| 118. The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric: Buddhism and Pauline Christianity

27 Feb 1910, Cologne Translated by Barbara Betteridge, Ruth Pusch, Diane Tatum, Alice Wuslin, Margaret Ingram de Ris |

|---|

| Gautama Buddha came to knowledge through his enlightenment under the Bodhi tree; he then taught that this world is maya. It cannot be considered real, because therein lies maya, the great illusion, that one believes it to be real. |

| The beginnings of this idea were given through Goethe in his plant morphology, but he was not understood. One will gradually begin to see the etheric, because it is that which is characteristic of the plant realm. |

| This will all lead human beings to know in which direction they must go. You must undertake to transform abstract ideals into concrete ideals in order to contribute to an evolution that moves forward. |

| 118. The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric: Buddhism and Pauline Christianity

27 Feb 1910, Cologne Translated by Barbara Betteridge, Ruth Pusch, Diane Tatum, Alice Wuslin, Margaret Ingram de Ris |

|---|

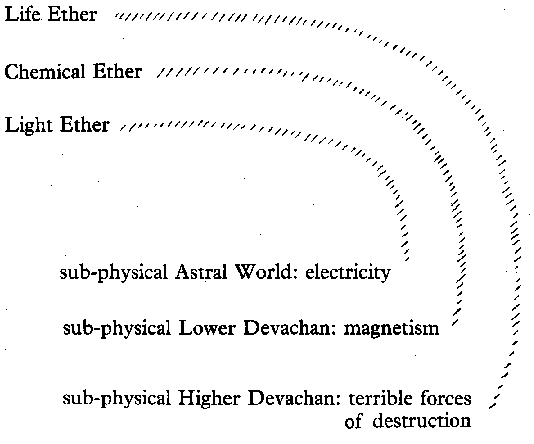

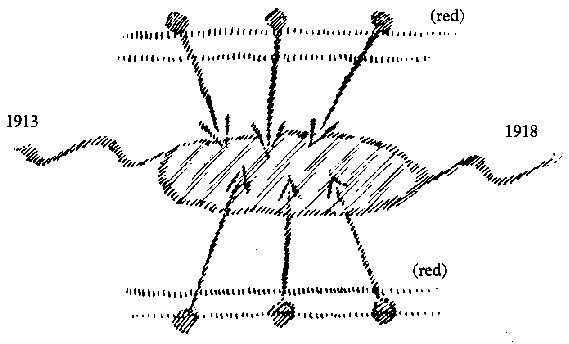

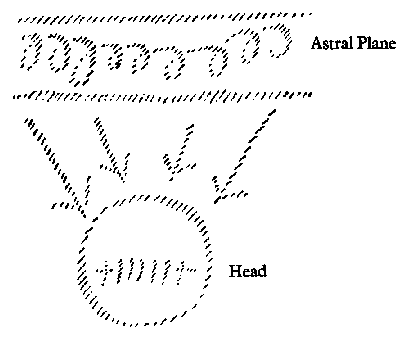

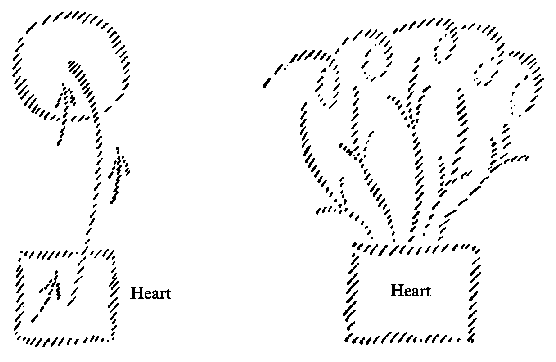

We will concern ourselves today with something that will show us how significant it is, based on research that can be done in the higher worlds, to experience what the future holds in store for humanity. The mission of the spiritual scientific movement is connected with the important events of the transition period in which we live. From this we can be certain that much still lies before us in the future, and we therefore seek in spiritual science for guidance in taking the appropriate measures in the present. We must know, therefore, what is of special significance in thinking, feeling, and willing in our time. There is a great distinction between the spiritual stream that came from Buddha and the one that arose from the Christ impulse. This is not meant to place these streams in opposition to one another; it is rather necessary to understand in what regard each of these streams can be fruitful. Both streams must unite in the future, and Christianity must be fructified by spiritual science. For a time, Christianity had to set aside the teaching of reincarnation. It was included in the esoteric teaching but could not be received in exoteric Christianity for certain universal pedagogical reasons. In contrast, reincarnation was a fundamental principle of Buddhism. There it was bound up with the teaching of suffering, which is exactly what Christianity is intended to overcome. Once we have recognized the purposes and missions of both streams, we will also be able to distinguish clearly between them. The main distinction can be seen most strongly when one examines the two individualities, Buddha and Paul. Gautama Buddha came to knowledge through his enlightenment under the Bodhi tree; he then taught that this world is maya. It cannot be considered real, because therein lies maya, the great illusion, that one believes it to be real. Man must strive to be released from the realm of the elements; then he comes into a realm, Nirvana, where neither names nor things exist. Only then is man freed from illusion. The realm of maya is suffering. Birth, death, sickness, and age are suffering. It is the thirst for existence that brings man into this realm. Once he has freed himself from this thirst, he no longer needs to incarnate. One can ask oneself why the great Buddha preached this doctrine. The answer can follow only from a consideration of the evolutionary course of humanity. Man was not always the way he is today. In earlier times, man not only had his physical body at his disposal for achieving knowledge, but there was also a kind of clairvoyant knowledge diffused among human beings. Man knew that there were spiritual hierarchies in the same way that we know that there are plants. He had no power of judgment but could see the creative beings themselves. This wisdom gradually disappeared, but a memory of it remained. In ancient India, Persia, even in Egypt, there was still a memory of previous earthly lives. The human soul