Karmic Relationships I

GA 235

Lecture IX

15 March 1924, Dornach

In these lectures we are speaking of karma, of the paths of human destiny, and in the last lecture we studied certain connections which can throw light on the way in which destiny works through the course of successive earthly lives. I have decided—although needless to say it was a decision fraught with risk—to speak in detail of such karmic connections, and today we will carry our studies a little further.

You will have seen that in describing karmic connections it is necessary to mention many details in the life and character of a human being which in the ordinary way might escape attention. In the case of Dühring, I pointed out how a bodily peculiarity of one incarnation became a particular trend and attitude of soul in the next. For it is a fact that when one presses through to the spiritual worlds in search of the true being of man, the spiritual loses its abstractness and becomes full of force; on the other hand, the corporeality, all that comes to expression in the bodily nature of man, loses, one may truthfully say, its materiality; it assumes a spiritual significance and acquires a definite place in the interconnections of human life.

How does destiny actually work? Destiny arises from the whole being of man. What a man seeks in life as the result of a karmic urge, and which then comes to him in the form of destiny, depends upon the fact that forces of destiny, as they pass from life to life, influence and condition the very composition of the blood in its more delicate qualities and regulate the activity of the nerves; to their working is due also the instinctive sensitiveness of the soul to this or that influence. We shall not easily find our way into the innermost nature of karmic connections if we do not pay attention—with the eye of the soul, of course—to the particular mannerisms of an individual. Believe me, for the study of karma it is just as important to be interested in a gesture of the hand as in some great spiritual talent. It is just as important to be able to observe—from the spiritual side (astral body and ego)—how a man sits down on a chair as to observe, let us say, how he discharges his moral obligations. If a man is given to frowning, to knitting his brow, this may be just as important as whether he is virtuous or the reverse.

Much that in ordinary life seems to be quite insignificant is of very great importance when we begin to consider destiny and observe how it weaves its web from life to life; while many a thing in this or the other human being that appears to us particularly important becomes of negligible significance,

Generally speaking, it is not, as you know, very easy to pay real attention to bodily peculiarities. They are there and we must learn to observe them naturally without wounding our fellow-men—as we certainly shall do if we observe merely for observation's sake. That must never be. Everything must arise entirely of itself. When, however, we have trained our powers of attention and perception, individual peculiarities do show themselves in every human being, peculiarities which may be accounted trifling but are of paramount importance in connection with the study of karma. A really penetrating observation of human beings in respect of their karmic connections is possible only when we can discern these significant peculiarities.

Some decades ago, a personality whose inner, spiritual life as well as his outer life were intensely interesting to me, was the philosopher Eduard von Hartmann.

When I try to study von Hartmann's life in such a way as to lead to a perception of his karma, I have to picture. to myself what was of value in his life somewhat in the following way.—Eduard von Hartmann, the philosopher of the Unconscious, was really an explosive influence in philosophy, but thinkers of the 19th century—pardon me if I sound critical, I mean it not unkindly—received the effects of this explosive effect in the realm of the spirit with extraordinary apathy. Indeed, the men of the 19th century simply cannot be wakened—and I include, of course, the 20th century that has now begun; it is impossible to shake them out of their phlegmatic attitude towards anything that really stirs the world inwardly. No enthusiasm of any depth is to be found in this phlegmatic age—phlegmatic, that is to say, in respect of spiritual life.

