The Building Concept of the Goetheanum

GA 289

7 September 1921, Stuttgart

Translated by Steiner Online Library

8. The building idea of Dornach

Dear attendees!

It is my task today to speak about the place that is to be a center of activity for everything that can radiate from the work in which you have participated here in such a deeply satisfying way over the last eight days. I may say in a deeply satisfying way, for the reason that you will believe me when I say that I am connected with this work in the deepest sense and therefore may express the deepest satisfaction about the course of this congress.

Now, my dear attendees, the Goetheanum is, so to speak, a physical manifestation of that which, in the most diverse ways and in the most diverse fields, would like to emerge as the result of anthroposophical spiritual science in the world. When it first emerged in the world, anthroposophy naturally did not immediately have its own place of activity, and it could not even be thought of, not even remotely, to build a place of activity for it. After about a decade of activity, a number of people who believed in the anthroposophical worldview came up with the idea of creating such a center for anthroposophy. The idea had initially come from the impressions gained from the performance of the mystery plays, which we started in Munich in 1910. It struck a number of our friends how unsuitable the architecture of an ordinary theater, such as we had to use to stage the mysteries at the time, is for what is actually artistically intended by anthroposophy.

And so the plan arose to found a kind of college for anthroposophy. The first attempt was to build in Munich. Land had already been acquired in Munich. But now the question was that precisely because anthroposophical spiritual science wants to be what has been spoken of here again in these days, the same could not be said for such a building as is otherwise the case. You have a society or an association, as you will, that has set itself some goal and believes it needs its own building. You get in touch with some master builder, an architect, and receive his suggestions. The building is constructed in the antique, Renaissance, Gothic style or similar, and then the events of the respective association or society are held in such a building.

Those who are thoroughly connected with their own soul life, as it should be, with an anthroposophical worldview, can never agree to such an outward agreement for a framework, for a wrapping of that which is to be created through anthroposophy. Because it has been emphasized over and over again: Anthroposophy is, on the one hand, a science of the spirit, of the supersensible, arising from the deepest sources of human knowledge. But it is not a theory, it is not a sum of abstractions, it is not something about the world and about life; it becomes, as it develops, life itself, it takes hold of the deepest inner impulses of the whole, of the full human being, and pursues everything from the inner being of this full human being, whatever it can be for him. In this way, it not only stimulates the impulses for scientific research, but also for artistic creation.

Not as if out of the true anthroposophical spirit – I have already mentioned this in my evening lectures – not as if out of this spirit an allegorizing or symbolizing art wanted to arise; that would not be art at all. Not ideas are to be transformed into symbolic or allegorical forms. No, anthroposophical spiritual knowledge penetrates into the depths of the human soul and takes its origin from sources that can flow into the world in other currents than in the field of the presentation of ideas. And so the one stream of the presentation of ideas arises as the one, and the other stream, the stream of artistic creation, in addition to many others, from the same source. But it is not about the translation of spiritual science into art or into sham art, but rather about an elementary, very original, I would say, expression of the artistic. In Dornach today, one can see how nothing symbolic or allegorical is striven for, but how what is intended to be art is conceived as art and created out of the artistic.

I would like to express myself with an image: if the relationship between the anthroposophical worldview and art is really as I have just described it, then this anthroposophical worldview must not allow itself to be built a place from the outside, in some style that for the Greek, for the Renaissance, for the Gothic worldview. Instead, the anthroposophical worldview must be housed in a building that has arisen out of the most original impulses of anthroposophy. Then the matter must be such that, for example, speaking takes place from the podium, singing or reciting or acting in eurythmy takes place on the stage, and so on; that which emerges in this way to the people must, so to speak, be the one language, and the other language must be the building forms, must be the architecture that envelops that which wants to reveal itself within the space. Anthroposophy must not accept a style from outside; Anthroposophy itself, being intimately related to the artistic, must appear as a creator of style.

This is what was there, I would like to say, with the same inner spiritual necessity as - now I would like to express myself through an image - as the nutshell cannot be different in its formation, in its design, than it is. The nut fruit and also the nutshell arise from the same lawfulness, from the same forms and life forces. He who sees the one can judge the other. This must also be the case with the structure for the anthroposophical world view. Therefore, what was to become the style for such a structure could arise out of all that was alive in the ideas of anthroposophy.

It is understandable that this met with resistance at first from all those who cling to the old, who cannot imagine that the development of humanity can only come about through the constant emergence of new and new metamorphoses of human labor, human creativity and human insight, and so – and I emphasize this – it was not the police or the government that rejected us at first, but the art world rejected our styles for Munich. It is not our fault that the building was not built in Munich, where it was originally intended to be. Of course, in the end people grew tired of submitting, I might say, to the yoke of what would have been dictated to them from the old ways of thinking. Those who knew what kind of architectural style must arise from the anthroposophical worldview were not allowed to have their wings broken.

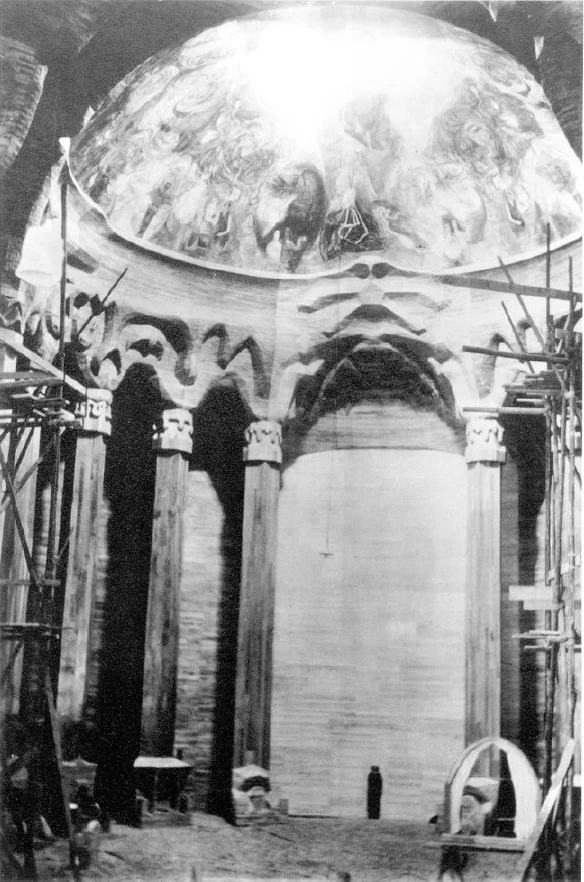

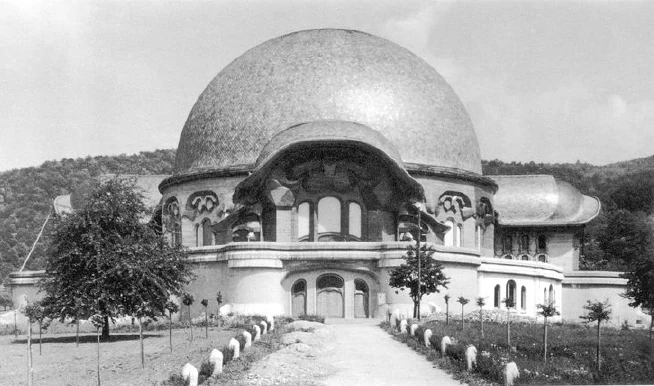

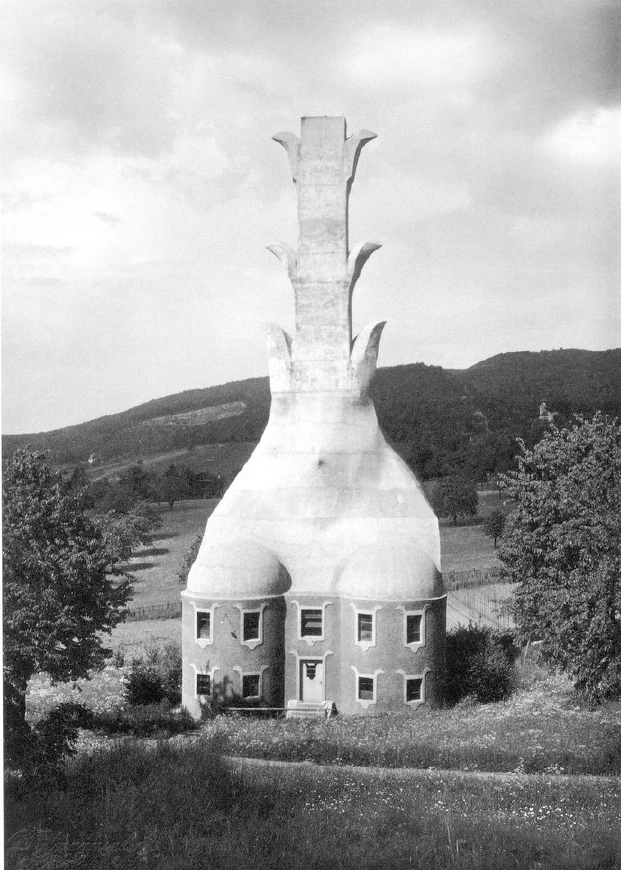

And so it happened that through the donation of a friend, our project on the hill near Basel, in Dornach, in the northwestern corner of Switzerland, could be realized, and that the foundation stone could be laid in the fall of 1913. Of course, we fell into the most difficult period of Western cultural development. But we have at least already come so far that a whole series of university courses have been held in the building since last fall, which is still far from completion.

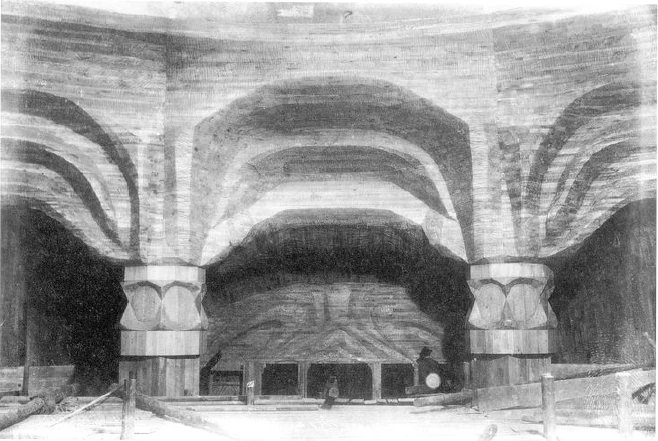

Now I would like to characterize in just a few words how that which lives in anthroposophy has poured out into an architectural style. That, ladies and gentlemen, is precisely the essence of anthroposophical research, of anthroposophical knowledge: that the concepts, that the whole forms of knowledge live, unfold in free activity, and this led, I would like to say, in a very elementary, naive way, to transferring the old architectural styles, which are based on the geometric, symmetrical, mechanical-static, into the organic. And so the previous architectural styles are, I would like to say, external images of that which can live in the static, in the carrying, in the load-bearing and in the symmetrical, in the geometric.

Of course, the Dornach building and my words here are not a criticism – it would be foolish towards these architectural styles – but it is a matter of drawing on progress. In this case, it could only consist of the geometric, the symmetrical, the static being transferred into something that, in all its forms of expression, in all its formation, also represents the organic, just as the inorganic is otherwise represented in architectural styles. I am well aware, esteemed attendees, of all the objections that can be raised against such a thing; but it had to be done at some point, based on the fundamental impulses of an anthroposophical attitude. There had to be a building idea that is lived and woven through the contemplation of the organic.

And consider what that actually means in terms of the human body itself. Take the smallest organ, perhaps it will be most illustrative. Please take your earlobe, a very small organ, it has a certain shape and size. If you feel the whole meaning of the human organic structure, feel it artistically, then you will say to yourself: firstly, this earlobe could not be in any other place in the human organism than where it is, and secondly,

in the place where it is, it could not be other than it is. The same had to be achieved with all the individual forms in the construction of the Goetheanum. One had to connect inwardly with the metamorphosing formative forces that otherwise live in the organic, and one had to experience what must of course be observed as the basis for every building idea: the geometric, the symmetrical, the static. One had to experience this through what can be experienced in this way in harmony with organic creation. Every single shape, every door, every window, every column, every detail [of this building] had to be individually felt. And the whole, in turn, had to be the one that, as a unified organic building idea, could absorb these individual organic building elements.

One difficulty arose from the fact that the matter was initially conceived for Munich in such a way that, in fact, only interior design would have been considered in the main. The building was to be surrounded by houses that anthroposophical members wanted to acquire, so that the exterior architecture would have been of little consequence. When the building had to be moved to Dornach, the space available was a completely open field on a hill, on a Jura hill, in a Jura configuration. There were unobstructed views in all directions and a clear view of the building. The mountain formations were there, and the whole thing had to be adapted to them. Since the interior design could not be changed much due to the haste with which I promoted the matter at the time, it was necessary to design the exterior in accordance with the finished interior. That is the thing that still leaves me somewhat dissatisfied today, because the person who will fully appreciate the whole can already see a certain discrepancy between the exterior and the interior design. However, every effort has been made to overcome the difficulties as far as possible. And in such a matter, basically only something incomplete can be created in the first attempt. But that is also the only reason for the Dornach building, to start a new architectural style, which cannot arise from any other foundations than those that can be made at all for modern civilized life from the knowledge of the spirit of the world.

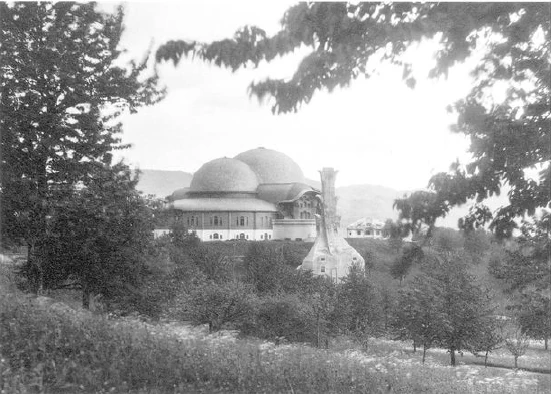

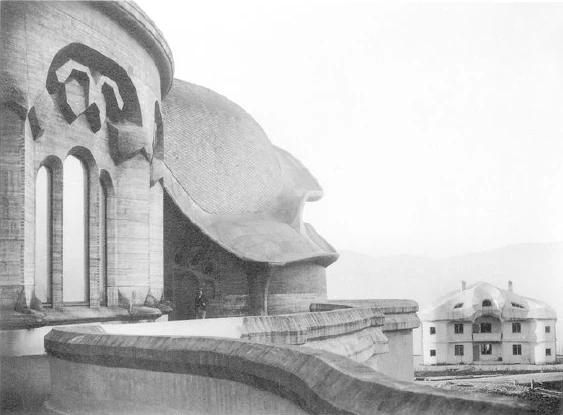

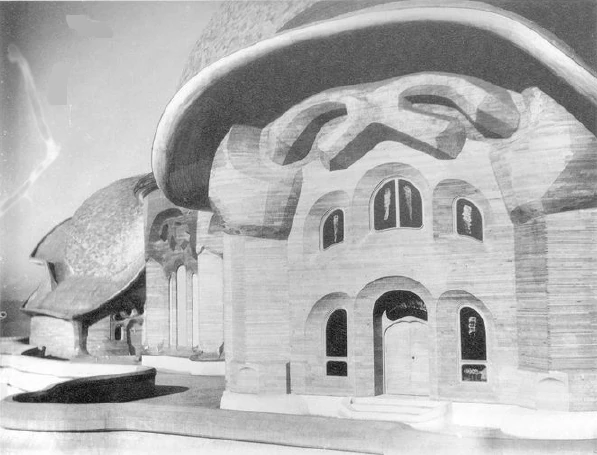

The way the Goetheanum presents itself to the observer when approaching from afar is connected with the overall task: one is dealing with something that arises in the depths of the human soul, be it art or science, and that the person who has fathomed it has a duty to communicate to others. We are dealing with something that comes from the bottom of the heart, with something that is taken from the whole soul by someone who truly understands. This can be felt. And it may be demanded of the one who can feel it that this is now translated into contemplation. As I said, nothing should be thought up, no idea should be cast into form. But what I have just hinted at can be felt, can be experienced inwardly, this relationship of an intimate unity to a receptive other unity and the union of the two. By feeling this, it arose for me quite naturally only in contemplation, not as an allegory or as symbolism, a double-domed building, designed in such a way that two domed spaces met in a segment of a circle. And it seems to me that in this form of construction one can feel everything that a soul can feel in relation to anthroposophy and the world, as it must actually be felt as the ideal relationship, as the blissful relationship. And I believe that, just by looking at the outer form, one can feel this when approaching the hill at Dornach, just as one feels the inner necessity of the form of the nutshell compared to the form of the nut fruit; one can feel that there is something in the two juxtaposed domes of a large and a smaller dome structure that should be explored in the most intimate way, and yet at the same time wants to openly communicate with the world. That is what is expressed first in the external forms that I will take the liberty of showing you.