at that time was such that one knew: I was descended from divine beings, but my incarnations have gradually penetrated the physical so strongly that my spiritual gaze has been darkened. Man experienced the progress in this time as a degeneration, as a step backward. This was felt especially by all those who could still, even in much later times, leave their physical bodies at particular moments. The everyday world appeared to them in these moments as a world of illusion, as maya, the great deception. Buddha only spoke out of what lived in the human soul. The physical, sensible world was experienced as that which had pulled man down; he wished to leave this world and ascend again. The world of the senses bore the guilt for the descent of humanity. Let us compare this conception with the Christ impulse and the teachings of Paul. Paul did not call the sensible world an illusion, although he knew as well as Buddha that man had descended from the spiritual worlds and that it was his urge for existence that had brought him into this world. One speaks in a Christian sense, however, when one asks if this urge for existence is always something bad. Is the physical, sensible world only deception? According to Paul's conception, it is not the urge for existence in itself that is evil; this urge was originally good but became harmful through the fall of man, under the influence of Luciferic beings. This urge was not always harmful, but it has become so and has brought sickness, lies, suffering, and so on. What was a cosmic event in Buddha's conception became a human event for Paul. Had the Luciferic influence not interfered, man would have seen the truth in the physical world rather than illusion. It is not the world of the senses that is wrong but human knowledge that has been dulled through the Luciferic influence. The differences in these conceptions bring different conclusions with them. Buddha sought redemption in a world in which nothing of this world of the senses remained. Paul said that man should purify his forces, his thirst for existence, because he himself had corrupted them. Man should tear away the veil that covers the truth and, through purifying himself, see again the truth he himself had covered. In place of the veil that conceals the plant world, for example, he will see the divine-spiritual forces that work on and behind the plants. Rend the veil, and the world of the senses becomes transparent; we finally see the realm of the spirit. We believed we saw the animal, the plant, and the mineral kingdoms; that was our error. In reality, we saw the hierarchies streaming toward us. That is why Paul said, “Kill not the pleasure of existence; rather purify it, because it was originally good.” This can occur when man takes the power of Christ into himself. When this power has permeated the soul, it drives away the soul's darkness. The gods did not place man on the earth for no purpose. It is man's duty to overcome what hinders him from seeing this world spiritually. Buddha's conclusion that one must shun incarnation points to an archetypal wisdom for humanity. Paul, in contrast, said, “Go through incarnation, but imbue yourselves with Christ, and in a distant future all that man has cast up as illusion will vanish.” This teaching, which put the blame not on the physical, sensible world but on man himself, had of necessity to become a historic doctrine. Exactly for this reason, however, it could not be given in its entirety at the beginning. Only the initial impulse could be given, which must be penetrated. This impulse would then gradually enter all spheres of life. Although almost two thousand years have passed since the Mystery of Golgotha, the Christ impulse is only beginning today to be received. Whole spheres of life, such as philosophy and science, have yet to be imbued with it. Buddha was more able to give his teaching all at once, because he referred to an ancient wisdom that was still experienced in his time. The Christ impulse, however, must prevail gradually. A theory of knowledge based on these facts contrasts sharply with that of Kant, who did not know that it is our knowledge itself that must be purified. Paul had to instruct human beings that the work in each