Goethe and the Crisis of the Nineteenth Century

GA 171

21 October 1916, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

Thirteenth Lecture

We have tried to visualize the main ideas that are struggling for expression, or one might say for existence, in our fifth post-Atlantean period, struggling for existence in such a way that they develop one-sidedly under the characterized twofold impulses. Under the influence of the one impulse, more or less everything that can be connected to the fact of birth, the fact of the relationship between living beings, and in general the beings and forces within our earthly existence, is formed and shaped. Influenced by the other impulse, we see the facts that follow death, what is called suffering, pain, evil. And how one-sidedly the series of facts in human thinking develop, which follow on from what has been characterized, we have tried to illuminate from various sides. Now it must be clear that the two most important ideals for this fifth post-Atlantic period are: firstly, the ideal of presenting purely what is present in the sense world and tracing it back to the original phenomena, as Goethe did, as we have already discussed, who tried to trace the phenomena back to what he called the archetypal phenomena. On the other hand, the fifth post-Atlantic period must strive to achieve free imagination arising in the human soul. In the synthesizing of imaginations, which the human being receives from the spiritual world, of which only a few can be present now, because the fifth post-Atlantic period, as we know, only began in the 15th century. With these free imaginations, the human being should comprehend what presents itself in the outer world of the senses. As you can see from various of my statements, some of which have been given in lectures and some of which can be found in my books, it was Goethe who made a great beginning with such a view of the world. That is why Goethe can also be the genuine, appropriate basis for a world view that is truly required by the fifth post-Atlantic epoch.

It is a peculiar feature of world evolution that it must, as it were, take place in waves, that certain impulses arise, have a strong effect, then subside and can only arise again later, and so on. This is felt particularly strongly by those who understand the Goethean worldview in its nerve. Of course, spiritual science itself cannot yet be found in the Goethean world view, but it will be able to arise more and more under the influence of the understanding of the Goethean world view. For it is truly the case that everything that could still be given without the actual form of spiritual science as a world view is given in the Goethean world view. And this Goethean world view has cast its light first into circles that are narrow for the world at large, but wide for spiritual life, and much in spiritual life has already been influenced by the Goethean world view, even if what has been influenced has basically also been swept away, just as the Goethean world view itself has been swept away. For there is no need to deceive ourselves: even if Goethe is mentioned by many today, even if many believe they know his works, that which actually lives and breathes in his world view is still something that belongs to the most unknown in the development of mankind and which, when it enters more and more into human evolution, will substantially transform not only scientific and social thinking, but also the rest of human thinking, but also the impulses of human action. In our time, there are still few favorable forces and impulses working outside of the anthroposophical movement for an understanding of Goethe's world view. For as justified and as magnificent as the so-called democratic principle is for the development of humanity, when it is understood in the right sense, it has a corrupting effect in our time, when it is often grasped and applied in the wrong way. In our time there is an intense dislike, antipathy, yes more than that, in many souls an intense hatred and antagonism towards a world view of the kind that has its sources in Goethean thinking and Goethean sentiment. For this world-view requires much that our time, in particular, is least willing to accept. In our time, everyone wants to have, as it were, their own world-view, to build up their own world-view, to be a loner in their world-view, without having laid the foundations for it. And the next feeling that everyone has is something like that the individual world-views stand side by side with equal rights. What Goethe so uniquely characterizes in Faust's striving, is something that every journalistic drip and everyone who parrots these drips speaks of today; but today, there can be no question of knowing the innermost nerve of this Faustian striving. And we will still have much to discuss when we consider what has only been sketched out here, and what is unfavorable to a harmonious balance of the impulses mentioned in modern times, and then also discuss how this harmonious balance of the one-sided impulses that we have come to know should be brought about.

Today, I would like to add a few more random thoughts to help you understand how it could come about that Goethe's world view, which was already at such a high level, petered out in the 19th century and all sorts of other world views came to the fore. This nineteenth century increasingly came to find the world surrounding man uninteresting. One often pays little attention to this, but it is nevertheless the case. This is because in the nineteenth century, in the spiritual development of mankind, there arose a crisis that caused the contemplation of the spiritual life in things to dry up more and more. People only saw the external sensory qualities, sensory properties, and modes of activity of things, and these became less and less interesting. What lives and breathes through the sensory world spiritually was no longer seen. The sensory world as such became less and less interesting. Hence the dream of seeking something hidden within this world of sense itself, which after all was the only thing that corresponded to the spirit of the time. The spiritual hiddenness in the world of sense was not perceived. So people sought the hidden in the world of the senses itself, and that led to the fact that one sought to deepen the view spatially in another direction, though in a highly fruitful way, through microscopic and telescopic research, through that which can be seen purely sensually in the smallest and largest. Faith in the spiritual and hidden vanished. So people wanted to be allowed to believe at least that the riddles of the world would be solved by exploring what was immediately hidden from the senses, and in this field they did indeed go an enormous way. One need only think of the great and powerful progress that microscopic research has made in relation to living things in the 19th century. The science of cells has emerged from this. It was realized that the living organism of plants and animals and humans consists of the smallest parts, cells, and the perfection of microscopic research made it possible to study the life of these smallest cell creatures, about which one could previously only make more or less guesses. In this way, one wanted to explain the sensory from another sensory. And this mode of explanation became especially important for a series of facts that emerged in the fifth post-Atlantic period, for the facts that are connected with birth, with the becoming of living beings. One saw a living being, up to and including the human being, emerge from a cell; one saw it develop by observing the progressive life and multiplication of cells, and one finally arrived at an understanding of how the simple round cell that multiplies gradually in the course of its life before birth, also in humans, and finally becomes the human form, how it comes into existence through birth, is transformed.

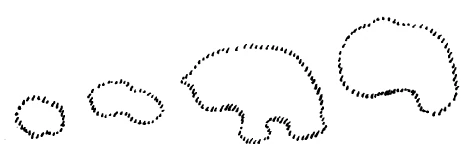

As I said, people began to develop ideas about how the simple cell becomes that which then enters into existence through birth as a human being, and these ideas led to what can be called the problem of birth, the riddle of birth in humans, being closely linked to the processes in animal life. It was seen that the animal world in its simplest forms presents itself in such beings, which themselves are only like a single cell, that there are therefore animal beings in the world which, so to speak, take on the form throughout their entire life that humans only take on in the very earliest period in the mother's body. Other animals present themselves in forms that are similar to a later developmental form of man. In a certain period of development before birth, that is, in embryonic development, the human form presents itself in such a way that it looks, or at least resembles, a little fish, and between the cell form and the form of a little fish lie the other forms, which in turn live outside as independent beings. In a sense, then, through his embryonic development, the human being gradually recapitulates the forms that are outside. As we know, this led to the formulation of the biogenetic law, made famous by Aaeckel, which states that during his development before birth, the human being recapitulates the animal forms in abbreviated form, as it were. This, however, led to the belief that man, as he enters earthly existence, must have descended from animal forms. It was thought that in ancient times only cell-forms existed, and that somewhat more complicated beings developed from these cell-forms through these or those processes, which were thought of as being more or less accidental or purely scientifically necessary – which is ultimately the same. So that in the next stage of the development of the world, we have the simple cell creatures and somewhat more complicated ones, but the somewhat more complicated ones first go through the stage of simple cell development; then came the more complicated ones, which in turn had gone through cell forms, that is, what had emerged earlier, and then their form. And so, it was thought, the whole animal world had developed, finally man, who, during his embryonic development, briefly recapitulates all animal forms.

In this way, an idea arose about the connection between what one can call human birth and the gradual emergence, as one thought, of organic life forms. This linked man directly to the various animal forms, and since man is easily dazzled by what he sees directly, in the course of the 19th century one forgot to take into account anything other than what thus appeared to be a similarity between human embryonic development and the formations of the other organic forms. The thoughts and ideas by which the connection that had been recognized or believed to have been recognized through the advanced means of research was recognized were only as narrow as they were, and could only take on the materialistic form that they did because, in the course of the 19th century, Goethean thinking and imagination had really dried up completely. One need only recall how Goethe, in the course of his life, came to what he calls his theory of metamorphosis.

