Third Scientific Lecture-Course:

Astronomy

GA 323

16 January 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture XVI

What we are doing, as you will have seen, is to bring together the diverse elements by means of which in the last resort we shall be able to determine the forms of movement of the heavenly bodies, and—in addition to the forms of movement—what may perhaps be described as their mutual positions. A comprehensive view of our system of heavenly bodies will only be gained when we are able to determine first the curve-forms (inasmuch as forms of movement are called curves), i.e. the true geometrical figures, and then the centres of observation. Such is the task before us along our present lines of study, which I have formed as I have done for very definite reasons.

The greatest errors that are made in scientific life consist in this: they try to make syntheses and comprehensive theories when they have not yet established the conditions of true synthesis. They are impatient to set up theories—to gain a conclusive view of the thing in question,—they do not want to wait till the conditions are fulfilled, subject to which alone theories can properly be made. Our scientific life and practice needs this infusion badly,—needs to acquire a feeling of the fact that you ought not to try and answer questions when the conditions for an intelligent answer are not yet achieved. I know that many people (present company of course excepted) would be better pleased if one presented them with curves all ready made, for planetary or other movements. For they would then be in possession of tangible answers. What they are asking is in effect to be told how such and such things are in the Universe, in terms of the ideas and concepts they already have. What if the real questions are such as cannot be answered at all with the existing ideas and concepts? In that case, theoretic talk will be to no purpose. One's question may be set at rest, but the satisfaction is illusionary. Hence, in respect to scientific education, I have attempted to form these lectures as I have done.

The results we have gained so far have shown that we must make careful distinctions if we wish to find true forms of curves for the celestial movements. Such things as these, for instance, we must differentiate: the apparent movements seen in the paths of Venus and of Mars respectively,—Venus making a loop when in conjunction, Mars when in opposition to the Sun. We came to this conclusion when trying to perceive how diverse are the forms of curves that arise in man himself through the forces that build and form him. We ascertained quite different forms of curve in the region of the head-nature and in the organization of the metabolism and the limbs. The two types of form are none the less related, but the transition from one to the other must be sought for outside of space,—at least beyond the bounds of rigid Euclidean space.

Then comes a further transition, which still remains for us to find. We have to pass from what we thus discover in our own human frame, to what is there outside in Universal Space, which only looks to us plainly Euclidean. We think it nicely there, a rigid space, but that is mere appearance. As to this question, we only gain an answer by persevering with the same method we have so far developed. Namely we have to seek the real connection of what goes on in man himself and what goes on outside in Universal Space, in the movements of the celestial bodies. Then we are bound to put this fundamental question: What relation is there, as to cognition itself, between those movements that may legitimately be considered relative and those that may not? We know that amid the forming and shaping forces of the human body we have two kinds: those that work radially and those which we must think of as working spherically. The question now is, with regard to outer movements: How, with our human cognition do we apprehend that element of movement which takes its course purely within the Sphere, and how do we apprehend that element which takes its course along the Radius?

A beginning has been made in Science as you know, even experimentally, in respect of these two kinds of spatial movement. The movements of a heavenly body upon the Sphere can of course be seen and traced visually. Spectrum analysis however also enables us to detect those movements that are along the line of sight, spectrum analysis enables us to recognise the fact. Interesting results have for example been arrived at with double stars that move around each other. The movement was only recognizable by tackling the problem with the help of Doppler's principle,—that is the experimental method to which I am referring.

For us, the question now is whether the method which includes man in the whole cosmic system will give us any criterion—I express myself with caution—any criterion to tell whether a movement may perhaps only be apparent or whether we must conclude that it is real. Is there anything to indicate that a given movement must be a real one? I have already spoken of this. We must distinguish between movements that may quite well be merely relative and on the other hand such movements as the “rotating, shearing and deforming movements” (so we described them), the very character of which will indicate that they cannot be taken in a merely relative sense. We must look for a criterion of true movement. We shall gain it in no other way than by envisaging the inner conditions of what is moving. We cannot possibly confine ourselves to the mere outer relations of position.

A trite example I have often given is of two men whom I see side by side at 9 am and again at 3 in the afternoon. The only difference is, one of them stayed there while the other went on an errand lasting six hours. I was away in the meantime and did not see what happened. At 3 pm I see them side by side again. Merely observing where they are outwardly in space, will never tell me the true fact. Only by seeing that one is more tired than the other—taking account of an inner condition therefore—shall I be able to tell, which of them has been moving. This is the point. If we would characterize any movement as an inherent and not a merely relative movement, we must perceive what the thing moved has undergone in some more inward sense. For this, a further factor will be needed, of which tomorrow. Today we will at least approach the problem.

We must in fact get hold of it from quite another angle. If we in our time study the form and formation of the human body and look for some connection with what is there in cosmic space, the most we can do to begin with is in some outward sense to see that the connection is there. Man is today very largely independent of the movements of cosmic space; everything points to the fact that this is so. For all that comes to expression in his immediate experience, man has emancipated himself from the phenomena of the Universe. We therefore have to look back into the time when what he underwent depended less upon his conscious life of soul than in his ordinary, by which I mean, post-natal life on Earth. We must look back into the time when he was an embryo. In the embryo the forming and development of man does indeed take place in harmony with cosmic forces. What afterwards remains is only what is carried forward, so to speak. Implanted in the whole human organization during the embryonal life it then persists. We cannot say it is "inherited" in the customary sense, for in fact nothing is inherited, but we must think of some such process, where entities derived from an earlier period of development stay on.

We must now look for an answer to the question: Is there still anything in the ordinary life we lead after our birth—after full consciousness has been attained—is there still any hint of our connection with the cosmic forces? Let us consider the human alternation of waking and sleeping. Even the civilized man of today still has to let this alternation happen. In its main periodicity, if he would stay in good health, it still has to follow the natural alternation of day and night. Yet as you know very well, man of today does lift if out of its natural course. In city life we no longer make it coincide with Nature. Only the country folk do so still. Nay, just because they do so, their state of soul is different. They sleep at night and wake by day. When days are longer and nights shorter they sleep less; when nights are longer the sleep longer. These aspects however can at most lead to vague comparisons; no clear perception can be derived from them. To recognize how the great cosmic conditions interpenetrate the subjective conditions of man, we must go into the question more deeply. So shall we find in the inner life of man some indication of what are absolute movements in the great Universe.

I will now draw your attention to something you can very well observe if only you are prepared to extend your observation to wider fields. Namely, however easily man may emancipate himself from the Universe in the alternation of sleeping and waking as regards time, he cannot with impunity emancipate himself as regards spatial position. Sophisticated folk—for such there are—may turn night into day, day into night, but even they, when they do go to sleep, must adopt a position other than the upright one of waking life. They must, as it were, bring the line of their spine into the same direction as the animal's. One might investigate a thing like this in greater detail. For instance, it is a physiological fact that there are people who in conditions of illness cannot sleep properly when horizontal but have to sit more upright. Precisely these deviations from the normal association of sleep with the horizontal posture will help to indicate the underlying law. A careful study of these exceptions—due as they are to more or less palpable diseases (as in the case of asthmatic subjects for example)—will be indicative of the true laws in the domain. Taking the facts together, you can quite truly put it in this way: To go to sleep, man must adopt a position whereby his life is enabled in some respects to take a similar course, while he is sleeping, to that of animal life. You will find further confirmation in a careful study of those animals whose spinal axis is not exactly parallel to the Earth's surface.

Here again I can only give you guiding lines. For the most part, these things have not been studied in detail; the facts have not been looked at in this manner, or not exhaustively. I know they have never been gone into thoroughly. The necessary researches have not been undertaken.

And now another thing: You know that what is trivially called “fatigue” represents a highly complex sequence of events. It can come about by our moving deliberately. When we move deliberately, we move our centre of gravity in a direction paralleled to the surface of the Earth. In a sense, we move about a surface parallel to the Earth's surface. The process which accompanies our outward and deliberate movements takes its course in such a surface. Now here again we can discover what belongs together. On the one hand we have our movement and mobility parallel to the surface of the earth, and our fatigue,—becoming tired. Now we go further in our line of thought. This movement parallel to the surface of the Earth, finding its symptomatic expression in fatigue, involves a metabolic process—an expenditure of metabolism. Underlying the horizontal movement there is therefore a recognizable inner process in the human body.

Now the human being is so constituted that he cannot well do without such movement—including all the concomitant phenomena, the metabolic expenditure of substance and so on. He needs all this for bodily well-being. If you're a postman, your calling sees to it that you move about horizontally; if you are not a postman you take a walk. Hence the relationship, highly significant for Economics, between the use and value of that mobility of man which enters into economic life and that which stays outside it—as in athletics, games and the like. Physiological and economic aspects meet in reality. In my critique of the economic concept of Labour, you may remember I have often mentioned this. It is at this point that the relation emerges between a purely social science and the science of physiology, nor can we truly study economics if we disregard it. For us however at the present moment, the important thing is to observe this parallelism of movement in a horizontal surface with a certain kind of metabolic process.

