Practical Course for Teachers

GA 294

1 September 1919, Stuttgart

X. Arranging the Lesson up to the Fourteenth Year

Let now try to get further in the method by keeping one eye in future on the curriculum and the other on what will form the subjects of the curriculum. It does not immediately have everything in it which it ought to contain, for we build up the method of our observations by degrees.

We have already begun to consider the lessons for the various ages. How many stages of teaching can we differentiate during the school course? We have learnt that an important break occurs towards the age of nine, which enables us to affirm: if we get a child under the age of nine we shall be concerned with the first stage of school-teaching. What subjects shall we then teach? We shall take the artistic element as our point of departure. We shall study music and painting-drawing with the child as we have discussed. We shall gradually allow writing to arise from painting-drawing. We shall therefore gradually evolve the written forms from the drawn forms and we shall then go on to reading.

It is important for you to understand the reasons for this procedure: it is important that you do not first take reading and then tack writing on to it, but that you go from writing to reading. Writing is, in a sense, more living than reading. Reading isolates man very much, in the first place, and isolates him from the world. In writing we have not yet ceased to imitate world-forms, as long as we derive it from drawing. The printed letters have become extraordinarily abstract. They have arisen, of course, without exception from written letters. Consequently, we re-create them in our teaching from the written letters. It is quite correct to preserve intact, in teaching writing at least, the thread which connects the drawing forms with the written letters, so that the child still always feels in some degree the original image behind the letter. In this way you overcome the abstract character of writing. When man adjusts himself to writing he is obviously assimilating something very foreign to the universe. But if we link the written forms with the universal forms—with f = fish, etc.—at least we lead man back again to the world. And it is very important indeed that we should not wrench him away from it. The further back we go into the history of civilization the more living do we find this relation of man to the world. You only need to picture a scene in your soul to understand what I have just said: Transport yourself to ancient times and imagine, in my place, a Greek rhapsodist is reciting Homer to his audience in the manner of those days, between song and speech which we have lost, and imagine, sitting next to this rhapsodist, someone taking down the recital in shorthand. A grotesque scene, and impossible, quite impossible. Impossible for the simple reason that the Greek had quite a different kind of memory from ours and was not dependent on the invention of anything so far-fetched as the forms of shorthand to enable him to remember the revelations to men in language. You see from this that an unusually disturbing element is bound to be constantly interfering with our culture. We need this disturbing element. We cannot, of course, dispense with shorthand in our civilization. But we should be aware that it is a disturbing influence. For what actually is the significance of this appalling short-hand-copying in our civilization? It simply means that in our civilized life we are no longer capable of adjusting ourselves to the right rhythm of waking and sleeping, and that we employ the hours of sleep in doing all kinds of things which implant in our soul-life things which from its very nature it cannot assimilate. With our shorthand-copying we keep stored up what we should do better to forget if only left to ourselves. That is, we artificially maintain in a waking condition in our civilization things which disturb it as much as the nocturnal cram of over-eager students upsets their health. That is why our civilization is no longer healthy. But we must be clear in our minds that we have already crossed the Rubicon of the Greek age. A Rubicon was crossed then, on the far side of which humanity still had a quite sound civilization. Civilization will continue to grow unhealthier and people will more and more have to turn the process of education into a process of healing of the ills created by their surroundings. As to this there is room for no illusions. That is why it is so infinitely important to link up writing with drawing again, and to teach writing before reading.

Arithmetic should be begun somewhat later. This can be adjusted according to outer necessities as there is no point marked for it in life evolution itself. But into this complete plan there can always be inserted at the first stage a certain study of foreign languages, because this has been made essential by civilization. At this stage these foreign languages must only be studied in the form of practice of speaking.

Only in the second stage, from nine to about twelve, do we begin to develop the self-consciousness more. And we do this in grammar. At this point the human being is already capable, because of the change which he has undergone and which I describe to you, of absorbing into his self-consciousness the significance of grammar. At this point we take “word teaching” in particular. But we also embark on the natural history of the animal kingdom, as I showed you with the cuttle-fish, mouse, and human being. And only later do we add the plant kingdom.

Further, at this stage in the life of the human being we can go on to geometry, whereas we have hitherto restricted the elements of geometry to drawing. In drawing, of course, we can evolve for him the triangle, the square, the circle, and the line. That is, we evolve the actual forms in drawing, by drawing them and then saying: “This is a triangle, this is a square.” But what geometry adds to these, with its search for the relations between the forms, is only introduced at about nine years of age. At the same time, of course, the foreign language is continued and becomes part of the grammar teaching.1See the Table at the end of this lecture.

Last of all we introduce the child to physics. Here we come to the third stage which goes to the end of the elementary school course, that is to fourteen and fifteen years of age. Here we begin to teach syntax. The child is only really ready for this at about twelve years of age. Before this we study instinctively those elements of language which the child can make into sentences.

Here, too, the time has come when, using geometrical forms, we can go on to the mineral kingdom. We take the mineral kingdom in constant conjunction with physical phenomena which we then apply to man, as I have already explained: light refraction—the lens in the eye. The physical aspect, that is, and the chemical. We can also go on to history. All this time we study geography, which we can always reinforce with natural history by introducing physical concepts and with geometry by the drawing of maps, and finally we connect geography with history. That is, we show how the different peoples have developed their characteristics. We study this subject throughout these entire stages of childhood, from nine to twelve, and from twelve to fifteen. The foreign language teaching is, of course, continued and extended to syntax.

Now naturally various things will have to be taken into account. For we cannot take music with little beginners who have come to us, at the same time and in the same classroom as a lesson with other children for whom everything should be quite still if they are to learn. We shall therefore have to arrange the painting and drawing with the little children as a morning lesson and music late in the afternoon. We shall also have to divide up the space available in the school so that one subject can be taken side by side with another. For example, we cannot have poems recited aloud and a talk about history going on if the little ones are playing flutes in the next room. These matters are involved in the drawing up of the time-table and we must carefully take into account, when we organize our school, that many subjects will have to be arranged for the morning and others for the afternoon, and so on. Now our problem is: to be able, with our knowledge of these three stages in the curriculum, to pay attention to the greater or lesser aptitudes of the children. Naturally we shall have to make compromises, but I will now assume rather ideal conditions and throw light later on the time-tables of modern schools for the purpose of striking an adequate balance. We shall generally do well to draw a less sharp distinction between the classes within the different stages than we draw at the transition from one stage to the next. We shall remember that a general move up can actually take place only between the first and second, and between the second and third stage. For we shall discover that the so-called less-gifted children generally speaking understand things later. Consequently, in the years comprised in the first stage we shall have the intelligent children who can simply understand more quickly and who assimilate later, and the less able, who have difficulties at first but at last understand. We shall definitely make this discovery and must not therefore form an opinion too early as to which children are unusually able and which are less able.

Now I have already emphasized the fact that we shall, of course, get children who have gone through the most various classes. Dealing with them will be all the more difficult the older they are. But we shall nevertheless be able to remould to a great extent whatever about them has been badly started, provided that we take enough trouble. We shall not delay, after having done what we have found important in a foreign language, in Latin, French, English, Greek, to go on as soon as possible to what gives the children the greatest imaginable pleasure: to let them talk to each other in class in the language concerned and, as teachers, to do no more than guide this conversation. You will discover that it gives the children really great pleasure to converse with each other in the language concerned and to have the teacher confining himself to correcting their efforts or, at the most, guiding the conversation; for example, a child who is saying something particularly tedious is diverted to something more interesting. Here the presence of mind of the teacher must do its quite peculiar work. You must really feel the children in front of you like a choir which you have to conduct, but you have to enter into your work even more intimately.

