| 259. The Fateful Year of 1923: The International Delegates' Assembly

22 Jul 1923, Dornach |

|---|

| (See below for more details.) Between now and Christmas, we need two things more than ever: courage, so that we can secure all the physical foundations for the new structure by then; and love, so that the International Anthroposophical Society can be born at Christmas, an act that must mean something for the spiritual aura of the Earth. |

| Stuten proposed that one or more of Dr. Steiner's mystery plays be performed during a festival week on large stages in Switzerland and abroad in the course of this year. |

| The building of the new Goetheanum and the carrying out of anthroposophical truths into the spiritual life of the whole earth will show that the signals of the Anthroposophical Society, which are to be born at Christmas, are a living and active being. Please come, dear friends, to Dornach at Christmas, equipped for such tasks and with loving intentions. |

| 259. The Fateful Year of 1923: The International Delegates' Assembly

22 Jul 1923, Dornach |

|---|

Mr. Albert Steffen opened the meeting and said that many people were probably rudely awakened by cannon shots this morning. This is because today, down in the village, there is a celebration of the anniversary of the Battle of Dornach, which took place in 1499 on the same hill where we are now gathered. This battle marked the culmination of the wars of independence that had begun when the three founders of the Swiss Confederation met to swear an oath on the Rütli. As can be read in Swiss history books, this confederation was the model for the United States of America, which in turn became the model for the republics and democracies of Europe. The hill of Dornach is therefore a crucially important point for the history of humanity. The anthroposophical movement, which now has its spiritual center here, is neither political nor national. During the last Goetheanum, people of all nationalities worked peacefully side by side on the hill of Dornach, even during the world war. It is of the greatest historical significance, said Mr. Steffen, that he can make the announcement today that the International Anthroposophical Society will be founded here in Dornach at Christmas this year. Mr. Steffen then gave some examples of the spiritually low-level spite and dishonesty with which the opposition to Anthroposophy and the Goetheanum works, so that the unanimous and tireless support of members in all countries is needed to establish and maintain the new Goetheanum. Dr. Guenther Wachsmuth briefly reported on the results of the special meeting of the country delegates the previous afternoon. A significant step forward had been taken, both practically and morally. It had to be emphasized that it was not enough to indicate approximately how much funding might be collected over the course of a year; rather, Dr. Steiner could only be asked to take the reconstruction into his own hands if a certain sum were guaranteed now. It was a great moral success that a few delegates had taken such a heavy responsibility upon their own shoulders. The following sums have been guaranteed in writing by individual delegates: England... ..... 115,000 Swiss francs Netherlands... 150,000 Switzerland... 200,000 Denmark... 100,000 Honolulu... 200,000 America... 30,000 Czechoslovakia. 30,000 (from German members there) Italy. 20,000 Austria. 10,000 Sweden. 10,000 865,000 Swiss francs As was expressly emphasized by all the delegates, this is only a first step, so that construction can begin immediately. It is hoped that in the coming months, through vigorous activity, significantly larger sums can be secured. A second problem, which must now be discussed here and also after the delegates return to their countries, is the founding of the International Anthroposophical Society in Dornach at Christmas. In the course of this year, several national societies, e.g. in England, Holland, etc., will be founded on their own initiative, and it is to be hoped that several other countries will follow this example as soon as possible. The rebuilding of the movement in Dornach will result in a great deal of correspondence with all countries and branches, which is why the founding of national societies will greatly facilitate joint work, reporting, etc. Some grotesque examples were given to show why members who do not affiliate with other branches and country groups are unjustifiably dissatisfied when they are not notified of events in good time. It is hoped that this will be much easier and better in the future, thanks to the creation of country groups, which will simplify the exchange of information, and to the creation of a comprehensive address archive. (See below for more details.) Between now and Christmas, we need two things more than ever: courage, so that we can secure all the physical foundations for the new structure by then; and love, so that the International Anthroposophical Society can be born at Christmas, an act that must mean something for the spiritual aura of the Earth. Mr. Leinhas explained clearly and unambiguously that according to the existing laws it is absolutely necessary to leave the contributions collected in Germany, which are deposited with the trust company in Stuttgart, in Germany and to use them up there. He suggested, as one of several possibilities, that these funds be used for a study fund to make it easier for students to devote themselves intensively to the study of the various anthroposophical fields of teaching. Mr. Heywood-Smith pointed out that today, July 22, was an important day in the history of Switzerland's wars of liberation. We are now facing another decisive historical moment, where another deed is to be accomplished that also demands trust in the ideal and the commitment of the whole being. We still need three million Swiss francs to rebuild the Goetheanum. The three confederates at Rütli had risked their lives for the cause of freedom. Are there three people in our Society who would be willing to guarantee the three million from their own means and thereby perform a deed of love for humanity? The members could then, in turn, perform a deed of love by ensuring that the guarantors do not suffer any loss once the contributions flow into the fund at the same rate as they are needed for the reconstruction. Dr. Büchenbacher described the difficult moral tasks that have to be overcome by the friends in Germany; as Dr. Steiner showed us in his lectures, we have to help the genius of the time to overcome the demon of the time. Germany is a particularly difficult and important battleground for these forces at this time. Mr. Scott Pyle, America, expressed in a heartfelt way how unfortunate it was that the German contributions could not directly benefit the Goetheanum this time and that it would be a beautiful act of international community spirit if the other countries, going beyond their own foundations, would also distribute the German contribution among themselves. He himself set a good example by donating a large sum. Miss Woolley, England, added to it by donating jewelry to the German contribution. Mr. Jan Stuten impressed upon the audience the necessity of the new Goetheanum, especially for a rebirth of artistic life. In the old Goetheanum, all forms were so harmonious and musical that they had a direct inspiring effect on the artist. A new music could have been born from the contemplation of the capitals, architraves and other living organic forms of the Goetheanum. He described the uninspired, uncreative decadence of modern compositions with examples to the contrary. The anthroposophical artists asked the Friends of the Arts to help them with the new Goetheanum, so that a place full of stimulation for the creative powers of artists on earth could be created again. Eurythmy also needs the Goetheanum as a setting of the same spirit. The performance that the delegates saw yesterday, for example of Shakespeare's “Midsummer Night's Dream”, would have been an event, a renaissance of Shakespeare's works in a new spirit. We felt deeply grateful to Dr. Steiner for this event. Mr. Stuten proposed that one or more of Dr. Steiner's mystery plays be performed during a festival week on large stages in Switzerland and abroad in the course of this year. Ms. Henström, Sweden, reported on anthroposophical work in Sweden and guaranteed, at her own responsibility, a nice contribution from Sweden for the fund. Miss