Third Scientific Lecture-Course:

Astronomy

GA 323

2 January 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture II

[ 1 ] Yesterday I showed a connection between two branches of science which according to our modern ideas are widely separated. I sought to show that the science of Astronomy should provide certain items of knowledge which must then be turned to account in quite a different branch of science, from which the study and method of Astronomy is completely excluded nowadays. In effect, I sought to show that Astronomy must be linked with Embryology. It is impossible to understand the phenomena of cell-development, especially of the sex-cells, without calling to our aid the realities of Astronomy, which lie apparently so far removed from Embryology.

[ 2 ] I pointed out that there must come about a regrouping of the sciences, for a man specializing nowadays along certain lines finds himself hemmed in by the circumscribed divisions of science. He has no possibility of applying his specialized knowledge and experience to spheres which may lie near to hand but which will only have been presented to him from certain aspects, insufficient to give him a deeper understanding of their full significance. If it is true, as will emerge in these lectures, that we can only understand the successive stages in human embryonic development when we understand their counterpart, the phenomena of the Heavens; if this is a fact—and it will turn out to be so—then we cannot work at Embryology without working at Astronomy. Nor can we occupy ourselves with Astronomy without bringing new light to the facts of Embryology. In Astronomy we are studying something which reveals its most important activity in the development of the human embryo. How, then, shall we explain the meaning and reason of astronomical facts, if we bring into the kind of connection with these facts the very realm in which this meaning and reason are revealed?

[ 3 ] You see how necessary it is to come to a reasonable world-conception, out of the chaos in which we are today in the sphere of science. If, however, one only accepts what is fashionable nowadays, it will be very difficult to grasp, even as a general idea, anything like what I said yesterday. For the evolution of our time has brought it about that astronomical facts are only grasped through mathematics and mechanics, while embryological facts are recorded in such a way that in dealing with them anything of the nature of mathematics or mechanics is discarded. At most, even if the mathematical-mechanical is brought into some kind of relation to Embryology, it is done in a quite an external way, without considering where lies the origin of what, in embryonic development, might truly be expressed in mathematical and mechanical terms.

[ 4 ] Now I need only point to a saying of Goethe's, uttered out of a certain feeling—a ‘feeling knowledge’ I might call it—but indicating something of extraordinary significance. (You can read of it in Goethe's “Spruche in Prosa”, and in the Commentary which I added to the publication in the Kurschner edition of the Deutsche National-Literatur, where I spoke in detail about this passage.) Goethe says there: People think of natural phenomena so entirely apart from man that they are tending ever more and more to disregard the human being in their study of the phenomena of Nature. He, on the contrary, believed that natural phenomena only reveal their true meaning if they are regarded in full connection with man—with the whole organization of man. In saying this, Goethe pointed to a method of research which is well-nigh anathematized nowadays. People today seek an 'objective' understanding of Nature through research that is completely separated from the human being. This is particularly noticeable in such a science as Astronomy, where no account at all is taken of the human being. On the contrary, people are proud that the apparently ‘objective’ facts have shown that man is only a grain of dust upon an Earth which has somehow been fused into a planet, moving first round the Sun and then, in some way or other, moving with the Sun in space. They are proud that one need pay no attention to this ‘grain of dust’ which wanders about on Earth,—that one need only pay attention to what is external to the human being in considering the great celestial phenomena.

Now the question is, whether any real results are to be obtained by such a method.

[ 5 ] I should like once more to call attention, my dear friends, to the path we must pursue in these lectures. What you will find as proof will only emerge in the further course of the lectures. Today we must take a good deal simply from observation in order to form certain preliminary ideas. We must first build up certain necessary concepts; only then shall we be able to pass on to the verification of these concepts.

[ 6 ] From what source, then, can we gain a real perception of the celestial phenomena merely through the mathematics which we apply to them? The course of development of human knowledge can disclose—if one does not take up the proud position of thinking how ‘wonderfully advanced’ we are today and how all that went before was childish—the course of human development can teach us how the prevailing points of view can change.

[ 7 ] From certain aspects one can have great reverence for the celestial observations carried out, for instance, by the ancient Chaldeans. The ancient Chaldeans made very exact observations concerning the connection of human time-reckoning with the heavenly phenomena. They had a highly develop ‘Calendar-Science’. Much that appears to us today as self-evident really dates back to the Chaldeans. Yet the Chaldeans were satisfied with a mathematical picture of the Heavens which portrayed the Earth more or less as a flat disc, with the hollow hemisphere of the heavenly vault arched above, the fixed stars fastened to it, and the planets moving over it. (Among the planets they also included the Sun.) They made their calculations with this picture in the background. Their calculations for the most part were correct, in spite of being based upon a picture which the science of today can only describe as a fundamental error, as something ‘childish’.

[ 8 ] Science, or more correctly, the scientific tendency and direction, then went on evolving. There was a stage when men pictured that the Earth stood still, but that Venus and Mercury moved round the Sun. The Sun formed the central point, as it were, for the motions of Venus and Mercury, while the other planets—Mars, Jupiter and Saturn—moved round the Earth. [ 9 ] Thereafter, men progressed to making Mars, Jupiter and Saturn also revolved around the Sun, but the Earth was still supposed to stand still, while the Sun with its encircling planets as well as the starry Heavens revolved round the Earth. This was still the fundamental view of Tycho Brahe, whereas his contemporary Copernicus established the other concept, namely, that the Sun was to be regarded as standing still and that the Earth was to be reckoned among the planets revolving round the Sun. Following hard one upon the other in the time of Copernicus were the two points of view, one which existed in ancient Egypt, of the stationary Earth with the other planets encircling the Sun, still represented by Tycho Brahe; the other, the Copernican concept, which broke radically with the idea of the center of coordinates being in the center of the Earth, and transferred it to the center of the Sun. For in reality the whole alteration made by Copernicus was nothing else than this,—the origin of coordinates was removed from the center of the Earth to the center of the Sun.

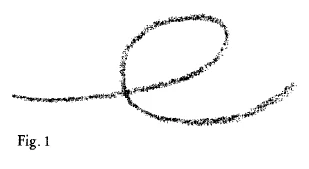

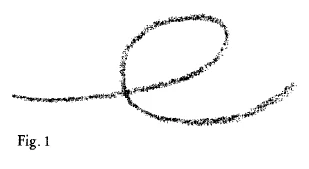

[ 10 ] What was actually the problem of Copernicus? His problem was, how to reduce to simple lines and curves these complicated apparent motions of the planets,—; for so they appear as observed from the Earth. When the planets are observed from the Earth, their movements can only be described as a variety of looped lines, such as these (Fig. 1). So, when taking the center of the Earth as the center of coordinates it is necessary to base the planetary movements on all sorts of complicated curves. Copernicus said, in effect: ‘as an experiment, I will place the center of the whole coordinate system in the center of the Sun.’ Then the complicated planetary curves are reduced to simple circular movements, or as was stated later, to ellipses. The whole thing was purely the construction of a world-system which aimed at being able to represent the paths of the planets in the simplest possible curves.

[ 11 ] Now today we have a very remarkable fact, my dear friends. This Copernican system, when employed purely mathematically, supplies the necessary calculations concerning the observed phenomena as well as and no better than any of the earlier ones. The eclipses of the Sun and Moon can be calculated with the ancient Chaldean system, with the Egyptian, with the Tychonian and with the Copernican. The outer occurrences in the Heavens, in so far as they relate to mechanics or mathematics, can thus be foretold. One system is as well suited as another. It is only that the simplest thought-pictures arise with the Copernican system. But the strange thing is that in practical Astronomy, calculations are not made with the Copernican system. Curiously enough, in practical Astronomy,—to obtain what is needed for the calendar,—the system of Tycho Brahe is used! This shows how little that is really fundamental, how little of the essential nature of things, comes into question when the Universe is thus pictured in purely mathematical curves or in terms of mechanical forces.

[ 12 ] Now there is another very remarkable fact which I will only indicate today, so that we shall understand each other about the aim of these lectures. I shall speak further about it in succeeding lectures. Copernicus in his deliberations bases his cosmic system upon three axioms. The first is that the Earth rotates on its own North-South axis in 24 hours. The second principle on which Copernicus bases his picture of the Heavens is that the Earth moves round the Sun. In its revolution round the Sun the Earth itself, of course, also revolves in a certain way. This rotation, however, does not occur round the North-South axis of the Earth, which always points to the North Pole, but round the axis of the Ecliptic, which, as we know, is at an angle with the Earth's own axis. Therefore the Earth goes through a rotation during a 24-hour day round its own N. S. Axis, and then, inasmuch as it performs approximately 365 such rotations in the year, there is added another rotation, an annual rotation, if we disregard the revolution round the Sun. The Earth, then, if it always rotates thus, and then again revolves round the Sun, behaves like the Moon as it rotates round the Earth, always turning the same side towards us. The Earth does this too, inasmuch as it revolves round the Sun, but not on the same axis as the one on which it rotates for the daily revolution. It revolves through this 'yearly day' on another axis; this is an added movement, besides the one taking place in the 24-hour day.

[ 13 ] Copernicus' third principle is that not only does such a revolution of the Earth take place round the North-South axis, but that there is yet a third revolution which appears as a retrograde movement of the North-South axis round the axis of the Ecliptic. Thereby, in a certain sense, the revolution round the axis of the Ecliptic is canceled out. By reason of this third revolution the Earth's axis continuously points to the North celestial Pole (the Pole-Star). Whereas, by virtue of revolving round the Sun, the Earth's axis would have to describe a circle, or an ellipse, round the pole of the Ecliptic, its own revolution, which takes the opposite direction (every time the Earth proceeds a little further its axis rotates backwards), causes it to point continually to the North Pole. Copernicus adopted this third principle, namely: The continued pointing of the Earth's axis to the Pole comes about because, by a rotation of its own—a kind of ‘inclination’ (?)—it cancels out the other revolution. This latter therefore has no effect in the course of the year, for it is constantly being annulled.

