Second Scientific Lecture-Course:

Warmth Course

GA 321

8 March 1920, Stuttgart

Lecture VIII

[ 1 ] Yesterday we carried out an experiment which brought to your attention the fact that mechanical work exerted by friction of a rotating paddle in a mass of water has changed into heat. You were shown that the water in which the paddle turned became warmer.

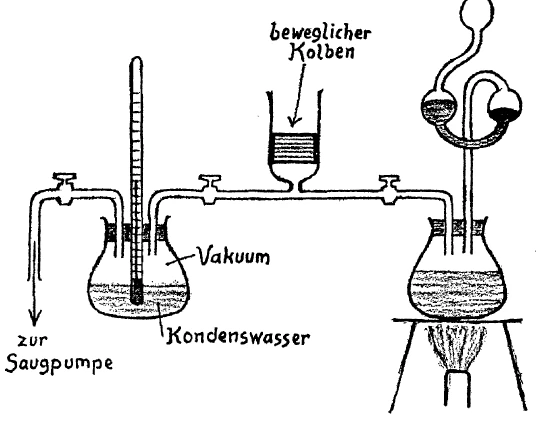

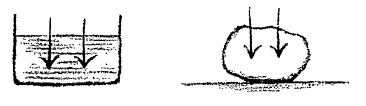

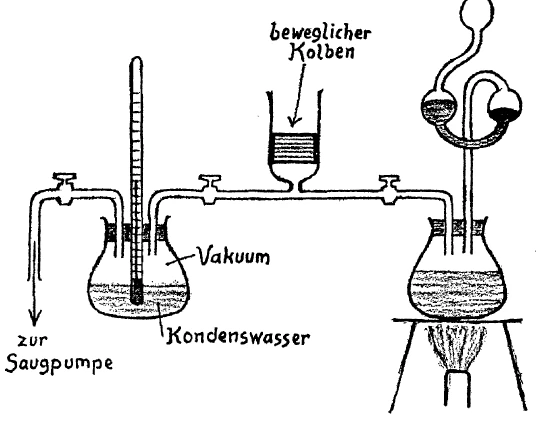

[ 2 ] Today we will do just the opposite. We showed yesterday that we must in some ways seek an explanation for the coming of heat into existence upon the expenditure of work. Now let us follow the reverse process. We will first of all heat this air (see Figures at end of Chapter) using a flame, raise the pressure of the vapor, and thus bring about a mechanical effect by means of heat, in a way similar to that by which all steam engines are moved. Heat is turned into work through pressure change. By letting the pressure come through from one side we raise the bell up and by letting the vapor cool, the pressure is lessened, the bell goes down again and we have performed mechanical work, consistive in this up and down movement. We can see the condensation water which reappears when we cool, and runs into this flask. After we have let the entire process take place, after the heat that we have produced here has transformed itself into work, let us determine whether this heat has been entirely transformed into the up and down movement of the bell or whether some of it has been lost. The heat not changed into work must appear as such in the water. In case of a complete transformation the condensation water would not show any rise in temperature. If there is a rise in temperature which we can determine by noting whether the thermometer shows a temperature above the ordinary, then this temperature rise comes from the heat we have supplied. In this case, we could not say that the heat has been completely changed over into work; there would be portion remaining over. Thus we can ascertain whether the whole of the heat has gone over into work or whether some of it appears as heat in the condensate. The water is 20° and we can see whether the condensate is 20° or shows a higher temperature indicating a loss of heat to this condensate. Now we condense the vapor; the condensate water drops in the flask. A machine can be run in this way. If the experiment succeeds fully, you may determine for yourselves that the condensate shows a considerable increase in temperature. In this way we can demonstrate, when we carry out the reverse of yesterday's experiment, that it is not possible to get back as mechanical work in the form of up and down movement of the bell all the heat left over. The heat used in producing work does not change completely, but a portion always remains.

We wish first to grasp this phenomenon. Now let us consider how ordinary physics and those who use ordinary physical principles handle these things.

[ 3 ] We have at the beginning to deal with the fact that we in fact do change heat into work and work into heat just as it is said we do. As previously stated an extension of this idea has been made. It is supposed that every form of so-called energy—heat energy, mechanical energy, and the experiment may be made with other forms—that all such energies are mutually changeable the one into the other. We will for the moment neglect the quantitative aspect of the transformation and consider only the fact. Now, the modern physicist says: It is therefore impossible for energy to arise anywhere except from energy of another sort already present. If I have a closed system of energy, let us say of a certain form, and another energy appears, then this must be considered as transformation of the energy already present in the closed system. In a closed system, energy can never appear except as a transformation product. Eduard von Hartmann, who, as I have said, expressed current physical views in the form of philosophical concepts, states the so-called first law of the mechanical theory of heat as follows: “A perpetuum mobile of the first kind is impossible.”

[ 4 ] Now we come to the second series of phenomena illustrated for us by today's experiment. This is that in an energy system apparently closed, we have one form of energy changing over to another form. In this transformation however, it is apparent that a certain law underlies the process and this law is related to the quality of the energy. In this case of heat energy, the relation is such that it cannot go over completely to mechanical energy, but there is always a certain amount unchanged. Thus it is impossible in a closed system to transform completely all the heat energy into its mechanical equivalent. If this were possible the reverse transformation of mechanical energy completely into heat energy would also be possible. We would then have in a closed energy system one type of energy transformed into another. This law is stated, again by Eduard von Hartmann, as follows: A closed energy system in which for instance, the entire amount of heat could be changed into work, or where work could be completely changed into heat, when a cycle of complete transformation could exist, this would be a perpetuum mobile of the second type. But, says he, a perpetuum mobile of the second type is impossible. Fundamentally, these two are the principle laws of the mechanical theory of heat as this theory is understood by thinkers in the realm of physics in the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century.

[ 5 ] “A perpetuum mobile of the first type is an impossibility.” This concept is intimately connected with the history of physics in the 19th century. The first person to call attention to this change of heat into other forms of energy or vice-versa was Julius Robert Mayer. He had observed, as a physician, that the venous blood showed a different behavior in the tropics and in the colder regions, and from this concluded that there was a different sort of physiological work involved in the human organism in the two cases. Using principally these experiences, he later presented a somewhat confused theory which as he worked it out meant little more than this, that it was possible to transform one type of energy into another. The matter was then taken up by various people, Helmholtz among others, and further developed. In the case of Helmholtz a characteristic form of physical-mechanical thinking was taken as the starting point for these things.

[ 6 ] If we consider the most important treatise by which Helmholtz sought to support the mechanical theory of heat in the forties of the 19th century, we see that such ideas as expressed by Hartmann are really postulated as their foundation. A perpetuum mobile of the first type is impossible. Since it is impossible the various forms of energy must be transformations of each other. No form of energy can arise from nothing. The axiom from which we proceed—“a perpetuum mobile of the first type is impossible”—can be changed into another: the sum of the energy in the universe is constant. Energy never is created, never disappears, it is only transformed. The sum of the energy in the universe is constant.

These two principles fundamentally, then, mean precisely the same thing. “There is no perpetuum mobile of the first type.” “The sum of all the energy in the cosmos is constant.” Now applying the method of thinking that we have used before in all our observations, let us throw a little light on this whole point of view.

[ 6 ] Note now, when we make an experiment with the object of transforming heat into what we call work, that some of the heat is lost so far as the transformation is concerned. Heat reappears as such and only a portion of it can be turned into the other energy form, the mechanical form. What we learn from this experiment we may apply to the cosmos. This is what the 19th century investigators did. They reasoned somewhat as follows: “In the world about us work is present and heat is present. Processes are continually going on by which heat is transformed into work. We see that heat must be present if we would produce work. Only recollect how great a part of our technical achievements rest on the fact that we produce work by the use of heat. But it always comes out that we cannot completely transform heat into work, a portion remains as heat. And since this is so, these remainders not capable of yielding work, accumulate. These non-transformable residues accumulate. And the universe approaches a condition in which all mechanical work will have been turned into heat.”

It has even been said that the universe in which we live is approaching what has been learnedly called its “warmth-death.” We will speak in coming lectures of the so-called entropy concept. For the present our interest lies in the fact that certain ideas have been drawn from experiment bearing on the fate of the universe in which we find ourselves.

[ 7 ] Eduard von Hartmann has presented the matter very neatly. He says: physical observation shows that the world-process in the midst of which we live, exhibits two sorts of phenomena. In the end, however, all mechanical work can be produced, and the universe will have to come to an end. Thus says Eduard von Hartmann; physical phenomena shows that the world process is running down. This is the way he expresses himself about the conditions within which we live. We live in a universe whose processes preserve us, but which has a tendency to become more and more sluggish and finally to lapse into a state of complete inaction. I am merely repeating Eduard von Hartmann's own words.

