Supplements to Member Lectures

GA 246

17 August 1908, Stuttgart

Translated by Steiner Online Library

12. Philosophy and Theosophy

After a long series of purely theosophical lectures, we want to speak today from a different tone, so to speak, [speaking from a completely different point of view, namely more philosophical]. I would therefore ask you to take into consideration from the outset that today's lecture is not theosophical in the true sense of the word, and that the purely philosophical tone that must be struck may appear somewhat abstract and difficult to some who are not used to moving in such directions of thought. This happens for a very specific reason; it happens because again and again, and especially in those circles that have or believe to have a certain philosophical education, the opinion must arise (I expressly choose the word “must”) that Theosophy is actually only to be approved of by people who have not progressed beyond a certain dilettantism in philosophical or scientific matters. However, one could easily think in these circles that those who have a thorough philosophical education, who have learned what the foundations of scientific certainty and conviction are, cannot really concern themselves with all the fantasy, with all that which confronts them as supposedly higher experience; this is something for those who are not yet ripe for scientific thinking. In order to recognize what such a judgment is actually about, let us take a look at the philosophical activity itself, so to speak. Of course, this can only be done very briefly today, only in hints [and sketchily, because strictly and thoroughly proven]; but if we ever have the opportunity to speak in more detail about such things, then you will see that these hints are taken out of a large [and true] context [which is easily apparent on closer examination].

Philosophy is generally regarded by those who practise it as something absolute, not as something that had to arise in the course of human development. It is precisely with regard to philosophy that one is able to indicate, even from external historical documents, when it as such took and had to take its origin within the evolution of mankind. Most, especially the older, depictions of the history of philosophy have done this quite well. In all these accounts you will find that it begins with Thales and then progresses from him to our time.

However, some more recent historians of philosophy, who wanted to be particularly complete and particularly clever, have shifted the beginning of philosophy to even earlier times and drawn in all sorts of things from earlier wisdom teachings. But this all arose from a very specific form of dilettantism, which is unaware that everything that preceded wisdom teachings in India, Egypt and Chaldea also has a completely different methodological origin than purely philosophical thinking, which tends towards the speculative. This only developed in the Greek world; and the first to come into consideration is really Thales. We do not even need to begin a characterization of the various Greek philosophers from Thales, not from Anaxagoras, Heraclitus, Anaximenes, nor from Socrates and Plato; we can start immediately with the personality who actually stands first and foremost as the philosopher catexochen, and that is Aristotle.

[Everything else before him has either emerged directly from the Mysteries or is closely related to them]. All other philosophies are basically still abstractions inspired by the wisdom of the Mysteries; this could easily be demonstrated for Thales and Heraclitus, for example. But philosophers in the true sense of the word are not even Plato or Pythagoras, both of whom have their sources in seership. For what matters when we characterize philosophy as such is not that someone expresses himself in concepts, but where his sources are, that is what matters. Pythagoras has mystery wisdom as his sources and has transformed it into concepts; he is a clairvoyant, only he has put into philosophical form what he experienced as a shearer, and the same is the case with Plato.

What characterizes the philosopher, however, and what we first encounter in Aristotle, is that he works from the pure conceptual technique and that he must necessarily reject other sources or they are inaccessible to him. [Aristotle is a philosopher in the most eminent sense, because he worked out pure thinking with the pure conceptual technique.] And because this is only the case with Aristotle, it is not without world-historical reason that it is he who founded logic, the science of the technique of thinking. Everything else was only a precursor. The way in which concepts are formed, judgments are formed, conclusions are drawn, all this was first found by Aristotle as a kind of natural history of subjective human thought, and everything we encounter in his work is closely linked to this foundation of the technique of thinking. Since we will come back to a number of things that are fundamentally important in his work for all later considerations, it is now only necessary to make this historical allusion in order to briefly characterize the starting point.

Aristotle remained the leading philosopher in later times. His achievements not only flowed into the post-Aristotelian period of antiquity up to the foundation of Christianity, but it was precisely in the first Christian period up to the Middle Ages that he was the thinker who was followed in the development of all worldview endeavors. This is not to say that, especially in the Middle Ages, when people did not have the original texts, they had Aristotle before them as a system, as a sum of dogmas; but they had become accustomed to the way in which knowledge, right up to the highest divine knowledge, was arrived at using the ladder of pure conceptual technique. And so it came about that Aristotle became more and more the logical teacher. In the Middle Ages, people said something like this: Let the positive factual knowledge of the world come from wherever, let it come from the fact that man examines external reality with his senses or that a revelation takes place through divine grace as through Christ Jesus - these are things that are simply to be accepted, on the one hand as statements of the senses, on the other as revelation. But if you want to justify something given in this or that way through pure concepts, then you have to do it with the technique of thought that Aristotle justifies.

[Especially in early scholasticism, logic and to some extent Aristotle's actual teachings were current]. And indeed, Aristotle's justification of the technique of reasoning was so significant that Kant said, and rightly so, that logic had not actually advanced a single sentence since Aristotle. And basically, this is still true today; even today, the basis of logical and logical-technical doctrines has remained pretty much unchanged compared to what Aristotle gave. What we want to add today arises from a rather amateurish approach to the concept of logic, even in philosophical circles.

Now not only the study of Aristotle, but above all the familiarization with his thinking technique became topical for the middle period of the Middle Ages, for the early scholastic period, as it could also be called, when scholasticism was in its heyday. In terms of its heyday, this period was brought to a close by Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century. When we talk about this early scholastic period, we must be aware that we can only talk about it philosophically today if we are free of all authority and dogma. Today it is almost more difficult to speak about these things in a purely objective way than in a derogatory way. If one speaks disparagingly about scholasticism, one does not run the risk of being heretized by the so-called free spirits; but if one speaks objectively about it, there is a good chance of being misunderstood, and this is because today, within the positive and especially the most intolerant church movement, Thomistic is often referred to in a very misleading way.

What is considered orthodox Catholic philosophy today should not affect us; but neither should we be deterred by the accusation that we are cultivating the same thing that is driven and commanded from the dogmatic side. Rather, regardless of everything that can be asserted from the right and the left, we want to characterize the sentiments of the heyday of scholasticism with regard to science, the technique of thought and supernatural revelation.

Early scholasticism is not what one would usually characterize it as today with a catchphrase; on the contrary, it is monism, a doctrine of unity - it is not even remotely dualistic in nature. The primordial ground of the world is for it a thoroughly unified one; only the scholastic has a certain feeling with regard to the perception of this primordial ground. He says: "There is a certain supersensible truth, a wisdom, which was first revealed to mankind; human thought with all its technique is not so far advanced as to penetrate from itself into the regions whose essence [is] the content of the highest revealed wisdom. Therefore, for the early scholastics there is a certain wisdom that is initially inaccessible to the technique of thinking [although this does reach as far as the limits of those revelations]. - It is only accessible insofar as thought is able to clarify what has been revealed.

For this part of wisdom it is therefore incumbent on the thinker to accept it as revealed; and to use the technique of thought only to clarify it. What man can find by himself only moves in certain subordinate regions of reality. For these, the scholastic applies the activity of thinking to his own research. He penetrates to a certain limit where he encounters revealed wisdom. In this way, the contents of his own research and revelation come together to form an objectively unified monistic worldview. The fact that a kind of dualism, necessitated by human peculiarity, enters into the matter is only secondary. It is a dualism of knowledge, not one of the reasons for the world.

The scholastic thus declares the technique of thought suitable for rationally processing what is gained in empirical science, in sensory observation, and also for penetrating a little way up to spiritual truth. And then the scholastic modestly presents a piece of wisdom as revelation, which he cannot find himself, which he only has to accept.

However, what the scholastic uses as this special technique of thought has its origins in Aristotelian logic. There was a twofold necessity for early scholasticism, which came to a close around the thirteenth century, to engage with Aristotle. The first necessity was due to historical developments: Aristotelianism had just settled in. The other necessity was the result of the fact that an opponent had gradually emerged from another side to the traditional Christian doctrine.

Aristotle had not only spread in the West, but also in the East; and everything that had been brought to Europe via Spain by the Arabs was saturated with Aristotelianism in terms of thought. In particular, it was a certain form of philosophy, of natural science, extending into medicine, which had been brought over there and which was imbued with Aristotelian thought in the most eminent sense. From there, the opinion had formed that nothing else could follow as a consequence of Aristotle than a kind of pantheism, which had emerged from a very vague mysticism, especially in philosophy. Thus, in addition to the one reason that Aristotle had lived on in the technique of thought, there was another reason to deal with him: In the interpretation of the Arabs, Aristotle appeared to be an opponent, an enemy of Christianity.

