The Ideas Behind the Building of the Goetheanum

GA 289

28 December 1921, Dornach

Translated by Peter Stewart

9. The Living Organic Style I

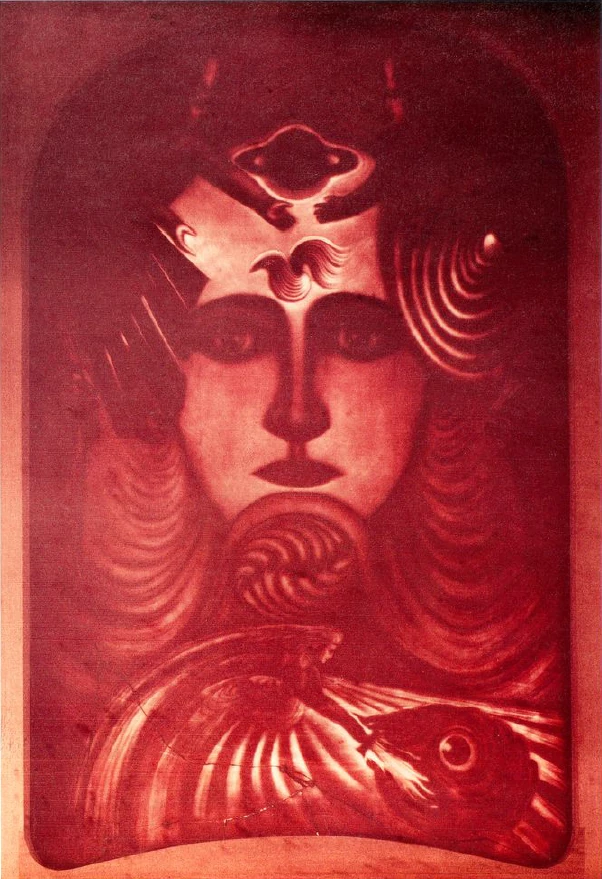

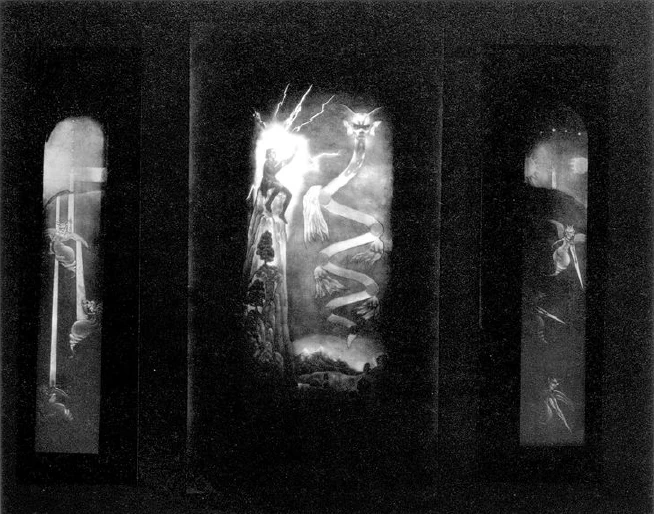

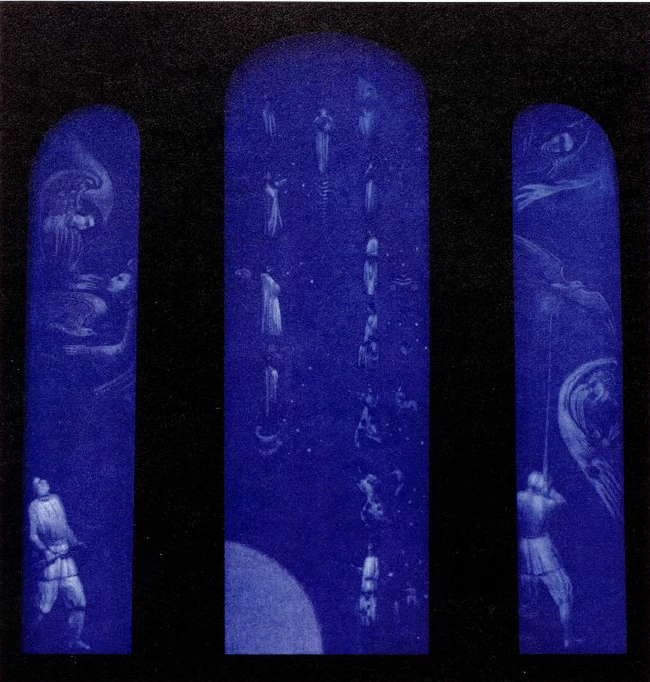

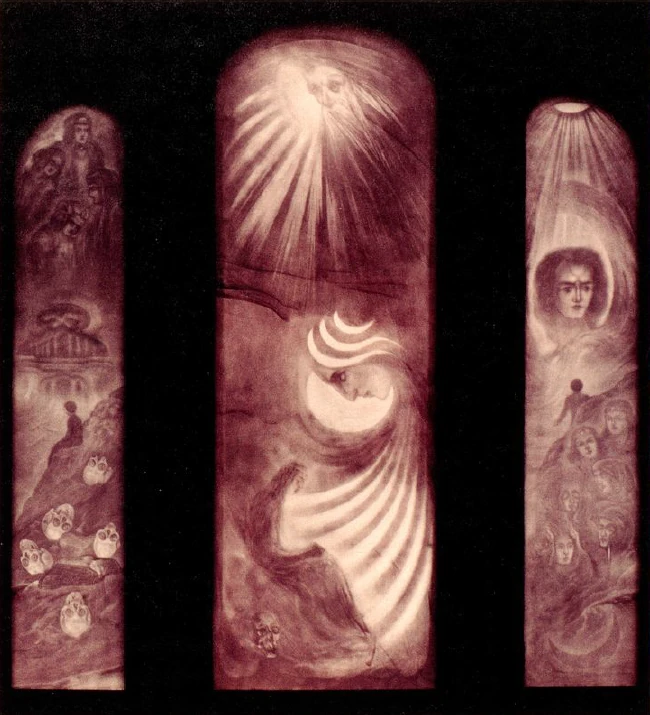

Form: The Creative Forces of Nature

[ 2 ] The building of the Goetheanum became necessary at a time when the anthroposophical movement had expanded to such an extent that it needed its own space. According to the whole nature of the anthroposophical movement, it could not be a question of having a building for its purposes constructed in this or that style. A movement which merely expresses itself in ideas and maxims can be wrapped up in any desired form, but not so a spiritual movement which is predisposed from the outset to let its currents flow into the whole of cultural life. The anthroposophical movement wants its impulses to flow into the artistic, religious and social spheres as well as into the scientific. When it speaks, its words, its ideas, are to come from the whole human being, and these ideas are to be only the outer language for experienced spiritual reality. But this experience of spiritual reality, of spiritual being, can also express itself in artistic forms, in outer social life, etc.

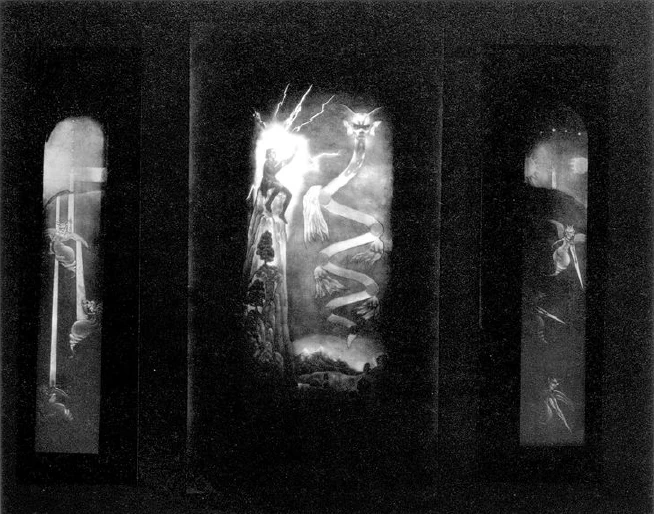

It had to be so, that in a place where that which stands behind the anthroposophical movement resounds in thoughts, resounds in words and ideas, is also revealed in the forms which surround the listeners, in the paintings which speak down from the walls.

[ 3 ] This is how it has always been when a civilisation, a culture wanted to manifest itself in the world. The content of such a culture does not form one-sidedly, but forms a cosmic or human totality. And the individual fields, science, art, etc., appear only as the individual members of such a totality, just as in an organism the individual members appear as born out of the totality of the organism.

Therefore, the anthroposophical movement had to create its own artistic style, just as it had to create a certain way of expressing itself in ideas. [ 4 ] The latter is still little considered today. It is, for example, necessary that anthroposophical spiritual-science should be expressed in a different way from what has hitherto been customarily contained in human civilisation.

Anthroposophy, for example, must in many respects depart from the principle, still habitually held today, of rigidly, one-sidedly, adopting a single point of view. Today, people are still often a materialist or a spiritualist, a realist or an idealist, and so on. For an unprejudiced, complete world-view this only means that when someone says “I am a materialist”, they are expressing just one side of reality, when someone says “I am a spiritualist”, they are expressing another side of reality. And anthroposophy requires all-sidedness. One is a materialist for material processes, a spiritualist for the spiritual, an idealist for the ideal, a realist for the real, and so on. Just as a tree, when seen from different standpoints, is always the same tree, but the representations of it are quite different, so the world can be represented differently from the most diverse points of view. [ 5 ] Therefore, in the field of anthroposophy, one must simply take this path when considering some spiritual or material aspect of reality. One then chooses a point of view from which to illuminate it, one feels and thereby shows a one-sidedness, but one then characterises the same thing from the opposite point of view. So that it is often necessary—let us say—to begin a lecture by speaking from the one side, and then to let the style of the lecture flow over into a characterisation using the converse forms of thought.

But this can also be necessary in an individual sentence! [ 6 ] And something else is necessary for the anthroposophical world-view. A world-view which adheres to the outer, naturalistic aspect, it can preferably work subjectively in, let us say, for example, one which is juxtaposed to it. Anthroposophy must make many things fluid, which are otherwise presented with rigid outlines, so that the sentence becomes elastic, inwardly mobile.

One then experiences that people call this style "terrible" because they have not got used to the fact that a particular spirituality also demands a particular form of expression. [ 7 ] However, it also happens, and this may perhaps be said, that from some quarters, spiritual-scientific content is taken up but clothed in the stylistic form which people are accustomed to today. Then, of course, it looks like a person wearing clothes that do not fit. Such presentations of anthroposophical content, which look like a person wearing ill-fitting clothes, are not even very rare today.

But all of this is only a sign that with anthroposophy something is to be created which is not only a new instance, a new standpoint, but which is a new, complete world-conception.

[ 8 ] And this is connected with the fact that the style, the artistic, architectural, painting and sculptural style, which had to be used in the Goetheanum, had to stand out from what had hitherto existed in the world in terms of style. In accordance with the fact that anthroposophy expresses the spiritual content of the present, which must represent progress in comparison with the spiritual content of earlier times, it was necessary to transform the old architectural styles, which were based on geometry, symmetry, a certain regularity, in short, on that which has a mathematical character, into an organic architectural style, a style which passes from the geometric-dynamic into the organic-living.

[ 9 ] I can well understand that those who feel firmly rooted in the older styles of architecture, and who see in these older styles something which they once had brought to a certain understanding, feel that what is now departing in such a radical way from everything they were accustomed to before is dilettantish. I can fully understand that. But we had to take the risk of transforming the more mathematical-dynamic style into an organic-living style.

This may still have happened as imperfectly as possible today, but a beginning had to be made. And it is as an expression of these efforts that the "Goetheanum" confronts you.

