The Philosophy of Thomas Aquinas

GA 74

23 May 1920, Dornach

II. The Essence of Thomism

The point I tried yesterday particularly to emphasize was that in the spiritual development of the West, which found its expression ultimately in the Schoolmen, not only is a part played by what we can grasp in abstract concepts, and what happened, as it were, in abstract concepts, and in a development of abstract thoughts, but rather that behind it all, there stands a real development of the impulses of Western mankind. What I mean is this: we can first of all, as happens mostly in the history of philosophy, direct our eyes on to what we find in each philosopher; we can follow how the ideas, which we find in a philosopher of the sixth, seventh, eighth or ninth century are further developed by philosophers of the tenth, eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries; and from such a review we can get the impression that one thinker has taken over the ideas from another, and that we are in the presence of a certain evolution of ideas. This is an historical review of spiritual life which had gradually to be abandoned. For what takes place there, what so to speak is revealed by the individual human souls, is merely a symptom of something deeper which lies behind the scenes of the outer events; and this something which was going on already a few centuries before Christianity was founded, and continued in the first centuries A.D.. up to the time of the Schoolmen, is an entirely organic process in the development of Western humanity. And unless we take this organic process into account, it is as impossible to get an explanation of it, as we could of the period of human development between the ages of twelve to twenty, if we do not consider the important influence of those forces which are connected with adolescence, and which at this time rise to the surface from the deeps of human nature. In the same way out of the depth of the whole great organism of European humanity there surges up something which can be defined—there are other ways of definition,—but which I will define by saying: Those ancient poets spoke honestly and sincerely, who, like Homer, for instance, began their epic poems: “Sing to me, Goddess, of the wrath of Achilles,” or “Sing to me, O Muse, of the much-travelled man.” These people did not wish to make a phrase, they found as an inner fact of their consciousness, that it was not a single, individual Ego that wanted to express itself, but what in fact they felt to be a higher spiritual-psychic force which plays a part in the ordinary conscious condition of man. And again—I mentioned it yesterday—Klopstock was right and saw this fact to a certain extent, even if only unconsciously, when he began his “Messiah Poem” not “Sing, O Muse,” or “Sing, O Goddess, of man's redemption,” but when he said “Sing, immortal Soul. ...” In other words, “Sing, thou individual being, that livest in each man as an individuality.” When Klopstock wrote his “Messiah,” this feeling of individuality in each soul was, it is true, fairly widespread. But this inner urge, to bring out the individuality, to shape an individual life, grew up most pronouncedly in the age between the foundation of Christianity and the higher Scholasticism. We can see only the merest surface-reflection in the thoughts of the philosophers of what was taking place in the depths of all human beings—the individualization of the consciousness of European people. And an important thing in the spread of Christianity throughout these centuries is the fact that the leaders of its propagation had to address themselves to a humanity which strove more and more, from the depth of its being, towards an inner feeling of human individuality.

We can understand the separate events that occurred in this epoch only by keeping this point of view before us. And only thus can we understand what battles took place in the souls of such people who, in the profundity of the human soul, wanted to dispute with Christianity on the one side and philosophy on the other, like Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas. The authors of the usual histories of philosophy to-day have understood so little of the true form of these soul-battles which had their culmination in Albertus and Thomas, that this epoch is only approximately clearly depicted in their histories. There are many things to consider in the soul-life of Albertus and Thomas.

Superficially it looks as if Albertus Magnus, who lived from the twelfth into the thirteenth century, and Thomas, who lived in the thirteenth, had wished only to harmonize dialectically Augustinism, of which we spoke yesterday, on the one hand, and Aristotelianism on the other. One was the bearer of the church ideas, the other of the modified philosophical ideas. The attempt to find assonance between them runs, it is true, like a thread through everything either wrote. But there was in everything which thus became fixed in thoughts as in a flowering of Western feeling and will, a great deal which did not survive into the period which stretches from the fifteenth century into our own day, a period from which we have drawn our customary ideas for all sciences and for the whole of our daily life.

The man of to-day finds it really paradoxical when he hears what we heard yesterday of Augustine's beliefs; that Augustine actually believed that a part of mankind was from the beginning destined to receive God's grace without earning it—for really after original sin all must perish—to receive God's grace and be spiritually saved; and that another part of mankind must be spiritually lost—no matter what it does. To a modern man this paradox appears perhaps meaningless. But if you can get the feeling of that age in which Augustine lived, in which he absorbed all those ideas and influences I described yesterday, you will think differently. You will feel that it is possible to understand that Augustine wanted to hold on to the thoughts which, as contained in the ancient philosophies, did not take the individual man into consideration; for they, under the influence of such ideas as those of Plotinus, which I outlined yesterday, had in their minds nothing but the idea of universal mankind. And you must remember that Augustine was a man who stood in the midst of the battle between the thought which regarded mankind as a unity, and the thought which was trying to crystallize the individuality of man out of this unified mankind. But in Augustine's soul there also surged the impulse towards individuality. For this reason, these ideas take on such significant aspects—significant of soul and heart; for this reason they are so full of human experience, and Augustine becomes the intensely sympathetic figure which makes so great an impression if we turn our eyes back to the centuries which preceded Scholasticism.

After Augustine, therefore, there survived for many—but only in his ideas—those links which held together the individual man as Christian with his Church. But these ideas, as I explained them to you yesterday, could not be accepted by those Western people who rejected the idea of taking the whole of humanity as one unity, and feeling themselves as it were only a member in it, moreover a member which belongs to that part of humanity whose lot is destruction and annihilation.

And so the Church saw itself compelled to snatch at a way out. Augustine still conducted his gigantic fight against Pelagius, the man who was already filled with the individuality-impulse of the West. This was the person in whom, as a contemporary of Augustine, we can see how the sense of individuality such as later centuries had it, appears in advance. So he can only say: There is no question but that man must remain entirely without participation in his destiny in the material-spiritual world. The power by which the soul finds the connection with that which raises it from the entanglements of the flesh to the serene spiritual regions, where it can find its release and return to freedom and immortality—this power must be born of man's individuality itself. This was the point which Augustine's opponents stressed, that each man must find for himself the power to overcome inherited sin. The Church stood half-way between the two opponents, and sought a solution. There was much discussion concerning this solution—all the pros and cons, as it were—and then they took the middle way—and I can leave it to you to judge if in this case it was the golden or the copper mean—at any rate they took the middle way: semi-Pelagianism. A formula was found which was really neither black nor white, to this effect: It is as Augustine has said, but not quite as Augustine has said; nor is it quite as Pelagius has said, though in a certain sense, it is as he has said. And so one might say, that it is not through a wise divine judgment, that some are condemned to sin and others to grace, but that the matter is this, that it is a case not of a divine pre-judgment, but of a divine prescience. The divine being knows beforehand if one man is to be a sinner or the other filled with grace. At the same time no further attention was paid, when this dogma was agreed, to the fact that at bottom it is in no way a question of prescience but rather a question of taking a definite stand, whether individual man is able to join with those powers in his individual soul-life which raise him up out of his separation from the divine-spiritual being of the world and which can lead him back to it.

In this way the question really remains unsolved. And I might say that, compelled on one side to recognize the dogmas of the Church but on the other filled from deepest sensibility with profound respect for the greatness of Augustine, Albertus and Thomas stood face to face with what came to be the Western development of the spirit within the Christian movement. And yet several things from earlier times left their influence. One can see them, for instance, when one looks carefully at the souls of Albertus and of Thomas, but one realizes also that they themselves were not quite conscious of it; that they enter into their thoughts, but that they themselves cannot bring them to a precise expression. We must consider this, ladies and gentlemen, more in respect of this time of the high Scholasticism of Albertus and Thomas, we must consider it more than we would have to consider a similar phenomenon, for instance, in our day. I have permitted myself to stress the “Why?” in my Welt-und Lebensanschauung des 19 Jahrhundert,—and it was further developed in my book Die Rätzel der Philosophie, where the proposition was put in another way so that the particular passage was not repeated, if I may be allowed to say so. This means—and it will occupy us in detail tomorrow, I will only mention it now—this means that from this upward-striving of individuality among the thinkers who studied philosophically that in these thinkers we get the highest flowering of logical judgment; we might say the highest flowering of logical technique.

Ladies and gentlemen, one can quarrel as one will about this or that party-standpoint on the question of Scholasticism—all this quarrelling is as a rule grounded on very little real understanding of the matter. For whoever has a sense of the manner quite apart from the subjective content in which the accuracy of the thought is revealed in the course of a scientific explanation—or anything else; whoever has a sense of appreciating how things that hang together are thought out together, which must be thought out together if life is to have any meaning; whoever has a sense of all this, and of several other things, realizes that thought was never so exact, so logically scientific, either before or afterwards as in the age of high Scholasticism. This is just the important thing, that pure thought so runs with mathematical certainty from idea to idea, from judgment to judgment, from conclusion to conclusion, that these thinkers account to themselves for the smallest, even the tiniest, step. We have only to remember in what surroundings this thinking took place. It was not a thinking that took place as it now takes place in the noisy world; rather its place was in the quiet cloister cell or otherwise far from the busy world. It was a thinking that absorbed a thought-life, and which could also, through other circumstances, formulate a pure thought-technique. It is to-day as a matter of fact difficult to do this; for scarcely do we seek to give publicity to such a thought-activity which has no other object than to array thought upon thought according to their content, than the stupid people come, and the illogical people raise all sorts of questions, interject their violent partisanship, and, seeing that one is after all a human being among human beings, we have to make the best of these things which are, in fact, no other than brutal interruptions, which often have nothing whatever to do with the subject in question. In these circumstances that inner quiet is very soon lost to which the thinkers of the twelfth or thirteenth centuries could devote themselves, who did not have to yield so much to the opposition of the uneducated in their social life.