individual incarnation is actually of great importance. In contrast to the relatively recent doctrine of the Buddha that the individual incarnation is worthless, he almost had to overstate this teaching. One must learn to declare, “Not I, but Christ in me!” This is the purified I. Through Paul, the spiritual life became dependent upon this one incarnation for all the future. Now that such an education of the soul has, been completed and a sufficient number of human beings have gone through it in the past two thousand years, the time has come again to teach reincarnation and karma. We must seek to restore our I to the condition in which it was before incarnations began. It is always said that Christ is constantly in our midst. “I am with you every day until the end of the earth.” Now, however, man must learn to behold Christ and to believe that what he sees is real. This will happen in the near future, already in this century, and in the following two thousand years more and more people will experience it. How will this actually occur? We might ask, for example, how we now see our planet. The earth is described mechanically, chemically, and physically by science, according to the Kant-Laplace theory and the like. Yet we are now approaching a reversal in these fields. A conception will arise that will see the earth not in terms of purely mineral forces but in terms of plant, or what could be called etheric, forces. The plant directs its root toward the earth's center, and its upper part stands in relation to the sun. These are the forces that make the earth what it is; gravity is only secondary. The plants preceded minerals just as coal was once plant life; this will soon be discovered. Plants give the planet its form, and they then give off the substance from which its mineral foundation originates. The beginnings of this idea were given through Goethe in his plant morphology, but he was not understood. One will gradually begin to see the etheric, because it is that which is characteristic of the plant realm. When man is able to receive the growth forces of the plant kingdom, he will be released from the forces that now hinder him from beholding the Christ. Spiritual science should be an aid to this, but this will be impossible as long as man believes that the ascent of the physical into the etheric has nothing to do with his inner being. It is of no matter in the laboratory whether a man has a strong or weak moral character. This is not the case, however, when one is concerned with etheric forces. Then one's moral constitution affects one's results. For this reason, it is impossible for modern man to develop this ability if he remains as he is. The laboratory table must first become an altar, just as it was for Goethe who, as a child, kindled his small altar to nature with the rays of the rising sun. This will happen before long. Those who are able to say, “Not I, but Christ in me,” will be able to work with the plant forces in the same way that mineral forces are now understood. Man's inner being and his outer surroundings work into one another reciprocally; what is outside transforms itself for us, depending on whether our vision is clear or clouded. Even in this century, and increasingly throughout the next 2,500 years, human beings will become able to behold Christ in His etheric form. They will behold the etheric earth from which the plant world springs up. They will also be able to see, however, that inner goodness works differently on the environment from evil. He who possesses this science in the highest degree is the Maitreya Buddha, who will come in approximately 3,000 years. “Maitreya Buddha” means the “Buddha of right-mindedness.” He is the one who will make clear for human beings the significance of right-mindedness. This will all lead human beings to know in which direction they must go. You must undertake to transform abstract ideals into concrete ideals in order to contribute to an evolution that moves forward. If we do not succeed in this, the earth will sink into materialism, and humanity will have to begin again, either on the earth, after a great catastrophe, or on the next planet. The earth needs anthroposophy! Whoever realizes this is an anthroposophist. |

