Third Scientific Lecture-Course:

Astronomy

GA 323

1 January 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture I

[ 1 ] To-day I should like to make some introductory remarks to what I am going to lay before you in the coming days. My reason for doing this is that you may know the purpose of these talks from the outset.

It will not be my task during the following days to deal with any narrowly defined, special branch of science, but to give various wider viewpoints, having in mind a quite definite goal in relation to science. I should therefore like to warn people not to describe this as an ‘Astronomical Course’. It is not meant to be that. But it will deal with something that I feel is especially important for us to consider at this time. I have therefore given it the title “The relation of the diverse branches of Natural Science to Astronomy,” and today in particular I shall explain what I actually intend with the giving of this title.

[ 2 ] The fact is that in a comparatively short time much will have to be changed within what we call the sphere of science, if it is not to enter upon a complete decline. Certain groups of sciences which are now comprised under various headings and are permitted to be represented under these headings, in our ordinary schools, will have to be taken out their grooves and be classified from quite other aspects. This will necessitate a far reaching regrouping of our sciences. The grouping at present employed is entirely inadequate for a world-conception based upon reality, and yet our modern world holds so firmly to such traditional classification that it is on this basis that candidates are chosen to occupy the professorial chairs in our Universities. People confine themselves for the most part to dividing the existing, circumscribed fields of Natural Science into yet further special branches, and they then look to the specialists or experts as they are called. But a change must come into the whole scientific life by the advent of quite different categories, within which will be united, as in a whole new field of science, things that today are dealt with in Zoology or Physiology, or again, let us say, in the Theory of Knowledge. The older forms of scientific classification, often extremely abstract, must die out, and quite new scientific combinations must arise. This will meet with great obstacles at first, because people today are trained in the specialized branches of science and it will be difficult for them to find an approach to what they will urgently need in order to bring about a combination of scientific material in accordance with reality.

[ 3 ] To put in concisely, I might say: We have today a science of astronomy, of Physics, of Chemistry, of Philosophy, we have a science of Biology, of Mathematics, and so on. Special branches have been formed, almost, I might say, so that the various specialists will not have such hard work in order to become well grounded in their subject. They do not have too much to do in mastering all the literature concerned, which, as we know, exists in immense quantities. But it will be a matter of creating new branches which will comprise quite different things, including perhaps at the same time something from Astronomy, something from Biology, and so on. For this, a reshaping of our whole life of science will of course be essential. Therefore, what we term Spiritual Science, which does indeed aim to be of a universal nature, must work precisely in this direction. It must make it its special mission to work in this direction. For we simply cannot get any further with the old grouping. Our Universities confront the world today, my dear friends, in a way that is really quite estranged from life. They turn out mathematicians, physiologists, philosophers, but none of them have any real relation to the world. They can do nothing but work in their narrowly confined spheres, putting before us a picture of the world that becomes more and more abstract, less and less realistic.

It is the change here indicated—a deep necessity for our time—to which I want to do justice in these lectures. I should like you to see how impossible it will be to continue the older classifications indefinitely, and I therefore want to show how other branches of science of the most varied kinds, which, in their present way of treatment, take no account of Astronomy, have indeed definite connections with Astronomy, that is, with a true knowledge of universal space. Certain astronomical facts must perforce be taken into account in other branches of science too, so that we may learn to master these other fields in a way conformable to reality.

[ 4 ] The task of these lectures is therefore to build a bridge from the different fields of scientific thought to the field of Astronomy, that astronomical understanding may appear in the right way in the various fields of science.

[ 5 ] In order not to be misunderstood, I should like to make one more remark about method. You see, the manner of presenting scientific facts which is customary nowadays must undergo considerable change, because it actually arises out of the scientific structure which has to be overcome. When today facts are referred to, which lie somewhat remote from man's understanding,—remote, just because he does not meet with them at all in his scientific knowledge,—it is usual to say: “That is stated, but no proved.” Yet in scientific work is often quite inevitable that statements must be made at first purely as results of observation, which only afterwards can be verified as more and more facts are brought to support them. So it would be wrong to assume, for instance, that right at the beginning of a discourse someone could break in and say, “That is not proved.” It will be proved in the course of time, but much will first have to be presented simply from observation, so that the right concept, the right idea, may be created.

And so I beg of you to take these lectures as a whole, and to look in the last lectures for the plain proof of many things which seem in the first lectures to be mere statements. Many things will then be verified which I shall have to handle at first in such a way as to evoke the necessary concepts and ideas.

[ 6 ] Astronomy as we know it today, even including the domain of Astrophysics, is fundamentally a modern creation. Before the time of Copernicus or Galileo men thought about astronomical phenomena in a way which differed essentially from the way we think today. It is even extraordinarily difficult to indicate the way in which man still thought of Astronomy in, say, the 13th and 14th centuries, because this way of thinking has become completely foreign to modern man. We only live in the ideas which have been formed since the time of Galileo, Kepler, Copernicus; and from a certain point of view that is perfectly right. They are ideas which treat of the distant phenomena of universal space, in so far as they are concerned with Astronomy, in a mathematical and mechanical way. Men think of these phenomena in terms of mathematics and mechanics. In observing the phenomena, men base their ideas upon what they have acquired from an abstract mathematical science, or an abstract science of mechanics. They calculate distances, movements and forces. But the qualitative outlook still in existence in the 13th and 14th centuries, which distinguished Individualities in the stars, an Individuality of Jupiter, of Saturn ... this has become completely lost to modern man. I will make no criticism of the things at the moment, but will only point out that the mechanical and mathematical way of treating what we call the domain of Astronomy has become the exclusive one. Even if we acquaint ourselves with the stars in a popular fashion without understanding mathematics or mechanics, we still find it presented, even if in a manner suitable for the lay-mind, entirely in ideas of space and time, of a mathematical and mechanical kind. No doubts of any kind exist in the minds of our contemporaries—who believe that their judgment is authoritative—that this is the only way in which to regard the starry heavens. Anything else, they are convinced, would be merely amateurish.

[ 7 ] Now, if the question arises as to how it has actually come about that this view of the starry heavens has emerged in the evolution of civilization, the answer of those who regard the modern scientific mode of thought as absolute, will be different from the reply which we are able to give. Those who regard the scientific thought of today as something absolute and true, will say: Well, you know, among earlier humanity there were not yet any strictly scientifically formed ideas; man had first to struggle through to such ideas, i. e., to the mathematical, mechanical mode of regarding celestial phenomena of the Universe, a later humanity has worked through to a strictly scientific comprehension of what does actually correspond to reality.

[ 8 ] This is an answer that we cannot give, my dear friends. We must take up our position from the standpoint of the evolution of humanity, which in the course of its existence, has introduced various inner forces into its consciousness. We must say to ourselves: The manner of observing the celestial phenomena which existed among the ancient Babylonians, the Egyptians, perhaps even the Indian people, was due to the particular form which the development of the human soul-forces was taking in those times. Those human soul-forces had to be developed with the same inner necessity with which a child between the 10th and 15th year must develop certain soul-forces, while in another period it will developing other faculties, which lead it to different conclusions about the world. Then came the Ptolemaic system. That arose out of different soul-forces. Then our Copernican system. That arose from yet other soul-forces. The Copernican system did not develop because humanity had happily struggled through to objectivity, whereas before they had all been as children, but because humanity since the middle of the 15th century needed precisely the mathematical, mechanical faculties for its development. That is why modern man sees the celestial phenomena in the picture formed by the mathematical, mechanical faculties. And he will some day see them again in a different way, when in his development he has drawn up out of the depths of the soul other forces,—to his own healing and benefit. Thus it depends upon humanity what form the world-concept takes. But it is not a question of looking back in pride to earlier times when men were “more childlike,” and then thinking that in modern times we have at last struggled through to an objective understanding which can now endure for all future ages.

[ 9 ] There is something which has become a real necessity to later humanity and has given color to the requirements of the scientific mind. It is this: Men strive on the one hand for ideas that are clear and easy to control—namely, mathematical ideas—, and on the other hand they strive for ideas through which they can surrender most strongly to an inner compulsion. The modern man at once becomes uncertain and nervous when he does not feel the strong inner compulsion presented, for instance, by the argument of the Pythagorean theorem, but realizes, let us say, that the figure which is drawn does not decide for him, but that he must develop an activity of soul and decide for himself. Then he at once becomes uncertain and nervous and is no longer willing to continue the line of thought. So he says: That is not exact science; subjectivity comes into it. Modern man is really dreadfully passive; he would like to be led everywhere by a chain of infallible arguments and conclusions. Mathematics satisfies this requirement, at least in most cases; and where it does not, where man have interposed their own opinion in recent times,—well, my dear friends, the results are according! Men still believe that they are being exact, while they hit upon the most incredible ideas.

Thus in mathematics and mechanics men think they are being led forward by leading-strings of concepts which are linked together through their own inherent logic. They feel then as if they had ground under their feet, but the moment they step off it they do not want to go on any further. Concepts which are easy to grasp on the one hand, and the element of inner compulsion on the other: this is what modern man needs for his “safety.” Fundamentally, it is on this basis that the particular form of world-conception, supplied by the modern science of Astronomy, has been built up. I am not at the moment speaking of the single facts, but merely of the world-conception as a whole.

[ 10 ] This attitude towards a mathematical, mechanical conception of the world has so penetrated the consciousness of humanity, my dear friends, that people have come to regard everything that cannot be treated in this way as more or less unscientific. From this feeling proceeded such a phrase as that of Kant, who said: In every domain of science there is only so much real science as there is mathematics in it; one ought really to bring Arithmetic or Geometry into all the sciences. But this idea, as we know, breaks down when we think how remote the simplest mathematical ideas are to those, for instance, who study Medicine. Our present division of the sciences gives to a medical student practically nothing in the way of mathematical ideas.

