Spiritual Science as a Foundation for Social Forms

GA 199

21 August 1920, Dornach

Lecture VII

Genuine knowledge of the impulses holding sway in humanity, knowledge that must be acquired if we wish to take a Position in life in any direction, is possible only if we attempt to go deeply into the differences of soul conditions existing between the members of the human race. In respect to the right progress for all mankind, it is certainly necessary that human beings understand one another, that an element common to all men is present. This common element, however, can only develop when we focus on the varieties of soul dispositions and developments that exist among the different members of humanity. In an age of abstract thinking and mere intellectualism such as the one in which we find ourselves, people are only too prone to look only for the abstract common denominators. Because of this they fail to arrive at the actual concrete unity, for it is precisely by grasping the differences that one comprehends the former. From any number of viewpoints, I have referred in particular to the mutual relationships resulting out of these differences between the world's population of the West and East. Today, I should like to point to such differentiations from yet another standpoint.

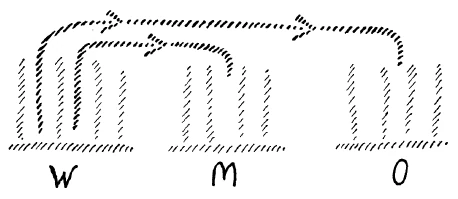

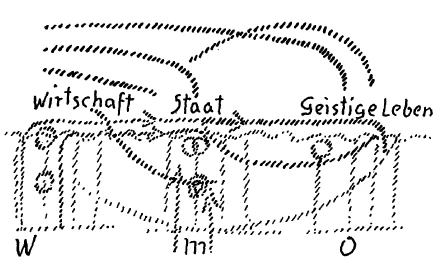

When we look at the obvious features of present general culture, what do we actually find? The form taken by the thoughts of most people in the civilized world really shows an essentially Western coloring, something originating in the characteristic tendencies of the West. Look at newspapers today that are published in America or England, in France, Germany, Austria or Russia. Although you will definitely sense certain differences in the mode of thinking, and so on, you will also notice one thing they have in common. If this is the Western region here (see sketch), this the middle one and that the Eastern, this common element, which comes to light everywhere, say, in newspapers as well as in ordinary popular literary and scientific publications, does not derive its impulse from the depths of the national characteristics. In a St. Petersburg paper, for instance, you do not find what arises from the heritage of the Russian people. You do not discover the heritage of Central European peoples by reading a Viennese paper or one from Berlin. The element determining the basic configuration and character (of all publications) has basically arisen in the West, and then poured itself into the individual regions. The fundamental coloring of what has come to the fore from among the peoples of the West has, therefore, essentially spread out over the civilized world.

When things are viewed superficially, one might doubt this; but if you go more deeply into the matters under discussion here, you can no longer doubt them. Consider the attitude, the basic sentiment, the conceptual form, expressed in a newspaper from Vienna or Berlin, or a literary or scientific work from either city. Compare this with a publication from London—quite aside from the language—and you will discover that there is a greater similarity between the publication from London and the book from Vienna, Paris, or even New York or Chicago than there is between the present thoughts and ideas in literary and scientific works from Vienna and Berlin, and the special nuance which Fichte53Johann Gottlieb Fichte: Appellation an das Publikum ueber die ihm beigemessenen atheistischen Aeusserungen, 1799. for example, poured into his thoughts as an enlivening element. I shall demonstrate this to you by citing just one example.

There is a saying by Johann Gottlieb Fichte, the great philosopher who was born at the turn of the nineteenth century, that is so characteristic of him that no one today understands it. It goes, “The external world is the substance of duty become visible.” The sentence means nothing less than this. When we look out into the world of mountains, clouds, woods and rivers, of animals, plants and minerals, all this is in itself something devoid of meaning, without reality, it is merely a phenomenon. It is only there to enable the human being in his evolution to fulfill his duty. For I could not carry out my obligations in a world in which I would not be surrounded by things that I could touch. There must be wood, there must be a hammer. In itself, it has no significance and no materiality. It is only the substance of my duty which has become sense-perceptible. Everything outside exists primarily for the purpose of bringing duty to light.

This saying was coined by a man a century ago out of the innermost sentiments of his soul and character as well as his folk spirit. It did not become generally known. When people talk about Johann Gottlieb Fichte today, when they write books about him and mention him in newspaper articles, they only perceive the external form of his words. No one really understands anything about Fichte. You may take everything you find on him today, either literary or scientific, but it has nothing whatever to do with Johann Gottlieb Fichte. It does, however, have a great deal to do with what arose out of the Western folk spirit, and has spread over the rest of the civilized world.

These more delicate relationships are not discerned. That is the reason why nobody even thinks of characterizing in a deep and exhaustive manner the essential feature of what arises from the spirit of the various nationalities. For it is all inundated today by what arises from the West. In Central Europe, in the East, people imagine that they are thinking along their own ethnic lines. This is not the case, they think in accordance with what they have adopted from the West.

In what I am now saying lies the key to much of what is really the riddle of the present age. This riddle can be solved only when we become aware of the specific qualities arising from the various regions of the world. There is, first of all, the East that today certainly offers us no true picture of itself. If untruthfulness were not the underlying characteristic of all public life in our time, the world would not be so ignorant of the fact that what we call Bolshevism is spreading rapidly throughout the East and into Asia; that it has gone far already. People have a great desire to sleep through the actual events, and are glad to be kept in ignorance. It is therefore easy to withhold from them what is really taking place. Thus, people will live to see the East and the whole of Asia inundated by the most extreme, radical product of Western thought, namely Bolshevism, an element utterly foreign to these people.

If we wish to look into what it is that the world of the East brings forth out of the depths of its folk character, it becomes obvious that it is possible to discover the fundamental nuance of feeling in the East only by going back into earlier times and learning through them. For, in regard to its original character, the East has become completely decadent. Forgetting its very nature, the East has allowed itself to be inundated by what I have described as the most extreme, radical offshoots of Western thought. Certainly, it is true that what was once there is still living within Eastern humanity, but today it is all covered up. What once lived in the East, what once vibrated through Eastern souls, survives in its final results where it is no longer understood, where it has turned into a superstitious ritual, where it has become the hypocritical murmurings of the popes of the Orthodox Russian ritual, incomprehensible even to those who believe they understand it. A direct line runs from ancient India to these formulas of the Russian church ritual, which are now only rattled off to the multitudes in the form of lip service. For this whole inclination which thus expressed itself, which bestowed on the Eastern soul its imprint and also does so today in a suppressed form, is the potential for developing a spiritual state of mind that guides the human being towards the prenatal, to what exists in our life before birth, before conception. In the very beginning, the nature of what permeated the East as a world conception and religious attitude was connected with the fact that this East possessed a concept which has been completely lost to the West. As I have said here before, the West has the concept of immortality, not that of “not having been born,” of “unbornness.” We have the word immortality, we do not have the term “unbornness.” This implies that in our thinking we continue life after death, but not into the time before birth. On the other hand, the East possessed that special soul inclination it had that still included Imagination and Inspiration in its thoughts and concepts. By means of this particular manner of expressing the conceptual content of its soul world, the East was far less predisposed to pay heed to the life after death than to that before birth. In regard to the human being it viewed life here in the sense world as something that comes to man after he has received his tasks prior to birth, as something that he has to absolve here in the sense of the task given him. He was disposed to regard this life as a duty set human beings by the gods before they descended into this earthly body of flesh. It goes without saying that such a world conception encompasses both repeated earth lives and the lives between death and birth; for one can quite well speak of a single life after death, but not of only one before birth. That would be an impossible teaching. After all, one who refers at all to pre-existence would then not speak of one earth life only, which is something that should be obvious to you upon reflection. It was the way they had of looking up into the supersensory world, which was brought about by the whole predisposition of these Eastern souls, but it was one that focused their attention on the life we lead between death and a new birth prior to being drawn down to earthly life. Everything else, everything in the way of political, social, historical and economical ideas was only the consequence of what dwelt in the soul due to the orientation towards the life between birth and conception.

This life, this mood of soul, is particularly fitted to turn the human soul's gaze to the spiritual, to fill man with the super-sensible world. For even here on earth, man considers himself entirely a creation of the spiritual world, indeed, as a being who, in the world of the senses, is merely pursuing his super-sensible life. Everything that became decadent in later ages, the establishment of kingdoms, the social structure of the ancient Orient and its very constitution, developed from this special underlying mood of soul. This soul condition might be said today to be overpowered, because it became weak and crippled, because it was only promulgated as if out of what I would like to call “rachitic” soul members, as for example, in the works of Rabindranath Tagore,54Rabindranath Tagore: 1861–1941, Indian poet and religious philosopher. which are like something that is poured into vague, nebulous formulas. In actual practice, we are today inundated by what expresses itself in Bolshevism as the most extreme, radical wing of Western thinking. The West will have to experience that something it did not wish to have for itself is moving over into the East, that in a not very distant future, what the West pushed off on the East will surge back upon it from there. This will result in a strange kind of self-knowledge.

What has this remarkable development in the East led to? It has led the people of the East to employ the holy inner zeal they once utilized to foster the impulse for the supersensory world and to apprehend the spiritual in all its purity, to accept the most materialistic view of outer life with religious fervor. Even though Bolshevism is the most extreme consequence of the most materialistic view of the world and social life, it will, as it moves further into Asia, increasingly transform itself into something that is received there with the same religious zeal as was the spiritual world in former times. In the East, people will speak of the economic life in the same terminology once used to speak of the sacred Brahma. The fundamental disposition of the soul does not change; it endures, for it is not the content (of the soul) that matters here. The most materialistic views can be approached with the same fervor formerly used to grasp the most spiritual.

