Spiritual Science as a Foundation for Social Forms

GA 199

20 August 1920, Dornach

Lecture VI

Once again, I would like to sum up some of what has been presented here recently. We spoke about the external sense world in its relation to the inner world of the human being and I pointed out two things in particular. I stressed that the external sense world certainly must be understood as a world of phenomena and that it is a sign of the prejudices of our age not to interpret correctly this view of the world of phenomena. Certainly, here and there, a certain perception surfaces concerning the fact that the outer sense world is a world of phenomena, of appearances, not one even of merely material realities. Then, however, behind this world of external phenomena, one seeks for material realities, for example, for atoms and molecules, and the like. This search for atoms and molecules, in short, for any world of physical reality standing behind the world of phenomena, is just as if one were to seek for some kind of molecular materiality behind the rainbow that is obviously only an appearance, a phenomenon. This search for material reality in regard to the external world is something quite unfounded, as spiritual science points out from the most diverse directions. We have to understand clearly that surrounding us in what we perceive as the sense world is a world of phenomena, and we may not interpret the sense of touch differently from the other senses in regard to the sense world. Just as we see the rainbow with our eyes without searching for a material reality behind it, accepting it as appearance, so we must accept the entire external world as it is, namely, in the sense I depicted it decades ago in my introduction to the volume an color theory42See Note #4 in Goethe's natural scientific writings. The question then is posed to us: What is it that really stands behind this world of phenomena? The material atoms are not behind it; there are spiritual beings behind it—there is spirituality. This recognition signifies a lot, for it means that we admit that we do not live in a material world but in one of spiritual realities.

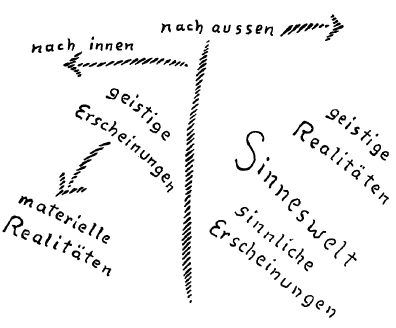

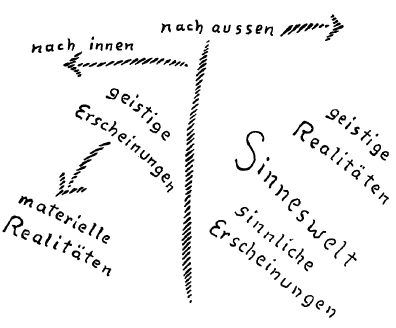

When we as human beings turn to the external world this drawing representing, as it were, the boundary of our body—we have here the sense world and behind it the world of spiritual realities, spiritual beings (right side).

Now, when we turn to the human interior, when we move from our senses inward, we have first of all the content of our world of conceptions, our soul world. If we call the sense world the world of sense phenomena, of sensory appearances, we have the world of spiritual phenomena when we turn from our senses inward (left). Naturally, in the manner in which they are present within us, our thoughts, our conceptions, are not realities, they are spiritual phenomena. Now, if we descend from this soul world still deeper into our inner being, it is all-important for us not to believe that we thereby arrive at a special, higher world, something that mystic dreamers presuppose. There, we actually come into the world of our organism, the world of material realities.

This is why it is important not to assume that by inward brooding one could discover something spiritual; there, we should seek for the constitution of the material human organism. One should not seek for all manner of mystical realities within oneself, as I have pointed out from a number of viewpoints. Instead, behind what pushes up into the soul and thus turns into a spiritual phenomenon, especially when one penetrates more and more deeply into oneself, we should seek the interaction of liver, heart, lungs, and other organs that mystics in particular do not like to hear mentioned. There we become acquainted with the essentially material element of our earthly existence. As I have often emphasized, many a person who believes he has encountered mystical realities by descending deeply into his inner being only finds what is given off by his liver, gall bladder and other related organs. Just as tallow turns into flame, so everything that liver, lungs, heart and stomach give off turns into mystical phenomena when it lights up into consciousness.

The important point is that true spiritual science guides the human being beyond any sort of illusion. Materialists cling to the illusion that they can find physical, material realities, not spiritual realities, behind the sense world. It is the illusion of mystics that when they descend into their own being, they can find, not the world of the material organization, but different kinds of special divine sparks, and such like.

In genuine spiritual science, it is important that we do not search for material substance in the outer world and do not seek the Spirit in the inner world, which initially appears as such through inward brooding.

What I have now said is of significant consequence for our entire world view. Bear in mind that from the time man falls asleep until he wakes up he is outside his physical and etheric bodies with his astral body and I. Where is he then? This is the question we must ask ourselves. If we assume that out there is the world described by the physicists, it makes no sense whatever to speak about an existence of the astral body or the ego outside the physical body. If we know, however, that beyond the sense world lies the world of spiritual realities, out of which the sense world blossoms forth, then we are able to imagine that the astral body and ego move into the spiritual world which lies behind the sense world. Indeed, astral body and ego find themselves in that part of the spiritual world that underlies the sense world. Thus, we can say that in sleep man penetrates into the spiritual world which is the basis of the physical world. Of course, upon awakening, his ego and astral body first penetrate his etheric being and then what constitutes the realm of the material organization.

Clear concepts of an anthroposophical world-view can only be attained if one is able to form intelligible ideas concerning such matters. For, above all, one will not succumb to the illusion of seeking the divine, or the spiritual underlying our human condition, behind the sensory surroundings. There, only that spiritual element is found which, out of itself, brings forth the sense world. As human beings we have our roots in the spiritual world, but in which spiritual world? We have our roots in the very spiritual world that we leave when incarnating into our physical body. We come from the spiritual world that we live in between death and a new birth; through birth or conception we enter this physical existence. The world we inhabit between death and a new birth, which we then leave, is a different spiritual world than this one [behind the sense world], although, because it is a spiritual world, it is related to the latter from which springs forth our sense world. We will not grasp the spiritual world of which we are speaking—I have described it in the lecture cycle, Inner Nature of Man and the Life Between Death and a New Birth,43Rudolf Steiner: Inner Nature of Man and the Life Between Death and a New Birth, GA 153 (London, Anthroposophical Publishing Co., 1959). namely, the spiritual world we experience between death and rebirth which creates and brings us forth—if we seek it behind the sense world. We will not take hold of it if we seek it within ourselves. There, we only discover the material element of our own organization. We can only grasp it when we leave space altogether. This spiritual world is not within space. As I have often emphasized, we can only speak about it when we base it solely on time, thinking of it as a world of time. Consequently, it goes without saying that all the descriptions we have about this world between death and rebirth can only be images, merely pictures. We must not confuse these pictures, in which we must of necessity express ourselves, with the realities in which we dwell between death and a new birth. It is vital that on the basis of the anthroposophical world-view we do not merely talk about all manner of fantastic things, depicting them in the ancient terminology which actually does not designate anything new. What matters is that we enrich our world of concepts and ideas when we try to send our thoughts into the world in which we live between death and rebirth. Thus we can acquire a most important concept that can also give rise to profound, albeit uncomfortable, reflection. It is this: When we have absolved the life between death and birth, we incarnate here in space. We penetrate into space out of a condition that is not spatial. Space has significance only for our experiences between birth and death. Again, it is important to know that when we pass through the portal of death, not only do we leave the body with our soul, we also leave space behind.

This concept was quite familiar to people until the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries A.D. Even a person like Scotus Erigena,44Scotus Erigena: 810–877 A.D. Translator of the writings by Dionysius Areopagita; author of “De divina praedestinatione,” “ De divisione naturae.” In 1225, the Vatican ordered all his writings burned. who lived in the ninth century, was fully conversant with it. Yet the modern age has completely lost the concept of the spirituality underlying human existence, within which the human being lives after death—as was thought then, only after death; today we must say: between death and rebirth we are outside space. The modern age is proud and arrogant regarding its thinking, yet it can actually think only of what is spatial, holding any and every thought in a spatial context. In order to conceive of spiritual matters, on the one hand, we must make the effort to overcome space within our thinking. Otherwise we will never reach the truly spiritual; above all, we will never attain to an even approximately correct natural science, much less a spiritual science. Particularly in our time it is infinitely important to become acquainted with these finer distinctions of spiritual-scientific knowledge. For, what we acquire through such concepts is not just any kind of world concept, any sort of thought content. The acquisition of a thought content is, after all, the very least we can achieve through anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. For it is one and the same whether someone believes the world consists of molecules and atoms, or if he believes man consists of a physical body, a somewhat less dense etheric body, then something more nebulous and tenuous, the astral body, followed by whatever is next, say, a still finer mental body, or something even more and more rarefied; for one doesn't come anywhere near the etheric body by just thinking of something more rarefied. It is really the same thing whether one is a materialist picturing the world as atoms, or whether one harbors this coarsely materialistic conception that is the common factor of the so-called theosophical society teachings, or whatever they are called now. Something quite different is what really matters, namely, that we become capable of changing our entire soul constitution. We have to make every effort to think about the spiritual in a manner different from the one in which we are accustomed to think about the external sense world. We do not comprehend spiritual science if we conceive of something other than the sense world as being spiritual; we enter into spiritual science if we think about the spiritual in a different way than we think about the sense realm. We think of the latter in terms of space. We can think about the spiritual world in terms of time within certain limits, because we have to think of ourselves within this spiritual world. And we are in a certain sense spiritually conditioned by time, in that at a certain moment in time we are transposed from the life between death and rebirth into the life between birth and death.

