Second Scientific Lecture-Course:

Warmth Course

GA 321

11 March 1920, Stuttgart

Lecture XI

My dear friends,

At this point I would like to build a bridge, as it were, between the discussions in this course and the discussion in the previous course. We will study today the light spectrum, as it is called, and its relation to the heat and chemical effects that come to us with the light. The simplest way for us to bring before our minds what we are to deal with is first to make a spectrum and learn what we can from the behavior of its various components. We will, therefore, make a spectrum by throwing light through this opening—you can see it here. (The room was darkened and the spectrum shown.) It is to be seen on this screen. Now you can see that we have something hanging here in the red portion of the spectrum. Something is to be observed on this instrument hanging here. First we wish to show you especially how heat effects arise in the red portion of the spectrum. Something is to be observed on this instrument hanging here. These effects are to be observed by this expanding action of the energy cylinder on the air contained in the instrument, which expanding action in turn pushes the alcohol column down on this side and up on this one. This depression of the alcohol column shows us that there is a considerable heat effect in this part of the spectrum. It would be interesting also to show that when the spectrum is moved so as to bring the instrument into the blue-violet portion, the heat effect is not noticeable. It is essentially characteristic of the red portion. And now, having shown the occurrence of heat effects in the red portion of the spectrum by means of the alcohol column, let us show the chemical activity of the blue-violet end. We do this by allowing the blue portion to fall on a substance which you can see is brought into a state of phosphorescence. From the previous course you know that this is a form of chemical activity. Thus you see an essential difference between the portion of the spectrum that disappears on the unknown on this side and the portion that disappears on this other side; you see how the substance glows under the influence of the chemical rays, as they are called. Moreover, we can so arrange matters that the middle portion of the spectrum, the real light portion, is cut out. We cannot do this with absolute precision, but approximately we can make the middle portion dark by simply placing the path of the light a solution of iodine in carbon disulphate. This solution has the property of stopping the light. It is possible to demonstrate the chemical effect on one side and the heat effect on the other side of this dark band. Unfortunately we cannot carry out this experiment completely, but only mention it in passing. If I place an alum solution in the path of the light the heat effect disappears and you will see that the alcohol column is no longer displaced because the alum, or the solution of alum, to speak precisely, hinders its passage. Soon you will see the column equalize, now that we have placed alum in the path, because the heat is not present. We have here a cold spectrum.

Now let us place in the light path the solution of iodine in carbon disulphate, and the middle portion of the spectrum disappears. It is very interesting that a solution of esculin will cut out the chemical effect. Unfortunately we could not get this substance. In this case, the heat effect and the light remain, but the chemical effect ceases. With the carbon disulphide you see clearly the red portion—it would not be there if the experiment were an entire success—and the violet portion, but the middle portion is dark. We have succeeded partly in our attempt to eliminate the bright portion of the spectrum. By carrying out the experiment in a suitable way as certain experimenters have done (for instance, Dreher, 50 years ago) the two bright portions you see here can be done away with. Then the temperature effect may be demonstrated on the red side, and on the other side phosphorescence shows the presence of the chemically active rays. This has not yet been fully demonstrated and it is of very great importance. It shows us how that which we think of as active in the spectrum can be conceived in its general cosmic relations.

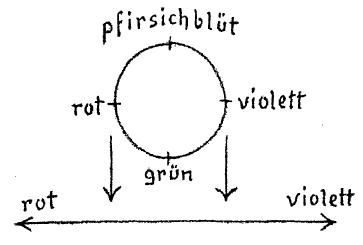

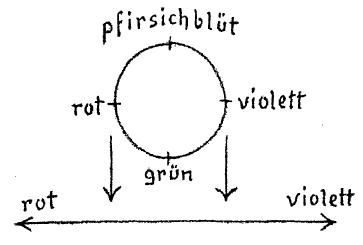

In the course that I gave here previously I showed how a powerful magnet works on the spectral relations. The force emanating from the magnet alters certain lines, changes the picture of the spectrum itself. It is only necessary for a person to extend the thought prompted by this in order to enter the physical processes in his thinking. You know from what we have already said that there is really a complete spectrum, a collection of all possible twelve colors; that we have a circular spectrum instead of the spectrum spread out in one dimension of space. We have (in the circular spectrum) here green, peach blossom here, here violet and here red with the other shades between. Twelve shades, clearly distinguishable from one another.

Now the fact is that under the conditions obtaining on the earth such a spectrum can only exist as a mental image. When we are dealing with this spectrum we can only do so by means of a mental picture. The spectrum we actually get is the well-known linear one extending as a straight line from red through the green to the blue and violet—thus we obtain a spectrum formed from the circular one, as I have often said, by making the circle larger and larger, so that the peach blossom disappears, violet shades off into infinity on one side and red shades off on the other, with green in the middle.

We may ask the question: how does this partial spectrum, this fragmentary color band arise from the complete series of color, the twelve color series which must be possible? Imagine to yourselves that you have the circular spectrum, and suppose forces to act on it to make the circle larger and larger and finally to break at this point (see drawing). Then, when it has opened, the action of these forces would make a straight line of the circle, a line extending apparently into infinity in each direction. (Fig. 1).

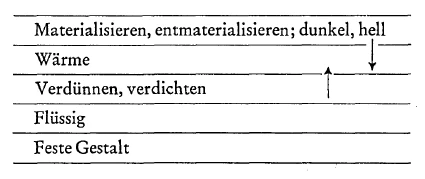

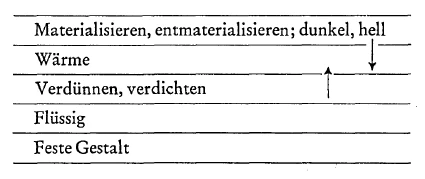

Now when we come upon this straight line spectrum here under our terrestrial conditions we feel obliged to ask the question: how can it arise? It can arise only in this way, that the seven known colors are separated out. They are, as it were, cut out of the complete spectrum by the forces that work into it. But we have already come upon these forces in the earth realm. We found them when we turned our attention to the forces of form. This too is a formative activity. The circular form is made over into the straight-line form. It is a form that we meet with here. And considering the fact that the structure of the spectrum is altered by magnetic forces, it becomes quite evident that forces making our spectrum possible are everywhere active. This being the case, we have to assume that our spectrum, which we consider a primary thing, has working within it certain forces. Not only must we consider light variation in our ordinary spectrum, but we have to think ofthis ordinary spectrum as including forces which render it necessary to represent the spectrum by a straight line. This idea we must link up with another, which comes to us when we go through the series, as we have frequently done before (Fig. 2), from solids, through fluids, to condensation and rarefaction, i.e. gases, to heat and then to that state we have called X, where we have materialization and dematerialization. Here we meet a higher stage of condensation and rarefaction, beyond the heat condition, just as condensation and rarefaction proper constitute a kind of fluidity of form.

When form itself becomes fluid, when we have a changing form in a gaseous body, that is a development from form as a definite thing. And what occurs here? A development of the condensation-rarefaction condition Keep this definitely in mind, that we enter a realm where we have a development of the condensation-rarefaction state.

What do we mean by a “development of rarefaction”? Well, matter itself informs us what happens to it when it becomes more and more rarefied. When I make matter more and more dense, it comes about that a light placed behind the matter does not shine through. When the matter becomes more and more rarefied, the light does pass through. When I rarefy enough, I finally come to a point where I obtain brightness as such. Therefore, what I bring into my understanding here in the material realm is empirically found to be the genesis of brightness or luminosity as a heightening of the condition of rarefaction; and darkening has to be thought of as a condensation, not yet intense enough to produce matter, but of such an intensity as to be just on the verge of becoming material.

Now you see how I place the realm of light above the heat realm and how the heat is related to the light in an entirely natural fashion. But when you recollect how a given realm always gives a sort of picture of the realm immediately above it, then you must look in the being of heat for something that foreshadows, as it were, the conditions of luminosity and darkening. Keep in mind that we do not always find only the upper condition in the lower, but also always the lower condition in the upper. When I have a solid, it foreshadows for me the fluid. What gives it solidity may extend over into the non-solid realm. I must make it clear to myself, if I wish to keep my concepts real, that there is a mutual interpenetration of actual qualities. For the realm of heat this principle takes on a certain form; namely this, that dematerialization works down into heat from above (see arrow). From the lower side, the tendency to materialization works up into the heat realm.