Then comes the point to ascertain from the children what poems or other memorized reading passages they have previously learnt, that is, what treasure they can produce for you from the store of their memories. And with this store in the child's memory, you must link every lesson in the foreign language, especially grammar and syntax, for it is of quite particular importance that anything the children have learnt by heart—poems, etc., should be remembered. I have said that it is not a good thing to abuse the memory by having written down the sentences which are formed during grammar lessons to illustrate rules. These may well be forgotten. On the other hand, the points learnt from these sentences must be applied to the store of things already memorized, so that this possession of the memory contributes to the mastery of the language. If, later, you are writing a letter in the language, or conversing in it, you should be able rapidly to recall a good turn of phrase from things once learnt in this way. The consideration of such facts is part of the economy of teaching. For we must know what makes the teaching of a foreign language particularly economical and what wastes time. Delay is caused by reading aloud to the children in class while they follow in the books in front of them. That is nothing but time stolen from the child's life. It is the very worst thing that you can do. The right way is for the teacher to introduce the desired material in the form of a story, or even for him to repeat a reading passage verbatim or to recite a poem, but to do this without book himself, from memory, and for the children to do nothing at the time but listen to him; not, that is, follow his reading: then, if possible, the children reproduce what they have listened to, without first reading it at all. This is valuable in teaching a foreign language. In teaching the mother tongue it need not be so carefully considered. But in a foreign language greater regard must be paid to making things intelligible by speech and to aural comprehension, rather than to visual comprehension. Now when this has been sufficiently practised, the children can take the book and read after you, or, if you do not abuse this suggestion, you can simply give them for homework to read in their book the passage taken orally in school. Homework in foreign languages should first and foremost be confined to reading work. Any written work should really be done in the school itself. In a foreign language the least possible amount of homework should be given, none before the later stages, that is, before thirteen, and then only work connected with real life: the writing of letters, business correspondence, and so on. Only, that is, what really happens in life. To have compositions written in a foreign language during school hours, compositions unrelated to life, is really, in the deepest sense, a monstrosity. We ought to be content with work of a letter-character, concerned with business and similar things. At the most we should go as far as cultivating the telling of pieces of narrative. In the elementary school, to fourteen, we should practise, far more than the so-called free composition, the recounting of incidents that have occurred, of experiences. Free composition does not really belong to this elementary school course. But the narrative description of things seen and heard certainly does belong there, for the child must learn this art of reporting; otherwise he will not be able to play his proper social part in human social life. In this respect our cultured folk to-day only see half the world, as a rule, and not the whole.

You know, of course, that experiments are now being carried on in the service of criminal psychology. These experiments are planned, for example—I will take a case—in this way. Everybody to-day tries to ascertain facts by means of experiment. Somebody decides to undertake a course of lectures. The experiments are carried out in connection with advanced education and are held in the universities. In order to organize this course of lectures as an experiment the following arrangement is very carefully made beforehand with a student, or “listener,” as he is called: “I, as Professor, will mount the platform and will say the first few words of a lecture.—Good, write that down.—At this moment you jump on to the platform and tear from its hook the coat which I have previously hung up.” The listener then has to carry out accurately some plan as arranged. Then the professor behaves accordingly. He makes a rush at the student to prevent him from unhooking the coat. The next step is then arranged: we have a free fight. We decide on the exact movements to be made. We study our part carefully and learn it well by heart, in order to enact the whole scene as arranged. Then the audience, which knows nothing of this—all this is only discussed with a “listener”—reacts in its own way. This is impossible to calculate. But we will try to draw a third person into the secret, and he now carefully notes the reaction of the audience. Well, there is the experiment carried out. Afterwards we have an account of the scene written down by the audience, by every single listener.

Such experiments have been carried on in universities. The one which I have described has, in fact, been tried, and the result was as follows: In an audience of about thirty people, at the most four or five gave an accurate account of the occurrence. This can be verified because everything was previously discussed in detail and carried out according to plan. Hardly a tenth of the spectators write out the experiment correctly. Most of them make absurd statements when surprised by an occurrence of this kind. In these days, when experiments are popular, such incidents are staged with great enthusiasm, and the important scientific result is obtained that the witnesses who are called up in a court of law are not reliable. For when the educated people of a university audience—they are, after all, all “educated” people—respond to an incident in such a way that only a tenth of them write anything true about it and many of them write quite senseless stuff, how are we to expect of the witnesses in a trial an accurate account of what they saw perhaps weeks or months ago? Sound common sense is aware of these facts from experience. For after all, in life, too, people report on what they have seen almost always incorrectly, and very seldom accurately. You simply have to scent out whether a matter is being reported wrongly or rightly. Hardly a tenth of what people say around you is true, in the strict sense of being a report of what happened in actual fact.

But in the case of this experiment people only half-achieve their aim: they emphasize the half which, if one uses sound common sense, can be left out of the calculation, for the other half is more important. We ought to see that our civilization develops in such a way that more reliance can be placed on witnesses and that people speak the truth more and more. But to achieve this aim we must begin with childhood. And for this reason it is important to give descriptions of what has been seen and heard rather than to practise free composition. Then there will be inculcated in the children the habit of inventing nothing in life or, if need be, in a court of law, but to relate the truth about external physical facts. In this field, too, the will-element ought to be considered more than the intellect. In the case of that audience I took, with the previous discussion of the experiment and the deductions made after it from the statements of the spectators, the aim was to find out how far people are liars. This is quite conceivably understood in an intellectually minded age like our own. But we must convert the intellectually minded age back to the will-element. For this reason we must notice details in education, such as letting the children, once they can write, and particularly after twelve years of age, tell about what they have really seen, and not practise free composition to any great extent in the elementary school,2Up to fourteen. for it does not really belong to this stage of childhood.

It is further particularly important in a foreign language gradually to bring the children to the point of being able to reproduce in a short story what they have seen and heard. But it is also necessary to give the children orders: “Do this, do that”—and then let them carry these out, so that in such exercises in class the teacher's words are succeeded less by reflection on what has been said or by a slow spoken answer than by action. That is, the will-element, the aspect of movement, is cultivated in the language lesson. These, again, are things which you must think over and absorb, and which you must take especially into account in teaching foreign languages. We have, in fact, always to know how to combine the will-element with the intellect in the right way.

It will be indeed important to cultivate object lessons, but not to make them banal. The child must never have the feeling that what we do in our object lessons is simply obvious. “Here is a piece of chalk. What colour is the chalk? It is yellow.—What is the chalk like at the top? It is broken off.” Many an object lesson is given on these lines. It is horrible. For what is really obvious in life should not be turned into an object lesson. The whole object lesson should be elevated to a much higher level. When the child is given an object lesson he should be transported to a higher plane of the life of his soul. You can effect this elevation particularly, of course, if you connect your object lesson with geometry.

Geometry offers you an extraordinarily good opportunity of combining the object lesson with geometry itself.

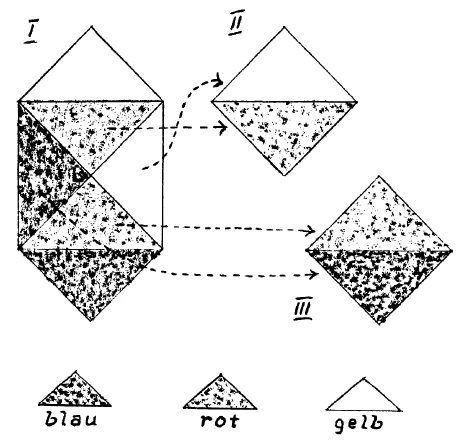

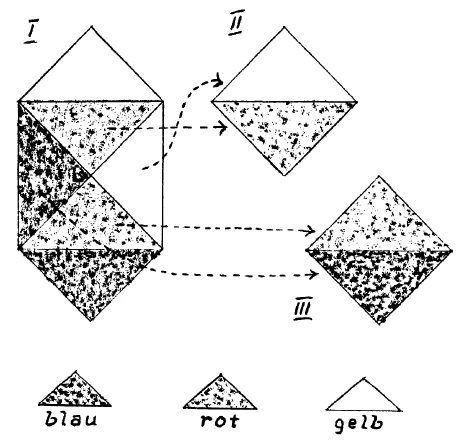

You begin, for instance, by drawing on the board a right-angled isosceles triangle (∆ Ð Ð’ C in the given figure) and make the children realize—if you have not already taught it—that AC and BC are the sides which contain the right-angle and AB is the hypotenuse. Then you add a square underneath, adjacent to the hypotenuse of the right-angled triangle and divide it by its diagonal lines. (Dr. Rudolf Steiner used colours to mark the various parts.) Now you say to the child: “I am going to cut out this part here (∆ A Ð’ D) and put it to one side of our figure (follow the arrow). Now I take another part (∆ B D F), bring it also to the side, and place it above the other one already removed (follow the arrow). So I have set up a square composed of the two triangles and you can see that it is equal to the square on one of those sides of the original right-angled triangle which contain the right-angle. At the same time it has the size of half the area of the square on the hypotenuse.”

Now you do the same on the other side (follow the arrows to the left) and finally prove that the square on the hypotenuse equals in area the sum of both the squares on the sides of the right-angled triangle which contain the right-angle.