In modern Astronomy, founded as it is on the Copernican system, it has come about that the first two axioms are accepted and the third is ignored. This third axiom is lightly brushed aside by saying that the stars are so far away that the Earth-axis, remaining parallel to itself, always points practically to the same spot. Thus it is assumed that the North-South axis of the Earth, in its revolution, remains always parallel to itself. This was not assumed by Copernicus; on the contrary, he assumed a perpetual revolving of the Earth's axis. Modern Astronomy is therefore not really based on the Copernican system, but accepts the first two axioms because they are convenient and discards the third, thus becoming lost in the prevarication that it is not necessary to suppose that the Earth's axis itself must move in order to keep pointing to the same spot in the Heavens, but that the place itself is so far away that even if the axis does move parallel to itself it will still point to the same spot. Anyone can see that this is a prevarication. To-day therefore we have a ‘Copernican system’ from which a most important element has actually been discarded.

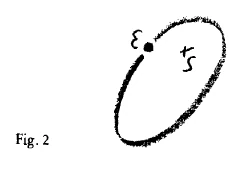

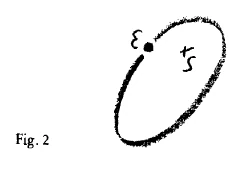

[ 14 ] The development of modern Astronomy is presented in such a way that no one notices that an important element is missing. Yet only in this way is it possible to describe it all so neatly: “Here is the Sun the Earth goes round in an ellipse with the Sun in one of the foci.” (Fig. 2)

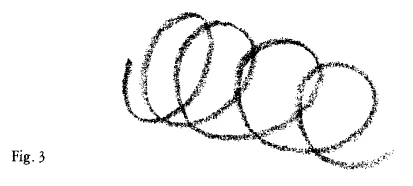

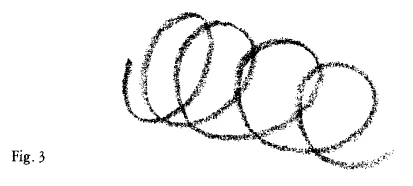

As time went on it became no longer possible to hold to the starting-point of the Copernican theory, namely that the Sun stands still. A movement is now attributed to the Sun, which is said to move forward with the whole ellipse, perpetually creating new ellipses, so to speak (Fig. 3). It became necessary to introduce the Sun's own movement, and this was done simply by adding something new to the picture they had before. A mathematical description is thus obtained which is admittedly convenient, but few questions are asked as to its possibility or its reality. It is only from the apparent movement of the stars that the Earth's movement is deduced by this method. As we shall presently see, it is of great significance whether or no one assumes a movement—which indeed must be assumed—namely the aforesaid ‘inclination’ (?) of the Earth's axis, perpetually annulling the annual rotation. Resultant movements, after all, are obtained by adding up the several movements. If one is left out, the whole is no longer true. Thus the whole theory that the Earth moves round the Sun in an ellipse comes into question.

[ 15 ] You see, purely from these historical facts, that burning questions exist in Astronomy today, though it is seemingly a most exact science because it is mathematical. The question arises: Why do we live in such uncertainty with regard to a real astronomical science? We must then ask further, turning the question in another direction: Can we reach any real certainty through a purely mathematical approach? Only think that in considering a thing mathematically we lift the observation out of the sphere of external reality. Mathematics is something that ascends from our inner being; in mathematics we lift ourselves out of external reality. It must therefore be understood from the outset that if we approach an external reality with a method of investigation that lifts itself out of reality, we can, in all probability, only arrive at something relative.

[ 16 ] To begin with, I am merely putting forward certain general considerations. We shall soon come to the realities. The point is that in regarding things purely from the mathematical standpoint, man does not put reality into his thought with sufficient energy, in order to approach the phenomena of the outer world rightly. This, indeed, demands that the celestial phenomena be brought nearer to man; they must not be regarded as quite apart from man, but must be brought into relationship with man. It was only one particular instance of this associating of the heavenly phenomena with the human being, when I said that we must see what takes place out there in the starry world in its reflection in the embryonic process. But let us look at the matter at first somewhat more generally. Let us ask whether we cannot perhaps find another approach to the celestial phenomena than the purely mathematical one.

[ 17 ] We can indeed bring the celestial phenomena, in their connection with earthly life, somewhat nearer to man in a purely qualitative way. We will not disdain to form a basis today with seemingly elementary ideas, these ideas being just the ones that are excluded from the foundations of modern Astronomy. We will ask the following question: How does man's life on Earth appear, in relation to Astronomy? We can regard the external phenomena surrounding man from three different points of view. We can regard them from the standpoint of what I will call the solar life, the life of the Sun; the lunar life; and the terrestrial, the tellurian life.

[ 18 ] Let us think first in quite a popular, even elementary way how these three domains play around man and upon him. Clearly there is something on the Earth which is in complete dependence upon the Sun-life, including also that aspect of the Sun's life which we shall have to look for in the Sun's movement or state of rest, and so on. We will leave aside the quantitative aspect and today merely consider the qualitative. Let us try to be clear as to how, for instance, the vegetation of any given region depends upon the solar life. Here we need only call to mind what is very well known with regard to vegetation, namely, the difference in the vegetation of spring, summer, autumn and winter; we shall be able to say that we see in the vegetation itself an imprint of the solar life. The Earth opens herself in a given region to what is outside her in heavenly space, and this reveals itself in the unfolding of vegetative life. If the Earth closes herself again to the solar life, the vegetation recedes.

[ 19 ] There is, however, an interplay of activity between the terrestrial or tellurian and the solar life. There is a difference in the solar life according to the variation of tellurian conditions. We must here bring together quite elementary facts and you will see how they lead us further. Take, for example, Egypt and Peru, two regions in the tropical zone.—Egypt, a low-lying plain, Peru a table land, and compare the vegetation. You will see how the tellurian element, simply the distance from the center of the Earth in this instance, plays its part in conjunction with the solar life. You only need study the vegetation over the earth, regarding the Earth, not as mere mineral but as incorporating plant-nature as well, and in the picture of vegetation you have a starting-point for an understanding of the connection of the earthly with the celestial. But we perceive the connection most particularly when we turn our attention to mankind.

[ 20 ] We have, in the first place, two opposites on the Earth: the Polar and the Tropical. The Polar and the tropical form a polarity, and the result of this polarity shows itself very clearly in human life.

Is it not so that life in the polar regions brings forth in man a condition of mind and spirit which is more or less a state of apathy: The sharp contrast of a long winter and a long summer which are almost like one long day and one long night, produces a certain apathy in man; it is as though the setting in which man lives makes him apathetic. In the Tropics, man also lives in a region which makes him apathetic. But the apathy of the polar region is based upon a sparse external vegetation—sparse and meager in a peculiar way even where it develops to some extent. The tropical apathy of man is caused by a rich, luxuriant vegetation. Putting together these two pictures of environment one can say that the apathy which affects man in polar regions is different from that affecting him in tropical regions. He is apathetic in both regions, but the apathy results from different causes. In the Temperate Zone lies the balance. Here the human capacities are developed in a certain equilibrium.

[ 21 ] No-one will doubt that this has something to do with the solar life. But what is the connection: (I will, as I said, first make a few remarks based on observation and in this way arrive at essential concepts.) Going to the root of things, we find that in the life around the Poles there is a very strong working-in of the Sun-forces upon man. In those regions the Earth tends to withdraw from the life of the Sun; she does not let her activity shoot upward from below into the vegetation. But the human being is exposed in these parts to the true Sun-life (you must not only look for the Sun-life in mere warmth). That this is so, the vegetation itself bears witness.

[ 22 ] We have, then, a preponderance of solar influence in the Polar zones. What kind of life predominates in the Tropical? There it is the tellurian, the Earth-life. This shoots up into the vegetation, making it rich and luxuriant. This also robs man of a balanced development of his capacities, but the causes in the North and in the Tropics come from different directions. In Polar regions the sunlight represses man's inner development. In the Tropics, what shoots up from the Earth represses his inner powers. We thus see a certain polarity, the polarity shown in the preponderance of the Sun-life around the Poles, and of the tellurian life in tropical regions—; in the neighborhood of the Equator.

[ 23 ] If we then observe man and have in mind the human form, we can say the following. (Please do not object at once if it seems paradoxical, but wait a little. We shall be taking the human form seriously.) The head, the part of the human form which in its outer configuration copies universal space,—namely the sphere, the spherical shape of the Universe as a whole—the head is exposed by life in polar regions to what comes from the Cosmos outside the Earth. In the Tropics, the metabolic system in its connection with the limbs is exposed to the Earth-life as such.

We come to a special relationship, you see, of the human head to the cosmic life outside the Earth and of the human metabolic and limb-system to the Earth-life. Man is so placed in the Universe as to be more co-ordinated with the cosmic surroundings of the Earth in his head, his nerve-senses system, and with the Earth-life in his metabolic system. And in the temperate zones we shall have to look for a kind of perpetual harmonizing between the head-system and the metabolic system. In the temperate zones there is a primary development of the rhythmic system in man.

[ 24 ] You see then that there exists a certain connection between this threefold membering of man—nerves-and-senses system, rhythmic system, metabolic system—and the outer world. The head-system is more related to the whole Cosmos, the rhythmic system is the balance between the Cosmos and the earthly world, and the metabolic system is related to the earth itself. [ 25 ] Then we must take up another indication, which points to a working of the solar life upon mankind in a different direction.

