The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1920–1922

GA 277c

17 September 1922, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

Eurythmy Address

Rudolf Steiner's explanation of the performance

The third Sunday in September — September 17, 1922 — is a public holiday in Switzerland, the federal Day of Thanksgiving, Repentance, and Prayer, on which events for entertainment purposes were prohibited. Rudolf Steiner issued a statement explaining why a eurythmy event was justified on this day. The context in which he made this statement — whether it was, for example, a draft letter to the community — is unknown. The performance took place in the dome room of the Goetheanum building.

The following should be noted regarding the eurythmy performance on September 17, 1922: The organizers cannot possibly regard the performance as one of the prohibited kind, for eurythmy is not entertainment or something like dancing, but serious art; and the audience is in the same position as someone visiting an art museum.

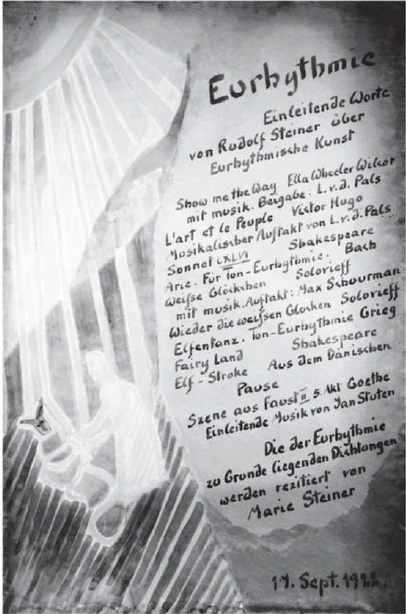

Furthermore, the seriousness of the day was taken into account on the 17th by the fact that only serious poems and the scene of sorrow from the second part of “Faust” were performed, which is not cheerful, but rather points people deeply to the seriousness of life. — Poster for the performance

Poster for the performance

Ladies and gentlemen!

Allow me, as usual, to say a few words by way of introduction before these eurythmic experiments. Not to explain what is being offered artistically, for that would be an inartistic beginning, because art must work through direct viewing, through itself – and that should be the case to a very special degree with eurythmy. But since what appears here as a new art, eurythmy, is drawn from new artistic sources that are still unfamiliar today, since it works in an artistic language of form that is still unfamiliar today, allow me to say a few words about this artistic language of form.

What you will see here on stage is by no means to be understood as dance, as [mimic] or pantomime art, but is a truly visible language. For, if I may use Goethe's expression, one can study through sensual-supersensual observation how the entire human organism seeks a special expression through the larynx and its neighboring organs when singing or speaking. Singing—that is, the music that comes from within the human being—and spoken language are in fact such that they engage the whole person. And basically, what happens in other people is only announced in ordinary speech and metamorphoses in a special way in the special organs of singing and speaking.

If one really studies what underlies movement tendencies and creative tendencies, then one can transfer this to the whole human being. However, this will be changed in a corresponding way, because it must then be seen, whereas the movements of the speech organs cannot be seen, but their translation into air movement can be heard. What is otherwise heard in singing or speech is seen in eurythmic movement. Therefore, a eurythmic gesture differs completely from a mimic or pantomime or dance art. Just as one cannot arbitrarily associate any human sound with a soul experience, one cannot associate any gesture with a soul experience. If a person wants to reveal themselves through eurythmy in a very specific, lawful way, movements are related to sound, words, word stress, word formation, [sentence structure], and so on – just as in speech and singing. Therefore, one should not direct one's perception to the individual gesture: Just as in melody one must direct one's feeling to the sequence of tones, so here it is a matter of the feeling that must be drawn out of the movements – both when the individual moves eurythmically in artistic transformation and when groups of people, as you can see here on stage, face each other or move in eurythmic norms. Eurythmy can certainly be understood as a moving sculpture.