Schopenhauer in his day was furiously angry because the theorem of Pythagoras was not taught like this in the schools, and in his book Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (“The World as Will and Idea”), he says as much in his rather

drastic way: “How stupid school is not to teach things of this kind simply, by placing one part on top of another, and making the theorem of Pythagoras clear by observation.” This only holds, in the first place, of an isosceles triangle, but exactly the same can be done for a scalene right-angled triangle by fitting one part over another as I have explained. That is an object lesson. You can turn geometry into an object lesson. But there is a certain value—and I have often tested it myself—if you wish to give the child over nine a visual idea of the theorem of Pythagoras—in constructing the whole theorem for him directly from the separate parts of the square on the hypotenuse. And if, as a teacher, you realize what is taking place in a geometry lesson, you can teach the child in seven or eight hours at the most all the geometry necessary to introduce a lesson on the theorem of Pythagoras, the famous Pons Asinorum. You will proceed with tremendous economy if you demonstrate the first rudiments of geometry graphically in this way. You will save a great deal of time and, besides that, you will save something very important for the child—which prevents a disturbing effect on teaching—and that is: you keep him from forming abstract thoughts in order to grasp the theorem of Pythagoras. Instead of this let him form concrete thoughts and go from the simple to the composite. First of all, as is done here in the figure with the isosceles triangle, you should put together the theorem of Pythagoras from the parts and only then go on to the scalene triangle. Even when this is practised in pictures in these days—for that happens, of course—it is not with reference to the whole of the theorem of Pythagoras. The simple process, which is a good preparation for the other, is not usually first demonstrated with the isosceles triangle and only then the transition made to the scalene right-angled triangle. But it is important to make this quite consciously part of the aim of geometry-teaching. I beg you to notice the use of different colours. The separate surfaces must be coloured and then the colours laid one on top of the other.

- (Until the ninth year of age.)

Music. Painting with drawing.

Writing. Reading.

Foreign languages. A little later, arithmetic.- (Up to the twelfth year of age.)

Grammar. (Parts of Speech: Word Teaching.)

Natural history of the animal kingdom and of the plant kingdom.

Foreign languages. Geometry.

Physics.- (To the end of the elementary school course, age fourteen.)

Syntax.

Mineralogy.

Physics and Chemistry.

Foreign languages.

History.

Zehnter Vortrag

Wir werden nun versuchen, in der Didaktik etwas weiterzukommen, indem wir künftighin in diesen Stunden den einen Blick mehr nach dem Lehrplan werfen, den andern Blick mehr nach dem, was innerhalb des Lehrplans der Unterrichtsstoff sein wird. Wir werden nicht gleich alles im Lehrplan drinnen haben, was drinnen liegen soll, denn wir werden unsere künftige Betrachtungsweise eben aufbauend gestalten.

Ich habe Ihnen zuerst Betrachtungen gegeben, die die Möglichkeit bieten, überhaupt schon etwas hineinzutun in die Unterrichtsstufen. Wie viele Unterrichtsstufen werden wir im wesentlichen während der Volksschulzeit überhaupt unterscheiden? Nach dem, was wir kennengelernt haben, sehen wir einen wichtigen Einschnitt gegen das 9. Lebensjahr, so daß wir sagen können: Wenn wir ein Kind bis zum 9. Lebensjahr bekommen, haben wir die erste Periode des Volksschulunterrichts. Was werden wir denn da treiben? Wir werden den Ausgangspunkt nehmen vom Künstlerischen. Wir werden sowohl Musik als MalerischZeichnerisches mit dem Kinde so treiben, wie wir das besprochen haben. Wir werden allmählich aus dem Malerisch-Zeichnerischen das Schreiben entstehen lassen. Wir werden also nach und nach aus den gezeichneten Formen die Schriftformen entstehen lassen und werden dann übergehen zum Lesen.

Es ist wichtig, daß Sie die Gründe für diesen Gang einsehen, daß Sie nicht zuerst mit dem Lesen beginnen und dann das Schreiben daranknüpfen, sondern daß Sie vom Schreiben zum Lesen übergehen. Das Schreiben ist gewissermaßen noch etwas Lebendigeres als das Lesen. Das Lesen vereinsamt den Menschen schon sehr und zieht ihn von der Welt ab. Im Schreiben ahmen wir noch Weltenformen nach, wenn wir aus dem Zeichnen heraus das Schreiben betreiben. Die gedruckten Buchstaben sind auch schon außerordentlich abstrakt geworden. Sie sind ja durchaus aus den Schriftbuchstaben entstanden; wir lassen sie daher auch im Unterricht aus den Schriftbuchstaben entstehen. Es ist durchaus richtig, wenn Sie wenigstens für den Schriftunterricht den Faden nicht abreißen lassen, der da führt von gezeichneter Form zum geschriebenen Buchstaben, so daß das Kind gewissermaßen im Buchstaben die ursprünglich gezeichnete Form immer noch spürt. Dadurch überwinden Sie das Weltfremde des Schreibens. Indem der Mensch sich in das Schreiben hineinfindet, eignet er sich ja etwas sehr Weltenfremdes an. Aber wenn wir an Weltenformen, an f = Fisch und so weiter die geschriebenen Formen anknüpfen, so führen wir den Menschen wenigstens wiederum zurück zur Welt. Und das ist sehr, sehr wichtig, daß wir den Menschen nicht von der Welt abreißen. Je weiter wir zurückgehen in der Kultur, desto lebendiger finden wir ja auch diesen Zusammenhang des Menschen mit der Welt. Sie brauchen nur ein Bild vor Ihre Seele zu rufen und Sie werden das verstehen, was ich jetzt gesagt habe. Denken Sie sich, statt meiner, der ich hier spreche, indem Sie sich in alte Zeiten zurück versetzen, einen griechischen Rhapsoden, der seinen Leuten den Homer in jener eigentümlichen Weise von dazumal, in jenem Zwischending zwischen Gesang und Sprache, das wir nicht mehr haben, vorträgt, und denken Sie sich neben diesem homerischrezitierenden Rhapsoden jemand sitzen, der stenographiert. Ein groteskes Bild! Unmöglich, ganz unmöglich! Aus dem einfachen Grunde ganz unmöglich, weil der Grieche ein ganz anderes Gedächtnis hatte als wir und nicht darauf angewiesen war, etwas so Weltenfremdes, wie es die Stenographieformen sind, zu erfinden, um das zum Behalten zu bringen, was durch die Sprache an die Menschen herankommt. Sie sehen daran, daß sich in unsere Kultur fortwährend etwas ungemein Zerstörendes hineinmischen muß. Wir brauchen dieses Zerstörende. Wir können ja in unserer gesamten Kultur die Stenographie nicht missen. Aber wir sollten uns bewußt werden, daß sie etwas Zerstörerisches hat. Denn eigentlich — was ist denn in unserer Kultur dieses entsetzliche Nachstenographieren? Das ist in unserer Kultur nichts anderes, als wenn wir eben nicht mehr zurechtkämen mit unserem richtigen Rhythmus zwischen Wachen und Schlafen und die Schlafenszeit dazu verwendeten, allerlei Dinge zu treiben, so daß wir unserem Seelenleben etwas einpflanzten, was es naturgemäß eigentlich nicht mehr aufnimmt. Mit unserem Stenographieren behalten wir etwas in der Kultur drinnen, was eigentlich unserer jetzigen Naturanlage nach der Mensch, wenn er sich nur sich selbst überließe, nicht achten, sondern vergessen würde. Wir erhalten also in unserer Kultur künstlich etwas wach, was ebenso unsere Kultur zerstört, wie das nächtliche Ochsen der Studenten, wenn sie überfleißig sind, ihre Gesundheit zerstört. Unsere Kultur ist deshalb keine ganz gesunde mehr. Aber wir müssen uns klar sein, daß wir eben schon den Rubikon überschritten haben; der lag in der Griechenzeit. Da wurde der Rubikon überschritten, wo die Menschheit noch eine ganz gesunde Kultur hatte. Die Kultur wird immer ungesunder werden, und die Menschen werden immer mehr und mehr aus dem Erziehungsprozeß einen Heilungsprozeß zu machen haben gegen dasjenige, was in der Umgebung krank macht. Darüber darf man sich keinen Illusionen hingeben. Daher ist es so unendlich wichtig, das Schreiben wiederum anzuknüpfen an das Zeichnen und das Schreiben vor dem Lesen zu lehren.

Dann sollte man etwas später mit dem Rechnen beginnen. Das kann man — weil ein ganz exakter Punkt in der Lebensentwickelung des Menschen nicht gegeben ist — nach andern Dingen einrichten, die man notwendig berücksichtigen muß. Man sollte also etwas später beginnen mit dem Rechnen. Was dazu gehört, wollen wir dann später dem Plane einfügen und mit dem Rechnen so beginnen, wie ich es Ihnen gezeigt habe. Immer wird sich aber schon einfügen in diesen ganzen Plan auf der ersten Stufe ein gewisses Betreiben des fremdsprachlichen Unterrichts, weil wir das aus der Kultur heraus notwendig haben; aber man muß für dieses Lebensalter diese fremden Sprachen durchaus noch betreiben als Sprechenlernen, indem man die Kinder in bezug auf die fremde Sprache so behandelt, daß sie sprechen lernen.

