Third Scientific Lecture-Course:

Astronomy

GA 323

15 January 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture XV

Today I will deal with some of the things that may be causing you difficulty in understanding what we have done hitherto. I will lead over from these difficulties into a realm of ideas which will show up the inadequacy of those lines of thought on which the people of our time, with all their comfortable mental habits, would gladly found their understanding of universal phenomena.

We have been studying the universal phenomena in their relation to man. We have done so in manifold directions. Again and again we have indicated how a relationship reveals itself between the forming of man and what appears in the celestial phenomena. Whether we go by some ancient cosmic system of by the Copernican theories in forming our pictured synthesis of the movements of heavenly bodies, we must relate the picture to man in diverse ways of course, accordingly. This we have seen. For a true Science we must accept that there is this relation.

Yet the difficulties are formidable. Earlier in these lectures we drew attention to one such difficulty. The moment we try to form ratios between the periods of revolution of the planets of our system we come to incommensurable numbers. Arithmetic runs out, as we might say; we get no farther with it, for where incommensurable numbers enter in there is no palpable unit. Thus, when we look for a synthesis of the phenomena of cosmic space with our accustomed mathematical method and way of thinking, the phenomena themselves are such that we find ourselves driven farther and farther from reality. We may not therefore take for granted that we shall ever be able to explain the cosmic phenomena on the accustomed basis of our Geometry, that is to say, within a rigid three-dimensional space. Nay more, another difficulty has emerged. Yesterday we found ourselves obliged to assume a certain relationship of Sun and Moon and Earth, finding expression in some way in man—in man's very structure. We would fain grasp how the relation is. Yet if we posit this working-together of the Three*, we get into formidable difficulties in spatial calculation.

All these things we have mentioned. Now we can reach a certain starting-point at least, through pure Geometry—yet a Geometry of a higher kind. Thence we may gain an idea of where the difficulties come from when we are trying by dint of spatial calculation to grasp the inter-connection of celestial phenomena. Let us recall our precious attempts to comprehend the form of man himself. We are then let to this:- We can and we should try to take seriously that 'memberment' of the human being of which we have also spoken in these lectures. The human head-organization, we may truly say, centring as it does in the nerves-and-senses system, is relatively independent. So is the rhythmic system with all that belongs to it. The metabolic system too, and all that goes with it in the organization three independent systems are revealed. Taking our start now in an intelligent way from the principle of metamorphosis, as we must always do when dealing with organic Nature, we can try to form ideas upon this question: How are the three members of the three-fold human system related to each other, according to this principle of metamorphosis?

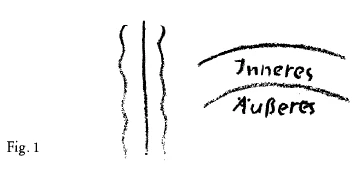

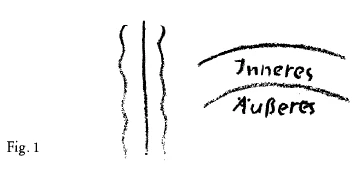

Understand me rightly, my dear friends. We want to gain an idea-though it be only pictorial to begin with—of how the three members of the human system are related to each other. On the face of it, it will of course be difficult. Such organs as are met with in the human head, it will be difficult to recognise in them at all clearly the metamorphosis of those organs which are fundamental to the metabolic and lymph system. But if we go into the morphology of man deeply enough, we can find our way. We only have to think most thoroughly along the lines already indicated. Namely, the essence of the mutual relation of the long bone to the skull-bone and vice-versa is a complete turning-inside-out. The inner surface of the bone becomes the one turned outward. It is the principle by which you turn a glove inside-out, provided only that the turning-inside-out involves a simultaneous change in the inherent relationships of inner forces. If I should turn a tubular bone or long bone inside-out like a mere glove, I should again get the form of a tubular bone, needless to say. But it will not be so if we take our start, as we must do, from the inherent configuration of the bone. As I described before, in its inherent configuration the long bone is oriented inward towards the radial quality that runs right through it. It is obliged therefore to subject its material structure and arrangement to the radial principle. When I have "flipped" it, so that the inner side opens outside, in its configuration it will no longer follow the radial but the spheroidal principle. The "inner side", now turned outward towards the Sphere, will then receive this form (Fig. 1).

What was outside before, is now inside, and vice-versa. Take this into account for the extreme metamorphosis-tubular bone into skull-bone and you will say: The outermost ends of human memberment—lymph-system and skull system—represent opposite poles in man's organization. But we must not think of "opposite poles" in the mere trivial, linear sense of the word. In that we go from one pole to the other, we must adopt the transition which this involves, namely from Radius to surface of a Sphere. Without the help of such ideas and mental pictures, intricate as they may seem, it is quite impossible to gain a just or adequate notion of what the human body is.

We come now to what constitutes the middle, in a certain sense,—the middle member of man's organization. This will be all that belongs to the rhythmic system, and it will somehow form the transition from radial structure to spheroidal.

In the threefold system thus presented we have the key to the morphological understanding of the entire human organism. Of course we need to realise how it will be. Suppose we have some organ in the metabolic system—the liver for example—or any one of the organs mainly assigned to the metabolism. (We must qualify it with the word 'mainly' for there is always an overlapping and interlocking of these things). Suppose then we begin with such an organ and seek what answers to it in the head. We try to find which of the organs in the head-nature of man m ay be connected with it by the metamorphosis of turning-inside-out. We shall then have to recognise the organ when entirely transformed, de-formed; only by so doing shall we understand it. It will therefore not be easy to take hold of mathematically. Yet without finding some mathematical way of access we shall never adequately grasp it. And if you call to mind (even if you only take this as a picture)—if you call to mind that the real understanding of the human form and figure will lead us out among the movements of celestial bodies, you will divine what must be needful also when we wish to comprehend the latter. For a true synthesis of the phenomena of movement among the heavenly bodies, it will be quite inadequate to think of them as if these movements were accessible to a Geometry that simply reckons with ordinary rigid space and therefore cannot master the turning-inside-out. For when we speak of a turning-inside-out in the way we have been doing, we can no longer be thinking of ordinary space. Ordinary space holds good where we can calculate volumes, cubicle contents in the conventional way. We cannot do so if obliged to make the inner outer. We can no longer go on calculating them with the same conceptions which hold good in ordinary space.

If then in thinking of the human form and figure I need the turnings-inside-out, in thinking of the movements of heavenly bodies I shall need them too. I cannot proceed like the current Astronomy which tries to comprehend the celestial phenomena within an ordinary rigid form of space.

Take, to begin with, simply the head-organization and the metabolic organization of man. To pass from one to the other you must imagine, once again, a turning-inside-out—and, what is more, one that involves variations of form. Let us at least try to get a picture of the kind of think involved. We did preliminary work in this direction when speaking of the Cassini curves, and of the circle differently conceived. Ordinarily the circle is defined as a curve, all of whose points are equidistant from one central point. We were speaking of the circle as a curve, all of whose points are at measured distances from two fixed points, and so that the quotient of the two distances is constant. This was our other conception of the circle.

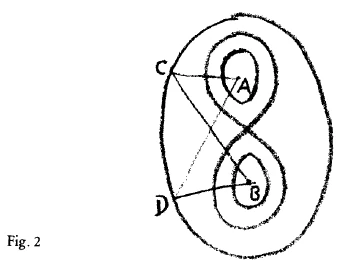

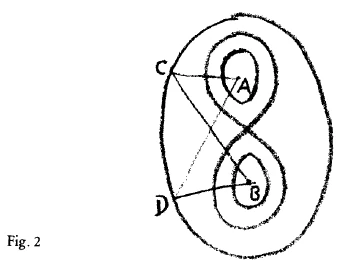

Speaking of the Cassini curve, we showed that it has three essential forms. One, not unlike an ellipse:—this form arose when the parameters of the curve bore a certain relation, the which we indicated. The second form was the lemniscate. The third form is that while in the idea of it—and also analytically—it is a single entity, to look at it is not. It has two branches (Fig. 2),

yet the two branches are one curve. To draw the line, we should somehow have to go out of space, coming back into space again when we draw the second branch. Conceptually, our hand would be drawing a continuous line when drawing the two regions which look separate. We cannot draw the line continuously within ordinary space, and yet conceptually what is here above and what is here below (the inner curve in Figure 2) is a single line. Now as I also mentioned, the same curve can be thought of in another way. You can ask what will be the path of a point which when illumined from a fixed point A appears with constant intensity of illumination, seen from another fixed point B. Answer: a Cassini curve. A curve a Cassini will be the focus of all points through which a point must run, if when illumined from a fixed point A it is seen ever with the same intensity of light from another fixed point B (Fig. 2 again).

Now it will not be hard for you to imagine that if something shines from A to C (Fig. 2) and thence by reflection from C to B, the intensity of light will be the same as if reflected from D instead. But it gets rather more difficult to imagine when you come to the Lemniscate. The ordinary geometrical constructions by the laws of reflection and so on, will not be quite so easy to carry through. And it gets still more difficult to imagine with the two-branched curve, that the same intensity of light should always be observed from the point B, inside the one branch of the curve, when the original point-source of light is in A. You would have to imagine (as you pass from the one branch to the other) that the ray of light goes out of space and then shines into space again. You are up against the same difficulty as before, when you were simply asked to draw the two branches as one—with a single sweep of the hand through space.

Yet if we do not develop these conceptions we shall be unequal to the other task, namely of finding the transmutation—or even the mere relationship of form—as between any organ in the head of man and the corresponding organ in the metabolism. To find the connection you simply must go out of space. Once again—strange as it may sound—if with your understanding of any form in the human head you wish to make a transition to the understanding of a form in the human metabolic system then you will not be able to remain in space. You must get out of space. You must get right out of yourself , looking for something that is not there in space. You will find something that is as little inside ordinary space as is what intervenes between the upper and lower branches of a two-branched Cassini curve. This is in fact only another way of expressing what was said before that the metamorphosis must be so conceived as to turn the form completely inside out.