Lina Schwarz, Italy, spoke about the wishes of her Italian friends and hoped that in the future it might be possible to send a newsletter from Dornach to all countries. Count Polzer, Austria, said that in a properly conducted budget debate, spiritual human areas of interest should also be addressed; he welcomed the fact that in the last few days the budget negotiations here had been brought to such a level that at the same time, deep spiritual problems such as the consolidation of the Society in its connection with the reconstruction of the Goetheanum could be discussed. A center should be formed here in Dornach, in lively exchange with the life in the branches of all countries. He hoped that despite the growing difficulties, the delegates and members would meet quite often in Dornach and thus get to know each other more and more personally and warmly. Graf Polzer requested that the members of the other countries now also accept the resolution adopted by Switzerland. Mr. Steffen asked those in favor of the resolution to rise. - (All the delegates remained silent for a few moments.) — The international assembly has thus unanimously endorsed this resolution. The international assembly of delegates was closed by Dr. Steiner on the evening of July 22, at the end of the third of his lectures on “Three Perspectives of Anthroposophy”, with the following words: This was an attempt to characterize the three perspectives that anthroposophy can open up: the physical, the soul and the spiritual perspective. It will undoubtedly be a memorable meeting, my dear friends, if the building of a new Goetheanum can now emerge from it. And it would be wonderful if this new Goetheanum could become such that it could also radiate to us in its forms what is to be said through the word on the basis of anthroposophy to humanity. In this way, my dear friends, you will have done a great deal for anthroposophy. I may speak impersonally in all these matters at this moment; it really does not depend on me. I also do not want to speak about the decision that has been made, the content of which is that it should be left to me to make the internal arrangements for the construction. For my request that I be allowed to carry out the building work under these conditions was made because I can only take responsibility for the building work under these conditions. And all this remains within the objective. It is commendable that this request has been sympathetically received. The anthroposophical movement as such will benefit from the outcome. And so, as I bid farewell to our friends who have come here, I would just like to be the interpreter of the anthroposophical understanding, and the repercussions of this anthroposophical understanding will not fail to materialize for those who have this understanding. It can truly be seen from the spiritual realm what a difficult sacrifice our friends are making for the reconstruction of the Goetheanum. But the feeling has now entered our ranks that the will for what stands as an ideal before the soul's eye cannot be realized without such great sacrifices. The Goetheanum will only be truly blessed if those who make the sacrifices truly want them and if the sacrifices come from a sacred will. But the beauty and beautiful sincerity of this will can already be expressed by the interpreter of anthroposophy as a warm farewell greeting. And I can assure you of this: now that the sacrifices have been made, the Goetheanum will be rebuilt to the best of our ability. Building this second Goetheanum will require stronger, harder struggles than building the first, and a moral fund to supplement the physical one would be highly necessary. So, in the name of anthroposophy, I am deeply grateful to all those who have rushed here, and if it is the case that the right understanding will increasingly take hold, then in a sense the blessing cannot fail to come, and then one can also look forward calmly to the difficult struggles that this work in particular will entail. Therefore, today, in a particularly serious and also in a particularly warm way, I would like to say goodbye to the friends. Some preliminary remarks for the founding of the International Anthroposophical Society in Dornach, Christmas 1923.A large number of the delegates who had been present at the conference from July 20 to 23 met again after the conference to determine the issues that require preliminary discussion in the various countries and groups during the next few months, so that the delegates can arrive at Christmas well informed about the views of their friends at home and armed with fruitful proposals for the development of the International Anthroposophical Society. We therefore sincerely request that the following points be thoroughly discussed in the assemblies of the Anthroposophical branches and groups in the time between now and Christmas, so that harmony of opinion can be achieved all the more quickly in Dornach on the basis of the clarified views of friends from all countries: 1. There will be a discussion about the merger of the national societies that have already been founded or will be founded by Christmas to form an International Anthroposophical Society. Reports will be given on the different ways in which the individual national societies are organized. 2. Possible revision of statutes by the national societies, insofar as the current draft 1 needed to be changed or added. 3. Those countries, such as Belgium, Poland, etc., that have expressed the wish to remain affiliated to the Swiss Anthroposophical Society for the time being, until their membership has grown stronger, are asked to send the Swiss Anthroposophical Society a precise list of the addresses of the members of their group, as well as to indicate which individuals are to be notified of any events, communications, etc. who are then responsible for passing this on to all members belonging to their group. 4. Proposals for the person of a General Secretary of the International Anthroposophical Society. The decision, of course, lies with Dr. Steiner. 5. Some delegates had proposed appointing so-called envoys in Dornach, i.e. prominent individuals from the various countries who already live in Dornach and could be consulted or called upon to assist in dealings with the individual countries. Opinions were divided on the expediency of such an organization. It would, of course, only be useful if it facilitated, rather than complicated, communication between Dornach and the national societies. 6. The amount and due date of the contribution to be paid to Dornach per member (upon admission and annually) to cover the expenses of the General Secretariat. (It should not be forgotten that the sending of such communications, the organization of meetings, the handling of the constantly increasing number of requests in Dornach, etc., which result from the international growth of the Society, require funds that cannot be covered permanently by the Swiss Society or from private funds, but must be borne jointly by all countries). 7. Regular additions to the address archive of members in Dornach (unless otherwise agreed). (It is proposed that contributions and lists of new members, resignations, changes of address, etc. be sent to Dornach on 7 January and 1 July respectively). 8. Determination of the responsibility of the general secretaries, boards of directors, etc. of the national associations and of the International General Secretary with regard to the admission of new members to the Society. — (For example, during discussions with Dutch friends, it was suggested that the admission card of a new member be signed by the general secretary of a country and countersigned by the International General Secretariat). 9. The question of publishing a journal can only be resolved by specific proposals regarding the person and the means. 10. Organization of a dignified and effective defense against opponents in all countries. The International Anthroposophical Society must take on this task to such an extent through increased collaboration across the whole earth that Dr. Steiner is not impeded in important work by the tiresome defense against opponents. 11. Members in all countries to work together to support the initiatives launched by the Anthroposophical Society in the fields of education, therapy (distribution of remedies, support for clinical-therapeutic institutes, etc.), scientific research, art, etc. It would be very nice if, in this respect, the delegates could come to Dornach at Christmas with concrete proposals and reports of their own activities in all countries after intensive discussions. 