Second Scientific Lecture-Course:

Warmth Course

GA 321

4 March 1920, Stuttgart

Lecture IV

My dear friends,

You will perhaps have noticed that in our considerations here, we are striving for a certain particular goal. We are trying to place together a series of phenomena taken from the realm of heat in such a manner that the real nature of warmth may be obvious to us from these phenomena. We have become acquainted in a general way with certain relations that meet us from within the realm of heat, and we have in particular observed the relation of this realm of the expansionability of bodies. We have followed this with an attempt to picture to ourselves mentally the nature of form in solid bodies, fluids and gaseous bodies. I have also spoken of the relation of heat to the changes produced in bodies in going from the solid to the fluid and from the fluid to the gaseous or vaporous condition. Now I wish to bring before you certain relations which come up when we have to do with gases or vapors. We already know that these are so connected with heat that by means of this we bring about the gaseous condition, and again, by appropriate change of temperature that we can obtain a liquid from a gas. Now you know that when we have a solid body, we cannot by any means interpenetrate this solid with another. The observation of such simple elementary relations is of enormous importance if we really wish to force our way through to the nature of heat. The experiment I will carry out here will show that water vapor produced here in this vessel passes through into this second vessel. And now having filled the second vessel with water vapor, we will produce in the first vessel another vapor whose formation you can follow by reason of the fact that it is colored. (The experiment was carried out.) You see that in spite of our having filled the vessel with water vapor, the other vapor goes into the space filled with the water vapor. That is, a gas does not prevent another gas from penetrating the space it occupies. We may make this clear to ourselves by saying that gaseous or vaporous bodies may to a certain extent interpenetrate each other.

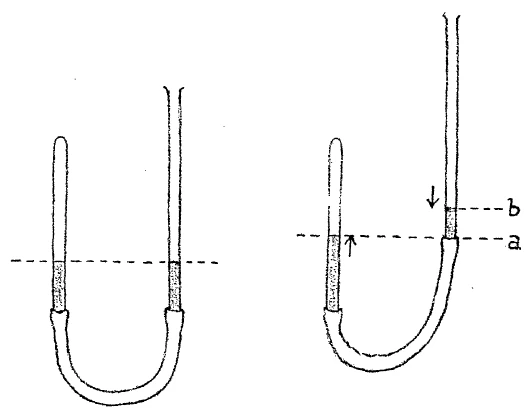

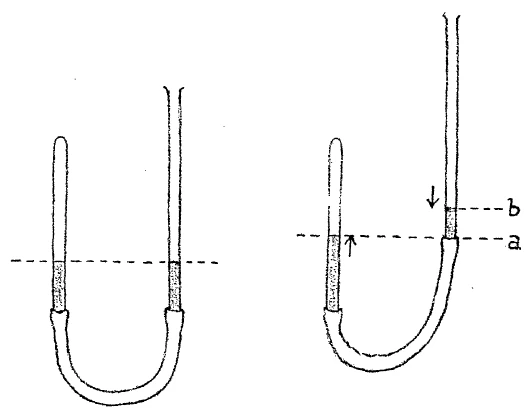

I will now show you another phenomenon which will illustrate one more relation of heat to certain facts. We have here in the left hand tube, air which is in equilibrium with the outer air with which we are always surrounded. I must remind you that this outer air surrounding us is always under a certain pressure, the usual atmospheric pressure, and it exerts this pressure on us. Thus, we can say that air inside the left hand tube is under the same pressure as the outer air itself, which fact is shown by the similar level of mercury in the right and left hand tubes. You can see that on both right and left hand sides the mercury column is at the same height, and that since here on the right the tube is open to the atmosphere the air in the closed tube is at atmospheric pressure. We will now alter the conditions by bringing pressure on the air in the left hand tube, (\(2\) × \(p\)). By doing this we have added to the usual atmospheric pressure, the pressure due to the higher mercury column. That is, we have simply added the weight of the mercury from here to here. (Fig. 1b from \(a\) to \(b\)). By thus increasing the pressure exerted on this air by the pressure corresponding to the weight of the mercury column, the volume of the air in the left hand tube is, as you can see, made smaller. We can therefore say when we increase the pressure on the gas its volume decreases. We must extend this and consider it a general phenomenon that the space occupied by a gas and the pressure exerted on it have an inverse ratio to each other. The greater the pressure the smaller the volume, and the greater the volume the smaller must be the pressure acting on the gas. We can express this in the form of an equation where the volume \(V_1\) divided by the volume \(V_2\) equals the pressure \(P_2\) divided by the pressure \(P_1\).

$$V_1:V_2 = P_1:P_2$$From which it follows:

$$V_1P_1 = V_2P_2$$This expresses a relatively general law (we have to say relative and will see why later.) This may be stated as follows: volume and pressure of gases are so related that the volume-pressure product is a constant at constant temperature. As we have said, such phenomena as these must be placed side by side if we are to approach the nature of heat. And now, since our considerations are to be thought of as a basis for pedagogy we must consider the matter from two aspects. On the one hand, we must build up a knowledge of the method of thinking of modern physics and on the other, we must become acquainted with what must happen if we are to throw aside certain obstacles that modern physics places in the path to a real understanding of the nature of heat.

Please picture vividly to ourselves that when we consider the nature of heat we are necessarily dealing at the same time with volume increases, that is with changes in space and with alterations of pressure. In other words, mechanical facts meet us in our consideration of heat. I have to speak repeatedly in detail of these things although it is not customary to do this. Space changes, pressure changes. Mechanical facts meet us.

Now for physics, these facts that meet us when we consider heat are purely and simply mechanical facts. These mechanical occurrences are, as it were, the milieu in which heat is observed. The being of heat is left, so to speak, in the realm of the unknown and attention is focused on the mechanical phenomena which play themselves out under its influence. Since the perception of heat is alleged to be purely a subjective thing, the expansion of mercury, say, accompanying change of heat condition and of sensation of heat, is considered as something belonging in the realm of the mechanical. The dependence of gas pressure, for instance, on the temperature, which we will consider further, is thought of as essentially mechanical and the being of heat is left out of consideration. We saw yesterday that there is a good reason for this. For we saw that when we attempt to calculate heat, difficulties arise in the usual calculations and that we cannot, for example, handle the third power of the temperature in the same way as the third power of an ordinary quantity in space. And since modern physics has not appreciated the importance of the higher powers of the temperature, it has simply stricken them out of the expansion formulae I mentioned to you in former lectures.

Now you need only consider the following. You need consider only that in the sphere of outer nature heat always appears in external mechanical phenomena, primarily in space phenomena. Space phenomena are there to begin with and in them the heat appears. This it is, my dear friends, that constrains us to think of heat as we do of lines in space and that leads us to proceed from the first power of extension in space to the second power of the extension.

When we observe the first power of the extension, the line, and we wish to go over to the second power, we have to go out of the line. That is, we must add a second dimension to the first. The standard of measurement of the second power has to be thought of as entirely different from that of the first power. We have to proceed in an entirely similar fashion when we consider a temperature condition. The first power is, so to speak, present in the expansion. Change of temperature and expansion are so related that they may be expressed by rectilinear coordination (Fig. 2). I am obliged, when I wish to make the graph representing change in expansion with change in temperature, to add the axis of abscissae to the axis of ordinates. But this makes it necessary to consider what is appearing as temperature not as a first power but as a second power, and the second power as a third. When we deal with the third power of the temperature, we can no longer stay in our ordinary space. A simple consideration, dealing it is true with rather subtle distinctions, will show you that in dealing with the heat manifesting itself as the third power, we cannot limit ourselves to the three directions of space. It will show you how, the moment we deal with the third power, we are obliged, so far as heat effects are concerned, to go out of space.

In order to explain the phenomena, modern physics sets itself the problem of doing so and remaining within the three dimensional space.

You see, here we have an important point where physical science has to cross a kind of Rubicon to a higher view of the world. And one is obliged to emphasize the fact that since so little attempt is made to attain clarity at this point, a corresponding lack enters into the comprehensive world view.

Imagine to yourselves that physicists would so present these matters to their students as to show that one must leave ordinary space in which mechanical phenomena play when heat phenomena are to be observed. In such a case, these teachers of physics would call forth in their students, who are intelligent people since they find themselves able to study the subject, the idea that a person cannot really know it without leaving the three dimensional space. Then it would be much easier to place a higher world-view before people. For people in general, even if they were not students of physics, would say, “We cannot form a judgment on the matter, but those who have studied know that the human being must rise through the physics of space to other relations than the purely spatial relations.” Therefore so much depends on our getting into this science such ideas as those put forth in our considerations here. Then what is investigated would have an effect on a spiritually founded world view among people in general quite different from what it has now. The physicist announces that he explains all phenomena by means of purely mechanical facts. This causes people to say, “Well, there are only mechanical facts in space. Life must be a mechanical thing, soul phenomena must be mechanical and spiritual things must be mechanical.” “Exact sciences” will not admit the possibility of a spiritual foundation for the world. And “exact science” works as an especially powerful authority because they are not familiar with it. What people know, they pass their own judgment on and do not permit it to exercise such an authority. What they do not know they accept on authority. If more were done to popularize the so-called “rigidly exact science,” the authority of some of those who sit entrenched in possession of this exact science would practically disappear.

