| 303. Soul Economy: Body, Soul and Spirit in Waldorf Education: Aesthetic Education

05 Jan 1922, Dornach Translated by Roland Everett |

|---|

| It will become a truly stimulating task for us to develop such ideas in practice once we have a kindergarten in the Waldorf school. Of course, it would be perfectly all right for you to develop these ideas yourself, since it would take too much of our time to go into greater detail now. |

| Question: Should children be taught to play musical instruments, and if so, which ones? Rudolf Steiner: In our Waldorf school, I have advocated the principle that, apart from being introduced to music in a general way (at least those who show some special gifts), children should also learn to play musical instruments technically. |

| Here one should definitely approach each child individually. Naturally, in the Waldorf school, these things are still in the beginning stage, but despite this, we have managed to gather very acceptable small orchestras and quartets. |

| 303. Soul Economy: Body, Soul and Spirit in Waldorf Education: Aesthetic Education

05 Jan 1922, Dornach Translated by Roland Everett |

|---|

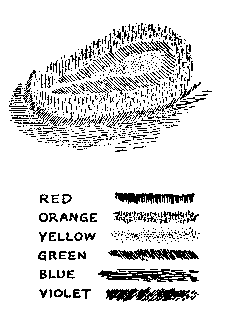

Rudolf Steiner: Several questions have been handed in and I will try to answer as many as possible in the short time available. First Question: This question has to do with the relationship between sensory and motor nerves and is, primarily, a matter of interpretation. When considered only from a physical point of view, one’s conclusion will not differ from the usual interpretation, which deals with the central organ. Let me take a simple case of nerve conduction. Sensation would be transmitted from the periphery to the central organ, from which the motor impulse would pass to the appropriate organ. As I said, as long as we consider only the physical, we might be perfectly satisfied with this explanation. And I do not believe that any other interpretation would be acceptable, unless we are willing to consider the result of suprasensory observations, that is, all-inclusive, real observation. As I mentioned in my discussions of this matter over the past few days, the difference between the sensory and motor nerves, anatomically and physiologically, is not very significant. I never said that there is no difference at all, but that the difference was not very noticeable. Anatomical differences do not contradict my interpretation. Let me say this again: we are dealing here with only one type of nerves. What people call the “sensory” nerves and “motor” nerves are really the same, and so it really doesn’t matter whether we use sensory or motor for our terms. Such distinctions are irrelevant, since these nerves are (metaphorically) the physical tools of undifferentiated soul experiences. A will process lives in every thought process, and, vice versa, there is an element of thought, or a residue of sensory perception, in every will process, although such processes remain mostly unconscious. Now, every will impulse, whether direct or the result of a thought, always begins in the upper members of the human constitution, in the interplay between the I-being and the astral body. If we now follow a will impulse and all its processes, we are not led to the nerves at all, since every will impulse intervenes directly in the human metabolism. The difference between an interpretation based on anthroposophic research and that of conventional science lies in science’s claim that a will impulse is transmitted to the nerves before the relevant organs are stimulated to move. In reality, this is not the case. A soul impulse initiates metabolic processes directly in the organism. For example, let’s look at a sensation as revealed by a physical sense, say in the human eye. Here, the whole process would have to be drawn in greater detail. First a process would occur in the eye, then it would be transmitted to the optic nerve, which is classified as a sensory nerve by ordinary science. The optic nerve is the physical mediator for seeing. If we really want to get to the truth of the matter, I will have to correct what I just said. It was with some hesitation that I said that the nerves are the physical instruments of human soul experiences, because such a comparison does not accurately convey the real meaning of physical organs and organic systems in a human being. Think of it like this: imagine soft ground and a path, and that a cart is being driven over this soft earth. It would leave tracks, from which I could tell exactly where the wheels had been. Now imagine that someone comes along and explains these tracks by saying, “Here, in these places, the earth must have developed various forces that it.” Such an interpretation would be a complete illusion, since it was not the earth that was active; rather, something was done to the earth. The cartwheels were driven over it, and the tracks had nothing to do with an activity of the earth itself. Something similar happens in the brain’s nervous system. Soul and spiritual processes are active there. As with the cart, what is left behind are the tracks, or imprints. These we can find. But the perception in the brain and everything retained anatomically and physiologically have nothing to do with the brain as such. This was impressed, or molded, by the activities of soul and spirit. Thus, it is not surprising that what we find in the brain corresponds to events in the sphere of soul and spirit. In fact, however, this is completely unrelated to the brain itself. So the metaphor of physical tools is not accurate. Rather, we should see the whole process as similar to the way I might see myself walking. Walking is in no way initiated by the ground I walk on; the earth is not my tool. But without it, I could not walk. That’s how it is. My thinking as such—that is, the life of my soul and spirit—has nothing to do with my brain. But the brain is the ground on which this soul substance is retained. Through this process of retention, we become conscious of our soul life. So you see, the truth is quite different from what people usually imagine. There has to be this resistance wherever there is a sensation. In the same way that a process occurs (say in the eye) that can be perceived with the help of a so-called sensory nerve, in the will impulses (in one’s leg, for example), a process occurs, and it is this process that is perceived with the help of the nerve. The so-called sensory nerves are organs of perception that spread out into the senses. The so-called motor nerves spread inward and convey perceptions of will force activities, making us aware of what the will is doing as it works directly through the metabolism. Both sensory and motor nerves transmit sensations; sensory nerves spread outward and motor nerves work inward. There is no significant difference between these two kinds of nerves. The function of the first is to make us aware, in the form of thought processes, of processes in the sensory organs, while the other “motor” nerves communicate processes within the physical body, also in form of thought processes. If we perform the well-known and common experiment of cutting into the spinal fluid in a case of tabes dorsalis, or if one interprets this disorder realistically, without the usual bias of materialistic physiology, this illness can be explained with particular clarity. In the case of tabes dorsalis, the appropriate nerve (I will call it a sensory nerve) would, under normal circumstances, make a movement sense-perceptible, but it is not functioning, and consequently the movement cannot be performed, because movement can take place only when such a process is perceived consciously. It works like this: imagine a piece of chalk with which I want to do something. Unless I can perceive it with my senses, I cannot do what I want. Similarly, in a case of tabes dorsalis, the mediating nerve cannot function, because it has been injured and thus there is no transmission of sensation. The patient loses the possibility of using it. Likewise, I would be unable to use a piece of chalk if it were lying somewhere in a dark room where I could not find it. Tabes dorsalis is the result of a patient’s inability to find the appropriate organs with the help of the sensory nerves that enter the spinal fluid. This is a rather rough description, and it could certainly be explained in greater detail. Any