Discussions with Teachers

GA 295

24 August 1919, Stuttgart

Translated by Helen Fox

Discussion Three

Someone told the story of “Mary’s Child,” first for melancholic and then for sanguine children.

RUDOLF STEINER: I think in the future you will have to pay more attention to your articulation. The two versions, as you gave them, were too much alike. The difference must also lie in the articulation. If you bring out these details more emphatically you will not fail to impress the melancholic children. For the sanguines I would introduce more pauses into the story, especially at the beginning, so that the children are compelled to listen to you again each time their attention wanders. But now I would like to ask how you would apply these stories when you are actually teaching? Imagine yourselves standing in front of the class; what would you do? I would advise you to tell the story in the melancholic version and then have it retold by a sanguine child and vice versa.

A person comments: First, I think it would be advisable to seat the sanguine children directly in front of the teacher so they may be constantly within view, whereas melancholic children should be sitting where they like as much as possible.

RUDOLF STEINER: An excellent suggestion.

The individual who commented then related the story of “The Long-tailed Monkey,” first in a style for the sanguine and then for the melancholic children, adding the remark that melancholic children do not want to hear too many sad stories.

RUDOLF STEINER: You should also remember that, but the contrasting styles were good. Now I think we can go on to how we should make further use of these things later. I would not decide which child is to tell the story, but after a day or two I would say (in a lively way): “Now listen! You can choose for yourselves which part of the story you would like to retell. Then the next day or the day after that any child who wants to can come out and tell a portion of the story to the class.

Someone else told another story in two versions.

RUDOLF STEINER: You all have the feeling, don’t you, that something like this can be done in various ways. Now it is really very important, particularly for those who want to work as teachers, to get rid of the habit of unnecessary criticism. As a teacher you should develop a strong feeling for this; you should definitely be conscious that it is not a question of always trying to improve on what has already been done. A thing can be good in a variety of ways. And so I think it will be good to view what has been presented as something that can certainly be done as you have proposed.

But there is one thing I would like to add. In all three stories I think I noticed that the first rendering, both in style and purpose, was the better of the two. Which did you work out first in your mind, Miss A? Which did you feel you could do better? [It was determined that the version worked out first was for the melancholic temperament, and this was the better of the two]. I would now like to recommend that all three of you work out a version for the phlegmatic child. This version is very important from the perspective of style. But if possible please try to work this out tentatively today, then sleep on it and come to your final decision about the style tomorrow. It has been found by experience that when you have something like this to do, you can only discover its new form in a different spirit when, after the preparation, you allow it to pass through a period of sleep. On Monday bring us a version for the phlegmatics, but prepare it first and then later work out its final form. Having the Sunday in between will make this possible.

Someone showed a drawing, a design in blue and yellow for a melancholic child. Dr. Steiner drew the same design in green and red for a sanguine child.

RUDOLF STEINER: Now you can say to the children: This blue and yellow one can be seen best when it is getting dark; you take it into sleep with you, because that is the color with which you can appear before God. This one, the green and red one, can meet your eyes when you awake. You can gaze at it when you wake up in the morning and enjoy it for the rest of the day!

A drawing for a sanguine child was then displayed, red on a white ground. Dr. Steiner drew the same design for a melancholic child, long and thin on a black ground. Dr. Steiner called the impudent form sticking out a “little kicker.”1Kickerling = indicating a small football player.

RUDOLF STEINER: In the design for the melancholics this little creature withdraws into the form. Here you see the contrast, a kind of contrast where you would primarily use the colors in order to work on one child or another, and you should certainly show the same thing twice. What would you say to the children?

I would ask them which one they liked best.

RUDOLF STEINER: You would then make your own discoveries! You would recognize the sanguine children from their joy in this contrast of colors. You should not miss the opportunity to use simple forms like these for the children.

