| 250. The History of the German Section of the Theosophical Society 1902-1913: Protocol of the Extraordinary General Assembly of the German Theosophical Society (DTG)

05 Feb 1905, Berlin |

|---|

| At the time, I readily agreed to fulfill this wish, and in the pursuit of this matter, I asked to form an executive committee. I did not dream what came of it. We still have no branch in the north, south, or east. It was my intention to work not only in the west, but in all parts of the city. |

| 250. The History of the German Section of the Theosophical Society 1902-1913: Protocol of the Extraordinary General Assembly of the German Theosophical Society (DTG)

05 Feb 1905, Berlin |

|---|

Dr. Steiner: “Careful scrutiny of the lines along which we were moving showed me that it is necessary to contribute something to clarify the things that were suggested at the time. That is why I asked you to appear at this General Assembly. I would like to emphasize from the outset that it will not be a matter of somehow interpreting the steps that three members of the Executive Board felt compelled to take in such a way that they could be directed against anyone, even remotely. The aim is to clarify the situation by means of a full clarification that cannot be achieved in any other way. In order to make this completely clear, I must still refer to a few words on the essentials, to the history of the Theosophical movement since the founding of the German section, namely insofar as it concerns members of the board, who come into consideration above all. When the German Section was to be founded, the leaders of the Theosophical movement, insofar as they belonged to the Adyar Society, were to be persuaded to hand over the leadership to others. The personalities involved in the continuation of the theosophical work were Fräulein von Sivers and I. I myself was not yet ready to join the Theosophical Society, even a few months before I was called upon to contribute not only to the Berlin group but also to the entire movement of the Theosophical Society in my capacity as General Secretary of the German Section. I had already given lectures for two winters, in the Berlin branch. Two courses that have been printed, so that I am connected with the Theosophical Society in Berlin in a certain respect, am connected only personally. When Count and Countess von Brockdorff left Berlin, I had already been a member of the Theosophical Society for several months, and when other measures failed, I was designated as General Secretary. I did not oppose the request at the time. I had no merit in the Theosophical Society at the time. Berlin was considered a kind of center in Germany. Berlin was to become a kind of parent company. The German Theosophical Society (DTG) was built on this. The aim was to run the society from Berlin. At that time, Count and Countess Brockdorff went to great lengths to recruit Fräulein von Sivers, who was in Bologna, for their Berlin lodge. Even after she had been asked, she was not at all inclined to accept. Only when the leaders of the Theosophical Society deemed it necessary did Miss von Sivers decide to go to Berlin and lead the Theosophical movement with me under the conditions that were possible at the time. We adapted ourselves to the circumstances in an absolutely conservative way. The circumstances naturally required that we take the initiative of the German movement into our own hands and try to bring the intentions to fruition in the right way. The situation in Germany was such that it would not have been possible at that time without initiative in a material sense. In addition to this material theosophical work, there were many other things, such as, for example, the management of the library, which was in a loose connection with the German Theosophical Society, the later Berlin branch of the Theosophical Society. This management of the library naturally required a certain amount of work, which had to be done between classes. The actual Theosophical work could only be done in the free breaks. I myself could devote myself to these library matters only in an advisory capacity. I had more important things to do. Besides, for two years I had been able to study the way the branch had been run, and I had no intention of making any kind of change in the external administration. What was factually given should be preserved. It was our endeavor to operate within the framework and to throw what we had to give into the framework of the Theosophical movement. That was our endeavor. The basic prerequisite for Fräulein von Sivers to take over the management of the various agencies of the Theosophical Society in Berlin was that complete trust prevailed. Without this trust, nothing can be done in the practical part of the Theosophical movement. Trust in the practical part of the movement itself is necessary. The administration is a kind of appendage. Since we could not engage in any particular pedantry, it was natural that we expected complete trust in what is the basic requirement for working together in the theosophical field. This trust does not appear to have been given to the extent that we would need it to conduct the business calmly and objectively. We will only make the final point by linking it to the meeting two weeks ago and contrasting it with it. This meeting was based on things that were even referred to as gossip; they were based on public appearances. Everything is to be discussed in public. The fact that there is dissatisfaction was admitted in the meeting, and the expression of a mood of discontent is in itself enough to bring about such a step as is to be taken today. I am - let this be accepted as an absolutely true interpretation - I am, not only because every occultist is, but on much more esoteric principles, opposed to all aggression. Every act of aggression hinders the activity that I would be able to unfold. Please regard this step as something that merely follows from the principle of not acting aggressively. Everyone must behave in such a way that the wishes of all can be fully expressed. Everyone must suppress their personal desires so that our work can be done. Otherwise, the Berlin branch cannot be managed as desired. That is what I would like to achieve. When opposing views are expressed, it is impossible to work together. If we work in such a way, as desired from various sides, then in my opinion we would flatten the Theosophical movement, we would reduce it to the level of a club. The words that were spoken at the last meeting must be heard, the words: that I am in diametrical opposition to those who want a club-like community. I do not intend to attack anyone. I just cannot be there. Anyone who considers this properly will have to say that this is the absence of any aggressiveness. I would like to set the tone for this matter. This is what I emphasized at the general assembly in October, where I emphasized that I do not conform to such a form, that I cannot conform to a club-like society. Those who wish that the Berlin branch be administered differently, that the members interact with each other in a different way, must act accordingly. It is necessary for them to take matters into their own hands and carry them out for themselves, so that it seems self-evident that no one can object if their wishes are fulfilled in the manner mentioned. I could not fulfill these wishes. I have always tried to satisfy wishes as best I could. In order for the Theosophical Society to continue to develop peacefully, I have to take this step. I have the task of maintaining the continuity of the movement in Germany. It is clear to me that only on an occult basis – given our confused circumstances in the world – can this movement be taken forward. A movement on a social basis does not need to be Theosophical; its people may already have ideal aspirations and become dear to one another, and that does not need to be Theosophical. But we need a theosophical movement, and that is why I cannot be a leader in a club-like organization. Please understand that I am obliged to bring the full depth of the theosophical movement, which is based on occultism, to it. Today, only those who live by the Aristotelian principle are truly called to actively participate within the Theosophical Society: Those who seek truth must respect no opinion. Perhaps I would also like to work in a different way. But here it is a matter of duty, and therefore I will take this step because I have this obligation to build the Theosophical movement on a truly deeper foundation, and in the process of building, any attempt to run the society in a club-like manner will lead to a flattening out. No one can better understand that such things are necessary for some, and no one's relationship with me should change. Everyone will always be welcome with me. I will continue to conduct the business that relates to the material aspects of Theosophy in the same way, so that in the future everything can be found as it has been found. But precisely for this reason I must withdraw. The consistency is, of course, in the lines that I have executed. I cannot and must not lose sight of the theosophical movement at any point. That is why I have asked those members of our Theosophical Society – all the other organizations are of a secondary nature – individual members of the Theosophical Society, to hold a meeting with me and asked them whether they would be willing to continue the Theosophical movement with me in the way I have led it, against which a discord has arisen and dissatisfaction has been expressed. This had to be so, because I must maintain continuity. I will only mention the case I have in Munich. There is a strictly closed lodge there that only accepts those who meet the requirements of the whole. But now we will have a second lodge in which all others can be admitted. I have endeavored to draw attention to the conditions of the work of the lodges, which is the daily bread of a lodge. I also want to found a Besant Lodge soon, for whose name I will ask Annie Besant for permission soon. In addition, there will be completely free activity from which no one can be excluded. That is the reason for my resignation. (The names of a number of members are then listed.) Krojanker: “After these explanations from Dr. Steiner, those who were unable to attend the last meeting will have gained an insight into the cause of the discord and also the background to the matter, which led three members of the board to take the above-mentioned step. There must have been trouble brewing long before those involved knew anything about it. Since I have known about these things, it has been impossible for me to get over them. At first it was impossible for me to realize that these things could drive the gentlemen to this conclusion. What was it actually? The starting point for me was simply the decision of City Councillor Eberty and Miss Schwiebs, who had set out to see the members in their home for free, informal discussions. It was not foreseeable that such conclusions could be drawn from this. The suggestion came from Miss von Sivers; members should be encouraged to approach each other, and the feeling should not arise that one does not quite feel at home, so that everything rushes home immediately after the lecture. But even with Miss von Sivers, this was noticeable to a certain extent. As long as we had no headquarters, she had to help herself in a different way, visiting friends and talking to them. These are things that were purely personal and private in nature, and in the previous session I had hoped that they would not affect us. I still have the same opinion of these things today, the opinion that they must not be touched. The polite couple who had invited us were not yet part of the branch. A distinction must be made between association work, associationism and theosophical work. But committees are not formed and elected, and members of the board are not elected, for nothing, so that they do not have to worry about running the association. They are elected and will then also have the authority to speak about business matters and to allow themselves to make judgments from time to time. If autocratic management [...] is desired, then statutes and so on would not be necessary either. If Dr. Steiner had said at the time: We must renounce such a form, had he shown or said, only under such and such conditions is it possible for me to work and participate, then things would have happened immediately and quite naturally. Those who would have liked it would have gone along with it, and the rest would have stayed out. I don't understand why a whole business apparatus has been set up and why it is resented if, as a member of one of its branches, I take an interest in it. I think it cannot be considered a crime to inquire about these things. I would recommend the introduction of wish lists. I must protest against the accusation that we are aggressive. We have heard Dr. Steiner speak for two years about what Theosophy is and what Theosophical life entails. Surely other ways could have been found to steer the discussions in a different direction. But now that it has come to this, the consequences must be drawn under all circumstances. I imagine them to be – I don't know if I have understood correctly – that this Berlin branch continues to exist as a continuation of the Berlin branch of the German Theosophical Society, and that the three board members and the other gentlemen whom Dr. Steiner has read out are now founding a new lodge. Further negotiations and consultations will be needed before this step can be taken. The first task will be to elect a committee, because the Berlin branch currently has neither a committee nor a leadership. We will therefore have to form a provisional committee to discuss how this is to be done. I would like to leave it up to you to make proposals in this regard. In any case, we deeply regret the way in which the matter has been handled so far. When Dr. Steiner speaks of discord and soul currents, there is in fact nothing that I know and perhaps some personal matters that must never be made the business of the Berlin branch." Dr. Steiner: “I myself had good reason to take the personal into account. At the general assembly, 300 marks were approved for my work last year. I had already raised concerns at the time, but soon after that I felt compelled to put these 300 marks back into the treasury because of the prevailing mood, because I did not want to work on the basis of ill will. You see that I have kept quiet for long enough. 