| 191. Cosmogony, Freedom, Altruism: Social Impulses for the Healing of Modern Civilization

10 Oct 1919, Dornach Translator Unknown |

|---|

| They knew that they were not merely beings that had gone astray and were wandering about over the face of the green earth like lost sheep, but that they were part and parcel of the whole wide universe, and had their own functions in the universe as a whole. |

| 191. Cosmogony, Freedom, Altruism: Social Impulses for the Healing of Modern Civilization

10 Oct 1919, Dornach Translator Unknown |

|---|

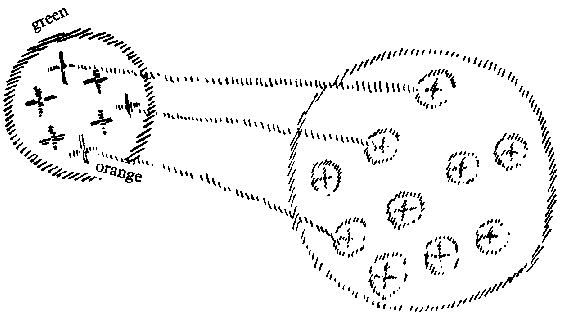

I want during the next few evenings to talk to you about various things in connection with our present civilisation, things which are necessary to right understanding and action in the world to-day. It is not very difficult—in view of the many facts that meet one almost at every turn—to perceive signs of decline within our civilisation, and that it contains forces that make for its downfall. Recognising these forces of decline and fall within our civilisation, we have then to seek out the quarters from which it may draw fresh sources of new strength. If we survey our present civilisation we shall see that there are present in it three main downward forces,—three forces which gradually and inevitably must bring about its overthrow. All the distressing phenomena which we have hitherto experienced in the course of man's evolution, and all those that we have still to go through,—for in many respects we are only just at the beginning,—are all only so many symptoms of a vast process going on in our age, which, taken as a whole, presents a phenomenon of decline and fall. If we look beyond our own immediate civilisation, beyond what has taken place in our own times merely, or during the last three or four hundred years,—if we take a wide survey of the whole course of man's evolution we may observe that earlier ages had a groundwork for their civilisation, a foundation for the habits and thoughts of everyday life, such as we to-day only believe ourselves to have. These old civilisations, especially the heathen civilisations, had something of a scientific character about them, a scientific character of a sort which made men realise that what lived within their own souls was part of the life of the whole universe. Just think what a vivid conception the Greeks still possessed of worlds extending beyond the bounds of everyday existence, of a world of gods and spirits behind the world of sense. One has but to recall how great a part was played in everyday life by whatever could form any sort of link between the people of those older civilisations and a spiritual world to which they were no strangers. In all their daily transactions, these men of the old civilisations were conscious of forming part of a creation that was not exhausted within the limits of the everyday world, but where spiritual beings made their activities felt. The commonest everyday affairs were carried on under the guidance of spiritual forces. Thus, in the heathen civilisations especially, we find when we look back on them, a dominant scientific character, which is best described by saying: in those days people—we can put it in that way—people had a COSMOGONY; that is, they recognised themselves to be members of the whole universe. They knew that they were not merely beings that had gone astray and were wandering about over the face of the green earth like lost sheep, but that they were part and parcel of the whole wide universe, and had their own functions in the universe as a whole. The men of old days possessed a COSMOGONY. Our civilisation possesses no instinct for the creation of a cosmogony in real life. Our mode of conception is not, in the strict sense of the term, a genuinely scientific one. We have tabulated isolated facts and have constructed a logical system of concepts, but we have not got a real science, forming a practical link between us and the spiritual world. How paltry is the part played by the science of our day in common life, compared with what a man of old felt pulsing through him from forces of the spiritual world! In all his actions, he had a cosmogony; he knew himself a member of the whole vast universe. When he looked up at the sun and the moon and the stars, they were not to him strange worlds; for he knew himself, in his own deepest nature, akin to the sun and moon and world of stars. Thus, the old civilisation possessed a Cosmogony; but for our civilisation this cosmogony is lost. Without a cosmogony in life, man cannot be strong.—That is one thing,—what I might call the scientific element,—that is bringing about the downfall of our civilisation. Another, the second element that is bringing about its downfall, is that there is no true impulse for FREEDOM. Our civilisation lacks the power to ground life upon a broad basis of general freedom. Only very few people in our day arrive at any real conception of freedom. There are plenty who talk about it; but very few to-day arrive at any real conception of what freedom really is, and fewer still have any real impulse for it. And so, it comes, that our civilisation is gradually sinking into something where it can find neither strength nor support—into fatalism. Either we have religious fatalism, in which men yield themselves up to religious forces of some sort or another, make these religious forces their master, and ask nothing better than to be pulled about by strings, like puppets at a show; or else we have the fatalism of natural science. And the effects of such scientific fatalism are seen in the way people have come to regard everything that happens as happening by natural necessity, or by economic necessity, and as leaving no scope for free action on the part of man. When men feel themselves fettered