The Evolution of the Earth and Man

and the Influence of the Stars

GA 354

6 August 1924, Dornach

Lecture VIII

Rudolf Steiner: Good morning, gentlemen! A number of questions have been handed in, which lead up in quite an interesting way to what we want to discuss today. Someone has asked:

“How did man's cultural development come about?” I will consider this in connection with a second question:

“Why did primitive man have such a strong belief in the spirit?”

It is certainly interesting to investigate how human beings lived in earlier times. As you know, even from a superficial view there are two opposing opinions about this. One is that man was originally at a high level of perfection, from which he has fallen to his present imperfect state. We don't need to take exception to this, or to be concerned with the way different peoples have interpreted this perfection—some talking of paradise, some of other things. But until a short time ago the belief existed that man was originally perfect and gradually degenerated to his present state of imperfection. The other view is the one you've probably come to know as supposedly the only true one, namely, that man was originally imperfect, like some kind of higher animal, and that he gradually evolved to greater and greater perfection. You know how people point to the primitive conditions prevailing among the savage peoples—the so-called savage peoples—in trying to form an idea of what man could have been like when he still resembled an animal. People say: We Europeans and the Americans are highly civilized, while in Africa, Australia, and so on, there still live uncivilized races at their original stage, or at least at a stage very near the original. From these one can study what humanity was like originally.

But, gentlemen, this is making far too simple a picture of human evolution. First of all, it is not true that all civilized peoples imagine man to have been a physically perfect being originally. The people of India are certainly not much in agreement with opinions of our modern materialists, and yet, even so, their conception is that the physical man who went about on the earth in primitive times looked like an animal. Indeed, when the Indians, the wise men of India, speak of man in his original state on earth, they speak of the ape-like Hanuman. So you see, it is not true that even people with a spiritual world view picture primeval man similarly to the way we imagine him in paradise. And in fact, it is not so.

We must rather have a clear knowledge that man is a being who bears within him body, soul, and spirit, with each of these three parts undergoing its own particular evolution. Naturally, if people have no thought of spirit, they can't speak of the evolution of spirit. But once we acknowledge that a human being consists of body, soul, and spirit, we can go on to ask how the body evolves, how the soul evolves, and how the spirit evolves. When we speak of the human body we will have to say: Man's body has gradually been perfected from lower stages. We must also say that the evidence we have for this provides us with living proof. As I have already pointed out, we find original man in the strata of the earth, exhibiting a very animal-like body—not indeed like any present animal but nevertheless animal-like, and this must have developed gradually to its present state of perfection. There is no question, therefore, of spiritual science as pursued here at the Goetheanum coming to loggerheads with natural science, for it simply accepts the truths of natural science.

On the other hand, gentlemen, we must be able to recognize that in the period of time of only three or four thousand years ago, views prevailed from which we can learn a great deal and which we also can't help but admire. When we are guided by genuine knowledge in seriously studying and understanding the writings that appeared in India, Asia, Egypt, and even Greece, we find that the people of those times were far ahead of us. What they knew, however, was acquired in quite a different way from the way we acquire knowledge today.

Today there are many things we know very little about. For instance, from what I have told you in connection with nutrition you will have seen how necessary it is for spiritual science to come to people's aid in the simplest nutritional matters. Natural science is unable to do so. But we have only to read what physicians of old had to say, and rightly understand it, to become aware that actually people up to the time of, for instance, Hippocrates12Hippocrates of Cos, 460–377 BC. Greek physician, founder of ancient medicine. in Greece knew far more than is known by our modern materialistic physicians. We come to respect, deeply respect, the knowledge once possessed. The only thing is, gentlemen, that knowledge was not then imparted in the same form as it is today. Today we express our knowledge in concepts. This was not so with ancient peoples; they clothed their knowledge in poetical imaginations, so that what remained of it is now just taken figuratively as poetry. It was not poetry to those men of old; that was their way of expressing what they knew. Thus we find when we are able to test and thoroughly study the documents still existing, that there can no longer be any question of original humanity being undeveloped spiritually. They may once have gone about in animal-like bodies, but in spirit they were infinitely wiser than we are!

But there is something else to remember. You see, when man went about in primeval times, he acquired great wisdom spiritually. His face was more or less what we would certainly call animal-like, whereas today in man's face his spirit finds expression; now his spirit is, as it were, embodied in the physical substance of his face. This, gentlemen, is a necessity if man is to be free, if he is to be a free being. These clever men of ancient times were very wise; but they possessed wisdom in the way the animal today possesses instinct. They lived in a dazed condition, as if in a cloud. They wrote without guiding their own hand. They spoke with the feeling that it was not they who were speaking but the spirit speaking through them. In those primeval times, therefore, there was no question of man being free.

This is something in the history of culture that constitutes a real step forward for the human race: that man acquired consciousness, that he is a free being. He no longer feels the spirit driving him as instinct drives the animal. He feels the spirit actually within him, and this distinguishes him from the man of former times.

When from this point of view we consider the savages of today, it must strike us that the men of primeval times—called in the question here primitive men—were not like the modern savages, but that the latter have, of course, descended from the former, from the primeval men. You will get a better idea of this evolution if I tell you the following.

In certain regions there are people who have the idea that if they bury some small thing belonging to a sick person—for instance, bury a shirttail of his in the cemetery—that this can have the magical effect of healing him. I have even known such people personally. I knew one person who, at the time the Emperor Frederick13Emperor Frederick III, 1831–1888. Suffered from a disease of the larynx. It is not known who wrote the request. was ill (when he was still Crown Prince—you know all about that), wrote to the Empress (as she was later), asking for the shirttails belonging to her husband. He would bury them in the cemetery and the Emperor would then be cured. You can imagine how this request was received. But the man had simply done what he thought would lead to the Emperor's recovery. He himself told me about it, adding that it would have been much less foolish to let him have that shirttail than to send for the English Doctor Mackenzie, and so on; that had been absurd—they should have given him the shirttail.

Now when this kind of thing comes to the notice of a materialist he says: That's a superstition which has sprung up somewhere. At some time or other someone got it into his head that burying the shirttails of a sick man in the cemetery and saying a little prayer over it would cure the man.

Gentlemen, nothing has ever arisen in that way. No superstition arises by being thought out. It comes about in an entirely different way. There was once a time when people had great reverence for their dead and said to themselves: So long as a man is going about on earth he is a sinful being; beside doing good things he does many bad things. But, they thought, the dead man lives on as soul and spirit, and death makes up for all deficiencies. Thus when they thought of the dead, they thought of what was good, and by thinking of the dead they tried to make themselves better.

Now it is characteristic of human beings to forget easily. Just think how quickly those who have left us—the dead—are forgotten today! In earlier times there were persons who would give their fellowman various signs to make them think of the dead and thus to improve them. Someone in a village would think that if a man was ill, the other villagers should look after him. It was certainly not the custom to collect sick pay; that kind of thing is a modern invention. In those days the villagers all helped one another out of kindness; everyone had to think of those who were ill. The leading man in the village might say: People are egoists, so they have no thought of the sick unless they are encouraged to get out of themselves and have thoughts, for instance, of the dead. So he would tell them they should take—well, perhaps the shirttail of the sick man by which to remember him, and they should bury this in the earth, then they would surely remember him. By thinking of the dead they would remember to take care of someone living. This outer deed was contrived simply to help people's memory.

Later, people forgot the reason for this and it was put down to magic, superstition. This happens with very much that lives on as superstition; it has arisen from something perfectly reasonable. What is perfect never arises from what is imperfect. The assertion that something perfect can come from what is not perfect appears to anyone with insight as if it were said: You're to make a table, but you must make it as clumsy and unfinished as you can to begin with, so that it may in time become a perfect table. But things don't happen that way. We never get a well-made table from one that is ill-made. The table begins by being a good one and becomes battered in the course of time. And that's the way it happens outside in nature too, anywhere in the world. You first have things in a perfect state, then out of them comes the imperfect. It is the same with the human being: his spirit in the beginning, though lacking freedom, was in a certain state of perfection. But his body—it is true—was imperfect. And yet precisely in this lay the body's perfection: it was soft and therefore capable of being formed by the spirit so that cultural progress could be made.

So you see, gentlemen, we are not justified in thinking that human beings were originally like the savages of today. The savages have developed into what they now are—with their superstitions, their magical practices and their unclean appearance-from states originally more perfect. The only superiority we have over them is that, while starting from the same conditions, we did not degenerate as they did. I might therefore say: The evolution of man has taken two paths. It is not true that the savages of today represent the original condition of mankind. Mankind, though to begin with it looked more animal-like, was highly civilized.

Now perhaps you will ask: But were those original animal-like men the descendants of apes or of other animals? That is a natural question. You look at the apes as they are today and say: We are descended from those apes. Ah! but when human beings had their animal form, there were no such animals as our present apes! Men have not descended, therefore, from the apes. On the contrary! Just as the present savages have fallen from the level of the human beings of primeval times, so the apes are beings who have fallen still lower.

On going back further in the evolution of the earth, we find human beings formed in the way I described here recently, out of a soft element-not out of our present animals. Human beings can never evolve out of the apes of today. On the other hand it could easily be possible that if conditions prevailing on earth today continue, conditions in which everything is based on violence and power, and wisdom counts for nothing—well, it could indeed happen that the men who want to found everything on power would gradually take on animal-like bodies again, and that two races would then appear. One race would be those who stand for peace, for the spirit, and for wisdom, while the other would be those who revert to an animal form. It might indeed be said that those who care nothing today for the progress of mankind, for spiritual realities, may be running the risk of degenerating into an ape species.

You see, all manner of strange things are experienced today. Of course, what newspapers report is largely untrue, but sometimes it shows the trend of people's thinking in a remarkable way. During our recent trip to Holland we bought an illustrated paper, and on the last page there was a curious picture: a child, a small child, really a baby—and as its nurse, taking care of it, bringing it up, an ape, an orangutan. There it was, holding the baby quite properly, and it was to be engaged, the paper said,—somewhere in America, of course—as a nursemaid.