And so it comes about that on the one hand what is called astronomical knowledge has been set up as an ideal. DuBois-Raymond has defined this in his address on the limits of the knowledge of Nature by saying: We only grasp truths in Nature and satisfy our need of causality inasmuch as we can apply the astronomical type of knowledge. That is to say, we regard the celestial phenomena in such a way that we draw the stars upon the chart of the sky and calculate with the material which is there given us. We can state exactly: There is a star, it exercises a force of attraction upon other stars. We begin to calculate, having the different things, to which our calculations apply, visibly before us. This is what we have brought into Astronomy in the first place. Now we observe, let us say, the molecule. Within the complex molecule we have the atoms, exercising a force of attraction on one another, moving around each other,—forming, as it were, a little universe. We observe this molecule as a small cosmic system and are satisfied if it all seems to fit. But then there is the great difference that when we look out into the starry sky all the details are given to us. We can at most ask whether we understand them rightly, whether after all, there might not be some other explanation than the one given by Newton. We have the given details and then we spin a mathematical, mechanical web over them. This web of thought is actually added to the given facts, but from a scientific point of view it satisfies the modern need of man. And now we carry the system, which we have first thought out and devised, into the world of the molecule and atom. Here we add in thought what in the other case was given to us. But we satisfy our so-called need of causality by saying: What we think of as the smallest particle, moves in such and such a way, and it is the objective counterpart of what we experience subjectively as light, sound, warmth etc. We carry the astronomic form of knowledge into every phenomenon of the world and thus satisfy our demand for causality. Du-Bois Raymond has expressed it quite bluntly: “When one cannot do that, there is no scientific explanation at all.”

[ 11 ] Yes, my dear friends, what is here claimed should actually imply that if, for example, we wished to come to a rational form of therapy, that is to say, to understand the activity of a remedy, we should have to be able to follow the atoms in the substance of the remedy as we follow the movements of the Moon, the Sun, the planets and the fixed stars. They would all have to become little cosmic systems. We should have to be able to calculate how this or that remedy would work. This was actually an ideal for some people not so very long ago. Now they have given up such ideals. Such an idea collapses not only in reference to such a far off sphere as a rational therapy, but in those lying more within reach, simply because our sciences are divided as they are today. You see, the modern doctor is educated in such a way that he masters extraordinarily little of pure mathematics. We may talk to him perhaps of the need for a knowledge of astronomy but it would be of no use to speak of introducing mathematical ideas into his field of work. But as we have seen, everything outside mathematics, mechanics and astronomy should be described, according to the modern notion, as being unscientific in the strict sense of the word. Naturally that is not done. People regard these other sciences too as exact, but this is most inconsistent. It is, however, characteristic of the present time that the demand should have been made at all for everything to be understood on the model of mathematical Astronomy.

[ 12 ] It is hard today to talk to people in a serious way about such thing; how hard this is I should like to make clear to you by an example.

You know of course that the question of the form of the human skull has played a great role in modern biology. I have also spoken of this matter may times in the course of our anthroposophical lectures. Goethe and Oken put forward magnificent thoughts on this question of the human skull-bones. The school of Gegenbauer also carried out classical researches upon it. But something that could satisfy the urge for a deeper knowledge in this direction does not in fact exist today.

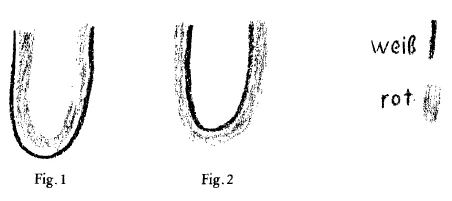

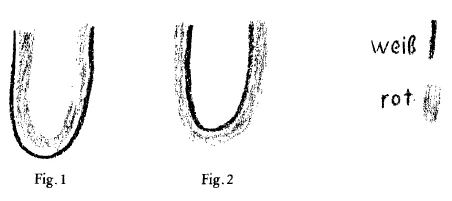

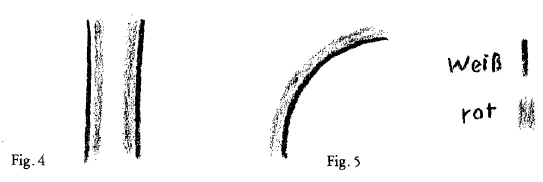

People discuss, to what extent Goethe was right in saying that the skull-bones are metamorphosed vertebrae, bones of the spine. But it is impossible to arrive at any really penetrating view of this matter today, because in the circles where these things are discussed one would scarcely be understood, and where an understanding might be forthcoming these things are not talked of because they are not of interest. You see, it is practically impossible today to bring together in close working association a thoroughly modern doctor, a thoroughly modern mathematician,—i.e., one who is master of higher mathematics—, and a man who could understand both of them passably well. These three men could scarcely understand one another. The one who would sit in the middle, understanding both of them slightly, would be able at a pinch to talk a little with the mathematician and also with the doctor. But the mathematician and the doctor would not be able to understand each other upon important questions, because what the doctor would have to say about them would not interest the mathematician, and what the mathematician would have to say—or would say, if he found words at all,—would not be understood by the doctor, who would be lacking the necessary mathematical background. This is what would happen in an attempt to solve the problem I have just put before you. [ 13 ] People imagine: If the skull-bones are metamorphosed vertebra, then we ought to be able to proceed directly, through a transformation which it is possible to picture spatially, from the vertebra to the skull. To extend the idea still further to the limb-bones would, on the basis of the accepted premises, be quite out of the question. The modern mathematician will be able, from his mathematical studies, to form an idea of what it really means when I turn a glove inside out, when I turn the inside to the outside. One must have in mind a certain mathematical handling of the process by which what was formerly outside is turned inward, and what was inside is turned to the outside. I will make a sketch of it (Fig. 1)—a structure of some sort that is first white on the outside and red inside. We will treat this structure as we did the glove, so that it is now red outside and white inside (Fig. 2).

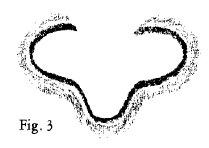

[ 14 ] But let us go further, my dear friends, and picture to ourselves that we have something endowed with a force of its own that does not admit of being turned inside out in such a simple way as a glove which still looks like a glove after being inverted. Suppose that we invert something which has different stresses of force on the outer surface from those on the inner. We shall then find that simply through the inversion quite a new form arises. The form may appear thus before we have reversed it (Fig. 1): we turn it inside out and now different forces come into consideration on the red surface and on the white, so that perhaps, purely through the inversion, this form arises (Fig. 3). Such a form might arise merely in the process of inversion. When the red side faced inward, forces remained dominant which are developed differently when it is turned outward. And so with the white side; only when turned towards the inside can it develop its inherent forces.

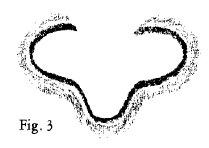

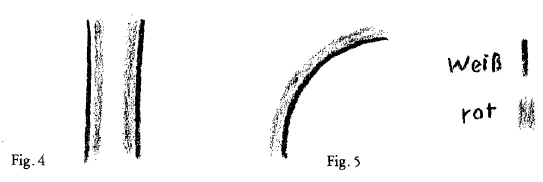

[ 15 ] It is of course quite conceivable to give a mathematical presentation of such a subject, but people are thoroughly disinclined nowadays to apply to reality what is arrived at conceptually in such a way. The moment, however, we learn to apply this to reality, we become able to see in our long bones or tubular bones (that is, in the limb bones), a form which, when inverted, becomes our skull bones! In the drawing, let the inside of the bone, as far as the marrow, be depicted by the red, the outside by the white (Fig. 4). Certain forms and forces, which can of course be investigated, are turned inward, and what we see when we draw away the muscle from the long bone is turned outward. But now imagine these hollow bones turned inside out by the same principle as I have just given you, in which other conditions of stress and strain are brought into play; then you may easily obtain this form (Fig. 5). Now it has the white within, and what I depicted by the red comes to the outside. This is in fact the relationship of a skull-bone to a limb-bone, and in between lies the typical bone of the back—the vertebra of the spinal column. You must turn the tubular bone inside out like a glove according to its indwelling forces; then you obtain the skull-bone. The metamorphosis of the bones of the limbs into the skull-bones is only to be understood when keeping in mind the process of inversion, or ‘turning inside-out’. The important thing to realizes is that what is turned outward in the limb-bones is turned inward in the skull. The skull-bones turn towards a world of their own in the interior of the skull. That is one world. The skull-bone is orientated to the world, just as the limb-bone is orientated outward, towards the external world. This can be clearly seen in the case of the bones. Moreover, the human organism as a whole is so organized that it has on the one hand a skull organization, and on the other a limb-organization, the skull-organization being oriented inward, the limb-organization outward. The skull contains an inner world, the limb-man an outer world, and between the two is a kind of balancing system which preserves the rhythm.