This and other things called forth in this epoch that wonderfully plastic but also finely-outlined thought-activity which distinguishes Scholasticism and for which people like Augustine and Thomas consciously strove.

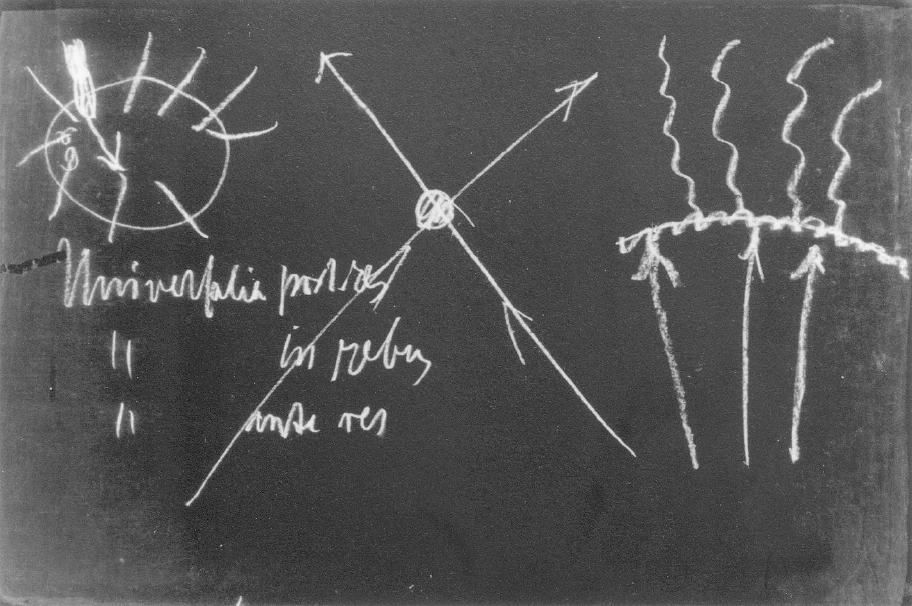

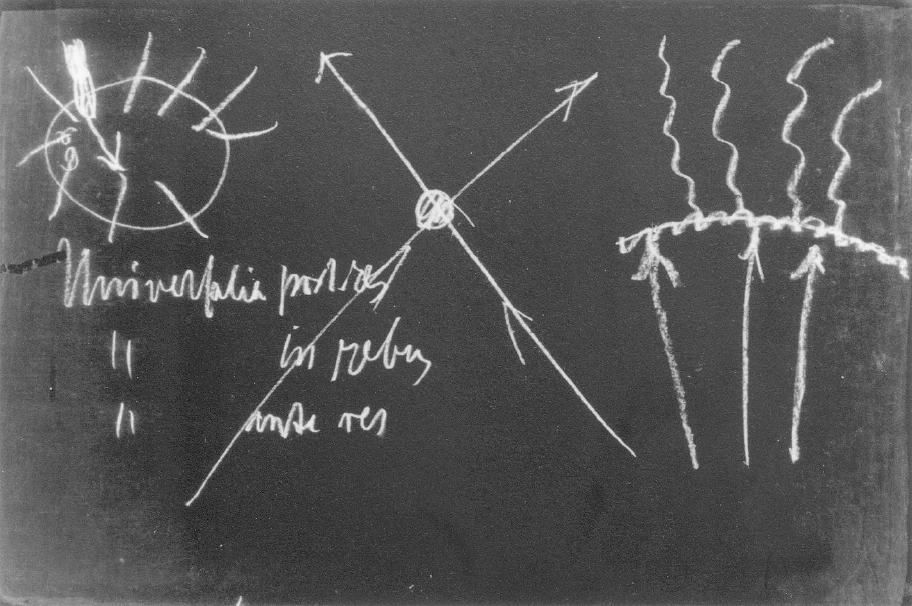

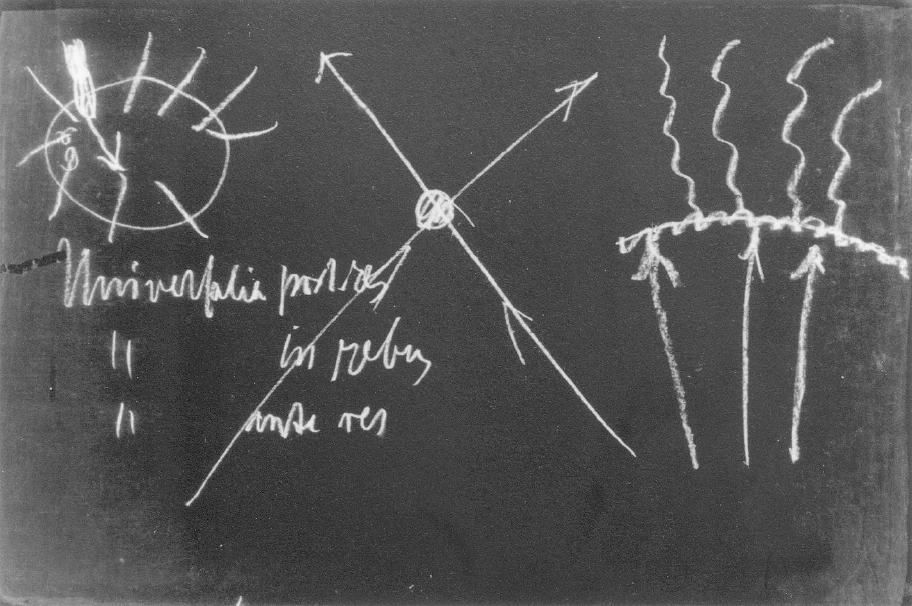

But now think of this: on the one side are demands of life which appear as if one had to do with dogmas that have not been made clear, which in a great number of cases resembled the semi-Pelagianism already described; and as if one fought in order to uphold what one believed ought to be upheld, because the Church justifiably had set it up; and as if one wanted to maintain this with the most subtle thought. Just imagine what it means to light up with the most subtle thought something of the nature of what I have described to you as Augustinism. One must look closely into the inside of scholastic effort and not only attempt to characterize this continuity from the Patristic age to the age of the Schoolmen from the threads of concepts which one has picked up. These spirits of High Scholasticism did a great deal half unconsciously and we can really only understand it, if we consider, looking beyond what I already described yesterday, such a figure as that which entered half mysteriously from the sixth century into European spiritual life and which became known under the name of Dionysius the Areopagite. To-day, because time is too short I cannot enter into all the disputes on the question of whether there is any truth in the view that these writings were first made in the sixth century, or whether the other view is right which ascribes at any rate the traditional element of these writings to a much earlier time. All that is after all not important, but the important thing is, that the philosophy of Dionysius the Areopagite was available for the thinkers of the seventh and eighth centuries right up to the time of Thomas Aquinas, and that these writings throughout have a Christian tinge and contain in a special form that which I yesterday defined as Plotinism, as the Neo-Platonism of Plotinus. And it had become particularly important for the Christian thinkers of the outgoing old world and the beginning of the Middle Ages up to the time of High Scholasticism, what attitude the author of the Dionysius writings took to the uprising of the human soul till it achieved a view of the divine. This Dionysius is generally described as if he had two paths to the divine; and as a matter of fact there are two. One path requires the following: if man wishes to raise himself from the external things which surround him in the world to the divine, he must attempt to extract from all those things their perfections, their nature; he must attempt to go back to absolute perfection, and must be able to give a name to absolute perfection in such a way that he has a content for this divine perfection which in its turn can reveal itself and can bring forth the separate things of the world by means of individualization and differentiation. So I would say, for Dionysius divinity is that being which must be given names to the greatest extent, which must be labelled with the most superlative terms which one can possibly find amongst all the perfections of the world; take all those, give them names and then apply them to the divinity and then you reach some idea of the divinity. That is one path which Dionysius recommends.