The connection of the solar life with the life of man which we have just been considering can only be related to the interplay of the earthly and extra-earthly life in the course of the year. But as a matter of fact, in the course of the day we are also concerned with a kind of repetition, even as in the yearly course. The yearly course is determined by the relation of the Sun to the Earth, and so is the daily course. In the language of purely mathematical astronomy we speak of the daily rotation of the Earth on its axis, and of the revolution of the Earth round the Sun in the course of the year. But we are then confining ourselves to very simple aspects. We have then no justification for assuming that we are really starting from adequate premisses, giving an adequate basis for our investigations. Let us call to mind all that we have considered with regard to the yearly course. I will not say ‘the revolution of the Earth round the Sun’, but the course of the year with its alternating conditions. This must have a connection with the three-fold being of man. Since through the earthly conditions it finds different expression in the Tropics, in the Temperate Zones and at the Poles, this yearly course must be connected in some way with the whole formation of man—with the relations of the three members of the threefold man. When we bring this into consideration, we acquire a wider basis from which to proceed and can perhaps arrive at something quite different from what we reach when we merely measure the angles which one telescopic direction makes with another. It is a matter of finding broader foundations in order to be able to judge the facts.

[ 26 ] Speaking of the daily course, we speak in the astronomical sense of the rotation of the Earth on its axis. But something rather different is here revealed. There is revealed a far-reaching independence of man upon this daily course. The dependence of man on the yearly rhythm, namely on what is connected with the yearly course, the shaping of the human form in the various regions of the Earth, shows us a very great dependence of man on the solar life,—on the changes that appear on Earth in consequence of the solar life. The daily course shows it far less. True, very much of interest will also be revealed in connection with the daily course, but as regards the life of mankind as a whole it is relatively insignificant. [ 27 ] The differences appear in individual human beings. Goethe, who can be regarded in a certain respect as a normal type of man, felt himself best attuned to production in the morning; Schiller at night. This points to the fact that the daily rhythm has a definite influence upon certain subtler parts of human nature. A man who has a feeling for such things, will tell us that he has met many persons in his life who have confided to him that their really important thoughts were worked out in the dusk, that is, in the temperate period of the day-to-day rhythm, not at midday nor at midnight, but in the temperate time of the day. It is however, a fact that man is in a way independent of the daily course of the Sun. We have still to go into the significance of this independence and to show in what way a certain dependence does nevertheless exist.

[ 28 ] A second element is the lunar life, the life that is connected with the Moon. It may be that a great deal of what has been said on this subject in the course of human evolution appears today as mere fantastic nonsense. But in one way or another we see that the Earth-life as such, for example in the phenomena of tidal ebb and flow, is connected quite evidently with the movement of the Moon. Nor must it be overlooked that the female functions, although they do not coincide in time with the Moon's phases, coincide with them in their periodicity, and that therefore something essentially concerned with human evolution is shown to be dependent in time and duration upon the phases of the Moon. It is as though this process of the female function were lifted out of the general course of Nature, but has remained a true image of Nature's process; it is accomplished in the same period of time as the corresponding natural phenomenon.

[ 29 ] Just as little must it be overlooked—only people do not make rational, exact observations of these things if they turn aside from them at the very outset—just as little must it be overlooked that as a matter of fact, man's life of fancy and imagination is extraordinarily bound up with the phases of the Moon. If anyone were to keep a calendar-record of the upward and downward flow of his life of imagination, he would notice how much it had to do with the Moon's phases. The fact that the Moon-life, the lunar life, has an influence upon certain lower organs should he studied in the phenomenon of the sleep-walker. In the sleep-walker, interesting phenomena can be studied; phenomena which are overlaid by normal human life, but are present in the depths of human nature and point in their totality to the fact that the lunar life is just as much connected with the rhythmic system of man as is the solar life with his nerves-and-senses system.

[ 30 ] This gives a sort of crossing of influences. We have seen how the solar life, in its interplay with the forces of the Earth, works on the rhythmic system in the temperate zones. Crossing this influence, we now have the direct influence of the lunar life upon the rhythmic system.

[ 31 ] When we now look at the tellurian, the Earth-life as such, we must not disregard a domain in which the earthly influence makes itself felt; though, to be sure, this is not ordinarily taken into account. I ask you to turn your attention to such as phenomenon as home-sickness. It is difficult to from any clear ideas about home-sickness. It can no doubt be explained from the point of view of habit, custom, and so on. But I ask you to note that real physiological effects can be produced entirely as a result of this so-called home-sickness. Home-sickness can go so far as to make a man ill. It can express itself in such phenomena as asthma. Study the complex of the phenomena of home-sickness with its consequences, asthmatic conditions and general ill-health, a kind of emaciation, and it is possible to come to the following conclusion. One comes to see that ultimately the feeling of home-sickness results from an alteration of the metabolism—the whole metabolic system. Home-sickness is the reflection in consciousness of changes in the metabolism—changes entirely due to the man's removal from one place, with its tellurian influences from below, to another place, with different influences coming from below. Please take this in connection with other things which, unfortunately, Science as a rule leaves unconsidered.

Goethe, I said, felt most inspired to poetry, to the writing of his works in the morning. If he needed a stimulant however, he took that stimulant which in its nature takes least hold of the metabolic system, but only stirs it up via the rhythmic system, namely wine. Goethe took wine as a stimulant. In this respect he was, indeed, altogether a Sun-man; he let the influence of the solar life work upon him. With Schiller or Byron this was reversed. Schiller preferred to write his poetry when the Sun has set, that is to say when the solar life was hardly active any more. And he stimulated himself with something which takes thorough hold of the metabolic system—with hot punch. The effect was quite different from that obtained by Goethe from wine. It worked into the whole metabolism. Through the metabolism the Earth works upon man; so we can say that Schiller was essentially tellurian—an Earth-man. Earth-men work more through the emotions and what belongs to the will; the Sun-man works rather through calm and contemplation. For those persons, therefore, who could not endure the solar element, but only liked the tellurian, only what is of the Earth Goethe increasingly became “the cold literary Greybeard” as they called him in Weimar—“the cold, literary greybeard with the double chin.” That was the name which was so often given to Goethe in Weimar in the 19th century.

[ 32 ] Now I should like to bring something rather different to your notice. We have observed how man is set into the universal connections of Earth, Sun, Moon: the Sun working more on the nerves-and-senses system; the Moon working more on the rhythmic system; the Earth, inasmuch as she gives man of her substance as nourishment and makes substance directly active in him, working upon the metabolic system, working tellurically. We see something in man through which we can perhaps find starting-point for an explanation of the Heavens as they exist outside man, upon broader foundations than merely through the measurement of angles by the telescope and so on.

This is especially so if we go yet further, if we now consider Nature outside of man,—but consider it so as to see more in it than a mere register of external data. Look at the metamorphosis of insects. In the course of the year it is a complete reflection of the external solar life. I would say that with man we must make our researches more in the inner being in order to follow what is solar, lunar and tellurain in him, whereas in the insect-life with its metamorphoses, we see the direct course of the year expressed in the successive forms the insect assumes. We can now say to ourselves: Maybe we have not to only proceed quantitatively, but should also take into account the qualitative impression which such phenomena make upon us Why always merely ask what a phenomenon of the outer Universe looks like in the objective of the telescope? Why not ask what relation is given, not merely by the objective of the telescope, but by the insect? How does human nature react? Is anything revealed to us through human nature regarding the celestial phenomena? Are we not led in this way to broader foundations, making it impossible that on the one hand, theoretically, we should be Copernicans when desiring to explain the world philosophically, while on the other we use Tychonic System as our basis for calculating the calendar etc., as practical Astronomy still does to this day. Or that we are Copernicans, but set aside the most important part of his theory, namely his third axiom Can we not overcome the uncertainties which create burning problems even in the most fundamental realms of Astronomy today, by working on a broader basis—working in this sphere too from the quantitative to the qualitative?

[ 33 ] Yesterday I sought to point out the connection of the celestial with the embryonic phenomena; today, the connection with fully developed man. Here you have an indication towards a necessary regrouping of the sciences. Now take another thing to which I have also referred to in the course of today's remarks. I indicated the connection of human metabolism with the Earth-life. In man we have the faculties of sense-perception mediated through the nerves-and-senses system, connected as a whole with the solar and cosmic life. We have the rhythmic system connected with what lies between Heaven and Earth. We have the metabolism related especially to the Earth, so that in contemplating metabolic man we should be able to get nearer to the real essence of the tellurian. But what do we do today if we want to approach the tellurian realm? We behave as we habitually do, and investigate things from the outside. But things have an inner side also! Will they perhaps only show it in its true form when they pass through the human being?

[ 34 ] It has become an ideal nowadays to regard the relationship of substances quite apart from man and to rest there; to observe by experimentation in chemical laboratories the reciprocal actions of substances in order to arrive at their nature. But if the substances only disclosed their nature within the human being, then we should have to practice Chemistry in such a way as to reach man. Then we should have to form a connection between true Chemistry and the processes undergone by matter within man, just as we see a connection between Astronomy and Embryology, or between Astronomy and the whole human form—the threefold being of man. Thus do the things work into one another. We only come to real life when we perceive them in their interpenetration.

[ 35 ] On the other hand, inasmuch as the Earth is poised in cosmic space, we shall have to see the connection between the tellurian and the starry realm.