'I also wanted to let this matter pass quietly, to bridge the gap with positive work. In the long run, this was not possible for good reason. Of course, we are not discussing private matters here, nor is a conversation about professional life appropriate. I have said that, as far as I am concerned, what was requested has been largely satisfied. The wish had arisen that we should have lectures elsewhere than here or in the architects' house, and I agreed to give lectures at Wilhelmstraße 118 as well. But now we have to make a few comments about such a matter. The things are not as crude as they might initially appear, but are more subtly connected. At the time, I readily agreed to fulfill this wish, and in the pursuit of this matter, I asked to form an executive committee. I did not dream what came of it. We still have no branch in the north, south, or east. It was my intention to work not only in the west, but in all parts of the city. When an executive committee was formed in the Berlin branch, it was intended that this committee should take charge of the actual agitation. No one here has ever been prevented from taking care of business matters, but the view is that anyone who wants to do something has to create the space for themselves. No one could demand anything from us. If someone had come to us with positive suggestions, we would have taken them up. But when it is said that our activities have not been attacked, I say that only this week I received a written accusation that we are managing the library in such a way that one can threaten to go to court about it. We cannot accept hidden accusations. We will also hand over the library. When I have presented these things, you can assume that they are based on the firmest possible foundation. The statutes and so on could have been adhered to if there had been goodwill. When one talks about business, it must be practical. What was done at the time was impractical. I spoke three times in relatively beautiful rooms, but then in a room that was referred to as a stable, and finally in a room where speaking was almost impossible. I had to speak with glasses knocking behind me and so on. That was no atmosphere for Theosophy. I had to think of doing things in a practical way. This was the reason for my decision to hold the lectures in the architect's house. Such measures were in favor of the Berlin branch. Nevertheless, I was told: These lectures are ones that we can attend or not attend. - So you see that this is a silent discourtesy. Nothing has been done precisely because the other view of business matters, of statutes and committees, gave the opportunity to try out how it works. A letter from a theosophist reads: “I would like to see the Berlin branch work well for once. Most of all, I would be pleased if it could work in a favorable way.“ But then a wish list has also been worked out, you think - on the wish list it said: ‘The chairman has to be there half an hour before the start’ - that's what made the step so special.” Ms. Eberty: “Don't you think this fragmentation is very sad?” Dr. Steiner: “I have worked against these things. Whether a fragmentation will result from it remains to be seen. If the members of the Berlin branch will understand how to act in a theosophical way, there will be no need for fragmentation at all. There is no need to speak of fragmentation, I will do nothing to promote it.” Mrs. Eberty: “If you had had something against the meetings, it would have been enough to say: There are reasons why the meetings cannot take place. We had the best intentions for this. We only did it to serve the cause of Theosophy. It did not even remotely occur to us that this was against your intentions, not even when it was on the agenda eight days ago, when there were indications that our afternoon could be meant by it." Dr. Steiner: “If the form is dropped, there is no objection to the private meetings. What has happened at my request? That the teas at Fräulein von Sivers's have been abolished because I have not seen any benefit for Theosophy in such tea meetings. It was difficult for me that Countess Brockdorff took it badly. But nevertheless, I just said it. We ourselves would not be able to manage things differently. Krojanker: “It seems that the Executive Committee is being made the scapegoat. If you are on the Executive Committee, useful work is only possible if you are informed about the entire business situation. If you don't have insight and don't find opportunities to gain insight, what do you want to make suggestions for? The Executive Committee needs this knowledge because it has to report to the Board. I am increasingly lacking tangible documents that have given rise to these matters. Now comes the library question. A library commission has been set up. It is not really understandable why the members of the branch should be held responsible for this. Mr. Werner: “Dr. Steiner is a man called from a higher place. Now it is difficult to get what is needed to perfect us. If you approach him now with demands and questions, such as, ”Where did you leave the money you raised with your lectures? Give us information about what you got out of these lectures! Give us information about where the money has gone. If you say, 'We decide here, because we have a completely free hand to say what you have to do', then that is not the way to harmonious cooperation. I think that when you first accept teachings and instructions from someone, the demands and questions should not go so far that they are unbearable in detail. These would be thoughts that shun the light and lead to disharmony. But we can prevent disharmony if we want to. If that is not the case, then we have no right to come here and quibble about what has happened. Krojanker: “A distinction must be made between the theosophical teaching and the leadership of the Berlin branch. This will make it possible to avoid any mistrust.” Dr. Steiner: “The harmony may have to be bought at the expense of excluding some members. The arranged lectures were intended for the Berlin branch. It is true that we could not have done the work better. I am of the opinion that for the time being we have done the work as well as we could, since nothing better has been offered to us from the other side. At the moment something better would have been offered to us from the other side, we would not have ignored it. But what we have done, I consider to be the best so far. Fränkel: “Two meetings have been convened that have caused the discord. On both occasions, accusations have been made, followed by disharmony, so that a club has been formed, as it were, and we consist of two classes of members, so to speak. There are two ways of proceeding. There is a civil case and a criminal case. This is a public matter, not a private one. The complaint should therefore be made. However, it is not clear what is actually at issue. The first point is the tea with the ladies, the second point is that only the business committee has taken the wrong measures. The error seems to lie in the fact that at the founding, there was no discussion about how the business of the committee should be handled. There is no real discord yet, only the complaint of a few gentlemen based on factual reasons. Dr. Steiner: “If we had come to accuse anyone, then you could blame us for something. We are returning the management to those who have a wish list. The way of thinking expressed in the wish list is such that it cannot lead to anything in the Theosophical Society.” Krojanker: “A desire for power emerges from those who perhaps believe they are superior. But I have heard from Dr. Steiner that Theosophy does not submit to any authority.” Tessmar: “It is all much too materialistic. We are members of the Theosophical Society, but the whole Berlin branch can go home if Dr. Steiner says, ‘I will no longer give lectures here.’ Dr. Steiner gives Theosophical lectures, not lectures about speakers. I myself do not want to be held accountable; I want to hear Theosophical lectures in order to progress. And now the complaint about authority comes up. The theosophical lectures are authority for me. I show trust by not asking: What does the library do, what do the six Dreier do, who come in?" Krojanker: “I now see where the debate is leading us today. We have to come to terms with the facts. From Dr. Steiner's reply, I see that he is not to be convinced in any way, and that perhaps only time can bring understanding of the individual things. We are faced with the fact that this separation is taking place. What must happen now? Perhaps we should devote another hour to this question.” (A motion is made to end the debate, which is carried.) (Dr. Steiner, Fräulein von Sivers and Mr. Kiem resign.) Dr. Steiner: “My only remaining duty is to recommend that a managing director be elected for the time being. The process will be as follows: The managing director will have the task of informing the other members of the resignation. I myself will also inform the external members that I have resigned on my part.” Krojanker: ‘Can't a general statement be communicated to the members from both sides about what has happened here?’ (A number of members declare their resignation from the Berlin branch. Krojanker: Asks what he has done wrong and is told that he disagrees with the management. Dr. Steiner: “Why did I do it in general? It is done this way because it could not be done any other way. The Berlin branch can now experiment and so on, and do its own things. Mrs. Eberty: “We all received invitations.” Dr. Steiner: “I invited some with my name and with a personal greeting. But the list is not complete.” Mrs. [Johannesson]: “We felt separated by the tone of your address. We felt as if you had carried out a separation.” Ms. [Voigt]: “Could the ladies be asked which topic was discussed? And also about the question from which Mr. Fränkel started. It is perhaps of interest.” Tessmar: “I belong to Dr. Steiner. I will not be influenced. Please make a note of that if necessary. I really feel offended. As a seasoned seaman, I would choose different words. I forbid personal tapping.” Dr. Steiner: “It has therefore been decided that a manager must be appointed for the German Theosophical Society. It would have been impossible for me to continue my work without taking this step. I cannot give intimate lectures in this mood. I only had the choice of either leaving Berlin or taking this step. Maintaining continuity was the reason for this. Mrs. Annie Besant said, when she saw the current here, that I should go to Munich, where the work that Miss von Sivers has done can be continued. But I will not change my whole relationship into a mere point. It is precisely the outward appearance that is at issue here, not the inwardness. Present were: about 30 members. The meeting ended at eight o'clock [in the evening]. |

