| 73. Anthoposophy Has Something to Add to Modern Science: Anthroposophy and sociology

14 Nov 1917, Zurich |

|---|

| Because of this, I must again start today by relating the fundamental concept in developing social life, which is the concept of freedom, to such natural scientific ideas as can be gained with the help of the science of the spirit. |

| We know that economic laws live in our social structure, and that we need to know these laws. Anyone involved in legislation or government and anyone who runs any kind of firm which is after all part of the social structure in life as a whole must work with the laws of economics. |

| Time being short, I have of course only been able to give brief indications that the sphere of social science, of economics, of social morality in the widest sense, law and everything connected with it, will only be mastered when people overcome the laziness which is such an obstacle today. |

| 73. Anthoposophy Has Something to Add to Modern Science: Anthroposophy and sociology

14 Nov 1917, Zurich |

|---|

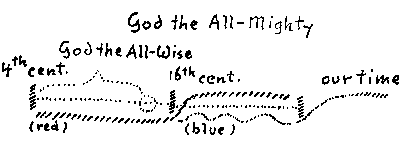

Spiritual scientific findings concerning rights and moral and social forms of life You will have seen from the three lectures I have given here to characterize the way anthroposophically orientated spiritual science relates to three different fields of human endeavour in the sciences, that with this spiritual science it is above all important to develop ideas that relate to the reality of things and make it possible to enter into the fullness of real life in order to gain knowledge of that real world. We may say—and this will have been evident from the whole tenor of my lectures—that for a relatively long period in the evolution of human science, concepts in accord with reality have only been gained in the field of natural science that is based on the evidence of the senses. In some respects these concepts are exemplary scientific achievements. However, with regard to reality they only go as far as lifeless nature—I think it is reasonable to say this. Lifeless nature exists not only where it is immediately apparent to the senses but also as a mineral element in the life forms and mind-endowed entities that live in the physical world. In modern science, people have a grasp of things that is exemplary. I think we have very clear evidence of this in the applications of natural science in human life, applications that have been perfected and are tremendously successful. When concepts are applied to human life we can, under certain conditions, see how far they are in accord with reality. A watch cannot be constructed if one has the wrong concepts of mechanics and physics; it would soon tell us that the wrong concepts have been used. This is not the case with all areas of life, and especially in the areas we are going to consider today, reality does not always immediately make it clear if we are dealing with concepts that are in accord with it, if they have been gained on the basis of reality or not. In the field of natural science it is relatively safe to use concepts that are not in accord with the truth, for they will show themselves to be erroneous or inadequate for as long as one stays within the field of natural science, that is, theoretical discussion which may then also be put into practice. However, when it comes to social life, the life of human communities in any form, we have to consider not only how to gain concepts but also how to bring these to realization. Under present-day conditions there are spheres of life where inadequate concepts can indeed be introduced. The inadequacies of the ideas, notions, reactions and so on will then show themselves; but in some respect people living entirely with a natural scientific bias will be helpless in face of the consequences of such concepts. In a sense it would be reasonable to say that the tragic events which have now come upon the human race are essentially connected—more than one would think, and more so than can be even hinted at in one brief lecture—with the fact that for long periods of time people did not know how to develop concepts that were in accord with reality, concepts that could be used to encompass the facts of real life. These facts of real life have become too much to handle for humanity today. In many ways the inadequate ideas humanity developed in the course of centuries are being reduced to absurdity in a most terrible way in these tragic events. We discover what really lies behind this if—let us now take a view that is different from those taken in the previous lectures—we first of all look at the way attempts have been made again and again in recent times to establish a general human philosophy on the basis of natural science, the way people have tried to introduce natural scientific thinking, so exemplary in its own sphere—let me repeat this over and over again—to all spheres of human life—psychology, education, politics, social studies, history, and so on. Anyone who knows about developments in this direction will know the efforts people who think in the natural scientific way have made to apply the ideas and concepts they have evolved in natural science to all the above spheres of life. Proof of this is available in hundreds of ways, but let me just give some characteristic details. They may go some way back, but 1 think we can say that the trend they reflect has continued to this day and has indeed been growing. Someone who in my view is an outstanding scientist spoke at two scientific gatherings in 1874 and 1875 on the sphere of rights, issues concerning morality and law, and human social relationships. In the course of those lectures he said some highly characteristic things. He actually claimed that anyone who in terms of modern scientific education has the necessary maturity ought to demand that the natural scientific way of thinking should be made part of people’s general awareness, like a kind of catechism. The inner responses, needs and will impulses arising in human beings as the basis of their social aspirations would thus have to be closely connected as time goes on with a purely natural-scientific view of the world that would be spreading more and more. This is what Professor Benedikt said at the 48th science congress.80 He said the scientific view of the world needed to gain the breadth, depth and clarity to create a catechism that would govern the cultural and ethical life of the nation. It is his ideal, therefore, that everything in social life that speaks out of the cultural, heart-felt and will-related needs of people should be a reflection of natural-scientific ideas! With regard to psychology, the same scientist said that it, too, had become a natural science since it followed physics and chemistry in casting off the ballast of metaphysics and no longer took hypotheses for its premises that were unfathomable for our present-day organization. Many scientists—including Oscar Hertwig, whom I mentioned the day before yesterday, Naegeli and many others—emphasize again and again that natural science can only work effectively in its own field. The scientific ideas that are developed are such, however, that the way in which they are developed, as it were, prevents humanity from searching and striving for other spheres of reality than those that can at best be reached with natural science. I have quoted things people said some time ago, but if we were to quote today’s speakers we would find that they are entirely in the same spirit. It is reasonable to quote Benedikt, who is a criminal anthropologist, for although he wants to take the purely scientific point of view also in looking at social life, he still has so much purely naive conceptual material in him which is in accord with reality that much of what he says—really going against his own theoretical theses—does truly extend into the reality of the world. On the whole, however, one may say that this tendency or inclination to develop a whole philosophy based on natural-scientific concepts, which are excellent in their own field, has gradually produced a quite specific philosophy, and one might almost get oneself a bad name by actually putting the philosophy that has developed out of this tendency into words. Today someone may do excellent work in his field, and if he then establishes a philosophy he extends knowledge which in its own field is indeed excellent to the whole world, and above all also to areas of which he in fact knows nothing. We can certainly say therefore that we have an excellent science today and its contents relate to things which people understand thoroughly. But then there are also philosophies which generally speaking are about things people do not understand at all! This is certainly not without significance when it comes to the sphere of social life. Here man himself is the reality factor. Human beings are in these social spheres and anything they do is indeed such that anything that lives in their philosophy of life does enter into their impulses and into the social structures and the way in which people live together. This is why the kind of things were created which I referred to briefly at the beginning today. In what I am saying today, I want again, as in the first three talks, base myself more on individual aspects of real life, on findings made in what I call spiritual investigation. I hope that with the aid of these I will be able to show how we should approach the fields of social studies