[What the Arabs possessed of false mysticism and pantheistic teachings in general, they sought to support with Aristotle. Scholastics had to ask themselves whether this was really the true Aristotle imported to Europe by the Arabs]. One had to say to oneself: if what the Arabs brought over as an interpretation of Aristotle is true, then Aristotelianism would be a scientific basis that would be suitable for refuting Christianity. Now let us imagine how the scholastics must have felt about this? On the one hand, they held firmly to the truth of Christianity, but on the other hand, according to all tradition, they could not help but admit that logic, the thinking technique of Aristotle, was the true, the correct one. This dichotomy gave rise to the scholastics' task: to prove that Aristotle's logic could be applied, that his philosophy could be practiced, and that it was precisely through him that one had the instrument to truly comprehend and understand Christianity. It was a task set by the development of the times. Aristotelianism had to be treated in such a way that it became clear: What had been brought by the Arabs as the teachings of Aristotle was then only a misunderstanding of the same if it proved hostile to Christianity. That one only had to interpret it correctly in order to have the foundation for understanding Christianity: That was the task which scholasticism set itself and to which the whole of Aquinas' writings were devoted. [It was therefore necessary to demonstrate that Christian doctrines could be supported precisely on the basis of a correctly understood Aristotle. This was the only way to effectively combat the half-materialism and blurred pantheism coming from the East.

Now, however, something else is happening. In the course of development, after the heyday of the scholastics, a complete break occurs in the entire logical philosophical development of human thought. The natural thing would have been (but this is not meant to be a criticism, it is not even meant to say that it could only have happened at all; the actual course was just necessary - only hypothetically the following should be put forward), the natural thing would have been that one would have extended the technique of thinking more and more, that one would have grasped ever higher and higher parts of the supersensible world through thinking. However, this was not how things initially developed.

The basic idea that initially applied to the highest realms for Thomas Aquinas, for example, and which could have developed in such a way that the boundaries of human research could have been extended ever higher into the supersensible realm, was distorted to the point of caricature and now lived on in the conviction: The highest spiritual truths are entirely beyond the reach of purely human thought activity, of elaboration in terms to which man can bring it out of himself. This has caused a rift in human spiritual life. Supersensible knowledge was presented as something that absolutely eluded all human thought, that could not be achieved through subjective acts of cognition, that could only arise from faith. [At most, one can approach these areas with a kind of emotional conviction, with mere faith. This abyss between faith and knowledge thus opened up became a powerful impulse for later times]. This had already been the case earlier, but it was taken to an extreme towards the end of the Middle Ages. The distinction between faith, which must be achieved through a subjective emotional conviction, and that which can be processed through logical activity as the basis of a secure judgment, became increasingly clear.

And it was only natural that, once this abyss had opened up, knowledge and belief were pushed further and further apart. And it was also natural that Aristotle and his thinking technique were drawn into this rift that had opened up through historical development. In particular, he was drawn into it at the beginning of the modern era. The scientists said - and we can regard much of what they said as well-founded: You can't make any progress in empirical truth research by merely continuing what Aristotle had already said. Moreover, the historical development was such that it became unfortunate to have an association with the Aristotelians; indeed, when the time of Kepler and [Galileo] came along, misunderstood Aristotelianism had become a real scourge.

It happens again and again that the successors, the confessors of a worldview, spoil an immense amount of what the founders had put down as quite correct. Instead of looking into nature itself, instead of observing it, at the end of the Middle Ages people found it convenient to take Aristotle's old books and base all academic lectures on what Aristotle had written. [It is characteristic of this that an orthodox Aristotelian was asked to convince himself on a corpse that the nerves did not emanate from the heart, as he had misunderstood from Aristotle, but that the nervous system had its center in the brain. The Aristotelian then said: “Observation shows me that this is really the case, but Aristotle says the opposite, and I believe it more.” So the Aristotelians had indeed become a plague on the land. And that is why empirical science had to do away with this false [misunderstood] Aristotelianism and [in order to make any progress at all] rely on pure experience, as we see particularly strongly in the great Galileo.

On the other hand, something else developed. Those who wanted to protect faith, so to speak, from the intrusion of thinking that was now focused on itself, developed an aversion, a dislike of the technique of thinking. They were of the opinion that this thinking technique was powerless in the face of the revealed wisdom. If the secular empiricists referred to Aristotle's book, the others referred to something they had taken - admittedly in a misleading way - from another book, the Bible. We see this expressed most strongly at the beginning of the modern era when we hear Luther's harsh words: “Reason is the stone-blind, deaf fool”, which should have nothing to do with spiritual truths; and when he further asserts that the pure conviction of faith can never dawn in the right way through rational thinking, which is based on Aristotle. He calls him “a hypocrite, a sycophant, a stinking goat”. As I said, these are harsh words, but from the standpoint of the new age they seem understandable to us; a deep gulf had just opened up between reason and its thinking technique on the one hand and supersensible truth on the other.

This gulf found its final expression in a philosopher under whose influence the nineteenth century was caught in a net from which it can hardly escape: Kant. Basically, he is the last outgrowth of the split caused by the medieval rift. He strictly separates faith from that which man can achieve through knowledge. [He undertook a complete separation of purely theoretical and practical reason, whereby the latter stands on the mere standpoint of faith, while in theoretical reason only things of thought play a role, which, however, can never reach reality and essence, the “thing in itself”. Man always remains stuck in the subjective; he cannot approach truly objective thinking. This is the fundamental error of Kant's philosophy.

On the face of it, the “Critique of Pure Reason” stands alongside the “Critique of Practical Reason”, and practical reason attempts to gain a position of faith, albeit a rationalistic one, in relation to what can be called knowledge. In contrast, Kant's theoretical reason stigmatizes in the most extreme way that it is incapable of grasping the real, the thing in itself. The thing in itself makes impressions on man, but he can only live in his mental images, in his own concepts. Now we would actually have to go deep into the history of Kant's philosophy if we wanted to characterize Kant's devastating fundamental error; but that would take us too far away from our task. - Incidentally, you will find all you need to know about this in my “Truth and Science”.

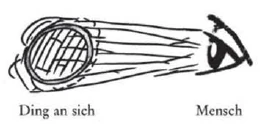

For today, we are much more interested in something else, namely the web in which philosophical thought of the nineteenth century has become entangled. Let us examine how this came about. Above all, Kant felt the need to show to what extent there was something absolute in thinking, something in which there could be no uncertainty. But everything that comes from experience, he said, is not certain. Certainty can only be given to our judgment by the fact that part of our knowledge does not come from things, but from ourselves. Now, in Kant's sense, we look at things in our cognition as if through a colored glass; in our cognition we catch things in the lawful connections that derive from our own being. Our cognition has certain forms - the spatial form, the temporal form, the category of cause and effect - which have no meaning for the thing in itself, at least man can know nothing of whether the thing in itself exists in space, time or causality. These are forms that arise only from the subject of man, and which man spins about the “thing-in-itself” at the moment in which the latter approaches him, so that the thing-in-itself remains unknown to him. Thus, where man confronts this thing-in-itself, he weaves the form of space and time around it, grasps it in cause and effect; and so man lays his whole web of concepts and forms over the thing-in-itself. That is why there is a certain certainty of knowledge for man, because - as long as he is what he is - time, space and causality apply to him: What man himself sees into things, he must unravel out of them again. But man cannot know what the thing itself is, because he remains eternally caught up in the mental image. Schopenhauer expressed this classically in the sentence: “The world is my mental image”.

[An example:

With his “feeling horns”, man now looks, as it were, at the unknown “thing in itself”, without, of course, ever getting into it. He only ever sees his mental images reflected in the “thing in itself”; he literally spins the “thing in itself” into the forms of imagination.

This whole conclusion was carried over into the entire thinking of the nineteenth century; not only into epistemology, but also, for example, into the theoretical foundations of physiology. Certain experiences came to the rescue. If we look, for example, at the doctrine of specific sensory energies, it seems to confirm Kant's opinion. At least this is how the matter was viewed in the course of the nineteenth century. It is said thus: The eye perceives light. But if the eye is affected in other ways, for example by pressure, by electrical impulse and so on, it also shows light perception. This is why it is said that the perception of light is generated from the specific energy of the eye and is superimposed on the thing itself. Helmholtz in particular expressed this in a blatant way as a physiological-philosophical doctrine by saying: "Everything that we perceive cannot even be thought of as pictorially similar to the things that are outside of us. The image has a resemblance to that which it represents; but that which we call sense-perception cannot even have such a resemblance to the original as the image has to its original. Therefore, he goes on to say, one cannot address what man experiences within himself in any other way than as a “sign” of the thing in itself. A sign need have nothing in common with what it expresses.

And that which had been in the pipeline for a long time then became ingrained in the philosophical thinking of our time, so to speak, so that people became incapable of understanding anything else, or even of thinking that it could be different. Eduard von Hartmann, for example, was completely incapable of finding his way out of his conceptual convolutions. For example, in a conversation I once had the opportunity to have with him, it was quite impossible to get beyond the fact that he said: "Yes, we must start from the mental image, and if we define the mental image, then we must say that it is that through which man brings a non-imagined thing to perception! But if the mental image, from which we start, is something subjective, then we can't get beyond the subjective either.