[ 8 ] Now we must make clear to ourselves the following point. Is there ever really the possibility of calling forth a series of processes in a closed system? Note well what I am saying. If I consider the totality of my experimental implements, I certainly am not myself in a vacuum, in empty space. And even when I believe myself to be standing in empty space, I am still not entirely certain but that this empty space is empty only because I am unable to perceive what is really in it. Do I therefore ever really carry out my experiments in a closed system? Is it not so that what I carry out in the simplest experiment has to be thought of as dovetailed into the world process immediately around me? Can I conceive of the matter otherwise than in this fashion, that when I do all these things it is as though I took a small needle and pricked myself here? When I prick myself here I experience pain which prevents me from having an idea that I would otherwise have had. It is quite certain indeed, that I cannot consider merely the prick of the needle and the reaction of the skin and muscles as the whole of the process. In such a case I would not be placing the whole process before my eyes. The process is not entirely contained in these factors. Imagine for a moment that I am so clumsy as to pick up a needle, prick myself and experience the pain. I will pull the needle away. What appears thus as an effect is very definitely not comprehended when I hold in mind only what goes on in the skin. The drawing back of the needle is in reality nothing other than a continuation of what I apprehend when I hold before my mind the first part of the process. If I wish to describe the whole process, I must take into account that I have not stuck the needle into my clothes, but into my organism. This organism must be considered as a regulating whole, calling forth the consequences of the needle prick.

[ 9 ] Is it legitimate for me to speak of an experiment such as we have before our eyes in the following way: “I have produced heat, and caused mechanical work. The heat not transformed remains over in the condensation water as heat.” It is not in this way that I stand in relation to the whole thing. The production or retention of heat, the passage of it into the condensation water are related to the reaction of the whole great system as the reaction of my whole organism is to the small activity of being pricked with the needle. What must be taken into account especially is: That it is never valid for me to consider an experimental procedure as a closed system. I must keep in mind that this whole experimental procedure falls under the influence of energies that work out of this environment.

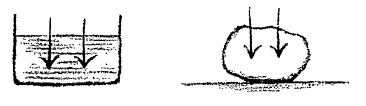

[ 10 ] Consider along with this another fact. Suppose you have to begin with a vessel containing a liquid with its liquid surface which implies an action of forces at right angles to this surface. Suppose now that through cooling, this liquid goes over into a solid state. It is impossible for you to think of the matter otherwise than that the forces in the liquid are short through by another set of forces. For the liquid forces are such as to make it imperative that I hold this liquid, say water, in a vessel. The only form assumed by the water on its own account is the upper surface. When by solidification a definite form arises it is absolutely necessary to assume that forces are added to those formerly present. More observation convinces us of it. And it is quite absurd to think that the forces creating the form are present in some way or other in the water itself. For if they were there they would create the form in the water. They are thus added to the system, but must have come into it from the outside. If we simply take the phenomenon as it is presented to us we are obliged to say: when a form appears, it represents as a matter of fact a new creation. If we simply consider what we can determine from observation we have to think of the form as a new creation. It is simply a matter of observation that we bring about the solid state from the fluid. We see that the form arises as a new creation. And this form disappears when we change the solid back into a liquid. One simply rests on that which is given as an observable fact. What follows now from this whole process when one makes it over into a concept? It follows that the solid seeks to make itself an independent unit, that it tends to build a closed system, that it enters into a struggle with its surroundings in order to become a closed system.

[ 11 ] I might put the matter in this way, that here in the solidification of a liquid we can actually lay our hands on nature's attempt to attain a perpetuum mobile. But the perpetuum mobile does not arise because the system is not left to itself but is worked upon by its whole environment. The view may therefore be advanced: in space as given us, there is always present the tendency for a perpetuum mobile to arise. But a counter tendency appears at once. We can therefore say that wherever the tendency arises to form a perpetuum mobile, the opposite tendency arises in the environment to prevent this. If you will orient your thinking in this way you will see that you have altered the abstract method of modern 19th century physics through and through. The latter starts from the proposition: a perpetuum mobile is impossible, therefore etc. etc. If one stands by the facts the matter has to be stated thus: a perpetuum mobile is always striving to arise. Only the constitution of the cosmos prevents it.

[ 12 ] And the form of the solid, what is it? It is the impress of the struggle. This structure that forms itself in the solid is the impress of the struggle between the substance as individuality which strives to form a perpetuum mobile and the hindrance to its formation by the great whole in which the perpetuum mobile seeks to arise. The form of a body is the result of opposition to this striving to form a perpetuum mobile. It might be better understood in some quarters if, instead of perpetuum mobile, I spoke of a self-contained unit, carrying its own forces within itself and its own form-creating power.

[ 13 ] Thus we arrive at a point where we have to reverse completely the entire point of view, the manner of thinking of 19th century physics. Physics itself, insofar as it rests on experiment, which deals with facts, we do not have to modify. The physical way of thinking works with concepts that are not valid and it cannot realize that nature strives universally for that which it holds as impossible. For this manner of thinking it is quite easy to consider the perpetuum mobile as impossible, but it is not impossible because of the abstract reasons advanced by the physicists. It is impossible because the instant the perpetuum mobile strives to establish itself in any given body, at that instant the environment becomes jealous, if I may borrow an expression from the realm of morals, and does not let the perpetuum mobile arise. It is impossible because of facts and not because of logic. You can appreciate how twisted a theory is that departs from reality in its very foundation postulate. If the facts are adhered to, it is not possible to get around what I presented to you yesterday in a preliminary sketchy way. We will elaborate this sketchy presentation in the next few days.

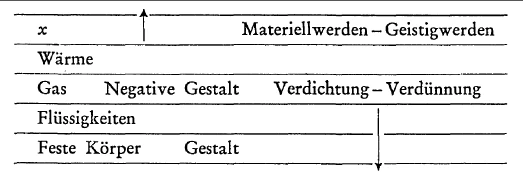

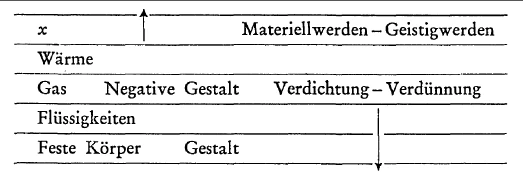

[ 14 ] I said to you: we have, to begin with, the realm of solids. Solids are the bodies which manifest in definite forms. We have, touching on the realm of the solids as it were, the realm of fluids. Form is dissolved, disappears, when solids become liquids. In the gaseous bodies we have a striving in all directions, a complete formlessness—negative form. Now how does this negative form manifest itself? If we look in an unbiased manner on gaseous or aeriform bodies we can see in these that which may be considered as corresponding to the entity elsewhere manifested as form. Yesterday I called your attention to the realm of acoustics, the tone world. In the gas, as you know, the manifestation of tone arises through condensations and rarefactions. But when we change the temperature we also have to do with condensation and rarefaction in the body of the gas as a whole. Thus if we pass over the liquid state and seek to find in the gas what corresponds to form in the solid, we must look for it in condensation and rarefaction. In the solid we have a definite form; in the gas, condensation and rarefaction.

| X | Materiality-Spirituality |

| Heat | |

| Gas—Negative Form | Condensation-rarefaction |

| Fluid | |

| Solids—Form |

[ 15 ] And now we pass to the realm next adjacent to the gaseous. Just as the fluid realm borders on the solid, and just as we know how the solid pictures the fluid, the fluid gives the foreshadowing of the gaseous, so the gas pictures the realm which we must conceive as lying next to the gaseous, i.e. the realm of heat. The realm lying next above heat, we will have to postulate for the time being and call it the X region.

If now, I seek to advance further, at first merely through analogy, I must look in this X region for something corresponding to but beyond condensation and rarefaction (this will be verified in our subsequent considerations.) I must look for something else there in the X region, passing over heat, just as we passed over the fluid state below. If you begin with a definitely formed body, then imagine it to become gaseous and by this process to have simply changed its original form into another manifesting as rarefaction and condensation and if then you think of the condensation and rarefaction as heightened in degree, what is the result? As long as condensation and rarefaction are present, obvious matter is still there. But now, if you rarefy further and further you finally pass entirely out of the realm of the material. And this extension we have spoken of must, if we are to be consistent, be made thus: a material-becoming—a spiritual-becoming. When you pass over the heat realm into the X realm you enter a region where you are obliged to speak of the condition in a certain way. Holding in mind this passage from solid to fluid and the condensation and rarefaction in gases you pass to a region of materiality and non-materiality. You cannot do other than enter the region of materiality and non-materiality. Stated otherwise: when we pass through the heat realm we actually enter a realm which is in a sense a consistent extension of what we have observed in the realms beneath it. Solids oppose heat—it cannot come to complete expression in them. Fluids are more susceptible to its action. In gases there is a thorough-going manifestation of heat—it plays through them without hindrance. They are in their material behavior a complete picture of heat. I can state it thus: the gas is in its material behavior essentially similar to the heat entity. The degree of similarity between matter and heat becomes greater and greater as I pass from solids through fluids to gases. Or, liquefaction and evaporation of matter means a becoming similar of this matter to heat. Passage through the heat realm, however, where matter becomes, so to speak, identical with heat leads to a condition where matter ceases to be. Heat thus stands between two strongly contrasted regions, essentially different from each other, the spiritual world and the material world. Between these two stands the realm of heat. This transition zone is really somewhat difficult for us. We have on the one hand to climb to a region where things appear more and more spiritualized, and on the other side to descend into what appears more and more material. Infinite extension upwards appears on the one hand and infinite extension downward on the other. (Indicated by arrows.)

