Third Scientific Lecture-Course:

Astronomy

GA 323

13 January 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture XIII

In popular works, as you are well aware, the evolution of astronomical ideas is thus presented—Until Copernicus, they say the Ptolemaic system was prevailing. Then through the work of Copernicus the system we accept—though with modifications—to this day, became the intellectual property of the civilised world. Now for the thoughts we shall pursue in the next few days it will be most important for us to be aware of a certain fact in this connection. I will present it simply by reading, to begin with, a passage from Archimedes. Archimedes describes the cosmic system or starry system as conceived by Aristarchus of Samos, in these words—“In Aristarchus' opinion the Universe is far, far greater. He takes the stars and the Sun to be immobile, with the Earth moving around the Sun as centre. He then assumes that the sphere of the fixed stars,—its centre likewise in the Sun,—is so immense that the circumference of the circle, described by the Earth in her movement, is to the distance of the fixed stars as is the centre of a sphere to the surface thereof.”

Taking these words to be a true description of the spatial World-conception of Aristarchus of Samos, you will admit: Between his spatial picture of the Universe and ours, developed since the time of Copernicus, there is no difference at all. Aristarchus lived in the third Century before the Christian era. We must therefore assume that among those who like Aristarchus himself were leaders of cultural and spiritual life in a certain region at that time, fundamentally the same spatial conception of the World held good as in the Astronomy of today. Is it not all the more remarkable that in the prevailing consciousness of men who pondered on such things at all, this work-conception—heliocentric, as we may call it,—thereafter vanished and was supplanted by that of Ptolemy? Till, with the rise of the new epoch in civilisation, known to us as the Fifth post-Atlantean, the heliocentric idea comes forth again, which we have found prevailing among such men as Aristarchus in the 3rd Century B.C.! (For you will readily believe that what held good for Aristarchus, held good for many people of this time.) Moreover if you are able to study the evolution of mankind's spiritual outlook—though it is difficult to prove by outer documents—you will find this heliocentric conception of the World the more widely recognised by those who counted in such matters, the farther you go back from Aristarchus into more distant times. Go back into the Epoch we are wont to call the Third post-Atlantean, and it is true to say that among those who were the recognised authorities the heliocentric conception prevailed during the Epoch. The same conception prevailed which Plutarch says was held by Aristarchus of Samos. Plutarch moreover described in such terms that we can scarcely distinguish it from that of our own time.

This is the noteworthy fact. The heliocentric conception of the World is there in human thought, the Ptolemaic system supplants it, and in the Fifth post-Atlantean Epoch it is re-conquered. In all essentials we may aver that the Ptolemaic system held good for the Fourth post-Atlantean Epoch and for that alone. Not without reason do I bring this in today, after speaking yesterday of an ‘ideal point’ in the evolution of the Kingdoms of Nature. As we shall see in due course, there is an organic relationship between these diverse facts. But we must first enter more fully into the one adduced today.

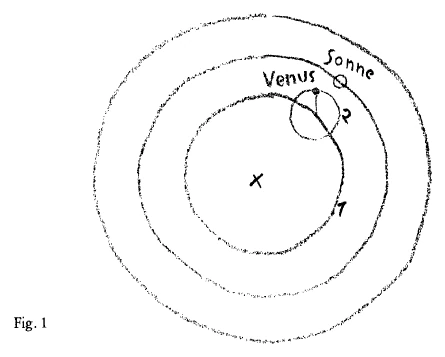

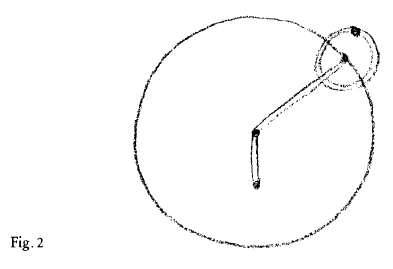

What is the essence of the Ptolemaic cosmic system? The essence of it is that Ptolemy and his followers go back again to the idea of an Earth at rest, with the fixed-star Heavens moving around the Earth; likewise the Sun moving around the Earth. For the movement of the planets, the apparent forms of which we have been studying, he propounds peculiar mathematical formulae. In the main, he thinks in this way: Let this be the Earth (Fig. 1). Around it he conceives the Heaven of fixed stars. Then he imagines the Sun to be moving in an eccentric circle round the Earth. The planets also move in circles. But he does not imagine them to move like the Sun in one circle only. No; he assumes a point (Fig. 1) moving in this eccentric circle which he calls the ‘Deferent’, and he makes this point in its turn the centre of another circle. Upon this other circle he lets the planet move, so that the true path of the planet's movement arises from the interplay of movements along the one circle and the other. Take Venus for example. Says Ptolemy: around this circle another circle is rotating; the centre of the latter circle moves along the former. The actual path of Venus would then be, as we should say, a resultant of the two movements. Such is the planet's movement around the Earth; to comprehend it we must assume the two circles, the large one, called the “deferent”, and the small one, know as the ‘epicyclic’ circle. Movements of this kind he attributes to Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus an Mercury, only not to the Sun. The Moon he conceives to move in yet another small circle,—an epicyclic circle of its own.

These assumptions were due to the Ptolemaic astronomers having calculated with great care the positions on the Heavens at which the planets were at given times. They computed these circling movements so as to understand the fact that the planets were at given places at given times. It is astonishing how accurate were the calculations of Ptolemy and his followers,—relatively speaking at least. Draw the path of any planet—Mars, for instance—from modern astronomical data. Compare this 'apparent path', so-called, of Mars, drawn as observed today, with the path derived from Ptolemy's theory of deferent and epicyclic circles. The two curves hardly differ. The difference, relatively trifling, is only due to the still more accurate results of modern observation. In point of accuracy these ancients were not far behind us. That they assumed this queer system of planetary movements, which seems to us so complicated, was not due therefore to any faulty observation. Of course the Copernican system is simpler,—that will occur to everyone. There is the Sun in the midst, with the planets moving in circles or ellipses round it. Simple, is it not? Whereas the other is very complicated: a circular path superimposed upon another circle, and an eccentric one to boot.

The Ptolemaic system was adhered to with a certain tenacity throughout the Fourth post-Atlantean epoch, and we should ask ourselves this question: Wherein lies the essential difference in the way of thinking about cosmic space and the contents of cosmic space, such as we find it in the Ptolemaic school on the one hand and in Aristarchus and those who thought like him in the other? What is the real difference between these ways of thinking about the cosmic system? It is difficult to describe popularly, for many things seem outwardly alike, whilst inwardly they can be very different. Reading Plutarch's description of Aristarchus system, we shall say: This heliocentric system is fundamentally no different from the Copernican. Yet if we enter more deeply into the spirit of the Aristarchian world-picture, we find it different. Aristarchus too, no doubt, follows the outer phenomena's with mathematical lines. In mathematical lines he represents to himself the movements of the heavenly bodies.

The Copernican's do likewise. Between the two there intervenes this other system—the strange one of the Ptolemaic school. Here it cannot be said that the forming of mathematical pictures coincides in the same way with what is observed. The difference in this respect is all-important. In the Ptolemaic school, the mathematical imagination does not directly rest upon the sequence of observed points in space. It is rather like this: In order ultimately to do justice to them it goes right away from the observed phenomena and works quite differently, not merely putting the observed results together. Yet in the end it is found that if one does admit the mathematical thought-pictures of the Ptolemaic school, one thereby comprehends what is observed.

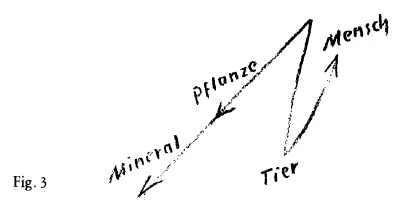

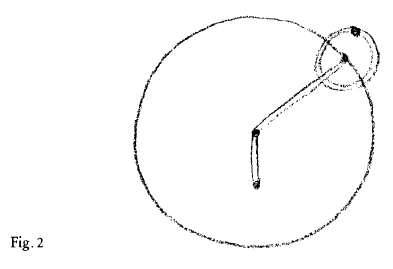

Suppose a man of today were to make a model of the planetary system. Somewhere he would attach the Sun, them he would draw wires to represent the orbits of the planets; he would really think of them as representing the true orbits. In purely mathematical lines he would comprise the logic of the planets' paths. Ptolemy would not have done so. He would have had to construct his model somewhat in this fashion (Fig. 2). Here would have been a pivot, fixed to it a rod, leading to the rim of a rotating wheel, upon this again another wheel rotating. Such would be Ptolemy's model. The model he makes, the mathematical picture living in his thought, is not in the least like what is outwardly seen. For Ptolemy the Mathematical picture is quite detached from what is seen externally. And now, in the Copernican system we return to the former method, simply uniting by mathematical lines the several places, empirically observed, of the planet. These mathematical lines correspond to what was there in Aristarchus's system. Yet is it really the same? This is the question we must now be asking: Is it the same?