He had no idea that he had first made up this definition himself and then could not escape a concept that he had made up. And yet his entire “transcendental realism” is based on the fact that he has spun himself into something that he has made himself and which he assumes to be an objective truth. In this way, man never gets beyond the judgment: what I grasp in the mental image only ever goes as far as the limit of the thing in itself, it is therefore only subjective. - This habit of thought has become so firmly established over time that all those epistemologists who pride themselves on understanding Kant consider anyone who cannot admit that their definition of the mental image and the subjective nature of what is observed is correct to be a limited person. All this has been brought about by the rift in the development of the human mind described above. [In his ethical investigations, Eduard von Hartmann provided important suggestions, but his epistemological investigations did not bring anything new or important. Thus Kantian thinking has developed into a formal habit of thought in modern intellectual life.

However, anyone who really studies Aristotle would find that in a straightforward, i.e. in a sense unbent development from Aristotle, something quite different could have emerged as a principle and theory of knowledge. Aristotle already recognized things in the field of epistemology that people today will only be able to slowly and gradually rise to through all the academic undergrowth that has arisen under the influence of Kant. Above all, he must learn to understand that Aristotle already had the possibility, through the technique of thought, of bringing about concepts that are correctly conceived and that lead directly to transcending these human boundaries that we have drawn ourselves here [and lead us beyond the realm of the empirical].

We only need to look at some of Aristotle's fundamental concepts to realize this. It is quite in his spirit to say: when we analyze the things around us, we first find what gives us knowledge of these things by perceiving with the sense: Sense provides us with the individual thing. But when we begin to think, things are grouped together, we combine different things into a unit of thought. - And now Aristotle finds the right relationship between this unity of thought and an objective reality, that objective which leads to the thing in itself - by showing that with consistent thinking we must think of the world of experience around us as composed of matter and what he calls form. For Aristotle, matter and form are two concepts that he really separates in the only correct sense in which they must be separated. We could talk for hours if we wanted to exhaust these two concepts and everything that is connected with them. But let us at least bring up a few elementary points in order to understand what Aristotle distinguishes between form and matter. He is clear about the fact that in relation to all things that are initially around us, that form our world of experience, it is important for cognition that we grasp the form, because it is the form that gives things their essence, not the matter. For Aristotle, form is the essence.

Even in our time, however, there are still people who have a real understanding of Aristotle. Vinzenz Knauer, who was a university lecturer in Vienna in the eighties of the nineteenth century, usually made the difference between matter and form and what is important clear to his listeners with an illustration that may be mocked. He said that one should think of a wolf that has eaten nothing but lambs for some time in its life, how it is then actually composed of the matter of the lambs - and yet the wolf never becomes a lamb! This is the difference between matter and form, if you follow it correctly. Is the wolf a wolf through matter? No. Its essence is implanted through form - we find it not only in this wolf, but in all wolves. Thus we find the form through a concept which, in contrast to what the senses grasp in detail, is something universal.

Now, in the sense of Aristotle, we can distinguish this universal in a properly epistemological sense in precisely three ways. One can say that this universal is the essential, that which matters. But is that which lives in human thinking the same as that which we address in the true sense as form? No. Man approaches the various wolves and forms the concept, a universal, from the individual wolves. But what he has formed there as a concept that summarizes the same qualities is only a “representative” of the true universal. (All this can only be sketchily indicated.) So that one can distinguish: A universal that is before the details that confront us externally; then, because it is the essence within, a universal that lies within things; and a third form of the universal that man forms in thought afterwards. Thus there are: 1) universalia ante rem, 2) universalia in re, 3) universalia post rem. The latter unfold in the subjective mind and are the inner experiences “representing the objective real universals”.

Unless one addresses the threefold distinction, one cannot arrive at a correct understanding of what is important here. For consider what is involved! It is the insight that man, insofar as he lives within the universalia post rem, has a subjective element. But at the same time something essential is pointed out, namely that the concept of man is a “representation” of what has universal existence as real forms (entelechies). And these - the universalia in re, have in turn only flowed into things because they already existed before things as universalia ante rem.

There we have as universalia ante rem that which we must assume to exist first in the Godhead, in the wisdom of God. As a Christian theologian, as a scholastic, we understand it in a similar way, except that we do not go right up to the highest divine. As theosophists, we know that the universalia in re, for example when it comes to animals, mean their group soul, and so we do indeed have in Aristotelianism a foundation for what can really support theosophy conceptually. But there is something else to all that we encounter in Aristotle that has become increasingly unpopular in modern times: it is necessary to be comfortable thinking in sharp, finely chiseled concepts, in concepts that one first prepares for oneself; it is necessary to have the patience to proceed from concept to concept; it is necessary, above all, to have a tendency towards conceptual purity and cleanliness, to know what one is talking about when one uses a concept. If, for example, one speaks in the scholastic sense of the relationship of the concept to what it represents, one must first work through long definitions in the scholastic writings. You have to know what it means when you say that the concept is formally grounded in the subject and fundamentally grounded in the object: what the concept has as its actual form comes from the subject, what it has as its content comes from the object - that is just a small sample. Really only a small one. If you go through scholastic works, you have to wade through thick volumes of definitions, and that is very unpleasant for today's scientist; he therefore regards the scholastics as school foxes and dismisses them as such. He does not even know that true scholasticism is nothing other than the thorough elaboration of the art of thought, so that it can form a foundation for the real comprehension of reality.

As I say this, you will feel that it is a great blessing when efforts emerge within the Theosophical Society that are aimed in the very best (epistemological) sense at an elaboration of epistemological principles. And if we have a worker of extraordinary importance in this field here in Stuttgart (Doctor Unger), then this is to be regarded as a beneficial current within our movement. For this movement in its deepest parts will not achieve its validity in the world through those who only want to hear the facts of the higher world, but through those who have the patience to penetrate into a thought technique that creates a real basis for truly solid work, that creates a skeleton for work in the higher world.

[We should not only want to receive interesting and new thoughts from Theosophy, but also, which is admittedly not so convenient, work on the correct foundation of our own conceptual technique]. In this way, it will perhaps only be understood within the Theosophical movement and from within Theosophy itself what scholasticism, which has been turned into a distorted image by its followers and opponents, actually wanted. It is of course more convenient to want to understand everything that confronts us as a higher reality with a few concepts that we bring with us than to create a solid foundation in the conceptual technique - but what are the consequences of this? There is an unfortunate impression when you pick up philosophical books today. People no longer understand each other when they talk about higher things; they are not clear about how they use the terms. This could not have happened in scholastic times, because back then you had to be clear about the contours of a concept.

[Nowadays, the correct use of concepts has been completely lost, and the concepts themselves only have blurred contours. If one had once proceeded in a straight line along the path that Aristotle had uncovered, one would always have had a correct technique of thought, but in the end one had to become entangled in Kant's web of concepts. Then the gap between knowledge and belief would never have arisen.

You see, there was indeed a way to penetrate the depths of the technique of thought. And if this path had been taken further, if we had not allowed ourselves to be caught up in Kant's web of the “thing-in-itself” and the mental image, which is supposed to be subjective, then we would have achieved two things: firstly, we would have arrived at an epistemology that is secure in itself, and secondly - and this is of great importance - we would not have been able to misunderstand so completely those great philosophers in the authoritative circles who worked after Kant. There follows, for example, the trio of Fichte, Schelling and Hegel. What are they to people today? They are thought to be philosophers who wanted to spin a world out of purely abstract concepts. That never occurred to them. But they were trapped in Kant's concepts and therefore they could neither philosophically nor objectively understand the world's greatest philosopher. You know, he is the one who spent his youth in the house opposite, as can be seen from the memorial plaque that you can see when you enter the street here: Hegel. Only gradually will you mature to understand what he gave to the world; only then will you be able to understand him, when you come out of the theoretically spun, constricting web of knowledge. And that would be so easy! One would only have to be comfortable with natural, unbiased thinking and free oneself from the habits of thought that have developed in philosophical literature under the influence of the clouded currents of Kantianism. We must be clear about the question: Is it really the case that man starts from the subject, builds his mental image in the subject and then spins this image over the object? Is that really the case? Yes, it is. - But does it necessarily follow that man can never penetrate the thing itself?12. Philosophy and Theosophy

