Supersensible Influences in the History of Mankind

GA 216

30 September 1922, Dornach

Lecture V

We have been hearing in recent lectures how fundamental impulses in the development of history are expressed in such phenomena as the strange custom in Egyptian culture of mummifying the human body and in the modern age the preservation of ancient cults—which is also a kind of “mummification”, in this latter case of ceremonies and rites.

Thinking again of Egyptian culture as expressed outwardly in the phenomenon of mummification, we will combine the picture thus outlined with a theme of which I have spoken recently and have frequently expounded here, namely, the theme of ordinary human thinking, how this thought-activity is exercised by man, how he gradually unfolds the faculty of thinking during childhood, becomes to a certain degree accomplished in it during his youth and then puts it into operation until his death. This thinking, this intellectual activity, is a kind of inner corpse of the soul. Thinking, as exercised by the human being in earthly life, is viewed in the right light only when it is compared, as far as its relation to the true being of man is concerned, with the corpse left behind at death.

The principle, which makes man truly man, departs at death, and something remains over in the corpse, which can only have this particular form because a living human being has left it behind him. Nobody could be so foolish as to believe that the human corpse, with its characteristic form, could have been produced by any play of nature, by any combination of nature-forces. A corpse is quite obviously a remainder, a residue. Something must have preceded it, namely, the living human being. Outer nature has, it is true, the power to destroy the form of the human corpse but not the power to produce it. This human form is produced by the higher members of man's being—but they pass away at death.

Just as we realise that a corpse derives from a living human being, so the true conception of thinking, of human thought, is that it cannot, of itself, have become what it is in earthly life, but that it is a kind of corpse in the soul—the corpse of what it was before the human being came down from worlds of soul-and-spirit into physical existence on the earth. In pre-earthly existence the soul was alive in the truest sense, but something died at birth, and the corpse, which remains from this death in the life of soul, is our human thinking. Those who have known best what it means to live in the world of thought have, moreover, felt the deathlike character of abstract thinking. I need only remind you of the moving passage with which Nietzsche begins his description of philosophy in the era of Greek tragedy. He describes how Greek thought, as exemplified by pre-Socratic philosophers such as Parmenides or Heraclitus, rises to abstract notions of being and becoming. Here, he says, one feels the onset of an icy coldness. And it is so indeed.

Think of men of the ancient East and how they tried to comprehend outer nature in living, inwardly mobile pictures, dreamlike though these pictures were. In comparison with this inwardly mobile, live thinking, which quickened the whole being of man and blossomed forth in the Vedanta philosophy, the abstract thinking of later times is veritably a corpse. Nietzsche was aware of this when he felt an urge to write about those pre-Socratic philosophers who, for the first time in the evolution of humanity, soared into the realm of abstract thoughts.

Study the sages of the East who preceded the Greek philosophers and you will find in them no trace of any doubt that the human being lived in worlds of soul-and-spirit before descending to the earth. It is simply not possible to experience thinking as a living reality and not believe in the pre-earthly existence of man. To experience living thinking is just like knowing a living human being on earth. Those who no longer experienced living thinking—and this applies to Greek philosophers even before the days of Socrates—such men may, like Aristotle, have doubts about the fact that the human being does not come into existence for the first time at birth. And so a distinction must be made between the once inwardly mobile and living thinking of the East wherewith it was known that man comes down from spiritual worlds into earth-existence, and the thinking that is a corpse, bringing knowledge only of what is accessible to man between birth and death.

Try to put yourselves in the position of an Egyptian sage, living, let us say, about 2000 B.C.. He would have said: Once upon a time, over in the East, men experienced living thinking. But the Egyptian sage was in a strange situation; his life of soul was not like ours today; experience of living thinking had faded away, was no longer within his grasp, and abstract thinking had not yet begun. A substitute was created by the embalming of mummies whereby, in the way I have described, a picture, a concept of the human form was made possible. Men trained themselves to unfold a picture of the dead human form in the mummy and began, for the first time, to develop abstract, dead thinking. It was from the human corpse that dead thinking first came into existence.

The counterpart of this in modern times is that in occult societies here and there, rituals, cults and ceremonial enactments once filled with living reality have been preserved as dead traditions. Think only of rituals that you may have read, perhaps those of the Freemasons. You will find that there are ceremonies of the First Degree, the Second Degree, the Third Degree, and so forth. All of them are learnt, written or enacted in an external way. Once upon a time, however, these cults were charged with life as real as the life-principle working in the plants. Today, the ceremonies and rites are dead forms. Even the Mystery of Golgotha was only able to evoke in certain priestly natures here and there, those inner, living experiences which sometimes arose in connection with rites of the Christian Churches after the time of Christ. But up to now mankind has not been able to infuse real life into ceremonies and rites—and indeed something else is necessary here.

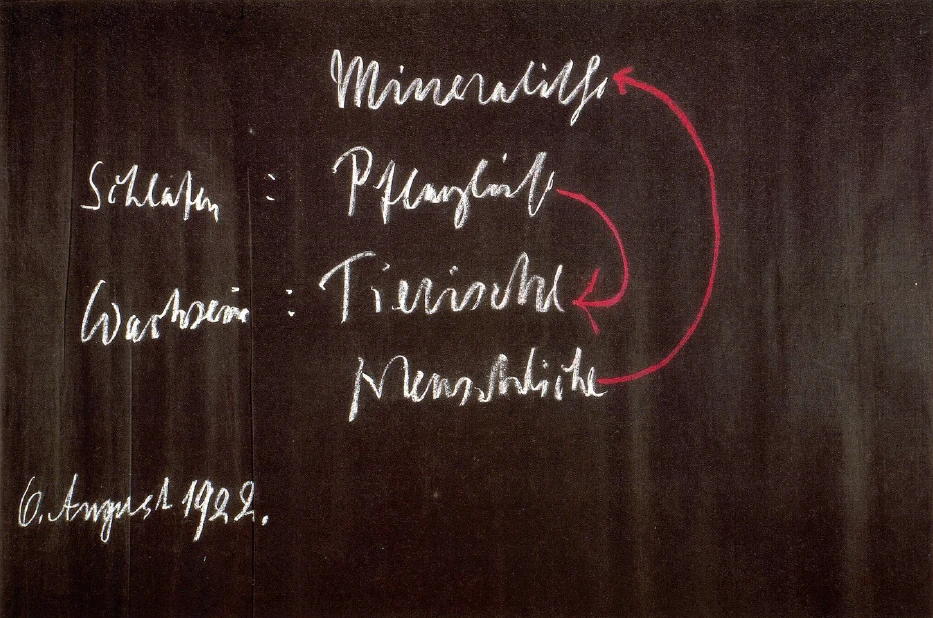

All present-day thinking is directed essentially to the dead world. In our time there is simply no understanding of the nature of the living thinking which once existed. The intellectualistic thinking current since the middle of the fifteenth century of our era is, in very truth, a corpse and that is why it is applied only to what is dead in nature, to the mineral kingdom. People prefer to study plants, animals and even the human being, merely from the aspect of mineral, physical, chemical forces, because they only want to use this dead thinking, this corpse of thoughts indwelling the purely intellectualistic man.

In the present series of lectures I have mentioned the name of Goethe. Goethe was, as you know, a member of the community of Freemasons and was acquainted with its rites. But he experienced these rites in a way of which only he was capable. For him, real life flowed out of the rites which, for others, were merely forms preserved by tradition. He was able to make actual connection with that spiritual reality of being, which flowed in the way described from pre-earthly into earthly existence and which, as I said, always rejuvenated him. For Goethe underwent actual rejuvenation more than once in his life. It was from this that there came to him the idea of metamorphosis1See The Mystery of the Trinity lecture II, by Rudolf Steiner—one of the most significant thoughts in the whole of modern spiritual life and the importance of which is still not recognised.

