Karmic Relationships I

GA 235

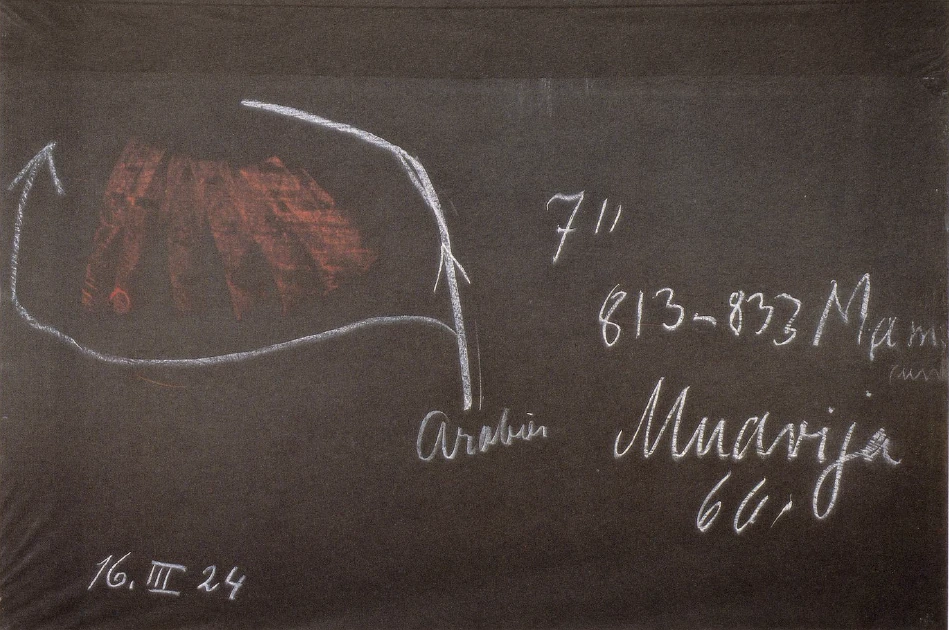

16 March 1924, Dornach

Lecture X

In our study of karmic connections I have hitherto followed the practice of starting from personalities in more recent times and then going back to their previous lives on earth. Today, in order to amplify the actual examples of karmic connections, I propose to go the other way, starting from certain personalities of the past and following them into later times, either into some later epoch of history, or right into the life of the present day. What I want to do is to give you a picture of certain historic connections, presenting it in such a way that at every point some light is shed on the workings of karma.

If you follow the development of Christianity from its foundation, tracing the various paths taken by the Christian Impulse on its way across Europe, you will encounter a different stream of spiritual life which, although little heed is paid to it today, exercised an extraordinarily deep influence upon European civilisation under the surface of external events. It is the stream known as Mohammedanism, the Mohammedan religion, which, as you know, came into existence rather more than 500 years after the founding of Christianity, together with the mode of life associated with it.

We see, in the first place, that monotheism in a very strict form was instituted by Mohammed. It is a religion that looks up, as did Judaism, to a single Godhead encompassing the universe. “There is one God and Mohammed is his herald.”—That is what goes forth from Arabia as a mighty impulse, spreading far into Asia, passing across Africa and thence into Europe by way of Spain.

Anyone who studies the civilisation of our own time will misjudge many things if he ignores the influences which, having received their initial impetus from the deed of Mohammed, penetrated into European civilisation as the result of the Arabian campaigns, although the actual form of religious feeling with which these influences were associated did not make its way into Europe.

When we consider the form in which Mohammedanism made its appearance, we find, first and foremost, the uncompromising monotheism, the one, all-powerful Godhead—a conception of Divinity that is allied with fatalism. The destiny of man is predetermined; he must submit to this destiny, or at least recognise his subjection to it. This attitude is an integral part of the religious life. But this Arabism—for let us call it so—also brought in its train something entirely different. The strange thing is that while, on the one hand, the warlike methods adopted by Arabism created disturbance and alarm among the peoples, on the other hand it is also remarkable that for well-nigh a thousand years after the founding of Mohammedanism, Arabism did very much to promote and further civilisation. If we look at the period when Charlemagne's influence in Europe was at its prime, we find over in Asia, at the Court in Baghdad, much wonderful culture, a truly great and splendid spiritual life. While Charlemagne was trying to spread an elementary kind of culture on primitive foundations—he himself only learnt to write out of sheer necessity—spiritual culture of a very high order was flourishing over yonder in Asia, in Baghdad. Moreover, this spiritual culture inspired tremendous respect in the environment of Charles the Great himself.

At the time when Charles the Great was ruling—768 to 814 are the dates given—we see over in Baghdad, in the period from 786 to 809, Haroun al Raschid as the figure-head of a civilisation that had achieved great splendour. We see Haroun al Raschid, whose praises have so often been sung by poets, at the centre of a wide circle of activity in the sciences and the arts. He was himself a highly cultured man whose followers were by no means men of such primitive attainments as, for example, Einhard, the associate of Charles the Great. Haroun al Raschid gathered around him men of real brilliance in the field of science and art. We see him in Asia—not exactly ruling over culture, but certainly giving the impulse to it at a very high level.

And we see how there emerges within this spiritual culture, of which Haroun al Raschid was the soul, something that had been spreading in Asia in a continuous stream since the time of Aristotle. Aristotelian philosophy and natural science had spread across into Asia and had there been elaborated by oriental insight, oriental imagination, oriental vision. Its influence can be traced over the whole of Asia Minor, almost to the frontier of India, and its effectiveness may be judged from the fact that a widespread and highly developed system of medicine, for example, was cultivated at this Court of Haroun al Raschid.

Profound philosophic thought is applied to what had been founded by Mohammed with a kind of religious furor; we see this becoming the object of intense study and being put to splendid application by the scholars, poets, scientists and physicians living at this Court in Baghdad.

Mathematics was cultivated there, also geography. Unfortunately, far too little is heard of this in European history, and the primitive doings at the Frankish Court of Charles the Great are apt to obscure what was being achieved over in Asia.

When we consider all that had developed directly out of Mohammedanism, we have before us a most remarkable picture. Mohammedanism was founded in Mecca and carried further in Medina. It spread into the regions of Damascus, Baghdad and so forth, indeed, over the whole of Asia Minor, exercising the dominating influence I have described. This is the one direction in which Mohammedanism spreads—northwards from Arabia and across Asia Minor. The Arabs continually lay siege to Constantinople. They knock at the doors of Europe. They want to force their way across Eastern Europe towards Middle Europe.

On the other hand, Arabism spreads across the North of Africa and thence into Spain. It takes hold of Europe as it were from the other direction, by way of Spain.

We have before us the remarkable spectacle of Europe tending to be surrounded by Arabism—by a forked stream of Arabic culture.

Christianity, in its Roman form, spreads upwards from Rome, from the South, starting from Greece; this impulse is made manifest later on by Ulfila's translation of the Bible, and so forth. And then, enclosing this European civilisation as it were with two forked arms, we have Mohammedanism. Everything that history tells concerning what was done by Charles the Great to further Christianity must be considered in the light of the fact that while Charles the Great did much to promote Christianity in Middle Europe, at the same time there was flourishing over yonder in Asia that illustrious centre of culture of which I have spoken, the centre of culture around Haroun al Raschid.

When we look at the purely external course of history, what do we find? Wars are waged all along a line stretching across North Africa to the Iberian Peninsula; the followers of Arabism come right across Spain and are beaten back by the representatives of European Christianity, by Charles Martel, by Charles the Great himself. Then, later, we find how the greatness of Mohammedanism is overclouded by the Turkish element which assumes the guise of religion but extinguishes everything that went with the lofty culture to which Haroun al Raschid gave the impetus.

These two streams gradually die out as a result of the struggle waged against them by the warlike Christian population of Europe. Towards the end of the first thousand years, the only real menace in Europe comes from the Turks, but this has nothing much to do with what we are here considering. From now onwards no more is to be heard of the spread of Arabism.

Observation of history in its purely external aspect might lead us to the conclusion that Arabism had been beaten back by the European peoples. Battles were fought such as that of Tours and Poitiers, and there were many others; the Arabs were also defeated from the side of Constantinople, and it might easily be thought that Arabism had disappeared from the arena of world-history.

On the other hand, when we think deeply about the impulses that were at work in the sciences, and also in many respects in the field of art in European culture, we find Arabism still in evidence—but as if it had secretly poured into Christianity, had been secretly inculcated into it.

How has this come about? You must realise, my dear friends, that in spiritual life, events do not take the form in which they reveal themselves in external history. The really significant streams run their course beneath the surface of ordinary history and in these streams the individualities of the men who have worked in one epoch appear again, born into communities speaking an entirely different language, with altogether different tendencies of thought, yet working still with the same fundamental impulse. In an earlier epoch they may have accomplished something splendid, because the trend of events was with them, while in a later they may have had to bring it into the world in face of great hindrances and obstructions. Such individuals are obliged to content themselves with much that seems trivial in comparison with the mighty achievements of their earlier lives; but for all that, what they carry over from one epoch into another is the same in respect of the fundamental trend and attitude of soul. We do not always recognise what is thus carried over because we are too prone to imagine that a later earthly life must resemble an earlier one. There are people who think that a musician must come again as a musician, a philosopher as a philosopher, a gardener as a gardener, and so forth. By no means is it so. The forces that are carried over from one incarnation into another lie on far deeper levels of the life of soul.