Let me make a simple comparison. Imagine you have a seal with the name Müller on it. Now you press the seal into a sealing wax and take it away. Don't you realize that if this seal is made of, say, brass, none of the brass will pass into the sealing wax? Now if this sealing wax were cognitive in Kant's sense, it would say: “I am all lacquer, nothing comes into me from the brass, so there is no relationship that I could know about the nature of what confronts me.” But this completely forgets the fact that what matters, namely the name Müller, is objectively inside the sealing wax as an imprint, without anything having passed over from the brass. As long as one thinks materialistically and believes that, in order to establish relationships, matter must pass from one to the other, one will also say theoretically: “I am sealing wax, and the other is brass in itself; and since nothing can enter into me from the ”brass in itself", the name Müller can also be nothing other than a sign. But the thing in itself, which was inside the seal, which has imprinted itself on me so that I can read it: That remains eternally unknown to me." There you see the final formula that is used. If you take the comparison further, the result is: Man is all sealing wax (mental image), the thing itself is all petals (that which is outside the mental image). Because I, as the varnish (the imaginer), can only reach the limit of the petshaft (the thing in itself), I remain within myself, nothing of the thing in itself comes over into me. As long as materialism is extended to epistemology, we will not find out what is important. The preliminary proposition applies: we do not get beyond our mental image; but what comes over is to be called spiritual; it does not need material atoms to let it over. Nothing of a material nature enters into the subject - but nevertheless the spiritual comes over into the subject, as true as the name Müller into the sealing wax. A healthy epistemological research must be able to start from this again, then one will see how much modern materialism itself has become naturalized in the epistemological concepts without being noticed. Nothing else follows from an unbiased consideration of the situation than that Kant can only imagine a “thing-in-itself” materially, however grotesque such an assertion may seem at first glance.

Now, however, if we want to consider the matter completely, we need to outline something else. We have said that Aristotle pointed out that in everything that is around us it is necessary to distinguish between what is form (entelechy) and what is matter. Now we can say that in the process of cognition we arrive at form in the sense that has just been described. But is it also possible to get as far as the material? It should be noted that Aristotle understands the material to mean not only the material, but also the substance, that which also underlies reality as the spiritual. Is it possible not only to grasp what flows across, but also to crawl into things, to identify with matter? This question is also important for epistemology. It can only be answered by those who have immersed themselves in the nature of thinking, of pure thinking. One must first rise to this concept of pure thinking. According to Aristotle, we can describe pure thinking as actuality. It is pure form, it is initially, as it appears, without content in relation to the immediate individual things in sensory reality outside. Why? Let's take a look at how the pure concept arises in contrast to perception.

Imagine that you want to form the concept of a circle. You can do this, for example, if you go out to sea until you see nothing but water all around you; then you have formed the mental image of a circle through perception. But there is another way to arrive at the concept of a circle, namely by saying to yourself, without appealing to the senses, the following: I construct in my mind the sum of all places that are equidistant from a point. In order to form this construction, which takes place entirely within the life of thought, you do not need to appeal to anything external: This is absolutely pure thinking in the sense of Aristotle, pure actuality.

But now something special is added. Those pure thoughts that are formed in this way fit in with experience. Without them, experience cannot even be understood. Just think, for example, when Kepler works out a system through pure conceptual construction that shows elliptical orbits for the planets, with the sun at a focal point, and when one then states through the telescope that the observation corresponds to the pure conceptual image formed before the experience! It then becomes apparent to any unbiased mind that what arises as pure thought is not meaningless for reality because it corresponds to reality. A researcher like Kepler illustrates through his method what Aristotelianism has established in terms of epistemology. He grasps what belongs to the universals post rem and, when he approaches things, finds that these universalia post rem have previously been placed in them as universalia ante rem. Now, if the universals are not made into mere subjective mental images in the sense of a perverse theory of knowledge, but are shown to be found objectively in things, they must first have been put into the form which Aristotle assumes to underlie the world.

So you find that what is first the most subjective, what is established independently of experience, is precisely what leads most objectively into reality. What, then, was the reason why the subjective of the mental image could not come out into the world at first? The reason was that it came up against a “thing in itself”. When man constructs a circle, he does not come up against a thing in itself, he lives in the thing itself, even if initially only formally.

Now the next question is: do we arrive at any reality at all from such subjective thinking, at something permanent? And now it is a matter of the fact that, as we have characterized, the subjective is initially, precisely constructed in thinking, formal, that it initially looks like something added to the objective. Certainly, we can say: basically, a circle or a sphere in the world is completely indifferent to whether I think it or not. My thought, which is added to reality, is completely indifferent to the world of experience around us. This exists in itself, independently of our thinking. It is therefore possible that although our thinking is an objectivity for us, it is none of our business. How do we get beyond this apparent contradiction? Where is the other pole that we must now grasp? Where is there a way within pure thinking to create not only form, but also reality with form? As soon as we have something that generates reality at the same time as form, then we can connect to a fixed point in terms of epistemology. We are everywhere, for example when we construct a circle, in the special case that we say: What I say about this circle is objectively correct - whether it is applicable to things depends on the fact that when I encounter things, they show me whether they carry the laws that I have constructed. If the sum of all entelechies dissolves in pure thinking, then a remainder must remain, which Aristotle calls matter, if it is not possible to arrive at a reality from pure thinking itself.

Aristotle can be supplemented here by Fichte. In Aristotle's sense, one can first arrive at the formula: Everything that is around us, including that which belongs to invisible worlds, makes it necessary for us to counter the formal of entelechy with a material. - For Aristotle, the concept of God is a pure actuality, a pure act, that is, an act in which the actuality, i.e. the formation, simultaneously has the power to produce its own matter, not to be something that is opposed by matter, but something that in its pure activity is itself matter.

The image of this pure actuality is now found in man himself when he comes to the concept of the “I” from pure thinking. There he is in the ego with something that Fichte calls action. He comes to something within himself which, by living in actuality, simultaneously produces its matter with this actuality. If we grasp the I in pure thought, then we are in a center where pure thinking at the same time essentially produces its material being. If you grasp the ego in thinking, there is a threefold ego: a pure ego that belongs to the universals “ante rem”, an ego in which you are inside, which belongs to the universals “in re”, and an ego that you comprehend, which belongs to the universals “post rem”. But there is something else very special here: For the ego, it is the case that when one rises to a real grasp of the ego, these three “egos” coincide. The ego lives in itself by producing its pure concept and can live in the concept as reality. For the ego it is not indifferent what pure thinking does, because pure thinking is the creator of the ego. Here the concept of the creative coincides with the material, and we need only recognize that in all other cognitive processes we initially come up against a limit, except in the case of the ego: we encompass it in its innermost essence by grasping it in pure thinking.

This is the epistemological foundation for the proposition that even in pure thinking a point can be reached where reality and subjectivity are in complete contact, where the human being experiences reality. - If he starts there and fertilizes his thinking in such a way that his thinking in turn emerges from there, then he grasps things from within. There is therefore something present in the I, which is grasped through a pure act of thinking and thus created at the same time, through which we penetrate the boundary that must be set for everything else between entelechy (form) and matter.

Thus, such a theory of knowledge, which proceeds thoroughly, becomes something that also shows the way to enter reality in pure thinking. If you follow this path, you will find that you have to get into theosophy from there. Very few philosophers have an understanding of this path. They have spun themselves into a self-made web of concepts; they can also, because they know the concept only as something abstract, never grasp the single point where it is archetypally creative; they can therefore also find nothing through which they could connect with a “thing in itself”. You see what is necessary before the philosophers will come to realize that the theosophists are not mere dilettantes. It is necessary that the philosophers first have the philosophy that there is a philosophy that really goes into the foundations. It is not the case that philosophy contradicts theosophy, but rather that philosophers do not understand philosophy. They know nothing of the deeper foundations of philosophy, they are blinded, caught up in an epistemological aberration from which they cannot escape. Once they come out, they will also find their way to theosophy. Theosophy is not so much dilettantish for philosophers (because they just can't understand it); what is dilettantish is rather that which today often dominates the world as philosophy. Once this philosophy is able to think professionally, then the bridge will be built between philosophy and theosophy.