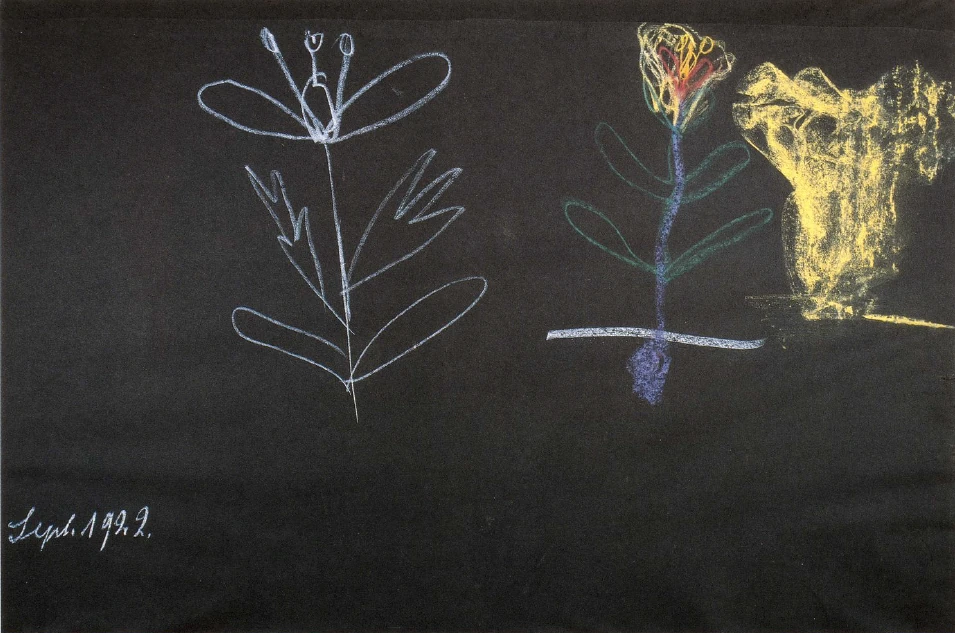

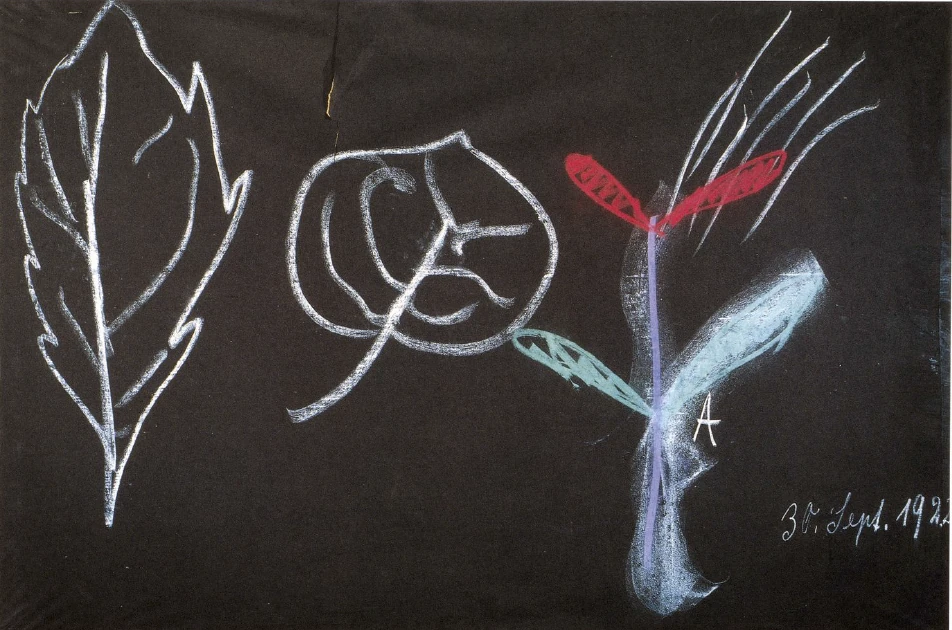

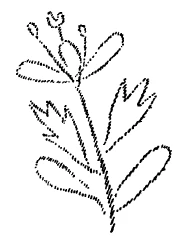

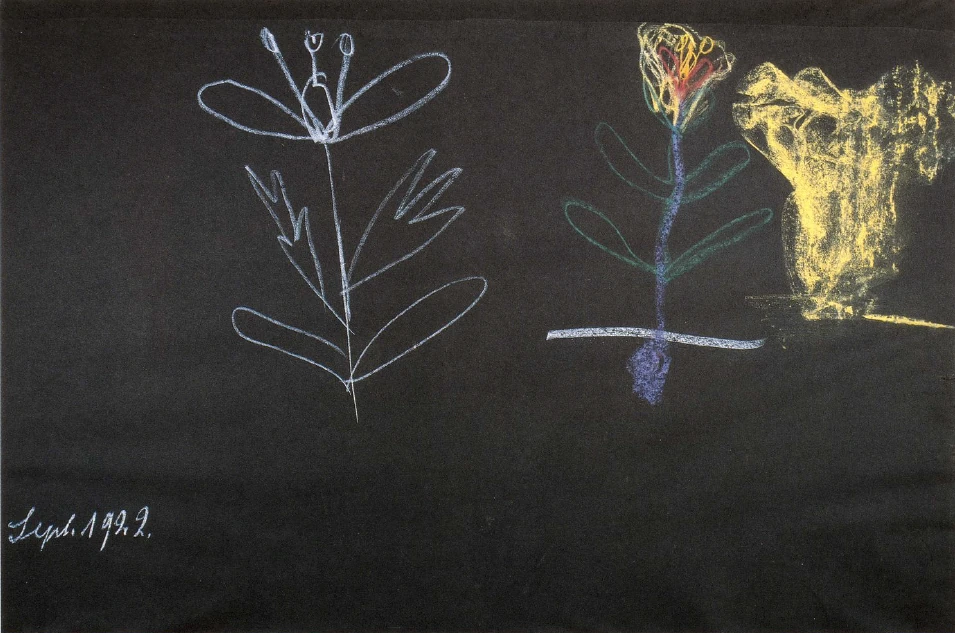

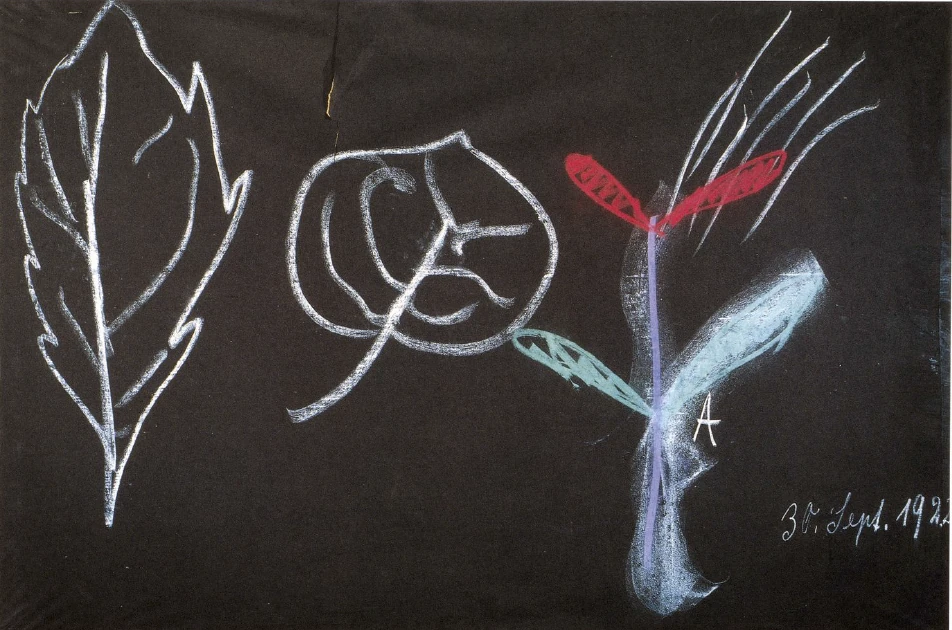

What had Goethe actually achieved when he evolved the idea of metamorphosis? He had re-kindled an inwardly living thinking, which is capable of penetrating into the cosmos. Goethe rebelled against the botany of Linnaeus in which the plants are arranged in juxtaposition, each of them placed in a definite category and a system made out of it all. Goethe could not accept this; he did not want these dead concepts. He wanted a living kind of thinking, and he achieved it in the following way. First of all he looked at the plant itself and the thought came to him that down below the plant develops crude, unformed leaves, then, higher up, leaves which have more developed forms but are transformations, metamorphoses of those below; then come the flower-petals with their different colour, then the stamens and the pistil in the middle—all being transformations of the one fundamental form of the leaf itself. Goethe did not say: Here is a leaf of one plant and here a leaf of another, different plant.2Sketches of leaves of various shapes were made on the blackboard. He did not look at the plant in this way, but said: The fact that one leaf has a particular shape and another leaf a different shape, is a mere externality. Viewed inwardly, the matter is as follows. The leaf itself has an inner power of transformation, and it is just as possible for it to appear outwardly in one shape as in another. In reality there are not two leaves, but one leaf, in two different forms of manifestation. A plant has the green leaf below and the petal above. Intellectualistic pedants say: “The leaf and the petal are two quite different things.” Nothing could be more obvious, as far as the pedants are concerned, for the one form is red and the other green. Now if someone wears a green shirt and a red jacket—here there is a real difference. As regards clothing, at any rate in the modern age, philistinism prevails and is, moreover, in its right place. In that domain one cannot help being a philistine. But Goethe realised that the plant cannot be comprised within such theories. He said to himself: The red petal is the same, fundamentally, as the green leaf; they are not two separate and distinct phenomena. There is only one leaf, manifesting in different formations. The same force works, sometimes down below and sometimes higher up. Down below it works in such a way that the forces are, in the main, being drawn out of the earth. Here the plant is drawing forces from the earth, sucking them upwards, and the leaf, growing under the influence of the earth-forces, becomes green. The plant continues to grow; higher up the sun's rays are stronger than they are below, and the sun has the mastery. Thus the same impulse reaches into the sphere of the sunlight and produces the red petals.

Goethe might have spoken somewhat as follows. Suppose a man who has nothing to eat sees another who has quantities of food and gets envious, literally pale with envy. Another time someone gives him a blow and then he reddens. According to the principle that speaks of two distinct and different leaves, it might be argued: Here are two men—two, because one is pale and the other is red. Just as little as there are two men, one who is red on account of a blow and the other who is pale because of envy—as little are there two leaves. There is one leaf; at one place it has a particular form, at another place a different form. Goethe did not regard this as particularly wonderful for, after all, a man can run from one place to another and the men you will see in different places are certainly not two different persons. Briefly, Goethe realised that this observation of things in strict juxtaposition is not truth but illusion, that there is only one leaf—green at one place, red at another; and he applied to the different plants the same principle he applied to the several parts of the single plant. Think of the following. Suppose some plant lives in favourable conditions. Out of the seed it forms a root, a stem, leaves on the stem, then petals, stamens and pistil within the stamens. Goethe maintained that the stamens too are only different formations of the leaf. He might also have said: Intellectualists argue that, after all, the red petals are wide and the stamen as thin as a thread, except perhaps for the anther at the top. In spite of this, Goethe maintained that the wide flower petal and the slender stamen are only different formations of one and the same fundamental leaf. He might have asked: Have you not noticed some person who at one time in his life was as thin as a reed and afterwards became very stout? There were certainly not two different people. Petals and stamens are basically one, and the fact that they are situated at two different places on the plant is immaterial. No man can run swiftly enough to be in two places at once, although the story goes that a clever banker in Berlin when he was being pestered on all sides, once exclaimed: “Do you think I am a bird which can be in two places at once?” ... A human being cannot be in two places simultaneously. The point here is that Goethe was seeking everywhere for manifestations of the principle of metamorphosis, of the unity within multiplicity, of the unity within the manifold. And thereby he imbued the concept with life.

If you grasp what I have now said, my dear friends, you will grasp the idea of Spirit. I have said that the whole plant is really a leaf manifesting in different formations. This cannot be pictured in the physical sense; something must be grasped spiritually—something that transforms itself in every conceivable way. It is spirit that is living in the plant kingdom. Now we can go further. We can take a plant that is normal and healthy because its seed has been properly placed in the earth, it has absorbed the gentle sun of spring, then the full summer sun and has been able to develop its seeds under the weakening sun of autumn. But suppose a plant exists in such conditions of nature that it has no time to develop a root, an adequate stem, leaves or petals, but is obliged to unfold very rapidly—so rapidly indeed that everything about it lacks definition. Such a plant becomes a mushroom, a fungus.