Now the same metabolic process can also be looked for along another line. We think once more of the alternation of sleeping and waking. But there is this essential difference. The metabolic transformation, when it takes place with our deliberate movements, makes itself felt at once as an external process, even apart from what goes on inside the human being. If I may put it so, something is then going on, for which the surface of the human body is no exclusive frontier. Substance is being transformed, yet so that the transformation takes place as it were in the absolute; the importance of it is not only for the inside of man's body. (The world “absolute” must of course again be taken relatively!)

That we get tired is, as I said, a symptomatic concomitant of movement and of the metabolic process it involves. Yet we also get tired if we have only lived the life-long day while doing nothing. Therefore the same entities which are at work when we move about with a will, are also at work in the human being in his daily life simply by virtue of his internal organization. The metabolic transformation must also be taking place when we just get tired, without our bringing it about by any deliberate action.

We put ourselves into the horizontal posture so as to bring about the same metabolism which takes place when we are not acting deliberately,—which takes place simply with the lapse of time, if I may so express it. We put ourselves into the horizontal posture during sleep, so that in this horizontal position our body may be able to carry out what it also carries out when we are moving deliberately in waking life. You see from this that the horizontal position as such is of great significance. It is not a matter of indifference, whether or not we get into this position. To let our inner organism carry out a certain process without our doing anything to the purpose, we must bring ourselves into the horizontal position in which there happens in our body something that also happens when we are moving by our deliberate will.

A movement must therefore be going on in our body, which we do not bring about by our deliberate will. A movement which we do not bring about by our deliberate will must be of significance for our body. Try to observe and interpret the given facts and you will come to the following conclusion, although again—for lack of time—in saying this I must leave out many connecting links. Human movement, as we said just now, involves an absolute metabolic process or change of substance, so that what then goes on in our metabolism has, so to speak, real chemical or physical significance, for which the limits of our skin are in some sense non-existent;—so that the human being in this process belongs to the whole Cosmos. And now the very same metabolic change of substance is brought about in sleep, only that then its significance remains inside the human body. The change of substance that takes place in our deliberate movement takes place also in our sleep, but the outcome of it is then carried from one part of our body to another. During sleep, in effect, we are supplying our own head. We are then carrying out or rather, letting the inside of our body carry out for us—a metabolic process of transformation for which the human skin is an effective frontier. The transmutation so takes place that the final process to which it leads has its significance within the bodily organization of man.

Once more then, we may truly say: We move of our own will, and a metabolic process (a transformation of substance) is taking place. We let the Cosmos move us; a transformation of substance is taking place once more. But the latter process goes on in such a way that the outcome of it—which in the former metabolic process takes its course, so to speak, in the external world—turns inward to make itself felt as such within the human head. It turns back and does not go flowing outward and away. Yet to enable it to turn back, nay to enable it to be there at all, we have to bring ourselves into the horizontal posture. We must therefore study the connection between those processes in the human body that take place when we move deliberately and those that take place when we are sleeping. And from the very fact that we are obliged to do this at a certain stage of our present studies, you may divine how much is implied when in the general Anthroposophical lectures I emphasize—as indeed I must do, time and gain,—that our life of will, bound as it is to our metabolism, is to our life of thought and indeation even as sleeping is to waking.

In the unfolding of our will, as I have said again and again, we are always asleep. Here now you have the more exact determination of it. Moving of his own will and in a horizontal surface, man does precisely the same as in sleep. He sleeps by virtue of his will. Sleep, and deliberate or wilful movement, are in this relation. When we are sleeping in the horizontal posture, only the outcome is different. Namely, what scatters and is dispersed in the external world when we are moving deliberately, is received and assimilated, made further use of, by our own head-organisation when we are asleep.

We have then these two processes, clearly to be distinguished from one another:—the outward dispersal of the metabolic process when we move about deliberately in day-waking life, and the inward assimilation of the metabolic process by all that happens in our head when we are sleeping. And if we now relate this to the animal kingdom, we may divine how much it signifies that the animal spends its whole life in the horizontal posture. This turning-inward of the metabolism to provide the head must be quite different in the animal. Also deliberate movement must be quite different in the animal from what it is in man.

This is the kind of thing so much neglected in the Science of today. They only speak of what presents itself externally, failing to see that the same external process may stand for something different in the one creature and in the other. For example—quite apart now from any religious implication—man dies and the animal dies. It does not follow that this is psychologically the same in either case. A scientist who takes it to be the same and bases his research on this assumption is like a man who would pick up a razor and declare: This is a kind of knife, therefore the same function as any other knife; so I will use it to cut my dumpling. Put on this simple level, you may answer: No-one would be so silly. Yet have a care, for this is just what happens in the most advanced researches.

This then is what we are led to see. In our deliberate movements we have a process finding its characteristic expression in curves that run parallel to the surface of the Earth; we cannot but make curves of this direction. What have we taken as fundamental now, in this whole line of thought? We began with an inner process which takes its course in man. In sleep this is the given thing, yet on the other hand we ourselves bring a like process about by our own action. Through what we do ourselves, we can therefore define the other. The possibility is given, logically. What is done to our bodily nature from out of cosmic space when are sleeping, this we can treat as the thing to be defined,—the nature of which we seek to know. And we can use as the defining concept what we ourselves do in the outer world—what is therefore well-known to as to its spatial relations. This is the kind of thing we have to look for altogether, in scientific method: Not to define phenomena by means of abstract concepts, but to define phenomena by means of other phenomena. Of course it presupposes that we do really understand the phenomena in question, for only then can we define them by one-another. This characteristic of Anthroposophical scientific endeavour. It seeks to reach a true Phenomenalism,—to explain phenomena by phenomena instead of making abstract concepts to explain them. Nor does it want a mere blunt description of phenomena, leaving them just as they are in the chance distributions of empirical fact and circumstance, where they may long be standing side by side without explaining one-another.

I may digress a moment at this point, to indicate the far-reaching possibilities of this “phenomenological” direction in research. The empirical data are at hand, for us to reach the right idea. There is enough and to spare to empirical data. What we are lacking in is quite another thing, namely the power to synthesize them,—in other words, to explain one phenomenon by another. Once more, we have to understand the phenomena before w can explain them by each other. Hence we must first have the will to proceed as we are now trying to do,—to learn to penetrate the phenomenon before us. This is so often neglected. In our Research Institute we shall not want to go on experimenting in the first place with the old ways and methods, which have produced enough and to spare of empirical data. (I speak here not from the point of view of technical applications but of the inner synthesis which is needed.) There is no call for us to go on experimenting in the old ways. As I said in the lectures on Heat last winter, we have to arrange experiments in quite new ways. We need not only the usual instruments from the optical instrument makers; we must devise our own, so as to get quite different kinds of experiments, in which phenomena are so presented that the one sheds light on the other. Hence we shall have to work from the bottom upward. If we do so, we shall find an abundance of material for fresh enlightenment. With the existing instruments our contemporaries can do all that is necessary; they have acquired admirable skill in using them in their one-sided way. We need experiments along new lines, as you must see, for with the old kind of experiment we should never get beyond certain limits. Nor on the other hand will it do for us merely to take our start from the old results and then indulge in speculation. Again and again we need fresh experimental results, to bring us back to the facts when we have gone too far afield. We must be always ready to find ways of means, when we have reached a certain point in our experimental researches, not just to go on theorising but to pass on to some fresh observation which will help elucidate the former one. Otherwise we shall not get beyond certain limits, transient though they are, in the development of Science.

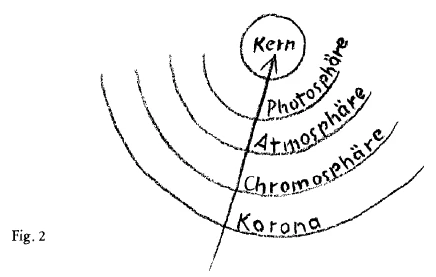

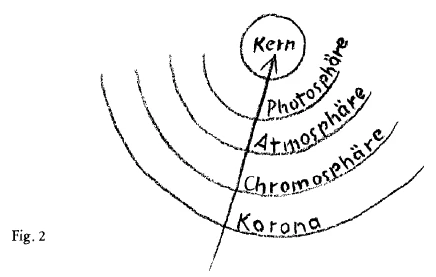

I will here draw attention to one such limit, which, though not felt to be insurmountable by our contemporaries, will in fact only be surmounted when fresh kinds of experiment are made. I mean the problem of the constitution of the Sun. Careful and conscientious observations have of course been made by all the scientific methods hitherto available, and with this outcome: First they distinguish the inner most part of the Sun; what it is, is quite unclear to them. They call it the solar nucleus, but none can tell us what it is; the methods of research do not reach thus far. To say this is no unfriendly criticism; everyone admits it. They then suppose the Sun's nucleus to be surrounded by the so-called photo-sphere, the atmosphere, the chromosphere and the corona. From the photosphere onward they begin to have definite ideas abut it. Thus they are able to form some idea about the atmosphere, the chromosphere. Suppose for instance that they are trying to imagine how Sun-spots arise. Incidentally, this strange phenomenon does not happen quite at random; it shows a certain rhythm, with maxima and minima in periods of about eleven years. Examine the Sun-spot phenomena, and you will find they must in some way be related to processes that take place outside the actual body of the Sun. In trying to imagine what these processes are like, our scientists are apt to speak of explosions or analogous conditions. The point is that when thinking in this way they always take their start from premisses derived from the earthly field. Indeed, this is almost bound to be so if one has not first made the effort to widen out one's range of concepts,—as we did for instance when we imagined curves going out of space. If one has not done something of this kind for one' s own inner training, one has no other possibility than to interpret on the analogy of earthly conditions such observations as are available of a celestial body that is far beyond this earthly world.

