The Philosophy of Thomas Aquinas

GA 74

22 May 1920, Dornach

I. Thomas and Augustine

Ladies and Gentlemen, I should like in these three days to speak on a subject which is generally looked at from a more formal angle, as if the attitude of the philosophic view of life to Christianity had been to a certain extent dictated by the deep philosophic movement of the Middle Ages. As this side of the question has lately had a kind of revival through Pope Leo XIII's Ordinance to his clergy to make “Thomism” the official philosophy of the Catholic Church, our present subject has a certain significance. But I do not wish to treat the subject which crystallized as mediaeval philosophy round the personalities of Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas, only from this formal side; rather I wish in the course of these days to reveal the deeper historical background out of which this philosophic movement, much underrated to-day, has arisen. We can say: Thomas Aquinas tries in the thirteenth century quite clearly to grasp the problem of the total human knowledge of philosophies, and in a way which we have to admit is difficult for us to follow, for conditions of thought are attached to it which people to-day scarcely fulfil, even if they are philosophers. One must be able to put oneself completely into the manner of thought of Thomas Aquinas, his predecessors and successors; one must know how to take their conceptions, and how their conceptions lived in the souls of those men of the Middle Ages, of which the history of philosophy tells only rather superficially.

If we look now at the central point of this study, at Thomas Aquinas, we would say: in him we have a personality which in face of the main current of mediaeval Christian philosophy really disappears as a personality; one which, we might almost say, is only the co-efficient or exponent of the current of world philosophy, and finds expression as a personality only through a certain universality. So that, when we speak of Thomism, we can focus our attention on something quite exceptionally impersonal, on something which is revealed only through the personality of Thomas Aquinas. On the other hand we see at once that we must put into the forefront of our inquiry a full and complete personality, and all that term includes, when we consider the individual who was the immediate and chief predecessor of Thomism, namely Augustine. With him everything was personal, with Thomas Aquinas everything was really impersonal. In Augustine we have to deal with a fighting man, in Thomas Aquinas, with a mediaeval Church defining its attitude to heaven and earth, to men, to history, etc., a Church which, we might say, expressed itself as a Church, within certain limitations it is true, through the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas.

A significant event separates the two, and unless one takes this event into consideration, it is not possible to define the mutual relationship of these mediaeval individuals. The event to which I refer is the declaration of heresy by the Emperor Justinian against Origen. The whole direction of Augustine's view of the world becomes clear only when we keep in mind the whole historical background from which Augustine emerged. This historical background, however, becomes in reality, completely changed from the fact that the powerful influence—it was actually a powerful influence in spite of much that has been said in the history of philosophy—that this powerful influence on the Western world which had spread from the Schools of Philosophy in Athens, ceased to exist. It persisted into the sixth century, and then ebbed, but so that something remains which in fact, in the subsequent philosophical stream of the West, is quite different from that which Augustine knew in his lifetime. I shall have to ask you to take note that to-day's address is more in the nature of an introduction, that we shall deal tomorrow with the real nature of Thomism, and that on the third day I shall make clear my object in bringing before you all I have to say in these three days.

For you see, ladies and gentlemen, if you will excuse the personal reference, I am in rather a special position with regard to Christian mediaeval philosophy, that is, to Thomism. I have often mentioned, even in public addresses, what happened to me once when I had put before a working-class audience what I must look upon as the true course of Western history. The result was that though there were a good many pupils in agreement with me, the leaders of the proletarian movement at the turn of the century hit on the idea that I was not presenting true Marxism. And although one could assert that the world in future must after all recognize something like freedom in teaching, I was told at the final meeting: This party recognizes no freedom in teaching, only a rational compulsion! And my activity as a teacher, in spite of the fact that at the time a large number of students from the proletariat had been attracted, was forced to a sudden and untimely end.

I might say I had the same experience in other places with what I wanted to say, now about nineteen or twenty years ago, concerning Thomism and everything that belonged to mediaeval philosophy. It was of course just the time when what we are accustomed to call “Monism” reached its height, round the year 1900. At this time there was founded in Germany the “Giordano-Bruno-Bund” apparently to encourage a free, independent view of life, but au fond really only to encourage the materialistic side of Monism. Now, ladies and gentlemen, because it was impossible for me at the time to take part in all that empty phrase-making which went out into the world as Monism, I gave an address on Thomism in the Berlin “Giordano-Bruno-Bund.”

In this address I sought to prove that a real and spiritual Monism had been given in Thomism, that this spiritual Monism, moreover, had been given in such a way that it reveals itself through the most accurate thought imaginable, of which more recent philosophy, under the influence of Kant and Protestantism has at bottom not the least idea, and no longer the capacity to achieve it.

And so I fell foul also of Monism. It is, in point of fact, extraordinarily difficult to-day to speak of these things in such a way that one's word seems to be based sincerely on the matter itself and not to be in the service of some Party or other. I want in these three days to try once more to speak thus impartially of the matters I have indicated.

The personality of Augustine fits into the fourth and fifth centuries, as I said before, as a fighting personality in the fullest sense. His method of fighting is what sinks deep into the soul if we can understand in detail the particular nature of this fight. There are two problems which faced Augustine's soul with an intensity of which we, with our pallid problems of knowledge and of the soul, have really no idea.

The first problem can be put thus: Augustine strives to find the nature of what man can recognize as truth, supporting him, filling his soul. The second problem is this: How can you explain the presence of evil in a world which after all has no sense unless its purpose at least has something to do with good? How can you explain the pricks of evil in human nature which never cease—according to Augustine's view—the voice of evil which is never silent, even if a man strives honestly and uprightly after the good?

I do not believe that we can get near to Augustine if we take these two questions in the sense in which the average man of our time, even if he were a philosopher, would be apt to take them. You must look for the special shade of meaning these questions had for a man of the fourth and fifth centuries. Augustine lived, after all, at first a life of inner commotion, not to say a dissipated life; but always these two questions ran up before him. Personally he is placed in a dilemma. His father is a Pagan, his mother a pious Christian; and she takes the utmost pains to win him for Christianity. At first the son can be moved only to a certain seriousness, and this is directed towards Manichaeism. We shall look later at this view of life, which early came into Augustine's range of vision, as he changed from a somewhat irregular way of living to a full seriousness of life. Then—after some years—he felt himself more and more out of sympathy with Manichaeism, and fell under the sway of a certain Scepticism, not driven by the urge of his soul or some other high reason, but because the whole philosophical life of the time led him that way. This Scepticism was evolved at a certain time from Greek philosophy, and remained to the day of Augustine. Now, however, the influence of Scepticism grew ever less and less, and was for Augustine, as it were, only a link with Greek philosophy. And this Scepticism led to something which without doubt exercised for a time a quite unusually deep influence on his subjectivity, and the whole attitude of his soul. It led him into a Neoplatonism of a different kind from what in the history of philosophy is generally called Neoplatonism. Augustine got more out of this Neoplatonism than one usually thinks. The whole personality and the whole struggle of Augustine can be understood only when one understands how much of the neoplatonic philosophy had entered into his soul; and if we study objectively the development of Augustine, we find that the break which occurred in going over from Manichaeism to Platonism was hardly as violent in the transition from Neoplatonism to Christianity. For one can really say: in a certain sense Augustine remained a Neoplatonist; to the extent he became one at all he remained one. But he could become a Neoplatonist only up to a point. For that reason, his destiny led him to become acquainted with the phenomenon of Christ-Jesus. And this is really not a big jump but a natural course of development in Augustine from Neoplatonism to Christianity. How this Christianity lives in Augustine—yes—how it lives in Augustine we cannot judge unless we look first at Manichaeism, a remarkable formula for overcoming the old heathenism at the same time as the Old Testament and Judaism.

Manichaeism was already at the time when Augustine was growing up a world-current of thought which had spread throughout North Africa, where, you must remember, Augustine spent his youth, and in which many people of Western Europe had been caught up. Founded in about the third century in Asia by Mani, a Persian, Manichaeism had extraordinarily little effect historically on the subsequent world. To define this Manichaeism, we must say this: there is more importance in the general attitude of this view of life than in what one can literally describe as its contents. Above all, the remarkable thing about it is that the division of human experience into a spiritual side and a material side had no meaning for it. The words or ideas “spirit” and “matter” mean nothing to it. Manichaeism sees as “spiritual” what appears to the senses as material and when it speaks of the spiritual it does not rise above what the senses know as matter. It is true to say of Manichaeism—much more emphatically true than we with our world grown so abstract and intellectual usually think,—that it actually sees spiritual phenomena, spiritual facts in the stars and their courses, and that it sees at the same time in the mystery of the sun that which is manifest to us on earth as something spiritual. It conveys no meaning for Manichaeism to speak of either matter or spirit, for in it what is spiritual has its material manifestation and what is material is to it spiritual. Therefore, Manichaeism quite naturally speaks of astronomical things and world phenomena in the same way as it would speak of moral phenomena or happenings within the development of human beings. And thus this apposition of “Light” and “Darkness” which Manichaeism, imitating something from ancient Persia, embodies in its philosophy, is to it at the same time something completely and obviously spiritual. And it is also something obvious that this same Manichaeism still speaks of what apparently moves as sun in the heavens as something which has to do with the moral entities and moral impulses in the development of mankind; and that it speaks of the relation of this moral-physical sun in the heavens, to the Signs of the Zodiac as to the twelve beings through which the original being, the original source of light delegates its activities. But there is something more about this Manichaeism. It looks upon man and man does not yet appear to its eyes as what we to-day see in man. To us man appears as a kind of climax of creation on earth. Whether we think more or less in material or spiritual terms, man appears to man now as the crown of creation on earth, the kingdom of man as the highest kingdom or at least as the crown of the animal kingdom. Manichaeism cannot agree to this.