There you have two extremes: a plant that has time to differentiate into all its detailed parts, to develop roots, stem, leaves, flowers, fruit; and a plant placed in such conditions of nature that it has no time to form a root, with the result that everything about it remains indication only; it cannot develop stem and leaves, and is obliged to unfold rapidly and without definition the principle underlying the formation of petals, fruit and seed. Such a plant only just manages to take its place in the earth and unfolds with amazing rapidity what other plants unfold slowly. Think, for example, of the corn poppy. After slowly putting out its green leaves it can proceed to unfold its petals, then the stamens, then the jaunty pistil in the centre. But a mushroom must do all this very rapidly; there is no time for differentiation, no time for exposure to the sun, which would bring the beautiful colours, because the sun is absent during its brief period of development. In the mushroom we have a flower without definition; development has taken place far too rapidly. Here, too, there is fundamental unity. Two quite different plants are basically the same.

But before all this can be really thought through, one must change a little, inwardly. An intellectualist—Goethe might have said, a “rigid philistine”—looks at a poppy with its sappy, red flower and well-developed pistil in the centre. What he really ought to do is at the same time to look at a mushroom and keep the concept he has formed of the poppy so mobile and flexible that he is able to see within the poppy itself, in tendency at least, some kind of mushroom or toadstool. But that, of course, is asking too much of a pedant. You will have to place before him the actual mushroom so that his intellect may drag itself away from the poppy without inner exertion, without being kindled to life—for all he need do is to incline his head very slightly. Then he will be able to visualize the one object beside the other separately, and all is well!

Such is the difference between dead thinking and the inwardly alert, live thinking unfolded by Goethe in connection with the principle of metamorphosis. He enriched the world of thought by a glorious discovery. For this reason, in the Introductions to Goethe's works on Natural Science which I wrote in the eighties of last century, you will find the sentence: Goethe is both the Galileo and the Copernicus of the science of organic nature, and what Galileo and Copernicus achieved in connection with dead, outer nature, namely, clarification of the concept of nature to enable it to embrace both the astronomical and the physical aspects, Goethe achieved for the science of organic nature with his living concept of metamorphosis. Such was his supreme discovery.

This concept of metamorphosis can, if desired, be applied to the whole of nature. When a picture of the plant-form came to Goethe out of this concept of metamorphosis, it immediately occurred to him that the principle must also be applicable to the animal. But this is a more difficult matter. Goethe was able to conceive of one leaf proceeding from another; but he found it much more difficult to picture the form of one of the spinal vertebrae, for instance, being metamorphosed, transformed, into a bone of the head—which would have meant the application of the principle of metamorphosis to the animal and also to the human being. Nevertheless Goethe was partially successful in this too, as I have often told you. In the year 1790, while he was walking through a graveyard in Venice, he was lucky enough to come across a sheep's skull, the bones of which had fallen apart in a way very favourable for observation. As he examined these animal bones the thought dawned upon him that they looked like spinal vertebrae, although greatly transformed. And then he conceived the idea that the bones, at least, can also be pictured as representing one, basic bone-creating impulse, which merely manifests in different forms.

With respect to the human being, however, Goethe did not get very far because he did not succeed in passing on from his idea of metamorphosis to real Imagination. When real Imagination advances to Inspiration and Intuition, the principle of uniformity is revealed still more strikingly. And I have already indicated how this uniformity is revealed in the being of man when the concept of metamorphosis is truly understood. When Goethe contemplated the dicotyledons and visualised the flowers of such plants in simpler and more and indefinite forms, he could finally see them as a mushroom or fungus. And from this same point of view, when we study the human head, we can conceive of it as a metamorphosis of the rest of the skeleton.

Try to look at one of the lower jaws in a human skeleton with the eye of an artist. You will hardly be able to do otherwise, than compare it with the bones of the arm and of the leg. Think of the leg bones and arm bones transformed and then, in the lower jaws, you have two “legs”, except that here they have stultified. The head is a lazybones that never walks, but is always sitting. The head “sits” there on its two stultified legs. Imagine a man in the uncomfortable position of sitting with his legs bound together by some kind of cord, and you have practically a replica of the formation of the jaws. Look at all this with the eye of an artist and you can easily imagine the legs becoming as immobile as the lower jawbones—and so on.

But the truth of the matter is realised for the first time when the human head is conceived as a transformation of the rest of the body. I have told you that the head of our present earth-life is the transformed body (the body apart from the head) of our previous earth-life. The head, or rather the forces of the head, as they then were, have passed away. In some cases indeed they actually pass away during life! The head—I am speaking, of course, of forces, not substances—the forces of the head are not preserved; the forces now embodied in your head were the forces which were embodied in the other parts of your body in your previous life. In that life, again, the forces of the head were those of the body of the preceding life; and the body that is now yours will be transformed, metamorphosed, into the head of the future earth-life. For this reason the head develops first. Think of the embryo in the body of the mother. The head develops first and the rest of the organism, being a new formation, affixes itself to the head. The head derives from the previous earth-life; it is the transformed body, a form that has been carried across the whole span of existence between death and a new birth; it then becomes the head-structure and attaches to itself the other members. Accepting the fact of repeated earthly lives, we can thus see the human being as a metamorphosis recently perfected. The idea of plant-metamorphosis discovered by Goethe at the beginning of the eighties of the eighteenth century leads on to the living concept of development through the whole animal kingdom up to the human being, and contemplation here leads on to the idea of repeated earthly lives.

Goethe's participation in the ceremonial enactments of the cult to which he belonged was responsible for this inner quickening in his life of thought. Although it was not fully clear to his consciousness, he nevertheless had an inkling of how the human being, still living entirely as a soul in pre-earthly life, carries over forces which have remained from the bodily structure of the previous earth-life and which, having entered into the present life, develop within the protective sheaths of the mother's body into the head structure.

Goethe did not know this consciously but he had an inkling of it and applied it, in the first place, to the simplest phenomena of plant life. Because the time was not ripe, he could not extend the principle to the point that is possible today, namely to the point where the metamorphosis of the human being from one earth-life over to the next can be understood. As a rule it is said, with a suggestion of compassion, that Goethe evolved this idea of metamorphosis because, owing to his artistic nature, something had gone wrong with him. Pedants and philistines speak like this out of compassion. But those who are neither pedants nor philistines will realise with joy that Goethe knew how to add the element of art to science and precisely because of this was able to make his concepts mobile. Pedants insist, however, that nature cannot be grasped by this kind of thinking; strictly logical concepts are necessary, they say, for the understanding of nature. Yes, but what if nature herself is an artist ... presuming this, the whole of natural science which excludes art and bases itself only upon the concepts of logical deduction might find itself in a position similar to one of which I once heard when I was talking to an artist in Munich. He had been a contemporary of Carriere, the well-known writer on Aesthetics. We began, by chance, to speak about Carriere and this man said: “Yes, when we were young, we artists used not to attend Carriere's lectures; if we did go once, we never went again; we called him ‘the aesthetic rapture-monger’.” Now just as it might be the fate of a writer on Aesthetics to be called a “rapture-monger” by artists, so, if nature herself were to speak about her secrets she might call the strictly logical investigator ... well, not a rapture-monger, but a misery-monger perhaps, for nature creates as an artist. One cannot order nature to let herself be comprehended according to the laws of strict logic. Nature must be comprehended as she actually is.

Such, then, is the course of historical evolution. Once upon a time, in the ancient East, concepts and thoughts were full of life. I have described how, to begin with, these living concepts became actual perception through a metamorphosis of the breathing process. But human beings were obliged to work their way through to dead, abstract concepts. The Egyptians could not reach this stage but forced themselves in the direction of dead concepts through contemplating the human being himself in the state of death, in the mummy. We, in our day, have to awaken concepts to new life. This cannot happen by the mere elaboration of ancient, occult traditions, but by growing into, and moreover elaborating, the living concept which Goethe was the first to evolve in the form of the idea of metamorphosis. Those who are masters of the living concept, in other words, those who are able to grasp the Spiritual in their life of soul—they are able, out of the Spirit, to bring a new and living impulse into the external actions of men. This will lead to something of which I have often spoken to Anthroposophists, namely, that men will no longer stand in the laboratory or at the operating table with the indifference begotten by materialism, but will feel the secrets revealed by nature to listening ears as deeds of the Spirit which pervades and is active in her. Then the laboratory table will become an altar. Forces leading to progress and ascent will not be able to work in the evolution of humanity until true reverence and piety enter into science, nor until religion ceases to be a mere bolster for human egoism and to be regarded as a realm entirely distinct from science. Science must learn, like the pupils of the ancient Mysteries, to have reverence for what is being investigated. I have spoken of this in the book Christianity as Mystical Fact. All research must be regarded as a form of intercourse with the spiritual world and then, by listening to nature we shall learn from her those secrets, which in very truth promote the further evolution of humanity. And then the process of mummification—which was once a necessary experience for man—will be reversed. The Egyptians embalmed the human corpse, with the result that even now we can witness the almost terrifying spectacle of whole series of mummies being brought by Europeans from Egypt and deposited in museums. Just as human thinking was once rigidified as the outcome of the custom of mummification, so it must now be awakened to life.

The ancient Egyptians took the corpses of men, embalmed them, conserved death. We, in our day, must feel that we have a veritable death of soul within us if our thoughts are purely abstract and intellectualistic. We must feel that these thoughts are the mummy of the soul, and learn to understand the truth glimpsed by Paracelsus when he took some substance from the human organism and called this the “mummy”. In the tiny material residue of the human being, he saw the mummy. Paracelsus did not need an embalmed corpse in order to see the mummy, for he regarded the mummy as the sum-total of those forces which could at every moment lead man to death if new life did not quicken him during the night.

Dead thinking holds sway within us; our thinking represents death of soul. In our thinking we bear the mummy of the soul which produces precisely those things that are most prized in modern civilisation. If we have a wider kind of perception, the kind of perception, for example, which enabled Goethe to see metamorphoses, we can go through rooms where mummies are exhibited in museums and then out into the streets and see the same thing there ... it is merely a question of the level from which we are looking, for in the modern age of intellectualism there is little difference—the fact that mummies do not walk as human beings walk in the streets, is only an externality. The mummies in the museums are mummies of bodies; the human beings who walk about the streets in this age of intellectualism are mummies of soul because they are filled with dead thoughts, with thoughts that are incapable of life. Primordial life was rigidified in the mummies of Egypt and this rigidified life of soul must be quickened again for the sake of the future of mankind. We must not continue to study anatomy and physiology in the way that has hitherto been customary. This was permissible among the ancient Egyptians when corpses of the physical human being lay before them. We must not further mummify the corpse of abstract soul-life we bear in our intellectualistic thinking. There is a real tendency today to embalm thinking so that it becomes pedantically logical, without a single spark of fiery life.