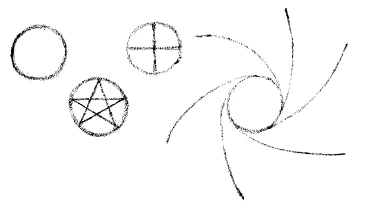

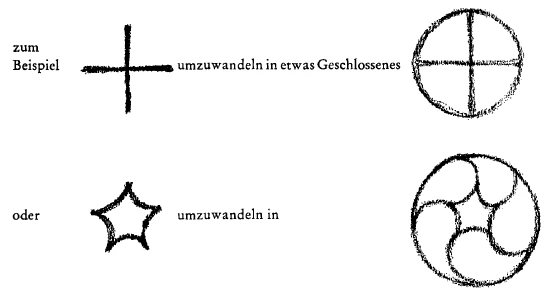

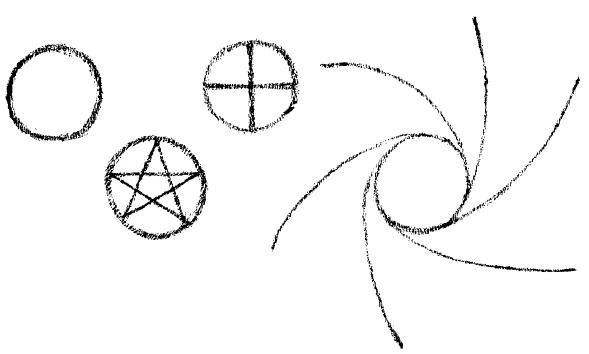

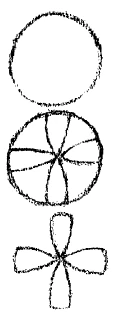

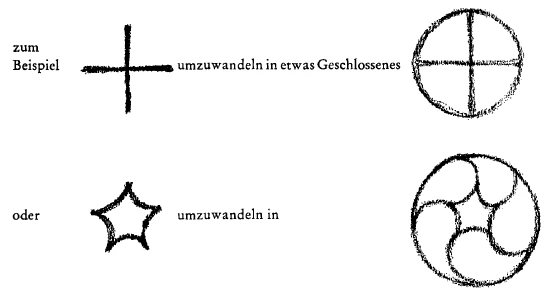

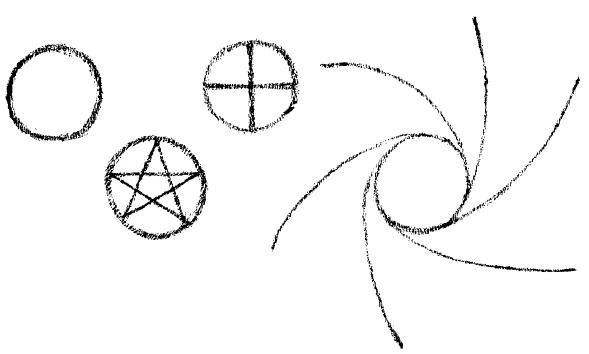

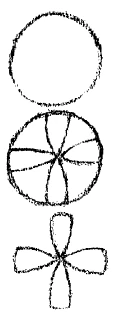

Someone recommended forms pointed outward for the choleric:

to be changed to an enclosed form

or to be changed to:

For the phlegmatic he recommended the opposite way, to start from the circle and have figures drawn inside it or to break up a circle in some way:

RUDOLF STEINER: For the phlegmatic child I would add the following in this method. I should say:

“Look, here is a circle. You like that don’t you?

“But now I’ll draw something else for you:

“And if I simply take away the circle, then you have the form as it should be. You must get into the habit of not muddling things up together.”

By drawing things and rubbing them out again the phlegmatic child can be torn out of his phlegma. Now I will also ask you, Frau E., to work out the same design for other temperaments again, making use of the method of sleeping over what you have done.

A description of a gorilla was given in two versions.

RUDOLF STEINER: Of course nothing can be said against your inventing things without depending on any particular naturalists, although you may very well get suggestions from them. I would ask you, however, to awaken a closer contact with your students when you tell them a story of this kind. It would also be possible to use a long story and to make an impression with that. You must, however, not be absorbed in your own thoughts, but maintain closer contact with your students. If you are too absorbed in yourself you could easily lose contact with the children.

A horse was described for phlegmatic and choleric children.

RUDOLF STEINER: In giving descriptions of animals it is especially important that, in every detail, we should remain clear in our minds that a human being is really the whole animal kingdom. The animal kingdom in its entirety is humankind. You cannot, of course, present ideas of this kind to the children theoretically, and you certainly should not do so.