Before arriving at his theory of metamorphosis, Goethe was probably concerned with the knowledge of the spiritual world that was available to him in his time, and he became familiar with various ways, various means, through which man can try to approach the spiritual world. Only after Goethe's mind had been greatly deepened by his experiences with these means and ways did he begin to formulate scientific ideas. And there we see, first of all, how Goethe, after coming to Weimar and gradually having the resources of the University of Jena at his disposal, does everything to enrich his scientific knowledge and insights, but at the same time does everything to gain coherent ideas about the various forms of organisms. And then again we see how Goethe sets out on his Italian Journey, how he, while on the Italian Journey, takes in everything he encounters in plant and animal forms, in order to study the inner relationship of the plant and animal forms in the rich diversity that now presents itself to him. And in Sicily, finally, he thought he had found what he then called his 'primordial plant'. What did Goethe have in mind when he thought of the primal plant? This primal plant is not a physical structure. Goethe himself calls the primal plant a physical-supernatural form. It is something that can only be seen in the spiritual, but it is seen in this spiritual in such a way that when you see a particular plant, you know: this particular plant is a special manifestation of the primal plant. Every plant is a particular form of the original plant, but the original plant is not a plant that can be perceived by the senses. The original plant is a being that lives in all plants, both sensually and supernaturally. Goethe's idea was to not just follow the various sensory forms, but to seek the one original plant in all plants. In doing so, he had, one might say, essentially deepened, very, very much deepened, what had always existed as a doctrine of metamorphoses, and it was obvious to him that he should now also apply the idea of this doctrine of metamorphoses to a broader extent to the organic, to the living.

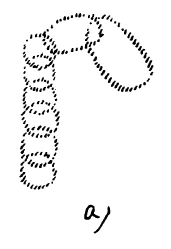

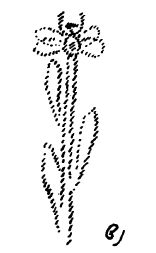

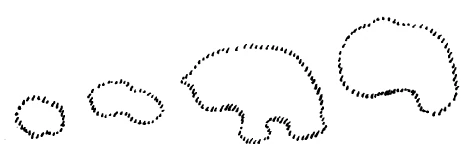

It is interesting to see how he now describes how he wanted to conceive of the human form itself in such a way that its individual limbs represent transformation products, so to speak, that the human being is the complication of an idea. He recounts how, in 1790, he found a sheep's skull in the Jewish cemetery in Venice that had decomposed particularly well, so that he could see from the individual skull bones how these skull bones are formed in such a way that one can recognize in them transformed vertebral bones. He had noticed that the spinal column consists of individual bones, which I will only draw schematically, but that the skull then consists of such remodeled vertebral bones. Of course, when they are remodeled, they take on completely different forms, but then the skull bones are only remodeled vertebral bones. The vertebral bones lie one above the other in a ring shape. By thinking of them as rubber and pulling the rubber apart in a variety of ways, one can imagine that the forms of the skull bones arise from the vertebral bones (see drawing a). For Goethe, it was something extraordinarily important to be able to say: in the vertebral bone that envelops the spinal cord, something is given like a basic element of human development, which only needs to be transformed in order to shape itself into more complicated elements of this human development. Thus, on the one hand, Goethe had recognized in the plant leaf: When a plant grows, it develops leaf after leaf; but then, at a certain point, the development of the leaf comes to an end. Through the transformation of the leaf, first the petals arise (see drawing b), but then also the stamens, which are organs of a completely different design, which are also nothing other than leaves, but transformed leaves. For Goethe, the whole plant is contained in the leaf.

There is much that is invisible and supersensible in a leaf; the whole plant is in a leaf. In the same way, however, the whole skull skeleton is already in the spinal column. The spinal column and the skull together form a whole, and the complicated skull bones are just as much transformed vertebral bones as the petals, just as the stamens and pistils are transformed green leaves of the plant. Thus Goethe has the idea that that which underlies the leaf in a supersensible way is transformed in the most diverse ways and then becomes the whole plant; that that which lies in the spine is transformed in a complex way and becomes the head. Goethe came to this conclusion in his views.

Spiritual science did not yet exist at that time, and it is particularly interesting to see how Goethe is a spirit who always remains at the level of consciousness to which he can penetrate through his rich observation, and does not does not grasp any speculative thoughts, does not hypothesize, for example, in order to penetrate beyond this point, to which he can penetrate through his rich experiences, in an unjustified way, in a fantastic way.

Now, although it is a long way, but it is a way that can now be taken, more than a hundred years after Goethe formulated these ideas. In relation to the human being, Goethe more or less stopped: the human being has a spinal column, one vertebra lies on top of the other, then the vertebra transforms into the skull bone. Goethe stopped there. Today, there is no longer any need to stop at what he stopped at. For from there to an idea that allows a wide, wide view, there really is a path, and a path must even be created through spiritual science. When one looks at the human being as a whole, with the same spirit with which Goethe, after — as they say, by a “coincidence” — a sheep's skull happily came across him in the Jewish Cemetery in Venice, when one looks with the same spirit with which one examined the individual bones of this sheep's skull and recognized through this spirit that they were transformed vertebrae, one sees the human being as a whole, then one notices something today. I have already hinted at this, but I must mention it again in this context and illuminate it from a different point of view. Today we recognize that the human being is essentially a twofold creature: he consists of his head and the rest of his organism. Just as the petal develops from the stem leaf of the plant, as the petal is a transformation of the stem leaf of the plant, so the human head is also a transformation of the whole rest of the organism. I have said that in order for this transformation to come about completely, the human being must develop from one incarnation to the next. What we carry today, as I said, in our other organism, that becomes our head in the next incarnation.

You see, this view is only a fully developed impulse that arises when one inwardly follows what began in Goethe's world view. If one really stands on the ground of this doctrine of metamorphosis, one attempts to describe the organism in its individual members; but these members are conceived in their connection in such a way that the connection is only possible if one sees through to something that lives there as a spiritual essence. For, of course, if a leaf were what the senses see, it would never be able to become a petal or a stamen; if a vertebra were what the senses see, it would never be able to become a be able to become a limb of the head skeleton; if the human body were to be what it presents to the external senses, then, however much it might transform its powers, it would never be able to become a human head. But now, even with regard to external observation, this Goethean world view is clearer in the demands of the fifth post-Atlantic period than the natural science of the 19th century, which prided itself so much on its external observation and experimentation. Goethe is truly better at looking, and those who try to rely on him are better at looking at what happens in nature and what is present in nature than the biological science of the 19th century in particular.

As two members, I said, man presents himself to us: as the head and as the rest of his organism. This fact, that the head is, so to speak, a transformed rest of the organism, must first be understood if one wants to build further. Only then will one be able to ask: Yes, what then is on the one hand this human head, and what on the other hand is the rest of the human organism? To answer this question, one must take quite different things as important than the usual modern natural science takes.

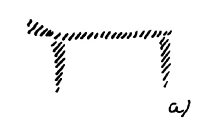

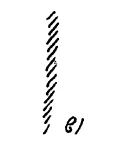

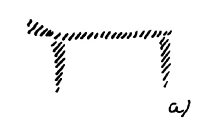

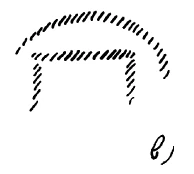

You see, when you imagine an animal, the essential thing about the animal is that its spinal cord - I have also mentioned this several times - is parallel to the earth's surface, and that the animal stands on the earth's surface with its front and hind legs (a) and carries its head horizontally in the extension of the spinal cord, essentially as an extension of this spinal cord. What is known as the human spinal cord is now aligned vertically, exactly perpendicular to the direction of the animal's spinal cord (b).

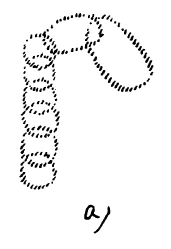

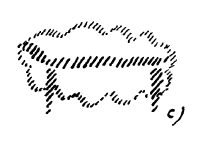

But we do not want to consider this spinal cord for the time being, because it does not belong to the head; it belongs to the rest of the organism. We want to consider another spinal cord first. Yes, but what kind of another spinal cord? We want to consider the human brain. You will say: Is that a spinal cord? Yes, that is a spinal cord! It is nothing more than a transformed spinal cord, so to speak, an expanded spinal cord. Imagine a horizontal spinal cord, as found in animals, expanded, transformed, metamorphosed, and you get the human brain (c).

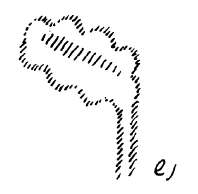

The true fact is this: during the development of the moon, what is now the brain looked like the spinal cord of an animal today. And only during the transition from the lunar to the terrestrial development did this spinal cord, which man had on the moon, become more complicated, becoming the present human brain; but it retained its horizontal position. For essentially its axis is perpendicular to the spinal cord belonging to the body, and this spinal cord belonging to the body was only acquired by man during his time on earth. That is still at the stage at which the spinal cord that became brain was on the moon during the lunar evolution (d).

