Second Scientific Lecture-Course:

Warmth Course

GA 321

1 March 1920, Stuttgart

Lecture I

My dear friends,

[ 1 ] The present course of lectures will constitute a kind of continuation of the one given when I was last here. I will begin with those chapters of physics which are of especial importance for laying a satisfactory foundation for a scientific world view, namely the observations of heat relations in the world. Today I will try to lay out for you a kind of introduction to show the extent to which we can create a body of meaningful views of a physical sort within a general world view. This will show further how a foundation may be secured for a pedagogical impulse applicable to the teaching of science. Today we will therefore go as far as we can towards outlining a general introduction.

[ 2 ] The theory of heat, so-called, has taken a form during the 19th century which has given a great deal of support to a materialistic view of the world. It has done so because in heat relationships it is very easy to turn one's glance away from the real nature of heat, from its being, and to direct it to the mechanical phenomena arising from heat.

[ 3 ] Heat is first known through sensations of cold, warmth, lukewarm, etc. But man soon learns that there appears to be something vague about these sensations, something subjective. A simple experiment which can be made by anyone shows this fact.

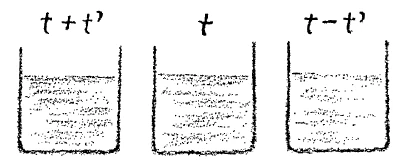

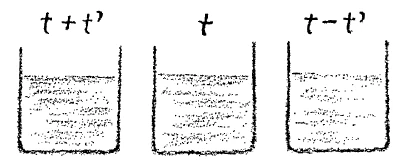

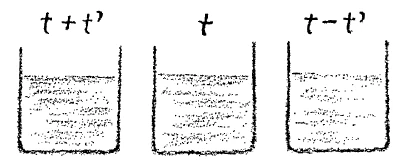

[ 4 ] Imagine you have a vessel filled with water of a definite temperature, \(t\); on the right of it you have another vessel filled with water of a temperature \(t-t_1\), that is of a temperature distinctly lower than the temperature in the first vessel. In addition, you have a vessel filled with water at a temperature \(t+t_1\). When now, you hold your fingers in the two outer vessels you will note by your sensations the heat conditions in these vessels. You can then plunge your fingers which have been in the outer vessels into the central vessel and you will see that to the finger which has been in the cold water the water in the central vessel will feel warm, while to the finger which has been in the warm water, the water in the central vessel will feel cold. The same temperature therefore is experienced differently according to the temperature to which one has previously been exposed. Everyone knows that when he goes into a cellar, it may feel different in winter from the way it feels in summer. Even though the thermometer stands at the same point circumstances may be such that the cellar feels warm in the winter and cool in the summer. Indeed, the subjective experience of heat is not uniform and it is necessary to set an objective standard by which to measure the heat condition of any object or location. Now, I need not here go into the elementary phenomena or take up the elementary instruments for measuring heat. It must be assumed that you are acquainted with them. I will simply say that when the temperature condition is measured with a thermometer, there is a feeling that since we measure the degree above or below zero, we are getting an objective temperature measurement. In our thinking we consider that there is a fundamental difference between this objective determination in which we have no part and the subjective determination, where our own organization enters into the experience.

[ 5 ] For all that the 19th century has striven to attain it may be said that this view on the matter was, from a certain point of view, fruitful and justified by its results. Now, however, we are in a time when people must pay attention to certain other things if they are to advance their way of thinking and their way of life. From science itself must come certain questions simply overlooked in such conclusions as those I have given. One question is this: Is there a difference, a real objective difference, between the determination of temperature by my organism and by a thermometer, or do I deceive myself for the sake of getting useful practical results when I bring such a difference into my ideas and concepts? This whole course will be designed to show why today such questions must be asked. From the principal questions it will be my object to proceed to those important considerations which have been overlooked owing to exclusive attention to the practical life. How they have been lost for us on account of the attention to technology you will see. I would like to impress you with the fact that we have completely lost our feeling for the real being of heat under the influence of certain ideas to be described presently. And, along with this loss, has gone the possibility of bringing this being of heat into relation with the human organism itself, a relation which must be all means be established in certain aspects of our life. To indicate to you in a merely preliminary way the bearing of these things on the human organism, I may call your attention to the fact that in many cases we are obliged today to measure the temperature of this organism, as for instance, when it is in a feverish condition. This will show you that the relation of the unknown being of heat to the human organism has considerable importance. Those extreme conditions as met with in chemical and technical processes will be dealt with subsequently. A proper attitude toward the relation of the unknown being of heat to the human organism has considerable importance. Those extreme conditions as met with in chemical and technical processes will be dealt with subsequently. A proper attitude toward the relation of the heat-being to the human organism cannot, however, be attained on the basis of a mechanical view of heat. The reason is, that in so doing, one neglects the fact that the various organs are quite different in their sensitiveness to this heat-being, that the heart, the liver, the lungs differ greatly in their capacity to react to the being of heat. Through the purely physical view of heat no foundation is laid for the real study of certain symptoms of disease, since the varying capacity to react to heat of the several organs of the body escapes attention. Today we are in no position to apply to the organic world the physical views built up in the course of the 19th century on the nature of heat. This is obvious to anyone who has an eye to see the harm done by modern physical research, so-called, in dealing with what might be designated the higher branches of knowledge of the living being. Certain questions must be asked, questions that call above everything for clear, lucid ideas. In the so-called “exact science,” nothing has done more harm than the introduction of confused ideas.

[ 6 ] What then does it really mean when I say, if I put my fingers in the right and left hand vessels and then into a vessel with a liquid of an intermediate temperature, I get different sensations? Is there really something in the conceptual realm that is different from the so-called objective determination with the thermometer? Consider now, suppose you put thermometers in these two vessels in place of your fingers. You will then get different readings depending on whether you observe the thermometer in the one vessel or the other. If then you place the two thermometers instead of your fingers into the middle vessel, the mercury will act differently on the two. In the one it will rise; in the other it will fall. You see the thermometer does not behave differently from your sensations. For the setting up of a view of the phenomenon, there is no distinction between the two thermometers and the sensation from your finger. In both cases exactly the same thing occurs, namely a difference is shown from the immediately preceding conditions. And the thing our sensation depends on is that we do not within ourselves have any zero or reference point. If we had such a reference point then we would establish not merely the immediate sensation but would have apparatus to relate the temperature subjectively perceived, to such a reference point. We would then attach to the phenomenon just as we do with the thermometers something which really is not inherent in it, namely the variation from the reference point. You see, for the construction of our concept of the process there is no difference.

[ 7 ] It is such questions as these that must be raised today if we are to clarify our ideas, or all the present ideas on these things are really confused. Do not imagine for a moment that this is of no consequence. Our whole life process is bound up with this fact that we have in us no temperature reference point. If we could establish such a reference point within ourselves, it would necessitate an entirely different state of consciousness, a different soul life. It is precisely because the reference point is hidden for us that we lead the kind of life we do.

[ 8 ] You see, many things in life, in human life and in the animal organism, too, depend on the fact that we do not perceive certain processes. Think what you would have to do if you were obliged to experience subjectively everything that goes on in your organism. Suppose you had to be aware of all the details of the digestive process. A great deal pertaining to our condition of life rests on this fact that we do not bring into our consciousness certain things that take place in our organism. Among these things is that we do not carry within us a temperature reference point—we are not thermometers. A subjective-objective distinction such as is usually made is not therefore adequate for a comprehensive grasp of the physical.

[ 9 ] It is this which has been the uncertain point in human thinking since the time of ancient Greeks. It had to be so, but it cannot remain so in the future. For the old Grecian philosophers, Zeno in particular, had already orientated human thinking about certain processes in a manner strikingly opposed to outer reality. I must call your attention to these things even at the risk of seeming pedantic. Let me recall to you the problem of Achilles and the tortoise, a problem I have often spoken about.

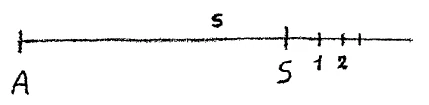

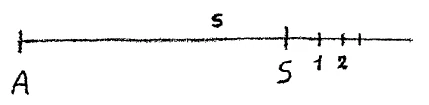

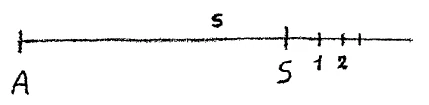

Let us assume we have the distance traveled by Achilles in a certain time \(a\). This represents the rate at which he can travel. And here we have the tortoise \(s\), who has a start on Achilles. Let us take the moment when Achilles gets to the point marked \(1\). The tortoise is ahead of him. Since the problem stated that Achilles has to cover every point covered by the tortoise, the tortoise will always be a little ahead and Achilles can never catch up. [ 10 ] But, the way people would consider it is this. You would say, yes, I understand the problem all right, but Achilles would soon catch the tortoise. The whole thing is absurd. But if we reason that Achilles must cover the same path as the tortoise and the tortoise is ahead, he will never catch the tortoise. Although people would say this is absurd, nevertheless the conclusion is absolutely necessary and nothing can be urged against it. It is not foolish to come to this conclusion but on the other hand, it is remarkably clever considering only the logic of the matter. It is a necessary conclusion and cannot be avoided. Now what does all this depend on? It depends on this: that as long as you think, you cannot think otherwise than the premise requires. As a matter of fact, you do not depend on thinking strictly, but instead you look at the reality and you realize that it is obvious that Achilles will soon catch the tortoise. And in doing this you uproot thinking by means of reality and abandon the pure thought process. There is no point in admitting the premises and then saying, “Anyone who thinks this way is stupid.” Through thinking alone we can get nothing out of the proposition but that Achilles will never catch the tortoise. And why not? Because when we apply our thinking absolutely to reality, then our conclusions are not in accord with the facts. They cannot be. When we turn our rationalistic thought on reality it does not help us at all that we establish so-called truths which turn out not to be true. For we must conclude if Achilles follows the tortoise that he passes through each point that the tortoise passes through. Ideally this is so; in reality he does nothing of the kind. His stride is greater than that of the tortoise. He does not pass through each point of the path of the tortoise. We must, therefore, consider what Achilles really does, and not simply limit ourselves to mere thinking. Then we come to a different result. People do not bother their heads about these things but in reality they are extraordinarily important. Today especially, in our present scientific development, they are extremely important. For only when we understand that much of our thinking misses the phenomena of nature if we go from observation to so-called explanation, only in this case will we get the proper attitude toward these things.

