Third Scientific Lecture-Course:

Astronomy

GA 323

14 January 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture XIV

Today we will develop the different notes we touched on,—the notes which we were striking yesterday. From the material at our disposal, consisting as it does in the last resort of things observed, the true aspect of which we seek to divine,—from this observed material we shall try to gain ideas, to lead us into the inner structure of the celestial phenomena. I will first point to something that will naturally follow on the more historical reflections of yesterday.

We realise that in the last resort both the Ptolemaic system and that used by modern Astronomy are attempts to synthesise in one way or another, what is observed. The Ptolemaic system and the Copernican are attempts to put together in certain mathematical or kindred figures what has in fact been perceived. (I say “perceived”, for in the light of yesterday's lecture it would not be enough to say “seen”.) All our geometry in this case, all of our measuring and mathematizing, must take its start from things perceived, observed. The only question is, are we conceiving the observed facts truly? We must really take it to heart—we must take knowledge of the fact—that in the scientific life and practice of our time what is observed, what is perceivable, is taken far to easily, too cursorily for a true conception to be gained.

Here for example is a question we cannot escape; it springs directly from the observable facts—(In the shortness of time these lectures have to be in bare outline and I have not been able to discuss or even to bring forward all the details. I could do little more than indicate directions.) Now among other things I have tried to show that the movements of heavenly bodies in celestial space must in some way be co-ordinated with what is formed in the living human body, and in the animal too in the last resort, we should by now perceive from the whole way the facts have been presented. And I assure you, the more deeply you go into the facts, the more of the connection you will see. Nevertheless, I have not done nor claimed to do any more than indicate the pathway (let me say again), the pathway along which you will be led to the result: The human living body, also the animal and plant body, are so formed that if we recognise the characteristic lines of form (as for example we did in tracing the Lemniscate in various directions though the human body) we find in them a certain likeness to the line-systems which we are able to draw amid the movements of the celestial bodies. Granted it is so, the question still remains however: What is it due to? How does it come about? What prospect is there for us not merely to ascertain it but to find it cogent and transparent, inherent in the very nature of things?

To get nearer to this question we must once more compare the kind of outlook which under-lay the Ptolemaic system and the kind that underlies the Copernican world-system of today.

What are we doing when we set to working the spirit of the latter system, and by dint of thinking, calculating and geometrising, figure out a world-system? What do we do in the first place? We observe. Out in celestial space we observe bodies which, from the simple appearance of them, we regard as identical. I express myself with caution, as you see. We have no right to say more than this . From the appearance of them to our eye, we regard these bodies (in their successive appearance) as identical. A few simple experiments will soon oblige you to be thus cautious in relating what you see in the outer world. I draw your attention to this little experiment; of no value in itself, it has significance in teaching us to be careful in the way we form our human thoughts.

Suppose it trained a horse to trot very regularly,—which, incidentally, a horse will do in any case. Say now I photograph the animal in twelve successive positions. I get twelve pictures of the horse. I put them in a circle, at a certain distance from myself, the onlooker. Over it all I put a drum with an aperture, and make the drum rotate so that I first see one picture of the horse, then, when the drum has totalled, a second picture, and so on. I get the appearance of a running horse, I should imagine a little horse to be running round in a circle. Yet the fact is not so. No horse is running round; I have only been looking in a certain way at twelve distinct pictures of a horse, each of which stays where it is.

You can therefore evoke an appearance of movement not only by perspective but in purely qualitative ways. It does not follow that what appears to be a movement is really a movement. He then who wants to speak with care, who wants to reach the truth by scrupulous investigation, must begin by saying, whimsical as this may seem to our learned contemporaries: I look at three successive positions of what I call a heavenly body, and assume what underlies them to be identical. So for example I follow the Moon in its path, with the underlying hypothesis that it is always the same Moon. (That may be right without question, with such a “Standard” phenomenon, keeping so very regular a time-table!) What do we do then? We see what we take to be the identical heavenly body, in movement as we call it; we draw lines to unite what we thus see at different places, and we then try to interpret the lines. This is what gives the Copernican system. The school from which the Ptolemaic system derived did not proceed in this way, not originally. At that time the whole human being still lived in his perceiving, as I said yesterday. And inasmuch as man was thus alive and aware, perceiving with all his human being, the idea he then had of a heavenly body was essentially different from what it afterwards became.

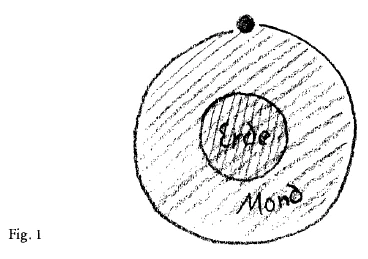

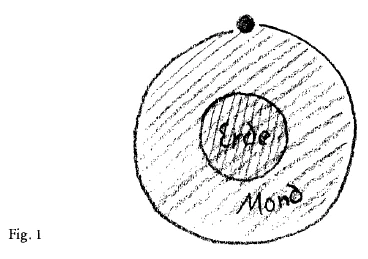

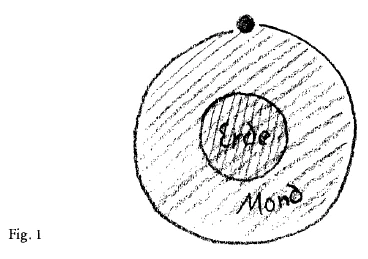

A man who still lived thus perceivingly amid the Ptolemaic system did not say. There is the Moon up yonder. No, he did not; the people of today only attribute that idea to him, nor does it do the system justice. If he had simply said, "Up yonder is the Moon", he would have been relating the phenomenon to his whole human being, and in so doing the following was his idea:—Here am I standing on the Earth. Now, even as I am on the Earth, so too am I in the Moon,—for the Moon is here (Figure 1, lightly shaded area).

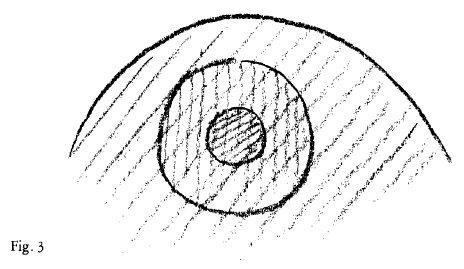

This (the small central circle in the Figure) is the Earth, whilst the whole of that is the Moon,—far greater than the Earth. The diameter (or semi-diameter) of the Moon is as great as what we now call the distance of the Moon (I must not say, of the Moon's centre) from the centre of the Earth. So large is the Moon, in the original meaning of the Ptolemaic system. Elsewhere invisible, this cosmic body at one end of it develops a certain process by virtue of which a tiny fragment of it (small outer circle in the Figure) becomes visible. They rest is invisible, and moreover of such substance that one can live in it and me permeated by it. Only at this one end of it does it grow visible. Moreover, in relation to the Earth the entire sphere is turning, (Incidentally it is not a perfect sphere, but a spheroid or ellipsoid-of-rotation. The whole of it is turning and with it turns the tiny reagent that is visible, i.e. the visible Moon. The visible Moon is only part of the full reality of it.

The idea thus illustrated really lived in olden time. The form at least, the picture it presents, will not seem so entirely remote if you think of an analogy,—that of the human or animal germ-cell in its development (Fig. 2).

You know what happens at a certain stage. While the rest of the germinal vesicle is well-nigh transparent, at one place it develops the germinative area, so called, and from this area the further development of the embryo proceeds. Eccentrically therefore, near the periphery, a centre forms, from which the rest proceeds. Compare the tiny body of the embryo with this idea of the Moon which underlay the Ptolemaic system and you will have a notion of how they conceived it for it was analogous to this.

In the Ptolemaic conception of the Universe, we may truly say, quite another reality was ‘Moon’—mot only what is contained in the Moon's picture, the illuminated orb we see. This, then, is what happened to man after the time when the Ptolemaic system was felt as a reality. The inner experience, the bodily organic feelings of being immersed in the Moon was lost. Today man has the mere picture before him, the illuminated orb out yonder. Man of the Fifth post-Atlantean Epoch cannot say, for he no longer knows it: “I am in the Moon,—the Moon pervades me”. In his experience the Moon is only the little illuminated disc or sphere which he beholds.

It was from inner perceptions such as these that the Ptolemaic system of the Universe was made: These perceptions we can henceforth regain if we begin by looking at it all in the proper light: we can re-conquer the faculty whereby the whole Moon is experienced. We must admit however, it is understandable that those who take their start from the current idea of ‘the Moon’ find it hard to see any such inner relation between this “Moon” and life inside them. Nay, it is surely better for them to reject the statement that there are influences from the Moon affecting man than to indulge in so many fantastic and unfounded notions.

All this is changed if in a genuine way we come again to the idea that we are always living in the Moon, so that what truly deserves the name of 'Moon' is in reality a realm of force, a complex of forces that pervades us all the time. Then it will no longer be a cause of blank astonishment that this complex of forces should help form both man and beast. That forces working in and permeating us should have to do with the forming and configuration of our body, is intelligible. Such then are the ideas we must regain. We have to realise that what is visible in the heavens is nor more than a fragmentary manifestation of cosmic space, which in reality is ever filled with substance. Develop this idea: you live immersed in substance—substances manifold, inter-related. Then you will get a feeling of how very real a thing it is. The accepted astronomical outlook of our time has replaced this 'real' by something merely thought-out, namely by 'gravitation' as we call it. We only think there is a mutual force of attraction between what we imagine to be the body of the moon and the body of the Earth respectively. This gravitational line of force from the one to the other—we may imagine it as it turns to get a pretty fair picture of what was called the 'sphere' in ancient astronomical conceptions—the Lunar sphere or that of any planet. This, then, has happened: What was once felt to be substantial and can henceforth be experienced in this way once more, has in the meantime been supplanted by mere lines, constructed and thought-out.