What appears simpler in humans today, their spinal cord, was acquired later in the course of evolution than what appears more complicated today, their brain. Only the brain that humans have today used to be a spinal cord. So we see that humans have a spinal cord that has been transformed into a brain, and only later in the course of evolution was an original spinal cord added to it.

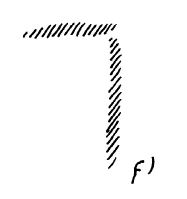

Thus, when we look at the human head, it does not appear to us to be very different from that of an animal; for the direction of the head is like the direction of the backbone of the animal, which is also the direction of the head of the animal, horizontal, parallel to the earth (f).

And many other characteristics could be indicated that would show that the human head, when viewed as it is in the whole development, is a transformed 'animality', and that the rest of the human organization has been added to this transformed animality. This idea is not at all similar to the one that natural science development in the 19th century came to. For the scientific development in the 19th century, because it places the main emphasis on the external-sensual, will find precisely the human head most different from the animal. Here (see drawing) the human head does not appear to us to be so different from the rest of the animal, only ennobled: the brain is a fluffed-up spinal cord, which the animal also has.

You will now have the question on your lips: Yes, do you perhaps believe that the rest of the human organism is now even nobler than the head organism in terms of external form, that the rest of the human organism might even resemble the animal less than the head? And you yourself may find it paradoxical today, but you will already find your way into the idea that this must be said. And basically, doesn't our head, after all, look most like animal forms, of all our limbs taken as a whole? At least for a large part of our lives, we are hairy on the head, men more so than women. The rest of the organism is by no means as hairy. This already strongly suggests its relationship to the animal organism. I will leave it at this suggestion for the time being, but we will elaborate on this over time. But it will lead us more and more to the realization that something quite different takes place in nature than what is very often believed. Man looks down from man to the lower animals and sees, for example, a turtle or a shell or a snail, and he believes in the sense of today's natural science that the snail, the shell, in fact the lowly creatures, first developed gradually, and the human head was added to the lowly organisms of the lowly animal world. This is nonsense, complete nonsense! If you look at a shellfish or a turtle today, you see a human head at a subordinate level, and the rest of our organism has been added to it. After what are lower animal forms – I will schematize them – have gradually been transformed into the human head, the rest of the organism has been added to it.

So we have an evolution that goes from lower animal forms further and further, and what is animal nature has formed the human head and the rest of the organism is attached to this human head as the later. In our head alone we carry within us what connects us to the other animals, not in our other organism. Therefore, the human head has the same direction in its main axis as an animal: parallel to the earth's surface. The rest of the organism is built upright, perpendicular to the earth's surface.

It is very unfortunate that this false idea, which is characterized by this, has been incorporated into the scientific development of the 19th century. For this reason, it is thought that man as such, as he is, emerges with his whole organism as a somewhat more developed form from earlier animal forms. The truth is that what could have become of earlier animal forms can only be the head, but that what is completely new within the evolution of the earth has been added to this head.

Now, therefore, we are dealing with two things at once. The first is this: that in our head we actually have a transformed form for the other animal forms. And yet, from that which has only just been added to the head and which we have as the rest of the organism in an incarnation, we develop the form of the head through corresponding forces in the next incarnation. This might seem like an apparent contradiction. We shall see, by looking at these things more closely, that it is not a contradiction.

I wanted to show you, by recalling the fact that man actually carries the animal within himself, that with his earthly organism he supports the animal that has become his head, just how wrong today's external ideas can be. But I would also like to show you something else in a positive way. If the human head is only a transformed animal, how did the human head become what it is today? How can the head, as it is today, develop through being prepared by an earthly organism in a previous incarnation, to become the human head? Well, the animal walks on the earth with its two pairs of legs, that is, with four legs. Anyone who believes that this animal only walks over the earth and that nothing else happens but that this animal walks over the earth is greatly mistaken. Forces are constantly rising from the earth into the animal, going up through the spine, and then, as it were, always influencing the brain, going back down into the earth again (a). The animal belongs to the earth. And the way it stands on it, how the forces that are active in the earth go through its legs into its spine and back again, that is part of the animal's whole life.

The relationship that the animal has to the whole earth is what the human being, the human head, has to the rest of the human organism. The fact that the human being has an organism that stands vertically out of the earth makes this rest of the organism the same for the human head as the earth, the whole earth, is for the animal. Thus, in our head-attached organism, we have the secrets of the whole earth within us. And it can easily be shown, though today it can only be hinted at, that when we study the head and the brain within it, the rudiments, the appendages, are there for front and back limbs , by means of which man, with his head, stands on himself like the animal on the earth, as we do, only transformed into internal, other organs, have hind limbs and forelimbs. And the whole formation of the head is such that it is in fact related to the rest of the human organism as the animal is to the earth (b).

This is so significant that one can see what kind of significance such an idea, which of course only arises from the views fertilized by spiritual science, has. For with this idea one must now go back to what the 19th century, with its crude means, observed only insufficiently; with this idea one must now go back and follow embryonic development. Then something quite different will emerge from what 19th-century science was able to find. But then, in turn, ideas will arise that can be fruitful for human life, even beyond mere inanimate technology. But without these ideas, humanity will not get out of the deadlock it has now entered. For the real progress of humanity is based on the development of ideas, not of general ideas, which are cultivated today in associations with great ideals, not in these ideas, which anyone can grasp by spending three hours in a coffee house, but in the ideas that are borrowed from reality through research and are then applied to life. It is easy enough to come up with fine ideas that can be used to found associations, but they do not prevent culture from reaching dead ends like the one it is in now. Only concrete ideas can prevent this.

We must truly feel this, then we will first understand the great tasks of spiritual science, and we will correctly assess the reality around us. This reality is bent on preventing spiritual science from emerging, especially in its most important form. The spirit that caused the Goethean world view to dry up in the 19th century is still present to a sufficient extent, and this spirit finds expression in a certain mania for persecution: a mania for persecuting everything that strives for ideas saturated with reality. To this spirit of the age, these ideas, saturated with reality, often seem fantastic, because it is not suited to assimilate them. And what will increasingly come to be faced by spiritual science and its strongest adversary is this: a worldview that seeks real spiritual paths and seeks to research realities without prejudice will be rejected precisely because one wants to reject this research into realities. It is too uncomfortable to get to know what is necessary to arrive at a truly comprehensive worldview. Therefore, this comprehensive worldview will be vilified and will not let the world see how comprehensive it is, but will pretend to the world that it is based on just as superficial, narrow-minded, limited concepts and research results as other worldviews are at present. And more and more will be felt a certain recognition of the dishonesty of the pursuit, namely, that pursuit which insists on narrow-mindedness and a rejection of precisely that which, with the consciousness that only leads satisfactorily forward, really wants to research the realities and thereby also come to a certain comprehensive point of view. Arrogance and presumption are qualities that have not yet reached their peak. What will yet come about under the influence of that arrogance, which will be fostered not by natural science but by the world view that is often drawn from natural science, is something that people of the present still have no conception of. And what tyranny will arise when more and more external powers allow themselves to be privileged by materialism in the field of medicine, in the field of other so-called science, what will arise from this, the present man is still far too comfortable to even feel. He much prefers to accept bit by bit how, day by day, the spiritual is allowed to be privileged more and more by the external powers. And there are still few people who feel what a dreadful future humanity is heading for if they do not learn to feel what is at stake in this very area, what a decline can be observed in this very area compared to the points of view that have already been reached.

I just wanted to hint at this feeling, which is necessary for people of the present day. For this feeling is countered by an enormous sleepiness, especially among the idealistically minded people of the present. In the face of what one should feel to be one's task, it seems to be the worst sin when those who, precisely imbued with idealistic attitudes, find their way into a newer world view, then withdraw from the rest of the world's work and life and found all kinds of colonies and the like, while the most urgent thing is that the newer world view, the spiritual-scientific world view, be fully integrated into life and not sleepily stumble towards the enormous abyss that opens up from what one can thus hint at, as I have hinted at again today.

I wanted to present something episodic today. Because to explain the very important things that I still have to say, I need three consecutive lectures.