in spiritual research. A particular problem arises for modern people who have scientific knowledge, and whose life of ideas is based entirely on scientific training, when they approach the sphere of social life and immediately have to consider a fundamental concept, which is the concept of human freedom. This concept, which doubtless has many nuances, has in some respect become a cross that has to be borne in modern thinking about the world. For on the one hand it is extraordinarily difficult to understand the social structure of today without having clarity with regard to the concept of freedom. On the other hand, however, someone who is thinking in the natural scientific way, in the thinking habits of our time, will hardly know what to do with the concept of freedom. We know that disputes concerning this concept go back a long way and that there have always been two factions, though the nuance has varied—the ‘determinists’ who assumed that all human actions are in a way predetermined, in a more naturalistic or some other way, so that a person only does things under an unknown yet existing compulsion or causality; then there were the ‘indeterminists’ who denied this and concentrated more on subjective reality, that is, on what human beings experience inwardly as they develop their conscious awareness, and who maintained that genuinely free human actions were independent of such fixed predetermination which would exclude the concept of freedom. Considering the way in which natural science has developed so far it is truly impossible to make something of the concept of freedom in that science. Anyone who makes a training in natural science the basis for establishing a sociology will be forced, in many respects, to take the wrong view of that concept of freedom and produce a structure for life that takes no account of the concept of freedom, ascribing everything to particular causes that lie either outside or inside the human being. In some respects such an approach is easy, for it allows one in a way to determine the social structure from the beginning. It is easier to reckon with human actions if they are predetermined than if one must expect a spirit of freedom in the human being to play a role. It would be wrong to present as a concept of freedom some kind of visionary concepts, vague mystical ideas that would tend to be more or less the opposite of what modern natural science has to offer. We have to realize that a science of the spirit is only justifiable if it does not go against the true meaning of progress in natural science. Because of this, I must again start today by relating the fundamental concept in developing social life, which is the concept of freedom, to such natural scientific ideas as can be gained with the help of the science of the spirit. According to the customary natural scientific concepts, human beings depend for their actions on the peculiarities of their organization. These are themselves investigated, as I have shown the last time, by applying the law of conservation of energy like a formula to the inner life, and this leads to the concept of freedom being excluded. If it is true that human beings are only able to develop energies and powers by transforming things they have taken in, then it will, of course, be impossible for the soul to develop any energies and powers of its own—which would be the requirement if freedom were to become a reality. In the science of the spirit it is, however, evident that it is absolutely necessary to put the whole of the knowledge gained in the natural sciences on a new basis in this particular area. Admirable factual discoveries have been made in the natural sciences, as I have also said in the preceding lectures. But concepts and ideas about nature are so narrowly defined that it is not possible to have a comprehensive view of those discoveries. In the last lecture I referred to the way in which the science of the spirit makes it possible to relate the whole sphere of the human soul and spirit to the whole sphere of the living body, and that it then emerges that we need to relate the actual life of ideas to the life of the nerves, the life of feeling to the ramifications and to anything depending on the breathing rhythm, and the life of the will to metabolism. If, for a starting point, we take the natural scientific view of the relationship between the life of ideas in the human soul and the life of the nerves, someone familiar with modern scientific ideas will have to say: ‘Processes occur in the life of the nerves; they are the causes of parallel processes in the life of ideas.’ Since there has to be a process in the nerves—and by definition this has its causal origin in the whole organism—for every idea-forming process in the soul, the corresponding process in the mind cannot be free, seeing that the process in the nerves is apparently the result of causal conditions existing in the organism. It thus has to be subject to the same necessity as the corresponding process in the nerves. That is still the view taken today. It will not be like this in future, seen from the natural scientific point of view! People will then look with very different eyes at certain new approaches that have already been developed in natural scientific research. It will however mean that the directions to be taken in research are indicated out of the science of the spirit, for this alone can make it possible to throw a truly comprehensive light on the findings made in natural science. The strange thing the spiritual investigator finds is that the life of our nerves relates in a quite specific way to the corresponding rest of the organism. We have to say it is like this: In the life of the nerves the organism destroys itself in a specific way, it is not built up in it. And in the life of the nerves—if we take it as pure life in the nerves, not nutritional life in the nervous system—the first processes to be considered are not growth or development processes, but processes of involution, of destruction. One is easily misunderstood in this area, for it is still completely new today. And in one short lecture it is difficult to bring in all the concepts that will prevent such misunderstanding. So I simply have to accept the danger of being misunderstood. What I can say is that the life of the nerves as such proceeds in a way that is completely different from all the other organic processes that serve growth, reproduction and the like. The latter mean development in the ascent. This includes the development of cells, the cell division processes we can observe in reproduction and growth processes, as something side by side with cells that are still in the life of reproduction, or at least a degree of partial reproduction. When the human organisation—it is similar for the animal organization, but this is only of minor interest to us today—extends into the life of the nerves, it partly dies off in that life of the nerves. Going into the life of the nerves, developing processes are broken down. We may thus say that even from a purely natural scientific point of view it is evident—and the life of the red blood cells runs to some degree parallel to the life of the nerves—that division processes come to a stop as they enter into nerve cells and red blood cells. This is wholly factual evidence of something which a conscious mind with vision is able to perceive: that the nerve cannot have part in anything that is in any way productive, but that the nerve inwardly brings life to a halt, so that life comes to an end where the nerve branches. By having a nervous system, we are, as it were, bearing death in us at the organic level. To compare what is really going on in the life of the nerves with something else in the organism, I’d have to say, strange though it may sound: ‘The unconscious processes in the life of the nerves cannot be compared with the process, for example, which happens when someone has taken in food and this food is processed in the organism for constructive development. No, the actual process in the nerves—as a process in the nerves, and not a nerve nutrition process—can be compared to what happens in the organism when it breaks down its tissues because of hunger.’ It is thus a destructive and not a constructive process which extends into the nervous system. Nothing of any kind can emerge or result directly from this nervous system. This nervous system represents a process that has been stopped, a process that shows itself in progress in the cell life of reproductive cells and growth cells. There it is progressive; in the neural organs it is stopped. In reality, therefore, the life of the nerves merely provides the basis, the soil, on which something else may spread. The principle which spreads on top of this life of the nerves, extending over this life of the nerves, is the life of ideas—initially stimulated by the outer senses—entering into the life of the nerves. It is only if we understand that the nerves are not the reason for forming ideas but merely provide a basis by having destroyed organic life, that we understand that the principle which develops on the basis of this life of nerves is something foreign to the life of nerves itself. The mind and soul principle developing on the basis of a life in the nerves which is destroying itself is so foreign to it that we may say: It really is just as when I walk along a road and leave my footprints behind me. Someone following those footprints should not derive the shapes he sees in my footprints from any kind of forces in the soil itself, coming, as it were, from inside the soil to produce my footprints. Every expression of inner life may be seen in the nervous system, like my footprints in the soil, yet it would be wrong to explain the life of mind and soul as something inwardly ‘arising from the nervous system’. The life in mind and soul leaves tracks in the prepared soil, a soil that has been prepared by ‘forgoing’ the possibility of the nerve continuing its own productivity, if I may put it like this in symbolic terms. Perceptive vision also shows the life in mind and spirit which thus develops on a basis of destruction, of a dying process in the human being, to be connected with organic life, initially the life of nerves; but in such a way that this life of nerves provides only the conditions, the soil, something which has to be there to provide the basis on which it can be active in this place. Seen from the outside, the principle which is active here may seem to arise from the nervous system, to be bound to the nervous system, but this life in soul and spirit is as independent of the nervous system as a child is of his parents when he develops independent inner activity, though the parents are, of course, the soil or basis on which the child must develop. Just as we may see the parents as the cause of the child if we look at this from outside, and just as the child is wholly free in developing his individual spirit and we cannot say that when the child develops independence there is not an activity in him which is in no way connected with his parents, we have to say in exactly the same way that the principle which is coming alive and developing in terms of mind and spirit becomes independent of the soil which it needs to thrive. I am just referring briefly here to a system of ideas that will develop further in the course of time—the science of the spirit is only in its beginnings now—by taking certain ideas from natural science to their highest extreme. Those very ideas from natural science will not lead to the exclusion of human freedom but to a way of explaining and understanding freedom actually in natural scientific terms, for they will make people observe not only constructive and progressive processes in the organism but also those that are destructive, paralysing themselves in themselves. They will show that if the element of soul and spirit is to arise, the organic principle cannot continue in a straight line of development and so produce something non-physical. No, as the non-physical, spiritual principle begins to come into existence, this organic principle must first prepare the soil by destroying itself, breaking itself down, within itself. When the ideas of constructive development, which are the only ones to be considered nowadays, have ideas about destructive development added to them, this will bring tremendous advances in the natural scientific approach. A bridge will be built that needs to be built because natural science must not be shut out today—a bridge from nature as it is understood to the sphere of social life which still needs to be understood. A natural science that is incomplete prevents us from developing the concepts needed for the sphere of social life; once it is completed, its inner sterling character, inner greatness, will help us to establish the right kind of sociology. I have thus presented, albeit briefly, the fundamental concept of social life, the concept of freedom. This has been set out fully in my Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, published in 1894, and the inner reasons given there accord fully with what I have now shown in a more natural scientific way. This is also evident from what I have written in my book The Riddle of Man81 which appeared almost two years ago. Let us now continue our consideration of the connection between man’s life in spirit and soul and other spheres of existence. The last time and today I referred briefly to the way in which this element of mind, spirit and soul is connected—as life of ideas with the life of the nerves, as life of feeling with life in the breathing rhythm, and as life of will with metabolic life. This only shows the connection in one aspect, however. Just as natural science will one day, when it has perfected itself in this direction, relate the threefold soul as a whole—as I have shown—to the whole bodily human organism, so will spiritual science be able to look for the connections of the human mind and soul with this spiritual principle, that is, in the other direction. On the one hand, the life of ideas has its bodily foundation in the life of the nerves, on the other it is connected with the world of the spirit, a world to which it belongs. This world, with which the life of ideas is also connected, can only be discerned through perceptive vision. It is perceived by a mind that has reached the first level of this vision, which I have called imaginative perception, or perception in images. This is gained out of the soul itself, like the opening of an inner eye. I characterized this in my first lecture. As the life of ideas relates to the life of nerves in the body, which is its physical foundation, so it also arises from the realm of the spirit, a purely non-physical world that is seen to be a real world when we come to observe this reality with that vision in images. This real world is not contained within the sense-perceptible world. It is, as it were, the first world that goes beyond the senses, bordering directly on our own. Here one finds that the relationship which the human being has to the world around him, as he is aware of it in his mind, is only part of his total relationship to the world; anything we have in our conscious awareness is a segment of the reality in which we are. Below this level of awareness lies another relationship to the surrounding world, to the natural world and the world of the spirit. Even the connection between our life of ideas and the life of the nerves in the body has been pushed below the threshold of conscious awareness and can only be brought up from there with an effort if one wishes to characterize it the way I have done today. On the other hand the relationship of our life of ideas to the spiritual world which we can only perceive in images is also such that it does not enter into our ordinary conscious awareness, though it does enter into human reality. In the human mind we have first of all everything that has been stimulated by the senses and by the rational mind which is bound to the senses; this is the usual content of the conscious mind. Below this, however, lies a sum total of processes that initially do not come to ordinary awareness, but arise as a spiritual principle, which can only be perceived in images; this plays into our soul nature just as sounds, colours, smells and so on play into the everyday life of our souls. Ordinary conscious awareness thus rises, as it were, from another sphere which itself can only be brought to conscious awareness if we are able to perceive in images. The fact that people do not know of these things does not mean that they do not exist in reality. Moving through the world we bear the content of our ordinary conscious awareness with us; we also bear with us everything that comes from the ‘imaginative’ spiritual world, as I’ll call it for the moment. It is of tremendous importance, especially at the present time, to understand that the human being relates to the world around him in this way. A field for research—I am far from underestimating this field, I appreciate its significance—and there was every reason for it to come up at the present time, has indeed come up at the present time. It is like a powerful pointer to man’s relationship to the world around him which I have just characterized as the spiritual world of images, a relationship that is only little known so far. It is a feature of our present time that much comes to human awareness that can really only be encompassed with the means of insight given through the science of the spirit. Humanity is called upon to perceive these things today in that one’s nose is rubbed in them, to put it plainly, with life taking a course where people cannot avoid seeing them. Yet modern people still cannot overcome their reluctance to tackle this with the means for insight provided by the science of the spirit. They therefore try to use the means of ordinary natural science or concepts developed in relation to other things to approach areas which today literally cry out for investigation. The field I am referring to is that of analytical psychology, also called psychoanalysis, which is, of course, particularly well known in this city.82 What makes it remarkable is that a field opens up to challenge the investigator that lies outside our ordinary conscious awareness; it must refer to something that lies below the threshold of that awareness. People are, however, trying to work with what I may call inadequate tools in this field. As they endeavour to apply these inadequate tools also in practice—only therapeutically and educationally, to begin with, perhaps, but perhaps also pastorally—we have to say that the matter has more than theoretical significance. I am, of course, not in a position to discuss the whole field of psychoanalysis. That would need many lectures.83 Let me, however, refer to some of the principles, some of the real