The Philosophy of Thomas Aquinas

GA 74

24 May 1920, Dornach

III. Thomism in the Present Day

Yesterday I endeavoured at the conclusion of our consideration of Scholasticism to point out how in a current of thought the most important things are the problems which presented themselves in a quite definite way to the human soul, and which, when you think of it, really all culminated in the desire to know: How does man attain the knowledge which is essential to his life, and how does this knowledge join up with that which at the time governed the dispositions of men in a social aspect? How does the knowledge which can be won join up with the contents of faith of the Christian Church in the West? The militant Scholiasts had to deal first of all with human individuality which, as we have seen, emerged more and more, but which was no longer in a position to carry the experience of knowledge up to the point of real, concrete, spirit-content, as it still flickered in the course of time from what survived of Neoplatonism, of the Areopagite, of Scotus Erigena. I have also pointed out that the impulses set in motion by Scholasticism still continued in a certain way. They continued, so that one can say: The problems themselves are great, and the manner in which they were propounded (we saw this yesterday) had great influence for a long time. And, in point of fact—and this is to be precisely the subject of to-day's study—the influence of what was then the greatest problem—the relationship of men to sensory and spiritual reality—is still felt, even if in quite a different form, even if it is not always obvious, and even if it takes to-day a form entirely contrary to Scholasticism. Its influence still lives. It is still all there to a large extent in the spiritual activities of to-day, but distinctly altered by the work of important people in the meantime on the European trend of human development in the philosophical sphere. We see at once, if we go from Thomas Aquinas to the Franciscan monk who originated probably in Ireland and at the beginning of the fourteenth century taught at Paris and Cologne, Duns Scotus, we see at once, when we get to him, how the problem has, so to speak, become too large even for all the wonderful, intensive thought-technique which survived from the age of the real master-ship in thought-technique—the age of Scholasticism. The question that again faced Duns Scotus was as follows: How does the psychic part of man live in the physical organism of man? Thomas Aquinas' view was still—as I explained yesterday—that he considered the psychic as working itself into the physical. When through conception and birth man enters upon the physical existence, he is equipped by means of his physical inheritance only with the vegetative powers, with all the mineral powers and with those of physical comprehension; but that without pre-existence the real intellect, the active intellect, that which Aristotle called the “nous poieticos” enters into man. But, as Thomas sees it, this nous poieticos absorbs as it were all the psychic element, the vegetative-psychic and the animal-psychic and imposes itself on the corporeality in order to transpose that in its entirety—and then to combine living for ever with what it had won, from the human body, into which it had itself entered, though without pre-existence, from eternal heights. Duns Scotus cannot believe that such an absorption of the whole dynamic system of the human being takes place through the active understanding. He can only imagine that the human bodily make-up exists as something complete; that the vegetative and animal principles remain through the whole of life in a certain independence, and are thrown off with death, and that really only the spiritual principle, the intellectus agens, enters into immortality. Equally little can he imagine the idea which Thomas Aquinas toyed with: the permeation of the whole body with the human-psychic-spiritual element*. Scotus can imagine it as little as his pupil William of Occam, who died at Munich in the fourteenth century, the chief thing about him being that he returned to Nominalism. For Scotus the human understanding had become something abstract, something which no longer represented the spiritual world, but as being won by reflection, by observation of the senses. He could no longer imagine that Reality was the product only of the universals, of ideas. He fell back again into Nominalism, and returned to the view that what establishes itself in man as ideas, as general conceptions, is conceived only out of the physical world around him, and that it is really only something which lives in the human spirit—I might say—for the sake of a convenient comprehension of existence—as Name, as words. In short, he returned again to Nominalism.

That is really a significant fact, for we see: Nominalism, as for instance Roscelin expounds it—and in his case the Trinity itself broke in pieces on account of his Nominalism—is interrupted only by the intensive thought activity of Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, and others, and then Europe soon relapses again into the Nominalism which is really the incapacity of human individuality, ever struggling to rise higher and higher to comprehend as a spiritual reality something which is present in its spirit in the form of ideas; so to comprehend it as something which lives in man and in a certain way also in things. Ideas, from being realities, become again Names, merely empty abstractions.

You see the difficulties which European thought encountered in greater and greater degree when it opened up the quest of knowledge. For in the long run we human beings must acquire knowledge through ideas—at any rate, in the first stages of knowledge we are bound to make use of ideas. The big question must always crop up again: How do ideas enable us to attain reality? But, substantially, an answer becomes impossible if ideas appear to us merely as names without reality. And these ideas, which in Ancient Greece, or, at any rate, in initiated Greece were the final demonstration, coming down from above, of a real spirit world, these ideas became ever more and more abstract for the European consciousness. And this process of becoming abstract, of ideas becoming words, we see perpetually increasing as we follow further the development of Western thought. Individuals stand out later, and for example Leibnitz, who actually does not touch upon the question whether ideas lead to knowledge. He is still in possession of a traditional point of view and ascribes everything to individual world-monads, which are really spiritual. Leibnitz towers over the others because he has the courage to expound the world as spiritual. Yes, the world is spiritual; it consists of a multitude of spiritual beings. But I might say that that particular thing which in a former age, with, it is true, a more distinctive knowledge not yet illuminated by such a logic as Scholasticism had, that moreover which meant in such an age differentiated spiritual individuals, was for Leibnitz a series of graduated spiritual points, the monads. Individuality is saved, but only in the form of the monads, in the form, as it were, of a spiritual, indivisible, elemental point. If we exclude Leibnitz, we see in the whole West an intensive struggle for certainty concerning the origins of existence, but at the same time an incapacity everywhere really to solve the Nominalism problem.

This is particularly met with in the thinker who is rightly placed at the beginning of the new philosophy, in the thinker Descartes, who lived at the opening or in the first half of the seventeenth century. We learn everywhere in the history of philosophy the basis of Cartesian philosophy in the sentence: Cogito ergo sum; I think, therefore I am. There is something of Augustine's effort in this sentence. For Augustine struggles out of that doubt of which I have spoken in the first lecture, when he says: I can doubt everything, but the fact of doubt remains and I live all the same while I doubt. I can doubt the existence of concrete things round me, I can doubt the existence of God, of clouds and stars, but not the existence of the doubt in me. I cannot doubt what goes on in my soul. There is something certain, a certain starting point to get hold of. Descartes takes up this thought again—I think, therefore I am. In such things one is, of course, exposed to grave misunderstandings, if one has to set something simple against something historically recognized. But it is necessary. Descartes and many of his followers—and in this respect he had innumerable followers—considers the idea: if I have a thought-content in any consciousness, if I think, I cannot get over the fact that I do think. Therefore, I am, therefore my existence is assured through my thinking. My roots are, so to speak, in the world-existence, as I have assured my existence through my thought. So modern philosophy really begins as Intellectualism, as Rationalism, as something which wants to use thought as its instrument, and to this extent is only the echo of Scholasticism, which had taken the turning towards Intellectualism so energetically.

Two things we observe about Descartes. First, there is necessarily the simple objection: Is my existence really established by the fact that I think? All sleep proves the contrary. We know every morning when we awake that we must have existed from the evening before to the morning, but we have not been thinking. So the sentence: I think, therefore I am—cogito ergo sum—is in this simple way disproved. This simple fact, which is, I might say, a kind of Columbus' egg, must be set against this famous sentence which found an uncommon amount of success. That is one thing to say about Descartes. The other is the question: What is the real objective of all his philosophic effort? It is no longer directed towards a view of life, or receiving a cosmic secret for the consciousness, it is really turned towards something entirely intellectualistic and concerned with thought. It is directed to the question: How do I gain certainty? How do I overcome doubt? How do I find out that things exist and that I myself exist? It is no longer a material question, a question concerned with the continual results of observing the world, it is a question rather that concerns the certainty of knowledge. This question arises out of the Nominalism of the Schoolmen, which only Albertus and Thomas suppressed for a certain time, but which after them appeared again. And so these people can only give a name to what is hidden in their souls in order to find somewhere in them a point from which they can make for themselves, not a picture or conception of the world, but the certainty that not everything is deception and untruth; that when one looks out upon the world one sees a reality and when one looks inward upon the soul one also sees a reality. In all this is clearly noticeable what I pointed to yesterday in conclusion, namely, that human individuality has arrived at intellectualism, but has not yet felt the Christ-problem. The Christ-problem occurs for Augustine because he still looks at the whole of humanity. Christ begins to dawn in the human soul, to dawn, I might say, on the Christian Mystics of the Middle Ages; but he does not dawn clearly on those who sought to find him by that thought which is so necessary to individuality—or by what this thought would produce. This process of thought as it comes forth from the human soul in its original condition is such that it rejects precisely what ought to have been the Christian idea for the innermost part of man; it rejects the transformation, the inner metamorphosis; it refuses to take the attitude towards the life of knowledge in which one would say: yes, I think and I think first of all concerning myself and the world. But this kind of thought is still very undeveloped. This thought is, as it were, the kind that exists after the Fall. It must rise above itself. It must be transformed and be raised into a higher sphere. As a matter of fact, this necessity has only once clearly flashed up in one great thinker, and that is in Spinoza, follower of Descartes. Spinoza really did make a deep impression on people like Herder and Goethe with good reason. For Spinoza, although he is still completely buried apparently in the intellectualism which survived or had survived in another form from the Scholiasts, still understands this intellectualism in such a way that man can finally come to the truth—which for Spinoza is ultimately a kind of intuition—by transforming the intellectual, inner, thinking, soul-life, not by being content with everyday life or the ordinary scientific life. And so Spinoza reaches the point of saying to himself: This thought replenishes itself with spiritual content through the development of thought itself.. The spiritual world, which we learned to know in Plotinism, yields again, as it were, to thought, if this thought tends to run counter to the spirit. Spirit replenishes thought as intuition. And I consider it is very interesting that this is what Spinoza says: If we survey the existence of the world, how it continues to develop in its highest substance, in spirit, how we then receive this spirit in the soul by raising ourselves by thought to intuition, by being so intellectualistic that we can prove things as surely as mathematics, but in the proof develop ourselves at the same time and continue to rise so that the spirit can come to meet us, if we can rise to this height, then, from this angle of vision we can comprehend the historic process of what lies behind the evolution of mankind. And it is remarkable that the following sentence stands out from the writings of the Jew Spinoza: The highest revelation of divine substance is given in Christ. In Christ intuition has become Theophany, the incarnation of God, and the voice of Christ is therefore in truth the voice of God and the path to salvation. In other words, the Jew Spinoza comes to the conclusion that man can so develop himself by his intellectualism, that the spirit comes down to him. If he is then in a position to apply himself to the mystery of Golgotha, then the filling with the spirit becomes not only intuition, that is, the appearance of the spirit through thought, but intuition changes into Theophany, into the appearance of God Himself. Man is on the spiritual path to God. One might say that Spinoza was not reticent about what he suddenly realized, as this expression shows. But it fills what he had thus discovered from the evolution of humanity with a kind of tune, a kind of undercurrent of sound, it completes his Ethics.