Those who have a feeling for such things say to themselves: when I have a statue, a sculptural work, standing quietly before me, it is actually an expression of human silence, of the silence of the soul in a certain form. What is expressed here by the moving human being is the expression of the stirring of the soul, which now makes use of gestures in the same way, but regular gestures that belong to it in a lawful manner, just as sound belongs to the soul experience in a lawful manner. Thus, when eurythmy unfolds as an art, it can be developed as a moving sculpture.

We are gradually striving to incorporate everything in eurythmy into the stage design, so that the entire stage design appears as a eurythmic revelation. Those of you in the audience who have been here often will see how we have endeavored in recent months not to add the lighting and successive lighting effects to the individual in a naturalistic way, but to shape them eurythmically from the colored forms in their sequence and in their harmony with the accompanying eurythmy. So that here, too, one should not look at the individual elements, but at the emergence of a preceding movement or also at the retarding, the retroactive effect that the stage lighting has on the accompaniment of the individual performances.

In this respect, eurythmy in particular can lead back to a more artistic conception of recitation and declamation than is available today in what is, in a sense, an unartistic age. Today, although some people already realize that something else must be sought, recitation and declamation are still often performed in such a way that only the prose content of a poem is expressed. The prose content is emphasized, as they say, out of the depth of feeling. The real poet does not initially work with the prose content in his soul, but rather with uncertain melodious, harmonious, musical elements—or he works with the imagery of language. For the true poet, insofar as he is an artist, the prose content of his poetry is preceded by an inner necessity, a weaving, living or rounding off, or a deepening or rising, or a forming of this or that thought in language. The truly artistic form has nothing to do with the prose form of thought, which is expressed in two four-line stanzas [and] in two three-line stanzas, but rather with a departure that is first struck, with a return in the first two stanzas, with a look at the departure, with a look back at the decline in the last two stanzas—or in similar imagery lives the one who creates a sonnet out of a real sense of art, out of artistic imagination.

And so it is that something like this really underlies everything, for example in Schiller, for whom the prose content was never the most important thing in his main lyrical poems – he only strung it together after he first had an indefinite melody in his mind, just as Goethe had an indefinite feeling. Goethe, who lives more in vague feelings than Schiller: this must be expressed in the recitation and declamation that accompany eurythmy as well as the music. One cannot declaim in a prosaic manner when one has to accompany eurythmy with declamation and recitation.

It can also be sung visibly. Then eurythmy accompanies the music, the instrument, the instrumental. But eurythmy can also run parallel to recitation and declamation. We will allow ourselves to demonstrate both to you. But then, when reciting and declaiming to eurythmy, attention must be paid to the special form, to the visualization of language, to the musicality of language. And in this sense, the art of recitation and declamation, as we are attempting it here, must return to what it was in more artistic ages than our own. Therefore, the special form of declamation and recitation that we are training here as a purely artistic form may still be perceived as something unusual today. However, when our age returns to a truly artistic one, this will be truly understood.

Nevertheless, despite all this, I must say today—as always at the beginning of our performances—that we ourselves are our strictest critics, that we know exactly what needs to be improved, and that we ask our esteemed audience for their indulgence, because eurythmy is only at the beginning of its development. We know this very well. But we also know how much potential for development, immeasurable potential for development, lies within this eurythmy.

For today's performance in particular, I would like to add that in the second part after the intermission, we will be presenting a scene from the second part of Goethe's “Faust,” from the fifth act, where the four gray women—mainly “Sorrow”—appear. And in this context it must be said that the usual style of stylization that comes about through the art of eurythmy — where every single gesture, every single movement must be elevated to a higher stylistic form because it springs from the whole human organism — makes this eurythmy particularly suitable for dramatic — not lyrical — [for] such representations that ascend into the supersensible, where the human being is connected in his soul with the supersensible of the world. There are many such scenes in Goethe's “Faust.” One such scene is the scene where the four gray women appear. However, it must be taken into account that where Faust stands as an earthly human being, what he says must be portrayed using ordinary naturalistic stagecraft. But what is going on in his soul and what he sees from his relationship to the supersensible worlds, and what is dramatically, truly, not merely allegorically portrayed by Goethe in the four gray women – this can be translated particularly well into eurythmic language.