[ 11 ] The observable, however, is something which only needs to be described. That I can do the following for instance, calls simply for a description: here I have a ball which will pass through this opening. We will now warm the ball slightly. Now you see it does not go through. It will only go through when it has cooled sufficiently. As soon as I cool it by pouring this cold water on it, the ball goes through again. This is the observation, and it is this observation that I need only describe. Let us suppose, however, that I begin to theorize. I will do so in a sketchy way with the object merely of introducing the matter. Here is the ball; it consists of a certain number of small parts—molecules, atoms, if you like. This is not observation, but something added to observation in theory. At this moment, I have left the observed and in doing so I assume an extremely tragic role. Only those who are in a position to have insight into these things can realize this tragedy. For you see, if you investigate whether Achilles can catch the tortoise, you may indeed begin by thinking “Achilles must pass over every point covered by the tortoise and can never catch it.” This may be strictly demonstrated. Then you can make an experiment. You place the tortoise ahead and Achilles or some other who does not run even so fast as Achilles, in the rear. And at any time you can show that observation furnishes the opposite of what you conclude from reasoning. The tortoise is soon caught.

[ 12 ] When, however, you theorize about the sphere, as to how its atoms and molecules are arranged, and when you abandon the possibility of observation, you cannot in such a case look into the matter and investigate it—you can only theorize. And in this realm you will do no better than you did when you applied your thinking to the course of Achilles. That is to say, you carry the whole incompleteness of your logic into your thinking about something which cannot be made the object of observation. This is the tragedy. We build explanation upon explanation while at the same time we abandon observation, and think we have explained things simply because we have erected hypotheses and theories. And the consequence of this course of forced reliance on our mere thinking is that this same thinking fails us the moment we are able to observe. It no longer agrees with the observation.

[ 13 ] You will remember I already pointed out this distinction in the previous course when I indicated the boundary between kinematics and mechanics. Kinematics describes mere motion phenomena or phenomena as expressed by equations, but it is restricted to verifying the data of observation.

The moment we pass over from kinematics to mechanics where force and mass concepts are brought in, at this moment, we cannot rely on thinking alone, but we begin simply to read off what is given from observation of the phenomena. With unaided thought we are not able to deal adequately even with the simplest physical process where mass plays a role. All the 19th century theories, abandoned now to a greater or lesser extent, are of such a nature that in order to verify them it would be necessary to make experiments with atoms and molecules. The fact that they have been shown to have a practical application in limited fields makes no difference. The principle applies to the small as well as to the large. You remember how I have often in my lectures called attention to something which enters into our considerations now wearing a scientific aspect. I have often said: From what the physicists have theorized about heat relations and from related things they get certain notions about the sun. They describe what they call the “physical conditions” on the sun and make certain claims that the facts support the description. Now I have often told you, the physicists would be tremendously surprised if they could really take a trip to the sun and could see that none of their theorizing based on terrestrial conditions agreed with the realities as found on the sun. These things have a very practical value at the present, a value for the development of science in our time. Just recently news has gone forth to the world that after infinite pains the findings of certain English investigators in regard to the bending of starlight in cosmic space have been confirmed and could now be presented before a learned society in Berlin. It was rightly stated there “the investigations of Einstein and others on the theory of relativity have received a certain amount of confirmation. But final confirmation could be secured only when sufficient progress had been made to make spectrum analysis showing the behavior of the light at the time of an eclipse of the sun. Then it would be possible to see what the instruments available at present failed to determine.” This was the information given at the last meeting of the Berlin Physical Society. It is remarkably interesting. Naturally the next step is to seek a way really to investigate the light of the sun by spectrum analysis. The method is to be by means of instruments not available today. Then certain things already deduced from modern scientific ideas may simply be confirmed. As you know it is thus with many things which have come along from time to time and been later clarified by physical experiments. But, people will learn to recognize the fact that it is simply impossible for men to carry over to conditions on the sun or to the cosmic spaces what may be calculated from those heat phenomena available to observation in the terrestrial sphere. It will be understood that the sun's corona and similar phenomena have antecedents not included in the observations made under terrestrial conditions. Just as our speculations lead us astray when we abandon observation and theorize our way through a world of atoms and molecules, so we fall into error when we go out into the macrocosm and carry over to the sun what we have determined from observations under earth conditions. Such a method has led to the belief that the sun is a kind of glowing gas ball, but the sun is not a glowing ball of gas by any means. Consider a moment, you have matter here on the earth. All matter on the earth has a certain degree of intensity in its action. This may be measured in one way or another, be density or the like, in any way you wish, it has a definite intensity of action. This may become zero. In other words, we may have empty space. But the end is not yet. That empty space is not the ultimate condition I may illustrate to you by the following: Assume to yourselves that you had a boy and that you said, “He is a rattle-brained fellow. I have made over a small property to him but he has begun to squander it. He cannot have less than zero. He may finally have nothing, but I comfort myself with the thought that he cannot go any further once he gets to zero!” But you may now have a disillusionment. The fellow begins to get into debt. Then he does not stop at zero; the thing gets worse than zero. It has a very real meaning. As his father, you really have less if he gets into debt than if he stopped when he had nothing.

[ 14 ] The same sort of thing, now, applies to the condition on the sun. It is not usually considered as empty space but the greatest possible rarefaction is thought of and a rarefied glowing gas is postulated. But what we must do is to go to a condition of emptiness and then go beyond this. It is in a condition of negative material intensity. In the spot where the sun is will be found a hole in space. There is less there than empty space. Therefore all the effects to be observed in the sun must be considered as attractive forces not as pressures of the like. The sun's corona, for instance, must not be thought of as it is considered by the modern physicist. It must be considered in such a way that we have the consciousness not of forces radiating outward as appearances would indicate, but of attractive force from the hole in space, from the negation of matter. Here our logic fails us. Our thinking is not valid here, for the receptive organ or the sense organ through which we perceive it is our entire body. Our whole body corresponds in this sensation to the eye in the case of light. There is no isolated organ, we respond with our whole body to the heat conditions. [ 15 ] The fact that we may use our finger to perceive a heat condition, for instance, does not militate against this fact. The finger corresponds to a portion of the eye. While the eye therefore is an isolated organ and functions as such to objectify the world of light as color, this is not the case for heat. We are heat organs in our entirety. On this account, however, the external condition that gives rise to heat does not come to us in so isolated a form as does the condition which gives rise to light. Our eye is objectified within our organism. We cannot perceive heat in an analogous manner to light because we are one with the heat. Imagine that you could not see colors with your eye but only different degrees of brightness, and that the colors as such remained entirely subjective, were only feelings. You would never see colors; you would speak of light and dark, but the colors would evoke in you no response and it is thus with the perception of heat. Those differences which you perceive in the case of light on account of the fact that your eye is an isolated organ, such differences you do not perceive at all in the case of heat. They live in you. Thus when you speak of blue and red, these colors are considered as objective. When the analogous phenomenon is met in the case of heat, that which corresponds to the blue and the red is within you. It is you yourself. Therefore you do not define it. This requires us to adopt an entirely different method for the observation of the objective being of heat from the method we use of the objective being of light. Nothing had so great a misleading effect on the observers of the 19th century as this general tendency to unify things schematically. You find everywhere in physiologies a “sense physiology.” Just as though there were such a thing! As though there were something of which it could be said, in general, “it holds for the ear as for the eye, or even for the sense of feeling or for the sense of heat. It is an absurdity to speak of a sense physiology and to say that a sense perception is this or that. It is possible only to speak of the perception of the eye by itself, or the perception of the ear by itself and likewise of our entire organism as heat sense organ, etc. They are very different things. Only meaningless abstractions result from a general consideration of the senses. But you find everywhere the tendency towards such a generalizing of these things. Conclusions result that would be humorous were they not so harmful to our whole life. If someone says—Here is a boy, another boy has given him a thrashing. Also then it is asserted—Yesterday he was whipped by his teacher; his teacher gave him a thrashing. In both cases there is a thrashing given; there is no difference. Am I to conclude from this that the bad boy who dealt out today's whipping and the teacher who administered yesterday's are moved by the same inner motives? That would be an absurdity; it would be impossible. But now, the following experiment is carried out: it is known that when light rays are allowed to fall on a concave mirror, under proper conditions they become parallel. When these are picked up by another concave mirror distant form the first they are concentrated and focused so that an intensified light appears at the focus. The same experiment is made with so-called heat rays. Again it may be demonstrated that these too can be focused—a thermometer will show it—and there is a point of high heat intensity produced. Here we have the same process as in the case of the light; therefore heat and light are fundamentally the same sort of thing. The thrashing of yesterday and the one of today are the same sort of thing. If a person came to such a conclusion in practical life, he would be considered a fool. In science, however, as it is pursued today, he is no fool, but a highly respected individual.