During the course of the 19th century there was added to the facts that we have already observed, another one of which I have spoken briefly. This is that mechanical phenomena not only appear in connection with the phenomena of heat, but that heat can be transformed into mechanical phenomena. This process you see in the ordinary steam locomotive where heat is applied and forward motion results. Also mechanical processes, friction and the like, can be transformed back again into heat since the mechanical processes, as it is said, bring about the appearance of heat. Thus mechanical processes and heat processes may be mutually transformed into each other.

We will sketch the matter today in a preliminary fashion and go into the details pertaining to this realm in subsequent lectures.

Further, it has been found that not only heat but electrical and chemical processes may be changed into mechanical processes And from this has been developed what has been called during the 19th century the “mechanical theory of heat.”

This mechanical theory of heat has as its principal postulate that heat and mechanical effects are mutually convertible one into the other. Now suppose we consider this idea somewhat closely. I am unable to avoid for you the consideration of these elementary things of the realm of physics. If we pass by the elementary things in our basic consideration, we will have to give up attaining any clarity in this realm of heat. We must therefore ask the questions: what does it really mean then when I say: Heat as it is applied in the steam engine shows itself as motion, as mechanical work? What does it mean when I draw from this idea: through heat, mechanical work is produced in the external world? Let us distinguish clearly between what we can establish as fact and the ideas which we add to these facts. We can establish the fact that a process subsequently is revealed as mechanical work, or shows itself as a mechanical process. Then the conclusion is drawn that the heat process, the heat as such, has been changed into a mechanical thing, into work.

Well now, my dear friends, if I come into this room and find the temperature such that I am comfortable, I may think to myself, perhaps unconsciously without saying it in words: In this room it is comfortable. I sit down at the desk and write something. Then following the same course of reasoning as has given rise to the mechanical theory of heat, I would say: I came into the room, the heat condition worked on me and what I wrote down is a consequence of this heat condition. Speaking in a certain sense I might say that if I had found the place cold like a cellar, I would have hurried out and would not have done this work of writing. If now I add to the above the conclusion that the heat conducted to me has been changed into the work I did, then obviously something has been left out of my thinking. I have left out all that which can only take place through myself. If I am to comprehend the whole reality I must insert into my judgment of it this which I have left out. The question now arises: When the corresponding conclusion is drawn in the realm of heat, by assuming that the motion of the locomotive is simply the transformed heat from the boiler, have I not fallen into the error noted above? That is, have I not committed the same fallacy as when I speak of a transformation of heat into an effect which can only take place because I myself am part of the picture? It may appear to be trivial to direct attention to such a thing as this, but it is just these trivialities that have been completely forgotten in the entire mechanical theory of heat. What is more, enormously important things depend on this. Two things are bound together here. First, when we pass over from the mechanical realm into the realm where heat is active we really have to leave three dimensional space, and then we have to consider that when external nature is observed, we simply do not have that which is interpolated in the case, where heat is changed over into my writing. When heat is changed into my writing, I can note from observation of my external bodily nature that something has been interpolated in the process. Suppose however, that I simply consider the fact that I must leave three dimensional space in order to relate the transformation of heat into mechanical effects. Then I can say, perhaps the most important factor involved in this change plays its part outside of three dimensional space. In the example that concerned myself which I gave you, the manner in which I entered into the process took place outside of three dimensions. And when I speak of simple transformation of heat into work I am guilty of the same superficiality as when I consider transformation of heat into a piece of written work and leave myself out.

This, however, leads to a very weighty consequence. For it requires me to consider in external nature even lifeless inorganic nature, a being not manifested in three dimensional space. This being, as it were, rules behind the three dimensions. Now this is very fundamental in relation to our studies of heat itself.

Since we have outlined the fundamentals of our conception of the realm of heat, we may look back again on something we have already indicated, namely on man's own relation to heat. We may compare the perception of heat to perception in other realms. I have already called attention to the fact that, for instance, when we perceive light, we note this perception of light to be bound up with a special organ. This organ is simply inserted into our body and we cannot, therefore, speak of being related to color and light with our whole organism, but our relation to it concerns a part of us only. Likewise with acoustical or sound phenomena, we are related to them with a portion of our organism, namely the organ of hearing. To the being of heat we are related through our entire organism. This fact, however, conditions our relation to the being of heat. We are related to it with our entire organism. And when we look more closely, when we try, as it were, to express these facts in terms of human consciousness, we are obliged to say, “We are really ourselves this heat being. In so far as we are men moving around in space, we are ourselves this heat being.” Imagine the temperature were to be raised a couple of hundred degrees; at that moment we could no longer be identical with it, and the same thing applies if you imagine it lowered several hundred degrees. Thus the heat condition belongs to that in which we continually live, but do not take up into our consciousness. We experience it as independent beings, but we do not experience it consciously. Only when some variation from the normal condition occurs, does it take conscious form.

Now with this fact a more inclusive one may be connected. It is this. You may say to yourselves when you contact a warm object and perceive the heat condition by means of your organism, that you can do it with the tip of your tongue, with the tip of your finger, you can do it with other parts of your organism: with the lobes of your ears, let us say. In fact, you can perceive the heat condition with your entire organism. But there is something else you can perceive with your entire organism. You can perceive anything exerting pressure. And here again, you are not limited strictly as you are in the case of the eye and color perception to a certain member of your entire organism. If would be very convenient if our heads, at least, were an exception to this rule of pressure perception; we would not then be made so uncomfortable from a rap on the head.

We can say there is an inner kinship between the nature of our relationship to the outer world perceived as heat and perceived as pressure. We have today spoken of pressure volume relations. We come back now to our own organism and find an inner kinship between our relation to heat and to pressure. Such a fact must be considered as a groundwork for what will follow.

But there is something else that must be taken into account as a preliminary to further observations. You know that in the most popular text books of physiology, a good deal of emphasis is laid on the fact that we have certain organs within our bodies by means of which we perceive the usual sense qualities. We have the eye for color, the ear for sound, the organ of taste for certain chemical processes, etc. We have spread over our entire organism, as it were, the undifferentiated heat organ, and the undifferentiated pressure organ.

Now, usually, attention is drawn to the fact that there are certain other things of which we are aware but for which we have no organs. Magnetism and electricity are known to us only through their effects and stand, as it were, outside of us, not immediately perceived. It is said sometimes that if we imagine our eyes were electrically sensitive instead of light sensitive, then when we turned them towards a telegraph wire we would perceive the streaming electricity in it. Electricity would be known not merely by its effects, but like light and color, would be immediately perceived. We cannot do this. We must therefore say: electricity is an example of something for whose immediate perception we have no organ. There are aspects of nature, thus, for which we have organs and aspects of nature for which we do not have organs. So it is said.

The question is whether perhaps a more unbiased observer would not come to a different conclusion from those whose view is expressed above. You all know, my dear friends, that what we call our ordinary passive concepts through which we apprehend the world, are closely bound up with the impressions received through the eye, the ear and somewhat less so with taste and smell impressions. If you will simply consider language, you may draw from it the summation of your conceptual life, and you will become aware that the words themselves used to represent our ideas are residues of our sense impressions. Even when we speak the very abstract word Sein (being), the derivation is from Ich habe gesehen, (I have seen.) What I have seen I can speak of as possessing “being.” In “being” there is included “what has been seen.” Now without becoming completely materialistic (and we will see later why it is not necessary to become so), it may be said that our conceptual world is really a kind of residue of seeing and hearing and to a lesser extent of smelling and tasting. (Those last two enter less into our higher sense impressions.) Through the intimate connection between our consciousness and our sense impressions, this consciousness is enabled to take up the passive concept world.

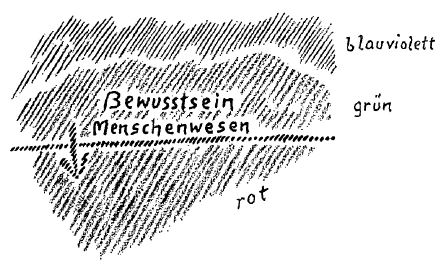

But within the soul nature, from another side, comes the will, and you remember how I have often told you in these anthroposophical lectures that man is really asleep so far as his will is concerned. He is, properly considered, awake only in the passive conceptual realm. What you will, you apprehend, only through these ideas or concepts. You have the idea. I will raise this glass. Now, in so far as your mental act contains ideas, it is a residue of sense impressions. You place before yourself in thought something which belongs entirely in the realm of the seen, and when you think of it, you have an image of something seen. Such an immediately derived image you cannot create from a will process proper, from what happens when you stretch out your arm and actually grasp the glass with your hand and raise it. That act is entirely outside of your consciousness. You are not aware of what happens between your consciousness and the delicate processes in your arm. Our unconsciousness of it is as complete as our unconsciousness between falling asleep and waking up. But something really is there and takes place, and can its existence be denied simply because it does not enter our consciousness? Those processes must be intimately bound up with us as human beings, because after all, it is we who raise the glass. Thus we are led in considering our human nature from that which is immediately alive in consciousness to will processes taking place, as it were, outside of consciousness. (Fig. 3) Imagine to yourselves that everything above this line is in the realm of consciousness. What is underneath is in the realm of will and is outside of consciousness. Starting from this point we proceed to the outer phenomena of nature and find our eye intimately connected with color phenomena, something which we can consciously apprehend; we find our ear intimately connected with sound, as something we can consciously apprehend. Tasting and smelling are, however, apprehended in a more dreamlike way. We have here something which is in the realm of consciousness and yet is intimately bound up with the outer world.

