The Evolution of the Earth and Man

and the Influence of the Stars

GA 354

2 August 1924, Dornach

Lecture VII

Rudolf Steiner: Today I would like to add a little more in answer to Herr Burle's question last Thursday. You remember that I spoke of the four substances necessary to human nutrition: minerals, carbohydrates, which are to be found in potatoes, but especially in our field grains and legumes, then fats, and protein. I pointed out how different our nutrition is with regard to protein as compared, for instance, to salt. A man takes salt into his body and it travels all the way to his head, in such a way that the salt remains salt. It is really not changed except that it is dissolved. It keeps its forces as salt all the way to the human head. In contrast to this, protein—the protein in ordinary hens' eggs, for instance, but also the protein from plants—this protein is at once broken down in the human body, while it is still in the stomach and intestines; it does not remain protein. The human being possesses forces by which he is able to break down this protein. He also has the forces to build something up again, to make his own protein. He would not be able to do this if he had not already broken down other protein.

Now think how it is, gentlemen, with this protein. Imagine that you have become an exceptionally clever person, so clever that you are confident you can make a watch. But you've never seen a watch except from the outside, so you cannot right off make a watch. But if you take a chance and you take some watch to pieces, take it all apart and lay out the single pieces in such a way that you observe just how the parts relate to one another, then you know how you are going to put them all together again. That's what the human body does with protein. It must take in protein and take it all apart.

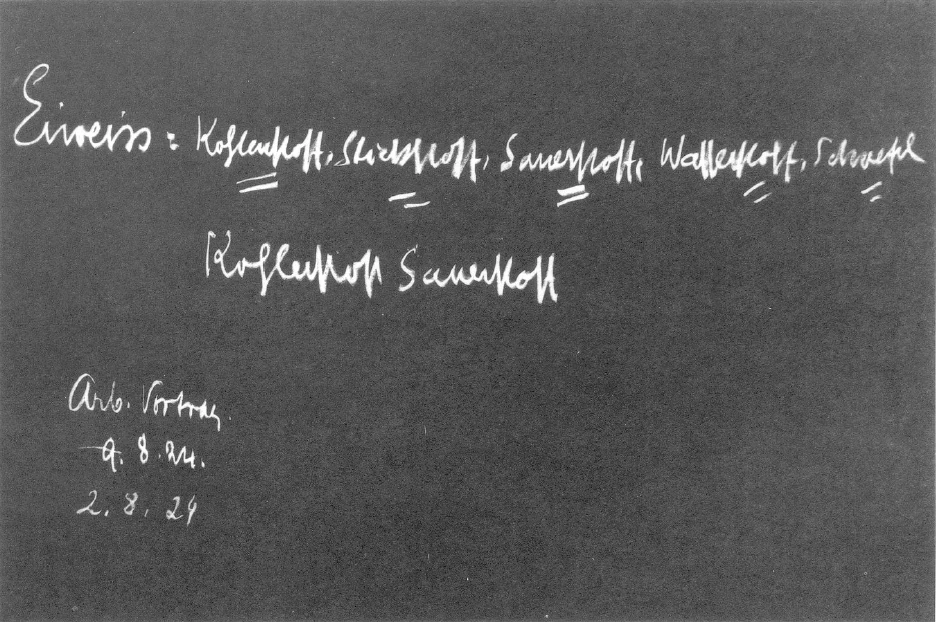

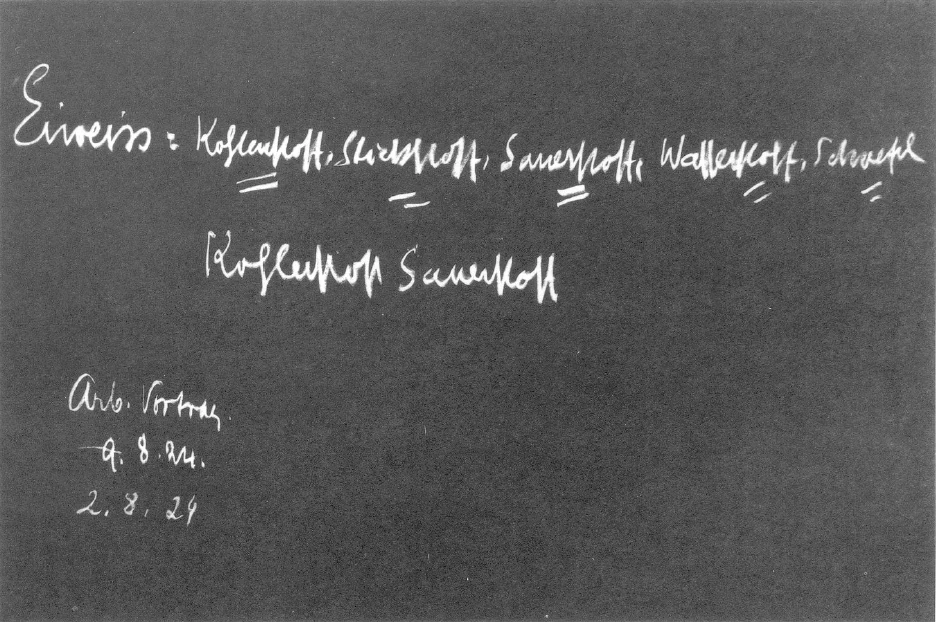

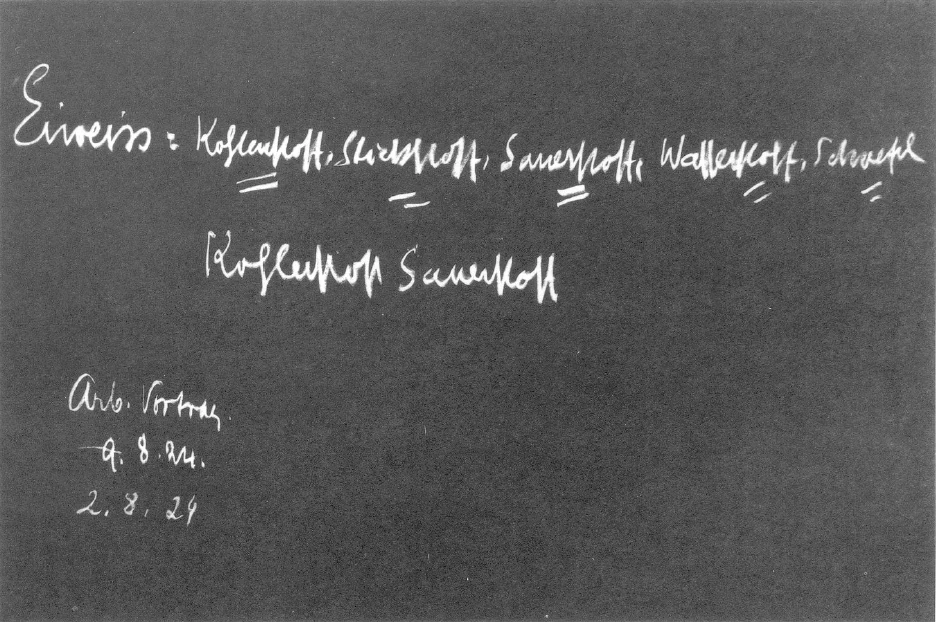

Protein consists of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen and sulphur. Those are its most important components. And now the protein is completely separated into its parts, so that when it all reaches the intestines, man does not have protein in him, but he has carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen, and sulphur. You see how it is?—now the man has the protein all laid out in its parts as you had the watch all laid out on the table. So now you will say, Sure! when I took that watch apart, I observed it very carefully, and now I can make watches. Likewise I only need to eat protein once; after that, I can make it myself. But it doesn't happen that way, gentlemen. A human being has his memory as a complete human entity; his body by itself does not have the kind of memory that can take note of something, it uses its “memory” forces just for building itself up. So one must always be eating new protein in order to be able to make a protein.

The fact is, the human being is involved in a very, very complicated activity when he manufactures his own protein. First he divides the protein he has eaten into its separate parts and puts the carbon from it into his body everywhere. Now you already know that we inhale oxygen from the air and that this oxygen combines with the carbon we have in us from proteins and other food elements. And we exhale carbon in carbon dioxide, keeping a part of it back. So now we have that carbon and oxygen together in our body. We do not retain and use the oxygen that was in the protein; we use the oxygen we have inhaled to combine with the carbon. Thus we do not make our own protein as the materialists describe it: namely, that we eat a great many eggs which then are deposited throughout our body so that eggs we have eaten are spread over our whole body. That is not true.

Actually, we are saved by the organization of our body so that when we eat eggs, we don't all turn into crazy hens! It's a fact. We don't become crazy hens because we break the protein down in our intestines and instead of using the oxygen that was in the protein, we use oxygen coming out of the air. Also, as we breathe oxygen in we breathe nitrogen in too; nitrogen is always in the air. Again, we don't use the nitrogen that comes to us in the hens' eggs; we use the nitrogen we breathe in from the air. And the hydrogen we've eaten in eggs, we don't use that either, not at all. We use the hydrogen we take in through our nose and our ears, through all our senses; that's the hydrogen we use to make our protein. Sulphur too—we receive that continually from the air. Hydrogen and sulphur we get from the air. From the protein we eat, we keep and use only the carbon. The other substances, we take from the air. So you see how it is with protein.

There is a similar situation with fat. We make our own protein, using only the carbon from the external protein. And we also make our own fat. For the fats too, we use very little nitrogen from our food. So you see, we produce our own protein and fat. Only what we consume in potatoes, legumes, and grains goes over into our body. In fact, even these things do not go fully into our body, but only to the lower part of our head. The minerals we consume go up into the entire head; from them we have what we need to build up our bones.