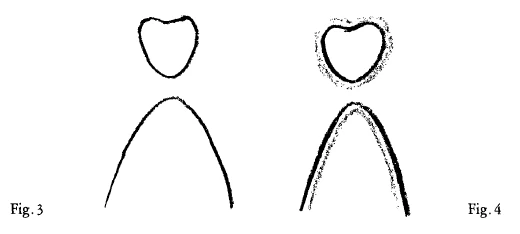

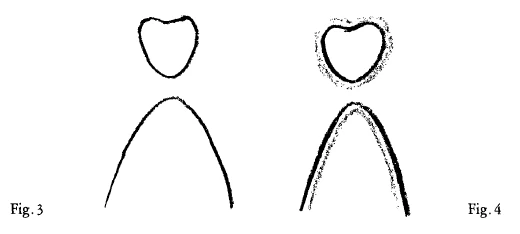

In thinking thus of the connection between the upper and lower branches of the discontinuous curve of Cassini (as shown in Fig. 3) we are still presupposing actual constants, rigid and unchanged, in the equation. Now if we vary the constants themselves as in an earlier lecture, forming equations of twofold variability, we shall be able to imagine the upper branch say, in this form and the low one in this (Fig. 3).

The upper branch will take this form eventually. If then you alter the curve of Cassini by taking variables in place of constants—so that you start with equations instead of starting with invariable constants—you will get two different kinds of branches. Then there will also be the possibility for one of the two branches to come in as it were from the infinite and go out to the infinite again. This is precisely the relationship from which you should take your start when following certain forms within the human head, comprising them in curves and lines, and then relating them to the forms of organs or of complexes of organs in the metabolic system, which in their turn you will comprise in curves and lines. Such is the intricacy of the human form. To make it still less simple, you must imagine the one line (Fig. 3a) with an outward tendency and the other with its tendency turned inward.

You will be prone to say (I hope without insisting on it, but as a passing impression): If this be so, the human organization is so complicated that one would almost prefer to do without such understanding and fall back on the ordinary philistine idea of the body, as in the present-day Anatomy and Physiology. There we are not called upon to make such prodigious efforts, as to let mental pictures vanish and yet again not vanish, or turn them inside-out, and all the rest! May be; but then you never really understand the human form; your understanding is, at most, illusionary.

Now, to go on: Suppose you thus look into it and recognize that there is something in the human organization which falls right out of space, is not in space at all, but obliges you for instance to imagine spatially separated line-systems, inherently united with each other and yet united by another principle than three dimensional space affords. Thinking in this way, you will no longer be too far removed from what I shall now bring forward. You will at least be able to entertain the thought in a formal sense. No-one, I mean can validly object to thinking it as a pure form of thought. For to begin with, all we are called upon to do is to conceive a clear idea, as in mathematics generally. It cannot be objected that the thing is unproved, or the like. We are only concerned to reach a self-contained and consistent idea.

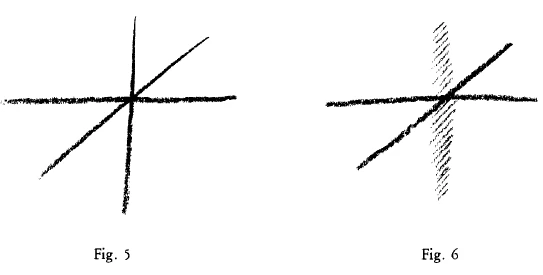

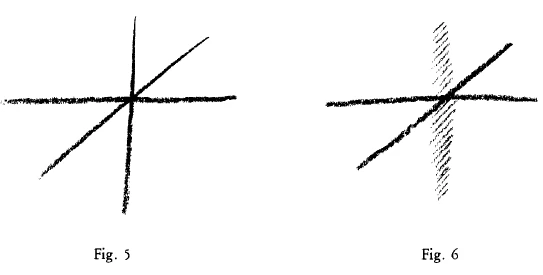

Think therefore for a moment that you had to do not only with ordinary space, conceived in its three dimension, but with a "counter-space" or anti-space". Let me call it so for the moment, and I will try to evoke an idea of it, as follows. Suppose I form the thought of ordinary, three-dimensional, rigid space. I form the first dimension, I form the second dimension and I form the third dimension (Fig. 4).

Then I have, so to speak, filled-in in thought—in the idea and mental presentation of it—three-dimensional space with which I am ordinarily confronted. Now as you know, in any such domain you can not only advance up to a certain degree of intensity; you can subtract from it too, and as you go on subtracting—taking away—you come at last to the negation of ti. As you are well aware, there is not only wealth but debt. Likewise I cannot only make the three dimensions to arise in thought but I can also make them vanish. Only I now imagine the arising and vanishing to be a real process,—something hat is really there. Of course it is possible to think only two dimensions instead of three, but that is not my meaning. What I now mean is this: The reason why I only have two dimensions (Fig. 4a)

is not that I never had a third. The reason is, I had a third and it has vanished. The two dimensions are an outcome of the coming-into being and vanishing-again of the third. I now have a space, which, though it outwardly shows only two dimensions, must inwardly be conceived as having two third dimensions, one positive and the other negative. The negative dimension springs from a source that can no longer be there in my three-dimensional space at all. Nor must I think of it as a "fourth dimension" in the conventional sense. No, I must think of it as being, to the third dimension, as positive to negative (Fig. 4a once more).

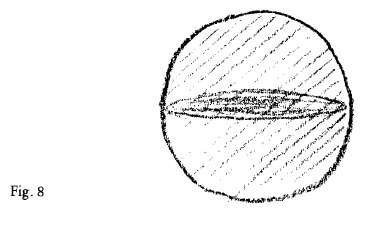

And now suppose that what I have been indicating is really there in the Universe; yet, as things generally are in the real world, approximately so. It would then be not a pedantically accurate but an approximate rendering of what I have here drawn. This need not cause you any great surprise, for in outer sense-perceptible reality you never find mathematical figures reproduced in any other way, always approximately. If then I claim that the picture represents something real, you will only expect it to do so in an approximate sense. To represent a reality corresponding to it, I need not repeat exactly the same drawing, but I should have to draw something flattened; that would answer to it. The fact that something has been there and has then vanished, I may perhaps suggest in this way: I will suppose that the density of an effect, indicated by the dark shading, came into being and then partly faded out again, drew weaker (Fig. 5).

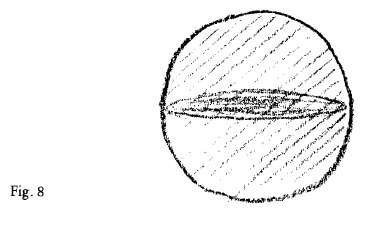

You are then left with a sphere that has a denser portion in the middle region. I beg you know, compare what is here drawn with the real cosmic system, such as we see it with our eyes,—the cosmic sphere with all the stars widely dispersed, and then the stars more densely packed in the region of the Milky Way, or what we call the Galactic System.

Yet you may also compare it with something else. Take any popular star-map. The picture we have shown (Fig. 5a)

—let us still take it simply as a picture—is fundamentally equivalent to what is always being shown: the passage of the Sun or of the Earth through the Zodiac, with the with the North and South poles of the ecliptic somewhere out yonder. The idea we have been forming is, as you see, not so very remote from what is there in the outer Universe. In coming lectures we shall of course still have to look for more detailed relations.

Now for an understanding of what was said before about the human being we have not yet gone for enough. We must go farther and make the second dimension also vanish; so then we shall be left with only one,—with a straight line. But this is no ordinary straight line drawn into three-dimensional space. It is the line that has remained when we have made the third and also the second dimension vanish. And now we make the last remaining one to vanish. Then we are left with a mere point. Bear in mind however that we have arrived at the point by the successive vanishing of three dimensions. Now let us suppose that this point were to present itself to us in reality,—as having existence in itself. If it is there, and making itself felt, how then shall we imagine its activity? We cannot relate its activity to any point in the space determined by the x-axis. The x-axis is not there, since it has vanished. Nor can we relate it to anything with an x—and a y-coordinate, for all of this has gone; all this has vanished out of space. Nor can we relate it in its activity to the third dimension of space. What then shall we say? When it reveals its activity we shall have to relate it to what is quite outside three-dimensional space. What then shall we say? When it reveals its activity we shall have to relate it to what is quite outside three-dimensional space. Consistently with the procedure we have been through in our thinking, we cannot possibly relate it to anything that could still be included in this space. We can only relate it to what is outside it three-dimensional space altogether. We can relate it neither to "x deleted" nor to "y deleted" not to "z deleted", but only to what deletes all three of them, z, y, and z together, and is therefore into within three-dimensional space at all.

We put this forward to begin with as a purely formal, mathematical notion. Yet is soon grows real. It grows exceedingly real when we begin to enter into things more deeply than with the easy-going notions with which Science nowadays would gladly master them. Look, with this deeper tendency of understanding,—look at the process of sight and the whole organisation of the eye. You are perhaps aware (in other lectures I have often spoken of it) of how the eye is not merely to be regarded as a thing formed from within the body outward; for it is largely organized into the body from outside. You an trace the forming of it from without inward by studying the phylogenetic development of lower animals and then considering the act of sight itself. You will contrive to understand how the process of sight is stimulated from without and how the organ too is adapted to this stimulation from without. Then as the process works on inward to the optic nerve and farther in, it vanishes at length,—vanishes as it were into the organisation as a whole. I know you can find the termination of the optic nerves, and yet—this too comes to expression approximately—if you go into the inner organisation you will have to admit that it there vanishes.