We must then think of the whole configuration of cosmic space—manifoldly filled and differentiated in itself—in quite another way than we are wont to do. Today we go by the idea of universal gravitation. We say for instance that the tides are somehow due to gravitational forces from the Moon. We speak of gravitational force proceeding from a heavenly body, lifting the water of the sea. The other way of thought would make us say: The Moon pervades the Earth, including the Earth's hydrosphere. In the Moon's sphere, something is going on which at one place it manifests in a phenomenon of light. We need not think of any extra force of attraction. All we need think is that this Moon-sphere, permeating the Earth, is one with it, one organism all together , an organic whole. In the two kinds of phenomenon we see two aspects of a single process.

In yesterday's more historical lecture my object was to lead you up to certain notions,—essential concepts. I could equally well have tried to present them without recourse to the ideas of olden time, but to do so we should have had to take our start from premises of Spiritual Science. This would have led us to the very same essential concepts.

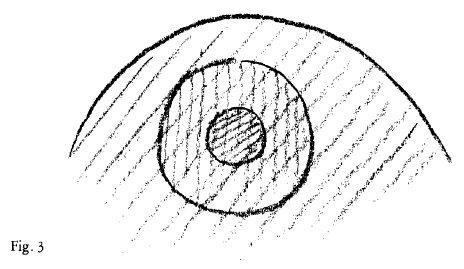

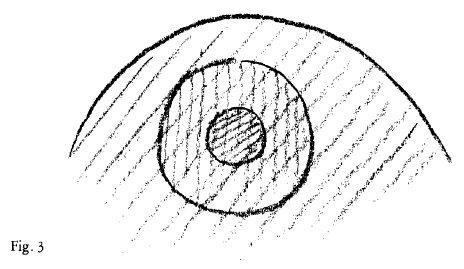

Imagine now (Fig. 3): Here is the Earth-sphere,—the solid sphere of Earth. And now the Lunar sphere: I must imagine this, of course, of very different consistency and kind of substance. And now I can go further. The space that is permeated by these two spheres,—I can imagine it permeated by a third sphere and a fourth. Thus in one way or another I imagine it to be permeated by a third sphere. It might for instance be the Sun-sphere,—qualitatively different form the Moon-sphere.

I then say I, am permeated—I, man, am permeated by the sun—and by the Moon-sphere. Moreover naturally there is a constant interplay between them. Permeating each other as they do, they are in mutual relation. Some element of form and figure in the human body is then an outcome of the mutual relation. Now you will recognise how rational it is to see the two things together: On the one hand, these different cosmic substantialities permeating the living body; and on the other hand the organic forms in which you can well imagine that they find expression. Form and formation of the body is then the outcome of this permeation. And what we see in the heavens—the movement of heavenly bodies—is like the visible sign. Certain conditions prevailing, the boundaries of the several spheres become visible to us in phenomena of movement.

What I have now put before you is essential for the regaining of more real conceptions of the inner structure of our cosmic system. Now you can make something of the idea that the human organisation is related to the structure of the cosmic system. You never gain a clear notion of it if you conceive the heavenly bodies as being far away yonder in space. You do gain a clear notion, the moment you see it as it really is. Though, I admit, it gets a little uncanny to feel yourself permeated by so many spheres,—just a little confusing!

And there is worse to come, for the mathematician at least. In effect, we are also permeated by the Earth-sphere itself, in a wider sense. For to the Earth belongs not only the solid ball on which we stand but all the volume of water; also the air,—this is a sphere in which we know ourselves to be immersed. Only the air is still very coarse, compared to the effects of heavenly phenomena. Think then of this: Here we are in the Earth-sphere, in the Sun sphere, in the Moon-sphere, and in others too. But let us single out the three, and we shall say to ourselves: Something in us is the outcome of the substantialities of these three spheres. Here then is qualitatively, what in its quantitative form is the mathematician's bugbear—the “problem of three bodies”, as it is called! It is working in us. In us is the outcome of it, in all reality. We must face the truth: to read the hieroglyphic of reality is not so simple. That we are wont to take it simply and think it so convenient of access, springs after all from our fond comfort,—human indolence of thought. How many things, held to be "scientific", have their origin in this! Let go the springs of comfortableness, and you must set to work with all the care which we have tried to use in these lectures. If now and then, they do not seem careful enough, it is again because they are given in barest outline; so we have often had to jump from one point to another and you yourselves must look for the connecting links. The links are surely there.

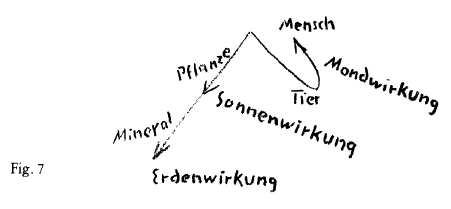

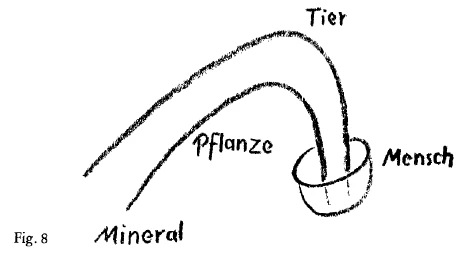

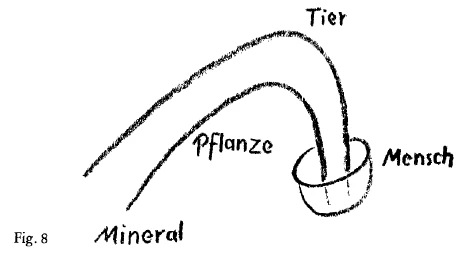

Now you must set to work with equal care to tackle the same problem from another aspect to which I have referred before, namely the body of man compared to the creatures of the remaining Nature-kingdoms. We can imagine, I said, a line that forks out on either hand from an ideal starting-point. Along the one branch we put the plant-world, along the other the animal. If we imagine the evolution of the plant-world carried further in a real Kingdom of Nature, we find it tending towards the mineral. How real a process it is, we may recall by the most obvious example. In the mineral coal, we recognised a mineralised plant-substance. What should detain us from turning attention to the analogous processes which have undoubtedly taken hold of other realms of vegetable matter? Can we not also derive the siliceous and other mineral substances of the Earth in the same way, recognising in them the mineralisation of an erstwhile plant-life?

Not in the same way (I went on to say) can we proceed if we are seeking the relation of the animal to the human kingdom. Here on the contrary we must imagine it somewhat as follows. Evolution moves onward through the animal kingdom; then however it bends back, returns upon itself, and finds physical realisation upon a higher than animal level. We may perhaps put it this way: Animal and human evolution begin from a common starting—point, but the animal goes farther before reaching outward physical reality. Man on the other hand keeps at an earlier stage, man makes himself physically real at an earlier stage. It is precisely by virtue of this that he remains capable of further evolution after birth, incomparably more so then the animal. (For, once again, the processes of which we speak relate to embryo-development.) That man retains the power to evolve, is due to his not carrying the animal-forming process to extremes. Whilst in the mineral, the plant-forming process has overreached itself; in man on the contrary the animal-forming process has stopped short of the extreme. It has withheld, kept back, and taken shape at an earlier stage amid external Nature.

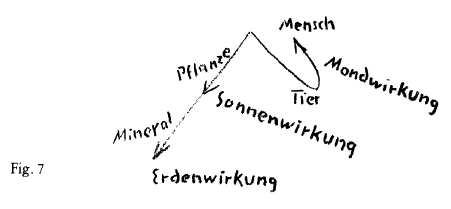

We have then this ideal point from which it branches (Fig. 6). There is the shorter branch and the longer. The longer is of undetermined length; the other, we may say, no less so, but negatively speaking. So then we have the mineral and plant kingdoms, and animal and human.

Now we must seek to gain a more precise idea: What is it that really happens, in this formation of man as compared to the animal? The process of development, once more, is kept back in man. It does not go so far; that which is tending to realisation is, as it were, made real before its time. Now think how it must be imagined according to what I have told you in these lectures. Study the share of the Solar entity in the forming of the animal body,—via the embryo-development, of course. You then know that the direct sunshine (so to describe it) has to do with the configuration of the animal head, whilst the indirect aspect of the sunlight, as it were the Sun's shadow by relation to the Earth, has in some way to do with the opposite pole of the creature. Strictly envisage this permeation of animal form and development with cosmic Sun-substantiality. Look at the forms as they are. Then you will gain a certain idea, which I shall try to indicate as follows.

Assume to begin with,—assume that in some way the forming of the animal is really brought about by relation to the Sun. And now, apart from the constellation that will be effective in each case as between Sun and animal, let us ask, quite in the sense of the Sun's light in the cosmos, not so immediately connected with the Sun itself? There is indeed. For every time the Full Moon, or the Moon at all, shines down upon us, the light is sunlight. The cosmic opportunity is being made then, so to speak, for the Sun's light to ray down upon us. It is so of course also when the human being comes into life—in the germinal and embyonal period. In earlier stages of Earth-evolution the influence was most direct; today it is a kind of echo, inherited from then. Here then again we have an influence, in the other it is indirect, through the raying back of the Sun's light by the Moon.