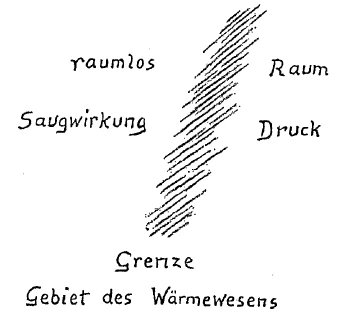

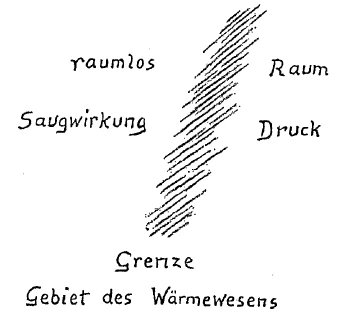

Thus you see that I draw near to the heat nature when I see in it a striving for dematerialization, on the one hand, and on the other a striving for materialization. (If I wish to grasp its nature I can do it only by conceiving a life, a living weaving, manifesting itself as a tendency to materialization penetrated by a tendency to dematerialization.) Note, now, what an essential distinction exists between this conception of heat based on reality and the nature of heat as outlined by the so-called mechanical theory of heat of Clausius. In the Clausius theory we have in a closed space atoms or molecules, little spheres moving in all directions, colliding with each other and with the walls of the vessel, carrying on an outer movement. (Fig. 3) And it is positively stated: heat consists in reality in this chaotic movement, in this chance collision of particles with each other and with the walls of the vessel. A great controversy arose as to whether the particles were elastic or non-elastic. This is of importance only as the phenomena can be better explained on the assumption of elasticity or on the assumption that the particles are hard, non-elastic bodies. This has given form to the conviction that heat is purely motion in space. Heat is motion. We must now say “heat is motion,” but in an entirely different sense. It is motion, but intensified motion. Wherever heat is manifest in space, there is a motion which creates the material state striving with a motion which destroys the material state. It is no wonder, my friends, that we need heat for an organism. We need heat in our organism simply to change continuously the spatially-extended into the spatially non-extended. When I simply walk through space, my will carries out a movement in space. When I think about it, something other than the spatial is present. What makes it possible for me as a human organism to be inserted into the form relationships of the earth? When I move over the earth, I change the entire terrestrial form. I change her form continually. What makes it possible that I am in relation to the other things of the earth, and that I can form ideas, outside of space, within myself as observer, of what is manifested in space? This is what makes it possible, my being exists in the heat medium and is thus continually enabled to transform material effects, spatial effects, into non-spatial ones that no longer partake of the space nature. In myself I experience in fact what heat really is, intensified motion. Motion that continually alternates between the sphere of pressure and the sphere of suction.

Assume that you have here (Fig. 4) the border between pressure and suction forces. The forces of pressure run their course in space, but the suction forces do not, as such, act in space—they operate outside of space. For my thoughts, resting on the forces of suction, are outside of space. Here on one side of this line (see figure) I have the non-spatial. And now when I conceive of that which takes place neither in the pressure nor in the suction realms, but on the border line between the two, then I am dealing with the things that take place in the realm of heat. I have a continually maintained equilibrium tendency between pressure effects of a material sort and suction effects of a spiritual sort. It is very significant that certain physicists have had these things right under their noses but refuse to consider them. Planck, the Berlin physicist, has made the following striking statement: if we wish to get a concept of what is called ether nowadays, the first requisite is to follow the only path open to us, in view of the knowledge of modern physics, and consider the ether non-material. This from the Berlin physicist, Planck. The ether, therefore, is not to be considered as a material substance. But now, what we are finding beyond the heat region, the realm wherein the effects of light take place, that we consider so little allied to the material that we are assuming the pressure effects—characteristic of matter—to be completely absent, and only suction effects active there. Stated otherwise, we may say: we leave the realm of ponderable matter and enter a realm which is naturally everywhere active, but which manifests itself in a manner diametrically opposite to the realm of the material. Its forces we must conceive of as suction forces while material things obviously manifest through pressure forces. Thus, indeed, we come to an immediate concept of the being of heat as intensified motion, as an alternation between pressure and suction effects, but in such a way that we do not have, on the one hand, suction spatially manifested and, on the other hand, pressure spatially manifested. Instead of this, we have to think of the being of heat as a region where we entirely leave the material world and with it three-dimensional space. If the physicist expresses by formulae certain processes, and he has in these formulae forces, in the case where these forces are given the negative sign—when pressure forces are made negative—they become suction forces. Attention must be paid to the fact that in such a case one leaves space entirely. This sort of consideration of such formulae leads us into the realm of heat and light. Heat is only half included, for in this realm we have both pressure and suction forces.

These facts, my dear friends, can be given, so to speak, only theoretically today in this presentation in an auditorium. It must not be forgotten that a large part of our technical achievement has arisen under the materialistic concepts of the second half of the 19th century. It has not had such ideas as we are presenting and therefore such ideas cannot arise in it. If you think over the fruitfulness of the one-sided concepts for technology, you can picture to yourselves how many technical consequences might flow from adding to the modern technology, knowing only pressures—the possibility of also making fruitful these suction forces. (I mean not only spatially active suction which is a manifestation of pressure, but suction forces qualitatively opposite to pressure.)

Of course, much now incorporated in the body of knowledge known as physics will have to be discarded to make room for these ideas. For instance, the usual concepts of energy must be thrown out. This concept rests on the following very crude notions: when I have heat I can change it into work, as we saw from the up and down movement of the flask in the experiment resulting from the transformation of heat. But we saw at the same time that the heat was only partly changed and that a portion remained over of the total amount at hand. This was the principle that led Eduard von Hartmann to enunciate the second important law of the modern physics of heat—a perpetuum mobile of the second type is impossible.

Another physicist, Mach, well known in connection with modern developments in this field, has done quite fundamental thinking on the subject. He has thought along lines that show him to be a shrewd investigator, but one who can only bring his thinking into action in a purely materialistic way. Behind his concepts stands the materialistic point of view. He seeks cleverly to push forward the concepts and ideas available to him. His peculiarity is that when he comes to the limit of the usual physical concepts where doubts begin to arise, he writes the doubts down at once. This leads soon to a despairing condition, because he comes quickly to the limit where doubts appear, but his way of expressing the matter is extremely interesting. Consider how things stand when a man who has the whole of physics at his command is obliged to state his views as mach states them. He says (Ernst Mach, Die Prinzipien der Warme Lehre, p. 345): “There is no meaning in expressing as work a heat quantity which cannot be transformed into work.” (We have seen that there is such a residue.) “Thus it appears that the energy principle like other concepts of substance has validity for only a limited realm of facts. The existence of these limits is a matter about which we, by habit, gladly deceive ourselves.”

Consider a physicist who, upon thinking over the phenomena lying before him, is obliged to say the following: “Heat exists, in fact, that I cannot turn into work, but there is no meaning in simply thinking of this heat as potential energy, as work not visible. However, I can perhaps speak of the changing of heat into work within a certain region—beyond this it is not valid.” And in general it is said that every energy is transformable into another, but only by virtue of a certain habit of thinking about those limits about which we gladly deceive ourselves.

It is extremely interesting to pin physics down at the very point where doubts are expressed which must arise from a straightforward consideration of the facts.

Does this not clearly reveal the manner in which physics is overcome when physicists have been obliged to make such statements? For, fundamentally, this is nothing other than the following: one can no longer hold to the energy principle put forth as gospel by Helmoltz and his colleagues. There are realms in which this energy principle does hold.

Now let us consider the following: How can one make the attempt symbolically (for fundamentally it is symbolic when we try to set the outlines of something), how can we make the attempt to symbolize what occurs in the realm of heat? When you bring together all these ideas I have developed, and through which in a real sense I have tried to attain to the being of heat, then you can get a concept of this being in the following manner.