| 318. Pastoral Medicine: Lecture II

09 Sep 1924, Dornach Translated by Gladys Hahn |

|---|

| Sense impressions in general fade away and the person falls into a kind of dizzy dream state. But then in the most varied way moral impulses can appear with special strength. The person can be confused and also extremely argumentative if the rest of the organism is as just described. |

| 318. Pastoral Medicine: Lecture II

09 Sep 1924, Dornach Translated by Gladys Hahn |

|---|

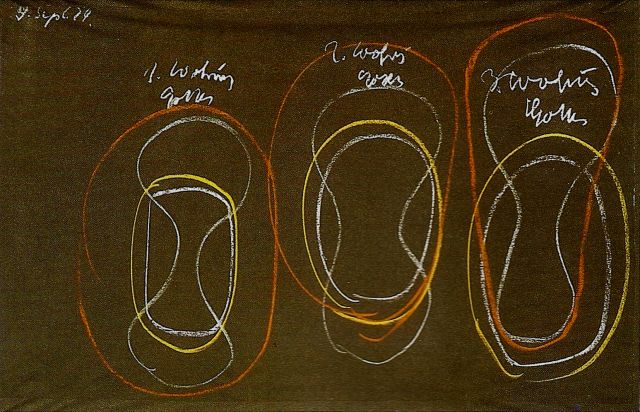

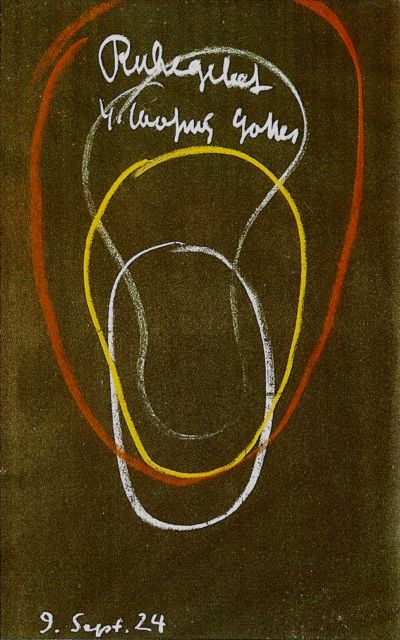

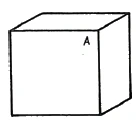

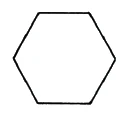

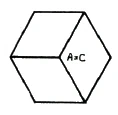

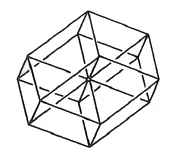

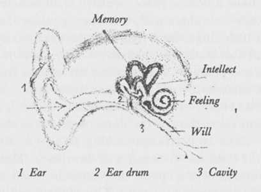

Dear friends, If we are going to consider the mutual concerns of priest and physician, we should look first at certain phenomena in human life that easily slide over into the pathological field. These phenomena require a physician's understanding, since they reach into profound depths, even into the esoteric realm of religious life. We have to realize that all branches of human knowledge must be liberated from a certain coarse attitude that has come into them in this materialistic epoch. We need only recall how certain phenomena that had been grouped together for some time under the heading “genius and insanity” have recently been given a crass interpretation by Lombroso1 and his school and also by others. I am not pointing to the research itself—that has its uses—but rather to their way of looking at things, to what they brought out as “criminal anthropology,” from studying the skulls of criminals. The opinions they voiced were not only coarse but extraordinarily commonplace. Obviously the philistines all got together and decided what the normal type of human being is. And it was as near as could possibly be to a philistine! And whatever deviated from this type was pathological, genius on one side, insanity on the other; each in its own way was pathological. Since it is quite obvious to anyone with insight that every pathological characteristic also expresses itself bodily, it is also obvious that symptoms can be found in bodily characteristics pointing in one or the other direction. It is a matter of regarding the symptoms in the proper way. Even an earlobe can under certain conditions clearly reveal some psychological peculiarity, because such psychological peculiarities are connected with the karma that works over from earlier incarnations. The forces that build the physical organism in the first seven years of human life are the same forces by which we think later. So it is important to consider certain phenomena, not in the customary manner but in a really appropriate way. We will not be regarding them as pathological (although they will lead us into aspects of pathology) but rather will be using them to obtain a view of human life itself. Let us for a moment review the picture of a human being that Anthroposophy gives us. The human being stands before us in a physical body, which has a long evolution behind it, three preparatory stages before it became an earthly body—as is described in my book An Outline of Esoteric Science.2 This earthly body needs to be understood much more than it is by today's anatomy and physiology. For the human physical body as it is today is a true image of the etheric body, which is in its third stage of development, and of the astral body, which is in its second stage, and even to a certain degree of the ego organization that humans first received on earth, which therefore is in its first stage of development. All of this is stamped like the stamp of a seal upon the physical body—which makes the physical body extraordinarily complicated. Only its purely mineral and physical nature can be understood with the methods of knowledge that are brought to it today. What the etheric body impresses upon it is not to be reached at all by those methods. It has to be observed with the eye of a sculptor so that one obtains pictorial images of cosmic forces, images that can then be recognized again in the form of the entire human being and in the forms of the single organs. The physical human being is also an image of the breathing and blood circulation. But the entire dynamic activity that works and weaves through the blood circulation and breathing system can only be understood if one thinks of it in musical forms. For instance, there is a musical character to the formative forces that were poured into the skeletal system and then became active in a finer capacity in the breathing and circulation. We can perceive in eurythmy how the octave goes out from the shoulder blade and proceeds along the bones of the arm. This bone formation of the arm cannot be understood from a mechanical view of dynamics, but only from musical insight. We find the interval of the prime extending from the shoulder blade to the bone of the upper arm, the humerus, the interval of the second in the humerus, the third from the elbow to the wrist. We find two bones there because there are two thirds in music, a larger and a smaller. And so on. In short, if we want to find the impression of the astral body upon the physical body, upon the breathing and blood circulation, we are obliged to bring a musical understanding to it. Still more difficult to understand is the ego organization. For this one needs to grasp the meaning of the first verse of the Gospel of St. John: “In the beginning was the Word.” “The Word” is meant there to be understood in a concrete sense, not abstractly, as commentators of the Gospels usually present it. If this is applied concretely to the real human being, it provides an explanation of how the ego organization penetrates the human physical body. You can see that we ought to add much more to our studies if they are to lead to a true understanding of the human being. However, I am convinced that a tremendous amount of material could be eliminated not only from medical courses but from theological courses too. If one would only assemble the really essential material, the number of years medical students, for instance, must spend in their course would not be lengthened but shortened. Naturally it is thought in materialistic fashion today that if there's something new to be included, you must tack another half-year onto the course! Out of the knowledge that Anthroposophy gives us, we can say that the human being stands before us in physical, etheric and astral bodies, and an ego organization. In waking life these four members of the human organization are in close connection. In sleep the physical body and etheric body are together on one side, and the ego organization and astral body on the other side. With knowledge of this fact we are then able to say that the greatest variety of irregularities can appear in the connection of ego organization and astral body with etheric body and physical body. For instance, we can have: physical body, etheric body, astral body, ego organization. (Plate I, 1) Then, in the waking state, the so-called normal relation prevails among these four members of the human organization.  