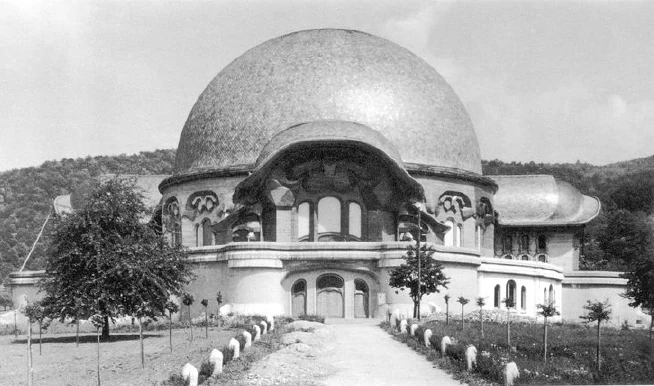

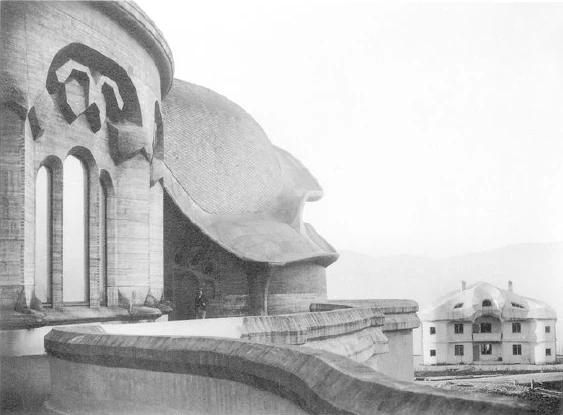

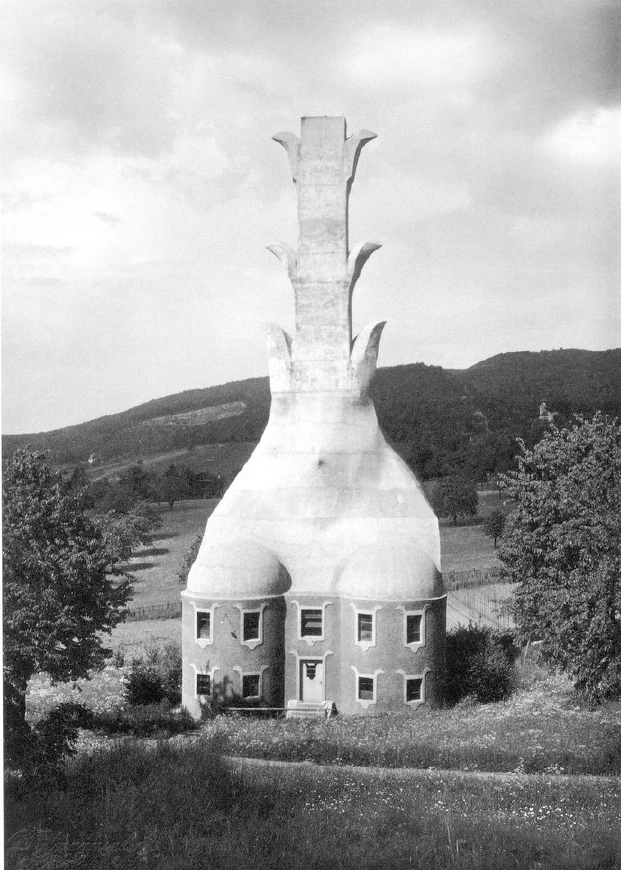

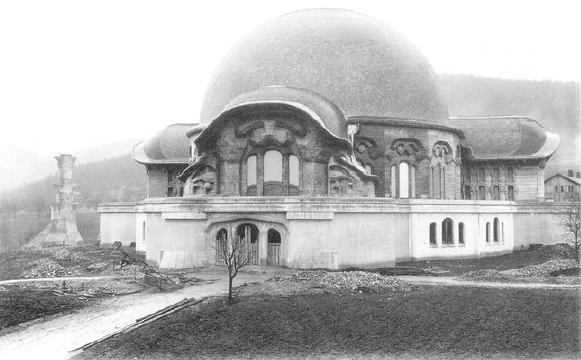

Yes, please, now the first picture (Fig. 5).

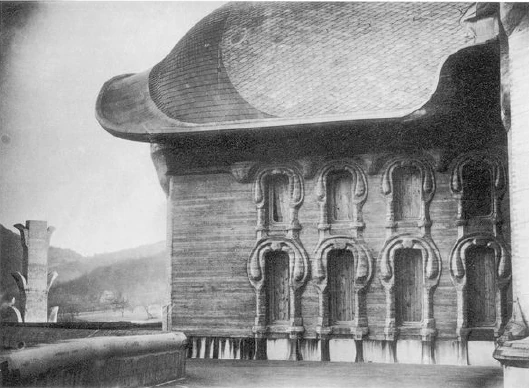

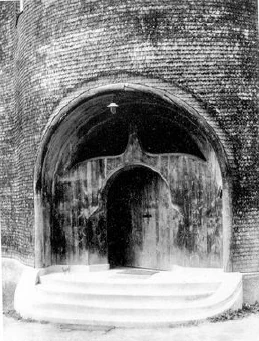

You see, dear attendees, here is the road that leads to the west side of the building. The building is a concrete structure down to the upper terrace. From here on, it is a wooden structure. You first enter the concrete structure. In the concrete structure - we will see later - is stored. Then you go up the stairs and come to a foyer and from there to the actual auditorium. You can see here in this motif how an attempt has been made to transfer the otherwise existing forms of construction, which, as I said, are based on the purely geometric, symmetrical, static or dynamic, into organic forms, but not in a naturalistic sense, not in such a way that natural forms would have been imitated. No one can ask what something depicts, just as one cannot ask what a plant leaf or a human ear depicts. It is something that has its inner form of life and vitality and life force within itself; something that justifies itself through its own form and its own unfolding of life.

When you create such a form, you do not feel that you are imitating something, but rather you feel, as a human soul, inwardly connected to that which lives metamorphosing in the plant from leaf to flower to fruit, shaping and reshaping everything, if I may use this Goethean expression. And that is what we have here, not something copied, but something formed in such a way that is otherwise only formed in the organic world. Those who then see the building itself may perhaps be able to see how we have tried to sense artistically from the material all around. It was rather difficult – I will have to come back to this later – to find forms for the concrete, a new material.

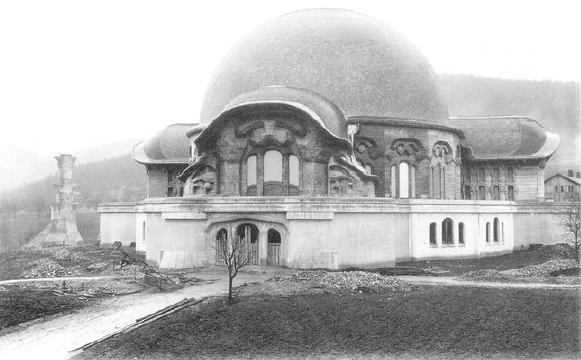

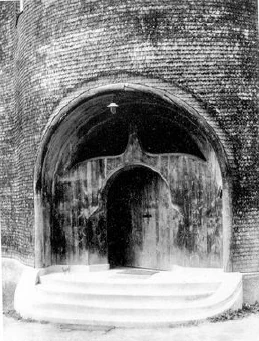

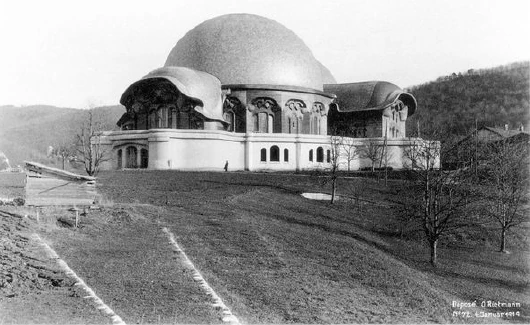

The next picture (Fig. 6): You can see the entrance to the west portal again. Here you go in, here left and right up, then you enter a vestibule, then the actual auditorium. The second, smaller dome is now completely covered by the larger dome of the auditorium. All the individual such secondary forms are in complete harmony, and in fact in organic harmony with the larger forms.

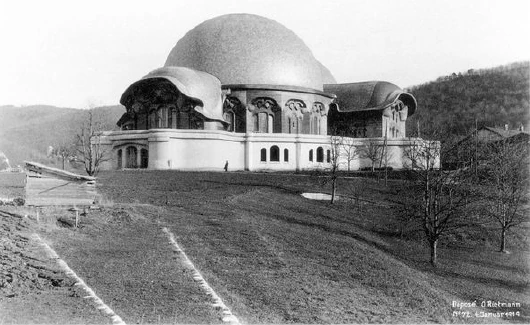

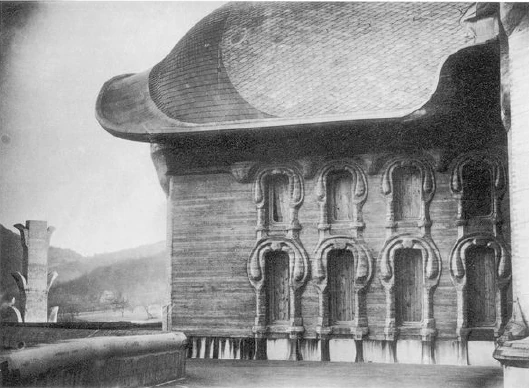

The next picture (Fig. 7): Here you can see the building from the southwest side; here the entrance, here the west portal; here the south side, here a transverse building, which we will see in more detail; here the entrance from the south side. You can see how this main form reappears here in some window forms, but actually in such a way that the main form is formed quite differently than the window forms. It is really the case that, when designing in this architectural style, one has to form organic shapes in such a way that, let us say, at the bottom of the plant there is an entire unnotched leaf, further up the leaf is notched, becomes of a very different shape, then in the sepal again something else. One must have the possibility, so to speak, to slip with one's feeling through all the possible forms that arise within, which are quite different according to external sensuality, but are inwardly spiritual and yet quite the same.

Here the large dome, there the small one. One of the issues, for example, was to find the right roofing for this building. The building had to appear as a unified whole, and, I would say, fate brought it about: While I was still occupied with the idea of building, I had to undertake a lecture tour in Norway, from Kristiania to Bergen, and from a train I saw the wonderful slate quarries of Voss. And just as this Voss slate presented itself to me in brilliant sunlight at the time, I said to myself at that moment: this belongs to the covering of this building. And indeed, a certain necessity for it will be felt by anyone who comes to Dornach and sees the wonderful grey-blue of this slate, shining and radiant in the sunlight.

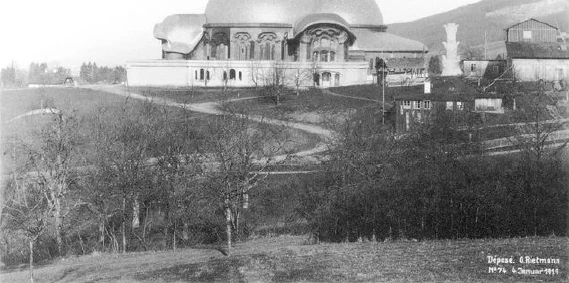

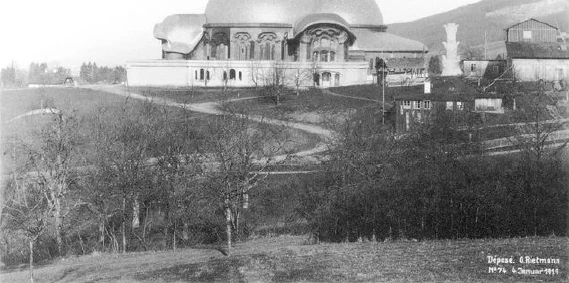

The next picture (Fig. 8): Here you see the building from the south side. I emphasize, here would be the entrance, here is the side wing, as there is one on each side of the building. Here are the storerooms for the equipment, dressing rooms for performances, here the dome of the stage area. This is where the two domes meet. And it is precisely at the point where they meet that these side wings are located.

The next picture (Fig. 2): Here we have the construction from the northeast, and you can see the stage area, the dressing room, the storage room, [the large dome partially covered by the small dome]. Here is the so-called boiler house, which is completely made of concrete, and it is perhaps the one that is most [challenged by individuals], and that is because, firstly, an attempt was made to find a form out of the concrete material with a real sense of the material, but then to find a form in the way that is only possible for utility buildings. The lighting and firing systems had to be accommodated in it. It was important to see what the whole thing looked like and how it would appear. That was the nut to crack, so to speak, and the concrete shell had to be built around it according to the same principles. And I tried to think it through to the point where the whole shape of this building is only complete when the smoke comes out here, when it is in full operation. The shapes of the smoke clouds actually belong to the whole shape.

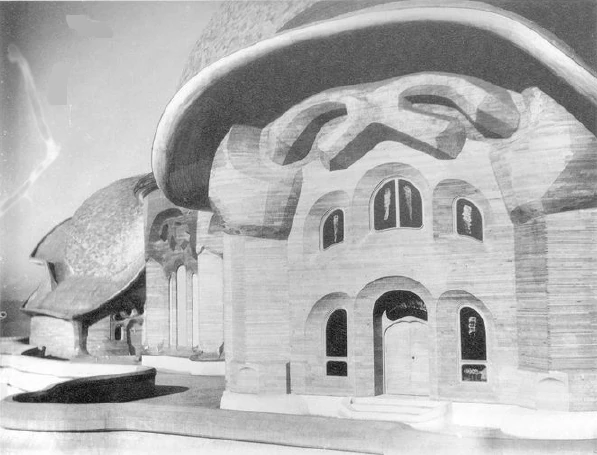

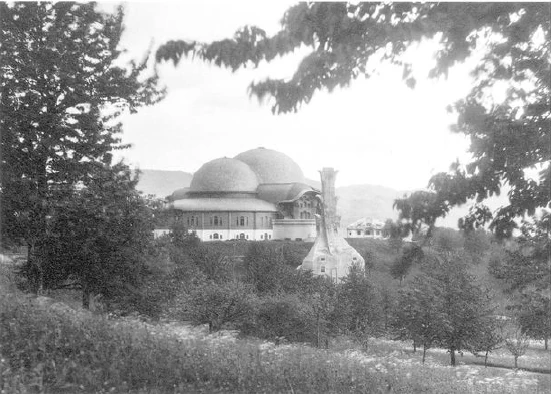

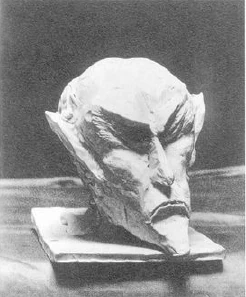

The next picture (Fig. 3) offers a completely different view. There is a small domed structure nearby that had to be built for a reason that I will explain later. This composition of a building with two domes is intended to be another metamorphosis. Here the domes are intertwined, intersecting, while there they are separate, on the adjoining building. But this then means that all the details of the structure had to be designed differently.