| 118. The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric: Mysteries of the Universe: Comets and the Moon

05 Mar 1910, Stuttgart Translated by Barbara Betteridge, Ruth Pusch, Diane Tatum, Alice Wuslin, Margaret Ingram de Ris |

|---|

| There are, of course, contrasts everywhere in the cosmos, but one must understand how to discover them in the right way. The first contrast in the cosmos whose significance for human life we can mention is that between sun and earth. |

| The cosmic regularity manifesting in the whole of human evolution takes its course under the influence of the moon, of the lunar body. In contrast to these events, there are things that always bring about a step forward, that are naturally distributed over wider spans of time; these events occur under the influence of the comets. |

| Today I wished to give the preliminaries, in order that tomorrow we may understand through greater relationships an important question of the present time. Much that has been said today is admittedly remote, but we are living in a cometary year. |

| 118. The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric: Mysteries of the Universe: Comets and the Moon

05 Mar 1910, Stuttgart Translated by Barbara Betteridge, Ruth Pusch, Diane Tatum, Alice Wuslin, Margaret Ingram de Ris |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

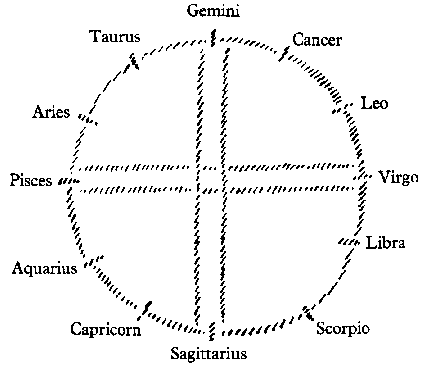

On a night when the stars are clear and we gaze at the expanse of the heavens, it is a feeling of sublimity that first flows through our souls as we let the innumerable wonders of the stars work upon us. This feeling of sublimity will be stronger in one person, less strong in another, according to his particular individual character. When faced with the appearance of the starry heavens, however, a person will soon be aware of his longing to understand something of these wonders of cosmic space. Least of all in regard to the starry heavens will he be deterred by the thought that this direct feeling of sublimity and grandeur might disappear if he wishes to penetrate the mystery of the starry world with his comprehension. We are justified in feeling that understanding and comprehension in this sphere cannot injure the direct feeling that arises in us. Just as in other spheres it soon becomes evident to a greater or lesser degree that spiritual scientific knowledge enhances and strengthens our feelings and experiences if only we have a healthy understanding (Sinn), so will a person become more and more convinced that, regarding these sublime cosmic facts, his life of feeling will not wither in the least when he learns to grasp what is really passing through space or remaining, in appearance, at rest. In any presentation it is, of course, possible to deal only with a tiny corner of the world, and we must take time to learn to grasp, step by step, the facts of the world. Today we will concern ourselves with a part, a small, trifling part, of the world of space in connection with the life of man. Although a person may dimly divine it, he will learn with greater and greater precision through spiritual science that he is born out of the totality of the universe and that the mysteries of the universe are connected with his own special mysteries. This becomes particularly evident when we enter with exactitude into certain mysteries of existence. A contrast is manifest in human life as it evolves on this earth—a contrast to be found everywhere and at all times. It is the contrast between the masculine and the feminine. We know that this contrast in the human race has existed since the time of ancient Lemuria; we know, too, that it will last for a certain period in our earthly existence and ultimately resolve itself again into a higher unity. If we recollect that all human life is born out of cosmic life, we may then ask, if it is indeed true that what has shown itself in human life since the old Lemurian time as the contrast between man and woman has to a certain extent accompanied evolution on the earth, can we find something in the universe that in a higher sense represents this contrast? Can we find in the cosmos that which comes to birth in the masculine and feminine on earth? This question can be answered. If we stand on the ground of spiritual science, we cannot proceed according to the maxims of a present-day materialist. A materialist can visualize nothing apart from what lives in his immediate environment and is therefore prone to seek for this contrast of masculine and feminine in everything, whereas it now applies only to human and animal life on earth. This is an offense of our time. We must bear clearly in mind that the designations “masculine” and “feminine” in the human kingdom hold good in the strict sense only since the Lemurian epoch and up to a certain moment in earthly evolution and, in so far as animals and plants are concerned, only during the ancient Moon evolution and the earth evolution. The question remains, however: are masculine and feminine as they exist on earth born out of a higher, cosmic contrast? If we were able to find this contrast, a wonderful and at first mysterious connection would emerge between this phenomenon and a phenomenon in the cosmos. There are, of course, contrasts everywhere in the cosmos, but one must understand how to discover them in the right way. The first contrast in the cosmos whose significance for human life we can mention is that between sun and earth. In our various studies of earthly evolution we have seen how the sun separated from our earth, how both became independent bodies in space, but we may also ask: how does the contrast between sun and earth in the macrocosm, in the great world, repeat itself in man, the microcosm? Is there in the human being himself a contrast that corresponds to the contrast between sun and earth in our planetary system? Yes, there is. In the human organism—the whole organism, bodily and spiritual—it occurs between all that expresses itself externally in the organ of the head and all that expresses itself externally in the organs of movement, the hands and feet. All that is expressed in the human being in this contrast between the head and the organs of movement corresponds to the contrast or polarity that arises in the cosmos between sun and earth. We shall soon see how this is consistent with the correspondence between the sun and the heart. The point here, however, is that in the human being there is on the one hand the head and on the other what we call the organs of movement. You can readily understand that, in so far as his limbs were concerned, man was a totally different being during the ancient Moon evolution. It was the earth