The other path is different. Here he says: you will never attain the divinity if you give it only a single name, for the whole soul-process which you employ to find perfections in things and to seek their essences, to combine them in order to apply the whole to divinity, all this never leads to what one can call knowledge of a divinity. You must reach a state in which you are free from all that you have known of things. You must purify your consciousness completely of all that you have experienced through things. You must no longer know anything of what the world says to you. You must forget all the names which you are accustomed to give to things and translate yourself into a condition of soul in which you know nothing of the whole world. If you can experience this in your soul-condition, then you experience the nameless which is immediately misunderstood if one attaches any name to it. Then you will know God, the Super-God in His super-beauty. But the names Super-God and super-beauty are already disturbing. They can only serve to point towards something which you must experience as nameless, and how can one deal with a character who gives us not one theology but two theologies, one positive, one negative, one rationalistic and one mystic? A man who can put himself into the spirituality of the time out of which Christianity was born can understand it quite well. If one pictures the course of human evolution even in the first Christian centuries as the materialists of to-day do, anything like the writings of the Areopagite appears more or less foolishness or madness. In this case they are usually simply rejected. If, however, one can put oneself into the experience and feeling of that time, then one realizes what a man like the Areopagite really wanted—at bottom only to express what countless people were striving for. Because for them the divinity was an unknowable being if one took only one path to it. For him the divinity was a being which had to be approached by a rational path through the finding and giving of names. But if one takes this one way one loses the path. One loses oneself in what is as it were universal space void of God. And then one does not attain to God. But one must take this way, for otherwise one can also not reach God. Moreover, one must take yet another way, namely, the one that strives towards the nameless one. By either road alone the divinity cannot be found, but by taking both one finds the divinity at the point where they cross. It is not enough to dispute which of the roads is the right one. Both are right, but each taken alone leads to nothing. Both roads when the human soul finds itself at the crossing lead to the goal. I can understand how some people of to-day who are accustomed to what is called polemics recoil from what is here advanced concerning the Areopagite. But what I am advancing here was alive in those men who were the leading spiritual personalities in the first Christian centuries, and continued traditionally in the Christian-philosophical movement of the West to the time of Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas. For instance, it was kept alive through that individual whose name I mentioned yesterday, Scotus Erigena, who lived at the court of Charles the Bald. This Scotus Erigena reminds one forcibly of what I said yesterday. I told you: I have never known such a meek man as Vincenz Knauer, the historian of philosophy. Vincenz Knauer was always meek, but he began to lose his temper when there was mention of Plotinus or anything connected with him; and Franz Brentano, the able philosopher, who was always conventional became quite unconventional and abusive in his book Philosophies that Create a Stir—referring to Plotinus.

Those who, with all their discernment and ability, lean more or less towards rationalism, will be angry when they are faced with what so to speak poured forth from the Areopagite to find a final significant revelation in this Scotus Erigena. In the last years of his life he was a Benedictine Prior, but his own monks, as the legend goes—I do not say it is literally true, but it is near enough—tortured him with pins till he died, because he introduced Plotinism even in the ninth century. But his ideas survived him and they were at the same time the continuation of the ideas of the Areopagite. His writings more or less disappeared till later days; then ultimately they reappeared. In the twelfth century Scotus Erigena was declared a heretic. But that did not mean as much then as it did later or does to-day. All the same, Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas were deeply influenced by the ideas of Scotus Erigena. That is the one thing which we must recognize as a heritage from former times when we wish to speak of the essence of Thomism.

But there is another thing. In Plotinism, which I tried to describe to you yesterday with regard to its Cosmology, there is a very important presentation of human nature which is derived from a material/super-material view. One really regains respect for these things if one discovers them again on a background of spiritual science. Then one admits at once the following: one says, if one reads something like Plotinus or what has come down to us of him, unprepared, it looks rather chaotic and intricate. But if one discovers the corresponding truths oneself, his views take on a quite special appearance, even if the method of their expression in those times was different from what it would have to be to-day. Thus, one can find in Plotinus a general view which I should describe as follows:

Plotinus considers human nature with its physical and psychic and spiritual characteristics. Then he considers it from two points of view, first from that of the soul's work on the body. If I spoke in modern terms, I should have to say: Plotinus says first of all to himself; if one considers a child that grows up in the world, one sees how that which is formed as human body out of the spiritual-psychic attains maturity. For Plotinus everything material in man is, if I may use an expression to which I trust you will not object, a “sweating out” of the spiritual-physic, a “crustation” as it were of the spiritual-psychic. But then, when a human being has grown to a certain point, the spiritual-psychic forces cease to have any influence on the body.

We could, therefore, say: at first we are concerned with such a spiritual-psychic activity that the bodily form is created or organized out of it. The human organization is the product of the spiritual-psychic. When a certain condition of maturity has been reached by some part of the organic activity, let us say, for example, the activity on which the forces are employed which later appear as the forces of the memory, then these forces which formerly have worked on the body, make their appearance in a spiritual-psychic metamorphosis. In other words, that part of the spiritual-psychic element which had functioned materially, now liberates itself, when its work is finished, and appears as an independent entity: a mirror of the soul, one would have to call it if one were to speak in Plotinus' sense. It is extraordinarily difficult with our modern conceptions to describe these things. You get near it, if you think as follows: you realize that a human being, after his memory has attained a certain stage of maturity, has the power of remembering. As a small child he has not. Where is this power of remembering? First it is at work in the organism, and forms it. After that it is liberated as purely spiritual-psychic power, and continues still, though always spiritual-psychically, to work on the organism. Then inside this soul-mirror inhabits the real vessel, the Ego. In characteristics, in an idea-content which is extraordinarily pictorial, these views are worked out from that which is spiritually active, and from that which then remains over, and becomes, as it were, passive towards the outer world—so that it takes up, like the memory, the impressions of the outer world and retains them. This two-fold work of the soul, this division of the soul into an active part, which practically builds up the body, and a passive part, derived from an older stratum of human growth and human attitude to the world, which found in Plotinus its best expression and then was taken up by Augustine and his successors, was described in an extraordinarily pictorial manner.

We find this view in Aristotelianism, but rationalized and translated into more physical conceptions. And Aristotle had it in his turn from Plato and again from the same sources as Plato. But when we read Aristotle we must say: Aristotle strives to put into abstract conceptions what he found in the old philosophies. And so we see in the Aristotelian system which continued to flourish, and which was the rationalistic form of what Plotinus had said in the other form, we see in this Aristotelianism which continued as far as Albertus and Thomas a rationalized mysticism, as it were, a rationalized description of the spiritual secret of the human being. And Albertus and Thomas are conscious of the fact that Aristotle has brought down to abstract conceptions something which the others had had in visions. And therefore they do not stand in the same relation to Aristotle as the present day philosopher-philologists, who have developed strange controversies over two conceptions which originate with Aristotle; but as the writings of Aristotle have not survived complete, we find both these conceptions in them without having their connection—which is after all a fact which affords ground for different opinions in many learned disputes. We find two ideas in Aristotle. Aristotle sees in human nature something which brings together into a unity the vegetative principle, the animal principle, the lower human principle, then the higher human principle, that Aristotle calls the nous, and the Scholiasts call the intellect. But Aristotle differentiates between the nous poieticos, and the nous patheticos, between the active and the passive spirit of man. The expressions are no longer as descriptive as the Greek; but one can say that Aristotle differentiates between the active understanding, the active spirit of man, and the passive. What does he mean? We do not understand what he means unless we revert to the origin of these concepts. Just like the other forces of the soul the two points of understanding are active in another metamorphosis in building up the human soul:—the understanding, in so far as it is actively engaged in building up the man, but still the understanding, not like the memory which comes to an end at a certain point and then liberates itself as memory—but working throughout life as understanding. That is the nous poieticos; the factor which in Aristotle's sense, becoming individualized out of the universe, builds up the body. It is no other than the active, bodybuilding soul of Plotinus. On the other hand, that which liberates itself, existing only in order to receive the outer world, and to form the impressions of the outer world dialectically, is the nous patheticos—the passive intellect—the intellectus possibilis. These things, presented to us in Scholasticism in keen dialectics and in precise logic, refer back to the old heritage. And we cannot properly understand the working of the Schoolmen's souls without taking into consideration this intermixture of age-old traditions.

Because all this had such an influence on the souls of the Scholiasts, they were faced with the great question which one usually feels to be the real problem of Scholasticism. At a time when men still had a vision which produced such a thing as Platonism or a rationalized version of it such as Aristotelianism, at a time when the sense of individuality had not yet reached its highest, these problems could not have existed; for what we to-day call understanding, what we call intellect, which had its origin in the terminology of Scholasticism, is the product of the individual man. If we all think alike, it is only because we are all individually constituted alike, and because the understanding is bound up with the individual which is constituted alike in all men. It is true that in so far as we are different beings we think differently; but that is a shade of difference with which logic as such is not concerned. Logical and dialectical thought is the product of the general human, but individually differentiated organization.

So man, feeling that he is an individual says to himself: in man arise the thoughts through which the outer world is inwardly represented; and here the thoughts are put together which in turn are to give a picture of the world; there, inside man, emerge on the one hand representations which are connected with individual things, with a particular book, let us say, or a particular man, for instance, Augustine. But then man arrives at the inner experiences, such as dreams, for which he cannot straightway find such an objective representation. The next step is the experience of pure chimaeras, which he creates for himself, just as here the centaur and similar things were chimaeras for Scholasticism. But, on the other hand, are the concepts and ideas which as a matter of fact reflect on to both sides: humanity, the lion-type, the wolf-type, etc.; these are general concepts which the Schoolmen according to ancient usage called the universals. Yes, as the situation for mankind was such as I described to you yesterday, as one rose, as it were, to these universals and perceived them to be the lowest border of the spiritual world which was being revealed through vision to mankind, these universals, humanity, animality, lion-hood, etc., were simply the means whereby the spiritual world, the intelligible world, revealed itself, and simply the soul's experience of an emanation from the supernatural world.