Philosophie und Theosophie

Nachdem wir eine lange Reihe von rein theosophischen Vorträgen hinter uns haben, wollen wir heute einmal sozusagen aus einem anderen Ton heraus sprechen, [einmal von einem ganz anderen Gesichtspunkte aus reden, nämlich mehr vom philosophischen]. Daher bitte ich Sie, von vornherein darauf Rücksicht nehmen zu wollen, dass der heutige Vortrag nicht im eigentlichen Sinne theosophisch ist, und dass der rein philosophische Ton, der angeschlagen werden muss, für manchen, der nicht gewöhnt ist, sich in solchen Denkrichtungen zu bewegen, etwas abstrakt und schwierig erscheinen kann. Es geschieht das aus einem ganz bestimmten Grunde; es geschieht, weil immer wieder und wieder, und gerade in denjenigen Kreisen, die eine gewisse philosophische Bildung haben oder zu haben glauben, die Meinung auftauchen muss (ich wähle ausdrücklich das Wort «muss»), Theosophie sei eigentlich nur zu billigen von Menschen, welche es in philosophischen oder wissenschaftlichen Dingen über einen gewissen Dilettantismus nicht hinausgebracht haben. Derjenige aber, so könnte man leicht in diesen Kreisen denken, der eine gründliche philosophische Bildung hat, der kennengelernt hat, welches die Grundlagen einer wissenschaftlichen Sicherheit und Überzeugung sind, der könne sich mit all der Phantasterei, mit all dem, was einem da als angeblich höhere Erfahrung entgegentritt, eigentlich gar nicht befassen; das sei etwas für solche, die noch nicht reif für wissenschaftliches Denken sind. Um nun zu erkennen, was cs eigentlich mit einem solchen Urteil auf sich hat, wollen wir uns sozusagen die philosophische Betätigung selbst einmal anschauen. Natürlich kann das heute nur ganz kurz geschehen, nur in Andeutungen [und skizzenhaft, denn streng und ausführlich bewiesen]; aber wenn wir einmal Gelegenheit haben werden, ausführlicher über solche Dinge zu sprechen, dann werden Sie sehen, dass diese Andeutungen aus einem großen [und wahrhaftigen] Zusammenhange herausgenommen sind [, was bei genauerer Prüfung leicht ersichtlich ist].

Philosophie wird gemeiniglich von denjenigen, die sie treiben, als etwas Absolutes angesehen, nicht als etwas, was erst im Laufe der Menschheitsentwicklung hat entstehen müssen. Gerade der Philosophie gegenüber ist man imstande, auch aus äußerlichen historischen Dokumenten anzugeben, wann sie als solche ihren Ursprung innerhalb der Menschheitsevolution genommen hat und nehmen musste. Das haben auch die meisten, namentlich älteren Darsteller der Philosophie-Geschichte ziemlich gut getroffen. In allen diesen Darstellungen werden Sie finden, dass mit dem Thales begonnen wird und dass von ihm dann fortgeschritten wird bis in unsere Zeit herein.

Allerdings haben einige neuere Philosophie-Geschichtsschreiber, die ganz besonders vollständig und ganz besonders gescheit sein wollten, den Anfang der Philosophie in noch frühere Zeiten verlegt und allerlei aus früheren Weisheitslehren hereingezogen. Aber das ist alles entsprungen aus einer ganz bestimmten Form des Dilettantismus, der nicht weiß, dass alles, was in Indien, Ägypten und Chaldäa an Weisheitslehren vorangegangen ist, auch methodisch einen ganz anderen Ursprung hat als das rein philosophische, dem Spekulativen zuneigende Denken. Dieses hat sich erst in der griechischen Welt entwickelt; und der Erste, welcher da in Betracht kommt, ist wirklich erst Thales. Wir brauchen gar nicht erst eine Charakteristik der verschiedenen griechischen Philosophen von Thales ab, nicht von Anaxagoras, Heraklit, Anaximenes , auch nicht von Sokrates und Platon; wir können gleich anknüpfen an diejenige Persönlichkeit, die eigentlich zu allererst als der Philosoph katexochen dasteht, und das ist Aristoteles.

[Alles andere vor ihm ist entweder direkt aus den Mysterien hervorgegangen, oder doch mit ihnen in enger Beziehung stehend.] Alle anderen Philosophien sind im Grunde genommen noch durch Mysterienweisheit angeregte Abstraktionen; für Thales und Heraklit ließe sich das zum Beispiel leicht nachweisen. Aber Philosophen im eigentlichen Sinne des Wortes sind auch noch nicht einmal Platon oder Pythagoras, die beide ihre Quellen im Sehertum haben. Denn nicht darauf kommt es an, wenn wir die Philosophie als solche charakterisieren, dass irgendjemand sich in Begriffen ausdrückt, sondern wo seine Quellen sind, darauf kommt es an. Pythagoras hat als Quellen die Mysterienweisheit und hat diese in Begriffe umgewandelt; er ist Hellseher, nur hat er das, was er als Scher erfahren, in philosophische Form gebracht, und dasselbe ist auch bei Platon der Fall.

Was aber den Philosophen ausmacht, und was uns gerade erst bei Aristoteles entgegentritt, ist, dass er aus der reinen Begriffstechnik heraus arbeitet und dass er andere Quellen notwendig ablehnen muss oder sie ihm unzugänglich sind. [Aristoteles ist im eminentesten Sinn Philosoph, weil er mit der bloßen Begriffstechnik das reine Denken herausarbeitete.] Und weil das erst bei Aristoteles der Fall ist, deshalb ist es auch nicht ohne welthistorischen Grund, dass eben er es ist, der die Logik, die Wissenschaft der Denktechnik, begründet hat. Alles andere ist nur Vorläufertum gewesen. Die Art und Weise, wie man Begriffe bildet, Urteile formt, Schlüsse zicht, das alles hat erst Aristoteles als eine Art Naturgeschichte des subjektiven menschlichen Denkens gefunden, und alles, was uns bei ihm entgegentritt, ist mit dieser Grundlegung der Denktechnik eng verknüpft. Da wir noch auf einiges zurückkommen werden, was bei ihm fundamental wichtig ist für alle späteren Betrachtungen, so bedarf es jetzt nur dieser historischen Andeutung, um den Ausgangspunkt kurz zu charakterisieren.

Aristoteles bleibt auch für die spätere Zeit der tonangebende Philosoph. Seine Leistungen flossen nicht nur ein in die nacharistotelische Zeit des Altertums bis zur Begründung des Christentums, sondern gerade in der ersten christlichen Zeit bis hinein in das Mittelalter war er derjenige Denker, nach dem man sich bei der Ausarbeitung aller Weltanschauungsbestrebungen richtete. Damit soll nicht gesagt werden, dass man etwa, namentlich im Mittelalter, wo man nicht die Urtexte hatte, den Aristoteles als System, als eine Summe von Dogmen vor sich gehabt hatte; aber man hatte sich eingelebt in die Art, wie man an der Leiter der reinen Begriffstechnik zu einem Wissen, bis hinauf zum höchsten göttlichen Wissen, kommt. Und so kam es, dass Aristoteles immer mehr und mehr der logische Lehrer wurde. Man sagte sich im Mittelalter etwa so: Möge die positive Tatsachenerkenntnis der Welt wo immer herkommen, möge sie daher kommen, dass der Mensch mit seinen Sinnen die äußere Wirklichkeit untersucht oder dass eine Offenbarung durch göttliche Gnade stattfindet wie durch den Christus Jesus - so sind das Dinge, die einfach hinzunehmen sind, auf der einen Seite als Aussagen der Sinne, auf der andern als Offenbarung. Will man aber etwas in dieser oder jener Art Gegebenes durch reine Begriffe begründen, dann muss man es mit jener Denktechnik tun, die Aristoteles begründet.

[Besonders in der Frühscholastik waren die Logik und zum Teil auch die eigentlichen Lehren des Aristoteles aktuell.] Und in der Tat, die Begründung der Denktechnik ist von Aristoteles so bedeutsam geleistet worden, dass Kant, und zwar mit Recht, gesagt hat, dass seit Aristoteles die Logik eigentlich um keinen einzigen Satz fortgeschritten sei. Und im Grunde genommen gilt das im Wesentlichen auch noch für heute; auch heute ist der Grundstock logischer, denktechnischer Lehren ziemlich unverändert geblieben gegenüber dem, was Aristoteles gegeben hat. Das, was man heute hinzufügen will, entspringt aus einem ziemlich dilettantischen Verhalten gegenüber dem Begriffe der Logik, auch in philosophischen Kreisen.

Nun wurde nicht bloß etwa das Studium des Aristoteles, sondern vor allen Dingen das Sichhineinfinden in seine Denktechnik aktuell für die mittlere Zeit des Mittelalters, für die frühscholastische Zeit, wie man sie auch nennen könnte, wo die Scholastik in der Blüte stand. Diese Zeit fand ja in Bezug auf ihre Blüte ihren Abschluss durch Thomas von Aquin im dreizehnten Jahrhundert. Wenn man von dieser frühscholastischen Zeit spricht, muss man sich klar darüber sein, dass man heute nur dann philosophisch darüber sprechen kann, wenn man frei von aller Autorität und allem Dogmenglauben ist. Es ist ja heute fast schwerer, rein objektiv als abfällig über diese Dinge zu sprechen. Wenn man abfällig über die Scholastik spricht, kommt man nicht in die Gefahr, von den sogenannten freien Geistern verketzert zu werden; spricht man aber objektiv darüber, so liegt die Wahrscheinlichkeit nahe, missverstanden zu werden, und zwar deshalb, weil man sich heute innerhalb der positiven und gerade der intolerantesten Kirchenbewegung vielfach ganz missverständlich auf die Thomistik beruft.