And once more it is taken up by a sensitive human being. We can realize that for somebody who could also certainly read between the lines of this Ethics who could sense in his own heart the heart that lives in this Ethics, in short, that for Goethe this book of Spinoza's became the standard. These things should not be looked at so purely abstractly, as is usually done in the history of philosophy. They should be viewed from the human standpoint, and we must look at the spark of Spinozism which entered Goethe's soul. But actually what can be read between Spinoza's lines did not become a dominating force. What became important was the incapacity to get away from Nominalism. And Nominalism next becomes such that one might say: Man gets ever more and more entangled in the thought: I live in something which the outer world cannot comprehend, a something which cannot leave me to sink into the outer world and take upon itself something of its nature. And so it is that this feeling, that one is so isolated, that one cannot get away from oneself and receive something from the outer world, is already to be found in Locke in the seventeenth century. Locke's formula was: That which we observe as colours, as tones in the outer world is no longer something which leads us to reality; it is only the effect of the outer world on our senses; it is something in which we ourselves are wrapped also, in our own subjectivity. That is one side of the question.

The other side is seen in such minds as that of Francis Bacon in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, where Nominalism becomes such a penetrating philosophy that it leads him to say: one must do away with man's false belief in a reality which is, in point of fact, only a name. We have reality only when we look out upon the world of the senses, which alone supply realities through empiric knowledge. By the side of these, those realities on which Albertus and Thomas have built up their theory of rational knowledge play no longer a really scientific part. In Bacon the spiritual world has, so to speak, evaporated into something which can no longer well up from man's inmost heart with the certainty and safety of a science. The spiritual world becomes the subject of faith, which is not to be touched by what is called knowledge and learning. On the contrary, knowledge is to be won only by external observation and by experiment, which is, after all, only a more spiritual kind of external observation.

And so it goes on till Hume, in the eighteenth century, for whom the connection between cause and effect becomes something which lives only in human subjectivity, which men attribute to things from a sort of external habit. We see that Nominalism, the heir of Scholasticism, weighs down humanity like a mountain. What is primarily the most important sign of this development?

The most important sign is surely this, that Scholasticism stands there with its hard logic, that it arises at a time when the sum of reason is to be divided off from the sum of truth concerning the spiritual world. The Scholiast's problem was, on the one hand, to examine this sum of truth concerning the spiritual world, which, of course, was handed down to him through the faith and revelation of the Church. On the other hand, he had to examine the possible results of man's own human knowledge. The point of view of the Scholiasts overlooked at first the change of front which the course of time and nothing else had made necessary. When Thomas and Albertus had to develop their philosophies, there was as yet no scientific view of the world. There had been no Galileo, Giordano Bruno, Copernicus or Kepler; the forces of human understanding had not yet been directed to external nature. At that time there was no cause for controversy between what the human reason can discover from the depth of the soul and what can be learned from the outer empiric sense-world. The question was only between the results of rational thought and the spiritual truths as handed down by the Church to men who could no longer raise themselves through individual development to this wisdom in its reality, but who saw it in the form handed down by the Church simply as tradition, as Scripture, etc. Does not the question now really arise: What is the relation between the rationalism, as developed by Albertus and Thomas in their theory of knowledge, and the teaching of the natural scientific view of the world? We may say that from now on the struggle was indecisive up to the eighteenth century.