But it can also happen that the physical body and etheric body are in some kind of normal connection and that the astral body sits within them comparatively normally, but that the ego organization is somehow not properly sitting within the astral body. (Plate I, 2) Then we have an irregularity that in the first place confronts us in the waking condition. Such people are unable to come with their ego organization properly into their astral body; therefore their feeling life is very much disturbed. They can even form quite lively thoughts. For thoughts depend, in the main, upon a normal connection of the astral body with the other bodies. But whether the sense impressions will be grasped appropriately by the thoughts depends upon whether the ego organization is united with the other parts in a normal fashion. If not, the sense impressions become dim. And in the same measure that the sense impressions fade, the thoughts become livelier. Sense impressions can appear almost ghostly, not clear as we normally have them. The soul-life of such people is flowing away; their sense impressions have something misty about them, they seem to be continually vanishing. At the same time their thoughts have a lively quality and tend to become more intense, more colored, almost as if they were sense impressions themselves. When such people sleep, their ego organization is not properly within the astral body, so that now they have extraordinarily strong experiences, in fine detail, of the external world around them. They have experiences, with their ego and astral body both outside their physical and etheric bodies, of that part of the world in which they live—for instance, the finer details of the plants or an orchard around their house. Not what they see during the day, but the delicate flavor of the apples, and so forth. That is really what they experience. And in addition, pale thoughts that are after-effects in the astral body from their waking life. You see, it is difficult if you have such a person before you. And you may encounter such people in all variations in the most manifold circumstances of life. You may meet them in your vocation as physician or as priest—or the whole congregation may encounter them. You can find them in endless variety, for instance, in a town. Today the physician who finds such a person in an early stage of life makes the diagnosis: psychopathological impairment. To modern physicians that person is a psychopathological impairment case who is at the borderline between health and illness; whose nervous system, for instance, can be considered to be on a pathological level. Priests, if they are well-schooled (let us say a Benedictine or Jesuit or Barnabite or the like; ordinary parish priests are sometimes not so well-schooled), will know from their esoteric background that the things such a person tells them can, if properly interpreted, give genuine revelations from the spiritual world, just as one can have from a really insane person. But the insane person is not able to interpret them; only someone who comprehends the whole situation can do so. Thus you can encounter such a person if you are a physician, and we will see how to regard this person medically from an anthroposophical point of view. Thus you can also encounter such a person if you are a priest—and even the entire congregation can have such an encounter. But now perhaps the person develops further; then something quite special appears. The physical and etheric bodies still have their normal connection. But now there begins to be a stronger pull of the ego organization, drawing the astral body to itself, so that the ego organization and astral body are now more closely bound together. And neither of them enters properly into the physical and etheric bodies. (Plate I, 3) Then the following can take place: the person becomes unable to control the physical and etheric bodies properly from the astral body and ego. The person is unable to push the astral body and ego organization properly into the external senses, and therefore, every now and then, becomes “senseless.” Sense impressions in general fade away and the person falls into a kind of dizzy dream state. But then in the most varied way moral impulses can appear with special strength. The person can be confused and also extremely argumentative if the rest of the organism is as just described. Now physicians find in such a case that physical and biochemical changes have taken place in the sense organs and the nerve substance. They will find, although they may take slight notice of them, great abnormalities in the ductless glands and their hormone secretion, in the adrenal glands, and the glands that are hidden in the neck as small glands within the thyroid gland. In such a case there are changes particularly in the pituitary gland and the pineal gland. These are more generally recognized than are the changes in the nervous system and in the general area of the senses. And now the priest comes in contact with such a person. The person confesses to experiencing an especially strong feeling of sin, stronger than people normally have. The priest can learn very much from such individuals, and Catholic priests do. They learn what an extreme consciousness of sin can be like, something that is so weakly developed in most human beings. Also in such a person the love of one's neighbor can become tremendously intense, so much so that the person can get into great trouble because of it, which will then be confessed to the priest. The situation can develop still further. The physical body can remain comparatively isolated because the etheric body—from time to time or even permanently—does not entirely penetrate it, so that now the astral and etheric bodies and the ego organization are closely united with one another and the physical organism is separate from them. (Plate II) To use the current materialistic terms (which we are going to outgrow as the present course of study progresses), such people are in most cases said to be severely mentally retarded individuals. They are unable from their soul-spiritual individuality to control their physical limbs in any direction, not even in the direction of their own will. Such people pull their physical organism along, as it were, after themselves. A person who is in this condition in early childhood, from birth, is also diagnosed as mentally retarded. In the present stage of earth evolution, when all three members—ego organization, astral organization, and etheric body—are separated from the physical, and the lone physical body is dragged along after them, the person cannot perceive, cannot be active, cannot be illumined by the ego organization, astral body, and etheric body. So experiences are dim and the person goes about in a physical body as if it were anesthetized. This is extreme mental retardation, and one has to think how at this stage one can bring the other bodies down into the physical organism. Here it can be a matter of educational measures, but also to a great extent of external therapeutic measures.  But now the priest can be quite amazed at what such a person will confess. Priests may consider themselves very clever, but even thoroughly educated priests—there really are such men in Catholicism; one must not underestimate it—they pay attention if a so-called sick person comes to them and says, “The things you pronounce from the pulpit aren't worth much. They don't add up to anything, they don't reach up to the dwelling place of God, they don't have any worth except external worth. One must really rest in God with one's whole being.” That's the kind of thing such people say. In every other area of their life they behave in such a way that one must consider them to be extremely retarded, but in conversation with their priest they come out with such speeches. They claim to know inner religious life more intimately than someone who speaks of it professionally; they feel contempt for the professional. They call their experience “rest in God.” And you can see that the priest must find ways and means to relate to what such a person—one can say patient, or one can use other terms—to what such a human being is experiencing within. One has to have a sensitive understanding for the fact that pathological conditions can be found in all spheres of life, for the fact that some people may be quite unable at the present time to find their way in the physical-sense world, quite unable to be the sort of human being that external life now requires all of us to be. We are all necessarily to a certain degree philistines as regards external life. But such people as I am describing are not in condition to travel along our philistine paths; they have to travel other ways. Priests must be able to feel what they can give such a person, how to connect what they can give out of themselves with what that other human being is experiencing. Very often such a person is simply called “one of the queer ones.” This demands an understanding of the subtle transition from illness to spirituality. Our study can go further. Think what happens when a person goes through this entire sequence in the course of life. At some period the person is in a condition (Plate I, 2) where only the ego organization has loosened itself from the other members of the organism. In a later period the person advances to a condition where neither ego nor astral enter the physical or etheric