Anthroposophy, An Introduction

GA 234

3 February 1924, Dornach

6. Respiration, Warmth and the Ego

When we study human life on earth, we see it proceed in a kind of rhythm expressed in the alternating states of waking and sleeping. It is from this point of view that one must consider what was said in the last lectures about the constitution of man. Let us look, with ordinary consciousness, and in what might be called a purely external way, at the facts before us. In the waking man there is, first, the inner course of his vital processes; but these remain subconscious or unconscious. There is also what we know as sense impressions—that relation to our earthly and cosmic environments which is mediated by the senses. Further, there is the expression of the will—the ability to move as an expression of impulses of will.

Now, when we study man with ordinary cognition we find that the inner life-process, which runs its course in the subconsciousness, continues during sleep; sense activity and the thinking based upon it are, however, suppressed. The expression of the will is also suppressed; likewise the active life of feeling that connects willing and thinking, standing between them to a certain extent.

Now if we simply study, in an unbiased way and without succumbing to preconceived opinions, what we have just found by ordinary consciousness, we are led to say: The processes described as psychical, and the processes taking place between the psychical and the external world, cease in sleep. At most we can say that the dream life finds expression when man sleeps. But we must certainly not assume that these psychical processes are created anew—out of nothing, as it were—every time we wake. This would doubtless be a quite absurd thought, even for ordinary consciousness. On unbiased consideration we must assume that the vehicle of man's psychical processes is also present in sleep. We must admit, however, that this vehicle does not act on man during sleep, i.e. that which evokes in man's senses a consciousness of the external world, and stimulates this consciousness to think, does not act on man in sleep. Moreover, that which sets the body in motion from out of the will is also absent; likewise, what evokes feeling from the organic processes, is not there.

During waking life we are aware that our thoughts act upon our bodily organism. But, with ordinary consciousness, we cannot see how a thought or idea streams down, as it were, into the muscular and bony systems so that the will is involved. Nevertheless, we are aware of this action of our psychic impulses upon our body, and have to recognise that it ceases while we sleep.

Thus even external considerations show us that sleep takes something from man. The only question is, what? If, to begin with, we look at what we have designated man's physical body, we see that it is continually active, in sleep as in the waking state. Moreover, all the processes we described as belonging to the etheric organism continue during sleep. In sleep man grows, he carries on the inner activities of digestion and metabolism, he continues to breathe, etc. All these activities cannot belong to the physical body as such, for they cease when it becomes a corpse. It is then taken over by external, earthly Nature and destroyed. But these destructive forces do not overpower man in sleep; therefore there are counter-forces present, opposing the disintegration of his physical body. Thus we may conclude, from mere external considerations, that the etheric organism is also present during sleep.

Now we know from the preceding lectures that this etheric organism can become an object of knowledge through ‘imagination’; one can experience it ‘in a picture’, just as one experiences the physical body through sense impressions. And we know too that what may be called the astral organism is experienced through ‘inspiration’.

We will now go further—Of course, we could go on drawing conclusions in the above way. But, in the case of the astral body and ego-organisation, we prefer first to study how they actually appear to higher consciousness.

Let us recall how we had to describe the activity of the astral body in man. We saw that it works through the medium of what is airy, or gaseous, in the human organism. Thus we must recognise, to begin with, the astral body in all the activities of the airy element in man.

Now we know that the first and most essential activity of the astral body within the airy element is breathing; and we know from ordinary experience that we have to distinguish between breathing in and breathing out. Further, we know that it is the act of breathing in that vitalises us. We deprive the outer air of its life-giving power and return, not a vitalising, but a devitalising element. Physically speaking, we take in oxygen and give off carbonic acid. But we are not so much concerned with this aspect at the moment; it is the fact of ordinary experience that interests us here: we breathe in the vitalising and breathe out the devitalising element.

The higher knowledge which, as discussed in these last few days, is acquired through ‘imagination’, ‘inspiration’, and ‘intuition’, must now be directed to the life of sleep. We must actually investigate whether there is something that confirms the conclusion to which we were led, namely: that something is lifted out of man when he sleeps.

This question can only be answered by putting and answering another. If there is something that is outside man in sleep, how does it behave when outside?

Well, suppose a man, by such soul exercises as I have described, has actually acquired ‘inspiration’, i.e. a content for his emptied consciousness. He is now able to receive ‘inspired’ knowledge. At this stage he can induce the state of sleep artificially; this, however, is no mere sleep but a conscious condition in which the spiritual world flows into him.

I should now like to describe this in quite a crude way. Suppose such a man is able to feel, as it were, in an element of spiritual music, the spiritual beings of the cosmos speaking ‘into’ him. He will then have certain experiences. But he will also say to himself: These experiences which I now have, reveal something very peculiar; through them what I had to assume as outside of man during sleep no longer remains unknown. What now happens can really be made clear by the following comparison.

Suppose you had a certain experience ten years ago. You have forgotten it, but through something or other you are led to remember it. It has been outside your consciousness; but now, after applying sonic aid to memory or the like, you recall it. It is now in your consciousness. You have brought back into your consciousness something that was outside it, though connected with you in some way. It is like that with one who has a more inner consciousness and reaches inspiration. The events of sleep begin to emerge, as memories do in ordinary life. Only, the experiences we recall in memory were once in consciousness; the experiences of sleep, however, were not there before. But they enter consciousness in such a way that we really feel we are remembering something not experienced quite consciously before, at least in this life. They come to us like memories. And, as we formerly learnt to understand and experience through memory, we now begin to understand what happens during sleep. Thus into ‘inspired’ consciousness there simply emerges the experience of what leaves man and remains outside him during sleep, and what was unknown becomes known. We learn to know what it is really doing while he sleeps.

If you were to put into words what you experience with your breath during life, you would say: That I am inwardly permeated with life is owing to the element I breathe in. I cannot owe it to the element I breathe out, for that has the forces of death.

But when, as we saw just now, you are outside your body during sleep, you become extremely partial to the air you breathe out. When awake you did not notice what can be experienced with this exhaled air; you have only heeded the inhaled air which is the vitalising element while you and your soul are within the physical body. But now you have the same—indeed a more exalted—feeling towards the air you so anxiously avoid when you find it accumulated in a room. You express your dislike of the exhaled air. Now the physical body cannot bear it, even in sleep, but your soul and spirit, outside the body, actually breathe in—to put it physically—the carbonic acid you have exhaled. Of course, it is a spiritual, not a physical process; you receive the impression made by your exhaled air. In this exhaled air you remain connected with your physical body. You belong to your body, for you say to yourself: There is my body and it is breathing out this devitalising air. You say this unconsciously. You feel yourself connected with your body through its returning the air in this condition. Youfeel yourself entirely within the air you have exhaled. And this air you breathe out brings you continually the secrets of your inner life. You perceive these, although this perception is, of course, unconscious for the untrained sleeping consciousness. This exhaled air ‘sparkles forth’ from you and its appearance leads you to say: That is I myself, my inner human being, sparkling out into the universe.

And your own spirit, streaming towards you in the exhaled air has a sun-like appearance.

You now know that man's astral body, when within the physical, delights in the inhaled air, using it unconsciously to set the organic processes in action and induce in them inner mobility. But you also realise that the astral body is outside the physical when you sleep and receives, in its feelings, the secrets of your own human being from the exhaled air. While you ray forth towards the cosmos, your soul beholds unconsciously the inner process involved. Only in ‘inspiration’ does this become conscious.

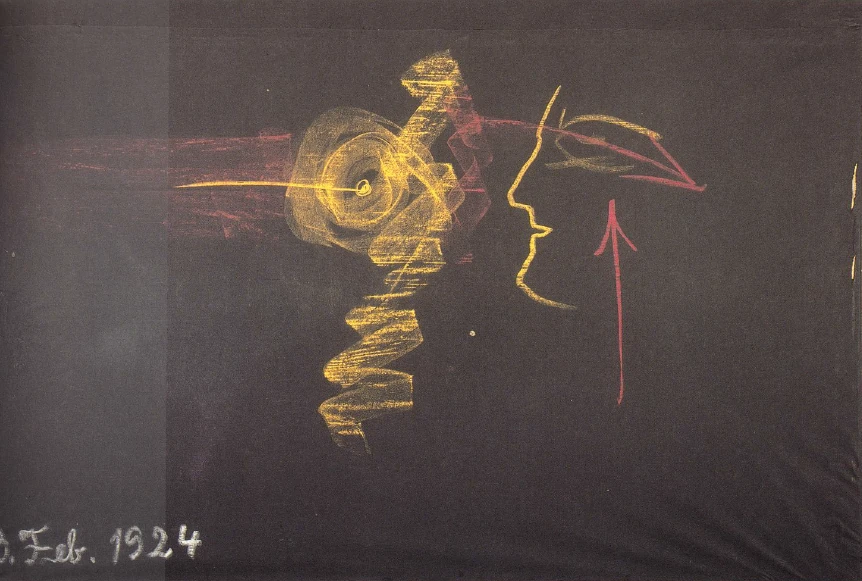

Further, we receive a striking impression. It is as if what confronts the sleeping man stood out against a dark background. There is darkness behind, and against this darkness the exhaled air appears luminous: one can put this in no other way. We recognise its essential nature, inasmuch as our everyday thoughts now leave us and the active, cosmic thoughts—the objective, creative thoughts of the world—appear before us in what is flowing out of ourselves. There is the dark background, and the sparkling radiating light; in the latter the creative thoughts gradually arise. The darkness is a veil covering our ordinary, every day thoughts—brain thoughts, as we might call them. We receive a very clear impression that what we regard as most important for physical, earthly life, is darkened as soon as we leave the physical body. And we realise, much more strongly than we could have believed in ordinary consciousness, the dependence of these thoughts upon their physical instrument—the brain. The brain retains these, by an adhesive force as it were. Out there we need no longer ‘think’ in the sense of everyday life. We behold thoughts; they surge through what appears to us as ourself in the exhaled air.

Thus inspired knowledge perceives how the astral body is in the physical during waking life, initiating, with the help of the inhaled air, the functions it has to perform; how it is outside during sleep and receives the impressions of our own human being. While we are awake the world on which we stand, the world which surrounds us as our earthly environment and the vault of heaven above, form our outer world. When we sleep what is inside our skin, and is otherwise our inner world, becomes our outer world. Only, to begin with, we feel what is here streaming towards us in the exhaled air; it is a felt outer world, that we have at first.