Erst auf der zweiten Stufe, vom 9. Jahre bis etwa zum 12. Jahr beginnen wir das Selbstbewußtsein mehr auszubilden. Und das tun wir in der Grammatik. Da ist der Mensch dann schon in der Lage, durch die Veränderung, die er durchgemacht hat und die ich Ihnen charakterisiert habe, das in sein Selbstbewußtsein hinein aufzunehmen, was ihm aus der Grammatik werden kann; namentlich die Wortlehre behandeln wir da. Dann aber beginnen wir da mit der Naturgeschichte des Tierreiches, so wie ich Ihnen das bei Tintenfisch, Maus und Mensch gezeigt habe. Und wir lassen dann erst später das Pflanzenreich folgen, wie Sie es mir heute nachmittag zeigen wollen.

Und jetzt können wir in diesem Lebensalter des Menschen auch zur Geometrie übergehen, während wir vorher dasjenige, was dann Geometrie wird, ganz im Zeichnerischen drinnen gehalten haben. Am Zeichnerischen können wir ja dem Menschen Dreieck, Quadrat, Kreis und Linie entwickeln. Die eigentlichen Formen entwickeln wir also am Zeichnerischen, indem wir zeichnen und dann sagen: Das ist ein Dreieck, das ist ein Quadrat. Aber was als Geometrie hinzutritt, wo wir die Beziehungen zwischen den Formen suchen, das beginnen wir erst so um das 9. Jahr herum. Dabei wird natürlich das Fremdsprachliche fortgesetzt und läuft auch ein in die grammatikalische Behandlung.

Zuletzt bringen wir an das Kind physikalische Begriffe heran. Dann kommen wir zur dritten Stufe, welche bis zum Ende der Volksschule geht, also bis ins 14., 15. Jahr. Da beginnen wir nun die Satzlehre einzuprägen. Zu der wird das Kind erst gegen das 12. Jahr hin eigentlich reif. Vorher treiben wir instinktiv dasjenige, was das Kind Sätze aufbauen läßt.

Nun ist auch die Zeit da, wo wir, die Geometrieformen benützend, übergehen können zum Mineralreiche. Das Mineralreich behandeln wir unter fortwährenden Beziehungen zum Physikalischen, das wir auch auf den Menschen anwenden, wie ich es schon gesagt habe: Strahlenbrechung - die Linse für das Auge; also physikalisch und chemisch. Dann können wir in dieser Zeit zur Geschichte übergehen. Die Geographie, die wir immer unterstützen können durch die Naturgeschichte, indem wir physikalische Begriffe hineinbringen, und durch die Geometrie, indem wir Karten zeichnen, indem wir physikalische Begriffe hineinbringen, die Geographie treiben wir durch alles das und verbinden sie zuletzt mit der Geschichte. Das heißt, wir zeigen, wie die verschiedenen Völker ihre Charaktere ausgebildet haben. Das treiben wir durch diese ganzen zwei kindlichen Lebensalter hindurch. Das Fremdsprachige wird natürlich wiederum fortgesetzt und auf die Satzlehre ausgedehnt.

Nun wird natürlich sorgfältig auf verschiedenes Rücksicht genommen werden müssen. Denn wir können ja natürlich nicht, indem wir mit den kleinen Kindern, die uns übergeben werden, beginnen Musik zu treiben, dieses Musikalische in der gleichen Zeit in irgendeinem Klassenzimmer treiben, wenn die andern irgend etwas haben, wozu es recht still sein soll, wenn sie lernen sollen. Wir werden also bei den kleinen Kindern das Malerisch-Zeichnerische an einen Vormittag verlegen müssen, das Musikalische etwa auf den späten Nachmittag. Wir werden uns also auch in der Schule räumlich so gliedern müssen, daß eines neben dem andern bestehen kann. Wir können nicht zum Beispiel Gedichte aufsagen lassen und über Geschichte sprechen, wenn die Kleinen im Nachbarzimmer trompeten. Also das sind Dinge, die schon etwas mit der Gestaltung des Lehrplanes zusammenhängen, und die wir bei der Einrichtung unserer Schule werden sorgfältig berücksichtigen müssen, wie manches auf den Vor- und Nachmittag zu verlegen sein wird und dergleichen. Nun handelt es sich darum, daß uns ja die Möglichkeit geboten wird, indem wir diese drei Stufen des Lehrplanes kennen, bei den Kindern auf größere oder geringere Befähigung Rücksicht zu nehmen. Natürlich müssen wir Kompromisse schließen, aber ich werde jetzt mehr den idealen Zustand annehmen und später Lichter werfen hinüber zu den Lehrplänen der gegenwärtigen Schulen, damit wir das Kompromiß ordentlich brav schließen können. Wir werden gut tun - also jetzt ideal betrachtet -, die Begrenzung zwischen den Klassen weniger scharf sein zu lassen innerhalb der Stufen, als wenn es von einer Stufe zur andern übergeht. Wir werden uns denken, daß einheitliches Aufsteigen eigentlich nur stattfinden kann zwischen der ersten und zweiten und zwischen der zweiten und dritten Stufe. Denn wir werden die Erfahrung machen, daß die sogenannten Minderbegabten meistens nur später begreifen. So daß wir haben werden durch die Jahrgänge der ersten Stufe die befähigten Schüler, die nur früher werden begreifen können und die dann später verarbeiten, und die Minderbefähigten, die zuerst Schwierigkeiten machen, aber zuletzt doch begreifen. Diese Erfahrung werden wir durchaus machen, und daher sollen wir auch nicht zu früh uns ein Urteil bilden darüber, welche Kinder besonders befähigt seien und welche weniger befähigt seien. Nun habe ich ja schon betont, daß wir Kinder bekommen werden, die schon die verschiedensten Klassen durchgemacht haben. Sie zu behandeln wird um so schwieriger werden, je älter sie sind. Aber wir werden doch bis zu einen hohen Grade das, was an ihnen verbildet worden ist, wiederum zurückbilden können, wenn wir uns nur entsprechend Mühe geben. So werden wir nicht versäumen, wenn wir das mit Bezug auf das Fremdsprachige getan haben — das Lateinische, Französische, Englische, Griechische -, was wir vorgestern betont haben, möglichst bald dazu überzugehen, das zu betreiben, was den Kindern die allermeiste Freude macht: sie in der Klasse miteinander in der betreffenden Sprache Konversation treiben zu lassen und diese Konversation als Lehrer nur zu leiten. Sie werden die Erfahrung machen, daß das den Kindern wirklich große Freude macht, wenn sie miteinander durch Konversation in der betreffenden Sprache sich unterhalten und der Lehrer nichts anderes tut, als immer nur verbessern, oder höchstens die Konversation leiten; so zum Beispiel wenn einer besonders langweiliges Zeug sagt, er abgelenkt wird auf etwas Interessantes. Da muß die Geistesgegenwart des Lehrers ihre ganz besonderen Dienste tun. Da müssen Sie wirklich die Schüler vor sich fühlen wie einen Chor, den Sie zu dirigieren haben, aber noch mehr ins Innere hinein als ein Dirigent sein Orchester zu dirigieren hat.