Now it is possible that this may not yet be actual fact, but it shows what some people are fancying: they would like to use apes today as nursemaids. And if apes become nursemaids, gentlemen, what an outlook for mankind! Once it is discovered that apes can be employed to look after children—it is, of course, possible to train them to do many things; the child will have to suffer for it, but the ape could be so trained: in certain circumstances it could be trained to look after the physical needs of children—well, then people will carry the idea further and the social question will be on a new level. You will see far-reaching proposals for breeding apes and putting them to work in factories. Apes will be found to be cheaper than men, hence this will be looked upon as the solution of the social problem. If people really succeed in having apes look after their children—well, we'll be deluged by pamphlets on how to solve the social question by breeding apes!

It is indeed conceivable that this might easily happen. Only think: other animals beside apes can be trained to do many things. Dogs, for instance, are very teachable. But the question is whether this will be for the advance or the decline of civilization. Civilization will most definitely decline. It will deteriorate. The children brought up by ape-nurses will quite certainly become ape-like. Then indeed we shall have perfection changing into imperfection. We must realize clearly that it is indeed possible for certain human beings to have an ape-like nature in the future, but that the human race in the past was never such that mankind evolved from the ape. For when man still had an animal form—quite different indeed from that of the ape—the present apes were not yet in existence. The apes themselves are degenerate beings; they have fallen from a higher stage.

When we consider those primitive peoples who may be said to have been rich in spirit but animal-like in body, we find they were still undeveloped in reason, in intelligence—the faculty of which we are so proud. Those men of ancient times were not capable of thinking. Hence, when anyone today who prides himself particularly on his thinking comes across ancient documents, he looks for them to be based on thought—and looks in vain. He says, therefore: This is all very beautiful, but it's simply poetry. But, gentlemen, we can't judge everything by our own standards alone, for then we go astray. That ancient humanity had, above all, great powers of imagination, an imagination that worked like an instinct. When we today use our imagination we often pull ourselves up and think: Imagination has no place in what is real. This is quite right for us today, but the men of primeval times, primitive men, would never have been able to carry on without imagination.

Now it will seem strange to you how this lively imagination possessed by primitive men could have been applied to anything real. But here too we have wrong conceptions. In your history books at school you will have read about the tremendous importance for human evolution that is accorded to the invention of paper. The paper we write on—made of rags—has been in existence for only a few centuries. Before that, people had to write on parchment, which has a different origin. Only at the end of the Middle Ages did someone discover the possibility of making paper from the fibers of plants, fibers worn threadbare after having first been used for clothes. Human beings were late in acquiring the intellect that was needed for making this paper.

But the same thing (except that it is not as white as we like it for our black ink) was discovered long ago. The same stuff as is used for our present paper was discovered not just two or three thousand years ago but many, many thousands of years before our day. By whom, then? Not by human beings at all, but by wasps! Just look at any wasp's nest you find hanging in a tree. Look at the material it consists of—paper! Not white paper, not the kind you write on, for the wasps are not yet in the habit of writing, otherwise they would have made white paper, but such paper as you might use for a package. We do have a drab-colored paper for packages that is just what the wasps use for making their nests. The wasps found out how to make paper thousands and thousands of years ago, long before human beings arrived at it through their intellect.

The difference is that instinct works in animals while in the man of primeval times it was imagination; they would have been incapable of making anything if imagination had not enabled them to do so, for they lacked intelligence. We must therefore conclude that in outward appearance these primeval men were more like animals than are the men of today, but to a certain extent they were possessed by the spirit, the spirit worked in them. It was not they who possessed the spirit through their own powers, they were possessed by it and their souls had great power of imagination. With imagination they made their tools; imagination helped them in all they did, and enabled them to make everything they needed.

We, gentlemen, are terribly proud of all our inventions, but we should consider whether we really have cause to be so; for much of what constitutes the greatness of our culture has actually developed from quite simple ideas. Listen to this, for instance: When you read about the Trojan War, do you realize when it took place?—about 1200 years before the founding of Christianity. Now when we hear about wars like that—which didn't take place in Greece, but far away, over there in Asia—well, hearing the outcome the next day in Greece by telegram, as we would now do: that, gentlemen, didn't happen in those days! Today if we receive a telegram, the Post Office dispatches it to us. Naturally this didn't happen at that time in Greece, for the Greeks had no telegraph. What then could they do? Well, now look, the war was over here in one place; then there was the sea and an island, a mountain and again sea; over there another island, a mountain and then sea; and so on, till you came to Greece—here Asia, sea, and here in the midst, Greece. It was agreed that when the war was ended three fires would be kindled on the mountains. Whoever was posted on the nearest mountain was to give the first signal by running up and lighting three fires. The watch on the next mountain, upon seeing the three fires, lit three fires in his turn; the next watchman again three fires; and in this way the message arrived in Greece in quite a short time. This was their method of sending a telegram. It was done like that. It's a simple way of telegraphing. It worked fast—and before the days of the telegram people had to make do with this.

And how is it today? When you telephone—not telegraph but telephone—I will show you in the simplest possible way what happens. We have a kind of magnet which, it is true, is produced by electricity; and we have something called an armature. When the circuit is closed, this is pulled close; when the circuit is open, the armature is released, and thus it oscillates back and forth. It is connected by a wire with a plate, which vibrates with it and transmits what is generated by the armature—in just the same way as in those olden times the three fires conveyed messages to men. This is rather more complicated, and, of course, electricity has been used in applying it, but it is still the same idea.

When we hear such things we must surely respect what the human beings of those ancient times devised and organized out of their imaginative faculty. And when we read the old documents with this feeling we must surely say: Those men accomplished great things on a purely spiritual level and all out of imagination. To come to a thorough realization of this you need only to consider what people believe today. They believe they know something about the old Germanic gods—Wotan, Loki, for instance. You find pictures of them in human form in books: Wotan with a flowing beard; Loki looking like a devil, with red hair, and so on. It is thought that the men of old, the ancient Germans, had the same ideas about Wotan and Loki. But that is not true. The men of old had rather the following conception: When the wind blows, there is something spiritual in it—which is indeed true—and that is Wotan blowing in the wind. They never imagined that when they went into the woods, they would meet Wotan there in the guise of an ordinary man. To describe a meeting with Wotan they would have spoken of the wind blowing through the woods. This can still be felt in the very word Wotan by anyone who is sensitive to these things. And Loki—they had no image of Loki sitting quietly in a corner staring stupidly; Loki lived in the fire!

Indeed, in various ways the people were always talking about Wotan and Loki. Someone would say, for instance: When you go over the mountain, you may meet Wotan. He will make you either strong or weak, whichever you deserve. That is how people felt, how they understood these things. Today one says that's just superstition. But in those times they didn't understand it to be so. They knew: When you go up there to that corner so difficult to reach, you don't meet a man in a body like any ordinary man. But the very shape of the mountain gives rise to a special whirlwind in that place, and a special kind of air is wafted up to that corner from an abyss. If you withstand this and keep to your path, you may become well or you may become ill. In what way you become well or ill, the people were ready to tell; they were in harmony with nature and would speak not in an intellectual way but out of their imagination. Your modern doctor would try to express himself intellectually: If you have a tendency to tuberculosis, go up to a certain height on the mountain and sit there every day. Continue to do this for some time, for it will be most beneficial. That is the intellectual way of talking. But if you speak imaginatively you say: Wotan is always to be found in that high corner; if you visit him at a certain time every day for a couple of weeks, he will help you.

This is the way people coped with life out of their imagination. They worked in this way, too. Surely at some time or other you have all been far out in the country where threshing is not done by machine but is still being done by hand. You can hear the people threshing in perfect rhythm. They know that when they have to thresh for days at a time, if they go at their work without any order, just each one on his own, they will very soon be overcome by exhaustion. Threshing can't be done that way. If, however, they work rhythmically, all keeping time together, exhaustion is avoided—because their rhythm is then in harmony with the rhythm of their breathing and circulation. It even makes a difference whether they strike their flail on the out-breathing or the in-breathing or whether they do it as they are changing over from one to the other. Now why is this? You can see that it has nothing to do with intellect, for today this old way of threshing is almost unheard of. Everything of that kind is being wiped out. But in the past, all work was done rhythmically and out of imagination. The beginnings of human culture developed out of rhythm.

Now I don't suppose you really think that if you take a chunk of wood and some bits of string and fool about with them in some amateurish fashion, you'll suddenly have a violin. A violin comes about when mind, when spirit, is exerted, when the wood is carefully shaped in a particular way, when the string is put through a special process, and so forth. We have to say then: These primeval people, who were not yet thinking for themselves, could attribute the way machines were originally made only to the spirit that possessed them, that worked in them. Therefore, these people, working not out of the intellect, but out of their imagination, naturally tended to speak of the spirit everywhere.

When today someone constructs a machine by the work of his intellect, he does not say that the spirit helped him—and rightly so. But when a man of those early times who knew nothing about thinking, who had no capacity for, thinking, when that man constructed something, he felt immediately: the spirit is helping me.

It happened therefore that when the Europeans, those “superior” humans, first arrived in America and also later, in the nineteenth century, when they came to the regions where Indians such as belonged to ancient times were still living, these Indians spoke of (it was possible to find out what they were saying) the “Great Spirit” ruling everywhere. These primitive men have always continued to speak in this way of the Being ruling in everything. It was this “Great Spirit” that was venerated particularly by the human beings living in Atlantean times when there was still land between Europe and America; the Indians retained this veneration, and knew nothing as yet of intellect. They then came gradually to know the “superior” men before being exterminated by them. They came to know the Europeans' printed paper on which there were little signs which they took to be small devils. They abhorred the paper and the little signs, for these were intellectual in origin, and a man whose activities arise out of imagination abominates what comes from the intellect.