Bearing in mind the original premises of the Copernican system and the kind of reasoning by which it is maintained, I think you will admit: It is just like the way we relate ourselves, mathematically, to empirical reality in general. You may confirm it from his works. Copernicus began by constructing his planetary system ideally, much in the same way as we construct a triangle ideally and then find it realised in empirical reality outside us. He took his start from a kind of a priori mathematical reasoning and them applied it to the empirically given facts.

What then is at the bottom of this complicated Ptolemaic system, to make it so complicated? You remember the well-known anecdote. When it was shown to Alphonso of Spain, he from his consciousness of royalty declared: Had God asked his advice at the Creation of the World, he would have made it more simply than to require so many cycles and epicycles.

Or is there something in it after all—in this construction of cycles and epicycles—related to a real content of some kind? I put the question to you: Is it only fantasy, only a thing thought-out, or does this thought out system after all contain some indication that it relates to a reality? We can only decide the question by entering into it in greater detail.

It is like this. Suppose that with the Ptolemaic system taking you start from Ptolemaic theories—you follow the movements, or, as we should say, the apparent movements of the Sun, and of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn: to begin with you will have angular movements of a certain magnitude each time. You can therefore compare the movements indicated by the successive positions of these heavenly bodies in the sky. The Sun has no epicyclic movement. The epicyclic daily movement of the Sun is therefore zero. For Mercury on the other hand we must put down a number, representing his daily movement along his epicyclic circle, which we shall them compare with that of other planets. Let us call the epicyclic daily movements—\(x_1\) for Mercury, \(x_2\) for Venus, \(x_3\) for Mars, \(x_4\) for Jupiter, \(x_5\) for Saturn.

Now take the movements Ptolemy attributes to the centres of the epicycles along their different circles. Let the daily movement be y for the Sun. It is then remarkable that if we seek the corresponding value for Mercury we get precisely the same figure. The movement of the centre of Mercury's epicycle equals the movement of the Sun. We must write \(y\) again, and so for Venus. This then holds good of Mercury and Venus. The centres of their epicycles move along paths which correspond exactly to the Sun's path,—run paralleled to it. For Mars, Jupiter and Saturn on the other hand the movements of the centres of the epicycles are diverse,—shall we say \(x’\) for Mars, \(x’’\) for Jupiter, \(x’’’\) for Saturn.

Yet the remarkable fact is that by taking the corresponding sums, namely: \(x_3 + x’ + x_4 + x’’ , x_5 + x’’’\), adding the movements along the several epicycles to the movements of the centres of these epicycles,—I get the same magnitude for all three planets. Nay more, it is the identical which we obtained just now for the movement of the Sun and of the centres of the epicycles of Mercury and Venus—

$$x_3+x'=y,$$ $$x_4+x''=y,$$ $$x_5+x'''=y.$$A noteworthy regularity, you see. This regularity will lead us to attribute a different cosmic significance to the centres at the epicycles of Venus and Mercury, the planets near the Sun as they are called, and of Jupiter, Mars, Saturn etc. called distant from the Sun. For the distant planets, the centre of the epicycle has not the same cosmic meaning. Something is there, by virtue of which the whole meaning of the planet's course is different than for the planets near the Sun.

The fact was well-known in the Ptolemaic school and helped determine the whole idea—the peculiar construction of cycles and epicycles in the mind, detached from the empirically given facts. This very fact obliged them, as they saw it, to propound their system, and is implicit in it. The human being of today would scarcely recognise it there; he listens more or less obtusely when told how they set up their cycles and epicycles. To their way of thinking on the other hand the thought was palpable and eloquent???. If Mercury and Venus have the same values as Jupiter, Saturn and Mars, yet in another realm, we cannot treat the matter so simply, with an indifferent circling motion or the like. A planet, in effect, is of significance not only within the space it occupies but outside it. We have not merely to stare at it, fixing its place in the Heavens and in relation to other celestial bodies; we must go out of it to the centre of the epicycle. The centre of its epicycle behaves in space even as the Sun does. Once more, translated into modern forms of speech, the Ptolemaists said: For Mercury and Venus the centres of the epicycles so far as movement is concerned behave in cosmic space as the Sun itself behaves. Not so the other planets—Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. They claim another right. In effect, only when we add their epicyclic movements to their movements along the deferent, only then do they grow like the Sun in movement. They therefore are differently related to the Sun.

This difference of behaviour in relation to the Sun was what they really built on in the Ptolemaic system. This among others was an essential reason for its development. Their aim was not merely to join the empirically given places in the Heavens by mathematical lines, building it all into a system of thought in this way. They were at pains to build a thought-system on another basis, and what is more, a piece of true knowledge under-lay their efforts; it is undeniable if we go into it historically. Modern man naturally says: We have advanced to the Copernican system, why bother about these ancient thinkers? He bothers not, but if he did, he would perceive that this was what the Ptolemaists meant. 'Truth is', they said to themselves, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn have quite another relation to Man than Mercury and Venus. What corresponds to them in Man is different. Moreover they connected Jupiter, Saturn and Mars with the forming of the human head, Venus and Mercury with the forming of what is beneath the heart in man. Rather than speak of the head, perhaps I should put it in these words: they related Jupiter, Saturn and Mars with the forming of all that is above the heart; Venus and Mercury with what is situated below the heart in man. The Ptolemaists did indeed relate to man, what they were trying to express in their cosmic system.

What under-lay it really? To gain true judgement on this question, my dear Friends, I think you should read and mark the inmost tone and essence of my Riddles of Philosophy, in writing which I tried to show how very different was the way man met the world in his life or knowledge before the 15th Century and after. Since then, if I may use this image we unpeel ourselves from the world,—we detach ourselves completely. Before the 15th Century we did not do so. I must admit, at this point it is difficult to make oneself understood in the modern world. Man of to-day says to himself: “I think thus and thus about the world. I have my sense perceptions, thus or thus. In modern times we have become enlightened; the men of former times were simple, with many childish theories.” And as to our enlightenment and their simplicity the modern man's idea of it amounts to this, or something very like it: "If only our ancestors had tried hard enough, they might have grown just as clever as we are. But it took time, this eduction of mankind; it evidently had to take some time for men to get as enlightened as they afterwards became.”

What is today left unconsidered, is that man's very seeing of the world, his seeing and his contemplating, his whole relation to the world was different. Compare the different stages of it, described in my Riddles of Philosophy. Then you will say: Through the whole time from the beginning of the Fourth Epoch until the end, the sharp distinction we now have, of concept and idea on the one hand and sense-perceived data on the other, did not exist. They coincided rather. In and with the sensory quality, men saw the quality of thought, the idea. And it was ever more so, the farther we go back in them. In this respect we need more real notions as to the evolution of mankind. What Dr. Stein has written for example in his book, upon the essence of sense-perception, is true of our time and excellently stated. I he had had to write a dissertation on this subject in the School of Alexandria in olden time, he would have had to write very differently of sense-perception. This is what people of today persist in disregarding; they will have everything made absolute.

And if we go still farther back, for example into the time when the Egypto-Chaldean Epoch was at its height, we find an even more intensive union of concept and idea with sense-perceptible, outward and physical reality. It was from this moreover—from this more intensive union—that the conceptions arose which we still find in Aristarchus of Samos. They were already decadent in his time; they had been entertained even more vividly by his predecessors. The heliocentric system was simply felt, when with their thoughts and mental pictures men lived in and with the outer sense-perceptible reality. Then, in the Fourth post-Atlantean Epoch, man had to get outside the sense-world; he had to wean himself of this union of his inner life with the sense-world. In what field was it easiest to do so? Obviously, in the field where it would seem most difficult to bring the outer reality and the idea in the mind together. Here was man's opportunity to wrest himself away—in his life of ideas—from sense-impressions.

Look at the Ptolemaic system from this angle; see in it an important means toward the education of mankind; then only do we recognise the essence of it. The Ptolemaic system is the great school of emancipation of human thoughts from sense-perception. When this emancipation had gone far enough when a certain degree of the purely inner capacity of thought had been attained—then came Copernicus. A little later, I may add, this attainment became even more evident, namely in Galileo and others, whose mathematical thinking is in the highest degree abstracted and complicated. Copernicus presented to himself the facts of which we have been speaking—the observation of the equality of y at diverse points in the equation, and, working backward from these mathematical results, was able to construct his cosmic system. For the Copernican system is based on these results. It represents a return, from the ideas now abstractly conceived, to the external, physically sense-perceptible reality.

It is most interesting to witness, how in the astronomical world-picture above all, mankind gets free of the outer reality. And in perceiving this, my dear Friends, we also gain a truer estimate of the returning pathway,—for in a wider sense we must return. Yet how? Kepler still had a feeling of it. I have often quoted his rather melodramatic saying, to the effect: I have stolen the sacred vessels of the Egyptian Temples to bring them back again to modern man. Kepler's planetary system, as you know, grew from a highly romantic conception of how the Universe is built. In deed he feels it like a renewal of the ancient heliocentric system. Yet the truth is, the ancient heliocentric system was derived, not from a mere looking outward with the eyes, but from an inner awareness, an inner feeling of what was living in the stars.