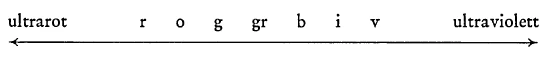

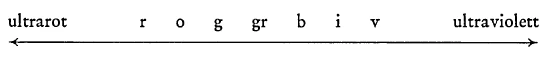

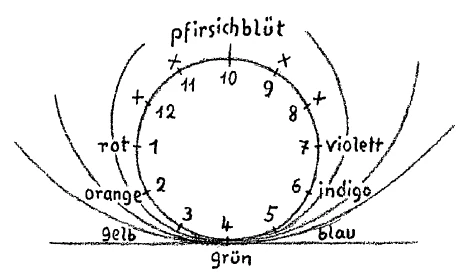

[ 16 ] But now we use another analogy that I am bringing before you today because through a general view of individual natural facts a sound science may be developed. It will perhaps be useful to array these facts before our souls. (See below.) If you observe the usual spectrum you have red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet.

Infra red——————————roygrbiv——————————Ultra Violet

[ 17 ] You have the colors following each other in a series of approximately seven nuances. But you know that the spectrum does not break off at either end. If we follow it further below the red we come to a region where there is more and more heat, and finally we arrive at a region where there is no light, but only heat, the infra red region. On the other side of the violet, also, we no longer have light. We come to the ultra violet where chemical action is manifested, or in other words effects that manifest themselves in matter.

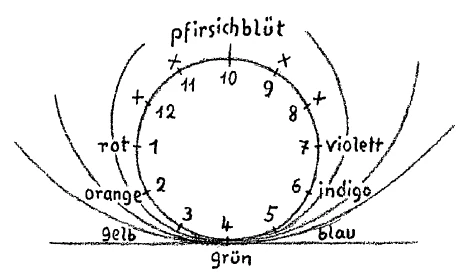

[ 18 ] But you know also that according to the color theory of Goethe, this series of colors can be bent into a circle, and arranged in such a way that one sees not only the light from which the spectrum is formed, but also the darkness from which it is formed. In this case the color in the middle is not green but the peach-blossom color, and the other colors proceed from this. When I observe darkness I obtain the negative spectrum. And if I place the two spectra together, I have 12 colors that may be definitely arranged in a circle: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. On this side the violet becomes ever more and more similar to the peach blossom and there are two nuances between. On the other side there are two nuances between peach blossom and red. You have, if I may employ the expression, 12 color conditions in all. This shows that what is usually called the spectrum can be thought of as arising in this way: I can by any suitable means bring about this circle of color and can make it larger and larger, stretching out the upper five colors (peach blossom and the two shades on each side) until they finally disappear. The lower arc becomes practically a straight line, and I obtain the ordinary spectrum array of colors, having brought about the disappearance of the upper five colors.

[ 19 ] I finally bring these colors to the vanishing point. May it not be that the going off into infinity is somewhat similar to this thing that I have done to the spectrum? Suppose I ask what happens if that which apparently goes off into infinity is made into a circle and returns on itself. May I not be dealing here with another kind of spectrum that comprehends for me on the one hand the condition extending from heat to matter, but that I can close up into a circle as I did the color spectrum with the peach blossom color? We will consider this train of thought further tomorrow.

Achter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Wir haben gestern das Experiment gemacht, das zeigen soll nach den gebräuchlichen Anschauungen, wie sich mechanische Arbeit, die wir hervorgerufen haben, indem wir ein Schaufelrad zur Drehung und damit zur Reibung an einer Wassermasse gebracht haben, in Wärme umwandelt. Wir haben Ihnen gezeigt, daß das Wasser, an dem sich das Schaufelrad rieb, wärmer wurde.

[ 2 ] Heute wollen wir gewissermaßen das Umgekehrte machen. Wir haben gestern gezeigt, daß irgendwie gesucht werden muß eine Erklärung dafür, daß, wenn wir jetzt die Tatsachen besser aussprechen als durch den Gedanken der bloßen Verwandlung, unter dem Einfluß einer geleisteten Arbeit Wärme entstehen kann. Jetzt wollen wir einen umgekehrten Vorgang verfolgen. Wir wollen hier zunächst Dampf erzeugen, wollen also richtig auf dem Weg eines Verbrennungsprozesses Druck erzeugen, Spannung hervorrufen — also ein Mechanisches aus der Wärme — und wollen nach demselben Prinzip, nach dem alle Dampfmaschinen bewegt werden, umsetzen diese Wärme auf dem Umweg des Druckes in mechanische Arbeit. Dadurch, daß wir den Druck wirken lassen nach der einen Seite hier auf die Fläche unten, dadurch wird dieser Kolben hier in die Höhe getrieben (siehe Zeichnung Seite 118). Dadurch, daß wir wiederum abkühlen den Dampf, wird der Druck vermindert, der Kolben geht wiederum zurück, und wir bekommen die mechanische Arbeit, die auf- und absteigende Bewegung. Wir werden dabei verfolgen können, wie das Wasser, das wiederum entsteht, wenn wir hier abkühlen, das Kondensationswasser, in dieses Gefäß hineingeht, und wir werden dann untersuchen, ob nun, nachdem wir den ganzen Vorgang sich haben abwickeln lassen, die Wärme, die wir hier erzeugt haben, sich ganz umgewandelt hat in solche Arbeit, in die Arbeit des Auf-und-Abbewegens dieses Kolbens, oder ob uns irgendwie eine Wärme verlorengegangen ist. Die Wärme, die verlorengeht, die sich nicht umwandelt, würde in der Hitze des Wassers erscheinen müssen. Es würde dann das Kondensationswasser in dem Fall, wo die ganze beweglicher Wärme verwendet wird zur Erzeugung von mechanischer Arbeit, unfähig sein, eine Erhöhung der "Temperatur aufzuzeigen. Findet eine Erhöhung der’ Temperatur statt, das heißt, können wir an diesem Thermometer konstatieren, daß das Wasser über die gewöhnliche Temperatur erwärmt ist, dann rührt diese Erwärmung her von der Wärme, die wir angewendet haben. Dann hat sich nicht die ganze Wärme in Arbeit verwandelt, wir waren nicht imstande dazu, es ist noch etwas übriggeblieben. Wir wollen also konstatieren, ob die ganze Wärme in Arbeit verwandelt werden kann, oder noch etwas übrigbleibt und sich an der Erwärmtheit des Kondensationswassers zeigt. Das Wasser hat 20°, wir werden dann sehen, ob das Kondensationswasser wirklich bis 20° abgekühlt ist, also alle Wärme zur Arbeit verwendet wird, oder ob die Temperatur dieses Kondensationswassers steigt und dadurch Wärme verlorengehen würde. Jetzt kondensieren wir den Dampf, das Kondenswasser tropft hinüber, und auf diese Art kann natürlich jetzt eine Maschine getrieben werden. Wenn der Versuch vollständig gelingt, können Sie sicher sein, daß das Kondenswasser hier eine wesentliche Erhöhung der Temperatur aufzeigt, und es ist dieses der Weg, auf dem man zeigen kann, daß, wenn man den zum gestrigen umgekehrten Versuch macht, Wärme überzuführen in mechanische Arbeit, die eben darin besteht, daß der Kolben sich auf und ab bewegt, daß es dann unmöglich ist, alle Wärme, die man erzeugt hat, vollständig in mechanische Arbeit überzuführen; daß, wenn Wärme in mechanische Arbeit übergeführt wird, immer Wärme zurückbleibt, daß wir also in jeder solchen zur Erzeugung mechanischer Arbeit verwendeten Wärme einen Teil haben, der als Rest bleibt, sich nicht umwandeln läßt in mechanische Arbeit. Wir wollen zunächst auch hier nur die Erscheinung festhalten, aber jetzt uns die Gedanken vorführen, welche sich die gebräuchliche Physik und diejenigen, die auf ihr mit ihren Anschauungen fußen, über die ganze Sache machen.

[ 3 ] Wir haben es zunächst mit der ersten Tatsache zu tun, daß wir überhaupt verwandeln können, wie man sagt, Wärme in mechanische Arbeit, und mechanische Arbeit in Wärme. Daraus hat sich, wie ich ja schon erwähnte, die Ansicht gebildet, daß jede solche Form von sogenannter Energie — Wärmeenergie, mechanische Energie, und man könnte das Experiment auch für andere Energien machen - in eine andere sich umwandeln läßt. Von dem Maße der Umwandlung wollen wir jetzt absehen, und nur an der Tatsache festhalten. Nun sagt der gegenwärtige physikalische Denker: Es ist also unmöglich, daß, wenn irgendwo eine Energie erscheint, eine Kraftwirkung erscheint, diese von irgend etwas anderem herkommt als von einer schon vorhandenen anderen Energie. Wenn ich also irgendwo ein in sich geschlossenes System von Energien habe, zunächst von Energien einer bestimmten Form, und es treten andere Energien mit auf, so müssen diese die Umwandlung der schon vorhandenen Energien des geschlossenen Systems sein. Nirgends kann in einem geschlossenen System eine Energie anders denn als Umwandlungsprodukt erscheinen. Eduard von Hartmann, der, wie ich schon angedeutet habe, die gegenwärtigen physikalischen Ansichten in seine philosophischen Begriffe faßt, hat diesen sogenannten ersten Satz der mechanischen Wärmetheorie ausgesprochen mit den Worten: «Ein Perpetuum mobile der ersten Art ist eine Unmöglichkeit.» Was wäre ein Perpetuum mobile der ersten Art? Ein Perpetuum mobile der ersten Art wäre eben eine Einrichtung, wodurch eine Energie als solche in einem geschlossenen Energiesystem entstehen würde. So daß also Eduard von Hartmann die hierauf bezügliche Tatsachenreihe eben dahin zusammenfaßt, daß er sagt: «Ein Perpetuum mobile der ersten Art ist eine Unmöglichkeit.»