So much for the process of sight and the associated organs. And now compare with this the process of secretion of the kidneys. Go into it conscientiously. and you will have to relate the duct that leads outward, for the secretion of the kidneys, to what is working from without inward where the eye passes into the optic nerve. If you then look for ideas whereby the two things can be related, so that their mutual relation will help you understand the phenomena of either process, you will find indispensable such forms of thought as we have just been indicating. If you conceive the ideas of three-dimensional space as applying to the process of sight (we might also replace the one by the other, but if you do it in this way. ...), then, if you seek what answers to it in the secretion of the kidneys, you must realize that what is there enacted takes you right out of three-dimensional space. You must go through the same procedure in your thinking as I did just now in extinguishing the spatial dimensions. Otherwise you will not find your way.

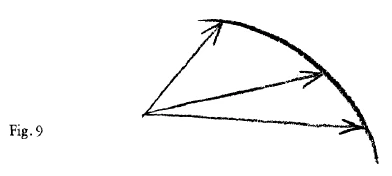

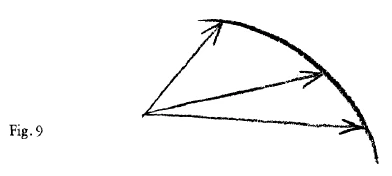

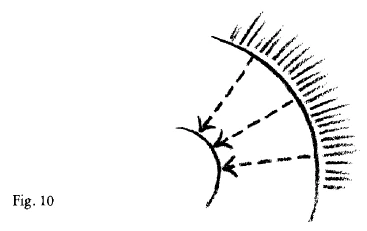

In like manner you must proceed if you are trying to understand the curves formed in the Heavens by the apparent paths of Venus and Mercury on the one hand, Jupiter and Mars on the other, I mean quite simply the apparent paths as we observe them with our eyes,—the loops and all. If you use polar coordinates for example, then for the loop of Venus you may make the origin of your coordinate system in three-dimensional space. Here you can do so. But you will not come to terms with reality if you adopt the same principle when examining the curve of Mars. In this case you must start from the ideal premise that the origins of any relevant system of polar coordinates will be outside three-dimensional space. You are obliged to take the coordinates in this way. In the former case you may start from the pole of the coordinate system, taking coordinates in the normal way, as in Figure 6.

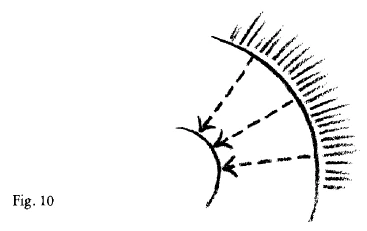

But if you do this for the one planetary curve—say for the path of Venus with its loop—you will do equal justice to the paths of Jupiter or Mars with their loops, only by saying to yourself: This time I will not pre-suppose a polar-coordinate system with an origin such that I always have to add a piece to get the polar-coordinates, as in Figure 6. No, I will take as origin of my polar-coordinate system the encompassing Sphere (Fig. 6a),

i.e. what is there behind it, indeterminately far. Then I get such coordinates as these (dotted lines), where in each case, instead of adding, I must leave so much out. The curve I then obtain also has something like a centre, but the centre is in the infinite sphere.

It might prove necessary then, for more profound research into the paths of the planets, that we make use of this idea: In constituting the paths of the inner planets we must indeed attribute to these paths some centre or other within ordinary space. But if we want to think of centres for the path of Jupiter, the path of Mars and so on, we must go right outside this ordinary space.

In fine, we have to overcome space; we must transcend it . There is no help for it. If you are conscientious in your efforts to comprehend the phenomena, the mere ideas of three-dimensional space will not suffice you. You must envisage the interplay of two kinds of space. One of them, with the ordinary three dimensions, may be conceived as issuing radially from a central point. The other, which is all the time annulling and extinguishing the first, may not be thought of as issuing from a point at all. It must be thought of as issuing from the encompassing Sphere—that is, the Sphere infinitely far away. While in the former case the "point" is of zero areas which it turns outward, and a point with the area of an infinite spherical surface which it turns inward. Geometrically it may suffice to conceive the notion of a point abstractly. In the realm of reality it will not. We shall not do justice to reality with the mere notion of an abstract point. In every instance we must ask whether the point we are conceiving has its curvature turned inward or outward; its field of influence will be according to this.

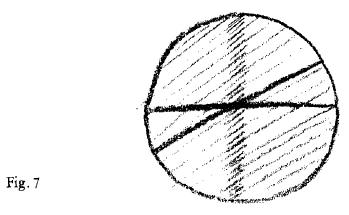

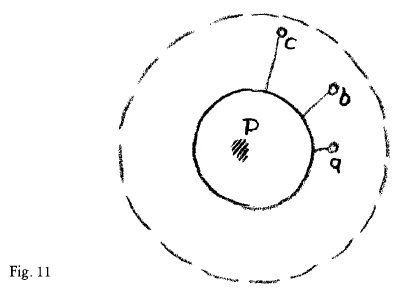

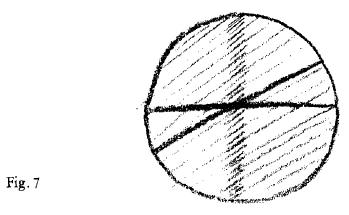

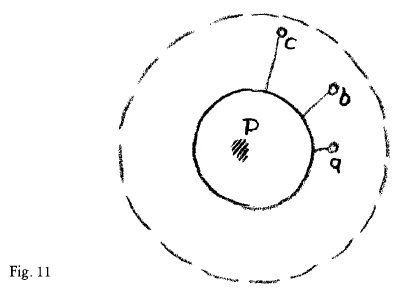

But you must think still farther, my dear friends; there is a another thing. Of course you may imagine that you had somewhere caught this point which is really a Sphere. To begin with, since it is in the infinite far spaces you need not imagine it just here (s, Fig. 7). You can equally well imagine it a little farther out, (b, or c). You can imagine it to be anywhere out there; you only have to leave this sphere free (strongly drawn sphere in Fig. 7).

For this is hollowed out, so to speak; this is the inverted circle or the inverted sphere, if you like. But now suppose the following might be the case. Think of what is within this peculiar circle (namely at a, b, c, etc,) Think of this point that has its curvature turned inward. For in effect, the entire space outside this spherical surface is then a point with its curvature turned inward. And now imagine that this space had, after all, its limit somewhere. You might be able to go far away out,—very far. Suppose however the reality were such that you could not just go anywhere, but somewhere after all there was a limit of quite another kind (dotted circle in Figure7). What there would appear, as if by inner necessity, what in effect belongs to the realm beyond the limit. An equivalent sphere would have to arise within, belonging to what is there outside. You would then have to realize: Out there, beyond a certain sphere, something is still existing, it is true, but if I want to see it I must look in here (P), for here it re-appears. The continuation of what is faraway out there make itself felt in here. What I am looking for as I go out into infinite distances, makes its appearance within, and becomes manifest to me from this centre.

These are the kind of ideas you should develop to an adequate extent. In a formal sense they look sound enough. As forms of thought there can surely be no objection to them. Truly remarkable results will be obtained however, if with their help you try to penetrate outer reality. Think for example that there might be a phenomenon in celestial space,—we may call it "Moon" to begin with,—yet this phenomenon were not to be understood simply by saying: "This Moon is a body, here is its central point; we will investigate it on the understanding that it is a body and that its central point is here." Assume (and please forgive my saying, I put it euphemistically) assume that this way of thinking did not fit the reality, but that I ought to express it quite differently. I ought rather to say: "If I, in my Universe, start from a certain point and go farther and farther out, I come at length to where I shall no longer find heavenly bodies. Yet neither shall I find a mere empty Euclidean space. No, I shall find something, the inherent reality of which obliges me to recognize the continuation of it here (at P)." I should then be obliged to conceive the space contained within the Moon as a portion of the entire Universe with the exception of all that exists by way of stars, etc., outside the Moon. I should have to think on the one hand of all the stars here are in cosmic space. These, I am now assuming I have to treat in one way, according to a single principle; but the inside of the Moon—the space contained within the Moon—could not be treated in this way. It would require me to think as follows: There on the one hand I go out into the far spaces. Somewhere out there, I presume, is the celestial Sphere. Though it be only the "apparent" Sphere to begin with; something effective, something real must be conceived to underlie it. Yet whatsoever realities I find out there, the space within the spherical surface of the Moon has nothing whatever to do with it. It only has to do with what begins where the stars come to an end. It is a fragment, in some strange way, belonging not to my Universe but to that Universe to which all the stars do not belong.

If there is such a thing within a Universe, it is a thing inserted in this Universe, occluded as it were,—thing of altogether different nature and revealing different inner properties from all that is there around it. And we may then compare the relation of such Moon to its surrounding Heavens with the relation which obtains for instance between the secretions of the kidneys—with the organic structure that underlies them—and on the other hand the structure and functioning of the eyes. From this we shall proceed tomorrow.

It is not due to me that I must try to form, and to acquaint you with, such complicated notions of how the Universe is built. Truth is, equipped with any other notions you will not make headway, save on the convention: "Let us comprise the phenomena with our given range of ideas, and if we come to a limit somewhere, well then we do, and we go no further". Ascribe it then to the reality and not to any craving for remote ideas, if in the effort to impart an understanding of how the Universe is built I have unfolded complicated notions.

Fünfzehnter Vortrag

Ich möchte heute versuchen, einiges von dem, was vielleicht Schwierigkeiten macht in der Auffassung der Dinge, die wir bisher betrachtet haben, hinüberzuführen zu Vorstellungen, welche Ihnen zeigen werden, wie man in der Tat mit demjenigen nicht auskommen kann im Begreifen der Welterscheinungen, das man so gerne, natürlich nach der Bequemlichkeit der menschlichen Denkgewohnheiten, zugrunde legen möchte. Wir haben ja die Welterscheinungen im Zusammenhang mit dem Menschen nach den verschiedensten Richtungen hin betrachtet. Wir haben namentlich immer wiederum darauf hingewiesen, wie ein gewisser Zusammenhang sich zeigt zwischen der menschlichen Gestaltung und demjenigen, was uns in den Himmelserscheinungen entgegentritt, gleichgültig, ob wir im Sinne eines älteren Weltsystems oder im Sinne der kopernikanischen Theorien die Bewegungen der Weltenkörper zu einem Bilde zusammenfassen. Das Bild muß immer in verschiedener Weise zum Menschen in ein Verhältnis gebracht werden, das haben wir gesehen, aber wir kommen in einer wirklichen Wissenschaft nicht darum herum, dieses Verhältnis auch wirklich anzunehmen.