So that here, eurythmic style will be mixed with ordinary stage style. But it is precisely with the eurythmic style that one can perceive that certain parts of Faust—certain scenes, especially in the second part of Faust—also come into their own on stage in their special language form, if they are not presented naturalistically, but in a higher stylization through eurythmic art.

There are two other sides to eurythmy: One is therapeutic eurythmy, where the movements you see embodied artistically here are transformed so that, because all eurythmy flows from the healthy human organism and sets it in motion as a healthy organism itself requires, these movements can also be used therapeutically as a healthy organism, as has already been demonstrated in our institutes in Arlesheim and elsewhere.

A third element is the pedagogical-didactic side of eurythmy. Here, eurythmy is used in school lessons alongside gymnastics, as a kind of animated gymnastics. And we have already seen for ourselves at the Waldorf School in Stuttgart how such an application of eurythmy, from the youngest children to the oldest children we currently have at the Waldorf School, has such an effect – especially on the initiative of the will – that the child finds its way into the eurythmic language in the same way that it otherwise finds its way into spoken language. It is precisely in animated gymnastics that one can see what an important educational and teaching tool eurythmy is. One can see the soul, spirit, and body of the child becoming healthy through the use of eurythmic gymnastics—if I may express it that way—in teaching and education.

Through eurythmy, the human being itself is used as a tool in its liveliness. When Goethe says: When the human being finds itself confronted with nature, it takes measure, harmony, order, and meaning from it and, by using them, rises to the creation of a work of art. So it can be said that because human beings, as microcosms, hold all the secrets of the world within themselves, when these secrets are brought out – and this happens especially through the art of eurythmy, where no external instrument is used for art, but the human being themselves is the instrument – then the secret of the human form can be brought out through them. In this way, the human being can be a reflection of the mysteries of the greater world, of the entire macrocosm.

Precisely for this reason, because eurythmy brings out harmony, order, measure, and meaning from within the human being and also represents them through the human being, one can nevertheless say: even though eurythmy is still in its infancy today, it will certainly undergo further refinement and will be able to stand alongside the fully established older arts as a fully justified and worthy art form.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Erklärung Rudolf Steiners zur Aufführung

Der dritte Sonntag im September — 1922 der 17. September - ist in der Schweiz ein Feiertag, der eidgenössische Dank-, Buß- und Bettag, an dem Veranstaltungen, die dem Vergnügen dienen, verboten waren. Rudolf Steiner gab eine Erklärung ab, warum eine Eurythmie-Veranstaltung an diesem Tag gerechtfertigt sei. In welchem Kontext er diese Erklärung abgab- ob es sich z. B. um einen Briefentwurfan die Gemeinde handelt -, ist unbekannt. - Die Aufführung fand im Kuppelraum des Goetheanumbaues statt.

Bezüglich der eurythmischen Aufführung am 17. Sept. 1922 ist folgendes zu bemerken: Die Veranstalter können unmöglich die Aufführung als eine solche ansehen, die unter die verbotenen gehört, denn es handelt sich bei der Eurythmie nicht um Belustigung oder um etwas Tanzartiges, sondern um ernste Kunst; und die Zuschauer sind in demselben Falle, wie jemand, der ein künstlerisches Museum besucht.