As I have often indicated, it is this transformation of the state of mind that is so absolutely essential for mankind of today. For how did we become caught up in the calamities of the present? It is because, along with so-called modern progress, humanity has altogether forgotten to admit the spiritual into its conceptions. The theosophical teachings of the so-called Theosophical Society are actually the attempt to characterize spiritual facts in materialistic forms of thought, hence, to drive materialism all the way into the spirit. We do not attain to a spiritual concept merely by calling something spiritual, only by transforming our thinking to what is suited to the sensory realm.

Human beings do not live with each other only in purely spatial relationships that can be constructed by means of what has become the general thinking of natural science. We can no longer develop social concepts based on the present-day world view. The kind of thinking that humanity has become accustomed to owing to natural science cannot lead to a characterization of social life. In this way arise the aberrations we experience today as a variety of social ideologies that only come about because it is impossible to think realistically about the social problems based on the conceptions from which we proceed to regard something as right or wrong. Not until people are willing to penetrate spiritual science will it become possible again to think of the social life in the manner it has to be conceived if further decline is to be halted and, instead, progress is to ensue. The discipline brought about in us by spiritual science is more important than its content. Otherwise we shall finally reach the stage of demanding that spiritual matters be popularized, that is to say, that they be presented in coarsely sensory, realistic terms. Things that must be expressed in a certain manner if one doesn't want to fantasize but to speak of realities, as I have done in our anthroposophical presentations as well as in my book, Towards Social Renewal,45See Note #13 are found to be not graphic enough. Well, “graphic” is a word that has a peculiar connotation for people today. There are people today who have much to say about this longing of mankind to have everything presented in a crudely senseperceptible manner. This is true all over the world, not just in certain countries.

I found an interesting passage, for example, in a recently published book, Les forces morales aux Etats-Unis,46Sophie Cheftele, “Les forces morales aux Etats-Unis (l'eglise, l'ecole, la femme),” Paris, 1920. written by a French lady. It has the following subdivisions: l'eglise, l'ecole, la femme. The book contains an interesting little episode which demonstrates how, in certain quarters, one triel “graphically” to describe matters pertaining to man's relationship with the spiritual world. The author relates:

One evening a friend and I strolled down Broadway. I came to a church. A quick glance showed us the place was filled with men only. Offended by seeing this, we avoided moving further inside. A priest clad in a soutane saw us, approached and invited us to come in. Since we hesitated, he asked about our confession. “We are not Catholics,” I said. He urged us to enter the church and, index finger pointing upward, he said with conviction “Come here and listen to me. If, for instance, you wish to travel to Chicago, how would you go about it? You might go on foot, take a car, a boat, or travel by train. It stands to reason that you would choose the fastest and most comfortable means. In this case that's the train. Obviously, if you wish to get to the Garden of God you will choose the religion that will get you there in the fastest and safest way. That's the Catholic religion, which is the express train to Paradise.”

The Lady telling the story only concluded that she was so perplexed she did not think of telling him that he had forgotten the airplane in his graphic comparison, which he could have mentioned as a still quicker means of getting to Paradise.

You see, here was someone eager to counter people's prejudices, and he chose graphic conceptions. The description of the Catholic Church as the “express train to heaven” is a graphic image. It is indeed the tendency of our time to search for graphic images, meaning concepts that do not make any demands on people's thinking. It is precisely here that we must already discern the gravity of modern life which demands that we do away with such graphicness which turns into banality and triviality, thus pulling man down into materialism in regard to those matters that must be comprehended spiritually. Even in symptoms such as these we have to search for what is needed most in our age. It must be said again and again: Such symptoms cannot be ignored; we cannot afford to go blindfolded through the world, which is an organism asking to be understood by means of its symptoms. For these symptoms contain what we must comprehend if we wish to arrive at an ascent again from our general decline.

At this point, however, it is necessary to see a number of things in the right light. What has actually been produced from spiritual-scientific foundations in Towards Social Renewal truly has not been created out of some theory but out of the whole breadth of life, with the difference that this life is viewed spiritually. Mankind today cannot progress if people do not adjust to such a view of life.

I would like to put in here two points taken from life that once again showed me recently how necessary it is to lead humanity today to a life-filled comprehension of reality, but at the same time a spiritual comprehension of reality. Yesterday I read an article by a journalist whose name, so I am told, is Rene Marchand,47The source of this quote could not be found. who, for a long time, was a correspondent for Figaro, Petit Parisien, and so on. He participated in the war on the Russian front, being a radical opponent of the Bolsheviks. He then had dealings with the general of the counter-revolution, becoming a follower of it. Overnight, he became converted to the idea of workers' councils, to Bolshevism. From an opponent of Bolshevism, so it says here, he turned into a protagonist, an unreserved supporter of the leadership and the ideology of workers' councils. Here is a man who belongs to the intellectual class, for he is a journalist, who, after all, lives with a deeper understanding of life, a deeper sensitivity for life, who dwells in the old traditions as do most of today's sleeping souls. It is interesting how such a person suddenly realizes: All this will assuredly lead to destruction!—and now the only goal worth aiming at for him appears to be Bolshevism! In other words, the man now perceives that everything that is not Bolshevism leads to ruin. I explained to you how Spengler described this.48Rudolf Steiner: Oswald Spengler, Prophet of World Chaos, in GA 198 (New York, Anthroposophic Press, 1949). Marchand sees only Bolshevism; initially, he believes that Bolshevism is merely a Russian affair. Then he discovers something quite different. He feels that Bolshevism is an international matter that must spread over the whole world. He says:

It now became clear to me that peace can only be restored when the people in all the countries freely take their destiny into their own hands. The principles, hitherto proclaimed by the bourgeois governments merely to deceive the masses, can only become reality when this new imperialism (that of the Entente powers) has in turn broken down.

He then relates how he has now arrived at the conviction that justice, unity, peace, and law will only rule when the world has become bolshevistic through and through; not till then will reconstruction be possible. This man now sees that all else leads to destruction. And basically he is quite correct in pointing out: If anything outside Bolshevism is to be cultivated further, it must turn into the dictatorship of the old capitalism, the Bourgeoisie and its trappings. It must become the dictatorship of people like Lloyd George,49David Lloyd George: 1863–1945, British statesman, prime minister from 1916 until 1922. Clemenceau,50Eugene Clemenceau: 1841–1929, French statesman. Scheidemann,51Philipp Scheidemann: 1865–1939, German secretary of state, later minister president. and so on. If one does not wish for this, if one does not want ruin, there is no other choice but the dictatorship of Bolshevism. He sees the only salvation in the letter.

In a certain sense this man is honest, more honest than all the others who see the approach of Bolshevism and believe they can oppose it with the old regime. At least Marchand sees that all the old ideas are ready to perish. A question arises, however, especially if one stands on spiritual scientific ground and experiences this; for a man like Rene Marchand is an exception. The question forces itself upon one's mind: Where has the man gained knowledge of all this? He has acquired such knowledge where most of our contemporaries have gathered it, namely, from newspapers and books. He does not know life. To a large extent, people living today know -life only from newspapers and books. Particularly the people in leading circles know life just from newspapers. Think of all that we have experienced in this regard through newspapers, by means of books! We have witnessed that a few decades ago people still formed their world conceptions by reading French comedies, that they knew the events occurring in a comedy better than what takes place in life. They ignored the realities of life and informed themselves by what they had seen on the stage. Later, we saw that people formed their view of life based on Ibsen, Dostoevsky, or Tolstoy. They did not know life; neither could they judge the books on the basis of life. Actually, people only assimilated the secondhand life printed on paper. From that they developed their slogans, founded societies for all manner of reforms without any real knowledge of life. It was a life which they knew only from Ibsen or Dostoevsky, or a life they knew in a manner that frequently could not help becoming quite obnoxious to a person when, in all the big cities of Europe, Hauptmann's “Weber” (weavers),52Gerhart Hauptmann: 1862–1946, playwright; “Die Weber,” Berlin, 1892. for example, was being performed. The lifestyle of weavers appeared on stage. People with no idea of what transpires in life, having seen only its caricature on the stage, observing the misery of weavers on stage, and because it was a time of social involvement—began talking about all sorts of social questions, having become acquainted with these matters only in this way. Basically, they are all people who do not know life except vicariously from newspapers or books such as exist today. I have nothing against the books; one must be familiar with them, but one must read them in such a manner that through them one is able to perceive life. The problem is that we live in an age of abstraction today, abstract demands by political parties, societies, and so on.