The thing which had walked the earth as man and in its time was still walking it, is to it only a pitiful remnant of that being which ought to have become man through the divine essence of light. Man should have become something entirely different from the man now walking the earth. The being now walking on earth as man was created through original man losing the fight against the demons of darkness, this original man who had been created by the power of light as an ally in its fight against the demons of darkness, but who had been transplanted into the sun by benevolent powers and had thus been taken up by the kingdom of light itself. But the demons have managed nevertheless to tear off as it were a part of this original man from the real man who escaped into the sun and to form the earthly race of man out of it, the earthly race which thus walks about on earth as a weaker edition of that which could not live here, for it had to be removed into the sun during the great struggle of spirits. In order to lead back man, who in this way appeared as a weaker edition on earth, to his original destination the Christ-being then appeared and through its activity the demonic influences are to be removed from the earth.

I know very well, that all that part of this view of life which is still capable of being put into modern language, can hardly be intelligible; for the whole of it comes from substrata of the soul's experience which differ vastly from the present ones. But the important part which is interesting us to-day is what I have already emphasized. For however fantastic it may appear, this part I have been telling you about the continuation of the development on earth in the eyes of the Manichaeans—Manichaeism did not represent it at all as something only to be viewed in the spirit, but as a phenomenon which we would to-day call material, unfolding itself to our physical eyes as something at the same time spiritual.

That was the first powerful influence on Augustine, and the problems connected with the personality of Augustine can really only be solved if one bears in mind the strong influence of this Manichaeism, with its principle of the spiritual-material. We must ask ourselves: What was the reason for Augustine's dissatisfaction with Manichaeism? It was not based on what one might call its mystical content as I have just described it to you, but his dissatisfaction arose from the whole attitude of Manichaeism. At first Augustine was attracted, in a sense sympathetically moved by the physical self-evidence, by the pictorial quality with which this philosophy was presented to him; but then something in him appeared which refused to be satisfied with this very quality which regarded matter spiritually and the spiritual materially. And one can come to the right conclusion about this only if one faces the real truth which often has been advanced as a formal view; namely, if one considers that Augustine was a man who was fundamentally more akin to the men of the Middle Ages and even perhaps to the men of modern times than he could possibly be to those men who through their soul-mood were the natural inheritors of Manichaeism. Augustine has already something of what I would call the revival of spiritual life. In other places I have often pointed, even in public lectures, to what I mean. These present times are intellectual and inclined to the abstract, and so we always see in the history of any century the influences at work from the preceding century, and so on. In the case of an individual it is of course pure nonsense to say: something which happens in, let us say, his eighteenth year is only the consequence of something else which happened in his thirteenth or fourteenth year. In between lies something which springs from the deepest depths of human nature, which is not just the consequence of something that has gone before in the sense in which one is justified in speaking of cause and effect, but is rather something which is inherent in the nature of man, and takes place in human life, namely, adolescence. And such a gap has to be recognized also at other times in human evolution—in individual human evolution, when something struggles from the depths to the surface; so that we cannot say: what happens is only the direct uninterrupted consequence of whatever has preceded it. And such gaps occur also in the case of all humanity. We have to assume that before such a gap Manichaeism occurred, and after such a gap occurred the soul-attitude, the soul-conception in which Augustine found himself. Augustine could simply not come to terms with his soul unless he rose above what a Manichaean called material-spiritual to something purely spiritual, something built and seen in the spiritual sphere; Augustine had to rise to something much more free of the senses. So he had to turn away from the pictorial, the evidential philosophy of Manichaeism. This was the first thing that developed so intensively in his soul. We read it in his words: the heaviest and almost the only reason for error which I could not avoid was that I had to imagine a bodily substance when I wanted to think of God.

In this way he refers to the time when Manichaeism with its material spirituality and its spiritual materiality lived in his soul; he refers to it in these words and characterizes this period of his life thus as an error. He needed something to look up to, something which was fundamental to human nature. He needed something which, unlike the Manichaean principles, does not look upon the physical universe as spiritual-material. As everything with him struggled with intensive and overpowering earnestness to the surface of his soul, so also this saying: “I asked the earth and it said: `I am not it,' and all things on it confessed the same.”

What does Augustine ask? He asks what the divine really is, and he asks the earth and it says to him, “I am not it.” Manichaeism would have: “I am it as earth, in so far as the divine expresses itself through earthly works.” And again Augustine says: “I asked the sea and the abysses and whatever living thing they cover:” “We are not your God, seek above us.” “I asked the sighing winds,” and the whole nebula with all its inhabitants said: “The philosophers who seek the nature of things in us were mistaken, for we are not God.”

(Thus not the sea and not the nebula, nothing in fact which can be observed through the senses.)

“I asked the sun, the moon, and the stars.” They said: “We are not God whom thou seekest.”

Thus he gropes his way out of Manichaeism, precisely out of that part of it which must be called its most significant part, at least in this connection. Augustine gropes after something spiritual which is free of all sensuousness. And in this he finds himself exactly in that era of human soul-development in which the soul had to free itself from the contemplation of matter as something spiritual and of the spiritual as something material. We entirely misunderstand Greek philosophy in reference to this. And because I tried for once to describe Greek philosophy as it really was, the beginning of my Riddles of Philosophy seems so difficult to understand. When the Greeks speak of ideas, of conceptions, when Plato speaks of them, people now believe that Plato or the Greeks mean the same by ideas as we do. This is not so, for the Greeks spoke of ideas as something which they observed in the outer world like colours or sounds. That part of Manichaeism which we find slightly changed, with—let us say—an oriental tinge, that is already present in the whole Greek view of life. The Greek sees his idea just as he sees colours. And he still possesses that material-spiritual, spiritual-material life of the soul, which does not rise to what we know as spiritual life. Whatever we may call it, a mere abstraction or the true content of our soul, we need not decide at the present moment; the Greek does not yet reckon with what we call a life of the soul free from matter; he does not distinguish, as we do, between thinking and outward use of the senses. The whole Platonic philosophy ought to be seen in this light to be fully understood.

We can now say, that Manichaeism is nothing but a post-Christian variation (with an oriental tinge) of something already existing among the Greeks. Neither do we understand that wonderful genius who closes the circle of Greek philosophy, Aristotle, unless we know that whenever he speaks of concepts, he still keeps within the meaning of an experienced tradition which regarded concepts as belonging to the outer world of the senses as well as perceptions, though he is already getting close to the border of understanding abstract thought free from all evidence of the senses. Through the point of view to which men's souls had attained during his era, through actual events happening within the souls of men in whose rank Augustine was a distinctive, prominent personality, Augustine was forced not just only to experience within his soul, as the Greeks had done, but he was forced to rise to thoughts free from sense-perceptions, to thoughts which still kept their meaning even if they were not dealing with earth, air and sea, with stars, sun and moon; thoughts which had a content beyond the sense of vision.

And now only philosophers and philosophies spoke to him which spoke of what they had to say from an entirely different point of view, that is, from the super-spiritual one just explained. Small wonder, then, that these souls striving in a vague way for something not yet in existence and trying with their minds to seize what was there, could only find something they could not absorb; small wonder that these souls sought refuge in scepticism. On the other hand, the feeling of standing on a sound basis of truth and the desire to get an answer to the question of the origin of Evil was so strong in Augustine, that equally powerful in his soul lived that philosophy which stands under the name of Neoplatonism at the end of Greek philosophic development. This is focused in Plotinus and reveals to us historically what neither the Dialogues of Plato and still less Aristotelian philosophy can reveal, namely, the course of the whole life of the soul when it looks for a greater intensiveness and a reaching beyond the normal. Plotinus is like a last straggler of a type which followed quite different paths to knowledge, to the inner life of the soul, from those which were gradually understood later. Plotinus must appear fantastic to present-day men. To those who have absorbed something of mediaeval scholasticism Plotinus must appear as a terrible fanatic, indeed, as a dangerous one.

I have noticed this repeatedly. My old friend Vincenz Knauer, the Benedictine monk, who wrote a history of philosophy and who has also written a book about the chief problems of philosophy from Thales to Hamerling was, I may well say, good-nature incarnate. This man never let himself go except when he had to deal with Neoplatonism, in particular with Plotinus, and he would then get quite angry and would denounce Plotinus terribly as a dangerous fanatic. And Brentano, that intelligent Aristotelian and Empiric, Franz Brentano, who also carried mediaeval philosophy deeply and intensely in his soul, wrote a little book: Philosophies that Create a Stir, and there he fumes about Plotinus in the same way, for Plotinus the dangerous fanatic is the philosopher, the man who in his opinion “created a stir” at the close of the ancient Greek period. To understand him is really extraordinarily difficult for the modern philosopher.

