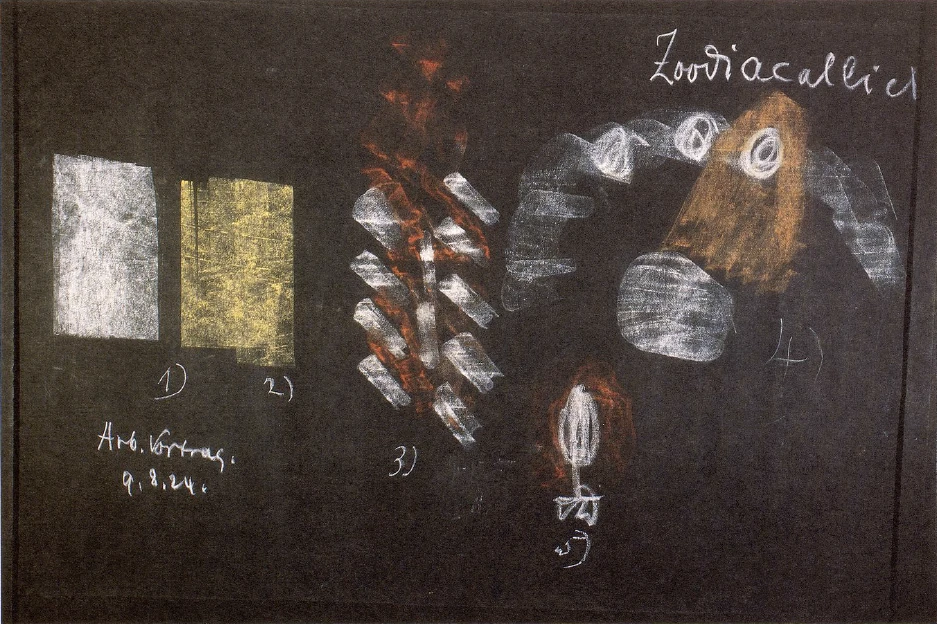

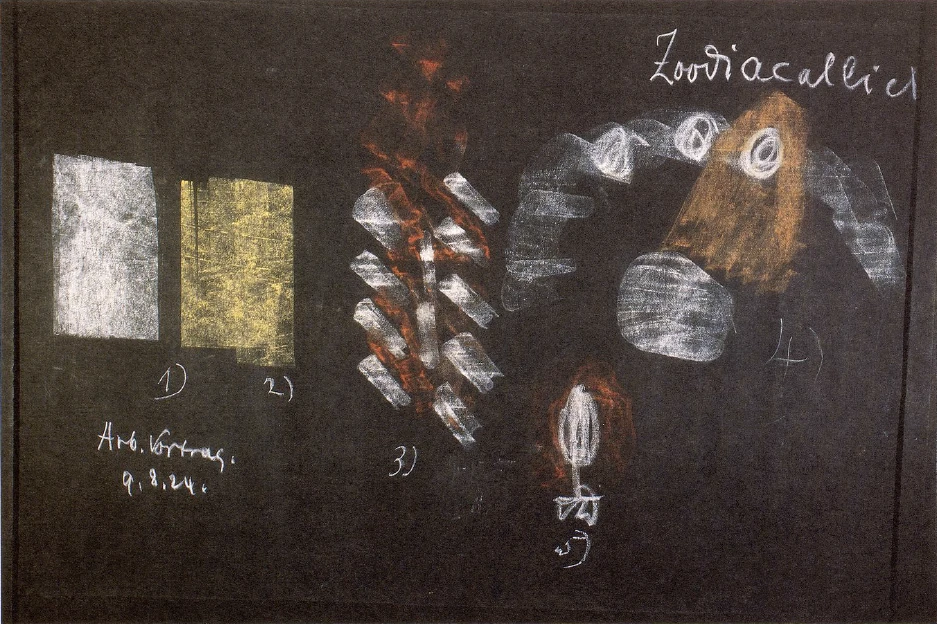

For the moment let us disregard what Copernicus taught, namely, that the earth revolves around the sun; let us take things as they appear.14Nicholas Copernicus, 1473–1543. Astronomer. We have the earth with the sun moving around it, rising in the east and setting in the west. The sun is always at a different point. But there is something remarkable here. In certain regions—but everywhere, really; one only has to observe carefully—at sunrise and at sunset, other times too, there is not only twilight but something else that is always a thing of wonder. Around the sun there is a kind of radiating light. Whenever we look at the sun, but especially toward morning and evening, this radiating light is apparent as well as the twilight. Light radiates around the sun. It has a name: the zodiacal light. People rack their brains about this zodiacal light—especially those who think in a materialistic way. They say to themselves: The sun shines in empty space and when it shines, it illumines other celestial bodies, but where does this zodiacal light around the sun come from? Countless theories have been put forward as to its origin. Whether one assumes that the sun moves around through empty space, or—as Copernicus taught—merely stands still, this does not account in any way for the presence of that light. So where does the light come from?

This is a very simple matter to explain. You will certainly on a very clear evening have walked through the town and seen the street lamps. On a clear evening the lights have definite outlines. But on a misty, foggy evening there is always a haze of light around them. Why is this? The haze is caused by the mist. At certain times the sun moves over the sky in a haze because heavenly space is not empty but filled with fine mist. The radiance that is present in this fine mist is the zodiacal light. All kinds of explanations have been given: for example, that comets are always flashing through space out there. And so, of course, they are. But the reason why this zodiacal light that accompanies the sun is sometimes strong, sometimes faint, sometimes not visible at all is that the mist in the universe is sometimes dense and sometimes thin. Thus we can say: The whole of cosmic space is filled with something.

But as I have already told you, it is not correct to think that there is substance or matter everywhere. I have told you that materialistic physicists would be immensely astonished if they went up into space expecting to find the sun as they describe it in their science. Their descriptions are nonsense. If by some convenient transport the physicists could reach the sun, they would be amazed to find no gas whatsoever. They would find hollow space, a real vacuum. This vacuum radiates light. And what they would find is spirit. We cannot say there is only matter everywhere: we must say there is also spirit everywhere, real spirit. So you see, everything on the earth is worked upon from outer space, not only by matter but also by spirit.

And now, gentlemen, let us consider how the spiritual is connected with the physical in man.