Dann handelt es sich darum, daß Sie bei den Schülern konstatieren, was sie früher an Gedichten aufgenommen haben, was sie behalten haben an sonstigen Lehrstücken und dergleichen, was sie Ihnen also aus ihrem Gedächtnis als einen Schatz vorbringen können. Und an diesen Schatz, den die Kinder gedächtnismäßig innehaben, knüpfen Sie jeden Unterricht in der fremden Sprache an, knüpfen Sie namentlich das an, was Sie nachzuholen haben an Grammatikalischem und Syntaktischem; denn es ist von ganz besonderer Bedeutung, daß so etwas bleibt, was die Kinder gedächtnismäßig an Gedichten und dergleichen aufgenommen haben, und daß die Kinder an so etwas anknüpfen können, wenn sie später die Regeln der Grammatik oder der Syntax sich vergegenwärtigen wollen, um eine Sprache zu betreiben. Ich habe gesagt, daß es nicht gut ist, wenn man an den Sätzen, die man sich während des Grammatikunterrichts bildet und an denen man die Regeln lernt, auch das Gedächtnis malträtiert, wenn man also diese Sätze aufschreiben läßt. Die können vergessen werden. Dagegen soll herübergeleitet werden das, was man an diesen Sätzen lernt, zu den Dingen, die man gedächtnismäßig behalten hat. So daß man später für das Beherrschen der Sprache eine Hilfe hat an dem, was man gedächtnismäßig besitzt. Schreibt man später einen Brief in der Sprache, unterhält man sich in der Sprache, dann soll man sich an dem, was man einmal in dieser Weise gelernt hat, geistesgegenwärtig schnell erinnern können, was eine gute Wendung ist. Solche Dinge zu berücksichtigen, gehört zur Ökonomie des Unterrichts. Man muß auch wissen, was bei fremdsprachlichem Unterricht diesen Unterricht besonders ökonomisch macht, oder was ihn aufhält. Wenn man den Kindern in der Klasse etwas vorliest und sie die Bücher vor sich haben und mitlesen, so ist das nichts als aus dem Kindesleben ausgestrichene Zeit. Das ist das Allerschlimmste, was man tun kann. Das Richtige ist, daß der Lehrer dasjenige, was er vorbringen will, erzählend vorbringt, oder, selbst wenn er ein Lesestück wörtlich vorbringt oder ein Gedicht rezitiert, es persönlich ohne Buch selber gedächtnismäßig vorbringt und daß die Schüler dabei nichts anderes tun als zuhören, daß sie also nicht mitlesen; und daß dann womöglich dasjenige reproduziert werde, was angehört worden ist, ohne daß es vorher gelesen worden ist. Das ist für den fremdsprachigen Unterricht von Bedeutung. Für den Unterricht in der Muttersprache ist das nicht so sehr zu berücksichtigen. Aber bei der fremden Sprache ist sehr zu berücksichtigen, daß hörend verstanden wird und nicht lesend, daß sprechend etwas zum Verstehen gebracht wird. Wenn dann die Zeit zu Ende ist, wo man so etwas getrieben hat, kann man die Kinder das Buch nehmen lassen und sie hinterher lesen lassen. Oder man kann, wenn man damit die Kinder nicht malträtiert, ihnen einfach als Hausaufgabe geben, aus ihrem Buche zu lesen, was man mündlich vorgenommen hat während der Schulzeit. Die Hausaufgabe sollte sich auch in fremden Sprachen vornehmlich darauf beschränken, das Lesen zu betreiben. Also was geschrieben werden soll, das sollte eigentlich in der Schule selbst geleistet werden. In den fremden Sprachen sollten möglichst wenig Hausaufgaben gegeben werden, erst auf den späteren Stufen, also nach dem 12. Jahre; aber auch dann nur über so etwas, was im Leben wirklich vorkommt: Briefe schreiben, Geschäftsmitteilungen machen und dergleichen. Also das, was im Leben wirklich vorkommt. Im Unterricht schulmäßig in einer fremden Sprache Aufsätze machen lassen, die nicht an das Leben anknüpfen, das ist eigentlich nicht ganz, aber in einem höheren Grade ein Unfug. Man sollte stehenbleiben bei dem Briefmäßigen, Geschäftsmitteilungsmäßigem und Ähnlichem. Man könnte höchstens so weit gehen, daß man die Erzählung pflegt. Die Erzählung über Geschehenes, Erlebtes, soll man ja viel mehr als den sogenannten freien Aufsatz in der Volksschule pflegen.Der freie Aufsatz gehört eigentlich noch nicht in die Volksschulzeit. Aber die erzählende Darstellung des Geschehenen, des Gehörten, das gehört schon in die Volksschule, denn das muß das Kind aufnehmen, weil es sonst nicht in der richtigen Weise sozial an der Menschenkultur teilnehmen kann. Auf diesem Gebiet beobachten unsere gegenwärtigen Kulturmenschen in der Regel auch nur die halbe Welt, nicht die ganze.

Sie wissen ja, daß jetzt Versuche gemacht werden, die namentlich der Kriminalpsychologie dienen sollen. Diese Versuche werden zum Beispiel so gemacht - ich will einen Fall anführen, man will ja heute alles durch Versuche konstatieren: Man nimmt sich vor, ein Kolleg zu halten, die Versuche werden hochschulmäßig gehalten, sie werden namentlich an den Universitäten gemacht. Man macht also, um dieses Kolleg experimentell zu gestalten, mit einem Schüler oder Hörer, wie man ja sagt, genau ab: Ich werde als Professor das Katheder besteigen und werde die ersten Worte eines Vortrages sagen. So, das schreiben wir jetzt auf. In diesem Augenblick springen Sie hinauf auf das Katheder und reißen den Rock vom Haken herunter, den ich vorher aufgehängt habe. — Der Hörer hat also etwas genau so auszuführen, wie es festgelegt wird. Dann benimmt sich der Professor auch entsprechend: er schießt auf den Schüler los, um ihn zu verhindern, den Rock herabzunehmen. Nun wird weiter festgelegt: Wir kommen in ein Handgemenge. Genau legen wir die Bewegungen fest, die wir machen. Wir studieren es genau ein, lernen es gut auswendig, um die ganze Szene so auszuführen. Dann wird das Auditorium, das nichts weiß — man bespricht ja das alles nur mit einem Hörer -, sich in irgendeiner Weise benehmen. Das können wir nicht mit festsetzen. Aber wir werden versuchen, einen dritten ins Geheimnis zu ziehen, der sich nun genau notiert, was das Auditorium macht. So, jetzt haben wir das Experiment ausgeführt. Nachher lassen wir das Auditorium, jeden einzelnen Hörer, die Szene aufschreiben.

Solche Versuche sind an Hochschulen gemacht worden. Der Versuch, den ich jetzt beschrieben habe, ist in der Tat gemacht worden, und dabei hat sich herausgestellt: Wenn ein Auditorium von etwa 30 Personen da ist, schreiben höchstens 4 bis 5 den Vorgang richtig auf! Man kann das konstatieren, weil man ja vorher alles genau besprochen und nach der Besprechung ausgeführt hat. Also kaum ein Zehntel der Zuschauer schreibt den Vorgang richtig auf. Die meisten schreiben ganz tolle Sachen auf, wenn ein solcher Vorgang sie überrascht. Heute, wo man das Experimentieren liebt, ist das etwas, was sehr gerne gemacht wird und woraus man dann das wichtige wissenschaftliche Ergebnis zieht, daß die Zeugen, die vor Gericht aufgerufen werden, nicht glaubwürdig sind. Denn wenn schon gebildete Leute eines Hochschulauditoriums — das sind doch alles gebildete Leute - einen Vorgang so behandeln, daß nur ein Zehntel von ihnen etwas richtig aufschreibt, die andern etwas Unrichtiges und sogar mancher ganz tolles Zeug, wie soll man denn von den Zeugen in gerichtlichen Verhandlungen verlangen, daß sie irgend etwas, was sie vielleicht vor Wochen oder vor Monaten gesehen haben, als Vorgang richtig erzählen? Der gesunde Menschenverstand weiß solche Sachen aus dem Leben. Denn schließlich erzählen einem ja auch im Leben die Menschen die Dinge, die sie gesehen haben, meistens falsch und ganz selten richtig. Man muß schon einen Riecher dafür haben, ob etwas falsch oder richtig erzählt wird. Kaum ein Zehntel ist wahr von dem, was die Leute von rechts und links einem sagen in dem strengen Sinne, daß es eine Nacherzählung ist von tatsächlich Geschehenem.

Nun aber, die Menschen machen das nur halb, was da getan wird; sie bilden diejenige Hälfte aus, die man eigentlich, wenn man sich wirklich des gesunden Menschenverstandes bedient, weglassen könnte, denn die andere Hälfte ist die wichtigere. Man sollte dafür sorgen, daß unsere Kultur sich so entwickelt, daß man sich auf die Zeugen mehr verlassen kann und die Leute mehr die Wahrheit reden. Um das aber zu erreichen, muß man schon im Kindesalter anfangen. Und deshalb ist es wichtig, daß man Gesehenes und Erlebtes nacherzählen läßt, mehr als daß man freie Aufsätze pflegen läßt. Da werden die Kinder die Gewohnheit eingeimpft bekommen, im Leben und auch eventuell vor Gericht nichts zu erfinden, sondern den äußeren sinnlichen Tatsachen gegenüber die Wahrheit zu erzählen. Das Willensmäßige müßte auch auf diesem Felde mehr berücksichtigt werden als das Intellektuelle. Indem dazumal in jenem Auditorium jener Vorgang vorher besprochen worden ist und nachher das Ergebnis der Aussagen der Zuschauer festgelegt worden ist, war man darauf bedacht, zu erfahren, inwieweit die Menschen lügen. Das ist etwas, was in einer intellektualistisch gesinnten Zeit, wie es die unsrige ist, begreiflich ist. Aber wir müssen die intellektualistisch gesinnte Zeit zum Willensmäßigen zurückbringen. Daher müssen wir solche Einzelheiten in der Pädagogik beobachten, daß wir die Kinder, wenn sie einmal schreiben können, und namentlich nach dem 12. Jahre, wirklich Gesehenes erzählen lassen, daß wir nicht so sehr den freien Aufsatz pflegen, der eigentlich noch nicht in die Volksschule gehört.