In order to have this experience it was essential not to have acquired that feeling of individuality which afterward developed in the centuries I have named. This sense of individuality led one to say: we rise from the things of the senses up to that border where are the more or less abstract things, which are, however, still within our experience—the universals such as humanity, lion-hood, etc. “Scholasticism” realized perfectly that one cannot simply say: these are pure conceptions, pure comprehensions of the external world:—rather, it became a problem for Scholasticism, with which it grappled. We have to create such general and universal conceptions out of our individuality. But when we look out upon the world, we do not have “humanity,” we have individual man, not “wolf-hood” but individual wolves. But, on the other hand, we cannot only see what we formulate as “wolf-hood” and “lamb-hood” as it were in such a way as if at one time we have formulated the matter as “agnine” and at another as “lupine,” and as if “lamb-hood” and “wolf-hood” were only a kind of composition and the material which is in these connected ideas were the only reality: we cannot simply assume this; for if we did we should have to assume this also:—If we caged a wolf and saw to it that for a certain period he ate nothing but lambs he is filled with nothing but lamb-matter; but he doesn't become a lamb; the matter doesn't affect it, he remains a wolf. “Wolf-hood” therefore is after all not something which is thus merely brought into contact with the material, for materially the whole wolf is lamb, but he remains a wolf.

There is to-day everywhere a problem which people do not take seriously enough. It was a problem with which the soul in its greatest development grappled with all its fibre. And this problem stood in direct connection with the Church's interests. How this was we can picture to ourselves if we consider the following:—

Before Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas appeared with their special exposition of philosophy, there had already been people, like Roscelin, for example, who had put forward the theory, and believed it implicitly, that these general concepts, these universals are really nothing else but the comprehension of external individual objects; they are really only words and names. And a Nominalism grew up which saw only words in general things, in universals. But Roscelin took Nominalism with dogmatic earnestness and applied it to the Trinity, saying: if something which is an association of ideas is only a word, then the Trinity is only a word, and the individuals are the sole reality—the Father, Son and Holy Ghost; then only the human understanding grasps these Three through a name. Mediaeval Churchmen stretched such points to the ultimate conclusions; the Church was compelled, at the Synod of Soissons, to declare this view of Roscelin partial polytheism and its teaching heretical. Thus one was in a certain difficult position towards Nominalism; it was a dogmatic interest which was linked with a philosophic one.

To-day we no longer take, of course, such a situation as something vital. But in those days it was regarded as most vital, and Thomas and Albertus grappled with just this question of the relationship of the universals to individual things; for them it was the supreme problem. Fundamentally, everything else is only a consequence, that is, a consequence in so far as everything else has taken its colour from the attitude they adopted towards this problem. But this attitude was influenced by all the forces which I have described to you, all the forces which remained as tradition from the Areopagite, which remained from Plotinus, which had passed through the soul of Augustine, through Scotus Erigena and many others—all this influenced the manner of thought which was now first revealed in Albertus and then, on a wide-reaching philosophic basis, in Thomas. And one knew also that there were people then who looked up beyond concepts to the spiritual world, to the intellectual world, to that world of which Thomism speaks as of a reality, in which he sees the immaterial intellectual beings which he calls angels. These are not just abstractions, they are real beings, but without bodies. It is these beings which Thomas puts in the tenth sphere. He looks upon the earth as encircled by the sphere of the Moon, of Mercury, of Venus, of the Sun, and so on, and so comes through the eighth and ninth spheres to the tenth, which was the Empyreum. He imagines all this pervaded by intelligences and the intelligences nearest are those which, as it were, let their lowest margins shine down upon the earth so that the human soul can get into touch with them.

But in this form in which I have just now expressed it, a form more inclined to Plotinism, this idea is not the result of pure individual feeling to which Scholasticism had just fought its way, but for Albertus and Thomas a belief remained that above abstract concepts there was up there a revelation of those abstract concepts. And the question faced them: What reality have, then, these abstract concepts? Now Albertus as well as Thomas had an idea of the influence of the psychic-spiritual on the physical body and the subsequent self-reflection of the psychic-spiritual when its work on the physical body was sufficiently performed: they had an idea of all this. Also they had an idea of what man becomes in his own individual life, how he develops from year to year, from decade to decade precisely through the impressions he receives and digests from the external world. Thus the thought came that though, of course, we have the external world all round us, this world is a revelation of something super-worldly, something spiritual. And while we look at the world and turn our attention to the separate minerals, plants, and animals, we surmise all the same that there lies behind them a revelation from higher spiritual worlds. And if we look at the natural world with logical analysis, with everything of which our soul makes us capable, with all the power of thought we possess, we arrive at those things which the spiritual world has implanted in the natural world. But then we must get clear on this point: we turn our eyes and all the other senses on to this world, and so are in definite relationship with the world. We then go away from it and retain, as it were, as a memory what we have absorbed from it. We look back once more into memory; and then there first appears to us really the universal, the generality of things, such as humanity, and so on; that appears to us first in the inner conceptual form. So that Albertus and Thomas say: if you look back, and if your soul reflects its experiences of the external world, then you have the universals preserved in it. Then you have universals. From all the human beings whom you have met, you form the concept of humanity. If you remembered only individual things you could, in any case, live only in earthly names. But as you do not live only in earthly names, you must experience the universals. There you have the universalia post res—the universals which live in the soul after the things have been experienced. While a man's soul concentrates on things, its contents are not the same as afterwards when it remembers them, when they are, as it were, reflected from inside, but rather he stands in a real relationship to the things. He experiences true spirituality of the things and translates them only into the form of universals post rem.

Albertus and Thomas assume that at the moment when man through his power of thought stands in real relationship with his surroundings, that is, not only with what is “wolf” because the eye sees and the ear hears it, but because he can meditate on it and formulate the type “wolf,” at this moment he experiences something which, though invisible, in the objects, is comprehended in thought independently of the senses. He experiences the universalia in rebus—the universals in things.

Now the difference is not quite easy to define, because we usually think that what we have in the soul as a reflection is the same in the things. But it is not the same in the sense of Thomas Aquinas. That which man experiences as an idea in his soul and explains with his understanding, is the same thing with which he experiences the real, and the universal. So that according to their form, the universals in the things are different from those after them, which remain then in the soul: but inwardly they are the same. There you have one of the scholastic concepts which one does not generally put to the soul in all its subtlety. The universals in things and the universals after things are, as far as content is concerned the same, and differ only in form. But then we must not forget that that which is distributed and individualized in things points in its turn to what I described yesterday as being inherent in Plotinism, and called the actually intelligible world: there again the same contents which are in things and in the human soul after things are, as far as content goes, alike, but different in form; they are contained in another form, but of similar content. These are the universalia ante res, before things. These are the universals as contained in the divine mind, and in the mind of the divine servants—the angelic beings. Thus what was for a former age a direct spiritual-sensory/super-sensory vision becomes a vision which was represented only in sense-images, because what one sees with the super-senses cannot, according to the Areopagite, be even given a name, if one wished to deal with it in its true form: one can only point to it and say: it is not anything such as external things are. Thus what was for the ancient's vision and appeared as a reality of the spiritual world, became for Scholasticism something to be decided by all that acuteness of thought, all that suppleness and nice logic of which I have spoken to you to-day. The problem which formerly was solved by vision, is brought down into the sphere of thought and of reason. That is the essence of Thomism, the essence of Albertinism, the essence of Scholasticism. It realized, above all, that in its epoch, the sense of human individuality has reached its culmination. It sees, above all, all problems in their rational and logical form, in the form, in fact, in which the thinker must comprehend them. Scholasticism grapples chiefly with this form of world-problems, this form of thinking, and thus stands in the midst of the life of the Church, which I illumined for you yesterday and to-day in many ways, if only with a few rays of light. There is the belief of the thirteenth and twelfth centuries; it is to be attained with thinking, with the most subtle logic; on the other side, are the traditional Church dogmas, the content of Faith.

Let us take an example of how a thinker like Thomas Aquinas stands to both. Thomas Aquinas asks: Can one prove the existence of God by logic? Yes, one can. He gives a whole series of proofs. One, for instance, is when he says: We can at first gain knowledge only by approaching the universalia in rebus, by looking into things. We cannot—it is the personal experience of this age—we cannot enter into the spiritual world through vision. We can only enter the spiritual world by using our human powers if we saturate ourselves in things, and get out of them what we can call the universalia in rebus. Then we can draw our conclusions concerning the universalia ante res. So he says: We see the world in movement; one thing always gives motion to another, because it is itself in motion. So we go from one thing in motion to another, and from this to a third thing in motion. This cannot be continued indefinitely, for we must get to a prime mover. But if this were itself in motion, we should have to proceed to another mover. We must, therefore, in the end reach a stationary mover.