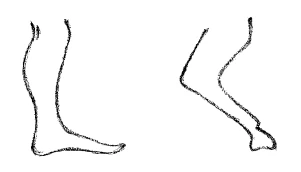

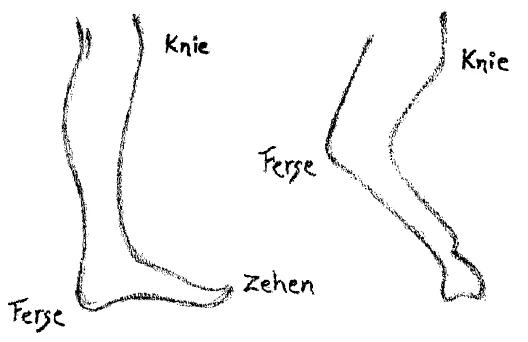

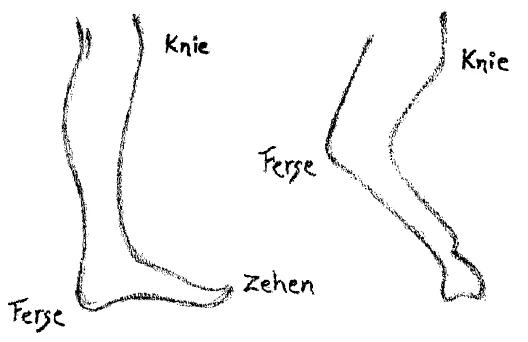

Let’s suppose, however, that someone has to work out in detail the subject Mr. L. introduced, and also distinguish between the phlegmatic and choleric groups. The phlegmatics are not as easily interested and they are not likely to remember much of what you tell them about an ordinary animal, such as a horse. They have seen horses often enough that they have very little interest in them.2This statement may not apply to the children of today, as it did in 1919. But it is important to focus their attention, so I should say to the phlegmatic children, “Well now, what is the real difference between you and a horse? Let’s take some minor differences. You all have a foot like this, don’t you? Here are the toes, here is the heel and here is the instep.

“Now look at a horse’s foot. This is the hind foot of a horse. Where are the toes? Where is the heel? And where is the ankle? With you the knee is farther up. Where is the knee of a horse? Now look, here are the toes, the heel is right up there and the knee farther up still. It is very different. Just imagine how different a horse’s foot looks from yours.” You will now find that this will surprise the phlegmatic child into alertness, and what you have said will not be forgotten.

For the choleric children I would tell a story about how a child meets a horse out in the woods somewhere. The horse is running; and far behind, running after it, there is a man from whom it has bolted, and the child has to catch the horse by the bridle. If I know I have a choleric child before me I can try to show how the child should do this, how to get hold of the bridle. To get the child’s fantasy working to discover how the horse should be caught is a very good thing. Even a choleric child feels a little nervous about such a procedure, but you are meeting the need of the choleric temperament when you expect the child to do it. Such a child will become a little disconcerted and less arrogant. Something is expected of the child that can only be expected of a choleric child.

I would also like to say that, especially at first, you should make all such stories very short. So I will ask Mr. M. in this case to tell his story for sanguine and melancholic children, but let both stories be exceedingly short. Mr. L., you could do the same but choose particular incidents that will be remembered and serve to arouse the children’s eager interest.

We must realize that we should use the subject matter of our teaching primarily to capture the child’s powers of will, feeling, and thought; it is not so important to us that the children remember what they are told, but that they develop their soul faculties.

Someone spoke of how to consider the four temperaments in arithmetic, but explained that he had not really managed to work this out properly.

RUDOLF STEINER: I had foreseen that, because this problem is very difficult. You will have to sleep on it very thoroughly.

But please take the following as a fresh problem. Imagine to yourself a class in which there are children of eight and nine years old. In the teaching of the future it will, of course, be important that we develop as many social instincts as possible, that we educate the social will. Now imagine three children of whom one is a pronounced phlegmatic, another a pronounced choleric, and the third a pronounced melancholic. I will say nothing about their other qualities. Let’s suppose that in the third or fourth week after school had begun these children come to you and say, “None of the other children can stand me!” Immediately it would be obvious that these are the “Cinderellas” of the class, and all the other children are inclined to avoid them. By Monday I would like you to think over how the teacher can best try to remedy this evil. Please give your whole mind to thinking this through, and view it as a very important educational problem.