aspects in this context. Psychoanalysis is a field where investigation and social life meet in a point, as happens also in other fields of this kind which we’ll be considering today. Above all, and as you are no doubt aware, analytical psychology essentially has to do with bringing ‘lost’ memories back to mind for therapeutic purposes. The thesis is that the psyche contains certain elements that do not come to conscious awareness. It is then widely assumed that these memories have gone down into the unconscious or the like, and efforts are made to go and cast light below the threshold of consciousness by using the ordinary memory concept and enter into regions not illuminated by our ordinary consciousness. Now I did already mention in these lectures that the science of the spirit has the task of illuminating the human memory process in a very major way. Again it will not be possible, of course, to avoid all the misunderstandings that can arise with such a brief review of the subject. I have heard it said, for example—several times, not just once—that psychoanalysis was really on the same road as the science of the spirit which I represent; it was only that psychoanalysts took some things in a symbolic way, whilst I took things which those enlightened psychoanalysts considered to be symbolic to be realities. That is a grotesque misapprehension, and you cannot characterize the relationship of psychoanalysis to the science of the spirit in a worse way than by saying that. To understand this we need to take another look at the nature of the memory process. Let me emphasize once again that the process of forming ideas, the activity of doing so, is something which in the inner life of man essentially relates only to the present. An idea as such never goes down to some unconscious level of the mind, just as a mirror image seen when passing a mirror will not settle down somewhere so that it may come up again the next time you pass the mirror. The coming up of an idea is a phenomenon that begins and ends in the present moment. And anyone thinking that memory consists in there ‘having been’ an idea which ‘comes up’ again, may well be an excellent Herbartian psychologist, or a psychologist in some other direction, but is not basing himself on a genuinely observed fact. What we have here is something entirely different. The world in which we live is filled not only with the sensory perceptions that enter into our present life of ideas through eye or ear. This whole world—and that of course also means the natural world—is based on a world that has to be perceived in images, a world which initially does not come to conscious awareness. The contents of this world of images act parallel to my momentary life of ideas: as I form an idea, letting these momentary processes take their course in me, another process runs parallel to them, with a current of unconscious life moving through my soul. This parallel process causes inner tracks to be left—I could characterize these in all detail, but have to limit myself to brief indications here—and these are observed when memory arises later. When memory arises, therefore, it is not a matter of an old idea, which might have been stored somewhere, being brought back again. Instead we look inwards at tracks left in a parallel process. Memory is a process of perception directed inwards. The human soul is capable of many things at an unconscious level which it is not able to do consciously in ordinary life. To compare the process that occurs when a ‘forgotten’ event ‘comes back to mind’, doing so in very general terms—let me emphasize this: in very general terms—with something else, I would say that it is quite similar to sensory perception using the outer senses. The difference is that with the latter I recreate my perceptions in temporary images that only exist for the moment. Anything I recreate from memory is a specific form of inner perception. Within myself, I perceive the residue of the parallel process; this has remained stationary. As a crude analogy, recall is a process in which the soul reads at a later time something that had gone parallel to the forming of an idea. The soul has this ability, at an unconscious level, to read in itself what had been developing when I formed an idea. I did not know this at the time, for the idea blocked it out. Now it is recalled. Instead of having a sensory perception of something on the outside, I perceive my own inner process. That is the real situation. I am fully aware that a fanatical psychoanalyst—none of them see themselves as fanatical, of course, and I know this, too—will say that he has no problem in agreeing to this explanation of memory. But in fact he’ll never do so when considering these things in practice. Anyone who knows the literature will know that it is never done and that this is in fact the source of countless errors. For people do not know that it is not a matter of past ideas that linger somewhere in the unconscious, but concerns a process that can only be understood if we understand the way in which an imaginative world plays into our world in a process that runs parallel to the life of forming ideas. The first significant errors arise because a wrongly understood memory process forms the theoretical basis and is applied in practice in analytical psychology. When we penetrate to the real process of remembering, there can be no question of looking for elements in the soul which psychoanalysts consider to be pathological in memories that linger somewhere. It is a matter of perceiving how the patient relates to a real, objective world of non-physical processes, which he is, however, adopting in an abnormal way. This makes a huge difference, something which we must of course think through in every possible aspect. Psychoanalysts who apply their natural scientific training one-sidedly in an important sphere of real life also fall into another kind of error. They use dream images for psychological diagnosis in a way that cannot be justified in the face of genuine observation. We need genuine observation and concepts that relate to reality so that we may enter into this strange, mysterious world of dreams in the right way. This is only done if we know that human beings have their roots not only in the environment in which they live with their ordinary conscious minds but—even in the life of ideas, as we have seen, and later we’ll also see some other things—in a world of spirit. Our ordinary conscious awareness comes to an end when we sleep, but that connection with the world that remains at a subconscious level does not come to an end. There is a process—I cannot characterize it in detail, time being short—in which the special conditions pertaining in sleep cause the things we live through in connection with our spiritual environment to be clothed in symbolic dream images. The content of those dream images is quite immaterial. The same process—the relationship of the human being to his spiritual surroundings—may appear as a particular sequence of symbolic images for one individual and as a different one for another. Anyone with the necessary knowledge in this field knows that typical unconscious processes in the psyche assume the garb of widely differing reminiscences of life in all kinds of different people, and that the content of the dream does not matter. You only come to realize what lies behind this if you train yourself to ignore the content of the dream completely and consider instead what I’d call the inner dynamic of the dream. It is a question of whether a foundation is first laid with a particular dream image, then tension is created and then an evolution, or whether the sequence is different, starting with tension which is then followed by resolution. It needs a great deal of preparation before one can consider the evolution of a dream, the whole drama of it, wholly leaving aside the content of the images. To understand dreams one must be able to do something that would be like seeing a play and taking an interest in the scenes only in so far as one perceives the writer behind it and the ups and downs of his inner experience. We must stop wanting to grasp dreams by abstract interpretation of their symbolism. We need to be able to enter into the inner drama of the dream, the inner context, quite apart from the symbolism, the content of the images. Only then will we realize how the soul relates to its spiritual surroundings. These cannot be seen in the dream images which someone who does not have vision in images uses for reality under the abnormal conditions of sleep, but only through awareness in images. The drama that lies beyond the dream images can only be understood if we have imaginative awareness. As you are probably aware, research in analytical psychology also extends—and in a way this is most praiseworthy—to mythology. Many interesting things have been discovered, and other things that are enough to make your hair stand on end. I won’t go into detail, but it is important to see that individual scientists still work in such a way today that they one-sidedly develop a limited area, taking no account of scientific discoveries that have already been made, though these can often throw much more light on the matter than one is able to do oneself. An old friend of mine who died quite some time ago wrote a very good book on mythology. He was Ludwig Laistner.84 After going right round the world, as it were, with regard to the origin of myths, he