Astronomy and Anthroposophy

by Elisabeth Vreede

May 1928

Translated by Steiner Online Library

9. About Solar and Lunar Eclipses

The Feast of Pentecost

(This year, the month of May marks the beginning of the first period of eclipses, which then continues into June. A second period follows six months later, in November and December.) Every year there are two periods, each comprising one to three eclipses; but each year they begin earlier, on average 20 days earlier, but it can also be as little as 8 days or as much as 4 weeks—a full lunar period. To give an idea of the recurring and increasingly early occurrence of eclipses, the corresponding data for the years 1924–1928 are given here (M = lunar eclipse, S = solar eclipse).

1924,

Feb. 20 M — March 5 S

July 31 S — Aug. 14 M — Aug. 24 S1925

Jan. 24 S

July 20/21 S — Aug. 4 M1926

Jan. 14 S

July 9/10 S1927

Jan. 3 S

June 15 M — June 29 S

Dec. 8 M — Dec. 24 S1928

May 19 S — June 3 M — June 17 S

Nov. 12 S — Nov. 27 M

This table clearly shows the two periods. The fact that there appear to have been three eclipse periods in 1927 — in January, June, and December — is only due to the fact that the third period is, in a sense, the period of January 1928, which was carried over due to the advance at the turn of the year. It can also be seen that — as already mentioned — the number of eclipses in each period can vary between 1 and 3, that within a period a solar eclipse must always be followed by a lunar eclipse and vice versa, but that each new period can start afresh, so to speak, with either a solar or a lunar eclipse. If only two eclipses occur in a year (as in 1926), which is the minimum, then both of these eclipses are always solar eclipses. Of course, it is not possible to provide proof for all of these rules here in a nutshell.

What has been referred to here as “periods of eclipses” is not only related to the movement of the sun and moon (or the Earth), but also to the movement of the intersections of the sun's and moon's orbits, which are called nodes and which the ancients referred to as the dragon's head (☊, ascending node) and dragon's tail (☋, descending node). These nodes represent something similar for the moon's orbit as the vernal and autumnal equinoxes do for the sun's orbit around the Earth, in that they signify the moon's ascent and descent on its orbit and are also in retrograde motion. This backward motion of the nodes, which make a full revolution once every 18 years and 7 months, causes eclipses to occur earlier each year, as these are linked to the position of the nodes.

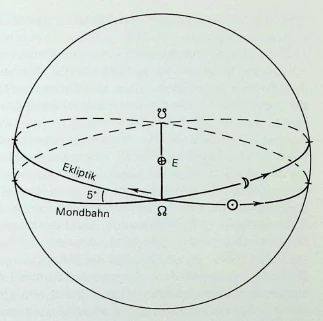

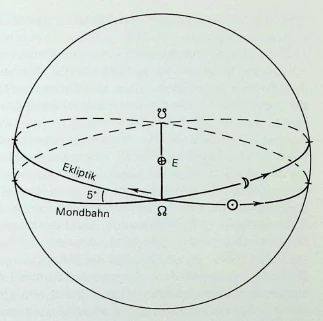

The moon's orbit forms an angle of 5° with the ecliptic or sun's orbit (which is somewhat exaggerated in Figure 15) . The other planets also have orbits in the sky that are more or less inclined to the sun's orbit, the ecliptic, but all of them lie within the zodiac, which is a fairly wide belt. The only exceptions are some of the small planets or planetoids between Mars and Jupiter, which often have such strongly inclined orbits that they can wander far outside the zodiac. They do not belong to the “normal” structures of our solar system, but are the result of a cosmic battle (5th lecture).

It is good to locate the nodes, which also play an important role in our spiritual life, in the sky and then imagine the moon's orbit for the month in question. (Currently, the ascending node is in Taurus, not far from the star Aldebaran (see drawing 16), and the descending node is at the opposite point of the zodiac, in Scorpio, above the red Antares. In the region of Gemini, Cancer, Leo, etc., the moon's orbit rises above the highest position of the sun's orbit. However, all these conditions change quite rapidly with the moon. As early as April next year, one node will be in Aries and the other in Libra. (This always refers to the constellations themselves.)

Before we go into more detail about the nodes, we must consider the principle of eclipses as they appear externally. There is a very different basis for lunar and solar eclipses.