[ 16 ] My dear friends, take any literature dealing with the theory of functions, or, say, with non-Euclidean geometry, and see what countless ideas of every kind are brought forward in order to get beyond the ordinary geometrical conception of three-dimensional space;—to extend the domain—widen out the concept of geometry. You will see what industry and ingenuity are employed. But now suppose that you have become an expert at mathematics, who knows the theory of functions well and understands all that can be understood today of non-Euclidean geometry. I should like now to put a question concerning much that tends in this direction (Forgive me if it seems as if one did not value them highly, speaking of these things in such trivial terms. And yet I must do so, and I beg the audience, especially trained mathematicians, to turn it over in their minds and see if there is not truth in what I say.) The question could be put as follows: What is the use of all this spinning of purely mathematical thoughts? What is it worth to me, so to speak, in pounds, shillings and pence? No one is interested in the spheres in which it might perhaps find concrete application. Yet if we were to apply to the structure of the human organism all that has been thought out in non-Euclidean geometry, then we should be in the realm of reality, and applying immeasurably important ideas to reality, not wandering about in mere speculations. If the mathematician were so trained as to be interested also in what is real,—in the appearance of the heart, for example, so that he could form an idea of how through a mathematical process he could turn the heart inside out, and how thereby the whole human form would arise,—if he were taught to use his mathematics in actual life, then he could be working in the realm of the real. It would then be impossible to have the trained mathematician on the one hand, not interested in what the doctor learns, and on the other, the physician, understanding nothing of of how the mathematician—though in a purely abstract element—is able to change and metamorphose forms. [ 17 ] This is the situation we must alter. If not, our sciences will fall into decay. They grow estranged from one another; people no longer understand each other's language.

How then is science to be transformed into a social science, as is implied in all that I shall be telling you in these lectures? A science which leads over into social science is not yet in existence.

[ 18 ] On the one hand we have Astronomy, tending more and more to be clothed in mathematical forms of thought. It has become so great in its present form just because it is a purely mathematical and mechanical science. But there is another branch of science which stands, as it were, at the opposite pole to Astronomy, and which cannot be studied in its real nature without Astronomy. It is however, impossible, as science is today, to build a bridge between Astronomy and this other pole of science, namely, Embryology. He alone is studying reality, who on the one hand studies the starry skies and on the other hand the development of the human embryo. How is the human embryo generally studied today? Well, it is stated: The human embryo arises from the interaction of two cells, the sex-cells or gametes, male and female. These cells develop in the parent organism in such a way as to attain a certain state of independence before they are able to interact. They then present a certain contract, the one cell, the male, calling forth new and different possibilities of development in the other, the female. The question is put: What is a cell? As you know, since about the middle of the 19th century, Biology has largely been built upon the cell theory. The cell is described as a larger or smaller, spherule, consisting of albuminous or protein-like substances. It has a nucleus within it of a somewhat different structure and around the whole is an enclosing membrane. As such, it is the building-stone for all that arising by way of living organisms. The sex-cells are of a similar nature but are formed differently according to whether they are male or female, and from such cells every more complicated organism is built up.

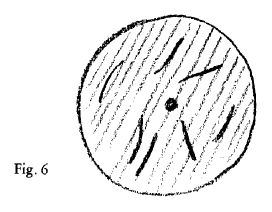

[ 19 ] But now, what is actually meant when it is said that an organism builds itself up from these cells? The idea is that substances which are otherwise in Nature are taken up into these cells and then no longer work in quite the same way as before. If oxygen, nitrogen or carbon are contained in the cells, the carbon, for instance, does not have the effect upon some other substance outside, that it would have had before; such power of direct influence is lost to it. It is taken up into the organism of the cell and can only work there as conditions in the cell allow. That is to say, the influence is exerted not so much by the carbon, but by the cell, which makes use of the particular characteristics of carbon, having incorporated a certain amount of it into itself. For example, what man has within him in the form of metal—iron for instance—only works in a circuitous way, via the cell. The cell is the building-stone. So in studying the organism, everything is traced to the cell. Considering at first only the main bulk of the cell, without the nucleus and membrane, we distinguish two parts: a transparent part composed of this fluid, and another part forming sort of framework. Describing it schematically, we may say that there is the framework of the cell, and this is embedded, as it were, in the other substance which, unlike the framework, is quite unformed. (Fig. 6) Thus we must think of the cell as consisting of a mass which remains fluid and unformed and a skeleton or framework which takes on a great variety of forms. This then is studied. The method of studying cells in this way has been pretty well perfected; certain parts in the cell can be stained with color, others do not take the stain. Thus with carmine or saffron, or whatever coloring matter is used, we are able to distinguish the form of the cell and can thus acquire certain ideas about its inner structure. We note, for instance, how the inner structure changes when the female germ-cell is fructified. We follow the different stages in which the cell's inner structure alters; how it divides; and how the parts become attached to one another, cell upon cell, so that the whole becomes a complicated structure. All this is studied. But it occurs to no-one to ask: With what is this whole life in the cell connected? What is really happening? It does not occur to anyone to ask this.

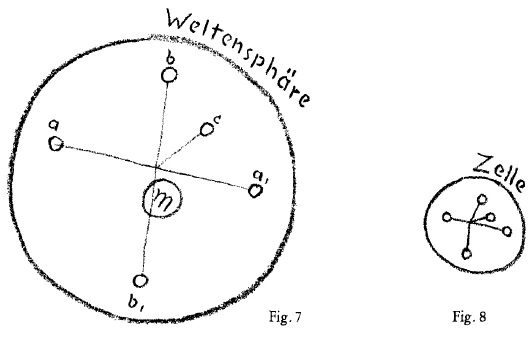

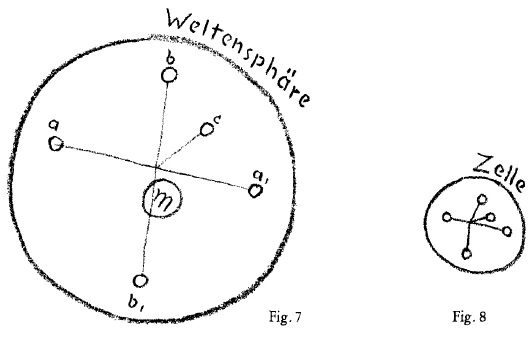

[ 20 ] What happens in the cell is to be conceived, my dear friends, in the following way,—though to be sure, it is still a rather abstract way. There is the cell. For the moment let us consider it in its most usual form, namely the spherical form. This spherical form is partially determined by the thin fluid substance, and enclosed within it is the delicate framework. But what is the spherical form? The thin fluid mass is as yet left entirely to itself and therefore behaves according to the impulses it receives from its surroundings. What does it do? Well, my dear friends, it mirrors the universe around it! It takes on the form of the sphere because it mirrors in miniature the whole cosmos, which we indeed also picture to ourselves ideally as a sphere. Every cell in its spherical form is no less than an image of the form of the whole universe. And the framework inside, every line of the form, is conditioned by its relationship to the structure of the whole cosmos. To express myself abstractly to begin with, think of the sphere of the universe with its imaginary boundary (Fig. 7). In it, you have here a planet, and there a planet (\(a\), \(a_1\)). They work in such a way as to exert an influence upon one another in the direction of the line which joins them. Here (\(m\)) let us say—diagrammatically, of course,—a cell is formed; its outline mirrors the sphere. Here, within the framework it has a solid part which is due to the working of the one planet on the other. And suppose that here there were another constellation of planets, working upon each other along the line joining them (\(b\), \(b_1\)).

And here again there might be yet another planet (\(c\)), this one having no counterpart;—it throws the whole construction, which might otherwise have been rectangular, out of shape, and the structure takes on a somewhat different form. And so you have in the whole formation of the framework of the cell a reflection of the relationships existing in the planetary system,—altogether in the whole starry system. You can enter quite concretely into the formation of the cell and you will reach an understanding of this concrete form only if you see in the cell an image of the entire cosmos.

[ 21 ] And now take the female ovum, and picture to yourselves that this ovum has brought the cosmic forces to a certain inner balance. They have taken on form in the framework of the cell, and are in a certain way at rest within it, supported by the female organism as a whole. Then comes the influence of the male sex-cell. This has not brought the macrocosmic forces to rest, but works in the sense of a very specialized force. It is as though the male sex-cell works precisely along this line of force (indicated by Dr. Steiner on the blackboard) upon the female ovum which has come to a condition of rest. The cell, which is an image of the whole cosmos, is thereby caused to relinquish its microcosmic form once more to a changing play of forces. At first, in the female ovum, the macrocosm comes to rest in a peaceful image. Then through the male sex-cell the female is torn out of this state of rest, and is drawn again into a region of specialized activity and brought into movement. Previously it had drawn itself together in the resting form of the image of the cosmos, but the form is drawn into movement again by the male forces which are, so to speak, images of movement. Through them the female forces, which are images of the form of the cosmos and have come to rest, are brought out of this state of rest and balance.

[ 22 ] Here we may have some idea, from the aspect of Astronomy, of the forming and shaping of something which is minute and cellular. Embryology cannot be studied at all without Astronomy, for what Embryology has to show is only the other pole of what is seen in Astronomy. We must, in a way, follow the starry heavens on the one hand, seeing how they reveal successive stages, and we must then follow the process of development of a fructified cell. The two belong together, for the one is only the image of the other. if you understand nothing of Astronomy, you will never understand the forces which are at work in Embryology, and if you understand nothing of Embryology, you will never understand the meaning of the activities with which Astronomy has to deal. For these activities appear in miniature in the processes of Embryology.

[ 23 ] It is conceivable that a science should be formed, in which, on the one hand, astronomical events are calculated and described, and on the other hand all that belongs to them in Embryology, which is only the other aspect of the same thing.

[ 24 ] Now look at the position as it is today: you find that Embryology is studied on its own. It would be regarded as madness if you were to demand of a modern embryologist that he should study Astronomy in order to understand the phenomena in his own sphere of work. And yet it should be so. This is why a complete regrouping of the sciences is necessary. It will be impossible to become a real embryologist without studying Astronomy. It will no longer be possible to educate specialists who merely turn their eyes and their telescopes to the stars, for to study the stars in that way has no further meaning unless one knows that it is out of the great universe that the minute and microscopical is fashioned.