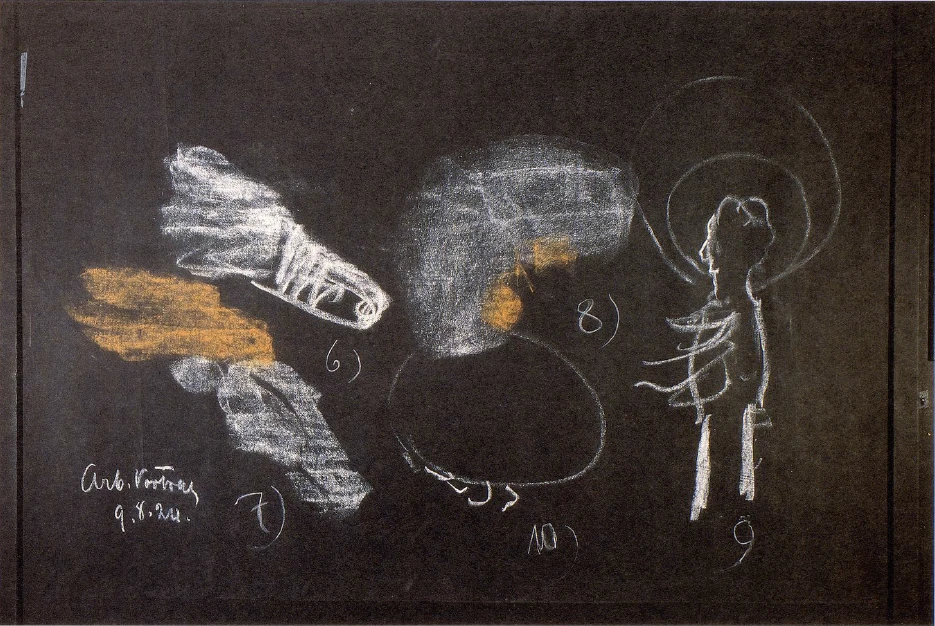

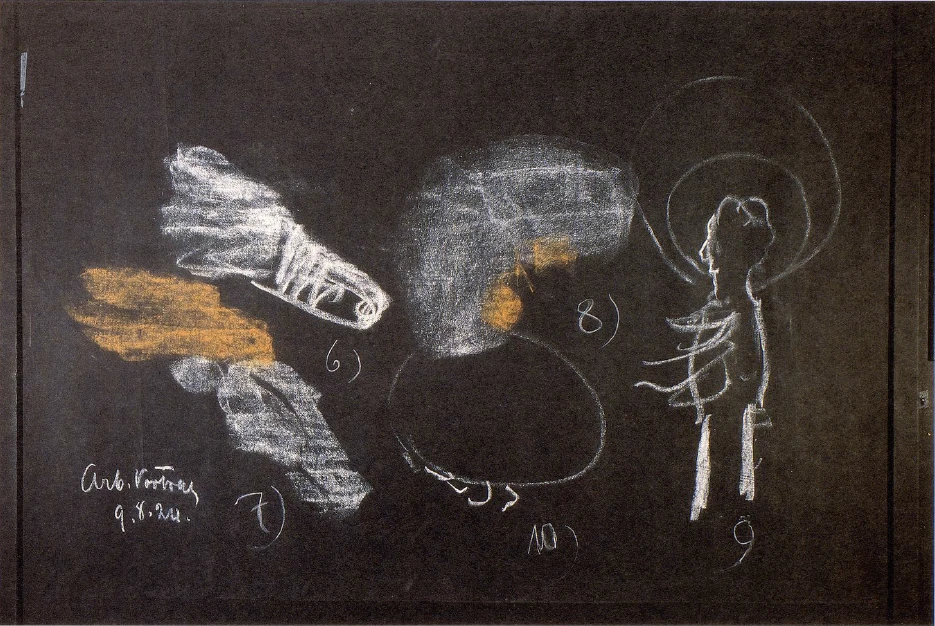

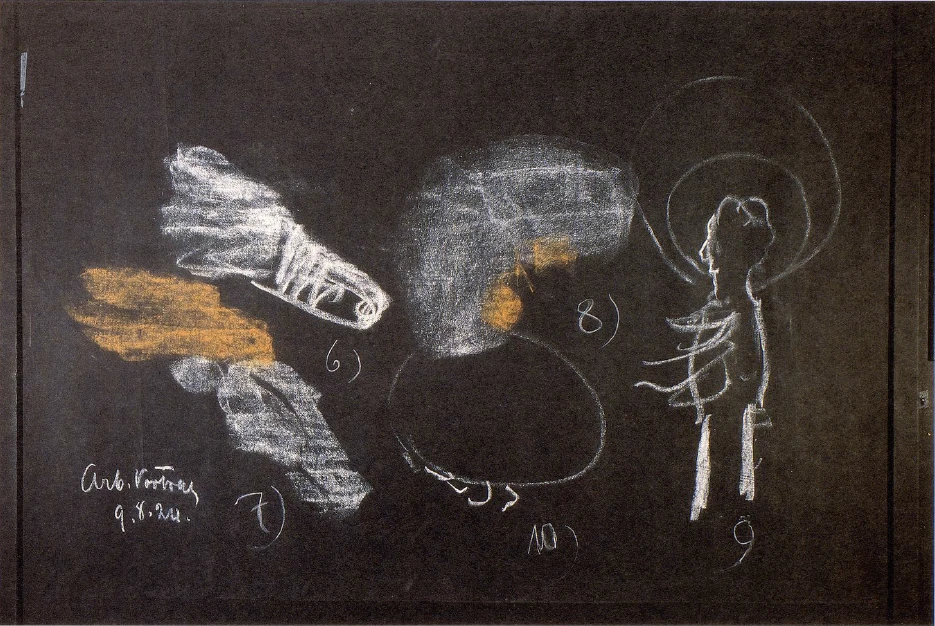

There is a creature familiar to us all that has a better sense of smell than you or I, namely the dog. Dogs have a much more delicate sense of smell than human beings. And you know to what use this is put nowadays. Think of the police dogs that through their sense of smell find persons who have run away after committing some crime. The dog picks up a scent at the spot where the crime was committed and follows it until it leads to the criminal. The dog has very delicate olfactory nerves. It is extremely interesting to study this fine sense-perception and to see how these olfactory nerves are connected with the rest of the dog's organism. Behind its nose, in its brain the dog has a very interesting organ of smell. Its nose is only one part. The larger part of a dog's organ of smell is situated behind the nose, in the brain.

Now let us compare the dog's organ of smell with that of the human being. The dog has a brain that is clearly made for smelling, a brain that becomes an organ of smell. In the human being the greater part of this “smell-brain” has been transformed into an “intelligence-brain.” We understand things; the dog doesn't understand things, he smells them. We understand them because at the place where the dog has his organ of smell, we have that organ transformed. Our organ of intelligence is a transformed organ of smell. In us there is only a tiny remnant left of this “smell-brain.” That is why our sense of smell is inferior to the dog's. And so you can imagine that when a dog runs over the fields, he finds everything terribly interesting; so many smells come to him that if he were able to describe it, he would say the world is all smell. If among dogs there were a thinker like Schopenhauer,15Arthur Schopenhauer, 1788–1860. Philosopher. he would write interesting books! Schopenhauer wrote a book called “The World as Will and Idea”—but he was a man and his organ of smell had become an organ of thinking. The dog could write a book called “The World as Will and Smell.” In the dog's book there would be a great deal beyond the discernment of a human being, because while a human being forms an idea, a mental image of things, a dog smells them. And it is my private opinion that the dog's book—if the dog were a Schopenhauer—would actually be more interesting than the book that Schopenhauer himself wrote!

So you see how it is. We live in a world that can be smelled, and other creatures—the dog, for instance—are much more acutely aware of this than we are.

Now since the universe is filled with the gaseous substance we perceive in the zodiacal light, this universe would be found to be emitting all kinds of different smells if organs of smell existed which were even more delicate than that of the dog. Imagine some creature sniffing toward the sun, not seeing the beauty of the sun but becoming aware through its sniffing of how the sun smells. Such a creature would not say as the poets do: The lovers went a-roaming in the enchanting moonlit night—but he would say: The lovers went a-roaming in the enchanting moon-scented night, in a world of sweet fragrance—or perhaps, since it's to do with the moon, the scents would not be so very pleasantly fragrant! Again, such a creature might sniff toward the evening star, and its smell would be different from that of the sun. Then it might sniff toward Mercury, toward Venus, toward Saturn.

It would have no picture of these stars like that transmitted through the eyes, but it would get the sun smell, the moon smell, the Saturn smell, the Mars smell, the Venus smell. If there were such creatures, they would be guided by what the Spirit inscribed in the smell of the cosmic gas, by what the spirit of Venus, Mercury, Sun, Moon inscribes into world existence.

But now, gentlemen, think of fish. Fish don't smell things. But they take on colors according to how the sun shines upon them. They reflect in their own coloring what comes to them from the sun. So you see, a being with a very delicate sense of smell would actually adjust its being to the way it smells the universe.

Such beings do exist. There are beings that can actually smell the universe: namely, the plants. The plants smell the universe and adapt themselves accordingly. What does the violet do? The violet is really all nose, a very, very delicate nose. The violet is beautifully aware of what streams from Mercury and forms its scent-body accordingly, while the asafetida has a delicate perception of what streams from Saturn and forms its gas-body accordingly, having thereby an offensive odor. And so it is that every being in the plant world is perceiving the smells that come from the planetary world.

But now what about plants that have no fragrance? Why have they no scent? As a matter of fact, to sensitive noses all plants do have a certain scent—at the least, they have what can be called a refreshing aroma—and this has a very strong effect upon them. This refreshing smell comes from the sun. A large number of plants are only receptive to this sun smell. But various plants, like the violet or the asafetida, are receptive to the planetary influences: these are the sweet-smelling or the bad-smelling plants.

And so we can say when we smell a violet: This violet is really all nose—but a delicate nose, inhaling the cosmic scent of Mercury. It holds the scent, as I have indicated, between its solid parts and exhales it; then the scent is dense enough for us to be able to smell it. So when Mercury comes toward us through the violet, we smell Mercury. If with our coarse noses we were to sniff toward Saturn, we would smell nothing. But when the asafetida, which has a keen nose for Saturn, sniffs toward that planet, it smells what comes from it, adapts its gas content accordingly, and has a most foul odor. Suppose you are walking through an avenue of horse chestnuts—you know the scent of horse chestnut, or of linden blossoms? They both have such perfume because their flowers are sensitive noses for everything that streams into the universe from Venus. And so in very truth the fragrances of heaven come to us out of the plants.

Now let us turn to something else Herr Erbsmehl mentioned in his question, namely the human races. Originally, different races lived in different regions of the earth. One race developed in one region, another race in another. Why was this? It is quite correct to say that one planet has a particularly strong influence upon one part of the earth, another planet upon another part. In Asia, for instance, the land is strongly affected by what streams to the earth from Venus—Venus, the evening star. What streams from Saturn works with particular strength upon the American soil. And Mars works particularly strongly upon Africa. So we find that each of the planets works particularly strongly upon some specific part of the earth. They radiate their light from the various places where they stand in the heavens. The light of Venus, for instance, works quite differently upon the earth from the light of Mercury. This is connected with the different formations of mountains, of rocks. Thus the different races inhabiting different regions of the earth are dependent upon the fact that one part of the earth is particularly receptive to the influences of Venus, another part to the influences of Saturn, and so on. And the plant-nature in man is determined in accordance with this.

The human being has the whole of nature within himself: mineral, plant, animal, and man. The plant-nature in the human being adjusts itself to the scents of the planets just as do the plants themselves. Certain minerals which still retain much of the plant-nature, also have an odor. So whether something does or does not have an odor depends upon whether it is perceiving the scents of the universe.

It is very important that you should understand these things, for people talk today about plants having perception, having a soul like human beings. That, of course, is nonsense. I spoke about it once. There are plants—like the one called Venus's flytrap16Venus's-flytrap: Dionaea muscipula, found in swamps in the warmer part of North America. See Charles Darwin, Insectivorous Plants, 1875.—that are supposed to have feeling. When an insect comes close enough, the “trap” closes and the insect is caught. It would be just as logical to say that a mousetrap has a soul, for the reason that when a mouse comes close enough, the trap shuts and the mouse is caught! Externalities of this kind should be ignored if one wants to acquire real knowledge. If knowledge is our aim, we must get to the root of things. Thus, if we know that with their fragrance the plants are breathing out what they inhale from the universe, then we can say that plants are the delicate organs of smell that belong to the earth. And the human nose, gentlemen—that's really a coarse plant. It grows out of man like a kind of blossom, but it has become coarse. It is a coarse flower that grows out of the human being. It no longer has such delicate perception as the plants. These are pictures, of course, but they are true. And it's the way things are.

So we can say: wherever we go in the world of plants, we find the earth covered with noses—the plants. But it never occurs to us that our own strange noses really derive from the plants. As a matter of fact, many blossoms look like a human nose. There are indeed such plants—the snapdragons, also the mints—they look just like a nose. You find them growing everywhere.