If now, we go to magnetic and electrical phenomena, the entity which is active in these is withdrawn from us in contrast with those phenomena of nature which have immediate connection with us through certain organs. This entity escapes us. Therefore, say the physicists and physiologists: we have no organ for it; it is cut off from us. It lies outside us. (Fig. 3 above) We have realms that we approach when we draw near the outer world—the realms of light and heat. How do electrical phenomena escape us? We can trace no connection between them and any of our organs. Within us we have the results of our working over of light and sound phenomena as residues in the form of ideas. When, however, we plunge down (Fig. 3 below), our own being disappears from us into will.

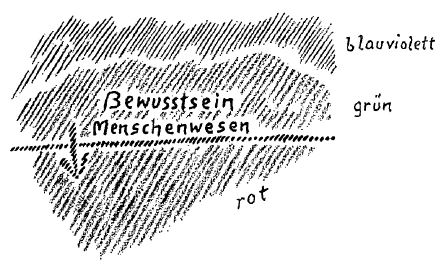

I will now tell you something a bit paradoxical, but think it over until tomorrow. Imagine we were not living men, but living rainbows, and that our consciousness dwelt in the green portion of the spectrum. On the one side we would trail off into unconsciousness in the yellow and red and this would escape us inwardly like our will. If we were rainbows, we would not perceive green, because that we are in our beings, we do not perceive immediately; we live it. We would touch the border of the real inner when we tried, as it were, to pass from the green to the yellow. We would say: I, as a rainbow, approach my red portion, but cannot take it up as a real inner experience; I approach my blue-violet, but it escapes me. If we were thinking rainbows, we would thus live in the green and have on the one side a blue-violet pole and on the other side a yellow-red pole. Similarly, we now as men are placed with our consciousness between what escapes us as external natural phenomena in the form of electricity and as inner phenomena in the form of will.

Vierter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Sie werden vielleicht bemerkt haben, daß es bei diesen Betrachtungen im wesentlichen auf eine gewisse Zielsetzung ankommt. Wir wollen eine Reihe von Erscheinungen aus dem Gebiete des Wärmewesens so zusammenstellen, daß wir zuletzt herausfinden können, worin dieses Wärmewesen eigentlich besteht. Wir haben uns im wesentlichen bisher bekanntgemacht mit gewissen Zusammenhängen, die uns durch Erscheinungen innerhalb des Gebietes des Wärmewesens entgegentreten können, und wir haben namentlich beobachtet, in welchem Zusammenhange das Wärmewesen mit der Ausdehnungsfähigkeit der Körper steht. Wir haben dann versucht, zunächst einige Bildvorstellungen festzusetzen über die Gestalt eines festen Körpers, eines flüssigen Körpers und eines luft- oder gasförmigen Körpers. Und ich habe auch gesprochen über die Zusammenhänge des Wärmewesens mit diesen ja an den Körpern hervorzurufenden Verwandlungen: dem Übergang vom festen in den flüssigen, in den gas- oder dampfförmigen Zustand. Nun möchte ich Ihnen jetzt vorführen diejenige Erscheinung, die uns wird zeigen können, welche Verhältnisse auftreten, wenn wir es zu tun haben mit Gasen, mit Dämpfen, von denen wir ja schon wissen, daß sie einen gewissen Zusammenhang haben mit dem Wärmewesen dadurch, daß wir durch das Wärmewesen den gasförmigen Zustand hervorrufen können, daß wir wiederum durch eine gewisse Veränderung des Wärmegrades aus einem dampf- und gasförmigen Körper einen flüssigen herstellen können. Sie wissen, daß, wenn wir einen festen Körper haben, wir unmöglich diesen festen Körper mit einem anderen festen Körper durchdringen können. Die Beobachtung solcher einfacher elementarer Verhältnisse ist außerordentlich wichtig, wenn wir eindringen wollen in das eigentliche Wärmewesen. Dasjenige, was hier jetzt vorgeführt werden soll, das soll zeigen, wie Wasserdampf, den wir hier erzeugen, zunächst hier herübergeht in diesen Kolben und dann eben in diesem Kolben drinnen sein wird. Wir werden also diesen Kolben mit Wasserdampf allmählich anfüllen und werden nun von der anderen Seite zuleiten einen anderen Dampf, dessen Bildung Sie verfolgen können dadurch, daß er hier in einem gefärbten Zustand ist. (Das Experiment wird vorgeführt.) Sie sehen also, trotzdem wir den Kolben gefüllt hatten mit Wasserdampf, ging der andere Dampf von der anderen Seite in den mit Wasserdampf gefüllten Raum hinein, das heißt: Ein Gas hindert nicht, daß ein anderes Gas in denselben Raum eindringt, in dem schon eines drinnen ist. Wir wollen auch diese Erscheinung zunächst als eine solche festhalten, wollen uns also klar darüber sein, daß gas- oder dampfförmige Körper in einem bestimmten Maße füreinander durchdringlich sind.

[ 2 ] Ich will Ihnen nun eine andere Erscheinung vorführen, welche Ihnen zeigen soll noch einen anderen Zusammenhang des Wärmewesens mit anderen Tatsachen. Wir haben hier in der linken Röhre Luft, die einfach in demselben Zustand ist wie die äußere Luft, von der wir fortwährend umgeben sind. Ich muß erwähnen, daß diese äußere Luft, von der wir fortwährend umgeben sind, unter einem gewissen Druck, unserem gewöhnlichen Atmosphärendruck steht, der ja fortwährend auch auf uns selbst drückt. So daß wir sagen können: Die Luft, die wir hier drinnen haben, links, ist unter genau demselben Druck wie die äußere Luft selbst, was sich dadurch zeigt, daß die Quecksilbersäule links und rechts auf demselben Niveau stehen bleibt — daraus, daß links und rechts die Quecksilbersäule gleich hoch steht, ersehen Sie, daß hier (rechts) die äußere Luft, die ja noch von oben freien Zugang hat, unter genau demselben Druck steht wie die Luft hier in dem allseitig geschlossenen Glasrohr (links). Wir wollen nun eine Veränderung dadurch hervorrufen, daß wir den Druck, der auf die Luft in dem linken Glasrohr ausgeübt wird, vergrößern. Das können wir dadurch erreichen, daß wir die rechte Röhre hier heben (Zeichnung rechts). Indem wir diese gehoben haben, haben wir links hinzugefügt zu dem gewöhnlichen Atmosphärendruck noch jenen Druck, der von der erhöhten Quecksilbersäule herrührt. Also einfach das Gewicht der Quecksilbersäule von hier \((a)\) bis hierher \((b)\) habe ich hinzugefügt. Dadurch aber, daß wir auf diese Weise den Druck, der auf diese Luft hier ausgeübt wird, vermehrt haben um jenen Druck, der entspricht dem Gewicht dieser Quecksilbersäule, ist, wie wir sehen, der Rauminhalt, das Volumen, wie man es nennt, in der anderen Glasröhre ein kleinerer geworden, so daß wir sagen können: Wenn wir auf ein Gas einen erhöhten Druck ausüben, so nimmt sein Volumen, sein Rauminhalt ab. Dieses müssen wir als eine weitere Erscheinung festhalten, müssen festhalten, daß Rauminhalt und auf das Gas ausgeübter Druck sich in einem umgekehrten Verhältnis zueinander verhalten. Je größer der Druck, desto geringer der Rauminhalt; je größer der Rauminhalt wird, desto geringer muß der Druck sein, der auf das Gas ausgeübt wird. Wir können aus dieser Erscheinung die Gleichung ableiten, daß sich der Rauminhalt \(V_1\), zu dem Rauminhalt \(V_2\), verhält wie umgekehrt der Druck \(P_2\), zum Druck \(P_1\)

$$V_1:V_2 = P_2:P_1,$$

woraus folgt:

$$V_1 \cdot P_1 = V_2 \cdot P_2.$$

[ 3 ] Daraus ergibt sich also als ein relativ allgemeines Gesetz — wir können ja immer nur von relativen Gesetzen sprechen, bei späteren Betrachtungen werden wir dann sehen warum -, daraus ergibt sich für den Zusammenhang zwischen Volumen und Druck bei Gasen, daß das Produkt aus dem Volumen und aus dem Druck für Gase konstant bleibt, ‘wenn wir die Wärme dieselbe sein lassen. Solche Erscheinungen müssen, wie gesagt, zusammengestellt werden, um uns dem Wesen der Wärme zu nähern. Weil wir ja durch unsere Betrachtungen zugleich auch eine Grundlage für die pädagogische Behandlung in der Schule schaffen wollen, andererseits uns Erkenntnisse verschaffen wollen, handelt es sich darum, daß wir auf der einen Seite kennen die Denkweise der gegenwärtigen Physik und auf der anderen Seite uns bekanntmachen mit dem, was zu geschehen hat, damit man aus verschiedenen, ich könnte sagen, Hindernissen herauskommt, die in der gegenwärtigen Physik für eine wirkliche Erkenntnis des Wärmewesens waltend sind.