Picture this to yourselves (Fig. 5). Here is space (blue) filled with certain effects, pressure effects. Here is the non-spatial (red) filled with suction effects. Imagine that we have projected out into space what we considered as alternately spatial and non-spatial. The red portion must be thought of as non-spatial. Using this intermediate region as an image of what is alternately spatial and non-spatial, you have in it a region where something is appearing and disappearing. Think of something represented as extended and disappearing. As substance appears, there enters in something from the other side that annihilates it, and then we have a physical-spiritual vortex continually manifesting in such a manner that what is appearing as substance is annihilated by what appears at the same time as spirit. We have a continual sucking up of what is in space by the entity which is outside of space.

What I am outlining to you here, my dear friends, you must think of as similar to a vortex. But in this vortex you should see simply in extension that which is “intensive” in its nature. In this way we approach, I might say figuratively, the being of heat. We have yet to show how this being of heat works so as to bring about such phenomena as conduction, the lowering of the melting point of an alloy below the melting point of its constituents, and what it really means that we should have heat effects at one end of the spectrum and chemical effects at the other.

We must seek the deeds of heat as Goethe sought out the deeds of light. Then we must see how knowledge of the being of heat is related to the application of mathematics and how it affects the imponderable of physics. In other words, how are real formulae to be built, applicable to heat and optics.

Elfter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Jetzt möchte ich gewissermaßen die Brücke schlagen, weil ich sie für die nächsten Betrachtungen brauchen werde, zwischen den Auseinandersetzungen dieses Kurses und den Auseinandersetzungen des vorigen Kurses. Wir werden heute das sogenannte Lichtspektrum mit seinen Beziehungen zu den am Lichtspektrum uns entgegentretenden Wärmewirkungen und chemischen Wirkungen etwas studieren. Wir können am einfachsten uns dasjenige, um was es sich handelt, vielleicht versinnlichen, wenn wir zunächst ein Spektrum darstellen und studieren, wie das Verhalten der verschiedenen Teile des Spektrums sich uns zeigt. Wir wollen also hier ein Spektrum entwerfen, indem wir Licht durch diesen Spalt gehen lassen. (Das Zimmer wird verdunkelt und durch das Experiment das Spektrum gezeigt.) Sie sehen, wir haben hier ein Spektrum auf dieser Platte. Sie können sich nun davon überzeugen, daß wir in den roten Teil des Spektrums hier etwas hineingehängt haben. Wir werden an diesem Instrument dann etwas beobachten können. Wir werden jetzt versuchen, Ihnen zu zeigen, wie im roten Teil des Spektrums vorzugsweise Wärmewirkungen auftreten. Diese Wärmewirkungen können Sie jetzt schon dadurch beobachten, daß Sie sehen, wie unter dem Einfluß des Energiezylinders, wenn ich so sagen darf, hier die Luft ausgedehnt wird, drückt und dadurch die Weingeistsäule hier heruntersteigt und hier hinauf. Durch dieses Heruntersteigen der Weingeistsäule wird uns gezeigt, daß hier in diesem Teil des Spektrums im wesentlichen eine Wärmewirkung da ist. Es wäre ja natürlich interessant noch zu zeigen, es läßt sich aber nicht so schnell machen, daß, wenn wir das Spektrum verschieben würden und dieses Instrument in dem blauvioletten Teil hätten, sich die Wärmewirkung nicht zeigen würde. Diese Wärmewirkung ist also im wesentlichen im roten 'Teil des Spektrums zu sehen. Und jetzt werden wir, ebenso wie wir geprüft haben durch das Fallen der Weingeistsäule das Auftreten der Wärmewirkung im rotgelben Teil des Spektrums, das Auftreten der chemischen Wirkung des Spektrums im Blauviolett prüfen, indem wir hier eine Substanz hineinstellen in den Raum, der durchmessen wird von dem blauvioletten Teil des Spektrums, und Sie werden sehen, daß dadurch diese Substanz zum Phosphoreszieren aufgerufen wird, also, wie Sie aus den Betrachtungen des vorigen Kurses wissen, chemische Wirkungen nachgewiesen werden. Sie sehen daraus, daß in der Tat noch eine innere Verschiedenheit zwischen demjenigen Teil des Spektrums besteht, der nach der einen Seite wie ins Unbestimmte verläuft, und dem anderen Teil des Spektrums, der nach der anderen Seite verläuft. Sie sehen, wie die Substanz leuchtend geworden ist unter dem Einfluß der sogenannten chemischen Strahlen. Wir können nun noch bewirken, daß auch der mittlere Teil des Spektrums, der der eigentliche Lichtteil ist, abgesondert wird. Ganz wird es uns wohl nicht gelingen, aber wir werden doch den mittleren Teil absondern können, also Dunkelheit im mittleren Teil hervorrufen können statt der Helligkeit, indem wir einfach hineinträufeln lassen in die Substanz, die uns ein Schwefelkohlenstoff-Prisma gebildet hat, etwas Jodtinktur. Dadurch bekommen wir die Mischung zwischen Schwefelkohlenstoff und Jodtinktur. Sie erweist sich als eine Substanz, welche das Licht nicht durchläßt, und wir würden, wenn wir den Versuch vollständig machen könnten — wir können es ja leider nicht, sondern wir können nur auf den Weg. weisen —, vollkommen zeigen können, daß auf der einen Seite Wärmewirkungen, auf der anderen Seite chemische Wirkungen auftreten, während der eigentliche Lichtteil, der mittlere Teil des Spektrums, verschwindet. Wenn ich Alaun in den Weg hineinstellen würde, würden die Wärmewirkungen aufhören, und Sie würden dann sehen, daß die Weingeistsäule wiederum steigt, weil der Alaun, die Alaunlösung den Durchgang der Wärmewirkungen — so will ich vorsichtig sagen — verhindert. Es würde jetzt sehr bald, weil Alaun im Wege steht, diese Weingeistsäule wiederum steigen, weil die Erwärmung nicht stattfinden würde. Wir würden hier ein kaltes Spektrum bekommen.

[ 2 ] Sehr interessant ist, daß man auch verschwinden lassen kann den chemischen Teil, wenn man in den Weg der Ausbreitung des Spektrums eine Äskulinlösung stellt, die wir leider auch nicht bekommen konnten. Es bleiben die Wärmewirkungen und die Lichtwirkungen vorhanden, aber es hören auf die chemischen Wirkungen. Wir wollen jetzt in den Weg stellen die Auflösung von Jod in Schwefelkohlenstoff, und es wird der mittlere Teil des Spektrums verschwinden. Sie sehen deutlich den roten Teil, der aber, wenn das Experiment vollständig gelingen würde, weg wäre, Sie sehen den violetten Teil und in der Mitte nichts. Also, es ist uns gelungen dadurch, daß wir eine Art von Fragment des Versuches ausgeführt haben, den hauptsächlichsten Lichtteil, das Mittlere wegzuschaffen. Wenn wir das Experiment vollständig machten, wie es einzelnen Experimentatoren, zum Beispiel Dreher in Halle vor fünfzig Jahren gelungen ist, könnten wir auch die zwei leuchtenden Stellen vollständig wegschaffen und dann nachweisen die Erhöhung der Temperatur, die dableibt, und auf der anderen Seite die Wirkungen der chemischen Strahlen durch die «leuchtende Materie». Das ist eine Versuchsreihe, die noch nicht zu ihrem Ende gebracht ist, eine Versuchsreihe, die außerordentlich wichtig ist. Sie zeigt uns, wie sich hineinstellt dasjenige, was im Spektrum wirksam gedacht werden kann, in den allgemeinen Weltzusammenhang.

[ 3 ] Ich habe bei dem Kursus, den ich bei meinem früheren Aufenthalt hier gehalten habe, gezeigt, wie auf die Spektralverhältnisse zum Beispiel ein kräftiger Magnet wirkt, indem sich durch die Einwirkung, durch die Kraft, die von dem Magneten ausgeht, gewisse Linien, gewisse Bildungen im Spektrum selber ändern. Und es handelt sich nun darum, daß man einfach den Gedankengang, der damit angeschlagen ist, wiederum so erweitert, daß man in seinen Gedanken drinnen die physikalischen Vorgänge wirklich hat. Sie wissen aus unseren Betrachtungen, die wir jetzt angestellt haben, daß eigentlich ein vollständiges Spektrum, das heißt eine Zusammenfassung aller möglichen Farben, zwölf Farben ergeben würde, daß wir bekommen würden gewissermaßen ein Kreisspektrum statt eines in der einen Richtung des Raumes ausgedehnten Spektrums. Wir würden hier Grün haben, hier Pfirsichblüt, hier Violett und hier Rot, dazwischen die anderen Farbennuancen, zwölf deutlich voneinander zu unterscheidende Farbennuancen (siehe Zeichnung).