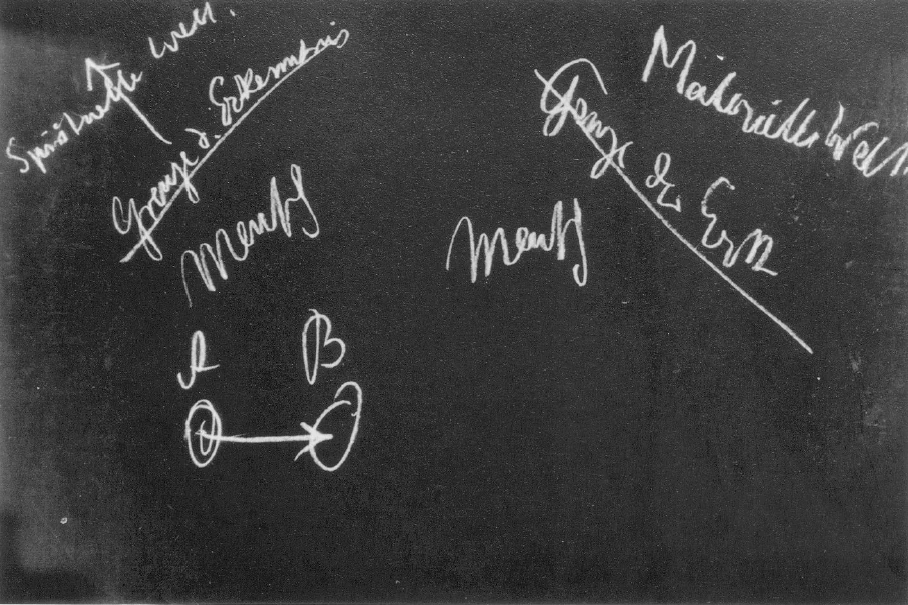

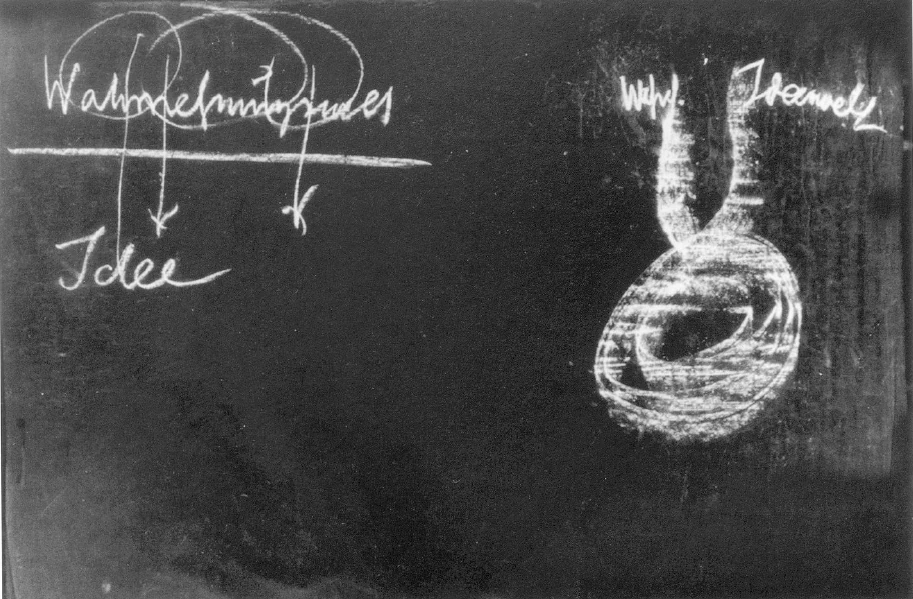

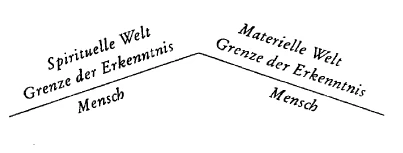

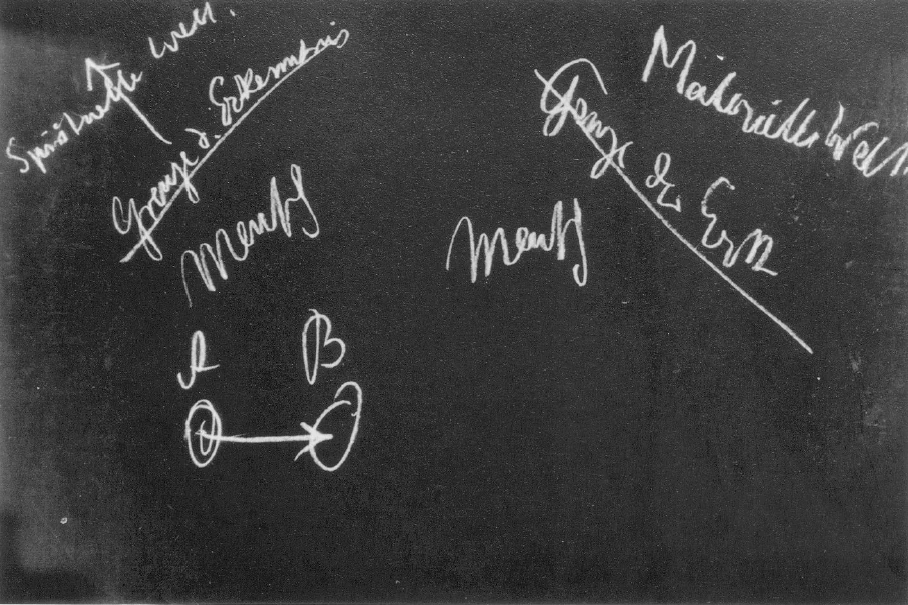

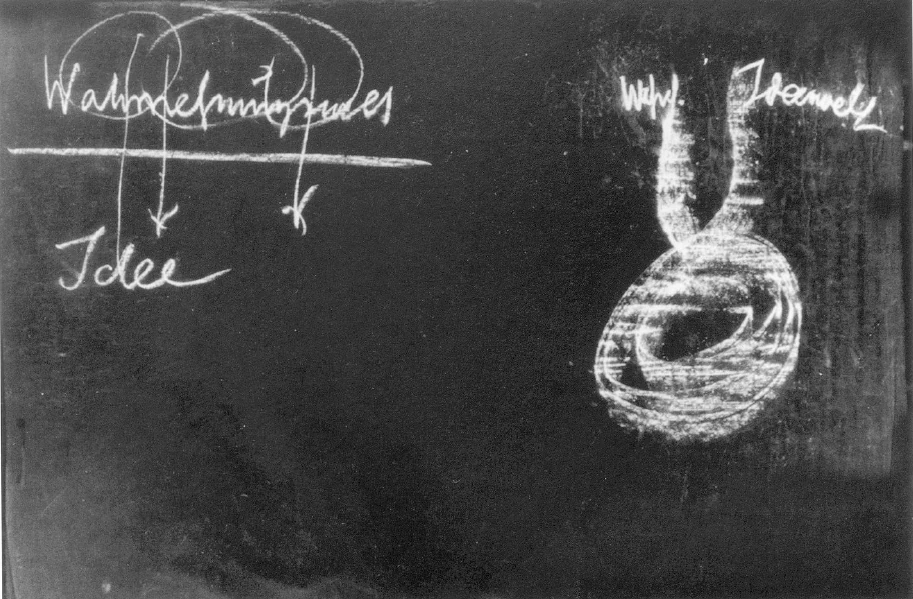

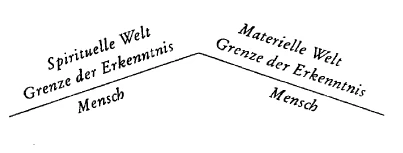

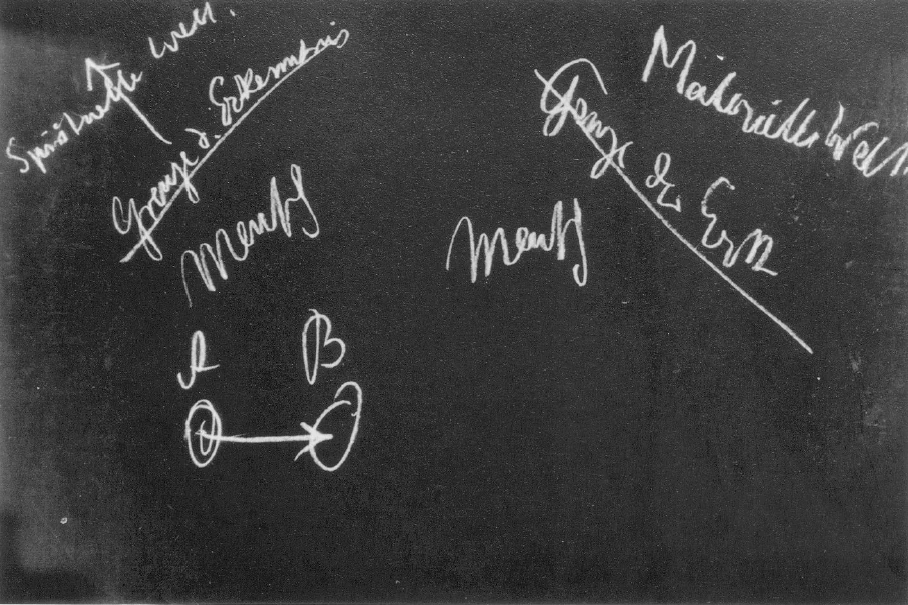

And here we find something very remarkable. When we look back into the thirteenth century and see Albertus and Thomas leading humanity across the frontiers of rational knowledge as contrasted with faith and revelation, we see how they show step by step that revelation yields only to a certain part of rational human knowledge, and remains outside this knowledge, an eternal riddle. We can count these riddles—the Incarnation—the filling with the Spirit at the Sacraments, etc.—which lie on the further side of human knowledge. As they see it, man stands on one side, surrounded as it were by the boundaries of knowledge, and unable to look into the spiritual world. This is the situation in the thirteenth century. And now let us take a look at the nineteenth century. We see a remarkable fact: in the seventies, at a famous conference of Natural Scientists at Leipzig, Dubois-Raymond gave his impressive address on the boundaries of Nature-Knowledge and soon afterwards on the seven world-riddles.

What has the problem now become? There is man, here is the boundary of knowledge; but beyond the boundary lies the material world, the atoms, everything of which Dubois-Raymond says: We do not know what this is that moves in space as material. And on this side lies that which is evolved in the human soul. Even if, compared with the imposing work which shines as Scholasticism from the Middle Ages, this contribution of Dubois-Raymond, which we find in the seventies is a trifle, still it is the real antithesis: there the search for the riddles of the spiritual world, here the search for the riddles of the material world; here the dividing line between human beings and atoms, there between human beings and angels and God. We must examine this gap of time if we want to see all this that crops up as a consequence, immediate or remote, of Scholasticism. From this Scholasticism the Kantian philosophy comes into being, as something important at best for the history of the period. This philosophy, influenced by Hume, still has to-day a hold on philosophers, since after its partial decline, the Germans raised the cry in the sixties, “Back to Kant!” And from that time an uncountable number of books on Kant have been published, and independent Kantians like Volkelt, Cohen, etc.—one could mention a whole host—have appeared.

To-day we can, of course, give only a sketch of Kant; we need only point out what is important in him for us. I do not think that anyone who really studies Kant can find him other than as I have tried to depict him in my small paper Truth and Knowledge. At the end of the sixties and beginning of the seventies of the eighteenth century Kant's problem is not the content-problem of world-philosophy in full force, not something which might have appeared for him in definite forms, images, concepts, and ideas concerning objects, but rather his problem is the formal knowledge-question: How do we gain certainty concerning anything in the outer world, concerning the existence of anything? Kant is more worried about certainty of knowledge than about any content of knowledge. One feels this surely in his Critic. Read his “Critic of Pure Reason,” his “Critic of Practical Reason,” and see how, after the chapter on Space and Time, which is in a sense classic, you come to the categories, enumerated entirely pedantically, only, we may say, to give the whole a certain completeness. In truth the presentation of this “Critic of Pure Reason” has not the fluency of someone writing sentence on sentence with his heart's blood.

For Kant the question of what is the relation of what we call concepts, of what is in fact, the whole content of knowledge to an external reality, is much more important than this content of knowledge itself. The content he pieces together, as it were, from everything philosophic which he has inherited. He makes schemes and systems. But everywhere the question crops up: How does one get certainty, the kind of certainty which one gets in mathematics? And he gets such certainty in a manner which actually is nothing else than Nominalism, changed, it is true, and unusually concealed and disguised—a Nominalism which is stretched to include the forms of material nature, space and time, as well as universal ideas. He says: that particular thing which we develop in our soul as the content of knowledge has nothing really to do with anything we derive from things. We merely make it cover things. We derive the whole form of our knowledge from ourselves. If we say event A is related to event B by the principle of causation, this principle is only in ourselves. We make it cover A and B, the two experiences.

We apply causality to things. In other words, paradoxical though it sounds—though it is paradoxical only historically in face of the vast following of Kant's philosophy—we shall have to say: Kant seeks the principle of certainty by denying that we derive the content of our knowledge from things and assuming that we derive it from ourselves and then apply it to things. This means—and here is the paradox—we have truth, because we make it ourselves, we have subjective truth, because we produce it ourselves. And it is we who instil truth into things. There you have the final consequence of Nominalism. Scholasticism strove with universals, with the question: What form of existence do the ideas we have in ourselves, have in the outer world? It could not arrive at a real solution of the problem which would have been completely satisfactory. Kant says: All right. Ideas are merely names. We form them only in ourselves but we see them as names to cover things; whereby they become reality. They may not be reality by a long way, but I push the “name” on to the experience and make it reality, for experience must be such as I ordain by applying to it a “name.”

Thus Kantianism is in a certain way the expansion of Nominalism, in a certain way the most extreme point and in a certain way the extreme collapse of Western philosophy, the complete bankruptcy of man in regard to his search for truth, despair that one can in any way learn truth from things. Hence the saying: Truth can exist only in things if we ourselves instil it into them. Kant has destroyed all objectivity and all man's possibility of getting down to the truth in things. He has destroyed all possible knowledge, all possible search for truth, for truth cannot exist only subjectively.

This, ladies and gentlemen, is a consequence of Scholasticism, because it could not acquiesce in the other side, where there appeared another boundary to be crossed. Just because there emerged the age of Natural Science, to which Scholasticism did not adapt itself, Kantianism came on the scene, which ended really as subjectivity, and then from subjectivity in which it extinguished all knowledge, sprouted the so-called Postulates—Freedom, Immortality, and the Idea of God. We are meant to do the good, to obey the categoric imperative, and so we must be able to. That is, we must be free, but as we live here in the physical body, we cannot be. We do not attain perfection so that we may carry out the categoric imperative, till we are clear of the body. Therefore, there must be immortality. But even then we cannot realize it as human beings. Everything we are concerned with in the world, if we do what we ought to, can be regulated only by a Godhead. Therefore, there must be a Godhead. Three postulates of faith, whose source in Reality it is impossible to know—such is the extent of Kant's certainty, according to his own saying: I had to annihilate knowledge in order to make room for faith. And Kant now does not make room for faith-content in the sense of Thomas Aquinas, for a traditional faith-content, but for an abstract one: Freedom, Immortality, and the Idea of God; for a faith-content brought forth from the human individual dictating truth, that is, the appearance of it.