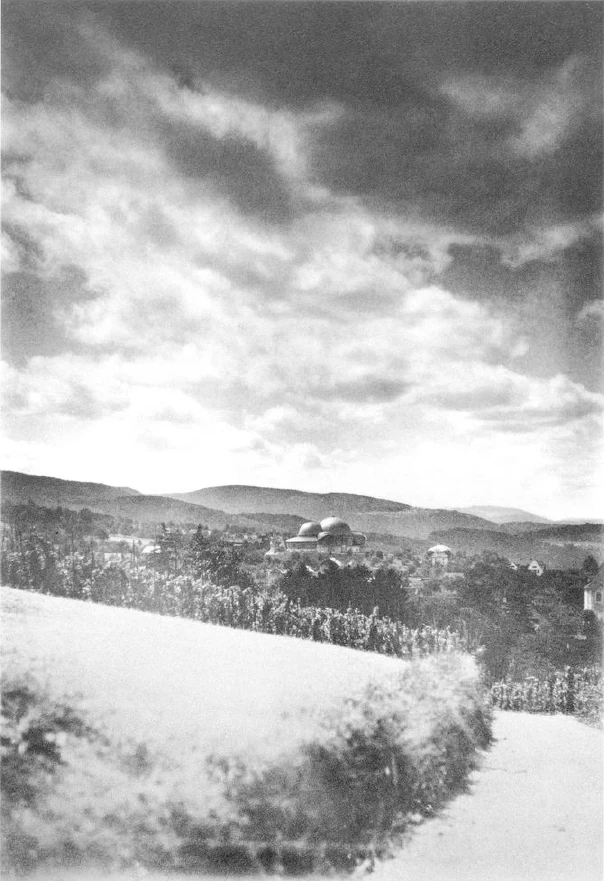

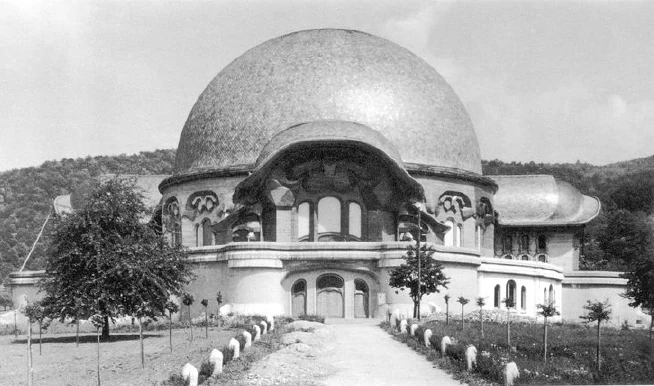

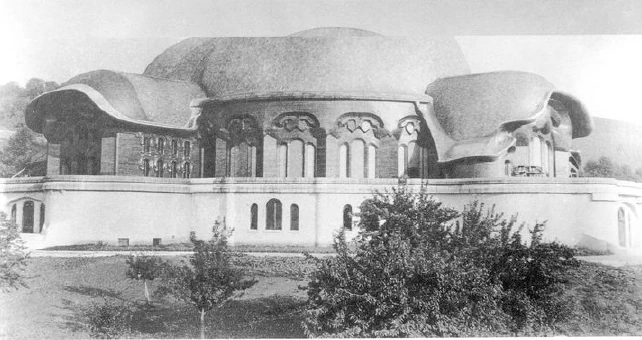

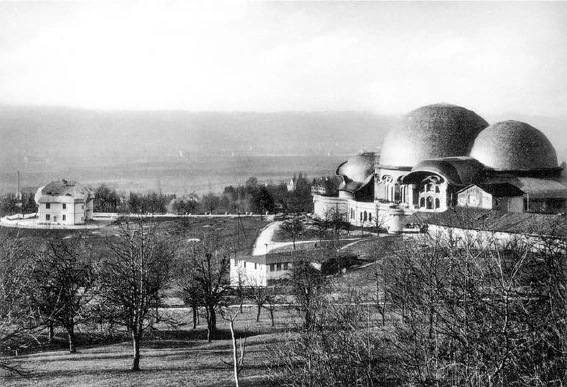

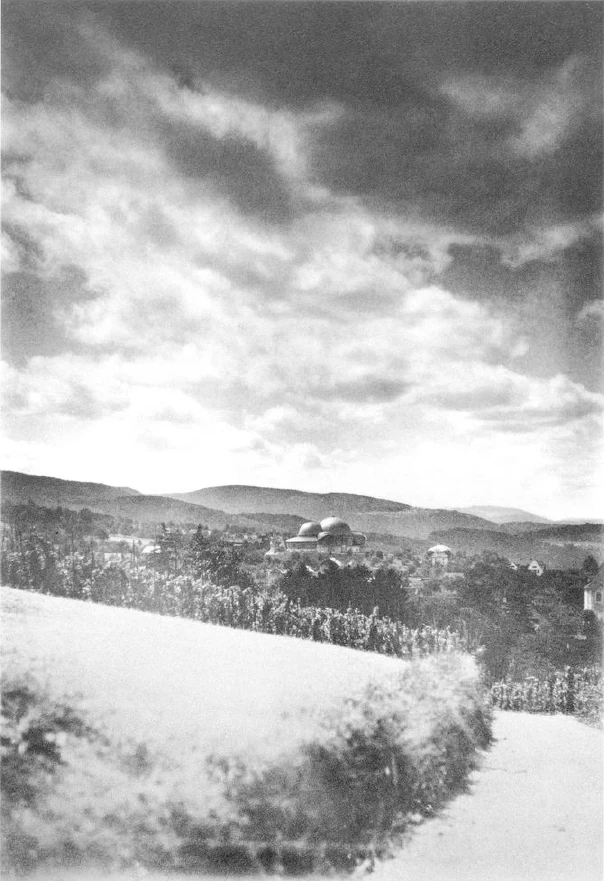

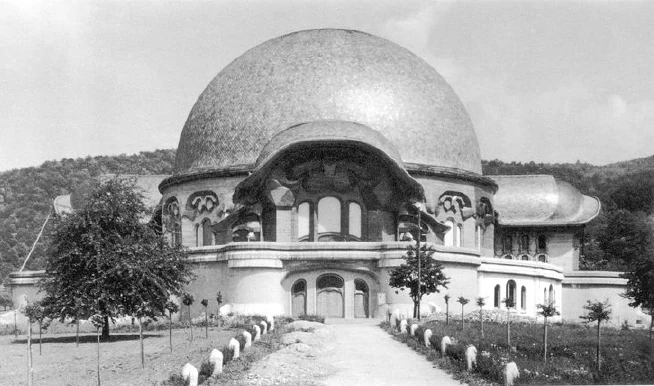

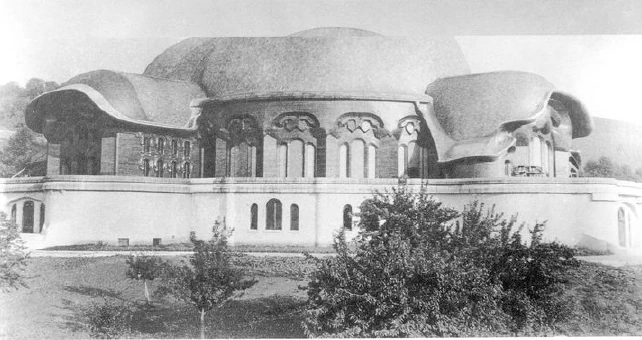

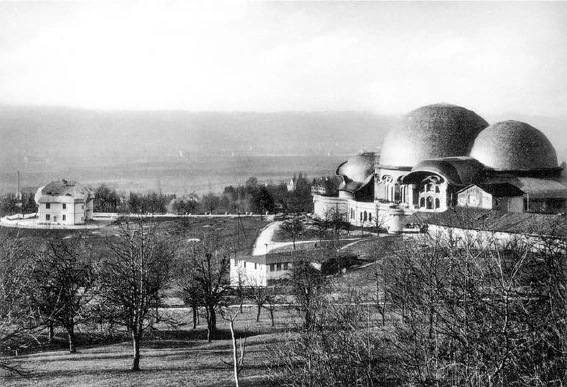

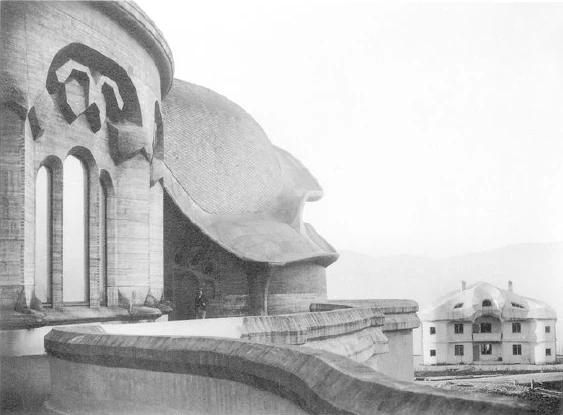

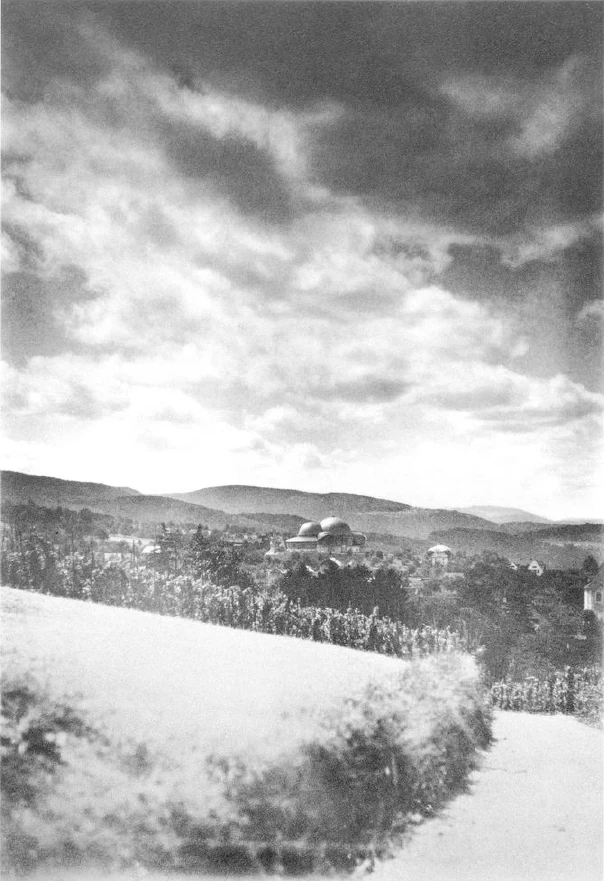

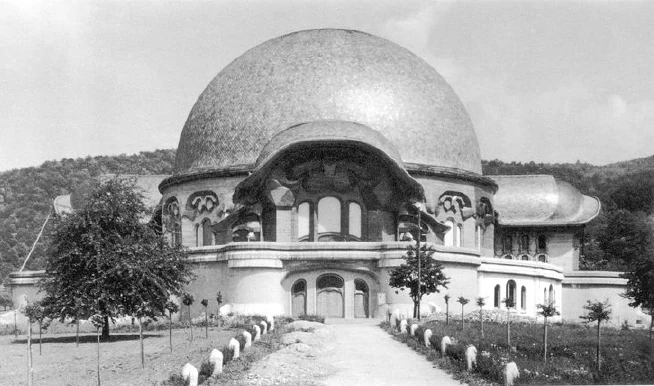

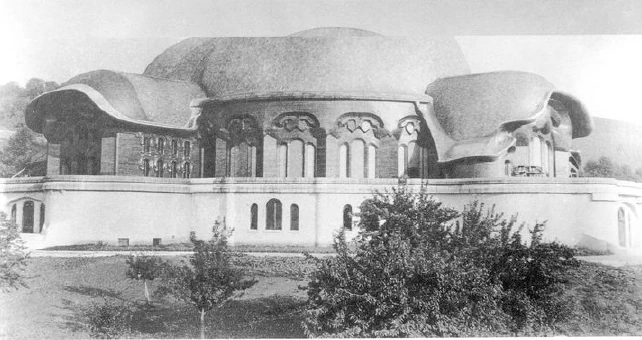

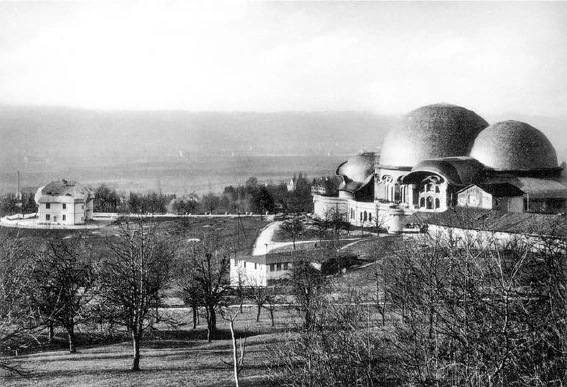

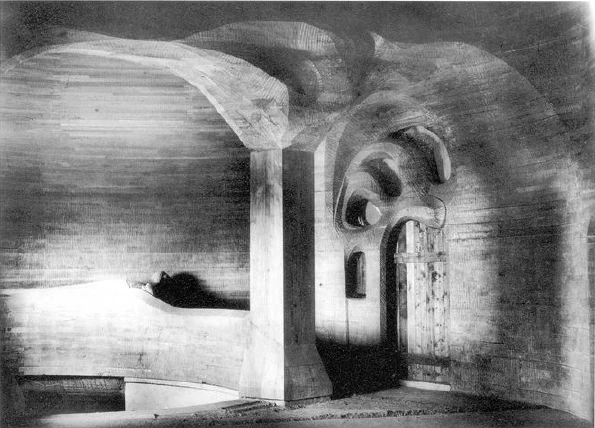

[ 10 ] Whoever approaches the "Goetheanum" from any direction will already find in its outer form that it is, without falling into abstract symbolism or arid allegory, a revelation of the particular spiritual life which wants to realise itself here. This spiritual life is more concerned with the human being as an expression of the world, a revelation of the world, than earlier stages of our human civilisation have been. This is expressed in the way the building is divided into two parts.

[ 11 ] In our present age, the human being is more dependent on sensory impressions than was the case in earlier times. In Greece, for example, human beings still had a life that perceived thoughts in the external world in the same way as we perceive only colours or sounds today, or sensory impressions in general. Just as we see red today, for example, the Greek still saw a thought expressing itself. The Greek did not have the feeling that the thought was something that they formed in their inner being, that they experienced in their inner being as separate from external reality. The separation of the human being, and with it the increase in the individuality of the human being, has progressed in the course of human evolution.

I explained this in the first chapter of my "Riddles of Philosophy". And so, it was quite natural—as I said, without symbolism, without allegorising—to perceive the building as something in two parts: as one part that contains within itself that which the human being experiences more when turned inwards, that which the human being experiences when contemplatively turned inwards, and the other part which the human being experiences when turned outward towards the world. This complete architectural idea of Dornach is not somehow thought out, symbolised, or spun from groundless thoughts, but is purely felt. It had to become so, this building, if it was thought and felt as that which should be in it. Entirely in accordance with the natural principle which I have already characterised on another occasion during these days. Just as the nutshell gets its form from the same forces which formed the nut inside, just as one can only feel that the nutshell corresponds to the nut that is inside it, so also this shell had to be the sheath for what pulsates here as art, as knowledge.

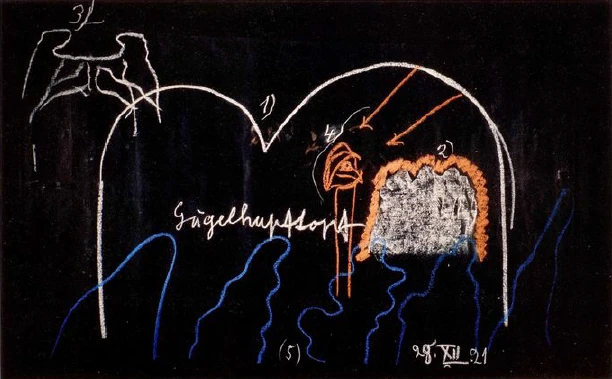

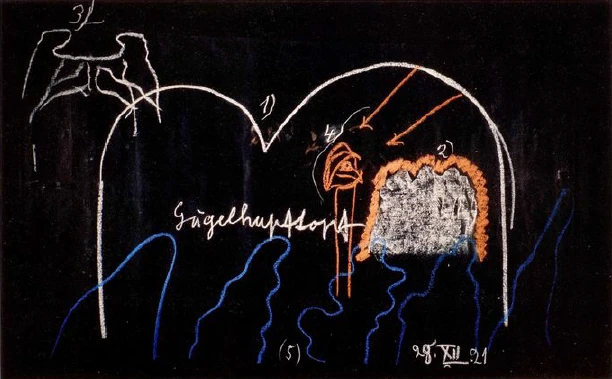

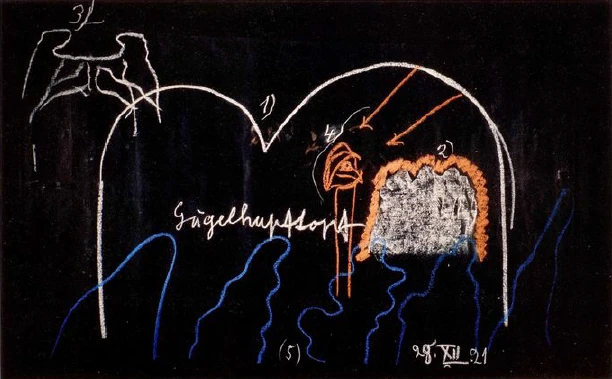

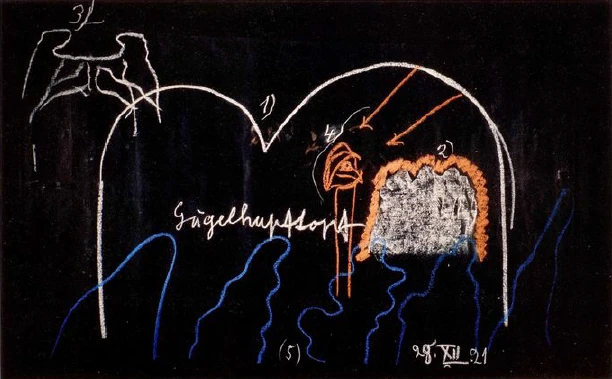

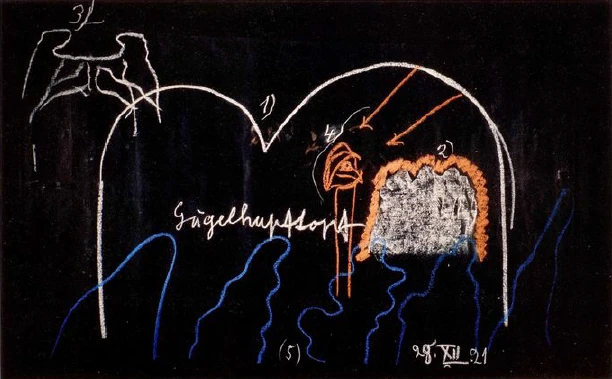

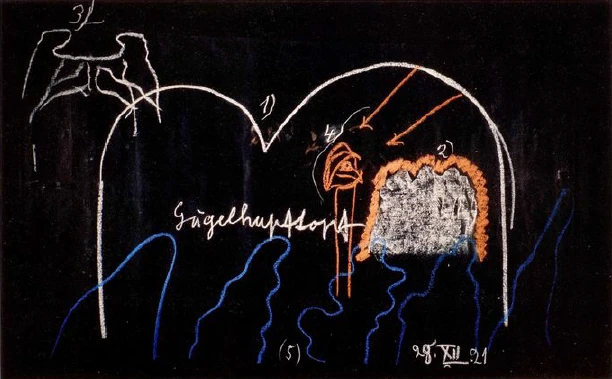

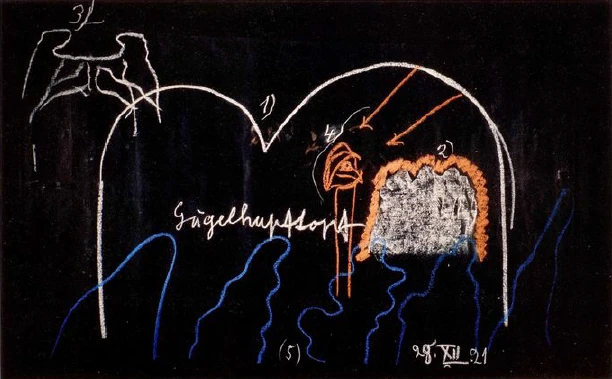

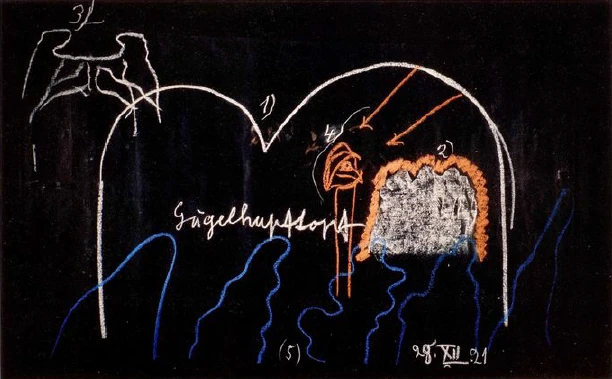

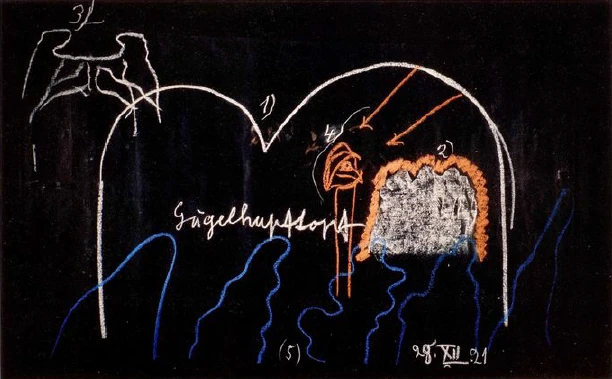

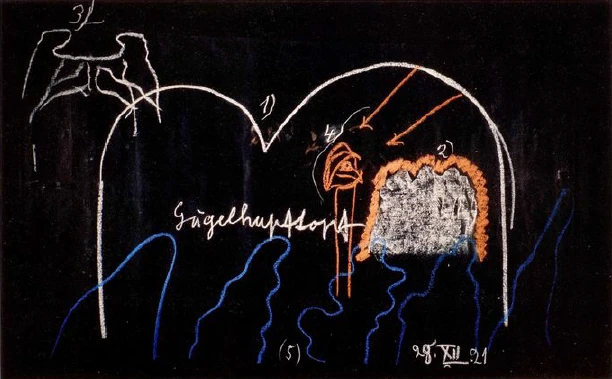

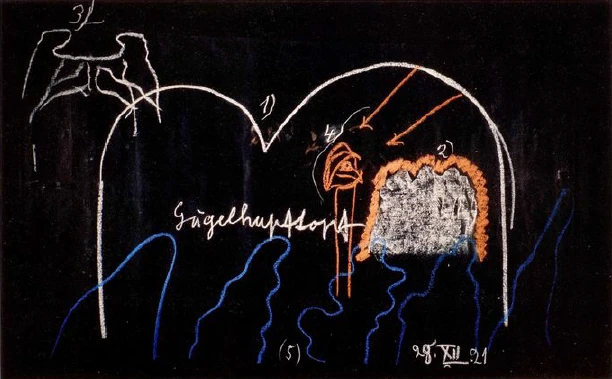

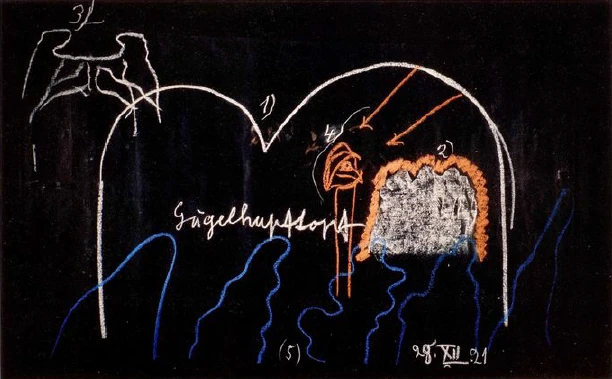

I have often used another comparison that looks more trivial, but I did not mean it trivially. I said, the building in Dornach must be like what they call a Gugelhupf mould in Vienna, pardon the expression. A Gugelhupf is a special kind of cake, a baked cake that has a special shape, baked from flour and eggs and many other beautiful things. And it has to be baked in a mould. This mould must be formed in a very specific way, because it is precisely this mould that gives the Gugelhupf its shape. So, there must always be a lovely Gugelhupf mould around the cake: that is, it must be there in the first place. The cake is baked in it, so the mould must be conceived and felt in such a way that the right thing can be baked.