[ 25 ] All this,—which is quite real and concrete,—has in scientific circles been changed into the utmost abstraction. It is reality to say: We must strive for astronomical knowledge in cellular theory, especially in Embryology. If DuBois-Raymond had said that the detailed astronomical facts should be applied to the cell-theory, he would have spoken out of the sphere of reality. But what he wanted corresponds to no reality, namely that something thought-out and devised—the atoms and molecules—should be examined with astronomical precision. He wanted the astronomical type of mathematical thoughts, which have been added to the world of the stars, to be sought for again in the molecule.

Thus you see, upon the one hand lies reality: movement, the active forces of the stars and the embryonic development in which there lives, in all reality, what lives in the starry heavens. That is where the reality lies and that is where we must look for it. On the other hand lies abstraction. The mathematician, the mechanist, calculates the movements and forces of the heavenly bodies and then invents the molecular structure to which to apply this kind of astronomical knowledge. Here he is withdrawn from life, living in pure abstractions.

[ 26 ] These are the things about which we must think, remembering that now we must renew, in full consciousness, something which was in a certain sense present in earlier times. Looking back to the Egyptian Mysteries, we find astronomical observations such as were made at that time. These observations, my dear friends, were not used merely to calculate when an eclipse of the Sun or Moon would take place, but rather to arrive at what should come about in social evolution. Men were guided by what they saw in the heavens, as to what must be said to the people, what instructions should be given, so that the development of the whole social life should take its right course. Astronomy and Sociology were dealt with as one. We too, though in a different way from the Egyptians, must again learn how to connect what happens in social life with the phenomena of the great universe. We do not understand what came about in the middle of the 15th century, if we cannot relate the events of that time to the phenomena which then prevailed in the universe. It is like a blind man talking about color to speak of the changes in the civilized world in the middle of the 15th century without taking all this into account.

Spiritual Science is already a starting point. But we shall not succeed in bring together the complicated domain of Sociology—social science—with the observations of natural phenomena, unless we first begin by connecting Astronomy with Embryology, linking the embryonic facts with astronomical phenomena.

Erster Vortrag

[ 1 ] Meine lieben Freunde! Zu den Auseinandersetzungen, die ich hier in den folgenden Tagen geben will, möchte ich heute eine Einleitung sprechen. Schon aus dem Grunde möchte ich dieses tun, damit Sie von vorneherein unterrichtet sind über die Absicht dieser Besprechungen. Es soll nicht meine Aufgabe sein, irgendein engbegrenztes Fach gerade in diesen Tagen abzuhandeln, sondern einige weitere Gesichtspunkte mit einem ganz bestimmten Ziele in wissenschaftlicher Beziehung zu geben. Ich möchte warnen davor, diesen sogenannten «Kurs» als einen «astronomischen Kurs» zu bezeichnen. Das soll er nicht sein. Sondern er soll gerade etwas behandeln, was in dieser Zeit zu behandeln mir von ganz besonderer Wichtigkeit scheint. Ich habe deshalb als Titel angegeben: «Das Verhältnis der verschiedenen naturwissenschaftlichen Gebiete zur Astronomie.» Und ich will heute namentlich auseinandersetzen, was ich mit dieser Titelgebung eigentlich meine.

[ 2 ] Es ist durchaus so, daß in verhältnismäßig kurzer Zeit innerhalb des sogenannten wissenschaftlichen Lebens, wenn es nicht zu einem vollständigen Verfall kommen soll, manches sich wird ändern müssen. Namentlich werden gewisse Wissenschaftsmassen, die man jetzt unter gewissen Titeln zusammenfaßt und die man unter diesen Titeln vertreten läßt durch unsere gebräuchlichen Schulen, aus ihrem Gefüge genommen werden müssen und nach anderen Rücksichten einzuteilen sein, so daß gewissermaßen eine weitgehende Umgruppierung unserer wissenschaftlichen Gebiete wird stattfinden müssen. Denn die Gruppierung, welche man jetzt hat, reicht eben durchaus nicht aus, um zu einer wirklichkeitsgemäßen Weltanschauung zu kommen. Auf der anderen Seite haftet so stark unser gegenwärtiges Leben an dieser Gliederung, daß eben einfach die Lehrkanzeln besetzt werden nach dieser traditionellen Gliederung. Man beschränkt sich höchstens darauf, die bestehenden wissenschaftlich umgrenzten Gebiete wiederum in Spezialgebiete zu zerlegen und für die Spezialgebiete einzelne Fachleute, wie man sie nennt, zu suchen. Aber in diesem ganzen Wissenschaftsleben wird insofern eine Änderung eintreten müssen, als ganz andere Kategorien werden erscheinen müssen, und in diesen Kategorien wird man Verschiedenes, das heute, sagen wir, in der Zoologie behandelt wird, meinetwillen in der Physiologie behandelt wird, dann wiederum in der Erkenntnistheorie behandelt wird, zusammengefaßt finden in ein neu entstehendes Wissenschaftsgebiet. Dagegen die älteren Wissenschaftsgebiete, die stark mit Abstraktionen arbeiten, die werden verschwinden müssen. Es werden eben ganz neue wissenschaftliche Zusammenfassungen stattfinden müssen. Das wird zunächst Schwierigkeiten begegnen nach der Richtung hin, daß ja heute die Leute dressiert werden auf die bestimmten wissenschaftlichen Kategorien und nur sehr schwer eine Brücke finden zu dem, was sie notwendig brauchen für ein wirklichkeitsgemäßes Zusammenfügen des wissenschaftlichen Stoffes.

[ 3 ] Wenn ich mich schematisch ausdrücken soll, so möchte ich sagen: Wir haben heute eine Astronomie, wir haben eine Physik, wir haben eine Chemie, wir haben eine Philosophie, wir haben eine Biologie, meinetwillen, wir haben eine Mathematik und so weiter. Dadrinnen hat man Spezialgebiete geschaffen, mehr, möchte ich sagen, aus dem Grunde, damit die einzelnen Fachleute nicht so viel zu tun haben, um sich zurechtzufinden, auch damit sie nicht zuviel zu tun haben, um all die einschlägige Literatur, die ja ins Unermeßliche sich ausweitet, zu beherrschen. Aber es wird sich darum handeln, daß man neue Gebiete schafft, welche ganz anderes umfassen, ein Gebiet, das vielleicht etwas von der Astronomie, etwas von der Biologie und so weiter umfaßt. Dazu wird natürlich ein Umgestalten unseres ganzen Wissenschaftslebens unbedingt notwendig sein. Da muß gerade das, was wir Geisteswissenschaft nennen und was ja etwas Universelles sein will, nach dieser Richtung hin wirken. Sie muß es sich zur besonderen Aufgabe machen, nach dieser Richtung hin zu wirken. Denn wir kommen einfach mit den alten Gliederungen nicht mehr weiter. Unsere Hochschulen stehen heute so vor der Welt, daß sie eigentlich ganz lebensfremd sind. Sie bilden uns Mathematiker, Physiologen, sie bilden uns Philosophen aus, aber die haben alle eigentlich gar keinen besonderen Bezug zur Welt. Die können alle nichts anderes, als gerade in ihren engbegrenzten Gebieten arbeiten. Sie machen uns die Welt immer abstrakter und abstrakter, immer wirklichkeitsunmöglicher und -unmöglicher. Und diesem in der Zeitnotwendigkeit Liegenden möchte ich gerade in diesen Vorträgen Rechnung tragen. Ich möchte Ihnen zeigen, wie es auf die Dauer unmöglich sein wird, bei den alten Gliederungen zu bleiben. Und daher möchte ich zeigen, wie die verschiedensten anderen Gebiete, die sich heute um Astronomie nicht kümmern, gewisse Beziehungen haben zu einer ja räumlich universellen Erkenntnis, zur Astronomie, so daß einfach gewisse astronomische Erkenntnisse in anderen Gebieten werden auftauchen müssen, damit man diese anderen Gebiete in einer wirklichkeitsgemäßen Weise bezwingen lernt.

[ 4 ] Also darum wird es sich handeln in diesen Vorträgen, daß die Brücke geschlagen wird von verschiedenen Wissenschaftsgebieten hinüber in das Gebiet des Astronomischen und daß in richtiger Weise in den einzelnen Wissenschaftsgebieten das Astronomische erscheine.

[ 5 ] Damit ich nicht mißverstanden werde, möchte ich noch eine methodische Bemerkung dazu vorausschicken. Sehen Sie, die Art und Weise des Darstellens in der Wissenschaft, die heute üblich ist, die wird ja manche Änderung erfahren müssen aus dem Grunde, weil sie eigentlich auch herausgeboren ist aus unserer heute zu überwindenden wissenschaftlichen Struktur. Es ist heute üblich, daß, gerade wenn auf irgendwelche Tatsachen hingewiesen wird, die dem Menschen ferner liegen, weil er heute mit seinen Wissenschaften eben gar nicht darauf kommt, oftmals gesagt wird: Das wird behauptet, aber nicht bewiesen. - Es handelt sich allerdings darum, daß man einfach bei der wissenschaftlichen Betätigung heute eben in die Notwendigkeit versetzt wird, manches zunächst rein aus der Anschauung heraus zu sagen, was man dann zu verifizieren hat, indem man immer mehr und mehr Tatsachen heranträgt, die die Verifizierung leisten. Daß man also nicht voraussetzen kann, daß, sagen wir, gleich im Beginne irgendeiner Betrachtung alles so erscheint, daß nicht irgendeiner einhaken könnte und sagen könnte: Es ist nichts bewiesen. Es wird schon im Laufe der Zeit bewiesen, verifiziert werden, aber es muß manches zunächst aus der Anschauung heraus einfach dargestellt werden, damit der betreffende Begriff, die betreffende Idee geschaffen ist. Und so bitte ich Sie, diese Vorträge als ein Ganzes zu fassen, also für manches, was in den ersten Stunden so erscheinen wird, als ob es zunächst nur hingestellt wäre, die deutlichen Belege dann in den letzten Stunden zu suchen. Da wird sich dann eben manches verifizieren, was ich zunächst so behandeln werde, daß überhaupt einmal Ideen und Begriffe vorhanden sind.