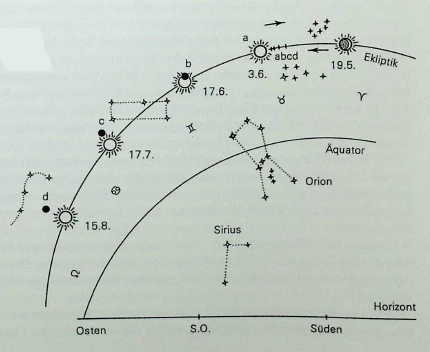

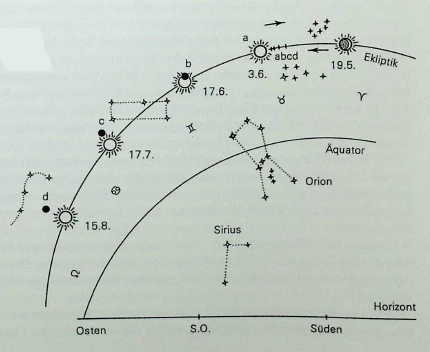

Because the moon's orbit and the sun's orbit form an angle of 5° with each other, an eclipse of the sun by the moon, i.e., a solar eclipse, can only occur if, first, it is a new moon and, second, both are near one of the nodes. If the Sun has already moved too far away from the node on its annual orbit, or if it is still too far away from it (the limit is 18° for solar eclipses and 12° for lunar eclipses), the Moon's orbit and the Moon itself rise above or descend below the Sun, so that no eclipse can occur. This is what happens during every ordinary new moon; it is then a conjunction, but not an eclipse. Only near the nodes can the sun and moon discs coincide. This can be seen in Figure 16. It shows the part of the ecliptic in which the eclipses of the first period of 1928 take place. The ascending node is indicated for four consecutive points in time in its retrograde motion as a, b, c, d, corresponding to the position of the Sun on June 3, June 17, July 17, and August 15.

On May 19, there is a total solar eclipse, and the node would then be slightly to the left of a. At this point, the moon's orbit actually passes quite far below the sun's orbit, because the moon is still ahead of the ascending node. The fact that an eclipse, and even a total one, can still occur is only because the moon is closest to the Earth (at its “perigee”) during these days, and its disk is therefore at its largest, so that it can cover the sun for at least a short time. The eclipse takes place in the regions of the South Pole and, even in its partial phase, is hardly visible in inhabited areas.

Fourteen days later, on June 3, there is a full moon, with the sun located directly at the ascending node (a) and the moon opposite it at the descending node in Scorpio: total lunar eclipse. (In this case, of course, the moon could not be shown in the drawing.)

Another 14 days later: June 17, new moon. But now there is only a very small partial solar eclipse, the moon's orbit rises, and the moon passes diagonally across the upper edge of the sun's disk.

For the next position: July 17, the sun is already too far from the node, and the moon no longer touches it. At the next new moon, August 15, the difference is even greater. Only when the sun reaches the other node in November will there be another eclipse. The sun passes this node on November 23, and the new and full moon dates for that month (November 12 and 27) are such that only two eclipses can occur, not three. Of these 5 eclipses, only the partial solar eclipse on November 12 will be visible in Central Europe.

The solar and lunar eclipses of a given year repeat themselves in the same order and, with only a 10-day difference, on the same dates, always after 18 years. Thus, the five eclipses of this year correspond to those of 1910, but instead of May 19, they occur on May 9, instead of June 3, on May 21, and so on. Only this year's new moon on June 17 did not result in an eclipse at that time, on June 7. We will discuss this interesting fact about the occurrence and disappearance of eclipses later (see page 101 ff.). We have the famous Saros period, already known to the Chaldeans, which is closely related to the retrograde motion of the nodes. Many extremely important things are linked to the Saros period, which we will also discuss later.

In order to describe eclipses and explain them in an external sense, we must consider a spatial-perspective element that we would not otherwise need to use. Eclipses involve a spatial alignment of the sun, moon, and Earth, and even the casting of shadows by one body onto another. Whereas we were previously able to chart the orbits of the moon and sun in the celestial sphere and represent their points of intersection, the nodes, we must now consider the eclipse itself, bearing in mind that the moon's orbit lies within the sun's orbit and that the moon is closer to the earth than the sun, which is, in a sense, a radial rather than a spherical view. This dual way of looking at eclipses reveals something of their ambivalent nature.