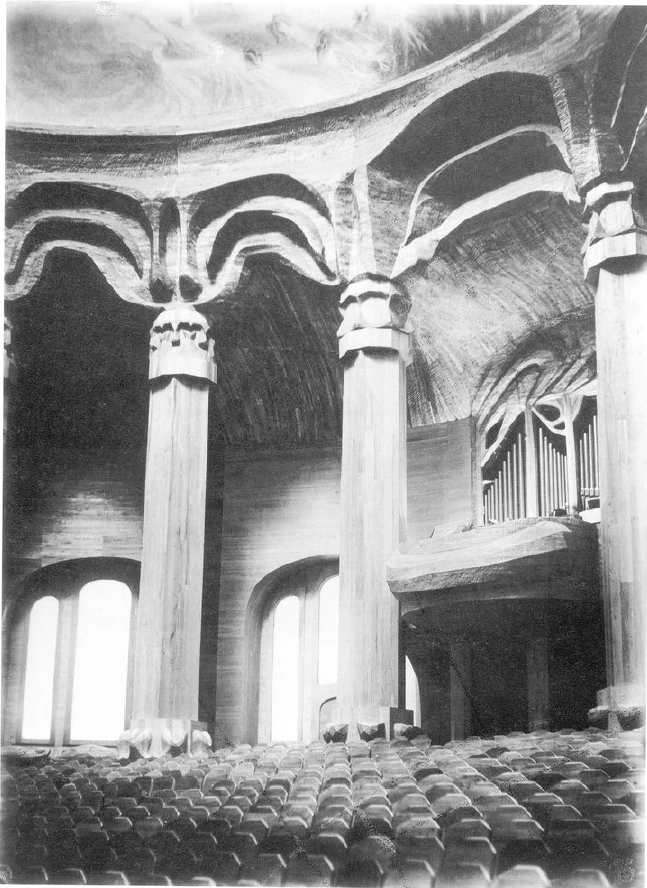

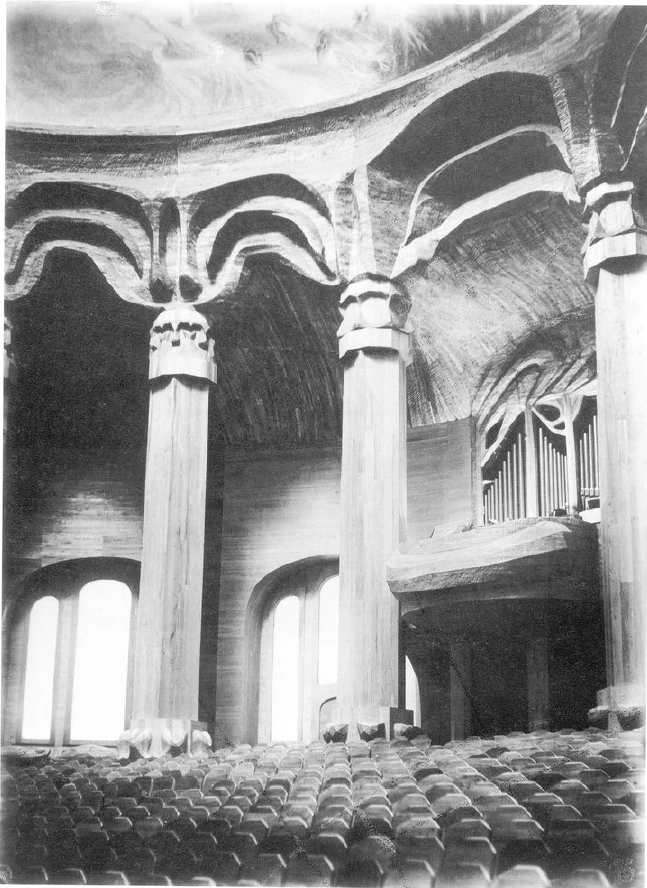

Anthroposophy strives to bring into a living flow the ideas which are more adapted to the fixed forms of nature, and thus to bring into a living flow the mechanical-geometric style of architecture. Therefore, when you enter the building and look at its various areas, you will find everywhere that the attempt has been made to continue the geometric-symmetrical design in such a way that organic forms or forms reminiscent of organic forms are present everywhere.

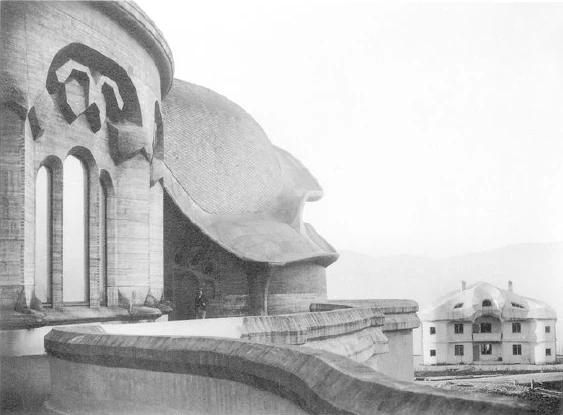

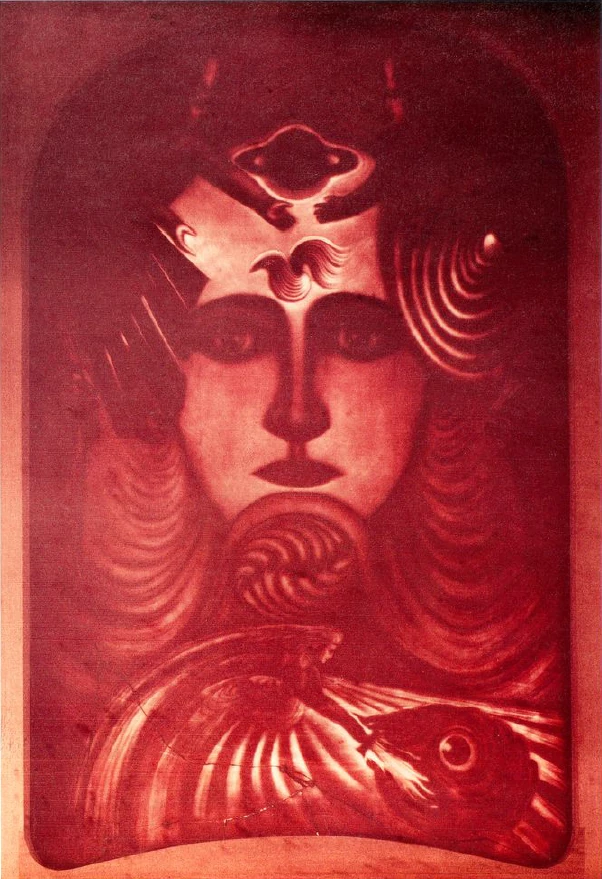

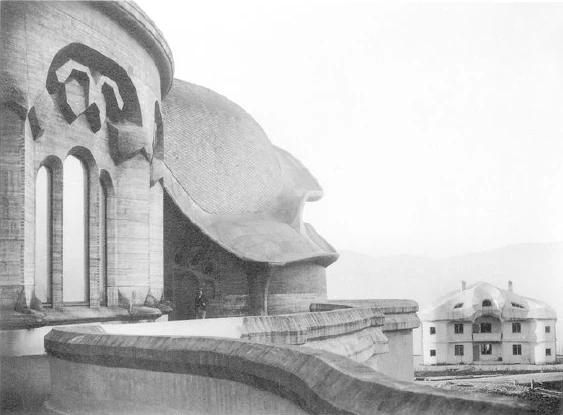

First go to the main door, you will find that there is something like an organic form above the door. This organic form is not felt in a naturalistic way, by reproducing this or that organic thing, but is based on a living surrender to organic creation in general.

One cannot, as mere naturalists do, obtain a stylistic form by imitating leaf-like, flower-like, horn-like or eye-like forms, but by bringing oneself, with one's own soul-life, into such an inner movement as corresponds to the creation of the organic. Then, when one erects a building, which of course is not a plant or an animal, then, when the whole is conceived from the organic-living, natural forms do not arise, but forms that remind one of the natural, and which nowhere imitate the natural, but which remind one of the same.

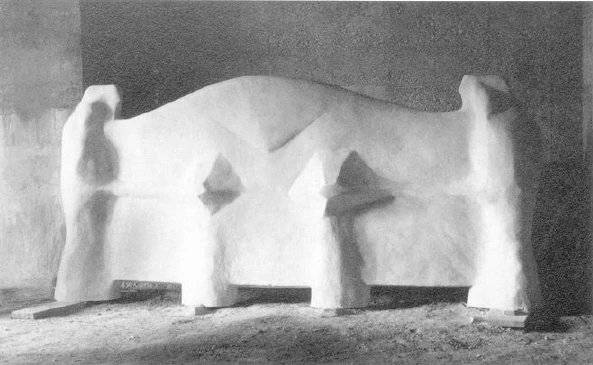

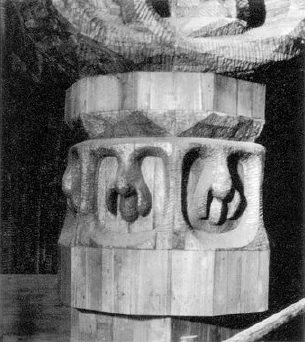

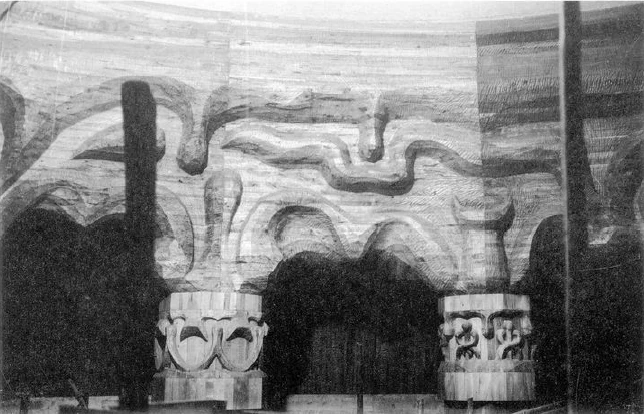

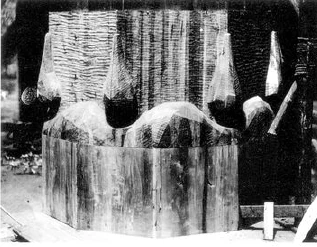

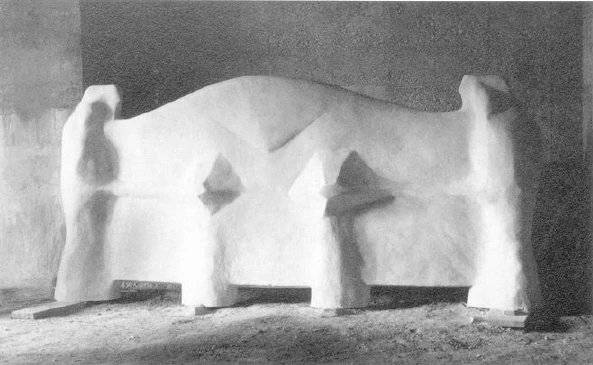

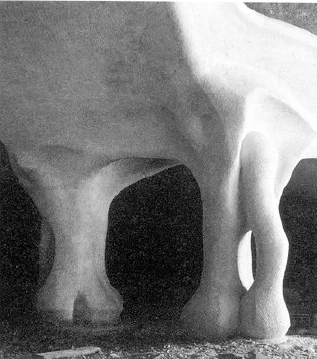

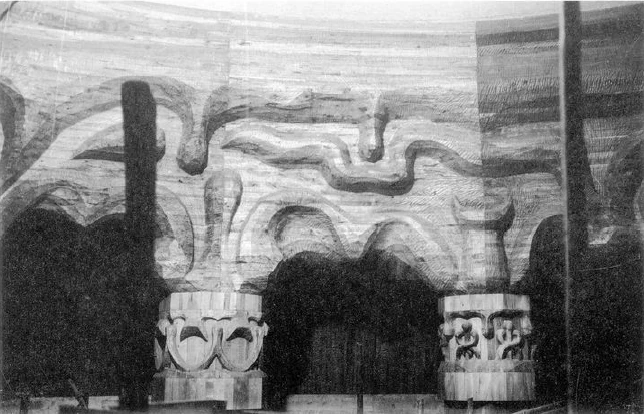

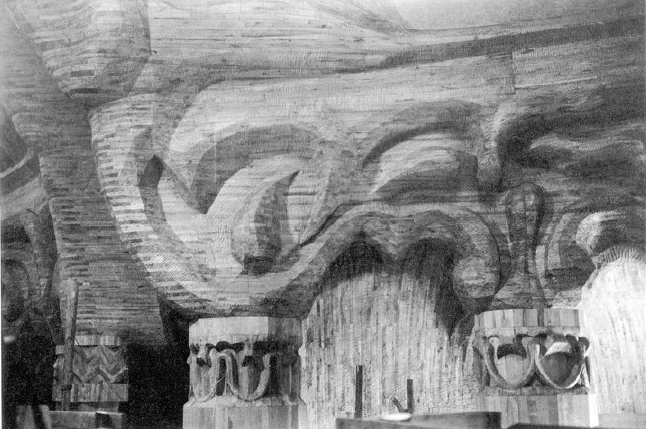

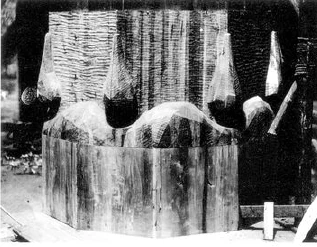

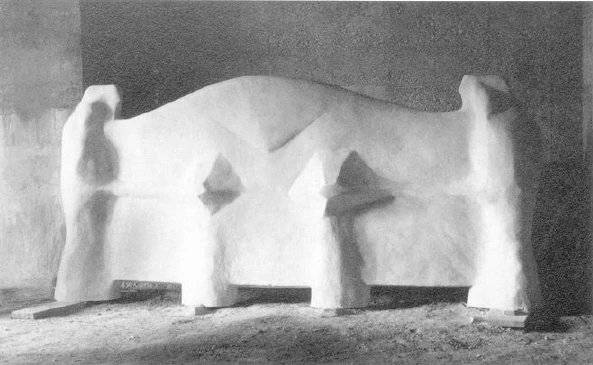

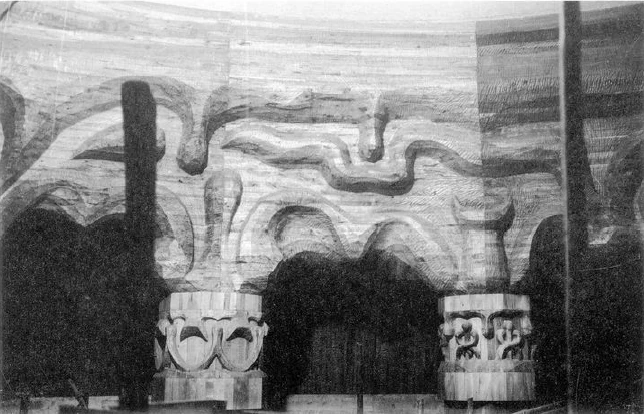

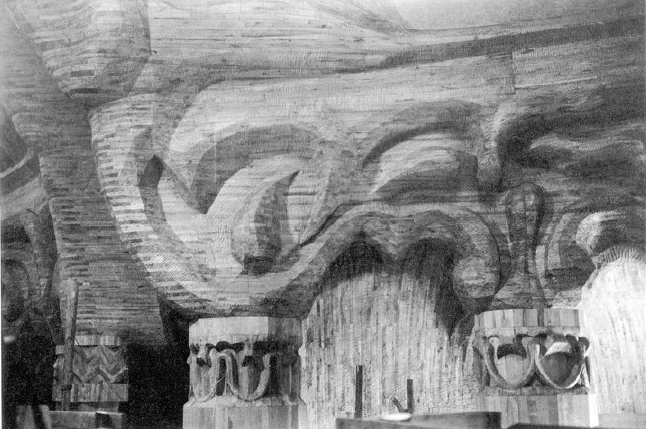

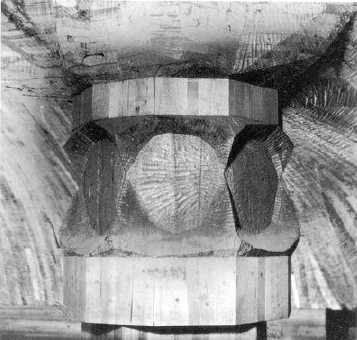

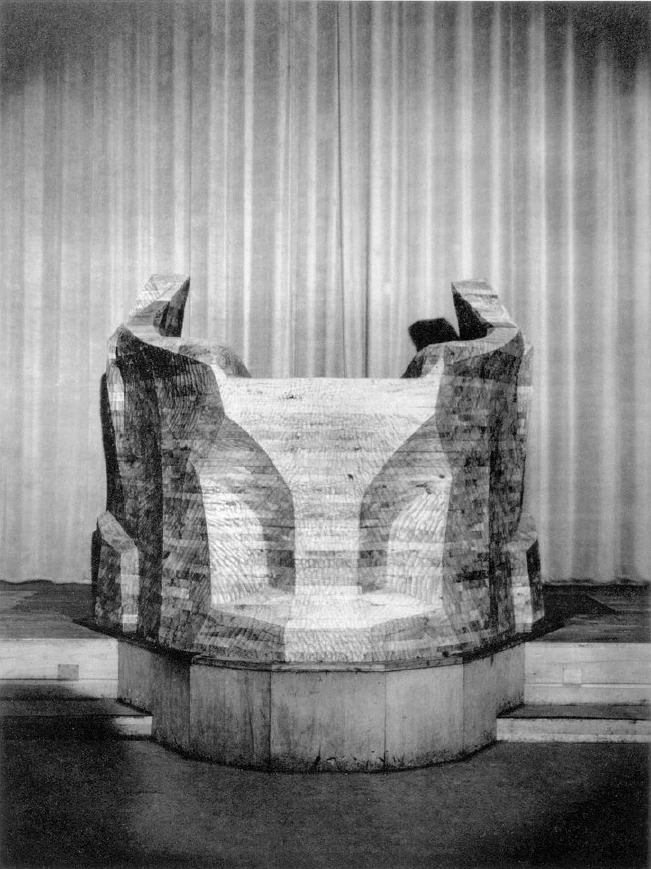

And when you have entered the building, then go through the gallery, you will find certain forms which are intended to serve as heating elements. These forms are shaped in such a way that you have the feeling that they are growing out of the earth, that there is a living growth force in them, something that is not a plant, not an animal, but something that is growing, something organic. That takes shape. That even takes shape in such a dual form. It is something like beings speaking to each other, and their mutual relationship is also expressed.

All of this, by itself, creates according to the principle of Goethean metamorphosis, which was first created by Goethe in order to gain a cognitive overview of the organic. The organic is such that it repeats certain forms, but it does not repeat them in the same way. Goethe expresses this in such a way that in the living-organic the individual organs, let us say the leaves of a plant from the bottom up into the flower, the stamens, the pistils, and into the fruit organs, are according to the idea the same, but in their outer forms, appear in the most varied ways.

When one delves into the living, one does indeed have to form things in such a way that something which is only taken hold of spiritually, ideally, can, in its external shape, form itself in the most manifold ways. This, in turn, can be led up into the artistic, whereas Goethe first of all developed it cognitively to comprehend the organs, and must be led up into the artistic if the geometric, symmetrical, dynamic style of architecture is to be transferred into the organic style of architecture. The essential thing in such an organic style of architecture is that the whole is not only a unity through the repetition of the individual parts, but is also a unity as a whole. This means that each individual element that is there, must be as it can only be in that place.