Therefore you see, gentlemen, we must take care to bring healthy plant protein into our body. Healthy plant protein! That is what our body needs in large quantity. When we take in protein from eggs, our body can be rather lazy; it can easily break the protein down, because that protein is easily broken down. But plant protein, which we get from fruit—it is chiefly in that part of the plant, as I told you on Thursday—that is especially valuable to us. If a person wants to keep himself healthy, it is really necessary to include fruit in his diet. Cooked or raw, but fruit he must have. If he neglects to eat fruit, he will gradually condemn his body to a very sluggish digestion.

You can see that it is also a question of giving proper nourishment to the plants themselves. And that means, we must realize that plants are living things; they are not minerals, they are something alive. A plant comes to us out of the seed we put in the ground. The plant cannot flourish unless the soil itself is to some degree alive. And how do we make the soil alive? By manuring it properly. Yes, proper manuring is what will give us really good plant protein.

We must remember that for long, long ages men have known that the right manure is what comes out of the horses' stalls, out of the cow barn and so on; the right manure is what comes off the farm itself. In recent times when everything has become materialistic, people have been saying: Look here! we can do it much more easily by finding out what substances are in the manure and then taking them out of the mineral kingdom: mineral fertilizer!

And you can see, gentlemen, when one uses mineral fertilizer, it is as if one just put minerals into the ground; then only the root becomes strong. Then we get from the plants the substance that helps to build up our bones. But we don't get a proper protein from the plants. And the plants, our field grains have suffered from the lack of protein for a long time. And the lack will become greater and greater unless people return to proper manuring.

There have already been agricultural conferences in which the farmers have said: Yes, the fruit gets worse and worse! And it is true. But naturally the farmers haven't known the reason. Every older person knows that when he was a young fellow, everything that came out of the fields was really better. It's no use thinking that one can make fertilizer simply by combining substances that are present in cow manure. One must see clearly that cow manure does not come out of a chemist's laboratory but out of a laboratory that is far more scientific—it comes from the far, far more scientific laboratory inside the cow. And for this reason cow manure is the stuff that not only makes the roots of plants strong, but that works up powerfully into the fruits and produces good, proper protein in the plants which makes man vigorous.

If there is to be nothing but the mineral fertilizer that has now become so popular, or just nitrogen from the air—well, gentlemen, your children, more particularly, your grandchildren will have very pale faces. You will no longer see a difference between their faces and their white hands. Human beings have a lively, healthy color when the farmlands are properly manured.

So you see, when one speaks of nutrition one has to consider how the foodstuffs are being obtained. It is tremendously important. You can see from various circumstances that the human body itself craves what it needs. Here's just one example: people who are in jail for years at a stretch, usually get food that contains very little fat, so they develop an enormous craving for fat; and when sometimes a drop of wax falls on the floor from the candle that the guard carries into a cell, the prisoner jumps down at once to lick up the fat. The human body feels the lack so strongly if it is missing some necessary substance. We don't notice this if we eat properly and regularly from day to day; then it never happens that our body is missing some essential element. But if something is lacking in the diet steadily for weeks, then the body becomes exceedingly hungry. That is also something that must be carefully noticed.

I have already pointed out that many other things are connected with fertilizing. For instance, our European forefathers in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, or still earlier, were different from ourselves in many ways. One doesn't usually pay any attention to that fact. Among other things, they had no potatoes! Potatoes were not introduced until later. The potato diet has exercised a strong influence. When grains are eaten, the heart and lungs become particularly strong. Grains strengthen heart and lungs. A man then develops a healthy chest and he is in fine health. He is not so keen on thinking as on breathing, perhaps; but he can endure very much when he has good breathing. And let me say right here: don't think that someone has strong lungs if he's always opening the window and crying, “Let's get some fresh air in here!” No! a person has strong lungs if he is so conditioned that he can endure any kind of air. The toughened-up person is not the one who can't bear anything but the one who can!

In these days there is much talk about being hardy. Think how the children are “hardened”! Nowadays (in wealthy homes, of course, but then other people quickly follow suit) the children are dressed—well, when we were children, we wore long breeches and were well covered—at the most, we went barefoot-now, the clothes only go down to the knee or are still shorter. If parents knew that this is the best preparation for later attacks of appendicitis, they would be more thoughtful. But fashion is a tyrant!—no thought is given to the matter, and the children are dressed so that their little dresses only reach to the knee, or less. Someday they will only reach to the stomach—that will be the fashion! Fashion has a strong influence.

But what is really at stake? People pay no attention to it. It is this: A human being is constituted throughout his organism so that he is truly capable of doing inner work on all the food he consumes. And in this connection it is especially important to know that a man becomes strong when he works properly on the foods he eats. Children are not made stronger by the treatment I have just mentioned. They are so “hardened” that later in their life—just watch them!—when they have to cross an empty square with the hot sun beating down on them, they drip with perspiration and they can't make it. Someone has not become toughened up when he is not able to stand anything; the person who can endure all possible hardships is the one who has been toughened up. So, in earlier days people were not toughened up; yet they had healthy lungs, healthy hearts, and so on.

And then came the potato diet! The potato takes little care of lung and heart. It reaches the head, but only, as I said, the lower head, not the upper head. It does go into the lower head, where one thinks and exercises critical faculties. Therefore, you can see, in earlier times there were fewer journalists. There was no printing industry yet. Think of the amount of thought expended daily in this world in our time, just to bring the newspapers out! All that thinking, it is much too much, it is not at all necessary-and we have to thank the potato diet for that! Because a person who eats potatoes is constantly stimulated to think. He can't do anything but think. That's why his lungs and his heart become weak. Tuberculosis, lung tuberculosis, did not become widespread until the potato diet was introduced. And the weakest human beings are those living in regions where almost nothing else is grown but potatoes, where the people live on potatoes.

It is spiritual science that is able to know these material facts. (I have said this often.) Materialistic science knows nothing about nutrition; it has no idea what is healthy food for humanity. That is precisely the characteristic of materialism, that it thinks and thinks and thinks—and knows nothing. The truth is finally this: that if one really wants to participate in life, above all one has to know something! Those are the things I wanted to say about nutrition.

And now perhaps you may still like to ask some individual questions?

Question: Dr. Steiner, in your last talk you mentioned arteriosclerosis. It is generally thought that this illness comes from eating a great deal of meat and eggs and the like. I know someone in whom the illness began when he was fifty; he had become quite stiff by the time he was seventy. But now he is eighty-five or eighty-six, and he is much more active than he was in his fifties and sixties. Has the arteriosclerosis receded? Is that possible? Or is there some other reason? Perhaps I should mention that this person has never smoked and has drunk very little alcohol; he has lived a really decent life. But in his earlier years he did eat rather a lot of meat. At seventy he could do very little work, but now at eighty-five he is continually active.

Dr. Steiner: So—I understand you to say that this person became afflicted with arteriosclerosis when he was fifty, that he became stiff and could do very little work. You did not say whether his memory deteriorated; perhaps you did not notice. His condition continued into his seventies; then he became active again, and he is still living. Does he still have any symptom of his earlier arteriosclerosis or is he completely mobile and active?

Questioner: Today he is completely active and more mobile than when he was sixty-five or seventy. He is my father.

Dr. Steiner: Well, first of all we should establish the exact nature of his earlier arteriosclerosis. Usually arteriosclerosis takes hold of a person in such a way that his arteries in general become sclerotic. Now if a man's arteries in general are sclerotic, he naturally becomes unable to control his body with his soul and spirit, and the body becomes rigid. Now it can also happen that someone has arteriosclerosis but not in his whole body; the disease, for instance, could have spared his brain. Then the following is the case. You see, I am somewhat acquainted with your own condition of health. I don't know your father, but perhaps we can discover something about your father's health from your own. For instance, you suffer somewhat, or have suffered (I hope it will be completely cured), from hay fever. That means that you carry in you something that the body can develop only if there is no tendency to arteriosclerosis in the head, but only outside the head. No one who is predisposed to arteriosclerosis in his entire body can possibly suffer an attack of hay fever. For hay fever is the exact opposite of arteriosclerosis. Now you suffer from hay fever. That shows that your hay fever—of course it is not pleasant to have hay fever, it's much better to have it cured: but we are talking of the tendency to have it—your hay fever is a kind of safety valve against arteriosclerosis.

But everyone gets arteriosclerosis to a small degree. One can't grow old without having it. If one gets it in the entire body, that's different: then one can't help oneself, one becomes rigid through one's whole body. But if one gets arteriosclerosis in the head and not in the rest of the body, then—well, if one is growing old properly, the etheric body is growing stronger and stronger (I've spoken of this before), and it no longer has such great need of the brain, and so the brain can now become old and stiff. The etheric body can control this slight sclerotic condition—which in earlier years made one old and stiff altogether; now the etheric body can control it very cleverly so that it is no longer so severe.

Your father, for example, does not need to have had hay fever himself, he can just have had the tendency to it. And you see, just this tendency to it has been of benefit to him. One can even say—it may seem a little far-fetched, but a person who has a tendency to hay fever can even say, Thank God I have this tendency! The hay fever isn't bothering me now, and it gives me permanently the predisposition to a softening of the vessels. Even if the hay fever doesn't come out, it is protecting him from arteriosclerosis. And if he has a son, the son can have the hay fever externally. A son can suffer externally from some disease that in the father was pushed inward.

Indeed, that is one of the secrets of heredity: that many things become diseases in the descendants which in the forefathers were aspects of health. Diseases are classified as arteriosclerosis, tuberculosis, cirrhosis, dyspepsia, and so forth. This can be written up very attractively in a book; one can describe just how these illnesses progress. But one hasn't obtained much from it, for the simple reason that arteriosclerosis, for instance, is different in every single person. No two persons have arteriosclerosis alike; everyone becomes afflicted in a different way. That is really so, gentlemen. And it shouldn't surprise anyone.