showed in a very interesting way that if you want to understand myths it is not at all important to consider the content, that is, what they tell—doing so in one way in one place and in a different way in another—or the actual images of those myths; no, in that case, too, it is important to let the dramatic events come to light that come to expression in the different mythological images. Laistner also considered the connection between mythological images and the dream world, doing so in a way that was still elementary but nevertheless correct. His studies therefore provided an excellent basis for connecting research into dreams with the investigation of myths. If in mythology, too, people were aware that it is merely images that come across into dream consciousness from the creative sphere of myths, images which arbitrarily, I would say, represent the actual process, that would be a much more intelligent way of working. As it is, people working in analytical psychology—and I do fully recognize their importance and that they work with the best and truly honest good will—attempt things that must be askew and one-sided because their means are inadequate. There is very little inclination to go really deeply into things, and to get help from spiritual life to understand reality in terms that relate to reality. More recent research in psychoanalysis did, apart from the ordinary concept of memory and the kind of dreams that have their origin in individual life, also involve taking account of a ‘super-individual unconscious’,85 as it is called. At this point, however, a research method pursued with such inadequate means has led to a most peculiar result. There is a feeling—and we have to be thankful that such a feeling at least exists—that this inner life of the human psyche is connected with a life of the spirit that lies outside it; however, there is nothing one can do to perceive this connection in real terms. I honestly don’t want to find fault with these scientists, and I greatly respect their courage, for in a present world which is so full of prejudice it needs real courage to speak of such things; but it has to be pointed out—especially because these things also enter into practical considerations—that there is a way of overcoming such one-sidedness. Jung, a scientist of great merit who lives here in Zurich, has taken refuge, as it were, in trans-individual, super-individual unconscious spirit and soul contents. According to him the human soul relates not only to memories which the individual has somehow stored or the like, but also to things that lie outside its individual nature. An excellent, bold idea—to relate this life in the human psyche not only by the means of the body but also in itself to soul qualities in the outside world; it certainly merit's recognition. The same man does, however, ascribe what happens in the soul in this way to a kind of memory again, even if it is super-individual. You cannot get away from the concept of mneme, or memory, though we can’t really speak of memory any longer when we go beyond the individual element. Jung puts it like this: you come to see that ‘archetypal images' live in the soul, images of the myths evolved among the ancient Greeks—archetypes, to use Jacob Burckhardt’s term. Jung says, significantly, that everything humanity and not only the individual person has gone through may be active in the soul; and as we do not know of this in ordinary conscious awareness, this rages and rises up unconsciously against the conscious mind, and you get the strange phenomena that show themselves today as hysterical and other conditions. Everything humanity has ever known of the divine and also of devilish things rises up again, Jung says in his latest book; people know nothing about it, but it is active in them. Now it is highly interesting to look at an investigation done with inadequate means, taking a characteristic instance. This scientist has come to say, in an extraordinarily significant way that when people do not consciously establish a connection with a divine world in their souls, this connection is created in their subconscious, even though they know nothing about it. The gods live in the subconscious, below the threshold of conscious awareness. And a content of which they know nothing in their conscious minds may come to expression in that they ‘project’ it, as the term goes, on to their physician or another person. Thus a memory of some devilry may be active in the subconscious but not come to conscious awareness; it rages inside, however; the individual must rid himself of it; he transfers it to some other person. The other person is made into a devil; this may be the physician, or, if he does not manage to do this, the individual does it to himself. From this point of view it is most interesting to see how a scientist comes to his conclusions about these things. Let us look at one of the latest books on psychoanalysis, The Psychology of the Unconscious by Carl Gustav Jung.86 He writes that the idea of God is simply a necessary psychological function of an irrational kind. Jung deserves great merit for acknowledging this, for it means that for once recognition is given to the nature of the human subconscious as being such that people establish connections with a divine world in their subconscious. The author then goes on to say that this idea of God has absolutely nothing to do with the question as to the existence of God. This last question, he says, is one of the most stupid questions anyone may ask. We are not concerned with the scientist’s own view of the idea of God. He may be a very devout person. What concerns us here is what lives in the scientist’s own subconscious life of ideas, if I may use that term. Inadequate means of research mean no less than that one says to oneself: The human soul has to establish relationships to the gods below the threshold of consciousness; but it has to make these relationships such that they have nothing to do with the existence of God. It means that the soul must of necessity content itself with a purely illusory relationship; yet this is eminently essential to it, for without this it will be sick. This is of tremendous import, something we should not underestimate! I have merely indicated how inadequate the means are with which people are working in a quite extensive field. I’ll now continue my description of the human being and the way he needs to relate to his social environment. The life of feelings—not now the life of ideas, but the life of feelings—has its physical counterpart in the breathing rhythm, as I said, and on the other hand also relates to spiritual contents. The element in the spirit which corresponds to the life of feelings the way the life of the breathing rhythm does at the physical level, can only be penetrated, being a spiritual content, a content of spiritual entities, spiritual powers, with an ‘inspired’ mind, as I have called it in these lectures. This inspired mind opens up not only the spiritual content that fills our existence from birth, or let us say conception, until death, one also comes to see things that go across birth and death and have to do with our life between death and rebirth, that is, of a spirit that is alive even when the human being no longer has this physical body. Whereas the human being gains a basis for this physical body through physical heredity, the principle which is born out of the inspired world, creates its physical expression in the breathing rhythm. But into this life of feeling—whereas initially only elements coming between birth and death play into the life of ideas which the human being knows in his ordinary conscious awareness—enters everything by way of powers and impulses that has been active during the time from the last death to the present birth. This will be active again between this death and a new birth. The core of the human being’s eternal reality plays into this life of feeling. The third thing to be noted is that the human being’s life of will relates on the one hand really to the lowest functions in the human organism, to metabolism, something which in the widest sense comes to expression in hunger and thirst. On the other hand it relates in the spirit to the highest spiritual world, the intuitive world, which I have mentioned on several occasions in these lectures. We thus do indeed have a complete reversal of the situation. Initially the life of ideas is subconsciously in touch with the world of images, and with the life of nerves in its other aspect. In a world that projects beyond our personal life in a body as the core of our reality, the life of feeling goes towards the spiritual side. And the life of will, which comes to physical expression whenever there is a will impulse in some metabolic process, and therefore in the lowest processes in the organism, is on the spiritual side connected with the highest spiritual world, the intuitive world. We have to enter into this region if we want to investigate ‘repeated lives on earth’, as they are called. Impulses that go from one life on earth to another cannot be grasped in images, let alone in our ordinary conscious awareness, and not even with inspired consciousness. This needs intuitive awareness. Impulses from earlier lives on earth enter into our life. Impulses from this life will enter into later lives on earth. The only possible character our investigations can have at this point is one of having developed a sense