bodies. Still later, (Plate I, 3) the person enters a condition where the physical body separates from the other bodies. (Plate II) The person only goes through this sequence if the first condition, perhaps in childhood, which is still normal, already shows a tendency to lose the balance of the four members of the organism. If the physician comes upon such a person destined to go through all these four stages—the first very slightly abnormal, the others as I have pictured them—the physician will find there is tremendous instability and something must be done about it. Usually nothing can be done. Sometimes the physician prescribes intensive treatment; it accomplishes nothing. Perhaps later the physician is again in contact with this person and finds that the first unstable condition has advanced to the next, as I described it with the sense impressions becoming vague and the thoughts highly colored. Eventually the physician finds the excessively strong consciousness of sin; naturally a physician does not want to take any notice of that, for now the symptoms are beginning to play over into the soul realm. Usually it is at this time that the person finally gets in touch with a priest, particularly when the fourth stage becomes apparent. Individuals who go through these stages—it is connected with their karma, their repeated earth lives—have purely out of their deep intuition developed a wonderful terminology for all this. Especially if they have gone through the stages in sequence, with the first stage almost normal, they are able to speak in a wonderful way about what they experience. They say, for instance, when they are still quite young, if the labile condition starts between seventeen and nineteen years: human beings must know themselves. And they demand complete knowledge of themselves. Now with their ego organization separated, they come of their own initiative to an active meditative life. Very often they call this “active prayer,” “active meditation,” and they are grateful when some well-schooled priest gives them instruction about prayer. Then they are entirely absorbed in prayer, and they are experiencing in it what they now begin to describe by a wonderful terminology. They look back at their first stage and call what they perceive “the first dwelling place of God,” because their ego has not entirely penetrated the other members of their organism, so to a certain extent they are seeing themselves from within, not merely from without. This perception from within increases; it becomes, as it were, a larger space: “the first dwelling place of God.” What next appears, what I have described from another point of view, is richer; it is more inwardly detailed. They see much more from within: “the second dwelling place of God.” When the third stage is reached, the inner vision is extraordinarily beautiful, and such a person says, “I see the third dwelling place of God; it is tremendously magnificent, with spiritual beings moving within it.” This is inner vision, a powerful, glorious vision of a world woven by spirit: “the third dwelling place of God,” or “the House of God.” There are variations in the words used. When they reach the fourth stage, they no longer want advice about active meditation, for usually they have reached the view that everything will be given them through grace and they must wait. They talk about passive prayer, passive meditation, that they must not pray out of their own initiative, for it will come to them if God wants to give it to them. Here the priest must have a fine instinct for recognizing when this stage passes over into the next. For now these people speak of “rest-prayer,” during which they do nothing at all; they let God hold sway in them. That is how they experience “the fourth dwelling place of God.” Sometimes from the descriptions they give at this stage, from what—if we speak medically—such “patients” say, priests can really learn a tremendous amount of esoteric theology. If they are good interpreters, the theological detail becomes clear to them—if they listen very carefully to what such “patients” tell them, to what they know. Much of what is taught in theology, particularly Catholic pastoral theology, is founded on what various enlightened, trained confessors have heard from certain penitents who have undergone this sequence of development. At this point ordinary conceptions of health and illness cease to have any meaning. If such a man is hidden away in an office, or if such a woman becomes an housewife who must spend her days in the kitchen or something similar in bourgeois everyday life, these people become really insane, and behave outwardly in such a way that they can only be regarded as insane. If a priest notices at the right moment how things are developing and arranges for them to live in appropriate surroundings, they can develop the four stages in proper order. Through such patients, the enlightened confessor is able to look into the spiritual world in a modern way but similarly to the Greek priests, who learned about the spiritual world from the Pythians, who imparted all kinds of revelations concerning the spiritual world through earthly smoke and vapor.3 What sense would there be today in writing a thesis on the pathological aspect of the Greek Pythians? It could certainly be done and it would even be correct, but it would have no meaning in a higher sense. For as a matter of fact, very much of what flowed in a magnificent way from Greek theology into the entire cultural life of Greece originated in the revelations of the Pythians. As a rule, the Pythians were individuals who had come either to this third stage or even to the fourth stage. But we can think of a personality in a later epoch who went through these stages under the wise direction of her confessors, so that she could devote herself undisturbed to her inner visions. Something very wonderful developed for her, which indeed also remained to a certain degree pathological. Her life was not just a concern of the physician or of the priest but a concern of the entire Church. The Church pronounced her a saint after her death. This was St. Teresa.4 This was approximately her path. You see, one must examine such things as this if one wants to discover what will give medicine and theology a real insight into human nature. One must be prepared to go far beyond the usual category of ideas, for they lose their value. Otherwise one can no longer differentiate between a saint and a fool, between a madman and a genius, and can no longer distinguish any of the others except a normal dyed-in-the-wool average citizen. This is a view of the human being that must first be met with understanding; then it can really lead to fundamental esoteric knowledge. But it can also be tremendously enlightening in regard to psychological abnormalities as well as to physical abnormalities and physical illnesses. Certain conditions are necessary for these stages to appear. There has to be a certain consistency of the person's ego so that it does not completely penetrate the organism. Also there must be a certain consistency of the astral body: if it is not fine, as it was in St. Teresa, if it is coarse, the result will be different. With St. Teresa, because of the delicacy of her ego organization and astral body, certain physical organs in the lower body had been formed with the same fragile quality. But it can happen that the ego organization and astral body are quite coarse and yet they have the same characteristic as above. Such an individual can be comparatively normal and show only the physical correlation: then it is only a physical illness. One could say, on the one hand there can be a St. Teresa constitution with its visions and poetic beauty, and on the other hand its physical counterimage in diseased abdominal organs, which in the course of this second person's life is not reflected in the ego and astral organization. All these things must be spoken about and examined. For those who hold responsibility as physicians or priests are confronted by these things, and they must be equal to the challenge. Theological activity only begins to be effective if theologians are prepared to cope with such phenomena. And physicians only begin to be healers if they also are prepared to deal with such symptoms.