12. How much have the individual countries and groups been able to contribute to the reconstruction of the Goetheanum? (It would be helpful for the continuity of the work if a preliminary report on this could be given by October 15, 1923). Please send the names of the delegates who are to represent their countries in Dornach at Christmas to Dornach by December 1, 1923. Similarly, information is needed about accommodation, etc. In addition to the responsible delegates, all members of the Society are of course most warmly and urgently invited to attend. The exact date of the Christmas meeting will be announced. All correspondence should be addressed to “The Secretariat of the Anthroposophical Society”, Dornach near Basel, Switzerland, Haus Friedwart, 1st floor. We repeat Dr. Steiner's closing words: “It would be wonderful if this new Goetheanum could become such that it could radiate to us in its forms what is to be said through the word on the basis of anthroposophy for humanity. The building of the new Goetheanum and the carrying out of anthroposophical truths into the spiritual life of the whole earth will show that the signals of the Anthroposophical Society, which are to be born at Christmas, are a living and active being. Please come, dear friends, to Dornach at Christmas, equipped for such tasks and with loving intentions. Albert Steffen Dr. Chronological overview of the days of the conference with a literal rendering of Rudolf Steiner's wordsFirst day, Friday, July 20, 1923 11:30 a.m., Friedwart House: preliminary discussion of the Swiss delegates (without Rudolf Steiner). The official delegates are elected and the question is discussed of whether Switzerland can raise the planned 400,000 francs for the reconstruction. 4 p.m., Glass House: Preliminary discussion of the German delegates (without Rudolf Steiner). Carl Unger mentions three points for the conference: 1. Rebuilding the Goetheanum, 2. Appeal for donations, 3. Following the “resolution” of the Swiss. The composition of the German delegation is decided: Dr. Unger, Emil Leinhas, Wolfgang Wachsmuth, Hans Büchenbacher, Maria-Röschl, Felix Peipers, Graf Lerchenfeld, Kurt Walther, Frau Goyert, Oberstleutnant Seebohm (Johanna Mücke has resigned). 5 p.m., Glass House: preliminary discussion of all the delegates named by the various countries to determine the conference program and the chairmanship. Albert Steffen is elected chairman, George Kaufmann from London vice-chairman, and Guenther Wachsmuth secretary. The Swiss delegate E. Etienne from Geneva reports the following from this meeting in a private letter dated July 29, 1923: "This first discussion was actually more of a get-together. The various country delegates had come here more or less informed, some hardly knew the purpose of the meeting; they had therefore not been given any powers of attorney and were more here to find out something that they could then inform their country and their branches about. Of course, this was a hindrance and an obstacle to the smooth running of the purely financial part of the work program. It was interesting to see how the mentality of their people was reflected in the statements of the various delegates. Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany and Austria were the most willing to make sacrifices. The tragedy is that for the last two countries, the exchange rate situation is such that their enormous sacrifices appear so small when converted into francs. The Nordic countries, on the other hand, failed to contribute. Italy and France are willing but have few members and little money. England and America have disappointed... In contrast, the German group has been exemplary for Czechoslovakia. Of the 27 members, 150,000 Czech crowns (about 10,000 francs) have been delivered so far, and their delegate has personally committed to a further 20,000 francs. Will the three Czech groups be as loyal to the cause? They were not represented. 8 p.m., carpentry workshop: Rudolf Steiner's first lecture on “Three Perspectives on Anthroposophy” (in CW 225). Second day, Saturday, July 21, 1923 10 a.m., carpentry hall: First general assembly of the delegates and members of the Anthroposophical Society. Welcome address by Albert Steffen and report by Dr. Guenther Wachsmuth on yesterday's preliminary negotiations. In the discussion that followed, various suggestions were made as to how the funds for the reconstruction could be raised. Cf. the report by Albert Steffen and Dr. Guenther Wachsmuth on page 557. At the end of the morning session, Rudolf Steiner took the floor: See GA 252 George Kaufmann translates Rudolf Steiner's remarks into English. Then, until 1 p.m., the negotiations continue on the financing of the building and the proposed brochure. 3 p.m., Glass House: Special meeting of all delegates about the sums to be provided by the individual countries. (There are no minutes of this meeting.) 5 p.m., Carpentry: Eurythmy performance with introductory address by Rudolf Steiner (in CW 277). 8 p.m., carpentry workshop: Rudolf Steiner's second lecture on “Three Perspectives on Anthroposophy” (in CW 225). 10:30 p.m., glass house: assembly of delegates after Rudolf Steiner's lecture. There are no minutes available, but the Swiss delegate E. Etienne from Geneva reports in a private letter dated July 29 about this meeting, at which Rudolf Steiner was also present, as follows: "It was sometimes exhausting to listen to the haggling and haggling. The committee, which was pushing for large sums to achieve something worthwhile, and the delegates, some of whom had no authority to make real commitments. It is therefore to be hoped that they will really do everything they can in their countries to increase the guaranteed minimum amounts, in line with the number of members and their actual financial possibilities. After the minimum amounts had been agreed (which depended on whether or not the doctor considered the guarantee offered to be sufficient – he wanted to be absolutely sure and only took note of guaranteed amounts), it was concluded that at least 25% of the guaranteed amounts must be paid by 15 October of the following year. The original plan was to reconvene on this date. However, all the delegates were sufficiently empowered and well informed about the final amounts that their country would contribute to the reconstruction and in which installments. Doctor Itten said that he would now immediately start planning the new Goetheanum for the funds that had now been made available (insurance and minimum amounts). If in October the delegates are able to guarantee larger sums than those currently foreseen, then these funds would be used for the extensions. This met with long faces, and the immediate objection was raised that nothing of this should be mentioned at tomorrow's general assembly (we delegates would keep silent about everything anyway), because everyone wants to give their money for the Goetheanum and not for extensions. The sense of sacrifice could wane if this became known. The doctor replied that if our old Goetheanum had not burnt down, we would have been forced to build extensions anyway, because the work that awaited us could not have been done in the old building; we felt that ourselves at the time. And we should not imagine that greater sacrifices are now being demanded of us than we would have had to make without the fire in the next three years (we would not have had three million to start with!). In short, Dr. Itten was keen to make it clear to us that the extensions were not only not a disaster, but something desirable, and he tried to encourage us. — Later, he came up again and said very kindly: Don't think I'm making a joke: you can very well proceed in such a way that I design a Goetheanum for the available money, right up to the roof, so for the time being without a roof. (Much laughter.) I suppose most anthroposophists would then still want the roof and raise the necessary money for it. The suggestion was generally liked – but whether Doctor really proceeds in this way will probably depend on the degree of trust in our willingness to make sacrifices. Doctor just said clearly that he did not want to go through the misery of raising money a second time. He would only build with what was actually raised and would not rely on promises.