[ 16 ] It is on account of things like this that we should strive for clear and lucid concepts, and without these we will not progress. Without them physics cannot contribute to a general world view. In the realm of physics especially it is necessary to attain to these obvious ideas.

You know quite well from what was made clear to you, at least to a certain extent, in my last course, that in the case of the phenomena of light, Goethe brought some degree of order into the physics of that particular class of facts, but no recognition has been given to him.

[ 17 ] In the field of heat the difficulties that confront us are especially great. This is because in the time since Goethe the whole physical consideration of heat has been plunged into a chaos of theoretical considerations. In the 19th century the mechanical theory of heat as it is called has resulted in error upon error. It has applied concepts verifiable only by observation to a realm not accessible to observation. Everyone who believes himself able to think, but who in reality may not be able to do so, can propose theories. Such a one is the following: a gas enclosed in a vessel consists of particles. These particles are not at rest but in a state of continuous motion. Since these particles are in continuous motion and are small and conceived of as separated by relatively great distance, they do not collide with each other often but only occasionally. When they do so they rebound. Their motion is changed by this mutual bombardment. Now when one sums up all the various slight impacts there comes about a pressure on the wall of the vessel and through this pressure one can measure how great the temperature is. It is then asserted, “the gas particles in the vessel are in a certain state of motion, bombarding each other. The whole mass is in rapid motion, the particles bombarding each other and striking the wall. This gives rise to heat.” They may move faster and faster, strike the wall harder. Then it may be asked, what is heat? It is motion of these small particles. It is quite certain that under the influence of the facts such ideas have been fruitful, but only superficially. The entire method of thinking rests on one foundation. A great deal of pride is taken in this so-called “mechanical theory of heat,” for it seems to explain many things. For instance, it explains how when I rub my finger over a surface the effort I put forth, the pressure or work, is transformed into heat. I can turn heat back into work, in the steam engine for instance, where I secure motion by means of heat. A very convenient working concept has been built up along these lines. It is said that when we observe these things objectively going on in space, they are mechanical processes. The locomotive and the cars all move forward etc. When now, through some sort of work, I produce heat, what has really happened is that the outer observable motion has been transformed into motion of the ultimate particles. This is a convenient theory. It can be said that everything in the world is dependent on motion and we have merely transformation of observable motion into motion not observable. This latter we perceive as heat. But heat is in reality nothing but the impact and collision of the little gas particles striking each other and the walls of the vessel. The change into heat is as though the people in this whole audience suddenly began to move and collided with each other and with the walls etc. This is the Clausius theory of what goes on in a gas-filled space. This is the theory that has resulted from applying the method of the Achilles proposition to something not accessible to observation. It is not noticed that the same impossible grounds are taken as in the reasoning about Achilles and the tortoise. It is simply not as it is thought to be. Within a gas-filled space things are quite otherwise than we imagine them to be when we carry over the observable into the realm of the unobservable. [ 18 ] My purpose today is to present this idea to you in an introductory way. From this consideration you can see that the fundamental method of thinking originated during the 19th century, begins to fail. For a large part of the method rests on the principle of calculating from observed facts by means of the differential concept. When the observed conditions in a gas-filled space are set down as differentials in accordance with the idea that we are dealing with the movements of ultimate particles, then the belief follows that by integrating something real is evolved. What must be understood is this: when we go from ordinary reckoning methods to differential equations, it is not possible to integrate forthwith without losing all contact with reality. This false notion of the relation of the integral to the differential has led the physics of the 19th century into wrong ideas of reality. It must be made clear that in certain instances one can set up differentials but what is obtained as a differential cannot be thought of as integrable without leading us into the realm of the ideal as opposed to the real. The understanding of this is of great importance in our relation to nature.

[ 19 ] For you see, when I carry out a certain transformation period, I say that work is performed, heat produced and from this heat, work can again be secured by reversal of this process. But the processes of the organic cannot be reversed immediately. I will subsequently show the extent to which this reversal applies to the inorganic in the realm of heat in particular. There are also great inorganic processes that are not reversible, such as the plant processes. We cannot imagine a reversal of the process that goes on in the plant from the formation of roots, through the flower and fruit formation. The process takes its course from the seed to the setting of the fruit. It cannot be turned backwards like an inorganic process. This fact does not enter into our calculations. Even when we remain in the inorganic, there are certain macrocosmic processes for which our reckoning is not valid. Suppose you were able to set down a formula for the growth of a plant. It would be very complicated, but assume that you have such a formula. Certain terms in it could never be made negative because to do so would be to disagree with reality. In the face of the great phenomena of the world I cannot reverse reality. This does not apply, however, to reckoning. If I have today an eclipse of the moon I can simply calculate how in time past in the period of Thales, for instance, there was an eclipse of the moon. That is, in calculation only I can reverse the process, but in reality the process is not reversible. We cannot pass from the present state of the earth to former states—to an eclipse of the moon at the time of Thales, for instance, simply by reversing the process in calculation. A calculation may be made forward or backward, but usually reality does not agree with the calculation. The latter passes over reality. It must be defined to what extent our concepts and calculations are only conceptual in their content. In spite of the fact that they are reversible, there are no reversible processes in reality. This is important since we will see that the whole theory of heat is built on questions of the following sort: to what extent within nature are heat processes reversible and to what extent are they irreversible?

Erster Vortrag

[ 1 ] Die naturwissenschaftlichen Betrachtungen, die bei meinem letzten Aufenthalt hier gepflogen worden sind, sollen jetzt eine Art von Fortsetzung erfahren. Ich werde ausgehen diesmal von demjenigen Kapitel physikalischer Betrachtungen, das insbesondere wichtig sein kann für die Grundlegung einer naturwissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung überhaupt, nämlich von der Betrachtung der Wärmeverhältnisse der Welt. Ich werde heute in einer Einleitung versuchen, Ihnen gerade darzulegen, inwiefern durch eine solche Betrachtung, wie wir sie jetzt pflegen wollen, eine Anschauung geschaffen werden kann für die Bedeutung der physikalischen Erkenntnisse innerhalb einer allgemein menschlichen Weltanschauung und wie dadurch der Grund gelegt werden kann zu einer Art pädagogischer Impulse für den naturwissenschaftlichen Unterricht. Wie gesagt, heute wollen wir von einer Art prinzipieller Einleitung ausgehen und sehen, wie weit wir damit kommen.

[ 2 ] Die sogenannte Wärmelehre hat ja im 19. Jahrhundert eine Gestalt angenommen, durch die einer materialistischen Betrachtung der Welt außerordentlich viel Vorschub geleistet worden ist. Aus dem Grunde Vorschub geleistet worden ist, weil die Wärmeverhältnisse in der Welt vor allen Dingen Veranlassung dazu geben, den Blick abzuwenden von der eigentlichen Natur der Wärme, von der Wärmewesenheit, und ihn hinzulenken auf die mechanischen Erscheinungen, die aus den Wärmeverhältnissen sich ergeben.

[ 3 ] Wärme, sie kennt der Mensch zunächst dadurch, daß er die Empfindungen hat, die er mit kalt, warm, lau und so weiter bezeichnet. Allein, die Menschen werden sehr bald darauf aufmerksam, daß mit dieser Empfindung etwas zunächst Vages gegeben zu sein scheint, etwas jedenfalls Subjektives. Wer das einfache Experiment macht - wir brauchen es hier nicht zu machen, es würde uns nur aufhalten, aber es kann es jeder für sich selber immer machen -, kann sich von folgendem überzeugen:

[ 4 ] Denken Sie sich, Sie haben hier ein Gefäß, mit Wasser gefüllt, von irgendeiner ganz bestimmten Temperatur \(t\), rechts davon haben Sie ein Gefäß, ebenfalls mit Wasser gefüllt, mit einer bestimmten Temperatur \(t - t’\) das heißt, mit einer Temperatur, die wesentlich niedriger ist als jene in dem ersten Gefäß. Dann haben Sie weiter ein Gefäß mit Wasser der Temperatur \(t + t’\). Wenn Sie nun Ihre beiden Arme nehmen und die Finger eintauchen in die zwei äußeren Gefäße zunächst, so nehmen Sie empfindungsgemäß den Wärmezustand der zwei Gefäße wahr. Sie können dann die eben eingetauchten Finger in das mittlere Gefäß eintauchen, und Sie werden sehen, daß dem Finger, der in die Flüssigkeit niedriger Temperatur eingetaucht war, die Temperatur im mittleren Gefäß verhältnismäßig warm erscheint, während dem Finger, der in die wärmere Flüssigkeit eingetaucht war, die Temperatur kalt erscheint. So daß also dieselbe Temperatur verschieden erscheint für die subjektive Empfindung, je nachdem man vorher der einen oder anderen Temperatur subjektiv ausgesetzt war. Jeder Mensch weiß ja auch, daß, wenn er in einen Keller geht, das verschieden sein kann, je nachdem ob er im Sommer oder im Winter in den Keller geht. Geht er im Winter hinein, so kann ihm unter Umständen, selbst wenn das Thermometer dieselbe Temperatur zeigt, der Keller warm erscheinen, während, wenn er im Sommer hineingeht, ihm der Keller kühl erscheint. Und daraus schließt man zunächst nur: Ja, die subjektive Empfindung von Wärme ist nicht maßgebend; es handelt sich darum, irgendwie objektiv feststellen zu können, wie der Wärmezustand irgendeines Körpers oder irgendwo ist. Nun, ich brauche ja hier nicht auf die elementaren Erscheinungen einzugehen, und auch nicht auf die elementaren Werkzeuge des Wärmemessens. Die müssen als bekannt vorausgesetzt werden. Daher kann ich einfach sagen: Wenn man nun objektiv mit dem Thermometer den Stand der Temperatur eines Körpers oder eines Raumes mißt, so hat man das Gefühl: Ja, da mißt man eben die Grade vom Nullpunkt nach aufwärts oder abwärts, und man bekommt ein objektives Maß für den Wärmezustand. Man macht dann in seinen Gedanken einen wesentlichen Unterschied zwischen dieser objektiven Feststellung, an der gewissermaßen der Mensch nicht beteiligt ist, und der subjektiven Feststellung durch die Empfindung, an der der Mensch beteiligt ist.