Photographs of mummies are as rigid and stiff as the mummy itself. A typical standard work today on some branch of modern knowledge is a photograph, an image of the mummified soul; in this case it is the soul that has been embalmed. And if doubt arises because as well as the intellect which is certainly mummified, human beings have other characteristics, all kinds of bodily and other urges, for instance, so that the picture of the mummy is not very clear ... nevertheless it is there, unmistakably, in standard text books. The embalming process in such writings is very perceptible. This embalming of thought must cease. Instead of the embalming process applied by the Egyptians to the mummies, we need something different, namely, an elixir of life—not as many people think of this today, as a means of perfecting the physical body, but in a form which makes the thoughts alive, which de-mummifies them. When we understand this we have a picture of a profoundly significant impulse in historical evolution. It is a picture of how spiritual culture was once rigidified in the embalming of mummies and of how an elixir of spirit and soul must be poured into all that has been mummified in modern man in the course of his education and development, so that culture may flow onwards to the future. There are two forces: one manifests in the Egyptian custom of embalming and the other in the process of “de-embalming” which modern man must learn to apply.

To learn how to “de-embalm” the dead, rigid forces of the soul—this is a task of the greatest possible significance today. Failure to achieve it produces phenomena of which I gave one example here a short time ago. A man like Spengler realised that rigidified concepts and thoughts will not do, that they lead to the death of culture. In an article in Das Goetheanum I showed what really happened to Spengler. He realised that concepts were dead, but his own were not living! His fate was the same as that of the woman in the Old Testament who looked behind her. Spengler looked at all the dead, mummy-like thoughts of men and he himself became a pillar of salt. Like the woman in the Old Testament, Spengler became a pillar of salt, for his concepts have no more life in them than those of the others.

There is an ancient occult maxim that “wisdom lives in salt” ... but only when the salt is dissolved in human mercury and human phosphorus. Spengler's wisdom is wisdom that has rigidified in salt. But the mercury that brings the salt into movement, making it cosmic, universal—this is lacking; and phosphorus, too, is lacking in a still higher degree. For when one reads Spengler with feeling, above all with artistic feeling, it is impossible for his ideas to kindle inner enthusiasm, inner fire. They all remain salt-like and rigid and even produce a bitter taste. One has to be pervaded inwardly by the mercurial and phosphoric forces if it is a question of “digesting” this lump of salt that calls itself The Decline of the West. But it cannot really be digested ... I will not enlarge upon this particular theme because in polite society one does not mention what is done with indigestible matter! What we have to do is to get away from the salt, away from rigidity, and administer an elixir of life to the mummified soul, to our abstract, systematized concepts. That is the task before us.

Siebenter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Wir haben gesehen, wie sich die Grundimpulse des geschichtlichen Werdens der Menschheit in solchen Erscheinungen ausdrücken wie das merkwürdige Hinneigen der ägyptischen Kultur zu der Mumifizierung der menschlichen Form und in der neueren Zeit zu der Konservierung alter Kultformen, die auch in einer gewissen Beziehung eine Art Mumifizierung, aber eine Mumifizierung des Kulturgeschehens darstellt. Wenn wir noch einmal mit einigen Gedanken zu der ägyptischen Kultur zurückgreifen, wie sie sich in der Mumie äußerlich offenbart, so müssen wir das, was wir da als eine Anschauung gewonnen haben, mit einer Darstellung verbinden, die ich während des Kursus gegeben habe, der vor kurzem drüben im Goetheanum gehalten worden ist, die ich aber auch hier schon öfter gegeben habe. Ich meine die Darstellung von der gewöhnlichen menschlichen Denktätigkeit, wie sie vom Menschen ausgeübt wird so, daß er sie allmählich während seiner Kindheitszeit in sich heranerzieht, darinnen eine gewisse Fähigkeit erlangt und sie dann durchführt zwischen seinem Jugendalter und dem Tode. Diese Denktätigkeit, dieses, wie ich es öfter genannt habe, intellektualistische Sich-Betätigen haben wir kennengelernt als eine Art inneren Seelenleichnams.

[ 2 ] Wir haben es uns wiederholt vor die Seele geführt, daß das Denken, so wie es im Erdenleben von dem Menschen ausgeführt wird, nur dann in der richtigen Weise angeschaut wird, wenn man es zu seinem eigentlichen Wesen in die gleiche Beziehung zu setzen versteht, wie der Leichnam, den der Mensch übriggelassen hat, wenn er durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen ist, im Verhältnis zu dem lebendigen Erdenmenschen steht. Das, wodurch der Mensch Mensch ist, fährt eigentlich aus dem Menschen heraus, und im Leichnam bleibt etwas übrig, das nur diese Form haben kann, die uns entgegentritt, wenn sie eben von einem lebenden Menschen übriggelassen ist. Niemand könnte so einfältig sein zu glauben, daß durch irgendein Zusammenkommen von Kräften der menschliche Leichnam in seiner Form entstehen könnte. Er muß ein Rest sein, es muß ihm etwas vorangegangen sein, es muß ihm der lebendige Mensch vorangegangen sein. Die äußere Natur, die wir studieren, hat zwar die Macht, die Form des menschlichen Leichnams zu zerstören, sie hat aber nicht die Macht, sie zu bilden. Diese menschliche Form wird gebildet durch das, was dem Menschen an höheren Wesensgliedern eigen ist. Aber diese sind fort mit dem Tode. Geradeso wie wir einem Leichnam ansehen, daß er von einem lebendigen Menschen herrührt, so sehen wir es dem Denken an, wenn wir es in der richtigen Weise anschauen, daß es nicht durch sich selbst so sein kann, wie es uns im Erdenleben entgegentritt, sondern daß es eine Art Leichnam in der Seele ist, und zwar der Leichnam von dem, was es war, bevor der Mensch aus geistig-seelischen Welten in das physische Erdendasein heruntergestiegen ist. Da war die Seele etwas im vorirdischen Dasein, das gewissermaßen mit der Geburt gestorben ist; und der Leichnam dieses seelisch Gestorbenen ist das Denken.

[ 3 ] Wie sollte es auch nicht so sein, da doch gerade die Menschen, die mit dem Denken am meisten zu leben verstanden, diese Torheit, dieses Gestorbensein des abstrakten Denkens fühlten! Ich brauche Sie nur zu verweisen auf jene ergreifende Stelle, mit der Nietzsche beginnt, die Philosophie im tragischen Zeitalter der Griechen zu schildern, da, wo er schildert, wie die griechische Gedankenwelt in den vorsokratischen Philosophen, wie etwa in Parmenides oder in Heraklit, zu den abstrakten Gedanken des Seins und Werdens aufsteigt. Da, sagt Nietzsche, fühlt man eine eisige Kälte über sich kommen. Und so ist es auch. Vergleichen Sie nur damit, wie die Menschen des alten Orients in lebendigen, innerlich regsamen, allerdings mehr traumhaften Seelengebilden diese äußere Natur zu begreifen versuchten. Gegen dieses in sich regsame Denken, dessen Blüte uns entgegentritt in der Vedantaphilosophie, in den Veden, gegen dieses sich regende Denken, gegen dieses überall sprießende und sprossende Denken, das den ganzen Menschen innerlich lebendig durchwebt, ist tatsächlich das, was in späterer Zeit als abstrakter Gedanke auftritt, toter Leichnam. Das empfand Nietzsche, indem er sich gedrungen fühlte, die vorsokratischen Philosophen zu schildern, die zu solchen abstrakten Gedanken eigentlich in der Menschheitsentwickelung zuerst aufgestiegen sind.

[ 4 ] Aber sehen Sie hin auf diese orientalischen Weisen, die den griechischen Philosophen vorangegangen sind. Sie werden da nichts von einem Zweifel daran finden, daß der Mensch zuerst ein seelisches Dasein hatte, bevor er auf die Erde niedergestiegen ist. Man kann nicht das Denken als lebendiges erleben und nicht zugleich an das vorirdische Dasein des Menschen glauben. Wer das Denken als ein lebendiges erlebt, ist eben so wie einer auf der Erde, der den lebendigen Menschen erkennt. Wer nicht mehr das Denken als lebendiges erlebt, wie es die griechischen Philosophen auch schon vor Sokrates getan haben, der kann meinen, daß der Mensch ein Wesen ist, das erst mit der Geburt geboren wird, wie es Aristoteles getan hat. Also wir müssen unterscheiden zwischen dem einstmals orientalischen innerlich regsamen und lebendigen Denken, wodurch man wußte, daß man eben aus geistigen Welten in das Erdendasein eingezogen ist, und demjenigen Denken, das dann als das tote Denken, das Leichnamdenken aufgetreten ist, wodurch man nichts anderes kennenlernt als das, was einem eben zwischen Geburt und Tod zugänglich ist.

[ 5 ] Versetzen Sie sich nun in die Lage eines solchen Menschen innerhalb Ägyptens, sagen wir im 2. Jahrtausend vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha. Der mußte sich sagen: Da drüben im Orient waren einmal Menschen, die haben das Denken als ein lebendiges gehabt. - Aber dieser ägyptische Weise war noch in einer besonderen Lage. Er hatte noch nicht das Seelenleben, das wir heute haben. Stellen Sie sich nur ganz lebendig vor, wie das Seelenleben eines solchen ägyptischen Weisen war. Lebendiges Denken zu fühlen, das war schon aus der Seele entwichen, das konnte man nicht mehr, und das abstrakte Denken war noch nicht da. Man schuf Ersatz durch das Einbalsamieren der Mumien, wodurch man in der Art, wie ich es geschildert habe, zu dem Formbegriff, zu den Formvorstellungen des Menschen kam. Man bändigte sich hin zum Begreifen dieser toten Menschenform in der Mumie, und daran erlernte man zuerst das abstrakte Denken, das tote Denken.