In this way we attain true knowledge of the world. And we discover how mankind is indeed related to all the rest of the universe. It might well be said, man is a poor creature: he has a nose for smelling, but he can't smell much because his nose has become too coarse, whereas the blossoms of plants can smell the whole universe. The leaves of plants can be compared to the human tongue: they can taste the world. The roots of plants can be compared to the organ in man that looks at things: his eyes, but in man it's a weak organ. Poor human being! He has everything that the beings of outer nature have, but in him it has all become feeble.

But now, gentlemen, we sometimes come across strange things. If we were able to smell as keenly as the plants smell and were able to taste as delicately as their leaves taste—well, we wouldn't know where we were, for scents and tastes would come to us from every direction! We wouldn't have to eat anything in order to experience taste because taste would stream toward us from all sides. But this does not happen to us. Man no longer has such perceptions. Instead, he has his intelligence. Think of an animal that has a “smell-brain” strongly developed behind its nose. In the human being this kind of brain is stunted and his nose has become coarse; it is just a shrunken remnant. But instead, he has his reasoning brain. It is the same with his organ of taste. Most animals have a brain highly developed for tasting; they can at once distinguish one kind of food from another. It is impossible for us humans to conceive the intensity with which animals experience taste. Why, we would jump out of our chairs if our food tasted as strongly to us as their food tastes to them! Our feeble taste for sugar can give us no notion of the joy a piece of sugar gives to a dog. This is because most animals have a very highly developed “taste-brain.” Of this too, man has only a tiny remnant left. Instead, he is able to form ideas; the “taste-brain” has been metamorphosed so that he is able to form ideas.

Man has become the noblest being on the earth because only a tiny part of his brain is engaged in sense perception-, the rest of it has been transformed into an instrument of thinking and feeling. Thereby man becomes the highest being. So we can say: In the human brain a mighty transformation of the faculties of tasting and smelling has taken place and only tiny vestiges remain of the “taste-brain” and the “smell-brain.” In the animal, this does not exist, but these faculties are very highly developed. The outer structures themselves are evidence of it. If man had a “smell-brain” as highly developed as the dog's, he would have no forehead. The forehead would slope backward because the “smell-brain” would have developed towards the back of the head. Since the “smell-brain” is transformed, the forehead is lofty. The dog's nose stretches forward and its brain lies further back. Someone who trains himself to observe this can tell which kinds of animals have a particularly keen sense of smell. He needs only to observe whether the brain lies toward the back and the nose is highly developed; then he knows that this particular animal has a fine sense of smell.

Now let's look at the plants. Their noses continue right down to the root, down into the earth. Here, everything is nose, only—in contrast to man—this nose becomes aware of taste as well, of the world of taste. And you see, this shows us that man's higher development is due to the fact that these very faculties which the animals and plants possess are imperfect in him; they have been metamorphosed. So we can say that man is a being of greater perfection than the other creatures of nature because what is developed to perfection in them exists in him in an imperfect state!

You can easily understand this: just think of a chicken. It slips out of the shell and at once it can take care of its own needs; it can right away scratch about for its food. Think of the human being in comparison! The animal can do everything. Why? Because the organs of its brain have not yet been metamorphosed into organs of thinking. When a human being is born, his brain has to acquire mastery over these blunted remains of sense organs. And so a child has to learn, while the animal doesn't need to learn, for it knows everything from the start. Human beings, having one-sidedly developed only their brain, can think with great subtlety but are terribly clumsy fellows. It is important for the human being that not too much of his brain shall be transformed. If too much has been transformed, he may be a good poet but he will certainly not be a good mechanic. He will have no knack for doing things in the outside world.

This state of things is connected with what I was talking about the other day, namely, that many people, owing to an excessive consumption of potatoes, have transformed a very large part of their brain. The result is that such people are clever but unskillful. That is so often the case today. They have to struggle to do things that they should really be able to do quite easily. For instance, there are men who are quite unable to sew on a trouser-button. They are able to write a marvelously good book, but they are incapable of sewing on a button! This is because the nerves which are nerves of perception in the more delicate organs have been transformed almost entirely into brain-nerves.

Once I knew a man who had a terrible dread of the future.17Hermann Rollett, 1819–1904. Austrian writer. See Rudolf Steiner, The Younger Generation (mentioned above), page 150. He argued that in olden times man's senses were more delicate, more keen, just because he had less brain, that in the course of human evolution what had in earlier times belonged to the senses and enhanced their perception was metamorphosed into a clever brain. The man was afraid that this would go further, that more and more of the sensory brain would become thinking brain, so that finally human beings would be utterly incapacitated, going about with defective eyes and so forth. In olden times people went through life with good sight; now they need glasses. Their sense of smell is not nearly as keen as it was once. Their hands are becoming clumsy. And anything that becomes clumsy is bound to deteriorate. The man was afraid that everything would be transformed into brain and that the human head would get bigger and bigger and the legs smaller and smaller and all would atrophy. He thought quite seriously that human beings would someday be no more than round heads rolling around the world—and then what would happen? The man was completely, tragically in earnest.

And his thought was perfectly correct. For if the human being does not find his way again to what he was once able to grasp through imagination, if he does not come again to the spirit, then he will become a ball of this kind! It is literally true that spiritual science does not simply make a man clever. As a matter of fact, if he takes it merely as one more theory, far from becoming more clever, he will become definitely more stupid. But if he assimilates spiritual science in the right way, it will work into his very fingers! Clumsy fingers will become more skillful again because the external world is getting its rightful significance again.

Through spiritual science the outer world becomes spiritualized, but that does not make you clumsier. These are things to which attention must be paid.

You see, in the days when mankind created sagas, legends, mythologies (there was recently a question about this), much less sense activity had so far been transformed into brain. In those days, people dreamed more than we do now, and when they dreamed, pictures appeared to them. Our thoughts today are barren. And the stories you hear about Wotan, Loki, about the old Greek gods—Zeus, Aphrodite and so forth—these stories originated from the fact that man did not yet have so much of that cleverness which is valued so highly today. People become more clever, certainly—but one learns to know the world not merely through intelligence but rather by learning to observe it.

Think of an adult person with a child in front of him. The adult may be a bit conceited about his own cleverness; if so, the child will seem stupid. But if the adult has any sense for what comes from a child out of his very nature, he will regard that as having far higher value than his own cleverness. One cannot grasp what exists in nature by brainwork alone, but by being able to penetrate into the secrets of nature. Cleverness does not necessarily lead to knowledge. A clever man is not necessarily very wise. Clever people can't, of course, be stupid, but they may certainly lack wisdom; they may have no real knowledge of the world. Cleverness can be used in all sorts of ways: to classify plants and minerals, to make chemical compounds, to vote, to play dominoes and chess, to speculate on the Stock Exchange. The cleverness by which people cheat on the Stock Exchange is the same cleverness that one uses to study chemistry. The only difference is that a man is simply concentrating on something else when he is studying chemistry than when he is speculating on the Stock Exchange! Cleverness is present in both cases. It is simply a question of what one is concentrating on.

Obviously, too much should not be transformed into brain. If one were to dissect the heads of great financial magnates, one would find extraordinary brains. In this area, anatomy has brought a great deal to light. It has been possible to see in a brain proof of cleverness—but never proof of knowledge!

So—I have tried to develop a few aspects of the question. I hope you are not altogether dissatisfied with the answer. As soon as I return, we will have the next meeting. I'm sorry I can't give lectures here and in England at the same time—such a thing is still beyond us! When we reach that point, there will be no need for a break. But for the time being, gentlemen, I must say goodbye.

Neunter Vortrag

Vielleicht hat noch jemand eine Frage auf dem Herzen? Wir werden ja jetzt einige Zeit nicht zusammenkommen können; aber vielleicht hat noch jemand eine Frage?

Herr Erbsmehl: Ich habe eine ganz verworrene Frage. Ich weiß nicht, wie ich sie formulieren soll. Wenn man Pflanzen sieht, so bemerkt man, daß sie verschiedene Gerüche haben; auch die Menschenrassen haben verschiedene Gerüche. Herr Doktor hat zu uns doch schon gesprochen von der Entwickelung der Menschen vom Urzustande an. Da muß gewirkt haben, daß eine jede Art von Wesen sich dasjenige genommen hat, was ihr gut getan hat. Es haben ja zum Beispiel auch die verschiedenen Rassen verschiedene Gerüche. Da muß doch ein geistiger Zusammenhang sein: Wie die Pflanzen die Gerüche aus der Erde genommen haben, so haben auch die Menschen der verschiedenen Rassen die verschiedenen Gerüche angenommen. Wie hängt das mit der Entwickelung von Urzuständen her zusammen?

Dr. Steiner: Sehen Sie, wir wollen einmal die Frage so stellen, daß sie auf das kommt, worauf Sie vielleicht hinaus wollen. Sie haben zunächst also ins Auge gefaßt die verschiedenen Naturprodukte: Pflanzen, Tiere und auch den Menschen, nicht wahr? Es ist das ja auch bei den Mineralien der Fall, daß sie in verschiedener Weise riechen. Der Geruch ist nur eine Sinneswahrnehmung. Es gibt die verschiedensten Sinneswahrnehmungen. Und so kann man sagen: Sie möchten gerne wissen, wie das mit der ganzen Entstehung der Naturwesen zusammenhängt, daß verschiedene Naturwesen in der verschiedensten Weise riechen.