time we look at nerves in the right way, severing them proves this interpretation. This particular interpretation is the result of anthroposophic research. In other words, it is based on direct observation. What matters is that we can use outer phenomena to substantiate our interpretation. To give another example, a so-called motor nerve may be cut or damaged. If we join it to a sensory nerve and allow it to heal, it will function again. In other words, it is possible to join the appropriate ends of a “sensory” nerve to a “motor” nerve, and, after healing, the result will be a uniform functioning. If these two kinds of nerves were radically different, such a process would be impossible. There is yet another possibility. Let us take it in its simplest form. Here a “sensory” nerve goes to the spinal cord, and a “motor” nerve leaves the spinal cord, itself a sensory nerve (see drawing). This would be a case of uniform conduction. In fact, all this represents a uniform conduction. And if we take, for example, a simple reflex movement, a uniform process takes place. Imagine a simple reflex motion; a fly settles on my eyelid, and I flick it away through a reflex motion. The whole process is uniform. What happens is merely an interpretation. We could compare it to an electric switch, with one wire leading into it and another leading away from it. The process is really uniform, but it is interrupted here, similar to an electric current that, when interrupted, flashes across as an electric spark. When the switch is closed, there is no spark. When it is open, there is a spark that indicates a break in the circuit. Such uniform conductions are also present in the brain and act as links, similar to an electric spark when an electric current is interrupted. If I see a spark, I know there is a break in the nerve’s current. It’s as though the nerve fluid were jumping across like an electric spark, to use a coarse expression. And this makes it possible for the soul to experience this process consciously. If it were a uniform nerve current passing through without a break in the circuit, it would simply pass through the body, and the soul would be unable to experience anything. This is all I can say about this for the moment. Such theories are generally accepted everywhere in the world, and when I am asked where one might be able to find more details, I may even mention Huxley’s book on physiology as a standard work on this subject. There is one more point I wish to make. This whole question is really very subtle, and the usual interpretations certainly appear convincing. To prove them correct, the so-called sensory parts of a nerve are cut, and then the motor parts of a nerve are cut, with the goal of demonstrating that the sensations we interpret as movement are no longer possible. If you take what I have said as a whole, however, especially with regard to the interrupt switch, you will be able to understand all the various experiments that involve cutting nerves. [IMAGE REMOVED FROM PREVIEW] Question: How can educators best respond to requests, coming from children between five and a half and seven, for various activities? Rudolf Steiner: At this age, a feeling for authority has begun to make itself felt, as I tried to indicate in the lectures here. Yet a longing for imitation predominates, and this gives us a clue about what to do with these children. The movable picture books that I mentioned are particularly suitable, because they stimulate their awakening powers of fantasy. If they ask to do something—and as soon as we have the opportunity of opening a kindergarten in Stuttgart, we shall try to put this into practice—if the children want to be engaged in some activity, we will paint or model with them in the simplest way, first by doing it ourselves while they watch. If children have already lost their first teeth, we do not paint for them first, but encourage them to paint their own pictures. Teachers will appeal to the children’s powers of imitation only when they want to lead them into writing through drawing or painting. But in general, in a kindergarten for children between five and a half and seven, we would first do the various activities in front of them, and then let the children repeat them in their own way. Thus we gradually lead them from the principle of imitation to that of authority. Naturally, this can be done in various ways. It is quite possible to get children to work on their own. For instance, one could first do something with them, such as modeling or drawing, which they are then asked to repeat on their own. One has to invent various possibilities of letting them supplement and complete what the teacher has started. One can show them that such a piece of work is complete only when a child has made five or ten more such parts, which together must form a whole. In this way, we combine the principle of imitation with that of authority. It will become a truly stimulating task for us to develop such ideas in practice once we have a kindergarten in the Waldorf school. Of course, it would be perfectly all right for you to develop these ideas yourself, since it would take too much of our time to go into greater detail now. Question: Will it be possible to have this course of lectures published in English? Rudolf Steiner: Of course, these things always take time, but I would like to have the shorthand version of this course written out in long hand as soon as it can possibly be done. And when this is accomplished, we can do what is necessary to have it published in English as well. Question: Should children be taught to play musical instruments, and if so, which ones? Rudolf Steiner: In our Waldorf school, I have advocated the principle that, apart from being introduced to music in a general way (at least those who show some special gifts), children should also learn to play musical instruments technically. Instruments should not be chosen ahead of time but in consultation with the music teacher. A truly good music teacher will soon discover whether a child entering school shows specific gifts, which may reveal a tendency toward one instrument or another. Here one should definitely approach each child individually. Naturally, in the Waldorf school, these things are still in the beginning stage, but despite this, we have managed to gather very acceptable small orchestras and quartets. Question: Do you think that composing in the Greek modes, as discovered by Miss Schlesinger, means a real advance for the future of music? Would it be advisable to have instruments, such as the piano, tuned in such modes? Would it be a good thing for us to get accustomed to these modes? Rudolf Steiner: For several reasons, it is my opinion that music will progress if what I call “intensive melody” gradually plays a more significant role. Intensive melody means getting used to the sound of even one note as a kind of melody. One becomes accustomed to a greater tone complexity of each sound. This will eventually happen. When this stage is reached, it leads to a certain modification of our scales, simply because the intervals become “filled” in a way that is different from what we are used to. They are filled more concretely, and this in itself leads to a greater appreciation of certain elements in what I like to call “archetypal music” (elements also inherent in Miss Schlesinger’s discoveries), and here important and meaningful features can be recognized. I believe that these will open a way to enriching our experience of music by overcoming limitations imposed by our more or less fortuitous scales and all that came with them. So I agree that by fostering this particular discovery we can advance the possibilities of progress in music. Question: Is it also possible to give eurythmy to physically handicapped children, or perhaps curative eurythmy to fit each child? Rudolf Steiner: Yes, absolutely. We simply have to find ways to use eurythmy in each situation. First we look at the existing forms of eurythmy in general, then we consider whether a handicapped child can perform those movements. If not, we may have to modify them, which we can do anyway. One good method is to use artistic eurythmy as it exists for such children, and this especially helps the young children—even the very small ones. Ordinary eurythmy may lead to very surprising results in the healing processes of these children. Curative