[ 6 ] Dem steht in der neueren Zeit gegenüber, daß in einzelnen okkulten Gemeinschaften namentlich Rituale und Kultformen, zeremonielle Handlungen bewahrt worden sind, die einmal in der Art, wie ich es gestern charakterisiert habe, ganz lebendig waren in der Menschheit, die aber jetzt als tote aufbewahrt werden. Sie brauchen sich nur daran zu erinnern, was Sie vielleicht von den Ritualien, sagen wir, des Freimaurerordens gelesen haben. Da werden Sie finden, daß Zeremonien des ersten Grades, des zweiten Grades, des dritten Grades entwickelt werden. Diese Zeremonien werden in äußerlicher Weise gelernt und beschrieben oder auch verrichtet. Das war einstmals eine volle Lebendigkeit; darinnen lebten einstmals Menschen so, wie die Pflanze in ihrem Lebensprinzip lebt. Heute sind sie ein Totes geworden. Auch das Mysterium von Golgatha hat nur in einzelnen priesterlichen Naturen die innerliche Lebendigkeit hervorrufen können, die etwa verknüpft ist mit dem Kultus der Kirchen, die nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha entstanden sind. Aber die Menschheit hat bis jetzt nicht die Möglichkeit errungen, in das Kultusartige das volle Lebendige hineinzubringen. Dazu ist eben ein anderes notwendig.

[ 7 ] An das Denken, das die Menschheit gegenwärtig hat, geht eigentlich auf das Tote hin. Für das lebendige Denken, das einmal vorhanden war, ist vorläufig gar kein Verständnis vorhanden. Das intellektualistische Denken, das die Menschheit namentlich seit der Mitte des 14. Jahrhunderts betreibt, das ist ein Leichnam. Deshalb ist dieses Denken auch so sehr bestrebt, sich nur auf die tote Natur zu beschränken, das Mineralreich kennenzulernen. Und man möchte auch die Pflanzen, man möchte die Tiere, man möchte den Menschen selber nur nach den mineralisch-physikalisch-chemischen Kräften studieren, weil man nur dieses tote Denken, diesen Gedankenleichnam handhaben will, den der rein intellektualistische Mensch mit sich herumschleppt.

[ 8 ] Ich mußte in diesen Vorträgen, die ich jetzt in dieser Serie vor Ihnen halte, einmal Goethe nennen. Goethe war ja, wie Sie wissen, Mitglied der Freimaurergemeinschaft. Er hat den Kultus der Freimaurergemeinschaft erlebt, aber er hat ihn so erlebt, wie ihn eben nur Goethe erleben konnte. Aus den sonst nur traditionell bewahrten Kultusformen ging für ihn ein unmittelbares Leben hervor. Für ihn war es wirklich, daß er sich in Verbindung setzen konnte mit jener geistigen Wesenheit, die sich hereinlebt in der Art, wie ich es dargestellt habe, aus dem vorirdischen Dasein in dieses irdische Dasein; was für Goethe immer, wie ich sagte, eine Art Verjüngungskraft war, denn Goethe hat sich oftmals in seinem Leben wirklich verjüngt. Und aus diesem inneren Leben ist aus Goethe das hervorgegangen, was im Grunde genommen eine der größten, eine der bedeutendsten Erscheinungen im modernen Geistesleben ist, was aber eben bis heute nicht gewürdigt wird: das ist der Metamorphosegedanke.

[ 9 ] Was hat denn Goethe eigentlich getan, indem er den Metamorphosegedanken gefaßt hat? Das war eben das Wiederaufleuchten eines innerlich lebendigen Denkens, eines Denkens, das in den Kosmos eintreten kann. Goethe hat sich aufgelehnt gegen die Linnésche Botanik, wo man eine Pflanze neben die andere hinstellt, von jeder einzelnen Pflanze sich einen Begriff macht und der Meinung ist, man müsse das alles hübsch in ein System bringen. Goethe konnte das nicht mitmachen. Goethe wollte nicht allein diese toten Begriffe haben, er wollte ein lebendiges Denken haben. Das hat er dadurch erreicht, daß er zunächst in der Pflanze selber nachgesehen hat. Und für ihn wurde die Pflanze nun so, daß sie unten grobe, ungestaltete Blätter entwickelt, weiter dann gestaltete Blätter, die aber Umformungen, Metamorphosen des andern sind, dann die Blumenblätter mit einer andern Farbe, dann die Staubgefäße, in der Mitte den Stempel - alles Umwandlungen der einen Grundform des Blattes selber. Goethe hat nicht das Pflanzenblatt so angesehen, daß er etwa gesagt hat: Das ist ein Pflanzenblatt, und das ist ein anderes Pflanzenblatt. - So hat Goethe nicht die Dinge angesehen, die an der Pflanze wachsen, sondern er hat gesagt: Daß dieses Blatt so und jenes Blatt so aussieht, das ist eine Äußerlichkeit. Innerlich angesehen ist es so, daß das Blatt innerlich selber eine Verwandlungskraft hat, daß es äußerlich ebensogut so ausschauen kann (rechts) wie so (links). Es sind gar nicht zwei Blätter, es ist eigentlich es Blatt, in zwei verschiedenen Weisen dargestellt.

[ 10 ] Und wenn ich eine Pflanze habe (siehe Zeichnung), sagte sich Goethe: Da unten das grüne Blatt, da oben das Blumenblatt (rot) -; der intellektualistische Philister sagt: Das sind zwei, das sind eben zwei Blätter. - Was könnte denn auch für den intellektualistischen Philister selbstverständlicher sein, als daß dies zwei Blätter sind, denn es ist sogar das eine rot, das andere grün. Aber wenn der Mensch einen grünen Rock und eine rote Jacke hat, das sind allerdings zwei, denn in bezug auf die Bekleidung gilt zunächst, wenigstens in der modernen Zeit, die Philistrosität; da ist diese Philistrosität ja am Platze. Aber die Pflanze macht diese Philistrosität nicht mit, sagte sich Goethe, das rote Blatt ist dasselbe wie das grüne Blatt. Es sind gar nicht zwei Blätter, es ist eigentlich nur ein Blatt in verschiedenen Gestaltungen; das eine Mal wirkt dieselbe Kraft da unten an der Stelle A. Da wirkt sie so, daß die Kräfte hauptsächlich aus der Erde herausgezogen werden. Die Pflanze zieht die Kräfte aus der Erde heraus, saugt sie da hinauf, und das Blatt muß unter dem Einfluß der Erdenkräfte wachsen und wird grün. Und indem die Pflanze weiterwächst (violett), kommt die Sonne und bestrahlt sie immer stärker als da unten. Die Sonne überwiegt, derselbe Impuls wächst in die Sonne hinein und wird rot.

[ 11 ] Goethe hätte etwa sagen können: Wenn wir einen Menschen sehen, der einen andern furchtbar viel essen sieht und er selbst hat nichts, nun, da wird er eben blaß vor Neid. Ein andermal gibt ihm einer einen Puff und da wird er rot. Ja, nach demselben Prinzip, nach dem man das hier zwei Blätter nennt, könnte man auch sagen: Das sind zwei Menschen; das eine Mal ist er blaß, das andere Mal ist er rot, also sind es zwei Menschen. — Ebensowenig wie das zwei Menschen sind, ebensowenig sind das zwei Blätter. Es ist ein Blatt, das eine Mal ist es dieses, an einem andern Orte ist es jenes. Das ist ja auch nichts besonders Wunderbares für Goethe, denn schließlich kann der Mensch auch von einem Ort zum andern laufen, und es sind doch nicht zwei verschiedene Menschen, die Sie an verschiedenen Orten sehen! Kurz, Goethe kam darauf, daß dieses Nebeneinanderbetrachten der Dinge keine Wahrheit, sondern eine Täuschung ist, daß dies ein Blatt wäre, das grüne hier und das rote dort.

[ 12 ] Aber so wie er die verschiedenen Organe an der Pflanze sah, so sah er auch die verschiedenen Pflanzen an. Nehmen wir einmal die Sache so: Wir haben da irgendeine Pflanze. Sie hat es gut, sie kann aus dem Keim heraus eine ordentliche Wurzel bilden, einen Stengel, am Stengel ordentliche Blätter, eine ordentliche Blüte, sogar Staubgefäße und den Stempel in den Staubgefäßen drinnen (siehe Zeichnung). Goethe Do sagte: Die Staubgefäße sind auch nur dasselbe Blatt. — Er hätte sagen können: Ja, der Intellektualist behauptet, die roten Blumenblätter sind so breit, die Staubgefäße sind wie ein Faden so dünn, nur haben sie oben so eine Narbe. — Und dennoch sah Goethe im breiten Blumenblatt und im ganz schmalen Staubgefäß auch nur verschiedene Gestaltungen ein und desselben Blattes. Er hätte auch wieder bildlich sagen können: Habt ihr nicht schon einmal gesehen, daß ein Mensch einmal in seinem Leben ganz schlank war wie eine Gerte, nachher auseinandergegangen und ganz dick geworden ist? Das sind ja auch nicht zwei Menschen. — Also Blumenblätter und Staubgefäße sind eins, und wie gesagt, daß sie an verschiedenen Stellen sind, macht auch nichts aus, und das war auch für Goethe nichts Wesentliches, Der Mensch, der nicht so schnell laufen kann, kann nicht gleichzeitig an zwei Orten sein. Ein gebildeter Bankier in Berlin sagte einmal, als er von allen Seiten furchtbar ankrakeelt wurde: Glauben Sie, daß ich ein Vöglein bin, das an zwei Orten zugleich sein kann? - Ja, das kann eben der Mensch nicht, sondern hier handelt es sich darum, daß eben das Prinzip der Metamorphose, das Zeigen der Einheit in der Vielheit, der Einheit in der Mannigfaltigkeit überall von Goethe gesucht worden ist. Dadurch hat dann Goethe den Begriff der Metamorphose ins Leben gebracht.

[ 13 ] Wenn Sie das, was ich jetzt gesagt habe, erfassen, dann bekommen Sie eine Idee vom Geist. Denn denken Sie sich alles das, was ich Ihnen jetzt gesagt habe: Dieses, daß eigentlich die ganze Pflanze ein Blatt ist, in verschiedener Art gestaltet, das ist ganz gewiß nicht körperlich zu fassen. Da müssen Sie etwas geistig fassen, das sich in der verschiedensten Weise verändert. Es ist Geist, der im Pflanzenreich lebt. Und wir können weitergehen, wir können, wie gesagt, eine Pflanze nehmen, die es gut hat, die also in der richtigen Weise ihren Samen in die Erde versetzt bekommt, dann wiederum zur richtigen Zeit die schwache Frühlingssonne hat, dann die Sonne des Hochsommers, dann wiederum an der schwächer werdenden Sonne den Samen entwickeln kann. Aber nehmen wir an, die Pflanze wird in solche Naturverhältnisse versetzt, daß sie gar nicht Zeit hat, eine Wurzel zu entwickeln, auch keinen vernünftigen Stamm, keine vernünftigen Blätter, sondern daß sie alles das, was sonst eben in den Blumenblättern sich entwickelt, ganz furchtbar rasch und undeutlich entwickeln muß, weil sie gar nicht Zeit hat, das alles so schnell auszubilden. Da wird es ein Schwamm, ein Pilz.