Nun, schauen wir uns zunächst einmal das an, was eigentlich überhaupt den Geruch möglich macht. Was ist eigentlich der Geruch? Da müssen Sie sich zunächst klar sein darüber, daß ja der Mensch, indem er den Geruch wahrnimmt, sei es an einer Sache, sei es an anderen Naturprodukten, eigentlich in einer verschiedenen Lage ist. Ich mache Sie nur darauf aufmerksam, daß zum Beispiel derjenige, der Wein trinkt, sich in einer Umgebung, wo Wein getrunken wird, an dem Geruch wenig stößt; dagegen derjenige, der nicht selber Wein trinkt, empfindet es gleich unangenehm, wenn er in einer Lokalität ist, wo Wein getrunken wird, oder wo sich überhaupt nur Wein befindet. Ebenso ist es mit anderen Dingen. Da müssen wir zum Beispiel ins Auge fassen, daß es Menschen gibt, insbesondere Frauen, die sind nicht imstande, sich auch nur, ohne Kopfschmerzen zu bekommen, kurze Zeit in einem Zimmer aufzuhalten, in dem ein Hund ist. Also die verschiedenen Wesen sind in verschiedener Weise für Gerüche empfindlich. Das macht es überhaupt schwer, in solchen Dingen von vorneherein gleich das Richtige zu treffen.

Das ist aber nicht nur beim Geruch der Fall. Das ist auch bei anderen Sinnesempfindungen der Fall. Denken Sie nur einmal daran: Sie strecken Ihre Hand einfach, so wie Sie sind, sagen wir, in ein Wasser von siebenundzwanzig Grad. Dieses Wasser wird Ihnen so vorkommen, daß Sie nicht eine besondere Kälte empfinden. Dagegen, wenn Sie vorher Ihre Hand längere Zeit gewöhnt haben, unterzutauchen in ein Wasser von dreißig Grad, und Sie greifen dann hinein in ein Wasser von siebenundzwanzig Grad, dann kommt Ihnen das Wasser von siebenundzwanzig Grad kälter vor wie früher. — Das läßt sich leicht weiter denken. Denken Sie sich eine rote Fläche. Da kann Ihnen diese rote Fläche sehr rot vorkommen, wenn diese rote Fläche auf einem weißen Untergrund ist. Wenn Sie aber den Untergrund jetzt blau anstreichen, wird Ihnen die rote Fläche nicht mehr so rot vorkommen. So hängt alles in vieler Beziehung davon ab, wie sich der Mensch selber zu diesen Dingen verhält. Das hat gerade dazu geführt, daß man gemeint hat, der Mensch nehme die Dinge überhaupt nicht wahr, sondern nur, wie sie auf ihn wirken. Wir haben ja schon darüber gesprochen. Wir können also sagen: Wir müssen erst durchdringen zu dem, was eigentlich hinter einer solchen Sache ist. Dennoch kann man ganz genau dem Geruche nach unterscheiden das Veilchen und den Teufelsdreck oder Stinkasant. Das eine, das Veilchen, hat einen Geruch, der uns durchaus sympathisch ist; der andere hat einen Geruch, der nicht sympathisch ist, den wir wegbringen wollen von uns. Und es ist schon richtig, daß in dieser Weise verschiedene Rassen für den einen und den anderen verschiedene Rassengerüche haben. So kann derjenige, der, ich möchte sagen, eine feine Nase hat, einen Japaner sehr gut dem Geruche nach von einem Europäer unterscheiden. Das ist das eine.

Nun muß uns klar sein, worauf der Geruch beruht. Da kommt es darauf an, daß von dem Körper, der riecht, immer etwas ausgeht, was an unseren Körper in gasförmiger, in luftförmiger Gestalt herankommen kann. Wenn von einem Körper nichts ausgeht, was in gasförmiger, in luftförmiger Gestalt herankommen kann an uns, dann können wir den Körper nicht riechen. Es müssen also immer von dem Körper luftartige Stoffe, gasartige Stoffe ausgehen, damit wir den Körper riechen können. Und diese gasförmigen Stoffe müssen mit unserem Riechorgan, mit der Nase, innerlich in Berührung kommen. Eine Flüssigkeit als solche können wir nicht riechen, können wir nur schmecken. Erst wenn die Flüssigkeit Luft ausströmt, also Gasförmiges ausströmt, können wir sie riechen. Wir riechen unsere Speisen nicht aus dem Grunde, weil sie flüssig sind, sondern aus dem Grunde, weil sie Luft ausströmen, die dann durch unsere Nase in unser Inneres kommt. Nun sehen Sie, es gibt Menschen, die können überhaupt nicht riechen; für die ist also die ganze Welt geruchlos. Erst neulich ist mir ein Mensch entgegengekommen, der außerordentlich leidet daran, daß er nicht riechen kann, denn er hat einen Beruf, wo man riechen müßte und die Gegenstände geradezu nach ihrem Geruche unterscheiden müßte. Es stört ihn in seinem Berufe, daß er nicht riechen kann. Das hängt natürlich davon ab, daß die entsprechenden Riechnerven nicht ordentlich ausgebildet sind.

Nun müssen wir, um an die Frage heranzukommen, uns fragen: Woher kommt es, daß Körper Gas ausströmen, das man in einer gewissen Weise riechen kann? — Nun, sehen Sie, wenn wir an einen Körper herangehen, so finden wir immer, daß wir die Körper einteilen können in feste Körper, was man in früheren Zeiten erdige Körper genannt hat, und in flüssige Körper, was man in früheren Zeiten wässerige Körper genannt hat. Als Wasser bezeichnete man auch das, was man jetzt nicht mehr als Wasser benennt. In früheren Zeiten hat man alles, was fließt, als Wasser bezeichnet, also auch Quecksilber. Dann sind da noch die luftförmigen oder gasförmigen Körper. Wenn man diese drei Arten von Körpern nimmt - die festen, die flüssigen, die gasförmigen Körper -, so fällt vor allen Dingen eines auf. Wasser ist gewiß flüssig, aber es gefriert zu Eis; dann ist es ein fester Körper. Irgendein Metall, zum Beispiel Blei, ist fest; wenn Sie es richtig erwärmen, wird es flüssig, wird es so wie Wasser, Es können also diese verschiedenen Stoffe — die festen, flüssigen, gasförmigen -, ineinander übergeführt werden. Man kann heute schon Luft zu einem festen Körper machen, oder wenigstens zu einer Flüssigkeit machen. Und man kann hoffen, daß man es immer weiter und weiter darin bringt. Jeder Körper kann fest, flüssig, gasförmig sein.

Nehmen wir jetzt einen Körper, der riecht, dann ist das ein Körper, der gewissermaßen in sich Gas eingesperrt enthält. Wenn wir einen festen Körper haben für sich, den riechen wir nicht. Wenn wir einen flüssigen Körper für sich haben, den riechen wir auch nicht. Ein Gas können wir riechen, immer riechen. Aber das Veilchen ist ja kein Gaskörper, und dennoch riechen wir es. Wie ist es mit einem Körper bestellt, der scheinbar fest ist, wie das Veilchen, und den wir dennoch riechen? Den müssen wir uns so vorstellen, meine Herren, daß er nicht so ist wie dieses (es wird gezeichnet), sondern daß er solche feste Bestandteile enthält, und daß dazwischen dasjenige ist, was als Gas verdunstet. So daß wir also uns sagen: Das Veilchen enthält Gas, das verdunsten kann. — Dazu ist notwendig, daß das Veilchen eine Anziehung zu gewissen Kräften hat. Wenn Sie also das Veilchen abpflükken, dann ist es so, daß Sie eigentlich nur das Feste vom Veilchen abpflücken. Also Sie pflücken das Feste vom Veilchen ab und schauen dieses Feste an. Nun, in Wirklichkeit besteht das Veilchen nicht bloß in dem, was Sie als Festes abpflücken. Das Wesen des Veilchens, das, was es eigentlich ist, das steckt in diesem Festen drin, und man kann auch sagen: Das wirkliche Veilchen, dasjenige, was duftet, das ist eigentlich ein Gas. Das ist so, daß es drinsteckt im Blatt und so weiter, geradeso wie Sie in Ihren Schuhen oder Stiefeln stecken. Und wie Sie nicht Ihre Stiefel sind, so ist auch dasjenige, was in dem Veilchen duftet, nicht im Festen drin, sondern im Gasförmigen.