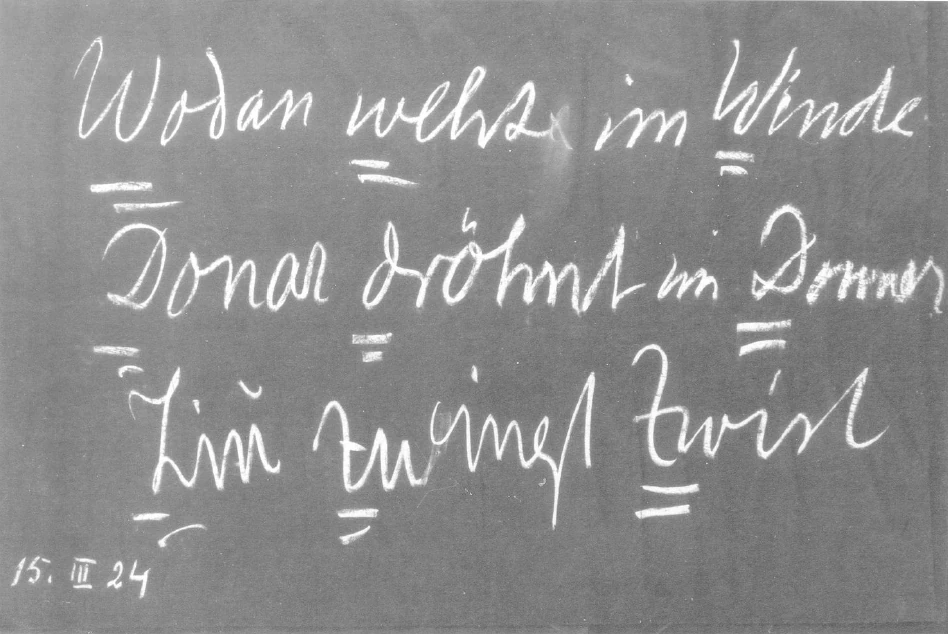

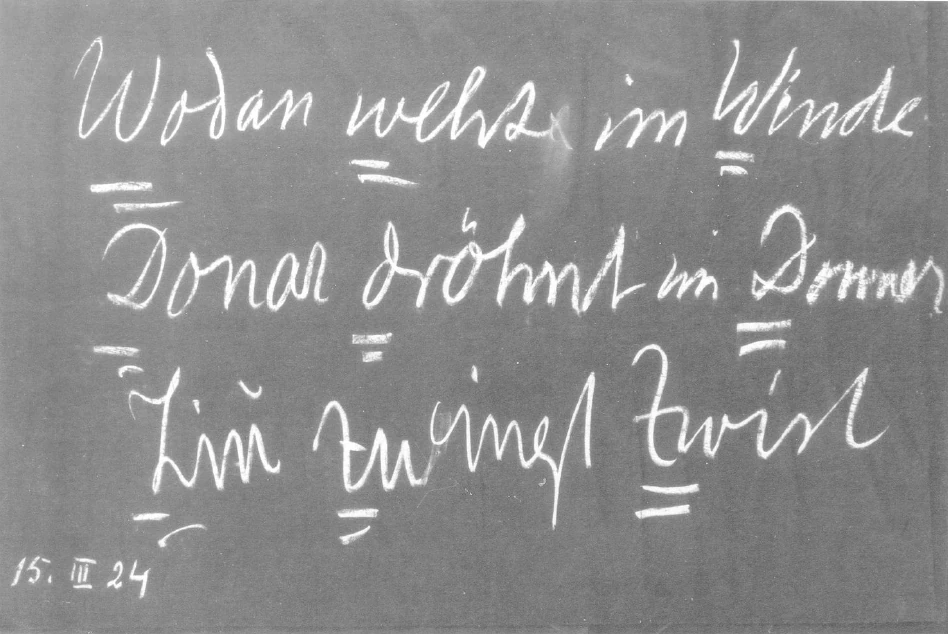

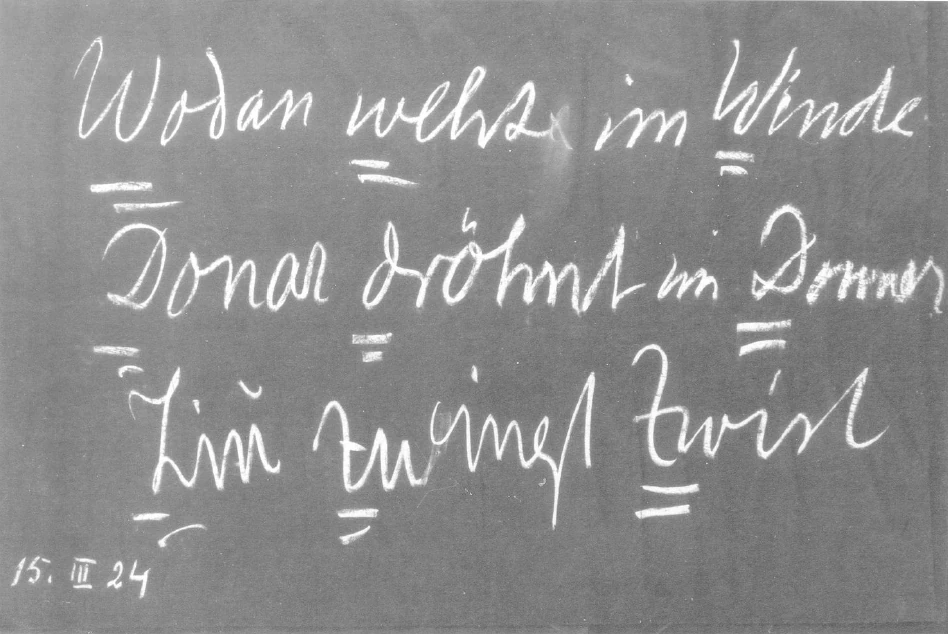

In another recent series of lectures I gave a picture of the encounter between the Roman world and the world of the Northern Germanic peoples at the time of the migrations, at the time when Christianity was beginning to spread to the North from the southerly regions of Greece and Rome. You have only to picture these physical forefathers of Middle and Southern Europe truly, and you will get some impression of the inner, dynamic vigour which once spurred men to action in the world. The Germanic tribes whom the Romans encountered in the early Christian centuries knew what it was to live in union with the spiritual powers of nature. The attitude of these men to the Spiritual was quite different from ours; in most of them, of course, there was still an instinctive inclination towards the Spiritual. And whereas we today speak for the most part phlegmatically, so that one word simply follows another, as though speech contained nothing real, these people poured out what they actually experienced into words and speech. For them the surging roar of the wind was as much a physical gesture, a manifestation of soul-and-spirit, as when a man moves his arm. In the surge of the wind and in the flickering of the light in the wind, they saw an expression of Wodan. And when they carried these realities over into speech, when they clothed them in language, they imbued their words with the character of what they experienced. If we were to express it in modern words, saying “Wodan weht im Winde” (Wodan weaves in the wind)—and the words were almost similar in olden times—there the weaving activity pours into the language itself. Think of how this direct participation in the life and forces of nature vibrates and pulsates in the words, how it surges into them! When a man of those times looked up to the heavens and heard the thunder roaring and rumbling out of the clouds, and behind this nature-gesture of the thunder beheld the corresponding spiritual reality of being, he brought the whole experience to expression in the words ”Donner (or Donar) dröhnt im Donner” (Thor rumbles in the thunder)—for thus we may hear, transposed into modern language, words that still echo the sound of the ancient speech. And just as these men felt the Spiritual in the workings of nature and expressed it in their speech, so did they also express their experience of the God who aided them when they went forth to battle, who lived in their very limbs and in their whole bearing and action. They held their mighty shields before them, shouting the words like a war-cry. And the fact that spirits, whether good spirits or demons, stormed into the words which rose and fell with powerful resonance—all this they expressed as they rushed forward to attack, in the words: “Ziu Zwingt Zwist.” Spoken behind the shield, spoken with all the rage and lust of battle, that really was like the breaking of a storm! You must imagine it shouted as it were against the shields by thousands of voices at once. In those early centuries, when the peoples of the South came into conflict with those pouring down from Middle Europe, it was not the outer course of the battle that had the decisive effect. No—it was rather this mighty shout accompanying the attack against the Romans! For in those early times it was this shout that filled the people coming from the South with a terrible fear. Knees trembled before the “Ziu Zwingt Zwist,” bellowed forth by a thousand throats behind the shields.

And so we are bound to say: these same men are there again in the world today, but they have become phlegmatic! Many a man alive today bellowed and roared in those days of yore but has now become utterly phlegmatic, has adopted the attitude of soul typical of the 19th and 20th centuries. But if those men were to return in the mood of soul that inspired them in the days when they yelled their war-cry, they would feel like donning a nightcap in their present incarnation, for they would say: This phlegmatic apathy out of which people simply cannot be roused, belongs properly under a nightcap; bed is the place for it, not the arena of human action!

I say this only because I want to indicate how little inclination there was among the men of von Hartmann's time to let themselves be roused by an explosive force like that contained in his Philosophy of the Unconscious. He spoke, to begin with, of how all that is conscious in man, all his conscious thinking is of less significance than that which works and weaves unconsciously in him, as it does in nature, and can never be raised into consciousness. Of clairvoyant Imagination and Intuition, Eduard von Hartmann knew nothing; he did not know that the unconscious can penetrate into the sphere of human cognition. And so he asserts that what is really essential in the world and in life remains in the unconscious. This very reasoning, however, gives him the ground for his view that the world in which we live is the worst world imaginable. He carried his pessimism even further than Schopenhauer and reached the conclusion that the evolution of culture must culminate in the destruction of the whole of earth-evolution. He would not insist, he said, that this would happen in the immediate future, because that would not give time to apply all that will be necessary for carrying the destruction so far that no human civilisation—which in any case, according to his view, is worthless—will be left. And he dreamed—you will find it in his Philosophy of the Unconscious—he dreamed of how men will ultimately invent a huge machine which they will be able to lower deeply enough into the earth to produce a terrific explosion, scattering the whole earth in fragments through universal space.

It is true that many people have been enthusiastic about this Philosophy of the Unconscious. But when they come to talk about it, one does not feel that it has taken any real hold of them. A statement like Hartmann's can, of course, be made, and there is something powerful in the mere fact of its utterance—but people quote it as though they were making a casual remark, and that is the really terrible thing.

Yes, there was actually a philosopher who spoke in this way. And this same philosopher went on to expound the subject of human morality on earth. It was his work Phänomenologie des sittlichen Bewusstseins (Phenomenology of the Moral Consciousness) that interested me most of all. He also wrote a book entitled Das religiöse Bewusstsein der Menschheit (The Religious Consciousness of Mankind), and another on Aesthetics—in fact he wrote a very great deal.[With the exception of the Philosophy of the Unconscious the works of Eduard von Hartmann mentioned in this lecture have not been translated into English.] And it was all extraordinarily interesting, particularly where one could not agree with him.

In the case of such a man one may very naturally desire to know the connections of his destiny. One may try, perhaps, to make a deep study of his philosophy, to glean from his philosophical thoughts some idea of his earlier earthly lives, but all such attempts will be fruitless. Nevertheless a personality like Eduard von Hartmann interested me in the highest degree.

When one has occultism in one's very bones—if I may put it so—the impulses for looking at things in the right way arise of themselves. And here one is confronted with the following circumstances.—Eduard von Hartmann was a soldier, an officer. The Kürschner Directory, besides recording his Doctorate of Philosophy and other academic degrees, put him down until the day of his death as “First Lieutenant.” Eduard von Hartmann was an officer in the Prussian Army and is said to have been a very good one.

From a certain day onwards this fact seemed to me more significant in connection with the threads of his destiny than all the details of his philosophy. As for his philosophy—well, one is inclined to accept certain things and reject others. But there is nothing much in that; everyone who knows a little philosophy can do the same and the result will not amount to anything very striking. But now let us ask ourselves: How comes it that a Prussian officer, who was a good officer, who took very little interest in philosophy while he was in the Army but was much more concerned with sword-exercises—how comes it that such a man turns into a representative philosopher of his age?

It was due to the fact that an illness left him with an affliction of the knee from which he suffered for the rest of his life, and he was invalided out of the Army on a pension. At times he was quite unable to walk and was obliged to recline with his legs stretched out on a sofa. And then, after having imbibed contemporary scholarship, he wrote one philosophical work after another. Eduard von Hartmann's philosophical writings are a whole library in themselves; his output was prodigious.

Now when I came to study this personality, it dawned upon me one day that there was very special importance in the onset of this knee affliction. The fact that at a certain age the man began to suffer from an affliction of the knee interested me much more than his transcendental realism, or even than his famous saying: “First there was the religion of the Father, then the religion of the Son, and in the future there will come the religion of the Spirit.” Such sayings show ability and astuteness of mind, but they were to be met with at every street comer, so to say, in the 19th century. But for a man to become a philosopher through contracting, while he was a Lieutenant, an infirmity of the knee—that is a most significant fact. Moreover until we can go back to such things and not allow ourselves to be dazzled by what appears to be the most striking feature in a man's life, we shall not be able to discover the karmic connections.

When I was able to bring the affliction of the knee into its right relation with the whole personality, I began to perceive how destiny manifested in the life of this man. And then I could go back. It was not by starting from the head of Eduard von Hartmann, but from the knee, that I found the way to his earlier incarnations. What seems to be of most importance in the life between birth and death does not, as a rule, afford the most reliable starting-point.

And now, what is the connection? Man as he stands before us as a physical being in earthly life, is a threefold being. He has his nerves-and-senses organism, which is concentrated mainly in the head but at the same time extends over the whole body. He has his rhythmic organisation, which manifests particularly clearly in the rhythm of the breath and of the circulation of the blood, but again extends over the whole human being and comes to expression every where within him. And thirdly, he has his motor organisation which is connected with the limbs, with the functioning of metabolism, with the reconstruction of the substances of the body and so forth. Man is a threefold being.

And then in regard to the whole constitution of life, we come to realise that on the journey through births and deaths, what we are accustomed to consider in earthly life as the most important part of man, namely the head, becomes of comparatively little importance shortly after death. The head that in the physical world is the most essentially human part of man, really expends itself in physical existence; whereas the rest of the organism—which, physically speaking, is subordinate—is of higher importance in the spiritual world. In his head, man is most of all physical and least of all spiritual. In the other members of his organism, in the rhythmic organisation and in the limbs-organisation, he is more spiritual. He is most spiritual of all in his motor organisation, in the activity of his limbs.

Now gifts and talents belonging to the head are lost comparatively soon after death. On the other hand, the soul-and-spirit which, in the realm of the unconscious, belongs to the lower part of the human organism, assumes great importance between death and a new birth. But whereas, speaking generally, the organism of man apart from the head becomes, in respect of its spiritual form, its spiritual content, the head of the next incarnation, it is also true that what is of the nature of will in the head, works especially into the limbs in the next incarnation. A man who is lazy in his thinking in one incarnation will most certainly be no fast runner in the next: the laziness of thinking becomes slowness of limb; and, vice versa, slowness of limb in the present incarnation comes to expression in sluggish, lazy thinking in the next.

Thus a metamorphosis, an interchange, takes place between the three members of the human being in passing over from one incarnation to another.

What I am telling you here is not put forward as a theory; it is based on the very facts of life. And in the case of Eduard von Hartmann, as soon as I turned my attention to the affliction of the knee, I was guided to his earlier incarnation, during which at a certain moment in his life he had a kind of sunstroke. In respect of destiny, this sunstroke was the cause that led in the next earthly life, through metamorphosis, to an infirmity of the knee—the sunstroke being, as you will realise, an affliction of the head. One day he was no longer able to think. He had a kind of paralysis of the brain, and this came to expression in the next incarnation as an affliction of one of the limbs. Now the destiny that led to paralysis of the brain was due to the following circumstances.—This individuality was one of those who went to the East with the Crusades and fought over in Asia against the Turks and Asiatic peoples, acquiring, however, a tremendous admiration for the latter. The Crusaders encountered very much that was great and sublime in the East, and the individuality of whom we are speaking absorbed it all with deep admiration. And now he came across a man concerning whom he felt instinctively that he had had something to do with him in a still earlier life. The account, so to speak, that had now to be settled between this and the still earlier incarnation, was a moral account. The metamorphosis of the sunstroke in one incarnation into the affliction of the knee in the next appears at first to be a purely physical matter, but when it is a question of destiny we are invariably led back to something that appertains to the moral life. This individuality bore with him from a still earlier incarnation the impulse to wage a fierce battle with the man whom he now encountered and in the heat of the blazing sun he set about persecuting his opponent. The persecution was unjust, and it recoiled upon the persecutor himself inasmuch as his brain was paralysed by the heat of the sun. What was to be brought to an issue in this fight originated in a still earlier incarnation when this individuality had been brilliantly, outstandingly clever. The opponent whom he encountered during the Crusades had suffered injury and embarrassment in an earlier incarnation at the hands of this brilliant individuality. As you see, it all leads back to the moral life, for the forces in play originated in the earlier incarnation.