that made him into an upright being, one who uses hands and feet as he does today; again, it was only on the earth that his head was enabled to gaze freely out into cosmic space, because the forces of the sun raised him upright, whereas during the ancient Moon evolution his spine was parallel with the surface of the moon. We may say that the earth is responsible for man being able to use his legs and feet as he does today. The sun, working upon the earth from outside and forming the contrast with the earth, is responsible for the fact that the human head, with its countenance, has in a sense torn itself free from bondage to the earth and is able to gaze freely out into space. That which in the planetary system is the contrast between sun and earth appears within the human being as the contrast between head and limbs. We find this contrast of head and limbs in every human being, whether man or woman, and we also find that here, in all essentials, men and women are alike, so that we can say that the contrast corresponding to that between sun and earth expresses itself in the same way in men and in women. The earth works to the same extent upon woman as upon man; woman is bound to the earth in the same way as man, and the sun frees the head of woman and of man alike from bondage to the earth. We shall be able to gauge the profundity of this contrast if we remember that those beings, for example, who fell into dense matter too early, as it were—the mammals—were not able to attain free sight into cosmic space; their countenance is bound to earthly existence. For the mammals, the contrast between sun and earth did not become, in the same sense, a contrast in their own being. For this reason we may not speak of a mammal as a microcosm, but we can call the human being a microcosm, and in the contrast between head and limbs we have evidence of the microcosmic nature of man. Here we have an example that at the same time shows how infinitely important it is not to become one-sided in our studies. One can count the bones of man and the bones of the higher mammals and also the muscles of man and of the mammals, and the connection that one can draw from this has led in modern times to a world view that places man in closest proximity to the higher mammals. That this can happen proceeds simply from the fact that people have yet to learn through spiritual science how important it is not merely to have truths but to add something to them. Be conscious, my dear friends, that in this moment something of great importance is being said, something that the anthroposophist should inscribe in his memory and in his heart: many things are true, but merely to know that a thing is true is not enough! For example, what modern natural science says about the kinship of man with the apes is undoubtedly true. With a truth, however, the point is not merely to possess it as a truth but to know the importance of it in the explanation of existence as a whole. A seemingly quite ordinary, everyday truth may fail to be regarded as decisive only because its importance is not recognized. A certain familiar truth, known to everyone, becomes deeply significant for our whole doctrine of earthly evolution if its real importance is only understood: the truth that man is the only being on earth who can direct his countenance with real freedom out into cosmic space. If we compare the human being in this respect with the apes who stand near to him, we must say that, although the ape has tried to raise himself into the upright posture, he has somehow made a hash of it ... and that is the point. One must have insight into the relative weight of a truth! We must feel the importance of the fact that man has this advantage, and then we shall also be able to relate it to the other cosmic fact just characterized: it is not the earth alone but the sun in contrast to the earth—something beyond the earth—that above all makes man a citizen of heavenly space and tears him away from earthly existence. In a sense we may say that this whole cosmic adjustment that we know today as the contrast between sun and earth had to be made in order that man might be given this place of precedence in our universe. This constellation of sun and earth had to be brought about for the sake of man, that he might be raised from the posture of the animals. In the human being we thus have the same contrast that we see when we look out into heavenly space and behold the sun with its counterpart, the earth. Now the question arises: can we discover in the cosmos the other contrast that is found on earth, that between masculine and feminine? Is there perhaps something in our solar system that brings about, as a kind of mirror-image on earth, the contrast between man and woman? Yes, this higher polarity can be designated as the contrast between the cometary and lunar natures, between comets and the moon. Just as the contrast of sun-earth is reflected in our head and limbs, so in feminine and masculine is reflected the contrast of comet-moon. This leads us into certain deep cosmic mysteries. Strange as it may sound to you, it is true that the different members of human nature that can confront us in the physical body are in different degrees an expression of the spiritual that lies behind them. In the physical body of man, it is the head, and in a certain other sense the limbs, that correspond most closely in outer form to their underlying, inner, spiritual forces. Let us be clear about this: everything that confronts us externally in the physical world is an image of the spiritual; the spiritual has formed it. If the spiritual is forming something physical, it can form it in such a way that at a certain stage of evolution this physical form is either more similar or less similar to it, or is more or less dissimilar from it. Only head and limbs resemble as external structures their spiritual counterparts. The rest of the human body does not at all resemble the spiritual picture. The outer structure of man, with the exception of head and limbs, is in the deepest sense a mirage, and those whose clairvoyant sight is developed always see the human being in such a way that a true impression is made only by the head and limbs. Head and limbs give a clairvoyant the feeling that they are true; they do not deceive. With regard to the rest of the human body, however, clairvoyant consciousness has the feeling that it is untrue form, that it is something that has deteriorated, that it does not at all resemble the spiritual behind it. Moreover, everything that is feminine appears to clairvoyant consciousness as if it had not advanced beyond a certain stage of evolution but had remained behind.