So Kant becomes the fulfiller of Nominalism. He is the philosopher who really denies man everything he could have which would enable him to get down to any kind of Reality. This accounts for the rapid reaction against Kant which for example, Fichte, and then Schelling, and then Hegel produced, and other thinkers of the nineteenth century. You need only look at Fichte and see how he was necessarily urged on to an experience of the soul that became more intensive and, one might say, ever more and more mystical in order to escape from Kantianism. Fichte could not even believe that Kant could have meant what is contained in the Kantian Critics. He believed at the beginning, with a certain philosophic naïveté that he drew only the final conclusion of the Kantian philosophy. His idea was that if you did not draw the “final conclusions,” you would have to believe that this philosophy had been pieced together by a most amazing chance, certainly not by a thoughtful human brain. All this is apart from the movement in Western civilization caused by the growth of Natural Science, which enters upon the scene as a reaction in the middle of the nineteenth century. This movement takes no count at all of Philosophy and therefore degenerated in many thinkers into gross materialism. And so we see how the philosophic development goes on, unfolding itself into the last third of the nineteenth century. We see this philosophic effort coming completely to nothing and we see then how the attempt came about, from every possibility which one could find in Kantianism and similar philosophies, to understand something of what is actually real in the world. Goethe's general view of life which would have been so important, had it been understood, was completely lost for the nineteenth century, except among those whose leanings were toward Schelling, Hegel and Fichte. For in this philosophy of Goethe's lay the beginning of what Thomism must become, if its attitude towards Natural Science were changed, for he rises to the heights of modern civilization, and is, indeed, a real force in the current of development.

Thomas could get no further than the abstract affirmation that the psychic-spiritual really has its effect on every activity of the human organism. He expressed it thus: Everything, even the vegetative activities, which exists in the human body is directed by the psychic and must be acknowledged by the psychic. Goethe makes the first step in the change of attitude in his Theory of Colour, which in consequence is not in the least understood; in his Morphology, in his Theory of Plants and Animals. We shall, however, not have a complete fulfilment of Goethe's ideas till we have a spiritual science which can of itself provide an explanation of the facts of Natural Science.

A few weeks ago I tried here to show how our spiritual science is seeking to range itself as a corrective side by side with Natural Science—let us say with regard to the theory of the heart. The mechanico-materialistic view has likened the heart to a pump, which drives the blood through the human body. It is the opposite; the blood circulation is living—Embryology can prove it, if it wishes—and the heart is set in action by the movement of the blood. The heart is the instrument by which the blood-activity ultimately asserts itself, by which it is absorbed into the whole human individuality. The activity of the heart is a result of blood-activity, not vice-versa. And so, as was shown here in detail in a Course for Doctors we can show with regard to each organ of the body, how the realization of man as a spirit-being really explains his material element. We can in a way make real the thing that appeared dimly in abstract form to Thomism, when it said: The spiritual-psychic permeates all the physical body. That becomes concrete, real knowledge. The Thomistic philosophy, which in the thirteenth century still had an abstract form, by rekindling itself from Goethe continues to live on in our day as Spiritual Science.

Ladies and gentlemen, if I may interpose here a personal experience, it is as follows: it is meant merely as an illustration. When at the end of the eighties I spoke in the “Wiener Goethe-Verein” on the subject “Goethe as the Father of a New Aesthetic,” there was in the audience a very learned Cistercian. I can speak about this address, for it has appeared in a new edition. I explained how one had to take Goethe's presentation of Art, and then this Father Wilhelm Neumann, the Cistercian, who was also Professor of Theology at Vienna University, made this curious remark: “The germ of this address, which you have given us to-day, lies already in Thomas Aquinas!” It was an extraordinarily interesting experience for me to hear from Father Wilhelm Neumann that he found in Thomas something like a germ of what was said then concerning Goethe's views on Aesthetics; he was, of course, highly trained in Thomism, because it was after the appearance of Neo-Thomism within the Catholic clergy. One must put it thus: The appearance of things when seen in accordance with truth is quite different from the appearance when seen under the influence of a powerless nominalistic philosophy which to a large extent harks back to Kant and the modern physiology based on him. And in the same way you would find several things, if you studied Spiritual Science. Read in my Riddles of the Soul which came out many years ago, how I there attempted as the result of thirty years' study, to divide human existence into three parts, and how I tried to show there, how one part of the physical human body is connected with the thought and sense organization; how the rhythmic system, all that pertains to the breathing and the heart activity, is connected with the system of sensation, and how the chemical changes are connected with the volition system: the attempt is made, throughout, to recover the spiritual-psychic as creative force. That is, the change of front towards Natural Science is seriously made. After the age of Natural Science, I try to penetrate into the realm of natural existence, just as before the age of Scholasticism, of Thomism—we have seen it in the Areopagite and in Plotinus—human knowledge was used to penetrate into the spiritual realm. The Christ-principle is dealt with seriously after the change of front—as it would have been, had one said: human thought can change, so that it really can press upwards, if it discards the inherited limitation of knowledge and develops through pure non-sensory thought upward to the spiritual world. What we see as Nature can be penetrated as the veil of natural existence. One presses on beyond the limit of knowledge, which a dualism believed it necessary to set up, as the Schoolmen set up the limit on the other side—one penetrates into this material world and discovers that this is in fact the spiritual world, that behind the veil of Nature there are in truth not material atoms, but spiritual beings. This shows you how progressive thought deals with a continued development of Thomism in the Middle Ages. Turn to the most important abstract psychological thoughts of Albertus and Thomas. There, it is true, they do not go so far as to say concerning the physical body, how the spirit or the soul react on the heart, on the spleen, on the liver, etc., but they point out already that the whole human body must be considered to have originated from the spiritual-psychic. The continuation of this thought is the task of really tracing the spiritual-psychic into each separate part of the physical organization. Philosophy has not done this, nor Natural Science: it can only be done by a Spiritual Science, which does not hesitate to bring into our time thoughts, such as those of the high Scholiasts which are looked upon as great thoughts in the evolution of humanity, and apply them to all the contributions of our time in Natural Science. It necessitates, it is true, if the matter is to have a scientific basis, a divorce from Kantianism.

This divorce from Kantianism I have attempted first in my small book Truth and Science, years ago, in the eighties, in my Erkenntnistheorie der Goetheschen Weltanschauung, and then again in my The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. Quite shortly and without consideration for the fact that things, when they are cursorily presented appear difficult, I should like to put before you the basic ideas to be found in these books. They start from the thought that truth cannot directly be found, at any rate in the observed world which is spread round about us. We see in a way how Nominalism infects the human soul, how it can assume the false conclusions of Kantianism, but how Kant certainly did not see the point with which these books seriously deal. This is, that a study of the visible world, if undertaken quite objectively and thoroughly leads to the knowledge that this world is not a whole. This world emerges as something which is real only through us. What, then, caused the difficulty of Nominalism? What gave rise to the whole of Kantianism? This, the visible world is taken and observed and then we spread over it the world of ideas through the soul-life. Now there we have the view, that this idea-world is to reproduce external observations. But the idea-world is in us. What has it to do with what is outside? Kant could answer this question only thus: By spreading the idea-world over the visible world, we make truth.

But it is not so. It is like this. If we consider the process of observation with an unprejudicial mind, it is incomplete, it is nowhere self-contained. I tried hard to prove this in my book Truth and Science, and afterwards in aThe Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. As we have been placed in the world, as we are born into it, we split the world in two. The fact is that we have the world-content, as it were, here with us. Since we come into the world as human beings, we divide the world-content into observation, which appears to us from outside, and the idea-world which appears to us from the inner soul. Anyone who regards this division as an absolute one, who simply says: there is the world, here am I—such a one cannot cross at all with his idea-world to the external world. The matter is this: I look at the visible world, it is everywhere incomplete. Something is wanting everywhere. I myself have with my whole existence arisen out of the world, to which the visible world also belongs. Then I look into myself, and what I see thus is just what is lacking in the visible world. I have to join together through my own self, since I have entered the world, what has been separated into two branches. I gain reality by working for it. Through the fact that I was born arises the appearance that what is really one is divided into two branches, outward perception and idea world. By the fact that I am alive and grow, I unite the two currents of reality. I work myself to reality by my acquiring knowledge. I should never have become conscious if I had never, through my entry into the world, separated the idea-world off from the outer world of perception. But I should never find the bridge to the world, if I did not bring the idea-world, which I have separated off, into unity again with that which, without it, is no reality.

Kant seeks reality only in outer perception and does not see that the other half of this reality is in us. The idea-world which we have in us, we have first torn from external reality. Nominalism is now at an end, for now we do not spread Space and Time and ideas, which are only “Nomina” over our external perception, but we return to it in our knowledge what we took from it on entering into our earth existence.

Thus is revealed to us the relation of man to the spiritual world in a purely philosophical form. And he who reads my The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, which rests entirely on the basis of this knowledge-theory of the nature of reality, of this transference of life into reality through human knowledge, he who takes up this basis, which is expressed already in the title of Truth and Science, that real science unites perceptions and the idea-world and sees in this union not only an ideal but a real process; he who can see something of a world-process in this union of the perception and idea-worlds—is in a position to overthrow Kantianism. He is also in a position to solve the problem which we saw opening up in the course of Western civilization, which produced Nominalism and in the thirteenth century threw out several scholastic lights but which finally stood powerless before the division into perception and idea-world.

Now one approaches this problem of individuality on ethical ground, and hence my The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity has become the philosophy of reality. Since the acquisition of knowledge is not merely a formal act, but a reality-process, ethical, moral behaviour appears as an effluence of that which the individual experiences in a real process through moral fantasy as Intuition; and there results, as set forth in the second part of my The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, the Ethical Individualism, which in fact is built upon the Christ-impulse in man, though this is not expressed in the book. It is built upon the spiritual activity man wins for himself by changing ordinary thinking into what I called “pure thinking,” which rises to the spiritual world and there produces the stimulus to moral behaviour. The reason for this is that the impulse of love, which is otherwise bound to the physical man, becomes spiritualized, and because the moral ideals are borrowed from the spiritual world through the moral phantasy, they express themselves in all their force and become the force of spiritual love. Therefore, the Philistine-Principle of Kant had to be resisted. Duty! thou exalted name, that knowest nothing of flattery, but demandest strict obedience—against this Philistine-Principle, against which Schiller had already revolted, the The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity had to set the “transformed Ego,” which has developed up into the spheres of spirituality and up there begins to love virtue, and therefore practises virtue, because it loves it of its own individuality.