When we perceive this, we realise that Arabism did not, in truth, die out. From the examples of Friedrich Theodor Vischer and of Schubert I was recently able to show you how the work and achievements of individualities in an earlier epoch continue, in a later one, in totally different forms.

Arabism most assuredly did not die out; far rather was it that individuals who were firmly rooted in Arabism lived in European civilisation and influenced it strongly, in a way that was possible in Europe in that later epoch.

Now it is easier to go forward from some historical personality in order to find him again than to go the reverse way, as in recent lectures—starting from later incarnations and then going back to earlier ones. When we learn to know the individuality of Haroun al Raschid inwardly in the astral light, as we say, when we have him before us as a spiritual individuality in the 9th century, bearing in mind what he was behind the scenes of world-history—and when what he was had been unfolded on the surface with the brilliance of which I have told you—then we can follow the course of time and find such an individuality as Haroun al Raschid passing through death, looking down from the spiritual world upon what is happening on earth, looking down, that is to say, upon the outward extermination of Arabism and, in accordance with his destiny, being involved in the process. We find such an individuality passing through the spiritual world and appearing again, not perhaps with the same splendour, but with a similar trend of soul.

And so we see Haroun al Raschid appearing again in the history of European spiritual life as a personality who is once again of wide repute, namely, as Lord Bacon of Verulam. I have spoken of Lord Bacon in many different connections. All the driving power that was in Haroun al Raschid and was conveyed to those in his environment, this same impulse was imparted by Lord Bacon in a more abstract form—for he lived in the age of abstraction—to the various branches of knowledge. Haroun al Raschid was a universal spirit in the sense that he united specialists, so to speak, around him. Lord Bacon—he has of course his Inspirer behind him, but he is a fit subject to be so inspired—Lord Bacon is a personality who is also able to exercise a truly universal influence.

When with this knowledge of an historic karmic connection we turn to Bacon and his writings, we recognise why these writings have so little that is Christian about them and such a strong Arabic timbre. We discover the genuine Arabist trend in these writings of Lord Bacon. And many things too in regard to his character, which has been so often impugned, will be explicable when we see in him the reincarnated Haroun al Raschid. The life and culture pursued at the Court of Haroun al Raschid, and justly admired by Charles the Great himself, become the abstract science of which Lord Bacon was the bearer. But men bowed before Lord Bacon too. And whoever studies the attitude adopted by European civilisation in the 8th/9th centuries to Haroun al Raschid, and then the attitude of European learning to Lord Bacon, will have the impression: men have turned round, that is all! In the days of Haroun al Raschid they looked towards the East; then they turned round in Middle Europe and looked towards the West, to Lord Bacon.

And so what may have disappeared, outwardly speaking, from history, is carried from age to age by human individualities themselves. Arabism seems to have disappeared; but it lives on, lives on in its fundamental trend. And just as the outer aspects of a human life differ from those of the foregoing life, so do the influences exercised by such a personality differ from age to age.

Open your history books, and you will find that the year 711 was of great significance in the situation between Europe and the Arabism that was storming across Spain. Tarik, Commander of the Arabs, sets out from Africa. He comes to the place that received its name from him: Gebel al Tarik, later called Gibraltar. The battle of Jerez de la Frontera takes place in the year 711. Arabism makes a strong thrust across Spain at the beginning of the 8th century. Battles are fought, and the fortunes of war sway hither and thither between the peoples who have come down into Spain to join with the old inhabitants, and the Arabs who are now storming in upon them. Even in those days the “culture,” as we would say today, of the attacking Arabs, commanded tremendous respect in Spain. Naturally, the Europeans had no desire to subject themselves to the Arabs. But the culture the Arabs brought with them was already in a sense a foreshadowing of what flourished later in such unexampled brilliance under Haroun al Raschid. In a man such as Tarik there was the attitude of soul that in all the storms of war wants to give expression to what is contained in Arabism. What we see outwardly is the tumult of war. But along the paths of these wars comes much lofty culture. Even outwardly a very great deal in the way of art and science was established in Spain. Many remains of Arabism lived on in the spiritual life of Europe. Spain itself soon ceased to play a part in the West of Europe. Nevertheless the fortunes of war swayed to and fro and the fighting continued from Spain; in men such as Spinoza we can see how deep is the influence of Arabist culture. Spinoza cannot be understood unless we see his origin in Arabism.

And then this stream flows across to England, but there it runs dry, comes to an end. We turn over the pages of history, and after the descriptions of the conflicts between Europe and the Arabs we find, as we read on further, that Arabism has dried up, externally at any rate. But under the surface this has not happened; on the contrary, Arabism spreads abroad in the spiritual life. And along this undercurrent of history, Tarik bears what he originally bore into Spain on the fierce wings of war. The aim of the Arabians in their campaigns was most certainly not that of mere slaughter; no, their aim was really the spread of Arabism. Their tasks were connected with culture. And what a Tarik had carried into Spain at the beginning of the 8th century, he now bears with him through the gate of death, experiencing how as far as external history is concerned it runs dry in Western Europe. And he appears again in the 19th century, bringing Arabism to expression in modern form, as Charles Darwin.

Suddenly we shall find a light shed upon something that seems to come like a bolt from the blue—we find a light shed upon it when we follow what has here been carried over from an earlier into a later time, appearing in an entirely different form.

It may at first seem like a paradox, but the paradox will disappear the more deeply we look into the concrete facts. Read Darwin's writings again with perception sharpened by what has been said and you will feel: Darwin writes about things which Tarik might have been able to see on his way to Europe!—In such details you will perceive how the one life reaches over into the next.

Now from times of hoary antiquity, especially in Asia Minor, astronomy had been the subject of profound study—astronomy, that is to say, in an astrological form. This must not, of course, in any way be identified with the quackery perpetuated in the modern age as astrology. We must realise the deep insight into the spiritual structure of the universe possessed by men in those times; this insight was particularly marked among the Arabians in the period when they were Mohammedans, continuing the dynasty founded by Mohammed. Astrological astronomy in its ancient form was cultivated with great intensity among them.

When the Residence of the dynasty was transferred from Damascus to Baghdad, we find Mamun ruling there in the 9th century. During the reign of Mamun—all such rulers were successors of the Prophet—astrology was cultivated in the form in which it afterwards passed over into Europe, contained in tracts and treatises of every variety which were only later discovered. They came over to Europe in the wake of the Crusades but had suffered terribly from erroneous and clumsy revision. For all that, however, this astronomy was great and sublime. And when we search among those who are not named in history, but who were around Mamun in Baghdad in the period from 813 to 833, cultivating this astrological-astronomical knowledge, we find a brilliant personality in whom Mamun placed deep confidence. His name is not given in history, but that is of no account. He was a personality most highly respected, to whom appeal was always made when it was a question of reading the portents of the stars. Many measures connected with the external social life were formulated in accordance with what such celebrities as the learned scholar at the Court of Caliph Mamun were able to read in the stars.

And if we follow the line along which the soul of this learned man at the Court of Mamun in Baghdad developed, we are led to the modern astronomer Laplace. Thus one of the personalities who lived at the Court of the Caliph Mamun appears again as Laplace.

The great impulses—those of less importance, too, which I need not now enumerate—that still flowed from this two-branched stream into Europe, even after the outer process had come to a halt, show us how Arabism lived on spiritually, how this two-pronged fork around Europe continued its grip.

You will remember, my dear friends, that Mohammed himself founded the centre of Mohammedanism, Medina, which later on became the seat of residence of his successors; this seat of residence was subsequently transferred to Damascus. Then, from Damascus across to Asia Minor and to the very portal of Europe, Constantinople, the generals of Mohammed's successors storm forward, again on the wings of war, bearing culture that has been fructified by the religion and the religious life founded by Mohammed, but is permeated also with the Aristotelianism which in the wake of the campaigns of Alexander the Great was carried over from Greece, from Macedonia, indeed from many centres of culture, to Asia.

And here, too, something very remarkable happens. Arabism is flooded, swamped, by the Turkish element. The Crusaders find rudimentary relics only, not the fruits of an all-prevailing culture. All this was eliminated by the Turks. What was carried by way of Africa and Spain to the West lives on and develops in the tranquil flow, so to speak, of civilisation and culture; points of contact are again and again to be found.

The unnamed scholar at the Court of Mamun, Haroun al Raschid himself, Tarik—all these souls were able to link what they bore within them with what was actually present in the world. For when the soul has passed through the gate of death, a certain force of attraction to the regions which were the scene of previous activity always remains; even when through other impulses of destiny there may have been changes, nevertheless the influence continues. It works on, maybe in the form of longing or the like. But because Arabism promotes belief in strict determinism, when the opportunity offered for continuing in a spiritual way what, at the beginning, was deliberately propagated by warlike means, it also became possible to carry these spiritual streams especially into France and England. Laplace, Darwin, Bacon, and many other spirits of like nature were led forward in this direction.