Dreizehnter Vortrag

Wir haben versucht, uns die Hauptideen vor Augen zu führen, welche in unserem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum nach Ausgestaltung, man könnte auch sagen, nach Dasein ringen, so nach Dasein ringen, daß sie unter den charakterisierten zweierlei Impulsen einseitig zur Ausbildung kommen. Unter dem einen Impuls bildet sich aus, gestaltet sich mehr oder weniger aus alles das, was angeschlossen werden kann an die Tatsache der Geburt, die Tatsache der Verwandtschaft der Lebewesen, überhaupt der Wesen und Kräfte innerhalb unseres Erdendaseins. Von dem anderen Impuls einseitig beeinflußt sehen wir diejenigen Tatsachen, die sich anschließen an den Tod, an dasjenige, was man Leiden, Schmerz, das Übel, das Böse nennt. Und wie sich einseitig ausgestalten die Tatsachenreihen im menschlichen Denken, die sich an das Charakterisierte anschließen, das haben wir von verschiedenen Seiten her zu beleuchten versucht. Nun muß man sich darüber klar sein, daß die beiden wichtigsten Ideale für diese fünfte nachatlantische Zeit sind: erstens das Ideal, rein dasjenige hinzustellen, was in der Sinneswelt vorliegt, und es zurückzuführen bis zu den ursprünglichen Erscheinungen, wie das — wir haben ja darüber schon gesprochen — Goethe getan hat, der versucht hat, die Erscheinungen bis zu dem zurückzuführen, was er die Urphänomene nannte. Auf der anderen Seite muß der fünfte nachatlantische Zeitraum danach streben, freie, in der menschlichen Seele aufsteigende Imaginationen zu erlangen. In dem Zusammenschauen gewissermaßen der Imaginationen, die der Mensch empfängt aus der geistigen Welt, von denen jetzt ja erst wenige da sein können, denn der fünfte nachatlantische Zeitraum hat, wie wir wissen, erst im 15. Jahrhundert begonnen, im Zusammenschauen der Imaginationen mit der Sinnenwelt besteht die Aufgabe unserer Zeit. Mit diesen freien Imaginationen soll der Mensch umfassen dasjenige, was sich in der äußeren Sinnenwelt ihm darbietet. Wie Sie ja aus verschiedenen meiner Ausführungen, die teilweise in Vorträgen gegeben worden sind, teilweise in meinen Büchern sich finden, entnehmen können, hat einen großen Anfang gemacht mit einer solchen Weltenbetrachtung eben gerade Goethe. Deshalb kann Goethe auch für eine wirklich von der fünften nachatlantischen Zeitepoche geforderte Weltanschauung die echte, sachgemäße Grundlage sein.

Es ist eigentümlich in der Weltentwickelung, daß sie gewissermaßen wellenförmig sich vollziehen muß, daß gewisse Impulse auftauchen, stark wirken, dann wiederum abfluten und erst später wieder auftreten können und so weiter. Das empfindet besonders stark derjenige, der die Goethesche Weltanschauung in ihrem Nerv versteht. Gewiß, Geisteswissenschaft selbst kann noch nicht gefunden werden in der Goetheschen Weltanschauung, aber sie wird gerade unter dem Einflusse des Verständnisses der Goetheschen Weltanschauung immer mehr und mehr entstehen können. Denn es ist wirklich so, daß alles dasjenige, was noch ohne die eigentliche Gestalt der Geisteswissenschaft als Weltanschauung gegeben werden konnte, in der Goetheschen Weltanschauung gegeben ist. Und diese Goethesche Weltanschauung hat zunächst in, wenn auch vielleicht für die große Welt enge, so doch für das Geistesleben weite Kreise ihr Licht geworfen, und vieles im Geistesleben ist schon durch die Goethesche Weltanschauung beeinflußt worden, wenn auch dasjenige, was beeinflußt worden ist, im Grunde ebenso zunächst abgeflutet ist, wie die Goethesche Weltanschauung ja selbst abgeflutet ist. Denn darüber braucht man sich ja keiner Täuschung hinzugeben: Wenn auch Goethe von vielen heute genannt wird, wenn auch viele glauben, seine Werke zu kennen, dasjenige, was eigentlich in seiner Weltanschauung lebt und webt, das ist doch etwas, was noch zu dem Unbekanntesten in der Menschheitsentwickelung gehört, und was, wenn es immer mehr und mehr eintreten wird in die Menschheitsentwickelung, das wissenschaftliche, das soziale und auch das übrige Denken, aber auch die Impulse desHandelns der Menschen wesentlich umgestalten wird. In unserer Zeit wirken noch außerhalb der anthroposophischen Bewegung für ein Verständnis der Goetheschen Weltanschauung wenig günstige Kräfte, wenig günstige Impulse. Denn so berechtigt und so großartig das sogenannte demokratische Prinzip für die Menschheitsentwickelung ist, wenn es in richtigem Sinne verstanden wird, so verderblich wirkt es in unserer Zeit, wo es oftmals am falschesten Ende angepackt und angewendet wird. In unserer Zeit herrscht eine intensive Abneigung, Antipathie, ja mehr als das, in vielen Seelen ein intensiver Haß und eine Gegnerschaft gegen eine so geartete Weltanschauung, wie sie ihre Quellen in Goethescher Denkungsart und Goethescher Gesinnung hat. Denn zu dieser Weltanschauung ist vieles, vieles nötig, was gerade unsere Zeit am allerwenigsten gern hat. In unserer Zeit möchte jeder, ohne sich Grundlagen dafür besonders geschaffen zu haben, gewissermaßen seine eigene Weltanschauung haben, seine eigene Weltanschauung sich aufbauen, ein Eigenbrötler der Weltanschauung sein. Und die nächste Empfindung, die jeder hat, ist ungefähr diese, daß die einzelnen Weltanschauungen so gleichberechtigt nebeneinanderstehen. Dasjenige, was einem gerade von Goethe so einzigartig charakterisiert im Faustischen Streben entgegentritt, von dem spricht heute jeder journalistische Tropf und jeder, der diesen Tröpfen nachspricht; aber vom Kennen des innersten Nerves dieses Faustischen Strebens kann ja gerade heute im allergeringsten Maße nur die Rede sein. Und wir werden noch viel zu besprechen haben, wenn wir das, was damit nur mit ein paar Strichen gekennzeichnet ist, was einem harmonischen Ausgleiche der genannten Impulse ungünstig ist in der neueren Zeit, ins Auge fassen werden, um dann auch zu besprechen, wie dieser harmonische Ausgleich der einseitigen Impulse, die wir kennengelernt haben, herbeigeführt werden soll.

Ich möchte heute gewissermaßen episodisch wiederum einiges einfügen, um Ihnen begreiflich zu machen, wie es hat kommen können, daß die schon auf einer solchen Höhe lebende Goethesche Weltanschauung versiegt ist im 19. Jahrhundert und sich allerlei anderes geltend gemacht hat. Dieses 19. Jahrhundert kam immer mehr und mehr dazu, wenn man so sagen darf, die Welt, die den Menschen umgibt, uninteressant zu finden — das beachtet man oftmals wenig, aber es ist doch so -, weil gerade im 19. Jahrhundert in der geistigen Menschheitsentwickelung jene Krisis heraufkam, die bedingte, daß das Anschauen des Geistigen, das in den Dingen lebt, immer mehr und mehr versiegte. Man sah nur die äußeren sinnlichen Qualitäten, sinnlichen Eigenschaften, Betätigungsweisen der Dinge, und diese wurden immer uninteressanter und uninteressanter. Dasjenige, was als Geistiges die Sinnenwelt durchlebt und durchwebt, sah man nicht mehr. Die Sinnenwelt als solche fand man immer uninteressanter und uninteressanter. Daher der’Iraum, innerhalb dieser Sinneswelt selber, die ja doch das einzige war, was man dem Geiste der Zeit nach hatte, innerhalb dieser Sinneswelt selber etwas Verborgenes zu suchen. Das Geistig-Verborgene in der Sinneswelt, das wurde man nicht gewahr. So suchte man nach dem Verborgenen in der Sinneswelt selber, und das führte dazu, daß man zunächst, allerdings in höchst fruchtbarer Weise, nach einer andern Seite hin die Anschauung räumlich zu vertiefen suchte durch die mikroskopische, durch die teleskopische Forschung, durch dasjenige, was im Kleinsten und im Größten rein sinnlich geschaut werden kann. Der Glaube an das Geistig-Verborgene schwand. So wollte man wenigstens glauben dürfen daran, daß sich die Weltenrätsel lösen durch Erforschung des sinnlich zunächst Verborgenen, und auf diesem Gebiete brachte man es ja ungeheuer weit. Man braucht nur daran zu denken, welche großen, gewaltigen Fortschritte die mikroskopische Forschung in bezug auf die Lebewesen im 19. Jahrhundert gemacht hat. Die Zellenlehre ist dadurch heraufgekommen. Man gelangte zu der Anschauung, daß der lebendige Organismus der Pflanzen und der Tiere und des Menschen aus kleinsten Teilen, Zellen bestehe, und die Vervollkommnung der mikroskopischen Forschung machte es möglich, das Leben dieser kleinsten Zellenwesen zu studieren, über das man früher mehr oder weniger ja nur Vermutungen hat anstellen können. Das Sinnliche wollte man auf diese Weise aus einem anderen Sinnlichen erklären. Und besonders wichtig wurde diese Erklärungsweise für die eine Reihe der Tatsachen, die sich heraufdrängte im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum, für die Tatsachen, die sich an die Geburt, an das Werden der Lebewesen anschließen. Man sah ein Lebewesen bis zum Menschen herauf hervorgehen aus einer Zelle, man sah es sich entwickeln, indem man das fortschreitende Leben, die Vermehrung der Zellen beobachtete, und man gelangte endlich dazu, sich Vorstellungen darüber zu machen, wie umgebildet wird die einfache runde Zelle, die sich vermehrt nach und nach im Verlaufe ihres Lebens vor der Geburt, auch beim Menschen, und endlich zu der menschlichen Gestalt wird, wie sie durch die Geburt ins Dasein tritt.