Just think, my dear guests, your earlobe—a small organ on you, it can only be at that place where it appears on the organism. It cannot be anywhere else on the organism. But it also cannot be formed in any other way than it is there. This earlobe could not be where the big toe is now, nor could it be shaped here like the big toe. In an organism, each element is in its place and can only be shaped in the way it is shaped in that place.

You will find this adhered to in this building. Wherever you look, you will feel (certainly, individual things are still imperfect, but this is the idea of the building) that the place for each individual thing is only found out of the whole and it can only be in this place.

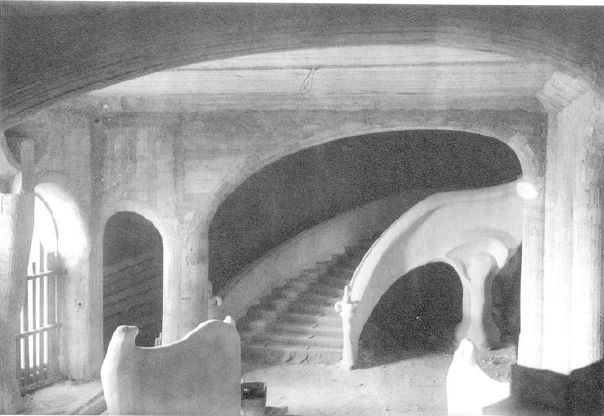

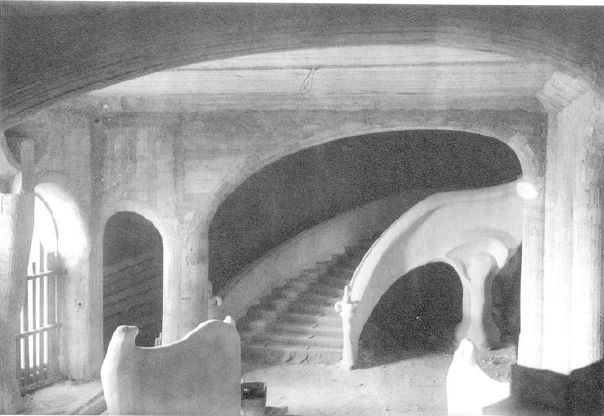

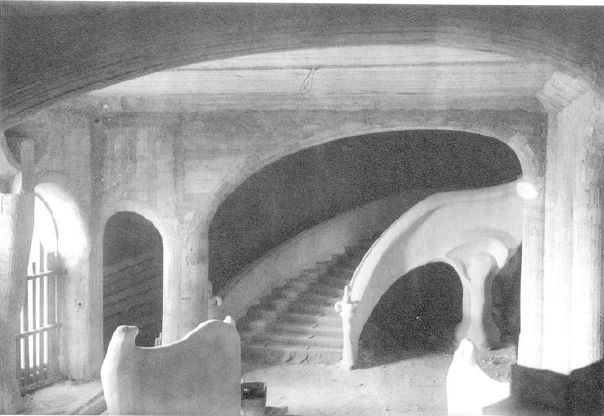

If you look at the balustrades of the staircase with their curves, you will see that the curves are formed in a quite definite way where the building opens outwards, where nothing can be held in place, so to speak, by the forces; on the other hand, the forms dam up towards the building, they contract, as is also quite the case with the organic.

Therefore, the venture had to be undertaken to replace the columns and pillars with something organic in design. So, you see the attempt: in the staircase you see the balustrades supported by organic forms that appear as supports, which in turn are not modelled on anything natural, but which are found out of the architectural idea itself. And each individual thickening, each individual thinning, then again, the circumference of such a pillar-like structure are absolutely conceived in their size in the sense of the whole, and again conceived in such a way as they must be in their place.

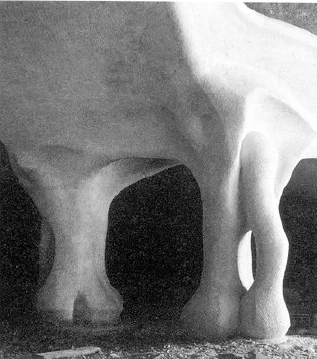

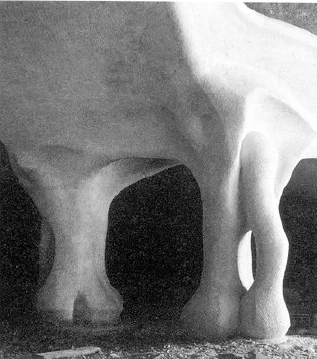

I can understand that something like the two organically formed pillars in the concrete porch still seem strange to those who are not used to such things. A critic once went into this building and found it strange that such a thing should be placed there. He could only think: something must have been copied!—There is nothing imitated at all, the whole thing is just formed out of the architectural idea through original feeling. Nothing at all is copied. But the critic, who prefers to stick to the old, does not like to get involved in this creative-productive process. And so, it occurred to him: this must be an elephant's foot. But it seems that with one eye he saw an elephant's foot out there, but with the other eye it didn't seem like an elephant's foot, because as an elephant's foot it's too small for the building. What is too small for something appears rickety in the organic, and that is why he said with a strange inner contradiction: one sees "rickety elephant feet" in the anteroom!

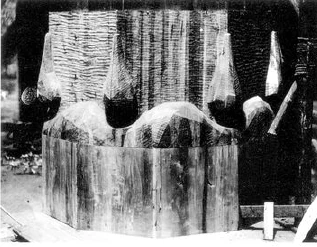

The lower part of the building is made of concrete. Even today, when building in concrete, it is necessary to first find the forms out of the concrete material. This is something that is of the utmost importance for artistic creation: that one must build out of the feeling of the material, out of the feeling for the material. You have to build differently out of wood than out of any stone material. And of course, you have to create differently out of concrete than you would out of marble.

When you form sculpturally and you form out of stone, you have to consider, for example, that which is raised in the form. When you work out of the stone, you have to work out the elevations, the convexities in particular. If you are shaping the eyes of a sculptural figure of a human being, and you have stone as your material, then direct your attention to the elevations, to the convexities, and work the whole eye out of the convexities. If you make a figure in wood, you cannot proceed in this way, then you must direct your attention everywhere to the depressions, to the concavities, and you must, as it were, carve out what is becoming deeper from the wood. This must be out of feeling. It must come from the feeling for the material.

For concrete, one must find very particular forms. Our friends the Großheintz, provided us with the site for this building, and the house that is built outside for Dr Großheintz and his family is made of concrete. For this house, this very special concrete style had first to be used, as it still can today, given the imperfections. Perhaps it is precisely in such a building that one can see the struggle for an architectural style, for an artistic style out of the material.

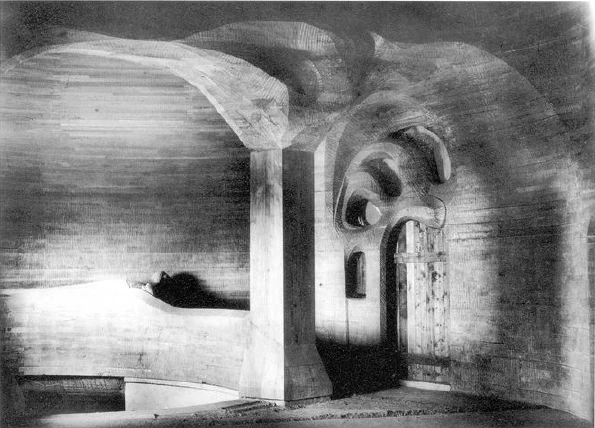

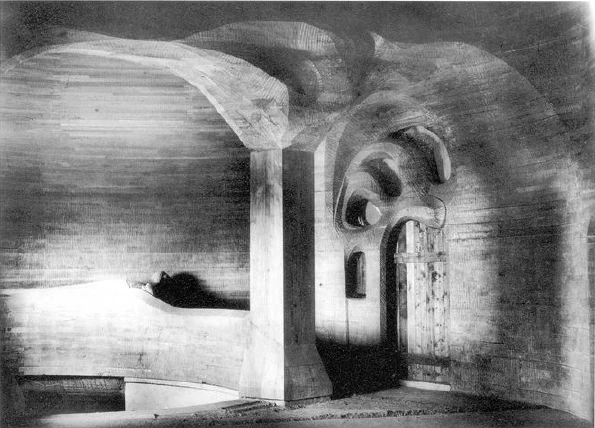

This aspiration was therefore the basis for the lower part of the building, which is made of concrete. The upper part is made of wood. When you go up the stairs, you enter the anteroom. And here you can already see how the ceiling and the side walls are formed differently from what you were used to. And I would like to mention that, in accordance with this new architectural style, the details have also been given a different meaning than in previous styles. This is expressed, for example, in the treatment of the wall.

What is a wall in buildings of the past? That which closes off to the outside. Here the wall does not close off to the outside, here the wall becomes, to a certain extent, transparent to feeling, it does not close off, but opens feeling to the vastness of the world. There is a profound difference between the formation of the wall as we have been accustomed to it up to now and the formation of the wall here. Everywhere else, the formation of walls closes you off from the world. But here you should have the feeling that you are not closed off. Just as you can see through glass, you feel artistically through the forms that are artistically created, and you feel in harmony with the whole cosmos.

We were therefore able to use artificial lighting for the entire building. One might have the feeling that compared to the open buildings of Greece, something like this, which reflects artificial lighting, is like a closed off cave. Well, that may be, but that is due to the conditions of modern life. We are not within the culture of ancient Greece.

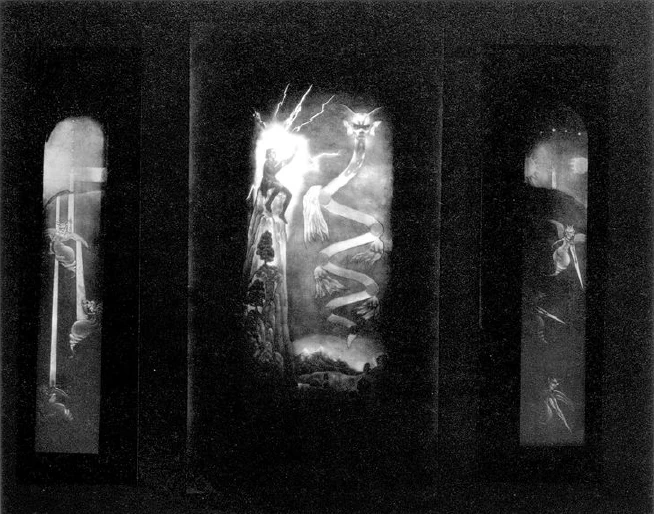

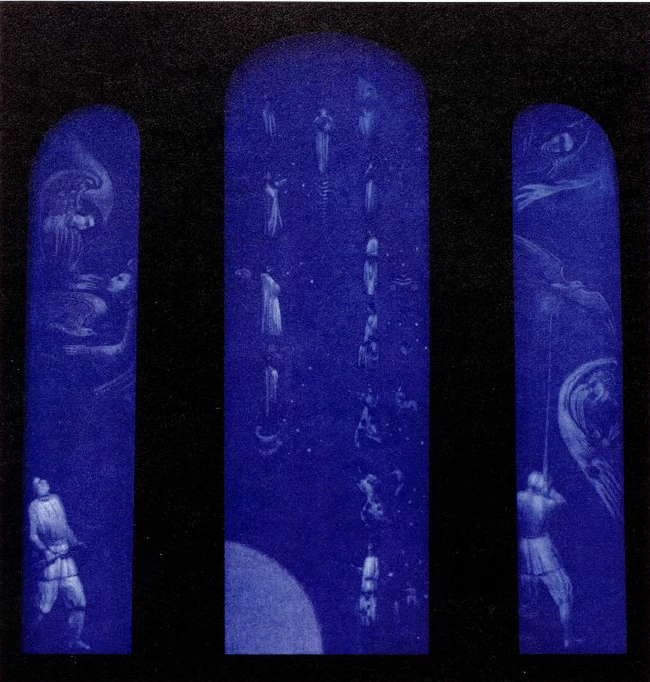

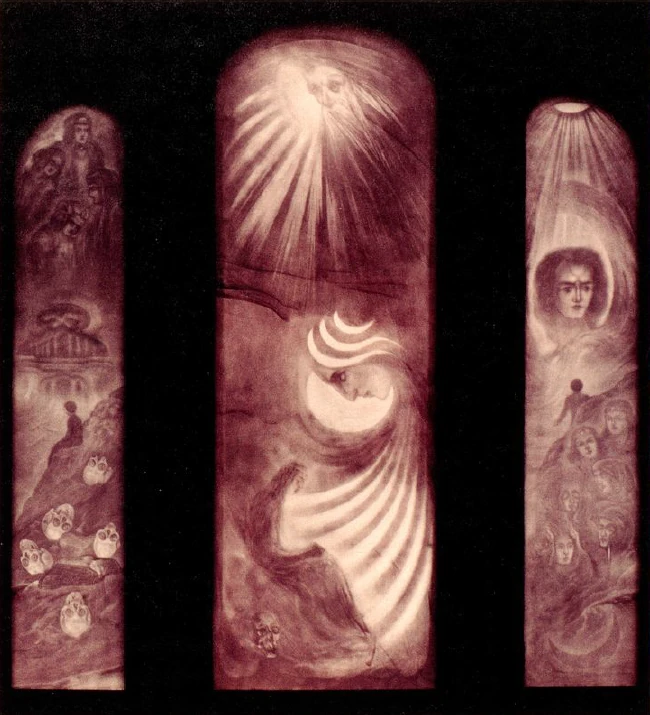

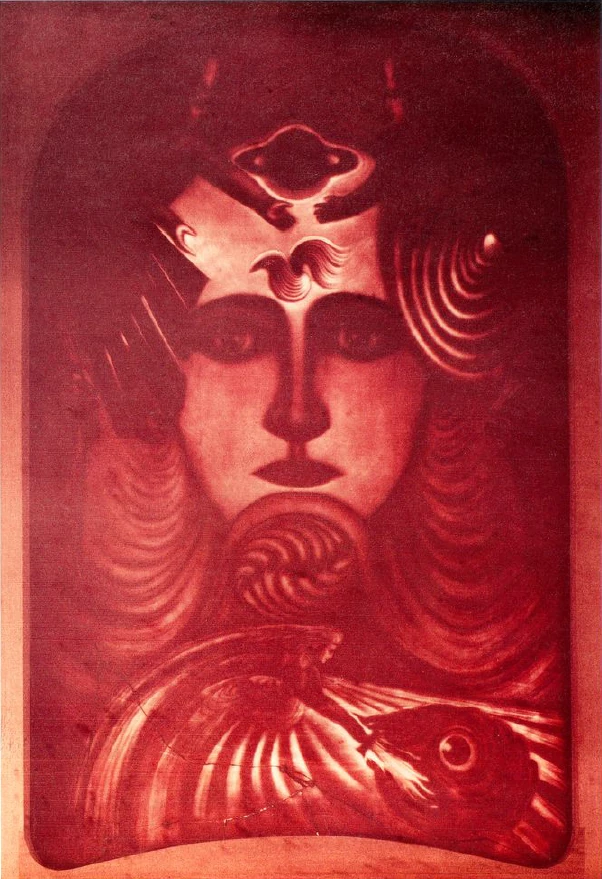

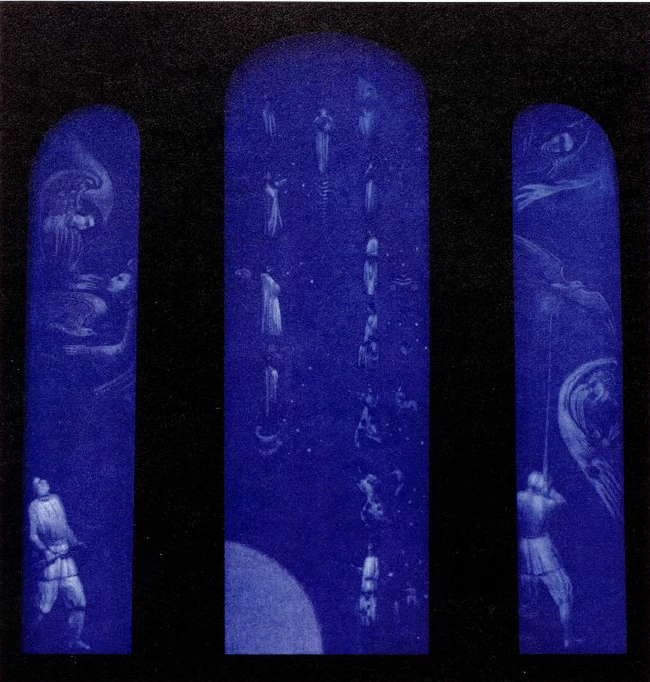

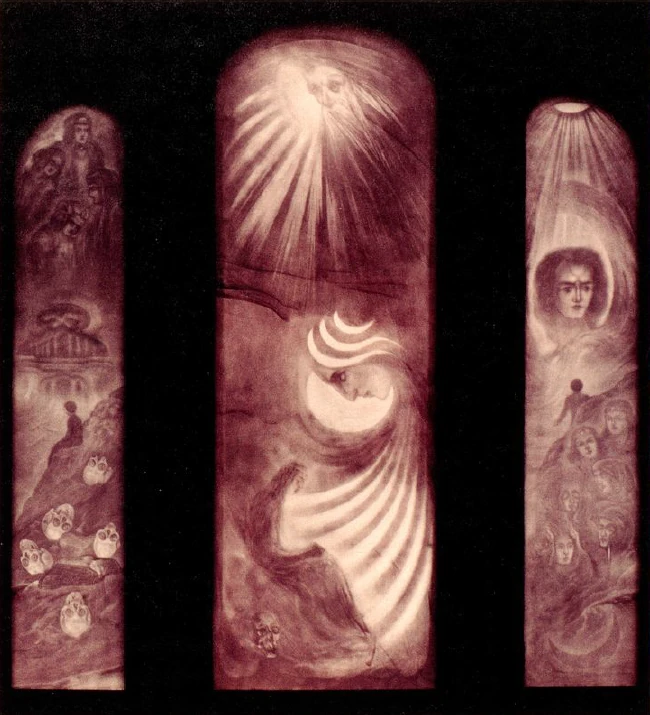

But if on the one hand, as is always the case in anthroposophy, one accepts our present civilisation, if in this way one relates quite positively to our present civilisation, then one must in turn also draw on all the consequences of this civilisation. That is why the walls here do not close off, but open one in the spirit to the whole cosmos. Even the paintings on the ceilings should not be such that they merely shine inwards with what they express in their colours, so that one merely has a painted ceiling that tells one something inwards. That should not be. Such a ceiling is first thought of in this way: there is the ceiling, there is the human being. It is painted in such a way that what is painted confronts you. That is not the case here. Here the colour is placed on the wall for the purpose of looking through the painting and having a connection with the whole cosmos. This is carried through to the physical form. You can see it in the windows that close off the building down here.