eurythmy was worked out systematically—initially by me during a supplementary course here in Dornach in 1921, right after the last course to medical doctors. It was meant to assist various healing processes. Curative eurythmy is also appropriate for children suffering from physical handicaps. For less severe cases, existing forms of curative eurythmy will be enough. In more severe cases, these forms may have to be intensified or modified. However, any such modifications must be made with great caution. Artistic eurythmy will not harm anyone; it is always beneficial. Harmful consequences arise only through excessive or exaggerated eurythmy practice, as would happen with any type of movement. Naturally, excessive eurythmy practice leads to all sorts of exhaustion and general asthenia, in the same way that we would harm ourselves by excessive efforts in mountain climbing or, for example, by working our arms too much. Eurythmy itself is not to blame, however, only its wrong application. Any wholesome activity may lead to illness when taken too far. With ordinary eurythmy, one cannot imagine that it would harm anyone. But with curative eurythmy, we must heed a general rule I gave during the curative eurythmy course. Curative eurythmy exercises should be planned only with the guidance and supervision of a doctor, by the doctor and curative eurythmist together, and only after a proper medical diagnosis. If curative exercises must be intensified, it is absolutely essential to proceed on a strict medical basis, and only a specialist in pathology can decide the necessary measures to be taken. It would be irresponsible to let just anyone meddle with curative eurythmy, just as it would be irresponsible to allow unqualified people to dispense dangerous drugs or poisons. If injury were to result from such bungling methods, it would not be the fault of curative eurythmy. Question: In yesterday’s lecture we heard about the abnormal consequences of shifting what was right for one period of life into later periods and the subsequent emergence of exaggerated phlegmatic and sanguine temperaments. First, how does a pronounced choleric temperament come about? Second, how can we tell when a young child is inclined too much toward melancholic or any other temperament? And third, is it possible to counteract such imbalances before the change of teeth? Rudolf Steiner: The choleric temperament arises primarily because a person’s I-being works with particular force during one of the nodal points of life, around the second year and again during the ninth and tenth years. There are other nodal points later in life, but we are interested in the first two here. It is not that one’s I-being begins to exist only in the twenty-first year, or is freed at a certain age. It is always present in every human being from the moment of birth—or, more specifically, from the third week after conception. The I can become too intense and work with particular strength during these times. So, what is the meaning and nature of such nodal points? Between the ninth and tenth years, the I works with great intensity, manifesting as children learn to differentiate between self and the environment. To maintain normal conditions, a stable equilibrium is needed, especially at this stage. It’s possible for this state of equilibrium to shift outwardly, and this becomes one of many causes of a sanguine temperament. When I spoke about the temperaments yesterday, I made a special point in saying that various contributing factors work together, and that I would single out those that are more important from a certain point of view. It is also possible for the center of gravity to shift inward. This can happen even while children are learning to speak or when they first begin to pull themselves up and learn to stand upright. At such moments, there is always an opportunity for the I to work too forcefully. We have to pay attention to this and try not to make mistakes at this point in life—for example, by forcing a child to stand upright and unsupported too soon. Children should do this only after they have developed the faculty needed to imitate the adult’s vertical position. You can appreciate the importance of this if you notice the real meaning of the human upright position. In general, animals are constituted so that the spine is more or less parallel to the earth’s surface. There are exceptions, of course, but they may be explained just on the basis of their difference. Human beings, on the other hand, are constituted so that, in a normal position, the spine extends along the earth’s radius. This is the radical difference between human beings and animals. And in this radical difference we find a response to strict Darwinian materialists (not Darwinians, but Darwinian materialists), who deny the existence of a defining difference between the human skeleton and that of the higher animals, saying that both have the same number of bones and so on. Of course, this is correct. But the skeleton of an animal has a horizontal spine, and a human spine is vertical. This vertical position of the human spine reveals a relationship to the entire cosmos, and this relationship means that human beings bear an I-being. When we talk about animals, we speak of only three members—the physical body, the ether body (or body of formative forces), and the astral body. I-being incarnates only when a being is organized vertically. I once spoke of this in a lecture, and afterward someone came to me and said, “But what about when a human being sleeps? The spine is certainly horizontal then.” People often fail to grasp the point of what I say. The point is not simply that the human spine is constituted only for a vertical position while standing. We must also look at the entire makeup of the human being—the mutual relationships and positions of the bones that result in walking with a vertical spinal column, whereas, in animals, the spine remains horizontal. The point is this: the vertical position of the human spine distinguishes human beings as bearers of I-being. Now observe how the physiognomic character of a person is expressed with particular force through the vertical. You may have noticed (if the correct means of observation were used) that there are people who show certain anomalies in physical growth. For instance, according to their organic nature, they were meant to grow to a certain height, but because another organic system worked in the opposite direction, the human form became compressed. It is absolutely possible that, because of certain antecedents, the physical structure of a person meant to be larger was compressed by an organic system working in the opposite direction. This was the case with Fichte, for example. I could cite numerous others—Napoleon, to mention only one. In keeping with certain parts of his organic systems, Fichte’s stature could have become taller, yet he was stunted in his physical growth. This meant that his I had to put up with existing in his compressed body, and a choleric temperament is a direct expression of the I. A choleric temperament can certainly be caused by such abnormal growth. Returning to our question—How can we tell when a young child is inclined too much toward melancholic or another temperament?