Man machte sich, wie ich sagte, Vorstellungen darüber, wie aus der einfachen Zelle dasjenige wird, was dann als Mensch durch die Geburt ins Dasein tritt, und die Vorstellungen führten dazu, das, was man nennen kann das Problem der Geburt, das Rätsel der Geburt beim Menschen eng anzuschließen an die Vorgänge im tierischen Leben. Man sah ja, daß die tierische Welt in ihren einfachsten Formen sich darstellt in solchen Wesen, die selber erst wie eine einzige Zelle sind, daß also es tierische Wesen in der Welt gibt, welche gewissermaßen in ihrem ganzen Leben die Gestalt haben, die der Mensch nur in der allerersten Zeit in dem Leibe der Mutter hat. Andere Tiere stellten sich dar in Formen, die ähnlich waren einer späteren Entwickelungsform des Menschen. In einer gewissen Zeit der Entwickelung vor der Geburt, also der embryonalen Entwickelung, stellt sich die Menschengestalt so dar, daß sie aussieht oder wenigstens daß sie erinnert an ein Fischchen, und zwischen der Zellenform und der Form eines Fischchens liegen die anderen Formen darinnen, die nun wiederum draußen als selbständige Wesen leben. Der Mensch macht also gewissermaßen durch in seiner Embryonalentwickelung nach und nach die Formen, welche draußen sind. Das hat ja, wie wir wissen, geführt zu der Aufstellung des durch Aaeckel so berühmt gewordenen biogenetischen Grundgesetzes, das da heißt, daß der Mensch während seiner Entwickelung vor der Geburt verkürzt gleichsam rekapituliert die Tierformen. Das aber hat weiter dazu geführt, zu glauben, daß der Mensch, so wie er ins irdische Dasein tritt, von denTierformen abstammen müsse. Man hat gedacht: Nun, in den alten Zeiten waren einfach eben nur Zellenwesen vorhanden, aus diesen Zellenwesen entwickelten sich durch diese oder jene Vorgänge, die man sich wieder mehr oder weniger zufällig oder rein naturwissenschaftlich notwendig dachte — was ja schließlich dasselbe ist —, etwas kompliziertere Wesen. So daß man also jetzt in einem nächsten Stadium der Weltentwickelung vor sich hat die einfachen Zellenwesen und etwas kompliziertere, aber die etwas komplizierteren machen zunächst das Stadium der einfachen Zellenentwickelung durch; dann kamen weiter kompliziertere, die wiederum durchgemacht hatten Zellenformen, also dasjenige, das früher entstanden ist, und dann ihre Form. Und so, dachte man sich, habe sich die ganze Tierwelt entwickelt, zuletzt der Mensch, der eben während seiner Embryonalentfaltung in Kürze die Tierformen alle rekapituliert.

Auf diese Weise ist eine Anschauung entstanden über den Zusammenhang desjenigen, was man menschliche Geburt nennen kann, mit dem allmählichen Entstehen, wie man es sich dachte, der organischen Lebensformen. Dies knüpfte also den Menschen unmittelbar an die verschiedenen Tierformen an, und da der Mensch durch dasjenige, was er unmittelbar sieht, leicht geblendet wird, so vergaß man im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts irgend etwas anderes zu berücksichtigen als das, was sich auf diese Weise wie eine Ähnlichkeit der menschlichen Embryonalentwickelung mit den Gestaltungen der übrigen organischen Formen ergab. Die Gedanken und Ideen, durch die man den Zusammenhang, den man also durch die fortgeschrittenen Mittel der Forschung erkannt hatte oder zu erkennen glaubte, diese Gedanken waren nur dadurch so eng wie sie waren, konnten nur dadurch jene materialistische Form annehmen, die sie angenommen haben, weil eben im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts Goethesche Denkungsart, Goethesche Vorstellung wirklich vollständig versiegte. Man braucht sich nur daran zu erinnern, wie Goethe im Verlaufe seines Lebens zu dem gekommen ist, was er seine Metamorphosenlehre nennt.

Goethe hat sich — das mag Ihnen ja zur Genüge hervorgehen aus dem, was aus dem «Faust» auf Sie gewirkt hat -, bevor er zu seiner Metamorphosenlehre gekommen ist, wohl beschäftigt mit demjenigen, was ihm in seiner Zeit zur Verfügung stehen konnte an Erkenntnissen der geistigen Welt, und er hat kennengelernt verschiedene Wege, verschiedene Mittel, durch die der Mensch versuchen kann, sich der geistigen Welt zu nähern. Erst nachdem durch die Erfahrungen, durch die Erlebnisse mit diesen Mitteln und Wegen Goethes Geist sehr, sehr vertieft war, ging er daran, naturwissenschaftliche Ideen zu fassen. Und da sehen wir denn zunächst, wie Goethe, als er nach Weimar gekommen war und ihm nach und nach die Mittel der Jenaer Universität zur Verfügung standen, alles, alles tut, um seine naturwissenschaftlichen Kenntnisse und Einsichten zu bereichern, aber zugleich auch alles tut, um zusammenhängende Ideen zu gewinnen über die verschiedenen Formen der Organismen. Und dann wiederum sehen wir, wie Goethe seine Italienische Reise antritt, wie er, während er auf der Italienischen Reise ist, alles, was ihm entgegentritt an Pflanzen- und Tierformen, ins Auge faßt, um die innere Verwandtschaft der Pflanzen- und Tierformen in der reichen Mannigfaltigkeit zu studieren, die ihm jetzt entgegentrat. Und in Sizilien endlich glaubte er dasjenige gefunden zu haben, was er seine Urpflanze dann nannte. Was dachte sich Goethe als Urpflanze? Diese Urpflanze ist nicht ein sinnliches Gebilde. Diese Urpflanze nennt Goethe selbst eine sinnlich-übersinnliche Form. Sie ist etwas, was nur im Geistigen angeschaut werden kann, was aber in diesem Geistigen so geschaut wird, daß wenn man eine bestimmte Pflanze sieht, man weiß: diese bestimmte Pflanze ist eine besondere Ausgestaltung der Urpflanze. Jede Pflanze ist eine besondere Ausgestaltung der Urpflanze, aber keine sinnlich-wirkliche Pflanze ist die Urpflanze. Die Urpflanze ist ein sinnlich-übersinnliches Wesen, das in allen Pflanzen lebt. Bis zu dieser Idee also brachte es Goethe: nicht bloß zu verfolgen die verschiedenen sinnlichen Formen, sondern die eine Urpflanze in allen Pflanzen zu suchen. Damit hatte er, man könnte sagen, das, was als Metamorphosenlehre immer existiert hat, wesentlich vertieft, sehr, sehr vertieft, und es lag ihm nahe, nun auch anzuwenden die Idee dieser Metamorphosenlehre im weiteren Umfange auf das Organische, auf das Lebendige.