to the world of economics or the world of nature, that is, to all intents and purposes, fatalism. Or else, again, we have that fatalism which has come in with the more modern forms of religious faith,—a fatalism that deliberately precludes freedom. Just ask yourselves how many hearts and souls there are to-day that consciously yearn to yield themselves up, for Christ, or a spiritual power of some kind, to do what he pleases with them. Why, it is even an accusation that one frequently hears made against Anthroposophy, that it lays too little stress on men being redeemed by Christ and not by themselves. People prefer to be led; they prefer to be guided; they would really prefer fatalism to be true. How often lately, in these troublous [troubled?] years, has one not heard that kind of talk from one person or another. They would say: “Why doesn't God, why doesn't Christ, come to the help of this or that set of people? There must, after all, be a divine justice somewhere!” People would like this divine Justice ... They would like to have it suspended aloft as a fate. They do not want to get to that ingrained innate strength which comes from the impulse of Freedom and permeates the whole being. A civilisation that does not know how to foster the impulse of Freedom weakens men and dooms itself to downfall. That is the second thing. Of the forces that are bringing about the decline of our civilisation, the first is the lack of a COSMOGONY, and the second is the lack of a genuine impulse for FREEDOM. The third is that our civilisation is incapable of evolving anything that can give fresh fire to religious feeling and purpose. Our civilisation, in truth, aims at nothing more than nursing the old religions and fanning their cold ashes. But to bring new religious impulses into life,—for that our civilisation lacks the strength. And lacking this, it lacks also the strength for true altruistic action in life. That is why all the processes of our civilisation are so egoistic, because it has within itself no real, no strong, altruistic motive-power. There is nothing, friends, that can supply altruistic motive-power, but a spiritual view of life. Only when a man comes to recognise himself as a member of the spiritual world, does he cease to be so tremendously interested in himself that the whole world revolves round him. When he does,—then, indeed, egoistic motives cease and altruistic ones set in. Our age, however, is little given to cultivating so great an interest in the spiritual world. The interest in the spiritual world has got to be a good deal further developed before people really feel themselves members of it. And so, one might say that it was like impulses given from on high that REINCARNATION and KARMA came amongst us and into our civilisation. But how were these impulses interpreted? At bottom it was in a very egoistic way that these ideas of Reincarnation and Karma were understood, even by those who took them up. For instance, they would say: “Oh, well! In some life or other everyone has deserved what he gets.” Even otherwise quite intelligent people have been known to say that the ideas of Reincarnation and Karma of themselves sufficiently warranted the existence of human suffering. There was at bottom no justification for the social question,—so said many otherwise intelligent people,—for, if a man was poor, it was what he had earned in his previous incarnation, and he has to work off in this incarnation only what he deserved from a previous one. Even the ideas of reincarnation and karma are unable to permeate our civilisation in any way except one which gives no stimulus to the altruistic sense. It is not enough for us merely to introduce ideas such as those of reincarnation and Karma,—the question is, in what way we introduce them. If they become merely an incentive to egoism, then they do not raise up our civilised life, they only serve to sink it lower. There is another way, again, in which reincarnation and karma become unethical, anti-ethical, ideas; many people say: “I must be good, so that I may have a good incarnation next time.” To act from such a motive, to be virtuous in order that one may have as pleasant a time as possible in one's next incarnation,—this is not mere simple egoism, it is double egoism; yet this double egoism is what many people did actually get out of the ideas of reincarnation and karma. So that one may say that our civilisation possesses so little of any altruistic religious impulse that it is incapable of conceiving even such ideas as those of reincarnation and karma in the sense that would make them a stimulus to altruistic, not to egoistic actions and sentiments. Those are the three things which are acting within our civilisation as forces of decline and fall:—lack of a COSMOGONY, lack of a sound foundation of FREEDOM, lack of an ALTRUISTIC SENSE. But without a cosmogony there is no real science or system of knowledge, there is no real knowledge; then all knowledge ultimately becomes a mere game, in which all the worlds and the civilisation of man are toys. And this is what knowledge has, in many respects, become in our age,—in so far as it is not merely a utilitarian incident of external culture, of external technical culture. Freedom has become in many respects in our age an empty phrase, because the force of our civilisation is not that which lays a large foundation of freedom nor spreads abroad the impulse of freedom. Neither have we in the economic field the possibility of progressing further in the social direction, because our civilisation contains no altruistic motive-force, but only egoistic, that means anti-social motive-forces,—and one cannot socialise with antisocial forces. For socialising means creating a social framework such that each man lives and works for