Was heute als orthodox-katholische Philosophie gilt, das alles darf uns nicht berühren; aber ebenso wenig darf uns abschrecken, dass uns der Vorwurf gemacht werden könnte, wir pflegten dasselbe, was von dogmatischer Seite getrieben und anbefohlen wird. Wir wollen vielmehr, unbekümmert um alles was von rechts und links sich geltend machen kann, einmal charakterisieren, welche Empfindung die Blütezeit der Scholastik in Bezug auf die Wissenschaft, die Denktechnik und die übernatürliche Offenbarung hatte.

Die Frühscholastik ist nicht das, als was man sie gewöhnlich heute mit einem Schlagwort charakterisieren möchte; sie ist im Gegenteil Monismus, Einheitslehre - nicht im Entferntesten ist sie dualistischer Natur. Der Urgrund der Welt ist für sie ein durchaus einheitlicher; nur hat der Scholastiker in Bezug auf das Erschauen dieses Urgrundes eine bestimmte Empfindung. Er sagt: Es gibt ein gewisses übersinnliches Wahrheitsgut, ein Weisheitsgut, das zunächst der Menschheit offenbart worden ist; das menschliche Denken mit all seiner Technik ist nicht so weit, um aus sich selbst in die Regionen zu dringen, deren Wesenheit der Inhalt der höchsten geoffenbarten Weisheit [ist]. Daher besteht für den Früh-Scholastiker ein gewisses Weisheitsgut, das zunächst der Denktechnik nicht zugänglich ist [; indessen reicht diese doch bis hart an die Grenze jener Offenbarungen]. - Nur insofern ist es ihr zugänglich, als der Gedanke imstande ist, das, was geoffenbart wurde, zu verdeutlichen.

Für diesen Teil des Weisheitsgutes obliegt also dem Denker, es als geoffenbartes hinzunehmen; und die Denktechnik nur zu seiner Verdeutlichung zu verwenden. Was der Mensch aus sich selbst finden kann, bewegt sich nur in gewissen untergeordneten Regionen der Wirklichkeit. Für diese wendet der Scholastiker die Denktätigkeit auf die eigene Forschung an. Er dringt da bis zu einer gewissen Grenze, an der ihm die geoffenbarte Weisheit begegnet. So schließen sich die Inhalte der eigenen Forschung und der Offenbarung zu einer objektiv einheitlichen monistischen Weltanschauung zusammen. Dass dabei eine Art von Dualismus, durch die menschliche Eigentümlichkeit geboten, in die Sache hineinkommt, ist nur sekundär. Es handelt sich um einen Dualismus der Erkenntnis, nicht um einen solchen der Weltgründe.

Der Scholastiker erklärt also die Denktechnik geeignet, dasjenige, was in der empirischen Wissenschaft, in der Sinnesbeobachtung gewonnen wird, rationell zu bearbeiten, ferner auch ein Stück hinaufzudringen bis zur spirituellen Wahrheit. Und dann stellt der Scholastiker in Bescheidenheit ein Stück der Weisheit als Offenbarung hin, die er nicht selbst finden kann, die er nur hinzunehmen hat.

Was nun aber der Scholastiker als diese besondere Denktechnik anwendet, das ist durchaus aus dem Boden aristotelischer Logik entsprungen. Es gab für die Frühscholastik, die etwa mit dem dreizehnten Jahrhundert sich ihrem Abschluss nähert, eine zweifache Notwendigkeit, sich mit Aristoteles zu befassen. Die eine Notwendigkeit war in der geschichtlichen Entwicklung gegeben: Der Aristotelismus hatte sich eben eingelebt. Die andere Notwendigkeit war die Folge davon, dass dem überlieferten christlichen Lehrgut nach und nach von einer anderen Seite ein Gegner erstanden war.

Aristoteles hatte nämlich nicht nur im Abendlande seine Verbreitung gefunden, sondern auch im Morgenlande; und alles, was durch die Araber über Spanien nach Europa gebracht war, war in Bezug auf die Denktechnik durchtränkt von Aristotelismus. Namentlich war es eine gewisse Form der Philosophie, der Naturwissenschaft, bis in die Medizin hineinreichend, was da herübergebracht war und was im eminentesten Sinne von aristotelischer Denktechnik durchdrungen war. Nun hatte sich von dort her die Meinung gebildet, dass gar nichts anderes als Konsequenz aus Aristoteles folgen könne als eine Art von Pantheismus, der namentlich in der Philosophie aus einer sehr verschwommenen Mystik herausgekommen war. Man hatte also außer dem einen Grunde, dass nämlich Aristoteles in der Denktechnik fortgelebt hatte, noch einen andern, sich mit ihm zu befassen: In der Auslegung der Araber erschien Aristoteles als Gegner, als Feind des Christentums.

[Was die Araber an falscher Mystik und überhaupt an pantheistischen Lehren besaßen, suchten sie mit dem Aristoteles zu stützen. Da musste man sich in der Scholastik doch fragen, ob denn tatsächlich jenes der wahre Aristoteles sei, der von den Arabern nach Europa importiert wurde.] Man musste sich sagen: Wenn das, was die Araber als Interpretation des Aristoteles herübergebracht haben, wahr ist, dann wäre der Aristotelismus eine wissenschaftliche Grundlage, die dazu geeignet wäre, das Christentum zu widerlegen. Nun stellen wir uns vor, was mussten demgegenüber die Scholastiker empfinden? Auf der einen Seite hielten sie fest an der Wahrheit des Christentums, auf der anderen aber konnten sie nach aller Tradition nicht anders, als eingestehen, dass die Logik, die Denktechnik des Aristoteles, die wahre, die richtige sei. Aus diesem Zwiespalt heraus ergab sich für die Scholastiker die Aufgabe: zu beweisen, dass man die Logik des Aristoteles anwenden könne, seine Philosophie treiben könne, und dass man gerade durch ihn das Instrument habe, das Christentum wirklich zu begreifen und zu verstehen. Es war eine Aufgabe, die durch die Zeitentwicklung gestellt war. Es musste der Aristotelismus so behandelt werden, dass ersichtlich wurde: Was als Lehre des Aristoteles von den Arabern gebracht worden war, ist dann nur eine missverständliche Auffassung desselben, wenn es dem Christentum feindlich sich erweist. Dass man es nur richtig deuten müsse, um in ihm das Fundament für das Begreifen des Christentums zu haben: Das war die Aufgabe, die sich die Scholastik stellte und der das gesamte Schrifttum des Aquinaten gewidmet war. [Daher war es nötig darzulegen, dass man gerade aus dem richtig verstandenen Aristoteles heraus die christlichen Lehren stützen könne. Nur so konnte man wirksam ankämpfen gegen den vom Morgenland kommenden halben Materialismus und verschwommenen Pantheismus.]

Nun aber geschieht etwas anderes. Im Laufe der Entwicklung tritt nach der Blütezeit der Scholastiker in der ganzen logischen philosophischen Denkentwicklung der Menschheit ein völliger Bruch ein. Das Natürliche wäre gewesen (aber das soll keine Kritik sein, nicht einmal soll damit gesagt sein, dass es überhaupt nur hätte geschehen können; der tatsächliche Verlauf war eben notwendig - nur hypothetisch soll das Folgende hingestellt werden), das Natürliche wäre gewesen, dass man die Denktechnik immer mehr ausgedehnt hätte, dass man immer höhere und höhere Teile der übersinnlichen Welt durch das Denken ergriffen hätte. So war aber die Entwicklung zunächst nicht.

Der Grundgedanke, der zum Beispiel für Thomas von Aquino zunächst für die höchsten Gebiete galt und welcher hätte durchaus sich so entwickeln können, dass die Grenze der menschlichen Forschung sich immer mehr nach oben in das übersinnliche Gebiet hätte erweitern können, wurde bis zur Karikatur verzerrt und lebte nun weiter in der Überzeugung: Die höchsten spirituellen Wahrheiten entziehen sich ganz und gar der rein menschlichen Denktätigkeit, der Ausarbeitung in Begriffen, zu denen es der Mensch aus sich selbst heraus bringen kann. Dadurch ist ein Riss im menschlichen Geistesleben eingetreten. Man stellte die übersinnliche Erkenntnis als etwas hin, das sich jeder menschlichen Denkarbeit absolut entziehe, das nicht durch subjektive Akte der Erkenntnis zu erreichen sei, das nur einem Glauben entspringen müsse. [Höchstens noch mit einer Art gefühlsmäßiger Überzeugung, mit bloßem Glauben, kann man sich jenen Gebieten nähern. Dieser so geöffnete Abgrund zwischen Glauben und Wissen nun ward ein mächtiger Impuls für spätere Zeiten.] Veranlagt war das schon früher, zum Extrem getrieben wurde es gegen das Ende des Mittelalters. Es wurde immer mehr herausgearbeitet die Scheidung zwischen dem Glauben, der durch eine subjektive Gefühlsüberzeugung erreicht werden muss, und dem, was als Grundlage eines sicheren Urteils durch logische Tätigkeit bearbeitet werden kann.