[ 4 ] Nun handelt es sich darum, daß wir uns ein solches Spektrum innerhalb der irdischen Verhältnisse nur im Bilde darstellen können. Wenn pfirsichblört wir in dem Bereiche des irdischen Lebens ein Spektrum darstellen, können wir es bloß im Bilde darstellen, und so bekommen wir ja immer das bekannte Spektrum, das verläuft in gerader Linie vom Rot durch das Grün zu dem Blau und Violett. Also, wir bekommen ein Spektrum, welches aus dem obigen, wie ich jetzt schon öfter gesagt habe, erhalten werden kann, indem der Kreis immer größer und größer wird, das Pfirsichblüt nach der anderen Seite verschwindet, das Violett hier (siehe Zeichnung, rechts) ins scheinbar Unendliche geht, das Rot scheinbar hier (links) ins Unendliche weist und das Grün in der Mitte bleibt.

[ 5 ] Wir können uns die Frage vorlegen: Wie entsteht aus der Vollständigkeit der Farbenbildung, aus der Zwölf-Farben-Bildung, die doch möglich sein muß, dieses fragmentarische Spektrum, dieses fragmentarische Farbenband? Wenn Sie hypothetisch annehmen, das vollständige Kreisspektrum würde hier (siehe Zeichnung) entstehen, so können Sie sich vorstellen, daß da Kräfte wirkten, die den Kreis vergrößerten, indem sie ihn hier auseinanderzerrten. Dann würde ein Moment eintreten, wo eben wirklich das hier oben zerreißt und durch die wirkenden Kräfte der Kreis zur geraden Linie, das heißt, zur unendlichen Länge, zur scheinbar unendlichen Länge, gemacht wird.

[ 6 ] Wenn wir im Bereich des irdischen Lebens dieses durch eine Gerade zu versinnlichende Spektrum finden, so müssen wir uns fragen: Wie kann es entstehen? Es kann nur dadurch entstehen, daß aus der Vollständigkeit der Farben die bekannten sieben Nuancen herausgesondert werden. Sie werden herausgesondert durch Kräfte, die in das Spektrum hinein gewissermaßen wirken müssen. Diese Kräfte haben wir aber eigentlich im Bereich des irdischen Daseins schon gefunden. Wir haben sie gefunden, indem wir auf die Gestaltungskräfte hingewiesen haben. Das ist ja auch eine Gestaltung: Die Kreisgestalt ist doch in die Gerade-Linien-Gestalt übergeführt worden. Das ist eine Gestaltung, die wir hier angetroffen haben. Und es ist, ich möchte sagen, handgreiflich, daß irgendwie im Bereich des Irdischen Kräfte wirken, die erst unser Spektrum möglich machen, wenn wir sehen können, daß durch den Einfluß der magnetischen Kräfte das innere Gefüge des Spektrums beeinflußt, verändert wird. Wenn das so ist, so müssen wir doch annehmen, daß in unserem Spektrum, das wir immer als primär betrachten, schon Kräfte wirksam sein können. Wir müssen also in unserem gewöhnlichen Spektrum nicht bloß Lichtvariationen konstatieren, sondern wir müssen in dieses gewöhnliche Spektrum hineindenken Kräfte, welche erst notwendig machen, daß dieses gewöhnliche Spektrum symbolisiert wird durch eine gerade Linie.

[ 7 ] Diesen Gedankengang wollen wir mit einem anderen verbinden, der sich uns ergeben wird, wenn wir noch einmal aufsteigen in solcher Weise, wie wir das schon öfter gemacht haben: vom fest Gestalteren durch das Flüssige zum Verdichteten, Verdünnten, das heißt Gasigen, zum Wärmewesen, zu dem, was wir Materialisierung und Entmaterialisierung im x genannt haben. Hier tritt uns auf eine höhere Steigerung des Verdichtens und Verdünnens über dem Wärmewesen, wie uns die Verdichtung und Verdünnung selber auftritt als eine Steigerung, als gewissermaßen ein Flüssigwerden der Gestalt. Wenn die Gestalt selber flüssig wird, wenn wir eine variable Gestaltung haben im Gas, so ist das eine Steigerung des bestimmten Gestaltens. Was tritt hier auf? Hier tritt auf eine Steigerung des Verdünnens und Verdichtens. Halten Sie das gut fest, daß wir in ein Gebiet hineinkommen, wo eine Steigerung des Verdünnens und Verdichtens auftritt.

[ 8 ] Was heißt eine Steigerung des Verdünnens? Nicht wahr, wenn Materie immer dünner und dünner wird, so kündigt sie uns schon an, wenn sie Materie einer gewissen Art ist, was mit ihr kämpft, wenn sie immer dünner und dünner wird. Wenn ich sie immer dichter und dichter mache, dann wird sich herausstellen, daß sie mir ein hinter ihr befindliches Licht nicht mehr durchläßt. Wenn ich sie immer dünner und dünner mache, läßt sie das Licht durch. Verdünne ich immer weiter und weiter, so kommt mir zuletzt überhaupt nur zum Vorschein die Helligkeit als solche. Dasjenige also, was ich hier als noch im Gebiete des Materiellen liegend aufzufassen habe, das wird mir empirisch immer erscheinen als Auftreten der Helligkeit. Entmaterialisierung wird mir auftreten als hell; Materialisierung wird mir immer auftreten als dunkel. Ich habe also im Gebiet der Weltwirkungen Erhellung aufzufassen als Steigerung der Verdünnung und Verdunkelung aufzufassen als eine noch nicht genügend eingetretene Verdichtung, so daß die Verdichtung noch nicht genügend als Materie erscheint, sondern die Wirkungen erst auf dem Wege zum Materiellen sind.

[ 9 ] Sie sehen, ich finde da oberhalb des Wärmegebietes das Lichtgebiet, und es stellt sich mir jetzt auf eine ganz naturgemäße Weise auch das Wärmegebiet in das Lichtgebiet hinein. Denn wenn Sie bedenken, daß immer das weiter nach unten Gelegene gewissermaßen das Bild gibt des darüber Gelegenen, so werden Sie im Wärmewesen finden müssen etwas, was gewissermaßen Bild ist der Aufhellung und der Verdunkelung. Im Wärmewesen, das uns ja an einem Ende des Spektrums auftritt, werden wir finden müssen etwas, was als Bild der Erhellung und Verdunkelung auftritt. Wir werden aber auch uns klar sein müssen darüber, daß wir nicht nur auf diese Art immer den oberen Teil unseres Wirklichkeitsgebietes in dem unteren finden, sondern auch den unteren Teil des Wirklichkeitsgebietes immer in dem oberen. Wenn ich einen Körper fest habe, so kann er durchaus in dem flüssigen Gebiet drinnen sein mit seiner Festigkeit. Dasjenige, was ihm Gestaltung gibt, kann hinaufragen in das nächste, in das nicht mehr gestaltete Gebiet. Ich muß mir klar sein darüber, daß ich, wenn ich mit Wirklichkeiten in meinen Vorstellungen umgehen will, ich es zu tun habe mit dem gegenseitigen Sich-Durchdringen der Wirklichkeitsqualitäten. Das aber nimmt eine besondere Form an für das Wärmegebiet. Es nimmt die Form an, daß auf der einen Seite das Entmaterialisieren in der Wärme wirken muß von oben herunter (Pfeil), auf der anderen Seite die Tendenz zum Materialisieren in die Wärme hineinwirkt.