|

| 322. The Boundaries of Natural Science: Lecture I

27 Sep 1920, Dornach Translated by Frederick Amrine, Konrad Oberhuber |

|---|

| If we look within our soul at what lies submerged beneath the surface consciousness arising in the interaction between senses and the outer world, we find a world of representations, faint, diluted to dream-pictures with hazy contours, each image fading into the other. Unprejudiced observation establishes this. |

| 322. The Boundaries of Natural Science: Lecture I

27 Sep 1920, Dornach Translated by Frederick Amrine, Konrad Oberhuber |

|---|

The theme of this cycle of lectures was not chosen because it is traditional within academic or philosophical disciplines, as though we thought epistemology or the like should appear within our courses. Rather, it was chosen as the result of what I believe to be an open-minded consideration of the needs and demands of our time. The further evolution of humanity demands new concepts, new notions, and new impulses for social life generally: we need ideas which, when realized, can create social conditions offering to human beings of all stations and classes an existence that seems to them humane. Already, to be sure, it is being said in the widest circles that social renewal must begin with a renewal of our thinking.1 Yet not everyone in these widest circles imagines something clear and distinct when speaking in this way. One does not ask: whence shall come the ideas upon which one might found a social economy offering man a humane existence? That portion of humanity which has received an education in the last three to four centuries, but particularly since the nineteenth century, has been raised with certain ideas that are outgrowths of the scientific world view or entirely schooled in it. This is particularly true of those who have undergone some academic training. Only those working in fields other than the sciences believe that natural science has had little influence on their pursuits. Yet it is easy to demonstrate that even in the newer, more progressive theology, in history and in jurisprudence—everywhere can be found scientific concepts such as those that arose from the scientific experiments of the last centuries, so that traditional concepts have in a certain way been altered to conform to the new. One need only allow the progress of the new theological developments in the nineteenth century to pass before the mind's eye. One sees, for example, how Protestant theology has arrived at its views concerning the man, Jesus, and the nature of Christ, because at every turn it had in mind certain scientific conceptions that it wanted to satisfy, against which it did not want to sin. At the same time, the old, instinctive ties within the social order began to slacken: they gradually ceased to hold human life together. In the course of the nineteenth century it became increasingly necessary to replace the instincts according to which one class subordinated itself to another, the instincts out of which the new parliamentary institutions, with all their consequences, have come with more-or-less conscious concepts. Not only in Marxism but in many other movements as well there has come about what one might call a transformation of the old social instincts into conscious concepts. But what was this new element that had entered into social science, into this favorite son of modern thought? It was the conceptions, the new mode of thinking that had been developed in the pursuit of natural science. And today we are faced with the important question: how far shall we be able to progress within a web of social forces woven from such concepts? If we listen to the world's rumbling, if we consider all the hopeless prospects that result from the attempts that are made on the basis of these conceptions, we are confronted with a dismal picture indeed. One is then faced with the portentous question: how does it stand with those very concepts that we have acquired from natural science and now wish to apply to our lives, concepts that—this has become clearly evident in many areas already—are actually rejected by life itself? This vital question, this burning question with which our age confronts us, was the occasion of my choosing the theme, “The Boundaries of Natural Science.” Just this question requires that I treat the theme in such a way that we receive an overview of what natural science can and cannot contribute to an appropriate social order and an idea of the kind of scientific research, the kind of world view to which one would have to turn in order to confront seriously the demands made upon us by our time. What is it we see if we consider the method according to which one thinks in scientific circles and how others have been influenced in their thinking by those circles? What do we see? We see first of all that an attempt is made to acquire data and to order it in a lucid system with the help of clear concepts. We see how an attempt is made to order the data gathered from inanimate nature by means of the various sciences—mechanics, physics, chemistry, etc.—to order them in a systematic manner but also to permeate the data with certain concepts so that they become intelligible. With regard to inanimate nature, one strives for the greatest possible clarity, for crystal-clear concepts. And a consequence of this striving for lucid concepts is that one seeks, if it is at all possible, to permeate everything that one finds in one's environment with mathematical formulae. One wants to translate data gathered from nature into clear mathematical formulae, into the transparent language of mathematics. In the last third of the nineteenth century, scientists already believed themselves very close to being able to give a mathematical-mechanical explanation of natural phenomena that would be thoroughly transparent. It remained for them only to explain the little matter of the atom. They wanted to reduce it to a point-force [Kraftpunkt] in order to be able to express its position and momenta in mathematical formulae. They believed they would then be justified in saying: I contemplate nature, and what I contemplate there is in reality a network of interrelated forces and movements wholly intelligible in terms of mathematics. Hence there arose the ideal of the so-called “astronomical explanation of nature,” which states in essence: just as one brings to expression the relationships between the various heavenly bodies in mathematical formulae, so too should one be able to compute everything within this smallest realm, within the “little cosmos” of atoms and molecules, in terms of lucid mathematics. This was a striving that climaxed in the last third of the nineteenth century: it is now on the decline again. Over against this striving for a crystal-clear, mathematical view of the world, however, there stands something entirely different, something that is called forth the moment one tries to extend this striving into realms other than that of inanimate nature. You know that in the course of the nineteenth century the attempt was made to carry this point of view, at least to some extent, into the life sciences. And though Kant had said that a second Newton would never be found who could explain living organisms according to a causal principle similar to that used to explain inorganic nature, Haeckel could nevertheless claim that this second Newton had been found in Darwin, that Darwin had actually tried, by means of the principle of natural selection, to explain how organisms evolve in the same “transparent” terms. And one began to aim for just such a clarity, a clarity at least approaching that of mathematics, in all explanations, proceeding all the way up to the explanation of man himself. Something thereby was fulfilled which certain scientists explained by saying that man's need to understand the causes of phenomena is satisfied only when he arrives at such a transparent, lucid view of the world. And yet over against this there stands something entirely different. One comes to see that theory upon theory has been contrived in order to construct a view of the world such as I have just described, and ever and again those who strove for such a view of the world called forth—often immediately—their own opposition. There always arose the other party, which demonstrated that such a view of the world could never produce valid explanations, that such a view of the world could never ultimately satisfy man's need to know. On the one hand it was argued how necessary it is to keep one's world view within the lucid realm of mathematics, while on the other hand it was shown that