Spiritual Science as a Foundation for Social Forms

GA 199

22 August 1920, Dornach

Lecture VIII

I would like to sum up once more what I said yesterday concerning the differences of the soul constitutions among the various nations and of human beings generally all over the world. I have indicated that various predispositions and soul qualities exist among people in different parts of the earth. Thus, the population of each region on earth can contribute to what all humanity accomplishes in regard to the whole of civilization. Yesterday we had to point out that the Oriental nations and all the people of Asia are especially predisposed by their nature to develop that element which makes its contribution to the spiritual life of the social organism. Oriental people are especially gifted for everything pertaining primarily to the spiritual development in mankind, hence to knowledge and formulation of the super-sensible realm. This is connected with the fact that Oriental people are particularly inclined to develop concepts and ideas on how the human being has descended into this earthly existence from spiritual worlds, in which he has lived since his last death until this birth. The realization or the doctrine of preexistence, which is based on the fact that the human being has undergone a spirit existence before entering into a physical body here, is a principal aspect of these Oriental predispositions. There is therefore also the capability of comprehending repeated earth lives. It is possible for a person to adhere to the view that life goes on after death, continuing on forever without his returning to the earth. It is not logically possible, however, to hold the view that life on earth is a continuation of a spiritual existence without also being obliged to take for granted the thought that this life must repeat itself. Thus, the Oriental was particularly predisposed to understand that he dwelt in spiritual worlds prior to this earth life, that in a sense he received the impulses for this life on earth from the divine spiritual world.

This is connected with the whole way in which the Oriental arrived at his knowledge, his whole soul constitution. I have already indicated this to some of you. Now there are a number of other friends present here, and I would like to characterize something once more that I have already outlined for some of you.

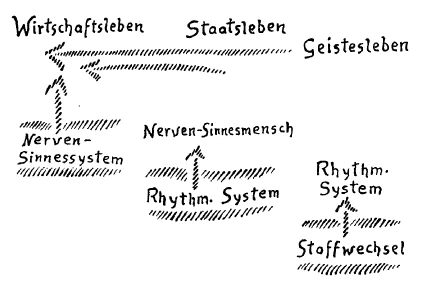

We know that man is a threefold being, that he is divided into the nerves-and-senses man, the rhythmic man—who includes the activities expressed in breathing, blood circulation, and so on—and the third, the metabolic man, everything that has to do with man's metabolism. Now these three members of the human organization do not come to expression in the same manner everywhere on earth; they are expressed in different ways in different parts of the world.

Speaking of the East, all this is in decadence in a sense; it is suppressed and slumbers today in the Oriental human being. We are not concerned now with his present soul condition. Instead, we must become principally acquainted with a soul state that he possessed in a distant past. For the very reason that this soul condition has diminished, Asia humanity is about to adopt Bolshevism with the same religious fervor and devotion with which it formerly received the teaching of the holy Brahman—something that Europeans and Americans will become aware of before very long to their horror. Which of the three members of human nature came to special expression in the Oriental? It was the metabolic man. It was particularly the ancient Oriental who dwelt completely in the metabolism. This will not appear a repulsive view to anyone who does not conceive of substance in terms of lumps of matter, but who knows that spirit lives in all matter. The lofty, admirable spirituality of Orientals was brought about by what rose out of their metabolic process, and radiated into consciousness. What occurs in the human metabolism is, of course, intimately related with what the external sense world is. From the latter, we receive what then turns into matter within us. We know that behind this outer sense world there is spirit. In reality, we consume spirit and the consumed spirit becomes matter first within us. Yet, what we consume in this manner produced spirit in the Oriental even after it had been consumed. Thus, a person who understands these things views the remarkable poetic achievements of the Vedas, the greatness of the Bhagavad Gita, the profound philosophy of the Vedas and Vedanta and the Indian philosophy of Yoga without admiring them any less—because he knows that they have emerged from the inner process as a product of metabolism, just like the blossoms of a tree are the result of its metabolism. Just as we look at the tree and see in its blossoms what the earth pushes toward air and light, so we view what human beings in ancient India produced in the Vedas, in the Vedanta and Yoga philosophies, as a blossom of earthly existence itself. What we see as a product of the earth in tree blossoms is, in a way, offered up to air and light. Nevertheless, it is a product of the earth in the same sense as are wheat and grain growing in the fields, and fruits an trees, which are then cooked, enjoyed and digested by the human being. Within the special nature of the ancient Indian, this—instead of turning into plant blossoms and fruits—became the marvelous formulations of the Vedas, the Vedanta and Yoga philosophies. One who must view the ancient Indian as one would a tree. Both are examples of what the earth is capable of producing in its metabolism—in a tree, through its roots and sap, in man through his nourishment. Thus, one learns to recognize the divine in something that the spiritualist scorns, because he finds matter to be of such a low order.

Moreover, the ancient Indian had an ideal. It was his ideal to go beyond this metabolic experience to the higher member of human nature, namely, the rhythmic system. This is why he did his Yoga exercises, his special breathing exercises, practicing them consciously. What the metabolism brought forth from him as a spiritual blossom of earth evolution came about unconsciously. What he did consciously was to bring his rhythmic system, the system of breathing and blood, into a regulated, systematic movement. What did he do by thus advancing himself, for this was his specific form of advancement. What did he accomplish? What happened in this rhythmic system? We inhale the air from outside; we give to this air something that comes from the human metabolism, namely, carbon. Within us, a metabolic process takes place between something that is a result of our metabolism and something contained in the air that we breathe in. Today's materialistic, physical world-view finds nitrogen and oxygen—ignorant of the true nature of both—mixed together in the air and considers it something purely material. The ancient Indian perceived the air as the process which occurs when the element derived from the metabolism unites in the human being with what is inhaled and is then absorbed. When he fulfilled his ideal inherent in Yoga philosophy, the ancient Indian perceived in the blood circulation the mysteries of the air, that is, what exists spiritually in the air. Through Yoga philosophy he became acquainted with what is spiritual in the air. What does one learn to know there? One comes to recognize what has come into us, insofar as we have become beings that breathe. We learn to perceive what entered into us when we descended from spiritual worlds into this physical body. Knowledge of preexistence, of life before birth, is then cultivated. Therefore, it was in a sense the secret of those who practiced Yoga to penetrate the mystery of life before birth.

We see that the ancient Indian dwelt within his metabolism, notwithstanding the fact that he produced much that was beautiful, grandiose, and powerful, and he artificially raised himself to the rhythmic system. All this has, however, fallen into decadence. Today, all this sleeps in Asia. It only makes itself felt nebulously in abstract forms in asiatic souls when enlightened spirits, such as Rabindranath Tagore, speak of and revel in the ideal of the Asians.

Going from Asia to Central Europe, we find that the European, provided that he really is one, can be characterized as in Fichte's statement which I pointed out to you yesterday: “The external material world is the substance of my duty become visible; on its own, it has no existence. It is there only so that I might have something with which to fulfill my duty.” The human being who lived and lives in the central regions of the earth on this basis, dwells in the rhythmic system, just as the ancient Indian lived in the metabolic system. One remains unconscious of the element in which one lives. The Indian still strove upward to the rhythmic system as to an ideal, and he became aware of it. The Central European lives in the rhythmic system and is not conscious of it. Dwelling in this way in the rhythmic system, he brings about all that belongs to the legal, democratic governmental element in the social organization. He forms it in a one-sided way, but he forms it in the sense I indicated yesterday, because he is especially talented in shaping matters dealing with relationships between people, and between a person and his environment. Yet he, in turn, also has an ideal. He has the ideal to rise to the next level, to the man of nerves and senses. Just as the Indian considered Yoga philosophy to be his ideal, the artistic breathing that leads to insight in a special manner, so the Central European considers it his ideal to lift himself up to conceptions that come from the being of nerves and senses, to conceptions that are pure ideas, attained through an inner elevation, just as the Indian by advancing himself attained to the Yoga philosophy.

Therefore, it is necessary to realize that if one really wishes to understand individuals who have worked from such a basis as did Fichte, Hegel, Schelling and Goethe, one must understand them in the same way an Indian understood his Yoga initiates. This special soul disposition, however, tones down the real spirituality. One still gets a clear awareness of it, for instance, in the way Hegel takes ideas as realities. Hegel, Fichte and Goethe possessed this clear awareness that ideas are truths, realities. One even comes to something like Fichte says: “The external sense world has no existence of its own; it is only the visible substance of my duty.” But one does not reach the fulfillment of ideas which the Oriental had. One can reach the point of saying, as did Hegel: “History begins, history lives. That is the living movement of ideas.” Yet one limits oneself only to this external reality. One views this external reality as spirit, as idea. Yet, particularly if one is in Hegel's place, one can speak neither of immortality nor of unbornness. Hegelean philosophy begins with logic; this means that it starts with what the human being thinks of as finite; then it extends over a certain philosophy of nature. It has a psychology, however, that deals only with the earthly soul. It also has a theory of government. Finally, it rises to its highest point when it reaches the threefold aspect of art, science and religion. Yet it goes no further; it does not enter into the spiritual worlds. In the most spiritual way, men like Hegel and Fichte have described what exists in the external world; but anything that would look beyond the outer world is suppressed. Thus we see that the very element that has no counterpart in the spiritual world, namely, the life of rights, of the state, something that is entirely of this world, makes up the greatness of the thought structures that appear here. One looks at the external world as spirit but is unable to go beyond it. Yet, in the process one trains the mind, teaching it a certain discipline. Then, if one values a certain inner development, this can be accomplished, because, by schooling oneself through what can be achieved in this area by occupying the mind with the realm of ideas, one is in a sense inwardly propelled into the spiritual world. This is indeed remarkable.