[ 10 ] Sie sehen, ich komme dem Wärmewesen nahe, indem ich in ihm den Aufgang sehen muß auf der einen Seite eines Strebens nach Entmaterialisierung, auf der anderen Seite eines Strebens nach Materialisierung. So daß ich, wenn ich nun fassen will das Wärmewesen, ich es nur so fassen kann, daß in ihm ein Leben, ein lebendiges Weben ist, welches dadurch sich offenbart, daß überall die Tendenz zum Materialisieren durchdrungen wird von der Tendenz zu entmaterialisieren. Jetzt merken Sie, was für ein beträchtlicher Unterschied zwischen diesem wirklich aufgefundenen Wärmewesen ist und dem Wärmewesen, das in der sogenannten mechanischen Wärmetheorie eines Clausius figuriert hat. Da finden Sie, wenn Sie einen geschlossenen Raum haben, atomistische oder molekulare Kügelchen, die stoßen nach allen Seiten, rempeln sich gegenseitig an, stoßen an die Wand an und vollführen rein äußere extensive Bewegungen. Und es wird dekretiert: Die Wärme besteht eigentlich in dieser chaotischen Bewegung, in diesem chaotischen sich gegenseitig Stoßen und an die Wand Stoßen der materiellen Teile, über die dann nur noch ein lebhafter Streit war, ob sie nun elastisch oder nicht elastisch aufzufassen sind. Das ist ja nur nach dem zu entscheiden, ob man für die eine oder andere Erscheinung die Elastizitätsformel oder die für unelastische, feste Körper mehr anwendbar findet. Es war also Ausdruck einer rein auf den Raum, auf räumliche Bewegung rücksichtnehmenden Überzeugung, wenn man gesagt hat: Wärme ist Bewegung. Wir müssen nun in ganz anderer Weise sagen: Wärme ist Bewegung - sie ist Bewegung, aber intensiv zu denkende Bewegung, Bewegung, bei der in jedem Raumteil, wo Wärme ist, das Bestreben besteht, materielles Dasein zu erzeugen und materielles Dasein wieder verschwinden zu lassen. Kein Wunder, daß auch wir Wärme brauchen in unserem Organismus. Wir brauchen einfach Wärme in unserem Organismus, um das räumlich Ausgedehnte stetig überzuführen in das räumlich Unausgedehnte. Wenn ich einfach den Raum durchschreite, ist dasjenige, was mein Wille vollführt, Raumgestaltung. Wenn ich es vorstelle, ist etwas ganz außerhalb des Raumes da. Was macht es mir möglich als menschliche Organisation, daß ich äußerlich eingereiht bin in die Gestaltverhältnisse der Erde? Indem ich auf ihr gehe, verändere ich ja die gesamte Gestalt der Erde, ich male schwarze Punkte auf eine Stelle, ich verändere ihre Gestalt fortwährend. Was macht es möglich, daß ich das, was ich im ganzen übrigen Erdenzusammenhang bin und was sich darstellt in räumlichen Wirkungen, daß ich das innerlich raumlos erfassen kann als Beobachter in meinen Gedanken? Daß ich selbst mein Dasein vollbringe in dem Medium der Wärme, das gestattet, daß fortwährend materielle Wirkungen, das heißt Raumeswirkungen, übergehen in unmaterielle Wirkungen, also in solche Wirkungen, die keinen Raum mehr einnehmen. Ich erlebe also in mir tatsächlich, was die Wärme in Wahrheit ist, intensive Bewegung, Bewegung, die fortwährend herüberpendelt aus dem Gebiet der Druckwirkungen in das Gebiet der Saugwirkungen.

[ 11 ] Nehmen Sie an, Sie haben hier die Grenze zwischen Druckwirkung und Saugwirkung. Die Druckwirkungen verlaufen im Raum, aber die Saugwirkungen verlaufen als solche nicht im Raum, sondern sie verlaufen außer dem Raum. Denn meine Gedanken sind beruhend auf den Saugwirkungen, verlaufen aber nicht im Raum. Hier habe ich jenseits dieser Linie (siehe Zeichnung Seite 170) das Raumlose. Und wenn ich mir vorstelle dasjenige, was nun weder im Gebiet des Druckes, im Raum, noch im Gebiet des Saugens geschieht, sondern im Gebiet der Grenze zwischen beiden, dann bekomme ich dasjenige, was im Gebiet des Wärmewesens geschieht: fortwährendes Gleichgewichtsuchen zwischen Druckwirkungen materieller Art und Saugwirkungen geistiger Art. Es ist sehr merkwürdig, wie gewisse Physiker heute schon, ich möchte sagen, mit der Nase auf diese Dinge gestoßen werden, wie sie aber durchaus nicht auf sie eingehen wollen. Planck, der Berliner Physiker, hat es einmal ausdrücklich ausgesprochen: Wenn man zu einer Vorstellung desjenigen, was immer Äther genannt wird, kommen will, so ist das erste Erfordernis heute, nach den Erkenntnissen, die man aus der Physik haben kann, daß man diesen Äther nur ja nicht materiell vorstelle. — Das ist ein Ausspruch des Berliner Physikers Planck. Also, materiell darf der Ather nicht vorgestellt werden. Ja, aber dasjenige, was wir hier finden als jenseits der Wärmewirkungen, wohinein dann auch schon die Lichtwirkungen gehören, das dürfen wir so wenig materiell vorstellen, daß wir die heutige Eigenschaft des Materiellen, die Druckwirkung, nicht mehr drinnen finden, sondern nur Saugwirkungen. Das heißt, wir gehen aus dem Gebiet der ponderablen Materie hinaus und kommen in ein Gebiet, welches natürlich überall sich geltend macht, das aber entgegengesetzt sich offenbart dem Gebiet des Materiellen; das wir nur durch Saugwirkungen, die von jedem Punkt des Raumes ausgehen, vorstellen können, während wir das Materielle selbstverständlich als Druckwirkungen vorstellen. Da aber kommen wir zum unmittelbaren Ergreifen des Wärmewesens als einer intensiven Bewegung, als eines Pendelns zwischen Saug- und Druckwirkungen, aber nicht so, daß die eine Seite der Saugwirkungen räumlich ist und die andere Seite der Druckwirkungen auch räumlich ist, sondern daß wir aus dem Gebiet des Materiellen, des dreidimensionalen Raumes überhaupt, hinauskommen, schon wenn wir die Wärme erfassen wollen. Drückt daher der Physiker gewisse Wirkungen mit Formeln aus, und hat er in diesen Formeln Kräfte drinnen, so wird man in dem Fall, daß diese Kräfte mit negativem Vorzeichen eingesetzt werden — wenn Druckkräfte so eingesetzt werden, daß sie als Saugkräfte gelten können, aber zu gleicher Zeit darauf Rücksicht genommen wird, daß man nun im Raume nicht bleibt, sondern ganz daraus herauskommt -, so wird man mit solchen Formeln erst hineinkommen in das Gebiet der Licht- und Wärmewirkungen, das heißt der Wärmewirkungen eigentlich nur halb, denn im Gebiet des Wärmewesens haben wir das Ineinanderspielen von Saug- und Druckwirkungen.

[ 12 ] Diese Sache, meine lieben Freunde, nimmt sich heute noch, ich möchte sagen, ziemlich theoretisch aus, wenn man sie so einem Auditorium mitteilt. Es sollte aber niemals vergessen werden, daß ein großer Teil unserer modernsten Technik unter dem Einfluß der materialistischen Vorstellungsweise der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts entstanden ist, die alle solche Vorstellungen nicht gehabt hat, und daß daher innerhalb unserer Technik diese Vorstellungen auch gar nicht auftreten können. Wenn Sie aber bedenken, wie fruchtbar die einseitigen Vorstellungen der Physik für die Technik geworden sind, so können Sie sich ein Bild machen von dem, was auch als technische Folgen auftreten würde, wenn man zu den heute in der Technik einzig figurierenden Druckkräften — denn die räumlichen Saugkräfte, die man hat, sind ja auch nur Druckkräfte; ich meine Saugkräfte, die qualitativ entgegengesetzt sind den Druckkräften - nun auch diese Saugkräfte wirklich fruchtbar machen würde.

[ 13 ] Allerdings muß da hinweggeräumt werden manches, was jetzt in der Physik eben durchaus noch figuriert. Das heißt, man muß nun wirklich wegräumen den gebräuchlichen Energiebegriff, der eigentlich von der ganz groben Vorstellung ausgeht: Wenn ich irgendwo Wärme habe, so kann ich sie umwandeln in Arbeit, so wie wir ja gesehen haben bei unserer Experimentieranordnung, daß Wärme umgewandelt werden konnte in auf und ab gehende Bewegung des kolbenartigen Körpers. Aber wir haben dabei zu gleicher Zeit gesehen, daß da immer Wärme übrigbleibt, daß wir also nur einen Teil der Wärme, die uns zur Verfügung steht, wirklich in das umwandeln können, was der Physiker mechanische Arbeit nennt, den anderen Teil können wir nicht umwandeln. Das war ja der Satz, der Eduard von Hartmann dazu geführt hat, eben als zweiten wichtigsten Satz der modernen Physik den hinzustellen: Ein Perpetuum mobile der zweiten Art ist unmöglich.