such a world view would, for example, remain entirely incapable of constructing even the simplest living organism in thought of mathematical clarity or, indeed, even of constructing a comprehensible model of organic substance. It was as though the one party continually wove a tissue of ideas in order to explain nature, and the other party—sometimes the same party—continually unraveled it. It has been possible to follow this spectacle—for it seems just that to anyone who is able to view it with an unprejudiced eye—within the scientific work and striving of the last fifty years especially. If one has sensed the full gravity of the situation, that with regard to this important question nothing but a weaving and unraveling of theories has taken place, one can pose the question: is not the continual striving for such a conceptual explanation of phenomena perhaps superfluous? Is not the proper answer to any question that arises when one confronts phenomena perhaps that one should simply allow the facts to speak for themselves, that one should describe what occurs in nature and forgo any more detailed accounting? Is it not possible that all such explanations show only that humanity is still tied to its mother's apron strings, that humanity in its infancy sought a kind of luxury? Would not humanity, come of age, have to say to itself: we must not strive at all for such explanation; we get nowhere in that way and must simply extirpate the need to know? Why not? As we become older we outgrow the need to play; why, if we were justified in doing so, should we not simply outgrow the need for explanations? Just such a question could already emerge in the most extraordinarily significant way when, on August 14, 1872, du Bois-Reymond stood before the Second General Meeting of the Association of German Scientists and Physicians to deliver his famous address, “The Boundaries of Natural Science” [“Grenzen des Naturerkennens”], an address still worthy of consideration today. Yet despite the amount that has been written about this address by the important physiologist, du Bois-Reymond, many still do not realize that it represents one of the important junctures in the evolution of the modern world view. In medieval Scholasticism all of man's thinking, all of his notional activity, was determined by the view that one could explain the broad realms of nature in terms of certain concepts but that one had to draw the line upon reaching the super-sensible. The super-sensible had to be the object of revelation. They felt that man should stand in a relation to the super-sensible in such a way that he would not even wish to penetrate it with the same concepts he formed concerning the realms of nature and external human existence. A limit was set to knowledge on the side of the super-sensible, and it was strongly emphasized that such a limit had to exist, that it simply lay within human nature and the order of the universe that such a limit be recognized. This placement of a limit to knowledge was then renewed from an entirely different side by thinkers and researchers such as du Bois-Reymond. They were no longer Schoolmen, no longer theologians, but just as the medieval theologian, proceeding according to his own mode of thinking, had set a limit to knowledge at the super-sensible, so these thinkers and researchers set a limit at the sensible. The limit was meant to apply above all to the realm of external sensory data. There were two concepts in particular that du Bois-Reymond had in mind, which to him established the limits natural science could reach but beyond which it could not proceed. Later he increased that number by five in his lecture, “The Seven Enigmas of the World,” but in the first lecture he spoke of the two concepts, “matter” and “consciousness.” He said that when contemplating nature we are forced, in thinking systematically, to apply concepts in such a way that we eventually arrive at the notion of matter. Just what this mysterious entity in space we call “matter” is, however, we can never in any way resolve. We must simply assume the concept “matter,” though it is opaque. If only we assume this opaque concept “matter,” we can apply our mathematical formulae and calculate the movements of matter in terms of the formulae. The realm of natural phenomena becomes comprehensible if only we can posit this “opaque” little point millions upon millions of times. Yet surely we must also assume that it is this same material world that first builds up our bodies and unfolds its own activity within them, so that there rises up within us, by virtue of this corporeal activity, what eventually becomes sensation and consciousness. On the one hand we confront a world of natural phenomena requiring that we construct a concept of “matter,” while on the other hand we confront ourselves, experience the fact of consciousness, observe its phenomena, and surmise that whatever it is we assume to be matter must also lie at the foundation of consciousness. But how, out of these movements of matter, out of inanimate, dead movement, there arises consciousness, or even simple sensation, is a mystery that we cannot possibly fathom. This is the other pole of all the uncertainties, all the limits to knowledge: how can we explain consciousness, or even the simplest sensation? With regard to these two questions, then—What is matter? How does consciousness arise out of material processes?—du Bois-Reymond maintains that as researchers we must confess: ignorabimus, we shall never know. That is the modern counterpart to medieval Scholasticism. Medieval Scholasticism stood at the limit of the super-sensible world. Modern natural science stands at the limit delineated in essence by two concepts: “matter,” which is everywhere assumed within the sensory realm but nowhere to be found, and “consciousness,” which is assumed to originate within the sense world, although one can never comprehend how. If one considers this development of modern scientific thought, must one not then say to oneself that scientific research is entangling itself in a kind of web, and only outside of this web can one find the world? For in the final analysis it is there, where matter haunts space, that the external world lies. If this is the one place into which one cannot penetrate, one has no way in which to come to terms with life. Within man one finds the fact of consciousness. Does one come at all near to it with explanations conceived in observing external nature? If in one's search for explanations one pulls up short at human life, how, then, can one arrive at notions of how to live in a way worthy of a human being? How, if one cannot understand the existence or the essence of man according to the assumptions one makes concerning that existence? As this course of lectures progresses it shall, I believe, become evident beyond any doubt that it is the impotence of the modern scientific method that has made us so impotent in our thinking about social questions. Many today still do not perceive what an important and essential connection exists between the two. Many today still do not perceive that when in Leipzig on August 14, 1872 du Bois-Reymond spoke his ignorabimus, this same ignorabimus was spoken also with regard to all social thought. What this ignorabimus actually meant was: we stand helpless in the face of real life; we have only shadowy concepts; we have no concepts with which to grasp reality. And now, almost fifty years later, the world demands just such concepts of us. We must have them. Such concepts, such impulses, cannot come out of lecture-halls still laboring in the shadow of this ignorabimus. That is the great tragedy of our time. Here lie questions that must be answered. We want to proceed from fundamental principles to such an answer and above all to consider the question: is there not perhaps something more intelligent that we as human beings could do than what we have done for the last fifty years, namely tried to explain nature after the fashion of ancient Penelope, by weaving theories with one hand and unraveling them with the other? Ah yes, if only we could, if only we could stand before nature entirely without thoughts! But we cannot: to the extent that we are human beings and wish to remain human beings we cannot. If we wish to comprehend nature, we must permeate it with concepts and ideas. Why must we do that? We must do that, ladies and gentlemen, because only thereby does consciousness awake, because only thereby do we become conscious human beings. Just as each morning upon opening our eyes we achieve consciousness in our interaction with the external world, so