[ 5 ] Nun, für alles das, was man während des 19. Jahrhunderts angestrebt hat, kann man sagen, ist diese Auseinanderhaltung etwas gewesen, was in einer gewissen Beziehung fruchtbar war, was seine Erfolge gezeitigt hat. Aber wir sind jetzt in einer Zeit, wo man auf gewisse Dinge durchaus aufmerksam werden muß, wenn man in fruchtbarer Weise auf diesem oder jenem Gebiet des Wissens oder der Lebenspraxis vorwärtskommen will. Und daher müssen heute aus der Wissenschaft selbst heraus gewisse Fragen gestellt werden, die man einfach unter dem Einfluß solcher Konklusionen, wie ich sie dargelegt habe, übersehen hat. Eine Frage ist die: Ist ein Unterschied, ein wirklich objektiver Unterschied zwischen dem Konstatieren durch meinen Organismus gegenüber der Temperatur eines Raumes oder Körpers und dem Konstatieren dieser Temperatur durch das Thermometer, oder täusche ich mich - es kann mir nützlich sein für das Leben, diesen Unterschied zu machen -, wenn ich diesen Unterschied in meine Ideen und Begriffe, die dann die Wissenschaft ausbauen soll, hineintrage? — Es wird der ganze Kursus dazu dienen müssen, zu zeigen, wie heute solche Fragen aufgestellt werden müssen. Denn ich werde, ausgehend von den prinzipiellen Fragen, aufzusteigen haben zu denjenigen Fragen, die heute, weil man solche Dinge nicht berücksichtigt hat, einfach dem praktischen Leben in wichtigen Gebieten entgehen. Wie sie auf dem Gebiete der Technik dem Leben entgehen, werden Sie noch sehen. Jetzt will ich nur prinzipiell auf folgendes aufmerksam machen: Unter den Betrachtungen, die ich gleich nachher charakterisieren will, ist eigentlich ganz verlorengegangen die Aufmerksamkeit auf das. Wärmewesen selbst. Und dadurch ist verlorengegangen die Möglichkeit, dieses Wärmewesen in ein Verhältnis zu bringen zu derjenigen Organisation, mit der wir es in bestimmten Gebieten der Lebenspraxis vor allen Dingen in ein Verhältnis bringen müssen: zum menschlichen Organismus selbst. Wenn wir heute bloß roh - es soll ja nur einleitungsweise sein charakterisieren, auf was es ankommt, so müssen wir aufmerksam machen darauf, daß wir ja in ganz bestimmten Fällen verpflichtet sind heute, die Temperatur des eigenen menschlichen Organismus zu messen, zum Beispiel wenn er in Fieberzuständen ist. Daraus können Sie ersehen, daß das Verhältnis des unbekannten, zunächst unbekannten Wärmewesens zum menschlichen Organismus eine gewisse Wichtigkeit hat. Das Radikalste, wie es sich bei chemischen und technischen Prozessen verhält, will ich später betrachten. Aber man wird niemals seine Aufmerksamkeit in der richtigen Weise auf diese Beziehung des Wärmewesens zum menschlichen Organismus richten können, wenn man von einer mechanischen Auffassung des Wärmewesens ausgeht, weil sich einem dann die Tatsache entzieht, daß im menschlichen Organismus, je nach den Organen, eine ganz verschiedene Wärmeempfänglichkeit besteht für das Wärmewesen selbst, daß das Herz, die Leber, die Lunge ganz verschiedene Kapazitäten haben, sich zum Wärmewesen zu verhalten. Daß man daher ein wirkliches Studium gewisser Krankheitssymptome ohne diese verschiedenen Wärmekapazitäten der einzelnen Organe nicht pflegen kann, das entzieht sich der Betrachtung einfach dadurch, daß durch die physikalische Anschauung von der Wärme keine Grundlage dazu geschaffen ist. Wir sind heute nicht in der Lage, die physikalische Anschauung, die wir im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts von der Wärme ausgebildet haben, hineinzutragen in das Gebiet des Organischen. Das ist heute demjenigen bemerklich, der ein Auge hat für die Schäden gegenwärtiger physikalischer sogenannter Forschungen für die höheren Zweige, sagen wir der Erkenntnis des organischen Wesens selber. Deshalb müssen gewisse Fragen aufgeworfen werden, Fragen, die vor allen Dingen bezwecken klare, durchschaubare Begriffe. An nichts leiden wir heute mehr, gerade in den sogenannten exaktesten Wissenschaften, als an unklaren, undurchschaubaren Begriffen.

[ 6 ] Was heißt es denn eigentlich, wenn ich sage: Wenn ich den Finger hier eingetaucht habe rechts und links (siehe Zeichnung Seite 12), so habe ich, wenn ich die beiden Finger dann in ein Gefäß mit einer Flüssigkeit von bestimmter Temperatur eintauche, verschiedene Empfindungen; was heißt es denn? Ist wirklich objektiv in der Begriffsfeststellung ein Unterschied gegenüber der sogenannten objektiven Feststellung durch das Thermometer? Denken Sie sich doch einmal: Sie tauchen statt des Fingers hier (siehe Zeichnung, rechts) das Thermometer ein und Sie tauchen es da (Mitte) ein, so werden Sie verschiedene Thermometerstände bekommen, je nachdem Sie hier oder da eintauchen. Wenn Sie die beiden Thermometer nehmen statt der beiden Finger, so wird auch die Quecksilbersäule andere Tatsachen vollziehen in dem einen und in dem anderen Thermometer. Sie werden hier (rechts) einen tieferen und hier (links) einen höheren Thermometerstand haben, der eine wird dann heraufgehen, der andere wird hinuntergehen. Sie sehen, die Thermometer machen nichts anderes, als was Ihre eigenen Empfindungen machen. Für die Feststellung eines Anschauungsbegriffes besteht kein Unterschied zwischen den beiden Thermometern und den Empfindungen Ihrer Finger. Da und dort wird genau dasselbe festgestellt, nämlich: Der Unterschied gegenüber dem früheren Stand. Und das, worauf es ankommt bei unserer Empfindung, das ist, daß wir nur in uns keinen Nullpunkt tragen. Würden wir einen Nullpunkt in uns tragen, würden wir also nicht bloß das, was unmittelbare Anschauung ist, konstatieren, sondern eine Vorrichtung in uns haben, die Temperatur, die wir subjektiv empfinden, auf einen Nullpunkt in uns selbst zu beziehen, dann würden wir durch das, was eigentlich nicht dazu gehört, was mit den Vorgängen nichts zu tun hat, dasselbe konstatieren können, was wir durch die Thermometer konstatieren können. Sie sehen also, für die Feststellung des Begriffs liegt ein Unterschied nicht vor.

[ 7 ] Das ist dasjenige, was als Frage heute gestellt werden muß, wenn man überhaupt in der Wärmelehre auf klare Begriffe kommen will. Denn all diese Begriffe, die da existieren, sind im wesentlichen unklar. Aber glauben Sie nicht, daß das keine Folgen hat. Daß wir keinen Nullpunkt in uns feststellen können, hängt zusammen mit unserem ganzen Leben. Könnten wir einen Nullpunkt in uns feststellen, so würden wir einen ganz anderen Bewußtseinszustand, ein ganz anderes Seelenleben haben müssen. Gerade dadurch, daß sich dieser Nullpunkt bei uns verbirgt, gerade dadurch leben wir in unserem Leben.

[ 8 ] Denn sehen Sie, vieles im Leben beruht ja darauf beim menschlichen Organismus —- und beim tierischen Organismus schließlich auch -, daß wir gewisse Prozesse in uns nicht wahrnehmen. Wenn Sie alles dasjenige in subjektiven Empfindungen erleben müßten, was in Ihrem Organismus vorgeht, denken Sie, was Sie da alles zu tun hätten. Denken Sie an den ganzen Verdauungsprozeß, wenn Sie den in allen Einzelheiten mitmachen müßten. Vieles von dem, was zu unseren Lebensbedingungen gehört, beruht gerade darauf, daß wir gewisse Dinge nicht in unserem Bewußtsein mitmachen, die sich in dem Organismus vollziehen. Dazu gehört einfach, daß wir keinen Nullpunkt bewußt in uns tragen, daß wir kein Thermometer sind. So daß eine solche Unterscheidung des Objektiven und Subjektiven, wie sie gemacht wird, einfach für die weitergehenden Betrachtungen des Physikalischen nicht mehr ausreicht.