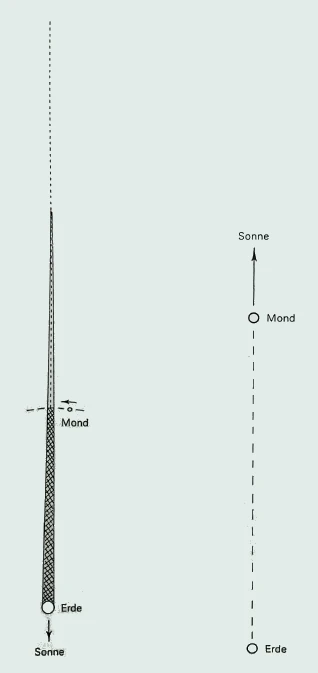

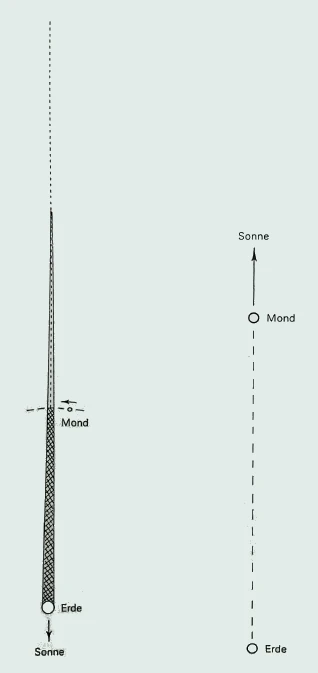

In external reality, a lunar eclipse occurs when the moon enters the shadow cone cast by the Earth in space on the side facing away from the sun. Even the ancient Greek astronomers knew this explanation of eclipses; indeed, they deduced the spherical shape of the Earth from the outline of the shadow on the moon's disk. This cone of Earth's shadow is usually depicted only schematically in standard astronomical works, without regard to the proportions, as these do not allow for clear reproduction on a standard printed page. The cone that the Earth casts into space as a shadow is enormously long and slender in relation to the Earth's diameter, based on the usual numerical ratios for the distances of the Moon and Sun. If we take the diameter of the Earth to be 12 mm (1 mm for 1000 km), for example, the shadow would be about 1.35 m long, while the Sun would be on the opposite side at a distance of 150 m. One-third of the shadow's length is cut off by the moon's orbit when the centers of the sun, Earth, and moon lie on a straight line that must intersect the celestial sphere near the moon's nodes. This is when a lunar eclipse occurs; otherwise, the moon's orbit passes just above or below the shadow during a full moon. Where the moon enters the shadow during eclipses, the shadow has a width of only 3 full moon discs. Figure 17 shows a schematic representation of the Earth's shadow, but in approximately the correct proportions, at least up to the moon's orbit; the last 2/3 are only indicated by the dotted line.

It is certainly justified to raise the question of whether this shadow actually exists, which, unless there is a lunar eclipse, falls into “empty space,” for is a shadow conceivable that would fall into nothingness? In the immediate vicinity of the Earth, in the Earth's atmosphere, it causes the phenomenon that we know as night by casting its shadow in the atmosphere. (The Earth rotates in 24 hours under the shadow cone, which itself would travel all the way around once in a year.) Outside the Earth, the shadow can actually only exist as a spiritual entity, as a gathering place for spiritual beings of darkness, and only when the moon enters its realm is the shadow embodied, so to speak, as it can then fall on a material body. Thus, through this observation, we already find a foreshadowing of what will later be said about the spiritual nature of eclipses.

In the case of solar eclipses, on the other hand, it is the moon that moves in front of the sun's disk and now produces a shadow itself, which can touch the earth with its outermost tip. During total eclipses, this shadow, which can be up to 200 km wide, can be seen moving across the earth's surface at great speed from west to east, enveloping everything in night and darkness. (In the same representation as that of the lunar eclipse, this moon shadow would also be only a thin line, and it would also only be real within the Earth's atmosphere, drawing 18.) If the moon does not pass centrally, but slightly higher or lower on the sun's disk, only partial coverage occurs: a partial solar eclipse. Moreover, every total solar eclipse is only a partial eclipse for areas that are not in the zone of centrality (to the left and right of the shadow band). If the moon is somewhat further away from the Earth (at its “apogee”), the tip of the shadow cone may not even reach the Earth, but instead hovers above it, as it were; then instead of a total eclipse, there is a so-called annular eclipse.

Perspective and parallax play an important role here. The situation is different with lunar eclipses. If the moon is completely immersed in the Earth's shadow, i.e., if the eclipse is total, then it is so for all places on Earth that have the moon above their horizon, at least for a significant part of the entire Earth. Solar eclipses are much more of a local phenomenon.

This is how eclipses appear when viewed from the outside. Rudolf Steiner already pointed out in 1910 in his lecture series on “The Mission of Individual Folk Souls in Connection with Germanic-Nordic Mythology” (9th lecture) that there is more to eclipses than meets the eye:

"When the ancient Norse people wanted to explain what they saw during a solar eclipse—of course, people in the days of ancient clairvoyance saw things differently than we do today when using telescopes—they chose the image of a wolf chasing the sun and causing the eclipse at the moment it catches up with it. This is in complete harmony with the facts ... Today's materialistic people will say: But that's superstition, no wolf pursues the sun ... For the occultist, there is something that is even more superstitious. That is that a solar eclipse is caused by the moon passing in front of the sun. This is quite correct from an external point of view, just as the astral view is correct from the point of view of the wolf. The astral view is even more correct than what you find in current books, for these are even more prone to error.

This passage39 speaks of what happens in the spheres when an eclipse approaches, not only of the celestial bodies moving in space. For eclipses are "transitional phenomena ... that stand in the middle between the purely physical-cosmic and the cosmic-spiritual. They deny the spiritual in favor of the outwardly spatial. Space, as we believe we know it on earth, as a legitimate phenomenon of our earthly existence, is, in a sense, carried into the cosmos during eclipses.

The shadow, whether from the moon or the earth, otherwise only present in the elemental realm, condenses into a visible formation.We know, precisely from Rudolf Steiner's lecture just quoted, that all this has its good reason and necessity in the universe. There must also be outlets for the evil that lives in will and thought, and these outlets are precisely the eclipses, the absence of sunlight or moonlight for shorter or longer periods of time. Since evil has been allowed in the world by divine decree, eclipses are also something that is entirely in accordance with the divine plan. One might almost say: when the world of creation was established, divine wisdom could easily have arranged it so that no eclipses would occur! If only the moon were a little further away from the earth than it is, its disk could never completely cover the sun's disk, and there would be no total solar eclipses. (At the same time, however, human beings would then have to be of a completely different nature!) When eclipses occur, the spirits of darkness and evil are allowed to enter the world space to the extent and in the places where it is necessary.