And then something further is experienced. The circulation of the blood, which follows closely the process of respiration and remains unconscious during waking life, begins to be very conscious in sleep. It comes before us like a new world, a world, indeed, that we do not merely feel but begin to understand from another point of view than that from which we understand external things with ordinary consciousness. With ‘inspired’ consciousness—though the will as a life process is present in the unconsciousness of every sleeper—we perceive the circulatory process, just as we perceive external processes of Nature during earthly life. We now come to see that all we do through that will of which we are ordinarily unconscious, involves a counter-process within us.

With every step you transport your body to another place, but something else occurs as well: a warmth-process takes place within you, setting the airy element in motion. This process is the furthest extension of those general processes of metabolism that, like it, occur inwardly and are connected with the circulation of the blood. With ordinary consciousness you observe externally a man's change of place as an expression of his will; but now you look back upon yourself and only find processes occurring within you, and these make up your world.

Truly, what we here behold is not what the theories of present-day science or medicine describe on anatomical grounds. It is a grand spiritual process, a process that conceals innumerable secrets and shows of itself that the real driving power at work within man is not his present ego at all. What man calls his ego in ordinary life is, of course, a mere thought. But it is the ego of man's past lives on earth that is active in him here. In the whole course of these processes, especially of the warmth-processes, you perceive the real ego, working from times long past. Between death and a new birth this ego has undergone an evolution in time; it now works in an entirely spiritual way. You perceive all these metabolic processes, the weakest as well as the most powerful, as the expression of just the highest entity in man.

Moreover, you now perceive that the ego has changed its field of action. It was active within, working upon the breath provided by the mere respiratory process; but now you perceive, from without, the further stages of the warmth-processes that the ego has elaborated from the respiratory processes. You behold the real, active ego of man, working from primeval times and organising him.

You now begin to know that the ego and astral body have actually left the physical and etheric bodies during sleep. They are outside, and now do and experience from without what they otherwise do and experience from within. In ordinary consciousness the ego and astral organisations are still too weak, too little evolved, to experience this consciously. ‘Inspiration’ really only consists in inwardly organising them so that they are able to perceive what is otherwise imperceptible.

Thus we must actually say: Through ‘inspiration’ we come to know the astral body of man, through ‘intuition’, the ego. During sleep, intuition and inspiration are suppressed in the ego and astral body; when they are awakened, man, through them, beholds himself from without. Let us see what this really means.

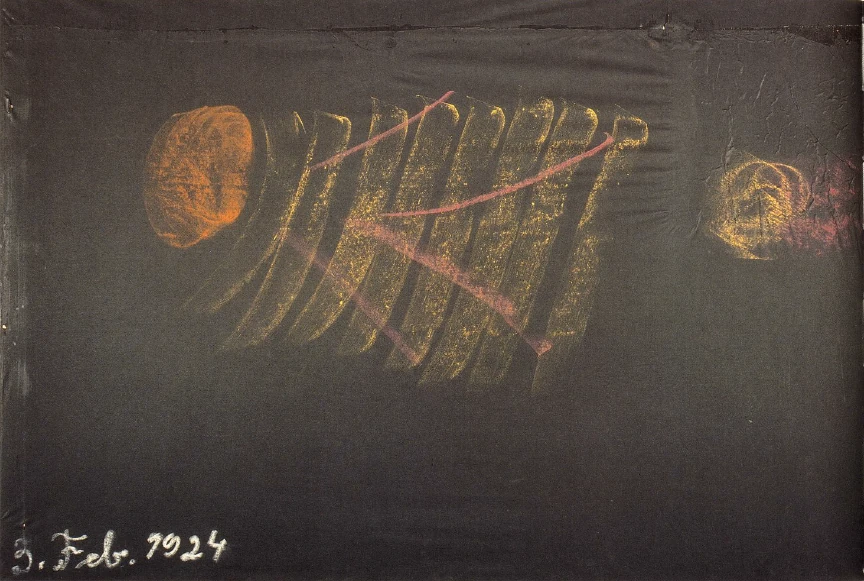

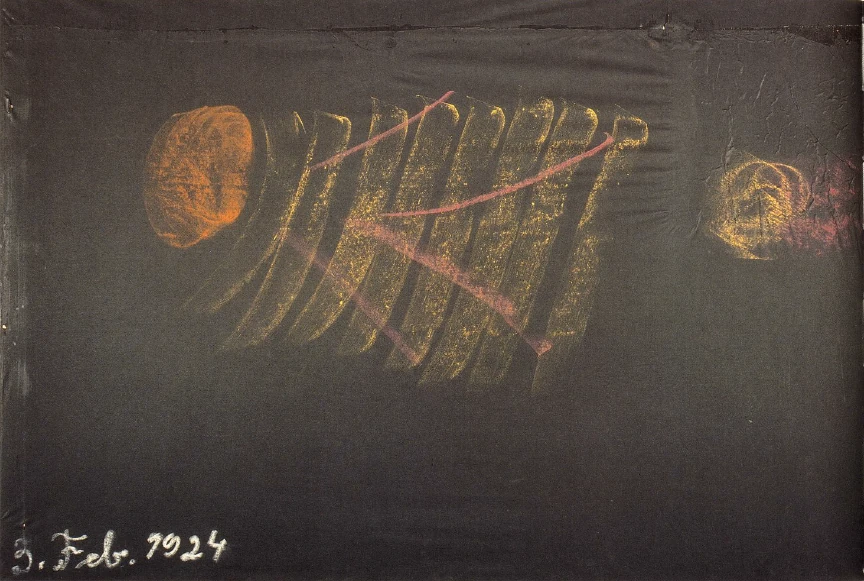

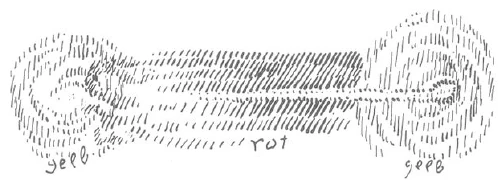

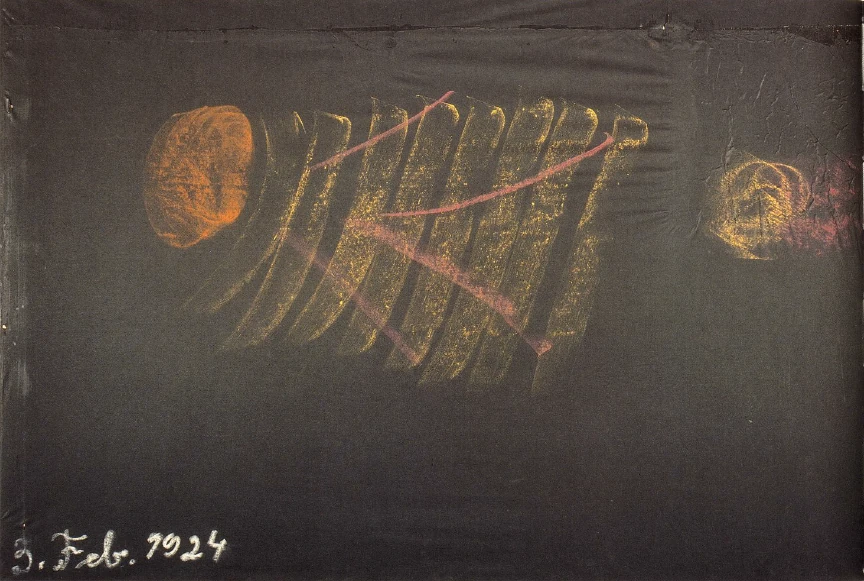

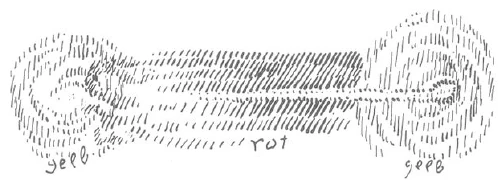

You remember what I have already said. I spoke of man in his present incarnation (sketch, right centre), and of the etheric body which extends back to a little before birth or conception (yellow); of his astral body which takes him back to the whole period between his last death and his present birth (red); and of ‘intuition’ that takes him back to his previous life on earth (yellow).

Now, to sleep means nothing else than to lead back your consciousness, which is otherwise in the physical body, and to accompany it yourself. Sleep is really a return in time to what I described as past for ordinary consciousness, though nevertheless there. You see, if one really wants to understand the Spiritual,

one must acquire different concepts from those one is accustomed to apply in ordinary life. One must actually realise that every sleep is a return to the regions traversed before birth—or, indeed, to former incarnations. During sleep one actually experiences, though without grasping it, what belongs to one's pre-earthly state and earlier incarnations.

Our concept of time must undergo a complete change. If we ask where a man is when asleep, the reply must be: he is actually in his pre-earthly state, or has returned to his former lives on earth. When talking simply we say: he is ‘outside’ his body. The reality is as I have explained. It is this that manifests as the rhythmic alternation of waking and sleeping.

All this becomes quite different at death. The most striking change is, of course, that man leaves his physical body behind in the earthly realm, where it is received, disintegrated and destroyed by the forces of the physical world. It can no longer give rise to the impressions I described as being made upon the sleeping man through the medium of the exhaled air. For the physical body no longer breathes; with all its functions it is now lost to man. There is something, however, that is not lost—and even ordinary consciousness can see that this is so. Thinking, feeling and willing live in our soul, but over and above these we have something very special, namely: memory. We do not only think about what is at present before, or around, us; our inner life contains fragments of what we have experienced, and these re-arise as thoughts. Now those people, often somewhat peculiar, who are known as psychologists have developed quite curious ideas about memory. These investigators of the human soul say something like this: man uses his senses; he perceives this or that and thinks about it. He has then a thought. He goes away and forgets the whole thing. But after a time he recalls it; the memory of what has been, re-appears. Man can recall what is past and has been out of his mind meanwhile; he can bring it to mind again. On this account, these people think that man forms a thought from his experience, this thought descends somewhere, to rest as it were in some chest or box and to re-appear when remembered. Either it bobs up of its own accord, or has to be fetched.