for real intuitions, not the wishy-washy kind of which we speak in ordinary life. The complete conscious mind thus perceives the complete human being as he lives in soul and spirit in three ways—in ideas, feelings and will impulses, all of which rise up and go down again. For he has his basis in three ways in a living physical body and takes his origin in the world of the spirit. The science of the spirit takes us to the eternal in man not in any speculative or hypothetical way, but by showing how the conscious mind must develop if it is to behold the eternal core of the human being who develops in successive lives on earth. This complete human being—not an abstract human being presented in natural science or by naturalists in an empty, abstract set of ideas that do not hold the whole of reality—this complete human being is part of a social life. Our ordinary conscious mind is able to understand the natural world outside in so far as it is not organic but something in the lifeless, mechanical sphere—in modern science this is often the only thing considered to have validity and be worth considering. This level of the mind is not able, however, to find concepts that are wholly viable when it comes to social life if they have evolved in the pattern used in everyday thinking. The secret of social life is that it does not develop according to the concepts we have in our ordinary thinking but does so outside the sphere of the conscious mind, in impulses that can only be grasped with the higher levels of conscious awareness of which I have spoken. This insight can throw light on many things which in our present social life must inevitably end in absurdity because the concepts people want to apply to it do not relate to reality. So there we are today, with concepts gained from an education based on natural scientific ideas, and we want to be creative in social life. But this social life needs additional concepts that differ from those we have in our ordinary thinking—just as the subconscious life of the psyche presenting in psychoanalysis also calls for additional concepts. In the first place three areas in social communities need to have light thrown on them through anthroposophically orientated spiritual science. I’ll only be able to give a rough outline, for the science of the spirit is still in its beginnings and many things still need to be investigated. I will thus merely characterize the general nature of the strands we have to see running from spiritual scientific insights to insight into social life. Three spheres of social life may be seen. The first sphere where what I have been characterizing just now applies, is the sphere of economics. We know that economic laws live in our social structure, and that we need to know these laws. Anyone involved in legislation or government and anyone who runs any kind of firm which is after all part of the social structure in life as a whole must work with the laws of economics. The economic structure, as it exists in real terms, cannot be grasped if we apply only the concepts gained in the natural scientific way of thinking, concepts that govern practically the whole of people’s thinking today. The impulses that are active in economic life are entirely different from those in the natural world, and that includes human nature. In basic human nature, our view rests on questions of need, for example. Issues concerning the meeting of needs are the basis of our external economic order. To gain genuine insight into a social community with its economic structure I need to perceive how depending on the geographical and other conditions the means are available to meet human needs. For the individual we start from the question of needs, but to consider the economy we must start from the opposite side. Then we do not consider what people need but what is available to people in a given area as community life develops. This is just a brief indication. Many things would need to be said if we wanted to consider the economic structure in its entirety. Yet the economic structure of a country or community, which is really an organism, cannot be dealt with by using concepts taken from ordinary natural science. That may lead to some very strange things! Here it is reasonable to say something in particular because I am truly not just referring to it in the light of current events. People might object that I have been influenced by these current events, but that is not the case. What I am going to say now is something I spoke of in a course of lectures I gave in Helsingfors before the present war started.87 My reasons for referring to it now have therefore nothing at all to do with the war. I need to say this in advance, so that there shall be no misunderstanding. At that time in Helsingfors—that is, before the war—I showed how we can go astray if we want to grasp the social structure of human communities wholly with natural scientific ideas. For my example I chose someone who falls into this error to the greatest degree—Woodrow Wilson.88 I referred to the strange way in which Woodrow Wilson—academic thinking had in this case advanced to statesmanship—said that if one considers the days of Newtonism, when a more mechanical view was taken of the whole world, one can see that the mechanical ideas which Newton and others had made current had also entered into people’s ideas of the state, their ideas of social life. It is wrong, however, to consider social life in such a narrow way, said Woodrow Wilson; we have to do it differently today and apply Darwinian ideas to social life. He was thus doing the same thing, only with the ideas that are now current in natural science. Yet Darwinian ideas are of as little use in understanding social structures as were Newtonian ones. As we have heard, not all Darwinian ideas are actually applicable in organic life. This remained at a subconscious level for Wilson, however, and he did not realize that he was making the very mistake which he had identified and censured just before. Here we have an outstanding example of people unable to realize that they are working with inadequate tools that will not cope with reality when they try to master and understand social life today. Such a situation, where the tools are inadequate even as people make world history, is something we come across wherever we go. And if people were able to see through what is happening here, they would be able to see deeply into the deeper causes of the phrase mongering that goes on at present, reasons that are generally not apparent to the world today. Economic structures cannot be understood if we use natural scientific concepts—whether gained from Darwinism or Newtonism—for these only apply to the facts of nature. Instead, we must move on to other concepts. I can only characterize these other concepts by saying that they must rest on if not perhaps a clear idea, then at least a feeling of entering wholly into the social structure, so that ideas come up that belong to life in images. It needs the help of image-based ideas to get a picture of a real social structure that exists in one place or another. Otherwise we only get abstractions of no value that have no substance to them. We no longer create myths today. But the power to create myths was an impulse in the human soul that went beyond everyday reality. Today, people must take the same inner impulse which our forebears used to create myths; they created, if I may put it like this, images of a spiritual reality out of powers of imagination that related to that reality; we must have ideas in images of economic systems. We cannot create myths, but need to be able to see the geographical and other situations of the terrain together with the given character of people, the needs of people, in such a way that they are seen together with the same power that was formerly used to create myths, a power that is alive and active in the spiritual sphere as the power to form images and which is also reflected in the economic structure. A second sphere in social life is the moral structure and the moral impulse that lives in a totality. Again we go down into all kinds of unconscious spheres to investigate the impulses revealed in human moral aspirations—moral in the widest possible sense. Anyone wishing to intervene in this, be it as a statesman, be it as a parliamentarian, or also as the head of some firm who wants to take a leading role, will only understand the structure if he is able to master it with concepts that have at least a basis in insights gained through inspiration. This is even more necessary today than people tend to think; intervening in this social aspect in so far as moral impulses are involved. These moral impulses need to be studied truthfully and in real terms, just as the impulses of organic life cannot be invented but have to be studied by considering the organism itself. If people were to think up concepts about lion nature, cat nature, or hedgehog nature, if you will, the way they think up concepts in thinking up Marxism today, or other socialist theories, and failed to study nature in reality, and if they were to construct purely a-priori concepts of animal nature, they would arrive at strange theories about the animal organization. The important point is that the social organism also has to be studied in absolutely real terms where moral principles in the widest sense are involved. The forces of need that human beings bring into play—they, too, are