But the good, the spirit we call the Holy Spirit, does not live in space or even in time. And in the feast of Pentecost we commemorate the experience that lifted Christ's disciples out of space and time for a while.

Let us consider the three feasts that early Christianity instituted at the beginning of the year, calculated from the lowest point of the sun. In the depths of winter, the baby Jesus is born into the earthly realm. The earth lies like a star in the cosmos, upon which the entire cosmos seems to be focused. Permeated by cosmic father forces, illuminated only by the midnight sun, Christmas reveals itself to us.

Space is already overcome in the Easter event. Christ is risen; he has conquered death, the earth, space. Even his spatial remains, his holy body, have disappeared from the tomb. But the risen Christ appears to the disciples here and there in a body that is like the physical body of space and yet not like it. There his work in time begins. Space is not important for the further development of the Christ impulse, not even the earthly space in which Christ Jesus lived. Christ died for the people of all nations, and only in time can we follow how his impulse spreads across the earthly space. The date of Easter is also determined according to principles of time, as we have already discussed.

The feast of Pentecost, however, is the remembrance and constant renewal of that event, which in its deepest essence is neither a spatial nor a temporal event. There, the human being is truly beyond space, and there, beyond space and time, the Holy Spirit shines into the human spirit. Like fiery tongues that are like lightning — and lightning has no time and tears through space — so what the Holy Spirit pours out upon them shines forth from the souls of the apostles. The Holy Spirit is the spirit that does not live in matter, which is therefore holy, that is, healing, restorative in human beings. He is the Spirit of whom Christ says that he could only come after Christ himself had passed through the mystery of Golgotha, after he had overcome space through death and reunited with the Father. And the people who were present when the Holy Spirit was able to reveal himself in human beings for the first time heard the apostles speak “each in his own language.” Space was overcome, for everyone was, as it were, in their own country, at home. Time was overcome, for the mystery of Golgotha stood before the souls of the apostles as an immediately experienced event. From beyond time and space shines forth — then and at all times — what the Holy Spirit has to say to human beings.

These thoughts are fitting to consider at a time that began with a solar eclipse on December 24, 1927, and which also has the feast of Pentecost falling in the middle of a period of darkness.

9. Über Sonnen- und Mondfinsternisse

Das Pfingstfest

(Der Monat Mai bringt für dieses Jahr den Anfang der ersten Periode der Finsternisse, die sich dann noch in den Juni hinein fortsetzt. Eine zweite Periode folgt 6 Monate später, im November und Dezember.) Jedes Jahr treten zwei Perioden auf, die jede 1 bis 3 Finsternisse umfassen; aber jedes Jahr liegt ihr Anfang früher, im Durchschnitt 20 Tage, doch können es auch bloss 8 Tage oder auch 4 Wochen — eine volle Mondperiode — sein. Um eine Vorstellung von dem Immer-Wiederkehren und immer früheren Eintreten der Finsternisse zu vermitteln, werden hier die entsprechenden Daten der Jahre 1924–1928 gegeben (M = Mond-, S = Sonnenfinsternis).

1924,

20. Febr. M — 5. März S

31. Juli S — 14. Aug. M — 24. Aug. S1925

24. Jan. S

20./21. Juli S — 4. Aug. M1926

14. Jan. S

9./10. Juli S1927

3. Jan. S

15. Juni M — 29. Juni S

8. Dez. M — 24. Dez. S1928

19. Mai S — 3. Juni M — 17. Juni S

12. Nov. S — 27. Nov. M

Man sieht aus dieser Tabelle die zwei Perioden deutlich auftreten. Dass es 1927 anscheinend 3 Finsternisperioden gegeben hat — im Januar, Juni und Dezember— rührt nur davon her, dass die dritte Periode gewissermassen die durch die Verfrühung um die Jahreswende hinübergekommene Periode von Januar 1928 ist. Auch sieht man, dass — wie schon gesagt — die Anzahl der Finsternisse in jeder Periode zwischen 1 und 3 schwanken kann, dass innerhalb einer Periode immer abwechselnd eine Sonnen- auf eine Mondfinsternis folgen muss und umgekehrt, dass aber jede neue Periode sozusagen frisch anfangen kann, entweder mit einer Sonnen- oder mit einer Mondfinsternis. Treten in einem Jahre nur 2 Finsternisse auf (wie 1926), was überhaupt das Minimum darstellt, so sind diese immer beide Verfinsterungen der Sonne. Der Beweis für alle diese Regeln kann hier selbstverständlich in Kürze nicht gegeben werden.