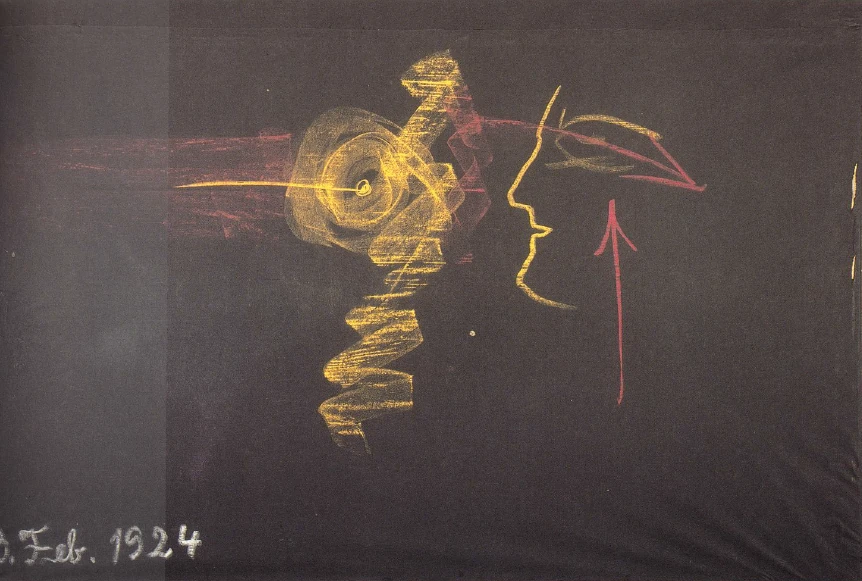

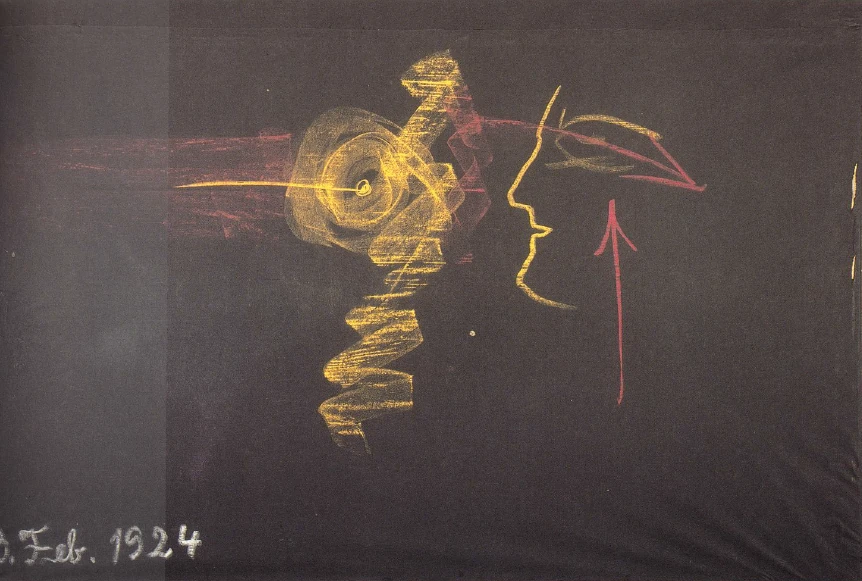

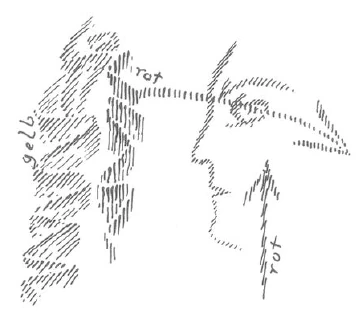

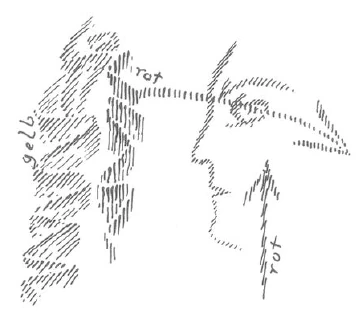

This sort of thing is a very model of confused thinking. For the whole belief that the thought is waiting somewhere whence it can be fetched, does not correspond to the facts at all. Just compare an immediate perception which you have, and to which you link a thought, with the way an image of memory, or a memory-thought, arises. You make no distinction at all. You receive a sense impression from without, and a thought links itself thereto. The thought is there; but what lies behind the sense impression and calls forth the thought, you usually speak of as unknown. The memory-thought that arises from within you is, indeed, no different from the thought that emerges for outer perception. In one case—representing it schematically—you have man's environment (yellow); the thought presents itself from without in connection with this environment (red); in the other it comes from within. The latter is a memory-thought (vertical arrow). The direction from which it comes is different.

While we are perceiving—experiencing—anything, something is continually going on beneath the mental presentation, beneath our thinking. It is really as follows: Thought accompanies perception. Our perceptions enter our body, whereas our thought ‘stands out’. Something does enter our body, and this we do not perceive. This goes on while we are thinking about the experience, and an ‘impression’ is made. It is not thought that passes down but something quite different. It is this something that evokes the process which we perceive later and of which we form the memory-thought—just as we form a thought of the outer world. The thought is always in the present moment. Even unprejudiced observation shows that this is so. The thought is not preserved somewhere or other as in a casket, but a process occurs which the act of memory transforms into a thought just as we transform outer perception into a thought.

I must burden you with these considerations, or you will not really come to an understanding of memory. That the thought does not want to go right down, is known to children—and to grown up people, too, in special cases—though only half consciously. So, when we want to memorise something, we have recourse to extraneous aids. Just think how many people find it helps to repeat a thing aloud; others make curious gestures when they want to fix something in their minds. The point is that an entirely different process runs parallel to the mere process of mental presentation. What we remember is really the smallest part of what is here involved.

Between waking up and falling asleep we move about the world, receiving impressions from all sides. We only attend to a few, but they all attend to us. It is a rich world that lives in the depths of our being, but only some few fragments are received into our thoughts. This world is like a deep ocean confined within us. The mental presentations of memory surge up like single waves, but the ocean remains within. It has not been given us by the physical world, nor can the physical world take it away. When man sheds his physical body, this whole world is there, bound up with his etheric body. Upon this all his experiences have been impressed, and these man bears within him immediately after death. In a certain sense, they are ‘rolled up’ in him.

Now man's first experience, immediately after death, is of everything that has made its impression upon him. Not only the ordinary shreds of memory which arise during earthly consciousness, but his whole earthly life, with all that has ‘impressed’ him stands before him now. But he would have to remain in eternal contemplation of this earthly life of his if something else did not happen to his etheric body, something different from what happens to the physical body through the earth and its forces. The earthly elements take over the physical body and destroy it; the cosmic ether, working (as I told you) from the periphery, streams in and dispels in all directions what has been impressed upon the etheric body. Thus man's next experience is as follows: During earthly life many, many things have made their impression upon me. All this has entered my etheric body. I now survey it, but it becomes more and more indistinct. It is as if I were looking at a tree that had made a strong impression upon me during my life. At first I see it life-size, as when it made its impression upon me from physical space. But it now grows, becomes larger and more shadowy; it becomes larger and larger, gigantic but more and more shadowy. Now it is like that with a human being whom I have learnt to know in his physical form. Immediately after death I have him before me as he impressed himself upon my etheric body. He now increases in size, becomes more and more shadowy. Everything grows, becomes more and more shadowy until it fills the whole universe, becomes thereby quite shadowy, and completely disappears.

This lasts some days. Everything has become gigantic and shadowy, thereby diminishing in intensity. Man sheds his second corpse; or, strictly speaking, the cosmos takes it from him. He is now in his ego and astral body. What had been impressed upon his etheric body is now within the cosmos; it has flowed out into the cosmos. We see the working of the universe behind the veils of our existence.

We are placed in the world as human beings. In the course of earthly life the whole world works upon us. We roll it all together in a certain sense. The world gives us much and we hold it together. The moment we die the world takes back what it has given. But it is something new that it receives, for we have experienced it all in a particular way. The world receives our whole experience and impresses it upon its own ether.

We now stand in the universe and say to ourselves, as we consider, first of all, this experience with our etheric body: truly, we are not only here for ourselves; the universe has its own intentions in regard to us. It has put us here that its own content may pass through us and be received again in the form into which we can transmute it. As human beings we are not here for our own ends alone; in respect to our etheric body, for example, we are here for the universe. The universe needs us because, through us, it ‘fulfils’ itself—fills itself again and again with its own content. There is an interchange, not of substance but of thoughts between the universe and man. The universe gives its cosmic thoughts to our etheric body and receives them back again in a humanised condition. We are not here for ourselves alone; we are here for the sake of the universe.

Now a thought like this should not remain merely theoretical and abstract; indeed it cannot. If it were to remain a mere thought, we would have to be creatures of pasteboard, not men with living feelings. In saying this I do not deny that our civilisation really does tend to make people often as apathetic towards such things as if they really were made of pasteboard. Civilised people today often appear to be such pasteboard figures. A thought like this preserves our human feeling and sympathy with the world, and leads us directly to the point from which we started. We began by saying that man feels himself estranged from the world in a two-fold way: on the one hand, in regard to external Nature which, he must admit, only destroys him as physical body; on the other hand, in regard to his inner life of soul which, again and again, lights up and dies away. This becomes for him a riddle of the universe. But now, as a result of spiritual study, man begins to feel himself no mere stranger in the universe. The universe has something to give him, and takes from him something in turn. Man begins to feel his inner kinship with the world. He now sees in a new light the two thoughts that I have put before you and which are really cosmic thoughts, namely:

Thou, O Nature, canst only destroy my physical body.

I, myself. have no kinship with thee, in spite of the thinking, feeling and willing of my inner life. Thou lightest up and diest down; and in my inner being I have no kinship with thee.

These two thoughts, evoked in us by the riddles of the universe, now appear in a new light, for we begin to feel ourselves akin to the cosmos and an organic part of its whole life. Thus anthroposophical reflection begins by making friends with the world, really learning to know the world that, on external observation, repulsed us at first. Anthroposophical knowledge makes us become more human. If we cannot bring to it this quality of heart, this mood of feeling, we are not taking it in the right way. One might compare theoretical anthroposophy to a photo-graph. If you are very anxious to learn to know someone you have once met, or with whom you have been brought into touch through something or other, you would not want to be offered a photograph. You may find pleasure in the photograph; but it cannot kindle the warmth of your feeling life, for the man's living presence does not confront you.