Now the European with his materialistic civilization knows how to construct a locomotive. The intellectual method by which he constructs his engine could never have been the way the ancient Greeks would have set about it, for the Greeks still lacked intellect. Intellect first came to man in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The Greeks would have carried out their construction with the help of their imagination. Since the Greeks ascribed all natural forms to good spirits and all that is not nature, all that is artificially produced, to bad spirits, they would have said: An evil spirit lives in the locomotive. They would certainly have contrived their construction from imagination; nothing else would ever have occurred to them than that they were being aided by the spirit.

Therefore, gentlemen, you see that we have actually to ascribe a lofty spirit to the original, primitive human being; for imagination is of a far more spiritual nature in the human soul than the mere intellect that is prized so highly today.

Former conditions, however, can never come back. We have to go forward—but not with the idea that what exists today in the animal as pure instinct could ever have developed into spirit. We ought not, therefore, to picture primitive men as having been possessed of mere instinct. They knew that it was the spirit working in them. That is why they had, as we say nowadays, such a strong belief in the spirit.

Perhaps this contributes a little to our understanding of how human culture has evolved. Also, we must concede that the people are right who contend that human beings have arisen from animal forms, for so indeed they have—but not from such forms as the present animals, for these forms only came into being later when humanity was already in existence. The early animal-like forms of man which gradually developed in the course of human evolution into his present form, together with the faculties which he already had at that time, came about because man's spiritual entity was originally more perfect than it is today—not in terms of intellect but of imagination. We have to remember always that this original perfection was due to the fact that man was not free; man was, as it were, possessed by the spirit. Only intellect enables man to become free. By means of his intellect man can become free.

You see, anyone who works with his intellect can say: now at a certain hour I'm going to think out such and such a thing. This can't be done by a poet, for even today a poet still works out of his imagination. Goethe was a great poet. Sometimes when someone asked him to write a poem or when he himself felt inclined to do so, he sat himself down to write one at a certain time—and, well, the result was pitiful! That people are not aware of this today comes simply from their inability to distinguish good poetry from bad. Among Goethe's poems there are many bad ones. Imaginative work can be done only when the mood for it is there, and when the mood has seized a poet, he must write the poem down at once. And that's how it was in the case of primeval humans. They were never able to do things out of free will. Free will developed gradually-but not wisdom. Wisdom was originally greater than free will and it must now regain its greatness. That means, we have to come back to the spirit by way of the intellect.

And that, you see, is the task of anthroposophy. It has no wish to do what would please many people, that is, to bring primitive conditions back to humanity-ancient Indian wisdom, for example. It is nonsense when people harp on that. Anthroposophy, on the other hand, sets value on a return to the spirit, but a return to the spirit precisely in full possession of the intellect, with the intellect fully alive. It is important, gentlemen, and must be borne strictly in mind, that we have nothing at all against the intellect; rather, the point is that we have to go forward with it. Originally human beings had spirit without intellect; then the spirit gradually fell away and the intellect increased. Now, by means of the intellect, we have to regain the spirit. Culture is obliged to take this course.

If it does not do so—well, gentlemen, people are always saying that the World War was unlike anything ever experienced before, and it is indeed a fact that men have never before so viciously torn one another to pieces. But if men refuse to take the course of returning to the spirit and bringing their intellect with them, then still greater wars will come upon us, wars that will become more and more savage. Men will really destroy one another as the two rats did that, shut up together in a cage, gnawed at each other till there was nothing left of them but two tails. That is putting it rather brutally, but in fact mankind is on the way to total extermination. It is very important to know this.

Achter Vortrag

Nun, meine Herren, es sind mir eine Reihe von Fragen überreicht worden, die ganz interessant zu der heutigen Besprechung gehören können. Jemand aus Ihrem Kreise hat die Frage überreicht:

Woraus ist die Kulturentwicklung des Menschen entstanden?

Ich werde es gleich im Zusammenhang dann betrachten mit der zweiten Frage:

Warum war bei den primitiven Menschen der Glaube an einen Geist so groß?

Nun, sehen Sie, es ist ja zweifellos interessant, sich zu fragen: Wie haben die Menschen in früheren Zeiten gelebt? - Und es gibt ja, wie Sie wissen, auch wenn man die Sache nur oberflächlich betrachtet, zwei Ansichten. Die eine Ansicht geht dahin, daß der Mensch ursprünglich recht vollkommen war und aus seiner Vollkommenheit heruntergefallen ist zu der heutigen Unvollkommenheit. Man braucht sich nicht besonders daran zu stoßen und damit zu beschäftigen, daß die verschiedenen Völker diese ursprüngliche Vollkommenheit sich in verschiedener Weise auslegen. Der eine spricht vom Paradies, der andere von etwas anderem; aber die Ansicht war ja noch bis vor ganz kurzer Zeit vorhanden, daß der Mensch ursprünglich vollkommen war und er sich erst nach und nach zu seiner jetzigen Unvollkommenheit heranbildete. Die andere Ansicht ist diejenige, die Sie ja wahrscheinlich kennengelernt haben als die, welche allein wahr sein soll: daß der Mensch ursprünglich ganz unvollkommen war, so eine Art höheres Tier war, und sich allmählich zu immer größerer Vollkommenheit entwickelt habe. Sie wissen ja, daß man dann versucht, diejenigen Urzustände, die heute noch unter den wilden Völkern sind — sogenannten wilden Völkern -, daß man diese benützt, um sich ein Ansicht darüber zu bilden, wie die Menschen ursprünglich, als sie noch tierähnlich waren, eigentlich haben sein können. Man sagt sich: Wir in Europa und die Leute in Amerika sind hoch zivilisiert; aber in Afrika, in Australien und so weiter, da leben noch unzivilisierte Völker, die sind auf der ursprünglichen Stufe oder wenigstens auf einer Stufe, die der ursprünglichen sehr nahe stand, stehengeblieben; an denen kann man studieren, wie die ursprüngliche war.

Sehen Sie, meine Herren, die Leute machen sich aber die Vorstellung, die man über die Entwickelung der Menschheit haben muß, dabei viel, viel zu einfach. Denn erstens ist es gar nicht wahr, daß zum Beispiel alle zivilisierten Völker sich vorstellen, daß der Mensch ursprünglich als physisches Wesen vollkommen gewesen wäre. Die Inder haben ganz gewiß nicht die Ansicht, welche die heutigen Materialisten haben, aber sie stellen sich doch vor, daß die Menschen, die in der Urzeit physisch auf der Erde herumgegangen sind, dennoch tierähnlich ausgesehen haben. Und wenn man bei den Indern, bei den indischen Weisen von dem ursprünglichen Menschen auf der Erde redet, so redet man auch von Hanuman, der affenähnlich ausgesehen hat. Nun, sehen Sie, das ist schon einmal nicht wahr, daß auch die Menschen, die eine geistige Weltanschauung haben, sich überall vorstellen, daß der Mensch ursprünglich irgendwie so war, wie sich ungefähr die Leute heute vorstellen, daß der Mensch im Paradiese war — das ist eben doch schon nicht so. Man muß sich vielmehr darüber klar sein, daß der Mensch ja ein Wesen ist, welches in sich trägt Leib, Seele und Geist, und daß Leib, Seele und Geist verschiedene Entwickelungen durchgemacht haben. Natürlich, wenn man gar nicht vom Geist spricht, so kann man auch nicht von der Entwickelung des Geistes sprechen. Aber sobald man darauf kommt, daß eben der Mensch aus Leib, Seele und Geist besteht, kann man durchaus davon sprechen: Wie entwickelt sich der Leib? Wie entwickelt sich die Seele? Wie entwickelt sich der Geist? — Soll man sprechen vom Leib des Menschen, dann kommt man schon dazu, sich zu sagen: Der Leib des Menschen, der hat sich allmählich aus niederen Stufen vervollkommnet. Da muß man auch sagen: Dafür sind schon die Zeugnisse, die man hat, ein lebendiger Beweis. - Man findet, wie ich Ihnen ja schon angedeutet habe, in den Schichten der Erde den ursprünglichen Menschen; er zeigt einen Leib, der eben noch sehr tierähnlich ist — nicht so wie irgendein heutiges Tier, aber der eben doch tierähnlich ist, und der sich vervollkommnet haben muß, damit er die heutige Gestalt hat annehmen können. Es ist also gar keine Rede, daß Geisteswissenschaft, so wie sie hier am Goetheanum getrieben wird, in einen Widerspruch kommt mit der Naturwissenschaft, weil sie einfach die Wahrheiten der Naturwissenschaft aufnimmt.

Dagegen, meine Herren, muß man auch wiederum das feststellen, daß in diesen Zeiten, die eigentlich nur, man könnte sagen um dreitausend oder viertausend Jahre zurückliegen, daß in solchen Zeiten Ansichten entstanden sind, aus denen wir heute nicht nur sehr viel lernen können, sondern die wir bewundern müssen. Wenn wir heute mit einer wirklichen Sachkenntnis die Schriften, die in Indien, in Asien, in Ägypten, selbst in Griechenland entstanden sind, wirklich studieren und verstehen, dann finden wir, daß die Leute damals uns weit voraus waren. Nur haben sie dasjenige, was sie gewußt haben, eben auf eine ganz andere Weise erworben, als es heute erworben wird.