But everything had been, as it were, damped down. In the East, Arabism was able to knock only feebly at the door of Europe; it could make no real progress there. And those who passed through the gate of death after having worked in this region felt repulsed, experienced a sense of inability to go forward. The work they had performed on earth was destroyed, and the consequence of this between death and rebirth was a kind of paralysis of the life of soul.—We come now to something of extraordinary interest.

Soon after the time of the Prophet, the Residence is transferred from Medina to Damascus. From there the generals of the successors of the Prophet go forth with their armies but are again and again beaten back; the success achieved in the West is not achieved here. And then, very soon, we see a successor of the Prophet, Muavija by name, ruling in Damascus. His attitude and constitution of soul proceed on the one side from the monotheism of Arabism, but also from the determinism which grew steadily into fatalism. But already at that time., although in a more inward, mystical way, the Aristotelianism that had been carried over to Asia was taking effect. Muavija, who sent his generals on the one side as far as Constantinople and on the other made attempts—without any success to speak of—in the direction of Africa, this Muavija was at the same time a thoughtful man; but a man who did not accomplish anything very much, either outwardly or in the spiritual life.

Muavija rules not long after Mohammed. He thus stands entirely within Mohammedanism, within the religious life of Arabism. He is a genuine representative of Mohammedanism at that time, but one of those who are growing away from its hide-bound form and entering into that mode of thought which then, discarding the religious form, appears in the sciences and fine arts of the West.

Muavija is a representative spirit in the first century after Mohammed, but one whose thinking is no longer patterned in absolute conformity with that of Mohammed; he draws his impulse from Mohammed, but only his impulse. He has not yet discarded the religious core of Mohammedanism, but has already led it over into the sphere of thought, of logic. And above all he is one of those who are ardently intent upon pressing on into Europe, upon forcing their way to the West. If you follow the campaigns and observe the forces that were put into operation under Muavija, you will realise that this eagerness to push forward towards the West was combined with tremendous driving power, but this was already blunted, was already losing its edge.

When such a spirit later passes through the gate of death and lives on, the driving force also persists, and if we follow the path further we get this striking impression.—During the life between death and a new birth, much that remained as longing is elaborated into world-encompassing plans for a later life, but world-encompassing plans that assume no very concrete form for the very reason that the force behind them was blunted.

Now I confess that I am always having to ask myself: Shall I or shall I not speak openly? But after all it is useless to speak of these matters merely in abstractions, and so one must lay aside reserve and speak of things that are there in concrete cases. Let the world think as it will: certain inner, spiritual necessities exist in connection with the spread of Anthroposophy. One lends oneself to the impulse that arises from these spiritual necessities, pursuing no outward “opportunism.” Opportunism has, in sooth, wrought harm enough to the Anthroposophical Society; in the future there must be no more of it. And even if things have a paradoxical effect, they will henceforward be said straight out.

If we follow this Muavija, one of the earliest successors of the Prophet, as he passes along the undercurrent and then appears again, we find Woodrow Wilson.

In a shattering way the present links itself with the past. A bond is suddenly there between present and past. And if we observe how on the sea of historical happenings there surges up as it were the wave of Muavija, and again the wave of Woodrow Wilson, we perceive how the undercurrent flows on through the sea below and appears again—it is the same current.

I believe that history becomes intelligible only when we see how what really happens has been carried over from one epoch into another. Think of the abstraction, the rigid abstraction, of the Fourteen Points. Needless to say, the research did not take its start from the Fourteen Points—but now that the whole setting lies before you, look at the configuration of soul that comes to expression in these Fourteen Points and ask yourselves whether it could have taken root with such strength anywhere else than in a follower of Mohammed.

Take the fatalism that had already assumed such dimensions in Muavija and transfer it into the age of modern abstraction. Feel the similarity with Mohammedan sayings: “Allah has revealed it”; “Allah will bring it to pass as the one and only salvation.” And then try to understand the real gist of many a word spoken by the promoter of the Fourteen Points.—With no great stretch of imagination you will find an almost literal conformity.

Thus, when we are observing human beings, we can also speak of a reincarnation of ideas. And then for the first time insight is possible into the growth and unfolding of history.

Zehnter Vortrag

In der Betrachtung karmischer Zusammenhänge habe ich bisher in der letzten Zeit die Regel verfolgt, von bestimmten Persönlichkeiten auszugehen, die Ihnen in der neueren Zeit entgegentreten können, um dann zu versuchen, zurückzukommen zu vorangehenden Erdenleben. Ich möchte nun heute, um die konkreten Beispiele für die karmischen Zusammenhänge zu ergänzen, ich möchte nun heute ausgehen umgekehrt von gewissen historischen Persönlichkeiten der Vergangenheit, und dann den Weg machen von diesen historischen Persönlichkeiten der Vergangenheit hinauf in die spätere Zeit, entweder in die spätere Zeit der Geschichte oder in das Leben bis herauf in die Gegenwart. Ich möchte also gewissermaßen eine von karmischen Betrachtungen durchsetzte geschichtliche Darstellung bestimmter Zusammenhänge geben.

Wenn man die Entwickelung des Christentums verfolgt von seiner Begründung auf der Erde weiterhin nach Europa hinüber, wenn man die verschiedenen Wege, welche die christlichen Impulse erfahren haben, verfolgt, dann stößt man ja auf eine andere religiöse Geistesströmung, die, wenn sie heute auch weniger bemerkt wird, einen außerordentlich tiefgehenden Einfluß, ich möchte sagen, gerade unter der Oberfläche der äußeren historischen Ereignisse auf die europäische Zivilisation ausgeübt hat. Es ist dasjenige, was bekannt ist unter dem Namen des Mohammedanismus, die etwas mehr als ein halbes Jahrtausend nach der Begründung des Christentums entstandene mohammedanische Religion, mit allem dem aber, was zusammenhängt mit dem Leben, das sich an die Entstehung dieser mohammedanischen Religion angeknüpft hat.

Wir sehen zunächst, wie von Mohammed eine Art von Monotheismus, eine Art von Religion begründet wird, welche aufschaut, so wie das Judentum, in strenger Weise zu einer einheitlichen, die Welt umspannenden Gottheit. Da ist ein einheitlicher Gott, den auch Mohammed verkündigen will. Das ist etwas, was wie ein mächtiger Impuls von Arabien ausgeht und weite, eindringliche Verbreitung drüben in Asien, durch Afrika herüber bis nach Europa herein über Spanien findet.

Wer heute die Zivilisation der Gegenwart betrachtet, der wird sogar heute noch vieles in dieser Zivilisation falsch beurteilen, wenn er nicht ins Auge faßt, wie — gerade auf dem Umwege durch die Araberzüge — alles das, was schließlich seine Stoßkraft durch die Tat Mohammeds gefunden hat, mit hineingewirkt hat in die europäische Zivilisation, ohne daß die Form des religiösen Fühlens, mit dem die Sache verbunden war, eben auch einen Einzug in Europa gehalten hat.

Wenn man auf die religiöse Form hinschaut, in der der Mohammedanismus aufgetreten ist in seiner arabischen Art, dann hat man zunächst den starren Monotheismus, die allmächtige Einheitsgottheit, die für das religiöse Leben etwas von fatalistischem Element in sich schließt. Das Schicksal der Menschen ist von vornherein bestimmt. Der Mensch hat sich diesem Schicksal zu unterwerfen, oder wenigstens sich unterworfen zu wissen. Das ist die religiöse Form. Allein dieser Arabismus — so wollen wir das nennen — hat doch noch etwas ganz anderes gezeitigt. Es ist das Merkwürdige, daß auf der einen Seite dieser Arabismus sich ausbreitet auf ganz kriegerische Weise, daß die Völker beunruhigt werden durch dasjenige, was kriegerisch vom Arabismus ausgeht. Es ist aber auf der anderen Seite im höchsten Grade auch merkwürdig, inwiefern fast das ganze erste Jahrtausend von der Begründung des Mohammedanismus an der Arabismus Zivilisationsträger gewesen ist. Sehen wir zum Beispiel auf die Zeit hin, in welcher innerhalb Europas Karl der Große, sagen wir, seinen größten Einfluß gehabt hat, so finden wir drüben in Asien in der Residenz in Bagdad eine wunderbare Zivilisation, eigentlich ein großartiges Geistesleben. Man möchte sagen, während Karl der Große aus primitiven Untergründen heraus - er lernt ja sogar erst das Schreiben, notdürftig sogar -, während er aus primitiven Untergründen heraus eine gewisse sehr anfängliche Bildung zu verbreiten versucht, sehen wir eine hohe Geisteskultur drüben in Asien, in Bagdad.

Wir sehen sogar, wie ein ungeheurer Respekt vor dieser Geisteskultur bis hinein in die Umgebung Karls des Großen besteht. Wir sehen in jener Zeit - es ist ja die Zeit, in der Karl der Große, wie man sagt, regierte, 768 bis 814 wird ja die Regierungszeit Karls des Großen gerechnet -, wir sehen in der Zeit von 786 bis 809 in Bagdad drüben an der Spitze einer großartigen Zivilisation Harun al Raschid. Wir sehen Harun al Raschid, den intensiv von Dichtern gepriesenen Mann, der der Mittelpunkt eines weiten Kreises in Wissenschaften und Künsten war, der selber ein feingebildeter Mensch war, der in seinem Gefolge nicht etwa bloß so primitive Menschen wie den Zinhard hatte, der um Kar! den Großen war, sondern der tatsächlich glänzende Größen in Wissenschaften und Künsten um sich versammelte. Wir sehen Harun al Raschid drüben in Asien eben eine große Zivilisation, sagen wir jetzt nicht beherrschen, sondern impulsieren.