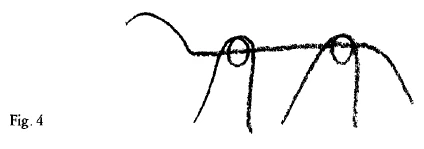

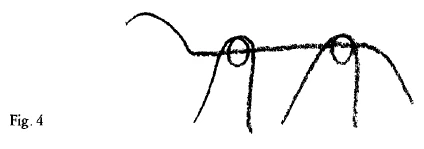

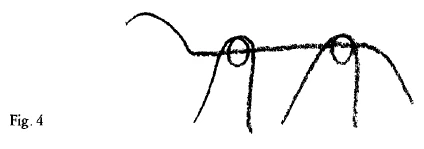

Now think the following. I will again draw it diagrammatically. Suppose the development of the animal were such that it comes into being under the Sun's influence according to this diagram (Fig. 4).

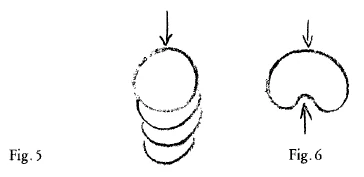

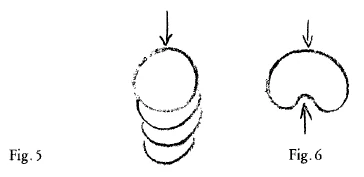

This then, to put it simply, would be the ordinary influence of day and night—head and the opposite pole of the creature. This, for the animal, would be the ordinary working of the Sun. Now take that other working of the Sun's light which occurs when the Moon is in opposition, i.e. when it is Full Moon,—when the Sun's light, so to speak works from the opposite side and by reflection counteracts itself. If we conceive this downward arrow (Fig. 5).

to represent the direction of the direct Sun-rays, animal formations, we must imagine animal-formation going ever farther in the sense of this direct Sun-ray. The animal would become animal, the more the Sun was working on it. If on the other hand the Moon is counteracting from the opposite direction—or if the Sun itself is doing so via the Moon,—something is taken away again from the animal-becoming process. It is withdrawn, drawn back into itself (Fig. 5a).

Precisely this withdrawal corresponds to the shortening of the second branch in Figure 6. We have found a true cosmic counterpart of the characteristic difference between man and animal of which we spoke before.

What I have just been telling you can be perceived directly by anyone who gains the faculty for such perception. Man really owes it to the counteracting of the Sunlight via the Moon.—owes it to this that his organisation is withheld from becoming animal. The influence of the Sun-light is weakened in its very own quality (for it is Sun-light in either case), in that the Sun places its own counterpart over against itself, namely the Moon and the Moon's influence. Were it not for the Sun meeting and countering itself in the Moonlight—influences, the tendency that is in us would give us animal form and figure. But the Sun's influence reflected by the Moon counteracts, it. The forming process is held in check, the negative of it is working; the human form and figure is the outcome.

Now, on the other branch of the diagram, let us follow up the plant and the plant-formative process. That the Sun is working in the plant, is palpably evident. Let us imagine the Sun's effect in the plant, not to be able to unfold during a certain time. During the Winter, in fact, the springing and sprouting life in the plant cannot unfold. Nay, you can even see the difference in the unfolding of the plant by day and night. Now think of this effect in oft-repeated rhythm, repeated endless times,—what have we then? We have the influence of the Sun and the influence of the Earth itself; the latter when the Sun cannot work directly but is hidden by the Earth. At one time the Sun is working, at another it is not the Sun but the Earth, for the Sun is working from below and the Earth is in the way. We have the rhythmic alternation: Sun-influence predominant, Earth-influence predominant in turn. Plant-nature therefore is alternately exposed to the Sun, and then withdrawn, figuratively speaking, into the Earth—drawn by the earthly, as it were, into itself. This is quite different from what we had before. For in this case the Sun-quality, working in the plant, is potently enhanced. The solar quality is actually enhanced by the earthly, and this enhancement finds expression in that the plant gradually falls into mineralization.

Such then is the divergence of two ways, as indicated once again in Figure 6. In the plant we have to recognize the Sun's effect, carried still further by the Earth, to the point of mineralization. In the animal we have to recognize the Sun's effect, which then in man is drawn back again, withdrawn into itself, by virtue of the Moon's effect. I might also draw the figure rather differently, like this (Fig. 6a),

—here receding to become human, here on the other hand advancing to become mineral, which of course ought to be shown in some other form. It is no more than a symbolic figure, but this symbolic figure, tends to express more clearly than the first, made of mere lines, the bifurcation—as again I like to call it—with the mineral and plant kingdoms upon the one hand, the human and animal upon the other.

We never do justice to the true system of Nature with all her creatures and kingdoms if we imagine them in a straight line. We have to take our start from this other picture. In the last resort, all systems of Nature which begin with the mineral kingdom and thence going on to the plant, thence to the animal and thence to man as if in a straight line, will fail to satisfy. In this quaternary of Nature we are face to face with a more complex inner relationship than a mere rectilinear stream of evolution, or the like, could possibly imply. If one the other hand we take our start from this, the true conception, then we are led, not to a generatic aequivoca or primal generation of life, but to the ideal centre somewhere between animal and plant—a centre not to be found within the physical at all, yet without doubt connected with the problem of three bodies, Earth, Sun and Moon. Though perhaps mathematically you cannot quite lay hold on it, yet you may well conceive a kind of ideal centre-of-gravity of the three bodies—Sun, Moon and Earth. Though this will not precisely solve you the 'problem of three bodies', yet it is solved, namely in Man. When man assimilates in his own nature what is mineral and animal and plant, there is created in him in all reality a kind of ideal point-of-intersection of the three influences. It is inscribed in man, and that is where it is beyond all doubt. Moreover inasmuch as it is so, we must accept the fact that what is thus in man will be empirically at many places at once, for it is there in every human being,—every individual one. Yes, it is there in all men, scattered as they are over the Earth; all of them must be in some relation to Sun and Moon and Earth. If we somehow succeeded in finding an ideal point-of-intersection of the effects of Sun and Moon and Earth, if we could ascertain the movement of this point for every individual human being, it would lead us far indeed towards an understanding of what we may, perhaps, describe as movement, speaking of Sun and Moon and Earth.

As I said just now, the problem grows only the more involved, for we have so many points,—as many as there are men on Earth,—for all of which points we have to seek the movement. Yet it might be, might it not, that for the different human beings the movements only seemed to differ, one from another ...

We will pursue our conversations on these lines tomorrow.

Vierzehnter Vortrag

Wir werden heute die gestern angeschlagenen Töne unserer Betrachtung in der Weise fortsetzen, daß wir versuchen werden aus dem Material, das ja schließlich zusammengesetzt ist aus Beobachtungen der Himmelserscheinungen, hinter deren wahre Gestalt wir zu kommen suchen, versuchen werden Vorstellungen zu gewinnen, die uns in das Gefüge der Himmelserscheinungen hineinführen können. Da möchte ich noch einmal zunächst auf etwas hinweisen, was aus der gestern anfänglich mehr historisch gehaltenen Betrachtung folgen kann.

Wir müssen ja uns klar sein darüber, daß schließlich sowohl das ptolemäische Weltensystem wie auch dasjenige, das in der gegenwärtigen Astronomie gebräuchlich ist, Versuche darstellen, dasjenige in irgendeiner Weise zusammenzufassen, was sich der Beobachtung darbietet. Und ein Versuch, dasjenige, was man wahrgenommen hat - Sie wissen, ich kann nach dem gestern Ausgeführten nicht sagen: «gesehen» hat -, in gewissen Mathematik-ähnlichen Figuren zusammenzufassen, der liegt sowohl im ptolemäischen System vor wie auch schließlich im kopernikanischen System. Denn dasjenige, was zugrunde gelegt werden muß einer jeglichen Geometrie oder einem jeglichen Rechnen und Messen, sind ja schließlich doch eben die Beobachtungen. Und um das richtige Auffassen des beobachtbaren Tatbestandes kann es sich ja im Grunde einzig und allein handeln. Aber man muß sich schon einmal vertraut machen mit der Erkenntnistatsache, daß im heutigen wissenschaftlichen Leben dasjenige, was beobachtet, was wahrgenommen werden kann, viel zu leicht hingenommen wird, um eine entsprechende Ansicht darüber wirklich zu gewinnen.