Dritte Seminarbesprechung

A. erzählt das Märchen vom «Marienkind» zunächst für melancholische und dann für sanguinische Kinder.

Rudolf Steiner: Ich meine, Sie werden in Zukunft berücksichtigen müssen, die Sachen artikuliert zu geben. Sie haben die beiden Fassungen in zu gleicher Art vorgebracht. Der Unterschied muß auch in der Artikulation liegen. Wenn Sie diese Details in etwas eindringlicherer Art vorbringen, werden Sie bei melancholischen Kindern den Eindruck nicht verfehlen. Bei Sanguinikern würde ich den Vortrag, besonders am Anfang, etwas mehr mit Zwischenpausen gestalten, so daß das Kind gezwungen ist, die Aufmerksamkeit, die es hat fallen lassen, immer von neuem wieder aufzunehmen.

Nun möchte ich aber noch fragen: Wie würden Sie diese Erzählung weiter verwenden, wenn Sie wirklich konkret zu unterrichten hätten? Stellen Sie sich vor, Sie stünden vor Ihrer Klasse, was würden Sie dann tun? — Ich würde Ihnen raten, nachdem Sie die melancholische Fassung vorgebracht haben, sie sich nacherzählen zu lassen von einem sanguinischen Kinde und umgekehrt.

D.: Ich will vorausschicken, daß ich für ratsam halte, das sanguinische Kind straff

vor sich zu setzen und dauernd in der Blickrichtung zu halten, während für die melancholischen Kinder möglichst eine behagliche, gemütliche Stimmung zu erzeugen ist.

Rudolf Steiner: Sehr gut bemerkt.

D. erzählt das Märchen vom «Meerkätzchen» zunächst in der Fassung für das sanguinische und dann für das melancholische Kind und bemerkt dazu, daß die melancholischen Kinder nicht viel Trauriges erzählt haben wollen.

Rudolf Steiner: So etwas kann man berücksichtigen. Aber die Kontrastierung war gut.

Nun würde ich meinen, daß noch übergegangen werden muß auf die Art, wie man das nun nach einiger Zeit weiter behandelt. Ich würde am nächsten Tage oder am darauffolgenden Tage nicht das Kind bestimmen, das erzählen soll, sondern ich würde sagen (lebhaft): « Jetzt merkt ihr euch das! Ihr könnt euch wählen, welches ihr euch merken wollt, um es selbst zu erzählen!» Am nächsten oder zweitnächsten Tag würde ich das Kind sich melden lassen.

G. erzählt das Märchen vom «Similiberg» in beiden Fassungen.

Rudolf Steiner: Nicht wahr, Sie haben doch alle das Gefühl, daß solch eine Sache auf verschiedene Weise gemacht werden kann. Nun ist es wirklich von einer großen Bedeutung, daß man sich gerade, wenn man als Lehrer wirken will, die unnötige Kritisiererei abgewöhnt; daß man als Lehrer ein starkes Gefühl dafür entwickelt, daß man sich bewußt wird, es kommt schließlich nicht darauf an, daß man immer auf etwas, was getan wird, etwas Besseres daraufsetzen muß. Eine Sache kann in mannigfaltiger Weise gut sein. Deshalb würde ich es auch für gut halten, wenn dieses hier Vorgebrachte als etwas betrachtet würde, was durchaus so ausgeführt werden kann, wie wir es gehört haben.

Ich möchte aber etwas anderes daran knüpfen. Bei allen drei Erzählungen glaube ich eines bemerkt zu haben: das ist, daß immer die erste Fassung auch in ihrer Zielsetzung die bessere war. Was haben Sie, Fräulein A., in Ihrer Seele zuerst ausgebildet, was haben Sie gefühlt, daß Sie besser machen würden?

Es wird festgestellt, daß die zuerst von Fräulein A. in der Seele ausgebildete Fassung die für das melancholische Temperament war, und daß diese die bessere war.

Rudolf Steiner: Nun möchte ich empfehlen: arbeiten Sie alle drei auch noch die Fassung für das phlegmatische Kind aus. Das ist von großer Bedeutung für das Stilgemäße der Form. Aber ich bitte Sie, versuchen Sie, womöglich diese Fassung sich heute noch auszuarbeiten, provisorisch, dann darüber zu schlafen und die endgültige Fassung morgen zu beschließen. Es ist eine Erfahrung, daß man, wenn man so etwas machen will, das Umgestaltete nur aus einem anderen Geiste heraus bekommt, wenn man es nach Vorbereitung durch den Schlaf hindurchgehen läßt. Bringen Sie uns am Montag eine Umgestaltung ins Phlegmatische, die Sie aber, bevor Sie die endgültige Ausgestaltung vornehmen, vorbereiten. Das ist ja möglich, weil der Sonntag dazwischen liegt.