[ 4 ] Wenn Sie sich vergegenwärtigen, daß wir es zu tun gehabt haben im wesentlichen neben dem Wärmewesen mit Volumenausdehnung, mit Veränderung also des Raumes und mit Veränderung des Druckes, so müssen Sie sich sagen, es sind uns aufgetreten — ich muß nämlich, um unser Ziel zu erreichen, möglichst genau sprechen, was sonst gewöhnlich nicht geschieht auf diesem Gebiete - im Verlauf unserer Betrachtung über das Wärmewesen mechanische Tatsachen: Raumänderungen, Druckänderungen. Mechanische Tatsachen sind uns entgegengetreten. Nun stand für die moderne Physikentwickelung diese Tatsache da, daß auftrat, wenn man das Wärmewesen betrachtete, mechanisches Geschehen. Dieses mechanische Geschehen wurde gewissermaßen überhaupt dasjenige, an dem man die Wärmeerscheinungen beobachtete. Das Wärmewesen läßt man gewissermaßen in der Sphäre des Unbekannten stehen, und man betrachtet im wesentlichen die mechanischen Vorgänge, die unter dem Einfluß des Wärmewesens sich abspielen. Man betrachtet, indem man von der Wärmeempfindung als von etwas angeblich Subjektivem absieht, bei der Veränderung des Wärmezustandes — des Wärmeempfindens — die Ausdehnung, sagen wir des Quecksilbers, also etwas, das in das Gebiet der mechanischen Erscheinungen gehört. Man betrachtet dann die Abhängigkeit des Wärmezustandes, sagen wir eines Gases, von den Druckverhältnissen, was wir noch weiter verfolgen werden, und haben es da wieder zu tun damit, daß man eigentlich etwas Mechanisches betrachtet und das Wärmewesen gewissermaßen links liegen läßt. Wir haben gestern gesehen, daß es eigentlich einen guten Grund hat, warum dieses Wärmewesen links liegen gelassen worden ist. Denn wir haben gesehen, wie dieses Wärmewesen in dem Augenblick, wo wir es in die Rechnung einführen, den gewöhnlichen Rechnungen Schwierigkeiten macht, wie wir zum Beispiel eine dritte Potenz der Temperatur gar nicht in derselben Weise behandeln können wie eine gewöhnliche dritte Raumpotenz. Und da die landläufige Wärmelehre mit den Potenzen der Temperatur nichts hat anfangen können, hat sie in der Ausdehnungsformel, wie ich Ihnen ja auch in den früheren Betrachtungen gesagt habe, die zweite und dritte Potenz der Temperatur einfach gestrichen.

[ 5 ] Nun brauchen Sie sich aber nur zu überlegen, daß uns ja in der Sphäre der äußeren Natur der Wärmezustand immer entgegentritt an äußeren mechanischen Vorgängen, vor allen Dingen an Raumvorgängen. Die Raumvorgänge sind schon da. An den Raumvorgängen erscheint dann die Wärme. Das bedingt, daß wir, durch diese einfache Überlegung gezwungen, die Wärme so behandeln müssen, wie wir behandeln jene Raumlinie, die uns aus der ersten Potenz einer Ausdehnung in die zweite Potenz der Ausdehnung führt. Wenn wir die erste Potenz der Ausdehnung, die Linie, betrachten, und wir wollen zur zweiten Potenz in der Betrachtung übergehen, so müssen wir aus der Linie hinausgehen. Wir müssen also zu der einen Dimension die andere hinzufügen, wir müssen irgendwie aus der ersten Potenz in die zweite übergehen. Wir müssen uns die Richtlinie der zweiten Potenz ganz anders denken, als wir uns die der ersten Potenz denken. Genau dasselbe aber müssen wir machen, wenn wir einen Temperaturzustand betrachten. Gewissermaßen ist die erste Potenz da in der Ausdehnung. Die Veränderung der Temperatur ist etwas, was im Verhältnis zur Ausdehnung so erscheint, wie hier die zweite Richtlinie zur ersten Richtlinie erscheint. Ich kann auch gar nicht anders, als die Zeichnung so machen, daß ich, indem ich zur Ausdehnung die Temperaturänderung hinzufüge, zu der Abszissenlinie die Ordinatenlinie hinzufüge. Das aber bedingt, daß wir genötigt sind, alles dasjenige, was aus dem Wärmewesen heraus auftritt, also die Temperaturänderung, nicht als erste Potenz zu behandeln, sondern schon von vornherein als zweite Potenz, und die zweite als eine dritte. Und wenn wir die dritte Potenz der Temperatur haben, so können wir nicht mehr in unserem gewöhnlichen Raum drinnen bleiben. Eine einfache Überlegung, die allerdings durch etwas subtile Begriffe angestellt werden muß, zeigt Ihnen, daß es unmöglich ist, wenn wir die im Raum, also in der dritten Dimension, waltende Wärme betrachten, zu bleiben bei der dritten Dimension des Raumes. Sie zeigt Ihnen, daß in dem Augenblick, wo wir es mit den drei Dimensionen des Raumes zu tun haben, wir genötigt sind, wenn wir die Wärmewirkung betrachten, aus dem Raume selber hinauszugehen.

[ 6 ] Nun macht sich ja die moderne Physik zur Aufgabe, behufs Erklärung der Erscheinungen innerhalb des dreidimensionalen Raumes zu bleiben. Und indem sie sich diese Aufgabe setzt, muß sie, da man innerhalb des dreidimensionalen Raumes das Wesen der Wärme nicht finden kann, an dem Wärmewesen vorübergehen. Sie kann das Wärmewesen nur durch seine Äußerungen im dreidimensionalen Raum erfassen.

[ 7 ] Sehen Sie, hier liegt ein sehr wichtiger Punkt, wo gewissermaßen schon innerhalb der unorganischen Naturerscheinungen, der physikalischen Erscheinungen, eine Art Rubikon zu einer höheren Weltanschauung überschritten werden muß. Und man muß schon sagen: Weil so wenig der Versuch gemacht wird, hier an diesen Punkten zu einer Klarheit zu kommen, deshalb herrscht auch diese Klarheit so wenig auf dem Gebiete unserer höheren Weltanschauung. Denken Sie sich nur einmal, wenn die Physiker ihren Studenten beibringen würden, daß man einfach aus den gewöhnlichen Raumverhältnissen, in denen sich die mechanischen Vorgänge abspielen, herauskommen muß, indem man die Wärmeerscheinungen beobachtet, dann würden diese Lehrer der Physik hervorrufen bei denjenigen Menschen, die als erkennende Menschen gelten, weil sie so etwas wie Physik sich angeeignet haben, sie würden die Vorstellung bei ihnen hervorrufen, daß man schon nicht in Wirklichkeit Physik kennenlernen kann, ohne aus dem dreidimensionalen Raum hinauszukommen. Und dann würde es viel leichter sein, eine höhere Weltanschauung zu begründen vor den Menschen der Welt. Denn diese Menschen der Welt würden sagen, selbst wenn sie nicht Physik gelernt haben: Wir können das zwar nicht beurteilen, aber diejenigen, die Physik gelernt haben, die wissen, daß man zunächst durch die Physik von dem Raum zu anderen Verhältnissen aufsteigen muß als denjenigen, die sich im Raum selber abspielen können. Daher hängt auch so sehr viel daran, daß wir in der Physik solche Verhältnisse bekommen, wie sie hier in diesen Betrachtungen werden versucht werden. Es würde sich sonst immer das herausstellen, daß auf der einen Seite versucht würde, in der populären Welt eine auf geistigen Grundlagen fußende Weltanschauung zu verbreiten, daß dann aber die Physiker geltend machen würden: Wir erklären alle Erscheinungen durch rein mechanische Vorgänge. — Das führt dazu, daß die Menschen dann sagen: Ja, im Raume sind überhaupt nur mechanische Vorgänge; Leben muß auch mechanischer Vorgang sein, Seelenvorgänge müssen auch nur mechanische Vorgänge sein, Geistesvorgänge auch. — Die «strenge Wissenschaft» will nichts wissen von irgendwelchen geistigen Grundlagen der Welt. Und die «strenge Wissenschaft» wirkt als eine besonders intensive Autorität aus dem Grunde, weil die Leute sie nicht kennen. Denn dasjenige, was man kennt, das beurteilt man gewöhnlich und läßt sich von ihm nicht eine autoritative Gewalt aufzwingen. Dasjenige, was man nicht kennt, dem verfällt man gewöhnlich als der Autorität. Würde mehr getan werden zur Popularisierung der sogenannten «strengen exakten Wissenschaft», dann würde die autoritative Gewalt gewisser Leute, die hinter Mauern im Besitz dieser «exakten Wissenschaft» sind, wesentlich schwinden.