Es muß sich ja für uns zunächst eine Frage aufwerfen, die unmittelbar aus den beobachtbaren Tatsachen erfließt. Natürlich, ich konnte nicht alle Einzelheiten in diesen Vorträgen, die so skizzenhaft wie möglich sein müssen wegen der Kürze der Zeit, auch wirklich vorführen und durchsprechen. Ich konnte nur die Richtungen angeben. Aber in diesem Angeben der Richtungen habe ich versucht, Sie darauf hinzuweisen, daß den Bewegungen der Himmelskörper im Himmelsraum in irgendeiner Weise zugeordnet sein muß dasjenige, was gestaltet ist im menschlichen Organismus, ja schließlich auch im tierischen, im pflanzlichen Organismus. Es muß da einen Zusammenhang geben. Daß es einen solchen Zusammenhang geben muß, das kann man ersehen aus der Art und Weise, wie wir die Tatsachen betrachtet haben. Und je weiter Sie auf die Tatsachen eingehen würden, desto mehr würden Sie diesen Zusammenhang eben sehen. Ich wollte Sie nur auf den Weg, ich sage das noch einmal, hinweisen, auf dem zum Schluß das Ergebnis gefunden werden kann: Dieser menschliche und auch der tierische, der pflanzliche Organismus, sie sind so gestaltet, daß, wenn man diese Gestalt linienhaft ins Auge faßt, wie wir es getan haben, indem wir zum Beispiel den Verlauf der Lemniskate nach den verschiedenen Richtungen hin im Organismus uns vor die Seele geführt haben, daß man dann zunächst etwas Ähnliches findet zwischen dieser Gestaltung und denjenigen Liniensystemen, die man ziehen kann, wenn man die Bewegungen der Weltenkörper ins Auge faßt. Dann aber entsteht die Frage: Ja, wodurch ist denn dieser Zusammenhang eigentlich bedingt? Welche Möglichkeit gibt es denn, diesen Zusammenhang sich wirklich als einen durchsichtigen, als einen in sich begründeten, vor Augen zu führen? Und um dieser Frage näherzutreten, müssen wir die besondere Anschauungsart, die dem ptolemäischen Weltensystem zugrunde liegt, vergleichen mit derjenigen Anschauungsart, die unserem heutigen kopernikanischen Weltensystem zugrunde liegt.

Was tun wir denn, wenn wir im Sinne des heutigen kopernikanischen Weltsystems uns denkend, rechnend, geometrisierend ein Weltensystem zurechtlegen? Wir beobachten. Wir beobachten Körper im Himmelstaum, die wir einfach nach dem Augenschein als identisch ansehen können. Sie sehen, ich drücke mich sehr vorsichtig aus. Mehr dürfen wir aber auch nicht sagen, als daß wir diese Körper dem Augenschein nach als identisch ansehen. Derjenige, der gewisse, ganz einfache Experimente macht, der wird nämlich durchaus zu solcher Vorsicht in der Ausdrucksweise gegenüber der Außenwelt aufgefordert. Ich mache Sie auf folgendes kleine Experiment aufmerksam, das an sich keinen Wert hat, sondern das nur eine Bedeutung hat zur Heranbildung gewisser Vorsichten im menschlichen Vorstellungsleben.

Denken Sie sich einmal, ich würde ein Pferd in einer gewissen Weise abrichten, so daß, indem es fortläuft, es eine gewisse Regelmäßigkeit der Schrittentfaltung hat - das hat ja ein Pferd sogar immer - und ich würde jetzt zwölf aufeinanderfolgende Stellungen des Pferdes photographieren. Ich würde also zwölf Bilder des Pferdes bekommen. Diese zwölf Bilder des Pferdes, die würde ich so anordnen, daß sie in einem Kreise angeordnet sind, vor dem ich in einer gewissen Entfernung als Beobachter mich befinde. Und jetzt würde ich hier drüber eine Trommel geben, welche ein Loch hat, eine Trommel, die ich ins Rotieren bringe, so daß ich zunächst nur ein Bild des Pferdes sehe, dann, wenn die Trommel weitergelaufen ist im Rotieren, sehe ich das nächste Bild und so weiter. Ich werde das Scheinbild bekommen eines herumlaufenden Pferdes. Ich werde meinen, ein kleines Pferdchen läuft da im Kreis herum. Und dennoch, der reale Tatbestand, der da zugrunde liegt, ist nicht der, daß da ein reales Pferd herumläuft, sondern der, daß zwölf Pferdebilder von mir in einer gewissen Weise angeschaut sind, von denen jedes eigentlich an seinem Ort bleibt.

Sie sehen also, ich kann nicht nur den Schein einer Bewegung im perspektivischen Sinn hervorrufen, ich kann auch den Schein einer Bewegung durchaus in qualitativer Weise hervorrufen. Es muß nicht alles, was wie eine Bewegung erscheint, eine Bewegung auch wirklich sein. Daher muß schon derjenige, der vorsichtig sprechen will und erst durch sorgfältige Untersuchung zur Wahrheit kommen will, eben zunächst sagen, so sonderbar und paradox es unseren ja so gescheiten Zeitgenossen klingt: Ja, ich betrachte drei aufeinanderfolgende Lagen desjenigen, was ich einen Himmelskörper nenne, so, daß ich dasjenige, was da zugrunde liegt, für identisch hinnehme. Das heißt: Ich verfolge den Mond in seiner Bahn und lege dabei zunächst hypothetisch das zugrunde, daß es immer derselbe Mond ist. Das ist durchaus richtig, aber nur gegenüber einer so progredierenden Erscheinung. Was tun wir also? Wir sehen dasjenige, was wir für identische Himmelskörper nehmen, in einer sogenannten Bewegung, verbinden, was wir an verschiedenen Orten sehen, in Linien und versuchen diese Linien zu interpretieren. Das ist dasjenige, was uns das kopernikanische Weltensystem gibt.

In einer solchen Weise ist nicht vorgegangen ursprünglich diejenige Schule, aus der das ptolemäische Weltensystem hervorgegangen ist. Man lebte noch immer wahrnehmend im ganzen Menschen, wie ich Ihnen gestern angedeutet habe. Und weil man noch wahrnehmend im ganzen Menschen lebte, war auch die ganze Vorstellung, die man da hatte gegenüber einem Himmelskörper, eine wesentlich andere, als sie später geworden ist. Derjenige, der noch im wahrnehmenden Sinne das ptolemäische Weltensystem vor sich hatte, der sagte nicht: Der Mond steht da oben. Das sagte er eben nicht, das interpretiert man nur jetzt hinein ins Weltensystem. Er sagte eben nicht: Der Mond ist da oben, denn da hätte er die Erscheinung bloß auf das Auge bezogen. Das tat er nicht, er bezog die Erscheinung auf den ganzen Menschen und meinte das so: Hier stehe ich auf der Erde, und ebenso wahr wie ich auf der Erde stehe, stehe ich auch im Mond drinnen, denn der Mond, das ist das da (Fig.1, S. 254 schraffierte Fläche). Das ist die Erde und das Ganze ist der Mond, der ja viel größer ist als die Erde. Der ist nämlich im Radius so groß, wie dasjenige ist, was wir jetzt nennen die Entfernung des Mondes, ich kann nicht sagen des Mondmittelpunktes, von dem Erdenmittelpunkt. So groß ist der Mond im Sinne des ptolemäischen Weltensystems, wie es ursprünglich ausgebildet worden ist. Und dieser Körper, der sonst überall unsichtbar ist, der entwickelt an dem einen Ende einen Vorgang, durch den dieses kleine Stückchen sichtbar wird. Alles andere ist unsichtbar und ist außerdem von solcher Substantialität, daß man drinnen leben kann, daß man von ihm durchdrungen wird. Nur an diesem einen Ende, da wird es sichtbar. Und im Verhältnis zur Erde dreht sich diese ganze Sphäre, die übrigens nicht eine Sphäre ist, sondern ein Rotations-Ellipsoid, und damit dreht sich dasjenige, was da das sichtbare Stückchen ist, also dasjenige, was der sichtbare Mond ist. Das ist nur ein Teil der vollen Wirklichkeit, mit der man es hier zu tun hat.

Es wird Ihnen dasjenige, was da auftritt als eine Vorstellung, die wirklich da war, in seinem Formbild nicht so schrecklich paradox erscheinen, wenn Sie ein Analogon sich vor die Seele führen. Führen Sie sich das Analogon der menschlichen oder tierischen Keimzelle vor das Auge (Fig.2). Sie wissen, in einem gewissen Stadium der Entwickelung bildet sich an der einen Stelle des sonst im wesentlichen durchsichtigen Eikeimes der sogenannte Fruchthof, und von dem Fruchthof geht die Bildung des übrigen Embryos aus. Also exzentrisch, peripher bildet sich ein Mittelpunkt, von dem dann die übrige Bildung ausgeht. Wenn Sie dieses kleine Körperchen vergleichen mit demjenigen, was hier als Vorstellung dem ptolemäischen Weltensystem zugrunde liegt zum Beispiel vom Monde, dann haben Sie Vorstellungen von demjenigen, was man da durchaus analog dachte. So daß man sagen kann: Im Sinne dieser ptolemäischen Weltauffassung ist eben noch eine ganz andere Wirklichkeit vorhanden als diejenige ist, welche nur eingeschlossen ist innerhalb des Lichtbildes des Mondes.