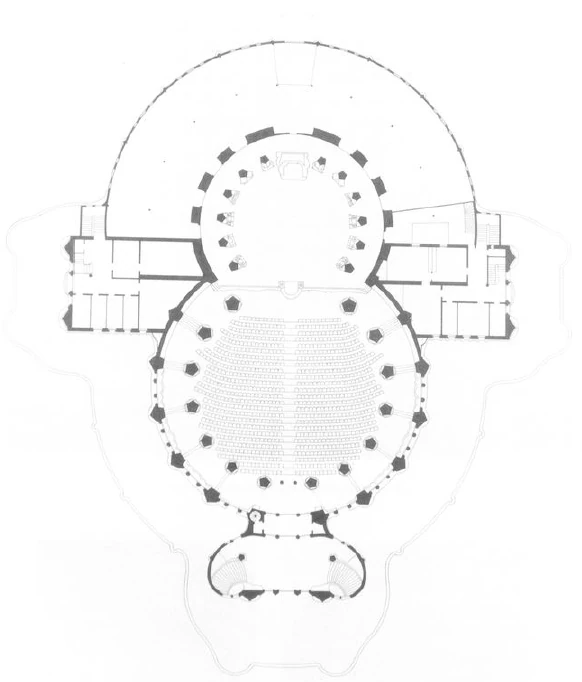

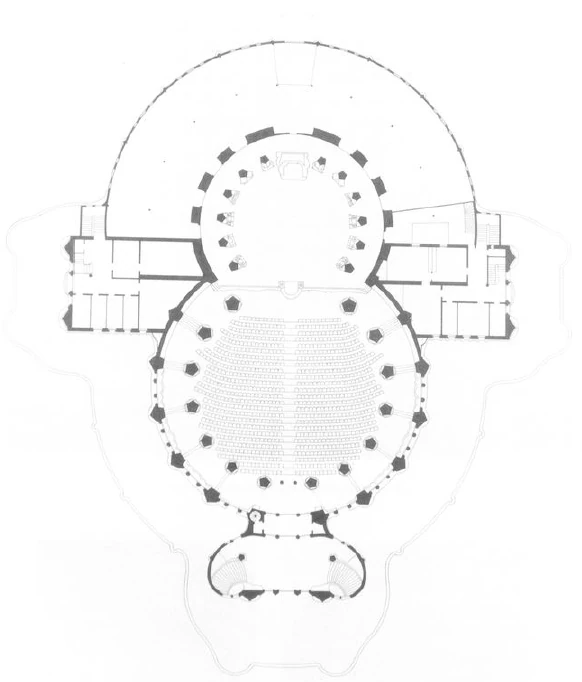

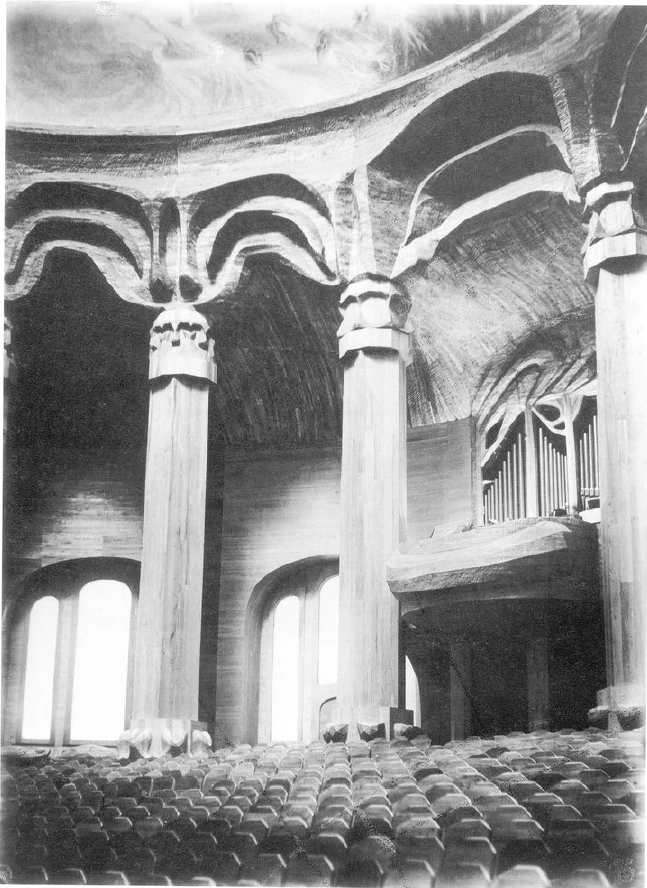

The next picture (Fig. 20): Here you can see the floor plan. Here is the entrance; below that would be the room for storing clothes. Here are the stairs. You go up these stairs and come into the vestibule, which we will see in a moment. Now you enter the auditorium. Here is the space below the organ, which is slightly elevated, with the other musical instruments. Here are the rows of benches for about a thousand spectators, here on each side are seven columns. These seven columns are, as we shall see, only symmetrical in relation to the only axis of symmetry that the whole building has, and which runs from west to east. The whole building is symmetrical in relation to this west-east direction, so that the capital of the second and third column is not a geometric repetition of the first column, but the capitals are progressive, metamorphosing forms from the first to the seventh column, and only this column is symmetrical with this one, the second with the second here and so on, so only symmetrical in relation to the one axis of symmetry. The rest in the course of this axis of symmetry is perceived in organically progressive transformation.

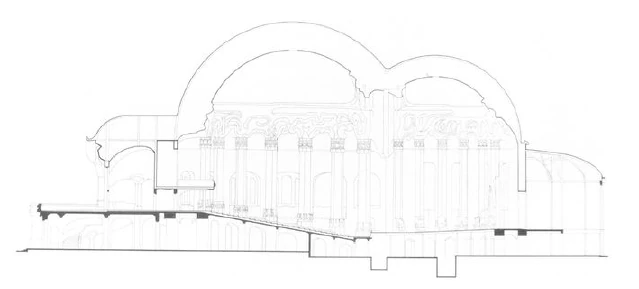

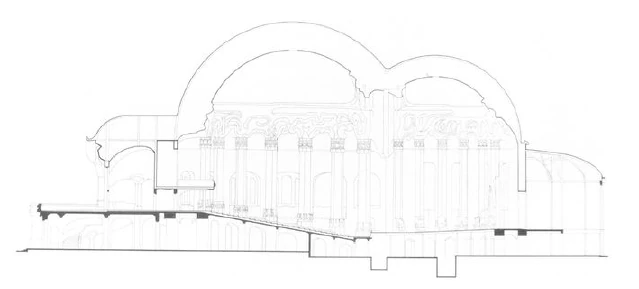

The next picture (Fig. 21): Here is an average in accordance with the axis of symmetry. Here are the storerooms, the stage rooms, the smaller domed room, the large domed room, here is the floor of the auditorium rising, here the entrance, here then the anteroom, here you come in, put your things down here, here is the staircase. You come into the anteroom here and go into the auditorium under the organ here.

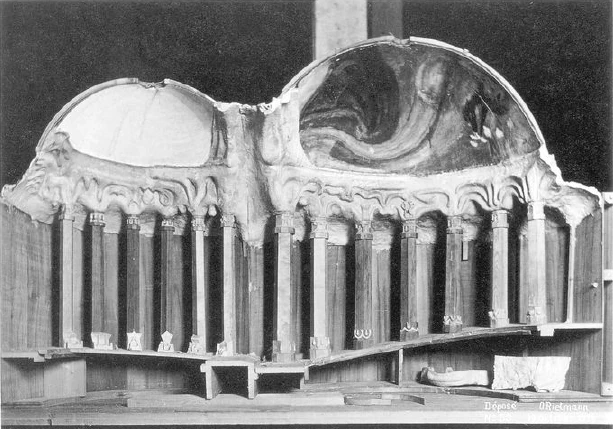

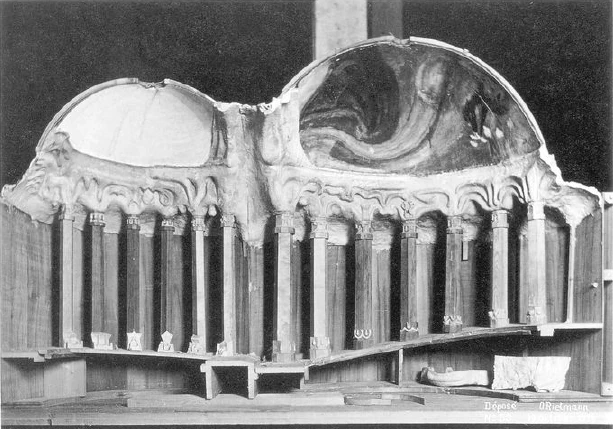

The next picture (Figure 22): Here I have taken the liberty of showing you the model, cut in the same section as the one I have just shown you. This is the first model of the structure, which I made in Dornach during the winter of 1913–1914, partly out of wood and partly out of wax. The structure was then built according to this model. The model contains the essential building idea.

The next picture (Fig. 10): Here we have the west portal, the main entrance, seen in more detail.

The next picture (Fig. 12) shows a detail. If you approach from the south side, you will see a similar detail here. You saw it earlier at the building itself. But here you see a concrete house, the house of the friend who provided us with the land back then. An attempt has been made to design this house as a concrete mold for the residential building in the style that it must have next to the building.

The next picture (Fig. 13): This is a side wing. You can see here the window forms in more detail, that is, the forms that the main form, which is on the west portal, takes on in metamorphosis. The next picture (Fig. 11): Here is such a metamorphosis of the main form above the west portal at one of the side entrances.

The next image (Fig. 14): Here, isolated so that it can be seen better, is a motif of one of the side entrances, and the concrete walkway, a gallery, a terrace.

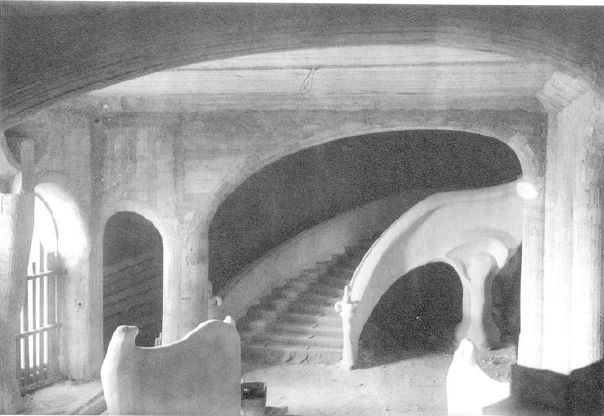

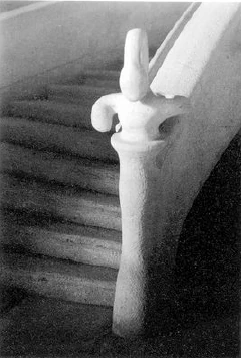

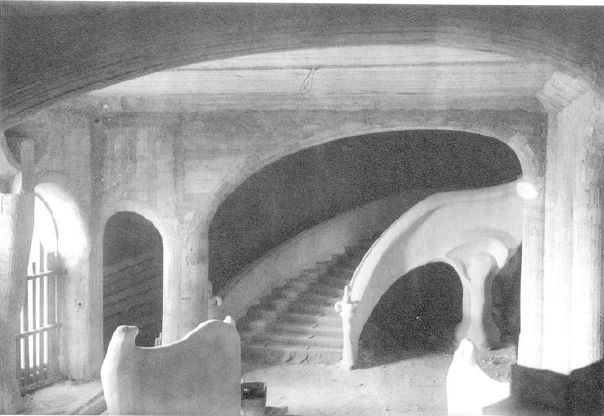

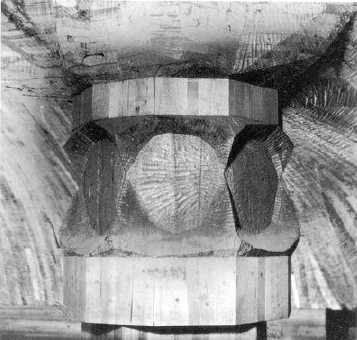

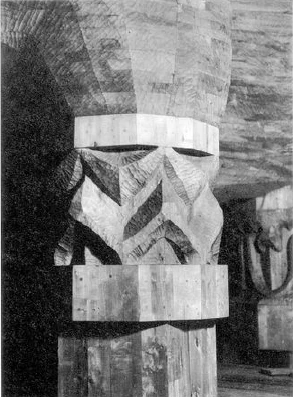

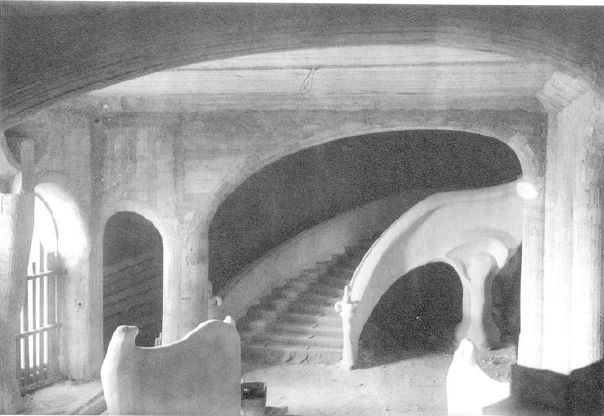

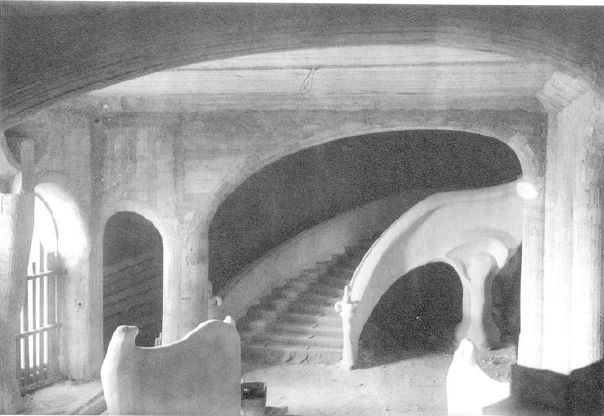

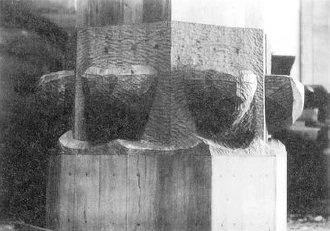

The next picture (Fig. 23): Imagine, dear attendees, that you have now gone down through the gate in the concrete building that I have often pointed out to you. You enter; here are the stairs leading up to the auditorium, here is the stairwell. You see, I have dared to replace the usual pillars or columns with something that is organically designed, and in such a way that, artistically speaking, it can only be in the overall organism of the building as it is, tapering outwards with reference to its curves towards the gate, where it has little to bear, bracing itself here, as a muscle braces itself where it has to bear, because here the whole weight of the building rests. But it was not attempted to make it out of thoughts, so that one can say that something is meant to express something. It does not express anything other than, for example, the human thigh expresses in its architectural structure. It expresses itself, that is, what it is for the organism as a whole. And one must have the feeling that it cannot be otherwise.

Of course, when people with habitual ways of thinking approach something like this, their desire to ridicule is stirred up. And since they can usually only think in a naturalistic way, they don't really know what to imagine by it. It seems organic to them, but they can only imagine the organic in naturalistic terms, as an imitation. Then along came an obviously very clever critic who noticed, as it seems, that it represents a certain strength. It has to bear weight, it has to represent a certain strength. But since he can only think in naturalistic terms, an elephant's foot occurred to him. But then again, it seems to him that something of an artistic-critical conscience has arisen, and he felt that it does not look like an elephant's foot. But now he already has this idea of the elephant's foot, it was already on his mind. He thought, but it must be an elephant foot. But now it was not as thick and clumsy as an elephant foot, and he thought it was rachitic, and now, in order to do justice to both these impressions, he said it was a “rachitic elephant foot”.

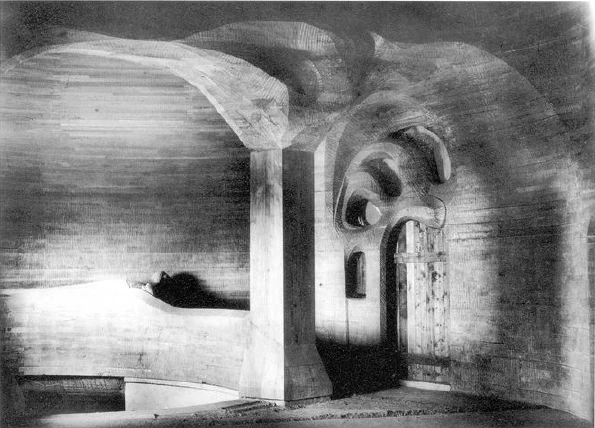

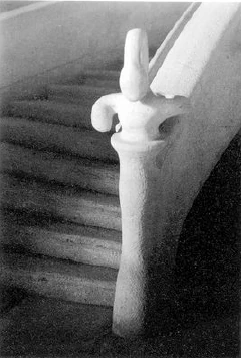

The next picture (Fig. 24): You see, at this point I felt how it must be for someone who enters our auditorium via these stairs. They must, so to speak, receive the feeling that Inside, my spiritual powers will be balanced by spiritual insight. Now, the whole feeling was realized for me in such a way that I had to make three such perpendicular forms, which stand perpendicular in the three directions of space. Believe it or not, it is still true: only when I had already done it in this way, when I had the model, did it occur to me that it reminds me of the three semicircular canals that are perpendicular in the ear and that, when injured, cause people to faint. One must unite one's own experiences of the soul with the sense of the creative forces of nature, then one discovers things that are by no means – I must keep saying it – symbolic or allegorical, but that come entirely from artistic feeling and yet have an inner necessity in themselves.

It is true that I actually prefer it when what I say about the building tonight is not expressed at all, but only felt when looking at the building, because the building should speak for itself. I don't really like talking about the building the way I am doing tonight. But not everyone can see the building over and over again; in art, one speaks of artistic works, and so perhaps one may try to talk about the building through a surrogate.

The next picture (Fig. 23): you can see here the staircase that was only hinted at there, here the form just discussed, here the “rachitic elephant foot”. You can see here, for example, this curve. I hope that whoever enters the building will feel the necessity of these forms at this point from the sense and view of the entire building.

The next picture (Fig. 26): Here you see a concrete mold – formed out of the wood above, it is somewhat different – for a radiator cover. This is also a form that arises from the feeling of saying to yourself, what do I have to put in front of a radiator, which grows out of nature like an organic thing, but which does not bring it to life, only the conclusion is for a radiator.