I must admit to you that whenever I read writings by the Scholastics, they evoke a feeling in me that induces me to say that they can think; they know how to live in thoughts. In a certain other way, directed more to the earthly sphere, I have to say the same of Hegel, Fichte or Schelling. They know how to live in thoughts. Even in the decadent way in which Scholasticism appears in Neo-Scholasticism, I find a much more developed life of thought than is found, for example, in modern science, popular books, or journalism. There, all thinking has already evaporated and disappeared. It is simply true that the better Scholastic minds, in the present time, for example, think in more precise concepts than do our university professors of philosophy. It is somewhat surprising that when one allows these thoughts to work upon oneself, for example, when reading a Scholastic book, even a truly Scholastic-Catholic text, and allows it to affect one, using it in a sense as a kind of self-education, one's soul is driven beyond itself. Such a book works like a meditation. Through its effect, one arrives at something different that brings about enlightenment. Here, we confront a very strange fact.

Consider that if such modern Dominicans, Jesuits and priests of other orders, who immerse themselves in what remains of Scholasticism, would permit the educational effect of Scholastic thought forms to work upon them all the way, they would all come through this discipline in a relatively easy manner to a comprehension of spiritual science. If one would allow those who study Neo-Scholasticism to follow their own soul development, it would not be long before those priests of Catholic orders in particular would become adherents of spiritual science. What had to be done so that this would not happen? They were given a dogma that curtails such study, and does not allow what would develop out of the soul to come about. Even today, someone wishing to develop towards spiritual science could be given as a meditation text the Scholastic book written by a contemporary Jesuit that I once showed here.65Reference to Alfons Lehmen, SJ: 1847–1910, and his book Lehrbuch der Philosophie auf aristotelisch-scholastischer Grundlage, Vol. I, Freiburg i. Br., 1917. Compare with this the lecture of July 10, 1920, reprinted in “Blaetter fuer Anthroposophie,” September, 1953. Not translated. Yet, as I told you, it bears the imprimatur of a certain archbishop. The enlightenment that would occur in a person, if he were completely free to devote himself to it, has been cut off.

We must be able to see through these things. For then we will realize how important it is for certain circles to prevent by all means the consequences of what would develop if free reign were given the effects of these matters in the souls. The Central European striving is, after all, aimed at lifting oneself out of the rhythmic man, where one dwells as a matter of fact, to the nerves-and-senses man, who possesses what he attains for himself in the ideal sphere. For these people, there is a special predisposition to understand earthly life as something spiritual. Hegel did this in the most all-encompassing sense.

Let us now go to Western man. Yesterday, I said that Western man, particularly as exemplified by the most brilliant minds as early as Bacon and others, followed by Bentham, John Stuart Mill, Spencer, Buckle, Thomas Reid, and the economist Adam Smith, has a special predisposition to develop the kind of thinking which can then be utilized in the economic part of the social organism.

If we consider Spencer's philosophy, for instance, we realize that this is a kind of thinking which stems completely from the nerves-and-senses man, that in all respects it is a product of the senses and nerves. It would be most appropriate for creating industrial organizations and associations. It is only out of place.when employed by Spencer for philosophy. If he had used this same thinking to set up factories and social organizations, it would have been applied in its rightful place. It was out of place when he used it for philosophy.

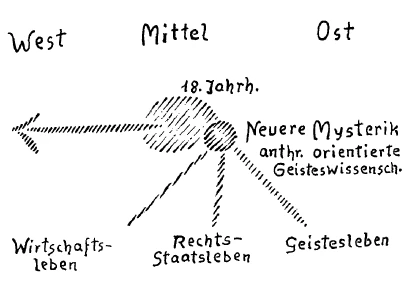

This comes from the fact that Western man no longer lives in the rhythmic system, but has taken a step upward, living as a matter of course in the human nerves-and-senses system. It is the nature of the Oriental to live in his metabolic system. It is the Central European's nature to live in the rhythmic system. It is Western man's nature to live in the nerves-and-senses system (see drawing). The Oriental lives in the metabolism; he strives upward, trying to attain to the rhythmic system. The Central European lives in the rhythmic system. He strives towards the nerves-and-senses system. Western man already lives in the latter. Where does he wish to ascend? He is not yet there, but he has the impulse to strive upwards beyond himself. It appears at first in a caricatured form, which I characterized for you yesterday as the denial of matter and the autosuggestion of the human being in Mrs. Eddy's Christian Science. Despite the fact that this is as yet a caricature, it is nevertheless a forerunner of what Western man must aim for. The aim must be something superhuman, by which I do not mean to imply that anyone who, instead of striving beyond the nerve-sense system, strives down into unconsciousness, and such as that, would thereby become superhuman.

Yesterday, I concluded by saying that it is in this way that the human faculties are distributed over the world's various regions, and it is necessary for real cooperation to come about. We are in a position today where, in regard to civilization, we are completely dependent on the nerves-and senses being of the West. I made use of a paradox, but this paradox quite clearly expresses the reality of the situation. The thoughts in Vienna and in Berlin are not the thoughts that arose from the folk spirit and then culminated in Fichte or Hegel. The spirits of Fichte and Hegel have been buried. What is written today in books and newspapers in Central Europe, in Vienna or Berlin, are not Fichte's thought forms; it is a lie when people quote Fichte today. Rather, the truth is that what reaches the public in Berlin or Vienna today is more closely related to what is being thought in Chicago or New York than to what was thought by Fichte or Hegel.

What had to happen, however, was that these three members, of which this one (in the East) was, to begin with, especially predisposed to the spiritual life, brought across the spiritual life as a tradition of its original, elementary form once existing in the Orient. There in the East the human being lived as fully within the life of the spirit itself as today he is firmly anchored here in Europe in physical life. Only the shadowy reflection of this spiritual life is found in Central Europe, and only its tradition in Western Europe. Western Europe is characterized by its own predisposition to the postmortem life, the life which is envisioned after death. I told you yesterday that in America an awareness is already in the process of developing, if only in a few sects, that man must not merely be passive about his soul life here on earth if he is to carry something through death and live on in spiritual worlds. He must acquire here through his work and actions what he wishes to carry through the gate of death. The awareness exists that the human being disintegrates if he does not provide for his immortality here, if, on earth, he does not develop a sense for ideals. This is already emerging in some Western sects, even though this ideal still appears in a distorted form.

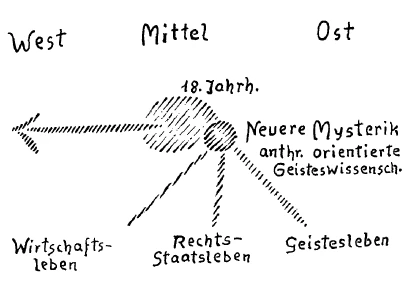

That which is the life of the state on the other hand was striven for by what existed in the rhythmic system and could be borne upward into thoughts. This has come into evidence especially in the man of the middle (the Central European). From there, it affected the West. We are dealing with an odd phenomenon here that is only understood when one looks at its inner aspect. Strange as it may seem, something was astir in Central Europe. It goes without saying that in the rhythmic system the inclination remained for a communal human life, for a social life together in freedom. This impulse remained, to start with, deep in the unconscious realm (see drawing below). It is true, however, that impulses are present among human beings even if people are not conscious of them. Let us say, therefore, that something definite lived, to begin with unconsciously, in Central Europe in the eighteenth century; it could not rise into consciousness, but its effects were transmitted to the West. Having been received there, but not having developed inwardly as a matter of course, it turned into passion and feeling, thus into the French Revolution.

Schiller had thoughts on this. Here (referring to the drawing on page 12), we have the French Revolution. There is even a symbolic event attesting to the fact that Schiller pondered on what actually happened there. You know that he had the honor of being made a French citizen. He therefore pondered on it all, but to begin with, it all lived in his rhythmic system. Then, through his own insight, he lifted it up into consciousness and wrote his letters concerning the aesthetic education of man.

You find in these letters what one could say at that time about people living together in a truly free state. Hume then merely took this concept of the state, which Schiller had lifted up into consciousness in his Aesthetic Letters, and somewhat pedantically fashioned it into a system. There is something extraordinarily important in what Schiller brought out from the depths of the folk spirit in these letters on aesthetic education. Because it was something so profound, it was subsequently not comprehended when the element of the nerves-and-senses man became dominant everywhere.