[ 9 ] Das ist dasjenige, was eigentlich im Grunde genommen eine Frage ist, die locker ist in der menschlichen Betrachtungsweise seit dem alten Griechentum, die aber locker gelassen werden konnte, Nicht mehr locker bleiben kann sie für die Zukunft. Denn schon die alten Griechenphilosophen, Zeno vor allen Dingen - ich muß heute darauf aufmerksam machen, trotzdem es Ihnen pedantisch erscheinen wird -, sie haben auf gewisse Vorgänge im menschlichen Denken hingewiesen, die in einer eklatanten Weise in Widerspruch stehen mit dem, was äußere Wirklichkeit ist. Ich brauche nur an den Achillesschluß zu erinnern, auf den ich oftmals aufmerksam gemacht habe. Nehmen wir an, wir haben hier den Weg s, den der Achilles \((A)\) durchmacht, sagen wir in einer bestimmten Zeit. So schnell kann er laufen. Und hier haben wir die Schildkröte \((S)\). Die hat den Vorsprung \((AS)\). Achilles läuft der Schildkröte nach. Nehmen wir den Moment, da Achilles hier in S ankommt. Die Schildkröte läuft weiter. Der Achilles muß ihr nachlaufen. In der Zeit, in der er diese Strecke \((A S)\) durchläuft, ist die Schildkröte hier angekommen (in 1), und in der Zeit, in der er diesen nächsten Raum \((S 1)\) durchläuft, ist sie hier angekommen (in 2). Und so läuft immer die Schildkröte ein kleines Stückchen vorwärts. Der Achilles muß erst hinter ihr her laufen, was sie schon durchlaufen hat. Und Achilles kann der Schildkröte nie nachkommen.

[ 10 ] Dieses wird gewöhnlich nun von den Menschen so behandelt, wie ganz gewiß manche Gemüter auch derer, die jetzt hier sitzen, die Sache behandeln. Ich sehe es Ihnen an. Sie denken: Das weiß ich ja ganz genau, der Achilles hat ganz natürlich die Schildkröte bald eingeholt, und die Sache ist einfach dumm, wenn man die Schlußfolgerung macht: Der Achilles muß immer das frühere Stück durchlaufen, die Schildkröte ist voraus, er kommt nie nach. Es ist einfach dumm - sagen die Leute. Das geht aber nicht, daß man so sagt, denn die Schlußfolgerung ist absolut zwingend und bindend, es läßt sich dagegen nichts sagen. Und es ist nicht etwa dumm, wenn dieser Schluß gemacht worden ist, sondern es ist ein außerordentlich — in der menschlichen Ratio — gescheiter Schluß, denn er ist absolut bindend, und man kommt nicht über ihn hinweg. Worauf beruht denn aber das Ganze? Solange Sie bloß denken, können Sie nicht anders denken, als dieser Schluß besagt. Aber Sie denken nicht so, weil Sie einfach die Wirklichkeit anschauen und wissen: Der Achilles kommt der Schildkröte selbstverständlich bald nach. Und da verwuseln Sie das Denken mit der Wirklichkeit, lassen sich auf das Denken nicht mehr ein. Den Menschen ist es ja nicht darum zu tun, sich auf das Denken einzulassen, und dann sagen sie: Der, der so denkt, ist einfach dumm. — Durch das Denken kriegt man nichts anderes heraus, als daß der Achilles der Schildkröte nicht nachkommt. Worauf beruht das aber? Das beruht darauf, daß, wenn wir unser Denken gerade konsequent auf die Wirklichkeit anwenden, dann das, was wir konstatieren, falsch wird gegenüber den Tatsachen der Wirklichkeit. Es muß falsch werden. Sobald wir unser rationalistisches Denken auf die Wirklichkeit anwenden, hilft uns nichts darüber hinweg, daß wir falsch sogenannte «Wahrheiten» konstatieren. Denn wir müssen einfach schließen, daß, wenn der Achilles der Schildkröte nachläuft, er jeden Punkt zu durchmessen hat, den die Schildkröte auch durchgemacht hat. Das ist ideell durchaus richtig. In Wirklichkeit aber macht er das nicht, er berührt nicht die Punkte. Seine Beine schreiten weiter aus als die der Schildkröte. Er macht das nicht durch, was die Schildkröte durchmacht. Wir müssen uns also anschauen, was der Achilles tut. Wir können uns nicht darauf einlassen, bloß darüber zu denken. Dann kommen wir zu anderen Resultaten. Diese Dinge berühren das Gewissen der Menschen manchmal recht wenig, in Wahrheit aber sind sie außerordentlich bedeutsam. Und gerade heute, in der gegenwärtigen Zeit wissenschaftlicher Entwickelung, sind sie von der allergrößten Bedeutung. Dann erst, wenn wir einsehen, wieviel Wirklichkeit in unserem Denken über die Naturerscheinungen ist, wenn wir übergehen von den Anschauungen zu der sogenannten Erklärung, dann kommen wir mit den Dingen zurecht.

[ 11 ] Nicht wahr, das Anschauliche, das ist etwas, was einfach beschrieben zu werden braucht. Daß ich folgendes machen kann, das braucht einfach beschrieben zu werden: Hier habe ich eine Kugel. Wenn ich sie durch dieses Loch werfe, geht sie durch. Das ist jetzt die Anschauung. Wir wollen jetzt einfach diese Kugel etwas erwärmen. Sie sehen, ich kann die Kugel jetzt auf das Loch legen, sie geht zunächst nicht durch. Sie wird erst wiederum durchfallen, wenn sie genügend abgekühlt ist. In dem Augenblick, wo ich sie abkühle, indem ich Wasser darauf gieße, geht sie wieder durch. Das ist die Anschauung. Das ist dasjenige, was ich einfach zu beschreiben brauche. Nehmen wir aber ar, ich fange jetzt an zu theoretisieren. Ich will es zunächst ganz roh machen, es handelt sich ja um eine Einleitung: Das wäre also die Kugel, die Kugel bestünde aus einer gewissen Anzahl von kleinen Teilen, von Molekülen, Atomen — wie Sie wollen. Das ist etwas, was nicht mehr Anschauung ist, was ich dazutheoretisiere. In diesem Augenblick bin ich verlassen von der Anschauung. Und in diesem Augenblick bin ich in einer außerordentlich tragischen Rolle. Die Tragik empfinden nur diejenigen, die auf solche Dinge eingehen können. Denn wenn Sie untersuchen, ob Achilles die Schildkröte erreichen kann oder nicht, so können Sie anfangen zu denken: Der Achilles muß den Weg der Schildkröte durchmessen, also wird er sie nie einholen. Das kann man strikte beweisen. Nun machen Sie das Experiment. Sie setzen die Schildkröte hin und den Achilles oder jemand anderen, auch wenn er nicht so schnell läuft wie Achilles. Sie können jederzeit beweisen, daß die Anschauung Ihnen das Gegenteil von dem liefert, was Ihnen die Schlußfolgerung liefert. Sie werden sehr bald die Schildkröte einholen.

[ 12 ] Wenn Sie aber nun über die Kugel theoretisieren wollen, wie ihre Atome und Moleküle angeordnet sind, wo Sie auch die Anschauung verläßt, da können Sie nicht hineinschauen und nachsehen, da werden Sie nur theoretisieren können, und das ist auf diesem Gebiet nicht besser als das, was Sie gegenüber dem Wegstück, das von Achilles nicht durchmessen ist, anführen. Das heißt: Sie tragen die ganze Unvollkommenheit Ihrer Ratio hinein in Ihr Nachdenken über dasjenige, was nicht mehr anschaulich ist. Das ist das Tragische. Wir bauen und bauen Erklärungen auf, indem wir das Anschauliche verlassen, und glauben es dadurch gerade erklären zu können, daß wir Hypothesen und Theorien aufstellen. Und die Folge davon ist, daß wir dann genötigt sind, unserem bloßen Denken zu folgen, daß dieses Denken uns aber in dem Augenblick verläßt, wo wir über die Anschauung hinauskommen. Es stimmt nicht mehr mit der Anschauung überein.