Das ist dasjenige, was eingetreten ist mit dem Menschen seit jener Zeit, da das ptolemäische Weltensystem als eine Realität empfunden wurde: Das innerliche Erleben, das innerliche Fühlen im Organismus, daß man da drinnen ist im Monde, das hat sich ganz verloren, und man ist beschränkt worden auf das Lichtbild. Der Mensch des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes kann nicht sagen, weil er es nicht mehr weiß: Ich stehe im Mond drinnen, respektive der Mond durchdringt mich, weil für ihn der Mond nur die kleine Lichtscheibe oder Lichtkugel oder Kugel überhaupt ist. Aus solch innerlichen Wahrnehmungen heraus wurde das ptolemäische Weltensystem konstruiert. Nun, auf diese Wahrnehmungen kommt man ja auch heute wieder, wenn man die Dinge im richtigen Licht betrachtet, wenn man sich zurückerobert die Möglichkeit, wiederum den ganzen Mond zu erleben. Aber es bleibt durchaus begreiflich, daß derjenige, der heute von der gebräuchlichen Vorstellung «der Mond» ausgeht, nun sagt: Ja, ich kann nicht recht fassen, was da eigentlich für ein Bezug sein sollte zwischen dem Mond und irgend etwas in mir. Und es ist wirklich schließlich noch besser, wenn die Leute absprechend urteilen über irgend etwas, was vom Mond ausgeht und auf den Menschen einen Einfluß hat, als wenn sie sich darüber allerlei phantastische Vorstellungen machen. Sobald aber wiederum die Vorstellung eine real entsprechende wird, daß wir ja im Mond drinnen leben, daß also das, was Mond genannt werden kann, ein Kraftzusammenhang ist, der uns fortwährend durchdringt, dann braucht nicht mehr Verwunderung darüber einzutreten, daß dieser Kraftzusammenhang auch gestaltend im Menschen auftritt und im Tier, daß wirklich dasjenige, was da uns durchdringend wirkt, eben etwas ist, was mit dem Gestalten unseres Organismus etwas zu tun hat. Solche Vorstellungen also sind es, die wir uns wiederum zurückerobern müssen. Wir müssen uns durchaus klar sein darüber, daß der sichtbare Himmel eben durchaus nur eine fragmentarische Offenbarung des wirklichen, substanzerfüllten Weltenraumes ist.

Wenn Sie nun die Vorstellung entwickeln, Sie leben so in einem Substanz-Zusammenhang drinnen, so werden Sie das Gefühl haben: Das ist etwas sehr, sehr Reales. Wir haben es aber heute in unserer gebräuchlichen astronomischen Anschauung durch etwas Erdachtes ersetzt. Wir haben es ersetzt durch dasjenige, was wir die Gravitation nennen. Wir finden nur, daß eine gegenseitige Anziehungskraft desjenigen, was wir als Körper des Mondes und was wir als Körper der Erde denken, stattfindet. Diese Gravitationslinie, die könnten wir uns rotierend denken, dann würden wir ungefähr aus dem Bilde, das entsteht durch diese rotierende Gravitationslinie, das herausbekommen, was in früheren astronomischen Ansichten die Sphäre genannt worden ist, die Sphäre irgendeines Planeten. Es ist im Grunde nichts anderes geschehen, als daß dasjenige, was substantiell empfunden worden ist und nun auch wiederum substantiell erlebt werden kann, in gedachte Linien verwandelt worden ist.

Sie sehen, wir müssen uns also die ganze Konfiguration der differenzierten Weltenraumerfüllung anders denken, als wir das gewohnt sind. Wir richten uns heute nach den Gravitationsvorstellungen, zum Beispiel sagen wir, daß Ebbe und Flut zusammenhängen mit gewissen vom Mond ausgehenden Gravitationskräften. Wir reden davon, wie da eine Gravitation vom Weltenkörper ausgeht und das Wasser hebt. Im Sinne jener anderen Vorstellungsweise müssen wir sagen, der Mond durchdringt auch die Erde, und indem er die wässerige Erdensphäre durchdringt, spielt sich etwas ab, was hier an dieser Stelle als Wassererhebung sich abspielt; an einer andern Stelle gibt sich die Mondensphäre als Lichterscheinung kund. Wir brauchen nicht zu denken, daß da eine besondere Anziehungskraft vorhanden ist, sondern wir denken, daß gewissermaßen diese die Erde durchdringende Mondensphäre mit der Erde zusammen eine Organsiation bildet, und wir sehen in den zwei Vorgängen bloß zwei Seiten eines Vorganges.

Ich habe die historische Betrachtungsweise von gestern nur zu Hilfe genommen, um Sie auf gewisse Begriffe zu führen. Ich hätte ebenso gut den Versuch machen können, diese Begriffe ganz ohne Anlehnung an ehemalige Vorstellungen zu gewinnen, aber da hätte ja die ganze Betrachtung von geisteswissenschaftlichen Voraussetzungen ausgehen müssen, aus denen heraus man zu denselben Vorstellungen kommen würde.

Stellen Sie sich nun hier die Erdensphäre vor (Fig.3). Ich stelle dasjenige, was die feste Erdkugel ist, als Erdensphäre vor. Natürlich muß ich mir in wesentlich anderer Konsistenz und Substantialität nun die Mondensphäre vorstellen. Ich kann natürlich auch dasjenige, was rauminhaltlich durchdrungen ist von diesen zwei Sphären, von einer dritten, vierten Sphäre durchdrungen denken. Also ich denke in irgendeiner Weise das durchdrungen von einer dritten Sphäre, das würde die Sonnensphäre sein können, die qualitativ innerlich verschieden ist von der Mondensphäre. Ich bin also durchdrungen, sage ich, als Mensch von der Sonnen- und Mondensphäre. Die stehen natürlich in einem Wechselverhältnis, indem sie sich durchdringen, und der Ausdruck dieser Wechselbeziehung ist irgend etwas im Organismus Gestaltetes. Und jetzt werden Sie darauf kommen, daß man schließlich zusammenschauen kann dasjenige, was in dieser Weise in verschiedener Substantialität durchdringt den Organismus, und das, was seinen Ausdruck finden kann in der Gestaltung; daß die Gestaltung einfach das Ergebnis ist dieser Durchdringung. Und dasjenige, was wir dann als Bewegungen der Himmelskörper sehen, das ist gewissermaßen das Zeichen, das Sichtbarwerden unter gewissen Verhältnissen der Grenze dieser Sphären. Das ist etwas, was zunächst durchaus notwendig ist, um wiederum zu realeren Vorstellungen über den Bau unseres Weltensystems zu kommen. Und Sie können jetzt schon etwas Wirklicheres als früher mit der Idee verbinden, daß die menschliche Organisation etwas zu tun hat mit diesem Bau des Weltensystems. So lange man da draußen die Himmelskörper sieht, so lange wird man keine sehr klaren Vorstellungen gewinnen können über diese Zusammenhänge. In dem Augenblick; wo man übergeht zu dem Wirklichen, kann man diese klare Vorstellung gewinnen, wenn auch natürlich die Dinge anfangen, etwas verwirrend zu werden, weil es so viele Sphären gibt, von denen man durchdrungen ist, so daß man tatsächlich ja etwas unangenehm von all diesem Durchdringen des Organismus berührt werden kann.

Die Sache wird aber noch schlimmer, möchte ich sagen. Wir sind zunächst ja von der Erdensphäre in einer gewissen, sogar erweiterten Weise durchdrungen, denn zur Erde gehört ja nicht nur die feste Erdkugel, auf der wir stehen, sondern auch die Wassermasse; es gehört aber auch die Luft, in der wir ja schon drinnen sind, dazu. Das ist schon eine Sphäre, in der wir da drinnen sind. Diese Luft, sie ist nur im Verhältnis zu demjenigen, was die Himmelserscheinungen bewirken, noch etwas sehr Grobes. Nun denken Sie sich also, wir stehen in der Erdensphäre drinnen, wir stehen in der Sonnensphäre drinnen, in der Mondensphäre und noch in vielen anderen. Aber wir wollen nur die drei einmal herausheben und uns also sagen: Irgend etwas in uns ist das Ergebnis der Substantialitäten dieser drei Sphären. Wir haben qualitativ jetzt etwas, was, wenn es quantitativ auftritt, der Mathematiker mit einem gewissen Horror empfindet, dasjenige, was er das Problem der drei Körper nennt. Das aber wirkt in seinem Ergebnis, in seiner Realität, in uns. Wir müssen uns dadurch klarwerden, daß das wirkliche Entziffern der Realität, der Wirklichkeit keine einfache Sache ist, und daß die Gewöhnung, in einfacher, bequemer Weise die Wirklichkeit aufzufassen, eigentlich wirklich nur ihren Ursprung hat in der menschlichen Denkbequemlichkeit. Und vieles von dem, was eben als wissenschaftlich gilt, hat nur seinen Ursprung in dieser menschlichen Denkbequemlichkeit. Sieht man von ihr ab, dann muß man eben so vorsichtig zu Werke gehen, wie wir das in diesen Vorträgen versuchten, die nur manchmal deshalb nicht vorsichtig genug aussehen, weil gesprungen werden mußte skizzenhaft von dem einen zum andern, so daß Sie sich selbst die Verbindungen suchen müssen; sie sind aber da.

Nun müssen wir aber ebenso vorsichtig vorgehen, wenn wir dasselbe Problem von einer anderen Seite anfassen wollen, auf die ich auch schon aufmerksam gemacht habe, nämlich von der Seite des menschlichen Organismus selbst im Vergleich mit den Wesen der anderen Naturreiche. Ich habe Ihnen gesagt, wir können uns vorstellen eine Gabelung, von einem ideellen Punkte ausgehend. Auf dem einen Aste haben wir dann zu verzeichnen die Pflanzenwelt, auf dem andern Ast die Tierwelt. Wenn wir uns das Werden der Pflanzenwelt fortgesetzt denken im wirklichen Naturreich, so kommen wir in das Mineralisieren des Pflanzenreiches hinein. Das werden wir uns ja durchaus als einen realen Vorgang vorstellen können, wenn wir es am gröbsten Beispiel anfassen. Wir treffen heute die mineralische Steinkohle und sehen in ihr mineralisiertes Pflanzliches. Was sollte uns denn abhalten davon, auf analoge Vorgänge, die sich abgespielt haben für anderes Pflanzenartiges, hinzuschauen und, sagen wir, die kieseligen und sonstigen Bestandteile der mineralischen Erdsubstanz aus dem Mineralisieren des Pflanzlichen abzuleiten?