The human being who originally set up the cosmic system, making the Sun the centre with the Earth circling round it after the manner of Aristarchus of Samos, felt in his heart the influences of the Sun, felt in his head the influences of Venus and Mercury. This was experience, direct experience throughout the human being, and out of this the system grew. In later time this all-embracing experience was lost. Perceiving still with eyes and ears and nose, man could no longer perceive with heart or liver. To have perception from the Sun with one's heart, or from Jupiter with one's nose, seems like sheer madness to the people of today. Yet it is possible and it is exact and true. Moreover one is well aware why they think it madness.

This living with the Universe, intensively and all-awarely, was lost in course of time. Then Ptolemy conceived a mathematical world-picture still with a little of the old feeling to begin with, yet in its essence already detached from the world. The earlier disciples of the Ptolemaic school still felt, though very slightly, that it is somehow different with the Sun than with Jupiter for instance. Later they felt it no more. In effect the Sun reveals his influence comparatively simply through the heart. Jupiter, we must admit, spins like a wheel in our head,—it is the whirling epicycle. Whilst in a different sense, here indicated (Fig. 1), Venus goes through beneath our heart. In later Ptolemaic times, all they retained of this was the mathematical aspect, the figure of the circle: the simple circle for the Sun's path and the more complicated for the planets. Yet in this mathematical configuration there was at least some remnant of relation to the human being.

Then even this was lost and the high tide of abstraction came. Today we must look for the way back,—to re-establish once again from the entire Man an inner relation to the Cosmos. We have not to go on from Kepler, as Newton did, into still further abstractions. For Newton put abstractions in the place of things more real; he introduced mass etc. into the equations—a mere transformation, in effect, yet there is no empirical fact to vouch for it. We need to take the other road, whereby we enter reality even more deeply then Kepler did. And to this end we must include in our ambit what after all is in its life connected with the rising of the stars across the Heavens, namely the Kingdoms of external Nature in all their variedness of form and kind.

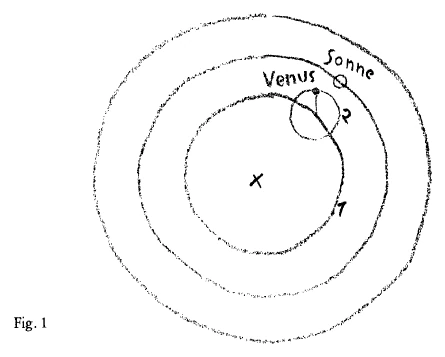

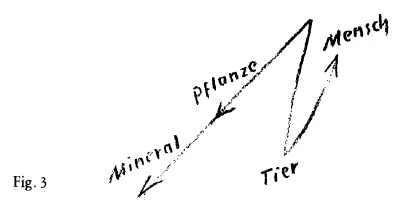

Is it not worthy of note that we find a contrast between the superior planets so-called and the inferior, with the Earth-entity between the mineral and plant kingdoms along the one branch, the animal and man along the other? And, that in drawing the two branches of the forked line, we must put plant and mineral in simple prolongation, while animal and man must be so drawn as to show the formative process returning upon itself? (Fig. 3)

We have put two things and of different kind before us: on the one hand the paths of the epicycle-centres and of the points on the epicyclic circumference, revealing a quite different relation to the Sun for the superior and inferior planets respectively; on the other hand the prolongation of the plant-forming process speeding on into the mineral, whilst the animal-forming process turns back upon itself to become man. (The symbolism of our diagram is justified; as I said yesterday, to recognise it you need only make a study of Selenka's work.)

These two things side by side we put as problems, and we will try from thence to reach a cosmic system true to reality.

Dreizehnter Vortrag

Sie wissen ja, es wird die Entwickelung unserer astronomischen Ansichten so dargestellt in der populären Literatur, daß man sagt, bis zur Zeit des Kopernikus habe geherrscht das ptolemäische Weltensystem, und durch Kopernikus sei dann dasjenige System geistiges Eigentum der zivilisierten Welt geworden, welches wir mit den entsprechenden Modifikationen heute noch anerkennen. Nun wird es für die Betrachtungsweise der folgenden Tage von einer besonderen Wichtigkeit sein, daß wir uns eine gewisse Tatsache heute vor Augen rücken, eine Tatsache, die ich Ihnen nur eben mitteilen will, indem ich Ihnen vorlese ein Zitat des Archimedes über die Anschauung vom Weltensystem, vom Sternensystem des Aristarch von Samos. Archimedes sagt: «Nach seiner Meinung ist die Welt viel größer, als soeben gesagt wurde, denn er setzt voraus, daß die Sterne und die Sonne unbeweglich seien, daß die Erde sich um die Sonne als Zentrum bewege, und daß die Fixsternsphäre, deren Zentrum ebenfalls in der Sonne liege, so groß sei, daß der Umfang des von der Erde beschriebenen Kreises sich zu der Distanz der Fixsterne verhalte wie das Zentrum einer Kugel zu ihrer Oberfläche.»

Wenn Sie diese Worte, die die räumliche Weltanschauung des Aristarch von Samos charakerisieren sollen, nehmen, so werden Sie sich sagen: Zwischen dem räumlichen Weltenbilde des Aristarch von Samos und unserem räumlichen Weltenbilde, wie es sich herausgebildet hat seit der Zeit des Kopernikus, ist absolut gar kein Unterschied. Aristarch von Samos hat ja gelebt im 3. Jahrhundert vor dem Anfang der christlichen Zeitrechnung, so daß wir für diejenigen Menschen, die wie Aristarch von Samos damals auf einem gewissen Gebiete führend waren im geistigen Leben, anzunehmen haben, daß sie durchaus der räumlichen Weltanschauung gehuldigt haben, der heute die Astronomie huldigt. Und es liegt demgegenüber doch die bedeutsame Tatsache vor, daß dann eigentlich im allgemeinen Bewußtsein derjenigen Menschen, die über solche Dinge nachgedacht haben, diese, nennen wir sie heliozentrische, Weltanschauung verschwunden ist, und daß die ptolemäische Weltanschauung an ihre Stelle trat, bis mit dem Heraufkommen desjenigen, was wir ja gewöhnt sind die fünfte nachatlantische Kulturperiode zu nennen, wiederum heraufkommt diese heliozentrische Weltanschauung, die wir finden bei solchen Menschen wie Aristarch von Samos, also im 3. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert. Und Sie werden ja leicht glauben können, daß dasjenige, was für diesen Aristarch von Samos gilt, für viele Menschen gegolten hat. Wer die Entwickelung der geistigen Anschauung der Menschheit studiert, der findet auf einem gewissen Gebiet der menschheitlichen Entwickelung, wenn das auch heute schwierig durch äußerliche Dokumente zu belegen ist, daß diese heliozentrische Weltanschauung gerade um so mehr anerkannt wird von denjenigen, die für diese Anerkennung in Betracht kamen, je weiter man von Aristarch von Samos in frühere Zeiten zurückgeht. Und geht man in diejenige Zeit zurück, die wir gewohnt sind die dritte nachatlantische Zeit zu nennen, so muß man sagen, daß bei den maßgebenden Menschen, bei denjenigen Menschen, die als Autoritäten galten in solchen Dingen, in dieser dritten nachatlantischen Zeit durchaus die heliozentrische Weltanschauung vorhanden war, die Archimedes als bei Aristarch von Samos vorhanden schildert, so schildert, daß wir sie von der heutigen nicht unterscheiden können.

Wir müssen also sagen: Es liegt gerade das Eigentümliche vor, daß die heliozentrische Weltanschauung im menschlichen Denken vorhanden ist, abgelöst wird von dem ptolemäischen System und wiederum zurückerobert wird im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum. Es ist geradezu so, daß das ptolemäische System eigentlich nur maßgeblich ist im wesentlichen für den vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum. Es ist nicht willkürlich, daß ich dieses jetzt gerade einschalte, nachdem ich Sie gestern hingewiesen habe auf einen gewissen ideellen Punkt in der Entwickelungsgeschichte der Naturreiche, sondern wir werden sehen, daß zwischen diesen Tatsachen durchaus ein organischer Zusammenhang waltet. Aber wir werden uns noch etwas nährer befassen müssen gerade mit dieser eben angeführten Tatsache.