[ 14 ] Da haben Sie zwei äußerste Extreme: eine Pflanze, die Zeit hat, sich in alle Einzelheiten hinein zu differenzieren, entwickelt Wurzeln, Stengel, Blätter, Blüten, Früchte, alles mögliche. Aber eine Pflanze, die in solche Naturverhältnisse versetzt wird, daß sie gar nicht Zeit hat, eine Wurzel zu bilden, bei der bleibt alles nur angedeutet, Stengel und Blätter kann sie auch nicht entwickeln, und das, was im Blütenprinzip ist und das Fruchtbilden, muß sie schnell und undeutlich machen. Sie setzt sich kaum auf der Erde auf, entwickelt mit furchtbarer Schnelligkeit das, was die andern Pflanzen langsam entwickeln. Denken Sie an den Klatschmohn, der, nachdem er die grünen Blätter so langsam hat vorangehen lassen, behutsam langsam die roten Mohnblätter ausbilden kann, dann die Staubgefäße, dann das kokette Pistill, das in der Mitte des Klatschmohns drinnen ist. Beim Pilz muß das rasch und überhastet gemacht werden; man hat nicht Zeit zu differenzieren, hat nicht Zeit, sich der Sonne auszusetzen, weil die auch gar nicht da ist, daß man so hübsch färben könnte, kurz, es wird ein Pilz. Im Pilz haben wir eine ganz undeutliche, rasch überhastet hingeworfene Blüte. Wiederum haben wir eins; zwei ganz verschiedene Pflanzen sind eigentlich ein und dasselbe.

[ 15 ] Aber man muß innerlich ein wenig anders werden, wenn man das alles wirklich denken will. Denn der Intellektualist - Goethe würde vielleicht gesagt haben: der steife Philister —, der schaut sich den saftig roten Klatschmohn an, mit dem bauchigen, wohlausgebildeten Pistill in der Mitte, und jetzt soll er sich einen Pilz anschauen. Gleichzeitig soll er sich den Begriff, den er sich von diesem Klatschmohn gebildet hat, so beweglich erhalten, daß er undeutlich werden kann und daß er im Klatschmohn selber schon der Anlage nach den Eierschwamm oder den Kaiserling oder so irgend etwas sieht; das geht nicht, nicht wahr? Damit sich sein Intellekt nicht zu bewegen braucht, so daß er eigentlich nicht den Verstand lebendig zu machen braucht, sondern höchstens den Kopf ein bißchen hinüberzulatschen hat, muß man ihm extra den Eierschwamm oder den Kaiserling vorführen. Dann kann er sie nebeneinander vorstellen - sehen Sie, dann gelingt es ihm!

[ 16 ] Das ist eben der Unterschied zwischen dem toten Denken und dem innerlich belebten, lebendigen Denken, das Goethe für die Metamorphose geformt hat. Es war schon eine innerliche Entdeckung von großartigster Art, die da durch Goethe in die Welt gekommen ist. Daher habe ich im allerersten Band von «Goethes naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften», den ich im Anfange der achtziger Jahre des vorigen Jahrhunderts erscheinen ließ, in der Einleitung den Satz niedergeschrieben: Goethe ist zu gleicher Zeit der Kopernikus und Kepler der organischen Naturwissenschaft, und was Kopernikus und Kepler für die äußere tote Natur getan haben, den Begriff gereinigt, um im gereinigten Begriff das Astronomische und Physikalische zu fassen, das hat Goethe durch den lebendigen Begriff, den Begriff der Metamorphose, für die organische Naturwissenschaft geleistet. Und das ist seine zentrale Entdeckung.

[ 17 ] Und wenn man will, so dehnt sich eben dieser Begriff der Metamorphose dann über die ganze Natur aus. Goethe hat sich natürlich sofort gedacht, als er die Pflanzenformen aus diesem Metamorphosegedanken heraus bekommen konnte: Das muß sich auch auf das Tier anwenden lassen. — Aber da geht es eben schwerer. Ein Blatt aus dem andern in Gedanken hervorgehen zu lassen, das hat Goethe ganz gut zustande gebracht. Aber wie man, sagen wir, einen Ringknochen aus dem Rückgrat sich der Gestalt nach metamorphosiert denken soll, daß ein Kopfknochen daraus wird, so daß man auch für das Tier und den Menschen die Metamorphose anwenden kann, das ging eben doch schwerer. Und dennoch ist es Goethe gelungen, wie ich Ihnen schon öfter erzählt habe, als er auf dem Lido bei Venedig, 1790, das Glück hatte, einen besonders günstig auseinandergefallenen Schafschädel vor sich liegen zu sehen. Es war ein Schafschädel, in die einzelnen Knochen auseinandergefallen. Da ging ihm auf: Die schauen doch aus, wenn sie auch sehr verwandelt sind, wie die Ringknochen des Rückgrats. — Und da bildete er sich diesen Gedanken, daß wenigstens die Knochen auch so vorgestellt werden können, daß sie alle eigentlich einen Knochenimpuls darstellen, der nur in verschiedenen Formen auftritt.

[ 18 ] Aber in bezug auf den ganzen Menschen ist eben Goethe doch nicht sehr weit damit gekommen, weil es ihm nicht gelungen ist, von seiner Metamorphoseidee zur wirklichen Imagination zu gelangen. Kommt man aber zur wirklichen Imagination und von da aus zur Inspiration, Intuition, dann ergibt sich einem die Einheit noch viel bedeutsamer. Und ich habe auch schon hinweisen können, wie sich diese Einheit am Menschen ergibt, wenn man den Metamorphosegedanken richtig faßt. Da muß man von demselben Gesichtspunkte, von dem aus Goethe in der Blüte der Dikotyledonenpflanzen, indem er sie immer einfacher und einfacher, verworrener und verworrener dachte, den Pilz sah, den Menschenkopf studieren, wie er heute uns entgegentritt; dann kann man ihn als eine Metamorphose des übrigen Skeletts denken.

[ 19 ] Versuchen Sie einmal so, mit einem künstlerischen Blick, einen halben Unterkiefer am Menschenskelett anzuschauen. Wenn Sie es mit künstlerischem Blick anschauen, werden Sie kaum anders können, als das, was Sie da unten haben, was hier ansitzt und dann so hinuntergeht, mit den Arm- und mit den Beinknochen zu vergleichen. Wenn Sie sich die Beinknochen und die Armknochen verwandelt denken, dann haben Sie hier auch zwei Beine — Unterkiefer -, nur sind diese verkümmert. Der Kopf ist ein fauler Kerl, der nicht geht, der immer sitzt. Daher sitzt er auch auf seinen zwei Beinen, die in der Dekadenz sind, die verkümmert sind. Aber wenn Sie sich denken, daß zum Beispiel der Mensch die Beine so mit einem Bindfaden zusammengebunden bekäme, so kann man schon fast nachahmen, was hier ist. Und wenn Sie mit künstlerischem Blick das ansehen, so könnte man sich schon denken, wie man die Beine dahin kriegen könnte, daß sie auch so wie die untere Kinnlade unbeweglich wären.

[ 20 ] Aber wie sich die Sache verhält, darauf kommt man erst, wenn man wirklich das Menschenhaupt als einen umgebildeten andern Menschenleib ansieht. Ich habe Ihnen dargestellt: dieses Menschenhaupt, das wir in dem gegenwärtigen menschlichen Erdenleben tragen, ist der umgestaltete Leib ohne Kopf, wie wir ihn im vorigen Erdenleben an uns getragen haben. Der Kopf von dazumal ist uns verlorengegangen manchen Menschen vermutlich schon während des Erdenlebens -, aber jedenfalls nach dem Erdenleben sind auch die Kräfte des Kopfes verlorengegangen. Der Kopf erhält sich nicht. Ich meine jetzt die Kräfte, natürlich nicht die Materie, sondern die Kräfte, aber diese Kräfte, die Sie jetzt in Ihrem Haupte tragen, die haben Sie früher, wenn Sie sich geköpft denken, an Ihrem übrigen Leib getragen. In einem vorigen Erdenleben haben Sie wiederum den Kopf aus dem vorvorigen Erdenleben getragen. Und das, was Sie jetzt als Leib haben, das wird wirklich metamorphosiert, umgestaltet, und Sie werden es als Ihren Kopf im nächsten Erdenleben tragen. Daher ist es auch zuerst da. Sehen Sie sich den menschlichen Embryo im menschlichen Mutterleibe an: der Kopf kommt zuerst, das übrige setzt sich an, weil es Neubildung ist; der Kopf aber stammt aus dem vorigen Erdenleben, der ist der umgestaltete Körper, ist Form, ist durch das ganze Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt herübergetragen, bildet sich als Kopf und setzt sich die andern Glieder an. Und so können wir sagen: Wir sehen, indem wir die wiederholten Erdenleben dazunehmen, in dem Menschen nun die letztlich ausgebildete Metamorphose. In dem, worauf Goethe gekommen ist im Anfang der achtziger Jahre des 13. Jahrhunderts, in dem Pflanzenmetamorphose-Gedanken, da ruht das, was einen nun zum lebendigen Begriff vom Werden führt, durch das ganze Tierreich hinauf bis zum Menschen, und zwar so, daß es auch noch die Idee hergibt, durch die wir die wiederholten Erdenleben in ihrer Form begreifen. Goethe ist das Denken innerlich dadurch so belebt worden, daß er das Zeremoniell seines Kultus mitgemacht hat. Da hat er, wenn ihm das auch nicht klar zum Bewußtsein gekommen ist, doch eine Ahnung davon bekommen, wie der noch ganz seelische Mensch im vorirdischen Dasein das herüberträgt, was vom Körperskelett an Kräften aus dem früheren Erdenleben geblieben ist; wie das von dem Menschen in dieses Erdenleben hereingetragen und zur Kopfform ausgestaltet worden ist unter der schützenden Hülle des mütterlichen Leibes.

