Second Scientific Lecture-Course:

Warmth Course

GA 321

9 March 1920, Stuttgart

Lecture IX

[ 1 ] The fact that we have spoken of the transformation of energy and force assumed by modern physics makes it necessary for us to turn our attention to the problem of indicating what really lies behind these transformations. To aid in this, I wish to perform another experiment to be ranged alongside of yesterday's. In this experiment we will perform work through the use of another type of energy than the one that is immediately evident in the work performed. We will, as it were, bring about in another sphere the same sort of thing that we did yesterday when we turned a wheel, put it in motion and thus performed work. For the turning of the wheel can be applied in any machine, and the motion utilized.

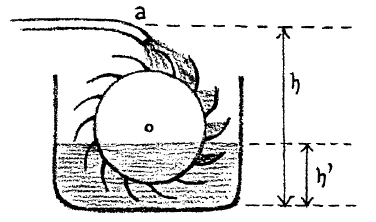

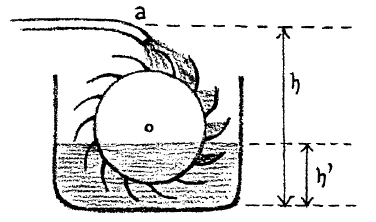

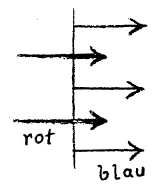

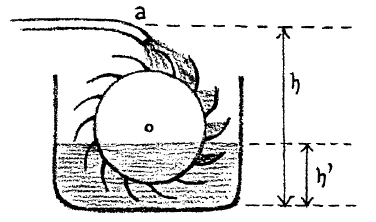

[ 2 ] We will bring about the turning of a wheel simply by pouring water on these paddle, and this water by virtue of its weight will bring the paddle wheel into motion. The force that somehow or other exists in the running water is transformed into the rotational energy of the wheel. We will let the water flow into this trough in order to permit it to form a liquid surface as it did in previous experiments. What we show is really this, that by forming a liquid surface below we make the motion of the wheel slower than it was before. Now, it will slow down in proportion to the degree to which the lower level approaches the upper level. Thus we can say: if we indicate the total height of the water from the point \(a\) here where it flows onto the wheel by \(h\) and the perpendicular distance to the liquid surface by \(h'\) then we can state the difference as \(h-h'\). We can further state that the work available for the wheel is connected in some way with the difference between the two levels. (The sense in which this is so we will seek in our further considerations.) Yesterday in our experiment we also had a kind of difference in levels, \(t-t'\). For you will recollect we denoted the heat of the surroundings at the beginning of our experiments by \(t'\) and the heat we produced in order to do work to raise and lower a bell, this we denoted by \(t\). Therefore you can say: the energy available for work depends on the difference between \(t\) and \(t'\). Here too, we have something that can be denoted as a difference in level.

[ 3 ] I must ask you to note especially how both these experiments show that wherever we deal with what is called energy transformation, we have to take account of difference in level. The part played by this, what is really behind the phenomenon of energy transformation, this we will find only where we pursue further the train of thought of yesterday. As we do this we will illuminate so to speak, the phenomena of heat and take into account that which Eduard von Hartmann set aside before he attempted a definition of physical phenomena. In this connection we must emphasize again and again a beautiful utterance of Goethe's regarding physical phenomena. He gave utterance to this in various ways, somewhat as follows: what is all that goes on in outer physical apparatus as compared to the ear of the musician, as compared to the revelation of nature that is given us in the musician's ear itself. What Goethe wishes to emphasize by this is that we will never understand physical things if we observe them separately from man himself. According to his view, the only way to attain the goal is to consider physical phenomena in connection with the human being, the phenomena of sound in connection with the sense of hearing. But we have seen that great difficulties arise when we try in this way to bring the phenomena of heat in connection with the human being—really seek to connect heat with the being of man. Even the facts that have led to the discover of the so-called modern mechanical theory of heat support this view. Indeed, that which appears in this modern mechanical theory of heat took its origin from an observation made on the human organism by Julius Robert Mayer. Julius Robert Mayer, who was a physician, had noticed from blood-letting he was obliged to do in the tropical country of Java, that the venous blood of tropical people was redder than that of people in northern climes. He concluded correctly from this that the process involved in the coloration of blood varies, depending on whether man lives in a warmer or cooler climate, and is thus under the necessity of giving off less or more heat to his surroundings. This in turn involves a smaller or greater oxidation. Essentially he discovered that this process is less intense when the human being is not obliged to work so intensely on his environment. Thus, the human being of the tropics, since he loses less heat to his environment, is not obliged to set up so active a relation with the outer oxygen as when he gives off more heat. Consequently man, in order to maintain his life processes and exist at all on the earth in the cooler regions, is obliged to tie himself in more closely with his environment. He must take in more oxygen from the air in the colder regions where he works more intensely in connection with his environment than in the warmer zones where he labors more intensely in his inner nature.

Right here you get an insight into the inner workings of the whole human organization. You see that it has only to become warmer and the human being then works more in his inner individuality than he does when his environment is colder and he is thereby obliged to link his activities more intimately with his outer environment.

[ 4 ] From this process in which we have represented a relation of man to his environment, there proceeded the observations that resulted in the theory of heat. These observations led Julius Robert Mayer to submit his small paper on the subject to the Poggnedorfschen Annalen. From this paper arose the entire movement in physics that we know about. This is strange enough since the paper that Mayer handed the Poggnedorfschen Annalen was returned as entirely lacking in merit. Thus we have the odd circumstance that physicists today say: we have turned physics into entirely new channels, we think entirely otherwise about physical things than they did before the year 1842. But attention has to be called to the fact that the physicists of that time, and they were the best physicists of the period, had considered Mayer's paper as entirely without merit and would not publish it in the Poggnedorfschen Annalen. [ 5 ] Now you can see that it might be said: this paper in a certain sense brings to a conclusion the kind of view of the physical that was, as it were, incompletely expressed in Goethe's statement. After the publication of this paper, a physics arises which sees science advancing when physical facts are considered apart from man. This is indeed the principle characteristic of modern views on the subject. Many publications bring this idea forward as necessary for the advance of physics, stating that nothing must enter in which comes from man himself, which has to do with his own organic processes. But in this way we shall arrive at nothing. We will however continue our train of thought of yesterday, a train of thought drawn from the world of facts and one which will lead us to bring physical phenomena nearer to man.

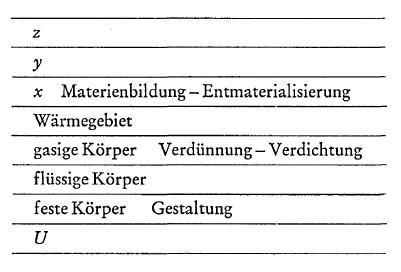

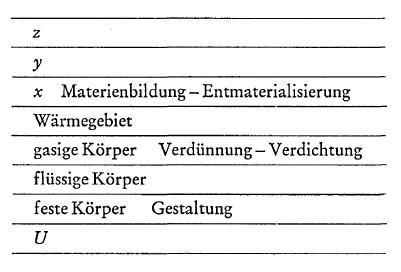

[ 6 ] I wish once more to lay before you the essential thing. We start from the realm of solids and find a common property at first manifesting as form. We then pass through the intermediate state of the fluid showing form only to the extent of making for itself a liquid surface. Then we reach the gaseous bodies, where the property corresponding to form manifests itself as condensation and rarefaction.

We then come to the region bordering on the gaseous, the heat region, which again, like the fluid, is an intermediate region, and then we come to our \(x\). Yesterday we saw that pursuing our thought further we have in \(x\) to postulate materialization and dematerialization. It is not difficult then to see that we can go beyond \(x\) to \(y\) and \(z\) just as, for instance, we go in the light spectrum from green to blue, from blue to violet and to ultra violet.

| z | |

| y | |

| x | materialization—dematerialization |

| Heat Realm | |

| Gaseous Bodies | condensation—rarefaction |

| Fluid Bodies | |

| Solid Bodies | form |

| U |

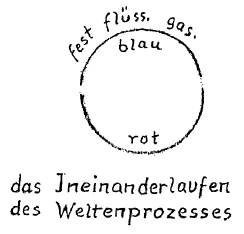

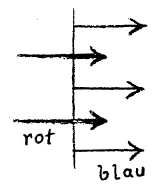

[ 7 ] And now it is a question of studying the mutual relations between these different regions. In each one we see appearing what I might call definitely characteristic phenomena. In the concrete realm we see a circumscribed for; in gas a changing form, so to speak, in condensations and rarefactions. This accompanies, and I am now speaking precisely, this accompanies the tone entity, under certain conditions. When we pass through the warmth realm into \(x\) realm, we see materialization and dematerialization. The question now arising is this: how does one realm work into another?

Now I have already called your attention to the fact that when we speak of gas, the phenomena there enacted present a kind of picture of what goes on in the realm of heat. We can say therefore, in the gas we find a picture of what goes on in the heat realm. This comes about in no other manner than that we have to consider gas and heat as mutually interpenetrating each other, as so related that gaseous phenomena are seized upon in their spatial relationship by the heat entity. What is really taking place in the realm of heat expresses itself in the gas through the interpenetration of the two realms. Furthermore we can say, fluids show us a relationship of forces similar to that obtaining between gases and heat. Solids show the same sort of relationship to fluids do to gases and as gases do to heat.