|

| Easter and the Awakening to Cosmic Thought

12 Apr 1907, Berlin Translated by Dorothy S. Osmond Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| The days leading up to this point of time become progressively shorter and the Sun's power steadily weakens. But from Christmas onwards greater and greater warmth again streams from the Sun. Christmas is the Festival of the reborn Sun. |

| It is precisely at this time that we celebrate our Christmas Festival. When the Easter Festival is celebrated the Sun is continuing its ascent which had been in process since the Christmas Festival. |

| He could bear and help this Karma, and we may be sure that the redemption through Him plays an essential role in its fulfilment. The thought of Resurrection and Redemption can in reality be fully grasped only through a knowledge of Spiritual Science. |

| Easter and the Awakening to Cosmic Thought

12 Apr 1907, Berlin Translated by Dorothy S. Osmond Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Goethe often described, in many different ways, a feeling of which he was persistently aware. He said, in effect: When I see the irrelevance manifesting in the passions, emotions and actions of men, I feel the strong urge to turn to all-powerful Nature and be comforted by her majesty and consistency. In such utterances Goethe was referring to what since time immemorial humanity had brought to expression in the Festivals. The Festivals are reminders of the striving to turn away from the chaotic life of men's passions, urges and activities to the consistent, harmonious processes and events in Nature. The great Festivals are connected with definite and distinctive phenomena in the Heavens and with ever-recurring happenings in Nature. Easter is one such Festival. For Christians today, Easter is the Festival of the Resurrection of their Redeemer; it was celebrated not only as a symbol of Nature's awakening but also of Man's awakening. Man was urged to awaken to the reality underlying certain inner experiences. In ancient Egypt we find a festival connected with Osiris. In Greece a Spring festival was celebrated in honour of Dionysos. There were similar institutions in Asia Minor, where the resurrection or return of a God was associated with the re-awakening of Nature. In India, too, there are festivals dedicated to the God Vishnu. Brahmanism speaks of three aspects of the Deity, namely, Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. The supreme God, Brahma, is referred to as the Great Architect of the World, who brings about order and harmony: Vishnu is described as a kind of redeemer, liberator, an awakener of slumbering life. And Shiva, originally, is the Being who blesses the slumbering life that has been awakened by Vishnu and raises it to whatever heights can be reached. A particular festival was therefore dedicated to Vishnu It was said that he goes to sleep at the time of the year when we celebrate Christmas and wakes at the time of our Easter Festival. Those who adhere to this Eastern teaching celebrate the days of their Festival in a characteristic way. For the whole of this period they abstain from certain foods and drinks, for example, all pod-producing plants, all kinds of oils, all salt, all intoxicating beverages and all meat. This is the way in which people prepare themselves to understand what was actually celebrated in the Vishnu Festival, namely, the resurrection of the God and the awakening of all Nature. The Christmas Festival too, the old festival of the Winter solstice, is connected with particular happenings in Nature. The days leading up to this point of time become progressively shorter and the Sun's power steadily weakens. But from Christmas onwards greater and greater warmth again streams from the Sun. Christmas is the Festival of the reborn Sun. It was the wish of Christianity to establish a link with these ancient Festivals. The date of the birth of Jesus can be taken to be the day when the Sun's power again begins to increase in the heavens. In the Easter Festival the spiritual significance of the World's Saviour was thus connected with the physical Sun and with the awakening and returning life in Spring. As in the case of all ancient festivals, the fixing of the date of the Easter Festival was also determined by a certain constellation in the heavens. In the first century A.D. the symbol of Christianity was the Cross, with a lamb at its foot. Lamb and Ram are synonymous. During the epoch when preparation was being made for Christianity, the Sun was rising in the constellation of the Ram or Lamb. As we all know, the Sun moves through all the zodiacal constellations, every year progressing a little farther forward. Approximately seven hundred years before the coming of Christ, the Sun began to rise in the constellation of the Ram (Aries). Before then it rose in the constellation of the Bull (Taurus). In those times the people expressed what seemed to them important in connection with the evolution of humanity, in the symbol of the Bull, because the Sun then rose in that constellation. When the rising Sun moved forward into the constellation of the Ram or Lamb, the Ram became a figure of significance in the sagas and myths of the people. Jason brings the golden fleece from Colchis. Christ Jesus Himself is called the Lamb of God and in the earliest period of Christianity He is portrayed as the Lamb at the foot of the Cross. Thus the Easter Festival is obviously connected with the Constellation of the Ram or Lamb. The Festival of the Resurrection of the Redeemer is celebrated at the time when, in Nature, everything awakens to new life after having lain as if dead during the Winter months. Between the Christmas and the Easter Festivals there is certainly a correspondence but in their relation to the happenings in Nature there is a great difference. In its deepest significance, Easter is always felt to be the festival of the greatest mystery connected with Man. It is not merely a festival celebrating the re-awakening of Nature but is essentially more than that. It is an expression of the significance in Christianity of the Resurrection after death. Vishnu's sleep sets in at the time when, in Winter, the Sun again begins to ascend. It is precisely at this time that we celebrate our Christmas Festival. When the Easter Festival is celebrated the Sun is continuing its ascent which had been in process since the Christmas Festival. We must penetrate very deeply into the mysteries of man's nature if we are to understand the feelings of Initiates when they wished to give expression to the true facts underlying the Easter Festival. Man is a two-fold being—on the one side he is a being of soul-and-spirit, and on the other side a physical being. The physical being is an actual confluence of all the phenomena of Nature in man's environment. Paracelsus speaks of man as the quintessence of all that is outspread in external Nature. Nature contains the letters, as it were, and Man forms the word that is composed of these letters. When we observe a human being closely, we recognise the wisdom that is displayed in his constitution and structure. Not without reason has the body been called the temple of the soul. All the laws that can be observed in the dead stone, in the living plant—all have assembled in Man into a unity. When we study the marvellous structure of the human brain with its countless cells cooperating among themselves in a way that enables all the thoughts and sentient experiences filling the soul of man to come to expression, we realise with what supreme wisdom the human body has been constructed. But in the surrounding world too we behold an array of crystallised wisdom. When we look out into the world, applying what knowledge we possess to the laws in operation there, and then turn to observe the human being, we see all Nature concentrated in him. That is why sages have spoken of Man as the Microcosm, while in Nature they beheld the Macrocosm. In this sense Schiller wrote to Goethe in a letter of 23rd August 1794: “You take the whole of Nature into your purview in order to shed light upon a single sentence; in the totality of her (Nature's) manifold external manifestations you seek the explanation for the individual. From the simple organisation you proceed, step by step, to the more complex, in order finally to build up genetically from the materials of Nature's whole edifice the most complex organisation of all—Man.” The wonderful organisation of the body enables the human soul to have sight of the surrounding world. Through the senses the soul beholds the world and endeavours to fathom the wisdom by which that world has been constructed. With this in mind let us now think of an undeveloped human being. The wisdom made manifest in his bodily structure is the greatest that can possibly be imagined. The sum-total of divine wisdom is concentrated in a single human body. Yet in this body there dwells a childlike soul hardly capable of producing the most elementary thoughts that would enable it to understand the mysterious forces operating in its own heart, brain and blood. The soul develops slowly to a higher stage where it can understand the powers that have been at work with the object of producing the human body. This body itself bears the hallmark of an infinitely long past. Physical man is the crown of the rest of creation. What was it that had necessarily to precede the building of the human body, what had to come to pass before the cosmic wisdom was concentrated in this human being? The cosmic wisdom is concentrated in the body of a human being standing before us. Yet it is in the