Theoretical Anthroposophy is a photograph of what Anthroposophy intends to be. It intends to be a living presence; it really wants to use words, concepts and ideas in order that something living may shine down from the spiritual world into the physical. Anthroposophy does not only want to impart knowledge; it seeks to awaken life. This it can do; though, of course, to feel life we must bring life to meet it.

Sechster Vortrag

Wenn man den Verlauf des menschlichen Erdenlebens betrachtet, so findet man ihn in einer Art von Rhythmus verlaufend, der sich ausdrückt in den Wechselzuständen zwischen Wachen und Schlafen. Unter den Gesichtspunkt des Wachens und Schlafens hat man zu rücken dasjenige, was in den letzten Vorträgen ausgeführt worden ist über die Gliederung des Menschen. Sehen wir uns einmal das, was dabei vorliegt, ich möchte sagen, mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein rein äußerlich an. Wir haben im wachenden Menschen den inneren Verlauf seiner Lebensprozesse, die aber im Unterbewußten oder Unbewußten verbleiben. Wir haben in diesem wachenden Menschen vorhanden das, was wir als die Sinneseindrücke kennen, jenes Verhältnis zu unserer irdischen und außerirdischen Umgebung, das durch die Sinneseindrücke vermittelt ist, und wir haben ferner im wachenden Menschen die Offenbarung seiner Willensnatur gegeben. Wir haben seine Bewegungsmöglichkeit als Ausdruck seiner Willensimpulse gegeben.

Wenn wir den Menschen äußerlich betrachten, so finden wir, daß der innere Lebensprozeß, der im Unbewußten für den wachen Menschen verläuft, fortdauert während des Schlafes. Wir finden, daß während des Schlafes die Sinnestätigkeit und das auf ihr sich aufbauende Denken unterdrückt ist. Wir finden, daß unterdrückt ist das, was Offenbarung des Willens ist, und das, was beides miteinander verbindet, was gewissermaßen zwischen drinnensteht, das aktive Gefühlsleben.

Wenn wir nun einfach unbefangen dieses, was so das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein ergibt, betrachten, ohne uns einzulassen in irgendwelche Vorurteile, so müssen wir uns doch sagen: Die als seelisch zu bezeichnenden Vorgänge und die Vorgänge, die zwischen dem Seelischen und der Außenwelt sich abspielen, die hören im Schlafe auf, höchstens daß aus dem Schlafe heraustönt dasjenige, was das Traumleben ist. Und wir dürfen ganz gewiß nicht annehmen, daß mit jedem Erwachen diese seelischen Prozesse gewissermaßen aus dem Nichts heraus neu geschaffen würden. Das wäre zweifellos auch für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein ein ganz absurder Gedanke. Es bleibt nichts anderes übrig für das unbefangene Betrachten, als vorauszusetzen, daß alles, was im Menschen Träger ist der seelischen Vorgänge, auch während des Schlafes vorhanden ist. Dann aber müssen wir uns gestehen, daß dieses, was so Träger der seelischen Vorgänge ist, während des Schlafes nicht eingreift in den Menschen; daß also nicht eingreift in den Menschen dasjenige, was in seinen Sinnen hervorruft ein Bewußtsein von der Außenwelt, und was dieses Bewußtsein der Außenwelt aufrüttelt zum Denken; daß ebenfalls nicht eingreift das, was vom Willen aus den Körper in Bewegung setzt, und daß auch nicht eingreift das, was die gewöhnlichen organischen Prozesse zum Gefühl aufruft.

Wir werden uns ja bewußt während des Wachlebens, daß die Gedanken in unseren Organismus eingreifen, wenn man auch mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nicht überschaut, wie der Gedanke, die Vorstellung gewissermaßen hinunterströmt in das Muskelsystem, in das Knochensystem und den Willen vermittelt. Aber wir sind uns bewußt dieses Eingreifens der seelischen Impulse in die Körperlichkeit, und wir müssen uns klar sein darüber, daß eben dieses Eingreifen der seelischen Impulse fehlt, während wir im Schlafe sind.

Daraus schon können wir rein äußerlich sagen: der Schlaf nimmt eben von dem Menschenwesen etwas weg. Und es wird sich nur fragen, was der Schlaf von diesem Menschenwesen wegnimmt. Wenn wir zunächst auf das sehen, was wir als den physischen Menschenleib bezeichnet haben - er ist im Schlafe fortdauernd tätig, wie er tätig ist während des Wachens. Aber auch all diejenigen Vorgänge, welche wir gekennzeichnet haben als die des ätherischen Organismus, sie dauern fort während des Schlafes. Der Mensch wächst während des Schlafes. Der Mensch verrichtet innerlich diejenigen Tätigkeiten, die der Ernährung, der Verarbeitung der Ernährung angehören. Er atmet weiter und so fort. Das alles sind Tätigkeiten, die nicht dem physischen Leibe angehören können, denn sie hören eben auf, wenn der physische Leib Leichnam wird. Da wird der physische Leib von der äußeren Natur, von der Erdennatur in Anspruch genommen. Die wirkt zerstörend. Das, was zerstörend wirkt, überfällt den Menschen im Schlafe noch nicht. Es sind also die Gegenwirkungen da gegen das Auseinanderfallen des menschlichen physischen Leibes. So daß wir schon daraus rein äußerlich uns sagen müssen: der ätherische Organismus ist auch während des Schlafes vorhanden.

Wir wissen aus den vorangehenden Vorträgen, daß dieser ätherische Organismus durch Imagination zur wirklichen Erkenntnis gebracht werden kann. Man kann ihn im Bilde erleben, geradeso wie man durch die Sinneseindrücke den physischen Leib erlebt. Wir wissen auch, daß dasjenige, was man den astralischen Organismus nennen kann, durch Inspiration erlebt wird.

Wir wollen nun nicht bei Schlußfolgerungen stehen bleiben, das könnten wir ja auch, aber wir werden diese Schlußfolgerungen in bezug auf den astralischen Leib und die Ich-Organisation lieber machen, nachdem zuerst die wirkliche Beobachtung für das entwickelte Bewußtsein vor unsere Seele getreten ist.

Wollen wir zunächst uns einmal vergegenwärtigen, wie wir sagen mußten, daß der astralische Leib im Menschen wirkt. Er wirkt durch das Mittel des Luftartigen, des Gasartigen im menschlichen Organismus. So daß wir in alledem, was im Menschen als Wirkung, als Impulse des Luftartigen vor sich geht, zunächst den astralischen Leib erkennen müssen.

Nun wissen wir, daß das Allerwesentlichste in bezug auf diese Tätigkeit des astralischen Leibes in dem Luftartigen zunächst die Artmung ist, und wir wissen schon aus der gewöhnlichen Erfahrung, daß wir zu unterscheiden haben zwischen der Einatmung und der Ausatmung. Und wir wissen weiter, die Einatmung ist für uns das Belebende. Wir entnehmen der äußeren Luft das Belebende, indem wir einatmen. Aber wir wissen auch, wir geben an die äußere Luft das ab, was nun nicht das Belebende ist, sondern das Ertötende. Physisch gesprochen, wir nehmen den Sauerstoff auf, geben die Kohlensäure ab. Allein das interessiert uns dabei weniger. Es interessiert uns eben das Ergebnis der gewöhnlichen Erfahrung, daß wir das Belebende einatmen, das Ertötende ausatmen.

Nun handelt es sich darum, die höhere Erkenntnis, die da verläuft in Imagination, Inspiration und Intuition — das haben wir ja in den letzten Tagen besprochen -, also die inspirierte Erkenntnis, anzuwenden auf das Schlafleben und einmal wirklich zu prüfen: ist da etwas, das der Schlußfolgerung entspricht, die wir haben müssen, daß vom Menschen etwas herausgehoben wird?

Diese Frage kann nur dadurch beantwortet werden, daß man die andere aufwirft und zur Beantwortung bringt: Wenn so etwas da ist, was außerhalb des Menschen ist, wie verhält sich nun dieses außerhalb des Menschen Befindliche?

Nun, nehmen Sie einmal an, der Mensch habe es durch solche innerlichen Seelenübungen, wie ich sie charakterisiert habe, dazu gebracht, wirklich Inspiration zu haben, also in das leere Bewußtsein etwas hereinzubekommen. Er lebt in der Möglichkeit, inspirierte Erkenntnis zu haben. In diesem Augenblicke ist es ihm auch möglich, den Schlafzustand künstlich herbeizuführen, aber so, daß er nicht ein Schlafzustand ist, sondern daß er eben nun ein bewußter Zustand ist, der Zustand der Inspiration eben ist, wo die geistige Welt hereinflutet.

Nun möchte ich ganz populär die Sache darstellen. Nehmen Sie an, derjenige, der ein solches inspiriertes Bewußtsein erlangt hat, ist imstande, gewissermaßen in einem Geistig-Musikalischen die Weltenwesen, die geistigen Weltenwesen in sich hereinsprechen zu fühlen. Dann wird er dabei, bei diesem inspirierten Erkennen, gewisse Erfahrungen machen. Aber er wird sich auch sagen: Ja, die Erfahrungen, die ich da mache, bewirken jetzt etwas sehr Eigentümliches; die bewirken, daß mir das, was ich vorausgesetzt habe, daß es während des Schlafes außerhalb des Menschen ist, nichts Unbekanntes mehr bleibt. Es ist wirklich so, daß man das, was da eintritt, mit folgendem vergleichen kann.

Nehmen Sie an, Sie haben vor zehn Jahren ein Erlebnis gehabt. Sie haben es vergessen. Und durch irgendeine Veranlassung kommen Sie dazu, an dieses Erlebnis vor zehn Jahren sich wieder zu erinnern. Es ist so, daß es außerhalb Ihres Bewußtseins war, daß Sie, nachdem Sie irgendwelche Gedächtnishilfe oder dergleichen angewendet haben, dieses Erlebnis vor zehn Jahren wiederum in Ihr Bewußtsein hereinbringen. Es ist nun darinnen. Da haben Sie etwas, was außerhalb Ihres Bewußtseins war, was aber doch mit Ihnen verbunden war, wieder in das Bewußtsein hereingebracht.