Let us now turn and look at the West. The West has given rise to the human soul's most recent development. It must be of special interest to us because it has brought forth the view which, rising like a mist, has since spread over the whole civilized world. It is the manner of conception that already found, its most significant expression in Francis Bacon and Hobbes; in minds of more recent times, in the economist Adam Smith, for example; among philosophers, in John Stuart Mill, and among historians, in Buckle, and so on.55Francis Bacon: 1561–1626, English philosopher and statesman, founder of empiricism; Thomas Hobbes: 1588–1679, English philosopher; Adam Smith: 1723–1790, English philosopher and sociologist; John Stuart Mill: 1806–1873, English philosopher and political economist, one of the founders of positivism; Henry Thomas Buckle: 1821–1862, English writer on social history. It is a form of thinking that no longer contains any Imagination and Inspiration in its conceptions and ideas, where the human being is dependent on directing his conceptual life entirely outwards to the sense world, absorbing the impressions of the latter according to the associations of thoughts resulting from that same world. This came to its most brilliant philosophical expression in David Hume, also in other such as Locke.56David Hume: 1711–1776, English philosopher and statesman; John Locke: 1632–1704, English philosopher.

There is something very strange here that must, however, be mentioned. When we focus on the West, we must pay heed to how minds like John Stuart Mill, for example, speak of human thought associations. The term “association of ideas” is in fact a completely Western thought form, but in Central Europe, for instance, it has been in such common use for more than half a century that people speak of it as if it had originated there. When psychology is taught in John Stuart Mill's sense, one says, for instance, that in the human soul, thoughts first connect themselves by means of one thought embracing another, or by one thought attaching itself to another, or by one permeating another. This implies that people look upon the thought world and view the individual thoughts as they would little spheres that relate themselves to each other (see drawing). To be consistent one would have to eliminate everything to do with the ego and astral body, inwardly referring only to a mere thought mechanism, something that a great number of people do, in fact, speak of. The soul of man is disemboweled, as it were. When you read a book by John Stuart Mill with its deductive and inductive logic, you feel as if you were mentally placed in a dissecting room where a number of animals hang that are having their innards taken out. Likewise, in the way Mill proceeds, one feels as if man's soul-spiritual being were disemboweled. He first empties the human being of everything within, leaving only the outer sheath. Then, thoughts do, indeed, appear only like so many associated atomistic formations that coalesce when we form an opinion. The tree is green. Here “green” is the one thought, “tree” is the other, and the two flow together. The inner being is no longer alive; it has been disemboweled and only the thought mechanism remains.

This manner of conceiving of things is not derived from the sense world; it is imposed upon it. In my book, The Riddles of Philosophy,57Rudolf Steiner: The Riddles of Philosophy, GA 18 (New York, Anthroposophic Press, 1973). I have drawn attention to how a mind such as John Stuart Mill's is in no way related to the inner world; it is simply given to behaving like a mere onlooker in whom the external world is reflected. Our concern here is that this method of thinking brings about what I have often described as the tragedy of materialism, which is that it no longer comprehends matter. For how can materialism fathom the nature of matter—and we have seen that, by going deeply into the human being, one penetrates into the true material element of the earth—if it first eliminates in thought what actually represents matter? In this regard, an extreme consequence already has been reached.

This extreme consequence could easily be traced today if it were not for the fact that people never look at the whole context of things, only at the details. Imagine where it must lead if all the actual inner flexible aspects of the ego are eliminated, if the human being is emptied of the very element that can enlighten him in the sense world concerning the spirit. Just think, where must this finally lead? It must result in the human being feeling that he no longer has anything of the actual content of the world. He looks outside at the sense world without realizing the truth of what we said yesterday, namely, that behind the external world of the senses there are spiritual beings. When he gives himself up to illusions, he assumes that atoms and molecules exist outside. He dreams of atoms and molecules. If man has no illusion concerning the external world, he can say nothing but that the whole outer world contains no truth, that it really is nothing. Inwardly, on the other hand, he has found nothing; he is empty. He must talk himself into believing that there is something inside him. He has no grasp of the spirit; therefore, he suggests spirit to himself, developing the suggestion of spirit. He is not capable of maintaining this suggestion without rigorously denying the reality of matter. This implies that he accommodates himself to a world view which does not perceive the spirit but only suggests it, merely persuading itself into the belief of spirit, while denying matter. You find the most extreme Western exponent of this in Mrs. Eddy's Christian Science58Mary Baker Eddy: 1821–1910, founder of Christian Science. as the counterpart of what I described just now for the East. This was bound to arise as the final outcome of such conceptions as those of Locke, David Hume or John Stuart Mill. Christian Science as a concept is, however, also the final consequence of what has been brought about in recent times by the unfortunate division of man's soul life into knowledge and faith.

Once people start restricting themselves to knowledge on one side and faith on the other, a faith that no longer even tries to be knowledge, this leads in the end to their not having the spirit at all. Faith finally ceases to have a content. Then, people must suggest a content to themselves. They make no attempt to reach the genuine spirit through a spiritual science. In their search for the spirit, they arrive at Mrs. Eddy's Christian Science, this spirit which has come to expression there as the final consequence. The politics of the West have for some time been breathing this spirit. It does not sustain itself on realities; it lives on self-made suggestions. Naturally, when it is not a matter of an in-depth cure, one can even effect cures with Christian Science, as has been reported, and accounts are given of its marvelous cures. Likewise, all kinds of edifying results can be achieved with the West's politics of suggestion.

Yet, this Western concept possesses certain qualities, qualities of significance. We can best understand them when we contrast them with those of the East. On looking back to the ages when the Eastern qualities came especially to the fore, we find that they were those which, first of all, were capable of focusing the soul's eye on the prenatal life. They were therefore preeminently fitted to constitute what can represent the spiritual part, the spiritual world, in a social organism. Fundamentally speaking, all that we have created in Central Europe and the West is in a certain sense the legacy of the East. I have already mentioned this on another occasion. The East was particularly predisposed to cultivate the spiritual life. The West, on the other hand, is especially talented at developing thought forms. I have just described them in a somewhat unfavorable light. They can, however, be depicted in a favorable light as well, namely, if we consider all that has originated with Bacon of Verulam, Buckle, Mill, Thomas Reid, Locke, Hume, Adam Smith, Spencer, and others of like mind, for example, Bentham.59Herbert Spencer: 1820–1903, English philosopher; Jeremy Bentham: 1748–1832, English Jurist, founder of philosophy of utilitarianism. On the one hand, we admit that these thought forms are certainly not suited to penetrate into a spiritual world by means of Imagination and Inspiration, to comprehend the life before birth. Yet, on the other hand, we are obliged to say, particularly when one studies how this manner of thinking has pervaded and lives in our Western science, that all this is especially appropriate for economic thinking; and one day, when the economic life of the social organism will have to be developed, we shall have to become students of Western thought, of Thomas Reid, John Stuart Mill, Buckle, Adam Smith, and the rest. They have only made the mistake of applying their form of thinking to science, to epistemology, and the spiritual life. This thinking is in order when we train ourselves by means of it and reflect on how to form associations, how best to manage the economy. Mill should not have written a book on logic; the spiritual capacity he applied to doing this should have been used for describing in detail the configuration of a given industrial association. We must realize that when anyone today wishes to produce a book such as my Towards Social Renewal, it is necessary for him to have learned to understand in what manner one attains to the spiritual sphere in the Oriental sense, and in what manner—although following a much more erratic path—one arrives at economic thinking in the West. For both directions belong together and are necessary to one another.

As far as a view of life is concerned, this Western thinking then does lead to pseudo-sciences like the one by Mrs. Eddy, her Christian Science. We must not, however, look at matters according to what they cannot be, but consider what they can be. For unity must come about through the cooperation of all human beings on earth, not by some abstract, theoretical structure of ideas that is simply laid down, and then viewed as a unity.

At this point, one may ask from where in the human organization this particular thinking of Mill, Buckle, and Adam Smith originates. We find that Oriental thinking has basically arisen from a contact with the world, especially when looking back to the more ancient forms of Oriental philosophy. It is a thinking, a feeling, which gives the impression that, out of the earth itself, the roots of a tree grow and produce leaves. In just this way, the ancient Indian, for example, seems to us to be united with the whole earth; his thoughts appear to us to have grown out of earthly existence in a spiritual manner, just as a tree's leaves and blossoms appear to have grown out of it by means of all the forces of the earth.