There were two professors11The philosopher Karl Ludwig Michelet, 1801–1893, and the theologian and philosopher Eduard Zeller, 1814–1908. See Rudolf Steiner, Study of Man: General Education Course, Stuttgart, Aug. – Sept. 1919. Anthroposophic Press, New York. See also The Younger Generation: Educational and Spiritual impulses for Life in the Twentieth Century, Stuttgart, October 1922. Anthroposophic Press, New York. at Berlin University. One was seventy years old, the other ninety-two. The younger one was quite well-known; he had written many books. But he was a man who lived with his philosophy entirely within materialism; he only had thoughts that were stuck deep in materialism. Now such thoughts also contribute to arteriosclerosis. And he got arteriosclerosis. When he reached seventy, he was obliged to retire. The colleague who was over ninety was not a materialist; he had stayed a child through most of his life, and was still teaching with tremendous liveliness. He said, “Yes, that colleague of mine, that young boy! I don't understand him. I don't want to retire yet, I still feel so young.” The other one, the “boy,” was disrobed, could no longer teach. Of course the ninety-two-year-old had also become sclerotic with his years, his arteries were completely sclerotic, but because of his mobility of soul he could still do something with those arteries. The other man had no such possibility.

And now something more in answer to Herr Burle's question about carrots. Herr Burle said, “The human body craves instinctively what it needs. Children often take a carrot up in their hands. Children, grownups too, are sometimes forced to eat food that is not good for them. I think this is a mistake when someone has a loathing for some food. I have a boy who won't eat potatoes.”

Gentlemen, you need only think of this one thing: if animals did not have an instinct for what was good for them, and what was bad for them, they would all long since have perished. For animals in a pasture come upon poisonous plants too—all of them—and if they did not know instinctively that they could not eat poisonous plants, they would certainly eat them. But they always pass them by.

But there is something more. Animals choose with care what is good for them. Have you sometimes fattened geese, crammed them with food? Do you think the geese would ever do that themselves? It is only humans who force the geese to eat so much. With pigs it is different; but how thin do you think our pigs might be if we did not encourage them to eat so much? In any case, with pigs it is a little different. They have acquired their characteristics through inheritance; their ancestors had to become accustomed to all the foods that produce fat. These things were taken up in their food in earlier times. But the primeval pigs had to be forced to eat it! No animal ever eats of its own accord what is not right for it.

But now, gentlemen, what has materialism brought about? It no longer believes in such an instinct.

I had a friend in my youth with whom I ate meals very often. We were fairly sensible about our food and would order what we were in the habit of thinking was good for us. Later, as it happens in life, we lost track of each other, and after some years I came to the city where he was living, and was invited to have dinner with him. And what did I see? Scales beside his plate! I said, “What are you doing with those scales?” I knew, of course, but I wanted to hear what he would say. He said, “I weigh the meat they bring me, to eat the right amount—the salad too.” There he was, weighing everything he should put on his plate, because science told him to. And what had happened to him? He had weaned himself completely from a healthy instinct for what he should eat and finally no longer knew! And you remember?—it used to be in the book: “a person needs from one hundred and twenty to one hundred and fifty grams of protein”; that, he had conscientiously weighed out. Today the proper amount is estimated to be fifty grams, so his amount was incorrect.

Of course, gentlemen, when a person has diabetes, that is obviously a different situation. The sugar illness, diabetes, shows that a person has lost his instinct for nutrition.

There you have the gist of the matter. If a child has a tendency to worms, even the slightest tendency, he will do everything possible to prevent them. You'll be astonished sometimes to see such a child hunting for a garden where there are carrots growing, and then you'll find him there eating carrots. And if the garden is far off, that doesn't matter, the child trudges off to it anyway and finds the carrots-because a child who has a tendency to worms longs for carrots.

And so, gentlemen, the most useful thing you can possibly do is this: observe a child when he is weaned, when he no longer has milk, observe what he begins to like to eat and not like to eat. The moment a child begins to take external nourishment, one can learn from him what one should give him. The moment one begins to urge him to eat what one thinks he should eat, at that moment his instinct is spoilt. One should give him the things for which he shows an instinctive liking. Naturally, if a fondness for something threatens to go too far, one has to dam it up—but then one must carefully observe what it is that one is damming up.

For instance, perhaps in your own opinion you are giving a child every nice thing, and yet the moment that child comes to the table he cannot help jumping up on his chair and leaning over the table to sneak a lump of sugar! That's something that must be regarded in the right way. For a child who jumps up on his chair to sneak a lump of sugar obviously has something the matter with his liver. Just the simple fact that he must sneak a bit of sugar, is a sign that his liver is not in order. Only those children sneak sugar who have something wrong with their livers—it is then actually cured by the sugar. The others are not interested in sugar; they ignore it. Naturally, such a performance can't be allowed to become a habit; but one must have understanding for it. And one can understand it in two directions.

You see, if a child is watching all the time and thinking, when will Father or Mother not be looking, so that I can take that sugar: then later he will sneak other things. If you satisfy the child, if you give him what he needs, then he doesn't become a thief. It is of great importance from a moral point of view whether one observes such things or not. It is very important, gentlemen.

And so the question that was asked just now must be answered in this way: One should observe carefully what a child likes and what he loathes, and not force him to eat what he does not like. If it happens, for instance, as it does with very many children, that he doesn't want to eat meat, then the fact is that the child gets intestinal toxins from meat and wants to avoid them. His instinct is right. Any child who can sit at a table where everyone else is eating meat and can refuse it has certainly the tendency to develop intestinal toxins from meat. These things must be considered.

You can see that science must become more refined. Science must become much more refined! Today it is far too crude. With those scales, with everything that is carried on in the laboratories, one can't really pursue pure science.

With nutrition, which is the thing particularly interesting us at this moment, it is really so, that one must acquire a proper understanding for the way it relates to the spirit. When people inquire in that direction, I often offer two examples. Think, gentlemen, of a journalist: how he has to think so much—and so much of it isn't even necessary. The man must think a great deal, he must think so many logical thoughts; it is almost impossible for any human being to have so many logical thoughts. And so you find that the journalist—or any other person who writes for a profession—loves coffee, quite instinctively. He sits in the coffee shop and drinks one cup after another, and gnaws at his pen so that something will come out that he can write down. Gnawing at his pen doesn't help him, but the coffee does, so that one thought comes out of another, one thought joins on to another.

And then look at the diplomats. If one thought joins on to another, if one thought comes out of another, that's bad for them! When diplomats are logical, they're boring. They must be entertaining. In society people don't like to be wearied by logical reasoning—“in the first place – secondly—thirdly”—and if the first and second were not there, the third and fourth would, of course, not have to be thought of! A Journalist can't deal with anything but finance in a finance article. But if you're a diplomat you can be talking about night clubs at the same time that you're talking about the economy of country X, then you can comment on the cream-puffs of Lady So-and-So, then you can jump to the rich soil of the colonies, after that, where the best horses are being bred, and so on. With a diplomat one thought must leap over into another. So anyone who is obliged to be a charming conversationalist follows his instinct and drinks lots of tea.

Tea scatters thoughts; it lets one jump into them. Coffee brings one thought next to another. If you must leap from one thought to another, then you must drink tea. And one even calls them “diplomat teas”!—while there sits the journalist in the coffee shop, drinking one cup of coffee after another. You can see what an influence a particular food or drink can have on our whole thinking process. It is so, of course, not just with those two beverages, coffee and tea; one might say, those are extreme examples. But precisely from those examples I think you can see that one must consider these things seriously. It is very important, gentlemen.

So, we'll meet again next Wednesday at nine o'clock.

Siebenter Vortrag

Ich möchte heute einiges noch beifügen zu dem, was vorigen Donnerstag auf die Frage von Herrn Burle gesagt werden konnte. Ich habe also auseinandergesetzt, wie vier Dinge zur Ernährung für jeden Menschen notwendig sind: Salze; dasjenige, was man Kohlehydrate nennt, was also vorzugsweise in Kartoffeln enthalten ist, was aber auch ganz besonders enthalten ist in den Körnerfrüchten unserer Felder, und auch in den Hülsenfrüchten. Und dann, sagte ich, braucht der Mensch außerdem Fette; und er braucht Eiweiß. Aber ich habe Ihnen auseinandergesetzt, wie ganz verschieden die Ernährung ist beim Menschen in bezug auf Eiweiß zum Beispiel und, sagen wir, Salz. Das Salz nimmt der Mensch in seinen Körper bis zum Kopfe hin so auf, daß es Salz bleibt, daß es sich eigentlich nicht anders verändert, als daß es aufgelöst wird. Aber es behält seine Kräfte als Salz bei bis in den menschlichen Kopf hinein. Dagegen das Eiweiß, also dasjenige, was wir im gewöhnlichen Hühnerei haben, was wir aber auch in den Pflanzen haben, dieses Eiweiß, das wird sogleich im menschlichen Körper, noch im Magen und in den Gedärmen, vernichtet, bleibt nicht Eiweiß. Aber jetzt hat der Mensch die Kraft aufgewendet, dieses Eiweiß zu vernichten, und die Folge davon ist, daß er auch wieder die Kraft bekommt, weil er Eiweiß vernichtet hat, Eiweiß wieder herzustellen; und so macht er sich sein eigenes Eiweiß. Er würde es sich aber nicht machen, wenn er nicht erst anderes Eiweiß zerstören würde.