Sehen Sie, heute weiß man von vielen Dingen sehr wenig. Zum Beispiel haben Sie gesehen aus dem, was ich Ihnen über die Ernährung dargestellt habe, wie die Geisteswissenschaft nachhelfen muß, damit man auf die einfachsten Dinge der Ernährung wieder kommt. Das kann nun eben die physische Wissenschaft nicht. Aber gerade wenn man bei alten Medizinern nachliest und ihre Worte richtig versteht, dann kommt man darauf, daß die Leute eigentlich zum Beispiel noch bis Hippokrates in Griechenland im Grunde genommen viel mehr wußten, als die heutigen materialistischen Mediziner wissen. Und man bekommt Respekt, man bekommt Hochachtung vor demjenigen, was einmal vorhanden war an Wissen. Nur, sehen Sie, meine Herren, war die Sache so, daß man das Wissen nicht so ausgedrückt hat wie heute. Man drückt heute das Wissen in Begriffen aus. Die alten Völker haben das Wissen nicht in Begriffen ausgedrückt, sie haben es ausgedrückt in dichterischen Vorstellungen, so daß dasjenige, was da übriggeblieben ist, heute eben vielfach als Dichtung genommen wird. Aber es war für die alten Menschen nicht Dichtung, es war dasjenige, wodurch sie ihr Wissen, ihre Erkenntnis ausgedrückt haben. Und so kommen wir darauf, daß schon, wenn wir dasjenige, was schriftlich vorhanden ist, prüfen und richtig studieren können, dann gar keine Rede davon sein kann, daß ursprünglich die Menschen ganz unvollkommen gewesen sind an Geist. Diese Menschen, die einmal in tierischen Körpern herumgegangen sind, die waren eben an Geist viel, viel weiser, als wir sind.

Aber auch das muß man wiederum festhalten: Sehen Sie, wenn solch ein ursprünglicher Mensch herumgegangen ist, so hatte er seinen Geist sehr weise ausgebildet. Sein Gesicht war mehr oder weniger — wir würden heute sagen: tierähnlich. Na ja, schön. Aber der heutige Mensch, der drückt in seinem Gesicht schon den Geist aus. In die Materie des Gesichtes ist der Geist schon hineingebaut. Das, meine Herren, ist notwendig, damit der Mensch frei sein kann, ein freies Wesen sein kann. Diese sehr gescheiten Menschen von ehemals, diese sehr gescheiten Menschen der Urzeit, waren zwar weise, aber sie haben die Weisheit so gehabt, wie heute das Tier seine Instinkte hat. Sie haben dumpf, wie im Nebel gelebt. Sie haben geschrieben, ohne daß sie selber irgendwie die Hand geführt hätten; sie haben gesprochen so, daß sie geglaubt haben, nicht sie selber sprechen, sondern eben der Geist spricht in ihnen. Also von einem freien Menschen war in diesen Urzeiten nicht die Rede.

Und das ist dasjenige, was ein wirklicher Fortschritt des Menschengeschlechtes in der Kulturgeschichte ist: daß der Mensch ein Bewußtsein gekriegt hat, daß er ein freies Wesen ist. Dadurch fühlt er den Geist nicht mehr als etwas, das ihn, wie der Instinkt das Tier, treibt, sondern er fühlt den Geist in sich. Und das ist dasjenige, was die heutigen Menschen unterscheidet von den früheren.

Sehen Sie, wenn wir von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus die heutigen Wilden anschauen, so müssen wir uns vorstellen, daß die Menschen in der Urzeit — die hier in der Frage die primitiven Menschen genannt werden — nicht so waren wie die heutigen Wilden. Und Sie werden eine Vorstellung bekommen, wie die heutigen Wilden aus den Menschen der Urzeit geworden sind, wenn ich Ihnen etwa das Folgende sage: Es gibt in gewissen Gegenden Menschen, die tragen sich mit der Idee, daß sie, wenn sie ein Stücklein von irgend jemandem, von einem Kranken, eingraben in die Erde, und dieses so machen, daß sie das Stück Hemdleinen zum Beispiel eingraben im Friedhof, sie damit eine Zauberwirkung bewirken, daß der Kranke gesund werden kann. Ich habe solche Menschen noch kennengelernt. Ich habe sogar einen kennengelernt, der hat ein Gesuch geschrieben, als der Kaiser Friedrich, der dazumal noch Kronprinz war, krank war — Sie wissen ja die Geschichte -, ein Gesuch an die spätere Kaiserin, daß man ihm einen Hemdzipfel vom Kaiser Friedrich schicken solle; er werde das dann im Friedhof eingraben und dann werde der Kaiser Friedrich gesund werden. Nun, Sie können sich denken, daß dieses Gesuch nicht gerade sehr gut beschieden worden ist! Aber der Mann hat das eben gemacht, weil er geglaubt hat, daß er dadurch den Kaiser Friedrich gesund machen könne. Er hat mir das selbst erzählt. Und er hat mir erzählt, daß es viel gescheiter gewesen wäre, wenn man ihm das Hemdzipferl geschickt hätte, als daß man solchen Unsinn gemacht hätte, den englischen Arzt Mackenzie zu dem Kaiser zu rufen und so weiter. Das wäre alles Unsinn gewesen, man hätte ihm müssen diesen Hemdzipfel schicken.

Sehen Sie, diese Sache verfolgt nun derjenige, der materialistisch denkt, und sagt: Das ist ein Aberglaube, der einmal irgendwo entstanden ist. Irgendeinmal hat ein Mensch sich in den Kopf gesetzt, wenn man auf dem Friedhof einen Hemdzipfel eingräbt und dabei ein gewisses Gebet verrichtet, so wird derjenige, für den man das Gebet verrichtet, gesund.

Aber auf diese Weise ist nie ein Aberglaube entstanden, meine Herren. Ein Aberglaube ist nie auf die Weise entstanden, daß das jemand sich ausgedacht hat, sondern er entsteht auf eine ganz, ganz andere Art. Es war einmal so, daß die Leute ihre Toten ganz stark verehrt haben und sich gesagt haben: Solange der Mensch auf der Erde herumgeht, ist er eben ein sündhafter Mensch, begeht neben dem Guten auch Schlechtes. — Sie haben die Vorstellung gehabt: Der Tote lebt in der Seele und im Geiste fort. Der Tod gleicht alles aus. - Und wenn sie an den Toten denken, dann denken sie an etwas Gutes. Diese Vorstellung haben die Leute gehabt: Wenn sie an einen Toten denken, dann denken sie an etwas Gutes. Und sie haben sich selber besser machen wollen dadurch, daß sie an ihre Toten gedacht haben.

Nun ist es aber bei den Menschen so, daß die Leute die Sache leicht vergessen. Denken Sie nur, wie schnell werden Tote, Abgeschiedene vergessen! Da fanden sich dann andere Leute, die wollten allerlei Merkzeichen an die Leute heranbringen, damit sie an die Toten denken und dadurch selber besser werden sollten.

Sagen wir, es hat jemand die Absicht gehabt, daß in einem Dorf, wenn einer krank ist, sich die Leute des Kranken annehmen. Ja, in den Dörfern war es doch früher so, daß man nicht Krankengeld gekriegt hat - Krankenkassen oder so etwas, das wissen Sie, ist eine neuere Einrichtung —; da mußte einer dem andern aushelfen im Dorfe aus gutem Willen. Er mußte an den Kranken denken. Nun hat sich derjenige, der das Dorf geleitet hat, gesagt: Die Leute werden, weil sie egoistisch sind, nicht an die Kranken denken, wenn sie nicht überhaupt angespornt werden, aus sich herauszugehen und zum Beispiel an die Toten zu denken. Und da hat er ihnen gesagt, sie sollen von dem Kranken ein Hemdzipferl nehmen — dadurch werden sie erinnert, daß der Kranke da ist — und das Hemdzipferl eingraben. Dadurch werden sie daran erinnert, daß man sorgen soll für jemanden, indem sie an den Toten denken. Und es ist dasjenige, was äußerliche Handlung ist, eigentlich nur für den Menschen wie eine Gedächtnishilfe eingerichtet worden. Später hat man vergessen, wozu das da war und hat der Sache Zauberwirkung, Aberglaubenwirkung zugeschrieben. So ist es mit sehr vielem, was da lebt als Aberglaube; es ist ausgegangen von etwas ganz Vernünftigem. Niemals ist etwas Vollkommenes ausgegangen von etwas Unvollkommenem. Derjenige, der das durchschaut, dem kommt die Behauptung, daß etwas Vollkommenes aus Unvollkommenem entstehen kann, so vor, als wenn man sagt: Du mußt einen Tisch machen, aber den mußt du zuerst möglichst plump und unvollkommen machen, damit er dann vollkommener werden kann. — So ist es doch nicht! Man kriegt niemals aus einem zerschlagenen Tisch einen richtigen. Erst ist der Tisch richtig und dann wird er auch zerschlagen. Und so ist es auch draußen in der Natur und in der Welt überhaupt. Zuerst müssen die vollkommenen Dinge da sein, dann können daraus die unvollkommenen entstehen. Und so ist es beim Menschen: er hat seinen Geist zuerst in einer gewissen Vollkommenheit gehabt, wenn auch noch unfrei — den Körper allerdings unvollkommen. Aber das war ja gerade wiederum das Vollkommene des Körpers, daß er weich war, daß er sich durch den Geist hat formen lassen, daß die Kultur dadurch höhersteigen konnte.

Also sehen Sie, meine Herren, wir dürfen nicht die Ansicht haben, daß ursprünglich die Menschen so waren wie die heutigen Wilden. Die heutigen Wilden sind so geworden, wie sie heute sind: abergläubisch, zauberisch, aber auch im Äußern schmutzig, aus ursprünglich vollkommeneren Zuständen; und wir haben den Wilden nur das voraus, daß wir von denselben Zuständen ausgegangen sind - nur, die sind heruntergekommen und wir sind eben nicht heruntergekommen. Also ich möchte sagen: Nach zwei Seiten hin hat sich eben die Menschheit entwickelt. Es ist gar nicht wahr, daß die heutigen Wilden darstellen einen Zustand, in dem die Menschheit ursprünglich war. Diese Menschen, die ursprünglich mehr tierisch ausgesehen haben, diese Menschen sind sehr zivilisiert gewesen.