soul of an undeveloped human being that this wisdom first begins to manifest. The soul hardly so much as dreams of the great cosmic thoughts according to which the human being has evolved. Nevertheless, we can glimpse a future when people will be conscious of the reality of soul and spirit still lying in man as though asleep. Cosmic thought has been active through ages without number, has been active in Nature, always with the purpose of finally producing the crown of all its creative work—the human body. Cosmic wisdom is now slumbering in the human body, in order subsequently to acquire self-knowledge in man's soul, in order to build an eye in man's being through which to be recognised. Cosmic wisdom without, cosmic wisdom within, creative in the present as it was in the past and will be in future time. Gazing upwards we glimpse the ultimate goal, surmising the existence of a great soul by which the cosmic wisdom that existed from the very beginning has been understood and absolved. Our deepest feelings rise up within us full of expectation when we contemplate the past and the future in this way. When the soul begins to recognise the wonders accomplished by the cosmic wisdom and when clarity and illumination have been achieved, the Sun may well be accepted as the worthiest symbol of this inner awakening. Through the gate of the senses the soul is able to gaze into the external world because the Sun illumines the contents of that world. Fundamentally speaking, what man perceives in the external world is the result of the Sun's reflected light. It is the Sun that wakens in the soul the power to behold the external world. An awakening soul, one that is beginning to recognise the seasons as expressions of cosmic thought—such a soul sees the rising Sun as its liberation. When the Sun again begins its ascent, when the days lengthen, the soul turns to the Sun, declaring: To you I owe the possibility of discerning, outspread around me, the cosmic thought that sleeps within me and within all other human beings. Such an individual is now able to survey his earlier existence—one which preceded his present understanding of the activities of cosmic thought. Man himself is more ancient than his senses. Through spiritual investigation we are able eventually to reach the point in the far past when man's senses were in process of coming into existence, when only their very earliest beginnings were present. At that stage the senses were not yet doors enabling the soul to become aware of the environment. Schopenhauer realised this and was referring to the turning-point when man acquired the faculty of sensory perception, when he stated: This visible world first came into existence when an eye was there to behold it. The Sun formed the eye for itself and for the light. In still earlier times, when as yet man had no outer vision, he had inner vision. In the primeval ages of evolution, outer objects did not give rise to ideas or mental conceptions in man, but these rose up in him from within. Vision in those ancient times was vision in the astral light. Men were then endowed with a faculty of dim, shadowy clairvoyance. It was still with a faculty of dim, hazy vision that they beheld the world of the Germanic Gods and formed their conceptions of the Gods accordingly. This dim clairvoyance faded into darkness and gradually passed away altogether. It was extinguished by the strong light of the physical Sun whereby the physical world was made visible to the senses. Astral vision then died away altogether. When man looks into the future, he realises that his astral vision must return, but at a higher stage. What has now been extinguished for the sake of physical vision will return and combine with physical vision in order to generate clairvoyance—clear seeing in the fullest sense. In the future, a still more lucid consciousness will accompany man's waking vision. To physical vision will be added vision in the astral light, that is to say, perception with organs of soul. Those whom we have called the leaders of men are individuals who through lives of renunciation have developed in themselves the condition which later on is established in all mankind—these leaders of men already possess the faculty of astral vision which makes soul and spirit visible to them. The Easter Festival is connected spiritually not only with the awakening of the Sun but with the unfolding of the plant world in Spring. Just as the seed-corn is sunk into the soil and slumbers in order eventually to awaken anew, so the astral light in man's constitution was obliged to slumber in order eventually to be reawakened. The symbol of the Easter Festival is the seed-corn which sacrifices itself in order to enable a new plant to come into existence. This is the sacrifice of a phase in the life of Nature in order that a new one may begin. Sacrifice and Becoming are interwoven in the Easter Festival. Richard Wagner was conscious of the beauty and majesty of this thought. In the year 1857 in the Villa Wesendonck by the Lake of Zurich, while he was looking at the spectacle of awakening Nature, the thought came to him of the Saviour who had died and had awakened, the thought of Jesus Christ, also of Parsifal who was seeking for what is most holy in the soul. All the leaders of humanity who know how the higher life of man wakes out of the lower nature, have understood the Easter thought. Dante too, in his Divine Comedy describes his awakening on a Good Friday. This is brought to our attention at the very beginning of the poem. It was in his thirty-sixth year, that is to say, in the middle of his life, that Dante had the great vision he describes. Seventy years being the normal span of human life, thirty-five is the middle of this period. Thirty-five years are reckoned to be the period devoted to the development of physical experience. At the age of thirty-five the human being has reached the degree of maturity when spiritual experience can be added to physical experience. He is ready for perception of the spiritual world. When all the waking, nascent forces of physical existence are amalgamated, the time begins for the spiritual awakening. Hence Dante connects his vision with the Easter Festival. Whereas the original increase of the Sun's power is celebrated in the Christmas Festival, the Easter Festival takes place at the middle point of the Sun's increasing power. This was also the point when, in the middle of his life, Dante became aware of the dawn of spiritual life within himself. The Easter Festival is rightly celebrated at the middle point of the Sun's ascent; for this corresponds with the time when, in man, the slumbering astral light is reawakened. The Sun's power wakens the seed-corn that is slumbering in the earth. The seed-corn is an image of what arises in man when what occultists call the astral light is born within him. Therefore, Easter is also the festival of the resurrection that takes place in the inner nature of man. It has been thought that there is a kind of contradiction between what a Christian sees in the Easter Festival, and the idea of Karma. There seems at first to be a contradiction between the idea of Karma and redemption by the Son of Man. Those who do not understand very much about the fundamentals of anthroposophical thought may see a contradiction between the redemption wrought by Christ Jesus and the idea of Karma. Such people say that the thought of redemption by the God contradicts the fact of self-redemption through Karma. But the truth is that they understand neither the Easter thought of redemption nor the thought of the justice of Karma. It would certainly not be right if someone seeing another person suffer were to say to him: you yourself were the cause of this suffering—and then were to refuse to help him because Karma must take its course. This would be a misunderstanding of Karma. What Karma says is this: help the one who is suffering for you are actually there in order to help him. You do not violate karmic necessity by helping your fellow man. On the contrary, you are helping him to bear his Karma. You are then yourself a redeemer of suffering. So too, instead of a single individual, a whole group of people can be helped. By helping them we become part of their Karma. When a Being as all-powerful as Christ Jesus comes to the help of the human race, His sacrificial death becomes a factor in the collective Karma of mankind. He could bear and help this Karma, and we may be sure that the redemption through Him plays an essential role in its fulfilment. The thought of Resurrection and Redemption can in reality be fully grasped only through a knowledge of Spiritual Science. In the Christianity of the future there will be no contradiction between the idea of Karma and Redemption. Because cause and effect belong together in the spiritual life, this great deed of sacrifice by Christ Jesus must also have its effect in the life of mankind. Spiritual Science adds depth to the thought underlying the Easter Festival—a thought that is inscribed and can be read in the world of the stars. In the middle of his span of life the human being is surrounded by inharmonious, bewildering conditions. But he knows too that just as the world came forth from chaos, so will harmony eventually proceed from his still disorderly inner nature. The inner Saviour in man, the bringer of unity and harmony to counter all disharmony—this inner Saviour will arise, acting with the ordered regularity of the course of the planets around the Sun. Let everyone be reminded by the Easter Festival of the resurrection of the Spirit in the existing nature of man. |