Thus we have three consecutive incarnations of an individuality. A remarkably clever and able personality in very ancient times—that is one incarnation. Following that, a Crusader, who at a certain time in his life gets paralysis of the brain, brought about as the result of a wrong committed by his cleverness which had, however, in the next incarnation, caused him to acquire tremendous admiration for oriental civilisation. Third incarnation: a Prussian officer who is obliged to retire owing to an affliction of the knee, does not know what to do with his time, goes in for philosophy and writes a most impressive book, a perfect product of the civilisation of the second half of the 19th century: The Philosophy of the Unconscious.

Once this connection of lives is perceived, things that were previously obscure become quite clear. When I was reading Hartmann while I was still young, without knowing anything about these connections, I always had the feeling: Yes, this is extremely clever! But when I had read one page I used to think: There is something brilliantly clever here, but the cleverness is not on this particular page! I always felt I must turn the page and look at the previous one to see if the cleverness were there. In short, the cleverness in this writing was not of today, but of yesterday, or of the day before yesterday.

Light came to me for the first time when I perceived: the outstanding cleverness really lies two incarnations ago and is working on from there. Great illumination is shed upon the whole of this Hartmann literature—which, as I said, is a library in itself—as soon as one realises that the cleverness in it is working on from a much earlier incarnation.

And when one came to know Eduard von Hartmann personally and was talking with him, one also felt: another man is there behind him, but even he is not the one who is talking; behind him again is a third, and it is the third who is really the source of the inspirations. For listening to Hartmann was often enough to drive one to despair! There was an officer, talking philosophy without enthusiasm, apathetically, speaking with a certain crudity of the loftiest truths. One could see how things really were only when one knew: the cleverness behind what he says is that of two incarnations ago.

It may seem disrespectful to relate such things, but no disrespect whatever is intended. Moreover I am convinced that it can be of great value for any human being to know of such connections and apply them to his own life, even if it means that he has to say to himself: Three incarnations ago I was an out-and-out scoundrel! It can be of immense benefit to life when a man can say to himself: In one incarnation or another, perhaps not only in one, I was a thoroughly bad lot! In speaking of such things, just as in other circumstances present company is always excepted, so here present incarnations are excepted!

I was also intensely interested in the connections of destiny of a man with whom my own life brought me into contact, namely Friedrich Nietzsche. I have studied the problem of Nietzsche in all its aspects and, as you know, have written and spoken a great deal about him.

His was indeed a strange and remarkable destiny. I saw him only once during his life. It was in Naumburg, in the nineties of last century, when his mind was already seriously deranged. In the afternoon, about half-past-two, his sister took me into his room. He lay on the couch, listless and unresponsive, with eyes unable to see that someone was standing by him: He lay there with the remarkable, beautifully formed brow that made such a striking impression upon one. Although the eyes were expressionless, one nevertheless had the feeling: This is not a case of insanity, but rather of a man who has been working spiritually the whole morning with great intensity of soul, has had his mid-day meal and is now lying at rest, pondering, half dreamily pondering on what his soul worked out in the morning. Spiritually seen, there were present only a physical body and an etheric body, especially in respect of the upper parts of the organism, for the being of soul-and-spirit was already outside, attached to the body as it were by a stubborn thread only. In reality a kind of death had already set in, but a death that could not be complete because the physical organisation was so healthy. The astral body and the ego that would fain escape were still held by the extraordinarily healthy metabolic and rhythmic organisations, while a completely ruined nerves-and-senses system was no longer able to hold the astral body and the ego. So one had the wonderful impression that the true Nietzsche was hovering above the head. There he was. And down below was something that from the vantage-point of the soul might well have been a corpse, and was only not a corpse because it still held on with might and main to the soul—but only in respect of the lower parts of the organism—because of the extraordinarily healthy metabolic and rhythmic organisation.

Such a spectacle may well make one attentive to the connections of destiny. In this case, at any rate, quite a different light was thrown upon them. Here one could not start from a suffering limb or the like, but one was led to look at the spirituality of Friedrich Nietzsche in its totality.

There are three strongly marked and distinct periods in Nietzsche's life. The first period begins when he wrote The Birth of Tragedy out of the Spirit of Music while he was still quite young, inspired by the thought of music springing from Greek tragedy which had itself been born from music. Then, in the same strain, he wrote the four following works: David Friedrich Strauss; Confessor and Author, Schopenhauer as Educator, Thoughts out of Season, Richard Wagner in Bayreuth. This was in the year 1876. (The Birth of Tragedy was written in 1871). Richard Wagner in Bayreuth is a hymn of praise to Richard Wagner, actually perhaps the best thing that has been written by any admirer of Wagner.

Then a second period begins. Nietzsche writes his books, Human, All-too Human, in two volumes, the work entitled Dawn and thirdly, The Joyful Wisdom.

In the early writings, up to the year 1876, Nietzsche was in the highest sense of the word an idealist. In the second epoch of his life he bids farewell to idealism in every shape and form; he makes fun of ideals; he convinces himself that if men set themselves ideals, this is due to weakness. When a man can do nothing in life, he says: Life is not worth any thing, one must hunt for an ideal.—And so Nietzsche knocks down ideals one by one, puts them to the test, and conceives the manifestations of the Divine in nature as something “all-too-human,” something paltry and petty. Here we have Nietzsche the disciple of Voltaire, to whom he dedicates one of his writings. Nietzsche is here the rationalist, the intellectualist. And this phase lasts until about the year 1882 or 1883. Then begins the final epoch of his life, when he unfolds ideas like that of the Eternal Recurrence and presents the figure of Zarathustra as a human ideal. He writes Thus spake Zarathustra in the style of a hymn.

Then he takes out again the notes he had once made on Wagner, and here we find something very remarkable! If one follows Nietzsche's way of working, it does indeed seem strange. Read his work Richard Wagner in Bayreuth.—It is a grand, enraptured hymn of praise. And now, in the last epoch of his life, comes the book The Case of Wagner, in which everything that can possibly be said against Wagner is set down!

If one is content with trivialities, one will simply say: Nietzsche has changed sides, he has altered his views. But those who are really familiar with Nietzsche's manuscripts will not speak in this way. In point of fact, when Nietzsche had written a few pages in the form of a hymn of praise to Wagner, he then proceeded to write down as well everything he could against what he himself had said! Then he wrote another hymn of praise, and then again he wrote in the reverse sense! The whole of The Case of Wagner was actually written in 1876, only Nietzsche put it aside, discarded it, and printed only the hymn of praise. And all that he did later on was to take his old drafts and interpolate a few caustic passages.

In this last period of his life the urge came to him to carry through an attack which in the first epoch he had abandoned. In all probability, if the manuscript he put aside as being out of keeping with his Richard Wagner in Bayreuth had been destroyed by fire, we should never have had The Case of Wagner at all.

If you study these three periods in Nietzsche's life you will find that all show evidence of a uniform trend. Even the last book, the last published writing at any rate, The Twilight of Idols, which shows entirely his other side—even this last book bears something of the fundamental character of Nietzsche's spiritual life. In old age, however, when this work was composed, he becomes imaginative, writing in a graphic, vividly descriptive style. For example, he wants to characterise Michelet, the French writer. He lights on a very apt expression when he speaks of him as having the kind of enthusiasm that takes off its coat. This is a marvelously apt description of one aspect of Michelet. Other similar utterances—graphic and imaginative—are also to be found in The Twilight of Idols.

If you once have this tragic, deeply moving picture before you of the individuality hovering above the body of Nietzsche, you will be compelled to say of his writings that the impression they make is as though Nietzsche were never fully present in his body while he was writing down his sentences. He used to write, you know, sometimes sitting but more often while walking, especially while going for long tramps. It is as though he had always been a little outside his body. You will have this impression most strongly of all in the case of certain passages in the fourth part of Thus Spake Zarathustra, of which you will feel that they could have been written only when the body no longer had control, when the soul was outside the body.

One feels that when Nietzsche is being spiritually creative, he always leaves his body behind. And this same tendency can be perceived, too, in his habits. He was particularly fond of taking chloral in order to induce a mood that strives to get away from the body, a mood of aloofness from the body. This tendency was of course due to the fact that the body was in many respects ailing; for example, Nietzsche suffered from constant and always very prolonged headaches, and so on.

All these things give a uniform picture of Nietzsche in this incarnation at the end of the 19th century, an incarnation which finally culminated in insanity, so that he no longer knew who he was. There are letters addressed to George Brandes signed “The Crucified One”—indicating that Nietzsche regards himself as the Crucified One; and at another time he looks at himself as at a man who is actually present outside him, thinks that he is a God walking by the River Po, and signs himself “Dionysos.” This separation from the body while spiritual work is going on reveals itself as something that is peculiarly characteristic of this personality, characteristic, that is to say, of this particular incarnation.

If we ponder this inwardly, with Imagination, then we are led back to an incarnation lying not so very long ago. It is characteristic of many such representative personalities that their previous incarnations do not lie in the distant past but in the comparatively near past, even, maybe, in quite recent times.

We come to a life where this individuality was a Franciscan, a Franciscan ascetic who inflicted intense self-torture on his body. Now we have the key to the riddle. The gaze falls upon a man in the characteristic Franciscan habit, lying for hours at a time in front of the altar, praying until his knees are bruised and sore, beseeching grace, mortifying his flesh with severest penances—with the result that through the self-inflicted pain he knits himself very strongly with his physical body. Pain makes one intensely aware of the physical body because the astral body yearns after the body that is in pain, wants to penetrate it through and through. The effect of this concentration upon making the body fit for salvation in the one incarnation was that, in the next, the soul had no desire to be in the body at all.