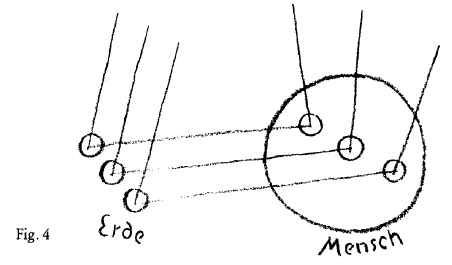

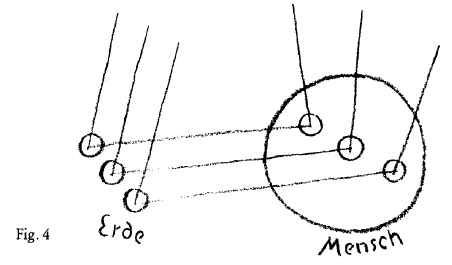

Now we have seen a connection between Astronomy and the substances of Earth; also between the Earth and human metabolism; and again a direct influence of the solar and celestial events upon man himself. In man we have a kind of meeting of what comes directly from the Heavens and what comes via earthly substance. Earthly substances work on the human metabolism, while the celestial influences work directly upon man as a whole. In man there meet the direct influences for which we are indebted to the solar life, and those influences which, passing indirectly through the Earth, have undergone a change by reason of the Earth. Thus we can say: The interior of the human being will become explicable even in a physical, anatomical sense as a resultant of cosmic influences coming directly from the Universe outside the Earth, and cosmic influences which have first passed through the earthly process. These flow together in man (Fig. 4).

[ 36 ] You see how, contemplating man in his totality, the whole Universe comes together. For a true knowledge of man, it is essential to perceive this.

What then has come about by scientific specialization? It has led us away from reality into a purely abstract sphere. In spite of its ‘exactness’, Astronomy—to calculate the calendar—cannot help using in practice something other than it stands for in theory. And then again, Copernican though it is in theory, it discards what was of great importance to Copernicus, namely the third axiom. Uncertainty creeps in at every point. These modern lines of research do not lead to what matters most of all,—to perceive how Man is formed from the entire Universe.

Zweiter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Ich habe gestern zwei nach unseren gegenwärtigen Anschauungen zunächst scheinbar weit auseinanderliegende Wissenschaftszweige in einer Art von Verbindung gezeigt. Ich versuchte nämlich zu zeigen, daß die Wissenschaft der Astronomie uns gewisse Erkenntnisse geben soll, welche verwertet werden müssen in einem ganz anderen Wissenschaftszweige, von dem man heute eine solche Betrachtung, die sich auf astronomische Tatsachen bezieht, gänzlich ausschließt; daß, mit anderen Worten, die Astronomie verbunden werden muß mit der Embryologie; daß man die Erscheinungen der Entwickelung der Zelle, insbesondere der Geschlechtszelle, nicht verstehen kann, ohne zu Hilfe zu rufen die scheinbar von der Embryologie so entfernt liegenden Tatsachen der Astronomie.

[ 2 ] Ich habe darauf hingewiesen, wie eine wirkliche Umgruppierung innerhalb unseres wissenschaftlichen Lebens wird eintreten müssen, weil man heute ja vor der Tatsache steht, daß einfach der Mensch, der einen gewissen Bildungsgang durchmacht, sich nur hineinfindet in die heutigen abgezirkelten Wissenschaftskategorien und dann nicht die Möglichkeit hat, dasjenige, was nur so behandelt wird in abgezirkelten Wissenschaftskategorien, anzuwenden auf Gebiete, die der Sache nach naheliegen, die er aber eigentlich nur nach Gesichtspunkten kennenlernt, nach denen sie nicht ihr volles Antlitz zeigen. Wenn es einfach, wie im Verlauf dieser Vorträge sich zeigen wird, wahr ist, daß wir die aufeinanderfolgenden Stadien der embryonalen Entwickelung des Menschen nur verstehen können, wenn wir ihr Gegenbild verstehen, die Erscheinungen des Himmels; wenn das wahr ist - und es wird sich eben zeigen, daß das wahr ist -, dann können wir nicht Embryologie treiben, ohne Astronomie zu treiben. Und wir können auf der anderen Seite nicht Astronomie treiben, ohne gewisse Ausblicke zu schaffen in die embryologischen Tatsachen. Wir studieren mit der Astronomie ja dann etwas, was eigentlich seine bedeutsamste Wirkung zeigt bei der Entwickelung des menschlichen Embryos. Und wie sollen wir uns denn über Sinn und Vernünftigkeit der astronomischen Tatsachen aufklären, wenn wir dasjenige, worin sie gerade diesen Sinn und diese Vernünftigkeit zeigen, in gar keinen Zusammenhang mit ihnen bringen?

[ 3 ] Sie sehen, wieviel heute notwendig ist, um zu einer vernünftigen Weltanschauung zu kommen heraus aus dem Chaos, in dem wir gerade im wissenschaftlichen Leben drinnen stecken. Wenn man aber nur dasjenige nimmt, was heute gang und gäbe ist, so wird es einem außerordentlich schwer, zunächst auch nur in einem allgemeinen Gedanken so etwas zu fassen, wie ich gestern charakterisiert habe. Denn es hat eben die Zeitentwickelung mit sich gebracht, daß man die astronomischen Tatsachen nur mit Mathematik und Mechanik erfaßt und daß man die embryologischen Tatsachen in einer solchen Weise registriert, daß man bei ihnen gänzlich absieht von alledem, was mathematisch-mechanisch ist, oder höchstens, wenn man das Mathematisch-Mechanische in irgendeine Beziehung zu ihnen bringt, dies in einer ganz äußerlichen Weise tut, ohne darauf Rücksicht zu nehmen, wo der Ursprung desjenigen ist, was sich auch als Mathematisch-Mechanisches ausdrücken könnte in der embryologischen Entwickelung.

[ 4 ] Nun braucht man nur auf ein Diktum hinzuweisen, das Goethe aus einer gewissen Empfindung, Erkenntnisempfindung möchte ich es nennen, heraus gesprochen hat, das aber im Grunde doch auf etwas außerordentlich Bedeutsames hinweist. Sie können darüber nachlesen in Goethes «Sprüchen in Prosa» und in dem Kommentare, den ich dazugefügt habe in der Ausgabe in der «Deutschen NationalLitteratur», wo ich über diese Stelle ausführlich spreche. Goethe sagt da, daß man die Naturerscheinungen so abgesondert vom Menschen betrachtet, daß man immer mehr und mehr bestrebt ist, die Naturerscheinungen nur so zu betrachten, daß man auf den Menschen gar keine Rücksicht nimmt. Er glaubte dagegen, daß die Naturerscheinungen ihre wahre Bedeutung erst dann zeigen, wenn man sie durchwegs im Zusammenhang mit dem Menschen, mit der ganzen menschlichen Organisation ins Auge faßt. Damit hat Goethe hingewiesen auf eine Forschungsart, die heute im Grunde genommen verpönt ist. Man möchte heute zur Objektivität dadurch kommen, daß man über die Natur ganz in Absonderung vom Menschen forscht. Nun zeigt sich ja das ganz besonders bei solchen Wissenschaftszweigen, wie die Astronomie einer ist. Da nimmt man ja heute schon gar nicht mehr irgendwie Rücksicht auf den Menschen, Man ist im Gegenteil stolz darauf geworden, daß die scheinbar objektiven Tatsachen das Resultat zutage gefördert haben, daß der Mensch nur solch ein Staubpunkt ist auf der zum Planeten zusammengeschmolzenen Erde, welche sich im Raume, zunächst um die Sonne, dann mit der Sonne oder sonst im Raume bewegt; daß man keine Rücksicht zu nehmen braucht auf diesen Staubpunkt, der da auf der Erde herumwandelt; daß man nur Rücksicht zu nehmen braucht auf das, was außermenschlich ist, wenn man vor allen Dingen die großen Himmelserscheinungen ins Auge faßt. Nur frägt es sich, ob denn wirklich auf eine solche Weise reale Resultate zu gewinnen sind.

[ 5 ] Ich möchte noch einmal aufmerksam darauf machen, wie der Gang der Betrachtung gerade in diesen Vorträgen sein muß: Dasjenige, was Sie als Beweise empfinden werden, wird sich erst im Laufe der Vorträge ergeben. Es muß manches heute aus der Anschauung herausgeholt werden, um zunächst gewisse Begriffe zu bilden. Wir werden zunächst gewisse Begriffe bilden müssen, die wir erst haben müssen, und dann werden wir zum Verifizieren dieser Begriffe schreiten können.

[ 6 ] Woher können wir denn überhaupt etwas Reales über die Himmelserscheinungen gewinnen? Diese Frage muß uns vor allen Dingen beschäftigen. Können wir dutch die bloße Mathematik, die wir anwenden auf die Himmelserscheinungen, über dieselben irgend etwas gewinnen? Der Gang der menschlichen Erkenntnisentwickelung kann schon enthüllen - wenn man nicht gerade auf dem Hochmutsstandpunkt steht, daß wir es heute «ganz herrlich weit gebracht» haben und alles übrige, was vorher gelegen hat, kindisch war —, wie die Gesichtspunkte sich verschieben können.

[ 7 ] Sehen Sie, man kommt von gewissen Ausgangspunkten aus zu einer großen Verehrung desjenigen, was für die Himmelsbeobachtung geleistet haben zum Beispiel die alten Chaldäer. Die alten Chaldäer haben außerordentlich genaue Beobachtungen über den Zusammenhang der menschlichen Zeitrechnung mit den Himmelserscheinungen gehabt. Sie haben eine außerordentlich bedeutsame Kalenderwissenschaft gehabt. Und vieles, was heute uns wie eine selbstverständliche Handhabung der Wissenschaft erscheint, führt eigentlich in seinen Anfängen auf die Chaldäer zurück. Und dennoch waren die Chaldäer zufrieden damit, sich das mathematische Bild des Himmels so vorzustellen, daß die Erde eine Art von flacher Scheibe wäre, über die sich hinübergewölbt hat die halbe Hohlkugel des Himmelsgewölbes, an der die Fixsterne angeheftet waren, gegenüber welcher sich die Planeten bewegt haben - zu den Planeten haben sie auch die Sonne gerechnet. Sie haben ihre Rechnungen angestellt, indem sie dieses Bild zugrunde gelegt haben, und sie haben in hohem Maße richtige Berechnungen gemacht trotz der Zugrundelegung dieses Bildes, das selbstverständlich die heutige Wissenschaft als einen Grundirrtum, als etwas Kindliches bezeichnen kann.