I have often referred to a lonely man, living in Vienna, by the name of Heinrich Deinhardt.66Heinrich Marianus Deinhardt: 1821–1879, “Beitraege zur Wuerdigung Schillers. Briefe ueber die aesthetische Erziehung des Menschen.” Published by G. Wachsmuth, Stuttgart, 1922. Heinrich Marianus Deinhardt: 1821–1879, “Beitraege zur Wuerdigung Schillers. Briefe ueber die aesthetische Erziehung des Menschen.” Published by G. Wachsmuth, Stuttgart, 1922. He wrote letters upon letters about this aesthetic education of the human being, most ingenious letters. This man had the misfortune of breaking a leg as the result of a fall in the street. The leg was set, but, being undernourished, Deinhardt could not recover and died from breaking a bone. That is to say, he who already in the second half of the nineteenth century had so conscientiously interpreted Schiller's Aesthetic Letters died of malnutrition. And Deinhardt's letters on Schiller's aesthetic education of man are completely forgotten!

Again, these Aesthetic Letters by Schiller would be a good preparation for purifying and uplifting the soul so as to gain a spiritual view of the world. Schiller himself was not yet able to do this. It is always effective, however, if another person engaged in soul development takes up something originating from the one who as yet does not reach up into the spiritual world. It then has the effect of letting him see into the spiritual world. To be sure, people in Europe have revered as special remedies for the soul Ralph Waldo Trine, Marden67Orison Swett Marden: 1850–1924, American author. and similar superficial minds instead of Schiller, forgetting the other views that would actually lead upward into the spiritual world.

It is indeed necessary that these matters be grasped and comprehended in the whole context of life and world conditions. People have to realize how differentiated human capabilities are all over the earth. And the following must be pointed out. Up to now, no effort has been spared to publicize Schiller's riotous early works, The Robbers, Fiesco, or Intrigue and Love. People become most enthusiastic about the sentimentalities of Mary Stuart, the very profitable dramatic scenes of Maid of Orleans or the Bride of Messina. Today, Schiller's Aesthetic Letters, in which he surpasses himself in significance for all humanity—his Robbers, the whole of Mary Stuart and Wallenstein notwithstanding should not only be taken up and studied, one should allow them to affect one. For today, it is up to us not just to indulge in the empty talk of philistine academics existing in regard to our classical writers such as Goethe and Schiller, but above all else to take our own stand and on our own to discover what was great about them. We go on repeating what philistine academia has said for over a century about Wallenstein, Mary Stuart, and so forth. Our task today is to grasp such greatness ourselves in a fundamental way, for only then can humanity progress. So, here too, we discover the necessity for a transformation, a renewal. Even what people in our schools read and hear about Mary Stuart, Wallenstein, The Robbers, and so forth, must be revised. In this critical age we need a complete renewal, for the times are critical indeed.

If we look over to the West, we see that with all that it can produce as the expression of mankind through the nerves-and-senses system, this West is asking for the ascent into what lies beyond human knowledge in the spiritual world. I told you yesterday that in order for the cultural life, the life of the state and the economic life to be able to assert themselves in the threefold social organism, they must work together. These three elements must work together. Let us not merely say, “Ex Oriente lux!” We can turn to the Orient, study the Bhagavad Gita, Yoga philosophy and the Vedas; we can grind away at these subjects just as we have become accustomed to grind away at others in Europe. We can start grinding away at Oriental philosophy after the other subjects have become boring to us. But we shall make no progress this way, for what was once right for the earth will not again be appropriate for the present and Future; it will remain something of the past. We can admire it as something that was once right for the earth; we cannot, however, simply adopt it again in a passive manner as does the Theosophical Society, for instance. Likewise, we cannot just carry over what has been handed down to us of the European past in the old tradition. We cannot say that what is contained in the national characteristics of the Orient, of Middle Europe, can simply be renewed by us. Rather, we must ask, if we wish to achieve a realistic union of these three elements that are inherent dispositions of human nature, how can we do that? We can only do it when we realize in what way the nerves-and-senses life, which has, after all, taken hold of all of us, must pass beyond itself. It means that we must rise to something different that can come neither from the East, the Middle nor the West. It can only come through the new initiation, through the new spiritual science. It is brought about by our ascending from the most current form of thinking, trained by natural science and the nerves-and-senses being, to the science of the new initiation; acquiring from this new initiation the ways and means for bringing about cooperation between what was once the nature of the ancient Orient, later that of the Middle and now that of the West. We need a new science of initiation that can bring about a unity of these three, a living unity. In this modern age, we will not arrive at a cultural life if we do not strive for this new initiation science. We will have no proper politics, no life of the state, if we just continue in the same old way, if we do not turn to those scientific branches born of the new initiation and inquire how the politics of the future must be shaped. Neither will we achieve a new economic life, if we do not understand that form of thinking which should be applied neither to philosophy as did Spencer, nor to the life of the state as did Adam Smith, but only to the organization of the economic life. Then, however, we must also know how to integrate the latter into the two other systems. For that we need the science of initiation. We cannot progress if we cannot say to ourselves: From a comprehension of what was once the Oriental disposition, we come to the essence of the cultural, the spiritual life. By truly comprehending the disposition of the human being of the Middle, we reach the point of really understanding the nature of the life of rights, of the state. By understanding the Western nature, we gain a comprehension of what the economic life is. The three fall apart, however, if we cannot unite them in a higher unity. And we can only accomplish that when we view the three from the perspective resulting for us from the new Mysteries, which are here called the anthroposophically oriented spiritual science.

These matters must be understood, for whoever has insight into them knows that all the aspirations coming to expression today are leading towards ruin. People simply do not reckon with the most important factors. Take the most radical socialists. Subjectively they may have honorable intentions for humanity, but they only count an forces of decline. They strike a wrong balance of life. We only take stock the right way when, out of spiritual science, we do not just grasp at anything arbitrarily put there, saying that this is the way it must be if humanity is to be happy, but when we ask ourselves: What will come into being when the cultural life, the life of rights and the economic life are brought into the right relationship with each other; what kind of social organism results from that? Then, such a social body will also contain its permeation with spirit. This implies the presence of a realistic economic life, not one that people dream and fantasize about, but one that can originate as the best possible one. Again, its political system will be the best possible; a cultural life will be present that will unite the prenatal life with that after death. Such a cultural life will see in the human being, dwelling here in this physical world, a being orienting himself according to his rights; a being into whom, in the cultural sphere, shines his prenatal life; a being who in the economic life cannot attain to an ideal, only to the best possible one, yet is able through initiation science in his will to transform the faculties active in the economic sphere so that they allow the life after death to shine forth. Because this is the case, anthroposophically oriented spiritual science is not just one theory among many, not something that takes its place as a party or sectarian program alongside others. Anthroposophy is something that is brought forth out of the knowledge that can be acquired when garth's and mankind's evolution are comprehended in their working together and in their totality.

In the present time, we have to admit that any other relationship to the world or to temporal reforms will lead to nothing, for what can bring progress to mankind must emerge out of the new initiation science.

Today, this must be expressed again and again in many different ways. It has been incorporated into this building; it is expressed in all the details of this structure. Looking even at its smallest segment, it can tell you about what is intended here, what is expressed in words in a variety of ways. This is what gives the whole matter here a certain uniform character. At the same time, a will comes to expression here that is intimately connected with the forces of ascent, not the declining forces of evolving humanity, something one could wish people would understand. This is what we should like to work for more and more. This is what we now wish to aim for by means of the courses68Reference to the first Course of the School of Spiritual Science at the Goetheanum from September 26 until October 16, 1920. that will be given here this fall, in which we intend to show that the knowledge derived from anthroposophically oriented spiritual science can work in a truly fructifying manner into the individual branches of science. Then, the day will perhaps come when people will understand what is really intended here, when sufficient comprehension will exist in the world so that we can reach the point at some future date when this building, still enshrouded in mist, can be opened up. For, as long as this building cannot be opened up, there still exists something that shows a lack of understanding for what is intended here.

I shall continue with this next Friday at eight o'clock.

At eight tomorrow, our friend, Count Polzer,69Ludwig Graf von Polzer-Hoditz: 1869–1945; his lecture was later published under the title, “Der Kampf gegen den Geist und das Testament Peters des Grossen,” Stuttgart, 1922. will lecture on European politics of the last century in connection with the testament of Peter the Great. This is an interesting subject about which, hopefully, a discussion will ensue. On Friday, I shall continue with the questions, already presented, and their application to the individual human being. On Saturday, at eight o'clock, I will continue with those particular questions that relate to religious problems. Sunday at six-thirty will be the next eurythmy performance, followed by a lecture.