Nay, what could be more natural—with the existing range of thought—than to imagine the processes of the solar life analogous to the terrestial, but for the obvious modifications. Yet in so doing one soon encounters almost insuperable obstacles. That which is commonly thought of as the physical constitution of the Sun can never really be understood with the ideas we derive from earthly life. We must of course begin with the results of simple observation, which are indeed eloquent up to a point; then however we must try to penetrate them with ideas that are true to their real nature. And in this effort we shall have to come to terms with a principle which I may characterize as follows.

It is so, is it not? Given some outer fact or distribution which we are able thoroughly to illumina with a truth of pre Geometry we say to ourselves: how well it fits: we build it up purely by geometrical thinking and now the outer reality accords with it. It hinges-in, so to speak. We feel more at one with outer reality when we thus find again and recognize what we ourselves first constructed, (yet the delight of it should not be carried too far. Somehow or other, one must admit, it always “hinges-in” even for those theorists who get a little unhinged themselves in the process: They too are always finding the ideas they first developed in their mind in excellent agreement with the external reality. The principle is valid, none the less.)

The following attempt must now be made. We may begin by imagining some process that takes place in earthly life. We follow the direction of it outward from some central point. It takes its course therefore in a radial direction. It may be a kind of outbreak, such for example as a volcanic eruption, or the tendency of deformation in an earthquake or the like. We follow such a process upon Earth in the direction of a line that goes outward from the given centre. And now in contrast to this you may conceive the inside of the Sun, as we are want to call it, to be of such a nature that its phenomena are not thrust outward from the centre, but on the contrary; they take their course from the corona inward, via the chromosphere, atmosphere and photosphere,—not from within outward therefore, but from without inward. You are to conceive , once more,—if this (Fig. 2) is the photosphere, this the atmosphere, this the chromosphere and this the corona,—that the processes go inward and, so to speak, gradually lose themselves towards the central point to which they tend just as phenomena that issue from the Earth lose themselves outward in expanding spheres, into the wide expanse. You will thus gain a mental picture which will enable you to bring some kind of synthesis and order into the empirical results. Speaking more concretely, you would have to say: If causes on the Earth are such as to bring about the upward outbreak for example of an active crater, the cause on the Sun will be such that if there is anything analogous to such an outbreak, it will happen from without inward. The whole nature of the phenomenon holds it together in quite another way. While on the Earth it tends apart, dispersing far and wide, here this will tend together, striving towards the centre.

You see, then what is necessary. First you must penetrate the phenomena and understand them truly. Only then can you explain them by one-another. And only when we enter thus into the qualitative aspect,—only when we are prepared, in the widest sense of the word, to unfold a kind of qualitative mathematics,—shall we make essential progress. Of this we shall speak more tomorrow. Here I should only like to add that there is a possibility, notably for pure mathematicians, to find the transition to a qualitative mathematics. Indeed this possibility is there in a high degree, especially in our time. We need only consider Analytical Geometry, with all its manifold results, in relation to Synthetic Geometry—to the real inner experience of Projective Geometry. True, this will only give us the beginning, but it is a very, very good beginning. You will be able to confirm this if you once begin along this pathway,—if for example you really enter into the thought and make it clear to yourself that a line has not two infinitely distant points (one in the one and one in the opposite direction) but only one,—fact of which there is no doubt. You will then find truer and more realistic concepts in this field, and from this starting-point you will find your way into a qualitative form of mathematics.

This will enable you to conceive the polarities of Nature no longer merely in the sense of outwardly opposite directions, where all the time the inner quality would be the same; whereas in fact the inner quality, the inner sense and direction, is not the same. The phenomena at the anode and the cathode for example have not the same inner direction; an inherent difference underlies them, and to discover what the difference is, we must take this pathway. We must not allow ourselves to think of a real line as though it had two ends. We should be clear in our mind that a real line in its totality must be conceived not with two ends but with one. Simple by virtue of the real conditions, the other end goes on into a continuation, which must be somewhere. Please do not underestimate the scope and bearing of these lines of thought. For they lead deep into many a riddle of Nature, which, when approached without such preparation, will after all only be taken in such a way that our thoughts remain outside the phenomena and fail to penetrate.

Sechzehnter Vortrag

Es handelt sich, wie Sie gesehen haben, darum, die Elemente zusammenzutragen, die zuletzt dazu führen können, die Formen der Bewegungen der Himmelskörper zu bestimmen und zu diesen Formen hinzuzubestimmen dasjenige, was man die gegenseitige Lage der Himmelskörper nennen könnte. Denn eine Anschauung unseres Himmelskörpersystems läßt sich nur gewinnen, wenn man imstande ist, insofern man Bewegungsformen Kurven nennt, erstens Kurvenformen zu bestimmen, also das Figurale, und dann die Zentren der Beobachtung zu bestimmen. Das ist die Aufgabe, die eigentlich einer solchen Betrachtung gestellt ist, wie wir sie jetzt eingeleitet haben. Ich habe mit voller Absicht diese Betrachtung zunächst hier diesmal so gehalten, wie es eben geschehen ist, aus bestimmten Gründen.

Die größten Fehler, die im Wissenschaftsleben gemacht werden, die bestehen darin, daß man versucht, Zusammenfassungen zu machen, bevor man die Bedingungen dieses Zusammenfassens wirklich hergestellt hat. Man hat den Hang, Theorien zu machen, das heißt abschließende Ansichten zu gewinnen. Man kann gewissermaßen nicht abwarten, bis die Bedingungen da sind zum Theorienmachen. Und das muß in unser Wissenschaftsleben hineingeworfen werden, daß man dazu kommt, ein Gefühl dafür zu bekommen, wie man einfach nicht versuchen darf, gewisse Fragen zu beantworten, bevor die Bedingungen zur Antwort wirklich hergestellt sind. Ich weiß, daß es natürlich — die Anwesenden sind selbstverständlich ausgenommen - vielen Leuten heute lieber ist, wenn man ihnen fertige Kurven hinstellt für planetarische und sonstige Bewegungen, weil sie dann etwas haben, was ihnen Antwort gibt auf ihre Frage: Wie verhält sich das und jenes gemäß der Summe der Begriffe, die vorhanden sind? Aber wenn die Fragen so liegen, daß man sie mit dieser Summe von Begriffen, die vorhanden sind, nicht beantworten kann, dann ist eben alles Reden in theoretischer Beziehung ein Unding. Man kommt dadurch nur zu einer scheinbaren, ganz illusionären Beruhigung über die Sache. Daher versuchte ich auch in bezug auf die Wissenschaftspädagogik diese Vorträge so zu gestalten, wie ich sie eben gestaltet habe.

Nun haben wir ja bisher Ergebnisse gewonnen, die uns zeigen, daß wir sorgfältig unterscheiden müssen, wenn wir die Kurvenformen für die Himmelsbewegungen herausfinden wollen, solche Dinge, wie sie uns auftreten in den scheinbaren Bewegungen, sagen wir zum Beispiel in der Schleifenform der Venusbahn, die in der Konjunktion auftritt, und die Schleifenform für die Marsbahn, die in der Opposition auftritt. Wir sind zu einer Ansicht gekommen, daß wir da sorgfältig unterscheiden müssen dadurch, daß wir ja aufmerksam machen wollten, wie verschieden die Kurvenformen sind, die sich in der menschlichen Gestaltungskraft geltend machen auf der einen Seite für die Kopforganisation, auf der anderen Seite für die Organisation des Stoffwechsels und der Gliedmaßen, und daß doch ein gewisser Zusammenhang zwischen diesen zwei Formen vorhanden ist, nur eben ein solcher, der gesucht werden muß durch einen Übergang außerhalb des Raumes, nicht in dem starren euklidischen Raum.