[ 8 ] Die Wissenschaft, oder besser gesagt die Wissenschaftstichtung, ist dann fortgeschritten. Wir können auf eine Etappe hinweisen, in welcher man sich vorgestellt hat, daß die Erde zwar stillsteht, daß aber Venus und Merkur sich um die Sonne bewegen, daß also gewissermaßen die Sonne den Mittelpunkt abgibt für die Bewegung von Venus und Merkur, die anderen Planeten, Mars, Jupiter und Saturn, sich aber noch um die Erde bewegen, nicht um die Sonne, der Fixsternhimmel wiederum sich um die Erde bewegt.

[ 9 ] Wir finden dann, wie fortgeschritten wird dazu, daß man nun auch um die Sonne sich herumbewegen ließ den Mars, den Jupiter, den Saturn, daß man aber immer noch die Erde stille stehen ließ und nun die Sonne mit den sich um sie herumbewegenden Planeten um die Erde herum sich bewegen ließ und den Sternenhimmel dazu. Im Grunde genommen war das noch die Ansicht des Tycho de Brahe, während sein Zeitgenosse Kopernikus dann die andere Auffassung geltend gemacht hat, daß die Sonne als stillstehend anzusehen wäre, die Erde zu den Planeten hinzuzurechnen sei und sich mit den Planeten um die Sonne herumbewege. Hart aneinander stoßen in der Zeit des Kopernikus eine Anschauung, die schon im alten Ägypten da war, von der stillstehenden Erde, von den um die Sonne sich bewegenden anderen Planeten, die noch Tycho de Brahe vertrat, und die Anschauung des Kopernikus, die radikal brach mit dem Annehmen des Koordinatenmittelpunktes im Mittelpunkt der Erde, die den Koordinatenmittelpunkt einfach in den Mittelpunkt der Sonne verlegte. Denn im Grunde genommen war das ganze Umändern des Kopernikus nichts anderes als dieses, daß der Koordinatenmittelpunkt verlegt worden ist von dem Mittelpunkt der Erde in den Mittelpunkt der Sonne.

[ 10 ] Welches war denn eigentlich die Frage des Kopernikus? - Die Frage des Kopernikus war: Wie kommt man dazu, diese kompliziert erscheinende Planetenbewegung - denn so erscheint sie von der Erde aus beobachtet — auf einfachere Linien zurückzuführen? Wenn man von der Erde aus die Planeten betrachtet, muß man allerlei Schleifenlinien ihren Bewegungen zugrunde legen, etwa solche Linien (Fig. 1). Wenn man also den Mittelpunkt der Erde als Koordinatenmittelpunkt ansieht, hat man nötig, außerordentlich komplizierte Bewegungskurven den Planeten zugrunde zu legen. Kopernikus sagte sich etwa: Ich verlege einmal zunächst probeweise den Mittelpunkt des ganzen Koordinatensystems in den Mittelpunkt der Sonne, dann reduzieren sich die komplizierten PlanetenbewegungsKurven auf einfache Kreisbewegungen oder, wie später gesagt worden ist, auf Ellipsenbewegungen. Es war das Ganze nur ein Konstruieren eines Weltensystems mit dem Zwecke, die Planetenbahnen in möglichst einfachen Kurven darstellen zu können.

[ 11 ] Nun, heute liegt ja eine sehr merkwürdige Tatsache vor. Dieses kopernikanische System, das läßt natürlich, wenn man es anwendet als rein mathematisches System, die Berechnungen, die man braucht, ebensogut auf die Wirklichkeit anwenden wie irgendein anderes früheres. Man kann mit dem alten chaldäischen, mit dem ägyptischen, mit dem tychonischen, mit dem kopernikanischen System Mond- und Sonnenfinsternisse berechnen. Man kann also die äußeren auf Mechanik, auf Mathematik beruhenden Vorgänge am Himmel voraussagen. Das eine System eignet sich dazu ebensogut wie das andere. Es kommt nur darauf an, daß man gewissermaßen mit dem kopernikanischen System die einfachsten Vorstellungen verbinden kann. Nur liegt das Eigentümliche vor, daß eigentlich in der praktischen Astronomie »1cht mit dem kopernikanischen System gerechnet wird. Kurioserweise wendet man, um die Dinge herauszubekommen, die man zum Beispiel in der Kalenderwissenschaft braucht, das tychonische System an! So daß man eigentlich heute folgendes hat: Man rechnet nach dem tychonischen System, richtig ist das kopernikanische System. Aber gerade daraus zeigt sich ja, wie wenig ganz Prinzipielles, wie wenig Wesenhaftes eigentlich bei diesen Darstellungen in rein mathematischen Linien und mit der Zugrundelegung mechanischer Kräfte in Betracht gezogen wird.

[ 12 ] Nun liegt noch etwas anderes, sehr Merkwürdiges vor, das ich heute zunächst nur andeuten will, damit wir, möchte ich sagen, über das Ziel unserer Vorträge uns verständigen, über das ich schon in den nächsten Vorträgen sprechen will. Es liegt das Merkwürdige vor, daß nun Kopernikus aus seinen Erwägungen heraus drei Hauptsätze seinem Weltensystem zugrunde legt. Der eine Hauptsatz ist der, daß sich die Erde in 24 Stunden um die eigene Nord-Süd-Achse dreht. Das zweite Prinzip, das Kopernikus seinem Himmelsbilde zugrunde legt, ist dieses, daß die Erde sich um die Sonne herum bewegt, daß also eine Revolution der Erde um die Sonne vorhanden ist, daß dabei natürlich sich die Erde auch in einer gewissen Weise dreht. Diese Drehung geschieht aber nicht um die Nord-Süd-Achse der Erde, die immer nach dem Nordpol hinweist, sondern um die Ekliptikachse, die ja einen Winkel bildet mit der eigentlichen Erdachse. So daß also gewissermaßen die Erde eine Drehung erfährt während eines vierundzwanzigstündigen Tages um ihre Nord-Süd-Achse, und dann, indem sie ungefähr 365 solcher Drehungen im Jahre ausführt, kommt noch dazu eine andere Drehung, eine Jahresdrehung, wenn wir absehen von der Bewegung um die Sonne. Nicht wahr, wenn sie sich immer so umdreht und sich noch einmal um die Sonne dreht, ist das so, wie sich der Mond um die Erde dreht, der dieselbe Fläche uns immer zuwendet. Das tut die Erde auch, indem sie sich um die Sonne dreht, aber nicht um dieselbe Achse, um die sie sich dreht, indem sie die tägliche Achsendrehung ausführt. Sie dreht sich also gewissermaßen in diesem Jahrestag, der zu den Tagen hinzukommt, die nur 24 Stunden lang sind, um eine andere Achse.

[ 13 ] Das dritte Prinzip, das Kopernikus geltend macht, ist dieses, daß nun nicht nur eine solche Drehung zustande kommt der Erde um die Nord-Süd-Achse und eine zweite um die Ekliptikachse, sondern daß noch eine dritte Drehung stattfindet, welche sich darstellt als eine rückläufige Bewegung der Nord-Süd-Achse um die Ekliptikachse selber. Dadurch wird in einem gewissen Sinne die Drehung um die Ekliptikachse wiederum aufgehoben. Dadurch weist die Erdachse stets auf den Nordpol (den Polarstern) hin. Während sie sonst, indem sie um die Sonne herumgeht, eigentlich einen Kreis beziehungsweise eine Ellipse beschreiben müßte um den Ekliptikpol, weist sie dutch ihre eigene Drehung, die im entgegengesetzten Sinne erfolgt - jedesmal, wenn die Erde ein Stück weiter rückt, dreht sich die Erdachse zurück -, immerfort auf den Nordpol hin. Kopernikus hat dieses dritte Prinzip angenommen, daß das Hinweisen auf den Nordpol dadurch geschieht, daß die Erdachse selber durch eine Drehung in sich, eine Art Inklination, fortwährend die andere Drehung aufhebt. So daß diese eigentlich im Laufe des Jahres nichts bedeutet, indem sie fortwährend aufgehoben wird. In der neueren Astronomie, die auf Kopernikus aufgebaut hat, ist das Eigentümliche eingetreten, daß man die zwei ersten Hauptsätze gelten läßt und den dritten ignoriert und sich über dieses Ignorieren des dritten Satzes in einer Art, ich möchte sagen, mit leichter Hand hinwegsetzt, indem man sagt: Die Sterne sind so weit weg, daß eben die Erdachse, auch wenn sie immerfort parallel bleibt, nach demselben Punkte immer zeigt. - So daß man also sagt: Die Nord-Süd-Erdachse bleibt bei dieser Drehung um die Sonne immer zu sich parallel. - Das hat Kopernikus nicht angenommen, sondern er hat eine fortwährende Drehung der Erdachse angenommen. Man steht also nicht auf dem Standpunkte des kopernikanischen Systems, sondern man hat, weil es einem bequem war, die zwei ersten Hauptsätze des Kopernikus genommen, den dritten weggelassen und sich in das Geflunker verloren, daß man das nicht anzunehmen brauche, daß die Erdachse sich bewegen müßte, um nach demselben Punkte zu zeigen, sondern der Punkt sei so weit weg, daß, wenn die Achse sich auch vorwärtsschiebt, sie doch auf denselben Punkt zeigt. Jeder wird einsehen, daß das einfach ein Geflunker ist. So daß wir also heute ein kopernikanisches System haben, das eigentlich ein ganz wichtiges Element wegläßt.