It is precisely this attachment to the external world in the Oriental person, the absorption of the spirituality, that I have referred to as lying beyond the sense world. In the West, everything is brought out of the instincts, the depth of the personality—I might say, from man's metabolic system, not the external world. For the Oriental, the world works upon both his senses and Spirit, kindling within him what he calls his holy Brahma. In the West, we have what arises from the body's metabolism and leads to associations of ideas; it is something that is particularly suited to characterize the economic life, something that does not apply until the next earth incarnation. For, with the exception of the head, what we bear as our physical organism is something that does not find its true expression, as we have outlined, until the following life on earth. We have been given our head from our previous earth life; our limbs and our metabolic system are Borne by us into the next earthly incarnation. This is a metamorphosis from one life on earth to the next. Hence, in the West, people think with something that only becomes mature in the following earth life. For this reason, Western thinking is particularly predisposed to focus on the life after death, to speak of immortality, not of eternity, not to know the term, “unbornness,” but only the word, “immortality.” It is the West which represents life after death as something that the human being should above all else be concerned about. Yet, even now, something I might call radical, but in a radical sense something noble, is preparing itself in the West out of the totally materialistic culture. One with the faculty to look a little more deeply into what is thus trying to evolve makes a strange discovery. Although people strive in the most intimate way for life after death, for some kind of immortality, hence, for an egotistic life after death, they strive in such a manner that, out of this effort, something special will develop. While a large part of humanity still harbors an illusion in this regard, something quite remarkable is, oddly enough, developing in the West. Since individual elements of the ideas concerning life after death being developed by the West are reflected to a certain extent in a great majority of Europeans, they, too, have especially perfected this preoccupation with the postmortem life. The European, however, would prefer to say, “Well, my religion promises me a life after death, but in this transitory, unsatisfactory, merely material earth life I need make no effort to secure the immortality of my soul. Christ died to make me immortal; I need not strive for immortality. It is mine once and for all; Christ makes me immortal.”—or something to that effect.

In the West, particularly in America, something different is preparing itself. Out of the most diverse, occasionally the most bizarre and trivial religious world conceptions, we see something trying to arise which, although it has quite materialistic forms, is nevertheless connected with. something that will be a part of life in the future, particularly in regard to this world-view of immortality. Among certain sects in America, the belief is prevalent that one cannot survive at all after death if one has made no effort in this earthly life, if one has not accomplished something whereby one acquires this life after death. A judgment concerning good and evil is envisioned after death that does not merely follow the pattern of earthly truth. He who makes no effort here on earth to bear through the portals of death what he has developed in his soul will be diffused and scattered in the cosmic all. What a person wishes to carry with him through death must be developed here. A man dies the second death of the soul—to use the saying of Paul—who does not provide here for his soul to become immortal. This is something that is definitely developing in the West as a world concept in place of the leisurely, passive, awaiting what will happen after death. It is something that is emerging in certain American sects. Perhaps today it is still little noticed, but there is a great deal of feeling in favor of viewing life here in a moral sense, and to arrange the conduct of life in such a manner that by means of what one does here, something is carried through the gate of death.

As I said, in the East, the particular attention to the life before birth developed long ago. This made it possible for life on earth to be viewed as a continuation of this prenatal, supersensory life in the spirit. Earthly life thus received its content, not out of itself, but out of the spiritual life. In the West, an attitude is developing today for the future that will have nothing to do with a passive, indifferent life of waiting here for death because the life beyond is guaranteed; instead, the knowledge is growing that man carries nothing through the portal of death unless care is taken on earth to make something out of what one already has here.

Thus, Western thinking is adapted, on the one hand, to organizing economic matters within the social organism; on the other hand, it is suited to develop further the one-sided doctrine of life after death. This is why spiritualism has had a special opportunity for developing in the West, and from there, could invade the rest of the world. After all, spiritualism was only devised to give a sort of guarantee of immortality to those who could no longer attain to any conviction concerning immortality by means of any kind of inner development. For, in most instances, a person actually becomes a spiritualist in order to receive by some means or the other the certain guarantee that he is immortal ,after death.

Between these two worlds lies something that is implied in Fichte's words, “The external world is the substance of my duty become visible.” As I said before, people really have no understanding for this mode of thinking, and what is written today about Fichte could well be compared to what a blind man might say about color. Particularly in the last few years, a tremendous amount of talking and lecturing has been done about this saying by Fichte, but it was all accomplished in such a way that one is disposed to say that Fichte, that out-and-out Central European mind, has really been americanized by the German newspapers and writers of literature. One is confronted with americanized versions of Fichte. There, we find the nuance of human soul life which, in a special way, is supposed to develop the middle member of the social organism, the one that arises from the relationship of man to man. It would be of benefit if some of you would for once make an in-depth study—it isn't easy—of one of Fichte's writings where he speaks as though nature did not exist at all. Duty, for example, and everything else is deduced by first proving that external human beings actually exist in whom the materialized substance of duty can become reality. Here, all the raw material is contained, so to speak, from which the rights and state organism of the threefold social order have to be put together.

What, then, is the actual cause of the catastrophic events in the past few years? The basic reason is that there was no living perception, no feeling, for such matters. Berlin's policies are American. This is fine for America, but it is not suitable for Berlin. This is why Berlin's politics amount to nothing. For, just imagine, since American policies were constantly carried out in Berlin or Vienna, we could just as well have called Berlin, New York, apart from the difference in language, and Vienna, Chicago for all the difference there would have been otherwise. When, in Central Europe, something is done that is completely foreign to it, something originating in the West where it has its rightful place, then the primal essence of the folk spirit is aroused and gives it the lie without the people being aware of it. This was basically the case in recent decades. This was the underlying phenomenon of what happened, the phenomenon that consists, for instance, in the fact that people have trampled Goethe's thinking underfoot, and as another example, have read Ralph Waldo Trine60Ralph Waldo Trine: 1866–1958, American author. out of a sort of instinct. Actually, all our aristocratic dandies in politics have shown an interest in Trine, and received their special inner stimulus or whatever from that direction. When affairs came to the boiling point, they even turned to Woodrow Wilson;61Woodrow Wilson: 1856–1924, president of the USA from 1913 until 1921. In an address to Congress on January 8, 1918, he outlined a “Program of World Peace,” condensed in fourteen points. and he62Prinz Max von Baden: 1866–1929, became German chancellor in the fall of 1918; on October 5, 1918, he directed a peace offer to President Wilson based on the latter's “Fourteen Points.” who would now again like to be President of the German Republic still has that frame of mind that allows his brain automatically to roll out Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points. Thus, in recent times, in the Grand Duchy of Baden, we experienced how a formerly truly representative German personality spouted forth americanisms. This is the best and most immediate example of how matters really stand at present. Indeed, we must be able to see through these archetypal phenomena if we wish to understand what is actually happening today. If we merely pick up a newspaper and read Prince Max von Baden's speeches, simply studying them out of context, then this is something absolutely worthless today. It is a mere kaleidoscope of words. Only when we are able to place such things into the whole context of the world can we hope to understand anything about the world. No progress can be made until people realize how necessary it is today that world understanding be acquired if one wishes to have a say. The most characteristic sign of the time is the belief that when a group of individuals have set up some trashy proposition as a general program—such as the unity of all men regardless of race, nation or color, and so forth—something has been accomplished. Nothing has been accomplished except to throw sand into people's eyes. Something real is attained only when we note the differences and realize what world conditions are. Formerly, human beings could live in accordance with their instincts. This is no longer possible; they must learn to live consciously. This can be done only by looking deeply into what is actually happening.

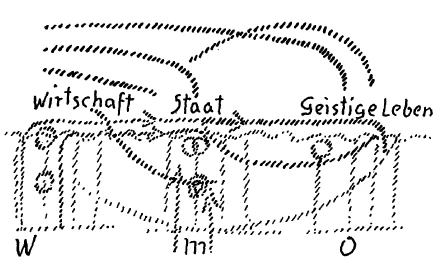

The East was supreme in regard to life before birth and repeated earthly lives that are connected with it. The greatness of the West consisted in its disposition in regard to life after death. Here, in the middle (see drawing an next page), the actual science of history has originated, although today it is as yet misunderstood. Take Hegel63Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: 1770–1831; complete edition of Hegel's works, Berlin, 1832–1844. as an example. In Hegel's works, we have neither preexistence nor postexistence; there is neither life before birth nor after death, but there is a spirited grasp of history. Hegel begins with logic, goes from there to a philosophy of nature, develops his doctrine of the soul, then that of the state, and ends with the triad of art, religion and science. They are his world content. There is no mention of preexistence or an immortal soul, only of the spirit that lives here in this world.

Preexistence, postexistence—this is really life in the present state of mankind, the permeation of history. Read what has been drawn up particularly by Hegel as a philosophy of history. In libraries, one generally finds the pages of his books still uncut! Not many editions have appeared of Hegel's works. In the eighties of the last century, Eduard von Hartmann64Eduard von Hartmann, 1842–1906. wrote that in all of Germany, where twenty universities exist that have faculties of philosophy, no more than two of the instructors had read Hegel! What he said could not be refuted; it was true. Nonetheless, it hardly needs to be said that all the students were ready to swear to what they had been told about Hegel by professors who had never read him. Do familiarize yourselves with his work and you will find that here, in fact, historical conception has come about, the experience of what goes on between human beings. There you also find the material from which the state, the rights sphere of the threefold social organism, has to be created. We can learn about the constitution of the spiritual organism from the Orient; the constitution of the economic sphere is to be learned from the West.

In this way, we have to look into the differentiations of humanity all over the whole earth, and can gain an understanding of the matter from one side or the other. If the goal is approached directly, namely, if the social life is studied, one arrives at the threefold order as developed in my book, Towards Social Renewal. By thus studying the life of mankind throughout the earth, we come to the realization that there is one part with a special disposition for the economy; there is another with a special aptitude for organizing the state; and yet another with a specific inclination towards the spiritual life. A threefold structure can then be created by taking the actual economy from the West, the state from the Middle, and from the East—naturally in a renewed form, as I have often said—the spiritual life. Here you have the state, here the economic life and here the spiritual life (see above sketch); the two others have to be taken across from here. In this way, all humanity has to work together, for the origins of these three members of the social organism are found in different regions of the earth, and therefore must be kept properly apart everywhere. If, in the old manner, human beings wish to mix up in a unified state what is striving to be threefold, nothing will result from it except that in the West the state will be a unity where the economic life overwhelms the whole, and everything else is only submerged into it. If the theorists then take hold of and study the matter, meaning, if Karl Marx moves from Germany to London, he then concludes that everything depends on the economic life. If Marx's insanity triumphs, the three spheres are reduced to one, the one being of a purely economic character. If one limits oneself to what wishes to be merely the state or rights configuration, one apes the economic life of the West, which for decades has been fashioning an illusory structure, which then naturally collapses when a catastrophe occurs—something that has indeed happened!