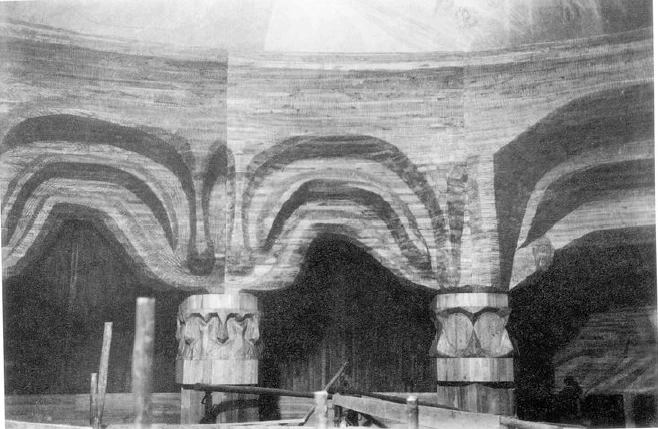

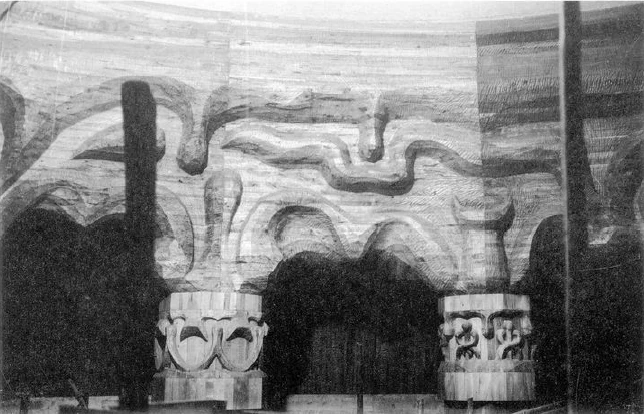

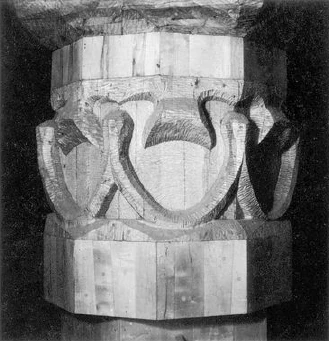

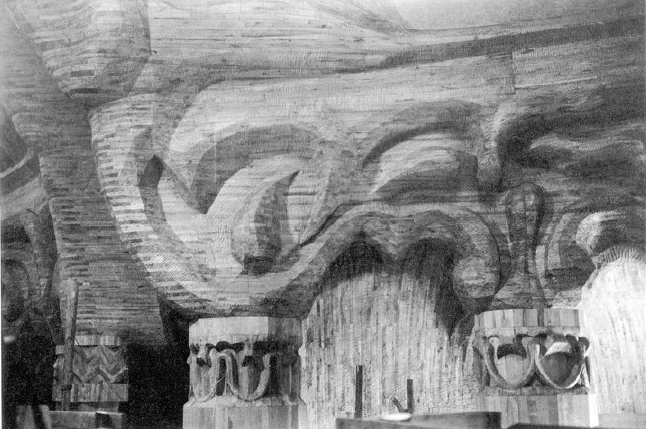

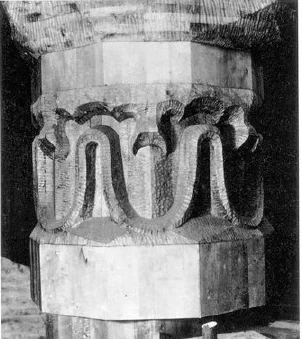

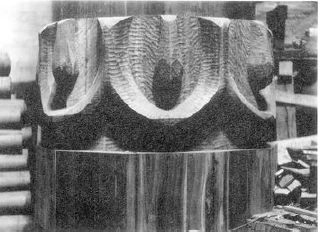

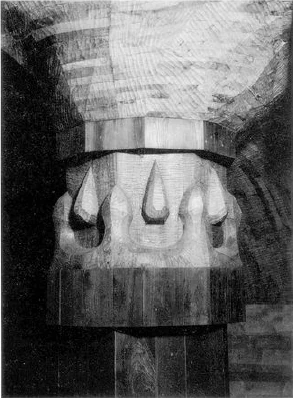

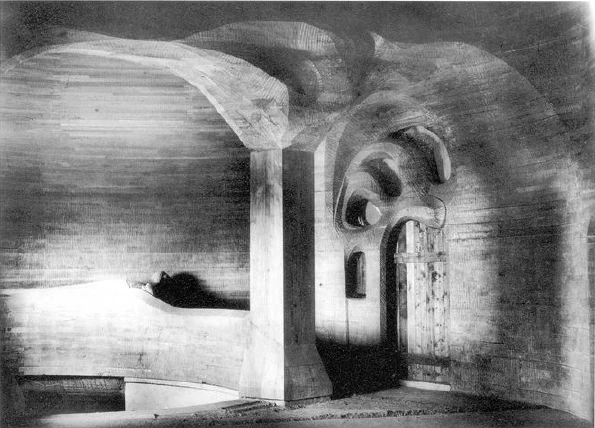

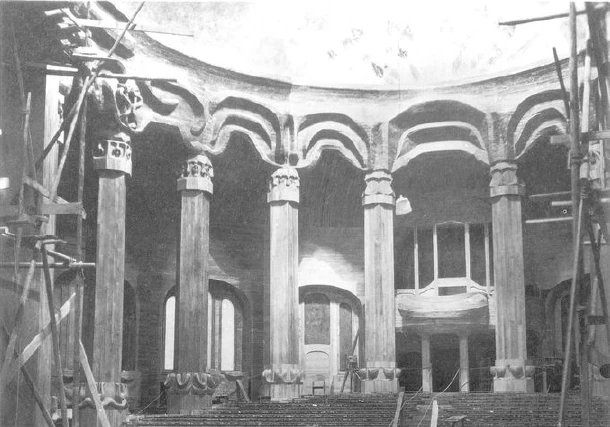

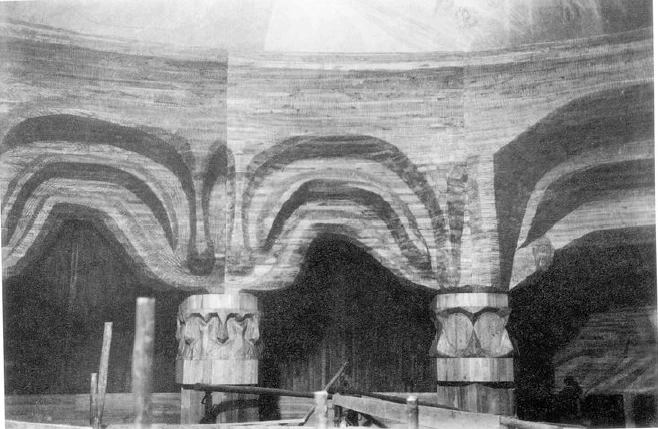

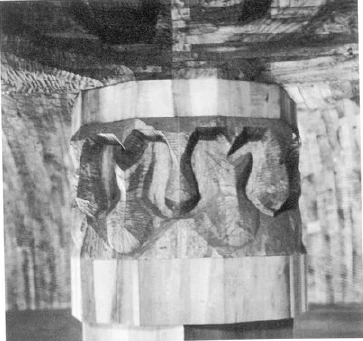

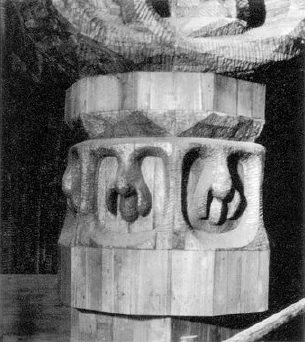

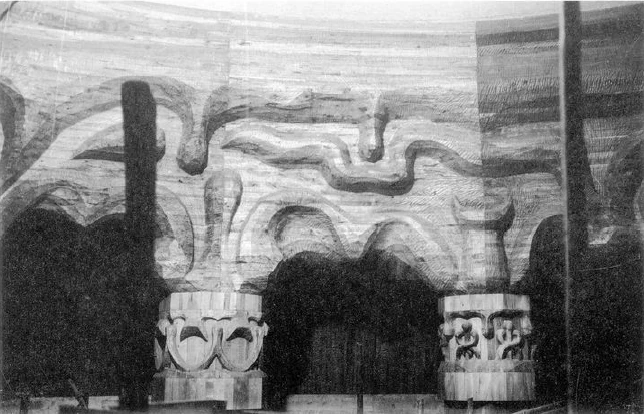

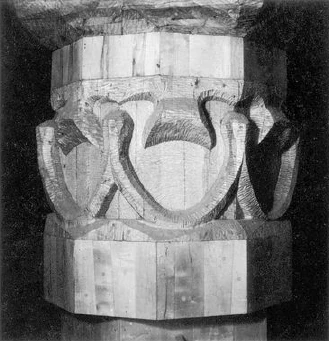

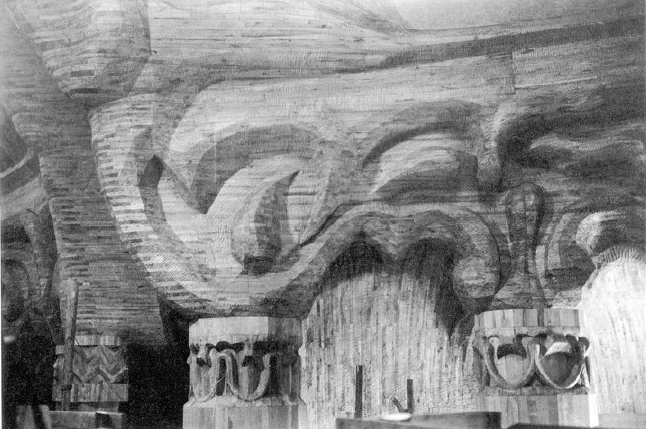

The next picture (Fig. 27): Now we have gone up the stairs and are here in the anteroom, which is only the anteroom, which is already quite in the area of timber construction. Here you see a column, and quite distinct from the sense of space in this place, you see this one column capital with its various curves, which reach out in the most diverse ways in the most varied directions in space, formed out of the sense of space itself. When you come to Dornach, I would ask you to see that in this room which is perhaps most clearly visible because it is the simplest. You will see that the whole thing is carved out of wood and it must be said again and again wherever there is an opportunity, that friends have devotedly worked for many years to bring about this building, because all of it is carved by hand after very crude carpentry work, all of it is carved by hand by our friends themselves, including this wall, which is individually designed in a variety of curves in different directions.

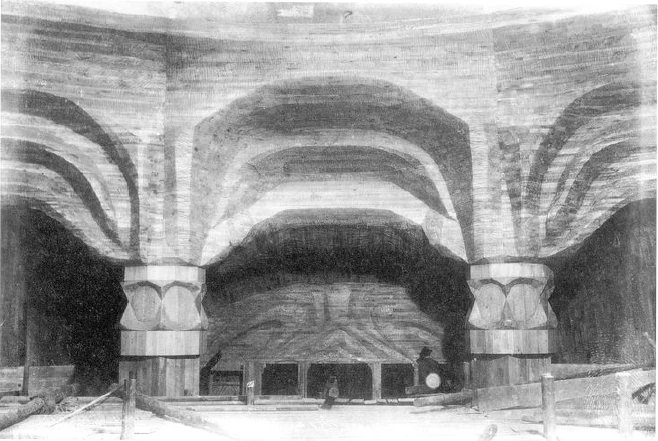

What I would particularly ask you to see is precisely the treatment of the wall. The whole building idea of Dornach resulted from the fact that the wall had to be conceived differently than one has been accustomed to, always thinking of walls. Walls are something final and limiting for the old architectural styles. Here they are not, here the thought should not arise: when you are inside the Dornach building, you are in a closed room. This thought should not arise. You come in and you should feel all the walls as if they were designed in an artistic way that actually makes the walls artistically transparent, so that you feel inside as if the wall does not close you off, but through its own form, which artistically makes the wall transparent, connects you with all the secrets of the macrocosm, allows you to look out, to look out inwardly, spiritually and soulfully into the vastness of the world.

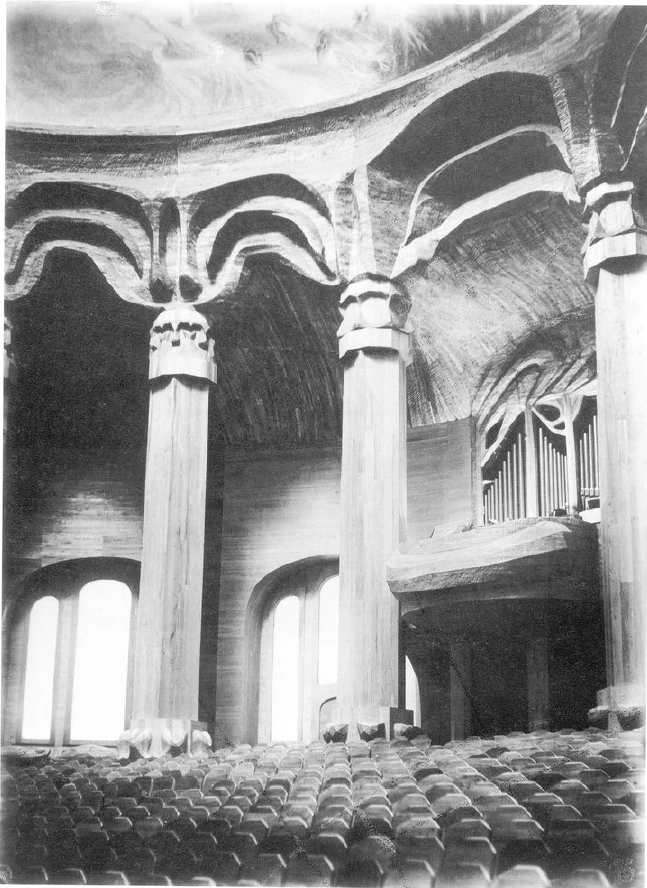

The next picture (Fig. 28): We have entered through the space below the organ, are standing in the auditorium, looking back and see here, somewhat elevated, the organ space.

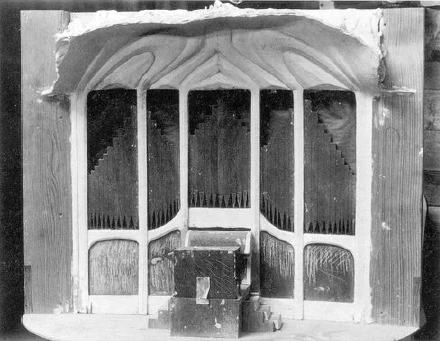

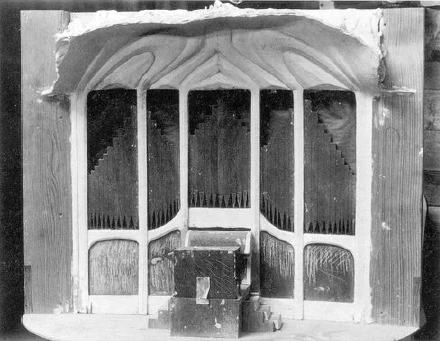

The next picture (Fig. 30): But this is not yet the finished organ motif, rather it is the model, which you can see here is still unfinished. The framing of the organ should also be developed in such a way that one has the feeling that the organ has not been placed in some corner or on some side, but that one has the feeling that the organ grows out of the whole organic structure as a necessary element. This motif would then have to be added later, in keeping with the height of the organ pipes. That was the first wax-wood model.

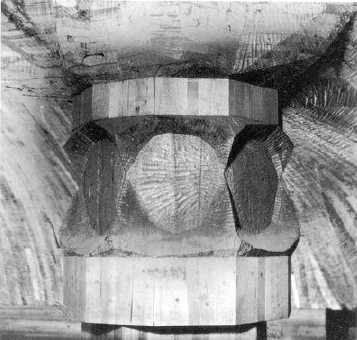

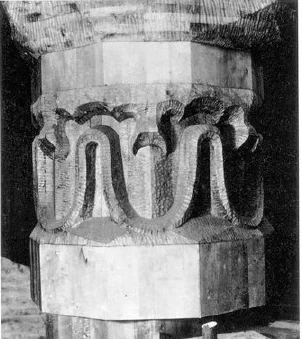

The next picture (Fig. 29): Here is the organ motif, here you enter. This is directly above the organ. These are the two columns to the right and left of the axis of symmetry. There you can see the sequence of columns. This sequence of columns with the architrave-like structure above it, I was already able to show in the first model earlier. But here I may draw attention to the fact that you see here the simplest capital motif; now the following capital motif is somewhat more complicated, the third again more complicated and so on. It is the case that the same formative forces, the same formative maxims that can be seen in nature, ascending the plant stem, metamorphosing the leaves, are at work here. The leaves are outwardly different in shape, but inwardly, in the sense of Goethe's theory of metamorphosis, they are ideally or spiritually the same.

If you now feel this form, descending, this ascending, but not in thought, but in artistic contemplation, and then connect with the creative forces of nature in such a way that you can really can deduce one from the other in the same way that the next plant leaf, which is shaped differently, emerges from the previous one, then you get these following forms; but, as I said, they are meant artistically. And it follows from this that it is actually of no particular value to focus attention on only one capital; what is important is that each capital emerges from the one that precedes it. For it is precisely this living transformation of one into the other that brings life to the building. And the same applies to the architraves.

I might say that you make some astonishing artistic discoveries. When I had designed the capitals according to the same principles as the advancing bases and architraves, I was able to follow a line of development. The idea of development has become a central tenet of modern knowledge. But one has – just look at this in the works of Herbert Spencer or others who have developed the idea of development in an abstract form, not in an inwardly living form – one has always believed that development progresses in such a way that first there is the primitive, simple form, then comes the complicated and so on and more and more complicated, and the last form is the most complicated. You can think that up if you think abstractly, but you can't express it artistically. If you express it artistically, the most complicated form is in the middle, then it becomes simpler again. One is simply pushed by artistic feeling to ascend to a middle most complicated form, and then to pass into the simpler one.

Then, however, one comes to realize that nature itself does it that way. The human eye is indeed the most perfect in the series of living beings, but not the most complicated. In its simplification, it no longer has the organs, for example, the fan and the xiphoid process, which are found in certain animals that have less perfect but more complicated intermediate forms of eyes. That is what I would particularly like to emphasize here.