—I think that hardly anyone who spends much time with children needs special suggestions, since the symptoms practically force themselves on us. Even with very naive and unskilled observation, we can discriminate between choleric and melancholic children, just as we can clearly distinguish between a child who “just sits” and seems morose and miserable and one who wildly romps around. In the classroom, it is very easy to spot a child who, after having paid attention for a moment to something on the blackboard, suddenly turns to a neighbor for stimulation before looking out the window again. This is what a sanguine child is like. These things can easily be observed, even on a very naive level. Imagine a child who easily flies into a fit of temper. If, at the right age, an adult simulates such tantrums, it may cause the child to tire of that behavior. We can be quite successful this way. Now, if one asks whether we can work to balance these traits before the change of teeth, we must say yes, using essentially the same methods we would apply at a later age, which have already been described. But at such an early age, these methods need to be clothed in terms of imitation. Before the change of teeth, however, it is not really necessary to counteract these temperamental inclinations, because most of the time it works better to just let these things die off naturally. Of course, this can be uncomfortable for the adult, but this is something that requires us to think in a different way. I would like to clarify this by comparison. You probably know something of lay healers, who may not have a thorough knowledge of the human organism but can nevertheless assess abnormalities and symptoms of illnesses to a certain degree. It may happen that such a healer recognizes an anomaly in the movements of a patient’s heart. When asked what should be done, a possible answer is, “Leave the heart alone, because if we brought it back to normal activity, the patient would be unable to bear it. The patient needs this heart irregularity.” Similarly, it is often necessary to know how long we should leave a certain condition alone, and in the case of choleric children, how much time we must give them to get over their tantrums simply through exhaustion. This is what we need to keep in mind. Question: How can a student of anthroposophy avoid losing the capacity for love and memory when crossing the boundary of sense-perceptible knowing? Rudolf Steiner: This question seems to be based on an assumption that, during one’s ordinary state of consciousness, love and the memory are both needed for life. In ordinary life, one could not exist without the faculty of remembering. Without this spring of memory, leading back to a certain point in early childhood, the continuity of one’s ego could not exist. Plenty of cases are known in which this continuity has been destroyed, and definite gaps appear in the memory. This is a pathological condition. Likewise, ordinary life cannot develop without love. But now it needs to be said that, when a state of higher consciousness is reached, the substance of this higher consciousness is different from that of ordinary life. This question seems to imply that, in going beyond the limits of ordinary knowledge, love and memory do not manifest past the boundaries of knowledge. This is quite correct. At the same time, however, it has always been emphasized that the right kind of training consists of retaining qualities that we have already developed in ordinary consciousness; they stay alive along with these new qualities. It is even necessary (as you can find in my book How to Know Higher Worlds) to enhance and strengthen qualities developed in ordinary life when entering a state of higher consciousness. This means that nothing is taken away regarding the inner faculties we developed in ordinary consciousness, but that something more is required for higher consciousness, something not attained previously. To clarify this, I would like to use a somewhat trivial comparison, even if it does not completely fit the situation. As you know, if I want to move by walking on the ground, I must keep my sense of balance. Other things are also needed to walk properly, without swaying or falling. Well, when learning to walk on a tightrope, one loses none of the faculties that serve for walking on the ground. In learning to walk on a tightrope, one meets completely different conditions, and yet it would be irrelevant to ask whether tightrope walking prevents one from being able to walk properly on an ordinary surface. Similarly, the attainment of a different consciousness does not make one lose the faculties of ordinary consciousness—and I do not mean to imply at all that the attainment of higher consciousness is a kind of spiritual tightrope walking. Yet it’s true that the faculties and qualities gained in ordinary consciousness are fully preserved when rising to a state of enhanced consciousness. And now, because it is getting late, I would like to deal with the remaining questions as quickly as possible, so I can end our meeting by telling you a little story. Question: What should our attitude be toward the ever-increasing use of documentary films in schools, and how can we best explain to those who defend them that their harmful effects are not balanced by their potential educational value? Rudolf Steiner: I have tried to get behind the mysteries of film, and whether or not my findings make people angry is irrelevant, since I am just giving you the facts. I have to admit that the films have an extremely harmful effect on what I have been calling the ether, or life, body. And this especially true in terms of the human sensory system. It is a fact that, by watching film productions, the entire human soul-spiritual constitution becomes mechanized. Films are external means for turning people into materialists. I tested these effects, especially during the war years when film propaganda was made for all sorts of things. One could see how audiences avidly absorbed whatever was shown. I was not especially interested in watching films, but I did want to observe their effects on audiences. One could see how the film is simply an intrinsic part of the plan to materialize humankind, even by means of weaving materialism into the perceptual habits of those who are watching. Naturally, this could be taken much further, but because of the late hour there is only time for these brief suggestions. Question: How should we treat a child who, according to the parents, sings in tune at the age of three, and who, by the age of seven, sings very much out of tune? Rudolf Steiner: First we would have to look at whether some event has caused the child’s musical ear to become masked for the time being. But if it is true that the child actually did sing well at three, we should be able to help the child to sing in tune again with the appropriate pedagogical treatment. This could be done by studying the child’s previous habits, when there was the ability to sing well. One must discover how the child was occupied—the sort of activities the child enjoyed and so on. Then, obviously, with the necessary changes according to age, place the child again into the whole setting of those early years, and approach the child with singing again. Try very methodically to again evoke the entire situation of the child’s early life. It is possible that some other faculty may have become submerged, one that might be recovered more easily. Question: What is attitude of spiritual science toward the Montessori system of education and what would the consequences of this system be? Rudolf Steiner: I really do not like to answer questions about contemporary methods, which are generally backed by a certain amount of fanaticism. Not that I dislike answering questions, but I have to admit that I do not like answering questions such as, What is the attitude of anthroposophy toward this or that contemporary movement? There is no need for this, because I consider it my task to represent to the world only what can be gained from anthroposophic research. I do not think it is my task to illuminate other matters from an anthroposophic point of view. Therefore, all I wish to say is that when aims and aspirations tend toward a certain artificiality—such as bringing to very young children something that is not part of their natural surroundings but has been artificially contrived and turned into a system—such goals cannot really benefit the healthy development of children. Many of these new methods are invented today, but none of them are based on a real and thorough knowledge of the human being. Of course we can find a great deal of what is right in such a system, but in each instance it is necessary to reduce also the positive aspects to what accords with a real knowledge of the human being. And now, ladies and gentlemen, with the time left after the translation of this last part, I would like to drop a hint. I do not want to be so discourteous as to say, in short, that every hour must come to an end. But since I see that so many of our honored guests here feel as I do, I will be polite enough to meet their wishes and tell a little story—a very short story. There once lived a Hungarian couple who always had guests in the evening (in Hungary, people were very hospitable before everything went upside down). And when the clock struck ten, the husband used to say to his wife, “Woman, we must be polite to our guests. We must retire now because surely our guests will want to go home.” |