[ 14 ] Andere Physiker, zum Beispiel Mach, von dem ja in der neueren physikalischen Entwickelung viel die Rede ist und der über manche Dinge wirklich sehr gründlich nachgedacht hat, der aber immer so nachdenkt, daß man sieht, er ist ein Mensch, der schon scharfsinnig war, aber der seinen Scharfsinn nur geltend machen konnte unter dem Einfluß der rein materialistischen Erziehungsweise, so daß immer zugrunde liegen die materialistischen Vorstellungen, Mach sucht dann die Begriffe und Vorstellungen, die ihm zur Verfügung stehen, scharfsinnig zu kontinuieren und anzuwenden. Dadurch ist das Eigentümliche bei ihm, daß er, wo es möglich ist, schon aus den gebräuchlichen physikalischen Vorstellungen bis zu der Grenze zu kommen, wo die Zweifel entstehen, dazu kommt, die Zweifel sehr schön zu beschreiben. Es tritt ja dann die Trostlosigkeit ein, denn er kommt gerade nur bis an die Grenze, wo er die Zweifel hinstellt. Schon seine Ausdrucksweise ist außerordentlich interessant. Denken Sie sich einmal, wenn man nötig hat in der physikalischen Betrachtung, wo also alles handgreiflich da ist, eine gewisse Ansicht, die man gewonnen hat, in folgender Weise zu stilisieren, wie Mach sie stilisiert hat. Er sagt: «Es hat aber keinen gesunden Sinn, einer Wärmemenge, die man nicht mehr in Arbeit verwandeln kann» — wir haben gesehen, daß es eine solche gibt —, «noch einen Arbeitswert beizumessen. Demnach scheint es, daß das Energieprinzip ebenso wie jede andere Substanzauffassung nur für ein begrenztes Tatsachengebiet Gültigkeit hat, über welche Grenze man sich nur einer Gewohnheit zu lieb gern täuscht.» Denken Sie sich: Ein Physiker, der beginnt nachzudenken über die ihm vorliegenden Erscheinungen, und der ist genötigt zu sagen: Ja, es entsteht mir in meinem Tatsachenverlauf Wärme, die ich nicht mehr in Arbeit verwandeln kann. Es hat aber dann doch keinen gesunden Sinn, die Wärme einfach aufzufassen als potentielle Energie, als Arbeit, die nur nicht sichtbar ist. Man kann vielleicht sprechen von der Umwandlung von Wärme in Arbeit innerhalb eines gewissen Tatsachengebietes; außerhalb desselben gilt das nicht mehr. Und man redet im allgemeinen davon, daß jede Energie in eine andere umzusetzen ist, nur einer Gewohnheit zuliebe, so daß man sich dieser Gewohnheit zuliebe leicht täuscht. — Es ist außerordentlich interessant, die Physik da festzunageln, wo sie ertappt werden kann in den Zweifeln, die sich notwendigerweise ergeben müssen, wenn man nur wirklich konsequent dasjenige ins Auge faßt, was als Tatsachenreihe vorliegt. Ist denn nicht eigentlich schon der Weg da, wo die Physik sich selber überwindet, wenn die Physiker bereits genötigt sind, solche Geständnisse zu machen? Denn es ist ja im Grunde genommen das Energieprinzip nichts anderes als eine Behauptung. Man kann es eigentlich, wie es ein Evangelium bei Helmholtz und seinen Zeitgenossen war, nicht mehr aufrechterhalten. Es kann Gebiete geben, in denen dieses Energieprinzip nicht mehr behauptet werden darf.

[ 15 ] Sehen Sie, wenn man nun fragen will: Wie könnte man einmal den Versuch machen, symbolisch — denn im Grunde genommen, wenn wir anfangen etwas aufzuzeichnen, wird alles symbolisch —, wie könnten wir den Versuch machen, symbolisch dasjenige, was da im Gebiet des Wärmewesens auftritt, darzustellen? Wenn Sie alle diese Vorstellungen zusammennehmen, die ich Ihnen entwickelt habe und durch die ich versucht habe, im Realen verbleibend heranzusteigen zum Wärmewesen, dann werden Sie dazu kommen, dieses Wärmewesen in der folgenden Weise sich zu versinnlichen: Stellen Sie sich einmal vor, hier wäre Raum (blau), der von gewissen Wirkungen, von Druckwirkungen ausgefüllt wäre; hier wäre das Raumlose (rot), das ausgefüllt wäre von Saugwirkungen. Wenn Sie sich das nun vorstellen, dann bekommen Sie hier ein Gebiet, und mit diesem Gebiet etwas anderes, was da immer hineinschlüpft und da drinnen verschwindet — wir haben ja nur in den Raum hinausprojiziert, was nur räumlich-unräumlich gedacht werden kann, denn der rote Teil muß unräumlich gedacht werden. Sehen Sie diesen Raum hier (blau und rot) an als ein Sinnbild für das, was räumlich-unräumlich ist. Denken Sie sich also Intensives dargestellt durch Extensives, durch das, wo fortwährend Materielles entsteht. Aber indem Materielles entsteht, entsteht auf der anderen Seite Immaterielles, das schlüpft in das Materielle hinein, vernichtet seine Materialität, und wir haben einen physisch-geistigen Wirbel, der sich so äußert, daß fortwährend dasjenige, was physisch entsteht, durch das Geistige, das auch dabei entsteht, vernichtet wird, wir haben also eine Wirbelwirkung, wo Physisches entsteht, durch Geistiges vernichtet wird; Geistiges entsteht, durch Physisches verdrängt wird. Wir haben ein fortwährendes Herüberspielen des Raumlosen in das Räumliche; wir haben ein fortwährendes Aufgesogenwerden desjenigen, was im Raume ist, durch diejenige Entität, die außer dem Raume ist.

[ 16 ] Was ich Ihnen schildere, meine lieben Freunde, das ist, wenn Sie es sich versinnlichen, hier wirbelartig zu gestalten. Aber man darf im Wirbel nur sehen eine äußere, extensive Versinnlichung des Intensiven. Damit haben wir uns, ich möchte sagen, sogar schon durch Figurales dem Wärmewesen genähert. Wir haben nun noch übrig, zu zeigen, wie dieses Wärmewesen jetzt so wirkt, daß solche Erscheinungen entstehen können wie: die Wärmeleitung; oder daß der Schmelzpunkt einer Legierung viel tiefer liegt als der Schmelzpunkt jedes einzelnen Metalles; oder was es eigentlich heißt, daß auf dem einen Ende des Spektrums Wärmewirkung, auf dem anderen chemische Wirkung sich zeigt.

[ 17 ] Wir werden die Taten der Wärme suchen müssen, wie Goethe die Taten des Lichtes gesucht hat, und werden dann zu untersuchen haben, wie die Erkenntnis des Wärmewesens sich auf die Anwendung der Mathematik, auf die Imponderabilien der Physik auswirkt, das heißt mit anderen Worten: Wie wirklich reale mathematische Formeln gestaltet werden müssen, die zum Beispiel in der Thermik, in der Optik angewendet werden können.