Such are the connections of destiny in certain typical cases. It can certainly be said that they are not what one would have expected! In the matter of successive earthly lives, speculation is impermissible and generally leads to false conclusions. But when we do come upon the truth, marvellous enlightenment is shed upon life.

Because studies of this kind can help us to look at karma in the right way, I have not been afraid—although such a course has its dangers—to give you certain concrete examples of karmic connections which can, I think, throw a great deal of light upon the nature of human karma, of human destiny.

Neunter Vortrag

Wir stehen in der Besprechung des Karmas, der Wege des menschlichen Schicksals, und haben schicksalsmäßige Zusammenhänge im letzten Vortrage betrachtet, die doch wohl geeignet sein können, einiges Licht zu werfen auf die Art und Weise, wie das Schicksal durch die verschiedenen Erdenleben hindurch wirkt. Ich habe mich entschlossen, trotzdem damit natürlich ein bedenklicher Entschluß notwendig war, über solche Einzelheiten karmischer Zusammenhänge einmal zu sprechen, und möchte auch mit solchen Betrachtungen ein wenig fortfahren.

Sie werden gesehen haben, wie bei der Besprechung karmischer Zusammenhänge es notwendig geworden ist, manche Einzelheiten im Leben und Wesen des Menschen zu besprechen, an denen man sonst vielleicht unaufmerksamer vorübergeht. So habe ich Ihnen eine solche Einzelheit im Herübergehen von körperlichen Eigentümlichkeiten der einen Inkarnation in eine gewisse seelische Verfassung der nächsten Inkarnation bei Dühring gezeigt. Es ist eben durchaus so, daß wenn man für das Menschenwesen an die geistigen Welten herandringt, auf der einen Seite alles Geistige seine Abstraktheit verliert, es wird kraftvoll, es wird impulsiv wirksam eben. Dagegen das Körperliche, dasjenige, was im Menschen auch körperlich zum Ausdruck kommt, verliert seine, ja, man kann eigentlich sagen, Stofflichkeit, bekommt eine geistige Bedeutung, bekommt einen gewissen Platz im ganzen Zusammenhang des menschlichen Lebens.

Wie wirkt denn eigentlich das Schicksal? Das Schicksal wirkt ja so, daß es aus der ganzen Einheit des Menschen heraus wirkt. Was der Mensch sich aufsucht im Leben aus einem Karmadrang heraus, was sich dann schicksalsmäßig gestaltet, das liegt ja daran, daß die Kräfte des Schicksals, die von Leben zu Leben gehen, die Blutzusammensetzung in ihrer Feinheit bewirken und bedingen, daß sie die Nerventätigkeit innerlich regeln, daß sie aber auch die seelisch-instinktive Empfänglichkeit für dies oder jenes anregen. Und man dringt nicht leicht in das Innere von schicksalsmäßigen, karmischen Zusammenhängen ein, wenn man nicht — natürlich immer vom seelischen Auge ist dabei gesprochen - Interesse hat für die einzelnen Lebensäußerungen eines Menschen. Wirklich, für die karmische Betrachtung ist es geradeso wichtig, Interesse zu haben für eine Handbewegung wie für eine geniale geistige Begabung. Es ist ebenso von Wichtigkeit, beobachten zu können — natürlich auch von der geistigen Seite her, nach astralischem Leib und Ich -, wie ein Mensch sich niedersetzt, wie beobachten zu können, sagen wir, wie er seinen moralischen Verpflichtungen nachkommt. Es ist ebenso wichtig, ob ein Mensch gerne die Stirne runzelt oder leicht die Stirne runzelt, wie es wichtig ist, ob er fromm oder unfromm ist. Es ist eben vieles von dem, was einem im gewöhnlichen Leben unwesentlich erscheint, außerordentlich wichtig, wenn man das Schicksal zu betrachten beginnt, wie es sich von Erdenleben zu Erdenleben hinwebt, und manches von dem, was einem als ganz besonders wichtig erscheint bei diesem oder jenem Menschen, das wird von einer geringeren Bedeutung.

Nun ist es im allgemeinen Menschenleben nicht so leicht, sagen wir, zum Beispiel auf körperliche Eigentümlichkeiten zu achten. Sie sind da, und man muß sich darauf eingeschult haben, natürlich ohne verletzend zu werden für seine Mitmenschen, und verletzend ist es, wenn man seine Mitmenschen betrachtet von dem Gesichtspunkte aus, um sie eben zu betrachten. Das sollte eigentlich niemals der Fall sein, sondern es sollte sich alles das, was nach dieser Richtung getan wird, ganz von selbst ergeben. Aber wenn man die Aufmerksamkeit geschult hat, dann ergeben sich auch schon im allgemeinen Menschenleben für jeden Menschen besondere Eigentümlichkeiten, die zu den Kleinigkeiten gehören, und die für die karmische Betrachtung im eminentesten Sinne von Bedeutung sind. Aber so recht eindringlich beobachten kann man die Menschen in bezug auf ihre karmischen Zusammenhänge doch nur, wenn man auf signifikante Eigentümlichkeiten hinweisen kann.

Für mich war vor Jahrzehnten eine außerordentlich interessante Persönlichkeit, sowohl mit Bezug auf das innere geistige Leben dieser Persönlichkeit wie auch in bezug auf das äußere Leben, der Philosoph Eduard von Hartmann. Tiefgehendes Interesse brachte ich gerade diesem Philosophen entgegen. Wenn ich nun aber sein Leben betrachte, so, daß diese Betrachtung hinlenkt zu einer karmischen Betrachtung, so muß ich mir das, was dabei wertvoll ist, etwa in der folgenden Weise vor die Seele stellen. Ich muß mir sagen, Eduard von Hartmann, der Philosoph des Unbewußten, hat eigentlich in einer zunächst explosiven Art in der Philosophie gewirkt. Es ist ja wirklich so: Solch ein explosives Wirken auf geistigem Gebiete ist von den Menschen des 19. Jahrhunderts — verzeihen Sie, wenn ich kritisiere, aber die Sache ist nicht so schlimm gemeint — mit einem großen Phlegma aufgenommen worden. Die Menschen des 19. Jahrhunderts, natürlich auch des angebrochenen 20. Jahrhunderts, sind ja nicht aus ihrem Phlegma herauszubringen in bezug auf das, was eigentlich innerlich die Welt bewegt. Enthusiasmus ist eigentlich wirklich kaum in tiefgehender Art in diesem unserem geistig so phlegmatischen Zeitalter zu finden.

Ich mußte zum Beispiel eine historische Tatsache in einer anderen Vortragsserie in diesen Zeiten einmal schildern: den Zusammenstoß der römischen Welt mit der nördlichen germanischen Welt zur Zeit der Völkerwanderung, zur Zeit, als das Christentum nach dem Norden sich ausgebreitet hat von den südlichen, griechisch-lateinischen Gegenden her. Man muß diese physischen Vorfahren der mitteleuropäischen Welt und der südeuropäischen Welt nur richtig vor sich haben, dann bekommt man schon einen Eindruck davon, wieviel menschliche Impulsivität einmal in der Welt war. Da war es schon so, daß das Miterleben mit den geistigen Mächten der Natur ein ganz reges war unter den verschiedenen germanischen Stämmen, auf welche die Römer trafen in den ersten Jahrhunderten der christlichen Zeitrechnung. Diese Menschen haben ganz anders sich verhalten zum Geistigen. Sie waren zum großen Teile noch mit einer instinktiven Hinneigung zum Geistigen durchaus behaftet. Und während wir heute meistens mit einem Phlegmatismus reden, so daß einfach ein Wort auf das andere folgt, wie wenn das gar nichts wäre, wenn man redet, haben diese Leute dasjenige, was sie erlebt hatten, auch in die Sprache hineinergossen. Da war für diese Leute das Wehen des Windes ebenso die physische Geste einer geistigen, seelischen Äußerung, wie wenn der Mensch seinen Arm bewegt. Man nahm wahr dieses Wehen des Windes, das Flackern des Lichtes im wehenden Winde als den Ausdruck des Wodan. Und wenn man diese Tatsachen in die Sprache hineinnahm, wenn man diese Dinge in die Sprache hineinlegte, so legte man den Charakter dessen, was man erlebte, in die Sprache hinein. Wenn wir es in der modernen Sprache ausdrücken wollten: Wodan weht im Winde - ähnlich hat es ja auch in der alten Sprache geheißen, das Wehen, es ergießt sich auch durch die Sprache —, nehmen Sie dieses Miterleben, das bis in die Sprache hinein erzittert und hineinwallt! Wenn dann der Mensch hinaufschaut, den Donner gewahr wird, der aus den Wolken erdröhnt, und hinter dieser Gebärde, hinter dieser Naturgebärde des Donners die entsprechende geistige Wesenhaftigkeit schaut und das Ganze zum Ausdrucke bringt: Donner oder Donar dröhnt im Donner — da ist in die moderne Sprache hineinergossen, was in einer ähnlichen Weise in der alten Sprache erklungen hat. Und dann, ebenso wie gefühlt haben diese Menschen in den Naturwirkungen das Geistige und es ausgedrückt haben in ihrer Sprache, so drückten sie aus, wenn sie zum Kampfe gingen, die helfende Gottheit, die in ihren Gliedern lebte, die in ihrem ganzen Gebaren lebte. Und da hatten sie ihren Schild, ihren mächtigen Schild, und da stürmten sie, könnte man sagen, die Worte hin, indem sie den Schild vorhielten. Und die ganze Tatsache dessen, daß sie, sei es einen guten, sei es einen dämonischen Geist hineinstürmten in die Sprache, die wiederum in mächtigem Anprall sich verdumpfte und erhöhte und gewaltig wurde, die drückte auch aus dasjenige, was sie wollen, im Vorstürmen: Ziu zwingt Zwist! Das hinter dem Schild gesprochen, mit all der Kampfeswut und Kampfeslust, das gab einen Sturm! Sie müssen sich das denken aus Tausenden von Kehlen auf einmal an die Schilde angesprochen. In den ersten Jahrhunderten, wo der Süden mit Mitteleuropa zusammenkam, da war nicht so sehr das, was äußerlich im Kampfe wirkte, das eigentlich Wirksame, sondern da war es dieses mächtige Gebrause, das sich entgegenstürzte den Römern. In den ersten Zeiten war es schon so, daß dann eine heillose Angst sich der von Süden herankommenden Völker bemächtigte. Die Knie zitterten vor dem «Ziu zwingt Zwist», das tausend Kehlen hinter den Schilden brüllten.