And here Thomas—and Albertus comes after all to the same conclusion—reaches the Aristotelian stationary mover, the First Cause. It is inherent in logical thinking to recognize God as a necessary First Being, as a necessary first stationary mover. For the Trinity there is no such path of thought which leads to it. It is handed down. With human thought we can only reach the point of testing if the Trinity is contrary to sense. We find it is not, but we cannot prove it, we must believe it, we must accept it as a content, to which the unaided human intellect cannot rise.

This is the attitude of Scholasticism to the question which was then so important: How far can the unaided human intellect go? And in the course of time it became involved in quite a special way with this deep problem. For, you see, other thinkers had gone before. They had assumed something apparently quite absurd, they had said: it is possible for something to be true theologically and false philosophically. One could say straight out: it is possible for things to be handed down as dogma, as, for instance, the Trinity; yet if one ponders over the same question, one arrives at a contrary result. It is certainly possible for the reason to lead to other consequences than those to which the faith-content leads. And that was so, that was the other thing which faced Scholasticism—the doctrine of the double truth, and it is on this that the two thinkers Albertus and Thomas laid special stress, to bring faith and reason into harmony, to seek no contradiction between rational thought—at any rate, up to a certain point—and faith. In those days that was radicalism, for the majority of the leading Church authorities clung to the doctrine of the double truth, namely, that man must on one side think rationally, the content of his thought must be in one form, and faith could give it him in another form, and these two forms he had to keep.

I believe we can get a feeling of historical development if we consider the fact that people of so few centuries ago, as these are of whom we speak to-day, are wrapped up in such problems with their whole soul. For these things still reverberate in our time. We still live with these problems. How we do it, we shall discuss tomorrow. To-day I wanted to describe the essence of Thomism as it was in those days.

So it was, you perceive, that the main problem in front of Albertus and Thomas was this: What is the relation of the content of human reason to that of human faith? How can that which the Church ordains for belief be, first, understood, and secondly, upheld against what contradicts it? With this, people like Albertus and Thomas had much to do, for the movement I have described was not the only one in Europe; there were all sorts of others. With the spread of Islam and the Arabs other creeds made themselves felt in Europe, and something of that creed which I yesterday called the Manichaean had remained all over the continent. But there was also, for instance, what we know as “Representation” through the doctrine of Averroës from the twelfth century, who said: The product of a man's pure intellect belongs, not specially to him, but to all humanity. Averroës says: We have not each a mind; we each have a body, but not each a mind. A has his own body, but his mind is the same as B has and C has. We might say: Averroës sees mankind as with a single intellect, a single mind; all individuals are merged in it. There they live, as it were, with the head. When they die, the body is withdrawn from this universal mind. There is no immortality in the sense of individual continuation after death. What continues, is the universal mind, that which is common to all men.

For Thomas the problem was that he had to reckon with the universality of mind, but he had to take the point of view that the universal mind is not so closely united with the universal memory in separate beings, but rather during life with the active forces of the bodily organization; and so united, forming such a unity, that everything working in man as the formative vegetable, and animal powers, as the power of memory, is attracted, as it were, during life by the universal mind and disposition. Thus Thomas imagines it, that man attracts the individual through the universal, and then draws into the spiritual world what his universal had attracted; so that he takes it there with him. You perceive, there can be no pre-existence for Albertus Magnus and Thomas, though there can be an after-existence. This was, after all, the same for Aristotle, and in this respect Aristotelianism is also continued in these thinkers.

In this way the great logical questions of the universals join up with the questions which concern the world-destiny of each individual. And even if I were to describe to you the Cosmology of Thomas Aquinas and the natural history of Albertus, which is extraordinarily wide-reaching, over almost all provinces and in countless volumes, you would see everywhere the influence of what I called the general logical nature of Albertinism and Thomism. And this logical nature consisted in this: with our reason—what was then called the Intellect—we cannot attain all heights; up to a certain point we can reach everything through logical acumen and dialectic, but then we have to enter into the region of faith. Thus as I have described it, these two things stand face to face, without contradicting each other: What we understand with our reason, and what is revealed through faith can exist side by side.

What does this really entail? I believe we can tackle this question from very different sides. What have we here before us historically as the essence of Albertinism and of Thomism? It is really characteristic of Thomas, and important, that while he is straining reason to prove the existence of God, he has to add at the same time that one arrives at a picture of God as it was rightly represented in the Old Testament as Jahve. That is, when Thomas departs from the paths of reason open to the individual human soul, he arrives at that unified God whom the Old Testament calls the Jahve-God. If one wants to arrive at the Christ, one has to pass over to faith; the individual spiritual experience of the human soul is not sufficient to attain to Him.

Now in the arguments which Scholasticism had to face (the spirit of the age demanded it), in these theories of the double truth—that a thing could be theologically true and philosophically false—there still lay something deeper; something which perhaps could not be seen in an age in which everywhere rationalism and logic were the pursuit of mankind. And it was the following: that those who spoke of this double truth were not of the opinion that what is theologically revealed and what is to be reached by reason are ultimately two things, but for the time being they are two truths, and that man arrives at these two truths because he has to the innermost part of his soul, shared in the faith. In the background of the soul up to the time of Albertus and Thomas flows, as it were, this question: Have we not assumed original sin in our thought, in what we see as reason in ourselves? Is it not just because reason has fallen from its spirituality that it deceives us with counterfeit truth for the real truth? If Christ enters our reason, or something else which it transforms and develops further, then only is it brought into harmony with that truth which is the content of faith.

The sinfulness of the reason was, in a way, responsible for the thinkers before Albertus and Thomas speaking of two truths. They wanted to take the doctrine of original sin and redemption through Christ seriously. But they had not the thinking power and the logic for it, though they were serious about it. They put the question to themselves: How does Christ redeem in us the truth of the reason which contradicts revealed spiritual truth? How do we become Christians through and through? For our reason is already vitiated through original sin, and therefore it contradicts the pure truth of faith.

And now appeared Albertus and Thomas, and to them it appeared first of all wrong that if we steep ourselves purely logically in the universalia in rebus, and if we take to ourselves the reality in things, we should launch forth in sinfulness over the world. It is impossible that the ordinary reason should be sinful. In this scholastic question lies really the question of Christology. And the question Scholasticism could not answer was: How does Christ enter into human thought? How is human thought permeated with Christ? How does Christ lead human thought up into those spheres where it can coalesce with spiritual faith-content? These things were the real driving force in the souls of the Schoolmen. Therefore, it is before all things important, although Scholasticism possessed the most perfect logical technique not to take the results, but to look through the answer to the question; that we ignore the achievements of the men of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and look at the large problems which were then propounded. They were not yet far enough to be able to apply the redemption of man from original sin to human thought. Therefore, Albertus and Thomas had to deny reason the right to mount the steps which would have enabled them to enter into the spiritual world itself. And Scholasticism left behind it the question: How can human thought develop itself upward to a view of the spiritual world? The most important outcome of Scholasticism is even a question, and is not its existing content. It is the question: How does one carry Christology into thought? How is thought made Christ-like? At the moment when Thomas Aquinas died in 1274 this question, historically speaking, confronted the world. Up to that moment he had been able to get only as far as this question. What is to become of it, one can for the time being only indicate by saying: man penetrates up to a certain point into the spiritual nature of things, but after that point comes faith. And the two must not contradict each other; they must be in harmony. But the ordinary reason cannot of its own accord comprehend the content of the highest things, as, for example, the Trinity, the incarnation of the Christ in the man Jesus, etc. Reason can comprehend only as much as to say: the world could have been created in Time, but it could also have existed from eternity. But revelation says it has been created in Time, and if you ask Reason again you find the grounds for thinking that the creation in Time is the rational and the wiser answer.

Thus the Scholiast takes his place for all the ages. More than one thinks, there survives to-day in Science, in the whole public life of the present what Scholasticism has left to us, although it is in a particular form. How alive Scholasticism really is still in our souls, and what attitude man to-day must adopt towards it, of this we shall speak tomorrow.

2. Das Wesen Des Thomismus

Was ich mich gestern besonders hervorzuheben bemühte, das war, daß in jener geistigen Entwickelung des Abendlandes, die dann ihren Ausdruck in der Scholastik gefunden hat, nicht bloß dasjenige spielt, was man in abstrakten Begriffen erfassen kann und was sich etwa in abstrakten Begriffen, in einer Entwickelung abstrakter Begriffe vollzogen hat, sondern daß dahinter eine reale Entwickelung der Impulse der abendländischen Menschheit steht. Ich meine das so: Man kann zunächst, wie man ja das zumeist in der Philosophiegeschichte macht, den Blick auf dasjenige richten, was man bei den einzelnen Philosophenpersönlichkeiten findet. Man kann verfolgen, wie gewissermaßen die Ideen, die man bei einer Persönlichkeit des 6., 7., 8., 9. Jahrhunderts findet, dann fortgesponnen werden von Persönlichkeiten des io0., I1., 12., 13. Jahrhunderts, und man kann durch eine solche Betrachtung den Eindruck gewinnen, ein Denker habe von dem anderen gewisse Ideen übernommen und es liege eine gewisse Evolution von Ideen vor.