Nun stellen sich aber dabei ganz erhebliche Schwierigkeiten ein. Wir haben zuerst im Verlauf dieser Vorträge auf die Schwierigkeit hingewiesen, die sich darin ausdrückt, daß, sobald man versucht, die Verhältnisse der Umlaufzeiten der Planeten unseres Systems zu betrachten, sich inkommensurable Zahlen ergeben, daß es also notwendig ist, gewissermaßen mit dem Rechnen aufzuhören. Denn wo sich inkommensurable Zahlen ergeben, da ist keine überschaubare Einheit vorhanden. Und so sehen wir, daß wir mit derjenigen mathematischen Denkweise und Methodik, durch die wir zusammenfassen möchten die Erscheinungen unseres Weltenraumes, durch die Erscheinungen selbst aus der Wirklichkeit herausgetrieben werden, daß wir also nicht voraussetzen dürfen, wir könnten mit demjenigen, was wir im gewöhnlichen, starren dreidimensionalen Raum für unsere Geometrie zugrunde legen, uns irgendwie die Welterscheinungen erklärlich machen. Insbesondere aber tauchte uns ja gestern eine Schwierigkeit auf: Wir waren in die Notwendigkeit versetzt, vorauszusetzen ein gewisses Verhältnis von Sonne, Mond und Erde, das in irgendeiner Weise im Menschen, im Bau des Menschen zum Ausdruck kommen muß und das man fassen möchte. Und in dem Augenblick, wo sich solch ein Zusammenwirken einer Dreiheit geltend macht, da kommt man mit dem Rechnen im Raum in beträchtliche Schwierigkeiten hinein. Auf alles das habe ich ja bisher aufmerksam gemacht. Nun kann sich uns etwas ergeben, wenigstens als ein Anhaltspunkt, um rein geometrisch, aber in einem erhöhteren Maße geometrisch, eine Vorstellung zu gewinnen von dem, was da eigentlich zugrunde liegt als Schwierigkeit, mit dem Rechnen im Raum die Zusammenhänge der Himmelserscheinungen zu erfassen.

Wenn wir noch einmal zurückgehen auf die verschiedenen Versuche, die ich Ihnen angedeutet habe, die Gestaltung des Menschen selber wirklich zu erfassen, so kommen wir auf folgendes. Wir können den Versuch machen, die Gliederung der menschlichen Wesenheit, von der wir ja auch in diesen Vorträgen öfter gesprochen haben, wirklich ernst zu nehmen, wie es ja sein muß. Wir können davon sprechen, daß die menschliche Hauptesorganisation mit ihrer Zentrierung im Nerven-Sinnessystem eine gewisse Selbständigkeit für sich hat; ebenso das rhythmische System mit allem, was dazu gehört; und schließlich hat auch das Stoffwechselsystem mit alledem, was in der Gliedmaßenorganisation dazu gehört, wiederum eine Art Selbständigkeit für sich. Wir können also in der menschlichen Organisation auf drei in sich selbständige Systeme hinweisen, und wit werden, wenn wir in einer venünftigen Weise dabei das Prinzip der Metamorphose zugrunde legen, das ja unbedingt in der organischen Natur zugrunde gelegt werden muß, uns Vorstellungen zu bilden haben darüber, wie sich nach dem Prinzip der Metamorphose diese drei Glieder der menschlichen Organisation zueinander verhalten.

Also, verstehen Sie mich recht! Wir wollen uns eine, wenn auch vielleicht zunächst nur bildhafte Vorstellung davon machen, wie sich die drei Glieder der menschlichen Organisation zueinander verhalten. Oberflächlich angesehen wird das natürlich schwierig sein. Es wird schwierig sein, dasjenige, was im menschlichen Haupte an Organen angetroffen werden kann, deutlich zu erkennen als Metamorphose derjenigen Organe, welche dem Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßensystem zugrunde liegen. Aber wenn man so weit auf die Morphologie des Menschen eingeht, wie ich es angedeutet habe, dann kommt man doch in einer gewissen Weise zurecht, wenn man wirklich die Vorstellung gründlich durchdenkt, daß wir es in dem Wechselverhältnis zwischen Röhrenknochen und Schädelknochen zu tun haben mit einer vollständigen Wendung der Innenfläche des Knochens nach außen nach dem Prinzip, wie man einen Handschuh umdreht, und daß man bei dieser Umwendung es zugleich zu tun hat mit einer Änderung der Kraftverhältnisse. Es würde, wenn ich so, wie ich einen Handschuh drehe, im Röhrenknochen das Innere nach außen wenden würde, wieder ein Röhrenknochen entstehen, natürlich. Wenn wir aber voraussetzen, daß der Röhrenknochen nur dadurch sich konfiguriert hat, daß er angeordnet ist, wie ich es dargestellt habe, nach innen zu in durchlaufendes Radiales, daß er also genötigt ist, seine Materienanordnung dem Radialen entsprechend zu machen, und ich ihn dann so umwende, daß das Innere nach außen kommt, und er dann nicht dem Radialen folgt in seiner Anordnung, sondern dem Sphäroidalen, so wird das Innere, das sich jetzt dem Sphäroidalen zuwendet, eben diese Form bekommen (Fig.1).

Das frühere Äußere ist jetzt das Innere und umgekehrt. Wenn Sie dieses ins Auge fassen im extremsten Fall der Umwandelung des Röhrenknochens in den Schädelknochen, dann werden Sie sich sagen: Die äußeren Enden der menschlichen Gliederung, das Gliedmaßensystem und das Schädelsystem, sie stellen gewissermaßen Pole der Organisation dar, aber so, daß wir nicht einfach die Pole im linearen Sinne als entgegengesetzt zu denken haben, sondern daß wit, wenn wir übergehen von einem Pol zum anderen, auch entsprechend einen Übergang annehmen müssen zwischen Radius und Kugeloberfläche. Ohne daß man so komplizierte Vorstellungen zu Hilfe nimmt, ist es durchaus unmöglich, irgendwie eine der Sache adäquate Vorstellung vom menschlichen Organismus zu bekommen.

Nun, dasjenige, was gewissermaßen die Mitte bildet, das mittlere Glied der Organisation des Menschen, dasjenige also, was zugeordnet ist dem rhythmischen Organismus, das wird in der Mitte drinnenstehen, wird gewissermaßen wie den Übergang bilden von Radialstruktur zu Sphäroidalstruktur. Aus diesem Prinzip heraus ist nun morphologisch die ganze menschliche Organisation zu begreifen. Wir müssen uns also klarmachen, wenn wir irgend etwas in der Stoffwechselorganisation haben als Organ, also sagen wir zum Beispiel die Leber oder irgendeines der Organe eben, die dem Stoffwechsel im eminentesten Sinne angehören - man kann immer nur sagen «im eminentesten Sinne angehören», denn die Dinge sind ja wiederum ineinandergeschoben -, wenn wir also ein solches Organ haben, und wir suchen entsprechend dasjenige Organ, das in der Hauptesorganisation durch Umwendung metamorphosiert mit ihm zusammenhängen kann, dann werden wir natürlich eine ganz gewaltige Deformation des betreffenden Organs zu konstatieren haben, wenn wir mit dem Begreifen der Form zurechtkommen wollen. Daher wird es schwierig sein, mathematisch irgendwie die Sache zu fassen. Aber ohne daß man irgendwo anfaßt mit dem Mathematischen, wird man überhaupt nicht zurechtkommen. Und wenn Sie bedenken - nehmen Sie es selbst nur wie ein Bild -, daß man in dem Begreifen der menschlichen Gestalt etwas hat, was hinausweist auf die Bewegungen der Himmelskörper, so wird es sich darum handeln, daß, wenn man zusammenfassen will dasjenige, was in den Bewegungen der Himmelskörper auftritt, man es auch in einer ähnlichen Weise auffassen muß; daß man nicht so vorgeht, als ob einfach die Dinge sich abspielten in einer Weise, an die man herankommt mit der Geometrie, die einfach mit dem gewöhnlichen Raum rechnet und die daher, weil sie das tut, ja mit keiner Umwendung rechnen kann. Sobald man von einer solchen Umwendung spricht, wie ich es getan habe, kann man nicht mehr mit dem gewöhnlichen Raum rechnen. Der gewöhnliche Raum gilt da, wo ich Kubikinhalte bilde im gewöhnlichen Sinne. Wenn ich aber genötigt bin, das Innere zum Äußeren zu machen, dann hört die Möglichkeit auf, mit denjenigen Vorstellungen rechnend fortzugehen, die ich im gewöhnlichen Raum habe.

Nun, wenn ich aber die menschliche Gestalt mir so vorstellen muß, daß ich Wendungen in dem entsprechenden Sinne dazu brauche, so muß ich mir auch die Bewegungen der Himmelskörper vorstellen so, daß ich Wendungen dazu brauche. Ich kann also unmöglich in demselben Sinne vorgehen, wie die gegenwärtige Astronomie vorgeht, die sich eben zum Begreifen der Himmelserscheinungen einfach nur des gewöhnlichen, starren Raumes bedient. Wenn Sie einfach zunächst die Kopforganisation und die Stoffwechselorganisation des Menschen nehmen, so müssen Sie, um von der einen zur anderen überzugehen, eine solche Wendung und noch dazu mit Variationen der Formen sich vorstellen. Nun, suchen wir uns eine Möglichkeit, zunächst bildhaft so etwas vorzustellen.