Concerning this philosopher of the third century we have next to say this: What we experience as the content of our understanding, of our reason, what we know as the sum of our concepts about the world is entirely different for him. I might say, if I may express myself clearly: we understand the world through sense-observations which through abstraction we bring to concepts, and end there. We have the concepts as inner psychic experience and if we are average men of to-day we are more or less conscious that we have abstractions, something we have sucked as it were out of things. The important thing is that we end there; we pay attention to the experiences of the senses and stop at the point where we make the total of our concepts, of our ideas. It was not so for Plotinus. For him this whole world of sense-experience scarcely existed. But that which meant something to him, of which he spoke as we speak of plants and minerals and animals and physical men, was something which he saw lying above concepts; it was a spiritual world and this spiritual world had for him a nether boundary, namely, the concepts. While we get our concepts by going to concrete things, make them into abstractions and concepts and say: concepts are the putting-together, the extractions of ideal nature from the observation of the senses, Plotinus said—and he paid little heed to the observation of the senses: “We, as men, live in a spiritual world, and what this spiritual world reveals to us finally, what we see as its nether boundary, are concepts.” For us the world of the senses lies below concepts: for Plotinus there is above concepts a spiritual world, the intellectual world, the world really of the kingdom of the spirit. I might use the following image: let us suppose we were submerged in the sea, and looking upward to the surface of the water, we saw nothing but this surface, nothing above the surface, then this surface would be the upper boundary. Suppose we lived in the sea, we might perhaps have in our soul the feeling: This boundary would be the limit of our life-element, in which we are, if we were organized as sea-beings. But for Plotinus it was not so. He took no notice of the sea round him; but the boundary which he saw, the boundary of the concept-world in which his soul lived, was for him the nether boundary of something above it; just as if we were to take the boundary of the water as the boundary of the atmosphere and the clouds and so on. At the same time this sphere above concepts is for Plotinus what Plato calls the “world of ideas” and Plotinus throughout imagines that he is continuing the true genuine philosophy of Plato. This “idea-world” is, first of all, completely a world of which one speaks in the sense of Plotinism. Surely it would not occur to you, even if you were Subjectivists or followers of the modern Subjectivist philosophy, when you look out upon the meadow, to say: I have my meadow, you have yours, and so and so has his meadow; even if you are convinced that you each have only before you the image of a meadow, you speak of the meadow in the singular, of one meadow which is out there. In the same way Plotinus speaks of the one idea-world, not of the idea-world of this mind, or of another or of a third mind. In this idea-world—and this we see already in the whole manner in which one has to characterize the thought-process leading to this idea-world—in this idea-world the soul has a part. So we may say: The soul, the Psyche, unfolds itself out of the idea-world and experiences it. And the Soul, just as the idea-world creates the Psyche, in its turn creates the matter in which it is embodied. So that the lower material from which the Psyche takes its body is chiefly a creation of this Psyche.

But precisely there is the origin of individuation, there the Psyche, which otherwise takes part in the single idea-world, becomes a part of body A, and body B, and so on, and through this fact there appear, for the first time, individual souls. It is just as if I had a great quantity of liquid in one mass, and having taken twenty glasses had filled each with the liquid, so that I have this liquid, which as such is a unity, thus divided, just so I have the Psyche in the same condition, because it is incorporated in bodies which, however, it has itself created. Thus in the Plotinistic sense a man can view himself according to his exterior, his vessel. But that is at bottom only the way in which the soul reveals itself, in which the soul also becomes individualized. Afterward man has to experience within him his very own soul, which raises itself upward to the idea-world. Still later there comes a higher form of experience. That one should speak of abstract concepts—that has no meaning for a Plotinist; for such abstract concepts—well, a Plotinist would have said: “What do you mean—abstract concepts? Concepts surely cannot be abstract: they cannot hang in the air, they must be suspended from the spirit; they must be the concrete revelations of the spiritual.”

The interpretation therefore that ideas are any kind of abstractions, is therefore wrong. This is the expression of an intellectual world, a world of spirituality. It is also what existed in the ordinary experience of those men out of whose relationships Plotinus and his fellows grew. For them such talk about concepts, in the way we talk about them, had absolutely no meaning, because for them there was only a penetration of the spiritual world into souls. And this concept-world is found at the limit of this penetration, in experiencing. Only when we went deeper, when we developed the soul further, only then there resulted something which the ordinary man could not know, which the man experienced who had attained a higher stage. He then experienced that which was above the idea-world—the One, if you like to call it so—the experience of the One. This was for Plotinus the thing that was unattainable to concepts, just because it was above the world of concepts, and could only be attained if one could sink oneself into oneself without concept, a state we describe here in our spiritual science as Imagination. You can read about it in my book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and How to Attain It. But there is this difference: I have treated the subject from the modern point of view, whereas Plotinus treated it from the old. What I there call the Imagination is just that which, according to Plotinus stands above the idea-world.

From this general view of the world Plotinus really also derived all his knowledge of the human soul. It is, after all, practically contained in it. And one can be an individualist in the sense of Plotinus if one is at the same time a human being who recognizes how man raises his life upwards to something which is above all individuality, to something spiritual; whereas in our age we have more the habit of reaching downwards to the things of the senses. But all this which is the expression of something which a thorough scientist regards as fanaticism, all this is in the case of Plotinus, not something thought out, these are no hypotheses of his. This perception—right up to the One which only in exceptional cases could be attained—this perception was as clear to Plotinus and as obvious, as is for us to-day the perception of minerals, plants and animals. He spoke only in the sense of something which really was directly experienced by the soul when he spoke of the soul, of the Logos, which was part of the Nous, of the idea-world and of the One. For Plotinus the whole world was, as it were, a spirituality—again a different shade of philosophy from the Manichaean and from the one Augustine pursued. Manichaeism recognizes a sense-supersense; for it the words and concepts of matter and spirit have as yet no meaning. Augustine strives to reach a spiritual experience of the soul that is free from the sense and to escape from his material view of life. For Plotinus the whole world is spiritual, things of the senses do not exist. For what appears material is only the lowest method of revealing the spiritual. All is spirit, and if we only go deep enough into things, everything is revealed as spirit.

This is something which Augustine could not accept. Why? Because he had not the necessary point of view. Because he lived in his age as a predecessor—for if I might call Plotinus a “follower” of the ancient times in which one held such philosophic views,—though he went on into the third century,—Augustine was a predecessor of those people who could no longer feel and perceive that there was a spiritual world underneath the idea-world. He just did not see that any more. He could only learn it by being told. He might hear that people said it was so, and he might develop a feeling that there was something in it which was a human road to truth. That was the dilemma in which Augustine stood in relation to Plotinism. But he was never completely diverted from searching for an inner understanding of this Plotinism. However, this philosophical point of view did not open itself to him. He only guessed: in this world there must be something. But he could not fight his way to it.

This was the mood of his soul when he withdrew himself into a lonely life, in which he got to know the Bible and Christianity, and later the sermons of Ambrosius and the Epistles of St. Paul; and this was the mood of his soul which finally brought him to say: “The nature of the world which Plotinus sought at first in the nature of the idea-world of the Nous, or in the One, which one can attain only in specially favourable conditions of soul, why! That has appeared in the body on earth, in human form, through Christ-Jesus.” That leapt at him as a conviction out of the Bible: “Thou hast no need to struggle upward to the One, thou needest but look upon that which the historical tradition of Christ-Jesus interprets. There is the One come down from heaven, and is become man.” And Augustine exchanges the philosophy of Plotinus for the Church. He expresses this exchange clearly enough. For instance, when he says, “Who could be so blind as to say: 'The Apostolic Church merits no Faith” the church which is so faithful and supported by so many brotherly agreements that it has transmitted their writings as conscientiously to those that come after, as it has kept their episcopal sees in direct succession down to the present Bishops. This it is on which Augustine, out of the soul-mood described, laid the chief stress:—that, if one only goes into it, it can be shown in the course of centuries that there were once men who knew the Lord's disciples, and here is a continuous tradition of a sort worthy of belief, that there appeared on earth the very thing which Plotinus knew how to attain in the way I have indicated.