Nun handelt es sich hier darum, daß man einen Übergang erst finden muß von dem, was man da gewissermaßen am eigenen menschlichen Organismus entdeckt, zu dem, was draußen im Weltenraum vorhanden ist, der ja zunächst eigentlich scheinbar nur als der euklidische Raum auftritt, als der starre Raum vorhanden ist. Man bekommt darüber eine Anschauung aber nur, wenn man dieselbe Methode fortsetzt, die wir gewonnen haben, wenn man nämlich wirklich den Zusammenhang sucht zwischen dem, was im Menschen selber vorgeht, und demjenigen, was draußen in der Bewegung der Himmelskörper im Weltenraum vor sich geht. Man kann dann nicht anders, als die Frage aufwerfen: Welche Erkenntnisbeziehung besteht zwischen Bewegungen, die im relativen Sinne aufgefaßt werden dürfen, und Bewegungen, die eben durchaus nicht im relativen Sinne aufgefaßt werden dürfen? Wir sind uns ja klar darüber, daß wir unter den Gestaltungskräften des menschlichen Organismus solche haben, die radial wirken, und solche, die wir uns in der Sphäre denken müssen (Fig.1). Nun handelt es sich darum, wie sich für unsere menschliche Erkenntnis bei einer äußeren Bewegung dasjenige darstellt, was nur in der Sphäre verläuft, und wie dasjenige, was nur verläuft in der Richtung des Radius.

Es ist ja heute schon ein gewisser Anfang gemacht, sogar in experimenteller Beziehung, solche Bewegungen auch im Raum zu unterscheiden. Man kann verfolgen die Bewegungen eines Weltenkörpers in der Sphäre durch den Augenschein; man kann aber heute durch die Spektralanalyse auch Bewegungen verfolgen, die in dem Sinne des Radius gehen, kann verfolgen in der Visierlinie liegende Annäherungen und Entfernungen der Weltenkörper. Sie wissen ja, daß die Verfolgung dieses Problems zu den interessanten Resultaten geführt hat der Doppelsterne, die sich umeinander bewegen, welche Bewegungen man ja nur feststellen konnte dadurch, daß man durch Anwendung des Dopplerschen Prinzipes eben das Problem, das ich da andeutete, verfolgt hat.

Nun aber handelt es sich darum, festzustellen, ob wir bei jenem Vorgehen, das den Menschen in das ganze Weltengebäude einbezieht, auch die Möglichkeit haben, irgend etwas auszumachen darüber, ob - ich will mich zunächst ganz vorsichtig ausdrücken - eine Bewegung nur eine scheinbare sein kann, oder ob diese Bewegung irgendwie eine wirkliche sein muß, ob irgend etwas darauf hindeutet, daß eine Bewegung eine wirkliche ist. Ich habe Ihnen ja schon erwähnt, wir müssen den Unterschied machen zwischen solchen Bewegungen, die eben relativ sein können, und solchen Bewegungen, die, wie die rotierenden, die scherenden, die deformierenden, hindeuten darauf, daß sie nicht im relativen Sinne aufgefaßt werden können. Da muß man suchen nach einem Kriterium der wirklichen Bewegungen. Dieses Kriterium der wirklichen Bewegungen kann sich nur dadurch ergeben, daß man die inneren Verhältnisse des Bewegten ins Auge faßt. Es kann sich niemals darauf beschränken, bloß die äußeren Beziehungen der Orte ins Auge zu fassen.

Ich habe öfter das ganz triviale Beispiel gebraucht von zwei Menschen, die ich nebeneinander stehen sehe um 9 Uhr vormittags und um 3 Uhr nachmittags, wobei nur der Unterschied besteht, daß der eine von den beiden stehengeblieben ist, und der andere, nachdem ich weggegangen war, nachdem ich mit der Beobachtung aufgehört habe, einen Gang gemacht hat, der ihn 6 Stunden beschäftigt hat. Jetzt steht er wieder neben dem andern um 3 Uhr. Ich werde doch aus den bloßen Beobachtungen der Orte niemals darauf kommen können, was da eigentlich vorliegt. Bloß dann, wenn ich die Ermüdung des einen oder anderen ins Auge fasse, also einen inneren Vorgang, werde ich mich über die Bewegung unterrichten können. Darum also handelt es sich, daß man darauf kommen muß, was von dem Bewegten mitgemacht, durchgemacht wird, wenn man eine Bewegung eben als Bewegung in sich charakterisieren will. Nun ist dazu noch etwas anderes notwendig, das ich dann morgen vornehmen will, aber wir wollen uns heute wenigstens dem Problem nähern.

Nun müssen wir da von einer ganz anderen Ecke her die Sache wiederum ins Auge fassen. Sehen Sie, wenn wir heute die Gestaltung des menschlichen Organismus betrachten, so können wir natürlich im Grunde zunächst nur eine Art Anschauungszusammenhang gewinnen mit demjenigen, was draußen im Weltenraum ist. Denn es weist ja alles darauf hin, daß der Mensch in einem hohen Grade unabhängig ist von den Bewegungen des Weltenraumes und daß er gewissermaßen gerade mit demjenigen, was sich ausdrückt in seinem unmittelbaren Erleben, sich emanzipiert hat von den Weltenerscheinungen, so daß wir nur zurückverweisen können auf Zeiten, in denen der Mensch noch weniger sein Seelenleben in bezug auf dasjenige, was er erlebt, in die Waagschale wirft als im gewöhnlichen, das heißt nachgeburtlichen Erdenleben. Wir können nur zurückverweisen auf die Embryonalzeit, wo ja in der Tat die Bildung im Einklang mit den Weltenkräften erfolgt. Und dasjenige, was dann noch bleibt, das ist gewissermaßen, was sich innerhalb der menschlichen Organisation aus dem während der Embryonalzeit Eingepflanzten forterhält. Man kann da nicht ganz in dem Sinne, wie es sonst üblich ist, von Vererbung sprechen, weil ja nichts eigentlich «vererbt» ist, aber man muß sich einen ähnlichen Vorgang denken in diesem Zurückbleiben von gewissen Entitäten aus einer früheren Entwickelungszeit.

Nun handelt es sich aber darum, die Frage zu beantworten: Ist denn in diesem gewöhnlichen Leben, das wir führen nach unserer Geburt, wenn wir schon zum vollen Bewußtsein gekommen sind, gar keine Andeutung mehr darauf zu finden, wie der Zusammenhang mit den kosmischen Kräften ist? Wenn wir den menschlichen Wechselzustand zwischen Wachen und Schlafen betrachten, so finden wir bei dem heutigen Kulturmenschen zwar noch, daß er einen solchen Wechsel eintreten lassen muß zwischen Wachen und Schlafen, aber Sie wissen ja alle sehr gut, daß er diesen Wechsel, obwohl er in seiner Zeitenfolge zur Erhaltung der menschlichen Gesundheit durchaus übereinstimmen muß mit dem natürlichen Wechsel von Tag und Nacht, heute heraushebt von demjenigen, was der Naturlauf ist. In den Städten läßt man das ja nicht mehr zusammenfallen, auf dem Lande bei den Bauern ist es doch noch da. Gerade dadurch sind diese in ihrer besonderen seelischen Konstitution, daß sie die Nacht durchschlafen und den Tag durchwachen. Wenn der Tag länger und die Nacht kürzer wird, schlafen sie weniger; wenn die Nacht länger wird, schlafen sie länger. Aber das sind schließlich doch Dinge, die nur zu vagen Vergleichen führen können, auf die sich keine klare Anschauung aufbauen läßt. Wir müssen schon nach etwas anderem fragen, wenn wir das Hereinragen desjenigen, was Weltverhältnisse sind, in die menschlichen subjektiven Verhältnisse ins Auge fassen wollen, um dadurch etwas herauszufinden im menschlichen Inneren, was uns auf absolute Bewegungen im Weltenall hinweisen kann.

Und da möchte ich auf etwas aufmerksam machen, was schließlich sehr gut beobachtet werden kann, wenn man nur seine Beobachtungen über größere Felder ausdehnt: daß zwar der Mensch sich leicht emanzipiert mit Bezug auf das Abwechseln von Schlafen und Wachen, sich leicht emanzipiert von der Zeitenfolge, daß er sich aber, ohne daß die Folgen bemerkbar werden, nicht emanzipieren kann in bezug auf seine Lage. Selbst diejenigen Menschen, die, wie es ja auch jetzt schon solche Kulturlinge unter uns gibt, die Nacht zum Tage und den Tag zur Nacht machen, selbst die müssen doch für das Schlafen diejenige Lage wählen, die nicht die aufrechte Lage des Wachens ist. Sie müssen gewissermaßen ihre Rückgratlinie in die Richtung der Rückgratlinie des Tieres bringen. Und gerade wenn man auf diese Dinge weiter eingeht, wenn man zum Beispiel auch in Erwägung zieht die physiologische Tatsache, daß es Menschen gibt, die unter gewissen Krankheitsverhältnissen nicht gut in der horizontalen Lage schlafen können, sondern möglichst aufrecht sitzen müssen, dann wird man gerade durch solche Abweichungen des Zusammenhanges zwischen der horizontalen Lage und dem Schlafen auf Gesetzmäßigkeiten kommen. Gerade wenn man die Ausnahmen betrachtet, die durch mehr oder weniger bemerkbare Krankheiten eintreten, bei Asthmatikern zum Beispiel, wird man auf die Gesetzmäßigkeiten in diesem Felde sehr deutlich hinweisen können. Und man kann durchaus, wenn man alle Tatsachen zusammenfaßt, sagen, daß der Mensch sich um des Schlafens willen in eine Lage bringen muß, die sein Leben so verlaufen läßt während des Schlafes, wie in einer gewisse Beziehung das Tierleben verläuft. Wenn Sie solche Tiere, die nicht genau ihre Rückgratlinie parallel zur Erdoberfläche haben, genau betrachten, werden Sie eine weitere Bestätigung der Sache finden. Das alles ist ja etwas, was ich nur in Richtlinien angeben kann, was im einzelnen vielfach ja erst Gegenstand der Wissenschaft werden muß, weil man die Dinge ja nicht in dieser Art bisher erschöpfend betrachtet hat. Da und dort sind ja immer wiederum kleine Hinweisungen von Leuten geschehen, aber nicht in erschöpfender Weise; es sind die für den wissenschaftlichen Fortgang notwendigen Untersuchungen nicht getrieben worden.