Thus we have a real world-content instead of something which remained for Kant merely a faith-content. For Kant the acquisition of knowledge is something formal, for the The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, it is something real. It is a real process. And therefore the higher morality is linked to a reality—but a reality to which the “Wertphilosophen” like Windelband and Rickert do not attain at all, because they do not see how what is morally valuable is implanted in the world. Naturally those people who do not regard the process of knowledge as a real process, also fail to provide an anchorage for morality in the world, and arrive, in short, at no kind of Reality-Philosophy. The philosophical basic principles of what we call here Spiritual Science have really been drawn from the whole course of Western philosophical development. I have to-day tried really to show you how that Cistercian Father was not altogether wrong, and in what way the attempt lies before us to reconcile the realistic elements of Scholasticism with this age of Natural Science through a Spiritual Science, how we laid stress on the transformation of the human soul and with the real installation of the Christ-impulse into it, even in the thought-life. The life of knowledge is made into a real factor in world-evolution and the scene of its fulfilment is the human consciousness alone—as I explained in my book, Goethe's Philosophy. But this, which is thus fulfilled is at the same time a world-process, it is an occurrence in the world, and it is this occurrence that brings the world, and us within it, forward. So the problem of knowledge takes on quite another form. Now our experience becomes a factor of spiritual-psychic development in ourselves. Just as magnetism functions on the shape of iron filings, so there functions on us that which is reflected in us as knowledge; it functions at the same time as our form-principle, and we grow to realize the immortal, the eternal in ourselves, and the problem of knowledge ceases to be merely formal. This problem used always, borrowing from Kantianism, to be put in such a way that one said: How does man come to see a reproduction of the external world in this inner world? But knowledge is not in the least there for the purpose of reproducing the external world, but to develop us, and such reproduction of the external world is a secondary process.

In the external world we suffer a combination in a secondary process of what we have divided into two by the fact of our birth, and with the modern problem of knowledge it is exactly as when a man has wheat or other products of the field and examines the food value of the wheat in order to study the nature of the principle of growth. Certainly one can become a food-analyst, but what function there is in wheat from the ear to the root, and still further, cannot be known through the chemistry of food values. That investigates only something which follows the continuous growth which is inherent in the plant.

So there is a similar growth of spiritual life in us, which strengthens us, and has something to do with our nature, just like the development of the plant from the root through the stem, through the leaf to the bloom and the fruit, and thence again to the seed and the root. And just as the fact that we eat it must not affect the explanation of the nature of plant growth, so also the question of the knowledge-value of the growth-impulse we have in us may not be the basis of a theory of knowledge; rather it must be clear that what we call in external life knowledge is a secondary result of the work of ideas in our human nature. Here we come to the reality of that which is ideal; it works in us. The false Nominalism and Kantianism arose only because the problem of knowledge was put in the same way as the problem of the nature of wheat would be from the point of view of bio-chemistry.

Thus we can say: when you once realize what Thomism can be in our time, how it springs up from its most important achievement in the Middle Ages, then you see it springing up in its twentieth century shape in Spiritual Science, then it re-appears as Spiritual Science. And so a light is already thrown on the question: How does it look now if one comes and says: We must go back to Thomas Aquinas, he must be studied, possibly with a few critical comments, as he wrote in the thirteenth century. We see what it means sincerely and honestly to take our place in the chain of development which started with Scholasticism, and also what it means to put ourselves back into the thirteenth century, and to overlook everything that has happened since then in the course of European civilization. This is, after all, what has really happened as a result of the Papal Encyclical of 1879, which enjoins the Catholic clergy to regard the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas as the official one of the Catholic Church. I will not here discuss the question: Where is Thomism? for one would have to discuss, ladies and gentlemen, the question: Is the rose which I have before me, best seen if I take no notice of the bloom, and only dig into the earth, to look at the roots, and overlook the fact that from this root something is already sprung—or if I look at everything which is sprung from this root?

Well, ladies and gentlemen, you can answer that for yourselves. We experience all that which is of value among us as a renewal of Thomism, as it was in the thirteenth century, by the side of all that which contributes honestly to the development of Western Europe. We may ask: Where is Thomism to be found to-day? One need only put the question: What was Thomas Aquinas' attitude to the Revelation-content? He sought a relationship with it. Our need is to adapt ourselves to the revelation-content of Nature. Here we cannot rest on dogma. Here the dogma of experience, as I wrote already in the eighties of last century, must be surmounted, just as on the other side must the dogma of revelation. We must, in fact, revert to the spiritual-psychic content of man, to the idea-world which contains the transformed Christ-principle, in order again to find the spiritual world through the Christ in us, that is, in our idea-world. Are we then to rest content to leave the idea-world on the standpoint of the Fall?

Is the idea-world of the Redemption to have no part? In the thirteenth century the Christian principle of redemption could not be found in the idea-world; and therefore the idea-world was set off against the world of revelation. The advance of mankind in the future must be, not only to find the principle of redemption for the external world, but also for human reason. The unredeemed human reason alone could not raise itself into the spiritual world. The redeemed human reason which has the real relationship with Christ, this forces itself upward into the spiritual world; and this process is the Christianity of the twentieth century,—a Christianity strong enough to enter into the innermost recesses of human thinking and human soul-life.

This is no Pantheism; this is none of those things for being which it is to-day calumniated. This is the most serious Christianity, and perhaps you can see from this study of Thomas Aquinas' philosophy, even if in certain respects it was bound to digress into the realm of the abstract, how seriously Spiritual Science concerns itself with the problems of the West, how Spiritual Science always will stand on the ground of the Present, and how it can stand on no other, whatever else can be brought against it.

These remarks have been made to demonstrate that a climax of European spiritual evolution took place in the thirteenth century with High Scholasticism, and that the present age has every reason to study this climax, that there is a vast amount to be learnt from such a study, especially with regard to what we must call in the highest sense the deepening of our idea-life; so that we may leave all Nominalism behind, so that we may find again the ideas that are permeated with Christ, the Christianity which leads to the spiritual Being, from whom man is after all descended; for if man is quite honest and open with himself, nothing else can satisfy him but the consciousness of his spiritual origin.

3. Die Bedeutung des Thomismus in der Gegenwart

Es war gestern mein Bemühen, am Schlusse der Betrachtungen über die Hochscholastik darauf hinzuweisen, wie das Wesentlichste in einer Gedankenströmung die Probleme sind, die Probleme, die in einer ganz bestimmten Weise in den Menschenseelen sich kundgaben, und die ja eigentlich doch alle gipfelten in einer gewissen Sehnsucht, zu begreifen: Wie erlangt der Mensch diejenigen Erkenntnisse, die ihm zum Leben notwendig sind, und wie gliedern sich diese Erkenntnisse in dasjenige ein, was dazumal in sozialer Beziehung die Gemüter beherrschte, wie gliedert sich das, was an Erkenntnissen gewonnen werden kann, ein in den Glaubensinhalt der christlichen Kirche des Abendlandes?

Die ringenden Scholastiker haben es zunächst zu tun gehabt mit der menschlichen Individualität, die, wie wir gesehen haben, als solche sich immer mehr herausrang, die zunächst nicht mehr als solche imstande war, das Erkenntnisleben hinaufzutragen bis zu wirklichem, konkretem Geistinhalt, wie er noch heraufleuchtete im Laufe der Zeit aus dem, was übriggeblieben war von dem Neuplatonismus, was übriggeblieben war von dem Areopagiten und von Scotus Erigena. Ich habe auch schon darauf hingewiesen, daß die Impulse, die durch die Hochscholastik gegeben waren, in einer gewissen Weise fortlebten. Aber sie lebten so fort, daß man sagen kann: DieProbleme selbst sind groß und gewaltig, und die Art und Weise, wie sie gestellt waren — wir haben gestern gesehen, wie sie gestellt waren -, die wirkte noch lange nach. Und - das soll gerade der Inhalt der heutigen Betrachtung sein — eigentlich wirkt, wenn auch in ganz veränderter methodischer Form, dasjenige, was dazumal als das größte Problem aufging, das Verhältnis des Menschen zur sinnlichen und geistigen Wirklichkeit, es wirkt noch immer nach, wenn man es auch nicht sieht in der heutigen Zeit, wenn es auch in der heutigen Zeit scheinbar ganz der Scholastik entgegengesetzte Gestalt annimmt. Es wirkt nach. Es ist gewissermaßen das alles in den geistigen Betätigungen der Gegenwart noch, aber wesentlich verändert durch alles das, was in der Zwischenzeit wiederum durch bedeutsame Persönlichkeiten hingestellt worden ist in die europäische Menschheitsentwickelung auf dem philosophischen Gebiete.

Wir sehen auch, wenn wir hinübergehen von Thomas von Aquino zu dem Franziskanermönch, der wahrscheinlich aus Irland stammte und im Beginne des 14. Jahrhunderts in Paris, später in Köln gelehrt hat, Duns Scotus, wir sehen da sogleich, wenn wir zu dieser Persönlichkeit herüberkommen, wie gewissermaßen das Problem zu groß wird selbst für alles das, was an wunderbarer, intensiver Denktechnik zurückgeblieben war aus den Zeiten der eigentlichen Meisterschaft in der Denktechnik, aus den Zeiten der Scholastik.

Vor Duns Scotus steht neuerdings die Frage: Wie lebt das Menschlich-Seelische in dem Menschlich-Leiblichen? Es war noch so bei Thomas von Aquino, daß er — wie ich gestern auseinandersetzte — das Seelische sich hinein wirksam dachte in die Gesamtheit des Leiblichen. So daß der Mensch zwar, wenn er durch Empfängnis und Geburt hereintritt in das physisch-sinnliche Dasein, nur ausgerüstet wird durch die physisch-leibliche Vererbung mit den vegetativen Kräften, mit den gesamten mineralischen Kräften und mit den Kräften des sinnlichen Auffassungsvermögens, daß sich aber ohne Präexistenz eingliedert in den Menschen der eigentliche Intellekt, der tätige Intellekt, dasjenige, was Aristoteles den Nous poietikos genannt hat. Aber für Thomas ist die Sache so, daß dieser Nous poietikos nun gewissermaßen aufsaugt das gesamte Seelische — das vegetativisch Seelische, das animalisch Seelische — und nur die Körperlichkeit durchsetzt, um das in seinem Sinne umzuwandeln, zu metamorphosieren, um dann unsterblich fortzuleben mit dem, was er, der selbst aus ewigen Höhen heraus in den Menschenleib, aber ohne Präexistenz, eingezogen ist, aus diesem Menschenleib gewonnen hat.