Stellen Sie sich einmal vor, meine Herren, wie das beim Eiweiß ist. Denken Sie sich einmal, Sie sind ein ganz verständiger Mensch geworden und sind so gescheit, daß Sie sich die Geschicklichkeit zutrauen, eine Uhr zu machen, Sie haben aber nichts gesehen als eine Uhr, wie sie von außen ausschaut — nun, da werden Sie nicht gleich eine Uhr machen können. Aber wenn Sie es riskieren, die Uhr ganz zu zerlegen, ganz auseinanderzunehmen, in ihre einzelnen Stücke zu zerlegen und sich dabei merken, wie die Geschichte zusammengesetzt war, dann lernen Sie aus dem Zerlegen der Uhr, wie Sie sie wiederum zusammensetzen müssen. So macht es der menschliche Körper mit dem Eiweiß. Er muß das Eiweiß in sich hineinbekommen, er zerlegt es ganz. Das Eiweiß besteht nämlich aus Kohlenstoff, Stickstoff, Sauerstoff, Wasserstoff und Schwefel; das sind die wichtigsten Bestandteile vom Eiweiß. Das Eiweiß wird nun ganz zerlegt; so daß der Mensch in sich nun nicht Eiweiß hat, wenn die Geschichte in die Gedärme kommt, sondern Kohlenstoff, Stickstoff, Sauerstoff, Wasserstoff und Schwefel. Sehen Sie, jetzt hat der Mensch das Eiweiß zerlegt, wie man eine Uhr zerlegt. — Sie werden sagen: Ja, aber wenn man einmal eine Uhr zerlegt, so kann man sich das ja merken, um weitere Uhren zu machen; und man braucht ja nur ein einziges Mal Eiweiß essen, und kann dann immer wieder Eiweiß machen. —- Das ist aber nicht wahr, weil der Mensch ein Gedächtnis hat als ganzer Mensch; aber der Körper als solcher, hat nicht ein solches Gedächtnis, daß er sich etwas merken kann, sondern der Körper verwendet die Kräfte zum Aufbauen. Also wir müssen immer wieder von neuem Eiweiß essen, damit wir das Eiweiß herstellen können.

Nun ist es so, daß der Mensch etwas sehr, sehr Kompliziertes macht, wenn er selber sich sein Eiweiß fabriziert. Nämlich er zerlegt zuerst das Eiweiß, das er ißt; dadurch bekommt er den Kohlenstoff überall in seinen Körper hinein. Nun wissen Sie: den Sauerstoff ziehen wir aber auch aus der Luft heran. Der vereinigt sich mit dem Kohlenstoff, den wir in uns haben. Diesen Kohlenstoff haben wir im Eiweiß und in den anderen Nahrungsmitteln. Da atmen wir zunächst Kohlenstoff in der Kohlensäure wieder aus. Aber einen Teil behalten wir zurück. Jetzt haben wir in unserem Körper Kohlenstoff und Sauerstoff miteinander drinnen; so daß wir nicht den Sauerstoff beibehalten, den wir gegessen haben mit dem Eiweiß, sondern wir vereinigen mit dem Kohlenstoff den Sauerstoff, den wir eingeatmet haben. Wir bauen also unser Eiweiß in unserem Inneren nicht so auf, wie es sich die Materialisten vorstellen: daß wir recht viel Hühnerei essen, das verteilt sich im ganzen Körper, und nachher haben wir das Hühnerei, das wir gegessen haben, im ganzen Körper ausgebreitet. Das ist nicht wahr. Wir sind schon bewahrt durch die Organisation unseres Körpers, daß, wenn wir Hühnerei essen, wir alle verrückte Hühner würden. Nicht wahr, wir werden nicht alle verrückte Hühner, weil wir schon in den Gedärmen das Eiweiß vernichten. Statt des Sauerstoffes, den es gehabt hat, nehmen wir den Sauerstoff aus der Luft. Den hat man jetzt da. Sehen Sie, mit dem Sauerstoff atmen wir, weil in der Luft immer auch Stickstoff ist, den Stickstoff ein. Und auch den Stickstoff verwenden wir nicht, den wir mit dem Hühnerei essen, sondern wiederum den Stickstoff, den wir aus der Luft einatmen. Den Wasserstoff, den wir mit dem Hühnerei essen, den verwenden wir schon gar nicht, sondern jenen Wasserstoff, den wir durch die Nase bekommen, und durch die Ohren, gerade durch die Sinne; das machen wir zu unserem eigenen Eiweiß. Und Schwefel - den bekommen wir fortwährend aus der Luft. Also Wasserstoff und Schwefel bekommen wir auch aus der Luft. Von dem Eiweiß, das wir essen, behalten wir überhaupt nur den Kohlenstoff. Das andere verwenden wir so, daß wir das nehmen, was wir aus der Luft bekommen.

Also sehen Sie, so ist es mit dem Eiweiß. Und in einer ganz ähnlichen Weise ist es auch so mit dem Fett. Unser eigenes Eiweiß machen wir uns selber, wir verwenden nur den Kohlenstoff vom fremden Eiweiß; und unser eigenes Fett machen wir uns auch selber. Wir verwenden auch dazu im Grunde genommen nur sehr ‘wenig von dem Stickstoff, den wir aufnehmen durch die Nahrung, für die Fette. Also die Sache ist so, daß wir Eiweiß und Fett auf eigene Weise erzeugen. Nur dasjenige, was wir in den Kartoffeln, Hülsenfrüchten, Körnerfrüchten aufnehmen, das geht in den Körper über, und zwar dasjenige, was wir mit den Körnerfrüchten und mit den Kartoffeln aufnehmen, nicht vollständig, man möchte sagen, nur bis zu den unteren Partien des Kopfes. Was wir aufnehmen mit den Salzen, das geht in den ganzen Kopf über, und daraus bilden wir uns dann das, was wir für unsere Knochen brauchen.

Sehen Sie, meine Herren, deshalb, weil das so ist, müssen wir dafür sorgen, daß wir namentlich gesundes Pflanzeneiweiß in unseren Körper hineinbringen! Gesundes Pflanzeneiweiß, das ist dasjenige, wovon unser Körper sehr viel hat. Wenn wir Hühnereiweiß in unseren Körper hineinbringen, kann unser Körper schon ziemlich faul sein, ein träger, fauler Körper sein: er wird es leicht zerstören können, weil das leicht zerstört ist. Das Pflanzeneiweiß, also dasjenige Eiweiß, das wir mit den Früchten der Pflanzen kriegen - in den Pflanzen ist es hauptsächlich drinnen, wie ich Ihnen vorgestern sagte —, das ist für uns ganz besonders wertvoll. Daher ist es für einen Menschen, der sich gesund halten will, wirklich notwendig, daß er in gekochtem oder rohem Zustande Früchte zu seiner Nahrung hinzu hat. Früchte muß er haben. Wenn ein Mensch ganz vermeidet, Früchte zu essen, so ist das so, daß er eigentlich nach und nach übergeht zu einer ganz trägen inneren Verdauung seines Körpers.

Nun sehen Sie, da handelt es sich aber auch darum, daß wir die Pflanzen selber in der richtigen Weise ernähren! Da müssen Sie bedenken, wenn wir die Pflanzen in der richtigen Weise ernähren wollen, daß die Pflanzen etwas Lebendes sind. Die Pflanzen sind keine Mineralien, die Pflanzen sind etwas Lebendes. Und wenn wir eine Pflanze bekommen, so bekommen wir sie ja aus dem Samen, der in den Boden hineingegeben wird. Die Pflanze kann nicht ordentlich gedeihen, wenn sie nicht den Boden selber ein bißchen lebendig kriegt. Und wie macht man ihn lebendig? Man macht den Boden lebendig, indem man ihn ordentlich düngt. Also das ordentliche Düngen, das ist dasjenige, was uns wirklich richtiges Pflanzeneiweiß liefert.

Und da wiederum müssen Sie folgendes bedenken. Sehen Sie, durch lange, lange Zeiten hindurch haben die Menschen gewußt: Richtiger Dünger ist der, der aus den Ställen kommt, aus dem Kuhstall und so weiter, richtiger Dünger ist der, der aus der Wirtschaft selber heraus kommt. Aber in der neueren Zeit, wo alles materialistisch geworden ist, haben die Leute gesagt: Ja, man kann ja die Sache so machen, daß man nachschaut, welche Stoffe in dem Dünger drinnen sind, und dann nehmen wir das aus dem Mineralreich — den mineralischen Dünger.

Ja, sehen Sie, meine Herren, wenn man mineralischen Dünger verwendet, so ist das gerade so, wie wenn man bloß Salze in den Boden bringt; da wird bloß die Wurzel kräftig. Da kriegen wir dann also aus der Pflanze bloß dasjenige heraus, was in den menschlichen Knochenbau geht. Wir kriegen aber aus der Pflanze nicht ein richtiges Eiweiß heraus. Daher leiden die Pflanzen, unsere Feldfrüchte, seit einiger Zeit alle an einem Eiweißmangel. Und der wird immer größer und größer werden, wenn die Leute nicht wiederum zu ordentlichem Düngen kommen.

Sehen Sie, es haben schon Versammlungen von Landwirten stattgefunden, da haben die Landwirte gesagt — aber sie wußten natürlich nicht, aus welchen Gründen -: Ja, die Früchte, die werden immer schlechter und schlechter! —- Und wahr ist es. Wer alt geworden ist, der weiß, daß, als er noch ein junger Kerl war, eigentlich alles besser war, was die Felder hervorgebracht haben. Man kann eben nicht so denken, daß man einfach den Dünger zusammensetzt aus den Stoffen, aus denen der Kuhmist besteht, sondern man muß sich klar sein: Dadurch, daß der Kuhmist nicht aus dem Laboratorium vom Chemiker kommt, sondern aus dem viel, viel wissenschaftlicheren Laboratorium, das in der Kuh drinnen ist — das ist ein viel wissenschaftlicheres Laboratorium —, dadurch kommt es, daß der Kuhdünger eben doch dasjenige ist, was nicht bloß die Wurzeln der Pflanzen stark macht, sondern bis in die Früchte hinauf stark wirkt, dadurch ordentliches Eiweiß in den Pflanzen erzeugt und der Mensch davon ganz kräftig wird.

Wenn man nur immer düngen würde mit mineralischem Dünger, wie man es in der neueren Zeit liebt, oder gar mit Stickstoff, der aus der Luft erzeugt wurde — ja, meine Herren, da werden schon Ihre Kinder, und noch mehr Ihre Kindeskinder ganz bleiche Gesichter haben. Sie werden die Gesichter nicht mehr von den Händen, wenn sie weiß sind, unterscheiden können. Daß der Mensch eine lebhafte Farbe haben kann, eine gesunde Farbe haben kann, hängt eben davon ab, daß die Acker ordentlich gedüngt werden.