The Orient, which possesses the spiritual life in a weakened state in the first place, simply has adopted the economic life from the West and has inoculated itself with something that is completely alien to it. When these matters are studied, we shall see particularly that blessings can only fall upon the earth when, everywhere, one gathers together into the threefold social organism through human activity what by its very nature develops in the various regions.

Siebenter Vortrag

Eine wirkliche Erkenntnis desjenigen, was in der Menschheit als verschiedene Impulse waltet, und was erkannt werden muß, wenn man nach irgendeiner Richtung hin Stellung nehmen will innerhalb der Menschheit, ist nur möglich, wenn man versucht, sich zu vertiefen in die Verschiedenheiten, die bestehen zwischen der Seelenverfassung des einen Gliedes der Menschheit und der des andern Gliedes der Menschheit. Gewiß, notwendig ist es zum richtigen Fortschritt innerhalb der ganzen Menschheit, daß sich die Menschen verstehen, daß es also unter den Menschen ein Gemeinschaftliches gibt. Aber dieses Gemeinschaftliche kann sich nur entwickeln, wenn der Blick gerichtet wird auf das, was als Verschiedenheiten in den Seelenveranlagungen, in den Seelenentwikkelungen bei den verschiedenen Gliedern der Menschheit da ist. In einem Zeitalter des abstrakten Denkens, des bloßen Intellektualismus, wie es dasjenige ist, in dem wir jetzt leben, sieht man zu gerne nur nach den abstrakten Einheiten. Dadurch kommt man überhaupt nicht zum Verständnis der wirklichen konkreten Einheit. Man muß gerade durch das Erfassen der Verschiedenheiten zu der Einheit kommen. Und ich habe von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus hingewiesen namentlich auf die gegenseitigen Beziehungen, die sich zwischen dem Westen und dem Osten der Erdenbevölkerung aus diesen Verschiedenheiten heraus ergeben. Heute möchte ich wiederum von einem andern Gesichtspunkte auf solche Differenzierungen innerhalb der Menschheit hinweisen. Wenn man heute dasjenige nimmt, was einem gewöhnlich in die Augen fällt, wenn man auf die allgemeine Bildung hinsieht, was hat man denn dann eigentlich? Man hat, wenn man den Blick auf das richtet, was gewissermaßen die meisten Menschen in der zivilisierten Welt als ihre Gedankenformen haben, im Grunde genommen darinnen etwas, was im wesentlichen westliche Färbung und seinen Ursprung in der besonderen Charakterveranlagung des Westens hat. Ich meine so: Wenn Sie heute eine Zeitung in die Hand nehmen, die in Amerika, in England, in Frankreich, in Deutschland, in Österreich oder in Rußland erscheint, so werden Sie ja gewiß verspüren, daß da gewisse Unterschiede in der Art des Denkens und so weiter sind, aber Sie werden ein Gemeinsames bemerken. Dieses Gemeinsame rührt aber nicht davon her, daß etwa, wenn ich da das westliche Gebiet, da das mittlere Gebiet und da das Ostgebiet habe (siehe Zeichnung), dasjenige, was, sagen wir, in den Zeitungen und auch in den gewöhnlichen populären und wissenschaftlichen Literaturwerken zutage tritt, überall aufsteigen würde aus dem, was in den Tiefen der Volkstümer ruht. Sie lesen nicht zum Beispiel in einer Petersburger Zeitung, was aus dem Volkstum des Russentums aufsteigt, Sie lesen heute nicht einmal in einer Wiener oder Berliner Zeitung, was aus dem Volkstum der mittleren Welt aufsteigt, sondern dasjenige, was die Grundkonfiguration, den Grundcharakter angibt, das ist im Grunde genommen aus dem Westen aufgestiegen und hat sich hier in diese einzelnen Gebiete herein ergossen. Es ist also im wesentlichen über die zivilisierte Welt verbreitet die Grundnuance desjenigen, was eigentlich aus den Volkstümern des Westens aufgestiegen ist.

Man kann das, wenn man oberflächlich die Dinge ansieht, bezweifeln; aber wenn man etwas tiefer geht, so kann man die Dinge nicht mehr bezweifeln, von denen hier die Rede ist. Nehmen Sie, was etwa heute Gesinnung, Grundempfindung, Vorstellungsform, sagen wir, einer Wiener, Berliner Zeitung oder eines Wiener oder Berliner belletristischen oder auch wissenschaftlichen Buches ist. Vergleichen Sie das mit einem Londoner Buche - ganz abgesehen jetzt von der Sprache -, dann finden Sie darinnen bei einem solchen Vergleichen zwischen dem Wiener, Berliner und Londoner oder Pariser Buch oder selbst New Yorker und Chicagoer Buche mehr Ähnlichkeit als zwischen dem, was heute in der belletristischen und wissenschaftlichen Literatur an Gedanken und Vorstellungsformen in Wien oder Berlin zutage tritt, und dem, was zum Beispiel Fichte als seine besondere Nuance hat, die er durch seine Gedanken hindurch als belebendes Element ergießt. Ich will Ihnen einen einzelnen Fall sagen, an dem Sie das sehen können.

Es gibt einen Satz von Fichte, der ist so charakteristisch für diesen Johann Gottlieb Fichte, den großen Philosophen von der Wende des 18. zum 19. Jahrhundert, daß ihn heute kein Mensch versteht. Dieser Satz heißt: «Die äußere Welt ist das versinnlichte Material der Pflicht.» Der Satz heißt nämlich nichts Geringeres als: Wenn man hinausschaut in die Welt der Berge, in die Welt der Wolken, Wälder, Flüsse, Tiere, Pflanzen, Mineralien, das alles ist etwas, was für sich selber gar keine Bedeutung, gar keine Realität hat, das alles ist eine bloße Erscheinung. Es ist bloß dazu da, daß der Mensch in seiner Entwickelung seine Pflicht verrichten kann; denn ich kann nicht meine Pflicht verrichten, wenn ich in einer Welt stehe, in der ich nicht umgeben bin von irgend etwas, das ich angreifen kann. Es muß Holz da sein, es muß ein Hammer da sein: das ist für sich gar nicht bedeutend, hat keine Materialität, sondern es ist nur das versinnlichte Material meiner Pflicht. Und dasjenige, was da draußen ist, ist dazu da, daß die Pflicht überhaupt zutage treten kann. Das hat ein Mensch aus den innersten Empfindungen seiner Seele, aus der innersten Nuance seiner Seelenverfassung heraus und dann aus dem Volkstum heraus vor einem Jahrhundert geprägt. Das ist nicht populär geworden. Wenn heute die Leute von Johann Gottlieb Fichte reden, Bücher über ihn schreiben, in Zeitungsartikeln von ihm reden, dann reden sie so, daß sie bloß die äußere Wortform wahrnehmen. Verstehen tut keiner etwas von Fichte. Sie können alles, was jetzt über Fichte so von der gewöhnlichen Belletristik und Wissenschaft notifiziert wird, ruhig als etwas nehmen, was mit Johann Gottlieb Fichte überhaupt nichts zu tun hat; aber viel hat es zu tun mit dem, was aus dem westlichen Volkstum aufgestiegen ist, und was sich herüberergossen hat in dasjenige, was auch sonstige zivilisierte Welt ist.

Diese feineren Zusammenhänge, die durchschaut man nicht. Daher kommt man gar nicht darauf, in einer intensiv erschöpfenden Weise zu charakterisieren, worin das Wesentliche liegt, das aus den verschiedenen Volkstümern aufsteigt. Denn es ist heute ja alles überflossen von dem, was vom Westen aufsteigt und in das übrige hineinfließt. In Mitteleuropa, im Osten glauben die Leute in ihrem Volkstum zu denken. Das ist nicht der Fall zunächst. Sie denken gar nicht in ihrem Volkstum, sie denken in dem, was sie vom Westen angenommen haben.

In dem, was ich jetzt sage, liegt viel beschlossen von dem, was eigentlich das Rätsel der Gegenwart ist. Dieses Rätsel der Gegenwart kann nur dann gelöst werden, wenn man sich bewußt wird, welche spezifischen Qualitäten aus diesen einzelnen Gebieten aufsteigen. Da haben wir zunächst den Osten, diesen Osten, der ja heute sein wahres Bild nicht darbietet. Wäre nicht überhaupt die Verlogenheit zunächst die Grundeigenschaft des ganzen öffentlichen Lebens unserer Zeit, so würde ja die Welt heute nicht so unbekannt sein damit, daß dasjenige, was man Bolschewismus nennt, sich mit rasender Eile über den ganzen Osten ausbreitet, nach Asien hinein, daß das schon sehr weit ist. Die Leute sehnen sich darnach, zu verschlafen, was eigentlich geschieht, und sind sehr froh, wenn man ihnen nicht sagt, was da eigentlich geschieht. Daher kann man ihnen auch das natürlich sehr leicht vorenthalten, was in Wirklichkeit geschieht. So wird man es erleben, daß der Osten, daß ganz Asien überflossen wird von dem, was das äußerste, radikalste Produkt des Westens ist, von dem Bolschewismus, das heißt von einem ihm durch und durch fremden Elemente.