[ 13 ] Auf diesen Unterschied habe ich schon im vorigen Kursus hingewiesen, indem ich die scharfe Grenze gesetzt habe zwischen dem Phoronomischen und dem Mechanischen. Die Phoronomie beschreibt bloß Bewegungsvorgänge oder Gleichgewichtsvorgänge, aber sie beschränkt sich darauf, das Anschauliche zu konstatieren. In dem Augenblick, wo Sie von der Phoronomie zur Mechanik übergehen, wo der Kraft- und Massebegriff einzuführen ist, in dem Augenblick können wir nicht ausreichen mit dem bloßen Denken, sondern wir beginnen einfach abzulesen von dem Anschaulichen, was vorgeht. Wir können in den einfachsten physikalischen Vorgängen, in denen die Masse eine Rolle spielt, mit dem bloßen Denken nichts mehr anfangen. Und diejenigen Theorien, die im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts aufgebaut worden sind, trotzdem sie sich —- das macht nichts aus — für eingeschränkte Gebiete als praktisch erwiesen haben, sind so entstanden, daß eigentlich, um sie zu verifizieren, notwendig wäre, bis in die Moleküle und Atome hinein Experimente zu machen. Das gilt in bezug auf das Kleine, das gilt aber auch in bezug auf das Große. Sie erinnern sich, daß ich in meinen Vorträgen oftmals aufmerksam gemacht habe auf etwas, das uns jetzt mit einem ganz wissenschaftlichen Charakter in diesen Betrachtungen entgegentreten wird. Ich habe oftmals gesagt: Aus dem, was der Physiker heute über Wärmeverhältnisse und auch über einige andere Dinge, die damit verknüpft sind, heraustheoretisiert, macht er sich gewisse Vorstellungen über die Sonne. Er beschreibt mit einem gewissen Anspruch darauf, daß die Sache stimme, wie die physikalischen Verhältnisse, wie er sagt, auf der Sonne sind. Nun habe ich immer gesagt: Die Physiker würden außerordentlich erstaunt sein, wenn sie das Experiment ausführen könnten, wirklich zur Sonne hinauf zu kutschieren und sähen, wie nichts von dem, was sie aus irdischen Verhäitnissen heraus rechnen oder theoretisieren, mit den Wirklichkeiten der Sonne übereinstimmt. Heute haben die Sachen tatsächlich schon eine ganz bestimmte praktische Bedeutung, namentlich gegenüber der wissenschaftlichen Zeitentwickelung. Erst in diesen Tagen ging ja die Nachricht durch die Welt, daß mit großen Mühen die Ergebnisse englischer Forschungen über die Ablenkung des Sternenlichtes im Weltenraum auch in Berlin vor einer Gelehrtengesellschaft vorgeführt werden konnten. Da wurde mit Recht auf folgendes hingewiesen. Es wurde gesagt: Ja, die Forschungen von Einstein und anderen über die Relativitätstheorie haben eine gewisse Bestätigung erfahren, aber etwas Endgültiges würde man erst sagen können, wenn man soweit wäre, daß man spektralanalytisch untersuchen könnte, wie es sich eigentlich mit dem Sonnenlicht letztlich, namentlich bei Gelegenheit der Sonnenfinsternis, verhält. Da würde man nämlich etwas sehen, was heute noch nicht mit den gangbaren physikalischen Instrumenten konstatierbar ist. - Das war die Nachricht, die sich anknüpfte an die letzte Sitzung der Berliner Physikalischen Gesellschaft. Das ist außerordentlich interessant. Denn es muß natürlich der nächste Schritt der sein, nach einer Möglichkeit zu suchen, wirklich spektralanalytisch das Sonnenlicht zu untersuchen. Der Weg muß der nach Meßinstrumenten sein, die heute noch nicht da sind. Dann wird man gewisse Dinge, die heute aus geisteswissenschaftlichen Grundlagen heraus schon gewonnen werden können, einfach nachträglich bestätigen können, wie das ja bei vielen Dingen der Fall war, die im Laufe der Jahre entstanden sind, die auch, wie Sie wissen, durch physikalische Experimente in der letzten Zeit herausgekommen sind. Dann wird man einsehen lernen, daß es einfach unmöglich ist, dasjenige, was man imstande ist herauszurechnen aus den Beobachtungen namentlich der Wärmeerscheinungen in der irdischen Sphäre, auf die Verhältnisse des Weltraumes, auf die Sonnenverhältnisse zu übertragen und sich vorzustellen, daß die Sonnenkorona und dergleichen entsteht aus Antezedenzien heraus, die entnommen sind der Betrachtung der irdischen Verhältnisse. Gerade wie uns unser Denken irreführt, wenn wir das Anschauliche verlassen und in die Welt der Moleküle und Atome hineintheoretisieren, so führt es uns auch irre, wenn wir ins Makrokosmische hinausgehen und das, was wir durch Anschauung in irdischen Verhältnissen festsetzen, auf so etwas wie die Sonne übertragen. Da glaubt man, daß man in der Sonne etwas wie eine Art glühenden Gasballes habe. Von einem glühenden Gasball kann nicht die Rede sein bei der Sonne. Man hat etwas ganz anderes in der Sonne vorliegend. Denken Sie sich einmal: Wir haben irdische Materie. Jede irdische Materie hat einen bestimmten Intensitätsgrad ihres Wirkens, ob man den auf diese oder jene Weise mißt, auf Dichtigkeit oder dergleichen, darauf kommt es nicht an. Sie hat eine gewisse Intensität des Wirkens. Diese kann auch zu Null werden, das heißt, wir können dem scheinbar leeren Raum gegenüberstehen. Aber damit hat es nicht seinen Schluß, ebensowenig wie es einen Schluß hat — nun, schauen wir einmal auf das Folgende; denken Sie sich, Sie sagen: Ich habe einen Sohn. Der Kerl ist eigentlich ein leichtsinniges Tuch. Ich habe ihm ja ein kleines Vermögen übergeben, aber nun hat er angefangen, es auszugeben. Mehr als bis Null kann er nicht heruntergehen. Er kann einmal nichts mehr haben, damit tröste ich mich, er kommt eben einmal bei Null an. — Ja, aber nachher kann ich eigentlich eine Enttäuschung erleben: Der Kerl fängt an, Schulden zu machen. Dann bleibt er nicht bei Null stehen, dann wird die Geschichte noch schlimmer als Null. Und das kann eine sehr reale Bedeutung haben. Denn als Vater werde ich eigentlich weniger haben, wenn der Kerl Schulden macht, als wenn er bei Null stehen bleibt.

[ 14 ] Sehen Sie, dieselbe Betrachtungsweise liegt zugrunde gegenüber den Sonnenverhältnissen. Man geht nicht einmal zur Null, sondern nur bis zur größtmöglichen Verdünnung; man spricht von dünnem, glühendem Gas. Aber man müßte erst bis Null gehen und dann darüber hinaus. Denn das, was man in der Sonne finden würde, wäre überhaupt nicht vergleichbar mit unserem Materiellen, wäre auch nicht vergleichbar mit unserem leeren Raum, der der Null entspricht, sondern es geht darüber hinaus. Es ist in einem Zustand negativer materieller Intensität. Da, wo die Sonne ist, würde man ein Loch finden, in den leeren Raum hineingehend. Es ist weniger als leerer Raum da. So daß alle Wirkungen, die auf der Sonne zu beobachten sind, als Saugwirkungen betrachtet werden müssen, nicht als Druckwirkungen oder dergleichen. Die Sonnenkorona darf also nicht so betrachtet werden, wie heute der Physiker sie betrachtet, sondern sie muß so betrachtet werden, daß man das Bewußtsein hat, es geschieht nicht dasjenige, als was es sich darstellt, etwa Druckwirkungen mit dem Index nach außen, sondern es liegen Saugwirkungen von dem Loch im Raum, von der Negation der Materie vor. Da verläßt uns die Ratio. Da verläßt uns unser Denken gegenüber dem Makrokosmischen, wie es uns verläßt gegenüber dem Mikrokosmischen. In dem Falle, den ich angedeutet habe, können wir nur theoretisieren über das Atomistische.