Also Sie sehen, man muß berücksichtigen, wenn man über die Ernährung spricht, wie man überhaupt die Nahrungsmittel gewinnt. Das ist außerordentlich wichtig. Daß der menschliche Körper die Notwendigkeit hat, selber zu begehren dasjenige, was er braucht, das können Sie aus verschiedenen Umständen sehen. Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel nur den Umstand, daß Gefangene, die verurteilt werden zu jahrelanger Strafe - die bekommen gewöhnlich Nahrung, die nicht fettreich genug ist — eine ungeheure Gier nach Fett bekommen, und wenn da irgendwie von einem Licht, das der Gefängniswärter in die Zelle hineinträgt, etwas heruntertropft und auf dem Boden ist, dann bücken sie sich gleich und lecken dieses Fett auf aus dem Grunde, weil der Körper das so ungeheuer stark spürt, wenn er irgendein Nahrungsmittel, das er braucht, eigentlich stark vermißt. Das kommt nicht zum Ausdruck, wenn man immerfort, Tag für Tag ordentlich essen kann. Da kommt es nie dazu, weil der Körper das nicht entbehrt, was er braucht. Aber wenn etwas dauernd durch Wochen hindurch fehlt in der Nahrung, dann wird der Körper außerordentlich gierig danach. Das ist dasjenige, was im besonderen noch hinzugefügt werden muß.

Nun habe ich Ihnen schon gesagt, daß mit solchem Düngen viel anderes noch zusammenhängt. Sehen Sie, unsere Vorfahren in Europa im 12.,13. Jahrhundert oder noch früher, ja, die haben sich durch manches unterschieden von uns. Das berücksichtigt man gewöhnlich gar nicht! Und unter alledem, wodurch sie sich von uns unterschieden haben, war das, daß sie keine Kartoffeln zu essen bekommen haben. Die Kartoffeln sind erst später eingeführt worden. Die Kartoffelnahrung hat aber einen starken Einfluß ausgeübt auf den Menschen. Sehen Sie, ißt man Körnerfrüchte, so werden dadurch insbesondere Lunge und Herz stark. Das verstärkt Lunge und Herz. Der Mensch wird so, daß er einen gesunden Brustkorb hat, und es geht ihm gut. Er ist nicht so erpicht aufs Denken, als wie aufs Atmen zum Beispiel; er kann auch etwas vertragen beim Atmen. Und da möchte ich Ihnen gleich sagen: Sie müssen sich nicht vorstellen, daß derjenige kräftig ist beim Atmen, der immer die Fenster aufmachen muß, der immer schreit: Oh, frische Luft! - und so weiter, sondern derjenige ist kräftig im Atmen, der schließlich so stark organisiert ist, daß er jede Luft verträgt. Wie es überhaupt darauf ankommt, daß abgehärtet nicht derjenige ist, der nichts vertragen kann, sondern derjenige, der etwas vertragen kann.

In unserer Zeit redet man viel von Abhärtung. Denken Sie nur, wie man die Kinder abhärtet. Jetzt schon werden die Kinder — namentlich von reichen Leuten, aber die anderen kommen auch schon und machen es nach -, jetzt werden die Kinder so angezogen: Während wir in unserer Jugend als Kinder ordentliche Strümpfe angehabt haben und ganz bedeckt waren, höchstens daß man bloßfüßig gegangen ist, ist es Jetzt so, daß die Anzüge nur bis an die Knie höchstens gehen, oder noch weniger weit. Wenn die Leute wüßten, daß das die größte Gefahr bildet für spätere Blinddarmentzündungen, so würden sie sich besinnen! Aber die Mode, die wirkt ja so tyrannisch, daß solch eine Gesinnung gar nicht aufkommt. Jetzt werden die Kinder so angezogen, daß die Kleidchen nur bis an die Knie oder noch weniger weit gehen, und es wird noch dazu kommen, daß sie später bloß bis an den Bauch gehen werden; das wird auch noch Mode werden. Also da wirkt die Mode außerordentlich stark ein.

Aber dasjenige, worauf es eigentlich ankommt, das merken eben die Leute gar nicht. Es kommt eben durchaus darauf an, daß der Mensch in seiner ganzen Organisation so sich einstellt, daß er nun eben wirklich innerlich alles verarbeiten kann, was er als Nahrungsmittel in sich aufnimmt. Und da meine ich, ist es ganz besonders wichtig, daß man weiß: Der Mensch wird stark, wenn er die Dinge ordentlich verarbeitet, die er in sich aufnimmt. Und er wird nicht abgehärtet dadurch, daß man das macht mit den Kindern, was ich Ihnen erzählt habe. Da werden die Kinder so abgehärtet, daß wenn sie später — schauen Sie sie einmal an — über einen erhitzten Platz gehen sollen, da triefen sie, da können sie nicht weiter. Nicht der ist abgehärtet, der dazu kommt, nichts vertragen zu können, sondern der ist abgehärtet, der alles mögliche vertragen kann. Also, so ist es auch, daß die Leute früher wenig abgehärtet waren; sie hatten eben gesunde Lungen, gesundes Herz und so weiter.

Nun kam die Kartoffelnahrung. Die Kartoffel versorgt weniger Herz und Lunge, die Kartoffel geht in den Kopf hinauf - allerdings, wie ich Ihnen gesagt habe, nur in den Unterkopf, nicht in den Oberkopf -, aber sie geht in den Unterkopf hinein, wo man besonders kritisch wird, denkt. Daher, sehen Sie, hat es in früheren Zeiten weniger Zeitungsschreiber gegeben. Die Buchdruckerkunst war ja noch nicht da. Bedenken Sie nur, was heute täglich gedacht wird auf der Welt, nur um die Zeitungen zustande zu bringen! Ja, dieses viele Denken, das ja gar nicht notwendig ist — es ist viel zu viel —, dieses viele Denken, das verdanken wir der Kartoffelnahrung! Denn der Mensch, der Kartoffeln ißt, der fühlt sich fortwährend angeregt zu denken. Der kann gar nicht anders, als denken. Dadurch wird seine Lunge und sein Herz schwach, und die Tuberkulose, die Lungentuberkulose, die nahm erst überhand, als die Kartoffelnahrung eingeführt wurde! Und die schwächsten Leute sind diejenigen in Gegenden, wo fast nichts mehr gebaut wird als Kartoffeln und die Leute von Kartoffeln leben.

Gerade die Geisteswissenschaft — ich habe Ihnen das öfter gesagt hat Gelegenheit, dieses Materielle kennenzulernen. Die materialistische Wissenschaft weiß nichts von der Ernährung, weiß nicht, was dem Menschen gesund ist. Das ist gerade das Eigentümliche vom Materialismus, daß er nur immer denkt, denkt, denkt, und nichts weiß! Es kommt darauf an: Wenn man eben im Leben richtig stehen will, muß man durchaus etwas wissen. Sehen Sie, das sind so Dinge, die ich Ihnen wegen der Ernährung sagen wollte.

Jetzt können Sie vielleicht, wenn Sie noch irgendwelche Wünsche haben, über einzelnes noch Fragen stellen.

Frage: Herr Doktor hat das vorige Mal etwas von Arterienverkalkung gesprochen. Diese Arterienverkalkung soll ja, wie man allgemein sagt, vom vielen Fleischund Eiergenuß und dergleichen herrühren. Ich kenne eine Person, die hat mit fünfzig Jahren Arterienverkalkung bekommen, ist bis zum siebzigsten Jahre steif geworden, und nun ist die Person fünfundachtzig, sechsundachtzig Jahre alt, ist heute viel rüstiger als in den Fünfziger-, Sechzigerjahren. Ist die Arterienverkalkung da zurückgegangen? Ist dies möglich, oder was kann da schuld sein? Nebenbei bemerkt, hat diese Person niemals Tabak geraucht, auch wenig Alkohol getrunken, ziemlich solid gelebt. Nur hat er in seinen jüngeren Jahren ziemlich viel Fleisch genossen, mit siebzig Jahren nur noch wenig arbeiten können; heute aber, mit fünfundachtzig, sechsundachtzig Jahren ist er dauernd noch tätig, lebt noch.

Dr. Steiner: Nicht wahr, Sie sagen, das war eine Persönlichkeit, die mit fünfzig Jahren etwa Arterienverkalkung bekommen hat, steif geworden ist, wenig arbeitsfähig war — ich weiß nicht, ob auch das Gedächtnis zurückgegangen ist; das werden Sie nicht bemerkt haben. Dieser Zustand ist bis zu den Siebzigerjahren geblieben; dann wurde diese Person wieder rüstig, lebt heute noch. — Nun aber, was hat sie denn heute noch, was an Arterienverkalkung erinnern könnte? Oder ist er so, daß er rüstig und beweglich ist?

Fragesteller sagt: Er ist heute vollständig rüstig und beweglicher als mit fünfundsechzig Jahren, siebzig Jahren; es ist mein Vater.