Das ist eine geschichtliche Betrachtung des geistigen Lebens, die allmählich verlassen werden müßte. Denn dasjenige, was sich so abspielt, was sich offenbart aus den einzelnen menschlichen Seelen heraus, das sind doch eigentlich nur Symptome für ein tieferes Geschehen, das gewissermaßen hinter der Szene der äußeren Vorgänge liegt. Und dieses Geschehen, das sich abspielte von etwa ein paar Jahrhunderten an schon bevor das Christentum begründet worden ist, dann in den ersten nachchristlichen Jahrhunderten bis in die Zeit der Scholastik hinein, ist ein ganz organischer Vorgang im Werden der abendländischen Menschheit. Ohne den Blick hinzurichten auf diesen organischen Vorgang, ist es ebenso unmöglich, darüber Aufschluß zu bekommen, wie über dasjenige, was Entwickelung, sagen wir vom zwölften bis zum zwanzigsten menschlichen Lebensjahre ist, wenn man nicht den wichtigen Einschlag in diesem Lebensalter ins Auge fassen würde, der mit der Geschlechtsreife und all den Kräften, die sich da aus den Untergründen der menschlichen Wesenheit heraufarbeiten, verbunden ist. So wühlt sich herauf aus den Tiefen dieses ganzen großen Organismus europäischer Menschheit etwas, was man eben dadurch charakterisieren kann - man könnte auch andere Charakteristiken erfinden —, daß man sagt: Sehr ehrlich und aufrichtig haben jene alten Dichter gesprochen, die etwa wie Homer begannen ihre epischen Gedichte: Singe mir, Göttin, den Zorn des Peleiden Achilleus —, oder: Singe mir, Muse, die Taten des vielgewanderten Mannes. - Diese Leute haben nicht eine Phrase sagen wollen, diese Leute haben empfunden als inneren Tatbestand ihres Bewußtseins, daß nicht ein einzelnes individuelles Ich sich da aussprechen will, sondern daß sich aussprechen will, was in der Tat empfunden wurde als ein höheres Geistig-Seelisches, das hereinspielt in den gewöhnlichen Bewußtseinszustand des Menschen.

Und wiederum - ich sagte es schon gestern — war Klopstock aufrichtig und durchschaute in einer gewissen Beziehung diesen Tatbestand, wenn auch vielleicht nur instinktiv, als er seine «Messias»-Dichtung begann; jetzt nicht: Singe, o Muse -, oder: Singe, o Göttin, von der Erlösung der Menschen —, sondern als er sagte: Singe, unsterbliche Seele -, also: Singe, individuelles Wesen, das in dem einzelnen Menschen als einer Individualität wohnt. - Als Klopstock seinen «Messias» schrieb, war allerdings dieses individuelle Fühlen in der einzelnen Seele schon weit vorgeschritten. Aber dieser innere Trieb, die Individualität herauszukehren, individuell das Leben zu gestalten, bildete sich im eminentesten Sinne in dem Zeitalter aus, das etwa von der Begründung des Christentums bis zu der Hochscholastik verläuft. In dem, was die Philosophen gedacht haben, kann man nur das Oberste sehen, dasjenige, was an die alleräußerste Oberfläche hinaufgeht von dem, was in den Tiefen der ganzen Menschheit sich vollzieht: das Individuellwerden des Bewußtseins europäischer Menschen. Und ein wesentliches Moment in der Verbreitung des Christentums durch diese Jahrhunderte ist die Tatsache, daß diejenigen, welche die Träger dieser Verbreitung waren, hineinsprechen mußten in eine Menschheit, die aus den Tiefen ihres Wesens heraus den Menschen immer mehr und mehr zu einem innerlichen Individuell-Erfühlen hindrängte.

Nur unter diesem Gesichtspunkte lassen sich die einzelnen Ereignisse verstehen, die sich in diesem Zeitalter vollziehen. Und auch nur mit dem Blick auf diese Tatsachen läßt sich verstehen, was an Seelenkämpfen in solchen Persönlichkeiten stattgefunden hat, die dann eben in den tiefsten Tiefen der Menschenseele sich auseinandersetzen wollten mit dem Christentum auf der einen Seite und mit der Philosophie auf der andern Seite, wie Albertus Magnus und Thomas von Aquino. Heute liegt den gebräuchlichen Philosophiegeschichtsschreibern viel zu wenig von den wahren Gestalten der Seelenkämpfe vor, die ihren letzten Abschluß gewissermaßen in Albert und Thomas gefunden haben, als daß dieses Zeitalter in den gebräuchlichen Philosophiegeschichten auch nur annähernd deutlich genug geschildert würde. Da spielt vieles herein in das Seelenleben des Albert und des Thomas.

Äußerlich sieht es so aus, als ob Albertus Magnus, der vom 12. ins 13. Jahrhundert hinüber lebte, und Thomas, der im 13. Jahrhundert lebte, nur gewissermaßen dialektisch hätten vereinigen wollen auf der einen Seite Augustinismus, von dem wir gestern gesprochen haben, und Aristotelismus. Der eine war der 'Träger der kirchlichen Ideen, der andere der Träger der ausgebildeten philosophischen Ideen. Den Einklang zwischen beiden zu suchen zieht sich allerdings wie ein Duktus hindurch durch all dasjenige, was die beiden geschrieben haben. Aber in alldem, was da in Gedanken fixiert wird wie in einer Blüte des abendländischen Fühlens und Wollens, lebt doch unendlich viel darinnen von dem, was dann nicht auf jenes Zeitalter übergegangen ist, das sich etwa von der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts bis in unsere Tage erstreckt, und aus dem wir unsere gebräuchlichen Ideen für alle Wissenschaften und auch für das gesamte öffentliche Leben entnehmen.

Dem heutigen Menschen erscheint es eigentlich nur wie etwas Paradoxes, wenn er hört, was wir gestern hören mußten von der Lebensanschauung des Augustinus: daß Augustinus tatsächlich der Anschauung war, daß ein Teil der Menschen von vornherein dazu bestimmt sei, die göttliche Gnade ohne Verdienst zu empfangen - denn eigentlich müßten sie nach der Erbsünde alle zugrunde gehen -, die göttliche Gnade zu empfangen und gerettet zu werden, seelisch-geistig gerettet zu werden; ein anderer Teil der Menschheit müsse seelisch-geistig zugrunde gehen, gleichgültig was er auch unternimmt. — Für den heutigen Menschen erscheint das paradox, vielleicht sogar sinnlos. Wer sich hineinfühlen kann in das Zeitalter, in dem Augustinus gelebt hat, in dem Augustinus all diejenigen Ideen und Empfindungen empfangen hat, die ich gestern charakterisierte, der wird anders fühlen. Der wird fühlen, daß man - noch dazu als ein Mensch wie Augustinus, der mittendrinnen stand in dem Kampfe zwischen dem Gedanken, der die ganze Menschheit als eine Einheit umfaßte, und jenem Gedanken, der die Individualität des Menschen herauskristallisieren wollte aus dieser einheitlichen Menschheit —, daß man es begreiflich finden kann, daß Augustinus auf diese Weise noch festhalten wollte an den Gedanken, die noch nicht als die altertümlichen Gedanken Rücksicht nahmen auf den einzelnen Menschen, die noch unter dem Einflusse solcher Ideen wie die des Plotinismus, den ich gestern charakterisiert habe, eben einzig und allein das Allgemeinmenschliche im Sinne hatten. Aber auf der anderen Seite wühlte auch in der Seele des Augustinus der Drang nach Individualität. Daher bekommen dieseIdeen eine so prägnante, seelen- und herzensmäßig prägnante Fassung, daher sind sie so erfüllt von menschlichem Erleben, und dadurch wird gerade Augustinus jene unendlich sympathische Gestalt, welche so tiefen Eindruck macht, wenn wir den Blick zurückwenden auf die Jahrhunderte, die der Scholastik vorangegangen sind.

Über Augustinus hinaus hat sich dann für viele dasjenige, was den einzelnen Menschen des Abendlandes als Christ zusammenhielt mit seiner Kirche — aber nur in den Ideen des Augustinus -—, erhalten. Nur waren diese Ideen, so wie ich sie Ihnen gestern gezeigt habe, eben nicht annehmbar für diese abendländische Menschheit, die den Gedanken nicht ertrug, die Gesamtmenschheit, das Einheitliche, als ein Ganzes zu nehmen und sich darinnen nur etwa zu fühlen wie ein Glied, noch dazu wie ein Glied, das zu dem Teil der Menschheit gehört, der dem Untergang, der Vernichtung verfallen ist. Und so sah sich die Kirche gedrängt, zu einem Ausweg zu greifen.