| 303. Soul Economy: Body, Soul and Spirit in Waldorf Education: Physical Education

06 Jan 1922, Dornach Translated by Roland Everett |

|---|

| 303. Soul Economy: Body, Soul and Spirit in Waldorf Education: Physical Education

06 Jan 1922, Dornach Translated by Roland Everett |

|---|

What I have to say today concerns primarily the physical education of children. It is in the nature of this subject that I can talk about it only aphoristically, mainly because people tend to have already formed their opinions in these matters. When it comes to talking about physical development, everyone seems to have definite likes and dislikes that too often strongly color people’s theories on this subject. But anything arising from personal sympathies or antipathies easily leads to fanaticism, which is far from the real goals and activities of spiritual science. Any form of fanaticism or agitation for some particular cause is entirely alien to the nature of the anthroposophic movement, which simply wants to point out the effects of various attitudes and actions in life and leave everyone free to relate personal sympathies and antipathies to the matter. Just consider the fanaticism that argues for or against vegetarianism today, each using unassailable, scientific proofs. And yet we cannot help noticing that never before has superficiality flourished so much as when people defend various movements of a similar nature. It is a fact that anthroposophy does not have the slightest leaning toward extremism in any form. It cannot go along with ardent vegetarians who wish to enforce their views on others whose attitudes differ, and who, in their fanaticism, go so far as to deny meat eaters a fully human status in society. If fanaticism occasionally creeps into the anthroposophic movement, it does not at all reflect the true nature of spiritual science. Now, there is another aspect we must consider within the context of these lectures. Perhaps you have noticed that until now we have emphasized appropriate educational methods in the realm of children’s soul and spirit, which also allows the best possibility for physical development in a natural, healthy way. One could say that we are studying an educational system that—if it is practiced correctly and effectively—offers the best means toward healthy physical development. So the fundamentals of a sound physical education have already been presented. Nevertheless, it will be useful to review and summarize them again, although we must do this aphoristically because of a shortage of time. To do justice to this subject I would have to devote a whole lecture cycle to it. Our theme falls naturally into three main parts: the way we feed children; the way we relate children to warmth or coldness; and our approach to gymnastics. Fundamentally, these three categories comprise everything important for the physical education of children. Modern methods of knowledge, based as they are on an intellectualistic approach, do not offer the possibility of coming to terms with the complex nature of the human organism. Despite the scientific attitude that people are so proud of today, we need to acquire a certain instinctive knowledge of what nurtures or damages health and includes the whole spectrum between these two poles. A healthy instinct for such matters is immensely important. After all, isn’t it true that our natural science is generally becoming more dyed-in-the-wool materialistic? Consider how many secrets have been drawn from nature through research under the microscope or by dissecting various lower animals to investigate the functions of their parts. How many times has human behavior been determined by observing animal behavior, without considering the fact that the human organization in its most important characteristic differs radically from that of all lower animal species? In any case, there has not been enough emphasis placed on this significant difference, primarily because science today depends on investigating every detail separately, thus getting only a partial view of life. Let me try to illustrate this by a comparison. Imagine that I meet two people at nine o’clock one morning. They are sitting on a bench, and I stop for a while to talk to them about various things, thus gaining a general impression of their characters. Then I go on my way again. At three o’clock in the afternoon I see them still sitting on that bench. Now, there are various possibilities of what may have happened in the meantime. It may be that they have been sitting there talking the whole time. Or, according to the different ways that people of various ethnic groups or nationalities behave, other things may have happened. Perhaps they sat together in silence. Or, unknown to me, one of them might left right after I did, while the other stayed on the bench. The first may have returned just before I reappeared, and so on. Externally, nothing appears to have changed between 9 A.M. and 3 P.M., despite the fact that the two seemed very different in temperament and lifestyle. Life will never reveal its secrets if we observe only outer appearances. Yet, with today’s scientific methods, this happens far more frequently than is generally realized, as anyone can discover. Present scientific attitudes can indeed lead to a situation such as I witnessed not long ago. In my youth, I had a friend whom I knew lived a normal and healthy life. Later, we went our different ways and did not meet for many years. Then, one day, I visited him again. When he sat down to his midday meal, the food was served in an unusual way, and a scale was placed on the table. He weighed the meat and the vegetables, because he had begun to eat “scientifically.” He had complete faith in a science that prescribed the correct amounts of various foods one eats to be healthy. Needless to say, such a method may be perfectly justified under certain conditions, but it thoroughly undermines one’s healthy instincts. An instinct for what is wholesome or damaging to health is an essential quality for any teacher worthy of the calling. Such teachers surely know how to elaborate and use all that was given in the previous lectures, and this includes the physical education of children. We have seen, for instance, that before the change of teeth children live entirely in the physical organism. This applies especially to babies, particularly with regard to nourishment. As you know, when babies begin to take in food, they are completely satisfied with a totally uniform diet. If we, as adults, had to live every day on exactly the same kind of food for breakfast, lunch, and any other meal, we would find it intolerable, both physically and mentally. Adults like to vary their food with a mixed diet. Babies, on the other hand, do not get a change of food at all. And yet, only a few people realize the bliss with which babies receive their “monotonous” diet; the whole body becomes saturated with intense sweetness from the mother’s milk. Adults have the possibility of tasting food only with the taste buds and adjacent organs. They are unfortunate, since all their sensations of taste are confined to the head and thus they are very different a baby, whose entire body becomes one great organ for the sense of taste. At the end of the baby stage, tasting with the whole body ceases and is soon forgotten for the rest of life. People who live with ordinary degrees of consciousness are completely unaware of how different their sensations of tasting food were during infancy. And, sure enough, later life does its best to wipe out this memory. For example, I once took part in a conversation between an “abstainer” and a person of the opposite position. (I won’t tell you the whole story, since it would take us too far from our theme.) The abstainer, like so many of these people, was inclined to be a fanatic and tried to convert the gourmand, who replied, “But I was completely temperate for two full years.” Greatly surprised, the abstainer asked him when this was, to which the other answered, “During the first two years of my life.” In this humorous, though rather frivolous way, important facts of life were discussed. Few people have a deeper and correct knowledge of these things. Babies are related to the physical body in such a way that they can eat only with their entire physical organization, deriving the greatest benefit and pleasure from this condition. The gradual transition to the next stage involves forces that begin to concentrate in the head and finally lead to the change of teeth. These forces are so powerful that they can force out the milk teeth as the second teeth push through. This slow and gradual process takes place between birth and second dentition, affecting various other regions. After babyhood, the sense of taste withdraws into the head. Children no longer eat only with their physical organization, but with their soul forces as well. They learn to distinguish various tastes through their soul forces. At this stage it is important to watch carefully children’s reactions to different foods. Their likes and dislikes are valuable indicators of their inner health. But, to judge such matters, we need at least an basic knowledge of