Was hier als «Perioden der Finsternisse» bezeichnet worden ist, hängt nicht nur mit der Bewegung von Sonne und Mond (oder der Erde) zusammen, sondern auch mit der Bewegung von den Schnittpunkten der Sonnen- und Mondbahn, die man die Knoten nennt und von denen die Alten sprachen als von dem Drachenkopf (☊, aufsteigender Knoten) und Drachenschwanz (☋, absteigender Knoten). Diese Knoten stellen für die Mondbahn etwas Ähnliches dar wie Frühlings- und Herbstpunkt für die Sonnen-Erdenbahn, insofern sie ein Auf- und Absteigen des Mondes auf seiner Bahn bedeuten und auch in rückläufiger Bewegung begriffen sind. Diese Rückwärtsbewegung der Knoten, die in 18 Jahren 7 Monaten einmal eine volle Umdrehung machen, bewirkt das frühere Eintreten der Finsternisse in jedem Jahr, denn diese sind an die Lage der Knoten gebunden.

Die Mondbahn macht einen Winkel von 5° mit der Ekliptik oder Sonnenbahn (der in der Zeichnung 15 etwas übertrieben dargestellt ist). Auch die anderen Planeten zeigen am Himmel Bahnen, die mehr oder weniger schräg zur Sonnenbahn, der Ekliptik, stehen, die aber alle innerhalb des Tierkreises, der ja ein ziemlich breiter Gürtel ist, liegen. Eine Ausnahme bilden nur manche von den kleinen Planeten oder Planetoiden zwischen Mars und Jupiter, die oft so stark geneigte Bahnen haben, dass sie weit ausserhalb des Tierkreises wandern können. Sie gehören ja nicht zu den «normalen» Gebilden unseres Sonnensystems, sondern sind das Ergebnis eines Weltenkampfes (5. Vortrag).

Es ist gut, sich die Knotenpunkte, die auch in unserem Seelenleben eine wichtige Rolle spielen, einmal am Himmel aufzusuchen und sich danach die Mondbahn für den betreffenden Monat vorzustellen. (Zurzeit liegt der aufsteigende Knoten im Stier, unweit vom Stern Aldebaran (siehe Zeichnung 16), der absteigende Knoten am gegenüberliegenden Punkt des Tierkreises, das ist im Skorpion, über dem roten Antares. In der Gegend von Zwillingen, Krebs, Löwe usw. steigt also die Mondbahn noch über die höchste Stellung der Sonnenbahn hinaus. Doch ändern sich beim Monde all diese Verhältnisse ziemlich rasch. Schon im April nächsten Jahres wird der eine Knoten im Widder, der andere in der Waage sein. (Es sind immer die Sternbilder selber gemeint.)

Bevor wir auf die Knoten weiter eingehen, muss das Prinzip der Finsternisse, so wie sie sich rein äusserlich darstellen, ins Auge gefasst werden. Und zwar liegt etwas sehr Verschiedenes den Mond- und den Sonnenfinsternissen zugrunde.

Weil Mond- und Sonnenbahn einen Winkel von 5° miteinander einschliessen, kann eine Bedeckung von der Sonne durch den Mond, also eine Sonnenfinsternis nur dann stattfinden, wenn erstens Neumond ist, zweitens beide in der Nähe von einem der Knoten stehen. Hat sich die Sonne auf ihrer jährlichen Bahn schon zu weit von dem Knoten entfernt, oder ist sie noch zu weit von ihr ab (die Grenze beträgt für Sonnenfinsternisse 18°, für Mondfinsternisse 12°), so steigt die Mondbahn und auf ihr der Mond selber über die Sonne hinauf oder unter sie hinunter, so dass keine Bedeckung zustande kommen kann. Das ist ja dasjenige, was bei jedem gewöhnlichen Neumond vorliegt, es ist dann Konjunktion, aber keine Bedeckung. Nur eben in der Nähe der Knoten können Sonnen- und Mondscheibe übereinanderfallen. Aus der Zeichnung 16 wird man das ersehen können. Es ist jener Teil der Ekliptik dargestellt, in welchem sich die Finsternisse der ersten Periode des Jahres 1928 abspielen. Der aufsteigende Knoten ist für vier aufeinanderfolgende Zeitpunkte in seiner rückläufigen Bewegung als a, b, c, d angegeben, entsprechend dem Sonnenstand am 3. Juni, 17. Juni, 17. Juli und 15. August.

Am 19. Mai ist eine totale Sonnenfinsternis, der Knoten würde dann etwas links von a liegen. Die Mondbahn geht an dieser Stelle eigentlich schon ziemlich stark unter der Sonnenbahn durch, denn der Mond ist noch vor dem aufsteigenden Knoten. Dass trotzdem eine Bedeckung und sogar eine vollständige zustandekommen kann, liegt nur daran, dass der Mond in den Tagen gerade der Erde am nächsten ist (im «Perigäum») und dadurch seine Scheibe am grössten ist, so dass diese wenigstens für kurze Zeit die Sonne bedecken kann. Die Finsternis spielt sich in den Gegenden des Südpols ab, sie ist, auch in ihrem partiellen Teil, kaum in bewohnten Gegenden sichtbar.

14 Tage später, am 3. Juni, ist Vollmond, die Sonne ist dann unmittelbar beim aufsteigenden Knoten gelegen (a), der Mond ihr gegenüber beim absteigenden Knoten im Skorpion: totale Mondfinsternis. (Der Mond konnte in diesem Falle selbstverständlich nicht auf der Zeichnung angegeben werden.)