Nun aber, meine Herren, wenn Sie in die Welt hinausschauen: Da glauben die Leute, wenn man so in die Welt hinausschaut, da ist es ja leer, und in dem leeren Raume leben die Sterne drinnen und so weiter. Früher haben die Bauern geglaubt, daß da, wo sie herumgehen, es auch leer sei. Heute weiß jeder, daß da Luft ist, daß es da nicht leer ist. Ebenso kann man wissen, daß es im Weltenraum draußen nirgends leer ist; entweder ist Materie da, oder es ist Geist da. Sehen Sie, daß es im Weltenraum nirgends leer ist, kann man geradezu beweisen. Das ist interessant, das einmal zu überlegen, daß es nicht leer ist. Ich will das an einem bestimmten Zeichen beweisen, daß es nirgends leer ist. Wir wollen einmal absehen davon, daß sich die Erde um die Sonne dreht, was Kopernikus den Menschen gelehrt hat. Wir wollen die Sache so nehmen, wie sie sich anschaut. Da haben wir hier die Erde, und da geht die Sonne um die Erde herum, geht im Osten auf und im Westen unter. Da ist immer irgendwo die Sonne (es wird gezeichnet). Nun ist da etwas Eigentümliches. In gewissen Gegenden, eigentlich überall, wenn man genau zuschaut, ist nämlich, wenn die Sonne aufgeht und untergeht, aber auch sonst, nicht bloß die Dämmerung da, sondern es ist etwas da, was die Welt immer in Erstaunen versetzt. Es ist etwas da um die Sonne herum, was eine Art von Strahlenlicht bildet. Immer wenn die Sonne angeschaut wird, namentlich aber gegen Morgen und Abend, ist außer der Dämmerung noch dieses erstrahlende Licht da. Es erstrahlt um die Sonne herum ein Licht. Man nennt es das Zodiakallicht. Dieses Zodiakallicht, meine Herren, das macht den Menschen viel Kopfzerbrechen, namentlich denjenigen, die materialistisch denken. Sie denken sich: Die Sonne im leeren Raume kann also leuchten, _ und wenn sie leuchtet, so sehen wir, daß sie die anderen Körper beleuchtet. Aber woher kommt dieses Licht, das da immer um die Sonne herum ist, dieses Zodiakallicht? — Unglaublich viele Theorien haben die Leute darüber aufgestellt, woher dieses Zodiakallicht kommt. Wenn die Sonne im leeren Raume herumfliegen soll, oder auch nur steht nach der kopernikanischen Lehre, kann doch dort nicht ein Licht sein! Woher kommt dieses Licht? — Es ist furchtbar einfach, zu finden, woher dieses Licht kommt. Sie werden ganz gewiß schon an einem sehr reinen Abend durch die Stadt gegangen sein und da Laternen gesehen haben. Diese Laternen haben feste Grenzen. An einem luftreinen Abend sieht man die Lichter ganz fest begrenzt. Aber gehen Sie jetzt an einem nebligen Abend, dann sehen Sie nicht so feste Grenzen, dann sehen Sie überall eine Art Lichtring herum. Woher kommt der? Weil Nebel da ist. Im Nebel drin bildet sich dieser Schein von einem Lichtring. Die Sonne geht mit einem Lichtring zu gewissen Zeiten über den Himmel hin, weil der Himmelsraum nicht leer ist, sondern weil er mit einem feinen Nebel überall ausgefüllt ist. Das Zodiakallicht, das ist, was in diesem feinen Nebel als ein Schein vorhanden ist. An alles mögliche haben die Leute da gedacht. Zum Beispiel, daß da allerlei Kometen durchfliegen. Gewiß tun sie das auch. Aber dieses Zodiakallicht, das mit der Sonne geht, das zu gewissen Zeiten stärker ist, manchmal schwach, manchmal gar nicht da ist, das ist, weil die Nebel im Weltenraum sich mehr oder weniger verdichten oder verdünnen. So daß wir sagen können: Eigentlich ist der ganze Weltenraum mit etwas angefüllt. — Aber ich habe Ihnen auch schon gesagt, es ist nicht so, daß man nun glauben kann, daß überall Stoff, Materie ist. Ich habe Ihnen gesagt, die Physiker, die materialistischen Physiker würden sehr erstaunt sein, wenn sie da hinaufkämen und erwarteten, daß die Sonne so ausschaut, wie sie sie heute in der Physik beschreiben. Das ist Unsinn. Wenn die Physiker da hinauffahren könnten, mit irgendeinem günstigen Zug, in die Sonne, die würden erstaunt sein, daß sie dort nichts finden würden, was so wäre wie ein Gas. Einen Hohlraum fänden sie, einen richtigen Hohlraum. Der scheint Licht. Und dasjenige, was sie finden würden, wäre gerade das Geistige. So daß wir nicht sagen können: Überall ist nur Stoff -, sondern wir müssen sagen: Überall ist auch Geistiges, richtiges Geistiges.

Nun, meine Herren, so wirkt nicht bloß der Stoff aus dem Weltenraum auf alles, was auf Erden ist; auch das habe ich schon ausgeführt, es wirkt das Geistige auf alles. Nun, schauen wir uns einmal an, wie im Menschen das Geistige mit dem Physischen zusammenhängt.

Meine Herren, es gibt ja ein naheliegendes Wesen, das noch besser riechen kann als Sie oder ich; das ist der Hund. Die Hunde haben einen viel feineren Geruch als der Mensch. Sie wissen, daß man diesen Geruch heute ausnützt. Es gibt Polizeihunde, die durch ihren Geruch die Menschen, die irgendwie Verbrecher sind, die davongelaufen sind, ausfindig machen. Man läßt den Hund riechen an einer Stelle, wo ein Verbrechen begangen wurde, er geht der Spur nach, er verfolgt die Spur und führt an den Ort, wo der Verbrecher angekommen ist. Der Hund hat in der Nase sehr feine Geruchsnerven. Das ist sehr interessant, diese feine Geruchsempfindung des Hundes zu studieren. Aber es ist auch sehr interessant, zu studieren, wie die Geruchsnerven des Hundes mit dem übrigen zusammenhängen. Hinter der Nase, im Gehirn, hat der Hund ein sehr interessantes Riechorgan. Die Nase ist nur ein Teil des Riechorganes. Hinter der Nase, im Gehirn, hat der Hund die Hauptmasse seines Riechorganes. Nun können wir vergleichen die Riechorgane des Hundes mit denen des Menschen.

Beim Hunde ist ein deutliches Riechorgan vorhanden, ein Gehirn, das im Grunde zum Riechorgan werden kann. Beim Menschen ist der größte Teil dieses Riechgehirns umgewandelt zum Verstandesgehirn. Was wir hinter der Nase haben, ist ein umgewandeltes Riechorgan. Wir verstehen die Dinge; der Hund versteht sie nicht, er riecht sie. Wir verstehen sie, weil an der Stelle, wo der Hund noch ein richtiges Riechorgan hat, wir ein umgewandeltes Riechorgan haben. Unser Verstandesorgan ist ein umgewandeltes Riechorgan. Wir haben nur einen kleinen Rest als riechendes Gehirn; daher riechen wir schlechter als der Hund. So können Sie voraussetzen: Wenn der Hund durch die Felder geht — das ist furchtbar interessant für den Hund; der riecht so vielerei, daß, wenn er das alles beschreiben könnte, würde er die Welt als Geruch beschreiben. Wenn es einen Schopenhauer unter den Hunden gäbe — der Denkweise nach -—, der könnte interessante Bücher schreiben. Schopenhauer hat ja ein Buch geschrieben «Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung», weil er ein Mensch war und sein Riechorgan zum Vorstellungsorgan geworden war. Der Hund würde ein interessantes Buch schreiben: «Die Welt als Wille und Geruch.» Da würde so vieles drinnenstehen, was der Mensch nicht wissen kann, weil der Mensch das Ding sich vorstellt, und der Hund riecht es. Ich glaube sogar, daß das Buch, das der Hund schriebe, viel interessanter sein würde, wenn der Hund ein Schopenhauer wäre, als das Buch, das Schopenhauer geschrieben hat, «Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung»!

Sie sehen also, wie es sich ergibt, daß wir in einer riechbaren Welt stehen, und wie andere Wesen, zum Beispiel der Hund, diese Welt in einem viel höheren Sinne als riechbar wahrnehmen.

Da müssen wir nun sagen: Wenn es noch feinere Riechorgane gäbe, ließe sich, weil die Welt überall angefüllt ist mit Gasigem — was wir am Zodiakallicht sehen -, die ganze Welt in verschiedenster Weise riechen. Denken Sie sich, da würde ein Wesen da sein, das schnüffelte zur Sonne hinauf. Das beschreibt nicht die Schönheit, wie man die Sonne sieht, sondern sein Schnüffeln lehrt es, wie die Sonne riecht. Ein anderes Wesen beschreibt die Mondnacht nicht wie die Dichter: In der mondbeglänzten Zaubernacht ging das Liebespaar -, in phantasievoller Handlung, sondern ein solches Wesen schriebe: In der mondriechenden Zaubernacht ging das Liebespaar und lebte in einer Welt von Wohlgerüchen -, oder vielleicht, weil es der Mond ist, gar nicht so starker Wohlgerüche. Dann könnte wiederum ein solches Wesen zum Abendstern hinaufschnüffeln und würde da im Abendstern anderes riechen als in der Sonne. Dann würde es zum Merkur, zur Venus, zum Saturn hinaufschnüffeln; es könnte nicht ein Lichtbild von diesen Sternen bekommen, nicht eine Vorstellung, wie sie das Auge vermittelt, aber es bekäme Sonnengeruch, Mondgeruch, Saturngeruch, Marsgeruch, Venusgeruch. Wenn es solche Wesen gäbe, die richteten sich nach dem, was der Geist hineinschreibt in den Geruch des Weltengases; was der Geist von Venus, Merkur, Sonne, Mond hineinschreibt in das Weltendasein. Diese Wesen richteten sich danach.

Aber weiter, meine Herren: Betrachten wir, wie die Geschichte ist bei den Fischen, sagen wir, die gar nicht riechen. Wir können ganz genau wahrnehmen, wie Fische Farben sich hinneigen, je nachdem sie von der Sonne beschienen werden. Sie geben mit ihrer eigenen Färbung dasjenige Licht wieder, was ihnen von der Sonne zukommt. So daß man sagen kann: Ein Wesen, das so fein riechen würde, würde nicht bloß riechen, sondern es würde sich danach bilden, wie es die Welt riecht.

Sehen Sie, es gibt solche Wesen. Es gibt Wesen, die einfach die Welt riechen können: das sind die Pflanzen. Die Pflanzen riechen den Weltenraum und richten sich danach ein. Was tut das Veilchen? Sehen Sie, es ist eben ganz Nase und eine ungeheuer feine Nase. Und das Veilchen nimmt sehr schön wahr gerade dasjenige, was zum Beispiel ausströmt vom Merkur, und danach bildet es sich seinen Geruchskörper, während der Stinkasant, Teufelsdreck, sehr fein wahrnimmt dasjenige, was vom Saturn ausströmt: er gestaltet sich danach seinen Gaskörper und stinkt. Und so nimmt ein jedes Wesen in der Pflanzenwelt, wenn es zum Riechen kommt, dasjenige wahr, was aus der Planetenwelt herein zu riechen ist.