[ 8 ] Es hat sich nun im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts hinzugefügt zu den Tatsachen, die wir. schon beobachtet haben, eben noch die andere, die ich auch schon angedeutet habe, die darin besteht, daß man nicht nur mechanische Vorgänge auftreten sieht im Verlauf der Vorgänge mit dem Wärmewesen, sondern daß man auch zunächst Wärme überführen kann in mechanische Vorgänge, was Sie ja sehen bei der gewöhnlichen Dampfmaschine, wo erhitzt wird und der mechanische Vorgang der Fortbewegung eintritt; daß man umgekehrt mechanische Vorgänge, Reibung und dergleichen wiederum überführen kann in Wärme, indem dasjenige, was der mechanische Vorgang ist, bewirkt, wie man sagt, das Auftreten von Wärme. So daß man also Wärmevorgänge und mechanische Vorgänge ineinander umwandeln kann. Wir wollen heute die Sache zunächst einmal vorläufig, präliminarisch betrachten und dann auf einzelne Erscheinungen eingehen, die in dieses Gebiet gehören.

[ 9 ] Man hat dann auch des weiteren gefunden, daß nicht nur Wärmevorgänge, sondern auch elektrische Vorgänge, Vorgänge, die in das Gebiet der Chemie gehören, sich umwandeln lassen in mechanische Vorgänge. Und daraus hat sich dasjenige entwickelt, was man gewohnt worden istim Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts eben die mechanische Wärmetheorie zu nennen. Diese mechanische Wärmetheorie hat also zunächst als ihre erste Grundlage: Wärme und mechanische Leistung, sagen wir, können ineinander umgewandelt werden. Nun müssen wir zunächst einmal uns dieses Urteil etwas näher ansehen. Ich kann Sie wirklich nicht davon befreien, Sie auf die elementaren Bestandteile der Urteile zu führen, welche in das Gebiet der Physik gehören. Würden wir gerade bei diesen entscheidenden Betrachtungen uns nicht darauf einlassen, die elementaren Urteilsbestände aufzusuchen, so würden wir überhaupt verzichten müssen, gerade im Gebiet des Wärmewesens, das ein entscheidendes ist, irgendeine Klarheit hervorzurufen. Wir müssen daher schon die Frage aufwerfen: Was heißt es denn überhaupt, wenn ich irgendwo aufzeige, daß Wärme, die ich hervorrufe wie in der Dampfmaschine, äußere Bewegung, also äußere mechanische Arbeit erzeugt? Was heißt das, wenn ich es umwandle in das Urteil: Durch Wärme ist äußere mechanische Arbeit geleistet worden? Unterscheiden wir einmal klar dasjenige, was wir als Tatsachen konstatierbar haben, und dasjenige, was wir dann als ein Urteil an diese Tatsachen angefügt haben. Wir haben konstatiert, daß sich ein Vorgang, der sich als ein Wärmevorgang zeigt, hinterher offenbart durch einen Arbeitsvorgang, durch einen mechanischen Vorgang. Nun wurde daran das Urteil gefügt, der Wärmevorgang, die Wärme als solche, habe sich umgewandelt in den mechanischen Vorgang, in die mechanische Arbeitsleistung.

[ 10 ] Ja, wenn ich in dieses Zimmer hereintrete und in diesem Zimmer irgendeine Temperatur finde, die mir behaglich ist, so trete ich herein und sage mir innerlich, vielleicht ganz unbewußt, ohne daß ich mir das selbst ausspreche: In diesem Zimmer ist es mir behaglich. Ich setze mich hin an den Schreibtisch und schreibe irgend etwas. Das ist entstanden im Gefolge desjenigen, was vorher geschehen ist — ich bin in das Zimmer getreten, der Wärmezustand hat auf mich gewirkt. Hinterher ist das entstanden, was ich niedergeschrieben habe. Ich könnte Ihnen in einer gewissen Weise ja sagen: Nun, wenn ich hier Kellerwärme gefunden hätte, so hätte ich mich aus dem Staube gemacht und hätte nicht diese Arbeit vollzogen, die Arbeit des Niederschreibens dessen, was dann herausgekommen ist. Wenn ich nun an diese Tatsache das Urteil anfüge: Die Wärme, die mir zugeführt worden ist, hat sich in die Arbeit, die hinterher sichtbar geworden ist, verwandelt -—, dann habe ich offenbar in meinem Urteilsbestand etwas ausgelassen. Alles dasjenige, was ich nur durch mich vollziehen konnte, habe ich ausgelassen. Ich muß aber alles das, was ich ausgelassen habe, wenn ich eine totale Wirklichkeit ins Urteil hereinbekommen will, aufnehmen. Die Frage entsteht nun: Wenn in der ganzen äquivalenten Tatsachenfolge Wärme vorhanden ist, die ich hervorgerufen habe wie in der Dampfkesselheizung, und nachher Arbeit entsteht, die Fortbewegung der Lokomotive, und ich einfach sage, es habe sich die Wärme in Arbeit verwandelt, habe ich nicht vielleicht da denselben Fehler gemacht wie den, den ich mache, wenn ich in dem vorhergehenden Urteil einfach spreche von der Verwandlung des Wärmezustandes in die Wirkung, die aber nur dadurch eingetreten ist, daß ich selbst mich eingeschaltet habe? Es ist scheinbar vielleicht sogar trivial, auf eine solche Sache aufmerksam zu machen, aber diese Trivialität wird gerade in der ganzen mechanischen Wärmetheorie übersehen, vergessen. Und darauf kommt außerordentlich viel an. Darauf kommt es an, daß man zwei Dinge miteinander verbindet, das erste, daß in dem Augenblick, wo man aus der Sphäre der mechanischen Vorgänge übertritt in die Sphäre, wo Wärme wirkt, man überhaupt den dreidimensionalen Raum verlassen muß. Und zweitens, daß man also einfach, indem man die äußeren Naturerscheinungen beobachtet, dasjenige vielleicht nicht hat, was man in dem Fall als Einschiebsel hat, wenn sich Wärme in mein Schreibprodukt verwandelt. Wenn sich Wärme in mein Schreibprodukt verwandelt, dann kann ich an meiner äußeren leiblichen Offenbarung beobachten, daß sich etwas eingeschaltet hat. Wenn ich aber einfach der Tatsache gegenüberstehe, daß ich den dreidimensionalen Raum verlassen muß, sofern sich mir Wärme in äußere Leistung verwandelt, so kann ich doch sagen: Vielleicht das Wichtigste, was zu dieser Umwandlung führt, vollzieht sich außerhalb des dreidimensionalen Raumes. Dasjenige, was dem entsprechen würde, daß ich mich einschalte, vollzieht sich außerhalb des dreidimensionalen Raumes. Und ich begehe dieselbe Oberflächlichkeit, wenn ich einfach von der Umwandlung der Wärme in mechanische Arbeit rede, wie ich sie begehe, wenn ich von der Umwandlung der Wärme in mein Schreibprodukt rede und dabei vergesse, daß ich selber eingeschaltet bin.

[ 11 ] Das hat aber eine sehr bedeutende, universelle Konsequenz, denn es nötigt mich dazu, daß ich mich bei der äußeren Natur auch in ihren leblosen, in ihren unorganischen Erscheinungen geführt denke in ein Wesen, das sich selbst nicht innerhalb des dreidimensionalen Raumes ausdrückt, das gewissermaßen waltet hinter dem dreidimensionalen Raum. Und dieses ist ein Entscheidendes in bezug auf die Beobachtung des Wärmewesens selber.

[ 12 ] Wir können jetzt, indem wir dieses als Elementarbestandteil des Urteils im Wärmegebiet aufgewiesen haben, ein wenig wiederum zurückblicken auf das, was wir schon angedeutet haben: auf des Menschen eigenes Verhältnis zum Wärmewesen. Wir können vergleichen andere Wahrnehmungssphären mit der Wahrnehmungssphäre des Wärmewesens. Ich habe schon darauf hingewiesen, daß, indem wir zum Beispiel Licht wahrnehmen, wir diese Wahrnehmung des Lichtes und der Farbe gebunden sehen an abgesonderte Organe, die einfach in unseren Organismus hineingelegt sind, so daß wir nicht davon sprechen können, daß wir mit unserem ganzen Organismus gegenüberstehen dem Farben- beziehungsweise Lichtwesen, sondern daß wir nur mit einem Teil unseres Organismus dem Licht- oder Farbenwesen gegenüberstehen. Ebenso ist es bei den akustischen, bei den Tonerscheinungen. Wir stehen mit einem Teil, mit den Gehörorganen, dem Tonwesen gegenüber. Dem Wärmewesen stehen wir gegenüber mit unserem ganzen Organismus. Dadurch ist aber unser Verhältnis zum Wärmewesen bedingt. Und wenn wir genauer zusehen, wenn wir versuchen, diese Tatsache, ich möchte sagen, in Menschenerkenntnis umzuwandeln, so müssen wir sagen: Wir sind eigentlich dieses Wärmewesen ja selbst. Insofern wir hier im Raume als Mensch wandeln, sind wir dieses Wärmewesen ja selbst. In dem Augenblick, wo Sie sich die Temperatur um ein paar hundert Grade erhöht denken würden, würden Sie nicht identisch sein können mit dem Temperaturzustand, ebensowenig wenn Sie sich die Temperatur um hundert Grade vertieft denken. So gehört das Wärmewesen zu dem, in dem wir stets drinnenstehen, das wir als selbstverständliches Wesen erleben, das wir aber nicht ins Bewußtsein hereinnehmen. Nur wenn Abweichungen vom normalen Zustand eintreten, werden sie uns in irgendeiner Form bewußt.