Das ist zunächst eine Tatsache. Eine andere Tatsache ist die folgende. Sie wissen, dasjenige, was man trival Ermüdung nennt, was eine sehr komplizierte Tatsachenteihe ist, das kann eintreten, wenn wir uns willkürlich bewegen. Wir bewegen uns dann willkürlich, indem wir unseren Schwerpunkt in der Richtung parallel zur Erdoberfläche führen. Wir bewegen uns gewissermaßen in einer Fläche, die parallel zur Erdoberfläche liegt. In einer solchen Fläche verläuft der Vorgang, der unsere äußeren willkürlichen Bewegungen begleitet. Und wir können in demjenigen, was sich da abspielt, etwas durchaus Zusammengehörendes finden. Wir können finden auf der einen Seite die Beweglichkeit parallel zur Erdoberfläche und das Ermüdetwerden; wir können weitergehen und können sagen: Durch diese Bewegung parallel zur Erdoberfläche, die sich symptomatisch in der Ermüdung zum Ausdruck bringt, liegt ja ein Stoffwechselvorgang, liegt Stoffwechselverbrauch vor. Es liegt also etwas zugrunde dem Horizontalbewegen, was wir durchaus beobachten können wie einen inneren Vorgang des menschlichen Organismus. Nun tritt aber erstens das auf, daß der Mensch so veranlagt ist, daß er diese Bewegung, selbstverständlich mit ihren Parallelerscheinungen des Umsatzes im Stoffwechsel, nicht entbehren kann, durchaus nicht entbehren kann für seine Organisation. Bei demjenigen, der Briefträger ist, sorgt schon der Beruf dafür, daß er sich in horizontaler Weise bewegt; und wer nicht Briefträger ist, der muß spazieren gehen. Es beruht ja darauf auch die volkswirtschaftlich interessante Beziehung zwischen der Verwertbarkeit der in die Volkswirtschaft einfließenden Beweglichkeit des Menschen und der aus der Volkswirtschaft draußen bleibenden Beweglichkeit des Menschen, im Spiel, im Sport und dergleichen. Da fließen schon die physiologischen Dinge mit den volkswirtschaftlichen zusammen. Nun, ich habe ja öfter bei der Kritik des Arbeitsbegriffes gerade auf diesen Zusammenhang hingewiesen, und man kann nicht Nationalökonomie treiben, wenn man nicht hier den Zusammenhang sucht eben zwischen der reinen Sozialwissenschaft und der Physiologie. Aber dasjenige, was für uns jetzt in diesem Augenblick wichtig ist, das ist, daß wir beobachten können diesen parallelen Vorgang: Bewegung in der horizontalen Fläche und einen gewissen Stoffwechselvorgang.

Wir können diesen Stoffwechselvorgang auch woanders aufsuchen. Wir können ihn aufsuchen in dem Wechselzustand zwischen Schlafen und Wachen. Nur wird gewissermaßen der Vorgang bei willkürlichen Bewegungen so vollzogen, daß, auch ganz abgesehen von dem, was im Inneren des Menschen vorgeht, der Stoffwechselumsatz zu gleicher Zeit ein äußerer Vorgang ist. Ich möchte sagen, es geschieht da etwas, wofür die Oberflächenbegrenztheit des menschlichen Leibes nicht einzig und allein maßgebend ist. Es wird Stoff umgesetzt, aber so, daß diese Stoffverwandlung, die da geschieht, gewissermaßen im Absoluten, im «relativ Absoluten» natürlich, sich vollzieht, so daß man nicht sagen kann, daß das nur eine Bedeutung für die menschliche innere Organisation hat.

Aber die Ermüdung, die wiederum die symptomatische Begleiterscheinung der Bewegung mit dem Stoffwechselumsatz ist, tritt auch dann ein, wenn man einfach einen Tag gelebt hat und nichts getan hat. Das heißt, dieselben Entitäten, die wirksam sind bei der willkürlichen Bewegung, wirken auch im Menschen im täglichen Leben rein durch die innerliche Organisation. Und es muß daher der Stoffwechselumsatz auch dann stattfinden, wenn dieser Vorgang der Ermüdung einfach eintritt, ohne daß wir ihn willkürlich herbeiführen. Wir bringen uns selbst in die horizontale Lage zum Herbeiführen dieses Stoffwechsels, der da eintritt bei dem nicht willkürlichen Handeln, der einfach im Lauf der Zeit eintritt, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf. Wir bringen uns in die horizontale Lage während des Schlafes, um in dieser horizontalen Lage unsern Leib etwas ausführen zu lassen, was er auch dann ausführt, wenn wir in willkürlicher Bewegung sind. Daher sehen Sie, daß die horizontale Lage etwas Bedeutsames ist, daß es nicht gleichgültig ist, ob wir die horizontale Lage einnehmen, daß wir, wenn wir unsern Organismus etwas ausführen lassen wollen, ohne daß wir etwas dazu tun, uns in diese Lage bringen müssen. Das heißt mit anderen Worten: Wir bringen uns während des Schlafes in eine Lage, wo etwas geschieht in unserem Organismus, was sonst geschieht, wenn wir uns willkürlich bewegen.

Es muß also eine Bewegung in unserem Organismus vor sich gehen, die wir nicht willkürlich herbeiführen. Es muß eine Bewegung Bedeutung haben für unseren Organismus, die wir nicht willkürlich herbeiführen. Und Sie brauchen sich nur ein wenig beobachtend die Tatsachen zurecht zu legen, so werden Sie zu dem folgenden Resultate kommen, wozu ich hier die Zwischenglieder weglassen muß, weil ich keine Zeit dazu habe. Genau ebenso, wie der absolute Stoffwechsel ausgeführt wird durch die menschliche Bewegung, so daß dasjenige, was da im Stoffwechsel vor sich geht, gewissermaßen eine reale chemische oder physikalische Bedeutung hat, für die die Begrenzung durch die Haut zunächst nicht da ist, die also im Menschen so geschieht, daß der Mensch dem Kosmos angehört, genau derselbe Vorgang, dieser selbe Stoffwechselumsatz wird beim Schlafen herbeigeführt so, daß er innerhalb des menschlichen Organismus seine Bedeutung hat. Dasjenige, was sich umsetzt bei der willkürlichen Bewegung, setzt sich auch um im Schlaf. Aber das Resultat wird übergeführt von dem einen Teil des Organismus in den andern Teil des Organismus. Wir versorgen unser Haupt, unsern Kopf während des Schlafes. Wir vollziehen oder lassen vielmehr unseren Organismus im Innern vollziehen einen Stoffwechselumsatz, für den jetzt die menschliche Haut als Abschließung eine Bedeutung hat, wo die Umwandlung so geschieht, daß der Endprozeß eine Bedeutung für das Innere der menschlichen Organisation hat.

Wir können also sagen: Wir bewegen uns willkürlich - ein Stoffwechselumsatz findet statt; wir lassen uns bewegen vom Kosmos ein Stoffwechselumsatz findet statt. Der letztere findet so statt, daß das Ergebnis, das bei dem ersteren Stoffwechselumsatz gewissermaßen in der Außenwelt verläuft, jetzt umkehrt und im menschlichen Haupte als solchem sich geltend macht. Es kehrt einfach um, es verfließt nicht weiter, aber wir müssen uns, damit es umkehrt, damit es überhaupt da ist, in die horizontale Lage bringen. Wir müssen also studieren den Zusammenhang zwischen jenen Vorgängen im menschlichen Organismus, die bei der willkürlichen Bewegung sich vollziehen, und jenen Vorgängen, die sich vollziehen im Schlafe. Und daraus, daß wir das an einem bestimmten Punkte unserer Betrachtung so tun müssen, daraus können Sie ja sehen, welche Bedeutung es hat, wenn in den allgemeinen anthroposophischen Vorträgen immer betont werden muß, daß wir unseren Willen, der an den Stoffwechsel gebunden ist, eigentlich in einem solchen Verhältnis zum Vorstellungsleben haben, wie das des Schlafens zum Wachen. In bezug auf die Entfaltung des Willens, sagte ich immer wieder und wiederum, schlafen wir fortwährend. Jetzt haben Sie hier die genaue Determination der Sache. Sie haben jetzt hier gewissermaßen den Menschen willkürlich bewegt in der horizontalen Fläche, und er vollzieht da dasselbe wie im Schlafe, nämlich Schlafen durch seinen Willen. Schlafen und Bewegung durch den Willen stehen in dieser Beziehung. Und wir schlafen in der horizontalen Lage, wobei nur das Ergebnis das andere ist, daß dasjenige, was in die Außenwelt verpufft bei der willkürlichen Bewegung, von unserer Hauptesorganisation aufgenommen und weiter verarbeitet wird.