Sehen Sie, dazu haben wir ja schon vorgearbeitet, indem wir hingewiesen haben auf die Cassinische Kurve und auch auf diejenige Auffassung des Kreises, in der der Kreis nicht einfach eine Linie ist, bei der jeder Punkt von einem Mittelpunkt gleichweit entfernt steht, sondern diejenige Linie, bei der jeder Punkt von zwei fixen Punkten in der Weise entfernt ist, daß der Quotient dieser Entfernungen eine konstante Größe ist. Da haben wir also den Kreis durch eine andere Auffassung gegeben. Wir haben zunächst also auf die Cassinische Kurve hingewiesen und haben gezeigt, wie diese Cassinische Kurve im wesentlichen drei Formen hat: Die eine Form ist ellipsenähnlich, wie ich Ihnen gesagt habe. Sie entsteht dann, wenn zwischen den Konstanten ein bestimmtes Verhältnis ist, das wir angegeben haben; die zweite Form ist die Lemniskate; die dritte Form, die ist so, daß wir der Vorstellung gemäß eine Einheit haben, daß wir auch analytisch eine Einheit haben, daß wir aber in der Anschauung eine Einheit nicht haben. Diese zwei Äste der Cassinischen Kurve sind eben eine Kurve. Wir müssen aber, wenn wir die Linie ziehen, eben aus dem Raum heraus und kommen dann eigentlich wiederum in den Raum herein, wenn wir den anderen Ast ziehen. Begrifflich ist es so, daß wir einen einzigen Zug mit unserer Hand machen, wenn wir diese zwei anschaulich voneinander getrennten Gebiete hinzeichnen. Wir können nicht im gewöhnlichen Raum diese Linie ziehen, aber begrifflich ist dasjenige, was da oben ist und dasjenige, was da unten ist, eben durchaus eire Linie (Fig.2). Nun aber habe ich Ihnen gesagt, daß diese Linie noch in einer anderen Weise vorgestellt werden kann. Sie kann so vorgestellt werden, daß man frägt: Welche Bahn muß ein von dem einen fixen Punkte \(A\) beleuchteter Punkt durchlaufen, damit er in dem anderen fixen Punkte \(B\) stets mit gleicher Glanzstärke erscheint? Also ich bekomme da die Cassinische Kurve als den geometrischen Ort all derjenigen Punkte, die durchlaufen muß ein von dem einen fixen Punkte \(A\) beleuchteter Punkt, damit dieser Punkt in dem anderen fixen Punkte \(B\) immer mit dem gleichen Leuchtglanz beobachtet werden kann.

Nun wird es Ihnen nicht schwer sein sich vorzustellen, daß, wenn etwas von \(A\) nach \(C\) leuchtet und durch Reflexion wiederum nach \(B\) leuchtet, daß das denselben Glanz liefern kann wie das, was von \(A\) nach \(D\) leuchtet und so weiter. Das wird Ihnen ja nicht sonderlich schwer sein sich vorzustellen. Aber Sie werden schon gewisse Schwierigkeiten haben vorzustellen, wenn es an die Lemniskate herankommt. Da werden Sie nicht so ganz leicht zurechtkommen mit dem gewöhnlichen Abzirkeln nach den Reflexionsgesetzen und so weiter. Und erst recht schwierig wird es Ihnen werden, nun die Vorstellung zu bilden, daß von dem Punkte \(B\) aus hier in diesem Ast der Cassinischen Kurve (welcher \(B\) umschlingt) immer derselbe Leuchteglanz beobachtet werden soll, der durch den Lichtpunkt A bewirkt wird. Denn Sie müßten sich ja vorstellen, daß da der Lichtstrahl (beim Übergang vom einen Ast zum andern) aus dem Raume herausgeht, und daß er da wiederum in den Raum hineinleuchtet. Es würde dieselbe Schwierigkeit geben, die es gibt, wenn ich eben einfach nur verlange, daß wir mit der Hand durch den Raum mit einem Linienzug die zwei Äste ziehen. Aber ohne daß man diese Vorstellung ausbildet, kommt man wiederum nicht zurecht, wenn man die Formumwandlung oder den Formzusammenhang sucht irgendeines Organes des Kopfes mit irgendeinem Organ des Stoffwechsels des Menschen. Da müssen Sie unbedingt, wenn Sie den Zusammenhang suchen wollen, aus dem Raum heraus. Das heißt mit anderen Worten, so sonderbar, so paradox es klingt: Wenn Sie mit dem Verstehen irgendeiner Form Ihres Kopfes zum Verstehen irgendeiner Form innerhalb des Stoffwechselsystems übergehen wollen, dann können Sie nicht im Raume verbleiben, dann müssen Sie aus dem Raume heraus. Sie müssen aus sich selber heraus und müssen etwas suchen, was nicht im Raume ist, was ebensowenig im gewöhnlichen Raume ist, wie dasjenige, was zwischen dem oberen und dem unteren Ast der Cassinischen Kurve liegt. Es ist das ja nichts anderes als ein anderer Ausdruck dafür, daß man die Metamorphose sich vorzustellen hat als eine vollständige Wendung.

Nun, wenn wir uns hier noch vorstellen den Zusammenhang zwischen dem oberen Ast der diskontinuierlichen Cassinischen Kurve und dem unteren Ast, dann legen wir zugrunde wirkliche Konstanten, unveränderliche, starte Konstanten. Wenn wit aber die Konstanten selbst, wie wir es getan haben, veränderlich machen, dann gibt es einfach die Möglichkeit, bei veränderlicher Konstante, also bei doppelt variablen Gleichungen, den oberen Ast zum Beispiel so vorzustellen und den unteren Ast so vorzustellen (Fig. 3). Wir werden allerdings darauf hinauskommen, daß der obere Ast so sich gestaltet. Wenn Sie also die Cassinische Kurve so verändern, daß Sie statt der Konstanten selber wieder Variable nehmen, das heißt Funktionen zugrunde legen statt der unveränderlichen Konstanten, dann werden Sie zwei verschiedene Äste bekommen. Und darunter wird auch der Fall sein können, daß der eine Ast gewissermaßen aus dem Unendlichen kommt und wiederum ins Unendliche fortgeht.

Dieses Verhältnis aber, das ist es, was Sie zugrunde legen können, wenn Sie gewisse Gestalten innerhalb des menschlichen Hauptes verfolgen, sie linienhaft zusammenfassen und dann sie beziehen auf die Gestalten gewisser Organzusammenhänge im Stoffwechselsystem, die Sie wiederum linienhaft zusammenfassen. Da haben wir die ganze Komplikation der menschlichen Gestalt. Und die Sache wird allerdings dadurch nicht einfacher, daß Sie sich eben vorstellen müssen, daß diese Linie mit der Tendenz nach außen vorzustellen ist, diese Linie mit der Tendenz nach innen gewendet zu denken ist (Fig. 4).

Sie werden sagen - ich hoffe es zwar nicht, daß Sie allzuviel Wert darauf legen, sondern das nur als vorübergehende Anwandlung empfinden -: Dann ist ja diese menschliche Organisation so kompliziert, daß man fast auf das Begreifen verzichten möchte. Da ist einem schon lieber das gewöhnliche Philisterbegreifen, wie es heute in der Physiologie und Anatomie geübt wird. Da braucht man sich nicht so anzustrengen, braucht nicht die Vorstellungen verschwinden zu lassen und doch wiederum nicht verschwinden zu lassen, die Vorstellungen umzuwenden und dergleichen! - Aber man gelangt dann eben nicht zu einer Erfassung der menschlichen Organisation, sondern man gibt sich nur der Täuschung hin, daß man dazu gelange.

Nun, wenn Sie in die menschliche Organisation so hineinsehen und sich sagen: Da ist also etwas in der menschlichen Organisation, was aus dem Raume herausfällt, was nicht im Raume drinnen ist, was mir die Notwendigkeit gibt, so vorzustellen, daß ich räumlich voneinander getrennte Liniensysteme habe, die nach einem anderen Prinzip zusammenhängen als demjenigen, das unser dreidimensionaler Raum bietet -, wenn Sie sich das vorstellen, dann werden Sie ja vielleicht nicht mehr weit davon entfernt sein, sich zunächst in formaler Weise auch das Folgende vorzustellen. Etwas eingewendet werden kann ja zunächst gegen das formale Vorstellen von dem, was ich jetzt sagen werde, von niemandem, denn es handelt sich nur darum, in der gleichen Weise zu einer Vorstellung zu kommen, wie man in der Mathematik zu einer Vorstellung kommt. Da kann niemand einwenden, daß man die Sache nicht beweisen könne oder dergleichen. Denn da handelt es sich nur darum, zu einer in sich geschlossenen Vorstellung zu kommen.