Dr. Steiner: Da handelt es sich darum, daß man erst genau feststellen müßte, wie die Arterienverkalkung war. Denn sehen Sie, die Sache ist diese: Meistens tritt die Arterienverkalkung so ein, daß der Mensch im ganzen seine Arterien verkalkt bekommt. Nun, wenn der Mensch im ganzen seine Arterien verkalkt bekommt, dann wird er natürlich unfähig, von der Seele und vom Geiste aus den Körper zu beherrschen; der Körper wird steif. Nun ist jetzt die Sache so: Nehmen wir an, jemand bekommt aber Arterienverkalkung nicht im ganzen Körper, die Arterienverkalkung verschont zum Beispiel das Gehirn; dann ist folgendes der Fall. Sehen Sie, ich kenne ja auch etwas Ihren Gesundheitszustand. Vielleicht darf man von Ihrem Gesundheitszustand — Ihren Vater kenne ich nicht — etwas auf den Ihres Vaters schließen. Sie leiden zum Beispiel, oder haben gelitten, es wird ja hoffentlich absolut gut werden, etwas an Heuschnupfen. Das bezeugt, daß Sie in sich tragen etwas, was der Körper nur dann ausbilden kann, wenn er für die Sklerose, für die Arterienverkalkung nicht im Kopf, sondern nur außer dem Kopf veranlagt ist. Keiner, der im ganzen Leib von vornherein für die Arterienverkalkung veranlagt ist, kann gut Heuschnupfen bekommen. Denn der Heuschnupfen ist gerade das Gegenteil von Arterienverkalkung. Nun leiden Sie an Heuschnupfen. Das bezeugt, daß Ihr Heuschnupfen - es ist ja nicht gut, wenn man Heuschnupfen hat; wird er kuriert, ist es besser; aber es kommt dabei auf die Anlage an -, also Ihr Heuschnupfen, der ist so etwas wie ein Ventil gegen die Sklerose, gegen die Arterienverkalkung.

Nun, Arterienverkalkung in geringerem Zustande kriegt aber jeder Mensch. Man kann nicht alt werden, ohne Arterienverkalkung zu bekommen. Bekommt man die Arterienverkalkung im ganzen Körper, so kann man sich nicht mehr helfen; da wird man steif im ganzen Körper. Bekommt man aber die Arterienverkalkung — ausgenommen den übrigen Körper - im Kopf, dann tritt ja das ein, wenn man nur recht alt wird: Da wird der Ätherleib, von dem ich Ihnen gesprochen habe, immer stärker und stärker. Und dann braucht der Ätherleib nicht mehr so stark das Gehirn. Das kann nun alt und steif werden. Der Ätherleib kann aber nun doch anfangen, diese geringfügige Arterienverkalkung, die einen früher alt und steif gemacht hat, so zu beherrschen, daß man sie geschickt beherrschen kann; die Arterienverkalkung ist dann nicht so stark eingetreten.

Ihr Vater braucht zum Beispiel nicht selber den Heuschnupfen gehabt zu haben, das ist gar nicht notwendig; aber die Anlage dazu kann er gehabt haben. Und die Anlage dazu, sehen Sie, die kann ihm gerade zugute kommen. Man kann sogar dieses sagen, was einem natürlich ein bißchen gegen den Strich gehen wird: Es kann ein Mensch da sein, der kann eine Anlage zum Heuschnupfen haben; er kann in dem Zustand sein, daß er sagt: Gott sei Dank, daß ich diese Anlage habe; der Heuschnupfen kommt zwar bei mir nicht heraus, aber so habe ich immer eine Anlage zur Erweichung meiner Gefäße. Wenn das nun nicht herauskommt, schützt ihn das vor Arterienverkalkung. Wenn nun der betreffende Mensch einen Sohn hat, so kann er gerade das haben, was beim Vater nach innen schießt; das kann er nach außen haben, das hängt beim Sohn mit irgendeiner Erkrankung nach außen zusammen.

Das sind ja überhaupt die Geheimnisse der Vererbung, daß manches bei den Nachkommen krank wird, was bei den Vorfahren gesund war. Man teilt die Krankheiten ein, spricht von Arterienverkalkung, Lungentuberkulose, Leberverhärtung, Magenverstimmung und so weiter. Das kann man nun hübsch im Buch hintereinanderschreiben, kann beschreiben, wie diese Krankheiten sind; man hat aber nicht viel davon, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil Arterienverkalkung bei jedem Menschen etwas anderes ist. Es sind gar nicht zwei Menschen gleich, die Arterienverkalkung haben; jeder Mensch kriegt die Arterienverkalkung auf andere Weise. Das ist schon so, meine Herren. Sehen Sie, das ist gar kein Wunder.

Es gab einmal zwei Professoren, Dozenten, die wirkten beide an der Berliner Universität. Der eine war siebzig Jahre alt, der andere zweiundneunzig; derjenige, der siebzig Jahre alt war, der war ein ganz berühmter Mensch. Er hat viele Bücher geschrieben, aber er war ein Mensch, der mit seiner Philosophie ganz im Materialismus drinnen gelebt hat, der nur Gedanken gehabt hat, die im Materialismus drinnenstecken. Solche Gedanken wirken nun auch bei der Arterienverkalkung mit. Und er bekam Arterienverkalkung. Als er siebzig Jahre alt war, konnte er nicht anders, als sich pensionieren zu lassen. Derjenige, der neunzig Jahre alt war, sein Kollege, war nicht Materialist, war ein Kind geblieben fast sein ganzes Leben hindurch, hat mit ungeheurer Lebhaftigkeit noch doziert. Der hat gesagt: Ja, ich begreife meinen Kollegen nicht, den jungen Knaben! Ich will mich jetzt noch nicht pensionieren lassen; ich fühle mich noch furchtbar jung. - Der andere war abgetakelt, der «Knabe» konnte nicht mehr weiter dozieren. Natürlich war der, als er zweiundneunzig Jahre alt war, auch verkalkt; er hatte ganz verkalkte Arterien, aber er konnte bei der Beweglichkeit seiner Seele mit seinen Arterien noch etwas anfangen. Der andere hatte keine Möglichkeit mehr dazu.

Nun noch etwas zu der Frage von Herrn Burle über die Gelbe Rübe; Herr Burle sagte:

Der menschliche Körper verlangt durch seinen eigenen Instinkt das, was er braucht. Kinder haben oft eine Gelbe Rübe in der Hand. Kinder und Große zwingt man manchmal zu einer Speise, welche ihnen nicht gut tut. Ich glaube, daß man das nicht machen sollte, wenn jemand einen Speiseabscheu hat. Ich habe einen Knaben, der mag die Kartoffeln nicht essen.

Meine Herren, Sie brauchen ja nur das eine zu bedenken. Wenn nämlich die Tiere keinen Instinkt hätten für dasjenige, was ihnen gut tut und nicht gut tut, so würden sie alle längst krepiert sein; denn die Tiere kommen ja alle auf der Weide auch an Giftpflanzen heran. Wenn sie nicht genau wüßten, Giftpflanzen können sie nicht fressen, so würden sie sie ja fressen. Sie gehen ja immer an den Giftpflanzen vorbei. Aber es ist noch vieles andere. Die Tiere wählen sich ja mit Sorgfalt dasjenige aus, was ihnen gut bekommt. Haben Sie schon jemals Gänse genudelt oder gestopft? Glauben Sie, daß das die Gänse von selber machen würden? Da zwingen ja nur die Menschen die Gänse dazu, so viel zu fressen. Natürlich, bei den Schweinen ist es schon etwas anderes; aber was glauben Sie, was wir für magere Schweine hätten, wenn man sie nicht zwingen würde, so viel zu fressen! Aber bei den Schweinen ist das noch etwas anderes. Sie haben etwas in der Vererbung aufgenommen, weil man schon die Schweinevorfahren gewöhnt hat an alle die Dinge, die fett machen; die wurden schon früher in der Nahrung aufgenommen. Aber die Urschweine, die mußte man dazu zwingen! Von selber nimmt kein Tier auf, was ihm nicht paßt. Nun aber, meine Herren, was hat der Materialismus gemacht? Der glaubt doch nicht mehr an solche Instinkte.

Sehen Sie, ich hatte einen Freund, es war ein Jugendfreund; und als wir zusammen waren, da waren wir ganz leidlich vernünftig mit dem Essen — wir haben sehr häufig zusammen gegessen als junge Leute; wir haben uns halt dasjenige geben lassen, was man so ißt und von dem man glaubt, wie man sagt, daß es anschlägt. Nun, wie das Leben es so fügt, wir sind auseinandergekommen, und ich kam später nach Jahren wiederum in die Stadt, wo er war, wurde eingeladen bei ihm zu Mittag. Und siehe da: Er hatte neben seinem Teller eine Waage. Da sagte ich zu ihm: Was machst du denn mit der Waage da? — Ich wußte es natürlich, wollte aber hören, was er sagen würde. Er erwiderte: Das Fleisch, das mir gerade dient, das wäge ich mir zu, daß es richtig ist für mich, und den Salat. - Da wog er sich auf der Waage alles zu, was er auf dem Teller haben soll, weil das die Wissenschaft vorgeschrieben hat. Was hat er aber damit getan? Er hat sich allen Instinkt abgewöhnt, wußte zuletzt überhaupt nicht mehr, was er essen sollte! Sehen Sie, was einst im Buch gestanden hat: an Eiweiß braucht der Mensch hundertzwanzig oder hundertfünfzig Gramm - heute ist es so, daß es heißt: nur fünfzig Gramm -, das hat er brav sich abgewogen. Das war gerade falsch!

Natürlich, meine Herren, wenn der Mensch zuckerkrank ist, dann ist es etwas anderes — das ist ganz selbstverständlich —, denn die Zuckerkrankheit, die Diabetes, die beweist immer, daß der Mensch den Instinkt für die Nahrung eigentlich verloren hat.

Also darum handelt es sich: daß, wenn ein Kind die Anlage hat, nur die geringfügige Anlage hat, Würmer zu bekommen, dann tut es nämlich alles mögliche. Sie können manchmal erstaunt sein darüber, wie ein solches Kind sich gerade ein Feld aufsucht, wo Gelbe Rüben sind, und dann werden Sie es finden, Gelbe Rüben essend. Und wenn das Feld weit weg ist, läuft das Kind hin und sucht sich die Gelben Rüben, weil das Kind, das Anlage hat zu Würmern, unbedingt Gelbe Rüben essen will. Und so ist eigentlich das Allernützlichste, was man tun kann, meine Herren: Achtgeben, wie ein Kind anfängt, das oder jenes gern zu essen, oder nicht gern zu essen, wenn es entwöhnt ist, wenn es nicht mehr die Milch hat. Sobald das Kind an die äußere Nahrung herankommt, kann man an dem Kinde lernen, was man dem Menschen geben soll. Wenn man erst das Kind zwingt, das zu essen, was man glaubt, daß es essen soll, wird der Instinkt verdorben. Also man soll sich nach dem richten, wonach das Kind Instinkt hat. Natürlich, man muß manches, was gleich zur Unsitte ausschlägt, ja eindämmen, aber da, wo man es eindämmt, muß man beobachten.

Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel ein Kind, von dem Sie bemerken, daß es, trotzdem Sie ihm alles schön geben nach Ihrer Meinung, gar nicht anders kann, wenn es zum ersten Mal zu Tisch kommt, als auf einen Stuhl hinaufzusteigen, sich ein bißchen hinüber über den Tisch zu beugen und ein Stückchen Zucker zu stibitzen! Ja, sehen Sie, solch eine Sache muß man in der richtigen Weise auffassen, denn ein solches Kind, das auf einen Stuhl steigt und sich ein Stückchen Zucker stibitzt, hat ganz gewiß etwas in seiner Leber nicht in Ordnung. Einfach das, daß das Kind sich etwas Zucker stibitzt, das beweist, daß irgend etwas in der Leber nicht in Ordnung ist. Nur Kinder, bei denen etwas in der Leber nicht in Ordnung ist — was sogar dann durch den Zucker kuriert wird -, die stibitzen Zucker; die anderen interessieren sich nicht für den Zucker, die lassen ihn stehen. Natürlich darf das nicht zur Unsitte ausarten, aber man muß für so etwas Verständnis haben. Und man kann da in zweifacher Weise Verständnis haben.

Sehen Sie, wenn ein Kind ganz fest fortwährend nur daran denkt: Wann guckt der Vater oder die Mutter nicht hin, daß ich den Zucker nehmen kann -, dann stibitzt das Kind später auch andere Sachen. Wenn man aber das Kind befriedigt, weil man ihm gibt, was es braucht, dann wird es kein Dieb. Also es hat auch in moralischer Beziehung eine große Bedeutung, ob man solche Dinge beobachtet oder nicht. Das ist sehr wichtig, meine Herren. Und so muß man die Frage, die Sie jetzt gestellt haben, so beantworten: Man soll gerade achtgeben, was das Kind will oder verabscheut, und es nicht zu dem zwingen, was es nicht will. Denn wenn es zum Beispiel geschieht, was bei sehr vielen Kindern der Fall ist, daß es kein Fleisch essen will, so ist es so, daß das Kind durch das Fleisch Darmgifte bekommt, und die will es vermeiden. Dieser Instinkt ist da. Ein Kind, das an einem Tisch sitzt, wo alle anderen Fleisch essen, und es verweigert das Fleisch, das hat gerade die Anlage, Darmgifte zu entwickeln durch das Fleisch. Das muß man alles berücksichtigen.

Daraus sehen Sie, daß die Wissenschaft überhaupt noch viel feiner werden muß. Die Wissenschaft muß noch viel feiner werden; die ist heute viel zu grob! Mit der Waage und allem, was man im Laboratorium treibt, kann man eigentlich nicht bloß Wissenschaft treiben.

Die Ernährung, die Sie jetzt so vorzugsweise interessiert, die ist schon so, daß man richtig verstehen muß, wie diese Ernährung mit dem Geist zusammenhängt. Da führe ich ja oftmals, wenn die Leute um so etwas fragen, oder so etwas wissen wollen, zwei Beispiele an. Denken Sie sich, meine Herren, ein Journalist, der muß ja so viel denken allerdings unnötig meistens —, aber er muß so viel denken, daß ja der Mensch so viele Gedanken, die logisch sind, gar nicht haben kann. Daher werden Sie finden, daß der Journalist oder überhaupt ein Mensch, der berufsmäßig schreiben soll, den Kaffee liebt, ganz instinktmäßig. Er setzt sich ins Kaffeehaus, trinkt eine Tasse Kaffee nach der anderen und nagt an der Feder, damit etwas herauskommt, das er schreiben kann. Das Federnagen hilft ihm nichts, aber der Kaffee hilft ihm dazu, daß ein Gedanke aus dem anderen hervorgeht, denn es muß sich ja ein Gedanke an den anderen anknüpfen.

Aber sehen Sie, wenn sich einer an den anderen anknüpft, wenn einer aus dem anderen folgt, das ist sehr schädlich bei Diplomaten. Wenn Diplomaten logisch sind, findet man sie langweilig; sie müssen recht unterhaltsam sein. In Gesellschaften, da liebt man es nicht, daß erstens, zweitens, drittens, «und wenn das erst’ und zweit’ nicht wär’, das dritt’ und viert” wär nimmermehr» -, wenn einer so logisch ist! Man darf nicht andere Dinge zum Beispiel in einem Finanzartikel behandeln als Journalist. Aber als Diplomat kann man reden von Tanzbars oder sonstigem zugleich, oder nachher von den Staatsfinanzen des Landes X, und nachher von den Schnecken der Frau Soundso, und nachher kann man gleich übergehen und reden von der Fruchtbarkeit der Kolonien; und nachher: wo das beste Pferd steht und so weiter. Da muß ein Gedanke in den anderen überspringen. Ja, da bekommt man, wenn man in dieser Weise gesellschaftsfähig werden will, den Instinkt, viel Tee zu trinken! Der Tee, der zerstreut die Gedanken; da springt man in Gedanken. Und der Kaffee, der setzt einen Gedanken an den anderen an. Wenn ein Gedanke zum anderen überspringen soll, da muß man Tee trinken! Ja, sehen Sie, beim Diplomaten-Tee — man sagt schon «Diplomaten-Tee»! -, da wird eben Tee getrunken! Der Journalist sitzt im Kaffeehaus, trinkt einen Kaffee nach dem anderen aus. Da sehen Sie schon, welchen Einfluß ein Nahrungs- oder Genußmittel auf das ganze Denken hat! Und so ist es natürlich nicht nur mit diesen Dingen; dies sind sozusagen radikale Dinge - Kaffee und Tee. Aber gerade daran sieht man, daß man darauf achten muß, wie diese Dinge stehen. Das ist sehr wichtig, meine Herren.

Wir werden dann den Vortrag am nächsten Mittwoch wiederum um neun Uhr haben.

Seventh Lecture

Today, I would like to add a few things to what was said last Thursday in response to Mr. Burle's question. I explained how four things are necessary for every human being's nutrition: salts; what are called carbohydrates, which are found primarily in potatoes, but also in the grains of our fields and in legumes. And then, I said, humans also need fats and proteins. But I explained to you how different human nutrition is in terms of protein, for example, and, let's say, salt. Humans absorb salt into their bodies up to their heads in such a way that it remains salt, that it does not actually change in any way other than being dissolved. But it retains its powers as salt right up to the human head. On the other hand, protein, that is, what we have in ordinary chicken eggs, but also what we have in plants, this protein is immediately destroyed in the human body, still in the stomach and intestines, and does not remain protein. But now the human being has expended the energy to destroy this protein, and the result is that, because he has destroyed protein, he also regains the energy to produce protein again; and so he makes his own protein. But he would not make it if he did not first destroy other protein.

Imagine, gentlemen, how it is with protein. Imagine that you have become a very intelligent person and are so clever that you believe you have the skill to make a watch, but you have seen nothing but a watch as it looks from the outside — well, you will not be able to make a watch right away. But if you risk taking the watch apart completely, dismantling it completely, breaking it down into its individual parts and remembering how it was put together, then you will learn from dismantling the watch how to put it back together again. This is what the human body does with protein. It has to get the protein inside itself, so it breaks it down completely. Protein consists of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen, and sulfur; these are the most important components of protein. The protein is now completely broken down, so that when it enters the intestines, the human body does not have protein, but carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen, and sulfur. You see, now the human body has broken down the protein, just as one breaks down a watch. — You will say: Yes, but once you have broken down a watch, you can remember how to do it in order to make more watches; and you only need to eat protein once, and then you can make protein again and again. — But that is not true, because humans have a memory as whole beings; but the body as such does not have a memory that allows it to remember anything; instead, the body uses its energy for building. So we have to eat protein again and again in order to be able to produce protein.

Now, when humans produce their own protein, they do something very, very complicated. First, they break down the protein they eat, which distributes carbon throughout their bodies. Now, as you know, we also draw oxygen from the air. This combines with the carbon we have inside us. We have this carbon in protein and in other foods. We first exhale carbon in carbon dioxide. But we retain some of it. Now we have carbon and oxygen inside our bodies, so that we do not retain the oxygen we have eaten with the protein, but combine the oxygen we have inhaled with the carbon. So we do not build up our protein inside our bodies in the way that materialists imagine: that we eat a lot of chicken eggs, which are distributed throughout the body, and afterwards we have the chicken eggs we have eaten spread throughout the body. That is not true. We are already protected by the organization of our body, so that if we eat chicken eggs, we would all become crazy chickens. It's not true, we don't all become crazy chickens because we already destroy the protein in our intestines. Instead of the oxygen it had, we take oxygen from the air. We have that now. You see, we breathe in nitrogen with the oxygen because there is always nitrogen in the air. And we don't use the nitrogen we eat with the chicken egg, but again the nitrogen we breathe in from the air. We certainly don't use the hydrogen we eat with the chicken egg, but the hydrogen we get through our nose and through our ears, through our senses; we turn that into our own protein. And sulfur—we get that continuously from the air. So we also get hydrogen and sulfur from the air. Of the protein we eat, we only retain the carbon. We use the rest by taking what we get from the air.

So you see, that's how it is with protein. And in a very similar way, it is also the case with fat. We make our own protein ourselves, we only use the carbon from foreign protein; and we also make our own fat ourselves. Basically, we only use very little of the nitrogen we absorb through food for fats. So the thing is that we produce protein and fat in our own way. Only what we absorb from potatoes, legumes, and grains goes into the body, and even then, what we absorb from grains and potatoes does not go completely only up to the lower parts of the head, so to speak. What we consume with salts is transferred to the entire head, and from this we then form what we need for our bones.