This is why it is interesting for me to encounter, on one side, such a realistic man like Rene Marchand who, being a journalist, is simultaneously an oracle for many people. It does not even occur to him to ask if this Bolshevism really leads to a viable life style. For he really does not know life; he only exchanges what he has become acquainted with and finds headed for destruction, with a new abstract formula, with new theories. On the other side, I must now compare a letter I received this morning with these utterances of an intellectual. Somebody who is fully grounded in life, who has experienced precisely what can be experienced today in order to form an opinion of the social condition, wrote to me. He wrote that my book, Towards Social Renewal, had become a sort of salvation for him. This man, who has worked in a weaving mill, was thoroughly familiar with the practical aspects. One will only grasp what is meant with the book, Towards Social Renewal, when one judges it from the standpoint of practical life. It is a book depicting reality, but derived completely from the spiritual world, as must be the case with anything that is to serve life today. One will only know what is meant if one understands that every line, every word of this book is in no way theoretical, but taken straight from practical life; when one realizes that it is a book for those who wish to intervene actively in life, not for those who want to engage in socialistic chatter and babble about life.

It is this that causes one such pain, namely, that a book steeped in reality is called utopian by those who have no idea of reality. Those who have no inkling of the reality of life, being themselves addicted to literature, view even such a book that is truly taken from life as a piece of literature. Today, the “how” matters more than the “what.” Everything depends an our acquiring thought forms that are suitable tools for the comprehension of the spiritual life, for in reality spiritual life is everywhere. We have spiritual realities here in our surroundings as well as from beyond the sense world. It is out of these spiritual realities that social reconstruction must come about, not out of the empty talk appearing in Leninism and Trotskyism, which is nothing but the squeezed-out lemon of old commonplace Western views that have no power to produce any viable kind of social idea. One may well ask: Where are the human beings today who are prepared to comprehend life with the necessary intensity? We will never penetrate life if we are unwilling to view it from the spiritual standpoint. The life between birth and death will not be understood as long as one is not willing to comprehend the life between death and rebirth. If people are unwilling to resort to the spiritual life, they will either become complete materialists or intellectuals living in theories that only enable them to comprehend life after having had it dramatically presented by an Ibsen, a Dostoevsky, or another writer. What matters is that we interpret library presentations as a kind of window through which we look out upon life. This will be possible for us only if we perceive the spiritual world, the world of spiritual entities, behind the sense world; if we finally dismiss all the fantasies concerning atoms and molecules from which present-day physics wishes to construct a world for us. It would follow from these fantasies that the whole present world in fact really consists basically only of atoms and molecules, effectively eliminating all spiritual, and with it, moral and religious ideas. I will say more about this tomorrow.

Sechster Vortrag

Ich möchte heute wieder einiges zusammenfassen von dem, was in den letzten Zeiten hier vorgebracht worden ist. Wir haben gesprochen von der sinnlichen Außenwelt im Verhältnis zu der menschlichen Innenwelt, und ich habe auf zweierlei besonders scharf hingewiesen. Ich habe darauf hingewiesen, daß die sinnliche Außenwelt durchaus aufgefaßt werden muß als eine Welt der Erscheinung, daß es zu den Vorurteilen unserer Zeit gehört, diese Anschauung von der Welt der Erscheinungen nicht in richtiger Weise zu deuten. Gewiß, da und dort taucht eine gewisse Erkenntnis davon auf, daß die sinnliche Außenwelt eine phänomenale, das heißt, eine Welt von Erscheinungen ist, nicht von irgendwelchen auch nur materiellen Wirklichkeiten. Aber man sucht dann hinter dieser Welt der äußeren Erscheinungen nach materiellen Realitäten, zum Beispiel nach Atomen, nach Molekülen und dergleichen. Dieses Suchen nach Atomen, Molekülen, kurz, überhaupt nach einer hinter der Erscheinungswelt stehenden Welt materieller Wirklichkeit, ist ganz genauso, wie wenn jemand, der zum Beispiel im Regenbogen, der eben augenscheinlich nur eine Erscheinung, ein Phänomen ist, nach allerlei molekularischen Entitäten suchen würde, nach molekularischen Materialitäten, die dahinterstehen müßten. Dieses Suchen nach materieller Realität gegenüber der Außenwelt, das ist, wie uns ja aus den verschiedensten Ecken her die Geisteswissenschaft zeigt, etwas völlig Unbegründetes. Wir müssen uns klar sein darüber: Wir haben um uns herum in dem, was Sinneswelt ist, eine Erscheinungswelt, und wir dürfen nicht den Tastsinn gegenüber der Sinneswelt anders auffassen als so wie die andern Sinne.So wie wir den Regenbogen mit Augen sehen und dahinter nicht eine materielle Realität suchen, sondern eben als Erscheinung ihn hinnehmen, so müssen wir die ganze äußere Welt so hinnehmen, wie sie ist, in dem Sinne, wie ich das in meiner Einleitung zum FarbenlehreBand der Goetheschen Naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften vor Jahrzehnten dargestellt habe. Und die Frage stellt sich dann vor uns hin: Was ist nun hinter dieser Welt der Erscheinungen? Da sind nicht materielle Atome dahinter, da sind dahinter geistige Wesenheiten, da ist Geistigkeit dahinter. Das bedeutet viel, dies anzuerkennen; denn es bedeutet ja, daß wir zugeben: Wir sind nicht in einer materiellen Welt, sondern wir sind in einer Welt geistiger Realitäten!

Also wir haben, wenn wir uns als Menschen nach außen wenden — wenn das (siehe Schema) gewissermaßen die Grenze unseres Leibes ist —, die Sinneswelt, und hinter derselben die Welt geistiger Realitäten, geistiger Wesenheiten (rechts).

Gehen wir jetzt in das menschliche Innere hinein, also wenden wir uns nach innen zu, dann haben wir zunächst, wenn wir von unseren Sinnen nach innen gehen, dasjenige, was Inhalt unserer Vorstellungswelt, Inhalt unserer Seelenwelt ist. Wenn wir die Sinneswelt die Welt sinnlicher Phänomene nennen, sinnlicher Erscheinungen, so haben wir, wenn wir von unseren Sinnen nach innen gehen, die Welt der geistigen Erscheinungen (links). Denn natürlich sind zunächst so, wie sie in uns sind, unsere Gedanken, unsere Vorstellungen keine Realitäten, sondern es sind geistige Erscheinungen. Und nun kommt eben alles darauf an, daß wir nicht glauben, wenn wir von dieser Seelenwelt noch tiefer in unser Inneres hineinsteigen, daß wir da kommen zu dem, was mystische Träumer voraussetzen, zu einer besonderen höheren Welt, sondern da kommen wir in die Welt unseres Organismus hinein, da kommen wir eben hinein in die Welt materieller Realitäten.

Und deshalb ist es wichtig, nicht zu glauben, daß man durch Hineinbrüten in sich ein Geistiges finden kann, sondern da soll man gerade suchen die Konstitution des menschlichen materiellen Organismus. Man soll nicht alle möglichen mystischen Realitäten in sich suchen, wie ich das ja von den verschiedenen Gesichtspunkten aus hervorgehoben habe, sondern man soll suchen hinter dem, was sich heraufdrängt in die Seele, das heißt, was geistige Erscheinung wird — gerade je tiefer und tiefer man in sich hineinsteigt —, das Zusammenwirken von Leber, Herz, Lunge und so weiter, von noch andern Organen auch, die gerade Mystiker nicht gerne genannt wissen wollen. Da lernen wir das eigentlich Materielle unseres irdischen Daseins kennen. Und gar mancher — das habe ich ja oft hervorgehoben -, der glaubt, da tief in sein Inneres hineinzusteigen und mystische Realitäten zu treffen, der trifft nur das, was seine Leber, seine Galle und ähnliche andere Organe ausbrüten. Wie sich der Talg zur Flamme bildet, so bildet sich dasjenige, was Leber, Lunge, Herz, Magen ausbrüten, zu dem, was dem Bewußtsein heraufleuchtet als mystische Erscheinungen.

Das ist es eben gerade, daß wirkliche Geisteswissenschaft den Menschen hinausführt über jegliche Art von Illusion. Es ist die Illusion der Materialisten, daß sie hinter der Sinneswelt nicht geistige Realitäten, sondern physische, materielle Realitäten finden können. Es ist die Illusion der Mystiker, daß sie finden können, wenn sie in ihre eigene Wesenheit hinuntersteigen, nicht die Welt der materiellen Organisation, sondern irgendwelche besonders göttliche Funken und dergleichen.