Eleventh Lecture

[ 1 ] Now I would like to build a bridge, so to speak, between the topics covered in this course and those covered in the previous course, because I will need it for the next considerations. Today we will study the so-called light spectrum and its relationship to the thermal and chemical effects we encounter in the light spectrum. The easiest way to understand what this is all about is perhaps to first represent a spectrum and study how the different parts of the spectrum behave. So let us design a spectrum here by passing light through this slit. (The room is darkened and the spectrum is shown through the experiment.) You see, we have a spectrum here on this plate. You can now see for yourselves that we have placed something in the red part of the spectrum here. We will then be able to observe something on this instrument. We will now try to show you how thermal effects occur predominantly in the red part of the spectrum. You can already observe these thermal effects by seeing how, under the influence of the energy cylinder, if I may say so, the air expands here, presses down, and causes the alcohol column to descend here and rise here. This descent of the alcohol column shows us that there is essentially a thermal effect in this part of the spectrum. It would of course be interesting to show that if we shifted the spectrum and had this instrument in the blue-violet part, the thermal effect would not occur, but this cannot be done so quickly. This thermal effect can therefore essentially be seen in the red part of the spectrum. And now, just as we tested the occurrence of the heat effect in the red-yellow part of the spectrum by the falling of the alcohol column, we will test the occurrence of the chemical effect of the spectrum in the blue-violet by placing a substance here in the space that is traversed by the blue-violet part of the spectrum, and you will see that this causes the substance to phosphoresce, which, as you know from the observations in the previous course, proves the chemical effects. You can see from this that there is indeed an internal difference between the part of the spectrum that runs into the indefinite on one side and the other part of the spectrum that runs in the other direction. You can see how the substance has become luminous under the influence of the so-called chemical rays. We can now also cause the middle part of the spectrum, which is the actual light part, to be separated. We will probably not succeed completely, but we will be able to separate the middle part, i.e., cause darkness in the middle part instead of brightness, by simply dripping some iodine tincture into the substance that has formed a carbon disulfide prism. This gives us a mixture of carbon disulfide and iodine tincture. This proves to be a substance that does not allow light to pass through, and if we could complete the experiment — unfortunately we cannot, but we can only point the way — we would be able to show perfectly that thermal effects occur on one side and chemical effects on the other, while the actual light part, the middle part of the spectrum, disappears. If I were to place alum in the path, the thermal effects would cease, and you would then see that the alcohol column rises again because the alum, the alum solution, prevents the passage of the thermal effects — I will say this cautiously. Because alum is in the way, this alcohol column would now rise again very quickly because the heating would not take place. We would then have a cold spectrum.

[ 2 ] It is very interesting that the chemical part can also be made to disappear if an esculin solution, which unfortunately we were also unable to obtain, is placed in the path of the spectrum's propagation. The heat effects and light effects remain, but the chemical effects cease. We now want to place the solution of iodine in carbon disulfide in the path, and the middle part of the spectrum will disappear. You can clearly see the red part, which would disappear if the experiment were completely successful. You can see the violet part and nothing in the middle. So, by carrying out a kind of fragment of the experiment, we have succeeded in removing the most important part of the light, the middle part. If we were to complete the experiment, as individual experimenters, for example Dreher in Halle fifty years ago, have succeeded in doing, we could also completely remove the two luminous spots and then demonstrate the increase in temperature that remains and, on the other hand, the effects of chemical rays through the “luminous matter.” This is a series of experiments that has not yet been completed, a series of experiments that is extremely important. It shows us how what can be thought of as effective in the spectrum fits into the general context of the world.

[ 3 ] In the course I gave during my previous stay here, I showed how, for example, a strong magnet affects the spectral conditions, in that certain lines, certain formations in the spectrum itself change as a result of the influence, the force emanating from the magnet. And now it is a matter of simply expanding the train of thought that has been set in motion in such a way that one really has the physical processes in one's mind. You know from our observations that a complete spectrum, that is, a combination of all possible colors, would actually result in twelve colors, that we would get, so to speak, a circular spectrum instead of a spectrum extending in one direction of space. We would have green here, peach blossom here, violet here, and red here, with the other color nuances in between, twelve clearly distinguishable color nuances (see drawing).

[ 4 ] Now, the point is that we can only represent such a spectrum within earthly conditions in an image. When we represent a spectrum in the realm of earthly life, we can only represent it in an image, and so we always get the familiar spectrum that runs in a straight line from red through green to blue and violet. So we get a spectrum which, as I have already said several times, can be obtained from the above by making the circle bigger and bigger, the peach blossom disappearing on the other side, the violet here (see drawing, right) going into apparent infinity, the red here (left) apparently pointing into infinity, and the green remaining in the middle.

[ 5 ] We can ask ourselves the question: How does this fragmentary spectrum, this fragmentary color band, arise from the completeness of color formation, from the twelve-color formation, which must be possible? If you hypothetically assume that the complete circular spectrum would arise here (see drawing), you can form a mental image of the forces at work that enlarged the circle by pulling it apart here. Then a moment would occur when what is above here would actually tear apart and, through the forces at work, the circle would be turned into a straight line, that is, into an infinite length, into a seemingly infinite length.

[ 6 ] If we find this spectrum, which can be visualized as a straight line, in the realm of earthly life, we must ask ourselves: How can it arise? It can only come about when the familiar seven shades are separated from the completeness of the colors. They are separated by forces that must, in a sense, act within the spectrum. But we have actually already found these forces in the realm of earthly existence. We found them when we pointed to the formative forces. This is also a form: the circular form has been transformed into the straight-line form. This is a form that we have encountered here. And it is, I would say, obvious that forces are at work in the earthly realm that make our spectrum possible, when we can see that the internal structure of the spectrum is influenced and changed by the influence of magnetic forces. If this is the case, then we must assume that forces can already be at work in our spectrum, which we always consider to be primary. So in our ordinary spectrum, we must not merely observe variations in light, but we must also consider forces that make it necessary for this ordinary spectrum to be symbolized by a straight line.

[ 7 ] Let us connect this train of thought with another that will arise when we ascend once again in the manner we have often done before: from the solid formative through the fluid to the condensed, diluted, that is, gaseous, to the heat entity, to what we have called materialization and dematerialization in x. Here we encounter a higher increase in condensation and dilution above the heat entity, just as condensation and dilution themselves appear to us as an increase, as a kind of liquefaction of the form. When the form itself becomes liquid, when we have a variable formation in the gas, this is an increase in definite formation. What occurs here? Here we see an intensification of rarefaction and condensation. Keep in mind that we are entering a realm where an intensification of rarefaction and condensation occurs.

[ 8 ] What does an intensification of rarefaction mean? When matter becomes thinner and thinner, it already tells us, if it is a certain kind of matter, what is fighting against it as it becomes thinner and thinner. If I make it denser and denser, it will turn out that it no longer allows light behind it to pass through. If I make it thinner and thinner, it allows light to pass through. If I continue to thin it out further and further, in the end only brightness as such will appear to me. So what I have to understand here as still lying in the realm of the material will always appear to me empirically as the appearance of brightness. Dematerialization will appear to me as bright; materialization will always appear to me as dark. In the realm of worldly effects, I must therefore understand illumination as an increase in thinning and darkening as a condensation that has not yet sufficiently occurred, so that the condensation does not yet appear sufficiently as matter, but the effects are only on their way to becoming material.

[ 9 ] You see, I find the realm of light above the realm of heat, and now the realm of heat also appears to me in a very natural way within the realm of light. For if you consider that what lies further down always gives, as it were, the image of what lies above, you will have to find something in the realm of heat that is, as it were, the image of illumination and darkening. In the realm of heat, which appears at one end of the spectrum, we will have to find something that appears as an image of illumination and darkening. But we will also have to be clear that we always find not only the upper part of our realm of reality in the lower part, but also the lower part of the realm of reality in the upper part. If I have a solid body, it can certainly be in the liquid realm with its solidity. That which gives it form can rise up into the next, no longer formed realm. I must be clear that if I want to deal with realities in my mental images, I am dealing with the mutual interpenetration of the qualities of reality. But this takes on a special form for the area of heat. It takes the form that, on the one hand, dematerialization must act in heat from above (arrow), and on the other hand, the tendency to materialize acts into heat.