Achter Vortrag

Ich möchte noch einmal den Extrakt desjenigen geben, was ich gestern ausgeführt habe über die Differenzierung der Seelenanlagen der Völker, der Menschen überhaupt über die Erde hin. Ich habe angedeutet, wie verschiedene Anlagen und verschiedene Arten von Seelenverfassung in den verschiedensten Gegenden der Erde bei den Menschen vorhanden sind, so daß in der Tat ein jedes Erdengebiet durch seine Völkerschaft ein Bestimmtes beitragen kann zu dem, was die gesamte Menschheit leistet mit Bezug auf die gesamte Erdenzivilisation. Wir haben darauf aufmerksam machen müssen gestern, wie die orientalischen Völker, die Völker Asiens und dasjenige, was zu ihnen gehört, vorzugsweise dazu veranlagt sind, dasjenige Element auszubilden, welches seinen Beitrag gibt in das geistige Glied der sozialen Organisation. Alles dasjenige, was vorzugsweise in der Menschheit geistige Entwickelung ist, also Wissen des Übersinnlichen, Gestalten des Übersinnlichen, dazu ist die orientalische Bevölkerung besonders veranlagt. Damit hängt es zusammen, daß diese orientalische Bevölkerung besonders dazu veranlagt ist, sich Vorstellungen, Ideen darüber zu machen, wie der Mensch aus geistigen Welten, die er durchlebt hat zwischen dem letzten Tode und dieser Geburt, heruntergestiegen ist in dieses irdische Dasein. Die Präexistenzlehre, jene Lehre, welche sich gewiß ist darüber, daß der Mensch ein geistiges Dasein durchgemacht hat, bevor er hier in den physischen Leib gekommen ist, das einzusehen, das liegt insbesondere in diesen orientalischen Anlagen. Daher auch die Anlage dazu, die Einsicht in die wiederholten Erdenleben zu haben. Man kann die Anschauung haben, daß das Leben nach dem Tode fortdauert, immer fortdauert, ohne daß man wiederkehrt auf die Erde. Aber man kann logischerweise nicht die Anschauung haben, daß das Leben hier auf der Erde eine Fortsetzung eines geistigen ist, ohne daran denken zu müssen, daß ja dann es selbstverständlich ist, daß dieses Leben sich wiederholen muß. So also war der Orientale ganz besonders dazu veranlagt, einzusehen, er habe gelebt in geistigen Welten vor diesem Erdenleben, und er habe gewissermaßen die Impulse, die Antriebe zu diesem Erdenleben erhalten eben aus der göttlich-geistigen Welt heraus.

Es hängt das zusammen mit der ganzen Art und Weise, wie der Orientale zu seinem Wissen, zu seiner ganzen Seelenverfassung gekommen ist. Für einige von Ihnen habe ich das schon angedeutet; es sind jetzt eine andere Anzahl von Freunden da, und ich möchte etwas noch einmal charakterisieren, das ich für einige schon charakterisiert habe.

Wir wissen, daß der Mensch ein dreigliedriges Wesen ist, daß er zerfällt in den Nerven-Sinnesmenschen, in den rhythmischen Menschen — der umfaßt jene Tätigkeiten, die in der Atmung, in der Blutzirkulation und so weiter gegeben sind -, und daß dann das dritte im Menschen der Stoffwechselmensch ist, alles dasjenige, was mit dem Stoffwechsel zusammenhängt. Nun kommen nicht über die ganze Erde hin etwa in gleichmäßiger Weise diese drei Glieder der menschlichen Organisation zum Ausdruck, sondern in verschiedener Weise.

Der orientalische Mensch ist heute daran — jetzt ist das alles, ich möchte sagen, in der Dekadenz, heute ist das alles unterdrückt, heute schläft das im orientalischen Menschen, aber wir müssen den orientalischen Menschen auch nicht kennenlernen nach seiner jetzigen Seelenverfassung, sondern wir müssen ihn vorzugsweise kennenlernen nach seiner Seelenverfassung, die er in einer sehr weit zurückliegenden Vorzeit gehabt hat -, der orientalische Mensch ist heute daran, gerade weil diese Seelenverfassung zurückgegangen ist, und die Europäer und Amerikaner werden das in nicht zu ferner Zeit zu ihrem großen Schrecken bemerken, mit derselben Inbrunst, mit derselben religiösen Hingebung den Bolschewismus aufzunehmen, wie er einstmals aufgenommen hat die Lehre von dem heiligen Brahman. Was ist von den drei Gliedern der menschlichen Natur dasjenige, das im orientalischen Menschen ganz besonders zum Ausdruck gekommen ist? Es ist der Stoffwechselmensch. Gerade der älteste Orientale hat ganz im Stoffwechsel gelebt. Das wird für denjenigen in der Auffassung keinen Horror hervorrufen, der den Stoff nicht denkt im Sinne von Klumpen von Materie, sondern der weiß, daß in allem Stoff Geist lebt. Und dasjenige, was gerade der hohe Geist, der bewunderungswürdige Geist der Orientalen war, das war dasjenige, was aus dem Stoffwechsel der orientalischen Natur aufgestiegen ist und ins Bewußtsein hineingeglänzt hat. Dasjenige, was sich im menschlichen Stoffwechsel abspielt, hängt ja innig zusammen mit dem, wie die äußere Sinneswelt ist. Wir entnehmen dasjenige, was dann in uns Materie wird, der äußeren Sinneswelt. Wir wissen, daß hinter dieser äußeren Sinneswelt Geist ist. In Wahrheit essen wir Geist, und der gegessene Geist wird erst in uns Materie. Aber dasjenige, was wir da aufnehmen, das war beim Orientalen so, daß es auch, nachdem es aufgenommen wurde, den Geist hergab. So daß derjenige, der die Dinge versteht, hinsieht auf die bewunderungswürdigen poetischen Leistungen der Veden, auf die Großartigkeit der Bhagavad Gita, auf die tiefe Philosophie der Veden und Vedanta, auf die indische Jogaphilosophie, und er wird sie deshalb nicht weniger bewundern, weil er weiß, daß das aus dem inneren Prozeß hervorgegangen ist als ein Produkt des Stoffwechsels, wie die Blüten des Baumes hervorgehen aus dem Stoffwechsel. Und wie wir den Baum anschauen und in seinen Blüten sehen dasjenige, was die Erde der Luft und dem Licht entgegentreibt, so sehen wir in dem, was der alte indische Mensch hervorgebracht hat in den Veden, in der Vedanta-, in der Jogaphilosophie, eine Blüte des irdischen Daseins selber. Es ist gewissermaßen auf der einen Seite dasjenige, was wir in den Blüten der Bäume sehen, Produkt der Erde, entgegengebracht der Luft und dem Lichte, aber Produkt der Erde, das heißt desjenigen, was auf dem Felde wächst als Weizen und Korn, auf den Bäumen als Obst und Früchte, genossen und verdaut von Menschen, verkocht von Menschen. In der besonderen alten indischen Natur wird es, statt zu Pflanzenblüten und Pflanzenfrüchten, zu den herrlichen Ausgestaltungen der Veden, der Vedanta- der Jogaphilosophie, man sieht diesen alten indischen Menschen an so wie einen Baum, als Zeugen desjenigen, was die Erde in ihrem Stoffwechsel aus sich selber hervorsprießen lassen kann, indem sie in den Menschen hineinschießt — beim Baum durch die Wurzeln und durch den Saftstrom, beim Menschen durch die Nahrung -, und man lernt erkennen das Göttliche in demjenigen, wo es der Spiritualist verachtet, indem ihm die Materie so niedrig vorkommt.

Und dann hat der alte Inder ein Ideal. Er hat das Ideal, aus diesem seinem Erleben in dem Stoffwechsel herauszukommen zu dem höheren Glied der Menschennatur, zu dem rhythmischen System. Daher machte er seine Jogaübungen. Er machte besondere Atemübungen. Das übte er mit Bewußtsein. Dasjenige, was der Stoffwechsel aus ihm hervorbringt als geistige Blüte der Erdenentwickelung, das kommt unbewußt. Dasjenige, was er bewußt macht, ist: sein rhythmisches System, das Atmungs- und Blutsystem, in eine geregelte, in eine systematisierte Bewegung zu bringen. Und was tut er, indem er sich erhebt, indem das gerade dasjenige ist, was seine Erhebung ist, was tut er da? In diesem rhythmischen System, was geschieht da? Wir atmen die äußere Luft ein, wir übergeben der äußeren Luft dasjenige, was aus des Menschen Stoffwechsel entsteht, Kohlenstoff. In uns findet ein Stoffwechsel statt zwischen dem, was in uns Ergebnis des Stoffwechsels ist, und demjenigen, was in der Luft ist, die wir aufnehmen. Die heutige materialistischphysikalische Weltanschauung sieht in der Luft Stickstoff — weiß nicht, was das ist — und Sauerstoff — weiß nicht, was das ist — miteinander gemischt, sieht etwas rein Materielles. Der alte Inder nahm wahr die Luft, das heißt dasjenige, was da vorgeht, indem sich im Menschen verbindet dasjenige, was aus dem Stoffwechsel kommt, mit dem, was eingeatmet wird, was sich verarbeitet. In der Blutzirkulation nahm der alte Inder dann, indem er sein Ideal, die Jogaphilosophie, erfüllte, wahr durch diesen Stoffwechsel die Geheimnisse der Luft, das heißt dasjenige, was geistig in der Luft ist. Er lernte kennen in der Jogaphilosophie dasjenige, was geistig in der Luft ist. Was lernt man da kennen? Da lernt man eben gerade kennen dasjenige, was in uns eingezogen ist, indem wir atmende Wesen geworden sind. Da lernt man erkennen dasjenige, was in uns eingezogen ist, als wir heruntergegangen sind aus den geistigen Welten in diesen physischen Leib. Da pflegt man dieses Wissen von der Präexistenz, von dem vorgeburtlichen Leben. Daher ist es in einem gewissen Sinne das Geheimnis derjenigen zunächst, die solche Jogaphilosophie ausführen, hinter das Geheimnis des vorgeburtlichen Lebens zu kommen.