Will man hineinschauen in das, was die Welt des Ostens aus den Tiefen des Volkstums aufsteigen läßt, dann kann man gewahr werden — weil der Osten in bezug auf das Urelement vollständig in die Dekadenz gekommen ist und eigentlich seiner selbst nicht mehr bewußt ist, weil der Osten gerade sich überschwemmen läßt von dem, was ich als den äußersten radikalen Ausläufer des Westens charakterisiert habe -, daß man die eigentliche Grundnuance des Empfindens des Ostens nur dann finden kann, wenn man in ältere Zeiten zurückgeht und sich an ihnen belehrt. Gewiß, es ist alles das noch in der Menschheit des Ostens enthalten, was einstmals in ihr enthalten war, aber es ist heute alles übergossen. Was im Osten gelebt hat, was im Osten die Seelen durchzittert hat, das lebt in den äußersten Ausläufern zuletzt da, wo es nicht mehr verstanden wird, wo es abergläubischer Kultus geworden ist, wo es heuchlerisches Gemurmel der Popen geworden ist in dem letzten, eben orthodox-russischen Kultus, unverstanden auch von denen, die diesen orthodoxen russischen Kultus zu verstehen glaubten. Es war eine Linie vom alten Indertum bis zu diesen bloß noch auf den Lippen heuchlerisch in die Menge hineingeplärrten Formeln des russischen Kultus. Denn diese ganze Veranlagung, die sich da auslebte, die diesem Osten seelisch das Gepräge gab, die es ihm auch heute gibt, aber unterdrückt, das ist die Veranlagung dazu, eine solche geistige Verfassung zu entwickeln, welche den Menschen zu dem Vorgeburtlichen hinlenkt, zu dem, was in unserem Leben vor der Geburt beziehungsweise vor der Empfängnis liegt. Ganz ursprünglich war dasjenige, was als Weltanschauung und Religiosität diesen Osten durchdrang, so, daß es zusammenhing damit, daß dieser Osten einen Begriff hatte, der dem Westen ja ganz verlorengegangen ist. Der Westen hat, wie ich das schon einmal hier erwähnt habe, den Begriff der Unsterblichkeit, aber nicht der Ungeburtlichkeit, des Ungeborenseins. Unsterblichkeit sagen wir, aber wir sagen nicht Ungeburtlichkeit. Das heißt, wir setzen in Gedanken das Leben fort nach dem Tode, wir setzen es aber nicht fort hinaus in die vorgeburtliche Zeit. Aber dieser Osten war durch die besondere Veranlagung seiner Seele, welche noch Imagination, Inspiration in die Gedanken, in die Vorstellungen hereinnahm, dazu veranlagt, durch dieses besondere inhaltliche Ausleben der Vorstellungswelt weniger hinzusehen auf das nachtodliche Leben als vielmehr auf das vorgeburtliche, und dieses Leben hier in der Sinneswelt für den Menschen als etwas zu betrachten, was ihm zukommt, nachdem er seine Aufgaben empfangen hat vor der Geburt, was er hier auszuführen hat im Sinne der empfangenen Aufgabe. Er war dazu veranlagt, dieses Leben als die Pflicht aufzufassen desjenigen, was einem von den Göttern gegeben worden ist, bevor man in diesen irdisch-fleischlichen Leib heruntergestiegen ist. Es ist eine selbstverständliche Forderung, daß eine solche Weltanschauung die wiederholten Erdenleben und die Leben zwischen Tod und Geburt in sich einbezieht, denn man kann wohl von einem einmaligen Leben nach dem Tode reden, aber nicht von einem einmaligen vor der Geburt. Das würde eine unmögliche Lehre sein. Denn derjenige, der überhaupt redet von der Präexistenz, der redet dann nicht von nur einem Erdenleben, wie Sie bei einer rechten Überlegung sich klarmachen können. Es war ein Hinaufblicken in die übersinnliche Welt, welches durch die ganze Veranlagung dieser östlichen Seelen hervorgerufen war, aber es war ein Hinaufblicken so, daß man im Grunde genommen im Auge hatte dieses Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, bevor wir hier in das Erdenleben eingezogen sind. Alles andere, was gedacht wurde in politischer, in sozialer, in historischer Beziehung, in wirtschaftlicher Beziehung, es war nur eine Konsequenz von dem, was in der Seele ruhte in bezug auf dieses Hingeordnetsein auf das Leben vor der Geburt beziehungsweise vor der Empfängnis.

Dieses Leben aber, diese Seelenverfassung ist besonders geeignet dazu, den menschlichen Seelenblick hinaufzurichten nach dem Geistigen, zu erfüllen den Menschen mit der übersinnlichen Welt. Denn er betrachtet sich ja hier ganz und gar als ein Geschöpf der übersinnlichen Welt, als etwas, was nur das übersinnliche Leben hier durch das sinnliche Leben fortsetzt. Alles das, was dann später in die Dekadenz gekommen ist an Reichsgebilden, an sozialen Gebilden des alten Orients bis in die Konstitution hinein, ist so geworden, weil diese besondere Seelenverfassung zugrunde lag. Und heute ist diese Seelenverfassung, ich möchte sagen, überschüttet, weil sie schwach geworden ist, gelähmt geworden ist, weil sie nur, ich möchte sagen, wie aus rachitischen Seelengliedern heraus so verkündet worden ist, wie etwa durch Rabindranath Tagore, wie etwas, das in unbestimmte, nebulose Formeln ergossen wird. Heute ist man in praxi überschwemmt von dem, was als äußerster radikaler Flügel des Westens im Bolschewismus sich auslebt, und der Westen wird es zu erleben haben, daß das, was er selbst nicht haben will, sich nach dem Osten hinüber abschiebt, und daß ihm in einer gar nicht fernen Zeit von dem Osten dasjenige entgegenkommt, was er selber dorthin abgeschoben hat. Und es wird dann eine merkwürdige Selbsterkenntnis sein.

Aber wozu hat diese merkwürdige Entwickelung des Ostens geführt? Sie hat dazu geführt, daß die Menschen des Ostens all den heiligen inneren Eifer, den sie einmal dazu verwendet haben, um dem Impuls nach der übersinnlichen Welt Nahrung zu geben, um das Geistige in seiner Reinheit zu begreifen, nunmehr dazu verwenden, um die allermaterialistischste Anschauung von dem äußeren Leben mit religiöser Inbrunst aufzunehmen. Und immer mehr wird sich der Bolschewismus nach Asien hin so verwandeln, trotzdem er die alleräußerste Konsequenz der allermaterialistischsten Weltanschauung und sozialen Anschauung ist, immer mehr wird er sich dahin verwandeln, daß er da mit derselben religiösen Inbrunst ergriffen wird, wie ergriffen worden ist einstmals die übersinnliche Welt. Und man wird im Osten in denselben Formeln, in denen man einstmalsgeredet hat von dem heiligen Brahman, reden von dem wirtschaftlichen Leben. Denn dasjenige, was Grundveranlagung des Seelischen ist, das ändert sich nicht, das bleibt; denn nicht der Inhalt ist es, auf den es dabei ankommt. Man kann mit derselben religiösen Inbrunst das Allermaterialistischste ergreifen, mit der man vorher das Geistigste, das Spirituellste ergriffen hat.

Wenden wir den Blick von da ab nach dem Westen. Der Westen hat die verhältnismäßig am spätesten liegende menschliche Seelenentwickelung heraufgebracht. Sie muß uns besonders interessieren, denn sie hat diejenige Anschauung gebracht, die aufgestiegen ist wie ein Nebel im Westen und sich herüber ergießt über die ganze zivilisierte Welt. Es ist die Anschauungsweise, die am bedeutsamsten zum Ausdruck gekommen ist schon in Baco von Verulam, in Hobbes, in solchen Geistern, wie etwa unter den neueren der Nationalökonom Adam Smith, unter den Philosophen John Stuart Mill, unter den Historikern Buckle und so weiter. Es ist diejenige Denkweise, wo in den Vorstellungen, in den Gedanken nichts mehr liegt von Imagination, Inspiration, wo der Mensch ganz und gar angewiesen ist, nur sein Vorstellungsleben nach außen, nach der Sinneswelt zu richten und die Eindrücke der Sinneswelt nach den Verkettungen von Gedanken aufzunehmen, die sich gerade an der Sinneswelt ergeben. Philosophisch ist es am eklatantesten zum Ausdruck gekommen in David Hume, auch in andern, in Locke und so weiter. Es ist etwas sehr Eigentümliches, das aber gesagt werden muß. Wenn man nach diesem Westen blickt, dann muß man hinsehen, wie Geister wie zum Beispiel John Stuart Mill über die menschliche Gedankenverkettung sprechen. Das Wort Vorstellungsassoziation ist eigentlich ganz ein westliches Gebilde; aber es ist zum Beispiel in Mitteleuropa schon seit mehr als einem halben Jahrhundert so gang und gäbe geworden, daß man von diesen Vorstellungsassoziationen wie von etwas eigenem spricht. Man sagt zum Beispiel, wenn man Psychologie lehrt in John Stuart Millschem Sinn: Gedanken in der menschlichen Seele verbinden sich erstens so, daß ein Gedanke den andern umspannt, oder daß ein Gedanke sich an den andern schließt, oder daß ein Gedanke den andern durchdringt. Das heißt, man schaut auf die Gedankenwelt hin und sieht die einzelnen Gedanken wie einzelne kleine Bälle, die sich miteinander verbinden, die sich assoziieren (siehe Zeichnung). Wenn man konsequent wäre, müßte man alles Ich und alles Astralische ausstreichen und müßte da innerlich einen bloßen Mechanismus der Gedanken aufführen, und sehr viele Leute sprechen ja auch von diesem innerlichen Mechanismus der Gedanken. Der Mensch wird gewissermaßen seelisch ausgeweidet. Wenn man John Stuart Mill liest und seine deduktive und induktive Logik, so fühlt man sich seelisch versetzt in einen Seziersaal, wo verschiedene Tiere hängen, die ausgeweidet werden, denen das Innere herausgenommen wird. So fühlt man bei Mill des Menschen geistig-seelisches Wesen herausgenommen. Er nimmt zuerst das Innere heraus und läßt die bloße äußere Hülle. Ja, da erscheinen dann die Gedanken nur wie sich assoziierende atomistische Gebilde, die sich zusammenballen, wenn wir ein Urteil bilden. Der Baum ist grün: da ist der eine Gedanke, grün, der andere, der Baum; die schwimmen zusammen. Da ist nicht das Innerste mehr lebendig, das ist ausgeweidet, da ist nur der Mechanismus der Gedanken und so weiter.