Und wir sehen, wie in diese Geisteskultur, deren Seele Harun al Raschid ist, dasjenige aufgeht, was in einem kontinuierlichen Strom seit dem Aristotelismus in Asien drüben sich verbreitet hat. Aristotelische Philosophie, aristotelische Naturwissenschaft, sie hat auch nach Asien hinüber ihre Verbreitung gefunden. Sie wurde durchgearbeitet mit orientalischer Einsicht, mit orientalischer Imagination, orientalischer Anschauung. Wir finden sie in ganz Vorderasien bis fast über die indische Grenze hinaus wirksam, und wir finden sie so verarbeitet, daß zum Beispiel ein weit ausgedehntes, weit ausgebreitetes medizinisches System gepflegt wurde an diesem Hofe Harun al Raschids.

Wir sehen in einer tief philosophischen Weise dasjenige, was mit einer Art religiösen Furors von Mohammed begründet worden war, sehen es in einer großartig intensiv eindringlichen Weise zur Geltung kommen unter den Gelehrten, Dichtern, Naturforschern, Medizinern, die am Hofe des Harun al Raschid lebten.

Mathematik wurde dort gepflegt, Geographie wurde gepflegt. Es wird leider viel zu wenig innerhalb der europäischen Geschichte dies betont, und man vergißt gewöhnlich über den Primitivitäten, sagen wir des Frankenhofes Karls des Großen, was da drüben in Asien war.

Und wir haben, wenn wir das in Betracht ziehen, was sich da doch in gerader Richtung aus dem Mohammedanismus herausentwickelt hatte, wir haben ein merkwürdiges Bild vor uns. Der Mohammedanismus wird in Mekka begründet, in Medina fortgesetzt. Er verbreitet sich herauf in die Gegenden von Damaskus, Bagdad und so weiter nach ganz Vorderasien. Wir sehen ihn herrschen in einer solchen Weise, wie ich es eben jetzt beschrieben habe. Wir haben damit sozusagen die eine Linie, in der sich der Mohammedanismus ausbreitet, von Arabien nach Norden, herüber über Kleinasien. Die Araber belagern fortwährend Konstantinopel. Sie pochen an die Tore Europas. Sie wollen sozusagen das, was sie an Stoßkraft haben, über den europäischen Osten vorschieben nach der europäischen Mitte.

Und wir haben auf der anderen Seite den Arabismus, sich ausbreitend durch Nordafrika bis nach Spanien. Er erfaßt da gewissermaßen über Spanien herüber Europa von der anderen Seite. Wir haben tatsächlich das Merkwürdige vorliegend, daß, wie in einer Kulturgabelung, Europa umspannt werden soll vom Arabismus.

Wir haben auf der einen Seite sich ausbreitend von Rom herauf, von dem Süden, das Christentum in der römischen Form, von Griechenland ausgehend dasjenige, was dann, sagen wir, in die Erscheinung tritt in Wulfilas Bibelübersetzung und so weiter; wir haben das in der Mitte drinnen. Und wir haben wie in einer Gabelung diese europäischchristliche Zivilisation umfassend den Mohammedanismus. Und alles dasjenige, was in der Geschichte Europas von den Taten Karls des Großen zur Förderung des Christentums erzählt wird, das darf ja nur so betrachtet werden, daß, während Karl der Große viel tut, um das Christentum in Europas Mitte zu verbreiten, zu fördern, gleichzeitig mit ihm in Asien drüben jenes gewaltige Kulturzentrum ist, von dem ich gesprochen habe: das Kulturzentrum Harun al Raschids.

Wenn man rein äußerlich-geschichtlich diese Sache ins Auge faßt, was tritt einem denn da entgegen? Da tritt einem entgegen, daß Kriege geführt werden längs der Linie, die über Nordafrika nach der iberischen Halbinsel sich zieht, daß über Spanien herüber die Bekenner des Arabismus kommen, daß sie zurückgeschlagen werden von den Vertretern des europäischen Christentums, von Karl Martell, von Karl dem Großen selber. Man erfährt dann später, daß sich gewissermaßen auslöschend über die Größe des Mohammedanismus ergießt das Türkentum, das die religiöse Form aufnimmt, aber eben auslöscht alles das, was an solcher Hochkultur vorhanden ist wie diejenige, die Harun al Raschid impulsiert hat.

So daß man eigentlich sieht, daß durch das Entgegenstemmen der europäisch-christlichen kriegerischen Bevölkerung nach und nach jene Strömungen ersterben, von denen wir eben gesprochen haben. Und wenn man so gegen das Ende des ersten Jahrtausends kommt, da bleiben allerdings noch die Türkengefahren in Europa übrig, aber die haben eigentlich mit dem, was hier gemeint ist, nicht mehr viel zu tun; denn von da an redet man nicht mehr von der Ausbreitung des Arabismus.

Man könnte, wenn man die rein äußerliche Geschichte betrachtet, zu dem Schlusse kommen: Nun, die Europäer haben eben den Arabismus zurückgeschlagen. Es haben solche Schlachten stattgefunden wie die Schlacht von Tours und Poitiers und so weiter, die Araber sind abgeschlagen worden auf der anderen Seite, auf der Konstantinopeler Seite, und man könnte glauben, damit sei der Arabismus eigentlich aus der Weltgeschichte verschwunden.

Aber auf der anderen Seite, wenn man sich vertieft in das, was namentlich in der europäischen wissenschaftlichen, in vieler Beziehung auch in der künstlerischen Kultur waltet, dann trifft man eben den Arabismus dennoch, aber wie zugeschüttet, wie im Geheimen ins Christentum hinein ergossen.

Woher kommt das? Ja, sehen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, die Dinge gehen innerhalb des geistigen Lebens doch anders vor sich, als sie sich äußerlich in den gewöhnlichen weltgeschichtlichen Ereignissen offenbaren. Unter der Oberfläche des gewöhnlichen geschichtlichen Lebens gehen die eigentlichen großen Strömungen, in denen die Individualitäten der Menschen, die in einer Epoche da waren, gewirkt haben, und die dann wieder und wieder erscheinen, indem sie in eine ganz andere Sprachgemeinschaft hineingeboren werden, in ganz andere Gedankenrichtungen hineingeboren werden, aber mit denselben Grundtypen ihres Wirkens. Was sie in einer Epoche vorher in großartiger Weise entfaltet haben, weil die Möglichkeit der Bewegung vorhanden war, das müssen sie in späteren Epochen unter großen Hemmungen und Hindernissen in die Welt setzen. Sie müssen sich mit manchem begnügen, was sich klein ausnimmt gegenüber dem, was sie in ihren früheren Epochen groß bewirkt haben, aber es ist dasselbe der Grundseelenverfassung, der Grundseelenstimmung nach, was die menschlichen Individualitäten aus einer Epoche in die andere hinübertragen. Nur erkennt man nicht immer, was da herübergetragen wird, weil man sich zu leicht vorstellt, ein folgendes Erdenleben müsse einem früheren Erdenleben sehr ähnlich schauen. Es gibt sogar Leute, die glauben, ein Musiker muß wieder als Musiker, ein Philosoph wieder als Philosoph, ein Gärtner wiederum als Gärtner und so weiter kommen. Das ist eben nicht so. Die Kräfte, die von einem Erdenleben in das andere herübergetragen werden, die ruhen in tieferen Schichten des menschlichen Seelenlebens.

Und wenn man dies anschaut, dann kommt man darauf: der Arabismus ist dennoch nicht ausgestorben. Ich konnte Ihnen ja vor einiger Zeit hier an dem Beispiel von Friedrich Theodor Vischer und von Schubert vorführen, wie durch das Herüberkommen der Individualitäten in der Tat in ganz anderer Form dasjenige sich fortsetzt in einer späteren Zeit, was in einer früheren Epoche gearbeitet, geleistet worden ist.

Nun, der Arabismus ist eben durchaus nicht in Wirklichkeit ausgestorben, sondern viel mehr Individualitäten, die im Arabismus festgewurzelt waren, leben innerhalb der europäischen Zivilisation, weil sie einfach geboren wurden unter Europäern, lebten sogar als tonangebende Persönlichkeiten, wie es in Europa dann in späterer Zeit möglich war.