Wenn Sie nun die Frage aufwerfen: Stammen denn aber diese ursprünglichen tierischen Menschen ab von den Affen oder von anderen Tieren? -, da kommen Sie natürlich dann auf folgendes: Sie schauen die heutigen Affen an und sagen sich: Von den Affen stammen die Menschen ab. — Ja, aber als der Mensch in dieser tierischen Form da war, da gab es die heutigen Affen noch gar nicht! Also von den heutigen Affen stammt der Mensch nicht ab. Im Gegenteil! So wie die heutigen Wilden heruntergekommene Menschen der Urzeit sind, so sind die heutigen Affen auch wiederum noch mehr heruntergekommene Wesen. Und wenn wir weiter in der Entwickelung der Erde hinaufgehen, so finden wir eben Menschenwesen, die sich so gebildet haben, wie ich es vor einigen Stunden hier dargestellt habe: aus einem weichen Element heraus, nicht aus dem heutigen Tiere. Aus dem heutigen Affen werden niemals Menschen entstehen. Dagegen könnte es sehr leicht sein, wenn diejenigen Zustände, die heute vielfach auf der Erde herrschen, wo alles auf Gewalt gegründet ist, wo alles auf Macht gegründet ist, wo die Weisheit gar nichts gilt - ja, das könnte sehr leicht sein, daß die Menschen, die heute alles auf Macht gründen wollen, daß die allmählich wiederum eine tierische Körperlichkeit annehmen, und daß zwei große Rassen entstehen: eine, also diejenigen, die für den Frieden, den Geist und die Weisheit sind, und eine andere, die tierische Gestalten wieder annimmt. Und wir könnten schon sagen: Diejenigen Menschen, die heute gar nichts geben auf den wirklichen Menschheitsfortschritt, auf das Geistige, die könnten in der Gefahr stehen, einmal in die Affenhaftigkeit zu verfallen.

Sehen Sie, man erlebt ja heute allerlei sonderbare Sachen. Natürlich ist dasjenige, was in den Zeitungen berichtet wird, meistens nicht wahr, aber manchmal weist es in ganz besonderer Art auf die Denkungsart der Menschen hin. Neulich, auf der holländischen Reise, kauften wir eine illustrierte Zeitung. In dieser illustrierten Zeitung war auf der letzten Seite ein ganz sonderbares Bild: Da war ein Kind, ein kleines Kind, ein Baby, und als Pfleger, als Aufzieher, als Erzieher ein Affe, ein Orang-Utan; der hält das Kind ganz wacker im Arm und sollte also angestellt werden — man berichtete, er wäre angestellt, natürlich irgendwo in Amerika - als Kinderaufzieher!

Nun, die Sache mag ja heute noch nicht wahr sein, aber es zeigt doch, wohin die Sehnsucht mancher Menschen geht: Die möchten die heutigen Affen aufziehen als Kinderwärter. Ja, meine Herren, da können wir ja weit kommen in der Menschheit, wenn die Affen Kinderwärter werden! Aber Sie wissen ja, die Sehnsucht mancher Menschen geht ja überhaupt noch weiter. Sollte es nur einmal entdeckt werden, daß Affen als Kinderwärter benützt werden können — einen Affen kann man zu manchem abrichten; das Kind wird es zwar zu büßen haben, aber einen Affen kann man zu manchem abrichten; rein äußerlich kann ja unter Umständen ein Affe schon einmal als Kinderwärter abgerichtet werden -, dann werden die Leute eine merkwürdige Sehnsucht bekommen. Dann wird zum Beispiel die soziale Frage auf eine ganz neue Stufe gestellt werden, denn dann werden Sie gleich sehen, wie die Vorschläge kommen, man solle große Affenzüchtereien einrichten und man solle sich die Fabrikarbeiten von Affen machen lassen! Denn die Menschen werden finden, daß die Affen billiger sind als die Menschen, und daher wird das als eine Lösung der sozialen Frage gebracht werden. Wenn es wirklich gelingen wird, die Affen zu Kinderwärtern zu machen - die Broschüren über die Lösung der sozialen Frage durch Aufzucht der Affen, die dann erscheinen, die werden massenhaft sein!

Ja, man kann sich denken, daß das sogar geschehen könnte. Denken Sie doch nur einmal, andere Tiere als die Affen kann man zu so manchem aufziehen; sogar die Hunde kann man zu manchem anlernen. Aber es frägt sich, ob damit die Zivilisation vorwärtskommt oder zurückkommt. Sie kommt ganz gewiß zurück! Herunter kommt sie. Die Kinder, die eben von Affenwärtern oder -wärterinnen aufgezogen werden, die werden ganz sicher affenartig werden! Dann wird sich das Vollkommene eben in das Unvollkommene verwandeln. So müßten wir eben uns klar sein darüber, daß zwar die Zukunft gewisser Menschen die Affenähnlichkeit sein könnte, aber daß die Vergangenheit des Menschengeschlechtes niemals eine solche war, daß wirklich aus der Affenhaftigkeit sich die Menschheit herausgebildet hat. Denn als die Menschen noch ihre tierische Gestalt, die ganz anders ausgeschaut hat als die heutige Affengestalt, hatten, da gab es eben noch nicht die heutigen Affen. Die sind selber heruntergekommene Wesen, von einer höheren Stufe heruntergekommen.

Wenn wir nun zu diesen primitiven Völkern gehen, die, wenn man so sagen darf, groß an Geist und tierisch an Körper waren, so findet man, daß bei denen der Verstand, die Intelligenz, auf die wir so stolz sind, eben noch nicht ausgebildet war. Denken haben diese alten Menschen nicht gekonnt. Wenn daher heute einer, der sich durch Denken besonders gescheit fühlt, herankommt an die alten Schriften, so sucht er Gedankengründe. Die findet er nicht. Also sagt er: Es ist zwar sehr schön, aber Dichtung. — Ja, meine Herren, wir können aber nicht alles nur nach uns beurteilen! Es ist ganz falsch, wenn wir alles bloß nach uns beurteilen. Diese Menschen in einer früheren Zeit, die haben vor allen Dingen eine ganz starke Phantasie gehabt, eine Phantasie, die wie ein Instinkt gewirkt hat. Wenn wir heute unsere Phantasie brauchen, dann werfen wir uns das oftmals sogar vor, weil wir sagen: Die Phantasie bezieht sich nicht auf etwas Wirkliches. -— Für uns heute haben wir damit ganz recht; aber die Menschen der Urzeit, die primitiven Menschen hätten überhaupt nichts anfangen können, wenn sie nicht die Phantasie gehabt hätten.

Nun wird Ihnen das merkwürdig erscheinen, daß die Menschen der Urzeit eine so lebhafte Phantasie gehabt haben, die auf irgend etwas Wirkliches gegangen ist. Aber sehen Sie, auch da hat man wiederum ganz falsche Vorstellungen. Sie werden in Ihren Schulbüchern der Geschichte gelesen haben, was es für eine große Bedeutung in der Entwickelung der Menschheit hatte, als das sogenannte Leinenlumpenpapier erfunden worden ist. Ja, meine Herren, das Papier, auf dem wir heute alle unsere Sachen drauf schreiben, das aus Lumpen gemacht wird, das besteht ja erst ein paar Jahrhunderte! Früher hat man auf Pergament schreiben müssen, das auf ganz andere Weise entstanden ist. Daß man die Pflanzenfasern, aus denen ursprünglich unsere Kleider gemacht wurden, nachdem die Kleider abgetragen sind, verarbeiten kann zu Papier, das ist eben erst, als das Mittelalter zu Ende war, von den Menschen entdeckt worden. Der Verstand ist über die Menschen spät gekommen. Und das haben die Menschen mit dem Verstand entdeckt, dieses Leinenlumpenpapier. Aber ganz dasselbe, nur nicht gerade so weiß, wie wir unser Papier für die schwarze Tinte haben wollen, das ist ja längst entdeckt gewesen! Derselbe Stoff wie unser heutiges Papier war ja längst entdeckt, und zwar nicht etwa ein paar tausend Jahre vorher, sondern viele, viele tausend Jahre vorher. Aber von wem? Überhaupt nicht von Menschen, sondern von den Wespen! Schauen Sie sich einmal ein solches Wespennest an, das an den Bäumen hängt. Nehmen Sie den Stoff, aus dem es besteht; aber Sie müssen nicht weißes Papier nehmen, nicht das Papier, das man zum Schreiben braucht, denn die Wespen haben sich eben das Schreiben noch nicht angewöhnt, sonst würden sie auch weißes Papier machen, auf dem sie schreiben könnten, sondern solches Papier, wie man es bloß zum Einwickeln braucht. Wir haben zum Einwickeln ja auch graues Papier. Dieses graue Papier, meine ‚Herren, das ist ganz dasselbe wie das, woraus die Wespen ihr Wespennest machen! Die Wespen haben viele, viele tausend Jahre vorher das Papier entdeckt, bevor die Menschen durch den Verstand darauf gekommen sind. Es ist eben der Unterschied: Bei den Tieren wirkte der Instinkt, bei den ursprünglichen Menschen die Phantasie. Die hätten gar nichts machen können, wenn sie nicht aus der Phantasie heraus etwas hätten machen können, denn Verstand hatten sie nicht. So daß man also sagen muß: Diese ursprünglichen Menschen schauten äußerlich mehr tierisch aus als die heutigen Menschen, sie waren aber gewissermaßen besessen von dem Geist; der wirkte in ihnen. Sie besaßen ihn noch nicht durch sich selber, sie waren besessen vom Geist, und ihre Seele hatte große Phantasie. Mit der Phantasie machten sie ihre Werkzeuge, mit der Phantasie machten sie alles, was sie überhaupt machen konnten, was sie brauchten.