[ 15 ] Wir erleben, indem wir subjektiv die Wärmezustände unserer Umgebung beurteilen, gar nicht wirkliche Wärmezustände, sondern wir erleben Differenzen. Das Thermometer zeigt auch Differenzen, es ist kein Unterschied. Wir erleben die Differenzen zwischen unserem eigenen Wärmezustand und demjenigen, in den wir hineinkommen. Den Tatsachen nach tut das auch das Thermometer. Nur haben wir durch Dinge, die nichts mit diesen vorliegenden Tatsachen zu tun haben, durch die Feststellung eines Nullpunktes, die Sache kaschiert. Hier liegt etwas vor, was außerordentlich wichtig ist zu berücksichtigen. Wenn wir unsere Aufmerksamkeit den Lichterscheinungen zuwenden, so liegt die Sache so, daß wir die Lichterscheinungen im wesentlichen verfolgen mit einem Organ, das sehr stark isoliert ist in unserem Organismus. Ich habe das im vorigen Kursus charakterisiert. Dadurch beobachten wir eigentlich niemals Licht — Licht ist Abstraktion —, sondern wir beobachten Farbenerscheinungen. Wenn wir Wärme beobachten, subjektiv, so ist dasjenige, was Empfindungsorgan bei uns ist, was Auffassungsorgan ist, unser ganzer Organismus. Unser ganzer Organismus entspricht da unserem Auge. Er ist nicht ein isoliertes Organ. Wir setzen uns als Ganzes dem Wärmezustand aus. Indem wir mit einem Glied, zum Beispiel mit einem Finger, uns der Wärme aussetzen, ist das nichts anderes als wie ein Teil des Auges gegenüber dem ganzen Auge. Während also das Auge ein isoliertes Organ ist und dadurch sich für uns die Welt des Lichtes in den Farben verobjektiviert, ist bei der Wärme ein solches nicht der Fall. Wir sind gleichsam ganz Wärmeorgan. Aber dadurch tritt uns auch nicht so isoliert von draußen entgegen dasjenige, was die Wärme macht, wie uns isoliert entgegentritt dasjenige, was das Licht macht. Unser Auge ist objektiviert in unserem Organismus. Was die Wärme Analoges macht — weil wir es selbst sind, können wir es nicht erleben. Denken Sie einmal, Sie würden mit dem Auge keine Farben sehen, sondern nur Helligkeit unterscheiden, und die Farben als solche würden ganz subjektiv bleiben, bloß Gefühle bleiben: Sie würden niemals Farben sehen. Sie würden von Hell-Dunkel reden, aber die Farben würden nichts in Ihnen bewirken. So ist es bei der Wahrnehmung der Wärme. Jene Differenzierungen, die Sie beim Licht wegen der Isolierung des Auges wahrnehmen, die nehmen Sie in der Welt der Wärme nicht mehr wahr. Die leben aber in Ihnen. Wenn Sie also von Blau und Rot sprechen bei der Farbe, so haben Sie dieses Blau und Rot außen. Wenn Sie von dem Analogen bei der Wärme sprechen, so haben Sie, weil Sie das Wärmeorgan selbst sind, das, was analog bei der Wärme blau und rot wäre, in sich, Sie sind es selbst. Daher sprechen Sie nicht davon. Und das macht, daß für die Betrachtung des objektiven Wärmewesens eine ganz andere Methode notwendig ist als für die Betrachtung des objektiven Lichtwesens. Und nichts hat, ich möchte sagen, so verführend in der Betrachtungsweise des 19. Jahrhunderts gewirkt, als überall schematisch zu vereinheitlichen. Sie finden überall in den Physiologien eine «Sinnesphysiologie». Als ob es so etwas überhaupt gäbe! Als ob es etwas gäbe, wo man einheitlich sagen kann, es gilt für das Ohr wie für das Auge oder gar für den Gefühls- oder Wärmesinn. Es ist ein Unding, von einer Sinnesphysiologie zu sprechen und zu sagen, eine Sinneswahrnehmung ist dies oder jenes. Man kann nur sprechen von der isolierten Wahrnehmung des Auges, von der isolierten Wahrnehmung des Ohres, von der isolierten Wahrnehmung unseres Organismus als Wärmeorgan und so weiter. Das sind ganz verschiedene Dinge, und man kann nur wesenlose Abstraktionen aufstellen, wenn man von einem einheitlichen Sinnesvorgang spricht. Aber Sie finden heute überall die Neigung dazu, diese Dinge zu vereinheitlichen. Und so kommen dann Schlüsse zustande, die eigentlich, wären sie nicht so schädlich für unser ganzes Leben, im Grunde genommen humoristisch wären. Wenn einer sagt: Da ist ein Bub, ein anderer Bub hat ihn durchgeprügelt. —- Und daneben wird behauptet: Gestern hat er Schläge bekommen von seinem Lehrer, der Lehrer hat ihn durchgeprügelt. Ich habe in beiden Fällen das Prügeln beobachtet. Es ist kein Unterschied. Ich schließe daraus, daß der Lehrer von gestern und der böse Bub, der heute die Prügel austeilte, von derselben inneren Wesenheit sind. — Das wäre ein Unding, nicht wahr, das wäre ganz unmöglich. Aber man macht folgendes Experiment. Man weiß, daß, wenn man Lichtstrahlen in einer gewissen Weise auf einen Hohlspiegel fallen läßt, sie parallel gehen; wenn man sie durch einen weiteren Hohlspiegel auffangen läßt, sie sich im Brennpunkt vereinigen und Lichterscheinungen hervorrufen. Man macht dasselbe mit den sogenannten Wärmestrahlen. Man kann wiederum konstatieren: Man läßt die Strahlen durch Hohlspiegel auffangen, sich im Brennpunkt vereinigen — man kann es mit dem Thermometer konstatieren, daß da eine Art Wärmebrennpunkt entsteht. Das sei dieselbe Geschichte wie beim Licht, also beruhe das Licht und die Wärme auf ein und demselben. Die Prügel von gestern und die Prügel von heute beruhen auf ein und demselben. Wenn man im Leben eine solche Schlußfolgerung ausführen würde, würde man ein Tor sein. Wenn man sie in der Wissenschaft ausführt, wie es heute überall gemacht wird, ist man kein Tor, sondern oftmals eine tonangebende Persönlichkeit.

[ 16 ] Dennoch, es kommt heute darauf an, nach klaren, durchschaubaren Begriffen zu streben, und ohne diese klaren, durchschaubaren Begriffe kommen wir nicht weiter. Sonst wird niemals durch eine physikalische Weltanschauung eine Grundlage geschaffen werden für eine universelle Weltanschauung, wenn man nicht gerade auf physikalischem Gebiet versucht, zu klaren, anschaulichen Begriffen vorzudringen. Sie wissen ja, und es ist auch durch meinen letzten Kursus hier klar geworden, bis zu einem gewissen Grade wenigstens klar geworden, daß auf dem Gebiete der Lichterscheinungen Goethe ein wenig Ordnung geschaffen hat, daß aber diese Dinge nicht anerkannt sind.

[ 17 ] Auf dem Gebiet der Wärmeerscheinungen ist es nun ganz besonders schwierig, weil in der nachgoetheschen Zeit ja die Wärmeerscheinungen vollständig in das Chaos der theoretischen Anschauungen eingelaufen sind und im 19. Jahrhundert die sogenannte mechanische Wärmetheorie Unfug über Unfug gestiftet hat; auf der einen Seite dadurch, daß sie Anschauungsbegriffe geliefert hat auf einem Gebiet, wo die Anschauung nicht hinreicht, und für jeden, der glaubt, auch denken zu können, aber es in Wirklichkeit nicht kann, leicht erlangbare Begriffe geliefert hat. Es sind die Begriffe, durch die man sich vorgestellt hat: Ein Gas in einem allseitig geschlossenen Gefäß besteht aus Gasteilchen, aber diese Gasteilchen sind nicht in Ruhe, sondern sie sind in fortwährender Bewegung. Und natürlich, wenn diese Gasteilchen in fortwährender Bewegung sind, wird in den meisten Fällen, da die Gasteilchen klein sind und ihre Entfernungen verhältnismäßig groß vorgestellt werden, so ein Gasteilchen sich durchschlängeln, wird lange nicht auf ein anderes auftreffen, aber zuweilen dann doch. Es prallt dann zurück, und so stoßen sich dann da drinnen die Gasteilchen. Sie kommen in eine Bewegung. Sie bombardieren sich fortwährend gegenseitig. Da geben sie, wenn man die verschiedenen kleinen Stöße summiert, einen Druck auf die Wand. Anderseits hat man die Möglichkeit zu messen, wie hoch die Temperatur ist. Dann sagt man sich: Nun ja, da sind die Gasteilchen drinnen in einem bestimmten Bewegungszustand, sie bombardieren sich. Das Ganze ist in aufgeregter Bewegung. Das stößt sich gegenseitig und stößt auf die Wand. Erwärmt man, so kommen sie immer schneller und schneller in Bewegung, stoßen immer stärker und stärker an die Wand, und man hat die Möglichkeit, zu sagen: Was ist also Wärme? — Bewegung der kleinsten Teile. Es ist gewiß, daß heute unter der Macht der Tatsachen solche Vorstellungen schon etwas abgekommen sind, allein sie sind nur äußerlich abgekommen. Die ganze Denkweise ruht doch noch auf demselben Grunde. Man ist sehr stolz geworden auf diese sogenannte mechanische Wärmetheorie, denn sie soll ja außerordentlich viel erklären. Sie soll zum Beispiel erklären: Wenn ich einfach mit dem Finger über irgendeine Fläche streiche, so wird die Anstrengung, die ich anwende, die Arbeit, die Wucht verwandelt in Wärme. Ich kann zurückverwandeln Wärme in Arbeit, zum Beispiel bei der Dampfmaschine, wo ich durch die Wärme Vorwärtsbewegungen wahrnehmen kann. Und man hat sich die gangbare, höchst bequeme Vorstellung gebildet: Ja, wenn ich äußerlich das beobachte, was da im Raum geschieht, so sind es mechanische Vorgänge. Die Lokomotive und die Waggons bewegen sich vorwärts und so weiter. Wenn ich dann, sagen wir, durch irgend etwas Arbeit leiste und daraus Wärme entsteht, so ist eigentlich nichts anderes geschehen, als daß die äußerlich wahrnehmbare Bewegung sich verwandelt hat in die Bewegung der kleinsten Teilchen. Das ist eine bequeme Vorstellung. Man kann sagen: Alles in der Welt beruht auf Bewegung, und es verwandelt sich bloß die anschauliche Bewegung in die unanschauliche Bewegung. Diese wird dann als Wärme wahrgenommen. Aber die Wärme ist doch nichts anderes als Stoßen und Drängen der kleinen Gasrüpel, die sich stoßen, die an die Wand stoßen und so weiter. Es ist die Wärme allmählich verwandelt worden im Wesen in das, was jetzt geschehen würde, wenn diese ganze Korona plötzlich anfinge, sich gegenseitig in Bewegung zu setzen, wenn sie sich fortwährend stoßen würde, an die Wand stoßen würde und so weiter. Das ist die Clausiussche Vorstellung von dem, was in einem gasgefüllten Raum vorgeht. Das ist die Theorie, die herausgekommen ist dadurch, daß man den Achillesschluß angewendet hat auf Unanschauliches, und nicht bemerkt, wie man derselben Unmöglichkeit unterliegt, wie wenn man das Denken anwendet auf Achilles und die Schildkröte. Das heißt, es wird nicht so, wie man denkt. Im Inneren eines gaserfüllten Raumes geht es anders zu, als wir uns ausmalen, wenn wir die unanschaulichen Begriffe auf Anschauung übertragen.