E. zeigt eine Zeichnung vor, ein Motiv in Blau-Gelb für ein melancholisches Kind (Farbtafel, Figur 1). Rudolf Steiner zeichnet dazu dasselbe Motiv in Grün-Rot für ein sanguinisches Kind (Farbtafel, Figur 2).

Da kann man zu den Kindern sprechen: «Das Blau-Gelbe schaut man am besten am Abend an, wenn es dunkel wird, vor dem Einschlafen. Das nehmt ihr auch herein in euren Schlaf, denn das ist die Farbe, womit ihr vor Gott erscheinen könnt. — Das Grün-Rote nehmt ihr vor morgens beim Erwachen, damit könnt ihr nach dem Erwachen leben. An dem erfreut euch den ganzen Tag!»

Nun zeigt E. eine Zeichnung vor für ein sanguinisches Kind, Rot auf weißem Grund (Farbtafel, Figur 5).

Rudolf Steiner zeichnet dasselbe Motiv für ein melancholisches Kind, lang und schlank, Blau auf schwarzem Grund (Farbtafel, Figur 6). Die frech vorragende Form heißt er «Kickerling». Beim melancholischen Motiv zieht sie sich einwärts.

Nun, sehen Sie, das würde ein solcher Gegensatz sein, daß Sie mehr die Farben benützen würden, um auf das eine Kind und auf das andere zu wirken. Sie müßten doch motivieren, daß Sie zweimal dieselbe Sache

vorbringen. Was würden Sie zu den Kindern sagen?

E.: Ich würde fragen, welches ihnen besser gefällt.

Rudolf Steiner: Da würden Sie Ihre eigenen Erfahrungen machen! Das sanguinische Kind würden Sie erkennen an seiner Freude an diesem Farbenkontrast.

Natürlich, solche einfache Formen, die sollte man nicht versäumen, für Kinder wirklich zu pflegen.

T. empfiehlt für den Choleriker Formen, die nach außen spitz sind,

Für den Phlegmatiker empfiehlt er den umgekehrten Weg: Vom Kreis auszugehen und Figuren einzeichnen zu lassen, oder den Kreis in irgendeiner Weise zu zerschneiden.

Rudolf Steiner: Ich würde nun beim phlegmatischen Kinde für diese Methode noch das Folgende anwenden. Ich würde sagen:

«Nun sieh einmal, das ist ein Kreis:

Nicht wahr, den magst du ganz gerne haben! Aber ich werde dir noch etwas anderes machen: Sieh einmal, ich nehme einfach diese Sachen weg, den Rand, jetzt ist es erst richtig: Du mußt dir angewöhnen, nicht alles mögliche durcheinander zu machen. Versuche das Gleiche von Anfang an zu machen.»

Durch Zeichnen und Auslöschen ist das phlegmatische Kind aus seinem Phlegma herauszureißen.

Nun würde ich Sie bitten, dieselbe Methode des Beschlafens anzuwenden, und Frau E. bitten, dasselbe Motiv auch für andere Temperamente auszuarbeiten.

M. beschreibt einen Gorilla in zweierlei Fassung.

Rudolf Steiner: Es ist natürlich nichts dagegen einzuwenden, daß man auch erfindet, ohne daß man sich anlehnt an bestimmte Naturforscher, von denen man sich zwar anregen lassen kann.

Ich möchte Sie jedoch bitten, einen größeren Kontakt mit den Schülern bei einer solchen Erzählung hervorzurufen. Es würde möglich sein, auch eine lange Erzählung zu verwenden und Eindruck damit zu machen. Aber Sie müßten nicht in sich versunken sein, sondern mehr in Kontakt mit den Schülern stehen. Wenn Sie es so versunken machen, könnten Sie den Kontakt vielleicht verlieren.