Und so muß man schon sagen: Gewiß, diese Menschen sind wieder da, aber sie sind phlegmatisch geworden! Gar mancher hat dazumal gebrüllt und ist heute phlegmatisch geworden, im höchsten Grade phlegmatisch geworden, hat die innere Seelenattitüde des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts angenommen. Wenn aber die Kerle aufstehen würden, die dazumal gebrüllt haben in ihrer damaligen Seelenverfassung, so würden sie sogar ihrer heutigen Inkarnation die Zipfelmütze aufsetzen und würden sagen: Dasjenige, was da in den Menschen an Phlegmatismus ist, den man nicht aufrütteln kann, das gehört unter die Zipfelmütze, unter die Schlafmütze, das gehört eigentlich ins Bett, nicht auf den Schauplatz des menschlichen Handelns!

Ich sage das nur aus dem Grunde, weil ich damit andeuten will, wie wenig Geneigtheit vorhanden war, etwas so Explosives wie das, was Eduard von Hartmann in seiner «Philosophie des Unbewußten» gebracht hat, zum Gefühl zu bringen. Zunächst hat er natürlich davon gesprochen, daß alles, was bewußt im Menschen ist, das bewußte Denken, eine geringe Bedeutung hat gegenüber dem, was unbewußt im Menschen waltet und webt, und unbewußt in der Natur waltet und webt, was nicht durch das Bewußtsein gehoben werden kann, niemals in das Bewußtsein eindringt. Von einer hellsichtigen Imagination, Intuition, hat ja Eduard von Hartmann nichts gewußt, nicht gewußt, daß das Unbewußte eindringen kann in die menschliche Erkenntnis. So hat er eben darauf verwiesen, wie das eigentlich Wesentliche im Unbewußten bleibt. Aber gerade aus diesen Untergründen heraus war er der Anschauung, daß die Welt, auf der wir leben, die denkbar schlechteste ist. Und den Pessimismus hat er weitergetrieben als Schopenhauer, und er hat gefunden, daß eigentlich der Gipfel der Kulturentwickelung darin bestehen müßte, diese ganze Erdenevolution eines Tages zu vernichten, so schnell als möglich sie zu vernichten. Er sagte nur, er wolle nicht darauf bestehen, daß man es schon morgen tut, weil dann nicht Zeit genug ist, all das anzuwenden, was notwendig ist, um die Erde nun wirklich so weit zu vernichten, daß keine menschliche Zivilisation, die ja nichts wert ist auf der Erde, mehr da sei. Und er träumte davon - das steht in der «Philosophie des Unbewußten» -, wie die Menschen dazu kommen werden, eine große Maschine zu erfinden, die sie tief genug in die Erde hinein versetzen können, damit diese Maschine eine mächtige Explosion hervorruft und die ganze Erde hinausexplodiert, hinaussplittert in den Weltenraum.

Gewiß, es waren manche Menschen begeistert für diese «Philosophie des Unbewußten». Aber wenn sie von so etwas sprechen, dann sieht man nicht, daß sie in ihrem ganzen Menschen ergriffen sind davon. So etwas kann gesagt werden! Das ist doch etwas Mächtiges, wenn so etwas gesagt werden kann! Die Menschen sprechen das so aus, als wenn sie «ad notam» sagen würden, und das ist eben das Entsetzliche.

Aber das trat eben auf, solch einen Philosophen gab es. Und dann betrachtete dieser Philosoph die Dinge der menschlichen Sittlichkeit auf der Erde. Und dieses Werk über die «Phänomenologie des sittlichen Bewußtseins» war sogar das, was mich am tiefsten interessiert hat. Er hat dann auch ein Werk über das religiöse Bewußtsein geschrieben, hat eine Ästhetik geschrieben, hat vieles geschrieben. Und all das war zunächst gerade dann, wenn man nicht mitgehen konnte, etwas außerordentlich Interessantes.

Nun kann man natürlich schon Begierde darnach haben, zu wissen, wie steht es mit dem schicksalsmäßigen Zusammenhang bei einem solchen Menschen? Da wird man vielleicht zunächst versucht sein, so recht auf seine Philosophie einzugehen. Man wird versuchen, aus den philosophischen Gedanken heraus etwas zu erraten in bezug auf seine früheren Erdenleben. Da wird man aber nichts finden. Aber es war mir doch gerade solch eine Persönlichkeit interessant, im höchsten Grade interessant.

Und sehen Sie, dann, wenn man eben, ich möchte sagen, Okkultismus im Leibe hat, dann ergeben sich die Anregungen, in der richtigen Weise hinzuschauen. Und da liegt ja eine Tatsache vor: Eduard von Hartmann war zunächst Soldat, Offizier. Immer erschien im Adressenbuch Kürschner neben seinem Dr. phil. und so weiter als Angabe seiner Charakteristik auch Premierleutnant, bis zu seinem Tode. Eduard von Hartmann war preußischer Offizier zunächst, und er soll ein sehr guter Offizier gewesen sein.

Sehen Sie, das erschien mir von einem Tage an in bezug auf die menschlichen Schicksalszusammenhänge viel wesentlicher als die Einzelheiten seiner Philosophie. Die Einzelheiten seiner Philosophie, nun, da hat man, nicht wahr, die Tendenz, das oder jenes anzunehmen, das oder jenes zu widerlegen. Aber das ist ja nichts so Bedeutsames; das kann jeder, der ein bißchen Philosophie gelernt hat. Da kommt auch nicht so viel Besonderes dabei heraus. Aber sich nun zu fragen: Wie kommt es, daß da ein preußischer Offizier war, der ein guter Offizier war, der sich um Philosophie während seiner Offizierszeit wenig, recht wenig gekümmert hat, sondern mehr um die Übungen mit dem Säbel gekümmert hat, wie kommt es, daß der nun gerade ein repräsentativer Philosoph seines Zeitalters wird? Und wodurch ist er das geworden?

Ja, sehen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, er ist es dadurch geworden, daß er durch einen Krankheitsfall, durch einen Erkrankungsfall ein Knieleiden bekommen hat, pensioniert werden mußte und an diesem Knieleiden nun sein ganzes späteres Leben laborierte. Er war zu Zeiten ganz am Gehen verhindert, darauf angewiesen, die Beine ausgestreckt zu halten, wenig zu gehen, zu sitzen, auf einem Sofa zu sitzen. Und da schrieb er denn, nachdem er die zeitgenössische Bildung in sich aufgenommen hatte, ein philosophisches Werk nach dem anderen. Die Hartmannsche Philosophie ist ja eine ganze Bibliothek. Er schrieb also viel.

Mir wurde aber, indem ich die Persönlichkeit betrachtete, von einer ganz besonderen Wichtigkeit eines Tages das Knieleiden, der Eintritt des Knieleidens. Das interessierte mich viel mehr, daß der Mann in einern bestimmten Lebensalter zu einem Knieleiden gekommen ist, als mich sein transzendentaler Realismus interessierte, oder daß er sagte: Erst gab es die Religion des Vaters, dann die Religion des Sohnes, und in der Zukunft kommt die Religion des Geistes. — Das sind geistreiche Dinge, aber die sind ja mehr oder weniger im geistreichen 19. Jahrhundert auf der Straße zu finden gewesen. Aber daß einer Philosoph wird dadurch, daß er ein Knieleiden bekommt als Leutnant, das ist eine ganz bedeutende Tatsache. Und ehe man nicht auf solche Dinge zurückgehen kann, solange man sich blenden läßt durch das, was scheinbar das Hervorstechendste ist, so lange kommt man nicht auf die karmischen Zusammenhänge.

Und als ich in der richtigen Weise mit der ganzen Persönlichkeit das Kniegebrechen zusammenbringen konnte, da eröffnete sich mir der Blick auf das, was an dieser Persönlichkeit eigentlich als Schicksalsgemäßes aufgetreten ist. Da konnte ich zurückgehen. Nicht vom Kopfe Eduard von Hartmanns, sondern von seinem Knie aus fand ich den Weg zu seinen früheren Inkarnationen. Bei anderen Menschen geht es von der Nase aus und so weiter. Es ist in der Regel nicht dasjenige, was man für das Erdenleben zwischen Geburt und Tod als das Wichtigste nimmt.

Nun, wie ist dieser Zusammenhang? Sehen Sie, der Mensch, wie er sich im Erdenleben darstellt, ist ja eigentlich auch schon als physisches Wesen, ich habe wiederholt darauf aufmerksam gemacht, eine dreigliedrige Wesenheit. Er hat seine Nerven-Sinnesorganisation, die hauptsächlich im Kopfe, im Haupte konzentriert ist, die sich aber über den ganzen Menschen erstreckt. Er hat seine rhythmische Organisation, die insbesondere deutlich als Rhythmus der Atmung, als Blutzirkulation herauskommt, die aber sich wiederum über den ganzen Menschen erstreckt und in allem sich ausdrückt, und er hat seine motorische, mit dem Stoffwechsel zusammenhängende Gliedmaßenorganisation, die mit dem Verbrauch des Stoffwechsels, mit dem Ersatz der Stoffe und so weiter zusammenhängt. Der Mensch ist ein dreigliedriges Wesen.