Nebulous mystics, people who want to ramble on about everything, naturally ask: Why are there seven pillars on each side? There is no other answer to that than: Why are there seven colors in the rainbow, seven tones and the octave as a repetition of the prime in the tone scale? It is an inner necessity. And precisely when one feels this inner necessity quite objectively, then one does not lapse into nebulous mysticism. That something was done in nebulous mysticism in the Dornach building is simply a calumny.

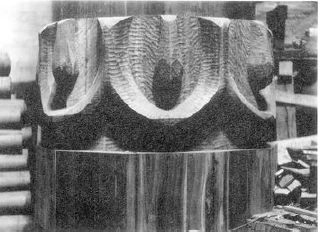

The next picture (Fig. 33): Here I present to you – here the organ motif – the two first forms, the simplest with the architrave motifs above them. I will now show the following in such a way that I always show a column, then this column together with the next, then the next in turn together with the next, and so on, so that you can see how the lively sense of progression from one column capital to the next and from one architrave motif to the next takes place.

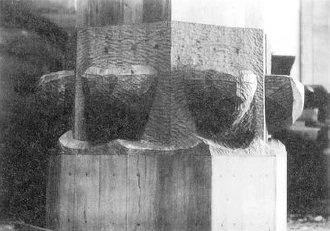

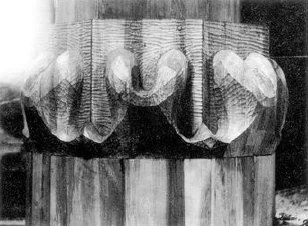

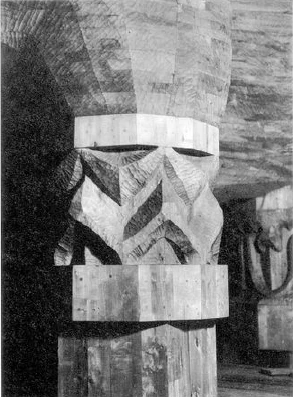

The next picture (Fig. 34): Here, then, the first column, isolated, leaning down, rising up, but the whole thing sensed in its polyhedral spherical form.

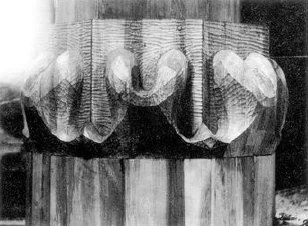

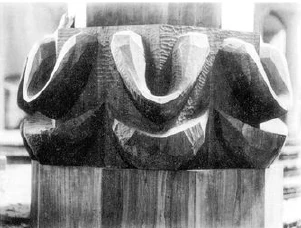

The next picture (Fig. 35): The first and second columns, progressing from a simpler motif to a more complicated one, as well as with the motifs above them.

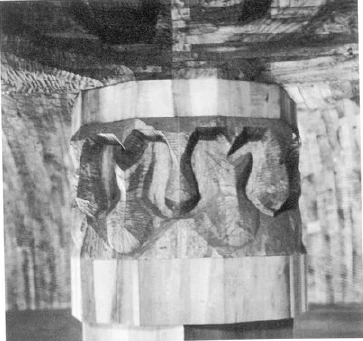

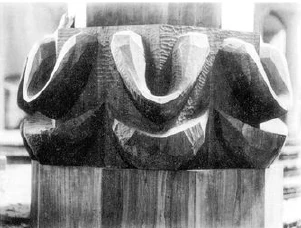

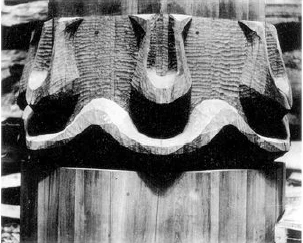

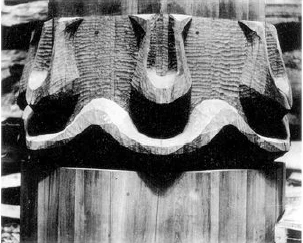

The next picture (Fig. 36): The next is the second column by itself. The next picture (Fig. 37): The second and third columns continue. The next picture (Fig. 38): The third column by itself.

The next picture (Fig. 39): the third and fourth columns. It is becoming even more complicated, and from these motifs one gets one such that any observer will believe that it was actually conceived as a single entity. However much it may seem familiar to you, if you have heard anything about mysticism – I hope not in a mystically nebulous way – it is simply obtained here by a metamorphic transformation of this motif. You can see it here, I would say, already in the forms.

The next picture (Fig. 40): This is the column still by itself, which was the fourth here.

The next picture (Fig. 41): Here you have the column that we just had. From this, then, by simply letting this motif continue to grow through metamorphosis, not by actually only developing this motif, this motif emerges. I believe that someone who had formed this concept intellectually, not emotionally, would have placed the same motif here [on the architrave above the fourth column] over the motif [on the fifth capital]. This did not occur to me because here [on the capital] I am dealing with columns in which the motifs that enclose a polyhedral shape can be felt. These motifs arise differently than those [of the architraves], where the surfaces are mounted; there they are distributed differently in space, and can only be understood from a sense of space.

The next image (Fig. 42): This [fifth] column on its own. It looks like a caduceus, but is simply the metamorphosis of the previous chapter.

The next picture (Fig. 43): This column and the one that emerges from its metamorphosis. When you have arrived at this most complicated one, the motif simply wants to become simpler again. It discards certain complications, it becomes more perfect, but simpler.

The next image (Fig. 44): This is the [sixth] column capital by itself.

The next picture (Fig. 45): So it has jumped over from one side to the other, it is this motif and then it becomes this through transformation.

The next picture (Fig. 46): This is the last motif.

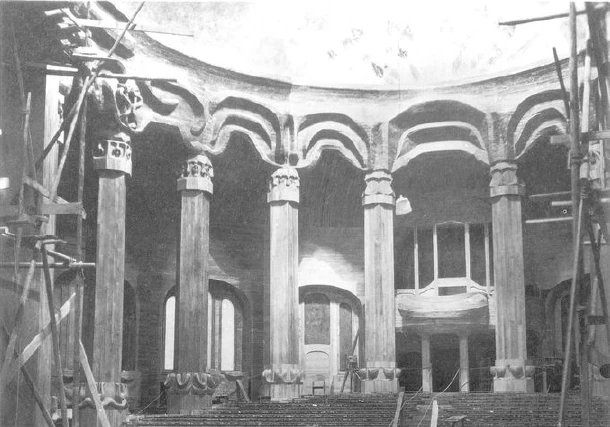

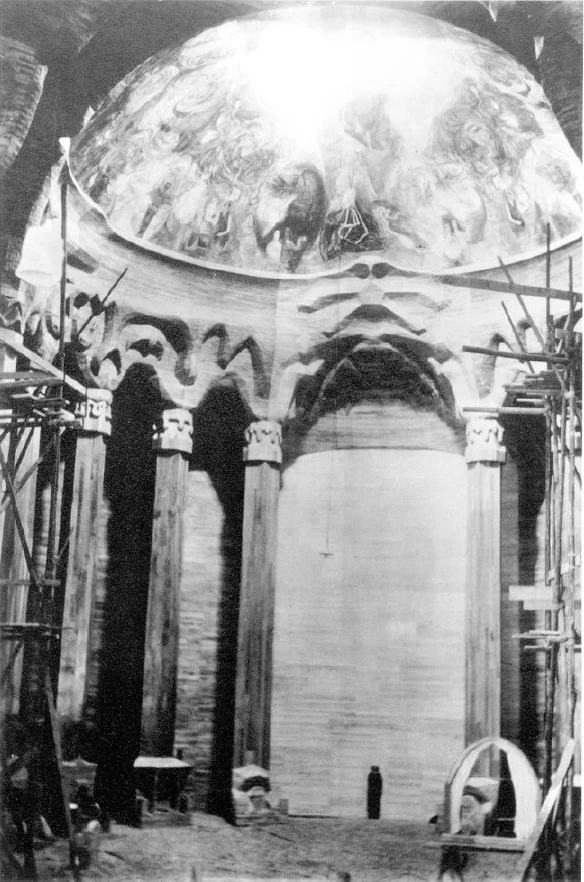

The next picture (Fig. 47): Here you have the last column of the auditorium, here is the slit between the auditorium and the stage, here is the first stage column. Here you can see into the stage area. Here is the dome of the stage area seen from the inside. It is still equipped with scaffolding. It is under construction.

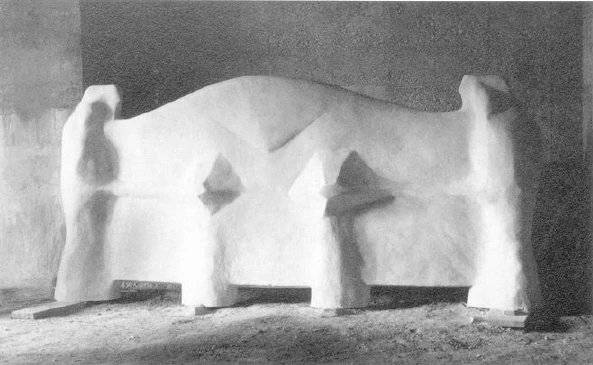

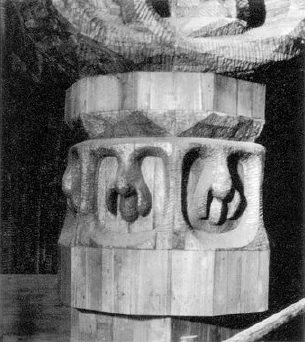

The next image (Fig. 48): I will now take the liberty of showing the metamorphosis of the pedestal figures in quick succession, so that it does not take us too long. You will see how one pedestal motif – for the columns of the auditorium – develops into the other.

The next picture (Fig. 49): So it gets more complicated. The next picture (Fig. 50): The third pedestal.

The next picture (Fig. 51): Next picture. The metamorphosis advances in this way. It is always the case with this metamorphosis, when it is felt through, that it tends to slope downwards again and new forms arise, expanding. The necessity for further development can only be felt artistically, not speculated upon.

The next picture (Fig. 52): The fifth base motif. The next picture (Fig. 53): The sixth motif. The next picture (Fig. 54). The seventh motif.

The next picture (Fig. 55): Here you can see into the stage area from the auditorium. This is the painting of the small dome, below it the stage area. The auditorium would then be here. You can see here into the small stage area from the auditorium facing east. This is the end of the auditorium. It is a motif; here the auditorium, then comes the curtain, which then belongs to the small stage area. It is the conclusion to the east. Below it will be the nine-and-a-half-meter-high wooden group, which I will talk about later, covered here by a wooden roof, which, in its various forms, synthesizes everything that is distributed over the other forms of the capitals and architraves.

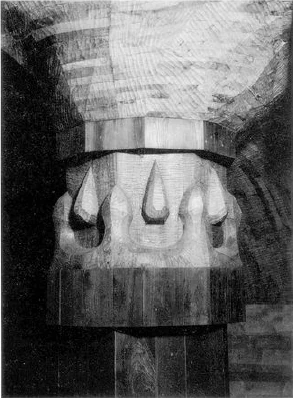

I would also like to show some columns from the small domed room, i.e. the stage area. These columns are made according to the same principle, but because of the small size of the room, because of the whole complex, the capital forms are different again, but they are asymmetrical in relation to the west-east axis.

The next picture (Fig. 58): Another column from the small domed room. The next picture (Fig. 59): Yet another. The next picture (Fig. 60): Yet another.

The next image (Fig. 57): Once again, the view from the auditorium into the small domed room. Here are the columns of the stage area. Performances will take place here. I have redesigned the bases of these columns in the small domed room as twelve seats. This was possible because this room can also be used as a meeting room. And because a meeting of twelve people was not intended to be mystical, but arose from the overall architecture.

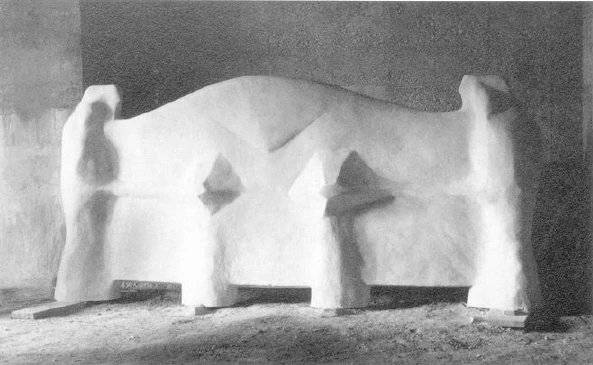

The next picture (Fig. 67): Here you can see what I just called the roofing. The columns of the small domed room would be here. Carved out of the wooden wall in various forms, these forms synthetically summarize the others. Below that is the nine-and-a-half-meter-high wooden group (Fig. 93).

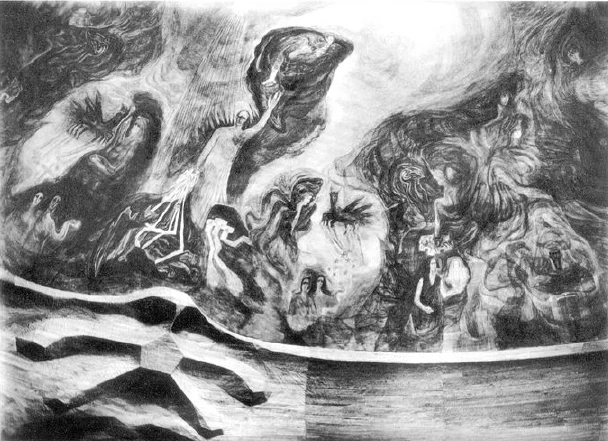

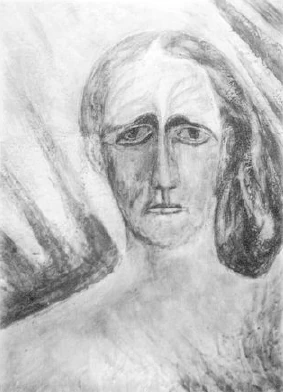

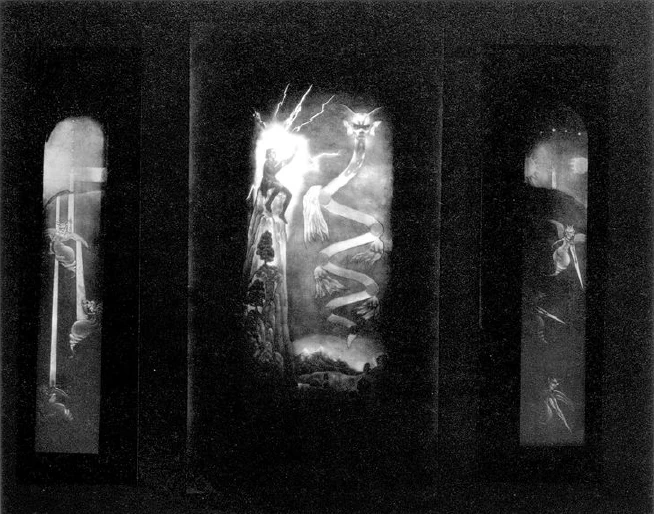

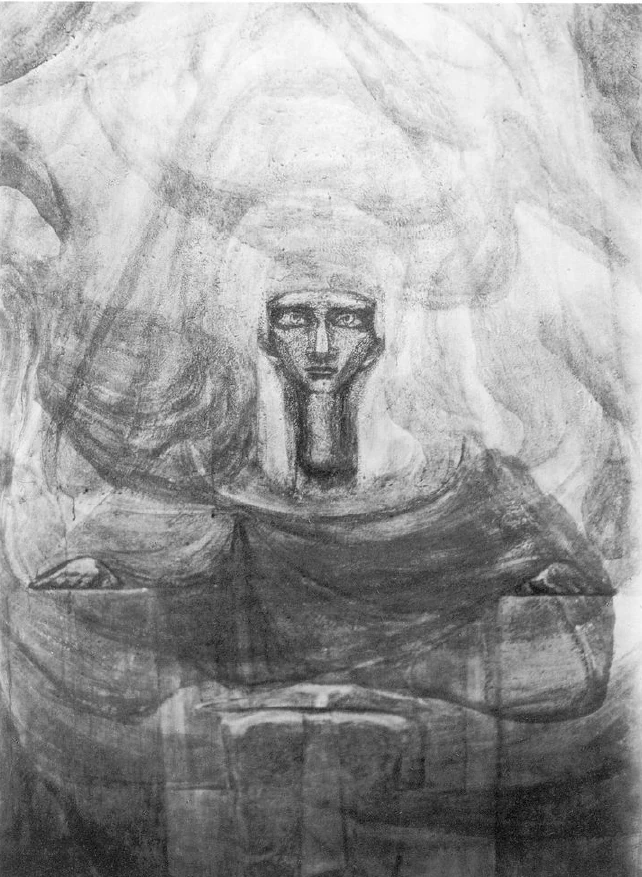

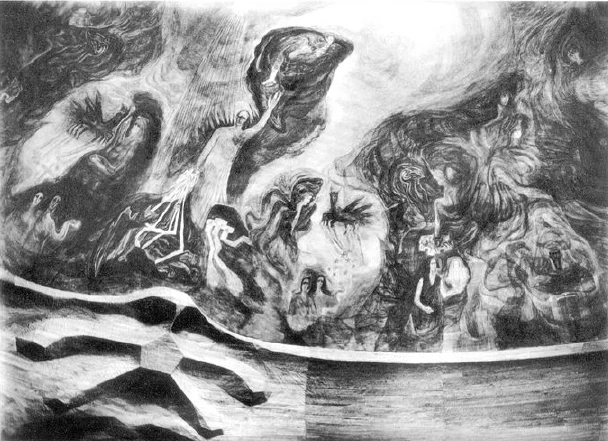

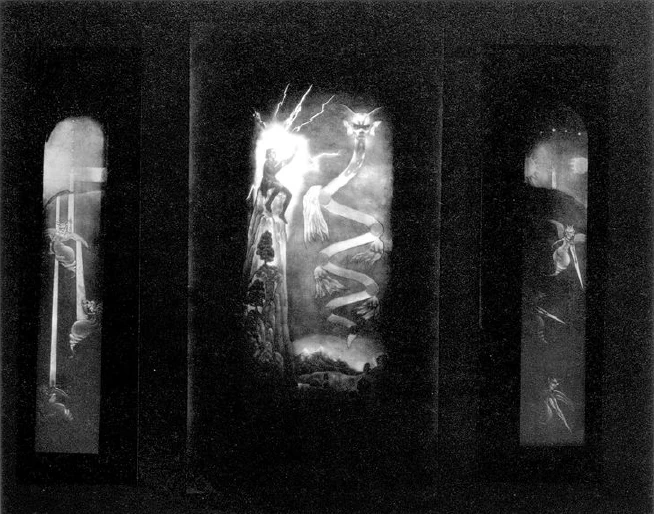

Now I come to the painting of the small dome. In this small dome, what must be aimed for in painting is gradually, perhaps, already achieved, despite all imperfections, not in the sense of artistic perfection, but in the sense of artistic intention. In one of my mystery dramas, I have a character suggest how painting should actually develop, so that gradually one no longer seeks the pictorial motif from the drawing, from the forms, but that one seeks it from the color and color harmony. That is how I had the character express it, that “form becomes the work of color”.