Nun diejenigen Pflanzen, die nicht riechen: Warum riechen sie nicht? Sehen Sie, etwas riechen für feine Nasen alle Pflanzen. Mindestens haben sie dasjenige, was man einen erfrischenden Geruch nennen kann. Aber dasjenige, was sie als einen solchen erfrischenden Geruch haben, das wirkt sehr stark auf sie. Das ist gerade das, was von der Sonne kommt. Währenddem eine große Anzahl von Pflanzen nur zugänglich sind für den Sonnengeruch, sind einzelne Pflanzen, wie Veilchen, Stinkasant, zugänglich für Planeteneinflüsse. Die sind die eigentlich wohl- oder übelriechenden Pflanzen. Und man kann, wenn man zum Beispiel ein Veilchen riecht, ganz gut sagen: Oh, dieses Veilchen hat eine feine Nase. Es ist ganz Nase; es nimmt den Weltengeruch des Merkur auf. - Es hält ihn fest, so wie ich das angedeutet habe, daß er zwischen den festen Bestandteilen festgehalten wird, und strömt ihn aus. Dann ist er so dicht, daß wir ihn riechen können. Wenn uns also der Merkur aus dem Veilchen entgegenkommt, riechen wir es. Wenn wir mit unserer ungeheuer groben Nase zum Saturn hinaufschnüffeln, merken wir nichts. Wenn aber der Stinkasant, der eine feine Nase für den Saturn hat, zum Saturn hinaufschnüffelt, riecht er das, was vom Saturn kommt und richtet danach seinen Gasgehalt ein; dann stinkt er. Wenn wir durch eine Allee gehen, wo Roßkastanien sind — Sie kennen diesen Geruch von Roßkastanien oder von Lindenblüten? Das ist ein Geruch, den die Roßkastanien und die Linden deshalb haben, weil sie in ihren Blüten feine Nasen haben für alles, was von der Venus strömt ins Weltendasein. Und so duftet uns aus den Pflanzen in Wirklichkeit der Himmel entgegen.

Nun gehen wir von den Pflanzen zu dem, was Herr Erbsmehl zunächst in seiner Frage angeschlagen hat: zu den Rassen. Die Rassen lebten ursprünglich an verschiedenen Stellen der Erde. Auf der einen Stelle der Erde bildete sich diese, auf der anderen Stelle der Erde eine andere Rasse. Woher kommt das? Wir könnten ganz gut reden davon, wie auf einzelne Teile der Erde besonders starken Einfluß hat der eine Planet, auf einen anderen Teil der andere Planet. Gehen wir zum Beispiel nach Asien hinüber, dann finden wir, daß auf asiatischen Boden besonders stark wirkt alles, was von der Venus auf die Erde herunterströmt — Venus, der Abendstern. Gehen wir auf amerikanischen Boden, so finden wir, daß alles dasjenige besonders stark wirkt auf den amerikanischen Boden, was herunterströmt aus dem Saturn. Und so finden wir eigentlich zum Beispiel auf Afrika alles dasjenige wirken, was vom Mars herunterströmt. So finden wir, daß auf jedes Stück der Erde eigentlich ein anderer Planet besonders stark wirkt. Das hängt damit zusammen, daß die Planeten verschiedene Stellungen haben am Himmel, je nachdem das Licht auffällt. Es fällt zum Beispiel das Licht von der Venus ganz anders auf als vom Merkur. Das hängt mit den Gebirgsformationen, mit der Steinformation zusammen. So hängen die verschiedenen Rassen auf verschiedenen Teilen der Erde davon ab, daß der eine Teil der Erde besonders stark aufnimmt die Venuseinflüsse, andere Teile die Saturneinflüsse. Danach richtet sich die Pflanzenheit im Menschen.

Der Mensch hat die ganze Natur in sich. Er hat die Steine in sich, er hat die Pflanzen in sich, er hat das Tierische in sich und hat extra das Menschliche in sich. Aber das Pflanzliche im Menschen richtet sich ebenso nach den Planetengerüchen wie das Pflanzliche selber. Bei denjenigen Mineralien, welche noch viel Pflanzliches in sich haben, gibt es auch einen Geruch. Also es hängt, ob etwas riecht oder nicht, davon ab, daß es die Weltengerüche wahrnimmt.

Das ist sehr wichtig, daß Sie solche Sachen auch auffassen. Denn man redet heute davon, daß die Pflanzen geradeso wahrnehmen können, daß sie eine Seele haben wie der Mensch. Das ist natürlich ein Unsinn. Ich habe schon einmal davon gesprochen. Es gibt Pflanzen, von denen man glaubt, daß sie Empfindung haben, wie zum Beispiel die Venusfliegenfalle. Wenn ein Insekt in den Bereich der Venusfliegenfalle kommt, schließt sich die Falle, und das Insekt ist gefangen. Ebenso könnte man von einer Mausefalle sagen, sie habe eine Seele, denn wenn die Maus in den Bereich der Mausefalle kommt, schließt sich die Mausefalle und die Maus ist eingeschlossen. Solche Äußerlichkeiten darf man nicht zur Erkenntnis gebrauchen; man muß eindringen in das Wesen der Sache. Dann kann man sagen — wenn man zu gleicher Zeit weiß, wie die Pflanzengerüche dasjenige wiedergeben, was in der Welt draußen ist: Die Pflanzen sind eigentlich feine Geruchsorgane der Erde. — Und die menschliche Nase, meine Herren, die ist im Grunde genommen eine grobe Pflanze. Sie wächst auch so wie eine Blüte aus dem Menschen heraus, aber sie ist gröber geworden — eine grobe Blüte, die aus dem Menschen herauswächst. Sie nimmt nicht mehr so fein wahr, wie wahrgenommen wird von der Pflanze im Weltenraum. Das sind schon die Bilder; die sind sehr wirklich. So ist es eben.

So können wir sagen: Wir finden eigentlich, wenn wir in der Pflanzenwelt dahingehen, die Erde überall bedeckt mit lauter Nasen; das sind die Pflanzen. Unserer merkwürdigen Nase sehen wir gar nicht mehr an, daß sie eigentlich von der Pflanze abstammt. Und manche Pflanzenblüten schauen wirklich so aus wie eine Menschennase. Schauen Sie so eine Pflanze an, die so ausschaut wie eine Menschennase. Es gibt solche Pflanzen: Man sagt, sie seien Rachenblütler, Lippenblütler, aber sie schauen so aus wie eine Nase. Sie finden sie überall am Wege wachsen.

Auf diese Weise kommt man hinein in die wirkliche Erkenntnis der Welt. Und dann, wenn man in dieser Weise die Sache verfolgt, dann erst findet man, wie sich der Mensch eigentlich verhält zu der ganzen übrigen Welt. Sehen Sie, man kann sagen: Dieser arme Mensch, nun hat er seine Nase zum Riechen, aber er riecht nicht mehr ordentlich; sie ist zu grob geworden. Sehen Sie, die Blüten der Pflanzen, die können die ganze Welt riechen. Die Blätter der Pflanzen lassen sich vergleichen mit der menschlichen Zunge. Sie können die Welt schmecken. Die Wurzel der Pflanzen, die läßt sich vergleichen mit demjenigen, was da guckt, schaut: Es ist ein Auge, aber ein schlechtes Auge. - Da steht der arme Mensch. Er hat alles in sich, was draußen die Wesen der Natur haben, aber es ist schwach und matt geworden.

Aber, meine Herren, wir begegnen auch ganz merkwürdigen Menschen. Wenn wir so gut riechen würden, wie durch die Pflanzen gerochen wird, wenn Sie so gut schmecken würden, wie durch die Pflanzenblätter geschmeckt wird — wir würden uns nicht auskennen; denn von allen Seiten duftete und schmeckte es! Wir brauchten nicht irgend etwas zu essen, um Geschmack zu empfinden; von allen Seiten her würde uns der Geschmack zulaufen. Das ist beim Menschen nicht der Fall; er hat alles dies nicht mehr. Dafür hat er aber seinen Verstand. Nehmen Sie ein Tier, das ein besonders starkes Riechgehirn ausgebildet hat hin ter der Nase (es wird auf die Zeichnung gezeigt). Beim Menschen ist dieses Riechgehirn verkümmert. Seine Nase ist grob geworden. Da ist nur ein kleines Stückchen. Dafür hat er aber sein Verstandesgehirn. Ebenso aber, meine Herren, ist es auch mit dem Geschmacksorgan des Menschen. Es gibt Tiere — die meisten Tiere sogar haben ein mächtig entwickeltes Geschmacksgehirn, können furchtbar gut ein Nahrungsmittel von dem anderen unterscheiden. Wissen Sie, so wie die Tiere genießen, davon haben wir gar keinen Begriff. Wir würden turmhoch springen, wenn uns all die Dinge, die wir essen, so geschmackvoll wären, wie den Tieren die Sachen geschmackvoll sind. Von der Art und Weise, wie der Hund vom Zucker beglückt ist, hat unser bißchen Zukkergeschmack gar keine Ahnung. Es kommt dies daher, daß bei den meisten Tieren ein mächtiges Geschmacksgehirn vorhanden ist. Beim Menschen ist auch davon nur ein kleiner Rest vorhanden. Dafür aber hat er wieder die Fähigkeit, Ideen zu bilden, mit dem umgewandelten Geschmacksgehirn Ideen zu bilden. Und auf diese Weise, sehen Sie, wird der Mensch das edelste Wesen auf der Erde, daß bei ihm von den Sinnesempfindungen im Gehirn immer nur ein Stückchen vorhanden ist; das andere ist umgewandelt zum Denken, zum Fühlen. Dadurch wird der Mensch das höchste Wesen. So können wir sagen: Da ist im menschlichen Gehirn mächtig umgewandelt Schmecken und Riechen, und nur Stückchen sind vorhanden vom Geschmacksgehirn und Geruchsgehirn. Beim Tier ist das nicht vorhanden, dagegen ist das mächtig ausgebildet (es wird auf die Zeichnung verwiesen). Das kann man schon an den äußeren Formen erkennen. Wenn der Mensch ein so mächtig ausgebildetes Geruchsgehirn hätte wie der Hund, dann hätte er keine Stirn. Die Stirn ginge zurück, weil das Geruchsgehirn nach hinten sich ausbilden würde. Aber indem es sich umwandelt, stülpt sich die Stirn auf. Weil der Hund die Nase nach vorne streckt, geht das Gehirn nach hinten. Wer darauf sich einschult, kann schon sagen, welche Tierformen besonders gute Geruchsempfindungen haben. Er braucht nur darauf zu sehen, daß das Gehirn nach hinten geht und die Nase mächtig ausgebildet ist, dann weiß er, das Tier hat eine gute Geruchsempfindung.