Wiederum 14 Tage später: 17. Juni, Neumond. Jetzt kommt aber nur eine ganz kleine partielle Sonnenfinsternis zustande, die Mondbahn hebt sich, der Mond geht schräg über den obersten Rand der Sonnenscheibe hinweg.

Für den nächsten Stand: 17. Juli, ist die Sonne schon zu weit vom Knoten, der Mond berührt sie nicht mehr. Beim nächsten Neumond, 15. August, ist der Unterschied noch grösser. Erst wenn die Sonne beim anderen Knoten angekommen sein wird, im November, entsteht wiederum eine Bedeckung. Die Sonne passiert diesen Knoten am 23. November, die Neu- und Vollmonddaten jenes Monats (12., 27. November) sind so gelegen, dass nur 2, nicht 3 Finsternisse entstehen können. Von diesen 5 Finsternissen wird nur die partielle Sonnenfinsternis am 12. November in Mitteleuropa zu sehen sein.

Die Sonnen- und Mondfinsternisse eines bestimmten Jahres wiederholen sich in derselben Reihenfolge und, mit nur 10 Tagen Unterschied, an denselben Daten, immer nach Ablauf von 18 Jahren. So entsprechen die 5 Finsternisse dieses Jahres denen vom Jahre 1910, aber statt am 19. Mai am 9. Mai, statt 3. Juni am 21. Mai usw. Nur der diesjährige Neumond vom 17. Juni hatte es damals, am 7. Juni, noch nicht zu einer Bedekkung gebracht. Auf diese so interessante Tatsache des Entstehens und Vergehens von Finsternissen wollen wir später (siehe Seite 101 ff.) eingehen. Wir haben da die berühmte, schon von den Chaldäern gekannte Sarosperiode, die eng mit der rückläufigen Bewegung der Knoten zusammenhängt. Vieles ausserordentlich Wichtige ist mit der Sarosperiode verknüpft, von dem wir ebenfalls später sprechen wollen.

Wir müssen, um die Finsternisse beschreiben und im äusseren Sinn erklären zu können, ein räumlich-perspektivisches Element in Betracht ziehen, dessen wir uns sonst nicht zu bedienen brauchten. Bei den Finsternissen handelt es sich um ein räumliches Voreinanderstehen von Sonne, Mond und Erde und sogar um das Schattenwerfen durch den einen Körper auf den anderen. Konnten wir vorher die Mond- und die Sonnenbahn am Himmelsgewölbe aufzeichnen und ihre Schnittpunkte, die Knoten, darstellen, muss jetzt für die Finsternis selber doch ins Auge gefasst werden, dass die Mondbahn innerhalb der Sonnenbahn liegt, der Mond näher zur Erde ist als die Sonne, gewissermassen eine radiale, statt einer sphärischen Anschauung. Diese zweifache Betrachtungsart, wozu die Finsternisse nötigen, offenbart uns schon etwas von ihrer zwiespältigen Natur.

In der äusseren Realität entsteht ja eine Mondfinsternis dadurch, dass der Mond in jenen Schattenkegel eintreten soll, den die Erde im Raume nach der von der Sonne abgewendeten Seite wirft. Schon die alten griechischen Astronomen kannten diese Erklärung der Finsternisse, ja sie schlossen gerade aus dem Umriss des Schattens auf der Mondscheibe zurück auf die Kugelgestalt der Erde. Man findet diesen Erdschattenkegel in den gebräuchlichen astronomischen Werken zumeist bloss schematisch abgebildet, ohne Rücksicht auf die Grössenverhältnisse, denn diese gestatten nicht die deutliche Wiedergabe auf einer gewöhnlichen Druckseite. Der Kegel, den die Erde als Schatten in den Raum hineinwerfen soll, ist nämlich ungeheuer lang und schlank im Verhältnis zum Erddurchmesser, wenn man von den gewöhnlichen Zahlenverhältnissen für Mond- und Sonnenentfernung ausgeht. Nimmt man den Durchmesser der Erde zum Beispiel als 12 mm (1 mm für 1000 km), so würde der Schatten etwa 1,35 m lang sein, während die Sonne auf der entgegengesetzten Seite in einer Entfernung von 150 m zu denken wäre. Auf 1/3 seiner Länge wird der Schatten von der Mondbahn geschnitten, wenn nämlich die Mittelpunkte von Sonne, Erde und Mond in einer Geraden liegen, die eben die Himmelskugel in der Nähe der Mondknoten treffen muss. Dann entsteht ja die Mondfinsternis, sonst geht die Mondbahn bei Vollmond gerade über oder unter dem Schatten durch. Der Schatten hat da, wo der Mond bei Finsternissen in ihn eintaucht, nur mehr eine Breite von 3 Vollmondscheiben. Auf Zeichnung 17 ist schematisch, aber annähernd im richtigen Verhältnis, der Erdschatten dargestellt, wenigstens bis zur Mondbahn, die letzten 2/3 sind nur durch die punktierte Linie angedeutet.