the rest. But just imagine in our present civilisation each man trying to live and work for the rest! Why, the whole order of society is so instituted that each one can only live and work for himself. All our institutions are like that. The question then arises:—How are we going to surmount these signs of our civilisation's decline and fall? To plaster over such signs of decline in our civilisation, my dear friends, is quite impossible. There is nothing for it but to recognise the facts as they have just been stated, to regard them dispassionately and without reservations, and to harbour no illusions. One must say to oneself: There they are, these forces of decline and fall, and one must not imagine that one can in any way turn them in another direction, or anything of that sort. No, they are very powerful forces of decline, and it is necessary to give them their proper name, and to speak of them as we are doing now. This being so, what we have got to do is to turn to where forces can be found for the re-ascent. That is not to be done by theorising, People in the present day may invent the most beautiful theories, may have the most beautiful principles, but with theories one can do nothing. To do anything in life, it must be by means of the forces that are actually present in the world; and one must summon them up. If our civilisation were through and through as I have been describing it,—I mean, if it were like that through and through,—then there would be nothing for it but to say to ourselves: “There is nothing for it, but just to let our civilisation go to pieces, and ourselves go to pieces along with it.” For to attempt in any way to redress the signs of the times by mere theories or conceptions would be an utter absurdity. One can but ask:—Does not the root of the matter perhaps lie really deeper? It does lie deeper; and in this way:—People to-day—and I have here often pointed out the same thing from different aspects,—people to-day are too much bent upon the absolute. When they ask: “What is true?” they mean, “What Is true absolutely?”—not what is true of a particular age. When they ask, “What is good?” they are asking, “What is good absolutely?” They are not asking, “What is good for Europe? What is good for Asia? What is good for the 20th century? What is good for the 25th century?” They are asking about absolute Goodness and Truth. They are not asking about what actually exists in the concrete evolution of mankind. We must put the question to ourselves in a different way, for we must look at the actuality of things, and from the point of view of actuality; questions must be differently put, very often so put that the answers seem paradoxical compared with what one is inclined to assume from a surface view of things. We must ask ourselves: Is there no possibility of arriving once more at a mode of conception which is cosmogonical, which takes in the universe as a whole? Is there no possibility of arriving at an impulse of freedom which shall be an actual influence in social life? Is there no possibility for an impulse which shall be religious and at the same time an impulse of brotherhood, and therefore the real basis for an economic social order? Is there no possibility^ of arriving at such an impulse? And if we put these questions before us from a real aspect, then we get real answers. For the point, we have here to remember is this: that the various types of people on the earth to-day are not all adapted to the whole all-comprehensive universal truth, but that the various types of men are only adapted to particular fields of the true activity. We must ask ourselves; Where in the life of earth to-day may there, perhaps, exist the possibility for a cosmogony to evolve? Where does the possibility exist for a sweeping impulse of freedom to evolve? And where does the impulse exist for a communal life among men, which is religious and also, in a social sense, brotherly? We will take the last question first; and if we contemplate the state of affairs on our earth impartially, we shall come to the conclusion that the temperament, the mode of thought for an actual brotherly impulse upon our earth is to be sought amongst the Asiatic peoples, the peoples of Asia, especially in the civilisations of Japan and India. Despite the fact that these civilisations are already fallen into decadence, and despite the fact that external, superficial appearances are against it, we find there enshrined in men's hearts those impulses of generous love towards all living things, which alone can supply foundations for religious altruism in the first place, and, in the second, for an actual, altruistic, industrial form of civilisation. But here we are met by a peculiar fact: that the Asiatics have, it is true, the temperament for altruism, but that they have not got the kind of human existence which would enable them to carry their altruism into practice; they have merely got the temperament but they have no possibility, no gift, for creating social conditions in which altruism could begin to be externally realised. For thousands of years the Asiatics have managed to nurse the instincts of altruism in human nature. And yet they brought this to a state in which China and India were devastated by monster famines. That is the peculiar thing about the Asiatic civilisation, that the temperament is there, and that this temperament is inwardly perfectly sincere, but that there exists no gift for realising this temperament in outward life. That is just the peculiar thing about this Asiatic civilisation, that it contains a tremendously strong instinct for altruism in men's inward nature, yet no possibility for the moment of realising 4t externally. On the contrary, if Asia were left to herself alone, this very fact, that she has this capacity