[ 4 ] Nun kommen wir zu der zweiten Tatsachenreihe, die sich uns durch das heutige Experiment veranschaulicht hat: Wir können in einem in sich scheinbar geschlossenen System von Energien die eine Energie in die andere umwandeln. Dabei zeigt sich, daß die Umwandlung aber doch gewissen Gesetzmäßigkeiten unterliegt, die mit der Qualität der Energien zusammenhängen, und zwar so, daß eben Wärmeenergie sich nicht ohne weiteres ganz umwandeln läßt in mechanische Energien, sondern immer ein Rest bleibt. So daß es also unmöglich ist, Wärmeenergie in einem geschlossenen System so in mechanische Energie umzuwandeln, daß nun wirklich alle Wärme als mechanische Energie erscheint. Würde man dies erreichen können, daß alle Wärme als mechanische Energie erscheint, dann würde man wiederum die mechanische Energie umwandeln können in Wärme. Es würde möglich sein, daß in einem solchen geschlossenen System eine Energiequalität in die andere sich umwandeln würde. Man würde damit die Möglichkeit geboten haben, immer das eine in das andere umzuwandeln. Eduard von Hartmann drückt wiederum diesen Satz so aus, daß er sagt: Ein solches geschlossenes System, in dem man zum Beispiel die ganze vorhandene Wärme umwandeln könnte in mechanische Arbeit, wo man mechanische Arbeit wiederum umwandeln könnte in Wärme, wo also ein Kreislauf entsteht, wäre ein Perpetuum mobile der zweiten Art. Aber auch ein solches Perpetuum mobile der zweiten Art ist eine Unmöglichkeit, sagt er, und dies sind im Grunde genommen für die Denker des 19. Jahrhunderts und des angehenden 20. Jahrhunderts auf dem Gebiete der Physik die zwei Hauptsätze der sogenannten mechanischen Wärmelehre:

[ 5 ] «Ein Perpetuum mobile der ersten Art ist eine Unmöglichkeit.» «Ein Perpetuum mobile der zweiten Art ist eine Unmöglichkeit.» Die Sache hängt sogar mit der Geschichte der Physik im 19. Jahrhundert zusammen. Der erste, der aufmerksam gemacht hat auf diese scheinbare Umwandlung des Wärmewesens in andere Energieformen oder anderer Energieformen in Wärme, das war ja Julius Robert Mayer, der im wesentlichen aufmerksam geworden ist auf den Zusammenhang zwischen Wärme und anderen Energieformen als Arzt, indem er in der heißen Zone eine andere Beschaffenheit des venösen Blutes bemerkt hat als in der kalten Zone und daraus schloß auf eine andere Art der physiologischen Arbeit in dem einen und in dem anderen Falle beim menschlichen Organismus. Er hat dann hauptsächlich aus diesen seinen Erfahrungen, die er vermehrt hat, später eine etwas verwuselte Theorie aufgestellt, und bei ihm hat eigentlich diese "Theorie noch keinen andcren Umfang als den: Man könne entstehen lassen aus der einen Energieform die andere. — Dann ist die Sache von verschiedenen anderen Leuten, unter anderen von Helmboltz, weiter ausgearbeitet worden. Schon bei Helmholtz tritt nun eine eigentümliche Form des physikalisch-mechanischen Denkens als Ausgangspunkt der ganzen Betrachtung auf. Nimmt man gerade die wichtigste Abhandlung von Helmholtz, durch die er die mechanische. Wärmetheorie zu stützen versucht in den vierziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts, so liegt diese schon und zwar als Postulat — dem Hartmannschen Gedanken zugrunde: Ein Perpetuum mobile der ersten Art ist eine Unmöglichkeit; weil ein Perpetuum mobile unmöglich ist, müssen die verschiedenen Energiearten nur Umwandlungen voneinander sein, es kann niemals eine Energieform aus dem Nichts entstehen. Man kann den Satz, von dem man ausgeht als einem Axiom: Ein Perpetuum mobile der ersten Art ist eine Unmöglichkeit -, umwandeln in den anderen: Die Summe der Energien im Weltensystem ist konstant. Es entsteht niemals eine Energie, es vergeht niemals eine Energie. Es verwandeln sich nur die Energien. Die Summe der Energien im Weltensystem ist konstant. — Die beiden Sätze

«Es gibt kein Perpetuum mobile der ersten Art.»

«Die Summe aller Energien im Weltenall ist konstant.»

enthalten im Grunde genommen genau dasselbe. Nun, darum handelt es sich, daß wir mit der Denkweise, die wir schon angewendet haben bei all unseren Betrachtungen, einmal in diese ganze Anschauungsart ein wenig hineinleuchten.

[ 6 ] Man sieht hier an einem solchen Experiment, daß, wenn man den Versuch macht, Wärme in sogenannte Arbeit umzuwandeln, dann Wärme gewissermaßen für die Umwandlung in Arbeit verlorengeht, daß Wärme wieder erscheint, daß also nur ein Teil der Wärme in Arbeit, in eine andere Energie, in mechanische Energieformen, umgewandelt werden kann. Man kann dann das, was man daran sieht, auf das Weltenall anwenden. Das ist auch geschehen von den Denkern des 19. Jahrhunderts. Etwa so sagten sich diese Denker: In der Welt, in der uns vorliegenden Welt, in der wir leben, ist mechanische Arbeit vorhanden, ist Wärme vorhanden. Fortwährend geschehen Prozesse, durch die Wärme in mechanische Arbeit umgewandelt wird. Wir sehen, daß Wärme da sein muß, damit wir überhaupt mechanische Arbeit erzeugen können. Denken Sie nur einmal, wie wir einen großen Teil unserer Technik darauf eben gestützt haben, daß wir aus der ursprünglichen Verwendung von Wärme mechanische Arbeit zutage treten lassen. Aber dabei wird sich immer zeigen, daß wir Wärme niemals vollständig umwandeln können in mechanische Arbeit, daß immer ein Rest bleibt. Und wenn das so ist, müssen sich diese Reste so summieren, daß keine mechanische Arbeit mehr geleistet werden kann, daß wir einfach nicht mehr zurückverwandeln können die Wärme in mechanische Arbeit. Die Reste der unverwendbaren Wärme summieren sich, und das Weltenall geht entgegen jenem Zustand, in dem sich alle mechanische Arbeit in Wärme verwandelt haben wird. Man hat auch gesagt, das Weltenall, in dem wir leben, geht seinem Wärmetod entgegen, wie man es auch etwas gelehrter nennen kann. Über den sogenannten Entropiebegriff wollen wir in einer der kommenden Betrachtungen noch sprechen. Jetzt interessiert uns zunächst, daß man hier aus einem Experiment heraus Gedanken schöpfte über den Gang unseres zunächst für den Menschen in Betracht kommenden Weltenalls.

[ 7 ] Eduard von Hartmann hat die Sache nett ausgeführt, indem er sagt: Man sieht also — physikalisch beweisbar -, daß der Weltenprozeß, in dem wir leben, zunächst dadurch verläuft, daß in ihm Vorgänge sind: auf der einen Seite Wärmeprozesse, auf der anderen Seite mechanische Prozesse, daß aber zuletzt alle mechanischen Prozesse übergehen werden in Wärmeprozesse. Dann wird keine mechanische Arbeit mehr geleistet werden können. Das Weltenall ist an seinem Ende angekommen. Es zeigen uns also die physikalischen Erscheinungen, sagt Eduard von Hartmann, daß der Weltenprozeß ausbummelt. Dieses ist seine Art, über die Vorgänge, innerhalb welcher wir leben, sich auszusprechen. Wir leben also in einem Weltenall, das uns durch seine Prozesse erhält, aber darin besteht die Tendenz, immer bummliger zu werden und zuletzt ganz auszubummeln — ich wiederhole nur Eduard von Hartmanns eigene Worte.