L. schildert das Pferd für phlegmatische und cholerische Kinder.

Rudolf Steiner: Bei Tierbeschreibungen wird es nun aber ganz besonders wichtig sein, daß wir in jeder Einzelheit besonders ins Auge fassen, daß der Mensch eigentlich das ganze Tierreich ist. Das ausgebreitete Tierreich ist der Mensch. Nicht wahr, solche Ideen kann man den Kindern nicht theoretisch beibringen. Das soll man auch nicht. Aber nehmen wir an, jemand sollte die Sache ausführen, die Herr L. angeschlagen hat, aber den Unterschied machen zwischen Phlegmatiker- und Cholerikergruppe. Die Phlegmatischen werden wenig leicht erfaßbar sein. Und es wird das nicht leicht haften, was Sie mit ihnen durchnehmen über ein bekanntes Tier. Sie haben das Pferd oft gesehen, haben daher nur wenig Interesse dafür. Solche Dinge sollen aber haften. Da würde ich zu den phlegmatischen Kindern sagen: «Seht einmal, wie unterscheidet ihr euch denn eigentlich von einem Pferde? Wir wollen nur kleine Unterschiede nehmen. Nicht wahr, ihr habt alle einen solchen Fuß: Da sind die Zehen, da ist die Ferse, da ist der Mittelfuß. Das ist euer Fuß.

Jetzt seht euch einmal den Pferdefuß an: Das ist der Hinterfuß vom Pferde. Wo sind die Zehen? Wo ist die Ferse und wo ist der Mittelfuß? Bei euch ist dann weiter herauf das Knie. Wo ist das Knie beim Pferde? Da seht einmal: Da sind die Zehen, die Ferse ist da ganz. oben, das Knie ist da noch weiter oben. Da ist das ganz anders. Nun stellt euch einmal vor, wie anders so ein Pferdefuß aussieht als euer Fuß!» Das wird das phlegmatische Kind in Spannung versetzen, und es wird das schon behalten.

Bei dem cholerischen Kinde würde ich eine Geschichte erzählen, wie das Kind ganz draußen ein Pferd findet im Walde. Das Pferd läuft, weit hinten läuft der Mann, dem es durchgegangen ist, nach, und das Kind muß das Pferd abfangen beim Zügel. Wenn ich weiß, daß ich ein cholerisches Kind habe, kann ich versuchen, ihm das beizubringen, wie es das machen soll, wie es die Zügel erfaßt. Es in die Phantasie zu versetzen, wie es das Pferd abfängt, das ist sehr gut. Auch das cholerische Kind hat im geheimen etwas Angst vor dieser Prozedur, aber man kommt einem cholerischen Temperament entgegen, wenn man ihm zumutet, das zu tun. Es wird dann etwas beschämt sein, etwas bescheidener. Es ist ihm etwas zugemutet, was man nur einem cholerischen Kinde zumuten kann.

Dann möchte ich bemerken, daß Sie namentlich im Anfang diese Dinge sehr kurz gestalten sollten. Daher würde ich in diesem Falle Herrn M. bitten, seine Erzählung auch für sanguinische und melancholische Kinder auszuführen, aber beide Male furchtbar kurz. Ebenso Herrn L., aber Einzelheiten herauszuheben, die dann bleiben, die dazu dienen, das Kind in Spannung zu versetzen.

Wir müssen uns klar sein, daß wir den Unterrichtsstoff hauptsächlich dazu verwenden, um die Willens-, Gemüts- und Denkfähigkeiten des Kindes zu ergreifen, daß es uns viel weniger darauf ankommt, was das Kind gedächtnismäßig behält, als daß das Kind seine seelischen Fähigkeiten ausgestaltet.

O. führt aus, wie man im Rechnen Rücksicht nehmen könnte auf die vier Temperamente, erwähnt aber, daß er mit seiner Aufgabe nicht richtig fertig geworden wäre.

Rudolf Steiner: Das ist etwas, was ich vorausgesehen habe, denn die Aufgabe ist etwas sehr Schwieriges. Sie werden das ganz gründlich beschlafen müssen.