Das ist wichtig für echte Geisteswissenschaft, daß wir nicht suchen in der Außenwelt das Materielle, daß wir nicht suchen in der Innenwelt so, wie man sie zunächst durch innerliches Bebrüten bekommt, das Geistige.

Dies nun, was ich jetzt sagte, hat ja bedeutsame Folgen für unsere ganze Weltanschauung. Bedenken Sie nur, daß wir ja darlegen müssen, daß der Mensch vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen mit seinem astralischen Leib und mit seinem Ich außerhalb des physischen Leibes und Ätherleibes ist. Wo ist er dann? — Das müssen wir uns ja als Frage vorlegen: Wo ist er denn dann? - Wenn wir annehmen, daß da draußen die Welt ist, welche die Physiker beschreiben, dann hat es überhaupt keinen Sinn, von einem Außer-dem-physischen-Leibe-Bestehen des astralischen Leibes oder des Ich zu sprechen. Wenn wir aber wissen, daß da jenseits der Sinneswelt die Welt der geistigen Realitäten liegt, aus der die Sinnenwelt hervorsprießt, dann haben wir eine Möglichkeit, uns vorzustellen, daß astralischer Leib und Ich in die geistige Welt, die hinter der Sinnenwelt liegt, hineinziehen. Sie sind wirklich in dem Teile der geistigen Welt, der der Sinnenwelt zugrunde liegt; so daß man also sagen kann: Schlafend dringt der Mensch in jene geistige Welt ein, die der Sinnenwelt zugrunde liegt. Aufwachend allerdings dringt er ein mit seinem Ich und mit seinem astralischen Leibe in dasjenige, was zunächst ätherische Wesenheit ist, und was die Welt materieller Organisation ist.

Man bekommt von dem, was man als anthroposophische Weltanschauung aufnehmen kann, überhaupt nur klare Vorstellungen, wenn man sich über solche Dinge klare Vorstellungen machen kann. Denn man wird sich dann vor allen Dingen nicht der Täuschung hingeben, daß man irgendwie das Göttliche oder das unserem Menschen zugrunde liegende Geistige hinter der sinnlichen Umgebung suchen könne. Da ist nur das Geistige, das diese Sinnenwelt aus sich hervorbringt. Wir selbst als Menschen, wir wurzeln in der Geisteswelt. Aber in welcher Geisteswelt? In derjenigen Geisteswelt, die wir ja verlassen, indem wir in unseren physischen Leib uns verkörpern. Wir kommen ja aus jener geistigen Welt, die wir durchleben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt; wir treten durch die Geburt oder durch die Empfängnis in dieses physische Dasein ein. Die Welt aber, in der wir sind zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, die wir da verlassen, die ist eine andere geistige Welt als diese; sie ist eine geistige Welt und dadurch mit dieser verwandt. Aber jene geistige Welt spritzt aus sich hervor unsere Sinnenwelt. Diejenige geistige Welt, von der wir sprechen - ich habe sie besprochen in dem Zyklus «Inneres Wesen des Menschen und Leben zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt» -, diejenige Welt, die wir da durchleben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, die uns hervorspritzt, die uns hervorbringt, die erfassen wir nicht, wenn wir sie hinter der Sinneswelt suchen, die erfassen wir auch nicht, wenn wir sie in uns selber suchen. Da finden wir nur das Materielle unserer eigenen Organisation. Die erfassen wir, wenn wir überhaupt aus dem ganzen Raume herauskommen. Die ist nicht im Raume. Von der kann nur gesprochen werden, wieich das auch oftmals betont habe, wenn wir einzig und allein die Zeit zugrunde legen, wenn wir sie als eine zeitliche auffassen. Daher kann alles, was wir an Beschreibungen haben über diese Welt zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, selbstverständlich nur Imagination, nur Bild sein. Und wir dürfen nicht verwechseln diese Bilder, in denen wir uns notwendigerweise ausdrücken müssen, mit den Realitäten, in denen wir leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Es ist so notwendig, daß man auf dem Boden anthroposophischer Weltanschauung nicht bloß von allerlei phantastischen Dingen spricht, die man mit den alten Worten bezeichnet, wobei man doch mit den alten Worten nichts Neues eigentlich bezeichnet, sondern es ist notwendig, daß man seine Begriffs-, seine Vorstellungswelt bereichert, wenn man in diejenige Welt hinein senden will seine Gedanken, seine Vorstellungen, die wir durchleben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. So daß wir uns eine Vorstellung aneignen können, welche außerordentlich wichtig ist, welche auch der Anlaß sein kann zu einem tiefen Nachdenken, allerdings zu einem unbequemen Nachdenken. Das ist die Vorstellung: Wenn wir durchlebt haben das Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, so verkörpern wir uns hier im Raume. Wir dringen aus etwas, was nicht räumlich ist, in den Raum ein. Der Raum hat nur eine Bedeutung für dasjenige, was hier von uns erlebt wird zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode. Und wiederum, wir dringen nicht nur aus unserem Leibe mit unserer Seele heraus, wenn wir durch die Pforte des Todes gehen, wir dringen aus dem Raume heraus; das ist wichtig.

Diese Vorstellung, die so geläufig war den Menschen noch bis zum 4, 5., 6. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert, ja noch geläufig war solch einem Menschen, der erst im 9. Jahrhundert gelebt hat, wie Scotus Erigena, diese Vorstellung, daß das dem Menschen zugrunde liegende Geistige, das er durchlebt, wie man damals gemeint hat, nur nach dem Tode — wie wir jetzt sagen müssen: überhaupt zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt -, diese Vorstellung ist der neueren Zeit ganz verlorengegangen. Die neuere Zeit ist stolz, hochmütig auf ihr Denken, aber sie kann ja eigentlich nur das Räumliche denken. Sie lebt in jedem Gedanken nur so, daß sie den Raum mitdenkt. Aber man muß sich bemühen, um das Geistige zu denken, den Raum selber in seinem Denken zu überwinden. Sonst werden wir niemals in das wirkliche Geistige hineinkommen und werden vor allen Dingen niemals auch nur zu einer annähernd richtigen Naturwissenschaft kommen, geschweige denn zu einer Geisteswissenschaft. Gerade gegenüber unserer Zeit ist es von unendlicher Wichtigkeit, sich mit diesen feineren Unterscheidungen geisteswissenschaftlichen Erkennens bekanntzumachen. Denn das, was wir durch solche Begriffe uns aneignen, ist ja nicht bloß irgendeine Weltanschauung, irgendein Gedankeninhalt. Dieses Sich-Aneignen eines Gedankeninhaltes ist schließlich das Allerwenigste, was uns werden kann durch anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft. Denn es ist ganz gleich, ob nun schließlich jemand glaubt, die Welt besteht aus Molekülen und Atomen, oder ob er glaubt, der Mensch besteht aus dem physischen Leib, dann aus etwas, was dünner ist, dem Ätherleib, dann aus etwas, was noch dünner, noch nebuloser ist, dem Astralleib, was noch dünner ist, was weiß ich, was dann kommt: aus Mentalleib, und was noch kommt —- immer dünner, dünner, dünner —, während schon der Ätherleib gar nicht mehr getroffen wird, wenn man nur von der Dünnheit spricht! Es ist schließlich gleich, ob man Materialist ist und die Welt als Atome sich vorstellt, oder ob man diese grobmaterialistische Vorstellung hegt, die gerade das Gemeingut der sogenannten theosophischen Gesellschaftslehren, oder wie man das nun nennen will, ist. Worauf es ankommt, das ist ja etwas ganz anderes, das ist, daß wir in der Lage sind, unsere ganze Seelenverfassung umzuwandeln, daß wir uns anstrengen müssen, anders zu denken für das Geistige, als wir gewohnt sind, für die äußere Sinneswelt zu denken. Nicht, wenn wir etwas anderes als die Sinneswelt als geistig denken, treten wir in Geisteswissenschaft ein, sondern wenn wir anders denken über das Geistige, als wir über die Sinneswelt denken. Über die Sinneswelt denken wir räumlich. Über das Geistige können wir höchstens innerhalb gewisser Grenzen zeitlich denken, weil wir uns selber in dieser geistigen Welt denken müssen. Und wir sind ja in der Zeit in einer gewissen Weise bedingt auch geistig, indem wir eben in einem bestimmten Zeitpunkte aus dem Leben zwischen Tod und Geburt in das Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod hineinversetzt werden.