Nicht in derselben Weise, sagte ich, können wir vorgehen, wenn wir die Beziehungen suchen des Tierreiches zum Menschenreich. Da müssen wir gewissermaßen uns vorstellen, die Entwickelung rückt im Tierreich vor, neigt sich aber dann auf sich selbst zurück und realisiert sich physisch auf früherer Stufe als diejenige des Tieres ist. So daß man gewissermaßen sagen kann: Die tierische und die menschliche Bildung marschiert von einem gemeinsamen Punkte aus. Das Tier geht aber weiter, bevor es äußerlich physisch real wird; der Mensch hält sich auf einer früheren Stufe zurück und macht sich auf dieser Stufe physisch real. Dadurch ist es ja möglich - denn diese Vorgänge müssen wir auf die Embryonal-Entwickelung beziehen -, daß der Mensch noch in ganz anderem Maße als das Tier entwickelungsfähig bleibt, nachdem er geboren ist. Im Mineral ist die pflanzliche Bildung über das Extrem des Pflanzlichen hinausgegangen; im Menschen wird die tierische Bildung nicht bis zum Extrem getrieben, sondern in sich zurückbehalten und auf einer früheren Stufe die äußere Ausgestaltung von der Natur vorgenommen. So daß wir eben diesen ideellen Punkt bekommen, von dem aus sich gabelt in einen längeren, unbegrenzt langen Ast und in einen kürzeren, in sich auch von der negativen Seite unbestimmten Ast: Pflanzenreich, Mineralreich; Tierreich, Menschenteich.

Nun handelt es sich darum, eine gewisse Vorstellung zu gewinnen von dem, was da eigentlich vorliegt mit dieser Bildung des Menschen im Verhältnis zur Bildung des Tieres. Zurückgehalten also ist die Entwickelung beim Menschen, gewissermaßen vorzeitig real gemacht ist dasjenige, was sich realisieren will. Wenn man studiert in der Weise, wie der Vorgang vorgestellt werden muß nach dem, was ich Ihnen bereits in diesen Vorträgen mitgeteilt habe, wenn man studiert den Anteil, den die Sonnenentität hat bei der Bildung des Tierkörpers - natürlich immer auf dem Umwege durch die Embryonalbildung -, so weiß man, daß gewissermaßen der direkte Sonnenschein etwas zu tun hat mit der Konfiguration des tierischen Kopfes, das Indirekte des Sonnenlichtes, also ich möchte sagen der Sonnenschatten im Verhältnis zur Erde, etwas zu tun hat mit dem polarischen Gegenteil des tierischen Kopfes. Wenn wir nun ins Auge fassen ganz stramm dieses Durchdringen der tierischen Bildung mit der kosmischen Sonnensubstanttalität und die Formen ins Auge fassen, dann werden wir damit eine Vorstellung verbinden lernen, die ich in der folgenden Weise vor Sie hinzeichnen möchte. Nehmen Sie einmal an, die tierische Bildung wird in irgendeiner Weise bewirkt im Zusammenhang mit der Sonne. Nun, nehmen wit jetzt eine gebräuchliche astronomische Vorstellung und fragen wir uns im Sinne dieser Vorstellung: Gibt es außer dem, was da durch besondere Konstellation eben vorliegen wird als Wirkungsweise zwischen Sonne und Tier, irgendwo die Möglichkeit einer Wirkung des Sonnenlichtes im Kosmos, die nicht so ohne weiteres mit der Sonne selbst zusarnmenhängt? Ja, die gibt es. Jedesmal, wenn uns der Vollmond bescheint oder überhaupt nur der beleuchtete Mond, so scheint uns das Sonnenlicht an. Da wird uns gewissermaßen kosmisch die Möglichkeit geschaffen, daß das Sonnenlicht uns bestrahlt. Das ist natürlich auch beim werdenden Menschen, in der Keimeszeit, der Embryonalzeit der Fall und war der Fall in früheren Erdenstadien so, daß es damals eine direkte Wirkung war. Das, was heute als Nachklang da ist, ist eben vererbt. Da haben wir also wiederum ein Sonnenwirken, einmal direkt und einmal ein indirektes, im Rückstrahlen des Sonnenlichtes vom Monde her.

Und nun stellen Sie sich das Folgende vor. Stellen Sie sich einmal vor, wenn ich es wiederum schematisch zeichnen will, beim Tiere läge es mit der Entfaltung, dem Werden des Tieres so, daß es unter dem Eindruck der Sonnenwirkungen nach diesem Schema entstünde (Fig.4). Ich möchte sagen, das wäre die gewöhnliche Tag- und Nachtwirkung, also Kopf und polarer Gegensatz des Kopfes. Das wäre die gewöhnliche Sonnenwirkung beim Tier. Und jetzt nehmen wir einmal jene Wirkung des Sonnenlichtes, die auftritt, wenn der Mond in Opposition steht, wenn Vollmond ist, wenn also gewissermaßen von der Gegenseite her das Sonnenlicht wirkt, durch die Reflexion sich entgegenwirkt. Wenn wir dieses (Pfeil senkrecht nach unten in Fig.5) als die Richtung für die tierischen Bildungen der direkten Sonnenstrahlen denken, so müßten wir uns vorstellen, die tierische Bildung ginge immer weiter im Sinne dieses direkten Sonnenstrahles (Fig.5), und es würde ein Tier immer mehr und mehr Tier, je mehr die Sonne auf es wirkt. Wenn aber von der Gegenseite her der Mond entgegenwirkt, beziehungsweise die Sonne auf dem Umweg des Mondes, dann wird von dem Tierwerden weggenommen, es wird in sich zurückgenommen (Fig.6). Das entspricht der Verkürzung des zweiten Gabelastes, dieses Zurücknehmen (Fig. 7). Sie sehen also, wir bekommen ein kosmisches Korrelat für dasjenige, was ich Ihnen als eine gewisse Charakteristik für den Unterschied des Menschen mit dem Tier gegeben habe.

Dasjenige, was ich Ihnen da jetzt gesagt habe, das ist unmittelbar wirklich wahrzunehmen für den, der sich die Möglichkeit verschafft, solche Dinge wahrzunehmen. Der Mensch verdankt tatsächlich dieses Zurückhalten seiner Organisation der Gegenwirkung des Sonnenlichtes auf dem Umweg des Mondes. Es wird die Wirkung des Sonnenlichtes dadurch, und zwar die eigene Qualität - es ist ja immer Sonnenlicht - abgeschwächt, indem sich die Sonne selbst in der Mondwirkung ein Gegenbild entgegenstellt. Würde sie sich nicht selber entgegenstellen in der Mondenlichtwirkung, so würde das, was als Bildungstendenz in uns liegt, uns die tierische Gestalt geben. So wirkt das entgegen, was eben Sonnenwirkung, reflektiert vom Monde, ist. Die Bildung wird angehalten, indem das Negative wirkt, und die Menschengestalt ist die Folge.

Verfolgen wir nun auf dem anderen Gabelast die Pflanze in ihrer Bildung und stellen wir uns vor dasjenige, was in der Pflanze Sonnenwirkung ist - daß eine Sonnenwirkung da ist, ist ja handgreiflich -, das würde sich nicht entfalten können zu einer gewissen Zeit. Es kann sich ja während des Winters dasjenige nicht entfalten, was in der Pflanze sprießendes, sprossendes Leben ist. Man sieht schon den Unterschied in der Entfaltung der Pflanze, wenn man einfach den Unterschied von Tag und Nacht ins Auge faßt. Aber denken Sie sich nun diese Wirkung, die immer im Rhythmus abläuft, in unbegrenzter Anzahl wiederholt, möchte ich sagen, was haben wir dann eigentlich? Wir haben Wirkung der Sonne, und Eigenwirkung der Erde, wenn die Sonne also nicht direkt wirkt, sondern von der Erde bedeckt ist. Die Sonne wirkt; die Sonne wirkt wiederum nicht, sondern die Erde, wenn die Sonne von unten wirkt, die Erde ihr entgegenliegt. Wir haben also den Rhythmus: Sonnenwirkung vorwiegend; Erdenwirkung vorwiegend. Wir haben also das Pflanzliche ausgesetzt abwechselnd der Sonne und dann wiederum hineingezogen, bildhaft ausgedrückt, in das Irdische, gewissermaßen vom Irdischen in sich gezogen. Wir haben da etwas anderes. Wir haben im letzten Falle eine wesentliche Verstärkung desjenigen, was in der Pflanze als das Sonnenhafte wirkt, und diese Verstärkung des Sonnenhaften durch das andere, Erdhafte, das drückt sich dadurch aus, daß die Pflanze allmählich dem Mineralisierungsprozeß verfällt. So daß wir also sagen müssen: Wir gabeln so, daß wir in bezug auf die Pflanze Sonnenwirkung sehen, fortgesetzt durch die Erde zur Mineralisierung; Sonnenwirkung im Tiere, in sich zurückgenommen durch die Mondenwirkung im Menschen (Fig.7). Ich könnte auch diese Figur noch etwas anders zeichnen, dann würde sie diese Gestalt bekommen können (Fig.8): hier zum Menschlichen zurückgehend; hier zum Mineralischen, das natürlich in einer anderen Form sein müßte, votschreitend. Es ist zunächst ja nur eine symbolische Figur, aber diese symbolische Figur drückt uns in einer gewissen Weise klarer als die erste Figur, die bloß in Linien da ist, dasjenige aus, was ich diese Gabelung nennen möchte zwischen dem Mineralreich und Pflanzenreich auf der einen Seite und dem menschlichen und tierischen Reich auf der anderen Seite.