nutrition. When talking about this today, people typically think of the aspect of weight. But this is not so important. What really matters is the fact that each kind of food contains a certain amount of forces. Each item of food holds a specific amount of forces through which it has adapted to the conditions of the outer world. But what takes place within the human organism is something entirely different. The human organism must completely transform the food it takes in. It must transform the processes that various foods have gone through while growing—forces that will become active within the human organism. What occurs there is a continual conflict, during which the dynamic forces in food are completely changed. We experience this inner reaction to the substances we eat as stimulating and life sustaining. Consequently, it is no good to merely ask how many ounces of this or that we should eat. Rather, we should ask how our organism will react to even the smallest amounts of a certain food. The human organism needs forces that generate resistance to outer natural processes. Though somewhat modified, processes in certain areas of the human organism (between the mouth and the stomach) can still be compared to forces in the external world. However, those in the stomach and in the subsequent stages of digestion are very different from what we find outside the human being. When it comes to what happens in the head, however, we find exactly the opposite processes from those in outer nature. This shows how the human organism, in its totality, must be stimulated in the right way through the food we eat. I must be brief, so there is no time to get into the terminology of the deeper aspects of this subject. For now, however, a less specialized and more popular terminology will do. As you know, in ordinary life there are foods we consider rich in nutrition, and others considered poor in nutrients. It is possible to live on food of poor nutritional value—just think of how many people are fed mainly on bread and potatoes, both of which are certainly low in nutritional value. On the other hand, you have to remember that, in cases of ill health, one must take great care not to overburden the digestion with foods having little nourishment. Bread and potatoes make great demands on the digestive system, with the effect that very little energy is left for the remaining functions. Consequently, a diet of bread and potatoes is not likely to promote physical growth. So we look for other foods that do not put unnecessary strain on the digestive system, foods that work the digestive system very little. If these things are taken to extremes, however, an abnormal activity begins in the brain, which in turn begins other processes that have absolutely no resemblance to those of outer nature. These again affect the rest of the human organism, and as a result the digestive system will become sluggish and too slack. All this is extremely complicated, and it is very difficult to understand all the ramifications of what happens. It is one of the most difficult tasks of a thorough scientific investigation—not the kind so common today—to know what really happens when, for instance, a potato or a piece of roast beef is taken into a human mouth. Each of these two processes is very complex, and each is very different from the other. To investigate the subsequent stages of digestion with scientific precision, a great deal of specialized knowledge is needed. A mere indication of what happens there must be enough. Imagine that a boy eats a potato. First the potato is tasted in his head, the location of one’s organs of taste, and then the sensation of taste induces further responses. Although the sense of taste no longer permeates the boy’s whole organism, it nevertheless affects it in certain ways. A potato does not have an especially stimulating taste and, consequently, leaves the organism somewhat indifferent and inactive. The organs are not particularly interested in what happens with the potato in the child’s mouth. Then, as you know, the potato passes into the stomach. The stomach, however, does not receive it with alacrity either, because it has not been stimulated by the sensation of taste. Taste always determines whether the stomach takes in food with sympathy or aversion. In this case, the stomach will not exert itself to incorporate the potato with its dynamic forces. Yet, this must happen, since the potato cannot be left there in the stomach. If the stomach has the strength, it will absorb the dynamic forces of the potato and work on them with a certain distaste. It allows the potato to enter without developing any significant response to it, because the potato has not stimulated it. This process continues through the rest of the digestive tract, in which the remains of the potato are again worked on with a certain reluctance. Very little of what was once the potato reaches the head organization. These few indications—which ought to be deepened considerably for any proper understanding—are intended as a mere suggestion of the complex processes that occur in the human organism. Nevertheless, educators should acquire a working knowledge of these things, and to do this I believe it is necessary to go into the whys and wherefores. I can imagine that some listeners might think it good enough just to be told what they should give children to eat and which foods to avoid. But this is not enough, because to do the right things—especially when physical matters are involved—teachers must have sufficient understanding of the problems. There are so many approaches to these things that one needs guidance to see what each case requires. And for this, teachers need at least a simplified picture of how children should be fed. In physical education, we see in particular how far educational principles have deviated from prevailing social conditions. Unless students happen to live in boarding schools, where it is possible to practice what I have been indicating, it will be necessary to win the cooperation of parents or others in charge of children, and, as we all know, this can cause considerable difficulties. It may not be possible to implement measures one deems right and beneficial for students until tremendous resistance has been overcome. Let me give you an example. Imagine you have a student in your class who has an excessively melancholic disposition. Extreme symptoms of this kind always indicate an abnormality in the physical organization. Abnormalities in the soul region always originate with physical abnormalities of one kind or another, and physical symptoms are a manifestation of the soul and spiritual life. So let us imagine such a child in a day school. In a boarding school, of course, one would deal with such a problem in cooperation with the dormitory. So what would I have to do? First I must contact the child’s parents and—if I am absolutely certain about the real causes of the problem—I may ask them to increase the child’s sugar consumption by at least 150 percent, or in some cases by as much as 200 percent, compared to what one gives a child who behaves normally. I would advise the parents not to withhold this additional sugar, which could be given, for instance, as sweets. Why would I do this? Perhaps the opposite example will make it clearer to you. Imagine that I have to deal with a pathologically sanguine child. If I am to make sense, we must assume this is an excessively sanguine child. Again, the symptoms betray an abnormality in the physical organization, and here I would have to ask the parents to decrease the amount of sugar given to the child. I would ask them to greatly reduce the amount of sweets given to the child. What are my reasons? One discovers whether to increase or decrease the amount of sugar only by becoming aware of these facts; all milk and milk products, but mother’s milk in particular, spread their effect uniformly throughout the entire human organism, so that each organ receives what it needs in a harmonious way. Other foods, however, have more influence on a particular organic system. Please note that I am not saying other foods exercise an exclusive influence, but that they influence some organs more than others. The way a child or an adult responds to a specific taste or a certain food depends on the general condition of a particular organic system. In this respect, certain luxury foods play as important a part, as do ordinary foods. Milk affects the entire human being, whereas other nutrients affect a particular organic system. With regard to sugar, we must look at activity in the liver. So, what am I doing by giving an abnormally melancholic child lots of sugar? I diminish the activity of the liver, because sugar, in a certain sense, takes over the activity of the liver. This causes the liver to direct its activity more toward something extraneous, and thus the activity is reduced. Under certain circumstances, pronounced melancholic symptoms may be the result of a child’s liver activity, so it is possible, purely through diet, to decrease an overly melancholic tendency in a child—which can also manifest as a tendency toward anemia. And why, in the case of an