Aber nehmen Sie folgendes als neue Aufgabe: Denken Sie sich eine Klasse, in der acht- bis neunjährige Kinder sitzen. Es kommt ja natürlich in dem Unterricht der Zukunft darauf an, daß möglichst viel soziale Instinkte, sozialer Wille, soziales Interesse erzogen werde. Nun denken Sie sich drei Kinder, wovon das eine ausgesprochen phlegmatisch, das andere ausgesprochen cholerisch und das dritte ausgesprochen melancholisch ist. Ich will ihre übrigen Eigenschaften nicht erwähnen. Die kämen in der dritten bis vierten Woche, nachdem der Unterricht begonnen hat, und sagen zu Ihnen: «Mich können alle anderen Kinder nicht leiden!» Diese werden sich nun gleichsam erweisen als die Aschenbrödel, denen gegenüber sich die andere Klasse etwas ablehnend verhält, die gepufft werden, die man stößt, die man überall zurücksetzt. — Ich möchte Sie bitten, bis Montag darüber nachzudenken, wie der Erzieher versuchen wird, diesem Übel am besten abzuhelfen. Wie man diese Kinder zu beliebten Kindern machen könne, das ist eine wichtige Aufgabe für die ganze Erziehung. Ich bitte Sie, das recht geistvoll durchzudenken, und das als eine sehr wichtige pädagogische Aufgabe zu betrachten.

Third Seminar Discussion

A. tells the fairy tale of “Marienkind” first to melancholic children and then to sanguine children.

Rudolf Steiner: I think you will have to take into account in future that you need to articulate things clearly. You presented both versions in the same way. The difference must also be in the articulation. If you present these details in a somewhat more emphatic manner, you will not fail to make an impression on melancholic children. With sanguine children, I would structure the presentation, especially at the beginning, with a few more pauses, so that the child is forced to refocus their attention whenever it wanders.

Now I would like to ask: How would you use this story if you really had to teach it? Imagine you were standing in front of your class, what would you do? — I would advise you, after presenting the melancholic version, to have a sanguine child retell it, and vice versa.

D.: I would like to start by saying that I think it is advisable to seat the sanguine child strictly

in front of you and keep them in your line of sight at all times, while creating a comfortable, cozy atmosphere for the melancholic children as far as possible.

Rudolf Steiner: Very well observed.

D. first tells the fairy tale of “The Sea Kitten” in the version for the sanguine child and then for the melancholic child, noting that the melancholic children did not want to hear much sad stories.

Rudolf Steiner: That is something that can be taken into account. But the contrast was good.

Now I would think that we need to move on to how to deal with this after some time has passed. The next day or the day after, I would not choose the child who is to tell the story, but I would say (lively): “Now remember this! You can choose which one you want to remember so that you can tell it yourself!” The next day or the day after, I would let the child volunteer.

G. tells the fairy tale of “Similiberg” in both versions.

Rudolf Steiner: Isn't it true that you all feel that such a thing can be done in different ways? Now it is really very important that, especially if you want to work as a teacher, you break the habit of unnecessary criticism; that as a teacher you develop a strong sense that you become aware that, ultimately, it is not important to always have to come up with something better than what has been done. A thing can be good in many different ways. That is why I would consider it good if what has been presented here were regarded as something that can be carried out exactly as we have heard it.

But I would like to add something else. In all three stories, I think I noticed one thing: that the first version was always the better one in terms of its objective. What did you, Miss A., first develop in your soul, what did you feel you could do better?

It is noted that the version first developed in Miss A.'s soul was the one for the melancholic temperament, and that this was the better one.

Rudolf Steiner: Now I would like to recommend that all three of you also work out the version for the phlegmatic child. This is of great importance for the stylistic appropriateness of the form. But I ask you to try, if possible, to work out this version today, provisionally, then sleep on it and decide on the final version tomorrow. Experience shows that when you want to do something like this, you can only get the transformed version out of a different spirit if you let it go through sleep after preparation. Bring us a transformation into the phlegmatic on Monday, but prepare it before you make the final design. That is possible because Sunday is in between.

E. shows a drawing, a motif in blue and yellow for a melancholic child (color chart, figure 1). Rudolf Steiner draws the same motif in green and red for a sanguine child (color chart, figure 2).

You can say to the children: “The blue and yellow is best viewed in the evening, when it gets dark, before going to sleep. You take this into your sleep, because it is the color with which you can appear before God. — You take the green and red in the morning when you wake up, so that you can live with it after waking up. It will delight you all day long!”

Now E. shows a drawing for a sanguine child, red on a white background (color chart, figure 5).

Rudolf Steiner draws the same motif for a melancholic child, long and slender, blue on a black background (color chart, figure 6). He calls the cheekily protruding shape “Kickerling.” In the melancholic motif, it curves inward.

Now, you see, that would be such a contrast that you would use the colors more to influence one child and the other. You would have to motivate them by presenting the same thing twice.