Duns Scotus kann sich ja schon nicht vorstellen, daß solch ein Aufsaugen des gesamten Kräftesystems der menschlichen Wesenheit durch den tätigen Verstand stattfinde. Er kann sich nur vorstellen, daß die menschliche Körperlichkeit gewissermaßen wie etwas Fertiges vorliegt, daß in einer gewissen selbständigen Weise durch das ganze Leben hindurch bleibt das vegetative, das animalische Prinzip, dann abgeworfen wird mit dem Tode, und daß nur das eigentlich geistige Prinzip, der intellectus agens, dann in die Unsterblichkeit übergeht. Scotus kann sich das ebensowenig vorstellen, was dem 'Thomas von Aquino noch vorgeschwebt hat: die Durchdringung des ganzen Leibes mit dem Menschlich-Seelisch-Geistigen, wie sein Schüler, Wilhelm von Ockham - der dann in München im 14. Jahrhundert gestorben ist, und der vor allen Dingen wieder zum Nominalismus zurückgekehrt ist —, weil ihm der menschliche Verstand etwas Abstraktes geworden ist, etwas, das ihm nicht mehr die geistige Welt repräsentierte, sondern was ihm nur aus der Überlegung gewonnen erschien, aus der sinnlichen Wahrnehmung. Er konnte sich nicht mehr vorstellen, daß nur in den Universalien, in den Ideen das gegeben sei, was nun eine Realität ergäbe. Er verfiel wiederum in den Nominalismus, wiederum in die Anschauung, daß dasjenige, was im Menschen sich festsetzt als Ideen, als allgemeine Begriffe, nur konzipiert ist aus der sinnlichen Umwelt, daß es eigentlich nur etwas ist, was im menschlichen Geiste, ich möchte sagen, um der bequemen Zusammenfassung des Daseins willen lebt als Name, als Worte. Kurz, er kehrte wiederum zurück zum Nominalismus.

Das ist im Grunde genommen eine bedeutsame Tatsache, denn man sieht, der Nominalismus, wie er zum Beispiel bei Roscellin aufgetreten ist — dem selbst die Trinität auseinandergefallen ist wegen seines Nominalismus —, dieser Nominalismus wird nur unterbrochen durch die intensive Gedankenarbeit des Albertus Magnus und Thomas von Aquino und einiger anderer, und gleich fällt die europäische Menschheit wiederum zurück in den Nominalismus, in jenen Nominalismus, der im Grunde genommen ist die Unfähigkeit der sich immer mehr und mehr heraufringenden Individualität des Menschen, das, was er im Geiste als Ideen gegenwärtig hat, zu fassen als eine geistige Realität, es so zu fassen, daß es etwas ist, was lebt in dem Menschen und lebt in einer gewissen Weise auch in den Dingen. Die Ideen werden von Realitäten sogleich wiederum zu Namen, zu bloßen leeren Abstraktionen.

Man sieht hin auf die Schwierigkeiten, welche das europäische Denken immer mehr und mehr hatte, indem es die Frage nach der Erkenntnis aufwarf. Denn erkennen müssen wir Menschen doch schließlich — wenigstens im Beginne des Erkennens müssen wir uns der Ideen bedienen -, erkennen müssen wir durch die Ideen. Die große Frage muß immer wieder auftreten: Wie vermitteln uns die Ideen die Wirklichkeit? Aber es ist im Grunde genommen kaum eine Möglichkeit für eine Antwort da, wenn einem die Ideen bloß als realitätslose Namen erscheinen. Und diese Ideen, die dem alten Griechentum, wenigstens dem eingeweihten Griechentum, noch waren die letzten von oben herunterkommenden Kundgebungen einer realen Geistwelt, diese Ideen verabstrahierten sich immer mehr und mehr für das europäische Bewußtsein. Diesen Prozeß des Verabstrahierens, des Wortwerdens der Ideen, sehen wir im Grunde genommen immer mehr und mehr zunehmen, indem wir weiterverfolgen die Entwickelung des abendländischen Denkens.

Einzelne Persönlichkeiten heben sich später noch heraus, wie zum Beispiel Leibniz, der sich im Grunde genommen nichteinläßtauf dieFrage: Wie erkennt man durch die Ideen?, weil er wohl traditionell noch im Besitze einer gewissen spirituellen Anschauung ist und alles zurückführt auf individuelle Weltenmonaden, die eigentlich geistig sind. Es ragt Leibniz über die anderen turmhoch empor, indem er noch den Mut hat, die Welt als geistige vorzustellen. Ja, die Welt ist ihm geistig; sie besteht ihm aus lauter geistigen Wesenheiten. Aber ich möchte sagen, was für eine frühere Zeit, deren Erkenntnis allerdings mehr instinktiv war, deren Erkenntnis noch nicht durchleuchtet war von einer solchen Logik, wie die Scholastik war, dasjenige, was für eine solche Zeit differenzierte geistige Individualitäten waren, das sind für Leibniz mehr oder weniger graduell abgestufte Geistpunkte, Monaden. Die geistige Individualität ist gesichert, aber sie ist nur in der Gestalt der Monade gesichert, in der Gestalt gewissermaßen eines geistigen Punktwesens.

Wenn wir absehen von Leibniz, dann sehen wir im ganzen Abendlande zwar ein starkes Ringen nach Gewißheit über die Urgründe des Daseins, aber zu gleicher Zeit überall das Unvermögen, die Nominalismusfrage wirklich zu lösen. Ganz besonders bedeutsam tritt das hervor bei dem Denker, der ja mit Recht immer an den Ausgangspunkt der neueren Philosophiegeschichte gestellt wird, es tritt entgegen bei dem Denker Cartesius, Descartes, der im Beginn oder in der ersten Hälfte des 17. Jahrhunderts lebte. Man lernt ja überall in der Philosophiegeschichte den eigentlichen Grundquell der Cartesiusschen Philosophie kennen in dem Satz: cogito ergo sum: ich denke, also bin ich. — In diesen Satz ragt noch herein ein Streben des Augustinismus. Denn Augustinus ringt sich aus jenem Zweifel heraus, von dem ich im ersten Vortrage gesprochen habe, indem er sich sagt: Zweifeln kann ich an allem, aber die Tatsache des Zweifelns besteht doch, und ich lebe doch, während ich zweifle. Ich kann daran zweifeln, daß Sinnendinge um mich herum sind, ich kann daran zweifeln, daß Gott ist, daß Wolken sind, daß Sterne sind, aber wenn ich zweifle, so ist der Zweifel da. An demjenigen, was in meiner eigenen Seele vorgeht, kann ich nicht zweifeln. Da ist eine Sicherheit, ein sicherer Ausgangspunkt zu erfassen. — Cartesius nimmt diesen Gedanken wieder auf: Ich denke, also bin ich.

Bei solchen Dingen setzt man sich selbstverständlich argen Mißverständnissen aus, wenn man genötigt ist, ein Einfaches gegen ein historisch Angesehenes setzen zu müssen. Und dennoch ist es notwendig. Nicht wahr, dem Cartesius und vielen seiner Nachfolger — in dieser Beziehung hat er ja unzählig viele Nachfolger gehabt - schwebt vor: Wenn ich in meinem Bewußtsein Denkinhalt habe, wenn ich denke, so ist nicht hinwegzuleugnen die Tatsache, daß ich denke; also bin ich, also ist mein Sein durch mein Denken gesichert. Ich wurzle gewissermaßen im Weltensein, indem ich mein Sein durch mein Denken gesichert habe.

Damit beginnt eigentlich die neuere Philosophie als Intellektualismus, als Rationalismus, als etwas, das ganz aus dem Denken heraus arbeiten will und insoferne nur der Nachklang ist der Scholastik, die ja die Wendung zum Intellektualismus hin in so energischer Weise genommen hat. Zweierlei sieht man bei Cartesius. Erstens muß man ihm den einfachen Einwand machen: Ist wirklich durch die Tatsache, daß ich denke, mein Sein ergriffen? Jeder Nachtschlaf beweist das Gegenteil. — Das ist eben das Einfache, das man einwenden muß: Wir wissen an jedem Morgen, an dem wir aufwachen, wir müssen gewesen sein vom Abend bis zum Morgen, aber wir haben nicht gedacht. Also ist der Satz: Ich denke, also bin ich, cogito ergo sum einfach widerlegt. Das Einfache, das, ich möchte sagen, wie eine Art Ei des Kolumbus ist, das muß schon einmal einem angesehenen Satze, der ungeheuer viel Nachfolge gefunden hat, entgegengehalten werden.

Das ist das eine, was in bezug auf Cartesius zu sagen ist. Das andere aber ist die Frage: Worauf ist denn eigentlich das ganze philosophische Streben des Cartesius gerichtet? Es ist nicht mehr auf Anschauung gerichtet, es ist nicht mehr auf das Empfangen eines Weltengeheimnisses für das Bewußtsein gerichtet, es ist wirklich ganz intellektualistisch, ganz denkerisch orientiert. Es ist auf die Frage hingerichtet: Wie erlange ich Gewißheit? Wie komme ich aus dem Zweifel heraus? Wie erfahre ich, daß Dinge sind, und daß ich selbst bin? Es ist nicht mehr eine materielle Frage, eine Frage des inhaltlichen Ergebnisses der Weltenbeobachtung, es ist eine Frage der Sicherung der Erkenntnis.