overly sanguine child, do I recommend a reduction of sugar intake? Here I try to decrease the stimulating effect of sugar and cause the liver to become a little more active on its own. In this way, I stimulate the child’s I-being, which helps the child overcome the physical symptoms of an excessively sanguine temperament. If we pay close attention over a period of time, we generally discover the necessary preventive measures. As a rule, this faculty develops only when it has become second nature in alert and dedicated teachers to spot even slightly unusual symptoms in students. Obviously, we must never allow abnormalities to deteriorate too much before taking action. To achieve this ability, teachers must be willing to continually deepen their understanding and to overcome numerous personal hindrances. Otherwise, I am afraid that teachers will not gain the necessary thoroughness until they reach retirement. This example illustrates the possibility of counteracting certain abnormalities if we observe the human physical organization as a whole. Thus, the whys and wherefores are important. Naturally, we must always contend with countless details, but it is not impossible to relate these to the broader aspects that generally lead to polarities. Truly good teachers (even better than those who already exist), through close contact with their students, know instinctively and beforehand how to handle children when specific circumstances present themselves. In any case, if they are to take the appropriate action, it is extremely important for teachers to perceive any deviation from the normal, healthy behavior of children. We must watch very closely how children—as beings of body, soul, and spirit—show an interest not only in themselves, but also in their environment. We have to develop an instinctive awareness of the children’s interest, or their lack of it. This represents the one side. The other is a teacher’s awareness of the first signs of fatigue in students. What is the source of each child’s characteristic interest? It arises in the metabolic and limb system, but mainly in the metabolism. I will know that there is a problem of improper diet if I see that a child is losing interest, for example, in mental activities (and this is the most obvious sign); or if a child shows little interest in outer activities and no longer wants to participate in games or similar pursuits; or if I see that a child has lost interest in food (which is the worst sign of all, since children are naturally interested in various tastes and should learn to distinguish between the various flavors); or if a child suffers from lack of appetite (since a lost appetite also means a lack of interest in food). Here, food demands too much of the child’s digestive system. So, I must find out what food this child is being given that has relatively little nutritive value, since such food burdens the digestive system. Just as I can determine the weather by reading the barometer, similarly I can deduce an improper diet when I see a marked lack of interest in a child. Interest and apathy are the most important indicators with regard to a correct diet for children. Now let’s take a look at the opposite pole. If I notice that a child tires too quickly because of mental or physical activities, again I can trace the cause to physical conditions. In this case, a child may eat with a normal appetite, but after eating, such a child may become drowsy, not unlike a snake after feeding. If a child has an abnormal desire to curl up on the sofa after eating, it shows an inability to cope with digestion, which causes the child to become tired. It is a sign that a child has been given too much of the sort of food that does not stimulate the digestion enough, with the result that the unfulfilled demands of the digestive system now enter the child’s head region, causing fatigue. So, I must give food having concentrated nutritional value to a child who shows a noticeable lack of interest. But there is no need to become a fanatic about these things. Fanatical vegetarians will say that this lack of interest in children is caused by a diet of meat, and that they must now get used to a diet of raw fruits, so they can recover a normal interest in the world. This may be true. But those who believe in giving meat to children will maintain that, if they tire too easily, we must stimulate them with a meat diet. These things should not provoke too much discussion, simply because it is possible to balance various foods through appropriate combinations that, in this case, might very well take the place of meat. Nor is it essential to turn children into vegetarians. The important thing is to recognize that, on the one hand, children who lack a healthy interest can be helped by an improved diet, one that contains especially nutritious foods and, on the other, that a tendency toward fatigue can be overcome by working in the opposite direction. This is one way to simplify and easily understand a very complex subject. If, for example, I find that a child tires too easily, I must realize that the digestion is not sufficiently engaged, and so I alter the diet accordingly. We must develop a kind of human symptomatology that helps us in a concrete and practical way. It is not always necessary to go into all the details. In matters of nutrition, if we interpret certain symptoms correctly, we begin to see through the situation and recognize what steps to take. Closely related to all this (though opposite in a certain sense) is the whole question of warmth in childhood. Here, external phenomena guide us even more clearly than does nutrition; we just need the correct interpretation. On the other hand, they easily lead to extremes and become harmful. I am referring to “hardening,” or “toughening.” Under certain circumstances, this can be good, and much has been done in its favor. Yet, if we are well grounded in our knowledge of the human being, we cannot help feeling a sense of alarm when we see adults who were systematically hardened as children, and now cannot cross a hot and sunlit square without feeling oppressed by the heat. This can reach a point where both their psychological and physical makeup prevents them from ever crossing a sunny, open square. Surely, hardening is inappropriate if does not enable a person to endure any kind of physical hardship. When considering the question of warmth or cold, two facts need to be kept in mind. First, nature has given us a clear directive; we have a sense of well-being only so long as we are unaware of the temperature surrounding us. If we are exposed to too much heat or cold, we quickly lose our sense of wellbeing. Obviously, we need our sensory perception of outer temperatures, but this must not adversely affect our whole organism. To protect ourselves from heat and cold, we neutralize their effects by the use of clothing. When exposed to too much cold, a person loses the ability to maintain normal functioning in certain inner organs. If, on the other hand, outer temperatures are too high, the body reacts with an excessive functioning of those organs. So we can say that, if a person is exposed to very low temperatures, the inner organs tend to coat themselves with a layer of mucus, giving rise to the type of illnesses I would call (in the vernacular) internal mucositis. Organs become lined with metabolic excesses, and this results in a hypersecretion of mucus. If, on the other hand, a person is exposed to too much heat, those organs respond by drying up. A tendency develops to form crusts, while the organs themselves ossify and become quite anemic. This way of looking at the human organism provides the correct indications for moving ahead in matters of education. Every symptom and phenomenon teaches us something. For example, as human beings, it is safe to expose our faces to much colder temperatures than we could other parts of our bodies. And because the face is exposed to colder temperatures, it prevents other organs from drying out by stimulating them. There is a continuous interplay between the face, which readily accepts certain degrees of cold, and the other members of the human physical organization. However, we must not confuse the face with a very different part of the human anatomy. Forgive me for putting it so crudely, but we must not confuse people’s faces with their calves. This is the sort of mischief we encounter so frequently today, because in cold weather children are allowed to walk around with their legs bare up to their knees, and sometimes even higher. This truly confuses the two ends of the physical human body. If people were only aware of the hidden connections here, they would realize how many cases of appendicitis develop later on because of this confusion between the two human extremities. On the other hand, it also needs to be said that we should not be too sensitive to minor changes of temperature, and that children should be brought up to bear them with equanimity. When children overreact to slight changes of temperature, again we must know that we can help by making corresponding changes in the diet. These things show us that warmth and nutrition must work together, for eating