[ 8 ] What then, comes about in the realm of solids? In this realm forms appear, definite forms. Forms circumscribed within themselves. These circumscribed forms are in a relative sense pictures of what is really active in fluids. Now we can pass here to a realm \(U\), below the solid, whose existence we at the start will merely postulate; and let us try to create concepts in the realm of the observable. By extending our thinking which you can feel is rooted in reality, we can create concepts and these concepts springing from the real bring into us a bit of the real world.

What must take place if there is to be such a reality as the \(U\) realm? In this realm there must be pictured that which in solids is a manifested fact. In a manner corresponding to the other realms the \(U\) realm must give us a picture of the solids. In the world of solids we have bodies everywhere, everywhere forms. These forms are conditioned from within their own being, or at least conditioned according to their relation to the world. We will consider this further in the next few days. Forms come into being, mutually inter-related.

[ 9 ] Let us go back for a moment to the fluid state. There we have, as it were, the fluid throwing out a surface and thus showing its relation to the entire earth. In gravity therefore, we have to recognize a force related to the creation of form in solids. In the \(U\) realm we must find something that happens in a similar manner to the form-building in the world of solids, if we are to pursue our thinking in accordance with reality. And this must parallel the picturing of the fluid world by solids. In other words: in the \(U\) world we must be able to see an action which foreshadows the solid world. We must in some way be able to see this activity. We must see how, under the influence of forms related to each other something else arises. There must come into existence as a reality what further manifests as varying forms in the solid world. We really have today only the beginning of such an insight. For, suppose you take a suitable substance, such as tourmaline, which carries in itself the principle of form. You then bring this tourmaline into such a relation that form can act on form. I refer to the inner formative tendency. You can do this by allowing light to shine through a pair of tourmaline crystals. At one time you can see through them and then the field of vision darkens. This you can bring about simply by turning one crystal. You have brought their form-creating force into a different relation. This phenomena, apparently related to the passage of light through systems of differing constitution, shows us the polarization figures. Polarization phenomena always appear when one form influences another. There we have the noteworthy fact before our eyes that we look through the solid realm into another realm related to the solid as the solid is to the liquid. Let us ask ourselves now, how come it is that under the influence of the form-building force there arises in the \(U\) realm that which we observe in the polarization figures as they are called, and which really lies in the realm beneath the solid realm? For we do, as a matter of fact, look into a realm here that underlies the world of the solids. But we see something else also.

[ 10 ] We might look long into such a solid system, and the most varied forces might be acting there upon each other, but we would see nothing. It is necessary to have something playing through these systems, just as the \(U\) realm plays through the world of solids in order to bring out the phenomenon. And the light does this and makes the mutual inter-working of the form-building forces visible for us.

[ 11 ] What I have here expressed, my friends, is treated by the physics of the 19th century in such a way that the light itself is supposed to give rise to the phenomenon while in reality the light only makes the phenomenon visible. Looking on these polarization figures, one must seek for their origin in an entirely different source from the light itself. What is taking place has nothing whatever to do with the light as such. The light simply penetrates the \(U\) realm and makes visible what is going on there, what is taking place there as a foreshadowing of the solid form. Thus we can say we have to do with an interpenetration of different realms which we have simply unfolded before our eyes. In reality we are dealing with an interpenetration of different realms.

[ 12 ] And now the facts lead us to the same point which we reached, for instance, in the realm of the gaseous by means of the forces of form. Our concepts of what has been said will be better if we consider condensation and rarefaction in connection with the relation of tone to the organ of hearing. We must not feel it necessary to identify these condensations and rarefactions in a gaseous body entirely with what we are conscious of as tone. We must seek for something in the gas that uses the condensations and rarefactions as an agency when these are present in a suitable fashion. What really happens we must express as follows: that which we call tone exists in a non-manifested condition. But when we bring about in a gas certain orderly condensations and rarefactions, then there occurs what we perceive consciously as tone. Is not this way of stating the matter entirely as though I should say the following: we can imagine in the cosmos heat conditions where the temperature is very high—about 100°C. We can also imagine heat conditions where very low temperatures prevail. Between the two is a range in which human beings can maintain themselves. It is possible to say that wherever in the cosmos there is a passage from the condition of high temperature to a condition of low temperature, there obtains at some intermediate point a heat condition in which human beings may exist. The opportunity for the existence of man is there, if other necessary factors for human existence are present. But we would on no account say: man is the temperature

Variation from high to low and the reverse variation. (For here the conditions would be right again for his existence.) We would certainly not say that. In physics, however, we are always saying, tone is nothing but the condensation and rarefaction of the air; tone is a wave-motion that expresses itself as condensation and rarefaction in the air. Thus we accustom ourselves to a way of thinking that prevents us from seeing the condensations and rarefactions simply as bearers of the tone, and not constituting the tone itself. And we should conceive for the gaseous something that simply penetrates it, but belongs to another realm, finding in the realm of the gaseous the opportunity so to manifest as to form a connection between itself and our higher organs. Concepts formed in this way about physical phenomena are really valid. If however, one forms a concept in which tone is merely identified with the air vibrations, then one is naturally led to consider light merely as ether vibrations. A person thus passes from what is not accurately conceived to the creation of a world of thought-out fantasies resulting simply from loose thinking. Following the usual ideas of physics, we bury ourselves in physical concepts that are nothing more than the creation of inaccurate thinking.

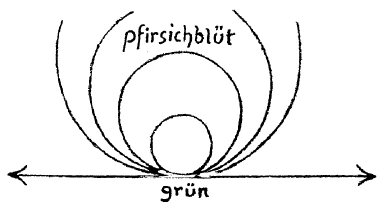

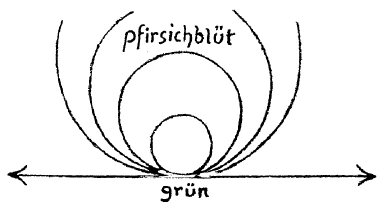

[ 14 ] But now we have to consider the fact that when we pass through the heat realm to the \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) realms, we have to pass out into infinity and here from the \(U\) region we have also to step into the infinite.

Recollect now what I told you yesterday. In the case of the spectrum also, when we try to get an idea of it as it exists ordinarily, we have to go from the green through the blue to the violet and then of to the infinite, or at least to the undetermined. So likewise at the red end of the spectrum. But we can imagine the spectrum in its completeness as a series of 12 independent colors in a circle, with green below and peach-blossom above, and ranged between these the other colors. When we can imagine the circle to become larger and larger, the peach blossom disappears above and the spectrum extends on the one hand beyond the red and on the other beyond the violet. In the ordinary spectrum therefore, we really have only a part of what would be there if the entire color series could appear. Only a portion is present.

[ 15 ] Now there is a very remarkable thing. I think, my friends, if you take as a basis the ordinary presentation of optics in the physic books and read what is there given as explanation of a special spectral phenomenon, namely the rainbow, you will be rather uneasy if you are a person who likes clear concepts. For the explanation of the rainbow is really given in such a manner that one has no foundation on which to stand. One is obliged to follow all sorts of things going on in the raindrop from the running together of extremely small reflections that are dependent on where one stands in relation to the rainbow. These reflections are said really to come from the raindrops. In brief you have in this explanation an atomistic view of something that occurs in our environment as unity. But even more perplexing is the fact that his rainbow or spectrum conjured up before us by nature herself, never occurs singly. A second rainbow is always present, although sometimes very completely hidden. Things that belong together cannot be separated. The two rainbows, of which one is clearer than the other, belong of necessity together, and if one is to explain this phenomenon, it is not possible to do so simply by explaining one strip of color. If we are to comprehend the total phenomenon we must make it clear to ourselves that something of a unique nature is in the center and that it shows two bands of color. The one band is the clearer rainbow, and the other band is the more obscure bow. We are dealing with a representation in the greatness of nature herself, which is an integral portion of the “All” and must be comprehended as a unity. Now, when we observe carefully we will see that the second rainbow, the accessory bow, shows colors in the reverse order from the first. It reflects, so to speak, the first and clearer rainbow. As soon as we go from the partial phenomenon as it appears in our environment, to a relatively more complete one, when we conceive of the whole earth in its relation to the cosmic system, we see in the rainbows a different aspect. I wish only to mention this here—we will go into it more completely in the course of our lecture. [ 16 ] But I wish to say here that the appearance of the second bow converts the phenomenon into a closed system, so to speak. The system is only an open one so long as I limit my consideration to the special spectrum arising in the \(U\) portion of my environment. The phenomenon of the rainbow really leads me to think of the matter thus, that when I produce a spectrum experimentally, I grasp nature only at one pole, the opposite pole escapes me. Something has slipped into the unknown, and I really have to add to the seven-colored spectrum the accessory spectrum.

[ 17 ] Now hold in mind this phenomenon and the ideas that arise from it and recollect the previous ideas that we have brought out here. We are trying to close up the band of color that stretches out indefinitely on both sides, and bring the two together. If now, we do a similar things in this other realm, what happens? (See sketch at end of Chapter) Then we will pass from solids to the U region and beyond, but as we do this we also come back from the other end of the series and the system becomes a closed one. But now, when the downward path and the upward one come together to make a closed system, what does that form for us? What happens then?