[ 14 ] Man stellt die Geschichte der modernen Astronomie-Entwickelung durchaus so dar, daß kein Mensch diese Tatsache bemerkt, daß man eine wichtige Sache wegläßt. Nur dadurch aber ist man überhaupt imstande, noch immer die Geschichte so schön zu zeichnen, daß man sagt: Hier die Sonne, die Erde geht herum in einer Ellipse, in deren einem Brennpunkt die Sonne steht (Fig. 2). Und nun ist man ja nicht mehr in der Lage gewesen, bei dem kopernikanischen Ausgangspunkt stehen zu bleiben, daß die Sonne stillstehe. Man gibt der Sonne eine Bewegung, aber man bleibt dabei, daß die Sonne fortrückt mit der ganzen Ellipse, daß irgend etwas entsteht, immer neue Ellipsen (Fig. 3). Man fügt einfach, indem man genötigt ist, die Sonnenbewegung einzuführen, zu dem, was man schon hat, ein Neues hinzu, und man bekommt dann auch eben eine mathematische Beschreibung heraus, die ja allerdings bequem ist, bei der man aber nach den Wirklichkeits-Möglichkeiten, nach den Wirklichkeiten wenig frägt. Wir werden sehen, daß man nach dieser Methode nur nach der Stellung der Sterne, der scheinbaren Stellung der Sterne, bestimmen kann, wie die Erde sich bewegt, und daß es eine große Bedeutung hat, ob man eine Bewegung, die man notwendig annehmen muß, nämlich die Inklination der Erdachse, die fortwährend die jährliche Drehung aufhebt, annimmt oder nicht. Denn man bekommt ja doch resultierende Bewegungen heraus, indem man sie zusammensetzt aus den einzelnen Bewegungen. Läßt man eine weg, so ist es schon zusammen nicht mehr richtig. Daher ist die ganze Theorie in Frage gestellt, ob nun gesagt werden kann, daß die Erde sich in einer Ellipse um die Sonne dreht.

[ 15 ] Sie sehen einfach aus dieser historischen Tatsache, daß heute in der scheinbar sichersten, weil mathematischsten Wissenschaft, in der Astronomie, brennende Fragen vorliegen, brennende Fragen, die sich einfach aus der Geschichte ergeben. Und daraus entsteht dann die Frage: Ja, wodurch lebt man denn in einer solchen Unsicherheit gegenüber dem, was eigentlich astronomische Wissenschaft ist? Und da muß man weiter fragen, muß die Frage nach einer anderen Richtung lenken: Kommt man denn überhaupt durch eine bloß mathematische Betrachtung zu irgendeiner realen Sicherheit? Bedenken Sie doch nur, daß, indem man mathematisch betrachtet, man die Betrachtung heraushebt aus jeder äußeren Realität. Das Mathematische ist etwas, was aus unserem Innern aufsteigt. Man hebt sich heraus aus jeder äußeren Realität. Daher ist es schon von vorneherein zu fassen, daß, wenn man nun mit einer Betrachtungsweise, die sich heraushebt aus jeder Realität, an die äußere Realität herantritt, man unter Umständen tatsächlich nur zu etwas Relativem kommen kann.

[ 16 ] Ich will im voraus bloße Erwägungen hinstellen. Wir werden schon hinkommen zur Wirklichkeit. Es handelt sich darum, daß vielleicht das vorliegt, daß man, indem man bloß mathematisch betrachtet und seine Betrachtung nicht genügend mit Wirklichkeit durchdringt, gar nicht genügend energisch Wirklichkeit in der Betrachtung drinnen hat, um an die Erscheinungen der Außenwelt richtig herantreten zu können. Das fordert dann auf, eventuell doch näher die Himmelserscheinungen an den Menschen heranzuziehen und sie nicht nur ganz abgesondert vom Menschen zu betrachten. Es war ja nur ein Spezialfall dieses Heranziehens an den Menschen, wenn ich sagte: Man muß dasjenige, was draußen am gestirnten Himmel vor sich geht, in seinem Abdruck in den embryonalen Tatsachen sehen. Aber betrachten wir die Sache zunächst etwas oberflächlicher. Fragen wir, ob wir vielleicht einen anderen Weg als denjenigen finden, der bloß auf das Mathematische losgeht in bezug auf die Himmelserscheinungen.

[ 17 ] Da können wir in der Tat die Himmelserscheinungen in ihrem Zusammenhang mit dem irdischen Leben zunächst qualitativ an den Menschen etwas näher heranbringen. Wir wollen heute nicht verschmähen, scheinbar elementare Betrachtungen zugrunde zu legen, weil diese elementaren Betrachtungen gerade ausgeschlossen werden von demjenigen, was man heute der Astronomie zugrunde legt. Wollen wir einmal uns fragen: Wie nehmen sich denn die Dinge aus, die auch hineinspielen in das astronomische Betrachten, wenn wir das menschliche Leben auf der Erde ins Auge fassen? Da können wit in der Tat die äußeren Erscheinungen um den Menschen herum aus drei verschiedenen Gesichtspunkten heraus betrachten. Wir können sie betrachten von dem Gesichtspunkte, den ich nennen möchte den des solarischen Lebens, des Sonnenlebens, den des lunarischen Lebens und den des tertestrischen, des tellurischen Lebens.

[ 18 ] Betrachten wir zunächst ganz populär, eben elementar, wie sich diese drei Gebiete um den Menschen und am Menschen abspielen. Da zeigt sich uns ganz klar, daß etwas auf der Erde in einer durchgreifenden Abhängigkeit ist vom Sonnenleben; vom Sonnenleben, innerhalb dessen wir dann auch jenen Teil suchen werden, der Bewegung oder Ruhe und so weiter der Sonne ist. Wollen wir aber zunächst vom Quantitativen absehen und heute einmal auf das Qualitative sehen, wollen wir einmal versuchen, uns klarzumachen, wie zum Beispiel die Vegetation irgendeines Erdengebietes von dem solarischen Leben abhängt. Da brauchen wir ja in bezug auf die Vegetation nur dasjenige, was allbekannt ist, uns vor Augen zu rufen, den Unterschied der Vegetationsverhältnisse im Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter, und wir werden sagen können: Wir sehen in der Vegetation selber eigentlich den Abdruck des solarischen Lebens. Die Erde öffnet sich auf einem bestimmten Gebiet demjenigen, was außer ihr am Himmelsraum ist, und dieses Öffnen zeigt sich uns in der Entfaltung des vegetativen Lebens. Verschließt sie sich wiederum dem solarischen Leben, so tritt die Vegetation zurück.

[ 19 ] Wir finden aber eine gewisse Wechselwirkung zwischen dem bloß Tellurischen und dem Solarischen. Fassen wir nur einmal ins Auge, welcher Unterschied besteht gerade innerhalb des solarischen Lebens, wenn das tellurische Leben ein anderes wird. Wir müssen elementare Tatsachen zusammentragen. Sie werden dann sehen, wie uns dies weiterführt. Nehmen wir einmal Ägypten und Peru als zwei Gebiete in der tropischen Zone, Ägypten als Tiefebene, Peru als Hochebene. Nun, vergleichen Sie die Vegetation, dann werden Sie sehen, wie das Tellurische, also einfach die Entfernung vom Mittelpunkt der Erde, hineinspielt in das solarische Leben. Sie brauchen also nur die Vegetation über die Erde hin zu verfolgen und die Erde nicht bloß als Mineralisches zu betrachten, sondern das Pflanzliche dazu zu rechnen zur Erde, so haben Sie im Bilde der Vegetation einen Anhaltspunkt, um über die Beziehungen des Irdischen zum Himmlischen Anschauungen zu bekommen. Ganz besonders bekommen wir sie aber, wenn wir auf das Menschliche Rücksicht nehmen.

[ 20 ] Da haben wir zunächst zwei Gegensätze auf der Erde: das Polarische und das Tropische. Die Wirkung dieses Gegensatzes zeigt sich ja deutlich im menschlichen Leben. Nicht wahr, das polarische Leben bringt im Menschen einen gewissen geistig-apathischen Zustand hervor. Der schroffe Gegensatz, ein langer Winter und langer Sommer, die fast Tag- und Nacht-Bedeutung haben, bringt im Menschen eine gewisse Apathie hervor, so daß man sagen kann, da lebt der Mensch in einem Weltmilieu drinnen, das ihn apathisch macht. In der tropischen Gegend lebt der Mensch auch in einem Weltmilieu drinnen, das ihn apathisch macht. Aber der Apathie der polarischen Gegenden liegt eine äußere spärliche Vegetation zugrunde, die auf eigentümliche Weise auch da, wo sie sich entfaltet, mager, spärlich ist. Der tropischen Apathie des Menschen liegt zugrunde eine reiche, üppige Vegetation. Und aus diesem Ganzen der Umgebung kann man sagen: Die Apathie, die den Menschen befällt in polarischen Gegenden, ist eine andere Apathie als diejenige, die den Menschen befällt in tropischen Gegenden. Apathisch wird er in beiden Gegenden, aber die Apathie ergibt sich gewissermaßen aus verschiedenen Untergründen. In der gemäßigten Zone ist ein Ausgleich vorhanden. Da entwickeln sich, möchte ich sagen, in einem gewissen Gleichgewicht die menschlichen Fähigkeiten.

[ 21 ] Nun wird niemand daran zweifeln, daß das etwas zu tun hat mit dem solarischen Leben. Aber wie ist der Zusammenhang mit dem solarischen Leben? Sehen Sie, wenn man - wie gesagt, ich will zuerst einiges dutch Anschauen entwickeln, damit wir zu Begriffen kommen -, wenn man den Dingen zugrunde geht, findet man, daß das polarische Leben auf den Menschen so wirkt, daß das Sonnenleben zunächst stark sich da auslebt. Die Erde entringt sich da dem Sonnenleben, sie läßt ihre Wirkungen nicht von unten herauf in die Vegetation schießen. Der Mensch ist dem eigentlichen Sonnenleben ausgesetzt — Sie müssen nur das Sonnenleben nicht bloß in der Wärme suchen -, und daß er das ist, bezeugt das Aussehen der Vegetation.