So geschieht es dem, der ein intimeres Bewußtsein hat und zur Inspiration kommt. Ihm fängt an das, was im Schlafe vor sich gegangen ist, aufzutauchen, wie sonst Erinnerungserlebnisse auftauchen. Nur daß die Erinnerungserlebnisse einmal da waren im Bewußtsein. Die Schlafeserlebnisse waren früher im Bewußtsein nicht da, aber sie kommen herein, so daß er eigentlich das Gefühl hat, er erinnert sich an etwas, was er allerdings in diesem Erdenleben nicht ganz bewußt erlebt hat, aber es kommt herein wie Erinnerungen; und man beginnt, wie man wieder verstehen lernt ein gehabtes Erlebnis durch die Erinnerung, so zu verstehen, was während des Schlafes sich vollzieht. Also in das inspirierte Bewußtsein hinein taucht das Erleben dessen, was außerhalb des Menschen während des Schlafes ist, einfach auf, und es wird ein Bekanntes aus einem Unbekannten. Und man lernt erkennen, was das, das da aus dem Menschen während des Schlafes herausschlüpft, nun während des Schlafes eigentlich tut.

Wenn Sie in Sprache verwandeln würden, was Sie im Wachleben mit dem Atem erleben, so würden Sie sagen: Ich danke es dem Elemente, das ich einatme, daß ich innerlich mit Leben durchsetzt werde, und ich könnte es nimmermehr dem Elemente, das ich ausatme, verdanken, daß ich lebe, denn das ist etwas Tötendes.

Sind Sie aber während des Schlafes außerhalb Ihres Leibes, wie wir es vorhin erschlossen haben, dann wird Ihnen die eigene Luft, die Sie ausatmen, gerade zu einem außerordentlich sympathischen Elemente. Sie haben das nicht beachtet, was mit der Ausatmungsluft erlebt werden kann, während Sie wachten, denn da haben Sie nur auf die Einatmungsluft geachtet, die das Belebende gibt, wenn Sie eben mit Ihrer Seele in Ihrem physischen Leibe drinnenstecken. Aber dasselbe, ja noch ein gehobeneres Gefühl haben Sie gegenüber der Luft, die Sie so meiden, wenn sie irgendwo angesammelt in einem Raume ist. Sie reden davon, daß Sie diese ausgeatmete Luft nicht mögen. Der physische Leib kann sie auch nicht während des Schlafes vertragen, aber das Seelisch-Geistige, das außerhalb des Leibes ist, das, ich möchte sagen, atmet gerade, physisch gesprochen, die ausgeatmete Kohlensäure ein. Es ist aber ein geistiger Vorgang. Es ist nicht ein Atmungsprozeß. Es ist ein Entgegennehmen des Eindruckes, den die ausgeatmete Luft macht. Aber nicht nur das. In dieser ausgeatmeten Luft bleiben Sie erstens auch während des Schlafes in Verbindung mit Ihrem physischen Leibe. Sie gehören dazu, weil Sie sich sagen: der atmet diese ertötende Luft aus, und das ist mein Leib. Sie sagen es unbewußt. Sie fühlen sich verbunden mit Ihrem Leibe dadurch, daß er Ihnen die Atmungsluft in diesem ertötenden Zustande zurückgibt. Sie fühlen sich ganz in der Atmosphäre, die Sie ausatmen.

Das aber, was Sie da ausatmen, das trägt Ihnen die Geheimnisse Ihres Innenlebens fortwährend entgegen. Sie nehmen sie — allerdings für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein, das im Schlafe ist, unbewußt — Ihrem Innenleben nach wahr. Es sprüht aus Ihnen die ausgeatmete Luft. Und diese ausgeatmete Luft erscheint Ihnen so, daß Sie sagen: Das bin ich ja selber, das ist meine innere Menschlichkeit, die aussprüht in das Weltenall. Und wie ein Sonnenhaftes erscheint Ihnen dasjenige, was Ihnen als ihr eigener Geist entgegenströmt in der ausgeatmeten Luft.

Und jetzt wissen Sie, daß der astralische Leib des Menschen, wenn er drinnen im menschlichen Leibe ist, sein Gefallen hat, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, an der Einatmungsluft, und diese Einatmungsluft dazu verwendet im Unbewußten, die organischen Prozesse in Bewegung zu setzen, mit innerer Regsamkeit zu durchströmen. Jetzt wissen Sie aber auch, daß der astralische Leib einfach, während Sie schlafen, außerhalb des physischen Leibes ist und empfängt, gefühlsmäßig empfängt die Geheimnisse der eigenen menschlichen Wesenheit in der ausgeatmeten Luft.

Während Sie sich hinaussprühend bewegen in den Kosmos, schaut die Seele unbewußt, erst in der Inspiration bewußt, auf dasjenige, was da ein innerlicher Prozeß ist.

Und es entsteht ferner ein merkwürdiger Eindruck. Es ist so, als ob aus einem Dunkel (es wird gezeichnet) sich abheben würde, was da dem schlafenden Menschen entgegenkommt, wie wenn dahinter ein Dunkles wäre, und in diesem Dunklen erscheint das - man kann es nicht anders sagen — als leuchtend, was Ausströmungsluft ist. Was da in dem Dunkel ist, das erkennt man seiner Wesenheit nach daran, daß einen dabei die täglichen Gedanken verlassen und einem in dem, was da herausflutet aus dem Menschen, gleichsam auftaucht das, was man die waltenden Weltgedanken nennen kann, die objektiven Gedanken, die schaffend sind. Das Dunkle, das aussprühende Helle, in dem treten allmählich auf die schaffenden Gedanken. Was da dunkel ist, das ist eine Finsternis, die sich über die gewöhnlichen alltäglichen Gedanken, wir können sagen, über die Gehirngedanken erstreckt. Da bekommt man sehr genau den Eindruck: Das, was man für das physische Erdenleben als das Wichtigste hält, das verdunkelt sich, sobald man aus dem physischen Leib heraußen ist, und man merkt viel intensiver, als man das voraussetzen kann im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein, wie diese Gedanken von dem physischen Werkzeug, dem Gehirn, abhängig sind. Das Gehirn hält sozusagen wie an sich klebend diese Alltagsgedanken, die gewöhnlichen Gedanken zurück. Da draußen braucht man nicht mehr zu denken in demselben Sinne, wie man im Alltagsleben denkt. Denn da schaut man die Gedanken, die fluten durch das, als was man sich selber erscheint in der ausströmenden Atemluft. Und so merkt die inspirierte Erkenntnis, wie der astralische Leib während des Wachens im physischen Leib ist und die Verrichtungen, die er im physischen Leibe zu vollziehen hat, mit Hilfe der eingeatmeten Luft zu vollziehen beginnt; wie dieser astralische Leib, wenn er während des Schlafens außerhalb ist, entgegennimmt die Eindrücke des eigenen menschlichen Wesens. Während des Wachens ist diese Welt, die uns umgibt als Horizont, auf der wir stehen in der irdischen Umgebung, und das, was sich darüber wölbt als das Himmelsgewölbe, unsere Außenwelt; während des Schlafes wird das, was innerhalb unserer Haut ist, was sonst unsere Innenwelt ist, unsere Außenwelt. Nur daß wir zunächst das, was uns da entgegenströmt in der Atmungsluft, fühlen. Eine gefühlte Außenwelt haben wir zunächst.

Des weiteren tritt aber noch etwas anderes ein. Unbewußt bleibt dem Menschen während des Wachens das, was sich anschließt an den Atmungsprozeß: der Zirkulationsprozeß, der Blutkreislaufprozeß. Er bleibt unbewußt während des Wachens. Der beginnt nun sehr bewußt zu werden während des Schlafes. Der beginnt wie eine ganz neue Welt aufzutauchen, und zwar wie eine Welt, die nun nicht bloß gefühlt wird, die man beginnt von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus zu verstehen, als man sonst mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein die äußeren Dinge versteht. Wie man hinsieht auf die äußeren Vorgänge der Natur während des Erdenlebens, so sieht man mit dem inspirierten Bewußtsein — aber der Wille als Lebensvorgang bleibt im Unbewußten bei jedem Schläfer vorhanden - auf diesen Zirkulationsprozeß. Jetzt lernt man erkennen, wie alles das, was wir durch den im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein eben unbewußten Willen entwickeln, überall im Inneren einen Gegenprozeß hat.

Wenn Sie irgendeinen Schritt machen, so findet nicht nur statt, daß Sie Ihren Körper bewußt an einen anderen Ort hintragen, sondern es findet auch das andere statt, daß ein wärmeartiger Prozeß, der Luftiges treibt, in Ihrem Inneren sich abspielt. Der ist der äußerste Ausläufer dessen, was dann gleichartig damit innerlich sich abspielt als die Stoffwechselprozesse überhaupt im Zusammenhange mit dem Blutkreislauf. Während Sie mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein außen die Ortsveränderung des Menschen bemerken als Äußerung seines Willens, schauen Sie jetzt auf sich zurück und finden lauter Vorgänge, die im Inneren des Menschen, das jetzt Ihre Welt ist, sich abspielen.

Dieser Prozeß, auf den Sie da hinschauen, ist dann wahrhaftig nicht so, wie ihn aus der gewöhnlichen Anatomie heraus der heutige Naturforscher oder Mediziner konstatiert, sondern der ist ein großartiger geistiger Prozeß, ein Prozeß, der ungeheuer viele Geheimnisse birgt, ein Prozeß, welcher schon bei sich selber zeigt, daß im Grunde genommen der eigentliche treibende Motor, der da im Inneren des Menschen wirkt, gar nicht das gegenwärtige Ich ist. Es ist ja ein bloßer Gedanke, was der Mensch sein Ich nennt im gewöhnlichen Leben. Aber was da im Menschen wirkt, das ist das Ich der vorigen Erdenleben. Und Sie schauen in diesem ganzen innerlichen Verlauf, namentlich von Wärmeprozessen, wie aus weit zurückliegenden Zeiten das reale Ich, das durch die Zeitentwickelung durchgegangen ist zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, da drinnen wirkt, wie da ein ganz Geistiges drinnen wirkt, wie der geringste Stoffwechselprozeß und der stärkste Stoffwechselprozeß überall der Ausdruck dessen ist, was gerade höchste Wesenheit des Menschen ist.

Und Sie kommen darauf, daß das Ich seinen Schauplatz gewechselt hat. Es wirkte innen in der Verarbeitung des Atems aus den bloßen Atmungsentwickelungen. Aber dasjenige, was als Wärmeentwickelungen aus den Atmungsentwickelungen hervorgeholt wird, das schauen Sie dann von außen an, schauen das ganze wirksame Ich, schauen es, wie es von Urzeiten herauf als reales Ich des Menschen wirkt, den Menschen eigentlich organisiert.