[ 13 ] Nun kann, angeknüpft an diese Tatsache, eine zweite beobachtet werden. Das ist diese: Wenn Sie irgendwie an einen erwärmten Gegenstand herantreten und den Wärmezustand mit Ihrem Organismus beobachten - Sie können es tun mit der Fingerspitze, auch mit der Zehenspitze, Sie können es tun an einem anderen Ort Ihres Organismus, meinetwillen mit dem Ohrläppchen; gewissermaßen mit dem ganzen Organismus können Sie den Wärmezustand wahrnehmen. Aber Sie können noch etwas anderes mit Ihrem ganzen Organismus wahrnehmen. Sie können das wahrnehmen, was auf Ihren Organismus drückt. Und da sind Sie wiederum nicht gebunden im strengen Sinne, so wie zum Beispiel bei der Farbenwahrnehmung an das Auge, an ein bestimmtes Glied Ihres Organismus. Es wäre ja sehr angenehm, wenn wenigstens zum Beispiel der Kopf ausgenommen wäre von dieser Druckwahrnehmung. Wir könnten ihn dann nicht in unbehaglicher Weise anschlagen und die Folgen davon tragen müssen. Wir können sagen: Es besteht eine innige Verwandtschaft in der Art unseres Verhältnisses zur Außenwelt zwischen den Wärmeempfindungen und den Druckempfindungen. Wir haben heute gesprochen von Druckverhältnissen im Verhältnis zur Volumenänderung. Wir kommen jetzt zurück auf unseren eigenen Organismus und finden die Wärmeverhältnisse in einer innigen Verwandtschaft mit den Druck verhältnissen. Solch eine Tatsache müssen wir auch zur Begründung des Folgenden durchaus ins Auge fassen.

[ 14 ] Aber es gibt noch etwas anderes, was wir unseren folgenden Betrachtungen vorausschicken müssen. Sie wissen, gerade in den gebräuchlichen Handbüchern über physikalische, physiologische Vorgänge wird eigentlich recht viel Wesens davon gemacht, daß wir bestimmte Organe haben, oder uns selbst haben zur Wahrnehmung der gewöhnlichen Sinnesqualitäten. Wir haben das Auge für die Farbe, das Ohr für den Ton, das Geschmacksorgan für gewisse chemische Vorgänge und so weiter; wir haben verteilt über unseren ganzen Organismus gewissermaßen das einheitliche Wärmeorgan, aber auch das einheitliche Druckorgan. Nun wird gewöhnlich darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß aber auch noch anderes wahrgenommen wird, wofür wir, wie man nun sagt, keine Organe haben: Magnetismus, Elektrizität, die wir nur in ihren Wirkungen wahrnehmen, die gewissermaßen draußen stehenbleiben, die wir nicht unmittelbar wahrnehmen. Man sagt dann wohl auch: Wenn unser Auge nicht lichtempfindlich, sondern elektrizitätsempfindlich wäre, so würde es, wenn es hinschaut auf einen Telegraphendraht, die strömende Elektrizität drinnen wahrnehmen. Es würde die Elektrizität nicht bloß in Wirkungen, sondern so wie die Farben- und Lichtvorgänge unmittelbar wahrnehmen. Das können wir nicht. Wir können also nur sagen: Elektrizität zum Beispiel ist etwas, wofür wir zur unmittelbaren Wahrnehmung keine Organe haben. Es gibt also Naturqualitäten, zu deren Wahrnehmung wir Organe haben, und Naturqualitäten, zu deren Wahrnehmung wir keine Organe haben. — So sagt man.

[ 15 ] Nun handelt es sich darum, ob sich nicht vielleicht für den, der etwas unbefangener die Erscheinungen betrachtet als diejenigen, die zu diesem Urteil kommen, doch noch etwas anderes ergibt. Sie wissen ja alle, wie innig zusammenhängt dasjenige, was wir unsere gewöhnlichen passiven Vorstellungen nennen, durch die wir die Welt wahrnehmen, mit den Eindrücken des Auges, des Ohres, weniger schon zusammenhängt mit dem, was wir durch Geschmack und Geruch wahrnehmen. Versuchen Sie nur einmal, rein aus dem Sprachbestand heraus, sich die Summe Ihres höheren Vorstellungslebens einmal zu ziehen, so werden Sie sehen, daß man noch in den Worten, die wir zur Repräsentierung unserer Begriffe brauchen, überall die Reste der höheren Sinnesqualitäten wahrnehmen kann. Sogar wenn wir das sehr abstrakte Wort «Sein» aussprechen, so hängt seine Bildung zusammen mit «Ich habe gesehen». Ich nenne dasjenige das Seiende, was ist, was ich gesehen habe. Im «Sein» steckt noch das «Gesehenhaben» drinnen. Und ohne daß man dabei in den Materialismus verfällt - wir werden sehen, aus welchem Grunde man ihm nicht zu verfallen braucht -, kann man sagen, daß unsere Vorstellungswelt eigentlich eine Art Filtrieren des Sehens und Hörens, schon weniger des Riechens und Schmeckens ist, denn weniger solche Sinneswahrnehmungen stecken in unserer Vorstellungswelt drinnen. Dadurch, daß unser Bewußtsein innig zusammen ist mit diesen unseren höheren Sinnesqualitäten, nimmt auch unser Bewußtsein dieses passive höhere Vorstellungswesen auf.

[ 16 ] Allein, wir haben innerhalb unseres Seelenwesens von der anderen Seite her auch unseren Willen, und Sie werden sich erinnern, wie oft ich gerade in den anthroposophischen Vorträgen betont habe, daß dem Willen gegenüber der Mensch eigentlich schläft. Er wacht im Grunde genommen nur im Gebiete seiner höheren passiven Vorstellungen. Was Sie wollen, nehmen Sie ja auch nur durch diese Vorstellungen wahr. Sie haben die Vorstellung: Ich hebe dieses Glas auf. Ja, was darin Vorstellungsbestandteile sind, das ist durchaus etwas, worin die Reste der Außenwahrnehmungen sind. Sie stellen sich etwas vor, was durchaus in das Gebiet der Sichtbarkeit gehört. Auch wenn Sie es denken, haben Sie das Nachbild des Sichtbaren. Solch ein Nachbild in unmittelbarer Art können Sie sich nicht verschaffen von dem eigentlichen Willensvorgang, von dem, was nun geschieht, indem Sie den Arm ausstrecken, mit der Hand das Glas umfassen, es heben. Das ist ein vollständig im Unbewußten bleibender Vorgang, was sich da abspielt zwischen Bewußtsein und feineren Vorgängen in dem Arm. Das bleibt so unbewußt, wie uns die Schlafzustände, in die wir verfallen vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen, unbewußt bleiben. Aber kann man denn leugnen, daß diese Vorgänge, wenn wir sie auch nicht wahrnehmen, doch da sind? Diese Vorgänge müssen doch innig verbunden sein mit unserem Menschenwesen, denn wir sind es doch, die das Glas heben. Wir werden also im Gebiet unseres Menschenwesens geführt von dem, was unmittelbar im Bewußtsein lebt, zu den Willensvorgängen, die gewissermaßen aus dem gewöhnlichen Gebiet des Bewußtseins herausragen. Nehmen wir an, alles das, was über dieser Linie liegt, sei im Gebiete des Bewußtseins. Was unterhalb liegt, also in die Willensvorgänge sich einsenkt, sei außerhalb des Bewußtseins. Gehen wir nun von da ab zum Gebiet der äußeren Naturerscheinungen: Wir finden unser Auge innig verbunden mit den Farbenerscheinungen, etwas, was wir im Bewußtsein überschauen; wir finden unser Ohr verbunden mit den Tonerscheinungen, etwas, was wir mit dem Bewußtsein überschauen. Dunkel, aber immerhin noch für das Bewußtsein traumhaft überschaubar, ist Schmecken und Riechen. Wir haben wieder etwas, was durchaus in das Gebiet des Bewußten hereingehört, aber mit der Außenwelt sich innig berührt.

[ 17 ] Indem wir aber übergehen zu magnetischen und elektrischen Erscheinungen, entzieht sich uns dasjenige, was in Elektrizität und Magnetismus und so weiter lebt, demjenigen, was wir überschauen in unmittelbarem Zusammenhang unserer Organe mit der Natur. Es entzieht sich uns. Da sagen eben die Physiker, die Physiologen: Wir haben dafür keine Organe, das kann nur äußerlich wahrgenommen werden, es sondert sich von uns ab, es ist da draußen (siehe Zeichnung, oben). — Wir haben also ein Gebiet, dem wir uns nähern, wenn wir nach der Außenwelt hingehen. Da haben wir Lichterscheinungen, Wärmeerscheinungen. Die Elektrizitätserscheinungen, wo entschlüpfen sie uns denn? Wir spüren nicht mehr den Zusammenhang mit den Organen. Wir haben in uns, indem wir Licht- und Tonerscheinungen verarbeiten, filtrierte Abdrücke in unserem Vorstellen. Wenn wir aber da hinuntergehen (unten, rot), entschlüpft unser eigenes Wesen uns in den: Willen hinein.