| 229. Four Seasons and the Archangels: The Easter Imagination

07 Oct 1923, Dornach Translated by Mary Laird-Brown, Charles Davy Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| He sees how everywhere the hopes of the Ahrimanic beings play over the Earth like an astral wind, and how the Ahrimanic beings strive with all their might to call down an astral rain, as it were. |

| 2. See the lecture entitled Christmas at a Time of Grievous Destiny, given in Basle, 21st December, 1916. Printed in The Festivals and their Meaning, Vol. I: Christmas. (Rudolf Steiner Press.) |

| 229. Four Seasons and the Archangels: The Easter Imagination

07 Oct 1923, Dornach Translated by Mary Laird-Brown, Charles Davy Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

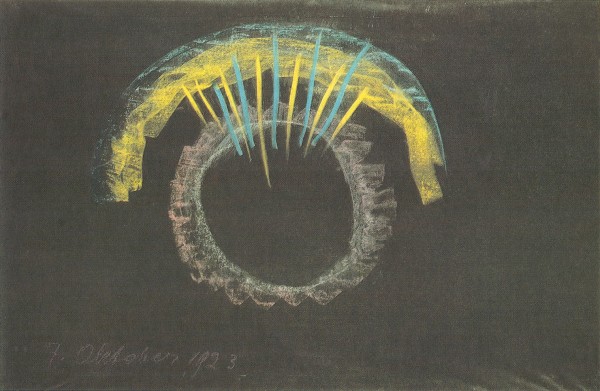

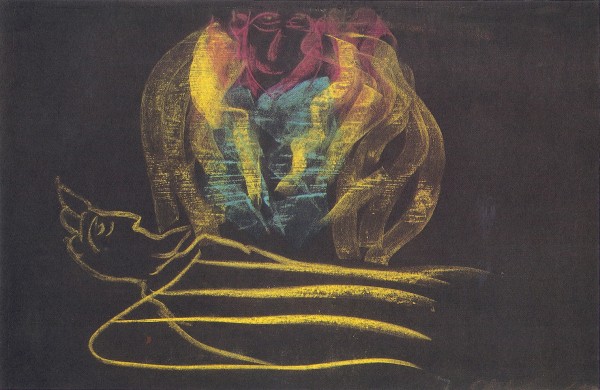

We must realise clearly how it is that in the depths of winter the Earth, in relation to the cosmos, is a being enclosed within itself. During the winter the Earth is, so to speak, wholly Earth, with a concentrated Earth-nature. In high summer—to add this contrast for the sake of clarity—the Earth is given over to the cosmos, lives with the cosmos. And in between, during spring and autumn, there is always a balance between these extremes. All this has the deepest significance for the Earth's whole life. Naturally, what I shall be saying applies only to that part of the Earth's surface where a corresponding transition from winter to spring takes place. Let us start, as we have always done in these lectures, by considering the purely material side. We will look at the salt-deposits which we have had to treat as the most important factor in winter-time. We will study this first in the limestone deposits, which are indeed a phenomenon of the utmost importance for the whole being of the Earth. You need only go out-of-doors here, where we are surrounded everywhere by the Jura limestone, and you will have before you all that I am going to begin by describing to-day. Ordinary observation is so superficial that for most people limestone is simply limestone, and outwardly there really is no perceptible difference between winter-limestone and spring-limestone. But this failure to distinguish between them comes from the standpoint which yesterday I called the flea-standpoint. The metamorphoses of limestone appear only when we look further out into the cosmos, as it were. Then we find a subtle difference between winter-limestone and spring-limestone, and it is precisely this which makes limestone the most important of all deposits in the soil. After all the various considerations we have gone into here, and since we know that soul and spirit are to be found everywhere, we can allow ourselves to speak of all such substance as vivified, ensouled beings. Thus we can say that winter-limestone is a being content within itself. If we enter into the being of winter-limestone with Intuition—the Intuition described in my book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds—we find it permeated throughout with the most diverse spirituality, made up of the elemental beings who dwell in the Earth. But the limestone is as it were contented, as a human head may be when it has solved an important problem and feels happy to have the thoughts which point to the solution. We perceive—for Intuition always embraces feeling—an inner contentment in the whole neighbourhood of the limestone formations during the winter season. If we were to swim under water, we should perceive water everywhere; and similarly, if we move spiritually through the process of limestone formation, we perceive this winter contentment on all sides. It expresses itself as an inner permeation of the winter-limestone by mobile, ever-changing forms—living, spiritual forms which appear as Imaginations. When spring approaches, however, and especially when March comes, the limestone becomes—we may say—dull in respect of its spiritual qualities. It loses them, for, as you know from previous accounts, the elemental beings now take their way, through a kind of cosmic-spiritual breathing-out into the cosmos. The limestone's spiritual thinking qualities are dulled, but the remarkable thing is that it becomes full of eager desire. It develops a kind of inner vitality. A subtle life-energy arises increasingly in the limestone, becoming steadily more active as spring draws on, and even more so towards summer, as the plants shoot up. These things are naturally not apparent in a crude outward form, but in a subtle, intimate way they do occur. The growing plants draw water and carbonic acid from the limestone in the soil. But this very loss signifies for the limestone an inner access of living activity, and it acquires on this account an extraordinary power of attraction for the Ahrimanic beings. Whenever spring approaches, their hopes revive. Apart from this, they have nothing particular to hope for from the realm of outer nature, because they are really able to pursue their activities only within human beings. But when spring draws near, the impression which the spring-limestone makes on them gives them the idea that after all they will be able to spread their dragon-nature through nature at large. Finding the spring-limestone full of life, they hope to be able to draw in also the astral element from the cosmos in order to ensoul the limestone—to permeate it with soul. So, when March is near, a truly clairvoyant observer of nature can witness a remarkable drama. He sees how everywhere the hopes of the Ahrimanic beings play over the Earth like an astral wind, and how the Ahrimanic beings strive with all their might to call down an astral rain, as it were. If they were to succeed, then in the summer this astral rain would transform the Earth into an ensouled being—or at least partly, as far as the limestone extends. And then, in autumn, the Earth would feel pain at every footfall on its surface. This endeavour, this illusion, lays hold of the Ahrimanic beings every spring, and every spring it is brought to nothing. From a human standpoint one might say—surely by now the Ahrimanic beings must have become clever enough to give up these hopes. But the world is not just as human beings imagine it to be. The fact is that every spring the Ahrimanic beings have new hope of being able to transform the Earth into an ensouled, living being through an astral rain from above, and every year their illusions are shattered. But man is not free from danger in the midst of these illusions. He consumes the nature-products which flourish in this atmosphere of hopes and illusions; and it is naïve to suppose that the bread he eats is merely corn, ground and baked. In outer nature these hopes are shattered, but the Ahrimanic beings long all the more to achieve their aim in man, who has a soul already. Thus every spring man is in danger of falling a victim—in subtle, intimate ways—to the Ahrimanic beings. In spring he is much more exposed to all the Ahrimanic workings in the cosmos than he is during other times of the year. But now, if we direct our gaze upwards, to where the elemental beings of the Earth ascend, where they unite themselves with the cloud-formations and acquire an inner activity which is subject to planetary life, something else can be seen. As March approaches, and down below the Ahrimanic beings are at work, the elemental beings—who are wholly spiritual, immaterial, although they live within the material Earth—are transported up into the region of vapour, air and warmth. And all that goes on up there, among the active elemental beings, is permeated by Luciferic beings. Just as the Ahrimanic beings nourish their hopes and experience their illusions down below, so the Luciferic beings experience their hopes and illusions up above. If we look more closely at the Ahrimanic beings, we find they are of etheric nature. And it is impossible for these beings, who are really those cast down by Michael, to expand in any other way than by trying to gain domination over the Earth through the life and desire that fill the limestone in spring. The Luciferic beings up above stream through and permeate all the activities that have risen up from the Earth. They are of a purely astral nature. Through everything that begins to strive upwards in spring, they gain the hope of being able to permeate their astral nature with the etheric, and to call forth from the Earth an etheric sheath in which they could then take up their habitation.  