Man wird niemals gerecht einer Systematik der Naturwesen, wenn man sie nur gradlinig vorstellt, wenn man nicht diese Vorstellung zugrunde legt. Daher werden alle Natursysteme immer unbefriedigend ausfallen, die bloß in gradliniger Weise vom Mineralreich angefangen zum Pflanzenreich übergehen, dann zum Tierreich, dann zum Menschen. Es handelt sich darum, daß man es, wenn man diese Vierheit darstellt, mit einem viel komplizierteren Zusammenhang zu tun hat als mit einem solchen, der bloß etwa in einer gradlinigen Entwickelungsströmung und dergleichen läge. Wenn man von einer solchen Vorstellung ausgeht, wird man ganz gewiß nicht zu irgendeiner generatio aequivoca, zu irgendeiner Urzeugung geführt, sondern zu diesem ideellen Mittelpunkt, der irgendwo zwischen Tier und Pflanze liegt, der überhaupt nicht im Physischen gefunden werden kann, der aber ganz gewiß einen Zusammenhang hat mit dem Problem der drei Körper: Erde, Sonne, Mond. Wenn Sie also auch vielleicht nicht mathematisch vorstellbar haben dasjenige, was man sich vorstellen könnte als eine Art von ideellem Schwerpunkt der drei Körper Sonne, Mond und Erde, wenn Sie auch damit das Problem der drei Körper nicht gut lösen können - im Menschen ist es gelöst! Indem der Mensch Mineralisches, Tierisches, Pflanzliches in sich verarbeitet, ist in ihm tatsächlich dasjenige geschaffen, was eine Art ideeller Durchschnittspunkt der drei Wirkungen ist. Es ist in ihm eingezeichnet, es ist ganz zweifellos da. Und weil es da ist, hat man sich damit abzufinden, daß gerade dasjenige, was da im Menschen ist, ganz gewiß empirisch an verschiedenen Orten ist, weil es in jedem einzelnen Menschen ist, in allen Menschen, die über die ganze Erde zerstreut sind, so daß sie in einer gewissen Beziehung stehen müssen zu Sonne, Mond und Erde. Und wenn es in einer gewissen Weise gelingt, eine Art ideellen Durchschnittspunkt zu finden von Sonnen-, Mond- und Erdenwirkung, und man die Bewegung dieses Punktes für jeden einzelnen Menschen finden könnte, dann würde uns das wesentlich weiter führen zu dem Begreifen desjenigen, was wir vielleicht Bewegung nennen können in bezug auf Sonne, Mond und Erde.

Aber, wie gesagt, hier wird das Problem eigentlich nur verwickelter, weil wir so viele Punkte haben, als Menschen auf der Erde sind, für die wir die Bewegungen suchen müssen. Aber es könnte ja sein, daß diese Bewegungen für die verschiedenen Menschen nur scheinbar verschieden sind. Darüber wollen wir uns dann morgen weiter unterhalten.

Fourteenth Lecture

Today we will continue the lines of thought we began yesterday by attempting to gain mental images from the material, which is ultimately composed of observations of celestial phenomena, whose true nature we are seeking to uncover. We will attempt to gain mental images that can lead us into the structure of celestial phenomena. First, I would like to point out something that can be deduced from yesterday's initially more historical considerations.We must be clear that both the Ptolemaic world system and the one commonly used in contemporary astronomy are attempts to summarize in some way what is presented to observation. And an attempt to summarize what has been perceived—you know, after what I said yesterday, I cannot say “seen”—in certain mathematical-like figures is present both in the Ptolemaic system and ultimately in the Copernican system. For what must be taken as the basis of any geometry or any calculation and measurement is, after all, observation. And it can really only be a matter of correctly understanding the observable facts. But we must first familiarize ourselves with the fact that in today's scientific life, what can be observed and perceived is too easily accepted in order to really gain a corresponding view of it.

First of all, we must ask ourselves a question that arises directly from the observable facts. Of course, I could not really present and discuss all the details in these lectures, which had to be as sketchy as possible due to the limited time available. I could only indicate the directions. But in indicating these directions, I have tried to point out to you that what is formed in the human organism, and ultimately also in the animal and plant organisms, must in some way be related to the movements of the heavenly bodies in the heavens. There must be a connection. That such a connection must exist can be seen from the way in which we have considered the facts. And the more you delve into the facts, the more you will see this connection. I just wanted to point you in the direction, I say this again, in which the result can ultimately be found: the human organism, and also the animal and plant organisms, are designed in such a way that, if one considers this design in terms of lines, as we have done, for example, by visualizing the course of the lemniscate in different directions in the organism, one then finds something similar between this design and the systems of lines that can be drawn when considering the movements of the celestial bodies. But then the question arises: What actually causes this connection? How can we really visualize this connection as something transparent, something that is self-evident? And in order to approach this question, we must compare the particular way of thinking that underlies the Ptolemaic world system with the way of thinking that underlies our current Copernican world system.

What do we do when we construct a world system in the spirit of today's Copernican world system by thinking, calculating, and geometrizing? We observe. We observe bodies in the sky that we can simply regard as identical based on their appearance. You see, I am expressing myself very cautiously. But we cannot say more than that we consider these bodies to be identical based on their appearance. Anyone who conducts certain very simple experiments will be called upon to exercise such caution in their expressions to the outside world. I would like to draw your attention to the following small experiment, which has no value in itself, but which is only significant in terms of developing certain precautions in human imagination.

Imagine that I were to train a horse in such a way that, as it runs, it has a certain regularity of stride – which a horse always has – and that I were now to photograph twelve consecutive positions of the horse. I would then have twelve pictures of the horse. I would arrange these twelve pictures of the horse in a circle, in front of which I would stand at a certain distance as an observer. And now I would place a drum with a hole in it over this, a drum that I would set in rotation, so that at first I would only see one picture of the horse, then, as the drum continued to rotate, I would see the next picture, and so on. I will get the illusion of a horse running around. I will think that a little horse is running around in a circle. And yet, the real fact underlying this is not that a real horse is running around, but that twelve images of horses are being viewed by me in a certain way, each of which actually remains in its place.

So you see, I can not only create the illusion of movement in a perspectival sense, I can also create the illusion of movement in a qualitative sense. Not everything that appears to be movement is actually movement. Therefore, anyone who wants to speak cautiously and only arrive at the truth through careful examination must first say, as strange and paradoxical as it may sound to our clever contemporaries: Yes, I observe three successive positions of what I call a celestial body in such a way that I accept what lies beneath as identical. That is to say: I follow the moon in its orbit and initially assume, hypothetically, that it is always the same moon. That is entirely correct, but only in relation to such a progressive phenomenon. So what do we do? We see what we take to be identical celestial bodies in a so-called movement, connect what we see in different places in lines, and try to interpret these lines. That is what the Copernican world system gives us.

The school from which the Ptolemaic world system emerged did not originally proceed in this way. People still lived perceptively in the whole human being, as I indicated to you yesterday. And because people still lived in perception in the whole human being, the whole mental image they had of a celestial body was also significantly different from what it later became. Those who still had the Ptolemaic world system in front of them in a perceptive sense did not say: The moon is up there. They did not say that; it is only now that this is interpreted into the world system. They did not say: The moon is up there, because then they would have related the phenomenon solely to the eye. They did not do that; they related the phenomenon to the whole human being and meant it this way: Here I stand on the earth, and just as truly as I stand on the earth, I also stand inside the moon, because the moon is that there (Fig. 1, p. 254, hatched area). That is the earth, and the whole thing is the moon, which is much larger than the earth. Its radius is as large as what we now call the distance of the moon, I cannot say the center of the moon, from the center of the earth. This is how large the moon is in the Ptolemaic world system, as it was originally conceived. And this body, which is otherwise invisible everywhere, develops a process at one end that makes this small piece visible. Everything else is invisible and, moreover, of such substantiality that one can live inside it, that one is permeated by it. Only at this one end does it become visible. And in relation to the Earth, this entire sphere, which, incidentally, is not a sphere but a rotating ellipsoid, rotates, and with it rotates that which is the visible piece, that is, that which is the visible moon. This is only part of the full reality with which one is dealing here.

What appears there as a mental image that was really there will not seem so terribly paradoxical in its form if you bring an analogy to mind. Form a mental image of the analogy of the human or animal germ cell (Fig. 2). You know that at a certain stage of development, the so-called yolk sac forms at one point of the otherwise essentially transparent egg, and the formation of the rest of the embryo proceeds from the yolk sac. Thus, eccentrically, peripherally, a center is formed, from which the rest of the formation then proceeds. If you compare this small body with what is here the mental image of the Ptolemaic world system, for example, of the moon, then you have an idea of what was thought there in a completely analogous way. So one can say that, in the sense of this Ptolemaic view of the world, there is a completely different reality than the one that is enclosed within the image of the moon.