for paying the inward basis of altruism, without any gift for realising it outwardly, would turn Asia into an appalling desert of civilisation. We may say, then, that of these three things: the impulse for COSMOGONY, the impulse for FREEDOM, the impulse for ALTRUISM, Asia possesses more especially the inward temperament for the third. It is, however, but one third of -what is necessary to bring our civilisation into the ascendant, which Asia possesses,—the inward temperament for altruism. What has Europe got? Well, Europe has got the utmost necessity for solving the social question; but she has not got the temperament for the social question. To solve the social question, she would need to have the Asiatic temperament. The social necessities of Europe are such as to supply all the conditions requisite for a solution of the social question; but the Europeans would first need to become permeated through and through with the way of thought which is natural to the Asiatic, only the Asiatic has no gift for actually perceiving social needs as they exist externally. Often, indeed, he even acquiesces in them. In Europe, there is every external incentive to do something about the social question, but the temperament is lacking. On the other hand, there is in Europe, in the very strongest degree, the talent, the ability which would provide the soil for Freedom,—for the impulse of freedom. The strong point of European talents, specifically European talents, lies in developing in the very highest degree the inner sentiment, the inner feeling for freedom. One might say that the gift for getting to a real idea of Freedom is specifically European; but among these Europeans there are no people who act freely, who could make freedom a reality. Of Freedom as an idea, the Europeans can form the loftiest conception. But just as the Asiatic would be able to set about doing something, if he possessed the clear thought of the Europeans without their other failings, if he could only get the clear-out European idea of Freedom, so the European can evolve the most beautiful conception of Freedom, but there is no possibility, politically, of realising this idea of freedom through the direct agency of the European peoples, for, of the three essentials to civilisation,—the impulse for altruism, the impulse for freedom, the impulse for cosmogony,—the European possesses only one-third, the impulse for Freedom. The other two he has not got. So, the European also has only got one-third of what is necessary in order really to bring forth a new age. It is very important that people should at last recognise these things as being the secrets of our civilisation. In Europe we can, at least, say that we have all the conditions of thought and feeling requisite for knowing what freedom is, but, without something more, there is no possibility for us to actualise this freedom. I can assure you, for instance, that in Germany the most beautiful things were written by various individuals about freedom, at the time when all Germany was groaning under the tyranny of Ludendorff and Co. Most beautiful things were written about freedom at the time. Here in Europe, a talent undoubtedly exists for conceiving the impulse of freedom. That is one-third, so far, towards the actual upraising of our civilisation,—one-third, not the whole. Leaving Europe and going westwards—and I take Great Britain and America together in this connection,—passing, then, to the Anglo-American world, we find there again, one-third of the impulses, just one out of the three impulses necessary to the upraising of our civilisation, and that is, the impulse towards a cosmogony. Anyone acquainted with the spiritual life of the Anglo-American world knows that, formalistic as Anglo-American spiritual life is in the first instance, that, materialistic as it is in the first instance, and though, indeed, it even tries to get what is spiritual in a materialistic fashion, yet it has got in it the makings of a cosmogony. Although this cosmogony is to-day being sought along altogether erroneous paths, yet it lies in Anglo-American nature to seek for it. Again, a third, the search for a cosmogony. But there the possibility of bringing this cosmogony into connection with free altruistic man does not exist. There is the talent for treating this cosmogony as an ornamental appendage, for working it out and giving it shape; but no talent for incorporating the human being in this cosmogony as a member of it. Even the spiritualist movement, in its early beginnings in the middle of the 19th century, of which it still preserves some traces, had, one may say, something of a cosmogony about it, although it led into the wilderness. What they were trying to get at were the forces that lay behind the sense-forces; only they took a materialistic road, a materialistic method, to find them. But they were not endeavouring through these means to arrive at a science of the formalist kind that you get, for instance, among the Europeans; they were trying to become acquainted with the real actual super-sensual forces. Only, as I said, they took a wrong road, what is still known as the “American” way. So here, again, we have one-third of what will have to be there before our civilisation can really rise again. One cannot to-day arrive at the secrets of our civilisation, my dear friends, unless one can distinguish how these three impulses needed for its rise are distributed among the different parts of our earth's surface; unless one knows that the tendency towards Cosmogony is an endowment of the Anglo-American world, that the tendency towards Freedom lies in the European world, whilst the tendency towards Altruism and towards that temperament which, properly realised, leads to socialism is, strictly speaking, peculiar to Asiatic