[ 8 ] Nun müssen wir uns aber über das Folgende klar werden: Gibt es denn irgend so etwas wie die Möglichkeit, in einem geschlossenen System eine Summe von Prozessen hervorzurufen? Merken Sie wohl, was ich sage: Wenn ich an der Summe meiner Experimentierwerkzeuge stehe, so stehe ich doch wahrlich nicht im Vakuum, im leeren Raum, und selbst dann, wenn ich glauben könnte, daß ich im leeren Raum stehe, bin ich ja noch nicht ganz sicher, ob nicht dieser leere Raum sich nur dadurch als leer zeigt, daß ich zunächst nicht wahrnehme, was in ihm noch drinnen ist. Stehe ich denn jemals mit meinem Experimentieren innerhalb irgendeines geschlossenen Systems? Ist denn nicht dasjenige, was ich selbst im einfachsten Experiment verrichte, ein Eingriff in den gesamten Prozeß des Weltenalls, das mich zunächst umgibt? Darf ich anders vorstellen, wenn ich zum Beispiel hier diese ganze Sache mache, als daß das in dem Zusammenhang des ganzen Weltenprozesses etwas Ähnliches ist, wie wenn ich eine kleine Nadel nehme und mich hier steche? Wenn ich hier steche, empfinde ich einen Schmerz, der hält mich ab, einen Gedanken zu fassen, den ich sonst erfaßt hätte. Aber ganz gewiß darf ich nicht, wenn ich das, was hier geschieht, in seinem ganzen Zusammenhang betrachten will, bloß den Druck der Nadel und die Lädierung der Haut, der Muskeln ins Auge fassen, denn ich würde ja dadurch nicht den ganzen Prozeß ins Auge fassen. Der Prozeß ist damit nicht erschöpft. Denken Sie einmal, ich nehme durch eine Ungeschicklichkeit eine Nadel, steche mich, spüre den Schmerz. Ich werde abrücken. Das, was da auftritt als eine Wirkung, das ist doch ganz entschieden nicht zu erfassen, wenn ich bloß dasjenige, was hier in diesem Hautteil vor sich geht, ins Auge fasse. Und dennoch ist das Abrücken von der Nadel nichts weiter als eine Fortsetzung derjenigen Prozesse, die ich beschreibe, wenn ich eben nur den ersten Teil ins Auge fasse. Wenn ich den ganzen Prozeß beschreiben will, muß ich Rücksicht nehmen darauf, daß ich da mit meiner Nadel nicht in die Kleider gestochen habe, sondern in den Organismus, den ich als Ganzes aufzufassen habe, der seinerseits wiederum reagiert als ganzer Organismus und als solcher dasjenige hervorruft, was dann die Folge des ersten ist.

[ 9 ] Darf ich ohne weiteres hier, indem ich solch ein Experiment mir vor Augen stelle, sagen: Ich habe erwärmt, mechanische Arbeit hervorgerufen, die Wärme, die da übriggeblieben ist im Kondensationswasser, die ist eben übriggeblieben durch sich selbst? Ich stehe ja nicht mit der ganzen Einrichtung hier so im Zusammenhang, wie wenn ich sie da (in den Finger) eingebohrt hätte. Es könnte ja die Entstehung oder das Behalten der Wärme, das Auftreten im Kondensationswasser, zusammenhängen mit der Reaktion des ganzen großen Systems auf den Prozeß hier, wie mein Organismus reagiert auf den kleinen Prozeß des Stechens der Nadel. Dasjenige, was ich also vor allen Dingen zu berücksichtigen habe, ist: Daß ich niemals die Experimentalanordnung als ein geschlossenes System ansehen darf, sondern mir bewußt bleiben muß, daß diese ganze Experimentalanordnung unter den Einflüssen der Umgebung steht und auch der Energien, die eventuell aus dieser Umgebung wirken.

[ 10 ] Halten Sie mit diesem nun ein anderes zusammen: Nehmen Sie an, Sie haben zunächst wieder im Gefäß eine Flüssigkeit mit der Niveaufläche, wodurch Sie voraussetzen Kraftwirkung senkrecht auf die Niveaufläche. Denken Sie nun, es gehe diese Flüssigkeit durch Abkühlung in einen gestalteten festen Körper über. Es ist ganz unmöglich, daß Sie sich jetzt nicht denken, daß diese Richtungen hier, diese Kraftrichtungen nicht von einer anderen in irgendeiner Weise durchkreuzt werden. Denn diese Kraftrichtungen bewirken ja eben, daß ich das Wasser in einem Gefäß aufbewahren muß, daß nur durch die Niveaufläche die Form des Wassers da ist. Wenn nun bei der Verfestigung eine geschlossene, gestaltete Form entsteht, ist es unbedingt notwendig, vorauszusetzen, daß nun Kräfte hinzutreten zu denen, die früher vorhanden waren. Das liefert die unmittelbare Anschauung, daß da Kräfte hinzutreten zu denen, die früher vorhanden waren. Und zunächst ist der Gedanke ganz absurd, zu glauben, daß jene Kräfte die Gestalt bewirken, die irgendwie schon im Wasser drinnen gewesen wären, denn sie hätten ja sonst, wenn sie drinnen gewesen wären, im Wasser die Gestalt bewirken müssen. Sie sind also aufgetreten. Sie können nicht im Wassersystem enthalten gewesen sein, sie müssen von außerhalb des Wassersystems an dieses herangekommen sein. Nehmen wir daher die Erscheinung so, wie sie ist, so müssen wir sagen: Wenn irgendwo eine Gestalt auftritt, so tritt sie tatsächlich als eine Neuschöpfung auf. Bleiben wir nur innerhalb desjenigen, was wir anschaulich konstatieren können, so tritt die Gestalt als eine Neuschöpfung auf. Wir sehen es ja förmlich anschaulich, wenn wir aus einer Flüssigkeit einen festen Körper entstehen lassen. Die Gestalt tritt anschaulich auf als Neuschöpfung, und sie wird wieder aufgehoben, wenn wir den Körper in eine flüssige Form umwandeln. Man fasse nur so etwas einmal auf nach dem, was die Anschauung liefert. Was folgt denn aus dem ganzen Vorgang, wenn man wirklich das Anschauliche in einen Begriff umwandelt? Es folgt daraus, daß sich der feste Körper selbständig zu machen versucht, daß er versucht, in sich ein geschlossenes System zu bilden, daß er einen Kampf mit seiner Umgebung eingeht, um ein geschlossenes System zu werden.

[ 11 ] Ich möchte sagen, man kann es hier mit Händen greifen, daß hier durch die Verfestigung des Flüssigen der Versuch der Natur vorliegt, zu einem Perpetuum mobile zu kommen. Das Perpetuum mobile entsteht nur nicht, weil das System sich nicht selbst überlassen wird, weil die ganze Umgebung darauf wirkt. So können Sie zu der Anschauung vorrücken: In unserem uns gegebenen Raum ist fortwährend an den verschiedenen Punkten die Tendenz vorhanden zur Entstehung eines Perpetuum mobile. Aber sofort entsteht gegen diese Tendenz eine Gegentendenz. So daß wir sagen können: Wenn irgendwo die Tendenz entsteht, ein Perpetuum mobile zu bilden, so bildet sich in der Umgebung die Gegentendenz, die Entstehung des Perpetuum mobile zu verhindern. Wenn Sie die Denkweise so orientieren, dann modifizieren Sie die abstrakte Denkweise der modernen Physik des 19. Jahrhunderts ganz und gar. Die geht davon aus: Ein Perpetuum mobile ist unmöglich, daher — und so weiter. Wenn man in der Tatsachenwelt stehen bleibt, muß man sagen: Ein Perpetuum mobile will fortwährend entstehen. Nur die Konstitution des Weltenalls verhindert dies.

[ 12 ] Und die Gestalt eines festen Körpers, was ist sie? Sie ist der Ausdruck des Kampfes. Dieses Bild, das sich im festen Körper bildet, das ist der Ausdruck des Kampfes zwischen der Substanz als Individualität, die ein Perpetuum mobile bilden will, und der Verhinderung der Bildung des Perpetuum mobile durch das ganze All, das relative All, in dem sich dieses Perpetuum mobile bilden will. Die Gestalt eines Körpers ist das Resultat der Verhinderung dieses Strebens, ein Perpetuum mobile zu werden, ich könnte auch sagen statt Perpetuum mobile, weil das vielleicht da oder dort besser gefallen würde, eine Monade, ein in sich selbst geschlossenes, seine eigenen Kräfte in sich tragendes und seine Form erzeugendes Körperwesen.

[ 13 ] Wir kommen, und hier liegt ein entscheidender Punkt, geradezu dazu, umzukehren den ganzen Ausgangspunkt nicht der Physik, insofern sie Experimente liefert, die auf Tatsachen beruhen, sondern der ganzen physikalischen Denkweise des 19. Jahrhunderts. Sie arbeitete mit ungültigen Begriffen. Sie konnte nicht sehen, wie in der Natur doch das Streben überall vorlag nach dem, was sie für unmöglich hielt. Es war dieser Denkweise verhältnismäßig leicht, es für unmöglich zu erklären, aber es ist nicht aus dem abstrakten Grunde unmöglich, aus dem heraus die Physiker angenommen haben, das Perpetuum mobile sei unmöglich, sondern es ist deshalb unmöglich, weil in dem Augenblick, wo es entstehen soll an irgendeinem Körper, sogleich die Umgebung den Neid empfindet — wenn ich jetzt einen Ausdruck moralischer Art anwenden darf - und das Perpetuum mobile nicht entstehen läßt. Es ist aus einer Tatsachengrundlage, nicht aus einer logischen Grundlage heraus unmöglich. Sie können sich denken, wieviel Verkehrtheiten in einer Theorie stecken müssen, die abseits von der Wirklichkeit gerade ihre Grundpostulate aufstellt. Wenn man bei der Wirklichkeit stehen bleibt, kommt man eben nicht herum um dasjenige, was ich Ihnen gestern zunächst im Schema anführte. Wir werden dieses Schema in den nächsten Tagen noch weiter ausarbeiten.