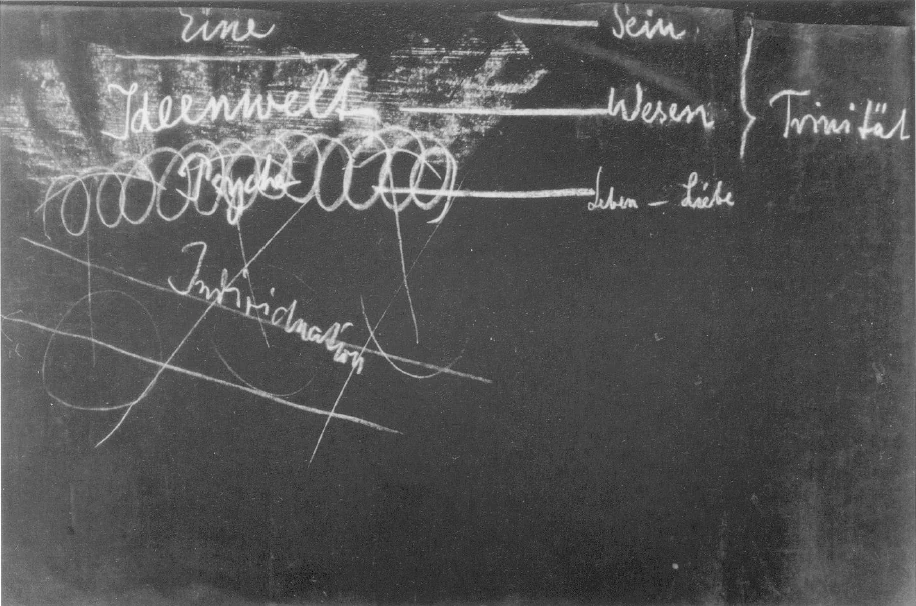

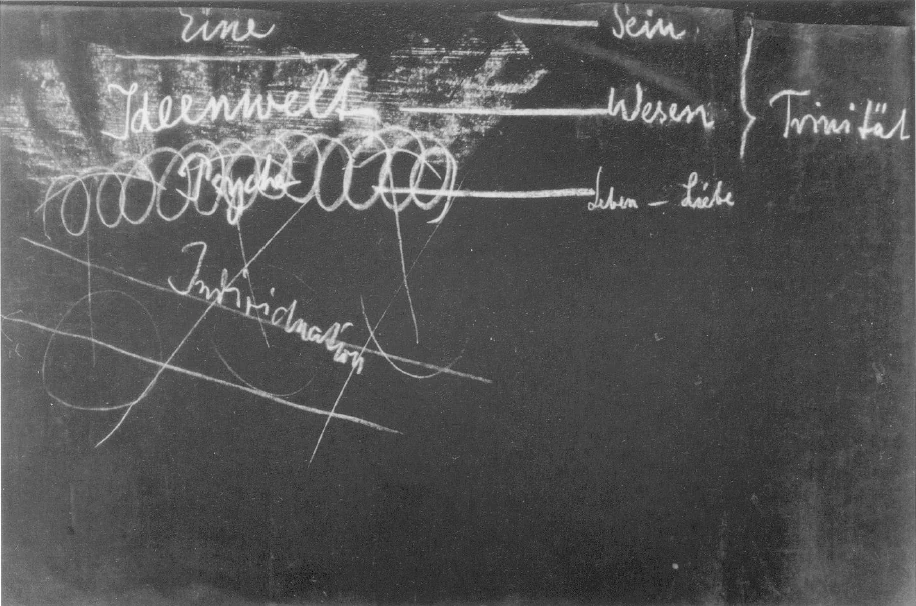

And now there arose in Augustine the effort, in so far as he could get to the heart of it, to make use of this Plotinism to comprehend that which had through Christianity been opened to his feeling and his inner perception. He actually applied the knowledge he had through Plotinism to understand Christianity and its meaning. Thus, for example, he transposed the concept of the One. For Plotinus the One was something experienced; for Augustine who could not attain this experience, the One became something which he defined with the abstract term “being”; the idea-world, he defined with the abstract concept “knowing,” and Psyche with the abstract concept “living,” or even “love.” We have the best evidence that Augustine proceeded thus in that he sought to comprehend the spiritual world, with neoplatonic and Plotinistic concepts, that there is above men a spiritual world, out of which the Christ descends. The Trinity was something which Plotinism made clear to Augustine, the three persons of the Trinity, the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost.

And if we were to ask seriously, of what was Augustine's soul full, when he spoke of the Three Persons—we must answer: It was full of the knowledge derived from Plotinus. And this knowledge he carried also into his understanding of the Bible. We see how it continues to function. For this Trinity awakens to life again, for example, in Scotus Erigena, who lived at the court of Charles the Bald in the ninth century, and who wrote a book on the divisions and classification of Nature in which we still find a similar Trinity: Christianity interprets its content from Plotinism.

But what Augustine preserved from Plotinism in a specially strong degree was something that was fundamental to it.

You must remember that man, since the Psyche reaches down into the material as into a vessel, is really the only earthly individuality. If we ascend slightly into higher regions, to the divine or the spiritual, where the Trinity originates, we have no longer to do with individual man, but with the species, as it were, with humanity. We no longer direct our visualization in this bald manner towards the whole of humanity, as Augustine did as a result of his Plotinism. Our modern concepts are against it. I might say: Seen from down there, men appear as individuals; seen from above—if one may hypothetically say that—all humanity appears as one unity. From this point of view the whole of humanity became for Plotinus concentrated in Adam. Adam was all humanity. And since Adam sprang from the spiritual world he was as a being bound with the earth, which had free will, because in him there lived that which was still above, and not that which arises from error of matter—itself incapable of sin. It was impossible for this man who was first Adam to sin or not to be free, and therefore also impossible to die. Then came the influence of that Satanic being, whom Augustine felt as the enemy-spirit. It tempted and seduced the man. He fell into the material, and with him all humanity.

Augustine stands, with what I might call his derived knowledge, right in the midst of Plotinism. The whole of humanity is for him one, and it sinned in Adam as a whole, not as an individual. If we look clearly between the lines particularly of Augustine's last writings, we see how extraordinarily difficult it has become for him thus to regard the whole of mankind, and the possibility that the whole fell into sin. For in him there is already the modern man, the predecessor as opposed to the successor; there lived in him the individual man who felt that individual man grew ever more and more responsible for what he did, and what he learnt. At certain moments it appeared to him impossible to feel that individual man is only a member of the whole of the human race. But Neo-Platonism and Plotinism were so deep in him that he still could look only at the whole of humanity. And so this condition in the whole man, this condition of sin and mortality—was transferred into that of the impossibility to be free, the impossibility to be immortal; all humanity had thus fallen, had been diverted from its origin. And God, were He righteous, would have simply thrown humanity aside. But He is not only righteous, He is also merciful—so Augustine felt. Therefore, he decided to save a part of mankind, note well, a part. That is to say, God's decision destined a part of mankind to receive grace, whereby this part is to be led back from the condition of bondage and mortality to the condition of potential freedom and immortality, which, it is true, can only be realized after death. One part is restored to this condition. The other part of mankind—namely, the not-chosen—remains in the condition of sin. So mankind falls into these two divisions, into those that are chosen and those who are cast out. And if we regard humanity in this Augustinian sense, it falls simply into these two divisions: those who are destined for bliss without desert, simply because it is so ordained in the divine management, and those who, whatever they do, cannot attain grace, who are predetermined and predestined to damnation.

This view, which also goes by the name of Predestination, Augustine reached as a result of the way in which he regarded the whole of humanity. If it had sinned it deserved the fate of that part of humanity which was cast out. We shall speak tomorrow of the terrible spiritual battles which have resulted from this Predestination, how Pelagianism and semi-Pelagianism grew out of it. But to-day I would add as a final remark: we now see how Augustine stands, a vivid fighting personality, between that view which reaches upward toward the spiritual, according to which humanity becomes a whole, and the urge in his soul to rise above human individuality to something spiritual which is free from material nature, but which, again, can have its origin only in individuality. This was just the characteristic feature of the age of which Augustine is the forerunner, that it was aware of something unknown to men in the old days—namely individual experience. To-day, after all, we accept a great deal as formula. But Klopstock was in earnest and not merely the maker of a phrase when he began his “Messiah” with the words: “Sing, immortal soul, of sinful man's salvation.” Homer began, equally sincerely: “Sing, O Goddess, of the wrath. ... “: or “Sing, O Muse, to me now of the man, far-travelled Odysseus.” These people did not speak of something that exists in individuality, they interpreted something of universal mankind, a race-soul, a Psyche. It is no empty phrase, when Homer lets the Muse sing, in place of himself. The feeling of individuality awakens later, and Augustine is one of the first of those who really feel the individual entity of man, with its individual responsibility. Hence, the dilemma in which he lived. The individual striving after the non-material spiritual was part of his own experience. There was a personal, subjective struggle in him. In later times that understanding of Plotinism, which it was still possible for Augustine to have, was—I might say—choked up. And after the Greek philosophers, the last followers of Plato and Plotinus, were compelled to go into exile in Persia, and after they had found their successors in the Academy of Jondishapur, this looking up to the spiritual triumphed in Western Europe—and only that remained which Aristotle had bequeathed to the after-world in the form of a filtered Greek philosophy, and then only in a few fragments. That continued to grow, and came in a roundabout way, via Arabia, back to Europe. This had no longer a consciousness of the idea world, and no Plotinism in it. And so the great question remained: Man must extract from himself the spiritual; he must produce the spiritual as an abstraction. When he sees lions and thereupon conceives the thought “lions” when he sees wolves and thereupon conceives the thought “wolves,” when he “sees man and thereupon conceives the thought” man these concepts are alive only in him, they arise out of his individuality. The whole question would have had no meaning for Plotinus; now it begins to have a meaning, and moreover a deep meaning.

Augustine, by means of the light Plotinism had shed into his soul, could understand the mystery of Christ-Jesus. Such Plotinism as was there was choked up. With the closing by the Emperor Justinian of the School of Philosophy at Athens in 529 the living connection with such views was broken off. Several people have felt deeply the idea: We are told of a spiritual world, by tradition, in Script—we experience by our individuality supernatural concepts, concepts that are removed from the material How are these concepts related to “being?” How so the nature of the world? What we take to be concepts, are these only something spontaneous in us, or have they something to do with the outer world? In such forms the questions appeared; in the most extreme abstractions, but such as were the deeply earnest concern of men and the mediaeval Church. In this abstract form, in this inner-heartedness they appeared in the two personalities of Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas. Then again, they came to be called the questions between Realism and Nominalism. “What is our relationship to a world of which all we know is from conceptions which can come only from ourselves and our individuality?” That was the great question which the mediaeval schoolmen put to themselves.

If you consider what form Plotinus had taken in Augustine's predestinationism, you will be able to feel the whole depth of this scholastic question: only a part of mankind, and that only through God's judgment, could share in grace, that is, attain to bliss; the other part was destined to eternal damnation from the first, in spite of anything it might do. But what man could gain for himself as the content of his knowledge came from that concept, that awful concept of Predestination which Augustine had not been able to transform—that came out of the idea of human individuality. For Augustine mankind was a whole; for Thomas each separate man was an individuality.

How does this great World-process in Predestination as Augustine saw it hang together with the experience of separate human individuality? What is the connection between that which Augustine had really discarded and that which the separate human individuality can win for itself? For consider: Because he did not wish to lay stress on human individuality, Augustine had taken the teaching of Predestination, and, for mankind's own sake, had extinguished human individuality. Thomas Aquinas had before him only the individual man, with his thirst for knowledge. Thomas had to seek human knowledge and its relationship to the world in the very thing Augustine had excluded from his study of humanity.

It is not sufficient, ladies and gentlemen, to put such a question abstractly and intellectually and rationally; it is necessary to grasp such a question with the whole heart, with the whole human personality. Only then shall we be able to assess the weight with which this question oppressed those men who, in the thirteenth century, bore the burden of it.