culture. America, Europe, Asia, each has one- third of what must be attained for any true regeneration, any real reconstruction of our civilisation. These are the fundamental ideas which must inspire thought and feeling to-day for anyone who is in earnest and sincere about working for a reconstruction of our civilisation. One cannot to-day shut oneself up in one's study and ponder over which is the best programme for the coming times. One has got to-day to go out into the world and search out the impulses already existing there. As I said, if one looks at our civilisation and at all that is hurrying it to its fall, one cannot avoid an impression that it is impossible to save it. And it cannot be saved unless people come to see that one thing is to he found amongst one people, and the second amongst another, the third amongst a third,—unless people all over the earth come together and set to work on big lines to give practical recognition to what none of them, singly, can of himself achieve, in the absolute sense, but which must be achieved by that one who is marked out, so to speak, by destiny for that particular work. If the American to-day, besides a cosmogony, wants also to evolve freedom and socialism, he cannot do it. If to-day the European, besides founding the impulse for freedom, wants to supply cosmogony and altruism, he cannot do it. No more can the Asiatic realise anything save his long- engrained altruism. Let this altruism be once taken over by the other groups of the earth's inhabitants, and saturated with that for which each has a special talent, then, and then only, we shall really get on. We have got once for all to admit to ourselves that our civilisation has grown feeble, and must again find strength. I have expressed this in a rather abstract way, and to make it more concrete will put it as follows:—The old pre-Christian civilisations of the East produced, as you know, great cities. Great cities existed in them. We can look back over a wide spread range of civilisations in the East, which all produced great cities. But the great cities they produced had, as well, a certain character about them. All the civilisations of the East had this speciality for creating, along with the life of great cities, the conception that, after all, man's life is a void, a nothing, unless he penetrates beyond the merely physical into the super-physical. And so, great cities such as Babylon, Nineveh, and the rest, were able to develop a real growth, because men were not led by these cities to regard what the cities themselves brought forth as being itself the actual reality, but, rather, what is behind it all. It was in Rome that people came to make the civilisation of cities a gauge of what was to be regarded as real. The Greek cities are inconceivable without the country round them. If history, as we have it, were not such a conventional fiction,—a “fable convenue,”—and would only revive past times in their time aspect, it would show us the Greek cities rooted in the country. But Rome no longer had her roots in the country. Indeed, the whole history of Rome consists in the conversion of an imaginary world into a real world, the conversion of a world which is unreal into one which is real. It was in Rome that the Citizen was first invented,—that ghastly mock-figure alongside the living being, Man. For man is a human being; and if he is a citizen besides, that is a fiction. His being a citizen is something that is entered in the church register, or the town register, or somewhere of the sort. That besides being a human being, endowed with particular faculties, he is also the owner of assessed property, duly entered in the land register,—that is a fiction alongside the reality. That is thoroughly Roman thought. But Rome achieved a great deal more than that. Rome managed to take all that results from the separation of the town from the country,—the real, actual country,—and to give it a fictitious reality. Rome, for instance, took the old religious concepts and introduced into them the Roman legal concepts. If we go back to the old religious concepts with an open mind, we do not find the Roman legal concepts contained in the old religious ones. Roman jurisprudence simply invaded religious ethics. All through religious ethics, thanks to what Rome has made of them, there is, at bottom, a notion of the supersensible world as of a place with judges sitting, passing judgment on human actions, just as they do on the Benches of our law-courts, that are modelled on the Roman pattern. Yes, so persistent is the influence of these Roman legal concepts, that when there is any talk of Karma, one actually finds that the majority of people to-day who accept the doctrine of Karma picture it working, as though Justice were sitting over there beyond, meting out rewards and punishments according to our earthly notions, a reward for a good deed, and a punishment for a bad one,—exactly the Roman conception of law. All the saints and supernatural beings exist after the fashion of these Roman legal concepts which have crept into the supernatural world. Who to-day, for instance, comprehends the grand idea of the Greek “Fate”? The concepts of Roman jurisprudence do not help us much to-day, do they, towards the understanding of the “Oedipus.” Indeed, men seem altogether to have lost the capacity for comprehending tragic grandeur, owing to the influence of Roman legal concepts. And these Roman legal concepts have crept into our modern civilisation; they live in every part of it; they have become in their very essence a fictitious reality, something imaginary,—not something one imagines, but something that is imaginary. It is absolutely necessary for us clearly to see that, in our whole way of conceiving things, we have lost touch with