[ 6 ] Sehen Sie, dasjenige, was wir heute Astronomie nennen, einschließlich des Gebietes der Astrophysik, das ist ja im Grunde genommen eine Schöpfung der neueren Zeit erst. Vor der Zeit des Kopernikus, des Galilei hat man über astronomische Dinge wesentlich anders gedacht, als man heute denkt. Es ist heute sogar schon außerordentlich schwierig, auf die besondere Art hinzuweisen, wie man astronomisch, ich will sagen, noch im 13., 14. Jahrhundert gedacht hat, weil das dem Menschen von heute ganz und gar fremd geworden ist. Wir leben nur mehr in den Vorstellungen - das ist ja von einer gewissen Seite her sehr berechtigt -, welche seit der Galilei-, Kepler-, Kopernikus-Zeit her geschaffen worden sind, und das sind Vorstellungen, welche im Grunde die weiten Erscheinungen des Weltenraumes, insofern sie für Astronomie in Betracht kommen, in einer mathematisch-mechanischen Weise behandeln. Man denkt über diese Erscheinungen mathematisch-mechanisch. Man legt dasjenige zugrunde bei der Betrachtung dieser Erscheinungen, was man aus einer abstrakten Wissenschaft der Mathematik oder einer abstrakten Wissenschaft der Mechanik gewinnt. Man rechnet mit Entfernungen, mit Bewegungen und mit Kräften, aber die qualitative Art der Betrachtung, welche eben noch im 13., 14. Jahrhundert durchaus vorhanden war, so daß man unterschied Individualitäten in den Sternen, daß man unterschied eine Individualität des Jupiter, eine Individualität des Saturn, die ist der heutigen Menschheit ganz abhanden gekommen. Ich will jetzt mich nicht kritisch ergehen über diese Dinge, sondern ich will nur darauf hinweisen, daß die mechanische und mathematische Behandlungsweise die ausschließliche geworden ist für dasjenige, was wir das astronomische Gebiet nennen. Auch wenn wir, ohne daß wir Mathematik oder Mechanik verstehen, uns in populärer Weise heute Kenntnisse verschaffen über den Sternenhimmel, so geschieht es trotzdem, wenn es auch in laienhafter Weise geschieht, nach rein räumlichzeitlichen Begriffen, also nach mathematisch-mechanischen Vorstellungen. Und es besteht bei unseren Zeitgenossen, die über diese Dinge glauben maßgebend urteilen zu können, gar kein Zweifel darüber, daß man nur so den Sternenhimmel betrachten könne, daß alles andere etwas Dilettantisches sei.

[ 7 ] Wenn man sich nun frägt, wie es denn eigentlich gekommen ist, daß diese Betrachtung des Sternenhimmels heraufgezogen ist in unsere Zivilisationsentwickelung, dann wird man bei denjenigen, die die heutige wissenschaftliche Denkweise als etwas Absolutes betrachten, eine andere Antwort bekommen müssen, als wir sie geben können. Derjenige, der die wissenschaftliche Entwickelung, wie sie heute üblich ist, als etwas absolut Gültiges betrachtet, wird sagen: Nun ja, bei der früheren Menschheit lagen eben noch nicht streng wissenschaftlich ausgebildete Vorstellungen vor; zu denen hat man sich erst durchgerungen. Und das, wozu man sich durchgerungen hat, die mathematisch-mechanische Betrachtungsweise der Himmelserscheinungen, das entspricht eben der Objektivität, das ist in der Wirklichkeit begründet. - Mit andern Worten wird man sagen: Die früheren Leute haben etwas Subjektives in die Welterscheinungen hereingebracht; die neuere Menschheit hat sich durchgearbeitet zur streng wissenschaftlichen Erfassung desjenigen, was nun der Wirklichkeit eigentlich entspricht.

[ 8 ] Diese Antwort können wir nicht geben, sondern wir müssen uns auf den Gesichtspunkt der Entwickelung der Menschheit stellen, die im Laufe ihres Daseins verschiedene innere Kräfte ins Bewußtsein hereingebracht hat. Wir müssen uns sagen: Für diejenige Art, die Himmelserscheinungen anzuschauen, wie sie bestanden hat bei den alten Babyloniern, den Ägyptern, vielleicht auch bei den Indern, für diese war maßgebend eine bestimmte Art der Entwickelung der menschlichen Seelenkräfte. - Diese Seelenkräfte der Menschheit mußten dazumal entwickelt werden mit derselben inneren Notwendigkeit, mit der ein Kind zwischen dem zehnten und fünfzehnten Jahr gewisse Seelenkräfte entwickeln muß, während es in einer anderen Zeit andere Seelenkräfte entwickelt. Entsprechend kommt die Menschheit in anderen Zeiten zu anderen Forschungen. - Dann ist gekommen das ptolemäische Weltsystem. Es ging wiederum aus anderen Seelenkräften hervor. Dann unser kopernikanisches Weltsystem. Es ging wiederum aus anderen Seelenkräften hervor. Die entwickelten sich nicht deshalb, weil wir gerade jetzt als Menschheit glücklich so geworden sind, daß wir uns nun zur Objektivität durchgerungen haben, während die anderen vorher alle Kinder waren, sondern weil die Menschheit seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts die Entwickelung gerade der mathematisch-mechanischen Fähigkeiten braucht, die früher nicht da waren. Die Menschheit braucht für sich das Hervorholen dieser mathematisch-mechanischen Fähigkeiten, und daher sieht die Menschheit heute die Himmelserscheinungen in dem Bilde der mathematisch-mechanischen Fähigkeiten an. Und sie wird sie einmal wieder anders anschauen, wenn sie zu ihrer eigenen Entwickelung, zu ihrem eigenen Heil und Besten andere Kräfte aus den Tiefen der Seele hervorgeholt haben wird. Es hängt also von der Menschheit ab, welche Gestalt die Weltanschauung annimmt, und es kommt nicht darauf an, daß man mit Hochmut zurückschauen kann auf frühere Zeiten, wo die Menschen kindlich waren, um auf die jetzige Zeit zu schauen, wo man sich endlich zur Objektivität, die nun für alle Zukunft bleiben könne, durchgerungen hat.

[ 9 ] Dasjenige, was ein besonderes Bedürfnis der neueren Menschheit geworden ist und was dann abgefärbt hat auch auf das wissenschaftliche Bedürfnis, das ist, daß man zwar darnach strebt, auf der einen Seite möglichst leicht überschaubare Vorstellungen zu haben - das sind die mathematischen -, auf der anderen Seite strebt man aber darnach, Vorstellungen zu bekommen, bei denen man möglichst stark sich einem inneren Zwang hingeben kann. Der moderne Mensch wird sogleich unsicher und nervös, wenn er nicht einen so starken inneren Zwang vorliegend hat, wie bei dem Urteil, das dem pythagoreischen Lehrsatz zugrunde liegt, sondern wenn er verspürt: Er muß selber entscheiden, es entscheidet für ihn nicht die aufgezeichnete Figur, sondern er muß selber entscheiden, muß Aktivität der Seele entwickeln. Da wird er sogleich unsicher und nervös. Da geht er nicht mit, der moderne Mensch. Da sagt er, das ist nicht exakte Wissenschaft, da kommt Subjektivität hinein. Der moderne Mensch ist eigentlich furchtbar passiv. Er möchte, daß er überall am Gängelband ganz objektiver Verkettungen der Urteilsteile geführt würde. Diesem genügt die Mathematik, wenigstens in den meisten Teilen, und wo sie nicht genügt, wo der Mensch in der neueren Zeit eingegriffen hat mit seinem Urteil - ja, da ist es auch danach! Da glaubt er zwar noch exakt zu sein, aber er gerät in die unglaublichsten Vorstellungen hinein. Also, in der Mathematik und Mechanik, da glaubt sich der Mensch am Gängelband der sich selbst verbindenden Begriffe fortgezogen. Da ist er so, daß er Boden unter den Füßen fühlt. Und in dem Augenblick, wo er da heraustritt, will er nicht mehr mit. Diese Überschaubarkeit auf der einen Seite und dieser innere Zwang auf der anderen Seite, das ist das, was die moderne Menschheit braucht zu ihrem Heil. Und aus dem heraus hat sie im Grunde genommen auch die moderne Wissenschaft der Astronomie in ihrer besonderen Gestalt gebildet als Weltbild. Ich sage jetzt nichts über die einzelnen Wahrheiten, sondern über das Ganze als Weltbild zunächst.