Es ist gewiss berechtigt, die Frage aufzuwerfen, ob es diesen Schatten denn in Wirklichkeit gibt, der eigentlich, wenn nicht gerade Mondfinsternis ist, in den «leeren Raum» hineinfällt, denn ist ein Schatten denkbar, der ins Nichts fallen würde? In der allernächsten Erdumgebung, in dem Luftkreis der Erde, bewirkt er diejenige Erscheinung, die für uns die Nacht ist, indem er eben in der Atmosphäre sich abzeichnet. (Die Erde dreht sich gleichsam in 24 Stunden unter dem Schattenkegel durch, der Kegel selber würde in einem Jahr einmal ganz herumwandern.) Ausserhalb der Erde kann der Schatten eigentlich nur als geistiges Gebilde vorhanden sein, als Sammelplatz von geistigen Finsterniswesen, und nur wenn der Mond in seinen Bereich tritt, wird der Schatten gewissermassen verkörpert, da er dann auf einen materiellen Körper auffallen kann. So finden wir durch diese Betrachtung schon vorgebildet dasjenige, was später über das geistige Wesen der Finsternisse noch zu sagen sein wird.

Bei den Sonnenfinsternissen wiederum ist es der Mond, der sich vor die Sonnenscheibe stellt und nun selber einen Schatten produziert, der mit seiner äussersten Spitze die Erde berühren kann. Man soll bei totalen Finsternissen diesen Schatten, der bis 200 km Breite haben kann, mit grosser Geschwindigkeit von West nach Ost über den Erdboden ziehen sehen, alles in Nacht und Dunkel hüllend. (In derselben Darstellung wie die der Mondfinsternis würde auch dieser Mondschatten nur wie ein dünner Strich sein, und es wäre ihm ebenso nur innerhalb der Erdatmosphäre Realität zuzuschreiben, Zeichnung 18.) Geht der Mond nicht zentral, sondern etwas höher oder tiefer an der Sonnenscheibe vorbei, so kommt bloss teilweise Bedeckung zustande: eine partielle Sonnenfinsternis. Jede totale Sonnenfinsternis ist überdies noch für die Gegenden, die nicht in der Zentralitätszone liegen (links und rechts vom Schattenband), bloss eine partielle. Der Schattenkegel kann bisweilen, wenn der Mond der Erde etwas ferner steht (im «Apogäum»), mit seiner Spitze die Erde gar nicht erreichen, sondern schwebt gleichsam oberhalb der Erde; dann gibt es statt einer totalen eine sogenannte ringförmige Finsternis.

Hier spielen Perspektive oder Parallaxe eine bedeutende Rolle. Anders ist das bei den Mondfinsternissen. Wenn der Mond überhaupt ganz in den Erdschatten eintaucht, die Finsternis also total ist, so ist sie das für sämtliche Orte der Erde, die den Mond überhaupt über ihrem Horizont haben, jedenfalls einen bedeutenden Teil der ganzen Erde. Die Sonnenfinsternisse sind viel mehr eine lokale Erscheinung.

So nehmen sich die Finsternisse im äusseren Betrachten aus. Dass mit ihnen anderes noch vorgeht als das bloss Äussere hat Rudolf Steiner schon 1910 im Vortragszyklus über«Die Mission einzelner Volksseelen im Zusammenhange mit der germanisch-nordischen Mythologie» ausgesprochen (9. Vortrag):

«Wenn der alte nordische Mensch sich verständlich machen will über das, was er sieht bei einer Sonnenfinsternis — natürlich sah der Mensch zur Zeit des alten Hellsehens noch anders, als heute bei Benutzung des Fernrohres —, so wählte er das Bild des Wolfes, der die Sonne verfolgt und der in dem Momente, wo er sie erreicht, die Sonnenfinsternis bewirkt. Das steht im innersten Einklang mit den Tatsachen ... Die materialistischen Menschen von heute werden sagen: Das ist aber doch Aberglaube, es verfolgt doch kein Wolf die Sonne ... Für den Okkultisten gibt es etwas, was noch in höherem Grad Aberglaube ist. Das ist, dass eine Sonnenfinsternis dadurch entsteht, dass sich der Mond vor die Sonne stellt. Das ist für die äussere Anschauung ganz richtig, ebenso richtig, wie für die astrale Anschauung die Sache vorn Wolf richtig ist. Die astrale Anschauung ist sogar richtiger als die, welche Sie in den gegenwärtigen Büchern finden, denn die ist noch mehr dem Irrtum unterworfen.»

Von dem, was nicht bloss mit den räumlich sich bewegenden Himmelskörpern, sondern was in den Sphären vorgeht, wenn eine Finsternis herannaht, spricht diese Stelle39. Denn die Finsternisse sind ja «solche Übergangserscheinungen ..., die zwischen dem rein Physisch-Kosmischen und dem Kosmisch-Geistigen mitten drinnen stehen. Sie verleugnen das Geistige zugunsten des äusserlich Räumlichen. Der Raum, so wie wir ihn auf Erden zu kennen glauben, wie er eine berechtigte Erscheinung unseres Erdendaseins ist, wird gewissermassen in den Kosmos hineingetragen bei den Finsternissen. Der Schatten, sei es vom Mond oder von der Erde, sonst nur im Elementarischen vorhanden, verdichtet sich zu einem sichtbaren Gebilde.