What would you say to the children?

E.: I would ask them which one they like better.

Rudolf Steiner: You would learn from your own experience! You would recognize the sanguine child by his joy in this color contrast.

Of course, such simple forms should not be neglected when working with children.

T. recommends forms that are pointed on the outside for the choleric child.

For phlegmatic children, he recommends the opposite approach: starting with a circle and having them draw figures inside it, or cutting the circle in some way.

Rudolf Steiner: For phlegmatic children, I would add the following to this method. I would say:

"Now look, this is a circle:

Isn't it true that you like it very much! But I'm going to make you something else: Look, I'll just take these things away, the edge, now it's just right: You have to get into the habit of not mixing everything up. Try to do the same thing from the beginning."

By drawing and erasing, the phlegmatic child can be pulled out of their phlegmatic state.

Now I would ask you to use the same method of sleeping, and ask Mrs. E. to work out the same motif for other temperaments as well.

M. describes a gorilla in two different versions.

Rudolf Steiner: Of course, there is nothing wrong with inventing things without relying on specific natural scientists, although they can be a source of inspiration.

However, I would ask you to establish greater contact with the students when telling such a story. It would be possible to use a long story and make an impression with it. But you should not be lost in your own thoughts, but rather in contact with the students. If you are so absorbed, you might lose contact with them.

L. describes the horse for phlegmatic and choleric children.

Rudolf Steiner: When describing animals, it is particularly important that we focus on every detail, that we realize that human beings are actually the entire animal kingdom. The entire animal kingdom is the human being. It is not possible to teach such ideas to children theoretically. Nor should one do so. But let us assume that someone should carry out what Mr. L. has suggested, but make a distinction between the phlegmatic and choleric groups. The phlegmatic children will be difficult to grasp. And what you go through with them about a familiar animal will not stick easily. They have seen horses many times and therefore have little interest in them. But such things should stick. I would say to the phlegmatic children: "Look, how do you actually differ from a horse? Let's just take small differences. Isn't it true that you all have a foot like this: there are the toes, there is the heel, there is the midfoot. That is your foot.

Now take a look at the horse's foot: this is the horse's hind foot. Where are the toes? Where is the heel and where is the midfoot? For you, the knee is further up. Where is the knee on a horse? Look: there are the toes, the heel is right at the top, and the knee is even further up. It's completely different. Now form a mental image of how different a horse's foot looks compared to your foot! This will excite the phlegmatic child, and they will remember it.

For the choleric child, I would tell a story about a child who finds a horse in the forest. The horse runs, far behind it runs the man who has lost control of it, and the child has to catch the horse by the reins. If I know that I have a choleric child, I can try to teach them how to do it, how to grasp the reins. It is very good to let them imagine how they catch the horse. Even the choleric child is secretly a little afraid of this procedure, but you can accommodate a choleric temperament by expecting them to do it. They will then be a little ashamed, a little more modest. You are expecting something of them that only a choleric child can be expected to do.

Then I would like to note that you should keep these things very brief, especially in the beginning. Therefore, in this case, I would ask Mr. M. to also tell his story for sanguine and melancholic children, but both times very briefly. The same goes for Mr. L., but he should highlight details that will remain and serve to put the child in suspense.

We must be clear that we use the teaching material mainly to engage the child's will, mood, and thinking abilities, that we are much less concerned with what the child remembers than with the child developing its soul abilities.

O. explains how the four temperaments could be taken into account in arithmetic, but mentions that he would not have been able to complete his task properly.

Rudolf Steiner: That is something I foresaw, because the task is very difficult. You will have to sleep on it thoroughly.

But take the following as a new task: Imagine a class of eight- to nine-year-old children. In the lessons of the future, it will of course be important to cultivate as much social instinct, social will, and social interest as possible. Now imagine three children, one of whom is decidedly phlegmatic, another decidedly choleric, and the third decidedly melancholic. I will not mention their other characteristics. They come in during the third or fourth week after classes have begun and say to you, “None of the other children like me!” These children will now prove to be the Cinderellas, whom the other class treats with some hostility, who are pushed around, who are shoved, who are put down everywhere. — I would ask you to think about how the teacher can best remedy this problem by Monday. How to make these children popular is an important task for the whole educational system. I ask you to think about this carefully and to regard it as a very important educational task.