[ 14 ] Ich sagte Ihnen: Wir haben zunächst das Gebiet der festen Körper. Diese festen Körper sind diejenigen, welche in sich feste Gestalten zeigen. Wir haben gewissermaßen anstoßend an das Gebiet der festen Körper das Gebiet der Flüssigkeiten. Die Gestalten lösen sich auf, verschwinden, wenn der feste Körper in die Flüssigkeit übergeht. Wir haben den vollen Gegensatz zum Festen in dem Auseinanderstreben, in dem Die-Gestalt-Aufheben des gasförmigen Körpers: negative Gestalt. Wie aber äußert sich denn diese negative Gestalt? Sehen wir vorurteilslos auf gasige oder luftförmige Körper hin, betrachten wir sie zum Beispiel da, wo sich bei ihnen zeigt, wie wahrnehmbar werden kann dasjenige, was bei ihnen der Gestalt entspricht. Ich habe Sie gestern hingewiesen auf das Gebiet der Akustik, der Tonwelt. Sie wissen, im Gasigen beruht das Tönende in seinem Entstehen auf den Verdichtungen und Verdünnungen. Mit Verdichtung und Verdünnung haben wir es aber auch beim ganzen Gas zu tun, wenn wir die Temperatur ändern. Suchen wir also, indem wir die Flüssigkeit überspringen, dasjenige, was dem bestimmt Gestalteten des festen Körpers im Gase entspricht, so müssen wir es suchen bei der Verdichtung und Verdünnung. Im festen Körper haben wir die bestimmte Gestalt; im Gas haben wir Verdichtung und Verdünnung.

[ 15 ] Und kommen wir zu dem, was das an das Gas angrenzende Gebiet ist, das wie die Flüssigkeit an das Gebiet der festen Körper angrenzt — und wir wissen ja: Wie die festen Körper das Bild der Flüssigkeit geben, die Flüssigkeit das Bild der Gase in ihrer Gesamtheit, so die Gase das Bild der Wärme -, so haben wir uns das Gebiet der Wärme als das nächste vorzustellen. Als nächstes Gebiet werde ich mir zunächst ein x zu postulieren haben. Und wenn ich zunächst nur durch Analogie — wir werden sie verifizieren in den nächsten Betrachtungen — weiterzukommen versuche, so muß ich statt Verdichtung und Verdünnung etwas weiteres suchen in diesem x-Gebiet drinnen. Ich muß für Verdichtung und Verdünnung etwas Entsprechendes in dem x suchen (mit Überspringung der Wärme), wie ich hier (unten) auch das Flüssige übersprungen habe. Wenn Sie zuerst eine feste, geschlossene Gestalt haben, dann dazu kommen, daß beim Körper, der gasig ist, sich das Gestaltete nur noch im flüssig Gestalteten der Verdichtung und Verdünnung ausdrückt, und Sie denken sich gesteigert die Verdichtung und Verdünnung, was muß denn da werden? Solange Verdichtung und Verdünnung da ist, ist natürlich noch immer Materie da. Aber wenn Sie nun weiter verdünnen und immer weiter verdünnen, so kommen Sie ja zuletzt aus dem Gebiet des Materiellen heraus. Und Sie müssen als die weitere Fortsetzung, einfach indem Sie in dem Charakter des Ganzen bleiben, sagen: materiell werden — geistig werden. Sie kommen, indem Sie über das Gebiet der Wärme hinaufsteigen, in das x hinein; Sie kommen, einfach wenn Sie festhalten den Charakter, der da liegt im Übergang von der festen Gestalt in die flüssige Gestalt, vom Verdichten und Verdünnen in das Materiesein und Nicht-Materiesein hinein. Sie können nicht anders, als von Materiesein und Nicht-Materiesein zu sprechen. Das heißt: Wir kommen, indem wir durch das Gebiet der Wärme durchschreiten, tatsächlich in etwas hinein, was sich in gewissem Sinne als eine gerechte Fortsetzung erweist dessen, was wir in den unteren Gebieten beobachtet haben. Der feste Körper widerstrebt der Wärme, die Wärme wird mit ihm nicht recht fertig. Der flüssige Körper geht schon mehr auf die Intentionen der Wärme ein. Das Gas folgt ganz und gar den Intentionen der Wärme, es läßt mit sich machen, was die Wärme mit ihm machen will, es ist in seinen materiellen Vorgängen ganz und gar ein Bild des Wärmewesens selber. Ich kann sagen: Das Gas ist im wesentlichen in seinem eigenen substantiellen Verhalten dem Wärmewesen ähnlich. Der Ähnlichkeitsgrad der Materie mit der Wärme wird immer größer, je weiter ich vorschreite vom festen Körper durch den flüssigen Körper zum Gas. Das heißt: Flüssigwerden und Verdampfen der Materie bedeutet ein Ähnlichwerden der Materie mit der Wärme. Aber indem ich dann das Gebiet der Wärme überschreite, indem also die Materie gewissermaßen ganz der Wärme ähnlich wird, hebt sie sich selber auf. So stellt sich für mich die Wärme hinein zwischen zwei sehr stark voneinander verschiedene Gebiete, die essentiell verschieden sind: das Geistgebiet und das Materiegebiet. Zwischen drinnen steht das Wärmegebiet. Nur wird uns jetzt der Übergang in die Realität etwas schwierig, denn wir haben auf der einen Seite da hinaufzusteigen in das, wo es immer geistiger zu werden scheint, und auf der anderen Seite da hinunter, wo es scheint immer materieller zu werden. Und da geht es scheinbar in die Unendlichkeit hinauf, in die Unendlichkeit hinunter (siehe Pfeile im Schema).

[ 16 ] Aber nun bietet sich eine andere Analogie, die ich Ihnen heute noch hinzeichne aus dem Grunde, weil durch anschauliche Verfolgung der einzelnen Naturtatsachen sich in der Tat eine gesunde Naturwissenschaft entwickeln kann und es vielleicht nützlich sein kann, die Sache sich einmal durch die Seele ziehen zu lassen. Wenn Sie das Spektrum, wie es gewöhnlich entsteht, betrachten, so haben Sie Rot, Orange, Gelb, Grün, Blau, Indigo, Violett.

[ 17 ] Sie haben die Farbenreihe in ungefähr sieben Nuancen wie in einem Bande nebeneinander verlaufend. Aber Sie wissen ja auch, daß das Spektrum hier nicht ein Ende hat und auch hier nicht, daß wir hier (links), indem wir das Spektrum verfolgen, zu immer wärmeren und wärmeren Gebieten kommen und zuletzt ein Gebiet haben, wo nicht mehr Licht, wohl aber noch Wärme auftritt, das ultrarote Gebiet. Jenseits des Violett haben wir auch kein Licht mehr, wir bekommen das Ultraviolett, das nur noch chemische, das heißt also materielle Wirkungen entfaltet.

[ 18 ] Aber Sie wissen ja auf der anderen Seite, daß im Sinne der Goetheschen Farbenlehre diese Linie hier dadurch zu einem Kreis gemacht werden kann und man die Farben anders anordnen kann, daß man nun nicht bloß betrachtet das Verhalten des Lichtes, aus dem ein Spektrum sich bildet, sondern betrachtet die Dunkelheit, aus der ein Spektrum sich bildet, das dann in der Mitte nicht Grün, sondern Pfirsichblüte hat und von da ausgehend die anderen Farben. Ich bekomme, wenn ich die Dunkelheit betrachte, das negative Spektrum. Und stelle ich die beiden Spektren zusammen, so bekomme ich zwölf Farben, die sich genau unterscheiden lassen in einem Kreis: Rot, Orange, Gelb, Grün, Blau, Indigo, Violett. Hier wird das Violett immer mehr und mehr der Pfirsichblüte ähnlich, hier sind zwei Nuancen zwischen Pfirsichblüte und Violett, hier wiederum zwei Nuancen zwischen Pfirsichblüte und Rot, und Sie bekommen dann, wenn Sie die Gesamtheit dieser Farbennuancen verfolgen, gewissermaßen zwölf Farbenzustände, wenn ich den Ausdruck gebrauchen darf. Daraus können Sie ersehen, daß das, was man gewöhnlich als Spektrum schildert, auch dadurch entstanden gedacht werden kann, daß Sie sich denken, ich könnte durch irgend etwas diesen Farbenkreis hier entstehen lassen, und würde ihn immer größer und größer machen nach der einen Seite hin; dadurch würden mir diese oberen fünf Farben immer mehr und mehr hinausrücken, bis sie mir zuletzt entschwänden; die untere Biegung ginge nahezu in die Gerade über, und ich bekäme dann die gewöhnliche Spektrumfolge der Farben, indem mir nur die anderen fünf Farben nach der anderen Seite entschwunden sind.

[ 19 ] Ich stellte jetzt zuletzt die Farben hin. Könnte es nicht auch da (Schema Seite 128) mit dem Gehen ins Unendliche so etwa der Fall sein, wie hier beim Spektrum? Daß ich nämlich etwas Besonderes herausbekäme, wenn ich nun suchte: Was wird, wenn das, was da (Schema) in die Unendlichkeit scheinbar fortgeht, sich zum Kreis rundet und da wiederum zurückkommt? Könnte es nicht so etwas geben wie eben eine Art von anderem Spektrum, das mir umfaßte auf der einen Seite den Zustand von über der Wärme bis hinunter zur Materie, das ich aber nach der anderen Seite hin auch so zum Schließen bringen kann wie hier das Farbenspektrum zur Pfirsichblüte-Farbe? Diesen Gedankengang wollen wir morgen weiter fortsetzen.