1. Thomas und Augustinus

In diesen drei Tagen möchte ich über ein Thema sprechen, das gewöhnlich von einer mehr formalen Seite her betrachtet wird, und dessen Inhalt gewöhnlich nur darinnen gesehen wird, daß durch die zugrunde liegende philosophische Bewegung des Mittelalters die Stellung der philosophischen Weltanschauung zum Christentum gewissermaßen festgelegt worden sei. Da gerade diese Seite der Sache in der neueren Zeit eine Art Wiederauffrischung gefunden hat durch die Aufforderung des Papstes Leo XIII. an seine Kleriker, den Thomismus zur offiziellen Philosophie der katholischen Kirche zu machen, so hat von dieser Seite her gewiß unser gegenwärtiges "Thema eine gewisse Bedeutung.

Allein, ich möchte eben nicht bloß von dieser formalen Seite her die Sache betrachten, die sich als mittelalterliche Philosophie gewissermaßen herumkristallisiert um die Persönlichkeit des Albertus Magnus und des Thomas von Aquino, sondern ich möchte im Laufe dieser Tage dazu kommen, den tieferen historischen Hintergrund aufzuzeigen, aus dem diese von der Gegenwart trotz alledem viel zu wenig gewürdigte philosophische Bewegung sich erhoben hat. Man kann sagen: In einer ganz scharfen Weise versucht Thomas von Aquino im 13. Jahrhundert das Problem der Erkenntnis, der Gesamtweltanschauung zu fassen, in einer Weise, die, man muß es ihr zugestehen, heute eigentlich schwer nachzudenken ist, weil zu dem Nachdenken Voraussetzungen gehören, die bei den Menschen der Gegenwart kaum erfüllt sind, auch wenn sie Philosophen sind. Es ist notwendig, daß man sich ganz hineinversetzen könne in die Art des Denkens des Thomas von Aquino, seiner Vorgänger und Nachfolger, daß man zu wissen vermag, wie die Begriffe zu nehmen sind, wie die Begriffe in den Seelen dieser mittelalterlichen Menschen lebten, von denen eigentlich die Geschichte der Philosophie in ziemlich äußerlicher Weise berichtet.

Sieht man nun auf der einen Seite hin auf den Mittelpunkt dieser Betrachtung, auf Thomas von Aquino, so möchte man sagen, in ihm hat man eine Persönlichkeit, die gegenüber der Hauptströmung der christlichen Philosophie des Mittelalters eigentlich als Persönlichkeit verschwindet, die, man möchte sagen, eigentlich nur der Koeffizient oder der Exponent ist für dasjenige, was in einer breiten Weltanschauungsströmung lebt und nur mit einer gewissen Universalität eben gerade durch diese eine Persönlichkeit zum Ausdrucke kommt. So daß man, wenn man von dem Thomismus spricht, sein Auge richten kann auf etwas außerordentlich Unpersönliches, auf etwas, das sich eigentlich nur offenbart durch die Persönlichkeit des Thomas von Aquino. Dagegen erblickt man sofort, daß man eine volle, ganze Persönlichkeit mit alledem, was eben in einer Persönlichkeit sich darlebt, in den Mittelpunkt der Betrachtung stellen muß, wenn man denjenigen ins Auge faßt, auf den zunächst als hauptsächlichsten Vorgänger der Thomismus zurückgeht, wenn man Augustinus ins Auge faßt: bei Augustinus alles persönlich, bei Thomas von Aquino alles eigentlich ganz unpersönlich. Bei Augustinus haben wir es zu tun mit einem ringenden Menschen, bei Thomas von Aquino mit der ihre Stellung zum Himmel, zur Erde, zu den Menschen, zu der Geschichte und so weiter feststellenden mittelalterlichen Kirche, die sich eigentlich sogar, könnte man, allerdings mit gewissen Einschränkungen, sagen, als Kirche ausdrückt durch die Philosophie des Thomas von Aquino.

Ein bedeutsames Ereignis liegt zwischen den beiden, und ohne daß man den Blick auf dieses Ereignis richtet, ist es nicht möglich, die Stellung dieser beiden mittelalterlichen Persönlichkeiten zueinander festzustellen. Das Ereignis, das ich meine, das ist die durch den Kaiser Justinian betriebene Verketzerung des Origenes. Die ganze Färbung der Weltanschauung des Augustinus wird erst verständlich, wenn man den ganzen historischen Hintergrund, aus dem sich Augustinus herausarbeitet, ins Auge faßt. Dieser historische Hintergrund wird aber in der Tat ein ganz anderer dadurch, daß jener mächtige Einfluß — es war in der Tat ein mächtiger Einfluß trotz vielem, was in der Geschichte der Philosophie gesagt wird - auf das Abendland aufhört, der ausgegangen ist von den Philosophenschulen in Athen, ein Einfluß, der im wesentlichen bis ins sechste Jahrhundert hinein dauerte, dann abflutete, so daß etwas zurückbleibt, was tatsächlich in der weiteren philosophischen Strömung des Abendlandes etwas ganz anderes ist als das war, in dem Augustinus noch lebendig drinnengestanden hat.

Ich werde Sie bitten müssen zu berücksichtigen, daß heute mehr eine Einleitung gegeben wird, daß morgen das eigentliche Wesen des Thomismus hier behandelt werden soll, und daß mein Ziel, dasjenige, warum ich all das vorbringe, was ich in diesen Tagen sagen will, eigentlich erst am dritten Tage ganz zum Vorschein kommen wird. Denn sehen Sie, auch mit Bezug auf die christliche Philosophie des Mittelalters, namentlich des Thomismus, bin ich ja — verzeihen Sie einleitend diese persönliche Bemerkung - in einer ganz besonderen Lage. Ich habe öfter hervorgehoben, auch in öffentlichen Vorträgen, wie es mir einmal gegangen ist, als ich vor einer proletarischen Bevölkerung dasjenige vorgetragen hatte, was ich als die Wahrheit in dem Verlauf der abendländischen Geschichte ansehen muß. Es hat dazu geführt, daß zwar unter den Schülern eine gute Anhängerschaft da war, daß aber die Führer der proletarischen Bewegung um die Wende des 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert darauf gekommen sind, es würde da nicht echter Marxismus vorgetragen. Und obschon man sich berufen konnte darauf, daß eine Zukunftsmenschheit eigentlich doch etwas wie Lehrfreiheit anerkennen müsse, wurde mir in der maßgebenden Versammlung dazumal erwidert, diese Partei kenne keine Lehrfreiheit, sondern nur einen vernünftigen Zwang! - Und meine Lehrtätigkeit mußte, obwohl dazumal eine große Anzahl von Schülern herangezogen waren im Proletariat, damit beschlossen werden.

In einer ähnlichen Weise ging es mir an anderer Stätte mit demjenigen, was ich vor etwa jetzt neunzehn bis zwanzig Jahren sagen wollte über den Thomismus und alles dasjenige, was sich als mittelalterliche Philosophie daranschließt. Es war das die Zeit, in welcher eben um die Wende des 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert zu ganz besonderer Hochflut gekommen war dasjenige, was man gewohnt worden ist, den Monismus zu nennen. Als eine besondere Färbung des Monismus, nämlich als materialistischer Monismus, scheinbar zur Pflege einer freien, unabhängigen Weltanschauung, aber im Grunde genommen doch nur zur Pflege dieser materialistischen Färbung des Monismus, war dazumal in Deutschland der «Giordano-Bruno-Bund» begründet worden. Weil es mir unmöglich war, all das leere Phrasengerede mitzumachen, das dazumal als Monismus in die Welt ging, hielt ich im Berliner «Giordano-Bruno-Bund» einen Vortrag über den Thomismus. In diesem Vortrage suchte ich den Nachweis zu führen, daß in dem Thomismus ein wirklicher spiritueller Monismus gegeben sei, daß dieser spirituelle Monismus gegeben sei außerdem in der Weise, daß er sich offenbart durch das denkbar scharfsinnigste Denken, durch ein scharfsinniges Denken, von dem die neuere, unter Kantschem Einfluß stehende und aus dem Protestantismus hervorgegangene Philosophie im Grunde genommen keine Ahnung hat, zu dem sie aber jedenfalls keine Kraft mehr hat. Und so hatte ich es denn auch mit dem Monismus verdorben! Es ist tatsächlich heute außerordentlich schwierig, von den Dingen so zu sprechen, daß das Gesprochene aus der wirklichen Sache herausklingt und nicht in den Dienst irgendeiner Parteifärbung sich stellt. So zu sprechen über die Erscheinungen, die ich angedeutet habe, möchte ich mich in diesen drei Tagen wiederum bestreben.

Die Persönlichkeit des Augustinus stellt sich hinein in das vierte und fünfte Jahrhundert als, wie ich schon sagte, eine im eminenten Sinne ringende Persönlichkeit. Die Art und Weise, wie Augustinus ringt, das ist dasjenige, was sich einem tief in die Seele gräbt, wenn man auf die besondere Natur dieses Ringens einzugehen vermag. Zwei Fragen sind es, die sich in einer Intensität vor des Augustinus Seele stellen, von der man heute, wo die eigentlichen Erkenntnis- und Seelenfragen verblaßt sind, wiederum eigentlich keine Ahnung hat. Die erste Frage ist die, die man etwa dadurch charakterisieren kann, daß man sagt: Augustinus ringt nach dem Wesen desjenigen, was der Mensch eigentlich als Wahrheit, als eine ihn stützende, als seine Seele erfüllende Wahrheit anerkennen könne, Die zweite Frage ist diese: Wie ist zu erklären in einer Welt, die doch nur einen Sinn hat, wenn wenigstens das Ziel dieser Welt mit dem Guten irgend etwas zu tun hat, wie ist zu erklären in dieser Welt die Anwesenheit des Bösen? Wie ist zu erklären in der menschlichen Natur namentlich der Stachel des Bösen, der eigentlich — wenigstens nach des Augustinus Ansicht - niemals zum Schweigen kommt, die Stimme des Bösen, die niemals zum Schweigen kommt, auch dann nicht, wenn der Mensch ein ehrliches und aufrichtiges Streben nach dem Guten entwickelt?