So sehen wir, daß der alte Inder im Stoffwechsel lebt, trotzdem er so Schönes, Großartiges, Gewaltiges hervorbringt, und sich künstlich hinaufschwingt zum rhythmischen System. Das alles ist in die Dekadenz gekommen. Das alles ist heute in Asien schlafend. In den asiatischen Seelen macht sich nur nebulos geltend in abstrakten Formen, wenn solche erleuchtete Geister wie Rabindranath Tagore von dem Ideal der Asiaten sprechen und schwelgen.

Und gehen wir von diesem Asien zu Mitteleuropa, da finden wir, daß sich dieser mitteleuropäische Mensch da, wo er wirklich ein solcher ist — ich habe ihn gestern dadurch charakterisiert, daß ich Sie hinwies auf Fichtes Satz: Die äußere Sinneswelt ist nur das versinnlichte Material meiner Pflicht, sie hat an sich keine Existenz, sie ist dazu da, damit ich etwas habe, womit ich meine Pflicht ausführen kann. —- Der Mensch, der aus diesem Untergrunde in den mittleren Gegenden der Erde lebte und lebt, der lebt nun, geradeso wie der Inder im Stoffwechsel lebt, im rhythmischen System. Dasjenige, worinnen man lebt, bleibt unbewußt. Der Inder strebte noch als zu einem Ideal zum rhythmischen System hinauf, und ihm wurde es bewußt. Der Mitteleuropäer lebt in diesem rhythmischen System, ihm wird es nicht bewußt, und er gestaltet aus dadurch, daß er in diesem rhythmischen System lebt, alles dasjenige, was das rechtliche, das demokratische, das staatliche Element in der sozialen Organisation ist. Er gestaltet es einseitig aus, aber er gestaltet es in dem Sinne aus, wie ich das gestern angedeutet habe, denn er ist besonders dazu veranlagt, dasjenige auszugestalten, was im Wechselspiel geschieht zwischen Mensch und Mensch, im Wechselspiel zwischen dem Menschen und seiner Umgebung. Aber er hat wiederum ein Ideal. Er hat das Ideal, sich nun zum nächsten zu erheben, zu dem Nerven-Sinnesmenschen. So wie der Inder die Jogaphilosophie, das kunstvolle Atmen, das zur Erkenntnis auf besondere Art führt, als sein Ideal betrachtete, so der mitteleuropäische Mensch das Sich-hinauf-Schwingen zu Vorstellungen, die aus dem Nerven-Sinnesmenschen kommen, zu Vorstellungen, die ideell sind, zu Vorstellungen, die errungen werden durch eine Erhebung, so wie die Jogaphilosophie errungen wird von dem Inder durch eine Erhebung.

Daher ist es auch notwendig, daß man sich bewußt werde, will man Leute, die aus solchen Untergründen heraus geschaffen haben, wie Fichte, Hegel, Schelling, wie Goethe, will man sie wirklich verstehen, so muß man sie so verstehen, wie der Inder seine Jogaeingeweihten verstand. Aber diese besondere Seelenveranlagung, die dämpft die eigentliche Geistigkeit. Man erlangt noch ein deutliches Bewußtsein davon, wie es zum Beispiel Hegel hat, daß die Ideen Wirklichkeiten sind. Dieses deutliche Bewußtsein hatte Hegel, Fichte, hatte Goethe, daß die Ideen Wirklichkeiten, Realitäten sind. Man gelangt eben auch dazu, so etwas zu sagen wie Fichte: Die äußere Sinneswelt ist für sich keine Existenz, sondern nur das versinnlichte Material meiner Pflicht. - Aber man kommt nicht zu jener Erfüllung der Ideen, welche der Orientale hatte. Man kommt dazu, zu sagen, wie Hegel sagte: Es beginnt die Geschichte, es lebt die Geschichte. Das ist die lebendige Bewegung der Ideen. — Aber man beschränkt sich allein auf diese äußere Wirklichkeit. Diese äußere Wirklichkeit sieht man geistig, ideell an. Aber man kann nicht, gerade wenn man Hegel ist, weder von Unsterblichkeit noch von Ungeburtlichkeit reden. Die Hegelsche Philosophie beginnt mit der Logik, das heißt mit demjenigen, was der Mensch endlich denkt, dehnt sich aus über eine gewisse Naturphilosophie, hat eine Seelenlehre, die aber nur von der irdischen Seele handelt, hat eine Staatslehre und hat zuletzt als das Höchste, zu dem sie sich aufschwingt, die Dreigliederung von Kunst, Religion, Wissenschaft. Aber darüber geht es nicht hinaus, da geht es nicht in die geistigen Welten hinein. Auf geistigste Art hat solch ein Mensch wie Hegel oder Fichte beschrieben dasjenige, was in der äußeren Welt ist; aber gedämpft ist alles dasjenige, was hinausschaut über die äußere Welt. Und so sehen wir, daß gerade dasjenige, was kein Gegenbild in der geistigen Welt hat, das Rechtsleben, das Staatsleben, was nur von dieser Welt ist, daß das gerade die Größe ausmacht dieser Ideengebäude, die da auftreten. Man sieht die äußere Welt als geistig an. Man kommt aber nicht über diese äußere Welt hinaus. Aber man schult den Geist, man bringt dem Geist eine gewisse Disziplin bei. Und legt man dann Wert auf eine gewisse innere Entwickelung, so findet das statt, daß dadurch gerade, wenn man sich heranschult an dem, was da in diesem Gebiete der Welt an Erziehung des Geistes durch die Ideenwelt geleistet werden kann, man gewissermaßen innerlich hinaufgetrieben wird in die geistige Welt. Das ist ja das Merkwürdige.

Ich muß Ihnen gestehen, mir ist, wenn ich Schriften der Scholastiker lese, immer bei diesen Schriften der Scholastiker so zumute, daß ich mir sage: Das kann denken, das weiß zu leben in Gedanken. — Auf eine gewisse andere Art, mehr dem Irdischen zugewandt, sage ich mir das auch bei Hegel: Der weiß zu leben in Gedanken - oder bei Fichte oder bei Schelling. Selbst in der dekadenten Art, wie die Scholastik in der Neuscholastik zutage tritt, muß ich sagen, finde ich in der Scholastik immer noch mehr von entwickeltem Gedankenleben als zum Beispiel in der modernen Wissenschaft oder in der modernen populären Bücher- oder Zeitungsliteratur. Da ist schon alles Denken verdunstet und verduftet. Es ist schon wahr, die besseren Geister der Scholastik, in der Gegenwart zum Beispiel, denken Begriffe genauer als unsere Universitätsprofessoren der Philosophie. Aber das ist ja eben das Eigentümliche, wenn nun diese Gedanken auf einen wirken, wenn man zum Beispiel ein scholastisches Buch liest, so ein richtig scholastisch-katholisches Buch liest und es auf sich wirken läßt, gewissermaßen es zu einer Art von Selbsterziehung verwendet, die Seele wird über sich hinausgetrieben. Es wirkt wie eine Meditation. Es wirkt so, daß man zu etwas anderem kommt, Erleuchtung bewirkend. Und eine sehr merkwürdige Tatsache liegt vor.

Denken Sie sich einmal, solche modernen Dominikaner, Jesuiten, andere Ordensgeistliche, die sich in dasjenige, was jetzt noch von Scholastik vorhanden ist, hineinvertiefen, wenn sie nun ganz zu Ende wirken ließen auf sich dasjenige, was da an scholastischen Gedankenformen in ihnen erziehend wirkt, sie würden alle auf eine verhältnismäßig leichte Weise durch diese Erziehung zum Begreifen der Geisteswissenschaft kommen. Überließe man diejenigen, die Neuscholastik studieren, ihrem eigenen seelischen Werdegang, es würde gar nicht lange dauern, würden gerade diese katholischen Ordensgeistlichen sehr bald Anhänger der Geisteswissenschaft werden. Daher hat man — was nötig, damit sie es nicht werden? Man verbietet es ihnen. Man gibt ihnen das Dogma, welches die ganze Sache kupiert, welches das nicht aufkommen läßt, was heraus aus der Seele die Entwickelung bewirken würde. Man könnte heute noch immer demjenigen, der sich entwickeln will zur Geisteswissenschaft, als Meditationsbuch zum Beispiel jenes scholastische Buch in die Hand geben, das ich einmal hier vorgezeigt habe, das von einem Gegenwartsjesuiten verfaßt ist; aber ich habe Ihnen gesagt, es hat das Imprimatur durch jenen Erzbischof; es ist dasjenige kupiert, was entstehen würde im Menschen, wenn der Mensch sich ihm ganz frei überlassen könnte.

Diese Dinge, die muß man durchschauen, denn dann wird man einsehen, welche Wichtigkeit es hat für gewisse Kreise, ja nicht es bis zu den Konsequenzen desjenigen kommen zu lassen, was entstehen könnte, wenn man die Dinge frei wirken ließe in den Seelen. Dieses mitteleuropäische Streben besteht eben darinnen, von dem selbstverständlichen rhythmischen Menschen hinauf sich zu erheben zum NervenSinnesmenschen, zu dem, der im ideellen Gebiete dasjenige hat, was er sich selbst erringt. Für diese Menschen ist die besondere Anlage vorhanden, das Leben der Erde als ein Geistiges zu begreifen. Das hat ja Hegel im umfassendsten Sinne getan.