You see, gentlemen, because this is the case, we must ensure that we introduce healthy plant protein into our bodies! Healthy plant protein is what our bodies have a lot of. When we introduce chicken protein into our bodies, our bodies can become quite lazy, sluggish, and sluggish: they can easily destroy it because it is easily destroyed. Plant protein, i.e., the protein we get from the fruits of plants—it is mainly found in plants, as I told you the day before yesterday—is particularly valuable for us. Therefore, it is really necessary for a person who wants to stay healthy to include fruit in their diet, either cooked or raw. They must have fruit. If a person completely avoids eating fruit, they will gradually transition to a completely sluggish internal digestion in their body.

Now you see, it is also a matter of feeding the plants themselves in the right way! You must remember that if we want to feed the plants in the right way, plants are living things. Plants are not minerals, plants are living things. And when we get a plant, we get it from the seed that is put into the soil. The plant cannot thrive properly unless it gets the soil itself a little bit alive. And how do you make it alive? You make the soil alive by fertilizing it properly. So proper fertilization is what really provides us with proper plant protein.

And here again, you have to consider the following. You see, for a long, long time, people have known that the right fertilizer is the one that comes from the stables, from the cowshed and so on; the right fertilizer is the one that comes from the farm itself. But in more recent times, when everything has become materialistic, people have said: Yes, we can do it this way: we can look at what substances are in the fertilizer, and then we take them from the mineral kingdom — mineral fertilizer.

Yes, you see, gentlemen, when you use mineral fertilizer, it is just like putting salt in the soil; it only makes the roots strong. So then we only get from the plant what goes into the human bone structure. But we don't get proper protein from the plant. That is why plants, our crops, have all been suffering from a protein deficiency for some time now. And this will become greater and greater if people do not return to proper fertilization.

You see, there have already been meetings of farmers where the farmers have said — but of course they didn't know why —: Yes, the fruit is getting worse and worse! — And it's true. Anyone who has grown old knows that when they were young, everything that came out of the fields was actually better. You can't just think that you can simply mix fertilizer from the substances that cow manure consists of, but you have to be clear: because cow manure does not come from a chemist's laboratory, but from the much, much more scientific laboratory that is inside the cow — which is a much more scientific laboratory — it is precisely this that makes cow manure not only strengthen the roots of plants, but also have a powerful effect on the fruits, producing proper protein in the plants and making people very strong.

If we were to fertilize only with mineral fertilizers, as is popular in recent times, or even with nitrogen produced from the air — yes, gentlemen, your children, and even more so your grandchildren, will have very pale faces. You will no longer be able to distinguish their faces from their hands when they are white. The fact that people can have a lively color, a healthy color, depends precisely on the fields being properly fertilized.

So you see, when talking about nutrition, one must take into account how food is produced in the first place. This is extremely important. You can see from various circumstances that the human body has a need to desire what it needs. Take, for example, the fact that prisoners who are sentenced to years of imprisonment usually receive food that is not rich enough in fat — develop an enormous craving for fat, and if some of it drips down from a light that the prison guard carries into the cell and lands on the floor, they immediately bend down and lick up this fat, because the body feels this so strongly when it is really missing some food that it needs. This does not happen when you can eat properly every day. It never happens because the body does not lack what it needs. But when something is constantly missing from the diet for weeks on end, the body becomes extremely greedy for it. That is what needs to be added in particular.

Now, I have already told you that there is much else connected with such fertilization. You see, our ancestors in Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries, or even earlier, differed from us in many ways. This is usually not taken into account at all! And among all the things that distinguished them from us was that they did not eat potatoes. Potatoes were only introduced later. However, eating potatoes has had a strong influence on humans. You see, eating grains strengthens the lungs and heart in particular. It strengthens the lungs and heart. People develop a healthy chest and feel good. They are not as eager to think as they are to breathe, for example; they can also tolerate a lot when breathing. And I would like to tell you right away: you must not imagine that the person who always has to open the windows, who always cries out, “Oh, fresh air!” and so on, is strong in breathing. Rather, the person who is strong in breathing is the one who is ultimately so strongly organized that they can tolerate any air. What matters is that it is not those who cannot tolerate anything who are hardened, but those who can tolerate something.

In our time, there is much talk of hardening. Just think of how children are hardened. Nowadays, children — especially those of rich people, but others are already following suit — are dressed like this: while we wore proper stockings as children in our youth and were completely covered, except perhaps when we went barefoot, now suits only go down to the knees at most, or even less. If people knew that this poses the greatest risk for appendicitis later in life, they would reconsider! But fashion is so tyrannical that such a mindset does not even arise. Now children are dressed in clothes that only reach to the knees or even less, and it will come to the point where they will only reach to the stomach; that will also become fashionable. So fashion has an extremely strong influence.

But people don't realize what really matters. It is absolutely essential that the human being adjusts his entire organization so that he can truly process everything he takes in as nourishment. And I think it is particularly important to know that human beings become strong when they properly process the things they take in. And they do not become hardened by doing what I have told you with children. Children become so hardened that when they later — just look at them — have to walk across a hot surface, they drip with sweat and cannot continue. It is not those who cannot tolerate anything who are hardened, but those who can tolerate everything. So it is also true that people used to be less hardened; they simply had healthy lungs, healthy hearts, and so on.

Then came the potato diet. Potatoes provide less nourishment for the heart and lungs; potatoes go to the head—though, as I have told you, only to the lower head, not the upper head—but they go to the lower head, where one becomes particularly critical and thinks. That is why, you see, there were fewer newspaper writers in earlier times. The art of printing did not yet exist. Just consider what is thought every day in the world today, just to produce the newspapers! Yes, all this thinking, which is not at all necessary—it is far too much—all this thinking, we owe to the potato diet! For the person who eats potatoes feels constantly stimulated to think. They cannot help but think. This weakens their lungs and heart, and tuberculosis, pulmonary tuberculosis, only became prevalent when the potato diet was introduced! And the weakest people are those in areas where almost nothing else is grown but potatoes and where people live on potatoes.

It is precisely spiritual science — as I have often told you — that has the opportunity to learn about this material aspect. Materialistic science knows nothing about nutrition, knows nothing about what is healthy for humans. That is precisely what is peculiar about materialism: it only ever thinks, thinks, thinks, and knows nothing! The point is: if you want to stand on solid ground in life, you absolutely must know something. You see, these are the things I wanted to tell you about nutrition.

Now, if you have any further questions, you can ask about specific issues.

Question: Last time, the doctor mentioned something about arteriosclerosis. This arteriosclerosis is generally said to be caused by eating a lot of meat and eggs and the like. I know someone who developed arteriosclerosis at the age of fifty, became stiff by the age of seventy, and now, at the age of eighty-five or eighty-six, is much more sprightly than he was in his fifties and sixties. Has the arteriosclerosis receded? Is this possible, or what could be the cause? Incidentally, this person never smoked tobacco, drank very little alcohol, and lived a fairly healthy life. However, he ate quite a lot of meat in his younger years and was only able to work a little at the age of seventy; but today, at the age of eighty-five, eighty-six, he is still active and alive.

Dr. Steiner: You say that this was a person who developed arteriosclerosis at around the age of fifty, became stiff, was barely able to work—I don't know if his memory also declined; you wouldn't have noticed that. This condition remained until his seventies; then this person became vigorous again and is still alive today. — But what does he have today that could be reminiscent of arteriosclerosis? Or is he sprightly and agile?

Questioner says: He is completely sprightly today and more agile than he was at sixty-five or seventy; he is my father.

Dr. Steiner: The point is that one would first have to determine exactly what the arteriosclerosis was like. You see, the thing is this: in most cases, arteriosclerosis occurs in such a way that the person's arteries become calcified throughout. Now, when a person's arteries calcify throughout the body, they naturally become unable to control the body from the soul and spirit; the body becomes stiff. Now, the situation is this: let's assume that someone does not develop arteriosclerosis throughout the body, but that arteriosclerosis spares the brain, for example; then the following is the case. You see, I know something about your state of health. Perhaps I can draw some conclusions about your father's state of health from yours — I don't know your father. For example, you suffer, or have suffered, from hay fever, but hopefully it will get completely better. This shows that you have something within you that the body can only develop if it is predisposed to sclerosis, to arteriosclerosis, not in the head, but only outside the head. No one who is predisposed to arteriosclerosis throughout their entire body can easily develop hay fever. Because hay fever is the exact opposite of arteriosclerosis. Now you suffer from hay fever. This proves that your hay fever — it's not good to have hay fever; it's better if it's cured; but it depends on your predisposition – so your hay fever is something like a valve against sclerosis, against arteriosclerosis.

Now, everyone gets arteriosclerosis to a lesser degree. You cannot grow old without getting arteriosclerosis. If you get arteriosclerosis throughout your whole body, there's nothing you can do about it; your whole body becomes stiff. But if you get arteriosclerosis in your head—except for the rest of your body—then what happens is that as you get really old, the etheric body I told you about gets stronger and stronger. And then the etheric body no longer needs the brain so much. It can now become old and stiff. But the etheric body can now begin to control this slight arteriosclerosis, which used to make you old and stiff, in such a way that you can skillfully control it; the arteriosclerosis is then not so severe.

Your father, for example, did not need to have had hay fever himself, that is not necessary at all; but he may have had the predisposition to it. And the predisposition to it, you see, can actually benefit him. One can even say this, which of course will go a little against the grain: There may be a person who has a predisposition to hay fever; he may be in a state where he says: Thank God I have this predisposition; I may not develop hay fever, but I always have a predisposition to softening of my blood vessels. If this does not develop, it protects him from arteriosclerosis. If this person has a son, he may have exactly what his father has inside him; he may have it on the outside, which in the son's case is associated with some kind of external illness.