Und von besonderer Wichtigkeit ist es auch, daß wir im fremdsprachigen Unterricht uns allmählich mit den Schülern dazu bringen, daß sie Gesehenes, Gehörtes in einer kurzen Erzählung wiedergeben können. Dann aber ist notwendig, besonders das Reflexbewegungsartige der Sprache zu pflegen, das heißt, den Kindern möglichst Befehle zu erteilen: Tu das, tu jenes — und dann sie es ausführen lassen, so daß bei solchen Übungen in der Klasse auf das vom Lehrer Gesprochene weniger das Nachdenken des vom Lehrer Gesprochenen oder die Antwort durch die Sprache langsam folgt, sondern das Tun. So daß also auch das Willensmäßige, das Bewegungsmäßige im Sprachunterricht kultiviert wird. Das sind wiederum Dinge, die Sie sich gut überlegen und einverleiben müssen und die Sie namentlich auch berücksichtigen müssen, wenn Sie den fremdsprachigen Unterricht pflegen. Immer wird es sich namentlich darum handeln, daß wir das Willensmäßige mit dem Intellekt in der richtigen Weise zu verbinden wissen.

Nun wird es wichtig sein, daß wir zwar auch Anschauungsunterricht pflegen, aber den Anschauungsunterricht nicht banalisieren. Das Kind soll niemals die Empfindung haben, daß das, was wir als Anschauungsunterricht pflegen, eigentlich selbstverständlich ist. Ich zeige dir ein Stück Kreide. Was hat die Kreide für eine Farbe? - Sie ist gelb. Wie ist da die Kreide oben? - Sie ist abgebrochen. — Es wird mancher Anschauungsunterricht nach diesem Muster gegeben. Greulich ist er. Denn das, was eigentlich im Leben selbstverständlich ist, sollte man nicht als Anschauungsunterricht geben. Den Anschauungsunterricht sollte man durchaus in eine höhere Sphäre heben. Das Kind soll zu gleicher Zeit in eine höhere Sphäre seines Seelenlebens entrückt werden, indem es Anschauungsunterricht pflegt. Das können Sie natürlich ganz besonders, wenn Sie den Anschauungsunterricht verknüpfen mit der Geometrie.

Die Geometrie bietet Ihnen ein außerordentlich gutes Beispiel, den Anschauungsunterricht mit dem Lehrstoff der Geometrie selber zu verbinden. Sie zeichnen zum Beispiel zunächst dem Kinde ein rechtwinkliges, gleichschenkliges Dreieck auf. Indem Sie dies dem Kinde aufzeichnen, können Sie unten an dieses Dreieck ein Quadrat ansetzen, so daß also an das rechtwinklige, gleichschenklige Dreieck ein Quadrat angrenzt (siehe Zeichnung I). Nun bringen Sie dem Kinde, wenn Sie es ihm noch nicht beigebracht haben, den Begriff bei, daß bei einem rechtwinkligen Dreieck die Seiten a und b die Katheten sind und c die Hypotenuse ist. Sie haben über der Hypotenuse ein Quadrat errichtet. Das gilt also alles selbstverständlich nur für ein gleichschenkliges Dreieck. Nun gliedern Sie das Quadrat durch eine Diagonale ab. Sie machen einen roten Teil (oben und unten) und einen gelben Teil (rechts). Nun sagen Sie dem Kinde: Den gelben Teil schneide ich hier heraus, und setze ihn daneben (siehe Zeichnung II). Und nun setzen Sie auch noch den roten Teil heraus an den gelben Teil. Jetzt haben Sie ein Quadrat über der einen Kathete errichtet, aber dieses Quadrat ist zusammengesetzt aus einem roten Stück und aus einem gelben Stück. Das, was ich daneben gezeichnet habe (siehe Zeichnung II), ist daher gerade so groß wie das, was in Zeichnung I rot und gelb zusammen ist und die Hälfte des Hypotenusenquadrats ist. Dasselbe mache ich nun für die andere Seite mit blauer Kreide und stückle das Blaue unten an, so daß ich wiederum ein gleichschenkliges rechtwinkliges Dreieck bekomme. Das zeichne ich jetzt wieder heraus (siehe Zeichnung III). Jetzt habe ich wiederum das Quadrat über der andern Kathete.

Schopenhauer hat sich zu seiner Zeit wahnsinnig geärgert, weil in den Schulen der pythagoräische Lehrsatz nicht so gelehrt wurde, und er hat das in seinem Buche «Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung» zum Ausdruck gebracht, indem er in seiner etwas groben Weise sagt: Wie dumm ist die Schule, daß sie nicht so etwas einfach durch Übereinanderlegen lehrt, so daß man aus der Anschauung heraus den pythagoräischen Lehrsatz zum Verständnis bringt. - Das gilt zunächst nur für ein gleichschenkliges Dreieck, aber man kann das für ein ungleichseitiges rechtwinkliches Dreieck auch genau so durch Übereinanderklappen machen, wie ich es Ihnen jetzt gesagt habe. Das ist Anschauungsunterricht. Sie können die Geometrie als Anschauungsunterricht gestalten. Aber es hat eine gewisse Bedeutung - und ich habe oftmals die Probe damit gemacht -, wenn Sie darauf hinarbeiten, auch den pythagoräischen Lehrsatz dem Kinde nach dem 9. Jahr anschaulich zu machen, die Sache so zu machen, daß Sie für sich selbst in Aussicht nehmen, den pythagoräischen Lehrsatz dem Kinde so recht aus den einzelnen Lappen des Hypotenusenquadrats zusammenzusetzen. Und wenn Sie sich als Lehrer bewußt sind, bei dem, was in der Geometriestunde vorhergeht, Sie wollen das erreichen, dann können Sie in 7 bis 8 Stunden höchstens dem Kinde alles dasjenige beibringen, was nötig ist in der Geometrie, um im Unterricht bis zum pythagoräischen Lehrsatz, der bekannten Eselsbrücke, zu kommen. Ungeheuer ökonomisch werden Sie verfahren, wenn Sie die ersten Anfangsgründe der Geometrie auf diese Weise anschaulich gestalten. Sie werden viel Zeit ersparen und außerdem werden Sie dem Kinde etwas sehr Wichtiges ersparen — was zerstörend für den Unterricht wirkt, wenn nicht damit gespart wird -, das ist: Sie lassen das Kind nicht abstrakte Gedanken ausführen, um den pythagoräischen Lehrsatz zu begreifen, sondern Sie lassen es konkrete Gedanken ausführen und gehen vom Einfachen ins Zusammengesetzte. Man sollte zunächst, so wie es hier in der Zeichnung für das gleichschenklige Dreieck gemacht ist, den pythagoräischen Lehrsatz aus den Lappen zusammensetzen und dann erst zum ungleichseitigen Dreieck übergehen. Selbst da, wo es heute anschaulich gemacht wird - das geschieht ja schon -, ist es nicht mit Bezug auf das Ganze des pythagoräischen Lehrsatzes. Es wird nicht zuerst der einfache Vorgang, der den andern gut vorbereitet, am gleichschenkligen Dreieck durchgemacht und dann erst übergegangen zum ungleichseitigen rechtwinkligen Dreieck. Das ist aber wichtig, daß man das in ganz bewußter Weise in die Zielsetzung des geometrischen Unterrichts einfügt. Also das Auftragen von verschiedenen Farben ist es, was ich Sie bitte zu berücksichtigen. Die einzelnen Flächen sind mit Farbe zu behandeln und dann die Farben übereinanderzulegen. Die meisten von Ihnen werden ja auch schon etwas Ähnliches gemacht haben, aber doch nicht in dieser Weise.

I. bis zum 9. Jahre

Musikalisches - Malerisch-Zeichnerisches

Schreiben - Lesen

Fremde Sprachen. Etwas später Rechnen.

II. bis zum 12. Jahre (Geographisches)

Grammatik, Wortlehre

Naturgeschichte des Tierreiches

und des Pflanzenreiches

Fremde Sprachen. Geometrie

Physikalische Begriffe.