reality, and that what we need is to impregnate our conceptions afresh with reality. It is because men's concepts are, at bottom, hollow, that our civilisation still remains unconscious of the need for the common co-operation of men all over the round earth. We are never really willing to go to the root of what is taking place under our eyes; we are always more or less anxious to keep on the surface of things. Just to give you another example of this. You know how in the various parliaments throughout the world in former days,—say, the first half of the 16th century, or a little later,—party tendencies took shape in two definite directions, the one Conservative the other Liberal,—which for a long time enjoyed considerable respect. The various other parties that have come up since were later accessions to these two main original ones. There was the party of a conservative tendency, and the party of a liberal tendency. But, my dear friends, it is so very necessary that one should nowadays get beyond the words to the real thing behind, and there are many matters about which one must ask, not what people, who stand for a certain thing, say about it, but what is going on subconsciously within the people themselves. If you do so, you will find that the people who attach themselves to one or other of the parties of a conservative tone are people who in some way are chiefly connected with agrarian interests, with the care of land and cultivation of the soil; that is to say, with the primal element of human civilisation. In some way or other this will be the ease. Of course, on the surface, there may be all sorts of other circumstances entering in as well. I do not say that every conservative is necessarily directly connected with agriculture. Of course there is here, as everywhere else, a fringe of people who adhere to the catchwords of a cause. It is the main feature that one has to consider; and the main feature is that that part of the population which has an interest in preserving certain forms of social structure and in keeping things from moving too fast, is agrarian. On the other hand, the more industrial element, drawn from labour that has been detached from the soil, is liberal, progressive. So that these two-party tendencies have their source in something that lies deeper; and one must, in every case, try to lift such things out of the mere phrases into which they have fallen,—to get through the words to the real thing behind them. But ultimately, it all tells the same tale,—that the form of civilisation in which we have been living is one whose strength lies in words. We must push forward to a civilisation built upon real things, to a civilisation of real things. We must cease to be imposed upon by phrases, by programmes, by verbal ideals, and must get to the clear perception of realities. Above all, we must get to a clear perception of realities of a kind that lie deeper than forms of civilisation in city or country, agricultural or industrial. And much deeper than these are those impulses which to-day are at work in the various members of the body human distributed over the globe,—of which the American is making towards Cosmogony, the European towards Freedom, and the Asiatic towards Socialism. At present, this certainly comes out, has and does come out, in a curious way. Anglo-American civilisation is conquering the world, But, in conquering the world, it will need to absorb what the conquered parts of the world have to give; the impulse to Freedom and the impulse to Altruism; for in itself it has only the impulse to Cosmogony. Indeed, Anglo-American civilisation owes its success to a cosmogonic impulse. It owes it to the circumstance that people are able to think in world-thoughts. We have often and often talked about this during the war, and how the successes of that side proceeded from supersensible impulses of a particular kind, which the others refused to recognise. The cosmogonic element cannot and must not be left thus isolated; it must be permeated from the domain of freedom. Yes, my dear friends, but then, to see the full meaning of this, it is, I need hardly say, necessary to get right, right away from phrases, and pierce to the realities. For anyone who is tied to phrases would naturally think; Well, but who of late has stood out as the representatives of Freedom, if not the Anglo- American world?—Why, of course, in words, yes, to any extent, but what matters about a thing is not how it is represented in words, but what it is in reality. We have had over and over again, as you know, occasion to refer to -the language of “Wilsonism.” Phraseology of the Wilson type has been gaining ground in Western countries for a long-time past. In October 1918, it even for a time laid hold of Central Europe. And over and over again here,—I remember there was always quite a little commotion here when, over and over again, as the years went on, one had to point out the futility of all that Woodrow Wilson's name stood for, how utterly hollow and abstract it all was, for which Woodrow Wilson's name stood. But now, you see, people even in America are apparently beginning to see through Wilsonism, and hour hollow and abstract it all is. Here, there was no question of any national feeling of hostility towards Wilson, there was no question of antagonism proceeding from Europe. It was an antagonism arising from the whole conception of our civilisation and its forces. It was a question of showing Wilsonism for what it is,—the type of all that is abstract, all that is most unreal in human thought. It is the Wilson type of thought which has had such one-sided results, because it has absorbed the American impulse without really possessing the impulse of freedom (for talking about freedom is by no means a proof that the impulse