Dann nehmen Sie die Pflanze. Deren Nase setzt sich bis zur Wurzel fort in die Erde hinunter. Da ist alles Nase. Nur kommt an die Nase, entgegen dem, wie es beim Menschen ist, der Geschmack heran, die Welt der Geschmäcke. Und dieses, sehen Sie, zeigt uns, daß der Mensch gerade dadurch vollkommen ist, daß er diese Dinge, die die Tiere und Pflanzen haben, unvollkommen hat, daß sie umgestaltet sind. So daß man sagen kann: Wodurch ist der Mensch vollkommener als die übrigen Naturwesen? Weil er dasjenige, was bei den anderen Wesen vollkommen ist, in Unvollkommenheit hat. — Das können Sie leicht einsehen. Schauen Sie sich einmal ein Hühnchen an. Es schlüpft aus dem Ei heraus — flugs kann es, was es überhaupt braucht. Es kann schon sein Futter suchen, kann schon scharren. Bedenken Sie, wie sich dagegen der Mensch anschickt! Das Tier kann alles. Warum? Weil seine äußeren Gehirnorgane noch nicht zu Denkorganen umgewandelt sind. Beim Menschen müssen erst, wenn er geboren ist, vom Gehirn aus diese stumpfen Reste von den Sinnesorganen erobert werden. Und deshalb muß das Kind lernen, während das Tier nicht zu lernen braucht, sondern alles von vorneherein kann. So ist es beim Menschen. Wir können alles ganz genau sehen: Menschen, die ganz einseitig nur ihr Gehirn ausgebildet haben, die können furchtbar fein denken, sind aber furchtbar ungeschickte Kerle. Beim Menschen kommt es darauf an, daß er nicht gar zu viel Gehirnmasse umgewandelt hat. Wenn er gar zu viel umgewandelt hat, kann er ein guter Dichter werden, aber er wird kein guter Mechaniker werden. Er wird in der äußeren Welt nicht geschickt sein. Heute, meine Herren, ist es so — das hängt zusammen mit dem, was ich neulich besprochen habe -, daß durch die reichliche Kartoffelnahrung bei vielen Menschen furchtbar viel umgewandelt wird von ihrem ganzen Gehirn. Daher werden die Menschen gescheit, aber ungeschickt. Heute sind die Menschen so ungeschickt: Das, was sie nicht lange gelernt haben, das können sie nicht — solche Dinge, die man doch eigentlich nur flüchtig lernt. Es gibt Menschen: wenn ihnen ein Hosenknopf abreißt, können sie ihn nicht annähen. Sie können furchtbar gute Bücher schreiben, aber Hosenknöpfe können sie nicht annähen. Das rührt davon her, daß diejenigen Nerven, die Empfindungsnerven sind in den feineren Organen, fast ganz in Gehirnnerven umgewandelt sind.

Ich habe einmal einen kennengelernt, der hatte eine heillose Angst vor der Zukunft, weil er sagte: In alten Zeiten war der Mensch mehr feinsinnig, weil tatsächlich noch nicht so viel Gehirn umgewandelt war. Worin besteht die Entwickelung der Menschheit? Sie besteht darin, daß vieles, was früher den Sinnen angehört hat, was zur Feinsinnigkeit geführt hat, heute in das Gescheitheitsgehirn umgewandelt ist. — Dieser Mann hatte eine heillose Angst, daß das so weitergehen würde, daß immer mehr von dem Sinnengehirn in das Gedankengehirn umgewandelt werde, so daß die Leute zuletzt ganz ungeschickt werden, daß die Augen verkrüppeln und so weiter. In früheren Zeiten sind die Leute mit guten Augen durchs Leben gegangen; jetzt brauchen sie schon Brillen! Die Leute riechen nicht mehr so gut. Die Hände werden ungeschickt. Aber was ungeschickt wird, das verkümmert. Er hatte Angst, daß alles sich in Gehirn umwandle, und daß der Mensch, der erst so ist (es wird gezeichnet) - hier ist der Rumpf mit den Gliedern, oben trägt er den Kopf -, nun hat er gemeint: Nach und nach kommt es dahin, daß alles verkümmert; der Kopf wird immer größer und größer, die Beine werden immer kleiner. — Aber der Mensch hat das im völligen Ernst gemeint, er hat das furchtbar tragisch gefunden. Die Menschen werden sich zuletzt nur mehr wie Kopfkugeln durch die Welt rollen. Was soll da werden? -- Aber es ist ein ganz richtiger Gedanke. Denn wenn der Mensch nicht wiederum zurückkommt zu dem, was einmal durch die Phantasie ergriffen worden ist, wenn der Mensch nicht wiederum zum Geiste kommt, dann wird er eine solche Kugel. Daher ist es so, daß tatsächlich die Beschäftigung mit der Geisteswissenschaft den Menschen nicht nur gescheit werden läßt — er wird nicht mehr gescheit als durch andere Theorien, wenn er sie nur als Theorie annimmt; er wird nicht gescheiter, er wird eher dümmer -, aber wenn er die Geisteswissenschaft richtig auffaßt, so wie sie aufgefaßt werden soll, dann geht das bis in die Finger! Die steif gewordenen Finger werden wieder geschickter, weil wiederum die Außenwelt zu ihrer Geltung kommt. Sie vergeistigen sie nur, aber Sie werden dadurch nicht ungeschickter. Also auf solche Dinge muß man schon hinschauen. Man sieht geradezu: Als die Menschen Mythen, Sagen, Mythologien ausgebildet haben — worum ich neulich gefragt worden bin -, war noch nicht so viel von dem, was in den Sinnen ist, in Gehirn umgewandelt. Nun sehen Sie, da waren, wenn die Menschen eben träumten — die alten Leute haben mehr geträumt, weil noch nicht so viel in Gehirn umgewandelt war —, wenn sie träumten, da waren Bilder vor ihnen. Wir haben heute ganz leere Gedanken. Und wenn Sie die Erzählungen hören von Wotan, Loki, von den alten griechischen Göttern, von Zeus, Aphrodite und so weiter, so rühren diese Erzählungen auch davon her, daß der Mensch noch nicht so viel von der heute so geschätzten Gescheitheit hatte. Die Menschen werden gescheiter, ja, aber man lernt die Welt nicht dadurch kennen, daß man mit Gescheitheit lernt, sondern dadurch, daß man sie anschauen lernt. Das können Sie an einem Vergleich erkennen.

Denken Sie sich einen Erwachsenen, der hat ein Kind vor sich. Er kann sich bloß etwas einbilden auf seine Gescheitheit; dann findet er das Kind nur dumm. Wenn er aber einen Sinn hat für das, was im Kinde naturhaft herauskommt, dann schätzt er das für mehr als seine eigene Gescheitheit. So kann man dasjenige, was in der Natur da ist, nicht durch Gescheitheit fassen, sondern dadurch, daß man eingehen kann auf die Geheimnisse der Natur. Unsere Gescheitheit haben wir für uns selber, nicht zur Erkenntnis. Ein gescheiter Mensch braucht noch nicht besonders weise zu sein. Gescheite Menschen können nicht dumm sein, natürlich, aber sie können unweise sein, nichts wissen von der Welt. Gescheitheit kann man auf alles mögliche anwenden: um Pflanzen einzuteilen, um Mineralien einzuteilen, um chemische Verbindungen zusammenzusetzen und zu bestimmen, man kann Domino und Schach spielen, kann an der Börse spielen. Dieselbe Gescheitheit ist es, die die Leute betrügt an der Börse, wie die Gescheitheit, die die Menschen haben, wenn sie Chemie studieren. Es kommt nur darauf an, daß man anderes wahrnimmt, wenn man Chemie treibt, anderes, wenn man an der Börse spielt. Die Gescheitheit ist in beiden da. Auf dasjenige, was man anschaut, kommt es an. Es darf nicht zu viel in Gehirn umgewandelt werden. Wenn man zum Beispiel einen großen Börsenspekulanten sezieren würde, würde man ein ausgezeichnetes, ein ganz glänzendes Gehirn finden. In dieser Richtung ist manches gelöst worden, da man gerade da durch die Anatomie vieles herausgebracht hat. Niemals aber hat sich Erkenntnis im Gehirn nachweisen lassen, wohl aber die Gescheitheit.

So habe ich versucht, diese Frage auszugestalten. Vielleicht sind Sie nicht ganz unzufrieden mit der Beantwortung. Nun, sobald ich zurückkomme, wollen wir uns wieder zusammenfinden. Ich hoffe, daß Sie damit ein bißchen ausreichen können. Es tut mir leid, daß ich nicht hier Vorträge halten kann und in England. So weit sind wir noch nicht. Wenn wir einmal so weit sein werden, dann brauchen wir keine Pause mehr zu machen. Aber vorläufig müssen wir eine Pause machen. Daher auf Wiedersehen, meine Herren.

Ninth Lecture

Does anyone else have a question? We won't be able to meet for some time now, but perhaps someone else has a question?

Mr. Erbsmehl: I have a very confusing question. I don't know how to phrase it. When you look at plants, you notice that they have different smells; human races also have different smells. The doctor has already spoken to us about the development of humans from their original state. It must have been the case that each type of being took what was good for it. For example, different races also have different smells. There must be a spiritual connection: just as plants have taken the smells from the earth, so too have the different races of humans taken on different smells. How does this relate to the development from primordial states?