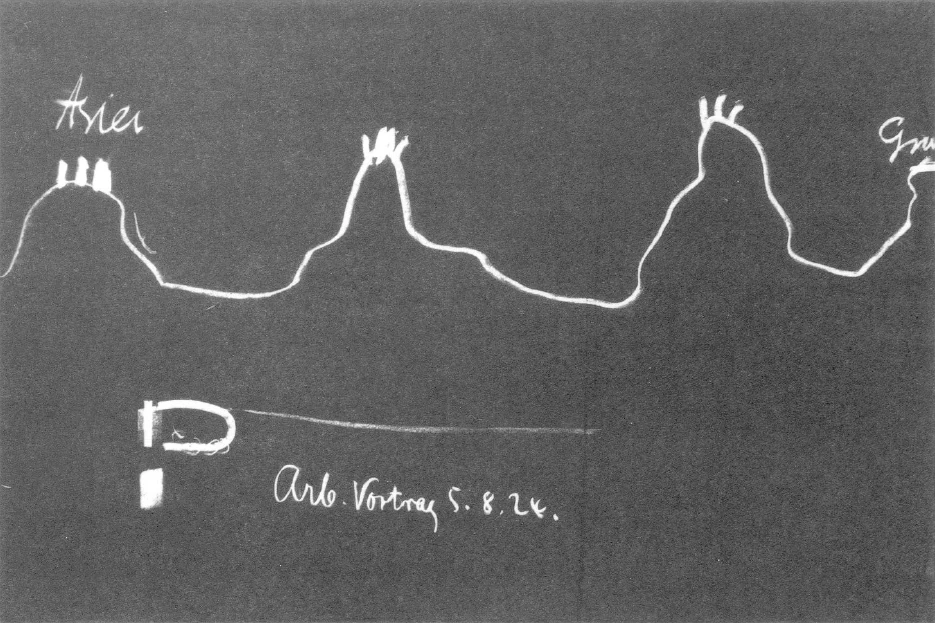

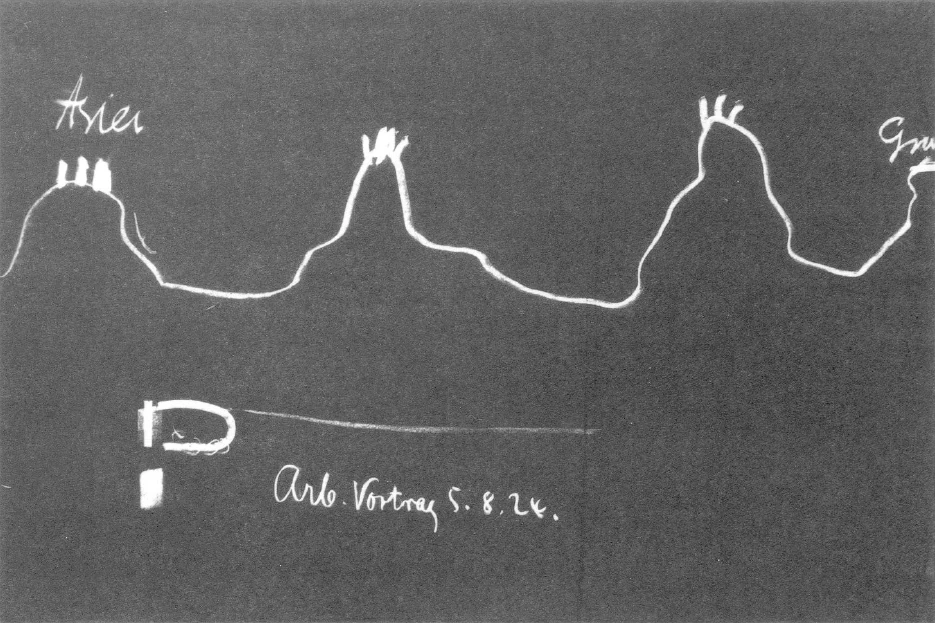

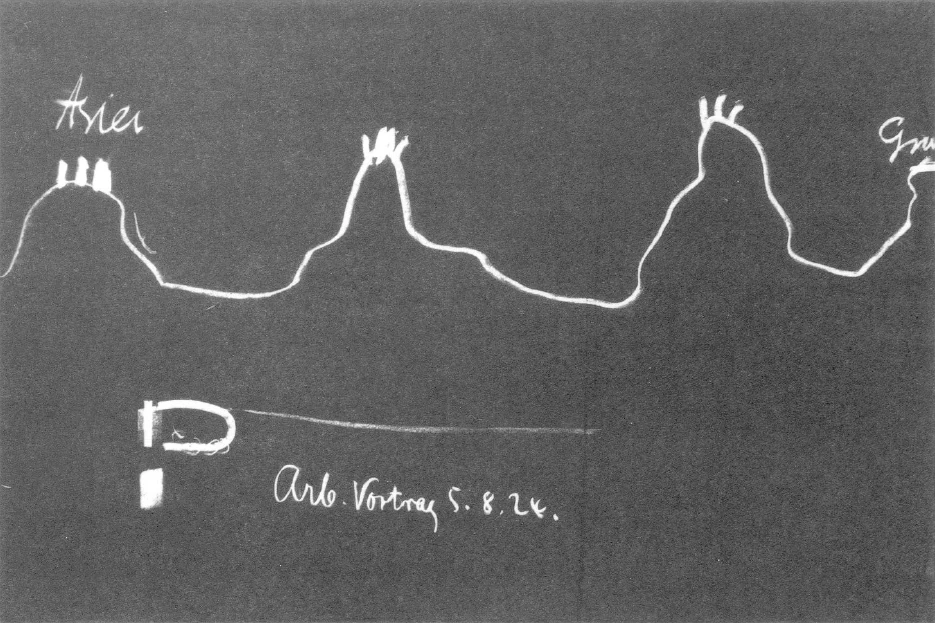

Wir sind auf alle unsere Erfindungen so furchtbar stolz, aber wir sollten auch bedenken, daß wir ja nicht gar so stolz zu sein brauchen, denn es ist vieles von dem, was heute die Größe der Kultur ausmacht, eigentlich entsprungen aus einfachen Gedanken. Sehen Sie, meine Herren, ich will Ihnen etwas sagen: Wenn wir über den Trojanischen Krieg lesen — wissen Sie, wann der stattgefunden hat? Etwa 1200 Jahre vor der Begründung des Christentums. Nun, wenn wir von solchen Kriegen hören, die nicht in Griechenland stattgefunden haben, sondern weit weg von Griechenland, in Asien drüben — ja, daß am nächsten Tag durch ein Telegramm in Griechenland die Leute erfahren haben, wie der Krieg ausgegangen ist, der drüben in Asien war, ja, so ist das nicht gegangen wie heute! Heute schickt einem, wenn man ein Telegramm kriegt, die Post das Telegramm herauf; so kriegt man es. Das ist natürlich in Griechenland nicht so gewesen, denn die Griechen haben keine elektrischen Telegraphen gehabt. Wie haben Sie es denn gemacht? Ja, sehen Sie, dahier war Krieg (es wird gezeichnet), dahier war Meer, da eine Insel, da ein Berg, da wieder Meer; da eine Insel, ein Berg und so weiter bis zu Griechenland herunter - hier Asien, dazwischen Meer, da Griechenland. Es war verabredet, daß wenn der Krieg ausgeht, auf dem Berg drei Feuer angezündet werden. Derjenige, der am nächsten Berg war, der hat zunächst dadurch, daß er hergelaufen ist und drei Feuer angezündet hat, das erste Signal gegeben. Derjenige, der am nächsten Berg war, hat wieder drei Feuer angezündet, wenn er die drei Feuer gesehen hat, der nächste wieder drei, und so ist das herübergekommen bis Griechenland in ganz kurzer Zeit. So hat man telegraphiert. Das hat man eben gemacht, das ist eine einfache Art zu telegraphieren. Schnell ist es gegangen; als man noch keinen elektrischen Telegraphen gehabt hat, hat man sich eben mit dieser Art begnügen müssen.

Nun, meine Herren, wie machen wir es denn heute? Sehen Sie, wenn wir telephonieren — gar nicht telegraphieren, sondern telephonieren: in der allereinfachsten Art, die nicht kompliziert ist, will ich es Ihnen zeigen. Wir haben eine Art von Magneten, der allerdings durch Elektrizität erzeugt wird; haben dahier (es wird gezeichnet) etwas, was man Anker nennt; wenn der Strom geschlossen ist, dann wird das angezogen; wenn der Strom wieder offen ist, geht die Platte weg, und so pendelt diese Platte hier hin und her. Das ist durch einen Draht mit dem nächsten verbunden, das pendelt mit, und dasjenige, was hier mit der Platte erzeugt wird - es ist nur verschlossen dem Telephongehilfen -, das überträgt sich geradeso, wie dazumal die drei Feuer durch Menschen übertragen wurden. Es ist etwas komplizierter, aber der Gedanke ist derselbe geblieben, nur daß man auf diesen Gedanken die Elektrizität angewendet hat.

Sehen Sie, man bekommt eben vor demjenigen, was die alten Menschen ersonnen und eingerichtet haben aus der Phantasie heraus, einen Respekt, wenn man es wirklich kennt. Und wenn man mit diesem Respekt die alten Schriften liest, dann sagt man sich: Auch im rein Geistigen haben diese Menschen Großartiges geleistet; aber alles aus der Phantasie heraus. — Da brauchen Sie nur zu nehmen etwas, wovon, sagen wir, die heutigen Menschen glauben, daß sie es ganz gut wissen. Die heutigen Menschen glauben, daß sie von den alten germanischen Göttern etwas wissen; Wotan zum Beispiel, Loki, die werden in Menschengestalt abgebildet in Büchern - der Wotan mit wallendem Bart, der Loki mit rotem Haar, teuflisch aussehend und so weiter. Und nun glaubt man, daß die alten Menschen, die alten Germanen dieselben Vorstellungen gehabt haben von Wotan und von Loki. Das ist aber nicht wahr, sondern diese alten Menschen haben die Vorstellung gehabt: Wenn der Wind weht, dann ist da auch Geistiges drinnen — das ist ja auch wahr -, und da weht der Wotan drinnen. Sie haben sich nicht vorgestellt, daß wenn sie in den Wald gehen, ein gewöhnlicher Mensch einem begegne als Wotan, sondern wenn sie von der Begegnung mit dem Wotan geredet haben, dann war es der wehende Wind im Walde. Derjenige, der noch einen Sinn hat für das Wort Wotan, der fühlt das heute noch aus dem Wort heraus. Loki — es war nicht die Vorstellung, daß der irgendwo in der Ecke glotzt, sondern der lebt im Feuer.