[ 22 ] Wir haben also ein Überwiegen des solarischen Einflusses in der polarischen Zone. Welches Leben überwiegt in der tropischen Zone? Dort überwiegt das tellurische Leben, das Erdenleben. Das schießt in die Vegetation hinein. Das macht die Vegetation üppig, reich. Das benimmt dem Menschen auch das Gleichmaß seiner Fähigkeiten, aber es kommt von einer anderen Seite her im Norden wie im Süden. Also, in polarischen Gegenden unterdrückt das Sonnenlicht seine innere Entfaltung; in den tropischen Gegenden unterdrückt dasjenige, was von der Erde aufschießt, seine inneren Fähigkeiten. Und wir sehen einen gewissen Gegensatz, den Gegensatz, der sich zeigt in einem Überwiegen des solarischen Lebens um den Pol herum; in einem Überwiegen des tellurischen Lebens in den tropischen Gegenden, in der Äquatornähe.

[ 23 ] Und wenn wir dann hinschauen auf den Menschen und die menschliche Gestalt ins Auge fassen, dann werden wir uns sagen: Dasjenige, was — bitte nehmen Sie zunächst nur als Paradoxie das hin, wenn ich jetzt die menschliche Gestalt in einem gewissen Sinne ernst nehme - in der äußeren Gestalt nachbildet den Weltenraum, die Kugel, die Sphärengestalt des Weltenraumes — das menschliche Haupt -, das ist auch während des Lebens in der polarischen Zone zunächst, ist dem Außerirdischen ausgesetzt. Dasjenige, was Stoffwechselsystem im Zusammenhang mit den Gliedmaßen ist, das ist in der tropischen Zone dem irdischen Leben ausgesetzt. Wir kommen so zu einer besonderen Beziehung des menschlichen Hauptes zum außerirdischen Leben und des menschlichen Stoffwechselsystems zusammen mit dem Gliedmaßensystem zum irdischen Leben. Wir sehen also, daß der Mensch so im Weltenall drinnensteht, daß er mit seinem Haupt, der Nerven-Sinnesorganisation, mehr der außerirdischen Umwelt zugeordnet ist, mit der Stoffwechselorganisation mehr dem irdischen Leben, und wir werden in der gemäßigten Zone eine Art fortwährenden Ausgleichs zu suchen haben zwischen dem Kopfsystem und dem Stoffwechselsystem. Wir werden in der gemäßigten Zone vorzugsweise das rhythmische System im Menschen in Ausbildung begriffen haben.

[ 24 ] Jetzt sehen Sie, daß ein gewisser Zusammenhang zwischen dieser Dreigliederung des Menschen - Nerven-Sinnessystem, rhythmisches System, Stoffwechselsystem - und der Außenwelt vorhanden ist. Sie sehen, daß das Kopfsystem mehr der ganzen Umwelt zugeordnet ist, daß das rhythmische System der Ausgleich zwischen der Umwelt und der irdischen Welt ist und das Stoffwechselsystem zugeordnet ist der irdischen Welt.

[ 25 ] Nun haben wir zugleich den anderen Hinweis aufzunehmen, der uns das solarische Leben in einer anderen Beziehung auf den Menschen zeigt. Nicht wahr, dasjenige, was wir jetzt betrachtet haben, diesen Zusammenhang des menschlichen Lebens mit dem solarischen Leben, das können wir ja schließlich nur beziehen auf dasjenige, was sich zwischen dem irdischen und außerirdischen Leben im Jahreslauf abspielt. Aber im Tageslauf haben wir es ja im Grunde genommen mit einer Art Wiederholung oder etwas Ähnlichem zu tun wie im Jahreslauf. Der Jahreslauf wird bestimmt durch die Beziehung der Sonne zur Erde, der Tageslauf aber auch. Wenn wir einfach mathematisch-astronomisch sprechen, so reden wir beim Tageslauf von der Umdrehung der Erde um ihre Achse, beim Jahreslauf von der Revolution der Erde um die Sonne. Aber wir beschränken uns dann beim Ausgangspunkt auf sehr einfache Tatsachen. Wir haben aber keine Berechtigung zu sagen, daß wir da wirklich ausgehen von etwas, das ein hinreichender Boden ist für eine Betrachtungsweise und uns hinreichende Unterlagen dafür gibt. Fassen wir beim Jahreslauf einmal alles das ins Auge, was wir jetzt gesehen haben. Ich will noch nicht sagen: Umdrehung der Erde um die Sonne, sondern daß der Jahreslauf, die Wechseltatsache des Jahreslaufes zusammenhängen muß mit der Dreigliederung des Menschen und daß, indem dieser Jahreslauf durch die irdischen Verhältnisse in einer verschiedenen Weise sich ausbildet im Tropischen, im Gemäßigten, im Polarischen, sich daran zeigt, wie dieser Jahreslauf mit der ganzen Bildung des Menschen, mit den Verhältnissen der drei Glieder des dreigliedrigen Menschen, etwas zu tun hat. Wenn wir das in Betracht ziehen können, dann bekommen wir eine breitere Basis und können vielleicht auf etwas ganz anderes kommen, als wenn wir einseitig bloß die Winkel abmessen, die die eine Fernrohrrichtung bildet mit der anderen. Es handelt sich darum, breitere Grundlagen zu gewinnen, um die Tatsachen beurteilen zu können.

[ 26 ] Und wenn wir vom Tageslauf sprechen, dann sprechen wir im Sinne der Astronomie von der Umdrehung der Erde um ihre Achse. Nun zeigt sich da allerdings zunächst etwas anderes. Es zeigt sich eine weitgehende Unabhängigkeit des Menschen von diesem Tageslauf. Die Abhängigkeit der Menschheit vom Jahreslauf, namentlich von dem, was zusammenhängt mit dem Jahreslauf, die Bildung der Menschengestalt in den verschiedensten Gegenden der Erde, das zeigt uns eine sehr weitgehende Abhängigkeit des Menschen vom solarischen Leben, von den Veränderungen, die auf der Erde auftreten infolge des solarischen Lebens. Der Tageslauf zeigt das weniger. Wir können allerdings sagen: Es tritt auch in bezug auf den Tageslauf gar manches Interessante zutage, aber es ist verhältnismäßig nicht sehr bedeutend im Zusammenhang des menschlichen Gesamtlebens.

[ 27 ] Gewiß, es ist ein großer Unterschied schon bei einzelnen menschlichen Persönlichkeiten vorhanden. Goethe, der ja schließlich schon in einer gewissen Beziehung für das Menschliche als eine Art Normalmensch, als eine Art Normalwesen angesehen werden kann, er fühlte sich am günstigsten zur Produktion aufgelegt am Morgen, Schiller mehr in der Nacht. Das weist darauf hin, daß dieser Tageslauf auf gewisse feinere Dinge in der menschlichen Natur dennoch einen gewissen Einfluß hat. Und derjenige, der für solche Dinge einen Sinn hat, wird ja die Tatsache bestätigen, daß ihm viele Menschen im Leben begegnet sind, die ihm anvertraut haben, daß die eigentlich bedeutsamen Gedanken, die sie gehabt haben, in der Dämmerung ausgebrütet worden sind, also auch gewissermaßen in der gemäßigten Zeit des Tageslaufes, nicht um die Mittagsstunde, nicht um die Mitternachtsstunde, sondern in der gemäßigten Zeit des Tageslaufes. Das ist aber doch sicher, daß der Mensch in einer gewissen Weise unabhängig ist von dem Tageslauf der Sonne. Wir werden auf die Bedeutung dieser Unabhängigkeit noch einzugehen und zu zeigen haben, worin dennoch eine Abhängigkeit besteht.

[ 28 ] Nun, ein zweites Element ist aber das lunarische Leben, das Leben, das zusammenhängt mit dem Monde. Es mag sein, daß unendlich vieles, was in dieser Beziehung gesagt worden ist im Laufe der Menschheitsentwickelung, heute sich nur als Phantasterei herausstellt. Aber in irgendeiner Weise sehen wir ja, daß das irdische Leben als solches in den Erscheinungen der Ebbe und Flut ganz zweifellos mit der Mondenbewegung etwas zu tun hat. Aber auch das darf doch nicht übersehen werden, daß schließlich die weiblichen Funktionen, wenn sie auch zeitlich nicht mit den Mondphasen zusammenfallen, so doch ihrer Länge und dem Verlauf nach mit den Mondphasen zusammenfallen, daß also dasjenige, was mit der menschlichen Entwickelung etwas Wesentliches zu tun hat, in bezug auf die Zeitlänge mit den Mondphasen zusammenhängend sich zeigt. Und man kann sagen: Es ist aus dem allgemeinen Naturlauf dieser Gang der weiblichen Funktionen herausgehoben, aber er ist doch ein treues Abbild geblieben. Er vollzieht sich in derselben Zeit.

[ 29 ] Ebensowenig darf übersehen werden - nur stellt man über diese Dinge keineswegs vernünftige, exakte Beobachtungen an, wenn man von vorneherein solche Dinge ablehnt -, es darf nicht übersehen werden, daß das Phantasieleben des Menschen tatsächlich außerordentlich viel zu tun hat mit den Mondphasen. Und wer einen Kalender führen würde über das Auf- und Abfluten seines Phantasielebens, der würde eben bemerken, wieviel das zu tun hat mit dem Gang der Mondesphasen. Das aber, daß auf gewisse untergeordnete Organe das Mondenleben, das lunarische Leben einen Einfluß hat, das muß eben an der Erscheinung des Nachtwandelns studiert werden. Und da können interessante Erscheinungen studiert werden, die überdeckt sind durch das normale Menschenleben, die aber in den Tiefen der menschlichen Natur vorhanden sind und die in ihrer Gesamtheit darauf hinweisen, daß das lunatische Leben ebenso zusammenhängt mit dem rhythmischen System des Menschen, wie das solare Leben mit dem Nerven-Sinnessystem des Menschen zusammenhängt.