We can also say that evolution has advanced forward from point A to B. If C were a kind of normal development, then we would be at point C as far as the human head and limbs are concerned. What appears in the form of the female body has remained as if it were at D, not advancing to a further point of development. If it will not be misunderstood, we can say that the female body, as it is today, has remained behind at a more spiritual stage; in its form it has not descended so deeply into matter as to be in accord with the average stage of evolution. The male body, however, has advanced beyond the average stage—apart from head and limbs. He has overshot this average stage, arriving at point E. A male body, therefore, has deteriorated, because it is more material than its spiritual archetype, because it has descended more deeply into the material than is called for today by the average stage of evolution. In the female body we thus have something that has remained behind normal evolution and in the male body something that has descended more deeply into the material than have the head and limbs. This same contrast is also to be found in our solar cosmos. If we take our earth and the sun as representing normal evolutionary stages, the comet has not advanced to this normal stage. It corresponds in our cosmos to the feminine in the human being. Hence, we must see cometary existence as the cosmic archetype of the feminine organism. Lunar existence is the counterpart of masculine existence. This will be clear to you from what has been said before. We know from before that the moon is a piece of the earth that had to be separated off. If it had remained in the earth, the earth could not have gone forward in its evolution. The moon had to be separated off on account of its density. The contrast between comet and moon out in the cosmos is therefore the archetype of feminine and masculine in the human being. This matter is exceedingly interesting, because it shows us that whether we are considering an earthly being, such as man, or the whole universe, we must not simply think of one member side by side with others as they appear to us in space; if we do this we give ourselves up to a dreadful illusion. The various members of a human organism are, of course, beside one another, and the ordinary materialistic anatomist will regard them as being at equal stages of development. For one who studies the truth of things, however, there are differences, inasmuch as one thing has reached a certain point of evolution, another has not—although it has made some progress—and another has passed beyond this point. A time will come when the whole human organism will be studied along these lines; only then will an occult anatomy exist in the real sense. As I have told you, things that lie side by side can be at different stages of evolution, and the organs in the human body are only to be understood when one knows that each of them has reached a quite different stage of evolution. If you recall that the ancient Moon evolution preceded that of our earth, you will realize from what has just been said that although the present moon is certainly part of the ancient Moon evolution, it is not now at that stage of evolution and does not represent it. The moon has not only advanced to the earth stage but has even gone beyond this; it was not able to wait until the earth becomes a Jupiter, and it has therefore fallen into torpor in so far as its material side is concerned—not, of course, in its spiritual relationships. The comets represent the relationship of the ancient Moon to the sun that prevailed at a certain time in the ancient Moon evolution. The comet has remained at this stage, but now it must express this somewhat differently. The comet has not advanced to the point of normal earthly existence. Just as in the present moon we have a portion of a later Jupiter that was born much too early and is therefore torpid, incapable of life, so in our comets we have a portion of the ancient Moon existence projecting into our present earthly evolution. I would like to mention here parenthetically a noteworthy point, through which our spiritual scientific ways of studying have won a little triumph. Those who were present at the eighteen lectures on cosmogony that I gave in Paris in 1906 (see Note 2) will remember that I spoke then of certain things that were not touched upon in my book, An Outline Of Occult Science (see Note 3) (one cannot always present everything; one must not write one book but endless books if one wishes to develop everything). In Paris I developed a point bearing more upon the material, chemical aspect of the subject, as it were. I said that the ancient Moon evolution—which projects itself in present cometary existence, because the comet has remained at this stage and, as far as present conditions allow, expresses those old relationships in its laws—I said that this ancient Moon evolution differs from that of the earth in that nitrogen and certain nitrogenous compounds—cyanide, prussic acid compounds—were as necessary to the beings on the ancient Moon as oxygen is necessary to the beings of our present earth. Cyanide and similar substances are compounds that are deadly to the life of higher beings, leading to their destruction. Yet compounds of carbon and nitrogen, compounds of prussic acid and the like, played an entirely similar role to that of oxygen on the earth. These matters were developed at that time in Paris out of the whole scope of spiritual science, and those who inscribed them in their memories will have had to say to themselves that, if this is true, there must be proof of something like compounds of carbon and nitrogen in today's comets. You may recall (the information was brought to me during the lecture course on St. John and the other three Gospels in Stockholm) that the newspapers have now been saying that the existence of cyanide compounds has actually been proved in the spectrum of the comet. This is a brilliant confirmation of what spiritual research was able to say earlier, and it has at last been confirmed by physical science. As proofs of this kind are always being demanded of us, it is quoted here. When such a striking case is available, it is important for anthroposophists to point it out and—without pride—to remind ourselves of this little triumph of spiritual science. So you see, we can truly say that the contrast between masculine and feminine has its cosmic archetype in the contrast between comet and moon. If we could proceed from this (it is not, of course, possible to go into all the ramifications) and could demonstrate the full effect of the body of the moon and of the comets, you would realize how great and powerful it is for the soul—how it surpasses all general feelings of sublimity—to experience that here on earth we see something reflected and that this, in its functioning, is an exact expression of the contrast between comet and moon in the universe. It is possible to indicate only a few of these matters. A few are very important, and to these we will allude. Above all, we must become conscious of how the contrast expressed in comet and moon works upon the human being. We must not think that this contrast expresses itself only in what constitutes man and woman in humanity, because we must be clear that masculine characteristics exist in every woman and feminine characteristics in every man. We also know that the etheric body of man is female and that of the woman, male, and this at once makes the matter extremely complicated. We must realize that the masculine-feminine contrast is thus reversed for the etheric bodies of man and woman, and so are the cometary and lunar effects. These