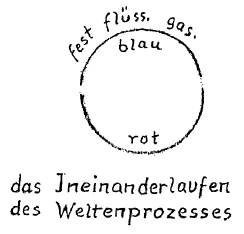

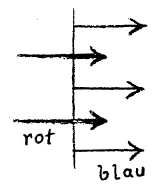

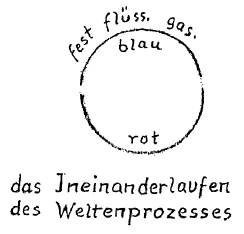

[ 8 ] I will try as follows to lead you to an understanding of this: suppose you really go in one direction in the sense indicated in our diagrams. Let us say we go out from the sphere where, as we have explained in these lectures, gravity becomes negative. We have, let us say, arrived in one of the realms. From this realm, suppose we go downward, and imagine that we pass through first the fluid and then the solid realms. Now when we go further, we must really come back from the other side—it is difficult to show this diagrammatically. Since we come back from the other side, that which belongs to this other side has to insert itself into the realm from which we have just passed. That is to say, while I pass from the solid to the U region, if I want to represent the whole cycle I must bend what is at the other end of the series around and thrust it in here. I can picture it in this way. From the null sphere I go through the fluid into the solid and then into the U region. Returning then, I come to the same point from the other side. Or, I might say: I observe the gas, it extends to here where I have colored with blue (referring to the drawing at end of Chapter). But from the other side comes that which inserts itself, interpenetrates it from the cosmic cycle, but appearing there only as a picture. It impregnates the gas, so to speak, and manifests as a picture. The fluid in its essence interpenetrates the sphere of the solid, and attains a form. Similarly, form appears in the gas as tone and this we have indicated in our diagram. Turn over in your minds this returning and interpenetration in these world-processes. You will of necessity have to think not of a world-cycle only, but of a certain sort of world-cycle. You will have to think of a world cycle that moves from one realm to another, but in which any realm shows reflection of other realms. In this way we get a basis for thinking about these things that has a root in reality. This way of thinking will help you, for instance, to see how light arises in matter, light which belongs to an entirely different realm; but you will see that the matter is simply “overrun” by the light, as it were. And you will then, if you treat these things mathematically, have to extend your formulae somewhat.

[ 19 ] You may, if you will, consider these things under the symbol of ancient wisdom, the snake that swallows its own tail. The ancient wisdom represented these things symbolically and we have to draw nearer to the reality. This drawing nearer is the problem we must solve.

Neunter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Gerade wenn man von den von der heutigen Physik angenommenen Verwandlungen der Kräfte und der Energien spricht, so wird es nötig, darauf aufmerksam zu machen, in welcher Weise etwa hinzudeuten ist auf dasjenige, was hinter diesen Verwandlungen eigentlich steckt. Wir werden uns in diesen Betrachtungen ganz systematisch nähern diesem hinter den Energieverwandlungen Steckenden. Zu diesem Zwecke möchte ich heute neben das gestrige Experiment ein anderes stellen, wo wir auch Arbeit verrichten durch die Aufwendung einer anderen Energie, als in dieser Art unmittelbar zum Vorschein kommt. Wir werden gewissermaßen in einer anderen Sphäre hervorrufen ein Bild desjenigen, was gestern auch geschehen ist, indem wir hier ein Rad zur Drehung bringen, zur Bewegung bringen, also eine Arbeit verrichten. Denn wir könnten ja dann die Drehung des Rades übertragen auf irgendwelche Maschinerie und diese Drehung des Rades als Bewegung verwenden. Wir werden die Drehung des Rades dadurch hervorrufen, daß wir in diese Schaufeln einfach Wasser hineinfließen lassen, das durch seine Schwerkraft uns das Schaufelrad in Bewegung bringt. Die Kraft, die einfach irgendwie drinnensteckt in dem fließenden Wasser, diese Kraft ist es, welche wir in die Rotationskraft des Rades übertragen (Experiment).

[ 2 ] Wir werden nun hier in diesen Trog Wasser hineinfließen lassen, um das herunterfließende Wasser früher, als das beim bisherigen Versuch der Fall war, einem Niveau begegnen zu lassen. Das, was eigentlich zu zeigen ist, das ist, daß dadurch, daß wir nun unten ein Niveau schaffen, wir bewirken, daß die Drehung des Rades doch eigentlich langsamer wird, als sie früher war. Nun, sie wird um so langsamer, je mehr das untere Niveau dem oberen näherrückt, so daß wir sagen können: Wenn wir bezeichnen die Höhe von dem absoluten Wasserstand zu diesem Punkte hier \((a)\), wo das Wasser anfließt an unser Rad, wenn wir diese bezeichnen mit \(h\), und die senkrechte Entfernung zwischen dem absoluten Wasserstand und der Niveaufläche, die wir da unten haben, mit \(h’\), so bekommen wir eine Differenz heraus von \(h-h’\), und wir können sagen: Dasjenige, was wir leisten können an dem Rad, wird irgendwie zusammenhängen - in welcher Weise, werden wir eben suchen im Laufe unserer Betrachtungen — mit der Differenz der beiden Niveaus. Wir haben auch gestern bei unserem Experiment eine Art Niveaudifferenz gehabt. Denn denken Sie sich, wir bezeichnen den Wärmezustand, der in unserem Raume herrscht am Beginn unseres Experiments, mit \(t’\), und wir bezeichnen den Wärmezustand, den wir hervorrufen durch die Erwärmung, die wir bewirken, damit die mechanische Arbeit geleistet werden kann, die wir gestern leisteten in dem auf- und absteigenden Kolben, wir bezeichnen diesen Wärmezustand durch \(t\), so werden wir auch in irgendeiner Weise sagen können: Von dieser Differenz zwischen \(t\) und \(t’\) hängt die geleistete Arbeit ab, also auch hier von etwas, das in einer gewissen Beziehung als eine Niveaudifferenz bezeichnet werden kann.

[ 3 ] Ich muß Sie besonders aufmerksam darauf machen, daß uns zunächst diese beiden Versuche darauf hinweisen, wie wir es zu tun haben überall da, wo so etwas eintritt, was man heute als Umwandlung der Energie bezeichnet, mit Niveaudifferenz. Was nun diese Niveaudifferenz für eine Rolle spielt, was da eigentlich hinter der Verwandlung der Energien steckt, was sich zum Beispiel Eduard von Hartmann erst hinweggeschafft hat, bevor er an eine Definition der physikalischen Erscheinungen geht, das werden wir nur finden, wenn wir, um nun den ganzen Umfang der Wärmeerscheinungen gewissermaßen zu beleuchten, den gestrigen Gedankengang heute fortsetzen und zu einem gewissen Abschluß bringen. Bei diesen Dingen muß man immer wieder und wiederum hinweisen auf ein schönes Wort, das Goethe gesprochen hat im Hinblick auf die physikalischen Erscheinungen. Dieses Wort, er hat es in verschiedener Art ausgesprochen, er sagte etwa: Was ist eigentlich alle Erscheinung an äußeren physikalischen Apparaten gegen das Ohr des Musikers, gegen dasjenige, was also als Erscheinung, als Offenbarung des Naturwirkens uns entgegentritt durch das Ohr des Musikers selbst! - Goethe wollte eben darauf hinweisen, daß man durchaus nicht zum Ziele kommt, wenn man die physikalischen Erscheinungen abgesondert vom Menschen betrachtet. Die physikalischen Erscheinungen im Zusammenhang mit dem Menschen, also die akustischen Erscheinungen im Zusammenhang mit den Gehörwahrnehmungen des Menschen nun in richtiger Art betrachten, das kann allein auch nach Goethes Ansicht zum Ziele führen. Aber wir haben gesehen, daß große Schwierigkeiten auftreten, wenn wir so etwas wie die Wärmeerscheinungen an den Menschen heranbringen und nun diese wirklich im Zusammenhang mit der Wesenheit des Menschen betrachten wollen. Und es weist auf eine solche Betrachtungsweise, ich möchte sagen, sogar die Tatsache hin, die zu der sogenannten Entdeckung der neueren mechanischen Wärmetheorie geführt hat. Dasjenige, was da in der neueren mechanischen Wärmetheorie spukt, das ist ja eigentlich ausgegangen von einer am menschlichen Organismus gemachten Beobachtung durch Julius Robert Mayer. Julius Robert Mayer, der Arzt war, hat bei Aderlässen, die er genötigt war in Java, also in den Tropengegenden, auszuführen, bemerkt, daß das venöse Blut dort bei Tropenleuten eine rötere Färbung hat als bei Leuten in nördlicheren Zonen. Daraus hat er mit Recht geschlossen, daß der Vorgang, der sich abspielt, um die Färbung des venösen Blutes herbeizuführen, ein anderer ist, je nachdem der Mensch in einer wärmeren oder kälteren Umgebung lebt, also genötigt ist, mehr Wärme oder weniger Wärme an seine Umgebung zu verlieren, also auch genötigt ist, mehr oder weniger Wärme durch die Sauerstoffaufnahme, durch die Atmung zu ersetzen. Davon ist Julius Robert Mayer ausgegangen, daß diese gewissermaßen innere Arbeit, die der Mensch verrichtet, indem er den Prozeß, dem er unterworfen ist durch die Sauerstoffaufnahme, weiter verarbeitet, daß dieser Prozeß wesentlich verinnerlicht wird, wenn der Mensch weniger genötigt ist, mit der äußeren Umgebung zu arbeiten. Der Mensch braucht in den Tropengegenden, also wenn er weniger genötigt ist, Wärme an seine Umgebung zu verlieren, weniger mit dem äußeren Sauerstoff zusammen eine Arbeit zu verrichten, als er nötig hat, wenn er mehr Wärme an seine Umgebung verliert. Und dadurch ist gewissermaßen in kälteren Zonen der Mensch so beschaffen, daß er die Lebensarbeit, die er verrichtet, um überhaupt auf der Erde da zu sein, mehr in Ge meinschaft mit seiner Umgebung verrichtet. Er muß mehr mit dem Sauerstoff der Luft zusammenarbeiten in kälteren als in wärmeren Gegenden, wo er weniger zusammen mit der Umgebung und mehr in seinem inneren Wesen arbeitet.