[ 10 ] Nun ist das so in das Bewußtsein der Menschheit eingedrungen, daß man überhaupt dazu gekommen ist, alles andere mehr oder weniger als unwissenschaftlich zu betrachten, was nicht auf diese Art behandelt werden kann. Daraus ging dann hervor so etwas wie der Ausspruch Kants, der gesagt hat: In allen einzelnen Wissenschaftsgebieten ist nur so viel wirkliche Wissenschaft darinnen, als Mathematik darin angetroffen werden kann. Also, man müßte eigentlich das Rechnen in alle Wissenschaften hineintragen oder die Geometrie hineintragen. Aber das scheitert ja daran, daß die einfachsten mathematischen Vorstellungen wiederum ferne liegen denjenigen Menschen, die zum Beispiel Medizin studieren. Mit denen läßt sich heute aus unserer wissenschaftlichen Gliederung heraus über einfache mathematische Vorstellungen gar nicht mehr reden. Und so kommt es, daß auf der einen Seite als Ideal hingestellt worden ist dasjenige, was man astronomische Erkenntnis nennt. Du Bois-Reymond hat das in seiner Rede über die Grenzen des Naturerkennens formuliert, indem er sagte: Wir begreifen nur dasjenige in der Natur und befriedigen nur mit dem unser Kausalitätsbedürfnis, was uns astronomische Erkenntnis werden kann. - Also die Himmelserscheinungen übersehen wir so, daß wir aufzeichnen die Himmelstafel mit den Sternen, daß wir rechnen mit dem, was uns als Material gegeben ist. Wir können genau angeben: Da ist ein Stern, er übt eine Anziehungskraft auf andere Sterne aus. Wir beginnen zu rechnen, wir haben die einzelnen Dinge, die wir in unsere Rechnung einbeziehen, anschaulich vor uns. Das ist dasjenige, was wir in die Astronomie zunächst hineingetragen haben. Jetzt betrachten wir, sagen wir, das Molekül. Wir haben darin, in dem Molekül, wenn es kompliziert ist, allerlei Atome, die aufeinander Anziehungskraft ausüben, die umeinander sich bewegen. Wir haben ein kleines Weltenall. Und wir betrachten dieses Molekül nach dem Muster, wie wir sonst den Sternenhimmel betrachten. Wir nennen das «astronomische Erkenntnis». Wir betrachten die Atome als kleine Weltkörper, das Molekül als ein kleines Weltsystem und sind befriedigt, wenn uns das gelingt. Aber es ist ja der große Unterschied: Wenn wir den Sternenhimmel anschauen, sind uns all die Einzelheiten gegeben. Wir können höchstens fragen, ob wir sie richtig zusammenfassen, ob nicht etwas doch anders ist, als es zum Beispiel Newton angegeben hat. Wir spinnen darüber ein mathematisch-mechanisches Netz. Das ist eigentlich hinzugefügt. Aber es befriedigt die modernen Menschheitsbedürfnisse in bezug auf das Wissenschaftliche. In die Atomen-Moleküle-Welt, da tragen wir dann das System hinein, das wir erst ausgedacht haben, und denken die Moleküle und Atome hinzu. Da denken wir dasjenige dazu, was uns sonst gegeben ist. Aber wir befriedigen unser sogenanntes Kausalitätsbedürfnis, indem wir sagen: Wenn sich das, was wir als kleinste Teile denken, so und so bewegt, ist das das Objektive für das Licht, für den Schall, für die Wärme und so weiter. Wir tragen astronomische Erkenntnisse in alle Welterscheinungen hinein und befriedigen so unser Kausalitätsbedürfnis. Du Bois-Reymond hat es geradezu trocken ausgesprochen: Wo man das nicht kann, da gibt es überhaupt keine wissenschaftliche Erklärung.

[ 11 ] Sehen Sie, dem, was da geltend gemacht wird, müßte eigentlich entsprechen, wenn man zum Beispiel zu einer rationellen Therapie kommen wollte, also einsehen wollte die Wirksamkeit eines Heilmittels, daß man in der Substanz dieses Heilmittels die Atome so verfolgen können müßte, wie man sonst den Mond, die Sonne, die Planeten und die Fixsterne verfolgt. Es müßten das alles kleine Weltsysteme werden können. Man müßte aus dem Errechnen heraus sagen können, wie irgendein Mittel wirkt. Das ist ja allerdings für manche ein Ideal sogar gewesen vor nicht zu ferner Zeit. Jetzt hat man solche Ideale ja aufgegeben. Aber es scheiterte nicht nur in bezug auf so entlegene Gebiete wie etwa die rationelle Therapie, sondern für viel näherliegende schon einfach daran, daß unsere Wissenschaften so gegliedert sind, wie es heute ist. Sehen Sie, der heutige Mediziner wird ja so gebildet, daß er außerordentlich wenig wirkliche Mathematik innehaben kann. Also man kann mit ihm vielleicht von der Notwendigkeit astronomischer Erkenntnisse reden, aber man kann nichts anfangen mit ihm, wenn man davon spricht, mathematische Vorstellungen in sein Gebiet einzugliedern. Daher müßte also dasjenige, was wir außer der Mathematik und Mechanik und Astronomie haben, im strengen Sinne des Wortes heute als unwissenschaftlich bezeichnet werden. Das tut man natürlich nicht. Man bezeichnet auch diese anderen Wissenschaften als exakt, aber das ist ja wiederum nur eine Inkonsequenz. Aber charakteristisch für die Gegenwart ist es, daß) man die Forderung, man solle alles nach dem Muster der Astronomie verstehen, überhaupt aufstellen konnte.

[ 12 ] Wie schwer es ist, heute mit den Leuten wirklich durchgreifend über gewisse Dinge zu reden, möchte ich Ihnen durch ein Beispiel anschaulich machen. Sie wissen ja, es hat eine große Rolle gespielt in der modernen Biologie die Frage nach der Form der menschlichen Schädelknochen. Ich habe ja auch im Zusammenhang unserer anthroposophischen Vorträge über diese Sache vielfach gesprochen. Die Form der menschlichen Schädelknochen: Goethe, Oken haben großartige Vorausnahmen gemacht in bezug auf diese Sache. Dann hat klassische Untersuchungen darüber angestellt die Schule des Gegenbaur. Aber etwas, was ein tiefergehendes Erkenntnisbedürfnis nach dieser Richtung befriedigen könnte, liegt im Grunde heute nirgends vor. Man streitet sich herum, ob Goethe mehr oder weniger Recht hatte, indem er sagte, die Schädelknochen seien umgewandelte Wirbelknochen, Knochen der Wirbelsäule, aber zu irgendeiner durchgreifenden Ansicht über diese Sache kann man ja heute aus einem ganz bestimmten Grunde heraus nicht kommen, weil man da, wo man über diese Dinge redet, kaum verstanden werden kann. Und wo man verstanden werden könnte, da redet man über diese Dinge nicht, weil sie nicht interessieren. Sehen Sie, es ist heute fast ein unmögliches Kollegium, das entstehen würde, wenn man einen richtigen heutigen Mediziner, einen richtigen heutigen Mathematiker, das heißt einen solchen, der die höhere Mathematik beherrscht, und einen Menschen zusammenbrächte, der beides ziemlich gut verstünde. Diese drei Menschen könnten sich heute kaum verständigen. Derjenige, der da in der Mitte säße, der beides ein bißchen verstünde, der würde zur Not mit dem Mathematiker reden können, auch mit dem Mediziner. Aber der Mathematiker und der Mediziner würden sich über wichtige Probleme nicht verständigen können, weil, was der Mediziner dazu zu sagen hat, den Mathematiker nicht interessiert, und was der Mathematiker zu sagen hat oder hätte, wenn es überhaupt zur Sprache käme -, das versteht der Mediziner nicht, weil er nicht die nötigen mathematischen Voraussetzungen hat. Das wird gerade anschaulich bei dem Problem, das ich eben angeführt habe.

[ 13 ] Man stellt sich heute eben vor: Wenn die Schädelknochen umgewandelte Wirbelknochen sind, so muß man in gerader Richtung fortgehen können durch irgendeine räumlich vorstellbare Metamorphose von dem Wirbelknochen zu dem Schädelknochen. Die Vorstellung noch auszudehnen auf den Röhrenknochen, das gelingt aus den angegebenen Untergründen eben schon gar nicht. Der Mathematiker wird sich heute nach seinen mathematischen Studien eine Vorstellung machen können, was es eigentlich bedeutet, wenn ich einen Handschuh umdrehe, wenn ich die Innenseite nach außen drehe. Man muß sich eine gewisse mathematische Behandlung der Tatsache denken, daß man das, was früher nach außen gekehrt war, nach innen kehrt, und das, was früher innen war, nach außen. Ich will das schematisch so aufzeichnen (Fig. 1): irgendein Gebilde, das nach außen hin zunächst weiß sei und nach innen rot. Dieses Gebilde behandeln wir nach dem Muster des Handschuhumdrehens, so daß es also jetzt außen rot wird und innen weiß ausgekleidet ist

[ 14 ] Aber jetzt gehen wir weiter. Stellen wir uns vor, daß das, was wir da haben, mit inneren Kräften ausgestattet ist, daß also das sich nicht so einfach umdrehen läßt wie ein Handschuh, der umgedreht auch wie ein Handschuh ausschaut, sondern nehmen wir an, daß das, was wir umdrehen, nach außen mit andern Kräftespannungen auftritt als nach innen. Dann werden wir erleben, daß durch die einfache Umdrehung eine ganz andere Form herauskommt. Dann wird das Gebilde eben so sein, bevor wir es umgedreht haben (Fig. 1). Drehen wir es um, so kommen andere Kräfte in Betracht beim Roten, andere beim Weißen, und die Folge ist vielleicht, daß durch die bloße Umdrehung aieses Gebilde entsteht (Fig. 3, S. 26). Es ist die Möglichkeit, daß durch die bloße Umdrehung dieses Gebilde entsteht. Als das Rote nach innen gestülpt war, konnte es nicht seine Kraft entwickeln. Jetzt kann es sie anders entwickeln, wenn es nach außen gestülpt wird. Und ebenso das Weiße. Es kann seine Kraft erst nach innen gestülpt entwickeln.