Gehen wir jetzt zum westlichen Menschen. Ich habe gestern gesagt, daß der westliche Mensch gerade in seinen erleuchtetsten Geistern, in solchen wie Bentham, John Stuart Mill, Spencer, Buckle, sogar schon Baco von Verulam und andern, Thomas Reid und so weiter, in der Nationalökonomie Adam Smith, daß dieser westliche Mensch besondere Veranlagung hat, dasjenige Denken auszubilden, das man dann verwenden kann im wirtschaftlichen Teile des sozialen Organismus. Wenn man zum Beispiel die Philosophie von Spencer nimmt, dann sagt man sich: das ist ein Denken, welches ganz aus dem Nerven-Sinnesmenschen stammt, ganz und gar Produkt der Sinne und der Nerven ist, welches am besten taugen würde, wirtschaftliche Organisationen und Assoziationen zu machen. Es ist nur deplaciert von Spencer zu der Philosophie verwendet worden. Würde Spencer mit demselben Denken Fabriken einrichten, soziale Organisationen machen, dann wäre das am richtigen Platze. Daß er mit diesem Denken eine Philosophie macht, das ist deplaciert.

Das kommt davon her, daß jetzt der westliche Mensch nicht mehr lebt im rhythmischen System, sondern wieder eine Stufe höhergestiegen ist, er lebt selbstverständlich im Nerven-Sinnessystem des Menschen. Der Orientale lebt seiner Natur nach im Stoffwechsel, der Mensch der Mitte lebt seiner Natur nach im rhythmischen System, der westliche Mensch lebt seiner Natur nach im Nerven-Sinnessystem (siehe Schema). Stoffwechsel beim Orientalen: Er wendet sich hinauf und erstrebt das rhythmische System. Der mitteleuropäische Mensch lebt im rhythmischen System; er strebt hin zum Nerven-Sinnesmenschen. Der westliche Mensch lebt schon im Nerven-Sinnessystem. Wo strebt er hinauf? Er ist noch nicht daran, aber er ist darauf angewiesen, hinaufzustreben; er ist darauf angewiesen, über sich hinauszustreben. In der Karikatur kommt es zunächst zum Vorschein in dem, was ich Ihnen gestern charakterisiert habe in der Ableugnung des Stoffes, in der Selbstsuggestion des menschlichen Wesens der Mrs. Eddy, der Christian Science. Aber das ist zunächst die Karikatur, trotzdem als Karikatur ein Vorbote desjenigen, was gerade vom westlichen Menschen erstrebt werden muß. Es muß etwas Übermenschliches erstrebt werden, wobei ich durchaus nicht dies behaupten möchte, daß jeder, wenn er nun, statt aus dem NervenSinnesmenschen nach oben zu streben, hinunterstrebt in die Ohnmacht und so weiter, dadurch deshalb ein Übermensch wird.

Aber ich habe dann gestern damit geschlossen, daß ich sagte: So sind verteilt die menschlichen Fähigkeiten auf die verschiedenen Gebiete der Erde, und notwendig ist, daß ein wirkliches Zusammenwirken geschieht. Heute sind wir so, daß wir in bezug auf die Zivilisation ganz und gar abhängig sind schon von dem Nerven-Sinneswesen des Westens. Ich habe ein Paradoxon gebraucht, aber dieses Paradoxon drückt sehr klar die Wirklichkeit aus. Dasjenige, was in Wien denkt, was in Berlin denkt, sind nicht die Gedanken, die etwa aus dem Volkstum herausgekommen sind und in Fichte oder bei Hegel kulminiert haben. Diese Geister sind überschüttet. Dasjenige, was heute in Mitteleuropa, in Wien oder Berlin in Büchern und Zeitungen steht, sind nicht die Gedankenformen Fichtes; das ist eine Lüge, wenn heute die Leute Fichte zitieren. Die Wahrheit ist vielmehr diese, daß verwandter ist das, was heute in Berlin oder Wien an die Öffentlichkeit dringt, mit dem, was in Chikago oder in New York gedacht wird, als mit dem, was in Fichte oder in Hegel gedacht worden ist.

Aber das mußte geschehen, daß diese drei Glieder, von denen dieses insbesondere zunächst als das Geistesleben veranlagt war, dann das Geistesleben herüberschickten als Tradition jenes Ursprünglichen, jenes Elementaren des geistigen Lebens, wie sie war im Oriente, wo der Mensch drinnen lebt — wie er hier im physischen Leben steht — lebendig im Geistesleben selber. Davon fand sich nur der schattenhafte Nachklang in Mitteleuropa, davon findet sich nur die Tradition in Westeuropa. Dieses Westeuropa ist durch seine eigene Anlage für das Post-mortem-Leben charakterisiert, für dasjenige Leben, das ersehnt wird nach dem Tode. Ich habe Ihnen gestern gesagt, es bereitet sich bereits in Amerika, wenn auch in einzelnen Sekten, das Bewußtsein davon vor, daß der Mensch nicht bloß passiv sein darf hier in bezug auf das Seelenleben überhaupt, um etwas durch den Tod durchzutragen und in der geistigen Welt weiterzuleben, sondern daß er hier dasjenige erwerben muß durch seine Arbeit, durch sein Tun, was er durch die Pforte des Todes hindurchtragen will. Das Bewußtsein davon, daß der Mensch sich auflöst, wenn er hier nicht für seine Unsterblichkeit sorgt, wenn er hier nicht einen idealen Sinn entwickelt, wenn dieser ideale Sinn auch noch in karikaturhafter Weise zum Vorschein kommt, dieses Bewußtsein dringt in einzelnen Sekten des Westens bereits durch.

Dasjenige aber, was Staatsleben war, das ist erstrebt so, daß man im rhythmischen Menschen lebte und es hinauftrug in die Gedanken. Das ist insbesondere beim mittleren Menschen zum Vorschein gekommen. Es strahlte dann herüber nach dem Westen. Da liegt eine eigentümliche Erscheinung vor, die man nur versteht, wenn man die Dinge innerlich anschaut. So sonderbar es manchem erscheinen wird, da ging etwas vor in Mitteleuropa. Es blieb selbstverständlich in dem rhythmischen System der Drang nach einem menschlichen Zusammenleben, nach einem sozialen menschlichen Zusammenleben in Freiheit. Das blieb zunächst tief im Unbewußten stecken (siehe Schema). Aber es lebt ja auch dasjenige unter den Menschen, was die Menschen nicht im Bewußtsein haben. Sagen wir also, im 18. Jahrhundert lebte zunächst unbewußt da etwas Bestimmtes in Mitteleuropa, ohne daß es herauf konnte ins Bewußtsein; aber es strahlte nach dem Westen hinüber. Indem es hinüberstrahlte nach dem Westen, indem es aufgenommen wurde, indem es sich nicht selbstverständlich im Innern entwickelte, wurde es zur Leidenschaft, wurde es zur Empfindung und wurde die Französische Revolution.

Schiller besann sich — (es wird auf das Schema gezeigt) da die Französische Revolution -; es gibt ja sogar ein Symbol davon, daß Schiller sich besonnen hat auf dasjenige, was da eigentlich vorging. Sie wissen ja, daß Schiller die Ehre widerfahren ist, zum französischen Bürger gemacht zu werden -, Schiller also, er besann sich; aber bei ihm lebte es zunächst im rhythmischen System. Nun, durch eigene Anschauung hob er es herauf und schrieb seine Briefe, die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen betreffend.

Darinnen haben Sie das, was man damals sagen konnte über menschliches Zusammenleben, über menschliches Zusammenleben in einem wirklich freien Staat. Hume hat ja dann nur, ich möchte sagen, dieses staatliche Glied, das Schiller da ins Bewußtsein heraufgehoben hat in seinen «Ästhetischen Briefen», etwas pedantisch ins System gebracht. Das ist gerade etwas außerordentlich Bedeutsames, was in diesen Briefen über ästhetische Erziehung von Schiller da aus den Tiefen des Volkstums herausgeholt ist. Weil es so tief ist, wurde es ja dann auch, als überall der Nerven-Sinnesmensch herrschend wurde, nicht verstanden.

Ich habe öfter erzählt, daß in Wien ein einsamer Mensch lebte, Heinrich Deinhardt hieß er. Er hat Briefe über Briefe über diese ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen geschrieben, sehr geistvolle Briefe. Der Mann hatte das Malheur, daß er einmal ein Bein brach auf der Straße, als er hinfiel. Das Bein konnte eingerichtet werden, aber er konnte nicht genesen, er starb an dem Beinbruch, weil er unterernährt war. Das heißt, derjenige, der in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts noch Schillers «Ästhetische Briefe» in gewissenhaftester Weise ausgelegt hat, starb den Hungertod. Und diese Deinhardtschen Briefe über Schillers ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen sind völlig vergessen!

Diese «Ästhetischen Briefe» Schillers, sie wären eine gute Vorbereitung wiederum, um die Seele hinaufzuläutern zu einem geistigen Anschauen der Welt. Schiller konnte das noch nicht selber. Aber es wirkt immer, wenn der andere etwas aufnimmt, die Seele selbst erziehend, was von einem Menschen herrührt, der noch nicht hinaufkommt in die geistige Welt, es wirkt da so, daß er in die geistige Welt hineinsehen kann. Allerdings hat man in Europa statt dessen Ralph Waldo Trine und Marden und ähnliche Oberflächlichkeiten als ein besonderes Heilmittel für die Seelen verehrt, und die andern Dinge vergessen, die nun wirklich in die geistige Welt hinaufführen würden.