Es ist leichter, von einer historischen Persönlichkeit weiterzugehen, um sie wieder aufzufinden, als der umgekehrte Weg, den ich in den letzten Vorträgen charakterisiert habe, wo von späteren Inkarnationen auf frühere zurückgegangen wird. Wenn man nun die Individualität des Harun al Raschid ins Auge faßt, wenn man sie innerlich kennenlernt, kennenlernt, wie man sagt, im astralischen Lichte, kennenlernt, wie sie als geistige Individualität in ihrer Zeit vorhanden war im 9. Jahrhundert, wenn man ins Auge faßt, was sie hinter den Kulissen der Weltgeschichte noch war, was sich nur eben mit jenem Glanz, den ich geschildert habe, an der Oberfläche der Geschichte entwickelt hat, dann verfolgt man die Zeiten, den Zeitenlauf — und findet solch eine Individualität, wie sie in Harun al Raschid war, durch den Tod gegangen, mitmachend, gewissermaßen von der geistigen Welt herunterschauend auf dasjenige, was auf der Erde geschieht: die äußerliche Ausrottung des Arabismus, schicksalsgemäß von der anderen Seite her mitmachend diese Ausrottung. Man findet, wie solch eine Individualität durchgeht durch die geistige Welt und wieder erscheint, vielleicht nicht in solchem Glanze, aber mit einer Seelenverfassung, die schon eine typische Ähnlichkeit hat mit derjenigen, die vorher da war.

Und so sehen wir Harun al Raschid tatsächlich in der Geschichte des europäischen Geisteslebens wieder auferstehen. Und er tritt auf als eine Persönlichkeit, die auch wieder weithin bekannt ist, er tritt auf als Lord Bacon von Verulam. Ich habe in den verschiedensten Zusammenhängen diesen Lord Bacon behandelt. Alles das, was in einer gewissen Weise in Harun al Raschid praktische Impulsivität war, die er auf Personen in seiner Umgebung übertragen hat, das überträgt in der mehr abstrakten Form, weil es im abstrakten Zeitalter ist, Lord Bacon auf die einzelnen Wissenschaften. Wie Harun al Raschid ein universeller Geist dadurch ist, daß er eben die einzelnen speziellen Geister um sich vereinigt hat, so ist Lord Bacon — mit seinem Inspirator hinter ihm natürlich, aber er ist eben geeignet, so inspiriert zu werden - eine Persönlichkeit, die universalistisch wirken kann.

Und wenn man mit diesem Wissen eines historischen karmischen Zusammenhanges nun wiederum auf Lord Bacon und seine Schriften hinschaut, dann findet man den Grund, warum diese eigentlich so wenig christlich und so stark arabisch klingen. Ja, man findet erst die richtige arabische Nuance heraus in diesen Schriften des Lord Bacon. Und auch mancherlei mit Bezug auf den Charakter Lord Bacons, der ja so viele Anfechtungen erfahren hat, wird man erklärlich finden, wenn man eben in Lord Bacon den wiedergeborenen Harun al Raschid sieht. Es ist aus einer Lebenspraxis, aus einer Kulturlebenspraxis, die am Hofe des Harun al Raschid in Bagdad geherrscht hat, vor der sich selbst Karl der Große mit Recht gebeugt hat, dasjenige geworden, was dann allerdings ein abstrakter Wissenschafter war in Lord Bacon. Aber wiederum hat man sich gebeugt vor Lord Bacon. Und man möchte sagen, wer die Geste studiert, wie sich die europäische Zivilisation gegenüber Harun al Raschid im 8., 9. Jahrhundert verhalten hat, und wer dann die Geste studiert, wie sich die europäische Wissenschaftlichkeit zu Lord Bacon verhält, der hat den Eindruck: die Menschen haben sich einfach umgedreht. Während Harun al Raschids Zeit schauten sie nach dem Osten, dann drehten sie sich um in Mitteleuropa und schauten nach dem Westen zu Lord Bacon hin.

Und so wird eben von Zeitalter zu Zeitalter durch die menschliche Individualität selber getragen, was vielleicht äußerlich im historischen Leben so hingeschwunden ist wie der Arabismus. Aber er lebt, in seiner Grundstimmung lebt er dann weiter. Und so verschieden ein folgendes Menschenleben seinen äußerlichen Seiten nach ist von dem vorangehenden Leben, so verschieden ist dann auch das, was geschichtlich auftritt durch eine solche Persönlichkeit.

Schlagen Sie die Geschichtsbücher auf, so werden Sie finden, 711 ist ein besonders wichtiges Ereignis in der Auseinandersetzung zwischen Europa und dem über Spanien heranstürmenden Arabismus. Tarik, Feldherr der Araber, setzt von Afrika herüber. Er kommt an derjenigen Stelle an, die selbst von ihm den Namen erhalten hat: Gebel al Tarik, Gibraltar später genannt. Es findet die Schlacht von Jerez de la Frontera statt 711; ein wichtiger Vorstoß des Arabismus im Beginne des 8. Jahrhunderts gegen Spanien herüber. Da finden wirklich Kämpfe statt, in denen das Kriegsglück hin und her schwankt zwischen den Völkerschaften, die da herübergekommen waren über Spanien zu den alten Einwohnern, die von früher da waren, und den nun heranstürmenden Arabern. Und es lebte schon damals in Spanien etwas von einer außerordentlich starken Achtung vor der Gebildetheit, würden wir heute sagen, der heranstürmenden Araber. Man wollte sich natürlich in Europa ihnen nicht unterwerfen; aber das, was sie an Kultur mitbrachten, war schon in einer gewissen Weise ein Abglanz dessen, was dann in einem so hohen Musterglanze unter Harun al Raschid später lebte. Wir haben durchaus bei einem Menschen wie Tarik noch die Seelenverfassung, die im Kriegssturm zum Ausleben bringen will, was im Arabismus veranlagt ist. Außerlich sieht man den Kriegssturm. Allein auf diesem Kriegswege gehen hohe Kulturrichtungen, geht ein hoher Kulturinhalt. Es ist ja auch äußerlich künstlerisch-wissenschaftlich in Spanien ungeheuer viel durch diese Araber begründet worden. Viele Reste dieses Arabismus lebten im europäischen Geistesleben weiter; die spanische Geschichte hört bald auf, ihre Rolle im Westen von Europa zu spielen.

Wir sehen allerdings im Westen von Europa, zunächst in Spanien selber, wie da hin und her das Kriegsglück geht, wie da von Spanien wieder weiter gekämpft wird, sehen noch bei Leuten wie Spinoza, wie tief der Einfluß ist der arabischen Kultur. Man kann Spinoza nicht verstehen, wenn man nicht seinen Ursprung eben im Arabismus sieht. Man sieht, wie das nach England herübergreift. Aber da versiegt es, da hört es wieder auf. Wir blättern in den Schilderungen, die uns von den kriegerischen Auseinandersetzungen zwischen Europa und den Arabern gegeben werden, weiter in der Geschichte und finden, daß es versiegt. Aber unter der Oberfläche der Geschichte versiegt es nicht, sondern breitet sich aus im geistigen Leben. Und wiederum dieser Tarik, er trägt im Unterton des geschichtlichen Werdens dasjenige, was er, man möchte sagen, auf den Sturmflügeln des Krieges ursprünglich nach Spanien hereingetragen hat. Die Araber wollten ja ganz gewiß nicht bloß Leute totschlagen auf ihren kriegerischen Wegen, sondern sie wollten eben den Arabismus ausbreiten. Sie hatten Kulturaufgaben. Dasjenige nun, was solch ein Tarik im Beginne des 8. Jahrhunderts nach Spanien hereingetragen hat, das trägt er nun mit, als er durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen ist, erlebt wiederum das äußerliche geschichtliche Versiegen in den westlichen europäischen Gegenden, und taucht im 19. Jahrhundert wieder auf, den Arabismus in moderner Form ausprägend, als Charles Darwin.

Man wird ganz plötzlich ein Licht verbreitet finden über das, was sonst, ich möchte sagen, historisch wie aus der Pistole herausgeschossen ist, wenn man in dieser Weise das Herübertragen dessen, was in einer ganz anderen Form vorhandene Geschichte ist, aus einer früheren Zeit in einer spätere Zeit verfolgt.

Es mag einem zunächst paradox erscheinen, aber die Paradoxie wird um so mehr schwinden, je mehr Sie auf die konkreten Tatsachen eingehen. Versuchen Sie nur einmal, mit dem durch diese Erwägungen geschärften Blicke in Darwin nachzulesen, da wird Ihnen eben doch auffallen: Donnerwetter, der Darwin schreibt ja geradezu Dinge, die der Tarik auf seinem Wege nach Europa gesehen haben könnte. — Gerade in diesen Kleinigkeiten werden Sie verspüren, wie das eine Leben in das andere herüberreicht.

Und sehen Sie, dasjenige, was überhaupt in Vorderasien seit Urzeiten außerordentlich stark gepflegt worden ist, das ist das Astronomische in der Form von Astrologischem; aber man darf das Astrologische von damals nicht identifizieren mit dem dilettantenhaften Zeug, das später als Astrologie gepflegt worden ist, das heute als Astrologie gepflegt wird, sondern man muß einen Begriff sich bilden können von den tiefen Einsichten, die in das geistige Gefüge des Weltenalls in diesen Zeiten vorhanden waren, und die in einer ganz besonderen Weise ausgeprägt wurden gerade unter den Arabern, als sie eben Mohammedaner waren, als sie die Dynastie, die Mohammed begründet hat, in der verschiedensten Weise fortsetzten. Gerade Astronomie, Astrologie in der alten Form wurden da gepflegt.