Interessant ist es, wenn er nun beschreibt, wie er die menschliche Gestalt selber sich denken wollte so, daß ihre einzelnen Glieder Verwandlungsprodukte darstellen, gewissermaßen der Mensch die Komplikation einer Idee ist. Er erzählt, wie er 1790 auf dem Judenkirchhof in Venedig einen Schöpsenschädel gefunden hat, der besonders glücklich zerfallen war, so daß er an den einzelnen Schädelknochen sehen konnte, wie diese Schädelknochen so gebildet sind, daß man in ihnen umgebildete Wirbelknochen erkennen kann. Es war ihm also aufgefallen, daß die Wirbelsäule aus einzelnen Knochen, die ich nur schematisch zeichnen will, besteht, daß aber dann der Schädel aus solchen umgestalteten Wirbelknochen besteht. Natürlich, wenn sie umgestaltet sind, dann nehmen sie ganz andere Formen an, aber doch sind die Schädelknochen dann nur umgestaltete Wirbelknochen. Die Wirbelknochen liegen ringförmig übereinander. Dadurch, daß man sie sich aus Kautschuk denkt und in der verschiedensten Weise der Kautschuk auseinandergezogen wird, kann man sich vorstellen, daß aus den Wirbelknochen die Formen der Schädelknochen entstehen (siehe Zeichnung a). Das war für Goethe etwas außerordentlich Wichtiges, sich sagen zu können: In dem Wirbelknochen, der das Rückenmark umhüllt, ist etwas gegeben wie ein Grundelement der menschlichen Entwickelung, das sich nur umzubilden braucht, um zu komplizierteren Elementen dieser menschlichen Entwickelung sich zu gestalten. So hatte Goethe auf der einen Seite im Pflanzenblatt erkannt: Wenn eine Pflanze wächst, so entwickelt sie Blatt nach Blatt; aber dann schließt sie ab an einem bestimmten Punkt die Blattentwickelung, und es entstehen durch die Umwandlung des Blattes zunächst die Blütenblätter (siehe Zeichnung b), dann aber auch die Staubgefäße, ganz anders gestaltete Organe, die auch nichts anderes sind als Blätter, aber umgestaltete Blätter. In dem Blatte ist also für Goethe die ganze Pflanze enthalten.

Es ist also viel Unsichtbares, Übersinnliches in einem Blatt, die ganze Pflanze ist in einem Blatt. Ebenso aber auch ist das ganze Kopfskelett in der Wirbelsäule schon. Wirbelsäule und Kopfskelett bilden zusammen ein Ganzes, und die komplizierten Kopfknochen sind ebenso umgebildete Wirbelknochen, wie die Blütenblätter, ja wie die Staubgefäße und der Stempel umgebildete grüne Blätter der Pflanze sind. So hat Goethe die Idee, daß dasjenige, was übersinnlich zugrunde liegt dem Blatte, in der mannigfaltigsten Weise kompliziert sich umwandelt und dann zur ganzen Pflanze wird; daß dasjenige, was in der Wirbelsäule liegt, kompliziert sich umgestaltet und zum Haupte wird. So weit im wesentlichen ist Goethe gekommen in seinen Anschauungen.

Geisteswissenschaft gab es damals noch nicht, und es ist gerade interessant zu sehen, wie Goethe ein Geist ist, der immer auf der Stufe bewußt stehen bleibt, bis zu der er durch sein reiches Anschauen vordringen kann, und nicht irgendwelche spekulative Gedanken faßt, Hypothesen etwa aufstellt, um über diesen Punkt, bis zu dem er eben durch seine reichen Erlebnisse dringen kann, in unberechtigter Weise, in phantastischer Weise hinauszudringen.

Nun ist zwar ein weiter Weg, aber doch ein Weg, auf dem jetzt, mehr als hundert Jahre, nachdem Goethe diese Ideen gefaßt hat, schon geschritten werden darf. In bezug auf den Menschen ist Goethe sozusagen dabei stehengeblieben: Der Mensch hat eine Wirbelsäule, ein Wirbel liegt über dem anderen, dann bildet sich der Wirbel um zu dem Schädelknochen. Dabei ist Goethe stehengeblieben. Bei dem, wo er stehengeblieben ist, braucht heute nicht mehr stehengeblieben zu werden. Denn von dem aus bis zu einer weiten, weite Umblicke gestattenden Idee ist wirklich ein Weg, und muß sogar ein Weg durch die Geisteswissenschaft geschaffen werden. Wenn man mit demselben Geiste, mit dem Goethe, nachdem — wie man sagt, durch einen «Zufall» - glücklich gespalten ihm auf dem Judenkirchhof in Venedig ein Schöpsenschädel entgegengetreten ist, wenn man mit demselben Geiste, mit dem man die einzelnen Knochen dieses Schöpsenschädels angeschaut hat und durch diesen Geist erkannt hat, daß sie umgewandelte Wirbelknochen sind, anschaut den Menschen, wie er im Ganzen vor uns steht, dann merkt man heute etwas. Ich habe schon darauf hingedeutet, ich muß es aber in diesem Zusammenhange wieder erwähnen und von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus beleuchten. Dann merkt man heute, daß der Mensch im wesentlichen ein zweigeteiltes Wesen ist: daß er besteht aus seinem Haupte und aus dem übrigen Organismus. Geradeso, wie sich das Blütenblatt aus dem Stengelblatt der Pflanze entwickelt, wie das Blütenblatt eine Umbildung des Stengelblattes der Pflanze ist, so ist der Kopf des Menschen auch eine Umbildung des ganzen übrigen Organismus. Ich habe ja gesagt, daß, damit diese Umbildung vollends zustande komme, der Mensch sich herüberentwickeln muß von einer Inkarnation zu der nächstfolgenden Inkarnation. Das, was wir heute, so sagte ich, an uns tragen als unseren übrigen Organismus, das wird in der nächsten Inkarnation unser Haupt.

Sie sehen, diese Anschauung ist nur ein vollkommener ausgebildeter Impuls, der sich ergibt, wenn man innerlich verfolgt dasjenige, was in Goethes Weltanschauung den Anfang genommen hat. So wird versucht, wenn man wirklich auf dem Boden dieser Metamorphosenlehre steht, den einzelnen Organismus in seinen Gliedern darzustellen; aber diese Glieder werden so im Zusammenhang gedacht, daß der Zusammenhang nur möglich ist, wenn man durchschaut auf etwas, was da als Geistiges in der Sache lebt. Denn natürlich, würde ein Blatt das sein, was die Sinne sehen, so würde es niemals zu einem Blütenblatt oder zu einem Staubgefäße werden können; würde ein Wirbel dasjenige sein, als was ihn die Sinne sehen, so würde er niemals zu einem Gliede des Kopfskelettes werden können; würde der menschliche Leib dasjenige sein, als was er sich den Außensinnen darbietet, so würde er, wenn er noch so sehr sich verwandelte in seinen Kräften, niemals zu einem menschlichen Haupte werden können. Nun aber, selbst mit Bezug auf das äußere Anschauen ist diese Goethesche Weltanschauung klarer darinnenstehend in den Anforderungen des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums, als die auf ihr äußeres Anschauen und Experimentieren so stolze Naturwissenschaft des 19. Jahrhunderts. Goethe kann wirklich besser anschauen, und derjenige, der sich auf ihn zu stützen versucht, kann besser anschauen dasjenige, was in der Natur geschieht und was in der Natur vorhanden ist, als namentlich die biologische Wissenschaft des 19. Jahrhunderts.

Als zwei Glieder, sagte ich, tritt uns zunächst der Mensch entgegen: als das Haupt und als sein übriger Organismus. Diese Tatsache, daß das Haupt gewissermaßen ein umgewandelter übriger Organismus ist, die muß man zunächst verstehen können, wenn man weiterbauen will. Denn dann erst wird man fragen können: Ja, was ist dann eigentlich auf der einen Seite dieses menschliche Haupt, und was ist auf der anderen Seite der übrige menschliche Organismus? — Um diese Frage sich zu beantworten, muß man ganz andere Dinge wichtig nehmen, als die gebräuchliche heutige Naturwissenschaft wichtig nimmt.