Eighth Lecture

[ 1 ] Yesterday, we conducted an experiment designed to demonstrate, according to common understanding, how mechanical work, which we produced by causing a paddle wheel to rotate and thus generate friction against a mass of water, is converted into heat. We showed you that the water rubbed against by the paddle wheel became warmer.

[ 2 ] Today, we want to do the opposite, so to speak. Yesterday, we showed that we must somehow find an explanation for the fact that, if we now express the facts more accurately than through the idea of mere transformation, heat can be generated under the influence of work performed. Now we want to follow a reverse process. First, we want to generate steam, i.e., we want to generate pressure and tension in the course of a combustion process—in other words, we want to create something mechanical from heat—and, following the same principle that drives all steam engines, we want to convert this heat into mechanical work via the detour of pressure. By applying pressure on one side here on the surface below, this piston is driven upwards (see drawing on page 118). By cooling the steam again, the pressure is reduced, the piston moves back, and we obtain mechanical work, the upward and downward movement. We will be able to observe how the water that is produced when we cool it down, the condensation water, enters this vessel, and we will then examine whether, after we have allowed the entire process to unfold, the heat we have generated here has been completely converted into such work, into the work of moving this piston up and down, or whether we have somehow lost heat. The heat that is lost, that is not converted, would have to appear in the heat of the water. In the case where all the mobile heat is used to generate mechanical work, the condensation water would then be unable to show an increase in temperature. If there is an increase in temperature, that is, if we can see on this thermometer that the water is heated above the usual temperature, then this heating comes from the heat we have applied. Then not all the heat has been converted into work; we were not able to do so, and something has remained. So we want to determine whether all the heat can be converted into work, or whether something remains and is reflected in the warmth of the condensed water. The water is at 20°, so we will see whether the condensed water has really cooled down to 20°, meaning that all the heat has been used for work, or whether the temperature of this condensed water rises and heat is lost as a result. Now we condense the steam, the condensation water drips over, and in this way, of course, a machine can now be driven. If the experiment is completely successful, you can be sure that the condensation water here shows a significant increase in temperature, and this is the way in which it can be shown that, if one performs the opposite experiment to yesterday's, converting heat into mechanical work, which consists precisely in the piston moving up and down, it is then impossible to convert all the heat that has been generated completely into mechanical work; that when heat is converted into mechanical work, heat always remains, so that in every instance of heat used to generate mechanical work, there is a portion that remains as a residue and cannot be converted into mechanical work. For now, we will simply note the phenomenon, but now we will present the ideas that conventional physics and those who base their views on it have about the whole matter.

[ 3 ] First, we are dealing with the initial fact that we can convert, as they say, heat into mechanical work and mechanical work into heat. From this, as I have already mentioned, the view has developed that every such form of so-called energy—heat energy, mechanical energy, and one could also conduct the experiment for other energies—can be converted into another. Let us now disregard the extent of the conversion and stick to the fact alone. Now, the current physical thinker says: It is therefore impossible that when energy appears somewhere, a force effect appears, that this comes from anything other than another already existing energy. So if I have a self-contained system of energies somewhere, initially energies of a certain form, and other energies appear, then these must be the conversion of the energies already present in the closed system. Nowhere in a closed system can energy appear other than as a product of conversion. Eduard von Hartmann, who, as I have already indicated, incorporates current physical views into his philosophical concepts, has expressed this so-called first law of mechanical heat theory in the following words: “A perpetual motion machine of the first kind is an impossibility.” What would a perpetual motion machine of the first kind be? A perpetual motion machine of the first kind would be a device by which energy as such would be generated in a closed energy system. Eduard von Hartmann summarizes the relevant facts by saying: “A perpetual motion machine of the first kind is an impossibility.”

[ 4 ] Now we come to the second series of facts, which has been illustrated to us by today's experiment: in a seemingly closed system of energies, we can convert one form of energy into another. However, it is apparent that this conversion is subject to certain laws that are related to the quality of the energies, in such a way that thermal energy cannot be completely converted into mechanical energy without residue. It is therefore impossible to convert thermal energy into mechanical energy in a closed system in such a way that all the heat actually appears as mechanical energy. If it were possible to achieve this, so that all heat appeared as mechanical energy, then it would in turn be possible to convert the mechanical energy into heat. It would be possible for one quality of energy to be converted into another in such a closed system. This would offer the possibility of always converting one into the other. Eduard von Hartmann expresses this sentence in such a way that he says: Such a closed system, in which, for example, all the heat present could be converted into mechanical work, where mechanical work could in turn be converted into heat, where a cycle is created, would be a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. But even such a perpetual motion machine of the second kind is impossible, he says, and these are basically the two main principles of the so-called mechanical theory of heat for thinkers of the 19th century and the early 20th century in the field of physics:

[ 5 ] “A perpetual motion machine of the first kind is an impossibility.” “A perpetual motion machine of the second kind is impossible.” The matter is even connected with the history of physics in the 19th century. The first person to draw attention to this apparent conversion of heat into other forms of energy, or other forms of energy into heat, was Julius Robert Mayer, who essentially became aware of the connection between heat and other forms of energy as a physician when he noticed that venous blood had a different composition in hot zones than in cold zones and concluded from this that there was a different type of physiological work in the human organism in each case. Based mainly on these experiences, which he expanded upon, he later developed a somewhat confused theory, and for him this “theory” had no other scope than this: that one form of energy can be converted into another. The matter was then further elaborated by various other people, including Helmholtz. Already in Helmholtz's work, a peculiar form of physical-mechanical thinking appears as the starting point for the entire consideration. If we take Helmholtz's most important treatise, in which he attempts to support the mechanical theory of heat in the 1840s, it is already based on Hartmann's idea as a postulate: A perpetual motion machine of the first kind is impossible; because a perpetual motion machine is impossible, the different types of energy must be mere transformations of each other; energy can never arise from nothing. The statement from which we start, “A perpetual motion machine of the first kind is impossible,” can be transformed into another: The sum of energies in the world system is constant. Energy is never created, energy is never destroyed. Energy is only transformed. The sum of energy in the world system is constant. — The two statements

“There is no perpetual motion machine of the first kind.”

“The sum of all energy in the universe is constant.”

basically contain exactly the same thing. Now, the point is that we should shed a little light on this whole way of thinking using the approach we have already applied in all our considerations.

[ 6 ] Such an experiment shows that when one attempts to convert heat into so-called work, heat is lost in the conversion into work, that heat reappears, and that therefore only part of the heat can be converted into work, into another form of energy, into mechanical energy. What we see here can then be applied to the universe. This is what the thinkers of the 19th century did. These thinkers said something like this: In the world we live in, mechanical work exists, heat exists. Processes are constantly taking place that convert heat into mechanical work. We see that heat must be present in order for us to generate mechanical work at all. Just think how we have based a large part of our technology on the fact that we can extract mechanical work from the original use of heat. But in doing so, it will always become apparent that we can never completely convert heat into mechanical work, that there will always be a residue. And if that is the case, these residues must accumulate to such an extent that no more mechanical work can be performed, that we simply cannot convert the heat back into mechanical work. The residues of unusable heat accumulate, and the universe is heading toward a state in which all mechanical work will have been converted into heat. It has also been said that the universe in which we live is heading toward heat death, as it is also known in more scholarly terms. We will discuss the concept of entropy in one of our future considerations. For now, we are interested in the fact that an experiment gave rise to ideas about the course of our universe, which is of primary concern to humans.

[ 7 ] Eduard von Hartmann explained the matter nicely by saying: We can see—and this can be proven physically—that the world process in which we live initially proceeds through processes: on the one hand, heat processes, and on the other, mechanical processes, but that ultimately all mechanical processes will transition into heat processes. Then no more mechanical work will be possible. The universe will have reached its end. Physical phenomena show us, says Eduard von Hartmann, that the world process is winding down. This is his way of expressing himself about the processes within which we live. We therefore live in a universe that sustains us through its processes, but there is a tendency for it to become increasingly sluggish and ultimately to come to a complete standstill — I am merely repeating Eduard von Hartmann's own words.

[ 8 ] Now, however, we must be clear about the following: Is there such a thing as the possibility of bringing about a sum of processes in a closed system? Please note what I am saying: when I stand with the sum of my experimental tools, I am certainly not standing in a vacuum, in empty space, and even if I could believe that I am standing in empty space, I am still not entirely sure whether this empty space only appears to be empty because I do not initially perceive what else is in it. Am I ever standing with my experimentation within any closed system? Is not what I do even in the simplest experiment an intervention in the entire process of the universe that surrounds me? When I do this whole thing here, for example, can I present it in a mental image other than something similar, in the context of the entire world process, to taking a small needle and pricking myself here? When I prick myself here, I feel a pain that prevents me from grasping a thought that I would otherwise have grasped. But if I want to consider what is happening here in its entire context, I certainly cannot just consider the pressure of the needle and the damage to the skin and muscles, because then I would not be considering the entire process. The process is not exhausted by this. Imagine that, through clumsiness, I take a needle, prick myself, and feel the pain. I will move away. What occurs as an effect cannot be grasped if I only consider what is happening here in this part of the skin. And yet, moving away from the needle is nothing more than a continuation of the processes I describe when I only consider the first part. If I want to describe the whole process, I must take into account that I did not prick my clothes with my needle, but rather the organism, which I must consider as a whole, which in turn reacts as a whole organism and as such causes what is then the consequence of the first.