Jetzt beginnen Sie zu wissen, daß tatsächlich während des Schlafes das Ich und der astralische Leib den menschlichen physischen und Ätherleib verlassen haben, außer ihnen sind und alles das, was sie sonst von innen erleben und treiben, nun von außen erleben und treiben. Dieses ist nun aber so, daß für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein diese Ich-Organisation und diese astralische Organisation noch zu schwach sind, zu wenig entwickelt sind, um das bewußt mitzuerleben. Die Inspiration besteht eben nur darin, das Ich und den astralischen Leib so innerlich zu organisieren, daß sie das, was sonst nicht wahrnehmbar ist, wahrnehmen können.

So daß in der Tat gesagt werden muß: Durch die Inspiration werden wir auf das geführt, was im Menschen astralischer Leib ist, durch die Intuition auf dasjenige, was im Menschen Ich ist. Intuition und Inspiration werden während des Schlafes im Ich und astralischen Leib unterdrückt; aber wenn sie erweckt werden, dann schaut sich durch sie der Mensch von außen an. Und was ist denn schließlich dieses Von außen-Ansehen?

Erinnern Sie sich an das, was ich schon gesagt habe. Ich sagte Ihnen: da ist der Mensch in seiner gegenwärtigen Inkarnation. (Es wird gezeichnet, rechts Mitte.) Wenn er Imagination entwickelt, so schaut er seinen Ätherleib etwas vor die Geburt oder Empfängnis hingehend (gelb); aber sein astralischer Leib führt ihn durch Inspiration hinein in die ganze Zeit, die verflossen ist zwischen dem letzten Tode und dieser Geburt (rot). Und die Intuition führt ihn in das vorangehende Erdenleben zurück (gelb).

Wenn Sie nun schlafen, so bedeutet das nichts anderes, als daß Sie das Bewußtsein, das sonst im physischen Leibe ist, zurück verlegen, zurückführen, daß Sie mit ihm zurückkehren. Der Schlaf ist also eigentlich ein Zurücklaufen in der Zeit zu dem, wovon ich Ihnen schon gesagt habe, daß es dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein als vergangen erscheint, aber doch da ist. Sie sehen, man muß auch da, wenn man wirklich zum Erfassen des Geistigen kommen will, die Begriffe ändern gegenüber den Begriffen, die man gewöhnt ist im physischen Leben zu verwenden. Man muß also eigentlich sich bewußt werden, daß der Schlaf jedesmal ein Zurückgehen ist in die Gefilde, die man durchgemacht hat im vorirdischen Dasein, oder sogar ein Zurückgehen ist in frühere Inkarnationen. Der Mensch erlebt tatsächlich während des Schlafes, nur kann er es nicht erfassen, dasjenige, was früheren Inkarnationen angehört, was er durchgemacht hat auch im vorirdischen Dasein.

Über den Zeitbegriff muß man eine völlige Begriffsmetamorphose durchmachen; der muß ein ganz anderer werden. Wenn man daher an jemanden die Frage stellt: Ja, wo ist er denn, wenn er schläft? - dann muß man sagen: Er ist eigentlich in seinem vorirdischen Dasein oder sogar zurückgekehrt zu früheren Erdenleben. — Populär ausgedrückt sagt man eben: Der Mensch ist außerhalb seines physischen und seines Ätherleibes. Das Reale dazu ist das, was ich Ihnen auseinandergesetzt habe. Das ist, was sich darstellt als der rhythmische Wechselzustand zwischen Wachen und Schlafen.

Ganz andere Verhältnisse treten nun mit dem Tode des Menschen ein. Da ist zunächst das Auffälligste dieses, daß der Mensch innerhalb des irdischen Lebens seinen physischen Leib läßt, der nun auch von den Kräften der physischen Welt aufgenommen und eben zersprüht wird, zerstört wird. Der kann jetzt nicht Eindrücke hervorrufen, wie ich es Ihnen beschrieben habe als auftretend vor dem schlafenden Menschen durch die ausgeatmete Luft, denn der atmet nicht mehr aus. Der physische Leib ist sozusagen auch in seinen Verrichtungen für den eigentlichen Menschen nun verloren. Aber etwas ist nicht verloren, dem man sein Nichtverlorensein schon ansehen kann auch für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein. Wir haben in unserem Seelenleben ein Denken, Fühlen und Wollen. Aber über dieses Denken, Fühlen und Wollen hinaus haben wir noch etwas ganz Besonderes. Das ist die Erinnerung. Wir denken nicht nur über dasjenige nach, was gegenwärtig vor uns oder um uns ist. Unser Inneres birgt Reste von dem, was wir durchlebt haben. In Gedanken tritt es wiederum auf, was wir durchlebt haben. Ja, über diese Erinnerung haben insbesondere die manchmal etwas merkwürdigen Leute der Welt, die man Psychologen nennt, ganz kuriose Gedanken entwickelt. Da sagen solche Seelenforscher etwa das Folgende: Der Mensch braucht seine Sinne; er nimmt dies oder jenes wahr, denkt darüber nach. Jetzt hat er den Gedanken. Er geht weg, vergißt das Ganze. Nach einiger Zeit hebt er das Ganze aus seinem Gedächtnis heraus. Die Erinnerung an das, was einmal da war, tritt ein. Man kann sich wieder vorstellen, was man sich in der Zwischenzeit nicht vorgestellt hat, was nicht mehr gegenwärtig ist, was vergangen ist. Deshalb, so meinen diese Leute, hat sich der Mensch eben eine Vorstellung, einen Gedanken gebildet an dem Erlebnis, der Gedanke ist irgendwo hinuntergegangen, ist da in irgendeinem Schrank, Kasten drinnen, und wenn man sich wieder erinnert, so kommt er aus diesem Schrank heraus. Entweder springt er frei heraus oder aber er wird herausgeholt.

Das, was so vorstellt, ist schon das Musterbild eines verworrenen Denkens. Denn dieser ganze Glaube, daß der Erinnerungsgedanke da irgendwo sitzt, wo er hervorgeholt werden kann, entspricht gar nicht dem Tatbestand, der eigentlich auftritt. Vergleichen Sie nur einmal eine unmittelbare Wahrnehmung, die Sie haben und an die Sie einen Gedanken anknüpfen, damit, wie eine Erinnerungsvorstellung, ein Erinnerungsgedanke auftaucht. Sie unterscheiden das ja gar nicht. Sie haben draußen einen Sinneseindruck, daran schließt sich ein Gedanke. Das, was hinter dem Sinneseindruck ist, was den Gedanken hervorruft, das nennen Sie ja gewöhnlich auch ein Unbekanntes. Der Gedanke, der aus dem Inneren aufsteigt als Erinnerungsgedanke, der ist ja gar nicht anders als der Gedanke, der außen an der Wahrnehmung auftritt. Das eine Mal haben Sie, wenn Sie den Menschen, schematisch gezeichnet, hier haben, seine Umgebung hier (gelb); der Gedanke tritt von außen auf, tritt an der Umgebung auf (roter Pfeil von links). Das andere Mal kommt er von innen. Da ist er ein Erinnerungsgedanke (Pfeil von unten). Die Richtung, von wo er herkommt, ist eine andere.

Während wir etwas wahrnehmen, erleben, geht fortwährend unter der Vorstellung, unter dem Denken etwas vor sich. Es ist ja so: wir nehmen wahr denkend. Aber das Wahrnehmen, das geht auch in unseren Körper herein. Der Gedanke hebt sich nur ab. Es geht etwas in unseren Körper herein, und das nehmen wir nicht wahr. Das spielt sich ab, während wir darüber nachdenken, und das bewirkt einen Eindruck. Das ist nicht der Gedanke, der da hinuntergeht, sondern etwas ganz anderes. Aber dieses ganz andere ruft wiederum einen Vorgang hervor, den wir später wahrnehmen und über den wir uns den Erinnerungsgedanken so bilden, wie wir uns an der Außenwelt den Gedanken bilden. Der Gedanke ist immer gegenwärtig. Das zeigt schon eben die unbefangene Beobachtung, daß das so ist, daß da nicht der Gedanke irgendwo in einem Kästchen aufbewahrt wird, sondern es ist ein Vorgang, der sich abspielt und den wir dann auch mit der Erinnerung in einen Gedanken verwandeln, so wie wir die äußere Wahrnehmung in einen Gedanken verwandeln.

Ich muß Sie mit diesen Erwägungen belasten, weil Sie sonst nicht eigentlich zum Verständnis der Erinnerung kommen. Die Kinder wissen es, wenn auch nur halb bewußt, manchmal aber auch die Erwachsenen in besonderen Fällen, daß der Gedanke nicht recht hinuntergehen will. Wenn man daher etwas memorieren will, so nimmt man ganz andere Dinge zu Hilfe. Denken Sie doch nur einmal, manche nehmen das laute Sprechen zu Hilfe, manche machen ganz merkwürdige Gesten, wenn sie sich irgend etwas einbläuen. Es handelt sich wirklich darum, daß sich da, parallel laufend dem bloßen Vorstellungsprozef, ein ganz anderer Prozeß noch abspielt. Und das, woran wir uns da erinnern, ist eigentlich das wenigste von dem, was dabei in Betracht kommt.

Ich bitte Sie, wir gehen ja vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen fortwährend durch die Welt; von allen Seiten her kommen die Eindrücke. Wir beachten zunächst wenige, aber sie beachten uns, und es prägt sich vieles, vieles, was dann nicht erinnert wird, ein. Da in den Tiefen unseres Wesens sitzt eine reiche Welt, von der wir nur einzelne Fetzen in die Gedanken heraufbekommen. Diese Welt, die ist eigentlich eingesperrt in uns, ist wie ein tiefes Meer in uns, und dasjenige, was Erinnerungsvorstellung ist, schlägt so wie einzelne Wellenschläge herauf. Aber es ist in uns. Sehen Sie, das, was in dieser Weise in uns ist, das hat uns nicht die physische Welt gegeben. Sie kann es uns auch nicht nehmen. Und wenn der physische Leib des Menschen abfällt, dann ist diese ganze Welt da, haftet an seinem Ätherleib. Unmittelbar nach dem Tode trägt der Mensch in der Tat alle seine Erlebnisse in seinem Ätherleibe wie eingeprägt in sich; gewissermaßen wie zusammengerollt trägt er sie in sich.