Worin besteht denn das Wesentliche des ptolemäischen Weltsystems? Das Wesentliche besteht darin, daß Pfolermäus und die Seinen wiederum zurückgehen auf die Anschauung von der stillstehenden Erde, von der Bewegung des Fixsternhimmels um die Erde herum, ebenso der Bewegung der Sonne um die Erde herum, und daß er für die Bewegungen der Planeten, mit deren Scheinbildern wir uns ja schon befaßt haben, ganz besondere mathematische Formeln aufstellt. Ptolemäus denkt sich im wesentlichen die Sache so, daß, wenn er hier die Erde annimmt, da herum den Fixsternhimmel, daß die Sonne sich in einem exzentrischen Kreis um die Erde herumbewegt. Auch die Planeten bewegen sich im Kreise, aber nicht so, daß er sie einfach wie die Sonne in einen Kreise herumbewegen lassen würde (Fig. 1). Das tut er nicht. Sondern er nimmt einen Punkt an, der sich in diesem exzentrischen Kreise bewegt, den er den «deferierenden Kreis» nennt, und läßt diesen Punkt wiederum den Mittelpunkt eines Kreises sein. Und nun läßt er den Planeten sich bewegen auf diesem Kreise, so daß also der wahre Weg der Planetenbewegung entsteht aus dem Zusammenwirken der Bewegungen in diesem Kreise (1) und auf diesem Kreise (2). Also sagen wir, Ptolemäus nimmt an etwa für die Venus, daß sie wiederum auf einem Kreis (2) rotiert, dessen Mittelpunkt sich in diesem Kreise (1) bewegt, so daß eigentlich der Weg der Venus eine resultierende Bewegung aus diesen zwei Bewegungen wäre. Man hat nötig, um diese Bewegung zu verstehen, diese zwei Kreise anzunehmen: diesen Kreis, den Deferent (1) und den kleinen, der dann der epizyklische Kreis (2) wäre. Solche Bewegungen nimmt Ptolemäus an für Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, Merkur, nicht aber für die Sonne, während er den Mond noch in einem kleinen Kreise, in einem epizyklischen sich bewegen läßt. Es beruhten diese Annahmen darauf, daß die Ptolemäer berechneten - man kann eigentlich nur sagen: sehr sorgfältig berechneten - die Orte am Himmel, in denen sich die Planeten befinden, und daß sie daraus diese Bewegungen zusammensetzten, um zu verstehen, daß die Planeten an einem bestimmten Orte zu einer bestimmten Zeit seien. Es ist erstaunlich, wie genau, relativ genau wenigstens, die Berechnungen der Ptolemäer, des Ptolemäus und seiner Anhänger, in dieser Beziehung eigentlich waren. Es ist so, daß, wenn man zum Beispiel die Bahn irgendeines Planeten, sagen wir des Mars, heute nach unseren gegenwärtigen astronomischen Berechnungen aufzeichnet und vergleicht dann das, was man heute nach den Beobachtungstesultaten als diese sogenannte scheinbare Bahn des Mars aufzeichnen kann mit dem, was man gezeichnet hat mit Zugrundelegung der Theorie der deferierenden und epizyklischen Kreise nach Ptolemäus, so unterscheiden sich diese zwei Kurven kaum. Es ist ein ganz geringfügiger Unterschied, der nur darauf beruht, daß man heute mit genaueren Beobachtungstesultaten rechnet. Also, in bezug auf die Genauigkeit der Beobachtungen waren eigentlich diese Leute nicht weit hinter den heutigen Resultaten zurückgeblieben. Es lag also nicht an ihren Beobachtungen, daß sie dieses merkwürdige System der Planetenbewegungen annahmen, bei dem einem ja vorzugsweise die Kompliziertheit auffällt; denn jeder wird sich natürlich sagen, das kopernikanische System ist wesentlich einfacher. - Da haben wir die Sonne in der Mitte, die Planeten bewegen sich in Kreisen oder Ellipsen um die Sonne herum. Das ist sehr einfach, nicht wahr. Das hier (Fig. 1), das ist sehr kompliziert, da hat man es zu tun mit einer kreisförmigen Bahn, noch einmal ein Kreis, und sogar noch mit einem exzentrischen Kreis.

Nun geht mit einer gewissen Zähigkeit das Festhalten an diesem ptolemäischen System gerade durch die ganze vierte nachatlantische Zeit hindurch, und man muß sich eigentlich fragen: Wodurch unterscheidet sich denn die Art und Weise des Denkens über den Weltenraum und seinen Inhalt bei den Ptolemäern von dem bei Aristarch von Samos und denjenigen, die so dachten wie er? Wodurch unterscheiden sich diese Denkweisen über das Weltsystem? Es ist allerdings schwer, über diesen Unterschied populär zu sprechen, aus dem Grunde, weil ja manches sich äußerlich gleich ausnimmt, aber innerlich durch und durch verschieden ist. Wenn so Archimedes beschreibt das System des Aristarch von Samos, so müssen wir sagen: Dieses heliozentrische System, das ist im Grunde gar nicht von dem kopernikanischen unterschieden. - Wenn wir aber genauer eingehen auf den ganzen Geist des Weltenbildes des Aristarch, so finden wir doch etwas anderes. Auch bei Aristarch von Samos ist ganz gewiß vorhanden ein Verfolgen der äußeren Erscheinungen mit mathematischen Linien. Er stellt durch mathematische Linien sich die Bewegungen der Himmelskörper vor. Die Kopernikaner stellen auch durch mathematische Linien diese Bewegungen der Himmelskörper dar. Dazwischen liegt dieses andere merkwürdige System, das System der Ptolemäer. Man kann nicht sagen, daß da in derselben Weise das mathematische Vorstellen zusammenfällt mit dem, was beobachtet wird.

Sehen Sie, das ist ein durchgreifender Unterschied. Das mathematische Vorstellen lehnt sich nicht an die Folge der Beobachtungspunkte an, sondern das mathematische Vorstellen nimmt sich aus als etwas, was, um den Beobachtungen gerecht zu werden, sich absondert von den Beobachtungen, etwas anderes wird als das bloße Verknüpfen der Beobachtungen, und findet dann, daß man die Beobachtungen verstehen kann, wenn man solche Vorstellungen hat. Denken Sie sich doch einmal, heute würde ein Mensch ein Modell machen von dem Planetensystem, er würde irgendwo die Sonne anbringen, würde Drähte ziehen, welche die Planetenbahnen darstellen, und diese Drähte würden ihm eben auch die Planetenbahnen bedeuten. Er würde also zusammenfassen die Orte der Planeten gewissermaßen durch mathematische Linien. Das hat Ptolemäus nicht getan. Ptolemäus würde sein Modell so konstruieren müssen, daß er etwa hier einen Drehpunkt annimmt, daß er dann hier eine Stange annimmt, am Ende dieser Stange ein Rad drehen läßt, dann hier wiederum ein Rad drehen läßt. So würde er ein Modell machen (Fig.2). Und dasjenige, was er da als Modell macht, was in seinen Vorstellungen lebt als mathematisches Bild, das hat gar keine Ähnlichkeit mit dem, was äußerlich gesehen wird. Das mathematische Bild ist bei ihm etwas anderes als dasjenige, was äußerlich gesehen wird. Und nun kommt man im kopernikanischen System darauf zurück, die einzelnen empirischen Beobachtungsorte wiederum zu verbinden durch die mathematischen Linien, die demselben entsprechen, was bei Aristarch von Samos da war. — Aber ist es dasselbe? Das ist es gerade, was wir fragen müssen: Ist es dasselbe?

Ich glaube, wenn Sie verfolgen, aus welchen Voraussetzungen heraus das kopernikanische System entstanden ist und wie es aufrechterhalten wird, dann werden Sie sich sagen: Das ist so, daß es eigentlich sehr ähnlich ist unserem ganzen mathematischen Verhalten im empirischen Felde. Kopernikus, das läßt sich ja nachweisen, hat zuerst sich so ideell konstruiert das Planetensystem, wie wir ideell ein Dreieck konstruieren, das wir dann in der empirischen Wirklichkeit draußen finden. Er ging also gewissermaßen aus von einer Art a priorischen mathematischen Urteils und wendete das an auf die empirischen Tatsachen.

Was liegt denn aber wohl zugrunde diesem komplizierten System des Ptolemäus, daß es eben so kompliziert wurde? Es war so kompliziert, daß ja, als man es dem bekannten König Alfons von Spanien — Sie kennen ja wohl die Geschichte - vorgelegt hat, der aus seinem königlichen Bewußtsein heraus gesagt hat: Wenn ihn Gott bei der Schöpfung der Welt zu Rate gezogen hätte, so wäre die ganze Welt auf eine einfachere Art entstanden als auf eine solche, wo so viele Zykel und Epizykel nötig sind. In diesem Aufstellen von Zykel und Epizykel ist da etwas darinnen, was doch einen Zusammenhang hat mit einem Wirklichkeitsinhalt? Diese Frage möchte ich einmal vor Sie hinstellen: Ist das wirklich nur etwas phantastisch Ersonnenes, oder ist darin irgend etwas, was doch vielleicht darauf hinweist, daß es sich auf eine Wirklichkeit bezieht, was da ausersonnen ist? Das können wir wohl nur entscheiden, wenn wir auf die Sache etwas genauer eingehen.