effects are also there in relation to the astral body and the I. Hence the contrast between comet and moon is of deep, incisive significance for the evolution of humanity on earth. The fact that the Moon evolution has a mysterious connection with the relationship of the sexes, a connection that eludes exoteric ways of thinking, you can recognize in something that might seem entirely accidental, namely, that the product of the union of male and female, the child, needs ten lunar months for its development from conception to birth. Even modern science reckons not with solar but with lunar months, because there the relation between the moon, representing the masculine in the universe and the earth, and the cometary nature, representing the feminine in the universe, is decisive, reflecting itself in the product of the sexes. If we now regard this from the other side, from the comets, we have another important consequence for the evolution of humanity. The cometary nature is as though feminine, and in the movements of the comets, in the whole style of their appearance from time to time, we have a kind of projection of the archetype of the feminine nature in the cosmos. It is something that really gives the impression of having come to a halt before reaching the normal, average stage of evolution. This cosmic feminine—the expression is not quite apt, but we lack suitable terms—shoots in from time to time like something that stirs up our existence from the depths of a nature existing before the dawn of history. In the mode of its appearance, a comet resembles the feminine. We can also express it this way: as what is done by a woman more out of passion, out of feeling, is related to the dry, reasonable, masculine judgment, so is the regular, reasonable course of the moon related to the cometary phenomenon that projects apparently irregularly into our existence. This is the peculiarity of feminine spiritual life. Mark well—I do not mean the spiritual life of woman but the feminine spiritual life. There is a difference. The spiritual life of a woman naturally includes masculine characteristics. Feminine spiritual life, whether in a man or a woman, projects into our existence something of the primitive, something elemental, and this is also what a comet does. Wherever this contrast between man and woman confronts us, we can see it, because it expresses itself with uncommon clarity. People who judge everything by externals criticize spiritual science because many women are drawn to it at the present time. They do not comprehend that this is quite understandable simply because the average brain of a man has overstepped a certain average point of evolution; it has become drier, more wooden, and therefore clings more rigidly to traditional concepts; it cannot free itself of the prejudices in which it is stuck. Someone who is studying spiritual science may at times feel it difficult that in this incarnation he must use this masculine brain! The masculine brain is stiff, resistant, and more difficult to manipulate than the feminine brain, which can easily overcome obstacles that the masculine brain, with its density, erects. Hence the feminine brain can more readily follow what is new in our way of looking at the world. To the extent to which the masculine and feminine principles come to expression in the structure of the human brain, it can even be said that for our present time it is most uncomfortable and unpleasant to be obliged to use a masculine brain. The masculine brain must be trained much more carefully, much more radically, than a feminine brain. You can thus see that it is not really so extraordinary that women today find their bearings more easily in something as eminently new as spiritual science. These matters are of the greatest importance in the history of culture, but one can hardly discuss them anywhere today except in anthroposophical circles. Except in our circles, who will take seriously the fact that to have a masculine brain is not so comfortable as to have a feminine brain? This, naturally, does not imply by any means that many a brain in a woman's body has not thoroughly masculine traits. These things are not as simple as we suppose with our modern notions. The cometary nature is something elemental; it stirs things up and in a certain sense is necessary in order that the advancing course of evolution may be supported in the right way from the cosmos. People have always had a premonition that this cometary nature is connected in some way with earthly existence. It is only in our day that they reject any such idea. Only think what a face the average scholar of today would make if the same thing happened to him as happened between Professor Bode and Hegel. Hegel once stated bluntly to an orthodox German professor that good wine years followed comets, and he tried to prove this by pointing to the years 1811 and 1819, good wine years that were preceded by comets. This made a fine commotion! But Hegel said that his statement was as well founded as many calculations concerning the courses of stars, that it was an empirical matter that was verified in these two cases. Even apart from such comical episodes, however, we can say that people have always conjectured something in this connection. It is not possible to enter into details now, since that would be an endless task, but we wish to shed some light on one main influence related to human evolution. The comets appear at great intervals of time. Let us ask: when they appear, is their relation to human evolution as a whole such that they stimulate, as it were, the feminine principle in human nature? There is, for example, Halley's Comet, which now again has a certain actuality. (see Note 4) The same could be said of many other comets. Halley's Comet has a quite definite task, and everything else that it brings with it stands in a particular connection to this task. Halley's Comet—we are speaking here of its spiritual aspect—has the task of impressing on human nature its own special being in such a way that this human nature and essence take a further step in the development of the I when the comet comes near the earth. It is that step which leads the I out to concepts on the physical plane. To begin with, the comet has its special influence on the two lower members of human nature, on what is masculine and feminine; there it joins company with the workings of the moon. When the comet is not there, the workings of the moon are one-sided; the workings change when the comet is present. This is how the working of the comet now expresses itself: when the human I takes a step forward, then, in order that the whole man can advance, the physical and etheric or life bodies must be correspondingly transformed. If the I is to think differently in the nineteenth century from the way it thought in the eighteenth, there must also be something that changes the outer expression of the I in the physical and etheric bodies—and this something is the comet! The comet works upon the physical and etheric or life bodies of man in such a way that they actually create organs, delicate organs that are suitable for the further development of the I—the I-consciousness as it has developed especially since the imbedding of the Christ impulse in the earth. Since that time the significance of the comet's appearance is that the I, as it develops from stage to stage, receives physical and etheric organs it can use. Just think of it—strange as it may sound and crazy as our contemporaries will find it—it is nonetheless true that if the I of a Büchner, of a Moleschott, (see Note 5) and of other materialists had not possessed, around the years 1850–60, suitable physical and etheric