Hence we can say: The Ahrimanic beings try to ensoul the Earth with astrality (reddish); the Luciferic beings try to take up the etheric into their own being (blue with yellow). When now in spring the plants begin to sprout, they assimilate and draw in carbonic acid. Hence the carbonic acid is active in a higher region than it is in winter; it rises into the realm of the plants, and there it comes under the attraction of the Luciferic beings. While the Ahrimanic beings strive to ensoul the living limestone with a kind of astral rain, the Luciferic beings try to raise up a sort of carbonic acid mist or vapour from the Earth (blue, yellow). If they were to succeed, human beings on Earth would no longer be able to breathe. The Luciferic beings would draw up all that part of man, his etheric nature, which is not dependent on physical breathing, and by uniting themselves with it they would be able to become etheric beings, whereas they are now only astral beings. And then, with the extinction of all human and animal life on Earth, up above there would be a sheath of etheric angel-beings. That is what the Luciferic spirits strive and hope for, when the end of March comes on. They hope to change the whole Earth into a delicate shell of this kind, wherein they, densified through the etheric nature of man, could carry on their own existence. If the Ahrimanic beings could realise their hopes, the whole of humanity would gradually be dissolved into the Earth: the Earth would absorb them. Finally there would arise out of the Earth—and that is Ahriman's intention—a single great entity into which all human beings would be merged: they would be united with it. But the transition to this union with the Earth would consist in this: man in his whole organism would become more and more like the living limestone. He would blend the living limestone with his organism and become more and more calcified. In this way he would transmute his bodily form into one that looked quite different—a sclerotic form with something like bat's wings and a head like this. This form would then be able to merge gradually into the earthly element, so that the whole Earth, according to the Ahrimanic idea, would become a living Earth-being.  If the Luciferic beings, on the other hand, could absorb the etheric nature of man, and thus condense themselves from an astral to an etheric condition, then out of them would arise something like an etheric form, in which the lower parts of the human organism would be more or less absent, with the upper part transformed. The body would be formed of Earth-vapour (blue), developed only as far down as the breast, with an idealised human head (red). And the peculiar thing is that this being would have wings, born as it were out of clouds (yellow). In front, these wings would concentrate into a sort of enlarged larynx; at the sides they would concentrate into ears, organs of hearing, which again would be connected with the larynx. You see, I tried to represent the sclerotic form through the figure of Ahriman in the painting in the dome of the Goetheanum and plastically in the wood-carving of the Group. Similarly, the Luciferic shape, created out of Earth-vapour and cloud-masses, as it would be if it could take up the etheric from the Earth, is represented there.1 Thus the two extremes of man are written into the life of the Earth itself: first, the extreme that man would come to if under the influence of Ahriman he were to take up the living limestone and thereby become gradually one with the Earth, dissolved into the whole living, sentient Earth. That is one extreme. The other extreme is what man would come to if the Luciferic beings were to succeed in causing a vapour of carbonic acid to rise from below, so that breathing would be extinguished and physical humanity would disappear, while the etheric bodies of men would be united with the astrality of the Luciferic angel-being up above. Again we can say: These are the hopes, the illusions, of the Luciferic beings. Anyone who looks out as a seer into the great spaces of the cosmos does not see in the moving clouds, as in Shakespeare's play, a shape which looks first like a camel and then like something else. When March comes, he sees in the clouds the dynamic striving forces of the Luciferic beings, who would like to create out of the Earth a Luciferic sheath. Man sways between these two extremes. The desire of both the Luciferic and the Ahrimanic beings is to blot out humanity as it exists to-day. These various activities are manifested within the life of the Earth. The hopes of the Luciferic beings are shattered once more every spring, but they work on in man. And in spring-time, while on one hand he is exposed to the Ahrimanic forces, he is also exposed more and more—and right on through the summer—to the Luciferic beings. These forces, certainly, work in so subtle a way that they are noticed to-day only by someone who is spiritually sensitive and can really live with the course of events in the cosmos round the year. But in earlier times, even in the later Atlantean period, all this had great significance. In those earlier times, for example, human reproduction was bound up with the seasons. Conception could occur only in the spring, when the forces were active in the way I have described, and births could therefore take place only towards the end of the year. The life of the Earth was thus wholesomely bound up with human life.2 Now a principle of the Luciferic beings is to set free everything on Earth, and among the things that have been freed are conception and birth. The fact that a human being can be born at any time of the year was brought about in earlier times by this Luciferic influence, which tends always to loosen man from the Earth, and it has become an established part of human freedom. Next time I will speak of influences that are still active, but to-day I wished to show you how in earlier times the aims of the Luciferic beings were actually achieved, up to a certain point. Otherwise, human beings could have been born only in winter. As against this, the Ahrimanic beings try with all their might to draw man back into connection with the Earth. And since the Luciferic beings had this great influence in the past, the Ahrimanic beings have a prospect of at least partly achieving their purpose of binding man to the Earth by merging his mind and disposition with the earthly and turning him into a complete materialist. They would like to make his capacity to think and feel depend entirely on the food he digests. This Ahrimanic influence bears particularly on our own epoch and it will go on getting stronger and stronger. If, therefore, we look back in time, we come to something accomplished by the Luciferic beings and bequeathed to us. If we look forward towards the end of the Earth, we see man faced with the threatening prospect that the Ahrimanic beings, since they cannot actually dissolve humanity into the Earth, will contrive at least to harden him, so that he becomes a crude materialist, thinking and feeling only what material substance thinks and feels in him. The Luciferic beings accomplished their work in freeing man from nature, in the way I have described, at a time when man himself had as yet no freedom. Freedom has not arisen through human resolve or in an abstract way, as the usual account suggests, but because natural processes, such as the timing of births, have come under human control. When in earlier times it became obvious that children could be born at any season, this brought a feeling of freedom into the soul and spirit of man. Those are the facts. They depend far more on the cosmos than is commonly imagined. But now that man has advanced in freedom, he should use his freedom to banish the threatening danger that Ahriman will fetter him to the Earth. For in the perspective of the future this threat stands before him. And here we see how into Earth-evolution there came an objective fact: the Mystery of Golgotha. Although the Mystery of Golgotha had indeed to enter as a once-for-all event into the history of the Earth, it is in a sense renewed for human beings every year. We can learn to feel how the Luciferic force up above would like to suffocate physical humanity in carbonic vapour, while down below, the Ahrimanic forces would like to vivify the limestone masses of the Earth with an astral rain, so that man himself would be calcified and reduced to limestone. But then, for a person who can see into these things, there arises between the Luciferic and the Ahrimanic forces the figure of Christ; the Christ who, freeing Himself from the weight of matter, has Ahriman under his feet; who wrested Himself free from the Ahrimanic and takes no heed of it, having overcome it, as we have shown here in painting and sculpture. And here is shown also how the Christ overcomes the force that seeks to draw the upper part of man away from the Earth. The head of the Christ-figure, the conqueror of Ahriman, appears with a countenance, a look and a bearing such that the dissolvent forces of Lucifer cannot touch them. The Luciferic power drawn into the earthly and held there—such is the form of the Christ as He appears every year in Spring. That is how we must picture Him: standing on the earthly, which Ahriman seeks to make his own; victorious over death; ascending from the grave as the Risen One to the transfiguration which comes from carrying over the Luciferic into the earthly beauty of the countenance of Christ. So there appears before our eyes, between the Luciferic and the Ahrimanic forms, the Risen Christ in his Resurrection form as the Easter picture; the Risen Christ, with Luciferic powers hovering above and the Ahrimanic powers under His feet. This cosmic Imagination comes before us as the Easter Imagination, just as we had the Virgin and Child as the Christmas Imagination in deep winter, and the Michael Imagination for the end of September. You will see how right it was to portray the Christ in the form you see here—a form born out of cosmic happenings in the course of the year. There is nothing arbitrary about this. Every look, every trait in the countenance, every flowing fold in the garment should be thought of as placing the Christ-figure between the forms of Lucifer and Ahriman as the