[ 30 ] Jetzt haben Sie schon eine Kreuzung. Wir haben gesehen, wie sich das solare Leben im Zusammenhang mit der Erde so entwickelt, daß für die gemäfßigte Zone schon auf das rhythmische System gewirkt wird. Nun tritt, sich kreuzend mit dieser Wirkung, das lunarische Leben als direkt beeinflussend das rhythmische System auf.

[ 31 ] Und wenn wir auf das eigentliche tellurische Leben sehen, dann darf doch nicht außer acht gelassen werden, daß der Einfluß des Tellurischen auf den Menschen sich zwar in einer Region vollzieht, die gewöhnlich nicht beobachtet wird, daß aber der Einfluß auf diese Region durchaus vorhanden ist. Ich bitte Sie, doch nur einmal Ihr Augenmerk zu lenken auf eine solche Erscheinung wie zum Beispiel das Heimweh. Man kann über das Heimweh gering denken. Gewiß, man kann es aus sogenannten seelischen Gewohnheiten und dergleichen erklären. Aber ich bitte Sie doch zu berücksichtigen, daß durchaus im Gefolge des sogenannten Heimwehs auftreten können physiologische Erscheinungen. Bis zum Siechtum des Menschen kann das Heimweh führen. In asthmatischen Erscheinungen kann es sich ausleben. Und wenn man den Komplex der Erscheinungen des Heimwehs mit seinen Folgen, eben mit den asthmatischen Erscheinungen und allgemeinem Siechtum, eine Art von Auszehrung, studiert, dann kommt man auch dazu einzusehen, daß schließlich das Heimweh als Gesamtgefühl auf einer Veränderung des Stoffwechsels beruht, auf einer Veränderung des Stoffwechselsystems; daß dieses Heimweh nur der Bewußtseinsreflex ist von Veränderungen im Stoffwechsel und daß diese Veränderungen lediglich herrühren von der Veränderung desjenigen, was in uns vorgeht, wenn wir von einem Ort mit seinen tellurischen Einflüssen von unten auf an einen anderen Ort mit seinen tellurischen Einflüssen von unten auf versetzt werden. Bitte nehmen Sie das zusammen mit anderen Dingen, die einem ja gewöhnlich keine wissenschaftliche Betrachtung abnötigen, aber leider eben nicht. Goethe, so sagte ich schon, fühlte sich besonders angeregt zum Dichten, zum Niederschreiben seiner Sachen am Morgen. Brauchte er aber eine Anregung, so nahm er diejenige Anregung, welche ihrer Natur nach am wenigsten unmittelbar in den Stoffwechsel eingreift, sondern ihn nur vom rhythmischen System aus irritiert, das ist der Wein. Goethe regte sich mit Wein an. Er war in dieser Beziehung überhaupt eben ein Sonnenmensch. Er ließ auf sich namentlich die Einflüsse des solarischen Lebens wirken. Bei Schiller oder Byron wat das umgekehrt. Schiller dichtete am liebsten, wenn die Sonne untergegangen war, wenn also das solare Leben wenig mehr tätig war, und er regte sich an mit etwas, was gründlich in den Stoffwechsel eingreift, mit warmem Punsch. Das ist etwas anderes als die Wirkung, die Goethe vom Wein hatte. Das ist eine Einwirkung auf das gesamte Stoffwechselsystem. Durch den Stoffwechsel wirkt die Erde auf den Menschen. So daß man sagen kann, Schiller ist im wesentlichen ein tellurischer Mensch gewesen. Die tellurischen Menschen wirken auch mehr durch das Emotionelle, das Willenhafte, die solarischen Menschen mehr durch das Ruhige, Kontemplative. Goethe wurde ja auch immer mehr und mehr für diejenigen Menschen, die das Solarische nicht mögen, die nur das Tellurische, dasjenige, was an der Erde haftet, mögen, «der kalte Kunstgreis», wie man ihn in Weimar nannte, «der kalte Kunstgreis mit dem Doppelkinn». Das war ein Name, der Goethe in Weimar im 19. Jahrhundert immer wiederum gegeben worden ist.

[ 32 ] Nun möchte ich Sie noch auf etwas anderes aufmerksam machen. Bedenken Sie einmal, nachdem wir beobachtet haben dieses Hineingestelltsein des Menschen in den Weltenzusammenhang: Erde, Sonne, Mond - die Sonne mehr wirkend auf das Nerven-Sinnessystem; der Mond mehr wirkend auf das rhythmische System; die Erde, dadurch, daß sie dem Menschen ihre Stoffe zur Nahrung gibt, also die Stoffe direkt in ihm wirksam macht, wirkt auf das Stoffwechselsystem, wirkt tellurisch. Wir sehen im Menschen etwas, wo wir vielleicht Anhaltspunkte finden können, uns das Außermenschliche, das Himmlische zu erklären auf breiterer Grundlage als durch die bloße Winkelstellung des Fernrohres und dergleichen. Insbesondere finden wir solche Anhaltspunkte, wenn wir noch weitergehen, wenn wit nun die außermenschliche Natur betrachten, aber auch so betrachten, daß wir in ihr mehr sehen als bloß eine Registratur der aufeinanderfolgenden Tatsachen. Betrachten Sie das Metamorphosenleben der Insekten. Es ist im Jahreslauf durchaus etwas, was das äußere solare Leben widerspiegelt. Ich möchte sagen: Beim Menschen müssen wir forschend mehr nach innen gehen, um Solarisches, Lunarisches und Tellurisches in ihm zu verfolgen. Beim Insektenleben in seinen Metamorphosen sehen wir direkt den Jahreslauf in den aufeinanderfolgenden Gestalten, die das Insekt annimmt, zum Ausdruck kommen. So daß wir uns sagen können, wir müssen vielleicht nicht nur quantitativ vorgehen, sondern wir müssen auch auf das Qualitative sehen, das sich uns in solchen Erscheinungen ausdrückt. Warum immer bloß fragen: Wie sieht im Objektiv darinnen irgendeine Erscheinung da draußen aus? - Warum nicht fragen: Wie reagiert nicht bloß das Objektiv des Fernrohres, sondern das Insekt? Wie reagiert die menschliche Natur? Wie wird uns dadurch etwas verraten über den Gang der Himmelserscheinungen? Und wir müssen uns zuletzt fragen: Werden wir da nicht auf breitere Grundlagen geführt, so daß es uns nicht passieren kann, daß wir theoretisch, wenn wir philosophisch das Weltenbild erklären wollen, Kopernikaner sind und wiederum für Kalender oder sonstwie rechnend das tychonische Weltbild zugrunde legen, was heute praktisch die Astronomie noch macht; oder daß wir zwar Kopernikaner sind, aber das Wichtigste bei Kopernikus, nämlich seinen dritten Hauptsatz, einfach weglassen? Können wir vielleicht nicht die Unsicherheiten, die heute geradezu die astronomischen Grundfragen zu brennenden machen, dadurch überwinden, daß wir auf breiterer Grundlage arbeiten, daß wir auch auf diesem Gebiet aus dem Quantitativen in das Qualitative hineinarbeiten?

[ 33 ] Ich habe gestern versucht hinzuweisen zunächst auf den Zusammenhang der Himmelserscheinungen mit den embryonalen Erscheinungen, heute mit dem fertigen Menschen. Da haben Sie einen Hinweis auf eine notwendige Umgruppierung des wissenschaftlichen Lebens. Aber nehmen Sie eines; was ich im Laufe der heutigen Betrachtung auch erwähnt habe. Ich habe Sie hingewiesen auf Zusammenhänge des menschlichen Stoffwechselsystems mit dem irdischen Leben. Wir haben im Menschen das Wahrnehmungsvermögen durch das Nerven-Sinnessystem vermittelt, das irgendwie zusammenhängt mit dem solarischen, dem Himmelsleben überhaupt; wir haben das rhythmische System zusammenhängend mit dem, was zwischen Himmel und Erde ist; wir haben das Stoffwechselsystem zusammenhängend mit dem, was mit der eigentlichen Erde zusammenhängt, so daß wir, wenn wir auf den eigentlichen Stoffwechselmenschen sehen würden, wir vielleicht dadrinnen nun wiederum näher kommen könnten der eigentlichen Wesenheit des Tellurischen. Was tun wir denn heute, wenn wir dem Tellurischen näher kommen wollen? Wir benehmen uns wie Geologen. Wir untersuchen die Dinge von der Außenseite. Aber sie haben doch auch eine Innenseite! Zeigen sie die vielleicht erst, wenn sie durch den Menschen gehen, in der wahren Gestalt?

[ 34 ] Es ist heute ein Ideal geworden, das Verhältnis der Stoffe zueinander abgesondert vom Menschen zu betrachten und dabei zu bleiben, im chemischen Laboratorium die gegenseitige Wirkung der Stoffe zu betrachten durch Hantierungen, um hinter das Wesen der Stoffe zu kommen. Wenn es aber so wäre, daß die Stoffe erst ihre Wesenheit enthüllen in der menschlichen Natur, dann müßten wir Chemie so treiben, daß wir bis zur menschlichen Natur herangehen. So würden wir einen Zusammenhang zu konstruieren haben zwischen wirklicher Chemie und den Stoffvorgängen im Menschen, so wie wir einen Zusammenhang sehen zwischen Astronomie und Embryologie, zwischen Astronomie und der menschlichen Gesamtgestalt, der dreigliedrigen menschlichen Wesenheit. Sie sehen, die Dinge wirken ineinander. Wir kommen erst in wirkliches Leben hinein, wenn wir diese Dinge ineinandergehend betrachten.