Wir wissen ja, gerade aus dem Vortrag Rudolf Steiners, der soeben angeführt wurde, dass all dieses seinen guten Grund und seine Notwendigkeit im Weltenall hat. Auch für das Böse, das in Willen und Gedanken lebt, müssen Ventile da sein, und diese Ventile sind eben die Finsternisse, das für kürzere oder längere Zeit abwesende Sonnen- oder Mondlicht. Da das Böse durch göttlichen Ratschluss in der Welt zugelassen worden ist, sind auch die Finsternisse durchaus etwas im göttlichen Plan Gelegenes. Man möchte fast sagen: als die Werkwelt eingesetzt wurde, hätte die göttliche Weisheit es leicht auch so einrichten können, dass keine Finsternisse entstehen ! Es brauchte nur der Mond der Erde ein klein wenig ferner zu sein als er ist, so könnte seine Scheibe niemals die Sonnenscheibe vollständig bedecken, es gäbe keine totalen Sonnenfinsternisse. (Zugleich aber würde dann der Mensch ganz anders geartet sein müssen!) Indem die Finsternisse auftreten, wird den Geistern des Finstern und des Bösen der Weg in den Weltenraum hinein offen gelassen in dem Masse und an den Orten, wie es nötig ist.

Das Gute aber, der Geist, den wir den Heiligen Geist nennen, lebt nicht im Raum und nicht einmal in der Zeit. Und in dem Pfingstfest haben wir das Gedenken desjenigen Erlebens, das die Jünger Christi für eine Weile aus dem Raum und der Zeit heraushob.

Betrachten wir so die drei Feste, die das Urchristentum am Jahresanfang — vom tiefsten Sonnenstand ab gerechnet — eingesetzt hat. Da wird in der Tiefwinterzeit das Jesuskind in den Erdenraum hinein geboren. Da liegt die Erde wie ein Stern im Kosmos, auf den der ganze Kosmos gleichsam den Blick gerichtet hält. Räumliches von kosmischen Vaterkräften durchzogen, sogar von der Sonne nur als Mitternachtssonne durchstrahlt, offenbart uns das Weihnachtsfest.

Im Osterereignis schon wird der Raum überwunden. Der Christus ist auferstanden, er hat den Tod, die Erde, den Raum besiegt. Sogar seine räumlichen Reste, der heilige Leichnam ist aus der Gruft verschwunden. Der Auferstandene aber erscheint den Jüngern da und dort in einem Leib, der wie der physische Raumesleib und doch nicht ihm ähnlich ist. Da beginnt sein Wirken in der Zeit. Für die Weiterentwicklung des Christus-Impulses ist nicht der Raum von Bedeutung, nicht einmal der Erdenraum, auf dem der Christus Jesus gelebt hat. Für die Menschen aller Völker ist Christus gestorben, und nur in der Zeit kann verfolgt werden, wie sein Impuls über den Erdenraum sich verbreitet. Auch die Festsetzung des Osterfestes richtet sich nach Prinzipien der Zeit, wie wir schon besprochen haben.

Das Pfingstfest aber ist die Erinnerung und immer wieder Erneuerung von jenem Ereignis, das im tiefsten Grunde weder ein räumliches noch ein zeitliches Ereignis ist. Da ist der Mensch tatsächlich jenseits des Raumes, und da leuchtet jenseits von Raum und Zeit der Heilige Geist in den Menschengeist hinein. Wie feurige Zungen, die wie Blitze sind — und der Blitz hat keine Zeit und zerreisst den Raum —, so strahlt aus den Seelen der Apostel heraus das, was der Heilige Geist über sie ausschüttet. Der Heilige Geist ist derjenige Geist, der nicht in der Materie lebt, der daher heilig ist, das heisst, heilend, gesundend wirkt im Menschen. Er ist derjenige Geist, von dem der Christus sagt, dass er erst kommen könne, nachdem Christus selber durch das Mysterium von Golgatha gegangen sein wird, nachdem er sich durch den Tod, den Raum überwindend, mit dem Vater wieder vereinigt hat. Und die Menschen, die da anwesend waren, als zum ersten Mal der Heilige Geist sich in Menschen offenbaren konnte; sie hörten die Apostel reden «ein jeglicher mit seiner Sprache». Der Raum war überwunden, denn jeder war gleichsam im eigenen Lande, daheim. Die Zeit war überwunden, denn das Mysterium von Golgatha stand als ein unmittelbar erlebtes Geschehnis vor der Seele der Apostel. Aus dem Jenseits von Zeit und Raum leuchtet herein — damals und zu allen Zeiten —, was der Heilige Geist den Menschen zu sagen hat.

Diese Gedanken geziemt es zu denken in einer Zeit, die mit einer Sonnenfinsternis am 24. Dezember 1927 anfing und die auch das Pfingstfest mitten in eine Finsternisperiode hineinfallend hat.