[ 9 ] Can I simply say here, when I imagine such an experiment: I have heated, caused mechanical work, and the heat that remains in the condensation water has remained there by itself? I am not connected to the entire setup here in the same way as if I had drilled it (into my finger). The generation or retention of heat, its occurrence in the condensation water, could be related to the reaction of the entire large system to the process here, just as my organism reacts to the small process of pricking the needle. So what I have to take into account above all else is that I must never view the experimental setup as a closed system, but must remain aware that this entire experimental setup is subject to the influences of the environment and also to the energies that may be acting from this environment.

[ 10 ] Now combine this with another: Suppose you again have a liquid in the vessel with a level surface, whereby you assume a force acting vertically on the level surface. Now imagine that this liquid is transformed into a solid body by cooling. It is quite impossible not to think that these directions here, these directions of force, are not crossed by another in some way. For these directions of force cause me to store the water in a vessel, so that the shape of the water is only there because of the level surface. If a closed, shaped form is created during solidification, it is absolutely necessary to assume that forces are now added to those that were previously present. This provides the immediate insight that forces are added to those that were previously present. And at first, the idea is quite absurd to believe that those forces that were somehow already present in the water cause the shape, because if they had been present, they would have had to cause the shape in the water. So they have appeared. They cannot have been contained in the water system; they must have come to it from outside the water system. If we therefore take the phenomenon as it is, we must say: when a form appears somewhere, it actually appears as a new creation. If we remain only within the realm of what we can clearly observe, the form appears as a new creation. We see this clearly when we create a solid body from a liquid. The form appears clearly as a new creation, and it is abolished again when we transform the body into a liquid form. Let us just consider this for a moment based on what our perception tells us. What follows from the whole process when we really transform what we perceive into a concept? It follows that the solid body tries to become independent, that it tries to form a closed system within itself, that it enters into a struggle with its environment in order to become a closed system.

[ 11 ] I would like to say that it is obvious here that the solidification of the liquid is nature's attempt to achieve perpetual motion. The perpetual motion machine does not come into being only because the system is not left to its own devices, because the entire environment acts upon it. So you can advance to the view that in our given space there is a constant tendency at various points for a perpetual motion machine to come into being. But immediately a counter-tendency arises against this tendency. So we can say: whenever the tendency to form a perpetual motion machine arises somewhere, a counter-tendency forms in the environment to prevent the formation of the perpetual motion machine. If you orient your thinking in this way, you completely modify the abstract thinking of 19th-century modern physics. It assumes that a perpetual motion machine is impossible, therefore — and so on. If you remain in the world of facts, you have to say: a perpetual motion machine wants to arise continuously. Only the constitution of the universe prevents this.

[ 12 ] And what is the form of a solid body? It is the expression of struggle. This image, which forms in the solid body, is the expression of the struggle between the substance as individuality, which wants to form a perpetual motion machine, and the prevention of the formation of the perpetual motion machine by the entire universe, the relative universe, in which this perpetual motion machine wants to form. The form of a body is the result of the prevention of this striving to become a perpetual motion machine. I could also say, instead of a perpetual motion machine, because that might be more appropriate here or there, a monad, a self-contained body that carries its own forces within itself and generates its own form.

[ 13 ] We come, and here lies a crucial point, to reverse the entire starting point, not of physics, insofar as it provides experiments based on facts, but of the entire physical way of thinking of the 19th century. It worked with invalid concepts. It could not see how, in nature, there was a universal striving toward what it considered impossible. It was relatively easy for this way of thinking declare it impossible, but it is not impossible for the abstract reason that physicists assumed perpetual motion to be impossible; rather, it is impossible because the moment it is supposed to arise in any body, the environment immediately feels envy—if I may use a moral expression here—and does not allow perpetual motion to arise. It is impossible on the basis of facts, not on the basis of logic. You can imagine how many contradictions there must be in a theory that establishes its basic postulates apart from reality. If one sticks to reality, one cannot avoid what I first presented to you yesterday in the diagram. We will continue to elaborate on this diagram in the coming days.

[ 14 ] I told you: First we have the realm of solid bodies. These solid bodies are those that have solid forms. Adjacent to the realm of solid bodies, so to speak, we have the realm of liquids. The forms dissolve and disappear when the solid body transitions into liquid. We have the complete opposite of the solid in the striving apart, in the dissolution of the shape of the gaseous body: negative shape. But how does this negative shape manifest itself? If we look at gaseous or airy bodies without prejudice, if we observe them, for example, where they show how perceptible that which corresponds to their shape can be. Yesterday I pointed you to the field of acoustics, the world of sound. You know that in gases, sound is produced by compressions and rarefactions. But we also deal with compression and rarefaction in the whole gas when we change the temperature. So if we skip over liquids and look for what corresponds to the definite form of solid bodies in gases, we must look for it in condensation and rarefaction. In solid bodies we have definite form; in gases we have condensation and rarefaction.

[ 15 ] And now let us turn to the area adjacent to gas, which, like liquid, is adjacent to the area of solid bodies — and we know that just as solid bodies represent the image of liquids, liquids represent the image of gases in their entirety, and gases represent the image of heat — we must imagine the area of heat as the next one. As the next area, I will first have to postulate an x. And if I initially try to proceed only by analogy—we will verify this in the following considerations—then I must look for something else in this x area instead of compression and rarefaction. I must look for something corresponding to compression and rarefaction in x (skipping heat), just as I have skipped the liquid here (below). If you first have a solid, closed form, then come to the conclusion that in the case of a gaseous body, the form is only expressed in the liquid form of condensation and dilution, and you imagine increased condensation and dilution, what must happen? As long as there is condensation and dilution, there is of course still matter. But if you continue to dilute and dilute further and further, you will eventually leave the realm of the material. And you must say, as a further continuation, simply by remaining in the character of the whole: become material — become spiritual. By ascending above the realm of warmth, you enter into x; you enter, simply by holding fast to the character that lies in the transition from solid form to liquid form, from condensation and dilution into materiality and non-materiality. You cannot help but speak of materiality and non-materiality. That is to say: as we pass through the realm of warmth, we actually enter into something that, in a certain sense, proves to be a just continuation of what we have observed in the lower realms. The solid body resists warmth; warmth cannot quite cope with it. The liquid body is already more responsive to the intentions of heat. The gas follows the intentions of heat completely; it allows heat to do with it what it wants; in its material processes, it is completely a reflection of the nature of heat itself. I can say that gas is essentially similar to the heat entity in its own substantial behavior. The degree of similarity between matter and heat increases the further I proceed from the solid body through the liquid body to the gas. This means that the liquefaction and evaporation of matter signifies a becoming similar of matter to heat. But when I then cross over into the realm of heat, when matter becomes, so to speak, completely similar to heat, it cancels itself out. Thus, for me, heat stands between two very different realms that are essentially different: the realm of spirit and the realm of matter. Between them lies the realm of heat. However, the transition to reality is now somewhat difficult for us, because on the one hand we have to ascend to where it seems to become more and more spiritual, and on the other hand we have to descend to where it seems to become more and more material. And there it seems to ascend into infinity and descend into infinity (see arrows in the diagram).

[ 16 ] But now another analogy presents itself, which I will outline to you today for the reason that, by vividly pursuing the individual facts of nature, a healthy natural science can indeed develop, and it may be useful to let the matter sink into the soul. If you look at the spectrum as it usually appears, you have red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet.

[ 17 ] You have the color series in about seven shades running side by side like in a band. But you also know that the spectrum does not end here, and also that here (on the left), as we follow the spectrum, we come to warmer and warmer areas and finally have an area where there is no more light, but still heat, the ultra-red area. Beyond violet, we also have no more light; we get ultraviolet, which only has chemical, i.e., material effects.

[ 18 ] But you know, on the other hand, that in the sense of Goethe's theory of colors, this line here can be turned into a circle and the colors can be arranged differently, so that one no longer merely observes the behavior of the light from which a spectrum is formed, but observes the darkness from which a spectrum is formed, which then has peach blossom in the middle instead of green, and the other colors starting from there. When I look at the darkness, I get the negative spectrum. And if I put the two spectra together, I get twelve colors that can be precisely distinguished in a circle: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. Here, the violet becomes more and more similar to peach blossom; here, there are two nuances between peach blossom and violet; here, again, two nuances between peach blossom and red; and then, if you follow the entirety of these color nuances, you get, so to speak, twelve color states, if I may use that expression. From this you can see that what is usually described as a spectrum can also be thought of as arising from the idea that I could create this color circle here through something, and would make it bigger and bigger on one side; as a result, these upper five colors would move further and further away until they finally disappeared; the lower curve would almost become a straight line, and I would then obtain the usual spectrum sequence of colors, with only the other five colors disappearing on the other side.

[ 19 ] I now placed the colors last. Couldn't it also be the case (diagram) with going into infinity, as it is here with the spectrum? Namely, that I would get something special if I now searched: What happens when what seems to go into infinity (diagram) rounds into a circle and comes back again? Could there be something like a different spectrum that encompasses, on the one hand, the state from above heat down to matter, but which I can also close on the other side, as here with the color spectrum to the color of peach blossoms? We will continue this train of thought tomorrow.