Und es war nur natürlich, dass, nachdem dieser Abgrund sich einmal aufgetan hatte, Wissen und Glauben immer mehr auseinandergedrängt wurden. Und natürlich war es auch, dass man Aristoteles und seine Denktechnik hineinzog in diesen Riss, der sich durch die historische Entwicklung aufgetan hatte. Insbesondere wurde er im Beginne der Neuzeit hineingezogen. Da sagte man auf der Seite der Wissenschafter - und vieles von dem, was sie sagten, können wir als begründet ansehen: Mit dem bloßen Fortspinnen des schon bei Aristoteles Gegebenen kann man doch keine Fortschritte in der empirischen Wahrheitsforschung machen. Außerdem gestaltete sich die geschichtliche Entwicklung so, dass es misslich wurde, mit den Aristotelikern eine Vereinigung zu haben, ja als die Zeit des Kepler und [des] Galilei heraufkam, da war der missverstandene Aristotelismus eine wahre Landplage geworden.

Es kommt ja immer wieder vor, dass die Nachfolger, die Bekenner einer Weltanschauung, ungemein viel von dem verderben, was die Begründer durchaus richtig hingestellt haben. Statt in die Natur selbst hineinzuschauen, statt zu beobachten, fand man es am Ende des Mittelalters bequem, die alten Bücher des Aristoteles zu nehmen und bei allen akademischen Vorlesungen das Geschriebene des Aristoteles zugrunde zu legen. [Der Aristoteles galt mehr als die direkte Beobachtung.] Charakteristisch dafür ist, dass ein orthodoxer Aristoteliker aufgefordert wurde, sich an einer Leiche zu überzeugen, dass nicht, wie er missverständlich aus Aristoteles herausgelesen hatte, die Nerven vom Herzen ausgehen, sondern dass das Nervensystem sein Zentrum im Gehirn habe. Da sagte der Aristoteliker: «Die Beobachtung zeigt mir, dass sich das wirklich so verhält, aber im Aristoteles steht das Gegenteil, und dem glaube ich mehr.» So waren die Aristoteliker in der Tat eine Landplage geworden. Und darum musste die empirische Wissenschaft aufräumen mit diesem falschen [falsch verstandenen] Aristotelismus und [um überhaupt wieder Fortschritte zu erzielen] sich auf die reine Erfahrung berufen, wie wir das besonders stark als Impuls gegeben sehen bei dem großen Galilei.

Auf der andern Seite entwickelte sich etwas anderes. Bei denen, die sozusagen den Glauben vor einem Einbruch des nun auf sich selbst gestellten Denkens schützen wollten, bei denen entwickelte sich eine Aversion, eine Abneigung gegen die Denktechnik. Sie waren der Meinung, dass diese Denktechnik ohnmächtig sei gegenüber dem geoffenbarten Weisheitsgut. Wenn die weltlichen Empiriker sich auf das Buch des Aristoteles beriefen, so beriefen sich die andern auf etwas, was sie - freilich in missverständlicher Weise - einem andern Buche, der Bibel, entnommen hatten. Das sehen wir am stärksten im Beginn der Neuzeit zum Ausdruck gebracht, wenn wir die harten Worte Luthers hören: «Die Vernunft ist die stockblinde, taube Närrin», die nichts zu schaffen haben soll mit den spirituellen Wahrheiten; und wenn er weiter behauptet, dass die reine Glaubensüberzeugung niemals in richtiger Weise aufdämmern kann durch das vernünftige Denken, das sich auf Aristoteles stützt. Diesen nennt er «einen Heuchler, einen Sykophanten, einen stinkenden Bock». Das sind, wie gesagt, harte Worte, aber vom Standpunkte der neuen Zeit erscheinen sie uns begreiflich; es hatte sich eben eine tiefe Kluft aufgetan zwischen der Vernunft und ihrer Denktechnik einerseits und der übersinnlichen Wahrheit anderseits.

Einen letzten Ausdruck hat diese Kluft in einem Philosophen gefunden, unter dessen Einfluss sich das neunzehnte Jahrhundert in einem Netz gefangen hat, aus dem es schwer wieder herauskommen kann: in Kant. Er ist im Grunde genommen der letzte Ausläufer jener durch den mittelalterlichen Riss hervorgebrachten Spaltung. Er trennt streng den Glauben und dasjenige, was der Mensch durch das Wissen erreichen kann. [Er unternahm eine völlige Trennung rein theoretischer und praktischer Vernunft, wobei letztere durchaus auf dem bloßen Glaubensstandpunkt steht, während in der theoretischen Vernunft nur denktechnische Dinge eine Rolle spielen, die aber niemals zur Wirklichkeit und Wesenheit, zum «Ding an sich» gelangen können. Der Mensch bleibt immer im Subjektiven stecken, an das wahrhaft objektive Denken kann er nicht herantreten. Das ist der Fundamentalirrtum der Kant’sehen Philosophie.]

Schon äußerlich steht die «Kritik der reinen Vernunft» neben der «Kritik der praktischen Vernunft», und die praktische Vernunft versucht, einen, wenn auch rationalistischen, Glaubensstandpunkt zu gewinnen gegenüber dem, was man Wissen nennen kann. Dagegen wird in der Kant’sehen theoretischen Vernunft in der extremsten Weise stigmatisiert, dass diese unfähig sei, das Wirkliche, das Ding an sich, zu begreifen. Das Ding an sich mache zwar Eindrücke auf den Menschen, aber dieser könne nur in seinen Vorstellungen, in seinen eigenen Begriffen leben. Nun müssten wir eigentlich tief in die Geschichte der Kant’sehen Philosophie hineingehen, wenn wir den verwüstenden Fundamental-Irrtum Kants charakterisieren wollten; aber das würde uns zu weit von unserer Aufgabe entfernen. - Sie finden übrigens das Nötige darüber in meiner «Wahrheit und Wissenschaft».

Für heute interessiert uns vielmehr etwas anderes, nämlich das Netz, in dem sich das philosophische Denken des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts gefangen hat. Wir wollen einmal untersuchen, wie das zustande gekommen ist. Kant hatte vor allen Dingen das Bedürfnis, zu zeigen, inwiefern in dem Denken etwas Absolutes vorliege, etwas, in dem es keine Unsicherheit geben könne. Alles aber, was aus der Erfahrung stammt, sagte er, das ist kein Sicheres. Die Sicherheit kann unserm Urteil nur dadurch gegeben werden, dass ein Teil der Erkenntnis nicht von den Dingen, sondern von uns selbst stammt. Wir sehen nun im Kant’sehen Sinne in unserer Erkenntnis die Dinge wie durch ein gefärbtes Glas an; wir fangen in unserer Erkenntnis die Dinge in die gesetzmäßigen Zusammenhänge ein, die von unserer eigenen Wesenheit herrühren. Unsere Erkenntnis hat gewisse Formen - die Raumform, die Zeitform, die Kategorie von Ursache und Wirkung -, die haben für das Ding an sich keine Bedeutung, wenigstens kann der Mensch nichts davon wissen, ob das Ding an sich in Raum, Zeit oder Kausalität existiert. Das sind Formen, die nur aus dem Subjekt des Menschen entspringen, und die der Mensch in dem Augenblicke über das «Ding an sich» spinnt, in dem dies letztere an ihn herantritt, sodass ihm das Ding an sich unbekannt bleibt. Wo also der Mensch diesem Ding an sich gegenübertritt, da umspinnt er es mit der Form des Raumes, der Zeit, fasst es in Ursache und Wirkung; und so legt der Mensch sein ganzes Netz von Begriffen und Formen über das Ding an sich hinüber. Deshalb gibt es ja für den Menschen eine gewisse Sicherheit der Erkenntnis, weil - so lange er ist, wie er ist - Zeit, Raum und Kausalität für ihn gelten: Was der Mensch selbst in die Dinge hineinschaut, das muss er wieder aus ihnen herausdröseln. Aber was das Ding an sich ist, kann der Mensch nicht wissen, denn er bleibt ewig in der Vorstellung befangen. Das hat Schopenhauer zum klassischen Ausdruck gebracht in dem Satze: «Die Welt ist meine Vorstellung».

[Ein Beispiel:

Der Mensch nun schaut mit seinen «Fühlhörnern» gleichsam das unbekannte «Ding an sich», ohne freilich je in dasselbe hineinzukommen. Er sieht immer nur seine am «Ding an sich» reflektierten Vorstellungen; er spinnt das «Ding an sich» förmlich in die Vorstellungsformen ein.]