[ 4 ] Sie sehen da zu gleicher Zeit hinein in ein Getriebe der ganzen menschlichen Organisation. Sie sehen, daß es einfach in der Umgebung wärmer zu sein braucht, und der Mensch arbeitet mehr innerlich individuell, als er arbeitet, wenn es in seiner Umgebung kälter ist und er daher mehr in der Gemeinsamkeit mit den äußeren Vorgängen seiner Umgebung arbeiten muß. Von diesem Prozeß, der also darstellt gewissermaßen eine Beziehung des Menschen zu seiner Umgebung, ist die Betrachtung der mechanischen Wärmetheorie ausgegangen. Diese Beobachtung hat Julius Robert Mayer 1842 dazu geführt, zuerst seine kleine Abhandlung an die Poggendorffschen Annalen damals zu schikken. Von ihr ist ja ausgegangen im Grunde genommen die ganze physikalische Bewegung, die dann nachher gekommen ist. Grund genug, als dazumal diese Abhandlung von Julius Robert Mayer den Poggendorffschen Annalen übergeben worden ist, sie zurückzuweisen als vollständig talentlos. Wir haben da die eigentümliche Erscheinung, daß heute die Physiker sagen: Wir haben die Physik auf ganz neue Bahnen geleitet, wir denken über die physikalischen Erscheinungen ganz anders als vor dem Jahre 1842 - aber zu gleicher Zeit darauf hingewiesen werden muß, daß die damaligen Physiker diese Abhandlung von Julius Robert Mayer — und es waren eigentlich die besten Physiker, die darüber zu entscheiden hatten — als gänzlich talentlos erklärt und sie nicht in die Poggendorffschen Annalen aufgenommen haben.

[ 5 ] Nun könnte man sagen: Mit dieser Abhandlung ist doch in gewisser Weise der Schluß gemacht worden mit den früheren, allerdings unvollkommenen, aber immerhin so gehaltenen physikalischen Betrachtungen, daß man sie in Goetheschem Sinne an den Menschen oder bis zum Menschen herangebracht hat. Nach dieser Abhandlung geht eine Physik auf, welche das Heil der physikalischen Betrachtung darin sieht, daß man gewissermaßen den Menschen als nicht daseiend betrachtet, wenn man von physikalischen Tatsachen sprechen will. Das ist ja auch das wesentliche Charakteristikum der physikalischen Betrachtungen der Gegenwart — in manchen Publikationen wird das sogar als etwas für das Heil der Physik Notwendiges hervorgehoben -, daß in ihnen nichts spielen soll, was irgendwie an den Menschen selber herangebracht ist, mit dem Menschen selber, und sei es auch nur mit dem eigenen organischen Prozeß, zu tun hat. Aber auf diesem Wege kann man eben zu nichts kommen. Und es wird uns die Fortsetzung des gestrigen Gedankenganges, der ja ein aus der Tatsachenwelt herausgeholter ist, dazu führen, die physikalischen Erscheinungen an den Menschen heranzubringen.

[ 6 ] Ich möchte das Wesentliche noch einmal vor Ihnen entwickeln. Wir gehen aus von dem Gebiet der festen Körper, finden ein Einheitliches, zunächst erscheinungsgemäß, in der Gestaltung. Wir gehen dann gewissermaßen durch den Mittelzustand des Flüssigen, der die Gestaltung nur noch in der Niveaubildung bewahrt, über zu den gasigen Körpern, welche dasjenige, was im Gebiet der festen Körper vorhanden ist, als gestaltenloses Wesen nur noch haben, als Verdünnung und Verdichtung. Wir kommen dann, angrenzend an das Gasgebiet, in das Wärmegebiet, wiederum gewissermaßen, wie es das flüssige Gebiet ist, ein Mittelgebiet, und kommen dann zu unserem \(x\). Wir haben gestern gesehen, daß, wenn wir denselben realen Gedanken fortsetzen, wir für das \(x\) zu denken haben an Materienbildung und Entmaterialisierung. Es ist nun ja fast selbstverständlich, daß wir von dem \(x\) weiterschreiten können zu einem \(y\) und zu einem z, geradeso wie wir weiterschreiten können, indem wir zum Beispiel im Lichtspektrum vorwärtsgehen von dem Grün ins Blau, ins Violett und zum Ultraviolett.

[ 7 ] Und nun handelt es sich darum, die gegenseitigen Beziehungen zu studieren zwischen diesen verschiedenen Gebieten. Wir sehen auftreten immer in jedem Gebiet ganz bestimmte charakteristische, ich möchte sagen Wesensträger: Wir sehen auftreten in dem untersten Gebiet eine geschlossene Gestalt, in dem gasigen Gebiet gewissermaßen eine flüssige Gestalt, das Verdichten und Verdünnen, das — ich will jetzt genau sprechen — unter gewissen Verhältnissen die Tonwesenheit begleitet. Wir sehen dann auftreten, indem wir hindurchschreiten durch das Wärmegebiet in das \(x\)-Gebiet, die Materialisierung und Entmaterialisierung. Und die Frage, die da entstehen muß, ist diese: Wie wirkt nun das eine Gebiet in das andere Gebiet hinein? Nun habe ich Sie schon darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß in einer gewissen Weise, wenn wir von Gas sprechen, die Vorgänge im Gasigen so gedacht werden können, daß sie in ihrem Verlauf das Bild geben desjenigen, was im Wärmewesen geschieht. Wir könnten sagen, das Gas wird gewissermaßen von dem Wärmewesen mitgerissen und fügt sich in seiner materiellen Gestalt demjenigen, was das Wärmewesen will, so daß wir in den Vorgängen innerhalb des gaserfüllten Raumes, den Vorgängen, die an das Gas gebunden sind, gewissermaßen Abbilder sehen desjenigen, was die Wärme tut. Wir können also sagen: Im Gas finden wir gewissermaßen Bilder desjenigen, was im Wärmewesen geschieht. Es geht nicht an, das unter einem anderen Bild vorzustellen, als daß wir uns Gas und Wärme in einer gewissen Weise voneinander durchdrungen denken, so daß tatsächlich das Gas ergriffen wird in seiner Raumesausdehnung von dem, was das Wärmewesen will. Gas und Wärme würden sich also durchdringen, würden gerade in ihrer Durchdringung uns an den Vorgängen im Gas verraten, was eigentlich im Wärmegebiet geschieht. Wiederum können wir sagen: Die Flüssigkeit zeigt uns in einer gewissen Weise zu dem Gasigen ein ähnliches Verhältnis wie das Gasige zum Wärmewesen. Das Feste zeigt uns zu der Flüssigkeit dasselbe Verhältnis, wie die Flüssigkeit zum Gas, das Gas zur Wärme.

[ 8 ] Was tritt denn aber im Gebiet des Festen auf? Im Gebiet des Festen treten Gestaltungen auf, richtige Gestaltungen, Gestaltungen, die in sich geschlossen sind. Diese sind gewissermaßen dasjenige, was uns wiederum Bild ist dessen, was im Flüssigen nur wirkt. Nun können wir hier gehen zu einem Gebiete \(U\) unter dem Festen, das wir zunächst hypothetisch annehmen, und wir wollen uns Begriffe verschaffen, um dann zu sehen, ob diese Begriffe irgendwo anwendbar sind im Reiche der äußeren wahrnehmbaren Erscheinungen. Wir wollen uns durch die Fortsetzung dieses Gedankenganges, der ja, wie Sie wohl empfinden, im Wirklichen wurzelt, Begriffe schaffen, von denen wir hoffen können, daß sie uns dann auch wiederum, weil sie aus dem Wirklichen gewonnen sind, ein Stück in die Wirklichkeit hineintragen. Was müßte denn geschehen, wenn so irgend etwas eine Wirklichkeit wäre wie das Gebiet \(U\) ? Da müßte gewissermaßen im Gebiet \(U\) wiederum bildhaft dasjenige auftreten, was im vorhergehenden Gebiet, im Gebiet der festen Körper, eigentlich äußere Tatsache ist. Es müßte dieses Gebiet \(U\) uns wiederum das Bildgebiet geben des Gebietes der festen Körper. Im Gebiet der festen Körper sind Gestalten, Gestalten, die ja aus ihrem inneren Wesen heraus gestaltet sind oder wenigstens aus ihrem Verhältnis zur Welt - das können wir erst in den nächsten Tagen weiter verfolgen -, aber es treten Gestalten auf, es müssen Gestalten auftreten in ihren gegenseitigen Verhältnissen.