Dieses Umgestalten der Gemütsverfassung, das ist es, worauf ich öfters hingewiesen habe, und was der gegenwärtigen Menschheit so not tut. Denn wodurch sind wir denn in die Kalamitäten der Gegenwart hineingekommen? Wir sind in die Kalamitäten der Gegenwart hineingekommen dadurch, daß mit den sogenannten neueren Fortschritten die Menschheit ganz und gar verlernt hat, in ihre Vorstellungen überhaupt noch das Geistige aufzunehmen. Dasjenige, was theosophische Lehre der sogenannten 'Theosophischen Gesellschaft ist, ist ja gerade der Versuch, mit materialistischen Gedankenformen das Geistige zu charakterisieren, also den Materialismus bis ins Geistige hineinzutreiben. Dadurch, daß man etwas geistig nennt, hat man ja nicht eine geistige Auffassung, sondern nur dadurch, daß man das für das Sinnliche geeignete Denken umgestaltet.

Wenn die Menschen nun miteinander leben sollen, dann sind sie eben nicht in bloß räumlichen Beziehungen, dann sind sie nicht in solchen Beziehungen, die sich ausdenken lassen mit dem, was heute durch die Naturwissenschaft allgemeines Denken geworden ist. Deshalb können wir keine sozialen Vorstellungen mehr ausbilden in der heutigen Weltanschauung, weil das Denken, an das sich die Menschheit gewöhnt hat durch die Naturwissenschaft, eben gar nicht dazu führt, das Zusammenleben der Menschen zu charakterisieren. Daher jene Abirrungen, die wir heute als allerlei soziale Weltauffassungen erleben, und die nur davon herrühren, daß es unmöglich ist, aus den Vorstellungen, von denen aus wir heute etwas als richtig oder unrichtig ansehen, auch wirklich über das Soziale zu denken. Erst wenn man sich bequemen wird, ins Geisteswissenschaftliche einzudringen, wird es wiederum möglich sein, das Soziale so zu denken, wie es gedacht werden muß, wenn nicht der Niedergang weiter erfolgen soll, sondern wenn ein Aufstieg erfolgen soll. Die Erziehung, welche Geisteswissenschaft an uns vollführt, ist viel wichtiger als der Inhalt der Geisteswissenschaft. Sonst kommen wir endlich dazu, immer mehr und mehr zu verlangen, daß die geistigen Dinge, wie man sagt, populär, das heißt, grobsinnlich-wirklich dargelegt werden. Man kommt dazu, solche Dinge, die einfach in einer gewissen Weise gesagt werden müssen, damit man nicht phantasiert, sondern Realitäten sagt, wie das zum Beispiel geschehen mußte sowohl in unseren anthroposophischen Darstellungen, wie auch in meinem Buche «Die Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage», man kommt dazu, das dann unanschaulich zu finden. Ja, «anschaulich» ist etwas, worunter heute die Menschheit etwas ganz Sonderbares versteht. Es gibt heute Leute, welche auf diese Sehnsucht der Menschen, grobsinnlich anschaulich alles zu bekommen, spekulieren. Und sie spekulieren schon über den ganzen Umfang der Erde hin, nicht etwa bloß in einzelnen Territorien.

So zum Beispiel finde ich eine interessante Stelle in einem ganz vor kurzem erschienenen Buche, «Les forces morales aux Etats-Unis», von einer Französin geschrieben. Die Unterabteilungen sind: l’élise, l’école, la femme. In diesem Buch findet sich eine interessante kleine Episode, welche zeigt, wie man von gewissen Seiten versucht, die Dinge der Beziehung des Menschen zur geistigen Welt anschaulich zu machen. Die Betreffende erzählt: Eines Abends promenierte ich mit einer Freundin im Broadway. Ich kam vor eine Kirche. Ein Überblick zeigte uns den Platz nur mit Männern angefüllt. Indigniert durch den Anblick, vermieden wir, etwas vorzudringen in das Innere. Ein Priester in der Sutane wurde unser ansichtig, kam heran, uns einzuladen, wir sollten weiter vorwärtsdringen. Da wir zögerten, fragte er uns über unsere Konfession. Wir sind nicht Katholiken, sagte ich. Er drang lebhaft in uns, in seine Kirche einzutreten und lud uns mit erhobenem Zeigefinger ein: Kommen Sie hierher, sagte er mit Überzeugung, hören Sie mich. Wenn Sie zum Beispiel nach Chicago gehen wollen, wie machen Sie das? Sie können, um dahin zu gehen, zu Fuß gehen, zu Wagen, zu Schiff oder mit dem Eisenbahnzug. Logischerweise werden Sie das schnellste und bequemste Mittel wählen. Das ist in diesem Fall der Eisenbahnzug. Selbstverständlich, wenn Sie wollen in den Garten Gottes kommen, werden Sie ebenso wählen diejenige Religion, welche Sie am schnellsten und sichersten dahin führen wird. Das ist die katholische Religion, welche der Expreßzug nach dem Paradiese ist. Die betreffende Mitteilerin sagt nur noch, daß sie so perplex war, daß es ihr gar nicht eingefallen ist, ihm zu sagen, daß er ja in seinem anschaulichen Vergleiche noch den Aeroplan vergessen habe, den er als eine noch schnellere Expedition hätte anführen können, um in das Paradies zu gelangen.

Sie sehen, hier wählt jemand, der darauf aus ist, den Vorurteilen der Menschen entgegenzukommen, anschauliche Vorstellungen. Es ist eine anschauliche Vorstellung für die katholische Religion, daß sie «der Exprefßzug nach dem Himmel» ist. Das ist überhaupt der Zug der Zeit, anschauliche Vorstellungen, das heißt, solche Vorstellungen zu suchen, welche an die Leute keine Anforderungen des Denkens stellen. Das ist es aber, wo wir schon sehen müssen den Ernst des heutigen Lebens, der darin besteht, daß wir heraus müssen aus jener Anschaulichkeit, die zur Banalität und Trivialität wird und dadurch gerade den Menschen in den Materialismus für diejenigen Dinge herunterzieht, die eben gerade geistig erfaßt werden müßten. Man muß auch in solchen Symptomen durchaus dasjenige suchen, was für unsere Zeit das Allernotwendigste ist. Und immer wieder muß gesagt werden: Es darf nicht vorbeigegangen werden an solchen Symptomen, wir dürfen nicht mit verbundenen Augen heute durch unsere Welt gehen, die ein Organismus ist, der eben aus seinen Symptomen erkannt sein will, weil in diesen Symptomen dasjenige ruht, was durchschaut werden muß, wenn wir aus unserem allgemeinen Niedergange zu einem Aufstieg kommen wollen.

Es ist aber notwendig, in diesem Punkte manche Dinge im rechten Lichte zu sehen. Dasjenige, was nun wirklich hervorgeholt ist aus geisteswissenschaftlichen Unterlagen in den «Kernpunkten der sozialen Frage», es ist wahrhaftig nicht entstanden aus irgendeiner Theorie heraus, sondern aus dem ganzen breiten Leben heraus, nur daß dieses Leben eben geistig angeschaut ist. Und es kann die Menschheit heute nicht vorwärtskommen, wenn man sich nicht auf ein solches Anschauen des Lebens einstellt.