Ich glaube nicht, daß man an Augustinus wirklich herankommt, wenn man diese zwei Fragen in dem Sinne nimmt, wie sie der Durchschnittsmensch der Gegenwart, auch wenn er Philosoph ist, zu nehmen geneigt ist. Man muß nach der besonderen Färbung suchen, die für diesen Menschen des vierten und fünften Jahrhunderts diese beiden Fragen hatten. Augustinus geht ja zunächst durch ein innerlich bewegtes, man möchte sagen ausschweifendes Leben. Aber aus diesem ausschweifenden und bewegten Leben heraus tauchen ihm doch immer wieder diese beiden Fragen auf. Persönlich ist er in einen Zwiespalt hineingestellt. Der Vater ist Heide, die Mutter ist fromme Christin. Die Mutter gibt sich alle Mühe, den Sohn für das Christentum zu gewinnen. Zunächst ist der Sohn nur für einen gewissen Ernst zu gewinnnen, und dieser Ernst richtet sich zunächst nach dem Manichäismus. Wir wollen nachher einige Blicke nach dieser Weltanschauung werfen, die zunächst in den Gesichtskreis des Augustinus hereintrat, als er von einem etwas lotterigen Leben zu einem vollen Lebensernst überging. Dann fühlte er sich aber immer mehr und mehr, allerdings erst nach Jahren, abgestoßen von dem Manichäismus, und es bemächtigte sich seiner nun wiederum, nicht etwa nur aus den Tiefen der Seele heraus oder aus irgendwelchen abstrakten Höhen her, sondern aus der ganzen Zeitströmung des philosophischen Lebens heraus ein gewisser Skeptizismus, der Skeptizismus, in den zu einer gewissen Zeit die griechische Philosophie ausgelaufen war, und der sich dann erhalten hat bis in die Zeit des Augustinus.

Aber nun tritt immer mehr und mehr der Skeptizismus zurück. Es ist der Skeptizismus für Augustinus gewissermaßen nur etwas, was ihn mit der griechischen Philosophie zusammenbringt. Und dieser Skeptizismus trägt ihm zu dasjenige, was zweifellos auf seine Subjektivität, auf die ganze Haltung seiner Seele für einige Zeit einen ganz außerordentlich tiefen Einfluß ausgeübt hat. Der Skeptizismus führt ihm eine ganz andere Richtung zu, dasjenige, was man in der Geschichte der Philosophie gewöhnlich den Neuplatonismus nennt. Und Augustinus ist viel mehr, als man gewöhnlich denkt, von diesem Neuplatonismus zugeführt worden. Die ganze Persönlichkeit und alles Ringen des Augustinus ist nur begreiflich, wenn man versteht, wie viel von neuplatonischer Weltanschauung hineingezogen ist in die Seele dieser Persönlichkeit. Und wenn man objektiv auf die Entwickelung des Augustinus eingeht, dann findet man eigentlich kaum, daß der Bruch, der in dieser Persönlichkeit war beim Übergang vom Manichäismus zum Plotinismus, sich in derselben Stärke wiederholt hat dann, als Augustinus vom Neuplatonismus zum Christentum überging. Denn man kann eigentlich sagen: Neuplatoniker in einem gewissen Sinne ist Augustinus geblieben; soweit er Neuplatoniker werden konnte, ist er es geblieben. Nur, daß er es eben nur bis zu einem gewissen Grade werden konnte. Und weil er es nur bis zu einem gewissen Grade werden konnte, trug ihn dann sein Schicksal dazu, bekannt zu werden mit der Erscheinung des Christus Jesus. Und eigentlich ist da gar kein enormer Sprung, sondern es ist in Augustinus eine naturgemäße Fortentwickelung vorhanden vom Neuplatonismus zum Christentum. $o, wie in Augustinus dieses Christentum lebt, kann man dieses augustinische Christentum nicht beurteilen, wenn man nicht zunächst hinschaut auf den Manichäismus, eine eigentümliche Form, die alte heidnische Weltanschauung zu überwinden zu gleicher Zeit mit dem Alten Testament, mit dem Judentum.

Der Manichäismus war in der Zeit, als Augustinus aufwuchs, schon eine Weltanschauungsströmung, die durchaus über Nordafrika, wo ja Augustinus aufwuchs, sich ausgedehnt hatte, in der viele Leute des Abendlandes schon lebten. Im dritten Jahrhundert etwa entstanden in Asien drüben durch Mani, einen Perser, ist vom Manichäismus historisch außerordentlich wenig auf die Nachwelt gekommen. Will man diesen Manichäismus charakterisieren, so muß man sagen: Mehr kommt es dabei an auf die ganze Haltung dieser Weltanschauung als auf dasjenige, was man heute wortwörtlich als Inhalt bezeichnen kann.

Dem Manichäismus ist vor allen Dingen eigentümlich, daß für ihn die Zweiteilung des menschlichen Erlebens als geistige Seite und als materielle Seite noch gar keinen Sinn hat. Die Worte oder Ideen «Geist» und «Materie» haben für den Manichäismus keinen Sinn. Der Manichäismus sieht in dem, was den Sinnen materiell erscheint, Geistiges und erhebt sich nicht über dasjenige, was sich den Sinnen darbietet, wenn er vom Geistigen spricht. Es ist in einem viel intensiveren Maße, als man gewöhnlich denkt, wo die Welt so abstrakt und intellektualistisch geworden ist, für den Manichäismus das der Fall, daß er in der Tat in den Sternen und in ihrem Gange geistige Erscheinungen, geistige Tatsachen sieht, daß er in dem Sonnengeheimnis zugleich dasjenige sieht, was als Geistiges, als Spirituelles hier auf der Erde sich vollzieht. Einerseits von Materie, andererseits von Geist zu sprechen, das hat für den Manichäismus keinen Sinn. Für ihn ist das, was geistig ist, zugleich materiell sich offenbarend, und dasjenige, was sich materiell offenbart, ist für ihn das Geistige. Daher ist es für den Manichäismus ganz selbstverständlich, daß er von Astronomischem, von Welterscheinungen so spricht, wie er auch von Moralischem und von Geschehnissen innerhalb der Menschheitsentwickelung spricht. So ist für den Manichäismus viel mehr als man denkt jener Gegensatz, den er in die Weltanschauung hineinsetzt — Licht und Finsternis, etwas Altpersisches nachahmend -, er ist für ihn zugleich durchaus ein selbstverständliches Geistiges. Und ein Selbstverständliches ist es, daß dieser Manichäismus noch spricht von dem, was da als Sonne scheinbar am Himmelsgewölbe sich bewegt, als von etwas, das auch mit den moralischen Entitäten und moralischen Impulsen innerhalb der Menschheitsentwickelung etwas zu tun hat, und daß er von den Beziehungen dieses Moralisch-Physischen, das da am Himmelsgewölbe dahingeht, zu den Zeichen des Tierkreises spricht wie zu zwölf Wesenheiten, durch die das Urwesen, das Urlichtwesen der Welt, seine Tätigkeiten spezifiziert.

Aber etwas anderes ist noch diesem Manichäismus eigen. Er sieht auf den Menschen hin, und dieser Mensch erscheint ihm keineswegs schon als dasjenige, als was uns heute der Mensch erscheint. Uns erscheint der Mensch wie eine Art Krone der Erdenschöpfung. Mag man nun mehr oder weniger materialistisch oder spiritualistisch denken, es erscheint dem Menschen heute der Mensch wie eine Art Krone der Erdenschöpfung, das Menschenreich wie das höchste Reich, oder wenigstens wie die Krönung des Tierreiches. Das kann der Manichäismus nicht zugeben. Für ihn ist das, was als Mensch auf der Erde gewandelt hat und eigentlich zu seiner Zeit noch wandelte, eigentlich nur ein spärlicher Rest desjenigen, was auf der Erde durch das göttliche Lichtwesen hätte Mensch werden sollen. Etwas ganz anderes hätte Mensch werden sollen als das, was jetzt als Mensch auf der Erde herumwandelt. Dasjenige, was jetzt als Mensch auf der Erde herumwandelt, ist dadurch entstanden, daß der ursprüngliche Mensch, den sich das Lichtwesen zur Verstärkung seines Kampfes gegen die Dämonen der Finsternis geschaffen hat, diesen Kampf gegen die Dämonen der Finsternis verloren hat, aber durch die guten Mächte in die Sonne versetzt worden ist, also aufgenommen worden ist von dem Lichtreiche selbst. Aber die Dämonen haben es doch zuwege gebracht, gewissermaßen ein Stück dieses Urmenschen dem in die Sonne entfliehenden wirklichen Menschen zu entreißen und daraus zu bilden, was das Menschen-Erdengeschlecht ist, dieses Menschen-Erdengeschlecht, das also herumwandelt wie eine schlechtere Ausgabe hier auf Erden desjenigen, was auf der Erde hier gar nicht leben könnte, weil es im großen Geisteskampfe in die Sonne entrückt werden mußte. Um wieder zurückzuführen den Menschen, der in dieser Weise wie eine schlechtere Auflage auf der Erde erschien, zu seiner ursprünglichen Bestimmung, ist dann die Christus-Wesenheit erschienen, und durch ihre Tätigkeit soll die Wirkung des Dämonischen von der Erde weggenommen werden.