Diese ganze Schlussfolgerung ist übergegangen in das gesamte Denken des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts; nicht bloß in die Erkenntnistheorie, sondern auch zum Beispiel in die theoretischen Grundlagen der Physiologie. Da kamen gewisse Erfahrungen zu Hilfe. Wenn man zum Beispiel auf die Lehre von den spezifischen Sinnesenergien blickt, so scheint in ihr eine Bestätigung der Kant’sehen Meinung zu liegen. Wenigstens hat man die Sache so im Laufe des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts angesehen. Man sagt so: Das Auge nimmt Licht wahr. Wenn man aber das Auge auf andere Weise affiziert, zum Beispiel durch Druck, durch elektrischen Impuls und so fort, so zeigt es auch Lichtwahrnehmung. Daher sagte man: Die Lichtwahrnehmung ist aus der spezifischen Energie des Auges heraus erzeugt und ist übergezogen über das Ding an sich. Insbesondere Helmholtz hat das in krasser Weise als physiologisch-philosophische Lehre zum Ausdruck gebracht, indem er sagt: Alles, was wir wahrnehmen, ist nicht einmal bildhaft ähnlich zu denken mit den Dingen, die außer uns sich befinden. Das Bild hat Ähnlichkeit mit dem, was es darstellt; aber das, was wir Sinnesempfindung nennen, das kann nicht einmal solche Ähnlichkeit mit dem Original haben, wie es das Bild mit seinem Original hat. Man kann daher, sagt er weiter, das, was der Mensch in sich erlebt, nicht anders ansprechen, denn als cin «Zeichen» des Dinges an sich. Ein Zeichen braucht ja nichts Ähnliches zu haben mit dem, was es ausdrückt.

Und das, was sich da lange vorbereitet hatte, das hat sich dann sozusagen eingefressen in das philosophische Denken unserer Zeit, sodass der Mensch unfähig wurde, etwas anderes zu begreifen, ja überhaupt nur zu denken, dass es auch anders sein könnte. So ist Eduard von Hartmann ganz unfähig gewesen, sich aus seinen Begriffsgespinsten herauszufinden. Es war zum Beispiel in einem Gespräch, das ich einmal Gelegenheit hatte, mit ihm zu führen, ganz unmöglich, darüber hinauszukommen, dass er sagte: Ja, wir müssen doch ausgehen von der Vorstellung, und wenn man die Vorstellung definiert, so muss man doch sagen, sie ist dasjenige, durch das der Mensch ein Nichtvorgestelltes sich zur Wahrnehmung bringt! Wenn aber die Vorstellung, von der wir doch ausgehen, etwas Subjektives ist, dann können wir doch auch nicht über das Subjektive hinauskommen.

Er hatte keine Ahnung davon, dass er sich diese Definition zuerst selbst zurechtgezimmert hatte und dann einem zurechtgelegten Begriffe nicht wieder entrinnen konnte. Und doch beruht sein ganzer «transzendentaler Realismus» darauf, dass er sich in etwas eingesponnen hat, was er selbst gemacht hat und von dem er annimmt, dass es eine objektive Wahrheit sei. Auf diese Weise kommt der Mensch niemals über das Urteil hinaus: Das, was ich im Vorstellen begreife, geht immer nur bis an die Grenze des Dinges an sich, es ist also nur subjektiv. - Diese Denkgewohnheit hat sich im Laufe der Zeit so fest eingelebt, dass alle diejenigen Erkenntnistheoretiker, die sich etwas darauf zugutetun, Kant zu verstehen, einen jeden für einen beschränkten Menschen halten, der nicht zugeben kann, dass ihre Definition von der Vorstellung und von der subjektiven Natur des Beobachteten richtig sei. Das alles ist durch den vorhin geschilderten Riss in der menschlichen Geistesentwicklung herbeigeführt worden. [In seinen ethischen Untersuchungen hat Eduard von Hartmann zwar bedeutsame Anregungen gegeben, seine erkenntnistheoretischen Untersuchungen haben nichts Neues und Wichtiges gebracht. So hat sich das kantische Denken im modernen Geistesleben zur förmlichen Denkgewohnheit entwickelt.]

Wer nun aber wirklich den Aristoteles studiert, der würde finden, dass in einer geraden, also gewissermaßen nicht umgebogenen Entwicklung von Aristoteles aus ganz anderes als Erkenntnis-Prinzip und -Theorie hätte kommen können. Aristoteles hat bereits Dinge eingesehen auf erkenntnistheoretischem Gebiet, zu denen sich der Mensch heute durch all das akademische Gestrüpp, das unter dem Einflusse Kants entstanden ist, erst wieder langsam und allmählich wird aufschwingen können. Er muss vor allen Dingen begreifen lernen, dass Aristoteles schon die Möglichkeit hatte, durch die Denktechnik Begriffe herbeizubringen, die richtig gefasst sind, und die unmittelbar dahin führen, diese hier selbst gezogenen menschlichen Grenzen zu überschreiten [und uns über das Gebiet des Empirischen hinausleiten].

Wir brauchen uns nur mit einigen Fundamental-Begriffen des Aristoteles zu befassen, um das einzusehen. Es ist durchaus in seinem Sinne zu sagen: Wenn wir die Dinge um uns herum analysieren, finden wir zunächst das, was uns eine Erkenntnis dieser Dinge verschafft, dadurch, dass wir mit dem Sinn wahrnehmen: Der Sinn liefert uns das einzelne Ding. Wenn wir aber anfangen zu denken, da gruppieren sich uns die Dinge, wir fassen verschiedene Dinge in einer Denkeinheit zusammen. - Und nunmehr findet Aristoteles die richtige Beziehung zwischen dieser Gedankeneinheit und einem objektiv Wirklichen, jenem Objektiven, das zu dem Ding an sich führt - indem er zeigt, dass wir bei konsequentem Denken die Erfahrungswelt um uns herum zusammengesetzt denken müssen aus Materie und aus dem, was er die Form nennt. Materie und Form sind für Aristoteles zwei Begriffe, die er in dem einzig richtigen Sinne, wie sie geschieden werden müssen, wirklich scheidet. Wir könnten stundenlang reden, wenn wir diese beiden Begriffe und alles, was damit zusammenhängt, erschöpfen wollten. Aber einiges Elementare wollen wir wenigstens herbeitragen, um zu verstehen, was Aristoteles als Form und Materie unterscheidet. Er ist sich klar darüber, dass es in Bezug auf alle Dinge, die zunächst um uns herum sind, die unsere Erfahrungswelt bilden, dass es bei all dem für das Erkennen darauf ankommt, dass wir die Form ergreifen, denn die Form gibt den Dingen das Wesentliche, nicht die Materie. Die Form ist für Aristoteles das Wesentliche.

Es gibt auch in unserer Zeit allerdings noch Persönlichkeiten, die ein richtiges Verständnis haben für Aristoteles. Vinzenz Knauer, der in den Achtzigerjahren des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts in Wien Universitätsdozent war, hat seinen Hörern den Unterschied zwischen Materie und Form und auf was es dabei ankommt, gewöhnlich durch eine Illustration klargemacht, über die man vielleicht spotten mag. Er sagte, man solle sich einmal denken, wie ein Wolf, der einige Zeit seines Lebens lauter Lämmer gefressen hat, wie der sich dann eigentlich aus der Materie der Lämmer zusammensetzt - und doch wird der Wolf niemals ein Lamm! Das gibt, wenn man es nur richtig verfolgt, den Unterschied zwischen Materie und Form. Ist der Wolf ein Wolf durch Materie? Nein! Seine Wesenheit hat er eingeimpft durch die Form - wir finden sie nicht nur bei diesem Wolf, sondern bei allen Wölfen. So finden wir die Form durch einen Begriff, der, im Gegensatz zu dem, was die Sinne im Einzelnen erfassen, etwas Universelles ist.

Nun kann man im Sinne des Aristoteles in einem richtig erkenntnistheoretischen Sinne dies Universelle ganz genau in dreifacher Weise unterscheiden. Man kann sagen, dieses Universelle ist das Wesentliche, das, worauf es ankommt. Aber ist dasjenige, was im menschlichen Denken lebt, dasselbe wie das, was wir im wahren Sinne als Form ansprechen? Nein. Der Mensch geht an die verschiedenen Wölfe heran und bildet sich den Begriff, ein Universelles, aus den einzelnen Wölfen. Aber das, was er da als einen Begriff sich gebildet hat, der die gleichen Eigenschaften zusammenfasst, das ist nur ein «Repräsentierende» des wahren Universellen. (Es kann das alles nur skizzenhaft angedeutet werden.) Sodass man also unterscheiden kann: Ein Universelles, das vor den Einzelheiten ist, die uns äußerlich entgegentreten; dann, weil es ja das Wesentliche darinnen ist, ein Universelles, das in den Dingen liegt; und eine dritte Form des Universellen, das sich der Mensch in Gedanken hinterher bildet. Es gibt somit: 1) universalia ante rem, 2) universalia in re, 3) universalia post rem. Die letzteren entrollen sich dem subjektiven Geiste und sind die «die objektiven realen Universalien repräsentierenden» inneren Erlebnisse.