[ 15 ] Es ist natürlich durchaus denkbar, daß man eine solche Sache einer mathematischen Behandlung unterwirft. Aber man ist heute ganz und gar abgeneigt, dasjenige, was man so in Begriffe bekommen kann, auf die Wirklichkeit anzuwenden. Denn in dem Augenblick, wo man lernt, dieses auf die Wirklichkeit anzuwenden, kommt man dazu, in unseren Röhrenknochen, also im Oberarmknochen, im Ober- oder Unterschenkelknochen und Unterarmknochen ein Gebilde zu sehen, das umgedreht zum Schädelknochen wird! Es sei das hier nach innen bis zum Mark hin durch Rot charakterisiert, nach außen durch das Weiße (Fig. 4). Es wendet nach innen diejenige Struktur, diejenigen Kräfteverhältnisse, die wir untersuchen können; nach außen das, was wir sehen, wenn wir den Muskel abziehen vom Röhrenknochen. Denken Sie diesen Röhrenknochen aber nach demselben Prinzip, das ich Ihnen angegeben habe, umgedreht und seine anderen Spannungsverhältnisse geltend gemacht, dann können Sie ganz gut das bekommen (Fig. 5). Jetzt hat er innerlich dieses (weiß) und nach außen macht sich dasjenige, was ich durch Rot kennzeichnete, so geltend. So ist in der Tat das Verhältnis eines Schädelknochens zu einem Röhrenknochen. Und in der Mitte drinnen steht der eigentliche Rückenknochen oder Wirbelknochen der Rückenmarksäule. Sie müssen einen Röhrenknochen umdrehen wie einen Handschuh nach seinen in ihm wirkenden Kräften, dann bekommen Sie den Schädelknochen heraus. Die Umwandlung des Schädelknochens aus dem Röhrenknochen ist nur zu verstehen, wenn Sie sich diese Umdrehung denken. Und Sie bekommen die ganze Bedeutung davon, wenn Sie sich vorstellen, daß das, was der Röhrenknochen nach außen wendet, beim Schädelknochen nach innen gewendet ist, daß der Schädelknochen einer Welt sich zuwendet, die im Inneren des Schädels liegt. Da ist eine Welt. Dahin ist der Schädelknochen orientiert, so wie der Röhrenknochen nach außen orientiert ist, nach der äußeren Welt. Beim Knochensystem kann man es besonders leicht anschaulich machen, Aber so ist der ganze menschliche Organismus orientiert, daß er zunächst eine Schädelorganisation und auf der anderen Seite eine Gliedmaßenorganisation hat so, daß die Schädelorganisation nach innen, die Gliedmaßenorganisation nach außen orientiert ist. Der Schädel faßt eine Welt nach innen, der Gliedmaßenmensch faßt eine Welt nach außen, und zwischen beiden ist wie eine Art von Ausgleichsystem dasjenige, was dem Rhythmus dient.

[ 16 ] Nehmen Sie heute irgendeine Schrift in die Hand, die von der Funktionentheorie handelt oder von der nichteuklidischen Geometrie, und sehen Sie sich an, was da für eine Summe von allerlei Erwägungen aufgewendet wird, um über die gewöhnliche geometrische Vorstellungsweise im dreigliederigen Raum hinauszukommen, um das, was euklidische Geometrie ist, zu erweitern, so werden Sie sehen, daß da ein großer Fleiß und großer Scharfsinn aufgewendet wird. Aber nun, sagen wir, sind Sie ein großer mathematischer Knopf geworden, der gut die Funktionentheorie kennt, der auch alles versteht, was heute über nichteuklidische Geometrie verstanden werden kann. Nun möchte ich aber die Frage aufwerfen - verzeihen Sie, es sieht etwas geringschätzig aus, wenn man in diese Trivialität hinein die Sache kleidet, aber ich möchte es doch tun gegenüber vielem, was nach dieser Richtung hintendiert, und ich bitte die Anwesenden, besonders geschulte Mathematiker, sich die Sache zu überlegen, ob es nicht so ist -, ich kann die Frage aufwerfen: Was kaufe ich mir für all dasjenige, was da rein mathematisch ausersonnen worden ist? Es interessiert einen gar nicht das Gebiet, wo es vielleicht eine reale Anwendung findet. Wenn man alles das, was man da ausersonnen hat über nichteuklidische Geometrie, auf den Bau des menschlichen Organismus anwenden würde, dann würde man in der Wirklichkeit stehen und ungeheuer Bedeutsames auf die Wirklichkeit anwenden und nicht in wirklichkeitslosen Spekulationen sich ergehen. Wenn der Mathematiker entsprechend vorbereitet würde, damit ihn auch die Wirklichkeit interessierte, damit ihn interessierte, wie zum Beispiel das Herz ausschaut, so daß er eine Vorstellung darüber gewinnen kann, wie er durch mathematische Operationen den Herzorganismus umdrehen kann und wie dadurch die ganze menschliche Gestalt entstehen würde; wenn er eine Anleitung darüber bekäme, so zu mathematisieren, dann würde dieses Mathematisieren in der Wirklichkeit drinnenstehen. Dann würde das nicht mehr möglich sein, daß man auf der einen Seite den geschulten Mathematiker sitzen hat, den die anderen Dinge nicht interessieren, die der Mediziner lernt, und auf der anderen Seite den Mediziner, der nichts versteht davon, wie der Mathematiker Formen umwandelt, metamorphosiert, aber im rein abstrakten Elemente.

[ 17 ] Das ist dasjenige, über das wir hinauskommen müssen. Wenn wir nicht über dieses hinauskommen, so versumpfen unsere Wissenschaften. Sie gliedern sich immer mehr und mehr. Die Leute verstehen einander nicht mehr. Wie soll man denn die Wissenschaft überführen in sozialwissenschaftliche Betrachtungen, wie alles das, was ich Ihnen zeigen werde in diesen Vorträgen, fordert? Aber sie ist nicht da, diese Wissenschaft, die übergeführt werden könnte in eine Sozialwissenschaft.

[ 18 ] Nun, wir haben also auf der einen Seite die Astronomie, die immer mehr und mehr zu der mathematischen Vorstellungsweise hintendiert, und die in ihrer jetzigen Gestalt dadurch groß geworden ist, daß sie eben rein mathematisch-mechanische Wissenschaft ist. Wir haben aber auch einen anderen Pol zu dieser Astronomie, der ohne diese Astronomie seiner Wirklichkeit gemäß überhaupt nicht studiert werden kann unter den heutigen wissenschaftlichen Verhältnissen. Aber es ist gar nicht möglich, eine Brücke zu bauen zwischen der Astronomie und diesem anderen Pol unserer Wissenschaften. Dieser andere Pol ist nämlich die Embryologie. Und nur derjenige studiert die Wirklichkeit, der auf der einen Seite den Sternenhimmel studiert und auf der anderen Seite die Entwickelung namentlich des menschlichen Embryos studiert. Aber wie studiert man nun in der heute üblichen Weise den menschlichen Embryo? Nun, man sagt: Der menschliche Embryo entsteht durch das Zusammenwirken von zwei Zellen, den Geschlechtszellen, der männlichen und der weiblichen Zelle. Diese Zellen entwickeln sich in dem übrigen Organismus so, daß sie bis zu ihrer Zusammenwirkensmöglichkeit eine gewisse Selbständigkeit erreichen, daß sie dann einen gewissen Gegensatz darstellen, daß die eine Zelle in der anderen Zelle andere Entwickelungsmöglichkeiten hervorruft, als sie vorher hat. Es bezieht sich das auf die weibliche Keimzelle. Davon ausgehend studiert man die Zellenlehre überhaupt. Man frägt sich: Was ist eine Zelle? - Sie wissen ja, ungefähr seit dem ersten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts baut man die Biologie eigentlich auf die Zellenlehre auf. Man sagt sich: Eine solche Zelle besteht aus einem mehr oder weniger großen oder kleinen Kügelchen von Substanz, die aus Eiweißverbindungen besteht. Sie hat in sich einen Kern, der etwas andere Struktur aufweist, und um sich herum eine Membran, die zum Abschließen notwendig ist. Sie ist so der Baustein alles desjenigen, was als organisches Wesen entsteht. Solche Zellen sind ja auch die Geschlechtszellen, nur in verschiedener Weise gestaltet als weibliche und männliche Zellen. Und aus solchen Zellen baut sich ein jeder komplizierter Organismus auf.

[ 19 ] Ja nun, was meint man eigentlich, wenn man sagt: Aus solchen Zellen baut sich ein Organismus auf? Man meint: Das, was man sonst an Substanzen in der übrigen Natur hat, wird in diese Zellen aufgenommen und es wirkt nun nicht mehr unmittelbar wie sonst in der Natur. Wenn in diesen Zellen zum Beispiel Sauerstoff, Stickstoff oder Kohlenstoff enthalten ist, so wirkt dieser Kohlenstoff auf irgendeine andere Substanz außerhalb nicht so wie sonst, sondern es ist diese unmittelbare Wirkung ihm entzogen. Er ist aufgenommen in den Organismus der Zelle und kann nur so wirken, wie er eben in der Zelle wirken kann, er wirkt nicht unmittelbar, sondern die Zelle wirkt und sie bedient sich seiner besonderen Eigenschaften, indem sie ihn in einer gewissen Menge in sich eingegliedert hat. Was wir zum Beispiel im Menschen haben als Metall, als Eisen, das wirkt erst auf dem Umweg durch die Zelle. Die Zelle ist der Baustein. Nun geht man also zurück, indem man den Organismus studiert, auf die Zelle. Und wenn man zunächst nur die sogenannte Hauptmasse der Zelle betrachtet, außer dem Kern, außer der Membran, so kann man in ihr zwei voneinander zu unterscheidende Teile nachweisen. Man hat einen dünnflüssigen, durchsichtigen Teil, und man hat einen Teil, welcher eine Art Gerüst bildet. So daß man schematisch gezeichnet eine Zelle etwa so darstellen kann, daß man sagt, man habe das Zellengerüst und dann dieses Zellengerüst gewissermaßen eingebettet in derjenigen Substanz, die nicht in dieser Weise geformt ist wie das Zellengerüst selbst (Fig. 6). Also, die Zelle würde man sich aufgebaut zu denken haben aus einer dünnflüssig bleibenden Masse, die nicht in sich Form annimmt, und aus ihrem Gerüste, das in sich Form annimmt, das in der verschiedensten Weise gestaltet ist. Das studiert man nun. Man bekommt es mehr oder weniger fertig, so die Zelle studieren zu können: Gewisse Teile in ihr sind färbbar, andere sind nicht färbbar. Dadurch bekommt man durch Karmin oder Saftanin oder so etwas, was man anwendet, um die Zellen zu färben, eine überschaubare Gestalt der Zelle, so daß man also sich gewisse Vorstellungen bilden kann auch über das innere Gefüge der Zelle. Und man studiert das. Man studiert, wie sich dieses innere Gefüge ändert, während die weibliche Keimzelle zum Beispiel befruchtet wird. Man verfolgt die einzelnen Stadien, wie die Zelle sich in ihrer inneren Struktur ändert, wie sie sich dann teilt, wie sich der Teil, Zelle an Zelle, angliedert und aus der Zusammenfügung eine kompliziert aufgebaute Gestalt entsteht. Das studiert man. Aber es fällt einem nicht ein, sich zu fragen: Ja, womit hängt denn eigentlich dieses ganze Leben in der Zelle zusammen? Was liegt denn da eigentlich vor? - Es fällt einem nicht ein, das zu fragen.