Ich möchte zwei Dinge des Lebens zusammenstellen, die mir in diesen Tagen wiederum gezeigt haben, wie nötig es ist, die Menschheit heute hinzuführen zu dieser lebensvollen Erfassung der Wirklichkeit, aber zu gleicher Zeit einer geistigen Erfassung der Wirklichkeit. Denn sehen Sie, da las ich gestern einen Artikel von einem Journalisten, der, wie mir mitgeteilt wird, René Marchand heißt und lange Zeit Journalist des «Figaro», des «Petit Parisien» war und so weiter, der dann mitgemacht hat den Krieg an der russischen Front, der ein gründlicher Gegner der Bolschewiki war, der dann mit dem General der Gegenrevolution zu tun hatte, ihr Anhänger war und der dann in einem Momente sich bekehrt hat zum Rätegedanken, zum Bolschewismus. Aus einem Gegner des Bolschewismus — steht hier - ist er zu einem Verfechter, zu einem rückhaltlosen Anerkenner ihrer Führer sowohl wie des Rätegedankens geworden. Es ist interessant, wie hier ein Mensch, der doch zu den Intellektuellen gehört, denn er ist Journalist, der immerhin mit einer tieferen Auffassung des Lebens, mit einer tieferen Empfindung für das Leben lebt, der in dem lebt, was alttraditionell ist in dem, worinnen die schlafenden Seelen heute zumeist leben, wie ein solcher Mensch dann plötzlich darauf kommt: Das führt ja ganz gewiß zum Untergange! — Und da erscheint ihm als der einzige Zielpunkt nichts anderes als der Bolschewismus. Das heißt, der Mensch sieht nun, daß alles, was nicht Bolschewismus ist, zum Untergange führt. Ich habe Ihnen ja gezeigt, wie Spengler das beschrieben hat. Marchand sieht nur den Bolschewismus, und von dem Bolschewismus glaubte er zunächst, daß er nur eine russische Angelegenheit sei. Aber dann fand er eben etwas ganz anderes, dann fand er, daß der Bolschewismus eine internationale Angelegenheit ist, die in der ganzen Welt sich ausbreiten muß, und: Es wurde mit jetzt klar, daß der Friede erst dann wiederhergestellt werden kann und die Prinzipien, die bis zu diesem Tag von den bürgerlichen Regierungen nur verkündet wurden, um die Massen zu täuschen, erst dann zur Wirklichkeit werden, wenn dieser neue Imperialismus — von der Entente — seinerseits zusammengebrochen ist, und wenn die Völker aller Länder die Leitung ihrer Schicksale frei in die eigenen Hände nehmen werden und so weiter. — Und dann erzählt er, wie er nun zu der Ansicht gekommen ist, daß nur dann, wenn die Welt durch und durch bolschewisiert wird, daß nur dann herrschen wird Gerechtigkeit, Eintracht, Friede, Recht, daß nur dadurch der Wiederaufbau kommen könne. Dieser Mann ist sich klar geworden, alles übrige führe zum Untergange. Und er sagt im Grunde genommen ganz zutreffend: Wenn das, was außer dem Bolschewismus da ist, weiter gepflegt werden soll, so muß es die Diktatur werden des alten Kapitalismus, des Bürgertums oder dessen, was dazugehört. Es muß die Diktatur werden der Lloyd George, Clemenceau, Scheidemann und so weiter. Will man das nicht, will man nicht in den Untergang hineinkommen, so gibt es nichts anderes als die Diktatur, die Diktatur des Bolschewismus. Und darin sieht er dann das einzige Heil.

Sie sehen, dieser Mann ist in einer gewissen Weise ehrlich, viel ehrlicher als alle die andern, die den Bolschewismus herankommen sehen und glauben, daß man das alte Regime ihm gegenüberstellen könnte. Er sieht wenigstens von all diesem Alten ein, daß es reif ist zum Uhntergange. Aber eine Frage muß sich einem aufdrängen gerade dann, wenn man auf geisteswissenschaftlichem Boden steht, wenn man so etwas erlebt; denn solch ein Mensch, wie dieser Ren& Marchand, ist eine Ausnahme. Es muß sich einem die Frage aufdrängen: Woher hat denn der Mann seine Kenntnis von dem allem? — Er hat seine Kenntnis daher, woher sie die meisten Menschen der Gegenwart haben, er hat sie aus den Zeitungen, aus den Büchern. Er kennt nicht das Leben. Denn die Menschen, die heute leben, kennen zum großen Teile das Leben überhaupt nur aus den Zeitungen, aus den Büchern. Gerade die führenden Schichten kennen das Leben ja nur aus den Zeitungen. Was haben wir alles erlebt in dieser Beziehung aus den Zeitungen, aus den Büchern! Wir haben es erlebt, daß die Leute sich ihre Weltanschauung gebildet haben vor Jahrzehnten noch aus französischen Komödien, daß sie die Literatur, die in einer Komödie vorkommt, besser kannten als das, was im Leben vorkommt, daß sie an den Wirklichkeiten des Lebens vorübergingen und sich eigentlich nur unterrichteten durch das, was sie von der Bühne herunter gesehen haben. Wir haben es später erlebt, daß die Menschen ihre Weltanschauung gebildet haben aus I/bsen oder aus Dostojewskij oder aus Tolstoj, daß sie nicht das Leben kannten, auch nicht die Bücher nach dem Leben beurteilen konnten, sondern im Grunde genommen nur das abgeleitete, auf dem Papier stehende Leben in sich aufnahmen. Und da entwickeln sie nun ihre Devisen, da gründen sie ihre Vereine für allerlei Reformen, ohne daß sie das wirkliche Leben kennen, das sie nur aus Ibsen oder aus Dostojewskij kennen, oder es so kennen, wie es einem oftmals zum Ekel werden mußte in der Zeit, als in allen Großstädten Europas zum Beispiel Hauptmanns «Weber» aufgeführt wurden. Die Lebensart der Weber, die erschien auf dem Theater. Diejenigen Menschen, die keine Ahnung hatten von dem, was im Leben vorgeht, dessen Karikatur ihnen hier auf der Bühne erschien, die betrachteten nun, weil es ja die «soziale Zeit» war, das Weberelend von den Brettern herunter und redeten auch über alle möglichen sozialen Fragen, indem sie nur in dieser Weise die Sachen kannten. Es sind im Grunde genommen alles Leute, die das Leben nicht kennen, die es nur in seiner Ableitung aus den Zeitungen, aus den Büchern kennen, aus dem, was eben heute Bücher sind. Ich rede nicht gegen die Bücher, man muß sie kennen; aber man muß die Bücher so lesen, daß man durch die Bücher hindurch auf das Leben schaut und schauen kann. Das aber ist es, daß wir heute in einem Zeitalter der Abstraktionen leben, der abstrakten Parteiforderungen, der abstrakten Vereinsforderungen und so weiter. Und so ist es mir interessant, daß auf einer Seite an einen herandringt ein so lebenswahrer Mann wie dieser Rene Marchand, der aber zu gleicher Zeit für viele ein Orakel ist, denn er ist ein Journalist, der also gar nicht in die Lage kommt, sich nun zu fragen: Ja, kommt man von diesem Bolschewismus aus zu einer möglichen Lebensgestaltung? — Denn er kennt ja gar nicht das Leben, er vertauscht nur das, was er kennengelernt hat und was er reif findet zum Untergang, mit einer neuen abstrakten Formel, mit neuen Theorien. Und da mußte ich denn mit diesen Auslassungen eines Intellektuellen einen Brief vergleichen, den ich heute morgen bekam, wo mir jemand schreibt, der im Leben drinnen gestanden hat, der im Leben gerade dasjenige erfahren hat, was man heute zur Beurteilung der sozialen Lage erfahren kann, wie ihm das Buch «Die Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage» eine Art Erlösung geworden sei, ein Praktiker, der in der Weberei gearbeitet hat und durch und durch die Praxis kennt. Erst dann wird man überhaupt eine Ahnung haben von dem, was gemeint ist mit den «Kernpunkten der sozialen Frage» als einem Realitätsbuche, das aber aus der geistigen Welt hervorgeholt worden ist, wie alles, was heute dem Leben dienen soll, aus der geistigen Welt hervorgeholt worden sein muß, erst dann wird man wissen, was damit gemeint ist, wenn man es von dem Gesichtspunkte der Lebenspraxis aus beurteilt, wenn man weiß, daß es überall, in jeder Zeile, in jedem Wort nicht Theorie ist, sondern aus der Lebenspraxis herausgeholt ist, wenn man verstehen wird, daß es ein Buch ist für diejenigen, die tatkräftig ins Leben eingreifen wollen, nicht für solche, die über das Leben spintisieren und sozialistisch schwätzen wollen.

Diese Dinge, die sind es, die einem heute solchen Schmerz machen, daß diejenigen, die keine Ahnung von der Wirklichkeit haben, ein Wirklichkeitsbuch ein utopisches nennen, daß diejenigen dann, die keine Ahnung von der Lebenswirklichkeit haben und selber die Literatitis haben, auch ein solches Buch, das herausgeholt ist aus dem Leben, als ein Literatenbuch etwa auffassen. Und heute kommt es auf das Wie an, nicht auf das Was. Es kommt darauf an, daß wir uns Gedankenformen aneignen, die geeignet sind, Instrumente zu sein für die Erfassung des geistigen Lebens, denn in der Wirklichkeit ist überall geistiges Leben. Es gibt in unserer Umgebung da oder von jenseits der Sinneswelt geistige Realitäten, und aus diesen geistigen Realitäten muß der soziale Neuaufbau gemacht werden, nicht aus jenem Geschwätz, das im Leninismus und Trotzkiismus auftritt und das nichts anderes ist als die ausgepreßte Zitrone uralter spießbürgerlicher westlicher Anschauungen, die keine Macht haben überhaupt, irgendeine soziale Idee aus sich hervorzubringen. Man muß fragen, wo die Menschen sind, die heute mit der genügenden Intensität das Leben in dieser Weise durchschauen wollen. Man wird es nicht durchschauen, wenn man es nicht vom Geiste aus durchschaut. Man wird das Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod nicht verstehen, wenn man sich nicht bequemen will, das Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt zu verstehen. Denn man wird entweder krasser Materialist, wenn man nicht zum geistigen Leben gehen will, oder man wird ein Intellektualist, der in solchen Theorien lebt, die ihn nur fähig machen, das Leben zu begreifen, nachdem er es von Ibsen hat dramatisch darstellen gehört, oder von Dostojewskij oder von so jemandem. Aber darauf kommt es an, daß wir alles, was uns literarisch entgegentritt, zu verstehen wissen als eine Art von Fensterscheibe, durch die wir auf das Leben blicken. Das werden wir nur, wenn wir hinter der Sinneswelt die Geisteswelt, die Welt der geistigen Entitäten erblicken, und wenn wir endlich Abschied geben jenen Phantastereien von Atomen und Molekülen, aus denen uns die heutige Physik eine Welt aufbauen will, und aus denen folgen würde, daß die ganze Gegenwartswelt im Grunde genommen wahrhaft real nur aus Atomen und Molekülen besteht, und damit herausgeworfen wird alles Geistige und damit auch alles sittliche und religiöse Ideal. Davon will ich dann morgen weitersprechen.