Sehen Sie, wenn man verfolgt ganz im Sinne des ptolemäischen Systems, also mit Zugrundelegung der ptolemäischen Theorien die Bewegungen der Sonne, die scheinbaren Bewegungen der Sonne, wie wir sagen, die scheinbaren Bewegungen von Merkur, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, so kann man sagen, die Bewegungswinkel ergeben immer eine gewisse Größe. Und wir können daher die Bewegungen vergleichen, welche die Orte der betreffenden Gestirne am Himmel zeigen. Die Sonne bewegt sich nicht in einem Epizykel. Daher können wir sagen, ihre Tagesbewegung im Epizykel ist gleich Null. Dagegen müssen wir, wenn wir damit vergleichen die Tagesbewegung im Epizykel beim Merkur, sie mit irgendeiner Zahl ansetzen, ich will sie nennen \(x_1\) bei Venus will ich sagen \(x_2\), bei Mars \(x_3\), bei Jupiter \(x_4\), Saturn \(x_5\). Und jetzt wollen wir ins Auge fassen jene Bewegungen, welche die Mittelpunkte der Epizykel im Sinne des ptolemäischen Systems auf den deferierenden Kreisen haben. Nehmen wir für die Sonne \(y\) an, dann stellt sich das Merkwürdige heraus, daß, wenn wir für die Bewegung des Mittelpunktes des Epizykels den Wert aufsuchen für Merkur, so ist er gleich der Bewegung der Sonne. Wir müssen wieder \(y\) ansetzen. Und bei Venus müssen wir auch \(y\) ansetzen. Das heißt: Für Merkur und Venus gilt dieses, daß sich die Mittelpunkte ihrer Epizykel auf Bahnen bewegen, die durchaus zusammenfallen mit der Sonnenbahn, entsprechen der Sonnenbahn, also parallel sind. Dagegen sind die Bewegungen der Mittelpunkte der Epizykel für Mars, Jupiter, Saturn verschieden, sagen wit: \(x’\), \(x’’\), \(x’’’\). Aber das Eigentümliche besteht, daß, wenn ich bilde \(x_3 + x’\), \(x_4 + x’’\), \(x_5 + x’’’\), daß ich dann durch Zusammenzählen der Bewegungen in den Epizykeln und der Bewegungen des Mittelpunktes der Epizykel, also im deferierenden Kereis, für diese Planeten bekomme eine konstante Größe, und zwar dieselbe, die ich bekomme als \(y\) für die Bewegung der Sonne und des Mittelpunktes der Merkur- und Venus-Epizykel:

$$x_3+x’ = y,$$ $$x_4+x’’ = y,$$ $$x_5+x’’’ = y.$$Sie sehen, da ist eine merkwürdige Regelmäßigkeit drinnen! Diese Regelmäßigkeit, die führt uns dazu, in anderer Art anzusehen die kosmische Bedeutung des Mittelpunktes des Epizykels bei Venus und Merkur, die wir also die sonnennahen Planeten nennen, wie bei Jupiter, Mars, Saturn und so weiter, die wir die sonnenfernen Planeten nennen. Bei diesen sonnenfernen Planeten hat der Mittelpunkt des Epizykels nicht dieselbe kosmische Bedeutung. Es ist irgend etwas drinnen, was die ganze Bedeutung des Bahnverlaufs zu einer andern macht als bei den sonnennahen Planeten. Diese Tatsache war gut bekannt den Ptolemäern und sie war mitbestimmend für den ganzen Ausbau dieses merkwürdigen, sich im Geiste von den empirischen Tatsachen loslösenden Zykel- und Epizykel-Gedankens. Sie haben geradezu in einer solchen Tatsache eine Notwendigkeit gesehen, ein solches System aufzustellen. Denn es liegt darin, für den heutigen Menschen mehr oder weniger ganz unausgesprochen, denn der läßt sich einfach erzählen, daß sie die Zykel gebildet haben und so weiter, für diese Leute aber nach ihrer besonderen Art der Anschauung durchaus faßbar der Gedanke: Wenn Merkur und Venus in etwas anderem dieselben Werte haben wie Jupiter, Saturn und Mars, so darf man nicht einfach die Sache so behandeln, daß man von einem gleichmäßigen Umkreis oder so etwas spricht. Denn ein Planet hat eine Bedeutung nicht nur innerhalb seines Raumes, sondern auch noch außerhalb seines Raumes. Er benimmt sich so, daß man nicht bloß auf ihn hinschauen soll, wenn man ihn ins Auge faßt an seinem Ort am Himmel und in seinen Beziehungen zu den andern Himmelskörpern, sondern man muß aus ihm hinausgehen zum Mittelpunkt des Epizykels. Und dieser Mittelpunkt seines Epizykels benimmt sich im Raum so wie die Sonne sich im Raum benimmt. So daß diese Leute sagten, wenn ich das in die moderne Sprache übersetze: Die Epizykelmittelpunkte für Merkur und Venus verhalten sich im kosmischen Raum mit Bezug auf ihre Bewegungen, wie sich die Sonne selbst verhält. Aber die anderen, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn verhalten sich nicht so, sondern die nehmen das Recht für sich in Anspruch, erst dann, wenn man summiert ihre Epizykelbewegungen mit den Bewegungen im deferierenden Kreis, so zu sein in ihren Bewegungen wie die Sonne. Also ihr Verhalten zur Sonne ist ein anderes.

Auf dieses verschiedene Verhalten zur Sonne hat man im ptolemäischen System gebaut, und das ist im wesentlichen ein Grund für die Ausbildung des Systems, weil man eben nicht einfach durch Zusarmmenfassung der empirisch gegebenen Planetenorte in Linien ein Gedankensystem aufbauen wollte, sondern man wollte auf etwas anderes ein Gedankensystem aufbauen. Zugrunde lag eine wirkliche Erkenntnis. Das ist ganz und gar nicht zu leugnen, wenn man sich einfach richtig historisch darauf einläßt. Der heutige Mensch sagt natürlich: Wir haben es mit der kopernikanischen Anschauung so weit gebracht und haben nicht nötig, uns auf diese Geister einzulassen. - Der heutige Mensch läßt sich nicht ein darauf, aber wenn man sich wirklich einläßt, so kommt man darauf, daß die Ptolemäer sich sagten: Ja, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, sie stehen eben in einem anderen Verhältnis zum Menschen als Merkur und Venus; es entspricht anderes im Menschen dem Jupiter, Saturn, Mars als dem Merkur und der Venus. Und sie brachten Jupiter, Saturn und Mars in Zusammenhang mit der Gestaltung des menschlichen Hauptes, dagegen Venus und Merkur mit der Gestaltung desjenigen, was in der menschlichen Organisation unter dem Herzen ist. Besser gesagt als «Haupt» wäre eigentlich, wenn ich sagte: Es wurden zusammengebracht Jupiter, Saturn und Mars mit der Gestaltung alles desjenigen, was über dem Herzen gelegen ist, Venus und Merkur mit demjenigen, was unter dem Herzen gelegen ist im Menschen. Also, sie bezogen schon, diese Ptolemäer, dasjenige, was sie ausdrückten in ihrem System, auf den Menschen.

Und worauf stützte sich denn das? Ich glaube, wenn Sie darüber ein richtiges Urteil gewinnen wollen, so müssen Sie recht sorgfältig den innersten Grundton meiner «Rätsel der Philosophie» lesen, wo ich versuchte herauszugestalten, wie ganz anders die Art, sich erkenntnismäßig zur Welt zu stellen, vor dem 15. Jahrhundert war und nachher. Dieses Sich-Herausschälen aus der Welt, das war erst nach dem 15. Jahrhundert vorhanden, vorher nicht. In diesem Punkte witd man allerdings nicht leicht verständlich der gegenwärtigen Welt. Heute sagen sich die Menschen: Ich denke mir dieses oder jenes über die Welt, habe so oder so meine Sinneswahrnehmungen. Wir sind in der neueren geschichtlichen Entwickelung furchtbar gescheit geworden, früher waren die Menschen dumm, haben allerlei Kindisches sich vorgestellt. - Aber viel anders stellt man sich die Sache doch nicht vor, als daß die Kerle, wenn sie sich früher nur genügend angestrengt hätten, schon ebenso gescheit geworden wären. Es habe nur erst die ganze Entwickelung im Unterricht der Menschheit dauern müssen, daß die Menschen so gescheit geworden sind wie dann später. Darauf nimmt man eben keine Rücksicht, daß das Anschauen selbst, das ganze Sich-Verhalten zur Welt ein anderes war. Wenn Sie die verschiedenen Stufen, die ich ja charakterisiert habe in meinen «Rätseln der Philosophie», vergleichen, so werden Sie sich sagen: Es war wirklich durch die ganze Zeit hindurch vom Beginn der vierten Epoche bis zu ihrem Ende eigentlich eine solche scharfe Trennung von Begriff, Vorstellung und sinnlichen Inhalten nicht wie später. Sie fielen mehr zusammen. Man sah zu gleicher Zeit in der Sinnesqualität das Vorstellungsmäßige. Das wird natürlich immer intensiver, je weiter man in der Zeit zurückgeht. In dieser Beziehung muß man sich wirkliche Vorstellungen machen über die Evolution der Menschheit. Denn sehen Sie, für unsere heutige Zeit ist dasjenige, was Dr.Szein in seinem Buch geschrieben hat über das Wesen der Sinneswahrnehmung, ja ganz ausgezeichnet, aber wenn er dazumal auf der Schule in Alexandrien über desselbe Thema eine Dissertation hätte schreiben sollen, dann würde er ganz anders über die Sinneswahrnehmung haben schreiben müssen. Das will man eben heute nicht anerkennen, in der Zeit, wo wir alles verabsolutieren.