[ 9 ] Gehen wir noch einmal zurück ins flüssige Gebiet. Da haben wir gewissermaßen durch die nach außen die Flüssigkeit abschließende Niveaufläche diese Flüssigkeit als einen Körper im Zusammenhang mit der ganzen Erde. Wir müssen also in der Schwerkraft etwas schen, was verwandt ist den Kräften, die gestaltend wirken auf den festen Körper. Wir müssen also, wenn wir den Gedankengang real fortsetzen, irgend etwas finden, was ebenso im Gebiet des \(U\) geschieht, wie die Gestaltenbildung im Gebiet der festen Körper geschieht, dadurch, daß das Gebiet der festen Körper das Bild gibt der Flüssigkeiten. Mit anderen Worten: Wir müssen die Wirkung sehen können im Gebiete \(U\), welche die verschiedenen Gestaltungen aufeinander ausüben. Wir müssen irgendwie die Wirkung sehen können. Wir müssen sehen können, wie unter dem Einfluß verschieden zueinander sich verhaltender Gestalten irgend etwas entsteht. Es müßte im Gebiet der Wirklichkeit etwas geben, was unter dem Einfluß der verschiedenen Gestaltungen im Gebiet des Festen entsteht. Man hat heute eigentlich nur den Beginn eines solchen. Denn nehmen Sie irgendwie einen Körper, zum Beispiel den Turmalin, der in sich trägt ein Prinzip der Gestaltung. Lassen Sie in verschiedener Weise den gestalteten Turmalin, ich meine die innere Tendenz des Gestaltens, so wirken, daß Gestalt auf Gestalt wirken kann, was Sie vorliegend haben, wenn Sie durch zwei Turmaline durchschauen, wenn Sie zum Beispiel die Turmalinzange nehmen und durchschauen: Bald können Sie durchschauen, bald verfinstert sich das Gesichtsfeld. Sie haben nur die Turmaline zueinander verdreht, haben ihre gestaltende Kraft in ein verschiedenes Verhältnis gebracht. Diese Erscheinung hängt innig zusammen mit derjenigen, wo, angeblich durch den Durchgang des Lichtes durch körperliche Systeme, die verschieden gestaltet sind, uns die sogenannten Polarisationsfiguren erscheinen. Diese Polarisationserscheinungen entstehen immer unter dem Einfluß der Wirkung des Gestalteten aufeinander. Wir haben die merkwürdige Tatsache vorliegend, daß wir im Gebiet des Festen gleichsam hinblicken auf ein anderes Gebiet, das sich zum Festen so verhält wie das Gebiet des Festen zum Flüssigen. Und indem wir uns fragen: Wo entsteht denn unter den Einflüssen der gestaltenbildenden Kraft im Gebiet des U dasjenige, was ebenso auftritt, wie wenn die Schwerkraft, die bei der Flüssigkeit nur niveaubildend ist, gestaltend im Gebiete des Festen auftritt? — so müssen wir sagen: Das geschieht, wenn wir die sogenannten Polarisationsfiguren beobachten, die in einem Gebiet liegen, das unterhalb des Festen sich befindet. Wir blicken da tatsächlich in ein Gebiet hinein, das unterhalb des Festen sich befindet.

[ 10 ] Aber wir sehen daraus noch etwas anderes. Wir könnten ja lange hineinschauen in ein solches Körpersystem, und es möchte da unter den verschiedenen Kräften das Verschiedenste vor sich gehen, was da die Wirkungen verschiedener Gestaltungen aufeinander darstellt, wir würden nichts sehen, wenn nicht in die festen Körper noch etwas anderes hineindränge, als daß sich zunächst das Gebiet des Festen mit dem Gebiete \(U\) durchdringt. Es dringt zum Beispiel noch da hinein Licht, das uns erst diese Wirkungen der Gestaltung sichtbar macht.

[ 11 ] Was ich jetzt ausgesprochen habe, das hat zuwege gebracht, daß die Physik des 19. Jahrhunderts sich innerhalb des Lichtes selber zu schaffen machte, und dasjenige, was durch das Licht nur sichtbar wird, als eine Wirkung des Lichtes selbst ansah. Wenn man auf diese Polarisationsfiguren hinschaut, muß man einen ganz anderen Ursprung als den aus dem Licht suchen. Was da geschieht, hat unmittelbar gar nichts mit dem Licht zu tun. Das Licht dringt nur auch ein in dieses Gebiet \(U\) und macht dasjenige, was dadurch geschieht, daß diese Gestaltungen Bildcharakter annehmen, sichtbar. So daß wir sagen können: Wir haben es mit einer Durchdringung zu tun der verschiedenen Gebiete, die wir hier auseinandergelegt haben fächerartig, wir haben es mit einer Durchdringung dieser verschiedenen Gebiete im Wirklichen zu tun.

[ 12 ] Und wir werden jetzt auch in einer sachgemäßen Weise zu dem kommen können, was uns zum Beispiel im Gebiet des Gasigen durch das Gestaltende noch in der gleichsam verflüssigten Gestalt auftritt. Wir werden zu besseren Begriffen geführt für das Gesagte, wo uns, wenn Verdichtung und Verdünnung auftreten, bei Gelegenheit dieser Verdichtung und Verdünnung die Tontatsachen vor die Seele treten durch die Vermittelung des Hörorgans. Und wir werden nicht nötig haben, die Verdichtungen und Verdünnungen im Gaskörper geradezu zu identifizieren mit demjenigen, was uns als die verschiedenen Tonwirkungen entgegentritt, sondern wir werden etwas zu suchen haben, was dann auftritt im Gebiet der Verdichtungen und Verdünnungen innerhalb des Gases, wenn diese in entsprechender Weise da sind. Wir werden genötigt, dasjenige, was eigentlich geschieht, so auszusprechen, daß wir sagen: Zunächst lassen wir im Unbestimmten dasjenige, was wir als Ton bezeichnen. Aber wenn wir im Gasigen herbeiführen gewisse gesetzmäßige Verdichtungen und Verdünnungen, so tritt dasjenige auf, was uns in der Tonwahrnehmung bewußt wird. Diese Art, die Sache auszusprechen, ist sie nicht ganz parallel der, wenn ich sagen würde: Wir können uns im Weltenall vorstellen Wärmezustände von sehr hohen Temperaturen, über 100°; wir können uns vorstellen Wärmezustände von sehr niedriger Temperatur, tief unten, Kältezustände; zwischen drinnen finden wir ein Gebiet, in dem der Mensch sich aufhalten und sich bilden kann? — Es wird uns möglich sein, zu sagen: Wenn irgendwo im Weltenall sich abspielt eine so große Schwingung, wo übergeht der Zustand der Wärme von einer sehr hohen Temperatur in eine sehr tiefe, so liegt etwas dazwischen, wo der Mensch entstehen kann. Es ist die Gelegenheit dazu gegeben, daß der Mensch entstehen kann, wenn sonst irgendwelche Ursachen zur Menschheitsentstehung da sind. Wir werden aber jedenfalls nicht sagen: Der Mensch ist das Abschwingen des Wärmezustandes der Körper in die tiefe Temperatur und das Zurückschwingen — beim Zurückschwingen würde ja auch wieder die Gelegenheit entstehen —, wir werden das nimmermehr sagen. Aber in der Physik sagen wir fortwährend: Der Ton ist nichts anderes als die Verdichtung und Verdünnung der Luft, der Ton ist eine Wellenbewegung, die sich ausdrückt in Verdichtung und Verdünnung der Luft. Wir gewöhnen uns dadurch vollständig ab, die Sache so anzusehen, daß wir in den Verdichtungen und Verdünnungen einfach den Träger sehen des Tones, nicht den Ton selbst. So daß wir uns auch für den gasigen Zustand etwas vorzustellen haben, was einfach in das Gas hineindringt, aber einem anderen Gebiet angehört, und was im Gebiet des Gases die Möglichkeit erhält, so aufzutreten, daß eine Vermittelung zwischen ihm und unserem Hörorgane möglich wird. Nur wenn man die Begriffe so formt, spricht man eigentlich über physikalische Erscheinungen richtig. Wenn man die Begriffe aber so formt, daß man einfach den Ton oder die Tonbildungen identifiziert mit den Luftschwingungen, dann wird man eben dazu verführt, das Licht auch zu identifizieren mit Ätherschwingungen. Man schreitet von etwas, was nur ungenau gefaßt wird, zu dem Ausdenken, Ausphantasieren einer Tatsachenwelt vorwärts, die eigentlich nur das Geschöpf eines ungenauen Denkens ist. In vieler Beziehung ist dasjenige, von dem die Physik namentlich am Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts spricht, nichts anderes als das Geschöpf eines ungenauen Denkens. Und wir stecken, wenn wir die gebräuchliche Physik verfolgen, noch tief darinnen, uns aneignen zu müssen in den physikalischen Begriffen nichts weiter als Geschöpfe des ungenauen Denkens.