Und so sehen wir, als die Residenz von Damaskus nach Bagdad verlegt wird, Mamun herrschen im 9. Jahrhundert. Wir sehen während Tafel 15 der Regierung des Mamun - all das waren ja Nachfolger des Propheten —, wir sehen da besonders Astrologie in der Weise gepflegt, in der sie dann dilettantisch in allerlei Traktate übergegangen ist in Europa. Die Dinge wurden später gefunden. Durch die Kreuzzüge kamen sie herüber, wurden aber furchtbar verballhornt. Aber es war das eigentlich eine großartige Sache. Und wenn wir unter denjenigen Persönlichkeiten nachforschen, die in der Geschichte nicht mit Namen genannt werden, die aber in der Umgebung des Mamun, 813 bis 833, gelebt haben in Bagdad, gerade dort Astrologisches-Astronomisches pflegend, so finden wir eine glänzende Persönlichkeit, die tief vertraut war mit Mamun — der Name wird historisch nicht genannt, ist auch gleichgültig —, eine Persönlichkeit, die in höchster Schätzung stand, die gefragt wurde immer, wenn es sich darum handelte, irgend etwas aus den Sternen heraus zu lesen. Und viele Maßnahmen wurden da drüben getroffen im äußeren sozialen Leben nach dem, was solche Zelebritäten, wie dieser Gelehrte am Hofe Mamuns, aus den Sternen heraus zu sagen wußten.

Und wiederum, verfolgt man die Linie, in der sich die Seele dieses Gelehrten vom Hofe des Mamun in Bagdad weiterentwickelt, verfolgt man diesen Weg, man wird heraufgetrieben bis zu dem modernen Astronomen Laplace. Und da erscheint also wiederum eine der Persönlichkeiten in Laplace, die am Hofe des Kalifen Mamun lebten.

Man möchte sagen, was an großen Impulsen, und auch an kleinen Impulsen — die kleinen brauche ich ja nicht alle aufzuzählen -, was an großen und an kleinen Impulsen hereingeflossen ist aus dieser Gabelung nach Europa, nachdem das äußere geschichtliche Werden schon versiegt war, das zeigt uns, wie auf geistige Art der Arabismus weiterlebt, wie diese Gabelung hier fortdauert.

Sie wissen, meine lieben Freunde, Mohammed selber hat noch den Hauptsitz des Mohammedanismus, Medina, begründet, dort, wo dann die Residenz seiner Nachfolger war. Später wurde diese Residenz nach Damaskus, wie ich schon erwähnt habe, verlegt. Und wir sehen dann, wie diese Residenz von Medina herauf nach Damaskus verlegt wird, wir sehen, wie von Damaskus aus durch Kleinasien bis an die Pforte von Europa, bis an Konstantinopel heran, die Feldherren der Nachfolger des Mohammed vorstürmen und eben wiederum auf den Sturmflügeln des Krieges dasjenige tragen, was sie an bedeutsamer Kultur von dem religiösen Leben des Mohammed zwar befruchten lassen, was aber durchsetzt ist eben mit dem, was auf dem Wege des Alexander, was an Aristotelismus herübergekommen ist von Griechenland, von Mazedonien aus, von allen möglichen Kulturzentren aus nach Asien.

Und hier geschieht ja auch etwas Merkwürdiges. Hier wird durch die türkische Überflutung dasjenige ganz ausgelöscht, was herangestürmt ist vom Arabismus. Nur Rudimente, nur Reste finden dann die Kreuzfahrer, aber nicht herrschende Kulturströmungen; die Türken löschen das aus. Was sich durch Afrika, Spanien, nach dem Westen herein fortpflanzt, das pflanzt sich gewissermaßen in Kultur-, in Zivilisationsruhe fort; da findet man immer wieder Anknüpfungspunkte. Der Gelehrte Mamuns, Harun al Raschid selber, Tarik, sie fanden als Seelen die Möglichkeit, das, was sie in der Seele trugen, anzuknüpfen an das, was da war, indem ja in der Seele, wenn sie durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen ist, immer eine gewisse Aneignungskraft bleibt für die Gebiete, auf denen man gewirkt hat. Wenn das auch durch andere Schicksalsimpulse verändert werden kann, es wirkt dennoch nach. Wird es verändert, so wirkt es als Sehnsuchten nach und dergleichen. Aber gerade weil an einen strengen Determinismus durch das Arabertum geglaubt worden ist, stellte sich, als die Möglichkeit geboten wurde, auf geistige Art fortzusetzen, was zunächst auf kriegerische Art impulsiert werden sollte, eben auch die Möglichkeit ein, diese geistigen Strömungen insbesondere nach Frankreich, nach England herauf zu tragen. Laplace, Darwin, Bacon, viele ähnliche Geister könnten in dieser Richtung vorgeführt werden.

Aber hier [im Osten] wurde alles abgestumpft, möchte ich sagen; im Osten konnte der Arabismus nur in sehr spärlicher Weise an die Pforte von Europa klopfen, konnte da nicht weiterkommen. Da erlebten dann diejenigen Persönlichkeiten, welche durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen waren, nachdem sie auf diesem Gebiete hier gewirkt hatten, etwas wie ein Zurückgestoßenwerden, wie ein Nicht-Weiterkönnen. Das irdische Werk wurde ihnen zerschlagen. Das bewirkte sogar eine gewisse Paralysierung des Seelenlebens zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Und da ist nun etwas ganz besonders Interessantes vorliegend.

Wir sehen, wie bald nach dem Propheten die Residenz von Medina nach Damaskus verlegt wird, wie die Feldherren der Nachfolger des Propheten da heraufziehen, wie sie aber immer wieder zurückgeschlagen werden, wie hier nicht in derselben Weise etwas gelingt wie drüben nach dem Westen hin. Und so sehen wir denn sehr bald, wie einer der Nachfolger des Propheten, 661, Muavija ist. Muavija, einer der Nachfolger des Propheten, herrscht in Damaskus und steht ganz drinnen in jener Seelenverfassung, welche auf der einen Seite aus dem Monotheismus des Arabismus herauswächst, aber auch aus dem Determinismus, der dann immer mehr und mehr zum Fatalismus geworden ist. Aber schon damals herrschte, wenn auch, ich möchte sagen, auf eine mehr mystische Art, auf eine mehr innerliche Art, das nach Asien herübergekommene Griechentum, der Aristotelismus. Und Muavija, der auf der einen Seite seine Feldherrn bis nach Konstantinopel herüberschickte, auf der anderen Seite allerdings auch nach Afrika hin einiges versuchte — aber da gelang ihm nichts Besonderes -, Muavija war zu gleicher Zeit ein sinniger Mann, aber ein Mann, dem eigentlich äußerlich nicht viel gelang, auch nicht auf den geistigen Gebieten.

Sie sehen, er herrscht nicht lange nach Mohammed. Er steht also noch ganz im Mohammedanismus als in dem eigentlich religiösen Element des Arabismus drinnen. Er ist einer der Repräsentanten des Mohammedanismus von dazumal, aber einer, der gerade herauswächst aus der starren religiösen Form des Mohammedanismus und hereinwächst in jene Denkungsweise, die ja dann, abstreifend die religiöse Form, in dem Wissenschaftlichen, in dem Schön-Wissenschaftlichen des Westens hervorgetreten ist.

Er ist schon ein repräsentativer Geist, dieser Muavija im ersten Jahrhundert nach Mohammed, ein Geist, der nicht mehr denkt wie Mohammed, der nur noch die Anregung von Mohammed hat, der noch nicht den eigentlichen religiösen Kern des Mohammedanismus abgestreift hat, aber ihn doch schon in die Denkform, in die logische Form hinübergeleitet hat. Und er gehört ja vor allen Dingen zu denen, die nun mit allem Eifer hinüber wollten nach Europa, mit allem Eifer nach dem Westen vordringen wollten. Wer die Kriegszüge, die aufgewendeten Kräfte verfolgt, die gerade unter Muavija tätig waren, der wird sehen: es war dieses Vorrücken-Wollen gegen den Westen dazumal verbunden mit einer ungeheuer starken Stoßkraft, die eben nur abgestumpft worden ist.

Wenn dann ein solcher Geist durch die Pforte des Todes geht, weiterlebt, so lebt natürlich eine solche Stoßkraft weiter, und man hat dann, wenn man den Weg weiter verfolgt, vor allen Dingen den Eindruck: Das geht durch das Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt durch, indem vieles von dem, was Sehnsucht geblieben ist, ausgebildet wird als weltumspannende Pläne für ein späteres Leben; aber weltumspannende Pläne, die keine sehr konkrete Form annehmen. Weil ja alles eben abgestumpft worden ist, nehmen sie keine konkrete Form an.

Nun, ich gestehe, ich muß mir immer jetzt die Frage stellen: Soll ich, oder soll ich nicht? Aber ich meine, es hilft ja nichts, wenn man von diesen Dingen nur in Abstraktionen redet. Und so müssen schon alle Rücksichten beiseitegesetzt werden, um in konkreten Fällen von den Dingen zu reden, die da sind. Möge die Welt die Sache nehmen, wie sie sie eben nehmen kann. Für die Verbreitung von Anthroposophie bestehen innerliche geistige Notwendigkeiten. Man fügt sich dem, was sozusagen in einem angeregt wird aus den geistigen Notwendigkeiten heraus und treibt keine nach außen gehende «Opportunität»: Opportunität hat ja der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft genugsam geschadet; sie soll in Zukunft nicht weiter getrieben werden. Und selbst wenn die Dinge recht paradox wirken sollten, so sollen sie doch in der Zukunft einfach gerade gesagt werden.