Denken Sie sich einmal, Sie hätten es nicht bloß zu tun mit dem gewöhnlichen Raum, der also drei gedachte Dimensionen hat, sondern Sie hätten es zu tun mit einem Gegenraum. Ich nenne ihn zunächst Gegenraum, und ich möchte ihn in der folgenden Weise für die Vorstellung zunächst entstehen lassen: Denken Sie sich, ich bilde in der Vorstellung den gewöhnlichen dreidimensionalen, starren Raum; ich bilde die erste Dimension, ich bilde die zweite Dimension und ich bilde die dritte Dimension (Fig. 5). Indem ich diese drei Dimensionen gebildet habe, habe ich gewissermaßen vorstellungsgemäß die Erfüllung geschaffen desjenigen, was sich mir darbietet als der gewöhnliche dreidimensionale Raum. Aber Sie wissen ja, man kann überall nicht bloß vorgehen bis zu einer gewissen Intensität, sondern man kann auch davon wegnehmen, immer weiter wegnehmen und kommt dann zur Negation. Sie wissen, es gibt nicht nur Vermögen, sondern auch Schulden. Es ist möglich, daß ich nicht nur die drei Dimensionen entstehen lasse, sondern daß ich sie auch verschwinden lasse. Nur stelle ich mir den Vorgang des Entstehens

und Verschwindens als einen realen vor, als etwas, was ist. Ich kann auch bloß in zwei Dimensionen vorstellen, aber das meine ich jetzt nicht, sondern ich meine: Daß da nur zwei Dimensionen sind, davon ist die Ursache nicht, daß ich nie eine dritte gehabt habe, sondern davon ist die Ursache, daß ich wohl eine dritte gehabt habe, aber daß sie mir wiederum entschwunden ist. Die zwei Dimensionen sind das Ergebnis des zuerst Entstehens und dann Vergehens der dritten Dimension. Ich habe also jetzt einen Raum, der nur äußerlich noch zwei Dimensionen zeigt, den ich aber innerlich mir so vorzustellen habe, daß er zwei dritte Dimensionen, eine positive und eine negative, zeigt; die negative Dimension kommt aus etwas heraus, was nicht mehr in meinem dreidimensionalen Raum drinnen sein kann, was ich natürlich nicht als vierte Dimension im gewöhnlichen Sinn vorstellen muß, sondern als etwas, was sich zur dritten verhält wie das Negative zum Positiven (Fig. 6).

Nun nehmen Sie einmal an, ich würde jetzt so etwas nun einfügen demjenigen, was wir uns da ausgebildet haben (Fig. 7); das wäre irgendwie real vorhanden, aber so, wie in der Wirklichkeit zumeist die Dinge real sind; so, daß es approximativ das nachbildet, was ich hier gezeichnet habe, nicht ganz pedantisch genau. Es ist das ja nicht etwas, worüber man sich besonders verwundern darf. Denn Sie finden in der äußeren sinnlichen Wirklichkeit die mathematischen Figuren nicht anders als approximativ. Sie brauchen also nicht zu verlangen, daß es hier anders sei, wenn ich für dieses Bild eine Wirklichkeit suche, daß die anders sein soll als approximativ. Aber denken Sie einmal, ich müßte eine Wirklichkeit zeichnen, die irgendwie dem entspräche, dann müßte ich dies nicht ganz genau ebenso zeichnen, sondern etwas Abgeflachtes zeichnen, was dem entsprechen würde. Nun, daß da etwas war und wieder verschwunden ist, das will ich jetzt so andeuten, daß meinetwillen die Dichtigkeit einer Wirkung, die durch diese starke Schattierung angedeutet ist, da entstanden ist, aber wiederum sich abgeschwächt hat (Fig. 8). Sie haben hier eine Sphäre, die aber eigentlich in der Mitte einen verdichteten Teil hat. Nun bitte ich Sie, vergleichen Sie mit dem, was hier aufgezeichnet ist, erstens das reale Weltensystem, wie es sich dem Augenschein darbietet, die Sphäre mit ihren seltener stehenden Sternen und das nach diesem Prinzip gehäufte Sternensystem, das man gewöhnlich das Milchstraßensystem nennt. Aber vergleichen Sie auch die gewöhnlichen Sternkarten. Sie werden finden, daß sich dieses bitte bleiben wir zunächst dabei, es als Bild zu betrachten -, daß sich dieses Bild gar nicht anders zeigt als dasjenige, was man immer aufzeichnet als Durchgang der Sonne oder der Erde durch den Tierkreis, während man da hinaus (oben und unten) irgendwo zu verlegen hat den Nord- und Südpol. Sie sehen, so ganz ferne stehe ich dem, was in der äußeren Wirklichkeit ist, mit der Vorstellung nicht, die hier gebildet worden ist. Die realen Beziehungen werden wir schon in den nächsten Vorträgen aufsuchen.

Zur Erfassung desjenigen aber, was wir vorhin gerade angeführt haben für den Menschen, ist dasjenige, was wir da ausgebildet haben, noch nicht hinreichend, sondern da müssen wir weiter gehen. Da müssen wir sagen: Wir lassen jetzt auch noch die zweite Dimension verschwinden, so daß wir nur eine Dimension, eine Gerade bekommen; aber diese Gerade ist eben nicht eine Gerade, die einfach im dreidimensionalen Raum gezogen ist, sondern sie ist noch stehengeblieben, nachdem ich die dritte und die zweite Dimension habe verschwinden lassen. Und jetzt lassen wir auch noch die dritte Dimension verschwinden und bekommen dadurch eben einfach den Punkt. Halten wir das fest, daß wir den Punkt bekommen haben dadurch, daß die drei Dimensionen verschwunden sind, und nehmen wir an, dieser Punkt böte sich uns dar in der Realität als irgend etwas selber Existierendes. Aber wie müssen wir dann, wenn er sich als etwas Wirksames zeigt, seine Wirksamkeit uns vorstellen? Wir könnten, wenn wir seine Wirksamkeit uns vorstellen, diese Wirksamkeit in keine Beziehung bringen zu irgendeinem Punkt, sagen wir, der im Raum der \(x\)-Achse liegt. Denn diese gibt es nicht, die ist verschwunden. Wir könnten ihn auch nicht beziehen auf etwas, was eine x- und y-Koordinate hätte, denn das gibt es auch nicht, das ist verschwunden aus dem Raum. Auch nicht auf die dritte Dimension des Raumes könnten wir ihn beziehen in seiner Wirksamkeit, sondern wir müßten sagen: Wenn er uns seine Wirksamkeit darbietet, dann müssen wir ihn beziehen auf dasjenige, was ganz außerhalb des dreidimensionalen Raumes liegt. Es ist unmöglich nach diesem Vorgehen unseres Denkprozesses, ihn auf etwas zu beziehen, das wir irgendwie hineinbeziehen können in den dreidimensionalen Raum. Wir können ihn nur auf etwas beziehen, was außerhalb des dreidimensionalen Raumes liegt, nicht auf «\(x\) ausgelöscht», «\(y\) ausgelöscht», «\(z\) ausgelöscht», sondern auf das, was \(x\) \(y\) \(z\) auslöscht, was also im dreidimensionalen Raum gar nicht darinnen ist.

Wir haben das zunächst als eine formale Vorstellung gebildet. Diese Vorstellung wird aber höchst real. Sie wird sehr, sehr real, wenn man nicht mit den bequemen wissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen, mit denen man heute die Dinge beherrschen möchte, vorgeht, sondern sich etwas tiefer in die Dinge einläßt. Betrachten Sie nämlich einmal mit der wirklichen Tendenz, etwas zu begreifen, den Sehvorgang in seinem Zusammenhang mit der Organisation des Auges. Betrachten Sie diese ganze Organisation des Auges, wie sie sich darstellt. Sie wissen ja vielleicht, ich habe es in andern Vorträgen öfter erwähnt, man muß das Auge begreifen nicht als eine bloße Bildung von innen nach außen, sondern als etwas, was von außen nach innen einorganisiert ist. Man kann die Bildung von außen nach innen verfolgen, indem man phylogenetisch die Bildung der niederen Tiere verfolgt und dann zum Sehvorgang übergeht. Wenn Sie den Sehvorgang studieren, müssen Sie versuchen, sich innerlich begreiflich zu machen, wie er von außen angeregt wird, wie das Organ ihm angepaßt ist, auch von außen angeregt zu werden, wie es nach dem Sehnerv zu nach innen weiter wirkt und dann in die allgemeine Organisation übergeht, gewissermaßen in der allgemeinen Organisation verschwindet. Man kann ja natürlich die Endigung der Sehnerven finden, aber - das ist ja etwas, was sich approximativ ausdrückt - wenn man in die feinere Organisation übergeht, kann man schon sagen: Es schwindet hinein in diese Organisation. Wenn Sie nun diesen Sehvorgang mit den zu ihm gehörigen Organen wiederum ganz gewissenhaft vergleichen, zum Beispiel mit dem Nierenabsonderungsvorgang, dann müssen Sie den Ausführungsgang bei der Nierenabsonderung beziehen auf dasjenige, was auf der andern Seite sich auslebt von außen nach innen, indem das Auge in den Sehnerv übergeht.

Wenn Sie zu Vorstellungen kommen wollen, die diese zwei Dinge miteinander in Beziehung bringen, so daß Sie dann aus diesen Beziehungen die Erscheinungen bei dem einen und dem anderen Prozeß begreifen können, dann müssen Sie zu Hilfe nehmen solche Vorstellungen wie die vorhin angedeuteten. In dem Augenblick, wo Sie, wir können ja das eine für das andere setzen, solche Vorstellungen sich im dreidimensionalen Raum denken für den Sehvorgang und dann das Entsprechende beim Nierenabsonderungsvorgang suchen, müssen Sie sich die Wirkung so denken, als ob Sie aus dem dreidimensionalen Raum herauskommen würden. Sie müssen ganz genau einen solchen Gedankenprozeß durchmachen, wie ich ihn jetzt mit dem Auslöschen der Dimensionen durchgemacht habe; Sie kommen sonst nicht zurecht.