Wir haben also zwei streng auseinander zu haltende Vorgänge: Das Verpuffen des Stoffwechselprozesses bei der willkürlichen Bewegung und das innerliche Verarbeiten des Stoffwechselumsatzes bei demjenigen, was während des Schlafes in unserem Haupte sich abspielt. Und wir können, wenn wir jetzt das Ganze auf die Tierheit beziehen, ermessen, welche Bedeutung es hat, wenn wir sagen: Das Tier vollbringt überhaupt sein Leben in der horizontalen Lage. Es muß in einer ganz anderen Weise beim Tier organisiert sein diese Umkehrung des Stoffwechsels für das Haupt, und es bedeutet die willkürliche Bewegung beim Tier durchaus etwas ganz anderes als beim Menschen. Das ist dasjenige, was in der Gegenwart so wenig wissenschaftlich berücksichtigt wird. Jetzt wird nur gesprochen von dem, was sich äußerlich darbietet, und es wird übersehen, daß derselbe äußere Vorgang bei dem einen Wesen etwas ganz anderes darstellen kann als bei dem anderen Wesen. Ich will jetzt absehen von allen religiösen Intentionen, sondern nur darauf hinweisen: Der Mensch stirbt, das Tier stirbt; das braucht in psychologischer Beziehung durchaus bei den beiden Wesen nicht dasselbe zu sein. Denn derjenige, der es dasselbe sein läßt und daraufhin seine Untersuchungen anstellt, der gleicht einem Menschen, der ein Rasiermesser findet und sagt, es ist ein Messer, die Funktion muß dieselbe Bedeutung haben wie bei einem anderen Messer, also schneide ich mit dem Rasiermesser meine Knödel. - Wenn man die Dinge so trivial ausspricht, wird man sagen: Das wird der Mensch doch nicht tun. Aber wenn er nicht acht gibt, passieren diese Dinge nämlich gerade mit dem vorgerücktesten Untersuchen.

Nun werden wir also darauf hingewiesen, daß wir in unseren willkürlichen Bewegungen eben denjenigen Vorgang finden, der sich ausdrückt in einer Kurvenrichtung, die parallel zur Erdoberfläche geht. Wir werden da also gedrängt zu einer Kurvenrichtung, die diesen Verlauf nimmt. Nun, was haben wir denn da zugrunde gelegt? Wir haben zugrunde gelegt einen inneren Vorgang, etwas, was im Menschen vor sich geht, was wir auf der einen Seite als etwas Gegebenes haben im Schlafe, was wir auf der anderen Seite als etwas haben, was wir selber ausführen, so daß wir in dem, was wir ausführen, die Möglichkeit haben, das andere zu bestimmen. Wir haben also die Möglichkeit, dasjenige, was aus dem Weltenraum heraus mit unserem Organismus im Schlafe getan wird, als das zu Definierende zu betrachten, das wir erkennen sollen, und das andere, das wir äußerlich vollziehen, das wir also kennen in bezug auf seine Lageverhältnisse, als den Oberbegriff des Definierens zu betrachten.

Das ist dasjenige, wonach man streben muß in einer wirklichen Wissenschaft: Nicht Erscheinungen durch abstrakte Begriffe zu definieren, sondern Erscheinungen durch Erscheinungen zu definieren. Das ist dasjenige, was natürlich notwendig macht, daß man zuerst die Erscheinungen wirklich versteht, dann kann man sie durch einander definieren. Das ist überhaupt das Charakteristische desjenigen, wonach gestrebt wird von anthroposophischer Geisteswissenschaft: Zum wirklichen Phänomenalismus zu kommen, Erscheinungen durch Erscheinungen zu erklären, nicht abstrakte Begriffe zu bilden, durch die die Erscheinungen erklärt werden; und auch nicht die Erscheinungen einfach hinzustellen und sie zu lassen, wie sie sind im zufälligen empirischen Tatbestand, denn da können sie nebeneinanderstehen, ohne daß sie einander irgendwie erklären können.

Von da aus möchte ich nun zu etwas übergehen, was Ihnen zeigen wird, welche Tragweite überhaupt dieses phänomenologische Streben hat. Man kann sagen, um zu entsprechenden Vorstellungen zu kommen, ist heute eine Überfülle von empirischem Material schon da. Dasjenige, was uns fehlt, ist nicht empirisches Material, sondern das sind die Zusammenfassungsmöglichkeiten, die ja zu gleicher Zeit die Möglichkeiten sind, das eine Phänomen durch das andere Phänomen wirklich zu erklären. Man muß die Phänomene zuerst verstehen, bevor man sie durch einander erklären kann. Man muß aber den Willen entwickeln, so vorzugehen, wie wir hier vorgehen, daß man zuerst die Tendenz entwickelt, eine Erscheinung wirklich zu durchdringen. Diese Tendenz läßt man heute vielfach außer acht. Daher wird in unserem Forschungsinstitut es sich in erster Linie nicht darum handeln, im Sinne der alten experimentellen Methoden weiter zu experimentieren, denn da ist eigentlich wirklich eine Überfülle von empirischem Material vorhanden, nicht zur Technik, wohl aber zum wirklichen Zusammenfassen. Es wird sich nicht darum handeln, die alten Experimentierrichtungen weiter fortzusetzen, sondern, wie ich ja auch in dem Wärmekurs im letzten Winter aufmerksam gemacht habe, handelt es sich darum, die Versuchsanordnungen anders zu machen. Wir werden nicht nur die Instrumente brauchen, die man heute in gewohnter Weise bei dem Optiker und so weiter kauft, sondern wir werden nötig haben, unsere Instrumente schon selbst zu konstruieren, damit wir andere Versuchsanordnungen haben, und die Phänomene so hinzustellen, daß das eine durch das andere erklärt werden kann. Wir müssen wirklich von Grund auf arbeiten. Dann wird sich aber auch eine Überfülle wiederum ergeben von demjenigen, was wirklich eine lichtvolle Perspektive darbieten kann. Mit denjenigen Instrumenten, die da sind, können die Leute der Gegenwart wirklich genügend viel machen. Sie sind außerordentlich geschickt geworden in ihrer Einseitigkeit, damit zu experimentieren. Wir brauchen neue Versuchsanordnungen, das muß durchaus ins Auge gefaßt werden, denn mit den alten Versuchsanordnungen kommen wir über gewisse Fragen einfach nicht hinaus. Und auf der anderen Seite darf auch wiederum nicht auf Grundlage der Resultate, die durch die alten Untersuchungen gewonnen sind, einfach blind weiter spekuliert werden, sondern es müssen uns die experimentellen Ergebnisse immer wiederum die Möglichkeit geben, so viel wie möglich, wenn wir uns entfernt haben von den Tatsachen, zu den Tatsachen zurückzukehren. Wir müssen immer gleich die Möglichkeit finden können, wenn man an einen bestimmten Punkt gekommen ist mit den Versuchen, nicht weiter zu theoretisieren, sondern mit dem, was sich ergibt, sogleich zu der Beobachtung zu gehen, die dann eine erläuternde Beobachtung ist. Sonst wird man über gewisse Grenzen, die aber nur Augenblicksgrenzen der Wissenschaft sind, nicht hinauskommen. Und da mache ich aufmerksam auf eine solche Grenze, die übrigens von keinem Menschen so genommen wird, als ob sie nicht überwindbar wäre, die aber nur überwindbar sein wird, wenn man auf dem betreffenden Felde zu anderen Versuchsanordnungen übergeht. Das ist die Frage der Sonnenkonstitution.