Verfolgt man diesen Muavija, der also einer der nächsten Nachfolger des Propheten war, weiter im Laufe der Geschichte, wie er in der Unterströmung weitergeht und wieder auftaucht, so findet man Woodrow Wilson.

Und in einer erschütternden Weise schließt sich einem zusammen die Gegenwart mit der Vergangenheit. Plötzlich steht eine Verbindung da zwischen der Gegenwart und der Vergangenheit. Und man kann dann sehen, wenn man schaut, wie gewissermaßen, ich möchte sagen, auf dem Meere des Geschehens, des geschichtlichen Geschehens da auftaucht die Woge Muavija, da auftaucht die Woge Woodrow Wilson, man sieht, wie die Unterströmung durch das Meer weitergeht, und wie da dieselbe Strömung vorliegend ist.

Und so erst wird die Geschichte, denke ich, begreiflich, wenn man sieht, wie aus der einen Epoche in die andere dasjenige herübergetragen wird, was eigentlich wirklich geschieht. Suchen Sie dieganze, ich möchte sagen, schon abstrakt-stierhafte Art der Vierzehn Punkte - es ist natürlich nicht die Betrachtung von den Vierzehn Punkten ausgegangen -, aber suchen Sie jetzt, nachdem die Sache da liegt, diese stierhafte Art, sich diesen abstrakten Vierzehn Punkten hinzugeben, suchen Sie diese in der Seelenkonfiguration auf, und fragen Sie sich dann, ob solche Seelenkonfiguration in solcher Stärke woanders veranlagt sein konnte als in einem Nachfolger Mohammeds! Und nehmen Sie den schon bei Muavija ausgebildeten Fatalismus, und übertragen Sie ihn in die Zeit der modernen Abstraktheit und fühlen Sie die Ähnlichkeit mit dem Mohammedanischen: Allah hat es geoffenbart; Allah wird es bewirken, das einzige Heil! - und versuchen Sie, manches Wort, das ausgegangen ist von dem Träger der Vierzehn Punkte, richtig zu verstehen: Sie werden cum grano salis eine fast wörtliche Übereinstimmung finden.

So können wir schon, wenn wir uns die Menschen anschauen, auch von einer Wiederverkörperung der Ideen sprechen. Dann wird das Werden der Geschichte eigentlich erst eingesehen.

Tenth Lecture

In the consideration of karmic connections, I have so far followed the rule of starting from certain personalities that you may encounter in recent times, in order to then try to return to previous earth lives. Today, in order to supplement the concrete examples of the karmic connections, I would like to start from certain historical personalities of the past and then make my way from these historical personalities of the past up into the later time, either into the later time of history or into life up to the present. I would therefore like to give, so to speak, a historical account of certain connections interspersed with karmic considerations.

If you follow the development of Christianity from its foundation on earth onwards to Europe, if you follow the various paths that the Christian impulses have taken, then you will come across another religious spiritual current which, even if it is less noticed today, has exerted an extraordinarily profound influence, I would say, on European civilization just beneath the surface of external historical events. It is what is known under the name of Mohammedanism, the Mohammedan religion that emerged a little more than half a millennium after the foundation of Christianity, but with everything that is connected with the life that followed the emergence of this Mohammedan religion.

First of all, we see how Mohammed founded a kind of monotheism, a kind of religion which, like Judaism, looks up in a strict manner to a unified deity that encompasses the world. There is a unified God that Mohammed also wants to proclaim. This is something that emanates like a powerful impulse from Arabia and spreads widely and forcefully across Asia, through Africa and into Europe via Spain.

Whoever looks at contemporary civilization today will still misjudge much in this civilization if he does not consider how - precisely in a roundabout way through the Arab campaigns - everything that finally found its impetus through the deeds of Muhammad had an impact on European civilization, without the form of religious feeling with which the matter was connected having also found its way into Europe.

If you look at the religious form in which Mohammedanism appeared in its Arab form, then you first have rigid monotheism, the omnipotent unified deity, which contains something of a fatalistic element for religious life. The fate of mankind is determined from the outset. Man must submit to this fate, or at least know himself to be subject to it. That is the religious form. But this Arabism - that's what we want to call it - has brought about something quite different. It is strange that, on the one hand, this Arabism is spreading in a quite warlike manner, that the peoples are disturbed by that which emanates warlike from Arabism. On the other hand, however, it is also highly remarkable to what extent Arabism has been the bearer of civilization for almost the entire first millennium since the foundation of Mohammedanism. If we look, for example, at the time when Charlemagne, let us say, had his greatest influence within Europe, we find a wonderful civilization, in fact a great spiritual life, in the residence in Baghdad over in Asia. One might say that while Charlemagne was trying to spread a certain very initial education from primitive foundations - he was even learning to write, in a makeshift way - while he was trying to spread a certain very initial education from primitive foundations, we see a high intellectual culture over in Asia, in Baghdad.

We even see how there is a tremendous respect for this intellectual culture right into Charlemagne's environment. We see in that time - it is the time in which Charlemagne, as they say, reigned, 768 to 814 is the reign of Charlemagne - we see in the time from 786 to 809 in Baghdad over there at the head of a great civilization Harun al Rashid. We see Harun al Rashid, the man who was intensely praised by poets, who was the center of a wide circle in the sciences and arts, who was himself a finely educated man, who did not just have such primitive people in his entourage as Zinhard, who was around Charlemagne, but who actually gathered brilliant greats in the sciences and arts around him. We see Harun al Rashid over in Asia, a great civilization, let us not say dominating, but stimulating.

And we see how this intellectual culture, of which Harun al Rashid is the soul, incorporates that which has spread in a continuous stream over there in Asia since Aristotelianism. Aristotelian philosophy, Aristotelian natural science, has also spread to Asia. It was worked through with oriental insight, with oriental imagination, oriental view. We find it effective throughout the Near East, almost beyond the Indian border, and we find it processed in such a way that, for example, a far-reaching, widespread medical system was cultivated at the court of Harun al Rashid.

We see in a deeply philosophical way that which had been founded with a kind of religious furor by Mohammed, we see it come to the fore in a magnificently intense way among the scholars, poets, naturalists, physicians who lived at the court of Harun al Rashid.

Mathematics was cultivated there, geography was cultivated. Unfortunately, far too little emphasis is placed on this in European history, and the primitivities of, say, Charlemagne's court in Franconia are usually overlooked in comparison to what was going on over there in Asia.

And if we take into account what had developed in a straight line out of Mohammedanism, we have a strange picture before us. Mohammedanism was founded in Mecca and continued in Medina. It spreads upwards to the regions of Damascus, Baghdad and so on to the whole of the Near East. We see it ruling in the way I have just described. We thus have, so to speak, the one line in which Mohammedanism is spreading, from Arabia to the north, across Asia Minor. The Arabs are constantly besieging Constantinople. They are knocking at the gates of Europe. They want to push, so to speak, what thrust they have across the European East towards the center of Europe.

And on the other side we have Arabism, spreading through North Africa to Spain. In a sense, it is reaching Europe from the other side via Spain. We actually have the strange thing that, as in a cultural bifurcation, Europe is to be embraced by Arabism.

On the one side we have Christianity in its Roman form spreading from Rome upwards, from the south, and from Greece that which then, let us say, appears in Wulfila's translation of the Bible and so on; we have this in the middle. And we have, as if in a fork, this European-Christian civilization encompassing Mohammedanism. And everything that is told in the history of Europe about Charlemagne's deeds to promote Christianity can only be viewed in such a way that, while Charlemagne does a lot to spread and promote Christianity in the middle of Europe, at the same time there is that enormous cultural center over there in Asia that I have spoken of: the cultural center of Harun al Rashid.

If you look at this from a purely external historical perspective, what do you see? You see that wars are being waged along the line that stretches across North Africa to the Iberian Peninsula, that the advocates of Arabism come across Spain, that they are repulsed by the representatives of European Christianity, by Charles Martel, by Charlemagne himself. We then learn later that Turkishness pours over the greatness of Mohammedanism, to a certain extent extinguishing it, absorbing the religious form, but extinguishing everything that is present in such a high culture as that which Harun al Raschid had inspired.

So that you can actually see that the currents we have just mentioned are gradually dying out as a result of the resistance of the European-Christian warlike population. And when we come to the end of the first millennium, the Turkish dangers in Europe still remain, but they no longer have much to do with what is meant here, because from then on we no longer talk about the spread of Arabism.

If you look at the purely external history, you could come to the conclusion: Well, the Europeans have just beaten back Arabism. Battles like the Battle of Tours and Poitiers and so on took place, the Arabs were defeated on the other side, on the Constantinople side, and one could believe that Arabism had actually disappeared from world history.