[ 18 ] Ich werde jetzt etwas Paradoxes sagen, aber denken Sie es durch bis morgen. Denken Sie, wir wären nicht lebendige Menschen, sondern lebendige Regenbögen, und wir würden mit unserem Bewußtsein gerade sitzen im grünen Teil des Regenbogens, des Spektrums. Wir würden mit unserem Unbewußten angrenzen auf der einen Seite an das Blauviolett des Regenbogens, das würde uns entschwinden nach der einen Seite hin wie die Elektrizität; nach der anderen Seite würden wir angrenzen an Gelb und Rot, das würde uns entschwinden, wie nach innen unser Wille. Wenn wir Regenbögen wären, würden wir Grün nicht wahrnehmen, so wie wir das, was wir unmittelbar sind, nicht wahrnehmen unmittelbar; wir erleben es. Wir würden aber angrenzen, indem wir hier gewissermaßen aus dem Grün herausgehend ins Gelb übergehen, an das eigene Innere. Wir würden sagen: Ich, Regenbogen, nähere mich meiner Röte, die ich aber als Inneres nicht mehr wahrnehme; ich, Regenbogen, nähere mich meinem Blauviolett, was sich mir aber entzieht. Ich bin da mitten drinnen. - Wären wir also denkende, lebendige Regenbögen, so würden wir so im Grün drinnensitzen und auf der einen Seite den blauvioletten Pol haben, auf der anderen Seite den rotgelben Pol, wie wir jetzt als Menschen mit unserem Bewußtsein irgendwo sitzen, auf der einen Seite die Naturqualitäten haben, die sich uns so entziehen wie Magnetismus und Elektrizität, auf der anderen Seite die inneren Qualitäten, die sich uns so entziehen wie die Willenserscheinungen.

Fourth Lecture

[ 1 ] You may have noticed that these considerations essentially depend on a certain objective. We want to compile a series of phenomena from the field of heat so that we can ultimately find out what heat actually consists of. So far, we have essentially familiarized ourselves with certain connections that we may encounter through phenomena within the field of heat, and we have observed in particular the connection between heat and the expansibility of bodies. We then attempted to establish some initial ideas about the form of a solid body, a liquid body, and an air or gas-like body. And I also spoke about the connections between the nature of heat and these transformations that can be brought about in bodies: the transition from a solid to a liquid to a gaseous or vaporous state. Now I would like to demonstrate to you the phenomenon that will show us what conditions arise when we are dealing with gases and vapors, which we already know have a certain connection with the nature of heat in that we can bring about the gaseous state through the nature of heat, and that we can again produce a liquid from a vaporous and gaseous bodies. You know that if we have a solid body, it is impossible to penetrate this solid body with another solid body. Observing such simple, elementary conditions is extremely important if we want to delve into the actual nature of heat. What is to be demonstrated here now is how water vapor, which we generate here, first passes over into this flask and then remains inside this flask. So we will gradually fill this flask with water vapor and then feed in another vapor from the other side, the formation of which you can follow because it is colored here. (The experiment is demonstrated.) So you see, even though we had filled the flask with water vapor, the other vapor from the other side entered the space filled with water vapor, which means that one gas does not prevent another gas from entering the same space in which one is already present. Let us also note this phenomenon for the time being, so that we are clear that gaseous or vaporous bodies are permeable to each other to a certain extent.

[ 2 ] I would now like to demonstrate another phenomenon to you, which will show you yet another connection between the nature of heat and other facts. Here in the left tube we have air that is simply in the same state as the outside air that constantly surrounds us. I must mention that this outside air that constantly surrounds us is under a certain pressure, our normal atmospheric pressure, which also constantly presses down on us. So we can say that the air we have here inside, on the left, is under exactly the same pressure as the outside air itself, which is shown by the fact that the mercury columns on the left and right remain at the same level — from the fact that the mercury columns on the left and right are at the same height, you can see that here (on the right), the outside air, which still has free access from above, is under exactly the same pressure as the air here in the glass tube (on the left), which is closed on all sides. We now want to bring about a change by increasing the pressure exerted on the air in the left glass tube. We can achieve this by lifting the right tube here (drawing on the right). By lifting it, we have added to the normal atmospheric pressure on the left the pressure resulting from the increased mercury column. So I have simply added the weight of the mercury column from here \((a)\) to here \((b)\). However, by increasing the pressure exerted on this air by the pressure corresponding to the weight of this mercury column, the volume in the other glass tube has become smaller, as we can see, so that we can say: When we exert increased pressure on a gas, its volume, its spatial content, decreases. We must note this as a further phenomenon, we must note that spatial content and the pressure exerted on the gas are inversely proportional to each other. The greater the pressure, the smaller the spatial content; the greater the volume, the lower the pressure exerted on the gas must be. From this phenomenon, we can derive the equation that the volume \(V_1\) is inversely proportional to the volume \(V_2\), and the pressure \(P_2\) is inversely proportional to the pressure \(P_1\).

$$V_1:V_2 = P_2:P_1,$$

from which it follows that:

$$V_1 \cdot P_1 = V_2 \cdot P_2.$$

[ 3 ] This results in a relatively general law—we can only ever speak of relative laws, and we will see why in later considerations—which states that the product of volume and pressure remains constant for gases, 'if we keep the heat the same. As mentioned, such phenomena must be compiled in order to approach the essence of heat. Because we want our observations to serve as a basis for teaching in schools, while also gaining insights ourselves, we need to familiarize ourselves with the thinking behind contemporary physics on the one hand, and on the other hand with what needs to be done to overcome the various obstacles that currently prevent physics from truly understanding the nature of heat. I might say, obstacles that prevail in contemporary physics to a real understanding of the nature of heat.

[ 4 ] If you remember that, in addition to the nature of heat, we have essentially had to deal with volume expansion, i.e., changes in space and changes in pressure, you must say to yourself that we have encountered—I must speak as precisely as possible in order to achieve our goal, which is not usually the case in this field—mechanical facts in the course of our consideration of the nature of heat: changes in space, changes in pressure. Mechanical facts confronted us. Now, modern physics was faced with the fact that, when considering the nature of heat, mechanical events occurred. These mechanical events became, in a sense, the very basis on which heat phenomena were observed. Heat is left, as it were, in the realm of the unknown, and we essentially observe the mechanical processes that take place under the influence of heat. By disregarding the sensation of heat as something supposedly subjective, one observes the change in the state of heat — the sensation of heat — the expansion, say, of mercury, something that belongs to the realm of mechanical phenomena. We then consider the dependence of the state of heat, say of a gas, on the pressure conditions, which we will pursue further, and again we are dealing with something mechanical and leaving the heat entity aside, so to speak. Yesterday we saw that there is actually a good reason why this thermal entity has been left out. For we have seen how, the moment we introduce this thermal entity into the calculation, it causes difficulties for ordinary calculations, how, for example, we cannot treat a third power of temperature in the same way as an ordinary third power of space. And since conventional thermodynamics has no use for the powers of temperature, it has simply eliminated the second and third powers of temperature from the expansion formula, as I have already mentioned in earlier considerations.

[ 5 ] Now, however, you only need to consider that in the sphere of external nature, the state of heat always confronts us in external mechanical processes, above all in spatial processes. The spatial processes are already there. Heat then appears in the spatial processes. This means that, forced by this simple consideration, we must treat heat in the same way as we treat the spatial line that leads us from the first power of an extension to the second power of the extension. If we consider the first power of extension, the line, and we want to move on to the second power in our consideration, we must go beyond the line. We must therefore add the other dimension to the first; we must somehow move from the first power to the second. We have to think of the guideline of the second power in a completely different way than we think of that of the first power. But we have to do exactly the same thing when we consider a temperature state. In a sense, the first power is present in the expansion. The change in temperature is something that appears in relation to the expansion in the same way that the second guideline appears in relation to the first guideline. I have no choice but to draw the diagram in such a way that, by adding the change in temperature to the expansion, I add the ordinate line to the abscissa line. But this means that we are forced to treat everything that arises from the thermal entity, i.e., the change in temperature, not as a first power, but from the outset as a second power, and the second as a third. And when we have the third power of temperature, we can no longer remain within our usual space. A simple consideration, which must, however, be made using somewhat subtle concepts, shows you that it is impossible, when we consider the heat prevailing in space, i.e., in the third dimension, to remain within the third dimension of space. It shows you that the moment we deal with the three dimensions of space, we are forced to leave space itself when we consider the effect of heat.

[ 6 ] Now, modern physics has set itself the task of remaining within three-dimensional space in order to explain phenomena. And in setting itself this task, it must, since the essence of heat cannot be found within three-dimensional space, pass over the essence of heat. It can only grasp the essence of heat through its manifestations in three-dimensional space.