Sehen Sie, wenn Sie sich ein Tier vorstellen, so ist das Wesentliche an dem Tier, daß seine Rückenmarkssäule - ich habe das auch öfter angedeutet — parallel ist der Erdenoberfläche, und daß das Tier mit den Vorder- und Hinterbeinen auf der Erdenoberfläche daraufsteht (a) und den Kopf in der Verlängerung der Rückenmarkssäule, im wesentlichen als Verlängerung dieser Rückenmarkssäule horizontal trägt. Dasjenige, was man beim Menschen als sein heutiges Rückenmark kennt, das ist nun vertikal gerichtet, ist gerade senkrecht zu der Richtung gerichtet, die das Rückenmark des Tieres hat (b).

Aber dieses Rückenmark wollen wir zunächst nicht ins Auge fassen, denn es gehört nicht zum Kopfe; es gehört zum übrigen Organismus. Wir wollen zuerst ins Auge fassen ein anderes Rückenmark. Ja, was für ein anderes? Wir wollen ins Auge fassen das menschliche Gehirn. Sie werden sagen: Ist denn das ein Rückenmark? Ja, das ist ein Rückenmark! Es ist nämlich nichts anderes als ein umgewandeltes Rückenmark, es ist gewissermaßen ein aufgeplustertes Rückenmark. Denken Sie sich ein horizontales Rückenmark, wie es das Tier hat, aufgeblasen, umgewandelt, metamorphosiert, so bekommen Sie das menschliche Gehirn (c).

Die wahre Tatsache ist diese, daß während der Mondenentwickelung das, was heute Gehirn ist, so ausschaute wie ein heutiges tierisches Rückenmark. Und nur beim Übergang von der Mondenentwickelung in die Erdenentwickelung herein ist dieses Rückenmark, das der Mensch auf dem Monde hatte, komplizierter geworden, ist zum heutigen menschlichen Gehirn geworden; aber seine horizontale Lage hat es behalten. Denn im wesentlichen ist seine Achse senkrecht auf dem dem Körper angehörigen Rückenmark, und dieses dem Körper angehörige Rückenmark hat der Mensch erst während der Erdenzeit erhalten. Das ist noch auf der Stufe, auf der jenes Rückenmark, welches Gehirn geworden ist, auf dem Monde war, während der Mondenentwickelung (d).

Dasjenige, was heute einfacher erscheint beim Menschen, sein Rükkenmark, das hat er später bekommen im Lauf der Entwickelung als dasjenige, was heute komplizierter erscheint, sein Gehirn. Nur war das Gehirn, das er heute hat, früher ein Rückenmark. So also sehen wir den Menschen ein zum Gehirn umgewandeltes Rückenmark haben, und dann erst während der Erdenentwickelung dazu gefügt ein ursprüngliches Rückenmark (e).

Also wenn wir das menschliche Haupt betrachten, so tritt es uns gar nicht so sehr verschieden vom tierischen entgegen; denn seine Hauptesrichtung ist wie die Rückgratsrichtung des Tieres, die auch beim Tiere die Hauptesrichtung ist, horizontal, parallel der Erde (f).

Und manche anderen Eigenschaften könnten angegeben werden, welche zeigen würden, daß das menschliche Haupt als solches, wenn es besehen wird, wie es in der ganzen Entwickelung drinnensteht, eine umgebildete 'Tierheit ist, und daß zu dieser umgebildeten Tierheit die übrige menschliche Organisation dazugekommen ist. Diese Idee, die ist gar nicht sehr ähnlich derjenigen, zu der die naturwissenschaftliche Entwickelung im 19. Jahrhundert gekommen ist. Denn die naturwissenschaftliche Entwickelung im 19. Jahrhundert wird, weil sie auf das Außerlich-Sinnliche den Hauptwert legt, gerade das menschliche Haupt am allerverschiedensten von der Tierheit finden. Hier (siehe Zeichnung) erscheint uns das menschliche Haupt gar nicht so verschieden von der übrigen Tierheit, nur veredelt: das Gehirn ein aufgeplustertes Rückenmark, das ja das Tier hat.

Sie werden nun die Frage auf den Lippen haben: Ja, glaubst du nun vielleicht, daß der übrige menschliche Organismus nun sogar edler ist als der Hauptesorganismus in bezug auf die äußere Gestaltung, daß der übrige menschliche Organismus vielleicht sogar weniger dem Tiere gleichen könnte als dasHaupt? Und Sie selbst werden es vielleicht paradox heute noch finden, aber Sie werden sich schon hineinfinden in die Anschauung, daß dies gesagt werden muß. Und im Grunde genommen: Sieht nicht schon äußerlich unser Haupt schließlich, von allen unseren Gliedern im ganzen genommen, am allerähnlichsten den Tierformen? Wir sind, wenigstens einen großen Teil unseres Lebens, die Männer noch mehr als die Frauen, am Haupte behaart. Das hat der übrige Organismus keineswegs in demselben Maße. Dadurch spricht das auch schon seine Verwandtschaft mit dem tierischen Organismus recht sehr aus. Dies, was ich Ihnen jetzt nur andeute - ich will es vorläufig bei der Andeutung lassen -—, dies werden wir schon im Laufe der Zeit weiter ausführen. Aber es wird uns immer mehr und mehr zu der Anerkennung führen, daß etwas ganz anderes stattfindet in der Natur als dasjenige, was man sehr häufig glaubt. Der Mensch blickt herunter vom Menschen zu den niederen Tieren und sieht zum Beispiel eine Schildkröte oder eine Muschel oder eine Schnecke, und er glaubt im Sinne der heutigen Naturwissenschaft, die Schnecke, die Muschel, überhaupt das niedrige Getier, das hat sich zuerst allmählich entwickelt, und zu den niedrigen Organismen der niedrigen Tierheit ist der menschliche Kopf dazugekommen. Unsinn ist dieses, völliger Unsinn! Wenn Sie sich heute ein Schalentier ansehen oder eine Schildkröte, so ist dieses ein menschliches Haupt auf einer untergeordneten Stufe, und unser übriger Organismus ist dazugekommen. Nachdem sich dasjenige, was niedere Tierformen sind - ich will sie schematisieren —, allmählich umgestaltet hat zum menschlichen Haupte, ist der übrige Organismus dazugekommen.

Also wir haben eine Entwickelung, die geht von den niederen Tierformen immer weiter und weiter, und das, was Tierheit ist, hat sich zum menschlichen Haupte gestaltet und der übrige Organismus ist diesem menschlichen Haupte als das Spätere angehängt. In unserem Haupte allein tragen wir dasjenige in uns, was uns mit den übrigen Tieren verbindet, nicht in unserem anderen Organismus. Deshalb hat das menschliche Haupt in seiner Hauptachse für sich dieselbe Richtung wie ein Tier: parallel der Erdenoberfläche. Der übrige Organismus ist aufrecht gebaut, ist senkrecht auf der Erdenoberfläche.

Es ist schon sehr verhängnisvoll, daß diese falsche Idee, die damit gekennzeichnet ist, in die naturwissenschaftliche Entwickelung des 19. Jahrhunderts eingezogen ist. Denn dadurch meint man eben, der Mensch als solcher, wie er ist, geht eben mit seinem ganzen Organismus als eine etwas ausgebildetere Gestalt aus früheren Tierformen hervor. Die Wahrheit ist, daß dasjenige, was aus früheren tierischen Formen hat werden können, nur Haupt sein kann, daß dagegen zu diesem Haupte hinzugekommen ist das, was innerhalb der Erdenentwickelung ganz neu eingetreten ist.

Nun wird es sich also um zweierlei handeln zunächst. Das erste ist dieses, daß wir eigentlich in unserem Haupte eine umgewandelte Form für die übrigen Tierformen haben. Und dennoch, aus demjenigen, was erst zum Haupte hinzugekommen ist und das wir als übrigen Organismus in einer Inkarnation haben, entwickeln wir durch entsprechende Kräfte in der nächsten Inkarnation die Form des Hauptes. Das könnte einem als ein scheinbarer Widerspruch vorkommen. Wir werden sehen, indem wir diese Dinge genau betrachten werden, daß es ein Widerspruch nicht ist.