This is what has happened to human beings since the time when the Ptolemaic world system was perceived as reality: the inner experience, the inner feeling in the organism that one is inside the moon, has been completely lost, and one has been limited to the image of light. Human beings of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch cannot say, because they no longer know: I am inside the moon, or rather, the moon penetrates me, because for them the moon is only a small disc of light, or a ball of light, or a ball in general. The Ptolemaic world system was constructed on the basis of such inner perceptions. Now, we are returning to these perceptions today when we look at things in the right light, when we recapture the possibility of experiencing the whole moon again. But it remains perfectly understandable that those who start from the common mental image of “the moon” today say: Yes, I cannot quite grasp what connection there should actually be between the moon and anything in me. And ultimately, it is really better if people are skeptical about anything that emanates from the moon and has an influence on human beings than if they have all kinds of fantastical mental images about it. But as soon as the mental image becomes a real one, that we live inside the moon, that what can be called the moon is a force that constantly permeates us, then it is no longer surprising that this force also has a formative effect on humans and animals, that what permeates us is indeed something that has to do with the formation of our organism. These are the mental images that we must reclaim. We must be absolutely clear that the visible sky is only a fragmentary revelation of the real, substance-filled world space.

If you now develop the mental image that you live in a context of substance, you will have the feeling that this is something very, very real. However, in our current astronomical view, we have replaced it with something imagined. We have replaced it with what we call gravity. We only find that there is a mutual attraction between what we think of as the body of the moon and what we think of as the body of the earth. We could imagine this line of gravity as rotating, and then we would get out of the image created by this rotating line of gravity what in earlier astronomical views was called the sphere, the sphere of some planet. Basically, nothing else has happened than that what has been felt as substantial and can now be experienced as substantial again has been transformed into imaginary lines.

You see, we must therefore think of the entire configuration of the differentiated filling of space in a different way than we are accustomed to. Today we base our thinking on ideas of gravity; for example, we say that the ebb and flow of the tides are connected with certain gravitational forces emanating from the moon. We talk about how gravity emanates from the world body and lifts the water. In the sense of that other way of thinking, we must say that the moon also penetrates the earth, and as it penetrates the watery sphere of the earth, something takes place that manifests itself here as the rising of the water; in another place, the moon's sphere manifests itself as a light phenomenon. We do not need to think that there is a special force of attraction, but rather we think that, in a sense, this lunar sphere penetrating the Earth forms an organization together with the Earth, and we see in the two processes merely two sides of one process.

I only used yesterday's historical approach to help you understand certain concepts. I could just as easily have attempted to convey these concepts without referring to previous mental images, but then the entire discussion would have had to be based on spiritual scientific assumptions, from which the same mental images would have been derived.

Now mentally image the Earth sphere here (Fig. 3). I present what the solid globe of the Earth is as the Earth sphere. Of course, I now have to mentally image the Moon sphere as having a significantly different consistency and substantiality. Of course, I can also mentally imagine what is permeated in terms of space by these two spheres as being permeated by a third or fourth sphere. So I think that in some way it is permeated by a third sphere, which could be the sun sphere, which is qualitatively different from the moon sphere. So I am permeated, I say, as a human being, by the sun and moon spheres. Of course, they are in a reciprocal relationship in that they permeate each other, and the expression of this reciprocal relationship is something formed in the organism. And now you will come to realize that one can ultimately see together that which permeates the organism in this way in different substantiality and that which can find expression in the formation; that the formation is simply the result of this permeation. And that which we then see as the movements of the heavenly bodies is, in a sense, the sign, the becoming visible under certain conditions of the boundary of these spheres. This is something that is absolutely necessary in order to arrive at more realistic mental images about the structure of our world system. And you can now connect something more real than before with the idea that the human organization has something to do with this structure of the world system. As long as you see the heavenly bodies out there, you will not be able to gain very clear mental images about these connections. The moment one moves over to the real, one can gain this clear mental image, even though, of course, things begin to become somewhat confusing because there are so many spheres that one is permeated by, so that one can actually be somewhat unpleasantly affected by all this permeation of the organism.

But I would say that the situation is even worse. We are initially permeated by the Earth sphere in a certain, even expanded way, because the Earth includes not only the solid globe on which we stand, but also the mass of water; it also includes the air in which we are already immersed. That is already a sphere in which we are inside. This air is still something very coarse in relation to what the celestial phenomena cause. So now imagine that we are inside the sphere of the earth, we are inside the sphere of the sun, inside the sphere of the moon, and inside many others. But let us just highlight these three and say to ourselves: something within us is the result of the substantialities of these three spheres. We now have something qualitative which, when it appears quantitatively, the mathematician perceives with a certain horror, that which he calls the problem of the three bodies. But this has an effect in its result, in its reality, within us. We must realize that truly deciphering reality is no simple matter, and that the habit of perceiving reality in a simple, convenient way actually has its origin only in human intellectual laziness. And much of what is considered scientific has its origin only in this human intellectual laziness. If we disregard this, then we must proceed as cautiously as we have attempted to do in these lectures, which only sometimes appear insufficiently cautious because we had to jump from one topic to another in a sketchy manner, so that you have to find the connections yourself; but they are there.

Now, however, we must proceed just as cautiously if we want to approach the same problem from another angle, which I have already pointed out, namely from the angle of the human organism itself in comparison with the beings of the other kingdoms of nature. I have told you that we can form a mental image of a fork in the road, starting from an ideal point. On one branch we then have the plant world, on the other branch the animal world. If we think of the development of the plant world continuing in the real natural kingdom, we come to the mineralization of the plant kingdom. We can certainly form a mental image of this as a real process if we take the crudest example. Today we encounter mineral coal and see in it mineralized plant matter. What should prevent us from looking at analogous processes that have taken place for other plant-like substances and, let us say, deriving the siliceous and other components of the mineral earth substance from the mineralization of plant matter?

We cannot proceed in the same way, I said, when we seek the relationships between the animal kingdom and the human kingdom. Here we must mentally image, as it were, that development advances in the animal kingdom, but then turns back on itself and realizes itself physically at an earlier stage than that of the animal. So that one can say, in a sense: animal and human formation march from a common point. But the animal goes further before it becomes physically real; the human being remains at an earlier stage and becomes physically real at this stage. This makes it possible — for we must relate these processes to embryonic development — that the human being remains capable of development to a much greater extent than the animal after it is born. In the mineral, plant formation has gone beyond the extreme of the plant; in humans, animal formation is not driven to the extreme, but is retained within and the external formation is carried out by nature at an earlier stage. So that we arrive at this ideal point, from which there is a fork into a longer, indefinitely long branch and a shorter branch, which is also undefined from the negative side: the plant kingdom, the mineral kingdom; the animal kingdom, the human kingdom.

Now it is a matter of gaining a certain mental image of what is actually at hand with this formation of the human being in relation to the formation of the animal. So development is held back in humans, and what wants to be realized is, in a sense, realized prematurely. If one studies the process as it must be given as a mental image according to what I have already told you in these lectures, if one studies the part that the sun entity plays in the formation of the animal body — naturally always indirectly through embryonic formation — then one knows that, in a sense, direct sunlight has something to do with the configuration of the animal head, while indirect sunlight, that is, I would say, the shadow of the sun in relation to the earth, has something to do with the polar opposite of the animal head. If we now consider very closely this permeation of animal formation with cosmic solar substance and consider the forms, then we will learn to associate this with a mental image that I would like to outline for you in the following way. Suppose that animal formation is brought about in some way in connection with the sun. Now, let us take a common astronomical mental image and ask ourselves in the spirit of this mental image: Apart from what will be present through a special constellation as a mode of action between the sun and animals, is there anywhere the possibility of an effect of sunlight in the cosmos that is not directly related to the sun itself? Yes, there is. Every time the full moon shines on us, or even just the illuminated moon, sunlight shines on us. In a sense, this creates the cosmic possibility for sunlight to shine on us. This is of course also the case with the developing human being, in the embryonic stage, and was the case in earlier stages of Earth's development, where it was a direct effect. What remains today as an echo is inherited. So here again we have the effect of the sun, once direct and once indirect, in the reflection of sunlight from the moon.

And now, form in your mind the following image. Imagine, if I may draw it schematically again, that in animals the development, the becoming of the animal, would be such that it would arise under the influence of the sun's effects according to this scheme (Fig. 4). I would say that this would be the normal day and night effect, i.e., the head and the polar opposite of the head. That would be the normal effect of the sun on animals. And now let us consider the effect of sunlight that occurs when the moon is in opposition, when there is a full moon, when, so to speak, sunlight acts from the opposite side, counteracting itself through reflection. If we think of this (arrow pointing vertically downwards in Fig. 5) as the direction for the animal formations of the direct sunbeams, we would have to form the mental image that the animal formation would continue in the direction of this direct sunbeam (Fig. 5), and that an animal would become more and more animal the more the sun acts on it. But when the moon counteracts from the opposite side, or rather the sun via the moon, then the animal nature is taken away, it is withdrawn into itself (Fig. 6). This corresponds to the shortening of the second fork, this withdrawal (Fig. 7). So you see, we get a cosmic correlate for what I have given you as a certain characteristic of the difference between humans and animals.

What I have just told you can be perceived directly by anyone who gives themselves the opportunity to perceive such things. Human beings actually owe this restraint of their organization to the counteraction of sunlight via the moon. The effect of sunlight, and specifically its own quality—it is always sunlight—is weakened by the sun itself counteracting the moon's effect. If it did not counteract the moon's effect, the formative tendency within us would give us an animal-like appearance. Thus, the effect of sunlight reflected by the moon counteracts this. Formation is halted by the negative effect, and the human form is the result.