These windows are designed in such a way that they are created from single-coloured glass panes according to a method that one could call glass engraving: a single-coloured glass pane, from which the form is carved out with a diamond bit. This sheet of glass, when it is finished and placed somewhere, is of course not a work of art, any more than a score is a work of art. Only when it is put in its right place and the light of the sun shines through, then the work of art is there. Only with outer nature, with the outer world, does it make sense.

And so, it is with all the details here: they only have meaning together with the whole world, with the totality of the world. There is no need to ramble on in thought, interpreting this or that in this or, that way. One should feel, completely naturally, naively, then one will find one's way best here in this building. Because that's how the whole thing is felt. Better still than to speak of the architectural idea of Dornach, I could speak of the architectural feeling of Dornach.

It has been said many times: "Up there on the Dornach hill, there is a building with all kinds of symbols.” There is not a single symbol here. Everything is poured out in artistic forms, everything is felt, nothing is thought. However, all kinds of symbols live in the imagination of some people. Yes, I could also imagine that some anthroposophists, who still have some theosophical airs about them, have even been annoyed by the fact that there is no symbolism here at all, that nothing symbolic can be spun from fantastic thoughts here, but that everything is to be understood in a purely artistic way.

It was precisely on this occasion that the real way in which the anthroposophical impulse streams into art had to be shown. First of all, a movement of this kind, which leads to the spiritual, is naturally predisposed, as is the case with sectarian movements, to seek a meaning, an inner meaning in everything.

You experience the most amazing things there. We have performed mystery plays in Munich, in which characters appear, created characters, which one should understand as they walk across the stage. I was asked whether this character in these plays meant the etheric body, another manas, another buddhi. Yes, there are even treatises that have emerged from the theosophical movement, where "Hamlet" is interpreted in such a way that the individual characters, Hamlet himself—mean this or that: one character is the etheric body, another the astral body, another manas, another buddhi. Please forgive me for not being able to explain this in detail with regard to Hamlet, for I have never been able to really read through such a treatise.

And so, it was naturally also something unfortunate that one came into the various anthroposophical working groups where there were still theosophical airs and graces, and one found all kinds of symbolic designs, black crosses with seven red splotches, which were supposed to represent roses, trafficked all around. One imagined there was something great about it! The whole thing was enough to drive one crazy! But these are—one might say—the dross that first brings forth a movement. That's what it's all about, that real artistic feeling came out of all this dross, that something was attempted in which there is nothing at all of a pale symbolism, of an empty allegory, but where at least the attempt is made to shape everything artistically.

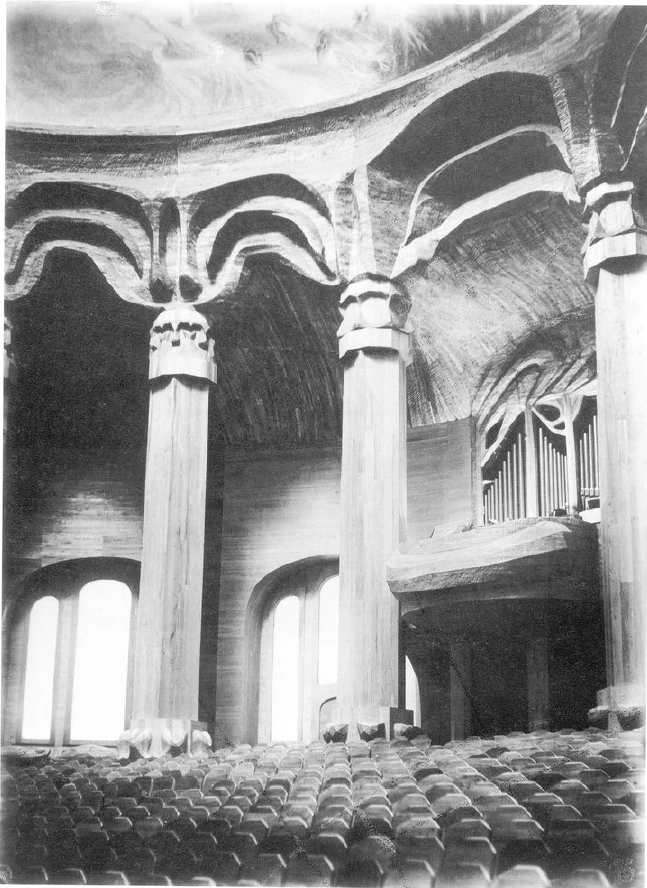

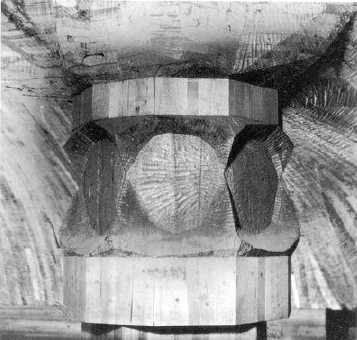

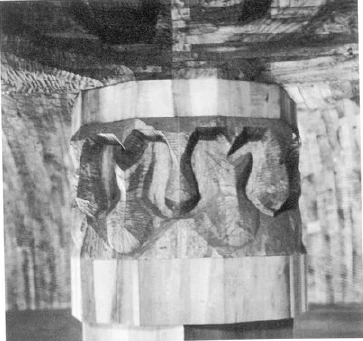

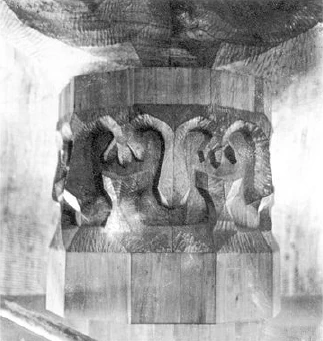

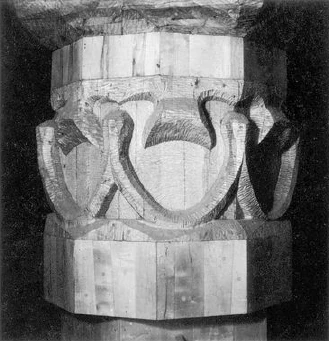

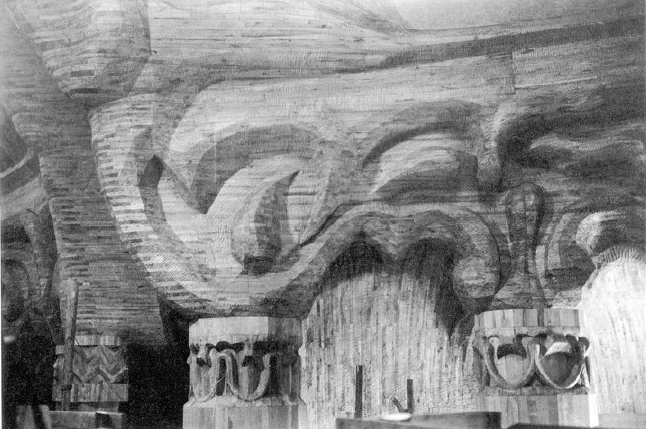

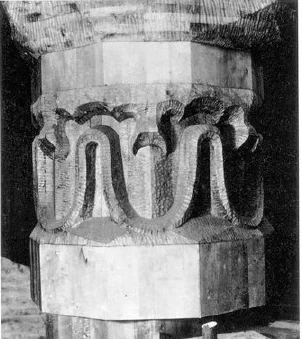

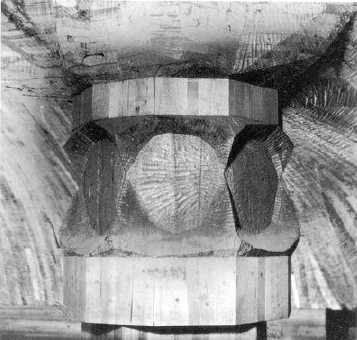

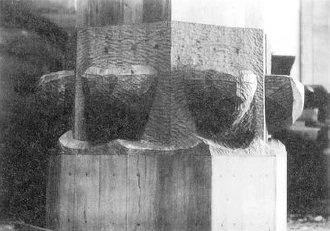

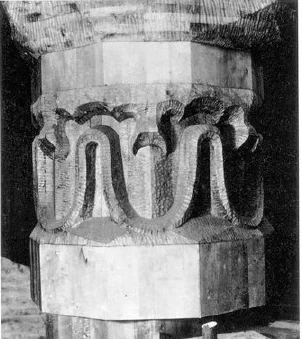

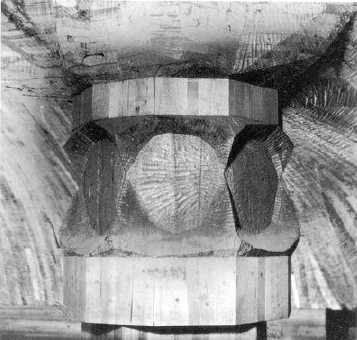

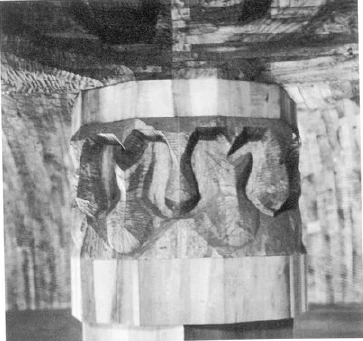

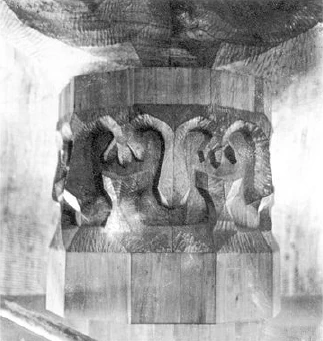

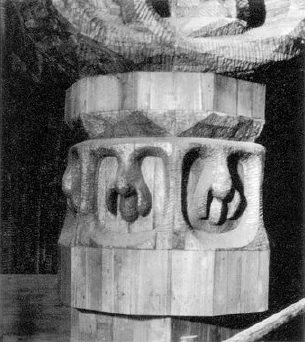

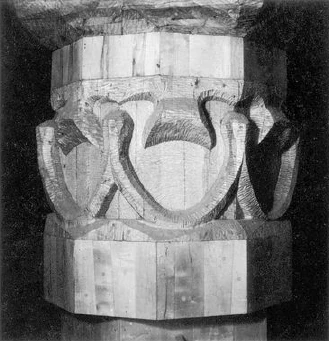

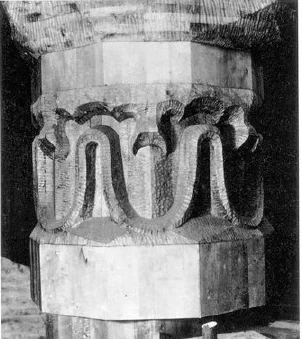

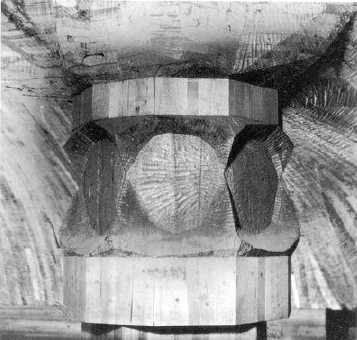

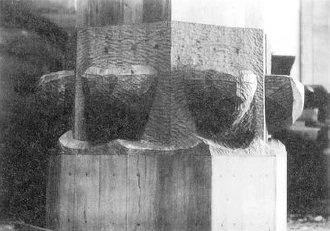

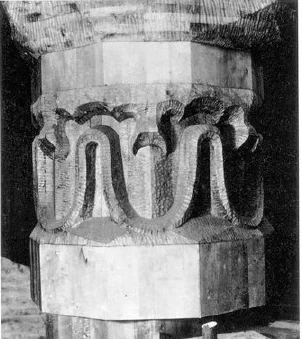

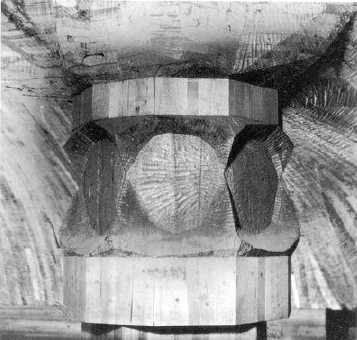

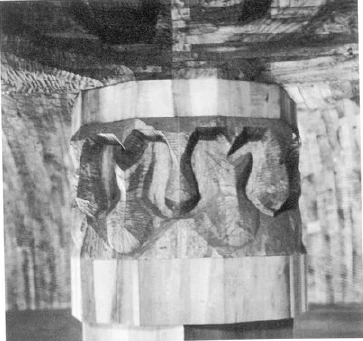

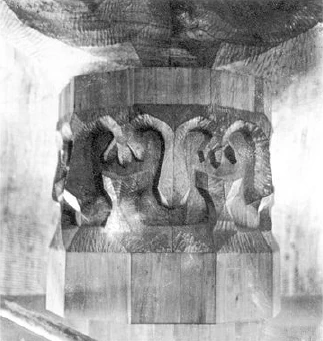

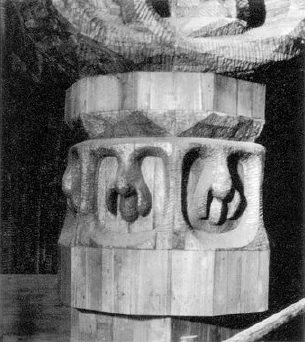

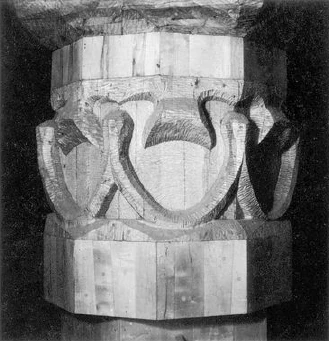

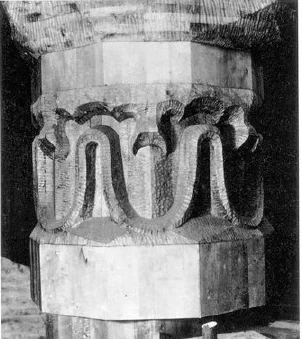

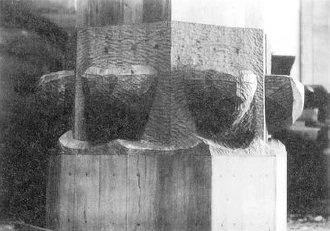

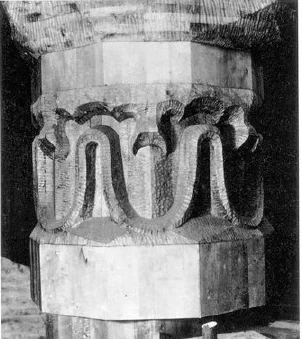

It is precisely the artistic that then becomes natural. You can see that in these columns. Column capitals are usually constructed according to the principle of geometric repetition. Column capitals usually repeat themselves. An organic style of architecture does not allow this. How did these column capitals, the architraves above them and the plinths, come about? They came about through the real incorporation of the principle of organic growth.

Here at the entrance—the simplest capital: a form is attempted that descends from above, another form that comes up to meet it. But all this is not thought out, but every surface, every line of the form is felt. And if one advances from the first column to the second column, and looks at the capital: it is the same feeling translated into the artistic, to which one must devote oneself to the sense of Goethean metamorphosis, when one has the simply formed leaves at the bottom of a plant and must find the transition to the leaves somewhat higher up. It reshapes itself, metamorphoses itself.

But if you look at these capitals, you will see that they really represent artistically that which appears so distinctly in abstract thoughts in the modern worldview: evolution, development. The second capital develops from the first, and so on.

But one peculiarity confronts you. If you look at the successive capitals, it contradicts the abstract idea of evolution, as it is often expressed. You will also find in Herbert Spencer, for example, the idea of evolution expressed in such a way that the first simply differentiates, then integrates again. But that is not how it is. That contradicts the natural course of evolution. Whoever delves into natural evolution will find that evolution rises to certain complicated forms, then again becomes simple, and the perfect is not that which is the most complicated, but the simple into which the complicated has again been transformed.

If I am to represent this in a simple way, I would have to represent it as follows: The middle form is the more complicated, the last form is the most perfect. You can see this, for example, in the evolution of the eye. The eyes of the lower animals are relatively simple, undifferentiated. In the middle series of animals, you find very complicated eyes, with the blade process and the fan inside the eye. These organs are again dissolved inside the human eye: the human eye is more perfect than that of the lower, the middle animal stage, but again more simplified. That which is in the middle stage is also spiritually within in the simplified form, but the perfect stage is again simplified for external observation. This simplification, however, is such that, as is the case with the capitals of the columns, with the architraves above, one feels in the simple that it has become, that it has been infused with that which was complicated.

I did not arrive at this design—if I may make this remark—when I worked out the model of this building, by trying to reproduce this abstract thought, which I have just expressed, externally in a symbolic way, but I arrived at it by surrendering myself to the creative forces of nature and trying to form something out of the same creative forces from which nature itself shapes. And that is how these forms came into being.

The most important thing that one encounters in the process is this: one creates quite naïve forms out of feeling. When they are finished, they show you all kinds of things that you did not intend to put into them at the beginning, just as natural forms show you all kinds of things that you discover in them. If, for example, you take the simple forms of base and capital there, and you accordingly make them somewhat elastic, then you can put the convexity of the first form into the concave part here. What is convex there is concave here, what is concave there is convex here. So that I later concluded—I did not intend it—that in terms of convexity and concavity the first column corresponds to the seventh column, the second column to the sixth column, the third column to the fifth column, and the middle one stands for itself.

That is precisely what is characteristic of artistic creation: that what one initially has in the mind is not everything that one then puts into the object. One is actually outside of oneself when creating artistically. One has only a little of what the creative forces are in one's consciousness. You create with the little that is alive, which then goes into the material. But what emerges surprises you, because you don't actually create alone, because you create together with the productive forces of the cosmos.

And purely out of feeling, the individual parts then acquire the character by which they fit into the whole, just as the members of an organism fit into the totality of the organism.