Nun aber erzählten die Menschen allerhand von Wotan und Loki. Sagen wir zum Beispiel, sie erzählten von Wotan: Ja, wenn man da hin- | überkommt über den Weg, über den Berg hinüber, dann kann man dem Wotan begegnen, und dann wird der Wotan einen entweder stark machen oder schwach, je nachdem man es verdient. — Sehen Sie, das haben die Leute erzählt, haben es auch verstanden. Die heutigen Menschen sagen: Nun ja, das ist eben ein Aberglaube, eine abergläubische Vorstellung. — Aber so haben es die Leute damals nicht verstanden; sondern die Leute haben gewußt: Wenn sie dorthin gehen an jene Ecke, die schwer zugänglich ist, da begegnen sie nicht einem Menschen, der so ist wie ein anderer leiblicher Mensch, sondern da ist ihnen durch die ganze Konfiguration des Gebirges Gelegenheit gegeben, daß da eine Art Wirbelwind besonders weht, und eine besondere Luft aus irgendeinem Abgrund auf einen zukommt — wenn man das aushält, und auch schon den Weg dahin aushält, so kann man von so etwas gesund werden, oder auch krank werden. Wie man gesund und krank wird, wollten die Leute eben erzählen; sie waren mit der Natur in Einklang und wollten das aus der Phantasie heraus erzählen, nicht durch den Verstand. Der heutige Arzt sagt es durch den Verstand; er sagt: Wenn du Anlagen hast zu Tuberkulose, dann gehe diesen Weg jeden Tag so hoch hinauf, setze dich ein bißchen nieder und gehe wieder herunter; das bekommt dir gut. — So sagt man es mit dem Verstand. Mit der Phantasie sagt man: Der Wotan sitzt da in der Ecke, hält sich da auf; der wird dir nützen, wenn du ihn durch vierzehn Tage zu einer gewissen Zeit besuchst.

So haben die Leute aus der Phantasie heraus das Leben angegriffen. Und sie haben ja auch aus der Phantasie gewirkt. Sehen Sie, meine Herren, Sie alle werden doch schon irgendeinmal auf dem Lande gewesen sein, wo man nicht mit Maschinen drischt, sondern wo man noch mit der Hand drischt. Hören Sie da nur einmal zu, wie man drischt, ganz nach dem Takt, nach dem Rhythmus. Die Leute wissen, wenn sie dreschen müssen durch viele Tage und ganz unregelmäßig dreschen würden, wie es ihnen einfällt hinschlagen würden: man würde zusammenfallen vor Müdigkeit! So kann man nicht dreschen. Wenn man aber im Rhythmus, im Takt drischt, so wird man weniger müde, weil sich das anpaßt dem Rhythmus, den man in sich selber hat in seiner Blutzirkulation, in seinem Atem. Es ist ja etwas anderes, ob Sie mit dem Schlegel schlagen, wenn Sie ausatmen, oder wenn Sie einatmen, oder wenn Sie mit dem Schlegel schlagen, wenn Sie gerade das Einatmen ins Ausatmen umwandeln sollen. Aber woher kommt das? Daß es vom Verstand nicht kommt, das sehen Sie, denn heute geschieht es nicht mehr; man rottet alles dieses aus. Aber alle Arbeit, die die Leute gemacht haben, war so, zum Beispiel, daß sie im Takt, im Rhythmus getan wurde; aus der Phantasie heraus wurde alle Arbeit getan. Und so hat sich eigentlich alles das, was sich ursprünglich an Kultur entwickelt hat, aus dem Rhythmus heraus entwickelt.

Nun, sehen Sie, ich glaube, daß Sie doch wirklich nicht der Meinung sein können, wenn ich irgendein Holz habe, einen Bogen und Saiten und so weiter, daß da durch irgendwelche zufällige Maßnahmen. eine Geige entsteht! Eine Geige entsteht, wenn man Geist anwendet, wenn man das Holz in einer bestimmten Fläche bearbeitet, die Saiten bearbeitet und so weiter. Also man muß schon sagen: Die Art und Weise, wie man ursprünglich Maschinen gemacht hat, konnten die Leute, namentlich weil sie selber noch nicht dachten, niemandem anderem zuschreiben als dem Geist, von dem sie besessen waren, der in ihnen wirkte. Deshalb waren diese ursprünglichen Menschen, die nicht aus dem Verstand, sondern aus der Phantasie arbeiteten, natürlich geneigt, überall von Geist zu sprechen. Wenn einer natürlich heute nach dem Verstand eine Maschine zusammensetzt, da sagt er nicht: Der Geist hat mir geholfen. - Er sagt es mit Recht nicht. Wenn aber der ursprüngliche Mensch, der es nicht gewußt hat, der überhaupt gar nicht daran denken konnte zu denken — wenn der ursprüngliche Mensch etwas zusammensetzte, fühlte er gleich: Der Geist hat mir geholfen.

Daher war es auch so, daß, als die Europäer, diese «besseren» Menschen, zuerst nach Amerika gekommen sind, ja auch noch später, als sie im 19. Jahrhundert in jene Gegenden gekommen sind, wo noch Indianer der alten Zeit gelebt haben, da sprachen diese Indianer - man kriegte das heraus, von was sie sprachen — von dem «Großen Geist», der alles beherrscht. Und so haben es diese primitiven Menschen überhaupt gehalten; sie haben von dem Großen Geist gesprochen, der alles beherrscht. Und diesen «Großen Geist», den haben namentlich diejenigen Menschen verehrt, die in dieser atlantischen Zeit gelebt haben, da, als noch Land war zwischen Europa und Amerika, und die Indianer haben das zurückbehalten. Die Indianer hatten noch keinen Verstand. Sehen Sie, die Indianer haben allmählich kennengelernt die «besseren» Menschen, die über sie gekommen sind, bevor diese sie ausgerottet haben. Das Papier haben sie kennengelernt, auf dem so kleine Zeichen standen. Die haben sie für kleine Teufelchen gehalten und verabscheut, weil das aus dem Verstand entsteht. Der Mensch, der aus der Phantasie heraus tätig ist, der verabscheut das, was aus dem Verstand kommt.

Nicht wahr, der Europäer in seiner materialistischen Zivilisation, der weiß, wie eine Lokomotive entsteht. So wie der Europäer eine Lokomotive nach dem Verstand zusammensetzt, hätten die Griechen noch nicht eine Maschine zusammengesetzt, weil bei den Griechen noch nicht der Verstand da war. Der Verstand kam ja erst im 15., 16. Jahrhundert zu den Menschen. Die Griechen hätten es noch aus der Phantasie heraus zusammengesetzt. Da die Griechen nun alles das, was in der Natur sich bildet, den guten Geistern zugeschrieben haben, und alles dasjenige, was nicht Natur ist, was bloß Kunstprodukt ist, den bösen Geistern zuschrieben, so hätten die Griechen gesagt: In der Lokomotive lebt eben ein böser Geist. — Ja, sie hätten es aus der Phantasie heraus erbaut, wären nicht auf etwas anderes gekommen, als daß der Geist eben geholfen hat beim Zusammenbringen.

Aber sehen Sie, meine Herren, so ist es, daß wir dazu kommen, dem ursprünglichen, primitiven Menschen wirklich auch mehr Geist zuzuschreiben, denn die Phantasie ist eben etwas Geistigeres in der Seele des Menschen als der bloße Verstand, den der heutige Mensch so schätzt.

Nun können aber niemals alte Zustände wiederum heraufkommen. Daher muß das so sein, daß wir allerdings fortschreiten, aber daß wir doch nicht denken, daß dasjenige, was bloß Instinkt in dem heutigen Tiere ist, sich zum Geistigen hin hätte entwickeln können. Wir dürfen uns also nicht die primitiven Menschen so vorstellen, daß sie bloßen Instinkt gehabt hätten. Sie wußten, der Geist ist es, der in ihnen wirkt. Und deshalb hatten sie auch diesen Glauben an den Geist.

Das ist ein kleiner Beitrag, wie die Kulturentwickelung in der Menschheit stattfand. So daß wir sagen müßten: Ja, diejenigen haben recht, die sich heute vorstellen, der Mensch ist aus tierischen Gestalten entstanden. — Er ist es ja auch, aber nicht aus solchen tierischen Gestalten, wie die heutigen es sind, denn die sind später entstanden, als der Mensch schon dagewesen ist. Aber diese tierischen Gestalten, die allmählich immer mehr und mehr zu den heutigen geworden sind in der menschlichen Entwickelung, und diese Fähigkeiten, die dazumal waren, die sind dadurch gekommen, daß allerdings das Geistige zwar nicht verstandesmäßig, aber phantasiemäßig ursprünglich vollkommener war, als es heute ist. Aber dabei müssen wir immer denken: Diese ursprüngliche Vollkommenheit war eben durchaus verbunden damit, daß der Mensch wie besessen war von dem Geiste, nicht frei war. Nur durch den Verstand kann der Mensch frei werden; durch den Intellekt kann er frei werden.