Dieses Vorstellen kommt nicht von der äußeren Sinneswelt, sondern es wird der äußeren Sinneswelt aufgedrängt. Ich habe daher in meinem Buche «Die Rätsel der Philosophie» darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß solch ein Geist wie John Stuart Mill gar nicht irgendwie verwandt ist mit der inneren Welt, sondern sich einfach hingibt und sich nur wie ein bloßer Zuschauer verhält, in dem die äußere Welt sich spiegelt. Es han-. delt sich darum, daß durch diese Denkweise gerade dasjenige kommt, was ich öfter charakterisiert habe: der Materialismus hat die Tragik, die Materie nicht mehr zu erkennen. Wie kann denn der Materialismus eindringen in die Materie, wenn er erst das, was die Materie eigentlich darstellt -— denn wir haben gesehen: wenn man untertaucht in den Menschen, taucht man ja in das wahre Materielle der Erde ein —, wenn er das erst ausweidet in Gedanken. Es ist das jetzt schon zu einer äußersten Konsequenz gekommen in dieser Beziehung.

Diese äußerste Konsequenz ist heute schon zu verfolgen, nur daß die Leute niemals die Dinge im Zusammenhange sehen, sondern heute nur immer Einzelheiten sehen. Bedenken Sie, wohin es kommen muß, wenn alles wirkliche innere bewegliche Ich weg ist, also das, was gerade über den Geist in der Sinneswelt Aufklärung geben kann, aus dem Menschen herausgeweidet wird - denken Sie, wohin muß es denn zuletzt kommen? Dazu kommt es, daß der Mensch dann fühlt, er hat ja eigentlich nichts mehr vom wirklichen Inhalt der Welt. Er schaut hinaus in die Sinneswelt. Er weiß nicht, daß dasjenige wahr ist, was wir gestern gesagt haben, daß hinter der äußeren Sinneswelt geistige Wesenheiten sind. Wenn er sich Illusionen hingibt, ja, dann nimmt er draußen Atome und Moleküle an. Er träumt von Atomen und Molekülen. Wenn er sich keiner Illusion hingibt in bezug auf das Äußere, so kann er nichts anderes sagen als: Dieses ganze Äußere enthält ja keine Wahrheit. Es ist ja eigentlich nichts. — Aber innerlich hat er nichts gefunden. Er ist leer. Er muß sich selber suggerieren, daß irgend etwas in seinem Inneren ist. Er hat den Geist nicht, daher suggeriert er sich den Geist. Er bildet sich die Suggestion des Geistes. Und er ist nicht imstande, diese Suggestion aufrechtzuerhalten, wenn er nicht mit aller Schärfe abweist die Realität der Materie. Das heißt, er lebt sich vollständig ein in eine Weltanschauung, die den Geist nicht erkennt, sondern sich ihn suggeriert, sich bloß den Glauben an den Geist einsuggeriert und die Materie ableugnet. Sie haben den äußersten Ausläufer im Westen, Sie haben das Gegenbild dessen, was ich Ihnen im Osten eben charakterisiert habe, in der Christian Science der Mrs. Eddy. Sie mußte entstehen als die letzte Konsequenz solcher Anschauungen, wie die von Locke oder David Hume oder von John Stuart Mill. Es ist die Anschauung, die aber auch die letzte Konsequenz desjenigen ist, was heraufgezogen ist in der neueren Zeit in der unseligen Gliederung des ganzen menschlichen Seelenlebens in das Wissen und in den Glauben.

Geht man einmal dazu über, das Wissen auf der einen Seite zu haben, den Glauben auf der andern Seite, jenen Glauben, der nicht mehr Erkenntnis sein will, so führt das in letzter Konsequenz dahin, daß man überhaupt nicht mehr den Geist hat. Der Glaube hört schließlich auf, einen Inhalt zu haben. Dann muß man sich den Inhalt suggerieren. Man sucht nicht durch eine geistige Wissenschaft zum reinen Geist zu gelangen, man sucht eben den Geist und gelangt zu der Christian Science der Mrs. Eddy, diesen Geist, der als letzte Konsequenz in der Christian Science der Mrs. Eddy zum Ausdruck gekommen ist. Und diesen Geist atmet schon die ganze Politik des Westens seit längerer Zeit. Sie lebt nicht von Wirklichkeiten, sie lebt von selbstgemachten Suggestionen. Man kann ja selbstverständlich dann, wenn man nicht in die Tiefe hinein zu kurieren hat, auch mit der Christian Science bekanntlich kurieren, und die wunderbarsten Kuren werden erzählt. Ebenso kann man mit der Suggestionspolitik des Westens allerlei Erbauliches ausführen.

Aber diese Anschauung des Westens, sie hat doch Qualitäten, sie hat bedeutende Qualitäten. Sie hat die Qualitäten, die wir am besten erkennen, wenn wir sie kontrastieren mit dem, was die Qualitäten des Ostens sind. Blicken wir zurück auf diejenigen Zeiten, wo die Qualitäten des Ostens besonders hervorgetreten sind, so waren es die Qualitäten, die zunächst das vorgeburtliche Leben ins Auge fassen konnten, ins Seelenauge fassen konnten, die also besonders auch geeignet sind, dasjenige eigentlich zu konstituieren, was in einem sozialen Organismus die geistige Welt sein kann, das geistige Glied sein kann. Im Grunde genommen ist alles, was wir in Mitteleuropa und im Westen aufgebracht haben, in einer gewissen Weise Erbgut des Ostens. Ich habe ja das schon einmal bei einer andern Gelegenheit erwähnt. Dieser Osten war besonders dazu veranlagt, das geistige Leben zu kultivieren. Der Westen ist ja besonders dazu veranlagt, Gedankenformen auszubilden; ich habe sie jetzt in einem etwas unvorteilhaften Lichte geschildert. Sie sind aber auch in einem vorteilhaften Lichte zu schildern, wenn man nämlich dasjenige, was von Baco von Verulam, von Buckle, von Mill, Thomas Reid, von Locke, von Hume, von Adam Smith, von Spencer oder von ähnlichen Geistern herrührt, Bentham zum Beispiel, wenn man all das nimmt und sich auf der einen Seite gesteht: Ja, das ist ja ganz gewiß nicht geeignet, durch Imagination oder Inspiration in eine geistige Welt einzudringen, die das vorgeburtliche Leben begreift. Aber andererseits muß man sagen, gerade wenn man studiert, wie eingedrungen ist diese Denkweise in unsere Wissenschaft des Abendlandes, wie sie lebt in unserer Wissenschaft des Abendlandes, man muß sagen, das alles zeigt sich besonders geeignet für das wirtschaftliche Denken. Und wenn einmal das wirtschaftliche Glied des sozialen Organismus ausgebildet werden soll, dann wird man in die Schule gehen müssen beim Westen: bei "Thomas Reid, John Stuart Mill, Buckle, Adam Smith und so weiter. Sie haben nur den Fehler, daß sie auf die Wissenschaft, auf die Erkenntnis, auf das Geistesleben ihr Denken angewendet haben. Wenn man sich schult an diesem Denken und darüber nachdenkt, wie man Assoziationen zu bilden hat, wie man am besten zu wirtschaften hat, dann ist dieses Denken am Platze. Mill hätte nicht eine Logik schreiben sollen, sondern er hätte die geistige Kapazität, die er gehabt hat, um eine Logik zu schreiben, dazu verwenden sollen, einmal das Gefüge einer gewissen gewerblichen Assoziation in allen Einzelheiten zu beschreiben. Und man muß sagen, wenn man heute so etwas zustande bringen will wie mein Buch «Die Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage», dann muß man gelernt haben, zu verstehen, auf welche Art im orientalischen Sinne man zum Geistigen gelangt, und auf welche Weise man, wenn auch noch jetzt sehr auf Irrpfaden, im Westen zum wirtschaftlichen Denken gelangt. Denn beide Dinge gehören zueinander, beide sind notwendig miteinander.