[ 14 ] Nun handelt es sich aber darum, daß wir ja, wenn wir vorschreiten von dem Wärmegebiet zu dem \(x\), \(y\), \(z\), gewissermaßen die Aussicht haben, da ins Unendliche fortgehen zu müssen, und hier (bei \(U\) ) haben wir die Aussicht, ebenfalls ins Unendliche fortgehen zu müssen. Ich habe Sie schon gestern darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß dasselbe ja im Spektrum vorliegt, wo wir auch gewissermaßen genötigt sind, wenn wir uns das Spektrum, so wie es gewöhnlich auftritt, vor Augen stellen, bei der Verfolgung des Weges vom Grün durch das Blau zum Violett, gewissermaßen ins Unendliche oder wenigstens ins Unbestimmte fortzuschreiten, ebenso nach dem Rot hin. Wir können aber, wenn wir das gesamte Spektrum, das gesamte Gebiet der Farbenerscheinungen ins Auge fassen, uns dieses Spektrum gebildet denken aus der wirklich vollständigen Reihe der zwölf Farben, die sich nur auf einem Kreis charakterisieren läßt, der unten Grün, oben Pfirsichblüte hat und dazwischen die anderen Farben. Und wir können uns denken, daß sich dieser Kreis nun immer mehr vergrößert; daß Pfirsichblüte uns hier nach oben verlorengeht und einerseits hier nach dem Rot, andererseits nach dem Violett verläuft und über beides hinaus. Wir haben also im gewöhnlichen Spektrum eigentlich einen Teil von dem, was da sein würde, wenn durch die den Menschen umgebende Erscheinungswelt die Vollständigkeit der Farben erscheinen könnte. Wir haben nur einen Teil davon.

[ 15 ] Nun gibt es etwas, was höchst merkwürdig ist. Ich glaube, wenn Sie die gebräuchlichen Darstellungen der Optik in den Physikbüchern zur Hand nehmen und vorrücken zu dem, was da gewöhnlich gegeben wird als Erklärung einer speziellen Spektralerscheinung, nämlich des Regenbogens, wird Ihnen doch, wenn Sie es gerne haben, bei klaren Begriffen zu bleiben, etwas unbehaglich zu Mute werden. Denn die Erklärungen des Regenbogens sind wirklich so gehalten, daß man ganz ohne Bogen dasteht. Man ist genötigt, zum Regentropfen seine Zuflucht zu nehmen und da allerlei Gänge der Lichtstrahlen im Regentropfen drinnen zu verfolgen, und man ist dann genötigt, sich dieses ziemlich einheitliche Bild des Regenbogens zusammenzufügen aus lauter kleinen Bildern, die noch besonders abhängig sind von der Art, wie man dazu steht, Bildern, die eigentlich durch Regentropfen entstehen. Kurz, Sie haben in diesen Erklärungen etwas von einer atomistischen Auffassung einer Erscheinung, die ziemlich als Einheit in unserer Umgebung wirkt. Aber noch unbehaglicher als gegenüber dem Regenbogen, also dem Spektrum, das die Natur selbst vor uns hinzaubert, kann uns werden, wenn wir gewahr werden, daß eigentlich dieser Regenbogen, von dem wir sprechen, gar niemals in Wirklichkeit allein auftritt. Er mag noch so sehr sich verbergen, es ist immer der zweite Regenbogen da. Und was zusammengehört, läßt sich einmal nicht auseinanderhalten. Die beiden Regenbögen, von denen der eine nur undeutlicher ist als der andere, die gehören notwendigerweise zusammen, und im Gebiet der Erklärungen für das Entstehen des Regenbogens darf man nicht einmal versuchen, nur den einen Farbenstreifen erklären zu wollen, sondern man muß sich klar sein darüber, daß die Totalität der Erscheinung - die relative Totalität — eben etwas ist, was nun in der Mitte etwas anderes ist und zwei Randbänder hat. Das eine Randband ist der etwas deutlichere Regenbogen, das andere der undeutlichere Bogen. Man hat es zu tun mit einem Bild, das uns in der großen Natur erscheint und das in der Tat sich hineinstellt fast in das ganze All. Wir müssen das ansehen als etwas Einheitliches. Nun, wenn wir genau zusehen, so werden wir ja ganz gut gewahr werden, daß der zweite Regenbogen, der Nebenregenbogen, eigentlich eine Umkehrung des ersten ist, daß der zweite tatsächlich in einer gewissen Weise aufgefaßt werden kann als eine Art Spiegelbild des ersten, daß er gewissermaßen den ersten, deutlicheren Regenbogen spiegelt. Wir haben also da, sobald wir übergehen von den Teilerscheinungen, die in unserer Umgebung auftreten, zu einer relativen Totalität, der wir gegenüberstehen, wenn wir unsere ganze Erde als im Verhältnis zum kosmischen System auffassen, etwas, was eigentlich sein Antlitz ganz verändert. Zunächst will ich nur auf diese Erscheinung hinweisen. Wir werden im Verlauf unserer Betrachtung diesen Erscheinungen schon nähertreten.

[ 16 ] Dadurch aber, daß uns der zweite Regenbogen auftritt, wird gewissermaßen die Sache, die da (siehe Zeichnung) erscheint, zu einem geschlossenen System. Das System ist nur ungeschlossen, solange ich meinem speziell hier in meiner Umgebung auftretenden Spektrum gegenüberstehe. Und die Erscheinung des Regenbogens müßte mich eigentlich dazu verführen, daran zu denken, daß ich, wenn ich mir dieses Spektrum vor Augen stelle durch ein Experiment, die Natur nur an einem Zipfel halte, daß mir irgendwo am entgegengesetzten Zipfel etwas verlorengeht; daß da doch irgendwo noch etwas ist im Unbekannten, daß ich eigentlich zu jedem siebenfarbigen Spektrum den Nebenregenbogen dazu brauche.

[ 17 ] Diese Erscheinung und ihre Verwandlung in Begriffe, halten Sie sie zusammen mit diesem Gang unseres realen Begriffes, den wir hier (siehe Schema) ins Auge gefaßt haben. Wir versuchen ja hier (siehe Zeichnung) das Farbenband, das sich uns ins Unbestimmte erweitert, zusammenzuschlagen, indem wir das eine in das andere hineinschlagen. Wenn wir das nun auch hier (Schema) machen würden, was würde da werden? Da würden wir, indem wir vom festen Körper in das \(U\) hinausgehen und vielleicht noch weiter den Weg da hinunter machen, ihn so machen, daß er uns von oben wieder zurückkommt und geschlossen würde. Aber jetzt, wenn wir diesen Weg nach unten machen und von oben wieder zurückkommen und ihn schließen, was würde sich denn da bilden? Was würde da geschehen?

[ 18 ] Ich will einmal, um Sie darauf zu führen, das Folgende versuchen; Nehmen Sie an, Sie gehen wirklich in irgendeiner die Sache versinnlichenden Zeichnung nach der einen Richtung. Wir gehen aus, sagen wir von der Sphäre, wo wir in diesen Betrachtungen haben sagen können, die Schwerkraft wird negativ. Wir sind gewissermaßen bei einer der Sphären angelangt. Wir gehen von da aus nach unten und wir stellen uns vor, bei unserem Weg nach unten, da müßten wir ins Gebiet der Flüssigkeit, des Festen hineinkommen. Jetzt, wenn wir aber da weiter fortgehen, müßten wir eigentlich - es ist schwer, es zu zeichnen — von der anderen Seite wiederum zurückkommen. Indem wir von der anderen Seite wieder zurückkommen, würde sich uns dasjenige, was von der anderen Seite zurückkommt, hineinschieben in das frühere Gebiet. Das heißt, indem ich da fortschreite vom Festen in das U-Gebiet, würde ich, wenn ich den ganzen Schwanz da nehmen würde und ihn umkehre und da hineinbringe, ihn hier durchstopfen müssen. Ich _ könnte das Bild auch so zeichnen (siehe obere Zeichnung 5.146), daß ich das Fortschreiten von der Nullsphäre durch die Flüssigkeit in das Feste, das \(U\)-Gebiet so mache, dann wiederum zurückgehe und hier wiederum hineinkomme. So daß ich etwa sagen könnte: Ich betrachte das Gas, das tendiert hierhin, wo ich das Blau gezeichnet habe, nach dieser Seite. Aber in der Weltenkreisung kommt von der anderen Seite her dasjenige, was da eindringt, durchsetzt es, erscheint aber darin nur als Bild. Es imprägniert gewissermaßen dasjenige, was da zurückkommt, das Hingehende, und erscheint darin als Bild. Die Flüssigkeit in ihrem Wesen durchdringt das Gebiet des Festen, indem sie ihm nachläuft, und erscheint darin als Gestaltung; oder irgend etwas, was in unserer symbolischen Zeichnung mehr nach oben gelegen ist, dringt in das Gasgebiet ein und erscheint darin als Ton. Überlegen Sie sich einmal dieses Zurückkommen und dadurch Ineinanderlaufen der Weltenprozesse, wodurch Sie zur Notwendigkeit geführt werden, eben nicht bloß einfach einen Weltenkreislauf sich zu denken, sondern einen solchen Kreislauf zu denken, daß, indem das hier weitergeht, das Weitergehende immer wiederum hereinkommt in dasjenige, was schon da war, also sich durchschiebt durch das, was schon da war. Dann bekommen Sie eine Grundlage für reale Gedanken, die Ihnen zum Beispiel auch helfen werden, das Auftreten, sagen wir des Lichtes, das auf einem ganz anderen Gebiet liegen muß, in der Materie zu sehen, indem die Materie einfach dasjenige ist, was davongelaufen ist, während das Licht hintennachläuft und sich hineinschiebt. Da sind Sie allerdings dann genötigt, wenn Sie diese Dinge mit mathematischen Formeln betrachten wollen, die mathematischen Formeln etwas zu erweitern.