But on the other hand, if you immerse yourself in what is going on in European scientific culture in particular, and in many respects in artistic culture as well, then you still come across Arabism, but as if it had been buried, as if it had been secretly poured into Christianity.

Where does that come from? Yes, you see, my dear friends, things happen differently within the spiritual life than they reveal themselves outwardly in ordinary world-historical events. Beneath the surface of ordinary historical life are the actual great currents in which the individualities of the people who were there in one epoch have worked, and who then reappear again and again by being born into a completely different language community, born into completely different schools of thought, but with the same basic types of their work. What they have previously developed in a magnificent way in one epoch, because the possibility of movement was present, they must bring into the world in later epochs under great inhibitions and obstacles. They must be content with some things that appear small in comparison with what they have accomplished in their earlier epochs, but it is the same in terms of the basic constitution of the soul, the basic mood of the soul, that human individualities carry over from one epoch into another. Only one does not always recognize what is being carried over, because it is too easy to imagine that a subsequent life on earth must look very similar to a previous life on earth. There are even people who believe that a musician must come back as a musician, a philosopher as a philosopher, a gardener as a gardener and so on. This is not the case. The forces that are carried over from one earthly life to another rest in deeper layers of human soul life.

And when you look at this, you realize that Arabism has not died out. Some time ago I was able to show you here, using the example of Friedrich Theodor Vischer and Schubert, how the coming over of individualities in fact continues in a completely different form in a later time what was worked on and achieved in an earlier epoch.

Now, Arabism has by no means died out in reality, but many more individuals who were firmly rooted in Arabism live within European civilization because they were simply born among Europeans, even lived as leading personalities, as was possible in Europe in later times.

It is easier to go on from a historical personality in order to find it again than the opposite way, which I have characterized in the last lectures, where one goes back from later incarnations to earlier ones. Wenn man nun die Individualität des Harun al Raschid ins Auge faßt, wenn man sie innerlich kennenlernt, kennenlernt, wie man sagt, im astralischen Lichte, kennenlernt, wie sie als geistige Individualität in ihrer Zeit vorhanden war im 9. If one considers what it still was behind the scenes of world history, what only developed on the surface of history with the brilliance that I have described, then one follows the times, the course of time - and finds such an individuality as it was in Harun al Raschid, gone through death, participating, so to speak, looking down from the spiritual world on what is happening on earth: the external eradication of Arabism, participating in this eradication from the other side in accordance with destiny. One finds how such an individuality passes through the spiritual world and reappears, perhaps not in such splendor, but with a soul constitution that already has a typical similarity to that which was there before.

And so we actually see Harun al Rashid rise again in the history of European spiritual life. And he appears as a personality who is also widely known again, he appears as Lord Bacon of Verulam. I have dealt with this Lord Bacon in various contexts. Everything that was in a certain way practical impulsiveness in Harun al Raschid, which he transferred to people around him, Lord Bacon transfers in a more abstract form, because it is in the abstract age, to the individual sciences. Just as Harun al Raschid is a universal spirit in that he united the individual special spirits around him, so Lord Bacon - with his inspirer behind him, of course, but he is suitable to be inspired in this way - is a personality who can have a universalistic effect.

And if you now look at Lord Bacon and his writings with this knowledge of a historical karmic connection, then you will find the reason why they actually sound so little Christian and so strongly Arabic. Indeed, it is only in these writings of Lord Bacon that one finds the real Arabic nuance. And many things relating to the character of Lord Bacon, who experienced so many challenges, can also be explained if one sees in Lord Bacon the reborn Harun al Rashid. A practice of life, a practice of cultural life that prevailed at the court of Harun al Rashid in Baghdad, to which even Charlemagne rightly bowed, became what was then, however, an abstract scientist in Lord Bacon. But again, people bowed to Lord Bacon. And if you study the gesture of how European civilization behaved towards Harun al Raschid in the 8th and 9th centuries, and if you study the gesture of how European science behaved towards Lord Bacon, you get the impression that people have simply turned around. During Harun al Rashid's time, they looked to the East, then they turned around in Central Europe and looked to the West towards Lord Bacon.

And so, from age to age, it is human individuality itself that carries what may have faded away in historical life, like Arabism. But it lives on, it lives on in its basic mood. And as different as a subsequent human life is in its outward aspects from the preceding life, so different is that which emerges historically through such a personality.

If you open the history books, you will find that 711 is a particularly important event in the conflict between Europe and the Arab invasion of Spain. Tarik, commander of the Arabs, crosses over from Africa. He arrives at the place that he himself gave his name to: Gebel al Tarik, later called Gibraltar. The battle of Jerez de la Frontera takes place in 711; an important advance of Arabism at the beginning of the 8th century against Spain. There were real battles in which the fortunes of war swung back and forth between the peoples who had come across Spain to the ancient inhabitants who had been there before and the Arabs who were now advancing. And even then in Spain there was something of an extraordinarily strong respect, we would say today, for the education of the approaching Arabs. Of course, people in Europe did not want to submit to them, but the culture they brought with them was in a certain way a reflection of what later lived in such a high standard of brilliance under Harun al Rashid. In a man like Tarik, we still have the state of mind that wants to bring to life in the storm of war what is inherent in Arabism. Outside of this we see the storm of war. Only on this path of war do high cultural directions, does a high cultural content go. These Arabs also founded an enormous amount of external artistic and scientific work in Spain. Many remnants of this Arabism lived on in European intellectual life; Spanish history soon ceased to play its role in the west of Europe.

We see, however, in the west of Europe, first of all in Spain itself, how the fortunes of war go back and forth, how Spain continues to fight again, and we can still see in people like Spinoza how deep the influence of Arab culture is. You can't understand Spinoza if you don't see his origins in Arabism. You can see how it reaches over to England. But there it dries up, there it stops again. We turn over the pages of history in the descriptions we are given of the warlike conflicts between Europe and the Arabs, and find that it dries up. But beneath the surface of history it does not dry up, but spreads out in spiritual life. And again this Tarik, he carries in the undertone of historical becoming that which he, one might say, originally carried into Spain on the storm wings of war. The Arabs certainly didn't just want to kill people in their warlike ways, they wanted to spread Arabism. They had cultural tasks. That which such a Tarik brought to Spain at the beginning of the 8th century, he now carries with him as he passed through the gate of death, again experiences the external historical drying up in the western European regions, and reappears in the 19th century, developing Arabism in a modern form, as Charles Darwin.

You will suddenly find a light shed on what is otherwise, I would like to say, historically shot out of the gun, if you follow in this way the transfer of what is history in a completely different form from an earlier time to a later time.

It may seem paradoxical at first, but the paradox will fade the more you look at the concrete facts. Just try reading Darwin with an eye sharpened by these considerations, and you will notice it: Gosh, Darwin actually writes things that Tarik could have seen on his way to Europe. - It is precisely in these little things that you will sense how one life reaches over into the other.

And you see, that which has been cultivated extremely strongly in the Near East since time immemorial is astronomy in the form of astrology; But one must not identify the astrology of that time with the dilettante stuff that was later cultivated as astrology, which is cultivated today as astrology, but one must be able to form a concept of the deep insights that were present in the spiritual structure of the universe in those times, and which were developed in a very special way precisely among the Arabs, when they were Mohammedans, when they continued the dynasty that Mohammed founded in the most diverse ways. Astronomy and astrology in the old form were cultivated there.

And so we see, when the residence is moved from Damascus to Baghdad, Mamun reigning in the 9th century. During plate 15 of Mamun's reign - all of them were successors of the prophet - we see astrology in particular being cultivated in the way in which it was then amateurishly passed on to all kinds of treatises in Europe. These things were found later. They came over through the Crusades, but were terribly distorted. But it was actually a great thing. And if we investigate among those personalities who are not mentioned by name in history, but who lived in the vicinity of Mamun, 813 to 833, in Baghdad, cultivating astrology and astronomy there, we find a brilliant personality who was deeply familiar with Mamun - the name is not mentioned historically, it is also irrelevant - a personality who was held in the highest esteem, who was always asked when it was a matter of reading something from the stars. And many measures were taken over there in external social life according to what such celebrities, like this scholar at the court of Mamun, knew how to tell from the stars.

And again, if one follows the line in which the soul of this scholar develops from the court of Mamun in Baghdad, one follows this path, one is driven up to the modern astronomer Laplace. And there again appears one of the personalities in Laplace who lived at the court of the Caliph Mamun.

I would like to say that the great impulses and also the small impulses - I need not enumerate all the small ones - which flowed into Europe from this bifurcation, after the external historical development had already dried up, show us how Arabism lives on in a spiritual way, how this bifurcation continues here.

You know, my dear friends, that Mohammed himself founded the headquarters of Mohammedanism, Medina, where the residence of his successors was located. Later, this residence was moved to Damascus, as I have already mentioned. And we then see how this residence was moved from Medina up to Damascus, we see how from Damascus through Asia Minor to the gate of Europe, up to Constantinople, the generals of the successors of Mohammed advance and in turn carry on the storm wings of war that which they have taken from the important culture of Mohammed, the significant culture that they allowed to be fertilized by the religious life of Mohammed, but which was interspersed with the Aristotelianism that had come over from Greece, from Macedonia, from all possible cultural centers to Asia by way of Alexander.