One who works in human evolution so that man may be wrested from the Luciferic and Ahrimanic powers at the very time, the time of Easter and Spring, when he could most readily fall victim to them. Here precisely in the figure of Christ we see again how nothing can be rightly done out of the arbitrary fancies which are favoured in artistic circles to-day. If a man wishes to develop full freedom in the realm of art, he does not bind himself in a slavish, Ahrimanic way to materials and models; he rises freely into spiritual heights and there he freely creates, for it is in spiritual heights that freedom can prevail. Then he will create out of a bluish-violet vapour a kind of breast-form for the Luciferic element, and a form consisting of wings, larynx and ear as though emerging from reddish clouds, so that this form can appear in full reality as an image both of what these beings are in their astral nature and of the etheric guise they threaten to assume. Place vividly before you these wings of Lucifer, working in the astral and striving towards the etheric. You will find that because these wings are actually feeling about in the cosmic spaces, they are sensitive to all the secrets of force in the cosmos. Through their undulating movement, these wings, with their wave-like formation, are in touch with the mysterious, spiritual wave-activities of the cosmos. And the experience brought by these waves passes through the ear-formation into the inwardness of the Luciferic being and is carried further there. The Luciferic-being grasps through his ear-formation what he has sensed with his wings, and through the larynx—closely connected with the ear—this knowledge becomes the creative word that works and weaves in the forms of living beings. If you picture a Luciferic being of this kind, with his reddish-yellow formation of wings, ears and larynx, you will see in him the activity which is sensitive to the secrets of the cosmos through his wings, experiences these secrets through the inward continuation of his ear-formation, and utters them as creative word through the larynx, bound up with wings and ears in one organic whole. So was Lucifer painted in the cupola, and so is he represented in the sculpture-group which was intended to be the central point of our Goetheanum. Thus, in a certain sense, the Easter mystery was to have stood at this central point. But a completion in some form will be necessary, if one is to grasp the whole idea. For all that can be seen as the threatening Luciferic influence and the threatening Ahrimanic influence belongs to the inner being of the Nature-forces and the direction they strive to take in spring and on into summer; and standing over against them is the healing principle that rays out from the Christ. But a living feeling for all this will be attained when the whole architectural scheme is completed and what I have described exists in architectural and sculptured form, and when in the future it will be possible to present in front of the sculpture a living drama with two leading characters—man and Raphael Within this architecture, and in the presence of the sculpture, there would have to be enacted a kind of Mystery Play, with man and Raphael as chief characters—Raphael with the staff of Mercury and all that belongs to it. In living artistic work everything is a challenge, and fundamentally there is no sculpture and no architecture which—if it is to be inwardly in accord with cosmic truth—does not call for a presentation in the space surrounding it of the artistic action it embodies. At Easter this architecture and sculpture would call for a Mystery Play, showing man taught by Raphael to see how far the Ahrimanic and Luciferic forces make him ill, and how through the power of Raphael he can be led to perceive and recognise the healing principle, the great world-therapy, which lives in the Christ-principle. If all this could be done—and the Goetheanum was designed for all of it—then at Easter there would be, amid much else, a certain crowning of all that can flow into mankind from the Ahrimanic and Luciferic secrets. You see, if we learn to recognise the springtime activity of the Ahrimanic influence in the living limestone, through which a greedy endeavour is being made to take up the cosmic astral element, then we learn also to recognise the healing forces that reside in everything of a salt-like nature. The difference is not apparent in the coarser kind of activities, but it comes out in the healing ones. Thus we learn to know these healing influences by studying the working of the Ahrimanic beings in the salt-deposits of the Earth. For whatever is permeated by Ahrimanic influences during one season of the year—we will go more closely into this next time—is transformed into healing powers at another season. If we know what is going on secretly in the products and beings of nature, we learn to recognise their therapeutic power. It is the same with the Luciferic element: we learn to recognise the healing forces active in volatile substances that rise up from the Earth, and especially those present in carbonic acid. For just as I explained that in all water there is a mercurial, quicksilver element, so in carbonic acid there is always a sulphurous, phosphoric element. There is no carbonic acid which consists simply—as the chemists say—of one carbon atom and two oxygen atoms: no such thing exists. In the carbonic acid we breathe out there is always a phosphoric, sulphurous element. This carbonic acid, CO2, one atom of carbon and two of oxygen, is merely an abstraction, an intellectual concept formed in the human mind. In reality there is no carbonic acid which does not contain a phosphoric, sulphurous element in an extraordinarily diluted state, and the Luciferic beings strive towards it in the rising vapour. Again, in this peculiar balance between the sulphur-element that becomes astral and the limestone that becomes living, the forces we can recognise as healing influences are expressed. And so, among much else that is connected with the Easter Mystery, we should have the Easter Mystery Play enacted in front of the painting and the sculpture, and through it the communications about ways of healing which are given in the course of the year to those willing to listen would reach a climax in a truly living, artistically religious form. They would indeed be crowned by being placed in the whole course of the cosmos and the seasons; and then the Easter festival would embrace something that could be expressed in the words: “The presence of the World-Healer is felt: the Saviour who willed to lift the great evil from the world. His presence is felt.” For in truth He was, as I have often said, the Great Physician in the evolution of mankind. This will be felt, and to Him will sacrifice be offered with all the wisdom about healing influences that man can possess. This would be included in the Easter Mystery, the Easter ritual; and by celebrating the Easter festival in this way we should be placing it quite naturally in the context of the seasonal course of the year. To begin with, in describing the powerful Imaginations which come before man at Michaelmas and Christmas, I was able to show them to you only as pictures. But in the case of the Easter Imagination, where over against the activities of the Nature-spirits there arises the higher life of the spirit, as this can develop in the neighbourhood of the Christ, I could show how the Imagination can lead directly to a ritual in the earthly realm, a ritual embracing things which must be cherished and preserved on Earth—the health-giving healing forces, and a knowledge of the Ahrimanic and Luciferic forces which could destroy the human organism. For Ahriman hardens man, while Lucifer wishes to dissolve and evaporate him through his breathing. In all this the forces that make for illness reside. All that can be learnt in this way under the influence of the great teacher Raphael—who is really Mercury in Christian terminology and in Christian usage should carry the staff of Mercury—can be worthily crowned only in so far as it is received into the mysteries and ritual of Easter. Much else can come into them; of this I will speak in later lectures.

|

| 238. Karmic Relationships IV: Introductory Lecture

05 Sep 1924, Dornach Translated by George Adams, Dorothy S. Osmond, Charles Davy Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Many friends have come here to-day for the first time since the Christmas Foundation Meeting and I must therefore speak of it, even if only briefly, by way of introduction. |

| Since the Christmas Foundation an esoteric impulse has indeed come into the Anthroposophical Society. Hitherto this society was as it were the administrative centre for Anthroposophy. |

| And a number of Anthroposophists have already heard how the different earthly lives of significant personalities have run their course, how the karma of the Anthroposophical Society itself and of the individuals connected with it has taken shape. Since the Christmas Foundation these things have been spoken of in a fully esoteric sense; but since the Christmas Foundation, also, our printed Lecture-Courses have been accessible to everyone interested in them. |

| 238. Karmic Relationships IV: Introductory Lecture

05 Sep 1924, Dornach Translated by George Adams, Dorothy S. Osmond, Charles Davy Rudolf Steiner |

|---|