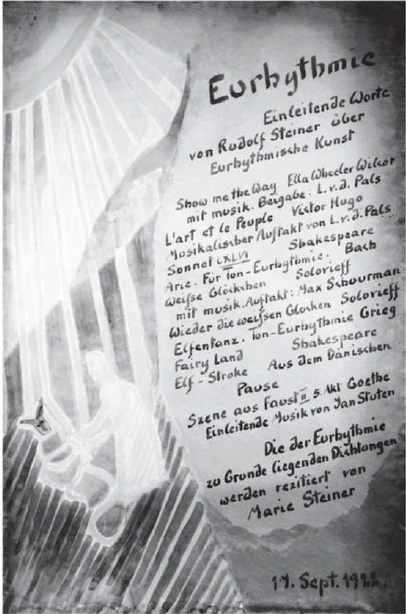

Außerdem wurde am 17. dem Ernst des Tages dadurch Rechnung getragen, dass nur ernste Gedichte und die Sorge-Szene aus dem zweiten Teil des «Faust» dargestellt wurden, was nicht heiter ist, sondern gerade den Menschen tief auf den Ernst des Lebens hinweist. — Plakat für die Aufführung

Plakat für die Aufführung

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Gestatten Sie, dass ich auch heute wie sonst vor diesen eurythmischen Versuchen ein paar Worte als Einleitung voraussende. Nicht zur Erklärung desjenigen, was künstlerisch geboten wird, das wäre selbst ein unkünstlerisches Beginnen, denn Kunst muss durch unmittelbares Anschauen, durch sich selbst wirken - und das soll ja in ganz besonderem Maße bei der Eurythmie der Fall sein. Aber da dasjenige, was hier als eine neue Kunst auftritt, die Eurythmie, was aus neuen Kunstquellen geschöpft wird, die heute noch ungewohnt sind, da sie in einer künstlerischen Formensprache arbeitet, die auch heute noch ungewohnt ist, gestatten Sie mir, in einigen Worten auf diese künstlerische Formensprache hinzuweisen.

Dasjenige, was Sie hier auf der Bühne sehen werden, das ist durchaus nicht so aufzufassen wie der Tanz, wie [mimische] oder pantomimische Kunst, sondern es ist eine wirklich sichtbare Sprache. Man kann nämlich, wenn ich mich des Goethe’schen Ausdruckes bedienen darf, durch sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen studieren, wie der ganze menschliche Organismus sich einen speziellen Ausdruck sucht durch den Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane, wenn gesungen oder gesprochen wird. Der Gesang - also das Musikalische, das aus dem Menschen selbst kommt - und die Lautsprache, sie sind eigentlich durchaus so, dass sie den ganzen Menschen mitengagieren. Und im Grunde ist dasjenige, was im sonstigen Menschen geschieht, nur im gewöhnlichen Sprechen angekündigt und metamorphosiert sich in einer besonderen Weise in den Spezialorganen des Singens und Sprechens.

Wenn man dasjenige, was da zugrunde liegt an Bewegungstendenzen, an Gestaltungstendenzen, wirklich studiert, dann kann man es auf den ganzen Menschen übertragen. Nur wird das in entsprechender Weise verändert werden, weil es dann gesehen werden muss, während man die Bewegungen der Sprachorgane nicht sieht, sondern ihre Umsetzung in die Luftbewegung hört. Dasjenige, was sonst gehört wird, an dem Gesang oder an der Sprache, das wird eben in der eurythmischen Bewegung gesehen. Daher unterscheidet sich eine eurythmische Geste durchaus von einer mimischen oder pantomimischen oder Tanzkunst. Geradeso wenig, wie man durch augenblickliche Willkür irgendeinen menschlichen Laut in Verbindung bringen kann mit einem Seelenerlebnis, ebenso wenig kann man eine beliebige Gebärde in Verbindung bringen mit einem Seelenerlebnis. Wenn der Mensch sich durch Eurythmie offenbaren will in ganz bestimmter, gesetzmäßiger Weise, stehen hier Bewegungen mit Laut, mit Wort, Wortbetonung, Wortgestaltung, [Satzgestaltung] und so weiter in Beziehung - so, wie in der Sprache und im Gesang. Daher sollte man auch die Empfindung nicht lenken auf dasjenige, was die Einzelgebärde ist: Wie man in der Melodie die Empfindung lenken muss auf die Aufeinanderfolge der Töne, so handelt es sich hier um die Empfindung, die herausgeholt werden muss aus den Bewegungen - sowohl wenn der einzelne Mensch in künstlerischer Umgestaltung sich eurythmisch bewegt, wie auch, wenn sich Menschengruppen, wie Sie es hier auch auf der Bühne sehen können, in eurythmischen Normen sich gegenüberstehen oder sich bewegen. Man kann die Eurythmie durchaus auffassen als eine bewegte Plastik.