[ 18 ] Das wollte ich heute einleitungsweise sagen. Sie werden daraus ersehen, daß im Grunde genommen die ganze methodische Art der Betrachtung, die namentlich im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts sich herausgebildet hat, in ihren Grundfesten wankt. Denn es beruht ein großer Teil dieser Betrachtungsweise darauf, daß man einfach dasjenige, was man beobachtet als anschauliches Faktum, sich so vorstellt, daß man den Ausdruck, auch den rechnerischen Ausdruck des Anschauens, so überleitet, daß man Differentialvorstellungen daraus bekommt. Wenn man das, was man als konstatierbares Faktum hat gegenüber einem gasgefüllten Raume unter einem bestimmten Druck, rechnerisch ausdrückt, so kann man dadurch, daß man die Vorstellung zugrunde legt: Da geschehen die Bewegungen der kleinsten Teile, es in Differentialvorstellungen umwandeln und kann sich dann dem Glauben hingeben, daß, wenn man wiederum integriert, man etwas über die Realität herausbekomme. Man muß einsehen, daß, wenn man den Übergang vollzieht von gewöhnlichen rechnerischen Vorstellungen zu Differentialgleichungen, daß man diese Differentialgleichungen, ohne aus der Wirklichkeit vollständig herauszufallen, nicht wiederum in Integralrechnungen behandeln darf. Das liegt der Physik im 19. Jahrhundert zugrunde, daß man durch ein falsches Verständnis über die Beziehung der Integrale zu den Differentialen sich gegenüber der Wirklichkeit falschen Vorstellungen hingegeben hat. Man muß sich klar darüber sein: In gewissen Fällen darf man differenzieren, aber was die Differentialzustände ergibt, darf nicht gedacht werden, als ob es zurückintegriert werden könnte, denn da kommt man nicht in die Wirklichkeit hinein, sondern zu etwas Ideellem. Es ist gegenüber der Natur von großer Wichtigkeit, daß man das durchschaut.

[ 19 ] Denn, sehen Sie, wenn ich einen bestimmten Verwandlungsvorgang ausführe, wenn ich sage, ich leiste Arbeit, bekomme Wärme, so kann ich aus dieser Wärme wiederum Arbeit bekommen, und wir werden sehen, in welchem Maße das innerhalb der unorganischen Natur gilt, gerade an den Wärmeerscheinungen. Aber ich kann nicht ohne weiteres einen organischen Prozeß umkehren. Auch große anorganische Prozesse kann ich nicht umkehren, zum Beispiel sind planetarische Prozesse nicht umkehrbar. Wir können uns nicht jenen Prozeß umgekehrt vorstellen, der verläuft von der Wurzelbildung einer Pflanze bis zur Blüte, bis zur Fruchtbildung. Der Prozeß verläuft vom Keime bis zur Fruchtbildung, er kann nicht zurückverlaufen wie ein Prozeß in der unorganischen Natur. In unsere Rechnungen fließt das nicht ein. Denn schon, wenn wir sogar im Unorganischen bleiben, gilt es für gewisse makrokosmische Prozesse nicht. Ich kann heute in keiner Rechnungsformel, wenn ich sie aufstellen könnte für das Wachstum einer Pflanze — sie würde aber sehr kompliziert ausfallen -, gewisse Werte negativ einsetzen; dies deckt sich nicht mit der Wirklichkeit. Die Gestaltung der Blüte aus der Gestaltung des Laubblattes könnte ich nicht negativ einsetzen. Ich würde nicht den Prozeß umkehren können. Ich kann auch gegenüber den größeren Erscheinungen der Welt den realen Prozeß nicht umkehren. Das berührt aber nicht die Rechnung. Wenn ich heute eine Mondfinsternis einzusetzen habe, kann ich einfach berechnen, wie eine Mondfinsternis vor unserer Zeitrechnung, zu Thales’ Zeiten war und so weiter, das heißt, ich kann in der Rechnung selbst durchaus den Prozeß umkehren, aber in der Wirklichkeit würde der Prozeß nicht umkehrbar sein. Wir können nicht vom gegenwärtigen Stadium der Weltentwickelung durch Umkehrung des Prozesses zu den früheren Stadien, zum Beispiel zu einer Mondfinsternis, die sich zu Thales’ Zeiten zugetragen hat, zurückschreiten. Eine Rechnung kann ich vorwärts und rückwärts behandeln, mit der Wirklichkeit deckt sich meist nicht, was ich mit der Rechnung erfasse. Diese Rechnung schwebt über der Wirklichkeit. Man muß sich klar darüber sein, inwiefern unsere Vorstellungen und Rechnungen nur Vorstellungsinhalte sind. Trotzdem sie umkehrbar sind, gibt es keine umkehrbaren Prozesse in der Wirklichkeit. Das ist wichtig, denn wir werden die ganze Wärmelehre auf Fragen dieser Art aufgebaut sehen: Inwiefern sind innerhalb des Gebietes der Wärmeverhältnisse Naturprozesse umkehrbar, und inwiefern sind sie es nicht?

First Lecture

[ 1 ] The scientific observations made during my last stay here will now be continued in a manner of speaking. This time, I will start with the chapter of physical observations that may be particularly important for establishing a scientific worldview in general, namely the observation of the thermal conditions of the world. In today's introduction, I will attempt to explain to you how such an observation, as we now intend to pursue, can create an understanding of the significance of physical knowledge within a general human worldview and how this can lay the foundation for a kind of pedagogical impulse for scientific education. As I said, today we want to start with a kind of basic introduction and see how far we can get with it.

[ 2 ] In the 19th century, the so-called science of heat took on a form that greatly promoted a materialistic view of the world. It promoted this view because the thermal conditions in the world primarily cause us to turn our gaze away from the actual nature of heat, from the essence of heat, and direct it toward the mechanical phenomena that result from thermal conditions.

[ 3 ] Humans first become aware of heat through the sensations they describe as cold, warm, lukewarm, and so on. However, humans very soon realize that there seems to be something vague about this sensation, something subjective in any case. Anyone who performs the simple experiment—we don't need to do it here, it would only slow us down, but anyone can do it for themselves at any time—can convince themselves of the following:

[ 4 ] Imagine you have a container filled with water at a specific temperature \(t\). To the right of it, you have another container, also filled with water, at a specific temperature \(t - t’\), i.e., at a temperature that is significantly lower than that in the first container. Then you have another container with water at a temperature \(t + t'\). If you now take both your arms and dip your fingers into the two outer containers first, you will perceive the thermal state of the two containers. You can then dip the fingers you just immersed into the middle container, and you will see that the finger that was immersed in the lower temperature liquid will perceive the temperature in the middle container as relatively warm, while the finger that was immersed in the warmer liquid will perceive the temperature as cold. So the same temperature appears different to the subjective perception, depending on which temperature one was previously exposed to. Everyone knows that when they go into a basement, it can feel different depending on whether they go in summer or winter. If they go in during winter, the basement may appear warm to them, even if the thermometer shows the same temperature, while if they go in during summer, the basement will appear cool to them. And from this we can initially conclude only that the subjective sensation of warmth is not decisive; the point is to be able to determine objectively, in some way, the state of warmth of any body or any place. Well, I don't need to go into the basic phenomena here, nor the basic tools for measuring heat. These must be assumed to be known. So I can simply say: when you objectively measure the temperature of a body or a room with a thermometer, you get the feeling that Yes, you measure the degrees from zero upwards or downwards, and you get an objective measure of the thermal state. You then make a fundamental distinction in your mind between this objective determination, in which humans are not involved, so to speak, and the subjective determination through sensation, in which humans are involved.

[ 5 ] Now, for everything that was strived for during the 19th century, one can say that this distinction was something that was fruitful in a certain sense and that it yielded successes. But we are now in a time when we must pay close attention to certain things if we want to make fruitful progress in this or that area of knowledge or practical life. And therefore, certain questions must be asked today from within science itself, questions that have simply been overlooked under the influence of conclusions such as those I have outlined. One question is this: Is there a difference, a truly objective difference, between my organism's perception of the temperature of a room or body and the thermometer's perception of this temperature, or am I mistaken—it may be useful for my life to make this distinction—when I carry this difference into my ideas and concepts, which science is then supposed to develop? The entire course will have to serve to show how such questions must be posed today. For, starting from the fundamental questions, I will have to move on to those questions which, because such things have not been taken into account, simply escape practical life in important areas today. You will see how they escape life in the field of technology. Now I just want to draw your attention to the following principle: Among the considerations that I will characterize in a moment, attention to the heat entity itself has actually been completely lost. And as a result, the opportunity has been lost to relate this heat phenomenon to the organization with which we must above all relate it in certain areas of practical life: to the human organism itself. If we are to characterize today, in a very rough way – it is only meant to be an introduction – what is important, we must point out that in very specific cases we are obliged today to measure the temperature of our own human organism, for example when it is in a feverish state. From this you can see that the relationship of the unknown, initially unknown, heat entity to the human organism has a certain importance. I will consider the most radical aspects of this in relation to chemical and technical processes later. But one will never be able to focus one's attention properly on this relationship between the heat entity and the human organism if one starts from a mechanical conception of the heat entity, because then one fails to recognize the fact that in the human organism, depending on the organs, there is a very different sensitivity to heat for the heat entity itself, that the heart, the liver, and the lungs have very different capacities to relate to the heat entity. The fact that one cannot truly study certain symptoms of disease without taking into account these different heat capacities of the individual organs is simply overlooked because the physical view of heat provides no basis for doing so. Today, we are not in a position to carry the physical view of heat that we developed in the course of the 19th century into the realm of the organic. This is noticeable today to anyone who has an eye for the damage caused by current physical so-called research to the higher branches, let us say, of the knowledge of the organic being itself. Therefore, certain questions must be raised, questions that above all aim at clear, transparent concepts. Nothing causes us more suffering today, especially in the so-called most exact sciences, than unclear, opaque concepts.