Und in einer ähnlichen Weise müssen Sie vorgehen, wenn Sie versuchen, die Kurven zu verstehen, die sich Ihnen ergeben, wenn Sie einschließlich der Schleifen die gewöhnliche, durch das Auge zu beobachtende Bahn von Venus und Merkur am Himmel untersuchen, und dann die Bahn von Jupiter und Mars untersuchen. Sie können, sagen wir unter Benützung von Polarkoordinaten, den Ausgangspunkt ihres Koordinatensystems bei der Venusschleife im dreidimensionalen Raum nehmen. Da können Sie das. Sie kommen aber nicht zurecht, wenn Sie nun die Schleifenlinie des Mars zum Beispiel begreifen wollen nach demselben Prinzip. Sie müssen ideell voraussetzen, daß hier die Ausgangspunkte für ein Polarkoordinatensystem außerhalb des dreidimensionalen Raumes liegen. Und Sie sind in die Notwendigkeit versetzt, überall die Koordinaten so zu nehmen, daß Sie das eine Mal, sagen wir für die Venusbahn mit der Schleife, von dem Koordinatenpol ausgehen und diese Koordinaten hier annehmen (Fig. 9); das andere Mal, für die Jupiterbahn oder die Marsbahn mit der Schleife, kommen Sie nur dann zurecht, wenn Sie sich sagen: Ich nehme nicht einen solchen Ausgangspunkt meines Polarkoordinatensystems, wo ich immer ein Stück zugeben muß, um die Polarkoordinaten zu bekommen, sondern ich nehme als Ausgangspunkt meines Polarkoordinatensystems die Sphäre, also alles dasjenige, was da ins Unbestimmte hinein dahinterliegt (Fig. 10), und bekomme dann solche Koordinaten (gestrichelte Linien); dann muß ich immer ein Stück weglassen. Und ich bekomme dann die Linie, die auch etwas hat wie einen Mittelpunkt, aber dieser Mittelpunkt ist in unermeßlichen Sphären. Es könnte also notwendig sein, daß wir zum weiteren Verfolgen der Bahnen der Planten schon die Vorstellung gebrauchen, daß bei der Konstitution der Bahn der inneren Planeten wir in die Notwendigkeit versetzt werden, uns vorzustellen, daß für sie irgendein Zentrum da ist im gewöhnlichen Raum, daß wir aber dann die Notwendigkeit hätten, aus dem gewöhnlichen Raum herauszugehen, wenn wir Zentren vorstellen wollen für die Jupiterbahn, die Marsbahn und so weiter.

Sie sehen, wir kommen hier dazu, den Raum überwinden zu müssen. Es ist durchaus notwendig. Sie werden sehen, wenn Sie wirklich gewissenhaft vorgehen im Begreifen der Erscheinungen, daß Sie nicht auskommen mit den bloßen dreidimensionalen Raumvorstellungen. Sie müssen das Zusammenwirken ins Auge fassen zwischen einem Raum, der die drei gewöhnlichen Dimensionen hat und den Sie sich ideell vorstellen können als von einem Mittelpunkt radial auslaufend, und einem anderen Raum, der diesen dreidimensionalen Raum fortwährend vernichtet, und der nun nicht von einem Punkte ausgehend gedacht werden darf, sondern der ausgehend gedacht werden muß von der in unbegrenzter Weite liegenden Sphäre; wobei also der Punkt das eine Mal den Flächeninhalt Null hat und das andere Mal den Flächeninhalt einer unermetßlich großen Kugelfläche. Wir müssen also unterscheiden zwischen zweierlei Punkten: zwischen einem Punkt, der den Flächeninhalt Null hat, den er nach außen wendet, und einem Punkt, der den Flächeninhalt einer unbegrenzt großen Kugelfläche hat, den er nach innen wendet. Im rein Geometrischen genügt es, wenn wir uns den abstrakten Punkt vorstellen. Im Reiche der Wirklichkeit genügt das nicht. Wir kommen nicht zurecht, wenn wir uns den bloß abstrakten Punkt vorstellen. Da müssen wir überall fragen, ob der Punkt, den wir uns vorstellen, nach innen oder nach außen gekrümmt ist, denn danach richtet sich sein Wirkungsfeld.

Aber noch etwas anderes müssen Sie ins Auge fassen. Sie können sich ja nun vorstellen, Sie hätten irgendwo diesen Punkt, der eine Sphäre ist (Fig. 11, starker Kreis). Zunächst ist für Sie keine Notwendigkeit, den Punkt, der ja in unermeßlichen Weiten liegt, gerade just hier (\(a\)) vorzustellen. Wir können ihn ja auch ein Stückchen weiter draußen vorstellen (\(b, c\)). Jeden Punkt können Sie irgendwo draußen vorstellen, nur müssen Sie sich diese Sphäre hier (innerer Kreis) frei lassen. Denn das ist ausgespart gewissermaßen, das ist der umgekehrte Kreis oder die umgekehrte Kugel, wenn Sie wollen. Aber denken Sie sich, es läge das Folgende vor: Dasjenige, was da außerhalb dieses abstrakten Kreises (starker Kreis) liegt, was also dieser Punkt ist, der seine Krümmung nach innen kehrt - denn der ganze Raum, der da außerhalb dieser Kugelfläche (starker Kreis) liegt, ist eben dann ein Punkt, der seine Krümmung nach innen kehrt -, dieser Raum, der wäre wiederum doch irgendwo begrenzt. Also, Sie können weit gehen, aber die Wirklichkeit wäre nicht so, daß Sie überall hingehen könnten, da läge wiederum irgendwo eine Grenze ganz anderer Art (gestrichelter Kreis). Was müßte denn das zur Folge haben? Das müßte zur Folge haben, daß hier irgendwo \((P)\) auftreten müßte dasjenige, was wiederum dazu gehört zu dem, was da draußen liegt. Es müßte da drinnen eine kleine Sphäre auftreten, die zu dem gehört, was da draußen liegt. Sie würden also sagen müssen: Da außerhalb einer Sphäre gibt es etwas; aber sehen kann ich das, was da draußen liegt, indem ich da \((P)\) hineinschaue. Denn das ist dasjenige, was da wieder erscheint, was da sich wieder geltend macht, was die Fortsetzung ist von dem, was da draußen liegt. Dasjenige, was ich suche, wenn ich in die unendlichen Fernen gehe, kommt mir aus dem Zentrum wiederum zum Vorschein.

Sehen Sie, solche Vorstellungen bilde man in genügender Weise aus. Sie machen ja immerhin den Eindruck von etwas, was schon formal durchaus berechtigt ist. Aber es wird noch etwas ganz anderes damit getan werden können, wenn man versucht, mit solchen Vorstellungen zu durchdringen dasjenige, was äußerlich wirklich ist. Denn denken Sie sich einmal, es gäbe eine Erscheinung innerhalb des Himmelsraumes, nennen wir sie zunächst Mond. Diese Erscheinung hätte man nicht dadurch zu begreifen, daß man einfach sagt: Der Mond, er ist ein Körper, er hat da seinen Mittelpunkt und wir untersuchen ihn nach dem Prinzip, daß er da seinen Mittelpunkt hat und ein Körper ist. - Nehmen Sie an - verzeihen Sie, wenn ich etwas euphemistisch rede -, diese Denkweise paßte nicht in die Wirklichkeit, sondern ich müßte anders sagen, ich müßte sagen: Wenn ich in meiner Welt von einem Punkt aus immer weiter und weiter gehe, dann komme ich dahin, wo ich nicht mehr andere Himmelskörper finde, wo ich, wenn es sich aber um eine Wirklichkeit handelt, doch auch nicht bloß den leeren euklidischen Raum finden kann, wo ich aber etwas finde, das mich durch seine Wirklichkeit nötigt, seine Fortsetzung hier \((P)\) zu denken. Ich wäre dann genötigt, den Raumesinhalt dieses Mondes als ein Stück der gesamten Welt zu denken, mit Ausnahme alles desjenigen, was an Sternen und so weiter außerhalb des Mondes ist. Ich müßte mir also denken auf der einen Seite alles dasjenige, was ich an Sternen im Weltenraum habe (\(a\), \(b\), \(c\) in Fig. 11). Die müßte ich in einer einheitlichen Weise behandeln, das setze ich zunächst voraus, Aber das Innere des Mondes, den Rauminhalt des Mondes dürfte ich nicht so behandeln, sondern nur so, daß ich sagte: Ich kann auf der einen Seite gehen ins Weite. Da setze ich voraus, daß da irgendwo die Sphäre ist - es ist ja zunächst die scheinbare Sphäre, aber es muß irgendwie gedacht werden, daß da auch etwas Effektives dem zugrunde liegt. Aber mit alle dem, was sich mir da in den Weiten ergibt, hat das nichts zu tun, was innerhalb der Kugeloberfläche des Mondes liegt; das hat zu tun mit demjenigen, was beginnt, wenn die Sterne aufhören. Das ist ein Stück, in einer sonderbaren Weise zugehörig nicht zu meiner Welt, sondern zu derjenigen Welt, der die anderen Sterne alle nicht angehören. Wenn sich so etwas innerhalb einer Welt findet, dann haben wit es zu tun mit einem Einschub in die Welt, der ganz anderer Natur ist, der ganz andere innere Qualitäten zeigt als dasjenige, was um ihn herum ist. Und wir dürfen dann vergleichen das Verhältnis eines solchen Mondes zu seinem umliegenden Himmel mit dem Verhältnis, das wir haben zum Beispiel zwischen den Nierenabsonderungen mit dem zugrunde liegenden Organismus und dem Augenorganismus. Von diesem Punkt aus wollen wir dann morgen weiter reden.

Es liegt nicht an mir, daß ich versuchen muß, Ihnen komplizierte Vorstellungen zu formen über den Bau des Weltenalls, sondern es liegt daran, daß man mit anderen Vorstellungen nur dann zurechtkommt, wenn man sagt: Nun, wir fassen die Erscheinungen mit diesen Vorstellungen zusammen, und dann - dann ist halt eine Grenze, dann kommt man halt nicht weiter. Es liegt an der Wirklichkeit und durchaus nicht an irgendeiner Sucht, besondere Vorstellungen auszubilden, wenn man, um Sie in das Verständnis des Weltenbaus einzuführen, eben solch komplizierte Vorstellungen ausbildet.

Fifteenth Lecture

Today, I would like to try to translate some of the things that may be difficult to understand from what we have considered so far into mental images that will show you how it is indeed impossible to comprehend world phenomena using the basis that we would so gladly like to use, naturally in accordance with the convenience of human thinking habits. We have considered world phenomena in relation to human beings from a wide variety of perspectives. We have repeatedly pointed out how a certain connection exists between human form and what we encounter in the phenomena of the heavens, regardless of whether we summarize the movements of the heavenly bodies in terms of an older world system or in terms of Copernican theories. We have seen that the picture must always be related to human beings in various ways, but in a true science we cannot avoid actually accepting this relationship.