Diese Frage steigt auf aus dem Nominalismus der Scholastiker, den nur Albertus und Thomas für eine gewisse Zeit überwunden haben, der aber nach ihnen sogleich wiederum auftritt. Und so stellt sich für die Leute dasjenige dar, was sie in ihrer Seele bergen und dem sie nur einen Namencharakter beilegen können, den sie hineinklauben in die Seele, um irgendwo in dieser Seele einen Punkt zu finden, von dem aus sie sich jetzt nicht ein Weltbild, eine Weltanschauung verschaffen können, sondern die Gewißheit, daß überhaupt nicht alles Täuschung, nicht alles Unwahrheit ist, daß man hinausschaut in die Welt und auf eine Realität schaut, daß man hineinschaut in die Seele und auf eine Realität schaut.

Es ist in alledem wohl deutlich wahrnehmbar dasjenige, worauf ich gestern am Schlusse hingedeutet habe, nämlich daß die menschliche Individualität zum Intellektualismus gekommen ist, aber gewissermaßen im Intellektualismus, im Denkerischen das Christus-Problem noch nicht empfunden hat. Das Christus-Problem tritt für Augustinus etwa auf, indem er noch auf die ganze Menschheit schaut. Der Christus da drinnen in der menschlichen Seele, der dämmert, möchte ich sagen, dann für die christlichen Mystiker des Mittelalters auf; aber er dämmert nicht klar und deutlich auf bei denjenigen, die ihn aus dem Denken heraus nur finden wollten, aus jenem Denken, das der sich gebärenden Individualität so notwendig ist, oder aus dem, das diesem Denken sich ergeben würde. Dieses Denken, das nimmt sich gewissermaßen in seinem Urzustand so aus, wie es herausquillt aus der menschlichen Seele, daß es ablehnt dasjenige, was gerade für das Innerste des Menschen das Christliche sein müßte. Es lehnt ab die Umwandlung, die innere Metamorphose, es lehnt ab, so sich zum Erkenntnisleben zu stellen, daß man sich sagen würde: Ja, ich denke, ich denke zunächst über mich und die Welt. Aber dieses Denken ist noch ein unentwickeltes. Dieses Denken ist gewissermaßen dasjenige, das nach dem Sündenfall liegt. Es muß sich über sich selbst erheben. Es muß sich verwandeln, es muß sich emporheben in eine höhere Sphäre.

Eigentlich hat nur einmal so recht deutlich diese Notwendigkeit aufgeleuchtet in einer Denkerpersönlichkeit, und das ist bei dem Nachfolger des Cartesius, bei Spinoza. Spinoza hat ja wirklich aus guten Gründen jenen tiefen Eindruck auf Leute wie Herder und Goethe gemacht; denn Spinoza, wenn er auch scheinbar ganz im Intellektualismus, der aus der Scholastik heraus geblieben ist oder sich umgewandelt hat, noch drinnensteckt, Spinoza faßt doch diesen Intellektualismus so auf, daß der Mensch zuletzt eigentlich nur zur Wahrheit komme - die zuletzt für Spinoza in einer Art Intuition besteht -, indem er das Intellektuelle, das innere denkerische Seelenleben umwandelt, nicht stehenbleibt bei dem, was im Alltagsleben und im gewöhnlichen wissenschaftlichen Leben da ist. Und da kommt gerade Spinoza dazu, sich zu sagen: Durch die Entwickelung des Denkens füllt sich dieses Denken wieder an mit geistigem Inhalt. — Gewissermaßen die geistige Welt, die wir kennengelernt haben im Plotinismus, ergibt sich wiederum dem Denken, wenn dieses Denken entgegengehen will dem Geiste. Der Geist erfüllt als Intuition wiederum das Denken.

Es ist sehr interessant, denke ich, 'daß es im Grunde genommen dieser Spinoza ist, welcher sagt: Überblicken wir das Weltendasein, wie es in seiner höchsten Substanz im Geiste sich weiterentwickelt, wie wir dann diesen Geist in die Seele aufnehmen, indem wir uns mit unserem Denken zur Intuition erheben, indem wir auf der einen Seite so intellektualistisch sind, daß wir strenge wie mathematisch beweisen, aber im Beweisen zu gleicher Zeit uns entwickeln und erheben, so daß der Geist uns entgegenkommen kann. — Wenn wir uns so erheben, dann begreifen wir auch von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus den historischen Werdegang desjenigen, was in der Menschheitsentwickelung drinnen ist. Und es ist merkwürdig, daß herausleuchtet aus den Schriften des Juden Spinoza folgender Satz: Die höchste Offenbarung der göttlichen Substanz ist in Christus gegeben. — In Christus ist die Intuition zur Theophanie geworden, zur Menschwerdung Gottes, und Christus’ Stimme ist daher in Wahrheit Gottes Stimme und der Weg zum Heil. — Das heißt, der Jude Spinoza kommt darauf, daß der Mensch aus seinem Intellektualismus heraus sich so entwickeln kann, daß ihm der Geist entgegenkommt. Ist er dann in der Lage, sich auf das Mysterium von Golgatha zu richten, so wird die Erfüllung mit dem Geiste nicht nur Intuition, das heißt Erscheinung des Geistes durch das Denken, sondern es verwandelt sich die Intuition in 'Theophanie, in die Erscheinung des Gottes selbst. Der Mensch tritt dem Gotte spirituell entgegen. Man möchte sagen, Spinoza war nicht zurückhaltend mit dem, was ihm plötzlich aufgegangen war, denn dieser Ausspruch beweist das. Aber es erfüllt wie eine Stimmung, wie ein Grundton dasjenige, was er in dieser Weise herausgefunden hat aus der Entwickelung der Menschheit, es erfüllt das seine «Ethik».

Und wiederum geht es über auf einen empfänglichen Menschen. Deshalb kann man einsehen, daß für jemanden, der ganz gewiß auch zwischen den Zeilen dieser «Ethik» lesen konnte, der das Herz, das in dieser «Ethik» lebt, in dem eigenen Herzen empfinden konnte, daß für Goethe diese «Ethik» des Spinoza ein so tonangebendes Buch wurde. Es wollen doch diese Dinge nicht bloß so abstrakt angesehen werden, wie man das gewöhnlich in der Philosophiegeschichte tut; sie wollen angesehen werden vom menschlichen Standpunkte aus, und man muß schon hinblicken auf dasjenige, was herüberleuchtet von Spinozismus in die Goethesche Seele hinein. Aber im Grunde genommen ist dasjenige, was da nur zwischen den Zeilen des Spinoza herausleuchtet, doch etwas, was schließlich nicht zeitbeherrschend wurde. Zeitbeherrschend wurde dennoch das Unvermögen, über den Nominalismus hinauszukommen. Ja, der Nominalismus wird zunächst so, daß man sagen möchte, der Mensch spinnt sich immer mehr und mehr ein in den Gedanken: Ich lebe ja in etwas, was die Außenwelt nicht erfassen kann, in etwas, was aus mir nicht herauskann, um in die Außenwelt sich hineinzuversenken und etwas von der Natur der Außenwelt aufzunehmen. — Und so kommt es, daß diese Stimmung, daß man so allein ist in sich selber, daß man nicht hinauskann über sich und von der Außenwelt etwas empfängt, dann schon auftritt bei Locke im 17. Jahrhundert in der Form, daß Locke sagt: Auch dasjenige, was wir als Farben, als Töne in der Außenwelt wahrnehmen, das ist nicht mehr etwas, was uns zur Realität der Außenwelt führt; es ist im Grunde genommen nur die Wirkung der Außenwelt auf unsere Sinne, es ist etwas, mit dem wir schließlich auch in unsere eigene Subjektivität eingesponnen sind. — Das ist die eine Seite der Sache.

Die andere Seite der Sache ist, daß bei solchen Geistern wie Baco von Verulam im 16. undi7z. Jahrhundert der Nominalismus eine ganz durchdringende Weltanschauung wird, daß bei Baco das so zutage tritt, daß er sagt: Man muß aufräumen mit alledem, was des Menschen Aberglaube an die Realität desjenigen ist, was im Grunde genommen nur als Name gegeben ist. Eine Realität liegt uns nur vor, wenn wir hinausschauen auf die Sinneswelt. Die Sinne allein liefern in der empirischen Erkenntnis Realitäten. — Neben diesen Realitäten spielen eine wirklich wissenschaftliche Rolle jene Realitäten bei Baco schon nicht mehr, um derentwillen eigentlich Albertus und Thomas ihre Vernunfterkenntnistheorie aufgebaut haben. Sozusagen verflüchtigt hat sich die geistige Welt bei Baco schon zu etwas, was nun nicht mehr mit einer wissenschaftlichen Gewißheit und Sicherheit aus dem Innern des Menschen hervorquellen kann. Nur Glaubensinhalt wird dasjenige, was geistige Welt ist, den man nicht berühren soll mit dem, was man Wissen, was man Erkenntnis nennt. Dagegen soll die Erkenntnis nur gewonnen werden aus der äußerlichen Beobachtung und aus dem Experiment, das ja nur eine gesteigerte äußere Beobachtung ist.

Und so geht es dann fort bis zu Hume im 18. Jahrhundert, dem sogar schon der Zusammenhang zwischen Ursache und Wirkung zu etwas wird, was nur in der menschlichen Subjektivität lebt, was schließlich der Mensch den Dingen nur beilegt aus einer gewissen äußeren Gewohnheit heraus. Man sieht, wie ein Alp lastet der Nominalismus, das Erbe der Scholastik, auf den Menschen.