Ich wollte Ihnen durch die Erinnerung an die Tatsache, daß der Mensch das Tier eigentlich an sich trägt, daß er mit seinem Erdenorganismus das Tier stützt, das zu seinem Kopfe geworden ist, nur zeigen, wie falsch die heutigen äußeren Ideen sein können. Aber auch positiv möchte ich Ihnen noch etwas anderes zeigen. Wodurch ist denn, wenn das menschliche Haupt nur ein umgestaltetes Tier ist, das Haupt des Menschen das geworden, was es heute ist? Wodurch kann sein Kopf, der, so wie er einmal heute ist, sich dadurch entwickelt, daß er vorbereitet wird durch einen irdischen Organismus in einer vorhergehenden Inkarnation, sich zu dem menschlichen Haupt heranbilden? Nun, das Tier geht durch seine zwei Paar Beine auf der Erde, das heißt durch vier Beine. Wer da glaubt, daß dieses Tier nur so über die Erde hinschreitet und daß nichts sonst geschieht, als daß dieses Tier über die Erde hinschreitet, der ist in großem Irrtume. Aus der Erde gehen fortwährend Kräfte in das Tier herauf, gehen durch das Rückgrat, gehen dann, indem sie gewissermaßen das Gehirn immer beeinflussen, wiederum in die Erde zurück (a). Das Tier gehört zur Erde. Und wie es darauf steht, wie die Kräfte, die in der Erde wirksam sind, durch seine Beine in sein Rückgrat gehen und wieder zurück, das gehört zum ganzen Leben des Tieres.

Das Verhältnis, das das Tier zur ganzen Erde hat, hat der Mensch, hat der Menschenkopf, das Menschenhaupt zu dem übrigen Organismus des Menschen. Dadurch, daß der Mensch einen Organismus hat, der sich senkrecht abhebt von der Erde, dadurch wird dieser übrige Organismus für das menschliche Haupt dasselbe, was die Erde, die ganze Erde, für das Tier ist. Wir haben also in unserem dem Haupte angehängten Organismus zusammengeschlossen die Geheimnisse der ganzen Erde in uns. Und es kann leicht nachgewiesen werden, washeute nur angedeutet werden kann, daß in der Tat, wenn wir das Haupt studieren und das Gehirn darinnen, die Rudimente, die Anhangsorgane da sind für vordere und hintere Gliedmaßen, durch die der Mensch sich auf sich selber mit seinem Haupte aufstellt wie das Tier auf der Erde, wie wir da, nur umgestaltet zu inneren, anderen Organen, hintere Gliedmaßen und vordere Gliedmaßen haben. Und die ganze Kopfbildung ist so, daß sie in der Tat sich verhält zu dem übrigen menschlichen Organismus wie das Tier zur Erde (b).

Das ist so bedeutend nun, daß man einsieht, was eine solche Idee, die sich natürlich nur aus den durch die Geisteswissenschaft befruchteten Anschauungen ergibt, für eine Bedeutung hat. Denn mit dieser Idee muß man jetzt wiederum zurückgehen zu dem, was nur ungenügend das 19. Jahrhundert mit seinen groben Mitteln beobachtet hat; mit dieser Idee muß man nun zurückgehen und die Embryonalentwickelung verfolgen. Dann wird sich etwas ganz anderes ergeben als dasjenige, was die Naturwissenschaft des 19. Jahrhunderts hat finden können. Dann werden sich aber auch wiederum Ideen ergeben, die fruchtbar sein können für das menschliche Leben auch über die bloße unlebendige Technik hinaus. Aber ohne diese Ideen wird die Menschheit aus jener Sackgasse nicht herauskommen, in die sie sich nun einmal hineinbegeben hat. Denn auf der Entwickelung der Idee, nicht der allgemeinen Ideen, die heute in Vereinen mit großen Idealen gepflegt werden, nicht in diesen Ideen, die jeder fassen kann, wenn er sich einmal drei Stunden ins Kaffeehaus setzt, sondern auf den Ideen, die aus der Forschung der Wirklichkeit entlehnt sind und dann erst auf das Leben angewendet werden, beruht der wirkliche Fortschritt der Menschheit. Schöne Ideen, mit denen man Vereine gründen kann, die kann man leicht haben; aber sie verhindern nicht, daß die Kultur in solche Sackgassen kommt, wie sie jetzt gekommen ist. Nur allein die konkreten Ideen verhindern dieses.

Das muß man so recht empfinden, dann wird man die großen Aufgaben der Geisteswissenschaft erst einsehen, und man wird die um uns liegende Wirklichkeit richtig beurteilen. Diese Wirklichkeit geht darauf aus, Geisteswissenschaft gerade in ihrem Wichtigsten nicht aufkommen zu lassen. Der Geist ist nämlich hinlänglich noch vorhanden, der die Goethesche Weltanschauung im 19. Jahrhundert hat versiegen lassen, und dieser Geist lebt sich namentlich dadurch aus, daß er von einer gewissen Verfolgungswut beseelt ist: von einer Wut, alles dasjenige zu verfolgen, was nach wirklichkeitsgesättigten Ideen strebt. Diesem Geist der Gegenwart kommen gerade die wirklichkeitsgesättigten Ideen oftmals phantastisch vor, weil er nicht geeignet ist, diese Ideen aufzunehmen. Und es wird sich schon das herausstellen, was der Geisteswissenschaft wie ihr stärkster Widersacher immer mehr und mehr gegenüberstehen wird: es wird sich das herausstellen, daß man gerade eine Weltanschauung, die wirkliche Geisteswege sucht und vorurteilslos in den Wirklichkeiten zu forschen sucht, deshalb ablehnt, weil man ablehnen will dieses Forschen in den Wirklichkeiten. Es ist einem zu unbequem, kennenzulernen, was alles notwendig ist, um zu einer wirklich umfassenden Weltanschauung zu kommen. Deshalb wird man verleumden diese umfassende Weltanschauung und wird nicht merken lassen die Welt, wie umfassend sie ist, sondern der Welt vormachen, daß sie auf ebenso oberflächlichen, engherzigen, eingeschränkten Begriffen und Forschungsresultaten stehe wie andere Weltanschauungen in der Gegenwart. Und geltend machen wird sich immer mehr und mehr eine gewisse Anerkennung der Unehrlichkeit des Strebens, nämlich desjenigen Strebens, das auf der Engherzigkeit besteht und eine Ablehnung gerade desjenigen, was mit dem Bewußtsein, das nur befriedigend vorwärtsführt, wirklich in den Wirklichkeiten forschen will und dadurch auch zu einem gewissen umfassenden Standpunkt kommen kann. Hochmut, Anmaßung sind Eigenschaften, die heute noch nicht ihren Höhepunkt erreicht haben. Was alles noch werden kann unter dem Einfluß jener Anmaßung, die nicht die Naturwissenschaft, sondern die Weltanschauung, die aus der Naturwissenschaft oftmals gezogen wird, großziehen wird, davon machen sich die Menschen der Gegenwart noch gar keine Vorstellung. Und welche Tyrannis auftreten wird, wenn von den äußeren Gewalten sich immer mehr und mehr privilegieren lassen wird der Materialismus auf dem Gebiet der Medizin, auf dem Gebiete anderer sogenannter Wissenschaftlichkeit, was aus dem hervorgehen wird, das auch nur zu empfinden, dazu ist der gegenwärtige Mensch noch viel zu bequem. Er liebt es vielmehr, Stück für Stück hinzunehmen, wie Tag um Tag mehr sich das Geistige privilegieren läßt von den äußeren Gewalten. Und wenige sind noch derjenigen Menschen, die fühlen, was für einer grausen Zukunft die Menschheit entgegengeht, wenn sie nicht fühlen lernt, um was es sich gerade auf diesem Gebiete handelt, welcher Rückgang gegenüber Standpunkten, die schon erreicht waren, gerade auf diesem Gebiete zu verzeichnen ist.

Nur diese Empfindung wollte ich einmal andeuten, die notwendig ist den Menschen der Gegenwart. Denn dieser Empfindung steht gegenüber eine ungeheure Schläfrigkeit gerade der idealistisch gesinnten Menschen der Gegenwart. Gegenüber dem, was man also empfinden soll an Aufgaben, scheint es aber die ärgste Sünde zu sein, wenn diejenigen, die, gerade von idealistischen Gesinnungen durchdrungen, in eine neuere Weltanschauung sich hineinfinden, sich dann zurückziehen von dem übrigen Wirken und Leben der Welt und allerlei Kolonien und dergleichen begründen, während das Notwendigste dieses ist, daß die neuere Weltanschauung, die geisteswissenschaftliche Weltanschauung sich voll in das Leben hineinstelle und nicht schläfrig dem ungeheuern Abgrunde entgegentaumle, der sich auftut aus dem, was man also andeuten kann, wie ich es heute wieder angedeutet habe.

Ich wollte heute etwas Episodisches geben. Denn um die Dinge, die sehr wichtig sind, die ich weiterhin vorzubringen habe, darzustellen, brauche ich gerade drei aufeinanderfolgende Vorträge.