However, this presents us with considerable difficulties. We first pointed out in the course of these lectures the difficulty that arises when, as soon as one attempts to consider the ratios of the orbital periods of the planets in our system, incommensurable numbers result, so that it is necessary, in a sense, to stop calculating. For where incommensurable numbers arise, there is no comprehensible unity. And so we see that with the mathematical way of thinking and methodology through which we would like to summarize the phenomena of our universe, we are driven out of reality by the phenomena themselves, so that we cannot assume that we can somehow explain the phenomena of the world with what we use as the basis for our geometry in ordinary, rigid three-dimensional space. In particular, however, a difficulty arose for us yesterday: We were forced to assume a certain relationship between the sun, moon, and earth, which must be expressed in some way in human beings, in the structure of human beings, and which we would like to grasp. And the moment such a triune interaction comes into play, we encounter considerable difficulties in calculating in space. I have already drawn attention to all of this. Now we may be able to gain some insight, at least as a starting point, purely geometrically, but to a greater degree geometrically, a mental image of what actually underlies the difficulty of understanding the connections between celestial phenomena by calculating in space.

If we go back once more to the various attempts I have indicated to you to really grasp the constitution of the human being itself, we come to the following. We can make the attempt to take the structure of the human being, which we have also spoken about frequently in these lectures, really seriously, as it must be. We can say that the human head organization, with its center in the nervous-sensory system, has a certain independence of its own; likewise the rhythmic system with everything that belongs to it; and finally, the metabolic system with everything that belongs to the limb organization also has a kind of independence of its own. We can therefore point to three independent systems within the human organism, and if we take the principle of metamorphosis as our basis, which must necessarily be taken as the basis in organic nature, we will have to form mental images about how these three members of the human organism relate to each other according to the principle of metamorphosis.

So, understand me correctly! Let us form a mental image, even if it is only a pictorial one at first, of how the three parts of the human organism relate to each other. At first glance, this will of course be difficult. It will be difficult to clearly recognize what can be found in the human head as a metamorphosis of the organs that underlie the metabolic-limb system. But if one goes into the morphology of the human being as far as I have indicated, then one can come to terms with it in a certain way, if one really thinks through the mental image thoroughly, that in the interrelationship between the long bones and the skull bones we are dealing with a complete turning of the inner surface of the bone outward, according to the principle of turning a glove inside out, and that this reversal also involves a change in the balance of forces. If I were to turn the inside of the tubular bone outward in the same way that I turn a glove, a tubular bone would naturally be created again. But if we assume that the tubular bone has only been configured in this way because it is arranged, as I have described, inward toward the continuous radial, so that it is compelled to arrange its matter in accordance with the radial, and I then turn it inside out so that the inside comes to the outside, and it then no longer follows the radial in its arrangement, but the spheroidal, then the inside, which now turns toward the spheroidal, will take on this very shape (Fig. 1).

The former exterior is now the interior and vice versa. If you consider this in the most extreme case of the transformation of the tubular bone into the skull bone, you will say to yourself: The outer ends of the human structure, the limb system and the skull system, represent, in a sense, the poles of the organization, but in such a way that we must not simply think of the poles in a linear sense as opposites, but that when we move from one pole to the other, we must also assume a corresponding transition between the radius and the surface of the sphere. Without resorting to such complicated mental images, it is quite impossible to get any kind of adequate mental image of the human organism.

Now, that which forms, so to speak, the center, the middle link in the organization of the human being, that which is assigned to the rhythmic organism, will be located in the center and will, so to speak, form the transition from radial structure to spheroidal structure. The entire human organization can now be understood morphologically on the basis of this principle. We must therefore realize that if we have anything in the metabolic organization as an organ, for example the liver or any of the organs that belong to the metabolism in the most eminent sense – one can only ever say “belong in the most eminent sense,” because things are intertwined – if we have such an organ and we look for the organ in the head organization that can be connected to it through metamorphosis, then we will of course have to acknowledge a tremendous deformation of the organ in question if we want to come to terms with the concept of form. Therefore, it will be difficult to grasp the matter mathematically in any way. But without approaching it mathematically somewhere, one will not be able to cope at all. And if you consider—take it as an image—that in understanding the human form we have something that points to the movements of the heavenly bodies, then it will be a matter of understanding that if we want to summarize what occurs in the movements of the heavenly bodies, we must also understand it in a similar way; that one does not proceed as if things simply took place in a way that can be approached with geometry, which simply calculates with ordinary space and which, because it does so, cannot calculate with any reversal. As soon as one speaks of such a reversal, as I have done, one can no longer calculate with ordinary space. Ordinary space applies where I form cubic contents in the ordinary sense. But when I am forced to make the interior the exterior, then the possibility of continuing to calculate with the mental images I have in ordinary space ceases.

Now, if I have to mentally image the human form in such a way that I need reversals in the corresponding sense, then I must also mentally image the movements of the heavenly bodies in such a way that I need reversals. So I cannot possibly proceed in the same way as present-day astronomy, which simply uses ordinary, rigid space to understand celestial phenomena. If you simply take the organization of the human head and the organization of the human metabolism, you must, in order to move from one to the other, mentally imagine such a turn and, in addition, variations in form. Well, let us look for a way to mentally create an image of something like this.

You see, we have already done some preliminary work on this by pointing out the Cassin curve and also the conception of the circle in which the circle is not simply a line in which every point is equidistant from a center point, but rather a line in which every point is equidistant from two fixed points in such a way that the quotient of these distances is a constant quantity. So we have given the circle through a different conception. We first pointed to the Cassini curve and showed how this Cassini curve essentially has three forms: One form is ellipse-like, as I told you. It arises when there is a certain ratio between the constants, which we have specified; the second form is the lemniscate; the third form is such that, according to our mental image, we have a unity, that we also have a unity analytically, but that we do not have a unity in our perception. These two branches of the Cassini curve are indeed a curve. However, when we draw the line, we must draw it out of space and then actually re-enter space when we draw the other branch. Conceptually, we make a single stroke with our hand when we draw these two visually separate areas. We cannot draw this line in ordinary space, but conceptually, what is above and what is below is indeed a single line (Fig. 2). But now I have told you that this line can be given a mental image in another way. It can be given a mental image by asking: What path must a point illuminated by one fixed point \(A\) travel so that it always appears with the same brightness at the other fixed point \(B\) ? So I get the Cassini curve as the geometric locus of all those points that a point illuminated by the one fixed point \(A\) must travel through so that this point can always be observed with the same brightness at the other fixed point \(B\).

Now, it will not be difficult for you to form a mental image of the fact that if something shines from \(A\) to \(C\) and, through reflection, shines again to \(B\), it can provide the same brightness as something that shines from \(A\) to \(D\), and so on. That will not be particularly difficult for you to form a mental image. But you will have some difficulty forming a mental image of it when it comes to the lemniscate. You will not find it so easy to cope with the usual circling according to the laws of reflection and so on. And it will be even more difficult for you to form the mental image that from point \(B\) here in this branch of the Cassini curve, which encircles \(B\), the same brightness caused by the light point A should always be observed. For you would have to form a mental image of the light ray (when passing from one branch to the other) leaving the space and then shining back into the space. The same difficulty would arise as when I simply ask us to draw the two branches with our hands through space with a line. But without forming this mental image, one cannot cope when seeking the transformation of form or the connection between the form of any organ of the head and any organ of the human metabolism. If you want to find the connection, you absolutely must leave space behind. In other words, as strange and paradoxical as it may sound, if you want to move from understanding some form in your head to understanding some form within the metabolic system, you cannot remain in space; you must leave space behind. You must step outside yourself and look for something that is not in space, something that is as little in ordinary space as that which lies between the upper and lower branches of the Cassini curve. This is nothing other than another way of saying that one must mentally image metamorphosis as a complete reversal.

Now, if we mentally image the connection between the upper branch of the discontinuous Cassini curve and the lower branch, then we are basing our calculations on real constants, unchanging, rigid constants. But if we make the constants themselves variable, as we have done, then with variable constants, i.e., with double variable equations, it is simply possible to mentally image the upper branch, for example, like this and the lower branch like this (Fig. 3). However, we will come to the conclusion that the upper branch is shaped like this. So if you change the Cassini curve in such a way that you use variables again instead of the constants themselves, i.e., you use functions instead of immutable constants, then you will get two different branches. And among these, there may also be the case that one branch comes from infinity, so to speak, and continues into infinity.

However, this relationship is what you can use as a basis when you follow certain forms within the human head, summarize them in lines, and then relate them to the forms of certain organ connections in the metabolic system, which you in turn summarize in lines. There we have the whole complexity of the human form. And the matter is certainly not made any easier by the fact that you have to mentally image that this line with the tendency outward is to be thought of as turned inward (Fig. 4).

You will say—I hope you will not attach too much importance to this, but will regard it only as a passing impulse—: Then this human organization is so complicated that one almost wants to give up trying to understand it. One would rather stick to the ordinary philistine understanding as practiced today in physiology and anatomy. There, one does not have to make such an effort, one does not have to let the mental images disappear and yet not let them disappear, turn the mental images around and so on! - But then you don't actually grasp human organization, you just delude yourself into thinking that you do.

Now, when you look into human organization and say to yourself: So there is something in human organization that falls outside of space, that is not inside space, that gives me the necessity imagine that I have spatially separate line systems that are connected according to a different principle than that offered by our three-dimensional space — if you form a mental image of that, then you may not be far from imagining the following in a formal way. No one can object to the formal presentation of what I am about to say, because it is only a matter of arriving at a mental image in the same way that one arrives at a mental image in mathematics. No one can object that the thing cannot be proven or anything of the sort. For it is only a matter of arriving at a self-contained mental image.