Augustinus führte noch seinen gewaltigen Kampf gegen den Pelagius, jenen Mann, der schon ganz erfüllt war von dem Individualimpuls des Abendlandes. Es war dies jene Persönlichkeit, bei der wir als einem Zeitgenossen des Augustinus sehen können, wie voraus erscheint das Sich-als-Individualität-Fühlen, wie es sonst erst die Menschen der späteren Jahrhunderte gehabt haben. Daher kann er nicht anders als sagen: Es kann keine Rede davon sein, daß der Mensch ganz unbeteiligt bleiben müsse an seinem Schicksal in der sinnlichen Welt; es muß aus der Menschenindividualität selbst herausgeboren werden können die Kraft, durch welche die Seele den Anschluß findet an das, was sie aus der Umstrickung der Sinnlichkeit erhebt in die reinen geistigen Regionen, wo sie ihre Erlösung und Rückkehr zur Freiheit und Unsterblichkeit finden kann. — Das war dasjenige, was Augustinus’ Gegner geltend machten: daß der einzelne Mensch die Kraft finden müsse, die Erbsünde zu überwinden.

Die Kirche stand mittendrinnen zwischen den beiden Gegnern, und sie suchte nach einem Ausweg. Dieser Ausweg wurde vielfach besprochen. Es wurde gewissermaßen hin und her geredet, und man ergriff dann die Mitte, und ich kann es jedem einzelnen von Ihnen überlassen, ob er diese Mitte in diesem Falle als die goldene Mitte oder als die kupferne Mitte ansieht. Man ergriff die Mitte: den Semipelagianismus. Man fand eine Formel, die eigentlich nicht recht Schwarz und nicht recht Weiß sagte, die verkündete: Es ist zwar so, wie Augustinus gesagt hat, aber es ist doch nicht ganz so, wie Augustinus gesagt hat; es ist auch nicht ganz so, wie Pelagius gesagt hat, aber es ist in einem gewissen Sinne auch so, wie er gesagt hat. Und so könne man sagen, daß zwar nicht durch einen weisheitsvollen ewigen Ratschluß der Gottheit die einen zur Sünde, die anderen zur Gnade verurteilt sind, daß die Menschen Anteil haben an ihrem Sündhaftwerden oder an ihrem Erfülltsein mit Gnade; aber die Sache sei denn doch so, daß zwar nicht eine göttliche Vorherbestimmung vorliege, aber ein göttliches Vorherwissen. Die Gottheit weiß vorher, ob der eine ein Sünder sein werde oder der andere ein Gnadenerfüllter sein werde.

Dabei wurde nicht weiter darauf Rücksicht genommen, als dieses Dogma verbreitet wurde, daß es sich im Grunde gar nicht um ein Vorherwissen handelte, sondern daß es sich darum handelte, klipp und klar Stellung zu nehmen zu dem, ob nun der einzelne individuelle Mensch sich verbinden kann mit den Kräften in seinem individuellen Seelenleben, die ihn herausheben aus seiner Trennung von dem göttlich-geistigen Wesen der Welt und ihn wieder zurückführen können zu dem göttlich-geistigen Wesen der Welt. So bleibt für das Dogmenwesen im Grunde genommen die Frage ungelöst, und ich möchte sagen: Auf der einen Seite genötigt, den Blick nach dem Dogmengehalt der Kirche zu richten, auf der anderen Seite aber aus innerster Empfindung heraus mit tiefster Verehrung für die Größe des Augustinus erfüllt, standen in der Hochscholastik Albertus und Thomas dem gegenüber, was sich als abendländische Geistesentwickelung innerhalb der christlichen Strömung ausbildete. Und hinein spielte doch noch manches aus früheren Zeiten. Es lebte fort so, daß man es sieht, wenn man genau hinblickt auf die Seele des Albertus, des Thomas, daß man es sieht auf dem Grunde ihrer Seele tätig sein, aber daß man auch einsieht, daß es ihnen selber nicht ganz vollbewußt ist, daß es in ihre Gedanken hineinspielt, daß sie es aber nicht zu einer präzisen Fassung bringen können.

Das muß man bedenken, mehr bedenken für diese Zeit der Hochscholastik des Albert und des Thomas, als man eine ähnliche Erscheinung zum Beispiel in unserer Zeit bedenken müßte. Das Warum habe ich mir schon erlaubt hervorzuheben in meinen «Welt- und Lebensanschauungen im neunzehnten Jahrhundert», die dann erweitert wurden zu meinem Buche «Die Rätsel der Philosophie», wo dann die Aufgabe anders gestellt war und daher die betreffende Stelle nicht wiederkehren konnte, wie ich mir noch erlauben will zu bemerken. Das gilt durchaus — und das wird uns morgen noch eingehend zu beschäftigen haben, jetzt will ich es nur erwähnen -, daß wir aus diesem Emporringen der Individualität bei den Denkern, die nun philosophisch ausbildeten dieses Emporringen der Individualität, dasjenige er-leben, was höchste Blüte logischer Urteilskraft ist, man könnte sagen höchste Blüte logischer Technik.

Man kann schimpfen wie man will von diesem oder jenem Parteistandpunkte über die Scholastik — all dieses Schimpfen ist in der Regel wenig von einer wirklichen Sachkenntnis erfüllt. Denn wer Sinn hat für die Art und Weise, wie sich, ganz abgesehen jetzt von.dem sachlichen Inhalt, der Scharfsinn der Gedanken abspielt bei irgend etwas, was wissenschaftlich oder sonst erklärt wird, wer Sinn dafür hat zu erkennen, wie Zusammenhänge zusammengedacht werden, die zusammengedacht werden müssen, wenn das Leben Sinn bekommen soll -, wer für alles das und für manches andere Sinn hat, für den geht es schon auf, daß so präzis, so innerlich logisch gewissenhaft niemals gedacht worden ist vorher, und nachher niemals gedacht worden ist als in der Zeit der Hochscholastik. Gerade das ist das Wesentliche, daß da das reine Denken mit mathematischer Sicherheit von Idee zu Idee, von Urteil zu Urteil, von Schlußfolgerung zu Schlußfolgerung so verläuft, daß über den kleinsten Schritt und über das kleinste Schrittchen diese Denker sich immer Rechenschaft geben.

Man muß nur bedenken, in welchem Milieu sich dieses Denken abspielte. Das war nicht ein Denken, das sich etwa so abspielte wie jetzt sich das Denken abspielt in der geräuschvollen Welt. Das war ein Denken, das sich abspielte in der stillen Klosterzelle oder sonst fern von dem Weltengetriebe. Das war ein Denken, das ganz aufging in dem Gedankenleben, und das war ein Denken, das auch noch durch andere Umstände die reine Denktechnik ausbilden konnte. Es ist heute tatsächlich schwer, diese reine Denktätigkeit auszubilden, denn kaum wird es irgendwie versucht, solche Denktätigkeit vor die Öffentlichkeit hinzustellen, die nichts anderes möchte als, durch ihren Inhalt bedingt, Gedanken an Gedanken reihen, dann kommen die unsachlichen Leute, die unlogischen Leute, greifen alles mögliche auf, werfen ihre brutalen Parteimeinungen entgegen. Und da man schon einmal ein Mensch unter Menschen ist, muß man sich auseinandersetzen mit diesen Dingen, die eigentlich nichts anderes sind als hineingeworfene Brutalitäten, die gar nichts zu tun haben oftmals mit demjenigen, um was es sich eigentlich handelt. Da ist sehr bald jene innere Ruhe verloren, der sich Denker des 12. und 13. Jahrhunderts hingeben konnten, die nicht auf den Widerspruch der Unvorbereiteten in ihrem sozialen Leben so außerordentlich viel zu geben brauchten.

Dieses und noch manches andere hat gerade in diesem Zeitalter jene auf der einen Seite wunderbare plastische, aber auch in feinen Konturen verlaufende Denktätigkeit hervorgerufen, welche die Scholastik kennzeichnet und welche namentlich bewußt angestrebt worden ist von Leuten wie Albertus und Thomas.

Aber nun bedenke man dieses: Auf der einen Seite sind Forderungen des Lebens da, die sich so ausnehmen, daß man es zu tun hat mit nicht ins Klaregebrachten Dogmen, was in zahlreichen Fällen ähnlich war dem charakterisierten Semipelagianismus, und daß man kämpfte, um aufrechtzuerhalten dasjenige, von dem man glaubte, daß es aufrechterhalten werden müsse, weil es die dazu berechtigte Kirche aufgestellt hat, daß man das aufrechterhalten wollte mit dem scharfsinnigsten Denken. Man stelle sich nur vor, was es heißt, gerade mit dem scharfsinnigsten Denken hineinzuleuchten in das, was so geartet war, wie ich es Ihnen nach dem Augustinismus charakterisieren mußte. Man muß schon in dieses Innere des scholastischen Strebens hineinschauen und nicht bloß am Faden der Begriffe, die man aufgelesen hat, diesen Hergang von der Parristik bis zu der Scholastik charakterisieren wollen.