Wer für solche Dinge eine Empfindung hat, der sagt sich: Wenn ich eine Bildsäule, ein plastisches Werk in ihrem ruhigen Dastehen vor mir habe, so ist eigentlich das der Ausdruck für das menschliche Schweigen, für das Schweigen der Seele in einer bestimmten Form. Dasjenige, was hier durch den bewegten Menschen selbst zum Ausdrucke kommt, ist aber der Ausdruck für die Regung der Seele, die sich nun in derselben Weise der Geste bedient, aber der regelmäßigen Gesten, die in gesetzmäßiger Weise dazugehören, wie der Laut in gesetzmäßiger Weise zum Seelenerlebnis dazukommt. So kann man also die Eurythmie, wenn sie sich als Kunst entfaltet, als eine bewegte Plastik ausbilden.

Wir haben nach und nach das Bestreben, im Eurythmischen alles in das Bühnenbild einzubeziehen, sodass das ganze Bühnenbild als eurythmische Offenbarung erscheint. Diejenigen der verehrten Zuschauer, die öfter hier waren, werden sehen, wie wir uns in den letzten Monaten bemüht haben, auch die Beleuchtungen, die aufeinanderfolgenden Lichteffekte nicht in naturalistischer Weise zu dem Einzelnen hinzuzufügen, sondern in ihrer Aufeinanderfolge und in ihrem Zusammenstimmen zu dem begleitenden Eurythmischen, es aus dem farbig Geformten eurythmisch zu gestalten. Sodass man hier wiederum nicht auf das Einzelne zu sehen habe, sondern auf das Hervorgehen einer vorhergehenden Bewegung oder auch auf das Retardierende, auf das Rückwirkende, welches die Bühnenbeleuchtung hat auf die Begleitung der einzelnen Darstellungen.

Gerade Eurythmie kann in dieser Beziehung auch wieder zurückführen zu einer künstlerische[re]n Auffassung des Rezitierens und Deklamierens, als sie heute vorhanden ist in einer gewissermaßen unkünstlerischen Zeit. Heute wird doch vielfach noch - obwohl einige schon einsehen, dass wiederum nach etwas anderem gestrebt werden muss —, heute wird doch vielfach noch so rezitiert oder deklamiert, dass eigentlich nur der Prosagehalt einer Dichtung zum Ausdrucke kommt. Man pointiert, wie man sagt aus der Empfindungstiefe heraus den Prosainhalt. Der wirkliche Dichter arbeitet ja zunächst in seiner Seele gar nicht mit dem Prosagehalt, sondern er arbeitet mit einem ungewissen melodiösen, harmonischen, musikalischen Elemente - oder er arbeitet mit der Bildgestaltung der Sprache. Bei dem wirklichen Dichter, insofern er Künstler ist, geht dem Prosagehalt seiner Dichtung voran eine innere Notwendigkeit, ein Webendes, Lebendes oder ein Sich-Rundendes oder ein Tiefer-oder-höher-Heraufsteigendes oder ein In-diesem-oder-jenem-Gedanken-Formendes in der Sprache zu gestalten. Die wirklich künstlerische Form hat es ja zunächst zu tun nicht mit der Prosaform des Gedankens, die sich in zwei vierzeiligen Strophen ausspricht [und] in zwei dreizeiligen Strophen ausspricht, sondern er hat es zu tun gewissermaßen mit einem Hingang, der zunächst angeschlagen wird, mit einem Rückgang [in] den zwei ersten Strophen, mit einem Hinschauen auf den Hingang, mit einem Zurückschauen auf den Rückgang in den zwei letzten Strophen - oder in ähnlichen Bildgestaltungen lebt derjenige, der aus dem wirklichen Kunstgefühl, aus der künstlerischen Phantasie heraus ein Sonett schafft.