Auf dem Gebiete der Weltanschauung führt das allerdings zu solchen Aftergebilden, wie dieses von Mrs. Eddy eines ist, die Christian Science. Aber man muß die Dinge nicht betrachten nach dem, was sie nicht sein können, man muß die Dinge betrachten nach dem, was sie sein können. Denn durch Zusammenwirken aller Menschen über das Erdenrund muß dasjenige entstehen, was Einheit der Menschen ist, nicht durch irgendein abstraktes theoretisches Gebilde, das man einfach hinpfahlt und das man dann als Einheit betrachtet.

Und man kann nun sich fragen: Woher eigentlich aus der menschlichen Organisation kommt dieses besondere Millsche, Bucklesche, Adam Smithsche Denken? Das orientalische Denken ist im Grunde genommen, besonders wenn man in die älteren Zeiten des Orientalismus zurückschaut, aus einem Verkehr mit der Welt entstanden, es ist dasjenige Denken, dasjenige Empfinden, welches einem so erscheint, wie wenn, ich möchte sagen, aus der Erde selbst die Wurzeln eines Baumes herauswachsen und Blätter kriegen. So erscheint einem zum Beispiel der altindische Mensch mit der ganzen Erde verbunden und seine Gedanken erscheinen einem hervorgewachsen aus dem irdischen Dasein auf geistige Weise, wie die Blätter, die Blüten eines Baumes einem hervorgewachsen erscheinen aus diesem Baume durch die ganzen Kräfte der Erde.

Das ist gerade dieses Verwachsensein mit der Außenwelt bei dem orientalischen Menschen, dieses Hereinnehmen jener Geistigkeit, von der ich Ihnen gesprochen habe, daß sie jenseits der Sinneswelt ist. Im Westen wird alles herausgeholt aus den Instinkten der Persönlichkeit, aus den Tiefen der Persönlichkeit. Ich möchte sagen, der Stoffwechsel des Menschen, nicht die äußere Welt ist es. Die Welt beim Orientalen wirkt auf die Sinne, wirkt auf den Geist, die in ihm aufleuchten lassen dasjenige, was er seinen heiligen Brahma nennt. Im Westen ist es das, was aus dem Stoffwechsel des Leibes aufsteigt, und was zu Vorstellungsassoziationen führt, was aber besonders taugt, eben das Wirtschaftsleben zu charakterisieren, was erst für das folgende Erdenleben ist. Denn was wir außer dem Kopf an uns tragen, ist ja das, was erst wahr zum Ausdrucke kommt, wie wir ausgeführt haben, in dem nächsten Erdenleben. Diesen Kopf haben wir von unserem vorigen Erdenleben; unsere Gliedmaßen, unseren Stoffwechsel tragen wir in das nächste Erdenleben hinein. Das ist Metamorphose von Erdenleben zu Erdenleben. Daher denkt man im Westen mit dem, was reif wird erst im nächsten Erdenleben. Es ist daher auch gerade dieses Denken des Westens darauf veranlagt, das Post-mortem-Leben ins Auge zu fassen, statt von der Ewigkeit, von der Unsterblichkeit zu sprechen, nicht zu haben das Wort «ungeburtlich», sondern nur zu haben das Wort «Unsterblichkeit». Es ist der Westen, welcher das Leben nach dem Tode als dasjenige hinstellt, wonach der Mensch vor allen Dingen sehen soll. Aber jetzt schon bereitet sich im Westen aus der ganz materialistischen Kultur in dieser Beziehung, ich möchte sagen, Radikales, aber gerade im radikalen Sinne Edles vor. Wer ein wenig sehen kann in die Tiefen desjenigen, was sich da vorbereiten will, der kommt zu einer merkwürdigen Entdeckung. Es wird zwar in der allerinnigsten Weise gestrebt nach dem Postmortem-Leben, nach irgendeiner Unsterblichkeit, also nach einem egoistischen Leben nach dem 'Tode, aber es wird so gestrebt, daß aus diesem Streben etwas Besonderes sich entwickeln wird; während ein großer Teil der Menschheit noch in einer Illusion lebt in diesem Punkte, entwickelt sich sonderbarerweise im Westen etwas ganz Merkwürdiges. Ein großer Teil der europäischen Menschheit hat ja, weil in ihm gewissermaßen einzelnes sich spiegelt von diesem Post-mortem-Leben, das der Westen sich ausbildete, er hat auch dieses Post-mortem-Leben, dieses Hinschauen auf das Leben nach dem Tode besonders ausgebildet. Aber am liebsten möchte dieser Europäer sagen: Ja, es ist mir verheißen von meiner Religion ein Leben nach dem Tode, aber ich brauche hier in diesem nichtigen, in diesem unbefriedigenden Erdenleben, in diesem nur materiellen Leben nichts zu tun, um die Seele unsterblich zu machen. Christus ist gestorben, damit ich unsterblich sei. Ich brauche nicht zu streben nach dieser Unsterblichkeit. Ich bin einmal unsterblich, Christus macht mich unsterblich. Oder dergleichen.

Im Westen bereitet sich etwas anderes vor, insbesondere in Amerika. Da sehen wir aus den verschiedensten, manchmal barocksten und trivialsten religiösen Weltanschauungen etwas aufstreben, was zwar ganz materialistische Formen hat, was aber zusammenhängt mit etwas, was Leben der Zukunft sein wird gerade mit Bezug auf diese Weltanschauung der Unsterblichkeit. Es macht sich geltend gerade in gewissen Sekten Amerikas der Glaube, daß man überhaupt nicht leben kann nach dem Tode, wenn man sich hier in diesem Erdenleben nicht angestrengt hat, wenn man nicht irgend etwas getan hat, wodurch man erwirbt dieses Leben nach dem Tode. Nicht bloß nach dem Muster irdischer Wahrheit ins Ewige verlegtes Richten nach Gut und Böse wird gesehen nach dem Tode, sondern derjenige zerfließt, zerflattert im Weltenall, der sich nicht hier anstrengt, damit er seine seelische Entwickelung eben durch den Tod tragen kann. Was man durch den Tod tragen will, das muß hier entwickelt werden. Und derjenige stirbt auch seelisch diesen zweiten Tod — um dieses Paulinische Wort zu gebrauchen -, der hier nicht dafür sorgt, daß seine Seele unsterblich werde. Das ist etwas, was sich allerdings im Westen als Weltanschauung entwickelt, nicht das langsame passive Dahinleben und Zuwarten, was wird nach dem Tode. Das ist dasjenige, was in gewissen Sekten Amerikas hervortritt. Es wird vielleicht heute noch wenig bemerkt, aber zahlreiche Empfindungen streben danach, dieses Leben hier moralisch und auch sonst so anzuschauen, die Lebensführung so einzurichten, daß man durch das, was man hier tut, etwas hindurchträgt durch die Pforte des Todes.

So hat sich einstmals im Orient entwickelt der besondere Hinblick auf das Leben vor der Geburt. Dadurch ist man in die Lage gekommen, dieses Leben hier als eine Fortsetzung dieses vorgeburtlichen, übersinnlichen Geisteslebens zu betrachten, und es hatte dadurch und nicht durch sich selbst seinen Inhalt. Und es entwickelt sich im Westen heute für die Zukunft etwas, was nicht in einer passiven, gleichgültigen Weise hier leben will und warten, bis man stirbt, weil einem dieses Leben nach dem Tode garantiert ist, sondern es entwickelt sich dasjenige, durch das man weiß: man trägt nichts durch die Pforte des Todes, wenn man hier nicht dafür sorgt, daß man etwas durch die Pforte des Todes trägt durch Aufnahme dessen, was aus demjenigen kommt, was man hat.

So ist das Denken des Westens auf der einen Seite eingestellt auf das wirtschaftliche Gestalten des sozialen Organismus, auf der andern Seite eingestellt darauf, die einseitige Post-mortem-Lehre auszubilden. Daher konnte auch dort der Spiritismus besonders sich entwickeln und von da aus die übrige Welt überfluten, der ja eigentlich nur erfunden worden ist, um den Menschen, die nicht mehr durch irgendwelche innere Entwickelung zu einer Unsterblichkeitsüberzeugung kommen können, eine Art Schein auszustellen, daß man wirklich unsterblich ist. Denn eigentlich wird man Spiritist zumeist aus dem Grunde, damit einem durch irgend etwas ein Schein der Gewißheit ausgestellt ist, man sei nach dem Tode unsterblich.

Zwischen diesen beiden Welten steht drinnen so etwas, wie es in Fichtes Worten liegt: Die äußere Welt ist das versinnlichte Material meiner Pflicht. — Diese Denkweise, ich sagte vorher, eigentlich verstehen sie die Leute heute nicht. Und was heute über Fichte geschrieben wird, das ist eigentlich ebenso, wie wenn der Blinde von der Farbe reden würde. Es ist namentlich in den letzten Jahren ungeheuer viel von dem Fichteschen Satz gesagt und gepredigt worden. Aber das alles war so, daß man sagen möchte: Fichte, der urmitteleuropäische Geist, ist eigentlich von den deutschen Zeitungen, von deutschen Belletristikund Bücherschreibern amerikanisiert worden. Das sind eigentlich amerikanisierte Fichtes, die da einem entgegentreten. Da ist jene Nuance des menschlichen Seelenlebens, welche das mittlere Glied des sozialen Organismus besonders auszubilden hat, dasjenige, welches hervorgeht aus der Beziehung von Mensch zu Mensch. Es wäre ja gut, wenn mancher von Ihnen sich einmal — es ist nicht leicht — vertiefen würde in eine Schrift von Fichte, wo eigentlich so geredet wird, als wenn es überhaupt keine Natur geben würde; es wird zum Beispiel Pflicht und alles deduziert, indem erst bewiesen wird, daß es äußere Menschen auch gibt, in denen das versinnlichte Material der Pflicht zum Dasein kommen kann. Da lebt alles darinnen, ich möchte sagen als Rohmaterial, aus dem sich zusammensetzen muß der Rechts-, der Staatsorganismus im dreigliedrigen sozialen Organismus.