Nun also, wenn wir noch weiter zurückgehen, gar in die ägyptisch-chaldäische Zeit in ihrer Blütezeit, dann finden wir ein noch intensiveres Zusammensein des Begriffes, der Vorstellung mit der äußeren physisch-sinnlichen Realität. Und sehen Sie, aus diesem intensiveren Zusammensein sind die Anschauungen entstanden, die wir zuletzt schon in der Dekadenz bei Aristarch von Samos finden. Bei den Früheren waren sie ja viel mehr vorhanden. Das heliozentrische System fühlte man, als man eben noch ganz und gar mit der Vorstellung drinnen lebte in der äußeren Sinnlichkeit. Und in der vierten nachatlantischen Zeit, vom 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert bis zum 15. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert, da mußte ja der Mensch heraus aus dieser ganzen Sinneswelt, mußte heraus aus diesem Zusammensein mit der Sinneswelt. In welchem Felde konnte er das am besten? Er konnte es am besten da, wo das Zusammenbringen der äußeren Realität mit der Vorstellung scheinbar die allergrößten Schwierigkeiten machte. Da konnte er sich losreißen in bezug auf sein Vorstellen von den sinnlichen Eindrücken.

Wenn wir von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus das ptolemäische System wie ein wichtiges Mittel der menschlichen Erziehung ansehen, dann kommen wir erst auf sein Wesen. Es ist die große Schule des Sich-Emanzipierens der menschlichen Vorstellungen von der sinnlichen Wahrnehmung. Und als diese Emanzipation soweit eingetreten war, daß ein gewisser Grad erreicht wurde im innerlichen Denkenkönnen, was sich später dadurch zeigte, daß solche Geister wie Galilei und die anderen im eminentesten Sinne mathematisch-abstrakt denken, sehr kompliziert mathematisch-abstrakt denken, da konnte Kopernikus kommen und konnte sich gerade diese Tatsachen, diese Beobachtungstesultate von dem Gleichsein des y an verschiedenen Orten vorlegen und konnte daraus dann wiederum zurück von diesen mathematischen Resultaten sein kopernikaniisches Weltensystem konstruieren. Denn das ist aus diesen Resultaten heraus gezeichnet. Das ist also ein Wiederzurückgehen von den abstrakt gefaßten Vorstellungen zu der äußeren, physisch-sinnlichen Wirklichkeit.

Es ist außerordentlich interessant, sich das einmal vorzuhalten, wie gerade im astronomischen Bild die Menschheit sich losreißt von der äußeren Wirklichkeit. Und wenn man sich das vorhält, dann wird man auch eine Möglichkeit gewinnen, in der richtigen Weise zu bewerten die Art, wie wir wiederum auch in umfassenderem Sinne zurück müssen. Aber wie zurück müssen? Kep/er hatte davon noch ein Gefühl. Ich habe öfter einen Ausspruch zitiert, der ganz pathetisch klingt, wo er etwa sagt: Ich habe die heiligen Gefäße der Ägypter aus ihren Tempeln entwendet, um sie den modernen Menschen wiederum zu bringen. - In seinem Planetensystem, das ja bei ihm entsprungen ist aus einer sehr, sehr romantischen Auffassung des Weltenbaues, empfand er so etwas wie eine Erneuerung des alten heliozentrischen Systems in seinem eigenen. Aber dieses alte heliozentrische System war eben nicht aus dem Anschauen mit den Augen heraus gemacht, sondern es war gemacht aus dem Erfühlen desjenigen, was in den Sternen lebte.

Der Mensch, der ursprünglich aufgestellt hat dasjenige Weltensystem, das in Aristartch von Samos’scher Weise die Sonne zum Zentrum macht und die Erde herumkreisen läßt und so weiter, dieser Mensch hat in seinem Herzen die Wirkungen der Sonne gefühlt, in seinem Kopf die Wirkungen von Jupiter, Saturn und Mars, und er hat in seinem Magen und in seiner Leber und seiner Milz die Wirkung von Venus und Merkur gefühlt. Das war reale Erfahrung, und aus dieser realen Erfahrung im ganzen Menschen ist dieses System herausgebildet. Dann verlor man diese umfassende Erfahrung. Man konnte noch wahrnehmen mit den Augen und Ohren und der Nase, aber nicht mehr mit dem Herzen, mit der Leber. So etwas, wie etwas aus der Sonne wahrnehmen mit dem Herzen, etwas aus dem Jupiter wahrnehmen mit der Nase, das ist natürlich der helle Wahnsinn für die Menschen der Gegenwart. Geradeso genau aber kann man so etwas erkennen, wie die andern es für einen Wahnsinn halten, man weiß schon warum. Dieses intensive Miterleben des Weltenalls, das verlor sich im Lauf der Zeit. Und Ptolemäus bildete zunächst ein mathematisches Weltbild heraus, das noch etwas hatte vom alten Fühlen, aber als Qualität, möchte man sagen, sich schon losgelöst hatte. Die Ptolemäer fühlten nur mehr in ihren älteren Zeiten, später gar nicht mehr, sie fühlten nur mehr ganz leise, daß mit der Sonne etwas anderes los ist als zum Beispiel mit dem Jupiter. Die Sonne äußert ihre Wirkung in verhältnismäßig einfacher Weise durch das Herz; der Jupiter geht einem schon wie ein Rad im Kopf herum, worin sich der Epizykel ausdrückt; und in einem anderen Sinn, der hier (Fig.1) charakterisiert ist, geht wiederum die Venus unter dem Herzen durch. Aber von dem hat man nur noch zurückbehalten in dieser Zeit das Mathematische, das man in Kreisform darstellt: das Einfachere, die Sonnenbahn, im Verhältnis zum Komplizierteren der Planetenbahn, aber das doch noch wenigstens in seiner mathematischen Konfiguration in Beziehung zur menschlichen Organisation.

Dann geht das ganz verloren und es tritt die völlige Abstraktion ein. Aber heute muß wiederum der Weg zurück gesucht werden, um vom ganzen Menschen aus wiederum eine Beziehung zum Kosmos herzustellen. Es muß nicht gewissermaßen von Kepler zu einer weiteren Abstraktion gegangen werden, wie es Newior gemacht hat, der Abstraktionen gesetzt hat an die Stelle der Konkretheit, Masse und so weiter eingesetzt hat, was ja nur eine Umformung, eine Transformation ist, wofür aber zunächst gar kein empirischer Tatbestand vorliegt. Es muß der andere Weg eingeschlagen werden, der Weg, wo in die Wirklichkeit noch tiefer hineingegangen wird, als Kepler hineingegangen ist. Dazu muß man aber allerdings nun auch dasjenige betrachten, was ja zusammenhängt mit Auf- und Untergang der Sonne, Sonnenwandel, Sternenwandel und so weiter: die besondere Artung und Gestaltung der Reiche der äußeren Natur. Es ist doch eigentümlich, daß wir einen Gegensatz finden zwischen den sogenannten äußeren Planeten und den inneren Planeten, und in der Mitte finden wir nach heliozentrischer Anschauung die Erdenwesenheit. Und ebenso finden wir in einer ganz merkwürdigen Weise eine Art von Gegensatz, wie wir gestern gesagt haben, zwischen Mineral, Pflanze auf der einen Seite, auf dem einen Ast liegend, und Tier und Mensch wie auf dem anderen Ast liegend, auf der andern Seite. Und wir müssen, wenn wir die Gabelung zeichnen, Pflanze und Mineral in der Fortsetzung zeichnen; wir müssen Tier und Mensch so zeichnen, daß die Bildung in sich selber zurückkehrt (Fig. 3).

So haben wir zweierlei vor uns hingestellt: Dasjenige, was genannt werden kann das besondere Verhältnis der Wege der Epizykelmittelpunkte und der Punkte an den Epizykelumfängen, wodurch ein ganz anderes Verhalten zur Sonne entsteht bei den oberen wie bei den unteren Planeten; und weiter das Fortschreiten im Pflanzenwerden, das Hineinsausen ins Mineralische einerseits, die Tierbildung und die Umkehrung von der Tierbildung zum Menschen andererseits. Sie brauchen, wie ich es schon gestern sagte, nur in der Selenka-Forschung ein wenig sich umzusehen, so werden Sie manches in diesem Symbolischen gerechtfertigt finden.

Diese zwei Dinge wollen wir als Probleme aufstellen und wollen von da aus versuchen, ein wirklichkeitsgemäßes Weltsystem zu bekommen.

Thirteenth Lecture

As you know, the development of our astronomical views is presented in popular literature in such a way that it is said that until the time of Copernicus, the Ptolemaic world system prevailed, and that Copernicus then made the system that we still recognize today, with the appropriate modifications, the intellectual property of the civilized world. Now, for the perspective of the following days, it will be of particular importance that we consider a certain fact today, a fact that I would like to share with you by reading you a quote from Archimedes on the view of the world system, the star system of Aristarchus of Samos. Archimedes says: "In his opinion, the world is much larger than has just been said, for he assumes that the stars and the sun are immovable, that the earth moves around the sun as its center, and that the sphere of fixed stars, whose center also lies in the sun, is so large that the circumference of the circle described by the earth is to the distance of the fixed stars as the center of a sphere is to its surface."