Diese Dinge müssen eben auch im ganzen Zusammenhange des Lebens und des Weltwesens erfaßt und begriffen werden. Man muß sich klar darüber sein, wie differenziert die verschiedenen menschlichen Fähigkeiten über die Erde hin sind. Und das ist schon zu sagen: während bisher dafür gesorgt worden ist, daß die tumultuarischen Schillerschen Jugendwerke «Die Räuber» oder «Fiesko» oder «Kabale und Liebe» bekannt werden, und während die Menschen sich höchstens aufschwingen zu den Sentimentalitäten der «Maria Stuart» oder zu den doch sehr veräußerlichten dramatischen Szenen der «Jungfrau von Orleans» oder der «Braut von Messina», sollte man heute damit beginnen, die «Ästhetischen Briefe» Schillers, in denen er sich selber — mit all seinen «Räubern», mit der ganzen «Maria Stuart» und mit dem «Wallenstein» — an Bedeutung für die Menschheit überragt, man sollte damit beginnen, diese «Ästhetischen Briefe» nicht bloß zu studieren, sondern auf sich wirken zu lassen. Denn wir sind heute darauf angewiesen, nicht bloß das Schulphilistergewäsche, das es gibt über unsere Klassiker, über Goethe, Schiller, vorzutradieren, sondern vor allen Dingen hier Revision zu machen und selber aufzusuchen, was an diesen Klassikern das Große war. Wir schwätzen fort dasjenige, was über den «Wallenstein» und die «Maria Stuart» und so weiter geredet worden ist von der Schulphilisterei mehr als ein Jahrhundert. Wir haben heute die Aufgabe, die Größe auf elementare Art selbst zu begreifen, denn nur dadurch kann die Menschheit vorwärtsschreiten. So liegt auch da die Notwendigkeit einer Umwandelung, einer Erneuerung. Auch dasjenige, was durch unsere Schulen die Menschen über «Maria Stuart», über den «Wallenstein», über die «Räuber» und so weiter lesen und hören, auch das muß umgestaltet werden. Wir bedürfen in dieser ernsten Zeit einer völligen Erneuerung, denn die Zeiten sind ernst.

Und sehen wir nach dem Westen hinüber, so fordert dieser Westen mit alledem, was er hervorbringen kann als den Ausdruck der Menschheit durch das Nerven-Sinnessystem, er fordert den Hinaufstieg in dasjenige, was über dem Menschenwissen in einer geistigen Welt liegt. Und ich habe Ihnen gestern gesagt: Zusammenwirken müssen, damit das Geistesleben, das Staatsleben, das Wirtschaftsleben im dreigliedrigen sozialen Organismus sich geltend machen könne, zusammenwirken müssen diese drei Elemente. Sagen wir nicht etwa bloß: Ex oriente lux! — Nehmen wir auf den Orient, studieren wir die Bhagavad Gita, studieren wir die Jogaphilosophie, studieren wir die Veden, ochsen wir dieses Zeug geradeso, wie wir gewohnt worden sind in Europa, die andern Dinge zu ochsen, fangen wir jetzt an, einmal die Orientalismen zu ochsen, nachdem uns das andere langweilig geworden ist. Nein, damit kommen wir nicht vorwärts, denn dasjenige, was einmal für die Erde richtig war, wird es für die Gegenwart und Zukunft nicht wieder sein, ist etwas Vergangenes. Wir können es bewundern als etwas, was einmal für die Erde richtig gewesen war; wir können es aber nicht, wie es etwa eine Theosophische Gesellschaft tut, einfach wieder übernehmen in passiver Weise. Ebensowenig können wir dasjenige, was uns nach der alten Art überliefert worden ist von der europäischen Vergangenheit, einfach herübernehmen, können nicht sagen: Dasjenige, was in den Volkstümern des Orients, der Mitte liegt, das können wir einfach erneuern —, sondern wir müssen sagen: Wollen wir eine wirkliche Verbindung dieser drei Elemente, die allerdings in der menschlichen Natur veranlagt sind, erreichen, wie können wir das? -— Nur wenn wir aufmerksam darauf werden, wie das Nerven-Sinnesleben, das schließlich schon auf uns alle übergegangen ist, über sich hinausgehen muß. Das heißt, wir müssen aufsteigen zu etwas anderem, was weder daraus (es wird gedeutet auf Zeichnung Seite 142), noch daraus, noch daraus kommen kann, sondern einzig und allein durch die neue Initiation, durch die neue Geisteswissenschaft, was wirklich dadurch geholt wird, daß hinaufgestiegen wird aus dem modernsten Denken, das geschult ist an der Naturwissenschaft, an dem Nerven-Sinneswesen, indem wir hinaufsteigen zu der Wissenschaft der neuen Initiation und herausholen aus dieser neuen Initiation die Art und Weise, wie zusammenwirken können dasjenige, was einst Orient war, was später mittleres Wesen war, was jetzt westliches Wesen ist. Wir brauchen eine neue Wissenschaft der Initiation, die gerade die Einheit bewirken kann, die lebendige Einheit bewirken kann. Wir kommen in der neueren Zeit nicht zu einem Geistesleben, wenn wir nicht zu dieser neueren Initiationswissenschaft hinstreben. Wir kommen nicht zu einer Politik, wir kommen nicht zu einem Staatsleben, wenn wir in der alten Art weiterwirtschaften, wenn wir nicht anfragen bei denjenigen wissenschaftlichen Zweigen, die herauskommen aus der neueren Initiation: Wie soll sich die Politik der Zukunft gestalten? — Wir gelangen auch nicht zu einem Wirtschaftsleben, wenn wir nicht verstehen dasjenige, was nicht angewendet werden soll auf eine Philosophie, wie es Spencer getan hat, auf ein Staatssystem, wie es Adam Smith getan hat, sondern was angewendet werden soll bloß auf die Organisation des Wirtschaftslebens, wenn wir das nicht auf die Organisation des Wirtschaftslebens anwenden. Aber wir müssen dann wissen, wie wir das eingliedern sollen in die beiden andern Systeme. Dazu brauchen wir aber die Wissenschaft der Initiation. Wir können nicht vorwärtskommen, wenn wir nicht uns sagen können: Vom Verstehen, was einstmals orientalische Anlage war, gelangen wir zu dem, was das Wesen des Geisteslebens ist. Indem wir wirklich verstehen, was die Anlage des mittleren Menschen ist, gelangen wir dazu, wirklich zu verstehen, was das Rechts- oder Staatsleben ist. Indem wir das Westliche verstehen, gelangen wir dazu, zu verstehen, was das Wirtschaftsleben ist. Aber die drei fallen auseinander, wenn wir sie nicht in einer höheren Einheit verbinden können. Und wir werden sie nur in einer höheren Einheit verbinden können, wenn wir sie alle drei anschauen von jenem Gesichtspunkte, der sich uns ergibt durch die neuere Mysterik, die hier genannt wird anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft.

Diese Dinge müssen durchschaut werden, denn derjenige, der sie durchschaut, der weiß, daß all das Streben, das sich heute auslebt, dem Untergang entgegenführt. Man rechnet mit den wichtigsten Faktoren nicht. Man sehe selbst auf die radikalsten Sozialisten hin. Sie mögen es subjektiv mit der Menschheit ehrlich meinen: sie rechnen aber nur mit Niedergangskräften. Sie machen eine falsche Lebensbilanz. Wir machen nur eine richtige Lebensbilanz, wenn wir aus der Wissenschaft des Geistes heraus erfassen nicht irgend etwas, was wir willkürlich hinstellen, indem wir sagen, so und so muß es sein, wenn die Menschheit glücklich sein soll und so weiter, sondern wenn wir uns fragen können: Was entsteht, wenn Geistesleben, Rechts- oder Staatsleben und Wirtschaftsleben in das richtige Verhältnis zueinander kommen, welcher soziale Organismus ergibt sich da? — Dann wird in diesem sozialen Organismus auch leben seine Durchgeistigung, das heißt, es wird in diesem sozialen Organismus neben dem, daß ein Wirtschaftsleben da sein wird, das möglich ist, das nicht dasjenige ist, von dem man träumt und von dem man phantasiert, sondern das dasjenige ist, das möglicherweise entstehen kann als das Bestmögliche, und wenn ein Staatswesen da ist, das wiederum das Bestmögliche ist, jenes Geistesleben da sein wird, das vereinigen wird das Leben vor der Geburt mit dem Leben nach dem Tode, welches sehen wird in dem Menschen, der hier in dieser physischen Welt lebt, das sich rechtlich orientierende Wesen, das hereinleuchten hat sein vorgeburtliches Leben im Geistesleben, das im wirtschaftlichen Leben kein Ideal, sondern nur ein Bestmögliches erreichen kann, das aber die Kräfte, die im Wirtschaftsleben sich betätigen, umwandeln kann gerade durch Initiationswissenschaft im Willen so, daß sie aufleuchten lassen das Post-mortem-Leben. Weil das so ist, ist anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft nicht irgendeine Theorie neben anderen, nicht irgend etwas, was sich als ein Partei- oder Sektenprogramm neben andere Parteien- oder Sektenprogramme hinstellt, sondern sie ist etwas, was hervorgeholt ist aus jenem Wissen, das man gewinnen kann, wenn man Erdenentwickelung und Menschheitsentwickelung in ihrem Zusammenwirken und in ihrer Ganzheit erfaßt.