Dr. Steiner: You see, let's put the question in such a way that it gets to what you may be getting at. So, first of all, you have considered the various products of nature: plants, animals, and also humans, right? This is also the case with minerals, which smell in different ways. Smell is only one sensory perception. There are many different sensory perceptions. And so one can say: You would like to know how this relates to the entire origin of natural beings, that different natural beings smell in different ways.

Well, let's first take a look at what actually makes smell possible. What is smell, really? First of all, you must be aware that when humans perceive smell, whether from an object or from other natural products, they are actually in different situations. I would just like to point out that, for example, someone who drinks wine is not bothered by the smell in an environment where wine is drunk; on the other hand, someone who does not drink wine themselves immediately finds it unpleasant when they are in a place where wine is drunk or where there is even just wine present. The same applies to other things. For example, we must take into account that there are people, especially women, who are unable to stay in a room with a dog for even a short time without getting a headache. So different beings are sensitive to smells in different ways. This makes it difficult to get things right from the outset in such matters.

But this is not only the case with smell. It is also the case with other sensory perceptions. Just think about it: you simply stretch out your hand, as you are, let's say, into water at twenty-seven degrees. This water will seem to you that you do not feel any particular coldness. On the other hand, if you have previously spent a long time getting used to immersing your hand in water at 30 degrees Celsius and you then reach into water at 27 degrees Celsius, the water at 27 degrees Celsius will seem colder to you than before. — It's easy to take this idea further. Imagine a red surface. This red surface may appear very red to you if it is on a white background. But if you now paint the background blue, the red surface will no longer appear so red to you. So in many respects, everything depends on how people themselves relate to these things. This has led to the belief that people do not perceive things at all, but only how they affect them. We have already talked about this. So we can say: we must first penetrate to what is actually behind such a thing. Nevertheless, one can distinguish very precisely by smell between the violet and the devil's dung or stinkasant. The one, the violet, has a smell that is quite pleasant to us; the other has a smell that is not pleasant, which we want to get rid of. And it is true that in this way different races have different racial smells for one and the other. Thus, someone who has, I would say, a fine nose can very easily distinguish a Japanese person from a European by smell. That is one thing.

Now we must understand what smell is based on. It depends on the fact that something always emanates from the body that smells, which can reach our body in gaseous, air-like form. If nothing emanates from a body that can reach us in gaseous, air-like form, then we cannot smell the body. Therefore, air-like substances, gaseous substances must always emanate from the body so that we can smell it. And these gaseous substances must come into contact with our olfactory organ, our nose, internally. We cannot smell a liquid as such, we can only taste it. Only when the liquid emits air, i.e., gaseous substances, can we smell it. We smell our food not because it is liquid, but because it emits air, which then enters our body through our nose. Now you see, there are people who cannot smell at all; for them, the whole world is odorless. Just recently, I met someone who suffers greatly from not being able to smell, because he has a job where you have to smell and distinguish objects by their smell. It bothers him in his job that he cannot smell. This depends, of course, on the corresponding olfactory nerves not being properly developed.

Now, to approach the question, we must ask ourselves: Why do bodies emit gases that can be smelled in a certain way? — Well, you see, when we approach a body, we always find that we can divide bodies into solid bodies, which in earlier times were called earthy bodies, and liquid bodies, which in earlier times were called watery bodies. Water was also used to describe what is no longer called water today. In earlier times, everything that flows was called water, including mercury. Then there are the air-like or gaseous bodies. If we take these three types of bodies — the solid, the liquid, and the gaseous bodies — one thing stands out above all else. Water is certainly liquid, but it freezes into ice; then it is a solid body. Some metals, such as lead, are solid; if you heat them properly, they become liquid, like water. So these different substances – solids, liquids, gases – can be transformed into one another. Today, it is already possible to turn air into a solid, or at least into a liquid. And we can hope that we will be able to take this further and further. Every body can be solid, liquid, or gaseous.

Now let's take a body that smells. This is a body that, in a sense, contains gas trapped inside it. If we have a solid body on its own, we cannot smell it. If we have a liquid body on its own, we cannot smell it either. We can always smell a gas. But the violet is not a gaseous body, and yet we smell it. What about a body that appears to be solid, like the violet, and yet we smell it? We must imagine, gentlemen, that it is not like this (it is drawn), but that it contains such solid components, and that in between is what evaporates as gas. So we say to ourselves: the violet contains gas that can evaporate. — For this to happen, the violet must be attracted to certain forces. So when you pick the violet, you are actually only picking the solid part of the violet. You pick the solid part of the violet and look at it. Now, in reality, the violet does not consist solely of what you pick as the solid part. The essence of the violet, what it actually is, is contained in this solid part, and one could also say: the real violet, the one that smells, is actually a gas. It is contained within the leaf and so on, just as you are contained within your shoes or boots. And just as you are not your boots, so too is that which smells in the violet not contained within the solid part, but within the gaseous part.

Now, gentlemen, when you look out into the world: people believe that when you look out into the world, it is empty, and that the stars live in that empty space and so on. In the past, farmers believed that where they walked around, it was also empty. Today, everyone knows that there is air there, that it is not empty. Likewise, we can know that nowhere in outer space is empty; either there is matter there, or there is spirit there. You see, it can be proven that nowhere in outer space is empty. It is interesting to consider that it is not empty. I want to prove with a specific sign that it is not empty anywhere. Let us disregard for a moment that the earth revolves around the sun, as Copernicus taught mankind. Let us take things as they appear. Here we have the earth, and there the sun revolves around the earth, rising in the east and setting in the west. The sun is always somewhere (it is drawn). Now there is something peculiar. In certain areas, actually everywhere, if you look closely, when the sun rises and sets, but also at other times, there is not only twilight, but there is something else that always amazes the world. There is something around the sun that forms a kind of radiant light. Whenever you look at the sun, especially in the morning and evening, there is this radiant light in addition to the twilight. A light shines around the sun. It is called the zodiacal light. This zodiacal light, gentlemen, causes people a lot of headaches, especially those who think materialistically. They think to themselves: The sun can shine in empty space, and when it shines, we see that it illuminates other bodies. But where does this light that is always around the sun come from, this zodiacal light? People have come up with an incredible number of theories about where this zodiacal light comes from. If the sun is supposed to fly around in empty space, or even just stand still according to Copernican doctrine, there can't be any light there! Where does this light come from? — It is terribly easy to find out where this light comes from. You have certainly walked through the city on a very clear evening and seen lanterns. These lanterns have fixed boundaries. On a clear evening, you can see the lights with very definite boundaries. But if you go out on a foggy evening, you will not see such definite boundaries; instead, you will see a kind of ring of light all around. Where does it come from? Because there is fog. This glow of a ring of light is formed in the fog. The sun travels across the sky with a ring of light at certain times because the sky is not empty, but is filled with a fine fog everywhere. The zodiacal light is what appears as a glow in this fine fog. People have thought of all kinds of things. For example, that all kinds of comets fly through it. Certainly, they do. But this zodiacal light that goes with the sun, which is stronger at certain times, sometimes weak, sometimes not there at all, is because the nebulae in space become more or less dense or thin. So we can say: Actually, the whole of space is filled with something. — But I have already told you that it is not the case that one can now believe that there is matter everywhere. I have told you that physicists, materialistic physicists, would be very surprised if they went up there and expected the sun to look the way they describe it in physics today. That is nonsense. If physicists could travel up there, on some favorable train, into the sun, they would be astonished to find that there was nothing there that resembled gas. They would find a cavity, a real cavity. It shines light. And what they would find would be precisely the spiritual. So we cannot say: There is only matter everywhere — but we must say: There is also spirit everywhere, true spirit.

Well, gentlemen, it is not only matter from outer space that affects everything on earth; I have already explained that the spiritual also affects everything. Now, let us take a look at how the spiritual is connected to the physical in human beings.

Gentlemen, there is an obvious creature that can smell even better than you or I; that is the dog. Dogs have a much finer sense of smell than humans. You know that this sense of smell is being put to use today. There are police dogs that use their sense of smell to track down people who are criminals of some kind and who have run away. The dog is allowed to smell at the scene of a crime, it follows the trail, pursues the trail, and leads to the place where the criminal has arrived. Dogs have very sensitive olfactory nerves in their noses. It is very interesting to study this fine sense of smell in dogs. But it is also very interesting to study how the dog's olfactory nerves are connected to the rest of its body. Behind the nose, in the brain, the dog has a very interesting olfactory organ. The nose is only part of the olfactory organ. Behind the nose, in the brain, the dog has the main mass of its olfactory organ. Now we can compare the olfactory organs of dogs with those of humans.

Dogs have a distinct olfactory organ, a brain that can basically become the olfactory organ. In humans, most of this olfactory brain has been converted into the intellectual brain. What we have behind our nose is a converted olfactory organ. We understand things; dogs do not understand them, they smell them. We understand them because where dogs still have a proper olfactory organ, we have a transformed olfactory organ. Our intellectual organ is a transformed olfactory organ. We only have a small remnant of the olfactory brain, which is why we have a poorer sense of smell than dogs. So you can assume that when a dog walks through the fields, it is terribly interesting for the dog; it smells so many things that, if it could describe them all, it would describe the world as a smell. If there were a Schopenhauer among dogs — in terms of thinking — it could write interesting books. Schopenhauer wrote a book called “The World as Will and Representation” because he was a human being and his olfactory organ had become an organ of imagination. The dog would write an interesting book: “The World as Will and Smell.” It would contain so much that humans cannot know, because humans imagine things, and dogs smell them. I even believe that the book the dog would write would be much more interesting if the dog were a Schopenhauer than the book Schopenhauer wrote, “The World as Will and Representation”!

So you see how it turns out that we live in a world that can be smelled, and how other beings, such as dogs, perceive this world in a much higher sense than just smelling it.