Und so ist es, dass überall wirklich so etwas zugrunde liegt, wie zum Beispiel bei Schiller, bei dem es nie zunächst ankam bei seinen hauptsächlichsten lyrischen Dichtungen auf den Prosagehalt - den hat [er] nur aufgereiht dann, nachdem er zuerst eine unbestimmte Melodie in seinem Sinne hatte, so wie Goethe ein unbestimmtes Fühlen. Goethe, der mehr im unbestimmten Fühlen lebt als Schiller: Das muss in der Rezitation und in der Deklamation, welche jeweils die Eurythmie begleiten ebenso wie das Musikalische, durchaus zum Ausdrucke kommen. Man kann nicht in prosaischer Weise deklamieren, wenn man die Eurythmie deklamatorisch und rezitatorisch zu begleiten hat.

Es kann ebenso sichtbar gesungen werden. Dann ist die Eurythmie Begleiterin des Musikalischen, des Instrumentes, des Instrumentalen. Aber es kann ebenso die Eurythmie parallellaufen der Rezitation und der Deklamation. Beides werden wir uns erlauben, Ihnen vorzuführen. Dann aber muss, wenn zur Eurythmie rezitiert und deklamiert wird, gesehen werden auf die besondere Gestaltung, auf das Verbildlichen der Sprache, auf das Musikalische der Sprache. Und in diesem Sinne muss die Rezitationskunst und Deklamationskunst, wie wir das hier versuchen, wiederum zurückkehren zu dem, was sie in künstlerischeren Zeitaltern war, als es das unsrige ist. Daher wird manchmal die besondere Form des Deklamierens und Rezitierens, die wir hier als eine rein künstlerische ausbilden, heute noch als etwas Ungewöhnliches empfunden werden können. Bei einer Rückkehr aber überhaupt unseres Zeitalters in ein wirklich Künstlerisches, wird das schon wirklich verstanden werden.

Dennoch, trotz alledem, muss ich auch heute - wie immer am Beginn unserer Vorführungen - sagen, dass wir selbst unsere strengsten Kritiker sind, genau wissen, was auszusetzen ist und dass die verehrten Zuschauer um Nachsicht gebeten werden, weil Eurythmie erst im Anfange ihres Werdens ist. Wir wissen das ganz genau. Aber wir wissen auch, wieviel Entwicklungsmöglichkeiten, unermessliche Entwicklungsmöglichkeiten in dieser Eurythmie darinnen liegen.

Für die heutige Vorstellung im Besonderen möchte ich noch das hinzufügen, dass wir im zweiten Teil nach der Pause Ihnen ja vorführen werden eine Szene aus dem zweiten Teil von Goethes «Faust», aus dem fünften Akt da, wo die vier grauen Weiber - hauptsächlich die «Sorge» - auftreten. Und in dieser Bezichung muss gesagt werden, dass die gewöhnliche Art des Stilisierens, die zustande kommt durch die eurythmische Kunst - wo jede einzelne Geste, jede einzelne Gebärde und Bewegung eben in eine höhere Stilform hinaufgehoben werden muss, weil sie aus der ganzen menschlichen Organisation entspringt -, dass dadurch diese Eurythmie sich ja ganz besonders eignet, im Dramatischen - nicht im Lyrischen - [für] solche Darstellungen, die ins Übersinnliche hinaufgehen, da, wo der Mensch mit dem Übersinnlichen der Welt zusammenhängt in seiner Seele. Solche Szenen gibt es in Goethes «Faust» viele. Eine solche Szene ist die Szene, wo die vier grauen Weiber erscheinen. Nur muss man berücksichtigen, dass da, wo Faust steht als ein Erdenmensch, dasjenige, was er spricht, mit der gewöhnlichen naturalistischen Bühnenkunst dargestellt werden muss. Dasjenige aber, was in seiner Seele vorgeht und [was] er schaut aus seiner Beziehung zu den übersinnlichen Welten und was dramatisch, wahrhaftig nicht bloß allegorisch durch Goethe zur Darstellung kommt in den vier grauen Frauen - das kann insbesondere gut in die eurythmische Sprache übersetzt werden.