Und gestehen muß man sich in der Gegenwart, daß jedes andere Verhältnis zur Welt oder die weltlichen Reformen zu nichts führen können, daß hervorgeholt werden muß aus der Wissenschaft der neueren Initiation dasjenige, was die Menschheit vorwärtsbringen kann.

Das muß heute immer wieder in den verschiedensten Formen ausgesprochen werden. Es ist hineingebaut worden in diesen Bau, es kommt in allen Einzelheiten dieses Baues zum Ausdruck. Wenn Sie das kleinste Stückchen hier sehen, so wird es Ihnen erzählen können von dem, was hier gemeint ist, was hier in verschiedener Art in Worten ausgesprochen wird. Das ist dasjenige, was der ganzen Sache hier einen gewissen einheitlichen Charakter gibt, was aber zu gleicher Zeit ausdrückt ein Wollen, welches innig zusammenhängt mit den Aufgangs-, nicht mit den Niedergangskräften der sich entwickelnden Menschheit, und wovon man daher wünschen möchte, daß es verstanden werde. Das ist es, wonach wir arbeiten möchten, wonach wir immer mehr und mehr arbeiten möchten, wonach wir jetzt arbeiten möchten durch die Herbstkurse, die abgehalten werden, in denen gezeigt werden soll, wie wirklich in die einzelnen Zweige der Wissenschaft hinein befruchtend wirken kann dasjenige, was von anthroposophisch orientierter Geisteswissenschaft kommt. Und dann wird vielleicht auch einmal die Zeit kommen, wo die Menschen verstehen werden, was von hier aus eigentlich gewollt wird, wo so viel Verständnis in der Welt sein wird, daß es dazu kommt, daß wir diesen Bau auch einmal später in irgendeiner Zukunft, die heute noch im Nebel liegt, auch eröffnen können. Denn solange dieser Bau nicht eröffnet werden kann, ist immer noch etwas da von dem, welches zeigt, daß ein nicht genügendes Verständnis für das vorhanden ist, was hier gewollt ist.

Davon werde ich dann am nächsten Freitag um acht Uhr weiterreden.

Morgen ist der Vortrag unseres Freundes, des Grafen Polzer, um acht Uhr hier über die europäische Politik des letzten Jahrhunderts im Zusammenhange mit dem Testament Peters des Großen, ein anregender Gegenstand, über den sich hoffentlich eine Diskussion eröffnen wird. Dann werde ich am Freitag weiterreden über die angefangenen Fragen in ihrer Anwendung auf den einzelnen Menschen und gerade auf die Fragen, die die besonderen religiösen Fragen sind, Samstag um acht Uhr dann fortsetzen; Sonntag um ein halb sieben Uhr wird die nächste eurythmische Vorstellung sein und daran sich ein Vortrag anschließen.

Eighth Lecture

I would like to repeat the essence of what I said yesterday about the differentiation of the soul dispositions of peoples, of human beings in general throughout the world. I indicated how different dispositions and different types of soul constitution are present in people in the most diverse regions of the earth, so that in fact each region of the earth, through its peoples, can contribute something specific to what humanity as a whole accomplishes in relation to the entire civilization of the earth. Yesterday we had to point out how the Oriental peoples, the peoples of Asia and those who belong to them, are particularly predisposed to develop that element which contributes to the spiritual element of social organization. Everything that is primarily spiritual development in humanity, that is, knowledge of the supersensible, the shaping of the supersensible, is something to which the Oriental population is particularly predisposed. This is connected with the fact that these Oriental peoples are particularly predisposed to form ideas and concepts about how human beings have descended into this earthly existence from the spiritual worlds they lived through between their last death and this birth. The doctrine of pre-existence, the doctrine which is certain that human beings have undergone a spiritual existence before coming into the physical body here, is particularly evident in these Oriental dispositions. Hence also the disposition to have insight into repeated earthly lives. One can hold the view that life after death continues, always continues, without returning to earth. But one cannot logically hold the view that life here on earth is a continuation of a spiritual life without having to think that it is then self-evident that this life must repeat itself. Thus, the Oriental was particularly inclined to believe that he had lived in spiritual worlds before this earthly life and that he had received the impulses, the drives for this earthly life, from the divine-spiritual world.

This is connected with the whole way in which Orientals have arrived at their knowledge and their entire soul constitution. I have already hinted at this to some of you; there are now a number of other friends here, and I would like to characterize once again something that I have already characterized for some of you.

We know that human beings are threefold beings, that they are divided into the nervous-sensory human being, the rhythmic human being — which encompasses those activities that are found in breathing, blood circulation, and so on — and that the third part of the human being is the metabolic human being, everything that is connected with metabolism. Now, these three parts of the human organism are not expressed in the same way all over the world, but in different ways.The Oriental human being today is at this stage — now all this is, I would say, in decline, today all this is suppressed, today it lies dormant in the Oriental human being, but we must not get to know the Oriental human being according to his present state of soul, but we must preferably get to know him according to the state of soul he had in a very distant past — Oriental people today are in this state precisely because this state of mind has receded, and Europeans and Americans will realize this in the not too distant future, to their great horror, when they embrace Bolshevism with the same fervor, with the same religious devotion with which they once embraced the teachings of the holy Brahman. Which of the three elements of human nature is most particularly expressed in Oriental people? It is the metabolic human being. The oldest Orientals lived entirely in metabolism. This will not cause horror to those who do not think of matter as lumps of material, but who know that spirit lives in all matter. And what was precisely the high spirit, the admirable spirit of the Orientals, was that which rose from the metabolism of the Oriental nature and shone into consciousness. What takes place in the human metabolism is intimately connected with the nature of the external sensory world. We take what then becomes matter in us from the outer sensory world. We know that behind this outer sensory world there is spirit. In truth, we eat spirit, and the spirit we eat only becomes matter in us. But what we take in, in the case of the Oriental, was such that even after it was taken in, it gave up its spirit. So that those who understand things look at the admirable poetic achievements of the Vedas, at the magnificence of the Bhagavad Gita, at the profound philosophy of the Vedas and Vedanta, at the Indian philosophy of yoga, and they do not admire them any less because they know that they have emerged from the inner process as a product of metabolism, just as the flowers of a tree arise from metabolism. And just as we look at the tree and see in its flowers that which the earth drives toward the air and light, so we see in what the ancient Indian man produced in the Vedas, in Vedanta, in the philosophy of yoga, a flower of earthly existence itself. On the one hand, what we see in the blossoms of trees is, in a sense, the product of the earth, brought forth by the air and light, but it is a product of the earth, that is, of what grows in the fields as wheat and grain, on the trees as fruit, enjoyed and digested by humans, cooked by humans. In the special ancient Indian nature, instead of plant flowers and plant fruits, it becomes the magnificent creations of the Vedas, the Vedanta philosophy, the yoga philosophy. One sees these ancient Indian people as trees, as witnesses of what the earth can bring forth from itself in its metabolism, by shooting into humans—in trees through the roots and the flow of sap, in humans through food—and one learns to recognize the divine in that which the spiritualist despises, because matter seems so low to him.

And then the ancient Indian has an ideal. He has the ideal of emerging from his experience in metabolism to the higher member of human nature, to the rhythmic system. That is why he did his yoga exercises. He did special breathing exercises. He practiced this consciously. What metabolism brings forth from him as the spiritual blossoming of the earth's evolution comes unconsciously. What he makes conscious is bringing his rhythmic system, the respiratory and circulatory systems, into a regulated, systematized movement. And what does he do when he rises, when that is precisely what his elevation is? What happens in this rhythmic system? We breathe in the outside air and give to the outside air what is produced by human metabolism, carbon. A metabolism takes place within us between what is the result of our metabolism and what is in the air we breathe in. Today's materialistic-physical worldview sees nitrogen — which it does not know what it is — and oxygen — which it does not know what it is — mixed together in the air and sees something purely material. The ancient Indians perceived the air, that is, what is happening there, in which what comes from the metabolism is combined with what is inhaled, what is processed. In the blood circulation, the ancient Indians, by fulfilling their ideal, the Yoga philosophy, perceived through this metabolism the secrets of the air, that is, what is spiritually in the air. In Yoga philosophy, they learned what is spiritually in the air. What do you learn there? You learn precisely what has entered into us by becoming breathing beings. You learn to recognize what entered into us when we descended from the spiritual worlds into this physical body. You cultivate this knowledge of pre-existence, of pre-birth life. Therefore, in a certain sense, it is initially the secret of those who practice such jogaphilosophy to discover the secret of pre-birth life.

Thus we see that the ancient Indian lives in metabolism, even though he produces such beautiful, magnificent, and powerful things and artificially raises himself up to the rhythmic system. All this has fallen into decadence. All this is dormant in Asia today. In Asian souls, it asserts itself only nebulously in abstract forms when such enlightened spirits as Rabindranath Tagore speak and revel in the ideal of the Asians.