essentially did consciousness awake within the evolution of humanity. Consciousness, as it is now, was first kindled through the interaction of the senses and thinking with the outer world. We can watch the historical development of consciousness in the interaction of man's senses with outer nature. In this process consciousness gradually was kindled out of the dull, sleepy cultural life of primordial times. Yet one must only consider with an open mind this fact of consciousness, this interaction between the senses and nature, in order to observe something extraordinary transpiring within man. We must look into our soul to see what is there, either by remaining awhile before fully awakening within that dull and dreamy consciousness or by looking back into the almost dreamlike consciousness of primordial times. If we look within our soul at what lies submerged beneath the surface consciousness arising in the interaction between senses and the outer world, we find a world of representations, faint, diluted to dream-pictures with hazy contours, each image fading into the other. Unprejudiced observation establishes this. The faintness of the representations, the haziness of the contours, the fading of one representation into another: none of this can cease unless we awake to a full interaction with external nature. In order to come to this awakening which is tantamount to becoming fully human—our senses must awake every morning to contact with nature. It was also necessary, however, for humanity as a whole to awake out of a dull, dreamlike vision of primordial worlds within the soul to achieve the present clear representations. In this way we achieve the clarity of representation and the sharply delineated concepts that we need in order to remain awake, to remain aware of our environment with a waking soul. We need all this in order to remain human in the fullest sense of the word. But we cannot simply conjure it all up out of ourselves. We achieve it only when our senses come into contact with nature: only then do we achieve clear, sharply delineated concepts. We thereby develop something that man must develop for his own sake—otherwise consciousness would not awake. It is thus not an abstract “need for explanations,” not what du Bois-Reymond and other men like him call “the need to know the causes of things,” that drives us to seek explanations but the need to become human in the fullest sense through observing nature. We thus may not say that we can outgrow the need to explain like any other child's play, for that would mean that we would not want to become human in the fullest sense of the word—that is to say, not want to awake in the way we must awake. Something else happens in this process, however. In coming to such concepts as we achieve in contemplating nature, we at the same time impoverish our inner conceptual life. Our concepts become clear, but their compass becomes diminished, and if we consider exactly what it is we have achieved by means of these concepts, we see that it is an external, mathematical-mechanical lucidity. Within that lucidity, however, we find nothing that allows us to comprehend life. We have, as it were, stepped out into the light but lost the very ground beneath our feet. We find no concepts that allow us to typify life, or even consciousness, in any way. In exchange for the clarity we must seek for the sake of our humanity, we have lost the content of that for which we have striven. And then we contemplate nature around us with our concepts. We formulate such complex ideas as the theory of evolution and the like. We strive for clarity. Out of this clarity we formulate a world view, but within this world view it is impossible to find ourselves, to find man. With our concepts we have moved out to the surface, where we come into contact with nature. We have achieved clarity, but along the way we have lost man. We move through nature, apply a mathematical-mechanical explanation, apply the theory of evolution, formulate all kinds of biological laws; we explain nature; we formulate a view of nature—within which man cannot be found. The abundance of content that we once had has been lost, and we are confronted with a concept that can be formed only with the clearest but at the same time most desiccated and lifeless thinking: the concept of matter. And an ignorabimus in the face of the concept of matter is essentially the confession: I have achieved clarity; I have struggled through to an awakening of full consciousness, but thereby I have lost the essence of man in my thinking, in my explanations, in my comprehension. And now we turn to look within. We turn away from matter to consider the inner realm of consciousness. We see how within this inner realm of consciousness representations pass in review, feelings come and go, impulses of will flash through us. We observe all this and notice that when we attempt to bring the inner realm into the same kind of focus that we achieved with regard to the external world, it is impossible. We seem to swim in an element that we cannot bring into sharp contours, that continually fades in and out of focus. The clarity for which we strive with regard to outer nature simply cannot be achieved within. In the most recent attempts to understand this inner realm, in the Anglo-American psychology of association, we see how, following the example of Hume, Mill, James, and others, the attempt was made to impose the clarity attained in observation of external nature upon inner sensations and feelings. One attempts to impose clarity upon sensation, and this is impossible. It is as though one wanted to apply the laws of flight to swimming. One does not come to terms at all with the element within which one has to move. The psychology of association never achieves sharpness of contour or clarity regarding the phenomenon of consciousness. And even if one attempts with a certain sobriety, as Herbart has done, to apply mathematical computation to human mental activity [das Vorstellen], to the human soul, one finds it possible, but the computations hover in the air. There is no place to gain a foothold, because the mathematical formulae simply cannot comprehend what is actually occurring within the soul. While one loses man in coming to clarity regarding the external world, one finds man, to be sure—it goes without saying that one finds man when one delves into consciousness—but there is no hope of achieving clarity, for one swims about, borne hither and thither in an insubstantial realm. One finds man, but one cannot find a valid image of man. It was this that du Bois-Reymond felt very clearly but was able to express only much less clearly—only as a kind of vague feeling about scientific research on the whole—when in August 1872 he spoke his ignorabimus. What this ignorabimus wants to say in essence is that on the one hand, we have in the historical evolution of humanity arrived at clarity regarding nature and have constructed the concept of matter. In this view of nature we have lost man—that is, ourselves. On the other hand we look down into consciousness. To this realm we want to apply that which has been most important in arriving at the contemporary explanation of nature. Consciousness rejects this lucidity. This mathematical clarity is entirely out of place. To be sure, we find man in a sense, but our consciousness is not yet strong enough, not yet intensive enough to comprehend man fully. Again, one is tempted to answer with an ignorabimus, but that cannot be, for we need something more than an ignorabimus in order to meet the social demands of the modern world. The limit that du Bois-Reymond had come up against when he spoke [about] his ignorabimus on August 14, 1872 lies not within the human condition as such but only within its present stage of historical human evolution. How are we to transcend this ignorabimus? That is the burning question.

|

| 322. The Boundaries of Natural Science: Lecture III

29 Sep 1920, Dornach Translated by Frederick Amrine, Konrad Oberhuber |

|---|

| And what has happened in the spiritual evolution of humanity, in man's gradual acquisition of knowledge about external nature, is actually nothing other than what happens every morning when we awake out of sleep or dream-consciousness by confronting an external world. This latter is a kind of moment of awakening, and in the course of the evolution of humanity we have to do with a gradual awakening, a kind of long, drawn-out moment of awakening. |

| 322. The Boundaries of Natural Science: Lecture III

29 Sep 1920, Dornach Translated by Frederick Amrine, Konrad Oberhuber |

|---|