[ 21 ] Goethe hat das nicht gewußt, aber er hat eine Ahnung bekommen und hat das zunächst auf das Einfachste, das Pflanzenleben, angewandt. Er konnte das, weil seine Zeit dazu noch nicht reif war, eben nicht so weit ausdehnen, wie es heute ausgedehnt werden kann, nämlich bis zum Begreifen der Menschenverwandlung von einem Erdenleben bis zum andern. Gewöhnlich wird es mit einem Gefühl von Mitleid gesagt, daß Goethe diese Metamorphose ausgebildet hat, weil ihm da seine Künstlernatur in die Quere gekommen sei. Das sagen die Pedanten, die Philister, aus Mitleid heraus. Wer kein Pedant und Philister ist, der muß mit Begeisterung sagen: Goethe konnte eben zur Wissenschaft das Künstlerische hinzufügen und konnte gerade dadurch zu beweglichen Begriffen kommen. — Aber so kann man doch nicht, sagt jetzt der philiströse Dialektiker, die Natur begreifen. Da muß man steif logische, streng logische Begriffe, wie er sagt, haben. — Aber wenn die Natur eine Künstlerin wäre, dann könnte der ganzen Naturwissenschaft, die die Kunst ausschließt und nur auf äußere Begriffe geht, passieren, was mir einmal ein Münchner Künstler, der noch ein Zeitgenosse des großen Ästhetikers Carrière war und mit dem wir über Carriere ins Gespräch kamen, erzählt hat. Er sagte: Wir Künstler dazumal in unserer Jugend, wir gingen nicht in die Vorlesungen des Carriere. Sind wir einmal hereingegangen, dann gingen wir wieder heraus und sagten: Das ist der ästhetische Wonnegrunzer! - So, wie es dem Ästhetiker passierte, daß der Künstler ihn einen Wonnegrunzer nennt, so könnte die Natur, wenn sie selber über ihre Geheimnisse sprechen würde, den bloß logischen Naturforscher vielleicht nicht einmal einen Wonne-, sondern einen Jammergrunzer nennen, denn die Natur schafft eben künstlerisch. Und man kann der Natur nicht befehlen, sie dürfe sich bloß logisch begreifen lassen, sondern man muß die Natur so begreifen, wie sie ist.

[ 22 ] So ist einmal die historische Entwickelung. Einstmals im alten Orient waren lebendige Begriffe. Ich habe Ihnen geschildert, wie zunächst durch die Umgestaltung, die Metamorphose des Atmungsprozesses diese lebendigen Begriffe zu einem Wahrnehmungsprozeß geworden waren. Die Menschen mußten sich zu den toten Begriffen hindurcharbeiten. Die Ägypter konnten es noch nicht. Sie bändigten sich heran zu den toten Begriffen, indem sie zunächst den Menschen selbst in seiner Torheit in der Mumie entwickelten. Jetzt aber sind wir in der Lage, daß wir den Begriff neu erwecken müssen. Und das kann nicht geschehen dadurch, daß wir nur alte okkulte Formen traditionell pflegen, sondern indem wir uns wirklich hineinleben, immer weiter und weiter nicht nur uns hineinfinden, sondern es ausbilden, was als erster Goethe als den Metamorphosegedanken gefaßt hat: den lebendigen Begriff. Wer den lebendigen Begriff, das heißt, die seelische Handhabe des Geistigen beherrscht, der ist auch imstande, aus dem Geiste heraus wiederum die äußere Handlung des Menschen zu beleben. Dann kommt es dahin, daß wirklich einmal erreicht werden kann, wovon ich öfter vor unseren anthroposophischen Freunden gesprochen habe, daß man sich nicht in einer solchen gleichgültigen materialistischen Weise an den Laboratoriumstisch oder an den Seziertisch stellt und da herumfuhrwerkt, sondern daß man empfindet, was man der Natur als ihre Geheimnisse ablauscht, als Taten des Geistes, der durch die Natur durchströmend sich betätigt: daß der Laboratoriumstisch zum Altar wird. Ehe nicht Verehrung, religiöses Empfinden in unsere Wissenschaft hineinkommt, solange eine abgesonderte Religion neben der Wissenschaft sich auftut und bloß dem menschlichen Egoismus dient, ehe nicht die Wissenschaft selber wiederum, was sie erforscht, verehren lernt — so wie die alten Mysterienschüler verehren gelernt haben, wie ich das in meinem Buche «Das Christentum als mystische Tatsache» nachgewiesen habe -, eher kommen wir nicht wieder zu aufsteigenden Kräften in der Menschheit. Wir müssen wiederum alles Forschen als einen Verkehr mit der geistigen Welt begreifen lernen. Dann werden wir der Natur dasjenige ablauschen, was die Menschheit wirklich in ihrer Entwickelung weiterbringt. Und dann werden wir den Mumifizierungsprozeß, den die Menschheit einmal durchmachen mußte, im umgekehrten Sinne durchmachen. So wie der Ägypter den Leichnam des Menschen genommen hat, um ihn einzubalsamieren, so daß jetzt noch in einer, ich möchte sagen, fast schauererregenden Weise ganze Kolonien von Mumien geschaut werden können in den Museen, wohin sie die Europäer verschleppt haben, so wie da einstmals das Denken der Menschen in der Mumie erstarrt ist, so muß es in der Zukunft wieder erweckt werden. Der alte Ägypter nahm den menschlichen Leichnam, balsamierte ihn ein, konservierte den Tod. Wir müssen fühlen, daß wir den Seelentod in uns tragen, wenn wir die bloß abstrakten, intellektualistischen Gedanken haben. Wir müssen fühlen: Das ist die Seelenmumie. Wir müssen verstehen lernen, was noch als eine Ahnung in Paracelsus lebte, als er, wenn er eine gewisse Substanz aus dem menschlichen Organismus nahm, dies die «Mumie» nannte. Er sah in einem kleinen substantiellen Rest des Menschen die Mumie. Er brauchte nicht den einbalsamierten Leichnam, um die Mumie zu sehen, denn für ihn war die Mumie die Summe der Kräfte, die den Menschen in jedem Augenblick zum Tode bringen konnten, wenn er sich nicht in der Nacht wiederum belebte.

[ 23 ] In uns waltet das tote Denken. Das Denken stellt den Seelentod dar. Wir tragen in unserem Denken die seelische Mumie in uns. Sie bildet gerade das, was man in der gegenwärtigen Kultur am meisten schätzt. Man kann, wenn man will, in den Museen, wo eine Mumie nach der andern ausgestellt ist, wenn man mit einem etwas universelleren Blick ausgestattet ist, mit dem Goetheschen Blick zum Beispiel, Metamorphosen sehen. Man kann da durch die Säle gehen und dann auf die Straße treten mit dem Gefühl: Da ist in der heutigen Zeit des Intellektualismus gar kein Unterschied, denn daß die Mumien nicht gehen und daß draußen auf der Straße die Menschen gehen, das ist ja nur ein Zufall, ist nur eine Äußerlichkeit. Die Menschen, die heute, im intellektuellen Zeitalter, draußen auf der Straße gehen, sind seelisch Mumien, Seelenmumien, weil sie ganz von toten, intellektualistischen Gedanken ausgefüllt sind, von Gedanken, die nicht leben können. Wie ein ursprüngliches Leben in den ägyptischen Mumien erstarrt ist, so ist das Seelenleben erstarrt, und es muß für die Zukunft der Menschheit wiederum lebendig gemacht werden. Wir dürfen es nicht so weitertreiben, wie wir es mit der Anatomie und Physiologie getrieben haben. Das war den Ägyptern gestattet mit den physischen Menschenleichnamen. Aber den abstrakten Seelenleichnam, den wir im intellektualistischen Denken in uns tragen, dürfen wir nicht weiter mumifizieren. Es ist heute überhaupt die Lust vorhanden, das Denken einzubalsamieren, damit es nur recht pedantisch logisch wird und nicht irgendwie ein Fünkchen von enthusiastischem Leben in dieses Denken hineinkommt.

[ 24 ] Wenn die Mumien photographiert werden, so sind es eben auch steife Bilder. Man kann so ein Mumienbild von der Mumie selbst in der Steifheit nicht gut unterscheiden. Wenn man aber heute ein Literaturwerk aus diesem oder jenem Fache in die Hand nimmt, so ist das eine Photographie der mumifizierten Seele. Da hat man ein Abbild der Seelenmumie, da ist die Seele einbalsamiert. Vielleicht könnte man noch ein bißchen im Zweifel sein, weil die Menschen außer ihrem Verstande, der eben mumifiziert ist, auch noch etwas anderes an sich haben. Deshalb laufen sie eben herum: sie haben so allerlei fleischliche und andere Antriebe. Es kommt dieses Bild von der Mumie nicht ganz deutlich heraus, aber bei den Büchern kommt es heute schon sehr deutlich heraus, da merken wir schon die Einbalsamierung sehr stark. Aber wir müssen weg von diesem Balsamieren, wir brauchen statt dieses Balsamierens der Ägypter, das sie für die Mumien verwendet haben, ein anderes Ingredienz, wir brauchen ein Lebenselixier. Nicht in der Weise, wie es sich heute vielleicht mancher denkt, um den physischen Körper zu vervollkommnen, sondern etwas, was die Gedanken lebendig macht, das sie entmumifiziert. Und wenn wir das verstehen, haben wir einen tiefen, einen bedeutenden historischen Impuls vor die Seele hingestellt. So wie die Menschheit ihre Geistkultur im Mumifizieren erstarren ließ, als sie die Mumien einbalsamierte, so müssen wir wiederum dasjenige, was nun einmal mumifiziert bei dem geistigen Menschen zur Welt kommt, im Laufe seiner Erziehung, seiner Entwickelung, mit geistig-seelischem Lebenselixier durchdringen, damit es weiter in die Zukunft hineindringen kann. Es sind zwei Kräfte: das Einbalsamieren der Ägypter und das Entbalsamieren, das die neuere Menschheit lernen muß.

[ 25 ] Die neuere Menschheit hat sehr nötig, das Entbalsamieren der versteiften, der toten Seelenkräfte zu lernen. Es liegt darin eigentlich eine ganz besonders wichtige Aufgabe. Denn sonst kommen solche Erscheinungen heraus wie die, von der ich Ihnen auch schon vor einiger Zeit hier gesprochen habe. Da merkt jemand wie Spengler, daß es mit diesen einbalsamierten Begriffen nicht geht, daß die einbalsamierten Begriffe eben zum Tode der Kultur führen. Ich habe in einem Artikel des «Goetheanums» gezeigt, was beim Spengler passiert. Er hat zwar gemerkt, wie die Begriffe alle tot sind, aber seine Begriffe leben auch nicht. Ihm ist es gegangen wie jener Frau aus dem Alten Testament, die sich umgeschaut hat. Der Spengler hat sich umgeschaut nach alldem, was an toten, mumienhaften Begriffen vorhanden ist, und so ist er zur Salzsäule geworden. Diese lebt ebensowenig. Es ist Spengler gegangen wie jener Frau des Lot. Er ist zur Salzsäule erstarrt, denn seine Begriffe leben ebensowenig wie die anderer.