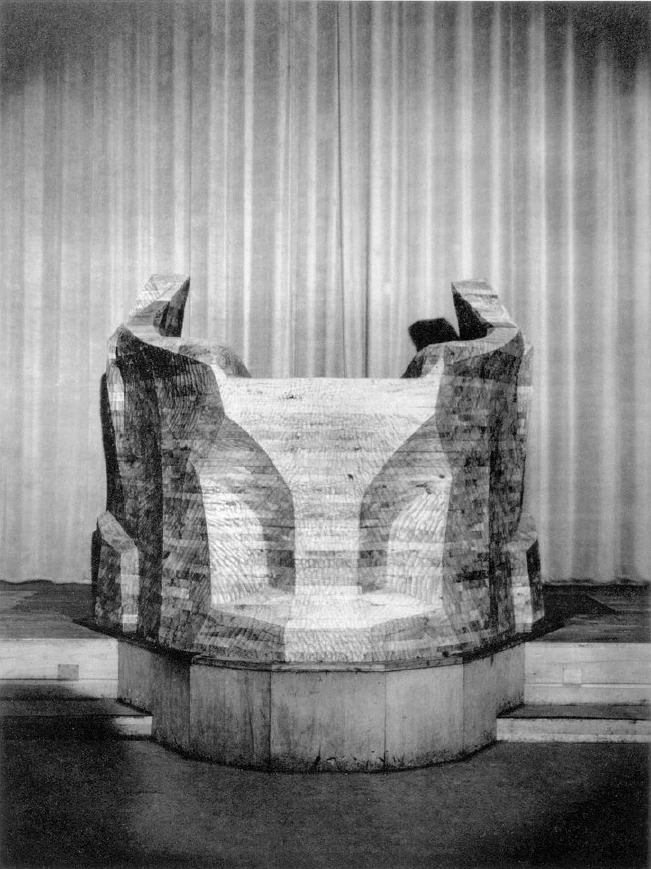

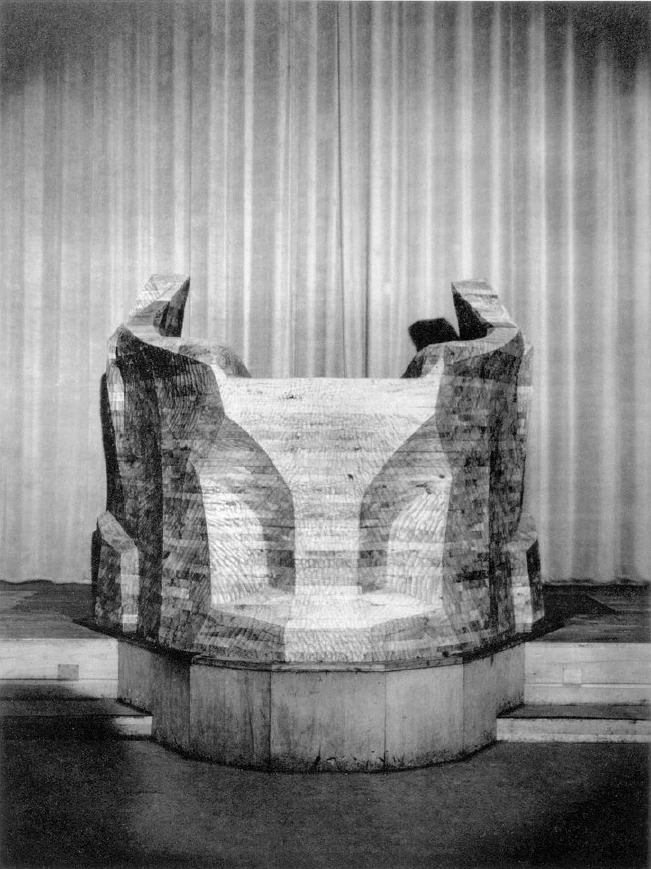

Look at this lectern here. You must feel, when you look at it, that it is a continuation of what proceeds from the mouth as the spoken word: there the words come down to you, but these forms say the same thing.

And again, if you take the columns as they are leaning here and think further about their form, if you combine them here: then the combination again becomes what stands here as a lectern. On the one hand, it leans towards the auditorium, on the other hand, it is a conclusion of what is present in the auditorium. The individual forms are conceived on this basis. However, the geometric-mathematical style of older forms is thereby transformed into a spatial-musical quality. But that, in turn, means something for human evolution, that the geometrical gradually passes over into the musical, so that the musical also confronts us in space.

However, if one wants to grasp this idea in its full livingness, one must not attach too much importance to the fact that the musical can be expressed in mathematical formulae. As a one-sided abstract scholar, one can be delighted when, let us say, a sequence of tones can be expressed by their mathematically calculated pitches and tonal ratios; one can feel that one has only now translated it into real knowledge. One can also feel it differently. One can also feel that when one has transferred the musical experience into the mathematical, one has buried the music, and that one finally has the corpse of the musical in the mathematical formulae.

These things must really be taken seriously here. The cognitive must be lifted up into artistic experience. Only by attempting this could these forms come about.

This Goetheanum is already felt to accord in many ways with Goethean impulses, but not according to the Goethean impulses that died with Goethe in 1832 within the physical world, but according to the impulses of that Goethe who is still lives today. Not as he is, however, according to the sense of ordinary Goethe scholars, but he is truly the reality of Goethe. For today's Goethe scholars, the very name "Goetheanum" is an abomination. One can understand that. The most one can do is to reply in private that everything that exists today as the "Goethe-Bund" and the "Goethe-Gesellschaft" is in turn—well, in private, you don't have to bring it out in the open—quite fatal to you. But something should be felt here of what Goethe meant when he travelled to Italy, out of a deep longing to find more intimate artistic impulses, to find the real essence of art. After looking at the works of art he saw in Italy, still feeling the after-effects of the Greek artistic principle, he wrote to his friends in Weimar: After what I see here in the works of art, I believe I have discovered the secret of Greek artistic creation. The Greeks followed the same laws in their artistic creation that nature itself follows.—And the pure abstract philosophy, which to his delight he encountered in Weimar through Herder, from the works of Spinoza, e.g. from the work "God" by Spinoza, this spiritual, essential quality in the world, this is what Goethe felt when he was confronted with the ideal works of art, and he wrote to his friends: There is necessity, there is God. And among his sayings we find the characteristic one: To whom nature reveals her open secrets, feels a deep longing for her most worthy interpreter, art.

That which appears in forms can be the same for a completely contemplated artistic impulse as that which expresses itself in thoughts. Only then the thoughts must be full of life and the forms must breathe spirit.

Erster Vortrag: Gestaltung Der Schaffenden Kräfte Der Natur

[ 1 ] Gestatten Sie, dass ich heute Abend über den Bau, in dem wir uns befinden, über das «Goetheanum»; einiges spreche mit Rücksicht darauf, dass wir ja zu unserer Befriedigung eine Anzahl auswärtiger Gäste in dieser Zeit hier begrüßen dürfen, für die vielleicht der Baugedanke von Dornach noch nicht im Besonderen ausgesprochen worden ist.

[ 2 ] Der Bau des Goetheanums wurde in einer Zeit notwendig, in welcher sich die anthroposophische Bewegung bis zu dem Grade ausgedehnt hatte, dass sie eben einen eigenen Raum brauchte, Es konnte sich der ganzen Natur deränthroposophischen Bewegung nach- wie ich schon bei anderer Gelegenheit im Laufe dieses Kurses bemerkt habe - nicht darum handeln, für die Zwecke der anthroposophischen Bewegung einen Bau in diesem oder jenem Baustile ausführen zu lassen. Eine Bewegung, die sich ausspricht in Ideen, in Maximen, eine solche Bewegung kann in einer beliebigen Umhüllung sein, nicht aber eine geistige Bewegung, die von vornherein veranlagt ist dazu, ihre Strömungen in das ganze Kulturleben einfließen zu lassen. Anthroposophische Bewegung will ebenso ihre Impulse in das künstlerische, in das religiöse, in das soziale Gebiet wie in das wissenschaftliche einfließen lassen. Wenn sie spricht, so sollen ihre Worte, ihre Ideen aus dem vollen Menschenwesen heraus sein, und es sollen diese Ideen nur die äußere Sprache sein für erlebte geistige Wesenheit. Dasjenige aber, was erlebte geistige Wesenheit ist, das kann sich aussprechen auch im Künstlerischen, in Formen, das spricht sich aus im äußeren sozialen Leben und so weiter. Es musste so sein, dass an einem Orte, in welchem in Gedanken dasjenige erklingt, was hinter der anthroposophischen Bewegung steht, auch in den Formen, welche die Zuhörer umgeben, in den Malereien, die von den Wänden herunter sprechen, dasselbe zur Offenbarung kommt, was hier in Worten, in Ideen erklingt.

[ 3 ] So war es ja immer, wenn irgendein Zivilisations-, ein Kulturinhalt sich in der Welt zur Offenbarung bringen wollte. Ein solcher Kulturinhalt bildet nicht Einseitigkeiten aus, sondern er bildet dasjenige aus, was kosmische oder menschliche Totalität ist. Und die einzelnen Gebiete - Wissenschaft, Kunst und so weiter - erscheinen eben nur als die einzelnen Glieder einer solchen Gesamtwesenheit, wie an einem Organismus die einzelnen Glieder als herausgeboren aus der Totalität des Organismus erscheinen. Daher musste die anthroposophische Bewegung sich einen eigenen Kunststil schaffen, so wie sie ja auch eine gewisse Art und Weise sich schaffen musste zu dem gedanklichen Ausdruck ihres Wesens.

[ 4 ] Der letztere Umstand wird ja heute noch zu wenig berücksichtigt. Es ist zum Beispiel notwendig, dasjenige, was anthroposophisch-geisteswissenschaftlich ist, bis in die Satzgestaltung hinein anders auszusprechen als das, was sonst gewohnheitsgemäß in der menschlichen Zivilisation äußerlich enthalten ist. Anthroposophie muss zum Beispiel in vieler Beziehung abkommen von dem heute noch gewohnheitsmäßig festgehaltenen Prinzip, dass man sich starr, einseitig auf einen Standpunkt stellt. Der Mensch ist auch heute vielfach noch immer Materialist oder Spiritualist, Realist oder Idealist und so weiter. Für eine unbefangene Totalweltanschauung hat das ja alles nur diejenige Bedeutung, dass, wenn man sagt: ich bin Materialist, man eben eine Seite der Wirklichkeit zum Ausdrucke bringt; wenn man sagt: ich bin Spiritualist, bringt man eine andere Seite der Wirklichkeit zum Ausdruck. Und das Anthroposophische erfordert Allseitigkeit. Man ist für die materiellen Vorgänge Materialist, für das Geistige Spiritualist, für das Idealische Idealist, für das Reale Realist und so weiter. Gerade wie ein Baum, wenn man ihn von verschiedenen Standpunkten aus abbildet, immer derselbe Baum ist, aber die Abbilder durchaus verschieden sich ausnehmen, so lässt sich die Welt von verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus verschieden darstellen.

[ 5 ] Daher muss auf anthroposophischem Gebiete einfach der Weg genommen werden, wenn man irgendein geistiges oder materielles Gebiet der Wirklichkeit ins Auge fasst, dass man sich einen Standpunkt wählt, von dem aus man es beleuchtet: Man fühlt, es zeigt sich dabei eine Einseitigkeit, und nun charakterisiert man dasselbe von einem entgegengesetzten Standpunkte. So hat man oftmals nötig, sagen wir, einen Vortrag damit zu beginnen, dass man von der einen Seite her spricht und dann den Vortrag stilmäßig ganz überfließen lässt in eine sich entgegengesetzter Gedankenformen bedienende Charakteristik. Das aber kann schon in dem einzelnen Satze notwendig sein!

[ 6 ] Und anderes noch ist für die anthroposophische Weltanschauung nötig. Die an das äußere Naturalistische sich haltende Weltanschauung, sie kann vorzugsweise in Nebeneinandergestelltem, sagen wir zum Beispiel [substantivisch] arbeiten. Anthroposophie muss [dagegen] vieles, was sonst in starren Satzkonturen hingestellt wird, flüssig machen, sodass der Satz elastisch, innerlich beweglich wird. Man erfährt dann, dass die Menschen das einen »schlechten Stil« nennen, weil sie sich nicht gewöhnt haben daran, dass ja eine ganz besondere Geistigkeit auch eine besondere Ausdrucksform fordert.

[ 7 ] Allerdings, es kommt ja auch vor, und das darf vielleicht gesagt werden, dass von mancher Seite her das Geisteswissenschaftliche, so wie es dem Inhalte nach gegeben wird, aufgenommen und dann eingekleidet wird in diejenige Stilform, die man heute gewöhnt ist. Dann nimmt sich das natürlich so aus, wie wenn ein Mensch Kleider anhat, die ihm nicht passen. Solche Darstellungen anthroposophischen Inhalts, die sich so ausnehmen wie ein Mensch, der Kleider trägt, die ihm nicht passen, findet man ja heute gar nicht einmal sehr selten. Aber das alles ist ja nur ein Zeichen dafür, dass eben mit der Anthroposophie etwas geschaffen werden soll, was nicht nur irgendein neuer Standpunkt ist, sondern was eine neue TotalWeltauffassung ist.

[ 8 ] Und damit hängt es zusammen, dass der Stil, der künstlerische, der architektonische, der malerische, der plastische Stil, welcher im Goetheanum angewendet werden musste, dass dieser sich herausheben musste, herausgestalten aus demjenigen, was an Stilformen in der Welt bisher vorhanden war. Man musste gemäß der Tatsache, dass Anthroposophie gerade den Geistesinhalt der Gegenwart ausdrückt, der ja einen Fortschritt darstellen muss gegenüber den Geistesinhalten früherer Zeiten, zum Beispiel die alten Stilformen der Architektur, die aufgebaut waren auf Geometrischem, Symmetrischem, auf gewisse Gleichmäßigkeit, kurz auf dasjenige, was mehr einen mathematischen Charakter trägt, überführen in einen organischen Baustil, in einen Baustil, der aus dem mehr Geometrisch-Dynamischen in das Organisch-Lebendige übergeht.

[ 9 ] Ich kann wohl verstehen, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, dass diejenigen, die sich fest fühlen in den alten Bauformen und die in diesen alten Bauformen eben etwas sehen, worin sie es einmal zu einem gewissen Verständnis gebracht haben, das, was nun in einer so radikalen Weise abfällt von allem bisher Gewohnten, als dilettantisch empfinden. Ich kann das voll verstehen. Aber es musste einmal das Wagnis unternommen werden, überzuführen die mehr mathematisch-dynamische Stilform in die organisch-lebendige Stilform. Das mag heute noch so unvollkommen wie möglich geschehen sein, aber es musste einmal damit der Anfang gemacht werden. Und als Ausdruck dieser Bestrebungen tritt Ihnen dieses Goetheanum entgegen.

[ 10 ] Derjenige, der von irgendeiner Seite her sich diesem Goetheanum nähert (Abb. 1), wird in seiner äußeren Form schon finden, dass es, ohne in das abstrakt Symbolische oder in das strohern Allegorische zu verfallen, eine Offenbarung des besonderen Geisteslebens ist, das hier sich verwirklichen will. Dieses Geistesleben geht ja auf den Menschen als den Ausdruck einer Weltoffenbarung mehr ein, als frühere Stufen unserer Menschheitszivilisation es getan haben. Es drückt sich das aus in der Zweiteiligkeit des Baues.

[ 11 ] Der Mensch ist eben in unserem heutigen Zeitalter mehr auf Verinnerlichung angewiesen als dies in früheren Zeitaltern der Fall war. Der Mensch hatte zum Beispiel noch in Griechenland ein Leben, das die Gedanken in der äußeren Welt so wahrnahm wie wir heute nur die Farben oder die Töne, überhaupt die Sinneswahrnehmungen. So wie wir heute etwas rot sehen, so sah der Grieche noch einen Gedanken sich äußern. Er hatte nicht das Gefühl, dass der Gedanke etwas ist, das er in seinem Innern ausgestaltet, das er in seinem Innern abgesondert von der äußeren Wirklichkeit erlebt.

[ 12 ] Diese Absonderung des Menschen, damit aber auch die Steigerung der Individualität des Menschen hat im Laufe der Menschheitsentwicklung einen Fortschritt erlebt. Ich habe das in dem ersten Kapitel meiner «Rätsel der Philosophie» auseinandergesetzt. Und so war es ganz naturgemäß gegeben - wie gesagt, ohne Symbolismus, ohne Allegorisieren -, den Bau zu empfinden als etwas Zweiteiliges: als den einen Teil, der in sich schließt dasjenige, was der Mensch mehr erlebt, wenn er nach innen gewendet ist, was der Mensch erlebt, wenn er die Beschauung nach innen kehrt, und den anderen Teil, den der Mensch erlebt, wenn er sich der Welt nach außen zukehrt.

[ 13 ] Nicht irgendwie ausgedacht, symbolisiert, spintisiert, sondern rein empfunden ist dieser Total-Baugedanke von Dornach. Er musste eben so werden, dieser Bau, wenn er gedacht, empfunden wurde als dasjenige, was in ihm sein soll. Ganz gemäß dem naturgemäßen Prinzip, das ich in diesen Tagen bei anderer Gelegenheit schon charakterisiert habe. Wie die Nussschale aus denselben Kräften heraus, aus denen auch die Nussfrucht im Innern gestaltet ist, ihre Form bekommt, wie man die Nussschale nur so empfinden kann, wie sie ist gemäß der Nussfrucht, die drinnen ist, so musste auch diese Schale die Umhüllung für dasjenige sein, was hier als Kunst, als Erkenntnis pulsiert. Ich habe früher öfter einmal einen anderen Vergleich gebraucht, der trivialer ausschaut; ich habe ihn nicht trivial gemeint. Ich habe gesagt: der Bau von Dornach, er muss dasjenige sein, was man in Wien einen Gugelhupftopf nennt, verzeihen Sie den Ausdruck. Gugelhupf ist ein besonderer Kuchen, ein gebackener Kuchen, der [es wird gezeichnet] eine besondere Form hat, aus Mehl und Eiern und noch manchen anderen schönen Geschichten gebacken. Und das muss in einer Kuchenform gebacken werden. Diese Form, die muss ganz bestimmt gestaltet sein, denn durch diese Form bekommt ja gerade der Gugelhupf seine Form (Abb. 115, Zeichnung Nr. 1). Es muss also für den Kuchen immer eine hübsche Gugelhupfform sein, das heißt, die Form muss überhaupt vorher da sein, es ist nur im Durchschnitt gezeichnet. Dasjenige, also, was da ist, das ist der Gugelhupftopf für den Gugelhupf «Anthroposophie». Die wird da drinnen gebacken (Abb. 115, Zeichnung Nr. 2), daher muss die Form so gedacht sein, so empfunden sein, dass da das Richtige gebacken werden kann.