of freedom itself is really there), and because it had not the impulse for really practical Altruism. The life of Central Europe, with all that it was, lies in the dust. What lived in Central Europe is, to a great extent, sunk in a fearful sleep. At the present moment, the German is, one might say, forced to think of freedom, not as they talked of it in all manner of fine phrases at the time when they were groaning under the yoke of Ludendorff,—when constraint of itself engendered an understanding of the idea of freedom. Mow they think of it, but with crippled powers of soul and body, in total inability to summon up the energy for real intense thought. We have in Germany all sorts of attempts at democratic forms, but no democracy. We have a republic, but no republicans. And this is in every way a symptom that has especially manifested itself in Central Europe, but it is characteristic of the European world in general. And Eastern Europe?—For years and years, the proletariat of the whole world have been boasting of all that Marxianism was going to do. Lenin and Trotsky were in a position to put Marxianism into practice; and it is turning into the wholesale plunder of civilisation, which is identical with the ruin of civilisation. And these things are only just beginning. Yet for all that, there does exist in Europe the capacity for founding freedom, ideally, spiritually. Only, Europe must supplement this in an actual practical sense, through the co-operation of the other people on the earth. In Asia, we can see the old Asiatic spirit lighting up again in recent years. Those people who are spiritual leaders in Asia (take, for example, the one I have already alluded to, Rabindranath Tagore),--the leading spirits of Asia show by their very way of speaking that the altruistic spirit is anything but dead. But there is still less possibility now than there was even in old days, of achieving a civilisation through this one third only of the impulses that go to the making of a civilisation. All this is the reason why to-day there is so much talk about things which are peculiar to the civilisation that is dying, but which people talk about as though they stood for something that could be effective as an ideal. For years, we have had it proclaimed that “Every nation must have the possibility of ...” well, I don't quite know of what, living its own life in its own way, or something of that sort. Now, I ask you: For the man of to-day, if he is frank and honest about it, what is a “nation”?—Practically just a form of words, certainly nothing real. If one talks about the Spirit of a Nation, in the sense in which we speak of it in Anthroposophy, then one can talk about a Nation, for then there is a reality at the back of it; but not when it merely signifies an abstraction. And it is an abstraction that people have in mind today when they talk of the “freedom” of nationalities, and so forth. For they certainly don't believe in the reality of any sort of national Being. And herein lies the profound inward falsity to which men to-day do homage. They don't believe in the reality of the national Being, yet they talk of the “Freedom of the Nation,” as if to the materialist man of our day, the “nation” meant anything at all. What is the German nation? Just ninety millions of persons, who can be added together and summed up, A plus A plus A. That is not a National Being—a self-contained entity—for men to believe in. And it is just the same with the other nations. Yet people talk about these things and believe that they are talking about realities, and all the while are lying to themselves in the depths of their souls. But it is with Realities we are dealing when we say; The Anglo- American Being—a striving towards cosmogony; the European Being—a striving towards freedom; the Asiatic Being—a striving towards altruism. When we then try to comprehend these three divided forces in a consciousness that embraces the universe as a whole,—when, from out of this consciousness of the universal whole, we say to ourselves: “The old civilisation is bursting through its partitions, it is doomed,” to try to save it -would be to work against one's age, not with it. We need a new civilisation upon the ruins of the old one. The ruins of the old civilisation will get ever smaller and smaller; and that man alone understands the present times who has will and courage for one that shall be really new. But the new must be grounded, neither in a sense of country as among the Greeks and Romans, nor in a sense of the Earth, as with men of modern times. It must proceed from a sense of the Universe, the world-consciousness of future man, that world-consciousness which once more turns its eyes away from the earth here, and looks up to the Cosmos. Only, we must arrive at a view of this Cosmos which shall carry us in practice beyond the Schools of Copernicus and Galileo. My dear friends, the Europeans have known how to express the earth's environment in terms of mathematics; but they have not known how, from the earth's environment, to extract a real science. For the times in which he lived, Giordano Bruno was a remarkable figure, a great personality; but to-day we need to realise that where he could only perceive a mathematical order, there a spiritual order reigns, reality reigns. The American does not really believe in this purely mathematical world, in the purely mathematical cosmos. His particular civilisation leads him to reach out to a knowledge of the supersensible forces beyond, even though he is, as yet, on the wrong road. In Europe, there was no sort of knowledge that they did not pursue; and yet when Goethe, in his own way, really put the question: “What is scientific knowledge?” there was no getting any further; for Europe had not got the power to take