Nicht wahr, zunächst ergibt sich ja aus wirklich sorgfältigen, gewissenhaften Beobachtungen, die mit allen heute zur Verfügung stehenden Mitteln angestellt worden sind, daß wir zu unterscheiden haben irgend etwas in der Sonnenmitte, worüber alle Menschen im unklaren sind. Es wird einfach vom Sonnenkern gesprochen. Was der ist, darüber kann kein Mensch eine Auskunft geben, bis dahin reicht die Untersuchungsmethode nicht. Das ist keine Kritik und kein Tadel, denn das gibt ja jeder zu. Den Sonnenkern läßt man dann umgeben sein von der Photosphäre, der Atmosphäre, der Chromosphäre und der Korona. Es beginnt die Möglichkeit, sich Vorstellungen zu machen, bei der Photosphäre. Man kann sich auch Vorstellungen über die Atmosphäre, die Chromosphäre machen. Nehmen Sie nun einmal an, man wolle sich Vorstellungen machen über das Auftreten der Sonnenflecken. Man wird finden, indem man an diese merkwürdige Erscheinung herantritt, die ja nicht ganz willkürlich verläuft, sondern die einen gewissen Rhythmus zeigt in Maxima und Minima der Sonnenfleckenbildung, nach ungefähr 11-jähriger Periode sich regelnd, daß diese Sonnenfleckenphänomene, wenn man sie verfolgt, in Zusammenhang gebracht werden müssen mit Vorgängen, die in irgendeiner Weise außerhalb des Sonnenkernes liegen. Man legt sich gewisse Vorgänge da zurecht und spricht von explosionsartigen oder ähnlichen Verhältnissen. Nun handelt es sich darum, daß man, wenn man so vorgeht, immer von Voraussetzungen ausgeht, die man im irdischen Felde gewonnen hat. Wenn man nämlich nicht versucht, sein Begriffsfeld zuerst zu bearbeiten und zu erweitern, wie wir es getan haben, indem wir Kurven uns vorgestellt haben, die aus dem Raum herausgehen; wenn man nicht zu seiner Selbsterziehung so etwas macht, möchte ich sagen, dann gibt es ja auch keine andere Möglichkeit als dasjenige, was vorliegt an Beobachtungsergebnissen von einem außerhalb der irdischen Welt befindlichen Körper, so zu erklären, wie es die irdischen Verhältnisse darstellen.

Was läge denn überhaupt im Sinne der heutigen Vorstellungswelt näher, als einfach sich die Vorgänge im Sonnenleben ähnlich den Vorgängen im Erdenleben, nur modifiziert, vorzustellen! Es bilden sich da aber zunächst relativ unübersteigbare Hindernisse. Das, was man physische Konstitution der Sonne nennt, das läßt sich nicht durchschauen mit den Vorstellungen, die man im irdischen Leben gewinnt. Es kann sich nur darum handeln, die Beobachtungstesultate, die bis zu einem gewissen Grade auf diesem Felde durchaus sprechend sind, in einer ihnen adäquaten Weise vorstellungsgemäß zu durchdringen. Man wird sich da schon ein wenig befreunden müssen mit dem, was ich charakerisieren möchte etwa in der folgenden Weise. Nicht wahr, hat man irgendeinen äußeren Zusammenhang, den man mit einer geometrischen Wahrheit durchleuchtet, so sagt man sich: Dasjenige, was man zuerst geometrisch konstruiert hat, schnappt ein; die äußere Wirklichkeit ist so. - Man fühlt sich verbunden mit der äußeren Wirklichkeit, wenn man das wiederfindet, was man zuerst konstruiert hat. Nun darf ja natürlich dieses innerliche Erfreutsein, daß es einschnappt, nicht zu weit getrieben werden, denn es schnappt auch immer ein bei denjenigen, die bei diesem Einschnappen schon übergeschnappt sind. Die finden auch immer, daß die Vorstellungen, die sie ausgebildet haben, durchaus übereinstimmen mit der äußeren Wirklichkeit. Aber es liegt doch etwas Gültiges in diesen Dingen.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß eben einfach der Versuch gemacht werden muß, sich vorzustellen zuerst einen Vorgang, der im irdischen Leben so verläuft, daß wir uns seinen Verlauf vorstellen durch das Verfolgen der Richtung vom Mittelpunkt nach außen, also in der Richtung des Radiialen. Wir fassen einen Vorgang ins Auge, sagen wir zum Beispiel einen gewissen Ausbruch, einen vulkanischen Ausbruch oder die Richtung irgendeiner Deformation bei Erdbeben und dergleichen. Wir verfolgen also Vorgänge auf der Erde im Sinne einer Linie, die vom Mittelpunkt nach auswärts geht. Nun können Sie sich aber auch vorstellen, das sogenannte Sonneninnere sei so geartet, daß es seine Erscheinungen nicht vom Mittelpunkt nach außen stößt, sondern daß die Erscheinungen von der Korona über die Chromosphäre, Atmosphäre, Photosphäre, nun statt von innen nach außen, von außen nach innen verlaufen. Daß die Vorgänge also (Fig.2), wenn das die Photosphäre ist, das die Atmosphäre, das die Chromosphäre, hier die Korona, nach innen verlaufen, und sich gewissermaßen nach dem Mittelpunkt hin, nach dem sie tendieren, verlieren, so wie sich die Erscheinungen, die von der Erde ausgehen, in der Flächenausdehnung verlieren. Dann kommen Sie zu einem Vorstellungsbilde, das Ihnen gestattet, in einer gewissen Weise die empirischen Resultate zusammenzufassen. Wenn Sie also konkret sprechen, so werden Sie sagen: Wenn auf der Erde Ursachen dazu vorliegen, daß nach oben hin ein Kraterausbruch erfolgt, so würde der Ursachenzusammenhang auf der Sonne so liegen, daß von außen nach innen so etwas geschieht wie ein Kraterausbruch, so daß seine Natur die ganze Sache anders zusammenhält, weil das eine Mal alles in die Weite auseinanderläuft, das andere Mal ins Zentrum zusammenstrebt.

Sie sehen, es würde sich darum handeln, die Phänomene, die man hier verfolgt, erst zu durchdringen, zu verstehen, um sie dann dutch einander erklären zu können. Und erst wenn man in dieser Weise auf das Qualitative der Dinge eingeht, wenn man sich wirklich darauf einläßt, im umfassendsten Sinne eine Art qualitativer Mathematik zu finden, kommt man vorwärts. Davon werden wir morgen noch sprechen. Heute möchte ich nur noch erwähnen, daß es ja auch noch die Möglichkeit gibt gerade für die Mathematiker, aus dem Mathematischen heraus schon Übergänge zu finden zu einer qualitativen Betrachtung, zu einer qualitativen Mathematik. Und diese Möglichkeit ist sogar in unserem Zeitalter in ganz intensiver Weise vorhanden, indem man einfach versucht, die analytische Geometrie und ihre Ergebnisse im Zusammenhang zu betrachten mit synthetischer Geometrie, mit innerem Erleben der projektiven Geometrie. Das liefert einen Anfang zwar, aber einen sehr, sehr guten Anfang. Und derjenige, der mit solchen Dingen den Anfang gemacht hat, der also durchaus darauf eingegangen ist, einmal sich klarzumachen, wie es doch so ist, daß eine Linie nicht zwei unendlich ferne Punkte hat, den einen auf einer, den andern auf der andern Seite, sondern unter allen Umständen nur einen unendlich fernen Punkt hat, der findet dann auch realere Begriffe auf diesem Gebiet und von da aus eine qualitative Mathematik, durch die er nicht mehr das, was sich polarisch ausnimmt, bloß entgegengesetzt, sondern gleichgerichtet denkt. Es ist ja auch nicht qualitativ gleich gerichtet. Die Erscheinungen der Anode und Kathode sind nicht gleich gerichtet, sondern es liegt etwas anderes dahinter. Und der Weg, einmal dahinterzukommen, was da für ein Unterschied vorliegt, der liegt eben darin, daß man sich nicht gestattet, überhaupt eine reale Linie mit zwei Enden zu denken, sondern daß man sich klar wird darüber, daß eine reale Linie in ihrer Totalität nicht mit zwei Enden gedacht werden darf, sondern mit einem Ende, und das andere Ende geht einfach durch reale Verhältnisse über in eine Fortsetzung, die irgendwo liegen muß.

Beachten Sie nur die Tragweite einer solchen Auseinandersetzung. Sie führt tief hinein in manches Rätsel der Natur, das, wenn man ohne diese Vorbereitung an es herangeht, eben doch nur so aufgefaßt werden kann, daß niemals die Vorstellung die Erscheinung durchdringen wird.

Sixteenth Lecture

As you have seen, it is a matter of bringing together the elements that can ultimately lead to determining the forms of the movements of the celestial bodies and adding to these forms what could be called the mutual position of the celestial bodies. For an understanding of our celestial system can only be gained if one is able, insofar as one calls forms of motion curves, first to determine curve forms, that is, the figurative, and then to determine the centers of observation. That is the task that is actually set for such a consideration as we have now introduced. I have deliberately kept this observation here for the time being, as it has just happened, for certain reasons.

The biggest mistakes made in scientific life are those that consist in attempting to make summaries before the conditions for such summaries have actually been established. There is a tendency to formulate theories, that is, to arrive at conclusive views. In a sense, people cannot wait until the conditions for theorizing are in place. And this must be brought into our scientific life, so that we come to understand that we simply must not try to answer certain questions before the conditions for answering them have actually been established. I know that, of course—with the exception of those present here, of course—many people today prefer to be given ready-made curves for planetary and other movements, because then they have something that answers their question: How does this or that behave according to the sum of the concepts that are available? But if the questions are such that they cannot be answered with the sum of the concepts that are available, then all talk in theoretical terms is simply absurd. It only leads to an apparent, completely illusory reassurance about the matter. That is why I tried to structure these lectures in relation to science education in the way that I have done.