[ 14 ] Es ist dasjenige, was Anthroposophie ist, gerade bestrebt, die mehr den festen Naturformen angepassten Vorstellungen in lebendigen Fluss zu bringen und so [auch] die mechanisch-geometrischen Baustile hier in einen lebendigen Fluss zu bringen. Sie werden daher, wenn Sie den Bau besuchen, betreten und in seinen verschiedensten Gebieten anschauen, überall finden, dass der Versuch gemacht worden ist, das geometrisch-symmetrisch Gestaltete so weiterzuführen, dass organische Formen oder dass ein Erinnern an organische Formen überall vorhanden ist.

[ 15 ] Gehen Sie zunächst zum Haupttore (Abb. 5) herein. Sie werden finden, da ist über dem Tor etwas wie eine organische Form. Diese organische Form, die ist nicht auf naturalistische Weise empfunden, indem man dieses oder jenes Organische nachgebildet hat, sondern sie beruht auf einem lebendigen Sich-Hingeben an das organische Schaffen überhaupt. Man kann nicht, wie bloße Naturalisten tun, eine Stilform dadurch herausbekommen, dass man Blattartiges oder Blütenartiges oder Hornartiges oder Augenartiges nachahmt, sondern dadurch, dass man mit seinem eigenen Seelenleben in eine solche innere Bewegung sich versetzt, wie es dem Schaffen des Organischen entspricht. Dann kommen, wenn man einen Bau aufführt, der ja natürlich nicht eine Pflanze oder ein Tier ist, wenn das Ganze aus dem OrganischLebendigen gedacht ist, nicht die natürlichen Formen heraus, aber solche Formen, die an das Natürliche erinnern; die nirgends naturalistisch das Natürliche nachahmen, die aber an dasselbe erinnern.

[ 16 ] Und wenn Sie den Bau betreten haben und dann durch den Umgang durchgehen, dann werden Sie gewisse Formen finden, die bestimmt sind, als Heizvorrichtungs-Vorsetzer zu dienen (Abb. 26, Abb. 115, Zeichnung Nr. 3). Diese Formen sind so gestaltet, dass man das Gefühl hat, sie wachsen aus der Erde heraus; es ist lebendige Wachstumskraft in ihnen, etwas, was nicht Pflanze, nicht Tier ist, aber ein Wachsendes, Organisches ist, das sich gestaltet. Das gestaltet sich sogar in einer solchen Form in der Dualität. Es ist etwas wie Wesen, die miteinander sprechen, und ihre gegenseitige Beziehung kommt auch zum Ausdrucke.

[ 17 ] All dieses stellt sich von selbst in das Schöpferische hinein nach dem Prinzip der Goethe’schen Metamorphose, die ja zunächst geschaffen ist von Goethe, um das Organische erkenntnismäßig zu überschauen. Das Organische ist so, dass es gewisse Formen wiederholt, aber nicht in gleicher Weise wiederholt. Goethe drückt das so aus, dass am OrganischLebendigen die einzelnen Organe - sagen wir, die Blätter einer Pflanze - von unten nach oben in die Blüte, in die Staubgefäße, in die Stempel, in die Fruchtorgane hinein, der Idee nach wohl dasselbe sind, aber in der äußeren Gestaltung in der mannigfaltigsten Art auftreten.

[ 18 ] Wenn man sich in das Lebendige vertieft, so kommt man in der Tat dazu, so gestalten zu müssen, dass etwas, was nur ideell geistig festgehalten wird, in der äußeren Gestalt in der mannigfaltigsten Weise sich ausbilden kann. Das kann nun wiederum, während es Goethe zunächst erkenntnismäßig zum Begreifen der Organe ausgebildet hat, ins Künstlerische heraufgeführt werden und es muss ins Künstlerische heraufgeführt werden, wenn man den geometrisch-symmetrisch-dynamischen Baustil in den organischen Baustil überführt.

[ 19 ] Das Wesentliche bei einem solchen, im organischen Stile Gebauten ist, dass das Ganze nicht bloß durch die Wiederholung von Einzelnem, sondern auch als Ganzes eine Einheit ist. Dadurch muss jedes einzelne Glied, das da oder dort ist, so sein, wie es nur an diesem Orte sein kann. Bedenken Sie einmal, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, Ihr Ohrläppchen — kleines Organ an Ihnen -, es kann nur an dem Orte sein, wo es am Organismus erscheint. Es kann nirgends anders am Organismus sein. Aber es kann auch gar nicht anders gestaltet sein, als es da ist. Dieses Ohrläppchen könnte nicht dort sein, wo jetzt die große Zehe ist, und könnte hier auch nicht so gestaltet sein wie die große Zehe. In einem Organischen ist ein jedes an seinem Orte und kann nur so ausgestaltet sein, wie es an seinem Orte ausgestaltet ist. Das werden Sie hier in diesem Bau festgehalten finden. Wo Sie hinschauen, werden Sie empfinden: Jedes Einzelne ist nur für seinen Ort aus dem Ganzen heraus empfunden und kann nur an diesem Orte sein.

[ 20 ] Wenn Sie die Geländer im Treppenhause ansehen mit ihren Kurven (Abb. 23), so werden Sie sehen, dass die Kurven in ganz bestimmter Weise geformt sind da, wo der Bau nach außen sich öffnet, wo nichts mehr gewissermaßen zu halten ist durch die Kräfte; dagegen stauen sich die Formen gegen den Bau hin, ziehen sich zusammen, wie das am Organischen auch durchaus der Fall ist. Es musste einmal das Wagnis unternommen werden, die Säulen, die Pfeiler durch etwas in organischer Gestaltung Auftretendes zu ersetzen. Sie sehen daher den Versuch im Treppenhaus: das Geländer getragen von organischen Formen, die als Träger auftreten, die wiederum nicht irgendetwas Natürlichem nachgebildet sind, sondern die aus dem Baugedanken selber heraus empfunden sind. Und jede einzelne Verdickung, jede einzelne Verdünnung, dann wiederum der Umfang eines solchen pfeilerartigen Gebildes, sind durchaus gedacht in ihrer Größe im Sinne des Ganzen und wiederum gedacht so, wie sie an ihrem Orte sein müssen.

[ 21 ] Ich kann verstehen, dass so etwas wie die zwei organisch gebildeten Pfeiler da im Betonvorbau (Abb. 25) demjenigen noch seltsam vorkommen, der so etwas eben nicht gewöhnt ist. So begab sich einmal in diesen Bau ein Kritiker, der fand das seltsam, dass man so etwas hinstellt. Er konnte sich ja wohl nur denken, da müsse was nachgebildet sein. Es ist gar nichts nachgebildet, es ist nur aus dem Baugedanken das Ganze eben gestaltet in ursprünglicher Empfindung. Gar nichts ist nachgebildet. Aber in dieses Schöpferisch-Produktive, da geht der Kritiker nicht gerne [hin]ein, der sich ja lieber an das Alte hält. Und so kam ihm in den Sinn, das müsse ein Elefantenfuß sein. Aber es scheint, mit dem einen Auge sah er einen Elefantenfuß, mit dem anderen Auge kam es ihm aber doch nicht wie ein Elefantenfuß vor, weil es als Elefantenfuß doch wiederum zu klein ist für den Bau. Was zu klein ist für etwas, das tritt im Organischen als rachitisch auf, und deshalb sagte er mit einem sonderbaren inneren Widerspruch: Man sieht da im Vorraum «rachitische Elefantenfüße».

[ 22 ] Der Unterbau (Abb. 4) ist aus Beton ausgeführt. Es ist heute noch notwendig, wenn man in Beton baut, erst die Formen aus dem Betonmaterial heraus zu finden. Das ist ja überhaupt etwas, was für künstlerisches Schaffen im eminentesten Sinne von Bedeutung ist: dass aus dem Materialgefühl, aus der Materialempfindung heraus gebaut werden muss. Man muss anders aus Holz bilden als aus irgendeinem Gesteinsmaterial. Und man muss natürlich anders aus Beton heraus bilden, als man aus Marmor heraus bilden würde.

[ 23 ] Wenn Sie plastisch gestalten und Sie gestalten aus dem Stein heraus, da müssen Sie zum Beispiel dasjenige, was erhöht ist an der Gestalt, besonders berücksichtigen. Sie müssen, wenn Sie aus dem Stein heraus arbeiten, die Erhabenheiten, die Konvexitäten ganz besonders herausarbeiten. Wenn Sie an einer plastischen Figur des Menschen die Augen gestalten, und Sie haben als plastisches Material den Stein, dann richten Sie Ihr Augenmerk auf die Erhabenheiten, auf die Konvexitäten und arbeiten das ganze Auge aus dem Konvexen heraus; Wenn Sie eine Holzfigur.machen, dann können Sie s6:nicht vorgehen, dann müssen Sie überall auf die Vertiefungen, auf die Konkavitäten hin Ihr Augenmerk richten, und Sie müssen gewissermaßen das sich Vertiefende herauskratzen aus dem Holze. Das muss in der Empfindung liegen, das muss aus dem Materialgefühl kommen. Für den Beton musste man erst ganz besondere Formen finden.

[ 24 ] Unsere Freunde Grosheintz haben uns ja die Baufläche hier für diesen Bau zur Verfügung gestellt, und das Haus, das draußen gebaut ist für Dr. Grosheintz und seine Familie (Abb. 9, 12), das ist aus Beton gebaut. Für dieses Haus musste der ganz besondere Betonstil zunächst unvollkommen, wie es heute erst sein kann, angewendet werden. Man sieht vielleicht gerade an einem solchen Bau das Ringen nach einem Baustil, nach einem künstlerischen Stil aus einem Material heraus. Diese Bestrebung lag also zugrunde dem Unterbau, der aus Beton ist. Der Oberbau ist in Holz gestaltet.

[ 25 ] Wenn Sie über die Treppe hinaufgehen, betreten Sie dann den Vorraum (Abb. 27), und schon in diesem sehen Sie, wie abweichend von dem bisher Gewohnten, sagen wir die Decke, die Seitenwände gestaltet sind. Und ich darf da erwähnen, dass ja gemäß diesem neuen Baustil auch die Einzelheiten durchaus eine von dem Bisherigen verschiedene Bedeutung bekamen. Das drückt sich aus zum Beispiel in der Behandlung der Wand. Was ist für ein bisheriges Gebäude eine Wand? Dasjenige, was nach außen abschließt. Hier ist die Wand nicht das, was nach außen abschließt, sondern hier ist die Wand dasjenige, was gewissermaßen für die Empfindung durchsichtig sein soll, was nicht abschließt, was in die Weiten der Welt die Empfindung öffnet. Es ist ein durchgreifender Unterschied zwischen der Wandbildung, wie man sie bisher gewohnt war, und der Wandbildung hier. Die Wandbildung schließt einen sonst überall gegenüber der Welt ab. Hier aber soll man das Gefühl haben: Sie ist nicht abgeschlossen. So wie man durch Glas durchsieht, so fühlt man künstlerisch durch die Formen, die künstlerisch geschaffen sind, durch und man fühlt sich mit dem ganzen Kosmos in Einklang.

[ 26 ] Wir konnten daher durchaus den ganzen Bau auch anlegen auf eine künstliche Beleuchtung. Man kann vielleicht das Gefühl haben, gegenüber den freien Bauten Griechenlands ist so etwas, was auf künstliche Beleuchtung reflektiert, etwas wie eine abgeschlossene Höhle. Nun, das mag sein, das liegt aber in den ganzen modernen Lebensverhältnissen. Wir sind nicht innerhalb der alten griechischen Kultur. Wenn man, wie es ja in der Anthroposophie immer der Fall ist, die gegenwärtige Zivilisation hinnimmt, und sich ganz positiv verhält zu dem, was die gegenwärtige Zivilisation ist, dann muss man auch wiederum alle Konsequenzen dieser Zivilisation ziehen. Deshalb sind die Wände hier nicht abschließend, sondern im Geiste öffnet man sich dem ganzen Kosmos.

[ 27 ] Auch die Malereien der Decken sollen nicht so sein, dass sie mit dem, was sie in ihren Farben aussprechen, bloß nach innen herein leuchten, sodass man eine bemalte Decke bloß hat, die einem nach innen herein etwas sagt. Das soll nicht sein. So eine Decke ist ja zunächst so gedacht (Abb. 115, Zeichnung Nr. 4). Da ist die Decke, da steht der Mensch. Es ist so gemalt, dass einem das Gemalte entgegentritt. Hier ist das nicht der Fall. Hier ist auf die Wand die Farbe gesetzt zu dem Zwecke, dass man durch die Malerei durchschauen soll und den Zusammenhang haben soll mit dem ganzen Kosmos. Das ist bis auf die physische Gestaltung durchgeführt.

[ 28 ] Sie sehen es an den Fenstern, die den Bau hier unten abschließen (Abb. 109-113). Diese Fenster sind so gestaltet, dass sie aus einfarbigen Glasscheiben heraus nach einer Methode geschaffen sind, die man nennen könnte ein Glasgravieren: Aus einer einfarbigen Glasscheibe wird die Form herausgekratzt mit einem Diamantstift. Diese Glasscheibe ist, wenn sie fertig ist, wenn man sie irgendwo aufstellt, natürlich noch kein Kunstwerk, so wenig eine Partitur ein Kunstwerk ist. Erst wenn sie eingesetzt ist an ihrer richtigen Stelle und das Licht der Sonne durchscheint, dann ist das Kunstwerk da. Mit der äußeren Natur, mit der äußeren Welt zusammen hat das erst einen Sinn.

[ 29 ] Und so ist es mit allen Einzelheiten hier: Sie haben nur mit der ganzen Welt, mit der Welt-Totalität zusammen einen Sinn. Man braucht hier nicht in Gedanken zu faseln, indem man dieses oder jenes so oder so interpretiert. Man soll empfinden, ganz ursprünglich naiv empfinden, dann wird man sich am besten zurechtfinden hier in diesem Bau. Denn so ist auch das Ganze durchempfunden. Besser noch als von einem Baugedanken von Dornach könnte ich von der Bauempfindung von Dornach sprechen.

[ 30 ] Man hat manchmal gesagt: Da oben auf dem Dornacher Hügel, da ist ein Bau mit lauter Symbolen. Kein einziges Symbol ist hier. Alles ist in künstlerische Formen ausgegossen, alles ist empfunden, nichts ist gedacht. In der Phantasie mancher Menschen leben allerdings allerlei Symbole. Ja, ich könnte mir auch vorstellen, dass manche Anthroposophen, die noch etwas theosophische Allüren in sich haben, sich sogar geärgert haben darüber, dass sich hier gar keine Symbolik findet, dass man da gar nichts Symbolisches spintisieren kann, sondern dass alles rein künstlerisch gestaltet aufgefasst werden soll. Es musste ja eben gerade bei dieser Gelegenheit das wirkliche Einfließen des anthroposophischen Impulses in das Künstlerische gezeigt werden. Zunächst ist ja eine solche Bewegung, die auf Geistiges hinausläuft, natürlich dazu veranlagt, wie es bei sektiererischen Bewegungen ist, in allem eine Bedeutung zu suchen, einen inneren Sinn.

[ 31 ] Man erlebt ja da die tollsten Sachen. Wir haben Mysterienspiele in München aufgeführt. In diesen Stücken kommen Personen vor, gestaltete Personen, die man so auffassen soll, wie sie über die Bühne schreiten. Ich bin gefragt worden, ob die eine Person in diesen Stücken den Ätherleib, eine andere Manas, eine andere Buddhi bedeutete. Ja, es gibt sogar Abhandlungen, die aus theosophischer Bewegung hervorgegangen sind, wo der «Hamlet» in seinen einzelnen Personen so interpretiert ist, dass die einzelnen Personen, Hamlet selber, das oder jenes bedeuten: die eine Person ist der Ätherleib; die andere der Astralleib, eine andere Manas, eine andere Buddhi.

[ 32 ] Dass ich Ihnen das nicht in Bezug auf Hamlet im Einzelnen auseinandersetzen kann, das verzeihen Sie mir bitte, denn ich war nie imstande, eine solche Abhandlung wirklich durchzulesen. Und so war es natürlich ja auch etwas Missliches, dass man in verschiedenen anthroposophischen Arbeitsgruppen, wo noch theosophische Allüren waren, allerlei symbolische Gestaltungen fand, schwarze Kreuze mit sieben roten Patzen, die Rosen darstellen sollten, rings herum traktiert. Man stellte sich etwas Großes darunter vor: Die Sache war zum Davonlaufen!

[ 33 ] Aber das sind eben, man möchte sagen, die Schlacken, die zunächst eine Bewegung hervorbringt. Nur das ist es, worum es sich handelt: dass das wirkliche künstlerische Gefühl herauskommt aus all diesen Schlacken, dass also etwas versucht wurde, worin gar nichts von einer blassen Symbolik, von einer strohernen Allegorie enthalten ist, sondern wo wenigstens der Versuch gemacht wird, alles künstlerisch zu gestalten. Gerade das Künstlerische wird ja dann auch naturgemäß. Sie sehen das an diesen Säulen (Abb. 28). Säulenkapitelle hat man sonst so, dass sie nach dem Prinzip der geometrischen Wiederholung aufgebaut sind. Säulenkapitelle wiederholen sich sonst. Das lässt ein organisch stilisierter Bau nicht zu. Wie sind diese Säulenkapitelle, auch die Architrave, die darüber sind, und die Sockel zustande gekommen? Sie sind durch ein wirkliches Hineinfügen in das Prinzip des organischen Wachstums zustande gekommen. Hier beim Eingang: Das einfachste Kapitell (Abb. 34). Eine Form ist versucht, die sich von oben nach unten senkt, eine andere Form, die ihr entgegenkommt. Das alles ist aber nicht ausgedacht, sondern jede Fläche, jede Linie an der Form ist empfunden. Und wenn man vorschreitet von der ersten Säule bis zur zweiten Säule (Abb. 36), das Kapitell anschaut: Es ist dieselbe Empfindung, ins Künstlerische umgesetzt, welcher man sich hingeben muss im Sinne der Goethe’schen Metamorphoscanschauung, wenn man die einfach gestalteten Blätter unten an einer Pflanze hat und den Übergang finden muss zu den etwas höheren Blättern. Das gestaltet sich um, das metamorphosiert sich.

[ 34 ] Und so kam in Bewegung das, was da von oben nach unten als Form sich senkt, was von unten nach oben strebt. Und aus dem ersten Kapitell ging das zweite hervor. Und indem das Wachstum fortdauert, indem sich alles differenziert und wiederum das Differenzierte sich harmonisiert, entsteht die dritte Form (Abb. 38) ganz der Empfindung gemäß aus der zweiten, und so fort, bis hier zu den letzten Kapitellen (Abb. 40-46). Wenn Sie aber diese Kapitelle sich ansehen, so werden Sie sehen, dass sie wirklich dasjenige künstlerisch darstellen, was in abstrakten Gedanken in der modernen Weltanschauung so ausgesprochen auftritt: die Evolution, die Entwicklung. Es entwickelt sich das zweite Kapitell aus dem ersten und so fort.