Ich weiß sehr gut, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, daß alles das, was man im heutigen Sprachgebrauche von dieser Weltanschauung noch in Worte fassen kann, eigentlich kaum genügend sein kann; denn das ganze geht eben aus Untergründen des seelischen Erlebens hervor, die von den jetzigen wesentlich verschieden sind. Aber das Wesentliche, worauf es heute ankommen muß, das ist dasjenige, was ich schon hervorgehoben habe. Denn wie phantastisch es auch erscheinen mag, was ich Ihnen so erzähle über den Fortgang der Erdenentwickelung im Sinne der Manichäer, der Manichäismus stellte das durchaus vor nicht wie etwas, das man etwa nur im Geiste erschauen müßte, sondern wie etwas, das sich wie eine heute sinnlich genannte Erscheinung vor den physischen Augen zugleich als Geistiges abspielt.

Das war das erste, was mächtig auf Augustinus wirkte. Und die Probleme, die sich an die Persönlichkeit des Augustinus anknüpfen, gehen einem eigentlich auch nur dadurch auf, daß man diese mächtige Wirkung des Manichäismus, seines geistig-materiellen Prinzips, ins Auge faßt. Fragen muß man sich: Woraus gingen denn die Unbefriedigtheiten des Augustinus mit dem Manichäismus hervor? Nicht eigentlich aus dem, was man den mystischen Inhalt, wie ich ihn Ihnen jetzt charakterisiert habe, nennen könnte, sondern die Unbefriedigtheit ging aus der ganzen Haltung dieses Manichäismus hervor.

Zuerst war es für Augustinus so, daß er in gewissem Sinne eingenommen war, sympathisch berührt war von der sinnlichen Anschaulichkeit, von der Bildhaftigkeit, mit der diese Anschauung vor ihn hintrat. Dann aber regte sich in ihm etwas, was gerade mit dieser Bildhaftigkeit, mit der das Materielle geistig und das Geistige materiell angeschaut wurde, nicht zufrieden sein konnte. Und man kommt wirklich nicht anders zurecht, als wenn man hier von dem, was man eigentlich oftmals bloß als eine formelle Betrachtung vor sich hat, zu der Realität übergeht, wenn man also den Blick darauf wirft, daß der Augustinus eben ein Mensch war, der im Grunde genommen den Menschen des Mittelalters und vielleicht selbst den Menschen der neueren Zeit schon ähnlicher war, als er irgendwie sein konnte denjenigen Menschen, die durch ihre Seelenstimmung die naturgemäßen Träger des Manichäismus waren. Augustinus hat bereits etwas von dem, was ich eine Erneuerung des seelischen Lebens nennen möchte.

Bei anderen Gelegenheiten mußte auch in öffentlichen Vorträgen auf das, was hier in Betracht kommt, öfters hingewiesen werden. In unserer heutigen intellektuellen, zum Abstrakten hingeneigten Zeit, da sieht man eigentlich immer in dem, was geschichtlich wird für irgendein Jahrhundert, die Wirkung, die hervorgehen soll aus dem, was das vorige Jahrhundert gebracht hat und so weiter. Beim individuellen Menschen ist es ja ein reiner Unsinn zu sagen, dasjenige, was sich zum Beispiel im achtzehnten Lebensjahre abspielt, sei in ihm eine bloße Wirkung von dem, was sich im dreizehnten, vierzehnten Jahre abgespielt habe; denn dazwischen liegt etwas, was aus den tiefsten Tiefen der Menschennatur sich heraufarbeitet, was nicht bloß Wirkung ist des Vorhergehenden in dem Sinne, wie man von Wirkung als hervorgehend aus einer Ursache berechtigt sprechen kann, sondern was eben sich hineinstellt in das menschliche Leben als aus dem Wesen der Menschheit herauskommende Geschlechtsreife. Und auch zu andern Zeiten der individuellen Menschheitsentwickelung müssen solche Sprünge in der Entwickelung anerkannt werden, wo sich etwas emporringt aus Tiefen heraus an die Oberfläche; so daß man nicht sagen kann: Was geschieht, ist nur die unmittelbar gradlinige Wirkung desjenigen, was vorangegangen ist.

Solche Sprünge vollziehen sich auch mit der Gesamtmenschheit, und man muß annehmen, daß vor einem solchen Sprung dasjenige lag, was Manichäismus war, nach einem solchen Sprung diejenige Seelenverfassung, diejenige Seelenhaltung, in der sich auch Augustinus befand. Augustinus konnte einfach nicht auskommen in seinem Seelenleben, ohne daß er aufstieg von dem, was ein Manichäer materiell-geistig vor sich hatte, zu einem reinen Geistigen, zu einem bloß im Geiste Erkonstruierten, Eranschauten. Zu etwas viel Sinnlichkeitsfreierem mußte Augustinus aufsteigen als ein Manichäer aufstieg. Deshalb mußte er sich abwenden von der bildhaften, von der anschaulichen Weltanschauung des Manichäismus. Das war das erste, was sich in seiner Seele so intensiv auslebte, und wir lesen es etwa aus seinen Worten: Daß ich mir, wenn ich Gott denken wollte, Körpermassen vorstellen mußte und glaubte, es könne nichts existieren als derartiges — das war der gewichtigste und fast der einzige Grund des Irrtums, den ich nicht vermeiden konnte.

So weist er auf diejenige Zeit zurück, in der der Manichäismus mit seiner Sinnlichgeistigkeit, Geistigsinnlichkeit in seiner Seele lebte; so weist er auf diese Zeit hin, und so charakterisiert er diese Zeit seines Lebens als einen Irrtum. Er brauchte etwas, zu dem er aufblickte als zu etwas, das der Menschenwesenheit zugrunde liegt. Er brauchte etwas, das nicht so, wie die Prinzipien des Manichäismus, in dem sinnlichen Weltenall als Geistig-Sinnliches unmittelbar zu schauen ist. Wie bei ihm alles intensiv ernst und stark sich an die Oberfläche der Seele ringt, so auch dieses: «Ich fragte die Erde, und sie sprach: Ich bin es nicht. Und was auf ihr ist, bekannte das gleiche.»

Wonach fragt Augustinus? Er fragt, was das eigentlich Göttliche sei, und er fragt die Erde, und die sagt ihm: Ich bin es nicht. — Im Manichäismus wäre ihm geantwortet worden: Ich bin es als Erde, insofern das Göttliche durch das irdische Wirken sich ausspricht. — Und weiter sagt Augustinus: «Ich fragte das Meer und die Abgründe und was vom Lebendigen sie bergen: Wir sind dein Gott nicht, suche droben über uns. — Ich fragte die wehenden Lüfte, und es sprach der ganze Dunstkreis samt allen seinen Bewohnern: Die Philosophen, die in uns das Wesen der Dinge suchten, täuschten sich, wir sind nicht Gott.» Also auch nicht das Meer und auch nicht der Dunstkreis, alles dasjenige nicht, was sinnlich angeschaut werden kann. «Ich fragte Sonne, Mond und Sterne. Sie sprachen: Wir sind nicht Gott, den du suchst.»

So ringt er sich heraus aus dem Manichäismus, gerade aus dem Element des Manichäismus, das eigentlich als das Bedeutsamste, wenigstens in diesem Zusammenhange, charakterisiert werden muß. Nach einem sinnlichkeitsfreien Geistigen sucht Augustinus. Er steht gerade in demjenigen Zeitalter der menschlichen Seelenentwickelung drinnen, in dem die Seele sich losringen muß von dem bloßen Anschauen des Sinnlichen als eines Geistigen, des Geistigen als eines Sinnlichen; denn man verkennt auch in dieser Beziehung durchaus die griechische Philosophie. Und deshalb wird der Anfang meiner «Rätsel der Philosophie» so schwer verstanden, weil ich versuchte, einmal diese griechische Philosophie so zu charakterisieren, wie sie war.

Wenn der Grieche spricht von Ideen, von Begriffen, wenn Plato so spricht, so glauben die heutigen Menschen, Plato oder der Grieche überhaupt meine mit seinen Ideen dasjenige, was wir heute als Gedanken oder Ideen bezeichnen. Das ist nicht so, sondern der Grieche sprach von Ideen als von etwas, das er in der Außenwelt wahrnimmt, geradeso, wie er von der Farbe oder von Tönen als Wahrnehmungen in der Außenwelt sprach. Was nur im Manichäismus umgestaltet war mit einer, ich möchte sagen, orientalischen Nuance, das ist im Grunde in der ganzen griechischen Weltanschauung vorhanden. Der Grieche sieht seine Idee, wie er die Farbe sieht. Und er hat noch das Sinnlichgeistige, Geistigsinnliche, jenes Erleben der Seele, das gar nicht aufsteigt zu dem, was wir als sinnlichkeitsfreies Geistiges kennen; wie wir es nun auffassen, ob als eine bloße Abstraktion oder als einen realen Inhalt unserer Seele, das wollen wir in diesem Augenblick noch nicht entscheiden. Das ganze, was wir sinnlichkeitsfreies Erleben der Seele nennen, das ist ja noch nicht etwas, womit der Grieche rechnet. Er unterscheidet nicht in dem Sinne wie wir zwischen Denken und äußerem sinnlichen Wahrnehmen.

Die ganze Auffassung der Platonischen Philosophie müßte eigentlich von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus korrigiert werden, denn erst dann gewinnt sie ihr rechtes Antlitz. So daß man sagen kann: Der Manichäismus ist nur eine nachchristliche Ausgestaltung — wie ich schon sagte, mit orientalischer Nuance — desjenigen, was im Griechentum war. Man versteht auch nicht jenen großen Genialen, aber Erzphilister, der die griechische Philosophie abschließt, Aristoteles, wenn man nicht weiß, daß, wenn er noch spricht von den Begriffen, er zwar hart an der Grenze schon steht vom Erfassen von etwas sinnlichkeitsfreiem Abstrakten, daß er aber im Grunde genommen doch noch im Sinne der gefühlten Tradition desjenigen spricht, was auch die Begriffe noch im Umkreise der sinnlichen Welt gesehen hat wie die Wahrnehmungen.