moral powers in the wider sense—can only be mastered if we investigate the real social organism on the basis of ideas that have their roots in the inspired world, even if these ideas are only dimly apparent. Today we are still a long way away from such a way of thinking! In the science of the spirit one comes to study the nature of the impulses that live among the people in Central Europe, Western Europe or Eastern Europe in real terms and in detail. One comes to see in very real terms how the different inner impulses arising from the social organism are just as real and well-founded as the impulses that arise from the physical organism. One comes to see that the way nations live together is also connected with these impulses that can be studied from deep down. In the science of the spirit one finds that the structure of the soul differs greatly between the West and the East of Europe, and one comes to know that such a structure must become part of the whole of European life. Let me remind you that I have been talking about the different soul structures that underlie European social life for decades, speaking out of purely spiritual scientific ideas.89 The discoveries made in the science of the spirit are confirmed by people with empirical knowledge who know the reality of life. Look in yesterday’s and today’s issues of the Nene Zürcher Zeitung [major Swiss paper] for what is said there about the soul of the Russian people and Russian ideals, taking a Dostoevskyan view.90 There you have complete proof—I can only refer you to this, time being too short for a detailed description—in observations made in an outer way of a result arising very evidently from something that has been put forward for years in the science of the spirit. You then come to study social impulses and energies in real life. As it is impossible to master life with concepts far removed from reality, this life gets on top of people. They no longer know how to encompass life with concepts as abstract as those used in the sphere of natural science. These prove inadequate in the social sphere. This life, which is surging and billowing deeper down and has not been grasped in conscious awareness, has therefore brought about the catastrophic events we are now going through in such a terrible way. A third sphere we meet in social life is the one we call the life of rights. Essentially the social structure of any body is made up of economic life, moral life and the life of rights. All these terms must be taken in the spiritual sense, however. Economic life can only be studied in a real sense if we think in images; moral life and its true content can only be studied with the help of inspired ideas; the life of rights can only be understood with the help of intuitive ideas, and these, too, must be gained from full and absolute reality. We can thus see how the insights sought into nonphysical aspects with the science of the spirit apply to different spheres of social life. In the field of education, too, which essentially is part of the social sphere, fruitful concepts will only arise if we are able to develop image-based concepts so that we may see life which is as yet unformed in images that arise in us—not in the abstract terms that are so common in education today but on the basis of genuine vision in images—and also guide it on that basis. The life of rights, concepts in the sphere of rights—just think how much has been written and said about this in recent times. Basically, however, people have no really clear idea of even the simplest concepts in the sphere of rights. Here, too, we merely need to consider the efforts of people who want to work entirely out of a training in the natural sciences, Fritz Mauthner, for instance, author of the highly interesting dictionary of philosophy.91 Read the entry on law, penal law or, in short, everything connected with this, and you’ll see that he dissolves all known ideas and concepts, and also existing institutions, showing that there is no possibility whatsoever, nor ability, to put anything in their place. It will only be possible to put something in their place if people look for what they are seeking in the structure of rights in the world that is the very foundation of social structures, a world open only to intuitive perception. Here in Zurich I am able to refer to a work in which the author, Dr Roman Boos, has made a start with looking at the sphere of rights in this way.92 An excellent beginning has been made in basing real issues in the sphere of rights on the situations pertaining to the structure of rights and the social structure and arriving at realistic ideas concerning individual details in the sphere of rights. Study such a work and you will see what is meant when we demand that social life as a life of rights should be studied in a realistic and not an abstract way, developing our ideas about it in real terms, encompassing it with concepts that relate to reality. It is of course harder to do than if we construct utopian programmes and utopian government structures. For it means that the whole human being has to be considered and one must truly have a sense of what is real. I have made the concept of freedom the fundamental one in order to show that although we are looking for laws pertaining to the world of the spirit, the concept of freedom is wholly valid in the science of the spirit. It will not be easy, however, to study these things in real terms. For we then come above all to realize the complexity of reality, which cannot be encompassed in one-sided concepts that are like stakes put in the ground here or there. One realizes that as soon as we go beyond the individual person we must encompass this reality in concepts that are like the concepts used in the science of the spirit which I have described in these lectures. Let me give you a powerful example. People like to live with biased ideas, concepts gained in their habitual way of thinking. When the first railway was built in Central Europe, a body of medical men—learned people, therefore—was also consulted. This has been documented, though it may sound like a children’s tale. The doctors found that no railway should be built, since it would cause damage to people’s nervous systems. And if people insisted after all on having railways, one should at least put high board fences on either side of the railway lines so that people would not get concussion when a train went past.93 This expert opinion from the first half of the 19th century was based on the habitual way of thinking at that time. Today we may find it easy to laugh about such a biased opinion; for those learned gentlemen were, of course, wrong. Developments have overtaken them. Progress will overtake many things which ‘esteemed gentlemen’ consider to be right. There is, however, another question, strange though it may seem. Were those learned gentlemen simply wrong? It only seems so. They were certainly wrong in one respect, but they were not simply wrong. Anyone who has a feeling for the more subtle things in the development of human nature will know that the development of railways does in a strange way relate to the development of some phenomena of nervousness which people suffer at present. Such a person will know that whilst it may not be as radical as those learned gentlemen put it, the trend of their opinion was partly right. Anyone who truly has a feeling for the differentiated nature of life, for the difference between our life today and life at the turn of the 18th to 19th century will know that railways did cause nervousness, so that the learned doctors were right in some respect. The idea of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, which is still applicable to some natural event or some natural human phenomenon, does not apply when it comes to the social structure. Here it is necessary for a person to develop a faculty for more comprehensive ideas by training his inner abilities in a wholly different way. Those ideas need to encompass a social life that goes far beyond anything which one-sidedly abstract ideas taken from natural science—and they have to be abstract—are able to encompass. Time being short, I have of course only been able to give brief indications that the sphere of social science, of economics, of social morality in the widest sense, law and everything connected with it, will only be mastered when people overcome the laziness which is such an obstacle today. For essentially it is laziness and a fear of genuine ways that lead to insight which prevent people from looking at the world in the light of spiritual science. In spite of being permitted to give a course of four lectures, I have of course only been able to refer briefly to some things. I am fully aware that I could only give some initial ideas. It also was merely my intention to make the connection to the individual sciences known today in form of initial ideas. I know that many objections can be raised, and am thoroughly familiar with the objections that may be raised. Anyone who bases himself on the science of the spirit must always raise all possible objections for himself at every step, for it is only by measuring his insights against the objections that one truly develops from the depths of the soul the potential vision in the spirit that can cope with reality. Yet though I am aware how imperfect the ideas I have presented have been—it would need many weeks to give all the details which I was able