Sixth Lecture

Today I would like to summarize some of what has been said here recently. We have spoken about the sensory external world in relation to the human inner world, and I have pointed out two things in particular. I pointed out that the sensory external world must be understood as a world of appearances, and that it is one of the prejudices of our time not to interpret this view of the world of appearances correctly. Certainly, here and there a certain recognition arises that the sensory external world is a phenomenal world, that is, a world of appearances, not of any material realities. But then one searches behind this world of external appearances for material realities, for example, for atoms, molecules, and the like. This search for atoms, molecules, in short, for a world of material reality behind the world of appearances, is exactly the same as if someone were to search for all kinds of molecular entities, for molecular materialities that must lie behind the rainbow, which is obviously only an appearance, a phenomenon. This search for material reality in relation to the external world is, as spiritual science shows us from many different angles, something completely unfounded. We must be clear about this: we have around us, in what is the sensory world, a world of appearances, and we must not perceive the sense of touch differently from the other senses.Just as we see the rainbow with our eyes and do not seek a material reality behind it, but accept it as an appearance, so we must accept the whole external world as it is, in the sense that I described decades ago in my introduction to the volume on color theory in Goethe's Scientific Works. And then the question arises: What is behind this world of appearances? There are no material atoms behind it, there are spiritual beings behind it, there is spirituality behind it. It means a lot to acknowledge this, because it means that we admit: We are not in a material world, but we are in a world of spiritual realities!

So when we turn outward as human beings — when that (see diagram) is, so to speak, the boundary of our body — we have the sensory world, and behind it the world of spiritual realities, spiritual beings (right).

If we now go into the human interior, that is, if we turn inward, then we first have, when we go inward from our senses, that which is the content of our world of ideas, the content of our soul world. If we call the sensory world the world of sensory phenomena, of sensory appearances, then when we go inward from our senses, we have the world of spiritual appearances (left). For, of course, as they are within us, our thoughts and ideas are not realities, but spiritual phenomena. And now it all depends on our not believing that when we go deeper into our inner soul world, we come to what mystical dreamers presuppose, to a special higher world, but rather that we enter the world of our organism, that we enter the world of material realities.

And that is why it is important not to believe that one can find something spiritual by brooding within oneself, but rather to seek the constitution of the human material organism. One should not seek all kinds of mystical realities within oneself, as I have emphasized from various points of view, but rather one should seek behind what pushes itself up into the soul, that is, what becomes a spiritual phenomenon — precisely the deeper and deeper one descends into oneself — the interaction of the liver, heart, lungs, and so on, and also of other organs that mystics in particular do not like to mention. There we come to know the actual material of our earthly existence. And many a person — as I have often emphasized — who believes they are delving deep into their inner being and encountering mystical realities, encounters only what their liver, their bile, and other similar organs are incubating. Just as tall forms a flame, so what the liver, lungs, heart, and stomach hatch out forms what shines up to consciousness as mystical phenomena.

This is precisely what real spiritual science does: it leads people out of all kinds of illusions. It is the illusion of materialists that behind the sensory world they can find not spiritual realities but physical, material realities. It is the illusion of mystics that when they descend into their own being they find not the world of material organization but some particularly divine sparks and the like.

It is important for genuine spiritual science that we do not seek the material in the outer world, that we do not seek the spiritual in the inner world as it is initially obtained through inner brooding.

What I have just said has significant consequences for our entire worldview. Just consider that we must explain that from the moment we fall asleep until we wake up, human beings are outside their physical body and etheric body with their astral body and their I. Where is he then? We must ask ourselves this question: Where is he then? If we assume that the world described by physicists is out there, then it makes no sense at all to speak of the astral body or the I existing outside the physical body. But if we know that beyond the sensory world lies the world of spiritual realities, from which the sensory world springs forth, then we have a way of imagining that the astral body and the I withdraw into the spiritual world that lies behind the sensory world. They are truly in that part of the spiritual world that underlies the sensory world, so that one can say: when sleeping, the human being enters into that spiritual world that underlies the sensory world. When waking up, however, he enters with his ego and his astral body into that which is initially etheric being and which is the world of material organization.

One can only gain clear ideas of what can be understood as the anthroposophical worldview if one is able to form clear ideas about such things. For then one will not fall prey to the delusion that one can somehow seek the divine or the spiritual underlying our human existence behind the sensory environment. There is only the spiritual that brings forth this sensory world out of itself. We ourselves, as human beings, are rooted in the spiritual world. But in which spiritual world? In the spiritual world that we leave behind when we incarnate in our physical bodies. We come from the spiritual world that we live through between death and a new birth; we enter this physical existence through birth or conception. But the world in which we are between death and a new birth, which we leave behind, is a different spiritual world than this one; it is a spiritual world and therefore related to this one. But that spiritual world spouts forth from itself our sensory world. The spiritual world of which we speak—I have discussed it in the cycle “The Inner Being of Man and Life Between Death and Rebirth”—the world we live through between death and rebirth, which springs forth from us, which brings us forth, we do not grasp when we seek it behind the sensory world, nor do we grasp it when we seek it within ourselves. There we find only the material aspects of our own organization. We perceive these when we emerge from the whole of space. They are not in space. As I have often emphasized, we can only speak of them when we take time as our sole basis, when we perceive them as temporal. Therefore, all the descriptions we have of this world between death and a new birth can, of course, only be imagination, only images. And we must not confuse these images, in which we necessarily have to express ourselves, with the realities in which we live between death and a new birth. It is so necessary that, on the basis of the anthroposophical worldview, we do not merely speak of all kinds of fantastic things that we describe with old words, whereby we do not actually describe anything new with the old words, but rather it is necessary that we enrich our conceptual world, our world of ideas, if we want to send our thoughts and ideas into that world that we experience between death and a new birth. So that we can acquire a conception that is extraordinarily important, that can also be the occasion for deep reflection, albeit uncomfortable reflection. This is the conception: when we have lived through the life between death and a new birth, we embody ourselves here in space. We penetrate space from something that is not spatial. Space has meaning only for what we experience here between birth and death. And again, when we pass through the gate of death, we do not merely emerge from our bodies with our souls; we emerge from space; that is important.

This idea, which was so familiar to people until the 4th or 5th 6th centuries after Christ, and was still familiar to someone like Scotus Erigena, who lived in the 9th century, this idea that the spiritual essence underlying human beings, which they experience, as people believed at that time, only after death — as we must now say: between death and a new birth — this idea has been completely lost in modern times. Modern times are proud and arrogant about their thinking, but they can really only think spatially. They live in every thought only in such a way that they think space along with it. But one must make an effort to think the spiritual, to overcome space itself in one's thinking. Otherwise, we will never enter into the real spiritual realm and, above all, we will never arrive at even an approximately correct natural science, let alone a spiritual science. Precisely in our time, it is of infinite importance to familiarize ourselves with these finer distinctions of spiritual-scientific knowledge. For what we acquire through such concepts is not merely some worldview, some content of thought. This acquisition of a content of thought is ultimately the least that can happen to us through anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. For it makes no difference whether someone ultimately believes that the world consists of molecules and atoms, or whether they believe that human beings consist of the physical body, then of something thinner, the etheric body, then of something even thinner, even more nebulous, the astral body, which is even thinner, and who knows what comes next: a mental body, and whatever else comes after that — thinner and thinner and thinner — while the etheric body is no longer even mentioned when one speaks of thinness! Ultimately, it is all the same whether one is a materialist and imagines the world as atoms, or whether one harbors this crude materialistic idea, which is precisely the common property of the so-called theosophical social teachings, or whatever one wants to call them. What matters is something quite different, namely that we are able to transform our entire soul constitution, that we must make an effort to think differently about the spiritual than we are accustomed to thinking about the outer sense world. It is not when we think of something other than the sensory world as spiritual that we enter into spiritual science, but when we think differently about the spiritual than we do about the sensory world. We think about the sensory world in terms of space. We can think about the spiritual world within certain limits in terms of time, because we have to think about ourselves in this spiritual world. And we are, in a certain sense, also spiritually conditioned by time, in that we are transferred at a certain point in time from the life between death and birth into the life between birth and death.