[ 26 ] Es ist ein alter okkulter Satz, daß im Salz Weisheit lebt, aber nur, wenn es im menschlichen Merkur und im menschlichen Phosphor aufgelöst ist. Die Weisheit, die im Salze erstarrt, die hat Spengler, aber es fehlt sowohl der Merkur, der dieses Salz in Bewegung bringt und es dadurch universell, kosmisch macht, und noch mehr fehlt der Phosphor. Denn anzünden - ich meine seelisch durch Begeisterung anzünden -, das kann man nicht mit Spenglers Begriffen, wenn man ihn mit Gefühl, namentlich mit künstlerischem Gefühl liest. Sie bleiben alle salzig-steif und schmecken sauer, und man muß erst hinterher sich ordentlich durchmerkurialisieren und durchphosphorisieren, wenn man diesen Salzklotz, der sich «Untergang des Abendlandes» nennt, verdauen will. Wir müssen aus dem Salze, aus der Erstarrung heraus. Wir müssen Lebenselixier auch gerade in bezug auf die Seelenmumie, die abstrakten Begriffssysteme anwenden. Das ist es, was uns nötig ist.

Seventh Lecture

[ 1 ] We have seen how the fundamental impulses of humanity's historical development are expressed in phenomena such as the remarkable inclination of Egyptian culture toward the mummification of the human form and, in more recent times, toward the preservation of ancient cult forms, which in a certain sense also represent a kind of mummification, but a mummification of cultural events. If we return once more to a few thoughts on Egyptian culture as it is revealed outwardly in the mummy, we must connect what we have gained there as an insight with a description that I gave during the course recently held over there at the Goetheanum, but which I have also given here on several occasions. I am referring to the description of ordinary human thinking activity as practiced by human beings in such a way that they gradually develop it within themselves during childhood, acquire a certain ability, and then carry it out between adolescence and death. We have come to know this thinking activity, this intellectualistic activity, as I have often called it, as a kind of inner soul corpse.

[ 2 ] We have repeatedly brought to mind that thinking, as it is carried out by human beings in earthly life, can only be viewed correctly if one understands how to relate it to its true nature in the same way as the corpse that human beings leave behind when they pass through the gate of death relates to the living human being on earth. That which makes a human being human actually departs from the human being, and something remains in the corpse that can only have this form, which confronts us when it is left behind by a living human being. No one could be so simple-minded as to believe that the human corpse could arise in its form through some coming together of forces. It must be a remnant; something must have preceded it; the living human being must have preceded it. The external nature that we study has the power to destroy the form of the human corpse, but it does not have the power to form it. This human form is formed by what is peculiar to the human being in its higher members. But these are gone with death. Just as we see in a corpse that it comes from a living human being, so we see in thinking, when we look at it in the right way, that it cannot be by itself as it appears to us in earthly life, but that it is a kind of corpse in the soul, namely the corpse of what it was before the human being descended from the spiritual-soul worlds into physical earthly existence. There, in pre-earthly existence, the soul was something that died, so to speak, with birth; and the corpse of this soul that has died is thinking.

[ 3 ] How could it be otherwise, since it was precisely those people who knew best how to live with thinking who felt this folly, this death of abstract thinking! I need only refer you to the moving passage with which Nietzsche begins his description of philosophy in the tragic age of the Greeks, where he describes how the Greek world of thought, in the pre-Socratic philosophers such as Parmenides and Heraclitus, ascends to the abstract ideas of being and becoming. There, says Nietzsche, one feels an icy coldness coming over one. And so it is. Just compare this with how the people of the ancient Orient tried to comprehend this external nature in lively, inwardly active, though more dreamlike soul formations. In contrast to this internally active thinking, which blossoms before us in Vedanta philosophy and in the Vedas, in contrast to this stirring thinking, this thinking that sprouts and shoots up everywhere and interweaves the whole human being with inner life, what appears in later times as abstract thought is in fact a dead corpse. Nietzsche felt this when he felt compelled to describe the pre-Socratic philosophers, who were actually the first in human development to ascend to such abstract thoughts.

[ 4 ] But look at these Eastern sages who preceded the Greek philosophers. You will find nothing there to doubt that man had a spiritual existence before he descended to earth. One cannot experience thinking as something alive and at the same time believe in the pre-earthly existence of man. Anyone who experiences thinking as something alive is just like someone on earth who recognizes living human beings. Those who no longer experience thinking as something living, as the Greek philosophers did even before Socrates, may believe that human beings are beings that are only born at birth, as Aristotle did. So we must distinguish between the once Oriental, inwardly active and living thinking, through which one knew that one had just entered earthly existence from spiritual worlds, and the thinking that then appeared as dead thinking, corpse thinking, through which one learns nothing other than what is accessible between birth and death.

[ 5 ] Now put yourself in the position of such a person in Egypt, say in the 2nd millennium before the Mystery of Golgotha. He had to say to himself: Over there in the Orient there were once people who had thinking as something living. But this Egyptian sage was still in a special situation. He did not yet have the soul life that we have today. Just imagine vividly what the soul life of such an Egyptian sage was like. Feeling living thinking had already escaped from the soul; it was no longer possible, and abstract thinking did not yet exist. A substitute was created by embalming mummies, which led, in the way I have described, to the concept of form, to ideas about the form of human beings. People forced themselves to understand this dead human form in the mummy, and in doing so they first learned abstract thinking, dead thinking.

[ 6 ] In more recent times, this has been countered by the preservation of rituals and cult forms, ceremonial acts, in individual occult communities, which were once very much alive in humanity in the way I characterized yesterday, but which are now preserved as dead. You need only remember what you may have read about the rituals of, say, the Masonic Order. There you will find that ceremonies of the first degree, the second degree, and the third degree are developed. These ceremonies are learned and described in an external manner, or even performed. These were once full of life; people once lived in them as plants live in their life principle. Today they have become dead. Even the mystery of Golgotha has only been able to evoke inner vitality in individual priestly natures, which is connected, for example, with the cult of the churches that arose after the mystery of Golgotha. But humanity has not yet gained the ability to bring full vitality into the cultic. For that, something else is necessary.

[ 7 ] The thinking that humanity currently possesses actually tends toward the dead. For the time being, there is no understanding at all of the living thinking that once existed. The intellectualistic thinking that humanity has been pursuing, especially since the middle of the 14th century, is a corpse. That is why this thinking is so eager to limit itself to dead nature, to get to know the mineral kingdom. And one would also like to study plants, animals, and human beings themselves only in terms of mineral, physical, and chemical forces, because one wants to deal only with this dead thinking, this corpse of thought that the purely intellectual person carries around with him.

[ 8 ] In the lectures I am now giving to you in this series, I had to mention Goethe once. Goethe was, as you know, a member of the Masonic community. He experienced the cult of the Masonic community, but he experienced it in a way that only Goethe could. For him, the cult forms, which were otherwise only preserved in tradition, gave rise to an immediate life. For him, it was real that he could connect with that spiritual being that lives its way, as I have described, from pre-earthly existence into this earthly existence; which, as I said, was always a kind of rejuvenating force for Goethe, for Goethe really did rejuvenate himself many times in his life. And out of this inner life emerged what is essentially one of the greatest, one of the most significant phenomena in modern intellectual life, but one that has not been appreciated to this day: the idea of metamorphosis.

[ 9 ] What did Goethe actually do when he conceived the idea of metamorphosis? It was the reawakening of an inner living thought, a thought that can enter the cosmos. Goethe rebelled against Linnaeus' botany, where one plant is placed next to another, a concept is formed of each individual plant, and it is believed that everything must be neatly organized into a system. Goethe could not go along with that. Goethe did not want to have only these dead concepts; he wanted to have a living way of thinking. He achieved this by first looking at the plant itself. And for him, the plant now developed coarse, unformed leaves at the bottom, then more formed leaves, which were, however, transformations, metamorphoses of the others, then the flower petals with a different color, then the stamens, and in the middle the pistil—all transformations of the one basic form of the leaf itself. Goethe did not look at the plant leaf and say, for example, “That is a plant leaf, and that is another plant leaf.” Goethe did not look at the things that grow on the plant in this way, but rather he said, “The fact that this leaf looks like this and that leaf looks like that is an external feature.” Viewed internally, it is such that the leaf itself has an internal power of transformation, so that it can just as easily look like this (right) as it can look like that (left). There are not two leaves at all; it is actually one leaf, represented in two different ways.

[ 10 ] And when I have a plant (see drawing), Goethe said to himself: Down there is the green leaf, up there is the flower petal (red) – the intellectual philistine says: There are two, there are two leaves. What could be more obvious to the intellectual philistine than that these are two leaves, since one is red and the other green? But if a person has a green skirt and a red jacket, these are indeed two, because when it comes to clothing, at least in modern times, philistine thinking prevails; there, philistine thinking is appropriate. But the plant does not participate in this philistinism, Goethe said to himself, the red leaf is the same as the green leaf. There are not two leaves at all, there is actually only one leaf in different forms; in one case, the same force acts down there at point A. There it acts in such a way that the forces are mainly drawn out of the earth. The plant draws the forces out of the earth, sucks them up, and the leaf has to grow under the influence of the earth's forces and turns green. And as the plant continues to grow (violet), the sun comes and shines on it more and more strongly than down below. The sun prevails, the same impulse grows into the sun and turns red.

[ 11 ] Goethe could have said, for example: When we see a person who sees another person eating a terrible amount and he himself has nothing, well, he turns pale with envy. Another time, someone gives him a slap and he turns red. Yes, according to the same principle by which we call these two things leaves, we could also say: These are two people; one time he is pale, the other time he is red, so they are two people. — Just as these are not two people, they are not two leaves. It is one leaf, one time it is this, in another place it is that. This is nothing particularly wonderful for Goethe, because after all, a person can also run from one place to another, and yet you do not see two different people in different places! In short, Goethe came to the conclusion that this side-by-side observation of things is not truth, but an illusion, that this is one leaf, the green one here and the red one there.