and keeping warm complement each other. Those who are oversensitive to temperature changes should be given food with a high caloric content, which generates the inner strength needed to withstand these changes. Again, you can see how a real knowledge of the human being also helps in such situations, and how, fundamentally, not only must everything in the human organism work harmoniously together, but mostly those entrusted with educating young people must be able to recognize this cooperation among the various organs. The third major aspect of physical education involves various forms of movement. The human makeup is such that we must be active in more than our bodily functions; we must also participate in the outer world. People must be able to experience a connection with the outer world. It is true that not one human organ can be understood when considered only in a state of rest. We must relate it to the inherent activities and movements of its functions; then we can understand an organ even in a state of rest. This is true whether it is an outer organ—whose form, even at rest, indicates its normal movements—or an inner organ, whose shape and configuration express the function and movement that make it part of the overall human organic processes. All this is considered when we introduce various forms of movement to children in the right way. Again, bear in mind the wholeness of the human being. We must try to give the physical, soul, and spiritual aspects their due. With children, we do this only by allowing them to perform the right kinds of movements, which bring satisfaction because they are in harmony with children’s innate intentions. Such movements are always accompanied by a sense of well-being. In an education based on knowledge of the human being, the first step in this direction is to learn the particular ways children want to move when given freedom. Typical games with their inhibiting rules are quite alien to the nature of young children, because they suppress what should remain freely mobile in children. Organized games gradually dull their inner activity, and children lose interest in such externally imposed movements. We can clearly see this by observing what happens when the free movements of playing children are channeled too much into fixed gymnastic exercises. As I said, I do not wish to condemn gymnastic lessons as such, but in general it must be said that when young students are doing gym exercises, their movements are being determined externally. Anyone working out of a real knowledge of the human being would much rather see young children play freely on parallel bars, on a horizontal bar, or on rope ladders, instead of having to follow the exact commands of a gym instructor shouting “one two three” as the children step on the first, second, and third rungs of a rope ladder or perform precise movements on gym apparatus—movements that tend to impose stereotyped forms on their bodies. I realize that these remarks go a little beyond the general trend of modern gymnastics, whose advocates are often a bit fanatic. One easily rouses antipathy by shedding light on the kind of gymnastic exercises that are imposed externally, and by comparing them with the natural movements of children arising from their own involvement in free play. Yet it is exactly this free play that we should observe and study. One must get to know children intimately, and then one sees what to do to stimulate the right kind of free play, in which boys and girls should, of course, participate together. In this way, through the inner flexibility that accompanies children’s outer movements, their organic functions work together harmoniously. This method also opens our eyes to what lies behind certain symptoms, such as those indicating anemia in young girls. In most cases such symptoms are simply the result of having been artificially separated from the boys, because it was considered unseemly for them to romp with the boys during free play. Girls, as well as boys, should be allowed to be boisterous when they play, although perhaps in slightly different ways. Conventional notions of what is “ladylike” are often are held up to young girls, but they frequently contribute to anemia in later life. However, I must ask you not to take this remark as a personal criticism of an established way of life, but simply as an objective observation. We can obviate a tendency toward anemia simply by allowing young girls to engage in the right kind of free play. In this way, we safeguard their inner functions from becoming so sluggish that they can no longer form the right kind of blood from their digestive activity. These days, it has become difficult to fully understand these matters, simply because the kind of knowledge fostered today is not the outcome of observing inner human nature, but comes from collecting detailed data. Through so-called induction, these facts are then turned into a hodge podge of general knowledge. Of course, by following this method it is possible to discover all kinds of interesting facts, but it is more important to observe what has real significance for life. Otherwise, an ardent admirer of modern science might argue by saying, “You told us that anemia can manifest because young girls have not been allowed to play freely; yet I have encountered several cases of anemia in a village where young girls had never been restrained in their play.” One would have to look into the causes of anemia in this particular situation; perhaps as a child, one of these girls nibbled an autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale), thus developing a tendency toward anemia in later life. Another important aspect of our theme concerns the consequences of mental strain in children. If we overburden their mental powers, we definitely exert a harmful influence on their general health. If we prevent children from discovering their natural tendency toward movement and play, the metabolic organization will not be sufficiently stimulated. By burdening children with too much knowledge of the world, we artificially increase metabolic activity in the head. Although human beings have a threefold nature, any activity that dominates one of the three spheres is, to a certain extent, also present in the other two systems. When we overload students with facts about the external material realm instead of with spiritual matters, we divert some of the normal digestive activity from the metabolism into the head, thus causing abnormal activity in the whole metabolic system. This, too, can cause anemia during puberty. Someone might argue that, in a certain village, students were never subjected to intellectual stress, but there were nevertheless cases of anemia in that town. Again we would have to look at the particular situation. For instance, we might discover that one of the houses in this village was covered by Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), and that a child whose curiosity had been roused by its black, glistening berries had eaten a few that were overripe, in this way increasing an innate tendency toward anemia. To conclude, I would like to say this: It might be correct to collect separate data from which one then extracts general knowledge. But if we want to gain the kind of knowledge that is closely allied to practical life, we have to observe real life carefully, so that we can discover where and how to tackle problems as they arise. Only a real knowledge of the human being offers educators this kind of insight. It enables them to fulfill their task by guiding children into the right forms of movement and by guarding against stressing the mental capacities of the children in their care. The realization of these possibilities is our first and foremost task. Of course, we cannot necessarily prevent a child from sucking on an autumn crocus or eating black berries from a Virginia creeper, but we can infuse intuitions into children—and at the right time. And this will enable them to develop physical powers in a well-rounded way and to cultivate greater flexibility. |

| 300b. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Thirty-Fifth Meeting

22 Jun 1922, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch |

|---|

| It would be very good to speak about that. The Waldorf teachers should speak. I also believe it would be good if some students spoke about their understanding of the youth movement. |

| Something I noticed often was that it was very detrimental that the Waldorf School was overburdened with rushing from one project to another during the past year. If you add up all of the different activities in which some of the Waldorf School teachers participated, then you would see it is quite a bad thing. |

| It is natural in the anthroposophical realm to have a cooperative working between the Waldorf School and an association of physicians. Teachers from the Waldorf School would have much to say, and such interactions within the anthroposophical movement would result in an all-round improvement. |

| 300b. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Thirty-Fifth Meeting

22 Jun 1922, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch |

|---|