Now, since everything depends on the color in this painting of the small dome, it cannot be shown in these black-and-white afterimages, what is meant. But I think you can gain something from the fact that you might feel that something is wrong with these reproductions, that what you see is actually nonsense. And this feeling that it is actually nonsense is just an expression of the fact that one actually feels the necessity, it must be created from the color everywhere. And the human form, no matter how individualized it is, is thoroughly felt from the color.

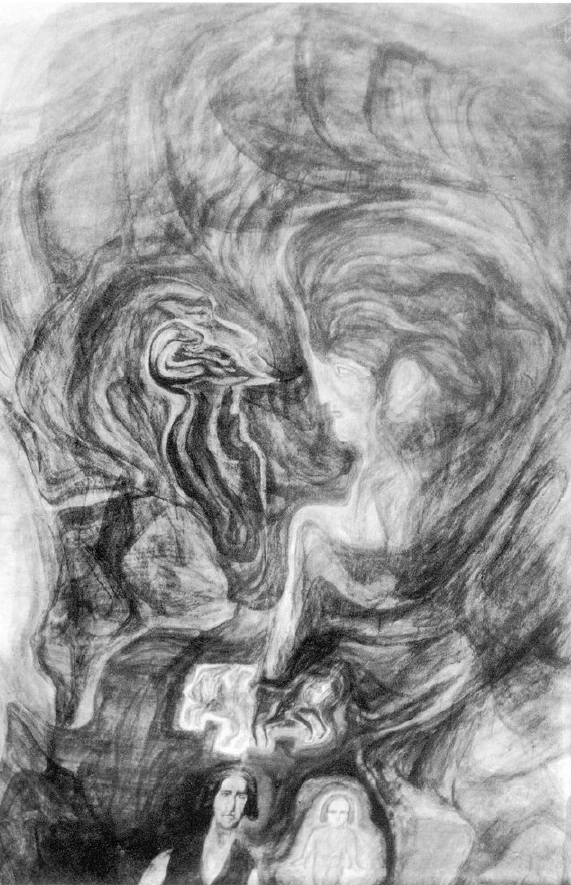

The next picture (Fig. 72): Here this child, which – here would be the first column, the other column of the auditorium here, here the curtain, here this orange-reddish-yellowish child painted – which stretches out its hands and its gaze towards this fist figure [Fig. 70]. Of course one can see a fist-like figure; but for the person painting, what matters is the blue bruise and how it relates to the other spots, that is, to the orange-yellow spots and so on. The colors represent a whole world, a cosmos in itself, with something creative in it; one can extract the form from what the colors speak to one another in the universe. It is the conversation of color, the color word, the creative color word. If one really feels all this artistically, then, just as the world is rightly described as emerging from the word, human, superhuman, and subhuman figures arise from color as it intensifies into the color word.

The next picture (Fig. 70): This is where the child would be, here the only word in the entire structure, here a kind of fist figure emerging out of the blue. As I said, the feeling arises from the color, and we are transported to the sixteenth century, to the culture of the sixteenth century. It is the dawning of that culture which we ourselves still carry within us in our spiritual life, the culture that rushes towards abstract knowledge. Those who do not experience it as it is largely experienced today by people, but who experience it with the whole, with the whole human being, feel the Faustian struggle within our modern knowledge. This Faustian struggle has led to the fact that only in recent times has man come to the full feeling of the I, and now of the unformed, inartistically written I, which is experienced darkly within. What can be borne is only that which one has in knowledge, when one feels it out of the fullness of the human being in the proximity of the child; for that which we will see in a moment, what is painted here, is linked from the brownish blackness below the fist, it is linked to the danger of modern knowledge for those who feel from the fullness, it is linked to death, because our knowledge only delivers the dead to us. And whoever not only thinks through theoretically, but inwardly experiences that our concepts themselves are corpses as concepts, always feels death standing beside him out of the Faustian striving, and so he longs for birth, which shows itself on the other side in the child.

The next picture (Fig. 71): Below Faust – here it would be Faust – [Death] is taken out of the black-brownish area.

The next picture (Fig. 73): Here the fist figure is merged out of the blue as a larger area, here the child, stretching out its hands, arms, and gaze, with Death below. Above it, a kind of inspirer, as these figures, which have been tried to be created out of colors, always represent - one can feel that, it is always initiated quite instinctively from the color harmony - the initiates, who receive the secrets of the world from inspirers. Here, then, is Faust, and above him is his inspirer.

The next picture (Fig. 74): This is the inspirer of Faust; below it, Faust would be taken out of the blue, yellowish, reddish colors.

The next image (Fig. 75): A Greek figure as you go further into the dome. Here there would be Faust with his inspirer, here a Greek figure with the inspirer above.

The next picture (Fig. 76): The inspirer; yellow and yellowish-white, sunny like an Apollo countenance, here below somewhat like an Athena countenance; but all this is drawn from the color word.

The next picture (Fig. 77): These are inspirers, spiritual beings that do not incarnate in the flesh, but who have an inspiring effect on those who live on earth in the flesh as human beings.

The next image (Fig. 78): An Egyptian person, inspired by the two preceding ones. An Egyptian initiate, brought out of the brownish-bluish-blackish coloration.

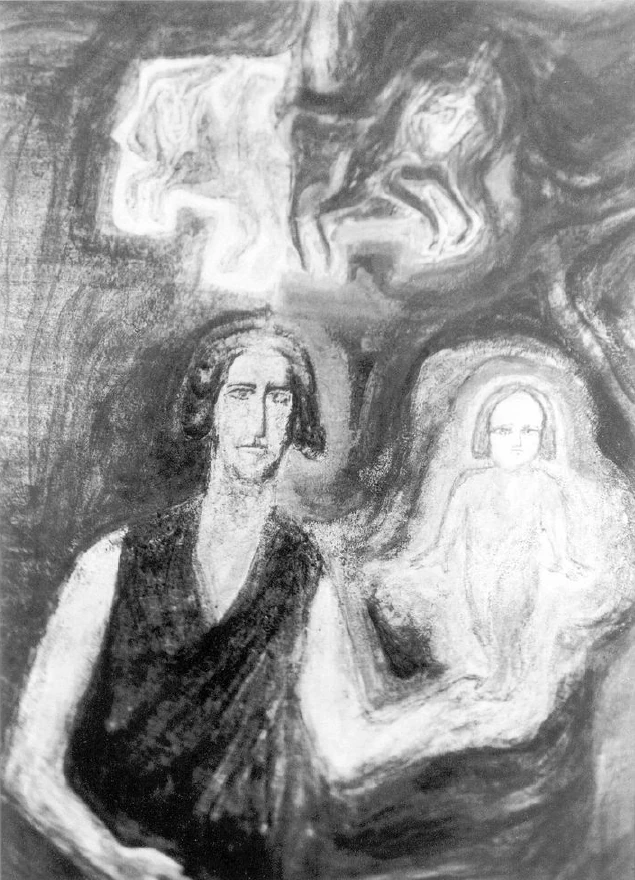

The next picture (Fig. 79): We are moving more and more towards the east, towards the center of the dome, so to speak. Here below is a type of human being that lived as an intellectual being in the whole zone from Persia north of the Black Sea in ancient times, and then developed in Central Europe in the Germanic being; here, in the arms of the child, is the aging human being who carries within himself the memory of the boy.

The ambivalence, the dualism that manifests itself in the Germanic nature when it becomes knowledge, reveals itself, precisely in this Germanic nature, always reveals itself by confronting powers: the Luciferic, which you see here, taken out of the yellowish-reddish, the Ahrimanic taken out of the brownish-yellowish. The Luciferic and the Ahrimanic, we shall see again later in the central figure, they are the two essential ingredients of the human being. Man can only be understood as a kind of state of equilibrium, which must be continually striven for, but which is continually in danger of falling out of itself, of falling towards what would present itself on one side, and on the other side, if the extremes were to develop one-sidedly. This is what man would be like if he had only a heart and no intellect. Then the rest of the human form would adapt to what the heart makes of the human being. This is how man would look if he only had reason and no heart: the Ahrimanic, ossified in himself.

This secret of human existence can be expressed in three ways: physically, psychologically and spiritually. In the luciferic form, which man does not become, but which he contains latently within him, towards which he always strives as towards one side of his nature, what is expressed is that which develops into pleurisy, which constantly places man in danger of fever. On the other hand, man carries within himself the forces of aging; he is always in danger; in morbid cases he succumbs to the physiological pathology of sclerosis, calcification. Between these two states man lives.

Here dualism is depicted, as it does not yet extend to the complete interpenetration of forms, in a kind of physiology that extends down to the animal kingdom, a kind of centaur. But then, something like this has been done before. I have just tried to reproduce the faces of Mr. and Mrs. Wilson in these figures, so that what is contemporary, what was particularly annoying in this period, is also immortalized to some extent.

The next picture (Fig. 81): Here we see the ahrimanic figure just discussed; that is, what the human being tends towards: physiologically in sclerosis, in calcification; psychologically, it is all that in man tends towards pedantry, towards moral intellectualism, and so on; spiritually, all that is actually most alive when man awakens and returns to his physical being.

The next picture (Fig. 82): the Luciferic figure all to itself. I have just discussed it physiologically. The psychic — that which drives people to enthusiasm, to wanting to go beyond themselves with their heads, so to speak, to falling into mysticism, into false theosophy — is something that can be found particularly in mystics and mystical societies. People are often in this mood of enthusiasm, of soulfulness, so that they are always half a meter above their physical head with their soul head, and with a certain inner arrogance - I have already spoken of this - they would then like to look down on their fellow human beings. Spiritually, this is the human being in the moment of falling asleep, of dreaming. These forces, to which the human being tends one-sidedly, are strongest in the moment of falling asleep, while the others, the Ahrimanic ones, are strongest in the moment of waking up.

The next picture (Fig. 82): The Germanic initiator, above him Mr. and Mrs. Wilson. He is holding the child by the arm, shining next to his dark figure.

The next picture (Fig. 83): Here we are already quite close to the eastern side of the small dome. Here is the Russian man, who actually always has his own shadow beside him. The one who sees spiritually actually always sees a real Russian twice, because the Russian always has the second man, the other, the double, with him spiritually. This is something that will only develop in the future; now it is rushing towards destruction, devastation and ruin. But out of this terrible devastation, out of this murder of human civilization, the good core of Russian-ness will one day develop. As here the Germanic has been shown, here is the Russian. Here the inspirer, out of the blue.

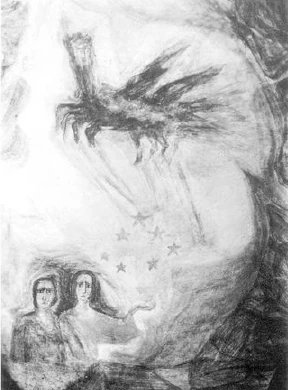

The next picture (Fig. 84): Here, if you note this point, you will find above the Russian – there is only one, as I said – the inspiring stars, above which there is a kind of cloud that forms the centaur, which, via the stars from the cosmos, stimulates that which is still present in the Russian today in an embryonic state of soul and spirit.

The next picture (Fig. 85): I will show you that from the other side in a moment. So over here [far right of the image] would be what I have just shown. Here is the actual central motif [directly to the right of the image], and here is the same inspiring angel from the north side; but it is created out of the orange and then, accordingly, this centaur figure. Below, there is again the one Russian who appears in two.

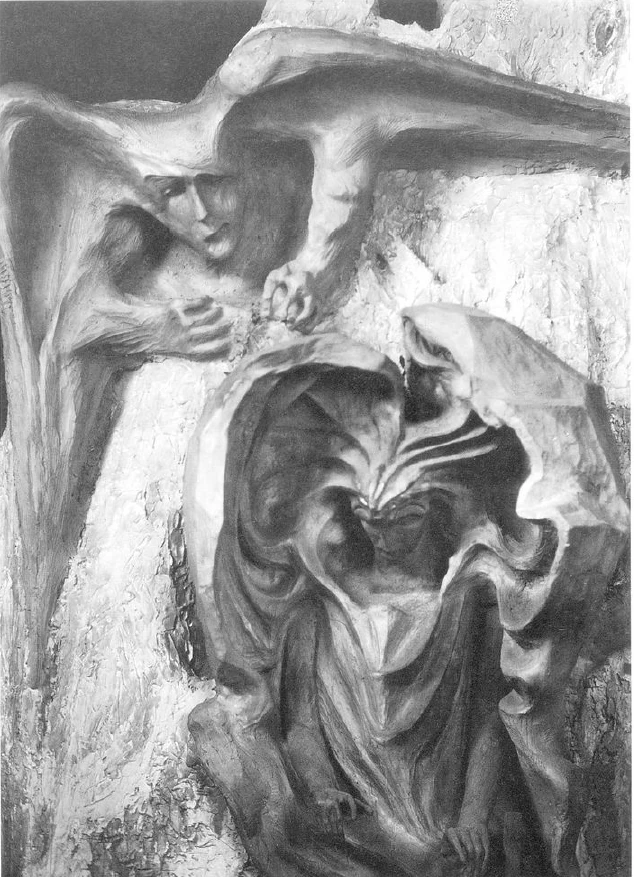

The next picture (Fig. 86): We are now in the middle. Here you see the Russian and here the inspiring blue angel and here the orange one, here in the middle the representative of humanity. Those who feel can feel the Christ in him. He stands there as the representative of human equilibrium; from his right side he sends out the rays of love, which, like serpents, entwine the ahrimanic form – that is, the sclerotic, pedantic, materialistic-intellectual human being; here above is the luciferic figure, which is physiologically, psychologically and spiritually what I have indicated.