Was ist zunächst das wichtigste Kennzeichen dieser Entwickelung? Das wichtigste Kennzeichen dieser Entwickelung ist doch dieses, daß die Scholastik mit ihrem Scharfsinn dasteht, daß sie entsteht in einer Zeit, wo das Vernunftgut abgegrenzt werden soll gegen das Wahrheitsgut einer geistigen Welt. Der Scholastiker hatte zur Aufgabe, auf der einen Seite hinzuschauen auf das Wahrheitsgut einer geistigen Welt, das für ihn ja natürlich durch den Glaubensinhalt, durch den Offenbarungsinhalt der Kirche überliefert war. Er hatte auf der andern Seite hinzuschauen auf dasjenige, was sich durch die eigene Kraft der menschlichen Erkenntnis ergeben kann. Das, was der Gesichtspunkt der Scholastiker war, das versäumte zunächst jene Frontänderung, die einfach die Zeitentwickelung notwendig gemacht hätte. Als Thomas, als Albertus ihre Philosophien zu entwickeln hatten, da gab es noch keine naturwissenschaftliche Weltanschauung. Da hatten noch nicht Galilei, Giordano Bruno, Kopernikus, Kepler gewirkt, da gab es noch nicht den Hinblick der Menschen auf die äußere Natur mit den Kräften des menschlichen Verstandes. Da hatte man nicht sich auseinanderzusetzen gebraucht mit dem, was die menschliche Vernunft aus den Tiefen der Seele heraus finden kann, und dem, was gewonnen wird aus der äußeren empirischen, aus der sinnlichen Welt. Da hatte man sich nur auseinanderzusetzen gebraucht mit dem, was die Vernunft zu finden hat aus den Tiefen der Seele heraus im Verhältnis zu dem, was geistiges Wahrheitsgut war, wie es die Kirche überliefert hatte, wie es dastand vor diesen Menschen, die nicht mehr durch innere spirituelle Entwickelung sich zu diesem Weisheitsgut selbst in seiner Realität erheben konnten, die es aber sahen in der Gestalt, wie es ihnen die Kirche überliefert hatte, eben einfach als Tradition, als Schriftinhalt und so weiter.

Entsteht da eigentlich nicht die Frage: Wie verhält sich der Vernunftinhalt, dasjenige, was Albertus und Thomas als Erkenntnistheorie für den Vernunftinhalt entwickelt haben, zum Inhalte der naturwissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung? Man möchte sagen, es ist jetzt ein ohnmächtiges Ringen bis in das 19. Jahrhundert hinein. Und da sehen wir etwas sehr Merkwürdiges. Während wir zurückblicken in das 13. Jahrhundert, Albertus und Thomas sehen, die Menschheit belehrend über die Grenzen der Vernunfterkenntnis gegenüber dem Glaubens-, dem Offenbarungsinhalt, sehen wir, wie Albertus und Thomas Stück für Stück zeigen: Der Offenbarungsinhalt ist da, aber er ergibt sich nur bis zu einem gewissen Teile der menschlichen Vernunfterkenntnis, er bleibt außerhalb dieser Vernunfterkenntnis, er bleibt für die Vernunfterkenntnis Welträtsel. - Wir können sie aufzählen, diese Welträtsel: die Inkarnation, das Enthaltensein des Geistes im Altarsakramente, und so weiter — das liegt jenseits der Grenze des menschlichen Erkennens. Für Albertus und Thomas ist es so, daß der Mensch auf der einen Seite steht, die Grenze der Erkenntnis gewissermaßen ihn umgibt und er nicht hineinblicken kann in die spirituelle Welt. Das ergibt sich für das 13. Jahrhundert.

Und jetzt blicken wir herüber in das 19. Jahrhundert. Da sehen wir eine merkwürdige Tatsache: In den siebziger Jahren, bei einer berühmten Naturforscherversammlung in Leipzig, hält Da Bois-Reymond seine eindrucksvolle Rede «Über die Grenzen des Naturerkennens» und bald darnach über «Die sieben Welträtsel». Was ist da die Frage geworden? (Es wird gezeichnet.) Da steht der Mensch, da ist die Grenze der Erkenntnis; jenseits dieser Grenze liegt aber die materielle Welt, liegen die Atome, liegt dasjenige, wovon Du Bois-Reymond sagt: Man weiß nicht, was das ist, was als Materie im Raume spukt. — Und diesseits der Grenze liegt dasjenige, was in der menschlichen Seele sich entwickelt.

Wenn auch, verglichen mit dem imposanten Werke, das als Scholastik vom Mittelalter heraufleuchtet, das eine Kleinigkeit ist, die einem da entgegentritt in den siebziger Jahren durch Du Bois-Reymond, so ist es doch das wahre Gegenstück: dort die Frage nach den Rätseln der spirituellen Welt, hier die Frage nach den Rätseln der materiellen Welt; hier die Grenze zwischen dem Menschen und den Atomen, dort die Grenze zwischen dem Menschen und den Engeln und Gott. In diese Zeitenspanne müssen wir hineinblicken, wenn wir anschauen wollen alles das, was nun wie eine nähere oder weitere Folge der Scholastik auftaucht. Als etwas wenigstens für die Zeitgeschichte Bedeutsames taucht auf aus dieser Scholastik die Kantsche Philosophie, von Hume beeinflußt, diese Kantsche Philosophie, unter deren Eindruck die Menschen, die philosophieren, auch heute noch stehen, nachdem in den sechziger Jahren, als die Kantsche Philosophie ein wenig zurückgetreten war, die Philosophen Deutschlands den Ruf erhoben haben: Zurück zu Kant! und seither eine unübersehbare Kantliteratur sich geoffenbart hat und auch selbständige Kantdenker wie Volkelt, Cohen und so weiter — ein ganzes Heer könnte man aufzählen — aufgetreten sind.

Wir können ja heute Kant selbstverständlich nur skizzenhaft charakterisieren. Wir brauchen nur hinzuweisen auf das, was das Wesentliche bei ihm ist. Ich glaube nicht, daß, wer Kant wirklich studiert, ihn anders finden kann als so, wie ich ihn versuchte zu finden in meiner kleinen Schrift «Wahrheit und Wissenschaft». Vor Kant steht Ende der sechziger Jahre und Anfang der siebziger Jahre des i8. Jahrhunderts mit aller Gewalt jetzt nicht eine Inhaltsfrage der Weltanschauung, nicht irgend etwas, was in bestimmten Gestalten, Bildern, Begriffen, Ideen über die Dinge bei ihm aufgetreten wäre, sondern vor ihm steht eigentlich die formelle Erkenntnisfrage: Wie gewinnen wir Sicherheit über irgend etwas in der Außenwelt, über ein Sein in der Außenwelt? — Mehr peinigt Kant die Frage der Gewißheit der Erkenntnis als irgendein Inhalt der Erkenntnis. Ich meine, das sollte man sogar fühlen, wenn man die Kantsche «Kritik» vornimmt, wie es nicht der Inhalt der Erkenntnis ist, sondern wie es das Streben nach einem Prinzip der Sicherheit der Erkenntnis ist, was bei Kant auftritt. Man lese doch die «Kritik der reinen Vernunft», die «Kritik der praktischen Vernunft», und sehe sich um, wie, nachdem das ja in einer gewissen Beziehung klassische Kapitel über Raum und Zeit überwunden ist, wie dann auftritt die Kategorienlehre, nur, man möchte sagen rein pedantisch abgezählt, um eine gewisse Vollständigkeit zu haben. Wahrhaftig, da läuft nicht die Darstellung, diese «Kritik der reinen Vernunft» so fort, wie bei jemandem, der von Satz zu Satz mit seinem Herzblut schreibt.

Wichtiger ist es für Kant, viel wichtiger: Wie verhält sich dasjenige, was wir Begriffe nennen, was überhaupt der ganze Inhalt der Erkenntnis ist, zu einer äußeren Wirklichkeit? — als dieser Inhalt der Erkenntnis selbst. Den Inhalt stoppelt er sozusagen aus alledem, was ihm philosophisch überliefert ist, zusammen. Er schematisiert, systematisiert. Aber überall tritt die Frage auf: Wie kommt man zu einer Gewißheit, zu einer solchen Gewißheit — das sagt er ja ganz deutlich -, wie siein der Mathematik vorhanden ist?—- Und zu einer solchen Gewißheit kommt er auf eine Art, die im Grunde genommen nichts weiter ist als ein verwandelter und noch dazu außerordentlich kaschierter und maskierter Nominalismus, nur ein Nominalismus, der nun auch noch auf die Formen der Sinnlichkeit, Raum und Zeit ausgedehnt wird außer auf die Ideen, auf die Universalien. Er sagt: Dasjenige, was wir in unserer Seele entwickeln als Inhalt der Erkenntnis, das hat im Grunde genommen gar nichts mit etwas zu tun, das wir aus den Dingen herausholen. Wir stülpen es über die Dinge drüber. Wir bekommen die ganze Form unserer Erkenntnis aus uns selber heraus. Wenn wir sagen: A hängt mit B nach dem Prinzip der Verursachung zusammen -, so ist dieses Prinzip der Verursachung nur in uns. Wir stülpen es über A und B, über die beiden Erfahrungsinhalte hinüber. Wir tragen die Ursächlichkeit in die Dinge hinein.

Mit andern Worten, so paradox das sich ausnimmt — aber wirklich nur historisch paradox gegenüber etwas, das solch maßloses Ansehen hat wie die Kantsche Philosophie -, es muß doch dieses Paradoxe gesagt werden: Kant sucht ein Prinzip der Gewißheit dadurch, daß er überhaupt leugnet, wir nehmen den Inhalt unserer Erkenntnis aus den Dingen, und behauptet, wir nehmen ihn aus uns selber und legen ihn in die Dinge hinein. Das heißt mit anderen Worten, und das ist eben die Paradoxie: Wir haben Wahrheit, weil wir sie selber machen, wir haben im Subjekte Wahrheit, weil wir sie selbst erzeugen. Wir tragen die Wahrheit erst in die Dinge hinein.

Da haben Sie die letzte Konsequenz des Nominalismus. Die Scholastik hat gerungen mit den Universalien, mit der Frage: Wie lebt dasjenige, was wir in die Ideen aufnehmen, draußen in der Welt? Sie konnte nicht zu einer wirklichen Lösung des Problems kommen, die vorläufig vollauf befriedigend geworden wäre. Kant sagt: Nun gut, die Ideen sind bloße Nomina. Wir bilden sie nur in uns, aber wir stülpen sie als Nomina hinüber über die Dinge; dadurch werden sie Realität. Sie mögen lange nicht Realität sein, aber indem ich mich den Dingen gegenüberstelle, schiebe ich die Nomina in die Erfahrung hinein und mache sie zu Realitäten, denn die Erfahrung muß so sein, wie ich es ihr durch die Nomina befehle.