This transformation of the state of mind is what I have often pointed out and what is so necessary for the present human race. For how did we get into the calamities of the present? We have fallen into the calamities of the present because, with the so-called newer advances, humanity has completely forgotten how to include the spiritual in its ideas at all. What is the theosophical teaching of the so-called ‘Theosophical Society’ is precisely the attempt to characterize the spiritual with materialistic thought forms, that is, to drive materialism into the spiritual. By calling something spiritual, one does not have a spiritual understanding, but only by transforming the thinking that is suitable for the senses.

If people are to live together, then they are not in mere spatial relationships, they are not in relationships that can be conceived with what has become general thinking today through natural science. That is why we can no longer form social ideas in today's worldview, because the thinking to which humanity has become accustomed through natural science does not lead to a characterization of human coexistence. Hence the aberrations that we experience today as all kinds of social worldviews, which stem solely from the fact that it is impossible to think about the social realm based on the ideas from which we today regard something as right or wrong. Only when we make the effort to delve into the spiritual sciences will it again be possible to think about society in the way it needs to be thought about if we want to avoid further decline and instead achieve progress. The education that spiritual science gives us is much more important than the content of spiritual science. Otherwise, we will end up demanding more and more that spiritual things be presented in a popular, that is, grossly sensual and realistic way. We come to find such things, which simply must be said in a certain way so that we do not fantasize but speak of realities, as had to be done, for example, in our anthroposophical presentations and in my book The Crucial Points of the Social Question, we come to find this unclear. Yes, “clear” is something that humanity today understands as something very strange. There are people today who speculate on this human longing to have everything presented in a grossly sensual, vivid way. And they speculate across the entire globe, not just in individual territories.

For example, I find an interesting passage in a book that was published very recently, Les forces morales aux Etats-Unis, written by a French woman. The subheadings are: l’élise, l’école, la femme. In this book there is an interesting little episode which shows how certain people try to illustrate the relationship between man and the spiritual world. The woman in question recounts: One evening I was walking with a friend on Broadway. I came to a church. A glance showed us that the square was filled with men. Indignant at the sight, we avoided going inside. A priest in a cassock saw us, came over, and invited us to come forward. As we hesitated, he asked us about our religion. We are not Catholics, I said. He urged us emphatically to enter his church and invited us with a raised index finger: Come here, he said with conviction, listen to me. If you want to go to Chicago, for example, how do you do it? You can go there on foot, by car, by ship, or by train. Logically, you will choose the fastest and most comfortable means of transportation. In this case, that is the train. Of course, if you want to come to the garden of God, you will likewise choose the religion that will lead you there most quickly and safely. That is the Catholic religion, which is the express train to paradise. The woman who reported this story said that she was so perplexed that it did not even occur to her to tell him that he had forgotten to mention the airplane in his vivid comparison, which he could have cited as an even faster means of transportation to paradise.

You see, here someone who is keen to accommodate people's prejudices chooses vivid images. It is a vivid image for the Catholic religion that it is “the express train to heaven.” That is the trend of the times, vivid images, that is, seeking images that do not demand any thought from people. But this is where we must already see the seriousness of today's life, which consists in the fact that we must break out of that vividness that becomes banality and triviality and thereby drags people down into materialism for those things that should be grasped intellectually. In such symptoms, too, we must seek what is most necessary for our time. And it must be said again and again: we must not ignore such symptoms; we must not go through our world today with blinders on, for it is an organism that wants to be recognized precisely through its symptoms, because these symptoms contain what must be seen through if we want to rise out of our general decline.

However, it is necessary to see some things in the right light on this point. What has now really been brought out of spiritual scientific documents in the “Key Points of the Social Question” has truly not arisen from any theory, but from the whole breadth of life, only that this life is viewed spiritually. And humanity cannot progress today unless it adopts such a view of life.

I would like to bring together two things in life that have shown me once again in recent days how necessary it is to lead humanity today to this lively understanding of reality, but at the same time to a spiritual understanding of reality. For you see, yesterday I read an article by a journalist who, I am told, is called René Marchand and was for a long time a journalist for Le Figaro, Le Petit Parisien, and so on, who then took part in the war on the Russian front, who was a thorough opponent of the Bolsheviks, who then had dealings with the general of the counterrevolution, was a supporter of the counterrevolution, and then at one point converted to the idea of the councils, to Bolshevism. From an opponent of Bolshevism—it says here—he became a defender, an unreserved admirer of their leaders and of the idea of the councils. It is interesting how a person who belongs to the intellectual class, because he is a journalist, who lives with a deeper understanding of life, with a deeper feeling for life, who lives in what is traditional, in what most people today live in, how such a person suddenly comes to the conclusion: This will certainly lead to ruin! And then Bolshevism appears to him as the only goal. That means that this person now sees that everything that is not Bolshevism leads to ruin. I have shown you how Spengler described this. Marchand sees only Bolshevism, and at first he believed that Bolshevism was only a Russian affair. But then he discovered something completely different, he discovered that Bolshevism is an international affair that must spread throughout the whole world, and: It became clear to me that peace can only be restored and the principles that have been proclaimed by bourgeois governments to deceive the masses can only become reality when this new imperialism—of the Entente—has collapsed and when the peoples of all countries take control of their destinies into their own hands, and so on. — And then he tells how he has now come to the conclusion that only when the world is thoroughly Bolshevized will justice, harmony, peace, and law prevail, and that only then can reconstruction take place. This man has realized that everything else will lead to ruin. And he says, quite correctly, that if anything other than Bolshevism is to be preserved, it must be the dictatorship of old capitalism, of the bourgeoisie or its allies. It must be the dictatorship of Lloyd George, Clemenceau, Scheidemann, and so on. If you don't want that, if you don't want to go downhill, there's nothing else but dictatorship, the dictatorship of Bolshevism. And that's where he sees the only way out.

You see, this guy is honest in a way, way more honest than all the others who see Bolshevism coming and think you can pit the old regime against it. At least he realizes that all this old stuff is ripe for destruction. But a question must arise, especially when you're on spiritual ground, when you experience something like this; because someone like Ren& Marchand is an exception. The question must arise: Where did this guy get all his knowledge? He got his knowledge from where most people today get theirs: from newspapers and books. He doesn't know life. Because most people today know life only from newspapers and books. The leading classes in particular know life only from newspapers. What have we not experienced in this regard from newspapers and books! We have seen that decades ago people formed their worldview from French comedies, that they knew the literature that appeared in a comedy better than what happens in real life, that they ignored the realities of life and actually educated themselves only through what they saw on stage. Later, we saw that people formed their worldview from Ibsen or Dostoyevsky or Tolstoy, that they did not know life, nor could they judge books by life, but basically only absorbed the derived life that was written on paper. And there they develop their mottos, there they found their associations for all kinds of reforms, without knowing real life, which they know only from Ibsen or Dostoyevsky, or know it as it often had to become repugnant in the days when, for example, Hauptmann's “The Weavers” was performed in all the major cities of Europe. The way of life of the weavers appeared on the stage. Those people who had no idea what goes on in life, whose caricature appeared here on the stage, now looked down from the boards at the misery of the weavers, because it was the “social era,” and talked about all kinds of social issues, knowing things only in this way. Basically, these are all people who do not know life, who only know it in its derivation from newspapers, from books, from what books are today. I am not speaking against books; one must know them, but one must read books in such a way that one can see life through them. But that is precisely the problem: we live in an age of abstractions, of abstract party demands, of abstract association demands, and so on. And so I find it interesting that on the one hand we have a man as true to life as this Rene Marchand, who at the same time is an oracle to many, because he is a journalist and therefore never in a position to ask himself: Yes, can one arrive at a possible way of life from this Bolshevism? — For he does not know life at all; he merely exchanges what he has come to know and what he considers ripe for destruction with a new abstract formula, with new theories. And then I had to compare these omissions of an intellectual with a letter I received this morning, in which someone who has been involved in life, who has experienced in life precisely what one can experience today in order to assess the social situation, writes to me that the book “The Key Points of the Social Question” has become a kind of salvation for him, a practitioner who has worked in a weaving mill and knows the practice through and through. Only then will one have any idea of what is meant by the “core points of the social question” as a book about reality, which, however, has been drawn from the spiritual world, as everything that is to serve life today must be drawn from the spiritual world. Only then will one know what is meant by it when one judges it from the point of view of practical life, when you know that everywhere, in every line, in every word, it is not theory, but has been taken from practical life, when you understand that it is a book for those who want to actively intervene in life, not for those who want to speculate about life and talk socialist nonsense.