Now we have obtained results that show us that we must carefully distinguish between the curve shapes for the movements of the heavens, such as those that occur in the apparent movements, for example, in the loop shape of the orbit of Venus, which occurs in conjunction, and the loop shape for the orbit of Mars, which occurs in opposition. We have come to the conclusion that we must carefully distinguish between them by drawing attention to how different the curve shapes are that assert themselves in human creative power, on the one hand for the organization of the head, and on the other hand for the organization of metabolism and the limbs, and that there is nevertheless a certain connection between these two forms, but one that must be sought through a transition outside of space, not in rigid Euclidean space.

Now, the point here is that one must first find a transition from what one discovers, so to speak, in one's own human organism to what exists outside in space, which at first glance appears to be only Euclidean space, rigid space. However, one can only gain an insight into this by continuing with the same method we have developed, namely by really seeking the connection between what is happening within the human being and what is happening outside in the movement of the heavenly bodies in outer space. One cannot help but ask the question: What is the relationship between movements that can be understood in a relative sense and movements that cannot be understood in a relative sense at all? We are well aware that among the formative forces of the human organism there are those that act radially and those that we must think of as spherical (Fig. 1). The question now is how our human cognition represents that which only occurs in the sphere and that which only occurs in the direction of the radius in the case of an external movement.

Today, a certain start has already been made, even in experimental terms, to distinguish such movements in space. One can follow the movements of a celestial body in the sphere by sight; but today, through spectral analysis, one can also follow movements that go in the direction of the radius, one can follow the approaches and distances of celestial bodies lying in the line of sight. You know that pursuing this problem has led to the interesting results of double stars moving around each other, movements that could only be determined by applying the Doppler principle to pursue the problem I mentioned.

Now, however, the question is whether, in this approach that includes human beings in the entire structure of the universe, we also have the possibility of determining anything about whether—I want to express myself very cautiously at first—a movement can only be an apparent one, or whether this movement must somehow be a real one, whether anything indicates that a movement is a real one. I have already mentioned that we must distinguish between movements that may be relative and movements that, like rotating, shearing, and deforming movements, indicate that they cannot be understood in a relative sense. We must therefore look for a criterion of real movements. This criterion of real movements can only be found by considering the internal conditions of the moving object. It can never be limited to merely considering the external relationships between locations.

I have often used the very trivial example of two people whom I see standing next to each other at 9 a.m. and 3 p.m., the only difference being that one of them has remained standing, while the other, after I have left, after I have stopped observing, has taken a walk that has occupied him for six hours. Now he is standing next to the other one again at 3 p.m. I will never be able to figure out what is actually going on from mere observations of the locations. Only when I consider the fatigue of one or the other, that is, an inner process, will I be able to learn about the movement. So it is a matter of figuring out what is being experienced by the moving object if one wants to characterize a movement as a movement in itself. Now there is something else that is necessary for this, which I will do tomorrow, but today we will at least approach the problem.

Now we must look at the matter again from a completely different angle. You see, when we consider the structure of the human organism today, we can of course initially only gain a kind of visual connection with what is out there in outer space. For everything points to the fact that human beings are highly independent of the movements of outer space and that, in a sense, they have emancipated themselves from world phenomena precisely through what is expressed in their immediate experience, so that we can only refer back to times when human beings weighed their soul life less in relation to what they experienced than in ordinary, that is, postnatal earthly life. We can only refer back to the embryonic period, when formation actually takes place in harmony with the forces of the universe. And what then remains is, in a sense, what continues within the human organization from what was implanted during the embryonic period. One cannot speak of heredity in the usual sense, because nothing is actually “inherited,” but one must imagine a similar process in this remnant of certain entities from an earlier period of development.

Now, however, the question must be answered: Is there no longer any indication in the ordinary life we lead after our birth, when we have already attained full consciousness, of how we are connected to the cosmic forces? If we consider the human state of alternation between waking and sleeping, we find that modern civilized people still have to allow such an alternation between waking and sleeping to occur, but you all know very well that, although this alternation must correspond in its timing to the natural alternation of day and night in order to maintain human health, today it is separated from the natural course of things. In cities, this no longer coincides, but in the countryside among farmers, it still does. It is precisely because of this that they have a special mental constitution, sleeping through the night and staying awake during the day. When the day gets longer and the night shorter, they sleep less; when the night gets longer, they sleep longer. But these are ultimately things that can only lead to vague comparisons, on which no clear view can be built. We must ask for something else if we want to consider the intrusion of world conditions into human subjective conditions in order to discover something within the human being that can point us to absolute movements in the universe.

And here I would like to draw attention to something that can ultimately be observed very well if one only extends one's observations over larger fields: that although human beings easily emancipate themselves with regard to the alternation of sleeping and waking, easily emancipate themselves from the sequence of time, they cannot emancipate themselves with regard to their situation without the consequences becoming noticeable. Even those people who, as there are already such cultured individuals among us, turn night into day and day into night, even they must choose a position for sleeping that is not the upright position of wakefulness. They must, so to speak, bring their spine into line with the spine of the animal. And precisely when one goes into these things further, when one also takes into consideration, for example, the physiological fact that there are people who, under certain medical conditions, cannot sleep well in a horizontal position but must sit as upright as possible, then one will arrive at laws precisely through such deviations from the connection between the horizontal position and sleeping. It is precisely when we consider the exceptions that occur due to more or less noticeable illnesses, for example in asthmatics, that we can point very clearly to the laws in this field. And when all the facts are summarized, it can definitely be said that in order to sleep, humans must place themselves in a position that allows their life to proceed during sleep in a manner similar to that of animal life in a certain respect. If you look closely at animals that do not have their spine exactly parallel to the earth's surface, you will find further confirmation of this. All this is something that I can only indicate in general terms, as the details must first become the subject of scientific study, because things have not yet been examined exhaustively in this way. Here and there, people have made small references to this, but not in an exhaustive manner; the research necessary for scientific progress has not been carried out.

That is one fact. Another fact is the following. You know that what is trivially called fatigue, which is a very complicated series of facts, can occur when we move arbitrarily. We then move arbitrarily by moving our center of gravity in a direction parallel to the Earth's surface. We move, as it were, in a plane that is parallel to the Earth's surface. In such a plane, the process that accompanies our external arbitrary movements takes place. And we can find something that definitely belongs together in what is happening there. On the one hand, we can find mobility parallel to the Earth's surface and fatigue; we can go further and say: this movement parallel to the Earth's surface, which is symptomatically expressed in fatigue, is based on a metabolic process, on metabolic consumption. So there is something underlying horizontal movement that we can observe as an internal process of the human organism. Now, however, the first thing that occurs is that human beings are predisposed in such a way that they cannot do without this movement, of course with its parallel phenomena of metabolic turnover, they absolutely cannot do without it for their organization. For those who are mail carriers, their profession ensures that they move horizontally; and those who are not mail carriers must go for walks. This is also the basis for the economically interesting relationship between the usability of human mobility that flows into the economy and the human mobility that remains outside the economy, in games, sports, and the like. Here, physiological factors converge with economic ones. Well, I have often pointed out this connection when criticizing the concept of work, and one cannot pursue economics without seeking the connection here between pure social science and physiology. But what is important for us at this moment is that we can observe this parallel process: movement in the horizontal plane and a certain metabolic process.

We can also find this metabolic process elsewhere. We can find it in the transitional state between sleeping and waking. However, in the case of voluntary movements, the process is carried out in such a way that, quite apart from what is going on inside the human being, the metabolic turnover is at the same time an external process. I would like to say that something is happening here for which the surface limitations of the human body are not solely decisive. Matter is being transformed, but in such a way that this transformation of matter, which is taking place, is, in a sense, taking place in the absolute, in the “relative absolute” of course, so that one cannot say that it only has significance for the human internal organization.

But fatigue, which in turn is the symptomatic accompaniment of movement with metabolic turnover, also occurs when one has simply lived a day and done nothing. This means that the same entities that are effective in voluntary movement also work in humans in daily life purely through internal organization. And therefore, the metabolic turnover must also take place when this process of fatigue simply occurs without us bringing it about voluntarily. We bring ourselves into the horizontal position to bring about this metabolism, which occurs during non-voluntary action, which simply occurs over time, if I may express it that way. We bring ourselves into the horizontal position during sleep in order to allow our body to perform something in this horizontal position, which it also performs when we are in voluntary movement. Therefore, you see that the horizontal position is something significant, that it is not indifferent whether we assume the horizontal position, that if we want our organism to perform something without us doing anything, we must put ourselves in this position. In other words, during sleep we put ourselves in a position where something happens in our organism that otherwise happens when we move voluntarily.