merely to refer to briefly as results—perhaps I may think after all that I have given some idea in at least one direction, and that is that spiritual science has nothing to do with stirring things up because one has some abstract ideal or other. It is a field of research which the progress of human evolution actually demands at this time. Someone who is working in this field of investigation and truly understands its impulses will know that it is exactly the areas that are demanded in the present time—like the field of psychoanalysis of which I spoke—which show, if truly penetrated, that they can in fact only come fully into their own if illuminated by what we are here calling spiritual science with an anthroposophical orientation. I wanted to show that this is not something dependent on sudden whims or vague mysticism but is pursued in all seriousness by people who are serious investigators, at least in their intentions. I therefore presented a number instances to show that current scientific thinking can gain a great deal from the science of the spirit which we have today. I do not believe this science of the spirit to be something completely new. We need go back no further than Goethe to find the elementary beginnings in his theory of metamorphosis. These merely need to be developed further in the science of the spirit—though not with abstract, logical scientific hypotheses. They need to be developed in a way that is full of life. As I myself have been working with the further development of the Goethean approach for more than 30 years, I privately like to refer to the approach called spiritual science with anthroposophical orientation as Goethe’s approach taken further. If it were entirely my own choice, I’d like to call the building in Dornach which is dedicated to this approach a Goetheanum,94 to indicate that this spiritual science with anthroposophical orientation is not something new suddenly emerging into the light of day as something arbitrarily developed from a single case but something which the spirit of our age is calling for and also the spirit of human evolution as a whole. It is my belief that people who have gone along with the spirit in human evolution have in their best endeavours at all times pointed to the principle which must today show itself as the fruits and flowers of scientific endeavour so that genuine, serious insight into the life of the spirit may be established. This must be done with the same seriousness and integrity which has also be brought to the development of natural science in recent centuries and especially in more recent times, a science which those working in the science of the spirit do not reject or denigrate. My aim in giving these lectures has not been to fight other sciences or go against them in any way, but to show—as I said in my introduction—that I appreciate them. I believe they are great not only in what they are today but also in what may still develop. In my view it shows greater appreciation of natural scientific and other modern ways of thinking if one does not merely stay at the point where one is, but believes that if we enter wholly into everything that is good in the different fields of science, this will not only permit the logical development of some philosophy or other which then does not take us further than what already exists in its basic premises, but will be able to bring forth something that is alive. Spiritual science with anthroposophical orientation wants to be something which thus has life and is not merely based on logical conclusions. Questions and answers From the question and answer session95 which followed the lecture given in Zurich on 14 November 1917 Question. How does the lecturer explain the process of forgetting? Well, this is something that can be dealt with briefly. The process of forgetting essentially is due to the fact that the process I referred to as running parallel to the forming of ideas and on which memory depends has a phase of ascent and one of descent. To be more easily understood I might mention that a process which is not the same, but exemplifies the process we are considering, was something Goethe called the ‘fading away of sensory perceptions’. This fading away of sensory perceptions—when a sensory perception has come to an end, the effect of it is still there but fading—is not the process on which forgetting is based, but it helps to clarify the situation. It is exemplary, as it were, of the whole process which occurs there. Let me emphasize that I see this as a process which is mental and physical and not physiological, though it does extend into the physiological aspect. You will find more details about this in my books. But this process, too, has a phase when the effect dies down, and that is the basis of forgetting. The ascending phase is the basis of remembering, and the descending phase of forgetting. The process of forgetting is not all that surprising, I would say, if one takes the view of remembering which I have been presenting. Question. What does it mean if someone never dreams, or is never aware of his dreams? How should we consider this phenomenon in psychological and anthroposophical terms respectively, that is, how does such a person differ from others in mind and spirit? This is quite a problematical issue. It is easy for people to say that they never dream, but it is not really the case. What we have here is a certain weakness relating to the subconscious processes that give rise to dreaming. This weakness means a person is unable to bring up from the subconscious what is meant to be read from this subconscious, as I put it metaphorically. Everyone dreams. But just as there are other weaknesses, so some people are in a condition where it is impossible to bring their dreams up to conscious awareness. This weakness should not, however, be regarded the way we may regard an organic weakness, say. It can easily arise if the mind is outstanding in some other area. Thus we are told that Lessing never dreamt. In his case this would have been due to the fact that his was an eminently critical mind. By concentrating his powers as strongly as we know him to have done, thus using them in one aspect of his inner nature, Lessing weakened them in another area. We therefore should not see this weakness as something really bad; it may have to do with strengths in other areas. To interpret such a thing ‘psychologically’ and ‘anthroposophically’ is, of course, one and the same thing for a spiritual scientist. It cannot even be said that someone with a certain weakness in bringing dreams to mind would also have a weakness, for example, relating to processes that are part of imaginative perception. This need not be the case at all. Someone may not have much of a gift for what is ordinarily called dreaming, and yet develop powers of imaginative perception and so on by using the methods I have given in my books, especially in Knowledge of the Higher Worlds. It may be the case that when he now uses his powers specifically for imaginative perception of the world, in full conscious awareness, to look into the world of the spirit—we might say clairvoyant insight if the term can be used without prejudice—this may actually suppress ordinary dreaming, though the reverse may also be the case. I know a great number of people who use the exercises described in Knowledge of the Higher Worlds in their souls and experience a transformation in the life of dreams, which is also described in the book. Ordinary dream life is vague in its contents. It changes strangely under the influence of awakening imaginative perception. The inability to bring dreams to mind thus points to nothing more than a partial weakness in someone’s nature, and this should be regarded in the same way as when someone has strong muscles in another sphere, and someone else’s muscles are weaker. It is something that lies entirely in the nuances of the way in which people are constituted.

|

| 184. The Cosmic Prehistoric Ages of Mankind: Romanism and Freemasonry

22 Sep 1918, Dornach Translated by Mabel Cotterell |

|---|

| But it is now required of man that he should get to know true reality according to its law and being. Social science, the science of human community-life and man's historical life must in particular always be permeated by a spiritual science that, as these lectures have shown, can really build the bridge between the nature-order and the spirit-order, real bridges, not those abstract ones built by monism. |

| Those who think and make research only along the lines of modern natural science cannot build the bridge from natural science to social and political science. Those alone who know the great laws resulting from spiritual science which relate to the greatness of nature in the way I have just explained, are able then to lead across the bridge from natural science to the science of man, above all to the historical and political life of mankind. |

| And if some day natural science is guided more into the right path of Goethe's world-conception, then natural science too will be still more Goetheanism than it can be today, when it is hardly so at all. Then the law of polarity in the whole of nature will be recognised as the fundamental law, as it has indeed already figured in the ancient Mysteries from atavistic clairvoyance. |

| 184. The Cosmic Prehistoric Ages of Mankind: Romanism and Freemasonry

22 Sep 1918, Dornach Translated by Mabel Cotterell |

|---|