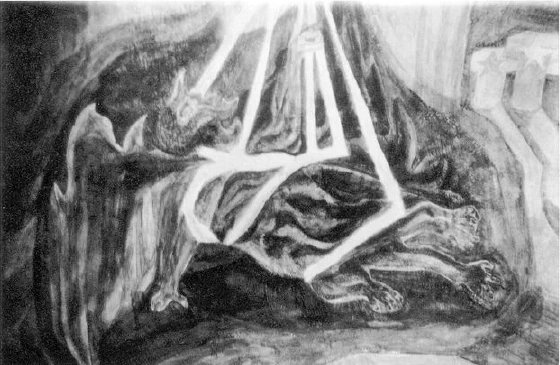

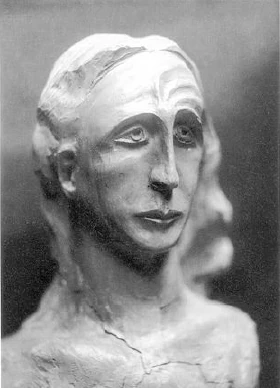

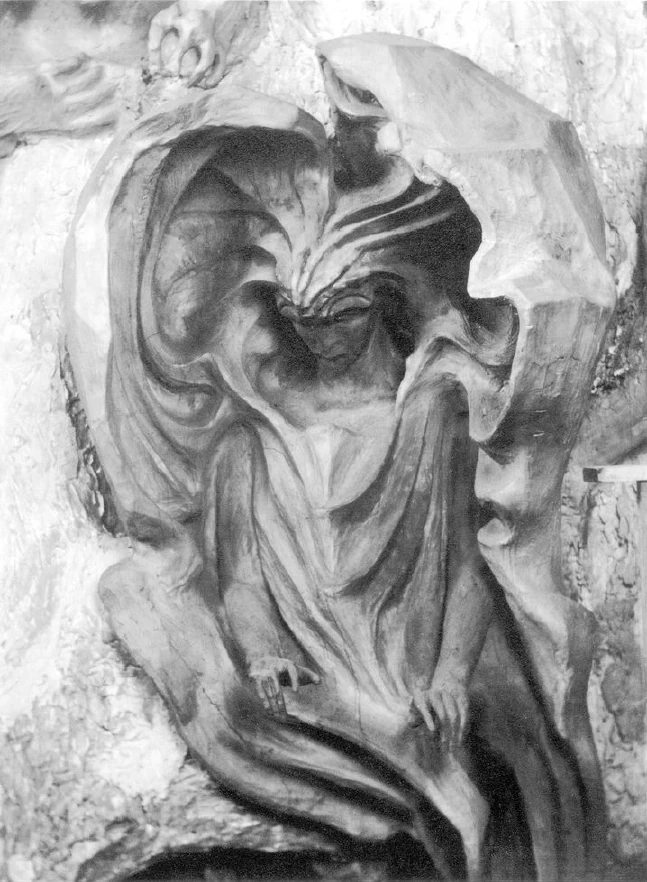

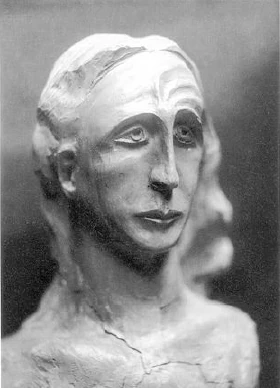

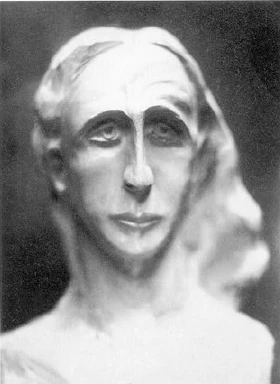

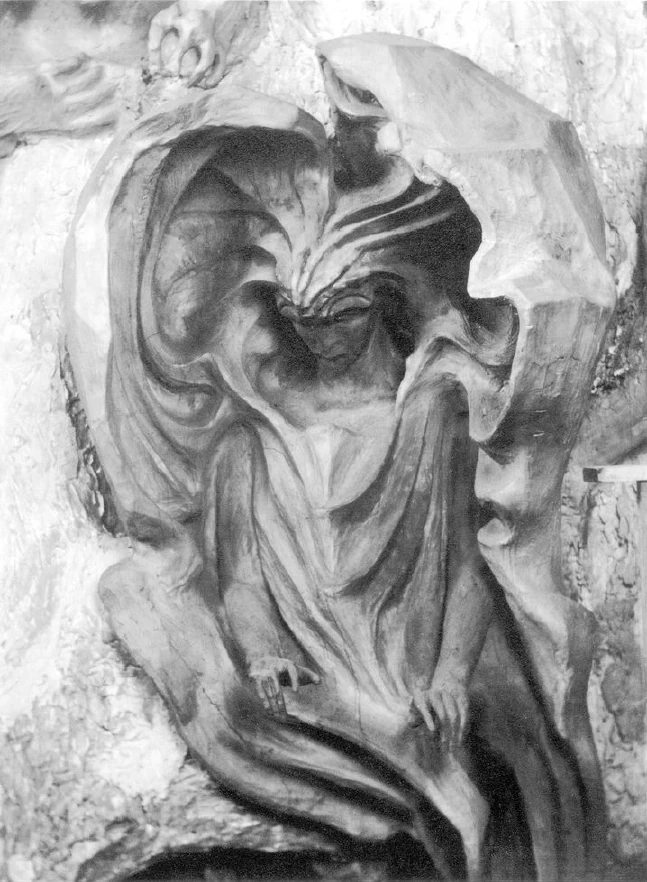

This will be in the far east. This is painted on the inside of the dome, and below it, though differently designed, as it must be for the sculpture, is the nine-and-a-half-meter-high wooden group, which also has the Representative of Humanity in the center, who brings balance between the Ahrimanic and the Luciferic.

It so happened that the famous and influential Frohnmeyer wrote a pamphlet, a defamatory pamphlet about anthroposophy, and in this pamphlet he makes the monstrous claim that “when one comes to Dornach, one can see, as Steiner claims, that this is what the Christ looked like in objective reality.” I don't say to anyone else that I see him that way and don't impose him dogmatically on anyone, but I could only shape him as I saw him, he is the one who walked in Palestine according to my vision. Above that is the Luciferic-Ahrimanic.

Frohnmeyer now says that he depicts a Christ there as objective, who has Luciferian traits above and animalistic traits below. He [supposedly] saw it that way. Lucifer is above, the Christ is shaped entirely humanly, below is Ahriman, here is still a piece of wood, it is not yet finished in the wood. But someone writes it down who doesn't feel the slightest obligation to research the truth, just as in the other case, as Mr. Kolisko told it today, someone writes down the objective untruth and then apologizes by saying that he didn't have time to research the truth.

Pastor Frohnmeyer was confronted with the matter. He then said that he had not seen it himself, but had copied it from another pastor, and since it had already appeared a long time ago, he simply believed he could copy it. We did, in fact, send a correction from Dornach, but it was not included. This is how things are spread today; it is the level of conscientiousness with which people work today. But one must keep saying: what should a theology look like that is shaped only in this way? The person in question was also a lecturer at the University of Basel.

The next picture (Fig. 87): the figure of Lucifer in itself – here the figure of Christ would be underneath – this has been brought out of the red.

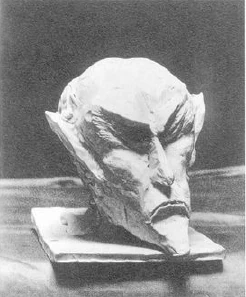

The next picture (Fig. 88): the Ahrimanic figure by itself. You see here the head, which is as it should be in a being that has only intellect and no powers of the heart.

The next picture (Fig. 90): the painted representative of humanity, the Christ.

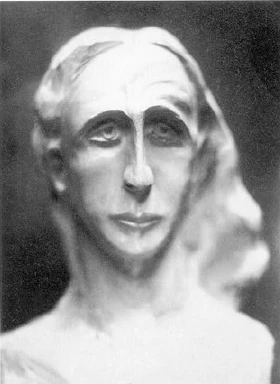

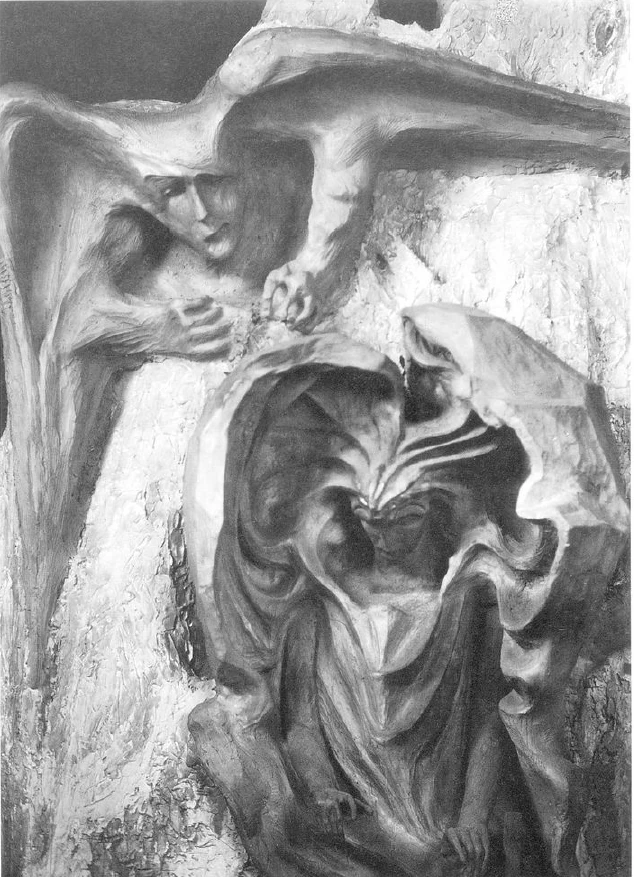

The next picture (Fig. 91): Here is my original model of the plastic Christ, seen in profile, who is thus a wooden figure. And in the middle again this Representative of Humanity; above it, repeated twice, the Luciferic figure; below it, twice, the Ahrimanic figure. And then, on the side, an elemental being growing out of the rock, which I will show you in illustrations so that you can see how asymmetry has been attempted in the Dornach sculpture. The next picture (Fig. 92) is my original model for the Christ of the wooden figure. The asymmetry is taken so far that, because the left arm is directed upwards and the right downwards, and the whole figure, not just the face, should have physiognomy, the whole figure should be soul, that the held-up arm on the left corresponds to the forehead, and the held-down arm corresponds to the forehead. This asymmetry, which is only subtly hinted at in humans, has been attempted here. Such things had to be dared because the sensual should not be imitated, but on the contrary, the spiritual, concrete [forming] behind the sensual should be observed, which underlies the sensual formation.

The next picture (Fig. 98): This is a piece [of the execution model]. Here would be Christ. Here is Lucifer, who aspires to the right hand of Christ. Here is this being, growing out of the rock as an elementary being in complete asymmetry. You see, here it is attempted to overcome the usual way of composing. Usually, one composes figures that one puts together. Here, the whole group, which consists of a series of figures, is conceived as a unit, and the individual figures are taken out of the whole down to their fingers, noses, eyes and eyebrows, so that, of course, when the left is at the top, an asymmetry results, but one that is taken from the life of the whole.

The next picture (Fig. 101): once again the striving Lucifer. Here would be the second Luciferian figure, here the Christ figure.

The next picture (Fig. 99): This is my original Ahriman-Mephistopheles model. Mephistopheles is, of course, only a later metamorphosis of Ahriman, who signifies physiologically, psychologically and spiritually what I have said. This model underlies all the Ahriman figures. It was originally designed by me for the wood group in 1915.

The next picture (Fig. 106): Now I come back to showing you this heating house, here in profile, so to speak, since I have already told you how it came about. It is often perceived as annoying; but people do not consider what would be there if one had not tried to shape something out of the concrete material, out of this brittle material, which might be more perfect later on. There would be a red chimney here! I wonder if it would be more beautiful in reality.

The next picture (Fig. 107): the boiler house, seen from the front. As I said, it is only when the smoke comes out that you feel a certain necessity for these outgrowths.

The next picture (Fig. 103): This is the house that was built nearby, the glass house that is now used as a construction office. Some eurythmy practice rooms are inside. It had to be built originally because the glass windows for the building were cut inside it. These glass windows came about in such a way that what is otherwise only artistically executed – that the wall is artistically transparent – is formed in these glass windows right down to the physical level. The motif that had been specified was engraved with a diamond pencil from monochrome glass panes by friends who worked on it for years with tremendous dedication and devotion. This had to be done first in this house. The glass panes are large and a separate studio building had to be erected for this purpose. But it is designed entirely in the style of the whole. Two domes, standing apart from each other, determine the very different shape of the building up to the gate; the whole asymmetry, so down to the stairs, everything is individualized. Those who come here will see that the lock and the door handle are individually designed.

The next picture (Fig. 104): the gate lifted out. The staircase individualized so that it can only be as it is at this location. Here (Fig. 105) the lock, which also returns in various metamorphoses on the building, then the gate.

The next picture (Fig. 112): Here you see a sample of windows, engraved out of a [same-colored] glass pane. One could allegorize and symbolize many things from these colors; but what the person who feels the matter artistically likes best is to simply stand in front of it and let this whole interplay of the light color tone with the dark color tone take effect on them because the interplay – the glass panes are, after all, arranged in succession in different colors – this entire play of colors undulates in the building, but in such a way that it does not make anyone nervous, but on the contrary = as has been attempted – has a healing effect.

The next picture (Fig. 110): other motifs. Such Ahrimanic figures, scratched out.

Now, dear attendees, that was what I took the liberty of bringing to you as a single image from this Goetheanum in Dornach. It is precisely the place where we should find the center of what has been cultivated here for a week, through this week, which was actually dedicated to Goethe's name, Goethe's essence and Goethe's work. And everything that the Goetheanum stands for should be dedicated to this. Perhaps it will have emerged from what I dared to say in the course of these discussions, that what wants to come before the world in anthroposophy can work both artistically and cognitively.

Unfortunately, we are not yet finished; a great deal of effort and, in particular, a great deal of sacrifice from our friends is still needed; unfortunately, it cannot come from the central states at the moment because of the currency difficulties. The sacrifice of other friends is needed if the building is to be completed. It cannot be completed otherwise than by this spirit of sacrifice being renewed. But it must be said that for a long time this spirit of sacrifice has been revealed in the most beautiful, significant and understanding way for Dornach. And from the feeling of the cultural significance of our cause, we cannot thank enough – I would say, from the genius of this anthroposophical sense, we cannot thank enough – those who have been able to possess this spirit of sacrifice. May it continue to exist so that Dornach does not remain a torso, but can be completed.

In the past week, a worthy and beautiful contribution has been made by our friends in Stuttgart and those who have joined them, and this is also intended to serve Dornach; and since I do not belong to the organizing committee, but am only an invited guest, it will not out of place if I also include myself – one knows how much effort a congress committee has, how it has to consider all the details and the big picture and prepare them over a long period of time – to express my heartfelt thanks to this committee, even now that we are at the end of this event.

And then, we must indeed consider, my dear attendees, what calls are going out into the world today. Everywhere we hear, in the broadest circles, the ethical needs - if only in words - of what, in deepest reality, spiritual science wants to bring to the world. Do we not hear everywhere the yearning and speak of world brotherhood, which is to come about through all kinds of world covenants in the most diverse areas of life, but unfortunately out of the old? World brotherhood is sought; it is believed that this or that external event could lead to it.

But, my dear attendees, this world brotherhood cannot be found unless one has the deepest conviction that it actually exists, but is hidden for our time in the deepest subconscious depths of the human soul. But that is where it must be sought. That which is in the depths of the human soul must be sought and realized in the outer life, in social life. Then there will be world brotherhood, then this world brotherhood will be able to create the outer institutions that belong to it. But this world brotherhood cannot be brought about through external institutions. This world brotherhood, however, can only be found if man searches his deepest inner being in the spirit, at the point where his own being is bound together with the world spirit.

Knowledge and art, so they should arise from anthroposophical attitude and anthroposophical insight, as we tried to show in this week. Then, when knowledge and art emerge from human spirituality, which experiences world spirituality within itself, then this experience will also be a deeply religious one, one that will arise in man, entirely in the spirit of Goetheanism, that Goetheanism that sought in Goethe himself the harmony of the three most ideal fruits of life: science, art and religion.

If these fruits of life are there, then social life can also flourish for the benefit of humanity. If we speak less of the religious, it is perhaps precisely out of true religious experience, out of that religious experience that arises when science is sought in a spiritual way, art in a spiritual way.

And in this sense, esteemed attendees, the conclusion may well sound as the beginning sounded! Our dear friend Uehli began with Goethe, and may this event end with Goethe, with his words, through which he expressed his attitude towards science, art and religion; for he said what can also be our motto, which only must be developed further, in accordance with the insight that we do not have before us the Goethe who died in 1832, but the one who has developed with the world, whom we want to serve with his further education and development. But as a shining motto, everything that comes out of this work in the spirit of Goetheanism will be able to draw on what lies in his words, with which this event should come to an end:

He who possesses science and art also has religion

He who does not possess both, may have religion

8. Der Baugedanke Von Dornach

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Es obliegt mir heute, von derjenigen Stätte zu sprechen, in welcher einen Mittelpunkt des Wirkens haben soll alles dasjenige, was ausstrahlen kann von jener Arbeit, an der Sie sich in einer so tief befriedigenden Weise in den letzten acht Tagen hier beteiligt haben. Ich darf sagen, in einer tief befriedigenden Weise, aus dem Grunde, weil Sie mir glauben werden, dass ich in tiefstem Herzen ja verbunden bin mit dieser Arbeit und daher gerade über den Verlauf dieses Kongresses die tiefste Befriedigung aussprechen darf.

Nun, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, das Goetheanum, es soll gewissermaßen eine bauliche Umhüllung sein desjenigen, was in der verschiedensten Weise und auf den verschiedensten Gebieten als das Ergebnis anthroposophischer Geisteswissenschaft für das Leben auftreten möchte. Anthroposophie hatte im Beginne ihres Auftretens in der Welt selbstverständlich nicht gleich eine eigene Wirkensstätte, und es konnte nicht einmal daran gedacht werden, im Entferntesten auch nur daran gedacht werden, ihr irgendeine Wirkungsstätte zu bauen. Nach ungefähr einem Jahrzehnt von Wirksamkeit entstand bei einer Reihe von Bekennern zur anthroposophischen Weltanschauung die Idee, eine solche Mittelpunktsstätte für diese Anthroposophie zu schaffen. Ausgegangen war ja der Gedanke zunächst von den Eindrücken, die man bekommen hat durch die Aufführung der Mysterienspiele, mit denen wir 1910 in München begonnen haben. Es ist da wohl einer Anzahl von unseren Freunden aufgefallen, wie wenig sich die Architektur eines gewöhnlichen Theaters, wie wir in einem solchen die Mysterien eben damals aufführen mussten, eignet für dasjenige, was eigentlich aus Anthroposophie heraus da auch künstlerisch gewollt werden muss.