Und dann wird man mit Bezug auf den ganzen Lebenszusammenhang gewahr: im Durchgehen durch Geburten und Tode ist dasjenige, was man jeweilig im Erdenleben als das Wichtigste hält, der Kopf, von einer verhältnismäßig geringen Bedeutung bald nach dem Tode. Der Kopf, der im Physischen das Menschlichste am Menschen ist, erschöpft ja auch im Physischen seine Wesenheit ganz stark; während für die übrige Organisation des Menschen, die im Physischen minderwertig ist, gerade im Geistigen das Höhere da ist. Im Kopf ist der Mensch am meisten physischer Mensch und am wenigsten geistiger Mensch. Dagegen ist er in den anderen Gliedern seiner Organisation, in der rhythmischen und in der Gliedmaßenorganisation, geistiger. Am geistigsten ist der Mensch in dem Motorischen, in der Tätigkeit seiner Glieder.

Und nun ist es so, daß dasjenige, was im Menschen Kopfbegabung ist, verhältnismäßig bald nach dem Tode sich verliert. Dagegen das, was im Unbewußten an Geistig-Seelischem den unteren Organisationen angehört, das wird besonders wichtig zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Aber während es im allgemeinen so ist, daß von einem Erdenleben ins nächste Erdenleben hinein die außer dem Kopf befindliche Organisation ihrer Gestalt nach, ihrem geistigen Inhalt nach gerade zum Kopfe der nächsten Inkarnation wird, wirkt allerdings das, was im Kopfe des Menschen willenhaft ist, in der nächsten Inkarnation besonders in die Gliedmaßen hinein. Wer in einer Inkarnation träge in seinem Denken ist, der wird ganz gewiß in der nächsten Inkarnation kein Schnelläufer, sondern das Träge des Denkens geht in die Langsamkeit der Gliedmaßen hinein, wie umgekehrt die Langsamkeit der Gliedmaßen der gegenwärtigen Inkarnation sich in dem trägen, langsamen Denken der nächsten Inkarnation zum Ausdruck bringt.

So besteht eine Metamorphose, eine Wechselwirkung der drei verschiedenen Gliederungen der menschlichen Wesenheit von einem Erdenleben in das andere hinüber, von einer Inkarnation in die andere hinüber.

Das, was ich Ihnen da sage, das sage ich Ihnen nicht als eine Theorie, sondern ich sage es aus den Tatsachen des Lebens heraus. Sehen Sie, als einmal, ich möchte sagen, diese Intention da war, bei Eduard von Hartmann besonders auf das Knieleiden zu sehen, da wurde ich auf seine frühere Inkarnation hingelenkt, in der er in einem bestimmten Lebensaugenblicke eine Art Sonnenstich erhalten hatte. Dieser Sonnenstich, der war zunächst die schicksalsmäßige Veranlassung in dem nächsten Erdenleben, metamorphosisch sich in der Gebrechlichkeit des Knies zum Ausdrucke zu bringen, war also ein Kopfgebrechen. Er konnte eines Tages nicht mehr denken; er hatte eine Art Lähmung des Gehirnes. Das kam in der nächsten Inkarnation in einer Lähmung eines der Gliedmaßen zum Vorschein. Und dieses Schicksalsmäßige, zu einer Gehirnlähmung zu kommen, das ergab sich durch das Folgende: Diese Individualität war ja eine derjenigen, die mitzogen während der Kreuzzüge nach dem Oriente und in Asien drüben gegen die Türken und gegen die Asiaten kämpften, die Asiaten aber zugleich ungeheuer bewundern lernten. Nachdem diese Individualität alles in Bewunderung aufgenommen hatte, was da den Kreuzfahrern entgegentrat an großartiger Geistigkeit im Orient, nachdem diese Individualität das alles aufgenommen hatte, wurde sie eines Menschen gewahr, von dem sie instinktiv fühlte, sie habe mit ihm in einem wieder früheren Leben etwas zu tun gehabt. Und was jetzt zwischen dieser und der früheren Inkarnation abzumachen war, das war das Moralische. Das Hinüberwirken des Sonnenstiches in das Knieleiden zwischen den zwei Inkarnationen scheint ja zunächst etwas bloß Physisches zu sein; es führt aber immer, wenn es sich um Schicksalsmäßiges handelt, die Sache auf etwas Moralisches zurück, hier auf die Tatsache, daß aus einer noch früheren Inkarnation diese Individualität den Impuls eines starken, wütenden Kampfes gegen einen Menschen in sich trug, dem sie da entgegentrat. Und in glühender Sonnenhitze wurde die Verfolgung dieses Gegners aufgenommen. Sie war ungerecht. Sie fiel auf die Individualität, die verfolgte, selbst zurück, indem durch das glühende Sonnenlicht das Gehirn gelähmt wurde. Und dasjenige, was da geschehen sollte in diesem Kampfe, das war davon hergekommen, meine lieben Freunde, daß in einer früheren Inkarnation diese Individualität besonders klug war, im höchsten Grade klug war. Jetzt hatte man einen Einblick in eine noch frühere Inkarnation, wo eine besondere Klugheit vorlag. Und der Gegner, dem diese Individualität während der Kreuzzüge entgegengetreten war, dieser Gegner war in einer früheren Inkarnation von dieser klugen Individualität in die Enge getrieben worden, zum Nachteile gekommen. Dadurch war der moralische Zusammenhang gegeben, dadurch war der Impuls zum Kampf gegeben und so weiter. Da ging es dann auf das Moralische zurück, indem die Kräfte, die sich da ausbildeten, eben auf die frühere Inkarnation zurückgingen.

So daß man drei aufeinanderfolgende Inkarnationen einer Individualität findet: Eine außerordentlich gescheite, kluge Persönlichkeit in sehr alten Zeiten — die eine Inkarnation. Darauf folgend ein Kreuzfahrer, der in einem bestimmten Zeitpunkte, bewirkt durch das, was gerade seine Klugheit verbrochen hatte, eine Gehirnläihmung bekommt, die Klugheit ausgelöscht wird, nachdem aber vorher diese Klugheit eine ungeheure Bewunderung orientalischer Zivilisation aufgenommen hatte. Dritte Inkarnation: ein preußischer Offizier, der durch ein Knieleiden den Abschied nehmen muß, jetzt nicht weiß, was er tun soll, sich auf die Philosophie schlägt und die eindrucksvollste, ganz aus der Zivilisation der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts herausgewachsene «Philosophie des Unbewußten» schreibt.

Nun, hat man einen solchen Zusammenhang, dann werden plötzlich Dinge licht, die vorher ganz dunkel waren. Denn sehen Sie, ich hatte immer, als ich Hartmann las, ohne daß ich diese Zusammenhänge als junger Mann wußte, das Gefühl: Ja, da ist was Gescheites drinnen. — Aber wenn ich eine Seite las: Ja, da ist was furchtbar Gescheites, aber das Gescheite ist nicht auf dieser Seite. Ich wollte immer umblättern und auf der Rückseite schauen, ob da das Gescheite ist. Es war das Gescheite nicht von heute, es war das Gescheite von gestern oder vorgestern.

Darüber breitete sich mir erst Licht, als ich sah: diese Gescheitheit, die besondere Klugheit, die liegt ja schon zwei Inkarnationen zurück und wirkt nach. Da fällt erst ein ungeheures Licht auf diese ganze Literatur, auf diese Hartmann-Literatur, die eine Bibliothek anfüllt, wenn man weiß: da wirkt aus einer viel früheren Inkarnation die Klugheit nach.

Und wenn man Hartmann persönlich kennenlernte, mit ihm sprach, so hatte man wirklich auch das Gefühl: dahinter ist erst einer, der redet noch immer nicht; aber dann ist ein Dritter dahinter, der liefert eigentlich die Inspirationen. Denn es war beim Hören manchmal zum Verzweifeln: da redete ein Offizier Philosophie, ohne Begeisterung, gleichgültig, mit einem gewissen Rauhton, über die höchsten Wahrheiten. Dann erst konnte man merken, wie sich die Dinge eigentlich verhalten, wenn man wußte: da steht die Klugheit von zwei Inkarnationen vorher dahinter.

Gewiß, es sieht sogar pietätlos aus, wenn man solche Dinge so erzählt, aber sie sind nicht pietätlos gemeint, sondern ich bin der Überzeugung, daß es für jeden Menschen selbst ganz wertvoll sein kann, solche Zusammenhänge für sein eigenes Leben zu haben, selbst für den Fall, daß sich irgendeiner sagen muß: In meiner drittletzten Inkarnation war ich eigentlich ein ganz gewaltig schlechter Kerl! - Es kann das ungeheuer förderlich sein für das Leben, wenn sich einer sagen kann: Ich war ein gewaltig schlechter Kerl. - Einmal in irgendeiner Inkarnation, ja, nicht einmal in irgendeiner Inkarnation, war man nämlich wirklich unter allen Umständen ein gewaltig schlechter Kerl! Bei diesen Dingen, sehen Sie, sind ja immer, wie auch sonst in der Gesellschaft die Anwesenden ausgenommen sind, die gegenwärtigen Inkarnationen ausgenommen.

Nun, ganz intensiv interessierte mich auch, weil ich wirklich durch mein Leben an diese Persönlichkeit herangeführt worden bin, der schicksalsmäßige Zusammenhang bei Friedrich Nietzsche. Das Problem Nietzsche, ich habe es von allen Seiten betrachtet; ich habe ja manches geschrieben und gesprochen über Nietzsche und von allen Seiten diesen Friedrich Nietzsche betrachtet.