[ 10 ] You see, I approach the heat entity by seeing in it, on the one hand, a striving for dematerialization and, on the other hand, a striving for materialization. So that when I now want to grasp the heat entity, I can only grasp it in such a way that there is a life, a living weaving within it, which reveals itself in that everywhere the tendency to materialize is permeated by the tendency to dematerialize. Now you can see what a considerable difference there is between this truly discovered heat entity and the heat entity that figured in Clausius's so-called mechanical theory of heat. There, if you have a closed space, you find atomistic or molecular globules that collide in all directions, bump into each other, collide with the wall, and perform purely external extensive movements. And it is decreed: heat actually consists of this chaotic movement, this chaotic mutual collision and collision with the wall of the material parts, about which there was then only a lively dispute as to whether they should be regarded as elastic or inelastic. This can only be decided by determining whether the elasticity formula or the formula for inelastic, solid bodies is more applicable to one phenomenon or the other. So it was an expression of a conviction based purely on space and spatial movement when it was said: heat is movement. We must now say in a completely different way: heat is movement—it is movement, but movement that must be thought of intensively, movement in which, in every part of space where there is heat, there is an endeavor to create material existence and to make material existence disappear again. No wonder that we too need heat in our organism. We simply need warmth in our organism in order to constantly transform the spatially extended into the spatially unextended. When I simply walk through space, what my will accomplishes is the shaping of space. When I bring it to mind as a mental image, something completely outside of space is there. What makes it possible for me, as a human organism, to be externally integrated into the form relationships of the earth? By walking on it, I change the entire shape of the earth, I paint black dots on a spot, I constantly change its shape. What makes it possible for me to grasp what I am in the whole rest of the earth's context and what is represented in spatial effects, to grasp it internally without space as an observer in my thoughts? That I myself accomplish my existence in the medium of warmth, which allows material effects, that is, spatial effects, to continually transition into immaterial effects, i.e., effects that no longer occupy space. So I actually experience within myself what heat really is, intense movement, movement that constantly oscillates from the realm of pressure effects to the realm of suction effects.

[ 11 ] Suppose you have here the boundary between pressure effects and suction effects. The pressure effects run in space, but the suction effects as such do not run in space, but outside of space. For my thoughts are based on the suction effects, but do not run in space. Here, beyond this line (see drawing on page 170), I have the spaceless. And when I form a mental image of that which now happens neither in the realm of pressure, in space, nor in the realm of suction, but in the realm of the boundary between the two, then I get that which happens in the realm of the heat being: a constant search for equilibrium between pressure effects of a material nature and suction effects of a spiritual nature. It is very strange how certain physicists today are, I would say, confronted with these things, but do not want to address them at all. Planck, the Berlin physicist, once said it explicitly: if one wants to arrive at a mental image of what is always called ether, the first requirement today, according to the knowledge that can be gained from physics, is that one must not imagine this ether as material. — That is a statement by the Berlin physicist Planck. So, the ether must not be imagined as material. Yes, but what we find here as beyond the effects of heat, which also includes the effects of light, we must not mentally image in such a way as to be material, for we no longer find the present-day property of the material, the pressure effect, but only suction effects. This means that we are leaving the realm of ponderable matter and entering a realm that naturally asserts itself everywhere, but which manifests itself in opposition to the realm of the material; which we can only form a mental image of through suction effects emanating from every point in space, while we naturally imagine the material as pressure effects. But here we come to the immediate grasping of the nature of heat as an intense movement, as an oscillation between suction and pressure effects, but not in such a way that one side of the suction effects is spatial and the other side of the pressure effects is also spatial, but rather that we leave the realm of the material, of three-dimensional space altogether, as soon as we want to grasp heat. Therefore, if the physicist expresses certain effects with formulas, and if he has forces in these formulas, then in the case that these forces are used with a negative sign—if pressure forces are used in such a way that they can be considered suction forces, but at the same time taking into account that we are no longer remaining in space but are leaving it entirely — then with such formulas we will only enter the realm of light and heat effects, that is, only half of the heat effects, because in the realm of heat we have the interaction of suction and pressure effects.

[ 12 ] This matter, my dear friends, still seems, I would say, rather theoretical today when communicated to an audience such as this. However, it should never be forgotten that a large part of our most modern technology was developed under the influence of the materialistic mental images of the second half of the 19th century, which did not have any such mental images, and that therefore these mental images cannot even arise within our technology. But if you consider how fruitful the one-sided mental images of physics have become for technology, you can imagine what the technical consequences would be if, in addition to the compressive forces that are the only ones that feature in technology today — for the spatial suction forces that we have are also compressive forces — I mean suction forces, which are qualitatively opposite to pressure forces—now also make these suction forces truly fruitful.

[ 13 ] However, some things that still feature in physics today must be dispensed with. That is, we must now really do away with the common concept of energy, which is actually based on the very crude mental image that if I have heat somewhere, I can convert it into work, as we have seen in our experimental setup that heat could be converted into the up-and-down motion of the piston-like body. But at the same time, we saw that there is always heat left over, so that we can only convert part of the heat available to us into what physicists call mechanical work; we cannot convert the other part. That was the statement that led Eduard von Hartmann to present it as the second most important statement in modern physics: A perpetual motion machine of the second kind is impossible.

[ 14 ] Other physicists, for example Mach, who is much talked about in recent developments in physics and who has really thought very thoroughly about some things, but who always thinks in such a way that one can see he is a man who was already astute, but who could only assert his astuteness under the influence of a purely materialistic education, so that materialistic mental images always underlie his thinking. Mach then seeks to astutely continue and apply the mental images and ideas available to him. This makes him unique in that, wherever possible, he takes the usual physical mental images to the limit where doubts arise and then describes those doubts very beautifully. This is where despair sets in, because he only goes as far as the limit where he raises the doubts. His way of expressing himself is extremely interesting. Just imagine if, in physical observation, where everything is tangible, it were necessary to stylize a certain view that one has gained in the way Mach has stylized it. He says: “But it makes no sense to attribute a work value to a quantity of heat that can no longer be converted into work” — we have seen that such a thing exists — “Accordingly, it seems that the energy principle, like any other conception of substance, is valid only for a limited range of facts, beyond which one is only too happy to deceive oneself out of habit.” Just imagine: a physicist who begins to think about the phenomena before him and is forced to say: Yes, in my course of facts, heat arises that I can no longer convert into work. But then it makes no sense to simply regard heat as potential energy, as work that is simply not visible. One can perhaps speak of the conversion of heat into work within a certain realm of facts; outside of this realm, this no longer applies. And one generally speaks of every form of energy being convertible into another, simply out of habit, so that one easily deceives oneself for the sake of this habit. — It is extremely interesting to pin physics down where it can be caught in the doubts that necessarily arise when one really consistently considers what is available as a series of facts. Is the path not already there, where physics overcomes itself, when physicists are already forced to make such admissions? For, after all, the energy principle is basically nothing more than an assertion. It can no longer be upheld as it was a gospel for Helmholtz and his contemporaries. There may be areas in which this energy principle can no longer be asserted.

[ 15 ] You see, if we now want to ask: How could we attempt to symbolically — because, basically, when we begin to record something, everything becomes symbolic — how could we attempt to symbolically represent what occurs in the realm of the heat entity? If you take all these mental images that I have developed for you, through which I have tried to approach the heat being while remaining in the realm of reality, then you will come to visualize this heat being in the following way: Imagine that here is space (blue) filled with certain effects, with pressure effects; here there would be the non-spatial (red), which would be filled with suction effects. If you now form a mental image of it, you will have an area here, and with this area something else that always slips in and disappears inside — we have only projected into space what can only be thought of as spatial-non-spatial, because the red part must be thought of as non-spatial. Look at this space here (blue and red) as a symbol of what is spatial-non-spatial. So think of the intensive represented by the extensive, by that which continually gives rise to the material. But as material things arise, immaterial things arise on the other side, slipping into the material, destroying its materiality, and we have a physical-spiritual vortex that manifests itself in such a way that what arises physically is continually destroyed by the spiritual that also arises in the process. So we have a vortex effect where the physical arises and is destroyed by the spiritual; the spiritual arises and is displaced by the physical. We have a continuous transfer of the spaceless into the spatial; we have a continuous absorption of that which is in space by that entity which is outside of space.

[ 16 ] What I am describing to you, my dear friends, is, if you can visualize it, a vortex-like formation. But in the vortex, one can only see an external, extensive visualization of the intense. With this, I would say, we have already approached the heat entity through figurative means. We now have to show how this heat being works in such a way that phenomena such as heat conduction can arise, or that the melting point of an alloy is much lower than the melting point of each individual metal, or what it actually means that heat effects appear at one end of the spectrum and chemical effects at the other.

[ 17 ] We will have to seek out the effects of heat, just as Goethe sought out the effects of light, and then we will have to investigate how the knowledge of the nature of heat affects the application of mathematics and the imponderables of physics. In other words: how truly real mathematical formulas must be designed that can be applied, for example, in thermodynamics and optics.