brains, their thinking could not have been as materialistic as it was. Then, perhaps, the worthy Büchner would have made a good, average clergyman. For him to be able to arrive at the thoughts expressed in his Kraft und Stoff, it was necessary not only for his I to evolve in this way but for the corresponding organization to be present in the physical and etheric bodies. If we are searching for the evolution of the I itself, we need only look around at the spiritual-cultural life of the period. If we wish, however, to know how it was that these people of the nineteenth century had a physical brain and an etheric body suitable for materialistic thinking, we must say that in 1835 Halley's Comet appeared. In the eighteenth century there was the so-called Enlightenment, which was also a certain stage in the development of the I. In the second half of the eighteenth century the average human being had in his brain this spiritual configuration that is called “Enlightenment.” What made Goethe so angry was that a few ideas were thrown out and people declared themselves satisfied. What was it that created the brain for this “Age of Enlightenment?” Halley's Comet of the year 1759 created this brain. That was one of its central effects. Every cometary body thus has a definite task. Human spiritual life takes its course with a certain cosmic regularity, as it were—a bourgeois regularity one could say. Just as a man undertakes with an earthly bourgeois regularity certain activities day by day, like lunch and dinner, so does human spiritual life take its course with cosmic regularity. Into this regularity there come other events, events that in ordinary, bourgeois life are also unlike those of every day and through which a certain noticeable advance occurs. So it is, for example, when a child is born into a family. The cosmic regularity manifesting in the whole of human evolution takes its course under the influence of the moon, of the lunar body. In contrast to these events, there are things that always bring about a step forward, that are naturally distributed over wider spans of time; these events occur under the influence of the comets. The various comets have here their different tasks, and when a comet has served its purpose it splinters. Thus we find that from a certain point of time onward, some comets appear as two and then splinter. They dissolve when they have completed their tasks. Regularity, all that belongs to the common round, is connected with the lunar influence; the entry of an elemental impulse, always incorporating something new, is connected with the influence of the comets. So we see that these apparently erratic wanderers in the heavens have their rightful place and significance in the whole structure of our universe. You can well imagine that when something new, like a product of the cosmic feminine, breaks into the evolution of humanity, it can cause tumults that are obvious enough but that people prefer not to notice! It is possible, however, to make people conscious that certain events of earthly existence are connected with the existence of comets. Just as something new, a gift from the woman, may enter into the everyday bustle of the family, so it is with the comets. As when a new little child is born, so it is when, through the return of a comet, something quite new is produced. We must remember, however, that with certain comets the I is always driven out more and more into the physical world, and this is something we must resist. If the influence of Halley's Comet were to continue, a new appearance of it might bring about a great enhancement of Büchnerian thought, and that would be a terrible misfortune. A reappearance of Halley's Comet should therefore give us warning that it might prove to be an evil guest if we were simply to give ourselves up to it, if we were not to resist its influence. It is a matter of holding fast to higher, more significant workings and influences of the cosmos than those of Halley's Comet. It is necessary, however, that human beings should regard this comet as an omen; they should realize that things are no longer as they were in earlier times, when in a sense it was fruitful for humanity that it should come under these influences. This influence is no longer fruitful. Human beings must now unite themselves with different powers in order to balance this dangerous influence from Halley's Comet. When it is said that Halley's Comet can be a warning; that its influence, working alone, might make people superficial and lead the I more and more onto the physical plane; and that precisely in our days this must be resisted—this truly is said not for the sake of reviving an old superstition. The resistance can occur only through a spiritual view of the world, such as that of anthroposophy, replacing the evolutionary trend caused by Halley's Comet. It could be said that once again the Lord is displaying His rod out there in the heavens in order to say to human beings through this omen: now is the time to kindle the spiritual life! On the other hand, is it not wonderful that cometary existence takes hold of the depths of life, including the animal and plant life that is bound up with human life? Those who pay close enough attention to such things would observe how there is actually something altogether different in the blossoming of flowers from what is usually the case. These things are there, but they are easily overlooked, just as people so often overlook the spirit, do not wish to see the spirit. We may now ask: is there something in the cosmos that corresponds to the ascent to a spiritual life that has just been indicated? We have seen that head and limbs and masculine and feminine have polar contrasts in the cosmos. Is there something in the cosmos that corresponds to this welling up of the spiritual, to this advance of man beyond himself, from the lower to the higher I? We will ask ourselves this question tomorrow in connection with the greatest tasks of spiritual life in—our time. Today I wished to give the preliminaries, in order that tomorrow we may understand through greater relationships an important question of the present time. Much that has been said today is admittedly remote, but we are living in a cometary year. It is therefore good to say something about the mysterious relationship of cometary existence to our earthly existence. Beginning with this, we will speak tomorrow about the great spiritual meaning of our time. |

| 118. The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric: The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric

06 Mar 1910, Stuttgart Translated by Barbara Betteridge, Ruth Pusch, Diane Tatum, Alice Wuslin, Margaret Ingram de Ris |

|---|

| If understanding is not created, however, if this faculty is trampled to death, so to speak, if one who talks about these faculties is locked up as a fool, it will prove disastrous for humanity. |

| Those, however, who absorb the essence of the teaching of the spirit as the content of their whole soul life—as vital life—should then really grow upward to a spiritual understanding of the matter. They should then make it clear to themselves that they must learn through spiritual science to understand our newly awakening age thoroughly. |

| It will be the event through which human beings will understand to a higher degree the Christ impulse. For the peculiar thing will be that, through this, wisdom will suffer no loss. |

| 118. The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric: The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric

06 Mar 1910, Stuttgart Translated by Barbara Betteridge, Ruth Pusch, Diane Tatum, Alice Wuslin, Margaret Ingram de Ris |

|---|