Es war ja ein merkwürdiges Schicksal. Im Leben habe ich ihn nur ein einziges Mal gesehen, in den neunziger Jahren in Naumburg, als er schon schwer geisteskrank war. Nachmittags, etwa halb drei Uhr, führte mich die Schwester in sein Zimmer. Er lag auf dem Ruhebette, mit einem Auge, das nicht gewahr werden konnte, daß man vor ihm stand, teilnahmslos; mit jener merkwürdigen, künstlerisch so schön geformten Stirn, die einem ganz besonders auffiel. Trotzdem das Auge teilnahmslos war, hatte man dennoch das Gefühl, nicht einen Wahnsinnigen vor sich zu haben, sondern einen Menschen, der den ganzen Vormittag intensiv in seiner Seele geistig gearbeitet hat, Mittag gegessen hat und sich nun ausruhend hingelegt hat, um zu sinnen, halb träumend zu sinnen über das, was am Vormittag in der Seele erarbeitet worden ist. Geistig gesehen, war da eigentlich ein physischer und ein Ätherleib, namentlich in bezug auf die oberen Partien des Menschen, denn das Seelisch-Geistige war eigentlich schon heraußen, es hing nur noch wie an einem dicken Faden an dem Körper. Es war im Grunde genommen schon eine Art Tod vorangegangen, aber ein Tod, der nicht völlig eintreten konnte, weil die physische Organisation eine so gesunde war, daß der entfliehen wollende Astralleib und das entfliehen wollende Ich eben immer noch gehalten wurden von der ungeheuer gesunden Stoffwechsel- und rhythmischen Organisation bei einem völlig zerstörten Nerven-Sinnessystem, das gar nicht mehr halten konnte den astralischen Leib und das Ich. So daß man den wunderbaren Eindruck hatte: da schwebt eigentlich der wirkliche Nietzsche über seinem Haupte. Da war er. Und da unten war schon etwas, das von der Seele aus Leichnam hätte sein können und nur nicht Leichnam war, weil es noch mit aller Gewalt festhielt an der Seele, aber nur für die unteren Partien des Menschen durch die außerordentlich gesunde Stoffwechselund rhythmische Organisation.

Es kann schon für die schicksalsmäßigen Zusammenhänge im tiefsten Sinne die Aufmerksamkeit erregen, wenn man so etwas sieht. Da allerdings wurde in die schicksalsmäßigen Zusammenhänge, ich möchte sagen, mit einem anderen Lichte hineingeleuchtet. Da konnte man nicht ausgehen von irgendeinem einzelnen leidenden Gliede oder dergleichen, sondern man wurde jetzt wiederum zurückgeführt auf die ganze geistige Individualität Friedrich Nietzsches.

In diesem Nietzsche-Leben sind ja drei streng voneinander zu scheidende Perioden vorhanden. Die erste Periode beginnt, als er als ganz junger Mensch seine «Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik» schrieb, begeistert über den Aufgang der Musik aus dem griechischen Mysterienwesen, die Tragödie dann wiederum aus dem Musikalischen herausleitend. Dann aus derselben Stimmung heraus die vier folgenden Schriften: «David Friedrich Strauß der Bekenner und der Schriftsteller», «Schopenhauer als Erzieher», «Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben», «Richard Wagner in Bayreuth». Das ist im Jahr 1876 — 1871 ist die Schrift «Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik» geschrieben -: «Richard Wagner in Bayreuth», ein begeisterter Hymnus auf Richard Wagner, tatsächlich vielleicht die beste Schrift, die von einem Anhänger Richard Wagners geschrieben worden ist.

Eine zweite Epoche bei Nietzsche beginnt. Er schreibt seine Bücher «Menschliches, Allzumenschliches» in zwei Bänden, die Schrift «Morgenröte» und die Schrift «Die fröhliche Wissenschaft».

Nietzsche, der in den ersten Schriften bis zum Jahre 1876 im höchsten Sinne Idealist war, alles zum Ideal hinaufheben wollte, er sagt allem Idealismus adieu in dieser zweiten Epoche seines Lebens. Er macht sich lustig über die Ideale. Er macht sich klar: Wenn die Menschen sich Ideale vorsetzen, so ist es, weil sie im Leben schwach sind. Wenn einer im Leben nichts kann, sagt er, das Leben ist nichts wert, man muß einem Ideal nachjagen. Und so nimmt Nietzsche die einzelnen Ideale aufs Korn, legt sie, wie er sagt, aufs Eis, indem er dasjenige, was das Göttliche in der Natur darstellt, als ein Allzumenschliches, gerade Kleinliches auffaßt. Da ist Nietzsche Voltairianer, er widmete auch eine Schrift Voltaire. Da ist Nietzsche ganz Rationalist, Intellektualist. Und das dauert etwa bis zum Jahre 1882/1883. Dann beginnt die letzte Epoche seines Lebens, wo er Ideen ausbildet wie die von der Wiederkunft des Gleichen, wo er den Zarathustra wie ein Ideal des Menschen ausbildet. Da schreibt er dann sein «Also sprach Zarathustra» im hymnischen Stil.

Da nimmt er seine Aufzeichnungen über Wagner wieder hervor. Es ist ja etwas höchst Merkwürdiges! Hat man so die Arbeitsweise Nietzsches kennengelernt, dann stellt sich diese in merkwürdiger Art dar. Lesen Sie heute die Schrift «Richard Wagner in Bayreuth»: es ist ein begeisterter Hymnus, großartig, genial begeisternd für Richard Wagner. In der letzten Epoche erscheint das Buch «Der Fall Wagner»: alles, was nur gegen Wagner gesagt werden kann, steht in dieser Schrift.

Man sagt, wenn man trivial sein will: Nietzsche hat eben umgesattelt, hat seine Ansicht geändert. Wer den Bestand der Nietzscheschen Manuskripte kennengelernt hat, der sagt nicht so. Denn wenn Nietzsche ein paar Seiten in seinem Buch «Richard Wagner in Bayreuth» als begeisterten Hymnus über Wagner hingeschrieben hat, so hat er all das, was er dagegen gehabt hat - gegen das, was er selber gesagt hat -, so hat er das auch gleich hingeschrieben. Dann hat er wiederum einen begeisterten Hymnus geschrieben, und wiederum, was er dagegen gehabt hat, geschrieben. Es war der ganze «Fall Wagner» eigentlich schon 1876 geschrieben. Er hat ihn nur noch zurückgelegt, hat ihn ausgeschaltet und hat nur dasjenige gedruckt, was sein begeisterter Hymnus war. Er hat sozusagen nur seine alten Aufzeichnungen vorgenommen und sie mit einigen scharfen Sätzen durchsetzt.

Aber er hatte doch eben die Tendenz, in diesem letzten Abschnitt seines Lebens gegen dasjenige anzustürmen, wogegen er in der ersten Epoche seines Lebens das Anstürmen sozusagen zurückgelegt hat. Wahrscheinlich, wenn die Manuskripte, die er zurückgelegt hat, als nicht recht hinzustimmend zur Schrift «Richard Wagner in Bayreuth», durch eine Feuersbrunst zugrunde gegangen wären, so hätte man keinen «Fall Wagner».

Sehen Sie, wenn man diese drei Epochen verfolgt, so sind sie alle wiederum durchzogen von einem einheitlichen Charakter. Und selbst die letzte Schrift, also wenigstens die gedruckte letzte Schrift, «GötzenDämmerung, oder: Wie man mit dem Hammer philosophiert», wo alles, ich möchte sagen, von seiner anderen Seite gezeigt wird, selbst diese letzte Schrift trägt etwas von dem Grundcharakter der ganzen Nietzscheschen Geistigkeit. Nur wird Nietzsche da, wo er wirklich das auch schreibt, im Alter — imaginativ, anschaulich. Zum Beispiel, er will Michelet, den französischen Schriftsteller Michelet charakterisieren. Es ist eine treffende Charakteristik, die er gibt: die Begeisterung, die sich den Rock auszieht, während sie begeistert ist. Es ist ganz ausgezeichnet von einer gewissen Seite Michelet erfaßt. Ähnliche solche Dinge sind da in dieser «Götzen-Dämmerung» — anschaulich.

Nun, hat man einmal dieses furchtbar erschütternde Bild des Schwebens der Nietzsche-Individualität über der Körperlichkeit, so wird man dazu gedrängt, jetzt sich den Schriften gegenüber zu sagen: Ja, eigentlich machen sie den Eindruck, wie wenn Nietzsche nie ganz mit seiner menschlichen Körperlichkeit dabeigewesen wäre, als er seine Sätze hingeschrieben hat, wie wenn er immer - er hat ja nicht im Sitzen, er hat im Gehen, namentlich im Fußwandern geschrieben etwas aus seinem Leibe heraus gewesen wäre. Am stärksten werden Sie diesen Eindruck haben bei gewissen Partien des vierten Teiles von «Also sprach Zarathustra», wo Sie direkt das Gefühl haben werden: das schreibt man nicht, wenn der Körper reguliert, das schreibt man nur, wenn der Körper nicht mehr reguliert, sondern wenn man mit dem Seelischen außerhalb des Körpers ist.

Man hat das Gefühl, daß im geistigen Produzieren Nietzsche seinen Leib immer zurückläßt. Und das lag schließlich auch in seinen Lebensgewohnheiten. Er nahm insbesondere gern Chloral, um in eine bestimmte Stimmung zu kommen, eine Stimmung, die unabhängig vom Körperlichen ist. Gewiß, es wurde ja auch diese Sehnsucht, in der Seelenstimmung unabhängig vom Körperlichen zu werden, dadurch veranlaßt, daß das Körperliche vielfach krank war, daß zum Beispiel ein immer sehr langdauernder Kopfschmerz vorhanden war und dergleichen.

Aber all das gibt ein einheitliches Bild Nietzsches in der NietzscheInkarnation am Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts, die dann zum Wahnsinn führte, so daß er überhaupt nicht mehr wußte zuletzt, wer er war. Denn es gibt Briefe an Georg Brandes, wo sich Nietzsche unterschreibt entweder: «Der Gekreuzigte» — das heißt, er sieht sich für den Gekreuzigten an —, oder er schaut auf sich selber hin wie auf einen objektiv außer ihm befindlichen Menschen, findet sich einen Gott, der am Po spazierengeht, und unterschreibt sich «Dionysos». Dieses Getrenntsein vom Körper, wenn geistig produziert wird, das ergibt sich dann als etwas, was für diese Persönlichkeit, für diese Inkarnation dieser Individualität ganz besonders charakteristisch ist.