III. bis Ende der Volksschulzeit (Geographisches)

Satzlehre

Mineralien

Physikalisches und Chemisches

Fremde Sprachen

Geschichte.

Tenth Lecture

We will now try to make some progress in didactics by taking a closer look at the curriculum in these lessons and focusing more on what will be taught within the curriculum. We will not immediately have everything in the curriculum that should be in it, because we will structure our future approach in a constructive manner.

I first gave you some considerations that offer the possibility of already putting something into the teaching levels. How many teaching levels will we essentially distinguish during elementary school? Based on what we have learned, we see an important turning point around the age of 9, so that we can say: when we receive a child up to the age of 9, we have the first period of elementary school education. What will we do there? We will take the artistic as our starting point. We will engage in music and painting and drawing with the child, as we have discussed. We will gradually develop writing from painting and drawing. So we will gradually develop written forms from the drawn forms and then move on to reading.

It is important that you understand the reasons for this approach, that you do not start with reading and then move on to writing, but that you move from writing to reading. Writing is, in a sense, even more alive than reading. Reading isolates people and draws them away from the world. In writing, we still imitate the forms of the world when we write from drawing. Printed letters have also become extremely abstract. They originated from cursive letters, which is why we also let them develop from cursive letters in class. It is absolutely right, at least for writing lessons, not to break the thread that leads from the drawn form to the written letter, so that the child can still feel the original drawn form in the letter, so to speak. In this way, you overcome the unworldliness of writing. As people find their way into writing, they acquire something very unworldly. But when we link the written forms to world forms, to f = fish and so on, we at least lead people back to the world. And it is very, very important that we do not tear people away from the world. The further back we go in culture, the more vividly we find this connection between people and the world. You only need to conjure up an image in your mind and you will understand what I have just said. Instead of me speaking here, imagine yourself transported back to ancient times, to a Greek rhapsode reciting Homer to his people in that peculiar manner of yesteryear, in that intermediate form between song and speech that we no longer have, and imagine someone sitting next to this Homer-reciting rhapsode, taking shorthand notes. What a grotesque image! Impossible, completely impossible! Impossible for the simple reason that the Greeks had a completely different memory than we do and did not need to invent something as alien as shorthand in order to retain what comes to people through language. You can see from this that something extremely destructive must constantly interfere with our culture. We need this destructive element. We cannot do without shorthand in our entire culture. But we should be aware that it has something destructive about it. For what is this appalling shorthand in our culture? In our culture, it is nothing other than when we can no longer cope with our proper rhythm between waking and sleeping and use our sleeping time to do all kinds of things, so that we implant something in our soul life that it naturally no longer absorbs. With our stenography, we keep something in our culture that, according to our current nature, humans would not respect but would forget if they were left to their own devices. So in our culture, we artificially keep something awake that destroys our culture just as much as the nightly plowing of students, when they are overzealous, destroys their health. Our culture is therefore no longer entirely healthy. But we must be clear that we have already crossed the Rubicon; that was in Greek times. The Rubicon was crossed when humanity still had a completely healthy culture. Culture will become increasingly unhealthy, and people will increasingly have to turn the education process into a healing process against what makes them sick in their environment. We must not delude ourselves about this. That is why it is so infinitely important to link writing back to drawing and to teach writing before reading.

Then one should start with arithmetic a little later. Since there is no exact point in human development when this should happen, it can be arranged according to other things that must necessarily be taken into account. So you should start with arithmetic a little later. We will then add what is needed to the plan and begin with arithmetic as I have shown you. However, a certain amount of foreign language teaching will always be included in this whole plan at the first stage, because we need it for cultural reasons; but at this age, foreign languages must still be taught as speaking skills, treating the children in such a way that they learn to speak the foreign language.

Only in the second stage, from the age of 9 to about 12, do we begin to develop self-awareness more. And we do this in grammar. At this stage, the child is already in a position, thanks to the changes they have undergone, which I have described to you, to absorb into their self-awareness what they can learn from grammar; in particular, we deal with word formation. But then we begin with the natural history of the animal kingdom, as I have shown you with the squid, the mouse, and the human being. And we leave the plant kingdom until later, as you want to show me this afternoon.

And now, at this age, we can also move on to geometry, whereas before we kept what would later become geometry entirely within the realm of drawing. Through drawing, we can develop the triangle, square, circle, and line for the child. So we develop the actual shapes through drawing, by drawing and then saying: this is a triangle, this is a square. But what comes in as geometry, where we look for the relationships between the shapes, we only begin around the age of 9. Of course, foreign languages are continued and also incorporated into the grammatical treatment.

Finally, we introduce the child to physical concepts. Then we come to the third stage, which lasts until the end of elementary school, i.e., until the age of 14 or 15. Here we begin to teach sentence structure. The child is only really ready for this around the age of 12. Before that, we instinctively encourage the child to construct sentences.

Now is also the time when we can move on to the mineral kingdom, using geometric shapes. We treat the mineral kingdom in constant relation to physics, which we also apply to humans, as I have already said: Refraction of light – the lens for the eye; in other words, physical and chemical. Then we can move on to history during this period. We can always support geography with natural history by introducing physical concepts, and with geometry by drawing maps and introducing physical concepts. We teach geography through all of this and ultimately connect it with history. That is, we show how different peoples have developed their characters. We do this throughout these two childhood ages. Foreign languages are of course continued and extended to include syntax.

Now, of course, various considerations will have to be taken into account. For we cannot, of course, begin to teach music to the little children who are entrusted to us and at the same time teach music in any classroom when the others have something that requires quiet if they are to learn. So we will have to move painting and drawing with the small children to the morning and music to the late afternoon. We will also have to organize the school spatially so that one activity can take place alongside the other. For example, we cannot have children reciting poetry and talking about history when the little ones are trumpeting in the next room. These are things that have something to do with the structure of the curriculum, and we will have to take them carefully into account when setting up our school, such as what needs to be moved to the morning or afternoon and so on. Now, the point is that, knowing these three levels of the curriculum, we have the opportunity to take into account the greater or lesser abilities of the children. Of course, we have to make compromises, but I will now assume the ideal situation and later shed light on the curricula of current schools so that we can make the compromise properly. We would do well – ideally speaking – to make the boundaries between classes less sharp within the stages than when moving from one stage to another. We will assume that uniform progression can actually only take place between the first and second and between the second and third stages. For we will find that the so-called less gifted usually only understand later. So that throughout the years of the first level, we will have the gifted students, who will be able to understand earlier and then process later, and the less gifted, who will cause difficulties at first but will ultimately understand. We will definitely have this experience, and therefore we should not form an opinion too early about which children are particularly gifted and which are less gifted. Now, I have already emphasized that we will have children who have already gone through a wide variety of classes. The older they are, the more difficult it will be to deal with them. But we will still be able to undo to a large extent what has been misformed in them, if we only make the appropriate effort. So, once we have done this with regard to foreign languages — Latin, French, English, Greek — we will not fail to do what we emphasized the day before yesterday, namely to move on as soon as possible to doing what gives the children the most pleasure: letting them converse with each other in class in the language in question and, as teachers, merely guiding this conversation. You will find that the children really enjoy conversing with each other in the language in question, and the teacher does nothing more than correct them or, at most, guide the conversation; for example, if someone says something particularly boring, they are distracted to something interesting. This is where the teacher's presence of mind must serve a very special purpose. You really have to feel as if the students in front of you are a choir that you have to conduct, but even more so than a conductor has to conduct an orchestra.