Sodass sich hier durcheinander mischen werden eurythmischer Stil mit gewöhnlichem Bühnenstil. Aber gerade mit dem eurythmischen Stil kann man die Wahrnehmung machen, dass gewisse Teile des «Faust» - gewisse Szenen insbesondere im zweiten Teil des «Faust» — auch in ihrer besonderen Sprachgestaltung auf der Bühne zur Geltung kommen, wenn man sie nicht naturalistisch darstellt, sondern in einer höheren Stilisierung durch eurythmische Kunst.

Es gibt dann zwei andere Seiten der Eurythmie noch: Die eine ist die Heileurythmie, wo die Bewegungen, die Sie hier künstlerisch verkörpert sehen, umgestaltet werden, sodass Sie, weil ja alle Eurythmie aus dem gesunden menschlichen Organismus herausfließt und ihn in Bewegung bringt, wie er es als gesunder Organismus selbst verlangt, sodass diese Bewegungen auch als gesunder Organismus schon therapeutisch verwendet werden können, wie sich in unseren Instituten in Arlesheim und anderswo bereits gezeigt hat.

Ein drittes Element ist die pädagogisch-didaktische Seite der Eurythmie. Da wird die Eurythmie im Schulunterricht verwendet neben dem Turnen, als ein gewissermaßen beseeltes Turnen. Und wir haben uns ja in der Waldorfschule in Stuttgart schon überzeugt, wie eine solche Anwendung der Eurythmie vom jüngsten Kinde an bis zu den ältesten Kindern, die wir vorerst in der Waldorfschule haben, durchaus so wirkt - insbesondere auf die Willensinitiative -, dass das Kind sich so in die eurythmische Sprache hineinfindet, wie es sich sonst in die Lautsprache hineinfindet. Gerade in dem beseelten Turnen kann man sehen, welch wichtiges Erziehungs- und Unterrichtsmittel gerade die Eurythmie ist. Man sieht Seele, Geist und Leib des Kindes gesunden durch die Verwendung des eurythmischen Turnens - wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf - im Unterricht und in der Erziehung.

Der Mensch selber wird durch die Eurythmie in seiner Lebendigkeit als ein Werkzeug verwendet. Wenn Goethe sagt: Wenn der Mensch sich der Natur gegenübergestellt findet, nimmt er Maß, Harmonie, Ordnung und Bedeutung zusammen aus derselben und erhebt sich, indem er sie verwendet, zu der Gestaltung des Kunstwerkes. So darf wohl gesagt werden: Weil der Mensch als ein Mikrokosmos alle Geheimnisse der Welt in sich verborgen hält, so kann, wenn diese Geheimnisse herausgeholt werden - und das geschieht besonders durch die eurythmische Kunst, wo nicht ein äußeres Instrument zur Kunst verwendet wird, sondern der Mensch selber das Instrument ist -, so kann durch ihn das Geheimnis der Menschengestalt aus ihm herausgeholt werden. So kann der Mensch ein Abglanz sein der Geheimnisse der großen Welt, des ganzen Makrokosmos.

Gerade aus diesem Grunde, weil durch die Eurythmie Harmonie, Ordnung, Maß und Bedeutung aus dem Menschen selber herausgeholt und auch durch den Menschen dargestellt werden, deshalb kann man trotzdem sagen: Wenn auch die Eurythmie heute noch in ihrem Anfange ist, sie wird eine weitere Vervollkommnung ganz gewiss durchmachen und als eine vollberechtigte, würdige Kunst auch neben der vollberechtigten älteren Kunst dastehen können.