Und durchdringt man sich nun mit diesem imaginativ-innerlich, dann wird man zurückgeführt in eine gar nicht sehr weit zurückliegende Inkarnation. Es ist ja das Eigentümliche bei vielen solchen Persönlichkeiten, die gerade repräsentativ auftreten, daß ihre Inkarnationen in der Regel nicht weit zurückliegen, sondern verhältnismäßig wenig weit gerade in der neueren Zeit zurückliegen. Und siehe da, man kommt in ein Dasein Nietzsches, wo diese Individualität Franziskaner war, ein asketischer Franziskaner, der ganz intensiv Selbstpeinigung des Körpers trieb. Jetzt hat man das Rätsel. Da fällt der Blick auf einen Menschen im charakteristischen Franziskanergewande, der stundenlang vor dem Altar liegt, sich die Knie wundbetet durch das Rutschen auf den Knien, um Gnade flehend, der sich furchtbar kasteit. Durch den Schmerz, namentlich den selbst verursachten Schmerz, kommt man ja ganz stark mit seinem physischen Leib zusammen. Man wird den physischen Leib ganz besonders gewahr, wenn man Schmerz leidet, weil der astralische Leib nach dem schmerzenden Körper besonders stark sich sehnt, ihn durchdringen will. Dieses so viel Geben auf die Zubereitung des Körpers zum Heil in der einen Inkarnation, das wirkte so, daß die Seele nun gar nicht mehr sein wollte im Körper in der nächsten Inkarnation.

Sehen Sie, so sind in charakteristischen Fällen schicksalsmäßige Zusammenhänge. Man darf auch da sagen: sie ergeben sich schon eigentlich anders, als man gewöhnlich wähnt. Es läßt sich über die aufeinanderfolgenden Erdenleben nichts erspekulieren. Da findet man in der Regel das Falsche. Wenn man aber auf das Richtige kommt, dann ist es im eminentesten Sinne Licht verbreitend über das Leben.

Und gerade weil eine sachgemäße Betrachtung in dieser Beziehung anregen kann dazu, Karma im rechten Lichte zu sehen, habe ich, trotzdem das seine bedenkliche Seite hat, mich nicht gescheut, vor Ihnen einzelne konkrete karmische Zusammenhänge zu entwickeln, von denen ich glaube, daß sie schon ein starkes Licht eben auf die Wesenheit des menschlichen Karmas, des menschlichen Schicksals werfen können. Nun, dann morgen weiter.

Ninth Lecture

We are discussing karma, the paths of human destiny, and in the last lecture we looked at fateful connections which may well be suitable for throwing some light on the way in which destiny works through the various lives on earth. I have decided to speak about such details of karmic connections, despite the fact that this naturally necessitated a questionable decision, and would like to continue with such considerations for a while.

You will have seen how, when discussing karmic connections, it has become necessary to discuss some details in the life and nature of man, which one might otherwise pass by more inattentively. Thus I have shown you such a detail in Dühring's passage from the physical peculiarities of one incarnation to a certain spiritual constitution of the next incarnation. It is precisely the case that when one approaches the spiritual worlds for the human being, on the one hand everything spiritual loses its abstractness, it becomes powerful, it becomes impulsively effective. On the other hand, the physical, that which is also expressed physically in the human being, loses its, one could actually say, materiality, acquires a spiritual meaning, acquires a certain place in the whole context of human life.

How does fate actually work? Fate works in such a way that it works out of the whole unity of man. What man seeks out in life out of a karmic urge, what then takes shape in terms of destiny, is due to the fact that the forces of destiny, which go from life to life, cause and condition the blood composition in its subtlety, that they regulate the nervous activity inwardly, but that they also stimulate the soul-instinctive receptivity for this or that. And it is not easy to penetrate into the interior of fateful, karmic connections if one is not interested in the individual expressions of a person's life - always speaking of the soul's eye, of course. Really, for karmic observation it is just as important to be interested in a hand movement as in a brilliant spiritual talent. It is just as important to be able to observe - naturally also from the spiritual side, according to the astral body and ego - how a person sits down as it is to be able to observe, let us say, how he fulfills his moral obligations. It is just as important whether a person likes to frown or frowns easily as it is whether he is pious or impious. Much of what seems insignificant in ordinary life is extraordinarily important when one begins to look at fate as it weaves its way from one earthly life to the next, and some of what seems particularly important in this or that person becomes of less significance.

Now in general human life it is not so easy, let us say, to pay attention to physical peculiarities, for example. They are there, and one must have trained oneself to pay attention to them without, of course, becoming hurtful to one's fellow human beings, and it is hurtful when one looks at one's fellow human beings from the point of view of looking at them. This should never actually be the case, but everything that is done in this direction should come naturally. But if one has trained one's attention, then even in general human life, special peculiarities arise for each person which belong to the minor details and which are of significance for karmic observation in the most eminent sense. But you can only really observe people with regard to their karmic connections if you can point out significant peculiarities.

Decades ago, the philosopher Eduard von Hartmann was an extraordinarily interesting personality for me, both with regard to the inner spiritual life of this personality as well as with regard to the outer life. I took a deep interest in this philosopher in particular. But if I now look at his life in such a way that this contemplation leads to a karmic contemplation, then I must place what is valuable here before my soul in the following way. I have to say to myself that Eduard von Hartmann, the philosopher of the unconscious, actually had an initially explosive effect on philosophy. It really is the case that such explosive work in the intellectual field was received by the people of the 19th century - forgive me if I criticize, but the matter is not meant so badly - with a great deal of phlegm. The people of the 19th century, and of course also of the dawning 20th century, cannot be brought out of their phlegm with regard to what actually moves the world inwardly. Enthusiasm is really hardly to be found in a profound way in this spiritually phlegmatic age of ours.

For example, I once had to describe a historical fact in another series of lectures in these times: the collision of the Roman world with the northern Germanic world at the time of the migration of peoples, at the time when Christianity spread to the north from the southern, Greek-Latin regions. You only have to have these physical ancestors of the central European world and the southern European world in front of you to get an impression of how much human impulsiveness there once was in the world. The various Germanic tribes encountered by the Romans in the first centuries of the Christian era had a very active co-existence with the spiritual forces of nature. These people had a completely different attitude towards the spiritual. For the most part, they still had an instinctive inclination towards the spiritual. And while today we mostly speak with a phlegmatism, so that one word simply follows another, as if it were nothing at all when one speaks, these people also poured into their language what they had experienced. For these people, the blowing of the wind was just as much the physical gesture of a spiritual, soulful expression as when a person moves his arm. This blowing of the wind, the flickering of the light in the blowing wind, was perceived as the expression of Wodan. And when one took these facts into language, when one put these things into language, one put the character of what one experienced into language. If we wanted to express it in modern language: Wodan blows in the wind - similarly, in the old language it was also called, the blowing, it also pours through language - take this co-experience, which trembles and surges into language! When man then looks up, becomes aware of the thunder that roars out of the clouds, and sees behind this gesture, behind this natural gesture of thunder, the corresponding spiritual beingness and expresses the whole: thunder or Donar roars in thunder - there is poured into modern language what resounded in a similar way in ancient language. And then, just as these people felt the spiritual in the effects of nature and expressed it in their language, so they expressed, when they went to battle, the helping deity that lived in their limbs, that lived in their whole demeanor. And there they had their shield, their mighty shield, and there they rushed, one might say, the words, holding out the shield. And the whole fact that they rushed, be it a good or a demonic spirit, into the language, which in turn dimmed and increased and became mighty in a powerful impact, also expressed what they wanted in the rushing forward: Ziu compels strife! That spoken behind the shield, with all the fighting rage and lust for battle, that created a storm! You must imagine that from thousands of throats at once addressed to the shields. In the first centuries, when the South came together with Central Europe, it was not so much what was outwardly effective in battle that was actually effective, but rather this mighty roar that rushed towards the Romans. In the early days, the peoples approaching from the south were seized by a hopeless fear. Their knees trembled from the “Ziu forces strife” that a thousand throats roared behind their shields.

And so it must be said: these people are certainly back, but they have become phlegmatic! Many a man roared back then and has become phlegmatic today, phlegmatic to the highest degree, has taken on the inner soul attitude of the 19th and 20th centuries. But if the people who roared back then in the state of their souls at that time were to stand up, they would even put the pointed cap on their present incarnation and say: That phlegmatism in people which cannot be shaken up belongs under the pointed cap, under the nightcap, it actually belongs in bed, not on the scene of human action!

I only say this because I want to indicate how little inclination there was to bring something as explosive as what Eduard von Hartmann brought to feeling in his “Philosophy of the Unconscious”. First of all, of course, he spoke of the fact that everything that is conscious in man, conscious thinking, is of little importance in comparison with that which rules and weaves unconsciously in man, and rules and weaves unconsciously in nature, which cannot be lifted by consciousness, never penetrates consciousness. Eduard von Hartmann knew nothing of clairvoyant imagination, intuition, did not know that the unconscious can penetrate human cognition. Thus he referred to the fact that what is actually essential remains in the unconscious. But it was precisely from these foundations that he was of the opinion that the world in which we live is the worst imaginable. And he carried his pessimism further than Schopenhauer, and he found that the pinnacle of cultural development should actually consist in destroying this entire earthly evolution one day, destroying it as quickly as possible. He only said that he did not want to insist that it should be done tomorrow, because then there would not be enough time to apply all that is necessary to really destroy the earth to such an extent that there would be no human civilization left, which is worth nothing on earth. And he dreamed - this is in the “Philosophy of the Unconscious” - of how people would come to invent a great machine that they could move deep enough into the earth so that this machine would cause a mighty explosion and the whole earth would explode outwards, splintering out into the universe.