Then it is a matter of ascertaining what the students have previously absorbed from poems, what they have retained from other lessons and the like, what they can present to you from their memory as a treasure. And you link every lesson in the foreign language to this treasure that the children hold in their memory, linking in particular what you have to catch up on in terms of grammar and syntax; because it is particularly important that what the children have absorbed in their memory in terms of poems and the like remains, and that the children can build on this when they later want to recall the rules of grammar or syntax in order to use a language. I have said that it is not good to maltreat the memory with the sentences that are formed during grammar lessons and used to learn the rules, i.e., by having these sentences written down. They can be forgotten. Instead, what is learned from these sentences should be transferred to the things that have been retained in the memory. This way, what you have memorized will later help you to master the language. When you later write a letter in the language or converse in the language, you should be able to quickly recall what you once learned in this way, which is a good turn of phrase. Taking such things into account is part of the economy of teaching. One must also know what makes foreign language teaching particularly economical, or what slows it down. If you read something aloud to the children in class and they have the books in front of them and read along, it is nothing but time taken away from the children's lives. That is the worst thing you can do. The right thing to do is for the teacher to present what he or she wants to say in a narrative form, or, even if he or she is presenting a reading passage verbatim or reciting a poem, to present it personally from memory without a book, and for the students to do nothing but listen, so that they do not read along; and that then, if possible, what has been heard is reproduced without having been read beforehand. This is important for foreign language teaching. It is not so important for teaching in the mother tongue. But with foreign languages, it is very important to ensure that understanding comes from listening and not from reading, that speaking leads to understanding. When the time for doing this is over, the children can be given the book to read afterwards. Or, if this does not overburden the children, they can simply be given homework to read from their book what they have done orally during school hours. Homework in foreign languages should also be limited primarily to reading. So what is to be written should actually be done at school. As little homework as possible should be given in foreign languages, only at later stages, i.e., after the age of 12; but even then, only on things that really happen in life: writing letters, business communications, and the like. In other words, things that really happen in life. Having students write essays in a foreign language in class that are not related to real life is not quite right, but to a greater extent it is nonsense. One should stick to letters, business communications, and the like. At most, one could go so far as to cultivate storytelling. Narratives about events and experiences should be cultivated much more than so-called free essays in elementary school. Free essays do not really belong in elementary school. But the narrative presentation of events and things heard does belong in elementary school, because children must absorb this in order to participate properly in human culture. In this area, our current cultured people generally only observe half the world, not the whole.

As you know, experiments are now being conducted that are intended to serve criminal psychology in particular. These experiments are conducted as follows, for example—I will cite one case, since today everything is to be established through experiments: One decides to give a lecture, the experiments are conducted in a university setting, specifically at universities. In order to make this lecture experimental, the following is agreed with a student or listener, as they say: I, as the professor, will climb onto the lectern and say the first words of a lecture. So, we'll write that down now. At that moment, you jump onto the lectern and pull down the skirt that I hung up beforehand. — The student must therefore carry out the task exactly as specified. Then the professor behaves accordingly: he lunges at the student to prevent him from taking down the skirt. Now we specify further: we get into a scuffle. We precisely define the movements we make. We study it carefully, learn it well by heart, in order to perform the whole scene. Then the audience, who knows nothing — after all, we only discuss all this with one listener — will behave in some way. We cannot determine that. But we will try to draw a third person into the secret, who will now make precise notes of what the audience does. So, now we have carried out the experiment. Afterwards, we let the audience, each individual listener, write down the scene.

Such experiments have been conducted at universities. The experiment I have just described has actually been carried out, and it turned out that when there is an audience of about 30 people, at most 4 to 5 of them write down the process correctly! This can be stated because everything was discussed in detail beforehand and carried out after the discussion. So barely a tenth of the audience writes down the event correctly. Most people write down all sorts of wonderful things when such an event surprises them. Today, when experimentation is popular, this is something that is done very often, and from which the important scientific conclusion is drawn that witnesses called to court are not credible. For if even educated people in a university auditorium—and they are all educated people—treat an event in such a way that only a tenth of them write something down correctly, while the others write something incorrect and some even write fantastic things, how can we expect witnesses in court proceedings to correctly recount something they may have seen weeks or months ago? Common sense knows such things from life. After all, in life, people usually tell you things they have seen incorrectly and very rarely correctly. You have to have a nose for whether something is being told correctly or incorrectly. Barely a tenth of what people tell you from right and left is true in the strict sense that it is a retelling of what actually happened.

But now, people only do half of what needs to be done; they make up the half that, if you really use your common sense, could be left out, because the other half is the more important one. We should ensure that our culture develops in such a way that we can rely more on witnesses and that people tell the truth more. But to achieve this, we must start in childhood. And that is why it is important to have children retell what they have seen and experienced, rather than encouraging them to write free essays. This will instill in children the habit of not inventing anything in life and possibly also in court, but of telling the truth about external sensory facts. In this field, too, the volitional should be given more consideration than the intellectual. By discussing the process beforehand in that auditorium and then determining the results of the audience's statements afterwards, the aim was to find out to what extent people lie. This is understandable in an intellectualistic age such as ours. But we must bring the intellectual age back to the volitional. Therefore, we must observe such details in education that, once children can write, and especially after the age of 12, we let them recount what they have actually seen, rather than cultivating free composition, which does not really belong in elementary school.

And it is also particularly important that in foreign language teaching we gradually encourage pupils to be able to recount what they have seen and heard in a short story. But then it is necessary to cultivate the reflexive nature of language, that is, to give the children commands as much as possible: do this, do that — and then let them carry them out, so that in such exercises in class, the teacher's words are followed less by reflection on what the teacher has said or by a slow response in language, but rather by action. In this way, the volitional and motor aspects of language teaching are also cultivated. These are things that you need to consider carefully and internalize, and which you must also take into account when teaching foreign languages. It will always be a matter of knowing how to combine the volitional with the intellectual in the right way.

Now it will be important that we also cultivate visual teaching, but that we do not trivialize visual teaching. The child should never have the feeling that what we cultivate as visual teaching is actually self-evident. I show you a piece of chalk. What color is the chalk? - It is yellow. What is the chalk like at the top? - It is broken off. — Some visual teaching is given according to this pattern. It is appalling. Because what is actually self-evident in life should not be given as visual teaching. Visual teaching should definitely be elevated to a higher sphere. At the same time, the child should be transported to a higher sphere of their soul life by practicing visual teaching. You can do this particularly well, of course, if you combine visual teaching with geometry.

Geometry offers you an exceptionally good example of combining visual teaching with the subject matter of geometry itself. For example, you first draw a right-angled, isosceles triangle for the child. As you draw this for the child, you can add a square at the bottom of this triangle so that a square adjoins the right-angled, isosceles triangle (see drawing I). Now, if you have not already taught the child this, explain that in a right-angled triangle, sides a and b are the cathetus and c is the hypotenuse. You have constructed a square above the hypotenuse. Of course, this only applies to an isosceles triangle. Now divide the square by a diagonal. Make a red part (top and bottom) and a yellow part (right). Now say to the child: I will cut out the yellow part here and place it next to it (see drawing II). And now you also place the red part next to the yellow part. Now you have constructed a square above one of the cathetus, but this square is composed of a red piece and a yellow piece. What I have drawn next to it (see drawing II) is therefore just as big as what is red and yellow together in drawing I and is half of the hypotenuse square. I now do the same for the other side with blue chalk and add the blue piece at the bottom so that I again get an isosceles right-angled triangle. I now draw this out again (see drawing III). Now I again have the square above the other cathetus.

Schopenhauer was extremely annoyed in his day because the Pythagorean theorem was not taught in schools, and he expressed this in his book “The World as Will and Mental Image” by saying, in his somewhat crude manner: How stupid are schools that they do not teach such things simply by superimposing them, so that the Pythagorean theorem can be understood from observation. This applies initially only to an isosceles triangle, but you can do the same for an unequal-sided right-angled triangle by superimposing, as I have just told you. This is visual teaching. You can design geometry as visual teaching. But it has a certain significance – and I have often tried it out – if you work towards making the Pythagorean theorem clear to the child after the age of 9, doing it in such a way that you yourself envisage putting the Pythagorean theorem together for the child from the individual flaps of the hypotenuse square. And if, as a teacher, you are aware that this is what you want to achieve in your geometry lessons, then in 7 to 8 hours at most you can teach the child everything that is necessary in geometry to get to the Pythagorean theorem, the well-known mnemonic device, in your lessons. You will be extremely economical if you illustrate the first principles of geometry in this way. You will save a lot of time and, in addition, you will spare the child something very important—something that has a destructive effect on teaching if it is not spared—namely, you do not let the child carry out abstract thoughts in order to understand the Pythagorean theorem, but rather you let them carry out concrete thoughts and move from the simple to the complex. First, as shown here in the drawing for the isosceles triangle, the Pythagorean theorem should be constructed from the flaps and only then should you move on to the scalene triangle. Even where it is made clear today – which is already happening – it is not done with reference to the Pythagorean theorem as a whole. The simple process that prepares the student well is not first carried out on the isosceles triangle and only then moved on to the scalene right-angled triangle. However, it is important that this is consciously incorporated into the objectives of geometry lessons. So, it is the application of different colors that I ask you to consider. The individual areas should be treated with color and then the colors should be superimposed. Most of you will have already done something similar, but not in this way.

I. up to the age of 9

Music - Painting and drawing

Writing - Reading

Foreign languages. A little later, arithmetic.

II. Up to age 12 (geography)

Grammar, word study

Natural history of the animal kingdom

and the plant kingdom

Foreign languages. Geometry

Physical concepts.

III. until the end of elementary school (geography)

Syntax

Minerals

Physics and chemistry

Foreign languages

History.