Und so entstand dann der Plan, für Anthroposophie eine Art Hochschule zu begründen. Im ersten Anlauf wollte man in München bauen. Grund und Boden war in München ja auch bereits gewonnen. Nun handelte es sich aber darum, dass gerade, weil anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft das sein will, von dem auch in diesen Tagen hier wiederum gesprochen worden ist, für einen solchen Bau nicht dasselbe eintreten konnte, was sonst in einem solchen Falle eintritt. Man hat eine Gesellschaft oder einen Verein, wie man es nennen will, der sich irgendein Ziel gesetzt hat, und der da glaubt, nötig zu haben einen eigenen Bau. Man setzt sich in Verbindung mit irgendeinem Baumeister, einem Architekten, und erhält seine Vorschläge. Es wird der Bau aufgeführt in antikem, in Renaissance-Stil, im gotischen Baustil oder dergleichen, und dann werden die Veranstaltungen des betreffenden Vereins oder der betreffenden Gesellschaft in einem solchen Bau abgehalten.

Wer mit seinem eigenen Seelenleben, so wie es sein sollte, durch und durch verbunden ist mit anthroposophischer Weltanschauung, der kann nimmermehr sich einverstanden erklären mit solch einer Abmachung nach außen hin für eine Umrahmung, für eine Umhüllung desjenigen, was durch Anthroposophie geschaffen werden soll. Denn es ist ja immer und immer wiederum betont worden: Anthroposophie, ja sie ist auf der einen Seite aus den tiefsten Quellen menschlicher Erkenntnis heraus eine Wissenschaft vom Geiste, vom Übersinnlichen. Aber sie ist nicht eine Theorie, sie ist nicht eine Summe von Abstraktionen, sie ist nicht etwas über die Welt und über das Leben; sie wird so, wie sie sich entwickelt, Leben selbst, sie ergreift die tiefsten inneren Impulse des ganzen, des Vollmenschen, und verfolgt alles aus dem Innern dieses Vollmenschen heraus, was sie ihm sein kann. Dadurch regt sie nicht nur die wissenschaftlichen Forschungsimpulse, sondern auch die künstlerischen Schaffensimpulse an.

Nicht als ob aus dem wahren anthroposophischen Geiste heraus - ich habe das in meinen Abendvorträgen bereits erwähnt -, nicht als ob aus diesem Geiste heraus eine allegorisierende ‚oder symbolisierende Kunst entstehen wollte; das wäre überhaupt keine Kunst. Nicht Ideen sollen umgesetzt werden in symbolischen oder allegorischen Formen. Nein, dasjenige, was anthroposophische Geisterkenntnis ist, dringt in die Tiefen der Menschenseele hinunter und nimmt seinen Ursprung aus Quellen, die noch in anderen Strömen sich in die Welt ergießen können als auf dem Gebiet der Ideendarstellung. Und so entspringt dann der eine Strom der Ideendarstellung als das eine, und der andere Strom, der Strom künstlerischen Schaffens neben noch manchem anderen, aus derselben Quelle. Aber es handelt sich nicht um eine Umsetzung von Geisteswissenschaft in Kunst oder in Scheinkunst, sondern um ein elementares, ganz ursprüngliches, ich möchte sagen, sich Ausleben des Künstlerischen. In Dornach wird man heute sehen, wie nichts Symbolisches oder Allegorisches angestrebt ist, sondern wie dasjenige, was da als Kunst dastehen sollte, eben auch als Kunst konzipiert ist, aus dem Künstlerischen heraus geschaffen ist.

Ich möchte mich durch ein Bild ausdrücken: Wenn das Verhältnis von anthroposophischer Weltanschauung zur Kunst wirklich so ist, wie ich es eben geschildert habe, dann darf diese anthroposophische Weltanschauung sich nicht eine Stätte bauen lassen von außen herein, in irgendeinem Stil, der für griechische, für Renaissance-, für gotische Weltanschauung war, dann muss diese anthroposophische Weltanschauung ihr Heim haben in einem Bau, der aus den eigensten ureigensten Impulsen der Anthroposophie her entstanden ist. Dann muss die Sache so sein, dass vom Podium zum Beispiel gesprochen wird, von der Bühne gesungen oder rezitiert oder in Eurythmie gespielt und so weiter wird; dasjenige, was auf diese Weise hinaustritt zu den Menschen, das muss gewissermaßen die eine Sprache sein, und die andere Sprache müssen die Bauformen sein, muss die Architektur sein, die dasjenige einhüllen, was innerhalb des Raumes sich offenbaren will. Anthroposophie darf nicht einen Stil von außen her hinnehmen, Anthroposophie muss selbst, da sie innig verwandt ist mit dem Künstlerischen, stilschaffend auftreten.

Das ist dasjenige, was vorlag, ich möchte sagen, mit derselben inneren geistigen Notwendigkeit, wie - jetzt möchte ich mich eben durch ein Bild ausdrücken — wie die Nussschale nicht anders sein kann in ihrer Formung, in ihrer Gestaltung, als wie sie ist. Aus derselben Gesetzmäßigkeit, aus denselben Formen und Lebenskräften geht hervor die Nussfrucht und auch die Nussschale. Derjenige, der das eine sieht, kann das andere beurteilen. So musste es auch bei dem Bau für die anthroposophische Weltanschauung sein. Daher konnte aus alledem, was lebte in den Ideen der Anthroposophie, entspringen dasjenige, was nun Stil werden sollte für einen solchen Bau.

Man kann sagen, es ist ja eigentlich begreiflich, dass das zunächst Widerstand fand bei all denjenigen, die eben am Alten hängen, die sich nicht vorstellen können, dass sich die Entwicklung der Menschheit nur dadurch ergeben kann, dass immer neue und neue Metamorphosen des menschlichen Arbeitens, menschlichen Schaffens und menschlichen Erkennens auftreten, und so lehnte uns - ich betone das ausdrücklich - nicht etwa die Polizei oder die Regierung, sondern es lehnte uns das Künstlertum zunächst unsere Stilformen für München ab. Es ist nicht unsere Schuld, dass der Bau nicht in München aufgeführt worden ist, wo er ursprünglich hätte hinkommen sollen. Natürlich wurde man es zuletzt überdrüssig, sich, ich möchte sagen, unter das [kautelische] Joch dessen zu begeben, was einem diktiert worden wäre aus den alten Anschauungen heraus. Flügellahm durften sich diejenigen nicht machen lassen, die wussten, was für ein Baustil aus der anthroposophischen Weltanschauung hervorgehen muss.

Und so ist es denn geschehen, dass durch die Schenkung eines Freundes unsere Sache auf dem Hügel in der Nähe von Basel, in Dornach, an der nordwestlichen Ecke der Schweiz dieser Bau zustande kommen konnte, dass der Grundstein dazu im Herbst 1913 gelegt werden konnte. Natürlich fielen wir damit hinein in die schwerste Zeit der abendländischen Kulturentwicklung. Aber wir haben es immerhin schon so weit gebracht, dass in dem noch ganz und gar nicht vollendeten Bau immerhin schon eine ganze Reihe von Hochschulkursen seit dem vorigen Herbst haben abgehalten werden können.

Nun möchte ich nur mit wenigen Worten charakterisieren, wie dasjenige, was in Anthroposophie lebt, sich ergossen hat in einen Baustil. Das, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, ist ja gerade das Wesentliche der anthroposophischen Forschung, des anthroposophischen Erkennens, dass die Begriffe, dass die ganzen Erkenntnisformen leben, in freier Aktivität sich entfalten, und das führte, ich möchte sagen, in ganz elementarer, naiver Weise dazu, die alten Baustile, die auf das Geometrische, Symmetrische, mechanisch-Statische begründet sind, überzuführen in das Organische. Und so sind die bisherigen Baustile, ich möchte sagen, äußerliche Abbilder desjenigen, was im Statischen, im Tragen, im Lasten und im Symmerrischen, im Geomertrischen leben kann.

Selbstverständlich sind der Dornacher Bau und meine Worte hier nicht eine Kritik - es wäre töricht gegenüber diesen Baustilen -, aber es handelt sich um die Heranziehung eines Fortschrittes. Der konnte in diesem Falle nur darin bestehen, dass das Geometrische, das Symmetrische, das Statische überführt wurde in ein solches, das in seinen ganzen Ausdrucksformen, in seiner ganzen Gestaltung ebenso das Organische darlebt, wie sonst in den Baustilen das Anorganische dargestellt wird. Ich weiß sehr gut, meine shr verehrten Anwesenden, was sich alles gegen eine solche Sache einwenden lässt; allein sie musste einmal aus den Grundimpulsen anthroposophischer Gesinnung heraus gemacht werden. Da musste ein Baugedanke da sein, der durchlebt und durchwebt wird von der Anschauung des Organischen.

Und bedenken Sie, bedenken Sie es am menschlichen Körper selber, was das eigentlich heißt. Nehmen Sie ein kleinstes Organ, vielleicht wird es da gerade am anschaulichsten sein. Bitte nehmen Sie Ihr Ohrläppchen, ein sehr kleines Organ, es hat eine bestimmte Form und Größe. Wenn Sie den ganzen Sinn des menschlichen organischen Baues empfinden, künstlerisch durchfühlen, dann werden Sie sich sagen: Dieses Ohrläppchen könnte erstens an keinem anderen Orte des menschlichen Organismus sein, als wo es ist, und es könnte zweitens

an dem Orte, wo es ist, nicht anders sein, als es ist. Dasselbe musste mit allen einzelnen Formen beim Bau des Goetheanum erreicht werden. Man musste sich gewissermaßen mit den sich metamorphosierenden Bildekräften, die sonst im Organischen leben, innerlich seelisch verbinden und musste dasjenige, was ja selbstverständlich als die Grundlage beachtet werden muss bei jedem Baugedanken, man musste das Geometrische, das Symmetrische, das Statische, das musste man durchleben mit demjenigen, was in dieser Weise im Einklang mit dem organischen Schaffen erlebt werden kann. Jede einzelne Gestalt, jede Türe, jedes Fenster, jede Säule, jede Einzelheit [an diesem Bau] musste individuell durchempfunden werden. Und das Ganze wiederum musste sein dasjenige, was als einheitlicher organischer Baugedanke aufnehmen kann diese einzelnen organischen Bauglieder.

Eine Schwierigkeit ergab sich dadurch, dass ja zunächst für München die Sache so gedacht war, dass eigentlich in der Hauptsache nur eine Innenarchitektur in Betracht gekommen wäre. Es sollte der Bau rings von Häusern umgeben werden, die sich anthroposophische Mitglieder zulegen wollten, sodass eine Außenarchitektur nur wenig in Betracht gekommen wäre. Als der Bau nach Dornach verlegt werden musste, da hatte man als Platz einen völlig freien Feldraum auf einem Hügel, auf einem Jurahügel, in Jurakonfiguration. Man hatte nach allen Seiten hin freien Ausblick und freien Hinblick auf den Bau. Man hatte die Gebirgsformationen, denen musste das Ganze angepasst werden. Da wegen der Eile, mit der dazumal die Sache von mir gefördert wurde, an der Innenarchitektur nicht viel geändert werden konnte, so war es notwendig, die Außenarchitektur in Gemäßheit der fertigen Innenarchitektur zu gestalten. Das ist dasjenige, was mich heute noch etwas unbefriedigt sein lässt, weil allerdings derjenige, der das Ganze voll empfinden wird, heute eine gewisse Diskrepanz schon sehen kann zwischen der Außen- und der Innenarchitektur. Allein es ist versucht worden, die Schwierigkeiten so weit zu überwinden, wie es möglich ist. Und bei einer solchen Sache kann ja im ersten Anhub im Grunde genommen nur Unvollkommenes geschaffen werden. Es handelt sich aber auch nur darum beim Dornacher Bau, den Anfang zu machen mit einem neuen Baustil, der ja doch aus keinen anderen Untergründen hervorgehen kann als aus denjenigen, die überhaupt für das moderne Zivilisationsleben aus der Erkenntnis des Geistes der Welt heraus gemacht werden können.

Es hängt nun mit der ganzen Aufgabe dieses Goetheanums zusammen, wie es dem Beschauer schon entgegentritt, wenn er sich von ferne nähert: Man hat es zu tun mit etwas, was — sei es Kunst, sei es Wissenschaft - in der Tiefe der Menschenseele erquillt, mit etwas, das derjenige, der es ergründet hat, seiner innersten Verpflichtung gemäß den anderen Menschen mitzuteilen hat. Man hat es zu tun mit einem aus tiefstem Herzen Gegebenen, mit einem aus ganzer Seele bei dem richtig Verstehenden Genommenen. Das kann empfunden werden. Und von demjenigen, der es empfinden kann, kann vielleicht auch verlangt werden, dass das sich nun in Anschauung umsetzt. Wie gesagt, es sollte nichts ausgedacht werden, es sollte keine Idee in Form umgegossen werden. Aber dasjenige, was ich jetzt eben angedeutet habe, kann empfunden werden, kann innerlich erlebt werden, dieses Verhältnis einer intimen Einheit zu einer aufnehmenden anderen Einheit und der Zusammenschluss beider. Indem ich das empfand, ergab sich mir von selbst eben durchaus nur im Anschauen, nicht als Allegorie oder als Symbolik, ein Doppelkuppelbau, der so aufgeführt ist, dass zwei Kuppelräume im Kreissegment aufeinanderstießen. Und mir scheint, dass man an dieser Bauform alles dasjenige empfinden kann, was eine Seele fühlen kann gegenüber jenem Verhältnisse von Anthroposophie zur Welt, wie es eigentlich als das ideale Verhältnis, als das beseligende Verhältnis empfunden werden muss. Und schon an der Außenform, glaube ich, kann man, sich nähernd dem Dornacher Hügel, dies so empfinden, wie man die innere Notwendigkeit der Form der Nussschale gegenüber der Form der Nussfrucht empfindet; Man wird in den zwei sich nebeneinander lagernden Kuppeln eines großen und eines kleineren Kuppelbaues fühlen, dass da etwas ist, das zu gleicher Zeit im Intimsten erforscht werden soll, und sich dennoch wiederum offen der Welt mitteilen will. Das ist dasjenige, was zum Ausdruck kommt zunächst in den äußeren Formen, die ich mir erlauben werde, Ihnen vorzuführen.

Ja bitte, nun das erste Bild (Abb. 5).

Sie sehen, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, hier jene Straße, welche führt gegen die Westseite des Baues. Der Bau ist unten ein Betonbau bis hierher zur oberen Terrasse. Von hier ab ist er ein Holzbau. Man begibt sich hier zunächst in den Betonbau hinein. Im Betonbau - wir werden es noch später sehen - wird abgelegt. Dann geht man durch eine Treppe herauf und kommt dann in einen Vorraum und von diesem in den eigentlichen Zuschauerraum. Sie sehen hier schon etwas an diesem Motiv, wie versucht worden ist, die sonst bestehenden Bauformen, die sich, wie gesagt, auf das bloß Geometrische, Symmetrische, Statische oder Dynamische begründen, in organische Formen überzuführen, aber nicht in naturalistischem Sinne, nicht so, dass etwa Naturformen nachgeahmt worden wären. Niemand kann fragen, was bildet so etwas ab, ebenso wenig wie man fragen kann, was bildet ein Pflanzenblatt oder ein Menschenohr ab. Es ist etwas, das seine innere Lebensform und Lebensmöglichkeit und Lebenskraft in sich hat; was sich durch seine eigene Form und seine eigene Lebensentfaltung rechtfertigt.

Nicht fühlt man, wenn man eine solche Form gestaltet, irgendetwas, das man nachahmen will, sondern man fühlt sich als Menschenseele innerlich verbunden mit demjenigen, was metamorphosierend in der Pflanze von Blatt zu Blatt bis zu der Blüte und Frucht lebt und alles gestaltet und umgestaltet, wenn ich diesen Goethe’schen Ausdruck gebrauchen darf. Und das ist es auch hier, nicht etwas nachgebildet, aber etwas so gebildet, was sonst nur im Organischen so gebildet wird. Es ist für denjenigen, der dann den Bau selber besieht, vielleicht ersichtlich, wie versucht worden ist, hier überall aus dem Materialgefühl heraus künstlerisch zu empfinden. Das war eine gewisse Schwierigkeit - ich werde später noch darauf zurückkommen müssen -, aus dem Betonmaterial heraus Bauformen zu finden, aus einem neuen Material.

Das nächste Bild (Abb. 6): Sie sehen noch mal den Zugang zum Westportal. Hier geht man hinein, hier links und rechts hinauf, dann betritt man einen Vorraum, dann den eigentlichen Zuschauerraum. Die zweite, kleinere Kuppel ist jetzt durch die größere Kuppel des Zuschauerraums völlig bedeckt. Alle einzelnen solche Nebenformen, sie sind durchaus im Einklange, und zwar im organischen Einklange mit den größeren Formen geschaffen.