If you take these words, which are supposed to characterize Aristarchus of Samos' spatial worldview, you will say to yourself: There is absolutely no difference between Aristarchus of Samos' spatial worldview and our spatial worldview, as it has developed since the time of Copernicus. Aristarchus of Samos lived in the 3rd century BC, so we must assume that people who, like Aristarchus of Samos, were leaders in intellectual life in a certain field at that time, certainly adhered to the spatial worldview that astronomy adheres to today. And yet, in contrast to this, there is the significant fact that this worldview, which we might call heliocentric, disappeared from the general consciousness of those people who thought about such things, and that the Ptolemaic worldview took its place, until, with the advent of what we are accustomed to calling the fifth post-Atlantean cultural period, this heliocentric worldview reappears, which we find in people such as Aristarchus of Samos, that is, in the 3rd century BC. And you will easily believe that what applies to this Aristarchus of Samos applied to many people. Anyone who studies the development of humanity's spiritual outlook will find that in a certain area of human development, even if it is difficult to prove today with external documents, this heliocentric worldview is recognized all the more by those who were eligible for this recognition, the further back one goes from Aristarchus of Samos into earlier times. And if we go back to the period we are accustomed to calling the third post-Atlantean epoch, we must say that among the influential people, among those who were considered authorities in such matters, the heliocentric worldview was certainly present in this third post-Atlantean epoch, which Archimedes describes as present in Aristarchus of Samos, describes it in such a way that we cannot distinguish it from today's view.

We must therefore say: It is precisely the peculiarity that the heliocentric worldview is present in human thinking, is replaced by the Ptolemaic system, and is recaptured in the fifth post-Atlantean period. It is precisely the case that the Ptolemaic system is actually only relevant for the fourth post-Atlantean period. It is not arbitrary that I am bringing this up now, after pointing out yesterday a certain ideal point in the evolutionary history of the natural kingdoms, but we will see that there is indeed an organic connection between these facts. But we will have to deal with this very fact in more detail.

What is the essence of the Ptolemaic world system? The essence is that Ptolemy and his followers again go back to the view of the stationary Earth, of the movement of the fixed stars around the Earth, as well as the movement of the Sun around the Earth, and that he establishes very special mathematical formulas for the movements of the planets, whose apparent images we have already dealt with. Ptolemy essentially conceives of the matter in such a way that, if he assumes the Earth here, with the fixed stars around it, the Sun moves in an eccentric circle around the Earth. The planets also move in circles, but not in such a way that he would simply have them move in circles like the Sun (Fig. 1). He does not do that. Instead, he assumes a point that moves in this eccentric circle, which he calls the “deferent circle,” and lets this point in turn be the center of a circle. And now he lets the planet move on this circle, so that the true path of the planet's motion arises from the interaction of the motions in this circle (1) and on this circle (2). So let's say that Ptolemy assumes, for example, that Venus rotates on a circle (2) whose center moves within this circle (1), so that the path of Venus is actually a resultant movement from these two movements. In order to understand this motion, it is necessary to assume these two circles: this circle, the deferent (1), and the small one, which would then be the epicyclic circle (2). Ptolemy assumes such motions for Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus, and Mercury, but not for the Sun, while he still has the Moon moving in a small circle, in an epicyclic one. These assumptions were based on the fact that the Ptolemarians calculated—one can only say: very carefully calculated—the locations of the planets in the sky, and that they used this information to reconstruct these movements in order to understand that the planets were at a certain location at a certain time. It is astonishing how accurate, or at least relatively accurate, the calculations of the Ptolemies, Ptolemy and his followers, actually were in this regard. The fact is that if, for example, one records the orbit of any planet, say Mars, today according to our current astronomical calculations and then compare what can be recorded today as the so-called apparent orbit of Mars based on the results of observations with what was drawn based on Ptolemy's theory of deferent and epicyclic circles, these two curves hardly differ. It is a very slight difference, which is only due to the fact that today we calculate with more accurate observation results. So, in terms of the accuracy of their observations, these people were not actually far behind today's results. It was not because of their observations that they adopted this strange system of planetary motion, in which one is struck above all by its complexity; for everyone will naturally say that the Copernican system is much simpler. We have the sun in the center, and the planets move in circles or ellipses around the sun. That is very simple, isn't it? This (Fig. 1) is very complicated; here we are dealing with a circular orbit, another circle, and even an eccentric circle.

Now, with a certain tenacity, adherence to this Ptolemaic system continues throughout the entire fourth post-Atlantean epoch, and one must actually ask oneself: How does the Ptolemies' way of thinking about outer space and its contents differ from that of Aristarchus of Samos and those who thought like him? How do these ways of thinking about the world system differ? It is difficult, however, to speak popularly about this difference, because some things appear the same on the outside but are completely different on the inside. When Archimedes describes the system of Aristarchus of Samos, we must say: this heliocentric system is basically no different from the Copernican one. But if we take a closer look at the whole spirit of Aristarchus' world view, we find something else. Aristarchus of Samos certainly also pursued external phenomena with mathematical lines. He mentally imaged the movements of the celestial bodies using mathematical lines. The Copernicans also represent these movements of the heavenly bodies using mathematical lines. In between lies this other remarkable system, the Ptolemaic system. It cannot be said that the mathematical mental image coincides with what is observed in the same way.

You see, that is a fundamental difference. Mathematical mental image does not rely on the sequence of observation points, but rather mathematical mental image takes itself to be something that, in order to do justice to the observations, separates itself from the observations, becomes something other than the mere linking of observations, and then finds that one can understand the observations if one has such mental images. Just imagine if someone today were to make a model of the planetary system. They would place the sun somewhere, draw wires representing the planetary orbits, and these wires would also represent the planetary orbits. In other words, they would summarize the locations of the planets by means of mathematical lines. Ptolemy did not do this. Ptolemy would have to construct his model in such a way that he assumes a pivot point here, for example, then assumes a rod here, has a wheel turn at the end of this rod, and then has another wheel turn here. That is how he would make a model (Fig. 2). And what he creates as a model, what lives in his mental image as a mathematical image, bears no resemblance to what is seen externally. For him, the mathematical image is something different from what is seen externally. And now, in the Copernican system, we come back to connecting the individual empirical observation points again by means of mathematical lines that correspond to what Aristarchus of Samos had. — But is it the same thing? That is precisely what we must ask: Is it the same thing?

I believe that if you follow the premises from which the Copernican system arose and how it is maintained, you will say to yourself: It is actually very similar to our entire mathematical behavior in the empirical field. Copernicus, as can be proven, first constructed the planetary system in his mind, just as we construct a triangle in our minds, which we then find in empirical reality outside. So, in a sense, he started from a kind of a priori mathematical judgment and applied it to empirical facts.

But what is the basis of this complicated system of Ptolemy, that it became so complicated? It was so complicated that when it was presented to the well-known King Alfonso of Spain—you probably know the story—he said from his royal consciousness: If God had consulted him when creating the world, the whole world would have been created in a simpler way than one that requires so many cycles and epicycles. Is there something in this arrangement of cycles and epicycles that has a connection with reality? I would like to pose this question to you: Is this really just something fantastically imagined, or is there something in it that perhaps indicates that what has been imagined refers to a reality? We can only decide this if we go into the matter in more detail.

You see, if we follow the Ptolemaic system, that is, if we base our understanding on Ptolemaic theories, and observe the movements of the sun, the apparent movements of the sun, as we say, the apparent movements of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, we can say that the angles of movement always result in a certain magnitude. And we can therefore compare the movements shown by the positions of the relevant celestial bodies in the sky. The sun does not move in an epicycle. We can therefore say that its daily movement in the epicycle is zero. On the other hand, when we compare the daily motion in the epicycle of Mercury, we must assign it a number, which I will call \(x_1\); for Venus, I will say \(x_2\); for Mars, \(x_3\); for Jupiter, \(x_4\); and for Saturn, \(x_5\). And now let us consider those movements which the centers of the epicycles have on the deferent circles in the sense of the Ptolemaic system. If we assume \(y\) for the Sun, then the strange thing turns out to be that if we look up the value for Mercury for the movement of the center of the epicycle, it is equal to the movement of the Sun. We must set \(y\) again. And for Venus, we must also set \(y\). This means that for Mercury and Venus, the centers of their epicycles move on paths that coincide completely with the path of the Sun, correspond to the path of the Sun, and are therefore parallel. In contrast, the motions of the centers of the epicycles for Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn are different, say: \(x'\), \(x’’\), \(x’’’\). But the peculiar thing is that if I form \(x_3 + x’\), \(x_4 + x’’\), \(x_5 + x’’’\)—that is, by adding together the motions in the epicycles and the motions of the centers of the epicycles, i.e., in the deferent circle—I obtain a constant quantity for these planets, namely the same quantity that I obtain as \(y\) for the motion of the sun and the centers of the epicycles of Mercury and Venus:

$$x_3+x’=y,$$ $$x_4+x’’=y,$$ $$x_5+x’’’=y.$$You see, there is a strange regularity in this! This regularity leads us to view the cosmic significance of the center of the epicycle in Venus and Mercury, which we call the inner planets, differently from Jupiter, Mars, Saturn, and so on, which we call the outer planets. In the case of these outer planets, the center of the epicycle does not have the same cosmic significance. There is something within it that makes the entire meaning of the orbital path different from that of the planets close to the sun. This fact was well known to the Ptolemies and was a determining factor in the entire development of this remarkable idea of cycles and epicycles, which detached itself from empirical facts. They saw in this fact a necessity to establish such a system. For it lies therein, more or less unspoken for today's people, who simply accept that they formed the cycles and so on, but for these people, according to their particular way of thinking, the idea is quite comprehensible: If Mercury and Venus have the same values as Jupiter, Saturn, and Mars in something else, then one cannot simply treat the matter by speaking of a uniform orbit or something like that. For a planet has a meaning not only within its space, but also outside its space. It behaves in such a way that one should not merely look at it when one observes it in its place in the sky and in its relationships to the other celestial bodies, but one must go beyond it to the center of the epicycle. And this center of its epicycle behaves in space in the same way as the Sun behaves in space. So that these people said, if I translate this into modern language: The centers of the epicycles for Mercury and Venus behave in cosmic space with respect to their movements as the sun itself behaves. But the others, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, do not behave in this way, but claim the right to be like the sun in their movements only when their epicyclic movements are added to the movements in the deferring circle. So their behavior towards the sun is different.

The Ptolemaic system was built on this different behavior in relation to the Sun, and that is essentially one reason for the development of the system, because the aim was not simply to construct a system of thought by summarizing the empirically given planetary locations in lines, but rather to build a system of thought on something else. It was based on real knowledge. This cannot be denied at all if one simply engages with it properly from a historical perspective. Of course, people today say: We have come so far with the Copernican view and do not need to engage with these spirits. People today do not engage with it, but if one really engages with it, one comes to the conclusion that the Ptolemies said to themselves: Yes, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, they are in a different relationship to humans than Mercury and Venus; something else in humans corresponds to Jupiter, Saturn, Mars than to Mercury and Venus. And they brought Jupiter, Saturn, and Mars into connection with the formation of the human head, whereas Venus and Mercury with the formation of what is below the heart in the human organism. Rather than “head,” it would be more accurate to say that Jupiter, Saturn, and Mars were associated with the structure of everything above the heart, and Venus and Mercury with everything below the heart in the human being. So these Ptolemies already related what they expressed in their system to the human being.

And what was this based on? I believe that if you want to form a correct judgment about this, you must read very carefully the innermost tone of my “Riddles of Philosophy,” where I attempted to describe how different the way of approaching the world in terms of knowledge was before the 15th century and after. This separation from the world only existed after the 15th century, not before. On this point, however, it is not easy to understand the present world. Today, people say to themselves: I think this or that about the world, I have my sensory perceptions in this or that way. We have become terribly clever in recent historical development; in the past, people were stupid and mentally imaged all kinds of childish things. But one does not mentally image things to be very different, except that if people in the past had only made enough effort, they would have become just as clever. It just took the whole development in the education of humanity for people to become as intelligent as they later became. People don't take into account that the way of seeing things, the whole attitude toward the world, was different. If you compare the different stages that I have characterized in my “Riddles of Philosophy,” you will say to yourself: Throughout the entire period from the beginning of the fourth epoch to its end, there was not actually such a sharp separation between concept, mental image, and sensory content as there was later. They coincided more. At the same time, one saw the mental image in the sensory quality. Of course, this becomes more and more intense the further back in time one goes. In this respect, one must form real ideas about the evolution of humanity. For you see, what Dr. Szein wrote in his book about the nature of sensory perception is quite excellent for our time today, but if he had had to write a dissertation on the same subject at the school in Alexandria at that time, he would have had to write quite differently about sensory perception. People don't want to acknowledge that today, in an age when we absolutize everything.

Now, if we go back even further, to the heyday of the Egyptian-Chaldean period in its bloom, we find an even more intense coexistence of the concept, the mental image, with external physical-sensory reality. And you see, this more intense connection gave rise to the views that we find most recently in the decadence of Aristarchus of Samos. They were much more prevalent among the ancients. The heliocentric system was felt when people still lived completely within the mental image of external sensuality. And in the fourth post-Atlantean epoch, from the 8th century BC to the 15th century AD, human beings had to leave this whole sensory world behind, had to leave this coexistence with the sensory world. In which field could they do this best? They could do it best where the bringing together of external reality and mental image seemed to cause the greatest difficulties. There they could break away from their mental images about sensory impressions.

If we view the Ptolemaic system from this perspective as an important means of human education, then we can understand its essence. It is the great school of emancipating human mental images from sensory perception. And when this emancipation had progressed to such an extent that a certain degree of inner thinking ability had been achieved, which later manifested itself in the fact that minds such as Galileo and others thought in the most eminent sense mathematically and abstractly, very complicated mathematically and abstractly, Copernicus was able to come along and present precisely these facts, these observational results of the sameness of y in different places, and from these mathematical results he was then able to construct his Copernican world system. For that is what emerges from these results. This is therefore a return from abstract mental images to external, physical, sensory reality. It is extremely interesting to consider how, precisely in the astronomical picture, humanity breaks away from external reality. And when we consider this, we can see how humanity breaks away from external reality.

It is extremely interesting to consider how, particularly in the astronomical image, humanity breaks away from external reality. And if we consider this, we will also gain the ability to correctly assess the way in which we must return in a more comprehensive sense. But how must we return? Kep/er still had a sense of this. I have often quoted a statement that sounds quite dramatic, in which he says something like: I have stolen the sacred vessels of the Egyptians from their temples in order to bring them back to modern man. In his planetary system, which arose from a very, very romantic conception of the structure of the world, he felt something like a renewal of the old heliocentric system in his own. But this old heliocentric system was not made from what could be seen with the eyes, but was made from a feeling for what lived in the stars.

The person who originally established the world system that, in the manner of Aristarchus of Samos, places the sun at the center and has the earth revolve around it, and so on, felt the effects of the sun in his heart, the effects of Jupiter, Saturn, and Mars in his head, and the effects of Venus and Mercury in his stomach, liver, and spleen. That was real experience, and this system was developed from this real experience in the whole human being. Then this comprehensive experience was lost. People could still perceive with their eyes, ears, and nose, but no longer with their heart or liver. Something like perceiving something from the sun with the heart, perceiving something from Jupiter with the nose, is of course pure madness for people today. But it is precisely this kind of thing that one can recognize, even though others consider it madness, and one knows why. This intense experience of the universe was lost over time. And Ptolemy initially developed a mathematical worldview that still had something of the old feeling, but as a quality, one might say, it had already detached itself. The Ptolemies only felt in their older times, later not at all, they only felt very quietly that something different was going on with the sun than, for example, with Jupiter. The sun expresses its effect in a relatively simple way through the heart; Jupiter goes round and round in one's head like a wheel, expressing the epicycle; and in another sense, which is characterized here (Fig. 1), Venus passes under the heart. But all that has been retained from this in our time is the mathematical aspect, which is represented in circular form: the simpler aspect, the path of the sun, in relation to the more complicated aspect of the path of the planets, but at least still in its mathematical configuration in relation to the human organism.

Then this is completely lost and complete abstraction sets in. But today, we must once again seek the way back, in order to reestablish a relationship between the whole human being and the cosmos. We must not, in a sense, go from Kepler to a further abstraction, as Newton did, who replaced concreteness with abstractions, mass and so on, which is only a transformation, but for which there is initially no empirical evidence. We must take the other path, the path that goes even deeper into reality than Kepler did. To do this, however, we must also consider what is connected with the rising and setting of the sun, the changing of the sun, the changing of the stars, and so on: the special nature and form of the realms of outer nature. It is peculiar that we find a contrast between the so-called outer planets and the inner planets, and in the middle, according to the heliocentric view, we find the Earth. And in a very remarkable way, we also find a kind of contrast, as we said yesterday, between minerals and plants on the one side, lying on one branch, and animals and humans on the other side, lying on the other branch. And when we draw the fork, we must draw plants and minerals in the continuation; we must draw animals and humans in such a way that the formation returns to itself (Fig. 3).

So we have two things before us: That which can be called the special relationship between the paths of the epicycle centers and the points on the epicycle circumferences, whereby a completely different behavior toward the sun arises in the upper planets than in the lower planets; and further, the progression in becoming a plant, the rushing into the mineral on the one hand, the formation of animals and the reversal from the formation of animals to humans on the other. As I said yesterday, you only need to look a little into Selenka's research to find much of this symbolism justified.

Let us pose these two things as problems and try from there to arrive at a realistic world system.