[ 35 ] Aber eine Eigentümlichkeit tritt Ihnen entgegen. Wenn Sie die aufeinanderfolgenden Kapitelle ansehen, so widerspricht das dem abstrakten Entwicklungsgedanken, wie man ihn oftmals ausspricht. Sie finden ja zum Beispiel bei Herbert Spencer den Entwicklungsgedanken so ausgedrückt, dass das Erste einfach sich differenziert, dann wiederum integriert. So ist es aber nicht. Das widerspricht dem natürlichen Gang der Evolution. Wer sich in die natürliche Evolution hineinvertieft, der wird finden, dass die Evolution ansteigt bis zu gewissen komplizierten Formen, dann wiederum einfach wird, und das Vollkommene ist nicht dasjenige, was das Komplizierteste ist, sondern das Einfache, in das sich das Komplizierte wiederum verwandelt hat (Abb. 115, Zeichnung Nr. 5).

[ 37 ] Soll ich das in einfacher Weise darstellen, müsste ich es etwa mit dem Folgenden darstellen: Die mittlere Form ist die kompliziertere, aber die letzte Form ist die vollkommenste. Man sieht das zum Beispiel in der Augenentwicklung. Die Augen der niederen Tiere sind verhältnismäßig einfach, undifferenziert. In der mittleren Tierreihe findet man sehr komplizierte Augen, da sind im Auge drinnen der Schwertfortsatz, der Fächer. Diese Organe sind im Innern des Auges beim Menschen wiederum aufgelöst; das menschliche Auge ist vollkommener als das der niederen, aber wiederum vereinfachter als das der mittleren Tierstufe. Geistig ist auch in der vereinfachten Form das drinnen, was in der mittleren Stufe ist, aber die vollkommene Stufe ist für das äußere Anschauen wieder vereinfacht. Dieses Vereinfachte ist jedoch so, dass man, wie dies bei diesen Säulenkapitellen und bei den Architraven oben der Fall ist, in dem Einfachen doch wiederum das Werden empfindet, man empfindet, dass in es eingeflossen ist dasjenige, was das Komplizierte war.

[ 38 ] Zu dieser Gestaltung - wenn ich diese Bemerkung machen darf - bin ich nicht, als ich das Modell dieses Baues ausgearbeitet habe, dadurch gekommen, dass ich diesen abstrakten Gedanken, den ich jetzt eben ausgesprochen habe, versuchte äußerlich symbolisch nachzubilden, sondern ich bin dazu gekommen dadurch, dass ich mich hingegeben habe den schaffenden Kräften der Natur und versuchte, aus denselben schaffenden Kräften heraus etwas zu gestalten, wie die Natur selbst gestaltet. Und so sind diese Formen entstanden.

[ 39 ] Das Wichtigste, das einem dabei begegnet, ist das: Man schafft ganz naiv Formen aus der Empfindung heraus. Sind sie dann fertig, so zeigen sie einem allerlei, das man anfangs durchaus nicht hat in sie hineinlegen wollen, wie einem die Naturformen auch allerlei zeigen, was man in ihnen entdeckt. Wenn Sie zum Beispiel die einfachen Formen von Sockel und Kapitell dort nehmen (Abb. 34, 48) und Sie entsprechend nur etwas elastisch nehmen, dann können Sie die erste Form in ihrer Konvexität in den konkaven Teil hier (Abb. 46, 54) hineinlegen. Was dort konvex ist, ist hier konkav, was dort konkav ist, ist hier konvex. Sodass ich später selber erst darauf gekommen bin - gar nicht das hineingelegt habe -, dass in Bezug auf Konvexität und Konkavität die erste Säule der siebenten Säule, die zweite Säule der sechsten Säule, die dritte Säule der fünften Säule entspricht und die mittlere für sich selber dasteht.

[ 40 ] Gerade das ist das Eigentümliche des künstlerischen Schaffens, dass dasjenige, was man zunächst im Gemüte hat, nicht alles ist, was man dann in das Objekt hineinlegt. Man ist aus sich heraus eigentlich, indem man künstlerisch schafft. Man hat ein Weniges von dem, was die schaffenden Kräfte sind, im Bewusstsein. Man schafft mit dem Wenigen lebendig, das geht dann in das Material hinein. Aber was entsteht, das überrascht einen, weil man eigentlich nicht allein schafft, weil man mit den Produktivkräften des Kosmos zusammen schafft. Und rein aus der Empfindung heraus bekommen dann die einzelnen Teile den Charakter, durch den sie sich in die Gesamtheit einfügen, wie das Glied eines Organismus sich in die Gesamtheit dieses Organismus einfügt. Sehen Sie dieses Rednerpult hier an (Abb. 68). Man muss empfinden, wenn man anschaut, dass es eine Fortsetzung desjenigen ist, was aus dem Munde als gesprochenes Wort kommt. Da kommen die Worte zu Ihnen herunter; aber diese Formen sagen dasselbe. Und wiederum, wenn Sie die Säulen, wie sie sich hier herneigen, nehmen und ihre Form weiterdenken, sie hier zusammenfassen, dann wird aus dem Zusammenfassen das, was hier als Rednerpult steht. Auf der einen Seite neigt es sich zum Publikumsraum, auf der andern Seite ist es ein Abschluss desjenigen, was da im Publikumsraum vorhanden ist; daraufhin sind seine einzelnen Formen empfunden. Es geht allerdings das geometrisch-mathematisch Stilvolle älterer Formen dadurch in ein Räumlich-Musikalisches über. Aber das ist ja wiederum im Sinne der Menschheitsentwicklung, dass das Geometrische allmählich übergeht in das Musikalische, sodass uns auch im Raume das Musikalische entgegentritt.

[ 41 ] Man darf allerdings nicht, wenn man diesen Gedanken in seiner vollen Lebendigkeit erfassen will, gar zu großen Wert darauf legen, dass ja das Musikalische in mathematischen Formeln ausgedrückt werden kann. Man kann als einseitig abstrakter Gelehrter entzückt sein davon, wenn man, sagen wir, eine Folge von Tönen durch ihre mathematisch zu berechnenden Tonhöhen und Tonverhältnisse ausdrücken kann; man kann das so empfinden, dass man es erst jetzt in wirkliche Erkenntnis umgesetzt hat. Man kann es auch anders empfinden. Man kann auch so empfinden, dass man, wenn man das musikalisch Erlebte in das Mathematische übergeführt hat, die Musik begraben hat und dass man zuletzt den Leichnam des Musikalischen in den mathematischen Formeln hat.

[ 42 ] Diese Dinge müssen hier wirklich ernst genommen werden. Man muss das Erkenntnismäßige heraufheben in das künstlerische Erleben. Nur dadurch, dass das versucht worden ist, konnten diese Formen zustande kommen. Dieses Goetheanum ist schon in vieler Beziehung nach den Goethe’schen Impulsen empfunden, aber nicht nach den Goethe’schen Impulsen, die mit Goethe 1832 innerhalb der physischen Welt gestorben sind, sondern nach den Impulsen jenes Goethe, der heute noch lebt. Der ist allerdings nicht nach dem Sinn der gewöhnlichen Goetheforscher, aber er ist doch eben die Realität des Goethe. Für die heutigen Goetheforscher ist schon die Namengebung «Goetheanum» ein Gräuel. Man kann das begreifen. Man kann höchstens das dann im Intimen damit erwidern, dass einem selber alles das, was als «Goethe-Bund» und «Goethe-Gesellschaft» heute existiert, auch wiederum - nun so in den intimen Stunden, man braucht es ja nicht gleich an die Öffentlichkeit zu tragen — recht faral ist.

[ 43 ] Aber hier soll etwas empfunden werden von dem, was Goethe meinte, als er nach Italien reiste aus einer tiefen Sehnsucht heraus, intimere Kunstimpulse zu finden, das eigentliche Wesen der Kunst zu finden. Nach dem Anschauen desjenigen, was er an Kunstwerken in Italien gesehen hat, indem er noch die Nachwirkung des griechischen künstlerischen Prinzips gefühlt hat, schrieb er an seine Freunde in Weimar: «Nach dem, was ich hier an Kunstwerken sehe, glaube ich dem Geheimnis des griechischen Kunstschaffens auf die Spur gekommen zu sein. Die Griechen verfuhren nach denselben Gesetzen bei ihrem künstlerischen Schaffen, nach denen die Natur selbst verfährt.» Und die bloße abstrakte Philosophie, die ihm zu seinem Entzücken in Weimar noch entgegengetreten ist durch Herder, aus den Werken über Spinoza, zum Beispiel aus Herders Werk «Gott» über Spinoza, dieses Geistige, Wesenhafte in der Welt, das fühlte Goethe, indem er den idealen Kunstwerken gegenüberstand, und er

[ 44 ] schrieb an seine Freunde: «Da ist Notwendigkeit, da ist Gott.» Und unter seinen Sprüchen findet sich ja der charakteristische: Wem die Natur ihr offenbares Geheimnis zu enthüllen anfängt, der empfindet eine unwiderstehliche Sehnsucht nach ihrer würdigsten Auslegerin, der Kunst. Dasjenige, was eben in Formen auftritt, kann für eine total angeschaute Kunstimpulsivität dasselbe sein, was sich auch in den Gedanken ausdrückt. Nur müssen dann die Gedanken voll Leben sein, und die Formen Geist atmen.

[ 45 ] Das war es, was ich zunächst heute wie ein paar Andeutungen über diesen Bau sagen wollte. Ich werde dann die Sache ergänzen und fortsetzen in dem nächsten Abendvortrag, den ich nach der Eurythmie-Aufführung hier in diesem Goetheanum halten werde. Der nächste Abendvortrag, der weiter den Baugedanken von Dornach interpretieren soll, zu Ende führen soll, wird am nächsten Freitag stattfinden.

First lecture: Shaping the creative forces of nature

[ 1 ] Allow me this evening to say a few words about the building in which we find ourselves, the Goetheanum, with the proviso that we are pleased to welcome a number of guests from outside here during this time, for whom the building idea of Dornach may not yet have been explicitly expressed.

[ 2 ] The building of the Goetheanum became necessary at a time when the anthroposophical movement had expanded to such an extent that it needed its own space. could not, as I have already mentioned on another occasion during this lecture series, be a matter of having a building in this or that architectural style built for the purposes of the anthroposophical movement. A movement that expresses itself in ideas and maxims can be contained in any kind of shell, but not a spiritual movement that is predisposed from the outset to let its currents flow into the whole of cultural life. The Anthroposophical Movement wants to let its impulses flow into the artistic, religious, social and scientific fields. When it speaks, its words and ideas should come from the fullness of the human being, and these ideas should be only the outer language for the spiritual essence that has been experienced. But that which is an experienced spiritual essence can also express itself in art, in forms, in outer social life, and so on. It had to be that in a place where the thoughts behind the anthroposophical movement resound, the same thing that resounds here in words and ideas is also revealed in the forms that surround the listeners, in the paintings that speak down from the walls.

[ 3 ] It has always been so when any content of civilization or culture in the world wanted to be revealed. Such a cultural content does not develop one-sidedness, but rather it develops that which is cosmic or human totality. And the individual fields — science, art and so on — appear only as the individual members of such an overall entity, just as the individual members of a living organism appear as having been born out of the totality of the organism. Therefore, the anthroposophical movement had to create its own artistic style, just as it also had to create a certain way of expressing its essence.

[ 4 ] The latter circumstance is still insufficiently taken into account today. For example, it is necessary to express what is anthroposophical and spiritual scientific differently, right down to the sentence structure, from what is otherwise habitually expressed in human civilization. Anthroposophy must, for example, depart in many respects from the principle, still held today as a matter of course, that one must rigidly and one-sidedly take up a point of view. Even today, people are still often materialists or spiritualists, realists or idealists, and so on. For an unbiased total worldview, all this has only the meaning that if one says, “I am a materialist,” one expresses only one side of reality; if one says, “I am a spiritualist,” one expresses another side of reality. And the anthroposophical requires comprehensiveness. One is a materialist for material processes, a spiritualist for spiritual, an idealist for ideal, a realist for real, and so on. Just as a tree, when depicted from different points of view, is always the same tree, but the images are quite different, so the world can be represented differently from a wide variety of points of view.

[ 5 ] Therefore, when considering any spiritual or material aspect of reality in the field of anthroposophy, one must simply choose a point of view from which to illuminate it: One feels that this reveals a one-sidedness, and so one then characterizes the same thing from an opposite point of view. Thus it is often necessary to begin a lecture, say, by speaking from one side and then letting the lecture flow entirely into a characteristic style that uses opposing thought forms. This can even be necessary within a single sentence!

[ 6 ] And yet more is needed for the anthroposophical world view. A world view that adheres to external naturalism can work primarily in juxtapositions, let us say, for example. Anthroposophy, on the other hand, must make much of what is otherwise presented in rigid sentence contours fluid, so that the sentence becomes elastic, internally mobile. One then experiences that people call this a “bad style” because they have not become accustomed to the fact that a very special spirituality also demands a special form of expression.

[ 7 ] However, it also happens, and perhaps this may be said, that from some quarters the spiritual-scientific, as it is given in terms of content, is taken up and then clothed in the style that one is accustomed to today. Then, of course, it looks as if a person is wearing clothes that do not fit him. And such representations of anthroposophical content, which look like a person wearing clothes that do not fit him, are not that uncommon today. But all this is just a sign that anthroposophy is supposed to create something that is not just any new point of view, but a new total world view.

[ 8 ] And this is why the artistic, architectural, pictorial and plastic style that had to be used at the Goetheanum had to stand out, had to be shaped out of the styles that already existed in the world. In accordance with the fact that Anthroposophy expresses the spiritual content of the present day, which must represent progress over the spiritual content of earlier times, for example, the old architectural styles, which were built on geometry, symmetry , on certain regularity, in short, on that which bears more of a mathematical character, transferred into an organic architectural style, into an architectural style that transitions from the more geometric-dynamic into the organic-living.

[ 9 ] I can well understand, dear attendees, that those who feel firmly rooted in the old forms and who see something in these old forms in which they have once achieved a certain understanding may perceive what is now being abandoned in such a radical way as dilettantish. I fully understand that. But the venture had to be undertaken to transfer the more mathematical-dynamic style into the organic-living style. It may still be done imperfectly today, but it had to be started. And this Goetheanum is the expression of these endeavors.

[ 10 ] Whoever approaches this Goetheanum from any side (Fig. 1) will find in its outward form that it is, without falling back on abstract symbolism or on a straw allegory, a revelation of the special spiritual life that is to be realized here. This spiritual life is more closely related to the human being as the expression of a world-revelation than earlier stages of our human civilization have done. This is expressed in the two-part structure.

[ 11 ] In our present age, the human being is more dependent on internalization than was the case in earlier ages. In ancient Greece, for example, people still had a life in which thoughts were perceived in the external world in the same way as we today only perceive colors or sounds, in fact, sensory perceptions in general. Just as we see something red today, the Greeks still saw a thought expressing itself. They did not have the feeling that a thought is something that they form within themselves, that they experience within themselves, separate from external reality.

[ 12 ] This separation of man, but also the increase of man's individuality, has experienced progress in the course of human development. I have discussed this in the first chapter of my “Riddles of Philosophy”. And so it was quite naturally given - as I said, without symbolism, without allegory - to perceive the structure as something in two parts: as the one part that encompasses what man experiences more when he is turned inwards, what man experiences when he turns his contemplation inwards, and the other part that man experiences when he turns outwards to the world.

[ 13 ] The idea of the complete building in Dornach is not the product of some kind of thinking, but is the pure expression of feeling. The building had to become what it was conceived and felt to be if it was to contain what was intended for it. This is entirely in accordance with the natural principle that I have already characterized on another occasion in recent days. Just as the nutshell takes on its form out of the same forces that shape the nut inside, just as one can only perceive the nutshell as it is in accordance with the nut inside, so too must this shell be the envelope for that which pulses here as art, as knowledge. I used to use another comparison that looks more trivial, but I didn't mean it to be. I said: the building in Dornach must be what they call in Vienna a Gugelhupf pan, excuse the expression. Gugelhupf is a special cake, a baked cake that has a special shape, made from flour and eggs and a few other tasty ingredients. And it has to be baked in a cake tin. This tin must be designed very precisely, because it is the tin that gives the Gugelhupf its shape (Fig. 115, Drawing No. 1). So there must always be a nice ring cake tin for the cake, which means that the form must be there in the first place; it is only drawn in outline. That which is there is the ring cake tin for the “Anthroposophical” ring cake. This is what is baked in there (Fig. 115, Drawing No. 2), so the form must be conceived and sensed in such a way that the right thing can be baked.

[ 14 ] Anthroposophy, which is what it is, is currently endeavoring to bring the ideas that are more adapted to the fixed forms of nature into a living flow and thus [also] to bring the mechanical-geometric architectural styles here into a living flow. When you visit the building, enter and look at its various areas, you will find that an attempt has been made to continue the geometric-symmetrical design in such a way that organic forms or a reminder of organic forms is present everywhere.

[ 15 ] Go in through the main gate (Fig. 5) first. You will find that there is something like an organic form above the gate. This organic form is not conceived in a naturalistic way, by copying this or that organic form, but is based on a living devotion to organic creation in general. One cannot, as mere naturalists do, create a style by imitating leaves, flowers, horns or eyes, but by putting oneself in such an inner movement with one's own soul life, as corresponds to the creation of the organic. Then, when you construct a building, which of course is not a plant or an animal, when the whole thing is conceived from the organic living, it is not the natural forms that come out, but forms that are reminiscent of the natural; that nowhere imitate the natural in a naturalistic way, but that are reminiscent of it.

[ 16 ] And when you enter the building and walk along the passageway, you will see certain shapes that are designed to serve as heaters (Fig. 26, Fig. 115, Drawing No. 3). These forms are designed in such a way that one has the feeling that they grow out of the earth; there is a living growth force in them, something that is not plant, not animal, but is a growing, organic thing that takes shape. This takes shape even in such a form in duality. It is something like beings that speak to each other, and their mutual relationship is also expressed.

[ 17 ] All this places itself in the creative process according to the principle of Goethean metamorphosis, which was initially created by Goethe in order to gain an insight into the organic. The organic is such that it repeats certain forms, but does not repeat them in the same way. Goethe expresses this in such a way that in the organic living, the individual organs - let us say the leaves of a plant - from bottom to top into the flower, into the stamens, into the pistils, into the fruit organs, are probably the same in idea, but appear in the most diverse ways in their external form.