[ 19 ] Wenn Sie wollen - es ist das alte Symbolum von der Schlange, die sich in den Schwanz beißt, das Symbol der alten Weisheit. Nur daß die alte Weisheit das alles eben in Symbolen ausgesprochen hat und wir genötigt sind, an die realen Dinge heranzutreten.

Ninth Lecture

[ 1 ] When discussing the transformations of forces and energies assumed by modern physics, it is necessary to draw attention to the way in which we can indicate what actually lies behind these transformations. In these considerations, we will approach what lies behind the energy transformations in a very systematic way. To this end, I would like to add another experiment to yesterday's, in which we also perform work by expending a different kind of energy than that which immediately appears in this way. We will, in a sense, evoke an image of what happened yesterday in another sphere by setting a wheel in motion, that is, by performing work. For we could then transfer the rotation of the wheel to some kind of machinery and use this rotation of the wheel as movement. We will cause the wheel to turn by simply allowing water to flow into these blades, which, through its gravity, will set the paddle wheel in motion. The force that is somehow contained within the flowing water is the force that we transfer to the rotational force of the wheel (experiment).

[ 2 ] We will now let water flow into this trough so that the water flowing down meets a level earlier than was the case in the previous experiment. What we actually want to show is that by creating a level at the bottom, we cause the wheel to rotate more slowly than it did before. The closer the lower level gets to the upper level, the slower it becomes, so we can say: If we designate the height of the absolute water level at this point here \((a)\), where the water flows onto our wheel, if we designate this with \(h\), and the vertical distance between the absolute water level and the level surface that we have down there with \(h'\), we get a difference of \(h-h’\), and we can say: What we can achieve with the wheel will somehow be related—in what way, we will explore in the course of our considerations—to the difference between the two levels. We also had a kind of level difference in our experiment yesterday. Imagine that we denote the thermal state prevailing in our room at the beginning of our experiment with \(t'\), and we denote the thermal state that we cause by the heating we effect so that the mechanical work we performed yesterday in the ascending and descending piston can be done with \(t\). we designate this thermal state by \(t\), then we will also be able to say in some way: The work performed depends on this difference between \(t\) and \(t’\), i.e., here too, on something that can be described in a certain sense as a level difference.

[ 3 ] I must draw your attention in particular to the fact that these two experiments initially indicate to us how we should proceed wherever something occurs that is today referred to as a conversion of energy with a level difference. What role this level difference plays, what actually lies behind the conversion of energies, what Eduard von Hartmann, for example, first eliminated before he proceeds to define physical phenomena, we will only find out if we continue yesterday's train of thought today and bring it to a certain conclusion, in order to illuminate the entire scope of thermal phenomena, so to speak. When dealing with these matters, one must repeatedly refer to a beautiful phrase that Goethe uttered with regard to physical phenomena. He expressed this thought in various ways, saying, for example: What are all the phenomena of external physical apparatus compared to the ear of the musician, compared to what we encounter as a phenomenon, as a revelation of the workings of nature, through the ear of the musician himself! Goethe wanted to point out that one cannot achieve one's goal if one considers physical phenomena separately from human beings. According to Goethe's view, only by considering physical phenomena in connection with human beings, i.e., acoustic phenomena in connection with human auditory perceptions, in the right way can we achieve our goal. But we have seen that great difficulties arise when we apply something like thermal phenomena to human beings and then want to consider them in connection with the essence of human beings. And I would say that even the fact that led to the so-called discovery of the newer mechanical theory of heat points to such a way of looking at things. What haunts the newer mechanical theory of heat actually originated from an observation made on the human organism by Julius Robert Mayer. Julius Robert Mayer, who was a physician, noticed during bloodletting, which he was forced to perform in Java, i.e., in the tropics, that the venous blood of tropical people there has a redder color than that of people in more northern zones. From this, he rightly concluded that the process that takes place to bring about the coloration of venous blood is different depending on whether a person lives in a warmer or colder environment, i.e., is forced to lose more or less heat to their environment, and is therefore also forced to replace more or less heat through oxygen uptake, through respiration. Julius Robert Mayer assumed that this internal work, which humans perform by further processing the process to which they are subjected through oxygen uptake, is essentially internalized when humans are less compelled to work with the external environment. In tropical regions, where humans are less compelled to lose heat to their environment, they need to perform less work with the external oxygen than they do when they lose more heat to their environment. And thus, in colder zones, humans are, in a sense, constituted in such a way that they perform the life work they do in order to be on earth at all more in communion with their environment. They must work more with the oxygen in the air in colder regions than in warmer regions, where they work less with their environment and more within their inner being.

[ 4 ] At the same time, you see into the workings of the entire human organization. You see that it simply needs to be warmer in the environment, and humans work more individually internally than they do when it is colder in their environment and they therefore have to work more in harmony with the external processes of their environment. The consideration of mechanical heat theory originated from this process, which in a sense represents a relationship between humans and their environment. This observation led Julius Robert Mayer in 1842 to first send his short treatise to the Poggendorff Annals at that time. It was this treatise that basically started the whole physical movement that came afterwards. Reason enough, when Julius Robert Mayer's treatise was submitted to Poggendorff's Annals at that time, to reject it as completely talentless. We have the peculiar phenomenon that physicists today say: We have taken physics in a completely new direction; we think about physical phenomena in a completely different way than we did before 1842—but at the same time, it must be pointed out that the physicists of that time—and they were actually the best physicists who had to decide on this—declared Julius Robert Mayer's treatise to be completely talentless and did not include it in Poggendorff's Annals.

[ 5 ] Now one could say: With this treatise, a certain conclusion was reached with regard to earlier physical considerations, which were admittedly imperfect, but nevertheless held in such a way that they were brought to the human being or to the human being in the Goethean sense. After this treatise, a physics emerges that sees the salvation of physical observation in the fact that, in a sense, humans are regarded as non-existent when one wants to speak of physical facts. This is also the essential characteristic of contemporary physical observations—in some publications, this is even emphasized as something necessary for the salvation of physics—that nothing should play a role in them that is in any way related to human beings themselves, to human beings themselves, even if it is only their own organic processes. But in this way, one can come to nothing. And continuing yesterday's train of thought, which is based on the world of facts, will lead us to relate physical phenomena to human beings.

[ 6 ] I would like to outline the essentials for you once again. We start from the realm of solid bodies and find a uniformity, initially in appearance, in their form. We then move, as it were, through the intermediate state of the liquid, which retains its form only in the formation of levels, to gaseous bodies, which have only what is present in the realm of solid bodies as formless beings, as dilution and condensation. We then arrive, adjacent to the gas realm, in the realm of heat, again, in a sense, as is the liquid realm, a middle realm, and then arrive at our \(x\). We saw yesterday that if we continue the same real thought, we have to think of matter formation and dematerialization for \(x\). It is now almost self-evident that we can proceed from \(x\) to a \(y\) and to a \(z\), just as we can proceed, for example, in the light spectrum from green to blue, to violet, and to ultraviolet.

[ 7 ] And now it is a matter of studying the mutual relationships between these different areas. We always see very specific characteristics, I would say essence carriers, appearing in each area: In the lowest realm, we see a closed form, in the gaseous realm a liquid form, so to speak, the condensation and rarefaction that—to be precise—accompanies the clay being under certain conditions. Then, as we pass through the heat realm into the \(x\) realm, we see materialization and dematerialization. And the question that must arise here is this: How does one region influence the other? Now, I have already pointed out to you that, in a certain way, when we speak of gas, the processes in the gaseous region can be thought of as giving, in their course, the picture of what happens in the heat being. We could say that the gas is, in a sense, carried away by the heat entity and, in its material form, conforms to what the heat entity wants, so that in the processes within the gas-filled space, the processes that are bound to the gas, we see, in a sense, images of what the heat does. We can therefore say that in the gas we find, in a sense, images of what happens in the heat entity. It is impossible to present this in any other mental image than by thinking of gas and heat as interpenetrating each other in a certain way, so that the gas is actually seized in its spatial extension by what the heat entity wants. Gas and heat would thus interpenetrate each other, and it is precisely in their interpenetration that they would reveal to us, through the processes in the gas, what is actually happening in the realm of heat. Again, we can say that liquid shows us a relationship to gas similar to that of gas to heat. Solids show us the same relationship to liquid as liquid to gas, and gas to heat.