Und worauf beruht im Grunde genommen unser katastrophales Ereignis der letzten Jahre? Es beruht darauf, daß solche Dinge eben nicht lebendig durchschaut, nicht lebendig erfühlt worden sind. In Berlin macht man amerikanische Politik. Das taugt für Amerika sehr gut, just für Berlin taugt es nicht. Daher kam diese Berliner Politik in die Nullität. Denn denken Sie, wenn fortwährend in Berlin oder in Wien amerikanische Politik gemacht wurde, im Grunde genommen hätte man, abgesehen von der Sprache, zu Berlin auch sagen können New York und zu Wien Chikago, es wäre gar nicht so besonders verschieden gewesen. Wenn da — in der Mitte — etwas gemacht wird, was eigentlich durch und durch fremd ist, was in den Westen gehört und da gut am Platze ist, dann kommt dasjenige, was Urelement des Volkstums ist, und straft es Lügen, ohne daß die Menschen es wissen. Und so war es im Grunde genommen in den letzten Jahrzehnten. Das ist das Urphänomen dessen, was sich zugetragen hat, das Urphänomen, das darin besteht, daß man zum Beispiel den Fichteanismus mit Füßen getreten hat und zum Beispiel aus einem Instinkt heraus gelesen hat Ralph Waldo Trine. Eigentlich alle die aristokratischen Politikgigerln haben sich mit Ralph Waldo Trine beschäftigt und daher ihre besondere innere Anregung bezogen, oder irgend etwas anderes. Als die Sache besonders heiß geworden ist, ist es sogar Woodrow Wilson geworden. Und derjenige, der jetzt wiederum Präsident der Deutschen Republik werden möchte, der ist jetzt noch immer so, daß sein Gehirn automatisch abrollt die vierzehn Punkte von Woodrow Wilson. So daß wir erlebt haben, daß in der letzten Zeit im Großherzogtum Baden wieder einmal eine ehemals repräsentative deutsche Persönlichkeit Amerikanismus in die Welt hinausgebrüllt hat. Es ist das beste, unmittelbar anschauliche Beispiel, wie die Dinge eigentlich stehen. Nicht wahr, diese Zusammenhänge, diese urphänomenalen Zusammenhänge, sie muß man tatsächlich durchschauen, wenn man verstehen will, was heute eigentlich geschieht. Wenn man bloß die Zeitung hernimmt, die Reden liest des Prinzen Max von Baden, so herausliest, ohne Zusammenhang, dann ist das heute absolut wertlos, hat gar keinen Wert, ist ein bloßes Kaleidoskop von Worten. Derjenige allein versteht etwas von der Welt, der so etwas hineinstellen kann in den ganzen Weltzusammenhang. Und ehe nicht begriffen wird, daß es notwendig ist, daß man heute Verständnis für die Welt sich zu erobern hat, wenn man mitreden will, eher kann es nicht besser werden. Das charakteristischste Zeichen der Gegenwart ist, daß man glaubt, wenn eine Gesellschaft einen blechösen Satz als allgemeines Programm aufstellt — allgemeine Einigkeit unter allen Rassen, Nationen, Farben und so weiter —, so sei damit etwas getan. Damit ist nichts getan, als der Menschheit Sand in die Augen gestreut. Getan ist erst etwas, wenn man auf die Differenzierungen hinschaut, wenn man erkennt, was in der Welt ist. Die Menschen konnten früher aus ihren Instinkten heraus leben. Das ist ihnen jetzt genommen. Sie müssen lernen, bewußt zu leben. Bewußt leben kann man aber nur, wenn man hineinschaut in das, was wirklich geschieht.

Groß war der Osten in bezug auf die Präexistenz und in bezug auf die damit zusammenhängenden wiederholten Erdenleben. Groß war der Westen in seiner Veranlagung mit Bezug auf das Post-mortem-Leben. Hier in der Mitte (siehe Zeichnung Seite 126) ist die eigentliche, heute aber noch mißverstandene Geschichtskunde entstanden. Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel Hegel. Bei Hegel ist weder eine Präexistenz noch eine Postexistenz. Es gibt weder eine Vorgeburtlichkeit noch eine Nachtodlichkeit, aber es gibt ein geistvolles Erfassen der Geschichte. Hegel beginnt mit der Logik, kommt dann zur Naturphilosophie, entwickelt die Seelenlehre, entwickelt die Staatslehre und endet mit der Dreiheit: Kunst, Religion, Wissenschaft. Das ist der Weltinhalt. Von einer Präexistenz, von einer unsterblichen Seele ist nicht die Rede, sondern nur von dem Geiste, der hier im Diesseits lebt.

Präexistenz — Postexistenz — hier ist das unmittelbare Leben in der menschlichen Gegenwart, das Durchdringen der Geschichte. Lesen Sie sich dasjenige durch, was gerade von Hegel als Geschichtsphilosophie verfaßt worden ist. In den Bibliotheken ist es zumeist so, daß, wenn man aufschlägt, eine Seite noch an der andern klebt, man muß sie erst voneinander lösen. Es sind nicht viele Auflagen erschienen gerade von Hegels Büchern. In den achtziger Jahren hat Eduard von Hartmann geschrieben, daß es im ganzen Deutschland, wo es zwanzig Universitäten gibt mit philosophischen Fakultäten, überhaupt nur zwei Menschen gibt unter den Universitätsdozenten, die Hegel gelesen haben! Unwidersprochen konnte es bleiben, denn es war wahr; trotzdem haben selbstverständlich alle Schüler geschworen auf das, was ihnen ihre, den Hegel nicht gelesen habenden Professoren über Hegel gesagt haben. Aber machen Sie sich mit dem bekannt, so werden Sie sehen, daß da in der Tat Geschichtsauffassung zustande gekommen ist, das Erleben dessen, was sich zwischen Mensch und Mensch abspielt. Da ist auch das Holz, aus dem geschnitzt werden muß das Staats- oder rechtliche Glied des dreigliedrigen sozialen Organismus. Die Konstitution des geistigen Organismus ist zu lernen am Orient, die Konstitution des Wirtschaftlichen ist zu lernen am Westen.

So muß man in die Differenzierung der Menschheit über die Erde hineinschauen, und man kann die Sache von der einen oder von der andern Seite verstehen. Geht man direkt auf das Ziel los, studiert man das soziale Leben, dann kommt man so zur Dreigliederung, wie ich sie in den «Kernpunkten der sozialen Frage» entwickelt habe. Studiert man so das Leben der Menschen über die Erde hin, dann kommt man dazu, sich zu sagen: Es ist etwas da mit besonderer Veranlagung für die Wirtschaft, es ist etwas da mit besonderer Veranlagung für den Staat, es ist etwas da mit besonderer Veranlagung für das geistige Leben. — Hier kann ein dreigliedriges Gebilde geschaffen werden, indem man die eigentliche Wirtschaft nimmt vom Westen, den Staat nimmt von der Mitte, das geistige Leben - selbstverständlich erneuert, das habe ich immer gesagt — vom Osten. Hier hat man den Staat, hier das wirtschaftliche Leben, hier das geistige Leben (siehe Zeichnung); man hat die beiden andern von hier herüberzunehmen. So hat die Menschheit zusammenzuwirken, weil an verschiedenen Orten der Erde die Ursprünge für diese drei Glieder des sozialen Organismus gefunden werden, die deshalb auch überall gehörig auseinandergehalten werden müssen. Und wenn die Menschen vermischen wollen in der alten Weise zum Einheitsstaat dasjenige, was dreigliedrig sein will, so wird doch nichts anderes daraus, als daß eine Einheit im Westen wird, wo das Wirtschaftsleben alles überflutet und alles andere nur in das Wirtschaftsleben eintaucht. Machen dann sich Theoretiker darüber her und studieren das, das heißt, geht Karl Marx von Deutschland nach London, dann studiert er: Alles muß wirtschaftliches Leben sein. - Und wird der Wahnsinn Marxens vollends, dann macht man die drei Glieder nur eingliedrig, aber nur mit dem Charakter der Wirtschaft. Beschränkt man sich auf das, was bloß Staats- oder Rechtsgebilde sein will, so äft! man das Wirtschaftsleben des Westens nach, macht ein Scheingebilde des Wirtschaftslebens durch Jahrzehnte, was dann selbstverständlich zusammenbricht, wenn die Katastrophe kommt, was ja auch geschehen ist!

Der Orient, der das geistige Leben zunächst abgeschwächt hat, nimmt einfach vom Westen herüber das Wirtschaftsleben und impft sich etwas vollständig Fremdes ein. Gerade wenn man diese Dinge studiert, wird man sehen, daß Segen nur über die Erde kommen kann, wenn man überall dasjenige, was sich an verschiedenen Orten durch Natur entwickelt, durch die menschliche Tätigkeit im dreigliedrigen sozialen Organismus zusammenfaßt.

Seventh Lecture