Es spielte eben vieles halb Unbewußte in diese Geister der Hochscholastik hinein, und man kommt eigentlich nur zurecht, wenn man über das, was ich schon gestern charakterisiert habe, hinausblickend, noch etwa eine solche Gestalt ins Auge faßt wie die, die halb mysteriös vom sechsten Jahrhundert an in das europäische Geistesleben eintrat, die bekannt geworden ist unter dem Namen des Dionysius des Areopagiten. Ich kann heute, weil die Zeit dazu nicht ausreichen würde, nicht eingehen auf all die Streitigkeiten darüber, ob nun irgend etwas daran ist, daß diese Schriften erst im sechsten Jahrhundert verfaßt worden sind oder ob die andere Anschauung die richtige ist, die wenigstens das Traditionelle dieser Schriften in viel frühere Zeiträume zurückführt. Auf all das kommt es ja nicht an, sondern darauf kommt es an, daß vorlagen die Anschauungen des Dionysius des Areopagiten für die Denker des siebenten, achten Jahrhunderts bis noch in die Zeiten des Thomas von Aquino, und daß diese Schriften durchaus mit christlicher Nuance dasjenige in einer besonderen Gestalt enthielten, was ich Ihnen gestern als den Plotinismus, als den Neuplatonismus des Plotin charakterisiert habe, aber eben in einer besonderen Gestalt, durchaus mit christlicher Nuance. Und ganz besonders bedeutsam ist es geworden für die christlichen Denker des ausgehenden Altertums und des Beginnes des Mittelalters bis in die Mitte des Mittelalters, eben bis zur Hochscholastik, wie sich der Schreiber der Dionysiusschen Schriften verhalten hat zu dem Aufsteigen der menschlichen Seele bis zu einer Anschauung über das Göttliche.

Dieser Dionysius wird ja gewöhnlich so geschildert, als ob er zwei Wege zum Göttlichen hätte. Die hat er auch. Der eine Weg ist der, daß er verlangt: Wenn der Mensch aufsteigen will von den Außendingen, die uns umgeben in der Welt, zu dem Göttlichen, so muß er versuchen herauszufinden aus all den Dingen, die da sind, ihre Vollkommenbheiten, ihr Wesentliches, muß versuchen zurückzugehen zu dem Allervollkommensten, muß die. Möglichkeit haben, das Allervollkommenste so mit Namen zu benennen, daß er einen Inhalt hat für dieses Göttlich-Vollkommenste, der nun wiederum sich gleichsam ausgießen und durch Individualisierung und Differenzierung die einzelnen Dinge der Welt aus sich hervorbringen kann. — So, möchte man sagen, ist für diesen Dionysius die Gottheit diejenige Wesenheit, die mit den Namen im reichlichsten Umfange versehen werden muß, die belegt werden muß mit den Prädikaten, die man als auszeichnendste Prädikate nur herausfinden kann aus allen Vollkommenheiten der Welt, die man zusammenfinden kann: Nimm all das, was dir auffällt in den Dingen der Welt an Vollkommenbheit, benenne es und benenne dann damit die Gottheit, dann kommst du zu einer Vorstellung über die Gottheit. — Das ist der eine Weg, den Dionysius vorschlägt.

Der andere Weg ist, daß er sagt: Du erreichst die Gottheit nie, wenn du ihr auch nur einen einzigen Namen gibst, denn der ganze Seelenprozeß, der darauf hinausgeht, Vollkommenheiten in den Dingen zu finden, der darauf hinausläuft, das Wesenhafte der Dinge zu suchen, es zusammenzufassen, um es dann in dieser Zusammenfassung der Gottheit anzuheften, das führt niemals zu dem, was man Erkennen der Gottheit nennen kann. Du mußt so werden, daß du dich frei machst von alledem, was du in den Dingen erkannt hast. Du mußt dein Bewußtsein vollständig reinigen von alldem, was du an den Dingen erfahren hast. Du mußt nichts mehr wissen von demjenigen, was dir die Welt sagt. Du mußt alle Namen, die du gewohnt bist, den Dingen zu geben, vergessen und dich in einen Seelenzustand versetzen, wo du von der ganzen Welt nichts weißt. Wenn du das in deinem Seelenzustand erleben kannst, dann erlebst du den Namenlosen, der sofort verkannt wird, wenn man ihm irgendeinen Namen beilegt; dann erkennst du den Gott, den Übergott in seiner Überschönheit. Aber schon die Namen Übergott und Überschönheit würden störend sein. Sie können nur dazu dienen, dich hinzuweisen auf dasjenige, was du als Namenloses erleben mußt.

Wie kommt man zurecht mit einer Persönlichkeit, die einem nicht eine Theologie gibt, die einem zwei Theologien gibt, eine positive und eine negative, eine rationalistische und eine mystische Theologie? Wer sich eben hineinversetzen kann in die Geistigkeit der Zeitalter, aus denen heraus das Christentum geboren ist, der kommt ganz gut damit zurecht. Wenn man allerdings den Verlauf der Menschheitsentwickelung auch für die ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte so schildert, wie die heutigen Materialisten das tun, dann erscheint einem so etwas wie die Schriften des Areopagiten mehr oder weniger als Narretei, als Hirnverbranntheit. Dann weist man sie in der Regel aber auch einfach zurück. Wenn man aber sich hineinversetzen kann in das, was damals erlebt und erfühlt worden ist, dann sieht man ein, was ein Mensch wie der Areopagite eigentlich wollte: im Grunde genommen nur ausdrücken, was Unzählige anstrebten. Für sie war nämlich die Gottheit ein Wesen, das man überhaupt nicht erkennen konnte, wenn man nur einen Weg zu ihr einschlug. Für ihn war die Gottheit ein Wesen, dem man sich nähern mußte auf rationellem Wege durch Namengebung und Namenfindung. Aber geht man nur diesen einen Weg, dann verliert man den Pfad, dann verliert man sich in dasjenige, was gewissermaßen der gottentleerte Weltenraum ist. Dann gelangt man nicht zu Gott. Aber man muß ihn gehen, diesen Weg, denn ohne ihn zu gehen, kommt man auch nicht zu dem Gotte. Aber man muß noch einen anderen Weg gehen. Das ist eben der, der das Namenlose anstrebt. Geht man jeden allein, dann findet man ebensowenig die Gottheit; aber geht man beide, so kreuzen sie sich, und man findet in dem Durchkreuzungspunkte die Gottheit. Es genügt nicht, zu streiten darüber, ob der eine Weg oder der andere Weg richtig sei. Beide sind sie richtig; aber jeder einzelne, für sich gegangen, führt zu nichts. Beide gegangen führen, wenn die Menschenseele sich im Kreuzungspunkte findet, zu dem, was angestrebt wird.

Ich kann begreifen, wie manche Menschen der Gegenwart, die gewöhnt sind an das, was als Polemik gilt, zurückschrecken vor dem, was hier von dem Areopagiten gefordert wird. Aber dasjenige, was hier gefordert wird, das lebte bei den Menschen, die in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten die führenden geistigen Persönlichkeiten waren, und es lebte dann traditionell noch weiter fort in der christlich-philosophischen Strömung des Abendlandes, und es lebte bis auf Albertus Magnus und bis auf Thomas von Aquino. Es lebte zum Beispiel durch jene Persönlichkeit, deren Namen ich schon gestern genannt habe, durch den am Hofe Karls des Kahlen lebenden Scotus Erigena. Dieser Scotus Erigena erinnert einen lebhaft an dasjenige, was ich Ihnen gestern sagte: Ich habe nie einen so sanften Menschen gekannt wie Vincenz Knauer, den Philosophiegeschichtsschreiber. Vincenz Knauer war immer sanft, aber er fing an wie ein Rohrspatz zu schimpfen, wenn die Rede kam auf Plotin oder das, was Plotin ähnlich war. Und Franz Brentano, der geistreiche Philosoph, der immer feierlich war, er wurde ganz unfeierlich und schimpfte in seinem Buch «Was für ein Philosoph manchmal Epoche macht» -, er meint «Plotin».

Diejenigen, die mehr oder weniger, wenn auch mit Scharfsinn und Geistreichigkeit, dem Rationalismus zugeneigt sind, die werden schon schimpfen, wenn sie das zu Gesicht, zum geistigen Gesichte bekommen, was etwa da ausströmte von dem Areopagiten, und was dann eine letzte bedeutende Offenbarung fand in diesem Erigena. Er war in den letzten Lebensjahren noch Benediktinerprior. Aber seine eigenen Mönche haben ihn, wie die Sage sagt — die Sage; ich sage ja nicht, daß das wörtlich wahr ist, aber wenn es nicht ganz wahr ist, so ist es annähernd wahr —, die haben ihn so lange mit Stecknadeln bearbeitet, bis er tot war, weil er noch den Plotinismus hereinbrachte in das neunte Jahrhundert. Aber über ihn hinaus lebten seine Ideen, die zugleich die weitere Fortbildung der Ideen des Areopagiten waren. Seine Schriften sind mehr oder weniger bis in späte Zeiten hinein verschwunden gewesen; sie sind dann ja doch auf die Nachwelt gekommen. Im 12. Jahrhundert ist Scotus Erigena als Ketzer erklärt worden. Aber das hat ja noch nicht eine solche Bedeutung gehabt wie später und wie heute. Trotzdem sind Albertus Magnus und Thomas von Aquino tief beeinflußt auch von den Ideen des Scotus Erigena.