[ 20 ] Was da vorliegt in der Zelle, das ist ja zunächst mehr abstrakt so zu fassen: Ich habe die Zelle. Nehmen wir sie zunächst in ihrer am häufigsten vorkommenden Form, in der kugeligen Form. Diese kugelige Form wird ja mitbedingt von der dünnflüssigen Substanz. Diese kugelige Form hat in sich eingeschlossen die Gerüstform. Und die kugelige Form, was ist sie? Die dünnflüssige Masse ist noch ganz sich selbst überlassen, sie folgt also denjenigen Impulsen, die um sie herum sind. Was tut sie? Ja - sie bildet das Weltenall nach! Sie hat deshalb ihre kugelige Form, weil sie den ganzen Kosmos, den wir uns auch zunächst ideell als eine Kugelform, als eine Sphäre vorstellen, weil sie den ganzen Kosmos in Kleinheit nachbildet. Jede Zelle in ihrer Kugelform ist nichts anderes als eine Nachbildung der Form des ganzen Kosmos. Und das Gerüst darin, jede Linie, die da im Gerüst gezogen ist, ist abhängig von den Strukturverhältnissen des ganzen Kosmos. - Wenn ich mich jetzt zunächst abstrakt ausdrücken soll: Nehmen Sie an, Sie haben die Weltensphäre, ideell begrenzt (Fig. 7). Darin meinetwillen haben Sie hier einen Planeten und hier einen Planeten (a, ai). Die wirken so, daß die Impulse, mit denen sie aufeinander wirken, in dieser Linie liegen. Hier (m) bildet sich, natürlich schematisch gezeichnet, eine Zelle, sagen wit. Ihre Umgrenzung bildet die Sphäre nach. Hier innerhalb ihres Gerüstes (Fig. 8) hat sie ein Festes, welches von der Wirkung dieses Planeten (a) auf diesen (a) abhängt. Nehmen Sie an, hier wäre eine andere Planetenkonstellation, die so aufeinander wirkt (b, b1). Hier wäre wiederum ein anderer Planet (c), der keinen Gegensatz hat. Der verrenkt diese ganze Sache, die sonst vielleicht rechtwinkelig stünde. Es entsteht die Bildung etwas anders. Sie haben in der Gerüststruktur eine Nachbildung der ganzen Verhältnisse im Planetensystem, überhaupt im Sternensystem. Sie können konkret hineingehen in den Aufbau der Zelle, und Sie bekommen eine Erklärung für diese konkrete Gestalt nur, wenn Sie in der Zelle sehen ein Abbild des ganzen Kosmos.

[ 21 ] Und nun nehmen Sie die weibliche Eizelle und stellen sich vor, diese weibliche Eizelle hat die kosmischen Kräfte zu einem gewissen inneren Gleichgewicht gebracht. Diese Kräfte haben Gerüstform angenommen und sind in der Gerüstform in einer gewissen Weise zur Ruhe gekommen, gestützt durch den weiblichen Organismus. Nun geschieht die Einwirkung der männlichen Geschlechtszelle. Die hat nicht den Makrokosmos in sich zur Ruhe gebracht, sondern sie wirkt im Sinne irgendwelcher Spezialkraft. Sagen wir, es wirkt die männliche Geschlechtszelle im Sinne gerade dieser Kraftlinie auf die weibliche Eizelle, die zur Ruhe gekommen ist, ein. Dann geschieht durch diese Spezialwirkung eine Unterbrechung der Ruheverhältnisse. Es wird gewissermaßen die Zelle, die ein Abbild ist des ganzen Makrokosmos, dazu veranlaßt, ihre ganze mikrokosmische Gestalt wiederum hineinzustellen in das Wechselspiel der Kräfte. In der weiblichen Eizelle ist zunächst in ruhiger Abbildung der ganze Makrokosmos zur Ruhe gekommen. Durch die männliche Geschlechtszelle wird die weibliche herausgerissen aus dieser Ruhe, wird wiederum in ein Spezialwirkungsgebiet hineingezogen, wird wiederum zur Bewegung gebracht, wird wiederum herausgezogen aus der Ruhe. Sie hat sich zur Nachbildung des Kosmos in die ruhige Form zusammengezogen, aber diese Nachbildung wird hineingezogen in die Bewegung durch die männlichen Kräfte, die Bewegungsnachbildungen sind. Es werden die weiblichen Kräfte, die Nachbildungen der Gestalt des Kosmos und zur Ruhe gekommen sind, aus der Ruhe, aus der Gleichgewichtslage gebracht.

[ 22 ] Da bekommen Sie Anschauungen über die Form und Gestaltung des Kleinsten, des Zellenhaften, von der Astronomie aus. Und Sie können gar nicht Embryologie studieren, ohne daß Sie Astronomie studieren. Denn das, was Ihnen die Embryologie zeigt, ist nur der andere Pol desjenigen, was Ihnen die Astronomie zeigt. Wir müssen gewissermaßen auf der einen Seite den Sternenhimmel verfolgen, wie er aufeinanderfolgende Stadien zeigt, und wir müssen nachher verfolgen, wie eine befruchtete Keimzelle sich entwickelt. Beides gehört zusammen, denn das eine ist nur das Abbild des anderen. Wenn Sie nichts von Astronomie verstehen, werden Sie niemals die Kräfte verstehen, die im Embryo wirken. Und wenn Sie nichts von Embryologie verstehen, so werden Sie niemals den Sinn verstehen von den Wirkungen, die dem Astronomischen zugrunde liegen. Denn diese Wirkungen zeigen sich im Kleinen in den Vorgängen der Embryologie.

[ 23 ] Es ist denkbar, daß man aufbaut eine Wissenschaft, daß man rechnet auf der einen Seite, daß man die astronomischen Vorgänge beschreibt, und auf der anderen Seite alles das beschreibt, was zu ihnen gehört in der Embryologie, denn es ist ja nur die andere Seite.

[ 24 ] Nun schauen Sie sich den heutigen Zustand an in den Wissenschaften. Da finden Sie: Die Embryologie wird als Embryologie studiert. Es würde als Wahnsinn aufgefaßt, wenn Sie einem heutigen Embryologen zumuten würden, er müsse Astronomie studieren, um die Erscheinungen seines Gebietes zu verstehen. Und doch ist es so. Das ist das, was notwendig macht eine vollständige Umgruppierung der Wissenschaften. Man wird kein Embryologe werden können, wenn man nicht Astronomie studiert hat. Man wird nicht Menschen ausbilden können, die bloß ihre Augen und ihre Teleskope auf die Sterne richten. Denn so die Sterne zu studieren, hat ja keinen weiteren Sinn, wenn man nicht weiß, daß aus der großen Welt nun wirklich die kleinste Welt hervorgebildet wird.

[ 25 ] Aber das alles, was ganz konkret ist, hat sich ja in der Wissenschaft in äußerste Abstraktionen verwandelt. Denken Sie, es gibt eine Wirklichkeit, wo man sagen kann: Man muß nach astronomischer Erkenntnis streben in der Zellenlehre, besonders in der Embryologie. Würde also Du Bois-Reymond gesagt haben: Man muß wirklich konkret Astronomie wiederum so für die Zellenlehre anwenden, dann hätte er aus der Wirklichkeit geschöpft. Er hat aber etwas verlangt, was keiner Wirklichkeit entspricht, was erdacht ist: Das Molekül; die Atome drinnen sollen astronomisch untersucht werden. Da soll das astronomische Mathematisieren, das hinzugefügt wurde zur Sternenwelt, wieder gesucht werden. Also, Sie sehen, auf der einen Seite liegt die Wirklichkeit: Die Bewegung, die Kraftwirkung der Sterne und die embryologische Entwickelung, worin nichts anderes lebt, als was in der Sternenwelt lebt. Da liegt die Wirklichkeit. Da müßte man sie suchen; auf der anderen Seite liegt die Abstraktion. Da rechnet der Mathematiker und Mechaniker die Bewegungen und Kraftwirkungen der Himmelskörper aus und erfindet die molekulare Struktur, auf die er seine astronomischen Erkenntnisse anwendet. Da hat er sich entfernt vom Leben, da lebt er in reinen Abstraktionen drinnen.