[ 8 ] But what occurs in the realm of the solid? In the realm of the solid, formations occur, proper formations, formations that are self-contained. These are, in a sense, what again is an image for us of what only acts in the liquid. Now we can go to a realm \(U\) beneath the solid, which we will initially assume hypothetically, and we want to acquire concepts in order to then see whether these concepts are applicable anywhere in the realm of externally perceptible phenomena. By continuing this line of thought, which, as you will appreciate, is rooted in reality, we want to create concepts that we can hope will then, because they are derived from reality, carry us a little way into reality. What would have to happen if something like the region \(U\) were real? In a sense, what is actually an external fact in the preceding region, the region of solid bodies, would have to appear pictorially in the region \(U\). This region \(U\) would have to give us, in turn, the image region of the region of solid bodies. In the region of solid bodies there are forms, forms that are shaped by their inner essence or at least by their relationship to the world – we can pursue this further in the next few days – but forms appear, forms must appear in their mutual relationships.

[ 9 ] Let us return once more to the liquid realm. There, in a sense, we have this liquid as a body in connection with the whole earth, through the level surface that encloses the liquid on the outside. So we must find something in gravity that is related to the forces that have a formative effect on solid bodies. So, if we continue this line of thought in reality, we must find something that happens in the realm of \(U\) in the same way that formation happens in the realm of solid bodies, in that the realm of solid bodies provides the image of liquids. In other words, we must be able to see the effect in the realm of \(U\) that the different formations exert on each other. We must somehow be able to see the effect. We must be able to see how something arises under the influence of forms that relate to each other in different ways. There must be something in the realm of reality that arises under the influence of the various forms in the realm of the solid. Today, we actually only have the beginning of such a thing. For take any body, for example tourmaline, which carries within itself a principle of formation. Let the shaped tourmaline, I mean the inner tendency to shape, work in different ways so that shape can act on shape, which you have at hand when you look through two tourmalines, when you take the tourmaline tongs, for example, and look through them: soon you can see through them, soon the field of vision darkens. You have only twisted the tourmalines in relation to each other, bringing their formative power into a different relationship. This phenomenon is closely related to the one where, supposedly through the passage of light through physical systems that are differently formed, the so-called polarization figures appear to us. These polarization phenomena always arise under the influence of the effect of the formed on each other. We have the remarkable fact that in the realm of the solid we are, as it were, looking at another realm that relates to the solid as the realm of the solid relates to the liquid. And when we ask ourselves: Where, under the influence of the formative force in the realm of the U, does that arise which occurs in the same way as when gravity, which in the realm of the liquid only forms levels, occurs in a formative way in the realm of the solid? — we must say: This happens when we observe the so-called polarization figures, which lie in a realm that is below the solid. We are actually looking into an area that is located below the solid.

[ 10 ] But we see something else from this. We could look into such a body system for a long time, and we would see a great variety of things happening there under the influence of various forces, representing the effects of different formations on each other, but we would see nothing if something else did not penetrate the solid bodies, other than the fact that the realm of the solid initially interpenetrates with the realm \(U\). For example, light penetrates it, which first makes these effects of the configuration visible to us.

[ 11 ] What I have just said has led to 19th-century physics creating itself within light itself and viewing that which only becomes visible through light as an effect of light itself. When one looks at these polarization figures, one must seek a completely different origin than that of light. What happens there has nothing directly to do with light. Light only penetrates this area \(U\) and makes visible what happens as a result of these formations taking on the character of images. So we can say that we are dealing with an interpenetration of the different areas that we have laid out here in a fan-like manner; we are dealing with an interpenetration of these different areas in reality.

[ 12 ] And we will now also be able to arrive in an appropriate manner at what appears to us, for example, in the area of the gaseous, through the formative, still in its quasi-liquid form. We will be led to better concepts for what has been said, where, when condensation and rarefaction occur, the tonal facts come before our soul through the mediation of the hearing organ on the occasion of this condensation and rarefaction. And we will not need to identify the condensations and dilutions in the gaseous body directly with what we encounter as the various sound effects, but we will have to look for something that then occurs in the realm of condensations and dilutions within the gas when these are present in the corresponding manner. We are compelled to express what actually happens in such a way that we say: First of all, we leave what we call sound in the indefinite. But when we bring about certain lawful condensations and dilutions in the gaseous medium, what becomes conscious to us in our perception of sound occurs. Isn't this way of expressing the matter quite parallel to saying: We can form a mental image of states of heat in the universe with very high temperatures, above 100°; we can form a mental image of states of heat with very low temperatures, deep down, states of cold; and in between we find a region where human beings can dwell and develop? — It will be possible for us to say: If somewhere in the universe there is such a great vibration that the state of heat changes from a very high temperature to a very low one, then there is something in between where human beings can arise. The opportunity for human beings to arise is given if there are other causes for the emergence of humanity. But we will certainly not say: Human beings are the oscillation of the heat state of bodies into low temperatures and the return oscillation — for with the return oscillation the opportunity would arise again — we will never say that. But in physics we constantly say: Sound is nothing other than the compression and rarefaction of air; sound is a wave motion that expresses itself in the compression and rarefaction of air. This completely disaccustoms us to seeing things in such a way that we simply see the compressions and rarefactions as the carrier of sound, not the sound itself. So that we also have to form a mental image of the gaseous state that simply penetrates into the gas but belongs to another realm, and which, in the realm of the gas, is given the opportunity to appear in such a way that a mediation between it and our hearing organs becomes possible. Only when one forms the concepts in this way does one actually speak correctly about physical phenomena. But if we form the concepts in such a way that we simply identify the sound or the sound formations with the vibrations of the air, then we are tempted to identify light with ether vibrations as well. We proceed from something that is only vaguely understood to the invention, the fantasizing of a world of facts that is actually only the creation of imprecise thinking. In many respects, what physics speaks of, especially at the end of the 19th century, is nothing more than the creation of imprecise thinking. And if we follow conventional physics, we are still deeply entrenched in having to acquire nothing more than the creations of imprecise thinking in physical concepts.

[ 14 ] Now, however, the point is that when we move from the heat region to \(x\), \(y\), \(z\), we have, in a sense, the prospect of having to go on to infinity, and here (at \(U\)) we have the prospect of also having to go on to infinity. I already pointed out to you yesterday that the same thing occurs in the spectrum, where we are also, in a sense, compelled, when we form a mental image of the spectrum as it usually appears, to proceed, in a sense, into infinity or at least into the indefinite when following the path from green through blue to violet, and likewise toward red. However, when we consider the entire spectrum, the entire range of color phenomena, we can imagine this spectrum as being formed from the truly complete series of twelve colors, which can only be characterized on a circle that has green at the bottom, peach blossom at the top, and the other colors in between. And we can imagine that this circle is now expanding more and more; that peach blossom disappears upwards and runs towards red on one side and violet on the other, and beyond both. So in the ordinary spectrum we actually have a part of what would be there if the completeness of colors could appear through the world of phenomena surrounding human beings. We only have a part of it.

[ 15 ] Now there is something that is highly remarkable. I believe that if you take the usual descriptions of optics in physics textbooks and turn to what is usually given as an explanation of a special spectral phenomenon, namely the rainbow, you will feel somewhat uncomfortable if you like to stick to clear concepts. For the explanations of the rainbow are really given in such a way that one is left completely baffled. One is forced to resort to raindrops and trace all kinds of paths of light rays inside them, and then one is forced to piece together this fairly uniform image of the rainbow from lots of small images that are particularly dependent on one's position, images that are actually created by raindrops. In short, these explanations have something of an atomistic view of a phenomenon that appears to be quite uniform in our environment. But even more uncomfortable than the rainbow, i.e., the spectrum that nature itself conjures up before us, can be the realization that this rainbow we are talking about never actually appears alone. No matter how much it may hide itself, the second rainbow is always there. And what belongs together cannot be separated. The two rainbows, one of which is only less distinct than the other, necessarily belong together, and when explaining the formation of the rainbow, one must not even attempt to explain only one strip of color, but must be clear that the totality of the phenomenon—the relative totality—is something that is now something else in the middle and has two bands at the edges. One band is the slightly clearer rainbow, the other the less distinct arc. We are dealing with an image that appears to us in the great outdoors and that in fact extends almost into the entire universe. We must view this as something unified. Now, if we look closely, we will become quite aware that the second rainbow, the secondary rainbow, is actually a reversal of the first, that the second can in fact be understood in a certain way as a kind of mirror image of the first, that it reflects, as it were, the first, clearer rainbow. So, as soon as we move from the partial phenomena that occur in our environment to a relative totality that we face when we perceive our entire Earth in relation to the cosmic system, we have something that actually completely changes its appearance. For now, I will only point out this phenomenon. We will take a closer look at these phenomena in the course of our consideration.

[ 16 ] But because the second rainbow appears to us, the thing that appears there (see drawing) becomes, in a sense, a closed system. The system is only open as long as I am confronted with the spectrum that appears specifically here in my environment. And the appearance of the rainbow should actually tempt me to think that when I visualize this spectrum through an experiment, I am only holding on to one end of nature, that somewhere at the opposite end I am losing something; that there is still something somewhere in the unknown, that I actually need the secondary rainbow for every seven-color spectrum.

[ 17 ] Keep this phenomenon and its transformation into concepts in mind, together with this progression of our real concept, which we have considered here (see diagram). Here (see drawing), we are trying to bring together the band of colors that expands into the indefinite by striking one into the other. If we were to do the same here (diagram), what would happen? By moving out of the solid body into \(U\) and perhaps continuing further down that path, we would make it such that it would come back to us from above and be closed. But now, if we take this path downwards and come back from above and close it, what would be formed? What would happen?