Denken Sie nur einmal über das eine nach: Derjenige, der mit seinem Verstand wirkt, der kann sagen: Nun ja, zu einer bestimmten Zeit werde ich das und das denken. — Das kann ein Dichter, der mit der Phantasie heute noch wirkt, nicht. Sehen Sie, Goethe war ein großer Dichter. Wenn er sich einmal hingesetzt hat, um ein Gedicht zu machen, weil irgend jemand es verlangt hat von ihm, oder weil er selbst gerade Lust gehabt hat, zu dieser Zeit ein Gedicht zu machen, so ist es ein spottschlechtes geworden. Daß das die Leute heute nicht wissen, das kommt bloß davon her, weil die Leute heute nicht mehr gute Gedichte von schlechten unterscheiden können. Aber in Goethes Gedichten stehen ja viele spottschlechte Gedichte. Das heißt, in der Phantasie wirken kann man eben nur, wenn es über einen kommt, und man soll, wenn es über einen kommt, eben das Gedicht niederschreiben. Und sehen Sie, so ist das bei den ursprünglichen Menschen gewesen: Die haben überhaupt nicht können vom freien Willen aus das eine oder andere tun. Dieser freie Wille, der ist das, was sich erst entwickelt hat — aber nicht die Weisheit. Die Weisheit war ursprünglich größer als der freie Wille und muß wiederum groß werden. Das heißt, wir müssen wiederum auch durch den Verstand zum Geist kommen.

Und das, sehen Sie, ist die Aufgabe der Anthroposophie; die will nicht, was heute viele Menschen wollen, primitive Zustände wieder heraufbringen, alte indische Weisheit etwa wiederum unter die Menschen bringen. Das ist ja nur ein Unsinn, wenn man uns das nachsagt, sondern die Anthroposophie legt Wert darauf, zum Geist zu kommen, aber mit dem vollen Verstand, gerade mit dem volien Verstand! Und das ist wichtig, das müssen Sie festhalten: Es fällt uns gar nicht ein, irgendwie etwas gegen den Verstand zu wollen, sondern es handelt sich darum, mit dem Verstand vorwärtszukommen. Erst waren die Menschen ohne Verstand mit dem Geist da; dann ist der Geist allmählich heruntergekommen, der Verstand ist groß geworden. Jetzt muß man aus dem Verstand heraus wiederum zum Geist kommen. Den Gang muß die Kultur nehmen. Wenn die Kultur diesen Gang nicht nehmen will — ja, meine Herren, man hat immer gesagt: Der Weltkrieg, so etwas ist überhaupt noch niemals dagewesen. — Es ist auch so: So haben sich die Menschen nie zerfleischt. Aber wenn die Menschen nicht diesen Gang machen, gehen wollen, daß sie den Verstand wiederum zum Geist kriegen, dann werden noch größere Kriege kommen. Immer wildere und wildere Kriege werden dann kommen, und die Menschen werden tatsächlich sich gegenseitig ausrotten, wie die zwei Ratten, die man in ein Rattenhaus gesperrt hat, die sich soweit aufgefressen haben, daß zuletzt nichts mehr da war als die zwei Schwänze. Das ist etwas stark ausgesprochen, aber eigentlich arbeitet die Menschheit darauf hin, daß schließlich gar nichts mehr von der Menschheit da ist. Das ist aber sehr wichtig zu wissen, wie eigentlich der Gang der Menschheit ist!

Eighth Lecture

Well, gentlemen, I have been given a number of questions that may be quite interesting in relation to today's discussion. Someone from your circle has submitted the following question:

What gave rise to the cultural development of humankind?

I will consider this in connection with the second question:

Why did primitive people have such a strong belief in spirits?

Well, you see, it is undoubtedly interesting to ask oneself: How did people live in earlier times? And, as you know, even if one considers the matter only superficially, there are two views. One view is that humans were originally quite perfect and fell from their perfection to their present imperfection. One need not be particularly bothered by or concerned with the fact that different peoples interpret this original perfection in different ways. One speaks of paradise, another of something else; but until very recently, the view prevailed that human beings were originally perfect and only gradually developed into their present state of imperfection. The other view is the one you have probably come to know as the only true one: that man was originally completely imperfect, a kind of higher animal, and gradually developed into ever greater perfection. You know that people then try to use the primitive conditions that still exist today among wild peoples—so-called wild peoples—to form an opinion about how humans may have actually been in the beginning, when they were still animal-like. People say to themselves: We in Europe and the people in America are highly civilized; but in Africa, Australia, and so on, there are still uncivilized peoples who have remained at the original stage, or at least at a stage very close to the original one; they can be studied to learn what the original state was like.

You see, gentlemen, people have a much, much too simple idea of the development of humanity. For, first of all, it is not at all true that all civilized peoples imagine that human beings were originally perfect physical beings. The Indians certainly do not hold the view that today's materialists hold, but they do imagine that the people who walked the earth in primeval times nevertheless looked like animals. And when one speaks to the Indians, to the Indian sages, about the original human beings on earth, one also speaks of Hanuman, who looked like a monkey. Now, you see, it is not true that even people who have a spiritual worldview imagine everywhere that human beings were originally somehow like people today imagine human beings in paradise to have been — that is simply not the case. Rather, one must be clear that human beings are beings who carry within themselves body, soul, and spirit, and that body, soul, and spirit have undergone different developments. Of course, if one does not speak of the spirit at all, one cannot speak of the development of the spirit either. But as soon as one realizes that human beings consist of body, soul, and spirit, one can certainly speak of it: How does the body develop? How does the soul develop? How does the spirit develop? — If one speaks of the human body, one is already led to say: The human body has gradually perfected itself from lower stages. One must also say: The evidence we have is living proof of this. As I have already indicated, we find the original human being in the layers of the earth; he has a body that is still very animal-like — not like any animal of today, but still animal-like, and which must have perfected itself in order to take on its present form. So there is no question that spiritual science, as practiced here at the Goetheanum, is in contradiction with natural science, because it simply takes up the truths of natural science.

On the other hand, gentlemen, we must also note that in those times, which actually lie only three or four thousand years in the past, views arose from which we can not only learn a great deal today, but which we must also admire. If we study and understand the writings that originated in India, Asia, Egypt, and even Greece with real expertise today, we find that the people of that time were far ahead of us. It's just that they acquired what they knew in a completely different way than it is acquired today.

You see, today we know very little about many things. For example, from what I have told you about nutrition, you have seen how spiritual science must help us to return to the simplest things in nutrition. Physical science cannot do that. But when you read the writings of ancient physicians and understand their words correctly, you realize that people up until Hippocrates in Greece, for example, actually knew much more than today's materialistic physicians know. And you gain respect, you gain admiration for the knowledge that once existed. But, you see, gentlemen, the thing was that knowledge was not expressed in the same way as it is today. Today, knowledge is expressed in terms. The ancient peoples did not express knowledge in terms; they expressed it in poetic ideas, so that what remains today is often taken as poetry. But for the ancient people, it was not poetry; it was the means by which they expressed their knowledge, their insights. And so we come to the conclusion that if we can examine and study what is available in writing, then there can be no question of people originally having been completely imperfect in spirit. These people, who once walked around in animal bodies, were much, much wiser in spirit than we are.

But we must also note that when such an original human being walked around, he had developed his spirit very wisely. His face was more or less — we would say today — animal-like. Well, fine. But today's human being already expresses the spirit in his face. The spirit is already built into the matter of the face. That, gentlemen, is necessary for man to be free, to be a free being. These very clever people of former times, these very clever people of primeval times, were wise, but they had wisdom in the same way that animals today have their instincts. They lived in a fog, as if in a daze. They wrote without actually guiding their own hands; they spoke in such a way that they believed it was not they themselves who were speaking, but rather the spirit speaking through them. So there was no question of free human beings in those primeval times.

And this is what constitutes real progress for the human race in cultural history: that human beings have gained the awareness that they are free beings. As a result, they no longer feel the spirit as something that drives them, like instinct drives animals, but they feel the spirit within themselves. And this is what distinguishes today's human beings from those of earlier times.

You see, when we look at today's savages from this point of view, we must imagine that the people of primeval times — who are referred to here as primitive people — were not like today's savages. And you will get an idea of how today's savages evolved from the people of primeval times when I tell you the following: In certain regions, there are people who believe that if they bury a small piece of something belonging to someone, for example a sick person, in the ground, and do so in such a way that they bury the piece of linen, for example, in a cemetery, they can bring about a magical effect that will enable the sick person to recover. I have met such people. I even met one who wrote a petition when Emperor Frederick, who was still crown prince at the time, was ill — you know the story — a petition to the future empress, asking her to send him a piece of Emperor Frederick's shirt; he would then bury it in the cemetery and Emperor Frederick would recover. Well, you can imagine that this request was not exactly well received! But the man did it because he believed that it would make Emperor Frederick healthy. He told me this himself. And he told me that it would have been much smarter to send him the corner of the shirt than to do such nonsense as calling the English doctor Mackenzie to the emperor and so on. That would all have been nonsense; they should have sent him this corner of the shirt.

You see, this is the view taken by those who think materialistically and say: this is a superstition that originated somewhere at some point. At some point, someone got it into their head that if you bury a shirt corner in the cemetery and say a certain prayer, the person for whom you are saying the prayer will recover.

But superstition never arose in this way, gentlemen. Superstition never arose in the way that someone thought it up, but rather it arises in a completely different way. Once upon a time, people revered their dead very strongly and said to themselves: as long as a person walks the earth, he is a sinful person, committing evil as well as good. They had the idea that the dead live on in soul and spirit. Death balances everything out. And when they think of the dead, they think of something good. People had this idea: when they think of a dead person, they think of something good. And they wanted to make themselves better by thinking of their dead.

But the thing is, people tend to forget things easily. Just think how quickly the dead, the departed, are forgotten! Then other people came along who wanted to give people all kinds of reminders so that they would think of the dead and thereby improve themselves.