Und das nächste, was der Mensch nun erlebt unmittelbar nach dem Tode, ist, daß nicht nur etwa die gewöhnlichen Erinnerungsfetzen, die sonst während des irdischen Bewußtseins auftreten, da sind, sondern daß alles da ist, was Eindruck macht auf den Menschen, daß der Mensch sein ganzes Erdenleben mit allem, was Eindruck gemacht hat, zunächst vor sich hat. Und der Mensch müßte im ewigen Anschauen dieses seines Erdenlebens bleiben, wenn jetzt nicht etwas anderes eintreten würde gegenüber dem Ätherleib, als durch die Erde und ihre Kräfte gegenüber dem physischen Leib eintritt. Die Elemente der Erde übernehmen den physischen Leib, zerstören ihn. Der Weltenäther, von dem ich Ihnen gesagt habe, er wirkt aus der Peripherie herein, er strahlt ein, der zerstrahlt dasjenige, was da eingeprägt ist, nach allen Seiten des Kosmos. So daß der Mensch als nächstes Erlebnis dieses hat: Während des Erdenlebens hat vieles, vieles auf mich Eindruck gemacht. Das ist alles in meinen Ätherleib eingetreten. Ich überschaue es, aber ich überschaue es immer undeutlicher. Wie wenn ich einen Baum sehen würde, der einen starken Eindruck auf mich gemacht hat während des Lebens. Ich sehe ihn zunächst in der Größe, in der er den Eindruck gemacht hat vom physischen Raum aus. Da wächst er. Da wird er größer, aber schattenhafter; da wird er immer größer, und er wächst ins Riesenhafte aus, wird immer größer und größer und immer schattenhafter und schattenhafter. Und so ist es: Ich habe einen physischen Menschen in seiner Gestalt kennengelernt, habe ihn unmittelbar nach dem Tode, so wie er sich mir eingeprägt hat in meinen Ätherleib, vor mir; da wächst er und wird immer schattenhafter und schattenhafter; alles wächst und wird schattenhafter und immer schattenhafter, bis es sich auswächst zum ganzen Kosmos und damit ganz schattenhaft wird, gänzlich verschwindet.

Darüber vergehen einige Tage. Alles ist ins Riesenhafte übergegangen, schattenhaft geworden durch dieses Riesigwerden und dabei an Intensität abnehmend, vom Menschen als der zweite Leichnam abfallend. Aber das heißt eigentlich: vom Menschen durch den Kosmos weggenommen. Jetzt ist der Mensch in seinem Ich und in seinem astralischen Leibe. Und das, was sich seinem Ätherleib eingeprägt hatte, das ist jetzt im Kosmos drinnen, das ist in den Kosmos ausgeflossen. Und wir sehen das Wirken der Welt hinter den Kulissen unseres eigenen Daseins.

Wir sind als Menschen hereingestellt in die Welt. Während wir das Erdenleben ablaufend haben, wirkt die ganze Welt auf uns ein. Wir rollen das, was da einwirkt, gewissermaßen zusammen. Die Welt gibt uns vieles. Wir halten es zusammen. In dem Augenblick, wo wir sterben, nimmt die Welt wieder an sich, was sie uns gegeben hat. Aber sie empfängt dadurch etwas Neues. Wir haben das alles in besonderer Weise erlebt. Das, was die Welt empfängt, ist etwas anderes, als sie uns gegeben hat. Sie nimmt unser ganzes Erleben auf. Sie prägt sich selbst in ihren eigenen Äther unser ganzes Leben ein.

Und jetzt stehen wir in der Welt und sagen uns, indem wir dieses Erlebnis mit unserem Ätherleib zunächst nehmen: Wir sind wirklich nicht bloß für uns in der Welt, sondern die Welt hat etwas vor mit uns; die Welt hat uns hereingestellt, damit sie das, was in ihr ist, durch uns durchgehen lassen kann und es in der von uns veränderten Gestalt wiederum empfangen kann. Wir sind als Menschen nicht bloß für uns da, wir sind zum Beispiel in bezug auf unseren ätherischen Körper für die Welt da. Die Welt hat die Menschen nötig, weil sie dadurch mit ihrem eigenen Inhalte sich immer wieder neu und neu erfüllt. Es ist ein nicht Stoff- aber Gedankenwechsel zwischen der Welt und dem Menschen. Die Welt gibt ihre Weltengedanken an den menschlichen Ätherleib ab, und die Welt empfängt sie im durchmenschlichten Zustande wiederum zurück. Der Mensch ist nicht um seiner selbst allein, der Mensch ist um der Welten willen da.

Nun, solch ein Gedanke darf nicht ein bloßer theoretisch-abstrakter Gedanke bleiben. Er kann es auch nicht. Man müßte nicht Mensch sein mit lebendigem Gefühl, sondern ein Wesen aus Papiermaché, wenn ein solcher Gedanke bloßer Gedanke bliebe, wobei ich nicht sagen will, daß nicht unsere Zivilisation wirklich dazu geeignet ist, den Menschen oftmals gegenüber solchen Dingen so gefühllos zu machen, wie wenn er aus Papiermaché wäre. Manchmal können einem schon die Zivilisationsmenschen der Gegenwart so erscheinen, als ob sie aus Papiermaché wären. Denn solch ein Gedanke, der verliert nicht das menschliche Fühlen und Empfinden mit der Welt, der tritt unmittelbar an dasjenige heran, wovon wir ausgegangen sind. Wir sind davon ausgegangen, daß wir sagten: Der Mensch fühlt sich in zweifacher Weise fremd der Welt gegenüber; auf der einen Seite in bezug auf die äußere Natur, von der er nur sagen kann, daß sie ihn zerstört seinem physischen Leibe nach, auf der anderen Seite innerlich in bezug auf sein Seelenleben, das aufglüht, aufsprüht, absprüht und so weiter, was eben für ihn zum Weltenrätsel wird. Jetzt beginnt aus einer geistigen Betrachtung heraus der Mensch zu fühlen: Er ist der Welt nicht bloß fremd, sondern die Welt gibt ihm, die Welt nimmt wiederum für sich etwas ab. Der Mensch beginnt sich innig verwandt zu fühlen mit der Welt. Die beiden Gedanken, die ich Ihnen gesagt habe, die die eigentlichen Weltengedanken sind: O Natur, du zerstörst nur meinen physischen Leib. Ich habe mit dir keine Verwandtschaft, trotz Denken, Fühlen und Wollen. In meinem Inneren, da glimmt es auf, da sprüht es ab. Ich habe meinem wirklichen Sein nach mit dir doch keine Verwandtschaft -, diese beiden Gedanken, die die Weltenrätsel in uns hervorzaubern, bekommen ein neues Gesicht, wenn wir jetzt beginnen, uns verwandt zu fühlen mit der Welt, uns zu fühlen wie ein Organisches, das in der Welt drinnen ist, das verwoben ist in den Weltenprozefßß. Und so ist der Beginn anthroposophischer Betrachtung der: Freundschaft zu schließen mit der Welt, Bekanntschaft zu schließen mit der Welt, die uns zunächst in der äußeren Betrachtung abgestoßen hat. Ein Menschlicherwerden ist die anthroposophische Erkenntnis. Und wer diese Gefühls-, diese Herzensnuance nicht aufnehmen kann in die anthroposophische Erkenntnis, der hat von der Anthroposophie nicht das Rechte. Denn die theoretische Anthroposophie ist eigentlich etwas, was man vergleichen könnte damit, daß man sagt: Jemand verlangt gar sehr, einen Menschen, den er einmal gekannt hat, oder der ihm durch irgend etwas anderes nahegetreten ist, kennenzulernen, und man reicht ihm eine Photographie. Er kann an der Photographie ja vielleicht seine Freude haben; aber warm kann er nicht werden, denn das Lebendige dieses Menschen tritt ihm nicht entgegen.

Dasjenige, was theoretische Anthroposophie ist, ist die Photographie dessen, was eigentlich die Anthroposophie sein will, und die will ein Lebendiges sein. Und sie will sich eigentlich der Worte, der Begriffe, der Ideen bedienen, um ein Lebendiges aus der geistigen Welt in die physische Welt herein erstrahlen zu lassen. Anthroposophie will nicht nur Erkenntnisse vermitteln, sie will Leben erwecken. Und sie kann dieses. Allerdings, um Leben zu fühlen, muß man selber Leben entgegenbringen.

Sixth Lecture

If one looks at the course of human life on earth, one finds it proceeding in a kind of rhythm which expresses itself in the alternating states between waking and sleeping. From the point of view of waking and sleeping, we have to place what has been said in the last lectures about the structure of the human being. Let us take a purely external look at what is involved, I would say, with ordinary consciousness. In the waking human being we have the inner course of his life processes, which, however, remain in the subconscious or unconscious. We have present in this waking man what we know as the sense impressions, that relationship to our earthly and extraterrestrial environment which is mediated through the sense impressions, and we have furthermore given in the waking man the revelation of his will nature. We have given his possibility of movement as an expression of his will impulses.

When we look at man externally, we find that the inner life process, which proceeds in the unconscious for the waking man, continues during sleep. We find that during sleep the activity of the senses and the thinking based on it is suppressed. We find that what is suppressed is that which is the revelation of the will and that which connects the two, that which stands, as it were, between them, the active emotional life.

If we now simply look impartially at that which results from ordinary consciousness, without engaging in any prejudices, then we must say to ourselves: The processes that can be described as psychic and the processes that take place between the psychic and the outer world cease in sleep, at most that which emerges from sleep is that which is dream life. And we must certainly not assume that with every awakening these psychic processes are created anew out of nothing, so to speak. That would undoubtedly be a completely absurd idea for ordinary consciousness. There is nothing left for the unbiased observer but to assume that everything that is the carrier of psychic processes in man is also present during sleep. But then we must admit to ourselves that this, which is the carrier of the soul processes, does not intervene in man during sleep; that therefore that does not intervene in man which evokes in his senses a consciousness of the outer world, and which arouses this consciousness of the outer world to thinking; that likewise that does not intervene which sets the body in motion from the will, and that also that does not intervene which arouses the ordinary organic processes to feeling.