what can be learnt from the study, say, of Man, and widen it into a cosmogony, a science of the universe. Goethe discovered metamorphosis, the metamorphosis of plants, the metamorphosis of animals, the metamorphosis of man. The head, in respect of its system of bones, is a vertebral column and spinal marrow, transformed. So far, so good; but you need to follow it up and develop it, until you realise that this head is the transformed man of the previous incarnation, and that the trunk and limbs are the man in the initial stage of the coming incarnation. Real science must be cosmic, otherwise it is not science. It must be cosmic, must be a cosmogony, otherwise this science is not something that can. give inward human impulses which will carry man on through life. The man of modern times cannot live instinctively; he must live consciously. He needs a cosmogony; and he needs a freedom that is real. He needs more than a lot of vague talk about freedom; he needs more than the mere verbiage of freedom; he needs that freedom should actually grow into his immediate life and surroundings. This is only possible along paths that lead to ethical individualism. There is a characteristic incident in connection with this. At the time when my Philosophy of Freedom appeared, Edouard von Hartmann was one of the first to receive a copy of the book, and he wrote me: “The book ought not to be called The Philosophy of Freedom,” but “A Study in Phenomena connected with the Theory of Cognition, and in Ethical Individualism.” Well, for a title that would have been rather long-winded; but it would no# have been bad to have called it “Ethical Individualism,” for ethical individualism is nothing but the personal realisation of freedom. The best people were totally unable to perceive how the actual impulses of the age were calling for the thing that is discussed in that book, The Philosophy of Freedom. Turning now to Asia,—indeed, my dear friends, Asia and Europe must learn to understand each other. But if things go on as they have in the past, then they will never understand each other, especially as Asia and America have to understand each other as well The Asiatics look at America and see that what they have there is really nothing more than the machinery of external life, of the State, of Politics, etc, The Asiatic has no taste for all this machinery; his understanding is all for the things that arise from the inmost impulses of the human soul. The Europeans have, it is true, dabbled in this same Asiatic spirit, the spiritual life of Asia; but it must be confessed that they have not, so far, given proof of. any very great understanding of it. Nor have they been in very perfect agreement, and the kind of disagreement that arose plainly showed that they had very little understanding of how to introduce into European culture what are the real actuating impulses of Asiatic culture. Just think of Mme. Blavatsky; she wanted to introduce into the civilisation of Europe every kind of thing out of the civilisation of India, of Thibet. Much of it was very dubious, that she tried to introduce. Max Müller tried another way of bringing Asiatic civilisation into Europe. One finds a good deal in Blavatsky that is not in Max Müller; and there is a good deal in Max Müller that is not in Blavatsky. But from the criticism Max Müller passed on Blavatsky it is plain how little insight there was into the subject. In Max Müller's opinion, it was not the real substance of the Indian spirit that Blavatsky had brought over to England, but a spurious imitation, and he expressed his opinion in a simile, by saying: That if people met a pig that was grunting, they would not be astonished; but if they met a pig talking like a man, then they would be astonished. Well, in the way Max Müller used the simile he can only have meant that he, with his Asiatic culture, was the pig that grunted, and that Blavatsky was as if a pig should start talking like a man! To me it certainly seems that there is nothing remarkably interesting about a pig grunting; but one would begin to feel rather interested if a pig were suddenly to start running about and talking like a man Here the simile of itself shows that the analogy they found was a very thin one and lies chiefly in the words. But people do not notice that nowadays; and if one does make bold to point out the absurd side of the matter, then people think one ought not to treat “recognised authorities” like Max Müller in that kind of way, it is not at all proper! That is just where it is, my dear friends, the time is at hand when one must speak out honestly and straightforwardly. And if one ie to be honest and straightforward, one must speak out quite plainly about the occult facts of our civilisation in the present day,—such facts as these: That the Anglo-American world has the gift for Cosmogony, that Europe has the gift for Freedom, Asia the gift for Altruism, for religion, for a social-economic order. These three temperaments must be fused together for a complete humanity. We must become men of all the worlds, and act from that standpoint, as inhabitants of the universe. Then, and then only, can that come about which the age really demands. We will talk more about this tomorrow. To-morrow we meet at 7 o'clock. First there will be the Eurhythmic performance, then a break, and after that the lecture. |

| 192. Social Basis For Primary and Secondary Education: Lecture I

11 May 1919, Stuttgart Translator Unknown |

|---|

| Nature continually makes leaps; it is a leap from the green leaf of a plant to the sepal which has a different form—another leap from sepal to petal. It is so too in the evolution of man's life. |

| 192. Social Basis For Primary and Secondary Education: Lecture I

11 May 1919, Stuttgart Translator Unknown |

|---|