[ 7 ] You see, this is a very important point, where, in a sense, even within inorganic natural phenomena, physical phenomena, a kind of Rubicon must be crossed to reach a higher worldview. And it must be said: because so little attempt is made to achieve clarity on these points, this clarity is also so lacking in the realm of our higher worldview. Just imagine if physicists taught their students that one must simply step outside the ordinary spatial conditions in which mechanical processes take place by observing thermal phenomena. Then these teachers of physics would evoke in those people who are considered knowledgeable because they have acquired something like physics they would give them the mental image that it is not really possible to learn physics without leaving three-dimensional space. And then it would be much easier to establish a higher worldview before the people of the world. For these people of the world would say, even if they have not studied physics: We cannot judge this, but those who have studied physics know that one must first ascend through physics from space to other conditions than those that can take place in space itself. Therefore, it is so important that we obtain such conditions in physics as will be attempted here in these considerations. Otherwise, it would always turn out that, on the one hand, attempts would be made to spread a worldview based on spiritual foundations in the popular world, but then physicists would assert: We explain all phenomena through purely mechanical processes. — This leads people to say: Yes, there are only mechanical processes in space; life must also be a mechanical process, soul processes must also be only mechanical processes, mental processes too. “Strict science” wants to know nothing about any spiritual foundations of the world. And “strict science” exerts a particularly intense authority precisely because people do not know it. For what one knows, one usually judges and does not allow it to impose an authoritative power on oneself. What one does not know, one usually succumbs to as authority. If more were done to popularize so-called “rigorous exact science,” the authoritative power of certain people who are behind walls in possession of this “exact science” would diminish considerably.

[ 8 ] In the course of the 19th century, another fact has been added to those we have already observed. have already observed, there is another, which I have already hinted at, which consists in the fact that not only do mechanical processes occur in the course of processes involving heat, but that heat can also be converted into mechanical processes, as you can see in the ordinary steam engine, where heating takes place and the mechanical process of motion occurs; Conversely, mechanical processes, friction, and the like can be converted back into heat, in that the mechanical process causes, as they say, the occurrence of heat. So heat processes and mechanical processes can be converted into one another. Today, we will first take a preliminary look at the matter and then discuss individual phenomena that belong to this field.

[ 9 ] It was then also discovered that not only heat processes, but also electrical processes, processes belonging to the field of chemistry, can be converted into mechanical processes. This led to the development of what became known in the 19th century as the mechanical theory of heat. The first principle of this mechanical theory of heat is that heat and mechanical energy can be converted into each other. Now we must first take a closer look at this judgment. I really cannot spare you the task of guiding you through the elementary components of judgments that belong to the field of physics. If we did not engage in these crucial considerations and seek out the elementary components of judgment, we would have to forego any attempt to achieve clarity, especially in the field of heat, which is a crucial one. We must therefore ask the question: What does it mean when I point out somewhere that heat, which I generate as in a steam engine, produces external motion, i.e., external mechanical work? What does it mean when I transform this into the judgment: external mechanical work has been performed by heat? Let us make a clear distinction between what we can state as facts and what we then add to these facts as a judgment. We have stated that a process that manifests itself as a heat process subsequently reveals itself through a work process, through a mechanical process. Now the judgment has been added that the heat process, the heat as such, has been converted into the mechanical process, into mechanical work.

[ 10 ] Yes, when I enter this room and find a temperature in this room that is comfortable for me, I enter and say to myself, perhaps quite unconsciously, without saying it out loud: I feel comfortable in this room. I sit down at the desk and write something. This arose as a result of what happened before—I entered the room, and the warmth had an effect on me. Afterwards, what I wrote down came into being. In a way, I could say to you: Well, if I had found the basement warm, I would have left and would not have done this work, the work of writing down what then came out. If I now add the judgment to this fact: The warmth that was conveyed to me was transformed into the work that became visible afterwards — then I have obviously omitted something in my judgment. I have omitted everything that I could only accomplish through myself. But if I want to include the whole reality in my judgment, I must include everything I have left out. The question now arises: if there is heat present in the whole equivalent sequence of facts, which I have produced, as in the steam boiler heating, and afterwards work is produced, the locomotive's movement, and I simply say the heat has been transformed into work, have I not perhaps made the same mistake as the one I make when, in the previous judgment, I simply speak of the transformation of the heat state into the effect, which, however, only occurred because I myself intervened? It may seem trivial to point out such a thing, but this triviality is overlooked and forgotten in the whole of mechanical heat theory. And this is extremely important. What matters is that two things are connected: first, that at the moment when one passes from the sphere of mechanical processes into the sphere where heat acts, one must leave three-dimensional space altogether. And secondly, that simply by observing external natural phenomena, one may not have what one has in this case as an insertion when heat is transformed into my written product. When heat is transformed into my writing product, I can observe from my external physical manifestation that something has been activated. But when I am simply faced with the fact that I must leave three-dimensional space when heat is transformed into external performance, I can still say: perhaps the most important thing that leads to this transformation takes place outside of three-dimensional space. That which would correspond to my switching on takes place outside three-dimensional space. And I commit the same superficiality when I simply talk about the transformation of warmth into mechanical work as I do when I talk about the transformation of warmth into my writing product and forget that I myself am switched on.

[ 11 ] But this has a very significant, universal consequence, because it compels me to think of myself in relation to external nature, even in its lifeless, inorganic manifestations, as a being that does not express itself within three-dimensional space, that, in a sense, reigns behind three-dimensional space. And this is a decisive factor in relation to the observation of the heat entity itself.

[ 12 ] Now that we have shown this to be an elementary component of judgment in the realm of warmth, we can look back a little at what we have already indicated: at man's own relationship to the warmth being. We can compare other spheres of perception with the sphere of perception of the warmth being. I have already pointed out that when we perceive light, for example, we see this perception of light and color as bound to separate organs that are simply placed within our organism, so that we cannot say that we face the color or light entity with our whole organism, but that we face the light or color entity with only a part of our organism. The same is true of acoustic phenomena, of sound. We face the sound entity with a part of ourselves, with our hearing organs. We face the heat entity with our whole organism. But this means that our relationship to the heat entity is conditional. And if we look more closely, if we try to transform this fact, I would say, into human knowledge, we must say: we are actually this heat entity ourselves. Insofar as we walk here in this room as human beings, we are this heat being ourselves. The moment you imagine the temperature rising by a few hundred degrees, you would not be able to be identical with the temperature state, any more than if you imagined the temperature falling by a hundred degrees. Thus, the heat being belongs to that in which we always stand, which we experience as a self-evident being, but which we do not take into our consciousness. Only when deviations from the normal state occur do they become conscious to us in some form.

[ 13 ] Now, based on this fact, a second one can be observed. This is: if you approach a heated object in some way and observe the state of heat with your organism—you can do this with your fingertip, or even with your toe, you can do it with another part of your organism, with your earlobe for example; in a sense, you can perceive the state of heat with your whole organism. But you can perceive something else with your entire organism. You can perceive what is pressing on your organism. And here again, you are not bound in the strict sense, as you are, for example, with color perception by the eye, to a specific part of your organism. It would be very pleasant if at least the head, for example, were exempt from this perception of pressure. Then we would not have to strike it in an uncomfortable way and suffer the consequences. We can say that there is an intimate relationship between the way we relate to the outside world, between the sensations of warmth and the sensations of pressure. Today we have talked about pressure conditions in relation to volume change. We now return to our own organism and find that heat conditions are closely related to pressure conditions. We must also take this fact into account in order to justify the following.

[ 14 ] But there is something else we must mention before proceeding with our considerations. As you know, standard textbooks on physical and physiological processes make quite a big deal of the fact that we have certain organs, or ourselves, for perceiving the usual sensory qualities. We have the eye for color, the ear for sound, the taste organ for certain chemical processes, and so on; we have, distributed throughout our entire organism, the uniform heat organ, so to speak, but also the uniform pressure organ. Now, attention is usually drawn to the fact that other things are also perceived for which, as they say, we have no organs: magnetism, electricity, which we perceive only in their effects, which remain outside, so to speak, and which we do not perceive directly. It is also said that if our eye were not sensitive to light but to electricity, it would perceive the flowing electricity inside when looking at a telegraph wire. It would perceive the electricity not only in its effects, but directly, just as it perceives colors and light. We cannot do that. So we can only say: Electricity, for example, is something for which we have no organs of direct perception. There are therefore qualities of nature for which we have organs of perception, and qualities of nature for which we have no organs of perception. — That is what people say.

[ 15 ] Now the question is whether something else might not emerge for those who view phenomena more impartially than those who come to this conclusion. You all know how closely connected what we call our ordinary passive mental images, through which we perceive the world, are with the impressions of the eye and the ear, and less so with what we perceive through taste and smell. Just try, purely from your vocabulary, to draw up a summary of your higher imaginative life, and you will see that even in the words we use to represent our concepts, you can still perceive the remnants of the higher sensory qualities everywhere. Even when we utter the very abstract word “being,” its formation is connected with “I have seen.” I call that which is, that which I have seen, being. “Being” still contains “having seen.” And without falling into materialism — we will see why there is no need to fall into it — we can say that our world of ideas is actually a kind of filtering of seeing and hearing, and to a lesser extent of smelling and tasting, because these sensory perceptions are less present in our world of ideas. Because our consciousness is intimately connected with these higher sensory qualities, our consciousness also takes in this passive higher realm of imagination.