We become aware during waking life that thoughts intervene in our organism, even if we do not see with our ordinary consciousness how the thought, the imagination, so to speak, flows down into the muscular system, into the bone system and mediates the will. But we are aware of this intervention of the mental impulses into the physicality, and we must be aware that precisely this intervention of the mental impulses is absent while we are asleep.

From this we can already say, purely outwardly, that sleep takes something away from the human being. And the question will only arise as to what sleep takes away from this human being. If we first look at what we have described as the physical human body - it is continually active during sleep, just as it is active during waking. But also all those processes which we have characterized as those of the etheric organism, they continue during sleep. The human being grows during sleep. The human being internally carries out those activities that belong to nourishment, to the processing of nourishment. He continues to breathe and so on. These are all activities that cannot belong to the physical body, for they cease when the physical body becomes a corpse. Then the physical body is taken up by external nature, by earth nature. This has a destructive effect. That which has a destructive effect does not yet overtake the human being in sleep. So the counter-effects are there against the disintegration of the human physical body. So that we must say to ourselves already from this purely outwardly: the etheric organism is also present during sleep.

We know from the previous lectures that this etheric organism can be brought to real realization through imagination. One can experience it in the image, just as one experiences the physical body through sensory impressions. We also know that that which can be called the astral organism is experienced through inspiration.

We do not want to stop at conclusions, we could do that too, but we will prefer to draw these conclusions with regard to the astral body and the ego organization after the real observation for the developed consciousness has first come before our soul.

First of all, let us realize how we had to say that the astral body works in man. It works in the human organism through the medium of the aerial, the gaseous. So that we must first recognize the astral body in everything that takes place in man as an effect, as impulses of the air-like.

Now we know that the most essential thing in relation to this activity of the astral body in the air-like is first of all respiration, and we already know from ordinary experience that we have to distinguish between inhalation and exhalation. And we also know that inhalation is the vitalizing element for us. We take the vitalizing from the outer air by breathing in. But we also know that we release into the outer air what is not invigorating, but what is deadening. Physically speaking, we take in oxygen and release carbon dioxide. But we are less interested in that. We are interested in the result of ordinary experience, that we inhale the vitalizing and exhale the deadening.

Now it is a matter of applying the higher cognition, which proceeds in imagination, inspiration and intuition - as we have discussed in the last few days - that is, inspired cognition, to the sleeping life and really examining for once: is there something there that corresponds to the conclusion that we must have, that something is lifted out of man?

This question can only be answered by raising the other question and answering it: If there is such a thing that is outside of man, how does that which is outside of man behave?

Now, suppose for a moment that through such inner exercises of the soul as I have characterized, man has brought himself to really have inspiration, that is, to bring something into the empty consciousness. He lives in the possibility of having inspired knowledge. At this moment it is also possible for him to artificially bring about the state of sleep, but in such a way that it is not a state of sleep, but that it is now a conscious state, the state of inspiration, where the spiritual world floods in.

Now I would like to present the matter in a very popular way. Suppose the person who has attained such an inspired consciousness is able to feel the world beings, the spiritual world beings, speaking into him in a spiritual-musical way. Then, in this inspired cognition, he will have certain experiences. But he will also say to himself: "Yes, the experiences I am having there are now having a very peculiar effect; they are having the effect that what I have assumed to be outside the human being during sleep no longer remains unknown to me. It really is the case that what happens can be compared to the following.

Suppose you had an experience ten years ago. You have forgotten it. And through some cause you come to remember this experience ten years ago. It is so that it was outside your consciousness that, after you have used some kind of memory aid or the like, you bring this experience ten years ago back into your consciousness. It is now inside. You have brought back into your consciousness something that was outside your consciousness, but which was nevertheless connected with you.

This is what happens to those who have a more intimate consciousness and come to inspiration. What happened in sleep begins to emerge to him, just as memory experiences usually emerge. Only that the memory experiences were once there in consciousness. The sleep experiences were not there in the consciousness before, but they come in, so that he actually has the feeling that he remembers something which he has not quite consciously experienced in this life on earth, but it comes in like memories; and one begins, as one learns to understand again an experience one has had through memory, thus to understand what takes place during sleep. So the experience of what is outside the human being during sleep simply emerges into the inspired consciousness, and it becomes a known from an unknown. And you learn to recognize what that which slips out of the person during sleep is actually doing during sleep.

If you were to transform into language what you experience in waking life with the breath, you would say: I thank the element that I breathe in that I am inwardly imbued with life, and I could never again owe it to the element that I breathe out that I live, for that is something killing.

But if you are outside your body during sleep, as we have just explained, then your own air, which you exhale, becomes an extraordinarily sympathetic element. You have not paid attention to what can be experienced with the exhaled air while you are awake, because there you have only paid attention to the inhaled air, which gives the invigorating effect when you are inside your physical body with your soul. But you have the same, indeed an even more exalted feeling towards the air which you avoid so much when it is accumulated somewhere in a room. You speak of not liking this exhaled air. The physical body cannot tolerate it during sleep either, but the soul-spiritual, which is outside the body, I would like to say, physically speaking, breathes in the exhaled carbonic acid. But it is a spiritual process. It is not a breathing process. It is a receiving of the impression that the exhaled air makes. But not only that. Firstly, in this exhaled air you remain in contact with your physical body even during sleep. You belong to it because you say to yourself: he exhales this deadening air, and that is my body. You say it unconsciously. You feel connected to your body by the fact that it gives you back the air you breathe in this extinguishing state. You feel completely in the atmosphere that you exhale.

But that which you exhale continually carries the secrets of your inner life towards you. You perceive them - albeit unconsciously for the ordinary consciousness that is asleep - according to your inner life. The exhaled air sprays out of you. And this exhaled air appears to you in such a way that you say: "That is I myself, that is my inner humanity that sprays out into the universe. And that which flows towards you as your own spirit in the exhaled air appears to you as something solar.

And now you know that the astral body of man, when it is inside the human body, has its pleasure, if I may express myself in this way, in the inhaled air, and uses this inhaled air in the unconscious to set the organic processes in motion, to flow through them with inner activity. But now you also know that the astral body is simply, while you are asleep, outside the physical body and receives, emotionally receives the secrets of your own human being in the exhaled air.

While you move out into the cosmos, the soul looks unconsciously, only consciously in inspiration, at that which is an inner process.

A strange impression also arises. It is as if out of a darkness (it is drawn) what comes towards the sleeping human being would stand out, as if there were a darkness behind it, and in this darkness appears - there is no other way to put it - as luminous what is emanating air. What is there in the darkness can be recognized by its essence, by the fact that the daily thoughts leave you and in what flows out of the human being there emerges, as it were, what can be called the ruling world thoughts, the objective thoughts that are creative. The dark, the emanating light, in which the creative thoughts gradually emerge. What is dark there is a darkness that extends beyond the ordinary everyday thoughts, we could say beyond the thoughts of the brain. You get a very precise impression that what you consider to be the most important thing in your physical life on earth becomes darker as soon as you are out of the physical body, and you realize much more intensely than you would expect in ordinary consciousness how these thoughts are dependent on the physical tool, the brain. The brain holds back these everyday thoughts, the ordinary thoughts, as if clinging to itself. Out there you no longer need to think in the same sense as you think in everyday life. Because there you see the thoughts that flow through what you appear to yourself as in the air you breathe. And so the inspired cognition notices how the astral body is in the physical body during waking and begins to carry out the tasks it has to perform in the physical body with the help of the inhaled air; how this astral body, when it is outside during sleep, receives the impressions of its own human being. During waking this world which surrounds us as the horizon on which we stand in the earthly environment, and that which arches above it as the vault of heaven, is our outer world; during sleep that which is within our skin, which is otherwise our inner world, becomes our outer world. Only that we first feel what flows towards us in the air we breathe. We initially have a perceived outer world.

But something else also occurs. What remains unconscious to the human being during waking is what follows the breathing process: the circulation process, the blood circulation process. It remains unconscious during waking. It now begins to become very conscious during sleep. It begins to emerge like a completely new world, a world that is now not merely felt, a world that one begins to understand from a different point of view than one usually understands external things with ordinary consciousness. As one looks at the outer processes of nature during life on earth, so one looks with the inspired consciousness - but the will as a life process remains present in the unconscious of every sleeper - at this process of circulation. Now one learns to recognize how everything that we develop through the will, which is just unconscious in ordinary consciousness, has a counter-process everywhere within.

When you take any step, it is not only that you consciously carry your body to another place, but the other thing also takes place, that a heat-like process, which drives airy things, takes place within you. This is the outermost offshoot of what then takes place internally in the same way as the metabolic processes in general in connection with the blood circulation. While with ordinary consciousness you notice the change of place of the human being on the outside as an expression of his will, you now look back at yourself and find nothing but processes that take place within the human being, which is now your world.

This process that you are looking at is then truly not as it is stated by today's natural scientist or physician on the basis of ordinary anatomy, but it is a magnificent spiritual process, a process that holds a tremendous number of secrets, a process that already shows in itself that basically the actual driving motor that is at work within the human being is not the present ego at all. After all, it is a mere thought what man calls his ego in ordinary life. But what is at work in the human being is the ego of previous earthly lives. And you see in this whole inner process, especially of heat processes, how the real ego, which has passed through the development of time between death and a new birth, works in there from times far in the past, how a completely spiritual being works in there, how the slightest metabolic process and the strongest metabolic process is everywhere the expression of that which is the highest essence of man.

And you come to the conclusion that the ego has changed its scene. It worked internally in the processing of the breath from the mere respiratory developments. But that which is brought forth from the respiratory evolutions as heat evolutions, you then look at it from the outside, look at the whole effective ego, look at how it works from time immemorial as the real ego of the human being, actually organizes the human being.

Now you begin to know that actually during sleep the ego and the astral body have left the human physical and etheric body, are outside them and now experience and do everything from the outside that they otherwise experience and do from the inside. But this is so that for the ordinary consciousness this ego-organization and this astral organization are still too weak, too little developed, to experience this consciously. Inspiration consists only in organizing the ego and the astral body so inwardly that they can perceive what is otherwise imperceptible.

So that it must indeed be said: Through inspiration we are led to that which is the astral body in man, through intuition to that which is the ego in man. Intuition and inspiration are suppressed during sleep in the ego and the astral body; but when they are awakened, then through them man looks at himself from outside. And what, after all, is this looking from the outside?