Augustinus war einfach durch den Gesichtspunkt, zu dem sich die Menschenseelen durchgerungen hatten in seinem Zeitalter, durch reale Vorgänge, die sich in den Menschenseelen abspielten, in deren Reihen Augustinus stand als eine besonders hervorragende Persönlichkeit, Augustinus war einfach gezwungen, nicht mehr so bloß in der Seele zu erleben, wie ein Grieche erlebt hat; sondern er war gezwungen, zu sinnlichkeitsfreiem Denken aufzusteigen, zu einem Denken, das noch einen Inhalt behält, wenn es nicht reden kann von der Erde, von der Luft, vom Meer, von den Sternen, von Sonne und Mond, das einen unanschaulichen Inhalt hat. Und nach einem Göttlichen rang Augustinus, das einen solchen unanschaulichen Inhalt haben sollte. Und nun sprachen zu ihm nur Philosophien, Weltanschauungen, die eigentlich das, was sie ihm zu sagen hatten, von einem ganz anderen Gesichtspunkte aus sagten, nämlich von dem eben charakterisierten des Sinnlich-Übersinnlichen. Kein Wunder, daß, weil diese Seelen in unbestimmter Art strebten nach etwas, was noch nicht da war, und, wenn sie hinlangten wie mit geistigen Armen nach dem, was da war, sie nur finden konnten dasjenige, was sie nicht aufnehmen konnten, kein Wunder, daß diese Seelen zum Skeptizismus kamen!

Aber auf der anderen Seite war das Gefühl, auf einem sicheren Wahrheitsboden zu stehen und Aufschluß zu bekommen über die Frage nach dem Ursprung des Bösen, so stark in Augustinus, daß doch in seine Seele noch ebenso beträchtlich diejenige Weltanschauung hereingeleuchtet hat, die als Neuplatonismus am letzten Ausgange der griechischen philosophischen Entwickelung steht, namentlich in der Person des Plotin, und die uns auch historisch verrät — was im Grunde genommen nicht die Dialoge des Platon und am wenigsten die Aristotelische Philosophie verraten können -, wie das ganze Seelenleben dann verlief, wenn es eine gewisse Verinnerlichung, ein Hinausgehen über das Normale suchte. Plotin ist wie ein letzter Nachzügler einer Menschenart, die ganz andere Wege zur Erkenntnis, zum inneren Leben der Seele einschlug als dasjenige, was überhaupt nachher verstanden worden ist, wovon man nachher eine Ahnung entwickelt hat. Plotin steht so da, daß er dem heutigen Menschen eigentlich als Phantast erscheint.

Plotin erscheint gerade denjenigen, die mehr oder weniger in sich aufgenommen haben von der mittelalterlichen Scholastik, wie ein schrecklicher Schwärmer, ja, wie ein gefährlicher Schwärmer. Ich habe das wiederholt erleben können. Mein alter Freund Vincenz Knauer, der Benediktinermönch, der eine Geschichte der Philosophie geschrieben hat, und der auch ein Buch geschrieben hat über die Hauptprobleme der Philosophie von 'Thales bis Hamerling, war die Sanftmut selber. Dieser Mann schimpfte eigentlich nie zu andern Zeiten, als wenn man mit ihm über die Philosophie des Neuplatonismus, namentlich des Plotin, zu verhandeln hatte. Da wurde er bös und schimpfte sehr, fürchterlich über Plotin wie über einen gefährlichen Schwärmer. Und Brentano, der geistvolle Aristoteliker und Empiriker Franz Brentano, der aber auch die Philosophie des Mittelalters in einer außerordentlich tiefen und intensiven Weise in seiner Seele trug, er schrieb sein Büchelchen «Was für ein Philosoph manchmal Epoche macht», und da schimpft er eigentlich geradeso über Plotin, denn Plotin ist der Philosoph, der Mann, der nach seiner Meinung als ein gefährlicher Schwärmer am Ausgange des griechischen Altertums Epoche gemacht hat. Plotin zu verstehen, wird für den heutigen Philosophen tatsächlich außerordentlich schwer.

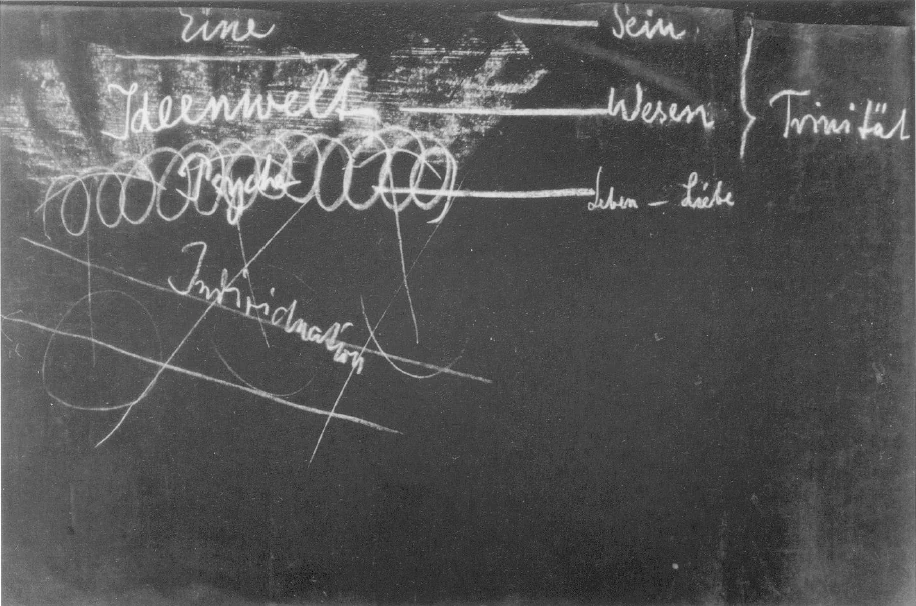

Von diesem Philosophen des dritten Jahrhunderts müssen wir zunächst sagen: Dasjenige, was wir als unseren Verstandesinhalt erleben, als unseren Vernunftinhalt erleben, was wir erleben als die Summe der Begriffe, die wir uns über die Welt machen, das ist für ihn durchaus nicht, was es für uns ist. Ich möchte sagen, wenn ich mich bildlich ausdrücken darf (es wird gezeichnet): Wir fassen die Welt auf durch Sinneswahrnehmungen, bringen dann durch Abstraktionen diese Sinneswahrnehmungen auf Begriffe und endigen so bei den Begriffen. Wir haben die Begriffe als inneres seelisches Erlebnis und sind uns, wenn wir Durchschnittsmenschen der Gegenwart sind, mehr oder weniger bewußt, daß wir ja Abstraktionen haben, etwas, was wir aus den Dingen wie herausgesogen haben. Das Wesentliche ist, wir endigen da; wir wenden unsere Aufmerksamkeit der Sinneserfahrung zu und endigen da, wo wir die Summe unserer Begriffe, unserer Ideen bilden.

Das war für Plotin nicht so. Für Plotin war diese ganze Welt der Sinneswahrnehmungen im Grunde genommen zunächst kaum vorhanden. Dasjenige aber, was für ihn etwas war, wovon er so sprach wie wir von Pflanzen, Mineralien, Tieren und physischen Menschen, das war etwas, was er nun über den Begriffen liegend sah, das war eine geistige Welt, und diese geistige Welt hatte für ihn eine untere Grenze. Diese untere Grenze waren die Begriffe. Während für uns die Begriffe dadurch gewonnen werden, daß wir zu den Sinnesdingen uns wenden, abstrahieren und die Begriffe uns bilden und sagen: Die Begriffe sind die Zusammenfassungen, die Extrakte ideeller Natur aus den Sinneswahrnehmungen -, sagte Plotin, der sich zunächst um die Sinneswahrnehmungen wenig kümmerte: Wir als Menschen leben in einer geistigen Welt, und dasjenige, was uns diese geistige Welt als ein Letztes offenbart, was wir wie ihre untere Grenze sehen, das sind die Begriffe.

Für uns liegt unter den Begriffen die sinnliche Welt; für Plotin liegt aber den Begriffen eine geistige Welt, die eigentliche intellektuelle Welt, die Welt des eigentlichen Geistesreiches. Ich könnte auch folgendes Bild gebrauchen: Denken wir uns einmal, wir wären in das Meer untergetaucht, und wir blicken hinauf bis zur Meeresoberfläche, sehen nichts als diese Meeresoberfläche, nichts über der Meeresoberfläche, so wäre die Meeresoberfläche die obere Grenze. Wir lebten im Meere, und wir hätten vielleicht eben in der Seele das Gefühl: Diese Grenze umschließt uns das Lebenselement, in dem wir sind —, wenn wir für das Meer organisierte Wesen wären.

Für Plotin war das anders. Er beachtete nicht dieses Meer um sich. Für ihn war aber seine Grenze, die er da sah, die Grenze der Begriffswelt, in der seine Seele lebte, die untere Grenze desjenigen, was über ihr war; also wie wenn wir die Meeresgrenze als die Grenze gegenüber dem Luftraum und der Wolkenwelt und so weiter auffassen würden. Für Plotin, der dabei durchaus für sich die Meinung hat, daß er die wahre, echte Anschauung des Plato fortsetzt, für Plotin ist dieses, was über den Begriffen liegt, zugleich dasjenige, was Plato die Ideenwelt nennt. Diese Ideenwelt ist zunächst durchaus etwas, wovon man als einer Welt spricht im i Sinne des Plotinismus.